Lexical semantics is the branch of semantics that studies word meaning. It examines whether words have one or several meanings and in what lexical relations they stand to one another. Phrasal semantics studies the meaning of sentences by exploring the phenomenon of compositionality or how new meanings can be created by arranging words. Formal semantics relies on logic and mathematics to provide precise frameworks of the relation between language and meaning. Cognitive semantics examines meaning from a psychological perspective and assumes a close relation between language ability and the conceptual structures used to understand the world. Other branches of semantics include conceptual semantics, computational semantics, and cultural semantics.

Theories of meaning are general explanations of the nature of meaning and how expressions are endowed with it. According to referential theories, the meaning of an expression is the part of reality to which it points. Ideational theories identify meaning with mental states like the ideas that an expression evokes in the minds of language users. According to causal theories, meaning is determined by causes and effects, which behaviorist semantics analyzes in terms of stimulus and response. Further theories of meaning include truth-conditional semantics, verificationist theories, the use theory, and inferentialist semantics.

The study of semantic phenomena began during antiquity but was not recognized as an independent field of inquiry until the 19th century. Semantics is relevant to the fields of formal logic, computer science, and psychology.

語彙意味論は語の意味を研究する意味論の一分野である。単語が単一の意味を持つか複数の意味を持つか、またそれらの単語が互いにどのような語彙関係にある かを検証する。句意味論は、構成性という現象、すなわち単語を配置することで新たな意味がどのように生成されるかを考察することで文の意味を研究する。形 式意味論は論理学と数学に依拠し、言語と意味の関係を正確に枠組み化する。認知意味論は心理学的視点から意味を考察し、言語能力と世界理解に用いられる概 念構造の密接な関係を仮定する。意味論の他の分野には概念意味論、計算意味論、文化意味論がある。

意味の理論とは、意味の本質と表現が如何にして意味を付与されるかについての一般的な説明である。参照理論によれば、表現の意味とはそれが指し示す現実の 一部である。観念論的理論は、意味を言語使用者の心の中で喚起される観念のような心的状態と同一視する。因果論的理論によれば、意味は原因と結果によって 決定され、行動主義的意味論はこれを刺激と反応の観点から分析する。その他の意味論には、真値条件論的意味論、検証主義的理論、使用理論、推論主義的意味 論がある。

意味論的現象の研究は古代に始まったが、独立した研究分野として認識されたのは19世紀になってからである。意味論は形式論理学、計算機科学、心理学の分 野に関連している。

Semantics is the study of meaning in languages.[1] It is a systematic inquiry that examines what linguistic meaning is and how it arises.[2] It investigates how expressions are built up from different layers of constituents, like morphemes, words, clauses, sentences, and texts, and how the meanings of the constituents affect one another.[3] Semantics can focus on a specific language, like English, but in its widest sense, it investigates meaning structures relevant to all languages.[4][a][b] As a descriptive discipline, it aims to determine how meaning works without prescribing what meaning people should associate with particular expressions.[7] Some of its key questions are "How do the meanings of words combine to create the meanings of sentences?", "How do meanings relate to the minds of language users, and to the things words refer to?", and "What is the connection between what a word means, and the contexts in which it is used?".[8] The main disciplines engaged in semantics are linguistics, semiotics, and philosophy.[9] Besides its meaning as a field of inquiry, semantics can also refer to theories within this field, like truth-conditional semantics,[10] and to the meaning of particular expressions, like the semantics of the word fairy.[11]

As a field of inquiry, semantics has both an internal and an external side. The internal side is interested in the connection between words and the mental phenomena they evoke, like ideas and conceptual representations. The external side examines how words refer to objects in the world and under what conditions a sentence is true.[12]

Many related disciplines investigate language and meaning. Semantics contrasts with other subfields of linguistics focused on distinct aspects of language. Phonology studies the different types of sounds used in languages and how sounds are connected to form words while syntax examines the rules that dictate how to arrange words to create sentences. These divisions are reflected in the fact that it is possible to master some aspects of a language while lacking others, like when a person knows how to pronounce a word without knowing its meaning.[13] As a subfield of semiotics, semantics has a more narrow focus on meaning in language while semiotics studies both linguistic and non-linguistic signs. Semiotics investigates additional topics like the meaning of non-verbal communication, conventional symbols, and natural signs independent of human interaction. Examples include nodding to signal agreement, stripes on a uniform signifying rank, and the presence of vultures indicating a nearby animal carcass.[14]

Semantics further contrasts with pragmatics, which is interested in how people use language in communication.[15] An expression like "That's what I'm talking about" can mean many things depending on who says it and in what situation. Semantics is interested in the possible meanings of expressions: what they can and cannot mean in general. In this regard, it is sometimes defined as the study of context-independent meaning. Pragmatics examines which of these possible meanings is relevant in a particular case. In contrast to semantics, it is interested in actual performance rather than in the general linguistic competence underlying this performance.[16] This includes the topic of additional meaning that can be inferred even though it is not literally expressed, like what it means if a speaker remains silent on a certain topic.[17] A closely related distinction by the semiotician Charles W. Morris holds that semantics studies the relation between words and the world, pragmatics examines the relation between words and users, and syntax focuses on the relation between different words.[18]

Semantics is related to etymology, which studies how words and their meanings changed in the course of history.[7] Another connected field is hermeneutics, which is the art or science of interpretation and is concerned with the right methodology of interpreting text in general and scripture in particular.[19] Metasemantics examines the metaphysical foundations of meaning and aims to explain where it comes from or how it arises.[20]

The word semantics originated from the Ancient Greek adjective semantikos, meaning 'relating to signs', which is a derivative of sēmeion, the noun for 'sign'. It was initially used for medical symptoms and only later acquired its wider meaning regarding any type of sign, including linguistic signs. The word semantics entered the English language from the French term semantique, which the linguist Michel Bréal first introduced at the end of the 19th century.[21]

意味論とは言語における意味の研究である。[1] 言語的な意味とは何か、またそれがどのように生じるかを体系的に探究する学問である。[2] 表現が形態素、単語、節、文、テキストといった異なる構成要素の層からどのように構築されるか、またそれらの構成要素の意味が互いにどのように影響し合う かを調査する。[3] 意味論は英語のような特定言語に焦点を当てることがあるが、最も広い意味では全ての言語に関連する意味構造を調査する。[4][a][b] 記述的学問として、特定の表現に人々が結びつけるべき意味を規定せず、意味がどのように機能するかを明らかにすることを目指す。[7] 語の意味がどのように組み合わさって文の意味を形成するのか、意味が言語使用者の心や語が指し示す対象とどう関連するのか、語の意味と使用される文脈の関 連性は何か、といった点が主要な問いである。[8] 意味論に関わる主な学問分野は、言語学、記号論、哲学である。[9] 意味論は研究分野としての意味に加え、真値条件論的意味論[10]のようなこの分野内の理論、あるいは「妖精」という言葉の意味論のような特定の表現の意 味を指すこともある。[11]

研究分野としての意味論には、内的側面と外的側面がある。内的側面は、言葉とそれが喚起する心的現象(概念や観念的表象など)との関連性を扱う。外的側面 は、言葉が世界の対象をどのように指し示すか、また文が真となる条件を考察する。[12]

言語と意味を扱う関連分野は多い。意味論は言語の異なる側面に焦点を当てる他の言語学分野と対照的だ。音韻論は言語で使用される様々な音の種類や、音が組 み合わさって単語を形成する仕組みを研究する。構文論は単語を並べて文を作る規則を調べる。こうした区分は、ある言語の側面を習得しつつ他の側面を欠くこ とが可能である事実にも表れている。例えば単語の発音は知っていてもその意味を知らない場合などだ。[13] 記号論の一分野として、意味論は言語における意味に焦点を絞る。一方、記号論は言語的・非言語的記号の両方を研究対象とする。記号論は非言語的コミュニ ケーションの意味、慣習的記号、人間相互作用に依存しない自然記号といった追加的テーマも扱う。例としては、同意を示すうなずき、階級を示す制服の縞模 様、近くの動物の死骸を示すハゲワシの存在などが挙げられる。[14]

意味論はさらに、人々がコミュニケーションで言語をどう使うかに興味を持つ語用論とも対照的だ。[15]「まさにそれだ」といった表現は、誰がどんな状況 で言うかによって様々な意味を持つ。意味論は表現の可能な意味、つまり一般的に何を意味し得るか、得られないかに興味を持つ。この点で、意味論は文脈に依 存しない意味の研究と定義されることもある。一方、語用論は、特定のケースにおいてこれらの意味の可能性のうちどれが関連しているかを検討する。意味論と は対照的に、語用論は実際の言語使用のパフォーマンス自体に関心を持ち、その背景にある一般的な言語能力には関心を向けない。[16] これには、特定の話題について話者が沈黙を守る場合の意味など、文字通り表現されていないにもかかわらず推測可能な追加的な意味の話題も含まれる。 [17] 記号論学者チャールズ・W・モリスによる密接に関連する区別では、意味論は言葉と世界との関係を研究し、語用論は言葉と使用者の関係を検証し、構文論は異 なる言葉同士の関係に焦点を当てる。[18]

意味論は語源学と関連しており、語とその意味が歴史の中でどのように変化したかを研究する。[7] もう一つの関連分野は解釈学であり、これは解釈の技法または科学であり、一般にテキスト、特に聖書を解釈する正しい方法論に関わっている。[19] 超意味論は意味の形而上学的基盤を検証し、意味がどこから来るのか、あるいはどのように生じるのかを説明することを目的とする。[20]

「意味論」という言葉は、古代ギリシャ語の形容詞「semantikos」(「記号に関連する」という意味)に由来する。これは「記号」を意味する名詞 「sēmeion」から派生したものである。当初は医学的症状を指すために用いられ、後に言語的記号を含むあらゆる種類の記号に関する広義の意味を獲得し た。セマンティクスという語は、19世紀末に言語学者ミシェル・ブレアルが初めて導入したフランス語の「sémantique」から英語に取り入れられ た。[21]

Meaning

Semantics studies meaning in language, which is limited to the meaning of linguistic expressions. It concerns how signs are interpreted and what information they contain. An example is the meaning of words provided in dictionary definitions by giving synonymous expressions or paraphrases, like defining the meaning of the term ram as adult male sheep.[22] There are many forms of non-linguistic meaning that are not examined by semantics. Actions and policies can have meaning in relation to the goal they serve. Fields like religion and spirituality are interested in the meaning of life, which is about finding a purpose in life or the significance of existence in general.[23]

Photo of a dictionary

Semantics is not focused on subjective speaker meaning and is instead interested in public meaning, like the meaning found in general dictionary definitions.

Linguistic meaning can be analyzed on different levels. Word meaning is studied by lexical semantics and investigates the denotation of individual words. It is often related to concepts of entities, like how the word dog is associated with the concept of the four-legged domestic animal. Sentence meaning falls into the field of phrasal semantics and concerns the denotation of full sentences. It usually expresses a concept applying to a type of situation, as in the sentence "the dog has ruined my blue skirt".[24] The meaning of a sentence is often referred to as a proposition.[25] Different sentences can express the same proposition, like the English sentence "the tree is green" and the German sentence "der Baum ist grün".[26] Utterance meaning is studied by pragmatics and is about the meaning of an expression on a particular occasion. Sentence meaning and utterance meaning come apart in cases where expressions are used in a non-literal way, as is often the case with irony.[27]

Semantics is primarily interested in the public meaning that expressions have, like the meaning found in general dictionary definitions. Speaker meaning, by contrast, is the private or subjective meaning that individuals associate with expressions. It can diverge from the literal meaning, like when a person associates the word needle with pain or drugs.[28]

意味

意味論は言語における意味を研究する学問であり、その対象は言語表現の意味に限定される。記号がどのように解釈され、どのような情報を含むかを扱う。例と して、辞書定義で同義表現や言い換えを用いて語の意味を提供する手法がある。例えば「ram」という用語を「成体の雄羊」と定義するといったものだ [22]。意味論が扱わない非言語的な意味の形態は数多く存在する。行動や政策は、それらが達成しようとする目標との関係において意味を持つことがある。 宗教や精神性といった分野は、人生の意味、つまり人生の目的や存在意義全般について探求する。[23]

辞書の写真

意味論は主観的な話者の意味に焦点を当てず、代わりに一般的な辞書定義に見られるような公的な意味に関心を持つ。

言語的な意味は様々なレベルで分析できる。語の意味は語彙意味論によって研究され、個々の単語の指示対象を調査する。これはしばしば実体の概念と関連し、 例えば「犬」という語が四本足の飼い動物という概念と結びつくように。文の意味は句意味論の領域に属し、完全な文の指示対象を扱う。通常、ある種の状況に 適用される概念を表現する。例えば「犬が私の青いスカートを台無しにした」という文のように。[24] 文の意味はしばしば命題と呼ばれる。[25] 異なる文が同じ命題を表現することもある。例えば英語の「the tree is green」とドイツ語の「der Baum ist grün」がそれにあたる。[26] 発話の意味は語用論が扱う領域であり、特定の状況における表現の意味を扱う。文の意味と発話の意味は、表現が文字通りの意味以外で使われる場合に分離す る。皮肉の場合がよくこれに該当する。[27]

意味論は主に、表現が持つ公的な意味、例えば一般的な辞書の定義に見られる意味に関心を持つ。これに対し、話者意味は個人が表現に関連付ける私的な、ある いは主観的な意味である。これは文字通りの意味から乖離することがあり、例えば針という言葉を痛みや薬物と関連付ける場合がそれにあたる。[28]

Bust of Gottlob Frege

The distinction between sense and reference was first introduced by the philosopher Gottlob Frege.[29]

