タートル・アイランド

Turtle Island, isla de

tortuga

☆タートル島/タートルアイランド(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turtle_Island)は、地球[1] または北米を指す名称で、一部のアメリカ先住民や先住民の権利活動家によって使用されている。この名称は、北米北東部の森林地帯に住む複数の先住民に共通 する創造神話に由来している[2]。多くの現代作品でも、タートル島の創造神話が使用され、語られている[2][3]。

| Turtle Island is a

name for Earth[1] or North America, used by some American Indigenous

peoples, as well as by some Indigenous rights activists. The name is

based on a creation myth common to several indigenous peoples of the

Northeastern Woodlands of North America.[2] A number of contemporary works continue to use and/or tell the Turtle Island creation story.[2][3] |

タートル島は、地球[1]

または北米を指す名称で、一部のアメリカ先住民や先住民の権利活動家によって使用されている。この名称は、北米北東部の森林地帯に住む複数の先住民に共通

する創造神話に由来している[2]。多くの現代作品でも、タートル島の創造神話が使用され、語られている[2][3]。 |

| Lenape Main article: Lenape mythology The Lenape story of the "Great Turtle" was first recorded by Europeans between 1678 and 1680 by Jasper Danckaerts. The story is shared by other Northeastern Woodlands tribes, notably the Iroquois peoples.[2][4] The Lenape believe that before creation there was nothing, an empty dark space. However, in this emptiness, there existed a spirit of their creator, Kishelamàkânk. Eventually in that emptiness, he fell asleep. While he slept, he dreamt of the world as we know it today, the Earth with mountains, forests, and animals. He also dreamt up man, and he saw the ceremonies man would perform. Then he woke up from his dream to the same nothingness he was living in before. Kishelamàkânk then started to create the Earth as he had dreamt it. First, he created helper spirits, the Grandfathers of the North, East, and West, and the Grandmother of the South. Together, they created the Earth just as Kishelamàkânk had dreamt it. One of their final acts was creating a special tree. From the roots of this tree came the first man, and when the tree bent down and kissed the ground, woman sprang from it. All the animals and humans did their jobs on the Earth, until a problem eventually arose. There was a tooth of a giant bear that could give the owner magical powers, and the humans started to fight over it. Eventually, the wars got so bad that people moved away, and made new tribes and new languages. Kishelamàkânk saw this fighting and decided to send down a spirit, Nanapush, to bring everyone back together. He went on top of a mountain and started the first Sacred Fire, which gave off a smoke that caused all the people of the world to come investigate what it was. When they all came, Nanapush created a pipe with a sumac branch and a soapstone bowl, and the creator gave him Tobacco to smoke with. Nanapush then told the people that whenever they fought with each other, to sit down and smoke tobacco in the pipe, and they would make decisions that were good for everyone. The same bear tooth later caused a fight between two evil spirits, a giant toad and an evil snake. The toad was in charge of all the waters, and amidst the fighting he ate the tooth and the snake. The snake then proceeded to bite his side, releasing a great flood upon the Earth. Nanapush saw this destruction and began climbing a mountain to avoid the flood, all the while grabbing animals that he saw and sticking them in his sash. At the top of the mountain there was a cedar tree that he started to climb, and as he climbed he broke off limbs of the tree. When he got to the top of the tree, he pulled out his bow, played it and sang a song that made the waters stop. Nanapush then asked which animal he could put the rest of the animals on top of in the water. The turtle volunteered saying he'd float and they could all stay on him, and that's why they call the land Turtle Island. Nanapush then decided the turtle needed to be bigger for everyone to live on, so he asked the animals if one of them would dive down into the water to get some of the old Earth. The beaver tried first, but came up dead and Nanapush had to revive him. The loon tried second, but its attempt ended with the same fate. Lastly, the muskrat tried. He stayed down the longest, and came up dead as well, but he had some Earth on his nose that Nanapush put on the Turtles back. Because of his accomplishment, Nanapush told the muskrat he was blessed and his kind would always thrive in the land. Nanapush then took out his bow and again sang, and the turtle started to grow. It kept growing, and Nanapush sent out animals to try to get to the edge to see how long it had grown. First, he sent the bear, and the bear returned in two days saying he had reached the end. Next, he sent out the deer, who came back in two weeks saying he had reached the end. Finally, he sent the wolf, and the wolf never returned because the land had gotten so big. Lenape tradition said wolves howl to call their ancestor back home.[5] |

