アチに関する民族誌的資料

Achi people and their language

©

Ministerio

de Cultura y Deportes / GMA PRO

☆アチ族は グアテマラのマヤ系民族である。彼らはバハ・ベラパス県の様々な自治体に住んでいる。彼らが住んでいる自治体は、グラナドスとエル・チョルの一部に加え て、クブルコ、ラビナル、サン・ミゲル・チカジ、サラマ、サン・ヘロニモ、プルルハである。彼らはアチ語を話し、その言語はキチェ語(Kʼicheʼ)に 近い。

★

アチ語

| Achi (Achí in

Spanish)

is a Mayan language very closely related to Kʼicheʼ (Quiché in the

older orthography). It is spoken by the Achi people, primarily in the

department of Baja Verapaz in Guatemala. There are two Achi dialects. Rabinal Achi is spoken in the Rabinal area, and Cubulco Achi is spoken in the Cubulco area west of Rabinal. One of the masterpieces of precolumbian literature is the Rabinal Achí, a theatrical play written in the Achi language. |

アチ語(スペイン語ではAchí)は、Kʼicheʼ(古い正書法では

Quiché)に非常に近いマヤ語である。グアテマラのバハ・ベラパス県を中心にアチ族によって話されている。 2つの方言がある。ラビナル方言はラビナル地域で話されており、クブルコ方言はラビナル西部のクブルコ地域で話されている。 先史時代文学の傑作のひとつに、アチ語で書かれた民衆演劇「ラビナル・アチ」がある。 |

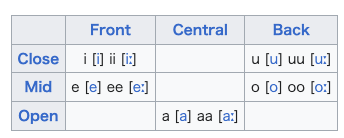

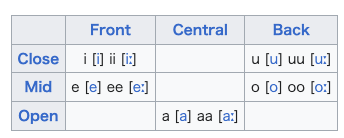

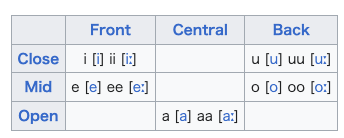

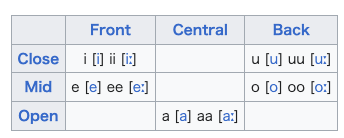

| Phonology The tables present the consonant[2] and vowel[3] phonemes of Achi. On the left is the spelling in use.[4] Consonants  Voiceless plosives can have aspirated allophones [pʰ tʰ kʰ qʰ], either when preceding a consonant or in word-final position. A uvular consonant /χ/ can also be heard as velar [x] in some environments. /n/ when preceding a velar consonant can be heard as a velar nasal [ŋ]. Sonorants /l r j/ when preceding a voiceless consonant or in word-final position can occur sounding voiceless [l̥ r̥ j̊].[5] Vowels  |

音韻 表はアチ語の子音[2]と母音[3]の音素を示している。左側は使用されている綴りである[4]。 子音  無声撥音は、子音に先行する場合、または語末の位置で、吸気同音 [pʰ tʰ kʰ] を持つことがあります。 環境によっては、声門子音 /χ/ が声門 [x] として聞こえることもあります。 舌骨子音に先行する /n/ は、舌骨鼻音 [↪Ll_14B] として聞こえることがあります。 子音 /l r j/ が無声子音に先行する場合、または語末位置にある場合、無声 [l̥ r̥ j̊] として聞こえることがある[5]。 母音  |

| Lopez, Manuel Antonio; Iboy,

Juliana Sis (1993). Gramática del Idioma Achi. La Antigua Guatemala,

Guatemala: Proyecto Lingüístico Francisco Marroquín. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achi_language |

|

+++

| The

Achi are a Maya ethnic group in Guatemala. They live in various

municipalities in the department of Baja Verapaz. The municipalities

they live in are Cubulco, Rabinal, San Miguel Chicaj, Salamá, San

Jerónimo, and Purulhá, in addition to parts of Granados and el Chol. They speak Achi, which is closely related to Kʼicheʼ. |

アチ族はグアテマラのマヤ系民族である。彼らはバハ・ベラパス県の様々

な自治体に住んでいる。彼らが住んでいる自治体は、グラナドスとエル・チョルの一部に加えて、クブルコ、ラビナル、サン・ミゲル・チカジ、サラマ、サン・

ヘロニモ、プルルハである。 彼らはアチ語を話し、その言語はキチェ語(Kʼicheʼ)に近い。 |

| History Pre-Columbian times Attack by the Kʼicheʼ The Kʼicheʼ cacique Quicab,[note 1] famous for his wealth of pearls, emeralds, gold, and silver, approached the Achi at Xetulul. At noon, the Kʼicheʼ began to fight the Achi, winning lands and villages without killing any of them, only tormenting them. When the Achi surrendered, they gave tribute of fish and shrimp. As a present, the Achi offered cocoa and pataxte to the main cacique, Francisco Izquin Ahpalotz y Nehaib, giving him validity as king and obeying him as tributaries. The Achi gave him the rivers Zamalá, Ucuz, Nil, and Xab. These rivers were of great benefit to Cacique Quicab, as they produced fish, shrimp, turtles, and iguanas.[2][3][4] Spanish conquest When Spanish Dominican friars arrived in present-day Guatemala, the only place they had yet to conquer was Tezulutlán, or "Tierra de Guerra" (Land of War). Bartolomé de las Casas was commissioned to "reduce" the indigenous people through Christianity.[5] One of the oldest references to Cubulco, a dialect of the Achi language, is found in el Título Real (The Royal Title) of Don Francisco Izquin Nehabib, written in 1558.[5] In 1862, the Kʼicheʼ-language play Rabinal Achí was published in Paris, France. This document was found by Abbé Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg. Expert studies state that the ethnodrama takes on values of military honor compared to Homer's Iliad.[5] The Dutch anthropologist Ruud Van Akkeren, in an interview on Mayan ethnic groups,[6] stated that: Los achíes del siglo XVI no eran los achíes de hoy; lo mismo pasa con los keqchíes o los quichés, sólo por mencionar algunos grupos. Estos pueblos tienen derecho a conocer su historia. The Achi of the 16th century were not the Achi of today; the same goes for the Qʼeqchiʼ or the Kʼicheʼ, just to mention a few groups. These peoples have the right to know their history. |

歴史 コロンブス以前 Kʼicheʼによる攻撃 真珠、エメラルド、金、銀の富で有名なKʼicheʼのカチケQuicab[注釈 1]がXetululでAchiに接近した。正午、Kʼicheʼはアチ族と戦い始め、誰一人殺すことなく、ただ苦しめるだけで土地と村を獲得した。アチ 族が降伏すると、魚とエビの貢ぎ物を与えた。アチ族は主要なカチケであるフランシスコ・イズキン・アハパロッツ・イ・ネハイブにココアとパタクテを献上 し、王としての正当性を与え、支族として従わせた。アキ族は彼にサマラ川、ウクズ川、ニル川、ザブ川を与えた。これらの川は魚、エビ、カメ、イグアナを産 出し、カチケ・キカブに大きな利益をもたらした[2][3][4]。 スペインによる征服 スペイン人ドミニコ会修道士が現在のグアテマラに到着した時、彼らがまだ征服していなかった唯一の場所はテズルトラン、または "Tierra de Guerra"(戦争の地)であった。バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスは、キリスト教によって先住民を「減らす」ことを命じられた[5]。 1558年に書かれたDon Francisco Izquin Nehabibのel Título Real(王家の称号)に、アチ語の方言であるクブルコに関する最も古い文献のひとつがある[5]。 1862年、Kʼicheʼ語の戯曲『Rabinal Achí』がフランスのパリで出版された。この文書はシャルル・エティエンヌ・ブラッスール・ド・ブルブール修道院長によって発見された。専門家の研究に よると、このエスノドラマはホメロスの『イリアス』と比較して、軍事的名誉の価値を帯びている[5]。 オランダの人類学者ルード・ヴァン・アッケレンは、マヤの民族集団に関するインタビューの中で次のように述べている[6]: ケッキ族やキチェ族も同様で、いくつかのグループを挙げるだけである。これらの人々は、自分たちの歴史を知る権利がある。 16世紀のAchiは今日のAchiではなく、QʼeqchiʼやKʼicheʼも同様で、いくつかのグループを挙げるだけである。これらの民族は自分た ちの歴史を知る権利がある。 |

| Geography The original name of Salamá, the capital of Baja Verapaz, is Tz'alam Ha', which means "tables on the water".[5] Salamá, Cubulco, Rabinal, San Miguel Chicaj and San Jerónimo are the only municipalities in Guatemala where the mother tongue is Achi.[5] In the municipality of Cubulco, there are less-visited archaeological sites such as Belejeb' Tzaq, Chilu, Los Cimientos, Nim Poco, and Pueblo Viejo. San Miguel Chicaj is known for its large Catholic church. Society In Achi society, youth and adults interact because the elders instill in the new generations the preservation of traditions and customs. It is believed that the elders have overcome great obstacles to transmit this knowledge.[7] Education There is a lack of bilingual schools, so illiteracy is common.[5] Culture Religion The Achi religion is a syncretic complex of Christianity-animism, which is why there are many sacred shrines and mounds. Traditional medicine The Achi have traditional empirical knowledge based in the use of temazcales, herbs, and medicinal plants. The work of the midwives is highly valued. |

