社会的つながり

Social connection

☆ 「 "つながり "とは、人と人との間に存在するエネルギーであり、それは、人に見られている、話を聞いてもらっている、大切にされていると感じるとき、判断することなく 与えたり受け取ったりすることができるとき、そして、その関係から糧や力を得ることができるときのものである」——ブレネー・ブラウン、 ヒューストン大学ソーシャルワーク教授

| Social connection is

the experience of feeling close and connected to others. It involves

feeling loved, cared for, and valued,[1] and forms the basis of

interpersonal relationships. "Connection is the energy that exists between people when they feel seen, heard and valued; when they can give and receive without judgement; and when they derive sustenance and strength from the relationship." —Brené Brown, Professor of social work at the University of Houston[2] Increasingly, social connection is understood as a core human need, and the desire to connect as a fundamental drive.[3][4] It is crucial to development; without it, social animals experience distress and face severe developmental consequences.[5] In humans, one of the most social species, social connection is essential to nearly every aspect of health and well-being. Lack of connection, or loneliness, has been linked to inflammation,[6] accelerated aging and cardiovascular health risk,[7] suicide,[8] and all-cause mortality.[9] Feeling socially connected depends on the quality and number of meaningful relationships one has with family, friends, and acquaintances. Going beyond the individual level, it also involves a feeling of connecting to a larger community. Connectedness on a community level has profound benefits for both individuals and society.[10] |

社会的つながりとは、他者との距離が近く、つながっていると感じる経験

である。愛されている、大切にされている、評価されていると感じることであり[1]、対人関係の基礎を形成する。 "つながり "とは、人と人との間に存在するエネルギーであり、それは、人に見られている、話を聞いてもらっている、大切にされていると感じるとき、判断することなく 与えたり受け取ったりすることができるとき、そして、その関係から糧や力を得ることができるときのものである。-ブレネー・ブラウン、ヒューストン大学 ソーシャルワーク教授[2]。 社会的なつながりは、人間の核となる欲求であり、つながりたいという欲求は根源的な原動力であると理解されるようになってきている[3][4] 。つながりの欠如、すなわち孤独は、炎症[6]、老化の促進、心血管健康リスク[7]、自殺[8]、全死因死亡率[9]に関連している。 社会的なつながりを感じるかどうかは、家族、友人、知人との有意義な関係の質と数によって決まる。個人レベルを超えて、より大きなコミュニティとのつなが りを感じることも含まれる。コミュニティレベルでのつながりは、個人にとっても社会にとっても大きな利益をもたらす[10]。 |

| Related terms Social support is the help, advice, and comfort that we receive from those with whom we have stable, positive relationships.[11] Importantly, it appears to be the perception, or feeling, of being supported, rather than objective number of connections, that appears to buffer stress and affect our health and psychology most strongly.[12][13] Close relationships refer to those relationships between friends or romantic partners that are characterized by love, caring, commitment, and intimacy.[14] Attachment is a deep emotional bond between two or more people, a "lasting psychological connectedness between human beings."[15] Attachment theory, developed by John Bowlby during the 1950s, is a theory that remains influential in psychology today. Conviviality has many different interpretations and understandings, one of which denotes the idea of living together and enjoying each other's company. This understanding of the term is derived from the French convivialité, which can be traced back to Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin in the 19th century. Other interpretations of conviviality include the art of living in the company of others; everyday experiences of community cohesion and togetherness in diverse settings; and the capacity of individuals to interact creatively and autonomously with one another and their environment for the satisfaction of their needs. This third interpretation is rooted in the work of Ivan Illich from the 1970s onwards. Social connection is fundamental to all of these interpretations of conviviality. |

関連用語 社会的支援とは、安定した良好な関係を築いている人たちから受ける助け、助言、慰めのことである[11]。重要なことは、ストレスを緩衝し、私たちの健康 や心理に最も強く影響するのは、客観的なつながりの数ではなく、支援されているという認識、つまり感覚であるようだ[12][13]。 親密な関係とは、愛情、思いやり、コミットメント、親密さを特徴とする友人や恋愛パートナー間の関係を指す[14]。 愛着とは、2人以上の人間の間の深い感情的な結びつきのことであり、「人間同士の持続的な心理的つながり」[15]である。1950年代にジョン・ボウル ビーによって開発された愛着理論は、今日でも心理学に影響力を持つ理論である。 和気あいあいにはさまざまな解釈や理解があるが、そのひとつは、一緒に生活し、互いの付き合いを楽しむという考えを示すものである。この用語の理解はフランス語のconvivialitéに由来し、19世紀のジャン・アンテル ム・ブリヤ=サヴァランにまで遡ることができる。このほかにも、他者とともに生きる術、多様な環境における共同体の結束や一体感といった日 常的な経験、自分の欲求を満たすために創造的かつ自律的に互いや環境と相互作用する個人の能力といった解釈もある。この第三の解釈は、1970年代以降の イヴァン・イリッチの研究に根ざしている。社会的なつながりは、これらすべての和気あいあいとした解釈の根底にある。 |

