“Stealing remains is criminal”:

Ethical,

Legal, and Social Issues of the repatriation of human remains to Ryukyu

islands, southern Japan

Mitsuho IKEDA

“Stealing remains is criminal”:

Ethical,

Legal, and Social Issues of the repatriation of human remains to Ryukyu

islands, southern Japan

Mitsuho IKEDA

In December 4, 2018, an activist group which claims indigenous rights has filed a lawsuit against Kyoto University for return of the remains of royal Ryukyuan Mumujana tomb in Nakijin village, Okinawa prefecture, Ryukyu-Japan. In this presentation, I will analyze the debates regarding the Rykyuan human remains among scholars, lawyers, and civil activists and Japanese university authority in terms of ethical, legal, and social aspects. The leader of activist group and his followers share the political ideology of independence of Ryukyu island as ethnic entity from mainland Japan. Their style of claiming for repatriation is influenced by the Ainu indigenous activism in northern Japan. Based on the codes of the definition of UNDRIP indigenous people the Ryukyuan activists have been formulating collective rights of indigenousness. The university authority delays the response to their claims because the authority always inquires the official response by central government office. At the moment, these disputes come to a deadlock. The indigenous activists want to establish the collective entitlement of indigenous rights for the repatriation of remains that has not been enacted on. The university officials reject their demands in terms of legal conformity of “successors to the rituals of the family” congruent to present Japanese civil laws. The royal descendants of Ryukyu family as well as activists are claiming that royal remains should be repatriated with compensations and finally be re-buried in traditional aerial sepulture. From these debates and disputes, we should ask a series of questions such as; 1. What is their concept of property or repatriation of human remains and burial materials? 2. What is the collective human rights of indigenous peoples? 3. Why do indigenous people ask to have both collective human rights and repatriation of their “ancestral” heritage from universities? and 4. What is the difference of property right among indigenous people from ordinary neighborhood citizen?

