アフリカ系プエルトリコ人

Afro–Puerto Ricans

In

the 1948 Summer Olympics (the XIV Olympics), celebrated in London,

boxer Juan Evangelista Venegas made sports history by becoming Puerto

Rico's first Olympic medal winne

☆ アフロ・プエルトリカンとは、アフリカ系黒人の血を引くプエルトリコ人 のことである[2][3]。 アフリカ系プエルトリコ人の歴史は、スペインのコンキスタドール(征服者)たちの島への侵攻に同行した、リベルトスと呼ばれる自由なアフリカ人男性から始ま る。

| Afro–Puerto

Ricans are Puerto Ricans who are of Black African descent.[2][3] The

history of Puerto Ricans of African descent begins with free African

men, known as libertos, who accompanied the Spanish Conquistadors in

the invasion of the island.[4] The Spaniards enslaved the Taínos (the

native inhabitants of the island), many of whom died as a result of new

infectious diseases and the Spaniards' oppressive colonization efforts.

Spain's royal government needed laborers and began to rely on African

slavery to staff their mining and fort-building operations. The Crown

authorized importing enslaved West Africans. As a result, the majority

of the African peoples who entered Puerto Rico were the result of the

Atlantic slave trade, and came from many different cultures and peoples

of the African continent. When the gold mines in Puerto Rico were declared depleted, the Spanish Crown no longer considered the island to be a high colonial priority. Its chief ports served primarily as a garrison to support naval vessels. The Spaniards encouraged free people of color from British and French possessions in the Caribbean to emigrate to Puerto Rico, to provide a population base to support the Puerto Rican garrison. The Spanish decree of 1789 allowed slaves to earn or buy their freedom; however, this did little to help their situation. The expansion of sugar cane plantations drove up demand for labor and the slave population increased dramatically as new slaves were imported. Throughout the years, there were many slave revolts in the island. Slaves who were promised their freedom joined the 1868 uprising against Spanish colonial rule in what is known as the Grito de Lares. On March 22, 1873, slavery was abolished in Puerto Rico. The contributions of ethnic Africans to the music, art, language, and heritage have been instrumental in Puerto Rican culture. |

アフロ・プエルトリカンとは、アフリカ系黒人の血を引くプエルトリコ人

のことである[2][3]。

アフリカ系プエルトリコ人の歴史は、スペインのコンキスタドール(征服者)たちの島への侵攻に同行した、リベルトスと呼ばれる自由なアフリカ人男性から始ま

る[4]。

スペイン人たちは、タイノス(島の先住民)を奴隷化し、その多くが新たな感染症やスペイン人たちの圧制的な植民地化の取り組みの結果、死亡した。スペイン

王室は労働者を必要とし、採掘や要塞建設にアフリカ人奴隷を使うようになった。王室は奴隷となった西アフリカ人の輸入を許可した。その結果、プエルトリコ

に流入したアフリカ系民族の大半は大西洋奴隷貿易の結果であり、アフリカ大陸の様々な文化や民族の出身であった。 プエルトリコの金鉱が枯渇したと宣言されると、スペイン王室はもはやこの島を植民地として重要視しなくなった。その主要港は主に海軍艦艇を支援するための 駐屯地として機能した。スペイン人は、カリブ海のイギリス領とフランス領からプエルトリコに移住する自由有色人種を奨励し、プエルトリコ守備隊を支える人 口基盤を提供した。1789年のスペイン法令により、奴隷は自由を得るか買うことができるようになった。サトウキビ・プランテーションの拡大により労働力 需要が高まり、新しい奴隷が輸入されたため奴隷人口は劇的に増加した。長年にわたり、島では多くの奴隷反乱が起こった。自由を約束された奴隷たちは、 1868年、グリト・デ・ラレスとして知られるスペイン植民地支配に対する蜂起に参加した。1873年3月22日、プエルトリコでは奴隷制度が廃止され た。 音楽、芸術、言語、遺産に対するアフリカ系民族の貢献は、プエルトリコ文化に多大な影響を与えた。 |

