嬰児殺しと棄老に関する考察ノート

嬰児殺しと棄老に関する考察ノート

000■ 赤の女王仮説( Red Queen's Hypothesis)

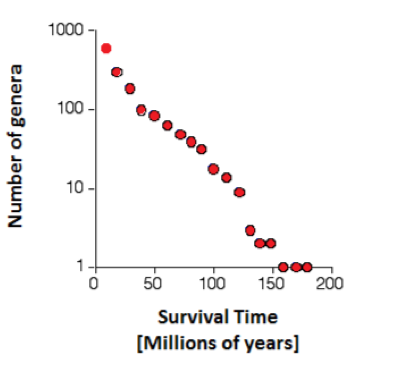

「進化に関する仮説の一つ。敵対的な関係にある種間 での進化的軍拡競走と、生殖における有性生殖の利点という2つの異なる現象に関する説明である。「赤の女王競争」や「赤の女王効果」などとも呼ばれる。 リー・ヴァン・ヴェーレンによって1973年に提唱された。 「赤の女王」とはルイス・キャロルの小説『鏡の国のアリス』に登場する人物で、彼女が作中で発した「その場にとどまるためには、全力で走り続けなければな らない(It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.)」という台詞から、種・個体・遺伝子が生き残るためには進化し続けなければならないことの比喩として用いられている。【軍拡戦争への応用】 生物学的な過程と国家間の軍拡競争の類似から着想された進化的な軍拡競走(もしくは軍拡競争)という表現は、リー・ヴァン・ヴェーレン(Leigh Van Valen)によって初めて発表された(1973年)。ヴァン・ヴェーレンは生物の分類の単位である科の平均絶滅率を地質学的期間にわたって調査し、そこから得られた絶滅の法則(1973年)を説明するために赤の女王仮説を提案した。 ヴァン・ヴェーレンは、科の生き残る可能性はその経過時間に関係なく、どんな科も絶滅する可能性はランダムであることを発見した。例えば、あ る種における改善は、それがどのようなものであってもその種に対する有利な選択を導くので、時間経過に従ってますます多くの有利な適応を身に付けるように なる。それは、ある種における改善が、その種が多くの資源を獲得し、競争関係にある他種との生存競争での生き残りに、有利になることを示唆している。そし て同時に、他種との競争で有利であり続けるための唯一の方法は、デザインの継続的な改善だけであることを示している(Heylighen, 2000)。 この効果のもっとも明白な一例は、捕食者と被食者の間の軍拡競走である(例えばVermeij, 1987)。捕食者はよりよい攻撃方法(例えば、キツネがより速く走る)を開発することで、獲物をより多く獲得できる。同時に獲物はよりよい防御方法(例 えば、ウサギが敏感な耳を持つ)を開発することで、より生き残りやすくなる。生存競争に生き残るためには常に進化し続けることが必要であり、立ち止まるも のは絶滅するという点で、赤の女王の台詞の通りなのである」赤の女王仮説)

Van Valen, A new revolutionary law, 1973. (pdf)

Francis Heylighen (2000): "The Red Queen Principle",

in: F. Heylighen, C. Joslyn and V. Turchin (editors): Principia

Cybernetica Web (Principia Cybernetica, Brussels), URL:

http://pespmc1.vub.ac.be/REDQUEEN.html.

Alice and Red Queen, by

John Tenniel

001■エピグラム

「人間というものはまことに奇妙な動物であって、そ

の習性を知れば知るほどその感を深うする。あらゆる動物のうちでもっとも理性的だと言えると同時に、

もっともバカげた動物だとも言える」——ジェームズ・フレイザー『金枝篇』(永橋卓介訳「解説」第5巻、154ページ、岩波書店,1967年)

002■エピグラム02

「この慣習——カニバリズムのこと——については、

「なぜ?」をつきとめることが問題なのではなく、それとは反対に、このような強奪=捕食の下限の出現に

ついて、「どのようにして?」と問うことが重要なのであり、そこから、おそらくはわれわれのは社会生活の問題に立ち戻ることになろう」——レヴィ=スト

ロース(2009:189)『パロール・ドネ』中沢新一訳、講談社、2009年。-

レヴィ=ストロース,クロード(2009)「カニバリズムと儀礼的異性装」『パロール・ドネ』中沢新一訳,Pp.185-196,講談社(Lévi-

Strauss, Claude (1984) Paroles données. Paris:Plon.)

003■

「私は決して望まない/横たわったままにされた骸骨

と同じように/あらゆる寵愛を失った徽章=杖の骸骨と同じように/わたくしの骨にも/そのような運命が

待ち受けていることを。/私はけっして望まない」——仲間が死んだときに霊感をうけたアチェのシャーマンの朗唱より(クラストル 1997:114)

004■悟性(Verstand)による暴力的介入、それは分離である

「分離の活動は、悟性という、[すなわち]最も驚嘆

に価し[あらゆるもののうちで]もっとも大きい威力、あるいはむしろ絶対的な[威力]のもつ力であり労

働である」——ヘーゲル(序論『精神現象学』原著29ページ)

Die Tätigkeit des Scheidens ist die Kraft und Arbeit des Verstandes, ,

der verwundersamsten und größten, oder vielmehr der absoluten Macht.

The activity of separation is the power and working of the mind, the

most astonishing and greatest, or rather the absolute power.

「分けるというはたらきは悟性、最も不思議で偉大で、あるいはむしろ絶対的な威力である悟性の力であり仕事である」樫山欽四郎訳、平凡社ライブラリー版

(上):48ページ。

「悟性が遂行する分離はまさに「奇跡的なこと」である。なぜならば、この分離は実際「自然に反して」いるからである。悟性の介入がないならば、「犬」とい

う本質は実在する犬において、そしてそれにより現存在するにすぎぬであろうし、実在する犬のほうが、逆にその現存在自体によって一義的にこの本質を規定す

るであろう。だからこそ犬と「犬」という本質との関係は「自然的」或いは「直接的」と言いうるのであるが、悟性の絶対的威力により本質が意味となり、一つ

の語の中に組み込まれるとき、もはや本質とその支えとの間には語を除いては「自然的な」関係は存在しなくなる。そして、音声上或いは書法上、その他何か時

間的空間的に実在するものとしては相互に何の共通点をもたぬさまざまの語(chien, dog, Hund

など)は、たとえそのすべてが唯一にして同一の意味をもちうるとしても、唯一にして同一の本質に支えるものとしては何ら役立つものではないのである。した

がって、ここには(本質と現存在との間の「自然的」な関係を含めた)在るがままの所与の否定があった、すなわち(概念、ないし意味をもつ語、しかも、語と

しては、それ自体からは、その中に込められた意味と何の関係ももたない語の)創造があった、すなわち行動ないし労働があったのである」。——アレクサンド

ル・コージェブ「ヘーゲル哲学における死の概念」p.381『ヘーゲル読解入門』上妻精・今野雅方訳、国文社、1987年。

___________________

◎本書の位置づけ

「第㈵部「動物殺しの政治学」では、文化的他者の屠畜の方法は恐ろしいという感覚が、いかに政治的に操作され、他者の排除に繋がっていくかを検証し、動物

殺しの政治学をつかむ。第㈼部「動物殺しの論理学」では、恐怖に感じられる他者の動物殺しの仕方が、どのような論理の下で展開されているかを露わにし、人

間対動物という二元論的な分析枠組みを再考する。第㈽部「動物殺しの系譜学」では、グローバル化に伴い屠畜の方法にも変化が現れ、多様化していく流れを見

定めながら、そのおおもとにある死生をめぐる論理の根源を問い尋ねていく。

『動物殺しの民族誌』と題する本書は、正面から人間と動物の間の行為を扱うが故に、取るべき基本姿勢は、ヒト中心主義的なものではなく、むしろマルチス

ピーシーズ人類学の確立を目指すものであり、とりわけ動物殺しという行為にまつわる人間社会の多種多様な論理や倫理の在り方を考察することを通じて、われ

われとは異なる生命観、環境観の存在とその意義を見出すことを試みる。本書の意義は、日本人読者に自ら慣れ親しんできたものとは全く異なる世界を提示し、

その現場を「体験」し、動物殺しをめぐる特定の感覚が人間の本能によるものではないということを会得することで、生命についての思考を深めることができる

点にある」——シンジルトと奥野による解説

___________________

005■著者=池田の当初案

(2)キーワード

動物殺し、殺人、嬰児殺し、棄老、老人虐待、安楽死

(3)構想

「狩猟動物殺しから現在の屠畜まで、タンパク源の入手をおこなうための「殺害行為」のみにハイライトをあてた研究への嗜好は、ジェフリー・ゴアラーの言う

「死のポルノグラフィー」に似て際物的扱いを受けてきた。当事者に話を聞くと、死というものは、それらの目的を完遂させる過程における副産物であり、死に

大きな意味をもたせないことがわかるからだ。他方、人間における代表的な「同種内殺害(intra-species

killing)」である、嬰児殺しと老人殺しあるいは棄老については、ヒューマニズムに基づく近代社会がもっとも畏れるもののひとつであり、専門家の好

奇の対象になり重要な論争のテーマにもなってきた。それゆえ「昨日までの社会」における比較的よく観察されてきた民族誌データとその解釈が、人類学教育に

おいても——当人たちは嫌がるかもしれないが、人間性について考えるためには——避けては通れない「テーマ」にもなっている。これらの歯切れの悪い議論に

対して、近年注目をあびている進化生物学的知見を交えて、文化人類学的解釈の再改訂の可能性を模索する。——池田光穂による最初の計画案

006■私の狙い

1.ヴィヴィッドな民族誌から、人間の現象への理解

を誘うこと

2.ギアーツの解釈学的人類学的「理解」を事例研究の中で、論点先取に陥ることなく実現(=実践)すること

007■ヴィヴィッドな民族誌がなぜ必要か?——我々のクランの始祖から忠告

「学術的な業績のなかには、部族生活のいわばみごと

な骨組みが描かれてはいるが、血肉与えられていない。彼らの社会の骨組みについて、そこから多くを学ぶ

けれども、その中では、人間生活の現実、日常の出来事の静かな流れ、祭りや儀式、またある珍しい事件をめぐって起こる興奮のざわめきを想像することも膚

(はだ)に感ずることもできない」(Malinowski 1922:17)『西太平洋の遠洋航海者』世界の名著版、Pp.84-86

- "In certain results of scientific work --- especially that which has

been called "survey work " --- we are given an excellent skeleton, so

to speak, of the tribal constitution, but it lacks flesh and blood. We

learn much about the framework of their society, but within it, we

cannot perceive or imagine the realities of human life, the even flow

of everyday events, the occasional ripples of excitement over a feast,

or ceremony, or some singular occurrence," (Malinowski 1922:17).

008■当初計画の章立て

1.序論

2.殺害と虐待の民族誌

3.人類学的解釈

4.進化学的心理学

5.科学の人類学

6.文化人類学と進化論の合意(consilience cultural anthropology and evolutionism)

009■棄老と老人殺害に関する人類学的説明の変異

1.啓蒙主義期の人類学:「高貴なる野蛮人」の気高

き行為

2.進化主義的人類学

3.機能主義

4.心理人類学:あるいは文化とパーソナリティ論

5.新進化主義

6.マルクス主義

7.構造主義

8.解釈人類学

9.ポストコロニアル派

10.ポストモダン派(=オントロジー派もこれに含める?)

11.(進化心理学が人類学的説明に与えたにインパクト)

010■進化心理学のマインドセット

(学派の類縁性・展開性)

・ダーウィン主義パラダイム→→→進化理論→→→脳科学A(マインドの研究)→→→進化心理学

・行動学→→→行動学的心理学→→→神経科学→→→脳科学B(自然科学的証明)→→→進化心理学

・動物生態学→→→行動生態学→→→進化生態学→→→進化心理学

・アリストテレス的目的論→→→エルンスト・マイヤー的(ネオダーウィニアン)目的論→→→進化心理学

(氏か育ちか:nature or nurture,の問題について)

・氏か育ちか、という発想はしない。自然淘汰(選択):natural selection

という点では、「氏」の立場にたつ。「育ち」を否認するのは、学習などの後天的形質を遺伝しないという点で「育ちの自然淘汰への寄与」という現象を、証拠

不十分として否定する。ただし、個体の成育過程において学習などの成育環境や個体の成長の刺激(=育ちの要素)が、後生的仕組み(epigenetic

mechanisms)のもとで、氏=遺伝子がもつ潜在的行動変容を発現するという仮説を容認する点で、氏と育ちという二分法を統合=合意

(consilience)するという解説も可能である。

・彼/彼女らの論理的命題は、自由意志を認めない、あるいは自由意志は(遺伝子の潜在力とそれらの発現という)ある種の決定論的な枠組みの中でのみ容認さ

れる。

・ローティ「自然の鏡」:我々のこころ(mind)のあり方を視覚的メタファーを通して表現する。視覚的メタファーとは、知識・真理・二元論・主観/客観

の図式を哲学にもたらした(ウィキペディア「哲学と自然の鏡」解説)。

011■進化心理学の要素還元主義

・これは民族誌における全体論的アプローチとは著し

く対照をなす。

012■現代の棄老としての安楽死と尊属殺人

・尊属殺人は、法の平等という観点から廃止される

(=殺される対象を区別して刑の軽重を判断してはならない)

・しかし、しばしば、尊属殺人は、罪の残忍性や獣性、精神異常性の代表と見なされてきた(『ピエール・リヴィエールの犯罪』)

・尊属殺人が多いのは被害者は「身近な他者」だからだという主張(ディリーとウィルソン 1999:54)

・L=Sが基本構造でとったアプローチを尊属殺人(親殺し)で適用することが可能か?

