比較優位

(ひかくゆうい)

Comparative

Advantage

比較優位

(ひかくゆうい)

Comparative

Advantage

比較優位(ひかくゆうい, comparative advantage)は、デヴィッド・リカード(David Ricardo, 1772-1823)が提唱した概念で、自由貿易体制では他国より優位な財の生産に集中することで、労働生産性が増え、高品位の財やサービスの提 供を受けれるという現象である。

具体的には、日本では自動車の生産は、機 会費用が少なく収益性を最大化できる自動車の生産拠点があるために、質の良い自動車を比較的安価で購入 することができ、日本製の自動車に乗ることはディーラーや修理品の確保、修理サービスなど、あらゆる点において、他国で日本車を入手し利用するよりも。こ れはウィキペディア(日本語)によると「比較生産費説やリカード理論と呼ばれる学説・理論の柱となる、貿易理論における最も基本的な概念である。アダム・ スミス(Adam Smith, 1723-1790)が提唱した絶対優位(absolute advantage)の概念を柱とする学説・理論を修正する形で提唱された」という。https://goo.gl/J3aCa4

ちなみ、絶対優位(absolute advantage)とは、ある国がべつの国に比べて効率的に財を生産できるということである。生産に必要な投下労働量が他国に比べて小さいということ が、絶対優位ということになる。しかしながら、比較優位とは、異なる2つ以上の財の生産において、「他国より優位な財の生産に集中することで、労働生産性 が増え、高品位の財やサービスの提 供を受けれる」という条件が整えれば、絶対優位の差は克服が可能になることを示す。

★ 比較優位(Comparative advantage)

| Comparative

advantage

in an economic model is the advantage over others in producing a

particular good. A good can be produced at a lower relative opportunity

cost or autarky price, i.e. at a lower relative marginal cost prior to

trade.[1] Comparative advantage describes the economic reality of the

gains from trade for individuals, firms, or nations, which arise from

differences in their factor endowments or technological progress.[2] David Ricardo developed the classical theory of comparative advantage in 1817 to explain why countries engage in international trade even when one country's workers are more efficient at producing every single good than workers in other countries. He demonstrated that if two countries capable of producing two commodities engage in the free market (albeit with the assumption that the capital and labour do not move internationally[3]), then each country will increase its overall consumption by exporting the good for which it has a comparative advantage while importing the other good, provided that there exist differences in labor productivity between both countries.[4][5] Widely regarded as one of the most powerful[6] yet counter-intuitive[7] insights in economics, Ricardo's theory implies that comparative advantage rather than absolute advantage is responsible for much of international trade. |

経済モデルにおける比較優位とは、特定の財を生産する上で

他者に対する優位性を指す。ある財は、相対的な機会費用または自給自足価格、すなわち貿易前の相対的な境界費用が低く抑えられる状態で生産できるのである

[1]。比較優位は、生産要素の賦存量や技術進歩の差異から生じる、個人・企業・国民にとっての貿易利益という経済的現実を説明する概念である。[2] デビッド・リカードは1817年、古典的比較優位理論を確立した。これは、たとえある国の労働者が他の国々の労働者よりもあらゆる財の生産において効率的 であっても、なぜ各国が国際貿易を行うのかを説明するためのものである。彼は、二つの商品を生産できる二つの国が自由市場で取引する場合(資本と労働力が 国際的に移動しないという仮定のもとで[3])、両国間に労働生産性の異なる点が存在すれば、各国は自国に比較優位のある商品を輸出し、他方の商品を輸入 することで総消費量を増大させると示した。[4][5] 経済学において最も強力[6]でありながら直感に反する[7]洞察の一つと広く認められているリカードの理論は、国際貿易の大部分は絶対的優位ではなく比 較優位によって説明されることを示唆している。 |

| Classical theory and David

Ricardo's formulation This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Comparative advantage" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Adam Smith first alluded to the concept of absolute advantage as the basis for international trade in 1776, in The Wealth of Nations: If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it off them with some part of the produce of our own industry employed in a way in which we have some advantage. The general industry of the country, being always in proportion to the capital which employs it, will not thereby be diminished [...] but only left to find out the way in which it can be employed with the greatest advantage.[8] Writing two decades after Smith in 1808, Robert Torrens articulated a preliminary definition of comparative advantage as the loss from the closing of trade: [I]f I wish to know the extent of the advantage, which arises to England, from her giving France a hundred pounds of broadcloth, in exchange for a hundred pounds of lace, I take the quantity of lace which she has acquired by this transaction, and compare it with the quantity which she might, at the same expense of labour and capital, have acquired by manufacturing it at home. The lace that remains, beyond what the labour and capital employed on the cloth, might have fabricated at home, is the amount of the advantage which England derives from the exchange.[9] In 1814 the anonymously published pamphlet Considerations on the Importation of Foreign Corn featured the earliest recorded formulation of the concept of comparative advantage.[10][11] Torrens would later publish his work External Corn Trade in 1815 acknowledging this pamphlet author's priority.[10]  David Ricardo In 1817, David Ricardo published what has since become known as the theory of comparative advantage in his book On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation.[12] |

古典派理論とデビッド・リカードの定式化 この節は検証可能な情報源を要する。信頼できる情報源をこの節に追加 し、記事の改善に協力してほしい。出典のない記述は削除される可能性がある。 出典を探す: 「比較優位」 – ニュース · 新聞 · 書籍 · 学術文献 · JSTOR (2021年7月) (このメッセージの削除方法と時期について) アダム・スミスは1776年、『国民富論』において、国際貿易の基盤としての絶対的優位性の概念に初めて言及した: もし外国が、我々自身が生産するよりも安価に商品を供給できるならば、我々の産業の産出物の一部を、我々に優位性のある方法で用いて、その商品を購入した 方がよい。国の総産業は、それを動かす資本に比例して常に存在するため、それによって減少することはない [...] ただ、最大の利益を得られる方法でそれを活用する方法を模索するだけである。[8] スミスより20年後の1808年、ロバート・トーレンズは比較優位を「貿易閉鎖による損失」として予備的に定義した: もしイングランドがフランスにブロードクロス百ポンドを渡し、レース百ポンドと交換することで生じる利益の規模を知りたければ、この取引で獲得したレース の量を、同じ労働と資本の費用で国内生産した場合に獲得できたであろう量と比較するのだ。布地製造に費やされた労働と資本で国内生産できた量を超える残り のレースこそが、この交換によってイングランドが得る利益の額である。[9] 1814年、匿名で出版された小冊子『外国穀物輸入に関する考察』は、比較優位概念の最も古い記録された定式化を特徴としていた。[10][11] トーレンズは後に1815年に『対外穀物貿易論』を出版し、この小冊子の著者の先駆性を認めている。[10]  デビッド・リカード 1817年、デビッド・リカードは著書『政治経済学及び租税原理』において、後に比較優位理論として知られるようになる理論を発表した。[12] |

