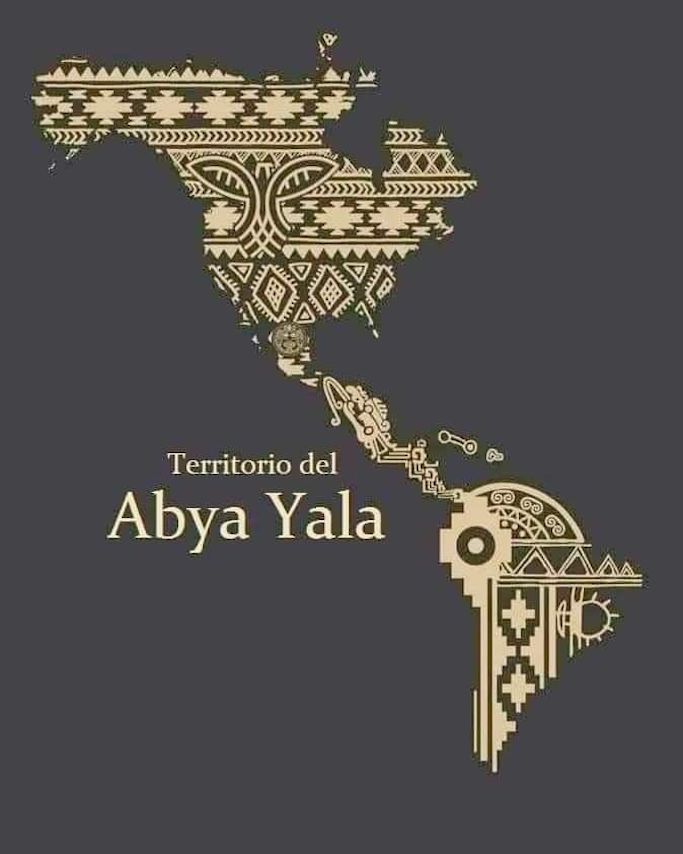

アビヤ・ヤラ

Abya Yala

☆ アビヤ・ヤラとは、パナマとコロンビア北西部のクナ語で、クリストファー・コロンブスやヨーロッパ人が到着する以前のアメリカ大陸の呼称である。

| Abya Yala ist ein

aus der Sprache der Kuna in Panamá und dem nordwestlichen Kolumbien

stammender, vorkolonialer Name für den amerikanischen Kontinent vor der

Ankunft von Christoph Kolumbus und der Europäer. |

アビヤ・ヤラとは、パナマとコロンビア北西部のクナ語で、クリスト

ファー・コロンブスやヨーロッパ人が到着する以前のアメリカ大陸の呼称である。 |

| Herkunft und Bedeutung Wörtlich aus der Kuna-Sprache übersetzt bedeutet er Land in voller Reife beziehungsweise Land des lebensnotwendigen Blutes.[1] Ursprünglich muss der Name sich auf die der Kuna bekannte Landmasse bezogen haben (in Unterscheidung zu ihrem eigenen Territorium im engeren Sinne, das Dule Nega „Heimat der Menschen, d. h. Kuna“), da die Kuna in vorkolumbischer Zeit von der Existenz anderer Kontinente nichts wissen konnten und ihnen auch die Ausdehnung des amerikanischen Doppelkontinents nicht klar sein konnte. |

由来と意味 クナ語から直訳すると、「完全に成熟した土地」または「生命に欠かせない血の土地」という意味だ。[1] もともとこの名前は、クナ族が知っていた大陸(より狭い意味での彼らの領土である「ドゥレ・ネガ(人々の故郷、すなわちクナ族)」とは区別される)を指し ていたはずだ。なぜなら、コロンブス以前、クナ族は他の大陸の存在を知らず、アメリカ大陸が2つの大陸から構成されていることも知らなかったからだ。 |

| Geschichte 1492 erreichte Christoph Kolumbus zum ersten Mal die Karibik. Für ihn war es ein neuer Kontinent. Doch lebten dort bereits Menschen seit 20.000 Jahren. Das Jahr 1492 wurde im eurozentrischen Weltbild als Entdeckung Amerikas gefeiert obwohl es hier bereits mehrere Hochkulturen gab wie beispielsweise die Moche-Kultur und die Inkas. Die präkolumbischen Kulturen wurden in der europäischen und nordamerikanischen Geschichtsschreibung ausgeblendet, in der Landesgeschichte der Länder des Kontinents ist die eigene Geschichte geschrieben. Kleider und Textilien zeigen die soziale Zugehörigkeit zur jeweiligen kulturellen Identität.[2] Der chilenische Künstler Alfredo Jaar thematisierte 1987 mit der Arbeit This is not America die Vereinnahmung des südlichen Kontinents.[3] |

歴史 1492年、クリストファー・コロンブスは初めてカリブ海に到達した。彼にとっては新しい大陸だった。しかし、その地にはすでに2万年前から人々が暮らし ていた。1492年は、ヨーロッパ中心の世界観ではアメリカ大陸の発見として祝われたが、この地域にはすでにモチェ文化やインカ文化などの高度な文明が存 在していた。コロンブス以前の文化は、ヨーロッパや北アメリカの歴史記述から排除され、大陸の各国では自国の歴史が記述されている。衣服や織物は、それぞ れの文化的アイデンティティへの社会的帰属を表している。[2] チリの芸術家アルフレド・ジャールは、1987年の作品「これはアメリカではない」で、南大陸の占領を題材にした。[3] |

| Verwendung Seit den 1990er Jahren wird der Begriff von verschiedenen Organisationen, Vereinigungen und Einrichtungen der Indigenen Völker Südamerikas verwendet, so zum Beispiel vom Verlag Editorial Abya Yala in Quito, Ecuador. Durch die Anwendung des Begriffs Abya Yala wird eine kritische Einstellung zu den Bezeichnungen Neue Welt oder Amerika zum Ausdruck gebracht. Im Zuge der Dekolonialisierungsdebatte werden Geschichte und bisherige Begriffe reflektiert und erweitert.[4] |

使用 1990年代以降、この用語は南米先住民の各組織、団体、機関によって使用されている。例えば、エクアドルのキトにある出版社「Editorial Abya Yala」などがその例だ。Abya Yala という用語を使用することで、「新世界」や「アメリカ」という呼称に対する批判的な立場が表現されている。脱植民地化に関する議論の中で、歴史とこれまで の用語が再考され、拡大されている。[4] |

| Sonstiges Im Nordosten Panamás besteht der Verwaltungsbezirk Guna Yala, der die Heimat der in Panamá lebenden Kuna/Guna ist. Ein ähnlicher Begriff ist „Turtle Island“ (Schildkröteninsel) für Nordamerika. Der Ausdruck stammt ursprünglich aus den Algonkin- und Irokesensprachen und geht auf Schöpfungsmythen zurück, die erzählen, wie der Kontinent auf dem Rücken einer Schildkröte entstand.[5][6] |

その他 パナマの北東部には、パナマに住むクナ/グナ族の故郷であるグナ・ヤラ行政地区がある。 類似の用語として、北アメリカでは「タートル・アイランド」(カメの島)がある。この表現は、アルゴンキン語とイロコイ語に由来し、大陸がカメの背中に 乗って誕生したという創造神話に由来している。[5][6] |

| Weblinks Commons: Abya Yala – Sammlung von Bildern, Videos und Audiodateien Abya Yala Net (en.) Argentinische Folkloregruppe (es.) (Memento vom 23. Juli 2013 im Internet Archive) Abya Yala oder Amerika? Indigene Lebenswelten nach 529 Jahren Kolonialismus auf YouTube vom Museum Fünf Kontinente mit Dr. Anka Krämer de Huerta, deutsch |

ウェブリンク コモンズ:アビア・ヤラ – 画像、動画、音声ファイルのコレクション アビア・ヤラ・ネット (英語) アルゼンチンのフォークロアグループ (es.) (2013年7月23日インターネットアーカイブに保存) アビア・ヤラかアメリカか?529年の植民地支配後の先住民の世界 YouTube、Museum Fünf Kontinente、アンカ・クレーマー・デ・ウエルタ博士、ドイツ語 |

| 1. Muyolema, A.: De la ‘cuestión

indígena’ a lo ‘indígena’ como cuestionamiento. Hacia una crítica del

latinoamericanismo, el indigenismo y el mestiz(o)aje. In: Rodríguez, I.

