Lévi-Strauss sought

to apply the structural linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure to

anthropology.[32] At the time, the family was traditionally considered

the fundamental object of analysis but was seen primarily as a

self-contained unit consisting of a husband, a wife, and their

children. Nephews, cousins, aunts, uncles, and grandparents all were

treated as secondary. Lévi-Strauss argued that akin to Saussure's

notion of linguistic value, families acquire determinate identities

only through relations with one another. Thus, he inverted the

classical view of anthropology, putting the secondary family members

first and insisting on analyzing the relations between units instead of

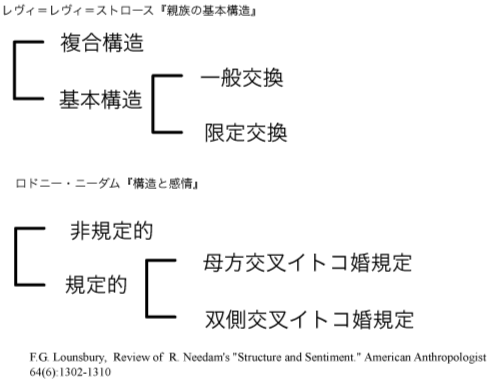

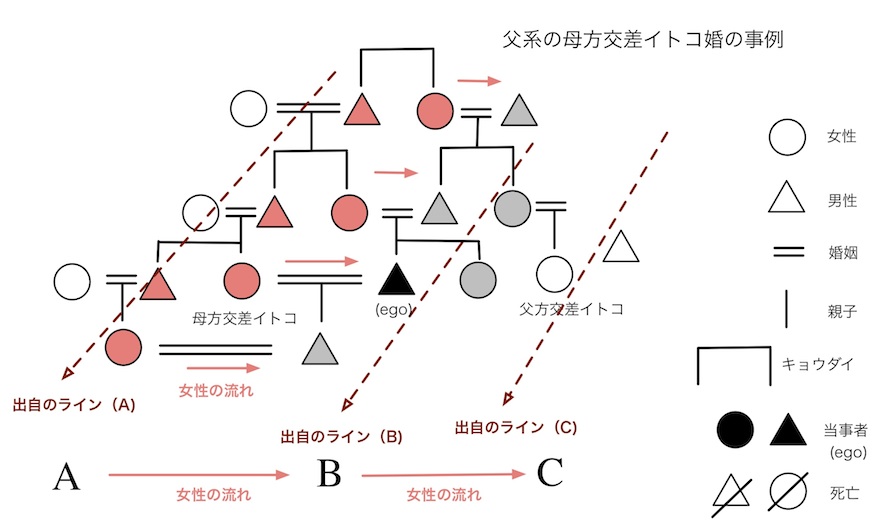

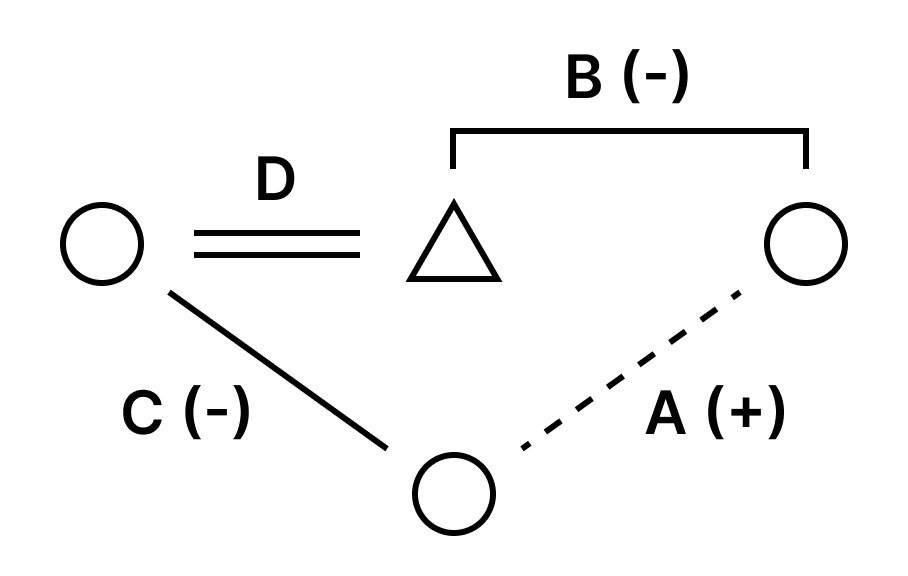

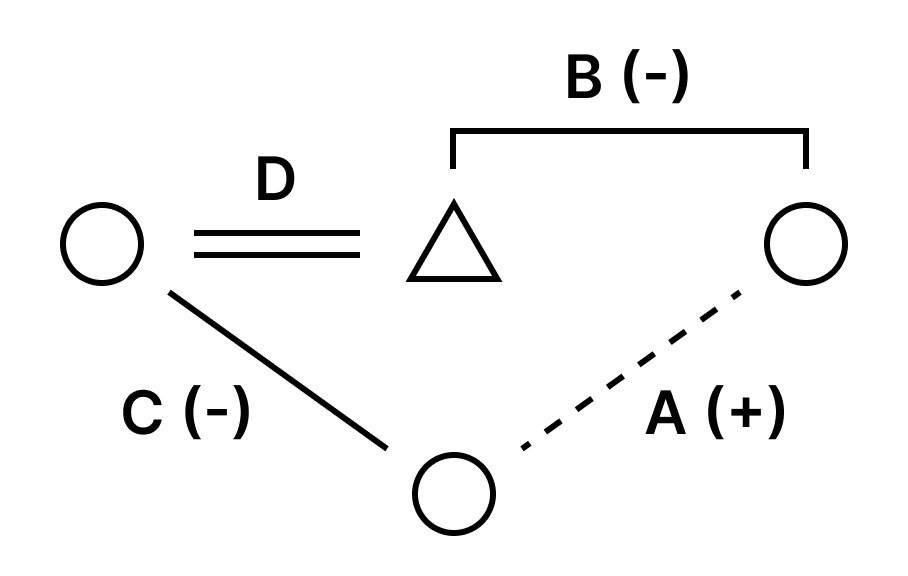

the units themselves.[33] A diagram illustrating Lévi-Strauss's theory of kinship. In such a case, one can infer that D is positive. In his own analysis of the formation of the identities that arise through marriages between tribes, Lévi-Strauss noted that the relation between the uncle and the nephew was to the relation between brother and sister, as the relation between father and son is to that between husband and wife,[34] that is, A is to B as C is to D. Therefore, if we know A, B, and C, we can predict D.[clarification needed] An example of this law is illustrated in the diagram. The four relation units are marked with A to D. Lévi-Strauss noted that if A is positive, B is negative, and C is negative, then it can inferred that D is positive, thereby satisfying the constraint 'A is to B as C is to D'; in this case, the relations are contrasting. The goal of Lévi-Strauss's structural anthropology, then, was to simplify the masses of empirical data into generalized, comprehensible relations between units, which allow for predictive laws to be identified, such as A is to B as C is to D.[33] Lévi-Strauss's theory is set forth in Structural Anthropology (1958). Briefly, he considers culture a system of symbolic communication, to be investigated with methods that others have used more narrowly in the discussion of novels, political speeches, sports, and movies. His reasoning makes the best sense when contrasted against the background of an earlier generation's social theory. He wrote about this relationship for decades. A preference for "functionalist" explanations dominated the social sciences from the turn of the 20th century through the 1950s, which is to say that anthropologists and sociologists tried to state the purpose of a social act or institution. The existence of a thing was explained, if it fulfilled a function. The only strong alternative to that kind of analysis was a historical explanation, accounting for the existence of a social fact by stating how it came to be. The idea of social function developed in two different ways, however. The English anthropologist Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown, who had read and admired the work of the French sociologist Émile Durkheim, argued that the goal of anthropological research was to find the collective function, such as what a religious creed or a set of rules about marriage did for the social order as a whole. Behind this approach was an old idea, the view that civilization developed through a series of phases from the primitive to the modern, everywhere in the same manner. All of the activities in a given kind of society would partake of the same character; some sort of internal logic would cause one level of culture to evolve into the next. On this view, a society can easily be thought of as an organism, the parts