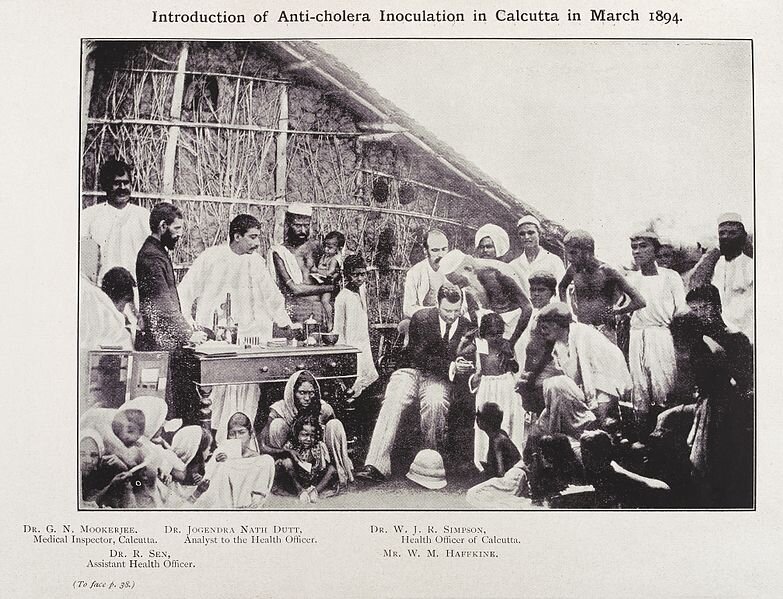

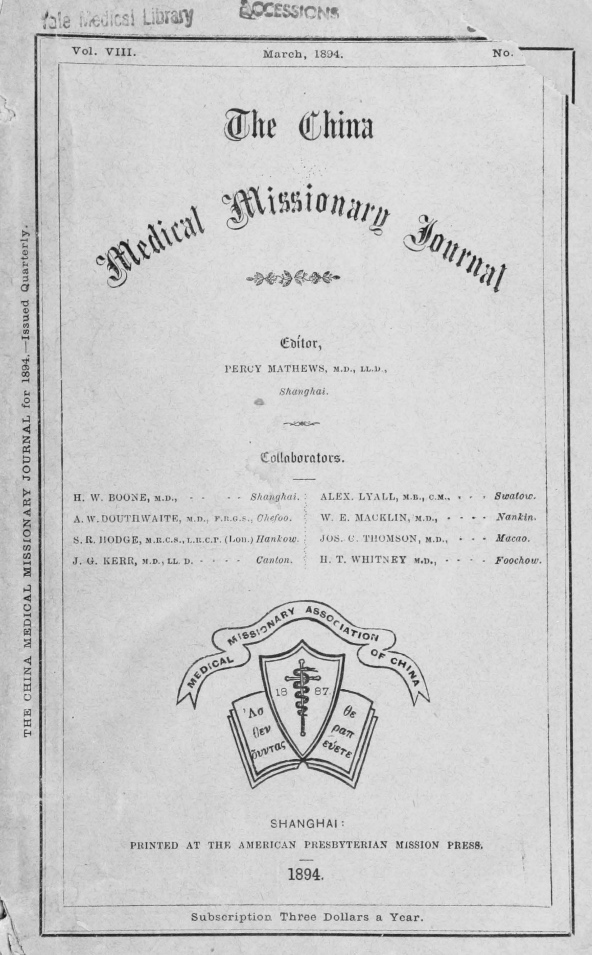

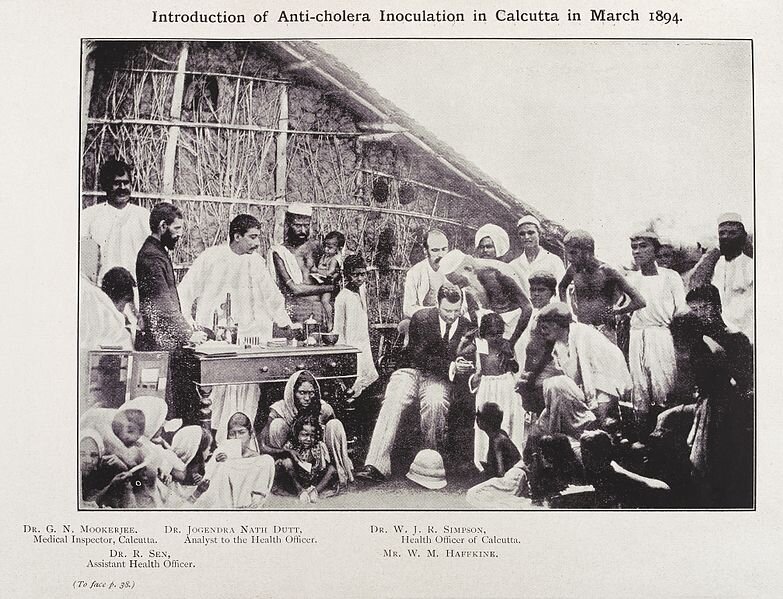

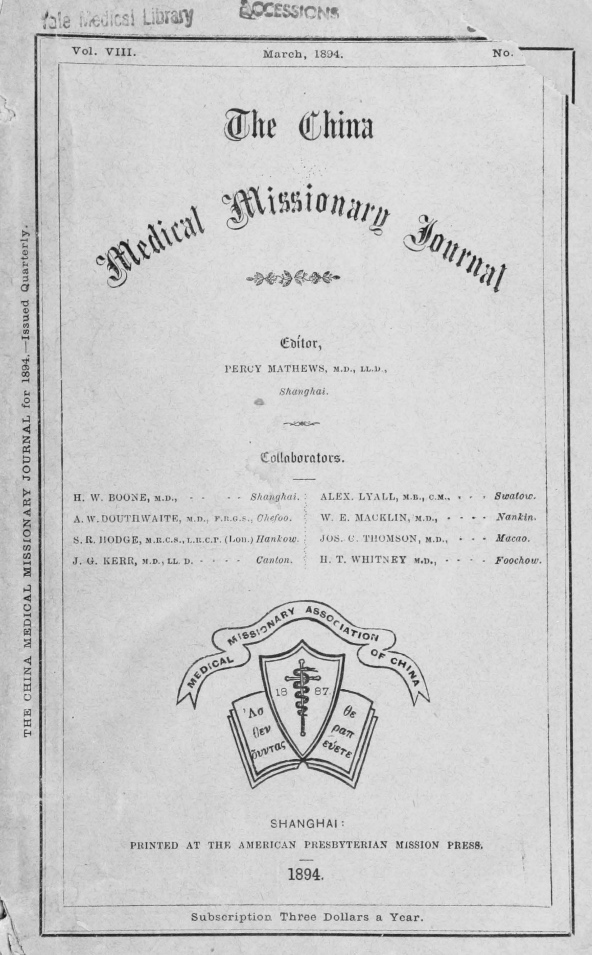

Introduction of Aiti-cholera inoculation in Culcutta, 1894/ The China Medical Missionary Journal; volume VIII, issue 1; 1894

医療宣教・医療伝道

途上国での医療プロジェクトに先行する形態としての ——

■「医療宣教とは、キリスト教の宣教活動のうち、医療行為を伴うものを指す。18世紀から

20世紀にかけての宣教活動によく見られたように、医療宣教には、アフリカ、アジア、東ヨーロッパ、ラテンアメリカ、太平洋諸島などの地域に

「西側世界 」の住民が行くことが多い。-医療宣教。

■新約聖書の中で、イエス・キリストは繰り返し、弟子たちに病人をいやし、貧しい人々に仕え

るように呼びかけている。このような命令に従おうと努力する中で、西洋のキリスト教徒は適切な伝道のあり方について議論し、しばしば宣教活動の中で終末論

的、あるいは物質的な現実を強調してきた。ヨーロッパ・アメリカのプロテスタンティズムの多くは、イエスの終末論(Eschatology)的・救済論(Soteriology)的言明を強調

し、物質的な必要を提供することよりも個人的な救いを強調する神学を発展させてきた。医療宣教の起源は、これら2つの視点のある種の融合にある。」

■エジンバラ医療宣教協会の遺産、(i)EMMSインターナショナル、(ii)ナザレ信託。

■エジンバラ医療宣教協会の遺産

エジンバラ医療宣教協会は、1843年から2002

年までその名を受け継いでいたが、2002年に2つの慈善団体に分割された:

