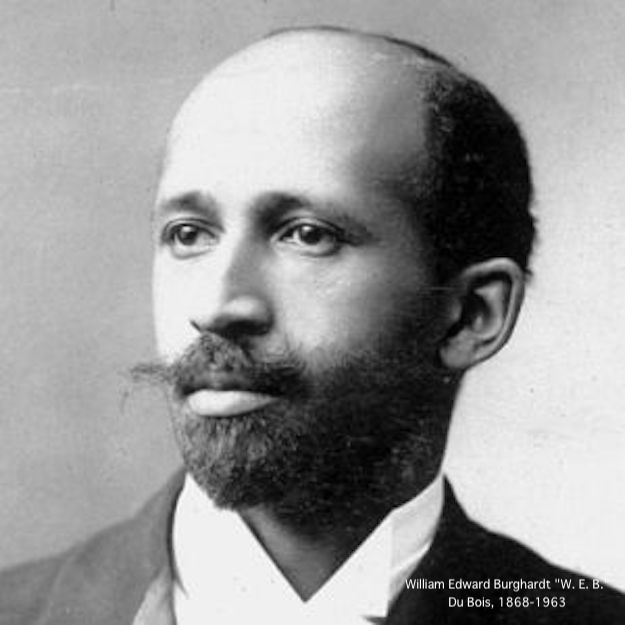

W.E.B.デュボイス

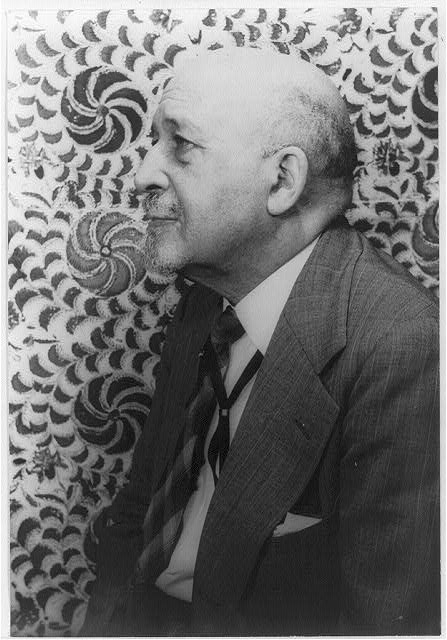

William Edward

Burghardt "W. E. B." Du Bois,

1868-1963

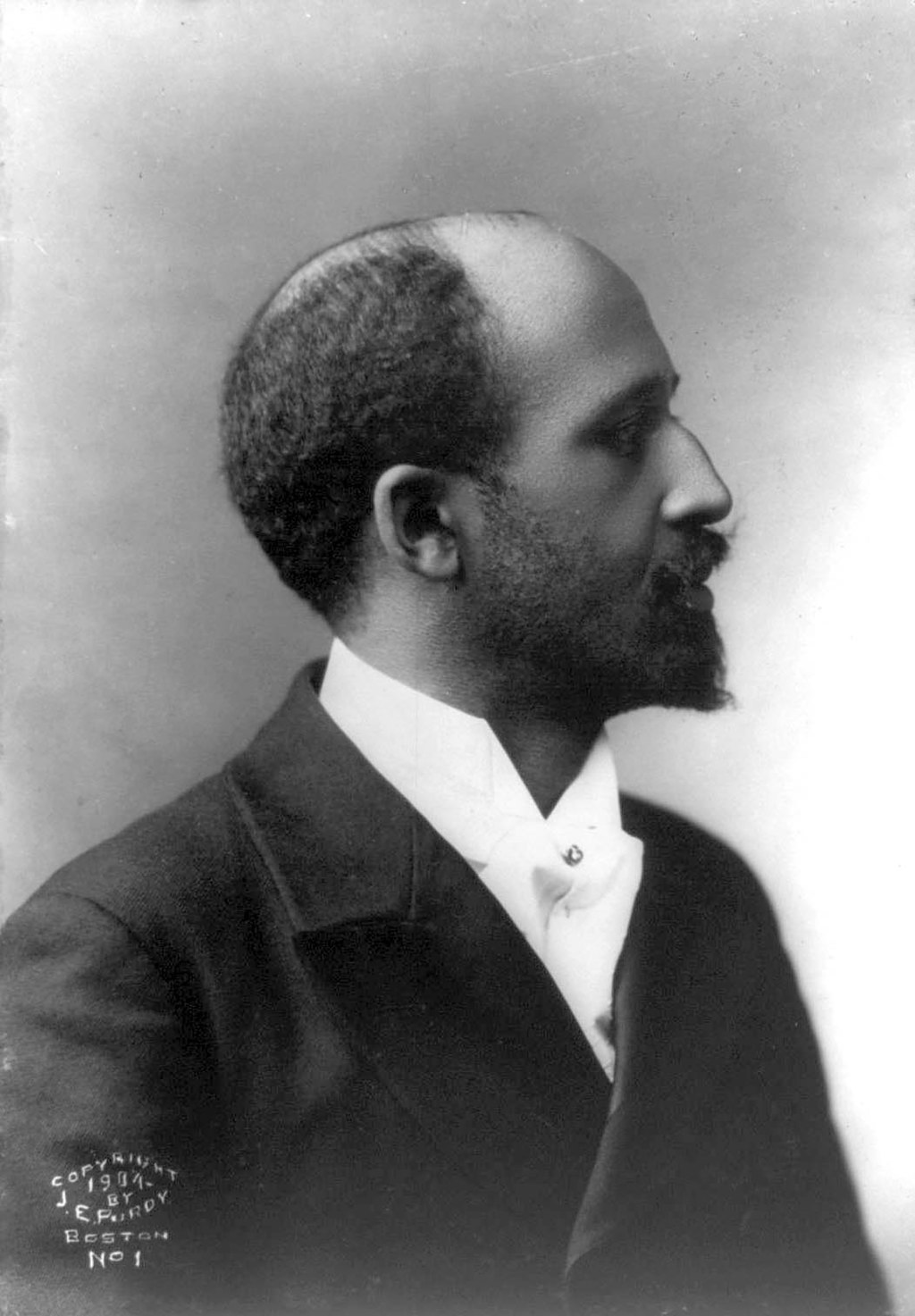

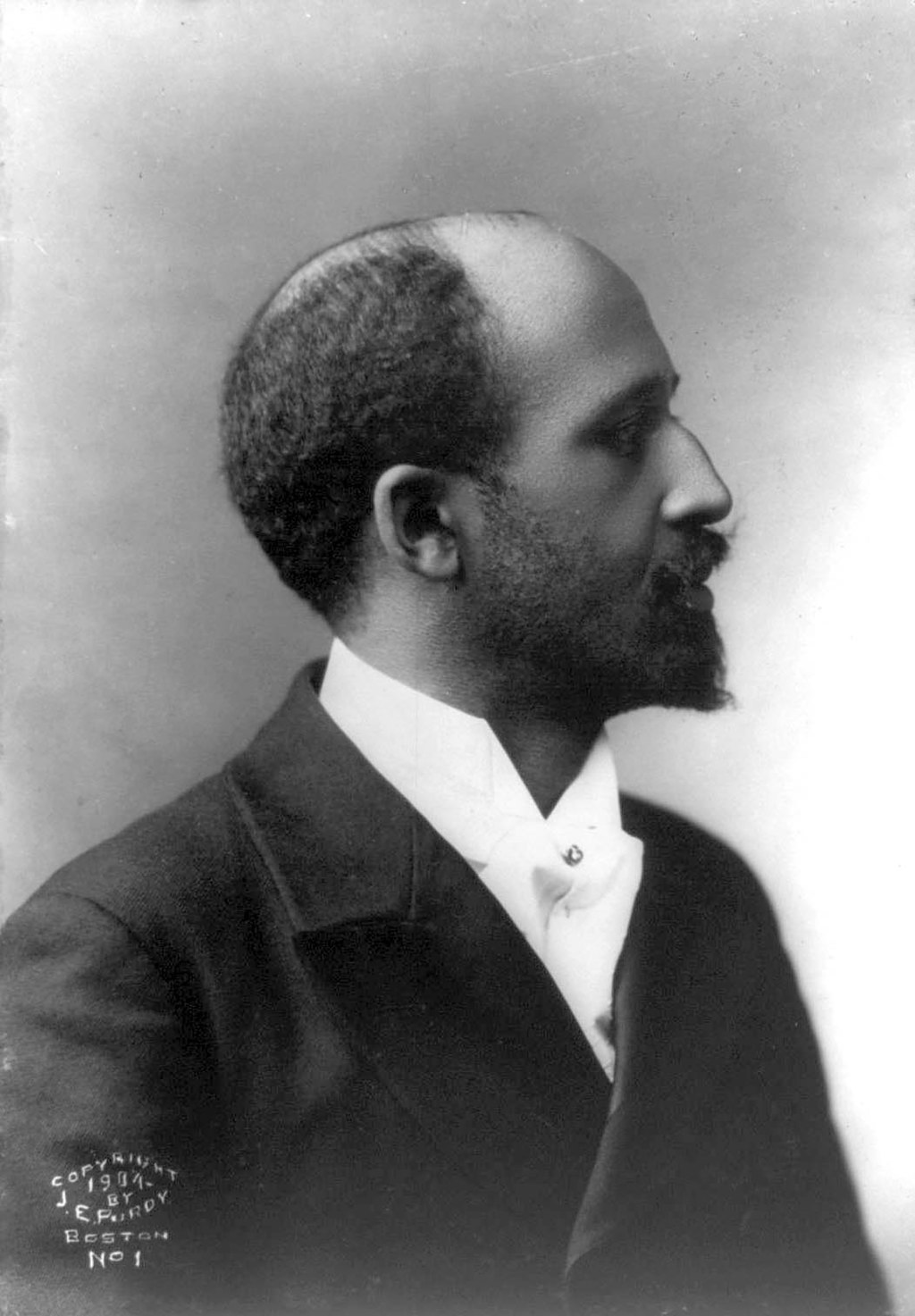

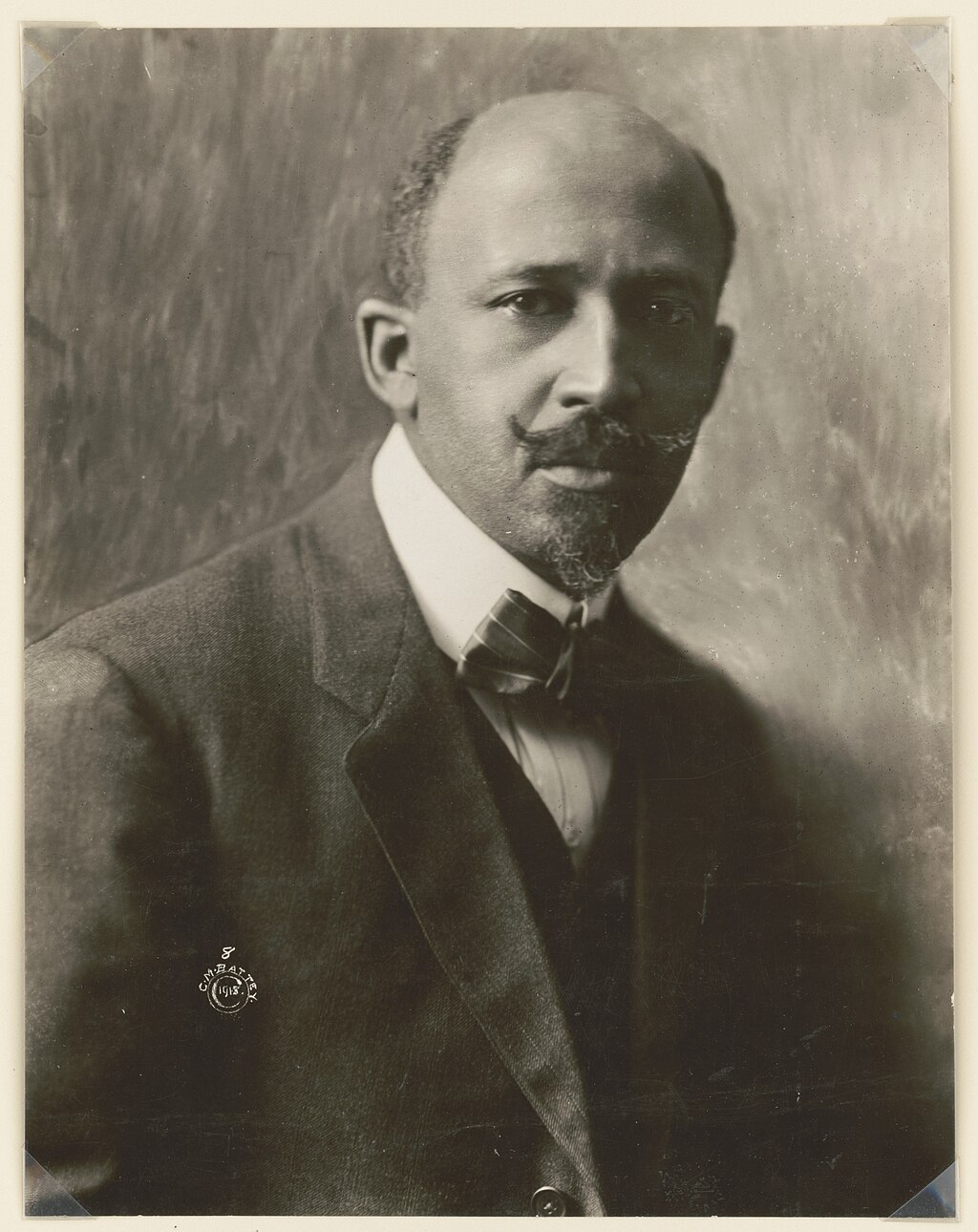

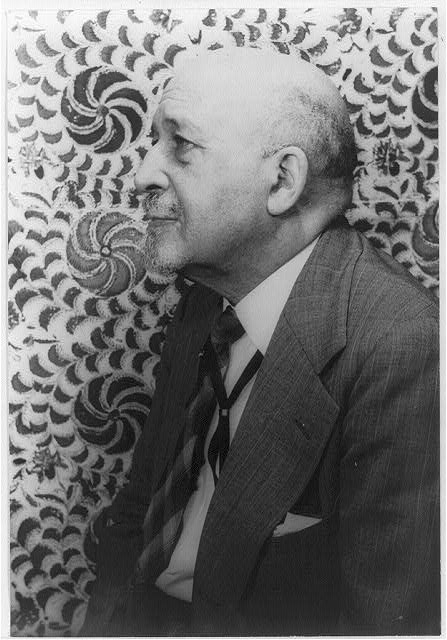

★ウィリアム・エドワード・バーグハルト・デュボイス ( William Edward Burghardt Du Bois1868年2月23日 - 1963年8月27日)は、アメリカの社会学者、社会主義者、歴史学者、汎アフリカ主義者、公民権運動家である。

| William Edward

Burghardt Du Bois

(/djuːˈbɔɪs/ dew-BOYSS;[1][2] February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was

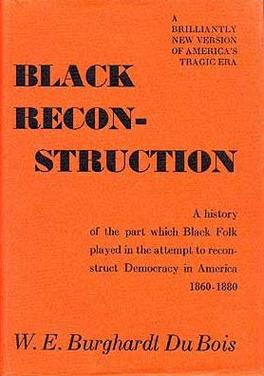

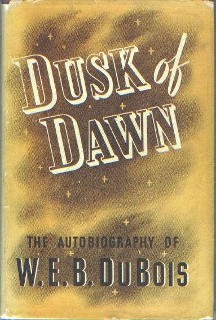

an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil

rights activist. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relatively tolerant and integrated community. After completing graduate work at the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin and Harvard University, where he was its first African American to earn a doctorate, Du Bois rose to national prominence as a leader of the Niagara Movement, a group of black civil rights activists seeking equal rights. Du Bois and his supporters opposed the Atlanta Compromise. Instead, Du Bois insisted on full civil rights and increased political representation, which he believed would be brought about by the African-American intellectual elite. He referred to this group as the Talented Tenth, a concept under the umbrella of racial uplift, and believed that African Americans needed the chances for advanced education to develop its leadership. Du Bois was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. Du Bois used his position in the NAACP to respond to racist incidents. After the First World War, he attended the Pan-African Congresses, embraced socialism and became a professor at Atlanta University. Once the Second World War had ended, he engaged in peace activism and was targeted by the FBI. He spent the last years of his life in Ghana and died in Accra on August 27, 1963. Du Bois was a prolific author. Du Bois primarily targeted racism in his polemics, which protested strongly against lynching, Jim Crow laws, and discrimination in education and employment. His cause included people of color everywhere, particularly Africans and Asians in colonies. He was a proponent of Pan-Africanism and helped organize several Pan-African Congresses to fight for the independence of African colonies from European powers. Du Bois made several trips to Europe, Africa and Asia. His collection of essays, The Souls of Black Folk, is a seminal work in African-American literature; and his 1935 magnum opus, Black Reconstruction in America, challenged the prevailing orthodoxy that blacks were responsible for the failures of the Reconstruction era. Borrowing a phrase from Frederick Douglass, he popularized the use of the term color line to represent the injustice of the separate but equal doctrine prevalent in American social and political life. His 1940 autobiography Dusk of Dawn is regarded in part as one of the first scientific treatises in the field of American sociology. In his role as editor of the NAACP's journal The Crisis, he published many influential pieces. Du Bois believed that capitalism was a primary cause of racism and was sympathetic to socialist causes. |