地理 バハ・ベラパスの州都サラマの原名はTz'alam Ha'で、「水上のテーブル」を意味する[5]。 サラマ、クブルコ、ラビナル、サン・ミゲル・チカジ、サン・ヘロニモはグアテマラで唯一アチ語を母語とする自治体である[5]。 クブルコ市には、ベレヘブ・ツァク(Belejeb' Tzaq)、チル(Chilu)、ロス・シミエントス(Los Cimientos)、ニム・ポコ(Nim Poco)、プエブロ・ビエホ(Pueblo Viejo)など、あまり訪問されていない遺跡がある。 サン・ミゲル・チカジは大きなカトリック教会で知られている。 社会 アチ州の社会では、若者と大人が交流する。それは、年長者が新しい世代に伝統や習慣を守ることを教えるからである。年長者はこの知識を伝えるために大きな 障害を乗り越えてきたと信じられている[7]。 教育 バイリンガルスクールがないため、非識字が一般的である[5]。 文化 宗教 アチ州の宗教はキリスト教とアニミズムのシンクレティックな複合体である。 伝統医学 アチ族はテマズケール、ハーブ、薬草を使った伝統的な経験的知識を持っている。助産婦の仕事は高く評価されている。 |

| Cuisine Drinks The main drinks in the Achi cuisine are: atol blanco (white atole) tres cocimientos (three concoctions) shuco atol de arroz (rice atole) arroz con leche (rice pudding; literally "rice with milk") The first three are made from corn. The atol blanco and tres cocimientos can be made with white or yellow corn, while shuco is made with black corn. Atol de arroz is made with panela de dulce and the essence of atol blanco. Atol de arroz is made with rice and milk, cow's or powdered. The drinks are made by the women and are used as a snack for workers and for the family. The custom of making these drinks is passed from mother to daughter. Foods The two most well-known dishes are pinol and bochbol (or boschbol). Pinol is made with roasted corn, which is ground. Then, other seasonings and chompipe (turkey) are added. In the creation of the bochbol, tender ayote leaves, corn dough, toasted ayote seed (which is then ground), and tomato are used. The bochboles are shaped in small cylindrical rolls which are then placed in a pot on the fire to be cooked. When they are served at the table, the ground seeds are added as well as the tomato. The custom is to eat them hot. Pinol is a food for special parties, while bochbol is a commonly consumed food. The recipes are passed from mothers to daughters. Clothing The clothing of the Achi is made with traditional instruments, and stands out for its colorfulness. The male attire was commonly created by the woman. Using cotton, she used the same thread to weave the shirt, the white pants, and the red sash. The man was in charge of planting the cotton and when it was harvested, he dedicated himself to the production of the thread and a natural paint was used to dye the prepared thread black. Modernity has influenced the loss of the costumes. There are few people who wear these costumes made with the backstrap loom and natural colors. In the past, women made their own güipil and its trim, both of which were black. At present, women who live in rural areas continue to make their own güipil, but not the trim, as they are the most technical, using the fine threads and colors from the western part of the country. The red trim was created later; it is manufactured in the urban area of Rabinal and other places of the Achi region. As well as the creation of the colored ribbon, the cord and the uxaryo (collar) were brown or black. In both cases, the costumes had two variants: ceremonial and everyday wear. Feminine dress The feminine dress of the Achi includes: Güipil: It has various colors, figures, embroidered with different names and thoughts related to the life of the human being. The meaning of the figures is a reserved matter for the women, as they weave without knowing the symbolism. Corte (trim) Cinta en colores (colored ribbon) Cordón (cord) Uxaryo (collar or necklace) Cordel (cord) Masculine dress The masculine dress of the Achi includes: Camisa (shirt) Pantalón blanco (calsonsillo Blanco) (white pants, white underpants) Banda roja (red ribbon) Meaning of colors Each color used is particular as it represents certain things in the life of the human being.[7] White: Represents the dawn of every day, color of bones and teeth, purity and well-being. Red: Connotes life, strength, the sun's rays that warm and chase away the darkness, and the blood that circulates in every human being. Black: Symbolizes the hair, the pupil of the eye, the night when the human being rests for having worked during the day, it is where the sun hides, where the dead lie. Yellow: Symbolizes the similarity with yellow, black, red and white corn, and the production of excellent crops and the family. Green: Embodies nature, the green area of the valleys, and all kinds of plantations. Blue or light blue: Represents the great rivers, lakes, seas and the color of the sky. Brown: Symbolizes the color of the earth. The cordel (cord) of the same color, used to tie women's hair, was very popular for a long time, in addition to the cinta (ribbon). In recent times, the cordel and the cinta can only be seen in the most remote communities. |

料理 飲み物 アチ料理の主な飲み物は以下の通り: アトール・ブランコ(白いアトール) トレス・コシミエントス(3つの調合酒) シューコ アトール・デ・アロス(米のアトール) アロス・コン・レチェ(ライス・プディング。) 最初の3つはトウモロコシから作られる。アトール・ブランコとトレス・コシミエントスは白または黄色のとうもろこしで作られ、シュコは黒いとうもろこしで 作られる。アトール・デ・アロスは、パネラ・デ・ドゥルセとアトール・ブランコのエッセンスで作られる。アトール・デ・アロスは、米と牛乳、または粉ミル クで作られる。この飲み物は女性たちによって作られ、労働者や家族のおやつとして使われる。この飲み物を作る習慣は、母から娘へと受け継がれていく。 料理 最も有名な料理は、ピノルとボシュボル(またはボシュボル)である。 ピノールは炒ったトウモロコシをすりつぶして作る。その後、他の調味料とチョンピペ(七面鳥)を加える。 ボシュボルは、柔らかいアヨテの葉、トウモロコシの生地、炒ったアヨテの実(挽いたもの)、トマトが使われる。ボッチボルは小さな円筒形に成形され、鍋に 入れて火にかける。食卓に出されるときには、挽いた種とトマトが加えられる。熱々を食べるのが習慣である。 ピノールは特別なパーティーの料理で、ボシュボルは一般的な料理である。レシピは母親から娘へと受け継がれる。 衣服 アチ族の衣服は伝統的な楽器で作られており、そのカラフルさが際立っている。 男性の服は女性が作るのが一般的である。綿を使い、同じ糸でシャツ、白いズボン、赤い帯を織る。男は綿花の植え付けを担当し、綿花が収穫されると糸の生産 に専念し、準備された糸を天然塗料で黒く染めた。 衣装が失われたのは、近代化の影響である。背負い織機と自然の色で作られた衣装を着る人はほとんどいない。 かつては、女性たちはギュイピルとその縁飾りを自作し、どちらも黒色だった。現在、地方に住む女性たちは、ギュイピルだけは自分で作り続けているが、トリ ムは作っていない。赤い縁取りは後から作られたもので、ラビナルの都市部やアチ地方の他の場所で製造されている。色のついたリボンが作られたのと同様に、 紐とウサリョ(襟)も茶色か黒だった。 いずれの場合も、衣装には儀式用と普段着用の2つのバリエーションがあった。 女性的な衣装 アチ族の女性的な衣装には以下のようなものがある: ギュイピル:様々な色、人物、様々な名前や人間の一生にまつわる思想が刺繍されている。彼女たちはその象徴を知らずに織るので、図形の意味は彼女たちだけ の問題である。 コルテ(縁飾り) カラーリボン Cordón(紐) Uxaryo (首輪またはネックレス) Cordel (紐) 男性用ドレス アチ族の男性的な服装には以下のようなものがある: カミサ(シャツ) Pantalón blanco (calsonsillo Blanco)(白いズボン、白いパンツ) バンダ・ロハ(赤いリボン) 色の意味 使用される各色は、人間の生活における特定の事柄を表すため、特殊である[7]。 白: 毎日の夜明け、骨と歯の色、純潔と幸福を表す。 赤: 生命力、力強さ、暗闇を暖め追い払う太陽の光、そしてすべての人間を循環する血液を意味する。 黒: 髪、目の瞳孔、昼間に働いた人間が休む夜、太陽が隠れる場所、死者が眠る場所を象徴する。 黄色: 黄色、黒、赤、白のトウモロコシとの類似性、優れた作物の生産と家族を象徴する。 緑: 自然、渓谷の緑地、あらゆる種類の農園を体現している。 青または水色: 大河、湖、海、空の色を表す。 茶色: 大地の色を象徴する。シンタ(リボン)に加えて、女性の髪を結ぶのに使われる同じ色のコルデル(紐)も長い間とても人気があった。最近では、コルデルとシ ンタは人里離れた地域でしか見られなくなった。 |