(Hrsg.): Convergencia de tiempos. Estudios subalternos/contextos

latinoamericanos estado, cultura, subalternidad. Rodopi, Amsterdam

2001, S. 329. 2. Abya Yala | Museum Fünf Kontinente. Abgerufen am 9. Dezember 2023. 3. Talks at The New School: Alfredo Jaar. Abgerufen am 10. Dezember 2023 (amerikanisches Englisch). 4. Worte im Kolonialismus benennen nicht, Sondern Sie Verschleiern: VOM KONTINENT ABYA YALA. In: Lateinamerika Nachrichten. Abgerufen am 9. Dezember 2023 (deutsch). 5. Amanda Robinson: Turtle Island. In: The Canadian Encyclopedia. (englisch, französisch). 6. Joan Garbutt: Walking Alongside: Poetic Inquiry into Allies of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, University of Calgary 18. September 2019, pdf, abgerufen am 15. Juni 2021, S. 4. |

1. Muyolema, A.:

「先住民問題」から「先住民」としての問題提起へ。ラテンアメリカ主義、先住民主義、メスティーソ(混血)に対する批判に向けて。In:

Rodríguez, I. (Hrsg.): Convergencia de tiempos. 下層研究/ラテンアメリカの文脈

国家、文化、下層性。ロドピ、アムステルダム 2001、329 ページ。 2. アビア・ヤラ | 5 大陸博物館。2023 年 12 月 9 日にアクセス。 3. ニュー・スクールでの講演:アルフレド・ジャール。2023 年 12 月 10 日にアクセス(アメリカ英語)。 4. 植民地主義の言葉は表現しない、隠蔽する:アビア・ヤラ大陸について。ラテンアメリカ・ニュース。2023年12月9日アクセス(ドイツ語)。 5. アマンダ・ロビンソン:タートル・アイランド。カナダ百科事典。(英語、フランス語)。 6. Joan Garbutt: Walking Alongside: Poetic Inquiry into Allies of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, University of Calgary 18. September 2019, pdf, abgerufen am 15. Juni 2021, S. 4. |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abya_Yala |

|

| アブヤ・

ヤラ (Abya Yala) は、「成熟した土地

(land in its full maturity)」ないし「活き活きとした血の土地 (land of vital

blood)」を意味するクナ語(英語版)の言葉であり、ダリエン地峡(現在のコロンビア北西部からパナマ南東部にかけての地域)付近に居住するアメリカ

先住民のひとつであるクナ族(英語版)が、クリストファー・コロンブスの到来以前からアメリカ大陸を指して用いていた表現[1]。 起源と用法 ボリビアのアイマラ族の指導者タキル・ママニ (Takir Mamani) は、アメリカ州の先住民族の自治組織を求めた正式な宣言書の中で、「アブヤ・ヤラ」という言葉を用い、「私たちの集落や都市、私たちの大陸に、外来の地名 を冠するのは、侵略者たちやその子孫に、私たちのアイデンティティをゆだねることなる」と述べた[2]。つまり、「新世界」とか、「アメリカ」という言い 方ではなく「アブヤ・ヤラ」を用いることで、イデオロギー的に先住民族の権利(英語版)を支持することになるわけである。 エクアドルの出版社である Editorial Abya Yala は、社名をタキル・ママニの示唆から採っている[3]。この名称は、コスタリカの独立系劇場 Teatro Abya Yala や[4]、サンフランシスコのビデオ・プロダクション兼ウェブ・デザイン会社 Abya-Yala Productions などにも用いられている[5]。 同様に北アメリカ大陸を指す呼称としては、「タートル・アイランド(英語版)」があり、北西部の森林地帯に居住するいくつかの先住民族たち、特にホデノ ショニ連邦あるいはイロコイ連邦によって用いられている[6]。 『Turtle Island to Abya Yala』と題された、60人の先住民やラテン系女性のアーティストや詩人による文集は、2011年に Kickstarter で初期資金を集めた[7]。 |

日本語ウィキペディアでは「アブヤ・ヤラ」と表記されている。 あるデザイナーによるアビヤ・ヤラのイメージ |

| https://x.gd/A91nA |

☆ アビア・ヤラ(グナ語:Abiayala、「成熟した土地」を意味する[1])は、アメリカ大陸の先住民の一部によって、アメリカ大陸を指す言葉として使 用されている[2]。この用語は、一部の先住民組織、機関、運動によって、自分たちの住む土地に対するアイデンティティと敬意の象徴として使用されてい る。[3] この用語の使用増加は、植民地化からの脱却の文脈で捉えることができる。これは、「土地と言説、テリトリオ・イ・パルabraは分離できない」という理解 を促進し、先住民コミュニティにとって主権の闘争と抵抗が日常的に展開される地理的枠組みを構築する役割を果たしている。[4]

| Abya Yala (from the

Guna language: 'Abiayala', meaning "mature land"[1]) is used by some

indigenous peoples of the Americas to refer to the Americas.[2] The

term is used by some indigenous organisations, institutions, and

movements as a symbol of identity and respect for the land one

inhabits.[3] The increasing usage of the term can be viewed in the

context of decolonization, as it serves to create an understanding that

"land and discourse, territorio y palabra, cannot be disjointed" and a

geography in which a struggle for sovereignty and resistance occurs on

an everyday basis for Indigenous communities.[4] |

アビア・ヤラ(グナ語:Abiayala、「成熟した土地」を意味する

[1])は、アメリカ大陸の先住民の一部によって、アメリカ大陸を指す言葉として使用されている[2]。この用語は、一部の先住民組織、機関、運動によっ

て、自分たちの住む土地に対するアイデンティティと敬意の象徴として使用されている。[3]

この用語の使用増加は、植民地化からの脱却の文脈で捉えることができる。これは、「土地と言説、テリトリオ・イ・パラブラは分離できない」という理解を促

進し、先住民コミュニティにとって主権の闘争と抵抗が日常的に展開される地理的枠組みを構築する役割を果たしている。[4] |

| The name, which translates to

"land in its full maturity", "land of lifeblood", or "noble land that

welcomes all" originates from the Guna people who once inhabited a

region spanning from the northern coast of Colombia to the Darién Gap,

and now live on the Caribbean coast of Panama, in the Comarca of Guna

Yala.[5] The term is Pre-Columbian. The first explicit usage of the expression in its political sense was at the 2nd Continental Summit of Indigenous Peoples and Nationalities of Abya Yala, held in Quito in 2004.[6] The symbolic and ideological significance of this summit is reflected in its rejection of neoliberal globalization, its reaffirmation of Indigenous peoples' rights to territorial autonomy, and its continuity with the earlier declarations made at the 2000 Teotihuacan Summit.[7] Despite each indigenous group on the continent having unique endonyms for the regions they live in (e.g. Tawantinsuyu, Anahuac or pt:Pindorama), the expression Abya Yala is increasingly used in search of building a sense of unity and belonging amongst cultures which have a shared cosmovision (for instance a deep relationship with the land) and history of colonialism. The designation Abya Yala lies in its ability to represent a shared vision rooted in indigenous ways of life. Many indigenous movements have adopted this designation to replace colonial names such as ‘Latin America’ to express a connection to the land, community and ancestral memory.[8] The Bolivian indigenist Takir Mamani argues for the use of the term "Abya Yala" in the official declarations of indigenous peoples' governing bodies, saying that "placing foreign names on our villages, our cities, and our continents is equivalent to subjecting our identity to the will of our invaders and their heirs."[9] Thus, use of the term "Abya Yala" rather than a term such as New World or America may have ideological implications indicating support for indigenous rights, as it is regarded as a symbolic shift in Indigenous self-identification. Escobar describes this as "a telling element in the constitution of a diverse set of indigenous peoples as a novel cultural-political subject."[8] |