ウィリアム・エドワード・バーグハルト・デュボイス

(/djuːˈbɔɪs/ dew-BOYSS;[1][2] 1868年2月23日 -

1963年8月27日)は、アメリカの社会学者、社会主義者、歴史学者、汎アフリカ主義者、公民権運動家である。 マサチューセッツ州グレートバリントンで生まれたデュボイスは、比較的寛容で統合されたコミュニティで育った。ベルリンのフリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム大学 とハーバード大学で大学院課程を修了し、ハーバード大学ではアフリカ系アメリカ人として初めて博士号を取得したデュボイスは、黒人の公民権運動家グループ であるナイアガラ運動のリーダーとして全米的に有名になった。デュボイスと彼の支持者たちはアトランタ妥協案に反対した。その代わりにデュボイスは完全な 公民権と政治参加の拡大を主張し、それはアフリカ系アメリカ人の知識人エリートによってもたらされると信じていた。彼はこのグループを「才能ある10%」 と呼び、人種的向上という概念のもと、アフリカ系アメリカ人がそのリーダーシップを育むためには、高等教育を受ける機会が必要だと信じていた。 デュボイスは、1909年に全米有色人地位向上協会(NAACP)の創設者の一人となった。デュボイスはNAACPでの地位を利用して人種差別事件に対応 していた。第一次世界大戦後は汎アフリカ会議に出席し、社会主義を受け入れ、アトランタ大学の教授に就任した。第二次世界大戦が終結すると、平和運動に取 り組み、FBIの監視対象となった。晩年はガーナで過ごし、1963年8月27日にアクラで死去した。 デュボイスは多作な作家でもあった。デュボイスは主に人種差別を論争の的とし、リンチ、ジム・クロウ法、教育や雇用における差別に対して強く抗議した。彼 の主張は、植民地のアフリカ人やアジア人など、あらゆる有色人種の人々を含んでいた。彼は汎アフリカ主義の提唱者であり、ヨーロッパ列強からのアフリカ植 民地の独立のために戦うために、いくつかの汎アフリカ会議の開催を支援した。デュボイスはヨーロッパ、アフリカ、アジアに何度も足を運んだ。彼のエッセイ 集『黒人魂』は、アフリカ系アメリカ人文学の重要な作品であり、1935年の代表作『アメリカの黒人復興』は、黒人が再建時代の失敗の原因であるという当 時の正統的な考え方に異議を唱えた。フレデリック・ダグラスから言葉を借り、彼は「カラーライン」という用語を普及させ、アメリカの社会生活や政治生活で 広く浸透していた「分離だが平等」という不公正な教義を象徴した。1940年に出版された自伝『夜明けの薄明』は、アメリカ社会学における最初の学術論文 の1つとして評価されている。NAACPの機関誌『クライシス』の編集者として、彼は多くの影響力のある論文を発表した。デュボイスは、資本主義が人種差 別の主な原因であると考えており、社会主義運動に共感していた。 |

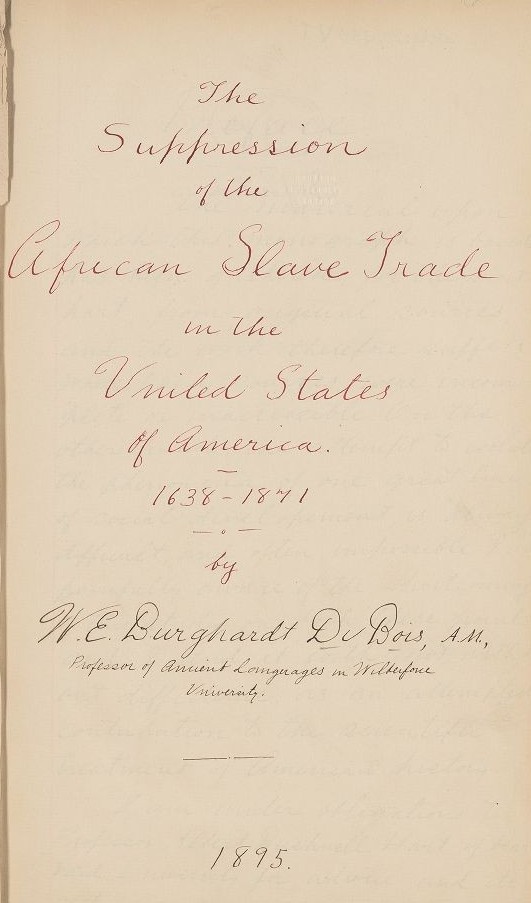

| Early life Family and childhood William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born on February 23, 1868, in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, to Alfred and Mary Silvina Burghardt Du Bois.[3] Mary Silvina Burghardt's family was part of the very small free black population of Great Barrington and had long owned land in the state. She was descended from Dutch, African, and English ancestors.[4] William Du Bois's maternal great-great-grandfather was Tom Burghardt, a slave (born in West Africa around 1730) who was held by the Dutch colonist Conraed Burghardt. Tom briefly served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, which may have been how he gained his freedom during the late 18th century. His son Jack Burghardt was the father of Othello Burghardt, who in turn was the father of Mary Silvina Burghardt.[5]  A photograph of Du Bois as an infant being held by his mother Du Bois as an infant with his mother William Du Bois claimed Elizabeth Freeman as his relative; he wrote that she had married his great-grandfather Jack Burghardt.[6][7] But Freeman was 20 years older than Burghardt, and no record of such a marriage has been found. It may have been Freeman's daughter, Betsy Humphrey, who married Burghardt after her first husband, Jonah Humphrey, left the area "around 1811", and after Burghardt's first wife died (c. 1810). If so, Freeman would have been William Du Bois's step-great-great-grandmother. Anecdotal evidence supports Humphrey's marrying Burghardt; a close relationship of some form is likely.[8] William Du Bois's paternal great-grandfather was James Du Bois of Poughkeepsie, New York, an ethnic French-American of Huguenot origin who fathered several children with slave women.[9] One of James' mixed-race sons was Alexander, who was born on Long Cay in the Bahamas in 1803; in 1810, he immigrated to the United States with his father.[10] Alexander Du Bois traveled and worked in Haiti, where he fathered a son, Alfred, with a mistress. Alexander returned to Connecticut, leaving Alfred in Haiti with his mother.[11] Sometime before 1860, Alfred Du Bois immigrated to the United States, settling in Massachusetts. He married Mary Silvina Burghardt on February 5, 1867, in Housatonic, a village in Great Barrington.[11] Alfred left Mary in 1870, two years after their son William was born.[12] Mary Du Bois moved with her son back to her parents' house in Great Barrington, and they lived there until he was five. She worked to support her family (receiving some assistance from her brother and neighbors), until she suffered a stroke in the early 1880s. She died in 1885.[13][14] Great Barrington had a majority European American community, who generally treated Du Bois well. He attended the local integrated public school and played with white schoolmates. As an adult, he wrote about racism that he felt as a fatherless child and being a minority in the town. But teachers recognized his ability and encouraged his intellectual pursuits, and his rewarding experience with academic studies led him to believe that he could use his knowledge to empower African Americans.[15] In 1884, he graduated from the town's Great Barrington High School with honors.[16][17][18] When he decided to attend college, the congregation of his childhood church, the First Congregational Church of Great Barrington, raised the money for his tuition.[19][20][21] University education  The title page of Du Bois's Harvard dissertation, Suppression of the African Slave Trade in the United States of America: 1638–1871 Relying on this money donated by neighbors, Du Bois attended Fisk University, a historically black college in Nashville, Tennessee, from 1885 to 1888.[22] Like other Fisk students who relied on summer and intermittent teaching to support their university studies, Du Bois taught school during the summer of 1886 after his sophomore year.[23] His travel to and residency in the South was Du Bois's first experience with Southern racism, which at the time encompassed Jim Crow laws, bigotry, suppression of black voting, and lynchings; the lattermost reached a peak in the next decade.[24] After receiving a bachelor's degree from Fisk, he attended Harvard College (which did not accept course credits from Fisk) from 1888 to 1890, where he was strongly influenced by professor William James, prominent in American philosophy.[25] Du Bois paid his way through three years at Harvard with money from summer jobs, an inheritance, scholarships, and loans from friends. In 1890, Harvard awarded Du Bois his second bachelor's degree, cum laude, in history.[26] In 1891, Du Bois received a scholarship to attend the sociology graduate school at Harvard.[27] In 1892, Du Bois received a fellowship from the John F. Slater Fund for the Education of Freedmen to attend the Friedrich Wilhelm University for graduate work.[28] While a student in Berlin, he traveled extensively throughout Europe. He came of age intellectually in the German capital while studying with some of that nation's most prominent social scientists, including Gustav von Schmoller, Adolph Wagner, and Heinrich von Treitschke.[29] He also met Max Weber who was highly impressed with Du Bois and would later cite Du Bois as a counter-example to racists alleging the inferiority of Blacks. Weber would again meet Du Bois in 1904 on a visit to the US just ahead of the publication of the seminal The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.[30] He wrote about his time in Germany: "I found myself on the outside of the American world, looking in. With me were white folk – students, acquaintances, teachers – who viewed the scene with me. They did not always pause to regard me as a curiosity, or something sub-human; I was just a man of the somewhat privileged student rank, with whom they were glad to meet and talk over the world; particularly, the part of the world whence I came."[31] After returning from Europe, Du Bois completed his graduate studies; in 1895, he was the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University.[32] Wilberforce Between me and the other world there is ever an unasked question: ... How does it feel to be a problem? ... One ever feels his two-ness, – an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder ... He would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face. —Du Bois, "Strivings of the Negro People", 1897[33] In the summer of 1894, Du Bois received several job offers, including from Tuskegee Institute; he accepted a teaching job at Wilberforce University in Ohio.[34][35] At Wilberforce, Du Bois was strongly influenced by Alexander Crummell, who believed that ideas and morals are necessary tools to effect social change.[36] While at Wilberforce, Du Bois married Nina Gomer, one of his students, on May 12, 1896.[37] Philadelphia After two years at Wilberforce, Du Bois accepted a one-year research job from the University of Pennsylvania as an "assistant in sociology" in the summer of 1896.[38] He performed sociological field research in Philadelphia's African-American neighborhoods, which formed the foundation for his landmark study, The Philadelphia Negro, published in 1899 while he was teaching at Atlanta University. It was the first case study of a black community in the United States.[39] Among his Philadelphia consultants on the project was William Henry Dorsey, an artist who collected documents, paintings and artifact pertaining to Black history. Dorsey compiled hundreds of scrapbooks on the lives of Black people during the 19th century and built a collection that he laid out in his home in Philadelphia. Du Bois used the scrapbooks in his research. By the 1890s, Philadelphia's black neighborhoods had a negative reputation in terms of crime, poverty, and mortality. Du Bois's book undermined the stereotypes with empirical evidence and shaped his approach to segregation and its negative impact on black lives and reputations. The results led him to realize that racial integration was the key to democratic equality in American cities.[40] The methodology employed in The Philadelphia Negro, namely the description and the mapping of social characteristics onto neighborhood areas was a forerunner to the studies under the Chicago School of Sociology.[41] While taking part in the American Negro Academy (ANA) in 1897, Du Bois presented a paper in which he rejected Frederick Douglass's plea for black Americans to integrate into white society. He wrote: "we are Negroes, members of a vast historic race that from the very dawn of creation has slept, but half awakening in the dark forests of its African fatherland".[42] In the August 1897 issue of The Atlantic Monthly, Du Bois published "Strivings of the Negro People", his first work aimed at the general public, in which he enlarged upon his thesis that African Americans should embrace their African heritage while contributing to American society.[43] |

