我々は甲冑で身を固めている、というマルチン・ブーバーのテーゼ

On Martin Buber's Dialogic Thinking

我々は甲冑で身を固めている、というマルチン・ブーバーのテーゼ

On Martin Buber's Dialogic Thinking

外部からやってくる「徴証(しるし)」を寄せつけまいとするように、我々は甲冑で身を固めている、というマルチン・

ブーバーのテーゼ

「われわれはみな、甲胃を身にまとい、われわれに生ずるしるしを近づけぬようにしている。しるしはたえず生じている。生きていることは、語りか

けられていることであり、われわれはただこのしるしに立ち向かい、これに耳を傾けることだけが必要である。しかしこの冒険はわれわれにとって非常に危険な

ものである。音のない雷は、われわれに破滅の威嚇をなすごとく見え、それゆえ、われわれは世代ごとに防禦の備えを完全なものにしようとする。われわれの知

識は、つぎのような確信を与える〈落着きなさい、すべては必然的に起るべくして起る。何もあなたに向けられているのではない、あなたがねらわれているので

はない。まさにこのようなのが世界である。あなたは自分で望むままに世界を体験することができる。しかしあなたが心の中でいつも思っていることは、すべて

あなたから生ずるのである。あなたは何も要求されず、だれもあなたに語りかけず、すべては静かである〉と。

われわれはみな、甲胃で身をかためており、習慣的になったものはもはやすぐには感じ ないようになっている。ただ時々、習慣を破り、魂を敏感にかき立てる瞬間がある。そのような瞬間が生じたとき、われわれははっとして自問する。〈何か特別 のことが起ったのか、それはわたしが毎日出合っているようなたぐいのものではないのか〉と。そしてこの自問にたいし、つぎのようにわれわれは自答する。 〈いや、何も特別なものというわけではない。それは毎日あるものと同じである。ただわれわれが毎日そこにいないだけである〉と。

語りかけのしるしは特別なものではない。事物の秩序からはみ出しているようなもので はない。それはいつも生ずるものであり、いずれにしても元来生じているのであって、語りかけによって何かが新たにつけ加わるわけではない。エーテルの波は つねに送られているが、しかし、われわれはたいてい、受信機をはずしているのである。

わたしに生起するものは、わたしへの語りかけである。わたしに生起するものである世

界の現象は、わたしへの語りかけである。この語りかけをわたしはひたすら去勢し、芽を摘むことによってのみ、わたしを目ざしているのではない世界現象の一

部として理解することができる。すべてのものを関連づけながら組織化することだけを求める去勢化のこの体系は、途方もない人類の怪物的行為である。言語も

またこの体系のために奉仕するように定められている」(ブーバー 1979:189-190)。

——マルティン・ブーバー『我と汝:対話』植田重雄訳、岩波文庫、東京:岩波書店,

Jeder von uns steckt in einem Panzer, dessen Aufgabe ist, die Zeichen abzuwehren. Zeichen geschehen uns unablässig, leben heißt angeredet werden, wir brauchten nur uns zu stellen, nur zu vernehmen. Aber das Wagnis ist uns zu gefährlich, die lautlosen Donner scheinen uns mit Vernichtung zu bedrohen, und wir vervollkommnen von Geschlecht zu Geschlecht den Schutzapparat. All unsere Wissenschaft versichert uns: »Sei ruhig, das geschieht eben alles vie es geschehen muß, aber an dich ist nichts gerichtet, du bist nicht gemeint, das ist eben >die Welt<, du kannst sie erleben wie du willst, aber was immer du in dir damit anfängst geht von dir allein aus, man fordert dir nichts ab, man redet dich nicht an, alles ist still.«

Jeder von uns steckt in einem Panzer, den wir bald vor Gewöhnung nicht mehr spüren. Nur Augenblicke gibt es, die ihn durchdringen und die Seele zur Empfänglichkeit aufrühren. Und wenn sich dergleichen uns angetan hat und wir dann aufmerken und uns fragen: »Was hat sich denn da Besondres ereignet? Wars nicht von der Art, wie es mir alle Tage begegnet?«, so dürfen wir uns erwidern: »Freilich, nichts Besondres, so ist es alle Tage, nur wir sind alle Tage nicht da.«

Die Zeichen der Anrede sind nicht etwas Außerordentliches, etwas was aus der Ordnung der Dinge tritt, sie sind eben das, was sich je und je begibt, eben das, was sich ohnehin begibt, durch die Anrede kommt nichts hinzu. Die Ätherwellen brausen immer aber wir haben zumeist unsern Empfänger abgestellt.

Was mir widerfährt ist Anrede an mich. Als das, was mir widerfährt, ist das Weltgeschehen Anrede an mich. Nur indem ich es sterilisiere, es von Anrede entkeime, kann ich das, was mir widerfährt, als einen Teil des mich nicht meinenden Weltgeschehens fassen. Das zusammenhängende, sterilisierte System, in das sich all dies nur einzufügen braucht, ist das TItanenwerk der Menschheit. Auch die Sprache ist ihm dienstbar gemacht worden. (Buber, 1962, SS.183-184)

Buber, Martin.1962. Schriften zur Philosophie,

[Werke, 1], München : Kösel. - Heidelberg : Schneider

マルチン(マルティンとも表記:Martin Buber, 1878-1965)・ブーバー

問い:

1.ブーバーが主張する「われわれ」とはいったいどのような存在なのか?

2.ブーバーは、この「われわれ」が置かれた状態を〈よし〉としているのか? それとも、なにか「われわれに」みずからの〈変化〉を促そうとしているの

か?

3.ブーバーの主張について、これを読んだ君は首肯(しゅこう:肯定すること)できるか? そうである場合は、さらに彼の主張を補強する意見を付け加えて

ほしい。また何らかの異論があればそれに対する反論や疑問を考えてみよう。

このハンドアウト:140410bialogic_Buber.pdf

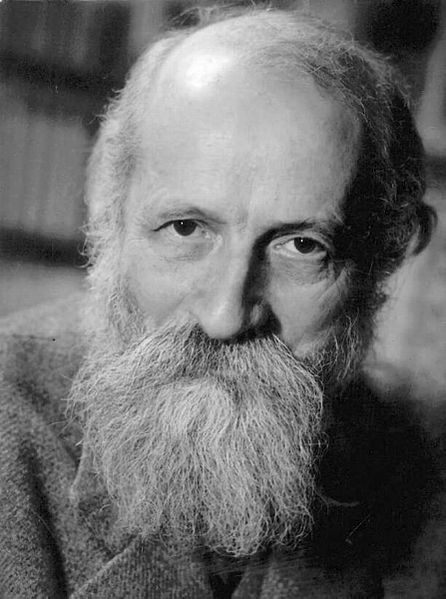

| Martin Buber

(Hebrew: מרטין בובר; German: Martin Buber, pronounced [ˈmaʁtiːn̩

ˈbuːbɐ] ⓘ; Yiddish: מארטין בובער; February 8, 1878 – June 13, 1965) was

an Austrian-Israeli philosopher best known for his philosophy of

dialogue, a form of existentialism centered on the distinction between

the I–Thou relationship and the I–It relationship.[1] Born in Vienna,

Buber came from a family of observant Jews, but broke with Jewish

custom to pursue secular studies in philosophy. He produced writings

about Zionism and worked with various bodies within the Zionist

movement extensively over a nearly 50-year period spanning his time in

Europe and the Near East. In 1923, Buber wrote his famous essay on

existence, Ich und Du (later translated into English as I and Thou),[2]

and in 1925 he began translating the Hebrew Bible into the German

language. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature ten times, and the Nobel Peace Prize seven times.[3] |

מארטין בובער; 1878年2月8日 -

1965年6月13日)は、オーストリア・イスラエルの哲学者であり、「私-汝」の関係と「私-汝」の関係の区別を中心とした実存主義の一形態である対話

の哲学で最もよく知られている。

[1]ウィーンで生まれたブーバーは、厳格なユダヤ教徒の家系に生まれたが、ユダヤ教の慣習にとらわれず、世俗的な哲学を学んだ。ブーバーはシオニズムに

関する著作を発表し、ヨーロッパと近東に滞在した約50年間にわたり、シオニズム運動のさまざまな組織と幅広く協力した。1923年、ブーバーは存在に関

する有名なエッセイ『Ich und Du』(後に『I and

Thou』として英訳される)を執筆し[2]、1925年にはヘブライ語聖書のドイツ語への翻訳を始めた。 ノーベル文学賞に10回、ノーベル平和賞に7回ノミネートされた[3]。 |

| Biography Martin (Hebrew name: מָרְדֳּכַי, Mordechai) Buber was born in Vienna to an Orthodox Jewish family. Buber was a direct descendant of the 16th-century rabbi Meir Katzenellenbogen, known as the Maharam (מהר"ם), the Hebrew acronym for “Mordechai, HaRav (the Rabbi), Meir”, of Padua. Karl Marx is another notable relative.[4] After the divorce of his parents when he was three years old, he was raised by his grandfather in Lemberg (now Lviv in Ukraine).[4] His grandfather, Solomon Buber, was a scholar of Midrash and Rabbinic Literature. At home, Buber spoke Yiddish and German. In 1892, Buber returned to his father's house in Lemberg. Despite Buber's putative connection to the Davidic line as a descendant of Katzenellenbogen, a personal religious crisis led him to break with Jewish religious customs. He began reading Immanuel Kant, Søren Kierkegaard, and Friedrich Nietzsche.[5] The latter two, in particular, inspired him to pursue studies in philosophy. In 1896, Buber went to study in Vienna (philosophy, art history, German studies, philology). In 1898, he joined the Zionist movement, participating in congresses and organizational work. In 1899, while studying in Zürich, Buber met his future wife, Paula Winkler, a "brilliant Catholic writer from a Bavarian peasant family"[6] who in 1901 left the Catholic Church and in 1907 converted to Judaism.[7] Buber, initially, supported and celebrated the Great War as a "world historical mission" for Germany along with Jewish intellectuals to civilize the Near East.[8] Some researchers believe that while in Vienna during and after World War I, he was influenced by the writings of Jacob L. Moreno, particularly the use of the term ‘encounter’.[9][10] In 1930, Buber became an honorary professor at the University of Frankfurt am Main, but resigned from his professorship in protest immediately after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933. He then founded the Central Office for Jewish Adult Education, which became an increasingly important body as the German government forbade Jews from public education. In 1938, Buber left Germany and settled in Jerusalem, Mandatory Palestine, receiving a professorship at Hebrew University and lecturing in anthropology and introductory sociology. In 1947, he was forced to flee his home in Abu Tor, Jerusalem, due to the advance of the Arab Liberation Army.[11] After the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, Buber became the best known Israeli philosopher. After 1948, Buber lived in Edward Said's family home in Jerusalem.[12] Buber and Paula had two children: a son, Rafael Buber, and a daughter, Eva Strauss-Steinitz. They helped raise their granddaughters Barbara Goldschmidt (1921–2013) and Judith Buber Agassi (1924–2018), born by their son Rafael's marriage to Margarete Buber-Neumann. Buber's wife Paula Winkler died in 1958 in Venice, and he died at his home in the Talbiya neighborhood of Jerusalem on June 13, 1965. Buber was a vegetarian.[13] |