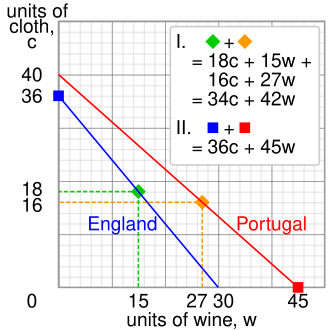

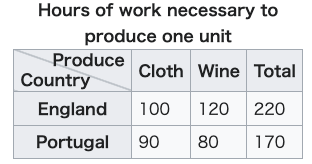

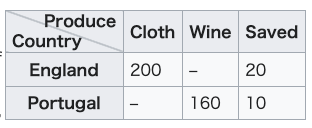

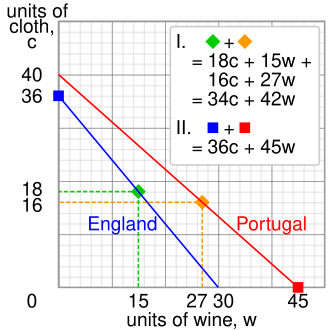

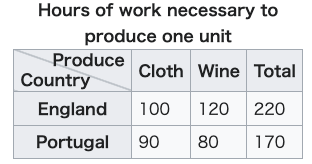

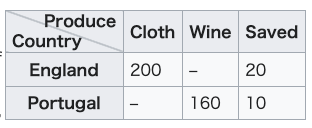

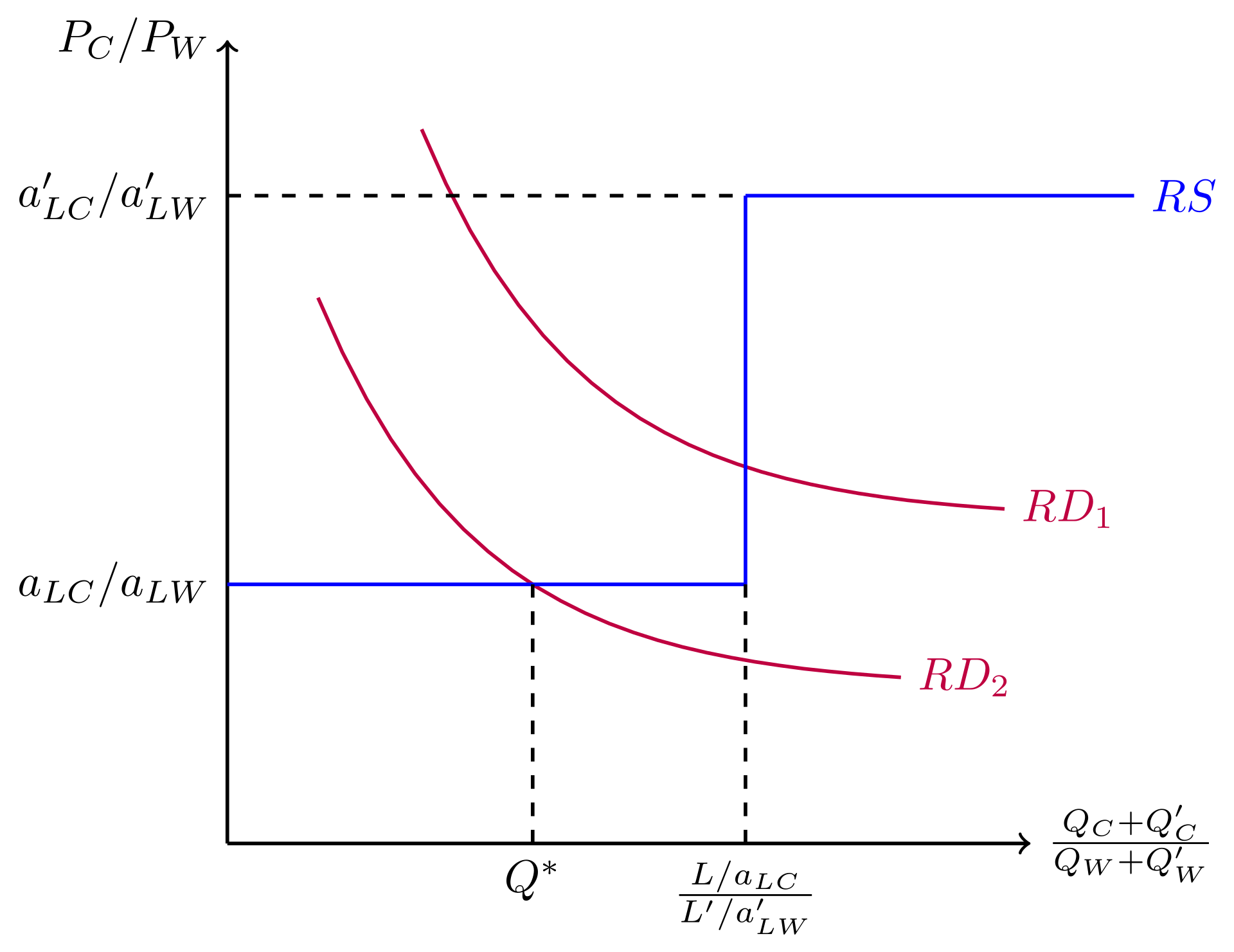

Ricardo's example Graph illustrating Ricardo's example: In case I (diamonds), each country spends 3600 hours to produce a mixture of cloth and wine. In case II (squares), each country specializes in its comparative advantage, resulting in greater total output. In a famous example, Ricardo considers a world economy consisting of two countries, Portugal and England, each producing two goods of identical quality. In Portugal, the a priori more efficient country, it is possible to produce wine and cloth with less labor than it would take to produce the same quantities in England. However, the relative costs or ranking of cost of producing those two goods differ between the countries. Hours of work necessary to produce one unit   In the absence of trade, England requires 220 hours of work to both produce and consume one unit each of cloth and wine while Portugal requires 170 hours of work to produce and consume the same quantities. England is more efficient at producing cloth than wine, and Portugal is more efficient at producing wine than cloth. So, if each country specializes in the good for which it has a comparative advantage, then the global production of both goods increases, for England can spend 220 labor hours to produce 2.2 units of cloth while Portugal can spend 170 hours to produce 2.125 units of wine. Moreover, if both countries specialize in the above manner and England trades a unit of its cloth units of Portugal's wine, then both countries can consume at least a unit each of cloth and wine, with 0 to 0.2 units of cloth and 0 to 0.125 units of wine remaining in each respective country to be consumed or exported. Consequently, both England and Portugal can consume more wine and cloth under free trade than in autarky. |

