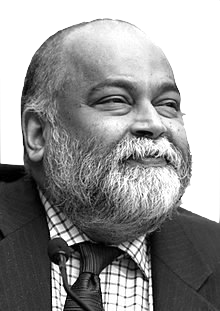

アルジュン・アパデュライ

Arjun

Appadurai (born 1949)

★アルジュン・アパデュライは、1949年生まれのインド系アメリカ人の人類学者であり、グ

ローバリゼーション研究の主要な理論家として知られている[1]。人類学の研究において、国民国家の近代化とグローバリゼーションの重要性を論じている

[1]。

元シカゴ大学人類学および南アジア言語・文明学教授、シカゴ大学人文学部長、イェール大学都心・グローバル化部長、ニューヨーク大学スタインハート文化学

部教育・人間開発学教授を務めた。

| Arjun Appadurai

(born 1949) is an Indian-American anthropologist recognized as a major

theorist in globalization studies. In his anthropological work, he

discusses the importance of the modernity of nation states and

globalization.[1] He is the former University of Chicago professor of

anthropology and South Asian Languages and Civilizations, Humanities

Dean of the University of Chicago, director of the city center and

globalization at Yale University, and the Education and Human

Development Studies professor at NYU Steinhardt School of Culture. Some of his most important works include Worship and Conflict under Colonial Rule (1981), Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy (1990), of which an expanded version is found in Modernity at Large (1996), and Fear of Small Numbers (2006). He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1997.[2] |

アルジュン・アパデュライは、1949年生まれのインド系アメリカ人の

人類学者であり、グローバリゼーション研究の主要な理論家として知られている[1]。人類学の研究において、国民国家の近代化とグローバリゼーションの重

要性を論じている[1]。

元シカゴ大学人類学および南アジア言語・文明学教授、シカゴ大学人文学部長、イェール大学都心・グローバル化部長、ニューヨーク大学スタインハート文化学

部教育・人間開発学教授を務めている。 代表的な著作に、Worship and Conflict under Colonial Rule (1981), Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy (1990), その拡大版が Modernity at Large (1996), Fear of Small Numbers (2006) などがある。1997年にアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローに選出された[2]。 |

| Early life Appadurai was born in 1949, into a Tamil family in Mumbai (Bombay), India and educated in India. He graduated from St. Xavier's High School, Fort, Mumbai, and earned his Intermediate Arts degree from Elphinstone College, Mumbai, before moving to the United States. He then received his B.A. from Brandeis University in 1970. |

生い立ち 1949年、インドのムンバイ(ボンベイ)のタミル人の家庭に生まれ、インドで教育を受ける。ムンバイのフォートにあるセント・ザビエルズ・ハイスクール を卒業後、ムンバイのエルフィンストーン・カレッジで中級芸術学位を取得し、渡米する。その後、1970年にブランダイス大学にて学士号を取得。 |

| Career He was formerly a professor at the University of Chicago where he received his M.A. (1973) and Ph.D (1976) in Anthropology. After working there, he spent a brief time at Yale. University of Pennsylvania Appadurai taught for many years at the University of Pennsylvania, in the departments of Anthropology and South Asia Studies. During his years at Penn, in 1984, he hosted a conference through the Penn Ethnohistory program; this conference led to the publication of the volume called The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (1986). Later he joined the faculty at the New School University. He currently is a faculty member of New York University's Media Culture and Communication department in the Steinhardt School. New School In 2004, after a brief time as administrator at Yale University, Appadurai became Provost of New School University. Appadurai's resignation from the Provost's office was announced 30 January 2006 by New School President Bob Kerrey. He held the John Dewey Distinguished Professorship in the Social Sciences at New School.[6] Appadurai became one of the more outspoken critics of President Kerrey when he attempted to appoint himself provost in 2008.[7] New York University In 2008 it was announced that Appadurai was appointed Goddard Professor of Media, Culture, and Communication at the NYU Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development.[8] Appadurai retired as emeritus from the department in 2021. Bard Graduate Center In 2021, Appadurai was appointed Max Weber Global Professor at the Bard Graduate Center, though he is based in Berlin and teaches remotely.[9] |

