From Tertium Bellum Servile to Soft Resistance

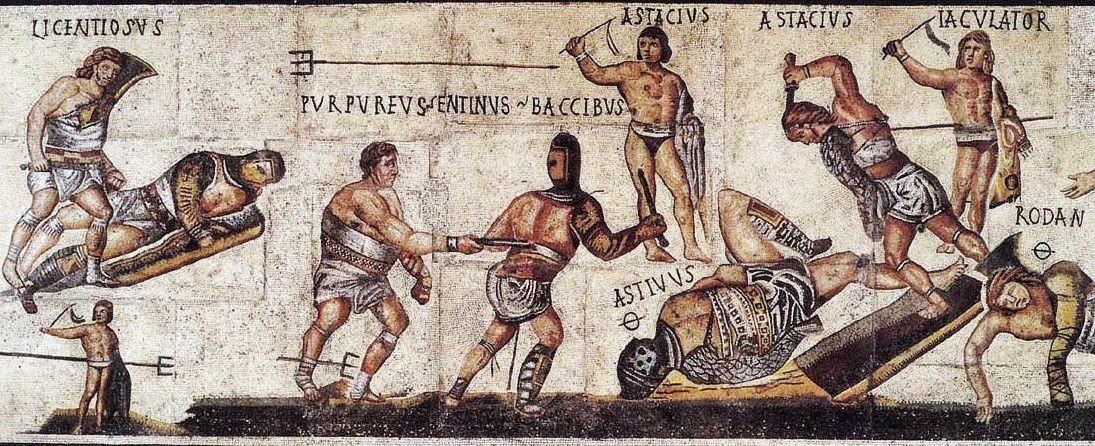

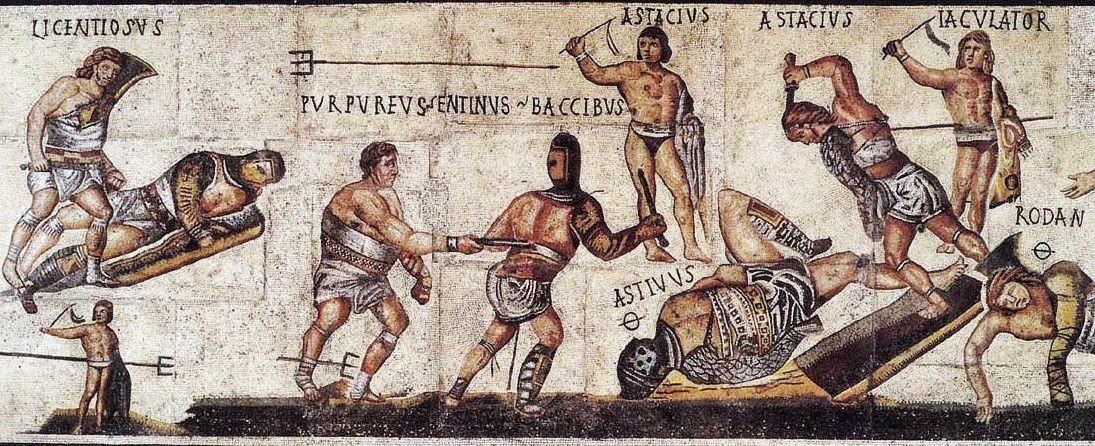

The Gladiator Mosaic at the Galleria Borghese

素朴な反逆者の系譜について

From Tertium Bellum Servile to Soft Resistance

The Gladiator Mosaic at the Galleria Borghese

池田光穂

★スパルタクスの反乱

「「歴史的認識の主体は、戦闘的な被抑圧階級そのも の である。マルクスにあっては、この階級はついに奴隷たることをやめて復讐する階級、幾世代の敗者において解放の仕事を完成する階級として、登場する」「ベンヤミン「歴史哲学テーゼ」」

| The Third Servile War,

also called the Gladiator War and the War of Spartacus by Plutarch, was

the last in a series of slave rebellions against the Roman Republic

known as the Servile Wars. This third rebellion was the only one that

directly threatened the Roman heartland of Italy. It was particularly

alarming to Rome because its military seemed powerless to suppress it. The revolt began in 73 BC, with the escape of around 70 slave gladiators from a gladiator school in Capua. They easily defeated the small Roman force sent to recapture them, and within two years, they had been joined by some 120,000 men, women, and children. The able-bodied adults of this large group were a surprisingly effective armed force that repeatedly showed they could withstand or defeat the Roman military, from the local Campanian patrols to the Roman militia and even to trained Roman legions under consular command. This army of slaves roamed across Italy, raiding estates and towns with relative impunity, sometimes dividing into separate but connected bands with several leaders, including the famous former gladiator Spartacus. The Roman Senate grew increasingly alarmed at the slave-army's depredations and continued military successes. Eventually Rome fielded an army of eight legions under the harsh but effective leadership of Marcus Licinius Crassus that destroyed the army of slaves in 71 BC. This happened after a long and bitter fighting retreat before the legions of Crassus and after the rebels realized that the legions of Pompey and Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus were moving in to entrap them. The armies of Spartacus launched their full strength against Crassus's legions and were utterly defeated. Of the survivors, some 6,000 were crucified along the Appian Way. Plutarch's account of the revolt suggests that the slaves simply wished to escape to freedom and leave Roman territory by way of Cisalpine Gaul. Appian and Florus describe the revolt as a civil war in which the slaves intended to capture the city of Rome. The Third Servile War had significant and far-reaching effects on Rome's broader history. Pompey and Crassus exploited their successes to further their political careers, using their public acclaim and the implied threat of their legions to sway the consular elections of 70 BC in their favor. Their actions as consuls greatly furthered the subversion of Roman political institutions and contributed to the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. |