| A basic need In his influential theory on the hierarchy of needs, Abraham Maslow proposed that our physiological needs are the most basic and necessary to our survival, and must be satisfied before we can move on to satisfying more complex social needs like love and belonging.[16] However, research over the past few decades has begun to shift our understanding of this hierarchy. Social connection and belonging may in fact be a basic need, as powerful as our need for food or water.[3] Mammals are born relatively helpless, and rely on their caregivers not only for affection, but for survival. This may be evolutionarily why mammals need and seek connection, and also for why they suffer prolonged distress and health consequences when that need is not met.[4] In 1965, Harry Harlow conducted his landmark monkey studies. He separated baby monkeys from their mothers, and observed which surrogate mothers the baby monkeys bonded with: a wire "mother" that provided food, or a cloth "mother" that was soft and warm. Overwhelmingly, the baby monkeys preferred to spend time clinging to the cloth mother, only reaching over to the wire mother when they became too hungry to continue without food.[17] This study questioned the idea that food is the most powerful primary reinforcement for learning. Instead, Harlow's studies suggested that warmth, comfort, and affection (as perceived from the soft embrace of the cloth mother) are crucial to the mother-child bond, and may be a powerful reward that mammals may seek in and of itself. Although historically significant, it is important to acknowledge that this study does not meet current research standards for the ethical treatment of animals.[18] In 1995, Roy Baumeister proposed his influential belongingness hypothesis: that human beings have a fundamental drive to form lasting relationships, to belong. He provided substantial evidence that indeed, the need to belong and form close bonds with others is itself a motivating force in human behavior. This theory is supported by evidence that people form social bonds relatively easily, are reluctant to break social bonds, and keep the effect on their relationships in mind when they interpret situations. He also contends that our emotions are so deeply linked to our relationships that one of the primary functions of emotion may be to form and maintain social bonds, and that both partial and complete deprivation of relationships leads to not only painful but pathological consequences.[3] Satisfying or disrupting our need to belong, our need for connection, has been found to influence cognition, emotion, and behavior.[19] In 2011, Roy Baumeister furthered this notion of belongingness by proposing the Need to Belong Theory, which asserts that humans have an inherent drive to maintain a minimum number of social relationships to foster a sense of belonging. Baumeister highlights the importance of satiation and substitution in driving human behavior and social connection. Motivational satiation is a phenomenon in which an individual may desire something, but at a certain point, they may reach a point where they have had enough and no longer want or need any more of it. This concept can be applied to the formation of friendships, where an individual may desire social connections, but they may reach a point where they have enough friends and do not seek any more. However, Baumeister suggests that people still require a certain minimum amount of social connection, and to some extent, these bonds can substitute for each other. The Need to Belong Theory is a primary motivator of human behavior, providing a framework for understanding social relationships as a basic, fundamental need for psychological health and well-being. |

基本的な欲求 アブラハム・マズローは、その影響力のある欲求階層説の中で、私たちの生理的欲求は最も基本的で生存に必要なものであり、愛や所属といったより複雑な社会 的欲求を満たす前に満たされなければならないと提唱した。哺乳類は比較的無力な状態で生まれてくるため、愛情だけでなく生存についても養育者に依存してい る。これは進化的に、哺乳類がつながりを必要とし、それを求める理由であり、またその必要性が満たされないときに長引く苦痛や健康被害を被る理由でもある のかもしれない[4]。 1965年、ハリー・ハーロウは画期的なサルの研究を行った。彼は子ザルを母親から引き離し、餌を与える針金の「母親」と、柔らかくて暖かい布の「母 親」、どちらの代理母親と子ザルが絆を結ぶかを観察した。圧倒的に、子ザルは布製の母親にしがみついて過ごすことを好み、食べ物がないと空腹で続けられな くなったときだけ、針金製の母親に手を伸ばした[17]。この研究は、食べ物が学習にとって最も強力な第一強化因子であるという考えに疑問を投げかけた。 その代わりに、ハーロウの研究は、温かさ、心地よさ、愛情(布製の母親の柔らかい抱擁から感じられる)が母子の絆にとって重要であり、哺乳類がそれ自体を 求める強力な報酬である可能性を示唆した。歴史的に重要ではあるが、この研究は動物の倫理的扱いに関する現在の研究基準を満たしていないことを認めること が重要である[18]。 1995年、ロイ・バウマイスターは影響力のある帰属性仮説を提唱した。バウマイスターは、人間には永続的な人間関係を形成し、帰属したいという根源的な 衝動があるという仮説を提唱し、実際に、他者に帰属し、親密な絆を形成したいという欲求そのものが、人間の行動の原動力となっているという実質的な証拠を 示した。この理論は、人は比較的容易に社会的な絆を形成し、社会的な絆を断ち切りたがらず、状況を解釈する際には人間関係への影響を念頭に置くという証拠 によって裏付けられている。彼はまた、私たちの感情は人間関係と非常に深く結びついており、感情の主要な機能の1つは社会的絆を形成し維持することである 可能性があり、人間関係の部分的な剥奪と完全な剥奪の両方が痛みを伴うだけでなく病的な結果をもたらすと主張している[3]。私たちの所属の欲求、つなが りの欲求を満足させたり中断させたりすることは、認知、感情、行動に影響を与えることがわかっている[19]。 2011年、ロイ・バウマイスターは「所属欲求理論」を提唱し、この所属欲求の概念をさらに発展させた。バウマイスターは、人間の行動と社会的つながりを 促進する上で、飽和と代替の重要性を強調している。動機づけの飽和とは、個人が何かを欲していても、ある時点で、もう十分だ、それ以上はいらないという状 態に達する現象である。この概念は友人関係の形成にも当てはめることができ、個人は社会的なつながりを望むかもしれないが、十分な友人がいてそれ以上は求 めないという段階に達するかもしれない。しかし、バウマイスターは、人は社会的なつながりのある一定の最低量をまだ必要としており、ある程度までは、これ らの結びつきが互いの代わりとなることを示唆している。所属する必要性理論は、人間の行動の主要な動機であり、心理的な健康と幸福のための基本的で基本的 な必要としての社会的関係を理解する枠組みを提供するものである。 |