経歴 シカゴ大学教授を経て、1973年に修士号、1976年に博士号(人類学)を取得。その後、エール大学に短期間在籍した。 ペンシルベニア大学 アパデュライは、ペンシルバニア大学の人類学と南アジア研究学科で長年にわたって教鞭をとってきた。ペンシルバニア大学在学中の1984年には、ペンシル バニア民族史プログラムを通じて会議を主催し、この会議が『The Social Life of Things』という本の出版につながった。この会議がきっかけとなり、『The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective』(1986年)という本が出版されました。その後、ニュースクール大学の教員となる。現在は、ニューヨーク大学スタインハート・ スクールのメディア文化・コミュニケーション学部の教員を務めている。 ニュースクール 2004年、アパデュライはイェール大学のアドミニストレーターを経て、ニュースクール大学のプロボーストに就任した。2006年1月30日、ニュース クールのボブ・ケリー学長により、同校のプロボーストを辞任することが発表された。アパデュライはニュースクールの社会科学部門のジョン・デューイ特別教 授を務めていた[6]。2008年にケリー学長が自分を学長に任命しようとしたとき、アパデュライはより率直な批判者の一人となった[7]。 ニューヨーク大学 2008年、アパデュライはニューヨーク大学スタインハート校文化・教育・人間開発学部のメディア・文化・コミュニケーション学科のゴダード教授に就任し たことが発表された[8]。 アパデュライは2021年に同学部を名誉教授として退任した。 バード・グラジュエート・センター 2021年、アパデュライはバード大学院センターのマックス・ウェーバー・グローバル・プロフェッサーに任命されたが、ベルリンを拠点に遠隔で教鞭をとっ ている[9]。 |

| Works Some of his most important works include Worship and Conflict under Colonial Rule (1981), Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy (1990), of which an expanded version is found in Modernity at Large (1996), and Fear of Small Numbers (2006). In The Social Life of Things (1986), Appadurai argued that commodities do not only have economic value; they have political value and social lives as well.[3] He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1997.[4] His doctoral work was based on the car festival held in the Parthasarathi temple in Triplicane, Madras. Arjun Appadurai is member of the Advisory Board of the Forum d'Avignon, international meetings of culture, the economy and the media. He is also an advisory member of the journal Janus Unbound: Journal of Critical Studies.[5] |

作品紹介 代表的な著作に『植民地支配下の礼拝と紛争』(1981年)、『グローバル文化経済における分断と差異』(1990年)、その拡大版が『モダニティ・アッ ト・ラージ』(1996年)、『少人数の恐怖』(2006年)などがある。アパデュライは『モノの社会生活』(1986年)で、商品は経済的価値だけでな く、政治的価値や社会生活も持っていると主張している[3]。1997年にアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローに選出された[4]。 彼の博士論文は、マドラスのトリプリケーンにあるパルタサラティ寺院で行われる車祭りを題材にしたものであった。文化、経済、メディアに関する国際会議で あるフォーラム・ダヴィニョンの諮問委員会メンバー。また、Janus Unboundという雑誌の諮問委員も務めている[5]。Journal of Critical Studies(批評研究ジャーナル)[5]。 |

| Appadurai is a co-founder of the

academic journal Public Culture;[10] founder of the non-profit Partners

for Urban Knowledge, Action and Research (PUKAR) in Mumbai; co-founder

and co-director of Interdisciplinary Network on Globalization (ING);