略歴 マルティン(ヘブライ語名:מָרְדֳּו)・ブーバーはウィーンの正統派ユダヤ人の家庭に生まれた。ブーバーは、16世紀にパドヴァのマハラム(ヘブ ライ語で 「Mordechai, HaRav (the Rabbi), Meir 」の頭文字)として知られたラビ、ミール・カッツェネレンボーゲンの直系の子孫である。カール・マルクスも有名な親戚である[4]。3歳のときに両親と離 婚した後、レンベルク(現在のウクライナのリヴィウ)で祖父に育てられた[4]。祖父のソロモン・ブーバーはミドラシュとラビ文学の学者であった。家では イディッシュ語とドイツ語を話していた。1892年、ブーバーはレンベルクの父の家に戻る。 ブーバーは、カッツェネレンボーゲンの子孫としてダビデの血筋につながるとされていたにもかかわらず、個人的な宗教的危機から、ユダヤ教の宗教的習慣と決 別するようになった。ブーバーはイマヌエル・カント、セーレン・キェルケゴール、フリードリッヒ・ニーチェを読み始める[5]。1896年、ブーバーは ウィーンに留学する(哲学、美術史、ドイツ学、言語学)。 1898年にはシオニスト運動に参加し、大会や組織活動に参加した。1899年、チューリッヒで学んでいたブーバーは、後に妻となるパウラ・ヴィンクラー に出会う。パウラは「バイエルンの農民家庭出身の優秀なカトリック作家」[6]で、1901年にカトリック教会を離れ、1907年にユダヤ教に改宗した [7]。 ブーバーは当初、第一次世界大戦をユダヤ人知識人たちとともにドイツが近東を文明化するための「世界史的使命」として支持し、祝福していた[8]。第一次 世界大戦中と戦後のウィーン滞在中に、ヤコブ・L・モレノの著作、特に「遭遇」という用語の使用に影響を受けたと考える研究者もいる[9][10]。 1930年、ブーバーはフランクフルト・アム・マイン大学の名誉教授となったが、1933年にアドルフ・ヒトラーが政権を握った直後、抗議して教授の職を 辞した。その後、ユダヤ人成人教育中央事務局を設立し、ドイツ政府がユダヤ人の公教育を禁じたため、ますます重要な組織となった。1938年、ブーバーは ドイツを離れ、委任統治領パレスチナのエルサレムに定住し、ヘブライ大学で教授職を得、人類学と社会学入門の講義を行った。1947年、アラブ解放軍の進 撃により、エルサレムのアブ・トーにあった自宅を追われた[11]。1948年のイスラエル建国後、ブーバーはイスラエルで最も知られた哲学者となった。 1948年以降、ブーバーはエルサレムにあるエドワード・サイードの実家に住んでいた[12]。 息子のラファエル・ブーバーと娘のエヴァ・ストラウス=シュタイニッツである。息子のラファエルがマルガレーテ・ブーバー=ノイマンと結婚したことで生ま れた孫娘のバーバラ・ゴールドシュミット(1921-2013)とジュディス・ブーバー・アガシ(1924-2018)の子育てにも協力した。ブーバーの 妻ポーラ・ウィンクラーは1958年にヴェネツィアで死去し、ブーバーは1965年6月13日にエルサレムのタルビヤ地区にある自宅で死去した。 ブーバーはベジタリアンであった[13]。 |

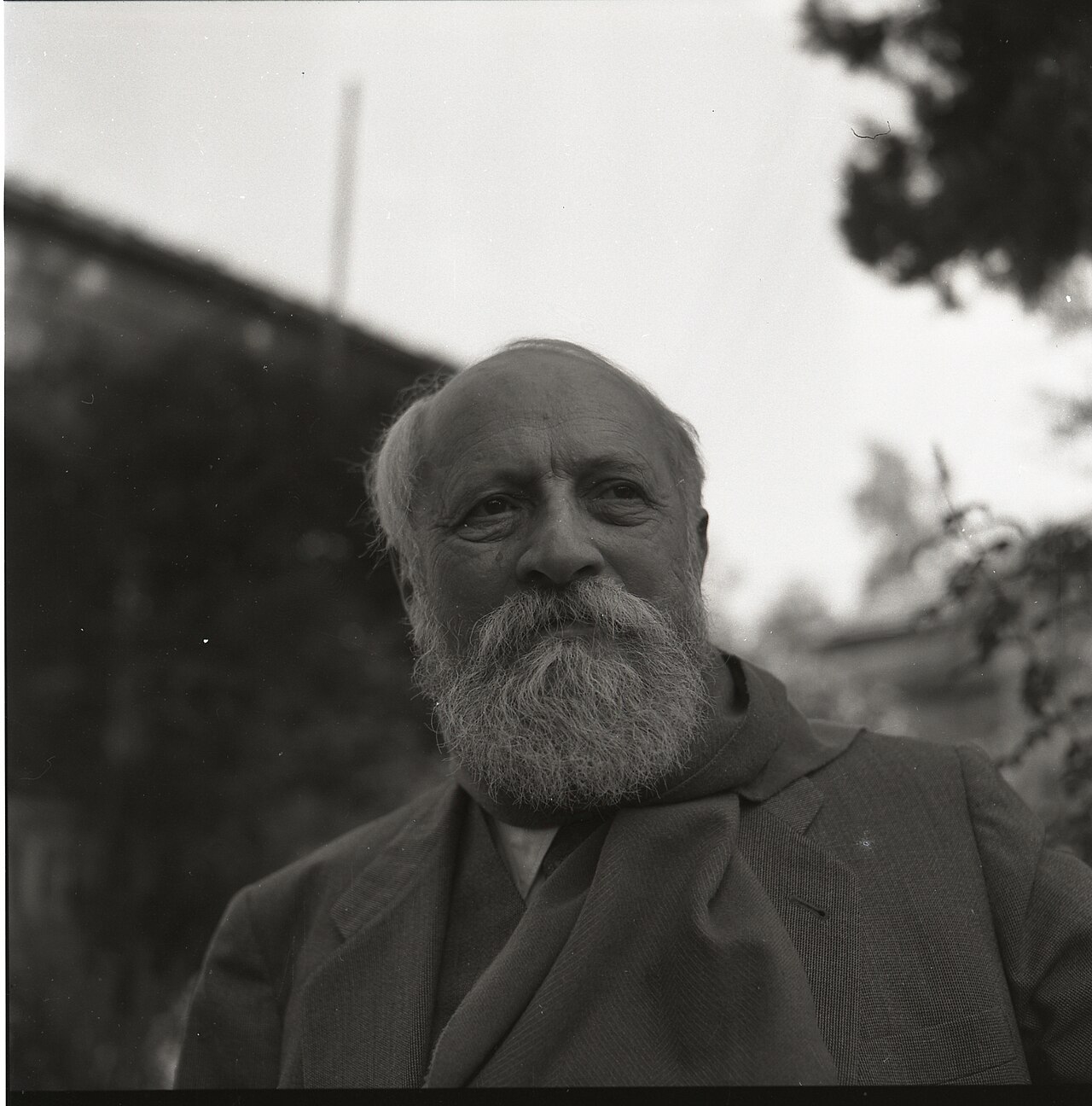

Buber in 1963 |

1963年のブーバー(85歳) |

| Buber's evocative, sometimes

poetic, writing style marked the major themes in his work: the

retelling of Hasidic and Chinese tales, Biblical commentary, and

metaphysical dialogue. A cultural Zionist, Buber was active in the

Jewish and educational communities of Germany and Israel.[14] He was

also a staunch supporter of a binational solution in Palestine, and,

after the establishment of the Jewish state of Israel, of a regional

federation of Israel and Arab states. His influence extends across the

humanities, particularly in the fields of social psychology, social

philosophy, and religious existentialism.[15] Buber's attitude toward Zionism was tied to his desire to promote a vision of "Hebrew humanism".[16] According to Laurence J. Silberstein, the terminology of "Hebrew humanism" was coined to "distinguish [Buber's] form of nationalism from that of the official Zionist movement" and to point to how "Israel's problem was but a distinct form of the universal human problem. Accordingly, the task of Israel as a distinct nation was inexorably linked to the task of humanity in general".[17] |

ブーバーは、ハシディックや中国の物語の再話、聖書の解説、形而上学的

な対話など、彼の作品の主要なテーマを、時に詩的で、喚起的な文体で表現した。文化的シオニストであったブーバーは、ドイツとイスラエルのユダヤ人社会と

教育界で活躍した[14]。また、パレスチナにおける二国間解決、そしてユダヤ人国家イスラエルの建国後は、イスラエルとアラブ諸国による地域連合を支持

した。ブーバーの影響は人文科学全般、特に社会心理学、社会哲学、宗教的実存主義の分野に及んでいる[15]。 シオニズムに対するブーバーの態度は、「ヘブライ・ヒューマニズム」のビジョンを推進したいという彼の願望と結びついていた[16]。 ローレンス・J・シルバースタインによれば、「ヘブライ・ヒューマニズム」という用語は、「ブーバーのナショナリズムの形式を公式なシオニズム運動のそれ と区別する」ため、また「イスラエルの問題は、普遍的な人間の問題の明確な形式にすぎない」ことを指摘するために作られた。したがって、別個の国家として のイスラエルの課題は、人類一般の課題と不可避的に結びついていた」[17]。 |