プルタークによって「グラディエーター戦争」「スパルタクスの戦争」と

も呼ばれた第三次奴隷戦争は、「奴隷戦争」として知られるローマ共和国に対する一連の奴隷反乱の最後のものである。この第3次反乱は、ローマの中心地であ

るイタリアを直接脅かした唯一のものだった。ローマにとってこの反乱は特に憂慮すべきものであった。 反乱は紀元前73年、カプアの剣闘士学校から約70人の奴隷剣闘士が逃げ出したことから始まった。彼らは、奪還のために派遣された少数のローマ軍を容易に 打ち破り、2年以内に約12万人の男、女、子供が加わった。この大集団の健康な大人たちは、驚くほど効果的な武装勢力であり、地元のカンパニア人のパト ロール隊からローマの民兵、さらには領事指揮下の訓練されたローマ軍団に至るまで、ローマ軍に耐えたり打ち負かしたりすることができることを繰り返し示し た。この奴隷の軍隊はイタリア全土を放浪し、領地や町を比較的容赦なく襲撃し、時には有名な元剣闘士スパルタカスを含む複数の指導者を擁する別々の、しか しつながりのあるバンドに分裂した。 ローマ元老院は、奴隷軍団の略奪行為と継続的な軍事的成功に次第に警戒を強めていった。最終的にローマは、マルクス・リキニウス・クラッススの厳しくも効 果的な指導の下、8個軍団からなる軍隊を編成し、紀元前71年に奴隷軍団を壊滅させた。これは、クラッススの軍団の前で長く苦しい戦闘が続いた後、反乱軍 がポンペイとマルクス・テレンティウス・ヴァロ・ルクルスの軍団が自分たちを陥れようとしていることに気づいた後に起こった。スパルタクス軍はクラッスス 軍団に全力を投入し、完敗した。生き残った約6000人は、アッピア街道沿いで十字架につけられた。 プルタークの反乱に関する記述によれば、奴隷たちは単に自由を求めて逃亡し、キサルピナス・ガウルを経由してローマ帝国の領土を離れようとしただけであっ た。アッピアヌスとフロルスは、この反乱を、奴隷たちがローマ市を占領することを意図した内乱として描写している。第三次隷属戦争は、ローマの広範な歴史 に重要かつ広範囲な影響を及ぼした。ポンペイとクラッススは、その成功を利用して政治的キャリアを高め、世間からの称賛と軍団の暗黙の脅威を利用して、前 70年の領事選挙を有利に進めた。彼らの執政官としての行動は、ローマの政治制度の破壊を助長し、ローマ共和国からローマ帝国への変貌に大きく貢献した。 |

| To varying degrees throughout

Roman history, the existence of a pool of inexpensive labor in the form

of slaves was an important factor in the economy. Slaves were acquired

for the Roman workforce through a variety of means, including purchase

from foreign merchants and the enslavement of foreign populations

through military conquest.[1] With Rome's heavy involvement in wars of

conquest in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, from tens to hundreds of

thousands of slaves at a time were imported into the Roman economy from

various European and Mediterranean acquisitions.[2] While there was

limited use for slaves as servants, craftsmen, and personal attendants,

vast numbers of slaves worked in mines and on the agricultural lands of

Sicily and southern Italy.[3] For the most part, slaves were treated harshly and oppressively during the Roman republican period. Under Republican law, a slave was property, not a person. Owners could abuse, injure or even kill their own slaves without legal consequence. While there were many grades and types of slaves, the lowest—and most numerous—grades who worked in the fields and mines were subject to a life of hard physical labor.[4] The large size and oppressive treatment of the slave population led to rebellions. In 135 BC and 104 BC, the First and Second Servile Wars erupted in Sicily, where small bands of rebels found tens of thousands of willing followers wishing to escape the oppressive life of a Roman slave. While these were considered serious civil disturbances by the Roman Senate, taking years and direct military intervention to quell, they were never considered a serious threat to the Republic. The Roman heartland had never seen a slave uprising, nor had slaves ever been seen as a potential threat to the city of Rome. This changed with the Third Servile War. |

ローマの歴史を通じて、程度の差こそあれ、奴隷という安価な労働力の存

在は経済の重要な要素であった。紀元前2世紀と1世紀にローマが征服戦争に大きく関与したことで、一度に数万から数十万の奴隷がヨーロッパや地中海の様々

な地域からローマ経済に輸入された。

[2]使用人、職人、個人的な付き人としての奴隷の用途は限られていたが、膨大な数の奴隷が鉱山やシチリアや南イタリアの農地で働いた[3]。 ローマ共和国時代、奴隷は過酷で抑圧的な扱いを受けていた。共和制の下では、奴隷は人ではなく所有物であった。所有者は法的な影響を受けることなく、自分 の奴隷を虐待したり、傷つけたり、あるいは殺したりすることができた。奴隷には多くの等級と種類があったが、畑や鉱山で働く最も低級で最も多くの等級の奴 隷は、過酷な肉体労働の生活を強いられた[4]。 奴隷の人数の多さと抑圧的な待遇は、反乱を引き起こした。紀元前135年と紀元前104年には、シチリア島で第一次、第二次奴隷戦争が勃発し、小さな反乱 軍がローマの奴隷の抑圧的な生活から逃れたいと願う何万人もの自発的な信者を見つけた。ローマ元老院はこれらを深刻な内乱とみなし、鎮圧に数年を要し、直 接軍事介入も行ったが、共和国にとって深刻な脅威とはみなされなかった。ローマ中心部では奴隷の反乱が起こったことはなく、奴隷がローマ市に対する潜在的 脅威と見なされたこともなかった。それが第3次奴隷戦争で一変した。 |

| Beginning of the revolt (73 BC) Capuan revolt In the Roman Republic of the 1st century BC, gladiatorial games were one of the more popular forms of entertainment. In order to supply gladiators for the contests, several training schools, or ludi, were established throughout Italy.[5] In these schools, prisoners of war and condemned criminals—who were considered slaves—were taught the skills required to fight in gladiatorial games.[6] In 73 BC, a group of some 200 gladiators in the Capuan school owned by Lentulus Batiatus plotted an escape. When their plot was betrayed, a force of about 70 men seized kitchen implements ("choppers and spits"), fought their way free from the school, and seized several wagons of gladiatorial weapons and armor.[7] Once free, the escaped gladiators chose leaders from their number, selecting two Gallic slaves—Crixus and Oenomaus—and Spartacus, who was said either to be a Thracian auxiliary from the Roman legions later condemned to slavery, or a captive taken by the legions.[8] There is some question as to Spartacus's nationality. A Thraex was a type of gladiator in Rome, so "Thracian" may simply refer to the style of gladiatorial combat in which he was trained.[9] On the other hand, names nearly identical to Spartacus were recorded among five out of twenty Thracian Odrysae rulers of Bosporan kingdom beginning with Spartokos I the founder of the Spartocid dynasty. The name came from the Thracian words *sparas "spear, lance" and *takos "famous" and thus meant "renowned by the spear".[10][11] These escaped slaves were able to defeat a small force of troops sent after them from Capua, and equip themselves with captured military equipment as well as their gladiatorial weapons.[12] Sources are somewhat contradictory on the order of events immediately following the escape, but they generally agree that this band of escaped gladiators plundered the region surrounding Capua, recruited many other slaves into their ranks, and eventually retired to a more defensible position on Mount Vesuvius.[13] |

反乱の始まり(紀元前73年) カプアンの反乱 紀元前1世紀のローマ共和国では、剣闘士試合は人気のある娯楽のひとつであった。この競技に剣闘士を供給するため、イタリア全土にいくつかの訓練学校(ル ディ)が設立された[5]。 これらの学校では、捕虜や死刑囚(奴隷とみなされた)が剣闘士競技に必要な技術を教えられていた[6]。 紀元前73年、レントゥルス・バティアトゥスが所有するカプアン学校にいた約200人の剣闘士の一団が脱走を企てた。彼らの計画が裏切られたとき、約70 人の男たちが台所道具(「チョッパーと串」)を奪い、学校から自由になるために戦い、剣闘士の武器と鎧を積んだワゴン数台を奪った[7]。 自由の身となった剣闘士たちは、自分たちの中からリーダーを選び、ガリア人の奴隷である2人-クリクススとオエノマウス-と、後に奴隷とされたローマ軍団 のトラキア人補助兵とも、軍団に捕らえられた捕虜とも言われるスパルタカスを選んだ。スレイクスはローマにおける剣闘士の一種であったため、「トラキア 人」とは単に彼が訓練された剣闘士の戦闘スタイルを指しているのかもしれない[9]。他方、スパルタコス王朝の創始者スパルトコス1世に始まるボスポラ王 国の20人のトラキア人オドリサエの支配者のうち5人に、スパルタカスとほぼ同じ名前が記録されている。この名前はトラキア語の*sparas「槍、ラン ス」と*takos「有名な」から来ており、したがって「槍で有名な」という意味であった[10][11]。 逃亡した奴隷たちは、カプアから送り込まれた小部隊を撃破し、剣闘士の武器だけでなく、捕獲した軍備を装備することができた[12]。逃亡直後の出来事の 順序については、資料によって多少矛盾があるが、この逃亡した剣闘士の一団がカプア周辺地域を略奪し、他の多くの奴隷たちを仲間に引き入れ、最終的には ヴェスヴィオ山のより防御しやすい位置に退いたという点では概ね一致している[13]。 |

