Associationism is the idea that mental processes operate by the association of one mental state with its successor states.[1]

It holds that all mental processes are made up of discrete

psychological elements and their combinations, which are believed to be

made up of sensations or simple feelings.[2] In philosophy, this idea

is viewed as the outcome of empiricism and sensationism.[3] The concept

encompasses a psychological theory as well as comprehensive

philosophical foundation and scientific methodology.[2]

|

アソシエイション主義(観念連合論)とは、ある精神状態とその後継状態との関連付けによって精神過程が作動するという考え方である[1]。

すべての精神過程は個別の心理的要素とその組み合わせによって構成されているとし、それらは感覚や単純な感情によって構成されていると考えられている

[2]。哲学においては、この考え方は経験主義と感覚主義の成果とみなされている[3]。この概念は心理学理論だけでなく、包括的な哲学的基礎と科学的方

法論を包含している[2]。

|

History

Early history

The idea is first recorded in Plato and Aristotle, especially with

regard to the succession of memories. Particularly, the model is traced

back to the Aristotelian notion that human memory encompasses all

mental phenomena. The model was discussed in detail in the

philosopher's work, Memory and Reminiscence.[4] This view was then

widely embraced until the emergence of British associationism, which

began with Thomas Hobbes.[4]

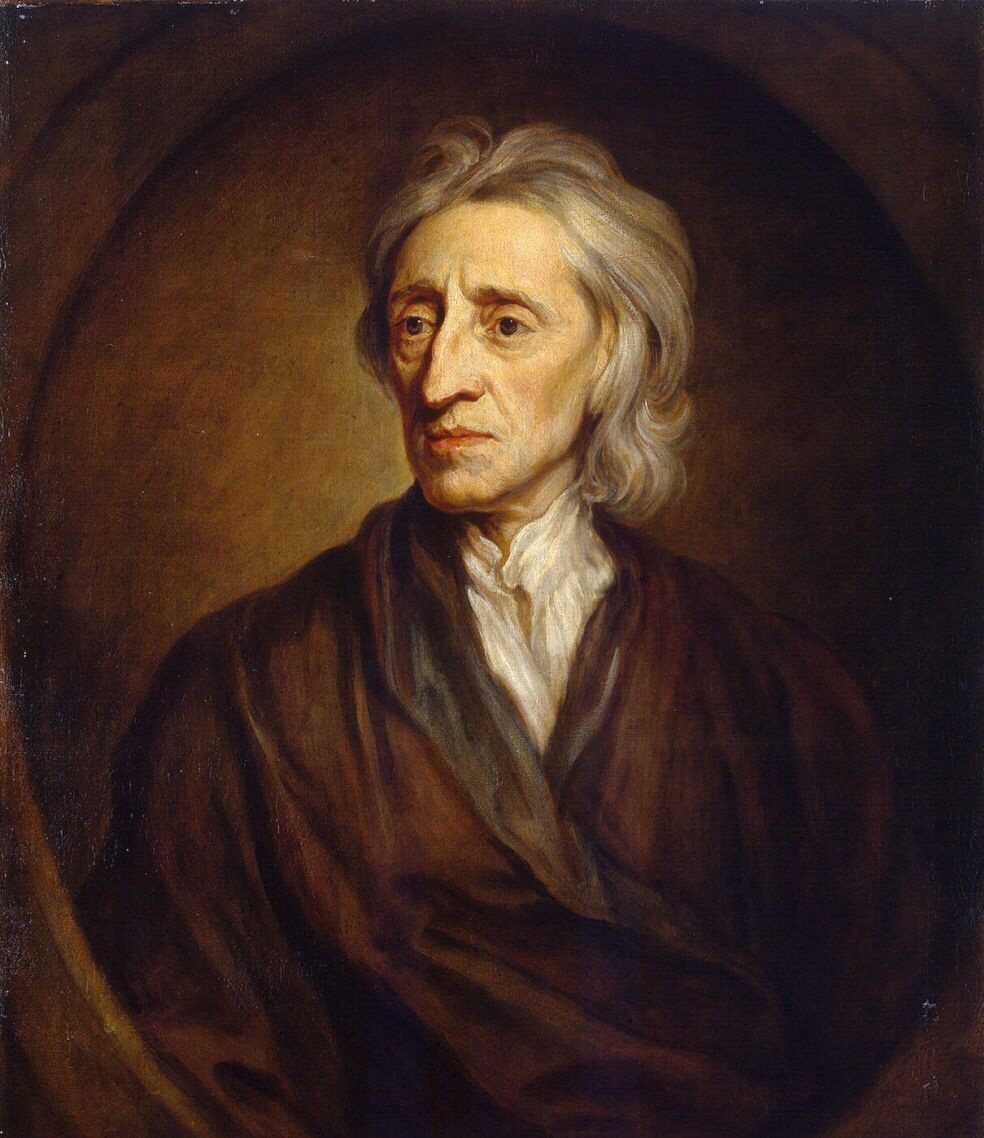

John Locke was the first person to use the phrase association of ideas

Associationist School

Members of the Associationist School, including John Locke, David Hume,

David Hartley, Joseph Priestley, James Mill, John Stuart Mill,

Alexander Bain, and Ivan Pavlov, asserted that the principle applied to

all or most mental processes.[5]

John Locke

The phrase "association of ideas" was first used by John Locke in 1689.