and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He has

served as a consultant or advisor to a wide range of public and private

organizations, including the Ford, Rockefeller and MacArthur

foundations; UNESCO; the World Bank; and the National Science

Foundation. Appadurai has presided over Chicago globalization plan, at many public and private organizations (such as the Ford Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, UNESCO, the World Bank, etc.) consultant and long-term concern issues of globalization, modernity and ethnic conflicts. Appadurai held many scholarships and grants, and has received numerous academic honors, including the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (California) and the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, as well as individual research fellowship from the Open Society Institute (New York). He was elected Arts and Sciences in 1997, the American Academy of Sciences. In 2013, he was awarded an honorary doctorate Erasmus University in the Netherlands.[citation needed] He holds concurrent academic positions as a Mercator Fellow, Free University and Humboldt University, Berlin; Honorary Professor in the Department of Media and Communication at Erasmus University, Rotterdam; and Senior Research Partner at the Max-Planck Institute for Religious and Ethnic Diversity, Gottingen. He also served as a consultant or adviser, extensive public and private organizations, including many large foundations (Ford, MacArthur and Rockefeller); the UNESCO; UNDP; World Bank; the US National Endowment for the Humanities; National Science Foundation; and Infosys Foundation. He served on the Social Sciences jury for the Infosys Prize in 2010 and 2017. He currently serves as the Asian Art Program Advisory Committee members in the Solomon Guggenheim Museum, and the forum D 'Avignon Paris Scientific Advisory Board.[citation needed] |

学術誌『Public

Culture』の共同創刊者[10]、ムンバイの非営利団体Partners for Urban Knowledge, Action and

Research(PUKAR)の創設者、Interdisciplinary Network on

Globalization(ING)の共同創設者および共同ディレクター、アメリカ芸術科学アカデミーフェローでもある。フォード財団、ロックフェラー

財団、マッカーサー財団、ユネスコ、世界銀行、全米科学財団など、官民のさまざまな組織でコンサルタントやアドバイザーを務めている。 フォード財団、ロックフェラー財団、ユネスコ、世界銀行など多くの公的・私的機関で、シカゴ・グローバリゼーション計画を主宰し、グローバリゼーション、 近代化、民族紛争などのコンサルタントや長期的関心を寄せている。 アパデュライは多くの奨学金や助成金を得ており、行動科学高等研究センター(カリフォルニア州)やプリンストン高等研究所、オープン・ソサエティ研究所 (ニューヨーク)の個人研究員など、数多くの学術的栄誉を受けている。1997年、アメリカ科学アカデミーの芸術科学部門に選出された。2013年、オラ ンダのエラスムス大学より名誉博士号を授与された[citation needed]。ベルリン自由大学・フンボルト大学メルカトール・フェロー、ロッテルダムのエラスムス大学メディア・コミュニケーション学部名誉教授、 ゲッティンゲンのマックスプランク宗教・民族多様性研究所シニア研究パートナーを兼任している。 また、フォード、マッカーサー、ロックフェラーなどの大規模財団、ユネスコ、UNDP、世界銀行、米国人文科学基金、米国科学財団、インフォシス財団な ど、官民の幅広い組織でコンサルタントやアドバイザーを務めている。2010年と2017年にインフォシス賞の社会科学部門の審査員を務めた。現在、ソロ モン・グッゲンハイム美術館のアジア美術プログラム諮問委員会メンバー、フォーラム・ダヴィニョン パリ科学諮問委員会委員を務める[要出典]。 |

| Theory In his best known work 'Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy' Appadurai lays out his meta theory of disjuncture. For him the ‘new global cultural economy has to be seen as a complex, overlapping, disjunctive order’.[11] This order is composed of different interrelated, yet disjunctive global cultural flows,[12] specifically the following five: 1. ethnoscapes; the migration of people across cultures and borders 2. mediascapes; the variety of media that shape the way we understand our world 3. technoscapes; the scope and movement of technology (mechanical and informational) around the world 4. financescapes; the worldwide flux of money and capital 5. ideoscapes; the global flow of ideas and ideologies |