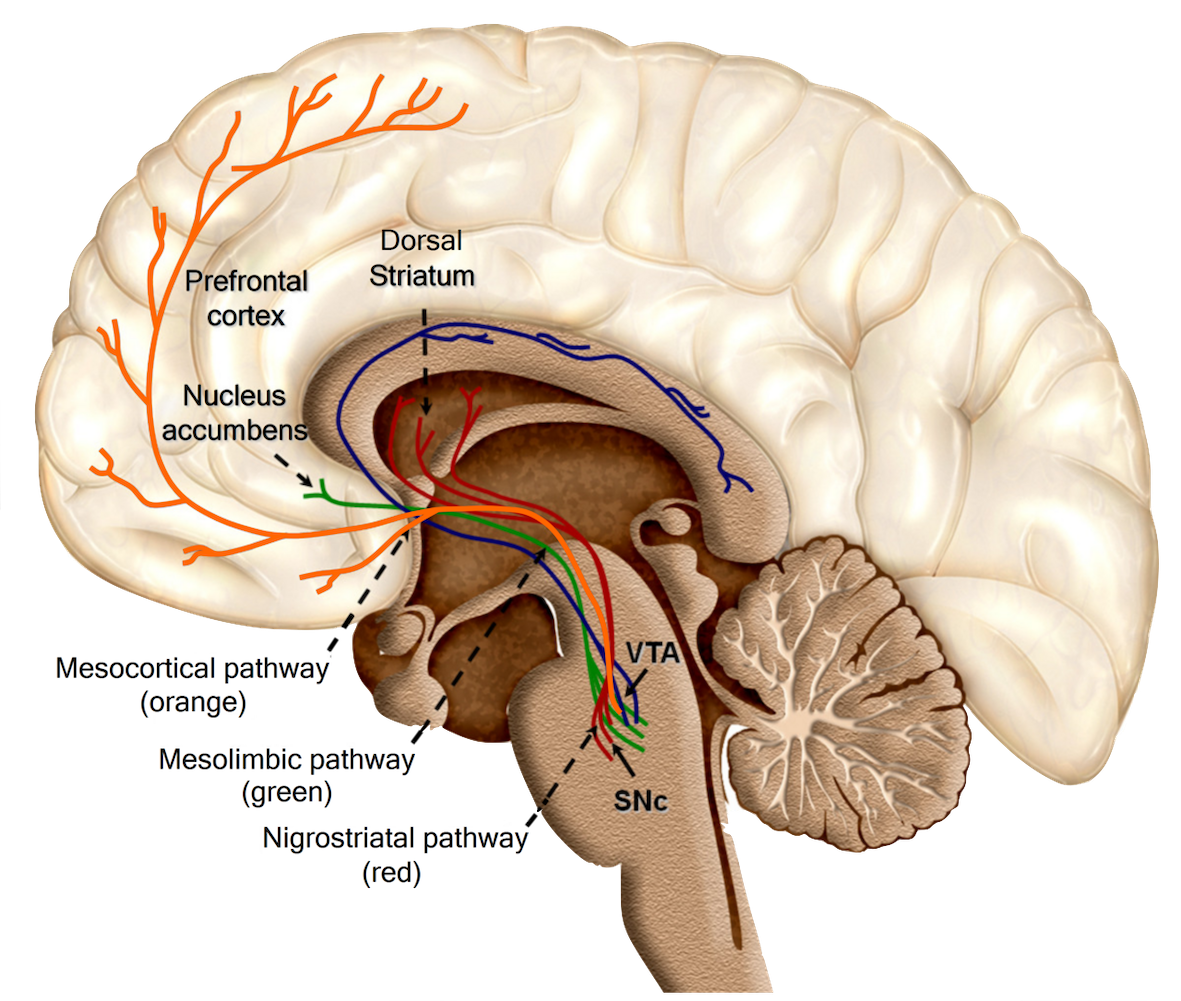

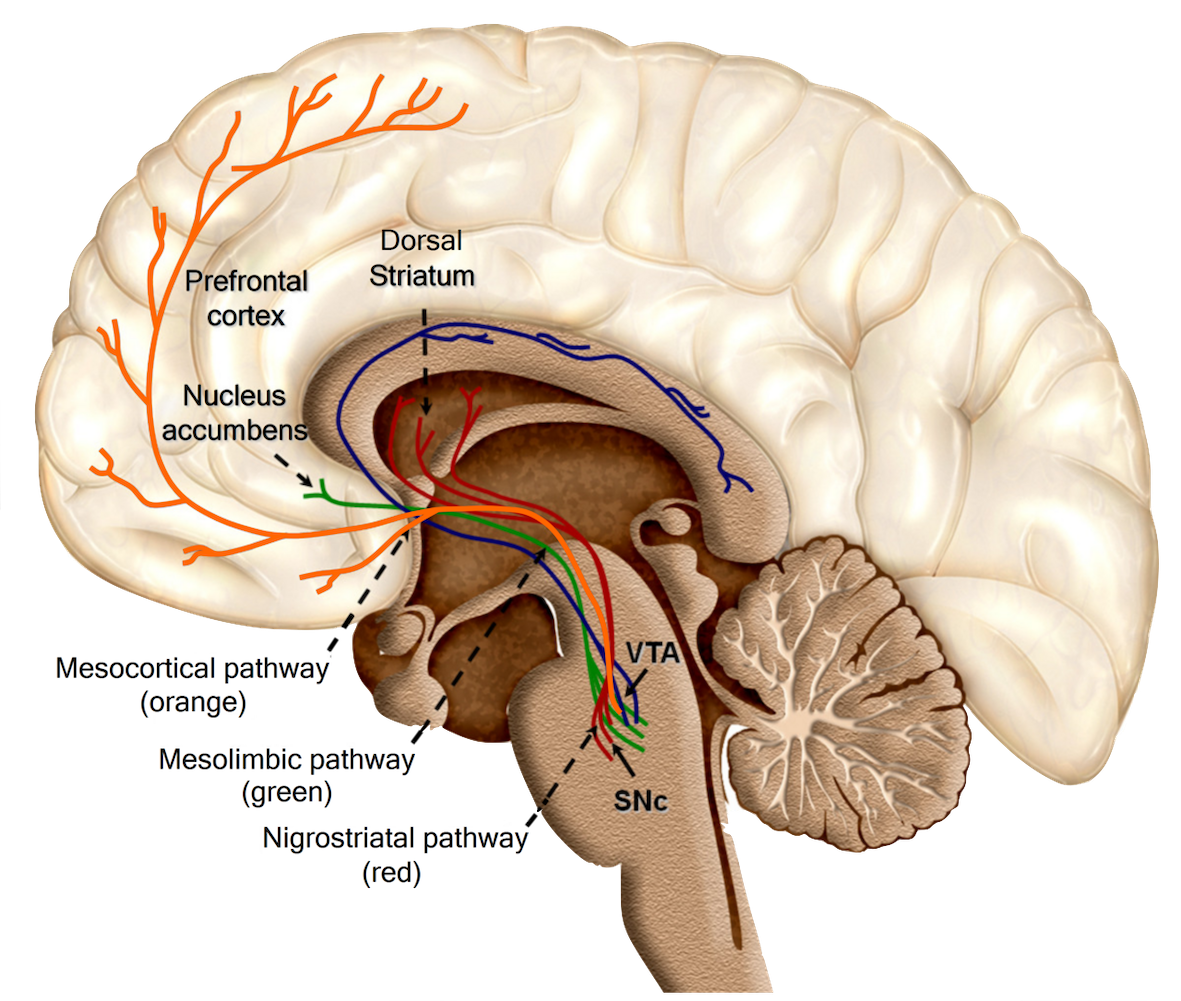

| Neurobiology Brain areas  Social connection activates the reward system of the brain. While it appears that social isolation triggers a "neural alarm system" of threat-related regions of the brain (including the amygdala, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), anterior insula, and periaqueductal gray (PAG)),[20] separate regions may process social connection. Two brain areas that are part of the brain's reward system are also involved in processing social connection and attention to loved ones: the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), a region that also responds to safety and inhibits threat responding, and the ventral striatum (VS) and septal area (SA), part of a neural system that is activated by taking care of one's own young.[1] Key neurochemicals Opioids In 1978, neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp observed that small doses of opiates reduced the distressed cries of puppies that were separated from their mothers. As a result, he developed the brain opioid theory of attachment, which posits that endogenous (internally produced) opioids underlie the pleasure that social animals derive from social connection, especially within close relationships.[21] Extensive animal research supports this theory. Mice who have been genetically modified to not have mu-opioid receptors (mu-opioid receptor knockout mice), as well as sheep with their mu-receptors blocked temporarily following birth, do not recognize or bond with their mother. When separated from their mother and conspecifics, rats, chicks, puppies, guinea pigs, sheep, dogs, and primates emit distress vocalizations, however giving them morphine (i.e. activating their opioid receptors), quiets this distress. Endogenous opioids appear to be produced when animals engage in bonding behavior, while inhibiting the release of these opioids results in signs of social disconnection.