もう「悪の陳腐さ」を忘れてもよい頃だ

Now the time we forgot about the "banality of evil."

もう「悪の陳腐さ」を忘れてもよい頃だ

Now the time we forgot about the "banality of evil."

ハンナ・アーレント(1963)の『エル サレムにおけるアイヒマン(Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil)』の副題、悪の陳腐さに関する報告の「悪の陳腐さ」は、近代におけ るナチのような組織犯罪がもつある種の皮肉 を見事に表現するもので、雑誌ニューヨーカーに掲載され、やがて出版物になり、さらに改訂版が出た後も常に、議論の的になってきたものである。それは、ア イヒマン裁判における、イスラエルのモサドが超法規的に拉致したアイヒマンが、ナチの士官においておこなった犯罪行為の重大さと、法廷における自己弁護の 奇妙な言い訳のちぐはぐさを「悪の陳腐さ」という表現であらわしたものである。洋の東西を問わずこの魅力的な用語の見せられ、大学の授業でも、またさまざ まな公開シンポジウムでも、また、警世家のエッセーのなかでも、ほとんど中身を理解していない愚かな者も含めてきわめて頻繁に使われる。しかし、真面目な 人ならすぐ気づくが、初学者にこの変な用語を説明するのは一苦労である。アーレントの「全体主義はなんでもありだ」という『全体主義の起源』の中の重要な テーゼと同様、主張してしまった瞬間に思考停止するバズワードなのである。

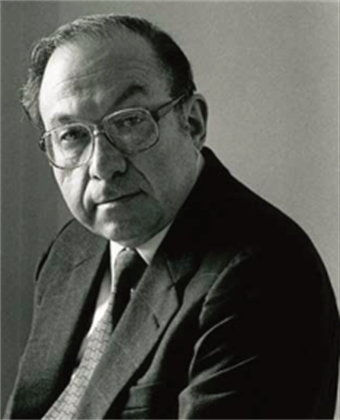

イスラエルのナショナリスト(シオニス ト)からの紋切り型の反発も含めて、この概念がどのような論争を呼んだのか、また、その舞台裏ではどのよ うな、意味のズレが生じたのか? アーレントへの偶像崇拝から距離をおくためにも「悪の陳腐さ」と「ハンナの陳腐な面」を相対化する必要がある。そのため の歴史の証人としてラウル・ヒルバーグ(Raul Hilberg, 1926-2007)をここで召喚しようと思う。その資料は彼の『記憶:ホロコーストの真実を求めて』徳留絹枝訳、柏書房、1998年、Pp.171- 185(The politics of memory: The journey of a Holocaust historian (Ivan R. Dee, Chicago, 1996).)を検証する。

| 邦訳【n】はパラグラフ番号 |

|

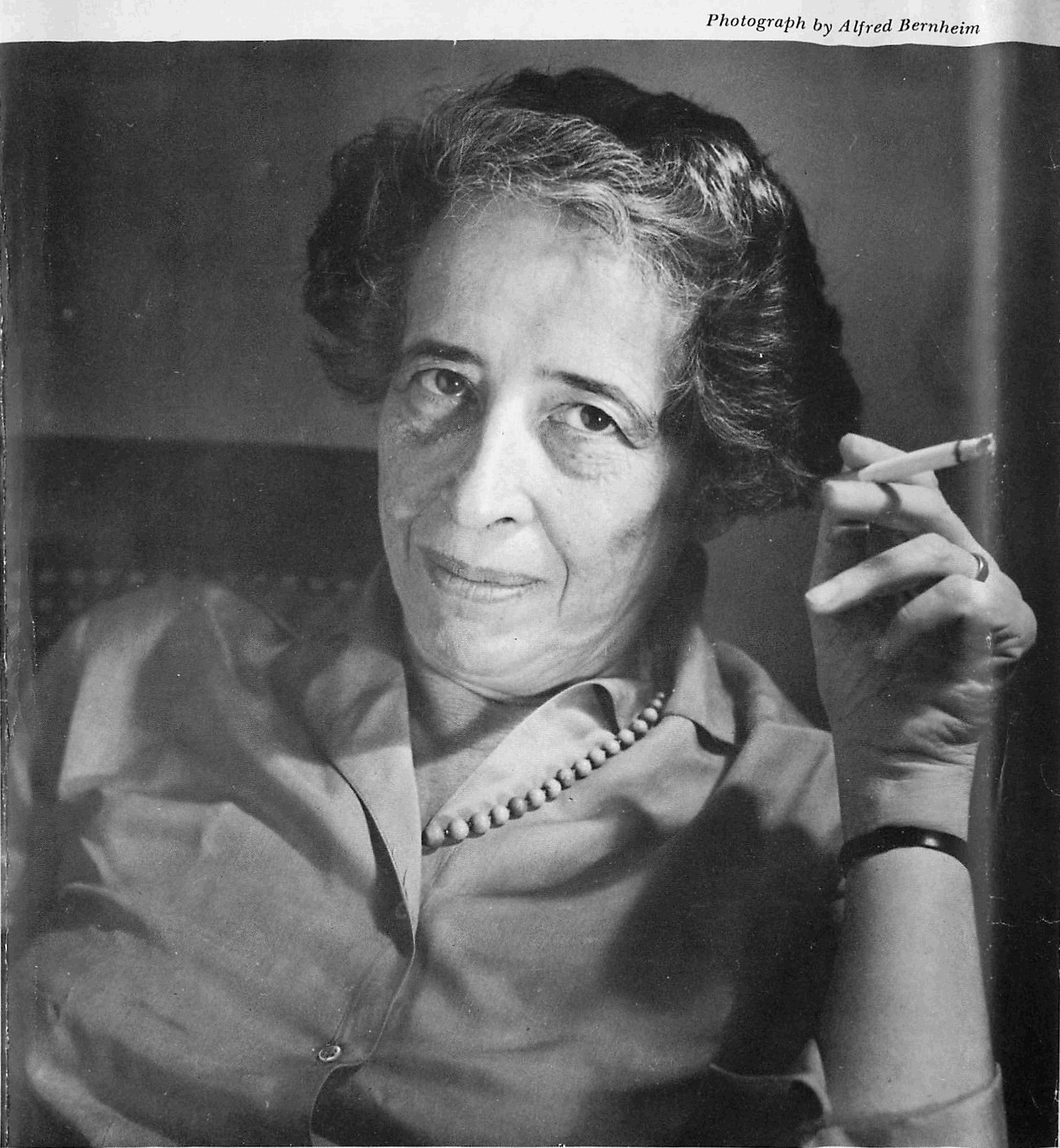

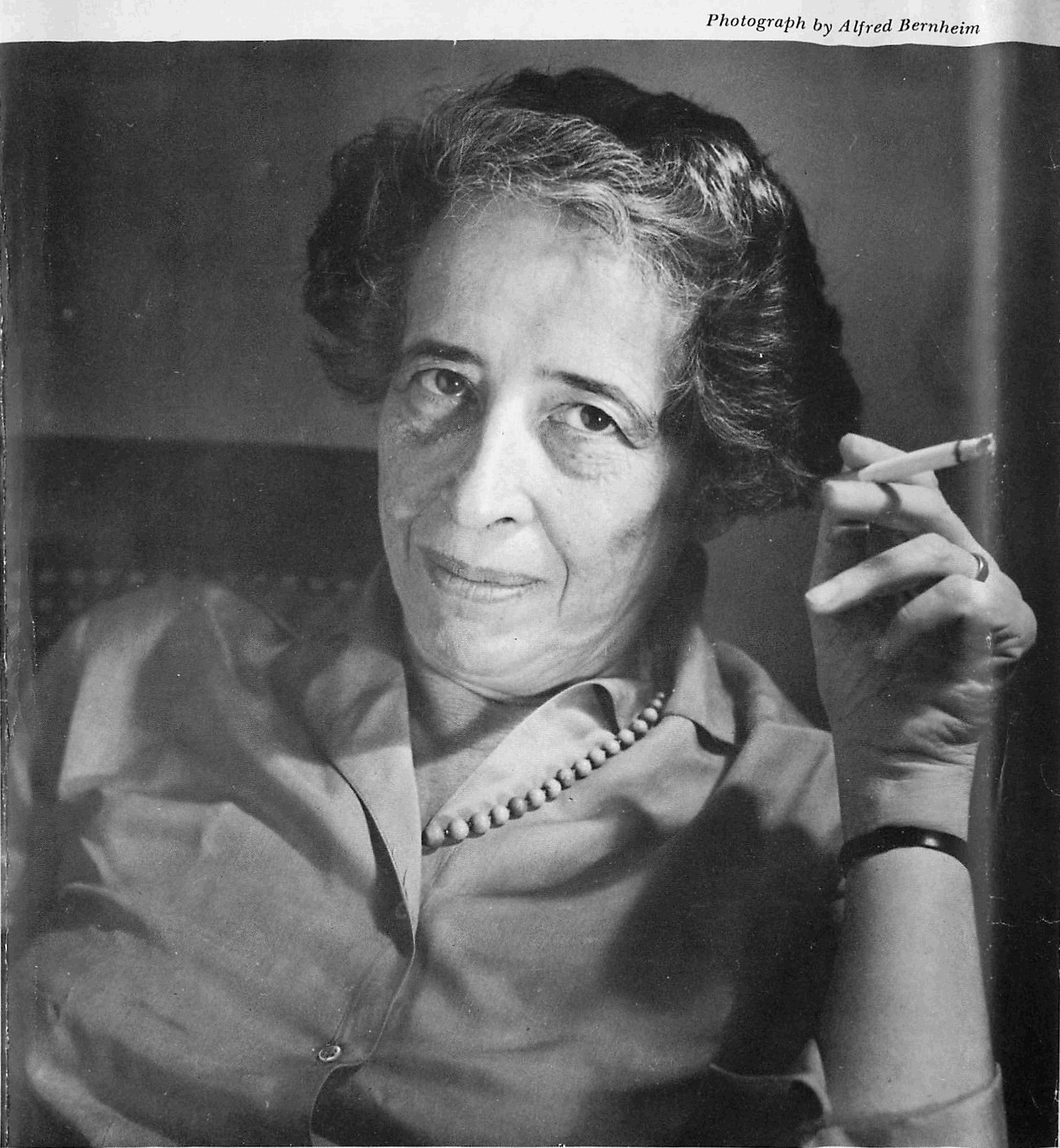

【1】ハンナ・アーレントは聖像だと、私

の著作権代理人のシーロン・レ

インズは言う。彼女

については数多くの本が書かれており、ドイツ連邦共和国では彼女の名前を冠した急行列

車が走り、彼女の顔は切手にまで描かれているという。彼女は1906年にドイツで生ま

れた。彼女の専門分野は哲学で、彼女の後見人はマルティン・ハイデガーとカール・ヤス

パースであった。1933年にはドイツから、1941年にはフランスからと、彼女は

度にわたって脱出しなければならなかった。アメリカに渡ってからは、彼女は自らを政治

理論家と称するようになった。彼女が得意とした二つのテーマは、全体主義と革命であっ

た。そのどちらも当時はもてはやされていた概念であった。特に全体主義は、アメリカが

その敗北を助けたばかりのナチス・ドイツと、自らが対峠することになったソ連との共通

項を見出すための合言葉であった。もちろん私もハンナ・アーレントの全体主義の起源に

ついての論文を読んでみた。しかし私がそこに見たものは、反ユダヤ主義、帝国主義、

そして「大衆」、プロパガンダ、「完全支配」といった全体主義に関連する一般的話題につい

ての、特に独創的とも言えないエッセイだけであった。私はその本を退けた。私は一度も

彼女に会ったことがないし、手紙のやりとりをしたこともないが、彼女が講演するのを二

度だけ聞いたことがある。これらの二度の講演で私の記憶に残っているのは、断定的でし

つこい彼女の語り口だけだ。 【1】ハンナ・アーレントは聖像だと、私

の著作権代理人のシーロン・レ

インズは言う。彼女

については数多くの本が書かれており、ドイツ連邦共和国では彼女の名前を冠した急行列

車が走り、彼女の顔は切手にまで描かれているという。彼女は1906年にドイツで生ま

れた。彼女の専門分野は哲学で、彼女の後見人はマルティン・ハイデガーとカール・ヤス

パースであった。1933年にはドイツから、1941年にはフランスからと、彼女は

度にわたって脱出しなければならなかった。アメリカに渡ってからは、彼女は自らを政治

理論家と称するようになった。彼女が得意とした二つのテーマは、全体主義と革命であっ

た。そのどちらも当時はもてはやされていた概念であった。特に全体主義は、アメリカが

その敗北を助けたばかりのナチス・ドイツと、自らが対峠することになったソ連との共通

項を見出すための合言葉であった。もちろん私もハンナ・アーレントの全体主義の起源に

ついての論文を読んでみた。しかし私がそこに見たものは、反ユダヤ主義、帝国主義、

そして「大衆」、プロパガンダ、「完全支配」といった全体主義に関連する一般的話題につい

ての、特に独創的とも言えないエッセイだけであった。私はその本を退けた。私は一度も

彼女に会ったことがないし、手紙のやりとりをしたこともないが、彼女が講演するのを二

度だけ聞いたことがある。これらの二度の講演で私の記憶に残っているのは、断定的でし

つこい彼女の語り口だけだ。【コメント】 ・ヒルバーグはアーレントと直接対話した ことすらなかった。 |

|

| 【2】1961年、ハンナ・アーレントは

『ニューヨーカー』誌のために

アイヒマン裁判を取

材した。その後に出版された彼女とヤスパースの間で取り交わされた書簡から判断すると、

彼女はエルサレムに10週間滞在した後で、アイヒマン本人の広範な証言が始まったわず

か三日後に、そこを去っている。 |

|

| 【3】『ニューヨーカー』の1963年2 月16日号に掲載された彼女の 第二報を読んだとき に、そこに私への誉め言葉を見つけた。迷路のようなドイツ機構を解きほぐすという困難 に直面した検察側について言及しながら、彼女は「もし裁判が今日聞かれていたとしたら、 その仕事はずっと容易なものであったろう。一九六一年にシカゴで出版された政治学者ラ ウル・ヒルバーグの『ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の絶滅」が、この信じがたいほど複雑な絶滅 機構を初めて解明することに成功したからだ」と書いている。もし彼女が、この裁判で検 察側に証拠資料の提供などの支援をしたヤド・ヴァシェムの専門家が一九五八年にすでに 絶滅機構に関する私の論文を読んでいたこと、にもかかわらず裁判の準備にあたって私に は何の協力依頼もなかったことを知ったら何と書くであろうと想像を巡らさずにはいられ なかった。 | |