Meaning is often analyzed in terms of sense and reference,[30] also referred to as intension and extension or connotation and denotation.[31] The referent of an expression is the object to which the expression points. The sense of an expression is the way in which it refers to that object or how the object is interpreted. For example, the expressions morning star and evening star refer to the same planet, just like the expressions 2 + 2 and 3 + 1 refer to the same number. The meanings of these expressions differ not on the level of reference but on the level of sense.[32] Sense is sometimes understood as a mental phenomenon that helps people identify the objects to which an expression refers.[33] Some semanticists focus primarily on sense or primarily on reference in their analysis of meaning.[34] To grasp the full meaning of an expression, it is usually necessary to understand both to what entities in the world it refers and how it describes them.[35]

The distinction between sense and reference can explain identity statements, which can be used to show how two expressions with a different sense have the same referent. For instance, the sentence "the morning star is the evening star" is informative and people can learn something from it. The sentence "the morning star is the morning star", by contrast, is an uninformative tautology since the expressions are identical not only on the level of reference but also on the level of sense.[36]

ゴットロップ・フレーゲの胸像

意味と参照の区別は、哲学者ゴットロップ・フレーゲによって初めて導入された。[29]

意味はしばしば、意味と参照という観点から分析される[30]。これは内包と外延、あるいは内包的意味と外延的意味とも呼ばれる[31]。表現の参照対象 とは、その表現が指し示す対象である。表現の意味とは、その対象を参照する方法、あるいは対象が解釈される方法である。例えば「明けの明星」と「夕の明 星」という表現は同じ惑星を指し示す。これは「2 + 2」と「3 + 1」という表現が同じ数を指し示すのと同様である。これらの表現の意味が異なるのは、参照のレベルではなく意味のレベルにおいてである[32]。意味は時 に、表現が指し示す対象を人々が識別するのを助ける心的現象として理解される。[33] 意味論者の中には、意味の分析において主に意味(センス)に焦点を当てる者もいれば、主に参照(リファレンス)に焦点を当てる者もいる。[34] 表現の完全な意味を把握するには、通常、それが世界のどの実体を指し示すか、そしてそれをどのように記述するかの両方を理解する必要がある。[35]

意味と参照の区別は同一性命題を説明できる。これは、意味が異なる二つの表現が同じ参照対象を持つことを示すために用いられる。例えば「明けの明星は夕の 明星である」という文は情報を含み、そこから何かを学べる。一方「明けの明星は明けの明星である」という文は、参照レベルだけでなく意味レベルでも表現が 同一であるため、情報を含まない同語反復に過ぎない。[36]

Compositionality is a key aspect of how languages construct meaning. It is the idea that the meaning of a complex expression is a function of the meanings of its parts. It is possible to understand the meaning of the sentence "Zuzana owns a dog" by understanding what the words Zuzana, owns, a and dog mean and how they are combined.[37] In this regard, the meaning of complex expressions like sentences is different from word meaning since it is normally not possible to deduce what a word means by looking at its letters and one needs to consult a dictionary instead.[38]

Compositionality is often used to explain how people can formulate and understand an almost infinite number of meanings even though the amount of words and cognitive resources is finite. Many sentences that people read are sentences that they have never seen before and they are nonetheless able to understand them.[37]

When interpreted in a strong sense, the principle of compositionality states that the meaning of a complex expression is not just affected by its parts and how they are combined but fully determined this way. It is controversial whether this claim is correct or whether additional aspects influence meaning. For example, context may affect the meaning of expressions; idioms like "kick the bucket" carry figurative or non-literal meanings that are not directly reducible to the meanings of their parts.[37]

構成性とは、言語が意味を構築する上での重要な側面である。これは、複雑な表現の意味がその構成要素の意味の関数であるという考え方だ。「ズザナは犬を 飼っている」という文の意味は、ズザナ、飼っている、を、犬という言葉の意味を理解し、それらがどのように組み合わさっているかを理解することで把握でき る。[37] この点において、文のような複雑な表現の意味は単語の意味とは異なる。通常、単語の意味をその文字を見て推測することは不可能であり、代わりに辞書を引く 必要があるからだ。[38]

構成性は、単語や認知資源の量が有限であるにもかかわらず、人間がほぼ無限の意味を形成し理解できる仕組みを説明するためによく用いられる。人間が読む文 の多くは、これまで見たことのない文であるにもかかわらず、理解できるのである。[37]

強意で解釈すると、構成性の原理は、複雑な表現の意味がその構成要素や結合方法に単に影響されるだけでなく、完全にそれによって決定されると主張する。こ の主張が正しいか、あるいは追加的な側面が意味に影響するかについては議論がある。例えば文脈が表現の意味に影響する可能性がある。「kick the bucket」のような慣用句は、比喩的または非文字通りの意味を持ち、その意味は構成要素の意味に直接還元できない。[37]

Truth is a property of statements that accurately present the world and true statements are in accord with reality. Whether a statement is true usually depends on the relation between the statement and the rest of the world. The truth conditions of a statement are the way the world needs to be for the statement to be true. For example, it belongs to the truth conditions of the sentence "it is raining outside" that raindrops are falling from the sky. The sentence is true if it is used in a situation in which the truth conditions are fulfilled, i.e., if there is actually rain outside.[39]

Truth conditions play a central role in semantics and some theories rely exclusively on truth conditions to analyze meaning. To understand a statement usually implies that one has an idea about the conditions under which it would be true. This can happen even if one does not know whether the conditions are fulfilled.[39]

真とは、世界を正確に表す文の性質であり、真の文は現実と一致する。文が真であるかどうかは、通常、その文と世界の他の部分との関係に依存する。文の真の 条件とは、その文が真であるために世界がどうあるべきかを示すものである。例えば、「外は雨が降っている」という文の真の条件には、空から雨粒が降ってい ることが含まれる。この文は、真条件が満たされた状況、つまり実際に外で雨が降っている状況で使われた場合に真となる。[39]

真条件は意味論において中心的な役割を果たし、一部の理論は意味を分析するために真条件のみに依存している。文を理解するとは、通常、その文が真となる条 件についての考えを持っていることを意味する。これは、その条件が満たされているかどうかを知らなくても起こり得る。[39]

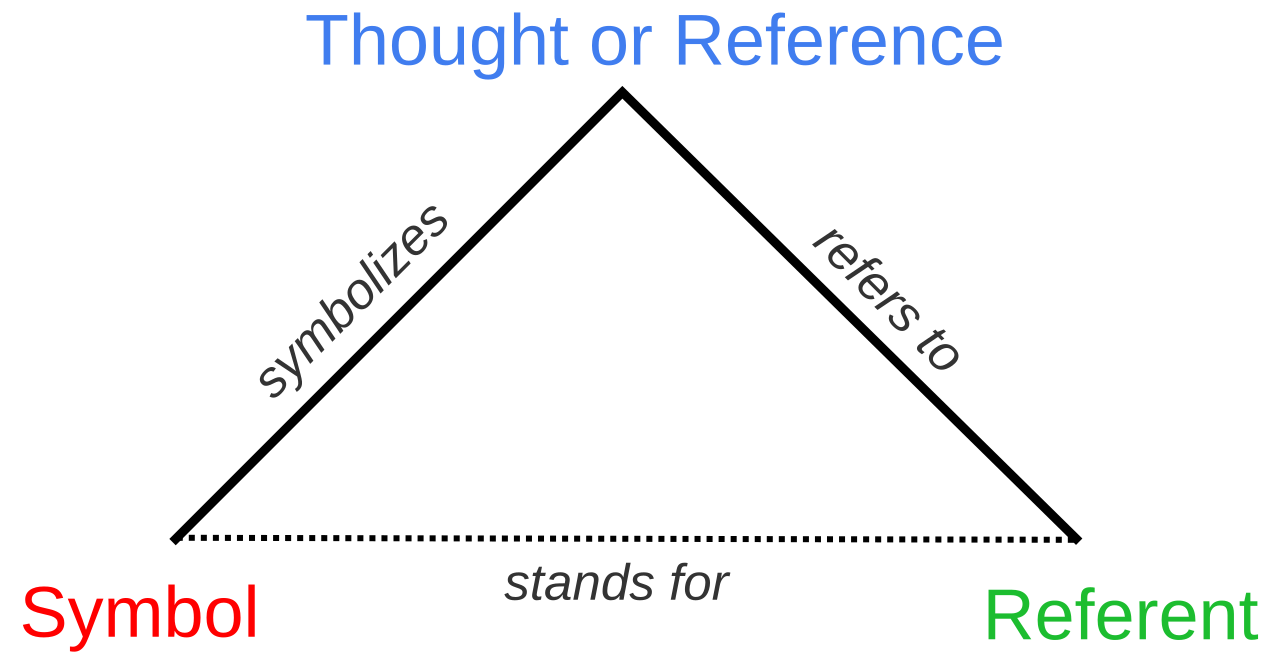

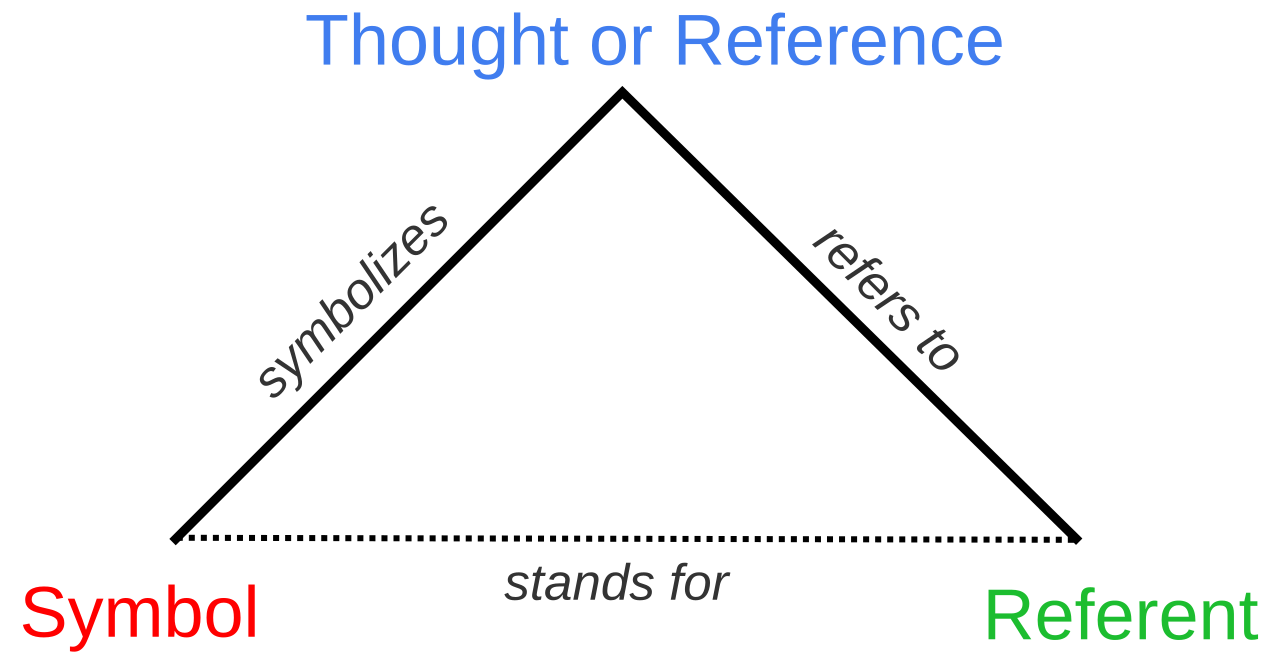

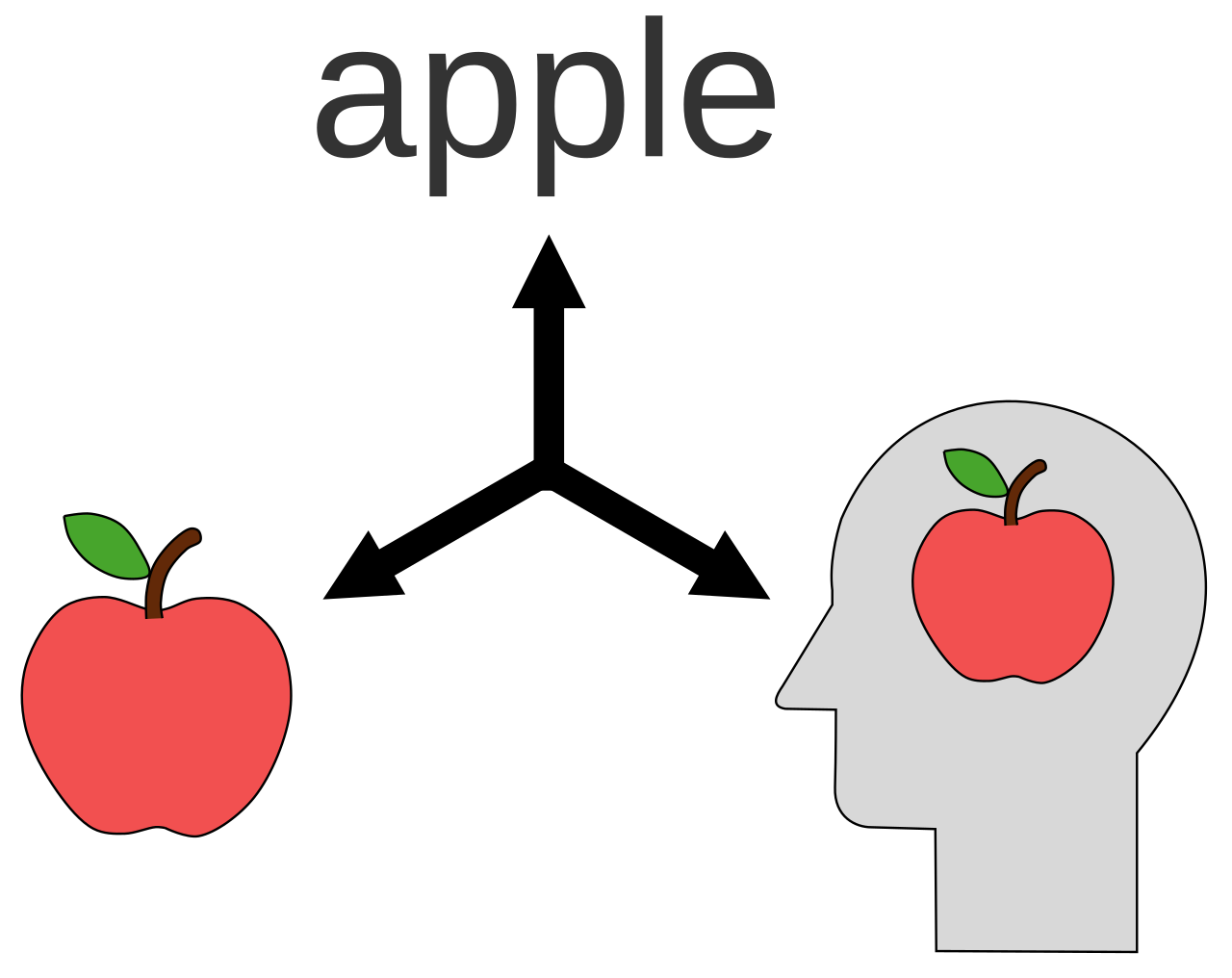

Diagram of the semiotic triangle

The semiotic triangle aims to explain how the relation between language (Symbol) and world (Referent) is mediated by the language users (Thought or Reference).