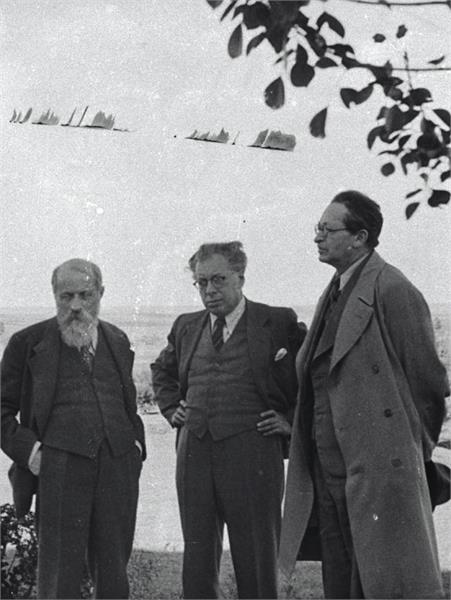

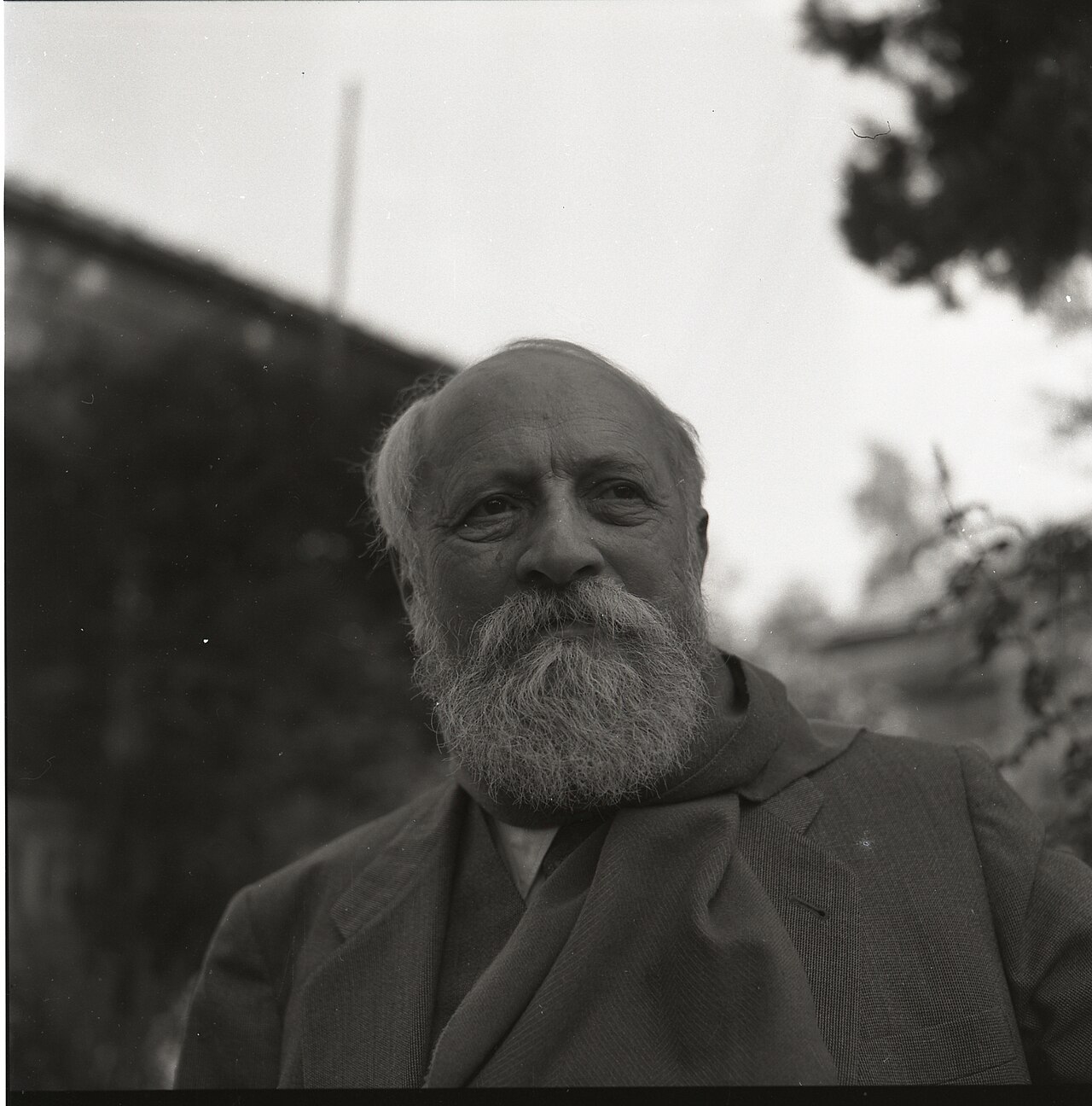

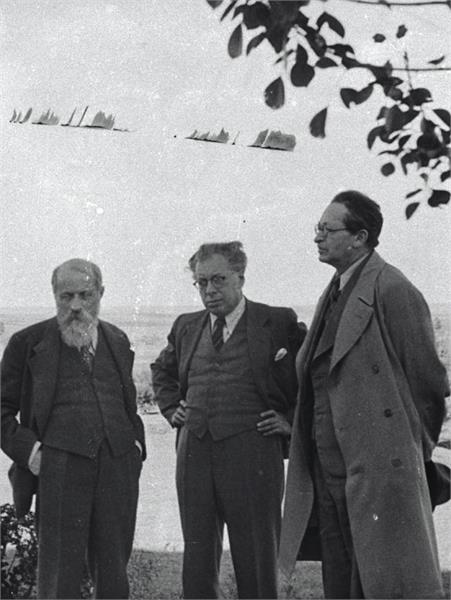

| Zionist views Pre-1915: Early engagement with Zionism  The Jewish Student Association in Leipzig, with Buber in the center surrounded by other members (1899) The Jewish Student Association in Leipzig with Buber in the center (1899) Approaching Zionism from his own personal viewpoint, a young Buber disagreed with Theodor Herzl about their respective positions on Zionism. Herzl did not envision Zionism as a movement with religious objectives. In contrast, Buber believed the potential of Zionism was for social and spiritual enrichment. For example, Buber argued that following the formation of the Israeli state, there would need to be reforms to Judaism: "We need someone who would do for Judaism what Pope John XXIII has done for the Catholic Church".[18] Herzl and Buber would continue, in mutual respect and disagreement, to work towards their respective goals for the rest of their lives. In 1902, Buber became the editor of the weekly Die Welt, the central organ of the Zionist movement. However, a year later he became involved with the Jewish Hasidic movement. Buber admired how the Hasidic communities actualized their religion in daily life and culture. In stark contrast to the busy Zionist organizations, which were always mulling political concerns, the Hasidim were focused on the values which Buber had long advocated for Zionism to adopt. In 1904, he withdrew from much of his Zionist organizational work, and devoted himself to study and writing, as in that same year, he published his thesis, Beiträge zur Geschichte des Individuationsproblems, on Jakob Böhme and Nikolaus Cusanus.[19] In a 1910 essay entitled "He and We," Buber established himself and Herzl as diametrically opposed in their perspectives on Zionism. Buber described Herzl by saying, "The impulse of the elementally active person (Elementaraktiver) to act is so strong that it prevents him from acquiring knowledge for the sake of knowledge," and, according to Buber, when a person like Herzl is aware of his Jewishness, "In him awakens the will to help the Jews to whom he belongs, to lead the where they can experience freedom and security. Now he does what his will tells He does not see anything else."[20] In that same essay, Buber would draw a parallel between Herzl and Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidism, arguing that both seek to reinstate the Jewish people, the difference coming in their approaches; Herzl affecting change indirectly via history whereas Baal Shem Tov sought to achieve improvement directly through religion.[20] 1915–38: Further development  Martin Buber, Yitzhak Ben Zvi, and Leo Herman in Jerusalem (1915) Martin Buber, Yitzhak Ben Zvi, and Leo Herman in Jerusalem (1915) Buber produced multiple writings on Zionism and nationalism during this time period, expanding upon broader ideas related to Zionism. In light of the outbreak of WWI, Buber engaged in debates with fellow German philosopher Hermann Cohen in 1915 on the nature of nationalism and Zionism.[21] Whereas Cohen, whose argument was based in messianic principles, believed that a Jewish minority was essential to a broader German national identity, Buber argued that, "Judaism may well be taken up in messianic humanity, to be melted into it; we do not, however, consider that the Jewish people must disappear among contemporary humanity so that a messianic humanity might arise."[22] Buber continued to explore and develop his views on Zionism in these years. One such notable piece of writing is a letter to a professor entitled "Concepts and Reality" in 1916. In this letter, Buber addresses the issues of nationalism, Messianism, and Hebrew within the Zionist movement of the period.[23] Buber argued that nationalism is not a natural phenomenon, and that Zionism is a movement centered around religiosity, not nationalism.[24] However, according to Buber, the messianic movement within Zionism is obscured by those in liberal Jewish and anti-Zionist circles, who argue that Messianism necessitates a diaspora.[25] On the importance of the Hebrew language, Buber believed, "Hebrew is not first and foremost a vernacular but the single language that can fully absorb and express the sublime values of Judaism."[26] In the early 1920s, Martin Buber started advocating a binational Jewish-Arab state, stating that the Jewish people should proclaim "its desire to live in peace and brotherhood with the Arab people, and to develop the common homeland into a republic in which both peoples will have the possibility of free development."[27] Buber rejected the idea of Zionism as just another national movement, and wanted instead to see the creation of an exemplary society; a society which would not be characterized by Jewish domination of the Arabs. It was necessary for the Zionist movement to reach a consensus with the Arabs even at the cost of the Jews remaining a minority in the country. In 1925, he was involved in the creation of the organization Brit Shalom (Covenant of Peace), which advocated the creation of a binational state, and throughout the rest of his life, he hoped and believed that Jews and Arabs one day would live in peace in a joint nation. In a 1929 essay entitled "The National Home and National Policy in Palestine," Buber explores Jewish right to the land of Israel before engaging with the question of Jewish-Arab relations.[28] According to Buber, the Zionist right to establish a country in Israel originates from their ancient, ancestral connection to the land, the fact that Jews have worked to cultivate the land in recent years, and the future prospect that a Jewish state offers as both a cultural center for Judaism and a model for creating a new social organization, referencing the emergence of kibbutzim.[29] Buber goes on to discuss, broadly, the necessity for injustice in order to survive, and focuses it to the Zionist perspective by writing, "It is indeed true that there can be no life without injustice. The fact that there is no living creature that can live and thrive without destroying another existing organism has a symbolic significance as regards our human life. But the human aspect of life begins the moment we say to ourselves: We will not do more injustice to others than we are forced to do to exist."[30] Buber then uses this perspective to argue in favor of Binationalism as means to establish a combination of potential coexistence and national independence.[31] Post 1938: Zionist views from Israel and post-Independence Zionism  Martin Buber in Israel (1962) Martin Buber in Israel (1962) Living and writing in Jerusalem, Buber increased his political involvement, and continued to develop his ideas on Zionism. In 1942, he co‑founded the Ihud party, which advocated a bi-nationalist program. Nevertheless, he was connected with decades of friendship to Zionists and philosophers such as Chaim Weizmann, Max Brod, Hugo Bergmann, and Felix Weltsch, who were close friends of his from old European times in Prague, Berlin, and Vienna to the Jerusalem of the 1940s through the 1960s. Buber evaluated the competing strains of cultural and political Zionism from a somewhat teleological perspective in a 1948 piece "Zionism and Zionism".[32] He summarizes these two competing perspectives as, on the one hand, "returning and restoring the true Israel, whose spirit and life would once again no longer exist beside each other," and, on the other hand, as a process of "normalization," and that to be "normal," a "nation needs a land, a language, and independence. Thus, one must only go and acquire those commodities, and the rest will take care of itself."[33] According Buber, as Jews and Israel succeed at being a "normal nation," the drive for a spiritual and cultural rebirth is lost, and the war being waged over political structure threatens to become a war for survival.[33] After the establishment of Israel in 1948, Buber advocated Israel's participation in a federation of "Near East" states wider than just Palestine.[34] Buber outlines this concept in "Zionism and Zionism". For Buber, Israel has the potential to serve as an example for the "Near East" as, in his Binationalist perspective, two independent nations, could each maintain their own cultural identity, "but both united in the enterprise of developing their common homeland and in the federal management of shared matters. On the strength of that covenant we wish to return once more to the union of Near Eastern nations, to build an economy integrated in that of the Near East, to carry out policies in the framework of the life of the Near East, and, God willing, to send the "living idea" forth to the world from the Near East once again."[35] During this same time period Buber remained critical of many policies and leaders of the new Israeli government. He was particularly vocal about the treatment of Arab refugees, and was unafraid to criticize top leadership like David Ben-Gurion, the first Prime Minister.[36] |