| 【4】ハンナ・アーレントが『ニューヨー カー』に書いた五編の記事に は、事実の記述が満載 されていた。その年の終わりに、ヴァイキング・プレス社がそれを『イェルサレムのアイ ヒマン』というタイトルで単行本で出版したときに、私は脚注を探してみた。何もなかっ た。彼女は巻末の2ページを使って、主な引用は公判記録と傍聴の際に手渡された報道機 関向けの文書からである旨を説明していた。証拠のなかで提出されたオリジナルのドイツ 文書は明らかにこれらの文書のなかには含まれていないようだった。1964年には、同 じくヴァイキング・プレス社から、この本の改訂拡大版が出版された。この版の追記のな かで、ハンナ・アーレントは裁判の完全記録は公開されておらず、また閲覧するのも困難であると 書いている。彼女はさらに続けて、「内容からわかるとおり、私は、ジェラルド・ライ ト リンガーの『最終的解決』を参考にし、ラウル・ヒルバーグの『ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の 絶滅」にさらに多くを依存した」と書いた。 | |

| 【5】彼女が私の著書に頼ったことは、彼女の第二版が出る以前から数人 の書評家によってす でに指摘されていた。彼女がどれだけ私を利用したかを考えれば、それは簡単にわかるこ とだった。しかし何人かの批評家は、列挙事実の類似を通り越して、彼女の意見を私自身 のものと同一視した。長期にわたって繰り返されたこの関連づけに際して、彼らは残念に も、私たちの間に二つの著しい違いがあることを見過ごしたのだ 。 | |

| 【6】ハンナ・アーレントの『イェルサレ

ムのアイヒマン』の副題は「悪

の陳腐さについての

報告」だった。その副題は、主題より有名になるという珍しい現象を引き起こした。それ

は、アドルフ・アイヒマンに関する、そして暗示的には他の無数のアイヒマンに関する、

彼女の理論を表したものであった。しかし、それは正しいのだろうか? 彼女は、ゲシユ

タポのユダヤ人担当課の責任者だったSS 中佐アドルフ・アイヒマンのなかに、SS 内の

ヒエラルキーを登りつめる前は、退屈で「落ちぶれた」生活をしていた欠陥人間を見出し

ていた。彼女は、彼の「過大な自己評価」に触れ、彼の「自慢話」

について詳しく説明し、

絞首刑になる前の——ボトル半分のワインを飲み干し、最後の言葉を残したときの——彼

の「グロテスクな愚かさ」について語った。彼女には、この男がごく少数のスタッフを使

ヨーロッパ各地ってどれだけの罪を犯したのか、その重大さがわかっていなかったのだ。

ヨーロッパ各地のユダヤ人評議会を監視し、巧みに操り、ドイツ、オーストリア、ボへミアモラヴィア

内に残っていたユダヤ人が所有していた財産を差し押さえ、衛星国内での反ユダヤ人法を

立案し、処刑所と絶滅収容所へのユダヤ人移送を指揮したという犯罪を。彼女は、アイヒ

マンがこのような前代未聞の行動を実行するためにドイツの入り組んだ行政機構のなかに

どのように活路を見出していったのかについて解き明かすことはなかった。彼女は彼のし

たことの規模を把握していなかったのだ。この「悪」のなかには決して「陳腐さ」などは

存在していなかった。 【コメント】 ・ ヒルバーグのこの対位法的な表現だと、アーレントは、アイヒマン収監後の彼の行状や態度にナチや絶滅機構の小さな一歯車であるというふうに「陳腐さ」を発 見して、(ヒルバーグが仔細に明らかにしたように)彼が最初は、陳腐な絶滅計画を、巧みに自分がおかれた環境をフルに活用して、とうとう最後には、戦争遂 行の障害にもなるような規模の巨大な予算と人員を使い、600万人を絶滅に追いやる巨大なシステムを構築してしまったのだことを語っている。 ・この奇怪な殺戮のアンサンブルをつくりあげたアイヒマンは、そのことについて自負しており、アルゼンチンで拉致される前から反ユダヤ主義者の集会でも吹 聴している(このことは後の時代に明らかになる)。つまり、アイヒマンの悪は陳腐なものではなく、帝国の一歯車であっても、巨大な殺戮行為を本当に実現さ せた立役者なのだ。 |

|

| 【7】彼女の考えと私のそれとが別れる第 二点は、彼女が単に自らの民族 の絶滅と呼んだ過程 で、ユダヤ人指導者が果たした役割に関する問題だった。彼女はそれは以前から知られて いたと述べ、今や私の「権威ある研究」を通して「哀れでみじめなその詳細」の全貌が明 らかにされたと言った。「真実を明かすなら……」と言って、彼女は「もしユダヤ人が組 織化されていなかったなら、そして指導者が存在していなかったなら、混乱と悲惨は起こ っていただろうが、450万から600万ものユダヤ人が死ぬことはなかったであろう」 という言葉を何度も引用してみせた。 | |

| 【8】ユダヤ人評議会について書いたとき には、私はドイツの組織が彼ら からの協力にどれだ け依存していたかを強調した。評議会の協力的な政策は破滅的結果をもたらした。しかし、 私には問題はもっと深いように思えた。評議会は、ドイツにとっての道具だっただけでは なく、ユダヤ人社会における機関でもあったのだ。彼らの戦術はユダヤ人が何世紀にもわ たって実行してきた適応と順応の延長だった。私はユダヤ人指導者と一般のユダヤ人を 別々に見ることはできない。指導者たちは、ユダヤ人によって長い間受け継がれてきた危 機に対する反応の基本的姿勢を代表していたからだ。 | |

| 【9】イスラエルにおいても、ユダヤ人評 議会とゲットーの一般ユダヤ人 住民が区別されたこ とは決してない。ユダヤ人の国家が建設された最初のころは、ホロコーストの被害者は依 然として盲目的で弱い人々だとみなされていた。1957年——歴史に関する私の記述が 問題だとして、メルクマン博士が私の原稿を拒否する手紙を書いてきたわずか一年前—— の時点でさえ、『ヤド・ヴァシェム研究』は、ヤド・ヴァシェム所長ベンジオン・ディヌ ールがこの問題について容赦のない言葉で書いた記事を掲載していた。彼は、評議会は、 「基本的に、ユダヤ人がナチ政権下にあってさえ依然としてドイツに抱いていた信頼を表 現」しているものなので、切り離して考えることはできないと宣言していた。ユダヤ人は 少しの危険を犯せばごまかすことができたのに、忠実に「規則を遂行」したと言うのだ。 オランダでは、ユダヤ人は東部行きの列車に「荷物を持って駆け込んだ」し、「ワルシヤ ワやヴィルナ、ビアリストック(ビアウィストック)、リヴオフでさえ、人々は長い間、 死の旅の話を本気にしようとしなかった」と彼は書いている。 | |

| 【10】ディヌールの一連の考えは、アイ ヒマンの裁判が始まった当時の イスラエルにおいて、 全く消え去っていたわけではなかった。その思いは、特にイスラエルの若者たちによって 受け継がれていた。そのため、ユダヤ人生還者がそれぞれの体験について公判中の法廷で 証言すると、この問題に関連づけて受け取られた。裁判にかけられているのは証言者の方 だと言ってもよかった。もし彼らが自分たちの取った行動を若い世代に説明できないとし たら、それまでのイメージは肯定され、彼らはただの操り人形であったと判定されてしま っただろう。ハンナ・アーレントが驚いたことに、検察側は数人の生還者になぜ命令に従 ったのかと尋ねた。主席検事の質問はこうだつた。「パズミンスキ博士、あなたはそれが 死への列車であることを知っていたのでしょう。なぜその貨車に乗ったのですか」その証 人は偶然にも列車から飛び降りた人物だったが、この質問は人々の心のなかに深く残るこ とになりエルサレムでもニューヨークでも、名誉回復のための組織立った活動が始まっ たのだ。ユダヤ人は勇敢だった、ユダヤ人は抵抗もした、そしてそれはユダヤ人指導者も 一般市民も同じだったという主張が、メトロノームのように何度も繰り返された。ハン ナ・アーレントの記事が『ニューヨーカー』に発表されると、彼女が「ユダヤ人エスタブ リッシュメントの激怒」と呼んだ現象が、当然のように彼女の上に、そして同時に私の上 にも降りかかってきたのだった。 | |

| 【11】1963年3月になると、ドイツ からのユダヤ人移民で組織する 国際的な団体であるド イツ系ユダヤ人協議会が報道機関に声明文を発表した。ナチ時代に関する「最近の意見」 につき、と前置きし、それらの意見に影響を受けた歴史的見解は誤りであると宣言した。 そして「これは1961年に出版されたラウル・ヒルバーグの『ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人 の絶滅』、そして『ニューヨーカー』誌に掲載されたハンナ・アーレントの記事に顕著に 言えることである」と付げ加えてあったのだ。 | |

| 【12】ハンナ・アーレントと私はあまり にたびたび一緒に論じられたの で、私は彼女の代役をこなすほどだった 。1963年10月18日、ニューヨークの文芸批評家兼政治評論家の アーヴィング・ハウは「アイヒマンとユダヤ人の悲劇」と題するシンポジウムの議長を務 めた。彼はこの事件に関してその年の『パルチザン・レヴュー』に二度書き、18年後(1981) 彼の自伝のなかでも、改めて詳細に書いている。彼は『パルチザン・レヴュー』の記事の なかで、彼とシンポジウムの主催者はハンナ・アーレント本人を招待して話してもらう計 画だったと書いていた。「彼女は招待を受けず」、アーレントと同様な視点を持っていると 考えられていたブルーノ・ベツテルハイムにも断られた。「それで我々は、ハンナ・アー レントが依存したという学術書の著者ラウル・ヒルバーグに依頼した」彼は、そのシンポ ジウムが「非常に活発で熱気に満ちていた」が、「決して、繰り返して言うが、決して怒 号などはなかった」と書いた。自伝のなかでは、彼はこの会合を「熱狂的」で、「時とし て悪質」であったが、同時に「緊迫して興奮状態」だったと表現していた。 | |

| 【13】私の印象はそれとは少し違ってい た。このシンポジウムに招待さ れたときに、与えられ た講演の時聞は30分であることを文書で知らされていた。その程度の時間で話すのが難 しいことは私にもわかっていたが、それでも私は講演の範囲を狭めたくなかった。その時 点で、私はまだアイヒマンとユダヤ人について話すつもりでいたのだが、それはとても手 に負えるような組み合わせではなかったのだ。 | |

| 【14】ホテルのホールは、何百人もの人 々で埋め尽くされていた。その なかに詩人のロバート ・ローウェルがいた。私がどうしてこのような会に来ているのかと尋ねると、彼は「面 白いことが起こりそうな場所にいないわけにはいかないんでね」と答えた。そう、これは 見せものだったのだ。アーヴィング・ハウは壇上で私の持ち時聞が20分しかなくなった と告げた。私は約束通りに30分をくれるように強く主張しなかったし、そのような場で の経験が浅くて、準備してきた講演の内容をすぐに放棄することも、自の前の聴衆がどん な人々なのかを判断することも、彼らに直接話しかけることもできなかった。私はアイヒ マン裁判の公判記録を用意していたので、ヴォルヒニアという田舎の村に住んでいたある 女性の証言を読み上げた。彼女は家族と一緒に処刑場に追い立てられたときに、若い娘に どうしてこうなる前に逃げなかったのかと聞かれた。いらいらした警備員はだれから先に 殺そうかと尋ね、子どもを殺してしまった。母親は負傷したものの、墓から這い出すこと ができた。私はこれこそ命令に従った者に何が起こったかを示す場面なのだと言いたかっ たのだ。これがユダヤ人が何世紀も守り通してきた政策の行き着く果てだったのだ。それ を語る私は友好的ではなかった。私は自分の立場を譲歩しなかったし、彼らの古傷を聞い てしまったことに気がつかなかった。私の講演は途中で遮られてしまった。あるパネリス トはテーブルを握りこぶしで叩いた。その強打の音はマイクで拡大され、会場からの嵐の ような野次がそれに続いた。アーヴィング・ハウは会場の参加者からの質問とコメントを 募った。そうすると、人々は次から次に立ち上がり、ある者は私をサディストと罵り、あ る者は用意してきた紙を読み上げながら、ワルシャワ蜂起時のドイツ人戦死者数に関する 私の数字に挑戦するなど、延々とそれが続いたのだった。 | |

