☆

☆

指標性

Indexicality

☆ ☆

☆

☆ 記号論、言語学、人類学、言語哲学において、指標性(indexicality)とは、記号が、それ が出現する文脈における何らかの要素を指し示す(または索引=インデックスを付ける)現象のことである。指標的に意味する記号は指標と呼ばれ、哲学では indexicalという。言語学では、直示あるはダイクシス(deixis) とは、文脈の中で特定の時間、場所、人を指すために一般的な単語や語句を使うことである。単語は、その意味上の意味は固定されているが、示された意味が時 間や場所によって変化する場合、大工ティックとなる。ダイクシス(deixis)と指標性(indexicality)という用語は、ほとんど同じ意味で 使われることが多く、どちらも文脈に依存した参照という本質的に同じ考え方を 扱っている。しかし、この2つの用語には異なる歴史と伝統がある。より重要なのは、それぞれが異なる研究分野と関連していることである。デイクシスは言語 学と関連し、指標性は語用論だけでなく哲学とも関連している。

| In

semiotics, linguistics, anthropology, and philosophy of language,

indexicality is the phenomenon of a sign pointing to (or indexing) some

element in the context in which it occurs. A sign that signifies

indexically is called an index or, in philosophy, an indexical. The modern concept originates in the semiotic theory of Charles Sanders Peirce, in which indexicality is one of the three fundamental sign modalities by which a sign relates to its referent (the others being iconicity and symbolism).[1] Peirce's concept has been adopted and extended by several twentieth-century academic traditions, including those of linguistic pragmatics,[2]: 55–57 linguistic anthropology,[3] and Anglo-American philosophy of language.[4] Words and expressions in language often derive some part of their referential meaning from indexicality. For example, I indexically refers to the entity that is speaking; now indexically refers to a time frame including the moment at which the word is spoken; and here indexically refers to a locational frame including the place where the word is spoken. Linguistic expressions that refer indexically are known as deictics, which thus form a particular subclass of indexical signs, though there is some terminological variation among scholarly traditions. Linguistic signs may also derive nonreferential meaning from indexicality, for example when features of a speaker's register indexically signal their social class. Nonlinguistic signs may also display indexicality: for example, a pointing index finger may index (without referring to) some object in the direction of the line implied by the orientation of the finger, and smoke may index the presence of a fire. In linguistics and philosophy of language, the study of indexicality tends to focus specifically on deixis, while in semiotics and anthropology equal attention is generally given to nonreferential indexicality, including altogether nonlinguistic indexicality. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indexicality |

記号論、言語学、人類学、言語哲学において、指標性とは、記号が、それ

が出現する文脈における何らかの要素を指し示す(または索引=インデックスを付ける)現象のことである。指標的に意味する記号は指標と呼ばれ、哲学では

indexicalという。 近代的な概念はチャールズ・サンダース・パースの記号論に端を発しており、そこでは指標性は記号がその参照者に関係する3つの基本的な記号様式の1つで ある(他は図像性と象徴性である)[1]: 55-57言語人類学、[3]英米言語哲学などである[4]。 言語における単語や表現は、しばしばその参照意味の一部を索引性から派生させる。例えば、「I」は「話している主体」を指し、「now」は「その言葉が話 された瞬間を含む時間枠」を指し、「here」は「その言葉が話された場所を含む場所枠」を指す。指標的に言及する言語表現はディクティクスとして知ら れ、したがって指標的記号の特定のサブクラスを形成しているが、学問的伝統の間には用語上の違いがある。 例えば、話者の音域の特徴がその社会階級を指標的に示す場合などである。例えば、人差し指は指の向きによって暗示される線の方向にある物体を指し示すこと があり、煙は火の存在を指し示すことがある。 言語学や言語哲学では、指標性の研究は特にデイクシスに焦点を当てる傾向があるが、記号論や人類学では一般的に、非言語的指標性を含む非参照的指標性にも 同等の注意が払われる。 |

| In linguistic pragmatics Main article: Deixis In disciplinary linguistics, indexicality is studied in the subdiscipline of pragmatics. Specifically, pragmatics tends to focus on deictics—words and expressions of language that derive some part of their referential meaning from indexicality—since these are regarded as "[t]he single most obvious way in which the relationship between language and context is reflected in the structures of languages themselves"[2]: 54 Indeed, in linguistics the terms deixis and indexicality are often treated as synonymous, the only distinction being that the former is more common in linguistics and the latter in philosophy of language.[2]: 55 This usage stands in contrast with that of linguistic anthropology, which distinguishes deixis as a particular subclass of indexicality. |

言語用論において 主な記事 ダイクシス(直示・ deixis) 学問的言語学では、語用論という下位分野で指標性が研究される。特に語用論では、「言語と文脈の関係が言語の構造そのものに反映される最も明白な唯一の方 法」[2]と見なされているため、デイクシス-参照意味の一部を指標性から派生させる言語の単語や表現-に焦点を当てる傾向がある: 54 実際、言語学ではdeixisとindexicalityという用語はしばしば同義語として扱われ、前者が言語学で、後者が言語哲学でより一般的であると いう違いがあるだけである[2]: 55 この用法は、deixisをindexicalityの特定のサブクラスとして区別する言語人類学の用法とは対照的である。 ※直示(deixis)は、語用論においてその意味が文脈によってはじめて決まる語や言語表現のことで、 代名詞、指示語、あるいは肯定や否定表現などの返事(代形式)などが含まる。 |