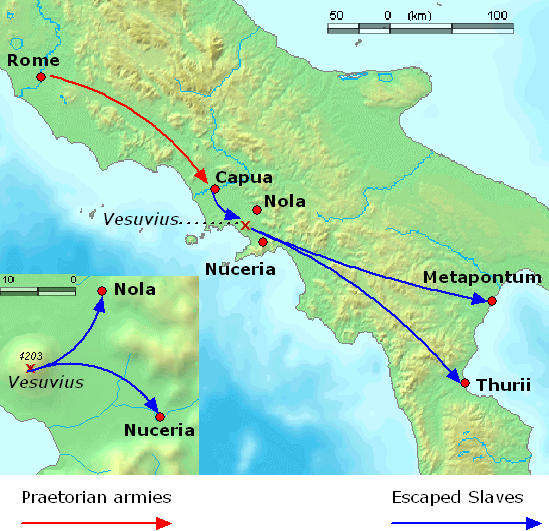

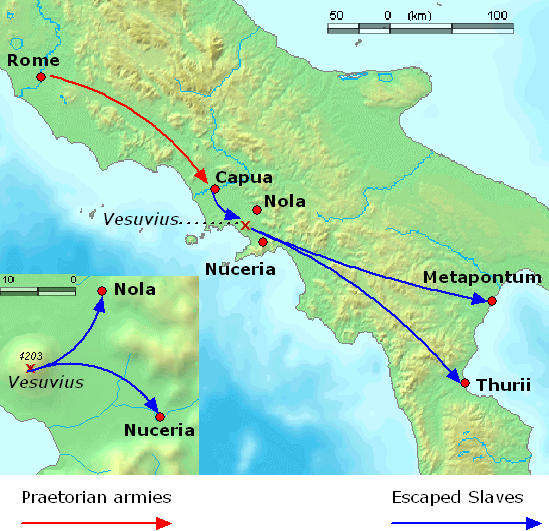

Defeat of the praetorian armies Defeat of the praetorian armiesAs the revolt and raids were occurring in Campania, which was a vacation region of the rich and influential in Rome, and the location of many estates, the revolt quickly came to the attention of Roman authorities. They initially viewed the revolt more as a major crime wave than an armed rebellion. However, later that year, Rome dispatched a military force under praetorian authority to put down the rebellion.[14] A Roman praetor, Gaius Claudius Glaber, gathered a force of 3,000 men, not regular legions, but a militia "picked up in haste and at random, for the Romans did not consider this a war yet, but a raid, something like an attack of robbery."[15] Glaber's forces besieged the slaves on Mount Vesuvius, blocking the only known way down the mountain. With the slaves thus contained, Glaber was content to wait until starvation forced the slaves to surrender. While the slaves lacked military training, Spartacus' forces displayed ingenuity in their use of available local tools, and in their use of clever, unorthodox tactics when facing the disciplined Roman infantry.[16] In response to Glaber's siege, Spartacus' men made ropes and ladders from vines and trees growing on the slopes of Vesuvius and used them to rappel down the cliffs on the side of the mountain opposite Glaber's forces. They moved around the base of Vesuvius, outflanked the army, and annihilated Glaber's men.[17] A second expedition, under the praetor Publius Varinius, was then dispatched against Spartacus. For some reason, Varinius seems to have split his forces under the command of his subordinates Furius and Cossinius. Plutarch mentions that Furius commanded some 2,000 men, but neither the strength of the remaining forces, nor whether the expedition was composed of militia or legions, appears to be known. These forces were also defeated by the army of escaped slaves: Cossinius was killed, Varinius was nearly captured, and the equipment of the armies was seized by the slaves.[18] With these victories, more and more slaves flocked to the Spartacan forces, as did "many of the herdsmen and shepherds of the region", swelling their ranks to some 70,000.[19] The rebel slaves spent the winter of 73–72 BC training, arming and equipping their new recruits, and expanding their raiding territory to include the towns of Nola, Nuceria, Thurii and Metapontum.[20] The victories of the rebel slaves did not come without a cost. At some time during these events, one of their leaders, Oenomaus, was lost—presumably in battle—and is not mentioned further in the histories.[21] |

プラエトリア軍の敗北 プラエトリア軍の敗北この反乱と襲撃は、ローマの富裕層や有力者の保養地であり、多くの邸宅があったカンパニア地方で起こったため、ローマ当局はすぐにこの反乱に注目した。ローマ当局は当初、この反乱を武力反乱というよりも、大規模な犯罪の波と見ていた。 しかし、その年の暮れ、ローマはこの反乱を鎮圧するため、プラエトリアの権限で軍隊を派遣した。ローマのプラエトリア、ガイウス・クラウディウス・グラ バーは、正規の軍団ではなく、「急ぎ、無作為に集められた民兵」である3,000人の兵力を集めた。こうして奴隷たちを封じ込めたグラバーは、飢餓によっ て奴隷たちが降伏するまで待つことに満足した。 奴隷たちは軍事訓練を受けていなかったが、スパルタクスの軍隊は、その土地で入手可能な道具の使用や、規律正しいローマ歩兵と対峙する際の巧妙で異例の戦 術の使用において、創意工夫を発揮した[16]。グラバーの包囲に対抗して、スパルタクスの部下たちは、ヴェスヴィオ山の斜面に生えている蔓や木でロープ や梯子を作り、グラバー軍とは反対側の山の側面の崖を懸垂下降するのに使用した。彼らはヴェスヴィオ火山のふもとに回り込み、軍を出し抜き、グラバーの兵 を全滅させた[17]。 プラエトル・プブリウス・ヴァリニウス率いる第二次遠征がスパルタクスに対して派遣された。何らかの理由で、ヴァリニウスは部下のフュリウスとコッシニウ スの指揮下で軍を分割したようである。プルタークは、フュリウスが2,000人ほどの兵を指揮したと述べているが、残りの兵力や、遠征軍が民兵で構成され ていたのか軍団で構成されていたのかは不明である。これらの軍勢は、逃亡した奴隷の軍勢にも敗れた: コッシニウスは殺され、ヴァリニウスは捕らえられそうになり、軍の装備は奴隷たちに奪われた[18]。 これらの勝利によって、より多くの奴隷がスパルタ軍に集まり、「この地域の牧畜民や羊飼いの多く」もスパルタ軍に集まり、その兵力は70,000人にまで 膨れ上がった[19]。反乱奴隷たちは紀元前73年から72年の冬にかけて、新兵の訓練、武装、装備を整え、ノーラ、ヌセリア、トゥリイ、メタポントゥム の町にまで襲撃地域を拡大した[20]。 反乱軍奴隷の勝利は、犠牲なしにもたらされたわけではなかった。これらの出来事の間のある時期、彼らの指導者の一人であるオエノマウスは、おそらく戦闘中に行方不明となり、それ以上歴史に言及されることはなかった[21]。 |