| 【15】後年、私は何百回となく公開講義 をした。会場からのスタンディ ング・オベーションと いう名誉にも一度ならず浴した。しかし、私はニューヨークのホテルでの不愉快なあの晩 のことを決して忘れないだろう。 | |

| 【16】アイヒマンの本の第二版への後書 きを書くころまでに、ハンナ・ アーレントはかなり辛辣 になっていた。「ユダヤ人は自らを殺したのだ」と主張したのは彼女ではなかった。 アーレントがイスラエル人のなかにあるとした「有名な」「ゲットー心理」という複合概念 は、彼女が指摘するようにブルーノ・ベッテルハイムによって支持されたもので、彼女の(が?) 言い出したわけではなかった。彼女は「この議論全体が明らかに退屈すぎると感じただれ がフロイトの理論を想起させ、それをユダヤ人全体の『死への願望』——もちろんそれ は潜在的なものだが——に結びつけるという素晴らしいアイデアを考えついたのだった」 と述べている。しかし、そんなことを考えた人物とはいったいだれなのだろう。最初にこ の文章を読んだときに、私はその謎を解くことができなかった。ユダヤ人の運命に関連さ せて、死の願望について書いたり発言したりした人物を、私は一人も思いつくことができ なかったからだ。アーレントがヤスパースとやりとりした手紙を私が読んだのは、それか ら20年以上たってからのことだった。1964年3月24日付の手紙で、ヤスパースは 私が彼女をかばう発言をしたかどうかを尋ねていた。彼女は4月24日付の返事で、次の ように書いている。 | |

| 【17】ヒルバーグが私の味方になったという話は全く聞いていません。 彼はかなり馬鹿で、 狂っています。彼は今や「ユダヤ人の死の願望」なんぞについて戯言を言っています。 彼の本は本当に素晴らしいんですが、それはそれが単なる事実報告だからです。より一般論的な序章は焦げた豚以下です。 (失礼……だれに書いているのか、一瞬忘れていま した。でもこれは取り消さずにおくことにします。) | |

| 【18】この書簡集は1985年にミュン ヘンのピーパー社から出版され た。1992年に出た アメリカの翻訳版からは「馬鹿」と「狂っている」という言葉を含んだ例の文は削除され ていた。不思議に思った私がこの削除について問い合わせてみると、その文章は法律家か らのアドバイスで削られたということだった。 | |

| 【19】1960年代のピーパー社は、名 誉殻損に関しては1985年よ りもはるかに心配して いた。『イェルサレムのアイヒマン』をドイツの読者向けに出そうとしたときに、名誉毅 損で訴えられる可能性が障害物になったのだ。脚注で引用先を明かさない限りは、ドイツ 国内で当時はまだ生きていた多くの人々に関するさまざまな描写は実証できないからだ。 クラウス・ピーパーからその点に関して詳細な質問を受けた彼女は、1963年1月22 日付の四枚の手紙のなかで何とかそれに答えようと苦労しているが、そのなかでこんな文 章も書いている。 | |

| 【20】ここでは、私が他の場所でしたように、1961年に出版された ラウル・ヒルバーグ の『ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の絶滅』に提示された内容を用いています。この本は、権威 ある優れた研究であり、ライトリンガーやポリアコフなどの先駆者による調査のすべて を時代遅れとするものです。著者は15年を費やして資料のみを調査しました。そして、 もし彼がドイツ史に関する無知をさらけ出した馬鹿げた第1章を書き加えなかったら、この本はいわゆる完壁な本と言えたでしょう。 いずれにしても、彼の著書から引用することなしに、だれもこれらの事柄について書くことはできないのです。 | |

| 【21】私はこの手紙を国会図書館の原稿

課に保管してある彼女に関する

書類のなかに発見した。

偶然にも私は、同じコレクションのなかに、それよりわずか4年前の1959年4月8日付で、

プリンストン大学出版局のゴードン・ヒューベルが彼女に宛てた手紙を発見したのだ。その手紙によって、

プリンストン大学出版局が彼女に私の原稿の評価を依頼していたことを知った。彼女への謝意を述べながら、ヒューベルは小切手を同封していた。すなわちここ

にあるのは、ヒューベルが私の原稿を拒否するのに用いた主張——現実的に見て、

ライトリンガー、ポリアコフ、アードラーによってこの分野の研究は達成されている——

の根拠なのだ。この評価は、アイヒマンがアルゼンチンで逮捕される一年前のハンナ・ア

ーレントの考えであった。 【コメント】 ・ プリンストン大学出版局のゴードン・ヒューベルの名 は、ヒルバーグが博士論文をもとにした論文を出版するために、原稿をさまざまな書店から拒否されたエピソードのひとつとして『記憶』の同邦訳書の p.132に登場する。ここにかかれてあるように、アイヒマン裁判が始まる前には、ヒルバーグの原稿を匿名で読んだアーレントは、彼の徹底的な資料追求の 姿勢をほとんど評価していなかったということである。 ・ところが、『エルサレムのアイヒマン』出版には、ヒルバーグの著作を仔細に検討して、それに負うていると記述している(【4】【5】) |

|

| 【22】私は今でも、彼女がなぜ私の書い た第1章にあのように噛み付いたのかを不思議に思つ ている。彼女は本当に、私が探そうとした歴史的前例——1933年から1941年まで の反ユダヤ行動の原因がカトリック教会法にあったこと、あるいはナチスのユダヤ人概念 の起源がマルティン・ルターの著書のなかにあったこと——に刺激を受けたのだろうか。 もちろん彼女にはナチ現象を孤立させたいという個人的な欲求があった。戦後のあらゆる 機会を見つけて彼女はドイツに帰り、昔の人脈や関係を復活させた。ハイデッガーは彼女 が学生だったころの愛人で、ヒトラーの時代にはナチ党員だったのだが、その彼とも再び 友人になり、彼を復権させている。しかし、私の考えを切り捨てることで、彼女は自尊心 を得ようとしたのだ。それでは私は結局は何者だったのだろう。彼女は思想家で、私は単 なる事実報告——彼女がその利用価値を発見した後には重要な報告になったとしても—— を書く記録者にすぎなかったというのだろうか。それが彼女の世界の理にかなった秩序だ ったのだ。 |

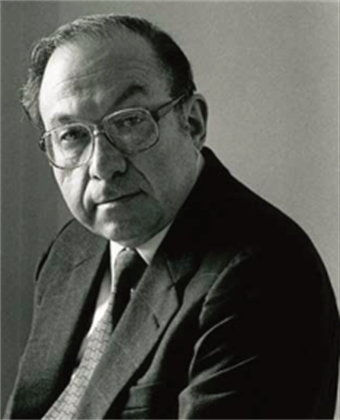

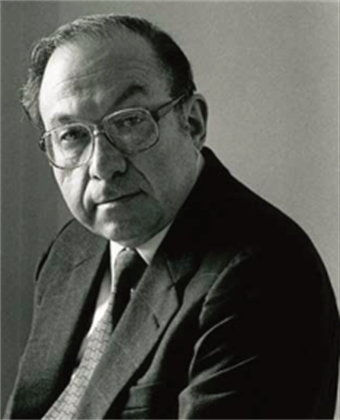

ラウル・ヒルバーグ(1926年6月2日

-

2007年8月4日)は

ユダヤ系オーストリア生まれのアメリカ人政治学者・歴史家。クリストファー・R・ブラウニングは、彼をホロコースト研究の創始者と

呼び、3巻1,273ページに及ぶ大著『ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の破壊』は、ナチスの最終解決に関する研究の精髄とみなされている。ヒルバーグはオーストリ

アのウィーンで、ポーランド語を話すユダヤ人の家庭に生まれた[3]。小物のセールスマンだった父親はガリシアの村で生まれ、10

代でウィーンに移り住み、ロシア戦線で勇敢な戦いをして勲章を受け、現在はウクライナにあるブシャシュ出身の母親と結婚した[4]。

幼いヒルバーグは一匹狼で、地理、音楽、列車探索など孤独な趣味を追求していた[5]。両親がシナゴーグに通うこともあったが、個人的には宗教の非合理性

を嫌悪し、宗教アレルギーを発症。しかし、ウィーンのシオニスト学校に通い、ナチズムの脅威の高まりに屈服するのではなく、むしろ防御する必要性を教え込

まれた。

[5]1938年3月のナチス・ドイツ平和条約締結後、ヒルバーグの家族は銃で家を追い出され、父親はナチスに逮捕された。キューバでの4ヶ月の滞在の

後、彼の家族は1939年9月1日にフロリダのマイアミに到着した[6]。続くヨーロッパでの戦争中、ヒルバーグの家族26人がホロコーストで殺害された

[7]。

ヒルバーグ一家はニューヨークのブルックリンに定住し、ラウルはエイブラハム・リンカーン高校とブルックリン・カレッジに通った。化学の道に進むつもり

だったが、自分には合わないと感じ、勉強をやめて工場で働いた。1942年の時点で、ヒルバーグは、後にナチスによる大量虐殺として知られるようになるも

のの散見される報告を読んだ後、スティーブン・サミュエル・ワイズに電話をかけ、「ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の完全な絶滅」に関して彼が何をするつもりなのか

を尋ねたほどであった[8]。ヒルバーグによると、ワイズは電話を切ったという[5]。

第二次世界大戦中、ヒルバーグはまず第45歩兵師団に従軍したが、彼の母国語の流暢さと学問的関心から、すぐに戦争文書部に所属し、ヨーロッパ中の公文書

の調査を担当することになった。ブラウネスハウスに宿舎を構えていたとき、彼はミュンヘンでヒトラーの私設図書館を偶然発見した。この発見と、自分の家族

26人が絶滅させられたという事実を知ったことが、ヒルバーグがホロコーストについて研究するきっかけとなった[9]。亡くなるしばらく前[vague]

にウィーンで行った講演の中で、彼は「ホロコーストについて私たちが知っているのはおそらく20パーセントであろう」と述べたと記録されている[10]。

ラウル・ヒルバーグ(1926年6月2日

-

2007年8月4日)は

ユダヤ系オーストリア生まれのアメリカ人政治学者・歴史家。クリストファー・R・ブラウニングは、彼をホロコースト研究の創始者と

呼び、3巻1,273ページに及ぶ大著『ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の破壊』は、ナチスの最終解決に関する研究の精髄とみなされている。ヒルバーグはオーストリ

アのウィーンで、ポーランド語を話すユダヤ人の家庭に生まれた[3]。小物のセールスマンだった父親はガリシアの村で生まれ、10

代でウィーンに移り住み、ロシア戦線で勇敢な戦いをして勲章を受け、現在はウクライナにあるブシャシュ出身の母親と結婚した[4]。

幼いヒルバーグは一匹狼で、地理、音楽、列車探索など孤独な趣味を追求していた[5]。両親がシナゴーグに通うこともあったが、個人的には宗教の非合理性

を嫌悪し、宗教アレルギーを発症。しかし、ウィーンのシオニスト学校に通い、ナチズムの脅威の高まりに屈服するのではなく、むしろ防御する必要性を教え込

まれた。

[5]1938年3月のナチス・ドイツ平和条約締結後、ヒルバーグの家族は銃で家を追い出され、父親はナチスに逮捕された。キューバでの4ヶ月の滞在の

後、彼の家族は1939年9月1日にフロリダのマイアミに到着した[6]。続くヨーロッパでの戦争中、ヒルバーグの家族26人がホロコーストで殺害された

[7]。

ヒルバーグ一家はニューヨークのブルックリンに定住し、ラウルはエイブラハム・リンカーン高校とブルックリン・カレッジに通った。化学の道に進むつもり

だったが、自分には合わないと感じ、勉強をやめて工場で働いた。1942年の時点で、ヒルバーグは、後にナチスによる大量虐殺として知られるようになるも

のの散見される報告を読んだ後、スティーブン・サミュエル・ワイズに電話をかけ、「ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の完全な絶滅」に関して彼が何をするつもりなのか

を尋ねたほどであった[8]。ヒルバーグによると、ワイズは電話を切ったという[5]。

第二次世界大戦中、ヒルバーグはまず第45歩兵師団に従軍したが、彼の母国語の流暢さと学問的関心から、すぐに戦争文書部に所属し、ヨーロッパ中の公文書

の調査を担当することになった。ブラウネスハウスに宿舎を構えていたとき、彼はミュンヘンでヒトラーの私設図書館を偶然発見した。この発見と、自分の家族

26人が絶滅させられたという事実を知ったことが、ヒルバーグがホロコーストについて研究するきっかけとなった[9]。亡くなるしばらく前[vague]