レナペ 主な記事:レナペ神話(Lenape mythology) レナペの「大亀」の物語は、1678年から1680年の間に、ジャスパー・ダンカーツによってヨーロッパ人に初めて記録された。この物語は、他の北東部の森林地帯の部族、特にイロコイ族も共有している。[2][4] レナペ族は、創造以前は、何もない、空っぽの暗い空間があったと信じている。しかし、この空虚の中に、彼らの創造主であるキシェラマカンクの精霊が存在し ていた。やがて、その空虚の中で、彼は眠りに落ちた。眠っている間、彼は、山や森、動物がいる、私たちが今日知っているような世界を見ました。また、人間 も想像し、人間が執り行う儀式も見た。そして、彼は夢から目覚め、以前と同じ何もない空間に戻った。キシェラマカンクは、夢で見たとおりに地球の創造を始 めた。 まず、彼は助っ人の精霊、北、東、西の祖父たち、そして南の祖母を創造した。彼らは力を合わせて、キシェラマカンクが夢で見たとおりに地球を創造した。彼 らの最後の仕事の一つは、特別な木を作ることだった。この木の根から最初の男性が生まれ、木が地面に頭を下げ、地面にキスをしたとき、女性たちがその木か ら飛び出した。 すべての動物と人間は、地球上でそれぞれの仕事をこなしていた。しかし、やがて問題が発生した。巨大な熊の歯には、その持ち主に呪術の力を与える力があっ たため、人間たちはその歯を奪い合うようになった。やがて戦争は激化し、人々は移り住み、新しい部族と新しい言語を作った。この争いを見たキシェラマカン クは、皆を再び一つにまとめるために、精霊ナナプッシュを地上に送ることにした。ナナプッシュは山の頂上に立ち、最初の聖なる火を灯した。その煙を嗅ぎつ けた世界中の人々が、その正体を探るためにやって来た。皆が集合すると、ナナプッシュは、スマック(ウルシ科の低木)の枝とソープストーン(石鹸石)の鉢 を使ってパイプを作り、創造主からタバコを吸うためのタバコ葉をもらった。ナナプッシュは、人々に、互いに争ったときは、座ってパイプでタバコを吸えば、 皆にとって良い決断ができるだろうと教えた。 同じ熊の歯は後に、巨大なカエルと悪の蛇という二つの悪霊の戦いを引き起こした。カエルはすべての水の支配者で、戦いの最中に歯と蛇を食べてしまった。蛇 はカエルの側を噛み、地球に大洪水を引き起こした。ナナプッシュはこの破壊を見て洪水を避けるため山を登り始め、見かけた動物を次々と帯に詰めていった。 山の頂上には杉の木があり、彼は登り始めた。登るうちに木の枝を折っていった。頂上に着くと、弓を取り出し、演奏して歌った。その歌で水が止まった。ナナ プッシュは、残りの動物たちを水の上に載せるために、どの動物に頼めばよいか尋ねた。カメが、自分が浮いて、皆を乗せてあげると申し出た。そのため、その 土地は「カメの島」と呼ばれるようになった。 ナナプッシュは、皆が住むにはカメはもっと大きくなければならないと決め、動物たちに、誰かが水中に潜って古い地球の一部を持ってくるよう頼んだ。ビー バーが最初に試みたが、死んでしまい、ナナプッシュは彼を蘇生させなければならなかった。次にルーンズが試みたが、その試みも同様の運命に終わった。最後 に、マスクラットが試みた。彼は最も長く水中に留まったが、やはり死んでしまった。しかし、彼の鼻には土が付着しており、ナナプッシュはそれをカメの背中 に塗った。その功績により、ナナプッシュはマスクラットに、彼は祝福されており、その種は永遠にこの土地で繁栄すると告げた。 ナナプッシュは弓を取り出し、再び歌った。すると、カメは大きくなり始めた。カメはどんどん大きくなり、ナナプッシュは、その大きさを確認するために、動 物たちをカメの端まで行ってみてくるよう命じた。まず、クマが送られたが、2 日後に戻ってきて、端までたどり着いたと報告した。次に鹿を送り出したが、鹿は二週間後に戻ってきて、端まで到達したと報告した。最後に狼を送り出した が、狼は戻ってこなかった。なぜなら、土地があまりにも広大になっていたからだ。レナペの伝統によると、狼は祖先を呼び戻すために遠吠えをするという。 [5] |