EMMSインターナショナルとナザレ信託である。

■EMMSインターナショナル

医療宣教は今日も世界の多くの地域で続けられてい

る。EMMSインターナショナルは、その起源をエジンバラ医療宣教協会にまで遡る宣教団体であり、現在も

活動を続けているのは、デイヴィッド・リヴィングストンにインスピレーションを受けたからである。EMMSのウェブサイトによると

「リビングストン博士は、EMMSインターナショナルにインスピレーションを与え続けている。EMMSは、インド、マラウイ、ネパール、イギリスの一部で

宣教活動を続けている。

■ナザレ信託

ナザレ信託は、イスラエルのナザレにあるEMMSナ

ザレ病院を運営する組織である。1866年、エジンバラ医療宣教協会は、1861年に診療所を設立した

カロースト・バルタンの活動を支援し始めた[9]。

■医療宣教における論争、1)医療宣教におけるオリエンタリズム、2)科学〈対〉霊性、3) 医療宣教における言語の役割、4)社会的福音〈対〉厳格な福音主義

| 1) 医療宣教におけるオリエンタリズム |

歴史家のデイヴィッド・ハーディマン

は、医療宣教師がオリエンタリズムに与えた永続的な影響を指摘している。宣教師たちによって広められた、「他者

」の社会的・文化的な悪意というイメージは、今日に至るまで西洋に響き続けている」[8]。宣教師たちによる西洋医学の優位性は、西洋社会が文明の

「金字塔

」であるという固定観念を永続させた。病気や治療に対する合理的な理解は、啓蒙主義を志向しない文化のそれよりも洗練され、情報に通じていると考えられて

いた。それゆえ、そのような価値観を世界の他の地域にもたらすことは、「情報通」で「理性的」で「文明的」な西洋人の義務であった。 |

| 2) 科学〈対〉霊性 |

西洋の宣教師にとって、その土地の「キ

リスト教化」は、しばしばその土地の住民の改宗以上の意味を持った。西洋的、近代的イデオロギーが非西洋社会に押し付けられ、キリスト教のメッセージは近

代的価値観と混同された。こうした価値観の中には、合理化された宇宙理解があり、超自然的な現実に対する懐疑が必要であるように思われた。近代化」あるい

は「文明化」の努力は、宣教師たちが迷信的で神話的な(すなわち非合理的な)健康や癒しに対する理解を否定する努力と手を携えていた。 |

| 3) 医療宣教における言語の役割 |

ワリマ・カルーサは植民地時代のザンビ

ア、ムイニルンガにおける医療宣教について書き、西洋の宣教師がアフリカ人の道徳的理解を変えるという目標を達成するのに苦労したことを説明している。カ

ルーサは、宣教師がザンビア人医療補助員の言語的知識に依存していたことが、そのような変革を妨げていたことを強調している。カルーサによれば、「ヨー

ロッパの医学者たちは、(医学用語の)現地語訳が 「異教的

」な意味合いを排除し、医学と病気に関する西洋的な概念を盛り込むことを想定していた」。ムウィニルンガの場合、病気や疾患に関する 「普遍的な真理

」は、西洋的な治癒手段を導入することで明らかになるという西洋的な思い込みが見られる。しかし、このような視点は、病気や健康に対する異なる理解の可能

性を否定するものである。ムウィニルンガでは、現地の人々は西洋医学に超自然的な性質を見いだし、この地を訪れた宣教師たちを悩ませた。 |

| 4) 社会的福音〈対〉厳格な福音主義 |

キリスト教界では、医療宣教における伝

道の役割について議論がなされてきた。伝道の手段としての医療行為の有効性に疑問を呈したデイヴィッド・リビングストンの例に見られるように、医療と福音

宣教を、キリストの命令に従うための別個の手段として切り離すことは珍しいことではなかった。ハーディマンは、「...現場の宣教師たちは、ますます社会

事業に携わるようになり、しばしばこれを自分たちの真の使命と考えるようになった。その過程で、説教は二の次になった。その結果、宣教師たちは、社会的福

音や、改心体験の重要性を過小評価する世俗的な人道主義的アジェンダを宣べ伝えているとして、原理主義者たちから批判を受けることになった。これらの問題

をめぐる議論は今日も続いている。 |

| 資料 |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medical_missions |

"Medical missions is the term used for Christian missionary endeavors that involve the administration of medical treatment. As has been common among missionary efforts from the 18th to 20th centuries, medical missions often involves residents of the "Western world" traveling to locales within Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America, or the Pacific Islands." -Medical missions.