| By the end of 73 BC, Spartacus

and Crixus were in command of a large group of armed men with a proven

ability to withstand Roman armies. What they intended to do with this

force is somewhat difficult for modern readers to determine. Since the

Third Servile War was ultimately an unsuccessful rebellion, no

firsthand account of the slaves' motives and goals exists, and

historians writing about the war propose contradictory theories. Many popular modern accounts of the war claim that there was a factional split in the escaped slaves between those under Spartacus, who wished to escape over the Alps to freedom, and those under Crixus, who wished to stay in southern Italy to continue raiding and plundering. This appears to be an interpretation of events based on the following: the regions that Florus lists as being raided by the slaves include Thurii and Metapontum, which are geographically distant from Nola and Nuceria.[22] This indicates the existence of two groups: Lucius Gellius eventually attacked Crixus and a group of some 30,000 followers who are described as being separate from the main group under Spartacus.[22] Plutarch describes the desire of some of the escaped slaves to plunder Italy, rather than escape over the Alps.[23] While this factional split is not contradicted by classical sources, there does not seem to be any direct evidence to support it. Fictional accounts sometimes portray the rebelling slaves as ancient Roman freedom fighters, struggling to change a corrupt Roman society and to end the Roman institution of slavery. Although this is not contradicted by classical historians, no historical account mentions that the goal of the rebel slaves was to end slavery in the Republic, nor do any of the actions of rebel leaders, who themselves committed numerous atrocities, seem specifically aimed at ending slavery.[24] Even classical historians, who were writing only years after the events themselves, seem to be divided as to what the motives of Spartacus were. Appian and Florus write that he intended to march on Rome itself[25]—although this may have been no more than a reflection of Roman fears. If Spartacus did intend to march on Rome, it was a goal he must have later abandoned. Plutarch writes that Spartacus merely wished to escape northwards into Cisalpine Gaul and disperse his men back to their homes.[23] It is not certain that the slaves were a homogeneous group under the leadership of Spartacus, although this is implied by the Roman historians. Certainly other slave leaders are mentioned—Crixus, Oenomaus, Gannicus, and Castus—and it cannot be told from the historical evidence whether they were aides, subordinates, or even equals leading groups of their own and traveling in convoy with Spartacus' people. |

脱走奴隷の動機と指導力 紀元前73年の終わりには、スパルタカスとクリクサスは、ローマ軍に対抗できることが証明された武装した大集団を率いていた。彼らがこの軍勢を使って何を するつもりだったのか、現代の読者が判断するのは少々難しい。第三次隷属戦争は最終的に反乱として失敗に終わったため、奴隷たちの動機や目標についての直 接の記述は存在せず、この戦争について書いている歴史家たちは矛盾した説を唱えている。 この戦争に関する現代の一般的な記述の多くは、アルプス越えの自由を求めて逃亡したスパルタクス配下の奴隷たちと、南イタリアに留まって略奪を続けようと したクリクスス配下の奴隷たちの間で派閥分裂が起こったと主張している。フローラスが奴隷によって襲撃された地域として挙げているのは、ノーラやヌケリア から地理的に離れたトゥーリイとメタポントゥムである[22]。 これは2つのグループが存在したことを示している: ルキウス・ゲリウスは最終的にクリクススを攻撃し、スパルタクス率いる主要グループとは別のグループとして記述されている約3万人の従者のグループも攻撃 した[22]。プルタークは、逃亡した奴隷の何人かがアルプス越えの逃避行よりもイタリア略奪を望んでいたことを記述している[23]。この派閥の分裂は 古典的な資料と矛盾するものではないが、それを裏付ける直接的な証拠はないようである。 フィクションでは、反乱を起こした奴隷たちを、腐敗したローマ社会を変え、ローマの奴隷制度を終わらせようと奮闘する古代ローマの自由の戦士として描くこ とがある。このことは古典派の歴史家たちによって否定されてはいないが、反乱軍の奴隷の目的が共和国の奴隷制度を終わらせることであったという歴史的記述 はなく、また反乱軍の指導者たちの行動も、彼ら自身が数々の残虐行為を犯していたにもかかわらず、奴隷制度を終わらせることを特に目的としていたようには 見えない[24]。 スパルタクスの動機が何であったのかについては、事件そのものからわずか数年後に書かれた古典的な歴史家でさえ意見が分かれているようである。アッピアヌ スとフロルスは、スパルタクスはローマそのものに進軍するつもりであったと書いている[25]。もしスパルタクスがローマへの進軍を意図していたとして も、それは後に彼が放棄した目標に違いない。プルタークは、スパルタクスは単に北のキサルピナ・ガウルに逃れ、部下を故郷に分散させることを望んだだけだ と書いている[23]。 ローマの歴史家たちによって暗示されてはいるが、奴隷たちがスパルタクスの指導のもとで均質な集団であったかどうかは定かではない。確かに、他の奴隷の指 導者たち-クリクスス、オエノマウス、ガンニクス、カストゥス-が言及されているが、彼らが側近であったのか、部下であったのか、あるいは自分たちのグ ループを率いてスパルタクスの仲間とともに護送していたのかさえ、史料からはわからない。 |

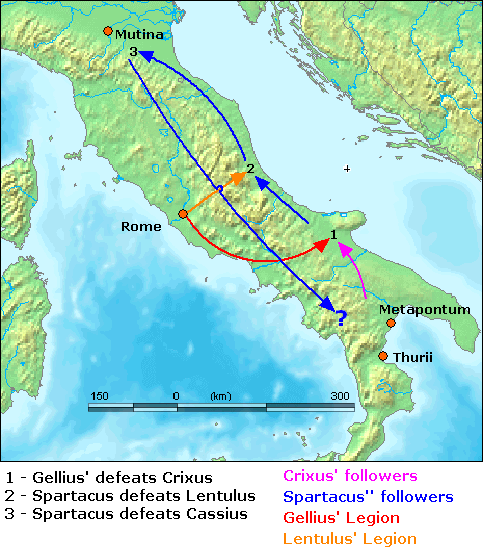

| In the spring of 72 BC, the

escaped slaves left their winter encampments and began to move

northwards towards Cisalpine Gaul. The Senate, alarmed by the size of

the revolt and the defeat of the praetorian armies of Glaber and

Varinius, dispatched a pair of consular legions under the command of

Lucius Gellius and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus.[26] Initially,

the consular armies were successful. Gellius engaged a group of about

30,000 slaves, under the command of Crixus, near Mount Garganus and

killed two-thirds of the rebels, including Crixus.[27] At this point, there is a divergence in the classical sources as to the course of events, which do not correspond until the entry of Marcus Licinius Crassus into the war. The two most comprehensive (extant) histories of the war by Appian and Plutarch detail very different events. Neither account directly contradicts the other but simply reports different events, ignoring some events in the other account and reporting events that are unique to that account. |

