近代医療が患者にたいして復讐する日

Medical nemesis, THE EXPROPRIATION OF HEALTH, by IVAN ILLICH, 1974-1976

近代医療が患者にたいして復讐する日

Medical nemesis, THE EXPROPRIATION OF HEALTH, by IVAN ILLICH, 1974-1976

イリイチは、医療制度は「専門家依存」をもたらすものであり、すなわち人間個々人の能力を奪

い、不能化するものであると批判し、これを広義の医原病(社会的医原病、文化的医原病)であるとしている(→「イヴァン・イリッチ」)

Source:

https://jech.bmj.com/content/57/12/919

| Within the last

decade medical professional practice has become a major threat to

health. Depression, infection, disability, dysfunction, and other

specific iatrogenic diseases now cause more suffering than all

accidents from traffic or industry. Beyond this, medical practice

sponsors sickness by the reinforcement of a morbid society which not

only industrially preserves its defectives but breeds the therapist’s

client in a cybernetic way. Finally, the so-called health-professions

have an indirect sickening power—a structurally health-denying effect.

I want to focus on this last syndrome, which I designate as medical

Nemesis. By transforming pain, illness, and death from a personal

challenge into a technical problem, medical practice expropriates the

potential of people to deal with their human condition in an autonomous

way and becomes the source of a new kind of un-health. Much suffering has always been man-made: history is the record of enslavement and exploitation. It tells of war, and of the pillage, famine, and pestilence which come in its wake. War between commonwealths and classes has so far been the main planned agency of man-made misery. Thus, man is the only animal whose evolution has been conditioned by adaptation on two fronts. If he did not succumb to the elements, he had to cope with use and abuse by others of his kind. He replaced instincts by character and culture, to be capable of this struggle on two frontiers. A third frontier of possible doom has been recognised since Homer; but common mortals were considered immune to its threat. Nemesis, the Greek name for the awe which loomed from this third direction, was the fate of a few heroes who had fallen prey to the envy of the gods. The common man grew up and perished in a struggle with Nature and neighbour. Only the élite would challenge the thresholds set by Nature for man. Prometheus was not Everyman, but a deviant. Driven by Pleonexia, or radical greed, he trespassed the boundaries of the human condition. In hubris or measureless presumption, he brought fire from heaven, and thereby brought Nemesis on himself. He was put into irons on a Caucasian rock. A vulture preys at his innards, and heartlessly healing gods keep him alive by regrafting his liver each night. The encounter with Nemesis made the classical hero an immortal reminder of inescapable cosmic retaliation. He becomes a subject for epic tragedy, but certainly not a model for everyday aspiration. Now Nemesis has become endemic; it is the backlash of progress. Paradoxically, it has spread as far and as wide as the franchise, schooling, mechanical acceleration, and medical care. Everyman has fallen prey to the envy of the gods. If the species is to survive it can do so only by learning to cope in this third group. |

この10年間で、医療従事者の行為は健康に対する大きな脅威となった。

うつ病、感染症、身体障害、機能障害、その他の特定の異所性疾患は、今や交通事故や産業事故よりも多くの苦しみを引き起こしている。それ以上に、医療行為

は、病的な社会を強化することで、病気を助長している。この社会は、産業的に欠陥を温存するだけでなく、セラピストのクライアントをサイバネティックな方

法で繁殖させている。最後に、いわゆる健康プロフェッションは、間接的に病気を悪化させる力、つまり構造的に健康を否定する効果を持っている。私はこの最

後の症候群に焦点を当てたい。痛みや病気、死を個人的な課題から技術的な問題へと変容させることで、医療行為は、人々が自律的な方法で人間の状態に対処す

る可能性を奪い、新たな種類の不健康の源となる。 歴史は奴隷化と搾取の記録である。歴史は奴隷化と搾取の記録であり、戦争と、それに伴う略奪、飢饉、疫病の記録である。連邦間や階級間の戦争は、今のとこ ろ、人間が作り出した不幸の主な計画的原因となっている。このように、人間は2つの面において適応することで進化を条件づけられてきた唯一の動物である。 風雨に屈しなければ、同類による利用や虐待に対処しなければならなかった。彼は本能を性格と文化に置き換えて、2つのフロンティアでの闘いを可能にした。 ホメロス以来、破滅の可能性のある第三のフロンティアは認識されてきた。ネメシスとは、この第三の方向から迫ってくる畏怖を表すギリシャ語の名前で、神々 の嫉妬の餌食になった少数の英雄の運命だった。庶民は自然や隣人との闘いの中で成長し、そして滅んでいった。自然が人間に設定した閾値に挑戦するのはエ リートだけだった。 プロメテウスは常人ではなく、逸脱者だった。プレオネクシア、つまり過激な貪欲さに突き動かされ、彼は人間の条件の境界を踏み越えた。傲慢に、あるいは無 謀に、彼は天から火をもたらし、それによって自分自身にネメシスをもたらした。彼はコーカサスの岩の上で牢獄に入れられた。ハゲワシが彼の内臓を捕食し、 無情にも癒しの神々が毎晩肝臓を移植することで彼を生かしている。ネメシスとの出会いによって、古典の英雄は逃れられない宇宙の報復を不滅のものとして思 い出させる存在となった。彼は叙事詩の悲劇の題材となったが、日常的な願望のモデルにはならなかった。今、ネメシスは風土病となり、進歩の反動となってい る。逆説的だが、ネメシスは、フランチャイズ、学校教育、機械的加速、医療と同じくらい広く広がっている。誰もが神々の嫉妬の餌食になっているのだ。種が 生き残るためには、この第3の集団に対処する術を身につけるしかない。 |