・L=Sテーゼ:自然/文化——親族の基本構造——婚姻ルール——文化的決定論(自由意志[−])←→自由意志[+]

013■目的論的思考の強み

・目的論は、設計者の存在を生物の外部ではなく、生

物自体にあると規定することで、生物の存在を自律的なものとみなすことができる。知は力なり。

014■進化理論アプローチの特徴=外挿法

・観察→→→仮説策定→→→予測→→→検証→→→理

論の確立

015■行動パターンの機能

「ある行動のパターンの直接的原因や発達、進化を理

解していなかったとしても、それでもその行動パターンの機能は可能だろうか?」デービス他『行動生態

学』第4版、翻訳、p.26.

016■石器時代の経済学

___________________

017■「多様な現象の中に体系的な関係を見出す必 要」——クリフォード・ギアーツ(文化の解釈学(I):77)

・ギアーツの人類進化(の大脳の解剖学)と文化の関

係は比較的容易である。

・人間は、いくら立派なハードウェア(=大脳)をもっていてもただの木偶の坊である。人間には大脳(=ハードウェア)を動かす「文化」というソフトウェア

——それもかなり高度の進化してきた——が必要だというものだ。

「中枢神経組織、とりわけ幸か不幸か新皮層(neocortex)が、主として文化との相互作用によって発達したので、人間は意味ある象徴体系による指示

なしに、行動を方向づけたり、体験を組織づけたりすることはできない。氷河時代にわれわれの身に起こったのは、われわれの行動を規制する詳細な遺伝的統御

の規則性と緻密性を放棄し、より一般化された、現実的でもある遺伝的統御の柔軟性と適応性に道を譲らざるをえなくなったことである。われわれは行動に必要

ないっそう多くの情報を供給するために、次にはますます文化的源泉——意味ある象徴の集積——に頼らざるをえなくなった。こうした象徴は、生物的・心理

的・社会的存在のたんなる表現でも、手段でも、また相関物でもない。象徴はそういう存在の前提条件である。人間なしには文化も同様に、あるいはより以上に

重要な意味において、文化なしには人間もないのである」(文化の解釈学(I)84)。

"As our central nervous system-and most particularly its crowning curse

and glory, the neocortex-grew up in great part in interaction with

culture, it is incapable of directing our behavior or organizing our

experience without the guidance provided by systems of significant

symbols. What happened to us in the Ice Age is that we were obliged to

abandon the regularity and precision of detailed genetic control over

our conduct for the flexibility and adaptability of a more generalized,

though of course no less real, genetic control over it. To supply the

additional information necessary to be able to act, we were forced, in

turn, to rely more and more heavily on cultural sources-the accumulated

fund of significant symbols., Such symbols are ,thus not mere

expressions, instrumentalities, or correlates of our biological,

psychological, and social existence; they are prerequisites of it.

Without men, no culture, certainly; but equally, and more

significantly, without culture, no men" (Geertz 1973:49).

・「概念的構造が無形の能力を形づくる(conceptual structures molding formless

talents)」(文化の解釈学(I)85/Geertz 1973:50)

018■パノフスキー「ゴチック建築とスコラ学」を示唆するギアーツ

「北フランスのシャルトルの聖堂は石とガラスででき

ている。しかしたんなる石とガラスではなく、それはゴシック建築の大寺院である。しかもたんなる大寺院

ではなく、特定の時代に特定の社会の特定の構成員によって建てられた特定の大寺院である。その意味するところを理解し、それが何であるかを認識するために

は、石やガラスの属性以上に、また大寺院に共通なものより以上に知らねばならぬことがある。すなわち、私の意見では最も重要な点であるが、神・人間・建物

の関係に関する特殊な概念もまた理解する必要がある。それらの概念が寺院の建設を統御したのだから、その結果、寺院がそれらの概念を具体的に表現している

のである。人間についても同様であり、人間もまた一人残らず文化的所産なのである」(文化の解釈学(I)86-87)。

"Chartres is made of stone and glass. But it is not just stone and

glass; it is a cathedral, and not only a cathedral, but a particular

cathedral built at a particular time by certain members of a particular

society. To understand what it means, to perceive it for what it is,

you need to know rather more than the generic properties of stone and

glass and rather more than what is common to all cathedrals. You need

to understand also --- and, in my opinion, most critically --- the

specific concepts of the relations among God, man, and architecture

hat, since they have governed its creation, it consequently embodies.

It is no different with men: they, too, every last one of them, are

cultural artifacts"(Geertz 1973:50-51).

019■古典的人類学の人間性について

「啓蒙主義と古典的人類学が採用した人間性の定義の

方法は、両者にいかなる相違があろうとも、1つの共通点をそなえている。それは基本的には類型論である

という点である。それらは人間に関するイメージをモデルや原型やプラトンのイデアやアリストテレスの形式として構成しようとする。それによれば、現実の人

間——あなた、私、チャーチル、ヒットラー、ボルネオの首狩り族——は単に反映・歪曲・近似に他ならない。啓蒙主義の場合には、現実の人間から文化の装飾

物を剥ぎとって、基本的本的類型の諸要素をむき出すべきで、そこに残ったもの、つまり自然人を見ょうとした。古典的学においては、文化の共通性を抽出して

それをむき出し、そこに顕われた平均的人間を見ようとしたどちらの場合でもその結果は、科学的問題に対するあらゆる類型的方法に一般的に生じやすい結果と

同じである。すなわち個人間や集団間の相違を副次的であるとすることである。個性は特異的なものとみなされ、各々の特徴は、真の科学者にとって唯一の正統

な研究対象——基本的・不変的・規則的類型——から派生した偶発的なものとみなされるようになる。こうした方法においては、どれほど入念に理論化し、どれ

ほど豊富な資料に基づいて主張したとしても、生活の詳細は血のかよわないステレオタイプの中にうずもれてしまう。つまりわれわれは形而上学的な概念であ

る、大文字の「M」がつくMan(人間)を探究するのあまり、われわれが実際に出会う経験的実質つまり小文字の「m」のつくman(

人間)を犠牲にしてしまうのである」(文化の解釈学(I)87-88)。

Whatever differences they may show, the approaches to the definition of

human nature adopted by the Enlightenment and by classical anthropology

have one thing in common: they are both basically typological. They

endeavor to construct an image of man as a model, an archetype, a

Platonic idea or an Aristotelian form, with respect to which actual

men-you, me, Churchill, Hitler, and the Bornean headhunter-are but

reflections, distortions, approximations. In the Enlightenment case, the

elements of this essential type were to be uncovered by stripping the

trappings of culture away from actual men and seeing what then was

left-natural man. In classical anthropology, it was to be uncovered by

factoring out the commonalities in culture and seeing what then

appeared --- consensual man. In either case, the result is the same as.

that which tends to emerge in all typological approaches to scientific

problems generally: the differences among individuals and among groups

of individuals are rendered secondary. Individuality comes to be seen

as eccentricity, distinctiveness as accidental deviation from the only

legitimate object of study for the true scientist: the underlying,

unchanging, normative type. In such an approach, however elaborately

formulated and resourcefully defended, living detail is drowned in dead

stereotype: we are in quest of a metaphysical entity, Man with a

capital "M," in the interests of which we sacrifice the empirical

entity we in fact encounter, man with a small "m"(Geertz 1973:51).

020■人類学における科学的証明の重要性

「ある科学的理論——科学自体といってもよい——が

評価されるべきなのは、特定の現象から一般的命題を引き出す能力にかかっているのである。もし人間が意

味あいに何であるかを知りたいと思うならば、個々人が何であるかを見出すことによってのみそれは可能となる。しかもその人びとは他の何ものにもまして千差

万別である。われわれが人間性の概念を構築するに到るのは、この多様性——その範囲、その性格、その基盤、その含蓄——を理解することにおいてである。こ

の人間性の概念は統計的な幻影以上のものではあるが、しかし未開を賛美する者の夢ほどではない、より実体と真実に近いものである」(文化の解釈学(I)

88)。

"It is, in fact, by its power to draw general propositions out of

particular phenomena that a scientific theory --- indeed, science

itself --- is to be judged. If we want to discover what man amounts to,

we can only find it in what men are: and what men are, above all other

things, is various. It is in understanding that variousness-its range,

its nature, its basis, and

its implications-that we shall come to construct a concept of human

nature that, more than a statistical shadow and less than a primitivist

dream, has both substance and truth"(Geertz 1973:51-52).

021■具体的なパターンのなかに「文化」をみる

「行動を規制する一連の象徴的な方法として、また情

報の身体外の源泉として文化を捉えると、文化は人間が生得的になりうべきものと、一人一人の実際の存在

との間の橋渡しをしている。人間になることは個人になることであり、われわれは文化のパターン、すなわち、歴史的につくられた意味の体系——それによって

われわれはわれわれの生活に形態・秩序・要点・方向を与える——の導くところに

よって個人となるのである。さらに文化のパターンは一般的なものではなく、特殊のものである。それはたとえばたんなる「結婚」ではなく、男と女のあるべき

姿ゃ、夫婦が互いにどのように相手を扱うべきか、ある人は誰と結婚すべきであるかということに関する一連の特殊の観念である。またそれはたんなる「宗教」

ではなく、それは輪廻の信仰であったり、一ヶ月の断食の励行であったり、牛の供犠であったりする」(文化の解釈学(I)88-89)。

"When seen as a set of symbolic devices for controlling behavior,

extrasomatic sources of information, culture provides the link between

what men are intrinsically capable of becoming and what they actually,

one by one, in fact become. Becoming human is becoming individual, and

we become individual under the guidance of cultural patterns,

historically created systems of meaning in terms of. which we give

form, order, point, and direction to our lives. And the cultural

patterns involved are not general but specific-not just "marriage" but

a particular set of notions about what men and women are like, how

spouses should treat one another, or who should properly marry whom;

not just "religion" but belief in the wheel of karma, the observance of

a month of fasting, or the practice of cattle sacrifice"(Geertz

1973:52).

022■行為とこころ(action and mind)

"The cleverness of the

clown may be exhibited in his tripping and

tumbling. He trips and tumbles just as clumsy people do, except that he

trips and tumbles on purpose and after much rehearsal and at the golden

moment and where the children can see him and so as not to hurt

himself. The spectators applaud his skill at seeming clumsy, but what

they applaud is not some extra hidden performance executed 'in his

head'. It is his visible performance that they admire, but they admire

it not for being an effect of any hidden internal causes but for being

an exercise of a skill. Now a skill is not an act. It is therefore

neither a witnessable nor an unwitnessable act. To recognise that a

performance is an exercise of a skill is indeed to appreciate it in the

light of a factor which could not be separately recorded by a camera.

But the reason why the skill exercised in a performance cannot be

separately recorded by a camera is not that it is an occult or ghostly

happening, but that it is not a happening at all. It is a disposition,

or complex of dispositions, and a disposition is a factor of the wrong

logical type to be seen or unseen, recorded or unrecorded. Just as the

habit of talking loudly is not itself loud or quiet, since it is not

the sort of term of which 'loud' and 'quiet' can be predicated, or just

as a susceptibility to headaches is for the same reason not itself

unendurable or endurable, so the skills, tastes and bents which are

exercised in overt or internal operations are not themselves overt or

internal, witnessable or unwitnessable. The traditional theory of the

mind has misconstrued the type-distinction between disposition and

exercise into its mythical bifurcation of unwitnessable mental causes

and their witnessable physical effects." Gilbert Ryle, 1949. The

Concept of Mind. p.33, Chicago : University of Chicago Press.

023■精神の「場」などない、というG・ライルは唯脳論(=脳を精神の座と考える俗説)を否定できるか?

"The statement "the

mind is its own place," as theorists might construe

it, is not true, for the mind is not even a metaphorical "place." On

the contrary, the chessboard, the platform, the scholar's desk, the

judge's bench, the lorry-driver's seat, the studio and the football

field are among its places. These are where people work and play

stupidly or intelligently. "Mind" is not the name of another person,

working or frolicking behind an impenetrable screen; it is not the name

of another place where work is done or games are played; and it is not

the name of another tool with which work is done, or another appliance

with which games are played." --- Gilbert Ryle, 1949. The Concept of

Mind. p.33, Chicago : University of Chicago Press.

024■人間がどのように心(=精神,こころ)をもつようになったか?——how man came to· have his mind?