The semiotic triangle, also called the triangle of meaning, is a model used to explain the relation between language, language users, and the world, represented in the model as Symbol, Thought or Reference, and Referent. The symbol is a linguistic signifier, either in its spoken or written form. The central idea of the model is that there is no direct relation between a linguistic expression and what it refers to, as was assumed by earlier dyadic models. This is expressed in the diagram by the dotted line between symbol and referent.[40]

The model holds instead that the relation between the two is mediated through a third component. For example, the term apple stands for a type of fruit but there is no direct connection between this string of letters and the corresponding physical object. The relation is only established indirectly through the mind of the language user. When they see the symbol, it evokes a mental image or a concept, which establishes the connection to the physical object. This process is only possible if the language user learned the meaning of the symbol before. The meaning of a specific symbol is governed by the conventions of a particular language. The same symbol may refer to one object in one language, to another object in a different language, and to no object in another language.[40]

記号論の三角形の図

記号論の三角形は、言語(記号)と世界(指称対象)の関係が、言語使用者(思考または参照)によって媒介される仕組みを説明することを目的としている。

記号論の三角形、別名意味の三角形は、言語、言語使用者、世界(モデル上では記号、思考または参照、指称対象として表される)の関係を説明するモデルであ る。記号は言語的表象であり、発話形態または記述形態のいずれかである。このモデルの核心は、言語表現とそれが指す対象との間に直接的な関係は存在しない という点にある。これは従来の二項関係モデルが想定していたものとは異なる。図式では記号と指称対象の間の点線でこれが表現されている。[40]

代わりにこのモデルは、両者の関係は第三の要素を介して成立すると主張する。例えば「りんご」という語は果物の種類を表すが、この文字列と対応する実体と の間には直接的な繋がりはない。関係は言語使用者の心を通じて間接的にのみ確立される。言語使用者が記号を見ると、それが心象や概念を喚起し、それによっ て物理的対象とのつながりが確立される。このプロセスは、言語使用者が事前に記号の意味を学習している場合にのみ可能である。特定の記号の意味は、特定の 言語の慣習によって規定される。同じ記号が、ある言語ではある対象を指し、別の言語では別の対象を指し、また別の言語では何の対象も指さない場合がある。 [40]

Many other concepts are used to describe semantic phenomena. The semantic role of an expression is the function it fulfills in a sentence. In the sentence "the boy kicked the ball", the boy has the role of the agent who performs an action. The ball is the theme or patient of this action as something that does not act itself but is involved in or affected by the action. The same entity can be both agent and patient, like when someone cuts themselves. An entity has the semantic role of an instrument if it is used to perform the action, for instance, when cutting something with a knife then the knife is the instrument. For some sentences, no action is described but an experience takes place, like when a girl sees a bird. In this case, the girl has the role of the experiencer. Other common semantic roles are location, source, goal, beneficiary, and stimulus.[41]

Lexical relations describe how words stand to one another. Two words are synonyms if they share the same or a very similar meaning, like car and automobile or buy and purchase. Antonyms have opposite meanings, such as the contrast between alive and dead or fast and slow.[c] One term is a hyponym of another term if the meaning of the first term is included in the meaning of the second term. For example, ant is a hyponym of insect. A prototype is a hyponym that has characteristic features of the type it belongs to. A robin is a prototype of a bird but a penguin is not. Two words with the same pronunciation are homophones like flour and flower, while two words with the same spelling are homonyms, like a bank of a river in contrast to a bank as a financial institution.[d] Hyponymy is closely related to meronymy, which describes the relation between part and whole. For instance, wheel is a meronym of car.[44] An expression is ambiguous if it has more than one possible meaning. In some cases, it is possible to disambiguate them to discern the intended meaning.[45] The term polysemy is used if the different meanings are closely related to one another, like the meanings of the word head, which can refer to the topmost part of the human body or the top-ranking person in an organization.[44]

The meaning of words can often be subdivided into meaning components called semantic features. The word horse has the semantic feature animate but lacks the semantic feature human. It may not always be possible to fully reconstruct the meaning of a word by identifying all its semantic features.[46]

A semantic or lexical field is a group of words that are all related to the same activity or subject. For instance, the semantic field of cooking includes words like bake, boil, spice, and pan.[47]

The context of an expression refers to the situation or circumstances in which it is used and includes time, location, speaker, and audience. It also encompasses other passages in a text that come before and after it.[48] Context affects the meaning of various expressions, like the deictic expression here and the anaphoric expression she.[49]

A syntactic environment is extensional or transparent if it is always possible to exchange expressions with the same reference without affecting the truth value of the sentence. For example, the environment of the sentence "the number 8 is even" is extensional because replacing the expression "the number 8" with "the number of planets in the Solar System" does not change its truth value. For intensional or opaque contexts, this type of substitution is not always possible. For instance, the embedded clause in "Paco believes that the number 8 is even" is intensional since Paco may not know that the number of planets in the solar system is 8.[50]

Semanticists commonly distinguish the language they study, called object language, from the language they use to express their findings, called metalanguage. When a professor uses Japanese to teach their student how to interpret the language of first-order logic then the language of first-order logic is the object language and Japanese is the metalanguage. The same language may occupy the role of object language and metalanguage at the same time. This is the case in monolingual English dictionaries, in which both the entry term belonging to the object language and the definition text belonging to the metalanguage are taken from the English language.[51]

意味論的現象を説明するために、他にも多くの概念が使われている。表現の意味役割とは、文の中で果たす機能のことだ。「少年がボールを蹴った」という文で は、少年は行為を行う主体としての役割を持つ。ボールはこの行為の主題、つまり行為者ではないが行為に関与したり影響を受けたりする対象だ。同じ存在が行 為者と行為対象の両方になることもある。例えば誰かが自分を切ってしまった場合だ。ある実体が行為を行うために用いられる場合、それは道具の語用論的役割 を持つ。例えばナイフで何かを切る場合、ナイフは道具である。一部の文では行為ではなく経験が記述される。例えば少女が鳥を見る場合、少女は経験者の役割 を持つ。その他の一般的な語用論的役割には、場所、出発点、到達点、受益者、刺激がある。[41]

語彙関係は、単語同士の関係性を説明する。二つの単語が同義語である場合、それらは同じ、あるいは非常に類似した意味を持つ。例えば「車」と「自動車」、 「買う」と「購入する」がそれにあたる。反意語は反対の意味を持つ。例えば「生きている」と「死んでいる」、「速い」と「遅い」の対比だ。[c]ある語が 別の語の基底語(ハイポニム)である場合、前者の意味は後者の意味に含まれる。例えば「蟻」は「昆虫」の基底語だ。原型(プロトタイプ)とは、属する類型 の特徴を典型的に示す基底語である。例えば「コマドリ」は鳥の原型だが、「ペンギン」はそうではない。発音が同じ二語は同音異義語であり、例えば「小麦 粉」と「花」が該当する。一方、綴りが同じ二語は同形異義語であり、例えば川の「岸」と金融機関の「銀行」が対比される。[d] 下位概念は部分と全体の関係を説明する部分概念と密接に関連している。例えば車輪は自動車のメローニムである。[44] 表現が複数の意味を持つ場合、それは曖昧である。場合によっては、意図された意味を判別するために曖昧さを解消できる。[45] 複数の意味が互いに密接に関連している場合、例えば頭という単語が人体の上部や組織の最高位者を指すように、多義性という用語が用いられる。[44]

語の意味はしばしば意味的特徴と呼ばれる意味要素に細分できる。馬という語は「生物」という意味的特徴を持つが、「人間」という特徴は持たない。全ての意 味的特徴を特定しても、語の意味を完全に再構築できない場合もある。[46]

意味的領域または語彙的領域とは、同じ活動や主題に関連する語の群を指す。例えば、調理の語彙領域には「焼く」「煮る」「香辛料」「フライパン」といった 語が含まれる。[47]

表現の文脈とは、それが使用される状況や環境を指し、時間、場所、話者、聴衆を含む。また、その表現の前後にあるテキストの他の部分も包含する。[48] 文脈は、指示表現「ここ」や指示代名詞「彼女」など、様々な表現の意味に影響を与える。[49]

構文環境は、同じ参照を持つ表現を交換しても文の真偽値に影響を与えない場合、外延的または透明である。例えば「8は偶数である」という文の環境は外延的 である。なぜなら「8」という表現を「太陽系の惑星の数」に置き換えても真偽値が変わらないからだ。内包的あるいは不透明な文脈では、この種の置換が常に 可能とは限らない。例えば「パコは8が偶数だと信じている」という文の従属節は内包的である。なぜならパコが太陽系の惑星の数が8であることを知らない可 能性があるからだ。[50]

意味論研究者は、研究対象の言語(対象言語)と研究成果を表現する言語(メタ言語)を区別するのが一般的だ。教授が日本語を使って学生に一階論理の言語解 釈法を教える場合、一階論理の言語が対象言語であり、日本語がメタ言語となる。同一言語が対象言語とメタ言語の役割を同時に担う場合もある。単一言語の英 語辞典がその例であり、対象言語に属する見出し語とメタ言語に属する定義文の両方が英語から取られている。[51]

Lexical semantics

Main article: Lexical semantics

Lexical semantics is the sub-field of semantics that studies word meaning.[52] It examines semantic aspects of individual words and the vocabulary as a whole. This includes the study of lexical relations between words, such as whether two terms are synonyms or antonyms.[53] Lexical semantics categorizes words based on semantic features they share and groups them into semantic fields unified by a common subject.[54] This information is used to create taxonomies to organize lexical knowledge, for example, by distinguishing between physical and abstract entities and subdividing physical entities into stuff and individuated entities.[55] Further topics of interest are polysemy, ambiguity, and vagueness.[56]

Lexical semantics is sometimes divided into two complementary approaches: semasiology and onomasiology. Semasiology starts from words and examines what their meaning is. It is interested in whether words have one or several meanings and how those meanings are related to one another. Instead of going from word to meaning, onomasiology goes from meaning to word. It starts with a concept and examines what names this concept has or how it can be expressed in a particular language.[57]

Some semanticists also include the study of lexical units other than words in the field of lexical semantics. Compound expressions like being under the weather have a non-literal meaning that acts as a unit and is not a direct function of its parts. Another topic concerns the meaning of morphemes that make up words, for instance, how negative prefixes like in- and dis- affect the meaning of the words they are part of, as in inanimate and dishonest.[58]

語彙意味論

主な記事: 語彙意味論

語彙意味論とは、語の意味を研究する意味論の分野である。[52] これは個々の語の意味的側面と語彙全体を考察する。これには、二つの語が同義語か対義語かといった語間の語彙的関係の研究も含まれる。[53] 語彙意味論は、語が共有する意味的特徴に基づいて語を分類し、共通の主題によって統一された意味領域にグループ化する。[54] この情報は、語彙知識を整理するための分類体系を作成するために用いられる。例えば、物理的実体と抽象的実体を区別し、物理的実体を物質と個別化された実 体に細分化する。[55] さらに、多義性、曖昧性、不明確性といった主題も研究対象となる。[56]

語彙意味論は時に二つの補完的アプローチに分けられる:セマシオロジーとオノマシオロジーである。セマシオロジーは語から出発し、その意味が何であるかを 検討する。語が単一の意味を持つか複数の意味を持つか、それらの意味が互いにどう関連するかに関心を寄せる。語から意味へ進むのではなく、オノマシオロ ジーは意味から語へ進む。概念から出発し、この概念がどのような名称を持つか、あるいは特定の言語でどう表現されるかを検討する。[57]

一部の語義学者たちは、語彙単位以外の語彙単位の研究も語彙意味論の分野に含める。例えば「体調が優れない」のような複合表現は、文字通りの意味ではな く、単位として機能する非文字通りの意味を持ち、その構成要素の直接的な関数ではない。別の論点として、単語を構成する形態素の意味がある。例えば「in -」や「dis-」といった否定接頭辞が、無生物(inanimate)や不誠実(dishonest)といった単語の意味に与える影響などが挙げられ る。[58]