| INDUSTRIAL NEMESIS Most man-made misery is now the byproduct of enterprises which were originally designed to protect the common man in his struggle with the inclemency of the environment and against wanton injustices inflicted by the elite. The main source of pain, disability, and death is now an engineered—albeit non-intentional—harassment. The prevailing ailments, helplessness and injustice, are now the side-effects of strategies for progress. Nemesis is now so prevalent that it is readily mistaken for part of the human condition. The desperate disability of contemporary man to envisage an alternative to the industrial aggression on the human condition is an integral part of the curse from which he suffers. Progress has come with a vengeance which cannot be called a price. The down payment was on the label and can be stated in measurable terms. The instalments accrue under forms of suffering which exceed the notion of “pain”. At some point in the expansion of our major institutions their clients begin to pay a higher price every day for their continued consumption, in spite of the evidence that they will inevitably suffer more. At this point in development the prevalent behaviour of society corresponds to that traditionally recognised in addicts. Declining returns pale in comparison with marginally increasing disutilities. Homo economicus turns into Homo religiosus. His expectations become heroic. The vengeance of economic development not only outweighs the price at which this vengeance was purchased; it also outweighs the compound tort done by Nature and neighbours. Classical Nemesis was punishment for the rash abuse of a privilege. Industrialised Nemesis is retribution for dutiful participation in society. War and hunger, pestilence and sudden death, torture and madness remain man’s companions, but they are now shaped into a new Gestalt by the Nemesis overarching them. The greater the economic progress of any community, the greater the part played by industrial Nemesis in the pain, discrimination, and death suffered by its members. Therefore, it seems that the disciplined study of the distinctive character of Nemesis ought to be the key theme for research amongst those who are concerned with health care, healing, and consoling. |

産業による復讐 人間が作り出した不幸の大半は、本来は庶民を守るために設計された企業の副産物である。苦痛、障害、死の主な原因は、今や、意図的ではないにせよ、エンジ ンによる嫌がらせである。無力感と不正義という一般的な病気は、今や進歩のための戦略の副作用である。宿敵は今や、人間の条件の一部であると誤解されるほ ど蔓延している。現代人が、人間的条件に対する産業的侵略の代替案を思い描くことができないのは、彼が苦しんでいる呪いの不可欠な部分なのだ。進歩は、代 償とは呼べない復讐を伴ってやってきた。頭金はラベルに記載され、測定可能な用語で説明することができる。その分割払いは、「痛み」という概念を超える苦 しみの形で発生する。 私たちの主要な機関が拡大するある時点で、顧客は、必然的にもっと苦しむことになるという証拠にもかかわらず、消費を続けるために日々高い代償を払い始め る。この時点で、社会の一般的な行動は、伝統的に常習者に見られるものと一致する。収穫の減少は、わずかに増加する不用量に比べれば淡いものである。ホ モ・エコノミクスはホモ・レリギオスに変わる。彼の期待は英雄的になる。経済発展の復讐は、この復讐を買った代償を上回るだけでなく、自然や隣人による複 合的な不法行為をも上回る。古典的なネメシスは、特権の軽率な乱用に対する罰であった。産業化されたネメシスは、社会への従順な参加に対する報いである。 戦争や飢餓、疫病や突然の死、拷問や狂気は依然として人間の仲間であるが、それらは今や、それらを統括するネメシスによって新たなゲシュタルトへと形作ら れている。どのような共同体であれ、経済的進歩が大きくなればなるほど、その構成員が被る苦痛、差別、死において産業ネメシスが果たす役割は大きくなる。 したがって、ネメシスの特徴的な性格を学問的に研究することは、医療、癒し、慰めに携わる人々の間で重要な研究テーマとなるはずである。 |

| TANTALUS Medical Nemesis is but one aspect of the more general “counter-intuitive misadventures” characteristic of industrial society. It is the monstrous outcome of a very specific dream of reason—namely, “tantalising” hubris. Tantalus was a famous king whom the gods invited to Olympus to share one of their meals. He purloined Ambrosia, the divine potion which gave the gods unending life. For punishment, he was made immortal in Hades and condemned to suffer unending thirst and hunger. When he bows towards the river in which he stands, the water recedes, and when he reaches for the fruit above his head the branches move out of his reach. Ethologists might say that Hygienic Nemesis has programmed him for compulsory counter-intuitive behaviour. Craving for Ambrosia has now spread to the common mortal. Scientific and political optimism have combined to propagate the addiction. To sustain it, the priesthood of Tantalus has organised itself, offering unlimited medical improvement of human health. The members of this guild pass themselves off as disciples of healing Asklepios, while in fact they peddle Ambrosia. People demand of them that life be improved, prolonged, rendered compatible with machines, and capable of surviving all modes of acceleration, distortion, and stress. As a result, health has become scarce to the degree to which the common man makes health depend upon the consumption of Ambrosia. |