にウィーンで行った講演の中で、彼は「ホロコーストについて私たちが知っているのはおそらく20パーセントであろう」と述べたと記録されている[10]。

| Raul Hilberg (June

2, 1926 – August 4, 2007) was a Jewish Austrian-born American

political

scientist and historian. He was widely considered to be the preeminent

scholar on the Holocaust.[1] Christopher R. Browning has called him the

founding father of Holocaust Studies and his three-volume, 1,273-page

magnum opus, The Destruction of the European Jews, is regarded as

seminal for research into the Nazi Final Solution.[2] |

ラウル・ヒルバーグ(1926年6月2日 -

2007年8月4日)はユダヤ系オーストリア生まれのアメリカ人政治学者・歴史家。クリストファー・R・ブラウニングは、彼をホロコースト研究の創始者と

呼び、3巻1,273ページに及ぶ大著『ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の破壊』は、ナチスの最終解決に関する研究の精髄とみなされている[2]。 |

| Life and career Hilberg was born in Vienna, Austria, to a Polish-speaking Jewish family.[3] His father, a small-goods salesman, was born in a Galician village, moved to Vienna in his teens, was decorated for bravery on the Russian front, and married Hilberg's mother who was from Buczacz, now in Ukraine.[4] The young Hilberg was a loner, pursuing solitary hobbies such as geography, music and train spotting.[5] Though his parents attended synagogue on occasion, he personally found the irrationality of religion repellent and developed an allergy to it. He did however attend a Zionist school in Vienna, which inculcated the necessity of defending against, rather than surrendering to, the rising menace of Nazism.[5] Following the March 1938 Anschluss, his family was evicted from their home at gunpoint and his father was arrested by the Nazis; he was later released because of his service record as a combatant (Frontkämpferprivileg) during World War I. One year later on April 1, 1939, at age 13, Hilberg fled Austria with his family; after reaching France, they embarked on a ship bound for Cuba. Following a four-month stay in Cuba, his family arrived in Miami, Florida, on September 1, 1939,[6] the day the Second World War broke out in Europe. During the ensuing war in Europe, 26 members of Hilberg's family were murdered in the Holocaust.[7] The Hilbergs settled in Brooklyn, New York, where Raul attended Abraham Lincoln High School and Brooklyn College. He intended to make a career in chemistry, but he found that it did not suit him, and he left his studies to work in a factory. He served in the United States Army from 1944 to 1946.[8] As early as 1942, Hilberg, after reading scattered reports of what would later become known as the Nazi genocide, went so far as to ring Stephen Samuel Wise and ask him what he planned to do with regard to "the complete annihilation of European Jewry". According to Hilberg, Wise hung up.[5] Hilberg served first in the 45th Infantry Division during World War II, but, given his native fluency and academic interests, he was soon attached to the War Documentation Department, charged with examining archives throughout Europe. While quartered in the Braunes Haus, he stumbled upon Hitler's crated private library in Munich. This discovery, together with learning that 26 close members of his family had been exterminated, prompted Hilberg's research into the Holocaust,[9] a term which he personally disliked,[10] though in later years he himself used it. In a lecture he gave in Vienna some time[vague] before his death he went on record as saying, "We know perhaps 20 per cent about the Holocaust."[10] |

生涯とキャリア ヒルバーグはオーストリアのウィーンで、ポーランド語を話すユダヤ人の家庭に生まれた[3]。小物のセールスマンだった父親はガリシアの村で生まれ、10 代でウィーンに移り住み、ロシア戦線で勇敢な戦いをして勲章を受け、現在はウクライナにあるブシャシュ出身の母親と結婚した[4]。 幼いヒルバーグは一匹狼で、地理、音楽、列車探索など孤独な趣味を追求していた[5]。両親がシナゴーグに通うこともあったが、個人的には宗教の非合理性 を嫌悪し、宗教アレルギーを発症。しかし、ウィーンのシオニスト学校に通い、ナチズムの脅威の高まりに屈服するのではなく、むしろ防御する必要性を教え込 まれた。 [5]1938年3月のナチス・ドイツ平和条約締結後、ヒルバーグの家族は銃で家を追い出され、父親はナチスに逮捕された。キューバでの4ヶ月の滞在の 後、彼の家族は1939年9月1日にフロリダのマイアミに到着した[6]。続くヨーロッパでの戦争中、ヒルバーグの家族26人がホロコーストで殺害された [7]。 ヒルバーグ一家はニューヨークのブルックリンに定住し、ラウルはエイブラハム・リンカーン高校とブルックリン・カレッジに通った。化学の道に進むつもり だったが、自分には合わないと感じ、勉強をやめて工場で働いた。1942年の時点で、ヒルバーグは、後にナチスによる大量虐殺として知られるようになるも のの散見される報告を読んだ後、スティーブン・サミュエル・ワイズに電話をかけ、「ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の完全な絶滅」に関して彼が何をするつもりなのか を尋ねたほどであった[8]。ヒルバーグによると、ワイズは電話を切ったという[5]。 第二次世界大戦中、ヒルバーグはまず第45歩兵師団に従軍したが、彼の母国語の流暢さと学問的関心から、すぐに戦争文書部に所属し、ヨーロッパ中の公文書 の調査を担当することになった。ブラウネスハウスに宿舎を構えていたとき、彼はミュンヘンでヒトラーの私設図書館を偶然発見した。この発見と、自分の家族 26人が絶滅させられたという事実を知ったことが、ヒルバーグがホロコーストについて研究するきっかけとなった[9]。亡くなるしばらく前[vague] にウィーンで行った講演の中で、彼は「ホロコーストについて私たちが知っているのはおそらく20パーセントであろう」と述べたと記録されている[10]。 |

| Academic career After returning to civilian life, Hilberg chose to study political science, earning his Bachelor of Arts degree at Brooklyn College in 1948. He was deeply impressed by the importance of elites and bureaucracies while attending Hans Rosenberg's lectures on the Prussian civil service. In 1947,[11] at one particular point in Rosenberg's course, Hilberg was taken aback when his teacher remarked: "The most wicked atrocities perpetrated on a civilian population in modern times occurred during the Napoleonic occupation of Spain." The young Hilberg interrupted the lecture to ask why the recent murder of 6 million Jews did not figure in Rosenberg's assessment. Rosenberg replied that it was a complicated matter, but that the lectures dealt only with history down to 1930, adding, "History doesn't reach down into the present age." Hilberg was amazed by this highly educated, German-Jewish emigrant passing over the genocide of European Jews in order to expound on Napoleon and the occupation of Spain. Moreover, Hilberg recalled, it was an almost taboo topic in the Jewish community, and he pursued his research as a kind of 'protest against silence'.[12] Hilberg went on to first complete a Master of Arts degree (1950) and then a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) degree (1955) at Columbia University,[13] where he entered the graduate program in public law and government. Meanwhile, in 1951, he obtained a temporary appointment to work on the War Documentation Project under the direction of Fritz T. Epstein. Hilberg was undecided under whom he should carry out his doctoral research. Having attended a course on international law, he was also attracted to the lectures of Salo Baron, the leading authority on Jewish historiography at the time, with particular expertise in the field of laws pertaining to the Jewish people. According to Hilberg, to attend Baron's lectures was to enjoy the rare opportunity of observing "a walking library, a monument of incredible erudition", active before his classroom of students. Baron asked Hilberg whether he was interested in working under him on the annihilation of Europe's Jewish population. Hilberg demurred on the grounds that his interest lay in the perpetrators, and thus he would not begin with the Jews who were their victims, but rather with what was done to them.[14] Hilberg decided to write the greater part of his PhD under the supervision of Franz Neumann, the author of an influential wartime analysis of the German totalitarian state.[15] Neumann was initially reluctant to take Hilberg on as his doctoral student. He had already read Hilberg's master's thesis, and found, as both a deeply patriotic German and a Jew, that certain themes sketched there were unbearably painful. In particular he had asked that the section on Jewish cooperation be removed, to no avail.[a] Neumann nonetheless relented, warning his student, however, that such a dissertation was professionally imprudent and might well prove to be his academic funeral.[5] Undeterred by the prospect, Hilberg pressed on without regard for the possible consequences.[16] Neumann himself contacted Nuremberg prosecutor Telford Taylor directly, to facilitate Hilberg's access to the appropriate archives. After Neumann's death in a traffic accident in 1954, Hilberg completed his doctoral requirement under the supervision of William T. R. Fox. His dissertation won him the university's prestigious Clark F. Ansley Award in 1955,[13] which carried with it the right to have his thesis published by his alma mater.[17] He taught the first college-level course in the United States dedicated to the Holocaust, when the subject was finally introduced into his university's curriculum in 1974.[5] Hilberg obtained his first academic position at the University of Vermont in Burlington, in 1955, and took up residence there in January 1956. Most of his teaching career was spent at that university, where he was a member of the Department of Political Science. He was appointed emeritus professor upon his retirement in 1991. In 2006, the university established the Raul Hilberg Distinguished Professorship of Holocaust Studies. Each year the University of Vermont's Carolyn and Leonard Miller Center for Holocaust Studies hosts the Raul Hilberg Memorial Lecture.[18] Hilberg was appointed to the President's Commission on the Holocaust by Jimmy Carter in 1979. He later served for many years on its successor, the United States Holocaust Memorial Council, which is the governing body for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.[19] Following his death, the Museum established the Raul Hilberg Fellowship, intended to support the development of new generations of Holocaust scholars.[20] For his seminal and profound services to the historiography of the Holocaust, he was honored with Germany's Order of Merit, the highest recognition that can be paid to a non-German.[16] In 2002, he was awarded the Geschwister-Scholl-Preis for Die Quellen des Holocaust (Sources of the Holocaust). He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2005 (AAAS). |

学歴 市民生活に戻ったヒルバーグは政治学を学び、1948年にブルックリン・カレッジで学士号を取得した。プロイセンの公務員に関するハンス・ローゼンバーグ の講義を受け、エリートと官僚の重要性に深い感銘を受ける。1947年[11]、ローゼンバーグの講義のある特定の場面で、教師がこう言ったとき、ヒル バーグは驚いた: 「近代において民間人に行われた最も邪悪な残虐行為は、ナポレオンによるスペイン占領の際に起こった」。若いヒルバーグは講義を中断して、なぜ最近起こっ た600万人のユダヤ人殺害がローゼンバーグの評価に含まれていないのかと尋ねた。ローゼンバーグは、それは複雑な問題だが、講義では1930年までの歴 史しか扱っていないと答え、「歴史は現代まで及ばない」と付け加えた。ヒルバーグは、この高学歴のドイツ系ユダヤ人移民が、ナポレオンとスペイン占領につ いて説明するために、ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の大量虐殺をスルーしたことに驚いた。さらにヒルバーグは、ユダヤ人社会ではほとんどタブー視されていたテーマ であったため、一種の「沈黙に対する抗議」として研究を進めたと回想している[12]。 ヒルバーグはまずコロンビア大学で文学修士号(1950年)を取得し、次いで哲学博士号(1955年)を取得した[13]。一方、1951年には、フリッ ツ・T・エプスタインの指揮の下、戦争記録プロジェクトに一時的に従事することになった。 ヒルバーグは、誰の下で博士課程研究を行うべきか決めかねていた。国際法の講義を受講した彼は、当時のユダヤ史研究の第一人者で、特にユダヤ人に関する法 律の分野に精通していたサロ・バロンの講義にも惹かれた。ヒルバーグによれば、バロンの講義に出席することは、「歩く図書館、驚異的な博識の記念碑」が学 生たちの教室で活躍する姿を目の当たりにする貴重な機会であった。バロンはヒルバーグに、彼の下でヨーロッパのユダヤ人絶滅について研究する気はないかと 尋ねた。ヒルバーグは、自分の興味は加害者にあるのだから、犠牲者であるユダヤ人から始めるのではなく、むしろ彼らに何が行われたのかから始めるという理 由で反対した[14]。 ノイマンは当初、ヒルバーグを博士課程の学生として迎えることに消極的だった。ノイマンはすでにヒルベルクの修士論文を読んでおり、深い愛国心を持つドイ ツ人として、またユダヤ人として、そこに描かれているあるテーマが耐え難いほど辛いものであることに気づいていた。ノイマンはそれでも容認し、そのような 論文は専門家として軽率であり、彼の学問的な葬式になるかもしれないと警告した[5]。ノイマンが1954年に交通事故で亡くなった後、ヒルバーグはウィ リアム・T・R・フォックスの指導の下、博士課程を修了した。彼の論文は1955年に同大学の栄誉あるクラーク・F・アンスレー賞を受賞し[13]、母校 から論文を出版する権利を得た[17]。1974年にようやくホロコーストが大学のカリキュラムに導入されると、彼はホロコーストに特化した米国初の大学 レベルの講義を担当した[5]。 ヒルバーグは1955年にバーリントンのバーモント大学で最初の職を得、1956年1月に同大学に着任した。教師としてのキャリアの大半を同大学で過ご し、政治学部に所属した。1991年に定年退職し、名誉教授に任命された。2006年、同大学はホロコースト研究のラウル・ヒルバーグ特別教授職を設立し た。バーモント大学のキャロリン&レナード・ミラー・ホロコースト研究センターでは毎年、ラウル・ヒルバーグ記念講演会を開催している[18]。ヒルバー グは1979年、ジミー・カーターによりホロコーストに関する大統領委員会の委員に任命された。彼の死後、ホロコースト記念博物館はラウル・ヒルバーグ・ フェローシップを設立し、新世代のホロコースト研究者の育成を支援している。 [20]ホロコーストの歴史学に対する画期的かつ深遠な貢献により、非ドイツ人としては最高の栄誉であるドイツ功労勲章を受章[16]。2002年、『ホ ロコーストの源泉』(Die Quellen des Holocaust)でゲシュヴィスター・ショール賞を受賞。2005年にはアメリカ芸術科学アカデミー(AAAS)のフェローに選出された。 |