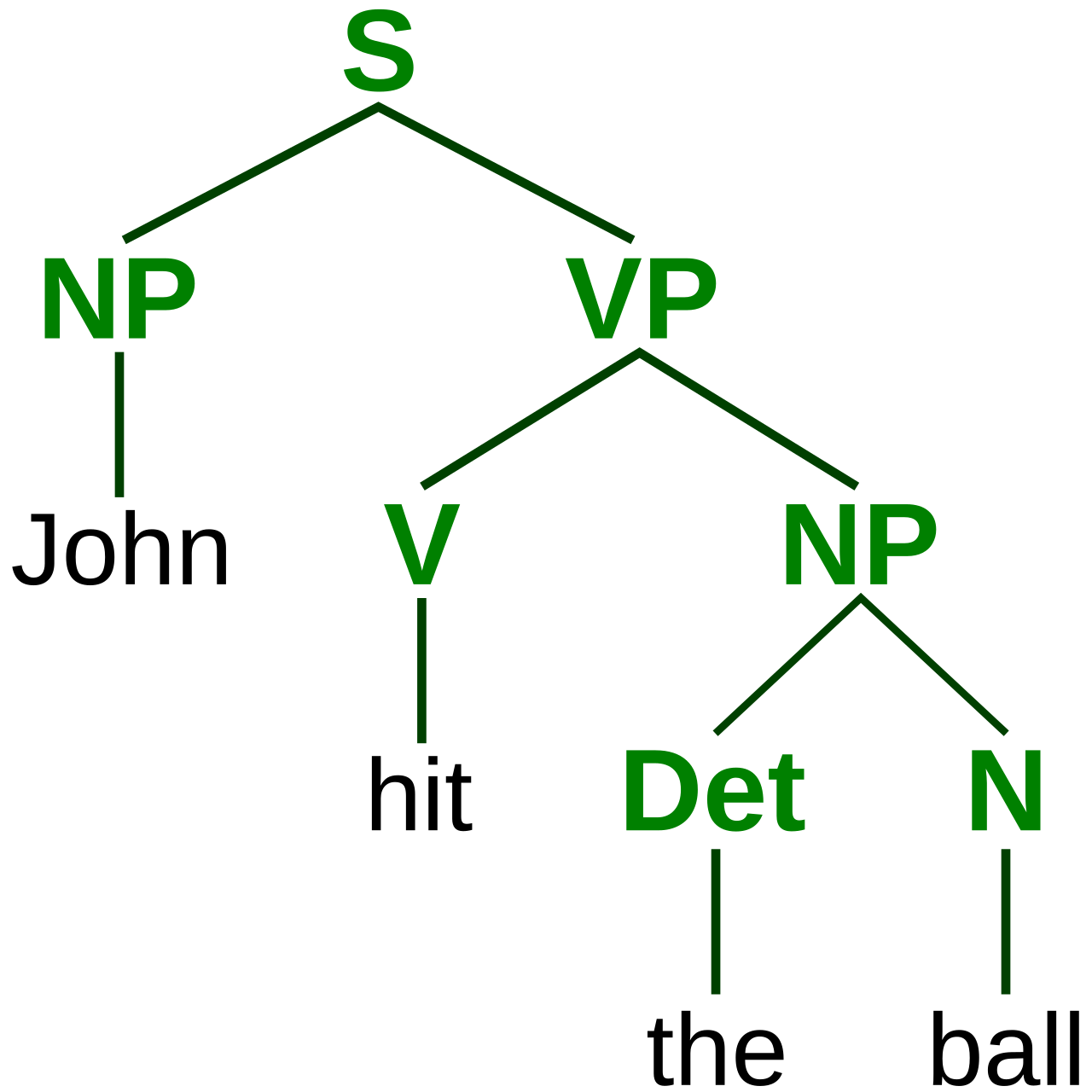

Phrasal semantics studies the meaning of sentences. It relies on the principle of compositionality to explore how the meaning of complex expressions arises from the combination of their parts.[59][e] The different parts can be analyzed as subject, predicate, or argument. The subject of a sentence usually refers to a specific entity while the predicate describes a feature of the subject or an event in which the subject participates. Arguments provide additional information to complete the predicate.[61] For example, in the sentence "Mary hit the ball", Mary is the subject, hit is the predicate, and the ball is an argument.[61] A more fine-grained categorization distinguishes between different semantic roles of words, such as agent, patient, theme, location, source, and goal.[62]

Diagram of a parse tree

Parse trees, like the constituency-based parse tree, show how expressions are combined to form sentences.

Verbs usually function as predicates and often help to establish connections between different expressions to form a more complex meaning structure. In the expression "Beethoven likes Schubert", the verb like connects a liker to the object of their liking.[63] Other sentence parts modify meaning rather than form new connections. For instance, the adjective red modifies the color of another entity in the expression red car.[64] A further compositional device is variable binding, which is used to determine the reference of a term. For example, the last part of the expression "the woman who likes Beethoven" specifies which woman is meant.[65] Parse trees can be used to show the underlying hierarchy employed to combine the different parts.[66] Various grammatical devices, like the gerund form, also contribute to meaning and are studied by grammatical semantics.[67]

句の意味論は文の意味を研究する。これは構成性の原理に基づいて、複雑な表現の意味がその構成要素の組み合わせからいかに生じるかを探る。[59][e] 異なる要素は主語、述語、または引数として分析できる。文の主語は通常特定の存在を指し、述語は主語の特徴や主語が関与する出来事を記述する。補語は述語 を完成させるための追加情報を提供する。[61] 例えば「メアリーがボールを打った」という文では、メアリーが主語、打ったが述語、ボールが補語である。[61] より細かい分類では、行為者、被行為者、主題、場所、出発点、到達点など、単語の異なる意味役割を区別する。[62]

構文解析ツリーの図

構文解析ツリーは、構成要素に基づく構文解析ツリーのように、表現が組み合わさって文を形成する過程を示す。

動詞は通常述語として機能し、異なる表現間の接続を確立してより複雑な意味構造を形成するのに役立つ。例えば「ベートーヴェンはシューベルトを好む」とい う表現では、動詞「好む」が好む者と好まれる対象を結びつける。[63] 他の文の構成要素は新たな接続を形成するのではなく、意味を修飾する。例えば形容詞「赤い」は「赤い車」という表現において、別の実体の色を修飾する。 [64] さらに、項の参照先を決定するために変数束縛という構成装置が使われる。例えば「ベートーヴェンが好きな女性」という表現の最後の部分が、どの女性を指す かを特定する。[65] 構文解析ツリーは、異なる部分を結合するために用いられる基盤となる階層構造を示すために利用できる。[66] 分詞構文のような様々な文法的装置も意味形成に寄与し、文法的意味論によって研究される。[67]

Main article: Formal semantics (natural language)

Formal semantics uses formal tools from logic and mathematics to analyze meaning in natural languages.[f] It aims to develop precise logical formalisms to clarify the relation between expressions and their denotation.[69] One of its key tasks is to provide frameworks of how language represents the world, for example, using ontological models to show how linguistic expressions map to the entities of that model.[69] A common idea is that words refer to individual objects or groups of objects while sentences relate to events and states. Sentences are mapped to a truth value based on whether their description of the world is in correspondence with its ontological model.[70]

Formal semantics further examines how to use formal mechanisms to represent linguistic phenomena such as quantification, intensionality, noun phrases, plurals, mass terms, tense, and modality.[71] Montague semantics is an early and influential theory in formal semantics that provides a detailed analysis of how the English language can be represented using mathematical logic. It relies on higher-order logic, lambda calculus, and type theory to show how meaning is created through the combination of expressions belonging to different syntactic categories.[72]

Dynamic semantics is a subfield of formal semantics that focuses on how information grows over time. According to it, "meaning is context change potential": the meaning of a sentence is not given by the information it contains but by the information change it brings about relative to a context.[73]

詳細な記事: 形式意味論 (自然言語)

形式意味論は、論理学や数学の形式的な手法を用いて自然言語の意味を分析する。[f] 表現とその指示対象の関係を明確にするため、精密な論理形式体系を開発することを目的とする。[69] その主要な課題の一つは、言語が世界をどのように表象するかの枠組みを提供することである。例えば、言語表現がそのモデルの個体群にどのように対応するか を示すために、存在論的モデルを用いる。[69] 一般的な考え方は、単語は個々の対象や対象群を指し示す一方で、文は出来事や状態に関連するというものである。文は、その世界描写が存在論的モデルと対応 しているか否かに基づいて真偽値に対応付けられる。[70]

形式意味論はさらに、形式的な仕組みを用いて言語現象を表現する方法を検討する。対象化、内包性、名詞句、複数形、集合語、時制、様態などがその対象だ。 [71] モンタギュー意味論は形式意味論における初期の有力理論であり、数学的論理を用いて英語を表現する方法を詳細に分析する。これは高階論理、ラムダ計算、型 理論に依拠し、異なる統語範疇に属する表現の組み合わせを通じて意味が如何に生成されるかを示す。[72]

動的意味論は、情報が時間とともにどのように成長するかに焦点を当てた形式意味論のサブ分野である。これによれば、「意味とは文脈変化の潜在性である」: 文の意味は、その文に含まれる情報によって与えられるのではなく、文脈に対してその文がもたらす情報の変化によって与えられる。[73]

Main article: Cognitive semantics

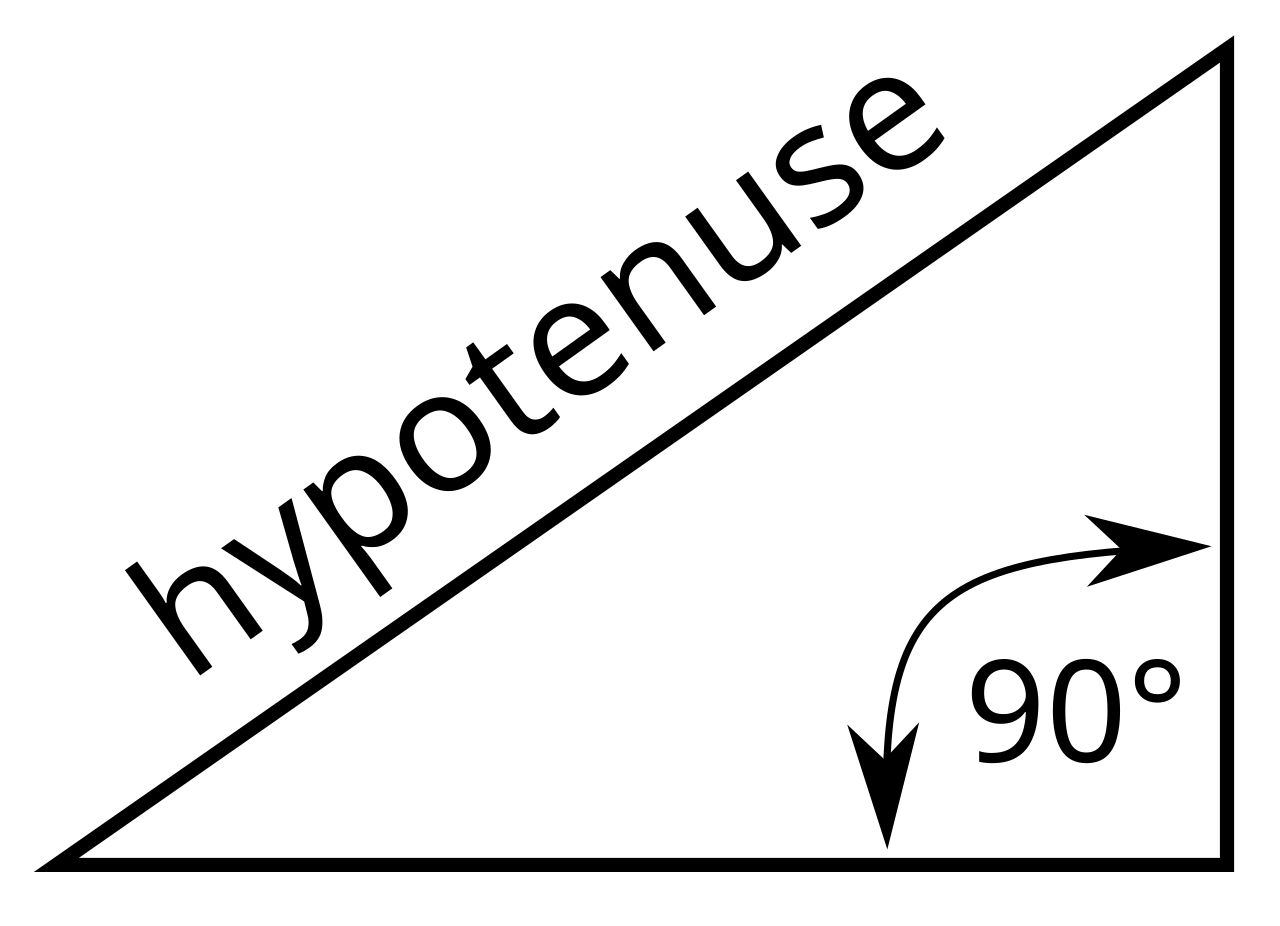

Diagram of a hypotenuse

Cognitive semantics is interested in the conceptual structures underlying language, which can be articulated through the contrast between profile and base. For instance, the term hypotenuse profiles a straight line against the background of a right-angled triangle.