Why did they participate?; "In the New Testament, Jesus Christ repeatedly calls for his disciples to heal the sick and serve the poor, but also for them to "make disciples of all nations". In striving to obey such commands, Western Christians have debated the nature of proper evangelism, often emphasizing either eschatological, or material realities within missionary efforts. Much of Euro-American Protestantism has emphasized Jesus' eschatological and soteriological statements in developing theologies that emphasize personal salvation over the provision of material needs. The origins of medical missions are found in a sort of fusion of these two perspectives."

Legacy of the Edinburgh Medical Missionary Society, (i) EMMS International, (ii) The Nazareth Trust.

■Legacy of the

Edinburgh Medical

Missionary Society

The Edinburgh Medical

Missionary Society bore its name from 1843 until

2002 when it split into two separate charities: EMMS International and

the Nazareth Trust.

■EMMS International

Medical missions

continue in many parts of the world today. EMMS

International is a missions organization that traces its origins back

to the Edinburgh Medical Missionary Society and credits David

Livingstone as an inspiration to their ongoing efforts. According to

the EMMS website: "Dr Livingstone continues to be an inspiration to

EMMS International. We continue in the footsteps of Livingstone, and

those like him, who sought to bring improvements in healthcare along

with Christian compassion to some of the world's poorest

communities."[6] EMMS maintains missionary efforts in India, Malawi,

Nepal, and parts of the United Kingdom.

■The Nazareth Trust

The Nazareth Trust is

the organization that runs EMMS Nazareth Hospital

in Nazareth, Israel. In 1866 the Edinburgh Medical Missionary Society

began supporting the work of Kaloost Vartan, who had founded a medical

dispensary in 1861.[9]

Controversies in medical missions, 1) Orientalism in medical missions; 2) Science vs. spirituality; 3) Role of language in medical missions; 4) Social gospel vs. strict evangelism.

| 1) Orientalism in medical missions | The historian

David Hardiman identifies the lasting Orientalist impact of medical

missionaries. "The image of the social and cultural malignancy of the

'Other' that was propagated and popularised by the missionaries

continues to resonate in the West to this day."[8] The perceived

superiority of Western medicine by missionaries perpetuated stereotypes

that Western societies were the "gold standard" of civilization.

Rationalized understandings of illness and healing were considered more

sophisticated and informed than those of non-Enlightenment oriented

cultures. Therefore, it was the duty of "informed", "rational",

"civilized" Westerners, to bring such values to the rest of the world. |

| 2) Science vs. spirituality | For Western

missionaries, the "Christianization" of a place often meant more than

the conversion of its residents. Western, Modern ideologies were

commonly imposed upon non-Western societies and the Christian message

was conflated with Modern values. Among these values was a rationalized

understanding of the cosmos, that seemingly necessitated skepticism

about supernatural realities. Efforts to "modernize" or "civilize" went

hand in hand with efforts to debunk what missionaries perceived as

superstitious and mythological (i.e. irrational) understandings of

health and healing. |

| 3) Role of language in medical missions | Walima Kalusa

writes about medical missions in colonial Mwinilunga, Zambia, and

illustrates the difficulties that western missionaries had in achieving

their goals of transforming the moral understanding of Africans. Kalusa

highlights missionaries’ dependence on the linguistic knowledge of

Zambian medical auxiliaries as preventing such transformation.

According to Kalusa, "European practitioners of medicine envisaged that

vernacular translations [of medical terms] would be drained of 'pagan'

connotations and loaded with Western notions of medicine and

disease."[9] In the case of Mwinilunga, we see the western assumption

that "universal truths" of sickness and disease would reveal themselves

through the implementation of western means of healing. Such

perspectives, however, dismiss the possibility of different

understandings of illness and health. In Mwinilunga, local people

attributed supernatural properties to Western medicine, much to the

chagrin of missionaries to the area. |

| 4) Social gospel vs. strict evangelism | Within Christian

communities there has been some debate regarding the role of evangelism

within medical missions. As seen in the example of David Livingstone,

who questioned efficacy of medical practice as a means of evangelism,

it was not uncommon to separate healthcare and proclamation of the

gospel as distinct means of obeying the commands of Christ. Hardiman

identifies that, "... missionaries in the field became more and more

involved in social work, and they often saw this as their authentic

life mission. In the process, preaching became secondary."[10] As a

result, missionaries commonly received criticism from fundamentalists

for proclaiming a social gospel or a secular humanitarian agenda that

undervalued the primacy of the conversion experience. Debates around

these issues continue today. |

| Source |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medical_missions |