幼少期 家族と子供時代 ウィリアム・エドワード・バーグハルト・デュボイスは、1868年2月23日、マサチューセッツ州グレートバリントンで、アルフレッドとメアリー・シル ヴィナ・バーグハルト・デュボイスの間に生まれた[3]。メアリー・シルヴィナ・バーグハルトの家族は、グレートバリントンのごく少数の自由黒人コミュニ ティの一員であり、長い間この州の土地を所有していた。彼女はオランダ人、アフリカ人、イギリス人の祖先から生まれた[4]。ウィリアム・デュボイススの 母方の曽祖父はトム・バーグハルトという奴隷(西アフリカで1730年頃に生まれた)で、オランダ人入植者コンラッド・バーグハルトが所有していた。トム はアメリカ独立戦争中に大陸軍に短期間従軍し、それが18世紀後半に自由を手に入れるきっかけとなった可能性がある。彼の息子ジャック・バーグハルトはオ セロ・バーグハルトの父親であり、オセロ・バーグハルトはメアリー・シルヴィナ・バーグハルトの父親である[5]。  母親に抱かれた幼児期のデュボイス 母親と幼児期のデュボイス ウィリアム・デュボイスはエリザベス・フリーマンを親戚であると主張し、彼女は彼の曽祖父ジャック・バーグハートと結婚したと書いている[6][7]。し かし、フリーマンはバーグハートよりも20歳年上で、そのような結婚の記録は見つかっていない。フリーマンの娘であるベッツィー・ハンフリーが、最初の夫 であるジョナ・ハンフリーが「1811年頃」にこの地域を去り、バーガードの最初の妻が亡くなった(1810年頃)後にバーガードと結婚したのかもしれな い。もしそうであれば、フリーマンはウィリアム・デュボイスの継曾曾祖母にあたる。伝聞によると、ハンフリーはバーグハルトと結婚していた。何らかの形で 親しい関係にあった可能性が高い[8]。 ウィリアム・デュボイスの父方の曽祖父は、ニューヨーク州ポキプシー出身のジェームズ・デュボイスで、ユグノーの血を引くフランス系アメリカ人であり、奴 隷の女性と数人の子どもをもうけていた[9]。ジェームズの混血の息子の一人が、1803年にバハマのロング・ケイで生まれたアレクサンダーである。 1810年、彼は父親とともに米国に移住した[10]。アレクサンダー・デュボイスはハイチを旅し、そこで愛人と息子をもうけた。アレクサンダーはコネチ カットに戻り、アルフレッドを母親とハイチに残した[11]。 1860年よりも前に、アルフレッド・デュボイスは米国に移住し、マサチューセッツに定住した。1867年2月5日、グレートバリントンにあるハウサト ニック村でメアリー・シルヴィナ・バーグハルトと結婚した[11]。アルフレッドは、息子のウィリアムが生まれて2年後の1870年にメアリーと別れた [12]。メアリー・デュボイスは息子とともにグレートバリントンの実家に戻り、息子が5歳になるまでそこで暮らした。彼女は家族を支えるために働き(兄 や近所の人たちから多少の援助も受けていた)、1880年代初頭に脳卒中を患うまで働いた。彼女は1885年に亡くなった[13][14]。 グレートバリントンにはヨーロッパ系アメリカ人が大半を占めるコミュニティがあり、彼らはデュボイスを概ねよく扱った。彼は地元の統合された公立学校に通 い、白人の同級生たちと遊んだ。大人になった彼は、父親のいない子供として感じた人種差別や、町でのマイノリティとしての経験について執筆した。しかし、 教師たちは彼の能力に気づき、知的な探求を奨励した。学問の充実した経験から、彼は自分の知識を使ってアフリカ系アメリカ人の地位向上に貢献できると確信 するようになった[15]。1884年、彼は町のグレートバリントン高校を優等で卒業した[16][17][18]。大学進学を決めたとき、彼が子供のこ ろ通っていたグレートバリントン第一長老教会の信徒たちが 、彼の学費を集めた[19][20][21]。 大学教育  デュボイスによるハーバード大学の論文『アメリカ合衆国におけるアフリカ奴隷貿易の抑制:1638年~1871年』のタイトルページ 近隣住民からの寄付金に支えられ、デュボイスは1885年から188 [22] 他のフィスク大学の学生たちと同様、デュボイスは夏期講習や不定期の授業で学費を賄いながら学業に励み、1886年の夏、2年生を終えた後に教職に就いた [23]。南部への旅行と滞在は、当時ジム・クロウ法、偏見、黒人投票権の抑制、リンチなどを含んでいた南部人種差別をデュボイスが初めて経験する出来事 となった。そのピークは次の10年間で迎えた[24]。 フィスク大学から学士号を取得後、彼は1888年から1890年までハーバード大学(フィスク大学の単位は認められなかった)に通い、そこでアメリカ哲学 界で著名なウィリアム・ジェームズ教授から強い影響を受けた[25]。デュボイスは、夏休みのアルバイト、遺産、奨学金、友人からの借金でハーバード大学 での3年間をやりくりした。1890年、ハーバード大学はデュボイスに歴史学の優等学位(cum laude)を授与した[26]。1891年、デュボイスはハーバード大学の社会学大学院で学ぶための奨学金を受けた[27]。 1892年、デュボイスはジョン・F・スレーター基金から奨学金を受け、フリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム大学に大学院生として入学した[28]。ベルリンの学 生時代、彼はヨーロッパ各地を広く旅した。彼は、ベルリンで知的成熟期を迎え、グスタフ・フォン・シュモーラー、アドルフ・ワグナー、ハインリッヒ・フォ ン・トリートシュケなど、ドイツで最も著名な社会学者たちから学んだ。ウェーバーは、1904年に『プロテスタント倫理と資本主義の精神』の出版を目前に 米国を訪問した際に、デュボイスと再会した[30]。 彼はドイツでの滞在について、「私はアメリカの世界の外側にいて、中を見ているような気分だった。私と一緒にいたのは、学生や知り合い、教師といった白人 の人々で、彼らは私と一緒にその光景を眺めていた。彼らは私を珍奇なものや人間以下の存在として見下すことはなかった。私は、学生というやや恵まれた地位 にある人間であり、彼らにとって、世界について語り合う相手として会うのが嬉しい存在だった。特に、私が来た世界の部分についてはそうだった。 デュボイスはヨーロッパから帰国後、大学院での研究を修了し、1895年にはハーバード大学から博士号を取得した初のアフリカ系アメリカ人となった [32]。 ウィルバーフォース 私と他の世界との間には、常に答えのない疑問がある。問題とされることはどんな気分だろうか?人は常に、アメリカ人であり黒人であるという二重性を感じ る。2つの魂、2つの思考、2つの和解できない努力、1つの暗い肉体の中にある2つの対立する理想。その頑強な強さだけが、体を引き裂かれることから守っ ているのだ。彼はアメリカをアフリカ化しようとは思わない。なぜなら、アメリカには世界とアフリカに教えるべきことが多すぎるからだ。彼は、白人至上主義 の洪水の中で黒人の魂を漂白しようとは思わない。なぜなら、黒人の血には世界に対するメッセージがあるということを知っているからだ。彼はただ、黒人であ りながらアメリカ人でもあることを可能にし、仲間から罵られたり唾を吐きかけられたりすることなく、機会の扉を無理やり閉ざされたりすることなく、生きて いきたいと願っているだけなのだ。 —デュボイス『黒人人民の奮闘』1897年[33] 1894年の夏、デュボイスはタスキーギ研究所を含む複数の就職オファーを受け、オハイオ州のウィルバーフォース大学で教職に就くことを承諾した[34] [35]。ウィルバーフォース大学で、デュボイスは アレクサンダー・クラメルから強い影響を受けた。クラメルは、社会変革を実現するには、思想と道徳が必要不可欠なツールであると考えていた[36]。ウィ ルバーフォース大学在学中の1896年5月12日、デュボイスは教え子のニーナ・ゴマーと結婚した[37]。 フィラデルフィア ウィルバーフォース大学に2年間在籍した後、デュボイスは1896年夏、ペンシルベニア大学から「社会学助手」として1年間の研究職を 1896年の夏、ペンシルベニア大学から「社会学助手」として1年間の研究職をオファーされた[38]。フィラデルフィアの黒人居住区で社会学的フィール ドワークを行い、その成果は、アトランタ大学で教鞭を執っていた1899年に出版された画期的な研究書『フィラデルフィア・ネグロ』の基礎となった。これ は、米国における黒人コミュニティの最初のケーススタディであった[39]。このプロジェクトでフィラデルフィアのコンサルタントを務めた人物の中に、黒 人史に関する文書、絵画、工芸品を収集した芸術家のウィリアム・ヘンリー・ドーシーがいた。ドーシーは、19世紀の黒人の生活に関する数百冊のスクラップ ブックをまとめ、フィラデルフィアの自宅に展示するコレクションを作った。デュボイスは、このスクラップブックを研究に用いた。 1890年代までに、フィラデルフィアの黒人居住区は、犯罪、貧困、死亡率などの点で悪い評判を得ていた。デュボイスの著書では、実証的な証拠によって固 定観念を覆し、人種隔離とそれが黒人の生活や評判に与える悪影響に対する彼のアプローチを形成した。その結果、彼は人種統合こそがアメリカの都市における 民主主義的平等の鍵であると悟った[40]。『フィラデルフィア・ネグロ』で用いられた方法、すなわち、社会的な特徴を地域ごとに記述し、マッピングする という手法は、 シカゴ社会学派の研究の先駆けとなった。 1897年にアメリカ黒人学会(ANA)に参加したデュボイスは、黒人アメリカ人が白人社会に統合することを求めるフレデリック・ダグラスの主張を否定す る論文を発表した。彼はこう書いている。「我々は黒人であり、創造の夜明けからずっと眠り続けてきた広大な歴史的人種のメンバーであり、アフリカの祖国で ある暗い森の中で半分目覚めているようなものである」。[42] 1897年8月号の 『アトランティック・マンスリー』誌1897年8月号に、デュボイスは「黒人社会の努力」を発表。これは一般大衆を対象とした彼の最初の作品であり、アフ リカ系アメリカ人はアフリカの伝統を受け継ぎながらアメリカ社会に貢献すべきであるという彼の主張を詳しく述べたものである[43]。 |

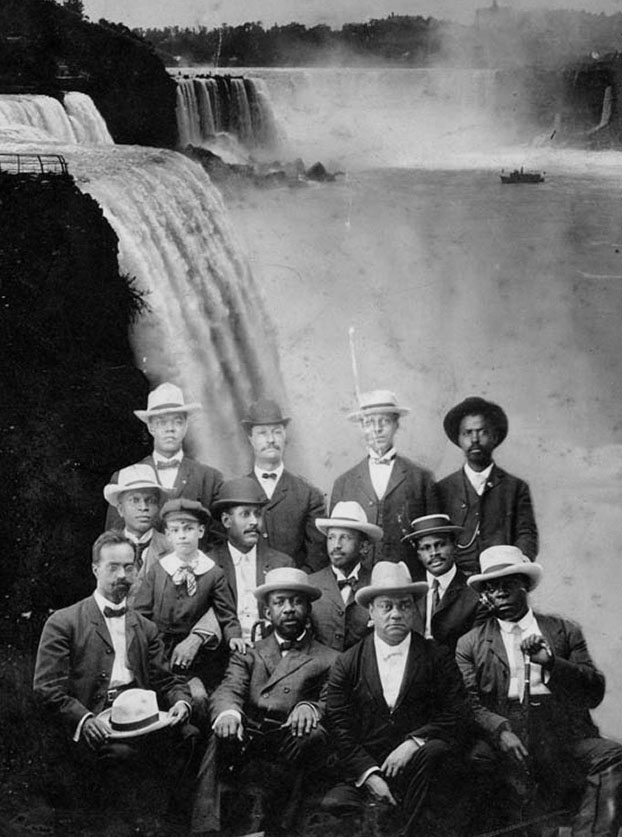

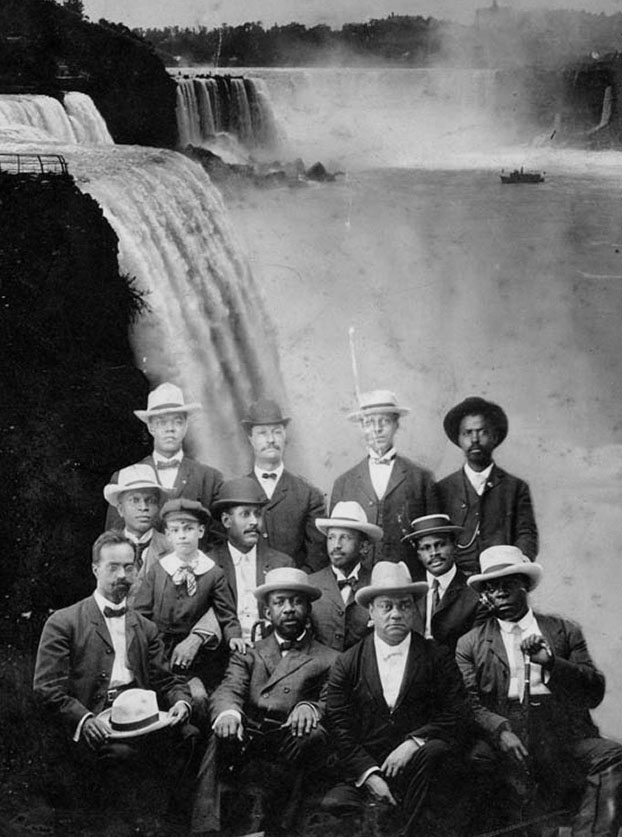

| Atlanta University In July 1897, Du Bois left Philadelphia and took a professorship in history and economics at the historically black Atlanta University in Georgia.[44][45] His first major academic work was his book The Philadelphia Negro (1899), a detailed and comprehensive sociological study of the African-American people of Philadelphia, based on his fieldwork in 1896–1897. This breakthrough in scholarship was the first scientific study of African Americans and a major contribution to early scientific sociology in the U.S.[46][47] Du Bois coined the phrase "the submerged tenth" to describe the black underclass in the study. Later in 1903, he popularized the term, the "Talented tenth", applied to society's elite class. His terminology reflected his opinion that the elite of a nation, both black and white, were critical to achievements in culture and progress.[48] During this period he wrote dismissively of the underclass, describing them as "lazy" or "unreliable", but – in contrast to other scholars – he attributed many of their societal problems to the ravages of slavery.[49] Du Bois's output at Atlanta University was prodigious, in spite of a limited budget: he produced numerous social science papers and annually hosted the Atlanta Conference of Negro Problems.[50] He also received grants from the U.S. government to prepare reports about African-American workforce and culture.[51] His students considered him to be a teacher that was brilliant, but aloof and strict.[52] First Pan-African Conference Du Bois attended the First Pan-African Conference, held in London on July 23–25, 1900, shortly ahead of the Paris Exhibition of 1900 ("to allow tourists of African descent to attend both events".)[53] The Conference had been organized by people from the Caribbean: Haitians Anténor Firmin and Benito Sylvain and Trinidadian barrister Henry Sylvester Williams.[54] Du Bois played a leading role in drafting a letter ("Address to the Nations of the World"), asking European leaders to struggle against racism, to grant colonies in Africa and the West Indies the right to self-government and to demand political and other rights for African Americans.[55] By this time, southern states were passing new laws and constitutions to disfranchise most African Americans, an exclusion from the political system that lasted into the 1960s. At the conclusion of the conference, delegates unanimously adopted the "Address to the Nations of the World", and sent it to various heads of state where people of African descent were living and suffering oppression.[56] The address implored the United States and the imperial European nations to "acknowledge and protect the rights of people of African descent" and to respect the integrity and independence of "the free Negro States of Abyssinia, Liberia, Haiti, etc."[57] It was signed by Bishop Alexander Walters (President of the Pan-African Association), the Canadian Rev. Henry B. Brown (vice-president), Williams (General Secretary) and Du Bois (chairman of the committee on the Address).[58] The address included Du Bois's observation, "The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the colour-line." He used this again three years later in the "Forethought" of his book The Souls of Black Folk (1903).[59] 1900 Paris Exposition Du Bois was the primary organizer of The Exhibit of American Negroes at the Exposition Universelle held in Paris between April and November 1900, for which he put together a series of 363 photographs aiming to commemorate the lives of African Americans at the turn of the century and challenge the racist caricatures and stereotypes of the day.[60][61] Also included were charts, graphs, and maps.[62][63] He was awarded a gold medal for his role as compiler of the materials, which are now housed at the Library of Congress.[61] Booker T. Washington and the Atlanta Compromise A formally dressed African American man, sitting for a posed portrait Du Bois in 1904 In the first decade of the new century, Du Bois emerged as a spokesperson for his race, second only to Booker T. Washington.[64] Washington was the director of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, and wielded tremendous influence within the African-American and white communities.[65] Washington was the architect of the Atlanta Compromise, an unwritten deal that he had struck in 1895 with Southern white leaders who dominated state governments after Reconstruction. Essentially the agreement provided that Southern blacks, who overwhelmingly lived in rural communities, would submit to the current discrimination, segregation, disenfranchisement, and non-unionized employment; that Southern whites would permit blacks to receive a basic education, some economic opportunities, and justice within the legal system; and that Northern whites would invest in Southern enterprises and fund black educational charities.[66][67][68] Despite initially sending congratulations to Washington for his Atlanta Exposition Speech,[69][70] Du Bois later came to oppose Washington's plan, along with many other African Americans, including Archibald H. Grimke, Kelly Miller, James Weldon Johnson, and Paul Laurence Dunbar – representatives of the class of educated blacks that Du Bois would later call the "talented tenth".[71][72] Du Bois felt that African Americans should fight for equal rights and higher opportunities, rather than passively submit to the segregation and discrimination of Washington's Atlanta Compromise.[73] Du Bois was inspired to greater activism by the lynching of Sam Hose, which occurred near Atlanta in 1899.[74] Hose was tortured, burned, and hanged by a mob of two thousand whites. When walking through Atlanta to discuss the lynching with newspaper editor Joel Chandler Harris, Du Bois encountered Hose's burned knuckles in a storefront display. The episode stunned Du Bois, and he resolved that "one could not be a calm, cool, and detached scientist while Negroes were lynched, murdered, and starved". Du Bois realized that "the cure wasn't simply telling people the truth, it was inducing them to act on the truth".[75] In 1901, Du Bois wrote a review critical of Washington's autobiography Up from Slavery,[76] which he later expanded and published to a wider audience as the essay "Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others" in The Souls of Black Folk.[77] Later in life, Du Bois regretted having been critical of Washington in those essays.[78] One of the contrasts between the two leaders was their approach to education: Washington felt that African-American schools should focus primarily on industrial education topics such as agricultural and mechanical skills, to prepare southern blacks for the opportunities in the rural areas where most lived.[79] Du Bois felt that black schools should focus more on liberal arts and academic curriculum (including the classics, arts, and humanities), because liberal arts were required to develop a leadership elite.[80] However, as sociologist E. Franklin Frazier and economists Gunnar Myrdal and Thomas Sowell have argued, such disagreement over education was a minor point of difference between Washington and Du Bois; both men acknowledged the importance of the form of education that the other emphasized.[81][82][83] Sowell has also argued that, despite genuine disagreements between the two leaders, the supposed animosity between Washington and Du Bois actually formed among their followers, not between Washington and Du Bois themselves.[84] Du Bois also made this observation in an interview published in The Atlantic Monthly in November 1965.[85]  Du Bois in 1904 Niagara Movement  Main article: Niagara Movement A dozen African American men seated with Niagara Falls in the background Founders of the Niagara Movement in 1905. Du Bois is in the middle row, with white hat. In 1905, Du Bois and several other African-American civil rights activists – including Fredrick McGhee, Max Barber and William Monroe Trotter – met in Canada, near Niagara Falls,[86] where they wrote a declaration of principles opposing the Atlanta Compromise, and which were incorporated as the Niagara Movement in 1906.[87] They wanted to publicize their ideals to other African Americans, but most black periodicals were owned by publishers sympathetic to Washington, so Du Bois bought a printing press and started publishing Moon Illustrated Weekly in December 1905.[88] It was the first African-American illustrated weekly, and Du Bois used it to attack Washington's positions, but the magazine lasted only for about eight months.[89] Du Bois soon founded and edited another vehicle for his polemics, The Horizon: A Journal of the Color Line, which debuted in 1907. Freeman H. M. Murray and Lafayette M. Hershaw served as The Horizon's co-editors.[90] The Niagarites held a second conference in August 1906, in celebration of the 100th anniversary of abolitionist John Brown's birth, at the West Virginia site of Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry.[89] Reverdy C. Ransom spoke, explaining that Washington's primary goal was to prepare blacks for employment in their current society: "Today, two classes of Negroes ...are standing at the parting of the ways. The one counsels patient submission to our present humiliations and degradations ... The other class believe that it should not submit to being humiliated, degraded, and remanded to an inferior place. ...[I]t does not believe in bartering its manhood for the sake of gain."[91] The Souls of Black Folk Main article: The Souls of Black Folk In an effort to portray the genius and humanity of the black race, Du Bois published The Souls of Black Folk (1903), a collection of 14 essays.[92][93] James Weldon Johnson said the book's effect on African Americans was comparable to that of Uncle Tom's Cabin.[93] The introduction famously proclaimed that "the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line".[94] Each chapter begins with two epigraphs – one from a white poet, and one from a black spiritual – to demonstrate intellectual and cultural parity between black and white cultures.[92] A major theme of the work was the double consciousness faced by African Americans: being both American and black. This was a unique identity which, according to Du Bois, had been a handicap in the past, but could be a strength in the future: "Henceforth, the destiny of the race could be conceived as leading neither to assimilation nor separatism but to proud, enduring hyphenation."[95] Jonathon S. Kahn in Divine Discontent: The Religious Imagination of Du Bois shows how Du Bois, in his The Souls of Black Folk, represents an exemplary text of pragmatic religious naturalism. On page 12, Kahn writes: "Du Bois needs to be understood as an African American pragmatic religious naturalist. By this I mean that, like Du Bois the American traditional pragmatic religious naturalism, which runs through William James, George Santayana, and John Dewey, seeks religion without metaphysical foundations." Kahn's interpretation of religious naturalism is very broad but he relates it to specific thinkers. Du Bois's anti-metaphysical viewpoint places him in the sphere of religious naturalism as typified by William James and others.[96] Racial violence Two calamities in the autumn of 1906 shocked African Americans, and they contributed to strengthening support for Du Bois's struggle for civil rights to prevail over Booker T. Washington's accommodationism. First, President Theodore Roosevelt dishonorably discharged 167 Buffalo Soldiers because they were accused of crimes as a result of the Brownsville affair. Many of the discharged soldiers had served for 20 years and were near retirement.[97] Second, in September, riots broke out in Atlanta, precipitated by unfounded allegations of black men assaulting white women. This was a catalyst for racial tensions based on a job shortage and employers playing black workers against white workers.[98] Ten thousand whites rampaged through Atlanta, beating every black person they could find, resulting in over 25 deaths.[99] In the aftermath of the 1906 violence, Du Bois urged blacks to withdraw their support from the Republican Party, because Republicans Roosevelt and William Howard Taft did not sufficiently support blacks. Most African Americans had been loyal to the Republican Party since the time of Abraham Lincoln.[100] Du Bois endorsed Taft's rival William Jennings Bryan in the 1908 presidential election despite Bryan's acceptance of segregation.[101] Du Bois wrote the essay, "A Litany at Atlanta", which asserted that the riot demonstrated that the Atlanta Compromise was a failure. Despite upholding their end of the bargain, blacks had failed to receive legal justice in the South. Historian David Levering Lewis has written that the Compromise no longer held because white patrician planters, who took a paternalistic role, had been replaced by aggressive businessmen who were willing to pit blacks against whites.[102] These two calamities were watershed events for the African American community, marking the ascendancy of Du Bois's vision of equal rights.[103] Academic work Once we were told: Be worthy and fit and the ways are open. Today, the avenues of advancement in the army, navy, civil service, and even business and professional life are continually closed to black applicants of proven fitness, simply on the bald excuse of race and color. —Du Bois, "Address at Fourth Niagara Conference", 1908[104] In addition to writing editorials, Du Bois continued to produce scholarly work at Atlanta University. In 1909, after five years of effort, he published a biography of abolitionist John Brown. It contained many insights, but also contained some factual errors.[105][106] The work was strongly criticized by The Nation, which was owned by Oswald Garrison Villard, who was writing his own, competing biography of John Brown. Possibly as a result, Du Bois's work was largely ignored by white scholars.[107] After publishing a piece in Collier's magazine warning of the end of "white supremacy", Du Bois had difficulty getting pieces accepted by major periodicals, although he did continue to publish columns regularly in The Horizon magazine.[108] Du Bois was the first African American invited by the American Historical Association (AHA) to present a paper at their annual conference. He read his paper, Reconstruction and Its Benefits, to an astounded audience at the AHA's December 1909 conference.[109] The paper went against the mainstream historical view, promoted by the Dunning School of scholars at Columbia University, that Reconstruction was a disaster, caused by the ineptitude and sloth of blacks. To the contrary, Du Bois asserted that the brief period of African-American leadership in the South accomplished three important goals: democracy, free public schools, and new social welfare legislation.[110] Du Bois asserted that it was the federal government's failure to manage the Freedmen's Bureau, to distribute land, and to establish an educational system, that doomed African-American prospects in the South.[110] When Du Bois submitted the paper for publication a few months later in The American Historical Review, he asked that the word 'Negro' be capitalized. The editor, J. Franklin Jameson, refused, and published the paper without the capitalization.[111] The paper was mostly ignored by white historians.[110] Du Bois later developed his paper as his 1935 book, Black Reconstruction in America, which marshaled extensive references to support his assertions.[109] The AHA did not invite another African-American speaker until 1940.[112] |