functioning together as do the parts of a body. In contrast, the more influential functionalism of Bronisław Malinowski described the satisfaction of individual needs, what a person derived by participating in a custom. In the United States, where the shape of anthropology was set by the German-educated Franz Boas, the preference was for historical accounts. This approach had obvious problems, which Lévi-Strauss praises Boas for facing squarely. Historical information seldom is available for non-literate cultures. The anthropologist fills in with comparisons to other cultures and is forced to rely on theories that have no evidential basis, the old notion of universal stages of development or the claim that cultural resemblances are based on some unrecognized past contact between groups. Boas came to believe that no overall pattern in social development could be proven; for him, there was no single history, only histories. There are three broad choices involved in the divergence of these schools; each had to decide: what kind of evidence to use; whether to emphasize the particulars of a single culture or look for patterns underlying all societies; and what the source of any underlying patterns might be, the definition of common humanity. Social scientists in all traditions relied on cross-cultural studies,[citation needed] as it was always necessary to supplement information about a society with information about others. Thus, some idea of a common human nature was implicit in each approach. The critical distinction, then, remained twofold: Does a social fact exist because it is functional for the social order, or because it is functional for the person? Do uniformities across cultures occur because of organizational needs that must be met everywhere, or because of the uniform needs of human personality? For Lévi-Strauss, the choice was for the demands of the social order. He had no difficulty bringing out the inconsistencies and triviality of individualistic accounts. Malinowski said, for example, that magic beliefs come into being when people need to feel a sense of control over events when the outcome is uncertain. In the Trobriand Islands, he found proof of this claim in the rites surrounding abortions and weaving skirts. But in the same tribes, there is no magic attached to making clay pots even though it is no more certain a business than weaving. So, the explanation is not consistent. Furthermore, these explanations tend to be used in an ad hoc, superficial way – one postulates a trait of personality when needed. However, the accepted way of discussing organizational function did not work either. Different societies might have institutions that were similar in many obvious ways and yet, served different functions. Many tribal cultures divide the tribe into two groups and have elaborate rules about how the two groups may interact. However, exactly what they may do—trade, intermarry—is different in different tribes; for that matter, so are the criteria for distinguishing the groups. Nor will it do to say that dividing in two is a universal need of organizations, because there are a lot of tribes that thrive without it. For Lévi-Strauss, the methods of linguistics became a model for all his earlier examinations of society. His analogies usually are from phonology (though also later from music, mathematics, chaos theory, cybernetics, and so on). "A really scientific analysis must be real, simplifying, and explanatory," he writes.