この名前は、「完全に成熟した土地」、「生命の源の土地」、「すべての

人を受け入れる高貴な土地」という意味で、かつてコロンビアの北海岸からダリエンギャップにかけての地域に住んでいたグナ族に由来し、現在はパナマのカリ

ブ海沿岸、グナ・ヤラ地方に住んでいる。この用語はコロンブス以前からのものだ。 この表現が政治的な意味で初めて明確に使用されたのは、2004年にキトで開催された第2回アビア・ヤラ先住民および民族大陸サミットだった。[6] このサミットの象徴的かつイデオロギー的な意味合いは、新自由主義的グローバル化の拒否、先住民の領土自治権の再確認、2000 年のテオティワカン・サミットでの以前の宣言の継続に反映されている。[7] 大陸の各先住民グループは、自分たちが住む地域に固有の固有名詞(タワンティンスユ、アナワック、ピンドラマなど)を持っているが、共通の世界観(例え ば、土地との深い関係)と植民地主義の歴史を持つ文化間の団結と帰属意識を構築するために、「アビア・ヤラ」という表現がますます使用されている。アビ ア・ヤラの呼称は、先住民の生活様式に根ざした共有されたビジョンを表現する能力に由来している。多くの先住民運動は、土地、コミュニティ、先祖の記憶と のつながりを表現するため、植民地時代の名称である「ラテンアメリカ」に代わってこの呼称を採用している。[8] ボリビアの先住民活動家、タキル・ママニ氏は、先住民統治機関の公式声明において「アビア・ヤラ」という用語の使用を主張し、「私たちの村、都市、大陸に 外国の名前を付けることは、私たちのアイデンティティを侵略者とその子孫の意志に委ねることに等しい」と述べています。[9] したがって、「新世界」や「アメリカ」といった用語ではなく「アビア・ヤラ」という用語を使用することは、先住民の自己認識における象徴的な変化とみなさ れ、先住民の権利を支持するイデオロギー的な意味合いを持つ可能性がある。エスコバルは、これを「多様な先住民集団が、新しい文化・政治的主体として成立 する上で重要な要素」と表現している[8]。 |

| Some critics assert that the

Guna people do not refer to the entire American continent when using

the term Abya Yala, arguing that, cosmologically, the Guna refer to

their ancestral lands. However, studies by Guna intellectuals, such as the ethnolinguist Abadio Green Stocel and the sociologist and poet Aiban Wagua, indicate that the construction of the cosmogonic meaning of Abya Yala is related to the partitioning of Mother Earth into continents. In this process of creation and separation of the world, Abya Yala corresponds to the continent inhabited by Indigenous peoples, effectively assuming a continental nuance, distinct from the term associated specifically with the territory occupied by the Guna people, Guna Yala. Moreover, the use of this term, which has been considered lacking demonstrable historical foundations, has been adopted by scholars proposing decolonial academic perspectives (Arturo Escobar and Walter Mignolo, among others) and by some Indigenous groups, in some cases associated with leftist ideological political movements in various countries on the continent, without a connection to the different cultures that have developed in the continental territory. In particular, the use of the term was promoted by the political movement of Bolivian Aymara Indianist Constantino Lima (self-named Takir Mamani, b. 1933) after a visit to Panama. Bolivian Indianists Pedro Portugal Mollinedo and Carlos Macusaya Cruz narrate this in their book El indianismo katarista. Una mirada crítica: “[Constantino Lima] stopped to visit the Indigenous peoples of Panama. There, he learned that they referred to their lands as Abya Yala: ‘It was an unforgettable day because after 500 years of artificial separation, the moment came when I met the Guna brothers. I arrived at the island of Ustupo, one of the 300 islands of San Blas (Republic of Panama). Indeed, it was a solemn meeting. As we embraced, our hearts seemed to be conversing as well, because the diastole and systole seemed to leap like the finish of a race. The saylas [keepers of traditional wisdom] were the first to welcome me with the rigors and customs of decent Indigenous people. Among many things, we reached the name of their lands. It was a 76-year-old sayla, accompanied by others, who narrated the history passed down verbally from generation to generation, and that could no longer be kept silent in front of a brother who arrives from such distant lands.’ Regarding whether that name would be restrictive for the use of the Guna and its meaning, [Constantino] Lima states: ‘When asked [by the sayla] if that name was only for what is called Central America, he exclaimed: “No: it is the name of the entire territorial mass, that is, everything they call North America, Central America, and South America. Abya-Yala encompasses all of this. In our language, abya means ‘land’ (like something from Pachamama and many additions) and yala is a young man in the prime of youth. Thus, Abya-Yala is the territory in full bloom of youth.”’ El indianismo katarista. Un análisis crítico (2016: 272) Pedro Portugal Mollinedo and Carlos Macusaya Cruz According to critics of the term, each culture gave a name in its respective language to the territory they occupied. The Guarani territory was called Yvy Marãe'ỹ by its inhabitants (translated in ancient times as ‘virgin land’ and currently as ‘land without evil’). This region extended into what is today Paraguay, southern Brazil, and northeastern Argentina. |

一部の批評家は、グナ族は「アビア・ヤラ」という用語を使用する場合、

アメリカ大陸全体を指しているのではなく、宇宙論的に、彼らの先祖の土地を指していると主張している。 しかし、グナ族の知識人である民族言語学者のアバディオ・グリーン・ストセルや社会学者兼詩人のアイバン・ワグアなどの研究によると、アビア・ヤラの宇宙 論的な意味の構築は、母なる地球を大陸に分割するプロセスと関連していることが示されています。この世界の創造と分離の過程において、アビア・ヤラは先住 民が住む大陸に対応し、グナ族が占領する領土を特に指す用語「グナ・ヤラ」とは区別される、大陸的なニュアンスを効果的に帯びている。 さらに、この用語は、歴史的に実証できる根拠がないと考えられてきたが、脱植民地化の学術的視点を提唱する学者たち(アルトゥーロ・エスコバル、ウォル ター・ミニョーロなど)や、大陸のさまざまな国々の左派イデオロギー政治運動と関連のある先住民グループによって、大陸の領土で発展してきた異なる文化と の関連性なく採用されている。特に、この用語の使用は、ボリビアのアイマラ族のインディオ主義者、コンスタンティーノ・リマ(自称タキル・ママニ、 1933 年生)がパナマを訪問した後、推進したものだ。ボリビアのインディオ主義者、ペドロ・ポルトガル・モリネドとカルロス・マクスヤ・クルスは、著書『El indianismo katarista. Una mirada crítica』の中で、次のように述べている。 「[コンスタンティーノ・リマ] は、パナマの先住民を訪ねるために立ち寄った。そこで、彼らが自分たちの土地を「アビア・ヤラ」と呼んでいることを知った。 「それは忘れがたい日だった。500年にわたる人為的な分離を経て、ついにグナ族の兄弟たちに会う瞬間が訪れたからだ。私は、サンブラス(パナマ共和国) の 300 の島のうちの 1 つであるウストポ島に到着した。それはまさに厳粛な出会いだった。私たちが抱き合ったとき、私たちの心も会話しているように感じられた。心拍の拡張期と収 縮期が、人種のレースのゴールのように飛び跳ねるようだったからだ。サイラス(伝統の知恵の守護者)たちが、先住民としての厳格な慣習に従って、最初に私 を迎えてくれた。多くのことを話した中で、彼らの土地の名前にも及んだ。76歳のサヤラが、他の者たちと共に、代々口承で伝えられてきた歴史を語り、遠く から来た兄弟の前で、もはや黙ってはいられないと述べた。その名前がグナ族の使用に制限的かどうか、その意味について、[コンスタンティーノ]・リマは次 のように述べる: 「[サヤラに]その名前が中央アメリカと呼ばれる地域のみを指すのかと尋ねられた時、彼は叫んだ:『いいえ:それは全領土の名称だ。つまり、彼らが北アメ リカ、中央アメリカ、南アメリカと呼ぶ全てを含む。アビア・ヤラはこれら全てを包含する。私たちの言語で、アビアは『土地』(パチャママや多くの追加要素 を含むもの)を意味し、ヤラは青春の真っ只中の若者だ。したがって、アビア・ヤラは青春の真っ只中にある領土だ。」 El indianismo katarista. Un análisis crítico (2016: 272) ペドロ・ポルトガル・モリネド、カルロス・マクスヤ・クルス この用語を批判する者たちは、各文化は、自分たちが占領した領土にそれぞれの言語で名前をつけたと主張している。グアラニーの領土は、その住民によって 「Yvy Marãe'ỹ」と呼ばれていた(古代には「処女の地」、現在は「悪のない土地」と訳されている)。この地域は、現在のパラグアイ、ブラジル南部、アルゼ ンチン北東部にまで広がっていた。 |

