★1980年代中頃に垂水源之介が、中央アメリカのホンジュラスの農村で経験した大晦日の儀 礼である、Testamento del año viejo - 「古い年の遺言」についての短い報告をしたあとに、儀礼とゲームの違いについて解説を終えます(上映時間 13分)

| We have seen that

there are analogies between mythical thought on

the theoretical, and 'bricolage' on the practical plane and that

artistic creation lies mid-way between science and these two forms of

activity; There are relations of the same type between games and

rites. (p.30) |

理論的な神話的思考と実践的な「ブリコラージュ」の間には類似性があり、芸術的創造は科学とこれら二つの活動の中間にあることを見てきた。 |

| All games are defined by a set of rules which in practice allow the playing of any number of matches. Ritual which is also 'played', is on the other hand, like a favoured instance of a game, remembered from among the possible ones because it is the only one which results in a particular type of equilibrium between the two sides. The transposition is readily seen in the case of the Gahuku-Gama of New Guinea who have learnt football but who will play, several days running, as many matches as are necessary for both sides to reach the same score (Read, p. 429 ). This is treating a game as a ritual.(pp.30-31) | す

べてのゲームは、実際にはいくつもの対戦を可能にする一連のルールによって定義されている。一方、「演じられる」される儀式は、ゲームの好例のようなもの

で、両者の間に特定の種類の均衡をもたらす唯一のものであるため、可能なゲームの中から記憶される。この転置は、ニューギニアのガフク・ガマ族がサッカー

を習ったが、両者が同じ得点になるために必要なだけの試合を何日も続けて行うという事例で容易にわかる(Read, p.429

)。これは、ゲームを儀式として扱っているのである。 |

| The same can be said of the games which took place among the Fox Indians during adoption ceremonies. Their purpose was to replace a dead relative by a living one and so to allow the final departure of the soul of the deceased.* The main aim of funeral rites among the Fox seems indeed to be to get rid of the dead and to prevent them from avenging on the living their bitterness and their regret that they are no longer among them. For native philosophy resolutely sides with the living: 'Death is a hard thing. Sorrow is especially hard'.(p.31) | 同

じことが、フォックス・インディアンの養子縁組の儀式で行われたゲームについても言える。フォックス族の葬儀の主な目的は、死者を追い払い、死者が生者に

恨みと自分がいなくなった悔しさをぶつけないようにすることにあるようだ。土着の哲学は断固として生者の味方である。「死は辛いもの。悲しみは特に辛いも

の」。 |

| Death originated in the destruction by supernatural powers of the younger of two mythical brothers who are cultural heroes among all the Algonkin. But it was not yet final. It was made so by the elder brother when, in spite of his sorrow, he rejected the ghost's request to be allowed to return to his place among the living. Men must follow this example and be firm with the dead. The living must make them understand that they have lost nothing by dying since they regularly receive offerings of tobacco and food. In return they are expected to compensate the living for the reality of death which they recall to them and for the sorrow their demise causes them by guaranteeing them long life, clothes and something to eat. 'It is the dead who make food increase', a native informant explains. 'They (the Indians) must coax them that way' (Michelson I, pp. 369, 407).(p.31) | 死

の起源は、アルゴンキン族の文化的英雄である神話上の2人の兄弟のうち、弟が超自然的な力によって破壊されたことである。しかし、それはまだ最終的なもの

ではなかった。兄が、悲しみにもかかわらず、生者の中に戻ることを許してほしいという幽霊の要求を拒否したときに、死は確定したのである。人間はこの例に

ならって、死者に対して毅然とした態度をとらなければならない。生きている者は、死んでも損はしないと理解させ、タバコや食べ物の供養を定期的に受けるよ

うにしなければなりません。その代わり、死者は生者に思い出させる死の現実と、その死が生者に与える悲しみに対して、長寿と衣服と食べるものを保証するこ

とで補償することが期待されているのです。食料を増やすのは死者だ」と、ある先住民は説明する。彼ら(インディアン)は彼らをそのようになだめなければな

らない」(『マイケルソンI』369、407ページ)。 |

| Now, the adoption rites which are necessary to make the soul of the deceased finally decide to go where it will take on the role of a protecting spirit are normally accompanied by competitive sports, games of skill or chance between teams which are constituted on the basis of an ad hoc division into two sides, Tokan and Kicko. I said explicitly over and over again that it is the living and the dead who are playing against each other. It is as if the living offered the dead the consolation of a last match before finally being rid of them. But, since the two teams are asymmetrical in what they stand for, the outcome is inevitably determined in advance: feast is given, the Kickoagi win, as in turn the Tokanagi do not win (Michelson I, p. 385).(pp.31-32) | さ

