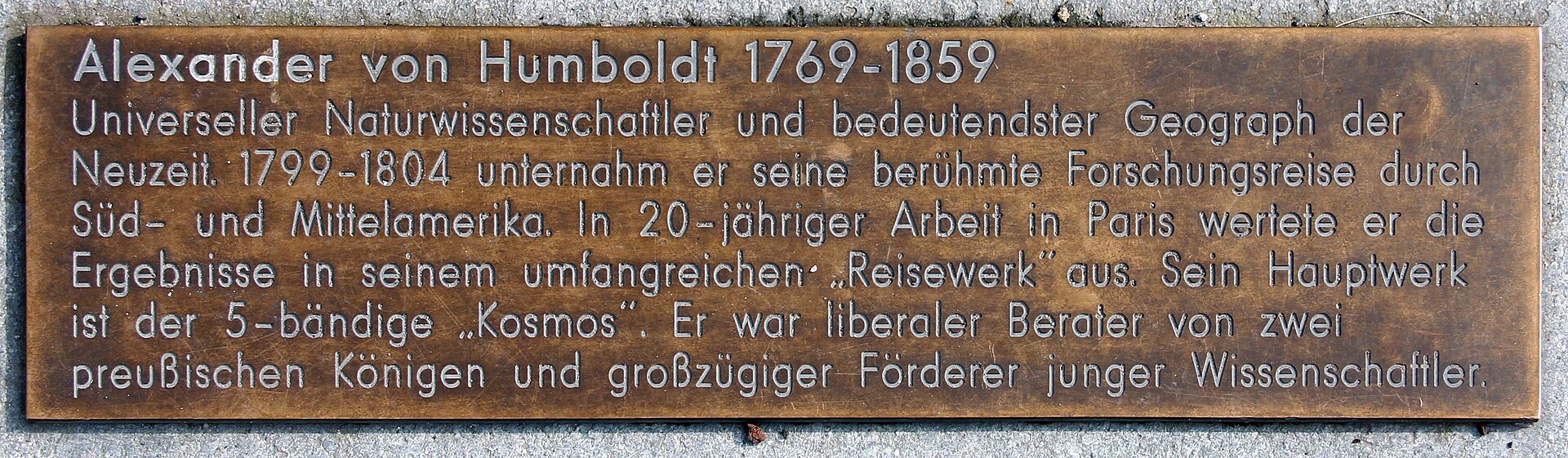

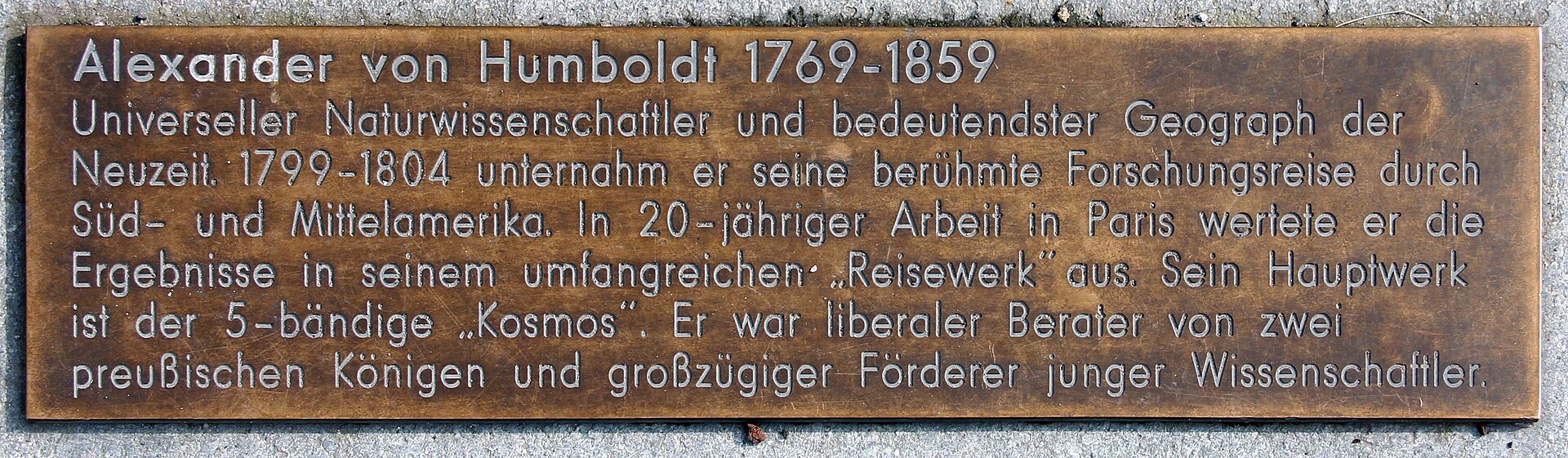

アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルト

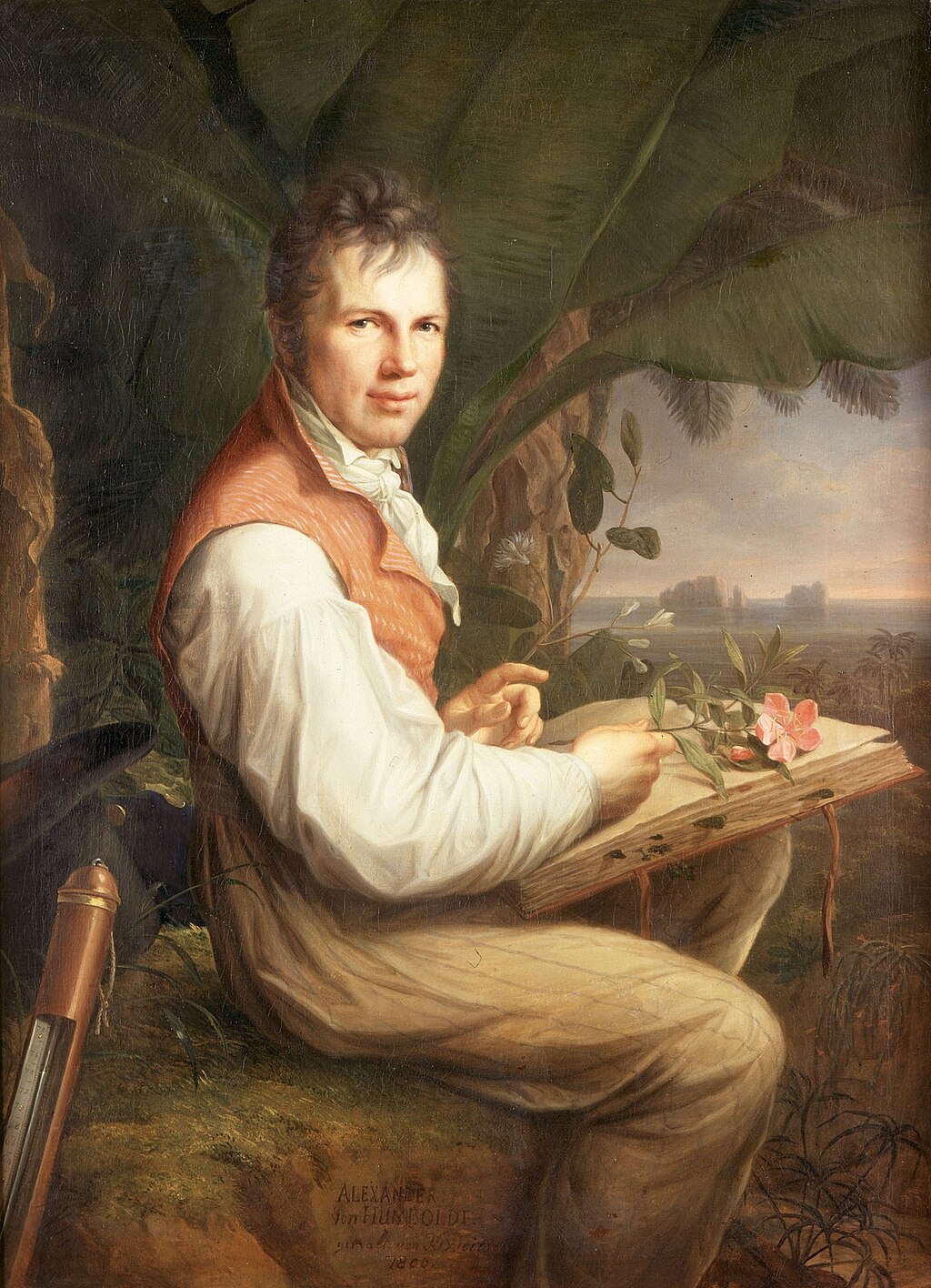

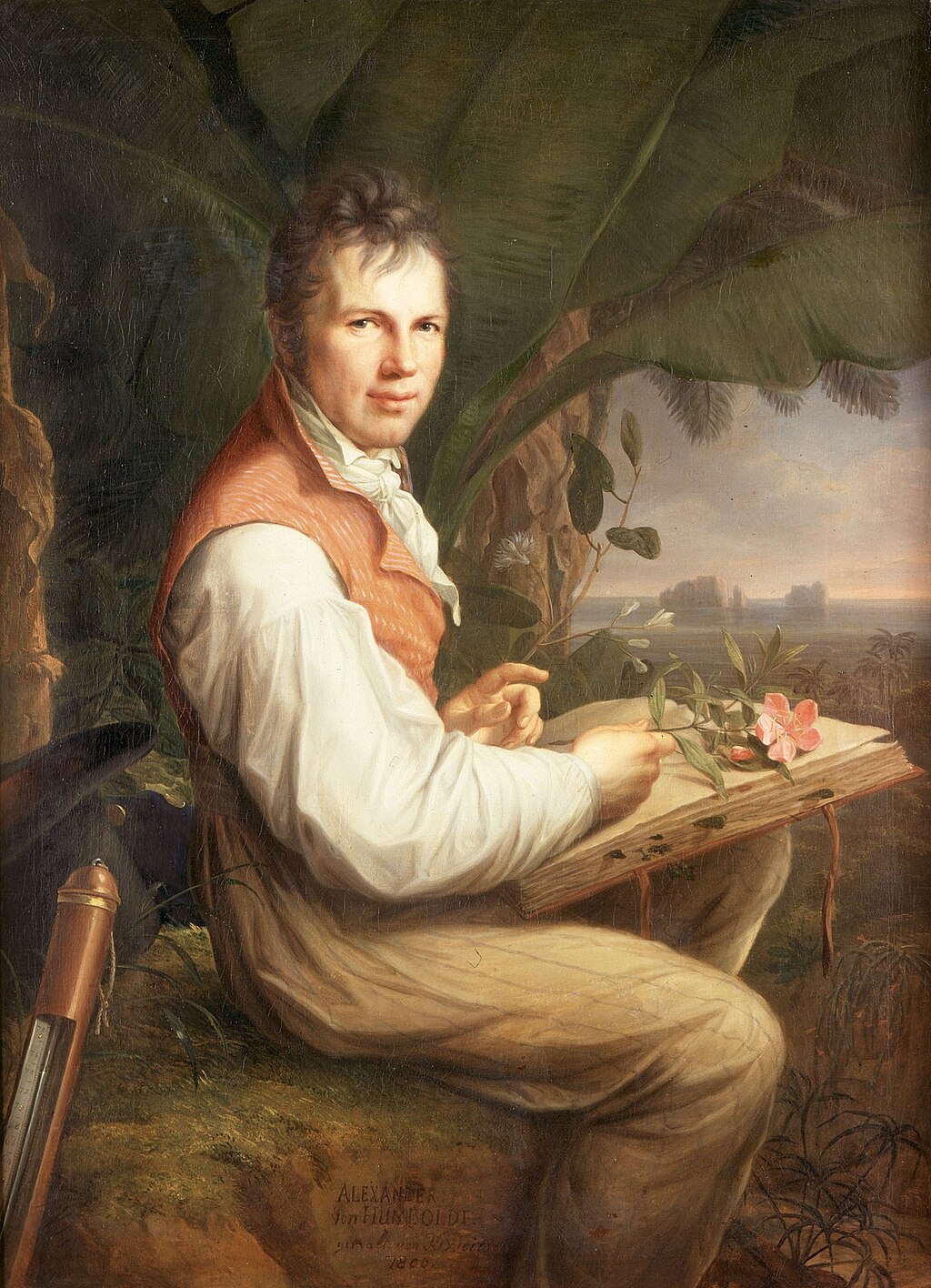

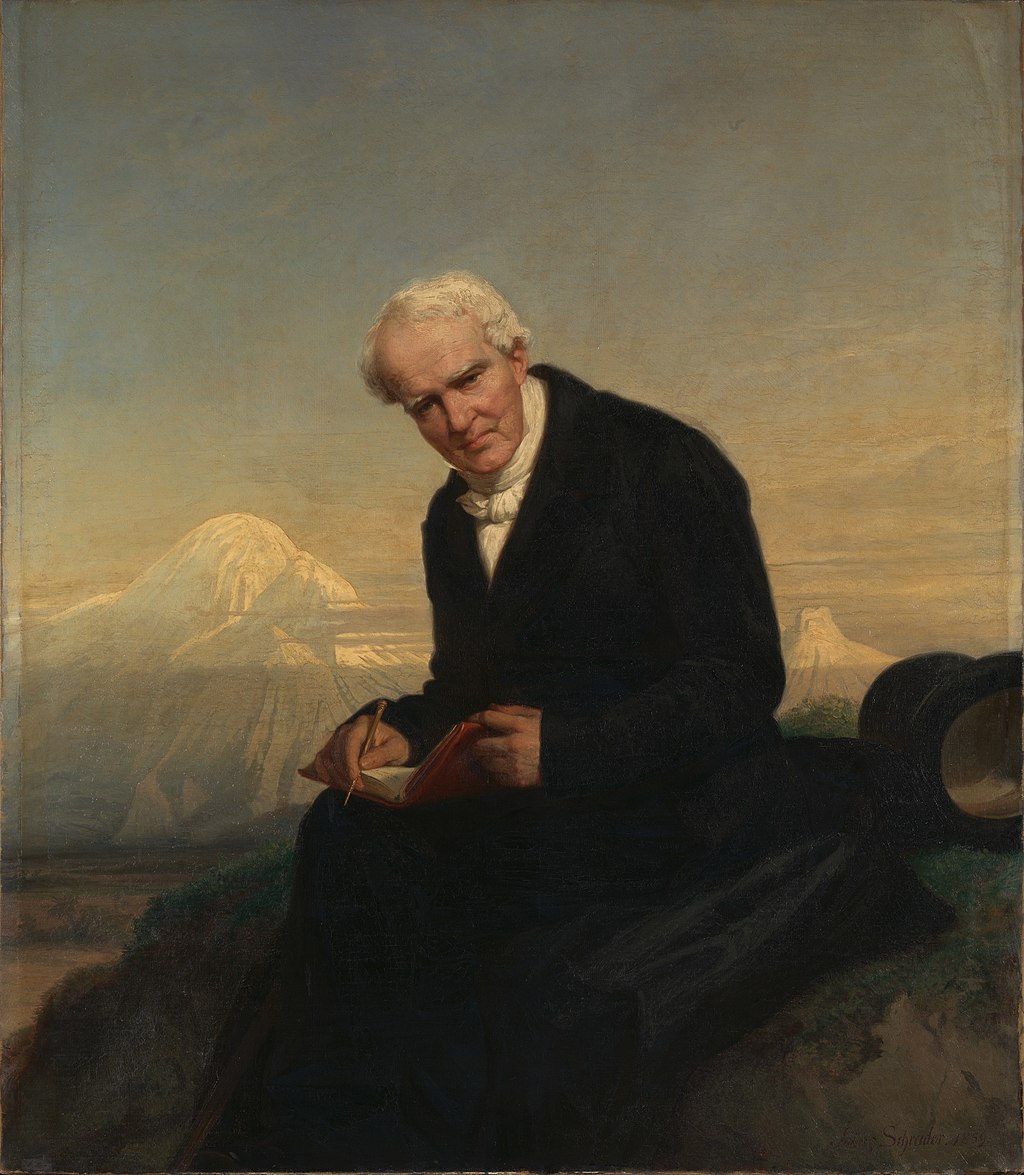

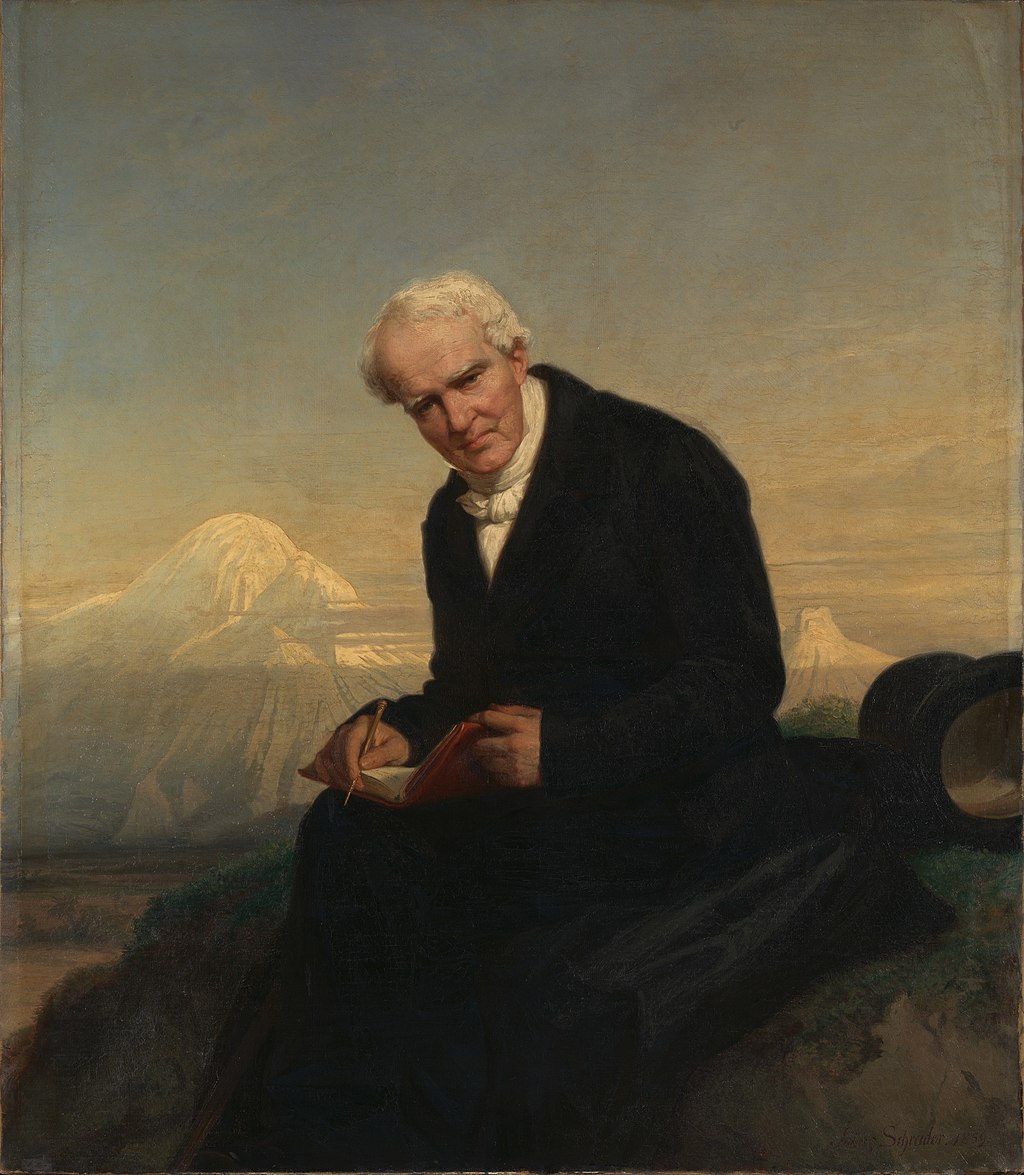

Friedrich Wilhelm

Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt, 1769-1859

sitting

next to a globe with a manuscript for his life's work "Cosmos" 1845-1862

☆

フリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム・ハインリッヒ・アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルト[a](1769年9月14日 -

1859年5月6日)は、ドイツの博学者、地理学者、自然学者、探検家、そしてロマン主義哲学と科学の提唱者であった[5]。彼は、プロイセンの大臣、哲

学者、言語学者であるヴィルヘルム・フォン・フンボルト(1767年 - 1835年)の弟であった。[6][7][8]

フンボルトの植物地理学に関する定量的研究は生物地理学の基礎を築き、長期にわたる体系的な地球物理学的測定の提唱は、現代の地磁気および気象観測の先駆

けとなった。[9][10]

フンボルトとカール・リッターは、地理学を独立した科学分野として確立したことから、現代地理学の創始者と見なされている。[11] [12]

1799年から1804年にかけて、フンボルトはアメリカ大陸を広く旅し、スペイン以外のヨーロッパ人科学者の視点から初めてこの地を探検し記述した。こ

の旅では、フランスの探検家エメ・ボンプランと共に、地球上で最も困難で知られていない地域を数千マイルにわたり横断した。オリノコ川の源流を特定し、

1802年にはエクアドル最高峰の標高19,286フィート(当時西洋人による世界最高到達記録)の山に登頂したのである。[13]