(心の進化はともかくとして、このような問いには意

味がある—— "legitimate questions --- and how man

came to have his mind is a legitimate question," (Geertz 1973:61))

”In perhaps no area of inquiry is such an avoidance of manufactured

paradoxes more useful than that of the study of mental evolution.

Burdened in the past by almost all the classic anthropological

fallacies --- ethnocentrism, an overconcern with human uniqueness,

imaginatively reconstructed history, a superorganic concept of culture,

a priori stages of evolutionary change --- the whole search for the

origins of human mentality has tended to fall into disrepute, or at any

rate to be neglected. But legitimate questions --- and how man came to

have his mind is a legitimate question --- are not invalidated by

misconceived answers. So far as anthropology is concerned, at least,

one of the most important advantages of a dispositional answer to the

question, "What is mind?" is that it permits us to reopen a classic

issue without reviving classic controversies.”

C. Geertz, 1973. The interpretation of cultures. Basic Books. Pp.60-61.

「おそらく精神的進化(mental

evolution)の研究ほど、そうした人為的な逆説の忌避が効を奏する分野はないであろう。ほとんどの古典的人類学の誤謬——自民族中心主義、人類の

特殊性に対する過大な関心、想像による歴史の再構成、文化の超有機的概念、先験的進化の段階ーーによって縛られていたために、人間の心性の起源に関する研

究は悪評をこうむる傾向にあった。あるいは、とにかく無視されてきた。しかし正当な疑問——人類がどのように精神をもつようになったかという疑問は正しい

疑問である——は、間違った解答によって無効にされることはない。少なくとも人類学に関する限り、「心は何ぞや(What is

mind?)」という疑問に対する一定の解答の最も重要な利点の一つは、古典的な議論をむしかえすことなく古典的な問題に再び取り組むことを可能にする点

にある」(ギアーツ(I)1987:103)。

025■心の進化と、文化的/社会的進化の関係についてコンセンサス

・(複雑な議論を経て、ギアーツは次のようにまとめ

る)「要するに現代人の生得的生物学的構造(以前はただ「人間性」とよばれていたもの)はいまや文化

的、生物的変化の結果であると思われている。それは「解剖学的にわれわれと同じような人間が文化をゆっくり発見していったと考えるよりも、われわれの身体

的構造の多くは文化の結果と考えるほうが恐らくいっそう正確である」からである」(ギアーツ(I)1987:111)——この引用は、ウォッシュバーン

(1959)による。

・(人間の文化発達の速度の加速化)「それ以降、ヒトの有機体的進化は減速し、文化の発達が加速度的に進行し続けたのである。したがって、「文化を学び、

保持し、伝え、変形するという[生得的]能力に関する限り、ホモ・サピエンスの異なる集団は同じような能力を持っている、とみなさなければならない」とい

う経験的に確立された一般論を擁護するために、人類の進化における「種類がちがう」というような非連続型を仮定することも、ヒトの進化の全段階において文

化に対する自然淘汰によらない役割を仮定する必要もなくなった。心的統一性はもはや同義反復ではなく、今なお事実なのである」(ギアーツ(I)1987:

114)。

・The Growth of Culture and the Evolution of Mind (§3)

026■動物がもつ洞察力について:ドナルド・ヘブの洞察

「系統進化論の進展の一つとして、ある分野で自由意

志として知られているものが存在するという証拠がふえていると述べることにより、私は生物学者を驚かさ

ないことを望む。私の学生時代にはハーバード法ともよばれていたもので、それは、よく訓線された実験動物はコントロールされた刺激に対して自分の満足のい

くように行動するという法別である。より学問的に述べれば、高等動物は刺激に条件づけられることが少ないといおっことである。すなわち頭脳活動はインプッ

トにコントロールされる度合が少なく、したがって行動は動物のおかれている状況からは予測がつきにくい。観念的な活動の果たす役割は、刺激に対する反応以

前にさまざまな刺激をしばらく「保つ」動物の能力や、目的をもつ行動の現象のなかに認められる。高等な頭脳にはより自律的な活動や選択性があって、求心的

な刺激は、行動を規制する支配的活動のとしての「思考の流れ」と融合される。従来、われわれは、主体が環境のあの部分ではなくこの部分に「関心をもってい

る」という言い方をし、そのことによって高等動物が広汎な関心をもっており、その時点の関心が行動に大きな影響を及ぼしているとみなしてきた。これは、い

かなる刺激に対しどういう反応をするかについて、またその反応の形態についても、いっそう予測しがたい事を意味している」(原出典はD. O.

Hebb, "The Problem of Consciousness and Introspection," in Brain

Mechanics and Consciousness: a symposium organized by the council for

international organizations of medical sciences, eds. Edgar D. Adrian,

Frederic Bremer, Herbert H. Jasper. (Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Pub,

1954), pp. 402-417. )(引用は(ギアーツ(I)1987:116-117))

・動物はランダムに試行錯誤しているのではなく、行動選択に内的な「仮説」をもつようになる——ドナルド・ヘッブ「第7章学習に関係した高次と低次の過

程」『行動の機構:脳メカニズムから心理学へ(上・下)』鹿取廣人 [ほか] 訳、岩波文庫、岩波書店、2014年(The organization

of behavior : a neuropsychological theory / D.O. Hebb, New York : John

Wiley & Sons. 1949)。

027■推論する(=行動のなかに「仮説」をもつ)ラット

「健常者のもっとも単純な行動でさえ,思いも寄らな

いほどの知能が含まれている.クレチェフスキー(1932)

も,ラットで同様のことを明らかにした.表面的には単純に見える学習が,刺激-反応の結合の単純な習得以上のものであって,“仮説"も含んでいることを示

したのである.クレチェフスキーの発見は,簡単に言うと,次のようなことである.空腹のラットに, 2

つのドア(たとえば,右側か左側のドア,あるいは白か黒のドア)の一方を選択する課題が繰り返し与えられる.白いドアは左側にくることもあれば,右側にく

ることもある. 2 つのドアの一方を通過すると,餌がおいてある(もう一方のドアは開かないようになっている)

.このような問題では,ラットはでたらめには選択しない.ほとんどの場合,最初は左右の一方の側のドアを続けて選択し,次にもう一方の側のドアを同様に続

けて選択する.さらに次には,左右を交互に選択したり,あるいは左右に関係なく,白いドアをつねに選んだりして,最終的には,解決へのこうした組織的な試

みの中のひとつが,一貫して報酬を受けることになる.この点で,ラットは一連の仮説をもっていたと言うことができる.明らかに,その学習は,最初でたらめ

になされた反応が少しずつ強化されたものではない.この行動は,霊長類の標準からすれば愚かとしか言いようがないが,ある種の知能を含んでおり,高等動物

の行動を解明する手がかりになる」(ヘッブ 2014:330-331)

028■大脳の発達と人間の文化的発達は相補的である

「この立場(=生物学的変化と社会文化的変化の重な

る時期に生じたニューロンの進化における重要な発展がある:引用者)からすると、精神活動は基本的に脳

内部の過程であり、その過程は、その過程そのものが人類に発明させたさまざまな人工的手段によってのみ副次的に支援され増幅されることができる、という従

来の見解は完全に間違っているように思われる。そこで、内的な要因にもとづく優勢なニューロンの過程の特定の適合的に充分な定義は不可能であるので、人間

の脳が作動するには全面的に文化的資源に依存することになる。したがって文化的資源は精神活動の付加物ではなく構成物である。事実、客観的素材の目的のた

めの操作を含む顕在的・公的行為としての思考は、おそらく人類にとって基本的なものである。客観的素材に依存しない潜在的・私的行為としての思考は、役に

立たないのではないが派生的能力といえる」(ギアーツ(I)1987:123)。

From this standpoint, the accepted view that mental functioning is

essentially an intracerebral process, which can only be secondarily

assisted or amplified by the various artificial devices which that

process has enabled man to invent, appears to be quite wrong. On the

contrary, a fully specified, adaptively sufficient definition of

regnant neural processes in terms of intrinsic parameters being

impossible, the human brain is thoroughly dependent upon cultural

resources for its very operation; and those resources are,

consequently, not adjuncts to, but constituents of, mental activity. In

fact, thinking as an overt, public act, involving the purposeful

manipulation of objective materials, is probably fundamental to human

beings; and thinking as a covert, private act, and without recourse to

such materials, a derived, though not unuseful, capability"(Geertz

1973:76).

029■多くの文献を利用してギアーツは、人間活動にとって情動が不可欠なのは脳のアイドリング状態が不可欠という生理学的制約とそれを文化というフィル

ターを

通した情動刺激の形で処理しているから(という)仮説を説明する。

・「こうしたことは人間の思考の知的側面のみならず

情的側面についてもいえる。ヘッブは一連の著作や論文のなかで、人間の神経組織は(下等動物においては

相対的に狭い範囲で)適切な行動をとる前提条件として環境からの最適な刺激の比較的継続的な流れを必要とする、という興味をそそる理論を展開した。一方で

は、人間の脳は「インプットがなければ無限に動かない電動計算機とは異なって、有効に機能するためには、少なくとも起きている間はたえずさまざまなイン

プットによってアップされていなければならない」。他方、人間の莫大な感受性が付与されれば、このようなインプットが大きすぎたり、多様すぎたり、混乱を

招いたりすることはありえない。というのは、その場合には情緒の崩壊と思考過程の完全な破壊が確実だからである。倦怠とヒステリーこそ思考の敵である」

(ギアーツ(I)1987:127)。

"All this is no less true for the affective side of human thought than

it is for the intellective. In a series of books and papers, Hebb has

developed the intriguing theory that the human nervous system (and to a

correspondingly lesser extent, that of lower animals) demands a

relatively continuous stream of optimally existing environmental

stimuli as a precondition to competent performance. [65] On the one

hand, man's brain is "not like a calculating machine operated by an

electric motor, which can lie idle, without input, for indefinite

periods; instead it must be kept warmed up and working by a constantly

varied input during the waking period at least, if it is to function

effectively." [66] On the other hand, given the tremendous intrinsic

emotional susceptibility of man, such input cannot be too intense, too

varied, too disturbing, because then emotional collapse and a complete

breakdown of the thought process ensue. Both boredom and hysteria are

enemies of reason. [67]"(Geertz 1973:79-80).

--

[65] D. O. Hebb, "Emotion in Man and Animal: An Analysis of the

Intuitive Process of Recognition," Psychol. Rev. 53 (1946):88-106; D.

O. Hebb, The Organization of Behavior (New York, 1949); D. O. Hebb,

"Problem of Consciousness and Introspection"; D.O.· Hebb and W. R.

Thompson, "Social Significance of Animal Studies."

[66] D. O. Hebb, "Problem of Consciousness and Introspection."

[67] P. Solomon et al., "Sensory Deprivation: A Review," American

Journal of Psychiatry, 114 (1957):357-363; L. F. Chapman, "Highest

Integrative Functions of Man During Stress," in The Brain and Human

Behavior, ed. H. Solomon

(Baltimore, 1958), pp. 491-534.

030■人間における情動の制御に関する文化的修整の問題

・(人間の感情をかき乱す恐怖・憤激・誘発などの情

動刺激に対して)洗練された文化的抑制による「合理化」が用意されていると同様に、情動に修整(=修正

を兼ねた変形)を加えていくことがみられる。ここでのギアーツは、行動科学的主張と文化的主張の間を「調停」しようとやっきになっているようにもみえる。

「しかし、人間はかなり高度で持続的な情緒活動なしには効率よく行動できないので、そうした活動を支える常に多様な感覚的体験を確保できる文化的メカニズ

ムもまた本質的である。とりきめられた範囲の外に遺体をさらすことを禁じる制度的規則(葬式など)は、死と死体の腐敗の恐怖におののく動物を守ってくれ

る。自動車レースを見たりそれに参加したりすることは(レースはレース揚で行なわれるとは限らない)、同様の恐怖をやさしく刺激する。賞をめぐる競争は敵

対感情をあおるが、強固に制度化された個人間の気やすさがそれを和らげてくれる。性欲は一連の間接的な方法によってたえず刺激されるが、性行為の私的性格

が性欲の暴発を防いでくれる」(ギアーツ(I)1987:127-127)。

"But, as man cannot perform efficiently in the absence of a fairly high degree of reasonably persistent emotional activation, cultural mechanisms assuring the ready availability of the continually varying sort of sensory experience that can sustain such activities are equally essential. Institutionalized regulations against the open display of corpses outside of well-defined contexts (funerals, etc.) protect a peculiarly high-strung animal against the fears aroused by death and bodily destruction; watching or participating in automobile races (not all of which take place at tracks) deliciously stimulates the same fears. Prize fighting arouses hostile feelings; a firmly institutionalized interpersonal affability moderates them. Erotic impulses are titillated by a series of devious artifices of which there is, evidently, no end; but they are kept from running riot by an insistence on the private performance of explicitly sexual activities"(Geertz 1973:80).