シオニストの見解 1915年以前 シオニズムとの初期の関わり  ライプツィヒのユダヤ人学生協会。中央がブーバーで、他の会員に囲まれている(1899年) ブーバーを中心としたライプチヒのユダヤ人学生協会(1899年) 個人的な視点からシオニズムに取り組んだ若き日のブーバーは、シオニズムに対するそれぞれの立場についてテオドール・ヘルツルと意見が対立した。ヘルツル はシオニズムを宗教的な目的を持つ運動とは考えていなかった。これに対してブーバーは、シオニズムの可能性は社会的、精神的な豊かさにあると考えた。例え ば、ブーバーは、イスラエルの国家形成の後には、ユダヤ教に対する改革が必要であると主張した。「ローマ教皇ヨハネ23世がカトリック教会に対して行った ことをユダヤ教に対して行うような人物が必要なのだ」[18]。1902年、ブーバーはシオニスト運動の中心的機関紙である週刊誌『ディ・ヴェルト』の編 集者となる。しかしその1年後、ブーバーはユダヤ教のハシディ運動と関わるようになる。ブーバーは、ハシディズムの共同体が日常生活や文化の中で自分たち の宗教をどのように現実化しているかを賞賛した。常に政治的な問題に頭を悩ませていた多忙なシオニスト組織とは対照的に、ハシディムはブーバーが長年シオ ニズムの採用を提唱してきた価値観に焦点を当てていた。1904年、ブーバーはシオニストの組織的活動から手を引き、研究と執筆に専念するようになった。 1910年の「彼と私たち」と題されたエッセイの中で、ブーバーは、シオニズムに対する考え方において、ヘルツルと正反対であるとした。ブーバーはヘルツ ルについて、「活動的な人間(Elementaraktiver)の行動への衝動は、知識のために知識を得ることを妨げるほど強い」と述べ、ブーバーによ れば、ヘルツルのような人間がユダヤ人であることを自覚したとき、「彼の中には、自分が属するユダヤ人を助け、彼らが自由と安全を経験できる場所に導こう とする意志が目覚める。今、彼は自分の意志が告げることを行い、それ以外には何も見ない」[20]。ブーバーは同じエッセイで、ヘルツルとハシディズムの 創始者であるバール・シェム・トフを並列に描き、両者ともユダヤ民族の復権を目指しているが、そのアプローチの違いは、ヘルツルが歴史を通じて間接的に変 化に影響を与えるのに対して、バール・シェム・トフは宗教を通じて直接的に改善を達成しようとしている点にあると論じている[20]。 1915-38年:さらなる発展  マーティン・ブーバー、イツハク・ベン・ズヴィ、レオ・ハーマン(1915年、エルサレムにて) マーティン・ブーバー、イツハク・ベン・ズヴィ、レオ・ハーマン(1915年、エルサレムにて) ブーバーはこの時期、シオニズムとナショナリズムに関する複数の著作を発表し、シオニズムに関連する広範な思想を発展させた。第一次世界大戦の勃発を踏ま えて、ブーバーは1915年に同じドイツの哲学者であるヘルマン・コーエンとナショナリズムとシオニズムの本質について議論を交わした[21]。メシア主 義に基づく主張をするコーエンが、ユダヤ人の少数派はより広範なドイツの国民的アイデンティティにとって不可欠であると考えていたのに対して、ブーバーは 「ユダヤ教はメシア的人間性の中に取り込まれ、その中に溶け込むかもしれない。 ブーバーはこの数年間、シオニズムに関する自身の見解を探求し、発展させ続けた。1916年にある教授に宛てた「概念と現実」と題された手紙がその一つで ある。この手紙の中でブーバーは、当時のシオニズム運動におけるナショナリズム、メシアニズム、ヘブライ語の問題を取り上げている[23]。ブーバーは、 ナショナリズムは自然現象ではなく、シオニズムはナショナリズムではなく宗教性を中心とした運動であると主張した[24]。 [24]しかし、ブーバーによれば、シオニズムの中のメシア的な運動は、メシア主義がディアスポラを必要とすると主張するリベラルなユダヤ人や反シオニス ト界の人々によって曖昧にされている[25]。ヘブライ語の重要性について、ブーバーは「ヘブライ語は何よりもまず方言ではなく、ユダヤ教の崇高な価値を 完全に吸収し表現することができる唯一の言語である」と考えていた[26]。 1920年代初頭、マルティン・ブーバーはユダヤ人とアラブ人の二国間国家を提唱し始め、ユダヤ人は「アラブ人と平和と同胞愛のうちに共存し、共通の祖国 を両民族が自由な発展の可能性を持つ共和国に発展させたいという願望」を表明すべきであると述べた[27]。シオニズム運動は、ユダヤ人がこの国で少数派 であり続けることを犠牲にしても、アラブ人とコンセンサスを得る必要があった。1925年、彼は二国間国家の創設を提唱するブリット・シャローム(平和の 誓約)という組織の創設に関わり、その後の生涯を通じて、ユダヤ人とアラブ人が共同国家で平和に暮らす日が来ることを願い、信じていた。 1929年の「パレスチナにおけるナショナル・ホームと国家政策」と題されたエッセイの中で、ブーバーはユダヤ人とアラブ人の関係の問題に関わる前に、イ スラエルの土地に対するユダヤ人の権利について探求している。 [28]ブーバーによれば、イスラエルに国を建国するシオニストの権利は、彼らの土地に対する古くからの先祖代々のつながり、近年ユダヤ人がこの土地の開 墾に努めてきたという事実、そしてユダヤ教国家がユダヤ教の文化的中心地として、またキブジムの出現を参照しながら新しい社会組織を創造するモデルとして 提供する将来の展望に由来する。 [29]ブーバーはさらに、生き延びるためには不公正が必要であることを大まかに論じ、シオニストの視点に焦点を合わせて、次のように書いている。現存す る他の生物を破壊することなく生き、繁栄できる生物は存在しないという事実は、私たち人間の生命に関して象徴的な意味を持つ。しかし、人生の人間的側面 は、私たちが自分自身に言い聞かせた瞬間から始まる: そしてブーバーは、この観点を用いて、潜在的な共存と国家の独立の組み合わせを確立する手段としての二国論を支持している[31]。 1938年以降: イスラエルと独立後のシオニズムからのシオニストの見解  イスラエルにおけるマルティン・ブーバー(1962年) イスラエルでのマルティン・ブーバー(1962年) エルサレムに住み、執筆活動を続けたブーバーは、政治的関与を強め、シオニズムに関する考えを発展させ続けた。1942年、ブーバーはイフッド党を共同設 立し、二国間主義を唱えた。とはいえ、チャイム・ワイツマン、マックス・ブロート、フーゴ・バーグマン、フェリックス・ウェルチといったシオニストや哲学 者たちとは、プラハ、ベルリン、ウィーンの古いヨーロッパ時代から、1940年代から1960年代のエルサレムに至るまで、数十年にわたって親交があっ た。 ブーバーは、1948年に発表した「シオニズムとシオニズム」[32]の中で、文化的シオニズムと政治的シオニズムの相反する系統を、やや望遠的な視点か ら評価している。彼は、この相反する2つの視点を、一方では、「精神と生命が再び隣り合わせに存在することのない真のイスラエルを復帰させ、回復させるこ と」であり、他方では、「正常化」のプロセスであり、「正常」であるためには、「民族は土地と言語と独立を必要とする。ブーバーによれば、ユダヤ人とイス ラエルが「普通の国家」になることに成功するにつれて、精神的・文化的な再生への意欲は失われ、政治構造をめぐって繰り広げられている戦争は生存をめぐる 戦争になる恐れがある[33]。 1948年のイスラエル建国後、ブーバーはパレスチナだけでなく、より広範な「近東」諸国の連合体へのイスラエルの参加を提唱した[34]。ブーバーに とってイスラエルは、彼の二国家主義的な視点において、「近東」の模範となる可能性を持っており、2つの独立した国家はそれぞれ独自の文化的アイデンティ ティを維持することができるが、「両者は共通の祖国を発展させるという事業と、共有する事柄の連邦的管理において団結している。その契約の強さの上に、わ れわれはもう一度近東諸国の連合に戻り、近東の経済と一体化した経済を構築し、近東の生活の枠組みの中で政策を実行し、神のご意思により、「生きた思想」 を再び近東から世界に発信することを望む」[35]。この同じ時期、ブーバーはイスラエル新政府の多くの政策や指導者たちに批判的であり続けた。特にアラ ブ難民の扱いについては声を荒げ、初代首相のダヴィド・ベン・グリオンのようなトップの指導者を臆面もなく批判した[36]。 |

