A Comparative Study of Japanese and Taiwanese

Cultures of the Elderly:

A Preliminary Discussion

Mitsuho IKEDA(Osaka University) & Keie SOU(Nara Women's University)

☆ If you read the Japanese edtion, please click here.

|

We

will present a study comparing the culture of senior citizens in Japan

and Taiwan. As this is a preliminary study, we will present our

thoughts on the basic differences between Japan and Taiwan, both of

which are facing declining birth rates and aging populations, and the

methodological implications of these differences. |

|

We

will present my research on “A Comparison of Elderly Culture in Japan

and Taiwan.” This time, as a preliminary consideration, We compared

basic information about Japan and Taiwan, which are both facing

declining birth rates and aging populations, and considered the

methodological implications. This was focused on three points: 1) an

introduction to global aging around the world, 2) a comparison between

Japan and Taiwan, and 3) methodological implications. The outline of this presentation is as follows: 1. Global aging and its introduction, 2. Comparison between Japan and Taiwan, 3. Methodological implications, 4. Summary of the presentation, 5. References and acknowledgments. |

|

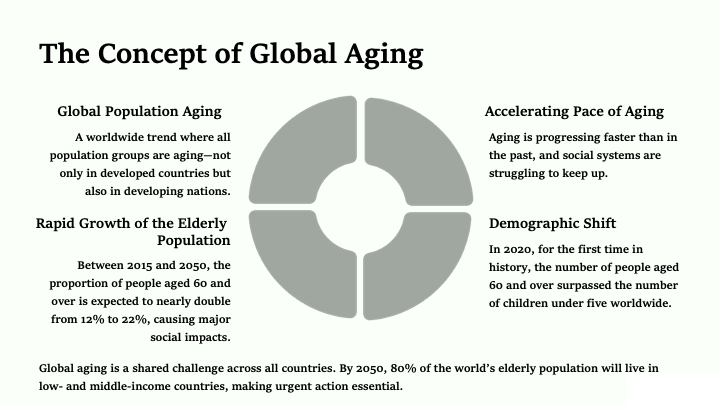

We will briefly introduce the concept of global aging. |

|

With

the rapid aging of the world's population, the United Nations has

designated the period from 2021 to 2030 as the “UN Decade of Healthy

Aging (2021-2030).” This period, following the conclusion of the

Millennium Development Goals in 2015, was designated as the “Post-2015

Development Agenda” from 2016 to 2030. Specifically, a program called

the “Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)” was launched. The World

Health Organization (WHO) has positioned the last 10 years of this

period as a “global collaborative effort to improve the lives of older

people, their families, and the communities in which they live,” and

has called on people to participate in the “Healthy Ageing

Collaborative.” |

|

The four items shown in the slide indicate that the global issues of declining birth rates and aging populations are not only problems for individual countries but also global issues that need to be addressed. |

