分析的-総合的区分

Analytic–synthetic distinction

☆分析的・総合的(分析的-綜合的)区別[analytic–synthetic distinction]

とは、主に哲学において命題(特に、肯定的主語-述語判断である陳述)を二種類に区別するために用いられる意味論的区別である。分析的命題は、その意味に

よってのみ真か偽かが決まる。一方、総合的命題の真偽は、その意味が世界とどう関連するかによって決まるのである。 [1]

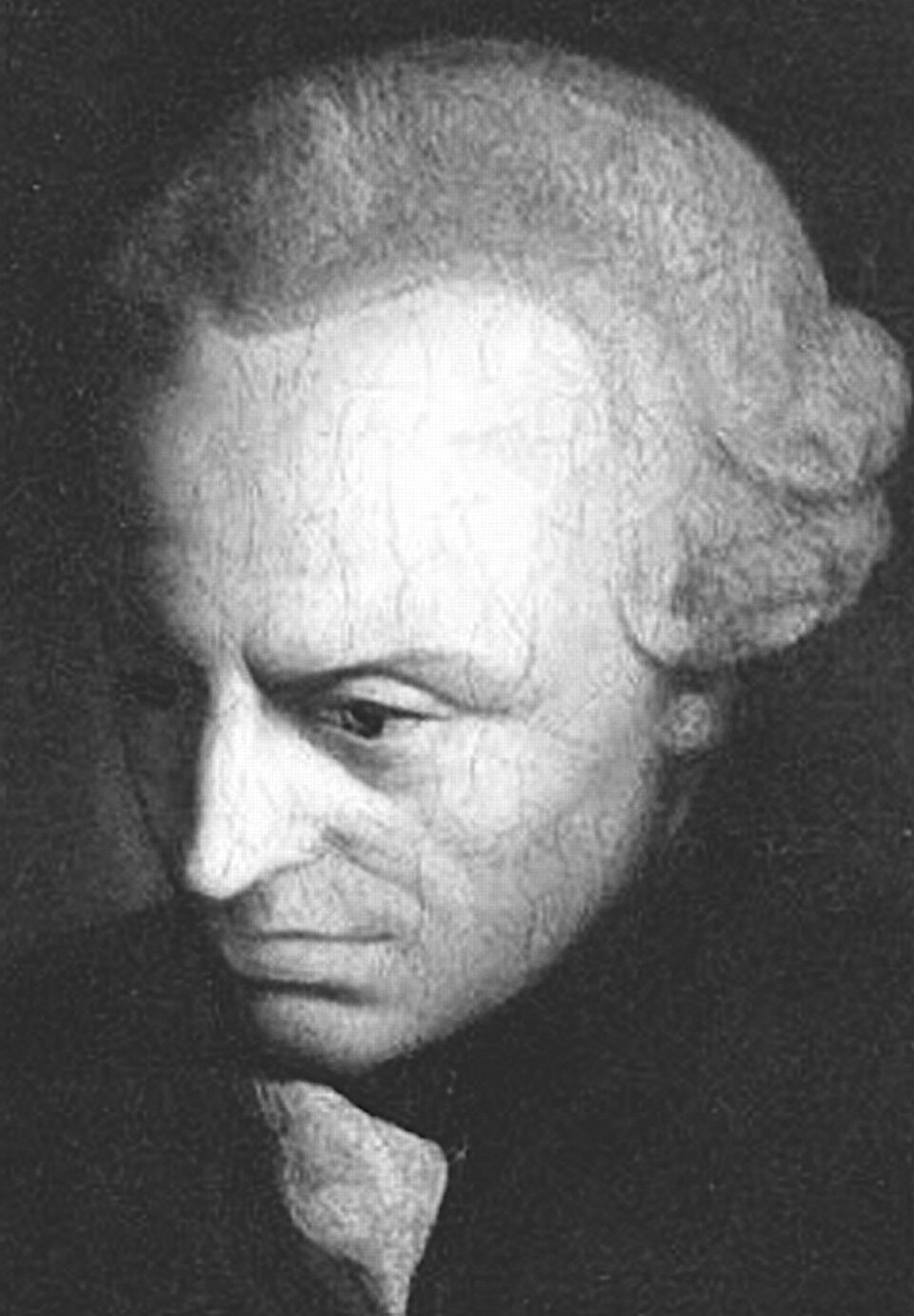

この区別はイマヌエル・カントによって最初に提唱されたが、時を経て大幅に修正され、異なる哲学者たちがこの用語を非常に異なる方法で用いてきた。さら

に、ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワインをはじめとする一部の哲学者は、分析的に真である命題と総合的に真である命題の間に、明確な区別が存在するか

どうかさえ疑問視している[2](→経験主義の2つのドグマ)。この区別の性質と有用性に関する議論は、現代の言語哲学において今日まで続いている。[2]。

| The

analytic–synthetic distinction is a semantic distinction used primarily

in philosophy to distinguish between propositions (in particular,

statements that are affirmative subject–predicate judgments) that are

of two types: analytic propositions and synthetic propositions.

Analytic propositions are true or not true solely by virtue of their

meaning, whereas synthetic propositions' truth, if any, derives from

how their meaning relates to the world.[1] While the distinction was first proposed by Immanuel Kant, it was revised considerably over time, and different philosophers have used the terms in very different ways. Furthermore, some philosophers (starting with Willard Van Orman Quine) have questioned whether there is even a clear distinction to be made between propositions which are analytically true and propositions which are synthetically true.[2] Debates regarding the nature and usefulness of the distinction continue to this day in contemporary philosophy of language.[2] |

分析的・総合的(分析的-綜合的)区別とは、主に哲学において命題(特

に、肯定的主語-述語判断である陳述)を二種類に区別するために用いられる意味論的区別である。分析的命題は、その意味によってのみ真か偽かが決まる。一

方、総合的命題の真偽は、その意味が世界とどう関連するかによって決まるのである。[1] この区別はイマヌエル・カントによって最初に提唱されたが、時を経て大幅に修正され、異なる哲学者たちがこの用語を非常に異なる方法で用いてきた。さら に、ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワインをはじめとする一部の哲学者は、分析的に真である命題と総合的に真である命題の間に、明確な区別が存在するか どうかさえ疑問視している[2](→経験主義の2つのドグマ)。この区別の性質と有用性に関する議論は、現代の言語哲学において今日まで続いている。[2]。 |

| Kant Conceptual containment The philosopher Immanuel Kant uses the terms "analytic" and "synthetic" to divide propositions into two types. Kant introduces the analytic–synthetic distinction in the Introduction to his Critique of Pure Reason (1781/1998, A6–7/B10–11). There, he restricts his attention to statements that are affirmative subject–predicate judgments and defines "analytic proposition" and "synthetic proposition" as follows: analytic proposition: a proposition whose predicate concept is contained in its subject concept synthetic proposition: a proposition whose predicate concept is not contained in its subject concept but related Examples of analytic propositions, on Kant's definition, include: "All bachelors are unmarried." "All triangles have three sides." Kant's own example is: "All bodies are extended": that is, they occupy space. (A7/B11) Each of these statements is an affirmative subject–predicate judgment, and, in each, the predicate concept is contained within the subject concept. The concept "bachelor" contains the concept "unmarried"; the concept "unmarried" is part of the definition of the concept "bachelor". Likewise, for "triangle" and "has three sides", and so on. Examples of synthetic propositions, on Kant's definition, include: "All bachelors are alone." "All creatures with hearts have kidneys." Kant's own example is: "All bodies are heavy": that is, they experience a gravitational force. (A7/B11) As with the previous examples classified as analytic propositions, each of these new statements is an affirmative subject–predicate judgment. However, in none of these cases does the subject concept contain the predicate concept. The concept "bachelor" does not contain the concept "alone"; "alone" is not a part of the definition of "bachelor". The same is true for "creatures with hearts" and "have kidneys"; even if every creature with a heart also has kidneys, the concept "creature with a heart" does not contain the concept "has kidneys". So the philosophical issue is: What kind of statement is "Language is used to transmit meaning"? |