理論 アパデュライは彼の最も有名な著作である「グローバル文化経済における分断と差異」において、分断のメタ理論を提示している[11]。彼にとって「新しい グローバル文化経済は複雑で、重なり合い、分断された秩序として見なければならない」[11]。この秩序は相互に関連しながらも分断された異なるグローバ ルな文化の流れ、特に以下の5つで構成されている[12]。 1.エスノスケープ:文化や国境を越えて人々が移動すること 2. メディアスケープ:私たちが世界を理解する方法を形成する様々なメディア 3.テクノスケープ:世界中の技術(機械的および情報的)の範囲と移動。 4. ファイナンススケープ:お金と資本の世界的な流動性 5. イデオスケープ:思想とイデオロギーの世界的な流れ |

| The social imaginary Appadurai articulated a view of cultural activity known as the social imaginary, which is composed of the five dimensions of global cultural flows. He describes his articulation of the imaginary as: The image, the imagined, the imaginary – these are all terms that direct us to something critical and new in global cultural processes: the imagination as a social practice. No longer mere fantasy (opium for the masses whose real work is somewhere else), no longer simple escape (from a world defined principally by more concrete purposes and structures), no longer elite pastime (thus not relevant to the lives of ordinary people), and no longer mere contemplation (irrelevant for new forms of desire and subjectivity), the imagination has become an organized field of social practices, a form of work (in the sense of both labor and culturally organized practice), and a form of negotiation between sites of agency (individuals) and globally defined fields of possibility. This unleashing of the imagination links the play of pastiche (in some settings) to the terror and coercion of states and their competitors. The imagination is now central to all forms of agency, is itself a social fact, and is the key component of the new global order.[13] Appadurai credits Benedict Anderson with developing notions of imagined communities. Some key figures who have worked on the imaginary are Cornelius Castoriadis, Charles Taylor, Jacques Lacan (who especially worked on the symbolic, in contrast with imaginary and the real), and Dilip Gaonkar. However, Appadurai's ethnography of urban social movements in the city of Mumbai has proved to be contentious with several scholars like the Canadian anthropologist, Judith Whitehead arguing that SPARC (an organization which Appadurai espouses as an instance of progressive social activism in housing) being complicit in the World Bank's agenda for re-developing Mumbai. |

社会的想像力 アパデュライは、グローバルな文化の流れの5つの側面から構成される社会的想像力=イマジナリー(social imaginary)として知られる文化活動の見方を提唱している。 彼は、このイマジナリーについて次のように説明している。 イメージ、想像、イマジナリー、これらはすべて、グローバルな文化プロ セスにおける重要かつ新しいもの、すなわち社会的実践としての想像力へと私たちを導く言葉である。もはや単なる空想(本業が別のところにある大衆のための アヘン)でもなく、(より具体的な目的や構造によって主に定義される世界からの)単純な逃避でもなく、エリートな娯楽(したがって普通の人々の生活とは無 関係)でもなく、単なる思索(新しい形式の欲求や主観性とは無関係)でもなく、想像力は社会実践の組織的な場、仕事の形式(労働と文化的に組織された実践 という意味で)、代理の場(個人)と世界に定義される可能性の場との交渉形式になってきているのである。このように想像力を解き放つことで、パスティー シュの遊びは(ある場面では)国家とその競争相手の恐怖と強制に結びつく。想像力(イマジネーション)は今やあらゆる形態のエージェンシーの中心であり、それ自体が社会的事実であり、新しい世界秩序の重要な構成要素である[13]。 ※[13] "Disjuncture and Difference", Modernity at Large, 31 アパデュライはベネディクト・アンダーソンが想像の共同体という概念を発展させたと評価している。また、コーネリアス・カストリアディス、チャールズ・テ イラー、ジャック・ラカン、ディリップ・ガオンカーなど、虚数について研究してきた重要な人物もいる。しかし、アパデュライによるムンバイの都市社会運動 のエスノグラフィーは、カナダの人類学者ジュディス・ホワイトヘッドのように、SPARC(アパデュライが住宅における進歩的社会活動の事例として支持す る組織)が世界銀行のムンバイ再開発の課題に加担していると主張する学者たちによって、議論を呼んできた。 |