● https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medical_missionsよ り発祥地の情報

- 中国

中国医学伝道雑誌; 第8巻第1号; 1894年

1830年代、E.C.ブリッジマンという名のアメ

リカ人中国宣教師は、西洋医学の方が中国医学よりも目の白内障を取り除くのに効果的であることに気づいた。彼の要請により、アメリカ対外伝道委員会は

1834年、ピーター・パーカーを最初のプロテスタント医学宣教師として中国に派遣した。西洋医学は、パーカーが宣教師に閉ざされていた中国社会の一部に

アクセスする手段を提供した。さらに多くのアメリカ人医師がこれに続き、1838年には世界初の医療宣教団体である中国医療宣教協会が設立された。

1841年、パーカーはスコットランドのエジンバラを訪れ、同市を代表する医師たちに訴えた。彼のプレゼンテーションの結果、エジンバラ医療宣教協会が設

立され、ヨーロッパで最初の医療宣教協会となった[2]。

- インド

イギリス統治下のインドでは、アーネスト・ミューア

らによるハンセン病の治療と予防の改善など、公衆衛生の取り組みに医療宣教師が活用された[3]。

医療宣教師の例としては、1956年12月6日に死亡記事が掲載されたエリザベス・マリア・ブライアント(旧姓ケープル)夫人が挙げられる[4]。ブライ

アント夫人は1870年にサマセット州イースト・ハンツピルで生まれ、1901年から1946年までアンドラ・プラデシュ州ウェスト・ゴダベリで働いた。

- アフリカ

病気のアフリカ人を診る医療宣教師(ハロルド・コッピング作、油絵、1930年

初期の医療宣教活動のもう一つの例は、著名な探検家

であり宣教師であったデイヴィッド・リビングストンの活動に見られる。リビングストンは、1841年から南アフリカのクルマンにある伝道所で医師として働

いた。リビングストンは治療者としての能力で知られるようになったが、やがて医療活動に嫌気がさし、キリスト教宣教の一形態としての効果に疑問を抱くよう

になった。彼は医学の実践をやめ、アフリカ内陸部の探検と奴隷貿易との闘いを開始した。エジンバラ医療宣教協会は1858年から1873年に亡くなるまで

リビングストンと関係を持った[6]。

- 20世紀

1901年までに、中国は医療宣教師にとって最も人

気のある目的地となった。150人の外国人医師が128の病院と245の診療所を運営し、170万人の患者を治療した。1894年には、男性の医療宣教師

は全宣教師の14パーセントを占め、女性医師は4パーセントであった[7]。1923年にはすでに、中国には世界の宣教師病院のベッド数の半分と、世界の

宣教師医師の半分がいた。1931年には、中国にある500の病院のうち、235がプロテスタント宣教団体、10がカトリック宣教団体によって運営されて

いた。ミッション病院は、西洋で訓練を受けた医師の61%、看護師の32%、医学部の50%を輩出している[8]

★以下では、ウォルター・R・ランバス(関西学院大学 の創始者でアジアにおける医療宣教の第一人者)の『医療宣教:二重の任務』(原著は1920年;邦訳は2016年)をとりあげる。

Walter

Russell Lambuth, 1854-1921

まずは本書の章立てからである(情報源:http: //www.kgup.jp/book/b220048.html)

■第4章志願者から宣教師へ:第4節「直面する諸問 題」

医療宣教師が直面する問題を、当該箇所では、6つの 点にわけて解説している。これは、現在でも、開発途上国の異文化の土地に赴く医療ミッション(宗教ではなく近代医療の)においてもつとに強調されるところ である。