カント 概念的包含 哲学者イマヌエル・カントは「分析的」と「総合的」という用語を用いて命題を二種類に分類する。カントは『純粋理性批判』序説(1781/1998, A6–7/B10–11)において分析的・総合的区別を導入している。そこで彼は、肯定的主語-述語判断に焦点を絞り、「分析的命題」と「総合的命題」を 次のように定義する: 分析的命題:述語概念が主語概念に含まれる命題 総合的命題:述語概念が主語概念に含まれないが、主語概念と関連する命題 カントの定義による分析的命題の例には以下がある: 「すべての独身者は未婚である」 「すべての三角形は三つの辺を持つ」 カント自身の例は次の通りである: 「すべての物体は広がりを持つ」すなわち、それらは空間を占める。(A7/B11) これらの各命題は肯定的主語-述語判断であり、いずれにおいても述語概念は主語概念に含まれている。「独身者」という概念は「未婚」という概念を含む。つまり「未婚」は「独身者」という概念の定義の一部だ。同様に「三角形」と「三辺を持つ」も同様である。 カントの定義による総合命題の例としては以下がある: 「全ての独身者は独りである」 「心臓を持つ全ての生物は腎臓を持つ」 カント自身の例は次の通りだ: 「全ての物体は重い」:すなわち、それらは重力の影響を受ける。(A7/B11) 前述の分析的命題に分類された例と同様に、これらの新たな命題もそれぞれ肯定的主語-述語判断である。しかし、いずれの例においても、主語概念が述語概念 を含むことはない。「独身者」という概念は「独り」という概念を含まない。「独り」は「独身者」の定義の一部ではない。「心臓を持つ生き物」と「腎臓を持 つ」についても同様だ。たとえ心臓を持つ全ての生き物が腎臓を持っていたとしても、「心臓を持つ生き物」という概念は「腎臓を持つ」という概念を含まな い。したがって哲学的問題はこうだ:「言語は意味を伝達するために用いられる」という文は、いったいどんな種類の文なのか? |

| Kant's version and the a priori–a posteriori distinction Main article: A priori and a posteriori In the Introduction to the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant contrasts his distinction between analytic and synthetic propositions with another distinction, the distinction between a priori and a posteriori propositions. He defines these terms as follows: a priori proposition: a proposition whose justification does not rely upon experience. Moreover, the proposition can be validated by experience, but is not grounded in experience. Therefore, it is logically necessary. a posteriori proposition: a proposition whose justification does rely upon experience. The proposition is validated by, and grounded in, experience. Therefore, it is logically contingent. Examples of a priori propositions include: "All bachelors are unmarried." "7 + 5 = 12." The justification of these propositions does not depend upon experience: one need not consult experience to determine whether all bachelors are unmarried, nor whether 7 + 5 = 12. (Of course, as Kant would grant, experience is required to understand the concepts "bachelor", "unmarried", "7", "+" and so forth. However, the a priori–a posteriori distinction as employed here by Kant refers not to the origins of the concepts but to the justification of the propositions. Once we have the concepts, experience is no longer necessary.) Examples of a posteriori propositions include: "All bachelors are unhappy." "Tables exist." Both of these propositions are a posteriori: any justification of them would require one's experience. The analytic–synthetic distinction and the a priori–a posteriori distinction together yield four types of propositions: analytic a priori synthetic a priori analytic a posteriori synthetic a posteriori Kant posits the third type as obviously self-contradictory. Ruling it out, he discusses only the remaining three types as components of his epistemological framework—each, for brevity's sake, becoming, respectively, "analytic", "synthetic a priori", and "empirical" or "a posteriori" propositions. This triad accounts for all propositions possible. Examples of analytic and examples of a posteriori statements have already been given, for synthetic a priori propositions he gives those in mathematics and physics. |

カントの区分とア・プリオリに・ア・ポステリオリな区別 詳細な説明: ア・プリオリに・ア・ポステリオリな 『純粋理性批判』序説において、カントは分析的命題と総合的命題の区別を、別の区別、すなわちア・プリオリに命題とア・ポステリオリな命題の区別と対比させる。彼はこれらの用語を次のように定義する: ア・プリオリに命題: その正当性が経験に依存しない命題。さらに、この命題は経験によって検証可能ではあるが、経験に根ざしてはいない。したがって、それは論理的に必然である。 ア・ポステリオリな命題:その正当化が経験に依存する命題。この命題は経験によって検証され、経験に根ざしている。したがって、それは論理的に偶然的である。 ア・プリオリな命題の例としては以下がある: 「すべての独身男性は未婚である」 「7 + 5 = 12」 これらの命題の正当性は経験に依存しない。すべての独身者が未婚であるか、あるいは7+5=12であるかを判断するのに経験を参照する必要はない(もちろ んカントが認めるように、「独身者」「未婚」「7」「+」といった概念を理解するには経験が必要である)。しかし、ここでカントが用いるア・プリオリに・ ア・ポステリオリな区別は、概念の起源ではなく命題の正当化を指す。概念を得た後は、経験はもはや必要ない。) ア・ポステリオリな命題の例としては: 「すべての独身者は不幸である」 「テーブルは存在する」 これらの命題はいずれもア・ポステリオリなものである。それらを正当化するには、必ず経験が必要となる。 分析的・総合的区別とア・プリオリに・ア・ポステリオリな区別を組み合わせると、四種類の命題が導かれる: 分析的ア・プリオリに 総合的ア・プリオリに 分析的ア・ポステリオリな 総合的ア・ポステリオリな カントは第三の類型を明らかに自己矛盾するものと位置づける。これを排除し、彼は残る三類型のみを認識論的枠組みの構成要素として論じる——簡潔さを期す ため、それぞれ「分析的」「総合的ア・プリオリに」「経験的」あるいは「ア・ポステリオリな」命題となる。この三つ組が可能な全ての命題を説明するのであ る。分析的命題とア・ポステリオリな命題の例は既に挙げた。合成的ア・プリオリな命題については、数学と物理学における例を挙げる。 |

| The ease of knowing analytic propositions Part of Kant's argument in the Introduction to the Critique of Pure Reason involves arguing that there is no problem figuring out how knowledge of analytic propositions is possible. To know an analytic proposition, Kant argued, one need not consult experience. Instead, one needs merely to take the subject and "extract from it, in accordance with the principle of contradiction, the required predicate" (B12). In analytic propositions, the predicate concept is contained in the subject concept. Thus, to know an analytic proposition is true, one need merely examine the concept of the subject. If one finds the predicate contained in the subject, the judgment is true. Thus, for example, one need not consult experience to determine whether "All bachelors are unmarried" is true. One need merely examine the subject concept ("bachelors") and see if the predicate concept "unmarried" is contained in it. And in fact, it is: "unmarried" is part of the definition of "bachelor" and so is contained within it. Thus the proposition "All bachelors are unmarried" can be known to be true without consulting experience. It follows from this, Kant argued, first: All analytic propositions are a priori; there are no a posteriori analytic propositions. It follows, second: There is no problem understanding how we can know analytic propositions; we can know them because we only need to consult our concepts in order to determine that they are true. |