アトランタ大学 1897年7月、デュボイスはフィラデルフィアを離れ、ジョージア州にある歴史的に黒人大学であるアトランタ大学で歴史と経済学の教授職に就いた[44] [45]。彼の最初の主要な学術作品は、1896年から1897年にかけてのフィールドワークに基づいて、フィラデルフィアの黒人について詳しく包括的に 社会学的に研究した著書『フィラデルフィア・ネグロ』(1899年)であった。この画期的な研究は、アフリカ系アメリカ人に関する最初の科学的調査であ り、初期の科学的社会学に対する大きな貢献となった[46][47]。 デュボアは、この研究の中で黒人下層階級を表すために「沈んだ10分の1」という表現を考案した。その後1903年に、彼はこの言葉を「才能ある10分の 1」として一般化し、社会のエリート層に当てはめた。彼の用語は、黒人も白人も含めた国家のエリート層が、文化の進歩と発展に不可欠であるという彼の意見 を反映していた[48]。この期間、彼は下層階級を「怠け者」や「信頼できない」と軽蔑的に表現したが、他の学者とは対照的に、彼らの社会問題の多くは奴 隷制度の弊害に起因すると考えていた[49]。 アトランタ大学でのデュボイスの業績は、限られた予算にもかかわらず、驚くほど多かった。 限られた予算にもかかわらず、デュボイスのアトランタ大学での業績は目覚ましかった。彼は数多くの社会科学論文を発表し、毎年アトランタ黒人問題会議を主 催した[50]。また、アフリカ系アメリカ人の労働力と文化に関する報告書を作成するために、米国政府から助成金も受け取っていた[51]。彼の学生たち は、デュボイスを聡明だが、高慢で厳しい教師だと考えていた[52]。 第1回汎アフリカ会議 デュボイスは、1900年7月23日から25日にロンドンで開催された第1回汎アフリカ会議に出席した。1900年7月23日から25日にかけてロンドン で開催された。パリ万博(1900年)の直前に開催されたこの会議は、「アフリカ系観光客が両方のイベントに参加できるように」開催された[53]。会議 はカリブ海地域の人々によって企画された。ハイチ人のアンテノール・ファーミン、ベニート・シルヴァン、トリニダード・トバゴの弁護士ヘンリー・シルベス ター・ウィリアムズである[54]。デュボイスは、 ヨーロッパの指導者たちに人種差別と闘い、アフリカと西インド諸島の植民地に自治権を認め、アフリカ系アメリカ人に政治的権利やその他の権利を要求するよ う求める手紙(「世界諸国民への演説」)の作成を主導した[55]。この頃には、南部諸州はアフリカ系アメリカ人の大半の選挙権を剥奪する新たな法律や憲 法を可決しており、政治システムからの排除は1960年代まで続いた。 会議の終わりに、代表団は全会一致で「世界諸国民への演説」を採択し、アフリカ系住民が居住し抑圧を受けている各国の首脳に送った[56]。演説では、米 国とヨーロッパの帝国主義国家に対し、「アフリカ系住民の権利を認知し保護すること」と、「アビシニア自由黒人国家、 リベリア、ハイチなど」[57] 署名者は、アレクサンダー・ウォルターズ司教(汎アフリカ協会会長)、ヘンリー・B・ブラウン牧師(副社長)、ウィリアムズ(事務総長)、デュボイス(演 説委員会委員長)であった[58]。演説には、デュボイスの「20世紀の問題は人種差別問題である」という見解が盛り込まれていた。彼は3年後の著書『黒 人魂』(1903年)の「序文」でもこの言葉を再び使用している[59]。 1900年パリ万博 デュボイスは、1900年4月から11月にかけてパリで開催された万国博覧会における「アメリカ黒人展」の主要企画者であり、世紀の変わり目におけるアフ リカ系アメリカ人の生活を記念し、当時の人種差別的な風刺画や固定観念に異議を唱えることを目的として、363枚の写真シリーズをまとめた。世紀の変わり 目にアフリカ系アメリカ人の生活を記念し、当時の人種差別的な風刺画や固定概念に異議を唱えることを目的としていた。新世紀の最初の10年間、デュボア は、ブッカー・T・ワシントンに次ぐ人種を代表する人物として頭角を現した[64]。ワシントンはアラバマ州タスキーギ研究所の所長であり、アフリカ系ア メリカ人と白人社会で絶大な影響力を持っていた[65]。ワシントンは、再建後に州政府を支配した南部白人指導者たちと1895年に結んだ、アトランタ妥 協と呼ばれる不文律の協定の立役者であった。この合意は、基本的に、農村部に圧倒的に多く住む南部黒人が、現行の差別、隔離、参政権剥奪、非組合雇用に従 うこと、南部白人が黒人に基礎教育、いくつかの経済機会、司法制度内での正義を受け入れること、北部白人が南部企業への投資と また、黒人の教育慈善事業に資金援助を行うことだった[66][67][68]。 デュボイスは当初、ワシントンがアトランタ博覧会で行った演説に対して祝意を送っていたが[69][70]、後に他の多くのアフリカ系アメリカ人、アーチ ボルド・H・グリムケ、ケリー・ミラー、ジェームズ・ウェルドン・ジョンソン、ポール・ローレンス・ダンバーらとともに、ワシントンの計画に反対するよう になった。ポール・ローレンス・ダンバーなど、後にデュボイスが「有能な10分の1」と呼ぶことになる教養ある黒人の代表たちである[71][72]。 デュボイスは、アフリカ系アメリカ人はワシントンのアトランタ妥協案による隔離や差別に受動的に従うのではなく、平等の権利とより高い機会を求めて闘うべ きだと感じていた[73]。 デュボイスは、1899年にアトランタ近郊で起こったサム・ホースのリンチ事件により、より積極的な活動を行う決意を固めた[74]。ホースは2000人 の白人暴徒により拷問、火あぶり、絞首刑に処された。デュボイスは、新聞編集者のジョエル・チャンドラー・ハリスとリンチについて話し合うためにアトラン タを歩いていると、店先でホースの火傷した指の関節を目にした。この出来事に衝撃を受けたデュボイスは、「黒人がリンチされ、殺され、餓死しているのに、 冷静で冷静で、客観的な科学者ではいられない」と決意した。デュボイスは、「治療とは単に人々に真実を伝えることではなく、真実に基づいて行動を起こさせ ること」だと気づいた[75]。 1901年、デュボイスはワシントンの自伝『奴隷の身分から』を批判的に論評した[76]。後にこの論評は拡大され、『黒人魂』に「ブッカー・T・ワシン トン氏について、そしてその他」というエッセイとして発表され、より幅広い読者層に読まれることとなった[77]。『黒人魂』に「ブッカー・T・ワシント ン氏について、そしてその他」というエッセイとして発表し、より幅広い読者層に公開した[77]。デュボイスは後年、これらのエッセイでワシントンを批判 したことを後悔した[78]。二人の指導者の違いの一つは、教育に対する考え方であった。ワシントンは、アフリカ系アメリカ人の学校は、農業や機械技術と いった産業教育に重点を置くべきだと考えていた。これは、南部黒人が大半が住む農村部の機会に備えるためである[79]。デュボイスは、黒人の学校は、リ ベラルアーツや学術カリキュラム(古典、芸術、人文科学を含む)に重点を置くべきだと考えていた。なぜなら、リベラルアーツは、 指導的エリートを育成するために必要だったからだ[80]。 し かし、社会学者 E. フランクリン・フレイザー、経済学者グンナー・ミルダール、トーマス・ソウェルが主張したように、ワシントンとデュボアの間で教育に関する意見の相違が あったのは些細な点であり、両者とも相手が重視する教育形態の重要性を認めていた[81][82][83]。 また、ソウェルは、2人の指導者の間に真の意見の相違があったにもかかわらず、ワシントンとデュボイスの間にあったとされる敵意は、実際にはワシントンと デュボイスの間ではなく、彼らの支持者たちの間に形成されたと主張している[84]。デュボイスも、1965年11月に『アトランティック・マンスリー』 誌に掲載されたインタビューで同様の見解を示している[85]。  Du Bois in 1904 ナイアガラ運動  メイン記事: ナイアガラ運動 ナイアガラの滝を背景に腰を下ろすアフリカ系アメリカ人男性12人 1905年のナイアガラ運動の創設者たち。ドゥ・ボワは白い帽子を被り、真ん中の列にいる。 1905年、デュボイスとフレデリック・マギー、マックス・バーバー、ウィリアム・モンロー・トロッターを含む他のアフリカ系アメリカ人の公民権活動家数 人が、ナイアガラの滝近くのカナダで会合を開き、アトランタ妥協案に反対する原則宣言を起草した。ほとんどの黒人向け定期刊行物はワシントンに同調的な出 版社が所有していたため、デュボイスは印刷機を購入し、1905年12月に『Moon Illustrated Weekly』の出版を開始した[88]。これはアフリカ系アメリカ人向けのイラスト入り週刊誌としては初めてのものであり、デュボイスはこれをワシント ンの立場を攻撃するために利用したが、この雑誌はわずか8か月ほどしか続かなかった[89]。デュボイスはすぐに、自身の論争のための別の媒体『The Horizon: 1907年に創刊された『The Horizon: A Journal of the Color Line』である。フリーマン・H・M・マレーとラファイエット・M・ハーショウが『The Horizon』の共同編集者を務めた[90]。 ナイアガラ派は、奴隷廃止論者ジョン・ブラウンの生誕100周年を記念して、1906年8月にウェストバージニア州ハーパーズ・フェリー襲撃事件の現場で あるブラウンズ・クリークで第2回会議を開催した[89]。レヴァディ・C・ ランサムは、ワシントンの主な目的は黒人が現在の社会で雇用されるための準備をすることであると説明し、「今日、2つのクラスの黒人が...岐路に立って いる。一方は、現在の屈辱と堕落に忍耐強く従うよう助言する...もう一方は、屈辱を受け入れ、堕落し、劣った立場に追いやられるべきではないと考えてい る。...[I]t does not believe in bartering its manhood for the sake of gain."[91] 『黒人魂』 メイン記事: 『黒人魂』 黒人の天才性と人間性を描写する試みとして、デュボイスは14編のエッセイをまとめた『黒人魂』(1903年)を出版した[92][93]。ジェームズ・ ウェルトン・ジョンソンは、この本がアフリカ系アメリカ人に与えた影響は『アンクル・トムの小屋』に匹敵すると述べた[93]。序文で、 「20世紀の問題は人種間の境界線の問題である」[94]。各章は、白人詩人と黒人霊歌の2つの銘文で始まる。これは、黒人と白人の文化の知的・文化的平 等を示すものである[92]。 この作品の主要なテーマは、アフリカ系アメリカ人が直面する二重意識、すなわちアメリカ人であり黒人でもあるということである。これはデュボイスによれ ば、過去においてはハンディキャップであったが、将来においては強みとなりうるユニークなアイデンティティであった。「今後は、人種の運命は、同化にも分 離主義にも向かわず、誇り高く永続的な結合へと向かうものと想定できる」[95]。 ジョナサン・S・カーン著『Divine Discontent: The Divine Discontent: The Religious Imagination of Du Bois』の中で、ジョナサン・S・カーンは、デュボイスが『The Souls of Black Folk』で、実践的な宗教的自然主義の模範的なテキストをどのように表現したかを示している。12ページでカーンは次のように書いている。「デュボイス は、アフリカ系アメリカ人の実践的な宗教的自然主義者として理解される必要がある。つまり、ウィリアム・ジェームズ、ジョージ・サンタヤナ、ジョン・ デューイに通じるアメリカの伝統的な実践的な宗教的自然主義と同様に、デュボイスは形而上学的な基盤を持たない宗教を求めているということだ」。カーンの 宗教的自然主義の解釈は非常に幅広いものであるが、彼はそれを特定の思想家と関連付けている。デュボイスの反形而上学的な視点は、ウィリアム・ジェームズ や他の人々に代表される宗教的自然主義の領域に位置づけるものである[96]。 人種的暴力 1906年の秋に起こった2つの悲劇はアフリカ系アメリカ人を震撼させ、ワシントンが示した融和主義に打ち勝つためにデュボアが繰り広げた公民権運動への 支持を強めることにつながった。まず、セオドア・ルーズベルト大統領が、ブラウンズビル事件の結果として兵士たちが犯罪を犯したとして、167人のバッ ファロー・ソルジャーを不名誉除隊させた。除隊兵士の多くは20年間勤務し、定年退職間近であった[97]。第2に、9月にはアトランタで暴動が発生し た。黒人男性が白人女性を暴行したという根拠のない疑惑がきっかけであった。これは、労働力不足と雇用主が黒人労働者を白人労働者に対抗させるという人種 的緊張のきっかけとなった[98]。1万人の白人がアトランタを暴れまわり、見つけることができるすべての黒人を殴り、25人以上の死者を出した [99]。1906年の暴動の後、デュボイスは黒人に対して、黒人を十分に支援していないルーズベルトとウィリアム・ハワード・タフトの共和党からの支持 を取りやめるよう促した。アブラハム・リンカーンの時代から、ほとんどの黒人たちは共和党に忠誠を誓っていた[100]。デュボイスは、1908年の大統 領選挙で、人種隔離政策を支持していたウィリアム・ジェニングス・ブライアンを、対立候補のタフト支持に回った[101]。 デュボイスは「アトランタの連祷」というエッセイを執筆し、暴動はアトランタ妥協が失敗だったことを証明したと主張した。黒人は妥協案を守ったにもかかわ らず、南部では法的な正義を得ることができなかった。歴史家のデビッド・レベリング・ルイスは、白人貴族プランテーション主が父権主義的な役割を担ってい たのに対し、黒人と白人を対立させることに積極的な実業家たちに取って代わられたため、もはや妥協案は機能しなくなったと書いている[102]。 学術研究 かつて私たちはこう教えられた。「ふさわしい人物となり、ふさわしい人物になれば、道は開ける」。今日、陸軍、海軍、文官、さらにはビジネスや専門職の世 界で、能力のある黒人志願者が、人種や肌の色というあからさまな口実だけで、昇進の機会から閉め出され続けている。 —デュボイス、「第4回ナイアガラ会議での演説」、1908年[104] 論説の執筆に加え、デュボイスはアトランタ大学で学術研究も続けていた。1909年、5年間の努力の末に、彼は奴隷廃止論者ジョン・ブラウンの伝記を出版 した。この本には多くの洞察が盛り込まれていたが、いくつかの事実誤認も含まれていた[105][106]。この本は、オズワルド・ギャリソン・ヴィラー ドが所有する雑誌『ザ・ネイション』から強い批判を受けた。ヴィラードは、ジョン・ブラウンの伝記を執筆していた。その結果、デュボアスの作品は白人学者 からほとんど無視された[107]。雑誌『コリアーズ』に「白人至上主義」の終焉を警告する論文を発表した後、デュボアスは主要な定期刊行物に論文が掲載 されるのに苦労したが、雑誌『ホライゾン』には定期的にコラムを寄稿し続けた[108]。 デュボアスは、アメリカ歴史学会(AHA)の年次総会で論文を発表するために招待された最初のアフリカ系アメリカ人であった。彼は、1909年12月の AHAの会議で、驚くべき聴衆を前にして論文「再建とその利益」を読み上げた[109]。この論文は、コロンビア大学のダンニング学派が唱える、再建は黒 人の無能さと怠惰が原因で起こった災難であるという歴史観の主流に反するものだった。それとは逆に、デュボイスは、南部におけるアフリカ系アメリカ人の短 い指導期間の間に、民主主義、無料の公立学校、新しい社会福祉立法という3つの重要な目標が達成されたと主張した[110]。 デュボイスは、連邦政府がフリーダムマンの 土地の分配、教育制度の確立を怠ったことが、南部におけるアフリカ系アメリカ人の将来を絶望的なものにしたとデュボイスは主張した[110]。数か月後、 デュボイスが『アメリカン・ヒストリカル・レビュー』に論文を投稿する際、「ネグロ」という単語を大文字で表記するよう求めた。編集者のJ.フランクリ ン・ジェイムソンはこれを拒否し、大文字表記のない論文を出版した[111]。この論文は、白人歴史家たちからほとんど無視された[110]。デュボイス は後にこの論文を発展させ、1935年に『Black Reconstruction in America』として出版した。この本では、彼の主張を裏付ける広範な参考文献がまとめられている[109]。AHAは1940年まで、他のアフリカ系 アメリカ人講演者を招待することはなかった[112]。 |