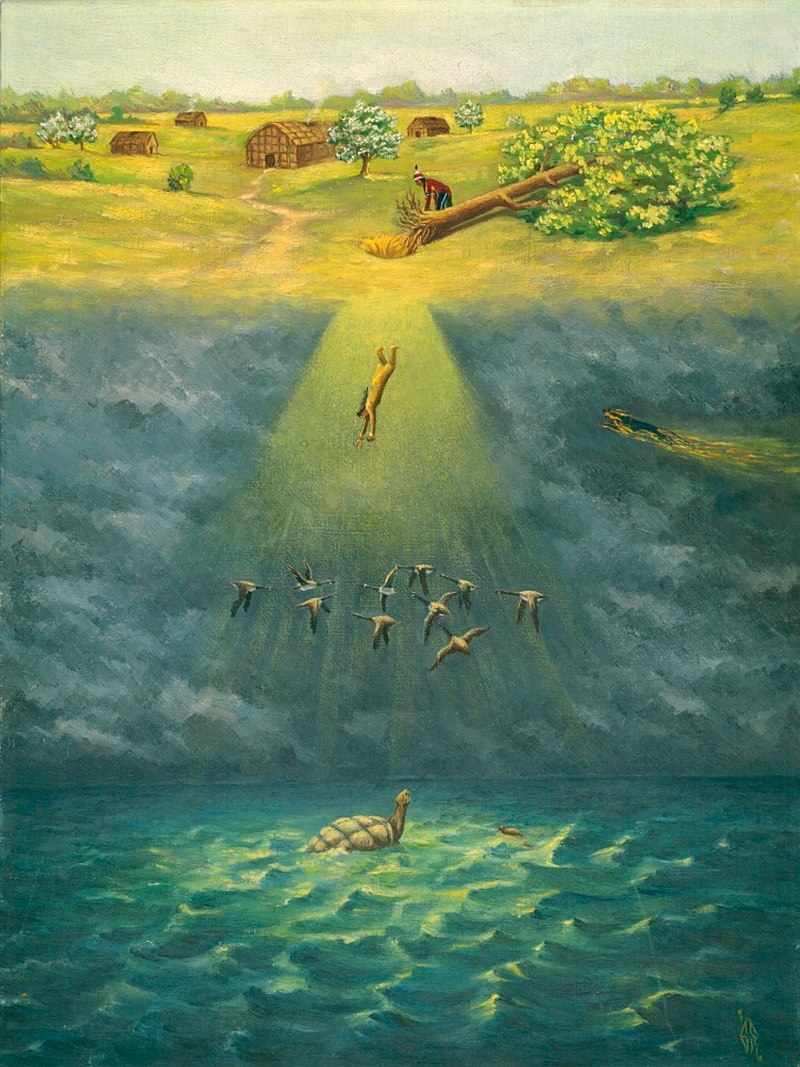

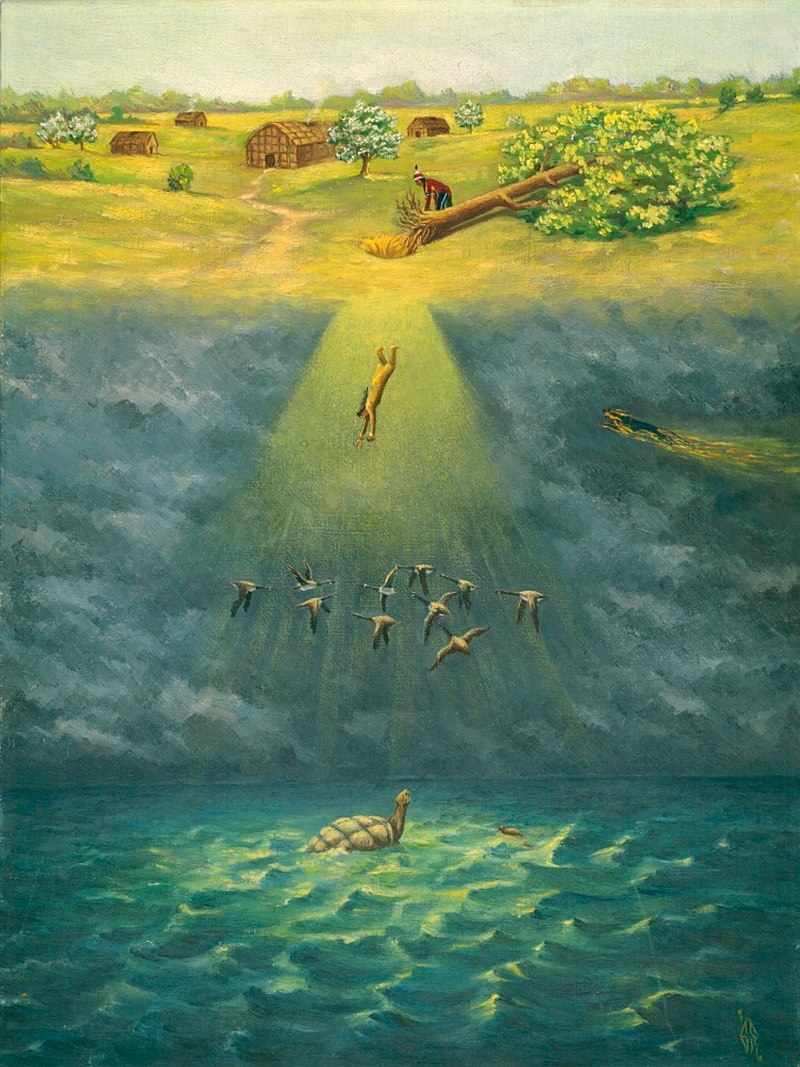

Haudenosaunee Sky Woman (1936), by Seneca artist Ernest Smith, depicts the story of Turtle Island. According to the oral tradition of the Haudenosaunee (or "Iroquois"), "the earth was the thought of [a ruler of] a great island which floats in space [and] is a place of eternal peace."[6][2] Sky Woman fell down to the earth when it was covered with water, or more specifically, when there was a "great cloud sea".[1] Various animals tried to swim to the bottom of the ocean to bring back dirt to create land. Muskrat succeeded in gathering dirt,[1] which was placed on the back of a turtle. This dirt began to multiply and also caused the turtle to grow bigger. The turtle continued to grow bigger and bigger and the dirt continued to multiply until it became a huge expanse of land.[1][7][8] Thus, when Iroquois cultures refer to the earth, they often call it Turtle Island.[8] According to Converse and Parker, the Iroquois faith shared with other religions the "belief that the Earth is supported by a gigantic turtle."[1] In the Seneca language, the mythical turtle is called Hah-nu-nah,[1] while the name for an everyday turtle is ha-no-wa.[9] In Susan M. Hill's version of the story, the muskrat or other animals die in their search for land for the Sky Woman (named Mature Flower in Hills's telling). This is a representation of the Haudenosaunee beliefs of death and chaos as forces of creation, as we all give our