・『文化の解釈』第3章の末尾もまた行動科学の統合

を謳い、分離主義者(Isolationist)——文化と神経メカニズムをそれぞれ別々な観点で独自

に説明しようとする学派——を批判する。

「指示的思考、感覚の形成、ならびに両者の動機ヘの統合という意味で、人類の精神的過程はまさに学者の机上やフットボール競技場、あるいはスタジオやト

ラックの運転席、あるいはプラットフォームやチェス盤、あるいは裁判官席で起きるのである。分離主義者(Isolationist)は文化、社会組織、個

人行動、あるいは神経生理学の閉鎖システムの実在を主張するが、人類の精神についての科学的分析を進展させるためにはほとんどすべての行動科学から共同で

追究する必要がある。そして行動科学の各分野の発見は他のすべての領域の理論的再評価をたえず要請するであろう」(ギアーツ(I)1987:130-

131;訳文:隔離主義者→分離主義者)。

"In the sense both of

directive reasoning and the formulation of

sentiment, as well as the integration of these into motives, man's

mental processes indeed take place at the scholar's desk or the

football field, in the studio or lorry-driver's seat, on the platform,

the chessboard, or the judge's bench. Isolationist claims for the

closed-system substantiality of culture, social organization,

individual behavior, or nervous physiology to the contrary

notwithstanding, progress in the scientific analysis of the human mind

demands a joint attack from virtually all of the behavioral sciences,

in which the findings of each will force continual theoretical

reassessments upon all of the others"(Geertz 1973:83).

031■心の進化概念の擁護(C・ギアーツ)

「「こころ」という用語は組織体の性向のある種の組

み合わせを指している。数える能力は精神的特性であり、恒常的快活も、食欲も——ここでは動機の問題を

検討することはできなかったが——またしかりである。精神の進化の問題は、したがって、まちがった形而上学によって生じた虚偽の問題でもなければ、生命の

どの段階で不可視のアニマが有機体に付与されたかを発見することにあるのでもない。それは有機体におけるある種の能力や性向の発展を跡づける問題であり、

かかる特徴の存在が依存する要因や要因の型を描写する問題である」(ギアーツ(I)1987:130-131;訳文:精神→こころ)。

"The term "mind" refers to a certain set of dispositions of an

organism. The ability to count is a mental characteristic; so is

chronic cheerfulness; so also-though it has not been possible to

discuss the problem of motivation here-is greed. The problem of the

evolution of mind is, therefore, neither a false issue generated by a

misconceived metaphysic, nor one of discovering at which point in the

history of life an invisible anima was superadded to organic material.

It is a matter of tracing the development of certain sorts of

abilities, capacities, tendencies, and propensities in organisms and

delineating the factors or types of factors upon which the existence of

such characteristics depends"(Geertz 1973:82).

032■人類の思考は共通文化の客観的素材による顕在的行為である(C・ギアーツ)

・"[H]uman thinking is

primarily an overt act conducted in terms of the

objective materials of the common culture, and only secondarily a

private matter"(Geertz 1973:83).

033■E・O・ウィルソンと交錯しないギアーツ

・チャールズ・テイラーの自然科学との対決に関する

エッセー(『現代社会を照らす光』に所収)のなかに、conciliation

に関する用法に関する脚注の中に自分の用法とは違うとはっきり断っている。

034■セネカにみる老人の利点

【ラテン語】

Nec enim excusione nec saltu nec eminus hastis aut comminus gladiis

uteretur, sed cosilio, ratione, sententia; quae nisi essent in senibus,

non summum consilium maiores nostri appellasseny senatum --- De

Senectute I, 16

【英訳】

"They wouldn't make use of running or jumping or spears from afar or

swords up close, but rather wisdom, seasoning and thought, which, if

they weren't in old men, our ancestors wouldn't have called the highest

council the senate."

****

035■サンブルの事例(gerontocracyの実態)

・サンブルは、マサイのような軍事的組織をもたない

(p.xviii)

・ポール・スペンサーのフィールドワーク、1957年11月〜1960年7月の27か月

・敵対する民族:サンブル〈対〉Turkana;Samburu 〈対〉 Boran

・モラン Moran(s. lmurani, pl. lmuran)は、未婚の若い男性の集団で、かつての戦士集団。

・サンブルはジェロントクラシー(gerontocracy)の社会(p.xxii)

・スペンサーの基本テーゼは、一夫多妻を可能にするために長老制(grontocracy)は存在するというもの

"[S]ociety as a gerontocracy, that is, as a society in which power is

essentially in the hands of the older men. Such a society inevitably

exihibits certain strains between young and old, and ill the present

InStance these strains are largely contained within the age-set system,

which is strong and restrictive. But in addition, the gerontocracy must

be supported by appropriate social values, the ecological balance of

the society must allow it, and other institutions must. be related with

it in some way. Polygamy,for instance, which is encouraged by the high

regard for autonomy and economic independence among older men can only

be practised on a wide scale when the younger men, the moran in fact,

are prevented from marrying" (Spencer 1965:xxii).

・エイジセットシステム:"... and the monopoly of the old men in marriage

becomes another aspect of the gerontocatic situation as does the

tendency for delinquent behaviour among the young men" (Spencer

1965:xxii)

[出典]

・Spencer, Paul. 1965. The Samburu : a study of gerontocracy in a

nomadic tribe. Berkeley: University of California Press.

・Nomads in alliance : symbiosis and growth among the Rendille and

Samburu of Kenya / Paul Spencer, London: Oxford University Press. 1973

[→阪大書庫にあり]

036■奴隷に関する生殺与奪

037■年齢原理(age principle)

・年齢階層で、そこに帰属する集団の行動や考え方を

規制するような原理

・社会や文化により、年齢原理の強度の強弱がある。

・日本社会は年齢原理が強く働くために、化粧や衣服における世代らしさに対する規範が、価値観として表出される。年齢の5つの側面(暦年齢、肉体年齢、心

理的年齢、社会的年齢、文化的年齢)が相互に一致しやすいために、その世代集団が使う語彙(ステレオ/蓄音機、石鹸/シャボンm等)で見分けることが容易

だった(片多 1981:37-38)。

038■gerontocracy と老人遺棄は結びつかない?

039■長老と祖先崇拝

「長老が死者を尊敬し貢物をささげるのは、子どもが

老親を尊敬し食物などを供給して世話をするのと同じことである」(片多 1981:57)

040■未開社会の戦争は不可視

「未開社会の戦争は不可視である。なぜなら、もはや

それを遂行する戦士が存在しないからである」(クラストル 2003:17)『暴力の考古学』

041■Bernard Sellato のプナン民族誌

《aged》での語彙は1箇所のみ

"In any case, among the

nomads the minimal residential unit and the

nuclear family are generally identical. According to the literature, a

shelter is shared only by a couple and their unmarried children. It is

rare to have a third generation represented (see Harrisson 1949:139) or

to find a sibling of one spouse. A shelter might be inhabited by only

one person, for example, an aged widower. Kedit gives, for the Penan of

the Mulu region, an average of 6.6 persons per shelter (1982:228). This

number is certainly lower for many other groups less demographically

dynamic (see, for example, Huehne 1959-1960: 199)."(Sellato 1994:145)-

Nuclear Family の箇所で。

《プナンは老人遺棄はしない》

"Although, according to

Needham (1954b:232), the Punan never abandon

old people and the sick, it nevertheless appears that among certain

groups, such as the Bukat, the dying were indeed abandoned(see Bouman

1924:175-176)." (Sellato 1994:160) - Disposal of the Dead(屍体の処理)

・この上記の記述を含む全体の記述「Disposal of the Dead(屍体の処理)」の抜粋

- "Like marriages, deaths in traditional nomad society are not

occasions for elaborate ritual. The literature is curiously rich in

descriptions of types of funerals among the Punan groups. In their

details these practices vary, the common characteristic being that they

are of a relatively rudimentary character compared to those of farming

societies. The body may simply be abandoned, just as it is, on a flat

stone (in the case of the Kereho), on a platform of branches hastily

set up in the forest, or in the shelter where the death occurred (Jayl

Langub 1974:296). In certain cases the body is wrapped in a sheet of

bark or a mat before being left on a platform (Harrisson 1949:142) or

buried (Sulaiman 1968:25-26). Among certain groups the body is buried

without a coffin (Jayl Langub 1974:296; Harrisson 1949:142) under the

hearth of the shelter (J. Nicolaisen 1978:33), or at a distance from

the camp (Urquhart 1951:511), downstream from the camp (Sulaiman

1968:25-26) or, conversely, upstream (Arnold 1958:59-60; 1967:97), or

just anywhere (Sandin 1957:135). Among other groups the body, in a

coffin, is buried under the hut (Urquhart 1951:512), or elsewhere

(Sandin 1965:187), or left under a lean-to (Tuton Kaboy 1974:292; see

also Urquhart 1951:511) or on a platform in the forest (as among the

Kereho)."(Sellato 1994:158-159)

- "Most commonly, no form of ceremony accompanies the disposal of the

body. Most authors make no mention of funeral rituals, and others

explicitly state that these are nearly or wholly nonexistent (Stohr

1959:164; Arnold 1967:97; Lumholtz 1920)."(Sellato 1994:159)

・屍体は、すぐに放棄されたり簡単な埋葬処理がされ る

"A common custom among

all known Punan groups is the immediate

abandonment of the body, of the place where the death occurred, of the

camp, and sometimes of that entire sector of the territory (see, above,

the discussion of the Bukat, and Mjoberg 1934; Harrisson 1949:142;

Urquhart 1951:512; Arnold 1958:59-60; Stohr 1959:164; Huehne 1959:201;

Ellis 1972:240; Jayl Langub 1974:296; Tuton Kaboy 1974:292; J.

Nicolaisen 1978:33). Among several groups, the camp, or at least the

hut of the deceased, is wrecked or burned before being abandoned

(Urquhart 1951 :512,532;]. Nicolaisen 1978:33)." (Sellato 1994:159)

《プナン社会の性的分業》——サゴを栽培しても男性は野生のものだけを食べる

- "The sexual division

of labor among the Bukat is an interesting

subject, but one on which there exists little historical information.

As among all the nomads of the area, women hunt and fish just as men

do, though less often. They carry burdens just as men do, according to

their individual ability, when the group travels. They are also in

charge of building a shelter and gathering firewood (Enthoven 1903:87).

The heavy work of extracting sago, such as felling, cutting up, and

splitting the sago palms, is usually done by men, but women participate

actively in the subsequent phases of the extraction and the preparation

of sago flour." (Sellato 1994:70)

- "When the Bukat began to farm on the Mendalam, as already mentioned,

Bouman reports the significant fact that it was women who took care of

farm work, while men continued to hunt and gather forest products

(1924:175). On the other hand, it may have been men who built the

village huts at that time. Among the Kayan, the different phases of

agricultural work are divided among men and women according to physical

aptitude, on the one hand, and ritual criteria, on the other. This new

type of sexual division of labor, permitting a dual orientation of

effort toward field and forest, made it possible for Bukat men to

invest more time in the collection of forest products for commercial

purposes. Even if the harvest of their farms was poor, field size being

small and these new farmers relatively unskilled, it had to feed only

women, young children, and old people, since the men were living on

wild sago. And as the band's women and children were settled on the

Mendalam, the Kayan (and later the Dutch) were assured of continuity in

the supply of forest products from the men of Bukat families." (Sellato

1994:70-71)

- "Work in the sago palm groves, as already stated, is carried out by

mixed groups of men and women. This is a complex activity, a many

staged and relatively long process. Although certain writers,like

Arnold (1967), claim that the different families of the band work

alternately to produce sago, my observations suggest that most often

several families will do the work together, completing the various

phases of the work in an unbroken sequence (see also Harrisson

1949:137). As for gathering, it is definitely an activity carried out

cooperatively by women, old people, and children, who scatter in small

groups in every direction, the better to comb through a sector of the

forest."(Sellato 1994:167)

《セラトの民族誌の書誌》

- Nomads of the Borneo

rainforest : the economics, politics, and

ideology of settling down / Bernard Sellato ; translated by Stephanie

Morga, Honolulu : University of Hawaii Press , 1994.

- Nomades et sédentarisation á Bornéo : histoire économique et sociale

/ Bernard Sellato, Paris : École des Hautes études en Sciences Sociales

, c1989. - (Etudes insulindiennes-Archipel ; 9).

《ニーダムの1954bの文献の関心とは?/[他の民族誌家とは異なり]プナンは老人や病人を放棄することもある》

SIRIONO AND PENAN, A

TEST OF SOME HYPOTHESES

RODNEY NEEDHAM

HOLMBERG in his study of the Siriono advances

certain generalizations "for futher refinement and investigation in

other societies where condition of food insecurity and hunger

frustration art comparable to those found among the Siriono"

(pp.98.99). He makes these with some reserve because: of lack of

library facilities and other reasons at the rime of writing (p. 92, fn.

7).

I wish to make an elementary test of these

generalizations by comparison of the Siriono with the forest nomad

Penan of the interior of northwestern Borneo. The Penan differ

considerably from the Siriono in matters such as kinship organization,

but they are comparable in that the defining character of the societies

to which the generalizations arc thought to apply is an insecure food

supply. In this feature also the Penan differ from the Siriono, for the

latter plant small crops of maize, manioc, and other plants (p. 29),

whereas the nomadic Penan plant no crops and rely entirely on their

search for game and the wild sago palm. But Penan life is certainly

characterized by food insecurity and hunger, in spite of a different

economy.