タンタロス 医療ネメシスは、産業社会に特徴的な、より一般的な「直感に反する誤算」の一側面にすぎない。タンタロスとは、神々がオリンポスに招いた有名な王である。 タンタロスとは、神々が食事を共にするためにオリンポスに招いた有名な王である。彼は神々に不老不死の命を与える神の薬、アンブロシアを盗み出した。罰と して、彼は黄泉の国で不死身とされ、果てしない渇きと飢えに苦しむことになった。彼が川に向かって頭を下げると水は引き、頭上の果物に手を伸ばすと枝は彼 の手の届かないところに移動する。衛生学的な宿命が、彼に直感に反する行動を強制するようプログラムしたのだと、倫理学者は言うかもしれない。アンブロシ アへの渇望は、今や普通の人間にまで広がっている。科学的楽観主義と政治的楽観主義が相まって、この中毒を広めている。それを維持するために、タンタロス の神官団が組織され、人間の健康を無制限に改善する医療を提供している。このギルドのメンバーは、自らを癒しのアスクレピオスの弟子であるかのように装っ ているが、実際にはアンブロシアを売りさばいている。人々は彼らに、生命を改善し、長持ちさせ、機械と互換性を持たせ、あらゆる加速、歪曲、ストレスに耐 えられるようにすることを要求する。その結果、庶民が健康をアンブロシアの消費に依存させるほどに、健康は希少なものとなってしまった。 |

| CULTURE AND HEALTH Mankind evolved only because each of its individuals came into existence protected by various visible and invisible cocoons. Each one knew the womb from which he had come, and oriented himself by the stars under which he was born. To be human and to become human, the individual of our species has to find his destiny in his unique struggle with Nature and neighbour. He is on his own in the struggle, but the weapons and the rules and the style are given to him by the culture in which he grew up. Each culture is the sum of rules with which the individual could come to terms with pain, sickness, and death—could interpret them and practise compassion amongst others faced by the same threats. Each culture set the myth, the rituals, the taboos, and the ethical standards needed to deal with the fragility of life—to explain the reason for pain, the dignity of the sick, and the role of dying or death. Cosmopolitan medical civilisation denies the need for man’s acceptance of these evils. Medical civilisation is planned and organised to kill pain, to eliminate sickness, and to struggle against death. These are new goals, which have never before been guidelines for social life and which are antithetic to every one of the cultures with which medical civilisation meets when it is dumped on the so-called poor as part and parcel of their economic progress. The health-denying effect of medical civilisation is thus equally powerful in rich and in poor countries, even though the latter are often spared some of its more sinister sides. |

文化と健康 人類が進化したのは、各個体が目に見えたり見えなかったりするさまざまな繭に守られて誕生したからにほかならない。一人一人が、自分が生まれてきた子宮を 知り、自分が生まれた星によって自分の方向を定めた。人間であるために、そして人間になるために、私たちの種の個体は、自然や隣人との独自の闘いの中で自 分の運命を見つけなければならない。その闘いの中で、彼は自分の力で、しかし武器やルールやスタイルは、彼が育った文化によって与えられる。それぞれの文 化は、個人が痛み、病気、死と折り合いをつけ、それらを解釈し、同じ脅威に直面する人々の中で思いやりを実践するためのルールの総体である。それぞれの文 化は、神話、儀式、タブー、そして生命のはかなさに対処するために必要な倫理基準を定め、痛みの理由、病人の尊厳、死や死の役割を説明した。 コスモポリタン的医療文明は、人間がこれらの弊害を受け入れる必要性を否定する。医療文明は、痛みを殺し、病気をなくし、死と闘うために計画され、組織化 されている。これらは、これまで社会生活の指針とされたことのない新たな目標であり、医療文明がいわゆる貧困層に経済的進歩の一部として押し付けられる際 に直面する、あらゆる文化に反目するものである。 医療文明がもたらす健康破壊の影響は、豊かな国でも貧しい国でも等しく強力である。 |

| THE KILLING OF PAIN For an experience to be pain in the full sense, it must fit into a culture. Precisely because each culture provides a mode for suffering, culture is a particular form of health. The act of suffering is shaped by culture into a question which can be stated and shared. Medical civilisation replaces the culturally determined competence in suffering with a growing demand by each individual for the institutional management of his pain. A myriad of different feelings, each expressing some kind of fortitude, are homogenised into the political pressure of anaesthesia consumers. Pain becomes an item on a list of complaints. As a result, a new kind of horror emerges. Conceptually it is still pain, but the impact on our emotions of this valueless, opaque, and impersonal hurt is something quite new. In this way, pain has come to pose only a technical question for industrial man—what do I need to get in order to have my pain managed or killed? If the pain continues, the fault is not with the universe, God, my sins, or the devil, but with the medical system. Suffering is an expression of consumer demand for increased medical outputs. By becoming unnecessary, pain has become unbearable. With this attitude, it now seems rational to flee pain rather than to face it, even at the cost of addiction. It also seems reasonable to eliminate pain, even at the cost of health. It seems enlightened to deny legitimacy to all non-technical issues which pain raises, even at the cost of disarming the victims of residual pain. For a while it can be argued that the total pain anaesthetised in a society is greater than the totality of pain newly generated. But at some point, rising marginal disutilities set in. The new suffering is not only unmanageable, but it has lost its referential character. It has become meaningless, questionless torture. Only the recovery of the will and ability to suffer can restore health into pain. |