| Turtle

Island, a similar term

referring to the continent of North America.[10] |

タートル

島、北米大陸を指す類似の用語。[10] |

| 1. Juncosa, José F. (September

1987). "Abya-Yala: una editorial para los indios" (PDF). Chasqui (in

Spanish) (23): 39–47. 2. "Abya Yala". Asociación Cultural para las Artes Escénicas. Retrieved 2013-05-11. 3. "Abya-Yala - ¿Quiénes somos?" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2013-05-28. Retrieved 2013-05-11. 4. "Decolonial: Abya Yala's Insurgent Epistemologies". THE FUNAMBULIST MAGAZINE. 2023-10-25. Retrieved 2024-04-12. 5. López-Hernández, Miguelángel (2004). Encuentros en los senderos de Abya Yala (in Spanish). Editorial Abya Yala. ISBN 978-9978-22-363-5. Retrieved 11 May 2013 – via Google Books. 6. "Abya-Yala Productions". Archived from the original on 2013-05-20. Retrieved 2013-05-11. 7. Becker, Marc (2008-03-01). "Third Continental Summit of Indigenous Peoples and Nationalities of Abya Yala: From Resistance to Power". Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies. 3 (1): 85–107. doi:10.1080/17442220701865879. ISSN 1744-2222. 8. Escobar, Arturo (2010-01-01). "Latin America at a Crossroads: Alternative modernizations, post-liberalism, or post-development?". Cultural Studies. 24 (1): 1–65. doi:10.1080/09502380903424208. ISSN 0950-2386. 9. Nativeweb.org 10 Johansen, Bruce E.; Mann, Barbara Alice (2000-05-30). Encyclopedia of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy). Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-313-30880-2. |

1. Juncosa, José F. (1987年9月).

「Abya-Yala: una editorial para los indios」 (PDF). Chasqui (スペイン語) (23):

39–47. 2. 「Abya Yala」. Asociación Cultural para las Artes Escénicas. 2013年5月11日取得。 3. 「アビア・ヤラ - 私たちは誰か?」(スペイン語)。2013年5月28日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2013年5月11日に閲覧。 4. 「脱植民地化:アビア・ヤラの反乱的な認識論」。THE FUNAMBULIST MAGAZINE。2023年10月25日。2024年4月12日に取得。 5. López-Hernández, Miguelángel (2004). Encuentros en los senderos de Abya Yala (スペイン語). Editorial Abya Yala. ISBN 978-9978-22-363-5. 2013年5月11日に取得 – Google Books 経由。 6. 「Abya-Yala Productions」。2013年5月20日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2013年5月11日に取得。 7. Becker, Marc (2008-03-01). 「アビア・ヤラ先住民および民族第 3 回大陸サミット:抵抗から権力へ」。ラテンアメリカおよびカリブ海地域民族研究。3 (1): 85–107. doi:10.1080/17442220701865879. ISSN 1744-2222. 8. エスコバル、アルトゥロ(2010年1月1日)。「岐路に立つラテンアメリカ:代替的近代化、ポスト自由主義、それともポスト開発?」。文化研究。24 (1): 1–65. doi:10.1080/09502380903424208. ISSN 0950-2386. 9. Nativeweb.org 10 Johansen, Bruce E.; Mann, Barbara Alice (2000-05-30). Encyclopedia of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy). Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-313-30880-2. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abya_Yala |