In chapter 33 of An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, which is

entitled “Of the Association of Ideas″, he describes the ways that

ideas can be connected to each other.[6] He writes,

"Some of our ideas have a natural correspondence and connection with one another."[7]

Although he believed that some associations were natural and justified,

he believed that others were illogical, causing errors in judgment. He

also explains that one can associate some ideas together based on their

education and culture, saying, "there is another connection of ideas

wholly owing to chance or custom".[6][7] The term associationism later

became more prominent in psychology and the psychologists who

subscribed to the idea became known as "the associationists".[6]

Locke's view that the mind and body are two aspects of the same unified

phenomenon can be traced back to Aristotle's ideas on the subject.[8]

|

歴史

初期の歴史

この考え方は、プラトンとアリストテレスに、特に記憶の継承に関して初めて記録されている。特に、このモデルは、人間の記憶はすべての精神現象を包含する

というアリストテレスの概念にまで遡る。このモデルは哲学者の著作である『記憶と追憶』において詳細に論じられている[4]。この見解はその後、トマス・

ホッブズに始まるイギリスの連合主義の出現まで広く受け入れられていた[4]。

ジョン・ロックが初めて連想という言葉を使った人格である。

連合主義学派

ジョン・ロック、デイヴィッド・ヒューム、デイヴィッド・ハートリー、ジョセフ・プリーストリー、ジェームズ・ミル、ジョン・スチュアート・ミル、アレク

サンダー・ベイン、イワン・パブロフを含む連合主義学派のメンバーは、この原理がすべての、あるいはほとんどの精神過程に適用されると主張していた

[5]。

ジョン・ロック

観念の連合」という言葉は、1689年にジョン・ロックによって初めて使われた。人間理解に関する試論』の第33章「観念の連合について」の中で、彼は観念が互いに結びつく方法について述べている[6]、

「われわれの観念のなかには、互いに自然な対応と結びつきをもつものがある」[7]。

彼は、いくつかの関連付けは自然で正当なものであると信じていたが、他のものは非論理的であり、判断の誤りを引き起こすと信じていた。彼はまた、人は教育

や文化に基づいていくつかの考えを結びつけることができると説明し、「偶然や習慣に完全に起因する考えの別の結びつきがある」と述べている[6][7]。

連想主義という用語は後に心理学において顕著になり、この考えを支持する心理学者は「連想主義者」として知られるようになった[6]。 |

David Hume

In his 1740 book Treatise on Human Nature David Hume outlines three

principles for ideas to be connected to each other: resemblance,

continuity in time or place, and cause or effect.[9] He argues that the

mind uses these principles, rather than reason, to traverse from idea

to idea.[6] He writes “When the mind, therefore, passes from the idea

or impression of one object to the idea or belief of another, it is not

determined by reason, but by certain principles, which associate

together the ideas of these objects, and unite them in the

imagination.”[9] These connections are formed in the mind by

observation and experience. Hume does not believe that any of these

associations are “necessary’ in a sense that ideas or object are truly

connected, instead he sees them as mental tools used for creating a

useful mental representation of the world.[6]

Later members

Later members of the school developed very specific principles

elaborating how associations worked and even a physiological mechanism

bearing no resemblance to modern neurophysiology.[10] For a fuller

explanation of the intellectual history of associationism and the

"Associationist School", see Association of Ideas.

|

デイヴィッド・ヒューム

デイヴィッド・ヒュームは1740年の著書『人間本性論』の中で、観念が互いに結びつくための3つの原理、すなわち類似性、時間または場所における連続

性、原因または結果について概説している。[それゆえ、心がある対象の観念や印象から別の対象の観念や信念に移るとき、それは理性によって決定されるので

はなく、これらの対象の観念を結びつけ、想像の中でそれらを一体化させるある原理によって決定される」[9]と書いている。ヒュームはこれらの結びつき

が、観念や対象が本当に結びついているという意味で「必要な」ものだとは考えておらず、その代わりに、世界の有用な心的表現を作り出すために用いられる心

的道具であると考えている[6]。

後のメンバー

この学派の後のメンバーは、連想がどのように機能するかを精緻に説明する非常に具体的な原理を開発し、現代の神経生理学とは似ても似つかない生理学的なメカニズムまで開発した[10]。

|

Applications

Associationism is often concerned with middle-level to higher-level

mental processes such as learning.[8] For instance, the thesis,

antithesis, and synthesis are linked in one's mind through repetition

so that they become inextricably associated with one another.[8] Among

the earliest experiments that tested the applications of

associationism, involve Hermann Ebbinghaus' work. He was considered the

first experimenter to apply the associationist principles

systematically, and used himself as subject to study and quantify the

relationship between rehearsal and recollection of material.[8]