痛みを殺す(=鎮痛) ある体験が完全な意味での苦痛であるためには、それが文化に適合していなければならない。それぞれの文化が苦しみの様式を提供するのだから、文化は健康の 特殊な形態なのである。苦しみという行為は、文化によって、述べられ、共有されうる問題へと形作られる。 医療文明は、文化的に決定された苦痛に対する能力を、各個人が自分の苦痛を制度的に管理することへの要求の高まりに置き換える。それぞれがある種の不屈の 精神を表現している無数の異なる感情が、麻酔消費者の政治的圧力として均質化される。痛みは苦情リストの一項目となる。その結果、新しい種類の恐怖が出現 する。概念的には痛みであることに変わりはないが、この無価値で不透明で非人間的な痛みが私たちの感情に与える影響は、まったく新しいものである。 このように、痛みは産業人にとって技術的な問題を提起するにすぎない。もし痛みが続くなら、その責任は宇宙や神、私の罪や悪魔にあるのではなく、医療制度 にある。苦痛は、医療生産量の増加に対する消費者の要求の表れである。不必要になることで、痛みは耐えられなくなったのだ。このような態度をとることで、 中毒になってでも痛みと向き合うよりも、痛みから逃れることが合理的に思えるようになった。また、健康を犠牲にしてでも痛みをなくすことも合理的に思え る。痛みがもたらす技術的な問題以外のすべての正当性を否定することは、たとえ痛みが残る犠牲者を無力化する代償を払っても、賢明なことのように思える。 しばらくの間は、社会で麻酔される痛みの総量は、新たに発生する痛みの総量よりも大きいと主張できる。しかしある時点で、限界効用は上昇する。新たな苦痛 は手に負えないだけでなく、その言及的性格を失っている。意味のない、疑問のない拷問になってしまったのだ。苦しむ意志と能力を回復させることだけが、苦 痛に健康を取り戻すことができる。 |

| THE ELIMINATION OF SICKNESS Medical interventions have not affected total mortality-rates: at best they have shifted survival from one segment of the population to another. Dramatic changes in the nature of disease afflicting Western societies during the last 100 years are well documented. First industrialisation exacerbated infections, which then subsided. Tuberculosis peaked over a 50–75-year period and declined before either the tubercle bacillus had been discovered or anti-tuberculous programmes had been initiated. It was replaced in Britain and the U.S. by major malnutrition syndromes—rickets and pellagra—which peaked and declined, to be replaced by disease of early childhood, which in turn gave way to duodenal ulcers in young men. When that declined the modern epidemics took their toll—coronary heart-disease, hypertension, cancer, arthritis, diabetes, and mental disorders. At least in the U.S., death-rates from hypertensive heart-disease seem to be declining. Despite intensive research no connection between these changes in disease patterns can be attributed to the professional practice of medicine. Neither decline in any of the major epidemics of killing diseases, nor major changes in the age structure of the population, nor falling and rising absenteeism at the workbench have been significantly related to sick care—even to immunisation. Medical services deserve neither credit for longevity nor blame for the threatening population pressure. Longevity owes much more to the railroad and to the synthesis of fertilisers and insecticides than it owes to new drugs and syringes. Professional practice is both ineffective and increasingly sought out. This technically unwarranted rise of medical prestige can only be explained as a magical ritual for the achievement of goals which are beyond technical and political reach. It can be countered only through legislation and political action which favours the deprofessionalisation of health care. The overwhelming majority of modern diagnostic and therapeutic interventions which demonstrably do more good than harm have two characteristics: the material resources for them are extremely cheap, and they can be packaged and designed for self-use or application by family members. The price of technology that is significantly health-furthering or curative in Canadian medicine is so low that the resources now squandered in India on modern medicine would suffice to make it available in the entire sub-continent. On the other hand, the skills needed for the application of the most generally used diagnostic and therapeutic aids are so simple that the careful observation of instruction by people who personally care would guarantee more effective and responsible use than medical practice can provide. The deprofessionalisation of medicine does not imply and should not be read as implying negation of specialised healers, of competence, of mutual criticism, or of public control. It does imply a bias against mystification, against transnational dominance of one orthodox view, against disbarment of healers chosen by their patients but not certified by the guild. The deprofessionalisation of medicine does not mean denial of public funds for curative purposes, it does mean a bias against the disbursement of any such funds under the prescription and control of guild-members, rather than under the control of the consumer. Deprofessionalisation does not mean the elimination of modern medicine, nor obstacles to the invention of new ones, nor necessarily the return to ancient programmes, rituals, and devices. It means that no professional shall have the power to lavish on any one of his patients a package of curative resources larger than that which any other could claim on his own. Finally, the deprofessionalisation of medicine does not mean disregard for the special needs which people manifest at special moments of their lives; when they are born, break a leg, marry, give birth, become crippled, or face death. It only means that people have a right to live in an environment which is hospitable to them at such high points of experience. |