[22][23] In humans, blocking mu-opioid receptors with the opioid antagonist naltrexone has been found to reduce feelings of warmth and affection in response to a film clip about a moment of bonding, and to increase feelings of social disconnection towards loved ones in daily life as well as in the lab in response to a task designed to elicit feelings of connection. Although the human research on opioids and bonding behavior is mixed and ongoing, this suggests that opioids may underlie feelings of social connection and bonding in humans as well.[24] Oxytocin In mammals, oxytocin has been found to be released during childbirth, breastfeeding, sexual stimulation, bonding, and in some cases stress.[25] In 1992, Sue Carter discovered that administering oxytocin to prairie voles would accelerate their monogamous pair-bonding behavior.[26] Oxytocin has also been found to play many roles in the bonding between mother and child.[27] In addition to pair-bonding and motherhood, oxytocin has been found to play a role in prosocial behavior and bonding in humans. Nicknamed the “love drug” or “cuddle chemical,” plasma levels of oxytocin increase following physical affection,[28] and are linked to more trusting and generous social behavior, positively biased social memory, attraction, and anxiety and hormonal responses.[29] Further supporting a nuanced role in adult human bonding, greater circulating oxytocin over a 24-hour period was associated with greater love and perceptions of partner responsiveness and gratitude,[30] however was also linked to perceptions of a relationship being vulnerable and in danger. Thus oxytocin may play a flexible role in relationship maintenance, supporting both the feelings that bring us closer and the distress and instinct to fight for an intimate bond in peril.[31] |

神経生物学 脳領域  社会的つながりは脳の報酬系を活性化する。 社会的孤立は脳の脅威関連領域(扁桃体、背側前帯状皮質 (dACC)、前部島皮質、脳橋周囲灰白質(PAG)を含む) [20] の「神経アラームシステム」を作動させるようであるが、別の領域が社会的つながりを処理することもある。脳の報酬系の一部である2つの脳領域は、社会的な つながりや愛する人への注意の処理にも関与している。安全性にも反応し、脅威反応を抑制する領域である内側前頭前皮質(VMPFC)と、腹側線条体 (VS)と中隔領域(SA)は、自分の子供の世話をすることで活性化される神経系の一部である[1]。 主要な神経化学物質 オピオイド 1978年、神経科学者のヤーク・パンクセップは、少量のアヘン剤を投与すると、母親から引き離された子犬の苦痛に満ちた鳴き声が減少することを観察し た。その結果、彼は愛着に関する脳内オピオイド理論を構築し、社会的動物が社会的つながり、特に親密な関係の中で得る快感の根底には、内因性(体内で生成 される)オピオイドが存在すると仮定した。mu-オピオイド受容体を持たないように遺伝子改変されたマウス(mu-オピオイド受容体ノックアウトマウス) や、出生後に一時的にmu-受容体を遮断したヒツジは、母親を認識せず、母親との絆を結ばない。母親や同種の動物から引き離されると、ラット、ヒヨコ、子 犬、モルモット、ヒツジ、イヌ、霊長類は苦痛の発声をしますが、モルヒネを与えると(すなわちオピオイド受容体を活性化させると)、この苦痛は静まりま す。内因性オピオイドは動物が絆を深める行動をとる際に産生されるようであり、一方、これらのオピオイドの放出を阻害すると、社会的断絶の徴候が生じる [22][23]。ヒトでは、オピオイド拮抗薬ナルトレキソンでmu-オピオイド受容体を遮断すると、絆を深める瞬間についての映画クリップに反応して温 かさと愛情の感情が減少し、日常生活や実験室で絆の感情を引き出すようにデザインされた課題に反応して、愛する人に対する社会的断絶の感情が増加すること が判明している。オピオイドと絆形成行動に関するヒトでの研究はまちまちであり、現在も進行中であるが、このことは、オピオイドがヒトにおいても社会的つ ながりと絆形成の感情の根底にある可能性を示唆している[24]。 オキシトシン 哺乳類では、オキシトシンは出産、授乳、性的刺激、結合、そして場合によってはストレスの際に分泌されることが発見されている。 [26]オキシトシンはまた、母子間の結合において多くの役割を果たすことが発見されている。[27]ペア結合と母性に加えて、オキシトシンはヒトの向社 会的行動と結合において役割を果たすことが発見されている。愛の薬」または「抱擁の化学物質」と呼ばれるオキシトシンの血漿濃度は、身体的愛情に続いて増 加し [28] 、より信頼し寛大な社会的行動、肯定的に偏った社会的記憶、魅力、不安およびホルモン反応と関連している。 [29] 成人期のヒトの絆における微妙な役割をさらに裏付けるように、24時間の循環オキシトシン濃度が高いほど、より大きな愛情や、パートナーの応答性や感謝の 認識と関連していた[30]が、同時に関係が脆弱で危険であるという認識とも関連していた。したがって、オキシトシンは関係維持において柔軟な役割を果た し、私たちを近づける感情と、危機に瀕した親密な絆のために戦う苦悩と本能の両方を支えているのかもしれない[31]。 |