bodies to the land to become soil, which in turn continues to support life. This concept plays out again when the Mature Flower's daughter dies during childbirth, becoming the first person to be buried on the turtle's back and whose burial post helped grow various plants such as corn and strawberries.[10] This, according to Hill, also shows how soil, and the land itself, has the ability to act and shape creation. Some tellings do not include this expanded edition as part of the Creation Story, however, these differences are important to note when considering Haudenosaunee traditions and relationships. |

ハウデノソーニー セネカ族の芸術家、アーネスト・スミスによる「スカイウーマン」(1936年)は、タートルアイランドの物語を描いています。 ハウデノソーニー(または「イロコイ」)の口承伝承によると、「地球は、宇宙に浮かぶ偉大な島の支配者の考えであり、永遠の平和の場所である」とされてい ます。[6][2] スカイ・ウーマンは、大地が水に覆われていた時、より正確には「大いなる雲の海」があった時に、地上に降り立った。[1] 様々な動物が海の底まで泳いでいき、土地を作るための土を持ち帰ろうとした。ムースラットが土を集めることに成功し、[1] その土はカメの背中に置かれた。この土は増え続け、カメも次第に大きくなっていった。カメはどんどん大きくなり、土も増え続け、やがて広大な陸地になっ た。[1][7][8] そのため、イロコイ族の文化では、地球を「カメの島」と呼ぶことが多い。[8] コンバースとパーカーによると、イロコイ族の信仰は他の宗教と同様に、「地球は巨大なカメによって支えられている」という信念を共有していた。[1] セネカ語では、神話上のカメは「ハヌナ」と呼ばれ[1]、日常のカメは「ハノワ」と呼ばれている。[9] スーザン・M・ヒルの物語では、ムスクラットや他の動物たちは、スカイウーマン(ヒルの物語では「成熟した花」と名付けられている)のために土地を探す途 中で死んでしまう。これは、私たち全員が自分の体を土地に捧げて土となり、その土が生命を支え続けるという、死と混沌を創造の力とするホードノソーニー族 の信仰を表している。この概念は、成熟した花の娘が出産で亡くなり、カメの背中に埋葬された最初の人格となり、その埋葬の柱がトウモロコシやイチゴなどの さまざまな植物の成長に役立ったことで、再び表現されている。[10] ヒルによると、これは、土壌、そして土地自体が創造を行動し、形作る能力を持っていることを示している。一部の伝承では、この拡張版は創造神話の一部とし て含まれていないが、ホードノソーニーの伝統や人間関係を考察する際には、このような相違点に注意することが重要である。 |