病気の撲滅 医療介入は総死亡率に影響を与えなかった。過去100年間に西洋社会を苦しめた病気の性質が劇的に変化したことは、よく知られている。まず工業化が感染症 を悪化させ、その後沈静化した。結核は50〜75年の間にピークを迎え、結核菌が発見されるか、抗結核プログラムが開始される前に衰退した。イギリスとア メリカでは、主要な栄養不良症候群であるくる病とペラグラがピークを迎えて衰退し、幼児期の病気に取って代わられた。それが衰退すると、冠状動脈性心臓 病、高血圧、ガン、関節炎、糖尿病、精神障害など、現代の伝染病が犠牲となった。少なくともアメリカでは、高血圧性心疾患による死亡率は減少しているよう だ。集中的な研究にもかかわらず、これらの疾病パターンの変化と専門的な医療行為との間に関連性はない。 殺傷能力の高い疾病の主要な流行が減少したことも、人口の年齢構成が大きく変化したことも、欠勤率が低下したり上昇したりしたことも、病気治療、それも予 防接種とは大きな関係がない。医療サービスは長寿の手柄にも、脅威的な人口圧力に対する非難にも値しない。 長寿は、新薬や注射器のおかげというよりも、鉄道や肥料や殺虫剤の合成のおかげのほうがはるかに大きい。専門的な診療は効果がなく、ますます求められるよ うになっている。技術的にも政治的にも手の届かない目標を達成するための魔術的儀式としてしか説明できない。それに対抗できるのは、医療の脱専門化を促進 する法律と政治的行動だけである。 明らかに害よりも益の方が多い現代の診断・治療介入の圧倒的多数には、2つの特徴がある。カナダの医療では、健康を増進させたり治療効果を高めたりする技 術の価格は非常に低く、現在インドで近代医療に浪費されている資源を使えば、亜大陸全域で利用できるようになる。その一方で、最も一般的に使用されている 診断・治療補助器具の使用に必要な技術は非常に単純であるため、個人的に気にかけている人々が注意深く指導を観察すれば、医療現場が提供できる以上の効果 的で責任ある使用が保証されるだろう。 医療の脱専門化は、専門化された治療者、能力、相互批判、公的統制の否定を意味するものではないし、そう読み取るべきでもない。しかし、神秘化に対する偏 見や、国境を越えた一つの正統的な見解の支配に対する偏見、患者に選ばれながらギルドに認定されていない治療者の資格剥奪に対する偏見は含意している。医 療の脱専門化は、治療目的のための公的資金の否定を意味するのではなく、そのような資金が、消費者の管理下ではなく、ギルドメンバーの処方と管理下で支出 されることへの偏見を意味する。脱専門化とは、近代医学を排除することでも、新しい医学の発明を妨げることでもなく、必ずしも古代のプログラムや儀式、器 具に戻ることでもない。それは、いかなる専門家も、自分の患者一人一人に、他のいかなる専門家も主張しうる以上の治療資源を惜しみなく提供する権限を持た ないということである。最後に、医療の脱専門化とは、人が人生の特別な瞬間、つまり、生まれたとき、足を折ったとき、結婚したとき、出産したとき、足が不 自由になったとき、死に直面したときに現れる特別なニーズを無視することではない。それはただ、そのような経験の頂点に立つ人々をもてなす環境で生きる権 利が人々にあるということを意味している。 |

| THE STRUGGLE AGAINST DEATH The ultimate effect of medical Nemesis is the expropriation of death. In every society the image of death is the culturally conditioned anticipation of an uncertain date. This anticipation determines a series of behavioural norms during life and the structure of certain institutions. Wherever modern medical civilisation has penetrated a traditional medical culture, a novel cultural ideal of death has been fostered. The new ideal spreads by means of technology and the professional ethos which corresponds to it. In primitive societies death is always conceived as the intervention of an actor—an enemy, a witch, an ancestor, or a god. The Christian and the Islamic Middle Ages saw in each death the hand of God. Western death had no face until about 1420. The Western ideal of death which comes to all equally from natural causes is of quite recent origin. Only during the autumn of the Middle Ages death appears as a skeleton with power in its own right. Only during the 16th century, as an answer European peoples developed the “arte and crafte to knowe ye Will to Dye”. For the next three centuries peasant and noble, priest and whore, prepared themselves throughout life to preside at their own death. Foul death, bitter death, became the end rather than the goal of living. The idea that natural death should come only in healthy old age appeared only in the 18th century as a class-specific phenomenon of the bourgeois. The demand that doctors struggle against death and keep valetudinarians healthy has nothing to do with their ability to provide such service: Ariès has shown that the costly attempts to prolong life appear at first only among bankers whose power is compounded by the years they spend at a desk. We cannot fully understand contemporary social organisation unless we see in it a multi-faceted exorcism of all forms of evil death. Our major institutions constitute a gigantic defence programme waged on behalf of “humanity” against all those people who can be associated with what is currently conceived of as death-dealing social injustice. Not only medical agencies, but welfare, international relief, and development programmes are enlisted in this struggle. Ideological bureaucracies of all colours join the crusade. Even war has been used to justify the defeat of those who are blamed for wanton tolerance of sickness and death. Producing “natural death” for all men is at the point of becoming an ultimate justification for social control. Under the influence of medical rituals contemporary death is again the rationale for a witch-hunt. |

死との闘い 医療的復讐の究極の効果は、死の収奪である。どの社会においても、死というイメージは、不確かな日付に対する文化的条件づけられた予期である。この予期 は、生前の一連の行動規範と、ある種の制度の構造を決定する。 近代医療文明が伝統的な医療文化に浸透したところではどこでも、死に関する新しい文化的理想が育まれてきた。この新しい理想は、技術とそれに対応する職業 倫理によって広まっていく。 原始社会では、死は常に敵、魔女、祖先、神といった行為者の介入として考えられてきた。キリスト教やイスラム教の中世では、それぞれの死は神の手によるも のであった。1420年頃まで、西洋の死は顔を持たなかった。すべての人に等しく自然死が訪れるという西洋の死の理想は、ごく最近になって生まれたもので ある。中世の秋になって初めて、死はそれ自体が力を持つ骸骨として現れる。16世紀になってようやく、ヨーロッパの人々はその答えとして「染まるべき意志 を知る術と技」を開発した。それからの3世紀、農民も貴族も、司祭も娼婦も、生涯を通じて自らの死を司る準備をした。汚れた死、苦い死は、生きることの目 的ではなく、むしろ終わりになった。自然死は健康な老年期にのみ訪れるべきだという考え方は、18世紀になってブルジョワの階級特有の現象として現れた。 医師が死と闘い、バレチュディナリアンを健康に保つことを求めるのは、そのようなサービスを提供する能力とは無関係である: アリエスは、費用のかかる延命の試みが、最初は銀行家の間にしか現れないことを示した。 現代の社会組織を完全に理解するには、そこにあらゆる邪悪な死の多面的な悪魔払いを見出さなければならない。私たちの主要な機関は、「人類」を代表して、 現在死をもたらす社会的不公正として考えられていることに関連しうるすべての人々に対して繰り広げられる巨大な防衛プログラムを構成している。医療機関だ けでなく、福祉、国際救援、開発プログラムもこの闘いに参加している。あらゆる色のイデオロギー官僚がこの聖戦に加わっている。戦争さえも、病と死をいた ずらに容認していると非難される人々の敗北を正当化するために利用されている。すべての人に "自然な死 "をもたらすことは、社会統制を正当化する究極の理由となりつつある。医療儀式の影響を受け、現代の死は再び魔女狩りの根拠となっている。 |