[35] Phonemic analysis reveals features that are real, in the sense that users of the language can recognize and respond to them. At the same time, a phoneme is an abstraction from language – not a sound, but a category of sound defined by the way it is distinguished from other categories through rules unique to the language. The entire sound structure of a language may be generated from a relatively small number of rules. In the study of the kinship systems that first concerned him, this ideal of explanation allowed a comprehensive organization of data that partly had been ordered by other researchers. The overall goal was to find out why family relations differed among various South American cultures. The father might have great authority over the son in one group, for example, with the relationship rigidly restricted by taboos. In another group, the mother's brother would have that kind of relationship with the son, while the father's relationship was relaxed and playful. A number of partial patterns had been noted. Relations between the mother and father, for example, had some sort of reciprocity with those of father and son– if the mother had a dominant social status and was formal with the father, for example, then the father usually had close relations with the son. But these smaller patterns joined in inconsistent ways. One possible way of finding a master order was to rate all the positions in a kinship system along several dimensions. For example, the father was older than the son, the father produced the son, the father had the same sex as the son, and so on; the matrilineal uncle was older and of the same sex, but did not produce the son, and so on. An exhaustive collection of such observations might cause an overall pattern to emerge. However, for Lévi-Strauss, this kind of work was considered "analytical in appearance only". It results in a chart that is far more difficult to understand than the original data and is based on arbitrary abstractions (empirically, fathers are older than sons, but it is only the researcher who declares that this feature explains their relations). Furthermore, it does not explain anything. The explanation it offers is tautological—if age is crucial, then age explains a relationship. And it does not offer the possibility of inferring the origins of the structure. A proper solution to the puzzle is to find a basic unit of kinship which can explain all the variations. It is a cluster of four roles – brother, sister, father, son. These are the roles that must be involved in any society that has an incest taboo requiring a man to obtain a wife from some man outside his own hereditary line.[clarification needed] A brother may give away his sister, for example, whose son might reciprocate in the next generation by allowing his sister to marry exogamously. The underlying demand is a continued circulation of women to keep various clans peacefully related. Right or wrong, this solution displays the qualities of structural thinking. Even though Lévi-Strauss frequently speaks of treating culture as the product of the axioms and corollaries that underlie it, or the phonemic differences that constitute it, he is concerned with the objective data of field research. He notes that it is logically possible for a different atom of kinship structure to exist–sister, sister's brother, brother's wife, daughter – but there are no real-world examples of relationships that can be derived from that grouping. The trouble with this view has been shown by Australian anthropologist Augustus Elkin, who insisted on the point that in a four-class marriage system, the preferred marriage was with a classificatory mother's brother's daughter and never with the true one. Lévi-Strauss's atom of kinship structure deals only with consanguineal kin. There is a big difference between the two situations, in that the kinship structure involving the classificatory kin relations allows for the building of a system which can bring together thousands of people. Lévi-Strauss's atom of kinship stops working once the true MoBrDa is missing.