| In linguistic anthropology The concept of indexicality was introduced into the literature of linguistic anthropology by Michael Silverstein in a foundational 1976 paper, "Shifters, Linguistic Categories and Cultural Description".[5] Silverstein draws on "the tradition extending from Peirce to Jakobson" of thought about sign phenomena to propose a comprehensive theoretical framework in which to understand the relationship between language and culture, the object of study of modern sociocultural anthropology. This framework, while also drawing heavily on the tradition of structural linguistics founded by Ferdinand de Saussure, rejects the other theoretical approaches known as structuralism, which attempted to project the Saussurean method of linguistic analysis onto other realms of culture, such as kinship and marriage (see structural anthropology), literature (see semiotic literary criticism), music, film and others. Silverstein claims that "[t]hat aspect of language which has traditionally been analyzed by linguistics, and has served as a model" for these other structuralisms, "is just the part that is functionally unique among the phenomena of culture." It is indexicality, not Saussurean grammar, which should be seen as the semiotic phenomenon which language has in common with the rest of culture.[5]: 12, 20–21 Silverstein argues that the Saussurean tradition of linguistic analysis, which includes the tradition of structural linguistics in the United States founded by Leonard Bloomfield and including the work of Noam Chomsky and contemporary generative grammar, has been limited to identifying "the contribution of elements of utterances to the referential or denotative value of the whole", that is, the contribution made by some word, expression, or other linguistic element to the function of forming "propositions—predications descriptive of states of affairs". This study of reference and predication yields an understanding of one aspect of the meaning of utterances, their semantic meaning, and the subdiscipline of linguistics dedicated to studying this kind of linguistic meaning is semantics.[5]: 14–15 Yet linguistic signs in contexts of use accomplish other functions than pure reference and predication—though they often do so simultaneously, as though the signs were functioning in multiple analytically distinct semiotic modalities at once. In the philosophical literature, the most widely discussed examples are those identified by J.L. Austin as the performative functions of speech, for instance when a speaker says to an addressee "I bet you sixpence it will rain tomorrow", and in so saying, in addition to simply making a proposition about a state of affairs, actually enters into a socially constituted type of agreement with the addressee, a wager.[6] Thus, concludes Silverstein, "[t]he problem set for us when we consider the actual broader uses of language is to describe the total meaning of constituent linguistic signs, only part of which is semantic." This broader study of linguistic signs relative to their general communicative functions is pragmatics, and these broader aspects of the meaning of utterances is pragmatic meaning. (From this point of view, semantic meaning is a special subcategory of pragmatic meaning, that aspect of meaning which contributes to the communicative function of pure reference and predication.).[5]: 193 Silverstein introduces some components of the semiotic theory of Charles Sanders Peirce as the basis for a pragmatics which, rather than assuming that reference and predication are the essential communicative functions of language with other nonreferential functions being mere addenda, instead attempts to capture the total meaning of linguistic signs in terms of all of their communicative functions. From this perspective, the Peircean category of indexicality turns out to "give the key to the pragmatic description of language."[5]: 21 This theoretical framework became an essential presupposition of work throughout the discipline in the 1980s and remains so in the present. Adaptation of Peircean semiotics Main article: Semiotic theory of Charles Sanders Peirce The concept of indexicality has been greatly elaborated in the literature of linguistic anthropology since its introduction by Silverstein, but Silverstein himself adopted the term from the theory of sign phenomena, or semiotics, of Charles Sanders Peirce. As an implication of his general metaphysical theory of the three universal categories, Peirce proposed a model of the sign as a triadic relationship: a sign is "something which stands to somebody for something in some respect or capacity."[7] Thus, more technically, a sign consists of A sign-vehicle or representamen, the perceptible phenomenon which does the representing, whether audibly, visibly or in some other sensory modality;[8]: "Representamen" An object, the entity of whatever kind, with whatever modal status (experienceable, potential, imaginary, law-like, etc.), which is represented by the sign;[8]: "Object" and An interpretant, the "idea in the mind" of the perceiving individual, which interprets the sign-vehicle as representing the object.[8]: "Interpretant" Peirce further proposed to classify sign phenomena along three different dimensions by means of three trichotomies, the second of which classifies signs into three categories according to the nature of the relationship between the sign-vehicle and the object it represents. As captioned by Silverstein, these are: Icon: a sign in which "the perceivable properties of the sign vehicle itself have isomorphism to (up to identity with) those of the entity signaled. That is, the entities are 'likenesses' in some sense."[5]: 27 Index: a sign in which "the occurrence of a sign vehicle token bears a connection of understood spatio-temporal contiguity to the occurrence of the entity signaled. That is, the presence of some entity is perceived to be signaled in the context of communication incorporating the sign vehicle."[5]: 27 Symbol: the residual class, a sign which is not related to its object by virtue of bearing some qualitative likeness to it, nor by virtue of co-occurring with it in some contextual framework. These "form the class of 'arbitrary' signs traditionally spoken of as the fundamental kind of linguistic entity. Sign vehicle and entity signaled are related through the bond of a semantico-referential meaning"[5]: 27 which permits them to be used to refer to any member of a whole class or category of entities. Silverstein observes that multiple signs may share the same sign-vehicle. For instance, as mentioned, linguistic signs as traditionally understood are symbols, and analyzed in terms of their contribution to reference and predication, since they arbitrarily denote a whole class of possible objects of reference by virtue of their semantic meanings. But in a trivial sense each linguistic sign token (word or expression spoken in an actual context of use) also functions iconically, since it is an icon of its type in the code (grammar) of the language. It also functions indexically, by indexing its symbol type, since its use in context presupposes that such a type exists in the semantico-referential grammar in use in the communicative situation (grammar is thus understood as an element of the context of communication).[5]: 27–28 So icon, index and symbol are not mutually exclusive categories—indeed, Silverstein argues, they are to be understood as distinct modes of semiotic function,[5]: 29 which may be overlaid on a single sign-vehicle. This entails that one sign-vehicle may function in multiple semiotic modes simultaneously. This observation is the key to understanding deixis, traditionally a difficult problem for semantic theory. Referential indexicality (deixis) Main article: Deixis In linguistic anthropology, deixis is defined as referential indexicality—that is, morphemes or strings of morphemes, generally organized into closed paradigmatic sets, which function to "individuate or single out objects of reference or address in terms of their relation to the current interactive context in which the utterance occurs.".[9]: 46–47 Deictic expressions are thus distinguished, on the one hand, from standard denotational categories such as common nouns, which potentially refer to any member of a whole class or category of entities: these display purely semantico-referential meaning, and in the Peircean terminology are known as symbols. On the other hand, deixis is distinguished as a particular subclass of indexicality in general, which may be nonreferential or altogether nonlinguistic. In the older terminology of Otto Jespersen and Roman Jakobson, these forms were called shifters.[10][11] Silverstein, by introducing the terminology of Peirce, was able to define them more specifically as referential indexicals.[5] Non-referential indexicality Non-referential indices or "pure" indices do not contribute to the semantico-referential value of a speech event yet "signal some particular value of one or more contextual variables."[5] Non-referential indices encode certain metapragmatic elements of a speech event's context through linguistic variations. The degree of variation in non-referential indices is considerable and serves to infuse the speech event with, at times, multiple levels of pragmatic "meaning."[12] Of particular note are: sex/gender indices, deference indices (including the affinal taboo index), affect indices, as well as the phenomena of phonological hypercorrection and social identity indexicality. Examples of non-referential forms of indexicality include sex/gender, affect, deference, social class, and social identity indices. Many scholars, notably Silverstein, argue that occurrences of non-referential indexicality entail not only the context-dependent variability of the speech event, but also increasingly subtle forms of indexical meaning (first, second, and higher-orders) as well.[12] Sex/gender indices One common system of non-referential indexicality is sex/gender indices. These indices index the gender or "female/male" social status of the interlocutor. There are a multitude of linguistic variants that act to index sex and gender such as: word-final or sentence-final particles:many languages employ the suffixation of word-final particles to index the gender of the speaker. These particles vary from phonological alterations such as the one explored by William Labov in his work on postvocalic /r/ employment in words that had no word final "r" (which is claimed, among other things, to index the "female" social sex status by virtue of the statistical fact that women tend to hypercorrect their speech more often than men);[13] suffixation of single phonemes, such as /-s/ in Muskogean languages of the southeastern United States;[5] or particle suffixation (such as the Japanese sentence-final use of -wa with rising intonation to indicate increasing affect and, via second-order indexicality, the gender of the speaker (in this case, female))[13] morphological and phonological mechanisms: such as in Yana, a language where one form of all major words are spoken by sociological male to sociological male, and another form (which is constructed around phonological changes in word forms) is used for all other combination of interlocutors; or the Japanese prefix-affixation of o- to indicate politeness and, consequently, feminine social identity.[14] Many instances of sex/gender indices incorporate multiple levels of indexicality (also referred to as indexical order).[12] In fact, some, such as the prefix-affixation of o- in Japanese, demonstrate complex higher-order indexical forms. In this example, the first order indexes politeness and the second order indexes affiliation with a certain gender class. It is argued that there is an even higher level of indexical order evidenced by the fact that many jobs use the o- prefix to attract female applicants.[14] This notion of higher-order indexicality is similar to Silverstein's discussion of "wine talk" in that it indexes "an identity-by-visible-consumption[12] [here, employment]" that is an inherent of a certain social register (i.e. social gender indexicality). Affect indices Affective meaning is seen as "the encoding, or indexing of speakers emotions into speech events."[15] The interlocutor of the event "decodes" these verbal messages of affect by giving "precedence to intentionality";[15] that is, by assuming that the affective form intentionally indexes emotional meaning. Some examples of affective forms are: diminutives (for example, diminutive affixes in Indo-European and Amerindian languages indicate sympathy, endearment, emotional closeness, or antipathy, condescension, and emotional distance); ideophones and onomatopoeias; expletives, exclamations, interjections, curses, insults, and imprecations (said to be "dramatizations of actions or states"); intonation change (common in tone languages such as Japanese); address terms, kinship terms, and pronouns which often display clear affective dimensions (ranging from the complex address-form systems found languages such a Javanese to inversions of vocative kin terms found in Rural Italy);[15] lexical processes such as synecdoche and metonymy involved in effect meaning manipulation; certain categories of meaning like evidentiality; reduplication, quantifiers, and comparative structures; as well as inflectional morphology. Affective forms are a means by which a speaker indexes emotional states through different linguistic mechanisms. These indices become important when applied to other forms of non-referential indexicality, such as sex indices and social identity indices, because of the innate relationship between first-order indexicality and subsequent second-order (or higher) indexical forms. (See multiple indices section for Japanese example). Deference indices Deference indices encode deference from one interlocutor to another (usually representing inequalities of status, rank, age, sex, etc.).[5] Some examples of deference indices are: T/V deference entitlement The T/V deference entitlement system of European languages was famously detailed by linguists Brown and Gilman.[16] T/V deference entitlement is a system by which a speaker/addressee speech event is determined by perceived disparities of 'power' and 'solidarity' between interlocutors. Brown and Gilman organized the possible relationships between the speaker and the addressee into six categories: Superior and solidary Superior and not solidary Equal and solidary Equal and not solidary Inferior and solidary Inferior and not solidary The 'power semantic' indicates that the speaker in a superior position uses T and the speaker in an inferior position uses V. The 'solidarity semantic' indicates that speakers use T for close relationships and V for more formal relationships. These two principles conflict in categories 2 and 5, allowing either T or V in those cases: Superior and solidary: T Superior and not solidary: T/V Equal and solidary: T Equal and not solidary: V Inferior and solidary: T/V Inferior and not solidary: V Brown and Gilman observed that as the solidarity semantic becomes more important than the power semantic in various cultures, the proportion of T to V use in the two ambiguous categories changes accordingly. Silverstein comments that while exhibiting a basic level of first-order indexicality, the T/V system also employs second-order indexicality vis-à-vis 'enregistered honorification'.[12] He cites that the V form can also function as an index of valued "public" register and the standards of good behavior that are entailed by use of V forms over T forms in public contexts. Therefore, people will use T/V deference entailment in 1) a first-order indexical sense that distinguishes between speaker/addressee interpersonal values of 'power' and 'solidarity' and 2) a second-order indexical sense that indexes an interlocutor's inherent "honor" or social merit in employing V forms over T forms in public contexts. Japanese honorifics Japanese provides an excellent case study of honorifics. Honorifics in Japanese can be divided into two categories: addressee honorifics, which index deference to the addressee of the utterance; and referent honorifics, which index deference to the referent of the utterance. Cynthia Dunn claims that "almost every utterance in Japanese requires a choice between direct and distal forms of the predicate."[17] The direct form indexes intimacy and "spontaneous self-expression" in contexts involving family and close friends. Contrarily, distal form index social contexts of a more formal, public nature such as distant acquaintances, business settings, or other formal settings. Japanese also contains a set of humble forms (Japanese kenjōgo 謙譲語) which are employed by the speaker to index their deference to someone else. There are also suppletive forms that can be used in lieu of regular honorific endings (for example, the subject honorific form of taberu (食べる, to eat): meshiagaru 召し上がる). Verbs that involve human subjects must choose between distal or direct forms (towards the addressee) as well as a distinguish between either no use of referent honorifics, use of subject honorific (for others), or use of humble form (for self). The Japanese model for non-referential indexicality demonstrates a very subtle and complicated system that encodes social context into almost every utterance. Affinal taboo index Dyirbal, a language of the Cairns rain forest in Northern Queensland, employs a system known as the affinal taboo index. Speakers of the language maintain two sets of lexical items: 1) an "everyday" or common interaction set of lexical items and 2) a "mother-in-law" set that is employed when the speaker is in the very distinct context of interaction with their mother-in-law. In this particular system of deference indices, speakers have developed an entirely separate lexicon (there are roughly four "everyday" lexical entries for every one "mother-in-law" lexical entry; 4:1) to index deference in contexts inclusive of the mother-in-law. Hypercorrection as a social class index Hypercorrection is defined by Wolfram as "the use of speech form on the basis of false analogy."[18] DeCamp defines hypercorrection in a more precise fashion claiming that "hypercorrection is an incorrect analogy with a form in a prestige dialect which the speaker has imperfectly mastered."[19] Many scholars argue that hypercorrection provides both an index of "social class" and an "Index of Linguistic insecurity". The latter index can be defined as a speaker's attempts at self-correction in areas of perceived linguistic insufficiencies which denote their lower social standing and minimal social mobility.[20] Donald Winford conducted a study that measured the phonological hypercorrection in creolization of English speakers in Trinidad. He claims that the ability to use prestigious norms goes "hand-in-hand" with knowledge of stigmatization afforded to use of "lesser" phonological variants.[20] He concluded that sociologically "lesser" individuals would try to increase the frequency of certain vowels that were frequent in the high prestige dialect, but they ended up using those vowels even more than their target dialect. This hypercorrection of vowels is an example of non-referential indexicality that indexes, by virtue of innate urges forcing lower class civilians to hypercorrect phonological variants, the actual social class of the speaker. As Silverstein claims, this also conveys an "Index of Linguistic insecurity" in which a speaker not only indexes their actual social class (via first-order indexicality) but also the insecurities about class constraints and subsequent linguistic effects that encourage hypercorrection in the first place (an incidence of second-order indexicality).[12] William Labov and many others have also studied how hypercorrection in African American Vernacular English demonstrates similar social class non-referential indexicality. Multiple indices in social identity indexicality Multiple non-referential indices can be employed to index the social identity of a speaker. An example of how multiple indexes can constitute social identity is exemplified by Ochs discussion of copula deletion: "That Bad" in American English can index a speaker to be a child, foreigner, medical patient, or elderly person. Use of multiple non-referential indices at once (for example copula deletion and raising intonation), helps further index the social identity of the speaker as that of a child.[21] Linguistic and non-linguistic indices are also an important ways of indexing social identity. For example, the Japanese utterance -wa in conjunction with raising intonation (indexical of increasing affect) by one person who "looks like a woman" and another who looks "like a man" may index different affective dispositions which, in turn, can index gender difference.[13] Ochs and Schieffilen also claim that facial features, gestures, as well as other non-linguistic indices may actually help specify the general information provided by the linguistic features and augment the pragmatic meaning of the utterance.[22] Indexical order In much of the research currently conducted upon various phenomena of non-referential indexicality, there is an increased interest in not only what is called first-order indexicality, but subsequent second-order as well as "higher-order" levels of indexical meaning. First-order indexicality can be defined as the first level of pragmatic meaning that is drawn from an utterance. For example, instances of deference indexicality, such as the variation between informal tu and formal vous in French, indicate a speaker/addressee communicative relationship built upon the values of power and solidarity possessed by the interlocutors.[16] When a speaker addresses somebody using the V form instead of the T form, they index (via first-order indexicality) their understanding of the need for deference to the addressee. In other words, they perceive or recognize an incongruence between their levels of power and/or solidarity and employ a more formal way of addressing that person to suit the contextual constraints of the speech event. Second-Order Indexicality is concerned with the connection between linguistic variables and the metapragmatic meanings that they encode. For example, a woman is walking down the street in Manhattan and she stops to ask somebody where a McDonald's is. He responds to her talking in a heavy "Brooklyn" accent. She notices this accent and considers a set of possible personal characteristics that might be indexed by it (such as the man's intelligence, economic situation, and other non-linguistic aspects of his life). The power of language to encode these preconceived "stereotypes" based solely on accent is an example of second-order indexicality (representative of a more complex and subtle system of indexical form than that of first-order indexicality). Oinoglossia (wine talk) For demonstrations of higher (or rarefied) indexical orders, Michael Silverstein discusses the particularities of "life-style emblematization" or "convention-dependent-indexical iconicity" which, as he claims, is prototypical of a phenomenon he dubs "wine talk." Professional wine critics use a certain "technical vocabulary" that are "metaphorical of prestige realms of traditional English gentlemanly horticulture."[12] Thus, a certain "lingo" is created for wine that indexically entails certain notions of prestigious social classes or genres. When "yuppies" use the lingo for wine flavors created by these critics in the actual context of drinking wine, Silverstein argues that they become the "well-bred, interesting (subtle, balanced, intriguing, winning, etc.) person" that is iconic of the metaphorical "fashion of speaking" employed by people of higher social registers, demanding notoriety as a result of this high level of connoisseurship.[12] In other words, the wine drinker becomes a refined, gentlemanly critic and, in doing so, adopts a similar level of connoisseurship and social refinement. Silverstein defines this as an example of higher-order indexical "authorization" in which the indexical order of this "wine talk" exists in a "complex, interlocking set of institutionally formed macro-sociological interests."[12] A speaker of English metaphorically transfers him- or herself into the social structure of the "wine world" that is encoded by the oinoglossia of elite critics using a very particular "technical" terminology. The use of "wine talk" or similar "fine-cheeses talk", "perfume talk", "Hegelian-dialectics talk", "particle-physics talk", "DNA-sequencing talk", "semiotics talk" etc. confers upon an individual an identity-by-visible-consumption indexical of a certain macro-sociological elite identity[12] and is, as such, an instance of higher-order indexicality. |