|

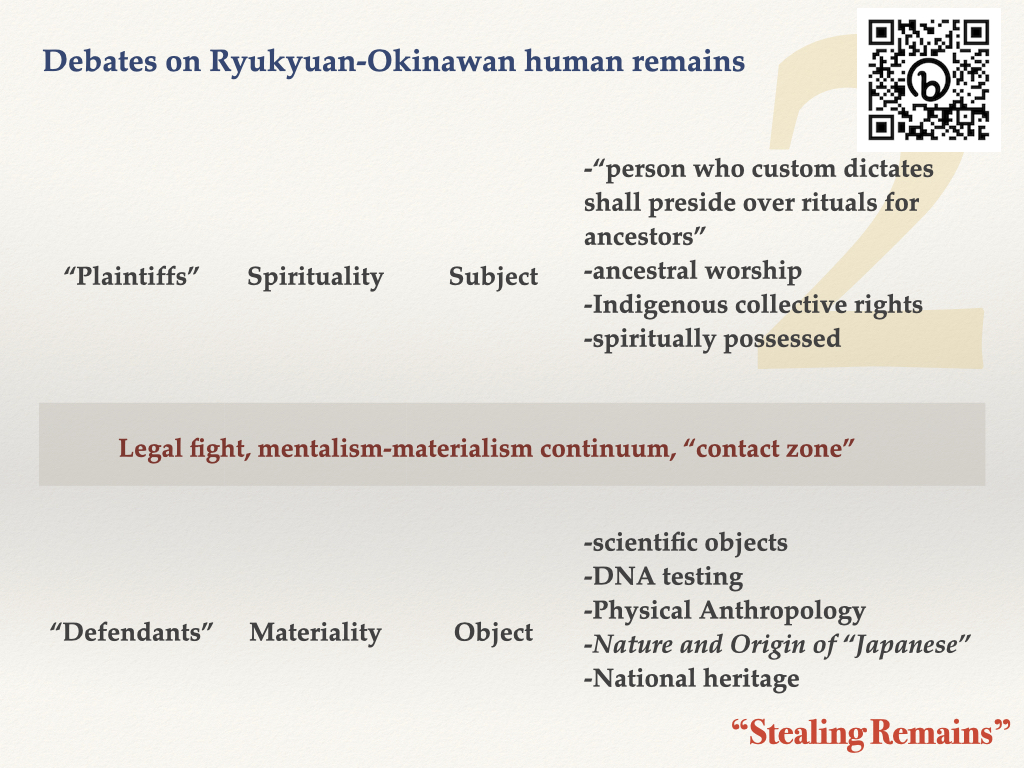

1 I will discuss the ethical, legal, and social implications (ELSI ) of the debates on the repatriation of Ryukyuan-Okinawan human remains. The debates between indigenous peoples with lawyers and civil activists, the so-called “plaintiff,”, who requested the repatriation, and the national universities that stored human remain, as “defendant”, which should negotiate formally with indigenous people, came to a deadlock for over ten years . The plaintiffs wanted to establish the collective entitlement of indigenous rights to the repatriation of remains and objects that have not been enacted. The defendant rejected repatriation claims to them by demanding in legal conformity with the “the person who custom dictates shall preside over rituals for ancestors” according to the article 897 in current Japanese Civil Code . |

|

2 Following the ratification of UNDRIP, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples by the Japanese government in 2007, the Ainu, one of Japanese northern ethnic minorities, began to promote the repatriation of human remains and burial materials. Meanwhile, the debate about the translocation of the US military base in Okinawa prefecture, southern Japan has evoked rising local Ryukyuan nationalism from 2008, when the Japanese government adopted a resolution recognizing the Ainu population. In plenary session during the U.N. forum (of the 19 April, 2008), a representative of the Japanese mission stated that the government “respects Okinawa’s culture and traditions” but also stated that “there is no widespread understanding in Japan that the people of Okinawa are indigenous people.” . In this context, the Ryukyuan activists have adopted the Ainu strategy demanding the repatriation of human remains. |