リカードの例 リカードの例を示す図: ケースI(ひし形)では、各国が布とワインの混合生産に3600時間を費やす。 ケースII(四角形)では、各国が比較優位分野に特化することで総生産量が増加する。 有名な例として、リカードはポルトガルとイングランドの二国からなる世界経済を考察する。両国は同品質の二品目を生産する。ポルトガルでは、ア・プリオリ により効率的とされる国であり、イングランドで同量を生産するのに必要な労働力より少ない労力で布とワインを生産できる。しかし、両国間でこれらの二つの 財を生産する相対的なコスト、あるいはコストの順位は異なる。 1単位を生産するのに必要な労働時間   貿易がない場合、イングランドは布とワインをそれぞれ1単位ずつ生産し消費するのに220時間の労働を要する。一方ポルトガルは同じ量を生産し消費するの に170時間の労働で済む。イングランドは布の生産においてワインより効率的であり、ポルトガルはワインの生産において布より効率的である。したがって、 各国が比較優位を持つ財を専門化すれば、両財の世界的な生産量は増加する。イングランドは220労働時間で2.2単位の布を生産でき、ポルトガルは170 時間で2.125単位のワインを生産できるからだ。さらに、両国が上記のように分業し、イングランドが自国の布1単位と引き換えにポルトガルのワイン 0.25単位を取引する場合、両国は少なくとも布とワインをそれぞれ1単位ずつ消費できる。そして、各国内には消費または輸出可能な布0~0.2単位とワ イン0~0.125単位が残る。結果として、自由貿易下では自給自足時よりもイングランドとポルトガル双方がより多くのワインと布を消費できる。 |