紀元前72年の春、逃亡した奴隷たちは冬の野営地を離れ、キサルピナ・

ガウルを目指して北上し始めた。元老院は、反乱の規模と、グラバーとヴァリニウスのプラエトリア軍の敗北に危機感を抱き、ルキウス・ゲリウスとグナエウ

ス・コルネリウス・レントゥルス・クローディアヌスの指揮する2つのコンスラー軍団を派遣した。ゲリウスはクリュクススの指揮下にあった約3万の奴隷の集

団とガルガヌス山付近で交戦し、クリュクススを含む反乱軍の3分の2を殺害した[27]。 この時点では、古典的な資料の中で事件の経過に相違があり、マルクス・リキニウス・クラッススの参戦まで一致しない。アッピアヌスとプルタークによる2つ の最も包括的な(現存する)戦史は、まったく異なる出来事を詳述している。どちらの記述も他方の記述と直接矛盾しているわけではなく、単に異なる出来事を 報告しているだけであり、他方の記述のいくつかの出来事を無視し、その記述独自の出来事を報告している。 |

| Appian's history According to Appian, the battle between Gellius' legions and Crixus' men near Mount Garganus was the beginning of a long and complex series of military maneuvers that almost resulted in the Spartacan forces attacking the city of Rome. After his victory over Crixus, Gellius moved northwards, following the main group of slaves under Spartacus who were heading for Cisalpine Gaul. The army of Lentulus was deployed to bar Spartacus' path and the consuls hoped to trap the rebel slaves between them. Spartacus' army met Lentulus' legion, defeated it, turned and destroyed Gellius' army, forcing the Roman legions to retreat in disarray.[28] Appian claims that Spartacus executed some 300 captured Roman soldiers to avenge the death of Crixus, forcing them to fight each other to the death as gladiators.[29] Following this victory, Spartacus pushed northwards with his followers (some 120,000) as fast as he could travel, "having burned all his useless material, killed all his prisoners and butchered his pack-animals in order to expedite his movement".[28] The defeated consular armies fell back to Rome to regroup while Spartacus' followers moved northwards. The consuls again engaged Spartacus at the Battle of Picenum somewhere in the Picenum region and were defeated again.[28] Appian claims that at this point Spartacus changed his intention of marching on Rome—implying this was Spartacus' goal following the confrontation in Picenum—as "he did not consider himself ready as yet for that kind of a fight, as his whole force was not suitably armed, for no city had joined him but only slaves, deserters, and riff-raff".[30] Spartacus decided to withdraw into southern Italy again. The serviles seized the town of Thurii and the surrounding countryside, arming themselves, raiding the surrounding territories, trading plunder with merchants for bronze and iron (with which to manufacture more arms) and clashing occasionally with Roman forces which were invariably defeated.[28] |

アッピアヌスの歴史 アッピアヌスによれば、ガルガヌス山付近でのゲリウスの軍団とクリクススの軍勢との戦いは、スパルタカス軍がローマ市を攻撃するところとなった、長く複雑 な一連の軍事作戦の始まりであった。クリクススに勝利した後、ゲリウスは北上し、キサルピナ・ガウルに向かうスパルタクス配下の奴隷の主力部隊を追った。 レントゥルスの軍はスパルタクスの進路を阻むように配備され、領事たちは反乱軍の奴隷たちを挟み撃ちにしようと考えた。スパルタクスの軍隊はレントゥルス の軍団と遭遇し、これを打ち破り、ゲリウスの軍団を撃破し、ローマの軍団は混乱したまま撤退を余儀なくされた[28]。 アッピアヌスは、スパルタクスはクリクサスの仇を討つために捕虜となったローマ兵300人ほどを処刑し、剣闘士として互いに死ぬまで戦わせたと主張してい る[29]。この勝利の後、スパルタクスは「移動を早めるために、無駄なものをすべて燃やし、捕虜をすべて殺し、群れをなしていた動物を屠殺した」 [28]。 敗走したコンスラ軍は再編成のためにローマに後退し、その間にスパルタクスの支持者たちは北上した。領事たちはピケヌム地方のどこかで行われたピケヌムの 戦いでスパルタクスと再び交戦し、再び敗北した。 [28]アッピアヌスは、この時点でスパルタクスはローマへの進軍の意図を変更したと主張し、これがピケヌムでの対決後のスパルタクスの目標であったこと を示唆した。隷属者たちはトゥーリの町とその周辺の田園地帯を占領し、武装し、周辺領土を略奪し、商人たちと略奪品を青銅や鉄(より多くの武器を製造する ための材料)と交換し、ローマ軍と時折衝突したが、必ず敗北した[28]。 |

Plutarch's history Plutarch's historyThe events of 72 BC, according to Plutarch's version of events Plutarch's description of events differs significantly from Appian's. According to Plutarch, after the battle between Gellius' legion and Crixus's men (whom Plutarch describes as "Germans") near Mount Garganus, Spartacus' men engaged the legion commanded by Lentulus, defeated it, seized the Roman supplies and equipment, then pushed into northern Italy.[31] After this defeat, both consuls were relieved of command of their armies by the Roman Senate and recalled to Rome.[32] Plutarch does not mention Spartacus engaging Gellius' legion at all, nor of Spartacus facing the combined consular legions in Picenum.[31] Plutarch then goes on to detail a conflict not mentioned in Appian's history. According to Plutarch, Spartacus' army continued northwards to the region around Mutina (modern Modena). There, a Roman army of some 10,000 soldiers, led by the governor of Cisalpine Gaul, Gaius Cassius Longinus attempted to bar Spartacus' progress and was also defeated.[33] Plutarch makes no further mention of events until the initial confrontation between Marcus Licinius Crassus and Spartacus in the spring of 71 BC, omitting the march on Rome and the retreat to Thurii described by Appian.[32] As Plutarch describes Crassus forcing Spartacus' followers to retreat southwards from Picenum, it could be inferred that the rebel slaves approached Picenum from the south in early 71 BC, implying that they withdrew from Mutina into southern or central Italy for the winter of 72–71 BC. Why they might do so, when there was apparently no reason for them not to escape over the Alps—Spartacus' goal according to Plutarch—is not explained.[34] |