|

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arjun_Appadurai |

|

| A

commodity pathway diversion

is the ability of an object to move in and out of the "commodity state"

over the course of its use life. Diversions can occur when an object is

removed from its commodity pathway for its protection and preservation,

or when a previously removed object is commoditized through reentry

into the commodity pathway after having gained value through its

absence. Diversion is an integrated part of the commodity pathway. |

商

品経路の転換とは、物体がその使用期間中に「商品状態」を出たり入ったりする能力のことである。転用は、ある物体がその保護と保存のために商品経路から取

り除かれたとき、あるいは、以前に取り除かれた物体が、その不在によって価値を得た後に商品経路に再突入することによって商品化されたときに起こることが

ある。転用は、商品経路の統合された部分である。 |

| Commodity Flows Rather than emphasize how particular kinds of objects are either gifts or commodities to be traded in restricted spheres of exchange, Arjun Appadurai and others began to look at how objects flowed between these spheres of exchange. They refocussed attention away from the character of the human relationships formed through exchange, and placed it on "the social life of things" instead.[1] They examined the strategies by which an object could be "singularized" (made unique, special, one-of-a-kind) and so withdrawn from the market. A marriage ceremony that transforms a purchased ring into an irreplaceable family heirloom is one example; the heirloom, in turn, makes a perfect gift. Singularization is the reverse of the seemingly irresistible process of commodification. They thus show how all economies are a constant flow of material objects that enter and leave specific exchange spheres. A similar approach is taken by Nicholas Thomas, who examines the same range of cultures and the anthropologists who write on them, and redirects attention to the "entangled objects" and their roles as both gifts and commodities.[2] This emphasis on things has led to new explorations in "consumption studies." Appadurai, drawing on the work of Igor Kopytoff suggests that "commodities, like persons, have social lives"[3] and, to appropriately understand the human-ascribed value of a commodity, one must analyze "things-in-motion" (commodity pathways)—the entire life cycle of an object, including its form, use, and trajectory as a commodity. The reason for this kind of analysis, Appadurai suggests, is that a commodity is not a thing, rather it is one phase in the full life of the thing.[4] According to anthropologist Arjun Appadurai, "the flow of commodities in any given situation is a shifting compromise between socially regulated paths and competitively inspired diversions."[5] At the heart of Appadurai's argument is the idea that commodities are "things in a certain situation."[6] This idea requires that an object be analyzed from production, through exchange/distribution, to consumption to identify in which phase of its life an object is considered a commodity. Appadurai defines a commodity situation as "the situation in which [an object's] exchangeability for some other thing is a socially relevant feature."[7] |