Any comparison such as this is unsatisfactory until

I have documented Penan life at lean as fully as Holmberg has described

tbe Siriono, and this is clearly out of the question here. However, no

interpretation of Penan data would, I think, quite reverse my comment

on any of the hypotheses. and it is the general confirmation of them or

otherwise that is initially important..

I find myself out of sympathy with Holmberg's posing

of problems in terms of primary and secondary drives. This has led to

certain difficulties in making useful comments, and is partly the

reason that I do not attempt any refinement of the hypotheses.

I quote Holmberg's hypotheses in full and comment on

their applicabitity to the Penan:

(1) "Such societies will be characterized by a general backwardness of

culture. A concern with food problems will so dominate the society that

other aspects of its culture will be little developed."

Allan R. Holmberg, Nomads of the Long Bow; the Siriono of Eastern

Bolovia, Publications, Institute of Social Anthropology, Smithonian

Institution, No. 10, 1950.

- Rodney Needham, 1954. Siriono and Penan: A Test of Some Hypotheses.

Southwestern Journal of Anthropology. Vol. 10, No. 2 (Summer, 1954),

pp. 228-232.

042■老人の地位処遇に関するドナルド・カウギル(Donaldo O. Cawgil, 1972)の仮説(13のテーゼ)[出典は(片多

1981:146-148)]

1.社会における老人の地位は近代化の程度と反比例

の関係にある。

2.全体社会の中の老齢人口の比率が低いほど老人の地位は高くなる。

3.老人の地位は社会変化——テクノロジー、職業構造、都市化など——の比率に反比例する。

4.居住地が固定していることは(米作農民のように)老人の高い地位につながり、(都市住民や狩猟採集民のような)居住地の移動性は地位の低さにつなが

る。

5.老齢になっても土地、家屋などの所有権を維持しうる場合には、その所有権が老人に経済的安定ばかりか威信や権力をも与える。

6.伝統や儀式を重んずる「民俗社会」で、それらの伝統を保持し正しい儀礼のあり方を伝えていくのは、主として老人たちである。

7.文字をもたない社会ほど老人の地位は高い。つまり、本や図書館・学校などに頼れない社会で、知識、経験を蓄積し伝達するのは主として老人たちであり、

かれらはしばしば多様な機能——歴史を語り、系譜を暗記し、職業指導をし、教師・書籍・図書館のかわりをつとめ、医師や祭司となるなど——を果しているの

である。

8.(当然のことながら)老人が有益かつ価値の高い機能を持続して遂行しうる社会ほどその地位は高い。

9.拡大家族が一般的で、それが世帯構成の単位として機能している社会ほど老人の地位は高い。非産業社会では、一般に老人に経済的安定を与えるのは家族の

役割であるが、それが産業社会ではより大きな集団、とくに国家などに移行しようとしている。

10.現代産業社会にくらべて部族社会では退職、定年などによって老人の役割が変容されたり奪されることが少い。

11.部族社会にくらべて現代産業社会では指導的役割を果している老人の数は少い。

12.部族社会でとくに重要な老人の役割は宗教的リーダーシップである。老人たちが祖先(死者)を個人的に知っており、自身も死に近い立場にあることがこ

うした地位をもたらす原因となっている。

13.自我の発達や個人的業績を強調するような価値体系のもとでは老人は不利な立場にたたされやすい。

[オリジナル出典]Cowgill, Donald O., 1972. A Theory of Aging in Cross-Cultural

Perspective. In Aging and Modernization, Pp.11-13., Donald O. Cowgill

and Lowell D. Holmes eds., New York: Meredith Corporation.

043■エルマン・サーヴィスの〈狩猟民の長老は尊敬される〉説

「どの社会でも成人は子供たちより優越している。そ

して、このことはまず説明を必要としないほど当然のことである。未開社会では老人が年下の成年男子より

も優越しているが、これもまったく同じ理由——より豊富な経験と知識の保有——によってのことである。……変化のない未開社会では、そんなことはまったく

ない。発展なり変化のない社会、とくに複雑な産業上の変化をこうむらない社会では、人間は年をとるほど生活について多くを知るようになる。与えられた環境

に適応し、その中で生活するという問題は、バンドのような社会ではどの時点でもそこに生きるすべての世代にとって同じである。あたかもそれは先祖にとって

同じだったのとまったく同様である。こうした社会は千年たってもおよそ変化しないでいるため、年長者はいかにすべきかをよく知っておりさらに年長者に敬意

を払い、とりわけその助言に従うことが有利となっている」エルマン・R・サーヴィス『狩猟民』(現代文化人類学2)蒲生正男訳、Pp.87-88、鹿島研

究所出版会、1972年。

044■老人遺棄の「動機」は、ゲーム論的にみるとマイナスの「依存」/放棄による利得(=リスク回避)があると考える

045■老人の側の戦略は、子どもに遺棄されたり/殺害されぬようにすることである

・サブシステンスが生存ぎりぎりのラインでは演技だけでは〈有用な老人〉を演技することができない。体力と気力が必要。

046■ラテンアメリカの農村での末子相続や高齢者夫婦の養子慣行は、老後の世話だが、子どもへのケアを通して、未来の被扶養〈資源〉への投資行為をして

いると

も解釈できる。

047■タブーと高齢者

・ブッシュマンの老人と子どもへのケア戦略(田中二

郎)

「ブッシュマンは動物性食物についての多くのタブーをもっており、動物を食べるとその人は病気になったり、災難にあって死ぬと信じられている。中でもス

ティーンボック(小型カモシカの一種)スプリシグヘアー(野ウサギの一種)、小型の陸ガメの三種は幼児と高齢者以外は食べてはならないものである。それは

これらの動物がいずれも小型で大勢の人への分配は不可能でああるため、老人と幼児に優先的に配分するという社会的配慮の結果であると田中(二郎)は考察し

ている」(片多 1981:213)。

[原出典:]田中二郎『ブッシュマン』Pp.76-77, 思索社、1971年(→現行の版は、1977年の第二版)。

048■シリオノの食物禁忌と高齢者

・シリオノ・インディアン

「ボリビアのシリオノ・インディアンは常に食糧不足に苦しみ、争いごとやかれらがみる夢の大部分が食べものに関することである。それでも、かれら自身は意

識してはいないものの、シリオノ文化は数多くのフード・タブーをもうけて老人には何とか飢えをしのいでもらおうとしている。いくつかのタブーとそれを破っ

たらどうなるか例をあげてみると、動物の頭(とくに脳)を食べれば白髪になるだろう、陸ガメの脂肪を食べるとカメのように動きが鈍くなる、若者がバナナを

食べと獲物が見つからなくなる、自然に落果したフルーツを食べると病気になる、などとなっており、これらのタブーは本来は老人にも適応されるが、老人はす

でにそういう状態になっているのでタブーを破っても平気であると考えられている。フード・タブーは一般に宗教的意味あいが強いとされているが、このように

老人など弱者への文化的対応策としても機能しているのである」(片多 1981:214)

・報告者は夏季言語学研究所(Summer Institute of Linguistics,

SII)の、ペリー・プリーストで、調査年代はホームバーグの調査報告(1950)がなされた1940年代よりも10年後の1955年から1965年の

10年間——SIIの所属であり、諺の記録なので、基本語彙の調査項目などで得た資料によるものだろう(ただしシリオノ語の記載はない)。

・プリーストによると、ホームバーグが採集した、75件の社会内紛争事例ではそのうち44件が直接食べ物に関するものだった。また、採集した50の夢のエ

ピソードのうち半分が食物のこと、獲物としての狩猟のこと、森の中での食用食物に関するものだった。

・ホームバーグは、そのような食糧不足と食糧に対する心配が、シリオノの性質を極端なケチにして、高齢者がすぐに死んでしまうという例外を除いて、あまり

にも高齢や病気であるものに対して食物が供給できない人たちへの放棄=放置(abandonment)へと繋がると言う(=プリーストの記述)。それにつ

づく文章、"That many do continue to live after their usefulness has passed

is due almost entirely to the Siriono system of food taboos, which do

not apply, or apply only very loosely, to the aged."

の前半部の文意が不詳だが、試訳すると「(食物欠乏への恐怖があるために)食物の有用性が確認されてもなお、シリオノは食物禁忌を守ろうとするが、高齢者

にはその禁忌が守られないか、ルーズにのみ適用されるだけである」。それゆえ、高齢者がシリオノ社会の福祉(=恩恵)を受けることはないが、他の成員が食

べてはならないものを、確保することはできる。

・[別記で→■シリオノの食物タブー一覧42項目]

・(狩猟動物が見つからなくなる、白髪になる、怠惰になるといった)禁忌を侵したことの帰結は、高齢者にとって不利な条件にはならない——そのような属性

自体が老人のそれだからゆえ。またタブー侵犯の帰結は子孫に祟るゆえに、若い年齢の女性は[狩猟に係わる]男性よりも自由に無視することができる——シリ

オノは母系制。

[原出典:]Priest, Perry N., Provision for the Aged among the Siriono

Indians of Bolivia. American Anthropologist 68(5):1245-1247, 1966.

[出典]Nomads of the long bow : the Siriono of Eastern Bolivia / Allan R.

Holmberg, U.S. Government Printing Office (1950)

049■シリオノの食物タブー一覧42項目(出典 Priest 1966:1245-1246)

01- If you eat the

young of spider monkey, howler monkey, or yellow

monkey, your lips will turn white (anemic).

02- If you eat the young of the big hawk, you will become very heavy.

03- If you eat the young of agouti or squirrel, your jaw will swell

(infected tooth, toothache).

04- If you eat fish heads, you will suffer from nosebleed.

05- If you eat animal heads (especially brains), your hair will turn

gray early. (An example of their evidence is that Hehe, who has never

eaten brains, still has black hair even though several men younger than

he are already pray.)

06- If you eat the heads of big birds such as ducks and water birds,

your children will have long necks.

07- If you eat the fat of the land turtle, you will be slow like the

land turtle.

08- If you eat turtle liver, you will shoot animals in the liver.

(Instead of in the more vital heart area. Recently when Simon killed

two turtles, he gave the liver of one turtle to old Hehe, and the other

to Julia, who had just been divorced by her husband.)

09- If you eat the small anteater, you will become disobedient.

10- If you eat anything that you yourself shoot, your running will be

impaired. (Good runners are the best hunters.)

11- If you eat honey containing baby bees, your children will become

cry-babies.

12- Porcupine meat will make you sick.

13- If you eat the very young of anything, your children’s lips will

turn white (anemic) and your children will be born foolish.

14- If you eat corn at night, your teeth will decay. (The explanation

being that one can’t see the worms and weevils, which are bad for the

teeth.)

15- If you eat dove meat at night, your armpits will smell. (The tiger

can smell you better and follow you.)

16- If you eat the small turtle, your neck will swell (goiter).

17- If young men eat bananas, they come home from the hunt empty handed.

18- Men and boys must give manioc and sweet potatoes that are damaged

(when being dug from the ground) to the old people.

19- Children must give their game and fish to the old people. They will

get sick if they don’t.

20- Young women must not eat palm cabbage that they themselves have

chopped out.

21- You should not use new gourd drinking-vessels. If you do, you will

be sick. You should let the old people use them until they are no

longer new; then you can use them.

22- If you eat quail, you will have fever and chills.

23- If you eat the feet of animals, you will fall frequently.

24- If you eat hip blades, your hip blades will become sore.

25- If a man or his wife eats breasts or teats, the wife’s breasts will

harden.

26- You should not eat the intestines or stomach of large animals such

as deer and tapir. If you do, your will have stomach ache and diarrhea

and have to stop when you are chasing an animal.

27- Only women and old people eat palm heart that grows near the ahai

tree. (The ahai tree is used in puberty rites for girls.)

28- If you eat bagre-fish (mbarae), your liver will be perforated.

(Some informants say your children’s livers will be involved.)

29- If you eat dove meat, your hands will peal.

30- If you eat electric eel, your children’s legs will not be sturdy

and their necks will swell (goiter).

31- If you eat surubi-fish (catfish), your children will have big

mouths.

32- If you eat pacu-fish, your children will be striped.

33- If you eat an ear of corn from which rats have eaten, your teeth

will hurt.

34- If you eat fruit from a tree that has fallen of itself, you will

become sick. The spirit that made the tree fall will make you sick.

35- If you eat striped agouti, your babies’ hair will fall out.

36- When a person kills his first tapir and tiger, he should trade or

give away his eating utensils and drinking vessels.

37- When a person kills his first tapir and tiger, he must not eat any

boiled meat or honey for several days. ( Yande's uncle broke this taboo

and died a few days later.)

38- If you eat what a tiger kills, tigers will steal and eat anything

you kill and leave to pick up later.

39- If you eat squirrel meat, you will have warts.