プルタークの歴史 プルタークの歴史プルターク版による紀元前72年の出来事 プルタークの記述とアッピアヌスの記述は大きく異なっている。プルタークによれば、ガルガヌス山付近でのゲリウス軍団とクリクスス軍団(プルタークは「ゲ ルマン人」と表現している)の戦いの後、スパルタクス軍団はレントゥルスの指揮する軍団と交戦し、これを破り、ローマの物資と装備を奪い、北イタリアに押 し寄せた。 [31]この敗北の後、両執政官はローマ元老院によって軍の指揮を解かれ、ローマに呼び戻された。プルタークはスパルタクスがゲリウスの軍団と交戦したこ とにも、ピケヌムでスパルタクスが執政官の連合軍団と対峙したことにもまったく触れていない[31]。 その後、プルタークはアッピアヌスの歴史には記されていない紛争について詳述する。プルタークによれば、スパルタクスの軍隊はムティナ(現在のモデナ)周 辺まで北上した。そこで、キサルピナ・ガウル総督ガイウス・カッシウス・ロンギヌスが率いる約1万人のローマ軍がスパルタクスの進行を阻止しようとした が、これも敗北した[33]。プルタークは、紀元前71年春のマルクス・リキニウス・クラッススとスパルタクスの最初の対決までの出来事についてはそれ以 上言及せず、アッピアヌスが記述したローマへの進軍とトゥーリイへの撤退は省略している。 [32] プルタークによれば、クラッススはスパルタクスの従者たちをピケヌムから南へ退却させていることから、反乱軍の奴隷たちは紀元前71年初頭に南からピケヌ ムに接近し、紀元前72年から71年の冬にかけてムティナからイタリア南部または中部へ撤退したと推測される。プルタークによれば、彼らがアルプス越えを 目指さない理由はなかったようだが、なぜそうしたのかは説明されていない[34]。 |

| Crassus takes command of the legions Despite the contradictions in the classical sources regarding the events of 72 BC, there seems to be general agreement that Spartacus and his followers were in the south of Italy in early 71 BC. The Senate, alarmed at the apparently unstoppable rebellion, gave the task of putting it down to Marcus Licinius Crassus.[32] Crassus had been a field commander under Lucius Cornelius Sulla during the civil war between Sulla and the Marian faction in 82 BC and had served under Sulla during the dictatorship that followed.[35] Crassus was given a praetorship and assigned six new legions in addition to the two formerly consular legions of Gellius and Lentulus, giving him an estimated army of some 32,000–48,000 trained Roman infantry plus auxiliaries (there being quite a range in the size of Republican legions).[36] Crassus treated his legions with harsh, even brutal, discipline, reviving the punishment of unit decimation within his army. Appian is uncertain whether he decimated the two consular legions for cowardice when he was appointed their commander or whether he had his entire army decimated for a later defeat (an event in which up to 4,000 legionaries would have been executed).[37] Plutarch only mentions the decimation of 50 legionaries of one cohort as punishment after Mummius' defeat in the first confrontation between Crassus and Spartacus.[38] Regardless of events, Crassus' treatment of his legions proved that "he was more dangerous to them than the enemy" and spurred them on to victory rather than running the risk of displeasing their commander.[37 |

クラッススが軍団の指揮を執る 紀元前72年の出来事に関する古典的な資料には矛盾があるものの、スパルタクスとその追随者たちが紀元前71年初頭に南イタリアにいたことは一般的に一致 しているようである。クラッススは、紀元前82年のスッラとマリア派の内乱の際にルキウス・コルネリウス・スッラの下で野戦司令官を務めており、その後の 独裁政権でもスッラの下で働いていた[35]。 クラッススはプラエト職を与えられ、ゲリウスとレントゥルスの2つの元コンセール軍団に加え、新たに6つの軍団を任命され、約32,000から 48,000の訓練されたローマの歩兵と補助兵(共和国軍の軍団の規模にはかなりの幅がある)の軍隊を得たと推定される[36]。 クラッススは自分の軍団を厳しく、残忍ですらある規律で扱い、軍隊内で部隊の壊滅という刑罰を復活させた。アッピアヌス帝は、彼が2つのコンスラー軍団を 指揮官に任命されたときに臆病を理由に壊滅させたのか、それとも後の敗戦(最大4,000人の軍団員が処刑されたであろう)を理由に全軍を壊滅させたのか は不明である[37]。 プルタークは、クラッススとスパルタクスの最初の対決でムミウスが敗北した後の罰として、1個大隊の50人の軍団が処分されたことにしか触れていない[38]。 |

| Crassus and Spartacus When the forces of Spartacus moved northwards once again, Crassus deployed six of his legions on the borders of the region (Plutarch claims the initial battle between Crassus' legions and Spartacus' followers occurred near the Picenum region, Appian claims it occurred near the region of Samnium).[32][39] Crassus detached two legions under his legate, Mummius, to maneuver behind Spartacus but gave them orders not to engage the rebels. When an opportunity presented itself, Mummius disobeyed, attacked the Spartacist forces and was routed.[38] Despite this initial loss, Crassus engaged Spartacus and defeated him, killing some 6,000 of the rebels.[39] The tide seemed to have turned in the war. Crassus' legions were victorious in several more engagements, killing thousands of the rebel slaves and forcing Spartacus to retreat south through Lucania to the straits near Messina. According to Plutarch, Spartacus made a bargain with Cilician pirates to transport him and some 2,000 of his men to Sicily, where he intended to incite a slave revolt and gather reinforcements. He was betrayed by the pirates, who took payment and then abandoned the rebel slaves.[38] Minor sources mention that there were some attempts at raft and shipbuilding by the rebels as a means to escape but that Crassus took unspecified measures to ensure the rebels could not cross to Sicily and their efforts were abandoned.[40] Spartacus' forces retreated towards Rhegium, Crassus' legions following; upon arrival Crassus built fortifications across the isthmus at Rhegium, despite harassing raids from the rebel slaves. The rebels were under siege and cut off from their supplies.[41] |

クラッススとスパルタクス スパルタクスの軍勢が再び北上すると、クラッススは6個軍団をこの地域の境界に配備した(クラッススの軍団とスパルタクスの従者との最初の戦闘はピケヌム 地方付近で起こったとプルタークは主張し、アッピアヌスはサムニウム地方付近で起こったと主張している)[32][39]。クラッススは公使ムミウスの下 に2個軍団をスパルタクスの背後で作戦を展開させたが、反乱軍と交戦しないように命令を下した。この最初の敗北にもかかわらず、クラッススはスパルタクス と交戦して彼を破り、約6,000人の反乱軍を殺害した[39]。 戦争の流れは変わったように見えた。クラッススの軍団はさらに数回の交戦で勝利を収め、反乱軍の奴隷数千人を殺害し、スパルタクスをルカニアを通ってメッ シーナ近郊の海峡まで南下させた。プルタークによると、スパルタクスはキリキアの海賊と交渉し、彼と彼の部下2,000人ほどをシチリア島に移送し、そこ で奴隷の反乱を扇動し、援軍を集めるつもりだった。彼は海賊に裏切られ、海賊は代金を受け取った後、反乱軍の奴隷を見捨てた。[38] 小規模な資料によれば、反乱軍は脱出の手段としていかだや造船を試みたが、クラッススは反乱軍がシチリア島に渡ることができないように不特定の措置を取 り、その努力は放棄されたという。 [40] スパルタクスの軍勢はレギウムに向かって退却し、クラッススの軍団もそれに続いた。到着後、クラッススは反乱軍の奴隷たちからの嫌がらせの襲撃にもかかわ らず、レギウムの地峡に要塞を築いた。反乱軍は包囲され、補給を断たれた[41]。 |

