|

|

私は、冷戦後のグアテマラの国民国家の

再編成過程

において「先住民(indio,

indígena)」という人種的・民族的カテゴリーが、土着性や劣等性のスティグマ(=他者表象)から、自己を形成すると同時に他者からの承認をも必要

とするアイデンティティ(=自己表象)として変容しつつあるものとして把握できることを、私の同地域での20数年間の調査経験からお話したいと思います。

I would like to talk about how the racial and ethnic category of

“indio, indígena” (indigenous people) can be understood as an identity

that is being transformed from a stigma of indigeneity and inferiority

(i.e., representation of the other) to an identity that is both

self-forming and requires recognition from the other (i.e.,

representation of self) in the process of reorganizing Guatemala's

nation-state after the Cold War. I would like to talk about my research

experience in the region over the past 20 years.

|

|

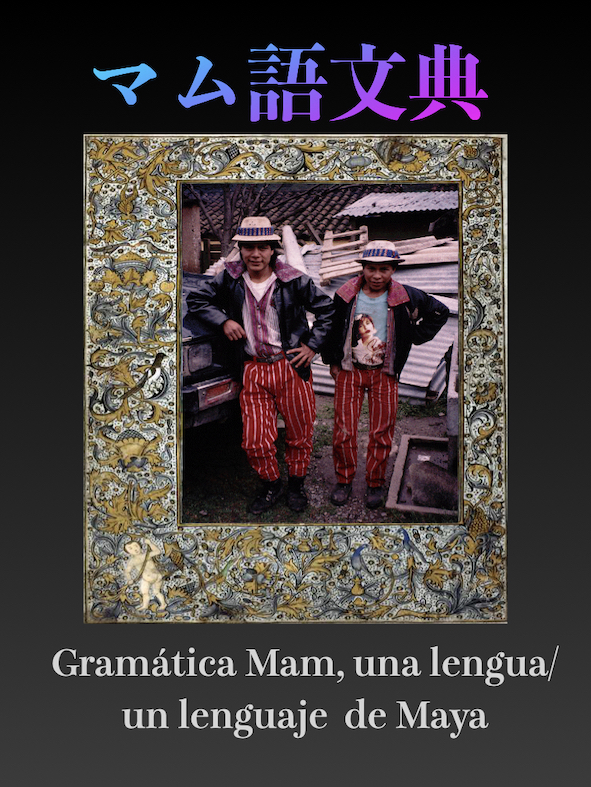

考察の対象となる集団は、グアテマラ共

和国西部高

地のマヤ系先住民のひとつ「マム」についてです。マムはマム語を話すグアテマラでは第三番目に人口の多

い——複数の統計や推計がありますが数十万以上——言語集団です。1996年末の和平合意後に設立された政府系グアテマラ言語学アカデミー公認のマヤの一

つの「言語コミュニティ」であると同時に、文化集団としても認められているものです。このことは、同アカデミー作成による社会経済変化のニーズに伴う新語

辞典や、語源的解釈を盛り込んだ地名辞典の編纂において、そこにマム語が使用されている点においても、その地域の「文化」をアカデミーが規定するという国

家的制度化と関連しているように思えます。

もちろん実際には政治的に脱色化されたこれらの「教

材」が現実的には十分に社会に膾炙したり公的教育に有効にフィードバックしたりしているとは言い難

く、この地域の先住民アイデンティティを単純にマム文化に帰属させることは困難です。しかしながら、古典的あるいは一見古くさい人類学・言語学的な意味で

設定されたマム、あるいはマヤ・マム(マヤ人としてのマム)という概念と名称が、今後彼ら自身の利用次第では、自らの先住民アイデンティティの要素の一つ

として取り込まれてゆく可能性があることを本発表では指摘したいと思います。

The population under consideration is about the Mam, one of the Mayan

indigenous peoples of the western highlands of the Republic of

Guatemala. The Mam are the third most populous Mam-speaking linguistic

group in Guatemala--more than several hundred thousand, according to

several statistics and estimates--and are the only Maya “language

community” recognized by the government-affiliated Guatemalan It is one

of the recognized Maya “language communities” as well as a cultural

group, recognized by the Academy of Linguistics. This seems to be

related to the national institutionalization of the academy's

definition of the “culture” of the area, in that the Mam language is

used there in the compilation of a dictionary of new words for the

needs of socioeconomic change and a dictionary of place names that

incorporates etymological interpretation, both of which were prepared

by the academy.

In reality, of course, it is difficult to attribute the indigenous

identity of the region simply to the Mam culture, as these politically

desiccated “teaching materials” are not, in reality, sufficiently

universalized in society or effectively fed back into public education.

However, I would like to point out that the concept and name “Mam” or

“Maya Mam” (Mam as Maya people), which is set in the classical or

seemingly archaic anthropological and linguistic sense, may be

incorporated as one of the elements of their own indigenous identity,

depending on their own use in the future. I would like to point out

that the concept and name “Mam” or “Maya Mam” (Mam as Mayan) may become

an element of their own indigenous identity depending on their own use.

|

|

|

その一方で、グアテマラ先住民研究をもっぱらとし

てきた古典的人類学の枠組みでは、地域研究の単位として、また行政共同体としての市町村に値するムニシ

ピオ(municipio)の位置が今のところ揺るぎそうにも思えない面もあります。本年になって中田英樹[2013]氏によって詳細な学説史的検討がな

されたアメリカの人類学者ソル・タックスの所論[Tax1937]によるもので、それを受け継いだエリック・ウルフ[Wolf

1957]らが当然のものとした「閉鎖的共同体(closed corporate

community)」としての先住民共同体であるムニシピオのことです。私自身も現在にいたるまでムニシピオは自然で当然な研究調査対象の基本単位とし

て捉えてきました[池田 2012]。彼らのアイデンティティ帰属の性質の特徴となす本源的な愛着(primordial

attachment)をムニシピオに見てきたのです。もちろん、研究単位としての先住民集団は、ムニシピオが持つような部族(tribe)的な境界と常

に一致するわけではなく、むしろエトニー——Anthony.D.

Smithの用語——の境界であるマムないしはマヤとして、この発表で述べるようにメディアや様々な社会運動の影響のもとに、より大きな広がりを持ちうる

ものだと考えています。

私は約26年前に遡る、1987年末から1988年

初頭にウェウェテナンゴ県のクチュマタン高地の西中部にあるマムのコミュニティを初めて訪れて、およ

そ2か月ほど滞在から始めて以来、南の隣県に位置するシェラマドレ高地のサン・マルコス県の別のマム・コミュニティを加えて、比較的長く、この地域に住む

マムの人たちの生活、言語、文化に強い関心を持ち続けてきました。1982年3月ベネディクト・ルカス・ガルシア大統領からそれを政変で倒した軍評議会の

リオス・モント将軍時代におこなわれたクチュマタン高地のこの町での虐殺経験から5年が経過していたにも関わらず、人びとはその軍事的暴力のトラウマから

癒されず、住民は外国人には非常に静かで、かつ必要不可欠な応対しかせず、村落の歴史については外国人どころか同胞人の間でも何も語るような様子はなかっ

たように記憶しています。ちなみに虐殺事件がおこった1982年は、国連の経済社会理事会(ECOSOC)の先住民への社会的差別に関する報告書の提出に

より国連人権委員会の下に先住民作業部会(WGIP, 1982-2006)が設置された時期でもあります(Study of the problem

of discrimination against indigenous populations, Economic and Social

Council Resolution 1982/34.)。

On the other hand, within the framework of classical anthropology,

which has focused exclusively on the study of indigenous peoples of

Guatemala, the position of the municipio as a unit of regional research

and as a municipality as an administrative community does not seem to

be shaky at the moment. This is due to the theory of the American

anthropologist Sol Tax [Tax 1937], which has been examined in detail by

Hideki Nakata [2013] this year, and the “closed corporate community” as

taken for granted by his successor, Eric Wolf [Wolf 1957], and others.