40- If boys eat squirrel meat, they will never be good tapir hunters.

41- If you eat the male howler monkey, you will have bad dreams and

yell at night.

42- The eating of any soft meat (the very young offspring, including

unborn offspring) is likely to cause toothache.

[出典]Priest, Perry N., Provision for the Aged among the Siriono Indians

of Bolivia. American Anthropologist 68(5):1245-1247, 1966.

050■シリオノの高齢者の取り扱い(Holmberg 1950:85)

OLD AGE

The aged experience an unpleasant time of it in

Siriono society. Since status is determined largely by immediate

utility to the group, the inability of the aged to compete with the

younger members of the society places them somewhat in the category of

excess baggage. Having outlived their usefulness, they are relegated to

a position of obscurity. ActuaJIy the aged are quite a burden. They eat

but are unable to hunt, fish, or collect food; they sometimes hoard a

young spouse but are unable to beget children; they move at a snail's

pace and hinder the mobility of the group.

Where existence depends upon direct utility,

however, longevity is not great. The aged and infirm are weeded out

shortly after their decrepitude

begins to appear. Consequently, the Siriono band rarely contains many

members who belong to generations above the parent or below the child.

At Tibaera there were only four grandparent-grandchild relationships,

and great-grandparents and great-grandchildren did not exist. Although

this is a hazardous guess, the average life span of the Siriono ---

discounting infant mortality --- probably falls somewhere between the

ages of 35 and 40.

Besides the inability of the aged to perform as well

as younger members of the society, certain physical signs of senescence

are also recognized. Women who have passed through the menopause are

assigned to the category of anility. Deep wrinkles, heavy beards in

men, gray hair (occurs very rarely), stooped shoulders, and a halting

gait are regarded as signs of old age.

When a. person becomes too ill or infirm to follow

the fortunes of the band, he is abandoned to shift for himself. Since

this was the fate of a sick Indian whom I knew, the details of her case

will best serve to illustrate the treatment accorded the aged in

Siriono society .. The case in question

occurred while I was wandering with the Indians near Yaguaru, Guarayos.

The band decided to make a move in the direction of the Rio Blanco.

While they were making preparations for the journey, my attention was

called to a middle-aged woman who was lying sick in her hammock, too

sick to speak. I inquired of the chief what they planned to do with

her. He referred me to her husband who told me that she would be left

to die because she was too ill to walk and because she was going to die

anyway. Departure was scheduled for the following morning. I was on

hand to observe the event. The entire band walked out of the camp

without so much as a farewell to the dying woman. Even her husband

departed without saying good-by. She was left with fire, a calabash of

water, her personal belongings, and nothing more. She was too sick to

protest.

After the band had left, I set out in company with.

a number of Indians for the Mission of Yaguaru to cure myself of an eye

ailment. On my return about 3 weeks later, I passed by the same spot

again. I went into the house, but found no sign of the woman there. I

continued my journey down the trail in the direction of Tibaera and

soon came upon a hut in which the band had camped the day I parted from

them. Just outside of this shelter were the remains (and hammock) of

the sick woman. By this time, of course, the ants and vultures had

stripped the bones clean. She had tried her utmost to follow the

fortunes of the band, but had failed and had experienced the same fate

that is accorded all Siriono whose days of utility are over.

[出典]Nomads of the long bow : the Siriono of Eastern Bolivia / Allan R.

Holmberg, U.S. Government Printing Office (1950)

051■シリオノの食糧不足の民族誌の代表なのか?

では、コリン・タンブールの『ブリンジ・ヌガク』は

どうだろうか?——要チェック

・The mountain people / Colin M. Turnbull,London : Cape , 1972(ブリンジ・ヌガグ:

食うものをくれ / コリン・M.ターンブル [著] ; 幾野宏訳,東京 : 筑摩書房 , 1974)

052■愛情(情動)の誕生

・リリーサー

053■老人遺棄方法としての安楽死と、遺棄場所としてのナーシング・ホーム

054■人間の協働性という事実と一見矛盾する「老人遺棄」をどのように解釈すべきか?

・マイケル・トマセロ(2013:2-4)『ヒトは

なぜ協力するのか』によると、人間の文化の特徴はつぎの2つに集約される;

1)文化の累積的進化

人間の行動的習慣が時間とともに複雑化をとげる事実。集団生活をし、知性を行使して、他者のものごとの発明ややり方をまねることができる。そしてそれを

世代を超えて歴史的に継承されること

2)社会制度の存在

婚姻の規則に代表されるように、規約があり、そこから人間の間の相互交渉がはじまる。相互交渉が先か規則(規約)が先かということはさておき、相互交渉

と規約は社会制度を成り立たせるバッググラウンドであり、相互交渉と規約を育み洗練させていく「場(=環境)」であることは、論を待たない。

[出典]ヒトはなぜ協力するのか / マイケル・トマセロ著 ; 橋彌和秀訳,勁草書房 (2013)(Michael Tomasello,

2009. Why we cooperate : based on the 2008 Tanner Lectures on Human

Values at Stanford, MIT Press.)

055■狩猟採集民に関する偏見を是正する田中二郎(2008:48-49)

・自然環境に依存し、つねに飢えと災害に苛まれる人

たち、と思われてきたがそうではない。20世紀後半の人類学的研究の多くが明らかにしたことは、狩猟よ

りも採集に比重が置かれる社会がほとんどで、それらの社会では豊かさと安定性が確保されたものだった。ただし、田中は例外もあげており、ユカギール(シベ

リア)、オナ(ティエラ・デル・フエゴ)のような高緯度地域で植物資源の入手が困難なところに限られていると指摘(田中 2008:48)。

・このような偏見の理由には「狩猟民」という呼び名により狩猟のイメージが「人びとの興味」を引きつけてきたからだという——ノミナリズムによる社会的見

方の偏りの助長。

・植物への依存がありながら、それでもなおブッシュマンは狩猟肉が「本当のたべもの」という象徴的重みづけがある——文化人類学は「生態」か「文化」とい

う二分法をとるのではなく、この点をバランスよく再解釈すべきかもしれないというのが私(=池田)の立場(田中 2008:50)。

・資源あふるる社会(田中 2008:51)は、マーシャル・サーリンズの『石器時代の経済学』の議論に通じる。

・サステイナブル

[出典]

・ブッシュマン、永遠に。 : 変容を迫られるアフリカの狩猟採集民 / 田中二郎著,京都 : 昭和堂 , 2008年

・石器時代の経済学 / マーシャル・サーリンズ [著] ; 山内昶訳,東京 : 法政大学出版局 , 1984年(Stone age

economics / Marshall Sahlins, Tavistock Publications (1974))

056■サステイナブルな狩猟採集民というのはポストモダンの「自然民族」?

・次の田中の言説を参照してみよう

・「土地の利用の仕方についても、またそこでの資源の利用の仕方についても、ブッシュマンはまことにぜいたくな流儀で振る舞っているといわざるをえない。

毎年、手もつけられないまま見捨られた膨大な量の食物が、彼らの居住地域のなかで朽ち果てているのである。これこそ、ブッシュマンが狩猟と採集の生活に

よって、いかにすばらしくカラハリの原野に適応しているかということを示す例証にほかならない。/彼らは、50人内外の集団で、数週間ぐらいを周期として

移動を繰り返すのだが、それぐらいの人数と日数でなら、キャンプ地周辺の食物資源を食べつくしてしまうことはない。つまり自然の一部を破壊してしまうこと

にはならないのである。/いってみれば、彼らの類繁な移動生活は、お気に入りのごちそうをつまみ食いして歩く生活なのであり、移動のサイクルを一巡して

戻ってくるころには、すでに自然の食車はもと通りに復元しているのである。同様のことは、プッシュマンたちがあまり頼みの綱とはしない動物の狩猟について

もいえる。彼らの用いる狩猟の技術がお粗末で、ほんのときたまにしか大好物の獲物を食卓に登場させることができない程度だからこそ、動物も絶滅を免れるこ

とができるのである」(田中 2008:50)。

・ブッシュマンの社会構造は、平等社会であり、「社会全体をまとめてゆくような組織化」がない(田中 2008:63)。

・馬の導入による狩猟法の改善も実際に得られる肉の量はそれほど増えていない(田中 2008:84)。

・それは「必要以上には求めることをしない従来の信念は確固と保持されている」からであるという(田中 2008:84-85)。

・ただし、肉の配分における平等原則が崩れてきたという(田中 2008:86-87)。

[出典]ブッシュマン、永遠に。:変容を迫られるアフリカの狩猟採集民 / 田中二郎著,京都 : 昭和堂 , 2008年

057■シリオノ・インディアンへの用語

(ポストコロニアル時代のシリオノ、あるいは帝国主

義的ノスタルジーVer2.0からの脱却について)

058■ヘヤー・インディアン(Dene, ディネ):Hare Indian

"The Dene people

(/ˈdɛneɪ/ DEN-ay) (Dené) are an aboriginal group of

First Nations who inhabit the northern boreal and Arctic regions of

Canada. The Dené speak Northern Athabaskan languages. Dene is the

common Athabaskan word for "people" (Sapir 1915, p. 558)." - Wiki

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dene

・(原ひろ子(1989:365)の報告によると、火傷したヘヤー・インディアンの生存率は、白人の10分の1〜20分の1だという。1961年に病院関

係者に調べたときに、医療関係者は「生への執着を簡単に棄てる」との見解を述べている。彼女の解説はこうだ:「ヘヤー・インディアンは、自分の守護霊が

「生きよ」といっている間は、生への意志を棄てない。しかし、守護霊が「お前はもう死ぬぞ」というと、あっさりと生への執着を棄ててしまう。そして良い死

に顔で死ねるようにと守護霊に助けを求め、まわりの人間にすがるのである」(原 1989:366)。

059■ヘヤー・インディアン「チャーニー」の死に方(死期を悟って死ぬまで/人類学者の直接観察)

「私がキャンプ生活に入ってかなりの日数がたち、ヘ ヤー・インディアンの方から「ヒロコは薪も割るし、ウサギもとる。歩くのも速い。インディアンの夢や幽 霊の話もわかるぞ。インディアンになってきたなあ」と言ってくれるようになってきた。そんな一九六二年八月末のある日、五歳の女の子マーサが、私のテント に真面目な顔をして入ってきた。いつもなら、するりと私のテントに入り込み、しばらく黙って坐って後、朝から何も食べていないとか、まだ飴はあるかなどと 言って、茶目気たっぷりな目つきをするのだが、その日は様子がちがった。世にも大事な任務を帯びている風情で、堂々とテントのフラップを聞け、日記をつけ ていた私のまん前に仁王立ちになって、「オジさんが死ぬことにしたから、すぐ行ってあげて。たくさん集まってるよ」と言う。/一週間前、大きなムースを鉄 砲で射とめたチャーニーは、五O歳の名ハンターだ。五日前に風邪をひいたのか、熱があるといって救護所の看護婦のところにアスピリンとビタミン剤を自分で もらいに行った。「安静にして熱いお茶をたくさん飲みなさいって言っておいたのよ。抗生物質も出しておいたから、すぐ治るでしょ」と看護婦は言っていた が、肺炎になったのかも知れない。迎えにきたマーサに、私は「チャーニーは、いつからそう言いだしたの」と聞いてみた。「昨日の夕方、夢から醒めてから。 だから遠くのキャンプに、お兄さんたちは報せに行ったよ。明日の夕方には皆集まれるって。そしたら、オジさんの話を聞くんだ」と言う」(原 1989:366-367)。

「私は朝食に使った食器を洗い、テントを整頓してか ら、マーサと一緒にチャーニーのテントへと出かけた。マーサはチャーニーの弟の娘で、チャーニーに可愛 がられていた。チャーニーは一昨日から食物を少ししかとらなくなり、死ぬと言いだしてからは、紅茶を時折口に含むだけになったという。たたみ六畳くらいの テントには、すでに一七〜八人集まっていた。たばこの煙の立ちこめるなか、全員チャーニーの話を聞いている。横臥してボソボソと思い出話をつづけるチャー ニーに、みんなはフム、フムと相槌を打っている。ふだんの冬の夜長の体験談を聞くときには、聞き手は「フム、フム、それから?」とつづきを催促したり、と きには冗談を言って話をまぜ返すのだが、死にゆく人には、本人が言いたいことだけを話してもらうために、「それから」と聞いてはいけないことになってい る。/チャーニー氏は時折、話を止めて、大きく息をし、紅茶を一口すすっては、目を閉じる。まわりの者は互いに身をすり寄せ合っては、チャーニーを見つめ る」(原 1989:367)。