分析的命題を知る容易さ 『純粋理性批判』序説におけるカントの議論の一部は、分析的命題の知識が可能であることの解明に問題はないと論じている。分析的命題を知るには、カントに よれば、経験を参照する必要はない。代わりに、主体を取り上げ、「矛盾の原理に従って、そこから必要な述語を抽出する」だけでよい(B12)。分析的命題 においては、述語概念は主語概念に含まれている。したがって、分析的命題が真であることを知るには、主語の概念を検討するだけでよい。もし述語が主語に含 まれていると確認できれば、その判断は真である。 例えば、「すべての独身者は未婚である」という命題が真かどうかを判断するのに、経験を参照する必要はない。単に主語概念(「独身者」)を検討し、述語概 念「未婚」がそこに含まれているかを確認すればよい。実際、「未婚」は「独身者」の定義の一部であり、主語概念に含まれている。したがって「すべての独身 者は未婚である」という命題は、経験を参照せずに真であると知ることができる。 カントはここから、第一にこう主張した:全ての分析命題はア・プリオリに存在する。ア・ポステリオリな分析命題は存在しない。第二にこう導かれる:分析命 題をいかにして知ることができるか理解する問題はない。我々は概念を参照するだけで真であると判断できるから、それらを知ることができるのだ。 |

| The possibility of metaphysics After ruling out the possibility of analytic a posteriori propositions, and explaining how we can obtain knowledge of analytic a priori propositions, Kant also explains how we can obtain knowledge of synthetic a posteriori propositions. That leaves only the question of how knowledge of synthetic a priori propositions is possible. This question is exceedingly important, Kant maintains, because all scientific knowledge (for him Newtonian physics and mathematics) is made up of synthetic a priori propositions. If it is impossible to determine which synthetic a priori propositions are true, he argues, then metaphysics as a discipline is impossible. The remainder of the Critique of Pure Reason is devoted to examining whether and how knowledge of synthetic a priori propositions is possible.[3] |

形而上学の可能性 分析的ア・ポステリオリな命題の可能性を排除し、分析的ア・プリオリに命題の知識をいかに得られるかを説明した後、カントはさらに合成的ア・ポステリオリ な命題の知識をいかに得られるかも説明する。残るは合成的ア・プリオリに命題の知識がいかに可能かという問題だけだ。カントによれば、この問題は極めて重 要である。なぜなら、あらゆる科学的知識(彼にとってそれはニュートン力学と数学である)は合成的ア・プリオリな命題から成り立っているからだ。もし合成 的ア・プリオリな命題の真偽を判断することが不可能ならば、形而上学という学問分野そのものが不可能だと彼は論じる。『純粋理性批判』の残りの部分は、合 成的ア・プリオリな命題の知識が可能かどうか、そしてその方法について検討することに捧げられている。[3] |

| Mathematics and Synthetic Apriori Propositions. One example Kant gives of a possibly synthetic apriori propositions are the propositions of mathematics. The mathematical equation that 10 = 0.2x 50 is true regardless of experience thus making it a priori, but not analytic. Mathematical propositions are not analytic in that 10 does not self evidently contain 0.2x50, in the same way that the concept bachelor contains the categories of unmarried and male. |

数学と合成的先天的命題。 カントが提示する合成的先天的命題の一例が数学の命題である。数学的方程式「10 = 0.2 × 50」は経験とは無関係に真であるため、それはア・プリオリに属するものの、分析的ではない。数学的命題が分析的ではないのは、10が自明に0.2 × 50を含むわけではないからだ。これは「独身男性」という概念が「未婚」と「男性」という範疇を含むのとは異なる。 |

| The Importance of Synthetic Apriori Propositions to Kant's metaphysics Kant's advocacy for his metaphysics in Critique of Pure Reason can be seen as relying on the possibility of synthetic apriori claims. If synthetic apriori propositions are possible, it supposes a certain metaphysical worldview, much of the Critique of Pure reason then relies on the possibility of synthetic apriori propositions to justify a worldview. One could reduce Kant's argument into a simple form: If Kant's metaphysics is true, then synthetic apriori propositions are possible. |

カントの形而上学における合成的先天的命題の重要性 カントが『純粋理性批判』で自らの形而上学を擁護する姿勢は、合成的先天的命題の可能性に依拠していると見なせる。もし合成的先天的命題が可能ならば、そ れは特定の形而上学的世界観を前提とする。したがって『純粋理性批判』の大部分は、世界観を正当化するために合成的先天的命題の可能性に依存しているの だ。カントの議論は単純な形に還元できる:カントの形而上学が真実ならば、合成的先天的命題は可能である。 |

| Frege and the logical positivists Frege revision of Kantian definition Over a hundred years later, a group of philosophers took interest in Kant and his distinction between analytic and synthetic propositions: the logical positivists. Part of Kant's examination of the possibility of synthetic a priori knowledge involved the examination of mathematical propositions, such as "7 + 5 = 12." (B15–16) "The shortest distance between two points is a straight line." (B16–17) Kant maintained that mathematical propositions such as these are synthetic a priori propositions, and that we know them. That they are synthetic, he thought, is obvious: the concept "equal to 12" is not contained within the concept "7 + 5"; and the concept "straight line" is not contained within the concept "the shortest distance between two points". From this, Kant concluded that we have knowledge of synthetic a priori propositions. Although not strictly speaking a logical positivist, Gottlob Frege's notion of analyticity influenced them greatly. It included a number of logical properties and relations beyond containment: symmetry, transitivity, antonymy, or negation and so on. He had a strong emphasis on formality, in particular formal definition, and also emphasized the idea of substitution of synonymous terms. "All bachelors are unmarried" can be expanded out with the formal definition of bachelor as "unmarried man" to form "All unmarried men are unmarried", which is recognizable as tautologous and therefore analytic from its logical form: any statement of the form "All X that are (F and G) are F". Using this particular expanded idea of analyticity, Frege concluded that Kant's examples of arithmetical truths are analytical a priori truths and not synthetic a priori truths. Thanks to Frege's logical semantics, particularly his concept of analyticity, arithmetic truths like "7+5=12" are no longer synthetic a priori but analytical a priori truths in Carnap's extended sense of "analytic". Hence logical empiricists are not subject to Kant's criticism of Hume for throwing out mathematics along with metaphysics.[4] (Here "logical empiricist" is a synonym for "logical positivist".) |

フレーゲと論理実証主義者たち フレーゲによるカント的定義の修正 百年以上後、カントとその分析的命題・総合的命題の区別に興味を持った哲学者たちが現れた。それが論理実証主義者たちである。 カントがア・プリオリに総合的な認識の可能性を検討した過程では、数学的命題の検証が含まれていた。例えば 「7 + 5 = 12」 (B15–16) 「二点間の最短距離は直線である」 (B16–17) カントは、こうした数学的命題が合成的ア・プリオリに命題であり、我々がそれを知っていると主張した。それらが合成的であることは明らかだと考えた。なぜ なら「12に等しい」という概念は「7 + 5」という概念に含まれておらず、「直線」という概念は「二点間の最短距離」という概念に含まれていないからだ。カントはここから、我々が合成的ア・プリ オリに命題の知識を持っていると結論づけた。 厳密には論理実証主義者ではないが、ゴットロブ・フレーゲの分析性概念は彼らに大きな影響を与えた。この概念は包含を超えた複数の論理的性質や関係——対 称性、推移性、反義性、否定など——を含んでいた。彼は形式性、特に形式的定義を強く重視し、同義語の置換という考え方も強調した。「すべての独身者は未 婚である」という命題は、独身者を「未婚の男性」と形式的に定義することで「すべての未婚の男性は未婚である」と展開できる。これは同語反復 (tautology)として認識可能であり、したがってその論理形式からして分析的である。「(FかつG)であるすべてのXはFである」という形式の命 題はすべて分析的だ。この拡張された分析性の概念を用いて、フレーゲはカントが挙げた算術的真理の例が、合成的ア・プリオリに真理ではなく分析的ア・プリ オリに真理であると結論づけた。 フレーゲの論理的意味論、特に分析性の概念のおかげで、「7+5=12」のような算術的真理は、もはや合成的ア・プリオリに真理ではなく、カルナップが拡 張した「分析的」の意味における分析的ア・プリオリに真理となった。したがって論理実証主義者は、数学を形而上学と共に捨て去ったというヒュームに対する カントの批判の対象とはならない。[4] (ここで「論理経験主義者」は「論理実証主義」の同義語である。) |