| Economy and production Rabinal is famous for producing the sweetest oranges in the country. San Jerónimo is well known for being where the best haciendas and vineyards of the Dominicans were located. In this region, people of African origin were "introduced" to work in the plantations. In addition to the production of oranges and other crops, other outstanding activities are: handicrafts in Morro (jícaras, huchas, chinchines and guacales) made of clay, maguey, and wicker. Rabinal is known for its traditional markets.[8] Located in the Zamaneb valley, Rabinal was an important trading post. Ceramics, textiles, oranges, pinol, boxboles, and atoles are traded. For its January festival, pack animals are traded.[8] Textiles An important part of the Achi culture, textiles are made with the telar de cintura (backstrap loom) or palitos (sticks), and in the way of Ixchel. In the production, processes are followed such as: placing the thread in the loom, separating the thread, placing other threads to embroider, and forming the different figures. On these looms, they create güipiles, bandas (sashes), servilletas (napkins), and manteles (tablecloths). The activity is carried out by housewives, who share the knowledge by teaching it to their daughters. The cortes (trims) or enaguas (petticoats) are made by men on telares de pie (standing looms).[9] They use ixkak, white and brown dyed cotton. The raw material is collected at the end of winter and is called mish. Ceramics The artistic objects created by the Achi are traded at markets of all levels, including internationally. In both types of ceramics, whether handmade or made with technology, the work is passed from generation to generation. There are also glazed and aniline-painted ceramics, typical of Rabinal and Chicaj. They are used to personify dances such as Rabinal Achí, Venado, Negritos, La Conquista, Torito and Animales. Handmade ceramics First, the raw material is obtained at a communal plot called "capilla del barro" (chapel of clay), then it is left to dry in the sun, then water is poured and the mud is stamped until it is very smooth, so it is ready for use. To give it shape, they turn it with the body creating pots, jars, pitchers, jugs, skillets, and bowls. They make shapes, painted in red clay which turns white when burned. Both the red clay, and the stone it is extracted from, have a natural origin. The handmade pottery is burned in the open air, in a flat place, surrounded by dung and wrapped entirely in dry straw (zacate or zacatón). Ceramics made with technology For the production of this type of pottery, the potter's wheel is used. The wheel is turned with the feet, leaving the hands free to mold the piece. For the creation of large and tall pieces, the pieces are made in parts. They are also decorated, then burned in a kiln. After burning, they are painted. The use of the wheel allows the creation of vases, flowerpots, lamps, amphorae, and tableware. Basketry The Achi practice basketry by weaving hard, semi-hard, and flat fibers to create baskets of different uses and sizes. These handicrafts are produced mainly in Cubulco, San Miguel Chicaj, Salamá, and Purulhá. Woodworking People in the Achi municipalities practice woodworking by making furniture of different woods, both fine and common. Chinchines (maracas), rattles, guitars, and violins are made in Rabinal, San Miguel Chicaj, Salamá, and Purulhá. Masks for ceremonies and parties are made in Granados and Rabinal. Toys are made in San Jerónimo. Metalworking Metalwork varies by region. Only in Cubulco, Rabinal, San Miguel Chicaj and Purulhá do people use wrought iron to make door knockers, balconies, doors, and ironwork. In Salamá and Rabinal, tin is used for lanterns, candelabras, and candlesticks. Fireworks In Rabinal, Salamá and Purulhá, fireworks are made with gunpowder for familial, religious, and civic festivities. Chinchines and guacales Chinchines (maracas) guacales (alternatively spelled huacales; bowls made of morro husks) are made with the raw morro material, obtained from the tree of the same name. First, the morros are collected, and they must be ripe. They use large ones to create guacales, and medium and small ones are used to make chinchines. Once collected, the morro are cooked in a barrel. The baseado (base) is made using special instruments, it is also sanded with a special blade. After this complex process, they are painted and special decorations are added, using natural and artificial paints. This practice is passed on from parents to children. There are chinchines with zoomorphic (animal), phytomorphic (vegetable) or anthropomorphic (human) forms. According to historian Luis Luján Muñoz, the oldest pieces have their owners' names written on them and sometimes have text that alludes to the events for which they were made.[10] The morro and the jícara are processed in three ways: Carving the jícara in its natural color. Coloring the items with palo amarillo and achiote to create the red tone. Providing the black color with ocote soot and embedding it with a fat removed from an insect called niij. It is then rubbed with a cloth to polish it, and then carved to create landscapes, human and animal figures, as well as names and various symbols. This is how jícaras, guacales and chinchines are made. Rabinal and San Miguel Chicaj have the largest production of these goods.[11] Importance of the niij The niij (Llaveia sp. Homoptera: Margarodidae) is an insect that biologists classify in the "scale" group (in the sub-order Homoptera). Their eggs are laid on jocote, piñón, or ixcanal trees. The niiij is related to the cochinilla (Dactylopius coccus), according to Universidad Rafael Landívar biologist Charles MacVean.[10] The fat extracted from the niij is rubbed against the dry morro, becoming a plant-drying oil or a kind of wax, which when mixed with tizne (fine charcoal from ocote) becomes a lacquer-like film. It is lustrous, water-resistant, heat-resistant, abrasion-resistant, and non-toxic. It has a long traditional usein cooking utensils. In Mexico, it is mixed with achiote, creating a red color. With the mixture of the sap of the palo amarillo, the yellow color is produced. There are accounts by Diego de Landa and Bernardino de Sahagún, who were the first to document such practices, similar to the current use. Sahagún, in his writings of 1582, reports that it was also used as a medicine for skin and throat diseases, uterine affections, inflammation of the testicles, and as an antidote for poisonous mushrooms. There are historical records that show that it inhabited from Sinaloa, Mexico to Chiriquí, Panama, but at altitudes of less than 1,372 meters. De todos los sitios mencionados en la región mesoamericana, los únicos donde actualmente se encuentra el niij, se practica su crianza y a la vez se utiliza artesanalmente son Rabinal y Chiapa de Corzo. Of all the sites mentioned in the Mesoamerican region, the only ones where the niij is currently found, where it is bred and used in handicrafts, are Rabinal and Chiapa de Corzo. —Charles MacVean Other products They also produce rope, palm products, wax, leather, construction materials, musical instruments (such as the tun and the chirimía or shawm), and tulle. |