Cognitive semantics studies the problem of meaning from a psychological perspective or how the mind of the language user affects meaning. As a subdiscipline of cognitive linguistics, it sees language as a wide cognitive ability that is closely related to the conceptual structures used to understand and represent the world.[74][g] Cognitive semanticists do not draw a sharp distinction between linguistic knowledge and knowledge of the world and see them instead as interrelated phenomena.[76] They study how the interaction between language and human cognition affects the conceptual organization in very general domains like space, time, causation, and action.[77] The contrast between profile and base is sometimes used to articulate the underlying knowledge structure. The profile of a linguistic expression is the aspect of the knowledge structure that it brings to the foreground while the base is the background that provides the context of this aspect without being at the center of attention.[78] For example, the profile of the word hypotenuse is a straight line while the base is a right-angled triangle of which the hypotenuse forms a part.[79][h]

Cognitive semantics further compares the conceptual patterns and linguistic typologies across languages and considers to what extent the cognitive conceptual structures of humans are universal or relative to their linguistic background.[81] Another research topic concerns the psychological processes involved in the application of grammar.[82] Other investigated phenomena include categorization, which is understood as a cognitive heuristic to avoid information overload by regarding different entities in the same way,[83] and embodiment, which concerns how the language user's bodily experience affects the meaning of expressions.[84]

Frame semantics is an important subfield of cognitive semantics.[85] Its central idea is that the meaning of terms cannot be understood in isolation from each other but needs to be analyzed on the background of the conceptual structures they depend on. These structures are made explicit in terms of semantic frames. For example, words like bride, groom, and honeymoon evoke in the mind the frame of marriage.[86]

主な記事: 認知意味論

斜辺の図式

認知意味論は言語の基盤となる概念構造に関心を持つ。これは輪郭と基底の対比を通じて明示される。例えば「斜辺」という用語は、直角三角形を背景として直 線を輪郭として描く。

認知意味論は、心理学的観点から意味の問題、すなわち言語使用者の心が意味に与える影響を研究する。認知言語学の一分野として、言語を世界を理解し表象す るために用いられる概念構造と密接に関連する広範な認知能力と捉える。[74][g] 認知意味論者は言語知識と世界知識を厳密に区別せず、相互に関連する現象と見なす。[76] 彼らは言語と人間認知の相互作用が、空間・時間・因果関係・行動といった非常に一般的な領域における概念組織にどう影響するかを研究する。[77] 輪郭と基盤の対比は、基盤となる知識構造を明示するために用いられることがある。言語表現の輪郭とは、それが前景化させる知識構造の側面であり、基盤とは 注目の中核にはないが、この側面の文脈を提供する背景である。[78] 例えば「斜辺」という語のプロファイルは直線であり、ベースは斜辺が一部を構成する直角三角形である。[79][h]

認知意味論はさらに、言語間の概念パターンと言語類型を比較し、人間の認知的概念構造がどの程度普遍的か、あるいは言語的背景に依存するかを考察する。 [81] 別の研究テーマは文法適用に関わる心理的プロセスである。[82] 調査対象となる現象には、情報過多を避ける認知的ヒューリスティックとして異なる実体を同一視する分類化[83]、言語使用者の身体的経験が表現の意味に 及ぼす影響を扱う身体化も含まれる。[84]

フレーム意味論は認知意味論の重要な分分野である。[85] その中心的な考え方は、用語の意味は互いに切り離して理解できず、それらが依存する概念構造を背景として分析する必要があるというものだ。これらの構造は 意味的フレームによって明示される。例えば、花嫁、花婿、新婚旅行といった言葉は、結婚というフレームを心に喚起する。[86]

Conceptual semantics shares with cognitive semantics the idea of studying linguistic meaning from a psychological perspective by examining how humans conceptualize and experience the world. It holds that meaning is not about the objects to which expressions refer but about the cognitive structure of human concepts that connect thought, perception, and action. Conceptual semantics differs from cognitive semantics by introducing a strict distinction between meaning and syntax and by relying on various formal devices to explore the relation between meaning and cognition.[87]

Computational semantics examines how the meaning of natural language expressions can be represented and processed on computers.[88] It often relies on the insights of formal semantics and applies them to problems that can be computationally solved.[89] Some of its key problems include computing the meaning of complex expressions by analyzing their parts, handling ambiguity, vagueness, and context-dependence, and using the extracted information in automatic reasoning.[90] It forms part of computational linguistics, artificial intelligence, and cognitive science.[88] Its applications include machine learning and machine translation.[91]

Cultural semantics studies the relation between linguistic meaning and culture. It compares conceptual structures in different languages and is interested in how meanings evolve and change because of cultural phenomena associated with politics, religion, and customs.[92] For example, address practices encode cultural values and social hierarchies, as in the difference of politeness of expressions like tu and usted in Spanish or du and Sie in German in contrast to English, which lacks these distinctions and uses the pronoun you in either case.[93] Closely related fields are intercultural semantics, cross-cultural semantics, and comparative semantics.[94]

Pragmatic semantics studies how the meaning of an expression is shaped by the situation in which it is used. It is based on the idea that communicative meaning is usually context-sensitive and depends on who participates in the exchange, what information they share, and what their intentions and background assumptions are. It focuses on communicative actions, of which linguistic expressions only form one part. Some theorists include these topics within the scope of semantics while others consider them part of the distinct discipline of pragmatics.[95]

概念的意味論は、認知意味論と同様に、人間が世界を概念化し体験する方法を考察することで、心理学的観点から言語の意味を研究するという考えを共有してい る。意味は表現が指す対象についてではなく、思考、知覚、行動を結びつける人間の概念の認知構造についてであると主張する。概念意味論は、意味と構文の厳 密な区別を導入し、意味と認知の関係を探るために様々な形式的手法に依拠する点で、認知意味論とは異なる。[87]

計算意味論は、自然言語表現の意味をコンピュータ上でどのように表現し処理できるかを検討する。[88] 形式意味論の知見に依拠し、計算的に解決可能な問題に応用することが多い。[89] その主要課題には、複雑な表現の意味を構成要素の分析によって計算すること、曖昧性・不明確性・文脈依存性の処理、自動推論における抽出情報の活用などが 含まれる。[90] これは計算言語学、人工知能、認知科学の一部を構成する。[88] 応用分野には機械学習や機械翻訳が含まれる。[91]

文化意味論は言語的意味と文化の関係を研究する。異なる言語の概念構造を比較し、政治・宗教・習慣といった文化的現象によって意味が如何に進化・変化する かに焦点を当てる。[92] 例えば、呼称慣行は文化的価値観や社会階層を反映する。スペイン語の「tu」と「usted」、ドイツ語の「du」と「Sie」といった表現の礼儀度の差 異がそれにあたる。これに対し英語では区別がなく、いずれの場合も代名詞「you」を用いる。[93] 密接に関連する分野として、異文化意味論、クロスカルチャー意味論、比較意味論がある。[94]

語用論的意味論は、表現の意味が使用される状況によってどのように形成されるかを研究する。これは、コミュニケーション上の意味は通常文脈依存であり、誰 がやり取りに参加するか、彼らが共有する情報、そして彼らの意図や背景にある前提に依存するという考えに基づいている。それはコミュニケーション行為に焦 点を当てており、言語表現はその一部に過ぎない。一部の理論家はこれらの主題を意味論の範囲内に含めるが、他の理論家はそれらを区別された学問分野である 語用論の一部と見なしている。[95]

Theories of meaning explain what meaning is, what meaning an expression has, and how the relation between expression and meaning is established.[96]

Referential

Diagram of referential theories

Referential theories identify meaning with the entities to which expressions point.

Referential theories state that the meaning of an expression is the entity to which it points.[97] The meaning of singular terms like names is the individual to which they refer. For example, the meaning of the name George Washington is the person with this name.[98] General terms refer not to a single entity but to the set of objects to which this term applies. In this regard, the meaning of the term cat is the set of all cats.[99] Similarly, verbs usually refer to classes of actions or events and adjectives refer to properties of individuals and events.[100]

Simple referential theories face problems for meaningful expressions that have no clear referent. Names like Pegasus and Santa Claus have meaning even though they do not point to existing entities.[101] Other difficulties concern cases in which different expressions are about the same entity. For instance, the expressions Roger Bannister and the first man to run a four-minute mile refer to the same person but do not mean exactly the same thing.[102] This is particularly relevant when talking about beliefs since a person may understand both expressions without knowing that they point to the same entity.[103] A further problem is given by expressions whose meaning depends on the context, like the deictic terms here and I.[104]

To avoid these problems, referential theories often introduce additional devices. Some identify meaning not directly with objects but with functions that point to objects. This additional level has the advantage of taking the context of an expression into account since the same expression may point to one object in one context and to another object in a different context. For example, the reference of the word here depends on the location in which it is used.[105] A closely related approach is possible world semantics, which allows expressions to refer not only to entities in the actual world but also to entities in other possible worlds.[i] According to this view, expressions like the first man to run a four-minute mile refer to different persons in different worlds. This view can also be used to analyze sentences that talk about what is possible or what is necessary: possibility is what is true in some possible worlds while necessity is what is true in all possible worlds.[107]

意味論は、意味とは何か、表現が持つ意味とは何か、表現と意味の関係がどのように確立されるかを説明する。[96]

参照論

参照論の図式

参照論は、意味を表現が指し示す実体と同一視する。

参照論は、表現の意味はそれが指し示す実体であると述べる。[97] 固有名詞のような単数項の意味は、それが指す個体である。例えば、ジョージ・ワシントンの名前の意味は、この名前を持つ人物である。[98] 総称項は単一の個体を指すのではなく、この用語が適用される対象の集合を指す。この点において、猫という用語の意味は全ての猫の集合である。[99] 同様に、動詞は通常、行為や事象の類を指し、形容詞は個体や事象の性質を指す。[100]

単純な参照理論は、明確な参照対象を持たない意味のある表現に対して問題を抱える。ペガサスやサンタクロースのような名前は、実在する実体を指し示さない にもかかわらず意味を持つ。[101] 他の困難は、異なる表現が同じ実体について言及する場合に関わる。例えば、「ロジャー・バニスター」と「4分切りを達成した最初の人間」という表現は同じ 人物を指すが、厳密には同じ意味を持たない。[102] 信念について論じる際にはこれが特に重要だ。なぜなら人は両方の表現を理解しつつ、それらが同一実体を指すことを知らない場合があるからだ。[103] さらに文脈依存の意味を持つ表現、例えば指示語「ここ」や「私」も問題となる。[104]

こうした問題を回避するため、参照理論はしばしば追加の仕組みを導入する。意味を直接対象ではなく、対象を指し示す機能と同一視するものもある。この追加 レベルには、表現の文脈を考慮に入れる利点がある。同じ表現が、ある文脈では一つの対象を指し示し、別の文脈では別の対象を指し示す可能性があるからだ。 例えば「ここ」という言葉の参照対象は、それが使われる場所によって変わる。[105] これと密接に関連するアプローチが、可能世界意味論である。これは表現が現実世界の存在だけでなく、他の可能世界の存在をも指し示すことを許容する。 [i] この見解によれば、「4分切りマイルを走った最初の人間」のような表現は、異なる世界では異なる人物を指す。この見解は、可能性や必然性について述べる文 の分析にも適用できる:可能性とは一部の可能世界において真となるものであり、必然性とは全ての可能世界において真となるものである。[107]

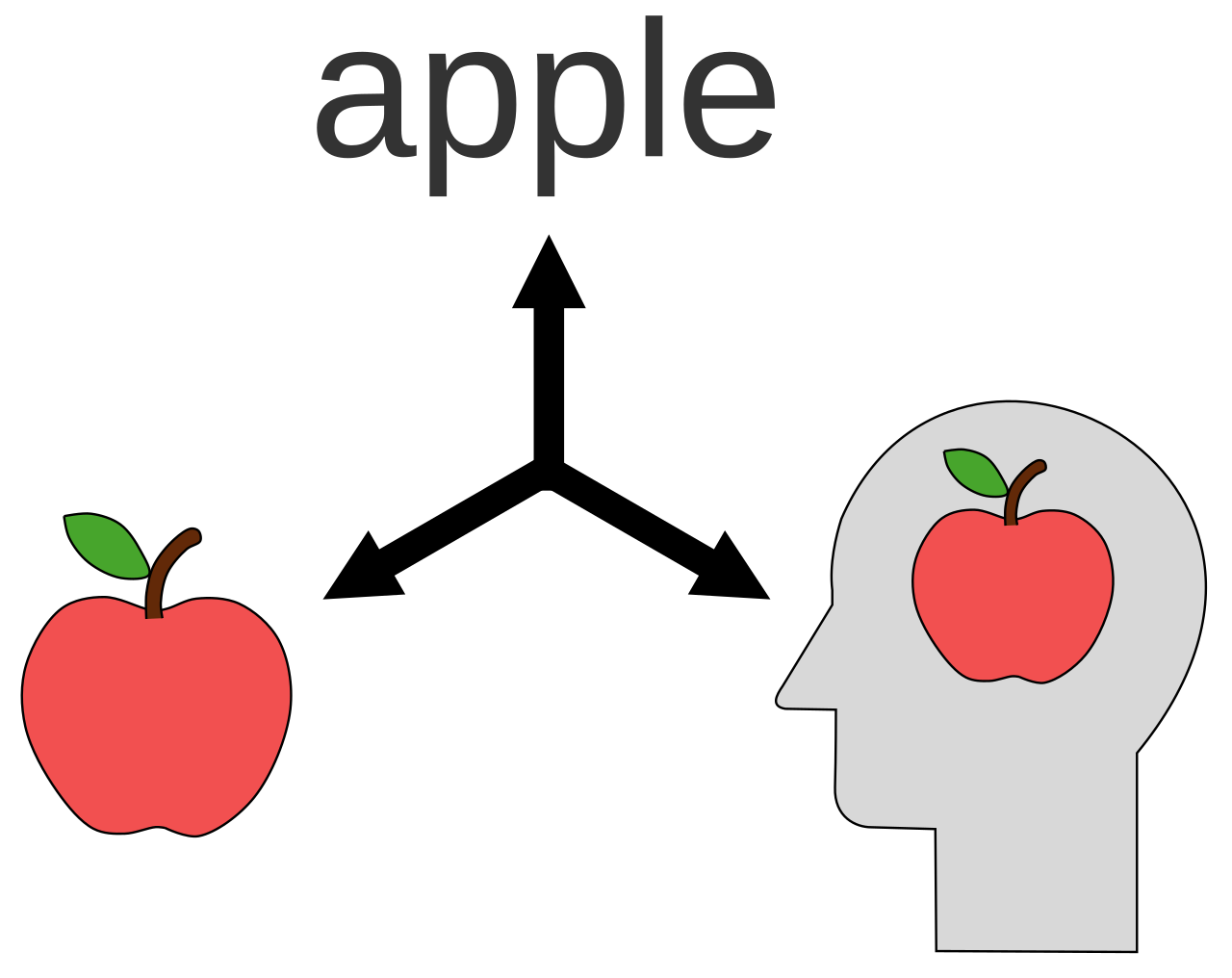

Diagram of ideational theories

Ideational theories identify meaning with the mental states of language users.