| The origin of the logical positivist's distinction The logical positivists agreed with Kant that we have knowledge of mathematical truths, and further that mathematical propositions are a priori. However, they did not believe that any complex metaphysics, such as the type Kant supplied, are necessary to explain our knowledge of mathematical truths. Instead, the logical positivists maintained that our knowledge of judgments like "all bachelors are unmarried" and our knowledge of mathematics (and logic) are in the basic sense the same: all proceeded from our knowledge of the meanings of terms or the conventions of language. Since empiricism had always asserted that all knowledge is based on experience, this assertion had to include knowledge in mathematics. On the other hand, we believed that with respect to this problem the rationalists had been right in rejecting the old empiricist view that the truth of "2+2=4" is contingent on the observation of facts, a view that would lead to the unacceptable consequence that an arithmetical statement might possibly be refuted tomorrow by new experiences. Our solution, based upon Wittgenstein's conception, consisted in asserting the thesis of empiricism only for factual truth. By contrast, the truths of logic and mathematics are not in need of confirmation by observations, because they do not state anything about the world of facts, they hold for any possible combination of facts.[5][6] — Rudolf Carnap, "Autobiography": §10: Semantics, p. 64 |

論理的実証主義者の区別の起源 論理的実証主義者は、数学的真理についての知識を持つこと、さらに数学的命題がア・プリオリにであるという点でカントに同意した。しかし彼らは、数学的真 理の知識を説明するために、カントが提供したような複雑な形而上学が必要だとは考えなかった。代わりに、論理実証主義者は「すべての独身者は未婚である」 といった判断に関する知識と、数学(および論理学)に関する知識は、基本的な意味で同じだと主張した。どちらも用語の意味や言語の慣習に関する知識から生 じているというのだ。 経験論は常に、すべての知識は経験に基づくと主張してきた。この主張は数学の知識も含まなければならない。一方で我々は、この問題に関して合理主義者たち が正しかったと考えた。彼らは「2+2=4」の真偽が事実の観察に依存するという古い経験論的見解を拒否した。この見解は、算術的命題が明日新たな経験に よって反証される可能性があるという受け入れがたい帰結を招くだろう。ウィトゲンシュタインの概念に基づく我々の解決策は、経験論の命題を事実的真理にの み適用すると主張することにあった。これに対し、論理学と数学の真理は観察による確認を必要としない。なぜならそれらは事実の世界について何も述べておら ず、あらゆる事実の組み合わせにおいて成立するからである。[5][6] — ルドルフ・カルナップ『自伝』: §10: 意味論, p. 64 |

| Logical positivist definitions Thus the logical positivists drew a new distinction, and, inheriting the terms from Kant, named it the "analytic-synthetic distinction".[7] They provided many different definitions, such as the following: analytic proposition: a proposition whose truth depends solely on the meaning of its terms analytic proposition: a proposition that is true (or false) by definition analytic proposition: a proposition that is made true (or false) solely by the conventions of language (While the logical positivists believed that the only necessarily true propositions were analytic, they did not define "analytic proposition" as "necessarily true proposition" or "proposition that is true in all possible worlds".) Synthetic propositions were then defined as: synthetic proposition: a proposition that is not analytic These definitions applied to all propositions, regardless of whether they were of subject–predicate form. Thus, under these definitions, the proposition "It is raining or it is not raining" was classified as analytic, while for Kant it was analytic by virtue of its logical form. And the proposition "7 + 5 = 12" was classified as analytic, while under Kant's definitions it was synthetic. |

論理実証主義の定義 こうして論理実証主義者たちは新たな区別を設け、カントから用語を継承して「分析的・総合的区別」と名付けた[7]。彼らは以下のような様々な異なる定義を示した: 分析命題:その真偽がその用語の意味にのみ依存する命題 分析命題:定義によって真(または偽)となる命題 分析命題:言語の慣習によってのみ真(または偽)となる命題 (論理実証主義者は必然的に真である命題は分析的命題のみだと考えていたが、「分析的命題」を「必然的に真の命題」や「あらゆる可能世界において真である命題」とは定義しなかった。) 合成的命題は次のように定義された: 合成的命題:分析的でない命題 これらの定義は、主語-述語形式であるか否かを問わず、全ての命題に適用された。したがって、これらの定義によれば、「雨が降っているか、降っていない か」という命題は分析的と分類されたが、カントにとっては論理形式によって分析的であった。また「7 + 5 = 12」という命題は分析的と分類されたが、カントの定義では合成的であった。 |

| Two-dimensionalism Two-dimensionalism is an approach to semantics in analytic philosophy. It is a theory of how to determine the sense and reference of a word and the truth-value of a sentence. It is intended to resolve a puzzle that has plagued philosophy for some time, namely: How is it possible to discover empirically that a necessary truth is true? Two-dimensionalism provides an analysis of the semantics of words and sentences that makes sense of this possibility. The theory was first developed by Robert Stalnaker, but it has been advocated by numerous philosophers since, including David Chalmers and Berit Brogaard. Any given sentence, for example, the words, "Water is H2O" is taken to express two distinct propositions, often referred to as a primary intension and a secondary intension, which together compose its meaning.[8] The primary intension of a word or sentence is its sense, i.e., is the idea or method by which we find its referent. The primary intension of "water" might be a description, such as watery stuff. The thing picked out by the primary intension of "water" could have been otherwise. For example, on some other world where the inhabitants take "water" to mean watery stuff, but, where the chemical make-up of watery stuff is not H2O, it is not the case that water is H2O for that world. The secondary intension of "water" is whatever thing "water" happens to pick out in this world, whatever that world happens to be. So if we assign "water" the primary intension watery stuff then the secondary intension of "water" is H2O, since H2O is watery stuff in this world. The secondary intension of "water" in our world is H2O, which is H2O in every world because unlike watery stuff it is impossible for H2O to be other than H2O. When considered according to its secondary intension, "Water is H2O" is true in every world. If two-dimensionalism is workable it solves some very important problems in the philosophy of language. Saul Kripke has argued that "Water is H2O" is an example of the necessary a posteriori, since we had to discover that water was H2O, but given that it is true, it cannot be false. It would be absurd to claim that something that is water is not H2O, for these are known to be identical. |