The Destruction of the European

Jews Main article:

The Destruction of the European Jews Main article:

The Destruction of the European JewsFront cover of the 2005 edition of The Destruction of the European Jews Hilberg is best known for his influential study of the Holocaust, The Destruction of the European Jews. His approach assumed that the event of the Shoah was not "unique". He said in a late interview: For me the Holocaust was a vast, single event, but I am never going to use the word unique, because I recognize that when one starts breaking it into pieces, which is my trade, one finds completely recognizable, ordinary ingredients.[21] His final doctoral supervisor, Professor Fox, worried that the original study was far too long. Hilberg therefore suggested submitting a mere quarter of the research he had written up, and his proposal was accepted. His PhD dissertation was awarded the prestigious Clark F. Ansley prize, which entitled it to be published by Columbia University Press in a print run of 850 copies.[17] However, Hilberg was firm in desiring that the whole work be published, not just the doctoral version. To obtain this, two opinions in favor of full publication were required. Yad Vashem as early as 1958, declined to participate in its projected publication, fearing that it would encounter "hostile criticism".[22] The work was duly submitted to two additional academic authorities in the field, but both judgments were negative, viewing Hilberg's work as polemical: one rejected it as anti-German, the other as anti-Jewish.[14] Struggle for publication Hilberg, unwilling to compromise, submitted the complete manuscript to several major publishing houses over the following six years, without luck. Princeton University Press turned down the manuscript, on Hannah Arendt's advice, after quickly vetting it in a mere two weeks. After successive rejections from five prominent publishers, it finally went to press in 1961 under a minor imprint, the Chicago-based publisher, Quadrangle Books. Yad Vashem also reneged on an initial agreement to publish the manuscript, since it treated as marginal the armed Jewish resistance central to the Zionist narrative.[19] By good fortune, a wealthy patron, Frank Petschek, a German-Czech Jew whose family coal business had suffered from the Nazi Aryanization program,[23] laid out $15,000, a substantial sum at the time, to cover the costs of a print run of 5,500 volumes,[14] of which some 1,300 copies were set aside for distribution to libraries.[16] Resistance to Hilberg's work, the difficulties he encountered in finding a US editor, and subsequent delays with the German edition, owed much to the Cold War atmosphere of the times, according to Norman Finkelstein. Finkelstein observed in a 2007 article for CounterPunch: It is hard now to remember that the Nazi holocaust was once a taboo subject. During the early years of the Cold War, mention of the Nazi holocaust was seen as undermining the critical U.S.–West German alliance. It was airing the dirty laundry of the barely de-Nazified West German elites and thereby playing into the hands of the Soviet Union, which didn't tire of remembering the crimes of the West German "revanchists."[24] The German rights to the book were acquired by the German publishing firm Droemer Knaur in 1963. Droemer Knaur, however, after dithering over it for two years, decided against publication, due to the work's documentation of certain episodes of cooperation by Jewish authorities with the executors of the Holocaust – material which the editors said would only play into the hands of the antisemitic right wing in Germany. Hilberg dismissed this fear as "nonsense".[14] Some two decades were to pass before it finally came out in a German edition in 1982, under the imprint of a Berlin publishing house.[25] Hilberg – a lifelong Republican voter, according to both Norman Finkelstein and Michael Neumann[26] – seemed to be somewhat bemused by the prospect of being published under such an imprint, and asked its director, Ulf Wolter, what on earth his massive treatise on the Holocaust had in common with some of the firm's staple themes, socialism and women's rights. Wolter replied succinctly: "Injustice!".[14] In a letter of July 14, 1982, Hilberg had written to Director Ulf Wolter the partner of Werner Olle in the firm Olle & Wolter, "Everything you said to me during this brief visit has impressed me very much and has given me a good feeling about our joint venture. I am glad that you are my publisher in Germany." He spoke about a "second edition" of his work, "solid enough for the next century".[citation needed] Approach and structure of book The Destruction of the European Jews provided, in Hannah Arendt's words, "the first clear description of (the) incredibly complicated machinery of destruction" set up under Nazism.[27] For Hilberg there was deep irony in the judgment since Arendt, asked to give an opinion of his manuscript in 1959, had advised against publication.[5] Her judgment influenced the rejection slip he received from Princeton University Press following its submission, thus effectively denying him the prestigious auspices of a mainstream academic publishing house. With a terse lucidity that ranged, with unsparing meticulousness, over the huge archives of Nazism, Hilberg delineated the history of the mechanisms, political, legal, administrative and organizational, whereby the Holocaust was perpetrated, as it was seen through German eyes, often by the anonymous clerks whose unquestioning dedication to their duties was central to the efficacy of the industrial project of genocide. To that end, Hilberg refrained from laying emphasis on the suffering of Jews, the victims, or their lives in the concentration camps. The Nazi program entailed the destruction of all peoples whose existence was deemed incompatible with the world-historical destiny of a pure master race – and to accomplish this project, they had to develop techniques, muster resources, make bureaucratic decisions, organize fields and camps of extermination and recruit cadres capable of executing the Final Solution. It was enough to chase down each intricate strand of communication over how to conduct the operation efficiently through the enormous archival papertrail to show how this took place. Thus his discourse probed the bureaucratic means for implementing genocide, in order to let the implicit horror of the process speak for itself.[28] In this he differed radically from those who had focused heavily on final responsibilities, as for example in the case of predecessor Gerald Reitlinger's groundbreaking history of the subject.[29] Because of this layered departmentalized structure of the bureaucracy overseeing the intricate policies of classifying, mustering and deporting victims, individual functionaries saw their roles as distinct from the actual 'perpetration' of the Holocaust. Thus,'(f)or these reasons, an administrator, clerk or uniformed guard never referred to himself as a perpetrator.'[16] Hilberg made it clear, however, that such functionaries were quite aware of their involvement in what was a process of destruction.[16] Hilberg's minute documentation thus constructed a functional analysis of the machinery of genocide, while leaving unaddressed any questions of historical antisemitism, and possible structural elements in Germany's historical-social tradition which might have conduced to the unparalleled industrialization of the European Jewish Catastrophe by that country. Yehuda Bauer, a lifelong adversary and friend of Hilberg, – he had assisted him in finally getting access to Yad Vashem's archives[19] – who often clashed polemically with the man he considered 'without fault' over what Bauer saw as the latter's failure to deal with the complex dilemmas of Jews caught up in this machinery, recalls often prodding Hilberg on his exclusive focus on the how of the Holocaust rather than the why. According to Bauer, Hilberg "did not ask the big questions for fear that the answers would be too little"[30] or, as Hilberg himself says interviewed in Lanzmann's film, "I have never begun by asking the big questions, because I was always afraid that I would come up with small answers." Hilberg's empirical, descriptive approach to the Holocaust, though it exercised a not fully acknowledged but pervasive influence on the far better-known work of Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem,[b] in turn aroused considerable controversy, not least because of its details concerning the cooperation of Jewish councils in the actual procedures of evacuation to the camps. Hilberg nonetheless responded graciously to Isaiah Trunk's pathfinding research on the Judenräte, which was critical of Hilberg's assessment of the issue.[31] Critical reception Hilberg's study was praised by scholars and the American press.[32] His findings that all of German society was involved in the "destruction process" drew attention.[32] Some scholars argued that Hilberg overlooked Nazi ideology and the nature of the regime type.[32] Hilberg's claim that Jews abetted their own persecutors sparked a debate among Jewish scholars and in Jewish press.[32] According to a 2021 study, "the reception of Hilberg’s work marks a crucial step in the formation of the Holocaust as part of historical consciousness."[32] At the time, most historians of the phenomenon subscribed to what would today be called the extreme intentionalist position, where sometime early in his career, Hitler developed a master plan for the genocide of the Jewish people and that everything that happened was the unfolding of the plan. This clashed with the lesson Hilberg had absorbed under Neumann, whose Behemoth: The Structure and Practice of National Socialism (1942/1944) described the Nazi regime as a virtually stateless political order characterised by chronic bureaucratic infighting and turf disputes. The task Hilberg set for himself was to analyse the way the overall policies of genocide were engineered within the otherwise conflicting politics of Nazi factions. It helped that the Americans classifying the huge amount of Nazi documents used, precisely, the categories his future mentor Neumann had employed in his Behemoth study.[33] Hilberg came to be considered as the foremost representative of what a later generation has called the functionalist school of Holocaust historiography, of which Christopher Browning, whose own life was changed by reading Hilberg's book,[c] is a prominent member. The debate is that Intentionalists see "the Holocaust as Hitler's determined and premeditated plan, which he implemented as the opportunity arose",[34] while functionalists see "the Final Solution as an evolution that occurred when other plans proved untenable". Intentionalists argue that the initiative for the Holocaust came from above, while functionalists contend it came from lower ranks within the bureaucracy.[35] It has often been observed that Hilberg's magnum opus begins with an intentionalist thesis but gradually shifts towards a functionalist position. At the time, this approach raised a few eyebrows but only later did it actually attract pointed academic discussion.[d] A further move towards a functionalist interpretation occurred in the revised 1985 edition, in which Hitler is portrayed as a remote figure hardly involved in the machinery of destruction. The terms functionalist and intentionalist were coined in 1981 by Timothy Mason but the debate goes back to 1969 with the publication of Martin Broszat's The Hitler State in 1969 and Karl Schleunes's The Twisted Road to Auschwitz in 1970. Since most of the early functionalist historians were West German, it was often enough for intentionalist historians, especially for those outside Germany, to note that men such as Broszat and Hans Mommsen had spent their adolescence in the Hitler Youth and then to say that their work was an apologia for National Socialism. Hilberg was Jewish and an Austrian who had fled to the United States to escape the Nazis and had no Nazi sympathies, which helps to explain the vehemence of the attacks by intentionalist historians that greeted the revised edition of The Destruction of the European Jews in 1985. Hilberg's understanding of the relationship between the leadership of Nazi Germany and the implementers of the genocide evolved from an interpretation based on orders to the RSHA originating with Adolf Hitler and proclaimed by Hermann Göring, to a thesis consistent with Christopher Browning's The Origins of the Final Solution, an account in which initiatives were undertaken by mid-level officials in response to general orders from senior ones. Such initiatives were broadened by mandates from senior officials and propagated by increasingly informal channels. The experience gained in fulfilling the initiatives fed an understanding in the bureaucracy that radical goals were attainable, progressively reducing the need for direction. As Hilberg put it: As the Nazi regime developed over the years, the whole structure of decision-making was changed. At first there were laws. Then there were decrees implementing laws. Then a law was made saying, "There shall be no laws." Then there were orders and directives that were written down, but still published in ministerial gazettes. Then there was government by announcement; orders appeared in newspapers. Then there were the quiet orders, the orders that were not published, that were within the bureaucracy, that were oral. Finally, there were no orders at all. Everybody knew what he had to do.[36] In earlier editions of Destruction, in fact, Hilberg discussed an "order" given by Hitler to have Jews killed, while more recent editions do not refer to a direct command. In a 1999 interview with D.D. Guttenplan, Hilberg commented that he "made this change in the interest of precision about the evidence ...". Notwithstanding Hilberg's focus on bureaucratic momentum as an indispensable force behind the Holocaust, he maintained that extermination of Jews was one of Hitler's aims: "The primary notion in Germany is that Hitler did it. As it happens, this is also my notion, but I'm not wedded to it" (qtd. in —Guttenplan 2002, p. 303). This contradicts the thesis advanced by Daniel Goldhagen that the ferocity of German anti-Semitism is sufficient as an explanation for the Holocaust; Hilberg noted that anti-Semitism was more virulent in Eastern Europe than in Nazi Germany itself. Hilberg criticized Goldhagen's scholarship, which he called poor ("his scholarly standard is at the level of 1946") and he was even harsher concerning the lack of primary sources or secondary literature competence at Harvard by those who oversaw the research for Goldhagen's book. Hilberg said, "This is the only reason why Goldhagen could obtain a PhD in political science at Harvard. There was nobody on the faculty who could have checked his work." This remark has been echoed by Yehuda Bauer. What is most contentious about Hilberg's work, the controversial implications of which influenced the decision by Israeli authorities to deny him access to the Yad Vashem's archives,[10] was his assessment that elements of Jewish society, such as the Judenräte (Jewish Councils), were complicit in the genocide.[e][f] and that this was partly rooted in long-standing attitudes of European Jews, rather than attempts at survival or exploitation. In his own words: I had to examine the Jewish tradition of trusting God, princes, laws and contracts ... Ultimately I had to ponder the Jewish calculation that the persecutor would not destroy what he could economically exploit. It was precisely this Jewish strategy that dictated accommodation and precluded resistance.[37] This part of his work was criticized harshly by many Jews as impious, and a defamation of the dead.[38] His master's thesis sponsor persuaded him to remove this idea from his thesis, though he was determined to restore it. Even his father, on reading his manuscript, was disconcerted.[39] The result of his approach, and the sharp criticism it aroused in certain quarters, was such, as he records in the same book, that: It has taken me some time to absorb what I should always have known, that in my whole approach to the study of the destruction of the Jews I was pitting myself against the main current of Jewish thought,[10] that in my research and writing I was pursuing not merely another direction but one which was the exact opposite of a signal that pulsated endlessly through the Jewish community ... The philistines in my field are everywhere. I am surrounded by the commonplace, platitudes, and clichés.[22] |

ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の破壊 主な記事 ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の破壊 ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の破壊』2005年版表紙 ヒルバーグは、ホロコーストに関する影響力のある研究書『ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の破壊』で最もよく知られている。彼のアプローチは、ショアの出来事が「特 殊」なものではないことを前提としていた。彼は晩年のインタビューでこう語っている: 私にとっては、ホロコーストは広大な、単一の出来事であった。しかし、私は決して独特という言葉を使うつもりはない。 博士課程の最終指導教官であるフォックス教授は、元の研究があまりにも長すぎることを心配していた。そこでヒルバーグは、自分が書き上げた研究のほんの4 分の1を提出することを提案し、その提案は受け入れられた。博士論文は栄誉あるクラーク・F・アンスレー賞を受賞し、コロンビア大学出版局から850部発 行されることになった[17]。そのためには、全著作を出版することに賛成する2つの意見が必要であった。ヤド・ヴァシェムは1958年の時点で、「敵対 的な批判」に遭遇することを恐れて、予定されていた出版に参加することを拒否した[22]。この著作は、この分野のさらに2人の学識経験者に提出された が、2人ともヒルベルクの著作を極論的なものとみなし、否定的な判断を下した。 出版への闘争 妥協を許さないヒルバーグは、その後6年間、いくつかの大手出版社に原稿を提出したが、うまくいかなかった。プリンストン大学出版局は、ハンナ・アーレン トの助言により、わずか2週間という短期間でこの原稿を審査した後、出版を断念した。著名な出版社5社から相次いで断られた後、1961年、シカゴの出版 社クアドラングル・ブックスというマイナーな版元でようやく出版された。ヤド・ヴァシェムもまた、この原稿がシオニストの物語の中心となるユダヤ人の武装 抵抗を限界的なものとして扱っていたため、出版するという最初の合意を破棄した[19]。幸運なことに、裕福な後援者であったドイツ系チェコ系ユダヤ人 で、家業の石炭業がナチスのアーリア人化計画の被害を受けたフランク・ペッチェク[23]が、当時としては相当な額であった15,000ドルを出して 5,500冊の印刷費を賄い[14]、そのうち約1,300冊は図書館に配布するために確保された[16]。 ノーマン・フィンケルシュタインによれば、ヒルバーグの仕事に対する抵抗、米国人編集者を見つける際に遭遇した困難、その後のドイツ語版の遅れは、当時の 冷戦の雰囲気に負うところが大きかったという。フィンケルシュタインは2007年の『カウンターパンチ』誌の記事でこう述べている: ナチスのホロコーストがかつてタブーだったことを思い出すのは難しい。冷戦の初期には、ナチスのホロコーストに言及することは、重要な米西ドイツ同盟を損 なうと見なされた。それは、かろうじて脱ナチス化した西ドイツのエリートたちの汚れた洗濯物を公にすることであり、それによって西ドイツの「レバンチス ト」の犯罪を飽くことなく記憶しているソ連の手に乗ることになった[24]。 この本のドイツでの権利は1963年にドイツの出版社Droemer Knaurによって取得された。しかし、Droemer Knaur社は、2年間悩んだ末に、ホロコーストの実行者とユダヤ人当局の協力に関するあるエピソードを記録しているという理由で、出版を断念した。ヒル バーグはこの恐れを「ナンセンス」だと一蹴した[14]。その後20年ほどの歳月を経て、1982年、ベルリンの出版社からドイツ語版が出版された。 [ノーマン・フィンケルシュタインとミヒャエル・ノイマン[26]の両氏によれば、終生共和党の有権者であったヒルバーグは、このような出版社から出版さ れることにいささか困惑していたようで、そのディレクターであるウルフ・ヴォルターに、ホロコーストに関する彼の大著が、この出版社の定番テーマである社 会主義や女性の権利といったいどのような共通点があるのかと尋ねた。ヴォルターは簡潔に答えた: 「1982年7月14日付の書簡で、ヒルバーグはヴェルナー・オレのパートナーであるウルフ・ウォルター取締役にこう書いている。あなたがドイツにおける 私の出版社であることをうれしく思います"。そして、"次の世紀にも十分通用する "作品の「第2版」について語った[要出典]。 本のアプローチと構成 ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の破壊』は、ハンナ・アーレントの言葉を借りれば、ナチズムの下で構築された「(信じられないほど複雑な)破壊の機械」についての最 初の明確な記述であった[27]。1959年に彼の原稿に対する意見を求められたアーレントは、出版に反対するよう助言していた[5]。 ヒルバーグは、ナチズムの膨大な史料を惜しげもなく綿密に網羅する簡潔な明晰さによって、ホロコーストが実行された政治的、法的、行政的、組織的なメカニ ズムの歴史を、ドイツ人の目を通して、しばしば、その職務に疑いもなく献身する匿名の事務員たちによって、大量殺戮という産業プロジェクトの有効性の中心 をなすものとして描き出した。そのため、ヒルバーグはユダヤ人の苦しみや犠牲者、強制収容所での生活を強調することを避けた。ナチスの計画には、純粋な支 配者民族という世界史的運命と相容れない存在とみなされたすべての民族の滅亡が含まれており、この計画を達成するためには、技術を開発し、資源を集め、官 僚的な決定を下し、絶滅の場と収容所を組織し、最終的解決を実行できる幹部を集めなければならなかった。それがどのように行われたかを示すには、膨大な記 録文書から、いかにして効率的に作戦を遂行するかをめぐる複雑なコミュニケーションの一本一本を追いかけるだけで十分であった。こうして彼の言説は、大量 虐殺を実行するための官僚的手段を探り、そのプロセスの暗黙の恐ろしさを自らに語らせるようにした[28]。 この点で、彼は、たとえば前任者ジェラルド・ライトリンガーの画期的なこの主題の歴史のように、最終的な責任に重きを置いてきた人々とは根本的に異なって いた[29]。犠牲者の分類、動員、国外追放という複雑な政策を監督する官僚機構のこのような重層的な部門別構造のために、個々の官僚は自分たちの役割を ホロコーストの実際の「実行」とは別個のものと考えていた。したがって、「(こうした理由から)管理者、事務員、制服衛兵が自分自身を加害者と呼ぶことは 決してなかった」[16]。しかし、ヒルバーグは、このような役人が、自分たちが破壊の過程に関与していることをはっきりと認識していたことを明らかにし ている。 [16] ヒルバーグの詳細な記録は、こうして大量殺戮の機械の機能的分析を構築したが、その一方で、歴史的反ユダヤ主義についての疑問や、ドイツの歴史的社会的伝 統の中にある構造的要素の可能性については、この国によるヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人大虐殺の比類なき産業化を招いたかもしれないことについては、未解決のまま であった。 ヒルバーグの生涯の敵であり友人でもあったイェフダ・バウアーは、ヤド・ヴァシェムの公文書館[19]にようやくアクセスできるようになったヒルバーグを 援助していたが、バウアーがこの機械に巻き込まれたユダヤ人の複雑なジレンマに対処できなかったとみなしたことをめぐって、彼が「落ち度がない」とみなし た人物としばしば極論的に衝突していた。バウアーによれば、ヒルバーグは「答えが小さすぎることを恐れて、大きな質問をしなかった」[30]。 ホロコーストに対するヒルバーグの実証的で記述的なアプローチは、ハンナ・アーレントの『エルサレムのアイヒマン』[b]というはるかによく知られた著作 に、十分には認められてはいないが、広く影響を及ぼした。それにもかかわらず、ヒルバーグは、この問題についてのヒルバーグの評価に批判的であったユダヤ 人収容所に関するイザヤ・トランクの道筋を探る研究に快く応じた[31]。 批評的評価 ヒルバーグの研究は学者やアメリカの新聞によって賞賛された[32]。 ドイツ社会のすべてが「破壊のプロセス」に関与していたという彼の発見は注目を集めた[32]。 [32]ユダヤ人が自分たちの迫害者を幇助したというヒルベルクの主張は、ユダヤ人学者の間やユダヤ人新聞で議論を巻き起こした[32]。 2021年の研究によれば、「ヒルベルクの著作の受容は、歴史意識の一部としてのホロコーストの形成において決定的な一歩を踏み出した」[32]。 当時、この現象に関する歴史家の多くは、今日でいうところの極端な意図主義者の立場に立っており、ヒトラーはそのキャリアの初期にユダヤ人虐殺のマスター プランを策定し、起こったことはすべてそのプランの展開であったと考えていた。これは、ヒルバーグがノイマンの下で吸収した教訓と衝突する: The Structure and Practice of National Socialism』(1942/1944)は、ナチス政権は慢性的な官僚の内紛と縄張り争いを特徴とする、事実上無国籍な政治秩序であると述べている。 ヒルバーグが自らに課した課題は、ナチス党派の対立する政治の中で、全体的な虐殺政策がどのように仕組まれたかを分析することであった。膨大なナチス文書 を分類していたアメリカ人が、後に彼の師となるノイマンが『ベヒーモス』研究で採用していた分類を正確に用いていたことが助けになった[33]。 ヒルバーグは、後の世代がホロコースト歴史学の機能主義学派と呼ぶものの代表的存在とみなされるようになり、そのクリストファー・ブラウニングは、ヒル バーグの著書を読んで自らの人生を変えた[c]著名なメンバーである。この議論では、意図主義者は「ホロコーストをヒトラーの決然とした計画的なものであ り、機会が到来したときに実行に移された」と見ており[34]、機能主義者は「最終的解決策を、他の計画が実行不可能であることが判明したときに生じた進 化」と見ているというものである。意図主義者は、ホロコーストの主導権は上層部からもたらされたと主張し、機能主義者は、官僚機構内の下層部からもたらさ れたと主張している[35]。 ヒルバーグの大著は意図主義的なテーゼから始まっているが、徐々に機能主義的な立場へとシフトしていることがしばしば観察されている。当時、このアプロー チは若干の眉をひそめたが、実際に学術的な論議を集めるようになったのは後のことである[d]。機能主義的解釈へのさらなる移行は1985年の改訂版で起 こり、そこではヒトラーは破壊の機械にはほとんど関与していない遠い存在として描かれている。機能主義者と意図主義者という用語は1981年にティモ シー・メイスンによって作られたが、この論争は1969年のマルティン・ブロザットの『ヒトラー国家』と1970年のカール・シュロイネスの『アウシュ ヴィッツへのねじれた道』の出版にまでさかのぼる。初期の機能主義的歴史家のほとんどは西ドイツ人であったため、意図主義的歴史家、とりわけドイツ国外の 歴史家にとっては、ブロザットやハンス・モムゼンのような人物が青年期をヒトラーユーゲントで過ごしたことを指摘し、彼らの著作が国家社会主義の弁明であ ると言うだけで十分であることが多かった。ヒルバーグはユダヤ人で、ナチスから逃れるためにアメリカに亡命したオーストリア人であり、ナチスへのシンパ シーを持っていなかった。このことは、1985年に『ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の破壊』の改訂版が出版された際に、意図主義的な歴史家たちから激しい攻撃を受 けたことを説明するのに役立っている。 ナチス・ドイツの指導部と大量虐殺の実行者との関係についてのヒルベルクの理解は、アドルフ・ヒトラーに端を発し、ヘルマン・ゲーリングによって宣言され たRSHAへの命令に基づく解釈から、クリストファー・ブラウニングの『最終解決の起源』(The Origins of the Final Solution)と一致するテーゼへと発展した。このような構想は、上級官僚からの命令によって拡大され、次第に非公式なルートによって広められた。イ ニシアティブを遂行する中で得られた経験は、急進的な目標は達成可能であるという官僚の理解を促し、指示の必要性を徐々に減らしていった。ヒルバーグは言 う: ナチス政権が長年にわたって発展するにつれて、意思決定の構造全体が変化した。最初は法律があった。そして法律を実施する政令ができた。そして、"法律が あってはならない "という法律ができた。その後、文書化された命令や指令ができたが、やはり官報に掲載された。その後、新聞に掲載されるようになった。そして、公表されな い命令、官僚機構内の命令、口頭による命令があった。最後に、命令はまったくなかった。誰もが自分のすべきことを知っていた。 実際、『破壊』以前の版では、ヒルバーグは、ユダヤ人を殺すようにヒトラーから与えられた「命令」について論じているが、最近の版では、直接的な命令には 言及していない。1999年のD.D.グッテンプランとのインタビューの中で、ヒルバーグは、「証拠についての正確さを期するために、このような変更を行 なった」とコメントしている。ヒルバーグは、ホロコーストの背後にある不可欠な力としての官僚的勢いに焦点をあてているにもかかわらず、ユダヤ人の絶滅が ヒトラーの目的の一つであったと主張している: 「ドイツでは、ヒトラーがやったというのが第一義的な考え方です。偶然にも、これは私の考えでもあるが、私はそれに固執しているわけではない」(qtd. in -Guttenplan 2002, p. 303)。 これは、ドイツの反ユダヤ主義の凶暴性がホロコーストの説明として十分であるというダニエル・ゴールドハーゲンの主張と矛盾する。ヒルバーグは、ゴールド ハーゲンの学識は稚拙であると批判し(「彼の学識水準は1946年レベルである」)、ゴールドハーゲンの本の調査を監督した者たちが、ハーバード大学で一 次資料や二次文献の能力を欠いていることについてはさらに辛辣であった。ヒルバーグは、「ゴールドハーゲンがハーバードで政治学の博士号を取得できた唯一 の理由はこれだ。彼の研究をチェックできる人物が教授陣の中にいなかったのです」。この発言はイェフダ・バウアーも同じことを言っている。 イスラエル当局がヤド・ヴァシェムの公文書館への立ち入りを拒否すると いう決定に影響を与えたヒルバーグの研究[10]について、最も論争の的となっているのは、ユダヤ人評議会(Judenräte)のようなユダヤ人社会の 要素が大量虐殺に加担したという彼の評価であり[e][f]それは生存や搾取の試みというよりも、ヨーロッパのユダヤ人の長年の態度に根ざしている部分が あるというものであった。。彼自身の言葉を借りれば 私は、神、君主、法律、契約を信頼するというユダヤ人の伝統を検証しなければならなかった......。最終的に私は、迫害者は経済的に搾取できるものは 破壊しないというユダヤ人の計算について考えなければならなかった。まさにこのユダヤ人の戦略こそが、融和を指示し、抵抗を排除するものであった [37]。 修士論文のスポンサーは、修士論文からこの考えを削除するよう彼を説得 したが、彼はこの考えを元に戻す決意を固めていた[38]。彼の父親でさえ、彼の原稿を読んで狼狽した[39]。 彼のアプローチの結果、ある方面から鋭い批判が巻き起こったが、彼は同書で次のように記録している: ユダヤ人滅亡の研究に対する私のアプローチ全体において、私はユダヤ人 思想の主要な流れに逆らっていること、私の研究と執筆において、私は単に別の方向性を追求しているだけでなく、ユダヤ人社会で際限なく脈打っている信号の 正反対の方向性を追求していること......。私の専門分野の俗人はどこにでもいる。私はありふれた、平凡な、決まり文句に囲まれている。 |