| Indigenous rights activism and environmentalism The name Turtle Island has been used by many Indigenous cultures in North America, and both native and non-native activists, especially since the 1970s when the term came into wider usage.[7] American author and ecologist Gary Snyder uses the term to refer to North America, writing that it synthesizes both indigenous and colonizer cultures, by translating the indigenous name into the colonizer's languages (the Spanish "Isla Tortuga" being proposed as a name as well). Snyder argues that understanding North America under the name of Turtle Island will help shift conceptions of the continent.[11] Turtle Island has been used by writers and musicians, including Snyder for his Pulitzer Prize-winning book of poetry, Turtle Island; the Turtle Island Quartet jazz string quartet; Tofurky manufacturer Turtle Island Foods; and the Turtle Island Research Cooperative in Boise, Idaho.[12][13] The Canadian Association of University Teachers has put into practice the acknowledgment of indigenous territory and claims, particularly at institutions located within unceded land or covered by perpetual decrees such as the Haldimand Tract. At Canadian universities, many courses, student and academic meetings, as well as convocation and other celebrations begin with a spoken acknowledgement of the traditional Indigenous territories, sometimes including reference to Turtle Island, in which they are taking place.[3] [14] |

先住民の権利活動と環境保護 「タートル・アイランド」という名称は、北米の多くの先住民文化によって使用されており、特に1970年代以降、この用語が広く使用されるようになった以 降、先住民および非先住民の活動家によって使用されている。[7] アメリカ人作家で生態学者のゲイリー・スナイダーは、この用語を北アメリカを指す言葉として使用し、先住民の名称を植民地支配者の言語に翻訳することで (スペイン語の「Isla Tortuga」も提案されている)、先住民と植民地支配者の文化を統合する概念として説明している。スナイダーは、タートル島という名称で北米を理解す ることで、この大陸に対する概念の変化につながるだろうと主張している[11]。タートル島は、スナイダーのピューリッツァー賞受賞詩集『タートル島』を はじめ、作家やミュージシャンにも使用されている。また、ジャズ弦楽四重奏団「タートル・アイランド・カルテット」、豆腐メーカー「タートル・アイラン ド・フーズ」、アイダホ州ボイジーにある「タートル・アイランド・リサーチ・コープ」などもこの名称を使用している[12][13]。 カナダ大学教員協会は、先住民領土の認識と主張を、特に、割譲されていない土地にある、あるいはハルディマンド・トラクトなどの永久法令の対象となってい る教育機関において実践している。カナダの大学では、多くの講義、学生や学者の会議、卒業式などの式典は、その開催地である先住民の伝統的な領土を口頭で 認識することから始まる。時には、その開催地であるタートル・アイランドについても言及される。[3] [14] |

| Contemporary works There are a number of contemporary works which continue to use and/or tell the story of the Turtle Island creation story. The Truth About Stories by Thomas King Thomas King's book tells us that "the truth about stories is they're all we are."[15] King's book explores the power of story both in native lives and in the lives of every person on this planet. Every chapter opens with a telling of the story of the world on the back of a turtle in space, and in each chapter, it is slightly altered to show how stories change through tellers and audiences. Their fluidity is itself a characteristic of the story as they traverse through time.[15] King provides us with his own telling of the story using a woman named Charm as his Sky Woman. Charm is from a different planet and is described as being curious to a fault, often asking the animals of her planet questions they deem to be too nosy. When she becomes pregnant, she develops a craving for Red Fern Root, which can only be found underneath the oldest tree. While digging for the Red Fern Root she digs so deep she makes a hole in the planet, and in her curiosity falls through all the way to earth. King tells us that this is a young Earth from before land was created, and in order to save Charm from falling hard and fast into the water and upsetting the stillness of the water, all the water birds fly up to catch her. With no land to set her on they offer her the back of the turtle. When Charm is almost ready to give birth the animals fear that the turtle will be too crowded, so she asks the animals to dive down to find mud so that she can use its magic to build dry land. Many animals try but most fail, until the otter dives down for days before finally surfacing, passed out from exhaustion, clutching mud in its paws. Charm creates land from the mud, magic, and the turtle's back and gives birth to twins which keep the earth in balance. One twin flattened out the land, created light, and created woman, while the other made valleys and mountains, shadows, and man. King emphasizes that the Turtle Island creation story creates "a world in which creation is a shared activity...a world that begins in chaos and moves toward harmony."[15] He explains that understanding and continuing to tell this story creates a world that values these ideas and relationships with nature. Without that understanding, we fail to uphold the relationships forged by Charm, the twins, and the animals that created the earth. |