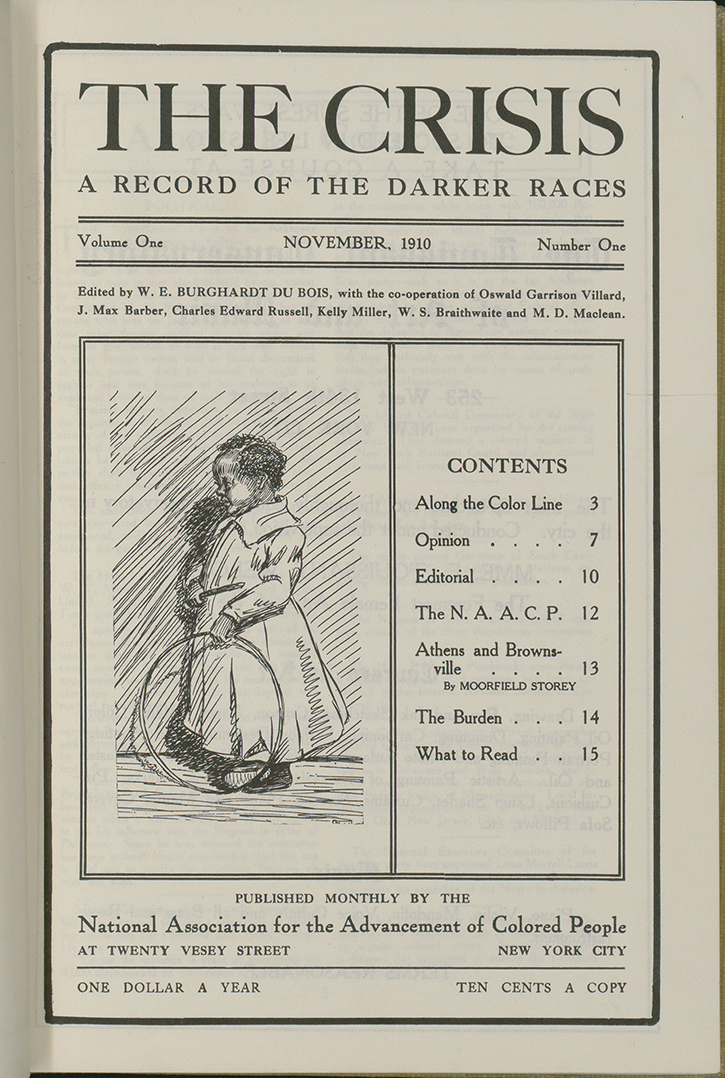

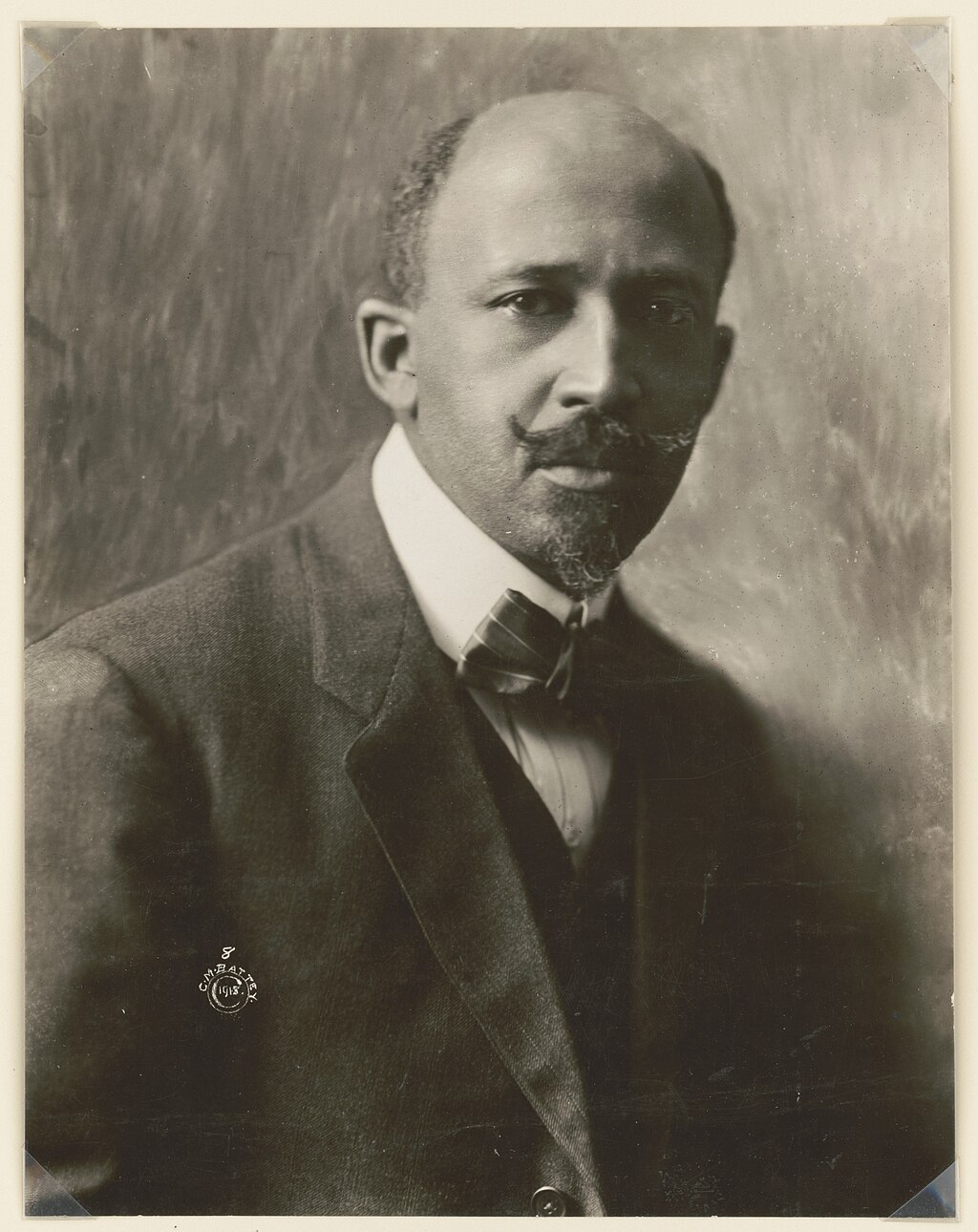

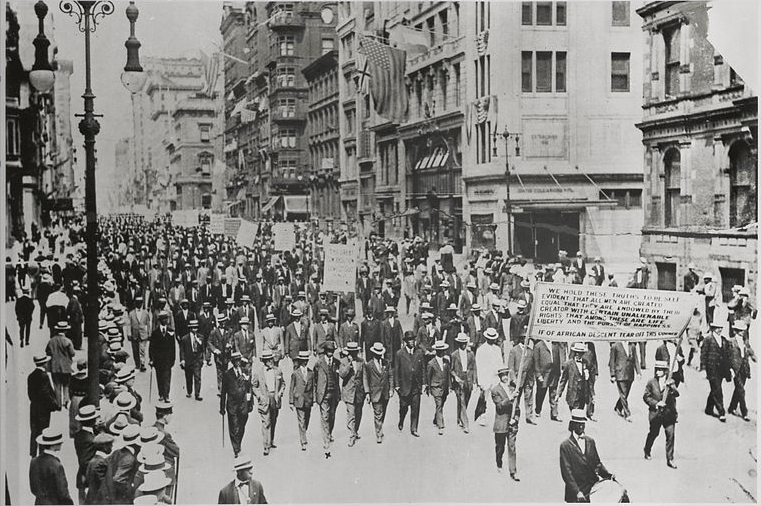

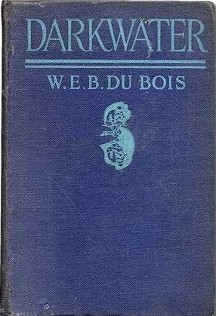

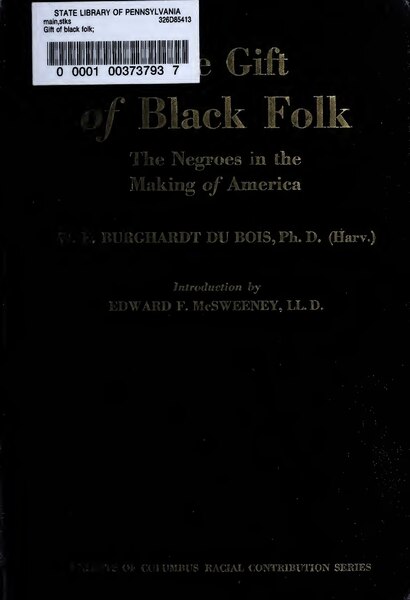

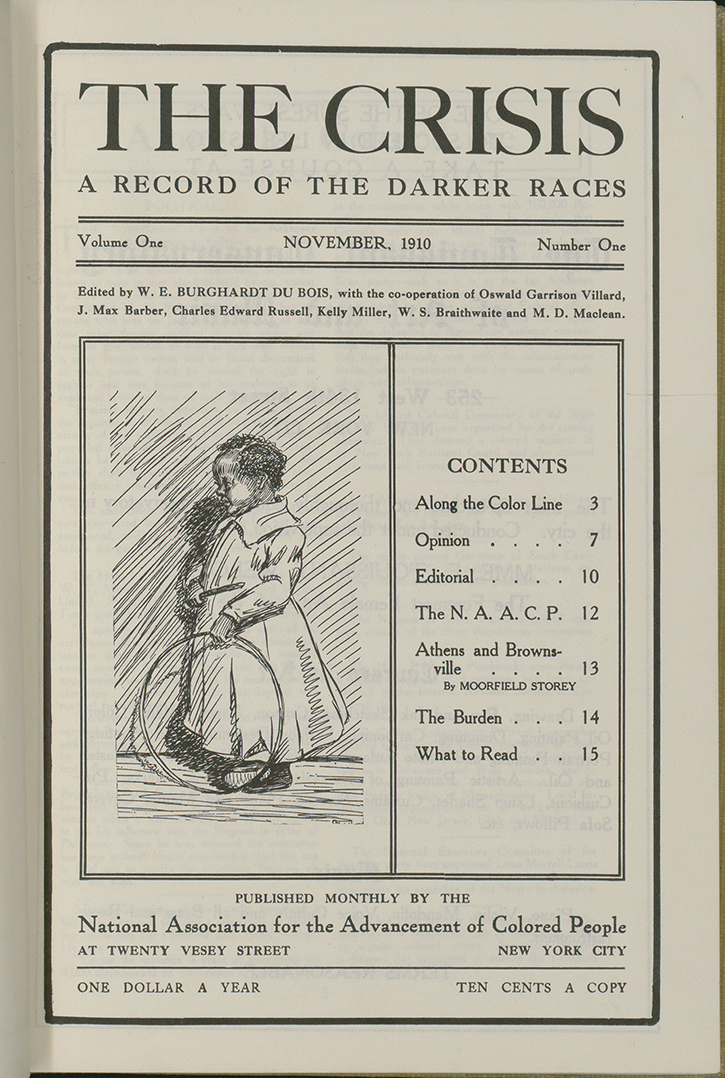

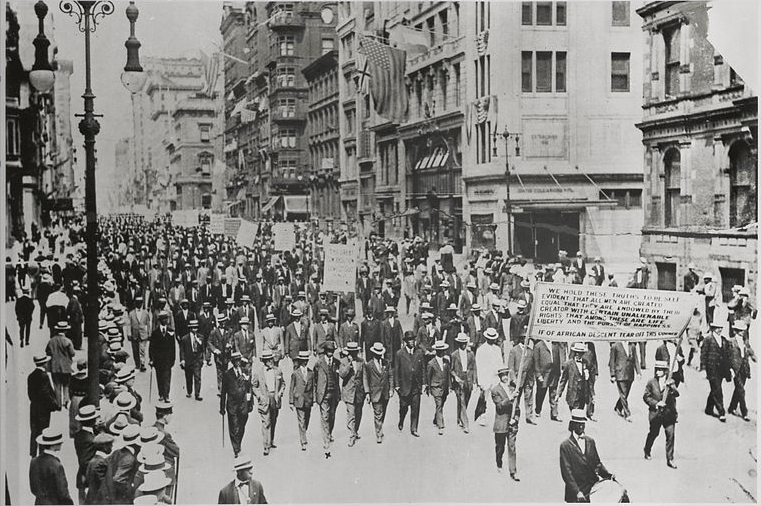

| NAACP era In May 1909, Du Bois attended the National Negro Conference in New York.[113] The meeting led to the creation of the National Negro Committee, chaired by Oswald Garrison Villard, and dedicated to campaigning for civil rights, equal voting rights, and equal educational opportunities.[114] The following spring, in 1910, at the second National Negro Conference, the attendees created the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).[115] At Du Bois's suggestion, the word "colored", rather than "black", was used to include "dark skinned people everywhere".[116] Dozens of civil rights supporters, black and white, participated in the founding, but most executive officers were white, including Mary White Ovington, Charles Edward Russell, William English Walling, and its first president, Moorfield Storey.[117] Feeling inspired by this, Indian social reformer and civil rights activist B. R. Ambedkar contacted Du Bois in the 1940s. In a letter to Du Bois in 1946, he introduced himself as a member of the "Untouchables of India" and "a student of the Negro problem" and expressed his interest in the NAACP's petition to the United Nations. He noted that his group was "thinking of following suit"; and requested copies of the proposed statement from Du Bois. In a letter dated July 31, 1946, Du Bois responded by telling Ambedkar he was familiar with his name, and that he had "every sympathy with the Untouchables of India."[118][119] The Crisis  An African American man, sitting for a posed portrait Du Bois, c. 1911 NAACP leaders offered Du Bois the position of Director of Publicity and Research.[120] He accepted the job in the summer of 1910, and moved to New York after resigning from Atlanta University. His primary duty was editing the NAACP's monthly magazine, which he named The Crisis.[121] The first issue appeared in November 1910, and Du Bois wrote that its aim was to set out "those facts and arguments which show the danger of race prejudice, particularly as manifested today toward colored people".[122] The journal was phenomenally successful, and its circulation would reach 100,000 in 1920.[123] Typical articles in the early editions polemics against the dishonesty and parochialism of black churches, and discussions on the Afrocentric origins of Egyptian civilization.[124] Du Bois's African-centered view of ancient Egypt was in direct opposition to many Egyptologists of his day, including Flinders Petrie, whom Du Bois had met a conference.[125] A 1911 Du Bois editorial helped initiate a nationwide push to induce the federal government to outlaw lynching. Du Bois, employing the sarcasm he frequently used, commented on a lynching in Pennsylvania: "The point is he was black. Blackness must be punished. Blackness is the crime of crimes ... It is therefore necessary, as every white scoundrel in the nation knows, to let slip no opportunity of punishing this crime of crimes. Of course if possible, the pretext should be great and overwhelming – some awful stunning crime, made even more horrible by the reporters' imagination. Failing this, mere murder, arson, barn burning or impudence may do."[126][127]  First Issue of The Crisis, November 1910 The Crisis carried Du Bois editorials supporting the ideals of unionized labor but denouncing its leaders' racism; blacks were barred from membership.[128] Du Bois also supported the principles of the Socialist Party of America (he held party membership from 1910 to 1912), but he denounced the racism demonstrated by some socialist leaders.[129] Frustrated by Republican president Taft's failure to address widespread lynching, Du Bois endorsed Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson in the 1912 presidential race, in exchange for Wilson's promise to support black causes.[130] Throughout his writings, Du Bois supported women's rights[131][132] and women's suffrage,[133] but he found it difficult to publicly endorse the women's right-to-vote movement because leaders of the suffragism movement refused to support his fight against racial injustice.[134] A 1913 Crisis editorial broached the taboo subject of interracial marriage: although Du Bois generally expected persons to marry within their race, he viewed the problem as a women's rights issue, because laws prohibited white men from marrying black women. Du Bois wrote "[anti-miscegenation] laws leave the colored girls absolutely helpless for the lust of white men. It reduces colored women in the eyes of the law to the position of dogs. As low as the white girl falls, she can compel her seducer to marry her ... We must kill [anti-miscegenation laws] not because we are anxious to marry the white men's sisters, but because we are determined that white men will leave our sisters alone."[135][136] During 1915−1916, some leaders of the NAACP – disturbed by financial losses at The Crisis, and worried about the inflammatory rhetoric of some of its essays – attempted to oust Du Bois from his editorial position. Du Bois and his supporters prevailed, and he continued in his role as editor.[137] In a 1919 column titled "The True Brownies", he announced the creation of The Brownies' Book, the first magazine published for African-American children and youth, which he founded with Augustus Granville Dill and Jessie Redmon Fauset.[138][139] Historian and author  Formal photograph of Du Bois, with beard and mustache, around 50 years old Du Bois in 1918, by C. M. Battey The 1910s were a productive time for Du Bois. In 1911, he attended the First Universal Races Congress in London[140] and he published his first novel, The Quest of the Silver Fleece.[141] Two years later, Du Bois wrote, produced, and directed a pageant for the stage, The Star of Ethiopia.[142] In 1915, Du Bois published The Negro, a general history of black Africans, and the first of its kind in English. The book rebutted claims of African inferiority, and would come to serve as the basis of much Afrocentric historiography in the 20th century. The Negro predicted unity and solidarity for colored people around the world, and it influenced many who supported the Pan-African movement.[143] In 1915, The Atlantic Monthly carried a Du Bois essay, "The African Roots of the War", which consolidated his ideas on capitalism, imperialism, and race.[144] He argued that the Scramble for Africa was at the root of World War I. He also anticipated later communist doctrine, by suggesting that wealthy capitalists had pacified white workers by giving them just enough wealth to prevent them from revolting, and by threatening them with competition by the lower-cost labor of colored workers.[145] Combating racism Du Bois used his influential NAACP position to oppose a variety of racist incidents. When the silent film The Birth of a Nation premiered in 1915, Du Bois and the NAACP led the fight to ban the movie, because of its racist portrayal of blacks as brutish and lustful.[146] The fight was not successful, and possibly contributed to the film's fame, but the publicity drew many new supporters to the NAACP.[147] The private sector was not the only source of racism: under President Wilson, the plight of African Americans in government jobs suffered. Many federal agencies adopted whites-only employment practices, the Army excluded blacks from officer ranks, and the immigration service prohibited the immigration of persons of African ancestry.[148] Du Bois wrote an editorial in 1914 deploring the dismissal of blacks from federal posts, and he supported William Monroe Trotter when Trotter brusquely confronted Wilson about the President's failure to fulfill his campaign promise of justice for blacks.[149]  A photograph of the lynching of Jesse Washington The Crisis continued to wage a campaign against lynching. In 1915, it published an article with a year-by-year tabulation of 2,732 lynchings from 1884 to 1914.[150] The April 1916 edition covered the group lynching of six African Americans in Lee County, Georgia.[151] Later in the June 1916 issue, the "Waco Horror" article covered the lynching of Jesse Washington, a mentally impaired 17-year-old African American. Du Bois included photographs of it in the article.[151] The article broke new ground by utilizing undercover reporting to expose the conduct of local whites in Waco, Texas.[152] The early 20th century was the era of the Great Migration of blacks from the Southern United States to the Northeast, Midwest, and West. Du Bois wrote an editorial supporting the Great Migration, because he felt it would help blacks escape Southern racism, find economic opportunities, and assimilate into American society.[153] Also in the 1910s the American eugenics movement was in its infancy, and many leading eugenicists were openly racist, defining Blacks as "a lower race". Du Bois opposed this view as an unscientific aberration, but still maintained the basic principle of eugenics: that different persons have different inborn characteristics that make them more or less suited for specific kinds of employment, and that by encouraging the most talented members of all races to procreate would better the "stocks" of humanity.[154][155] World War I As the United States prepared to enter World War I in 1917, Du Bois's colleague in the NAACP, Joel Spingarn, established a camp to train African Americans to serve as officers in the United States Armed Forces.[156] The camp was controversial, because some whites felt that blacks were not qualified to be officers, and some blacks felt that African Americans should not participate in what they considered a white man's war.[157] Du Bois supported Spingarn's training camp, but was disappointed when the Army forcibly retired one of its few black officers, Charles Young, on a pretense of ill health.[158] The Army agreed to create 1,000 officer positions for blacks, but insisted that 250 come from enlisted men, conditioned to taking orders from whites, rather than from independent-minded blacks who came from the camp.[159] Over 700,000 blacks enlisted on the first day of the draft, but were subject to discriminatory conditions which prompted vocal protests from Du Bois.[160]  Hundreds of African Americans peacefully parading down 5th avenue in New York, holding signs of protest Du Bois organized the 1917 Silent Parade in New York, to protest the East St. Louis riots After the East St. Louis riots occurred in the summer of 1917, Du Bois traveled to St. Louis to report on the riots. Between 40 and 250 African Americans were massacred by whites, primarily due to resentment caused by St. Louis industry hiring blacks to replace striking white workers.[161] Du Bois's reporting resulted in an article "The Massacre of East St. Louis", published in the September issue of The Crisis, which contained photographs and interviews detailing the violence.[162] Historian David Levering Lewis concluded that Du Bois distorted some of the facts in order to increase the propaganda value of the article.[163] To publicly demonstrate the black community's outrage over the riots, Du Bois organized the Silent Parade, a march of around 9,000 African Americans down New York City's Fifth Avenue, the first parade of its kind in New York, and the second instance of blacks publicly demonstrating for civil rights.[164] The Houston riot of 1917 disturbed Du Bois and was a major setback to efforts to permit African Americans to become military officers. The riot began after Houston police arrested and beat two black soldiers; in response, over 100 black soldiers took to the streets of Houston and killed 16 whites. A military court martial was held, and 19 of the soldiers were hanged, and 67 others were imprisoned.[165] In spite of the Houston riot, Du Bois and others successfully pressed the Army to accept the officers trained at Spingarn's camp, resulting in over 600 black officers joining the Army in October 1917.[166] Federal officials, concerned about subversive viewpoints expressed by NAACP leaders, attempted to frighten the NAACP by threatening it with investigations. Du Bois was not intimidated, and in 1918 he predicted that World War I would lead to an overthrow of the European colonial system and to the "liberation" of colored people worldwide – in China, in India, and especially in the Americas.