この旅の記録は21年をかけて数巻にまとめられ出版された。

フンボルトは古代ギリシャ語の「コスモス」という語を復活させ、自身の多巻にわたる大著『コスモス』に冠した。この著作で彼は科学知識と文化の多様な分野

を統合しようとしたのである。この重要な著作はまた、宇宙を相互作用する単一の実体として捉える全体論的認識を促し[14]、環境保護思想へとつながる生

態学の概念を導入した。1800年、そして1831年にも、彼は旅行中に得た観察結果に基づき、開発がもたらす局地的な影響が人為的な気候変動を引き起こ

すことを科学的に記述した[15][16][17]。

フンボルトは「生態学の父」および「環境保護思想の父」と見なされている[18][19]。

| Friedrich Wilhelm

Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt[a] (14 September 1769 – 6 May 1859) was

a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of

Romantic philosophy and science.[5] He was the younger brother of the

Prussian minister, philosopher, and linguist Wilhelm von Humboldt

(1767–1835).[6][7][8] Humboldt's quantitative work on botanical

geography laid the foundation for the field of biogeography, while his

advocacy of long-term systematic geophysical measurement pioneered

modern geomagnetic and meteorological monitoring.[9][10] Humboldt and

Carl Ritter are both regarded as the founders of modern geography as

they established it as an independent scientific discipline.[11][12] Between 1799 and 1804, Humboldt travelled extensively in the Americas, exploring and describing them for the first time from a non-Spanish European scientific point of view. On these travels, along with French explorer Aimé Bonpland, he traversed thousands of miles through some of the most difficult and little-known places on Earth, to include identifying the source of the Orinoco River and in 1802 climbing the highest mountain in Ecuador to a height of 19,286 feet, at the time a world record altitude for a Westerner.[13] His description of the journey was written up and published in several volumes over 21 years. Humboldt resurrected the use of the word cosmos from the ancient Greek and assigned it to his multivolume treatise, Kosmos, in which he sought to unify diverse branches of scientific knowledge and culture. This important work also motivated a holistic perception of the universe as one interacting entity,[14] which introduced concepts of ecology leading to ideas of environmentalism. In 1800, and again in 1831, he described scientifically, on the basis of observations generated during his travels, local impacts of development causing human-induced climate change.[15][16][17] Humboldt is seen as "the father of ecology" and "the father of environmentalism".[18][19] |

フリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム・ハインリッヒ・アレクサンダー・フォン・

フンボルト[a](1769年9月14日 -

1859年5月6日)は、ドイツの博学者、地理学者、自然学者、探検家、そしてロマン主義哲学と科学の提唱者であった[5]。彼は、プロイセンの大臣、哲

学者、言語学者であるヴィルヘルム・フォン・フンボルト(1767年 - 1835年)の弟であった。[6][7][8]

フンボルトの植物地理学に関する定量的研究は生物地理学の基礎を築き、長期にわたる体系的な地球物理学的測定の提唱は、現代の地磁気および気象観測の先駆

けとなった。[9][10]

フンボルトとカール・リッターは、地理学を独立した科学分野として確立したことから、現代地理学の創始者と見なされている。[11] [12] 1799年から1804年にかけて、フンボルトはアメリカ大陸を広く旅し、スペイン以外のヨーロッパ人科学者の視点から初めてこの地を探検し記述した。こ の旅では、フランスの探検家エメ・ボンプランと共に、地球上で最も困難で知られていない地域を数千マイルにわたり横断した。オリノコ川の源流を特定し、 1802年にはエクアドル最高峰の標高19,286フィート(当時西洋人による世界最高到達記録)の山に登頂したのである。[13] この旅の記録は21年をかけて数巻にまとめられ出版された。 フンボルトは古代ギリシャ語の「コスモス」という語を復活させ、自身の多巻にわたる大著『コスモス』に冠した。この著作で彼は科学知識と文化の多様な分野 を統合しようとしたのである。この重要な著作はまた、宇宙を相互作用する単一の実体として捉える全体論的認識を促し[14]、環境保護思想へとつながる生 態学の概念を導入した。1800年、そして1831年にも、彼は旅行中に得た観察結果に基づき、開発がもたらす局地的な影響が人為的な気候変動を引き起こ すことを科学的に記述した[15][16][17]。 フンボルトは「生態学の父」および「環境保護思想の父」と見なされている[18][19]。 |

| Early life, family and education Alexander von Humboldt was born in Berlin in Prussia on 14 September 1769.[20] He was baptized as a baby in the Lutheran faith, with the Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel serving as godfather.[21] His father, Alexander Georg von Humboldt (1720-1779), belonged to a prominent German noble family from Pomerania. Although not one of the titled gentry, he was a major in the Prussian Army, who had served with the Duke of Brunswick.[22] At age 42, Alexander Georg was rewarded for his services in the Seven Years' War with the post of royal chamberlain.[23] He profited from the contract to lease state lotteries and tobacco sales.[24] Alexander's grandfather was Johann Paul von Humboldt (1684-1740), who married Sophia Dorothea von Schweder (1688-1749), daughter of Prussian General Adjutant Michael von Schweder (1663-1729).[20][25] In 1766, his father, Alexander Georg married Maria Elisabeth Colomb, a well-educated woman and widow of Baron Friedrich Ernst von Holwede (1723-1765), with whom she had a son Heinrich Friedrich Ludwig (1762-1817). Alexander Georg and Maria Elisabeth had four children: two daughters, Karoline and Gabriele, who died young, and then two sons, Wilhelm and Alexander. Her first-born son, Wilhelm and Alexander's half-brother, Rittmaster in the Gendarme regiment was something of a ne'er-do-well, not often mentioned in the family history.[26] Alexander Georg died in 1779, leaving the brothers Humboldt in the care of their emotionally distant mother. She had high ambitions for Alexander and his older brother Wilhelm, hiring excellent tutors, who were Enlightenment thinkers, including Kantian physician Marcus Herz and botanist Carl Ludwig Willdenow, who became one of the most important botanists in Germany.[27] Humboldt's mother expected them to become civil servants of the Prussian state.[28] The money left to Alexander's mother by Baron Holwede became instrumental in funding Alexander's explorations after her death; contributing more than 70% of his private income.  Schloss Tegel, Berlin, where Alexander and his brother Wilhelm lived for several years Due to his youthful penchant for collecting and labeling plants, shells, and insects, Alexander received the playful title of "the little apothecary".[23] Marked for a political career, Alexander studied finance for six months in 1787 at the University of Frankfurt (Oder), which his mother might have chosen less for its academic excellence than its closeness to their home in Berlin.[29] On 25 April 1789, he matriculated at the University of Göttingen, then known for the lectures of C. G. Heyne and anatomist J. F. Blumenbach.[27] His brother Wilhelm was already a student at Göttingen, but they did not interact much, since their intellectual interests were quite different.[30] His vast and varied interests were by this time fully developed.[23] At the University of Göttingen, Humboldt met Steven Jan van Geuns, a Dutch medical student, with whom he travelled to the Rhine in the fall of 1789. In Mainz, they met Georg Forster, a naturalist who had been with Captain James Cook on his second voyage.[31] Humboldt's scientific excursion resulted in his 1790 treatise Mineralogische Beobachtungen über einige Basalte am Rhein (Brunswick, 1790) (Mineralogic Observations on Several Basalts on the River Rhine).[32] The following year, 1790, Humboldt returned to Mainz to embark with Forster on a journey to England, Humboldt's first sea voyage, the Netherlands, and France.[30][33] In England, he met Sir Joseph Banks, president of the Royal Society, who had travelled with Captain Cook; Banks showed Humboldt his huge herbarium, with specimens of the South Sea tropics.[33] The scientific friendship between Banks and Humboldt lasted until Banks's death in 1820, and the two shared botanical specimens for study. Banks also mobilized his scientific contacts in later years to aid Humboldt's work.[34] In Paris, Humboldt and Forster witnessed the preparations for the Festival of the Federation. Yet, Humboldt's take on the French Revolution remained ambivalent.[35][page needed] Humboldt's passion for travel was of long standing. He devoted to prepare himself as a scientific explorer. With this emphasis, he studied commerce and foreign languages at Hamburg, geology at Freiberg School of Mines in 1791 under A.G. Werner, leader of the Neptunist school of geology;[36] from anatomy at Jena under J.C. Loder; and astronomy and the use of scientific instruments under F.X. von Zach and J.G. Köhler.[23] At Freiberg, he met a number of men who were to prove important to him in his later career, including Spaniard Manuel del Río, who became director of the School of Mines the crown established in Mexico; Christian Leopold von Buch, who became a regional geologist; and, most importantly, Carl Freiesleben [de], who became Humboldt's tutor and close friend. During this period, his brother Wilhelm married, but Alexander did not attend the nuptials.[37] |

幼少期、家族、教育 アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトは、1769年9月14日にプロイセンのベルリンで生まれた[20]。彼は赤ん坊の頃にルーテル教徒として洗礼を受け、ブラウンシュヴァイク=ヴォルフェンビュッテル公が名付け親となった。[21] 彼の父、アレクサンダー・ゲオルク・フォン・フンボルト(1720-1779)は、ポメラニア出身の著名なドイツ貴族の家系に属していた。貴族の称号は 持っていなかったが、プロイセン陸軍の大佐であり、ブラウンシュヴァイク公に仕えていた。[22] 42歳のとき、アレクサンダー・ゲオルクは七年戦争での功績により、王室侍従長の職を授かった。[23] 彼は、国営宝くじとタバコ販売のリース契約から利益を得ていた。[24] アレクサンダーの祖父は、ヨハン・パウル・フォン・フンボルト(1684-1740)であり、プロイセンの副官ミヒャエル・フォン・シュヴェーダー (1663-1729)の娘、ソフィア・ドロテア・フォン・シュヴェーダー(1688-1749)と結婚した。[20][25] 1766年、彼の父であるアレクサンダー・ゲオルクは、教養のある女性であり、フリードリヒ・エルンスト・フォン・ホルヴェーデ男爵(1723- 1765)の未亡人であるマリア・エリザベート・コロンと結婚した。彼女には、フリードリヒ・エルンスト・フォン・ホルヴェーデ男爵との間に、息子ハイン リッヒ・フリードリヒ・ルートヴィヒ(1762-1817)がいた。アレクサンダー・ゲオルクとマリア・エリザベートには4人の子供があった。2人の娘、 カロラインとガブリエレは若くして亡くなり、2人の息子、ヴィルヘルムとアレクサンダーがいた。長男であるヴィルヘルムは、アレクサンダーの異母兄弟であ り、憲兵連隊の騎兵隊長だったが、あまり家系図には登場しない、あまり良くない人物だった。[26] アレクサンダー・ゲオルクは1779年に亡くなり、フンボルト兄弟は感情的に距離のある母親の世話に委ねられた。母親はアレクサンダーと兄のヴィルヘルム に高い野望を抱き、優れた家庭教師を雇った。その中には、カントの弟子である医師マルクス・ヘルツや、ドイツで最も重要な植物学者の一人となった植物学者 カール・ルートヴィヒ・ヴィルデノーなど、啓蒙思想家も含まれていた。フンボルトの母親は、彼らがプロイセン王国の公務員になることを期待していた。 [28] ホルヴェーデ男爵がアレクサンダーの母親に遺した財産は、彼女の死後、アレクサンダーの探検資金として重要な役割を果たし、彼の私的収入の 70% 以上を占めた。  アレクサンダーと弟のヴィルヘルムが数年間住んだ、ベルリンのテーゲル城 植物、貝殻、昆虫を収集し、分類することを好んだ少年時代の傾向から、アレクサンダーは「小さな薬剤師」という遊び心のある称号を授けられた。[23] 政治の道を志したアレクサンダーは、1787年にフランクフルト(オーデル)大学で6か月間金融学を学んだ。母親が同大学を選んだのは、その学術的な優秀 さよりも、ベルリンの自宅から近いという理由からだったかもしれない。[29] 1789年4月25日、彼はゲッティンゲン大学に入学した。当時、同大学はC. G. ハイネと解剖学者J. F. ブルメンバッハの講義で知られていた。[27] 兄のヴィルヘルムはすでにゲッティンゲン大学の学生だったが、2人の知的関心はまったく異なっていたため、あまり交流はなかった。[30] この頃までに、彼の広範かつ多様な関心が完全に発達していた。[23] ゲッティンゲン大学で、フンボルトはオランダ人医学生スティーブン・ヤン・ファン・ゲウンズと出会い、1789年の秋に彼と一緒にライン川へ旅をした。マ インツでは、ジェームズ・クック船長の第二航海に同行した自然学者ゲオルク・フォースターと出会った。[31] フンボルトのこの科学探検は、1790年の論文『ライン川沿いのいくつかの玄武岩に関する鉱物学的観察』(Mineralogische Beobachtungen über einige Basalte am Rhein、ブラウンシュヴァイク、1790年)として結実した。翌1790年、フンボルトはマインツに戻り、フォースターと共にイギリス、オランダ、フ ランスへの旅に出発した。これがフンボルト初の航海であった[30][33]。イギリスでは王立協会会長でクック船長と共に航海したジョセフ・バンクス卿 と会い、バンクスはフンボルトに南洋熱帯地域の標本を含む膨大な植物標本集を見せた[33]。バンクスとフンボルトの科学的友情は、バンクスが1820年 に亡くなるまで続き、二人は研究のために植物標本を交換した。バンクスは後年、自身の科学的ネットワークを動員してフンボルトの研究を支援した。[34] パリでは、フンボルトとフォースターは連邦祭の準備を目撃した。しかし、フンボルトのフランス革命に対する見解は依然として複雑なものだった。[35] [ページ番号が必要] フンボルトの旅行への情熱は古くからあった。彼は科学探検家としての準備に専念した。この重点を置いて、ハンブルクで商業と外国語を学び、1791年には フライベルク鉱山学校でA.G.ヴェルナー(ネプチューニスト地質学派の指導者)に師事して地質学を修めた[36]。またイエナではJ.C.ローダーに解 剖学を、F.X.フォン・ザックとJ.G.ケーラーには天文学と科学機器の使用法を学んだ。[23] フライベルクでは、後に彼のキャリアにおいて重要な役割を果たすことになる多くの人々に出会った。その中には、メキシコに設立された王立鉱山学校の校長と なったスペイン人のマヌエル・デル・リオ、地域地質学者となったクリスチャン・レオポルド・フォン・ブーフ、そして最も重要な人物である、フンボルトの家 庭教師であり親友となったカール・フライエスレーベン [de] がいた。この期間、兄のヴィルヘルムは結婚したが、アレクサンダーは結婚式に出席しなかった。 |

| Travels and work in Europe Humboldt graduated from the Freiberg School of Mines in 1792 and was appointed to a Prussian government position in the Department of Mines as an inspector in Bayreuth and the Fichtel Mountains. Humboldt was excellent at his job, with production of gold ore in his first year outstripping the previous eight years.[38] During his period as a mine inspector, Humboldt demonstrated his deep concern for the men laboring in the mines. He opened a free school for miners, paid for out of his own pocket, which became an unchartered government training school for labor. He also sought to establish an emergency relief fund for miners, aiding them following accidents.[39] Humboldt's researches into the vegetation of the mines of Freiberg led to the publication in Latin (1793) of his Florae Fribergensis, accedunt Aphorismi ex Doctrina, Physiologiae Chemicae Plantarum, which was a compendium of his botanical researches.[36] That publication brought him to the attention of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who had met Humboldt at the family home when Alexander was a boy, but Goethe was now interested in meeting the young scientist to discuss metamorphism of plants.[40] An introduction was arranged by Humboldt's brother, who lived in the university town of Jena, not far from Goethe. Goethe had developed his own extensive theories on comparative anatomy. Working before Darwin, he believed that animals had an internal force, an urform, that gave them a basic shape and then they were further adapted to their environment by an external force. Humboldt urged him to publish his theories. Together, the two discussed and expanded these ideas. Goethe and Humboldt soon became close friends. Humboldt often returned to Jena in the years that followed. Goethe remarked about Humboldt to friends that he had never met anyone so versatile. Humboldt's drive served as an inspiration for Goethe. In 1797, Humboldt returned to Jena for three months. During this time, Goethe moved from his residence in Weimar to reside in Jena. Together, Humboldt and Goethe attended university lectures on anatomy and conducted their own experiments. One experiment involved hooking up a frog leg to various metals. They found no effect until the moisture of Humboldt's breath triggered a reaction that caused the frog leg to leap off the table. Humboldt described this as one of his favorite experiments because it was as if he were "breathing life into" the leg.[41] During this visit, a thunderstorm killed a farmer and his wife. Humboldt obtained their corpses and analyzed them in the anatomy tower of the university.[42]  Schiller, Wilhelm, and Alexander von Humboldt with Goethe in Jena In 1794, Humboldt was admitted to the famous group of intellectuals and cultural leaders of Weimar Classicism. Goethe and Schiller were the key figures at the time. Humboldt contributed (7 June 1795) to Schiller's new periodical, Die Horen, a philosophical allegory entitled Die Lebenskraft, oder der rhodische Genius (The Life Force, or the Rhodian Genius).[23] In this short piece, the only literary story Humboldt ever authored, he tried to summarize the often contradictory results of the thousands of Galvanic experiments he had undertaken.[43] In 1792 and 1797, Humboldt was in Vienna; in 1795 he made a geological and botanical tour through Switzerland and Italy. Although this service to the state was regarded by him as only an apprenticeship to the service of science, he fulfilled its duties with such conspicuous ability that not only did he rise rapidly to the highest post in his department, but he was also entrusted with several important diplomatic missions.[23] Neither brother attended the funeral of their mother on 19 November 1796.[44] Humboldt had not hidden his aversion to his mother, with one correspondent writing of him after her death, "her death... must be particularly welcomed by you".[45] After severing his official connections, he awaited an opportunity to fulfill his long-cherished dream of travel. Humboldt was able to spend more time on writing up his research. He had used his own body for experimentation on muscular irritability, recently discovered by Luigi Galvani and published his results, Versuche über die gereizte Muskel- und Nervenfaser (Berlin, 1797) (Experiments on Stimulated Muscle and Nerve Fibres), enriched in the French translation with notes by Blumenbach. |

ヨーロッパでの旅と仕事 フンボルトは1792年にフライベルク鉱山学校を卒業し、プロイセン政府の鉱山局に配属された。バイロイトとフィヒテル山地を管轄する鉱山監督官として任 じられたのだ。フンボルトはその職務に非常に優れており、就任初年度の金鉱石の生産量は過去8年間の総量を上回った。[38] 鉱山監察官として勤務する間、フンボルトは鉱山で働く労働者たちへの深い関心を示した。自費で鉱夫のための無料学校を開設し、これは政府認可のない労働者 訓練校となった。また鉱夫のための緊急救済基金の設立を模索し、事故後の支援を図った。[39] フンボルトはフライベルク鉱山の植生を研究し、その成果を『Florae Fribergensis, accedunt Aphorismi ex Doctrina, Physiologiae Chemicae Plantarum』としてラテン語で出版した(1793年)。これは彼の植物学研究の要約であった。[36] この出版により、彼はヨハン・ヴォルフガング・フォン・ゲーテの注目を浴びた。ゲーテは、アレクサンダーが少年だった頃、フンボルトの自宅で彼と面識が あったが、植物の変態について議論するために、この若い科学者に会いたいと興味を持っていた。[40] ゲーテの住んでいたイェーナ大学からほど近い、フンボルトの兄弟が紹介を手配した。ゲーテは、比較解剖学について独自の広範な理論を展開していた。ダー ウィンより前に、動物には基本的な形を与える内的な力、つまり原形があり、さらに外的な力によって環境に適応していくと信じていた。フンボルトはゲーテ に、その理論を出版するよう強く勧めた。二人は一緒にこれらの考えについて議論し、発展させた。ゲーテとフンボルトはすぐに親しい友人となった。 その後もフンボルトは度々イエナを訪れた。ゲーテは友人たちに「これほど多才な人物に会ったことがない」とフンボルトについて語った。フンボルトの情熱は ゲーテの刺激となった。1797年、フンボルトは3ヶ月間イエナに滞在した。この間、ゲーテはワイマールの自宅からイエナに移り住んだ。二人は共に大学の 解剖学講義に出席し、独自の実験を行った。ある実験では、カエルの脚をさまざまな金属に接続した。フンボルトの息の湿気が反応を引き起こし、カエルの脚が テーブルから飛び跳ねるまで、何の効果もなかった。フンボルトは、この実験を「脚に命を吹き込んだ」かのようだったため、お気に入りの実験のひとつだと述 べている。[41] この訪問中、雷雨で農夫とその妻が死亡した。フンボルトは彼らの遺体を入手し、大学の解剖学塔で分析を行った。[42]  イエナでゲーテとシュイラー、ヴィルヘルム、アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルト 1794年、フンボルトはワイマール古典主義の有名な知識人・文化人グループに受け入れられた。当時、ゲーテとシラーが中心人物であった。フンボルトは、 シラーの新しい定期刊行物『ディ・ホーレン』に、哲学的寓話「生命力、あるいはロードス島の天才」を寄稿した(1795年6月7日)。この短い作品(フン ボルトがこれまでに書いた唯一の文学作品)の中で、彼は、これまでに行った何千ものガルバニック実験の、しばしば矛盾した結果をまとめようとしたのであ る。 1792年と1797年、フンボルトはウィーンに滞在した。1795年にはスイスとイタリアを地質学・植物学の調査旅行で巡った。この公務は彼にとって科 学への奉仕に向けた修業期間に過ぎなかったが、その職務を顕著な能力で遂行したため、部門の最高職位に急速に昇進しただけでなく、いくつかの重要な外交任 務も任された。[23] 1796年11月19日の母親の葬儀には、兄弟ともに出席しなかった。[44] フンボルトは母親への嫌悪を隠さなかったため、ある通信相手は彼女の死後「彼女の死は…特に君にとって歓迎すべきことだろう」と記している。[45] 公的な関係を断った後、彼は長年抱いていた旅行の夢を実現する機会を待った。 フンボルトは研究の記録作成により多くの時間を割けるようになった。彼はルイジ・ガルヴァーニが新たに発見した筋刺激性について、自らの身体を実験材料と して用い、その結果を『刺激された筋繊維と神経繊維に関する実験』(ベルリン、1797年)として発表した。この著作はブルメンバッハによる注釈を付した フランス語訳でさらに充実したものとなった。 |