て、死者の魂が最終的に守護霊の役割を担う場所に行くことを決意させるために必要な養子縁組の儀式には、通常、競技スポーツ、つまり、トーカンとキッコー

というその場限りの区分に基づいて構成されたチーム間の技術や偶然性のゲームが伴います。私は何度も何度もはっきりと、生きている者と死んだ者が対戦して

いるのだと言った。まるで、生者が死者を追い出す前に、最後の勝負を申し込むようなものだ。しかし、この二つのチームは、何を象徴しているのかが非対称な

ので、結果はあらかじめ必然的に決まっている。ごちそうが与えられ、キッコウギが勝ち、その代わりにトカナギが勝てない(マイケルソン I, p.

385)のである。 |

| And what is in fact the case? It is clear that it is only the living who win in the great biological and social game which is constantly taking place between the living and the dead. But, as all the North American mythology confirms, to win a game is symbolically to 'kill' one's opponent; this is depicted as really happening in innumerable myths. By ruling that they should always win, the dead are given the illusion that it is they who are really alive, and that their opponents, having been 'killed' by them, are dead. Under the guise of playing with the dead, one plays them false and commits them. The formal structure of what might at first sight be taken for a competitive game is in fact identical with that of a typical ritual such as the Mitawit or Midewinin of .these same Algonkin peoples in which the initiates get symbolically killed by the dead whose part is played by the initiated; they feign death in order to obtain a further lease of life. In both cases, death is brought in but only to be duped.(p.32) | そ して、実際にはどうなのだろうか。生者と死者の間で絶えず行われている生物学的・社会学的な大ゲームで勝つのは生者だけであることは明らかである。しか し、北米の神話に見られるように、ゲームに勝つということは、象徴的に相手を「殺す」ことであり、これは無数の神話の中で実際に起こっていることとして描 かれている。死者たちは、自分たちが常に勝つべきであるとすることで、本当に生きているのは自分たちであり、自分たちによって「殺された」相手は死んでい るのだと錯覚するのである。死者と遊ぶという名目で、人は死者を偽り、罪を犯す。一見、競争的なゲームのように見えるが、実は、同じアルゴンキン族のミタ ウィットやミデウィニンのような典型的な儀式と同じで、加入礼を受ける者が死者によって象徴的に殺され、その役を加入礼を受ける者が演じ、さらに命を得る ために死を装う。どちらの場合も、死が持ち込まれるが、それは騙されるためだけである。 |

| Games thus appear to have a disjunctive effect: they end in the establishment of a difference between individual players or teams where originally there was no indication of inequality. And at the end of the game they are distinguished into winners and losers. Ritual, on the other hand, is the exact inverse; it conjoins, for it brings about a union (one might even say communion in this context) or in any case an organic relation between two initially separate groups, one ideally merging with the person of the officiant and the other with the collectivity of the faithful. In the case of games the symmetry is therefore preordained and it is of a structural kind since it follows from the principle that the rules are the same for both sides. Asymmetry is engendered: it follows inevitably from the contingent nature of events, themselves due to intention, chance or talent. The reverse is true of ritual. There is an asymmetry which is postulated in advance between profane and sacred, faithful and officiating, dead and living, initiated and uninitiated, etc., and the 'game' consists in making all the participants pass to the winning side by means of events, the nature and ordering of which is genuinely structural Like science (though here again on both the theoretical and the practical plane) the game produces events by means of a structure; and we can therefore understand why competitive games should flourish in our industrial societies. Rites and myths, on the other hand, like 'bricolage' (which these same societies only tolerate as a hobby or pastime), take to pieces and reconstruct sets of events (on a psychical, socio-historical or technical plane) and use them as so many indestructible pieces for structural patterns in which they serve alternatively as ends or means.(pp.32-33) | こ