[167] NAACP chairman Joel Spingarn was enthusiastic about the war, and he persuaded Du Bois to consider an officer's commission in the Army, contingent on Du Bois writing an editorial repudiating his anti-war stance.[168] Du Bois accepted this bargain and wrote the pro-war "Close Ranks" editorial in June 1918[169] and soon thereafter he received a commission in the Army.[170] Many black leaders, who wanted to leverage the war to gain civil rights for African Americans, criticized Du Bois for his sudden reversal.[171] Southern officers in Du Bois's unit objected to his presence, and his commission was withdrawn.[172] After the war  An African-American family moves out of a house with broken windows A family evacuating their house after it was vandalized in the Chicago race riot When the war ended, Du Bois traveled to Europe in 1919 to attend the first Pan-African Congress and to interview African-American soldiers for a planned book on their experiences in World War I.[173] He was trailed by U.S. agents who were searching for evidence of treasonous activities.[174] Du Bois discovered that the vast majority of black American soldiers were relegated to menial labor as stevedores and laborers.[175] Some units were armed, and one in particular, the 92nd Division (the Buffalo soldiers), engaged in combat.[176] Du Bois discovered widespread racism in the Army, and concluded that the Army command discouraged African Americans from joining the Army, discredited the accomplishments of black soldiers, and promoted bigotry.[177] Du Bois returned from Europe more determined than ever to gain equal rights for African Americans. Black soldiers returning from overseas felt a new sense of power and worth, and were representative of an emerging attitude referred to as the New Negro.[178] In the editorial "Returning Soldiers" he wrote: "But, by the God of Heaven, we are cowards and jackasses if, now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land."[179] Many blacks moved to northern cities in search of work, and some northern white workers resented the competition. This labor strife was one of the causes of the Red Summer, a series of race riots across America in 1919, in which over 300 African Americans were killed in over 30 cities.[180] Du Bois documented the atrocities in the pages of The Crisis, culminating in the December publication of a gruesome photograph of a lynching that occurred during a race riot in Omaha, Nebraska.[180] The most violent episode during the Red Summer was a massacre in Elaine, Arkansas in which nearly 200 blacks were murdered.[181] Reports coming out of the South blamed the blacks, alleging that they were conspiring to take over the government. Infuriated with the distortions, Du Bois published a letter in the New York World, claiming that the only crime the black sharecroppers had committed was daring to challenge their white landlords by hiring an attorney to investigate contractual irregularities.[182] Over 60 of the surviving blacks were arrested and tried for conspiracy, in the case known as Moore v. Dempsey.[183] Du Bois rallied blacks across America to raise funds for the legal defense, which, six years later, resulted in a Supreme Court ruling authored by Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.[142] Although the victory had little immediate impact on justice for blacks in the South, it marked the first time the federal government used the 14th Amendment guarantee of due process to prevent states from shielding mob violence.[184]  Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil, first edition cover, 1920 In 1920, Du Bois published Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil, the first of his three autobiographies.[185] The "veil" was that which covered colored people around the world. In the book, he hoped to lift the veil and show white readers what life was like behind the veil, and how it distorted the viewpoints of those looking through it – in both directions.[186] The book contained Du Bois's feminist essay, "The Damnation of Women", which was a tribute to the dignity and worth of women, particularly black women.[187] Concerned that textbooks used by African-American children ignored black history and culture, Du Bois created a monthly children's magazine, The Brownies' Book. Initially published in 1920, it was aimed at black children, who Du Bois called "the children of the sun".[188] Pan-Africanism and Marcus Garvey Du Bois traveled to Europe in 1921 to attend the second Pan-African Congress.[189] The assembled black leaders from around the world issued the London Resolutions and established a Pan-African Association headquarters in Paris. Under Du Bois's guidance, the resolutions insisted on racial equality, and that Africa be ruled by Africans (not, as in the 1919 congress, with the consent of Africans).[190] Du Bois restated the resolutions of the congress in his Manifesto to the League of Nations, which implored the newly formed League of Nations to address labor issues and to appoint Africans to key posts. The League took little action on the requests.[191] Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey, promoter of the Back-to-Africa movement and founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA),[192] denounced Du Bois's efforts to achieve equality through integration, and instead endorsed racial separatism.[193] Du Bois initially supported the concept of Garvey's Black Star Line, a shipping company that was intended to facilitate commerce within the African diaspora.[194] But Du Bois later became concerned that Garvey was threatening the NAACP's efforts, leading Du Bois to describe him as fraudulent and reckless.[195] Responding to Garvey's slogan "Africa for the Africans", Du Bois said that he supported that concept, but denounced Garvey's intention that Africa be ruled by African Americans.[196] Du Bois wrote a series of articles in The Crisis between 1922 and 1924 attacking Garvey's movement, calling him the "most dangerous enemy of the Negro race in America and the world."[197] Du Bois and Garvey never made a serious attempt to collaborate, and their dispute was partly rooted in the desire of their respective organizations (NAACP and UNIA) to capture a larger portion of the available philanthropic funding.[198] Du Bois decried Harvard's decision to ban blacks from its dormitories in 1921 as an instance of a broad effort in the U.S. to renew "the Anglo-Saxon cult; the worship of the Nordic totem, the disfranchisement of Negro, Jew, Irishman, Italian, Hungarian, Asiatic and South Sea Islander – the world rule of Nordic white through brute force."[199] When Du Bois sailed for Europe in 1923 for the third Pan-African Congress, the circulation of The Crisis had declined to 60,000 from its World War I high of 100,000, but it remained the preeminent periodical of the civil rights movement.[200] President Calvin Coolidge designated Du Bois an "Envoy Extraordinary" to Liberia[201] and – after the third congress concluded – Du Bois rode a German freighter from the Canary Islands to Africa, visiting Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Senegal.[202] Harlem Renaissance  Du Bois's 1924 work The Gift of Black Folk celebrated the unique contributions of African Americans in building the United States Du Bois frequently promoted African-American artistic creativity in his writings, and when the Harlem Renaissance emerged in the mid-1920s, his article "A Negro Art Renaissance" celebrated the end of the long hiatus of blacks from creative endeavors.[203][204][205] His enthusiasm for the Harlem Renaissance waned as he came to believe that many whites visited Harlem for voyeurism, not for genuine appreciation of black art.[206] Du Bois insisted that artists recognize their moral responsibilities, writing that "a black artist is first of all a black artist."[207] He was also concerned that black artists were not using their art to promote black causes, saying "I do not care a damn for any art that is not used for propaganda."[208] By the end of 1926, he stopped employing The Crisis to support the arts.[209] Debate with Lothrop Stoddard In 1929, a debate organised by the Chicago Forum Council billed as "One of the greatest debates ever held" was held between Du Bois and Lothrop Stoddard, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, proponent of eugenics and so-called scientific racism.[210][211] The debate was held in Chicago and Du Bois was arguing the affirmative to the question "Shall the Negro be encouraged to seek cultural equality? Has the Negro the same intellectual possibilities as other races?"[212] Du Bois knew that the racists would be unintentionally funny onstage; as he wrote to Moore, Senator J. Thomas Heflin "would be a scream" in a debate. Du Bois let the overconfident and bombastic Stoddard walk into a comic moment, which Stoddard then made even funnier by not getting the joke. This moment was captured in headlines "DuBois Shatters Stoddard's Cultural Theories in Debate; Thousands Jam Hall ... Cheered as He Proves Race Equality," The Chicago Defender's front-page headline ran "5,000 Cheer W.E.B. DuBois, Laugh at Lothrop Stoddard".[211] Ian Frazier of The New Yorker wrotes that the comic potential of Stoddard's bankrupt ideas was left untapped until Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove.[211] Socialism When Du Bois became editor of The Crisis magazine in 1911, he joined the Socialist Party of America on the advice of NAACP founders Mary White Ovington, William English Walling and Charles Edward Russell. However, he supported the Democrat Woodrow Wilson in the 1912 presidential campaign, a breach of the rules, and was forced to resign from the Socialist Party. In 1913, his support for Wilson was shaken when racial segregation in government hiring was reported.[213][214] Du Bois remained "convinced that socialism was an excellent way of life, but I thought it might be reached by various methods."[215] Nine years after the 1917 Russian Revolution, Du Bois extended a trip to Europe to include a visit to the Soviet Union, where he was struck by the poverty and disorganization he encountered in the Soviet Union, yet was impressed by the intense labors of the officials and by the recognition given to workers.[216] Although Du Bois was not yet familiar with the communist theories of Karl Marx or Vladimir Lenin, he concluded that socialism might be a better path towards racial equality than capitalism.[217] Although Du Bois generally endorsed socialist principles, his politics were strictly pragmatic: in the 1929 New York City mayoral election, he endorsed Democrat Jimmy Walker for mayor of New York, rather than the socialist Norman Thomas, believing that Walker could do more immediate good for blacks, even though Thomas's platform was more consistent with Du Bois's views.[218] Throughout the 1920s, Du Bois and the NAACP shifted support back and forth between the Republican Party and the Democratic Party, induced by promises from the candidates to fight lynchings, improve working conditions, or support voting rights in the South; invariably, the candidates failed to deliver on their promises.[219] And herein lies the tragedy of the age: not that men are poor – all men know something of poverty; not that men are wicked – who is good? Not that men are ignorant – what is Truth? Nay, but that men know so little of men. —Du Bois, "Of Alexander Crummell", in The Souls of Black Folk, 1903[220] A rivalry emerged in 1931 between the NAACP and the Communist Party, when the communists responded quickly and effectively to support the Scottsboro Boys, nine African American youth arrested in 1931 in Alabama for rape.[221] Du Bois and the NAACP felt that the case would not be beneficial to their cause, so they chose to let the Communist Party organize the defense efforts.[222] Du Bois was impressed with the vast amount of publicity and funds which the communists devoted to the partially successful defense effort, and he came to suspect that the communists were attempting to present their party to African Americans as a better solution than the NAACP.[223] Responding to criticisms of the NAACP from the Communist Party, Du Bois wrote articles condemning the party, claiming that it unfairly attacked the NAACP, and that it failed to fully appreciate racism in the United States. In their turn, the communist leaders accused him of being a "class enemy", and claimed that the NAACP leadership was an isolated elite, disconnected from the working-class blacks they ostensibly fought for.[224] |