|

With that in mind, we will now compare Japan and Taiwan. |

|

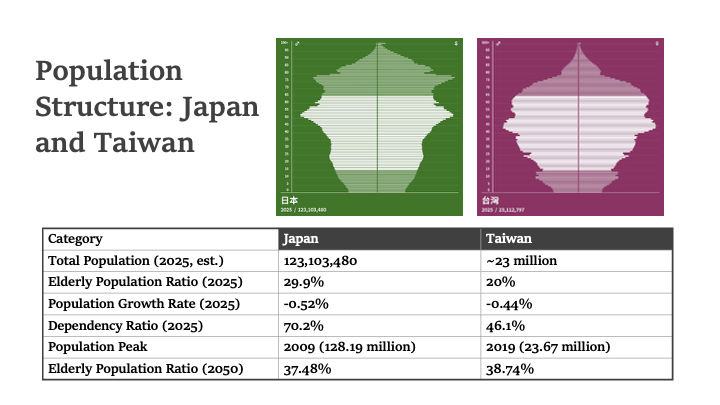

First,

let's look at the population structure. Japan began aging earlier than

Taiwan. Japan's population is five times that of Taiwan, so the impact

on the national economy is also greater than in Taiwan. Japan's GDP

(approximately $4.9 trillion in 2023) is about 5.5 times that of

Taiwan's GDP (approximately $890 billion in 2023), but the economic

growth rates of Japan and Taiwan are approximately 1.5% and 2.5%,

respectively. Therefore, it is clear that demographic factors are

contributing to the slowdown in growth rates. This is having a negative

impact on the slowdown in welfare services for the elderly in Japan. |

|

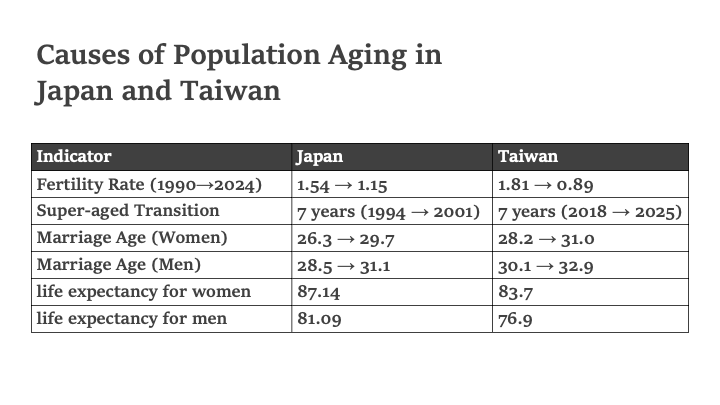

The

three factors contributing to aging are common to both Japan and

Taiwan: 1) declining birth rates, 2) late marriage and the trend toward

remaining unmarried, and 3) longer life expectancy. However, while

Japan is ahead in terms of declining birth rates and longer life

expectancy, Taiwan is ahead in terms of the trend toward late marriage

and remaining unmarried. |

|

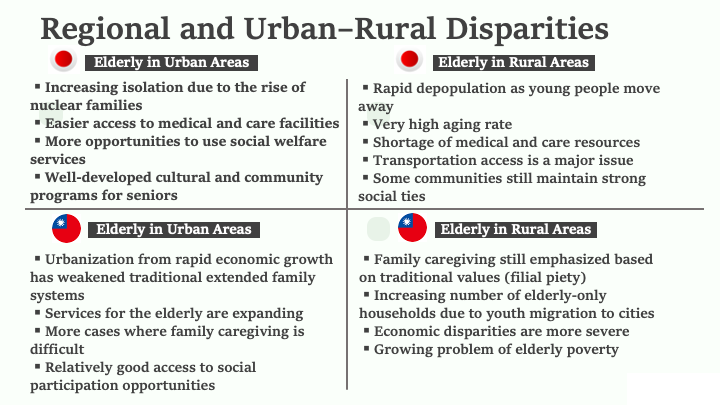

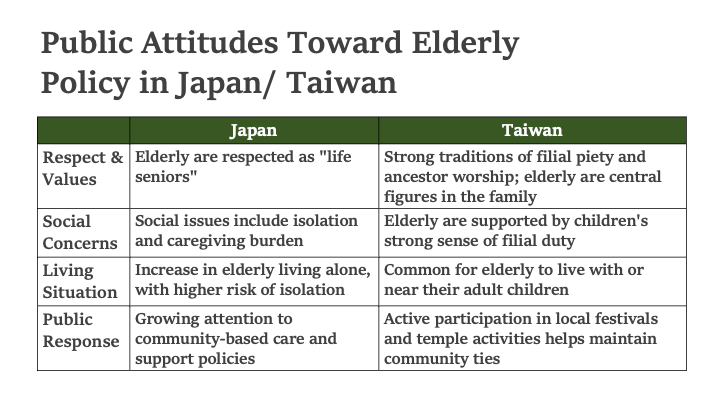

Regarding

regional disparities and urban-rural disparities, traditional culture

supporting the elderly has declined in Japanese rural areas, and this

is thought to be due to population outflow. In contrast, in Taiwanese

rural areas, traditional values (filial piety) and a culture of

family-based care still seem to persist. The geographical scale differences between Japan and Taiwan, and the migration from rural to urban areas, are more serious in Japan than in Taiwan, which may be reflected in the disparities in welfare care services. |