経済と生産 ラビナルは、グアテマラで最も甘いオレンジの産地として有名である。 サン・ヘロニモは、ドミニコ会の最高の農園とブドウ畑があった場所としてよく知られている。この地域では、アフリカ系の人々が農園で働くために「導入」さ れた。 オレンジやその他の農作物の生産に加え、モロでは粘土、マグエイ、籐で作られた手工芸品(ジカラス、フチャス、チンチーネ、グアカレス)が盛んである。 ラビナルは、伝統的な市場で知られている[8]。ザマネブ渓谷に位置するラビナルは、重要な交易拠点であった。陶器、織物、オレンジ、ピノール、ボックス ボール、アトレスなどが取引されている。1月の祭りでは、家畜が取引される[8]。 織物 アチ文化の重要な部分である織物は、テラール・デ・シントゥーラ(背負い織機)やパリトス(棒)を使い、イクシェルの方法で作られる。織機の中に糸を入 れ、糸を切り離し、刺繍のために他の糸を入れ、さまざまな形を作る。 この織機で、グイピレス、バンダ(帯)、セルビレタ(ナプキン)、マンテル(テーブルクロス)を作る。この活動は主婦たちによって行われ、主婦たちはその 知識を娘たちに教えて共有する。コルテス(縁飾り)やエナグアス(ペチコート)は、男性がテラレス・デ・パイ(立ち織機)で作る[9]。 彼らはイクスカック、白と茶色に染めた綿を使う。原料は冬の終わりに集められ、ミッシュと呼ばれる。 陶芸 アチ族によって作られた芸術品は、国際的なものも含め、あらゆるレベルの市場で取引されている。手づくりであれ技術によるものであれ、いずれのタイプの陶 器でも、作品は世代から世代へと受け継がれていく。 ラビナルやチカジに典型的な、釉薬やアニリンで彩色された陶器もある。これらは、ラビナル・アチ、ヴェナド、ネグリトス、ラ・コンキスタ、トリト、アニマ レスなどの踊りを擬人化するために使われる。 手作りの陶器 まず、"capilla del barro"(粘土の礼拝堂)と呼ばれる共同区画で原料を入手し、天日で乾燥させた後、水を注ぎ、泥をなめらかになるまで踏み固める。形を作るために、胴 体で回して鍋、壷、ピッチャー、水差し、スキレット、ボウルなどを作る。燃やすと白くなる赤土で絵を描き、形を作る。赤土も石も自然のものだ。手作りの陶 器は、野外の平らな場所で、糞に囲まれ、乾燥した藁(zacateまたはzacatón)で全体を包んで焼かれる。 技術による陶器 この種の陶器の製造には、ろくろが使われる。ろくろは足で回すので、手は作品の成形に自由に使える。大きく背の高い作品を作るために、作品は部分的に作ら れる。装飾も施され、窯で焼かれる。焼いた後、絵付けをする。ろくろを使うことで、花瓶、植木鉢、ランプ、アンフォラ、食器などを作ることができる。 籠細工 アチでは、硬い繊維、半硬質繊維、平らな繊維を編んで、さまざまな用途や大きさの籠を作る。これらの手工芸品は、主にクブルコ、サン・ミゲル・チカジ、サ ラマ、プルルハで生産されている。 木工 アチ州の人々は、上質なものから一般的なものまで、さまざまな木材で家具を作り、木工を実践しています。ラビナル、サン・ミゲル・チカジ、サラマ、プルル ハでは、チンチン(マラカス)、ガラガラ、ギター、バイオリンが作られている。儀式やパーティー用の仮面はグラナドスとラビナルで作られている。おもちゃ はサン・ヘロニモで作られている。 金属加工 金属加工は地域によって異なる。クブルコ、ラビナル、サン・ミゲル・チカジ、プルルハでのみ、人々はドアノッカー、バルコニー、ドア、鉄細工に錬鉄を使 う。サラマとラビナルでは、ランタン、燭台、燭台に錫が使われる。 花火 ラビナル、サラマ、プルルハでは、家族的、宗教的、市民的なお祭りのために、火薬を使った花火が作られます。 チンチンとグアカレス チンチーネ(マラカス)、グアカレス(huacalesの別称、モロの殻で作った鉢)は、同じ名前の木から取れるモロを原料として作られます。まず、熟し たモロを集める。グアカレスには大粒のものを使い、チンチーネには中・小粒のものを使う。 採集されたモロは樽の中で調理される。特殊な器具を使い、特殊な刃物でやすりをかけながら、ベセアド(土台)を作る。この複雑な工程を経て、天然塗料と人 工塗料を使って塗装され、特別な装飾が施される。この習慣は親から子へと受け継がれる。 チンチンには、ズーモルフィック(動物)、フィトモルフィック(植物)、擬人化(人間)の形がある。歴史家のルイス・ルハン・ムニョスによると、最も古い ものには持ち主の名前が書かれており、作られた出来事を暗示する文章が書かれていることもある[10]。 モロとジカラは3つの方法で加工される: ジカラを自然の色で彫る。 パロ・アマリージョとアチョーテで着色し、赤い色調を作り出す。 オコートの煤で黒く着色し、ニジと呼ばれる昆虫から取り出した脂肪を埋め込む。 その後、布でこすって磨き、風景や人間、動物の姿、名前やさまざまなシンボルを彫り込んでいく。ジカラ、グアカレス、チンチンはこうして作られる。 ラビナルとサン・ミゲル・チカジは、これらの商品の最大の生産地である[11]。 ニジの重要性 ニジ(Llaveia sp. Homoptera: Margarodidae)は、生物学者が「鱗翅目」に分類する昆虫である。卵はジョコテ、ピニョン、イクスカナルの木に産みつけられる。ラファエル・ラ ンディバル大学の生物学者チャールズ・マクベーンによれば、ニイジュはコチニラ(Dactylopius coccus)に近縁である[10]。 ニイジュから抽出された脂肪は、乾燥したモロにこすりつけられ、植物乾燥油または一種のワックスとなり、ティズネ(オコートの微炭)と混ぜ合わされると、 漆のような皮膜となる。光沢があり、耐水性、耐熱性、耐摩耗性に優れ、無害である。古くから調理器具に使われてきた。メキシコではアチョーテと混ぜて赤い 色を作る。パロアマリージョの樹液を混ぜると黄色になる。 ディエゴ・デ・ランダとベルナルディーノ・デ・サハグンは、現在の使用法と同じような習慣を最初に記録した人物である。サハグンは1582年の著作で、皮 膚や喉の病気、子宮の病気、睾丸の炎症、毒キノコの解毒剤としても使われたと報告している。 メキシコのシナロア州からパナマのチリキ州まで、標高1,372メートル以下に生息していたという歴史的記録がある。 中米地域で言及されているすべての場所の中で、現在ニジキノコが生息し、栽培が行われ、かつては芸術的に利用されているのは、ラビナルとチアパ・デ・コル ソだけである。 メソアメリカ地域で言及されているすべての遺跡の中で、ニイジュが現在生息し、飼育され、手工芸品に利用されているのは、ラビナルとチアパ・デ・コルソだ けである。 -チャールズ・マクヴィーン その他の製品 ロープ、ヤシ製品、ワックス、皮革、建材、楽器(トゥン、チリミア、ショームなど)、チュールなども生産している。 |

| Festivals and traditional

ceremonies The Achi share their customs from generation to generation. Their ceremonies revolve around the cofradías (fraternal groups) and the duty of the members to maintain the proper conduct of the festivities. Also noteworthy are the celebrations of Easter, Christmas and Christmas Eve. The Achi religion is a syncretic complex of Christianity-animism, which is why there are many sacred shrines and mounds. The most sanctified are Chipichek, Chusxan, B'ele tz'ak and Cuwajuexij.[12] The Tzolk'in calendar directs the agricultural rites and ritual cosmogony. Major festivals Calendar of Achi festivals [13] Municipality Date Patron saint Salamá 17 September San Mateo Cubulco 25 July Santiago Apóstol El Chol 8 December Virgen de Concepción Granados 29 June San Pedro Purulhá 13 June San Antonio de Padua Rabinal 25 January San Pablo San Jerónimo 30 September San Jerónimo San Miguel Chicaj 29 September San Miguel Arcángel Fiesta de la Virgen del Patrocinio The Fiesta de la Virgen del Patrocinio (Festival of the Patron Virgin) is celebrated in Rabinal. A carved image consisting of novenas is shared from house to house. This tradition has been practiced since the 18th century.[14] The family requesting la Virgen must have an exemplary home in the eyes of the community, and that the father and mother must be married, religiously and legally. The couple that has this right is called the "mayordomos de la cofradía de la Virgen" (stewards of the Virgin's cofradía), and a novena in her honor is held in their home. These activities take place from November 18 to November 22. During this period, the Convite de Rabinal and Santa Cruz del Quiché are presented and the cofradía members celebrate with fireworks. The legend of the Virgen del Patrocinio is well known by local historians, who say that in the mid-eighteenth century,[14] a woman appeared to an old man who was cutting wood on the summit of San Miguel Chicaj, asking him to tell the priest of Rabinal to go to confession. The woodcutter then sent the message to the priest, who was incredulous. Some time later, the lady materialized in the priest's dream, asking him to confess her. When he awoke, he went to the summit, where the image that is still known as the Virgen del Patrocinio appeared to him. Rabinal Achí Main article: Rabinal Achí The Rabinal Achí is a nationally- and internationally-recognized Kʼicheʼ-language performance.[7] Of pre-Hispanic origin, it is currently performed exclusively in the municipality of Rabinal. It is performed during the Festival of San Pablo Apóstol, 17 January to 25 January. Seven main characters participate. This drama portrays the 13th century proclamation of the Rabinal people to the Kʼicheʼ rulers. They refuse to pay tribute as the rulers destroyed the towns of the valley. Kʼicheʼ Achí is captured, imprisoned, and sentenced by the ruling court of the Rabinal. He is sacrificed after saying goodbye to his people. As part of the celebration, each year a new Alí Ajaw (Achí Princess) of Rabinal is elected. In 2004 the chosen one was Albertina Alvarado López of the Xococ village, a primary school teacher, who indicated that she would encourage the government to care for children, since infants are the present and future of Guatemala. She was joined in the proclamation by Rosa Glendy Pirir Coloch, her predecessor.[14] In 2005, Karla Yolanda López López was elected for the 2005–2006 term.[15] For the 2007–2008 term, Ana Julieta López Chen was elected. In a ballot of four candidates, Vivian Adriana Chen Piox, Rosalina Tot Morente and Ana Leticia López Yol also competed. Ana Julieta was awarded the crown and the chachal on 17 January, 2007.[16] Rabinal means "Lugar de la Hija del Señor" (Place of the Daughter of the Lord). Rabinal Achí is xajooj tun which means "dance of the tun". Cofradías Among the Achi, there are highly consolidated social organizations, called cofradías. In Rabinal there are 16, in San Miguel Chicaj there are 8, and in Salamá there are 3. There is also presence of cofradías in Cubulco and San Jerónimo.[7] The cofradías are part of Achi roots and the culture of their ancestors. At present, the elders transmit this knowledge to their children through oral tradition. One of the positions that has a strict hierarchy is that of Qajawxeel, the president of the cofradía. The cofradías are also present in Mayan festivities, in which the Achi venerate an image, which represents a being that is important during their life. In Rabinal, the cofradía of Corpus Christi is celebrated 60 days after Holy Week, in celebration of the "Divino" (Divine), called Ajaaw in the Achi language. The cofradía of Corpus Christi is one of the most important cofradías of Rabinal, because in their celebration they invoke the rain, wind, and clouds to have a good harvest in the planting of corn, which is sacred and the basis of their food. Dances The Achi perform multiple and varied dances. These also play an important role in the transmission of the knowledge of the custom. Their best-known deities are the Ajaaw (the Divine), uk'u'x kaaj, and uk'u'x uleew to whom permission is requested before performing the ceremonial dances. Elements of nature such as rain, wind, clouds, and corn are considered sacred and part of their subsistence. Dancing ritual In general, all dances are practiced in rehearsals before being performed in public. In these rehearsals, elders guide the young people through each of the different scenes and movements. Before performing these activities, offerings must be made to uk'u'x kaaj and uk'u'x uleew to give the necessary permission and prevent problems. This is done by ajq'iij (lieutenant) and consists of making a vigil with all the masks of the participants, using candles, incense, liquor (awasib'al), invoking the ancestors who have participated in these dances. There are marimba ensembles of all kinds, including drums, whistles, and chirimías (shawms). The use of three important instruments stands out: the tun, of pre-Hispanic origin, which accompanies with long trumpets the dance of the Rabinal Achí; the adufe, a square drum of Arab origin; and three small drums called aj ec, which is used in the dance of the Negritos in Rabinal. Harp, violin and guitarrilla groups, with their corresponding "puñetero" or "bordonero", of Q'eqchi' ancestry, are common in Baja Verapaz.[12]  chirimías (shawms) ●Regional dances In Rabinal, there is diversity of dances for the holidays:[8][7] Los Negritos De Cortés Nima Xajooj Moros y Cristianos San Jorge Patzka' Ixiim Keej Komoon Eq B'alam Keej El Costeño Charamiyeex (Soto Mayor) Aj Eq El Venado De Toritos La Conquista El Chico Mudo Los Huehuechos La Sierpe Los Animalitos Las Flores In Rabinal, they also perform the well-known ethno-historic dance, the Rabinal Achí (Xajooj Tuun).[8][7] In Cubulco, the Palo Volador is well known, as well as the dances of:[8] El Venado De Toritos Mexicanos De Cortés El Costeño El Chico Mudo Los Huehuechos Los Negritos Los Animalitos Los Judíos The dances of Salamá are El Venado and El Costeño.[8] In Purulhá, the dances are El Venado and Los Mazates.[8] In San Miguel Chicaj, they perform El Baile de la Pichona[5] and De Toritos.[8] |