The indigenous community, the municipio, as a “closed corporate

community,” which was taken for granted by its successor, Eric Wolf

[Wolf 1957], and others. I myself have taken the munisipio as the basic

unit of a natural and natural object of research and investigation up

to the present day [Ikeda 2012]. I have seen in the munisipio an

intrinsic primordial attachment that is characteristic of the nature of

their identity belonging. Of course, the indigenous group as a research

unit does not always correspond to the tribal boundaries that the

munisipio have, but rather to the boundaries of the etnies--Anthony D.

Smith's term --I believe that the mam or maya, which is the boundary of

the municipio, can have a greater reach under the influence of the

media and various social movements, as I will describe in this

presentation.

I first visited the Mam community in the west-central part of the

Cuchumatan Highlands in the province of Wewetenango in late 1987 or

early 1988, dating back about 26 years, starting with a stay of about

two months, adding another Mam community in the province of San Marcos

in the Sierra Madre Highlands located in the neighboring province to

the south, Five years had passed since the massacre in this town in the

Cuchumatan highlands during the reign of General Rios Montt, the

military council that overthrew President Benedicto Lucas Garcia in

March 1982 by political upheaval. Despite the fact that five years had

passed since the massacre in this town in the Cuchumatan highlands

during the reign of General Rios Montt, the military council that had

overthrown President Garcia in a political coup, the people had not

healed from the trauma of the military violence, and the residents were

very quiet and only gave essential responses to foreigners, and there

seemed to be no talk among foreigners or among fellow citizens about

the village's history. Incidentally, 1982, the year of the massacre,

was also the time when the Working Group on Indigenous Peoples (WGIP,

1982-2006) was established under the UN Commission on Human Rights,

following the submission of a report by the UN Economic and Social

Council (ECOSOC) on social discrimination against indigenous

populations (Study of the problem of (Study of the problem of

discrimination against indigenous populations, Economic and Social

Council Resolution 1982/34.)