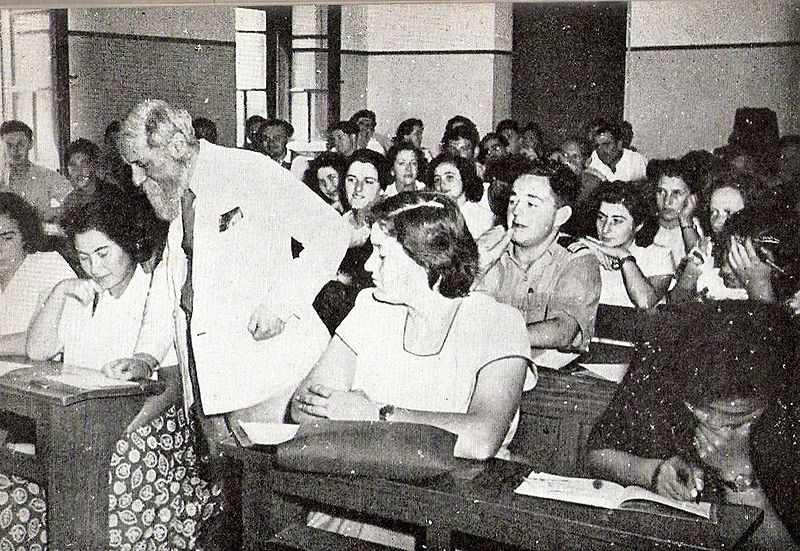

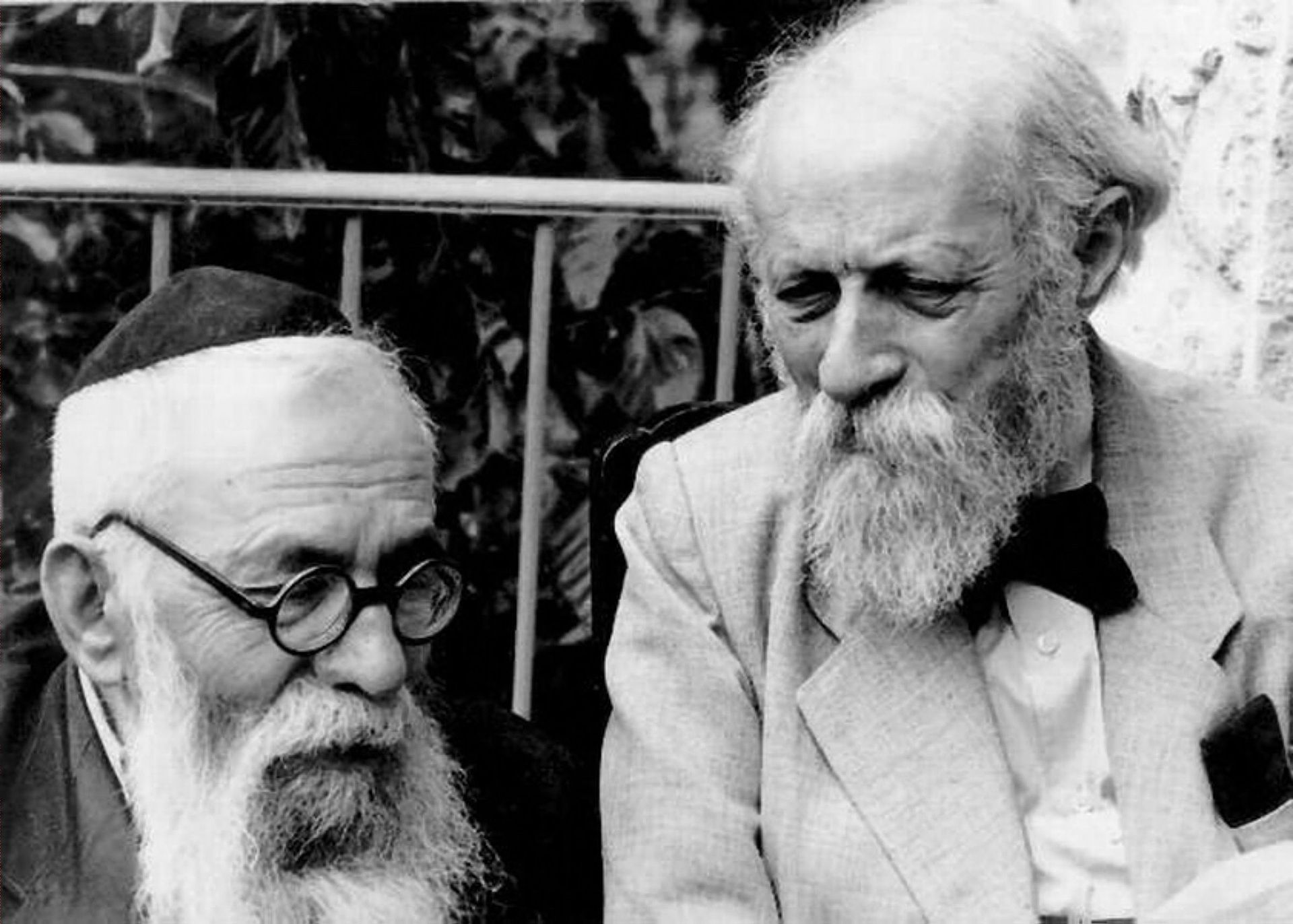

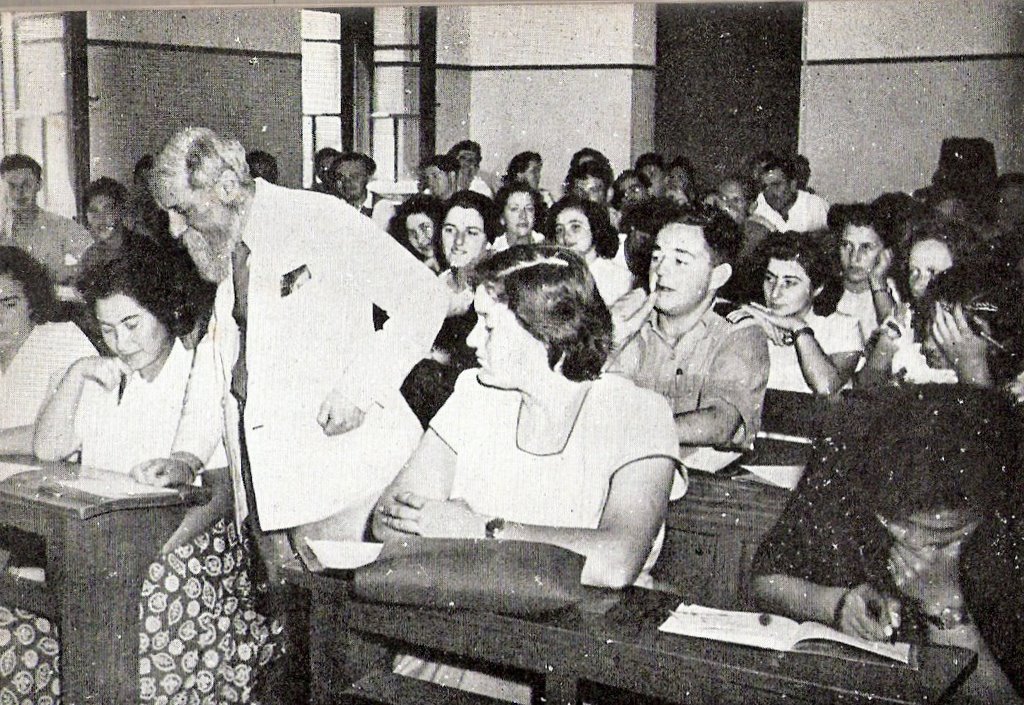

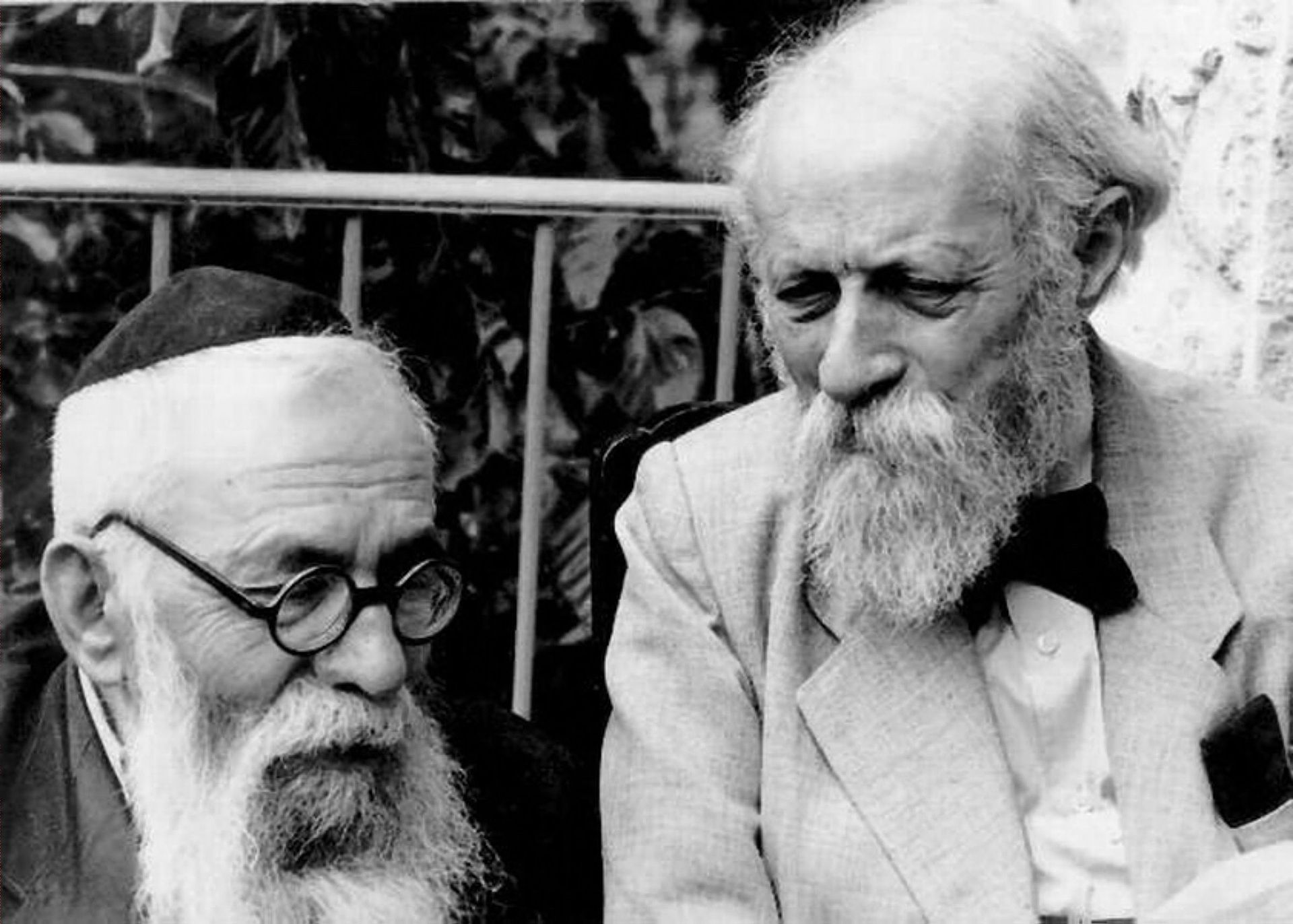

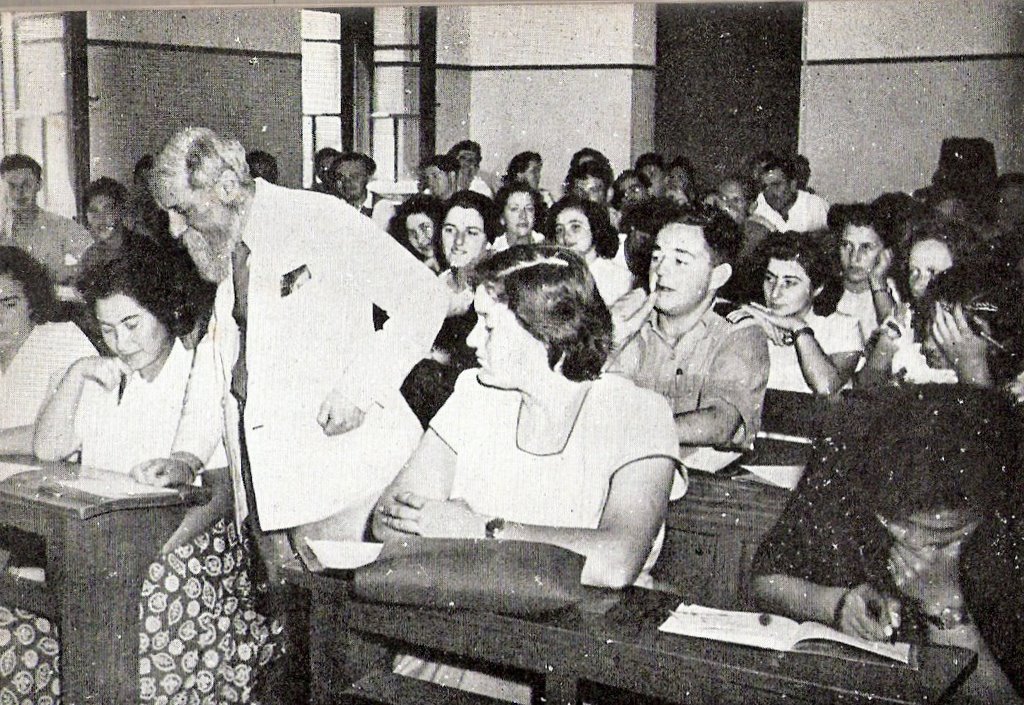

Literary and academic career Martin Buber's house (1916–38) in Heppenheim, Germany. Now the headquarters of the ICCJ.  Martin Buber and Rabbi Binyamin in Palestine (1950s)  Buber (left) and Judah Leon Magnes testifying before the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry in Jerusalem (1946)  Buber in the Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem, prior to 1948 From 1905 he worked for the publishing house Rütten & Loening as a lecturer; there he initiated and supervised the completion of the social psychological monograph series Die Gesellschaft [de]. From 1906 until 1914, Buber published editions of Hasidic, mystical, and mythic texts from Jewish and world sources. In 1916, he moved from Berlin to Heppenheim. During World War I, he helped establish the Jewish National Committee[37] to improve the condition of Eastern European Jews. During that period he became the editor of Der Jude (German for "The Jew"), a Jewish monthly (until 1924). In 1921, Buber began his close relationship with Franz Rosenzweig. In 1922, he and Rosenzweig co-operated in Rosenzweig's House of Jewish Learning, known in Germany as Lehrhaus.[38] In 1923, Buber wrote his famous essay on existence, Ich und Du (later translated into English as I and Thou). Though he edited the work later in his life, he refused to make substantial changes. In 1925, he began, in conjunction with Franz Rosenzweig, translating the Hebrew Bible into German (Die Schrift). He himself called this translation Verdeutschung ("Germanification"), since it does not always use literary German language, but instead attempts to find new dynamic (often newly invented) equivalent phrasing to respect the multivalent Hebrew original. Between 1926 and 1930, Buber co-edited the quarterly Die Kreatur ("The Creature").[39] In 1930, Buber became an honorary professor at the University of Frankfurt am Main. He resigned in protest from his professorship immediately after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933. On October 4, 1933, the Nazi authorities forbade him to lecture. In 1935, he was expelled from the Reichsschrifttumskammer (the National Socialist authors' association). He then founded the Central Office for Jewish Adult Education, which became an increasingly important body, as the German government forbade Jews to attend public education.[40] The Nazi administration increasingly obstructed this body. Finally, in 1938, Buber left Germany, and settled in Jerusalem, then capital of Mandate Palestine. He received a professorship at Hebrew University, there lecturing in anthropology and introductory sociology. The lectures he gave during the first semester were published in the book The problem of man (Das Problem des Menschen);[41][42] in these lectures he discusses how the question "What is Man?" became the central one in philosophical anthropology.[43] He participated in the discussion of the Jews' problems in Palestine and of the Arab question – working out of his Biblical, philosophic, and Hasidic work. He became a member of the group Ihud, which aimed at a bi-national state for Arabs and Jews in Palestine. Such a binational confederation was viewed by Buber as a more proper fulfillment of Zionism than a solely Jewish state. In 1949, he published his work Paths in Utopia,[44] in which he detailed his communitarian socialist views and his theory of the "dialogical community" founded upon interpersonal "dialogical relationships". After World War II, Buber began lecture tours in Europe and the United States. In 1952, he argued with Jung over the existence of God.[45] |