|

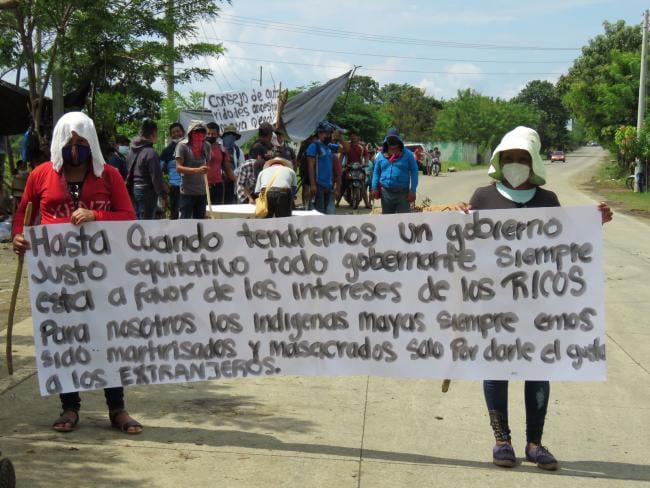

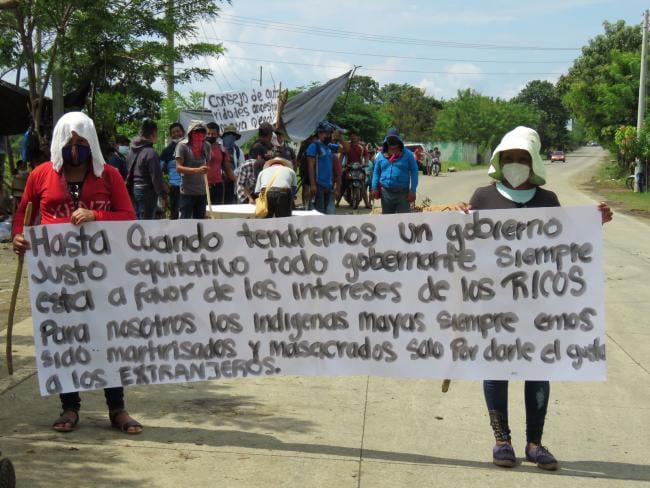

| Invisible No More Abiayala and Indigenous Liberation by Emil Keme | Apr 19, 2023 Read English Version// Leer Versión en Español I’ve been thinking a lot these days about what it means for an Indigenous person to navigate a colonial world. What does it mean to live and think about the world from the plurality of our Indigenous experiences? To understand and interreact with the world rooted in the diverse peoples, cultures, and languages in the hemisphere? These questions have led me to reflect on the dominant narratives—the ones most of us have grown up with and been exposed to through dominant institutions. I am a K’iche’ Maya person who moved to Guatemala City at the age of 13, and later, to the United States. Due to the armed conflict, we had to migrate from Momostenango to Quetzaltenango, then to Santa Rosa de Lima, and later, the capital city. Due to debilitating poverty, my mother emigrated to the United States in 1976. I was six years old, and I stayed in Guatemala with my grandmother. When we moved to the city, I did not know that my family was protecting me. At the time, the Guatemalan army forcibly recruited young men to become soldiers. My family insisted that I should get an education and learn to read and write well. I later learned that if someone was “educated”, the army then would not recruit you. They did not want educated people to join their ranks to avoid dissidence. As I become more socially and politically conscious about my own history, present and future as a Maya person, I have begun to feed myself with diverse Indigenous knowledges with the intention of thinking about Indigenous hemispheric alliances across settler colonial borders. I re-signify the colonial category of “Indigenous” to imagine collective struggles but recognizing that we represent more than a thousand distinct Indigenous nations fighting for our survival, sovereignty, self-determination, and the defense and/or recovery of our homelands. In this context, it is important to redefine Indigeneity as a political project not anchored to specific nation states, or dominant geo-linguistic and geopolitical territories, but rather, as a trans-hemispheric civilizational aspiration. On the other hand, we need to recover knowledges from our respective ancestral pasts to feed our anti-colonial struggles in the present. For example, as an Indigenous K’iche’ Maya person, my existence—and that of all the 31 Maya nations that walk this earth today—goes beyond settler colonial borders in what is now known as Guatemala, Mexico, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador, as well as categories of Hispanic, American, Latin American and Latinx. It also goes beyond the establishment of European institutions like vice-royalties, churches, and the legal system. These institutions were erected to justify colonial power and the rights of settlers on stolen lands. For us, these categories and institutions represent land dispossession, genocide, slavery, and ecocide. Settler colonialism has had other consequences. The destruction of our historical archives, memory and our connection to our peoples and communities, for many of us translates to, among other things, an inability to speak our languages, write, and read Maya hieroglyphic writings and understand the cosmological meaning of our sacred sites and temples. Instead of having access to these knowledges, dominant institutions for the most part offer Eurocentric knowledges as part of an active process of erasure. Therefore, in Guatemala today, many of us grow up embracing versions of history that speak of Maya “collapse”, “disappearance”, and “extinction”, and suggest that now, we are Guatemalan, “ladino” or mestizo (mixed). Likewise, dominant media similarly promotes narratives of whiteness that have become the norm. Lighter skin in many cases means “mejorar la raza” or bettering the race. Even our own people have internalized these ideas, perpetuating notions that “white is beautiful”, speaking good Spanish, having a “good education,” and dressing like ladinos opens doors to success. We end up rejecting our Maya identity with the hope of fitting in a racist and a heteropatriarchal society that aspires to be like the U.S. or a European country. In this context, as a K’iche’ Maya person, I navigate colonial spaces with contradictions. Though I may have an official Guatemalan passport, I do not necessarily recognize myself as Guatemalan. I now tend to say that for a Maya person to fully embrace a Guatemalan national identity would basically be suicidal given that one could only trace her/his/their histories to about two hundred years of settler colonial presence. Besides, our arguments about being a people with a rich ancestral history are paramount if we want to justify our struggles for and connections to our homelands. Hence, we recover Iximulew (land of corn) to refer to Guatemala, asserting that we are eminently part of the Mayab’ region (present day Southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador). Indeed, any person who travels to Iximulew, can immediately tell that most of the people are Indigenous. People can hear Maya peoples dressed in Maya trajes speaking different Maya languages. But these cultural, historical, and linguistic specificities are interpreted as a “problem” by the colonial Guatemalan state. That is, we are a problem because we are distinct Nations and peoples asserting our existence within a colonial society. Above all, we are a problem because we live in territories rich in natural goods, sacred elements that are seen not as relatives but as “resources” that can be extracted, placed in the global market, and exchanged for money. This is why during the armed conflict that we experienced between 1960-1996, the Guatemalan state—with the economic and logistic support of the United States—sought to eliminate Maya peoples, killing more than 200,000, forcibly disappearing about 40,000, and expelling about 1.5 million people (I am one of them that left Guatemala in 1990). During that horrific period, state-sponsored genocidal attacks were carefully orchestrated. If we see where transnational mining companies or hydroelectric dams operate today, one notices that they are located in territories where many of the massacres and expulsions took place. After the formal end of the internal armed conflict in December 1996, the government signed the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) in 2004. Since then, licenses are granted to national and foreign extractivist companies that devastate our rivers and lands, exacerbating the environmental crisis. These new forms of dispossession and forced displacement, obliges people to live in the most precarious and humiliating conditions. Environmental injustices now represent one of the root drivers of forced migration. We can mention the Q’eqchi’ Maya struggle in El Estor region, for example, where Indigenous land defenders are criminalized, persecuted, and assassinated. Hundreds of families have been constantly evicted from their communities to make way for extractivist companies. Many people have no other option than to migrate and survive in other places. |