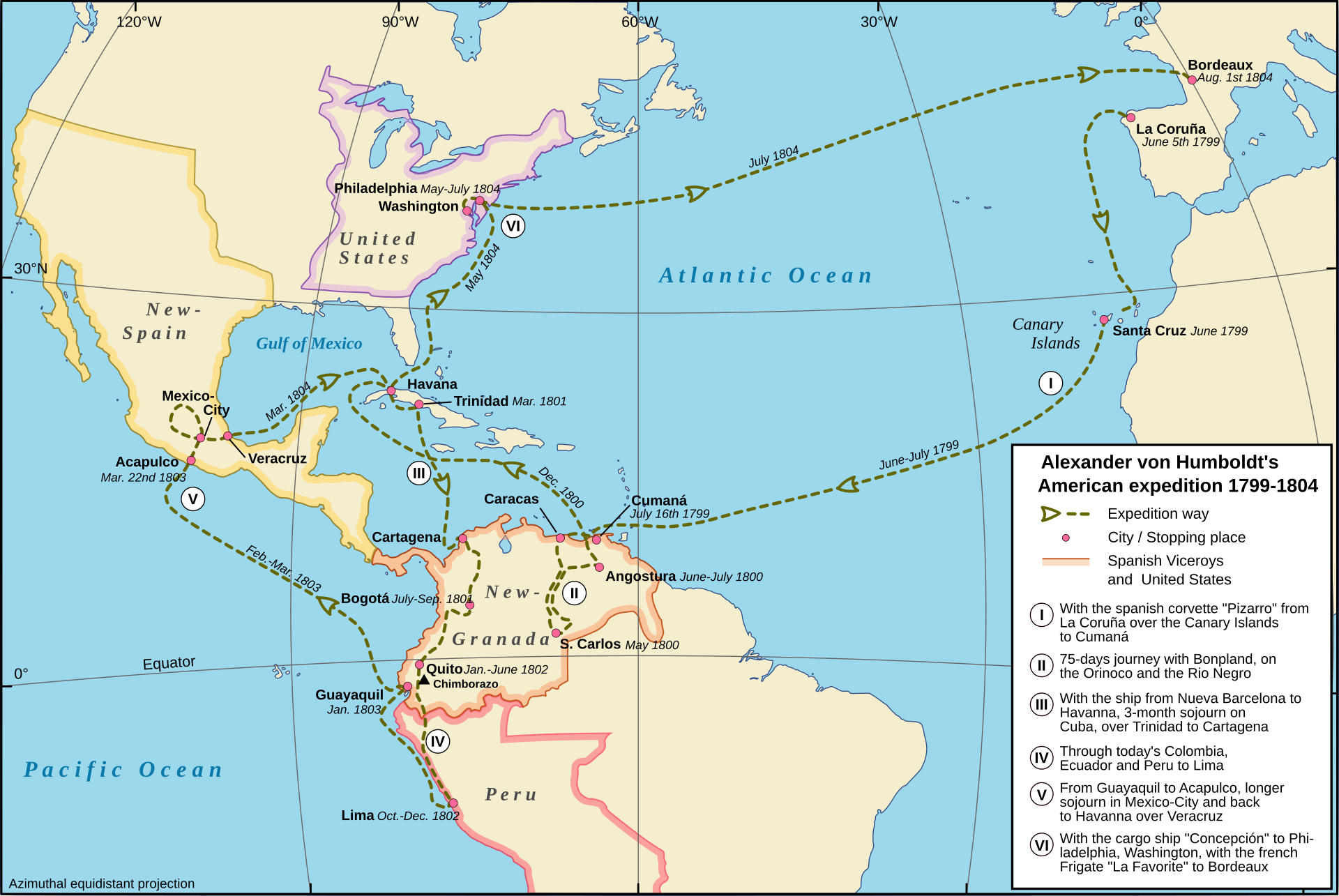

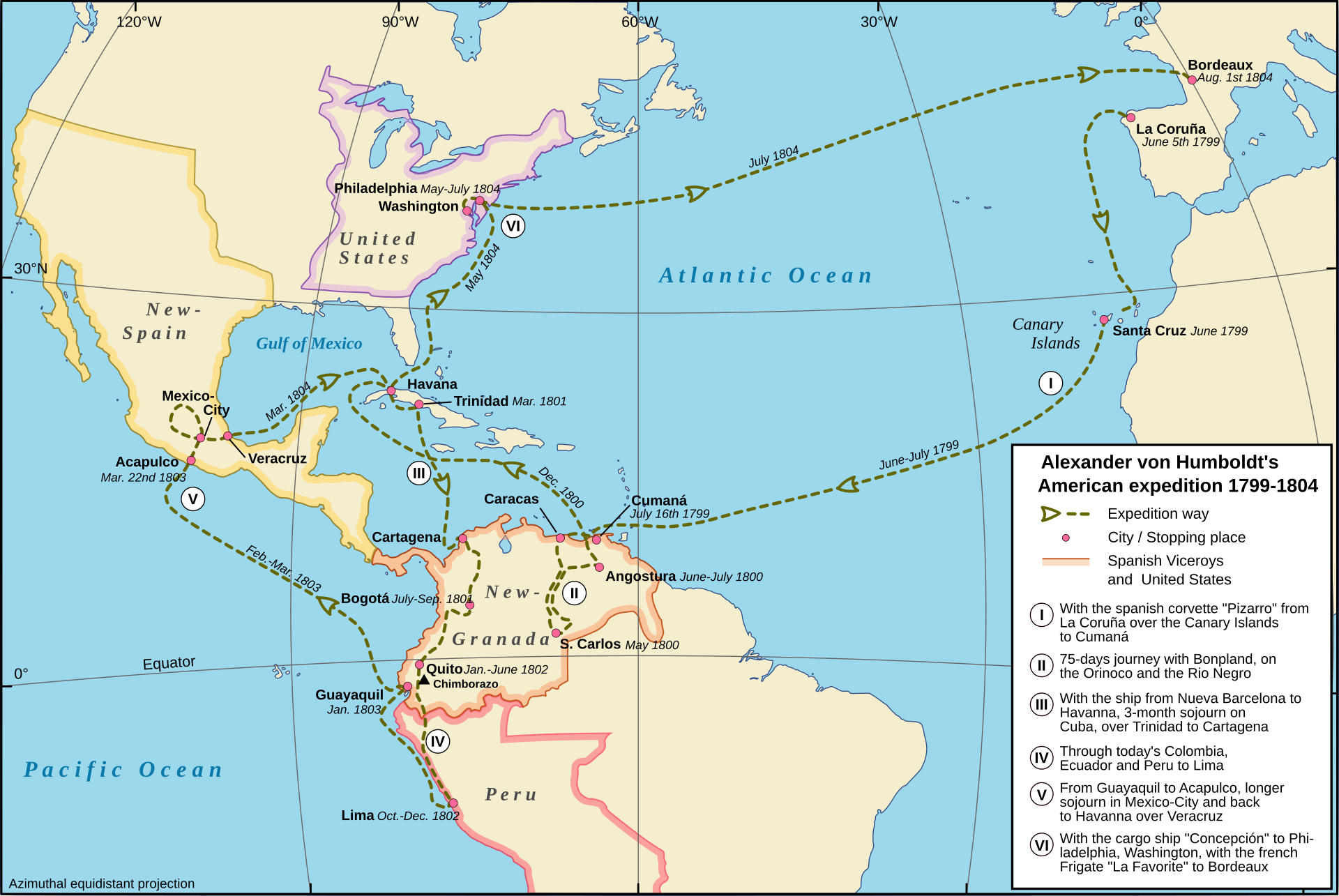

Spanish American expedition, 1799–1804 Alexander von Humboldt's Latin American expedition Seeking a foreign expedition With the financial resources to fund his scientific travels, he sought a ship on a major expedition. In the meantime, he went to Paris, where his brother Wilhelm was living. Paris was a great center of scientific learning and his brother and sister-in-law Caroline were well connected in those circles. Louis-Antoine de Bougainville urged Humboldt to accompany him on a major expedition, likely to last five years, but the French revolutionary Directoire placed Nicolas Baudin at the head of it rather than the aging scientific traveler.[46] On the postponement of Captain Baudin's proposed voyage of circumnavigation due to continuing warfare in Europe, which Humboldt had been officially invited to accompany, Humboldt was deeply disappointed. He had already selected scientific instruments for his voyage. He did, however, have a stroke of luck with meeting Aimé Bonpland, the botanist and physician for the voyage. Discouraged, the two left Paris for Marseille, where they hoped to join Napoleon Bonaparte in Egypt, but North Africans were in revolt against the French invasion in Egypt and French authorities refused permission to travel. Humboldt and Bonpland eventually found their way to Madrid, where their luck changed spectacularly.[47] |

スペイン領アメリカ遠征、1799年~1804年 アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトのラテンアメリカ遠征 海外遠征の機会を求める 科学的な旅の資金源を確保した彼は、大規模な遠征船を探した。その間、彼は兄ヴィルヘルムが住んでいたパリへ行った。パリは科学の学問の中心地であり、兄 と義姉のカロリーヌは、その界隈で幅広い人脈を持っていた。ルイ・アントワーヌ・ド・ブーゲンビルは、5年間続くと思われる大規模な探検にフンボルトを同 行させるよう促したが、フランス革命の指導部であるディレクトワールは、高齢の科学旅行者ではなく、ニコラ・ボードンをその指揮官に任命した。[46] ヨーロッパでの戦争が続いたため、フンボルトが正式に同行を招待されていたボードン船長の世界周航計画が延期されたことに、フンボルトは深く失望した。彼 は既に航海用の科学機器を選定していた。しかし、航海に同行する植物学者兼医師であるエメ・ボンプランとの出会いは幸運だった。 落胆した二人はパリを離れマルセイユへ向かった。ナポレオン・ボナパルトが率いるエジプト遠征軍に合流するつもりだったが、北アフリカではフランス軍のエ ジプト侵攻に反乱が起きており、フランス当局は渡航を許可しなかった。フンボルトとボンプランは結局マドリードへ辿り着き、そこで彼らの運は劇的に好転し た。[47] |

Spanish royal authorization, 1799 Charles IV of Spain who authorized Humboldt's travels and research in Spanish America In Madrid, Humboldt sought authorization to travel to Spain's realms in the Americas; he was aided in obtaining it by the German representative of Saxony at the royal Bourbon court. Baron Forell had an interest in mineralogy and science endeavors and was inclined to help Humboldt.[47] At that time, the Bourbon Reforms sought to reform administration of the realms and revitalize their economies.[48] At the same time, the Spanish Enlightenment was in florescence. For Humboldt "the confluent effect of the Bourbon revolution in government and the Spanish Enlightenment had created ideal conditions for his venture".[49] The Bourbon monarchy had already authorized and funded expeditions, with the Botanical Expedition to the Viceroyalty of Peru to Chile and Peru (1777–88), New Granada (1783–1816), New Spain (Mexico) (1787–1803), and the Malaspina Expedition (1789–94). These were lengthy, state-sponsored enterprises to gather information about plants and animals from the Spanish realms, assess economic possibilities, and provide plants and seeds for the Royal Botanical Garden in Madrid (founded 1755).[50] These expeditions took naturalists and artists, who created visual images as well as careful written observations as well as collecting seeds and plants themselves.[51] Crown officials as early as 1779 issued and systematically distributed Instructions concerning the most secure and economic means to transport live plants by land and sea from the most distant countries, with illustrations, including one for the crates to transport seeds and plants.[52] When Humboldt requested authorization from the crown to travel to Spanish America, most importantly, with his own financing, it was given positive response. Spain under the Habsburg monarchy had guarded its realms against foreigner travelers and intruders. The Bourbon monarch was open to Humboldt's proposal. Spanish Foreign Minister Don Mariano Luis de Urquijo received the formal proposal and Humboldt was presented to the monarch in March 1799.[47] Humboldt was granted access to crown officials and written documentation on Spain's empire. With Humboldt's experience working for the absolutist Prussian monarchy as a government mining official, Humboldt had both the academic training and experience of working well within a bureaucratic structure.[49]  Portrait of Alexander von Humboldt by Friedrich Georg Weitsch, 1806 Before leaving Madrid in 1799, Humboldt and Bonpland visited the Natural History Museum, which held results of Martín Sessé y Lacasta and José Mariano Mociño's botanical expedition to New Spain.[53] Humboldt and Bonpland met Hipólito Ruiz López and José Antonio Pavón y Jiménez of the royal expedition to Peru and Chile in person in Madrid and examined their botanical collections.[54] |

スペイン王室認可書、1799年 スペイン王カルロス4世はフンボルトのスペイン領アメリカにおける旅行と研究を認可した マドリードでフンボルトはスペイン領アメリカ諸王国への旅行許可を求めた。ザクセン公国のドイツ代表が王室ブルボン宮廷でこれを支援した。フォーレル男爵 は鉱物学と科学事業に関心があり、フンボルトを助ける意向だった。[47] 当時、ブルボン改革は領土の行政改革と経済活性化を目指していた。[48] 同時にスペイン啓蒙主義は隆盛期にあった。フンボルトにとって「政府におけるブルボン革命とスペイン啓蒙主義の相乗効果が、彼の冒険に理想的な条件を生み 出した」のである。[49] ブルボン王朝は既に、ペルー副王領への植物調査遠征(1777-88年)、チリ・ペルー遠征、ヌエバ・グラナダ遠征(1783-1816年)、ヌエバ・エ スパーニャ(メキシコ)遠征(1787-1803年)、マラスピナ遠征(1789-94年)といった遠征を認可・資金提供していた。これらは長期にわたる 国家主導の事業であり、スペイン領内の動植物情報を収集し、経済的可能性を評価するとともに、マドリード王立植物園(1755年創設)へ植物や種子を供給 することを目的としていた。[50] これらの探検隊には自然学者や芸術家が同行し、種子や植物そのものを収集するだけでなく、視覚的記録や詳細な観察記録を作成した。[51] 1779年には既に王室当局が『最も遠隔の国々から陸路及び海路で生きた植物を輸送する最も安全かつ経済的な方法に関する指示書』を発行し、体系的に配布 していた。この指示書には図解が含まれており、種子や植物を輸送するための木箱の設計図も掲載されていた。[52] フンボルトがスペイン領アメリカへの渡航許可を王室に申請した際、特に自己資金による渡航という条件が提示されたが、これは肯定的に応じられた。ハプスブ ルク家の支配下にあったスペインは、外国人の旅行者や侵入者から領土を守ってきた。しかしブルボン家の君主はフンボルトの提案に門戸を開いた。スペイン外 相ド・マリアーノ・ルイス・デ・ウルキホが正式な提案書を受け取り、フンボルトは1799年3月に国王に謁見した。[47] フンボルトは、王室関係者に面会し、スペイン帝国に関する文書を入手することを許可された。フンボルトは、絶対主義的なプロイセン王室で鉱山官吏として働 いた経験があり、学術的な訓練と官僚機構の中でうまく働く経験の両方を持っていた。[49]  フリードリヒ・ゲオルク・ヴァイツによるアレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトの肖像、1806年 1799年にマドリードを離れる前に、フンボルトとボンプランは、マルティン・セッセ・イ・ラカスタとホセ・マリアーノ・モシニョによる新スペインへの植 物調査の成果を所蔵する自然史博物館を訪れた。フンボルトとボンプランは、マドリードで、ペルーとチリへの王立探検隊のヒポリト・ルイス・ロペスとホセ・ アントニオ・パボン・イ・ヒメネスに直接会い、彼らの植物コレクションを調査した。 |

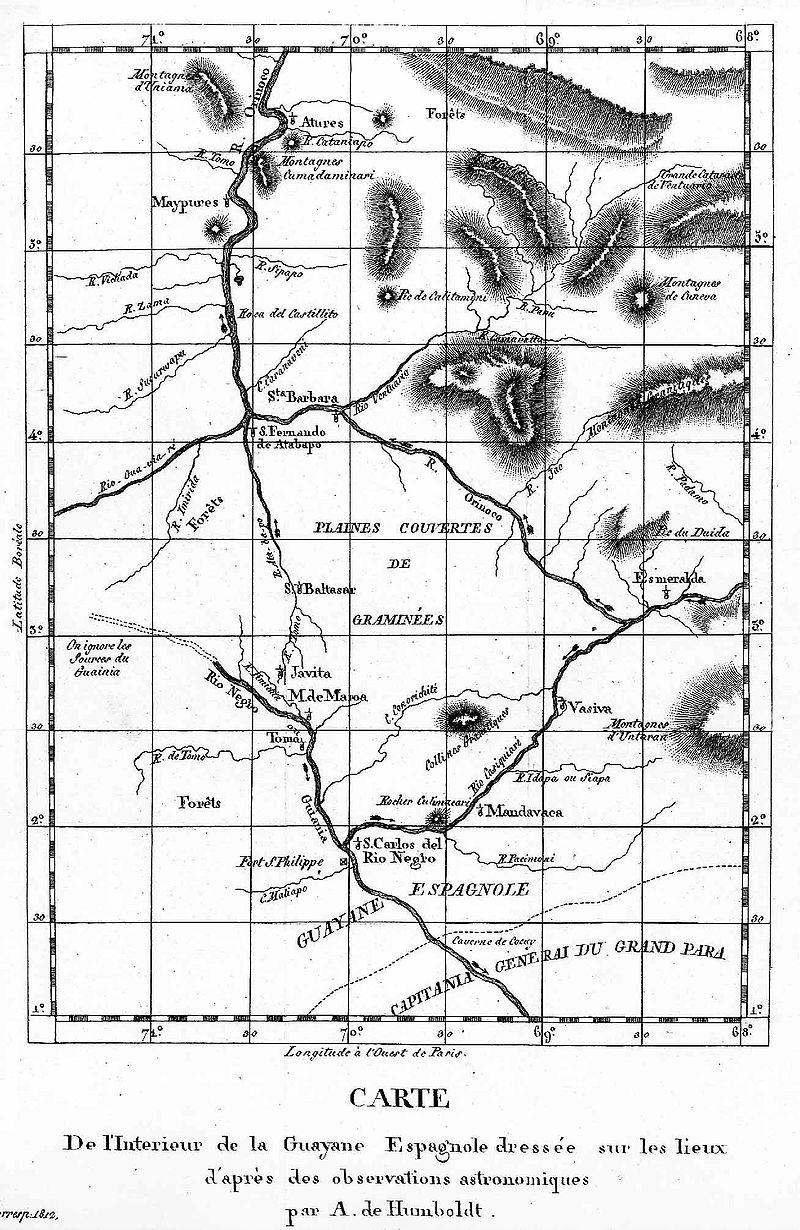

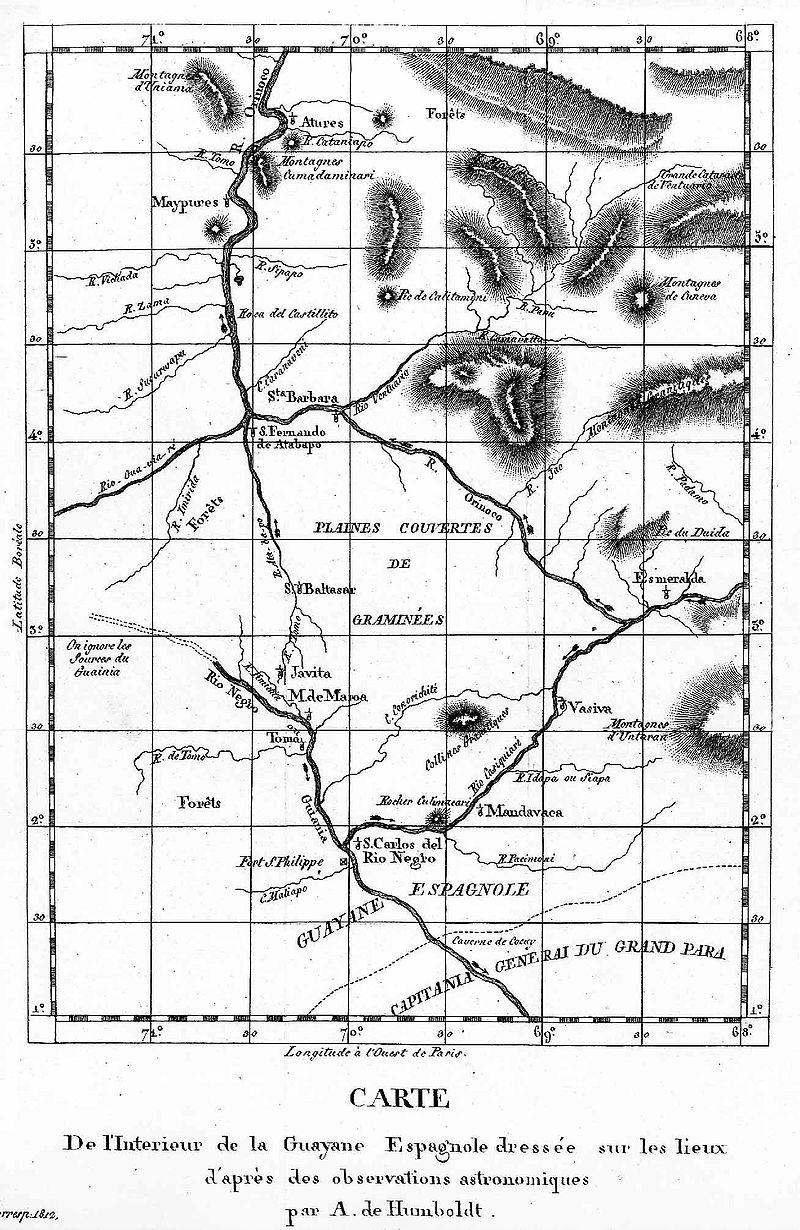

Venezuela, 1799–1800 Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland were in the Amazon rainforest by the Casiquiare River, with their scientific instruments, which enabled them to take many types of accurate measurements throughout their five-year journey. Oil painting by Eduard Ender, 1856. Humboldt did not like the painting as the instruments depicted were inaccurate.[55]  Map of the Casiquiare canal based on Humboldt's 1799 observations Armed with authorization from the King of Spain, Humboldt and Bonpland made haste to sail, taking the ship Pizarro from A Coruña, on 5 June 1799. The ship stopped six days on the island of Tenerife, where Humboldt climbed the volcano Teide, and then sailed on to the New World, landing at Cumaná, Venezuela, on 16 July. The ship's destination was not originally Cumaná, but an outbreak of typhoid on board meant that the captain changed course from Havana to land in northern South America. Humboldt had not mapped out a specific plan of exploration, so that the change did not upend a fixed itinerary. He later wrote that the diversion to Venezuela made possible his explorations along the Orinoco River to the border of Portuguese Brazil. With the diversion, the Pizarro encountered two large dugout canoes each carrying 18 Guayaqui Indians. The Pizarro's captain accepted the offer of one of them to serve as pilot. Humboldt hired this Indian, named Carlos del Pino, as a guide.[56] Venezuela from the 16th to the 18th centuries was a relative backwater compared to the seats of the Spanish viceroyalties based in New Spain (Mexico) and Peru, but during the Bourbon reforms, the northern portion of Spanish South America was reorganized administratively, with the 1777 establishment of a captaincy-general based at Caracas. A great deal of information on the new jurisdiction had already been compiled by François de Pons, but was not published until 1806.[49][57] Rather than describe the administrative center of Caracas, Humboldt started his researches with the valley of Aragua, where export crops of sugar, coffee, cacao, and cotton were cultivated. Cacao plantations were the most profitable, as world demand for chocolate rose.[58] It is here that Humboldt is said to have developed his idea of human-induced climate change. Investigating evidence of a rapid fall in the water level of the valley's Lake Valencia, Humboldt credited the desiccation to the clearance of tree cover and to the inability of the exposed soils to retain water. With their clear cutting of trees, the agriculturalists were removing the woodland's "threefold" moderating influence upon temperature: cooling shade, evaporation and radiation.[59] Humboldt visited the mission at Caripe and explored the Guácharo cavern, where he found the oilbird, which he was to make known to science as Steatornis caripensis. He also described the Guanoco asphalt lake as "The spring of the good priest" ("Quelle des guten Priesters").[60][61] Returning to Cumaná, Humboldt observed, on the night of 11–12 November, a remarkable meteor shower (the Leonids). He proceeded with Bonpland to Caracas where he climbed the Avila mount with the young poet Andrés Bello, the former tutor of Simón Bolívar, who later became the leader of independence in northern South America. Humboldt met the Venezuelan Bolívar himself in 1804 in Paris and spent time with him in Rome. The documentary record does not support the supposition that Humboldt inspired Bolívar to participate in the struggle for independence, but it does indicate Bolívar's admiration for Humboldt's production of new knowledge on Spanish America.[62] In February 1800, Humboldt and Bonpland left the coast with the purpose of exploring the course of the Orinoco River and its tributaries. This trip, which lasted four months and covered 1,725 miles (2,776 km) of wild and largely uninhabited country, had an aim of establishing the existence of the Casiquiare canal (a communication between the water systems of the rivers Orinoco and Amazon). Although, unbeknownst to Humboldt, this existence had been established decades before,[63] his expedition had the important results of determining the exact position of the bifurcation,[23] and documenting the life of several native tribes such as the Maipures and their extinct rivals the Atures (several words of the latter tribe were transferred to Humboldt by one parrot[64]). Around 19 March 1800, Humboldt and Bonpland discovered dangerous electric eels, whose shock could kill a man. To catch them, locals suggested they drive wild horses into the river, which brought the eels out from the river mud, and resulted in a violent confrontation of eels and horses, some of which died. Humboldt and Bonpland captured and dissected some eels, which retained their ability to shock; both received potentially dangerous electric shocks during their investigations. The encounter made Humboldt think more deeply about electricity and magnetism, typical of his ability to extrapolate from an observation to more general principles.[65] Humboldt returned to the incident in several of his later writings, including his travelogue Personal Narrative (1814–29), Views of Nature (1807), and Aspects of Nature (1849).[66] Two months later, they explored the territory of the Maipures and that of the then-recently extinct Atures Indians. Humboldt laid to rest the persistent myth of Walter Raleigh's Lake Parime by proposing that the seasonal flooding of the Rupununi savannah had been misidentified as a lake.[67] |