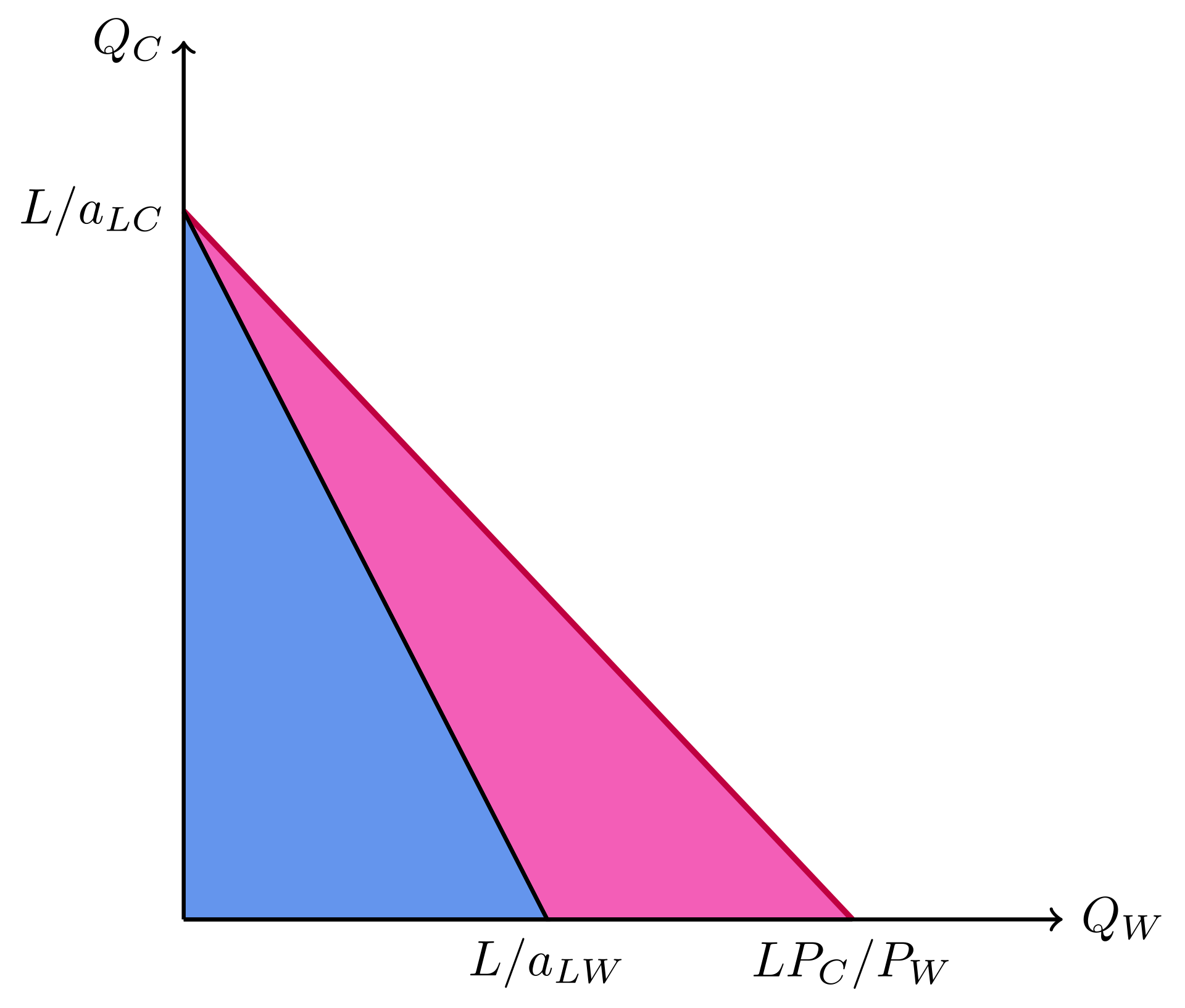

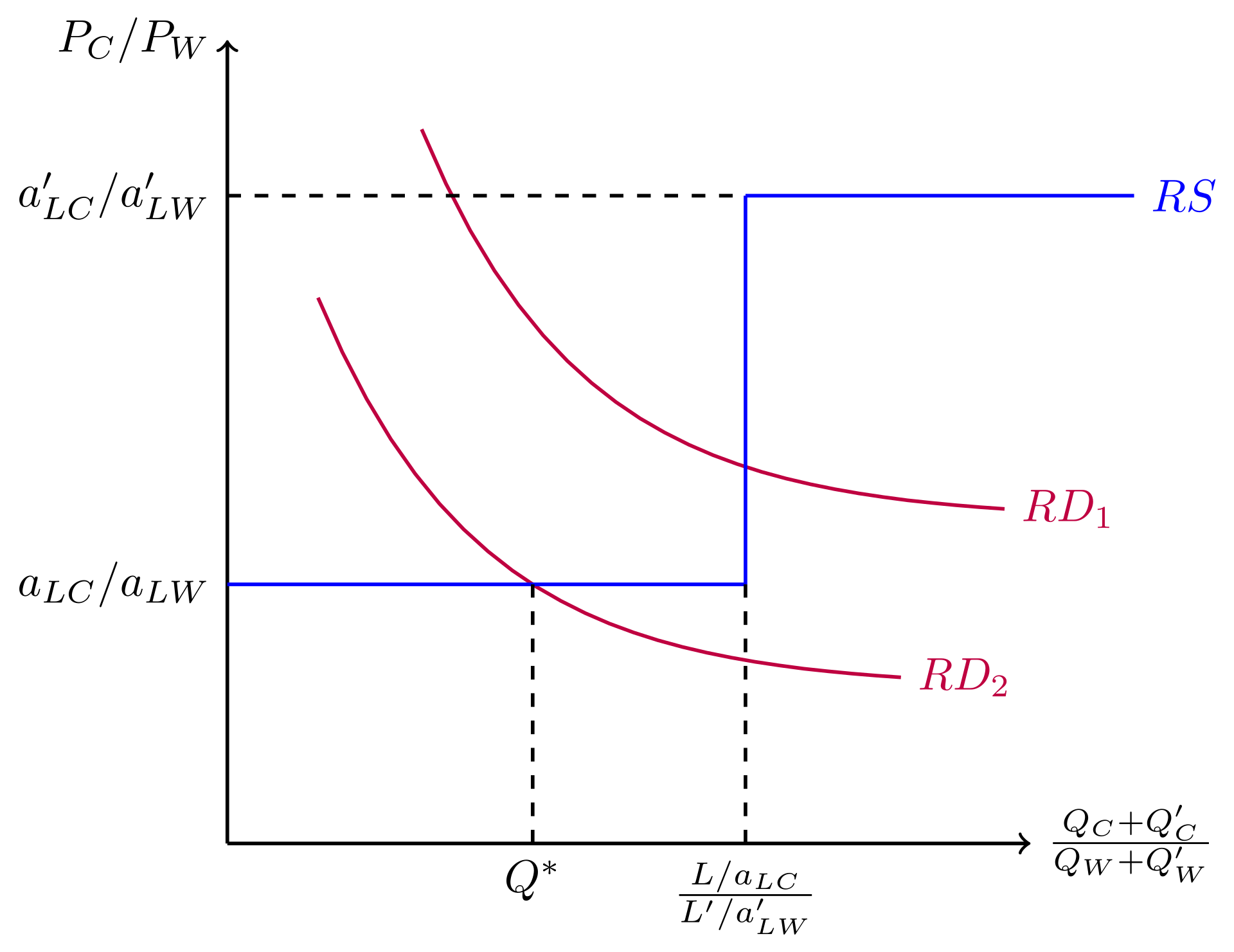

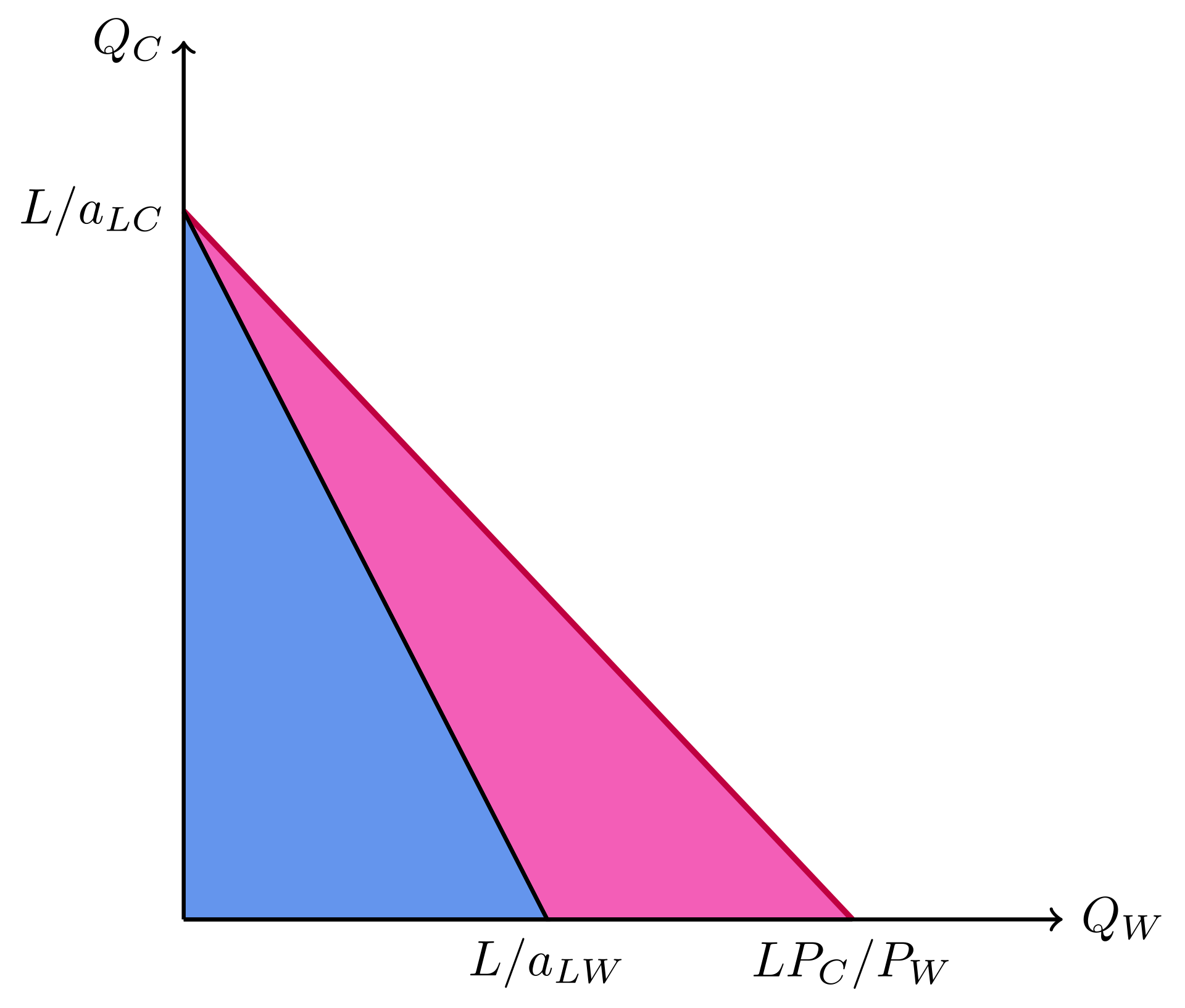

Ricardian model  The blue triangle depicts Home's original production (and consumption) possibilities. By trading, Home can also consume bundles in the pink triangle despite facing the same productions possibility frontier. |

リカードのモデル(数式があるので省略)  青い三角形はホームの本来の生産(および消費)可能性を表す。取引によって、ホームは同じ生産可能性フロンティアに直面しながらも、ピンクの三角形で示さ れる消費の組み合わせも可能となる。 |

| Haberler's opportunity costs

formulation In 1930 Austrian-American economist Gottfried Haberler detached the doctrine of comparative advantage from Ricardo's labor theory of value and provided a modern opportunity cost formulation. Haberler's reformulation of comparative advantage revolutionized the theory of international trade and laid the conceptual groundwork of modern trade theories. Haberler's innovation was to reformulate the theory of comparative advantage such that the value of good X is measured in terms of the forgone units of production of good Y rather than the labor units necessary to produce good X, as in the Ricardian formulation. Haberler implemented this opportunity-cost formulation of comparative advantage by introducing the concept of a production possibility curve into international trade theory.[19] |

ハーベルラーの機会費用の定式化 1930年、オーストリア系アメリカ人経済学者ゴットフリート・ハーベルラーは比較優位論をリカードの労働価値説から切り離し、現代的な機会費用の定式化 を提供した。ハーベルラーによる比較優位論の再構築は国際貿易理論に革命をもたらし、現代貿易理論の概念的基盤を築いた。 ハーベラーの革新は、比較優位理論を再構築した点にある。すなわち、財Xの価値を、リカード流の定式化のように財Xを生産するのに必要な労働単位ではな く、財Yの生産を放棄した単位で測定する方式を採用したのである。ハーベラーは、国際貿易理論に生産可能性曲線の概念を導入することで、この機会費用に基 づく比較優位定式化を実現した。[19] |

| Modern theories Since 1817, economists have attempted to generalize the Ricardian model and derive the principle of comparative advantage in broader settings, most notably in the neoclassical specific factors Ricardo–Viner (which allows for the model to include more factors than just labour)[20] and factor proportions Heckscher–Ohlin models. Subsequent developments in the new trade theory, motivated in part by the empirical shortcomings of the H–O model and its inability to explain intra-industry trade, have provided an explanation for aspects of trade that are not accounted for by comparative advantage.[21] Nonetheless, economists like Alan Deardorff,[22] Avinash Dixit, Victor D. Norman,[23] and Gottfried Haberler have responded with weaker generalizations of the principle of comparative advantage, in which countries will only tend to export goods for which they have a comparative advantage. Dornbusch et al.'s continuum of goods formulation In both the Ricardian and H–O models, the comparative advantage theory is formulated for a 2 countries/2 commodities case. It can be extended to a 2 countries/many commodities case, or a many countries/2 commodities case. Adding commodities in order to have a smooth continuum of goods is the major insight of the seminal paper by Dornbusch, Fisher, and Samuelson. In fact, inserting an increasing number of goods into the chain of comparative advantage makes the gaps between the ratios of the labor requirements negligible, in which case the three types of equilibria around any good in the original model collapse to the same outcome. It notably allows for transportation costs to be incorporated, although the framework remains restricted to two countries.