「以前にも述べたように、ヘヤー・インディアンの考 え方によると、霊魂は肉体を出たり入ったりする。目は開いていても、ボーッとあらぬ方向を見つめたりす るときや眠っているとき、霊魂は肉体をはなれて旅をする。霊魂が旅をして体験することが夢である。夢のなかで、そのときそのときの行動の指針を得るのであ る。人が目を閉じ、静止するとき、その人は自分の守護霊と交信するのだから、誰もそれを乱してはいけない。その人が目を開け、再びまわりの者と話しはじめ るまで待つのである。チャーニーが昨夕、夢から醒めてから自分は死ぬと言いだしたのは、守護霊のお告げがあったからだ。また今日思い出話をしていて、途中 で目を閉じ、沈黙するときも、守護霊と交信しているのだと人々は信じている。/肉体が生きているとき、霊魂は再び肉体に戻ってくるが、死ぬと霊魂が出て 行ったきり戻ってこなくなる。だから、チャーニーが話を休めると、まわりの者は互いに身をすり寄せ合っては、チャーニーが良い死に顔で死ぬようにと祈るの である。人が死ぬと、その霊魂は、自分のミウチや生前のキャンプ仲間のもとや、自分が一生の間に旅をしキャンプをして泊ったところを巡り歩くという。遺体 が埋葬されると、あの世への旅をはじめる。そして、良い死に顔をして死んだ者の霊魂は、再びこの世に生まれるべく旅につく。そして埋葬前にも、悪い死に顔 の人ほどには、この世の近しい人の霊を道連れにしようとつきまとわない。だから、良い死に顔で死ぬことは、死にゆく本人の願いでもあり、見送る人々の願い でもある」(原 1989:368)。

「チャーニーと一緒にキャンプしたこともなく、猟に 出かけたりしたことのない人々は、テントの中に入ってこないが、時折やってきては、テントの外に薪を運 んできたり、水をバケツに混んできてくれたりする。またテントの中でみとっている者も、ときには外に出てテントの支柱の杭を打ち直したり、薪を割ったりす る。/白人の看護婦は、「あんなに軽い風邪で、あんなに丈夫な人が死ぬ気になってしまったなんて」と、たいへん残念がっている。ヘヤー・インディアンたち は、もう駄目だと悟る時期をどう決めるのか。西欧医学の立場から治療が可能であるかどうかとか、あと何年しか生命をもちこたえられないのではないかといっ たこととは関係なく、それぞれの文化が何らかの基準をもっていたり、それぞれの個人が悟ったりすることは、ヘヤー・インディアンだけに見られる例ではない だろう」(原 1989:368-369)。

※【コメント】レヴィ=ストロースのブードゥ・デス

「次の日に入ると、遠くのあちこちのキャンプ地か

ら、チャーニーの近親や親友たちが報せを受けて駆けつけてきた。夕方、チャーニーは自分の愛用の銃二挺、

モーター・ボート、金属製罠、テント、ストーブ、ラジオ、犬などを贈る相手を指名した。20世紀に入る前、そして一部では1920年代までは、銃を用いず

手製の弓矢で狩猟し、毛皮を剥ぎ合わせたテントに住んでいたが、その時代には、死者の衣類、テント、生産用具、その他の所有物はすべて焼かれた。このよう

な品物には死者の霊魂がのり移りやすいと信じられ、畏れられたからである。狩猟地は部族全体の共有なので、土地相続の問題はへヤーの文化には存在していな

い。しかし、銃やラジオなど、運賃がかかって法外に高い品物が日常生活に入ってきてから、死を前にした新しい儀式がへヤー・インディアンの生活に導入され

た。これにのっとってチャーニーも自分の持ち物を近しい人々に贈ったのである。そしてカソリックの神父さんを招いて聖油の秘蹟(extreme

unction)を受けた。/そしてその次の日の未明、チャーニーは息をひきとった。良い死に顔をして。/すると、チャーニーのテントに詰めていた人々

は、それぞれ自分のテントに戻ったり、近くに新しくテントを張ったりして、眠らずに身を寄せ合う。チャーニーの肉体を離れた霊魂が道連れにしようとやって

くるのを防ぐためだ。そして、縁遠かった人々が、あるいは遺体を守り、あるいは食事や薪を遺族たちに配ってまわる。夕方にはチャーニーにとってもっとも最

遠い四人の男が遺体を教会堂に運び、ミサの後に埋葬に当たった。参列者が全員で土をかけてあげた」(原 1989:369)。

※【コメント】チャーニーが死期を悟り、ある意味でみんなが期待するタイミングにあわせて逝くのは、ある意味で「死者になる人の能力」ということもでき

る。瀕死のものは死者になってもまた、そのようなポテンシャルをもっている。なぜなら、生きている者たちは、見寄せて霊魂が道連れにされないように「予防

行動」をとるからである。

■「深い遊び(Deep play)」がなぜ論文として優れているのか?

A:バリ島人の動物嫌悪が、闘鶏の現場においてなぜ男性(性)/男性アイデンティティと見事なまでに同一化するのか?

B:ゲームに深く没入できる人たちには、自らの埋め込み、のめり込むことで、「文化における主体」を生きることができる。

C:その経験が他者(他の文化を担う外来者)が、バリ文化に解釈をとおして没入し、理解・経験することができる。

D:また、その解釈と身体経験の共有が、他者であるバリ島人からの承認を得て、その社会に加入(=文化構造に没入)することができる。

E:動物は、バリ島の文化理解のための解読格子であるが、単なる媒介以上の意味をもつ。

■バリ島における犬嫌悪(バリの動物観を含む)

「動物的と見なされる行為に対するバリ人の嫌悪はかなり強いものである。赤ん坊はこのため這うことができない。近親相姦はほとんど認められていないが、そ

れでも獣姦よりも軽罪である。(獣姦に対する処罰は溺死であるが、近親相姦に対するそれは動物のような生活の強制である。)たいていの悪魔は彫刻、踊り、

儀礼、神話において現実の、あるいは空想の動物の姿をとって表わされている。思春期における主要な儀礼では、子供の歯が動物の牙のようになるのを防ぐた

め、歯にやすりをかける。排池行為ばかりでなく食事行為も、動物性との間遠から嫌悪すべきもの、ほとんど淫らな行為と見なされ、急いでこっそりと済ますべ

きものとされている。転ぶことや、無器用な仕草までこういた理由から悪と見なされる。雄鶏と、牛やアヒルなどのバリ人の情緒としてはあまり意味をもたない

幾つかの少数の家畜を除いて、バリ人は動物を嫌悪し、たくさんの犬に冷淡なだけでなく、恐ろしく犬を残酷に扱っている。雄鶏と一体になることによってバリ

の男は、理想の自分や自分のペニスばかりでなく、同時に彼が最も恐れ憎み、また愛憎のまじった存在であるがために魅了されている力、「暗闇のカ」と一体化

しているのである」。(ギアーツ「ディーププレイ」Pp.400-401;『文化の解釈学 II』吉田禎吾ほか訳、岩波書店、1987年)

”The Balinese revulsion against any behavior regarded as animal-like

can hardly be overstressed. Babies are not allowed to crawl for that

reason. lncest, though hardly approved, is a much less horrifying crime

than bestiality. (The appropriate punishment for the second is death by

drowning, for the first being forced to live like an animal. 8) Most

demons are represented - in sculpture, dance, ritual, myth - in some

real or fantastic animal form. The main puberty rite consists in filing

the child's teeth so they will not look like animal fangs. Not only

defecation but eating is regarded as a disgusting, almost obscene

activity, to be conducted hurriedly and privately, because of its

association with animality. Even falling down or any form of clumsiness

is considered to be bad for these reasons. Aside from cocks and a few

domestic animals - oxen, ducks - of no emotional significance, the

Balinese are aversive to animals and treat their large number of dogs

not merely callously but with a phobic cruelty. In identifying with his

cock, the Balinese man is identifying not just with his ideal self, or

even his penis, but also, and at the same time, with what he most

fears, hates, and ambivalence being what it is, is fascinated by - The

Powers of Darkness." ( Deep Play, by C. Geertz)

8 An incestuous couple is forced to wear pig yokes over their necks and

crawl to a pig trough and eat with their mouths there. On this, see

Jane Relo. "Customs Pertaining to Twins in Bali," in Belo, ed.,

Traditional Balinese Culture, 49; on the abhorrence of animality

generally, Bateson and Mead, Balinese Character, 22.

060■Wynne-Edwards (1963)の嬰児殺し慣行の適応的解釈をめぐって

・テリトリーを守ることは「適応」と解釈する。なぜ

なら、(動物タンパクなどの)資源を直接求める争いに変わって、空間および社会的地位をめぐる競争がお

こなわれる。

・競争がおこなわれる単位として、淘汰は個人あるいはグループ(全体に?)好都合な方策になる。

・流産、嬰児殺し、性交禁止は出生力をコントロールする方法であるというCarr-Saunders の説を、ウィン=エドワーズは流用する。

・ウィン=エドワーズによると、このようなコントロール手段が有効なのは、利用できる資源が稀少な、狩猟採集民の環境だと言い、ブッシュマンの例をあげ

る。そこでは嬰児殺しや、乳児でもおこなわれたと主張。(「資源が稀少」→これは生態人類学者・田中二郎の主張と異なる)。

・そのためウィン=エドワーズは、農耕革命がおこった後は、嬰児殺しという人口調節方法が放棄されるようになったという。

・D・F・オーウェンが批判するように(オーウェン

1975:264)が批判するように、ウィン=エドワーズの説は、なぜ、人口調節の慣行が消失していったのかを上手に説明できない——人口調節の「必要」

がなくなったことが、慣行を「放棄」することについての説得的議論がないという点である。

・オーウェンは、ブッシュマンが子どもを意図的に「殺す」ということを自覚しておらず「子どもを見捨てる」という説明のもとで、子どもの運命が超自然に委

ねられるとブッシュマンが説明するからに他ならないという。

[文献]

- Carr-Saunders, A.M., 1922. The Population problem: a study in human

evolution. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Wynne-Edward, V.C., 1963. Intragroup selection in the evolution of

social systems. Nature, 200:623-626.

- オーウェン,D.F., 1975. 『人類生態学入門:熱帯アフリカにおける人間の生態』鈴木継美ほか訳、東京:白日社。(Owen,

Denis Frank., 1973. Man's environmental predicament : an introduction

to human ecology in tropical Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press.)

060■出生率のコントロールの歴史的変遷に関する批判的位相

・植民地期:医療問題(疫学的問題):熱帯病対策

・植民地期末期、独立期:人口問題から出生率制御、産児調整、家族計画

・女性の権利問題の浮上:ウィメンズ・ヘルス

・出生をめぐる安全や人権問題の浮上:リプロダクティブ・ヘルス

061■動物のライフサイクルについては、考えられているのか?

・動物は歳を食うのか? どのように死んでゆくの

か?

・動物の死後観、終末観(escatology)について

・動物に対して、そのような意識をもつ人たちの、今度は人間関係についての幼年期や老年期あるいは死についての考え方について

062■スティーブン・ピンカーの「よい天使」テーゼ(2011)

・大量虐殺などの報道を見聞きして杞憂している現在

の人類に対して、人類史からみれば人間集団は確実に暴力やそれに伴う殺人を犯す頻度は低下していると主

張。ピンカーは、その理由を人類の平和化、文明化のプロセスとして位置づけている。これをピンカーの広闊な書名「The better angels

of our nature : why violence has declined / Steven Pinker, New York:

Viking, 2011」に因んで、ピンカーの「よい天使」テーゼ(2011)と読んでもよいだろう。

063■先天障害、奇形、虚弱児の殺害の理由

・機能論で説明する以外の、幼児殺し、おもに先天障

害、奇形、虚弱児の殺害の理由として考えられるのは、彼らの民族育児科学(ethno-

pediatrics)的説明である。すなわち、医療的措置等で延命が望めず、実際に若齢で死んでいく子どもに関するライフサイクル上の情報についての蓄

積(=伝承、慣行、長老や専門家の知識等)があれば、それを前倒しで「実行」する。このことに対して、感情的逡巡が生じないように、文化的態度として、障

害をもった嬰児には殺害すべし、殺害にはいかなる意味においても罪は生じない、あるいは彼らの「理に叶っている」ためにそうすべきだとという「道徳観」が

パラレルに生じることがみられると予想される。

064■定住化政策と基本保健サービスの提供で劇的に変化?

・定住化政策と基本保健サービスの提供で、嬰児殺

し、障害者の生存危機、老人遺棄等は、劇的に変化した可能性がある(Hill and Hurtado

1996:157)。

[文献]Aché life history : the ecology and demography of a foraging people

/ Kim Hill and A. Magdalena Hurtado, New York:Aldine de Gruyter (1996).

065■偶然が支配する生きのびることの可能性

・アチェ(パラグアイの先住民)の民族誌を読んでい

ると、過酷な生存環境の中で、嬰児殺し、虚弱児の放棄、老人遺棄、病者の生き埋めなどが、それほど、残

虐な制度とは思えなくなってくる。もっとも面白いのは、そのようななかでもしぶとく生存する機会を享受したりタフに生きのびている人たち——毒蛇に噛まれ

て足がなくなった子どもをおんぶして移動する親がいたり、生き埋めにした老人が穴から這い出して来て助かる例など——のエピソード聞くたびに、俺たちが今

生きていることも偶然のチャンスの結果にすぎないということを逆に自覚させてくれる点なのである。http:

//ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA30468184

[文献]Aché life history : the ecology and demography of a foraging people

/ Kim Hill and A. Magdalena Hurtado, New York:Aldine de Gruyter (1996).