祭りと伝統儀式 アチ州では、代々受け継がれてきた習慣がある。彼らの儀式は、コフラディアス(友愛グループ)と、祭りの適切な実施を維持するメンバーの義務を中心に展開 される。 また、イースター、クリスマス、クリスマス・イブの祝いも注目に値する。アチ州の宗教は、キリスト教とアニミズムのシンクレティックな複合体である。最も 神聖視されているのは、チピチェク、チュサン、ビエレツァク、クワジュエキシである[12]。 ツォルクイン暦は農耕儀礼と儀礼的宇宙観を指示している。 主な祭り アチ族の祭りのカレンダー [13] 市町村 日付 守護聖人 サラマ 9月17日 サン・マテオ クブルコ 7月25日 サンティアゴ・アポストル エル・チョル 12月8日 ビルヘン・デ・コンセプシオン グラナドス 29 6月 サン・ペドロ 6月13日 サン・アントニオ・デ・パドヴァ ラビナル 1月25日 サン・パブロ サン・ヘロニモ 9月30日 San Jerónimo サン・ミゲル・チカジ 9月29日 サン・ミゲル・アルカンゲル 守護聖母フィエスタ ラビナルでは、守護聖母祭(Fiesta de la Virgen del Patrocinio)が祝われる。ノヴェナからなる彫像が家から家へと分け与えられる。この伝統は18世紀から行われている[14]。ラ・ビルヘンを求 める家族は、地域社会から見て模範的な家庭でなければならず、父親と母親は宗教的にも法的にも結婚していなければならない。この権利を持つ夫婦は、 "mayordomos de la cofradía de la Virgen"(聖母の共同体の執事)と呼ばれ、彼らの家で聖母を称えるノヴェナが行われる。これらの活動は11月18日から11月22日まで行われる。 この期間中、ラビナルのコンヴィテとサンタ・クルス・デル・キチェが披露され、コフラディアのメンバーは花火で祝う。 地元の歴史家によると、18世紀半ば、サン・ミゲル・チカジの山頂で薪を割っていた老人に女性が現れ[14]、ラビナルの司祭に告解に行くよう伝えたとい う。木こりはそのメッセージを司祭に送ったが、司祭は信じなかった。しばらくして、その女性は司祭の夢の中に現れ、司祭に告白するように頼んだ。目が覚め た司祭は山頂に行き、そこで現在もパトロシニオの聖母として知られている像が現れた。 ラビナル・アチ 主な記事 ラビナル・アチ ラビナル・アヒは、全国的、国際的に認知されているKʼicheʼ語のパフォーマンスである[7]。 ヒスパニック以前の起源を持ち、現在はラビナル市でのみ上演されている。1月17日から1月25日のサン・パブロ・アポストル祭で上演される。主な登場人 物は7人。 このドラマは、13世紀にラビナル人がKʼicheʼ支配者に宣言したことを描いている。支配者が渓谷の町を破壊したため、彼らは年貢の支払いを拒否す る。KʼicheʼのAchíは捕らえられ、投獄され、Rabinalの支配裁判所から判決を受ける。彼は民に別れを告げた後、生贄として捧げられる。 お祝いの一環として、毎年ラビナルの新しいAlí Ajaw(Achí王女)が選出される。2004年に選ばれたのは、小学校の教師であるXococ村のAlbertina Alvarado López(アルベルティナ・アルバラド・ロペス)で、彼女は、グアテマラの現在と未来は乳幼児が担っているため、政府に子供たちのケアを奨励することを 表明した。この宣言には、彼女の前任者であるロサ・グレンディ・ピリロ・コロチも加わった[14]。 2005年、2005-2006年の任期でカルラ・ヨランダ・ロペス・ロペスが選出された[15]。 2007-2008年の任期では、アナ・フリエタ・ロペス・チェンが選出された。4人の候補者による投票では、ビビアン・アドリアナ・チェン・ピオクス、 ロザリーナ・トット・モレンテ、アナ・レティシア・ロペス・ヨルも争った。2007年1月17日、アナ・ジュリエタが王冠とチャチャルを授与された [16]。 ラビナルとは「Lugar de la Hija del Señor」(主の娘の場所)という意味。ラビナル・アキとは、xajooj tunのことで、"unの踊り "を意味する。 コフラディアス アチ族には、コフラディアと呼ばれる社会的組織がある。ラビナルには16、サン・ミゲル・チカジには8、サラマには3ある。クブルコとサン・ヘロニモにも コフラディアがある[7]。 コフラディアはアチ州のルーツであり、祖先の文化の一部である。現在、長老たちは口承でこの知識を子供たちに伝えている。厳格なヒエラルキーがある役職の ひとつが、コフラディアの会長であるQajawxeelである。 コフラディアはマヤのお祭りにも参加し、アチ族は自分たちの人生において重要な存在を象徴する像を崇拝する。ラビナルでは、聖週間から60日後に、アチ族 の言葉でアジャウと呼ばれる「ディビーノ(神)」を祝って、聖体降臨祭が行われる。聖体顕示祭は、ラビナルで最も重要な祭典のひとつである。なぜなら、祭 典の中で彼らは、神聖なものであり、彼らの食物の基本であるトウモロコシの植え付けが豊作になるように、雨、風、雲を呼び起こすからである。 舞踊 アチ族は多種多様な踊りを披露する。これらはまた、習慣の知識を伝える上で重要な役割を果たしている。彼らの最もよく知られた神々はAjaaw(神)、 uk'u'x kaaj、uk'u'x uleewであり、儀式的な踊りを行う前にその許可を求める。雨、風、雲、トウモロコシなどの自然の要素は神聖なものであり、彼らの生活の一部であると考 えられている。 踊りの儀式 一般的に、すべてのダンスは人前で披露される前にリハーサルで練習される。リハーサルでは、年長者が若者たちを指導し、さまざまな場面や動きを見せてい く。踊りを披露する前に、uk'u'x kaajとuk'u'x uleewに供え物をし、必要な許可を得て、問題が起こらないようにする。この儀式はajq'iij(中尉)によって行われ、参加者全員の仮面をつけて、 ロウソク、線香、酒(awasib'al)を使い、これらの踊りに参加した先祖を呼び出します。 太鼓、笛、チリミア(ショーム)など、あらゆる種類のマリンバ・アンサンブルがある。3つの重 要な楽器の使用が際立っている。ラビナル・アチの踊りに長い トランペットで伴奏する先ヒスパニック起源のトゥン、アラブ起源の四角い太鼓アデュフェ、ラビナルのネグリトの踊りに使用されるアジ・エックと呼ばれる3 つの小太鼓である。バハ・ベラパスでは、ハープ、ヴァイオリン、ギタリラのグループと、それに対応するケチ族の祖先を持つ「プニョテロ」または「ボルドネ ロ」が一般的である[12]。  チリミア(ショーム) ● 地域の踊り ラビナルでは、祝日に多様な踊りがある[8][7]。 ロス・ネグリトス デ・コルテス ニマ・ザジュ モロス・イ・クリスティアノス サン・ジョルジェ パツカ イクシム・キージ コモン・エク バラム・キージ エル・コステニョ チャラミエックス(ソト・マヨール) Aj Eq エル・ヴェナド デ・トリトス ラ・コンキスタ エル・チコ・ムド ロス・フエチョス ラ・シエルペ ロス・アニマリトス ラス・フローレス ラビナルでは、有名な民族史的舞踊であるラビナル・アチ(Xajooj Tuun)も披露している[8][7]。 クブルコでは、パロ・ヴォラドール(Palo Volador)がよく知られている。 エル・ヴェナド デ・トリトス メキシカノス デ・コルテス エル・コステニョ エル・チコ・ムド ロス・フエチョス ロス・ネグリトス ロス・アニマリトス ロス・ジュディオス サラマの踊りはエル・ヴェナードとエル・コステーニョ[8]。 プルルハ(Purulhá)では、エル・ヴェナド(El Venado)とロス・マザテス(Los Mazates)を踊る[8]。 サン・ミゲル・チカジではEl Baile de la Pichona[5]とDe Toritosを踊る[8]。 |