ベネズエラ、1799–1800年 フンボルトとエメ・ボンプランはカシキアレ川沿いのアマゾン熱帯雨林にいた。彼らは科学機器を携えており、5年間の旅を通じて様々な正確な測定を行うこと ができた。エドゥアルト・エンダーによる油絵、1856年。フンボルトはこの絵を好まなかった。描かれた機器が不正確だったからだ。[55]  フンボルトの1799年観測に基づくカシキアレ水路図 スペイン国王の許可を得たフンボルトとボンプランは、1799年6月5日にア・コルーニャからピサロ号で急ぎ出航した。船はテネリフェ島で6日間停泊し、フンボルトはテイデ火山に登頂した後、新大陸へ向けて航海を続け、7月16日にベネズエラのクマナに上陸した。 当初の目的地はクマナではなかったが、船内で発生した腸チフスにより、船長はハバナから南米北部に寄港するコースを変更した。フンボルトは具体的な探検計 画を立てていなかったため、この変更は固定された旅程を覆すものではなかった。彼は後に、ベネズエラへの迂回がオリノコ川沿いの探検を可能にし、ポルトガ ル領ブラジル国境まで到達できたと記している。この迂回航路で、ピサロ号は18人のグアヤキ族インディアンを乗せた大型丸木舟2隻と遭遇した。ピサロ号の 船長は、そのうちの1人が案内役として同行する申し出を受け入れた。フンボルトはこのインディアン、カルロス・デル・ピノをガイドとして雇った。[56] 16世紀から18世紀にかけてのベネズエラは、ニュー・エスパーニャ(メキシコ)やペルーに本拠を置くスペイン副王領の中心地と比べると、比較的辺境の地 であった。しかしブルボン改革期に、スペイン領南アメリカの北部は行政的に再編され、1777年にはカラカスを本拠とする総督府が設置された。この新管轄 区域に関する膨大な情報はフランソワ・ド・ポンズによって既にまとめられていたが、出版されたのは1806年になってからだった。[49][57] フンボルトは行政の中心地カラカスを記述する代わりに、砂糖、コーヒー、カカオ、綿花といった輸出作物が栽培されていたアラグア渓谷から研究を始めた。カ カオ農園は最も収益性が高く、世界的なチョコレート需要の高まりを受けていた[58]。フンボルトが人為的気候変動の概念をここで発展させたとされる。同 地にあるバレンシア湖の水位急落の証拠を調査したフンボルトは、樹木の伐採と露出した土壌の保水力不足が干上がりの原因だと結論づけた。農耕民による森林 の伐採は、気温を調節する森林の「三つの」影響、すなわち冷却効果のある日陰、蒸発、放射を排除していたのである。[59] フンボルトはカリペの宣教所を訪れ、グアチャロ洞窟を探検した。そこで彼はオイルバードを発見し、後に科学界にステアトルニス・カリペンシスとして知られ るようにした。またグアノコ瀝青湖を「善き司祭の泉」(Quelle des guten Priesters)と記述した[60][61]。クマナに戻ったフンボルトは11月11日から12日にかけての夜、驚くべき流星群(レオニッド流星群) を観測した。ボンプランと共にカラカスへ進み、アビラ山に登った。同行したのは若き詩人アンドレス・ベジョで、彼は後に南米北部の独立指導者となるシモ ン・ボリバルの家庭教師を務めていた。フンボルトは1804年にパリでベネズエラのボリバル本人と出会い、ローマで共に過ごした。記録によれば、フンボル トがボリバルに独立闘争への参加を促したという推測は裏付けられないが、ボリバルがフンボルトのスペイン領アメリカに関する新たな知見の創出を称賛してい たことは示されている。[62] 1800年2月、フンボルトとボンプランはオリノコ川とその支流の探検を目的に海岸を離れた。この旅は4か月間続き、1,725マイル(2,776キロ メートル)に及ぶ未開でほとんど無人地帯を横断し、カシキアレ水路(オリノコ川とアマゾン川の流域を結ぶ水路)の存在を確認することを目的としていた。フ ンボルトは知らなかったが、この存在は数十年前に既に確認されていた[63]。しかし彼の探検は、分岐点の正確な位置を特定した[23]こと、マイプレ族 やその滅んだ敵対部族アトゥレ族など複数の先住民の生活を記録した点で重要な成果をもたらした(後者の部族の言葉の数語は、フンボルトに1羽のオウムに よって伝えられた[64])。1800年3月19日頃、フンボルトとボンプランは危険な電気ウナギを発見した。その放電は人を殺すほどだった。捕獲のた め、現地人は野生の馬を川に追い込むよう提案した。これによりウナギが泥底から現れ、ウナギと馬の激しい衝突が発生し、馬数頭が死亡した。フンボルトとボ ンプランは数匹のウナギを捕獲し解剖したが、それらは依然として電気ショックを与える能力を保持していた。調査中、両者とも危険な電気ショックを受ける可 能性があった。この遭遇はフンボルトに電気と磁気について深く考えさせるきっかけとなった。これは彼の観察からより一般的な原理へと推論する能力の典型例 である[65]。フンボルトは後年の著作、旅行記『個人旅行記』(1814-29年)、『自然の景観』(1807年)、『自然の諸相』(1849年)など でこの出来事を繰り返し言及している。[66] 二か月後、彼らはマイプレ族と、当時すでに絶滅したアトゥレ族の領域を探検した。フンボルトは、ルプヌニサバンナの季節的な洪水が湖と誤認されていたと提唱することで、ウォルター・ローリーのパリメ湖に関する根強い伝説に終止符を打った。[67] |

Cuba, 1800, 1804 Humboldt botanical drawing published in his work on Cuba On 24 November 1800, the two friends set sail for Cuba, landing on 19 December,[68] where they met fellow botanist and plant collector John Fraser.[69] Fraser and his son had been shipwrecked off the Cuban coast, and did not have a license to be in the Spanish Indies. Humboldt, who was already in Cuba, interceded with crown officials in Havana, as well as giving them money and clothing. Fraser obtained permission to remain in Cuba and explore. Humboldt entrusted Fraser with taking two cases of Humboldt and Bonpland's botanical specimens to England when he returned, for eventual conveyance to the German botanist Willdenow in Berlin.[70] Humboldt and Bonpland stayed in Cuba until 5 March 1801, when they left for the mainland of northern South America again, arriving there on 30 March. Humboldt is considered to be the "second discoverer of Cuba" due to the scientific and social research he conducted on this Spanish colony. During an initial three-month stay at Havana, his first tasks were to survey that city properly and the nearby towns of Guanabacoa, Regla, and Bejucal. He befriended Cuban landowner and thinker Francisco de Arango y Parreño; together they visited the Guines area in south Havana, the valleys of Matanzas Province, and the Valley of the Sugar Mills in Trinidad. Those three areas were, at the time, the first frontier of sugar production in the island. During those trips, Humboldt collected statistical information on Cuba's population, production, technology and trade, and with Arango, made suggestions for enhancing them. He predicted that the agricultural and commercial potential of Cuba was huge and could be vastly improved with proper leadership in the future. On their way back to Europe from the Americas, Humboldt and Bonpland stopped again in Cuba, leaving from the port of Veracruz and arriving in Cuba on 7 January 1804, staying until 29 April 1804. In Cuba, he collected plant material and made extensive notes. During this time, he socialized with his scientific and landowner friends, conducted mineralogical surveys, and finished his vast collection of the island's flora and fauna that he eventually published as Essai politique sur l'îsle de Cuba.[71] |

キューバ、1800年、1804年 フンボルトのキューバに関する著作に掲載された植物図譜 1800年11月24日、二人の友人はキューバに向けて出航し、12月19日に上陸した[68]。そこで彼らは植物学者であり植物収集家でもあるジョン・ フレイザーと出会った。[69] フレイザーとその息子はキューバ沖で難破しており、スペイン領インド諸島に滞在する許可を持っていなかった。既にキューバにいたフンボルトは、ハバナの王 室当局者に取り成し、金銭と衣服を提供した。フレイザーはキューバに留まり探検する許可を得た。フンボルトは、帰国時にフンボルトとボンプランの植物標本 2箱をイギリスへ持ち帰り、最終的にベルリンのドイツ人植物学者ヴィルデノウへ届けるようフレイザーに託した[70]。フンボルトとボンプランは1801 年3月5日までキューバに滞在し、再び南米大陸北部へ向けて出発、3月30日に到着した。 フンボルトは、このスペイン植民地で実施した科学的・社会的研究により、「キューバの第二の発見者」と見なされている。ハバナでの最初の3か月間の滞在 中、彼の最初の任務はハバナ市と近隣のグアナバコア、レグラ、ベフカルの各町を適切に調査することだった。彼はキューバの地主であり思想家であるフランシ スコ・デ・アランゴ・イ・パレニョと親交を深め、共にハバナ南部のギネス地域、マタンサス州の谷間、トリニダドの砂糖工場の谷間を訪れた。当時、これら三 地域は島における砂糖生産の最前線だった。これらの旅でフンボルトはキューバの人口、生産、技術、貿易に関する統計情報を収集し、アランゴと共にそれらを 向上させるための提案を行った。彼はキューバの農業と商業の潜在力が巨大であり、将来適切な指導力があれば大幅に改善できると予測した。 アメリカ大陸からヨーロッパへ戻る途中、フンボルトとボンプランは再びキューバに立ち寄った。ベラクルス港を出発し、1804年1月7日にキューバに到 着、同年4月29日まで滞在した。キューバでは植物標本を収集し、詳細な記録を残した。この期間、彼は科学者や地主の友人たちと交流し、鉱物調査を行い、 島の動植物に関する膨大な収集を完成させた。これは後に『キューバ島に関する政治的考察』として出版された。 |

The Andes, 1801–1803 Humboldt and his fellow scientist Aimé Bonpland near the foot of the Chimborazo volcano, painting by Friedrich Georg Weitsch (1810) After their first stay in Cuba of three months, they returned to the mainland at Cartagena de Indias (now in Colombia), a major center of trade in northern South America. Ascending the swollen stream of the Magdalena River to Honda, they arrived in Bogotá on 6 July 1801, where they met the Spanish botanist José Celestino Mutis, head of the Royal Botanical Expedition to New Granada, staying there until 8 September 1801. Mutis was generous with his time and gave Humboldt access to the huge pictorial record he had compiled since 1783. Mutis was based in Bogotá, but as with other Spanish expeditions, he had access to local knowledge and a workshop of artists, who created highly accurate and detailed images. This type of careful recording meant that even if specimens were not available to study at a distance, "because the images travelled, the botanists did not have to".[72] Humboldt was astounded at Mutis's accomplishment; when Humboldt published his first volume on botany, he dedicated it to Mutis "as a simple mark of our admiration and acknowledgement".[73] Humboldt had hopes of connecting with the French sailing expedition of Baudin, now finally underway, so Bonpland and Humboldt hurried to Ecuador.[71] They crossed the frozen ridges of the Cordillera Real and reached Quito on 6 January 1802, after a tedious and difficult journey. Their stay in Ecuador was marked by the ascent of the active volcano Pichincha and their climb of the extinct, snow-capped volcano Chimborazo, where Humboldt and his party, consisting of himself, Bonpland, a number of Indians and the Ecuadorian nobleman Carlos Montúfar, reached an altitude of 19,286 feet (5,878 m).[13] This was a world record at the time, higher even than had been ascended in a balloon, (for a westerner—Incas had climbed much higher altitudes centuries before),[74] but 1000 feet short of the summit.[75] Humboldt's journey concluded with an expedition to the sources of the Amazon en route for Lima, Peru.[76] At Callao, the main port for Peru, Humboldt observed the transit of Mercury on 9 November and studied the fertilizing properties of guano, rich in nitrogen, the subsequent introduction of which into Europe was due mainly to his writings.[23] |

アンデス山脈、1801年~1803年 フンボルトと彼の同僚科学者エイメ・ボンプランがチンボラソ火山麓付近にいる様子。フリードリヒ・ゲオルク・ヴァイツによる絵画(1810年) キューバでの3ヶ月の最初の滞在後、彼らは南米北部の主要貿易拠点であるカルタヘナ・デ・インディアス(現在のコロンビア)で本土に戻った。増水したマグ ダレナ川を遡りホンダへ至り、1801年7月6日にボゴタに到着した。そこで彼らは、ニューグラナダ王立植物調査隊の責任者であるスペイン人植物学者ホ セ・セレスティーノ・ムティスと面会し、1801年9月8日まで滞在した。ムティスは寛大にも時間を割き、1783年から編纂してきた膨大な図譜記録をフ ンボルトに閲覧させた。ムティスはボゴタを拠点としていたが、他のスペインの探検隊と同様、現地の知識と芸術家の工房を利用できた。芸術家たちは非常に正 確で詳細な画像を作成した。この入念な記録手法により、遠隔地で標本を直接研究できなくとも、「図像が移動したため、植物学者が移動する必要はなかった」 のである[72]。フンボルトはムティスの業績に驚嘆し、自身の植物学第一巻を出版した際には「単なる敬意と感謝の印として」ムティスに献呈した。 [73] フンボルトは、ようやく出航したフランスのボーダン航海隊との連携を望んでいたため、ボンプランとフンボルトは急いでエクアドルへ向かった。[71] 彼らはコルディジェラ・レアルの凍った尾根を越え、退屈で困難な旅を経て1802年1月6日にキトに到着した。 エクアドル滞在中の彼らの主な活動は、活火山ピチンチャの登頂と、雪を冠した死火山チンボラソの登攀であった。フンボルトと同行者(フンボルト自身、ボン プラン、数名のインディオ、エクアドル貴族カルロス・モントゥファル)は、チンボラソで標高19,286フィート(5,878メートル)に到達した。 [13] これは当時世界記録であり、気球での到達高度さえ上回っていた(西洋人にとって——インカ人は数世紀前にこれよりはるかに高い高度に到達していたが) [74]、頂上まであと1000フィート(約305メートル)に迫っていた。[75] フンボルトの旅は、ペルーのリマへ向かう途中、アマゾン川源流への探検で幕を閉じた。[76] ペルーの主要港カヤオでは、フンボルトは11月9日に水星の太陽面通過を観測し、窒素を豊富に含むグアノの肥料としての特性を研究した。その後グアノがヨーロッパに導入されたのは、主に彼の著作によるものである。[23] |