|

|

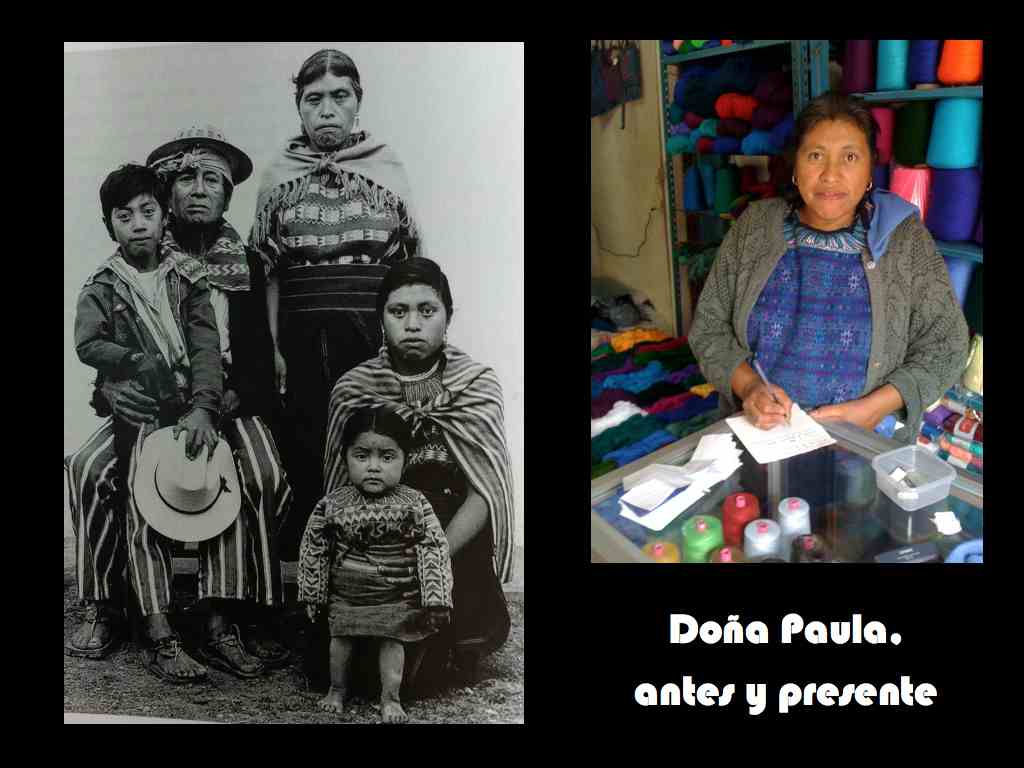

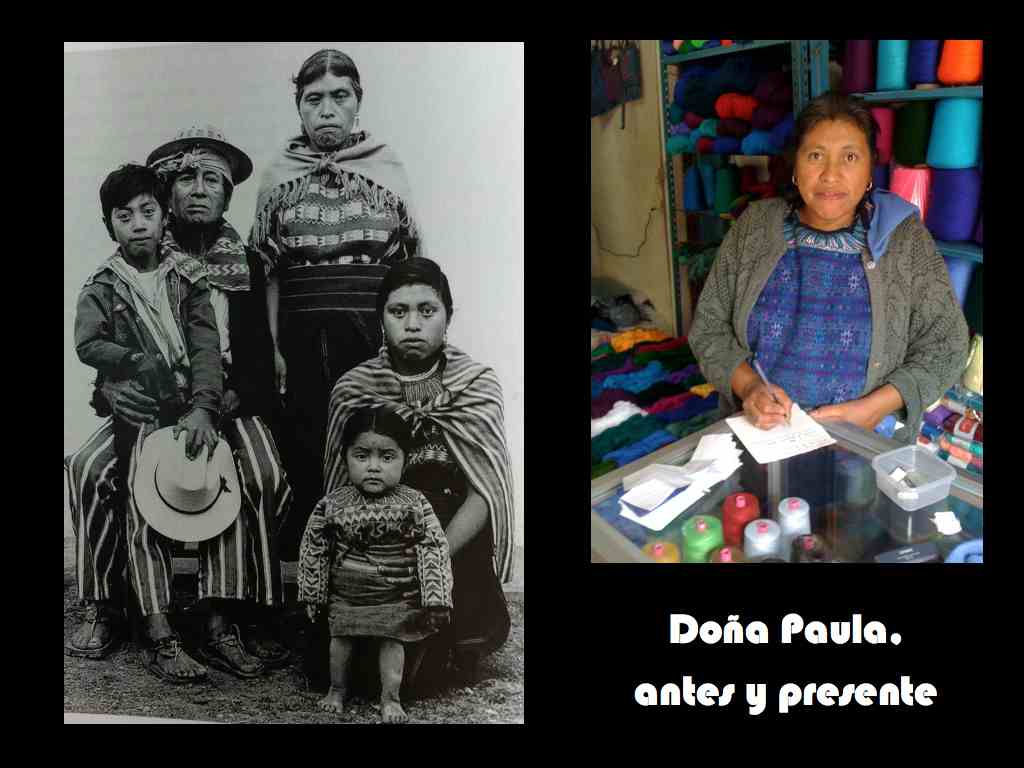

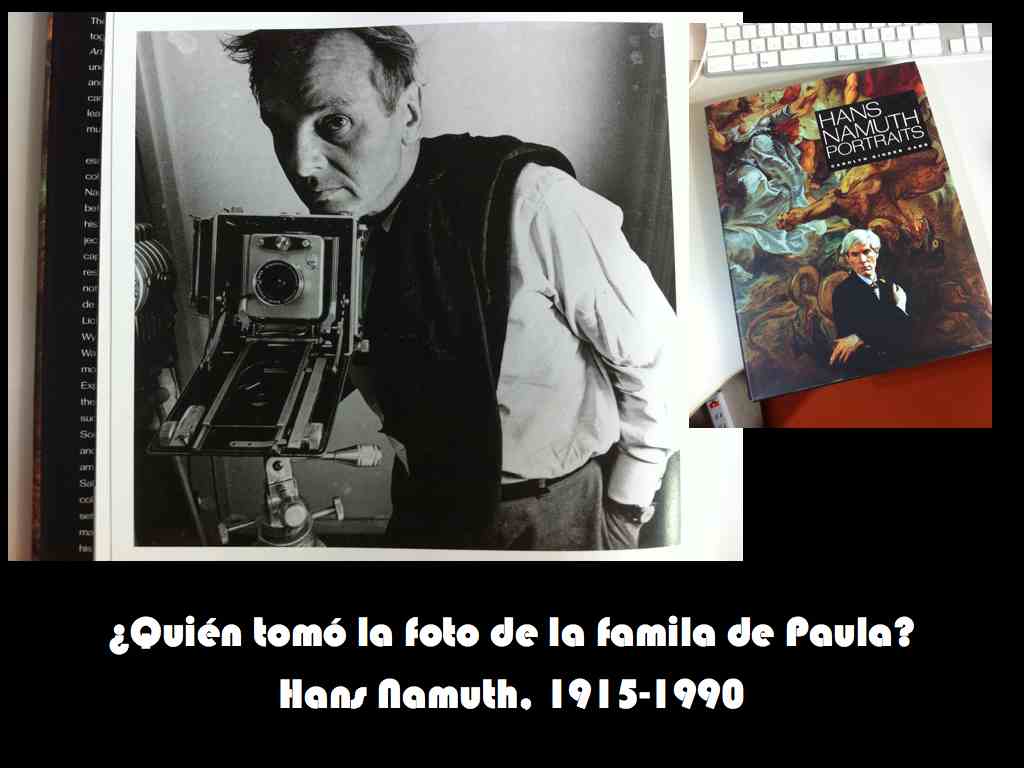

この当時(1987-1988年)、私

は内戦の犠

牲者の妻と既に成長していた子供たちのある家族と非常に親しい友人になりました。その子供たちとは4人

の男性兄弟と2人の女性姉妹なのですが、当時、未亡人となった母親の家に住んでいた結婚直後の彼女の息子とその弟とはとりわけ親友のような関係になりまし

た。知り合ってすぐに、この若い夫婦とのあいだで、彼らの娘の洗礼を介して、私たちはコンパドレ関係を取り結ぶことになりました。コンパドレとはすなわち

洗礼における娘(ないしは息子)であるアイハーダ/アイハードの宗教的道徳的な教えの親=パドリーノ/マドリーナになることを通して彼らとの擬制的親族関

係すなわちコンパドリナスゴを結ぶことなのです。教えの父としての私の「娘」は現在26歳になりますが、彼女は同じ共同体出身の若者と移民先の米国で知り

合い結婚して現在カリフォルニアのオークランドに住んでいます。当時20歳で地元の小学校教師だった私のコンパドレの祖父ドミンゴは、1945年から47

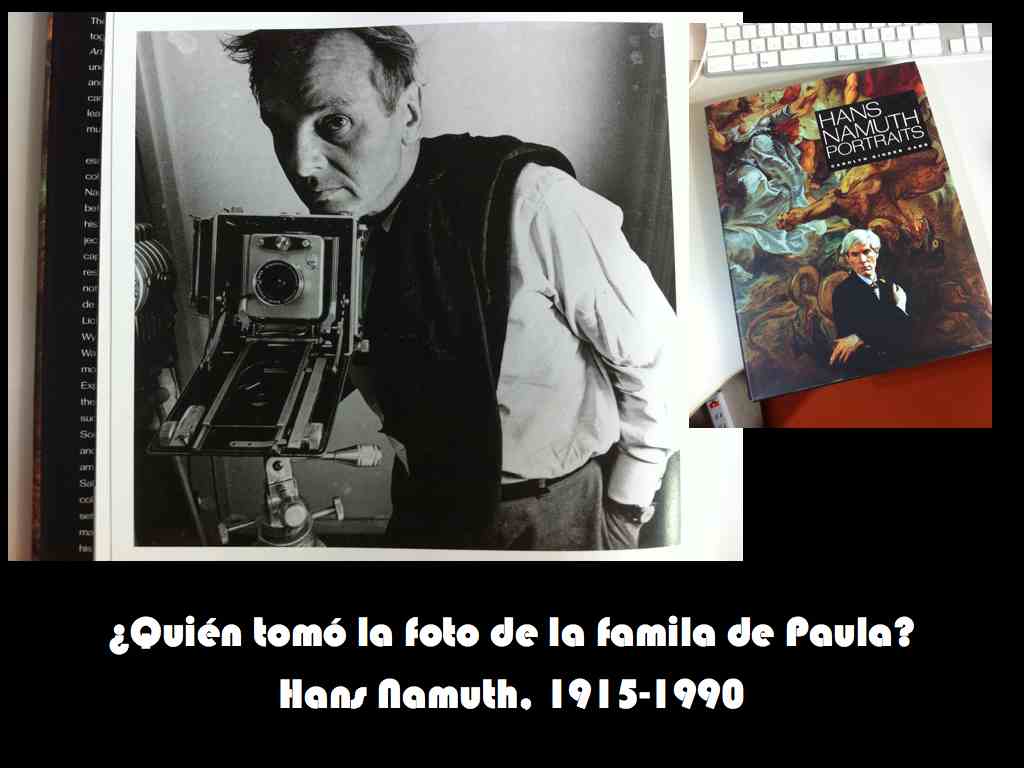

年にこの土地でフィールドワークをおこなった民族誌家マウド・オークス(Maud Oakes, 1903-1990)The two crosses

of Todos Santos: survivals of Mayan religious

ritual[1951]の使用人(moso)兼インフォーマントの1人でした。ドミンゴの子供、すなわち私のコンパドレの父は同書の写真の中で小さな子

供として写っています。この写真は、オークスに同行したスペイン市民戦争(内戦)期の作品で有名な写真家Hans

Namuthが撮影したものです。この子供がやがて成長して友人の父となり内戦期の(友人の説では)軍隊が侵攻する前に一時的に町を制圧していた反政府ゲ

リラEGP(Ejercito Guerrillero de los

Pobres)の部隊員に夜中に拉致されて翌朝ミルパ(トウモロコシ畑)で死体の姿で発見されます。

At this time (1987-1988), I became very close friends with a family of

civil war victims whose wives and children were already grown. These

children were four male brothers and two female sisters, but we became

especially close friends with her son and his brother, who had just

married and were living in the home of their widowed mother at the

time. Soon after our acquaintance, we entered into a compadre

relationship with this young couple through the baptism of their

daughter. Compadre means to enter into a pseudo kinship, or

compadrinasgo, with them through becoming the religious and moral

teaching parents, padrino/madrina, of their daughter (or son),

aihadah/aihad, in baptism. My “daughter” as a teaching father is now 26

years old, and she is currently living in Oakland, California, after

meeting and marrying a young man from the same community in the United

States, where she immigrated. My compadre grandfather Domingo, then a

20-year-old local elementary school teacher, was the subject of a book

by Maud Oakes (1903-1990), an ethnographer who did fieldwork in the

area from 1945-47, The two crosses of Todos Santos: survivals of Mayan

religious ritual. He was one of the servants (moso) and informants of

the “survivals of Mayan religious ritual” [1951]. Domingo's child, my

compadre's father, is shown as a small child in the photograph in the

same book. This photo was taken by Hans Namuth, a photographer famous

for his work during the Spanish Civil War (Civil War) who accompanied

Oakes. This child eventually grew up to become my friend's father and

was abducted in the middle of the night by members of the EGP (Ejercito

Guerrillero de los Pobres), a rebel guerrilla group that (according to

my friend's theory) had temporarily taken control of the town before

the military invasion and was found dead in the milpa (cornfield) the

next morning. The next morning, he was found dead in a milpa

(cornfield).