ももはや見えなくなることはない (Invisible nunca más.) アビヤラと先住民族の解放 エミル・ケメ | 2023年4月19日 英語版を読むLeer Versión en Español 近頃、先住民の人格が植民地化された世界で生きる意味について深く考えている。我々の多様な先住民的経験から世界を見つめ、生きることは何を意味するの か?この半球に根ざした多様な民族、文化、言語を通じて世界を理解し、関わることは何か?こうした問いが、支配的な物語——我々の多くが育ち、支配的な制 度を通じて触れてきた物語——について考えさせる。 私はキチェ・マヤの人格だ。13歳でグアテマラシティへ移り、後にアメリカへ渡った。内戦のため、モモステナンゴからケツァルテナンゴへ、次にサンタ・ロ サ・デ・リマへ、そして首都へと移住を余儀なくされた。極度の貧困のため、母は1976年にアメリカへ渡った。当時6歳の私は祖母と共にグアテマラに残っ た。都市に移った時、家族が私を守っていたとは知らなかった。当時グアテマラ軍は若い男性を強制的に徴兵していた。家族は私に教育を受けさせ、読み書きを しっかり学ばせようとした。後になって知ったのだが、もし「教育を受けた」人間なら、軍は徴兵しなかったのだ。反乱を避けるため、教育を受けた人民を兵役 に就かせたくなかったのだ。 マヤ人格としての自らの歴史、現在、未来について社会的・政治的に意識が高まるにつれ、私は多様な先住民の知恵を自らに取り入れ始めた。入植者による植民 地支配の境界を越えた、先住民の半球的な同盟について考えるためだ。植民地主義的なカテゴリーである「先住民」という概念を再定義し、集団的闘争を構想す る。ただし我々は、生存・主権・自己決定権、そして故郷の防衛もしくは回復を求めて戦う千を超える異なる先住民族の国民の集合体であることを認識しつつ。 この文脈において、先住性を特定の国民や支配的な地理的・言語的領域に縛られない政治的プロジェクトとして再定義することが重要だ。むしろそれは、半球を 越えた文明的志向として捉えるべきである。一方で、我々はそれぞれの祖先の過去から知識を回復し、現在の反植民地闘争に活かす必要がある。 例えば、先住民族キチェ・マヤの人格である私の存在——そして今日この地を歩む31のマヤ国民——は、現在のグアテマラ、メキシコ、ベリーズ、ホンジュラ ス、エルサルバドルと呼ばれる入植者による植民地境界や、ヒスパニック、アメリカ人、ラテンアメリカ人、ラティーノといったカテゴリーを超越している。そ れはまた、副王領、教会、法制度といったヨーロッパ式制度の確立をも超越する。これらの制度は、奪われた土地における植民地支配と入植者の権利を正当化す るために築かれたものだ。我々にとって、これらの区分や制度は土地の剥奪、ジェノサイド、奴隷制、そして生態系破壊を象徴している。 入植者植民地主義は他の結果も生んだ。歴史的記録や記憶、人民・共同体との絆の破壊は、多くの人々にとって、マヤ語を話せず、マヤ象形文字を読めず、聖地 や神殿の宇宙論的意義を理解できないことなどにつながっている。こうした知識にアクセスする代わりに、支配的な制度は、消去のプロセスの一環として、主に ヨーロッパ中心の知識を提供している。したがって今日のグアテマラでは、多くの者が「マヤの崩壊」「消滅」「絶滅」を語る歴史観を受け入れながら育ち、今 や我々はグアテマラ人、すなわち「ラディーノ」あるいはメスティーソ(混血の)であると示唆される。同様に支配的なメディアもまた、規範となった白人優位 の物語を推進している。肌が白いことは多くの場合、「人種を向上させる」ことを意味する。我々自身でさえこうした考えを内面化し、「白は美しい」「スペイ ン語が上手い」「良い教育を受けた」「ラディーノ風の服装をする」ことが成功への道を開くと信じ込んでいる。結局、我々はマヤとしてのアイデンティティを 拒絶し、米国や欧州諸国を模倣しようとする人種差別的でヘテロパトリアルカルな社会に溶け込もうとする。 こうした状況下で、キチェ・マヤ人格である私は矛盾を抱えながら植民地空間を生きている。公式のグアテマラパスポートを所持していても、必ずしも自らをグ アテマラ人とは認識しない。今や私はこう言う傾向にある。マヤ人格がグアテマラの国民的アイデンティティを完全に受け入れることは、基本的に自殺行為に等 しいと。なぜなら、その歴史を遡れるのは入植者による植民地支配が始まってから約200年しかなく、それ以前の歴史は存在しないからだ。さらに、我々が故 郷への闘争と結びつきを正当化したいなら、豊かな祖先の歴史を持つ人民であるという主張が最も重要だ。だからこそ我々はグアテマラを指す言葉として「イシ ムレウ(トウモロコシの地)」を再発見し、我々が明らかにマヤブ地域(現在のメキシコ南部、グアテマラ、ベリーズ、ホンジュラス、エルサルバドル)の一部 であると主張するのだ。 実際、イシムレウを訪れる者は誰でも、住民の大半が先住民だとすぐに気づくだろう。マヤの民族衣装を身にまとった人々が異なるマヤ語を話す声が聞こえる。 しかし、こうした文化的・歴史的・言語的特性は、植民地的なグアテマラ国家によって「問題」と解釈される。つまり我々は、植民地社会の中で自らの存在を主 張する独自の国民・人々であるゆえに問題なのだ。何よりも、我々が自然資源に富む土地に住んでいることが問題なのである。そこにある神聖な要素は、親族と してではなく「資源」として見なされ、採掘され、世界市場に流通させられ、金銭と交換される対象となる。だからこそ、1960年から1996年にかけて我 々が経験した武力紛争において、グアテマラ国家は米国による経済的・後方支援を得て、マヤ民族の消去法による抹殺を図った。その結果、20万人以上が殺害 され、約4万人が強制失踪させられ、約150万人が国外追放された(私も1990年にグアテマラを離れた一人だ)。あの恐ろしい時代、国家が支援するジェ ノサイド的攻撃は緻密に計画されていた。今日、多国籍鉱山企業や水力発電ダムが活動する地域を見ると、それらが虐殺や追放が頻発した地域に集中しているこ とに気づくだろう。 1996年12月に内戦が正式に終結した後、政府は2004年にドミニカ共和国・中米自由貿易協定(CAFTA-DR)に署名した。それ以来、国民および 外国の採掘企業に許可が与えられ、河川や土地を荒廃させ、環境危機を悪化させている。こうした新たな形態の収奪と強制移住により、人民は最も不安定で屈辱 的な状況で生活せざるを得ない。環境的不公正は今や強制移住の根本的要因の一つとなっている。例えばエル・エストール地域におけるケクチ・マヤ族の闘争が 挙げられる。ここでは先住民の土地防衛活動家が犯罪者扱いされ、迫害され、暗殺されている。数百の家族が採掘企業のため、絶えずコミュニティから追い出さ れている。多くの人々は移住し、他の場所で生き延びる以外に選択肢を持たない。 |

El Estor. Source: https://nacla.org/guatemala-maya-resistance-el-estor (Baudilio Choc / Radio Victoria) |

El Estor. Source: https://nacla.org/guatemala-maya-resistance-el-estor (Baudilio Choc / Radio Victoria) |

| Many

of the migrants trying to enter the United States are Indigenous. They

barely speak Spanish and are mislabeled Mexican, Guatemalan, Central

American, Hispanic or Latinx. Their rights to legally seek asylum are

violated and due process is denied given that interpreters in

Indigenous languages are not provided by border patrol officials. We

see how that journey has had tragic endings for many, including Maya

children who have died under the custody of the Mexican and U.S.

authorities. We can mention the case of Jakelin Caal Maquin, a

7-year-old Q’eqchi’ Maya girl who, under the Trump administration and

its zero tolerance policy, was separated from her father. She spoke

Q’eqchi’ Maya, and when she got a bacterial infection, could not

communicate her symptoms to officials. She died under U.S. custody. If

border patrol agents instead of seeing a “Guatemalan,” “Central

American” or “Hispanic” little girl, had knowledge about her distinct

Q’eqchi’ Maya identity, as well as the root causes of her migration,

they could have possibly addressed Jakelin’s needs and saved her life.

Bringing awareness to these “invisible” Indigenous migrant experiences

characterizes the work of Indigenous human rights organizations like,

among others, the International Mayan League, Indigenous Alliance

Without Borders, Red de pueblos transnacionales and Comunidades

Indígenas en Liderazgo (CIELO). Like in Guatemala, in the United States we also fight for our right to exist as distinct Indigenous peoples. News outlets, governmental officials, and even scholars contribute to our erasure by mislabeling us Hispanic or Latinx—now also “indigenous Hispanics” or “Indigenous Latinx”. It is here where the field of Indigenous studies can make a significant contribution given that we need to understand Indigenous migrations from Native frameworks, our shared histories, and critiques of settler colonial violence. Indeed, we must shed light on the colonial dimensions of Hispanism, Americanity and Latinity since they not only erase our distinct identities, but also our struggles for self-determination. That is why the philosophical and political concept of Abiayala is so important to break down these demeaning categories and invisibility. For the Indigenous Guna people in the Caribbean region of present-day Panama, Abiayala represents the original and ancestral name of the Western Hemisphere. This concept helps us to reimagine and materialize a global Indigenous framework to address the challenges we face in the present. Abiayala connotes a reclaiming of our own philosophies, existence, and knowledges prior to European invasion so we can advance our collective resurgence and anti-colonial struggles in contemporary times. It does not seek to cancel, erase, or displace other Indigenous ancestral categories such as Turtle Island, Mayab’, Wallmapu, Tawantinsuyu, Pindorama, Anahuac or any other indigenous term or category defined and used by Indigenous peoples to recognize their distinct and special relationships to their lands and environments. Rather, it seeks to create the conditions of possibility for Indigenous peoples’ collective emancipation and recenter our discussions about sovereignty, autonomy, self-determination, life and our own distinct ways of being in and understanding the world. Abiayala does not represent a space that is exclusive to Indigenous peoples. It is open to non-Indigenous allies who support our struggles for liberation. As a political project, Abiayala stands in relation to but also against dominant civilizational projects of Americanism, Hispanism and Latinity. As I have been suggesting in these lines, our relationship to these civilizational projects and dominant narratives of citizenship (that is, to identify oneself as Mexican, Guatemalan, Colombian, American, etc.) is colonial. The way modern governments and political entities employ these taxonomies to racialize and categorize their respective populations, has been detrimental for us given that they reduce us to relics from a remote past, or populations that have disappeared. |