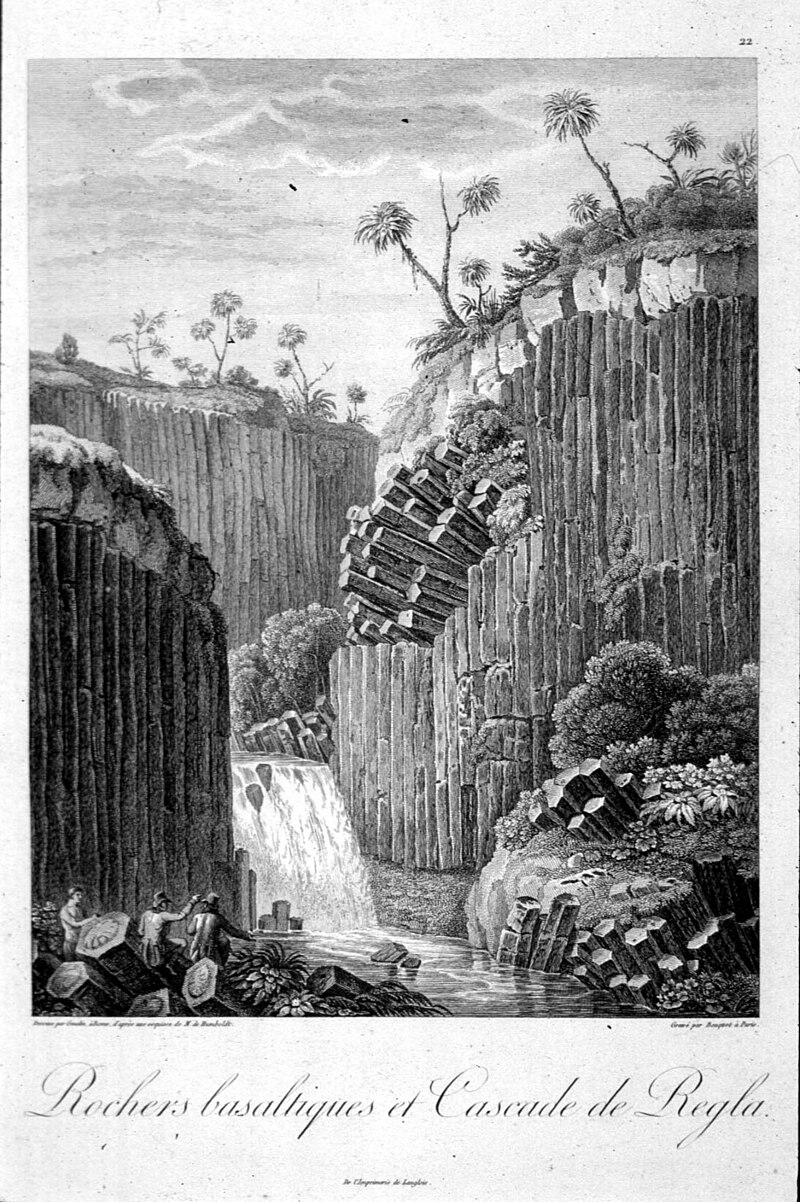

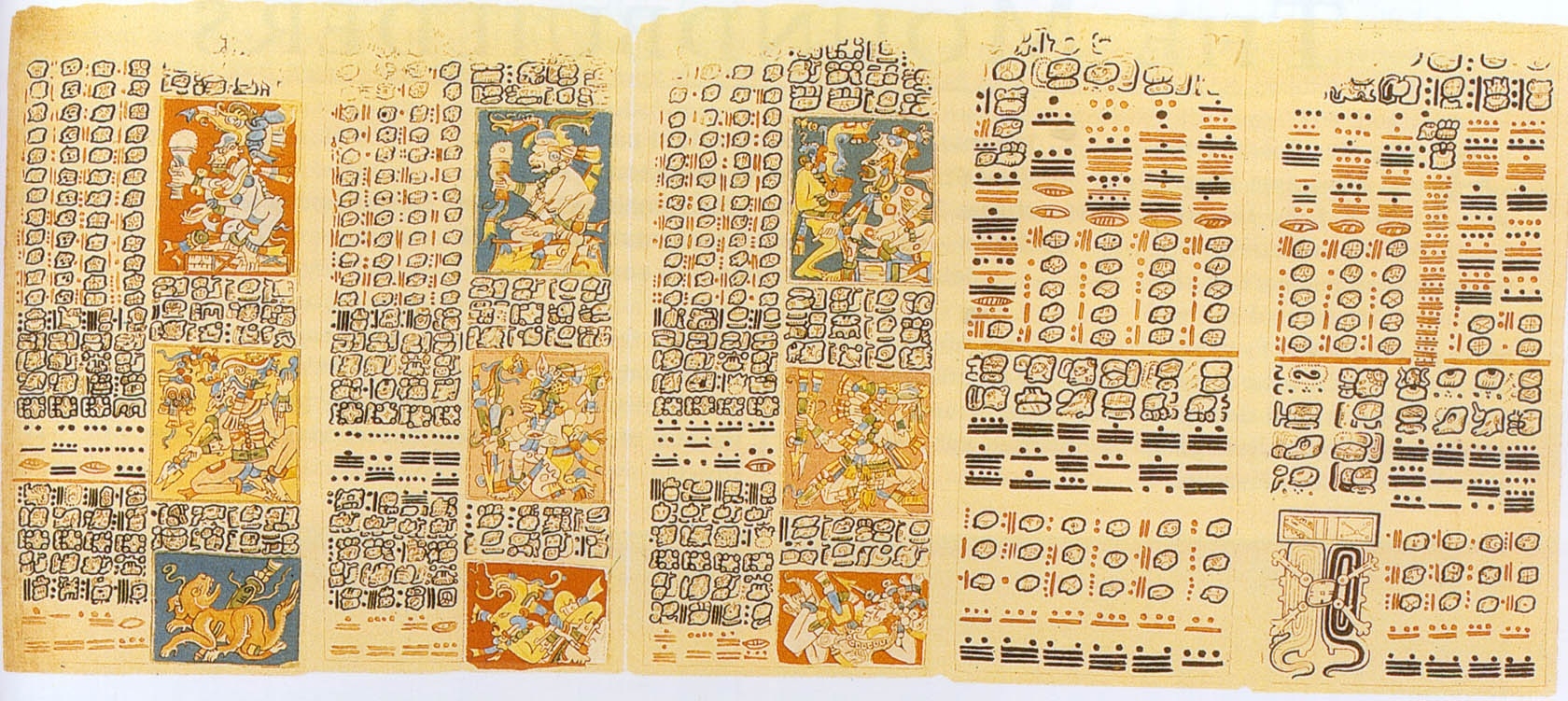

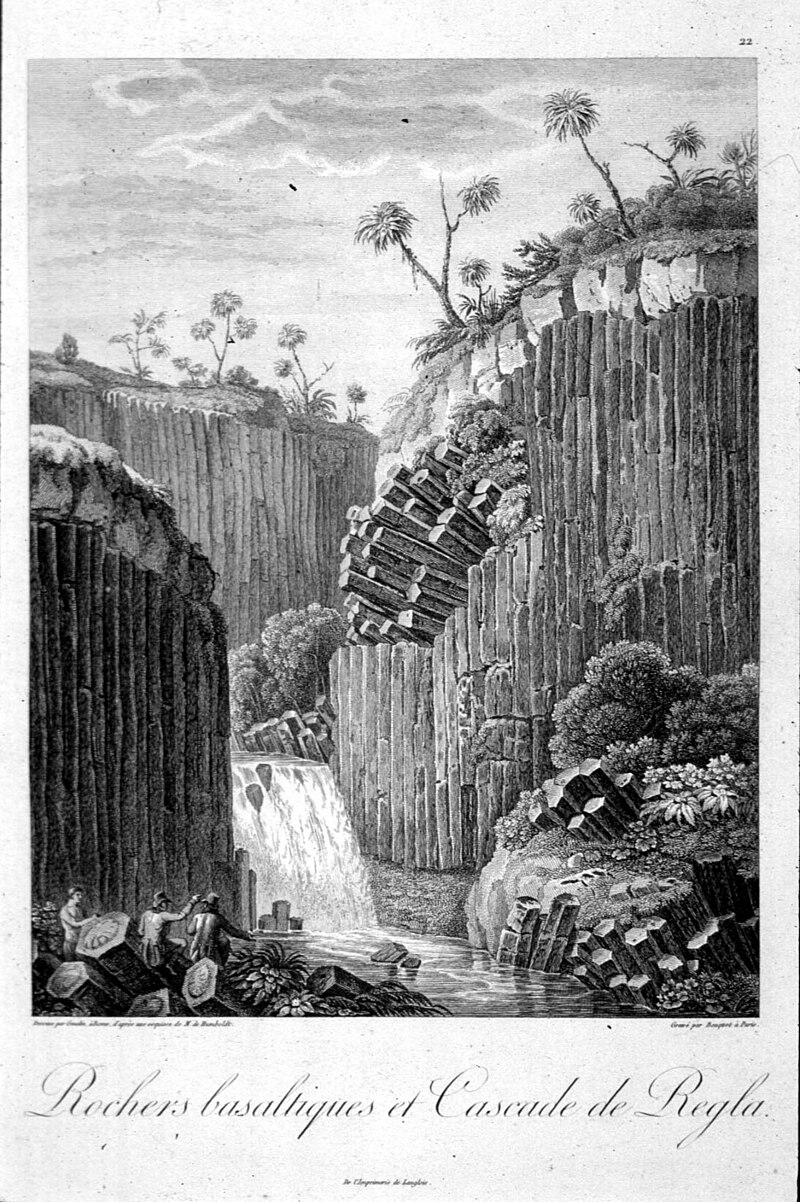

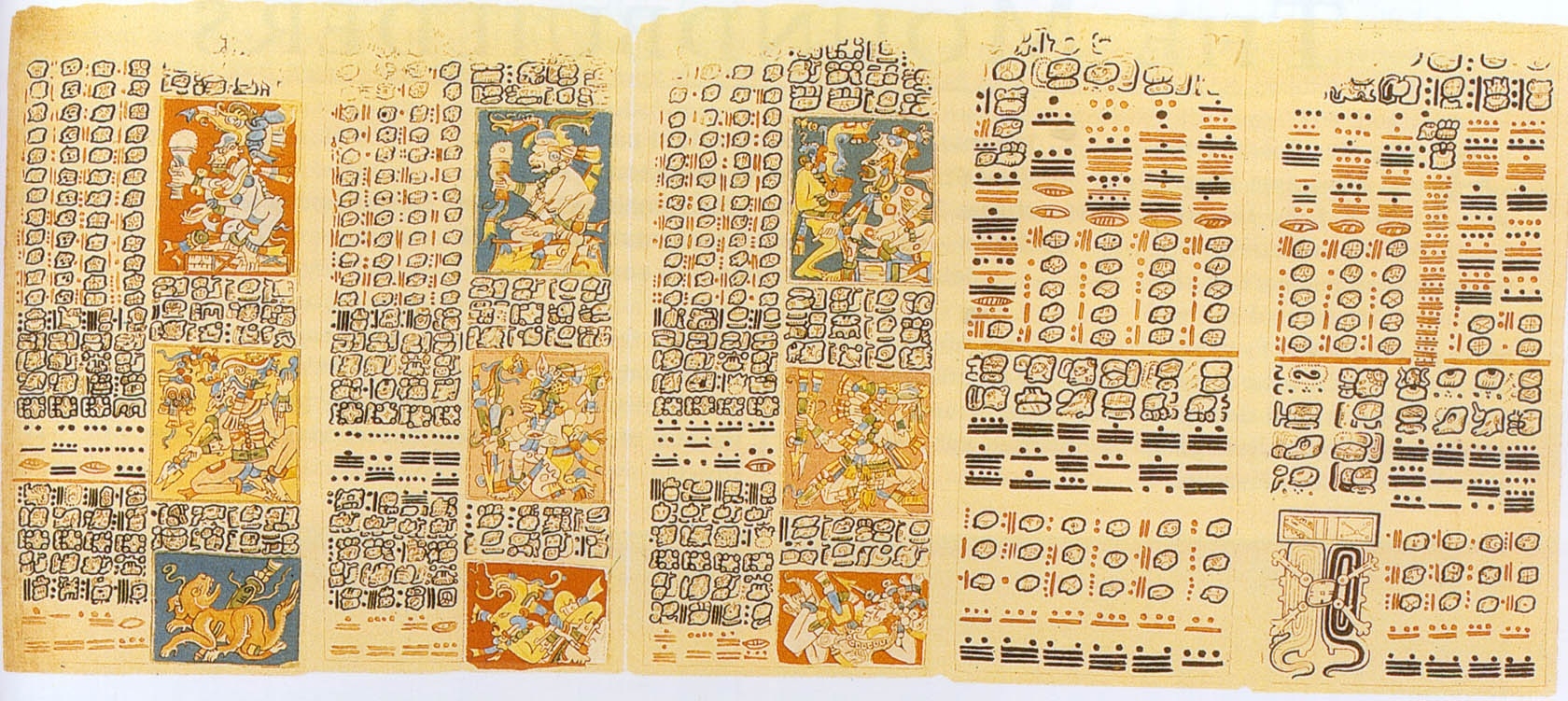

New Spain (Mexico), 1803–1804 Silver mining complex of La Valenciana, Guanajuato, Mexico  Basalt prisms at Santa María Regla, Mexico by Alexander von Humboldt, published in Vue des Cordillères et monuments des peuples indigènes de l'Amérique  Aztec calendar stone  Dresden Codex, later identified as a Maya manuscript, published in part by Humboldt in 1810 Humboldt and Bonpland had not intended to go to New Spain, but when they were unable to join a voyage to the Pacific, they left the Ecuadorian port of Guayaquil and headed for Acapulco on Mexico's west coast. Even before Humboldt and Bonpland started on their way to New Spain's capital on Mexico's central plateau, Humboldt realized the captain of the vessel that brought them to Acapulco had reckoned its location incorrectly. Since Acapulco was the main west-coast port and the terminus of the Asian trade from the Spanish Philippines, having accurate maps of its location was extremely important. Humboldt set up his instruments, surveying the deep-water bay of Acapulco, to determine its longitude.[77][78] Humboldt and Bonpland landed in Acapulco on 15 February 1803, and from there they went to Taxco, a silver-mining town in modern Guerrero. In April 1803, he visited Cuernavaca, Morelos. Impressed by its climate, he nicknamed the city the City of Eternal Spring.[79][80] Humboldt and Bonpland arrived in Mexico City, having been officially welcomed via a letter from the king's representative in New Spain, Viceroy Don José de Iturrigaray. Humboldt was also given a special passport to travel throughout New Spain and letters of introduction to intendants, the highest officials in New Spain's administrative districts (intendancies). This official aid to Humboldt allowed him to have access to crown records, mines, landed estates, canals, and Mexican antiquities from the prehispanic era.[81] Humboldt read the writings of Bishop-elect of the important diocese of Michoacan Manuel Abad y Queipo, a classical liberal, that were directed to the crown for the improvement of New Spain.[82] They spent the year in the viceroyalty, traveling to different Mexican cities in the central plateau and the northern mining region. The first journey was from Acapulco to Mexico City, through what is now the Mexican state of Guerrero. The route was suitable only for mule train, and all along the way, Humboldt took measurements of elevation. When he left Mexico a year later in 1804, from the east coast port of Veracruz, he took a similar set of measures, which resulted in a chart in the Political Essay, the physical plan of Mexico with the dangers of the road from Acapulco to Mexico City, and from Mexico City to Veracruz.[83] This visual depiction of elevation was part of Humboldt's general insistence that the data he collected be presented in a way more easily understood than statistical charts. A great deal of his success in gaining a more general readership for his works was his understanding that "anything that has to do with extent or quantity can be represented geometrically. Statistical projections [charts and graphs], which speak to the senses without tiring the intellect have the advantage of bringing attention to a large number of important facts".[84] Humboldt was impressed with Mexico City, which at the time was the largest city in the Americas, and one that could be counted as modern. He declared "no city of the new continent, without even excepting those of the United States, can display such great and solid scientific establishments as the capital of Mexico".[85] He pointed to the Royal College of Mines, the Royal Botanical Garden and the Royal Academy of San Carlos as exemplars of a metropolitan capital in touch with the latest developments on the continent and insisting on its modernity.[86] He also recognized important criollo savants in Mexico, including José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez, who died in 1799, just before Humboldt's visit; Miguel Velásquez de León; and Antonio de León y Gama.[82] Humboldt spent time at the Valenciana silver mine in Guanajuato, central New Spain, at the time the most important in the Spanish empire.[87] The bicentennial of his visit in Guanajuato was celebrated with a conference at the University of Guanajuato, with Mexican academics highlighting various aspects of his impact on the city.[88] Humboldt could have simply examined the geology of the fabulously rich mine, but he took the opportunity to study the entire mining complex as well as analyze mining statistics of its output. His report on silver mining is a major contribution, and considered the strongest and best informed section of his Political Essay. Although Humboldt was himself a trained geologist and mining inspector, he drew on mining experts in Mexico. One was Fausto Elhuyar, then head of the General Mining Court in Mexico City, who, like Humboldt was trained in Freiberg. Another was Andrés Manuel del Río, director of Royal College of Mines, whom Humboldt knew when they were both students in Freiberg.[89] The Bourbon monarchs had established the mining court and the college to elevate mining as a profession, since revenues from silver constituted the crown's largest source of income. Humboldt also consulted other German mining experts, who were already in Mexico.[82] While Humboldt was a welcome foreign scientist and mining expert, the Spanish crown had established fertile ground for Humboldt's investigations into mining. Spanish America's ancient civilizations were a source of interest for Humboldt, who included images of Mexican manuscripts (or codices) and Inca ruins in his richly illustrated Vues des cordillères et monuments des peuples indigènes de l'Amerique (1810–1813), the most experimental of Humboldt's publications, since it does not have "a single ordering principle" but his opinions and contentions based on observation.[90] For Humboldt, a key question was the influence of climate on the development of these civilizations.[91] When he published his Vues des cordillères, he included a color image of the Aztec calendar stone (which had been discovered in 1790 buried in the main plaza of Mexico City), along with select drawings of the Dresden Codex and others he sought out later in European collections. His aim was to muster evidence that these pictorial and sculptural images could allow the reconstruction of prehispanic history. He sought out Mexican experts in the interpretation of sources from there, especially Antonio Pichardo, who was the literary executor of Antonio de León y Gama's work. For American-born Spaniards (criollos) who were seeking sources of pride in Mexico's ancient past, Humboldt's recognition of these ancient works and dissemination in his publications was a boon. He read the work of exiled Jesuit Francisco Javier Clavijero, which celebrated Mexico's prehispanic civilization, and which Humboldt invoked to counter the pejorative assertions about the new world by Buffon, de Pauw, and Raynal.[92] Humboldt ultimately viewed both the prehispanic realms of Mexico and Peru as despotic and barbaric.[93] However, he also drew attention to indigenous monuments and artifacts as cultural productions that had "both ... historical and artistic significance".[94] One of his most widely read publications resulting from his travels and investigations in Spanish America was the Essai politique sur le royaum de la Nouvelle Espagne, quickly translated to English as Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain (1811).[95] This treatise was the result of Humboldt's own investigations as well as the generosity of Spanish colonial officials for statistical data.[96] |

新スペイン(メキシコ)、1803年~1804年 メキシコ、グアナフアト州、ラ・バレンシアナの銀鉱山  アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトによる、メキシコ、サンタ・マリア・レグラの玄武岩のプリズム(方解石?)。Vue des Cordillères et monuments des peuples indigènes de l'Amérique(アメリカ大陸の山脈と先住民遺跡)に掲載。  アステカ暦の石  ドレスデン写本、後にマヤの写本と確認され、1810年にフンボルトによって一部が刊行された フンボルトとボンプランは、ニュー・スペインに行くつもりはなかったが、太平洋への航海に参加できなかったため、エクアドルのグアヤキル港を出発し、メキ シコ西海岸のアカプルコに向かった。フンボルトとボンプランがメキシコ中央高原にある新スペインの首都へ向かう前に、フンボルトは彼らをアカプルコへ運ん だ船長がその位置を誤って計算していたことに気づいた。アカプルコは西海岸の主要港であり、スペイン領フィリピンからのアジア貿易の終着点であったため、 その位置の正確な地図を持つことは極めて重要だった。フンボルトは測量器具を設置し、アカプルコの深水湾を調査して経度を測定した。[77][78] フンボルトとボンプランは1803年2月15日にアカプルコに上陸し、そこから現代のゲレロ州にある銀鉱山の町タスコへ向かった。1803年4月、彼はモ レロス州クエルナバカを訪れた。その気候に感銘を受け、この街を「永遠の春の都」と称した[79][80]。フンボルトとボンプランはメキシコシティに到 着し、新スペイン総督ドン・ホセ・デ・イトゥリガライから国王代理人による書簡を通じ、公式に歓迎を受けた。フンボルトは新スペイン全域を移動するための 特別通行証と、各行政区(総督府)の最高責任者である総督への紹介状も授与された。この公的支援により、彼は王室記録、鉱山、土地所有地、運河、そして先 コロンブス期メキシコの古代遺跡へのアクセスを許可された[81]。フンボルトは、ミチョアカン教区の司教候補者マヌエル・アバド・イ・ケイポ(古典的自 由主義者)が新スペインの改善のために王室に提出した文書を読んだ。[82] 彼らは副王領で1年間を過ごし、中央高原や北部の鉱山地帯にある様々なメキシコの都市を旅した。最初の旅はアカプルコからメキシコシティへ、現在のゲレー ロ州を通るルートだった。このルートはラバ隊列にしか適さず、道中ずっとフンボルトは標高測定を行った。1年後の1804年にメキシコを去る際、東海岸の 港ベラクルスから同様の測定を行い、その結果は『政治論考』内の図表となった。これはメキシコの地形図であり、アカプルコからメキシコシティ、メキシコシ ティからベラクルスまでの道路の危険性を示していた。[83] この標高の視覚的表現は、フンボルトが収集したデータを統計図表よりも理解しやすい形で提示すべきだと主張した姿勢の一端である。彼の著作がより広範な読 者層を獲得できた大きな要因は、「範囲や量に関わる事象は幾何学的に表現できる」という理解にあった。知性を疲弊させずに感覚に訴える統計的投影(図表や グラフ)は、多数の重要事実に注意を向ける利点がある」という彼の理解に起因していた。[84] フンボルトは当時アメリカ大陸最大の都市であり、近代的と評せられるメキシコシティに感銘を受けた。彼は「新大陸のどの都市も、アメリカ合衆国の都市さえ 例外とせず、メキシコ首都のような偉大で堅固な科学施設を誇れない」と宣言した。[85] 王立鉱山大学、王立植物園、サン・カルロス王立アカデミーを、大陸の最新動向に触れつつその近代性を主張する首都の模範として挙げたのである。[86] また、フンボルト訪問直前の1799年に死去したホセ・アントニオ・デ・アルサーテ・イ・ラミレス、ミゲル・ベラスケス・デ・レオン、アントニオ・デ・レ オン・イ・ガマら、メキシコの重要なクリオージョの学者たちも認めた。[82] フンボルトは当時スペイン帝国で最も重要な鉱山であった、ヌエバ・エスパーニャ中央部のグアナファトにあるバレンシアナ銀山を訪れた。[87] 彼のグアナファト訪問二百周年を記念し、グアナファト大学で会議が開催され、メキシコの学者たちが同市への彼の影響の様々な側面を強調した。[88] フンボルトは単にこの驚異的な富を生み出す鉱山の地質を調査するだけでもよかったが、彼は鉱山施設全体を研究し、その産出量の統計分析を行う機会を得た。 彼の銀鉱業に関する報告書は重要な貢献であり、『政治論考』の中で最も力強く、最も情報量の多い部分とされている。フンボルト自身は訓練を受けた地質学者 であり鉱山監督官であったが、メキシコの鉱業専門家たちの知見も活用した。その一人、ファウスト・エルユアルは当時メキシコシティの鉱山総監を務めてお り、フンボルト同様フライベルクで学んだ経歴を持つ。もう一人は王立鉱山学院の院長アンドレス・マヌエル・デル・リオで、フンボルトはフライベルク在学中 に彼と知り合いだった。[89] ブルボン王朝は銀の産出が王室の最大の収入源であったため、鉱業を専門職として確立すべく鉱山裁判所と鉱山大学を設立していた。フンボルトは既にメキシコ に滞在していた他のドイツ人鉱山専門家にも助言を求めた。[82] フンボルトは歓迎される外国人科学者・鉱山専門家であったが、スペイン王室が整えた環境こそが彼の鉱業調査の肥沃な土壌となっていた。 スペイン領アメリカにおける古代文明はフンボルトの関心の対象であり、彼はメキシコの写本(コデックス)やインカ遺跡の画像を、豊富な図版を伴う著作『ア メリカ山脈と先住民遺跡の図譜』(1810-1813年)に収録した。これはフンボルトの著作の中で最も実験的なもので、「単一の体系化原理」を持たず、 観察に基づく彼の意見と主張で構成されていた。[90] フンボルトにとって重要な疑問は、気候がこれらの文明の発展に与えた影響であった。[91] 『山脈と先住民の遺跡』刊行時には、アステカ暦石(1790年にメキシコシティ中心広場から発掘)の彩色図版に加え、ドレスデン写本や欧州所蔵品から後年 収集した図版を掲載した。彼の目的は、こうした図像や彫刻が先スペイン時代の歴史再構築に資する証拠を提示することにあった。彼は現地資料の解釈に精通し たメキシコ人専門家、特にアントニオ・デ・レオン・イ・ガマの著作の文学的執行者であったアントニオ・ピチャルドを特に求めた。メキシコの古代過去に誇り の源泉を求めるアメリカ生まれのスペイン人(クリオージョ)にとって、フンボルトによるこれらの古代作品の認知と著作を通じた普及は大きな恩恵であった。 彼は亡命イエズス会士フランシスコ・ハビエル・クラビヘロの著作を読んだ。この著作はメキシコの先コロンブス期文明を称賛するものであり、フンボルトはブ フォン、ド・ポー、レイナルによる新世界への貶めるような主張に対抗するためにこれを引用した[92]。フンボルトは最終的に、メキシコとペルーの先コロ ンブス期領域の両方を専制的かつ野蛮なものとして見なした。しかし彼は同時に、先住民の建造物や工芸品を「歴史的かつ芸術的意義を併せ持つ文化的産物」と して注目した。[94] スペイン領アメリカでの旅行と調査から生まれた彼の最も広く読まれた著作の一つが『新スペイン王国に関する政治論考』(Essai politique sur le royaum de la Nouvelle Espagne)であり、これはすぐに英語に翻訳され『新スペイン王国に関する政治論考』(1811年)として出版された。[95] この論文はフンボルト自身の調査と、スペイン植民地当局者による統計データの提供という寛大さの結果であった。[96] |