二次元主義 二次元主義は分析哲学における意味論へのアプローチである。これは単語の意味と参照対象、および文の真偽値を決定する方法に関する理論だ。哲学を長年悩ま せてきた難問、すなわち「必然的真理が真であることを経験的に発見することはどうして可能なのか」を解決することを目的としている。二次元主義は、この可 能性を説明できる言葉と文の意味論の分析を提供する。この理論はロバート・スタナカーによって最初に発展したが、その後デイヴィッド・チャーマーズやベ リット・ブローガードを含む多くの哲学者によって支持されてきた。 例えば「水はH2Oである」という文は、 二つの異なる命題を表現していると見なされる。これらはしばしば一次的内包と二次的内包と呼ばれ、両者が合わせてその意味を構成する。[8] 単語や文の一次的内包とは、その意味、すなわち参照対象を見つけるための概念や方法である。 「水」の一義的意味は「水っぽいもの」といった記述かもしれない。この一義的意味によって特定される対象は、別の世界では異なる可能性がある。例えば、住 人が「水」を「水っぽいもの」と解釈するが、その水っぽいものの化学組成がH₂Oでない世界では、その世界において「水はH₂Oである」とは言えない。 「水」の二次的内包は、この世界で「水」がたまたま指し示すもの、つまりその世界がたまたま何であれ、そのもの自体である。したがって「水」に一次的内包 として「水っぽいもの」を割り当てた場合、「水」の二次的内包はH₂Oとなる。なぜならこの世界ではH₂Oが水っぽいものだからだ。我々の世界における 「水」の二次的意味はH₂Oである。これはあらゆる世界においてH₂Oである。なぜなら水質物質とは異なり、H₂OがH₂O以外のものとなることは不可能 だからだ。二次的意味に基づいて考察すれば、「水はH₂Oである」はあらゆる世界で真である。 二次元主義が成立するならば、言語哲学におけるいくつかの重要な問題を解決する。ソール・クリプキは「水はH₂Oである」が必要ア・ポステリオリな命題の 例だと論じた。なぜなら我々は水がH₂Oであることを発見しなければならなかったが、それが真である以上、偽り得ないからだ。水であるものがH₂Oではな いと主張するのは不合理である。これらが同一であることは周知の事実だからだ。 |

| Carnap's distinction Rudolf Carnap was a strong proponent of the distinction between what he called "internal questions", questions entertained within a "framework" (like a mathematical theory), and "external questions", questions posed outside any framework – posed before the adoption of any framework.[9][10][11] The "internal" questions could be of two types: logical (or analytic, or logically true) and factual (empirical, that is, matters of observation interpreted using terms from a framework). The "external" questions were also of two types: those that were confused pseudo-questions ("one disguised in the form of a theoretical question") and those that could be re-interpreted as practical, pragmatic questions about whether a framework under consideration was "more or less expedient, fruitful, conducive to the aim for which the language is intended".[9] The adjective "synthetic" was not used by Carnap in his 1950 work Empiricism, Semantics, and Ontology.[9] Carnap did define a "synthetic truth" in his work Meaning and Necessity: a sentence that is true, but not simply because "the semantical rules of the system suffice for establishing its truth".[12] The notion of a synthetic truth is of something that is true both because of what it means and because of the way the world is, whereas analytic truths are true in virtue of meaning alone. Thus, what Carnap calls internal factual statements (as opposed to internal logical statements) could be taken as being also synthetic truths because they require observations, but some external statements also could be "synthetic" statements and Carnap would be doubtful about their status. The analytic–synthetic argument therefore is not identical with the internal–external distinction.[13] |

カルナップの区別 ルドルフ・カルナップは、彼が「内部問題」と呼んだもの、つまり「枠組み」(数学理論のようなもの)の中で扱われる問題と、「外部問題」、つまりいかなる 枠組みの外で提起される問題——いかなる枠組みを採用する前に提起される問題——との区別を強く主張した。[9][10][11] 「内部」問題は二種類に分けられる:論理的(あるいは分析的、論理的に真)なものと、事実的(経験的、つまり枠組みの用語を用いて解釈される観察事項)な ものだ。「外部」の問いもまた二種類であった:混乱した疑似的問い(「理論的問いの形を装ったもの」)と、検討中の枠組みが「その言語が意図する目的に対 して、より便利で、実り多く、有益であるかどうか」という実践的・実用的な問いとして再解釈可能なもの。[9] 1950年の著作『経験主義、意味論、存在論』において、カルナップは「総合的」という形容詞を使用していない。[9] カルナップは『意味と必然性』において「総合的真理」を定義している:それは真であるが、単に「体系の意味論的規則がその真偽を確立するのに十分である」 という理由だけで真なのではない。[12] 合成的真理の概念とは、その意味内容と世界のあり方との両方によって真となるもののことであり、一方、分析的真理は意味内容のみによって真となる。した がって、カルナップが内部的事実的命題(内部的論理的命題と対比される)と呼ぶものは、観察を必要とする点で合成的真理と見なせるが、一部の外部的命題も 「合成的」命題となり得るため、カルナップはその地位について疑念を抱くだろう。したがって、分析的・総合的議論は、内的・外的区別と同一ではない。 [13] |

| Quine's criticisms See also: Willard Van Orman Quine § Rejection of the analytic–synthetic distinction, and Two Dogmas of Empiricism § Analyticity and circularity In 1951, Willard Van Orman Quine published the essay "Two Dogmas of Empiricism" in which he argued that the analytic–synthetic distinction is untenable.[14] The argument at bottom is that there are no "analytic" truths, but all truths involve an empirical aspect. In the first paragraph, Quine takes the distinction to be the following: analytic propositions – propositions grounded in meanings, independent of matters of fact. synthetic propositions – propositions grounded in fact. Quine's position denying the analytic–synthetic distinction is summarized as follows: It is obvious that truth in general depends on both language and extralinguistic fact. ... Thus one is tempted to suppose in general that the truth of a statement is somehow analyzable into a linguistic component and a factual component. Given this supposition, it next seems reasonable that in some statements the factual component should be null; and these are the analytic statements. But, for all its a priori reasonableness, a boundary between analytic and synthetic statements simply has not been drawn. That there is such a distinction to be drawn at all is an unempirical dogma of empiricists, a metaphysical article of faith.[15] — Willard V. O. Quine, "Two Dogmas of Empiricism", p. 64 To summarize Quine's argument, the notion of an analytic proposition requires a notion of synonymy, but establishing synonymy inevitably leads to matters of fact – synthetic propositions. Thus, there is no non-circular (and so no tenable) way to ground the notion of analytic propositions. While Quine's rejection of the analytic–synthetic distinction is widely known, the precise argument for the rejection and its status is highly debated in contemporary philosophy. However, some (for example, Paul Boghossian)[16] argue that Quine's rejection of the distinction is still widely accepted among philosophers, even if for poor reasons. |

クワインの批判 関連項目: ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワイン § 分析的・総合的区別の否定、および経験主義の二つの教条 § 分析性と循環性 1951年、ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワインは「経験主義の二つのドグマ」という論文を発表し、分析的・総合的区別は成り立たないと論じた。 [14] 根本的な論点は、「分析的」真理は存在せず、あらゆる真理には経験的側面が伴うというものだ。最初の段落でクワインはこの区別を次のように定義する: 分析的命題 – 事実問題に依存せず、意味に根差す命題。 総合的命題 – 事実に根差す命題。 分析的・総合的区別を否定するクワインの立場は以下のように要約される: 一般に真偽は言語と超言語的事実の両方に依存することは明らかだ。... したがって、一般に命題の真偽は言語的要素と事実的要素に何らかの形で分析可能だと仮定したくなる。この仮定のもとでは、次に、事実的要素がゼロである命 題が存在するはずだと考えるのが合理的だ。これらが分析的命題である。しかし、そのア・プリオリな妥当性にもかかわらず、分析的命題と総合的命題の境界線 は、単に引かれていないのである。そもそもそのような区別が存在するという考え自体が、経験論者たちの非経験的なドグマであり、形而上学的な信仰条項に過 ぎない。[15] — ウィラード・V・O・クワイン『経験主義の二つのドグマ』p. 64 クワインの議論を要約すると、分析的命題の概念には同義性の概念が必要だが、同義性を確立するには必然的に事実問題―つまり総合的命題―に帰着する。したがって、分析的命題の概念を非循環的(つまり維持可能な)方法で基礎づける道は存在しない。 クワインによる分析的・総合的区別の否定は広く知られているが、その否定の正確な論証とその地位については、現代哲学において激しい議論が交わされてい る。しかし、一部の研究者(例えばポール・ボゴシアン)[16]は、たとえその根拠が不十分であっても、クワインによる区別の否定は依然として哲学者の間 で広く受け入れられていると主張している。 |