|

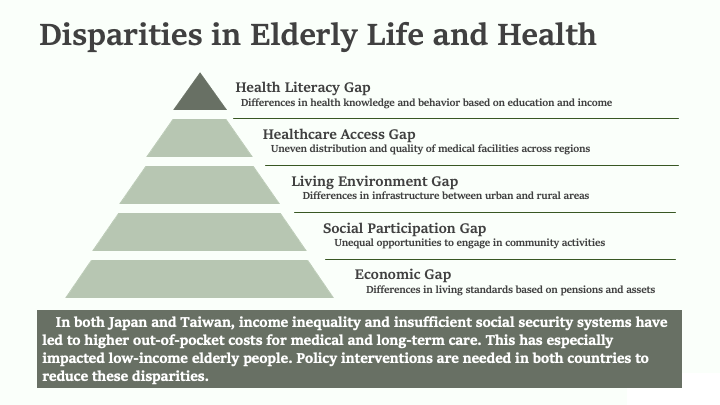

Japan

and Taiwan share common challenges regarding disparities in the lives

and health of the elderly between urban and rural areas. In this

regard, both countries are in a position to propose policies aimed at

resolving common issues through community-based information exchange. |

|

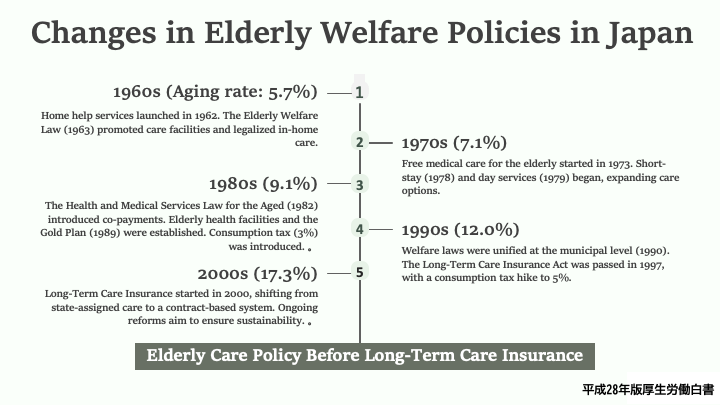

Policy makers in Japan, which is experiencing a rapid aging of its population, have been preparing for this since the 1960s. |

|

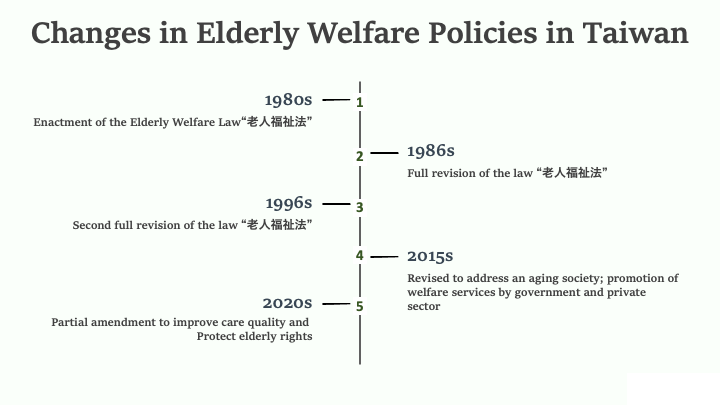

Taiwan

is about 20 years behind Japan in terms of the severity of its

population problem, and therefore, laws related to welfare for the

elderly were enacted at a similar time. However, due to the current

large youth population, the pace of aging is expected to accelerate

rapidly in the future, and laws are frequently revised to align with

current circumstances. |

|

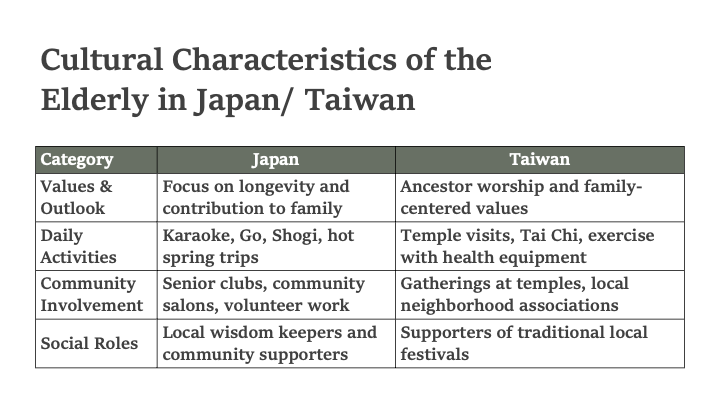

Compared

to Japan, Taiwan has a younger and smaller population, resulting in

faster adoption of ICT and more flexible services for providing

statistical data. Although there are many similarities between Japan and Taiwan in terms of population structure and welfare policies, there are several differences in the social roles of the elderly. In Japan, the elderly population consists mainly of people born before or during the period of high economic growth (early 1950s to 1973), and as a result of the major cultural changes that occurred during this period, there seems to be less of a tendency to return to traditional culture than in Taiwan. |