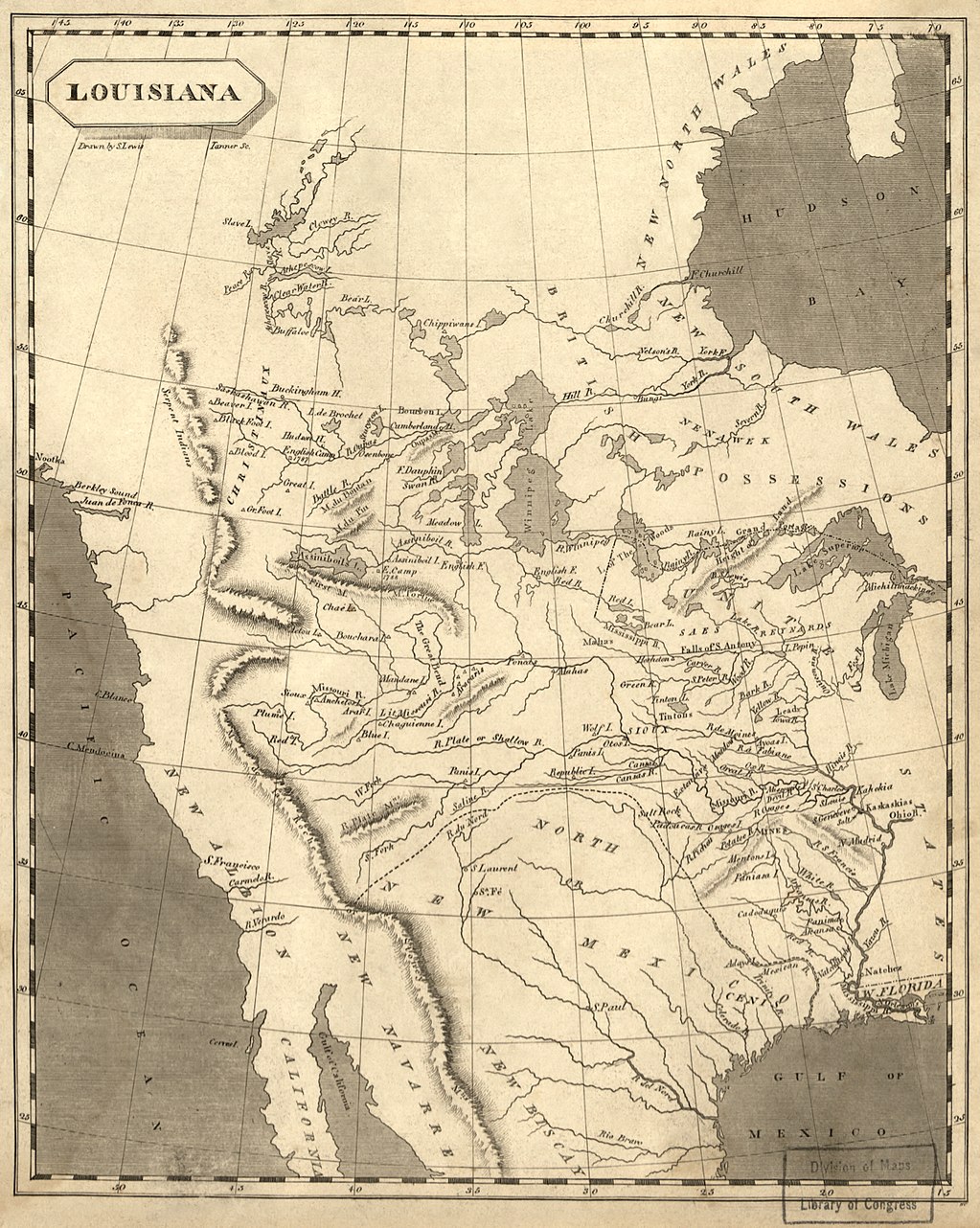

The United States, 1804 1804 map of the Louisiana Territory. Jefferson and his cabinet sought information from Humboldt when he visited Washington, D.C., about Spain's territory in Mexico, now bordering the U.S. Leaving from Cuba, Humboldt decided to take an unplanned short visit to the United States. Knowing that the current U.S. president, Thomas Jefferson, was himself a scientist, Humboldt wrote to him saying that he would be in the United States. Jefferson warmly replied, inviting him to visit the White House in the nation's new capital. In his letter Humboldt had gained Jefferson's interest by mentioning that he had discovered mammoth teeth near the Equator. Jefferson had previously written that he believed mammoths had never lived so far south. Humboldt had also hinted at his knowledge of New Spain.[97] Arriving in Philadelphia, which was a center of learning in the U.S., Humboldt met with some of the major scientific figures of the era, including chemist and anatomist Caspar Wistar, who pushed for compulsory smallpox vaccination, and botanist Benjamin Smith Barton, as well as physician Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, who wished to hear about cinchona bark from a South American tree, which cured fevers.[98] Humboldt's treatise on cinchona was published in English in 1821.[99] After arriving in Washington D.C, Humboldt held numerous intense discussions with Jefferson on both scientific matters and also his year-long stay in New Spain. Jefferson had only recently concluded the Louisiana Purchase, which now placed New Spain on the southwest border of the United States. The Spanish minister in Washington, D.C. had declined to furnish the U.S. government with information about Spanish territories, and access to the territories was strictly controlled. Humboldt was able to supply Jefferson with the latest information on the population, trade agriculture and military of New Spain. This information would later be the basis for his Essay on the Political Kingdom of New Spain (1810). Jefferson was unsure of where the border of the newly-purchased Louisiana was precisely, and Humboldt wrote him a two-page report on the matter. Jefferson would later refer to Humboldt as "the most scientific man of the age". Albert Gallatin, Secretary of the Treasury, said of Humboldt "I was delighted and swallowed more information of various kinds in less than two hours than I had for two years past in all I had read or heard." Gallatin, in turn, supplied Humboldt with information he sought on the United States.[97] After six weeks, Humboldt set sail for Europe from the mouth of the Delaware and landed at Bordeaux on 3 August 1804. |

アメリカ合衆国、1804年 1804年のルイジアナ準州の地図。ジェファーソン大統領とその閣僚は、フンボルトがワシントンD.C.を訪れた際、スペインのメキシコ領(現在のアメリカ国境地帯)に関する情報を求めた。 キューバを出発したフンボルトは、予定外の短い米国訪問を決めた。当時の米国大統領トーマス・ジェファーソン自身が科学者であることを知っていたフンボル トは、米国に滞在する旨を彼に手紙で伝えた。ジェファーソンは温かい返事を返し、新首都にあるホワイトハウスを訪問するよう招待した。フンボルトは書簡 で、赤道付近でマンモスの歯を発見したと述べ、ジェファーソンの関心を引いた。ジェファーソンは以前、マンモスがこれほど南の地に生息したことはないと記 していたのである。フンボルトはまた、新スペインに関する知識をほのめかしていた[97]。 フィラデルフィアに到着したフンボルトは、当時の主要な科学者たちと面会した。その中には、天然痘予防接種の義務化を推進した化学者・解剖学者カスパー・ ウィスター、植物学者ベンジャミン・スミス・バートン、そして独立宣言署名者であり医師のベンジャミン・ラッシュも含まれていた。ラッシュは南米産のキナ 樹皮について聞きたがっていた。この樹皮は熱病を治す効果があったのだ。[98] フンボルトのキナに関する論文は1821年に英語で出版された。[99] ワシントンD.C.に到着後、フンボルトはジェファーソンと科学問題や新スペインでの1年間の滞在について数多くの熱心な議論を交わした。ジェファーソン はルイジアナ購入を完了したばかりで、これにより新スペインは米国の南西国境に位置することになった。ワシントンD.C.のスペイン公使は、スペイン領土 に関する情報を米国政府に提供することを拒否し、領土へのアクセスは厳しく制限されていた。フンボルトはジェファーソンに、ニュー・スペインの人口、貿 易、農業、軍事に関する最新情報を提供することができた。この情報は後に、彼の『ニュー・スペイン政治王国論』(1810年)の基礎となる。 ジェファーソンは新たに購入したルイジアナの国境がどこにあるのか正確に把握できていなかった。フンボルトはこの件について2ページにわたる報告書を彼に 提出した。ジェファーソンは後にフンボルトを「この時代で最も科学的な人物」と呼んだ。財務長官アルバート・ガラティンはフンボルトについて「私は大いに 喜び、わずか2時間足らずで、過去2年間に読んだものや聞いたもの全てよりも多様な情報を吸収した」と述べた。ガラティンは逆に、フンボルトが求めていた アメリカ合衆国に関する情報を提供した。[97] 6週間後、フンボルトはデラウェア川河口からヨーロッパへ向けて出航し、1804年8月3日にボルドーに上陸した。 |

| Travel diaries Humboldt kept a detailed diary of his sojourn to Spanish America, running some 4,000 pages, which he drew on directly for his multiple publications following the expedition. The leather-bound diaries themselves are now in Germany, having been returned from Russia to East Germany, where they were taken by the Red Army after World War II. Following German reunification, the diaries were returned to a descendant of Humboldt. For a time, there was concern about their being sold, but that was averted.[100] A government-funded project to digitize the Spanish American expedition as well as his later Russian expedition has been undertaken (2014–2017) by the University of Potsdam and the German State Library–Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation.[101] |

旅行日記 フンボルトはスペイン領アメリカへの滞在について詳細な日記を記した。そのページ数は約4,000ページに及び、遠征後の複数の出版物に直接活用された。 革装丁の日記帳自体は現在ドイツにある。第二次世界大戦後、赤軍によってロシアから東ドイツへ持ち去られた後、返還されたのである。ドイツ再統一後、日記 はフンボルトの子孫に返還された。一時、売却の懸念があったが、それは回避された[100]。スペイン領アメリカ遠征および後のロシア遠征の日記をデジタ ル化する政府資金によるプロジェクトが、ポツダム大学とドイツ国立図書館・プロイセン文化財団によって実施されている(2014-2017年) [101]。 |

| Achievements of the Hispanic American expedition See also: Humboldtian science Humboldt's decades' long endeavor to publish the results of this expedition not only resulted in multiple volumes, but also made his international reputation in scientific circles. Humboldt came to be well-known with the reading public as well, with popular, densely illustrated, condensed versions of his work in multiple languages. Bonpland, his fellow scientist and collaborator on the expedition, collected botanical specimens and preserved them, but unlike Humboldt who had a passion to publish, Bonpland had to be prodded to do the formal descriptions. Many scientific travelers and explorers produced huge visual records which remained unseen by the general public until the late nineteenth century. In the case of the Malaspina Expedition, it was not until the late twentieth century when Mutis's botanical, some 12,000 drawings from New Granada, was published. Humboldt, by contrast, published immediately and continuously, using and ultimately exhausting his personal fortune, to produce both scientific and popular texts. Humboldt's name and fame were made by his travels to Spanish America, particularly his publication of the Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain; his image as the premier European scientist was a later development.[102] For the Bourbon crown, which had authorized the expedition, the returns were not only tremendous in terms of sheer volume of data on their New World realms, but in dispelling the vague and pejorative assessments of the New World by Guillaume-Thomas Raynal, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, and William Robertson. The achievements of the Bourbon regime, especially in New Spain, were evident in the precise data Humboldt systematized and published.[82] This memorable expedition may be regarded as having laid the foundation of the sciences of physical geography, plant geography, and meteorology. Key to that was Humboldt's meticulous and systematic measurement of phenomena with the most advanced instruments then available. He closely observed plant and animal species in situ, not just in isolation, noting all elements in relation to one other. He collected specimens of plants and animals, dividing the growing collection so that if a portion was lost, other parts might survive.  Humboldt depicted by American artist Charles Willson Peale, 1805, who met Humboldt when he visited the U.S. in 1804 Humboldt saw the need for an approach to science that could account for the harmony of nature among the diversity of the physical world. For Humboldt, "the unity of nature" meant that it was the interrelation of all physical sciences—such as the conjoining between biology, meteorology and geology—that determined where specific plants grew. He found these relationships by unraveling myriad, painstakingly collected data,[103] data extensive enough that it became an enduring foundation upon which others could base their work. Humboldt viewed nature holistically, and tried to explain natural phenomena without the appeal to religious dogma. He believed in the central importance of observation, and as a consequence had amassed a vast array of the most sophisticated scientific instruments then available. Each had its own velvet lined box and was the most accurate and portable of its time; nothing quantifiable escaped measurement. According to Humboldt, everything should be measured with the finest and most modern instruments and sophisticated techniques available, for that collected data was the basis of all scientific understanding. This quantitative methodology would become known as Humboldtian science. Humboldt wrote "Nature herself is sublimely eloquent. The stars as they sparkle in firmament fill us with delight and ecstasy, and yet they all move in orbit marked out with mathematical precision."[104] However, Andreas Daum has recently revisited the concept of Humboldtian Science and set it apart from "Humboldt's science".[105] |

ヒスパニック・アメリカ遠征の成果 関連項目: フンボルトの科学 フンボルトがこの遠征の成果を出版するために費やした数十年の努力は、複数の巻を成すだけでなく、科学界における彼の国際的な名声をもたらした。フンボル トは一般読者にも広く知られるようになり、彼の著作は多言語で、図版を豊富に盛り込んだ大衆向けの要約版として出版された。同行した科学者で共同研究者の ボンプランは植物標本を収集・保存したが、出版への情熱を持っていたフンボルトとは異なり、正式な記述を行うよう促される必要があった。多くの科学旅行者 や探検家は膨大な視覚的記録を残したが、それらが一般大衆の目に触れるようになったのは19世紀後半になってからだった。マラスピナ探検隊の場合、ムティ スがニューグラナダで描いた約12,000点の植物図譜が出版されたのは20世紀後半になってからである。これに対しフンボルトは、個人資産を使い果たす ほどに、科学的著作と大衆向け著作の両方を即座かつ継続的に出版した。フンボルトの名声はスペイン領アメリカへの旅行、特に『新スペイン王国に関する政治 論考』の出版によって確立された。彼がヨーロッパを代表する科学者としてのイメージを確立したのは、その後になってからのことである[102]。 この探検を許可したブルボン王朝にとって、その見返りは、新世界に関する膨大な量のデータというだけでなく、ギヨーム・トマ・レイナル、ジョルジュ・ル イ・ルクレール・ビュフォン伯爵、ウィリアム・ロバートソンによる新世界に対する曖昧で軽蔑的な評価を払拭したことでもあった。ブルボン王朝、特にニュー スペインにおけるその成果は、フンボルトが体系化し出版した正確なデータに明らかであった。[82] この記念すべき探検は、自然地理学、植物地理学、気象学の基礎を築いたものと見なすことができる。その鍵となったのは、フンボルトが当時入手可能な最先端 の機器を用いて、現象を綿密かつ体系的に測定したことである。彼は、植物や動物を単独で観察するだけでなく、その生息地で注意深く観察し、相互に関連する すべての要素を記録した。彼は動植物の標本を収集し、増え続けるコレクションを分割して保管した。これにより、一部が失われても他の部分が保存されるよう にしたのである。  1805年、アメリカ人画家チャールズ・ウィルソン・ピールが描いたフンボルトの肖像画。フンボルトが1804年にアメリカを訪問した際、ピールは彼と面会している。 フンボルトは、物理世界の多様性の中に存在する自然の調和を説明できる科学的アプローチの必要性を認識していた。彼にとって「自然の統一性」とは、生物 学・気象学・地質学といった全ての物理科学の相互関係が、特定の植物の生育地を決定するという意味であった。彼は、膨大な量の丹念に収集されたデータを解 きほぐすことでこれらの関係を発見した[103]。そのデータは極めて広範であり、後続の研究者が基盤とできる永続的な土台となった。フンボルトは自然を 全体として捉え、宗教的教義に頼らずに自然現象を説明しようとした。彼は観察の重要性を核心と信じ、その結果として当時入手可能な最も精巧な科学機器を数 多く集めた。各器具はベルベット張りの専用箱に収められ、当時最も正確かつ携帯性に優れていた。測定可能なものは何一つ逃さなかった。フンボルトによれ ば、あらゆるものは入手可能な最高峰の近代的器具と洗練された技術で計測されるべきであり、その収集データこそが科学的理解の基盤となるのだ。 この定量的手法は後にフンボルト科学として知られるようになる。フンボルトはこう記している。「自然そのものが崇高な雄弁さを備えている。大空にきらめく 星々は我々に歓喜と恍惚をもたらすが、それらはすべて数学的な精度で定められた軌道に沿って動いているのだ」[104]。しかしアンドレアス・ダウムは近 年、フンボルト的科学の概念を再検討し、「フンボルトの科学」とは区別する立場を取っている[105]。 |