| Responses Paul Grice and P. F. Strawson criticized "Two Dogmas" in their 1956 article "In Defense of a Dogma".[17] Among other things, they argue that Quine's skepticism about synonyms leads to a skepticism about meaning. If statements can have meanings, then it would make sense to ask "What does it mean?". If it makes sense to ask "What does it mean?", then synonymy can be defined as follows: Two sentences are synonymous if and only if the true answer of the question "What does it mean?" asked of one of them is the true answer to the same question asked of the other. They also draw the conclusion that discussion about correct or incorrect translations would be impossible given Quine's argument. Four years after Grice and Strawson published their paper, Quine's book Word and Object was released. In the book Quine presented his theory of indeterminacy of translation. In Speech Acts, John Searle argues that from the difficulties encountered in trying to explicate analyticity by appeal to specific criteria, it does not follow that the notion itself is void.[18] Considering the way that we would test any proposed list of criteria, which is by comparing their extension to the set of analytic statements, it would follow that any explication of what analyticity means presupposes that we already have at our disposal a working notion of analyticity. In "'Two Dogmas' Revisited", Hilary Putnam argues that Quine is attacking two different notions:[19] It seems to me there is as gross a distinction between 'All bachelors are unmarried' and 'There is a book on this table' as between any two things in this world, or at any rate, between any two linguistic expressions in the world;[20] — Hilary Putnam, Philosophical Papers, p. 36 Analytic truth defined as a true statement derivable from a tautology by putting synonyms for synonyms is near Kant's account of analytic truth as a truth whose negation is a contradiction. Analytic truth defined as a truth confirmed no matter what, however, is closer to one of the traditional accounts of a priori. While the first four sections of Quine's paper concern analyticity, the last two concern a-priority. Putnam considers the argument in the two last sections as independent of the first four, and at the same time as Putnam criticizes Quine, he also emphasizes his historical importance as the first top-rank philosopher to both reject the notion of a-priority and sketch a methodology without it.[21] Jerrold Katz, a one-time associate of Noam Chomsky, countered the arguments of "Two Dogmas" directly by trying to define analyticity non-circularly on the syntactical features of sentences.[22][23][24] Chomsky himself critically discussed Quine's conclusion, arguing that it is possible to identify some analytic truths (truths of meaning, not truths of facts) which are determined by specific relations holding among some innate conceptual features of the mind or brain.[25] In Philosophical Analysis in the Twentieth Century, Volume 1: The Dawn of Analysis, Scott Soames pointed out that Quine's circularity argument needs two of the logical positivists' central theses to be effective:[26] All necessary (and all a priori) truths are analytic. Analyticity is needed to explain and legitimate necessity. It is only when these two theses are accepted that Quine's argument holds. It is not a problem that the notion of necessity is presupposed by the notion of analyticity if necessity can be explained without analyticity. According to Soames, both theses were accepted by most philosophers when Quine published "Two Dogmas". Today, however, Soames holds both statements to be antiquated. He says: "Very few philosophers today would accept either [of these assertions], both of which now seem decidedly antique."[26] |

応答 ポール・グライスとP・F・ストローソンは、1956年の論文「教条の擁護」において「二つの教条」を批判した。[17] とりわけ彼らは、クワインの同義語に対する懐疑が意味に対する懐疑へとつながると主張する。もし文が意味を持つなら、「それは何を意味するのか?」と問う ことに意味があるはずだ。「それは何を意味するのか?」と問うことに意味があるならば、同義性は次のように定義できる:ある文に対して「それは何を意味す るのか?」と問う際の真の答えが、別の文に対して同じ問いを投げかけた際の真の答えと一致する場合に限り、二つの文は同義である。彼らはさらに、クワイン の議論を前提とすれば、翻訳の正誤に関する議論は不可能だという結論を導き出した。グライスとストローソンが論文を発表してから4年後、クワインの著書 『言葉と対象』が刊行された。クワインはこの本で翻訳の不確定性理論を提示した。 ジョン・サールは『発話行為』において、分析性を特定の基準によって説明しようとする際に直面する困難から、分析性という概念自体が空虚であるとは結論づ けられないと論じている[18]。提案された基準リストを検証する方法を、つまり分析的命題の集合との外延比較によって行うとすれば、分析性の意味を説明 するあらゆる試みは、我々が既に分析性の実用的な概念を手にしていることを前提としていることになる。 ヒラリー・パトナムは『「二つのドグマ」再考』において、クワインが二つの異なる概念を攻撃していると論じている[19]: 「『すべての独身者は未婚である』と『この机の上に本がある』との間には、この世界におけるいかなる二つの事物間、あるいは少なくとも世界におけるいかなる二つの言語表現間の区別と同様に、明らかな区別があるように思われる」 [20] — ヒラリー・パトナム、『哲学論文集』p. 36 同義語を同義語で置き換えることで同語反復から導出可能な真の命題として定義される分析的真実は、その否定が矛盾となる真実としてのカントの分析的真実論 に近い。しかし、いかなる場合でも確認される真実として定義される分析的真実は、伝統的なア・プリオリに解釈の一つに近い。クワインの論文の最初の四節は 分析性について論じているが、最後の二節は先験性について論じている。パトナムは最後の二節の議論を最初の四節とは独立したものと考えている。同時にパト ナムはクワインを批判しつつも、先験性の概念を拒否し、それを排除した方法論を初めて概説した第一級の哲学者としてのクワインの歴史的重要性を強調してい る。[21] ノーム・チョムスキーの元同僚であるジェロルド・カッツは、「二つのドグマ」の議論に直接反論し、文の構文的特徴に基づいて非循環的に分析性を定義しよう と試みた。[22][23][24] チョムスキー自身はクワインの結論を批判的に論じ、心や脳の先天的な概念的特徴間の特定の関係によって決定される分析的真理(事実の真理ではなく意味の真 理)を特定することは可能だと主張した。[25] スコット・ソームズは『20世紀の哲学的分析 第1巻:分析の夜明け』において、クワインの循環論法が有効であるためには、論理実証主義者たちの二つの中心的な命題が必要だと指摘した:[26] すべての必然的(およびすべてのア・プリオリに)真理は分析的である。 必然性を説明し正当化するには分析性が必要である。 この二つの命題が受け入れられて初めて、クワインの議論は成立する。必然性の概念が分析性の概念によって前提とされることは問題ではない。なぜなら、分析 性なしに必然性を説明できるならよいからだ。ソームズによれば、クワインが「二つのドグマ」を発表した当時、ほとんどの哲学者はこの二つの命題を受け入れ ていた。しかし今日、ソームズは両命題を時代遅れと見なしている。彼はこう述べている:「今日では、どちらの主張も明らかに古臭く見えるため、これらを受 け入れる哲学者はほとんどいないだろう。」[26] |

| In other fields This distinction was imported from philosophy into theology, with Albrecht Ritschl attempting to demonstrate that Kant's epistemology was compatible with Lutheranism.[27] |