[clarification needed] Lévi-Strauss also developed the concept of the house society to describe those societies where the domestic unit is more central to the social organization than the descent group or lineage. The purpose of structuralist explanation is to organize real data in the simplest effective way. All science, he says, is either structuralist or reductionist.[36] In confronting such matters as the incest taboo, one is facing an objective limit of what the human mind has accepted so far. One could hypothesize some biological imperative underlying it, but so far as social order is concerned, the taboo has the effect of an irreducible fact. The social scientist can only work with the structures of human thought that arise from it. And structural explanations can be tested and refuted. A mere analytic scheme that wishes causal relations into existence is not structuralist in this sense. Lévi-Strauss's later works are more controversial, in part because they impinge on the subject matter of other scholars. He believed that modern life and all history were founded on the same categories and transformations that he had discovered in the Brazilian backcountry—The Raw and the Cooked, From Honey to Ashes, The Naked Man (to borrow some titles from the Mythologiques). For instance, he compares anthropology to musical serialism and defends his "philosophical" approach. He also pointed out that the modern view of primitive cultures was simplistic in denying them a history. The categories of myth did not persist among them because nothing had happened–it was easy to find the evidence of defeat, migration, exile, and repeated displacements of all the kinds known to recorded history. Instead, the mythic categories had encompassed these changes. He argued for a view of human life as existing in two timelines simultaneously, the eventful one of history and the long cycles in which one set of fundamental mythic patterns dominates and then perhaps another. In this respect, his work resembles that of Fernand Braudel, the historian of the Mediterranean and 'la longue durée,' the cultural outlook and forms of social organization that persisted for centuries around that sea. He is right in that history is difficult to build up in a non-literate society, nevertheless, Jean Guiart's anthropological and José Garanger's archaeological work in central Vanuatu, bringing to the fore the skeletons of former chiefs described in local myths, who had thus been living persons, shows that there can be some means of ascertaining the history of some groups which otherwise would be deemed a historical. Another issue is the experience that the same person can tell one a myth highly charged in symbols, and some years later a sort of chronological history claiming to be chronic of a descent line (e.g., in the Loyalty islands and New Zealand), the two texts having in common that they each deal in topographical detail with the land-tenure claims of the said descent line (see Douglas Oliver on the Siwai in Bougainville). Lévi-Strauss would agree to these aspects be explained inside his seminar but would never touch them on his own. The anthropological data content of the myths was not his problem. He was only interested in the formal aspects of each story, considered by him as the result of the workings of the collective unconscious of each group, which idea was taken from the linguists, but cannot be proved in any way although he was adamant about its existence and would never accept any discussion on this point. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_L%C3%A9vi-Strauss |