[24][25] But in the case with many countries (more than 3 countries) and many commodities (more than 3 commodities), the notion of comparative advantage requires a substantially more complex formulation.[26] Deardorff's general law of comparative advantage Skeptics of comparative advantage have underlined that its theoretical implications hardly hold when applied to individual commodities or pairs of commodities in a world of multiple commodities. Deardorff argues that the insights of comparative advantage remain valid if the theory is restated in terms of averages across all commodities. His models provide multiple insights on the correlations between vectors of trade and vectors with relative-autarky-price measures of comparative advantage. "Deardorff's general law of comparative advantage" is a model incorporating multiple goods which takes into account tariffs, transportation costs, and other obstacles to trade. Alternative approaches Recently, Y. Shiozawa succeeded in constructing a theory of international value in the tradition of Ricardo's cost-of-production theory of value.[27][28] This was based on a wide range of assumptions: Many countries; Many commodities; Several production techniques for a product in a country; Input trade (intermediate goods are freely traded); Durable capital goods with constant efficiency during a predetermined lifetime; No transportation cost (extendable to positive cost cases). In a famous comment, McKenzie pointed that "A moment's consideration will convince one that Lancashire would be unlikely to produce cotton cloth if the cotton had to be grown in England."[29] However, McKenzie and later researchers could not produce a general theory which includes traded input goods because of the mathematical difficulty.[30] As John Chipman points it, McKenzie found that "introduction of trade in intermediate product necessitates a fundamental alteration in classical analysis."[31] Durable capital goods such as machines and installations are inputs to the productions in the same title as part and ingredients. In view of the new theory, no physical criterion exists. Deardorff examines 10 versions of definitions in two groups but could not give a general formula for the case with intermediate goods.[30] The competitive patterns are determined by the traders trials to find cheapest products in a world. The search of cheapest product is achieved by world optimal procurement. Thus the new theory explains how the global supply chains are formed.[32][33] |