|

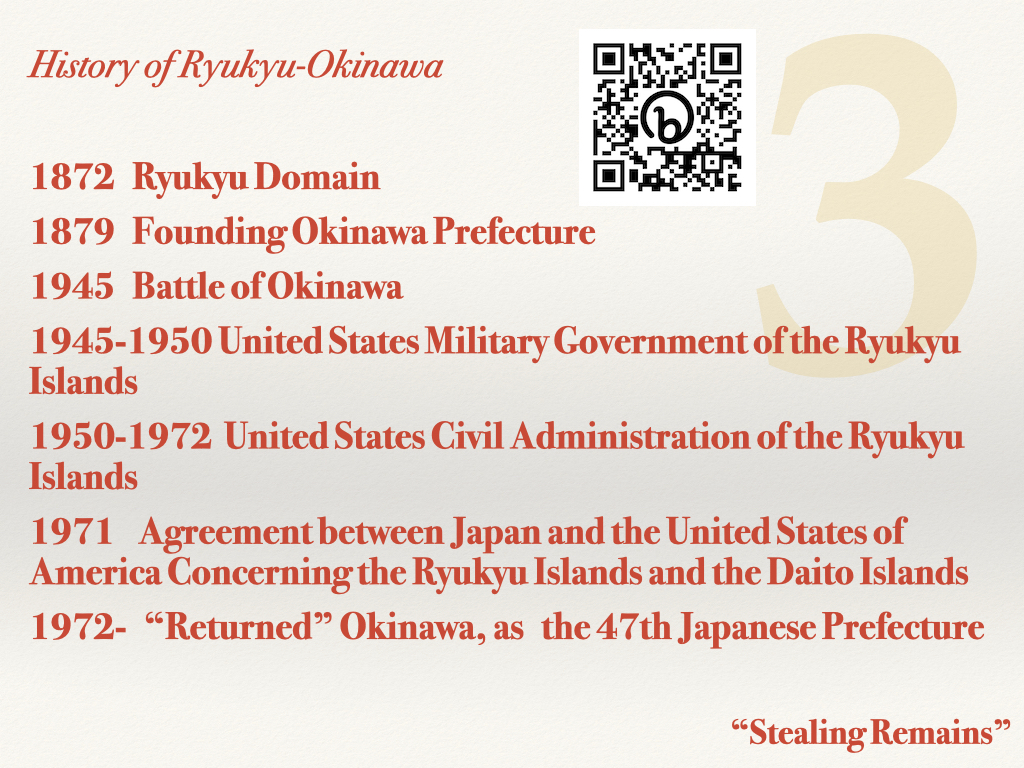

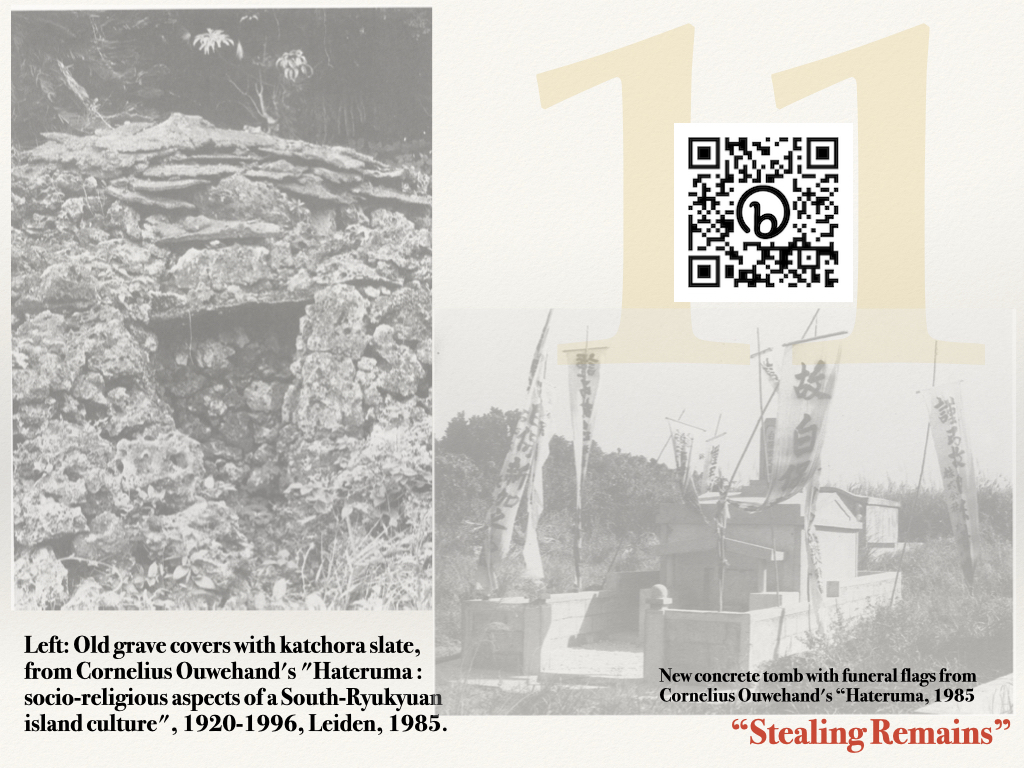

3 Ryukuan Story of Bones For the sake of our argument, let us take some stories about the repatriation of bones in Okinawa prefecture. In Ryukyu, the name of Kingdom, the authentic name of the southern prefecture of Okinawa, the repatriation movement developed along a different path to the Ainu. Ryukyuan intellectuals have tended to think that the Japanese central government has discriminated against their people since the settlement and domination of the Ryukyu Domain in 1872 and the founding of the Okinawa Prefecture in 1879. From 1945 it is thought that Ryukyu was placed under colonial rule by the Japanese central government, which permitted Allied Forces, chiefly the U.S. Army, to exercise trusteeship domination of their territory . The Ryukyu Trustee Government ended in 1972 . Due to this trend, the resettlement of Okinawa prefecture could be interpreted as the continuation of colonial domination. Even today, almost eighty percent of U.S. Forces military bases are located in Okinawa prefecture. |