文学と学問のキャリア ドイツのヘッペンハイムにあるマルティン・ブーバーの家(1916-38年)。現在はICCJの 本部となっている。  パレスチナでのマルティン・ブーバーとラビ・ビンヤミン(1950年代)  エルサレムの英米調査委員会で証言するブーバー(左)とユダ・レオン・マグネス(1946年)  1948年以前、エルサレムのユダヤ人地区でのブーバー 1905年からは出版社リュッテン&ローニング社で講師として働き、そこで社会心理学モノグラフシリーズ『Die Gesellschaft』[de]の創刊と完成を監督した。 1906年から1914年まで、ブーバーはユダヤ教と世界の資料からハシディック、神秘主義、神話のテキストを出版した。1916年、ベルリンからヘッペ ンハイムに移る。 第一次世界大戦中は、東ヨーロッパのユダヤ人の状態を改善するためにユダヤ民族委員会[37]の設立に協力した。その間、ユダヤ人の月刊誌『デア・ユー ド』(ドイツ語で「ユダヤ人」の意)の編集者となる(1924年まで)。1921年、ブーバーはフランツ・ローゼンツヴァイクとの親密な関係を始める。 1922年、ブーバーはローゼンツヴァイクと共同で、ドイツではレアハウスとして知られるローゼンツヴァイクの『ユダヤ人の学びの家』を設立した [38]。 1923年、ブーバーは存在に関する有名なエッセイ『Ich und Du』(後に『I and Thou』と英訳される)を書いた。ブーバーは後年この著作を編集したが、大幅な変更を加えることを拒んだ。1925年、彼はフランツ・ローゼンツヴァイ クと共同で、ヘブライ語聖書のドイツ語訳(Die Schrift)を始めた。彼自身はこの翻訳をVerdeutschung(「ドイツ語化」)と呼んだが、それは常に文学的なドイツ語を使うのではなく、 多義的なヘブライ語の原典を尊重するために、新しい動的な(しばしば新しく発明された)等価な表現を見つけようとするためである。1926年から1930 年にかけて、ブーバーは季刊誌『Die Kreatur』(『The Creature』)を共同編集した[39]。 1930年、ブーバーはフランクフルト・アム・マイン大学の名誉教授となる。1933年にアドルフ・ヒトラーが政権を握った直後、ブーバーは教授職を辞任 した。1933年10月4日、ナチス当局はブーバーに講義を禁じた。1935年、国家社会主義作家協会 (Reichsschrifttumskammer)から追放される。その後、ブーバーはユダヤ人成人教育中央事務局を設立し、ドイツ政府がユダヤ人の公 教育への出席を禁じていたため、同事務局はますます重要な組織となった[40]。 ついに1938年、ブーバーはドイツを離れ、当時委任統治領パレスチナの首都であったエルサレムに定住した。彼はヘブライ大学で教授職を得、そこで人類学 と社会学入門を講義した。前期に行った講義は『人間の問題』(Das Problem des Menschen)として出版された[41][42]。これらの講義の中で、「人間とは何か」という問いが哲学的人間学の中心的な問いとなった経緯につい て述べている[43]。 彼は、パレスチナのアラブ人とユダヤ人のための二国国家を目指すグループ「イフッド」のメンバーとなった。このような二国連合は、ユダヤ人だけの国家より もシオニズムの成就にふさわしいとブーバーは考えていた。1949年、ブーバーは『ユートピアの道』(Paths in Utopia)という著作を発表した[44]。この著作では、彼の共同体主義的な社会主義的見解と、対人的な「対話的関係」の上に成り立つ「対話的共同 体」についての理論が詳述されている。 第二次世界大戦後、ブーバーはヨーロッパとアメリカで講演旅行を始めた。1952年には、神の存在をめぐってユングと論争した[45]。 |

| Buber is famous for his thesis

of dialogical existence, as he described in the book I and Thou.[2]

However, his work dealt with a range of issues including religious

consciousness, modernity, the concept of evil, ethics, education, and

Biblical hermeneutics.[46] Buber rejected the label of "philosopher" or "theologian", claiming he was not interested in ideas, only personal experience, and could not discuss God, but only relationships to God.[47] Politically, Buber's social philosophy on points of prefiguration aligns with that of anarchism, though Buber explicitly disavowed the affiliation in his lifetime and justified the existence of a state under limited conditions.[48][49] Dialogue and existence In I and Thou,[2] Buber introduced his thesis on human existence. Inspired by Feuerbach's The Essence of Christianity and Kierkegaard's Single One, Buber worked upon the premise of existence as encounter.[50] He explained this philosophy using the word pairs of Ich-Du and Ich-Es to categorize the modes of consciousness, interaction, and being through which an individual engages with other individuals, inanimate objects, and all reality in general. Theologically, he associated the first with the Jewish Jesus and the second with the apostle Paul (formerly Saul of Tarsus, a Jew).[51] Philosophically, these word pairs express complex ideas about modes of being—particularly how a person exists and actualizes that existence. As Buber argues in I and Thou, a person is at all times engaged with the world in one of these modes. The generic motif Buber employs to describe the dual modes of being is one of dialogue (Ich-Du) and monologue (Ich-Es).[52] The concept of communication, particularly language-oriented communication, is used both in describing dialogue/monologue through metaphors and expressing the interpersonal nature of human existence. Ich-Du Ich‑Du ("I‑Thou" or "I‑You") is a relationship that stresses the mutual, holistic existence of two beings. It is a concrete encounter, because these beings meet one another in their authentic existence, without any qualification or objectification of one another. Even imagination and ideas do not play a role in this relation. In an I–Thou encounter, infinity and universality are made actual (rather than being merely concepts).[52] Buber stressed that an Ich‑Du relationship lacks any composition (e. g., structure) and communicates no content (e. g., information). Despite the fact that Ich‑Du cannot be proven to happen as an event (e. g., it cannot be measured), Buber stressed that it is real and perceivable. A variety of examples are used to illustrate Ich‑Du relationships in daily life—two lovers, an observer and a cat, the author and a tree, and two strangers on a train. Common English words used to describe the Ich‑Du relationship include encounter, meeting, dialogue, mutuality, and exchange. One key Ich‑Du relationship Buber identified was that which can exist between a human being and God. Buber argued that this is the only way in which it is possible to interact with God, and that an Ich‑Du relationship with anything or anyone connects in some way with the eternal relation to God. To create this I–Thou relationship with God, a person has to be open to the idea of such a relationship, but not actively pursue it. The pursuit of such a relation creates qualities associated with It‑ness, and so would prevent an I‑You relation, limiting it to I‑It. Buber claims that if we are open to the I–Thou, God eventually comes to us in response to our welcome. Also, because the God Buber describes is completely devoid of qualities, this I–Thou relationship lasts as long as the individual wills it. When the individual finally returns to the I‑It way of relating, this acts as a barrier to deeper relationship and community. Ich-Es The Ich-Es ("I‑It") relationship is nearly the opposite of Ich‑Du.[52] Whereas in Ich‑Du the two beings encounter one another, in an Ich‑Es relationship the beings do not actually meet. Instead, the "I" confronts and qualifies an idea, or conceptualization, of the being in its presence and treats that being as an object. All such objects are considered merely mental representations, created and sustained by the individual mind. This is based partly on Kant's theory of phenomenon, in that these objects reside in the cognitive agent's mind, existing only as thoughts. Therefore, the Ich‑Es relationship is in fact a relationship with oneself; it is not a dialogue, but a monologue. In the Ich-Es relationship, an individual treats other things, people, etc., as objects to be used and experienced. Essentially, this form of objectivity relates to the world in terms of the self – how an object can serve the individual's interest. Buber argued that human life consists of an oscillation between Ich‑Du and Ich‑Es, and that in fact Ich‑Du experiences are rather few and far between. In diagnosing the various perceived ills of modernity (e. g., isolation, dehumanization, etc.), Buber believed that the expansion of a purely analytic, material view of existence was at heart an advocation of Ich‑Es relations - even between human beings. Buber argued that this paradigm devalued not only existents, but the meaning of all existence. |

ブーバーは『我と汝』の中で述べているように、対話的存在というテーゼ

で有名である[2]。しかし彼の著作は、宗教意識、近代性、悪の概念、倫理、教育、聖書解釈学など、さまざまな問題を扱っていた[46]。 ブーバーは「哲学者」や「神学者」というレッテルを拒否し、自分は思想には興味がなく、個人的な経験にしか興味がなく、神について論じることはできない が、神との関係については論じることができると主張した[47]。 政治的には、ブーバーの予型に関する社会哲学はアナーキズムのそれと一致するが、ブーバーは生前、その提携を明確に否定し、限定された条件の下での国家の 存在を正当化していた[48][49]。 対話と存在 ブーバーは『我と汝』の中で、人間の存在に関するテーゼを紹介している[2]。フォイエルバッハの『キリスト教の本質』とキルケゴールの『単一なるもの』 に触発されたブーバーは、出会いとしての存在という前提に取り組んでいた[50]。 彼はこの哲学をIch-DuとIch-Esという言葉のペアを用いて説明し、個人が他の個人、無生物、そして現実全般と関わる意識、相互作用、存在の様式 を分類していた。神学的には、彼は前者をユダヤ人のイエスに、後者を使徒パウロ(元はユダヤ人であったタルソのサウロ)に関連づけた[51]。哲学的に は、これらの言葉のペアは、存在の様式、特に人がどのように存在し、その存在を実現するかについての複雑な考えを表現している。ブーバーが『我と汝』の中 で論じているように、人は常にこれらのモードのいずれかにおいて世界と関わっている。 ブーバーが存在の二重の様態を表現するために用いる一般的なモチーフは、対話(Ich-Du)と独白(Ich-Es)の一つである[52]。コミュニケー ションの概念、特に言語指向のコミュニケーションは、比喩を通じて対話/独白を説明する際にも、人間存在の対人的性質を表現する際にも用いられる。 イク・ドゥ Ich-Du(「I-Thou 」または 「I-You」)は、2つの存在の相互的で全体的な存在を強調する関係である。それは具体的な出会いである。なぜなら、これらの存在は、互いに修飾したり 客観化したりすることなく、本物の存在として出会うからである。この関係においては、想像や観念さえも役割を果たさない。I-Thouの出会いにおいて は、無限性と普遍性が(単なる概念ではなく)現実化される[52]。ブーバーは、Ich-Duの関係にはいかなる構成(例えば構造)もなく、いかなる内容 (例えば情報)も伝達されないことを強調した。イク=ドゥは出来事として起こることを証明することができない(例えば、測定することができない)にもかか わらず、ブーバーはそれが現実であり、知覚可能であることを強調した。日常生活におけるIch-Duの関係を説明するために、恋人同士、観察者と猫、著者 と木、電車の中の見知らぬ二人など、さまざまな例が用いられている。イク・ドゥの関係を表現するのに使われる一般的な英単語には、出会い、出会い、対話、 相互性、交換などがある。 ブーバーが特定した重要なIch-Du関係のひとつは、人間と神の間に存在しうる関係である。ブーバーは、これが神と相互作用することが可能な唯一の方法 であり、いかなるもの、あるいは誰とのIch-Du関係も、神との永遠の関係に何らかの形でつながると主張した。 この神とのI-Thou関係を創り出すためには、人はそのような関係のアイデアにオープンでなければならないが、積極的にそれを追求してはならない。その ような関係を追求することは、「それ」であることに関連する性質を生み出すため、「私-あなた」の関係を妨げ、「私-それ」に限定してしまうことになる。 ブーバーは、もし私たちがI-Thouに対してオープンであれば、神はやがて私たちの歓迎に応えてやってくると主張している。また、ブーバーの言う神には まったく性質がないため、このI-Thou関係は個人が望む限り続く。個々人が最終的にI-It的な関わり方に戻ったとき、これはより深い関係や共同体へ の障壁として作用する。 イク=エス Ich-Es(「I-It」)関係は、Ich-Duとはほぼ正反対である[52]。Ich-Duでは2つの存在が互いに出会うが、Ich-Es関係では存 在は実際には出会わない。その代わりに、「私」はその存在にある存在の観念、あるいは概念化に直面し、それを修飾し、その存在を対象として扱う。そのよう な対象はすべて、個々の心によって創造され、維持される、単なる心的表象に過ぎないと考えられる。これは、これらの対象が認識主体の心の中に存在し、思考 としてのみ存在するという点で、カントの現象論に部分的に基づいている。したがって、イク=エスの関係は、実際には自分自身との関係であり、それは対話で はなく、独白なのである。 Ich-Es関係では、個人は他の物や人などを、使用され経験される対象として扱う。本質的に、この客観性の形態は、自己の観点から世界と関係する-対象 が個人の利益にどのように役立つことができるかということである。 ブーバーは、人間の人生はIch-DuとIch-Esの間の揺れで構成され、実際、Ich-Duの経験はむしろ少なく、ほとんどないと主張した。ブーバー は、近代のさまざまな病弊(孤立、非人間化など)を診断する際、純粋に分析的で物質的な存在観の拡大は、本質的にはIch-Esの関係(人間同士でさえ も)の提唱であると考えた。ブーバーは、このパラダイムは存在者だけでなく、すべての存在の意味を軽んじていると主張した。 |