| CONCLUSION Rising irreparable damage accompanies industrial expansion in all sectors. In medicine these damages appear as iatrogenesis. Iatrogenesis can be direct, when pain, sickness, and death result from medical care; or it can be indirect, when health policies reinforce an industrial Organisation which generates ill-health: it can be structural when medically sponsored behaviour and delusion restrict the vital autonomy of people by undermining their competence in growing up, caring, ageing; or when it nullifies the personal challenge arising from their pain, disability, and anguish. Most of the remedies proposed to reduce iatrogenesis are engineering interventions. They are therapeutically designed in their approach to the individual, the group, the institution, or the environment. These so-called remedies generate second-order iatrogenic ills by creating a new prejudice against the autonomy of the citizen. The most profound iatrogenic effects of the medical technostructure result from its non-technical social functions. The sickening technical and non-technical consequences of the institutionalisation of medicine coalesce to generate a new kind of suffering—anaesthetised and solitary survival in a world-wide hospital ward. Medical Nemesis cannot be operationally verified. Much less can it be measured. The intensity with which it is experienced depends on the independence, vitality, and relatedness of each individual. As a theoretical concept it is one component in a broad theory to explain the anomalies plaguing health-care systems in our day. It is a district aspect of an even more general phenomenon which I have called industrial Nemesis, the backlash of institutionally structured industrial hubris. This hubris consists of a disregard for the boundaries within which the human phenomenon remains viable. Current research is overwhelmingly oriented towards unattainable “breakthroughs”. What I have called counterfoil research is the disciplined analysis of the levels at which such reverberations must inevitably damage man. The perception of enveloping Nemesis leads to a social choice. Either the natural boundaries of human endeavour are estimated, recognised, and translated into politically determined limits, or the alternative to extinction is compulsory survival in a planned and engineered Hell. In several nations the public is ready for a review of its health-care system. The frustrations which have become manifest from private-enterprise systems and from socialised care have come to resemble each other frighteningly. The differences between the annoyances of the Russian, French, Americans, and English have become trivial. There is a serious danger that these evaluations will be performed within the coordinates set by post-cartesian illusions. In rich and poor countries the demand for reform of national health care is dominated by demands for equitable access to the wares of the guild, professional expansion and sub-professionalisation, and for more truth in the advertising of progress and lay-control of the temple of Tantalus. The public discussion of the health crisis could easily be used to channel even more power, prestige, and money to biomedical engineers and designers. There is still time in the next few years to avoid a debate which would reinforce a frustrating system. The coming debate can be reoriented by making medical Nemesis the central issue. The explanation of Nemesis requires simultaneous assessment of both the technical and the non-technical side of medicine—and must focus on it as both industry and religion. The indictment of medicine as a form of institutional hubris exposes precisely those personal illusions which make the critic dependent on the health care. The perception and comprehension of Nemesis has therefore the power of leading us to policies which could break the magic circle of complaints which now reinforce the dependence of the plaintiff on the health engineering and planning agencies whom he sues. Recognition of Nemesis can provide the catharsis to prepare for a non-violent revolution in our attitudes towards evil and pain. The alternative to a war against these ills is the search for the peace of the strong. Health designates a process of adaptation. It is not the result of instinct, but of autonomous and live reaction to an experienced reality. It designates the ability to adapt to changing environments, to growing up and to ageing, to healing when damaged, to suffering and to the peaceful expectation of death. Health embraces the future as well, and therefore includes anguish and the inner resource to live with it. Man’s consciously lived fragility, individuality, and relatedness make the experience of pain, of sickness, and of death an integral part of his life. The ability to cope with this trio in autonomy is fundamental to his health. To the degree to which he becomes dependent on the management of his intimacy he renounces his autonomy and his health must decline. The true miracle of modern medicine is diabolical. It consists of making not only individuals but whole populations survive on inhumanly low levels of personal health. That health should decline with increasing health-service delivery is unforeseen only by the health manager, precisely because his strategies are the result of his blindness to the inalienability of health. The level of public health corresponds to the degree to which the means and responsibility for coping with illness are distributed amongst the total population. This ability to cope can be enhanced but never replaced by medical intervention in the lives of people or the hygienic characteristics of the environment. That society which can reduce professional intervention to the minimum will provide the best conditions for health. The greater the potential for autonomous adaptation to self and to others and to the environment, the less management of adaptation will be needed or tolerated. The recovery of a health attitude towards sickness is neither Luddite nor Romantic nor Utopian: it is a guiding ideal which will never be fully achieved, which can be achieved with modern devices as never before in history, and which must orient politics to avoid encroaching Nemesis. A review of modern alternatives to medical professionalism is in progress at the Center for International Documentation, APDO 479, Cuernavaca, Mexico. For information, write to Valentina Borremans. |