米国への

入国を試みる移民の多くは先住民だ。彼らはスペイン語をほとんど話せず、メキシコ人、グアテマラ人、中米出身者、ヒスパニック、ラティーノなどと誤って分

類される。国境警備当局が先住民言語の通訳を提供しないため、合法的に亡命を求める権利は侵害され、適正手続きも否定されている。メキシコと米国の当局の

保護下で死亡したマヤ族の子供たちを含め、この旅路が多くの者にとって悲劇的な結末を迎えた事例が確認されている。トランプ政権下の「ゼロ・トレランス政

策」下で父親から引き離された7歳のケクチ・マヤ族の少女、ハケリン・カアル・マキンの事例が挙げられる。彼女はケクチ・マヤ語を話したが、細菌感染にか

かった際、症状を当局者に伝えられなかった。米国当局の保護下で死亡したのである。もし国境警備隊員が、彼女を単なる「グアテマラ人」「中米人」「ヒスパ

ニック系」の少女と見なす代わりに、彼女のケクチ・マヤとしての独自のアイデンティティや移住の根本原因を理解していたなら、ジャケリンのニーズに対応

し、命を救えたかもしれない。こうした「見えない」先住民族移民の実態を可視化することが、国際マヤ連盟、国境なき先住民族同盟、トランスナショナル先住

民族ネットワーク、先住民族リーダーシップ共同体(CIELO)など、先住民族人権団体の活動の核心だ。 グアテマラ同様、米国でも我々は独自の先住民としての存在権を闘争している。報道機関、政府関係者、さらには学者までもが、我々をヒスパニックやラティー ノ(現在では「先住民族系ヒスパニック」や「先住民族系ラティーノ」とも呼ばれる)と誤って分類することで、我々の存在を消し去ろうとしている。先住民族 研究の分野が重要な貢献を果たせるのはまさにこの点だ。なぜなら、先住民族の移住を、我々の枠組み、共有された歴史、入植者による植民地暴力への批判とい う観点から理解する必要があるからだ。実際、ヒスパニズム、アメリカニティー、ラティニティーの植民地的側面を明らかにしなければならない。それらは我々 の独自のアイデンティティを消し去るだけでなく、自己決定権を求める闘争までも消し去るからだ。 だからこそ、アビアヤラの哲学的・政治的概念が、こうした侮蔑的なカテゴリーと不可視性を打破する上で極めて重要なのである。現在のパナマ・カリブ地域に 暮らす先住民グナ族にとって、アビアヤラは西半球の本来の祖先の名である。この概念は、現代の課題に取り組むためのグローバルな先住民枠組みを再構想し具 体化する助けとなる。アビアヤラは、ヨーロッパの侵略以前に存在した我々の哲学・存在・知識を取り戻すことを意味し、現代における集団的復興と反植民地闘 争を推進する基盤となる。アビアヤラは、タートル・アイランド、マヤブ、ワルマプ、タワンティンスユ、ピンドロマ、アナワックなど、先住民が自らの土地や 環境との独特かつ特別な関係を認識するために定義・使用する他の先住民の祖先のカテゴリーを、否定したり消し去ったり置き換えたりすることを目的としな い。むしろ、先住民の集団的解放の可能性を創出し、主権・自治・自己決定・生命、そして世界における我々独自の在り方と理解についての議論を再構築するこ とを目指す。 アビアヤラは先住民専用の空間ではない。解放闘争を支援する非先住民族の同盟者にも開かれている。政治的プロジェクトとして、アビアヤラはアメリカニズ ム、ヒスパニズム、ラティニズムといった支配的な文明化プロジェクトと関係を持ちつつも、それらに対抗する立場にある。これまで述べてきたように、我々が こうした文明化プロジェクトや支配的な市民権の物語(すなわち、自らをメキシコ人、グアテマラ人、コロンビア人、アメリカ人などと識別すること)と築く関 係は植民地的なものだ。現代の政府や政治主体がこれらの分類体系を用いてそれぞれの住民を人種化し、カテゴリー化する手法は、我々を遠い過去の遺物や消滅 した集団へと矮小化するため、我々にとって有害であった。 |

| By

unearthing and reclaiming our Indigenous ancestral knowledges and

connecting them to our present struggles, many of us now dignify our

individual and collective rights as Maya (Q’anjob’al, Mam, K’iche’,

Yucatec, Q’eqchi’ etc.), Mapuche, Wayuu, Yanomami, Ñuu Savi, Choctaw,

Dené, Mi’kmaq, Lakota, etc. Each of these nations have specific

ancestral histories predating European invasions, ideas of America and

the establishment of settler colonial states and borders. Here, we

bring into the conversation the work of Kanaka Maoli’s Haunani-Kay

Trask, who challenges U.S. imperialism in Hawaii by stating: “We are

not Americans. We will die as Hawaiian!” or Oneida Comedian Charlie

Hill, who reflecting on the racial category, “Native American”,

proposes to remove the word “American” and to just keep Native since

Indigenous peoples “are older than America.” For his part, Aymara

intellectual Fausto Reinaga in Bolivia, in his book, Revolución india

(“Indian Revolution,”1970) stated, “I am not a mestizo writer or man of

letters. I am an Indian. An Indian who thinks, who develops ideas, who

creates ideas. My ambition is to forge an Indian ideology, an ideology

of my people” (my translation, 45). These examples illustrate, as

Mohawk scholar Audra Simpson would say, a refusal to embrace settler

colonial narratives and a desire to affirm and dignify our distinct

Indigenous identities and ancestral histories. Indeed, for many of us,

integration or assimilation into settler colonial states is not what we

seek. What we want is our right to self-determination and the

ability to manage our lives, natural goods, and ways of knowing. Because constant violations to our existence occurs daily, I believe that it is important to establish a paradigm shift and articulate the project of Abiayala. Any indigenous person can relate to Maya experiences I shared, and the words of Trask, Hill, and Reinaga. Therefore, it is important to think Indigeneity from a hemispheric framework since for us, colonialism has not ended. What would happen if we disclosed, exchange and learn our diverse Indigenous histories and ways of knowing? Can we materialize—to invoke the words of the Zapatista movement—a world where many Indigenous worlds fit? The project of Abiayala can help us address these questions. Though we recognize the devastating impacts of colonization, we also know that our shared knowledges can guide us to our collective emancipation. The project of Abiayala can contribute to that endeavor. |