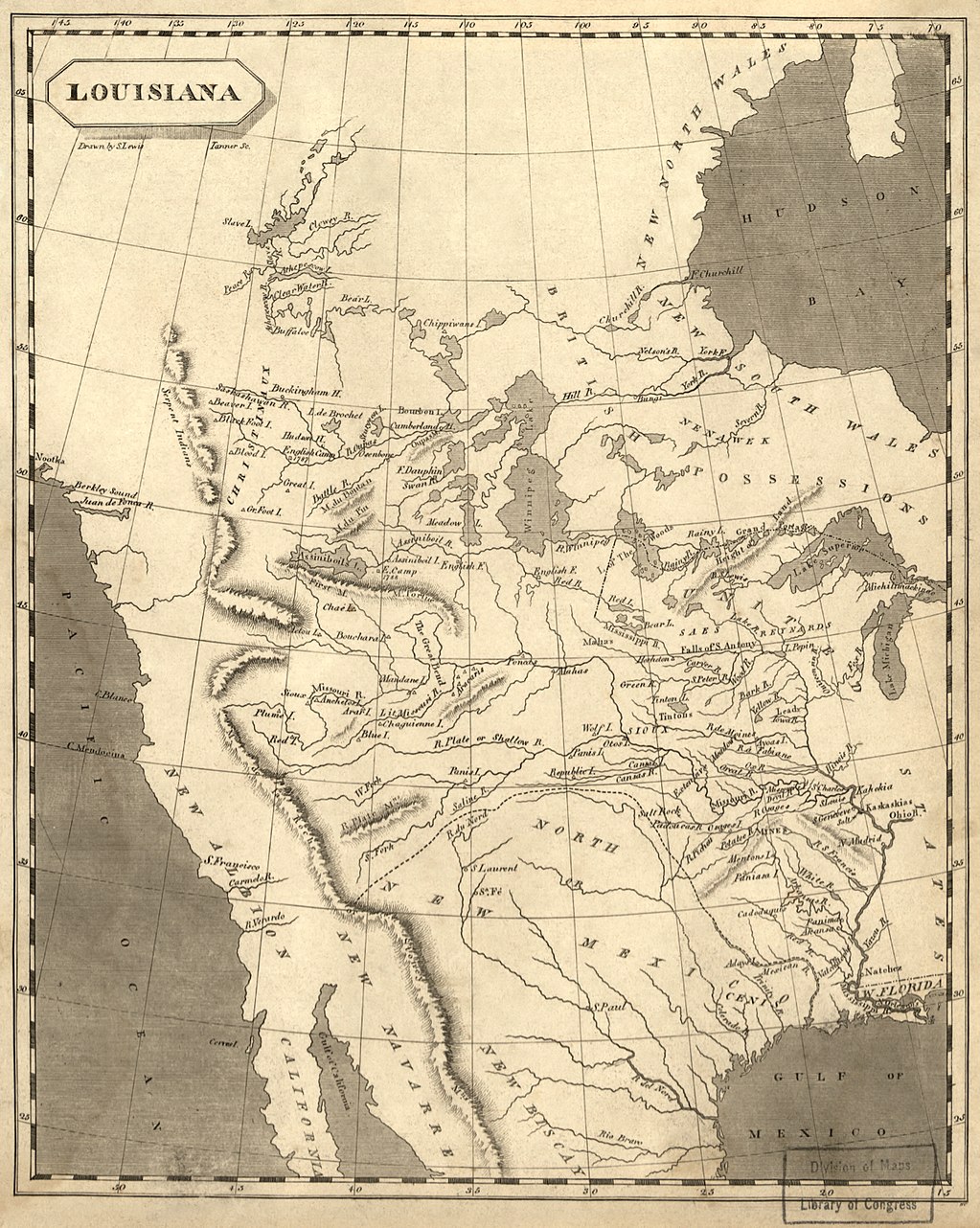

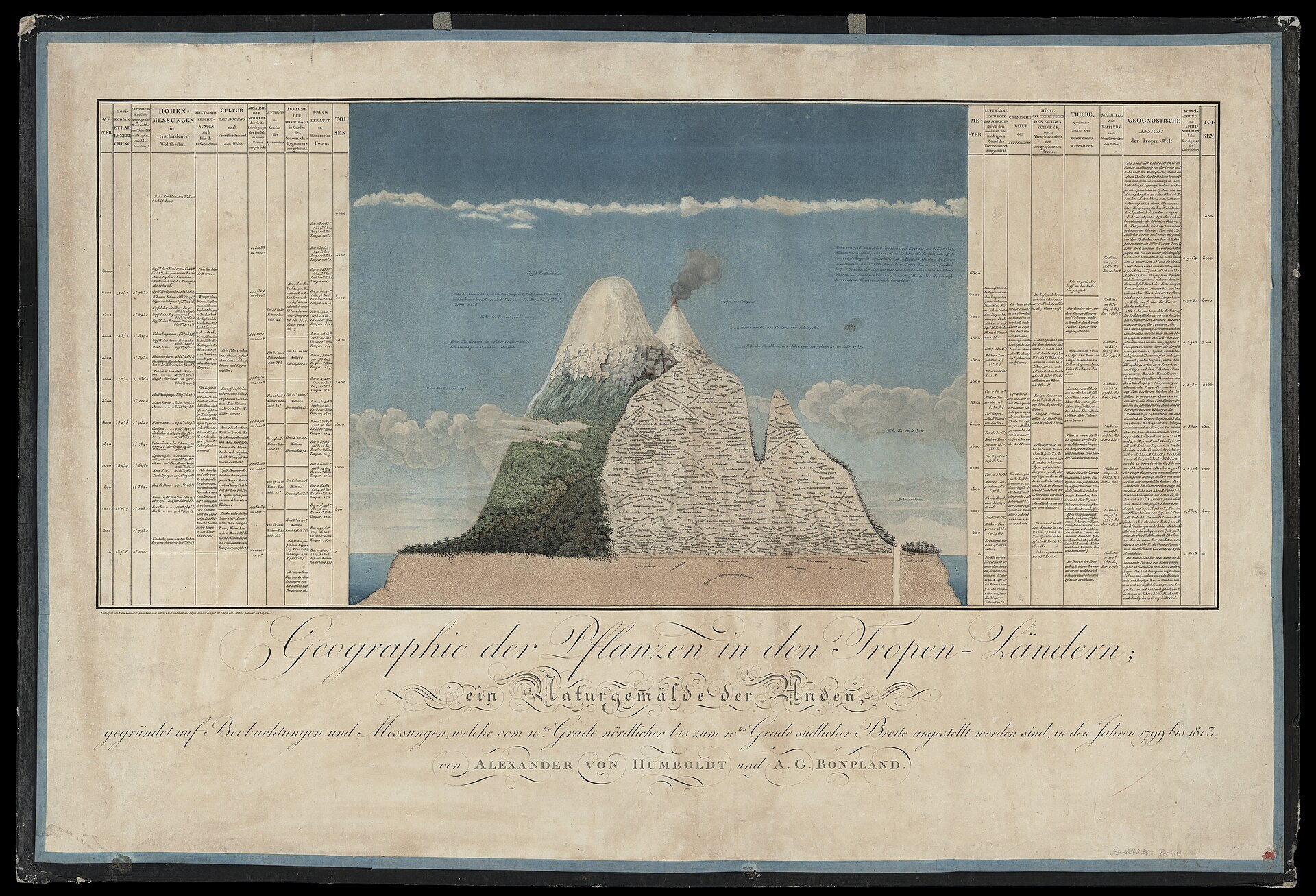

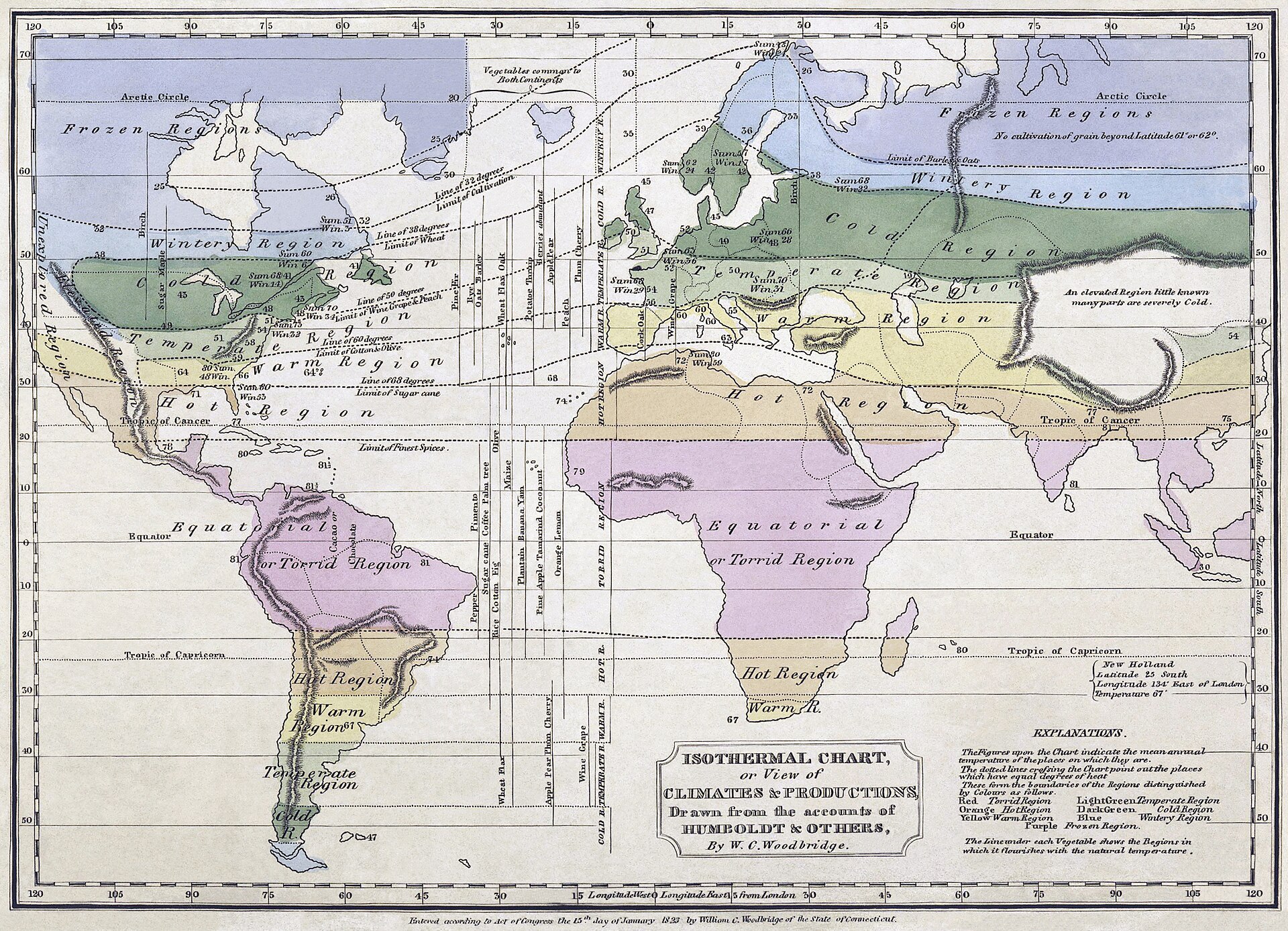

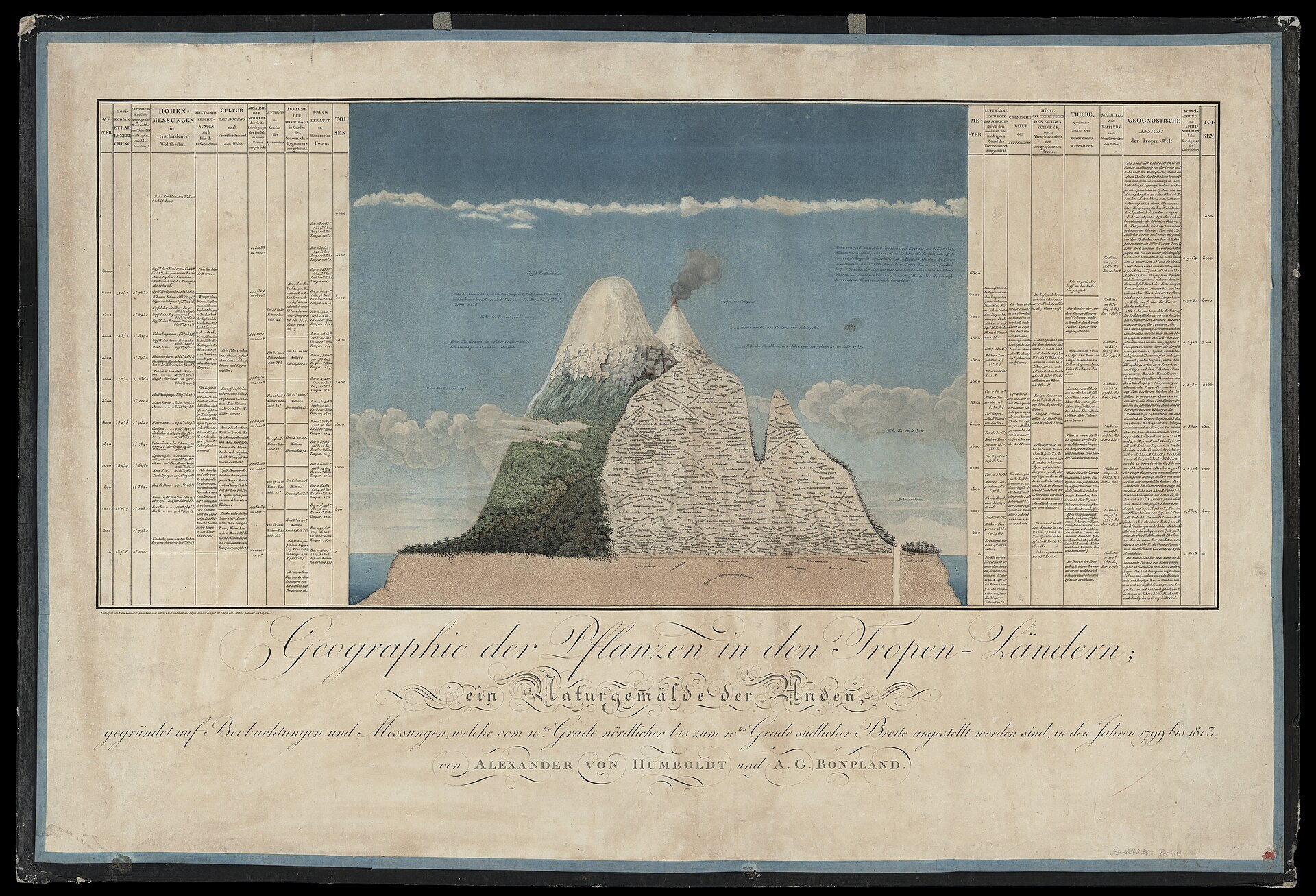

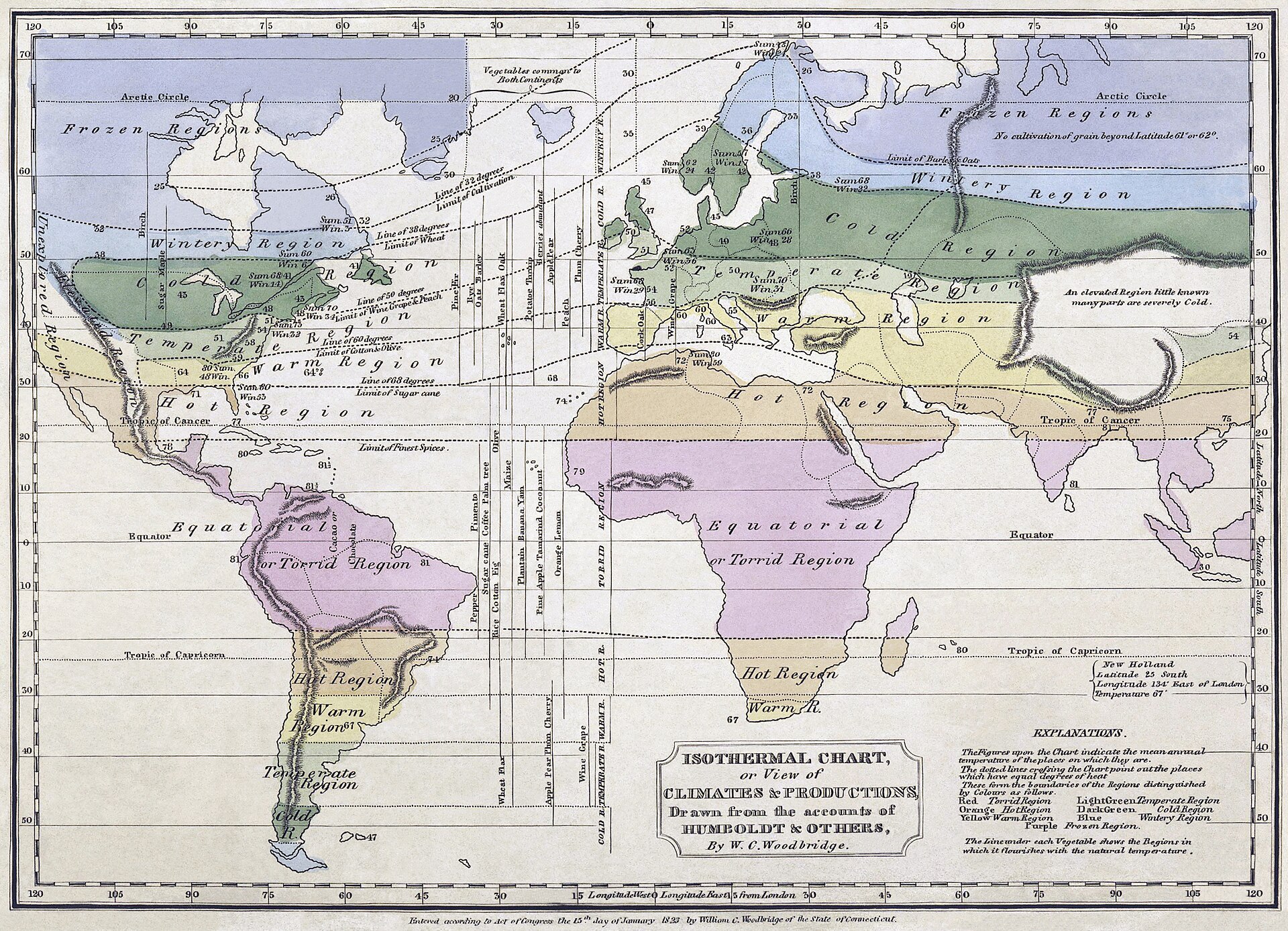

Humboldt's Naturgemälde, also known as the Chimborazo Map, is his depiction of the volcanoes Chimborazo and Cotopaxi in cross section, with detailed information about plant geography. The illustration was published in The Geography of Plants, 1807, in a large format (54 cm x 84 cm). Largely used for global warming analyses, this map depicts in fact the vegetation of another volcano: the Antisana.[106] His Essay on the Geography of Plants (published first in French and then German, both in 1807) was based on the then novel idea of studying the distribution of organic life as affected by varying physical conditions.[23] This was most famously depicted in his published cross-section of Chimborazo, approximately two feet by three feet (54 cm x 84 cm) color pictorial, he called Ein Naturgemälde der Anden and what is also called the Chimborazo Map. It was a fold-out at the back of the publication.[107] Humboldt first sketched the map when he was in South America, which included written descriptions on either side of the cross-section of Chimborazo. These detailed the information on temperature, altitude, humidity, atmosphere pressure, and the animal and plants (with their scientific names) found at each elevation. Plants from the same genus appear at different elevations. The depiction is on an east-west axis going from the Pacific coast lowlands to the Andean range of which Chimborazo was a part, and the eastern Amazonian basin. Humboldt showed the three zones of coast, mountains, and Amazonia, based on his own observations, but he also drew on existing Spanish sources, particularly Pedro Cieza de León, which he explicitly referred to. The Spanish American scientist Francisco José de Caldas had also measured and observed mountain environments and had earlier come to similar ideas about environmental factors in the distribution of life forms.[108] Humboldt was thus not putting forward something entirely new, but it is argued that his finding is not derivative either.[109] The Chimborazo map displayed complex information in an accessible fashion. The map was the basis for comparison with other major peaks. "The Naturgemälde showed for the first time that nature was a global force with corresponding climate zones across continents."[110] Another assessment of the map is that it "marked the beginning of a new era of environmental science, not only of mountain ecology but also of global-scale biogeophysical patterns and processes."[107]  Isothermal map of the world using Humboldt's data by William Channing Woodbridge By his delineation (in 1817) of isothermal lines, he at once suggested the idea and devised the means of comparing the climatic conditions of various countries. He first investigated the rate of decrease in mean temperature with the increase in elevation above sea level, and afforded, by his inquiries regarding the origin of tropical storms, the earliest clue to the detection of the more complicated law governing atmospheric disturbances in higher latitudes.[23][111] This was a major contribution to climatology.[112][113] His discovery of the decrease in intensity of Earth's magnetic field from the poles to the equator was communicated to the Paris Institute in a memoir read by him on 7 December 1804. Its importance was attested by the speedy emergence of rival claims.[23] His services to geology were based on his attentive study of the volcanoes of the Andes and Mexico, which he observed and sketched, climbed, and measured with a variety of instruments. By climbing Chimborazo, he established an altitude record which became the basis for measurement of other volcanoes in the Andes and the Himalayas. As with other aspects of his investigations, he developed methods to show his synthesized results visually, using the graphic method of geologic-cross sections.[114] He showed that volcanoes fell naturally into linear groups, presumably corresponding with vast subterranean fissures; and by his demonstration of the igneous origin of rocks previously held to be of aqueous formation, he contributed largely to the elimination of erroneous views, such as Neptunism.[23] Humboldt was a significant contributor to cartography, creating maps, particularly of New Spain, that became the template for later mapmakers in Mexico. His careful recording of latitude and longitude led to accurate maps of Mexico, the port of Acapulco, the port of Veracruz, and the Valley of Mexico, and a map showing trade patterns among continents. His maps also included schematic information on geography, converting areas of administrative districts (intendancies) using proportional squares.[115] The U.S. was keen to see his maps and statistics on New Spain, since they had implication for territorial claims following the Louisiana Purchase.[116] Later in life, Humboldt published three volumes (1836–39) examining sources that dealt with the early voyages to the Americas, pursuing his interest in nautical astronomy in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. His research yielded the origin of the name "America", put on a map of the Americas by Martin Waldseemüller.[117] |

フンボルトの『自然図譜』(別名チンボラソ図)は、チンボラソ山とコトパクシ山の断面図を描き、植物地理学の詳細な情報を記したものである。この図版は 1807年刊行の『植物地理学』に大型判(54cm×84cm)で掲載された。主に地球温暖化分析に用いられるこの地図は、実際には別の火山、アンティサ ナの植生を描いている。[106] 彼の『植物地理論』(1807年にまずフランス語で、次いでドイツ語で出版)は、変化する物理的条件が生物の分布に与える影響を研究するという当時として は斬新な考えに基づいていた。[23] この概念は、チンボラソ断面図として最も有名に表現された。約2フィート×3フィート(54cm×84cm)の彩色図版で、彼はこれを『アンデスの自然絵 画』(Ein Naturgemälde der Anden)と呼び、チンボラソ地図とも称される。出版物の裏表紙に折り込み図として掲載されていた。[107] フンボルトは南米滞在中にこの図を初めてスケッチした。チンボラソ断面図の両側には、各標高における気温・高度・湿度・気圧、そして発見された動植物(学 名付き)の詳細な記述が添えられていた。同じ属の植物が異なる標高に現れる。図示は太平洋沿岸の低地からアンデス山脈(チンボラソ山を含む)を経て東側の アマゾン盆地へと続く東西軸に沿って描かれている。フンボルトは自らの観察に基づき海岸部、山岳部、アマゾニアの三地域を示したが、既存のスペイン資料、 特にペドロ・シエサ・デ・レオンの著作を明示的に参照しながら描いた。スペイン系アメリカ人科学者フランシスコ・ホセ・デ・カルダスも山岳環境を測量・観 察し、生物分布における環境要因について先に同様の考えに至っていた[108]。したがってフンボルトが完全に新規なものを提示したわけではないが、彼の 発見が単なる模倣でもないことは議論されている[109]。チンボラソの地図は複雑な情報を分かりやすく示した。この地図は他の主要な山岳との比較の基礎 となった。「 『自然の絵画』は初めて、自然が大陸を越えて対応する気候帯を持つ地球規模の力であることを示した。」[110] この地図に対する別の評価では、「山岳生態学だけでなく、地球規模の生物地球物理学的パターンとプロセスにおいても、環境科学の新時代の始まりを画した」 とされている。[107]  ウィリアム・チャニング・ウッドブリッジによるフンボルトのデータを用いた世界等温線図 彼は(1817年に)等温線を明示したことで、様々な国の気候条件を比較する概念を即座に示唆し、その手段を考案した。彼はまず海抜高度の上昇に伴う平均 気温の低下率を調査し、熱帯暴風雨の起源に関する研究を通じて、高緯度地域の大気擾乱を支配するより複雑な法則の解明に向けた最初の手がかりを提供した。 [23][111] これは気候学への主要な貢献であった。[112][113] 彼が発見した、地球磁場の強度が極から赤道に向かって減少するという事実は、1804年12月7日に彼がパリ学士院で発表した論文で伝えられた。その重要性は、競合する主張が急速に現れたことで証明された。[23] 彼の地質学への貢献は、アンデス山脈とメキシコの火山に対する入念な研究に基づいていた。彼はこれらの火山を観察し、スケッチし、登頂し、様々な機器を用 いて測定した。チンボラソ山への登頂により、彼は高度測定の基準となる記録を確立し、これがアンデス山脈やヒマラヤ山脈の他の火山測定の基礎となった。他 の研究分野と同様に、彼は統合された結果を視覚的に示す手法を開発した。地質断面図という図解法を用いることで、火山が自然線状群をなすことを示した。こ れはおそらく広大な地下断層に対応するものであった。また、従来水成説で説明されていた岩石の火成起源を実証し、ネプチューニズムのような誤った見解の排 除に大きく貢献した。[23] フンボルトは地図学にも大きく貢献し、特にニュースペインの地図を作成した。それらは後のメキシコの製図家たちの模範となった。彼の緯度経度の精密な記録 は、メキシコ本土、アカプルコ港、ベラクルス港、メキシコ盆地の正確な地図、そして大陸間の貿易パターンを示す地図の制作につながった。彼の地図には地理 に関する概略情報も含まれており、行政区画(総督府)の面積を比例した正方形を用いて換算していた[115]。アメリカ合衆国は、ルイジアナ購入後の領土 主張に関わるため、彼のニュー・スペインに関する地図と統計を熱心に求めた。[116] その後、フンボルトは 3 巻(1836 年~1839 年)の著作を出版し、15 世紀および 16 世紀の航海天文学への関心を追求しながら、アメリカ大陸への初期の航海に関する資料を調査した。彼の研究により、マーティン・ヴァルトゼーミュラーがアメ リカ大陸の地図に付けた「アメリカ」という名前の由来が明らかになった。[117] |