|

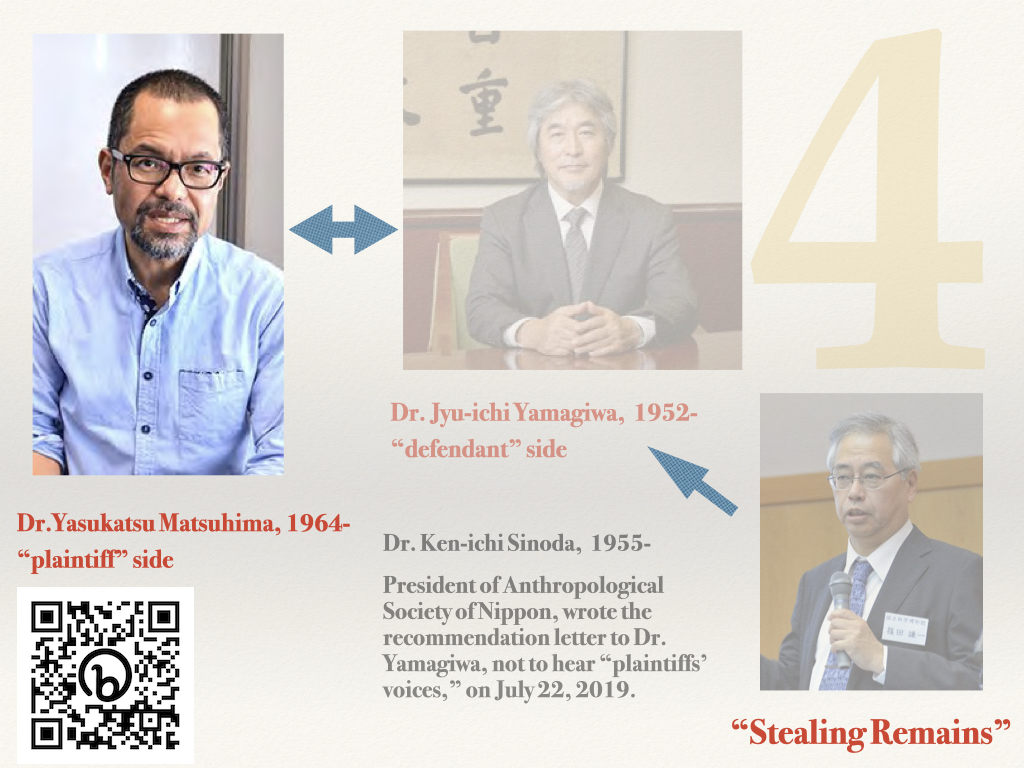

4 After the 1995 Okinawa 12 years girl rape incident, it can be said that the Ryukyu independent movement had been created. One of the most powerful intellectuals of the Ryukyu independent movement, Prof. Yasukazu Matsushima, a Rykyuan, of Ryukoku University in Kyoto, organized the Association of the Indigenous People of Ryukyu . He has published several books on the colonial history of Ryukyu and the possibility of her independence. |