1.言語の習得

2.現地人のものの見方を学ぶこと

3.医療宣教の動機を現地人に誤解されること

4.現地の設備の不備

5.仕事が苛烈であること

6.現地の習慣や宗教が近代医療の施術に障害になる こと。

この中で、もっとも興味深いことは、2.現地人のも のの観方を学ぶことのアドバイスであり、ランバスは、ダニエル・クロフォードの著作を引き合いにだし、アフリカ人の間での施術に対して、『黒人のことを考 える=黒く考えること(Thinking Black)』が重要だと指摘し、自分のアジアでの経験を「黄色く考えた」と次のように記述している。

「現地人のものの見方を学ぶこと。現地人と外国人は その考え方において対極にある。数千年に渡って発達してきた慣習、民話、生活や思考の習慣。それらは異なった丈明を代表している。ダニエル・クローフォド (Daniel Crawford, 1870-1926)はそのすべてを、『黒い思考(Thinking Black)』というアフリカに関する著書のタイトルに要約している。それはまた、著者の中国における若い時期の経験からも実証することができる。私は痔 に苦しむ患者に砕いた氷を処方した。驚いたことに、翌日見せられたのは数オンスの砕かれたガラスであった。ガラスは患者のためのものであったが、幸いにも 家族は医師が戻って正確な用量を確認するのを待っていてくれた。彼らは「黄色く考えた」のだった。当時の中国中部では、これらのことばの発 音が同一であっ たので、砕かれたガラスを砕かれた氷として与えようとしたのも無理からぬことだったのであろう。また、現地の思考法のもとにある患者たちは、医薬品を、ボ ウル一杯一度に一度に服用しようとする習慣がある。強力な医薬品をグレイン単位(grain, 約0.065グラム)で、あるいは滴剤で処方することの危険性に気づかされる。引き返せ、全部が 一服で飲まれてしまうから」(邦訳、堀忠訳、p.116)。

"Learning the native view point. The native and the foreigner are at opposite poles in their thinking. They represent different civilizations-the growth of a .thousand years of custom, folk lore, habits of thought and of life. Mr. Dan Crawford* has summed it all up in the title of his book on Africa, " Thinking Black.” It might be illustrated by an experience of the writer early in his practice in China. He had prescribed crushed ice for a patient suffering from hemorrhage. To his amazement, on the following day, he was shown a couple of ounces of pounded glass. The glass was intended for the patient, but fortunately the family had awaited the doctor’s return to ascertain the exact dose. They were “ thinking yellow.” In Central China, in those days, they would as readily have thought of giving pounded glass as pounded ice, the sound of the words being similar. Again, patients under the native system have been in the habit of taking medicine a bowlful at a time. One soon learns the danger of prescribing powerful medicines by the drop or by the grain. Turn your back and all goes down at a single dose." (Lambuth 1920:93-94).

*Thinking black : 22 years without a break in the long grass of Central Africa / by D. Crawford, George H. Doran (1912)

これは、レヴィ=ブリュル流の「未開人の思惟(mentalité

primitive)」を、医療宣教師が現地の文化や言語を学ぶことを通して学ぶことを示唆している。

●曺貞恩『近代中国のプロテスタント医療伝道』研文 出版、2020年——2014年度に東京大学人文社会系研究科に提出した博士論文「近代中国におけるプロテスタント医療宣教の展開 : 中国医療伝道協会を中心に(1886-1932)」を修正・補完したもの

序論

一 研究史の整理と課題の設定

二 主な史料と本書の構成

第一章 医療と伝道の間

一 医療伝道とは何か

二 医療や教育活動における伝道

三 理想と現実

四 医療宣教師から中国人へ

第二章 博医会から中華医学会へ

一 博医会の誕生

二 医療伝道団体から医学団体へ

三 中華医学会との協力

四 合併の要因

第三章 医療と教育活動からみた土着化

一 ミッション系病院の経済的な自立を求めて

二 医学教育をめぐる議論

第四章 医学用語翻訳活動

一 医学用語委員会

二 中国人との協力

三 医療宣教師の用語翻訳活動に対する評価

第五章 医療宣教師と中国伝統医学

一 医療宣教師の中薬研究

二 中薬研究の目的

三 中国伝統医学に対する多様な観点

四 医療宣教師と中国人

結論

一 博医会と医療伝道の土着化

二 土着化に対する医療宣教師の懸念

三 教会医事委員会の活動

四 韓国における教会医療伝道事業の土着化

五 医療伝道への評価

文献一覧/あとがき/索引

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Do not paste, but [re]think this message for all undergraduate students!!!