| The legions of Pompey were

returning to Italy, having put down the rebellion of Quintus Sertorius

in Hispania. Sources disagree on whether Crassus had requested

reinforcements or whether the Senate simply took advantage of Pompey's

return to Italy but Pompey was ordered to bypass Rome and head south to

aid Crassus.[42] The Senate also sent reinforcements under the command

of "Lucullus", mistakenly thought by Appian to be Lucius Licinius

Lucullus, commander of the forces engaged in the Third Mithridatic War

but who appears to have been the proconsul of Macedonia, Marcus

Terentius Varro Lucullus, the former's younger brother.[43] With

Pompey's legions marching from the north and Lucullus' troops landing

in Brundisium, Crassus realized that if he did not put down the slave

revolt quickly, credit for the war would go to the general who arrived

with reinforcements and he spurred his legions on to end the conflict

quickly.[44] Hearing of the approach of Pompey, Spartacus tried to negotiate with Crassus to bring the conflict to a close before Roman reinforcements arrived.[45] When Crassus refused, Spartacus and his army broke through the Roman fortifications and headed up the Bruttium peninsula with Crassus's legions in pursuit.[46] The legions managed to catch a portion of the rebels – under the command of Gannicus and Castus – separated from the main army, killing 12,300.[47] Even though Spartacus had lost many men, Crassus' legions had also suffered greatly. The Roman forces under the command of a cavalry officer named Lucius Quinctius were destroyed when some of the escaped slaves turned to meet them.[48] The rebel slaves were not a professional army and had reached their limit. They were unwilling to flee any farther and groups of men were breaking away from the main force to independently attack Crassus's legions.[49] With discipline breaking down, Spartacus turned his forces around and brought his entire strength to bear on the legions. In this last stand, the Battle of the Silarius River, Spartacus' forces were routed, the vast majority of them being killed on the battlefield.[50] All the ancient historians stated that Spartacus was also killed on the battlefield but his body was never found.[51] |

戦争の終結 ポンペイ軍団はイスパニアでのクィントゥス・セルトリウスの反乱を鎮圧し、イタリアに戻ろうとしていた。クラッススが援軍を要請したのか、それとも元老院 が単にポンペイのイタリア帰還を利用したのかについては諸資料によって見解が分かれるが、ポンペイはローマを迂回してクラッススを助けるために南下するよ う命じられた[42]。 [元老院はまた「ルクルス」の指揮下で援軍を送ったが、アッピアヌスは第三次ミトリダス戦争に従事した軍隊の指揮官ルキウス・リキニウス・ルクルスと誤解 しているが、マケドニアの元司令官マルクス・テレンティウス・ヴァロ・ルクルス(元司令官の弟)であったようである。 [ポンペイの軍団が北から進軍し、ルクッルスの軍団がブルンディシウムに上陸したため、クラッススは奴隷の反乱を迅速に鎮圧しなければ、戦争の手柄は援軍 とともに到着した将軍のものになると悟り、紛争を迅速に終結させるために軍団に拍車をかけた[44]。 ポンペイの接近を聞いたスパルタカスは、ローマの援軍が到着する前に紛争を終結させるためにクラッススと交渉しようとした[45]。クラッススが拒否する と、スパルタカスと彼の軍隊はローマの要塞を突破し、クラッススの軍団を追ってブルッティウム半島に向かった[46]。軍団は、主軍から分離した反乱軍の 一部(ガンニクスとカストゥスの指揮下)を捕らえることに成功し、12,300人を殺害した[47]。 スパルタクスが多くの兵士を失ったにもかかわらず、クラッススの軍団も大きな被害を受けた。ルキウス・クインティウスという騎兵将校の指揮下にあったロー マ軍は、脱走した奴隷の一部が出迎えたときに壊滅した[48]。彼らはこれ以上遠くへ逃げることを望まず、男たちの集団は主力部隊から離脱して独自にク ラッススの軍団を攻撃していた[49]。 規律が崩壊する中、スパルタクスは軍勢を立て直し、全兵力を軍団に投入した。この最後の抵抗であるシラリウス川の戦いでスパルタクスの軍は敗走し、その大 部分は戦場で戦死した[50]。すべての古代史家はスパルタクスも戦場で戦死したと述べているが、彼の遺体は発見されていない[51]。 |

| Aftermath The rebels of the Third Servile War were annihilated by Crassus. Pompey's forces did not directly engage Spartacus's forces but his legions moving from the north were able to capture some 5,000 rebels fleeing the battle, "all of whom he slew".[52] After this action, Pompey sent a dispatch to the Senate, saying that while Crassus certainly had conquered the slaves in open battle, he had ended the war, thus claiming a large portion of the credit and earning the enmity of Crassus.[53] While most of the rebel slaves were killed on the battlefield, some 6,000 survivors were captured by the legions of Crassus. All 6,000 were crucified along the Appian Way from Rome to Capua.[45] Pompey and Crassus reaped political benefit for having put down the rebellion; both returned to Rome with their legions and refused to disband them, instead camping outside Rome.[15] Both men stood for the consulship of 70 BC, even though Pompey was ineligible because of his youth and lack of service as praetor or quaestor.[54] Both men were elected consul for 70 BC, partly due to the implied threat of their armed legions encamped outside the city.[55][56] It is difficult to determine the extent to which the events of this war contributed to changes in attitudes toward, use of, and legal rights accorded to Roman slaves. However, the end of the Servile Wars seems to have coincided with the end of the period of the most prominent use of slaves in Rome and the beginning of a new perception of slaves within Roman society and law. Certainly the revolt had shaken the Roman people, who "out of sheer fear seem to have begun to treat their slaves less harshly than before".[57] The wealthy owners of the latifundia began to reduce the number of agricultural slaves, opting to employ the large pool of formerly dispossessed freemen in sharecropping arrangements.[58] With the end of Augustus' reign (27 BC – 14 AD), the major Roman wars of conquest ceased until the reign of Emperor Trajan (reigned 98–117 AD) and with them ended the supply of plentiful and inexpensive slaves through military conquest. This era of peace further promoted the use of freedmen as laborers in agricultural estates. The legal status and rights of Roman slaves also began to change. During the time of Emperor Claudius (reigned 41–54 AD), a constitution was enacted that made the killing of an old or infirm slave an act of murder and decreed that if such slaves were abandoned by their owners, they became freedmen.[59] Under Antoninus Pius (reigned 138–161 AD), laws further extended the rights of slaves, holding owners responsible for the killing of slaves, forcing the sale of slaves when it could be shown that they were being mistreated and providing a (theoretically) neutral third party to which a slave could appeal.[60] While these legal changes occurred much too late to be direct results of the Third Servile War, they represent the legal codification of changes in the Roman attitude toward slaves that evolved over decades. The Third Servile War was the last servile war and Rome did not see another slave uprising of this magnitude again.[61] |