現代の理論 1817年以来、経済学者たちはリカードモデルを一般化し、より広範な設定において比較優位原理を導出しようと試みてきた。特に顕著なのは、新古典派の特 定要素リカード・バイナーモデル(労働以外の要素もモデルに含めることを可能にする)[20]と、要素比率ヘックシャー・オリーンモデルである。その後、 新貿易理論の発展は、ヘクスチャー・オーリンモデルの経験的欠陥や産業内貿易を説明できない点に一部動機づけられ、比較優位では説明できない貿易の側面に 対する説明を提供した。[21] しかしながら、アラン・ディアードルフ[22]、アヴィナッシュ・ディクシット、ヴィクター・D・ノーマン[23]、ゴットフリート・ハーベラーといった 経済学者らは、比較優位原理の弱化された一般化を提示している。これによれば、各国は自国に比較優位がある財のみを輸出する傾向にある。 ドルンブッシュらの財の連続体モデル リカードモデルとH-Oモデルの両方において、比較優位理論は2カ国/2財のケースで構築されている。これを2カ国/多財のケース、あるいは多カ国/2財 のケースへ拡張することが可能だ。財を滑らかな連続体とするために財を追加するという発想こそが、ドルンブッシュ、フィッシャー、サミュエルソンの画期的 な論文の核心的洞察である。実際、比較優位連鎖に商品を増加させることで、労働必要量の比率差は無視できるほど小さくなる。この場合、原モデルにおける任 意の商品周辺の三種類の均衡は同一の結果に収束する。特に輸送コストの組み込みを可能とするが、枠組みは依然として二国間に限定される。[24][25] しかし、多くの国(3カ国以上)と多くの商品(3品目以上)が存在する場合には、比較優位概念ははるかに複雑な定式化を必要とする。[26] ディアードルフの一般比較優位法則 比較優位理論の懐疑論者は、複数の商品が存在する世界において、個々の商品や商品ペアに適用した場合、その理論的帰結がほとんど成立しない点を強調してき た。ディアードルフは、理論を全商品にわたる平均値で再定義すれば比較優位性の洞察は有効だと主張する。彼のモデルは、貿易ベクトルと相対的自給価格によ る比較優位性のベクトルとの相関関係について複数の知見を提供する。「ディアードルフの一般比較優位法則」は、関税、輸送コスト、その他の貿易障壁を考慮 した複数商品を含むモデルである。 代替アプローチ 近年、塩沢恭平はリカードの生産コスト価値論の伝統に則った国際価値理論の構築に成功した[27][28]。これは広範な仮定に基づいている:多数の国 々;多数の財;一国における同一製品の複数の生産技術;投入財貿易(中間財は自由に取引される); 耐久性のある資本財は定められた寿命期間中効率が一定である;輸送コストなし(正のコストの場合にも拡張可能)。 有名な指摘として、マッケンジーは「一瞬考えれば、綿をイングランドで栽培しなければならないなら、ランカシャーが綿織物を生産する可能性は低いと納得す るだろう」と述べた。[29] しかしマッケンジーや後続の研究者らは、数学的困難さゆえに、貿易される投入財を含む一般理論を構築できなかった。[30] ジョン・チップマンが指摘するように、マッケンジーは「中間財の貿易導入は古典的分析の根本的変更を必要とする」と結論づけた。[31] 機械や設備といった耐久性資本財は、部品や原料と同様に生産への投入物である。 新理論によれば、物理的基準は存在しない。ディアードルフは10種類の定義を二つのグループに分けて検討したが、中間財を含むケースの一般定式を提示でき なかった[30]。競争パターンは、世界中で最も安価な製品を探す取引者の試行によって決定される。最安製品の探索は、世界最適調達によって達成される。 こうして新理論は、グローバルサプライチェーンが形成される仕組みを説明する[32][33]。 |

| Empirical approach to

comparative advantage Comparative advantage is a theory about the benefits that specialization and trade would bring, rather than a strict prediction about actual behavior. (In practice, governments restrict international trade for a variety of reasons; under Ulysses S. Grant, the US postponed opening up to free trade until its industries were up to strength, following the example set earlier by Britain.[34]) Nonetheless there is a large amount of empirical work testing the predictions of comparative advantage. The empirical works usually involve testing predictions of a particular model. For example, the Ricardian model predicts that technological differences in countries result in differences in labor productivity. The differences in labor productivity in turn determine the comparative advantages across different countries. Testing the Ricardian model for instance involves looking at the relationship between relative labor productivity and international trade patterns. A country that is relatively efficient in producing shoes tends to export shoes. Direct test: natural experiment of Japan Assessing the validity of comparative advantage on a global scale with the examples of contemporary economies is analytically challenging because of the multiple factors driving globalization: indeed, investment, migration, and technological change play a role in addition to trade. Even if we could isolate the workings of open trade from other processes, establishing its causal impact also remains complicated: it would require a comparison with a counterfactual world without open trade. Considering the durability of different aspects of globalization, it is hard to assess the sole impact of open trade on a particular economy.[citation needed] Daniel Bernhofen and John Brown have attempted to address this issue, by using a natural experiment of a sudden transition to open trade in a market economy. They focus on the case of Japan.[35][36] The Japanese economy indeed developed over several centuries under autarky and a quasi-isolation from international trade but was, by the mid-19th century, a sophisticated market economy with a population of 30 million. Under Western military pressure, Japan opened its economy to foreign trade through a series of unequal treaties.[citation needed] In 1859, the treaties limited tariffs to 5% and opened trade to Westerners. Considering that the transition from autarky, or self-sufficiency, to open trade was brutal, few changes to the fundamentals of the economy occurred in the first 20 years of trade. The general law of comparative advantage theorizes that an economy should, on average, export goods with low self-sufficiency prices and import goods with high self-sufficiency prices. Bernhofen and Brown found that by 1869, the price of Japan's main export, silk and derivatives, saw a 100% increase in real terms, while the prices of numerous imported goods declined of 30-75%. In the next decade, the ratio of imports to gross domestic product reached 4%.[37] Structural estimation Another important way of demonstrating the validity of comparative advantage has consisted in 'structural estimation' approaches. These approaches have built on the Ricardian formulation of two goods for two countries and subsequent models with many goods or many countries. The aim has been to reach a formulation accounting for both multiple goods and multiple countries, in order to reflect real-world conditions more accurately. Jonathan Eaton and Samuel Kortum underlined that a convincing model needed to incorporate the idea of a 'continuum of goods' developed by Dornbusch et al. for both goods and countries. They were able to do so by allowing for an arbitrary (integer) number i of countries, and dealing exclusively with unit labor requirements for each good (one for each point on the unit interval) in each country (of which there are i).[38] Earlier empirical work Two of the first tests of comparative advantage were by MacDougall (1951, 1952).[39] A prediction of a two-country Ricardian comparative advantage model is that countries will export goods where output per worker (i.e. productivity) is higher. That is, we expect a positive relationship between output per worker and the number of exports. MacDougall tested this relationship with data from the US and UK, and did indeed find a positive relationship. The statistical test of this positive relationship was replicated with new data by Stern (1962)[40] and Balassa (1963).[41] Dosi et al. (1988)[42] conducted a book-length empirical examination that suggests that international trade in manufactured goods is largely driven by differences in national technological competencies. One critique of the textbook model of comparative advantage is that there are only two goods. The results of the model are robust to this assumption.[24] generalized the theory to allow for such a large number of goods as to form a smooth continuum. Based in part on these generalizations of the model,[43] provides a more recent view of the Ricardian approach to explain trade between countries with similar resources. More recently, Golub and Hsieh (2000)[44] presents modern statistical analysis of the relationship between relative productivity and trade patterns, which finds reasonably strong correlations, and Nunn (2007)[45] finds that countries that have greater enforcement of contracts specialize in goods that require relationship-specific investments. Taking a broader perspective, there has been work about the benefits of international trade. Zimring & Etkes (2014)[46] find that the blockade of the Gaza Strip, which substantially restricted the availability of imports to Gaza, saw labor productivity fall by 20% in three years. Markusen et al. (1994)[47] reports the effects of moving away from autarky to free trade during the Meiji Restoration, with the result that national income increased by up to 65% in 15 years. |