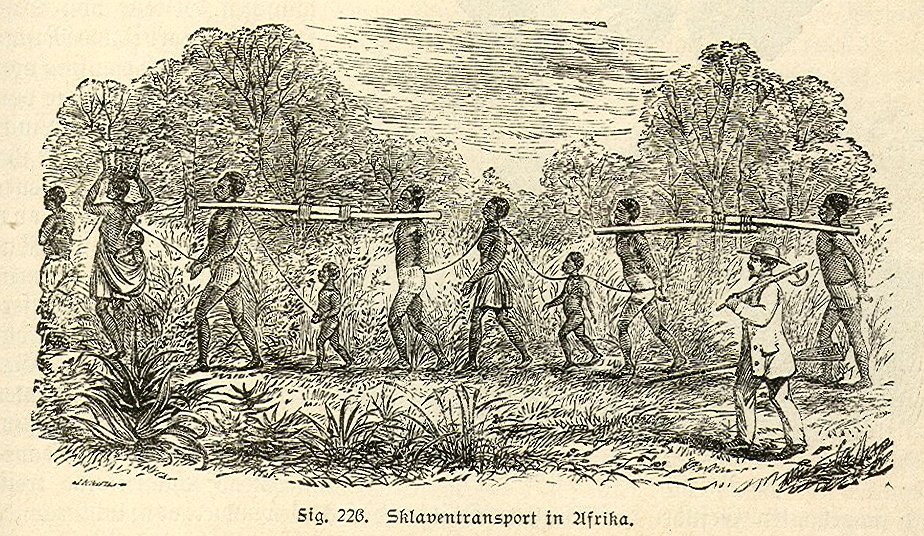

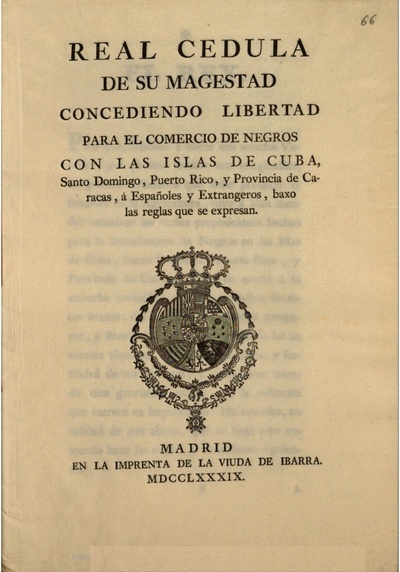

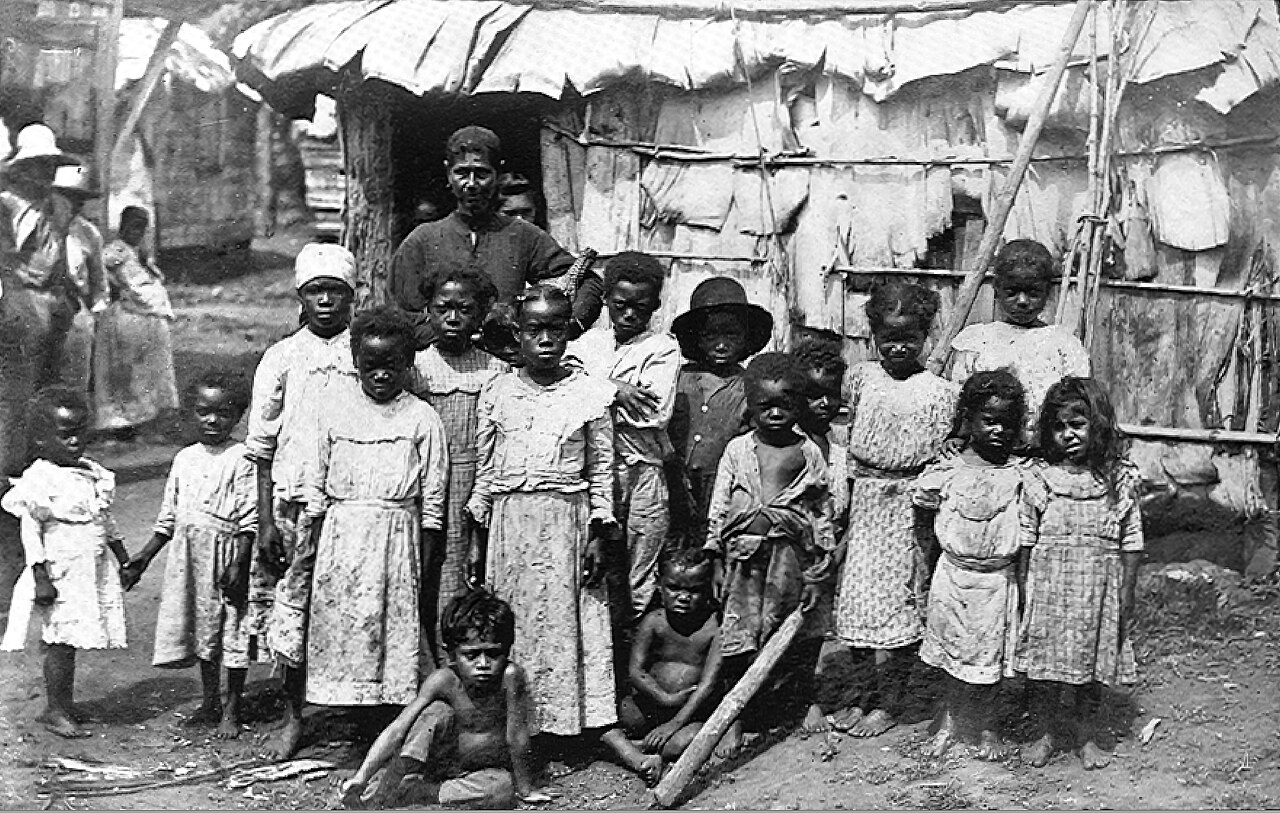

First Africans in Puerto Rico Slave transport in Africa, depicted in a 19th-century engraving. When Ponce de León and the Spaniards arrived on the island of Borinquen (Puerto Rico), they were greeted by the Cacique Agüeybaná, the supreme leader of the peaceful Taíno tribes on the island. Agüeybaná helped to maintain the peace between the Taíno and the Spaniards. According to historian Ricardo Alegria, in 1509 Juan Garrido was the first free African man to set foot on the island; he was a conquistador who was part of Juan Ponce de León's entourage. Garrido was born on the West African coast, the son of an African king. In 1508, he joined Juan Ponce de León to explore Puerto Rico and prospect for gold. In 1511, he fought under Ponce de León to repress the Carib and the Taíno, who had joined forces in Puerto Rico in a great revolt against the Spaniards.[5] Garrido next joined Hernán Cortés in the Spanish conquest of Mexico.[6] Another free African man who accompanied de León was Pedro Mejías. Mejías married a Taíno woman chief (a cacica), by the name of Yuisa. Yuisa was baptized as Catholic so that she could marry Mejías.[5][7] She was given the Christian name of Luisa (the town Loíza, Puerto Rico was named for her). The peace between the Spanish and the Taíno was short-lived. The Spanish took advantage of the Taínos' good faith and enslaved them, forcing them to work in the gold mines and in the construction of forts. Many Taíno died, particularly due to epidemics of smallpox, to which they had no immunity. Other Taínos committed suicide or left the island after the failed Taíno revolt of 1511.[8] Friar Bartolomé de las Casas, who had accompanied Ponce de León, was outraged at the Spanish treatment of the Taíno. In 1512 he protested at the council of Burgos at the Spanish Court. He fought for the freedom of the natives and was able to secure their rights. The Spanish colonists, fearing the loss of their labor force, also protested before the courts. They complained that they needed manpower to work in the mines, build forts, and supply labor for the thriving sugar cane plantations. As an alternative, Las Casas suggested the importation and use of African slaves. In 1517, the Spanish Crown permitted its subjects to import twelve slaves each, thereby beginning the African slave trade in their colonies.[9] According to historian Luis M. Diaz, the largest contingent of African slaves came from the areas of the present-day Ghana, Togo, Benin, Nigeria; all these current countries are located in the Gulf of Guinea, area also known as the Slave Coast. The large majority were Yoruba and Igbo, ethnic groups from Nigeria, and Bantu from the Guinea. The number of slaves in Puerto Rico rose from 1,500 in 1530 to 15,000 by 1555. The slaves were stamped with a hot iron on the forehead, a branding which meant that they were brought to the country legally and prevented their kidnapping.[7] African slaves were sent to work in the gold mines to replace the Taíno, or to work in the fields in the island's ginger and sugar industries. They were allowed to live with their families in a bohio (hut) on the master's land, and were given a patch of land where they could plant and grow vegetables and fruits. Africans had little or no opportunity for advancement and faced discrimination from the Spaniards. Slaves were educated by their masters and soon learned to speak the master's language, educating their own children in the new language. They enriched the "Puerto Rican Spanish" language by adding words of their own. The Spaniards considered Africans more malleable than the Taíno, since the latter were unwilling to assimilate. The slaves, in contrast, had little choice but to adapt to their lives. Many converted (at least nominally) to Christianity; they were baptized by the Catholic Church and were given the surnames of their masters. Many slaves were subject to harsh treatment; and women were subject to sexual abuse. The majority of the Conquistadors and farmers who settled the island had arrived without women; many of them intermarried with the African or Taíno women. Their Multiracial descendants formed the first generations of the early Puerto Rican population.[7] In 1527, the first major slave rebellion occurred in Puerto Rico, as dozen of slaves fought against the colonists in a brief revolt.[10] The few slaves who escaped retreated to the forests and mountains, where they resided as maroons with surviving Taínos. During the following centuries, by 1873 slaves had carried out more than twenty revolts. Some were of great political importance, such as the Ponce and Vega Baja conspiracies.[11] By 1570, the colonists found that the gold mines were depleted. After gold mining ended on the island, the Spanish Crown bypassed Puerto Rico by moving the western shipping routes to the north. The island became primarily a garrison for those ships that would pass on their way to or from richer colonies. The cultivation of crops such as tobacco, cotton, cocoa, and ginger became the cornerstone of the economy. With the scale of Puerto Rico's economy reduced, colonial families tended to farm these crops themselves, and the demand for slaves was reduced. [12] With rising demand for sugar on the international market, major planters increased their cultivation and processing of sugar cane, which was labor-intensive. Sugar plantations supplanted mining as Puerto Rico's main industry and kept demand high for African slavery. Spain promoted sugar cane development by granting loans and tax exemptions to the owners of the plantations. They were also given permits to participate in the African slave trade.[12] To attract more workers, in 1664 Spain offered freedom and land to African-descended people from non-Spanish colonies, such as Jamaica and Saint-Domingue (later Haiti). Most of the free people of color who were able to immigrate were of mixed-race, with African and European ancestry (typically either British or French paternal ancestry, depending on the colony.) The immigrants provided a population base to support the Puerto Rican garrison and its forts. Freedmen who settled the western and southern parts of the island soon adopted the ways and customs of the Spaniards. Some joined the local militia, which fought against the British in the many British attempts to invade the island. The escaped slaves and the freedmen who emigrated from the West Indies used their former master's surnames, which were typically either English or French. In the 21st century, some ethnic African Puerto Ricans still carry non-Spanish surnames, proof of their descent from these immigrants.[7] After 1784, Spain suspended the use of hot branding the slave's forehead for identification.[7] In addition, it provided ways by which slaves could obtain freedom: A slave could be freed by his master in a church or outside it, before a judge, by testament or letter. A slave could be freed against his master's will by denouncing a forced rape, by denouncing a counterfeiter, by discovering disloyalty against the king, and by denouncing murder against his master. Any slave who received part of his master's estate in his master's will was automatically freed (these bequests were sometimes made to the master's mixed-race slave children, as well as to other slaves for service.) If a slave was made a guardian to his master's children, he was freed. If slave parents in Hispanic America had ten children, the whole family was freed.[13] |

プエルトリコにおける最初のアフリカ人 19世紀の版画に描かれたアフリカでの奴隷輸送 ポンセ・デ・レオンとスペイン人がボリンケン島(プエルトリコ)に到着すると、島の平和なタイノ族の最高指導者であるカシケ・アグエイバナが出迎えた。ア グエイバナは、タイノ族とスペイン人との間の平和維持に貢献した。歴史家リカルド・アレグリアによると、1509年、フアン・ガリドは島に足を踏み入れた 最初の自由アフリカ人であり、フアン・ポンセ・デ・レオンの側近の一人であったコンキスタドールであった。ガリードはアフリカ王の息子として西アフリカ沿 岸で生まれた。1508年、彼はフアン・ポンセ・デ・レオンと共にプエルトリコを探検し、金を探鉱した。1511年、彼はポンセ・デ・レオンの下で、プエ ルトリコでスペイン人に対する大反乱を起こしたカリブ人とタイノー人を鎮圧するために戦った[5]。ガリードは次にエルナン・コルテスと共にスペインのメ キシコ征服に参加した[6]。メヒアスはユイサという名のタイノ族の女酋長(カチカ)と結婚した。ユイサはメヒアスと結婚するためにカトリックの洗礼を受 けた[5][7]。 スペインとタイノ族の平和は短命に終わった。スペイン人はタイノ族の善意を利用し、彼らを奴隷にし、金鉱や要塞建設で働かせた。特に天然痘の流行によって 多くのタイノー族が命を落とした。1511年のタイノ人の反乱の失敗の後、他のタイノ人は自殺したり島を去ったりした[8]。 ポンセ・デ・レオンに同行していたバルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス修道士は、スペイン人のタイノ族に対する扱いに憤慨した。1512年、彼はスペイン宮廷の ブルゴス会議で抗議した。彼は原住民の自由のために戦い、彼らの権利を確保することができた。労働力の喪失を恐れたスペイン人入植者たちもまた裁判所に抗 議した。彼らは、鉱山で働き、砦を築き、サトウキビ農園に労働力を供給するために人手が必要だと訴えた。代替案として、ラス・カサスはアフリカ人奴隷の輸 入と使用を提案した。1517年、スペイン王室は臣民に12人ずつの奴隷の輸入を許可し、植民地でのアフリカ人奴隷貿易が始まった[9]。 歴史家のルイス・M・ディアスによると、アフリカ人奴隷の最大の集団は、現在のガーナ、トーゴ、ベナン、ナイジェリアの地域から来た。大多数はナイジェリ アのヨルバ族とイボ族、そしてギニア湾のバンツー族であった。プエルトリコの奴隷の数は、1530年の1,500人から1555年には15,000人に増 加した。奴隷たちは額に熱い鉄の刻印を押され、これは合法的に入国したことを意味し、誘拐を防ぐための焼印であった[7]。 アフリカ人奴隷は、タイノ人に代わって金鉱で働かされたり、島の生姜産業や砂糖産業で畑仕事に従事させられたりした。彼らは主人の土地にあるボヒオ(小 屋)で家族と一緒に暮らすことが許され、野菜や果物を植えて育てることができる土地を与えられた。アフリカ人には出世のチャンスはほとんどなく、スペイン 人からの差別に直面した。奴隷たちは主人から教育を受け、すぐに主人の言葉を話せるようになり、自分の子供たちにも新しい言葉で教育を施した。彼らは自分 たちの言葉を加えることで、「プエルトリコのスペイン語」を豊かにしていった。スペイン人は、アフリカ人の方がタイノ人よりも融通が利くと考えていた。対 照的に、奴隷たちは自分たちの生活に適応するしかなかった。多くの奴隷は(少なくとも名目上は)キリスト教に改宗し、カトリック教会から洗礼を受け、主人 の姓を与えられた。多くの奴隷は過酷な扱いを受け、女性は性的虐待を受けた。島を開拓したコンキスタドールや農民の大半は女性を持たずに到着した。彼らの 多くはアフリカ人やタイノ族の女性と結婚した。彼らの多人種の子孫が初期のプエルトリコ人の最初の世代を形成した[7]。 1527年、プエルト・リコで最初の大規模な奴隷反乱が起こり、数十人の奴隷が植民者と戦い、短期間の反乱を起こした[10]。 逃げ延びた数人の奴隷は森や山に退却し、そこで生き残ったタイノー族と一緒にマルーンとして居住した。その後数世紀の間に、1873年までに奴隷たちは 20以上の反乱を起こした。中にはポンセやベガ・バハの陰謀のように政治的に重要なものもあった[11]。 1570年までに、入植者たちは金鉱が枯渇していることに気づいた。島での金鉱採掘が終わると、スペイン王室は西の航路を北に移すことでプエルトリコを迂 回させた。島は主に、より豊かな植民地へ向かう船や植民地から向かう船のための駐屯地となった。タバコ、綿花、ココア、ショウガなどの作物栽培が経済の要 となった。プエルトリコの経済規模が縮小したため、植民地の家族はこれらの作物を自分たちで栽培するようになり、奴隷の需要が減少した。[12] 国際市場での砂糖の需要が高まり、主要なプランターは労働集約的なサトウキビの栽培と加工を増やした。砂糖プランテーションはプエルトリコの主要産業とし て鉱業に取って代わり、アフリカ人奴隷の需要を高めた。スペインはプランテーションの所有者に融資と免税を与えることで、サトウキビ開発を促進した。ま た、アフリカ人奴隷貿易への参加許可も与えられた[12]。 より多くの労働者を惹きつけるために、1664年、スペインはジャマイカやサン・ドマング(後のハイチ)など、スペイン以外の植民地出身のアフリカ系住民 に自由と土地を提供した。移民することができた有色人種の自由民のほとんどは、アフリカ系とヨーロッパ系の混血であった(植民地によって父方の祖先がイギ リス系かフランス系であることが一般的)。移民たちはプエルトリコの守備隊とその砦を支える人口基盤を提供した。島の西部と南部に定住した自由民は、すぐ にスペイン人のやり方や習慣を取り入れました。何人かは地元の民兵に加わり、島を侵略しようとしたイギリスと戦いました。西インド諸島から移住してきた逃 亡奴隷や自由民は、元の主人の姓を名乗った。21世紀になっても、アフリカ系プエルトリコ人の中には、これらの移民の子孫であることを証明するために、ス ペイン語以外の姓を名乗る者がいる[7]。 1784年以降、スペインは奴隷の識別のために額に熱い焼印を押すことを停止した[7]: 奴隷は主人によって教会内または教会外で、裁判官の面前で、遺言または書簡によって解放されることができた。 奴隷は、強制強姦を糾弾することによって、偽造者を糾弾することによって、国王に対する不忠誠を発見することによって、主人に対する殺人を糾弾することに よって、主人の意に反して解放されることができた。 主人の遺言で主人の財産の一部を受け取った奴隷は、自動的に解放された(このような遺贈は、主人の混血奴隷の子供や、奉仕のために他の奴隷になされること もあった)。 奴隷が主人の子供たちの後見人になった場合、その奴隷は解放された。 ヒスパニック・アメリカの奴隷の親に10人の子供がいた場合、家族全員が解放された[13]。 |