のように、ゲームには分離的な効果があるように思われる。本来は不平等を示すことのなかった個々のプレーヤーやチームの間に差が生じることで、ゲームは終

わるのである。そして、ゲームの終わりには、勝者と敗者に区別されるのである。一方、儀式はその正反対である。儀式は結合し、二つの最初は別々だった集団

の間に結合(この文脈では交わりとさえ言えるかもしれない)、あるいはいずれにせよ有機的関係をもたらし、一方は理想的には司式者の個人と、他方は信者の

集団と融合するのだから。ゲームの場合、対称性はあらかじめ定められており、ルールが両者にとって同じであるという原則から生じるので、構造的なものであ

る。非対称性は意図されたものであり、事象の偶発性から必然的に生じるもので、それ自体は意図、偶然、才能によるものである。儀式はその逆である。儀式に

は、俗と聖、信徒と審判、死者と生者、入門者と未入門者などの間にあらかじめ想定された非対称性があり、「ゲーム」は、すべての参加者を出来事によって勝

利側に渡すことで成り立っており、その性質と順序は真に構造的である

科学同様(ここでも理論面と実践面の両方)、ゲームは構造によって出来事を生み出すもので、それゆえ私たちの産業社会で競技ゲームが盛んになる理由も理解

できるだろう。一方、儀式や神話は、「ブリコラージュ」(同じ社会が趣味や娯楽としてのみ許容している)のように、(心理的、社会歴史的、技術的な面で)

一連の出来事をバラバラにして再構築し、それらが目的または手段として交互に機能する構造パターンのための非常に多くの不滅の断片として使うのだ。 |

| The savage mind / Claude Lévi-Strauss. Chicago : University of Chicago Press , c1966 | |

+++

Links

- ︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎︎

リンク

- ▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

文献

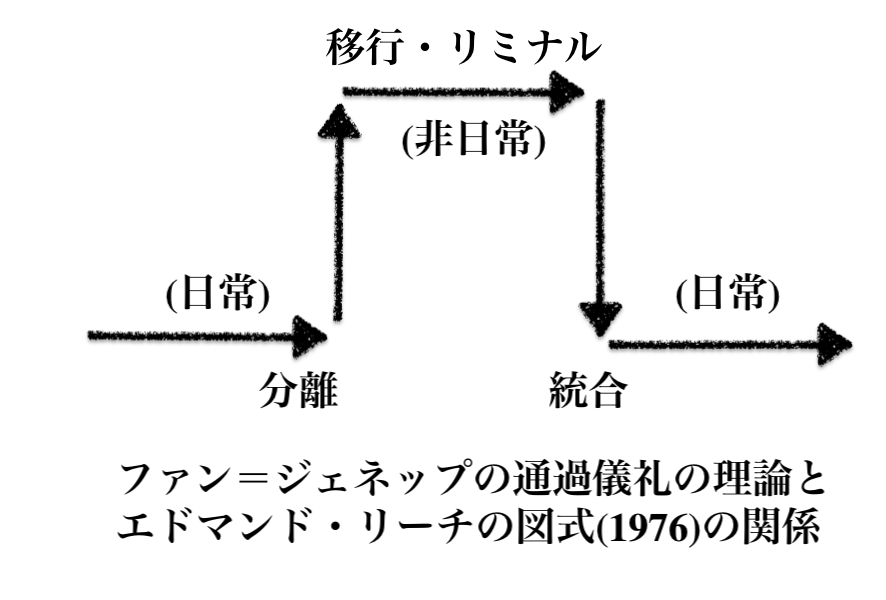

- 通過儀礼 / ファン・ヘネップ著 ; 綾部恒雄, 綾部裕子訳, 岩波書店 , 2012

- The savage mind / Claude Lévi-Strauss. Chicago : University of Chicago Press , c1966

その他の情報