| Oral tradition This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) There are several types of storytellers in oral traditions who are valued for their knowledge of legends. There are specialized storytellers, whose qualities include knowing how to pass on the historical memory of their people, giving advice to the community, and being true sentinels of the cultures of the region. For the Achi, this storyteller has the title of ajtzij (Anciano Mayordomo; Elder Steward). The other type of storyteller is the occasional one, who narrates with less mastery than the ajtzij, although they retain a large part of the wisdom and the ancestral traditions of their people. The legends that are narrated during rituals by the ajtzij on sacred hills and shrines recall the mythical history, which for the Achí of Rabinal, is true. An important genre is that of the Señores y Dueños de Cerros (Owners of the Hills), largely shared with those of Alta Verapaz. Rajawales It is said in Cubulco that the cerro Cajiup (Cajiup Hill) in the valle del Urram (Urram valley) in Rabinal, is inhabited by the rajawales, which are spirits of the community and the region. On one occasion, a couple of merchants who were going to sell ceramics in Rabinal stayed to sleep on the cerro Cajiup, with a view of the top of the cerro de los Yaguales (Yaguales Hill). They were very hungry. One of them saw a deer coming out of the side of the road, so he captured it and killed it. They ate it for dinner and fell asleep. One of the two heard the voice from the cerro Cajiup telling the Yaguales that they had killed "su caballito" (his little horse), and that now he could not go to the farm, to his animals. or to watch over the corn, and he asked to borrow his dogs to avenge "su caballito". "Why not, take them away," ("Como no, llévatelos,") said cerro de los Yaguales. The merchant got up, terrified, and told his companion what he had heard, but they thought they were dreaming. When the man who heard the voices returned home, his wife told him that the coyotes came one night and killed all the chickens without eating them. Then, the man was frightened and went to ask forgiveness from the Señor del Cerro (Lord of the Hill), "doing a ritual for him" ("haciéndole una costumbre") to calm his anger. Juan Caleb In El Chol, the ajtzij say that on one occasion, a man named Juan Caleb offered a baile de los moros (dance of the Moors) for the Virgen de la Concepción (The Virgin Mary). Due to his lack of money, he went to the cerro Pacoc (Pacoc Hill) and began to cry. Then, an old man appeared and led him to the inside of the hill, showing him all kinds of costumes and telling him to choose. The clothing that the Señor del Cerro offered to Juan Caleb was the most beautiful and striking and everyone admired it. Juan Caleb could not keep the secret and told them everything, which angered the Señor del Cerro Pacoc. With a great wind, he took the costumes away from the dancers in full celebration and Juan Caleb died soon after. but due to his lack of money, he went to the Pacoc hill and began to cry; then, an old man appeared and directed him to the interior of the hill and showed him all kinds of costumes and told him to choose. The costume that the Lord of the Hill offered to Juan Caleb was the most beautiful and striking; everyone admired it, but Juan Caleb could not keep the secret and told everything, for that reason the Lord of the Pacoc Hill got angry, and by means of a great wind took away the costumes to the dancers during the celebration, and Juan Caleb died soon after. Variants of this legend are found in every municipality of the region, but especially in Salamá, San Miguel Chicaj and Granados, and in Purulhá with those of Pocomchí ancestry. Origin of corn The Achi and Pocomchí indicate in their myths that they spread corn from their department to Guatemala and the world. There are variations of the legend "When the God of the World locked away the corn" ("Cuando el Dios Mundo encerró al maíz"), which is deeply rooted in Cubulco, San Jerónimo, San Miguel Chicaj, and Purulhá. In Granados, it is said that the cuervo (crow) found the corn locked in the cerro de Las Burras (Las Burras Hill), and for this reason there is a shrine on its summit, which is very sacred for the inhabitants of the site. Patron saints Current and widespread legends speak about the origin of the towns and their founding patron saints. The abuelos rezadores (religious-leader elders) of Rabinal say that in ancient times, when San Pablo lived in Tzamaneb', Rabinal, there was a man named Yew Achí or Kʼicheʼ, who stole San Pablo's children. The saint could never confront him because Yew Achí arrived at night. When San Pablo realized, his children had already been stolen from him. They say that Yew Achí took the children in a mecapal by the dozen. Santiago, the patron saint of Kub'ul (Cubulco), noticed what was happening to his younger brother and asked him what was going on. San Pablo began to cry, and Santiago suggested to him that they switch towns. Santiago, who was the strongest, started to fight Yew Achí, but the Yew Achí hid under the earth and the water. Santiago controlled him when he tried to come out, but Yew Achí did not allow him to do so. So that "he would not be bothering him" ("no lo estuviera fastidiando"), Yew Achí apologized to Santiago and offered all his riches so he would not be killed. Santiago did not want riches, as he was poor and good, so he did not forgive Yew Achí. Before Yew Achí was killed, he asked for permission to shout seven times, cursing the people of Cubulco. Because of that, Santiago had to stay in that place as protector and patron of the town. There are variants of this legend in Purulhá, Salamá and San Jerónimo, which are also characterized by the same details and elements. Kabracán (earthquake) The atzij say that the Dios Mundo is supported by four giant men, who when they get tired of holding it all up ("de sostenerlo a tuto"), change their position, and that is when earthquakes are generated. For this reason, earthquakes are called cabracanes in the region. It is also said that "as soon as the quake starts, the women must make 'tur tur' like they do when they call the hens." ("en cuanto empieza a temblar, las mujeres deben hacer 'tur tur' como cuando llaman a las gallinas.") They do this so that Kabracán does not take the heart of the corn, because it is the blood of the inhabitants of Baja Verapaz. A variant of this legend is known in San Jerónimo as "Sipac and the Three Spirits of Corn" ("Sipac y los Tres Espíritus del Maíz") and in Purulhá as "Sipac, The Powerful" ("Sipac, El Poderoso"). In San Miguel Chicaj, there is a legend that tells of the struggle between the snake, the angel of lightning, and the spirit of corn. La Monja Blanca In ancient times, there was a Gran Señor (Great Lord), owner of hills and valleys, who came down to the village once a year. One day he saw a very beautiful woman with whom he fell in love. The Gran Señor went to the house of the young woman to ask for her as a wife, giving as dowry a chest full of money. The woman decided to live with the Gran Señor, who spoiled her. However, the woman's parents took advantage of the situation to extort money, land, corn, cocoa, and other riches from their son-in-law. The woman suffered from shame due to her parents' greed. The parents wanted more money and went to visit the Gran Señor, but saw nothing, only a light through the trees. They believed that the light was the spirit of the girl. When the Gran Señor came near, upon seeing them he turned them into tree trunks. After mourning his wife for many days, he turned the light into a beautiful white flower. Thus, the Monja Blanca (white nun) was created. It is the national flower, adorning every corner of Baja Verapaz. Animistic legends In Salamá, el Sombrerón is a giant who wears a big hat and watches over the animals at night. It is only seen before dawn. La Siguanaba is found in all the towns and villages of the department. La Llorona in Chol, shows a very different variant, since instead of drowning her son, she eats him to enact revenge on her husband who had a relationship with a woman from Cobán. In San Miguel Chicaj, it is said that the siren was a disobedient woman who lived on the outskirts of San Miguel and bathed in the Ixcayán River on Good Friday, so God punished her by turning her into a siren. Other scary creatures are la Siguamonta, el Cadejo and los Tzizimites, of the sugar cane, which is abundant in San Jerónimo, Purulhá, and Cubulco. Griffin The griffin (el pájaro grifo) is characterized as a western literary figure from Salamá, and several stories are found in the mestizo population. In the neighborhood of Calvario, the story of the griffin is told. It tells of the adventures of a boy, inhabitant of El Chol, who has to obtain feathers of a magic bird called griffin to heal and marry the daughter of the Gran Señor of the water country (país del agua). After a series of incredible events, the teenager catches the bird and goes to live in the palace of the Señor del Agua (Lord of Water). Other literary figures A widespread tale is "Juan Oso" among the mestizos of Granados, and "Blanca Flor y Rosa Flor" ("White Flower and Pink Flower) in El Chol. Pedro Urdemales (or Ardimales), Tío Conejo (Uncle Rabbit) and Tío Coyote (Uncle Coyote) persist as characters in popular tales in San Miguel Chicaj and San Jerónimo. In Salamá, riddle-tales such as "Pan Mató a Panda" ("Bread Killed the Panda") and "Las Tres Adivinanzas" ("The Three Riddles) are well-known. Also in Salamá, part of the traditional oral poetry of medieval times is preserved, with the romances "Madre que sufría" ("Mother who suffered"), "Alfonsito llorón" ("Crying little Alfonso"), and "Dile, dile golondrina" ("Tell them, tell them, little bird"). There are also modern couplets, décimas, and romancillos (short romances) in the region. There is a myth in Rabinal that on the top of the Cerro Cuxbalám (Cuxbalám Hill) is the entrance to Xibalbá, the Maya underworld. It is said that the center of Xibalbá is Rabinal, where the men of Rabinal continue to play pelota. |