NAACP時代 1909年5月、デュボイスはニューヨークで開催された全米黒人会議に出席した[113]。この会議は、オズワルド・ギャリソン・ヴィラードが議長を務め る全米黒人委員会を設立し、公民権、平等な投票権、平等な教育機会を求める運動に専念することにつながった[114]。翌年の春、191 1910年の春、第2回全米黒人会議において、出席者たちは全米有色人地位向上協会(NAACP)を設立した[115]。デュボアスの提案により、「黒 人」ではなく「有色人」という言葉が用いられ、「肌の色が濃い人々」を広く包含するものとなった[116]。設立には数十人の公民権運動支持者が参加し た。しかし、ほとんどの役員は白人であり、メアリー・ホワイト・オーヴィントン、チャールズ・エドワード・ラッセル、ウィリアム・イングリッシュ・ウォー リング、初代会長のムーアフィールド・ストーリーなどがいた[117]。 これに感銘を受けたインドの社会改革者であり公民権運動家の B. R. アンベードカルは、1940年代にデュボイスに連絡を取った。1946年にデュボイスに宛てた手紙の中で、彼は「インドの不可触民」の一員であり、「黒人 問題の学生」であると自己紹介し、NAACPの国連への請願書に関心があることを表明した。 彼は、自分たちの団体も「同じことをしようと考えている」と書き、デュボイスに声明案のコピーを求めた。1946年7月31日付の手紙で、デュボアはアン ベードカルに、彼の名前はよく知っており、「インドの不可触民に深い同情を抱いている」と伝えた[118][119]。 危機  ポーズを決めて肖像画のモデルになるアフリカ系アメリカ人男性、 ポーズを決めて肖像画の撮影を受けている デュボイス、1911年頃 NAACPのリーダーたちはデュボイスに広報・調査担当理事の職を提示した[120]。彼は1910年の夏にこの職を引き受け、アトランタ大学を辞職した 後、ニューヨークに移住した。彼の主な職務は、NAACPの月刊誌の編集であり、彼はその雑誌を『クライシス』と名付けた[121]。1910年11月に 創刊号が発行され、デュボイスは、その目的は「人種的偏見の危険性を示す事実と議論、特に有色人種に対する偏見を明らかにすること」であると記した[1 22] この雑誌は驚異的な成功を収め、1920年には発行部数が10万部に達した[123]。初期の号に掲載された典型的な記事には、黒人教会の不誠実さや偏狭 さに対する論争や、エジプト文明のアフリカ中心起源に関する議論などが含まれていた[1 24] デュボアのアフリカ中心主義的な古代エジプト観は、会議でデュボアと出会ったフリンダース・ペトリを含む、同時代の多くのエジプト学者たちの見解と真っ向 から対立していた[125]。 1911年のデュボアの社説は、連邦政府にリンチを違法とするよう働きかける全国的な運動のきっかけとなった。デュボイスは、よく使う皮肉を交えて、ペン シルベニア州で起きたリンチ事件について次のようにコメントした。「重要なのは、彼が黒人だったということだ。黒人であることは罰せられるべきだ。黒人で あることは犯罪中の犯罪である...。したがって、この犯罪中の犯罪を罰する機会を決して逃さないことが、この国のすべての白人の悪党が知っているよう に、必要なのである。もちろん、可能であれば、その口実は大きくて圧倒的であるべきだ。つまり、報道陣の想像力を刺激してさらに恐ろしいものにするよう な、恐ろしい衝撃的な犯罪である。それができない場合は、単なる殺人、放火、納屋の放火、あるいは不遜な態度でも構わないだろう。」[126][127]  『クライシス』創刊号、1910年11月 『クライシス』は、組合労働の理想を支持する一方で、組合指導者の人種差別を糾弾するドゥ・ボアスの社説を掲載した。黒人は会員になることを禁じられてい た[128]。ドゥ・ボアスは、アメリカ社会党の理念も支持していた(1910年から1912年まで党員であった 1912年まで党員であった)。しかし、一部の社会主義指導者が示す人種差別を非難した[129]。共和党のタフト大統領が広範囲に及ぶリンチに対処しな いことに不満を抱いたデュボイスは、黒人の権利を支持するというウィルソンの約束と引き換えに、1912年の大統領選挙で民主党候補のウッドロウ・ウィル ソンを支持した[130]。 デュボイスは、著作を通じて女性の権利[131][132]と女性の参政権[ [133]しかし、彼は女性参政権運動の指導者たちが人種的不公正に対する彼の戦いを支持することを拒否したため、公に女性参政権運動を支持することが難 しかった[134]。1913年の『クライシス』紙は、人種間の結婚というタブーに触れた。デュボイスは一般的に、人は同種族と結婚すべきだと考えていた が、白人男性が黒人女性と結婚することを法律が禁じているため、この問題を女性の人権問題として捉えていた。デュボイスは「(異人種間結婚を禁じる)法律 は有色人種の少女たちを白人男性の欲望から完全に無力な状態にしている。法律の観点から見れば、有色人種の女性は犬の立場に落とされてしまう。白人女性が どんなに落ちぶれても、彼女を誘惑した男と結婚させることはできる... 私たちは、白人男性の姉妹と結婚したがっているからではなく、白人男性が私たちの姉妹に手を出さないよう決意しているからこそ、この(人種混合禁止法)を 廃止しなければならないのだ。」[135][136] 1915年から1916年にかけて、NAACPの指導者たちは、『クライシス』の財政的損失に頭を悩ませ、一部のエッセイの扇動的な表現を懸念し、デュ・ ボワを編集者の地位から追放しようとした。デュボイスと彼の支持者が勝利し、彼は編集者の役割を継続した[137]。1919年に「The True Brownies」と題したコラムで、彼はアフリカ系アメリカ人の子供や若者向けに初めて出版された雑誌「The Brownies' Book」の創刊を発表し、オーガスタス・グランビル・ディルとジェシー・レッドモン・ファセットと共に同誌を創刊した[138][139]。 歴史学者、作家  髭と口ひげを生やしたデュボア、50歳頃の公式写真 1918年のデュボア、C. M. バティによる 1910年代はデュボアにとって多作な時期であった。1911年には、ロンドンで開催された第1回世界人種会議に出席し[140]、処女作『銀の羊毛を求 めて』を発表した[141]。2年後、デュボイスは舞台用のパレード『エチオピアの星』の脚本、制作、演出を手がけた[142]。1915年には、黒人ア フリカ人の一般史である『The Negro』を出版した。この本は、アフリカ人の劣等性を主張する意見に反論し、20世紀のアフリカ中心の歴史学の基本となる。『The Negro』は、世界中の有色人種の結束と連帯を予言し、汎アフリカ運動を支持する多くの人々に影響を与えた[143]。 1915年、『The Atlantic Monthly』にデュボイスのエッセイ「The African Roots of the War」が掲載され、資本主義、帝国主義、人種に関する彼の考えが固まった[144]。彼は、アフリカ分割が 第一次世界大戦の根本原因であったと主張した。また、裕福な資本家が白人労働者の反乱を防ぐために必要なだけの富を与え、有色人種の労働者による低コスト の労働との競争をちらつかせることで白人労働者を懐柔したと示唆し、後の共産主義の教義を予見した[145]。 人種差別との戦い デュボイスは、NAACPの有力な立場を利用して、さまざまな人種差別的事件に反対した。1915年にサイレント映画『Birth of a Nation』が公開されると、デュボイスとNAACPは、この映画が黒人を野蛮で好色な存在として描いているという理由で、上映禁止運動を主導した [146]。成功したわけではなかったが、おそらくは映画の知名度に貢献し、NAACPに多くの新しい支持者を引きつけた[147]。 人種差別は民間部門だけの問題ではなかった。ウィルソン大統領の下で、政府機関に勤務するアフリカ系アメリカ人の苦境は深刻化した。多くの連邦機関が白人 限定の雇用慣行を採用し、陸軍は将校職から黒人を排除し、移民局はアフリカ系アメリカ人の入国を禁止した[148]。デュボイスは1914年に、連邦政府 ポストからの黒人の排除を嘆く社説を書き、 彼は、ウィリアム・モンロー・トロッターがウィルソン大統領に、大統領が選挙戦で掲げた黒人に対する公正な処遇の公約を果たしていないことを率直に問いた だした際、トロッターを支持した[149]。  ジェシー・ワシントンのリンチ事件の報道写真 クライシス誌はリンチ反対キャンペーンを継続した。1915年には、1884年から1914年までの2,732件のリンチ事件を年別に集計した記事を掲載 した[150]。1916年4月号では、 ジョージア州リー郡で起きたアフリカ系アメリカ人6人に対する集団リンチ事件を報じた[151]。その後、1916年6月号の「Waco Horror」という記事では、知的障害を持つ17歳のアフリカ系アメリカ人、ジェシー・ワシントンのリンチ事件を取り上げた。デュボイスは記事にこのと きの写真を掲載した[151]。この記事は、テキサス州ウェーコにおける白人地元住民の行為を暴露するために潜入取材を利用するという、新しい手法を用い た。 20世紀初頭は、アメリカ南部の黒人が北東部、中西部、西部へと大移動した時代であった。デュボイスは、黒人が南部の人種差別から逃れ、経済的な機会を見 つけ、アメリカ社会への同化に役立つと考えたため、大移動を支持する社説を書いた[153]。 また、1910年代には、アメリカ優生学運動がまだ初期段階にあり、多くの有力な優生学者たちが公然と人種差別主義者であり、黒人を「劣った人種」と定義 していた。デュボイスは、この見解を非科学的逸脱として反対したが、優生学の根本原則は維持していた。すなわち、異なる人々は異なる生まれつきの特性を 持っており、それが特定の種類の職業にどの程度適しているかを左右し、あらゆる人種の最も才能のある人々に出産を奨励することで、人類の「ストック」が向 上するというものである[154][155]。 第一次世界大戦 1917年に米国が第一次世界大戦への参戦を準備する中 、NAACPのデュボアスの同僚であるジョエル・スピングァーンは、アフリカ系アメリカ人がアメリカ軍将校として働くための訓練キャンプを設立した [156]。このキャンプは物議を醸した。なぜなら、黒人が将校になる資格はないと考える白人もいれば、アフリカ系アメリカ人は白人の戦争に参加すべきで はないと考える黒人もいたからだ[157]。デュボアスはスピングァーンの訓練キャンプを支持したが、 陸軍が、体調不良を理由に、数少ない黒人将校の一人、チャールズ・ヤングを強制的に退役させたことに失望した[158]。陸軍は黒人将校1,000人のポ ストを設けることに合意したが、そのうちの250人は、キャンプから来た自主性を持った黒人ではなく、白人の命令に従うように条件付けされた下士官から選 ぶと主張した[159]。しかし、彼らは差別的な条件に従わなければならず、デュボイスはこれに強く抗議した[160]。  抗議のプラカードを掲げ、ニューヨークの5番街を平和的に行進する数百人のアフリカ系アメリカ人 デュボイスは、1917年にニューヨークで「サイレント・パレード」を企画し、イーストセントルイスの暴動に抗議した 1917年の夏にイーストセントルイスの暴動が発生した後、デュボイスはセントルイスに赴き、暴動について報告した。40人から250人のアフリカ系アメ リカ人が白人によって虐殺された。その主な原因は、ストライキ中の白人労働者の代わりに黒人を雇用したセントルイスの産業に対する憤慨であった [161]。デュボアスの報道は、暴力を詳細に伝える写真とインタビュー記事を含む『クライシス』9月号の「イーストセントルイスの虐殺」という記事につ ながった[162]。歴史家のデビッド・レベリング・ルイスは、デュボアスの記事が デュボアは記事の宣伝効果を上げるために事実の一部を歪曲したと、歴史家のデビッド・レベリング・ルイスは結論付けた[163]。暴動に対する黒人社会の 怒りを公に示すために、デュボアはサイレントパレードを企画した。これは約9,000人のアフリカ系アメリカ人がニューヨークの5番街を歩く行進で、 ニューヨークでは初めてのパレードであり、黒人が公民権のために公にデモを行う2例目であった[164]。 1917年のヒューストン暴動はデュボイスを動揺させ、アフリカ系アメリカ人が軍将校になることを認める努力に大きな打撃を与えた。この暴動は、ヒュース トン警察が2人の黒人兵士を逮捕し、暴行を加えたことがきっかけで始まった。これに対し、100人以上の黒人兵士がヒューストンの街頭に繰り出し、16人 の白人を殺害した。軍事法廷が開かれ、19人の兵士が絞首刑に処され、67人が投獄された[165]。ヒューストン暴動にもかかわらず、デュボイスと他の 人々は陸軍に圧力をかけ、スプリングアーン・キャンプで訓練を受けた士官の採用に成功した。 1917年10月には、600人以上の黒人将校が陸軍に入隊した[166]。 NAACPの指導者が表明した破壊的な見解を懸念した連邦政府高官は、NAACPを調査すると脅して脅迫しようとした。デュボイスは怯むことなく、 1918年には第一次世界大戦がヨーロッパの植民地体制の崩壊につながり、中国、インド、そして特にアメリカ大陸の有色人種の「解放」につながるだろうと 予測した[167]。NAACPの会長ジョエル・スピングァーンは戦争に熱狂しており、デュボイスに陸軍将校になることを検討するよう説得した。ただし、 デュボイスが反戦姿勢を否定する社説を書くことが条件だった[168]。デュボイスはこの取引を受け入れ、1918年6月に親戦論の社説「Close Ranks」を書き[169]、まもなく陸軍から任命を受けた[170]。