言語人類学において 指標性の概念は、マイケル・シルヴァスタインが1976年に発表した論文「Shifters, Linguistic Categories and Cultural Description」において、言語人類学の文献に導入された[5]。シルヴァスタインは、現代の社会文化人類学の研究対象である言語と文化の関係を 理解するための包括的な理論的枠組みを提案するために、記号現象に関する思想の「パースからヤコブソンに至る伝統」を利用している。この枠組みは、フェル ディナン・ド・ソシュールによって創始された構造言語学の伝統にも大きく依拠しているが、ソシュール的な言語分析の方法を、親族関係や結婚(構造人類学を 参照)、文学(記号論的文学批評を参照)、音楽、映画など、文化の他の領域に投影しようとした構造主義として知られる他の理論的アプローチを否定してい る。シルバーシュタインは、「伝統的に言語学によって分析され、他の構造主義のモデルとなってきた言語の側面は、文化の現象の中で機能的にユニークな部分 にすぎない」と主張する。言語が文化の他の部分と共通に持つ記号論的現象として見られるべきは、ソシュールの文法ではなく、索引性なのである[5]: 12, 20-21 レナード・ブルームフィールドによって創設された米国の構造言語学の伝統や、ノーム・チョムスキーや現代の生成文法の研究を含む、ソシュール的な言語分析 の伝統は、「発話全体の参照価値または含意価値に対する発話の要素の寄与」、つまり、「命題-事物の状態を記述する述語」を形成する機能に対する、ある単 語や表現、その他の言語要素の寄与を特定することに限定されてきた、とシルヴァスタインは主張する。このような参照と述語の研究によって、発話の意味の一 側面である意味論的な意味が理解され、このような言語的な意味を研究する言語学の専門分野が意味論である[5]: 14-15 しかし、使用文脈における言語記号は、純粋な参照や述語とは別の機能を果たす。あたかも記号が複数の分析的に異なる記号論的モダリティで同時に機能してい るかのように、言語記号はしばしばそうするが。哲学の文献では、最も広く議論されている例は、J.L.オースティンによって音声の実行的機能として特定さ れたものである。例えば、話し手が相手に対して「明日雨が降ることに6ペンス賭けるよ」と言うとき、そう言うことによって、単にある状態についての命題を 立てるだけでなく、実際に相手と社会的に構成された一種の合意、つまり賭けを結ぶのである。 [このように、シルヴァーステインは、「言語の実際の広範な用法を考えるときに私たちに課される問題は、構成要素である言語記号の総体的な意味を記述する ことであり、意味的な意味はその一部でしかない」と結論づけている。このように、一般的なコミュニケーション機能に対する言語記号のより広範な研究が語用 論であり、発話の意味のより広範な側面が語用論的意味である。(この観点からは、意味的意味は語用論的意味の特別な下位範疇であり、純粋参照や述語のコ ミュニケーション機能に寄与する意味の側面である)[5]: 193 シルバーシュタインは、参照と述語が言語の本質的なコミュニケーション機能であり、他の非参照機能は単なる付加的機能であると仮定するのではなく、その代 わりに、言語記号のコミュニケーション機能すべてという観点から言語記号の総合的な意味を捉えようとする語用論の基礎として、チャールズ・サンダース・パ イアースの記号論のいくつかの要素を紹介している。この観点から、ピール海における指標性の範疇は「言語の語用論的記述の鍵を与える」ことが判明した [5]: 21。 この理論的枠組みは、1980年代には、この学問分野全体における研究の不可欠な前提条件となり、現在もそうである。 ピールシャン記号論の適応 主な記事 チャールズ・サンダース・パースの記号論 指標性という概念は、シルヴァースタインが導入して以来、言語人類学の文献の中で大いに推敲されてきたが、シルヴァースタイン自身は、チャールズ・サン ダース・パースの記号現象論、すなわち記号論からこの用語を採用した。彼の一般的な形而上学的理論である3つの普遍的カテゴリーの含意として、パイスは三 項関係としての記号のモデルを提唱した。 表象」(sign-vehicle or representamen)とは、表象を行う知覚可能な現象であり、それが聴覚的であれ、視覚的であれ、その他の感覚的モダリティであれ、表象を行う[8]: 「表象物 記号によって表象される、どのような種類であれ、どのような様態(経験可能、潜在的、想像的、法則的など)であれ、実体である「対象」[8]: 「対象」と 解釈者:記号-車両が対象を表していると解釈する、知覚する個人の「心の中の考え」[8]: 「解釈者 ペアースはさらに、3つの三分法によって記号現象を3つの異なる次元に沿って分類することを提案し、そのうちの2つ目は、記号-媒体とそれが表す対象との 間の関係の性質に従って記号を3つのカテゴリーに分類するものであった。シルヴァスタインによるキャプションによれば、これらは以下の通りである: アイコン:「標識の乗り物自体の知覚可能な性質が、(同一性を持つまで)合図される実体の性質と同型である」標識。つまり、実体はある意味で『類似』である」[5]: 27 索引:「標識ビークル・トークンの出現が、合図された実体の出現と理解される時空間的な連続性のつながりを持つ」標識。つまり、ある実体の存在は、記号ビークルを組み込んだコミュニケーションの文脈で合図されていると認識される」[5]: 27。 記号:残余のクラスであり、その対象との質的類似性を持つことでも、何らかの文脈的枠組みの中でその対象と共起することでも、その対象に関連していない記 号。これらは「言語的実体の基本的な種類として伝統的に語られてきた "恣意的な "記号のクラスを形成する」。記号のビヒクルと信号化された実体は、意味論的・参照的な意味の結びつきによって関連している」[5]: 27。 シルヴァーステインは、複数の記号が同じ記号-車両を共有することがあると述べている。例えば、前述のように、伝統的に理解されてきた言語記号は記号であ り、参照と述語への寄与という観点から分析される。しかし、些細な意味では、各言語記号トークン(実際に使用される文脈で話される単語や表現)は、言語の コード(文法)におけるそのタイプのアイコンであるため、図像的にも機能する。また、文脈における使用は、コミュニケーション状況において使用されている 意味・参照文法にそのような型が存在することを前提とするため(文法はこのようにコミュニケーションの文脈の要素として理解される)、その記号の型を指標 化することによって、指標的にも機能する[5]: 27-28 つまり、図像、索引、記号は相互に排他的なカテゴリーではなく、実際、それらは記号論的機能の別個のモードとして理解されるべきであるとシルヴァスタイン は主張する[5]: 29。このことは、一つの記号車両が複数の記号論的モードで同時に機能する可能性があることを意味している。この観察は、従来意味論の難問であったデイク シスを理解する鍵である。 参照指標性(デイクシス) 主な記事 デイクシス 言語人類学では、デイクシスは言及的指標性、つまり、形態素または形態素の文字列であり、一般に閉じたパラダイム集合に編成され、「発話が発生する現在の 相互作用的文脈との関係において、参照または対処の対象を個別化または単一化する」機能を持つと定義される[9]: このように、ダイクシス表現は、一方 では、クラス全体や実体のカテゴリーのあらゆるメンバーを潜在的に参照する普通名詞のような標準的な表意カテゴリーとは区別される。一方、デイクシスは一 般的な指標性の特殊なサブクラスとして区別され、非参照的であったり、完全に非言語的であったりする。 オットー・イェスパーセン(Otto Jespersen)やローマン・ヤコブソン(Roman Jakobson)の古い用語では、これらの形式はシフターと呼ばれていた[10][11]。 非参照的指標性 非参照的指標または「純粋な」指標は、発話イベントの意味的・参照的価値に寄与しないが、「1つ以上の文脈変数の特定の値を示す」[5] 。特に注目すべきは、性/ジェンダー指数、敬意指数(アフィナル・タブー指数を含む)、感情指数、および音韻の超補正や社会的アイデンティティの指数性な どの現象である[12]。 非参照的な指標性の例としては、性/ジェンダー、感情、敬意、社会階級、社会的アイデンティティ指標などがある。Silversteinをはじめとする多 くの学者は、非参照的な指標性の発生には、発話事象の文脈依存的な変動性だけでなく、指標的な意味のますます微妙な形態(1次、2次、高次)も含まれると 主張している[12]。 性別/性別 非参照的な指標性の一般的なシステムのひとつに、性別/性別指標がある。これらの指標は対話者の性別または「女性/男性」の社会的地位を示す。性別や性別を指し示すために作用する言語的なバリエーションは数多く存在する: 語末助詞または文末助詞:多くの言語は話者の性別を示すために語末助詞の接尾辞を用いる。これらの助詞は、ウィリアム・ラボフ(William Labov)により、語末に「r」がない単語の後母音の/r/の使用について研究されたような音韻的変化(これは、特に、女性が男性よりも頻繁に発話を超 修正する傾向があるという統計的事実によって、「女性」という社会的性ステータスを示すと主張されている)など、さまざまである; [13] 単音節の接尾辞(アメリカ南東部のマスコギア語における/-s/など)[5]、または助詞の接尾辞(日本語の文末における-waの上昇するイントネーショ ンによる使用など)[13]。 形態論的・音韻論的メカニズム:例えば、社会学的男性から社会学的男性に話される主要な単語と、それ以外のすべての対話者の組み合わせに使用される別の単 語(単語形式の音韻論的変化を中心に構成される)の形がある言語であるヤナ語や、礼儀正しさ、ひいては女性的な社会的アイデンティティを示す日本語の接頭 辞-接尾辞のo-など[14]。 実際、日本語の o- の接頭辞のように、複雑な高次の指標形式を示すものもある[12]。この例では、第1次が礼儀正しさを表し、第2次が特定の性別階級への所属を表してい る。この高次の指標性の概念は、ある社会的登録(すなわち社会的ジェンダーの指標性)に内在する「目に見える消費[12][ここでは雇用]によるアイデン ティティ」を指標化するという点で、シルバースタインの「ワイン・トーク」の議論に類似している。 感情指標 感情的な意味とは「話し手の感情を発話事象に符号化すること、またはインデックス化すること」[15]であると考えられている。事象の対話者は「意図性を 優先する」[15]ことで、つまり感情形式が意図的に感情的な意味をインデックス化していると仮定することで、これらの感情的な言語メッセージを「解読」 する。 感情形の例としては 短縮形(例えば、インド・ヨーロッパ語族やアメリカインディアンの言語における短縮形接辞は、同情、親愛、感情的な親密さ、または反感、見下し、感情的な 距離を示す)、イデオフォンとオノマトペ、エクスプレッション、間投詞、呪い、侮辱、インプレッション(「行為や状態のドラマ化」と言われる)、イント ネーションの変化(日本語のような声調言語によく見られる); ジャワ語のような複雑な住所形システムから、イタリア農村部に見られる語彙的親族関係の逆転まで)[15]。効果的な意味操作に関与する同義語やメトニ ミーなどの語彙的プロセス、証拠性、重複、量詞、比較構造などの特定の意味のカテゴリー、屈折形態論など。 感情形は、話し手がさまざまな言語的メカニズムを通じて感情状態を指標化する手段である。これらの指標は、性別指標や社会的アイデンティティ指標など、非 参照的な指標性の他の形態に適用される場合に重要になります。なぜなら、一次指標性とそれに続く二次(またはそれ以上)の指標性の間には生得的な関係があ るからです。(日本語の例については複数指数の項を参照)。 敬意指数 ディファレンス・インデックスは、ある対談相手から別の対談相手への敬意(通常、地位、階級、年齢、性別などの不平等を表す)を符号化する[5]: T/Vディファレンス・エンタイトルメント ヨーロッパ言語のT/Vディファレンス・エンタイトルメントシステムは、言語学者のブラウンとギルマンによって詳述されたことで有名である[16]。 T/Vディファレンス・エンタイトルメントは、話し手と聞き手の発話事象が、対話者間の「力」と「連帯感」の知覚された格差によって決定されるシステムで ある。BrownとGilmanは、話し手と被説明者の間に可能な関係を6つのカテゴリーに整理した: 優位で連帯的 優れているが連帯していない 対等で連帯的 対等で連帯していない 劣等と連帯 劣等で連帯しない 権力的意味」は、優位な立場の話し手がTを使い、劣位な立場の話し手がVを使うことを示す。「連帯的意味」は、話し手が親密な関係にはTを使い、より フォーマルな関係にはVを使うことを示す。この2つの原則はカテゴリー2と5で対立し、これらの場合はTかVのどちらかを使うことができる: 優れていて連帯している:T 優れており、連帯していない:T/V 対等で連帯している:T 同等で固くない:V 劣等かつ固体:T/V 劣等で連帯しない:V ブラウンとギルマンは、さまざまな文化において、連帯の意味づけが力の意味づけよりも重要になるにつれて、2つのあいまいなカテゴリーにおけるTとVの使用比率がそれに応じて変化することを観察している。 Silversteinは、T/Vシステムは基本的なレベルの一次的な指標性を示す一方で、「登録された名誉化」に対する二次的な指標性も用いているとコ メントしている[12]。彼は、V字形は、評価された「公的な」登録の指標としても機能し、公的な文脈でT字形よりもV字形を使用することによって伴う善 行の基準としても機能することを挙げている。したがって、人々は、1)「権力」と「連帯」という話し手/話し相手の対人的価値を区別する一次的な指標的な 意味と、2)公的な文脈でT字形よりもV字形を使用する際の、対話者に固有の「名誉」や社会的なメリットを指標化する二次的な指標的な意味で、T/V字形 従属性を使用することになる。 日本語の敬語 日本語は敬語の優れた事例を提供してくれる。日本語の敬語は、発話の相手に対する敬意を表す「相手敬語」と、発話の相手に対する敬意を表す「相手敬語」に 分けられる。シンシア・ダンは、「日本語のほとんどすべての発話は、述語の直説法と遠説法の選択を必要とする」と主張している[17]。直説法は、家族や 親しい友人が関わる文脈では、親密さと「自発的な自己表現」を示す。対照的に、遠位形は、遠くの知人、ビジネスの場、その他のフォーマルな場など、より フォーマルで公的な性質を持つ社会的文脈を表します。 日本語には謙譲語(けんじょうご:謙譲語)もあり、これは話し手が誰かに対して敬意を示すために使われる。また、通常の敬語の代わりに使うことができる助 動詞形もあります(例えば、たべる(食べる)の主語敬語形:めしあがる)。主語が人間である動詞は、遠方形か直接形(相手に向かって)かを選ぶ必要があ り、また、参照敬語を使わないか、主語敬語を使うか(他人に対して)、謙譲形を使うか(自分に対して)を区別しなければならない。日本語の非参照的表記の モデルは、ほとんどすべての発話に社会的文脈を符号化する、非常に微妙で複雑なシステムを示している。 アフィナル・タブー・インデックス クイーンズランド州北部のケアンズ熱帯雨林の言語であるディルバル語は、アフィナル・タブー・インデックスと呼ばれるシステムを採用している。この言語の 話者は、2つの語彙を保持している: 1)「日常的な」または一般的な対話のための語彙項目セットと、2)話し手が義理の母親との対話という非常に明確な文脈にいるときに使用される「義理の母 親」セットである。この特殊なディファレンス・インデックスのシステムでは、話し手は、義母を含む文脈でのディファレンスを示すために、まったく別の語彙 (「義母」の語彙項目1つに対して「日常」の語彙項目がおよそ4つ;4:1)を開発している。 社会階級指標としてのハイパーコレクション ハイパーコレクションは、Wolframによって「誤った類推に基づいて発話形式を使用すること」と定義されている[18]。DeCampはハイパーコレ クションをより正確に定義し、「ハイパーコレクションとは、話し手が不完全に習得した格調高い方言の形式との誤った類推である」と主張している[19]。 多くの学者が、ハイパーコレクションは「社会階級」の指標と「言語的不安の指標」の両方を提供すると主張している。後者の指標は、社会的地位の低さや社会 的流動性の低さを示す、言語的に不十分と思われる領域における話者の自己修正の試みと定義することができる[20]。 ドナルド・ウィンフォードはトリニダードの英語話者のクレオリゼーションにおける音韻の過修正を測定する研究を行った。彼は、格式高い規範を使用する能力 は、「より劣った」音韻の変種を使用することで与えられる汚名に関する知識と「密接に」関係していると主張している[20]。彼は、社会学的に「より劣っ た」人は、格式の高い方言で頻繁に使用される特定の母音の頻度を増やそうとするが、結局はその方言よりもさらにその母音を使用することになると結論づけ た。この母音の過矯正は、非参照的指標性の一例であり、低階級の一般市民が生得的な衝動によって音韻の変種を過矯正せざるを得なくなることで、話者の実際 の社会階級を指標化する。シルバースタインが主張するように、これは「言語的不安の指標」でもあり、話し手が実際の社会階級を指標化するだけでなく(一次 の指標性を介して)、そもそも過修正を促す階級的制約やその後の言語的効果に対する不安も指標化する(二次の指標性の発生)[12]。 ウィリアム・ラボフ(William Labov)をはじめとする多くの研究者も、アフリカ系アメリカ人のヴァナキュラー英語における超修正が、同様の社会階級の非参照的指標性をどのように示すかを研究している。 社会的アイデンティティにおける複数の指標 話者の社会的アイデンティティを指標化するために、複数の非参照的指標を用いることができる。複数の指標がどのように社会的アイデンティティを構成するこ とができるかの例は、コピュラの削除に関するオックスの議論に示されている: アメリカ英語の "That Bad "は、話し手が子供、外国人、医療患者、高齢者であることを示すことができる。一度に複数の非参照的な指標(例えばコピュラの削除やイントネーションの引 き上げ)を使用することで、話し手が子供であるという社会的アイデンティティをさらに指標化することができる[21]。 言語的および非言語的な指標も、社会的アイデンティティを指標化する重要な方法である。例えば、「女性のように見える」人と「男性のように見える」人がイ ントネーションを上げること(感情の高まりを示す指標)と連動した日本語の「〜わ」という発話は、異なる感情的な気質を示し、それが性差を示す可能性があ る[13]。 オックスとシーフィレンはまた、顔の特徴、ジェスチャー、その他の非言語的な指標は、言語的特徴によって提供される一般的な情報を特定し、発話の語用論的 意味を増強するのに役立つと主張している[22]。 索引的順序 現在、非参照的指標性の様々な現象について行われている研究の多くでは、一次指標性と呼ばれるものだけでなく、それに続く二次、さらに「高次」レベルの指 標的意味への関心が高まっている。一次的な指示性は、発話から引き出される語用論的意味の最初のレベルと定義できる。例えば、フランス語のインフォーマル なtuとフォーマルなvousの違いのような、敬意に基づく指標性の例は、対話者が持つ権力と連帯の価値観に基づいて構築された話し手と宛先のコミュニ ケーション関係を示している[16]。話し手がT形ではなくV形を使って誰かに話しかけるとき、彼らは(一次指標性を介して)宛先に対する敬意が必要であ るという理解を指標化している。言い換えれば、話し手は自分の権力レベルや連帯レベルの間に不一致があることを認識または認識し、スピーチイベントの文脈 的制約に合うように、よりフォーマルな話し方を採用するのである。 第二次的指標性は、言語的変数と、それらが符号化するメタ語用論的意味との間の関連に関係する。例えば、ある女性がマンハッタンの通りを歩いていて、誰か にマクドナルドの場所を聞こうと立ち止まったとする。すると彼は、「ブルックリン」訛りの強い話し方で彼女に答えた。彼女はこの訛りに気づき、この訛りに よって指数化される可能性のある個人的特徴(その男性の知性、経済状況、その他の非言語的側面など)を考える。アクセントだけに基づいて、このような先入 観に基づく「ステレオタイプ」を符号化する言語の力は、二次的指標性(一次的指標性よりも複雑で微妙な指標形式のシステムを代表する)の一例である。 オイノグロシア(ワイン談義) より高次の(あるいは希薄な)指標性の実証として、マイケル・シルヴァスタインは「生活様式の象徴化」あるいは「慣習に依存した指標的象徴性」の特殊性に ついて論じている。プロのワイン評論家たちは、「伝統的な英国紳士的園芸の威信の領域を比喩した」、ある種の「技術的語彙」を使う[12]。ヤッピー」が ワインを飲むという実際の文脈において、こうした批評家たちによって作られたワインの風味に関する専門用語を使うとき、シルヴァースタインは、彼らが「育 ちがよく、興味深い(繊細で、バランスが取れていて、興味をそそる、勝ち気な、など。 言い換えれば、ワインを飲む人は、洗練された紳士的な批評家になり、そうすることで、同じようなレベルの目利きと社会的洗練を身につけることになる。シル ヴァスタインはこれを、この「ワイン・トーク」の索引的秩序が「制度的に形成されたマクロ社会学的利害の複雑で連動した集合」の中に存在する、高次の索引 的「承認」の例と定義している[12]。英語の話者は、非常に特殊な「技術的」用語を用いて、エリート批評家たちのオイノグロシアによってコード化された 「ワイン界」の社会構造に、自分自身を比喩的に移入する。 ワインの話」、あるいは同様の「高級チーズの話」、「香水の話」、「ヘーゲル弁証法の話」、「素粒子物理学の話」、「DNA配列決定の話」、「記号論の 話」などの使用は、あるマクロ社会学的エリート・アイデンティティ[12]の指標となる、目に見える消費によるアイデンティティを個人に付与するものであ り、そのようなものとして、高次の指標性の一例である。 |