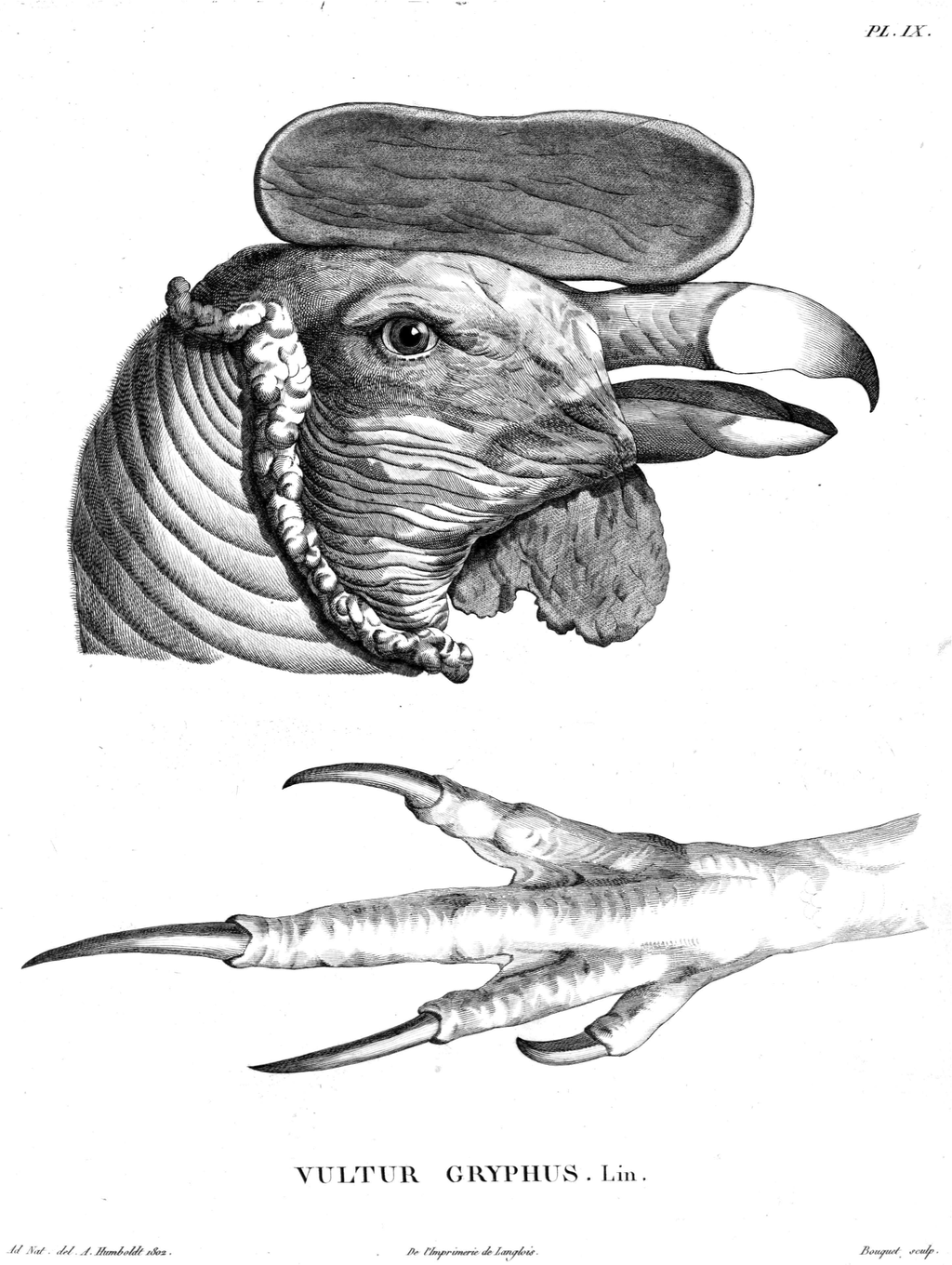

Humboldt's depiction of an Andean condor, an example of his detailed drawing Humboldt conducted a census of the indigenous and European inhabitants in New Spain, publishing a schematized drawing of racial types and populations distribution, grouping them by region and social characteristics.[118] He estimated the population to be six million individuals.[119][120] He estimated Indians to be forty percent of New Spain's population, but their distribution being uneven; the most dense were in the center and south of Mexico, the least dense in the north. He presented these data in chart form, for easier understanding.[121] He also surveyed the non-Indian population, categorized as Whites (Spaniards), Negroes, and castes (castas).[122] American-born Spaniards, so-called creoles had been painting depictions of mixed-race family groupings in the eighteenth century, showing father of one racial category, mother of another, and the offspring in a third category in hierarchical order, so racial hierarchy was an essential way elites viewed Mexican society.[123] Humboldt reported that American-born Spaniards were legally racial equals of those born in Spain, but the crown policy since the Bourbons took the Spanish throne privileged those born in Iberia. Humboldt observed that "the most miserable European, without education and without intellectual cultivation, thinks himself superior to whites born in the new continent".[124] The truth in this assertion, and the conclusions derived from them, have been often disputed as superficial, or politically motivated, by some authors, considering that between 40% and 60% of high offices in the new world were held by creoles.[125][126] The enmity between some creoles and the peninsular-born whites increasingly became an issue in the late period of Spanish rule, with creoles increasingly alienated from the crown. Humboldt's assessment was that royal government abuses and the example of a new model of rule in the United States were eroding the unity of whites in New Spain.[127] Humboldt's writings on race in New Spain were shaped by the memorials of the classical liberal, enlightened Bishop-elect of Michoacán, Manuel Abad y Queipo, who personally presented Humboldt with his printed memorials to the Spanish crown critiquing social and economic conditions and his recommendations for eliminating them.[128][126] One scholar says that his writings contain fantastical descriptions of America, while leaving out its inhabitants, stating that Humboldt, coming from the Romantic school of thought, believed '... nature is perfect till man deforms it with care'.[129] The further assessment is that he largely neglected the human societies amidst nature. Views of indigenous peoples as 'savage' or 'unimportant' leaves them out of the historical picture.[129] Other scholars counter that Humboldt dedicated large parts of his work to describing the conditions of slaves, indigenous peoples, mixed-race castas, and society in general. He often showed his disgust for the slavery[13]and inhumane conditions in which indigenous peoples and others were treated and he often criticized Spanish colonial policies.[130] Humboldt was not primarily an artist, but he could draw well, allowing him to record a visual record of particular places and their natural environment. Many of his drawings became the basis for illustrations of his many scientific and general publications. Artists whom Humboldt influenced, such as Johann Moritz Rugendas, followed in his path and painted the same places Humboldt had visited and recorded, such as the basalt formations in Mexico, which was an illustration in his Vues des Cordillères.[131][132] The editing and publication of the encyclopedic mass of scientific, political and archaeological material that had been collected by him during his absence from Europe was now Humboldt's most urgent desire. After a short trip to Italy with Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac for the purpose of investigating the law of magnetic declination and a stay of two and a half years in Berlin, in the spring of 1808, he settled in Paris. His purpose for being located there was to secure the scientific cooperation required for bringing his great work through the press. This colossal task, which he at first hoped would occupy but two years, eventually cost him twenty-one, and even then it remained incomplete. |

フンボルトによるアンデスコンドルの描写。彼の詳細な描画の一例である フンボルトは新スペインにおける先住民とヨーロッパ系住民の人口調査を実施し、人種類型と人口分布を地域別・社会的特性別に分類した模式図を発表した [118]。彼は人口を600万人と推定した。[119][120] 彼は先住民がヌエバ・エスパーニャ人口の40%を占めると推定したが、その分布は不均一であった。最も密集していたのはメキシコ中部と南部で、最も疎だっ たのは北部であった。彼はこれらのデータを理解しやすくするため、図表形式で提示した。[121] また、非先住民人口についても調査を行い、白人(スペイン人)、黒人、混血(カスタス)に分類した。[122] 18世紀には、いわゆるクレオールと呼ばれるアメリカ生まれのスペイン人たちが、混血家族の階層的構成を描いた絵画を残している。父親が一方の人種カテゴ リー、母親が別のカテゴリー、そして子孫が第三のカテゴリーに属するという順序で示されており、人種的階層はエリート層がメキシコ社会を見る上で不可欠な 視点であった。[123] フンボルトは、アメリカ生まれのスペイン人は法的にはスペイン生まれの者と同じ人種的地位にあると報告した。しかしブルボン家がスペイン王位を継承して以 来、王室政策はイベリア半島生まれの者を優遇していた。フンボルトは「最も貧しく、教育も知的教養もないヨーロッパ人ですら、新大陸生まれの白人より自分 の方が優れていると考えている」と観察した。[124] この主張の真実性、およびそこから導かれる結論は、新大陸の高官職の40%から60%がクレオールによって占められていたことを考慮すると、表面的である とか政治的動機によるものだと、一部の著者によってしばしば争われてきた。[125][126] スペイン統治後期には、一部のクレオールと半島生まれの白人との敵意が深刻な問題となり、クレオールは次第に王室から疎外されていった。フンボルトは、王 政の暴政とアメリカ合衆国における新たな統治モデルの事例が、ヌエバ・エスパーニャにおける白人社会の結束を蝕んでいると評価した。[127] フンボルトの新スペインにおける人種論は、古典的自由主義者で啓蒙主義者であるミチョアカン州司教候補マヌエル・アバド・イ・ケイポの陳情書に影響を受け た。ケイポは自らフンボルトに、社会経済状況を批判しその解消策を提言した印刷済みの陳情書をスペイン王室宛てに手渡したのである。[128][126] ある学者は、フンボルトの著作にはアメリカ大陸の幻想的な描写が含まれる一方、その住民は省かれていると指摘する。ロマン主義思想に根ざしたフンボルトは 「…自然は人間が注意深く歪めるまでは完璧である」と信じていたという。[129] さらに、彼は自然の中に存在する人間社会をほとんど無視していたと評価される。先住民を「野蛮」あるいは「取るに足らない」と見なす視点は、彼らを歴史的 描写から排除した。[129] これに対し他の学者は、フンボルトが著作の大部分を奴隷、先住民、混血のカスタス、そして社会全般の状況を記述することに費やしたと反論する。彼はしばし ば奴隷制[13]や先住民らが置かれた非人道的な状況への嫌悪を示し、スペイン植民地政策を頻繁に批判した。[130] フンボルトは主に芸術家ではなかったが、優れた画力を持ち、特定の場所とその自然環境を視覚的に記録することができた。彼の多くの素描は、数多くの科学出 版物や一般向け出版物の挿絵の基礎となった。フンボルトの影響を受けた画家たち、例えばヨハン・モーリッツ・ルゲンダスは彼の足跡を辿り、フンボルトが訪 れて記録した同じ場所を描いた。例えばメキシコの玄武岩地形は、彼の『コルディエラ山脈の眺め』の挿絵となったのである。[131][132] ヨーロッパを離れている間に収集した膨大な科学的・政治的・考古学的資料を編集し出版することが、今やフンボルトにとって最も切実な願いとなった。磁気偏 角の法則を調査するためジョゼフ・ルイ・ゲイ=リュサックと共にイタリアへ短期間旅行した後、ベルリンで2年半滞在し、1808年の春にパリに定住した。 彼がそこに拠点を置いた目的は、自身の偉大な著作を出版するために必要な科学的協力を確保するためであった。当初はわずか2年で完了すると期待していたこ の巨大な作業は、結局21年を費やすことになり、それでもなお未完のままだった。 |

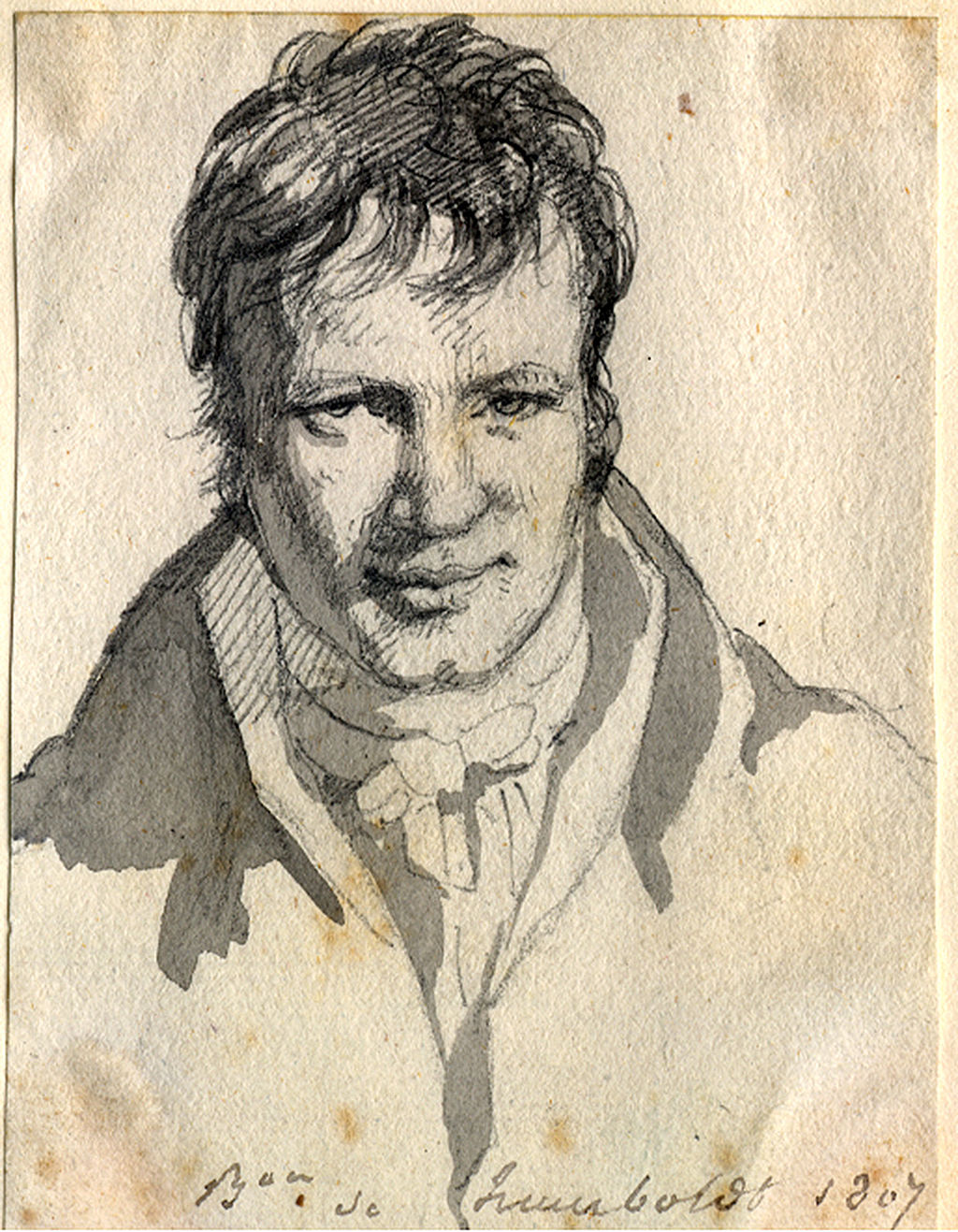

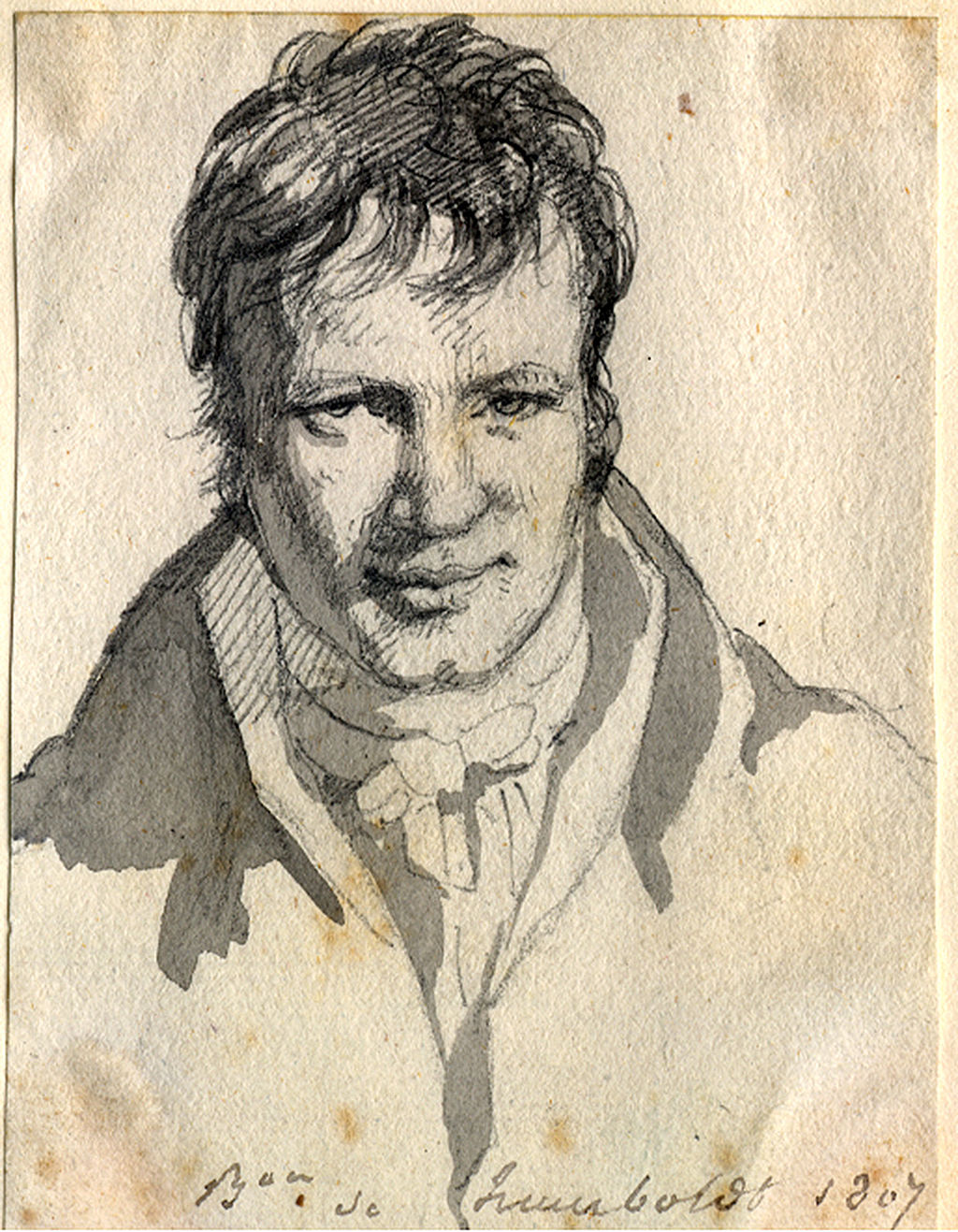

Scholarly and public recognition Humboldt in Berlin 1807 During his lifetime Humboldt became one of the most famous men in Europe.[133] Academies, both native and foreign, were eager to elect him to their membership, the first being The American Philosophical Society[134] in Philadelphia, which he visited at the tail end of his travel through the Americas. He was elected to the Prussian Academy of Sciences in 1805.[135] Over the years other learned societies in the U.S. elected him a member, including the American Antiquarian Society (Worcester, MA) in 1816;[136] the Linnean Society of London in 1818; the New York Historical Society in 1820; a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1822;[137] the American Ethnological Society (New York) in 1843; and the American Geographical and Statistical Society, (New York) in 1856.[138] He was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1810. The Royal Society, whose president Sir Joseph Banks had aided Humboldt as a young man, now welcomed him as a foreign member.[139] After Mexican independence from Spain in 1821, the Mexican government recognized him with high honors for his services to the nation. In 1827, the first President of Mexico, Guadalupe Victoria granted Humboldt Mexican citizenship[140] and in 1859, the President of Mexico, Benito Juárez, named Humboldt a hero of the nation (benemérito de la nación).[141] The gestures were purely honorary; he never returned to the Americas following his expedition. Importantly for Humboldt's long-term financial stability, King Frederick William III of Prussia conferred upon him the honor of the post of royal chamberlain, without at the time exacting the duties. The appointment had a pension of 2,500 thalers, afterwards doubled. This official stipend became his main source of income in later years when he exhausted his fortune on the publications of his research. Financial necessity forced his permanent relocation to Berlin in 1827 from Paris. In Paris he found not only scientific sympathy, but the social stimulus which his vigorous and healthy mind eagerly craved. He was equally in his element as the lion of the salons and as the savant of the Institut de France and the observatory.  Memorial plaque, Alexander von Humboldt, Karolinenstraße 19, Berlin-Tegel, Germany On 12 May 1827 he settled permanently in Berlin, where his first efforts were directed towards the furtherance of the science of terrestrial magnetism. In 1827, he began giving public lectures in Berlin, which became the basis for his last major publication, Kosmos (1845–62).[71] For many years, it had been one of his favorite schemes to secure, by means of simultaneous observations at distant points, a thorough investigation of the nature and law of "magnetic storms" (a term invented by him to designate abnormal disturbances of Earth's magnetism). The meeting at Berlin, on 18 September 1828, of a newly formed scientific association, of which he was elected president, gave him the opportunity of setting on foot an extensive system of research in combination with his diligent personal observations. His appeal to the Russian government, in 1829, led to the establishment of a line of magnetic and meteorological stations across northern Asia. Meanwhile, his letter to the Duke of Sussex, then (April 1836) president of the Royal Society, secured for the undertaking, the wide basis of the British dominions. The Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, observes, "Thus that scientific conspiracy of nations which is one of the noblest fruits of modern civilization was by his exertions first successfully organized".[142] However, earlier examples of international scientific cooperation exist, notably the 18th-century observations of the transits of Venus. In 1856, U.S. diplomat John Bigelow published Memoir of the Life and Public Services of John Charles Fremont. He dedicated it "To Alexander von Humboldt, this memoir of one whose genius he was among the first to discover and acknowledge, is respectfully inscribed by The Author."[143] In 1869, the 100th year of his birth, Humboldt's fame was so great that cities all over America celebrated his birth with large festivals. In New York City, a bust of his head was unveiled in Central Park.[144] Scholars have speculated about the reasons for Humboldt's declining renown among the public. Sandra Nichols has argued that there are three reasons for this: First, a trend towards specialization in scholarship. Humboldt was a generalist who connected many disciplines in his work. Today, academics have become more and more focused on narrow fields of work. Humboldt combined ecology, geography and even social sciences. Second, a change in writing style. Humboldt's works, which were considered essential to a library in 1869, had flowery prose that fell out of fashion. One critic said they had a "laborious picturesqueness". Humboldt himself said that, "If I only knew how to describe adequately how and what I felt, I might, after this long journey of mine, really be able to give happiness to people. The disjointed life I lead makes me hardly certain of my way of writing". Third, a rising anti-German sentiment in the late 1800s and the early 1900s due to heavy German immigration to the United States and later World War 1.[144] On the eve of the 1959 hundredth anniversary of the death of Humboldt, the government of West Germany planned significant celebrations in conjunction with nations that Humboldt visited.[145] |