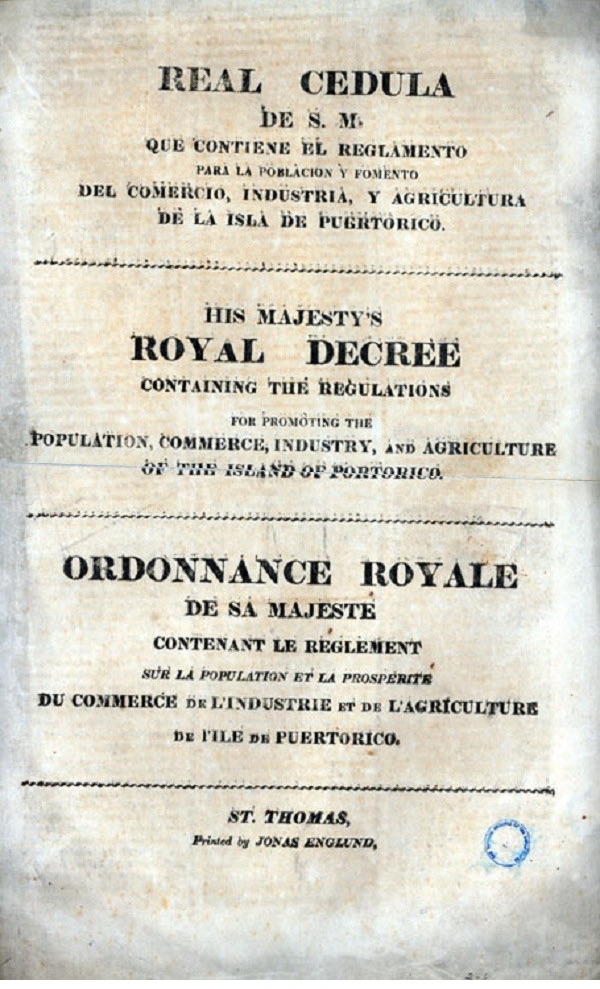

Royal Decree of Graces of 1789  The Royal Decree of Graces of 1789 which set the rules pertaining to the Slaves in Puerto Rico and the Caribbean In 1789, the Spanish Crown issued the "Royal Decree of Graces of 1789", which set new rules related to the slave trade and added restrictions to the granting of freedman status. The decree granted its subjects the right to purchase slaves and to participate in the flourishing slave trade in the Caribbean. Later that year a new slave code, also known as El Código Negro (The Black Code), was introduced.[14] Under "El Código Negro," a slave could buy his freedom, in the event that his master was willing to sell, by paying the price sought. Slaves were allowed to earn money during their spare time by working as shoemakers, cleaning clothes, or selling the produce they grew on their own plots of land. Slaves were able to pay for their freedom by installments. They pay in installments for the freedom of their newborn child, not yet baptized, at a cost of half the going price for a baptized child.[14] Many of these freedmen started settlements in the areas which became known as Cangrejos (Santurce), Carolina, Canóvanas, Loíza, and Luquillo. Some became slave owners themselves.[7] The native-born Puerto Ricans (criollos) who wanted to serve in the regular Spanish army petitioned the Spanish Crown for that right. In 1741, the Spanish government established the Regimiento Fijo de Puerto Rico. Many of the former slaves, now freedmen, joined either the Fijo or the local civil militia. Puerto Ricans of African ancestry played an instrumental role in the defeat of Sir Ralph Abercromby in the British invasion of Puerto Rico in 1797.[15] Despite these paths to freedom, from 1790 onwards, the number of slaves more than doubled in Puerto Rico as a result of the dramatic expansion of the sugar industry in the island. Every aspect of sugar cultivation, harvesting and processing was arduous and harsh. Many slaves died on the sugar plantations.[12] |

1789年勅令  プエルトリコとカリブ海地域の奴隷に関する規則を定めた1789年勅令 1789年、スペイン王室は「1789年勅令」を発布し、奴隷貿易に関する新たな規則を定め、自由民の地位付与に制限を加えた。この勅令は、臣民に奴隷を 購入する権利を与え、カリブ海で盛んに行われていた奴隷貿易に参加させた。その年の暮れには、「エル・コディゴ・ネグロ(黒人の掟)」とも呼ばれる新しい 奴隷法が導入された[14]。 El Código Negro」の下では、奴隷は、主人が売る意思がある場合、要求された価格を支払うことで自由を買うことができた。奴隷は余暇に靴職人や衣服のクリーニン グをしたり、自分の土地で栽培した農産物を売ったりして収入を得ることが許されていた。奴隷は分割払いで自由の代金を支払うことができた。彼らは、まだ洗 礼を受けていない生まれたばかりの子供の自由のために、洗礼を受けた子供の価格の半額を分割で支払った[14]。これらの解放者の多くは、カングレホス (サントゥルセ)、カロリーナ、カノバナス、ロイザ、ルキージョとして知られるようになった地域に入植を始めた。奴隷所有者となった者もいた[7]。 スペイン正規軍への従軍を希望する生粋のプエルトリコ人(クリオージョ)は、その権利をスペイン王室に請願した。1741年、スペイン政府はプエルトリコ 連隊(Regimiento Fijo de Puerto Rico)を設立。自由民となった元奴隷の多くは、フィホまたは地元の市民民兵に参加した。1797年のイギリスによるプエルトリコ侵攻では、アフリカ系 プエルトリコ人がラルフ・アバクロンビー卿の敗北に大きな役割を果たした[15]。 こうした自由への道にもかかわらず、1790年以降、プエルトリコでは砂糖産業が飛躍的に拡大した結果、奴隷の数が2倍以上に増加した。砂糖の栽培、収 穫、加工はあらゆる面で困難で過酷なものだった。多くの奴隷が砂糖プランテーションで死亡した[12]。 |