Ideational theories, also called mentalist theories, are not primarily interested in the reference of expressions and instead explain meaning in terms of the mental states of language users.[108] One historically influential approach articulated by John Locke holds that expressions stand for ideas in the speaker's mind. According to this view, the meaning of the word dog is the idea that people have of dogs. Language is seen as a medium used to transfer ideas from the speaker to the audience. After having learned the same meaning of signs, the speaker can produce a sign that corresponds to the idea in their mind and the perception of this sign evokes the same idea in the mind of the audience.[109]

A closely related theory focuses not directly on ideas but on intentions.[110] This view is particularly associated with Paul Grice, who observed that people usually communicate to cause some reaction in their audience. He held that the meaning of an expression is given by the intended reaction. This means that communication is not just about decoding what the speaker literally said but requires an understanding of their intention or why they said it.[111] For example, telling someone looking for petrol that "there is a garage around the corner" has the meaning that petrol can be obtained there because of the speaker's intention to help. This goes beyond the literal meaning, which has no explicit connection to petrol.[112]

観念論の図式

観念論は意味を言語使用者の心的状態と同一視する。

観念論(メンタル主義理論とも呼ばれる)は、表現の参照対象を主眼とせず、代わりに言語使用者の心的状態によって意味を説明する。[108] ジョン・ロックが提唱した歴史的に影響力のあるアプローチは、表現が話者の心の中の観念を表すと主張する。この見解によれば、「犬」という言葉の意味は、 人々が犬について持つ観念である。言語は、話者から聴衆へ観念を伝達するための媒体と見なされる。同じ記号の意味を学んだ後、話者は自身の心にある観念に 対応する記号を生成でき、この記号の知覚は聴衆の心にも同じ観念を喚起する。[109]

密接に関連する理論は、観念そのものではなく意図に焦点を当てる。[110] この見解は特にポール・グライスと結びついている。彼は人々が通常、聞き手に何らかの反応を引き起こすためにコミュニケーションを取ると指摘した。彼は表 現の意味は意図された反応によって与えられると主張した。これはコミュニケーションが話者の文字通りの発言を解読するだけでなく、その意図や発言理由を理 解することを必要とすることを意味する。[111] 例えば、ガソリンを探している人に「角を曲がったところにガソリンスタンドがある」と言う場合、話者の助けたいという意図から、そこでガソリンが入手でき るという意味を持つ。これは文字通りの意味を超えたものであり、文字通りにはガソリンとの明確な関連性はない。[112]

A central topic in semantics concerns the relation between language, world, and mental concepts.

意 味論における中心的な主題は、言語と世界と精神的概念の関係性に関するものである。

Causal theories hold that the meaning of an expression depends on the causes and effects it has.[113] According to behaviorist semantics, also referred to as stimulus-response theory, the meaning of an expression is given by the situation that prompts the speaker to use it and the response it provokes in the audience.[114] For instance, the meaning of yelling "Fire!" is given by the presence of an uncontrolled fire and attempts to control it or seek safety.[115] Behaviorist semantics relies on the idea that learning a language consists in adopting behavioral patterns in the form of stimulus-response pairs.[116] One of its key motivations is to avoid private mental entities and define meaning instead in terms of publicly observable language behavior.[117]

Another causal theory focuses on the meaning of names and holds that a naming event is required to establish the link between name and named entity. This naming event acts as a form of baptism that establishes the first link of a causal chain in which all subsequent uses of the name participate.[118] According to this view, the name Plato refers to an ancient Greek philosopher because, at some point, he was originally named this way and people kept using this name to refer to him.[119] This view was originally formulated by Saul Kripke to apply to names only but has been extended to cover other types of speech as well.[120]

因果論は、表現の意味はその表現が持つ原因と結果に依存すると主張する。[113] 行動主義的意味論(刺激反応理論とも呼ばれる)によれば、表現の意味は、話者がそれを使用するきっかけとなる状況と、それが聴衆に喚起する反応によって与 えられる。[114] 例えば「火事だ!」と叫ぶ意味は、制御不能な火災の存在と、それを制御しようとする試み、あるいは安全を求める行動によって与えられる。[115] 行動主義的意味論は、言語学習とは刺激-反応のペアという形で行動パターンを習得することだという考えに基づいている。[116] その主な動機の一つは、私的な精神的実体を避け、代わりに公的に観察可能な言語行動の観点から意味を定義することにある。[117]

別の因果理論は名称の意味に焦点を当て、名称と被称体の関連を確立するには命名行為が必要だと主張する。この命名行為は一種の洗礼として機能し、その後の 名称使用全てが参加する因果連鎖の最初の環を確立する。[118] この見解によれば、「プラトン」という名称が古代ギリシャの哲学者を指すのは、ある時点で彼が当初この名で呼ばれ、人々が彼を指すためにこの名称を使い続 けたからである。[119] この見解はもともとソール・クリプキによって名称のみに適用されるよう提唱されたが、他の種類の言語行為にも拡張されてきた。[120]

Truth-conditional semantics analyzes the meaning of sentences in terms of their truth conditions. According to this view, to understand a sentence means to know what the world needs to be like for the sentence to be true.[121] Truth conditions can themselves be expressed through possible worlds. For example, the sentence "Hillary Clinton won the 2016 American presidential election" is false in the actual world but there are some possible worlds in which it is true.[122] The extension of a sentence can be interpreted as its truth value while its intension is the set of all possible worlds in which it is true.[123] Truth-conditional semantics is closely related to verificationist theories, which introduce the additional idea that there should be some kind of verification procedure to assess whether a sentence is true. They state that the meaning of a sentence consists in the method to verify it or in the circumstances that justify it.[124] For instance, scientific claims often make predictions, which can be used to confirm or disconfirm them using observation.[125] According to verificationism, sentences that can neither be verified nor falsified are meaningless.[126]

The use theory states that the meaning of an expression is given by the way it is utilized. This view was first introduced by Ludwig Wittgenstein, who understood language as a collection of language games. The meaning of expressions depends on how they are used inside a game and the same expression may have different meanings in different games.[127] Some versions of this theory identify meaning directly with patterns of regular use.[128] Others focus on social norms and conventions by additionally taking into account whether a certain use is considered appropriate in a given society.[129]

Inferentialist semantics, also called conceptual role semantics, holds that the meaning of an expression is given by the role it plays in the premises and conclusions of good inferences.[130] For example, one can infer from "x is a male sibling" that "x is a brother" and one can infer from "x is a brother" that "x has parents". According to inferentialist semantics, the meaning of the word brother is determined by these and all similar inferences that can be drawn.[131]

真偽条件的意味論は、文の意味をその真偽条件に基づいて分析する。この見解によれば、文を理解するとは、その文が真となるために世界がどうあるべきかを理 解することを意味する。[121] 真偽条件自体は、可能世界を通じて表現され得る。例えば「ヒラリー・クリントンは2016年のアメリカ大統領選挙に勝利した」という文は現実世界では偽だ が、それが真となる可能世界がいくつか存在する。[122] 文の外延は真偽値として解釈され、内包はそれが真となる全ての可能世界の集合である。[123] 真理条件論的意味論は検証主義理論と密接に関連している。検証主義理論は、文が真であるかを評価するための何らかの検証手続きが存在すべきだという追加的 な考えを導入する。それらは、文の意味はその文を検証する方法、あるいはそれを正当化する状況にあると主張する。[124] 例えば、科学的命題はしばしば予測を行い、それらは観察を用いて確認または反証するために用いられる。[125] 検証主義によれば、検証も反証も不可能な文は無意味である。[126]

使用理論は、表現の意味はその使用方法によって与えられると主張する。この見解はルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインによって初めて導入され、彼は言語を 言語ゲームの集合体として理解した。表現の意味はゲーム内での使用方法に依存し、同じ表現でも異なるゲームでは異なる意味を持つことがある。[127] この理論のいくつかの形態は、意味を直接的な規則的使用パターンと同一視する。[128] 他には、特定の使用が特定の社会で適切と見なされるかどうかを追加的に考慮することで、社会的規範や慣習に焦点を当てるものもある。[129]

推論主義的意味論(概念的役割意味論とも呼ばれる)は、表現の意味は、それが妥当な推論の前提と結論において果たす役割によって与えられると主張する。 [130] 例えば、「xは男性の兄弟である」から「xは兄である」と推論でき、「xは兄である」から「xには両親がいる」と推論できる。推論主義的意味論によれば、 兄という言葉の意味は、こうした推論や、導き出せる類似の推論すべてによって決定される。[131]

Semantics was established as an independent field of inquiry in the 19th century but the study of semantic phenomena began as early as the ancient period as part of philosophy and logic.[132][j] In ancient Greece, Plato (427–347 BCE) explored the relation between names and things in his dialogue Cratylus. It considers the positions of naturalism, which holds that things have their name by nature, and conventionalism, which states that names are related to their referents by customs and conventions among language users.[134] The book On Interpretation by Aristotle (384–322 BCE) introduced various conceptual distinctions that greatly influenced subsequent works in semantics. He developed an early form of the semantic triangle by holding that spoken and written words evoke mental concepts, which refer to external things by resembling them. For him, mental concepts are the same for all humans, unlike the conventional words they associate with those concepts.[135] The Stoics incorporated many of the insights of their predecessors to develop a complex theory of language through the perspective of logic. They discerned different kinds of words by their semantic and syntactic roles, such as the contrast between names, common nouns, and verbs. They also discussed the difference between statements, commands, and prohibitions.[136]

Painting of Bhartṛhari

Bhartṛhari developed and compared various semantic theories of the meaning of words.[137]

In ancient India, the orthodox school of Nyaya held that all names refer to real objects. It explored how words lead to an understanding of the thing meant and what consequence this relation has to the creation of knowledge.[138] Philosophers of the orthodox school of Mīmāṃsā discussed the relation between the meanings of individual words and full sentences while considering which one is more basic.[139] The book Vākyapadīya by Bhartṛhari (4th–5th century CE) distinguished between different types of words and considered how they can carry different meanings depending on how they are used.[140] In ancient China, the Mohists argued that names play a key role in making distinctions to guide moral behavior.[141] They inspired the School of Names, which explored the relation between names and entities while examining how names are required to identify and judge entities.[142]

Statue of Abelard

One of Peter Abelard's innovations was his focus on the meaning of full sentences rather than the meaning of individual words.

In the Middle Ages, Augustine of Hippo (354–430) developed a general conception of signs as entities that stand for other entities and convey them to the intellect. He was the first to introduce the distinction between natural and linguistic signs as different types belonging to a common genus.[143] Boethius (480–528) wrote a translation of and various comments on Aristotle's book On Interpretation, which popularized its main ideas and inspired reflections on semantic phenomena in the scholastic tradition.[144] An innovation in the semantics of Peter Abelard (1079–1142) was his interest in propositions or the meaning of sentences in contrast to the focus on the meaning of individual words by many of his predecessors. He further explored the nature of universals, which he understood as mere semantic phenomena of common names caused by mental abstractions that do not refer to any entities.[145] In the Arabic tradition, Ibn Faris (920–1004) identified meaning with the intention of the speaker while Abu Mansur al-Azhari (895–980) held that meaning resides directly in speech and needs to be extracted through interpretation.[146]

An important topic towards the end of the Middle Ages was the distinction between categorematic and syncategorematic terms. Categorematic terms have an independent meaning and refer to some part of reality, like horse and Socrates. Syncategorematic terms lack independent meaning and fulfill other semantic functions, such as modifying or quantifying the meaning of other expressions, like the words some, not, and necessarily.[147] An early version of the causal theory of meaning was proposed by Roger Bacon (c. 1219/20 – c. 1292), who held that things get names similar to how people get names through some kind of initial baptism.[148] His ideas inspired the tradition of the speculative grammarians, who proposed that there are certain universal structures found in all languages. They arrived at this conclusion by drawing an analogy between the modes of signification on the level of language, the modes of understanding on the level of mind, and the modes of being on the level of reality.[149]

In the early modern period, Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) distinguished between marks, which people use privately to recall their own thoughts, and signs, which are used publicly to communicate their ideas to others.[150] In their Port-Royal Logic, Antoine Arnauld (1612–1694) and Pierre Nicole (1625–1695) developed an early precursor of the distinction between intension and extension.[151] The Essay Concerning Human Understanding by John Locke (1632–1704) presented an influential version of the ideational theory of meaning, according to which words stand for ideas and help people communicate by transferring ideas from one mind to another.[152] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) understood language as the mirror of thought and tried to conceive the outlines of a universal formal language to express scientific and philosophical truths. This attempt inspired theorists Christian Wolff (1679–1754), Georg Bernhard Bilfinger (1693–1750), and Johann Heinrich Lambert (1728–1777) to develop the idea of a general science of sign systems.[153] Étienne Bonnot de Condillac (1715–1780) accepted and further developed Leibniz's idea of the linguistic nature of thought. Against Locke, he held that language is involved in the creation of ideas and is not merely a medium to communicate them.[154]

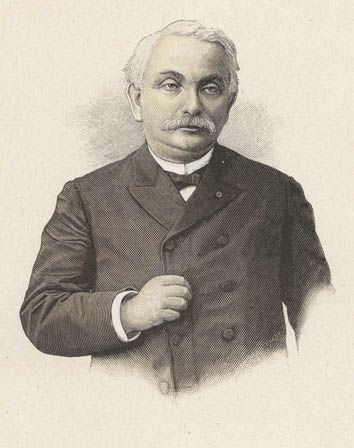

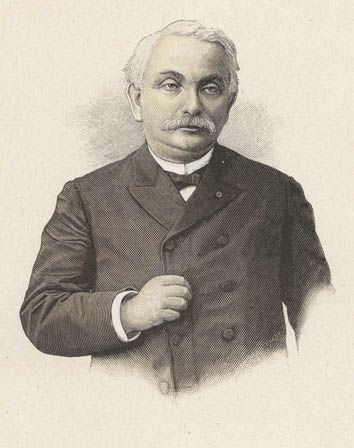

Photo of Michel Jules Alfred Bréal

Michel Bréal coined the French term sémantique and conceptualized the scope of this field of inquiry.