|

As

a result, demands for elderly policies in Japan tend to focus on

specific measures rather than cultural issues. On the other hand, (in a

relative sense), elderly issues in Taiwan are characterized by a higher

sense of crisis regarding neighborhood living and traditional values,

contrasting with Japan. |

|

Finally,

based on the comparison of the “problems” and policies related to the

elderly in Japan and Taiwan, as well as public opinion, we will

consider what methodological approach can be taken in this research. |

|

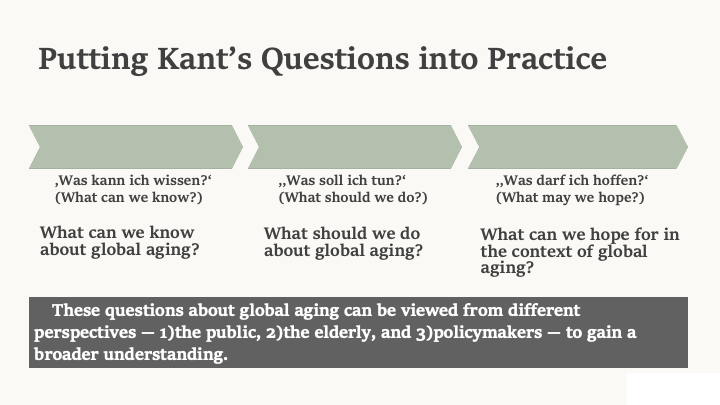

Let's

implement the Kant's questions. In the 18th century, German idealist

philosopher Immanuel Kant posed three questions when engaging in

philosophy. Namely, 1. What can I know? 2. What should I do? And 3.

What do I want? Let us apply this to our task of addressing global aging. In other words, what can we know about global aging? What should we do? And what do we want? By asking these questions, we can imagine whom we should address them. The answers would likely be the general public, the elderly, policymakers, and society (public opinion). |

|

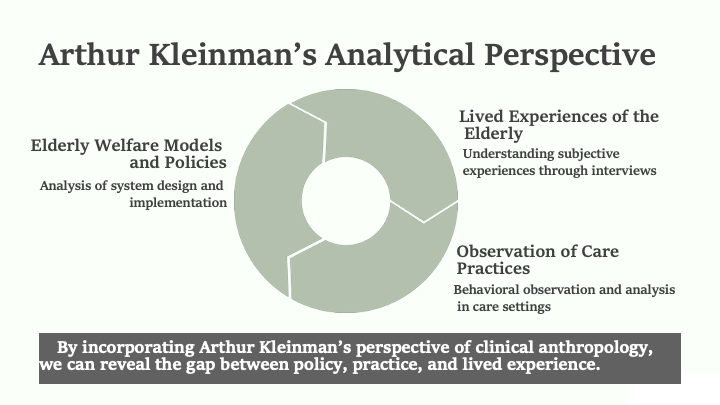

In

his classic medical ethnography “Patients and Healers in the Context of

Culture,” based on fieldwork conducted primarily in Taiwan in the

1970s, Kleinman proposed numerous theoretical frameworks to explain the

medical system embedded within a culture and the behaviors of patients

and their families, including clinical reality, sectoral classification

of medical resources, and explanatory models. This method can be applied to the research topic at hand. Of course, numerous adjustments will be necessary to address the unique characteristics of elderly care, which is a social practice distinct from healthcare. |

|

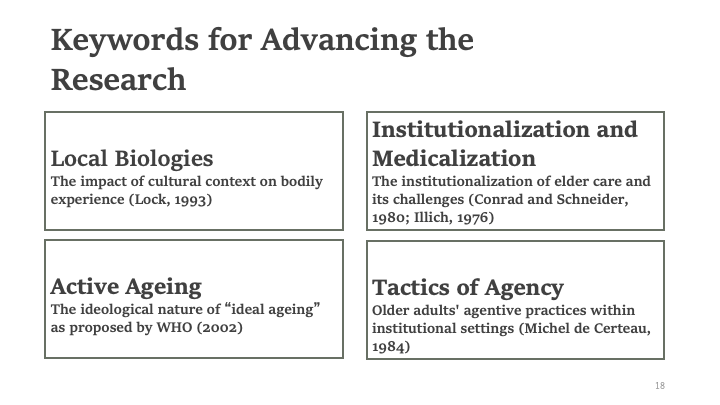

Building

on the achievements of subsequent developments in medical anthropology,

we believe that four additional perspectives are necessary in addition

to Kleinman's viewpoint: 1) local biologies, 2) institutionalization

and medicalization, 3) active aging as ideology, and 4) actor tactics.