他の分野では この区別は哲学から神学へ導入され、アルブレヒト・リッチルはカントの認識論がルター派神学と両立し得ることを示そうとした。[27] |

| Holophrastic indeterminacy Paradox of analysis Failure to elucidate |

全定形不確定性 分析のパラドックス 解明の失敗 |

| Footnotes 1. Rey, Georges. "The Analytic/Synthetic Distinction". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2010 Edition). Retrieved February 12, 2012. 2. "The Analytic/Synthetic Distinction". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 7 July 2020. 3. See Cooper Harold Langford (1949)'s ostensive proof: Langford, C. H. (1949-01-06). "A Proof That Synthetic A Priori Propositions Exist". The Journal of Philosophy. 46 (1): 20–24. doi:10.2307/2019526. JSTOR 2019526. 4. Jerrold J. Katz (2000). "The epistemic challenge to antirealism". Realistic Rationalism. MIT Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0262263290. 5. Reprinted in: Carnap, R. (1999). "Autobiography". In Paul Arthur Schilpp (ed.). The Philosophy of Rudolf Carnap. Open Court Publishing Company. p. 64. ISBN 978-0812691535. 6. This quote is found with a discussion of the differences between Carnap and Wittgenstein in Michael Friedman (1997). "Carnap and Wittgenstein's Tractatus". In William W. Tait; Leonard Linsky (eds.). Early Analytic Philosophy: Frege, Russell, Wittgenstein. Open Court Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-0812693447. 7. Gary Ebbs (2009). "§51 A first sketch of the pragmatic roots of Carnap's analytic-synthetic distinction". Rule-Following and Realism. Harvard University Press. pp. 101 ff. ISBN 978-0674034419. 8. For a fuller explanation see Chalmers, David. The Conscious Mind. Oxford UP: 1996. Chapter 2, section 4. 9. Rudolf Carnap (1950). "Empiricism, Semantics, and Ontology". Revue Internationale de Philosophie. 4: 20–40. Reprinted in the Supplement to Meaning and Necessity: A Study in Semantics and Modal Logic, enlarged edition (University of Chicago Press, 1956). 10. Gillian Russell (2012-11-21). "Analytic/Synthetic Distinction". Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 2013-05-16. 11. Mauro Murzi (April 12, 2001). "Rudolf Carnap: §3. Analytic and Synthetic". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 12. Rudolf Carnap (1988) [1947]. Meaning and Necessity: A study in semantics and modal logic (2nd ed.). University of Chicago. ISBN 978-0226093475.Google link to Midway reprint. 13. Stephen Yablo (1998). "Does ontology rest upon a mistake?" (PDF). Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume. 72 (1): 229–262. doi:10.1111/1467-8349.00044. The usual charge against Carnap's internal/external distinction is one of 'guilt by association with analytic/synthetic'. But it can be freed of this association 14. Willard v.O. Quine (1951). "Main Trends in Recent Philosophy: Two Dogmas of Empiricism". The Philosophical Review. 60 (1): 20–43. doi:10.2307/2181906. JSTOR 2181906. Reprinted in W.V.O. Quine, From a Logical Point of View (Harvard University Press, 1953; second, revised, edition 1961) On-line versions at http://www.calculemus.org and Woodbridge Archived February 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. 15.Willard v O Quine (1980). "Chapter 2: W.V. Quine: Two dogmas of empiricism". In Harold Morick (ed.). Challenges to empiricism. Hackett Publishing. p. 60. ISBN 978-0915144907. Published earlier in From a Logical Point of View, Harvard University Press (1953) 16. Paul Artin Boghossian (August 1996). "Analyticity Reconsidered". Noûs. 30 (3): 360–391. doi:10.2307/2216275. JSTOR 2216275. 17. H. P. Grice & P. F. Strawson (April 1956). "In Defense of a Dogma". The Philosophical Review. 65 (2): 41–158. doi:10.2307/2182828. JSTOR 2182828. 18. Searle, John R. (1969). Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0521096263. 19. Hilary Putnam (1983). Realism and Reason: Philosophical Papers Volume 3, Realism and Reason. Cambridge University Press. pp. 87–97. ISBN 9780521246729. 20. Hilary Putnam (1979). Philosophical Papers: Volume 2, Mind, Language and Reality. Harvard University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0521295512. 21. Putnam, Hilary, "'Two dogmas' revisited." In Gilbert Ryle, Contemporary Aspects of Philosophy. Stocksfield: Oriel Press, 1976, 202–213. 22. Leonard Linsky (October 1970). "Analytical/Synthetic and Semantic Theory". Synthese. 21 (3/4): 439–448. doi:10.1007/BF00484810. JSTOR 20114738. S2CID 46959463. Reprinted in Donald Davidson; Gilbert Harman, eds. (1973). "Analytic/Synthetic and Semantic Theory". Semantics of natural language (2nd ed.). pp. 473–482. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-2557-7_16. ISBN 978-9027703040. 23. Willard v O Quine (February 2, 1967). "On a Suggestion of Katz". The Journal of Philosophy. 64 (2): 52–54. doi:10.2307/2023770. JSTOR 2023770. 24. Jerrold J Katz (1974). "Where Things Stand Now with the Analytical/Synthetic Distinction" (PDF). Synthese. 28 (3–4): 283–319. doi:10.1007/BF00877579. S2CID 26340509. 25. Cipriani, Enrico (2017). "Chomsky on analytic and necessary propositions". Phenomenology and Mind. 12: 122–31. 26. Scott Soames (2009). "Evaluating the circularity argument". 'Philosophical Analysis in the Twentieth Century, Volume 1: The Dawn of Analysis. Princeton University Press. p. 360. ISBN 978-1400825790. There are several earlier versions of this work. 27. Palmquist, Stephen (1989). "Immanuel Kant: A Christian Philosopher?". Faith and Philosophy. 6: 65–75. doi:10.5840/faithphil1989619. |