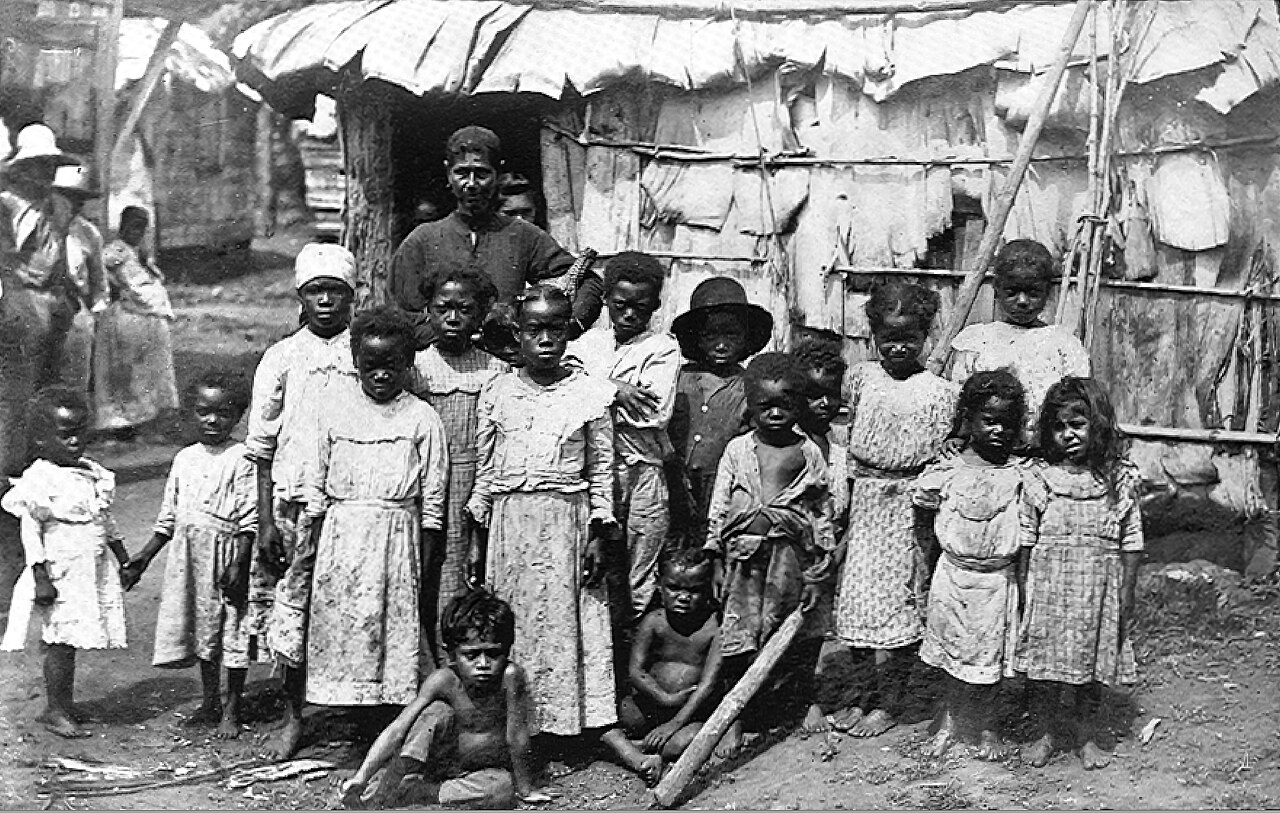

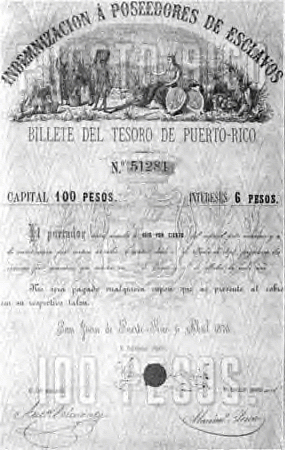

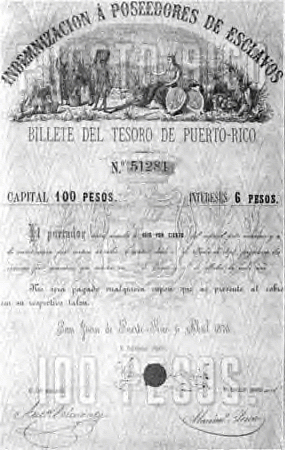

| 19th century Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 "Puerto Rican population in thousands according to Spanish Royal Census" Year White Mixed Free Blacks Slaves 1827 163 100 27 34 1834 189 101 25 42 1847 618 329 258 32 The Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 was intended to encourage Spaniards and later other Europeans to settle and populate the colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico. The decree encouraged the use of slave labor to revive agriculture and attract new settlers. The new agricultural class immigrating from other countries of Europe used slave labor in large numbers, and harsh treatment was frequent. The slaves resisted -from the early 1820s until 1868, a series of slave uprisings occurred on the island; the last was known as the Grito de Lares.[16] In July 1821, for instance, the slave Marcos Xiorro planned and conspired to lead a slave revolt against the sugar plantation owners and the Spanish Colonial government. Although the conspiracy was suppressed, Xiorro achieved legendary status among the slaves, and is part of Puerto Rico's heroic folklore.[17] The 1834 Royal Census of Puerto Rico established that 11% of the population were slaves, 35% were colored freemen (also known as free people of color in French colonies, meaning free mixed-race/black people), and 54% were white.[18] In the following decade, the number of the slave population increased more than tenfold to 258,000, the result mostly of increased importation to meet the demand for labor on sugar plantations. In 1836, the names and descriptions of slaves who had escaped, and details of their ownership were reported in the Gaceta de Puerto Rico. If an African presumed to be a slave was captured and arrested, the information was published.[19] Planters became nervous because of the large number of slaves; they ordered restrictions, particularly on their movements outside a plantation. Rose Clemente, a 21st-century black Puerto Rican columnist, wrote, "Until 1846, Blacks on the island had to carry a notebook (Libreta system) to move around the island, like the passbook system in apartheid South Africa."[20] After the successful slave rebellion against the French in Saint-Domingue (Haiti) in 1803, establishing a new republic, the Spanish Crown became fearful that the "Criollos" (native born) of Puerto Rico and Cuba, her last two remaining possessions, might follow suit. The Spanish government issued the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 to attract European immigrants from non-Spanish countries to populate the island, believing that these new immigrants would be more loyal to Spain than the mixed-race Criollos. However, they did not expect the new immigrants to racially intermarry, as they did, and to identify completely with their new homeland.[13] By 1850, most of the former Spanish possessions in the Americans had achieved independence. On May 31, 1848, the Governor of Puerto Rico Juan Prim, in fear of an independence or slavery revolt, imposed draconian laws, "El Bando contra La Raza Africana", to control the behavior of all Black Puerto Ricans, free or slave.[21] On September 23, 1868, slaves, who had been promised freedom, participated in the short failed revolt against Spain which became known as "El Grito de Lares" or "The Cry of Lares." Many of the participants were imprisoned or executed.[22] During this period, Puerto Rico provided a means for people to leave some of the racial restrictions behind: under such laws as Regla del Sacar or Gracias al Sacar, a person of African ancestry could be considered legally white if able to prove they also had ancestors with at least one person per generation in the last four generations who had been legally white. Therefore, people of black ancestry with known white lineage became classified as white. This was the opposite of the later "one-drop rule" of hypodescent in the United States, whereby persons of any known African ancestry were classified as black.[23] Abolitionists  Peones in Puerto Rico, 1898 During the mid-19th century, a committee of abolitionists was formed in Puerto Rico that included many prominent Puerto Ricans. Dr. Ramón Emeterio Betances (1827–1898), whose mixed-race parents were wealthy landowners, believed in abolitionism, and together with fellow Puerto Rican abolitionist Segundo Ruiz Belvis (1829–1867), founded a clandestine organization called "The Secret Abolitionist Society." The objective of the society was to free slave children by paying for freedom when they were baptized. The event, which was also known as "aguas de libertad" (waters of liberty), was carried out at the Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria Cathedral in Mayagüez. When the child was baptized, Betances would give money to the parents, which they used to buy the child's freedom from the master.[24] José Julián Acosta (1827–1891) was a member of a Puerto Rican commission, which included Ramón Emeterio Betances, Segundo Ruiz Belvis, and Francisco Mariano Quiñones (1830–1908). The commission participated in the "Overseas Information Committee" which met in Madrid, Spain. There, Acosta presented the argument for the abolition of slavery in Puerto Rico.[25] On November 19, 1872, Román Baldorioty de Castro (1822–1889) together with Luis Padial (1832–1879), Julio Vizcarrondo (1830–1889) and the Spanish Minister of Overseas Affairs, Segismundo Moret (1833–1913), presented a proposal for the abolition of slavery. On March 22, 1873, the Spanish government approved what became known as the Moret Law, which provided for gradual abolition.[26] This edict granted freedom to slaves over 60 years of age, those belonging to the state, and children born to slaves after September 17, 1868. The Moret Law established the Central Slave Registrar. In 1872 it began gathering the following data on the island's slave population: name, country of origin, present residence, names of parents, sex, marital status, trade, age, physical description, and master's name. This has been an invaluable resource for historians and genealogists.[27] Abolition of slavery  Indemnity bond paid as compensation to former owners of freed slaves On March 22, 1873, slavery was abolished in Puerto Rico, but with one significant caveat. The slaves were not emancipated; they had to buy their own freedom, at whatever price was set by their last masters. The law required that the former slaves work for another three years for their former masters, other people interested in their services, or for the state in order to pay some compensation.[28] The former slaves earned money in a variety of ways: some by trades, for instance as shoemakers, or laundering clothes, or by selling the produce they were allowed to grow, in the small patches of land allotted to them by their former masters. In a sense, they resembled the black sharecroppers of the southern United States after the American Civil War, but the latter did not own their land. They simply farmed another's land, for a share of the crops raised.[14] The government created the Protector's Office which was in charge of overseeing the transition. The Protector's Office was to pay any difference owed to the former master once the initial contract expired. The majority of the freed slaves continued to work for their former masters, but as free people, receiving wages for their labor.[29] If the former slave decided not to work for his former master, the Protectors Office would pay the former master 23% of the former slave's estimated value, as a form of compensation.[28] The freed slaves became integrated into Puerto Rico's society. Racism has existed in Puerto Rico, but it is not considered to be as severe as other places in the New World, possibly because of the following factors: In the 8th century, nearly all of Spain was conquered (711–718), by the Arab-Berber/African Moors who had crossed over from North Africa. The first African slaves were brought to Spain during Arab domination by North African merchants. By the middle of the 13th century, Christians had reconquered the Iberian peninsula. A section of Seville, which once was a Moorish stronghold, was inhabited by thousands of Africans. Africans became freemen after converting to Christianity, and they lived integrated in Spanish society. African women were highly sought after by Spanish males. Spain's exposure to people of color over the centuries accounted for the positive racial attitudes that prevailed in the New World. Historian Robert Martínez thought it was unsurprising that the first conquistadors intermarried with the native Taíno and later with the African immigrants.[30] The Catholic Church played an instrumental role in preserving the human dignity and working for the social integration of the African man in Puerto Rico. The church insisted that every slave be baptized and converted to the Catholic faith. Church doctrine held that master and slave were equal before the eyes of God, and therefore brothers in Christ with a common moral and religious character. Cruel and unusual punishment of slaves was considered a violation of the fifth commandment.[7] When the gold mines were declared depleted in 1570 and mining came to an end in Puerto Rico, the majority of the white Spanish settlers left the island to seek their fortunes in the richer colonies such as Mexico; the island became a Spanish garrison. The majority of those who stayed behind were either African or mulattoes (of mixed race). By the time Spain reestablished commercial ties with Puerto Rico, the island had a large multiracial population. After the Spanish Crown issued the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815, it attracted many European immigrants, in effect "whitening" the island into the 1850s. But, the new arrivals also intermarried with native islanders, and added to the multiracial population. They also identified with the island, rather than simply with the rulers.[7] Two Puerto Rican writers have written about racism; Abelardo Díaz Alfaro (1916–1999) and Luis Palés Matos (1898–1959), who was credited with creating the poetry genre known as Afro-Antillano.[31] |

19世紀 1815年勅令 「スペイン王室国勢調査によるプエルトリコ人口(単位:千人 年 白人混血 自由黒人 奴隷 1827 163 100 27 34 1834 189 101 25 42 1847 618 329 258 32 1815年の勅令は、スペイン人、後に他のヨーロッパ人がキューバとプエルトリコの植民地に定住し、人口を増やすことを奨励するものであった。この勅令 は、農業を復興させ新規入植者を呼び込むために奴隷労働の利用を奨励した。ヨーロッパの他の国々から移住してきた新しい農業階級は、奴隷労働を大量に使用 し、過酷な扱いが頻繁に行われた。奴隷たちは抵抗し、1820年代初頭から1868年まで、島では奴隷の反乱が相次ぎ、最後の反乱はグリト・デ・ラレスと して知られた[16]。 例えば、1821年7月、奴隷のマルコス・シオロは、砂糖プランテーションの所有者とスペイン植民地政府に対する奴隷の反乱を計画し、共謀した。陰謀は鎮 圧されたが、シオロは奴隷の間で伝説的な地位を獲得し、プエルトリコの英雄的フォークロアの一部となっている[17]。 1834年のプエルトリコ王立国勢調査では、人口の11%が奴隷、35%が有色自由人(フランス植民地では有色人種自由人とも呼ばれ、自由な混血・黒人を 意味する)、54%が白人であった[18]。その後の10年間で、奴隷人口は10倍以上の258,000人に増加したが、これは主に砂糖プランテーション の労働力需要を満たすために輸入が増加した結果であった。 1836年、Gaceta de Puerto Ricoに逃亡した奴隷の名前と説明、所有権の詳細が報告された。奴隷と推定されるアフリカ人が捕らえられ逮捕されると、その情報が公表された[19]。 多くの奴隷がいたため、プランターたちは神経質になり、特にプランテーションの外への移動を制限するように命じた。21世紀のプエルトリコの黒人コラムニ ストであるローズ・クレメンテは、「1846年まで、島の黒人は、アパルトヘイト下の南アフリカの通帳制度のように、島内を移動するために手帳(リブレタ 制度)を携帯しなければならなかった」と書いている[20]。 1803年、サン=ドマング(ハイチ)でフランスに対する奴隷の反乱が成功し、新しい共和制が確立されると、スペイン王室はプエルトリコとキューバの「ク リオロ」(原住民)がそれに追随することを恐れるようになった。スペイン政府は1815年、スペイン以外の国からのヨーロッパ系移民をこの島に呼び込むた め、勅令を発布した。しかし、彼らは新しい移民たちが、彼らのように人種間の婚姻を行い、新しい祖国と完全に同一化するとは思っていなかった。 1848年5月31日、プエルトリコのフアン・プリム知事は、独立や奴隷制の反乱を恐れて、「エル・バンド・コントラ・ラザ・アフリカーナ(El Bando contra La Raza Africana)」と呼ばれる、自由であれ奴隷であれ、すべての黒人プエルトリコ人の行動を統制するための強権的な法律を課した[21]。 1868年9月23日、自由を約束されていた奴隷たちは、「エル・グリト・デ・ラレス」(ラレスの叫び)として知られるようになったスペインに対する反乱 に参加し、短期間で失敗した。参加者の多くは投獄または処刑された[22]。 Regla del SacarやGracias al Sacarなどの法律により、アフリカ系の先祖を持つ人でも、過去4世代に1人以上の先祖が合法的に白人であったことを証明できれば、合法的に白人とみな すことができた。従って、白人の血統を持つ黒人の先祖を持つ人々は、白人に分類されるようになった。これは、後にアメリカにおいて、アフリカ系の祖先が判 明している者はすべて黒人に分類されるという「ワン・ドロップ・ルール」の逆であった[23]。 奴隷廃止論者  プエルトリコのペオンたち、1898年 19世紀半ば、プエルトリコでは多くの著名なプエルトリコ人を含む奴隷廃止論者の委員会が結成された。混血の両親が裕福な地主であったラモン・エメテリ オ・ベタンセス博士(1827年~1898年)は奴隷廃止主義を信じ、同じプエルトリコ人の奴隷廃止論者セグンド・ルイス・ベルヴィス(1829年 ~1867年)と共に、"秘密の奴隷廃止論者協会 "と呼ばれる秘密組織を設立した。この協会の目的は、奴隷の子供たちが洗礼を受ける際に自由を代償に解放することだった。マヤグエスのヌエストラ・セ ニョーラ・デ・ラ・カンデラリア大聖堂で行われたこの行事は、「自由の水(aguas de libertad)」とも呼ばれた。子供が洗礼を受けると、ベタンセスは両親に金を渡し、両親はその金で子供の自由を主人から買い取った[24]。 ホセ・フリアン・アコスタ(1827年~1891年)は、ラモン・エメテリオ・ベタンセス、セグンド・ルイス・ベルヴィス、フランシスコ・マリアーノ・キ ニョネス(1830年~1908年)を含むプエルトリコ委員会のメンバーであった。この委員会は、スペインのマドリードで開催された「海外情報委員会」に 参加した。1872年11月19日、ロマン・バルドリオティ・デ・カストロ(1822年-1889年)はルイス・パディアル(1832年-1879年)、 フリオ・ビスカロンド(1830年-1889年)、スペインの海外担当大臣セギスムンド・モレ(1833年-1913年)とともに奴隷制度廃止の提案を 行った。 1873年3月22日、スペイン政府は段階的廃止を定めたモレ法として知られるものを承認した[26]。この勅令は、60歳以上の奴隷、国家に属する奴 隷、1868年9月17日以降に奴隷から生まれた子供に自由を認めた。 モレ法は中央奴隷登録所を設立した。1872年、中央奴隷登録局は、島の奴隷の名前、出身国、現在の居住地、両親の名前、性別、婚姻状況、職業、年齢、身 体的特徴、主人の名前といったデータの収集を開始した。これは歴史家や系図学者にとって貴重な資料となっている[27]。 奴隷制度の廃止  解放された奴隷の元所有者への補償として支払われた賠償保証金 1873年3月22日、プエルトリコでは奴隷制度が廃止されたが、1つ重大な注意事項があった。奴隷は解放されたのではなく、最後の主人によって決められ た値段で、自らの自由を買わなければならなかった。法律では、元奴隷は、元主人、彼らの奉仕に関心を持つ他の人々、または国家に対して、いくらかの補償金 を支払うために、さらに3年間働くことが要求された[28]。 元奴隷たちは様々な方法でお金を稼いだ。例えば、靴職人や衣服の洗濯などの商売をしたり、元主人から割り当てられた小さな土地で栽培を許された農産物を 売ったりした。ある意味では、南北戦争後のアメリカ南部の黒人小作人に似ているが、後者は土地を所有していなかった。政府はこの移行を監督するために、保 護官事務所を設置した。護民官事務所は、最初の契約が満了すると、元の主人に支払うべき差額を支払うことになっていた。 解放された奴隷の大半は、元の主人のもとで働き続けたが、自由人として労働の賃金を受け取った[29]。元奴隷が元の主人のもとで働かないことを決めた場 合、保護官事務所は、補償の一形態として、元奴隷の推定価値の23%を元主人に支払うことになった[28]。 解放された奴隷はプエルトリコの社会に溶け込むようになった。プエルトリコにも人種差別は存在したが、新世界の他の地域ほど深刻ではないと考えられてい る: 8世紀、北アフリカから渡ってきたアラブ系ベルベル人/アフリカ系ムーア人によって、スペインのほぼ全土が征服された(711-718年)。最初のアフリ カ人奴隷は、北アフリカの商人によってアラブ支配下のスペインに連れてこられた。13世紀半ばには、キリスト教徒がイベリア半島を再征服した。かつてムー ア人の拠点だったセビリアの一角には、何千人ものアフリカ人が住んでいた。アフリカ人はキリスト教に改宗して自由民となり、スペイン社会に溶け込んで暮ら した。アフリカ人女性は、スペイン人男性から強く求められた。スペインが何世紀にもわたって有色人種に接してきたことが、新大陸に蔓延した肯定的な人種意 識を形成したのだ。歴史家ロバート・マルティネスは、最初の征服者が先住民のタイノ族と、後にアフリカ系移民と結婚したのは当然だと考えた[30]。 カトリック教会は、人間の尊厳を守り、プエルトリコにおけるアフリカ人の社会的統合のために重要な役割を果たした。教会は、すべての奴隷が洗礼を受け、カ トリックの信仰に改宗することを主張した。教会の教義では、主人と奴隷は神の目には平等であり、したがって共通の道徳的・宗教的性格を持つキリストにおけ る兄弟であるとされた。奴隷に対する残酷で異常な刑罰は、第五戒に違反すると考えられていた[7]。 1570年に金鉱の枯渇が宣言され、プエルトリコでの採掘が終了すると、スペイン系白人入植者の大半はメキシコなどの豊かな植民地に財産を求めて島を去 り、島はスペインの駐屯地となった。島はスペインの駐屯地となった。島に残った大多数はアフリカ系か混血だった。スペインがプエルトリコとの商業的関係を 回復する頃には、島には多くの多民族が住んでいた。スペイン王室が1815年に勅令を発布すると、多くのヨーロッパからの移民が集まり、事実上1850年 代まで島は「美白」された。しかし、新しくやってきた人々は、島の先住民とも結婚し、多民族に拍車をかけた。彼らはまた、単に支配者とではなく、島と同一 視した[7]。 アベラルド・ディアス・アルファロ(1916年-1999年)とルイス・パレス・マトス(1898年-1959年)は、アフロ・アンティリャーノとして知 られる詩のジャンルを創始したとされている[31]。 |