レヴィ=ストロースは、フェルディナン・ド・ソシュールの構造言語学を

人類学に応用しようとしたのである[32]。当時、家族は伝統的に分析の基本的な対象とみなされていたが、主に夫、妻、そしてその子どもたちからなる自己

完結的な単位とみなされていた。甥、いとこ、叔父、叔母、祖父母はすべて二次的なものとして扱われていた。レヴィ=ストロースは、ソシュールの言語的価値

の概念と同様に、家族は互いの関係を通じてのみ確定的なアイデンティティを獲得すると主張した。したがって、彼は古典的な人類学の見方を逆転させ、二次的

な家族構成員を第一に考え、単位そのものではなく、単位間の関係を分析することを主張した[33]。 レヴィ=ストロースの親族関係を示す図。このような場合、Dは肯定的であると推測できる。 部族間の結婚によって生じるアイデンティティの形成に関する彼自身の分析において、レヴィ=ストロースは、叔父と甥の関係は、父と息子の関係が夫と妻の関 係にあるように、兄と妹の関係にあると指摘した[34]。レヴィ=ストロースは、Aが正、Bが負、Cが負であれば、Dが正であると推論でき、それによって 「CがDであるように、AはBである」という制約を満たすと指摘した。レヴィ=ストロースの構造人類学の目標は、大量の経験的データを一般化された理解可 能な単位間の関係へと単純化することであった。 レヴィ=ストロースの理論は『構造人類学』(1958年)に示されている。簡単に言えば、彼は文化を象徴的なコミュニケーションのシステムだと考えてお り、小説、政治演説、スポーツ、映画などの議論において、他の人々がより狭い範囲で用いてきた方法で調査することを目的としている。彼の推論は、それ以前 の世代の社会理論を背景にして対比されるとき、最も理にかなっている。彼はこの関係について何十年も書き続けた。 つまり、人類学者や社会学者は、社会的行為や制度の目的を述べようとしたのである。つまり、人類学者や社会学者は、社会的行為や制度の目的を述べようとし たのである。ある物事の存在は、それがある機能を果たしている場合に説明された。この種の分析に代わる唯一の有力な方法は歴史的説明であり、ある社会的事 実がどのようにして存在するようになったかを述べることによって、その存在を説明することであった。 しかし、社会的機能という考え方は、2つの異なる方法で発展した。イギリスの人類学者アルフレッド・レジナルド・ラドクリフ=ブラウンは、フランスの社会 学者エミール・デュルケムの著作を読んで敬服し、人類学的研究の目標は、宗教的信条や結婚に関する一連の規則が社会秩序全体に対してどのような役割を果た しているかといった集団的機能を見出すことだと主張した。このアプローチの背後には、文明は原始から近代までの一連の段階を経て発展し、どこでも同じよう に発展するという古い考え方があった。ある種の社会における活動はすべて同じ性格を帯びており、ある種の内的論理が、あるレベルの文化を次のレベルへと進 化させるのである。この考え方では、社会は有機体として考えることが容易であり、身体の各部分のように、各部分は互いに機能し合う。これとは対照的に、よ り影響力のあったブロニスワフ・マリノフスキーの機能主義は、個人の欲求の充足、つまり人が習慣に参加することで得られるものについて述べている。 ドイツで教育を受けたフランツ・ボースによって人類学の形が定められたアメリカでは、歴史的記述が好まれた。このアプローチには明らかな問題があったが、 レヴィ=ストロースはボアスが正面から向き合ったことを称賛している。文字を持たない文化では、歴史的な情報が得られることはめったにない。人類学者は他 の文化との比較で埋め合わせをし、何の証拠もない理論、つまり普遍的な発達段階という古い概念や、文化的類似性は過去の集団間の認識されていない接触に基 づくという主張に頼らざるを得ない。ボースは、社会発展の全体的なパターンは証明できないと考えるようになった。彼にとって、単一の歴史は存在せず、歴史 だけが存在するのである。 これらの学派の分岐には、3つの大まかな選択肢がある: どのような証拠を使うか; ひとつの文化の特殊性を強調するか、それともすべての社会の根底にあるパターンを探すか。 どのようなパターンが根底にあるのか、共通の人間性の定義は何なのか。 ある社会についての情報を他の社会についての情報で補うことが常に必要であったため、あらゆる伝統の社会科学者は異文化研究に依存していた[要出典]。