|

|

|

私は1988年の調査期間の最後に、コ

ンパドレに対

して、国境を越境して同じマヤ人のチアパス先住民を見に行こうとSan Cristobal de

las

Casasへの旅行に誘います。彼は町の途中にある、当時まだ機能していた武装自警団(PAC)が駐在する検問所を通過し、やがて荒涼としたクチュマタン

高原の道でバスが加速しだすと、それまで着用していた妻が作った民族衣装をおもむろに脱ぎそれをリックサックに突っ込み、派手な民族衣装とは好対照なこ

ざっぱりしたジャンパーに着替えます。メキシコ国境に入ってからだとインディオと見まちがわれるし、ウェウェテナンゴの街ですら混血のラディーノが酷い差

別をするから街へ出る先住民はみんな服を着替えるのだと彼は言いました——隣町のサンファンの連中は街でも着替えないから彼らの[文化?]は強く

(fuerte)伝統的慣習を未だに維持しているのだとも言いました。

しかしながら、その5年後の1990年代初頭には

町の様相が大きく変わっていました。コヨーテと呼ばれるブローカーを利用して北米に移民した親兄弟から

送られてくるドルマネー、和平の機運が高まって再び戻ってきたエスニック・ツーリズムを通して、町は空前の経済的活況を呈していました。その時に、彼らは

国内外で知る外国人たちに、自らの先住民性やマムであることの自己表象を語り始める機運が生じたのです。

At the end of my research period in 1988, I invite Compadre to travel

to San Cristobal de las Casas to cross the border and see the

indigenous people of Chiapas, who are also Mayan. As the bus

accelerates through the desolate Cuchumatán Plateau, he suddenly takes

off the traditional costume his wife had made for him and puts it in a

rickshaw, and then puts on a simple jumper that contrasts nicely with

his flamboyant traditional costume. He then changed into a simple

jumper, which was a sharp contrast to his flashy traditional costume.

He told me that all natives who go into town change their clothes

because they are mistaken for Indians once they enter the Mexican

border, and even in the city of Wewetenango, mixed-race Ladinos are

severely discriminated against - even those in the neighboring town of

San Juan don't change their clothes in town, so how do you know what

their culture is? They don't change their clothes, so their [culture?]

He also said that the San Juan people in the next town over do not

change their clothes even in town, so they still maintain a strong

(fuerte) traditional practice.

However, five years later, in the early 1990s, the town had changed

dramatically. The town was experiencing an unprecedented economic boom

through dollar money sent by parents and siblings who had immigrated to

North America using brokers called coyotes, and ethnic tourism, which

had returned again with the growing momentum of peace. It was then that

the opportunity arose for them to begin talking about their indigeneity

and self-representation of being a Mam to the foreigners they knew at

home and abroad.

|

|

コンパドレによる「衣装変更作戦」に

よって、国境

を越えてチアパス州のコミタンを過ぎた道路脇でのメキシコ移民局の検問では、日本人である私のほうが目

立った対象になり、隣の座席に座った彼は現地メキシコ人ラディーノと思われ身分証明書を提示することもなく通過することができました——グアテマラの身分

証明書を持った人はコミタン以西のチアパス州には立入禁止となっていました。半日かけてサンクリスの街につきましたが、ちょうどその時、チアパス高原のサ

ン・ファン・チャムラでは四旬節(Cuaresma)直前のカーニバルの時期だったので、私たちは小型乗合バス(コンビ)に乗ってそこを訪問することにな

りました。彼は町の入り口で、インディオがカメラを向けた外国人観光客を殺害したという警告に驚き、自分の故郷の教会のように床をコンクリート敷きにせ

ず、かつての古代マヤ風に剥き出しの地面にしている「本物のインディオ」の教会を見て「(自分の故郷では)伝統的な慣習(コストゥンブレ)を捨てたから、

自分たちの町は軍隊に攻撃・放火されて住民が殺されたのだ」と私に説明しました。インディオはグアテマラでは土着性や劣等性のスティグマでしたが、彼に

とってメキシコでのインディオはプライドの表現なのだという指摘が驚きでした——カソリック的なニュアンスも混淆したメキシコの同胞兄弟たち

(nuestro hermanos)の有り様に感動したようです。これが1988年のインヴィエルノ(invierno, 冬)のことでした。

Due to the “costume change operation” by Compadre, I was the more

conspicuous target at the Mexican immigration checkpoint on the side of

the road across the border past Comitan in Chiapas, and I was able to

pass through without having to show identification because the man in

the seat next to me was assumed to be a local Mexican Ladino. He was a

local Mexican ladino, and we were able to pass through without having

to show ID - people with Guatemalan IDs are not allowed in the state of

Chiapas west of Comitán. After half a day we arrived at the town of San

Cris, just before the Lenten carnival in San Juan Chamula on the

Chiapas Plateau (Cuaresma), which we were to visit in a small

shared-ride bus (combi). He was surprised by the warning at the

entrance to the town that Indians had killed a foreign tourist who

pointed a camera at him, and when he saw the “real Indians” church,

which did not have a concrete floor like the church in his hometown,

but rather bare ground in the former ancient Mayan style, he said, “(In

my hometown) we abandoned traditional practices (costumbre ), so their

town was attacked and torched by the army and the inhabitants killed,”

he explained to me. Indios were a stigma of indigeneity and inferiority

in Guatemala, but I was surprised when he pointed out that for him,

Indios in Mexico were an expression of pride - a mixture of catholic

nuances of his Mexican brethren ( He was moved by the nuestro hermanos,

a mixture of catholic nuances. This was invierno (winter) 1988.