・上記はヒルとウルタドの民族誌だが、ピエール・クラストルの表現はもっと、行為者たちの視座に根ざしたものだ。また表現が文学的技巧にみちている——

「ワタ・クワ・イアン(彼女はもう歩けない)と。それが何を意味するのは皆は理解するだろう」[クラストル 2007:120]

・クラストルが描写する、彼女(=チャチュワイミギ)のケースは興味深く、彼女が斧で撃ち殺されんとした時に、ジャガー(これはアチェ自身でもある)が森

からあらわれてバンドのメンバーを襲撃しようとした時に、混乱のあげく、彼女がジャガーの餌食になるという描写のシーンがある。この中には、彼女を斧で殺

害しなければならない役割——ヒルらの民族誌(Hill and Hurtado

1996:236-237)にも老婆の殺害を逡巡する彼らの気持ちが表現されているものがある——時に、ジャガーに殺されることで、その苦役から逃れられ

るという気持ちと、ジャガーそのものがアチェであるという民族誌的な解釈が織り交ぜられる「厚い記述」になっているからだ。

066■進化学的説明は、妥当な解釈や「厚い記述」ではなく、パラメーターを単純にして、計算後あるいは現象的エビデンスを求める

・説明の原理の記号学的理解

067■「氏か育ちか」の解説——ウィキペディア英語の解説:https:

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nature_versus_nurture

The

phrase nature and nurture relates to the

relative importance of an individual's innate qualities ("nature" in

the sense of nativism or innatism) as compared to an individual's

personal experiences ("nurture" in the sense of empiricism or

behaviorism) in causing individual differences, especially in

behavioral traits. The alliterative expression "nature and nurture" in

English has been in use since at least the Elizabethan period[1] and

goes back to medieval French.[2] The combination of the two concepts as

complementary is ancient (Greek: ἁπό φύσεως καὶ εὐτροφίας[3]).

The phrase in its modern sense was popularized by

the English Victorian polymath Francis Galton, the modern founder of

eugenics, in discussion of the influence of heredity and environment on

social advancement.[4][5] Galton was influenced by the book On the

Origin of Species written by his half-cousin, Charles Darwin.

The view that humans acquire all or almost all their

behavioral traits from "nurture" was termed tabula rasa ("blank slate")

by John Locke in 1690. A "blank slate view" in human developmental

psychology assuming that human behavioral traits develop almost

exclusively from environmental influences, was widely held during much

of the 20th century (sometimes termed "blank-slatism"). The debate

between "blank-slate" denial of the influence of heritability, and the

view admitting both environmental and heritable traits, has often been

cast in terms of nature versus nurture. These two conflicting

approaches to human development were at the core of an ideological

dispute over research agendas during the later half of the 20th

century. As both "nature" and "nurture" factors were found to

contribute substantially, often in an extricable manner, such views

were seen as naive or outdated by most scholars of human development by

the 2000s.[6]

In their 2014 survey of scientists, many respondents

wrote that the dichotomy of nature versus nurture has outlived its

usefulness, and should be retired. The reason is that in many fields of

research, close feedback loops have been found in which "nature" and

"nurture" influence one another constantly (as in self-domestication),

while in other fields, the dividing line between an inherited and an

acquired trait becomes unclear (as in the field of epigenetics[7] or in

fetal development).[8][9]

- Rreference

-[1] In English at least since Shakespeare (The

Tempest 4.1: a born devil, on whose nature nurture can never stick) and

Richard Barnfield (Nature and nurture once together met / The soule and

shape in decent order set.); in the 18th century used by Philip Yorke,

1st Earl of Hardwicke (Roach v. Garvan, "I appointed therefore the

mother guardian, who is properly so by nature and nurture, where there

is no testamentary guardian.")

-[2]English usage is based on a tradition going back

to medieval literature, where the opposition of nature ("instinct,

inclination") norreture ("culture, adopted mores") is a common motif,

famously in Chretien de Troyes' Perceval, where the hero's effort to

suppress his natural impulse of compassion in favor of what he

considers proper courtly behavior leads to catastrophe. Norris J. Lacy,

The Craft of Chrétien de Troyes: An Essay on Narrative Art, Brill

Archive, 1980, p. 5.

-[3]in Plato's Protagoras 351b; an opposition is

made by Protagoras' character between art on one hand and constitution

and fit nurture (nature and nurture) of the soul on the other, art (as

well as rage and madness; ἀπὸ τέχνης ἀπὸ θυμοῦ γε καὶ ἀπὸ μανίας)

contributing to boldness (θάρσος), but nature and nurture combine to

contribute to courage (ἀνδρεία). "Protagoras, in spite of the misgiving

of Socrates, has no scruple in announcing himself a teacher of virtue,

because virtue in the sense by him understood seems sufficiently

secured by nature and nuture." R. W. Mackay, "Introduction to the Meno

in comparison with the Protagoras", Meno: A Dialogue on the Nature and

Meaning of Education (1869), p. 138.

-[4]Proceedings, Volume 7. Royal Institution of

Great Britain. 1875. Sir Francis Galton (1895). English Men of Science:

Their Nature and Nurture. D. Appleton.

-[5]David Moore (2003). The Dependent Gene: The

Fallacy of "Nature Vs. Nurture". Henry Holt and Company.

-[6]see e.g. Moore, David S. (2003). The Dependent

Gene: The Fallacy of Nature Vs. Nurture, Henry Holt. ISBN

978-0805072808 Esposito, E. A., Grigorenko, E.L., & Sternberg, R.

J. (2011). The Nature-Nurture Issue (an Illustration Using

Behaviour-Genetic Research on Cognitive Development). In Alan Slater,

& Gavin Bremner (eds.) An Introduction to Developmental Psychology:

Second Edition, BPS Blackwell.:85 Dusheck, Jennie, The Interpretation

of Genes. Natural History, October 2002 Carlson, N.R. et al.. (2005)

Psychology: the science of behaviour (3rd Canadian ed) Pearson Ed. ISBN

0-205-45769-X Ridley, M. (2003) Nature via Nurture: Genes, Experience,

& What Makes Us Human. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-200663-4 Westen,

D. (2002) Psychology: Brain, Behavior & Culture. Wiley & Sons.

ISBN 0-471-38754-1

-[7]Moore, David S. (2015). The Developing Genome:

An Introduction to Behavioral Epigenetics (1st ed.). Oxford University

Press. ISBN 9780199922345.

-[8]Edge.org: Nature Versus Nurture, accessed

01/25/2014

Time to Retire The Simplicity of Nature vs. Nurture by Alison Gopnik,

"Mind and Matter", published 01/25/2014, WSJ

068■リチャード・ローティ『哲学と自然の鏡』の解説(ウィキペディア・日本語)

「表題にある自然の鏡とは近代哲学における心、すな

わち視覚的メタファーを意味している。自然を忠実に映し出す心という視覚的なメタファーは知識、真理、

二元論、主観と客観の図式を哲学の研究においてもたらしてきた。デカルト、ロック、カントなどが論じたような近代哲学の認識論は知識の妥当性を基礎付ける

役割を担っており、ローティはこの役割を文化的監督官と呼んでいる。近代哲学が担ってきたこの役割は本来無意味なものであることをローティは指摘し、論理

実証主義の立場から研究されてきた言語哲学すらも同様に基礎付け主義の一種であると論じる。ここでローティはプラグマティズムの哲学を導入し、認識活動を

社会的実践として把握することによって、「プラグマティズム的転回」を提唱する。このことによって、哲学は完全かつ究極的な認識の合致を追及するものでは

なく、新しい生のあり方をもたらす会話として成立する。ローティは基礎付け主義という役割が終わることで「ポスト哲学的な文化」が成立するであろうと考え

ている」。http://bit.ly/1WxqJQv

[文献]

・Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, (Princeton University Press,

1979):野家啓一監訳 『哲学と自然の鏡』(産業図書, 1993年)

069■利他行動の進化論的解決を「老人殺し」に適応できるか?

・「……報復的な正義が倫理上よしとされる理由の一

部は、調停者の自己利益のためである。しかし、それ以上に、復讐において厳密に平等であることは、しば

しば、復讐者自身に最大の利益をもたらすようだ。やられたことと同じことをやり返すことの冷めた満足感は、すなわち、結局のところ、社会的交換に特化した

進化アルゴリズムを反映している。そう考える理由は、潜在的には競争者であるような個人の間に協力が生まれるかどうかという問題を論じた、最近のロバー

ト・アクセルロッドとW ・D・ハミルトンの理論的研究にある」(デイリーとウィルソン 1999:372-373)。

・「自然淘汰によって作られた社会における「利他行動の問題」は、ハミルトン(1964)の「包括適応度」の理論によっておおかたは解決された。これは、

行為者の表現型や繁殖の見通しに対して負の影響をもたらすような行動傾向も、それが血縁者に向けられたものであるならば、進化しうるという理論である。し

かし、血縁者でなくても、血縁者どうしほどの固い結束ではなく、もろいものではあっても、協力することはできる。自己利益のために相手を裏切る機会がある

にもかかわらず、そのような協力行動は、どうやって進化できるのだろうか? この問題の本質は、「囚人のジレンマ」と呼ばれるゲームによく表されている」

(デイリーとウィルソン 1999:373)。

《文献》

・人が人を殺すとき : 進化でその謎をとく / マーティン・デイリー, マーゴ・ウィルソン著 ; 長谷川眞理子, 長谷川寿一訳,東京 :

新思索社 , 1999( Homicide / Martin Daly, Margo Wilson,New York :A. de

Gruyter , c1988. - (Foundations of human behavior))

078■包括適応度(Inclusive fitness)

「適応度(fitness)をある個体の子孫だけで なくその親族、あるいは同じ対立遺伝子を持つ可能性のある他個体にまで広げたものを包括適応度と言う。 社会性行動の進化を扱うさいには包括適応度を用いなければならない。この場合は通常、子にも包括適応度における血縁度の計算が適用される(有性生殖では子 の遺伝的価値は親の半分であり、親子の進化的対立の原因である)。包括適応度は遺伝的適応度の概念の一つであり、包括適応度を個体の数で計算すると混乱の 原因となる。包括適応度の上昇はある社会行動の効果に対して用いられる。例えば自分が親族を助けたことでその親族が多くの子を残した場合、自分の「利他行 動に関する対立遺伝子」の包括適応度が上昇する。全く別の地域に移住し相互作用できなくなった親族が子を産んでも自分の包括適応度が上昇したことにはなら ない。/適応度の概念を提唱し、数学的なモデルとして構築したのは集団遺伝学者ロナルド・フィッシャー、J・B・S・ホールデン、シューアル・ライトらで あった。W.D.ハミルトンはこれを拡張して包括適応度を提唱した。さらに後年、G.プライスの共分散則を取り入れて、包括適応度を親族以外にも適用でき る概念へと拡張した」。——ウィキペディア(日本語)「適応度」http://bit.ly/1nFMRvM

"In evolutionary

biology inclusive fitness theory is a model for the

evolution of social behaviors (traits), first set forward by W. D.

Hamilton in 1963 and 1964. Instead of a trait's frequency increase

being thought of only via its average effects on an organism's direct

reproduction, Hamilton argued that its average effects on indirect

reproduction, via identical copies of the trait in other individuals,

also need to be taken into account. Hamilton's theory, alongside

reciprocal altruism, is considered one of the two primary mechanisms

for the evolution of social behaviors in natural species./ From the

gene's point of view, evolutionary success ultimately depends on

leaving behind the maximum number of copies of itself in the

population. Until 1964, it was generally believed that genes only

achieved this by causing the individual to leave the maximum number of

viable direct offspring. However, in 1964 W. D. Hamilton showed

mathematically that, because other members of a population may share

identical genes, a gene can also increase its evolutionary success by

indirectly promoting the reproduction and survival of such individuals.

The most obvious category of such individuals is close genetic

relatives, and where these are concerned, the application of inclusive

fitness theory is often more straightforwardly treated via the narrower

kin selection theory." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inclusive_fitness

079■数式にみる包括適応度(I)

・(利他行動にかかわる)遺伝子が共有される確率=

血縁度(r)と、利他行動の受益者の古典的適応度の増加分(B)を掛けた値が、利他個体の古典的適応度

の減少分(C)を上回れば、利他行動は進化しうる—— rB > C。(これはハミルトン則のことか?)

・もっと単純にすると、B/C > 1/r ゆえに、rBーC>0

・包括適応度(I)は、ある個体(A)が本来もっていた古典的適応度Wo(A)から、その個体が血縁個体と交渉することにより減少させた自らの適応度

△WAを差し引き、さらに、それにより血縁個体に生じた遺伝的利益の総和ΣWiriを加えたもの。

・もし、血縁個体どうしの相互作用が一切なければ、包括適応度は古典的適応度に等しい。

080■ESSの解説

「進化的に安定な戦略(しんかてきにあんていなせん

りゃく、ESS:evolutionarily stable