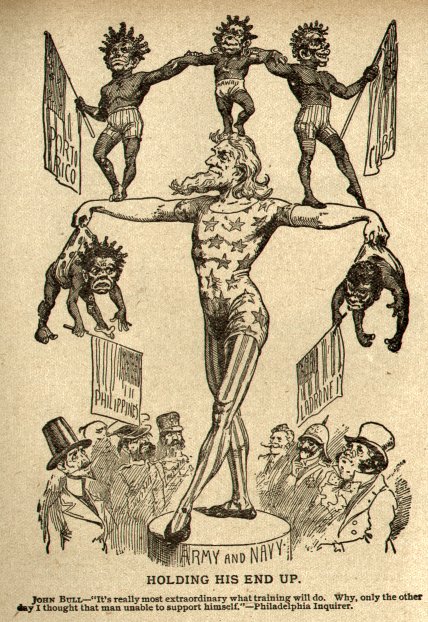

Spanish–American War In a 1899, newspaper cartoon the people of Puerto Rico as well as the people of the new possessions of the United States were depicted as black savage children. The Treaty of Paris of 1898 settled the Spanish–American War, which ended the centuries-long Spanish control over Puerto Rico. Like with other former Spanish colonies, it now belonged to the United States.[32][33] With the United States control over the island's institutions also came a reduction of the natives' political participation. In effect, the U.S. military government defeated the success of decades of negotiations for political autonomy between Puerto Rico's political class and Madrid's colonial administration.[34] Puerto Ricans of African descent, aware of the opportunities and difficulties for blacks in the United States, responded in various ways. The racial bigotry of the Jim Crow Laws stood in contrast to the African American expansion of mobility that the Harlem Renaissance illustrated.[35][36] One Puerto Rican politician of African descent who distinguished himself during this period was the physician and politician José Celso Barbosa (1857–1921). On July 4, 1899, he founded the pro-statehood Puerto Rican Republican Party and became known as the "Father of the Statehood for Puerto Rico" movement. Another distinguished Puerto Rican of African descent, who advocated Puerto Rico's independence, was Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (1874–1938). After emigrating to New York City in the United States, he amassed an extensive collection in preserving manuscripts and other materials of black Americans and the African diaspora. He is considered by some to be the "Father of Black History" in the United States, and a major study center and collection of the New York Public Library is named for him, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. He coined the term Afroborincano, meaning African-Puerto Rican.[37] |

米西戦争 1899年の新聞漫画では、プエルトリコの人々だけでなく、アメリカの新領土の人々も黒人の野蛮な子供として描かれていた。 1898年のパリ条約により米西戦争は終結し、数世紀にわたるスペインのプエルトリコ支配は終結した。他のスペインの旧植民地と同様に、プエルトリコはア メリカのものとなった[32][33]。事実上、アメリカ軍政は、プエルトリコの政治階級とマドリードの植民地政権との間の数十年にわたる政治的自治のた めの交渉の成功を打ち破ったのである[34]。アフリカ系のプエルトリコ人は、アメリカにおける黒人の機会と困難を認識しており、様々な方法で対応した。 ジム・クロウ法の人種偏見は、ハーレム・ルネッサンスが示したアフリカ系アメリカ人の移動の拡大とは対照的であった[35][36]。 この時期に頭角を現したアフリカ系プエルトリコ人の政治家の一人は、医師であり政治家であったホセ・セルソ・バルボサ(1857-1921)であった。 1899年7月4日、彼は国有化推進派のプエルトリコ共和党を設立し、「プエルトリコの国有化の父」運動として知られるようになった。プエルトリコの独立 を主張したアフリカ系プエルトリコ人のもう一人の著名人はアルトゥーロ・アルフォンソ・ションバーグ(1874-1938)である。彼はアメリカのニュー ヨークに移住した後、アメリカ黒人やアフリカン・ディアスポラに関する写本やその他の資料を保存し、膨大なコレクションを集めた。アメリカにおける「黒人 史の父」とも言われ、ニューヨーク市立図書館の主要な研究センターやコレクションは、彼の名を冠した「ションバーグ黒人文化研究センター」と名付けられて いる。彼はアフリカ系プエルトリコ人を意味するアフロボリンカーノという言葉を作った[37]。 |

| Discrimination Lieutenant Pedro Albizu Campos (U.S. Army) After the United States Congress approved the Jones Act of 1917, Puerto Ricans were granted US citizenship. As citizens Puerto Ricans were eligible for the military draft, and many were drafted into the armed forces of the United States during World War I. The armed forces were segregated until after World War II. Puerto Ricans of African descent were subject to the discrimination which was rampant in the military and the U.S.[38] Black Puerto Ricans residing in the mainland United States were assigned to all-black units. Rafael Hernández (1892–1965) and his brother Jesus, along with 16 more Puerto Ricans, were recruited by Jazz bandleader James Reese Europe to join the United States Army's Orchestra Europe. They were assigned to the 369th Infantry Regiment, an African-American regiment; it gained fame during World War I and was nicknamed "The Harlem Hell Fighters" by the Germans.[39][40] The United States also segregated military units in Puerto Rico. Pedro Albizu Campos (1891–1965), who later became the leader of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, held the rank of lieutenant. He founded the "Home Guard" unit of Ponce and was later assigned to the 375th Infantry Regiment, an all-black Puerto Rican regiment, which was stationed in Puerto Rico and never saw combat. Albizu Campos later said that the discrimination which he witnessed in the Armed Forces, influenced the development of his political beliefs.[41] Puerto Ricans of African descent were discriminated against in sports. Puerto Ricans who were dark-skinned and wanted to play Major League Baseball in the United States, were not allowed to do so. In 1892 organized baseball had codified a color line, barring African-American players, and any player who was dark-skinned, from any country.[42] Ethnic African-Puerto Ricans continued to play baseball. In 1928, Emilio "Millito" Navarro traveled to New York City and became the first Puerto Rican to play baseball in the Negro leagues when he joined the Cuban Stars.[43] [44] He was later followed by others such as Francisco Coimbre, who also played for the Cuban Stars. The persistence of these men paved the way for the likes of Baseball Hall of Famers Roberto Clemente and Orlando Cepeda, who played in the Major Leagues after the colorline was broken by Jackie Robinson of the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947; they were inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame for their achievements. Cepeda's father Pedro Cepeda, was denied a shot at the major leagues because of his color. Pedro Cepeda was one of the greatest players of his generation, the dominant hitter in the Professional Baseball League of Puerto Rico after its founding in 1938. He refused to play in the Negro leagues due to his abhorrence of the racism endemic to the segregated United States.[45]  Juan Evangelista Venegas Black Puerto Ricans also participated in other sports as international contestants. In 1917, Nero Chen became the first Puerto Rican boxer to gain international recognition when he fought against (Panama) Joe Gan at the "Palace Casino" in New York.[46] In the 1948 Summer Olympics (the XIV Olympics), celebrated in London, boxer Juan Evangelista Venegas made sports history by becoming Puerto Rico's first Olympic medal winner when he beat Belgium's representative, Callenboat, on points for a unanimous decision. He won the bronze medal in boxing in the Bantamweight division.[47] The event was also historic because it was the first time that Puerto Rico had participated as a nation in an international sporting event. It was common for impoverished Puerto Ricans to use boxing as a way to earn an income. On March 30, 1965, José "Chegui" Torres defeated Willie Pastrano by technical knockout and won the World Boxing Council and World Boxing Association light heavyweight championships. He became the third Puerto Rican and the first one of African descent to win a professional world championship.[48] Among those who exposed the racism and discrimination in the US which Puerto Ricans, especially Black Puerto Ricans, were subject to, was Jesús Colón. Colón is considered by many as the "Father of the Nuyorican movement." He recounted his experiences in New York as a Black Puerto Rican in his book Lo que el pueblo me dice--: crónicas de la colonia puertorriqueña en Nueva York (What the people tell me---: Chronicles of the Puerto Rican colony in New York).[49] Critics of discrimination say that a majority of Puerto Ricans are racially mixed, but that they do not feel the need to identify as such. They argue that Puerto Ricans tend to assume that they are of Black African, American Indian, and European ancestry and only identify themselves as "mixed" only if they have parents who appear to be of distinctly different "races". Puerto Rico underwent a "whitening" process while under U.S. rule. There was a dramatic change in the numbers of people who were classified as "black" and "white" Puerto Ricans in the 1920 census, as compared to that in 1910. The numbers classified as "Black" declined sharply from one census to another (within 10 years' time). Historians suggest that more Puerto Ricans classified others as white because it was advantageous to do so at that time. In those years, census takers were generally the ones to enter the racial classification. Due to the power of Southern white Democrats, the US Census dropped the category of mulatto or mixed race in the 1930 census, enforcing the artificial binary classification of black and white. Census respondents were not allowed to choose their own classifications until the late 20th and early 21st centuries. It may have been that it was popularly thought it would be easier to advance economically and socially with the US if one were "white".[50] |