コモディティの流れ アルジュン・アパデュライらは、特定の種類のモノがいかに限定された交 換圏で取引される贈与品か商品であるかを強調するのではなく、モノがいかに交換圏の間を流れていくかに注目するようになった[1]。彼らは 交換を通じて形成される人間関係の特徴から注意をそらし、代わりに「モノの社会生活」に焦点を当てた[1]。彼らはモノが「特異化」(ユニーク、特別、オ ンリーワン)され、市場から撤退するための戦略について検討した。購入した指輪をか けがえのない家宝に変える結婚の儀式はその一例であり、家宝は今度は完璧な贈り物になる。特異化とは、商品化という一見抗しがたいプロセスの逆である。 このように、彼らは、すべての経済が、特定の交換圏に出入りする物質的なものの絶え間ない流れであることを示す。ニコラス・トマスも同様のアプローチを とっており、同じ範囲の文化とそれについて執筆する人類学者を調査し、「もつれた物」と贈り物と商品の両方の役割に注意を向けている[2]。このように物 を強調することによって、「消費研究」における新しい探求が行われている。 アパデュライは、イゴール・コピトフの仕事を引きながら、「商品は、人と同じよう に、社会生活を持っている」[3] とし、商品の人間的価値を適切に理解するためには、「動いているもの」(商品経路)、すなわち商品の形態、使用、商品としての軌跡など物のライフサイクル 全体を分析しなければならないと提案している。このような分析を行う理由は、アパデュライが示唆するように、商品はモノではなく、むしろモノの全生涯にお ける一つの局面だからである[4]。 人類学者アルジュン・アパデュライによれ ば、「あらゆる状況における商品の流れは、社会的に規制された経路と競争的に刺激された転換の間で変化する妥協点」である[5]。 アパデュライの議論の中心は、商品とは「ある状況にあるもの」であるという考えである[6]。この考えは、ある対象がその生活のどの段階において商品とみなされるかを特定するために、生産、交換/流 通、消費を経て、対象を分析することを要求するものである。アパデュライは商品状況を「(ある物の)他の物との交換可能性が社会的に関連し た特徴である状況」と定義している[7]。 |

| Theoretical origins In his introduction to The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, Appadurai references the work of Nancy Munn and Igor Kopytoff as influential to the discussion of commodity pathways and diversions. Both scholars advocate analyzing the entire trajectory or "social life" of a commodity to understand its full value. In her article The Spatiotemporal Transformations of Gawa Canoes, anthropologist Nancy Munn, argues that "to understand what is being created when Gawans make a canoe, we have to consider the total canoe fabrication cycle which begins…with the conversion of raw materials into a canoe, and continues in exchange with the conversion of the canoe into other objects."[8] Here she helps lay the foundation of commodity pathway analysis. Similarly influential is Munn's study of the Australian Gawan Kula, in which she describes "strong paths."[9] These are sequences of exchange relationships forged by Gawa men in order to circulate objects, namely shells. Because shells are imbued with value through the process of circulation, the forging of object pathways is necessary for Gawa men to control circulation and, in turn, shell value. According to Munn, "kula shells may arrive on path, or are obtained from partners or non-partners in off-path transactions and later put on a path or used to make new paths.",[10] suggesting that diversion is an integral part of the commodity pathway because it is a means of "making new paths."[11] In The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as a Process, Igor Kopytoff argues that, while commodities are often thought of in Marxian terms as things which are produced and then exist, in fact, "commoditization is best looked upon as a process of becoming rather than as an all-or-none state of being."[12] He conceptualizes commoditization as a process which is both cultural and cognitive: …commodities must be not only produced materially as things, but also culturally marked as being a certain kind of thing. Out of the total range of things available in a society, only some of them are considered appropriate for marking as commodities. Moreover, the same thing may be treated as a commodity at one time and not at another. And finally, the same thing may, at the same time, be seen as a commodity by one person and something else by another. Such shifts and differences in whether and when a thing is a commodity reveal a moral economy that stands behind the objective economy of visible transactions.[13] In his discussion of commoditization, he also presents the idea of singularization which occurs because "there are things that are publicly precluded from being commoditized…[and are] sometimes extended to things that are normally commodities—in effect, commodities are singularized by being pulled out of their commodity sphere."[14] Kopytoff goes on to describe ways in which commodities can be singularized, for example, through restricted commoditization, sacralization, and terminal commoditization.[15] While singularization and commodity pathway diversion have stark similarities, and Kopytoff's singularization categories can be seen in Appadurai's description of types of commodity pathway diversions, Appadurai critiques placing singularization and commoditization in direct opposition because, as he argues, diversion (singularization) and commoditization are fluidly occupied positions in the use life of an object. |