|

|

|

ダイナミックに変貌する経済状況が、先

住民であるこ

とのこれまでの階級観、ジェンダー観、伝統文化観などに揺さぶりをかけて、先住民の自己表象の中にそ

れぞれ競合したり協調したり相互に影響を与える多様性が生み出された、とも言うことができます。ドミンガ(仮名)に関する以下のエピソードはその典型です

[池田 2005; Ikeda 2004]。

ドミンガはこの町でもっとも著名で、町の人々から力のあると目されている女性です。彼女は……調査当時39歳でした。ドミンガは髪結いの亭主とともに、

この町で観光客にもっとも有名になったホテルを5年間にわたって経営しています。彼女は非識字者ですが、町の人々にも外国人観光客にも雄弁で……ホテル経

営で儲けたお金をさまざまな町の公的活動に寄付するようになりました。……彼女はなかなかのアイディア・ウーマンで、それまで薄暗い部屋を間貸しするだけ

であったこの町の旅館の形態を、見晴らしのよい場所に立地させ、外国人向けに窓を大きくしたりバルコニーをつくったり、それまで観光客は道端から素知らぬ

顔でしか覗き込むことができなかった、インディヘナの女性の伝統的な機織りを彼女のホテルの中庭で実演し、かつ販売をするという工夫をおこないました。こ

の町の女性の地位向上や困窮のために米国に渡米する若者を引き留めておくためには、自分のように観光客を上手にもてなすことが大切だと彼女は考えていま

す。……町の外で起こったリゴベルタ・メンチュのノーベル平和賞の受賞という出来事、NGOが積極的にすすめるインディヘナの女性の地位向上運動などの、

一連の女性の社会的進出のイメージの渦中にドミンガを位置づけるということも認められます。経済的成功を成し遂げたのがインディヘナの女性であったという

ことは町の噂になりました。それゆえ、この町の新興の女性企業家となったドミンガは、近隣の同業者からさまざまな中傷を浴びることにもなりました。その中

には、強引な客引き、協同組合による運営と詐称する土産物販売、観光客に対して語られるこの町の女性の歴史の独善的な正統化(canonization)

などという、かつてこの町の人々がおこなったことのない特異な活動という評価からの非難も含まれています。

It can be said that the dynamically changing economic situation has

shaken the traditional views of class, gender, and traditional culture

of indigenous peoples, creating a diversity of competing, cooperating,

and mutually influencing self-representations of indigenous peoples.

The following episode concerning Dominga (a pseudonym) is typical

[Ikeda 2005; Ikeda 2004].

Dominga is the most prominent woman in the city and is considered

powerful by the people. She was 39 years old at the time of the ......

survey. Dominga and her hairdresser husband have been running the hotel

that has become the most famous tourist attraction in town for the past

five years. Although she is illiterate, she is eloquent to both the

townspeople and foreign tourists ...... and has started to donate the

money she makes from running the hotel to various public activities in

the town. ...... She is a woman of ideas, and has changed the town's

inns, which until then had only rented out dimly lit rooms, by locating

them in places with good views, enlarging the windows and creating

balconies for foreigners, and creating a place where tourists could

only peek in from the side of the road with a blank stare. She also

made an effort to demonstrate and sell the traditional weaving of

Indigena women in the courtyard of her hotel, which until then tourists

had only been able to observe from the sidewalk. She believes it is

important to entertain tourists well, as she does, in order to improve

the status of women in the town and to retain young people who come to

the U.S. because of their poverty. ...... It is also acknowledged that

Dominga is in the middle of a series of social advancement initiatives

for women, such as the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Rigoberta Menchu,

which took place outside the town, and the movement for the advancement

of Indigenous women, which is actively promoted by NGOs. It is also an

acknowledgement of Dominga's economic success. The fact that it was an

Indigenous woman who achieved economic success became the talk of the

town. Hence, Dominga, who became the town's emerging female

entrepreneur, was subjected to a variety of slurs from her peers in the

neighborhood. These included accusations of aggressive touting,

souvenir sales that falsely claimed to be cooperative operations, and

the self-righteous canonization of the town's women's history in the

eyes of tourists, an activity that had never been practiced by the

town's population.

|

|

|

私は2004年に国立民族学博物館で開

催されたマーガレット・ミード記念シンポジウム「現代世界における人類学の社会的利用」というセッションの中で、

およそこのようにドミンガを紹介しました。ドミンガは、この町の内戦後の記録に関する Olivia Carrescia (Dir.),

"Todos Santos: The Surviviors", First Run / Icaarus Films, 1989.

に覆面をかぶった姿で登場する女性で、この記録映画が撮影された時点ではホテルの経営はまだしていなかったと思います。ドミンガは、この町に軍隊がやって

くる1年以上の前に撮影されたカレシア監督の最初のドキュメンタリー作品(Olivia Carrescia (Dir.), "Todos

Santos Cuchumatan: Report from a Guatemalan Village", First Run /

Icaarus Films,

1982.)では新しい世代の屈託のない若い女性として登場し、その7年後の1989年の作品では、1982年の虐殺時の軍隊による暴虐と自警団によって

パトロールされる村の語り部——内戦の犠牲者——として映像の中に登場します。

I introduced Dominga in approximately this way during a session at the

Margaret Mead Memorial Symposium, “Social Uses of Anthropology in the

Modern World,” held at the National Museum of Ethnology in 2004.

Dominga is the woman who appears as a masked figure in Olivia Carrescia

(Dir.), “Todos Santos: The Surviviors”, First Run / Icaarus Films,

1989, on the town's post-civil war record, and at the time this

documentary film was shot I don't think she was running the hotel at

the time this documentary was shot. Dominga was the subject of

Carrescia's first documentary (Olivia Carrescia (Dir.), “Todos Santos

Cuchumatan: Report from a Guatemalan Village”, First Run / Icaarus

Films, 1989), filmed more than a year before the arrival of the army in

this town. ), and seven years later, in her 1989 film, as the narrator

of a village patrolled by the military and vigilantes during the 1982

massacre. -victims of the civil war- appear in the film as victims of

the civil war.

|

|

しかしながら、その5年後の1990年

代初頭には

町の様相が大きく変わっていました。コヨーテと呼ばれるブローカーを利用して北米に移民した親兄弟から

送られてくるドルマネー、和平の機運が高まって再び戻ってきたエスニック・ツーリズムを通して、町は空前の経済的活況を呈していました。その時に、彼らは

国内外で知る外国人たちに、自らの先住民性やマムであることの自己表象を語り始める機運が生じたのです。

Five years later, however, in the early 1990s, the face of the town had

changed dramatically. The town was experiencing an unprecedented

economic boom through dollar money sent by parents and siblings who had

immigrated to North America using brokers known as coyotes, and through

ethnic tourism, which had returned again as the momentum for peace

grew. It was then that the opportunity arose for them to begin talking

about their indigeneity and self-representation of being a Mam to the

foreigners they knew at home and abroad.