口承伝承 このセクションでは出典を引用していません。信頼できる情報源への引用を追加して、このセクションの改善にご協力ください。ソースのないものは、異議申し 立てがなされ、削除されることがあります。(2023年1月)(このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 口承伝承における語り部には、伝説の知識を評価されるいくつかのタイプがある。 専門的な語り部もおり、その資質には、民族の歴史的記憶を伝える方法を知っていること、地域社会に助言を与えること、地域の文化の真の歩哨であることなど が含まれる。アチ族の場合、この語り部にはアジジ(Anciano Mayordomo、長老執事)という称号がある。 もう一人の語り部は、時折登場する語り部であり、アジチほど達者ではないが、彼らの知恵と先祖伝来の伝統の大部分を保持している。 聖なる丘や祠でアジチが儀式中に語る伝説は、ラビナルのアキ族にとって真実である神話の歴史を思い起こさせる。 重要なジャンルは、アルタ・ベラパスと共通する「丘の所有者(Señores y Dueños de Cerros)」である。 ラジャワレス ラビナルのウラム渓谷にあるカジウプ丘(cerro Cajiup)には、ラジャワレス(rajawales)が住んでいるとクブルコでは言われている。 ある時、ラビナルに陶器を売りに行く商人たちが、ヤグアレス丘の頂上が見えるカジウプ丘に寝泊まりした。彼らはとても空腹だった。そのうちの一人が、道の 脇から出てきた鹿を見つけたので、捕まえて殺した。二人はそれを夕食に食べ、眠りについた。二人のうちの一人が、セロ・カジウプからヤグアレス族に、彼ら が「ス・キャバリート」(彼の小さな馬)を殺したので、農場に行くことも、家畜のところに行くことも、トウモロコシの番をすることもできないと言う声を聞 き、「ス・キャバリート」の仇を討つために犬を貸してほしいと頼んだ。 「セロ・デ・ロス・ヤグアレスは、「なぜダメなんだ、連れて行け」と言った。商人は怯えながら立ち上がり、聞いたことを仲間に話したが、二人は夢だと思っ ていた。その声を聞いた男が家に帰ると、妻が、ある晩コヨーテがやって来て、鶏を食べずに全部殺してしまったと言った。そこで男は怯え、セニョール・デ ル・セロ(丘の主)に許しを請いに行き、「彼のために儀式をして」("haciéndole una costumbre")怒りを鎮めたという。 フアン・カレブ エル・チョルでは、フアン・カレブという男がある時、聖母マリアのためにバイレ・デ・ロス・モロス(ムーア人の踊り)を捧げたとアジチが語っている。お金 がなかったため、彼はセロ・パコック(パコックの丘)に行き、泣き始めた。すると、一人の老人が現れ、彼を丘の中へと案内し、あらゆる種類の衣装を見せて 選ぶように言った。 セニョール・デル・セロがフアン・カレブに差し出した服は、最も美しく印象的で、誰もが賞賛した。フアン・カレブは秘密を守りきれず、すべてを話してし まった。セニョール・デル・セロ・パコックは大風を起こし、祝賀ムード一色の踊り子たちから衣装を取り上げ、フアン・カレブは間もなく亡くなった。 しかし、お金がなかったため、彼はパコックの丘に行き、泣き始めた。そこに老人が現れ、丘の奥に案内し、あらゆる種類の衣装を見せて選ぶように言った。丘 の主がフアン・カレブに差し出した衣装は、最も美しく印象的なもので、誰もがそれを賞賛したが、フアン・カレブは秘密を守ることができず、すべてを話して しまった。そのため、パコックの丘の主は怒り、大風によって祝宴中の踊り子たちの衣装を奪い去り、フアン・カレブは間もなく亡くなった。 この伝説の変種は、この地方のすべての自治体に見られるが、特にサラマ、サン・ミゲル・チカジ、グラナドス、そしてプルルハでは、ポコムチの先祖を持つ人 々に見られる。 トウモロコシの起源 アチ族とポコムチ族は、神話の中で、トウモロコシを自分たちの県からグアテマラや世界に広めたと語っている。 クブルコ、サン・ヘロニモ、サン・ミゲル・チカジ、プルルハには、「世界の神がトウモロコシを閉じ込めた時」("Cuando el Dios Mundo encerró al maíz")という伝説のバリエーションがあり、深く根付いている。 グラナドスでは、セロ・デ・ラス・ブラス(ラス・ブラスの丘)に閉じ込められたトウモロコシをカラスが見つけたと言われており、そのため、その頂上には祠 があり、この地の住民にとって非常に神聖な場所となっている。 守護聖人 現在、広く伝わっている伝説では、町の起源とその創始者の守護聖人について語られている。ラビナルのabuelos rezadores(宗教指導者の長老)たちによると、昔、サン・パブロがラビナルのTzamaneb'に住んでいたとき、Yew AchíまたはKʼicheʼという男がいて、サン・パブロの子供を盗んだ。Yew Achíは夜にやって来るので、聖人は彼に立ち向かうことができなかった。サン・パブロが気づいた時には、子供たちはすでに盗まれていた。イエウ・アチは 子供たちを1ダースずつメカパルに乗せて連れて行ったと言われている。 クブール(クブルコ)の守護聖人であるサンティアゴは、弟に何が起こっているのかに気づき、どうしたのかと尋ねた。泣き出したサンパブロに、サンティアゴ は町を変えようと提案した。一番強いサンチャゴはイチイ・アキと戦い始めたが、イチイ・アキは土と水の下に隠れた。サンチャゴは出てこようとするイワッチ を制したが、イワッチはそれを許さなかった。 そこでイチイ・アキはサンティアゴに謝り、殺されないようにと全財産を差し出した。サンティアゴは、貧しく善良であったため、富を欲しがらず、イエウアキ を許さなかった。イエウ・アチは殺される前に、クブルコの人々を呪って7回叫ぶ許可を求めた。そのため、サンティアゴは町の守護神としてその場所に留まる ことになった。 プルルハ(Purulhá)、サラマ(Salamá)、サン・ヘロニモ(San Jerónimo)にもこの伝説の亜種があり、同じ詳細や要素が特徴となっている。 カブラカン(地震) アジイ族によると、ディオス・ムンドは4人の巨人によって支えられており、彼らはすべてを支えるのに疲れると("de sostenerlo a tuto")、その位置を変え、その時に地震が発生するという。 このため、この地方では地震のことをカブラケネスと呼ぶ。また、「地震が始まるとすぐに、女性たちは鶏を呼ぶときのように『ター・ター』と鳴かなければな らない」とも言われている。("en cuanto empieza a temblar, las mujeres deben hacer 'tur tur' como cuando llaman a las gallinas.")。これはカブラカンにトウモロコシの心臓を取られないようにするためで、トウモロコシはバハ・ベラパスの住民の血だからである。 この伝説の変種は、サン・ヘロニモでは "シパックとトウモロコシの3つの精"("Sipac y los Tres Espíritus del Maíz")として、プルルハでは "強力なシパック"("Sipac, El Poderoso")として知られている。 サン・ミゲル・チカジには、蛇、稲妻の天使、トウモロコシの精の闘争を伝える伝説がある。 ラ・モンハ・ブランカ 昔、丘と谷の持ち主であるグラン・セニョール(大神)がいて、年に一度、村に降りてきた。ある日、彼はとても美しい女性を見て恋に落ちた。グラン・セ ニョールは、その若い女性を妻として迎えるため、その女性の家を訪ねた。女性はグラン・セニョールのもとで暮らすことを決め、グラン・セニョールは彼女を 甘やかした。しかし、女性の両親はこの状況を利用して、婿から金、土地、トウモロコシ、カカオなどの富を強奪した。 女性は両親の強欲のために恥辱に苦しんだ。両親はさらに金が欲しくなり、グラン・セニョールに会いに行ったが、何も見えず、ただ木漏れ日が見えただけだっ た。両親はその光を少女の霊だと信じた。グラン・セニョールが近づくと、二人を見て木の幹に変えてしまった。何日も妻を弔った後、光を美しい白い花に変え た。こうして、モンハ・ブランカ(白い修道女)が誕生した。バハ・ベラパスのいたるところに飾られている国花である。 動物伝説 サラマ(Salamá)では、ソンブレロン(El Sombrerón)は大きな帽子をかぶった巨人で、夜になると動物たちを見守る。夜明け前にしか見られない。 ラ・シグアナバ(La Siguanaba)は、県内のすべての町や村で見られる。 チョルのラ・ロロナは、コバン出身の女性と関係を持った夫に復讐するため、息子を溺死させる代わりに食べてしまう。 サン・ミゲル・チカジでは、サイレンはサン・ミゲル郊外に住んでいて、聖金曜日にイクスカヤン川で水浴びをしていた不従順な女性であったため、神は彼女を サイレンの姿に変えて罰したと言われている。 他にも、サン・ヘロニモ、プルルハ、クブルコに多く生息するサトウキビのシグアモンタ(la Siguamonta)、カデホ(el Cadejo)、ツジミテ(los Tzizimites)などが怖い生き物とされている。 グリフィン グリフィン(el pájaro grifo)は、サラマ(Salamá)出身の西洋文学の人物であり、メスティーソ(mestizo)人口にいくつかの物語が見られる。 カルバリオ近辺では、グリフィンの物語が語られている。この物語は、水の国(país del agua)のグラン・セニョールの娘を癒して結婚させるために、グリフィンと呼ばれる魔法の鳥の羽を手に入れなければならない、エル・チョル(El Chol)に住む少年の冒険を描いている。信じられないような出来事の後、ティーンエイジャーは鳥を捕まえ、セニョール・デル・アグア(水の主)の宮殿に 住むことになる。 その他の文学者 グラナドスのメスティーソの間では "Juan Oso"、エル・チョールでは "Blanca Flor y Rosa Flor"(白い花とピンクの花)が広く知られている。 ペドロ・ウルデマレス(またはアルディマレス)、ティオ・コネホ(ウサギおじさん)、ティオ・コヨーテ(コヨーテおじさん)は、サン・ミゲル・チカジとサ ン・ヘロニモで人気のある物語の登場人物として残っている。 サラマでは、"パンがパンダを殺した"(Pan Mató a Panda)や "3つのなぞなぞ"(Las Tres Adivinanzas)などのなぞなぞ物語が有名である。また、サラマには中世の伝統的な口承詩の一部が残されており、"Madre que sufría"(「苦しむ母」)、"Alfonsito llorón"(「泣く小人アルフォンソ」)、"Dile, dile golondrina"(「教えてあげて、小鳥さん」)などのロマンスがある。この地方には、現代的な連詩、デ シマ、ロマンチージョ(短いロマンス)もあ る。 ラビナルには、セロ・ククスバラン(ククスバランの丘)の頂上にマヤの冥界であるキシバルバへの入り口があるという神話がある。Xibalbáの中心は Rabinalであり、Rabinalの男たちはそこでペロタを続けていると言われている。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achi_people |