| Students and colleagues Buber was a sort of mentor figure in the lives of Gershom Scholem and Walter Benjamin, the 'Kabbalist of the Holy City' and the 'Marxist Rabbi' of Berlin during the era leading up to, overlapping with proceeding after the Holocaust (Benjamin died during his escape from Europe, but Buber retained contact with Scholem after the war).[53][54] While his relationship with these two was sometimes unilaterally contentious (with the students occasionally attacking or critiquing their patron somewhat viciously) Buber acted as an impresario, publisher and by various means as one of the great sponsors of their careers and growing reputations. Scholem was to be amongst the friends and interested parties who helped attend to and orchestrate Buber's eventual emigration to Palestine from the very beginning stages of that discussion during the rise of Hitler.[53][55] They corresponded also in regards to their work with Brit Shalom, an early think-tank that was tasked with figuring out the dynamics of two-state solution to be brokered between Israel and Palestine more than twenty years before Israel became a nation state--and also about a great many issues regarding their shared interest in ancient, sacred and often mystical Jewish literature whilst keeping tabs likewise on mutual acquaintances and important publications in their fields of interest.[56] Scholem dedicated his bibliography of the Zohar to Buber.[53] |

教え子と同僚 ブーバーは、ゲルショム・ショレムとヴァルター・ベンヤミン、「聖都のカバラ学者」とベルリンの「マルクス主義ラビ」の人生において、ホロコーストに至る まで、またホロコースト後の進行と重なる時代において、一種の指導的人物であった(ベンヤミンはヨーロッパからの逃亡中に死去したが、ブーバーは戦後も ショレムとの接触を保っていた)[53][54]。 この二人との関係は時に一方的に対立するものであったが(学生たちは時折彼らのパトロンをやや悪意を持って攻撃したり批評したりした)、ブーバーは興行 主、出版者として、また様々な手段で彼らのキャリアと高まる評判の偉大なスポンサーの一人として行動した。ショレムは、ヒトラーの台頭の最中、ブーバーが 最終的にパレスチナに移住することを議論し始めた初期の段階から、ブーバーに付き添い、指揮をとるのを助けた友人や利害関係者の一人であった[53] [55]。 [彼らは、イスラエルが国家となる20年以上前に、イスラエルとパレスチナの間で仲介されるべき二国家間解決の力学を解明することを任務とした初期のシン クタンクであるブリット・シャロームでの仕事に関しても、また、古代、神聖、そしてしばしば神秘的なユダヤ文学への共通の関心に関する多くの問題に関して も、同様に共通の知人や関心のある分野における重要な出版物に関しても連絡を取り合っていた[56]。 |

| Hasidism and mysticism Buber was a scholar, interpreter, and translator of Hasidic lore. He viewed Hasidism as a source of cultural renewal for Judaism, frequently citing examples from the Hasidic tradition that emphasized community, interpersonal life, and meaning in common activities (e. g., a worker's relation to his tools). The Hasidic ideal, according to Buber, emphasized a life lived in the unconditional presence of God, where there was no distinct separation between daily habits and religious experience. This was a major influence on Buber's philosophy of anthropology, which considered the basis of human existence as dialogical. In 1906, Buber published Die Geschichten des Rabbi Nachman, a collection of the tales of the Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, a renowned Hasidic rebbe, as interpreted and retold in a Neo-Hasidic fashion by Buber. Two years later, Buber published Die Legende des Baalschem (stories of the Baal Shem Tov), the founder of Hasidism.[38] |

ハシディズムと神秘主義 ブーバーはハシディズム伝承の研究者であり、解釈者であり、翻訳者であった。ブーバーはハシディズムをユダヤ教の文化的刷新の源泉とみなし、共同体、対人 生活、共同活動の意味(例えば、労働者と道具との関係)を強調するハシディズムの伝統の例を頻繁に引用した。ブーバーによれば、ハシディズムの理想は、神 の無条件の臨在の中で生きる生活を強調するもので、そこでは日常的な習慣と宗教的経験との間に明確な隔たりはなかった。これは、人間存在の基礎を対話的な ものと考えるブーバーの人間学哲学に大きな影響を与えた。 1906年、ブーバーは『Die Geschichten des Rabbi Nachman』を出版した。これは、有名なハシディズムの修道士であったブレスロフのラビ・ナッハマンの物語を、ブーバーが新ハシディズム風に解釈し、 再話したものである。その2年後、ブーバーはハシディズムの創始者であるバール・シェム・トフの物語(Die Legende des Baalschem)を出版した[38]。 |

| Published works In English 1937, I and Thou, transl. by Ronald Gregor Smith, Edinburgh: T. and T. Clark. 2nd Edition New York: Scribners, 1958. 1st Scribner Classics ed. New York, NY: Scribner, 2000, c1986 1952, Eclipse of God, New York: Harper and Bros. 2nd Edition Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1977. 1952, Good & Evil, New York: Scribner 1957, Pointing the Way, transl. Maurice Friedman, New York: Harper, 1957, 2nd Edition New York: Schocken, 1974. 1960, The Origin and Meaning of Hasidism, transl. M. Friedman, New York: Horizon Press. 1964, Daniel: Dialogues on Realization, New York, Holt, Rinehart and Winston. 1965, The Knowledge of Man, transl. Ronald Gregor Smith and Maurice Friedman, New York: Harper & Row. 2nd Edition New York, 1966. 1966, The Way of Response: Martin Buber; Selections from his Writings, edited by N. N. Glatzer. New York: Schocken Books. 1967a, A Believing Humanism: My Testament, translation of Nachlese (Heidelberg 1965) by M. Friedman, New York: Simon and Schuster. 1967b, On Judaism, edited by Nahum Glatzer and transl. by Eva Jospe and others, New York: Schocken Books. 1968, On the Bible: Eighteen Studies, edited by Nahum Glatzer, New York: Schocken Books. 1970a, I and Thou, a new translation with a prologue “I and you” and notes by Walter Kaufmann, New York: Scribner's Sons. 1970b, Mamre: Essays in Religion, translated by Greta Hort, Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. 1970c, Martin Buber and the Theater, Including Martin Buber's “Mystery Play” Elijah, edited and translated with three introductory essays by Maurice Friedman, New York, Funk &Wagnalls. 1972, Encounter: Autobiographical Fragments. La Salle, Ill.: Open Court. 1973a, On Zion: the History of an Idea, with a new foreword by Nahum N. Glatzer, Translated from the German by Stanley Godman, New York: Schocken Books. 1973b, Meetings, edited with an introduction and bibliography by Maurice Friedman, La Salle, Ill.: Open Court Pub. Co. 3rd ed. London, New York: Routledge, 2002. 1983, A Land of Two Peoples: Martin Buber on Jews and Arabs, edited with commentary by Paul R. Mendes-Flohr, New York: Oxford University Press. 2nd Edition Gloucester, Mass.: *Peter Smith, 1994 1985, Ecstatic Confessions, edited by Paul Mendes-Flohr, translated by Esther Cameron, San Francisco: Harper & Row. 1991a, Chinese Tales: Zhuangzi, Sayings and Parables and Chinese Ghost and Love stories, translated by Alex Page, with an introduction by Irene Eber, Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press International. 1991b, Tales of the Hasidim, foreword by Chaim Potok, New York: Schocken Books, distributed by Pantheon. 1992, On Intersubjectivity and Cultural Creativity, edited and with an introduction by S.N. Eisenstadt, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1994, Scripture and Translation, Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig, translated by Lawrence Rosenwald with Everett Fox. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 1996, Paths in Utopia, translated by R.F. Hull. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. 1999a, The First Buber: Youthful Zionist Writings of Martin Buber, edited and translated from the German by Gilya G. Schmidt, Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. 1999b, Martin Buber on Psychology and Psychotherapy: Essays, Letters, and Dialogue, edited by Judith Buber Agassi, with a foreword by Paul Roazin, New York: Syracuse University Press. 1999c, Gog and Magog: A Novel, translated from the German by Ludwig Lewisohn, Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. 2002a, The Legend of the Baal-Shem, translated by Maurice Friedman, London: Routledge. 2002b, Between Man and Man, translated by Ronald Gregor-Smith, with an introduction by Maurice Friedman, London, New York: Routledge. 2002c, The Way of Man: According to the Teaching of Hasidim, London: Routledge. 2002d, The Martin Buber Reader: Essential Writings, edited by Asher D. Biemann, New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 2002e, Ten Rungs: Collected Hasidic Sayings, translated by Olga Marx, London: Routledge. 2003, Two Types of Faith, translated by Norman P. Goldhawk with an afterword by David Flusser, Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. Original writings (German) Die Geschichten des Rabbi Nachman (1906) Die fünfzigste Pforte (1907) Die Legende des Baalschem (1908) Ekstatische Konfessionen (1909) Chinesische Geister- und Liebesgeschichten (1911) Daniel – Gespräche von der Verwirklichung (1913) Die jüdische Bewegung – gesammelte Aufsätze und Ansprachen 1900–1915 (1916) Vom Geist des Judentums – Reden und Geleitworte (1916) Die Rede, die Lehre und das Lied – drei Beispiele (1917) Ereignisse und Begegnungen (1917) Der grosse Maggid und seine Nachfolge (1922) Reden über das Judentum (1923) Ich und Du (1923) Translation: I and Thou by Walter Kaufmann (Touchstone: 1970) Das Verborgene Licht (1924) Die chassidischen Bücher (1928) Aus unbekannten Schriften (1928) Zwiesprache (1932) Kampf um Israel – Reden und Schriften 1921–1932 (1933) Hundert chassidische Geschichten (1933) Die Troestung Israels : aus Jeschajahu, Kapitel 40 bis 55 (1933); with Franz Rosenzweig Erzählungen von Engeln, Geistern und Dämonen (1934) Das Buch der Preisungen (1935); with Franz Rosenzweig Deutung des Chassidismus – drei Versuche (1935) Die Josefslegende in aquarellierten Zeichnungen eines unbekannten russischen Juden der Biedermeierzeit (1935) Die Schrift und ihre Verdeutschung (1936); with Franz Rosenzweig Aus Tiefen rufe ich Dich – dreiundzwanzig Psalmen in der Urschrift (1936) Das Kommende : Untersuchungen zur Entstehungsgeschichte des Messianischen Glaubens – 1. Königtum Gottes (1936 ?) Die Stunde und die Erkenntnis – Reden und Aufsätze 1933–1935 (1936) Zion als Ziel und als Aufgabe – Gedanken aus drei Jahrzehnten – mit einer Rede über Nationalismus als Anhang (1936) Worte an die Jugend (1938) Moseh (1945) Dialogisches Leben – gesammelte philosophische und pädagogische Schriften (1947) Der Weg des Menschen : nach der chassidischen Lehre (1948) Das Problem des Menschen (1948, Hebrew text 1942) Die Erzählungen der Chassidim (1949) Gog und Magog – eine Chronik (1949, Hebrew text 1943) Israel und Palästina – zur Geschichte einer Idee (1950, Hebrew text 1944) Der Glaube der Propheten (1950) Pfade in Utopia (1950) Zwei Glaubensweisen (1950) Urdistanz und Beziehung (1951) Der utopische Sozialismus (1952) Bilder von Gut und Böse (1952) Die Chassidische Botschaft (1952) Recht und Unrecht – Deutung einiger Psalmen (1952) An der Wende – Reden über das Judentum (1952) Zwischen Gesellschaft und Staat (1952) Das echte Gespräch und die Möglichkeiten des Friedens (1953) Einsichten : aus den Schriften gesammelt (1953) Reden über Erziehung (1953) Gottesfinsternis – Betrachtungen zur Beziehung zwischen Religion und Philosophie (1953) Translation Eclipse of God: Studies in the Relation Between Religion and Philosophy (Harper and Row: 1952) Hinweise – gesammelte Essays (1953) Die fünf Bücher der Weisung – Zu einer neuen Verdeutschung der Schrift (1954); with Franz Rosenzweig Die Schriften über das dialogische Prinzip (Ich und Du, Zwiesprache, Die Frage an den Einzelnen, Elemente des Zwischenmenschlichen) (1954) Sehertum – Anfang und Ausgang (1955) Der Mensch und sein Gebild (1955) Schuld und Schuldgefühle (1958) Begegnung – autobiographische Fragmente (1960) Logos : zwei Reden (1962) Nachlese (1965) Chinesische Geister- und Liebesgeschichten included the first German translation ever made of Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio. Alex Page translated the Chinesische Geister- und Liebesgeschichten as "Chinese Tales", published in 1991 by Humanities Press.[60] Collected works Werke 3 volumes (1962–1964) I Schriften zur Philosophie (1962) II Schriften zur Bibel (1964) III Schriften zum Chassidismus (1963) Martin Buber Werkausgabe (MBW). Berliner Akademie der Wissenschaften / Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, ed. Paul Mendes-Flohr & Peter Schäfer with Martina Urban; 21 volumes planned (2001–) Correspondence Briefwechsel aus sieben Jahrzehnten 1897–1965 (1972–1975) I : 1897–1918 (1972) II : 1918–1938 (1973) III : 1938–1965 (1975) Several of his original writings, including his personal archives, are preserved in the National Library of Israel, formerly the Jewish National and University Library, located on the campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem[61] |