現代作品 タートルアイランドの創造神話を題材にした、あるいはその物語を継承した現代作品も数多くある。 トーマス・キング『物語の真実』 トーマス・キングの著書は、「物語の真実は、それが私たちのすべてである」と語っている[15]。この本は、先住民たちの生活と、この地球上のすべての人 間の生活における物語の力を探求している。各章は、宇宙の亀の背中で世界が生まれたという物語で始まり、各章で物語が語り手や聴衆によって少しずつ変化し ていく様子が描かれている。物語の流動性は、時空を超えて伝承される物語そのものの特徴でもある。[15] キングは、チャームという女性のスカイウーマンを登場させて、この物語を独自に語っている。チャームは別の惑星からやってきて、好奇心旺盛で、自分の惑星 に住む動物たちに、彼らにとってはあまり聞きたくないような質問をよくする、と描写されている。彼女が妊娠すると、最も古い木の下にあるレッドファーン ルートが食べたくてたまらなくなる。レッド・フェルン・ルートを掘る際、彼女は深く掘りすぎて惑星に穴を開け、好奇心からその穴を通り抜けて地球まで落ち てしまう。キングは、これが陸地がまだ存在しない若い地球だと説明し、チャームが水に激しく落ちて水の静けさを乱さないように、すべての水鳥が飛んで彼女 を捕まえる。陸地がないため、彼らはチャームに亀の背を乗せる。チャームが出産を目前にしたとき、動物たちはカメの背中にチャームが乗ると狭すぎるのでは ないかと心配し、チャームは動物たちに泥を探して持ってきて、その泥を使って呪術で陸地を作るよう頼む。多くの動物たちが試みるが、ほとんどは失敗に終わ る。しかし、カワウソが何日も潜り続けて、ついに疲れ果てて水面に浮上すると、その足には泥が握られていた。チャームは泥と呪術、そしてカメの背中で陸地 を作り、双子を産む。双子は地球のバランスを保つ。一人は陸地を平らにし、光と女性を作り、もう一人は谷や山、影、そして男性を作った。 キングは、亀の島創造神話が「創造が共有された活動である世界…混沌から始まり調和へと向かう世界」を創造すると強調している。[15] 彼は、この物語を理解し語り継ぐことが、これらの思想と自然との関係を重視する世界を生み出すと説明している。その理解がなければ、チャーム、双子、そし て地球を創造した動物たちが築いた関係を維持することができない。 |

| Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer Robin Wall Kimmerer's book, Braiding Sweetgrass, addresses the need for us to understand our reciprocal relationships with nature in order for us to understand and use ecology as a means to save the earth. The version of the story from Kimmerer starts off with the Sky Woman falling from a hole in the sky, cradling something tightly in her hands. Geese rise up to soften her landing and place her on the back of a turtle so that she does not drown. All the animals congregate to help find dirt for the sky woman so that she can build her habitat, some giving their lives in the search. Finally, the muskrat surfaces, dead but clutching a handful of soil for the Sky Woman, who takes the offering gratefully and uses seeds from The Tree of Life to begin her garden using her gratitude and the gifts from the animals, thus creating Turtle Island as we know it. Through the Sky Woman story, Kimmerer tells us that we cannot "begin to move toward ecological and cultural sustainability if we cannot even imagine what the path feels like."[16] |

ロビン・ウォール・キマーラー『スイートグラスを編む』 ロビン・ウォール・キマーラーの著書『スイートグラスを編む』は、地球を救う手段として生態学を理解し活用するためには、自然との相互関係を理解する必要があることを説いている。 キマーラーの物語のバージョンでは、空の穴から落ちてきた空の女性が、手に何かを強く抱きしめているところから始まります。ガチョウが飛んで来て彼女の着 地を和らげ、彼女が溺れないように亀の背中に乗せます。すべての動物が集まり、空の女性が住処を築くための土を探す手伝いをします。その中には、命を捧げ る動物もいます。最後に、ムースラットが死んで水面から現れ、空の女性のために土を握りしめている。空の女性は感謝してその贈り物を受け取り、生命の木か ら種を取り出し、感謝の気持ちと動物たちの贈り物を使って庭を作り始める。これにより、私たちが知る亀の島が誕生した。空の女性の物語を通じて、キムマー ラーは「生態学的・文化的持続可能性への道を想像できない限り、その方向へ進むことはできない」と教えている。[16] |