結論 あらゆる分野における産業の拡大には、回復不可能な損害の増大がつきものである。医療においては、こうした損害は「異所性」として現れる。医原性とは、医 療によって痛み、病気、死がもたらされる直接的なものである場合もあれば、健康政策が不健康を生み出す産業組織を強化する間接的なものである場合もある。 また、医療が支援する行動や妄想が、成長、介護、老いにおける人々の能力を損なうことによって、人々の重要な自律性を制限する構造的なものである場合もあ れば、人々の痛み、障害、苦悩から生じる個人的な挑戦を無効にするものである場合もある。 異所性誘発を減らすために提案されている治療法のほとんどは、工学的介入である。それらは、個人、集団、施設、環境に対するアプローチにおいて、治療的に デザインされている。これらのいわゆる救済策は、市民の自律性に対する新たな偏見を生み出すことで、二次的な異所性疾患を発生させる。 医療テクノストラクチャーがもたらす最も深刻な異所性効果は、その非技術的な社会的機能から生じる。医療の制度化がもたらす技術的・非技術的な結果は、世 界規模の病棟で麻酔をかけられ孤独に生き延びるという、新しい種類の苦しみを生み出す。 医療復讐は、操作的に検証することはできない。ましてや測定することはできない。それが経験される強度は、各個人の独立性、活力、関連性に左右される。理 論的な概念としては、現代の医療システムを苦しめている異常を説明する広範な理論の構成要素のひとつである。それは、私が「産業的復讐」と呼んでいる、よ り一般的な現象の一側面であり、制度的に構造化された産業的傲慢の反動である。この傲慢さは、人間現象が存続しうる境界線を無視することから成っている。 現在の研究は、圧倒的に達成不可能な「ブレークスルー」を志向している。私が「カウンターフォイル研究」と呼んでいるのは、そのような余波が必然的に人間 にダメージを与えるレベルの、規律ある分析である。 包み込むような復讐の認識は、社会的選択をもたらす。人間の努力の自然の限界を推定し、認識し、政治的に決定された限界に変換するか、あるいは絶滅の代替 案として、計画され、設計された地獄の中で強制的に生き残るかである。 いくつかの国では、国民が医療制度を見直す用意ができている。民間企業のシステムと社会化されたケアから顕在化した不満は、恐ろしいほど互いに似てきてい る。ロシア人、フランス人、アメリカ人、イギリス人の不満の違いは些細なものになっている。このような評価が、カルテシアン以後の幻想によって設定された 座標軸の中で行われることになるのは、深刻な危険である。豊かな国でも貧しい国でも、国民医療の改革を求める声は、ギルドの商品への公平なアクセス、専門 職の拡大とサブ専門職化、進歩の宣伝におけるさらなる真実とタンタロス神殿の一般人の管理に対する要求によって支配されている。健康危機に関する公的な議 論は、バイオメディカル・エンジニアやデザイナーにさらなる権力、名声、資金をもたらすために容易に利用される可能性がある。 苛立たしいシステムを強化するような議論を避けるための時間は、今後数年の間にまだある。来るべき議論は、医学的復讐を中心的な問題とすることで、方向転 換することができる。復讐の説明には、医療の技術的側面と非技術的側面の両方を同時に評価する必要があり、産業と宗教の両方としての医療に焦点を当てなけ ればならない。制度的傲慢の一形態としての医療を告発することは、批判者を医療に依存させている個人的な幻想を正確に暴露することになる。 それゆえ、復讐を認識し理解することは、現在、原告が訴えている医療技術や計画機関への依存を強めている苦情の魔法陣を断ち切ることができる政策へと私た ちを導く力を持っている。復讐を認識することは、悪や痛みに対する私たちの態度に非暴力革命を起こすためのカタルシスを与えてくれる。これらの悪に対する 戦争に代わるものは、強者の平和を求めることである。 健康とは適応のプロセスを意味する。それは本能の結果ではなく、経験した現実に対する自律的で生きた反応の結果である。環境の変化に適応し、成長し、老 い、傷ついたときの治癒、苦しみ、そして穏やかな死の予感に適応する能力を意味する。健康は未来をも包含するものであり、それゆえに苦悩と、それとともに 生きるための内的資源を含む。 意識的に生きている人間のもろさ、個性、関連性は、痛み、病気、死の経験を彼の人生の不可欠な部分にしている。この三重苦に自律的に対処する能力は、彼の 健康にとって基本的なものである。親密さの管理に依存するようになる程度まで、彼は自律性を放棄し、健康は衰えるに違いない。現代医学の真の奇跡は極悪非 道である。それは、個人だけでなく集団全体を、人間離れした低レベルの健康状態で存続させることにある。医療サービス提供の増加とともに健康が低下するこ とは、健康管理者だけが予見できることであり、まさに彼の戦略は健康の不可侵性に対する盲目の結果なのである。 公衆衛生の水準は、病気に対処する手段と責任が全人口にどの程度分配されているかに対応している。この対処能力は、人々の生活や環境の衛生的特性に対する 医学的介入によって強化されることはあっても、決して取って代わることはない。専門家の介入を最小限に抑えることができる社会が、健康にとって最良の条件 を提供することになる。自己や他者、環境への自律的な適応の可能性が高ければ高いほど、適応のための管理は必要なくなるし、許容されることも少なくなる。 病気に対する健康的な態度の回復は、ラッダイトでもロマン派でもユートピアでもない。それは、完全に達成されることはないだろうが、歴史上かつてないほど 近代的な装置で達成することができ、復讐の侵食を避けるために政治を方向づけなければならない指導的理想である。 メキシコ、クエルナバカのAPDO479にある国際ドキュメンテーション・センターで、医療専門職の現代的な代替案のレビューが進行中である。お問い合わ せは、バレンティーナ・ボレマンスまで。 |