Some of the ideas of the Associationist School also anticipated the

principles of conditioning and its use in behavioral psychology.[5]

Both classical conditioning and operant conditioning use positive and

negative associations as means of conditioning.[10]

|

応用

連想主義は、学習のような中程度から高次レベルの精神過程を扱うことが多い。[8]

例えば、正論、反論、総合は、反復によって人の心の中で結びつけられ、互いに不可分に関連付けられるようになる。[8]

連想主義の応用を検証した最も初期の実験の一つに、ヘルマン・エビングハウスの研究がある。彼は連想主義の原理を体系的に応用した最初の実験者とされ、自

らを被験者として、復習と記憶内容の想起との関係を研究・定量化した。[8]

連想主義学派のいくつかの考え方は、条件付けの原理とその行動心理学への応用を先取りしていた。[5] 古典的条件付けとオペラント条件付けの双方が、条件付けの手段として正の連想と負の連想を用いる。[10]

|

Calculus of relations

Connectionism

Family resemblance

Prototype theory

|

関係計算

コネクショニズム

家族的類似性

プロトタイプ理論

|

1. Perler, Dominik (2015). The Faculties: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 256. ISBN 9780199935253.

2. Bailey, Richard (2018-02-06). Education in the Open Society - Karl Popper and Schooling. Routledge. ISBN 9781351726481.

3. Banerjee, J.C. (1994). Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Psychological

Terms. New Delhi: M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 19. ISBN 818588028X.

4. Anderson, John R.; Bower, G. H. (2014). Human Associative Memory. New York: Psychology Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781317769880.

5. Boring, E. G. (1950) "A History of Experimental Psychology" New York, Appleton-Century-Crofts

6. Warren, Howard C. (1921). A History Of The Association Psychology. Universal Digital Library. Charles Scribner's Sons.

7. Locke, John (2000). An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Infomotions, Inc. OCLC 927360872.

8. Sternberg, Robert (1999). The Nature of Cognition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. p. 69. ISBN 9780262692120.

9. Hume, David (1739-01-01), Nidditch, P. H; Selby-Bigge, Sir Lewis

Amherst (eds.), "A Treatise of Human Nature", David Hume: A Treatise of

Human Nature (Second Edition), Oxford University Press,

doi:10.1093/oseo/instance.00046221, ISBN 978-0-19-824587-2

10. Pavlov, I.P. (1927, 1960) "Conditioned Reflexes" New York, Oxford (1927) Dover (1960)

|

1. パーラー、ドミニク(2015)。『学部の歴史』。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。p. 256。ISBN 9780199935253。

2. ベイリー、リチャード(2018-02-06)。『開かれた社会における教育 - カール・ポッパーと学校教育』。ラウトレッジ。ISBN 9781351726481。

3. バナージー、J.C.(1994)。『心理学用語百科事典』。ニューデリー:M.D.パブリケーションズ社。p. 19。ISBN 818588028X。

4. アンダーソン、ジョン・R.;バワー、G. H.(2014)。人間の連想記憶。ニューヨーク:サイコロジー・プレス。16頁。ISBN 9781317769880。

5. ボリング、E. G. (1950) 「実験心理学の歴史」ニューヨーク、アップルトン・センチュリー・クロフツ

6. ウォーレン、ハワード・C. (1921). 連想心理学の歴史。ユニバーサル・デジタル・ライブラリー。チャールズ・スクリブナーズ・サンズ社。

7. ロック、ジョン(2000年)。『人間知性論』。インフォモーションズ社。OCLC 927360872。

8. スターンバーグ、ロバート(1999年)。『認知の本質』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:MITプレス。69頁。ISBN 9780262692120。

9. ヒューム、デイヴィッド (1739-01-01), ニディッチ、P. H; セルビー=ビッジ、サー・ルイス・アマースト (編),

「人間本性論」, デイヴィッド・ヒューム: 人間本性論 (第二版), オックスフォード大学出版局,

doi:10.1093/oseo/instance.00046221, ISBN 978-0-19-824587-2

10. パブロフ, イワン・ペトロヴィチ (1927, 1960) 「条件反射」 ニューヨーク, オックスフォード (1927) ドーバー (1960)

|

Further reading

"Associationism in the Philosophy of Mind". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Pre-History of Cognitive Science.

Howard C. Warren (1921). A History Of The Association Psychology. Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved 2010-02-10.

|

関連文献

「心哲学における連想主義」. インターネット哲学百科事典.

認知科学の先史時代.

ハワード・C・ウォーレン (1921). 『連想心理学の歴史』. チャールズ・スクリブナーズ・サンズ社. 2010年2月10日取得.

|

|

|

解

説:池田光穂

解

説:池田光穂