脚注 1. Rey, Georges. 「分析的・総合的区別」. スタンフォード哲学百科事典 (2010年冬版). 2012年2月12日取得. 2. 「分析的・総合的区別」. スタンフォード哲学百科事典. 2020年7月7日取得. クーパー・ハロルド・ラングフォード(1949)の示証的証明を参照のこと:Langford, C. H. (1949-01-06). 「ア・プリオリに総合された命題の存在の証明」. The Journal of Philosophy. 46 (1): 20–24. doi:10.2307/2019526. JSTOR 2019526. 4. ジェロルド・J・カッツ (2000). 「反現実主義に対する認識論的挑戦」. 『現実主義的合理主義』. MIT Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0262263290. 5. 再版: Carnap, R. (1999). 「自伝」. In Paul Arthur Schilpp (編). 『ルドルフ・カルナップの哲学』. Open Court Publishing Company. p. 64. ISBN 978-0812691535. 6. この引用は、Michael Friedmanによるカルナップとウィトゲンシュタインの異なる点の考察の中で見られる。(1997). 「カルナップとウィトゲンシュタインの『論理哲学論考』」. ウィリアム・W・テイト; レナード・リンスキー (編). 『初期分析哲学:フレーゲ、ラッセル、ウィトゲンシュタイン』. オープンコート出版. p. 29. ISBN 978-0812693447. 7. ゲイリー・エブス (2009). 「§51 カルナップの分析的・総合的区別の実用主義的根源に関する最初の概説」。『規則追従と現実主義』。ハーバード大学出版局。101頁以降。ISBN 978-0674034419。 8. より詳細な説明については、チャーマーズ、デイヴィッド『意識の心』オックスフォード大学出版局:1996年、第2章第4節を参照のこと。 9. ルドルフ・カルナップ (1950). 「経験主義、意味論、存在論」. Revue Internationale de Philosophie. 4: 20–40. 『意味と必然性:意味論と様相論理の研究』増補版(シカゴ大学出版局、1956年)の補遺に再録。 10. ギリアン・ラッセル (2012-11-21). 「分析的/総合的区別」. 『オックスフォード・バイオリグラフィーズ』. 2013-05-16 参照. 11. マウロ・ムルツィ (2001年4月12日). 「ルドルフ・カルナップ: §3. 分析的と総合的」. 『インターネット哲学百科事典』. 12. ルドルフ・カルナップ (1988) [1947]. 『意味と必然性:意味論と様相論理の研究』(第2版). シカゴ大学. ISBN 978-0226093475. ミッドウェイ社による再版へのGoogleリンク. 13. スティーブン・ヤーブロ (1998). 「存在論は誤りに基づいているのか?」 (PDF). アリストテレス学会補遺巻. 72 (1): 229–262. doi:10.1111/1467-8349.00044. カルナップの内在的/外在的区別に対する通常の批判は、「分析的/総合的との関連による罪」である。しかしこの関連から解放することは可能だ 14. ウィラード・V・O・クワイン (1951). 「近年の哲学における主要な傾向:経験主義の二つの教条」. フィロソフィカル・レビュー. 60 (1): 20–43. doi:10.2307/2181906. JSTOR 2181906. 再版:W.V.O. Quine, 『論理的観点から』(ハーバード大学出版局, 1953; 改訂第2版 1961)オンライン版:http://www.calculemus.org および Woodbridge Archived February 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. 15. ウィラード・V・O・クワイン (1980). 「第2章:W.V. クワイン:経験論の二つの教条」. ハロルド・モリック編『経験論への挑戦』. ハケット出版. p. 60. ISBN 978-0915144907. 先行出版:『論理的観点から』ハーバード大学出版局 (1953) 16. ポール・アルティン・ボゴシアン (1996年8月). 「分析性の再考」. Noûs. 30 (3): 360–391. doi:10.2307/2216275. JSTOR 2216275. 17. H. P. グライス & P. F. ストローソン (1956年4月). 「教条の擁護」. 『哲学評論』. 65 (2): 41–158. doi:10.2307/2182828. JSTOR 2182828. 18. サール, ジョンR. (1969). 『発話行為:言語哲学の試論』. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0521096263. 19. ヒラリー・プットナム (1983). 『現実主義と理性:哲学論文集 第3巻』. Cambridge University Press. pp. 87–97. ISBN 9780521246729. 20. ヒラリー・パトナム (1979). 『哲学論文集:第2巻、心、言語、現実』. ハーバード大学出版局. p. 36. ISBN 978-0521295512. 21. プットナム, ヒラリー, 「『二つのドグマ』再考」. ギルバート・ライル編, 『哲学の現代的側面』. ストックスフィールド: オリエル・プレス, 1976, 202–213. 22. レナード・リンスキー (1970年10月). 「分析的/総合的と意味論的理論」. Synthese. 21 (3/4): 439–448. doi:10.1007/BF00484810. JSTOR 20114738. S2CID 46959463. 転載:Donald Davidson; Gilbert Harman, eds. (1973). 「分析的/合成的および意味論的理論」。自然言語の意味論(第 2 版)。473–482 ページ。doi:10.1007/978-94-010-2557-7_16。ISBN 978-9027703040。 23. ウィラード・V・オ・クワイン (1967年2月2日). 「カッツの提案について」. 哲学ジャーナル. 64 (2): 52–54. doi:10.2307/2023770. JSTOR 2023770. 24. ジェロルド・J・カッツ (1974). 「分析的/総合的区別に関する現状」 (PDF). 『シンテーゼ』. 28 (3–4): 283–319. doi:10.1007/BF00877579. S2CID 26340509. 25. Cipriani, Enrico (2017). 「分析命題と必然命題に関するチョムスキー」. 『現象学と精神』. 12: 122–31. 26. Scott Soames (2009). 「循環論法の評価」. 『20世紀の哲学分析 第1巻:分析の夜明け』. プリンストン大学出版局. p. 360. ISBN 978-1400825790. この著作にはいくつかの初期版が存在する。 27. Palmquist, Stephen (1989). 「Immanuel Kant: A Christian Philosopher?」. Faith and Philosophy. 6: 65–75. doi:10.5840/faithphil1989619. |

| References and further reading Baehr, Jason S. (October 18, 2006). "A Priori and A Posteriori". In J. Fieser; B. Dowden (eds.). The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Boghossian, Paul. (1996). "Analyticity Reconsidered". Nous, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 360–391. Cory Juhl; Eric Loomis (2009). Analyticity. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415773331. Glock, Hans-Johann; Gluer, Kathrin; Keil, Geert (2003). Fifty Years of Quine's "Two dogmas". Rodopi. ISBN 978-9042009486. Kant, Immanuel. (1781/1998). The Critique of Pure Reason. Trans. by P. Guyer and A.W. Wood, Cambridge University Press . Rey, Georges. (2003). "The Analytic/Synthetic Distinction". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward Zalta (ed.). Soames, Scott (2009). "Chapter 14: Ontology, Analyticity and Meaning: The Quine-Carnap Dispute" (PDF). In David John Chalmers; David Manley; Ryan Wasserman (eds.). Metametaphysics: New Essays on the Foundations of Ontology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199546046.[permanent dead link] Frank X Ryan (2004). "Analytic: Analytic/Synthetic". In John Lachs; Robert B. Talisse (eds.). American Philosophy: An Encyclopedia. Psychology Press. pp. 36–39. ISBN 978-0203492796. Quine, W. V. (1951). "Two Dogmas of Empiricism". Philosophical Review, Vol.60, No.1, pp. 20–43. Reprinted in From a Logical Point of View (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1953). Robert Hanna (2012). "The return of the analytic-synthetic distinction". Paradigmi. Sloman, Aaron (1965-10-01). "'Necessary', 'a priori' and 'analytic'". Analysis. 26 (1): 12–16. doi:10.1093/analys/26.1.12. |

参考文献および追加文献(さらに読む) Baehr, Jason S. (2006年10月18日). 「ア・プリオリにおよびア・ポステリオリな」. J. Fieser; B. Dowden (編). インターネット哲学百科事典. Boghossian, Paul. (1996). 「Analyticity Reconsidered」. Nous, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 360–391. Cory Juhl; Eric Loomis (2009). Analyticity. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415773331. Glock, Hans-Johann; Gluer, Kathrin; Keil, Geert (2003). クワインの「二つの教義」の 50 年。Rodopi. ISBN 978-9042009486. カント、イマヌエル(1781/1998)。『純粋理性批判』。P.ガイヤー、A.W.ウッド訳、ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 レイ、ジョルジュ(2003)。「分析的/総合的区別」。『スタンフォード哲学百科事典』、エドワード・ザルタ編。 ソームズ、スコット(2009)。「第14章:存在論、分析性、意味:クワインとカルナップの論争」(PDF)。デイヴィッド・ジョン・チャーマーズ、デ イヴィッド・マンリー、ライアン・ワッサーマン(編)。『メタ形而上学:存在論の基礎に関する新論考』。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0199546046。[永久リンク切れ] フランク・X・ライアン (2004). 「分析的:分析的/総合的」. ジョン・ラックス、ロバート・B・タリッセ (編). 『アメリカ哲学事典』. サイコロジー・プレス. pp. 36–39. ISBN 978-0203492796. クワイン, W. V. (1951). 「経験主義の二つの教条」. 『哲学評論』, 第60巻, 第1号, pp. 20–43. 『論理的観点から』 (ケンブリッジ, マサチューセッツ: ハーバード大学出版局, 1953) に再録. ロバート・ハンナ (2012). 「分析的・総合的区別の復活」. Paradigmi. スローマン, アーロン (1965-10-01). 「『必然的』、『ア・プリオリに』、『分析的』」. Analysis. 26 (1): 12–16. doi:10.1093/analys/26.1.12. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Analytic%E2%80%93synthetic_distinction |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099