| Public role Hilberg was the only scholar interviewed for Claude Lanzmann's Shoah that actually made it into the film (interviews of other scholars, such as theologian Richard L. Rubenstein, remained as outtakes; they can be viewed at the U.S. Holocaust Museum). According to Guy Austin Hilberg was "a key influence on Lanzmann" in depicting the logistics of the genocide.[40] He was a strong supporter of the research of Norman Finkelstein during the latter's unsuccessful attempt to secure tenure; of Finkelstein's book The Holocaust Industry, which Hilberg endorsed "with specific regard" to his demonstration that the money claimed to be owed by Swiss banks to Holocaust survivors was greatly exaggerated;[41] and of his critique of Daniel Goldhagen's Hitler's Willing Executioners.[42] Hilberg also made a posthumous appearance in the 2009 film, American Radical: The Trials of Norman Finkelstein.[43] In regard to claims that a New anti-Semitism was emerging, Hilberg, speaking in 2007, was dismissive. Comparing incidents in recent times with the socially entrenched structural anti-Semitism of the past was like 'picking up a few pebbles from the past and throwing them at windows.'[42] Personal life Hilberg had two children, David and Deborah, by his first wife, Christine Hemenway. After his divorce, in 1980 he married Gwendolyn Montgomery. Deborah moved to Israel when she was 18, acquired dual citizenship, and became a specialist teacher of children with learning disabilities. She has written memorably of her father's approach to rearing in an article composed on the occasion of the publication of the Hebrew translation of The Destruction of the European Jews, in 2012.[44] Hilberg was not religious, and he considered himself an atheist. In his autobiographical reflections he stated, "The fact is that I have had no God."[45] In a 2001 interview that addressed the issue of Holocaust denial, he said, "I am an atheist. But there is ultimately, if you don't want to surrender to nihilism entirely, the matter of a [historical] record."[46] After his second wife's autonomous decision, 12 years into their marriage, to convert from Episcopalianism to Judaism, in 1993, Hilberg began quietly to attend services at Ohavi Zedek, a Conservative synagogue in Burlington. What he most esteemed, and identified with in his own tradition, was the ideal of the Jew as "pariah". As he put it in a 1965 essay, "Jews are iconoclasts. They will not worship idols ... The Jews are the conscience of the world. They are the father figures, stern, critical, and forbidding."[5] Though a non-smoker, Hilberg died following a recurrence of lung cancer on August 4, 2007, aged 81, in Williston, Vermont.[12] |

公的な役割 ヒルバーグは、クロード・ランツマン監督の『ショアー』のためにインタビューを受けた学者の中で、実際に映画に登場した唯一の人物である(神学者リチャー ド・L・ルーベンシュタインなど、他の学者のインタビューはNG集として残された。) ガイ・オースティン・ヒルバーグによれば、大虐殺の兵站を描く上で「ランツマンに重要な影響を与えた」人物である[40]。 ヒルバーグは、ノーマン・フィンケルシュタインが終身在職権獲得に失敗した際に、フィンケルシュタインの研究を強力に支持した。フィンケルシュタインの著 書『ホロコースト産業』(The Holocaust Industry)は、スイスの銀行がホロコースト生存者に貸したと主張する資金が大幅に誇張されていることを示すという点で、ヒルバーグが「特に」支持 した[41]。 [42] ヒルバーグは2009年の映画『American Radical: The Trials of Norman Finkelstein』にも死後出演している[43]。 新たな反ユダヤ主義が出現しつつあるという主張について、ヒルバーグは2007年に講演し、否定的な見解を示した。最近の事件と過去の社会的に根付いた構 造的な反ユダヤ主義を比較することは、『過去の小石を拾ってきて窓に投げつける』ようなものだ」[42]。 私生活 ヒルバーグは、最初の妻クリスティン・ヘメンウェイとの間にデヴィッドとデボラという2人の子供をもうけた。離婚後、1980年にグウェンドリン・モンゴ メリーと結婚。デボラは18歳でイスラエルに移り住み、二重国籍を取得し、学習障害を持つ子供たちの専門教師となった。彼女は、2012年に『ヨーロッ パ・ユダヤ人の滅亡』のヘブライ語翻訳版が出版された際に寄せた記事の中で、父親の子育てに対するアプローチについて印象深く書いている[44]。 ヒルバーグは無宗教であり、自らを無神論者だと考えていた。自伝的考察の中で、彼は「私には神がいなかったということです」と述べている[45]。ホロ コースト否定の問題を取り上げた2001年のインタビューの中で、彼は「私は無神論者です。しかし、ニヒリズムに完全に身をゆだねたくなければ、最終的に は、(歴史的)記録の問題がある」[46]。結婚12年目の1993年、2番目の妻がエピスコパリア派からユダヤ教に改宗するという自律的な決断を下した 後、ヒルバーグはバーリントンにある保守派のシナゴーグ、オハヴィ・ゼデクの礼拝に静かに出席するようになった。ヒルバーグが最も尊敬し、自身の伝統と同 一視していたのは、「亡者」としてのユダヤ人の理想であった。彼は1965年のエッセイでこう述べている。彼らは偶像を崇拝しない。ユダヤ人は世界の良心 である。彼らは父親のような存在であり、厳しく、批判的で、禁欲的である」[5]。 ヒルバーグは非喫煙者であったが、2007年8月4日、肺がんの再発によりバーモント州ウィリストンで81歳で死去した[12]。 |

| Bibliography Hilberg, Raul (1971). Documents of Destruction: Germany and Jewry, 1933–1945. Chicago: Quadrangle Books. ISBN 978-081290192-4. Hilberg, Raul (1988). The Holocaust Today. B.G. Rudolph lectures in Judaic studies. Syracuse University Press. Hilberg, Raul (1992). Perpetrators, Victims, Bystanders: The Jewish Catastrophe, 1933–1945. Aaron Asher Books. ISBN 0-06-019035-3. Hilberg, Raul (1995). "The Fate of the Jews in the Cities". In Rubenstein, Richard L.; Rubenstein, Betty Rogers; Berenbaum, Michael (eds.). What kind of God? Essays in honor of Richard L. Rubenstein. University Press of America. pp. 41–50. Hilberg, Raul (1996). The Politics of Memory: The Journey of a Holocaust Historian. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 1-56663-428-8. Hilberg, Raul (2000). "The Destruction of the European Jews: Precedents". In Bartov, Omer (ed.). Holocaust: Origins, Implementation, Aftermath. London: Routledge. pp. 21–42. ISBN 0-415-15035-3. Hilberg, Raul (2001). Sources of Holocaust Research: An Analysis. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 978-156663379-6. Hilberg, Raul (2003) [First published 1961]. The Destruction of the European Jews (3rd revised ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-030009592-0. Hilberg, Raul; Staron, Stanislav; Kermisz, Josef, eds. (1999) [First published in 1979 by Stein & Day]. The Warsaw Diary of Adam Czerniakow: Prelude to Doom (Reprint ed.). Ivan R Dee. ISBN 978-156663230-0. Hilberg, Raul (2019) with Christopher R. Browning and Peter Hays. German Railroads, Jewish Souls: The Reichsbahn, Bureaucracy, and the Final Solutions. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-78920-276-2. Hilberg, Raul (2019) edited by Walter H. Pehle and René Schlott. The Anatomy of the Holocaust: Selected Works from a Life of Scholarship. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-78920-489-6. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raul_Hilberg |