アフリカ系アメリカ人の公民権獲得のために戦争を利用しようとしていた多くの黒 人指導者は、 突然の態度転換を理由に、デュボイスを批判する黒人指導者たちもいた[171]。デュボイスの部隊に所属する南部出身の将校たちは、彼の存在に異議を唱 え、彼の任命は取り消された[172]。 戦争後  窓が割られた家から退去するアフリカ系アメリカ人家族 シカゴの暴動で家が荒らされたため避難する家族 戦争が終結すると、デュボイスは1919年にヨーロッパを訪れ、 第1回汎アフリカ会議に出席し、第一次世界大戦での経験について執筆予定の書籍のためにアフリカ系アメリカ人兵士たちにインタビューするためであった [173]。彼は、反逆行為の証拠を探していた米国の捜査官たちに尾行されていた[174]。デュボイスは、黒人アメリカ人兵士の大部分が港湾労働者や肉 体労働者などの単純労働に就いていることを知った[175]。一部の部隊は 武装していた部隊もあり、特に第92師団(バッファロー部隊)は戦闘に従事していた[176]。デュボイスは陸軍に広範囲にわたる人種差別があることを発 見し、陸軍司令部はアフリカ系アメリカ人の入隊を阻み、黒人兵士の功績を貶め、偏見を助長していると結論づけた[177]。 デュボイスは、アフリカ系アメリカ人の平等を獲得するという決意を新たにヨーロッパから帰国した。海外から戻った黒人兵士たちは、新たな力と価値を感じ、 ニュー・ネグロと呼ばれる新たな態度の代表となった[178]。彼は「帰還兵」という社説で次のように書いている。「しかし、天の神に誓って、戦争が終 わった今、 戦争が終わった今、自らの土地に巣食う地獄の勢力に対して、より厳しく、より長く、より屈しない戦いを繰り広げるために、頭脳と体力のすべてを尽くさない のであれば、私たちは臆病者で間抜けだ」[179]。 多くの黒人が仕事を探して北部の都市に移住し、一部の北部白人労働者はその競争を嫌った。この労働争議は、1919年に全米各地で発生した一連の人種暴動 「レッド・サマー」の原因のひとつであり、30以上の都市で300人以上のアフリカ系アメリカ人が殺害された[180]。デュボイスは『クライシス』誌に この残虐行為を記録し、12月にはネブラスカ州オマハで発生した人種暴動でリンチされた ネブラスカ州オマハで人種暴動中に起きたリンチ事件の写真である[180]。 レッドサマー」で最も暴力的だったのは、アーカンソー州エレインで起きた虐殺事件で、200人近くの黒人が殺害された[181]。南部から届いた報道は黒 人を非難し、彼らが政府を乗っ取る陰謀を企てていると主張した。この歪曲に激怒したデュボイスは、ニューヨーク・ワールド紙に手紙を掲載し、黒人小作人が 犯した唯一の罪は、契約上の不規則性を調査するために弁護士を雇い、白人の地主に果敢に挑戦したことだと主張した[182]。 生き残った黒人のうち60人以上が、ムーア対デンプシー事件として知られる陰謀容疑で逮捕・起訴された[183]。デュボイスは 彼は全米に住む黒人に呼びかけ、弁護費用を集めた。6年後、オリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズ・ジュニアが執筆した最高裁判決が下された[142]。この勝 利は南部における黒人の司法に即座の影響を与えることはなかったが、連邦政府が州による暴徒の暴力を防ぐために、正当な手続きを保障する第14条修正案を 初めて適用した。  『ダークウォーター: ヴェールの中の声』初版表紙、1920年 1920年、デュボイスは3冊の自伝の第1作目となる『Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil』を出版した[185]。「ヴェール」とは、世界中の有色人種を覆っていたものである。この本では、ヴェールを取り払い、ヴェール越しに見える世 界がどのようなものなのか、そしてヴェール越しに見る人々の見方をどのように歪めているのか、白人の読者に知ってもらおうと望んでいた。 アフリカ系アメリカ人の子供たちが使用する教科書が黒人の歴史や文化を無視していることに懸念を抱いたデュボイスは、月刊の子供向け雑誌『ブラウニーズ・ ブック』を創刊した。1920年に創刊されたこの雑誌は、デュボイスが「太陽の子ら」と呼んだ黒人の子供たちを対象としていた[188]。 汎アフリカ主義とマーカス・ガーベイ デュボイスは1921年、第2回汎アフリカ会議に出席するためヨーロッパを訪れた[189]。世界中から集まった黒人指導者はロンドン決議を採択し、パリ に汎アフリカ協会本部を設立した。デュボイスの指導の下、決議では人種的平等を主張し、アフリカはアフリカ人によって統治されるべきであると主張した (1919年の会議では、アフリカ人の同意を得て統治されるべきであるとされていた)。[190] デュボイスは国際連盟へのマニフェストの中で、会議の決議を改めて表明し、新たに設立された国際連盟に労働問題への取り組みとアフリカ人を要職に任命する ことを求めた。国際連盟はこれらの要求に対してほとんど行動を起こさなかった[191]。 ジャマイカの活動家マーカス・ガーベイは、アフリカ回帰運動の推進者であり、ユニバーサル・ネグロ・インプルーブメント・アソシエーション(UNIA)の 創設者でもあった[192]。彼は、統合による平等を達成しようとするデュボイスの努力を非難し、代わりに人種分離主義を支持した[193]。デュボイス は当初、ガーベイのブラック・スター・ラインというコンセプトを支持していた。これは、 アフリカ系ディアスポラ間の商業を促進することを目的としていた。[194]しかし、デュボイスは後にガーベイがNAACPの努力を脅かしているのではな いかと懸念するようになり、彼を詐欺師であり無謀であると評した。[195]ガーベイのスローガン「アフリカはアフリカ人のために」に対して、デュボイス は、その概念には賛成するが、アフリカをアフリカ系アメリカ人が支配するというガーベイの意図は非難すべきだと述べた。 デュボイスは 1922年から1924年にかけて『クライシス』誌にガーヴィーの運動を攻撃する一連の記事を掲載し、ガーヴィーを「アメリカと世界の黒人種にとって最も 危険な敵」と呼んだ[197]。デュボイスとガーヴィーは決して真剣に協力しようとはせず、彼らの論争は、それぞれの団体(NAACPとUNIA)が利用 可能な慈善資金のより大きな割合を獲得したいという願望に一部根ざしていた 。 デュボイスは、ハーバード大学が1921年に黒人の寮入りを禁止した決定を、米国における「アングロサクソン崇拝、北欧のトーテム崇拝、黒人、ユダヤ人、 アイルランド人、イタリア人、ハンガリー人、アジア人、南太平洋諸島民の選挙権剥奪、北欧白人の武力による世界支配」[ 199] 1923年、第3回汎アフリカ会議に出席するためヨーロッパへ向かったデュボイスが帰国した際、『ザ・クライシス』の部数は、第一次世界大戦時の10万部 から6万部に減少していたが、公民権運動の代表的な定期刊行物としての地位は揺るぎなかった[200]。カルビン・クーリッジ大統領はデュボイスをリベリ ア特命全権大使に任命した[2 01]、そして第3回会議の閉会後、デュボイスはカナリア諸島からアフリカ行きのドイツ貨物船に乗り込み、リベリア、シエラレオネ、セネガルを訪れた [202]。 ハーレムルネサンス  デュボイスの1924年の作品『The Gift of Black Folk』は、アメリカ合衆国を築き上げたアフリカ系アメリカ人の独自の貢献を称えた デュボイスは、自身の著作の中でアフリカ系アメリカ人の芸術的創造性を頻繁に称賛し、1920年代半ばにハーレムルネサンスが台頭すると、彼の記事「A Negro Art Renaissance」は、黒人が創造的な活動から長い間遠ざかっていた状況の終焉を祝した[203][204][205]。 920年代半ばにハーレムルネサンスが台頭すると、デュボアは「黒人芸術ルネサンス」と題した記事で、黒人が創造的な活動から長い間遠ざかっていた状況の 終焉を祝った[203][204][205]。しかし、ハーレムルネサンスに対する熱意は次第に薄れていった。というのも、多くの白人がハーレムを訪れる のは、黒人芸術を真に評価するためではなく、覗き見するためだと考えるようになったからだ[206]。デュボアは、芸術家たちが自らの道徳的責任を認識す べきだと主張し、「黒人芸術家は まず第一に黒人アーティストである」と主張した[207]。また、黒人アーティストが自分たちの芸術を黒人の権利擁護のために活用していないことを懸念 し、「宣伝に使われない芸術など、私にはまったく興味がない」と述べた[208]。1926年末までに、彼は『クライシス』誌を芸術支援のために利用する ことをやめた[209]。 ロスロップ・ストッダードとの論争 1929年 、シカゴフォーラム評議会が主催した「史上最大規模の討論会」として宣伝された討論会が、デュボイスと、ク・クラックス・クランのメンバーであり、優生学 といわゆる科学的人種差別の提唱者であるロスロップ・ストッダードの間で開かれた[210][211]。討論会はシカゴで行われ、デュボイスは「黒人は文 化的な平等を求めるよう奨励されるべきだろうか?黒人は他の人種と同じ知的能力を持っているのか?」[212] デュボアは、人種差別主義者がステージ上で思わず滑稽な態度を取るだろうことを知っていた。ムーアに宛てた手紙の中で、上院議員のJ・トーマス・ヘフリン は「議論では絶叫するだろう」と書いている。デュボアは自信過剰で大げさなストッダードを滑稽な状況に陥れ、ストッダードはジョークを理解できずにさらに 滑稽な状況を作り出した。この瞬間は、「デュボイス、ストッダードの文化理論を論破。数千人がホールを埋め尽くす。人種平等を証明し、喝采を浴びる」とい う見出しが『シカゴ・ディフェンダー』の1面に掲載された。「5,000人がW・E・B・デュボイスを歓呼し、ロスロップ・ストッダードを嘲笑する」 [211]。『ニューヨーカー』のイアン・フレイザーは、ストッダードの破綻したアイデアの滑稽な可能性については、スタンリー・キューブリック監督の 『博士の異常な愛情』まで注目されなかったと書いている[211]。 社会主義 1911年にデュボイスが『クライシス』誌の編集者となった際、NAACPの創設者であるメアリー・ホワイト・オーヴィントン、ウィリアム・イングリッ シュ・ウォーリング、チャールズ・エドワード・ラッセルの助言により、アメリカ社会党に入党した。しかし、彼は1912年の大統領選挙で民主党のウッドロ ウ・ウィルソンを支持し、規則違反を犯したため、社会党から脱退せざるを得なくなった。1913年、政府職員の雇用における人種的隔離が報道されたこと で、ウィルソンへの支持は揺らいだ[213][214]。デュボイスは「社会主義は素晴らしい生き方だと確信していたが、さまざまな方法で到達できるかも しれないと思っていた」[215]。 1917年のロシア革命から9年後、デュボイスはヨーロッパ旅行を延長し、 ソビエト連邦を訪れ、そこで目にした貧困と無秩序に衝撃を受けながらも、役人の激しい労働と労働者への敬意に感銘を受けた[216]。デュボイスは、カー ル・マルクスやウラジーミル・レーニンの共産主義理論にまだ詳しくなかったが、社会主義は資本主義よりも人種的平等を実現するより良い道であるかもしれな いという結論に達した[217]。 デュボイスは一般的に社会主義の原則を支持していたが、 社会主義の原則を支持していたが、彼の政治姿勢は厳密に現実的であった。1929年のニューヨーク市長選挙では、社会主義者のノーマン・トーマスではな く、民主党のジミー・ウォーカーをニューヨーク市長に推した。トーマスの公約はデュボアの見解と一致していたが、ウォーカーの方が黒人のために即効性のあ る利益をもたらすとデュボアは考えていたからである[218]。1920年代を通じて、デュボアとNAACPは 1920年代を通じて、デュボイスとNAACPは、共和党と民主党の間で支持を往復させた。これは、候補者たちが、リンチ撲滅、労働条件の改善、南部での 投票権支持を約束したことによるものであった。しかし、候補者たちは常にその約束を果たせなかった[219]。 そして、ここに時代の悲劇がある。それは、人々が貧しいからではない。すべての人は、貧困について何かしらは知っている。人々が邪悪だからでもない。善良 な人間などいるだろうか?人間が無知なのでもない。真理とは何か? そうではなく、人間は人間についてほとんど何も知らないのだ。 —デュボイス、『黒人魂』所収「アレクサンダー・クラメルについて」、1903年[220] 1931年、NAACPと共産党の間に対立が生じた。1931年にアラバマ州で強姦容疑で逮捕された9人のアフリカ系アメリカ人青年、スコッツボロー・ ボーイズの支援に共産党が迅速かつ効果的に反応したことがきっかけだった[221]。1931年にアラバマ州で強姦容疑で逮捕された9人のアフリカ系アメ リカ人の若者たちである。[221] デュボイスとNAACPは、この事件が自分たちの主張に有利に働かないと考え、共産党に弁護活動を任せることにした[222]。デュボイスは、共産党が弁 護活動に費やした膨大な宣伝活動と資金に感銘を受け、 共産党がアフリカ系アメリカ人に対して、NAACPよりも自分たちの党の方がより良い解決策であるとアピールしようとしているのではないかと疑うように なった[223]。 共産党によるNAACPへの批判に対し、デュボイスは共産党を非難する記事を書いた。共産党はNAACPを不当に攻撃しており、アメリカにおける人種差別 を十分に理解していないと主張した。これに対し、共産党の指導者は彼を「階級的敵」であると非難し、NAACPの指導部は、彼らが表向きのために戦ってい る黒人労働者階級と無関係な孤立したエリートであると主張した[224]。 |