In the 19th century, semantics emerged and solidified as an independent field of inquiry. Christian Karl Reisig (1792–1829) is sometimes credited as the father of semantics since he clarified its concept and scope while also making various contributions to its key ideas.[155] Michel Bréal (1832–1915) followed him in providing a broad conception of the field, for which he coined the French term sémantique.[156] John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) gave great importance to the role of names to refer to things. He distinguished between the connotation and denotation of names and held that propositions are formed by combining names.[157] Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914) conceived semiotics as a general theory of signs with several subdisciplines, which were later identified by Charles W. Morris (1901–1979) as syntactics, semantics, and pragmatics. In his pragmatist approach to semantics, Peirce held that the meaning of conceptions consists in the entirety of their practical consequences.[158] The philosophy of Gottlob Frege (1848–1925) contributed to semantics on many different levels. Frege first introduced the distinction between sense and reference, and his development of predicate logic and the principle of compositionality formed the foundation of many subsequent developments in formal semantics.[159] Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) explored meaning from a phenomenological perspective by considering the mental acts that endow expressions with meaning. He held that meaning always implies reference to an object and expressions that lack a referent, like green is or, are meaningless.[160]

In the 20th century, Alfred Tarski (1901–1983) defined truth in formal languages through his semantic theory of truth, which was influential in the development of truth-conditional semantics by Donald Davidson (1917–2003).[161] Tarski's student Richard Montague (1930–1971) formulated a complex formal framework of the semantics of the English language, which was responsible for establishing formal semantics as a major area of research.[162] According to structural semantics,[k] which was inspired by the structuralist philosophy of Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913), language is a complex network of structural relations and the meanings of words are not fixed individually but depend on their position within this network.[164] The theory of general semantics was developed by Alfred Korzybski (1879–1950) as an inquiry into how language represents reality and affects human thought.[165] The contributions of George Lakoff (1941–present) and Ronald Langacker (1942–present) provided the foundation of cognitive semantics.[166] Charles J. Fillmore (1929–2014) developed frame semantics as a major approach in this area.[167] The closely related field of conceptual semantics was inaugurated by Ray Jackendoff (1945–present).[168]

意味論は19世紀に独立した研究分野として確立されたが、意味現象の研究は古代期に哲学や論理学の一部として始まっている。[132][j] 古代ギリシャでは、プラトン(紀元前427–347年)が対話篇『クラテュロス』において名称と実体の関係を考察した。この著作では、名称は実体そのもの から自然に生じるとする自然主義と、名称は言語使用者の慣習や合意によって対象と結びつくとする慣習主義の立場を検討している。[134] アリストテレス(紀元前384-322年)の『解釈論』は、後の意味論研究に多大な影響を与えた様々な概念的区別を導入した。彼は、発話された言葉や書か れた言葉が精神的概念を喚起し、それらが外部の事物に類似することで参照すると主張し、意味論的三角形の初期形態を発展させた。彼によれば、概念は人間す べてに共通するものであるが、それらが結びつく慣習的な言葉は異なる。[135] ストア学派は先人の知見を多く取り入れ、論理学の観点から複雑な言語理論を構築した。彼らは語の意味的・文法的役割によって、名称・一般名詞・動詞といっ た異なる種類の言葉を区別した。また、陳述・命令・禁止の差異についても論じた。[136]

バルトリハリの絵画

バルトリハリは、言葉の意味に関する様々な意味論的理論を発展させ比較した。[137]

古代インドでは、正統派のニヤーヤ学派は、全ての名称が実在の物体を指し示すと主張した。言葉が如何にして対象の理解へと導くか、そしてこの関係が知識の 形成に如何なる帰結をもたらすかを探究した。[138] 正統派ミーマーンサー学派の哲学者たちは、個々の単語の意味と完全な文の意味の関係を論じ、どちらがより基本的であるかを考察した。[139] バーティハリ(4~5世紀)の著書『ヴァーキャパーディーヤ』は、異なる種類の単語を区別し、それらの使用方法によって異なる意味をどのように担うかを考 察した。[140] 古代中国では、墨家(モクカ)が、道徳的行動を導くための区別において名称が重要な役割を果たすと主張した。[141] 彼らは名家(めいか)に影響を与え、名家では名称と実体の関係を探求し、実体を識別し判断するために名称がどのように必要とされるかを考察した。 [142]

アベラールの像

ピエール・アベラールの革新の一つは、個々の単語の意味ではなく、文全体の意味に焦点を当てたことである。

中世において、ヒッポのアウグスティヌス(354–430)は、他の実体を表し知性へ伝達する実体としての記号の一般的な概念を発展させた。彼は自然記号 と言語記号を共通の属に属する異なる類型として区別する概念を初めて導入した。[143] ボエティウス(480–528)はアリストテレスの『解釈論』の翻訳と諸注釈を著し、その主要思想を普及させ、スコラ哲学における意味現象への考察を促し た。[144] ピエール・アベラール(1079–1142)の意味論における革新は、多くの先人たちが個々の単語の意味に焦点を当てたのに対し、命題や文の意味に関心を 持った点にある。彼はさらに普遍者の本質を探求し、普遍者を単なる共通名による意味現象と理解した。これは実体を指し示さない精神的抽象化によって生じる 現象である。[145] アラビア語学の伝統では、イブン・ファリス(920–1004)は意味を話者の意図と同一視した。一方アブー・マンスール・アル=アズハーリー (895–980)は、意味は言語そのものの中に直接存在し、解釈によって抽出されるべきだと主張した。[146]

中世末期における重要な論題は、範疇語と非範疇語の区別であった。範疇語は独立した意味を持ち、馬やソクラテスのように現実の何らかの部分を指す。非範疇 語は独立した意味を持たず、他の表現の意味を修飾したり量化したりするといった意味論的機能を果たす。例えば、いくつかの、ない、必然的にといった言葉が これに当たる。[147] 意味の因果理論の初期形はロジャー・ベーコン(1219/20年頃 - 1292年頃)によって提唱された。彼は、物事が名前を得る過程は、ある種の最初の洗礼を通じて人が名前を得る過程に類似していると主張した。[148] 彼の思想は思弁的文法学者の伝統に影響を与え、彼らは全ての言語に共通する普遍的構造が存在すると提案した。彼らは言語レベルでの意味の様式、精神レベル での理解の様式、現実レベルでの存在の様式を類推することでこの結論に至った。[149]

近世においてトマス・ホッブズ(1588–1679)は、個人が私的に自身の思考を想起するために用いる「印(marks)」と、公的に他者へ思想を伝達 するために用いる「記号(signs)」を区別した。[150] アントワーヌ・アルノー(1612–1694)とピエール・ニコール(1625–1695)は『ポルト・ロワイヤル論理学』において、内包と外延の区別の 初期の先駆的発展を成し遂げた。[151] ジョン・ロック(1632–1704)の『人間知性論』は、意味の観念論的理論の影響力ある一形態を提示した。それによれば、言葉は観念を表し、観念をあ る精神から別の精神へ移すことで人々のコミュニケーションを助ける。[152] ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツ(1646–1716)は言語を思考の鏡と捉え、科学的・哲学的真理を表現する普遍的形式言語の骨格を構想し ようとした。この試みは、理論家クリスティアン・ヴォルフ(1679–1754)、ゲオルク・ベルンハルト・ビルフィンガー(1693–1750)、ヨハ ン・ハインリヒ・ランベルト(1728–1777)に刺激を与え、記号体系の一般科学という概念を発展させた。[153] エティエンヌ・ボノ・ド・コンディヤック(1715–1780)は、思考の言語的本質というライプニッツの考えを受け入れ、さらに発展させた。ロックに反 して、彼は言語が観念の創造に関与しており、単にそれを伝達する媒体ではないと主張した。[154]

ミシェル・ジュール・アルフレッド・ブレアルの写真

ミシェル・ブレアルは、フランス語の「sémantique」という用語を考案し、この研究分野の範囲を概念化した。

19 世紀、意味論は独立した研究分野として出現し、確立された。クリスチャン・カール・ライジグ(1792-1829)は、その概念と範囲を明確にし、その重 要な考え方にさまざまな貢献をしたことから、意味論の父と評されることもある。[155] ミシェル・ブレアル(1832-1915)は、この分野について幅広い概念を提示し、フランス語で「セマンティック(sémantique)」という用語 を造語した。[156] ジョン・スチュワート・ミル(1806-1873)は、物事を指し示す名称の役割を非常に重要視した。彼は、名前の内包と外延を区別し、命題は名前を組み 合わせることで形成されると主張した。[157] チャールズ・サンダース・パース(1839-1914)は、記号論を、いくつかの下位分野を持つ記号の一般理論として構想した。これらの下位分野は、後に チャールズ・W・モリス(1901-1979)によって、統語論、意味論、語用論として特定された。ピアースは意味論への実用主義的アプローチにおいて、 概念の意味はその実践的帰結の総体にあると主張した[158]。ゴットロップ・フレーゲ(1848–1925)の哲学は様々なレベルで意味論に貢献した。 フレーゲは初めて「意味」と「参照」の区別を導入し、述語論理と構成性の原理を発展させた。これらは形式意味論における後続の多くの発展の基礎を形成し た。[159] エドムント・フッサール(1859–1938)は、表現に意味を与える精神的行為を考察することで、現象学的観点から意味を探求した。彼は、意味は常に対 象への参照を伴うものであり、参照対象を持たない表現(例えば「緑である」や「である」など)は無意味であると主張した。[160]

20世紀に入ると、アルフレッド・タルスキ(1901–1983)は形式言語における真を定義した。彼の意味論的真理理論は、ドナルド・デイヴィッドソン (1917–2003)による真条件的意味論の発展に影響を与えた。[161] タルスキの弟子リチャード・モンタギュー(1930–1971)は英語の意味論に関する複雑な形式的枠組みを構築し、これにより形式意味論が主要な研究領 域として確立された。[162] 構造主義的哲学のフェルディナン・ド・ソシュール(1857–1913)に触発された構造的意味論によれば、言語は構造的関係の複雑なネットワークであ り、単語の意味は個別に固定されるものではなく、このネットワーク内での位置に依存する。[164] 一般意味論の理論は、言語が現実をどのように表象し人間の思考に影響を与えるかを問うものとして、アルフレッド・コルジブスキー(1879–1950)に よって発展した。[165] ジョージ・レイコフ(1941–現在)とロナルド・ランガッカー(1942–現在)の貢献が認知意味論の基礎を築いた。[166] チャールズ・J・フィルモア(1929–2014)はこの分野における主要なアプローチとしてフレーム意味論を発展させた。[167] 密接に関連する概念意味論の分野はレイ・ジャッケンドフ(1945–現在)によって創設された。[168]

Logic

Main article: Semantics of logic

Logicians study correct reasoning and often develop formal languages to express arguments and assess their correctness.[169] One part of this process is to provide a semantics for a formal language to precisely define what its terms mean. A semantics of a formal language is a set of rules, usually expressed as a mathematical function, that assigns meanings to formal language expressions.[170] For example, the language of first-order logic uses lowercase letters for individual constants and uppercase letters for predicates. To express the sentence "Bertie is a dog", the formula D(b) can be used where b is an individual constant for Bertie and D is a predicate for dog. Classical model-theoretic semantics assigns meaning to these terms by defining an interpretation function that maps individual constants to specific objects and predicates to sets of objects or tuples. The function maps b to Bertie and D to the set of all dogs. This way, it is possible to calculate the truth value of the sentence: it is true if Bertie is a member of the set of dogs and false otherwise.[171]

Formal logic aims to determine whether arguments are deductively valid, that is, whether the premises entail the conclusion.[172] Entailment can be defined in terms of syntax or in terms of semantics. Syntactic entailment, expressed with the symbol ⊢, relies on rules of inference, which can be understood as procedures to transform premises and arrive at a conclusion. These procedures only take the logical form of the premises on the level of syntax into account and ignore what meaning they express. Semantic entailment, expressed with the symbol ⊨, looks at the meaning of the premises, in particular, at their truth value. A conclusion follows semantically from a set of premises if the truth of the premises ensures the truth of the conclusion, that is, if any semantic interpretation function that assigns the premises the value true also assigns the conclusion the value true.[173]

Computer science

Main article: Semantics (computer science)

In computer science, the semantics of a program is how it behaves when a computer runs it. Semantics contrasts with syntax, which is the particular form in which instructions are expressed. The same behavior can usually be described with different forms of syntax. In JavaScript, this is the case for the commands i += 1 and i = i + 1, which are syntactically different expressions to increase the value of the variable i by one. This difference is also reflected in different programming languages since they rely on different syntax but can usually be employed to create programs with the same behavior on the semantic level.[174]