出版作品 英語 1937年、ロナルド・グレゴール・スミス訳『我と汝』エディンバラ:T.アンドT.クラーク。2nd Edition New York: Scribners, 1958. New York, NY: Scribner, 2000, c1986. 1952, Eclipse of God, New York: Harper and Bros. 2nd Edition Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1977. 1952『善と悪』ニューヨーク:スクリブナー 1957, 『道を指し示す』 モーリス・フリードマン訳. モーリス・フリードマン、ニューヨーク:ハーパー、1957年、第2版ニューヨーク:ショッケン、1974年。 1960年、『ハシディズムの起源と意味』、モーリス・フリードマン訳。1960, The Origin and Mean of Hasidism, M. Friedman, New York: Horizon Press. 1964, 『ダニエル:実現に関する対話』, ニューヨーク, ホルト・ラインハート・ウィンストン. 1965, The Knowledge of Man, translated. ロナルド・グレゴール・スミス、モーリス・フリードマン、ニューヨーク:ハーパー&ロウ。第2版 ニューヨーク 1966年 1966, The Way of Response: Martin Buber; Selections from his Writings, edited by N. N. Glatzer. Glatzer. New York: Schocken Books. 1967a, A Believing Humanism: My Testament, M. FriedmanによるNachlese (Heidelberg 1965)の翻訳, New York: Simon and Schuster. 1967b『ユダヤ教について』ナフム・グラッツァー編、エヴァ・ヨスペ他訳、ニューヨーク:ショッケンブックス。 1968年、ナフム・グラッツァー編『聖書について:18の研究』ニューヨーク:ショッケンブックス。 1970a, I and Thou, a new translation with a prologue 「I and you」 and notes by Walter Kaufmann, New York: Scribner's Sons. 1970b, Mamre: Essays in Religion, Greta Hort訳, Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. 1970c, Martin Buber and the Theater, Including Martin Buber's 「Mystery Play」 Elijah, edited and translated with three introductory essays by Maurice Friedman, New York, Funk &Wagnalls. 1972, Encounter: 自伝的断片。イリノイ州ラサール:オープン・コート。 1973a, Nahum N. Glatzerによる序文、Stanley Godmanによるドイツ語からの翻訳。 1973b, Maurice Friedmanによる序文と参考文献を加えたMeetings, edited by Maurice Friedman, La Salle, Ill.: Open Court Pub. London, New York: Routledge, 2002. 1983, A Land of Two Peoples: 1983, A Land of Two Peoples: Martin Buber on Jews and Arabs, edited with commentary by Paul R. Mendes-Flohr, New York: Oxford University Press. 2nd Edition Gloucester, Mass: *ピーター・スミス 1994年 1985年、ポール・メンデス=フローア編、エスター・キャメロン訳『恍惚の告白』サンフランシスコ:ハーパー&ロウ。 1991a, Chinese Tales: Zhuangzi, Sayings and Parables and Chinese Ghost and Love stories, translated by Alex Page, with an introduction by Irene Eber, Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press International. 1991b, Tales of the Hasidim, foreword by Chaim Potok, New York: Schocken Books, distributed by Pantheon. 1992年『相互主観性と文化的創造性について』S.N.アイゼンシュタット編・序文、シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局。 1994年『聖典と翻訳』マーティン・ブーバー、フランツ・ローゼンツヴァイク著、ローレンス・ローゼンワルド、エヴェレット・フォックス共訳。 Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 1996年『ユートピアの道』R.F.ハル訳。Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. 1999a, The First Buber: Youthful Zionist Writings of Martin Buber, edited and translated from the German by Gilya G. Schmidt, Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. 1999b, Martin Buber on Psychology and Psychotherapy: Essays, Letters, and Dialogue, edited by Judith Buber Agassi, with a foreword by Paul Roazin, New York: Syracuse University Press. 1999c, Gog and Magog: Ludwig Lewisohn著、ドイツ語訳、ニューヨーク州シラキュース:シラキュース大学出版局。 2002a, The Legend of the Baal-Shem, Maurice Friedman訳, London: Routledge. 2002b, Between Man and Man, Ronald Gregor-Smith訳、モーリス・フリードマン序文、ロンドン、ニューヨーク: Routledge. 2002c, The Way of Man: According to the Teaching of Hasidim, London: Routledge. 2002d, The Martin Buber Reader: Essential Writings, edited by Asher D. Biemann, New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 2002e, Ten Rungs: Collected Hasidic Sayings, Olga Marx訳, London: Routledge. 2003, Two Types of Faith, ノーマン・P・ゴールドホーク著、デイヴィッド・フラッサー後書き訳、ニューヨーク州シラキュース:シラキュース大学出版局。 原著(ドイツ語) ラビ・ナハマンの物語 (1906) 第五十の門 (1907) バール・セムの伝説(1908年) 恍惚の宗派(1909年) 中国の幽霊と愛の物語(1911年) ダニエル-悟りの話(1913年) ユダヤ教運動-1900-1915年のエッセイと演説集(1916年) ユダヤ教の精神について-演説と序文 (1916) スピーチ、教え、歌 - 3つの例 (1917) 出来事と出会い(1917年) 偉大なマギドとその後継者たち(1922年) ユダヤ教についてのスピーチ(1923年) 我と汝(1923年) 訳:ワルター・カウフマン著『我と汝』(タッチストーン:1970年) 隠された光(1924年) ハシディック・ブックス(1928年) 未知の著作より (1928) 対話(1932年) イスラエルへの闘い-演説と著作1921-1932 (1933) 100のハシド物語(1933年) イスラエルの慰め:イェシャヤフ40章から55章まで(1933年);フランツ・ローゼンツヴァイクと共著 天使、精霊、悪魔の物語(1934年) 讃美の書(1935年);フランツ・ローゼンツヴァイクと共著 ハシディズムの解釈-3つの試み(1935年) ビーダーマイヤー時代の無名のロシア系ユダヤ人による水彩画によるヨセフ伝説(1935年) 聖典とそのドイツ語化(1936年);フランツ・ローゼンツヴァイクと共著 深淵より私はあなたに呼びかける-原典の詩篇23篇 (1936) 公約-メシヤの栄光の起源に関する研究-1.神の国 (1936 ?) 時と知識-演説とエッセイ1933-1935 (1936) 目標としてのシオン、そして課題としてのシオン-30年間の思想-ナショナリズムに関する演説を付録として(1936年) 若者への言葉(1938年) モセー(1945年) 対話の人生-哲学的・教育学的著作集(1947年) 人間の道:ハシディ教の教えによる(1948年) 人間の問題(1948年、ヘブライ語テキスト1942年) ハシディムの物語(1949年) ゴグとマゴグ-年代記(1949年、ヘブライ語テキスト 1943年) イスラエルとパレスチナ - ある思想の歴史(1950年、ヘブライ語テキスト 1944年) 預言者たちの信仰(1950年) ユートピアへの道(1950年) 二つの信じ方(1950年) 原初の距離と関係(1951年) ユートピア社会主義(1952年) 善と悪のイメージ(1952年) ハシディズムのメッセージ(1952年) 善と悪-いくつかの詩篇の解釈(1952年) 転換期に-ユダヤ教についての講演(1952年) 社会と国家の間(1952年) 真の対話と平和の可能性(1953年) 洞察:著作からの収集(1953年) 教育に関する講演(1953年) 神の蝕-宗教と哲学の関係についての考察(1953年) 翻訳 神の蝕-宗教と哲学の関係についての研究(ハーパー&ロウ:1952年) ノート-エッセイ集(1953年) 5つの教典-聖典の新訳に向けて(1954年);フランツ・ローゼンツヴァイクと共著 対話原理に関する著作(私と汝、対話、個人への問い、対人関係の要素)(1954年) 聖者性-始まりと終わり(1955年) 人間とその構造(1955年) 罪悪感と罪悪感(1958年) 出会い-自伝的断片(1960年) ロゴス:2つのスピーチ(1962年) レビュー(1965年) Chinesische Geister- und Liebesgeschichten』には、『Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio』の初のドイツ語訳が収録されている。アレックス・ペイジがChinesische Geister- und Liebesgeschichtenを『Chinese Tales』として翻訳し、1991年にHumanities Pressから出版された。] 作品集 全3巻(1962-1964) I 哲学についての著作(1962年) II 聖書についての著作(1964年) III ハシディズムに関する著作(1963年) マルティン・ブーバー著作集(MBW)。ベルリン科学・人文アカデミー/イスラエル科学・人文アカデミー編 Paul Mendes-Flohr & Peter Schäfer with Martina Urban; 21巻予定 (2001-) 通信 1897年から1965年までの70年間の書簡(1972-1975年) I : 1897-1918 (1972) ii : 1918-1938年(1973年) III : 1938-1965年(1975年) エルサレムのヘブライ大学構内にあるイスラエル国立図書館(旧ユダヤ国立大学図書館)には、彼の個人的なアーカイブを含む著作の原本がいくつか保存されて いる[61]。 |

| Existential therapy Guilt Humanistic psychology Intersubjectivity Contextual therapy André Neher List of Israel Prize recipients List of Bialik Prize recipients Jewish existentialism |

実存療法 罪悪感 人間性心理学 相互主観性 文脈療法 アンドレ・ネハー イスラエル賞受賞者一覧 ビアリク賞受賞者一覧 ユダヤ的実存主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_Buber |

リ ンク

文献

その他の情報

臨床コミュニケーション2014/ヒューマンコミュニケーション2014-2016

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

☆

☆

☆