|

|

|

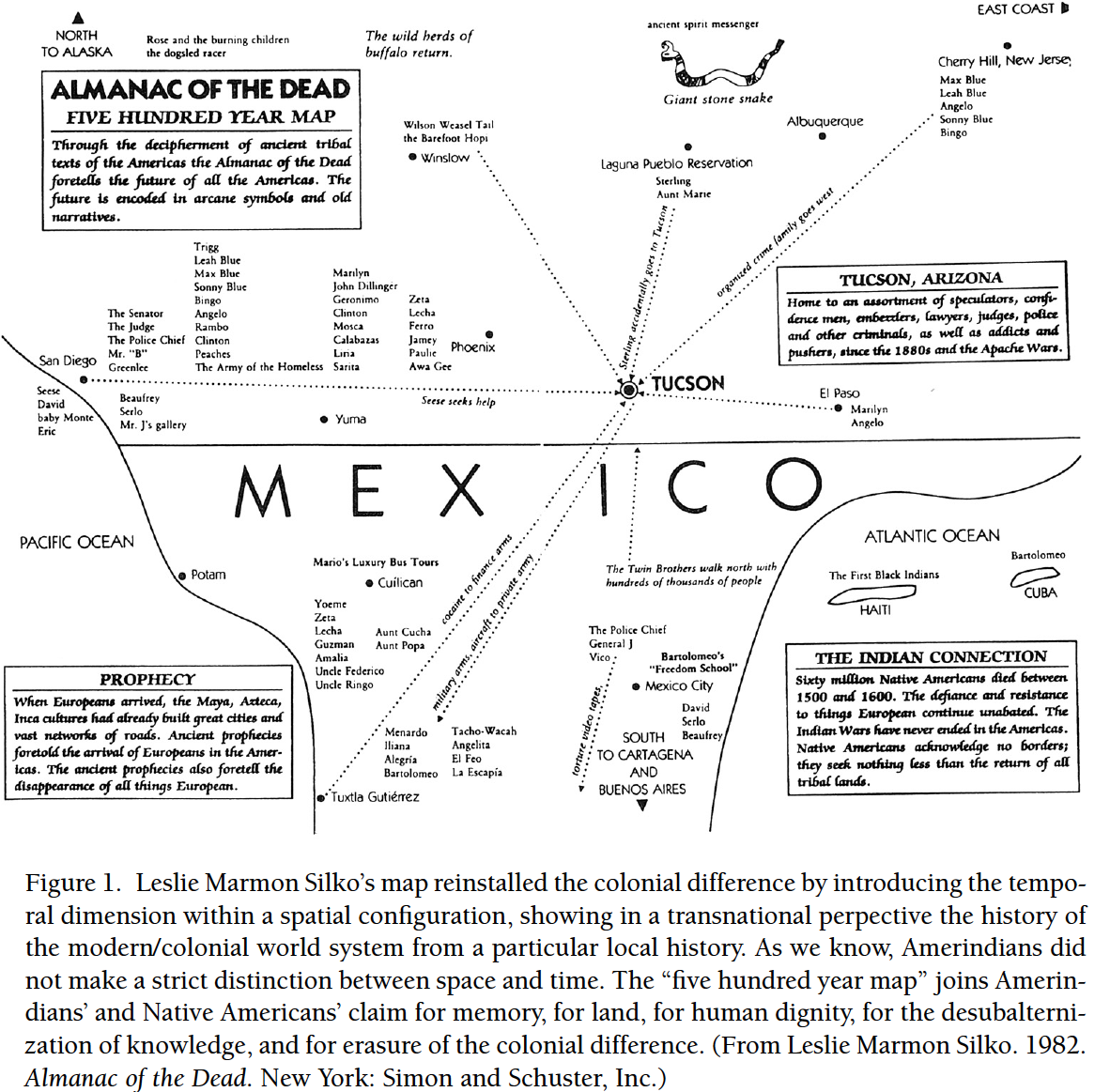

折しも新大陸発見・出会いの五百年紀で

あった

1992年はリゴベルタ・メンチュがノーベル平和賞を受賞し、その翌々年からは国連の先住民の10年

(1994-2004)が始まりました。先住民の教師たちは、先住民の発見の五百年は(エドワルド・ガレアーノの所論を使って)征服と搾取の五百年である

ことを学校の授業で取り上げました。私のコンパドレが関わる外国人にスペイン語を教える研修プロジェクトが始まりました。そのプロジェクトに契約している

町の住民は、白人(グリンゴ)の観光客に自宅の一室をレンタルさせ、下宿のための食事を提供することが、とても喜ばれ、また家計の十分な足しになることを

感じました。そしてその白人たちに先住民として様々に振る舞うことの意義について感じるようになりました。自分たちをしてインディオという用語よりも政治

的に正しい(corrección

política)スペイン語である「先住民」すなわちインディヘナ(indígena)という呼称を、以前よりも気兼ねなく自称として使えるようになっ

たと言います。当時、エスニック・ツーリズムを調査していた私のフィールドノートには、旅館や民宿の主(あるじ)が、白人たちがいかに「先住民」と友達に

なりたがっているのかを示すエピソードがいくつかありました。

The year 1992, which coincidentally was the Quinquennial of the

Discovery and Encounter of the New World, saw the Nobel Peace Prize

awarded to Rigoberta Menchu, and the following year the UN Decade of

Indigenous Peoples (1994-2004) began. Indigenous teachers addressed in

their school lessons that the Five Hundred Years of Indigenous

Discovery was (using Eduardo Galeano's theory of place) Five Hundred

Years of Conquest and Exploitation. A training project was started to

teach Spanish to foreigners that my compadre was involved in. The

residents of the town contracted for that project felt that allowing

white (gringo) tourists to rent a room in their home and provide meals

for their lodgers would be greatly appreciated and would be an ample

addition to their household income. I also began to feel the

significance of behaving in various ways as an indigenous person to

these whites. They said they were more comfortable using the

politically correct (corrección política) Spanish term “indígena,” or

“indigenous,” as a self-identification than the term “indio,” which

they had used in the past. In my field notes from my research on ethnic

tourism at the time, there were several episodes in which innkeepers

and innkeepers indicated how eager whites were to make friends with the

“indigena.

|

|

|

集団的アイデンティティの語義に戻って

「私たちは何者であるか?」という観点から、マムの人たちの自己意識について探るとすると、明らかに彼らを外部か

ら定義しようとする状況とのせめぎ合いの中で、この意識が形成されていることがわかります。そこでは先住民性を定義するような事象であるとか、事物など

が、ある特定の文脈のなかで意味論的に再配置されるように思われます。もちろんインフォーマントと調査者の間での絶え間のない対話を通してしか、このこと

は知ることができません。歴史的アイデンティティにおいては、我々がしばしばおこなうオーラルヒストリーを聞き出す際にみられる現地の人たちが保持してい

る/あるいは保持しているはずだと私たちが信じて対話をする際に、歴史上のエピソードが次々と関連づけられて想起されること、つまり「歴史記憶」の連想

ゲームをやるようなプロセスが不可欠です。「それほど遠くない」歴史的存在としてマムは、強制労働法令(1934年)や現在まで続くプランテーションでの

季節労働など、スペイン人征服者(コンキスタドーレス)から黒い遺産を引き継いだ非先住民クリオージョ(植民地生まれの白人)の「主人」や近代国家からの

搾取対象だったのだという記憶が語られます。

Returning to the terminology of collective identity, “Who are we?” we

can clearly see that this consciousness is formed in conflict with

situations that attempt to define them externally. It seems that the

events and things that define indigeneity are semantically rearranged

within a particular context. Of course, this can only be known through

a constant dialogue between the informant and the researcher. In

historical identity, the process of associative recall of historical

episodes, or “historical memory” as we interact with what we believe

the locals hold or should hold, as we often do in our oral history

elicitation, is essential. It is essential to have a process that is

like playing an association game. The memory of Mam as a “not so

distant” historical entity, an object of exploitation by the “masters”

or modern state of the non-indigenous criollos (colonial-born whites)

who inherited their black heritage from the Spanish conquistadores

(conquistadores), including forced labor laws (1934) and seasonal labor

on the plantations that continues to this day The memory of how they

were the “masters” of the Spanish conquistadores (conquistadores) is

recounted.

|

|

|

学校教育においては、コンキスタドーレ

スたちに武

力で抵抗した先住民反乱者の象徴で1524年2月に戦死したキチェ・マヤのテクン・ウマン(Tekun

Umam)の存在が大きく、それもマヤ人の英雄というよりもグアテマラのナショナル・ヒーロとして語られます。その一方で、先住民人口を激減させた流行

病、教会やエンコミエンダによる徴税、異端審問、密造酒取締などの歴史は、ほとんど取り上げられることがありません。しかしながら先住民出身の教師たち

は、このような「自分たちの」抑圧の歴史に通暁しており、学校教育の現場のなかで教科書を使って語られない歴史もまた語られることがあります。

In school education, Tekun Umam of the Quiché Maya, a symbol of the

indigenous rebels who resisted the Conquistadores by force and was

killed in February 1524, is a major presence, and he too is spoken of

as Guatemala's national hero rather than as a Mayan hero. On the other

hand, the history of the epidemic that decimated the indigenous

population, the tax collection by the church and encomienda, the

Inquisition, and the control of moonshine is rarely mentioned. However,

indigenous teachers are familiar with the history of these “own”

oppressions, and the history that is not told in textbooks is also told

in the school setting.