While there are various other theoretical frameworks, it is important

to first establish a clear direction regarding these four points. |

|

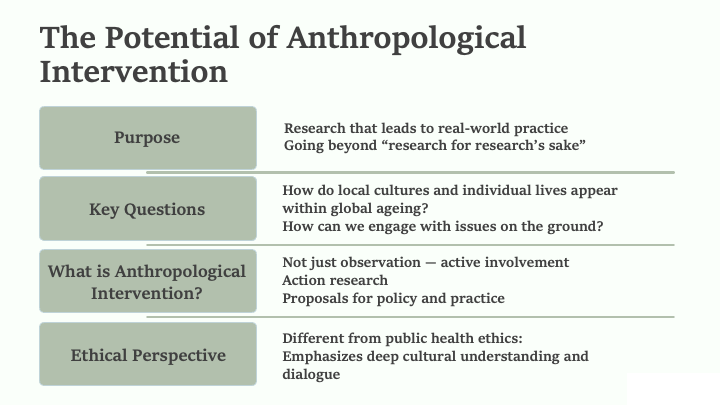

To

avoid our research becoming merely research for the sake of research,

we must consider, as in other medical anthropological research, what

kind of social significance our research may have or can be given. Such

questions must be addressed through ethical scrutiny (establishing

relationships between researchers and research subjects). The research ethics of medical anthropology may have similarities and differences from the research ethics that traditional public health scholars should consider. |

|

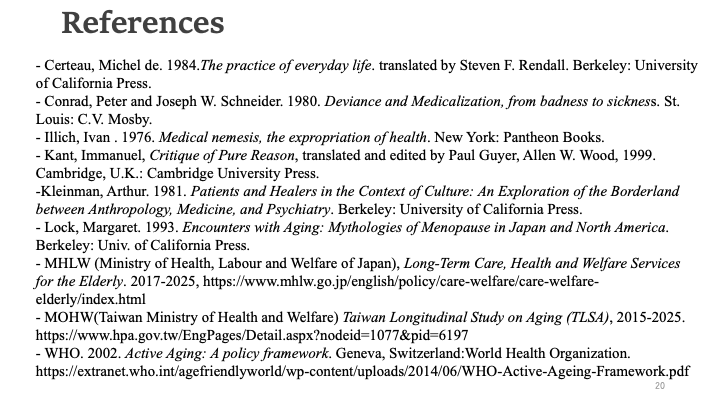

Thank you very much for your attention. - Certeau, Michel de. 1984.The practice of everyday life. translated by Steven F. Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press. - Conrad, Peter and Joseph W. Schneider. 1980. Deviance and Medicalization, from badness to sickness. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby. - Illich, Ivan . 1976. Medical nemesis, the expropriation of health. New York: Pantheon Books. - Kant, Immanuel, Critique of Pure Reason, translated and edited by Paul Guyer, Allen W. Wood, 1999. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. -Kleinman, Arthur. 1981. Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture: An Exploration of the Borderland between Anthropology, Medicine, and Psychiatry. Berkeley: University of California Press. - Lock, Margaret. 1993. Encounters with Aging: Mythologies of Menopause in Japan and North America. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press. - MHLW (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan), Long-Term Care, Health and Welfare Services for the Elderly. 2017-2025, https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy/care-welfare/care-welfare-elderly/index.html - MOHW(Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare) Taiwan Longitudinal Study on Aging (TLSA), 2015-2025. https://www.hpa.gov.tw/EngPages/Detail.aspx?nodeid=1077&pid=6197 - WHO. 2002. Active Aging: A policy framework. Geneva, Switzerland:World Health Organization. https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/WHO-Active-Ageing-Framework.pdf |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099