我

々は先住民の祖先の知恵を掘り起こし、取り戻し、現在の闘いへと繋げることで、マヤ(カンジョバル、マム、キチェ、ユカテク、ケクチなど)、マプチェ、ワ

ユー、ヤノマミ、ヌ・サビ、チョクトー、デネ、ミクマク、ラコタなどとして、個人と集団の権利を尊厳あるものとしている。これらの国民はそれぞれ、ヨー

ロッパの侵略やアメリカという概念、入植者による植民地国家と国境の確立以前に遡る固有の祖先の歴史を持つ。ここで我々はカナカ・マオリのハウナニ=ケ

イ・トラスクの主張を議論に持ち込む。彼女はハワイにおける米国の帝国主義にこう挑む:「我々はアメリカ人ではない。」

我々はハワイアンとして死ぬ!」と宣言している。あるいはオナイダ族のコメディアン、チャーリー・ヒルは「ネイティブ・アメリカン」という人種的カテゴ

リーについて考察し、「アメリカン」という語を削除し「ネイティブ」のみを残すよう提案している。なぜなら先住民は「アメリカよりも古い」からだ。一方、

ボリビアのアイマラ人知識人ファウスト・レイナガは著書『インドの革命』(1970年)でこう述べている。「私はメスティーソの作家でも文人でもない。私

はインドの。思考し、思想を育み、思想を創造するインドの。私の志はインドのイデオロギー、我が人民の思想体系を築くことにある」(訳者訳、45頁)。こ

れらの例は、モホーク族の学者オードラ・シンプソンが言うように、入植者による植民地主義の物語を受け入れることを拒み、我々の独自の先住民族としてのア

イデンティティと祖先の歴史を肯定し尊厳を与えることを望む姿勢を示している。実際、我々の多くにとって、入植者による植民地国家への統合や同化は求めて

いない。我々が望むのは、自己決定権と、自らの生活、自然の恵み、そして知の方法を管理する能力である。 我々の存在への侵害が日々繰り返される以上、パラダイムシフトを確立しアビアヤラの構想を明確にすることが重要だと考える。私が共有したマヤの経験や、ト ラスク、ヒル、レイナガの言葉は、あらゆる先住民が共感できるものだ。だからこそ、我々にとって植民地主義は終わっていないという観点から、半球的枠組み で先住性を考えることが重要なのである。もし我々が多様な先住民の歴史や知の在り方を開示し、交換し、学び合ったらどうなるか?ザパティスタ運動の言葉を 借りれば、多くの先住民の世界が共存する世界を具現化できるだろうか? アビアヤラのプロジェクトはこれらの問いに向き合う助けとなる。植民地化の壊滅的影響を認めつつも、我々の共有知識が集団的解放へ導くと知っている。アビアヤラのプロジェクトはその取り組みに貢献しうる。 |

| Emil’ Keme (K’iche’ Maya Nation)

-- (a.k.a., Emilio del Valle Escalante) --is 2022-2023 Fellow at

The Harvard Radcliffe Institute, member of the Community of Maya

Studies, and Professor of English and Indigenous Studies at Emory

University. His most recent book is Le Maya Q’atzij/Our Maya Word.

Poetics of Resistance in Guatemala (2021). Emil’ Keme (Nación Maya K’iche’) -- also known as Emilio del Valle Escalante-- es 2022-2023 becario del Instituto Radcliffe en Harvard, miembro de la Comunidad de Estudios Mayas, y profesor de inglés y estudios indígenas en la Universidad de Emory. Su más reciente libro es Le q’atzij Mayab’/Nuestra palabra maya. Poéticas de resistencia en Iximulew/Guatemala (2022). |

エミル・ケメ(キチェ・マヤ国民)は、ハーバード大学ラドクリフ研究所

の2022-2023年度フェローであり、マヤ研究コミュニティのメンバー、エモリー大学の英語・先住民研究教授である。近著は『Le Maya

Q’atzij/我らのマヤの言葉。グアテマラにおける抵抗の詩学』(2021年)である。 エミル・ケメ(キチェ・マヤ民族)は、2022-2023年度ハーバード大学ラドクリフ研究所フェロー、マヤ研究コミュニティメンバー、エモリー大学英文 学・先住民研究教授である。近著は『Le Maya Q’atzij/Our Maya Word. Poetics of Resistance in イシムレウ/Guatemala』(2021年)である。(2022年)。 |

| https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/invisible-no-more-abiayala-and-indigenous-liberation/ |

★アビヤ・ヤラ博物館(サレジオ工科大学、エクアドル)

| Museo Abya Yala El Museo Abya Yala es una institución cultural creada administrada por la Universidad Politécnica Salesiana cuyo objetivo es difundir la riqueza del patrimonio cultural de los pueblos y nacionalidades del Ecuador, especialmente de los pueblos indígenas amazónicos. Al mismo tiempo, ofrece la posibilidad de crear conciencia sobre los riesgos y desafíos que éstos atraviesan en la actualidad. El Museo cuenta, además, con una importante colección de piezas arqueológicas de la Costa, Sierra Norte y Sur Oriente del Ecuador. El Museo tiene tres áreas: 1. Arqueológica: con vestigios de las culturas de la Costa, Sierra Norte y Sur Oriente. 2. Etnográfica: se observa la cultura material de siete nacionalidades de la Amazonía. 3. Ambiental: se muestran los peligros y destrucción de la Amazonía por parte de empresas madereras y petroleras. |

アビア・ヤラ博物館 アビア・ヤラ博物館は、サレジオ工科大学が設立・運営する文化機関であり、エクアドルの諸民族、特にアマゾンの先住民の豊かな文化遺産を広く紹介すること を目的としています。同時に、彼らが現在直面しているリスクや課題について認識を高める機会も提供しています。また、この博物館は、エクアドルの海岸部、 北部山岳地帯、南東部山岳地帯の重要な考古学的遺物のコレクションも所蔵しています。 博物館には3つのエリアがあります: 1. 考古学:海岸部、北山岳地帯、南東部地域の文化の遺跡が残っている。 2. 民族誌的:アマゾンの7つの民族の物質文化が観察される。 3. 環境:アマゾンにおける木材会社や石油会社による危険性と破壊が示されている。 |

| Historia En el año 1957, misioneros salesianos de la Amazonía Ecuatoriana, como el P. Siro Pellizzaro, entre otros, impulsaron el conocimiento de la cultura Shuar a través de la recopilación de la tradición oral, información y objetos de cultura material y fundaron el Museo Shuar que funcionó, en sus inicios, en el Instituto Superior Salesiano, ubicado en El Girón. En el año 1992, el P. Juan Bottasso asigna un piso completo al museo en el nuevo edificio del Centro Cultural Abya Yala lo que permitió que se mostraran otras culturas de la Amazonía. Entonces, el nombre pasó de Museo Shuar a Museo Amazónico. Desde mayo del 2003 el Museo Amazónico es gestionado por la Universidad Politécnica Salesiana. En el año 2014, cambia su nombre a Museo Abya Yala transformándose el concepto museográfico con cambios en el diseño y distribución de las salas e incrementando su acervo con vestigios de las culturas de la Costa y Sierra Norte y una colección de cuadros de la pintora lojana Marcela Burneo. |

歴史 1957年、エクアドルのアマゾン地域で活動するサレジオ会の宣教師たち(シロ・ペリッツァーロ神父ら)は、口承伝承や情報、物質文化の品々を収集するこ とでシュアル文化の認知を促進し、シュアル博物館を設立しました。同博物館は当初、エル・ヒロンにあるサレジオ高等学院内に設置されました。 1992年、フアン・ボッタッソ神父は、アビア・ヤラ文化センターの新しい建物内のフロア全体を博物館に割り当て、アマゾンの他の文化も展示できるようにしました。それにより、博物館の名称はシュアル博物館からアマゾン博物館に変更されました。 2003年5月以降、アマゾン博物館はサレジオ工科大学によって運営されています。2014年には、その名称をアビア・ヤラ博物館に変更し、展示コンセプ トを一新。展示室のデザインやレイアウトを変更し、沿岸部および北部山岳地帯の文化の遺物や、ロハ出身の画家マルセラ・ブルネオの絵画コレクションを所蔵 品に加えました。 |

| Dirección: Av. 12 de Octubre 23-116 y Wilson, Edificio Centro Cultural Abya – Yala 1er Piso Torre Norte. Horario de atención: De lunes a viernes de las 09h00 a 13h00 y de 14h00 a 17h00 Teléfonos: (595) 2 3962800 – 3962900 Ext. 2165 Correo electrónico: museoabyayalauio@ups.edu.ec Costo: ingreso gratuito |

住所:アベニーダ・デ・オクトゥーブレ12番23-116番とウィルソン通り、アビア・ヤラ文化センタービル1階北棟。 営業時間:月曜日から金曜日 9:00~13:00、14:00~17:00 電話番号: (595) 2 3962800 – 3962900 内線 2165 メールアドレス:museoabyayalauio@ups.edu.ec 費用:入場無料 |

| https://www.ups.edu.ec/web/guest/museo-abyayala |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