比較優位への実証的アプローチ 比較優位とは、実際の行動に関する厳密な予測というよりは、専門化と貿易がもたらす利益についての理論である。(実際には、政府は様々な理由で国際貿易を 制限する。ユリシーズ・S・グラント政権下の米国は、英国の先例に従い、自国の産業が十分に強くなるまで自由貿易への開放を延期した。[34]) それにもかかわらず、比較優位理論の予測を検証する実証研究は数多く存在する。実証研究では通常、特定のモデルの予測を検証する。例えばリカードモデル は、国家間の技術格差が労働生産性の差異をもたらすと予測する。労働生産性の差異が、さらに異なる国家間の比較優位を決定する。リカードモデルの検証に は、相対的労働生産性と国際貿易パターンの関係を分析することが含まれる。靴の生産において比較的効率的な国は、靴を輸出する傾向がある。 直接検証:日本の自然実験 現代経済の事例を用いて比較優位理論の有効性を世界規模で評価することは、分析的に困難である。なぜなら、グローバル化を推進する要因は複数存在し、貿易 に加えて投資、移民、技術革新も役割を果たしているからだ。仮に自由貿易の作用を他のプロセスから切り離せたとしても、その因果的影響を立証することは依 然として複雑である。自由貿易が存在しない反事実的な世界との比較が必要となるからだ。グローバル化の異なる側面が持続していることを考慮すると、特定の 経済に対する自由貿易の単独の影響を評価することは困難である。[出典が必要] ダニエル・ベルンホーフェンとジョン・ブラウンは、市場経済における開放貿易への急激な移行という自然実験を用いてこの問題に取り組んだ。彼らは日本の事 例に焦点を当てている。[35][36] 日本経済は確かに数世紀にわたり自給自足と国際貿易からの準隔離状態の中で発展したが、19世紀半ばには3000万人の人口を擁する高度な市場経済となっ ていた。西欧諸国の軍事的圧力のもと、日本は一連の不平等条約を通じて対外貿易を開放した。 1859年の条約では関税を5%に制限し、西洋人への貿易を開放した。自給自足から開放貿易への移行が過酷であったことを考慮すると、貿易開始後20年間 は経済の基盤にほとんど変化は生じなかった。比較優位一般法則によれば、経済は平均的に自給自足価格の低い商品を輸出し、自給自足価格の高い商品を輸入す べきだとされる。ベルンホーフェンとブラウンの研究によれば、1869年までに日本の主要輸出品である絹及びその派生品の価格は実質100%上昇した一 方、多数の輸入品の価格は30~75%下落した。その後10年間で、輸入額が国内総生産に占める割合は4%に達した。[37] 構造推定 比較優位理論の妥当性を示すもう一つの重要な手法が「構造推定」アプローチである。この手法は、二国間・二品目というリカード式モデルを基盤とし、その後 多品目・多国間モデルへと発展した。その目的は、現実の状況をより正確に反映するため、複数商品と複数国を同時に考慮する定式化に到達することにある。 ジョナサン・イートンとサミュエル・コータムは、説得力のあるモデルには、商品と国の双方について、ドーンブッシュらが提唱した「商品の連続体」の概念を 取り入れる必要があると強調した。彼らは、国数を任意の整数 i と設定し、各商品について各国の単位労働要件(単位区間の各点に対応する)のみを扱うことでこれを実現した(国数は i 個)。[38] 先行する実証研究 比較優位に関する初期の実証検証の2例は、マクドゥーガル(1951年、1952年)によるものである。[39] 二国間リカード比較優位モデルの予測によれば、各国は労働者当たりの生産性が高い財を輸出する。つまり、労働者当たり生産量と輸出数量の間に正の相関関係 が期待される。マクドゥーガルは米国と英国のデータを用いてこの関係を検証し、実際に正の相関を確認した。この正の相関関係の統計的検証は、スターン (1962)[40]とバラッサ(1963)[41]によって新たなデータを用いて再現された。 ドシら(1988)[42]は書籍規模の実証研究を行い、製造財の国際貿易は主に国民間の技術的能力の異なる差異によって駆動されることを示唆した。 比較優位に関する教科書モデルの批判の一つは、対象商品が二品目のみである点だ。この仮定に対するモデルの結果は頑健である[24]。は理論を一般化し、 滑らかな連続体を形成するほど多数の商品を許容した。このモデル一般化を一部基盤として[43]は、類似資源を持つ国間の貿易を説明するリカード的アプ ローチのより現代的な見解を提供する。 さらに近年では、GolubとHsieh(2000)[44]が相対的生産性と貿易パターンの関係について現代的な統計分析を行い、かなり強い相関関係を 見出した。またNunn(2007)[45]は、契約履行がより徹底されている国ほど、関係特異的投資を必要とする財の専門化が進んでいることを明らかに した。 より広い視点では、国際貿易の便益に関する研究がある。Zimring & Etkes (2014)[46] は、ガザ地区への輸入を大幅に制限した封鎖により、3年間で労働生産性が20%低下したことを発見した。Markusen et al. (1994)[47]は、明治維新期における自給経済から自由貿易への移行効果を報告し、その結果として国民所得が15年間で最大65%増加したことを示 している。 |