|

|

1990年代以降に本格化する北米への

移民以降には、ネオリベラル経済のなかで優秀な労働力として、他のラテンアメリカ人、とりわけメキシコ人(チョ

ロ)よりも真面目でタフでよく働くグアテマラ先住民の「優秀性」について私はしばしば聞かされてきました。これは労働力主体としての先住民のこれまでのネ

ガティブな表象化が逆の方向に変化したひとつの事例です。グアテマラ第2の都市ケツァルテナンゴ(Xela)の郊外の交通ロータリーでは、現在のテクン・

ウマンの巨大な立像と共に、北米移民をする労働者の立像が建立されています。私のサン・マルコスの友人は、それは自分たちの同胞インディヘナの不法移民を

モデルにしたものだと、あたかも現在の自分たちにとってのテクン・ウマンであるかのごとく誇らしげに言います。

Since the full-scale immigration to North America that began in the

1990s, I have often heard about the “excellence” of Guatemalan natives

as a superior labor force in the neoliberal economy, more diligent,

tough, and hardworking than other Latin Americans, especially Mexicans

(choros). This is one example of a change in the opposite direction

from the previous negative representation of indigenous peoples as

labor force subjects. At a traffic roundabout on the outskirts of

Quetzaltenango (Xela), Guatemala's second largest city, a standing

statue of a North American migrant worker is erected alongside the

current giant standing statue of Tecun Uman. My friends in San Marcos

proudly tell me that it was modeled after their fellow Indigena illegal

immigrants, as if it were the Tecun Uman for them today.

|

|

自らの使用のために織物を紡いできた女

性達は、内戦の犠牲者となり、後に生活再建のための手工芸生産者あるいは組合のメンバーとなり、さらには内戦後の

社会復興のためのマイクロファイナンスの借り手になってゆきました。彼女たちの子供は、さらにグアテマラシティやケツァルテナンゴという大都市近郊のマキ

ラあるいはマキラドーラと言われる、中国や韓国資本の縫製工場でプロレタリアートとしてに自ら飛び込んでゆくことになりました。子供たちを訓育する先住民

の親たちが説く勤労のエートスとは、勤勉で真面目に働き「良きパトロン」に認められることだと言います——ただしマキラでの強度の高い労働の実態から想像

するに現実は親たちが期待するほど甘くはありません。グアテマラ先住民はかつてのペニーキャピタリスト(Sol

Tax)からケッツアルと米ドルを激しく求めるプロレタリアートへと大きく変貌してゆく様を私は目の当たりにしました。

Women who spun textiles for their own use became victims of the civil

war and later became handicraft producers or union members to rebuild

their lives, and even microfinance borrowers for post-civil war social

reconstruction. Their children would further plunge into the

proletariat in the maquilas or maquiladoras of Guatemala City and

Quetzaltenango, the major cities in the region, where sewing factories

were owned by Chinese and Korean capital. The ethos of work preached by

the indigenous parents who educate their children is that of hard work,

diligence, and recognition by “good patrons”-but as one might imagine

from the reality of the intense labor in the maquilas, the reality is

not as sweet as the parents might expect. The reality, however, is not

as sweet as parents might expect. I have witnessed the transformation

of the indigenous Guatemalan population from penny capitalists (Sol

Tax) to a proletariat that is in desperate need of ketzal and US

dollars.

|

|

私はこのクチュマタン高原のバブル経済の活況を生き

る人たちの新しい経済的エートスの誕生は、内戦後の暴力的な旧習の経済慣行の一掃こそが、彼らのグ

ローバル経済への急速な節合(articulation)を驚くほど容易にさせたしたという主張をある地域研究雑誌の論文にまとめて投稿しました

[Ikeda

2000]。しかしながら、この主張は1人の査読者の逆鱗にどうも触れたようです。査読者によると、私の立論は「日本の戦後の経済成長には戦争による破壊

が必要だったという説明」と同じであり「先住民地域の経済開発のために村落を破壊した軍部の存在を容認する」ものに他ならないと批判されてしまったので

す。私には先住民に対して血も涙もない軍部のマーズとプルートという忌むべき神のあの悪業を些かも擁護するつもりはありません。経済的エートスというもの

はつねに文化構造に根づくようなものではなく、政治構造の変化により変わりうる可能性を指摘したかったのです。そして論文に記載しているとおりに、町の人

びと自身が「金儲け」に血眼になる自分のたちの姿に驚いている様子とその社会的背景を記述したかっただけなのです。グアテマラの政治的暴力の犠牲者として

先住民を見続けるこの査読者と、その「偶発的な運命」に翻弄された人びとが「暴力後」に新しい経済主体としてのアイデンティティを身につけていることに着

目する私との間は、埋まりそうにありませんでした。

In an article in an area studies journal, I argued that the birth of a

new economic ethos among the booming bubble economy of the Kucumatan

Plateau was the result of a violent post-civil war cleanup of old

economic practices that made their rapid articulation into the global

economy surprisingly easy [Ikeda 2000]. Ikeda 2000]. However, this

claim apparently offended one of the reviewers. According to the

reviewer, my argument was the same as “explaining that Japan's postwar

economic growth required destruction by war,” and was criticized as

nothing more than “condoning the existence of a military that destroyed

villages for the sake of economic development in indigenous areas. I am

not going to defend in the slightest the evil deeds of the abominable

gods Mars and Pluto, the military that has no blood or tears for the

indigenous peoples. I wanted to point out that economic ethos is not

always rooted in cultural structures, but can change with changes in

political structures. I simply wanted to describe the social context in

which the townspeople themselves were surprised to find themselves so

focused on “making money,” as I describe in my paper. I could not seem

to bridge the gap between this reviewer, who continues to see

indigenous peoples as victims of Guatemala's political violence, and

me, who focuses on how those who were at the mercy of their “accidental

fate” have developed a new identity as economic actors “after the

violence.

|

|

それからさらに10年ちょっとの歳月が流れ、今日にいたりました。ク

チュマタン高原の町では、久々に訪れたホテルのオーナーたちは外国人観光客の激減の理

由を2000年5月に起こった日本人観光客とグアテマラ人のバス運転手の殺害事件に求めます。しかし実際には、観光客の減少は漸次(ぜんじ)的に起こり、

著しく減少するのは米国のサブプライムローン住宅危機が表面化する2007年から始まり、2009年のグアテマラ経済危機が、その致命傷を与えたように思

われます。それに追い討ちをかけるように、その頃から常態的におこるようになる夜間と早朝の自家用車やバスの往来を狙った襲撃強盗(山賊)の頻発が、この

地域を危険で観光客に魅力のないものへと転落させていったということも考えることができます。

A little more than ten years have passed since then, and here we are

today. In the town of Cuchumatan Plateau, hotel owners who have been

visiting for a long time blame the murder of a Japanese tourist and a

Guatemalan bus driver in May 2000 as the reason for the sharp decline

in the number of foreign tourists. In reality, however, the decline in

tourism has been gradual, beginning in 2007, when the U.S. subprime

mortgage housing crisis surfaced, and continuing until the Guatemalan

economic crisis of 2009, which seems to have dealt the fatal blow. This

was followed by the frequent attacks and robberies (banditry) of

private cars and buses at night and in the early morning, which became

a regular occurrence around that time, and which made the region

dangerous and unattractive to tourists.