| In philosophy of language Philosophical work on language from the mid-20th century, such as that of J.L. Austin and the ordinary language philosophers, has provided much of the originary inspiration for the study of indexicality and related issues in linguistic pragmatics (generally under the rubric of the term deixis), though linguists have appropriated concepts originating in philosophical work for purposes of empirical study, rather than for more strictly philosophical purposes. However, indexicality has remained an issue of interest to philosophers who work on language. In contemporary analytic philosophy, the preferred nominal form of the term is indexical (rather than index), defined as "any expression whose content varies from one context of use to another ... [for instance] pronouns such as 'I', 'you', 'he', 'she', 'it', 'this', 'that', plus adverbs such as 'now', 'then', 'today', 'yesterday', 'here', and 'actually'.[23] This exclusive focus on linguistic expressions represents a narrower construal than is preferred in linguistic anthropology, which regards linguistic indexicality (deixis) as a special subcategory of indexicality in general, which is often nonlinguistic. Indexicals appear to represent an exception to, and thus a challenge for, the understanding of natural language as the grammatical coding of logical propositions; they thus "raise interesting technical challenges for logicians seeking to provide formal models of correct reasoning in natural language."[23] They are also studied in relation to fundamental issues in epistemology, self-consciousness, and metaphysics,[23] for example asking whether indexical facts are facts that do not follow from the physical facts, and thus also form a link between philosophy of language and philosophy of mind. The American logician David Kaplan is regarded as having developed "[b]y far the most influential theory of the meaning and logic of indexicals".[23] |