| Cherokee Stories of the Turtle Island Liars' Club by Christopher B. Teuton Christopher B. Teuton book provides a comprehensive look into Cherokee oral traditions and art to bring them into the contemporary moment. He put together his collection with three friends, also master storytellers, who get together to swap stories from around the 14 Cherokee states.[17] The first chapter of the book Beginnings starts with a telling of the Sky Woman story. Notably, this telling of Turtle Island has the water beetle dive for the earth necessary for the sky woman, where often you will see a muskrat or otter. Turtle Island is a running theme throughout the book, as it is the beginning of life and story. |

クリストファー・B・テウトン著『チェロキーの亀の島嘘つきクラブの物語』 クリストファー・B・テウトンの著書は、チェロキーの口承伝統と芸術を現代に伝える包括的な内容となっている。彼は、3人の友人であり、物語の達人でもあ る仲間たちと協力して、チェロキーの14州から集めた物語を収録した。本書の最初の章「始まり」は、スカイウーマンの物語から始まる。特に、この「タート ル・アイランド」の物語では、スカイ・ウーマンのために大地を掘り出す役割を水生昆虫の「水生甲虫」が担っている点が特徴的だ。通常は「水ネズミ」や「カ ワウソ」が用いられることが多い。タートル・アイランドは、生命と物語の始まりを象徴するテーマとして、本書全体を通じて繰り返し登場する。 |

| We Are Water Protectors by Carole Lindstrom We Are Water Protectors is a children's storybook written by Carole Lindstrom in 2020 in response to the building of the Dakota Access Pipeline, represented as a large black snake in the book. The book says that water is the source of all life, and it is all of ours duty to protect our water sources so that we can preserve not only ourselves but those of animals and the environment. The story draws important meanings from the Turtle Island creation story such as water as the origin of life and closes with a drawing of the main character returning the turtle to the water saying "We are stewards of the earth. Our spirits are not to be broken."[18] |

『私たちは水の守護者』キャロル・リンドストローム 『私たちは水の守護者』は、ダコタ・アクセス・パイプラインの建設に反対して、キャロル・リンドストロームが2020年に書いた子供向け絵本です。この絵 本では、パイプラインは大きな黒い蛇として描かれています。この本は、水がすべての生命の源であり、私たち全員が水源を守る義務があることを述べていま す。そうすることで、私たちだけでなく、動物や環境も守ることができるからです。物語は、タートル・アイランドの創造神話から重要な意味を引き出し、主人 公が亀を水に戻すシーンで締めくくられています。その際、主人公は「私たちは地球の守護者です。私たちの精神は決して折れることはありません」と述べてい ます。[18] |

| Geographical renaming – the practice of political renaming Abya Yala – a similar name used by the Guna people and others to refer to the Americas as a whole Aotearoa – the Māori name for New Zealand Aztlán – the legendary ancestral home of the Aztec peoples Anahuac – Nahuatl name for the historical and cultural region of Mexico Cemanahuac – Nahuatl name used by the Mexica to refer to the larger region beyond their empire, between the Pacific and Atlantic Ocean Turtles in North American Indigenous Mythology World Turtle Discworld Turtle Island (Lake Erie) |

地理的な名称の変更 – 政治的な名称の変更の慣習 アビア・ヤラ – グナ族などがアメリカ大陸全体を指すために使用する類似の名称 アオテアロア – ニュージーランドのマオリ族の名称 アズトラン – アステカ族の伝説上の祖先の故郷 アナワック – メキシコの歴史的・文化的地域を指すナワトル語名 セマナワック – メキシカ族が、太平洋と大西洋の間にある自帝国を越えた広大な地域を指すために使用するナワトル語名 北米先住民の神話におけるカメ 世界のカメ ディスクワールド カメの島(エリー湖) |