|

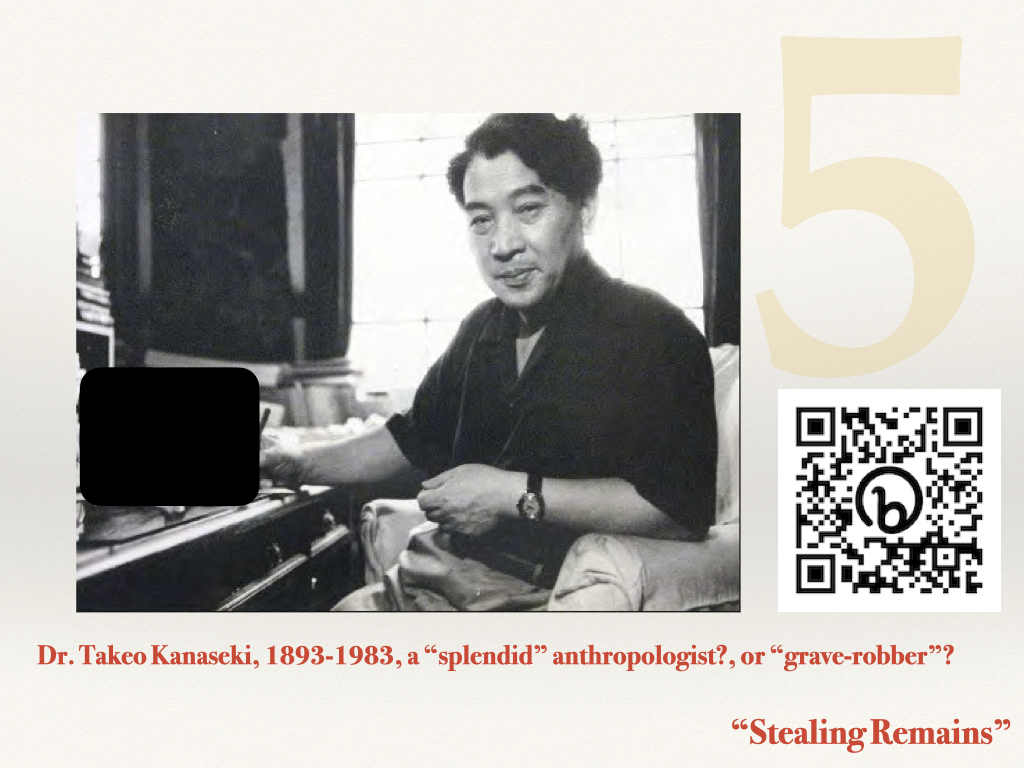

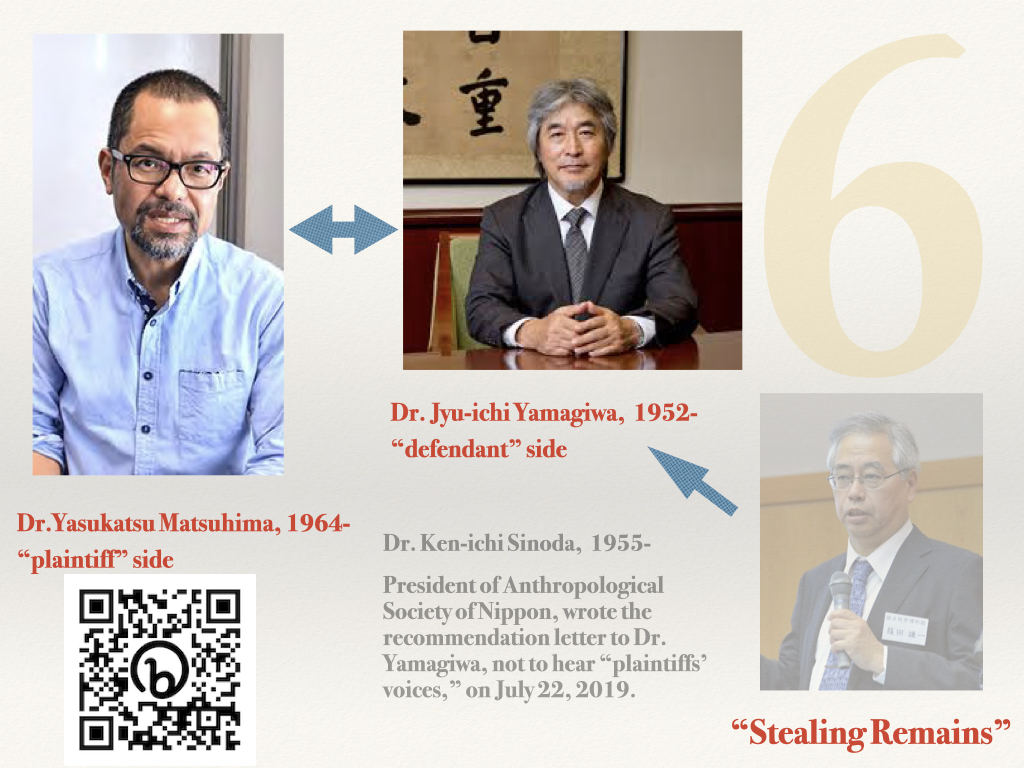

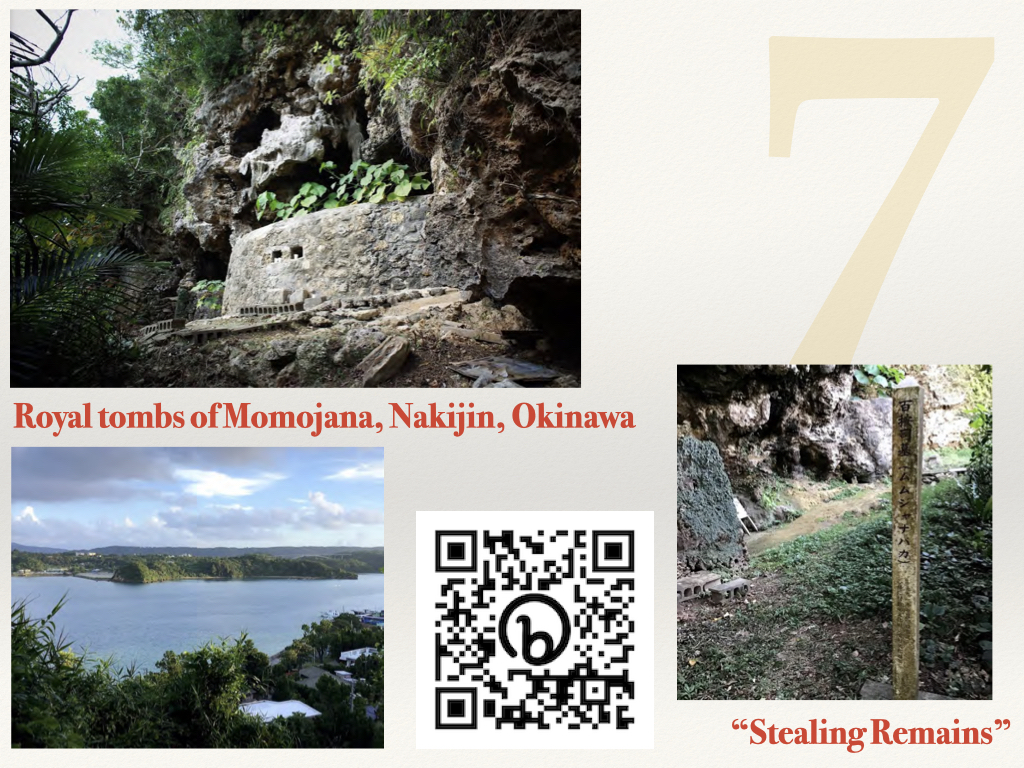

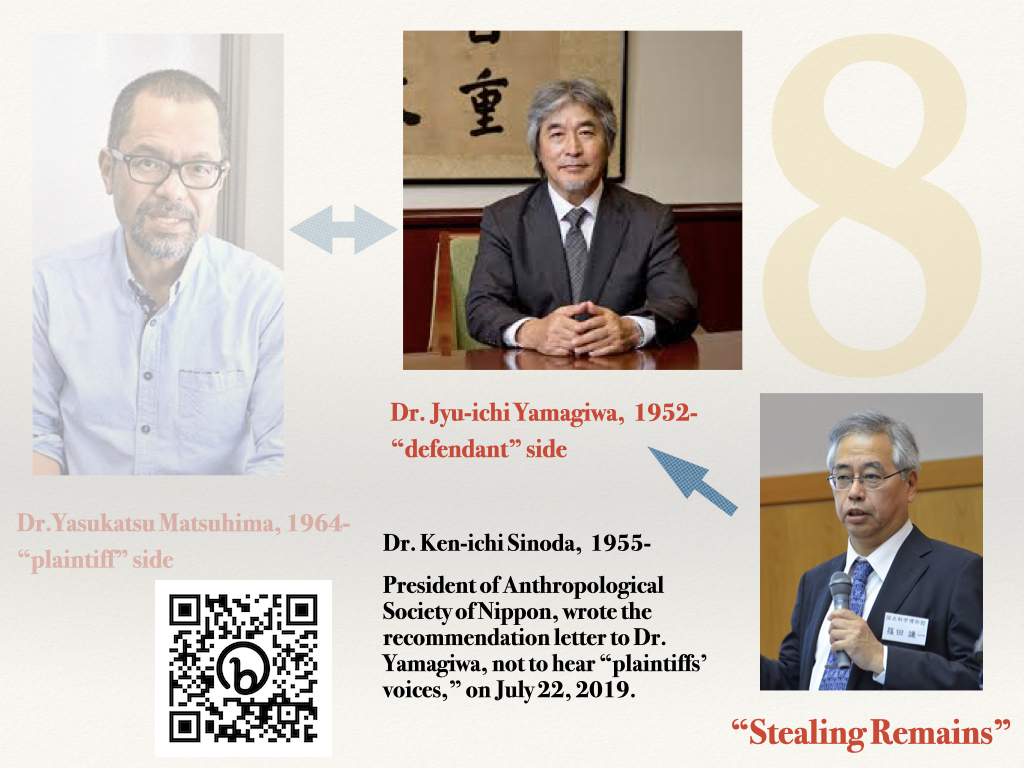

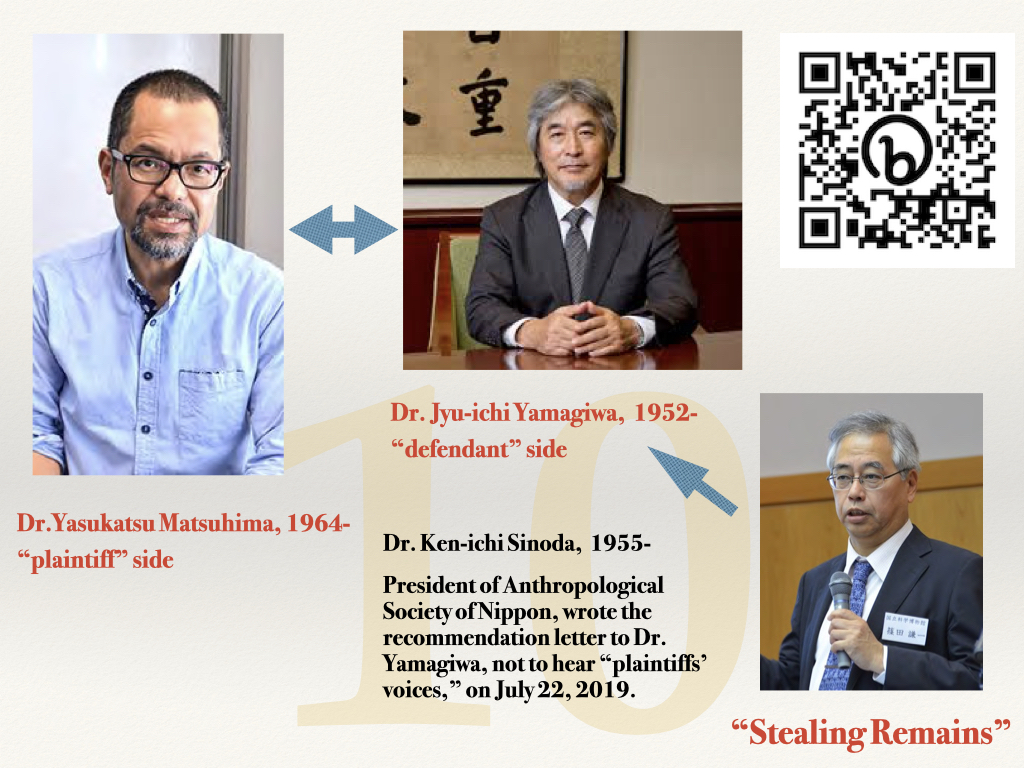

5 When Dr.Matsushima was conducting his research, he knew that a famous Japanese anatomist , Dr. Takeo Kanaseki (1897–1983), former professor of Taipei Imperial University, had “grave-robbed” over fifty bodies from the Royal Tombs of Momojyana, Nakijin from 1928 to 29. These bodies have remained in storage at both in Taiwan National University and in Kyoto University. However, 63 remains at the Taiwan National University were repatriated to the Okinawa Prefectural Center for Buried Cultural Properties in March 2019. Even though Prof. Matsushima had requested Kyoto University to disclose historical information about the “stealing” process and to repatriate the bodies, he and the descendants of the royal family brought the case before the Kyoto District Court at the end of 2018 . In this case Prof. Matsushima is the representative of the plaintiff, and the Kyoto University whose president is Dr. Jyu-ichi Yamagiwa, a worldly famous primatologist of Gorillas in Africa, takes defendant side. In his several lecture meetings for both academics and civil activists, Prof. Matsushima has repeatedly asserted, "Stealing human remains is criminal in our common sense, not only for Ryukyuan but for all the Japanese." |