し たがって、共通の人間性についての考え方は、それぞれのアプローチに暗黙のうちに含まれていた。そして、決定的な違いは2つあった: ある社会的事実が存在するのは、それが社会秩序にとって機能的だからなのか、それともその人にとって機能的だからなのか。 社会的事実が存在するのは、社会秩序にとって機能的だからなのか、それとも人間にとって機能的だからなのか。文化圏を超えた均一性が生じるのは、どこでも 満たされなければならない組織的欲求のためなのか、それとも人間の人格が持つ均一な欲求のためなのか。 レヴィ=ストロースにとって、その選択は社会秩序の要請によるものだった。彼は、個人主義的な説明の矛盾や矮小さを指摘するのに苦労はしなかった。例えば マリノフスキーは、魔術的な信仰は、結果が不確かな出来事に対して、人々が支配しているという感覚を感じる必要があるときに生まれるのだと言った。彼はト ロブリアンド諸島で、中絶やスカートを編む儀式にこの主張の証拠を見つけた。しかし同じ部族では、土鍋を作ることは機織りほど確実な仕事ではないにもかか わらず、魔法は存在しない。つまり、説明に一貫性がないのだ。さらに、こうした説明はその場しのぎの表面的な方法で使われがちである--必要なときに性格 の特徴を仮定するのである。しかし、組織機能を論じる方法として受け入れられているものも、うまく機能しなかった。異なる社会には、多くの明白な点で類似 していながら、異なる機能を果たす制度があるかもしれない。多くの部族文化では、部族を2つのグループに分け、2つのグループがどのように相互作用するか について入念なルールを定めている。しかし、部族によって貿易や婚姻など、具体的に何をするのかは異なる。また、2つに分けることは組織の普遍的な必要性 である、とも言えないだろう。 レヴィ=ストロースにとって、言語学の方法は、それ以前に彼が行っていた社会に関するすべての研究の手本となった。レヴィ=ストロースにとって、言語学の 手法は、それ以前に彼が行っていた社会に関する考察の手本となった。彼の例えに使われるのは、たいてい音韻論である(後に音楽、数学、カオス理論、サイバ ネティクスなどからも引用される)。「本当に科学的な分析は、現実的で、単純化され、説明的でなければならない」と彼は書いている[35]。音素解析は、 言語の使用者がそれを認識し対応できるという意味で、現実的な特徴を明らかにする。同時に、音素は言語から抽象化されたものであり、音ではなく、その言語 特有の規則によって他のカテゴリーと区別される方法によって定義された音のカテゴリーである。言語の音構造全体は、比較的少数のルールから生成される可能 性がある。 彼が最初に関心を抱いた親族制度の研究では、この理想的な説明によって、他の研究者によって部分的に秩序づけられていたデータを包括的に整理することがで きた。全体的な目標は、南米のさまざまな文化の間で家族関係が異なる理由を突き止めることだった。例えば、あるグループでは父親が息子に対して大きな権限 を持ち、その関係はタブーによって厳しく制限されていた。別のグループでは、母親の兄弟が息子とそのような関係を持ち、父親の関係はリラックスして遊び心 にあふれている。 いくつかの部分的なパターンが指摘されている。例えば、母親と父親の関係は、父親と息子の関係とある種の相互性を持っていた。例えば、母親が支配的な社会 的地位にあり、父親とフォーマルな関係であれば、父親は息子と親密な関係を持つのが普通であった。しかし、これらの小さなパターンは一貫性のない形で結合 していた。マスター・オーダーを見つける一つの可能な方法は、親族制度におけるすべての立場をいくつかの次元に沿って評価することであった。例えば、父親 は息子より年上である、父親は息子を産んだ、父親は息子と同性である、などである。母系の叔父は年上で同性であるが、息子を産んでいない、などである。こ のような観察を網羅的に集めれば、全体的なパターンが浮かび上がってくるかもしれない。 しかし、レヴィ=ストロースにとって、この種の作業は「外見だけの分析的なもの」であった。その結果、元のデータよりもはるかに理解しにくく、恣意的な抽 象論に基づいた図が出来上がる(経験的には、父親は息子よりも年上だが、この特徴で二人の関係が説明できると宣言するのは研究者だけである)。しかも、何 も説明していない。もし年齢が重要なら、年齢が関係を説明することになる。