| Bibliography Barnhill, David Landis, ed. (1999). At Home on the Earth: Becoming Native to Our Place: A Multicultural Anthology. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. xiv, 297–306, 327. ISBN 9780520216846. Converse, Harriet Maxwell; Parker, Arthur Caswell (1906). Myth and Legends of the New York State Iroquois. Albany, New York: New York State Museum. Hills, Susan M. (2017). The Clay We Are Made Of: Haudenosaunee Land Tenure on the Grand River. Winnipeg. Manitoba: University of Manitoba Press. pp. 16–25. ISBN 978-0-88755-717-0. Johansen, Bruce Elliott; Mann, Barbara Alice, eds. (2000). Encyclopedia of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy). Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-1-4294-7618-8. OCLC 154239396. Jones, Guy W.; Moomaw, Sally (October 2, 2002). Lessons from Turtle Island: Native Curriculum in Early Childhood Classrooms (Paperback, Ebook). St. Paul, Minnesota: Redleaf Press. ISBN 9781929610259. Kimmerer, Robin (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions. ISBN 9781571313560. King, Thomas (2008). The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 12–25. ISBN 9780816646272. Lindstrom, Carole; Goade, Michaela (2020). We are Water Protectors. New York: Roaring Brooks Press, a division of Holtzbrinck Publishing. ISBN 9781250203557. Porter, Tom; Forrester, Lesley; Ka-Hon-Hes (2008). And Grandma Said...: Iroquois Teachings, As Passed Down Through the Oral Tradition. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Xlibris Corp. pp. 52–53. ISBN 9781436335652. Robinson, Amanda; Filice, Michelle (November 6, 2018). "Turtle Island". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historic Canada. Retrieved February 6, 2022. For some Indigenous peoples, Turtle Island refers to the continent of North America. The name comes from various Indigenous oral histories that tell stories of a turtle that holds the world on its back. For some Indigenous peoples, the turtle is therefore considered an icon of life, and the story of Turtle Island consequently speaks to various spiritual and cultural beliefs. Teuton, Christopher B (August 2016). Cherokee Stories of the Turtle Island Liars' Club (Paperback, Ebook). Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3749-8. |

参考文献 バーンヒル、デビッド・ランディス編(1999)。『地球に生きる:私たちの土地のネイティブになる:多文化アンソロジー』。カリフォルニア州バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版。xiv、297–306、327 ページ。ISBN 9780520216846。 コンバース、ハリエット・マクスウェル、パーカー、アーサー・キャスウェル (1906)。『ニューヨーク州イロコイ族の神話と伝説』。ニューヨーク州アルバニー:ニューヨーク州立博物館。 ヒルズ、スーザン・M. (2017)。『私たちを構成する粘土:グランド川流域のホードノソーニー族の土地所有』。ウィニペグ。マニトバ:マニトバ大学出版。16-25 ページ。ISBN 978-0-88755-717-0。 Johansen, Bruce Elliott; Mann, Barbara Alice, eds. (2000). Encyclopedia of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy). コネチカット州ウェストポート: グリーンウッドプレス。ISBN 978-1-4294-7618-8。OCLC 154239396。 ジョーンズ、ガイ・W.; ムーモー、サリー (2002年10月2日)。 Lessons from Turtle Island: Native Curriculum in Early Childhood Classrooms (ペーパーバック、電子書籍)。ミネソタ州セントポール: レッドリーフ・プレス。ISBN 9781929610259。 キマーラー、ロビン(2013)。『甘い草を編む:先住民の知恵、科学的知識、そして植物の教え』。ミルクウィード・エディションズ。ISBN 9781571313560。 キング、トーマス(2008)。『物語の真実:先住民の物語』。ミネソタ州ミネアポリス:ミネソタ大学出版局。12-25 ページ。ISBN 9780816646272。 リンストロム、キャロル;ゴード、ミカエラ(2020)。『私たちは水の保護者だ』。ニューヨーク:ホルトツブリンク出版の一部門、ローリング・ブルックス・プレス。ISBN 9781250203557。 ポーター, トム; フォレスター, レスリー; カ・ホン・ヘス (2008). 『そして祖母は言った…:イロコイ族の教え、口承伝統を通じて伝えられたもの』. ペンシルベニア州フィラデルフィア: Xlibris Corp. pp. 52–53. ISBN 9781436335652. ロビンソン、アマンダ; フィリチェ、ミシェル (2018年11月6日). 「タートル島」. カナダ百科事典. 歴史的なカナダ. 2022年2月6日取得。一部の先住民にとって、タートル島とは北米大陸を指す。この名前は、世界を支えるカメの物語を伝えるさまざまな先住民の口承伝承 に由来している。そのため、一部の先住民にとって、カメは生命の象徴とみなされており、タートルアイランドの物語は、さまざまな精神的、文化的信念を物 語っている。 テウトン、クリストファー B (2016年8月)。『チェロキーのタートルアイランド・ライアーズ・クラブ物語』(ペーパーバック、電子書籍)。ノースカロライナ州チャペルヒル:ノースカロライナ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8078-3749-8。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turtle_Island |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099