|

6 In the same period some members of the Anthropological Society of Nippon, specialist group of physical anthropology in Japan, have organized open sessions for Japanese audience to discuss the "importance of their studies" (that means objects of both the Ainu and the ancient Jomon people of 16,000-3,000 BP) by using human remain including both Ainu and Ryukyuan people . However on July 2019, the president Dr. Ken-ichi Shinoda wrote the letter to the president of Kyoto university, Dr. Yamagiwa, not to hear the "plaintiff's voices and requests." Dr. Shinoda wrote that, |

|

7 "For the sake of the maintenance and inheritance of old human remains, the Anthropological Society of Nippon thinks following three principles mentioned below; (1) old human remains are cultural properties and national heritages that have own purposes for scientific studies, (2) In case of necessity, the organizations which maintain old human remains should discuss the methods for proper maintenance by holding counsels with local governments organizations that are only representatives of specimens of origin, (3) In case of transferring human remains, the applicable organizations should inherit specimens for scientific purposes and mention to offering for continuous opportunities for all kind of studies." |

|

8 Dr. Shinoda's statement seems to be very nervous by repatriating the human remains of the Kiyono's collection that Dr. Kanaseki had once collaborated to collect human remain from both the Amami and the Ryukyu islands. |

|

9 The Ryukyuan case was obviously inspired by the Ainu movement; Prof. Matsushima has traveled to Hokkaido to meet the Ainu repatriation movement activists prior to his own claim activities . Prof. Matsushima and the descendants of the royal family of the Momojyana have officially requested the prefectural government of Okinawa to perform a reburial of the returned remains with a Ryukyuan traditional funeral in March 2019. Yet, until today, the prefectural government has refused their request. The officials of the Okinawa prefectural government have announced that these human remains would be transferred from cardbord to wooden boxes and kept confirmedly in airconditioned store room because of “just returning from abroad Taiwan.” On the other hand, Professor Matsushima has also deeply concerned possibility that the prefectural government could use the remains for DNA tests without informed consent of the dependent royal family. |

|

10 Quest for harmony between plaintiffs and defendants In both the Ainu and Ryukyuan repatriation cases, indigenous people have taken the plaintiff’s side, and the defendants are the local and central governments and national universities. The reason why the government is potentially at fault is the lack of legislation governing acts of repatriation in Japan. Without legislation, the Japanese government can always take makeshift administrative respite in legal conformity with the “the person who custom dictates shall preside over rituals for ancestors” of the Civil Code of Japan, rather than legislation stipulating the collective rights of indigenous people. |

|

11 Many of intellectuals of the Ainu and Ryukyuan have sought a positive solution to repatriation issues by referring to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, NAGPRA , enacted in 1990 in the United States. Movements have expressed their support for NAGPRA as a progressive solution to the disputes between Indigenous people and their former oppressors. They want repatriation legislation in Japan like NAGPRA of the U.S. Actually, our government lacks any consciousness of the rights of Japan’s Indigenous people and has not had any dialog with Indigenous people. The real problem is also the lack of imagination in Japanese social scientists . Despite our academic tradition of cultural anthropology, we have not taken the plaintiff's side because almost all Japanese anthropologists receive grants from government and quasi-governmental agencies. Until today, the majority have taken the defendant's side in repatriation cases with the rare exception of those anthropologists who have been trained by indigenous leaders. We do not have Indigenous studies by their own . |

|

12 From the perspectivism of ELSI (ethical, legal, and social implications) , my conclusion is that the progressive repatriation requests of Indigenous people involve not only returning objects but also their recovery from violent colonial traumatic memories, which requires a sense of homecoming to the time and place of origin. We need more to examine the afterlife of human being and their belongings in the context of our "not passing away" colonial memories. The Ryukuan-Okinawan people and other Japanese ought to reconcile for the consensus of repatriation of human remain that could be returned to a certain time and space, that means the reconciliation between plaintiffs and defendants. How do cultural anthropologists engage with dialogues between the plaintiffs and the defendant in our future ? |

|

13 |

|

14 |

Links

Bibliography

other information