言語哲学において J.L.オースティンや通常の言語哲学者たちのような20世紀半ばからの言語に関する哲学的研究は、言語語用論における索引性の研究および関連する問題 (一般的にはdeixisという用語の下にある)に多くのインスピレーションを与えてきたが、言語学者は哲学的研究に由来する概念を、より厳密に哲学的な 目的ではなく、経験的研究の目的に流用してきた。 しかし、索引性は、言語を研究する哲学者にとって依然として関心の高い問題である。現代の分析哲学では、この用語の好ましい名詞形はindexical (indexではなく)であり、「使用される文脈によって内容が変化する表現」と定義されている。[例えば、'I'、'you'、'he'、'she'、 'it'、'this'、'that'などの代名詞や、'now'、'then'、'today'、'yesterday'、'here'、 'actually'などの副詞などである[23]。このように言語的表現にのみ焦点を当てることは、言語的指標性(deixis)を多くの場合非言語的 である指標性全般の特別な下位カテゴリーとみなす言語人類学で好まれる解釈よりも狭い範囲を表している。 索引性は、論理的命題の文法的符号化として自然言語を理解することの例外であり、それ故の挑戦である。 アメリカの論理学者であるデイヴィッド・カプランは、「指標(indexicals)の意味と論理について、圧倒的に影響力のある理論」を展開したとみなされている[23]。 |

| Conversational scoreboard Quasi-indexical |

|

| In

linguistics and philosophy of language, the conversational scoreboard

is a tuple which represents the discourse context at a given point in a

conversation. The scoreboard is updated by each speech act performed by

one of the interlocutors.[1][2][3][4][5] Most theories of conversational scorekeeping take one of the scoreboard's elements to be a common ground, which represents the propositional information mutually agreed upon by the interlocutors. When an interlocutor makes a successful assertion, its content is added to the common ground. Once in the common ground, that information can then be presupposed by future utterances. Depending on the particular theory of scorekeeping, additional elements of the scoreboard may include a stack of questions under discussion, a list of discourse referents available for anaphora, among other categories of contextual information.[4][3][5] The notion of a conversational scoreboard was introduced by David Lewis in his most-cited paper Scorekeeping in a Language Game. In the paper, Lewis draws an analogy between conversation and baseball, where the scoreboard tracks categories of information such as strikes, outs, and runs, thereby defining the current state of the game and thereby determining which future moves are licit.[1][5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conversational_scoreboard |

言語学や言語哲学において、会話のスコアボードとは、会話のある時点における談話の文脈を表すタプルのことである。スコアボードは対話者の一人が行う発話行為ごとに更新される[1][2][3][4][5]。 会話におけるスコアボードのほとんどの理論は、スコアボードの要素の1つを共通基盤としており、これは対話者によって相互に合意された命題情報を表してい る。対話者がアサーションに成功すると、その内容が共通基盤に追加される。一旦共通基盤に追加されると、その情報は以降の発話で前提とすることができる。 スコアボードの追加要素には、特定のスコアキーピング理論によって、文脈情報の他のカテゴリの中でも、議論中の質問のスタック、アナフォラのために利用可 能な談話参照語のリストなどが含まれる[4][3][5]。 会話のスコアボードという概念はDavid Lewisによって最も引用された論文「Scorekeeping in a Language Game」で紹介された。この論文でルイスは会話と野球のアナロジーを描いており、スコアボードはストライク、アウト、ランなどの情報のカテゴリーを追跡 し、それによってゲームの現在の状態を定義し、それによってどの将来の動きが合法であるかを決定している[1][5]。 |