|

| Achi (Achí in

Spanish)

is a Mayan language very closely related to Kʼicheʼ (Quiché in the

older orthography). It is spoken by the Achi people, primarily in the

department of Baja Verapaz in Guatemala. There are two Achi dialects. Rabinal Achi is spoken in the Rabinal area, and Cubulco Achi is spoken in the Cubulco area west of Rabinal. One of the masterpieces of precolumbian literature is the Rabinal Achí, a theatrical play written in the Achi language. |

アチ語(スペイン語ではAchí)は、Kʼicheʼ(古い正書法では

Quiché)に非常に近いマヤ語である。グアテマラのバハ・ベラパス県を中心にアチ族によって話されている。 2つの方言がある。ラビナル方言はラビナル地域で話されており、クブルコ方言はラビナル西部のクブルコ地域で話されている。 先史時代文学の傑作のひとつに、アチ語で書かれた民衆演劇「ラビナル・アチ」がある。 |

| Phonology The tables present the consonant[2] and vowel[3] phonemes of Achi. On the left is the spelling in use.[4] Consonants  Voiceless plosives can have aspirated allophones [pʰ tʰ kʰ qʰ], either when preceding a consonant or in word-final position. A uvular consonant /χ/ can also be heard as velar [x] in some environments. /n/ when preceding a velar consonant can be heard as a velar nasal [ŋ]. Sonorants /l r j/ when preceding a voiceless consonant or in word-final position can occur sounding voiceless [l̥ r̥ j̊].[5] Vowels  |

音韻 表はアチ語の子音[2]と母音[3]の音素を示している。左側は使用されている綴りである[4]。 子音  無声撥音は、子音に先行する場合、または語末の位置で、吸気同音 [pʰ tʰ kʰ] を持つことがあります。 環境によっては、声門子音 /χ/ が声門 [x] として聞こえることもあります。 舌骨子音に先行する /n/ は、舌骨鼻音 [↪Ll_14B] として聞こえることがあります。 子音 /l r j/ が無声子音に先行する場合、または語末位置にある場合、無声 [l̥ r̥ j̊] として聞こえることがある[5]。 母音  |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achi_language |

|

| Navarrete

Pellicer, Sergio. 2005. Maya Achi Marimba Music In Guatemala.

(Studies in Latin American and Caribbean Music). Temple University

Press. For the Achi, one of the several Mayan ethnic groups indigenous to Guatemala, the music of the marimba serves not only as a form of entertainment but also as a form of communication, a vehicle for memory, and an articulation of cultural identity. Sergio Navarrete Pellicer examines the marimba tradition -- the historical confluence of African musical influences, Spanish colonial power, and Indian ethnic assimilation -- as a driving force in the dynamics of cultural continuity and change in Rabinal, the heart of Achi culture and society. By examining the performance and consumption of marimba music as complementary parts of a system of social interaction, religious belief, and ethnic identification, Navarrete Pellicer reveals how the strains of the marimba resonate with the spiritual yearnings and cultural negotiations of the Achi as they try to come to terms with the political violence and economic hardship wrought by their colonial past. Listen to a clip (invalid NOW) from Amanecido son, Marimba La Reina Rabinalense. Esteban Uanche (treble); Celestino Cajbón (center); Mencho Uanche (bass). Recorded in Rabinal, Baja Verapaz, 1995.. |

Navarrete

Pellicer, Sergio. 2005. Maya Achi Marimba Music In Guatemala.

(Studies in Latin American and Caribbean Music). Temple University

Press. グアテマラ先住民であるマヤ系民族のひとつ、アチ族にとって、マリンバの音楽は娯楽の一形態としてだけでなく、コミュニケーションの一形態、記憶の手段、 文化的アイデンティティの明確化としても機能している。セルヒオ・ナバレテ・ペリセールは、アフリカ音楽の影響、スペインの植民地支配、インディアンの民 族的同化の歴史的合流点であるマリンバの伝統を、アチ文化と社会の中心であるラビナルにおける文化の継続と変化の原動力として考察する。ナバレテ・ペリ セールは、マリンバ音楽の演奏と消費を、社会的相互作用、宗教的信仰、民族的アイデンティティのシステムの補完的な部分として考察することで、マリンバの 音色が、植民地時代の過去がもたらした政治的暴力と経済的苦難と折り合いをつけようとするアチ族の精神的渇望と文化的交渉にいかに共鳴しているかを明らか にする。 |

| https://tupress.temple.edu/books/maya-achi-marimba-music-in-guatemala |

書評 『グアテマラのマヤ・アチ・マリンバ音楽』は、独自の現地調査から得られた新資料として、あらゆる言語、特に英語による中米の民族音楽研究に大きく貢献す る。マリンバは、グアテマラでは公式に国家楽器に最も近いと宣言されており、実際そうである。そのグアテマラのマリンバ音楽文化に関するこの詳細な研究 は、ラテンアメリカの主要な音楽伝統に対する我々の理解を深めるために、歴史的背景と知的な分析、そして現代の実践に対する鋭い解釈を組み合わせたもので ある。ナバレテ・ペリセールは、この本の中で、コミュニティーのメンバーの声を引き出し、詳細で豊かな、人格と人間関係を繊細に描写している。" -T. M.スクラッグス、アイオワ大学 「グアテマラのマヤ・アチ・マリンバ音楽は、マリンバの練習をはるかに超えた、繊細で魅力的な記述である。アンソニー・シーガー(Anthony Seeger, 1987年)やスティーブン・フェルド(1990年(1982年))といった音楽人類学者の画期的な著作に次ぐ正当な位置を占めている。本書は、世界のど こであれ、先住民の音楽実践に関心を持つ研究者にとって貴重なものである。" -音楽の世界 「グアテマラの社会、儀式、信仰、そして文化的・宗教的状況の形成と相互作用における音楽制作、音楽家、音楽的行動(中略)の役割を研究する者にとって、 本書は強く推薦される" -The World of Music -ラテンアメリカ研究ジャーナル "マリンバ音楽の徹底的な研究...ペリセルの本は、中米インディアン・コミュニティの社会的結束とアイデンティティを維持する上で、音楽的実践が果たす 重要な役割を実証している。著者のアプローチは、歴史的・社会的分析だけでなく、人類学的フィールドワークに根ざしている......これは(綿密な)人 類学的仕事である。" -音楽学 "音楽の意味について繊細な考察を求める者にとって、セルヒオ・ナヴァレテ・ペリセルの本書は外せない...(彼の分析は)この文献における相反する解釈 を明らかにし、(マリンバ)の出自に関する根強い誤解や論争に対処している...(読者は)正書法を詳述し、コフラディア、音楽アンサンブル、レパート リー、マリンバ音楽が特徴的な機会を目録化した有益な付録によって大いに助けられるだろう。" -人類音楽学の書評 -人類学の書評 "ナバレッテ・ペリセールは、「音楽家と聴衆が文化的変化を受容し、以前の世界観に対応する文化的実践についての見解を構築する方法」(212)を明らか にすることを主な目的として、アチのコスモヴィジョンとそれに付随する音楽要素の内的な働きと儀式的な発現を解明している。そのために彼は、植民地時代以 来、アチ族の生活とマリンバの伝統に深刻な影響を及ぼしてきた、より広範なグアテマラの社会的・政治的展開のいくつかに注意を向けている。" -カナダ・ラテンアメリカ・カリブ研究ジャーナル |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099