そして、その構造の起源を推論する可能性も提供しない。 パズルの適切な解決策は、すべてのバリエーションを説明できる親族関係の基本単位を見つけることである。それは、兄弟、姉妹、父親、息子という4つの役割 の集まりである。これらは、近親相姦のタブーがあり、男性が自分の世襲以外の男性から妻を得ることを要求する社会では、必ず関わってくる役割である。根底 にあるのは、さまざまな氏族が平和的に関係を保つための女性の継続的な流通である。 善し悪しは別として、この解決策には構造的思考の特質が表れている。レヴィ=ストロースは、文化をその根底にある公理や定理の産物、あるいは文化を構成す る音素の差異として扱うことを頻繁に口にするにもかかわらず、フィールド調査という客観的データに関心を寄せている。彼は、姉、姉の弟、弟の妻、娘という 異なる原子の親族構造が存在することは論理的に可能だが、そのグループ分けから導き出される関係の実例は現実には存在しないと指摘する。この見解の問題点 は、オーストラリアの人類学者オーガスタス・エルキンによって示されている。彼は、4分類の結婚システムでは、分類上の母親の兄弟の娘との結婚が好まれ、 決して本当の母親とは結婚しない、という点を主張した。レヴィ=ストロースの親族構造のアトムは、血縁関係にある親族のみを扱っている。この2つの状況に は大きな違いがある。分類的親族関係を含む親族関係構造は、何千人もの人々を結びつけることができるシステムを構築することを可能にするという点である。 レヴィ=ストロースの親族関係の原子は、真のMoBrDaが欠落した時点で機能しなくなる。[clarification needed] レヴィ=ストロースはまた、家社会という概念を発展させ、家単位が子孫集団や血統よりも社会組織の中心となっている社会を説明した。 構造主義的説明の目的は、現実のデータを最も単純で効果的な方法で整理することである。近親相姦のタブーのような問題に直面することは、人間の心がこれま で受け入れてきたことの客観的限界に直面することである。その根底にある生物学的な要請を仮定することはできるが、社会秩序に関する限り、タブーは還元不 可能な事実の効果を持つ。社会科学者が扱うことができるのは、そこから生じる人間の思考構造だけである。そして、構造的な説明は検証され、反論されること がある。因果関係の存在を願うような単なる分析スキームは、この意味で構造主義的ではない。 レヴィ=ストロースの後期の著作は、他の研究者の主題に影響を及ぼしていることもあり、より論争を呼んでいる。レヴィ=ストロースは、現代生活とすべての 歴史は、ブラジルの奥地で発見したのと同じカテゴリーと変容の上に成り立っていると考えていた。例えば、彼は人類学を音楽的直列主義と比較し、自らの「哲 学的」アプローチを擁護している。彼はまた、原始文化に対する近代的な見方が、彼らに歴史を否定するという単純なものであることを指摘した。敗北、移住、 追放、そして記録された歴史に知られているあらゆる種類の移住の繰り返しの証拠を見つけるのは簡単だった。その代わりに、神話のカテゴリーがこれらの変化 を包含していたのである。 彼は、人間の生活が2つの時間軸の中に同時に存在するという見方を主張した。それは、歴史という波乱に満ちた時間軸と、1つの基本的な神話的パターンが支 配し、その後おそらく別のパターンが支配するという長いサイクルである。この点で、彼の仕事は、地中海と「la longue durée」、つまり地中海周辺で何世紀にもわたって存続した文化的展望と社会組織の形態を研究した歴史家、フェルナン・ブローデルの仕事に似ている。と はいえ、バヌアツ中央部におけるジャン・ギアートの人類学的、ホセ・ガランジェの考古学的研究は、現地の神話に登場する、生きている人間であった元酋長の 骸骨を前面に押し出している。もうひとつの問題は、同一人物が、ある神話を象徴的に語り、その数年後に、ある系譜の年代史のようなものを語ることがあると いう経験である(ロイヤリティ諸島やニュージーランドなど)。レヴィ=ストロースは、ゼミ内でこうした側面が説明されることには同意したが、自分では決し て触れようとはしなかった。神話の人類学的データ内容は彼の問題ではなかった。レヴィ=ストロースが関心を持ったのは、それぞれの物語の形式的な側面だけ であり、それは各集団の集合的無意識の働きの結果であるとレヴィ=ストロースは考えた。 |