差別 ペドロ・アルビズ・カンポス中尉(アメリカ陸軍) 米国議会が1917年のジョーンズ法を承認した後、プエルトリコ人は米国市民権を与えられた。市民であるプエルトリコ人は徴兵される資格があり、第一次世 界大戦中、多くがアメリカ軍に徴兵された。アフリカ系のプエルトリコ人は、軍や米国で横行していた差別の対象となった[38]。 米国本土に居住する黒人プエルトリコ人は、黒人部隊に配属された。ラファエル・エルナンデス(1892年~1965年)と弟のジーザスは、さらに16人の プエルトリコ人と共に、ジャズバンドリーダーのジェームス・リース・ヨーロッパにスカウトされ、アメリカ陸軍のオーケストラ・ヨーロッパに参加した。彼ら はアフリカ系アメリカ人連隊である第369歩兵連隊に配属され、第一次世界大戦中に名声を博し、ドイツ軍からは「ハーレムの地獄の戦士たち」というニック ネームで呼ばれた[39][40]。 アメリカはプエルトリコでも軍隊を隔離していた。後にプエルトリコ民族主義党の指導者となるペドロ・アルビズ・カンポス(1891年-1965年)は中尉 の階級にあった。彼はポンセの「ホームガード」部隊を創設し、後にプエルトリコに駐屯していた黒人だけの歩兵第375連隊に配属されたが、戦闘に遭遇する ことはなかった。アルビズ・カンポスは後に、軍隊で目の当たりにした差別が彼の政治的信条の形成に影響を与えたと語った[41]。 アフリカ系のプエルトリコ人はスポーツで差別された。肌の黒いプエルトリコ人がアメリカのメジャーリーグでプレーすることは許されなかった。1892年、 組織化された野球はカラーラインを成文化し、アフリカ系アメリカ人選手や肌の黒い選手をどの国からも追放した[42]。1928年、エミリオ・"ミリト "・ナバーロはニューヨークに渡り、キューバ・スターズに入団してニグロリーグで野球をプレーした最初のプエルトリコ人となった[43] [44] 。 1947年にブルックリン・ドジャースのジャッキー・ロビンソンによってカラーラインが破られた後、メジャーリーグでプレーした野球殿堂入りのロベルト・ クレメンテやオーランド・セペダのような選手への道を開いたのは、こうした男たちの執念であった。セペダの父ペドロ・セペダは、肌の色が理由でメジャー リーグ入りを拒否された。ペドロ・セペダは同世代で最も偉大な選手の一人であり、1938年に設立されたプエルトリコのプロ野球リーグでは圧倒的な打者 だった。彼は、隔離されたアメリカに蔓延する人種差別を忌み嫌い、ニグロリーグでのプレーを拒否した[45]。  フアン・エヴァンジェリスタ・ベネガス 黒人プエルトリコ人は、国際的な出場者として他のスポーツにも参加した。1917年、ネロ・チェンはニューヨークの「パレス・カジノ」で(パナマの) ジョー・ガンと対戦し、国際的に認められた最初のプエルトリコ人ボクサーとなった[46]。1948年、ロンドンで開催された夏季オリンピック(第14回 オリンピック)で、ボクサーのフアン・エバンゲリスタ・ベネガスは、ベルギー代表のカレンボートをポイント制で下し、満場一致の判定でプエルトリコ初のオ リンピックメダル獲得者となり、スポーツの歴史に名を刻んだ。彼は、ボクシングのバンタム級で銅メダルを獲得した[47]。このイベントは、プエルトリコ が国家として初めて国際的なスポーツ・イベントに参加したという点でも歴史的なものであった。貧困にあえぐプエルトリコ人が収入を得る手段としてボクシング を利用するのは一般的なことであった。 1965年3月30日、ホセ・チェギ・トーレスはウィリー・パストラーノをテクニカル・ノックアウトで破り、世界ボクシング評議会と世界ボクシング協会の ライトヘビー級チャンピオンに輝いた。彼はプエルトリコ人で3人目、アフリカ系で初めてプロの世界チャンピオンになった[48]。 プエルトリコ人、特に黒人プエルトリコ人が受けていたアメリカでの人種差別と差別を暴露した人物の中に、ヘスス・コロンがいた。コロンは "ヌヨリカン運動の父 "として多くの人に知られている。彼は著書『Lo que el pueblo me dice--: crónicas de la colonia puertorriqueña en Nueva York(人々が私に語ること---: Chronicles of the Puerto Rican colony in New York)である[49]。 差別を批評する人々は、プエルトリコ人の大多数は人種的に混血であるが、そうである必要性を感じていないと言う。彼らは、プエルトリコ人は自分たちが黒人 アフリカ人、アメリカン・インディアン、ヨーロッパ人の祖先を持っていると思い込む傾向があり、両親が明らかに異なる「人種」であると思われる場合にの み、自分たちを「混血」であると認識すると主張する。プエルトリコは、米国の統治下にある間に「白人化」のプロセスを経た。1920年の国勢調査で「黒 人」と「白人」に分類されたプエルトリコ人の数は、1910年と比較して劇的に変化した。黒人」に分類される人数は、国勢調査ごとに(10年以内に)急激 に減少した。歴史家は、当時はそうすることが有利であったため、より多くのプエルトリコ人が他人を白人と分類したと示唆している。当時の国勢調査では、人 種分類を記入するのは一般的に調査員であった。南部の白人民主党の力により、米国国勢調査は1930年の国勢調査で混血または混血というカテゴリーを削除 し、黒人と白人という人為的な二元分類を強制した。20世紀後半から21世紀初頭まで、国勢調査の回答者が自分の分類を選ぶことは許されなかった。それ は、「白人」であった方が経済的・社会的に米国に進出しやすいと一般的に考えられていたからかもしれない[50]。 |

African influence in Puerto

Rican culture Masks in the African collection of the Museo de las Americas in San Juan, Puerto Rico The descendants of the former slaves became instrumental in the development of Puerto Rico's political, economic and cultural structure. They overcame many obstacles and have contributed to the island's entertainment, sports, literature and scientific institutions. Their contributions and heritage can still be felt today in Puerto Rico's art, music, cuisine, and religious beliefs in everyday life.[51] In Puerto Rico, March 22 is known as "Abolition Day" and it is a holiday celebrated by those who live in the island.[52] The Spanish's limited focus on assimilating the black population, and maroon communities established from slave plantations, contributed to the majority African influence in black Puerto Rican culture.[53] High amounts of interracial marriage and reproducing, since the 1500s, is the reason why the majority of Puerto Ricans are mixed-race European, African, Taino, but only a small number are of predominant or full African ancestry.[54]  African Collection at the Museo de las Americas in San Juan, Puerto Rico The first black people in the island came alongside European colonists as workers from Spain and Portugal known as Ladinos.[55][56] During the 1500s, the slaves that Spain imported to Puerto Rico and most of its other colonies, were mainly from the Upper Guinea region.[57] However, in the 1600s and 1700s, Spain imported large numbers of slaves from Lower Guinea and the Congo.[58] According to various DNA studies, majority of the African ancestry among black and mixed-race Puerto Ricans comes from a few tribes such as the Wolof, Mandinka, Dahomey, Yoruba, Igbo, and Congolese, correlating to the modern-day countries of Senegal, Mali, Benin, Nigeria, and Angola.[59][60][61] Slaves came from all parts of the western coast of Africa, from Senegal to Angola. The Yoruba and Congolese made the most notable impacts to Puerto Rican culture.[62] There's been evidence of intercolonial migration between Puerto Rico and its neighbors during the 1700s and 1800s, which consisted of migration of free blacks and purchases of slaves from neighboring islands.[63] Language Many African slaves imported to Cuba and Puerto Rico spoke "Bozal" Spanish, a Creole language that was Spanish-based, with Congolese and Portuguese influence.[64] Although Bozal Spanish became extinct in the nineteenth century, the African influence in the Spanish spoken in the island is still evident in the many Kongo words that have become a permanent part of Puerto Rican Spanish.[65] |

プエルトリコ文化におけるアフリカの影響 プエルトリコ、サンフアンにあるMuseo de las Americasのアフリカン・コレクションのマスク 元奴隷の子孫は、プエルトリコの政治、経済、文化構造の発展に貢献しました。彼らは多くの障害を乗り越え、島の娯楽、スポーツ、文学、科学機関に貢献して きた。彼らの貢献と遺産は、今日でもプエルトリコの芸術、音楽、料理、日常生活における宗教的信仰に感じることができる[51]。プエルトリコでは、3月 22日は「アボリション・デー」として知られ、島に住む人々によって祝われる祝日となっている。 [1500年代以降、異人種間の結婚や繁殖が盛んに行われたことが、プエルトリコ人の大多数がヨーロッパ系、アフリカ系、タイノ系の混血である理由である が、アフリカ系の祖先を持つ者は少数である[54]。  プエルトリコ、サンフアンのアメリカ博物館のアフリカン・コレクション 1500年代、スペインがプエルトリコとそのほかの植民地のほとんどに輸入した奴隷は、主に上部ギニア地域出身であった[57]。 しかし、1600年代から1700年代にかけて、スペインは下部ギニアとコンゴから大量の奴隷を輸入した。 [58]様々なDNA研究によると、黒人および混血プエルトリコ人のアフリカ系祖先の大部分は、ウォロフ族、マンディンカ族、ダホメー族、ヨルバ族、イボ 族、コンゴ族など、現代のセネガル、マリ、ベナン、ナイジェリア、アンゴラ諸国に関連するいくつかの部族に由来する[59][60][61]。ヨルバ人と コンゴ人がプエルトリコの文化に最も顕著な影響を与えた[62]。1700年代から1800年代にかけて、プエルトリコと近隣諸国との間に自由黒人の移住 と近隣の島からの奴隷の購入からなる植民地間移動の証拠がある[63]。 言語 キューバとプエルトリコに輸入された多くのアフリカ人奴隷は、スペイン語をベースにコンゴとポルトガルの影響を受けたクレオール言語である「ボザール」ス ペイン語を話していた[64]。ボザールスペイン語は19世紀に絶滅したが、島で話されているスペイン語におけるアフリカの影響は、プエルトリコのスペイ ン語の永久的な一部となった多くのコンゴ語にまだ現れている[65]。 |

| Music Puerto Rican musical instruments such as barriles, drums with stretched animal skin, and Puerto Rican music-dance forms such as Bomba or Plena are likewise rooted in Africa. Bomba represents the strong African influence in Puerto Rico. Bomba is a music, rhythm and dance that was brought by West African slaves to the island.[66] Plena is another form of folkloric music of African origin. Plena was brought to Ponce by blacks who immigrated north from the English-speaking islands south of Puerto Rico. Plena is a rhythm that is clearly African and very similar to Calypso, Soca and Dance hall music from Trinidad and Jamaica.[67] Bomba and Plena were played during the festival of Santiago (St. James), since slaves were not allowed to worship their own gods. Bomba and Plena evolved into countless styles based on the kind of dance intended to be used. These included leró, yubá, cunyá, babú and belén. The slaves celebrated baptisms, weddings, and births with the "bailes de bomba". Slaveowners, for fear of a rebellion, allowed the dances on Sundays. The women dancers would mimic and poke fun at the slave owners. Masks were and still are worn to ward off evil spirits and pirates. One of the most popular masked characters is the Vejigante (vey-hee-GANT-eh). The Vejigante is a mischievous character and the main character in the Carnivals of Puerto Rico.[68] Until 1953, Bomba and Plena were virtually unknown outside Puerto Rico. Island musicians Rafael Cortijo (1928–1982), Ismael Rivera (1931–1987) and the El Conjunto Monterrey orchestra introduced Bomba and Plena to the rest of the world. What Rafael Cortijo did with his orchestra was to modernize the Puerto Rican folkloric rhythms with the use of piano, bass, saxophones, trumpets, and other percussion instruments such as timbales, bongos, and replace the typical barriles (skin covered barrels) with congas.[69] |