| Criticism Several arguments have been advanced against using comparative advantage as a justification for advocating free trade, and they have gained an audience among economists. James Brander and Barbara J. Spencer demonstrated how, in a strategic setting where a few firms compete for the world market, export subsidies and import restrictions can keep foreign firms from competing with national firms, increasing welfare in the country implementing these so-called strategic trade policies.[48] There are some economists who dispute the claims of the benefit of comparative advantage. James K. Galbraith has stated that "free trade has attained the status of a god" and that " ... none of the world's most successful trading regions, including Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and now mainland China, reached their current status by adopting neoliberal trading rules." He argues that comparative advantage relies on the assumption of constant returns, which he states is not generally the case.[49] According to Galbraith, nations trapped into specializing in agriculture are condemned to perpetual poverty, as agriculture is dependent on land, a finite non-increasing natural resource.[50] 21st century In the 21st century, Ricardo's comparative advantage theory has faced new challenges due to the development of global value chains. Unlike Ricardo's model of trade between anonymous parties with equal bargaining power, modern global value chains operate between connected firms with unequal power, with nations specializing in particular production stages rather than complete goods.[51] The COVID-19 pandemic further challenged the theory when disruptions to globally distributed supply chains prompted nations to reconsider their reliance on foreign production, particularly for critical goods like medical equipment and pharmaceuticals.[52] In response, some countries have begun reinforcing supplier relationships or diversifying trade networks to mitigate future disruptions.[53] |

批判 比較優位を自由貿易の正当化根拠として用いることに対して、いくつかの反論が提起されており、それらは経済学者の間で支持を得ている。ジェームズ・ブラン ダーとバーバラ・J・スペンサーは、少数の企業が世界市場を争う戦略的状況において、輸出補助金と輸入制限が外国企業による国民企業との競争を阻み、いわ ゆる戦略的貿易政策を実施する国の福祉を向上させ得ることを示した。[48] 比較優位による利益の主張に異議を唱える経済学者もいる。ジェームズ・K・ガルブレイスは「自由貿易は神格化された」とし、「日本、韓国、台湾、そして現 在の中国本土を含む世界で最も成功した貿易地域は、新自由主義的貿易ルールを採用して現在の地位を築いたわけではない」と述べている。彼は比較優位が恒常 的収益の仮定に依存していると論じ、これは一般的に当てはまらないと主張する[49]。ガルブレイスによれば、農業への特化に縛られた国民は恒久的な貧困 に陥る運命にある。なぜなら農業は土地という有限で増加しない天然資源に依存しているからだ。[50] 21世紀 21世紀に入り、リカードの比較優位理論はグローバル・バリューチェーンの発展により新たな課題に直面している。リカードのモデルが対等な交渉力を持つ匿 名の当事者間の貿易を想定していたのに対し、現代のグローバル・バリューチェーンは不平等な力関係を持つ関連企業間で機能し、国民は完成品ではなく特定の 生産段階に特化している。[51] COVID-19パンデミックは、世界的に分散したサプライチェーンの混乱が国民に外国生産への依存、特に医療機器や医薬品のような重要物資への依存を見 直すよう促したことで、この理論にさらなる挑戦をもたらした。[52] これに対応し、一部の国々は将来の混乱を軽減するため、供給業者との関係強化や貿易ネットワークの多様化を開始している。[53] |

| Bureau of Labor Statistics Resource curse Revealed comparative advantage |

労働統計局 資源の呪い 顕在比較優位 |

| Bibliography Bernhofen, Daniel M.; Brown, John C. (2004). "A Direct Test of the Theory of Comparative Advantage: The Case of Japan". Journal of Political Economy. 112 (1): 48–67. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.194.9649. doi:10.1086/379944. S2CID 17377670. Bernhofen, Daniel M. (2005a). "Gottfried Haberler's 1930 reformulation of comparative advantage in retrospect". Review of International Economics. 13 (5): 997–1000. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9396.2005.00550.x. S2CID 9787214. Bernhofen, Daniel M.; Brown, John C. (2005b). "An Empirical Assessment of the Comparative Advantage Gains from Trade: Evidence from Japan". American Economic Review. 95 (1): 208–25. doi:10.1257/0002828053828491. Bernhofen, Daniel M.; Brown, John C. (2016). "Testing the General Validity of the Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem". American Economic Journal: Microeconomics. 8 (4): 54–90. doi:10.1257/mic.20130126. Galbraith, James K. (2008). The Predator State: How conservatives abandoned the free market and why liberals should too. New York: free Press. p. 70. ISBN 9781416566830. OCLC 192109752. Maneschi, Andrea (1998). Comparative Advantage in International Trade: A Historical Perspective. Cheltenham: Elgar. ISBN 9781781956243. Further reading Findlay, Ronald (1987). "Comparative Advantage". The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. 1: 514–517. |

参考文献 Bernhofen, Daniel M.; Brown, John C. (2004). 「A Direct Test of the Theory of Comparative Advantage: The Case of Japan」. Journal of Political Economy. 112 (1): 48–67. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.194.9649. doi:10.1086/379944. S2CID 17377670. Bernhofen, Daniel M. (2005a). 「ゴットフリート・ハーベラーによる1930年の比較優位理論再構築を顧みて」. 国際経済レビュー. 13 (5): 997–1000. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9396.2005.00550.x. S2CID 9787214. Bernhofen, Daniel M.; Brown, John C. (2005b). 「貿易による比較優位利益の実証的評価:日本の事例から」. American Economic Review. 95 (1): 208–25. doi:10.1257/0002828053828491. Bernhofen, Daniel M.; Brown, John C. (2016). 「ヘックシャー=オリーン定理の一般的妥当性の検証」. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics. 8 (4): 54–90. doi:10.1257/mic.20130126. ガルブレイス、ジェームズ・K. (2008). 『捕食国家:保守派が自由市場を放棄した理由、そしてリベラル派もそうすべき理由』. ニューヨーク:フリープレス. p. 70. ISBN 9781416566830. OCLC 192109752. マネスキ、アンドレア(1998)。『国際貿易における比較優位:歴史的視点』。チェルトナム:エルガー。ISBN 9781781956243。 参照文献 フィンドレー、ロナルド(1987)。「比較優位」。『ニュー・パルグレイブ経済学辞典』。1: 514–517。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparative_advantage |

★

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Do not paste, but [Re]Think our message for all undergraduate students!!!

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099