| Health Consequences of disconnection See also: Loneliness A wide range of mammals, including rats, prairie voles, guinea pigs, cattle, sheep, primates, and humans, experience distress and long-term deficits when separated from their parent.[4] In humans, long-lasting health consequences result from early experiences of disconnection. In 1958, John Bowlby observed profound distress and developmental consequences when orphans lacked warmth and love of our first and most important attachments: our parents.[32] Loss of a parent during childhood was found to lead to altered cortisol and sympathetic nervous system reactivity even a decade later,[33] and affect stress response and vulnerability to conflict as a young adult.[34] In addition to the health consequences of lacking connection in childhood, chronic loneliness at any age has been linked to a host of negative health outcomes. In a meta-analytic review conducted in 2010, results from 308,849 participants across 148 studies found that people with strong social relationships had a 50% greater chance of survival. This effect on mortality is not only on par with one of the greatest risks, smoking, but exceeds many other risk factors such as obesity and physical inactivity.[9] Loneliness has been found to negatively affect the healthy function of nearly every system in the body: the brain,[7] immune system,[6] circulatory and cardiovascular systems,[35] endocrine system,[36] and genetic expression.[37]  Between 15 and 30% of the general population feels chronic loneliness. Not only is social isolation harmful to health, but it is more and more common. As many as 80% of young people under 18 years old, and 40% of adults over the age of 65 report being lonely sometimes, and 15–30% of the general population feel chronic loneliness.[7] These numbers appear to be on the rise, and researchers have called for social connection to be public health priority.[38] Social immune system One of the main ways social connection may affect our health is through the immune system. The immune system's primary activity, inflammation, is the body's first line of defense against injury and infection. However, chronic inflammation has been tied to atherosclerosis, Type II diabetes, neurodegeneration, and cancer, as well as compromised regulation of inflammatory gene expression by the brain.[1] Research over the past few decades has revealed that the immune system not only responds to physical threats, but social ones as well. It has become clear that there is a bidirectional relationship between circulating biomarkers of inflammation (e.g. the cytokine IL-6) and feelings of social connection and disconnection; not only are feelings of social isolation linked to increased inflammation, but experimentally induced inflammation alters social behavior and induces feelings of social isolation.[6] This has important health implications. Feelings of chronic loneliness appear to trigger chronic inflammation. However, social connection appears to inhibit inflammatory gene expression and increase antiviral responses.[39] Performing acts of kindness for others were also found to have this effect, suggesting that helping others provides similar health benefits.[40] Why might our immune system respond to our perceptions of our social world? One theory is that it may have been evolutionarily adaptive for our immune system to "listen" in to our social world to anticipate the kinds of bacterial or microbial threats we face. In our evolutionary past, feeling socially isolated may have meant we were separated from our tribe, and therefore more likely to experience physical injury or wounds, requiring an inflammatory response to heal. On the other hand, feeling connected may have meant we were in relative physical safety of community, but at greater risk of socially transmitted viruses. To meet these threats with greater efficiency, the immune system responds with anticipatory changes.[1][41] A genetic profile was discovered to initiate this pattern of immune response to social adversity and stress — up-regulation of inflammation, down-regulation of antiviral activity — known as Conserved Transcriptional Response to Adversity.[42] The inverse of this pattern, associated with social connection, has been linked to positive health outcomes as well as eudaemonic well-being.[43] Positive pathways Social connection and support have been found to reduce the physiological burden of stress and contribute to health and well-being through several other pathways as well, although there remains a subject of ongoing research. One way social connection reduces our stress response is by inhibiting activity in our pain and alarm neural systems. Brain areas that respond to social warmth and connection (notably, the septal area) have inhibitory connections to the amygdala, which have the structural capacity to reduce threat responding.[44] Another pathway by which social connection positively affects health is through the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), the "rest and digest" system which parallels and offsets the "flight or fight" sympathetic nervous system (SNS). Flexible PNS activity, indexed by vagal tone, helps regulate the heart rate and has been linked to a healthy stress response as well as numerous positive health outcomes.[45] Vagal tone has been found to predict both positive emotions and social connectedness, which in turn result in increased vagal tone, in an "upward spiral" of well-being.[46] Social connection often occurs along with and causes positive emotions, which themselves benefit our health.[47][48] |