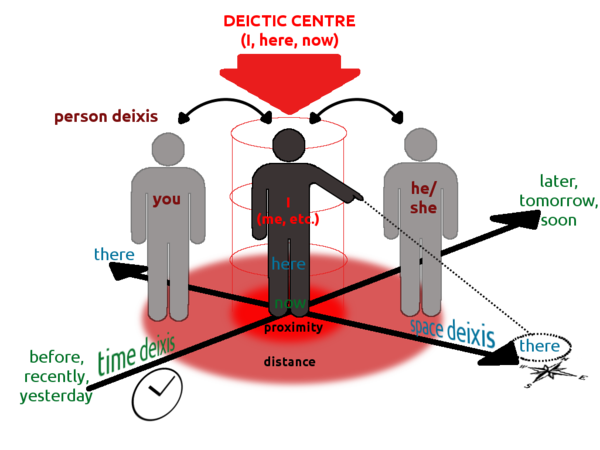

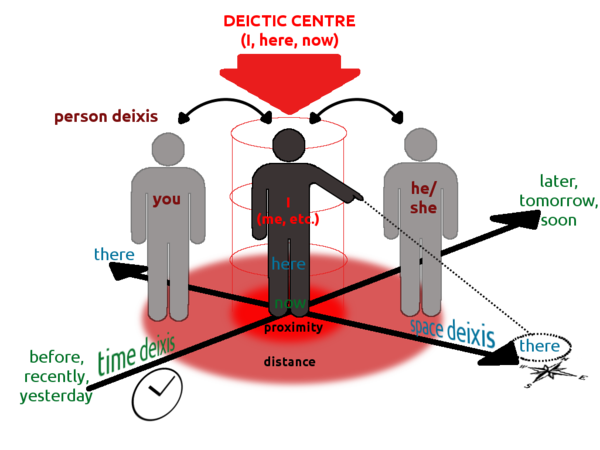

In linguistics, deixis

(/ˈdaɪksɪs/, /ˈdeɪksɪs/)[1] is the use of general words and phrases to

refer to a specific time, place, or person in context, e.g., the words

tomorrow, there, and they. Words are deictic if their semantic meaning

is fixed but their denoted meaning varies depending on time and/or

place. Words or phrases that require contextual information to be fully

understood—for example, English pronouns—are deictic. Deixis is closely

related to anaphora. Although this article deals primarily with deixis

in spoken language, the concept is sometimes applied to written

language, gestures, and communication media as well. In linguistic

anthropology, deixis is treated as a particular subclass of the more

general semiotic phenomenon of indexicality, a sign "pointing to" some

aspect of its context of occurrence. In linguistics, deixis

(/ˈdaɪksɪs/, /ˈdeɪksɪs/)[1] is the use of general words and phrases to

refer to a specific time, place, or person in context, e.g., the words

tomorrow, there, and they. Words are deictic if their semantic meaning

is fixed but their denoted meaning varies depending on time and/or

place. Words or phrases that require contextual information to be fully

understood—for example, English pronouns—are deictic. Deixis is closely

related to anaphora. Although this article deals primarily with deixis

in spoken language, the concept is sometimes applied to written

language, gestures, and communication media as well. In linguistic

anthropology, deixis is treated as a particular subclass of the more

general semiotic phenomenon of indexicality, a sign "pointing to" some

aspect of its context of occurrence.Although this article draws examples primarily from English, deixis is believed to be a feature (to some degree) of all natural languages.[2] The term's origin is Ancient Greek: δεῖξις, romanized: deixis, lit. 'display, demonstration, or reference'. To this, Chrysippus (c. 279 – c. 206 BCE) added the specialized meaning point of reference, which is the sense in which the term is used in contemporary linguistics.[3] |

言

語学では、直示あるはダイクシス(deixis)

とは、文脈の中で特定の時間、場所、人を指すために一般的な単語や語句を使うことである。単語は、その意味上の意味は固定されているが、示された意味が時

間や場所によって変化する場合、大工ティックとなる。例えば英語の代名詞のように、完全に理解するために文脈情報を必要とする単語や語句はディクシス

(deictic)である。デイクシスはアナフォラと密接な関係がある。この記事では主に話し言葉におけるデイクシスを扱いますが、この概念は書き言葉、

ジェスチャー、コミュニケーション・メディアにも適用されることがあります。言語人類学では、デイクシスは、より一般的な記号論的現象である「指標性」

(記号がその発生文脈のある側面を「指し示す」こと)の特定の下位分類として扱われる。 言

語学では、直示あるはダイクシス(deixis)

とは、文脈の中で特定の時間、場所、人を指すために一般的な単語や語句を使うことである。単語は、その意味上の意味は固定されているが、示された意味が時

間や場所によって変化する場合、大工ティックとなる。例えば英語の代名詞のように、完全に理解するために文脈情報を必要とする単語や語句はディクシス

(deictic)である。デイクシスはアナフォラと密接な関係がある。この記事では主に話し言葉におけるデイクシスを扱いますが、この概念は書き言葉、

ジェスチャー、コミュニケーション・メディアにも適用されることがあります。言語人類学では、デイクシスは、より一般的な記号論的現象である「指標性」

(記号がその発生文脈のある側面を「指し示す」こと)の特定の下位分類として扱われる。この記事では主に英語から例を引くが、デイクシスはすべての自然言語の(ある程度の)特徴であると考えられている[2]。 表示、実演、言及」。これにク リシッポス(紀元前279年頃~紀元前206年頃)が参照点という特殊な意味を加え、これが現代の言語学で使われる意味である[3]。 |

| Types Traditional categories Charles J. Fillmore used the term "major grammaticalized types" to refer to the most common categories of contextual information: person, place, and time.[4] Similar categorizations can be found elsewhere.[5][6] Personal deixis Personal deixis, or person deixis, concerns itself with the grammatical persons involved in an utterance: (1) those directly involved (e.g. the speaker, the addressee), (2) those not directly involved (e.g. those who hear the utterance but who are not being directly addressed), and (3) those mentioned in the utterance.[7] In English, the distinctions are generally indicated by pronouns (personal deictical terms are in italics): I am going to the movies. Would you like to have dinner? They tried to hurt me, but she came to the rescue. In many languages with gendered pronouns, the third-person masculine pronouns (he/his/him in English) are used as a default when referring to a person whose gender is unknown or irrelevant: To each his own. In contrast, English for some time used the neuter gender for cases of unspecified gender in the singular (with the use of the plural starting in around the fourteenth century), but many grammarians drew on Latin to come to the preference for "he" in such cases. However, it remains common to use the third-person plural (they/their/them/theirs) even when the antecedent is singular (a phenomenon known as singular they): To each their own. In languages that distinguish between masculine and feminine plural pronouns, such as French or Serbo-Croatian,[8] the masculine is again often used as default. "Ils vont à la bibliothèque", "Oni idu u biblioteku" (They go to the library) may refer either to a group of masculine nouns or a group of both masculine and feminine nouns. "Elles vont...", "One idu..." would be used only for a group of feminine nouns. In many such languages, the gender (as a grammatical category) of a noun is only tangentially related to the gender of the thing the noun represents. For example, in French, the generic personne, meaning a person (of either sex), is always a feminine noun, so if the subject of discourse is "les personnes" (the people), the use of "elles" is obligatory, even if the people being considered are all men. Spatial deixis Spatial deixis, or place deixis, concerns itself with the spatial locations relevant to an utterance. Similarly to personal deixis, the locations may be either those of the speaker and addressee or those of persons or objects being referred to. The most salient English examples are the adverbs here and there, and the demonstratives this, these, that, and those, although those are far from exclusive.[4] Some example sentences (spatial deictical terms are in italics): I enjoy living in this city. Here is where we will place the statue. She was sitting over there. Unless otherwise specified, spatial deictical terms are generally understood to be relative to the location of the speaker, as in: The shop is across the street. where "across the street" is understood to mean "across the street from where I [the speaker] am right now."[4] Although "here" and "there" are often used to refer to locations near to and far from the speaker, respectively, as in: Here is a good spot; it is too sunny over there. "there" can also refer to the location of the addressee, if they are not in the same location as the speaker, as in: How is the weather there?[7] Deictic projection: In some contexts, spatial deixis is used metaphorically rather than physically, i.e. the speaker is not speaking as the deictic center. For example: I am coming home now. The above utterance would generally denote the speaker's going home from their own point of reference, yet it appears to be perfectly normal for one to project his physical presence to his home rather than away from home. Here is another example: I am not here; please leave a message. Despite its common usage to address people who call when no one answers the phone, the here here is semantically contradictory to the speaker's absence. Nevertheless, this is considered normal for most people as speakers have to project themselves as answering the phone when in fact they are not physically present. Languages usually show at least a two-way referential distinction in their deictic system: proximal, i.e. near or closer to the speaker; and distal, i.e. far from the speaker and/or closer to the addressee. English exemplifies this with such pairs as this and that, here and there, etc. In other languages, the distinction is three-way or higher: proximal, i.e. near the speaker; medial, i.e. near the addressee; and distal, i.e. far from both. This is the case in a few Romance languages[note 1] and in Serbo-Croatian,[9] Korean, Japanese, Thai, Filipino, Macedonian, Yaqui, and Turkish. The archaic English forms yon and yonder (still preserved in some regional dialects) once represented a distal category that has now been subsumed by the formerly medial "there".[10] In the Sinhala language, there is a four-way deixis system for both person and place; near the speaker /me_ː/, near the addressee /o_ː/, close to a third person, visible /arə_ː/ and far from all, not visible /e_ː/. The Malagasy language has seven degrees of distance combined with two degrees of visibility, while many Inuit languages have even more complex systems.[11] Temporal deixis Temporal deixis, or time deixis, concerns itself with the various times involved in and referred to in an utterance. This includes time adverbs like "now", "then", and "soon", as well as different verbal tenses. A further example is the word tomorrow, which denotes the next consecutive day after any day it is used. "Tomorrow," when spoken on a day last year, denoted a different day from "tomorrow" when spoken next week. Time adverbs can be relative to the time when an utterance is made (what Fillmore calls the "encoding time", or ET) or the time when the utterance is heard (Fillmore's "decoding time", or DT).[4] Although these are frequently the same time, they can differ, as in the case of prerecorded broadcasts or correspondence. For example, if one were to write (temporal deictical terms are in italics): It is raining now, but I hope when you read this it will be sunny. the ET and DT would be different, with "now" referring to the moment the sentence is written and "when" referring to the moment the sentence is read. Tenses are generally separated into absolute (deictic) and relative tenses. So, for example, simple English past tense is absolute, such as in: He went. whereas the pluperfect is relative to some other deictically specified time, as in: He had gone. Other categories Though the traditional categories of deixis are perhaps the most obvious, there are other types of deixis that are similarly pervasive in language use. These categories of deixis were first discussed by Fillmore and Lyons,[7] and were echoed in works of others.[5][6] Discourse deixis Discourse deixis, also referred to as text deixis, refers to the use of expressions within an utterance to refer to parts of the discourse that contain the utterance—including the utterance itself. For example, in: This is a great story. "this" refers to an upcoming portion of the discourse; and in: That was an amazing account. "that" refers to a prior portion of the discourse. Distinction must be made between discourse deixis and anaphora, which is when an expression makes reference to the same referent as a prior term, as in: Matthew is an incredible athlete; he came in first in the race. In this case, "he" is not deictical because, within the above sentence, its denotative meaning of Matthew is maintained regardless of the speaker, where or when the sentence is used, etc. Lyons points out that it is possible for an expression to be both deictic and anaphoric at the same time. In his example: I was born in London, and I have lived here/there all my life. "here" or "there" function anaphorically in their reference to London, and deictically in that the choice between "here" or "there" indicates whether the speaker is or is not currently in London.[2] The rule of thumb to distinguish the two phenomena is as follows: when an expression refers to a second linguistic expression or a piece of discourse, it is discourse deictic. When the former expression refers to the same item as does a prior linguistic expression, it is anaphoric.[7] Switch reference is a type of discourse deixis, and a grammatical feature found in some languages, which indicates whether the argument of one clause is the same as the argument of the previous clause. In some languages, this is done through same subject markers and different subject markers. In the translated example "John punched Tom, and left-[same subject marker]," it is John who left, and in "John punched Tom, and left-[different subject marker]," it is Tom who left.[12] Discourse deixis has been observed in internet language, particularly with the use of iconic language forms resembling arrows.[13] Social deixis Social deixis concerns the social information that is encoded within various expressions, such as relative social status and familiarity. Two major forms of it are the so-called T–V distinctions and honorifics. T–V distinction Main article: T–V distinction T–V distinctions, named for the Latin "tu" and "vos" (singular and plural versions of "you"), is the name given to the phenomenon when a language has at least two different second-person pronouns. The varying usage of these pronouns indicates something about formality, familiarity, and/or solidarity between the interactants. So, for example, the T form might be used when speaking to a friend or social equal, whereas the V form would be used speaking to a stranger or social superior. This phenomenon is common in European languages.[14] Honorifics Main article: Honorifics (linguistics) Honorifics are a much more complex form of social deixis than T–V distinctions, though they encode similar types of social information. They can involve words being marked with various morphemes as well as nearly entirely different lexicons being used based on the social status of the interactants. This type of social deixis is found in a variety of languages, but is especially common in South and East Asia.[14] Persian also makes wide use of honorifics.[15] Technology Technological deixis is a reference to the forms and purposes literacy takes as technology changes the nature of literacy in general (e.g., how one reads a webpage, navigates new software, etc.), how those literacies might be expressed, and the speed and efficiency with which those literacies might change (Leu, Kinzer, Coiro, and Cammack, 2004; http://www.readingonline.org/electronic/elec_index.asp?HREF=/electronic/RT/3-01_Column/index.html). Anaphoric reference Main article: Anaphora (linguistics) Generally speaking, anaphora refers to the way in which a word or phrase relates to other text: An exophoric reference refers to language outside of the text in which the reference is found. A homophoric reference is a generic phrase that obtains a specific meaning through knowledge of its context. For example, the meaning of the phrase "the Queen" may be determined by the country in which it is spoken. Because there may be many Queens throughout the world when the sentence is used, the location of the speaker[note 2] provides the extra information that allows an individual Queen to be identified. An endophoric reference refers to something inside of the text in which the reference is found. An anaphoric reference, when opposed to cataphora, refers to something within a text that has been previously identified. For example, in "Susan dropped the plate. It shattered loudly," the word it refers to the phrase, "the plate". A cataphoric reference refers to something within a text that has not yet been identified. For example, in "Since he was very cold, David promptly put on his coat," the identity of he is unknown until the individual is also referred to as "David". |