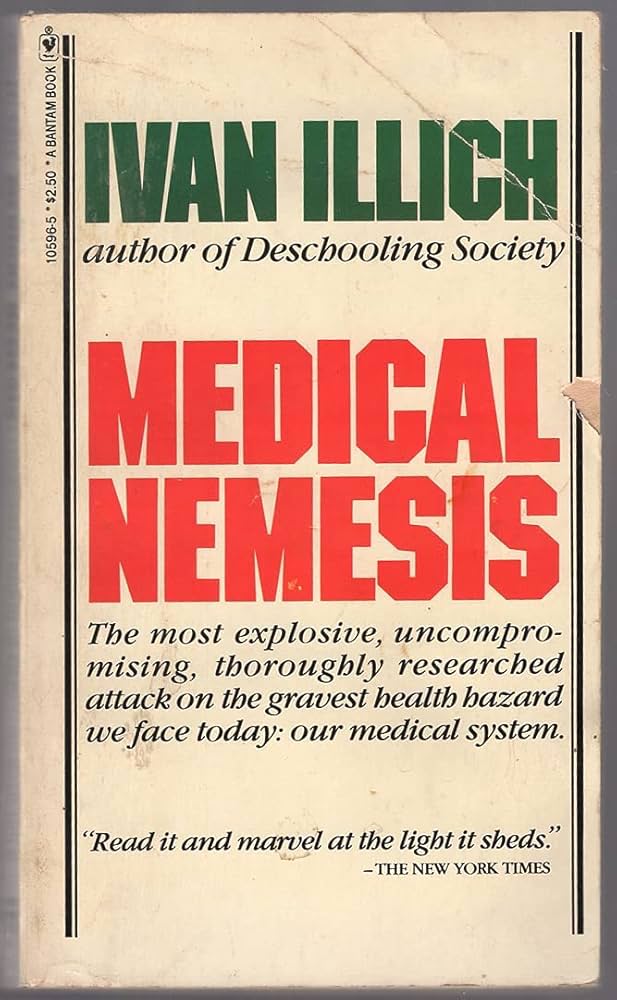

| Abridged from a lecture given in

Edinburgh on April 26 and in Nottingham on May 1, 1974. The lecture is

based on the book Medical Nemesis, which is to be published this autumn

by Calder and Boyars. Lancet1974;i:918–21CrossRef).

(http://www.elsevier.com/locate/lancet) |

|

| https://jech.bmj.com/content/57/12/919 |

MEDICAL NEMESIS, THE EXPROPRIATION OF HEALTH, by IVAN ILLICH, 1976

|

目次(再掲)

* Introduction

* PART I. Clinical latrogenesis:臨床的医原病

o 1. The Epidemics of Modern Medicine:現代医療の疫病化

+ Doctors' Effectiveness—an Illusion:医師の有効性という幻想

+ Useless Medical Treatment:役たたずの医療的処置

+ Doctor-Inflicted Injuries:医師が加える加虐行為

+ Defenseless Patients :何も防ぎきれない患者

* PART II. Social latrogenesis:社会的医原病

o 2. The Medicalization of Life:生活の医療化

+ Political Transmission of Iatrogemc Disease:医原性疾患の政治的伝染

# Social latrogenesis:社会的医原病

# Medical Monopoly:医療の独占

# Value-Free Cure?:価値自由な治療?

+ The Medicalization of the Budget:予算と財政の医療化

+ The Pharmaceutical Invasion:製薬産業の侵略

+ Diagnostic Imperialism:治療的帝国主義

+ Preventive Stigma:予防的スティグマ

+ Terminal Ceremonies:終末期の儀礼(化)

+ Black Magic:黒魔術(ブラック・マジック)

+ Patient Majorities:患者の多数派

* PART III. Cultural latrogenesis:文化的医療化

* Introduction

o 3. The Killing of Pain:痛みを取り去ること

o 4. The Invention and Elimination of Disease

o 5. Death Against Death

+ Death as Commodity

+ The Devotional Dance of the Dead

+ The Danse Macabre

+ Bourgeois Death

+ Clinical Death

+ Trade Union Claims to a Natural Death

+ Death Under Intensive Care

* PART IV. The Politics of Health

o 6. Specific Counterproductivity

o 7. Political Countermeasures

+ Consumer Protection for Addicts

+ Equal Access to Torts

+ Public Controls over the Professional Mafia

+ The Scientific Organization—of Life

+ Engineering for a Plastic Womb

o 8. The Recovery of Health

+ Industrialized Nemesis

+ From Inherited Myth to Respectful Procedure

+ The Right to Health

+ Health as a Virtue

リンク

文献

Do not copy and paste, but you might [re]think this message for all undergraduate students!!!