理論的な起源 アパデュライは『モノの社会的生活』(The Social Life of Things: The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective)の序文で、アパデュライは、商品の経路と転換の議論に影響を与えたものとして、ナンシー・マンとイゴール・コピトフの仕事を挙げ ている。両者とも、商品の価値を完全に理解するために、その軌跡全体あるいは「社会生活」を分析することを提唱している。 人類学者のナンシー・マンは、論文『The Spatiotemporal Transformations of Gawa Canoes』の中で、「ガワがカヌーを作るときに何が作られているかを理解するには、原材料をカヌーに変換することから始まり、カヌーを他の物に変換し て交換するカヌー製造サイクル全体を考慮しなければならない」と論じている[8] 。同様に影響力を持つのがオーストラリアのガワン・クラの研究で、彼女は「ストロングパス」[9]と呼ばれる、ガワの男たちが貝殻というモノを流通させる ために築く交換関係の連続を描いている。貝は循環の過程で価値を持つようになるため、ガワの男たちが循環をコントロールし、貝の価値をコントロールするた めには、物の経路を作ることが必要である。ムンによれば、「クラ貝は経路上に到着することもあれば、経路外の取引でパートナーや非パートナーから入手し、 後に経路上に置かれたり、新しい経路を作るために使われたりする」[10]といい、転用は「新しい経路を作る」手段であるために商品経路の不可欠の部分で あることが示唆されている[11]。 イゴール・コピトフは、『モノの文化伝記』のなかで、「商品化とは、生産され、存在するモノとしてマルクス主義的に考えられることが多い。イゴール・コピ トフは、『過程としての商品化』において、商品はしばしばマルクス主義的に生産され、そして存在するものとして考えられているが、実際には、「商品化は、 存在することのオール・オア・ナッシングの状態としてよりもむしろなることの過程として見るのが最もよい」[12]と主張している。彼は、商品化を文化的 にも認知的にもある過程として概念化したのだ。 ...商品はモノとして物質的に生産されるだけでなく、ある種のモノであることを文 化的にマークされなければならない。社会で入手可能なあらゆるもののうち、商品として標示するのに適していると考えられるのは、そのうちの一部だけであ る。さらに、同じものが、あるときには商品として扱われ、別のときには扱われないことがある。そして最後に、同じものが、ある人には商品とみなされ、別の 人には別のものとみなされることがある。あるものが商品であるかどうか、またいつ商品であるかについてのこのようなシフトや違いは、目に見える取引という 客観的な経済の背後に立つ道徳的な経済を明らかにする[13]。 コピトフはまた、商品化の議論の中で、「公的に商品化されることが排除されているものがあり...(中略)...時には、通常商品であるものにも拡大され る。つまり、商品はその商品圏から引き出されることによって特異化する」[14]という理由で生じる特異化の考え方を提示している。 [15] 特異化と商品経路の転換には著しい類似性があり、コピトフの特異化のカテゴリーはアパデュライの商品経路の転換のタイプの記述に見ることができるが、アパ デュライは特異化と商品化を直接対立させることを批判する。なぜなら、彼が主張するように、転換(特異化)と商品化は対象の使用生活において流動的に占有 されるポジションであるからだ。 |

| Enclaved Commodities Appadurai defines enclaved commodities as "objects whose commodity potential is carefully hedged."[16] These objects are diverted from the commodity pathway to protect whatever value or symbolic power the object may transfer as a commodity. Appadurai suggests that in societies where "what is restricted and controlled is taste in an ever changing universe of commodities…diversion may sometimes involve the calculated "interested" removal of things from an enclaved zone to one where exchange is less confined and more profitable."[17] Appadurai postulates that the diversion of commodities from commodity pathways, whether for aesthetic or economic reasons, is always a sign of either creativity or crisis. For example, individuals facing economic hardships may sell family heirlooms to commoditize and profit from previously enclaved items. Similarly, warfare often commoditizes previously enclaved items as sacred relics are plundered and entered into foreign markets. |