種類 伝統的なカテゴリー チャールズ・J・フィルモアは文脈情報の最も一般的なカテゴリーである人、場所、時間を指すために「主要文法類型」という言葉を使った[4]。同様の分類は他の場所でも見られる[5][6]。 人称デイクシス 人称デイクシス(person deixis)は、発話に関与する文法上の人物に関係するものである:(1)直接関与する人物(例えば、話し手、被呼者)、(2)直接関与しない人物(例 えば、発話を聞いているが、直接的に話しかけられていない人物)、(3)発話に言及されている人物[7]: 私は映画に行きます。 私は映画に行きます。 彼らは私を傷つけようとしましたが、彼女が助けに来てくれました。 性別を表す代名詞がある多くの言語では、性別が不明または無関係な人物を指す場合、三人称の男性代名詞(英語ではhe/his/him)がデフォルトとして使われる: 人それぞれである。 一方、英語ではしばらくの間、単数形で性別が特定できない場合には中性代名詞を使用していました(複数形の使用は14世紀ごろから)が、多くの文法家がラ テン語を参考にして、このような場合には「he」を優先するようになりました。しかし、先行詞が単数の場合でも、三人称複数形 (they/their/them/theirs)を使うことは依然として一般的である(singular theyとして知られる現象): 人それぞれである。 フランス語やセルボ・クロアチア語のように、男性代名詞と女性代名詞を区別する言語では[8]、やはり男性代名詞がデフォルトとして使われることが多い。 「Ils vont à la bibliothèque"(図書館に行く)、"Oni idu u biblioteku"(図書館に行く)は、男性名詞のグループ、または男性名詞と女性名詞の両方のグループを指す場合があります。「Elles vont...」、「One idu...」は女性名詞のグループにのみ使われます。このような多くの言語では、名詞の(文法上のカテゴリーとしての)性別は、その名詞が表す事物の性 別と間接的な関係しかありません。たとえば、フランス語では、人(性別は問わない)を意味する一般名詞personneは常に女性名詞であるため、談話の 主語が「les personnes」(人々)である場合、対象となる人々がすべて男性であっても、「elles」の使用が義務付けられている。 空間的接辞 空間的デイクシス(場所的デイクシス)は、発話に関連する空間的な場所に関係します。人称的デイクシスと同様に、その場所は話し手と聞き手のものであった り、言及される人物や物体のものであったりする。最も顕著な英語の例は、副詞のhereとthere、および指示詞のthis、these、that、 theseであるが、これらは排他的とは言い難い[4]。 いくつかの例文(空間的な指示語は斜体で示されている): この街に住むのは楽しい。 私はこの街に住むのが楽しい。 彼女はあそこに座っていた。 特に指定がない限り、空間的指示語は一般的に話し手の位置に対して相対的なものと理解される: その店は通りの向こう側にある。 ここで、"across the street "は、「私(話し手)が今いる場所から通りを隔てた向こう側」という意味に理解される[4]。"here "と "there "は、それぞれ話し手に近い場所と遠い場所を指すのによく使われるが、次のようになる: あそこは日当たりが良すぎる。 また、"there "は、話し手と同じ場所にいない場合、次のように相手の場所を指すこともある: そちらの天気はどうですか? ダイクシス投射: つまり、話し手がディクテ ィクスの中心として話しているわけではない。例えば 今から家に帰ります。 上記の発話は一般的に、話し手が自分自身の基準点から家に帰ることを表しているが、自分の物理的な存在を家から離れるのではなく、家に投影することはまったく普通のことのようだ。別の例を挙げよう: 不在です。メッセージをどうぞ。 誰も電話に出ないときに電話をかけてくる人への呼びかけとしてよく使われるにもかかわらず、ここでのhereは意味的には話し手が不在であることと矛盾し ている。とはいえ、実際には物理的に不在であるにもかかわらず、話し手は電話に出ているように自分を演出しなければならないため、ほとんどの人にとってこ れが普通だと考えられている。 通常、言語には、少なくとも双方向の参照区別があり、近位語は話し手の近く、遠位語は話し手から遠い、または聞き手に近いことを表す。英語では、thisとthat、hereとthereなどのペアがその例である。 他の言語では、近位、つまり話し手に近い、中位、つまり聞き手に近い、遠位、つまり両方から遠いというように、三者間またはそれ以上の区別があります。こ れは、いくつかのロマンス語[注 1]や、セルボ・クロアチア語、[注 9]韓国語、日本語、タイ語、フィリピン語、マケドニア語、ヤキ語、トルコ語に見られる。英語の古語形であるyonとyonder(いくつかの地方方言に 残っている)は、かつては遠位範疇を表していたが、現在では以前は中位 "there "に包含されている。 [10]シンハラ語では、人称と場所の両方について、話し手に近い/me_↪L2D0↩/、聞き手に近い/o_↪L2D0↩/、三人称に近い、見える /arə_↪L2D0↩/、遠い、見えない/e_↪L2D0↩/という四方向のデイクシスシステムがあります。マダガスカル語には7段階の距離と2段階の 可視性があり、多くのイヌイット語にはさらに複雑なシステムがある[11]。 時間的接辞 時間的デイクシス(temporal deixis)、または時間的デイクシス(time deixis)は、発話に含まれる、または言及されるさまざまな時間に関係する。これには、「now」、「then」、「soon」などの時間副詞や、さ まざまな時制が含まれる。さらに、tomorrowという単語は、その単語が使われる日の次の連続した日を表します。例えば、昨年のある日に 「Tomorrow」と言った場合、来週の「Tomorrow」とは別の日を表す。時間副詞は、発話が行われた時間(フィルモアの言う「エンコード時 間」、またはET)、または発話が聞かれた時間(フィルモアの言う「デコード時間」、またはDT)に対する相対的なものであることがある[4]。これらは 同じ時間であることが多いが、事前に録音された放送や通信の場合のように異なることもある。たとえば、次のように書くとする(時間的なデ ィクティカル用語は斜体): 今は雨が降っていますが、あなたがこれを読むときには晴れているといいですね。 と書くと、ETとDTは異なり、"now "は文章が書かれた瞬間を指し、"when "は文章が読まれた瞬間を指す。 時制は一般的に絶対時制(deictic)と相対時制に分けられる。つまり、例えば単純な英語の過去形は絶対時制で、次のようになる: 彼は行った。 のように、絶対的な時制であるのに対して、超完了体は、ある特定の時間に対する相対的な時制である: 彼は行った。 その他のカテゴリー 伝統的な仮定法のカテゴリーが最もわかりやすいかもしれませんが、その他にも同じように言語使用に広く浸透している仮定法があります。これらのデイクシス のカテゴリーはフィルモアとライオンズによって最初に議論され[7]、他の研究者たちの作品にも反映されている[5][6]。 談話デイクシス 談話デイクシスは、テキストデイクシスとも呼ばれ、発話そのものを含む、発話を含む談話の部分を指すために発話内で使われる表現を指す。たとえば This is a great story. 「this」は談話の次の部分を指す: それは素晴らしい説明だった。 「that」は談話の前の部分を指す。 談話デイクシスとアナフォラは区別しなければならない: マシューはすごいアスリートだ。 この場合、"he "は "deictical "ではない。というのも、上の文の中では、話し手や、文が使われる場所やタイミングなどに関係なく、"Matthew "の含意的な意味が維持されるからである。 ライオンは、ある表現がディクテイックであると同時にアナフォリックであることもあり得ると指摘する。彼の例では 私はロンドンで生まれ、ずっとここ/そこに住んでいる。 "here "または "there "は、ロンドンへの言及という点でアナフォリックに機能し、"here "か "there "かの選択が、話し手が現在ロンドンにいるかいないかを示すという点でデイクティックに機能する[2]。 この2つの現象を区別するための経験則は以下の通り:ある表現が第二の言語表現または談話の一部を参照する場合、それは談話決定的である。前者の表現が先行する言語表現と同じ項目を参照する場合、それはアナフォリックである[7]。 切り替え参照は談話デイクシス(discourse deixis)の一種であり、ある節の引数が前の節の引数と同じかどうかを示す、いくつかの言語に見られる文法的特徴である。いくつかの言語では、これは 同じ主語マーカーや異なる主語マーカーによって行われる。訳例「ジョンはトムを殴り、去った-[同じ主語マーカー]」では、去ったのはジョンであり、 「ジョンはトムを殴り、去った-[異なる主語マーカー]」では、去ったのはトムである[12]。 インターネット言語では、特に矢印に似た象徴的な言語形式の使用によって、談話デイクシスが観察されている[13]。 社会的デイクシス ソーシャル・デイクシスは、相対的な社会的地位や親近感など、さまざまな表現に符号化される社会的情報に関するものである。その2つの主要な形式は、いわゆるT-V区別と敬語である。 T-V区別 主な記事 T-V区別 T-V区別は、ラテン語の "tu "と "vos"("you "の単数形と複数形)にちなんで名付けられたもので、ある言語が少なくとも2つの異なる二人称代名詞を持つ場合に起こる現象につけられる名称である。これ らの代名詞の使い分けは、対話者間の形式、親しさ、連帯感などを表します。たとえば、友人や社会的な対等な立場の人と話すときにはT形が使われ、見知らぬ 人や社会的な目上の人と話すときにはV形が使われる。この現象はヨーロッパの言語では一般的である[14]。 敬語 主な記事 敬語(言語学) 敬語はT-Vの区別よりもはるかに複雑な社会的接辞の一形態であるが、似たような種類の社会的情報を符号化する。様々な形態素で単語が表記されるだけでな く、相互作用者の社会的地位に基づいて、ほぼ完全に異なる語彙が使用されることもある。この種の社会的接辞はさまざまな言語に見られるが、特に南アジアや 東アジアでよく見られる[14]。ペルシア語でも敬語が広く使われている[15]。 技術 テクノロジカル・デイクシスは、テクノロジがリテラシーの性質全般(ウェブページの読み方、新しいソフトウェアのナビゲート方法など)を変化させる際に、 リテラシーが取る形態や目的、それらのリテラシーがどのように表現されるか、それらのリテラシーが変化するスピードや効率について言及するものである (Leu, Kinzer, Coiro, and Cammack, 2004; http://www.readingonline.org/electronic/elec_index.asp?HREF=/electronic/RT/3 -01_Column/index.html)。 アナフォリック参照 主な記事 アナフォラ(言語学) 一般的にアナフォラとは、ある単語やフレーズが他のテキストに関連する方法のことである: 外来語参照は、その参照が見られるテキストの外の言語を指す。 同音異義語は、文脈を知ることによって特定の意味を持つ一般的な語句である。例えば、"the Queen "というフレーズの意味は、それが話されている国によって決まるかもしれない。この文が使われるとき、世界中に多くの女王がいる可能性があるため、話し手 [注釈 2]の位置が個々の女王を特定するための余分な情報を提供する。 内包的参照は、その参照が見られるテキストの内部の何かを指す。 アナフォリックな参照は、カタフォラとは対照的に、以前に特定されたテキスト内の何かを指す。例えば、"Susan dropped the plate. It shattered loudly "の場合、itは "the plate "というフレーズを指す。 カタフォリック参照は、まだ特定されていないテキスト内の何かを指す。例えば、"Since he was very cold, David promptly put on his coat"(彼はとても寒かったので、デイビッドはすぐにコートを着た)では、その個人が "David "とも呼ばれるまでは、彼が誰なのかはわからない。 |