|

|

新ミレニアム以降、麻薬問題と犯罪者の増加の社会不

安のなかで勝利した元軍人大統領(2012-15年期)のもとでは、2012年10月に西

部高地での農民抗議集団と警官隊との衝突で犠牲者を出す事件がおこりました。先週、別の日本ラテンアメリカ学会で私が組織したパネルディスカッションにお

いて、政治行動モデルで先住民と国家の関係を論じた政治学者は、冷静に合理的な解決を求めずに暴力と暴力の応酬という「悪い」サイクルに入っていると、不

気味な予言をしました。先住民と国家の暴力的な対峙は、先住民自身による主権や統治へ希求への要求をさらにエスカレートする可能性があるというのです。政

府はそれに対して国軍の投入など強行姿勢を崩していませんが、私はその予言が外れ、どこかの均衡点から、もっと別の政治的局面が展開することを信じていま

す。それは2002年以降の地方分権化法の施行のもとでコミュニティの自治に関する動きが活発になり、民主主義の定着や善き政府に関する話題は地方でもし

ばしば聞かれるテーマになりつつあるからです。地方自治というテーマはさらに、自分たちは何者で、何ができるか、何をなすべきかという西洋啓蒙主義の審問

をグアテマラ西部高地の諸都市にもたらすことになりましたが、それらは鉱山開発反対運動や、地元協議会(COCODE)という意見表明の回路の登場など

の、個別的な状況に応じて多様な変化を遂げているからです[池田a 2012, 池田b 2012]。

Under a former military president (2012-15 term) who won amid social

unrest since the new millennium, with a drug problem and rising

criminal population, a clash between a group of peasant protesters and

police forces in the western highlands in October 2012 resulted in

casualties. Last week, in a panel discussion I organized at another

Japan Association for Latin American Studies conference, a political

scientist who discussed the relationship between indigenous peoples and

the state in a political action model made the eerie prediction that we

are in a “bad” cycle of violence and violent exchanges, without calmly

seeking rational solutions. Violent confrontations between indigenous

peoples and the state could escalate demands for sovereignty and

governance by the indigenous peoples themselves. Although the

government has taken a forceful stance in response, including the

deployment of the national army, I believe that the prediction will be

wrong and that from some equilibrium point, a different political

dimension will develop. This is because since 2002, with the

implementation of the decentralization law, community autonomy has been

gaining momentum, and the topic of entrenching democracy and good

government is becoming a frequently heard theme in rural areas. The

theme of local autonomy has also brought Western Enlightenment

inquiries into who we are, what we can do, and what we should do to the

cities of the western highlands of Guatemala, but they have changed in

various ways in response to individual circumstances, such as the

movement against mining development and the emergence of the circuit of

opinion called the local council (COCODE). The reason is that they have

undergone diverse changes in response to their individual circumstances

[Ikeda a 2012, Ikeda b 2012].

|

|

先住の(indigenous)という言葉は、そ

もそも先住ではない探検家や植民者によって「発見」されてきたという歴史的意味付与という虚構の逸話を

持ちます。土着の動植物の同定(identification)に似て、当事者自身による再承認や内容の変更可能性という概念がこの用語には欠落している

のではないでしょうか。逆説的な言い方ですが、それゆえにこそ、先住という概念にはこの種の「変わらない」普遍性や本質性を内面化した時に外部からの圧力

に屈することのない「抵抗」の潜在力を持ちうる可能性も出てきます。国際連合による先住民の諸権利に関する宣言(Declaration on the

Rights of Indigenous Peoples,

2007)に明確な定義というものが欠けており、これまでに先住民が受けてきた人権上の侵害の歴史を踏まえて、数多くの禁止規定から構成されているのも、

先住民概念の定義を棚上げしてもなお具体的な人権の擁護を急務とする精神性が現れているのではないでしょうか。

The term indigenous has the fictional anecdote of historical meaning

assignment that it has been “discovered” by explorers and colonizers

who were not indigenous to begin with. Similar to the identification of

indigenous plants and animals, the term lacks the concept of

reaffirmation or changeability of content by the parties themselves.

Paradoxically, this is precisely why the concept of indigenous peoples

may have the potential for “resistance” to external pressures when it

comes to internalizing this kind of “unchanging” universality and

essentiality. The lack of a clear definition in the United Nations

Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007), which consists

of a number of prohibitions based on the history of human rights

violations suffered by indigenous peoples, is another reason why the

concept of indigenous peoples is not clearly defined in the

Declaration. The fact that the Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous

Peoples (Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 2007) lacks a

clear definition and consists of a number of prohibitions based on the

history of human rights violations suffered by indigenous peoples to

date is also a reflection of the mentality of the urgent need to

protect specific human rights even if the definition of indigenous

concepts is shelved.

|

|

柔軟に対応すればウィン=ウィンも可能だと甘い言

葉で囁くグローバリゼーション勢力が優勢な状況の中で、地道に先住民の生活に感情的に同化しアプローチ

する人類学者なら、この「抵抗」という実践概念に誰しもが魅了されることでしょう。しかしながら、マム人の共同体を比較的長く見続けてきた私にとって、こ

の抵抗の主体は何事にも闇雲に反対する集団ではないように思われます。頑迷で保守的な伝統主義者に見える時もあれば、非常に柔軟でしなやかな機会主義者に

も思われる時もあります。国内および国際的な状況のなかで、そして自らの集団が帰属する国家との関係のなかで、現在のマム人という先住民集団は、自らの歴

史のダイナミズムを、その都度、認識し、再解釈し、修正し、また自らのものとしています。私が冒頭で申し上げたこと、すなわち土着性や劣等性のスティグマ

(=他者表象)としてのインディオから、政治的に正しい用語としてのインディヘナとして徐々に自己表象ないしは名乗りとして集合的なアイデンティティを使

うようになり、さらに、マヤ人でありマム人であるというふうに振る舞うようになった時代的背景についてお話しました。これが本発表における主張であり、現

在の私の所感にほかなりません。

――Initium ut esset homo creatus est(人間が創造されるように始まりがつくられる:アウグスチヌス)

←Mitzub’ixi Quq Chi’j tuj Paxil, Chinab’jul, Ixim Tx’otx’, diciembre

1987

In a situation dominated by globalization forces that sweetly whisper

that win-win is possible if we are flexible, any anthropologist who

steadily and emotionally assimilates and approaches the lives of

indigenous peoples will be fascinated by this practical concept of

“resistance. However, having followed the Mamu community for a

relatively long time, it seems to me that this entity of resistance is

not a group that opposes everything in the dark. At times they seem

obstinate and conservative traditionalists, and at other times they

seem very flexible and flexible opportunists. In the national and

international context, and in relation to the nation to which they

belong, the indigenous Mamu people of today recognize, reinterpret,

revise, and own the dynamism of their history as it happens. What I

said at the beginning, that is, from the stigma of indigeneity and

inferiority (i.e., representation of the other) as Indians, they

gradually began to use their collective identity as a

self-representation or nomenclature as Indigena, a politically correct

term, and then to act as Mayans and Mamus, a historical background in

which they have come to act as Mayans and Mamus. This is the argument

of this presentation. This is the argument of this presentation, and it

is my current impression.

--Initium ut esset homo creatus est (The beginning is made as man is

created: Augustine)

|