音楽 バリレス(動物の皮を伸ばした太鼓)のようなプエルトリコの楽器や、ボンバやプレナのようなプエルトリコの音楽舞踊の形式も同様にアフリカに根ざしてい る。ボンバはプエルトリコにおけるアフリカの強い影響を象徴している。ボンバは西アフリカの奴隷が島に持ち込んだ音楽、リズム、ダンスである[66]。 プレナもアフリカ起源の民族音楽の一つである。プレナは、プエルトリコの南にある英語圏の島々から北に移住してきた黒人たちによってポンセにもたらされ た。プレナは明らかにアフリカ的なリズムで、トリニダードやジャマイカのカリプソ、ソカ、ダンスホール音楽と非常によく似ている[67]。 ボンバとプレナはサンティアゴ(聖ヤコブ)の祭りで演奏された。ボンバとプレナは、踊りの種類に応じて無数のスタイルに進化した。レロ、ユバ、クニャ、バ ブー、ベレンなどである。奴隷たちは洗礼、結婚式、出産を「バイレ・デ・ボンバ」で祝った。奴隷主は反乱を恐れて、日曜日に踊ることを許可した。女性ダン サーたちは、奴隷所有者の真似をしたり、からかったりした。仮面は、悪霊や海賊を追い払うために昔も今も着用されている。最も人気のある仮面のキャラク ターのひとつがヴェヒガンテ(vey-hee-GANT-eh)である。ベヒガンテはいたずら好きなキャラクターで、プエルトリコのカーニバルのメイン キャラクターである[68]。 1953年まで、ボンバとプレナはプエルトリコ以外ではほとんど知られていなかった。島の音楽家ラファエル・コルティージョ(1928-1982)、イス マエル・リベラ(1931-1987)、エル・コンジュント・モンテレイ楽団は、ボンバとプレナを世界に広めた。ラファエル・コルティージョが彼のオーケ ストラで行ったことは、ピアノ、ベース、サックス、トランペット、そしてティンバレス、ボンゴなどの打楽器を使用し、典型的なバリレス(皮で覆われた樽) をコンガに置き換えることで、プエルトリコの民俗的なリズムを現代化することであった[69]。 |

Cuisine Plantain "arañitas" & "tostones rellenos" Nydia Rios de Colon, a contributor to the Smithsonian Folklife Cookbook, also offers culinary seminars through the Puerto Rican Cultural Institute. She writes of the cuisine: Puerto Rican cuisine also has a strong African influence. The melange of flavors that make up the typical Puerto Rican cuisine counts with the African touch. Pasteles, small bundles of meat stuffed into a dough made of grated green banana (sometimes combined with pumpkin, potatoes, plantains, or yautía) and wrapped in plantain leaves, were devised by African women on the island and based upon food products that originated in Africa."—Nydia Rios de Colon, Arts Publications Similarly, Johnny Irizarry and Maria Mills have written: "The salmorejo, a local land crab creation, resembles Southern cooking in the United States with its spicing. The mofongo, one of the island's best-known dishes, is a ball of fried mashed plantain stuffed with pork crackling, crab, lobster, shrimp, or a combination of all of them. Puerto Rico's cuisine embraces its African roots, weaving them into its Indian and Spanish influences."[70][71] |

料理 プランテン "アラニータス "と "トストネス・レレノス" スミソニアン・フォークライフ・クックブックの寄稿者であるニディア・リオス・デ・コロンは、プエルトリコ文化研究所を通じて料理セミナーも開催してい る。彼女は料理についてこう書いている: プエルトリコ料理はアフリカの影響も強く受けています。典型的なプエルトリコ料理を構成する味のメランジは、アフリカン・タッチで数えられています。パス テールとは、すりおろした青バナナ(カボチャ、ジャガイモ、オオバコ、ヤウティアと組み合わせることもある)で作った生地に肉を詰め、オオバコの葉で包ん だ小さな束のことで、この島のアフリカ人女性たちによって考案され、アフリカ発祥の食品をベースにしている」-ニディア・リオス・デ・コロン、アーツ出版 社 同様に、ジョニー・イリザリーとマリア・ミルズはこう書いている: 「地元の陸ガニの創作料理であるサルモレホは、そのスパイス使いがアメリカ南部料理に似ている。島で最も有名な料理のひとつであるモフォンゴは、豚のひび 割れ肉、カニ、ロブスター、エビ、またはそれらの組み合わせが詰まった、揚げたマッシュプラタナスのボールである。プエルトリコの料理はアフリカのルーツ を受け入れ、インドやスペインの影響を織り交ぜている」[70][71]。 |

| Religion In 1478, the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, established an ecclesiastical tribunal known as the Spanish Inquisition. It was intended to maintain Catholic orthodoxy in their kingdoms.[72] The Inquisition maintained no rota or religious court in Puerto Rico. However, heretics were written up and if necessary remanded to regional Inquisitional tribunals in Spain or elsewhere in the western hemisphere. Africans were not allowed to practice non-Christian, native religious beliefs. No single organized ethnic African religion survived intact from the times of slavery to the present in Puerto Rico. But, many elements of African spiritual beliefs have been incorporated into syncretic ideas and practices. Santería, a Yoruba-Catholic syncretic mix, and Palo Mayombe, Kongolese traditions, are also practiced in Puerto Rico, the latter having arrived there at a much earlier time. A smaller number of people practice Vudú, which is derived from Dahomey mythology.[73] Palo Mayombe, or Congolese traditions, existed for several centuries before Santería developed during the 19th century. Guayama became nicknamed "the city of witches", because the religion was widely practiced in this town. Santeria is believed to have been organized in Cuba among its slaves. The Yoruba were brought to many places in the Caribbean and Latin America. They carried their traditions with them, and in some places, they held onto more of them. In Puerto Rico and Trinidad Christianity was dominant. Although converted to Christianity, the captured Africans did not abandon their traditional religious practices altogether. Santería is a syncretic religion created between the diverse images drawn from the Catholic Church and the representational deities of the African Yoruba ethnic group of Nigeria. Santería is widely practiced in the town of Loíza.[74] Sister traditions emerged in their own particular ways on many of the smaller islands. Similarly, throughout Europe, early Christianity absorbed influences from differing practices among the peoples, which varied considerably according to region, language and ethnicity. Santería has many deities said to be the "top" or "head" God. These deities, which are said to have descended from heaven to help and console their followers, are known as "Orishas." According to Santería, the Orishas are the ones who choose the person each will watch over.[75] Unlike other religions where a worshiper is closely identified with a sect (such as Christianity), the worshiper is not always a "Santero". Santeros are the priests and the only official practitioners. (These "Santeros" are not to be confused with the Puerto Rico's craftsmen who carve and create religious statues from wood, which are also called Santeros). A person becomes a Santero if he passes certain tests and has been chosen by the Orishas.[74] |

宗教 1478年、スペインのカトリック君主であるアラゴンのフェルディナンド2世とカスティーリャのイザベラ1世は、スペイン異端審問所として知られる教会法 廷を設立した。これは彼らの王国におけるカトリックの正統性を維持することを目的としていた[72]。 異端審問所はプエルトリコにはロタや宗教法廷を置かなかった。しかし、異端者は書面に記録され、必要であればスペインや西半球の他の地域の異端審問所に送 還された。アフリカ人はキリスト教以外の土着の宗教的信仰を実践することは許されませんでした。プエルトリコでは、奴隷時代から現在に至るまで、単一の組 織化されたアフリカ民族宗教がそのまま存続しているわけではありません。しかし、アフリカのスピリチュアルな信仰の多くの要素が、シンクレティックの思想 や実践に取り入れられてきた。ヨルバとカソリックの混血であるサンテリアや、コンゴの伝統であるパロ・マヨンベもプエルトリコで信仰されていますが、後者 はもっと早い時期にプエルトリコに伝わりました。ダホメイの神話に由来するヴドゥを実践する人々の数は少ない[73]。 パロ・マヨンベ(コンゴの伝統)は、19世紀にサンテリアが発展する以前から数世紀にわたって存在していた。グアヤマは、この宗教がこの町で広く行われて いたことから、「魔女の町」というニックネームで呼ばれるようになった。サンテリアはキューバの奴隷の間で組織されたと考えられている。ヨルバ人はカリブ 海やラテンアメリカの多くの場所に連れてこられた。彼らは自分たちの伝統を持ち運び、場所によってはより多くの伝統を保持した。プエルトリコとトリニダー ドではキリスト教が支配的だった。キリスト教に改宗したとはいえ、捕らえられたアフリカ人は伝統的な宗教的慣習を完全に捨てたわけではなかった。サンテリ アは、カトリック教会から引き出された多様なイメージと、ナイジェリアのアフリカ系ヨルバ民族の代表的な神々の間に生まれたシンクレティックな宗教であ る。サンテリアはロイザの町で広く信仰されている[74]。多くの小さな島々でも、姉妹的な伝統が独自の方法で生まれた。同様に、ヨーロッパ全土で、初期 キリスト教は、地域、言語、民族によってかなり異なる民族間の異なる慣習から影響を吸収した。 サンテリアには、「頂点」または「頭」の神と言われる多くの神々がいる。これらの神々は、信者たちを助け慰めるために天から降りてきたと言われ、"オリ シャ "として知られている。サンテリアによれば、オリシャはそれぞれが見守る人を選ぶ存在である[75]。 参拝者が宗派と密接に関係している他の宗教(キリスト教など)とは異なり、参拝者は必ずしも「サンテーロ」ではない。サンテロは司祭であり、唯一の正式な 修行者である。(この「サンテロ」は、宗教的な彫像を木彫りで作るプエルトリコの職人と混同してはならない。) ある一定のテストに合格し、オリシャに選ばれた者がサンテロとなる[74]。 |

| Current demographics Considering the 2020 Census is the first to allow respondents to apply multiple races in their responses, there is considerable overlap that while appearing contradictory is in reality reflective of Puerto Rico's mixed history and population. As of the 2020 Census, 17.1% of Puerto Ricans identify as white, 17.5% identify as black or black in combination with another race, 2.3% as Amerindian, 0.3% as Asian, and 74% as "Some Other Race Alone or in Combination."[76] Although estimates vary, most sources estimate that about 60% of Puerto Ricans have significant African ancestry.[23] The vast majority of blacks in Puerto Rico are Afro–Puerto Rican, meaning they have been in Puerto Rico for generations, usually since the slave trade, forming an important part of Puerto Rican culture and society.[77][78] Recent black immigrants have come to Puerto Rico, mainly from the [79] Dominican Republic, Haiti, and other Latin American and Caribbean countries, and to a lesser extent directly from Africa as well. Many black migrants from the United States and the Virgin Islands have moved and settled in Puerto Rico.[80][81] Also, many Afro–Puerto Ricans have migrated out of Puerto Rico, namely to the United States. There and in the US Virgin Islands, they make up the bulk of the U.S. Afro-Latino population.[82] Under Spanish and American rule, Puerto Rico underwent a whitening process. Puerto Rico went from around 50% of its population classified as black and mulatto in the first quarter of the 19th century, to nearly 80% classified white by the middle of the 20th century.[83][50][84][85][86] Under Spanish rule, Puerto Rico had laws such as Regla del Sacar or Gracias al Sacar, which classified persons of mixed African-European ancestry as white, which was the opposite of "one-drop rule" in US society after the American Civil War.[23] Additionally, the Spanish government's Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 encouraged immigration from other European countries. Heavy European immigration swelled Puerto Rico's population to about one million by the end of the 19th century, decreasing the proportion Africans made of Puerto Rico. In the early decades under US rule, census takers began to shift from classifying people as black to "white" and the society underwent what was called a "whitening" process from the 1910 to the 1920 census, in particular. During the mid 20th century, the US government forcefully sterilized Puerto Rican women, especially non-white Puerto Rican women.[87] Afro–Puerto Rican youth are learning more of their peoples' history from textbooks that encompass more Afro–Puerto Rican history.[50][88][89] The 2010 US census recorded the first drop of the percentage whites made up of Puerto Rico, and the first rise in the black percentage, in over a century.[90] Many of the factors that may possibly perpetuate this trend include: more Puerto Ricans may start to identify as black, due to increasing black pride and African cultural awareness throughout the island, as well as an increasing number of black immigrants, especially from the Dominican Republic and Haiti, many of whom are illegal immigrants,[91] and increasing emigration of white Puerto Ricans to the mainland US.[92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100] The following lists only include only the number of people who identify as black and do not attempt to estimate everyone with African ancestry. As noted in the earlier discussion, several of these cities were places where freedmen gathered after gaining freedom, establishing communities. The municipalities with the highest percentages of residents who identify as black, as of 2020, were:[101] Loiza: 64.7% Canóvanas: 33.4% Maunabo: 32.7% Rio Grande: 32% Culebra: 27.7% Carolina: 27.3% Vieques: 26% Arroyo: 25.8% Luquillo: 25.7% Patillas: 24.1% Ceiba: 23.8% Juncos: 22.9% San Juan: 22.2% Toa Baja: 22.1% Salinas: 22.1% Cataño: 21.8% |