| Deictic center A deictic center, sometimes referred to as an origo, is a set of theoretical points that a deictic expression is 'anchored' to, such that the evaluation of the meaning of the expression leads one to the relevant point. As deictic expressions are frequently egocentric, the center often consists of the speaker at the time and place of the utterance and, additionally, the place in the discourse and relevant social factors. However, deictic expressions can also be used in such a way that the deictic center is transferred to other participants in the exchange or to persons / places / etc. being described in a narrative.[7] So, for example, in the sentence; I am standing here now. the deictic center is simply the person at the time and place of speaking. But say two people are talking on the phone long-distance, from London to New York. The Londoner can say; We are going to London next week. in which case the deictic center is in London, or they can equally validly say; We are coming to New York next week. in which case the deictic center is in New York.[2] Similarly, when telling a story about someone, the deictic center is likely to switch to him, her or they (third-person pronouns). So then in the sentence; He then ran twenty feet to the left. it is understood that the center is with the person being spoken of, and thus, "to the left" refers not to the speaker's left, but to the object of the story's left, that is, the person referred to as 'he' at the time immediately before he ran twenty feet. Usages It is helpful to distinguish between two usages of deixis, gestural and symbolic, as well as non-deictic usages of frequently deictic words. Gestural deixis refers, broadly, to deictic expressions whose understanding requires some sort of audio-visual information. A simple example is when an object is pointed at and referred to as "this" or "that". However, the category can include other types of information than pointing, such as direction of gaze, tone of voice, and so on. Symbolic usage, by contrast, requires generally only basic spatio-temporal knowledge of the utterance.[7] So, for example I broke this finger. requires being able to see which finger is being held up, whereas I love this city. requires only knowledge of the current location. In a similar vein, I went to this city one time ... is a non-deictic usage of "this", which does not identify anywhere specifically. Rather, it is used as an indefinite article, much the way "a" could be used in its place. |

ディクテイック・センター ディクテイック・センターはオリゴと呼ばれることもあるが、ディクテイック表現が「固定」される理論的な点の集合であり、表現の意味を評価する際に関連す る点に導かれる。ディクテイック表現はしばしば自己中心的であるため、その中心は多くの場合、発話の時と場所における話者、さらに談話における場所や関連 する社会的要因から構成される。しかし、ディクテイック表現は、ディクテイック中心が、やりとりの他の参加者や、語りの中で描写される人物や場所などに移 されるように使われることもある[7]; 私は今ここに立っている。 という文では、ディクテイック・センターは単に話している時と場所にいる人である。しかし、二人の人間がロンドンからニューヨークまで、長距離電話で話しているとする。ロンドンの人はこう言うことができる; 私たちは来週ロンドンに行きます。 と言うこともできるし、同じようにこう言うこともできる; 私たちは来週ニューヨークに行きます。 同様に、誰かについての話をするとき、指示中心は彼、彼女、または彼ら(三人称代名詞)に切り替わる可能性が高い。つまり、次のような文章になる; 彼はそれから左へ20フィート走った。 という文では、中心は話されている人物にあると理解され、したがって「左へ」は話者の左ではなく、話の対象の左、つまり彼が20フィート走る直前の時点で「彼」と呼ばれていた人物を指す。 用法 デイクシスにはジェスチャー的用法と象徴的用法があり、また頻繁に使われるデイクシス語の非デイクシス的用法もある。ジェスチャー・デイクシスとは、大ま かに言えば、何らかの視聴覚情報を必要とするデイクシス表現を指す。簡単な例としては、物体を指差して「これ」「あれ」と言うような場合である。しかし、 このカテゴリーには、視線の方向や声のトーンなど、指さし以外の情報も含まれる。対照的に、記号的用法は、一般的に、発話に関する基本的な時空間的知識の みを必要とする[7]。 この指を折った には、どの指を立てているのかがわかる必要がある。 私はこの街が好きです。 は現在地の知識しか必要としない。同じような意味で 私はある時この街に行った. は "this "の非決定用法で、具体的にどこかを特定するものではない。むしろ、"a "がその代わりに使われるのと同じように、不定冠詞として使われている。 |

| Deixis and indexicality The terms deixis and indexicality are frequently used almost interchangeably, and both deal with essentially the same idea of contextually-dependent references. However, the two terms have different histories and traditions. In the past, deixis was associated specifically with spatiotemporal reference, and indexicality was used more broadly.[16] More importantly, each is associated with a different field of study. Deixis is associated with linguistics, and indexicality is associated with philosophy[17] as well as pragmatics.[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deixis |

接辞と指標性 deixisとindexicalityという用語は、ほとんど同じ意味で使われることが多く、どちらも文脈に依存した参照という本質的に同じ考え方を 扱っている。しかし、この2つの用語には異なる歴史と伝統がある。より重要なのは、それぞれが異なる研究分野と関連していることである。デイクシスは言語 学と関連し、指標性は語用論だけでなく哲学[17]とも関連している[18]。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