Static semantics focuses on semantic aspects that affect the compilation of a program. In particular, it is concerned with detecting errors of syntactically correct programs, such as type errors, which arise when an operation receives an incompatible data type. This is the case, for instance, if a function performing a numerical calculation is given a string instead of a number as an argument.[175] Dynamic semantics focuses on the run time behavior of programs, that is, what happens during the execution of instructions.[176] The main approaches to dynamic semantics are denotational, axiomatic, and operational semantics. Denotational semantics relies on mathematical formalisms to describe the effects of each element of the code. Axiomatic semantics uses deductive logic to analyze which conditions must be in place before and after the execution of a program. Operational semantics interprets the execution of a program as a series of steps, each involving the transition from one state to another state.[177]

Psychology

Main article: Semantics (psychology)

Psychological semantics examines psychological aspects of meaning. It is concerned with how meaning is represented on a cognitive level and what mental processes are involved in understanding and producing language. It further investigates how meaning interacts with other mental processes, such as the relation between language and perceptual experience.[178][l] Other issues concern how people learn new words and relate them to familiar things and concepts, how they infer the meaning of compound expressions they have never heard before, how they resolve ambiguous expressions, and how semantic illusions lead them to misinterpret sentences.[180]

One key topic is semantic memory, which is a form of general knowledge of meaning that includes the knowledge of language, concepts, and facts. It contrasts with episodic memory, which records events that a person experienced in their life. The comprehension of language relies on semantic memory and the information it carries about word meanings.[181] According to a common view, word meanings are stored and processed in relation to their semantic features. The feature comparison model states that sentences like "a robin is a bird" are assessed on a psychological level by comparing the semantic features of the word robin with the semantic features of the word bird. The assessment process is fast if their semantic features are similar, which is the case if the example is a prototype of the general category. For atypical examples, as in the sentence "a penguin is a bird", there is less overlap in the semantic features and the psychological process is significantly slower.[182]

論理学

主な記事: 論理学の意味論

論理学者は正しい推論を研究し、しばしば議論を表現しその正しさを評価するための形式言語を開発する。[169] この過程の一環として、形式言語の意味論を提供し、その用語が何を意味するかを正確に定義することがある。形式言語の意味論とは、通常は数学的関数として 表現される規則の集合であり、形式言語の表現に意味を割り当てるものである。例えば一階論理の言語では、個体定数には小文字を、述語には大文字を用いる。 「バートは犬である」という文を表現するには、式 D(b) が用いられる。ここで b はバートを表す個体定数であり、D は犬を表す述語である。古典的なモデル理論的意味論は、個体定数を特定の対象へ、述語を対象の集合またはタプルへ写す解釈関数を定義することで、これらの 項に意味を割り当てる。この関数はbをバーティへ、Dを全ての犬の集合へ写す。これにより文の真偽値を計算できる:バーティが犬の集合の要素であれば真、 そうでなければ偽となる。[171]

形式論理学は、議論が演繹的に有効かどうか、つまり前提が結論を包含するかどうかを決定することを目的とする。[172] 包含は構文論的または意味論的に定義できる。構文的含意(記号⊢で表される)は推論規則に依存する。これは前提を変換して結論に到達する手順と理解でき る。これらの手順は構文レベルでの前提の論理形式のみを考慮し、それらが表す意味は無視する。意味的含意(記号⊨で表される)は前提の意味、特にその真偽 値を考察する。ある結論が一組の前提から意味論的に導かれるとは、前提の真性が結論の真性を保証する場合を指す。つまり、前提に真の値を割り当てるあらゆ る意味論的解釈関数が、結論にも真の値を割り当てる場合である。[173]

コンピュータ科学

詳細記事: 意味論 (コンピュータ科学)

コンピュータ科学において、プログラムの意味論とは、コンピュータがそれを実行した際の動作を指す。意味論は構文論と対比される。構文論とは命令が表現さ れる特定の形式である。通常、同一の動作は異なる構文形式で記述可能だ。JavaScriptでは、変数iの値を1増加させる命令として、i += 1とi = i + 1が存在する。これらは構文的に異なる表現である。この差異は異なるプログラミング言語にも反映される。言語は異なる構文に依存するが、通常は意味論レベ ルで同一の挙動を持つプログラムを作成するために用いられるからだ。[174]

静的意味論は、プログラムのコンパイルに影響する意味論的側面に焦点を当てる。特に、演算が互換性のないデータ型を受け取った際に生じる型エラーなど、構 文的に正しいプログラムの誤りを検出することを扱う。例えば数値計算を行う関数が、引数として数値ではなく文字列を受け取った場合がこれに該当する。 [175] 動的意味論はプログラムの実行時挙動、すなわち命令実行中に何が起こるかに焦点を当てる。[176] 動的意味論の主なアプローチは、指示的意味論、公理的意味論、操作的意味論である。指示的意味論は、コードの各要素の効果を記述するために数学的形式論に 依存する。公理的意味論は、プログラム実行の前後にどのような条件が整っている必要があるかを分析するために演繹的論理を用いる。操作的意味論は、プログ ラムの実行を一連のステップとして解釈し、各ステップは一つの状態から別の状態への遷移を伴う。[177]

心理学

詳細記事: 意味論 (心理学)

心理意味論は意味の心理的側面を研究する。意味が認知レベルでどのように表象されるか、言語の理解と生成に関わる精神過程は何かを扱う。さらに、言語と知 覚的経験の関係など、意味が他の精神過程とどう相互作用するかを調査する。[178][l] その他の課題には、人々が新しい単語をどのように学習し、既知の事物や概念と関連付けるか、聞いたことのない複合表現の意味をどのように推論するか、曖昧 な表現をどのように解決するか、意味的錯覚がどのように文の誤解釈を招くかなどが含まれる。[180]

重要なテーマの一つが意味記憶である。これは言語・概念・事実の知識を含む、意味に関する一般的な知識の一形態だ。個人の人生で経験した出来事を記録する エピソード記憶とは対照的である。言語理解は意味記憶と、それが保持する語の意味情報に依存する。[181] 一般的な見解によれば、語の意味は意味的特徴に関連して保存・処理される。特徴比較モデルによれば、「ロビンは鳥である」のような文は、心理レベルで「ロ ビン」という語の意味的特徴と「鳥」という語の意味的特徴を比較することで評価される。両者の意味的特徴が類似している場合、つまり例文が一般カテゴリー の原型である場合には、この評価プロセスは高速に進行する。「ペンギンは鳥である」のような非典型例では、意味的特徴の重なりが少なく、心理的処理は著し く遅くなる。[182]

Semantic technology – Technology to help machines understand data

意味技術 – 機械がデータを理解するのを助ける技術

b. Semantics usually focuses on natural languages but it can also include the study of meaning in formal languages, like the language of first-order logic and programming languages.[6]

c. Antonym is an antonym of synonym.[42]

d. Some linguists use the term homonym for both phenomena.[43]

e. Some authors use the term compositional semantics for this type of inquiry.[60]

f. The term formal semantics is sometimes used in a different sense to refer to compositional semantics or to the study of meaning in the formal languages of systems of logic.[68]

g. Cognitive semantics does not accept the idea of linguistic relativity associated with the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis and holds instead that the underlying cognitive processes responsible for conceptual structures are independent of the language one speaks.[75]

h. Other examples are the word island, which profiles a landmass against the background of the surrounding water, and the word uncle, which profiles a human adult male against the background of kinship relations.[80]

i. A possible world is a complete way of how things could have been.[106]

j. The history of semantics is different from historical semantics, which studies how the meanings of words change through time.[133]

k. Some theorists use the term structural semantics in a different sense to refer to phrasal semantics.[163]

l. Some theorists use the term psychosemantics to refer to this discipline while others understand the term in a different sense.[179]

b. 意味論は通常、自然言語に焦点を当てるが、一階論理やプログラミング言語のような形式言語における意味の研究も含むことがある。[6]

c. 反意語は同義語の反意語である。[42]

d. 一部の言語学者は、両方の現象に対して同音異義語という用語を用いる。[43]

e. 一部の著者は、この種の研究に対して構成的意味論という用語を用いる。[60]

f. 形式意味論という用語は、構成的意味論や、論理体系の形式言語における意味の研究を指す異なる意味で用いられることがある。[68]

g. 認知意味論は、サピア=ウォーフ仮説に関連する言語相対性理論の考え方を認めず、代わりに、概念構造を担う根本的な認知プロセスは、話す言語とは独立して いると主張する。[75]

h. 他の例としては、周囲の水を背景に陸地を輪郭づける「島」という言葉や、親族関係を背景に成人男性を輪郭づける「叔父」という言葉がある。[80]

i. 可能世界とは、物事がどうあり得たかについての完全なあり方である。[106]

j. 意味論の歴史は、言葉の意味が時間とともにどう変化するかを研究する歴史的意味論とは異なる。[133]

k. 一部の理論家は「構造的意味論」という用語を異なる意味で用い、句の意味論を指すことがある。[163]

l. 一部の理論家は「心理意味論」という用語でこの分野を指すが、他の理論家はこの用語を異なる意味で理解している。[179]

AHD Staff (2022). "Semantics". American Heritage Dictionary. Harper Collins. Archived from the original on 31 January 2024. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

AHD Staff (2022a). "Hermeneutics". American Heritage Dictionary. Harper Collins. Archived from the original on 23 February 2024. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

Aklujkar, Ashok (1970). "Ancient Indian Semantics". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 51 (1/4): 11–29. ISSN 0378-1143. JSTOR 41688671.

Allan, Keith (2009). "Introduction". In Allan, Keith (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Semantics. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-080-95969-6. Retrieved 2024-02-04.

Allan, Keith (2015). "3. A History of Semantics". In Riemer, Nick (ed.). The Routledge Handbook of Semantics. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-41245-8. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

Anderson, Derek Egan (2021). Metasemantics and Intersectionality in the Misinformation Age: Truth in Political Struggle. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-73339-1. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

Andreou, Marios (2015). "Lexical Negation in Lexical Semantics: The Prefixes in- and dis-". Morphology. 25 (4): 391–410. doi:10.1007/s11525-015-9266-z.

Appiah, Kwame Anthony; Gutmann, Amy (1998). Color Conscious: The Political Morality of Race. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-400-82209-6. Retrieved 2024-02-18.

Bagha, Karim Nazari (2011). "A Short Introduction to Semantics". Journal of Language Teaching and Research. 2 (6). doi:10.4304/jltr.2.6.1411-1419.

Bekkum, Wout Jac van; Houben, Jan; Sluiter, Ineke; Versteegh, Kees (1997). The Emergence of Semantics in Four Linguistic Traditions: Hebrew, Sanskrit, Greek, Arabic. John Benjamins. ISBN 978-9-027-29881-2. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

Benin, Stephen D. (2012). The Footprints of God: Divine Accommodation in Jewish and Christian Thought. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-791-49628-2. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

Berto, Francesco; Jago, Mark (2023). "Impossible Worlds". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

Berwick, Robert C.; Stabler, Edward P. (2019). Minimalist Parsing. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-198-79508-7. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

Bezuidenhout, A. (2009). "Semantics–Pragmatics Boundary". In Allan, Keith (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Semantics. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-080-95969-6. Retrieved 2024-02-04.

Bieswanger, Markus; Becker, Annette (2017). Introduction to English Linguistics. UTB. ISBN 978-3-825-24528-3. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

Blackburn, Simon (2008). "Truth Conditions". The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-54143-0. Archived from the original on 2024-02-08. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

Blackburn, Simon (2008a). "Causal Theory of Meaning". The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-54143-0. Archived from the original on 2024-02-17. Retrieved 2024-02-18.

Blackburn, Simon (2008b). "Syncategorematic". The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-54143-0. Archived from the original on 2024-02-23. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

Blackburn, Simon (2008c). "Referentially Opaque/Transparent". The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-54143-0. Archived from the original on 2024-02-24. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

Bohnemeyer, Jürgen (2021). Ten Lectures on Field Semantics and Semantic Typology. Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-36262-8. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

Boyd, Richard; Gasper, Philip; Trout, J. D. (1991). The Philosophy of Science. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-52156-7. Retrieved 2024-02-18.

Bublitz, Wolfram; Norrick, Neal R. (2011). Foundations of Pragmatics. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-110-21426-0. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

Bunt, Harry; Muskens, Reinhard (1999). "Computational Semantics". Computing Meaning: Volume 1. Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-4231-1_1. ISBN 978-9-401-14231-1. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

Burch, Robert; Parker, Kelly A. (2024). "Charles Sanders Peirce". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 7 January 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

Burgess, Alexis; Sherman, Brett (2014). "Introduction: A Plea for the Metaphysics of Meaning". In Burgess, Alexis; Sherman, Brett (eds.). Metasemantics: New Essays on the Foundations of Meaning. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-191-64835-9. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

Cardona, Georgio R. (2019). Panini: A Survey of Research. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-110-80010-4. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

Carston, Robyn (2011). "Truth-conditional Semantics". In Sbisà, Marina; Östman, Jan-Ola; Verschueren, Jef (eds.). Philosophical Perspectives for Pragmatics. John Benjamins. ISBN 978-9-027-20787-6. Retrieved 2024-02-10.

Chakrabarti, A. (1997). Denying Existence: The Logic, Epistemology and Pragmatics of Negative Existentials and Fictional Discourse. Springer. ISBN 978-0-792-34388-2. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

Chapman, Siobhan; Routledge, Christopher (2009). "Ideational Theories". Key Ideas in Linguistics and the Philosophy of Language. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 84–85. doi:10.1515/9780748631421-033. ISBN 978-0-748-63142-1. Retrieved 2024-02-18.

Chatzikyriakidis, Stergios; Luo, Zhaohui (2021). Formal Semantics in Modern Type Theories. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-786-30128-4. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

Cohen, Jonathan (2009). The Red and the Real: An Essay on Color Ontology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-191-60960-2. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

Cornish, Francis (1999). Anaphora, Discourse, and Understanding: Evidence from English and French. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-198-70028-9. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

Crimmins, Mark (1998). "Semantics". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-U036-1. ISBN 978-0-415-25069-6.