現在の人口統計 2020年国勢調査が、回答者が複数の人種を適用できる初めての国勢調査であることを考慮すると、かなりの重複があり、矛盾しているように見えるが、実際 はプエルトリコの混合した歴史と人口を反映している。2020年の国勢調査の時点では、プエルトリコ人の17.1%が白人、17.5%が黒人または黒人と 他の人種の組み合わせ、2.3%がアメリカインディアン、0.3%がアジア人、74%が「他の人種単独または組み合わせ」[76]と回答している。 [23]プエルトリコの黒人の大多数はアフロ・プエルトリコ人であり、これは彼らが何世代にもわたって、通常は奴隷貿易以来プエルトリコに滞在し、プエル トリコの文化と社会の重要な部分を形成していることを意味する[77][78]。 最近の黒人移民は、主に[79]ドミニカ共和国、ハイチ、その他のラテンアメリカとカリブ海諸国からプエルトリコに移住してきた。また、多くのアフロ・プ エルトリコ人がプエルトリコから、すなわち米国に移住した。そことアメリカ領ヴァージン諸島で、彼らはアメリカのアフロ・ラティーノ人口の大部分を占めて いる[82]。 スペインとアメリカの統治下で、プエルトリコは白人化のプロセスを経た。19世紀第1四半期には人口の約50%が黒人および混血であったプエルトリコは、 20世紀半ばには80%近くが白人に分類されるようになった。 [83][50][84][85][86]スペイン統治下、プエルトリコにはRegla del SacarまたはGracias al Sacarのような法律があり、アフリカ人とヨーロッパ人の混血を白人として分類していた。ヨーロッパからの移民が多く、19世紀末までにプエルトリコの 人口は約100万人に膨れ上がり、プエルトリコに占めるアフリカ人の割合は減少した。米国統治下の初期数十年間、国勢調査員は人々を黒人から「白人」に分 類するようになり、特に1910年から1920年の国勢調査にかけて社会は「白人化」と呼ばれるプロセスを経た。20世紀半ば、アメリカ政府はプエルトリ コ人女性、特に非白人のプエルトリコ人女性に強制的に不妊手術を施した[87]。 50][88][89]2010年の米国国勢調査では、プエルトリコに占める白人の割合が1世紀以上ぶりに減少し、黒人の割合が1世紀以上ぶりに増加し た。 [特にドミニカ共和国とハイチからの黒人移民が増加しており、その多くが不法移民である[91]。また、白人プエルトリコ人の米国本土への移住が増加して いる[92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100]。 以下のリストには、黒人と自認する人の数のみが含まれており、アフリカ人の祖先を持つすべての人を推定しようとはしていない。先の考察で述べたように、こ れらの都市のいくつかは、自由を得た後に自由民が集まり、共同体を築いた場所である。 2020年現在、黒人と自認する住民の割合が最も高い自治体は以下の通りである[101]。 ロイザ:64.7% カノバナス:33.4% マウナボ 32.7% リオ・グランデ 32% クレブラ:27.7% カロリーナ:27.3% ビエケス:26% アロヨ:25.8% ルキージョ:25.7% パティージャス:24.1% セイバ:23.8% ジュンコス:22.9% サンファン:22.2% トア・バハ:22.1% サリナス:22.1% カタニョ:21.8 |

| Notable Afro–Puerto Ricans Main article: List of Afro–Puerto Ricans  "La escuela del Maestro Cordero" - 'The school of Master Cordero' - by Puerto Rican impressionist painter Francisco Oller. Rafael Cordero (1790–1868), was born free in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Of African descent, he became known as "The Father of Public Education in Puerto Rico". Cordero was a self-educated Puerto Rican who provided free schooling to children regardless of their race. Among the distinguished alumni who attended Cordero's school were future abolitionists Román Baldorioty de Castro, Alejandro Tapia y Rivera, and José Julián Acosta. Cordero proved that racial and economic integration could be possible and accepted in Puerto Rico. In 2004, the Roman Catholic Church, upon the request of San Juan Archbishop Roberto González Nieves, began the process of Cordero's beatification.[102] He was not the only one in his family to become an educator. In 1820, his older sister, Celestina Cordero, established the first school for girls in San Juan.[103] José Campeche (1751–1809), born a free man, contributed to the island's culture. Campeche's father, Tomás Campeche, was a freed slave born in Puerto Rico, and his mother María Jordán Marqués came from the Canary Islands. Since she was considered European (or white), her children were born free. Of mixed-race, Campeche was classified as a mulatto, a common term during his time meaning of African-European descent.[citation needed] Campeche is considered to be the foremost Puerto Rican painter of religious themes of the era.[104] Capt. Miguel Henriquez (c. 1680–17??), was a former pirate who became Puerto Rico's first black military hero by organizing an expeditionary force that defeated the British in the island of Vieques. Capt. Henriques was received as a national hero when he returned the island of Vieques back to the Spanish Empire and Puerto Rico. He was awarded "La Medalla de Oro de la Real Efigie"; and the Spanish Crown named him "Captain of the Seas," awarding him a letter of marque and reprisal which granted him the privileges of a privateer.[105][unreliable source?] Rafael Cepeda (1910–1996), also known as "The Patriarch of Bomba and Plena", was the patriarch of the Cepeda family. The family is one of the most famous exponents of Puerto Rican folk music, with generations of musicians working to preserve the African heritage in Puerto Rican music. The family is well known for their performances of the bomba and plena folkloric music and are considered by many to be the keepers of those traditional genres.[106] Sylvia del Villard (1928–1990) was a member of the Afro-Boricua Ballet. She participated in the following Afro–Puerto Rican productions, Palesiana y Aquelarre and Palesianisima.[107] In 1968, she founded the Afro-Boricua El Coqui Theater, which was recognized by the Panamerican Association of the New World Festival as the most important authority of Black Puerto Rican culture. The Theater group were given a contract which permitted them to present their act in other countries and in various universities in the United States.[108] In 1981, del Villard became the first and only director of the Office of Afro–Puerto Rican Affairs of the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture. She was known as an outspoken activist who fought for the equal rights of the Black Puerto Rican artist.[49] In Fiction The popular United States Marvel superhero Spider-Man is of African American and Puerto Rican descent in the alternate Ultimate Marvel timeline. Miles Morales, who is the current Spider-Man, was born to an African American father and a Puerto Rican mother.[109][110] |

著名なアフロ・プエルトリコ人 主な記事 アフロ・プエルトリコ人リスト  プエルトリコの印象派画家フランシスコ・オレールによる「La escuela del Maestro Cordero」(コルデロ先生の学校)。 ラファエル・コルデロ(1790-1868)はプエルトリコのサンフアンで自由人として生まれた。アフリカ系で、「プエルトリコの公教育の父」として知ら れるようになった。コルデロは独学で教育を受けたプエルトリコ人で、人種に関係なく子供たちに無料で学校教育を提供した。コルデロの学校に通った著名な卒 業生の中には、後に奴隷廃止論者となるロマン・バルドリオティ・デ・カストロ、アレハンドロ・タピア・イ・リベラ、ホセ・フリアン・アコスタがいた。コル デロは、プエルトリコにおいて人種と経済の統合が可能であり、受け入れられることを証明した。2004年、サンフアン大司教ロベルト・ゴンサレス・ニエベ スの要請により、ローマ・カトリック教会はコルデロの列福手続きを開始した[102]。1820年、姉のセレスティーナ・コルデロは、サン・ファンで最初 の女学校を設立した[103]。 ホセ・カンペチェ(1751-1809)は自由人として生まれ、島の文化に貢献した。カンペチェの父トマス・カンペチェはプエルトリコ生まれの解放奴隷 で、母マリア・ジョルダン・マルケスはカナリア諸島出身だった。母親はカナリア諸島出身のマリア・ジョルダン・マルケスで、彼女はヨーロッパ人(白人)と みなされていたため、子供たちは自由人として生まれた。混血であったカンペチェは、アフリカ系とヨーロッパ系の混血を意味する当時の一般的な言葉であるム ラート(混血)に分類された[citation needed]。カンペチェは、この時代の宗教的テーマを描いたプエルトリコ随一の画家と考えられている[104]。 ミゲル・エンリケス少佐(1680年頃-17年?)は元海賊で、ビエケス島でイギリス軍を破る遠征軍を組織し、プエルトリコ初の黒人軍事英雄となった。ヘ ンリケス少佐はビエケス島をスペイン帝国とプエルトリコに返還し、国民的英雄として迎えられた。彼は "La Medalla de Oro de la Real Efigie "を授与され、スペイン王室は彼を "Captain of the Seas "と命名し、私掠船の特権を与える私掠報復状を授与した[105][信頼できない情報源?] ラファエル・セペダ(1910-1996)は、"ボンバとプレナの家長 "としても知られ、セペダ・ファミリーの家長であった。この一族はプエルトリコの民族音楽の最も有名な演奏家の一人であり、何世代にもわたってプエルトリ コ音楽におけるアフリカの伝統を守るために活動してきた。一家はボンバとプレナの民族音楽の演奏でよく知られており、多くの人々からこれらの伝統的なジャ ンルの保持者とみなされている[106]。 シルヴィア・デル・ビジャール(1928-1990)は、アフロ・ボリクア・バレエ団のメンバー。1968年、彼女はアフロ・ボリクア・エル・コキ劇場を 設立し、新世界フェスティバルのパンアメリカン協会から黒人プエルトリコ文化の最も重要な権威として認められた。1981年、デル・ヴィラールはプエルト リコ文化研究所のアフロ・プエルトリカン・オフィスの最初で唯一のディレクターとなる。彼女は、黒人プエルトリコ人アーティストの平等な権利のために戦っ た率直な活動家として知られていた[49]。 フィクション アメリカ合衆国の人気マーベル・スーパーヒーローであるスパイダーマンは、アルティメット・マーベルの別タイムラインではアフリカ系アメリカ人とプエルト リコ人の血を引いている。現在のスパイダーマンであるマイルス・モラレスはアフリカ系アメリカ人の父とプエルトリコ人の母の間に生まれた[109] [110]。 |

| List of Puerto Ricans Immigration to Puerto Rico series: Cultural diversity in Puerto Rico Chinese immigration to Puerto Rico Corsican immigration to Puerto Rico French immigration to Puerto Rico German immigration to Puerto Rico Irish immigration to Puerto Rico Jewish immigration to Puerto Rico Spanish immigration to Puerto Rico Puerto Rican people Afro-Caribbean Afro-Latin Americans – North, Central and South America Afro-Spaniard Black Latino Americans – United States of America Bozal Spanish (language) List of topics related to Black and African people Racism in Puerto Rico |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afro%E2%80%93Puerto_Ricans |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