健康 断絶の結果 こちらもご覧ください: 孤独 ラット、プレーリーハタネズミ、モルモット、ウシ、ヒツジ、霊長類、ヒトなど、さまざまな哺乳類は、親から引き離されると苦痛を感じ、長期的な障害を経験 する[4]。1958年、ジョン・ボウルビィは、孤児が私たちの最初で最も重要な愛着である両親の温もりと愛情を欠いた場合、深刻な苦痛と発達に影響を及 ぼすことを観察した[32]。幼少期に親を失うと、10年後でもコルチゾールと交感神経系の反応性が変化し[33]、若年成人期のストレス反応と葛藤に対 する脆弱性に影響を及ぼすことが判明した[34]。 幼少期のつながりの欠如による健康への影響に加え、どの年齢においても慢性的な孤独は、多くの健康上の悪い結果につながっている。2010年に実施された メタ分析レビューでは、148の研究にわたる308,849人の参加者の結果から、強い社会的関係を持つ人は生存の可能性が50%高いことがわかった。こ の死亡率への影響は、最大のリスクのひとつである喫煙に匹敵するだけでなく、肥満や運動不足など他の多くの危険因子を上回るものである[9]。孤独は、脳 [7]、免疫系[6]、循環器系および心臓血管系[35]、内分泌系[36]、遺伝子発現[37]など、体内のほぼすべてのシステムの健全な機能に悪影響 を及ぼすことがわかっている。  一般人口の15~30%が慢性的な孤独を感じている。 社会的孤立は健康に有害であるだけでなく、ますます一般的になっている。18歳未満の若者の80%、65歳以上の成人の40%が時々孤独を感じると回答しており、一般人口の15~30%が慢性的な孤独を感じている[7]。 社会的免疫システム 社会的なつながりが私たちの健康に影響を与える主な方法の1つは、免疫系を通じてである。免疫系の主要な活動である炎症は、傷害や感染に対する身体の第一 の防御ラインである。しかし、慢性的な炎症は、動脈硬化、Ⅱ型糖尿病、神経変性、がんと関連しており、脳による炎症性遺伝子発現の制御が損なわれているこ ともわかっている。循環している炎症のバイオマーカー(サイトカインIL-6など)と、社会的なつながりや断絶の感情との間には双方向の関係があることが 明らかになっている。社会的孤立の感情は炎症の増加と関連しているだけでなく、実験的に誘発された炎症は社会的行動を変化させ、社会的孤立の感情を誘発す る[6]。慢性的な孤独感は慢性的な炎症を引き起こすようだ。しかし、社会的なつながりは炎症遺伝子の発現を抑制し、抗ウイルス反応を増加させるようであ る[39]。他人のために親切な行為をすることもこの効果があることが判明しており、他人を助けることも同様の健康効果をもたらすことが示唆されている [40]。 なぜ私たちの免疫システムは、私たちの社会的世界に対する認識に反応するのだろうか。一説によると、私たちが直面する細菌や微生物の脅威の種類を予測する ために、私たちの免疫系が社会的世界に「耳を傾ける」ことは、進化的に適応的であった可能性がある。私たちの進化の過去において、社会的に孤立していると 感じることは、私たちが部族から引き離されていることを意味し、それゆえ肉体的な傷や怪我を経験しやすく、治癒のために炎症反応を必要としたのかもしれな い。一方、社会的なつながりを感じるということは、物理的には比較的安全な共同体の中にいることを意味するが、社会的に感染するウイルスのリスクはより高 いことを意味する。社会的逆境やストレスに対する免疫反応のこのパターン(炎症のアップレギュレーション、抗ウイルス活性のダウンレギュレーション)を引 き起こす遺伝子プロファイルが発見され、「逆境に対する保存された転写反応(Conserved Transcriptional Response to Adversity)」として知られている[42]。社会的なつながりと関連するこのパターンの逆は、幸福感だけでなく、肯定的な健康アウトカムに関連し ている[43]。 ポジティブな経路 社会的なつながりと支援はストレスの生理的負担を軽減し、他のいくつかの経路を通じても健康と幸福に寄与することが判明していますが、現在も研究が進めら れています。社会的なつながりがストレス反応を軽減する方法のひとつは、痛覚や警報神経系の活動を抑制することである。社会的な温かさやつながりに反応す る脳領域(特に中隔領域)には扁桃体への抑制性結合があり、脅威反応を抑制する構造的な能力がある[44]。 社会的なつながりが健康にプラスの影響を与えるもう一つの経路は、副交感神経系(PNS)を介したもので、「逃走か闘争か」の交感神経系(SNS)と平行 して相殺する「休息と消化」のシステムである。迷走神経緊張によって指標化される柔軟なPNS活動は、心拍数の調節を助け、健康的なストレス反応だけでな く、多くのポジティブな健康転帰に関連している[45]。迷走神経緊張は、ポジティブな感情と社会的つながりの両方を予測することが判明しており、その結 果、迷走神経緊張が増加し、幸福の「上昇スパイラル」が生じる[46]。社会的つながりは、ポジティブな感情とともに生じ、それを引き起こすことが多く、 それ自体が私たちの健康に有益である[47][48]。 |