|

Jan

Tomasz Gross (born 1947) is a Polish-American sociologist and

historian. He is the Norman B. Tomlinson '16 and '48 Professor of War

and Society, emeritus, and Professor of History, emeritus, at Princeton

University.[1] Jan

Tomasz Gross (born 1947) is a Polish-American sociologist and

historian. He is the Norman B. Tomlinson '16 and '48 Professor of War

and Society, emeritus, and Professor of History, emeritus, at Princeton

University.[1]Gross is the author of several books on Polish history, particularly Polish-Jewish relations during World War II and the Holocaust, including Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland (2001); Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland after Auschwitz (2006); and (with Irena Grudzinska Gross) Golden Harvest (2012). Early life and education Gross was born in Warsaw to Hanna Szumańska, a member of the Polish resistance (Armia Krajowa) in World War II, and Zygmunt Gross, who was a Polish Socialist Party member before the war broke out. His mother was a Christian and his father Jewish. His mother lost her first husband, who was Jewish, after he was denounced by a neighbor.[2] She rescued several Jews during the Holocaust, including her future husband whom she married after the war.[3] Gross attended local schools and studied physics at the University of Warsaw.[3][4] He became one of the young dissidents known as Komandosi, and was among the university students who participated in the "March events", the Polish student and intellectual protests of 1968. Like many Polish students, he was expelled from the university, and was arrested and jailed for five months.[5] During the antisemitic campaign by the Polish communist government, Gross emigrated from Poland to the United States in 1969.[5][6][7] In 1975 he earned a PhD in sociology from Yale University for a thesis on the Polish underground state, which was published as Polish Society under German Occupation (1979).[1] Career Teaching Gross has taught at Yale, New York University, and in Paris. He became a naturalized US citizen. He has specialized in studies of Polish history and Polish-Jewish relations in Poland. He is the Norman B. Tomlinson '16 and '48 Professor of War and Society in the History Department at Princeton University. Gross has held this seat since 2003.[8] He is also Professor of History at Princeton, both positions emeritus.[1] Research Based on documentation on Polish citizens deported to Siberia, Gross and his wife Irena Grudzińska-Gross published In 1940, Mother, They Sent Us to Siberia. In the 80s Gross wrote Revolution From Abroad: Soviet Conquest of Poland’s Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia based primarily on Hoover Archive material.[9] His 2001 book about the Jedwabne massacre, Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland, addressed the role of local Poles in the massacre and resulted in controversy. He wrote that the atrocity was committed by Poles and not by the German occupiers, thus revising a major part of Polish self-understanding about their history during the war. Gross's book was the subject of vigorous debate in Poland and abroad. The political scientist Norman Finkelstein accused Gross of exploiting the Holocaust. Norman Davies described Neighbors as "deeply unfair to Poles".[10] A subsequent investigation conducted by the Polish Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) supported some of Gross's conclusions, but not his estimate of the number of people murdered. In addition, the IPN concluded there was more involvement by Nazi German security forces in the massacre.[11] Polish journalist Anna Bikont began an investigation at the same time, ultimately publishing a book, My z Jedwabnego (2004), later published in French and English as The Crime and the Silence: Confronting the Massacre of Jews in Wartime Poland (French, 2011; and English, 2015). Gross's book, Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland after Auschwitz, which deals with anti-semitism and anti-Jewish violence in post-war Poland, was published in the United States in 2006, where it was praised by reviewers. When published in Polish in Poland in 2008, it received mixed reviews and revived a nationwide debate about anti-Semitism in Poland during and after World War II.[12]"[13] Marek Edelman, one of the leaders of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, said in an interview with the daily newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza, "Postwar violence against Jews in Poland was mostly not about anti-Semitism; murdering Jews was pure banditry."[13] Gross's latest book, Golden Harvest (2011), co-written with his wife, Irena Grudzińska-Gross, is about Poles enriching themselves at the expense of Jews murdered in the Holocaust.[14] Critics in Poland have alleged that Gross dwelt too much on wartime pathologies, drawing "unfair generalizations".[15] The Chief Rabbi of Poland, Michael Schudrich, commented: "Gross writes in a way to provoke, not to educate, and Poles don't react well to it. Because of the style, too many people reject what he has to say."[14] Honors On 6 September 1996, Gross and his wife Irena Grudzińska-Gross were awarded the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland by President Aleksander Kwaśniewski,[16][17] for "outstanding achievement in scholarship". As Professor at the Department of Politics, New York University, Gross was a beneficiary of the Fulbright Program, for research on "Social and Political History of the Polish Jewry 1944-49" at the Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw, Poland (January 2001- April 2001).[18] In 1982 Jan T. Gross was awarded a fellowship in the field of sociology by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial.[19] Also in 1982, as an assistant professor of sociology at Yale University, he was among thirty-three Rockefeller Humanities Fellowship competition entrants awarded, his project entitled "Soviet Rule in Poland, 1939-1941."[20] Controversies In an essay published in 2015 in the German newspaper Die Welt, Gross wrote that during World War II, "Poles killed more Jews than Germans".[21] In 2016, Gross said that "Poles killed a maximum 30,000 Germans and between 100,000 and 200,000 Jews."[22] According to historian Jacek Leociak, "the claim that Poles killed more Jews than Germans could be really right – and this is shocking news for the traditional thinking about Polish heroism during the war."[23] Polish Foreign Ministry spokesman Marcin Wojciechowski dismissed Gross's statement as "historically untrue, harmful and insulting to Poland." On 15 October 2015, Polish prosecutors opened a libel inquiry against Gross; they acted under a paragraph of the criminal code that "provides that any person who publicly insults the Polish nation is punishable by up to three years in prison". Polish prosecutors had previously examined Gross's books Fear (2008) and Golden Harvest (2011), but closed those cases after finding no evidence of a crime.[24][22] In 2016, the Simon Wiesenthal Center said the decision to continue the investigation bore "all the hallmarks of a political witch-hunt," and a "form of alienating minorities and people who were victimized".[25] The investigation was closed in November 2019. Prosecutors stated that "there is no conclusive data on the numbers of Germans and Jews killed as a result of actions committed by Poles during the Second World War. The establishment of such numbers is still the subject of research by historians and the subject of dispute between them." One of the experts consulted was Piotr Gontarczyk, who said there is no conclusive evidence that Poles killed more Jews than Germans during the war, but such a view is impossible to show as untrue. According to Gontarczyk, such statements, while controversial, are within the limits of academic discourse.[26] On 14 January 2016, because of what he described as "an attempt to destroy Poland's good name", Polish President Andrzej Duda requested a re-evaluation of the award to Gross of the Knight's Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland.[27] The request was met with local and international protests.[28] Gross responded that "PiS [the Law and Justice party] is obsessed with stimulating a patriotic sense of duty. And given that most Poles do not know their own history very well, and think that Poles suffered as much as Jews during the war, the new regime is playing into a language of Catholic martyrology."[29] Timothy Snyder, an American historian noted for his work on European genocides, said that if the order were taken from Gross, he would renounce his own.[30] |

ヤン・トマシュ・グロス(1947年生まれ)はポーランド系アメリカ人の社会学者、歴史学者。プリンストン大学ノーマン・

B・トムリンソン教授(戦争と社会、名誉教授)、歴史学教授(名誉教授)[1]。 ヤン・トマシュ・グロス(1947年生まれ)はポーランド系アメリカ人の社会学者、歴史学者。プリンストン大学ノーマン・

B・トムリンソン教授(戦争と社会、名誉教授)、歴史学教授(名誉教授)[1]。グロスはポーランドの歴史、特に第二次世界大戦中のポーランド人とユダヤ人の関係やホロコーストに関する著書がある: Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland』(2001年)、『Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland after Auschwitz』(2006年)、(Irena Grudzinska Grossとの共著)『Golden Harvest』(2012年)など。 生い立ちと教育 グロスはワルシャワで、第二次世界大戦中のポーランド・レジスタンス(アルミア・クラジョワ)のメンバーだったハンナ・スマンスカと、開戦前のポーランド 社会党員だったジグムント・グロスの間に生まれた。母親はキリスト教徒、父親はユダヤ人だった。母親はユダヤ人であった最初の夫を隣人に糾弾された後に亡 くしている[2]。彼女はホロコースト中に数人のユダヤ人を救出し、その中には戦後に結婚した後の夫も含まれている[3]。 グロスは地元の学校に通い、ワルシャワ大学で物理学を学んだ[3][4]。コマンドシとして知られる若い反体制派の一人となり、1968年のポーランドの 学生・知識人の抗議活動である「行進イベント」に参加した大学生の一人であった。多くのポーランド人学生と同様、彼は大学から追放され、逮捕されて5ヶ月 間投獄された[5]。 1975年、ポーランドの地下国家に関する論文でイェール大学から社会学の博士号を取得し、その論文は『ドイツ占領下のポーランド社会』(1979年)と して出版された[1]。 経歴 教職 イェール大学、ニューヨーク大学、パリで教鞭をとる。米国に帰化。専門はポーランド史とポーランドとユダヤ人の関係。プリンストン大学歴史学部ノーマン・ B・トムリンソン教授(戦争と社会)。2003年より現職[8]。プリンストン大学歴史学部教授(いずれも名誉教授)[1]。 研究内容 シベリアに強制送還されたポーランド人に関する資料に基づき、グロスと妻のイレーナ・グルジンスカ=グロスは『In 1940, Mother, They Sent Us to Siberia』を出版した。80年代にグロスは『レボリューション・フロム・アブロード』を著した: Soviet Conquest of Poland's Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia』を主にフーヴァー・アーカイヴの資料に基づいて執筆した[9]。 2001年にはジェドワブネの虐殺についての著書『隣人たち』(Neighbors: Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland)は、虐殺における地元ポーランド人の役割を取り上げ、論争を巻き起こした。グロスは、この残虐行為はドイツ占領軍によるものではなくポーラ ンド人によるものだと書き、戦時中のポーランドの歴史に関する自己理解の主要部分を修正した。グロスの著書はポーランド国内外で活発な議論の対象となっ た。政治学者のノーマン・フィンケルシュタインは、グロスがホロコーストを悪用していると非難した。ノーマン・デイヴィスは、『隣人』を「ポーランド人に とって深く不公平なもの」と評した[10]。 その後、ポーランド国家追悼研究所(IPN)が行った調査では、グロスの結論の一部は支持されたが、殺害された人々の数についての彼の推定は支持されな かった。さらにIPNは、虐殺にはナチス・ドイツの治安部隊の関与がより大きいと結論づけた[11]。ポーランドのジャーナリストであるアンナ・ビコント も同時期に調査を開始し、最終的に『My z Jedwabnego』(2004年)という本を出版した: The Crime and the Silence: Confrontting the Massacre of Jews in Wartime Poland』(仏語版2011年、英語版2015年)として出版された。 グロスの著書『恐怖:アウシュヴィッツ後のポーランドにおける反ユダヤ主義』は、戦後ポーランドにおける反ユダヤ主義と反ユダヤ暴力を扱ったもので、 2006年に米国で出版され、批評家たちから賞賛を浴びた。ワルシャワ・ゲットー蜂起の指導者の一人であったマレク・エデルマンは、日刊紙『ガゼータ・ ヴィボルツァ』のインタビューで、「戦後のポーランドにおけるユダヤ人に対する暴力は、ほとんどが反ユダヤ主義に関するものではなく、ユダヤ人を殺害する ことは純粋な匪賊行為であった」と語っている[13]。 グロスの最新作『Golden Harvest』(2011年)は、妻のイレーナ・グルジンスカ=グロスとの共著であり、ホロコーストで殺害されたユダヤ人の犠牲の上に自分たち自身を豊 かにしてきたポーランド人について書いたものである[14]。ポーランドの批評家たちは、グロスは戦時中の病理にこだわりすぎ、「不公正な一般化」を引き 出していると主張している[15]: 「グロスは教育するためではなく、挑発するために書いている。その文体のせいで、彼の言うことを拒絶する人が多すぎる」[14]。 名誉 1996年9月6日、グロスと妻のイレーナ・グルジンスカ=グロスは、アレクサンデル・クワシュニエフスキ大統領から「学問における顕著な業績」に対して ポーランド共和国功労勲章を授与された[16][17]。 グロスはニューヨーク大学政治学部の教授として、フルブライト・プログラムの恩恵を受け、ポーランドのワルシャワにあるユダヤ歴史研究所で「ポーランド系 ユダヤ人の社会的・政治的歴史1944-49年」の研究を行った(2001年1月~2001年4月)[18]。 1982年、ヤン・T・グロスはジョン・サイモン・グッゲンハイム・メモリアルから社会学分野のフェローシップを授与された[19]。また1982年、 イェール大学の社会学助教授として、ロックフェラー人文科学フェローシップ・コンペティションに応募した33人のうちの1人に選ばれ、「ポーランドにおけ るソビエトの支配、1939-1941年」と題するプロジェクトを行った[20]。 論争 2015年にドイツの新聞『ディ・ヴェルト』に掲載されたエッセイで、グロスは第二次世界大戦中、「ポーランド人はドイツ人よりも多くのユダヤ人を殺し た」と書いた[21]。 2016年、グロスは「ポーランド人は最大で3万人のドイツ人と10万人から20万人のユダヤ人を殺した」と述べた。 "[22]歴史家のヤチェク・レオシアクによれば、「ポーランド人がドイツ人よりも多くのユダヤ人を殺したという主張は本当に正しい可能性があり、これは 戦時中のポーランドのヒロイズムに関する伝統的な考え方にとって衝撃的なニュースである」[23]。 ポーランド外務省のマルシン・ヴォイチェホフスキ報道官は、グロスの発言を "歴史的に真実ではなく、有害で、ポーランドを侮辱している "と断じた。 2015年10月15日、ポーランド検察はグロスに対する名誉毀損調査を開始した。彼らは「公にポーランド国家を侮辱した者は3年以下の懲役に処せられ る」と規定する刑法の一項に基づき行動した。ポーランドの検察当局は以前、グロスの著書『恐怖』(2008年)と『黄金の収穫』(2011年)を調査して いたが、犯罪の証拠が見つからなかったため、これらの事件を解決した[24][22]。 2016年、サイモン・ヴィーゼンタール・センターは、捜査継続の決定は「政治的魔女狩りのす べての特徴」を帯びており、「マイノリティや被害を受けた人々を疎外する形」であると述べた[25]。 2019年11月に捜査は終了した。検察は、「第二次世界大戦中にポーランド人が行った行為の結果として殺害されたドイツ人とユダヤ人の数に関する決定的 なデータは存在しない。そのような数の確定は、いまだに歴史家たちの研究対象であり、歴史家たちの間で論争の的となっている。" 相談を受けた専門家の一人はピョートル・ゴンタルチクで、戦時中にポーランド人がドイツ人よりも多くのユダヤ人を殺したという決定的な証拠はないが、その ような見解が真実でないことを示すことは不可能であると述べた。ゴンタルチクによれば、このような発言は物議を醸すものの、学術的な言説の範囲内である [26]。 2016年1月14日、ポーランドのアンドレイ・ドゥダ大統領は、「ポーランドの名誉を破壊しようとする試み」であるとして、グロスへのポーランド共和国 功労勲章騎士十字章の授与の再評価を要請した[27]。そして、ほとんどのポーランド人が自分たちの歴史をよく知らず、ポーランド人が戦争中にユダヤ人と 同じくらい苦しんだと思っていることを考えると、新政権はカトリックの殉教の言葉に踊らされている」[29]。ヨーロッパの大量虐殺に関する研究で知られ るアメリカの歴史家ティモシー・スナイダーは、もしグロスから勲章が取り上げられたら、自分も放棄するだろうと述べた[30]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jan_T._Gross |

リ ンク

文 献

そ

の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

★

★

Do not paste, but [Re]Think our message for all undergraduate students!!!

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099