余波 第三次隷属戦争の反乱軍はクラッススによって全滅させられた。ポンペイの軍隊はスパルタクスの軍隊と直接交戦しなかったが、北方から移動してきた彼の軍団 は、戦闘から逃走する約5,000人の反乱軍を捕らえることができた。 [この行動の後、ポンペイは元老院に派遣状を送り、クラッススは確かに公然の戦いで奴隷たちを征服したが、彼は戦争を終結させたので、手柄の大部分を主張 し、クラッススの恨みを買ったと述べた[53]。反乱軍の奴隷のほとんどは戦場で殺されたが、生き残った約6,000人がクラッススの軍団に捕らえられ た。6,000人全員がローマからカプアまでのアッピア街道で磔にされた[45]。 ポンペイとクラッススは反乱を鎮圧したことで政治的利益を得た。2人とも軍団とともにローマに戻り、解散を拒否してローマ郊外に野営した[15]。 この戦争の出来事が、ローマの奴隷に対する態度、使用、法的権利の変化にどの程度貢献したかを判断するのは難しい。しかし、隷属戦争の終結は、ローマにお ける奴隷の使用が最も顕著であった時期の終わりと、ローマ社会と法における奴隷の新たな認識の始まりとが重なったように思われる。 ラティフンディアの裕福な所有者たちは農業奴隷の数を減らし始め、かつて土地を奪われた多くの自由民を小作農として雇用することを選択した[57]。 [58] アウグストゥスの治世(紀元前27年-紀元後14年)が終わると、トラヤヌス帝(在位紀元後98年-117年)の治世までローマの大規模な征服戦争はなく なり、軍事征服による豊富で安価な奴隷の供給も終わった。この平和な時代は、農地での労働力として自由民の利用をさらに促進した。 ローマの奴隷の法的地位と権利も変化し始めた。クラウディウス帝(在位:紀元41-54年)の時代に、年老いた奴隷や病弱な奴隷の殺害を殺人行為とする憲 法が制定され、そのような奴隷が所有者から見捨てられた場合には自由民となることが定められた。 [59] アントニヌス・ピウス(Antoninus Pius 在位:紀元138年-161年)の時代には、奴隷の権利をさらに拡大する法律が制定され、奴隷の殺害について所有者に責任を負わせ、奴隷が虐待されている ことが証明された場合には奴隷の売却を強制し、奴隷が訴えることのできる(理論的には)中立的な第三者を規定した[60]。これらの法改正は第三次奴隷戦 争の直接的な結果というには遅すぎたが、数十年にわたって発展したローマの奴隷に対する態度の変化を法的に成文化したものである。 第三次隷属戦争は最後の隷属戦争であり、ローマがこれほど大規模な奴隷の反乱を再び見ることはなかった[61]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third_Servile_War |

☆素朴な反逆者たちの系譜について(ホブズボーム)

★コマシャインの戦い

コシャマインの戦い(コシャマインのたたかい)は、 1457年に発生したアイヌと和人との戦い。コシャマインの戦いを伝える文献は、1646年に書かれたとされる『新羅之記録』があるが、戦いから200年 後の文献なので検証が必要といわれている。

Koshamain's War

(コシャマインの戦い, Koshamain no tatakai) was an armed struggle between the

Ainu and Wajin that took place on the Oshima Peninsula of southern

Hokkaidō, Japan, in 1457. Escalating out of a dispute over the purchase

of a sword, Koshamain and his followers sacked twelve forts in southern

Ezo (道南十二館), before being overcome by superior forces under Takeda

Nobuhiro. The principal record of the conflict is Shinra no

Kiroku.[1][2]

応仁の乱のちょうど10年前の1457年(康正3

年、長禄元年)に起きた和人に対するアイヌの武装蜂起。現在の北海道函館市銭亀沢支所管内にあたる志濃里(志苔、志海苔、志法)の和人鍛冶屋と客であるア

イヌの男性の間に起きた口論をきっかけに、渡島半島東部の首領コシャマイン(胡奢魔犬[注釈

1]、コサマイヌとも呼ばれる)を中心とするアイヌが蜂起、和人を大いに苦しめたが最終的には平定され、松前藩形成の元となった。

製鉄技術を持たなかったアイヌは鉄製品を交易に頼っており、明や渡島半島から道南に進出した和人(渡党、道南十二館などを参照)との取引を行っていた。し

かし1449年の土木の変以後、明の北方民族に対する影響力が低下すると明との交易が急激に衰え、和人への依存度が高まった。一方、安藤義季の自害により

安藤氏本家が滅亡し、道南地域に政治的空白が生じた[1]。

そこにアイヌの男性「オッカイ」が志濃里の鍛冶屋に小刀(マキリ)を注文したところ、品質と価格について争いが発生した[1]。怒った鍛冶屋がその小刀で

アイヌの男性を刺殺したのがこの戦いのきっかけである[1]。なお、「オッカイ」については、『新羅之記録』では「乙孩(おつがい)」とありアイヌ語の

okkay(オッカイ)に相当する。『松前年代記』では「乙孩」は「少年夷」の意味としている。また、17世紀初頭に松前に来航したイタリア人アンジェリ

スも「少年」と訳しており、同時期に記された『松前の言』にも「わらんべの事」としている[1]。『松前の言』が最も古いオッカイを記した文献であり、採

集地が道南であることを考慮すると「オッカイ=少年」とすべきとの見解がある[1][注釈 2]。

道南十二館

1456年(康正2年)に発生したこの殺人事件の後、首領コシャマインを中心にアイヌが団結し、1457年5月に和人に向け戦端を開いた。胆振の鵡川から

後志の余市までの広い範囲で戦闘が行われ、事件の現場である志濃里に結集したアイヌ軍は小林良景の館を攻め落とした。アイヌ軍はさらに進撃を続け、和人の

拠点である花沢と茂別を除く道南十二館の内10までを落としたものの、1458年(長禄2年)に花沢館主蠣崎季繁によって派遣された季繁家臣武田信広に

よって七重浜でコシャマイン父子が弓で射殺されるとアイヌ軍は崩壊した[1]。

この事件の前年まで道南に滞在していた安東政季の動向などから、事件の背景に当時の北奥羽における南部氏と安東氏の抗争を見る入間田宣夫の見解や、武田信

広と下国家政による蝦夷地統一の過程を復元しようとする小林真人の説がある[2]。

アイヌと和人の抗争はこの後も1世紀にわたって続いたが、最終的には武田信広を中心にした和人側が支配権を得た。しかし信広の子孫により松前藩が成った後

もアイヌの大規模な蜂起は起こっている(シャクシャインの戦い、クナシリ・メナシの戦い)。

1994年(平成6年)より毎年7月上旬、北海道上ノ国町の夷王山で、アイヌ・和人の有志による慰霊祭が行われている

★モーナ・ルダオ(Mona Rudao, 1880-1930)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++

私は松田先生をプチブルジョア(petit-

bourgeois)のイデオローグなどとは決して、呼んでおりません。

松田素二『抵抗する都市 : ナイロビ移民の世界から』岩波書店、1999年

文献

Do not paste, but [re]think this message for all undergraduate students!!!