| Measures Social Connectedness Scale[49] This scale was designed to measure general feelings of social connectedness as an essential component of belongingness. Items on the Social Connectedness Scale reflect feelings of emotional distance between the self and others, and higher scores reflect more social connectedness. UCLA Loneliness Scale[50] Measuring feelings of social isolation or disconnection can be helpful as an indirect measure of feelings of connectedness. This scale is designed to measure loneliness, defined as the distress that results when one feels disconnected from others.[51] Relationship Closeness Inventory (RCI)[52] This measure conceptualizes closeness in a relationship as a high level of interdependence in two people's activities, or how much influence they have over one another. It correlates moderately with self-reports of closeness, measured using the Subjective Closeness Index (SCI). Liking and Loving Scales[53] These scales were developed to measure the difference between liking and loving another person—critical aspects of closeness and connection. Good friends were found to score highly on the liking scale, and only romantic partners scored highly on the loving scale. They support Zick Rubin's conceptualization of love as containing three main components: attachment, caring, and intimacy. Personal Acquaintance Measure (PAM)[54] This measure identifies six components that can help determine the quality of a person's interactions and feelings of social connectedness with others: Duration of relationship Frequency of interaction with the other person Knowledge of the other person's goals Physical intimacy or closeness with the other person Self-disclosure to the other person Social network familiarity—how familiar is the other person with the rest of your social circle |

測定方法 社会的つながり尺度[49] この尺度は、所属感の本質的な構成要素としての社会的つながりの一般的な感情を測定するために考案された。社会的連結性尺度の項目は、自己と他者との間の感情的距離の感情を反映し、得点が高いほど社会的連結性が高いことを示す。 UCLA孤独尺度[50]。 社会的孤立感や断絶感を測定することは、つながり感の間接的な尺度として有用である。この尺度は、他者から切り離されていると感じるときに生じる苦痛として定義される孤独感を測定するように設計されている[51]。 関係親密性目録(RCI)[52]。 この尺度は、関係における親密さを、2人の活動における相互依存の高さ、または2人がお互いにどれだけの影響力を持っているかを概念化したものである。主観的親密さ指数(SCI)を用いて測定された親密さの自己報告と中程度の相関がある。 好意尺度および愛情尺度[53]。 これらの尺度は、親密さとつながりの重要な側面である、他人を好きであることと愛していることの違いを測定するために開発された。好意尺度では仲の良い友 人が高得点を示し、愛情尺度ではロマンチックなパートナーだけが高得点を示した。この結果は、ジック・ルービンによる、愛着、思いやり、親密さという3つ の主要な要素を含む愛の概念化を支持するものである。 個人的知人度測定法(PAM)[54]。 この測定法は、人の相互作用の質および他者との社会的つながりの感情を決定するのに役立つ6つの要素を特定する: 関係期間 相手との相互作用の頻度 相手の目標に関する知識 相手との身体的な親密さまたは親密さ 相手に対する自己開示 ソーシャル・ネットワークの親密さ 相手があなたの他のソーシャル・サークルとどの程度親密であるか |

| Experimental manipulations Social connection is a unique, elusive, person-specific quality of our social world. Yet, can it be manipulated? This is a crucial question for how it can be studied, and whether it can be intervened on in a public health context. There are at least two approaches that researchers have taken to manipulate social connection in the lab: Social connection task This task was developed at UCLA by Tristen Inagaki and Naomi Eisenberger to elicit feelings of social connection in the laboratory. It consists of collecting positive and neutral messages from 6 loved ones of a participant, and presenting them to the participant in the laboratory. Feelings of connection and neural activity in response to this task have been found to rely on endogenous opioid activity.[24] Closeness-generating procedure Arthur Aron at the State University of New York at Stony Brook and collaborators designed a series of questions designed to generate interpersonal closeness between two individuals who have never met. It consists of 36 questions that subject pairs ask each other over a 45-minute period. It was found to generate a degree of closeness in the lab, and can be more carefully controlled than connection within existing relationships.[55] |

実験的操作 社会的なつながりは、私たちの社会的世界におけるユニークでとらえどころのない、その人固有の性質である。しかし、それを操作することはできるのだろう か?これは、社会的つながりをどのように研究し、公衆衛生の文脈で介入できるかどうかという点で、極めて重要な問題である。研究室で社会的つながりを操作 するために、研究者たちがとってきたアプローチは少なくとも2つある: あ 社会的つながり課題 この課題は、UCLAでTristen InagakiとNaomi Eisenbergerによって開発されたもので、実験室で社会的つながりの感情を引き出すためのものである。これは、参加者の愛する人6人から肯定的な メッセージと中立的なメッセージを集め、実験室で参加者に提示するというものである。この課題に対するつながりの感覚と神経活動は、内因性オピオイド活性 に依存していることが判明している[24]。 親近感生成手順 ニューヨーク州立大学ストーニーブルック校のアーサー・アロンと共同研究者らは、初対面の2人の間に対人的な親近感を生み出すようにデザインされた一連の 質問を考案した。これは、被験者ペアが45分間にわたって互いに質問する36の質問からなる。これは、研究室内である程度の親密さを生み出すことができ、 既存の人間関係の中でのつながりよりも注意深くコントロールできることがわかった[55]。 |

| Affection Attachment theory Friendship Interpersonal relationships Interpersonal ties Interpersonal emotion regulation Intimate relationships Human bonding Love Social isolation Social robot Social support |

愛情 愛着理論 友情 対人関係 対人関係 対人感情調節 親密な関係 人間の絆 愛情 社会的孤立 社会的ロボット 社会的支援 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_connection |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