囲い込まれた商品(Enclaved Commodities) アパデュライは囲い込まれた商品を「商品の可能性が注意深くヘッジされている物」と定義している[16]。これらの物は、その物が商品として移転しうる価 値や象徴的な力を守るために商品の経路から迂回させられている。アパデュライは「何が制限され制御されるかは、常に変化する商品の宇宙における味である」 社会では、転換は時として、封じられたゾーンから交換がより制限されずより利益をもたらすゾーンへの物の計算された「利害のある」移動を伴うかもしれない と示唆している[17]。 アパデュライは、美的または経済的理由のために商品経路からの商品の転換は、常に創造性か危機かの兆候であるとしている。例えば、経済的苦境に直面している個人は、以前は囲い込まれていたものを商品化して利益を得る ために、家宝を売却することがある。同様に、戦争によって神聖な遺物が略奪され、海外市場へ持ち込まれることで、それまで囲い込まれていたものが商品化さ れることも多い。 |

| Kingly Things "Kingly things" (term coined by Max Gluckman, 1983) are examples of institutionalized enclaved commodities that are diverted by royalty in order to "maintain sumptuary exclusivity, commercial advantage, and display of rank."[18] Examples of this may be landed and movable property, or the "exclusive rights to things" that aid in the "evolution and materialization of social institutions and political relationships."[19] According to Kopytoff, "kingly things" often make up the "symbolic inventory of a society: public lands, monuments, state art collections, the paraphernalia of political power, royal residences, chiefly insignia, ritual objects, and so on."[20] Some African chiefs, for example, have been known to claim rights over tangible animal and human body parts such as teeth, bones, skulls, pelts, and feathers, which are believed to connect humans to their ancestral origins. Anthropologist Mary Helms argues that by controlling "kingly things" chiefs control access to ancestors and origins, ultimately legitimizing whatever power this cosmological access affords them.[21 |

王的/王権的なもの 「王権的なもの」(マックス・グラックマンによる造語、1983年)とは、王族が「贅沢な独占権、商業的優位性、階級の誇示を維持する」ために流用する制 度化された囲い込み商品の例[18] この例は、土地や動産、あるいは「社会制度や政治関係の進化や具体化を助けるものへの独占権」であるかもしれない。 「コピトフによれば、「王権的なもの」はしばしば「社会の象徴的な目録:公有地、モニュメント、国有の美術品コレクション、政治権力の道具、王族の住居、 族長の記章、儀式用具など」を構成する[20]。 例えば、アフリカの族長の一部は、歯、骨、頭蓋骨、毛皮、羽など有形動物や人間の身体の一部に対して権利を主張していることが知られており、それは人間を その祖先に結び付けると考えられている。人類学者のメアリー・ヘルムスは、首長は「王のもの」を支配することによって祖先や起源へのアクセスをコントロー ルし、最終的にこの宇宙論的なアクセスが彼らに与えるいかなる権力も正当化すると論じている[21]。 |

| Sacred Things Appadurai argues that sacred things are "terminal commodities" because they are diverted from their commodity pathways after their production.[22] Diversion in this case is based on a society's understanding of an object's cosmological biography and sacred or ritual value.[23] Ritual Objects are often diverted from their commodity pathway after a long exchange and use life which constitutes its production. According to Katherine A. Spielmann, a ritual object's value accumulates through space and time. A ritual object is not produced as an immediately finished product, rather it is produced as it accumulates history and becomes physically modified and elaborated through circulation.[24] This, she explains, is evidenced by the archaeological record. In Melanesia, for example, the largest, thinnest, most obviously elaborated axes are used as ceremonial items. Similarly, in the Southwest, the most highly polished and elaborated glaze ware vessels are important ritual objects.[25] |

神聖なもの アパデュライは神聖なものが「末端商品」であると論じているが、それはそれらがその生産後に商品経路から転用されるからである[22]。この場合の転用 は、ある物の宇宙的伝記と神聖あるいは儀礼的価値に対する社会の理解に基づいている[23]。 儀礼的な対象はしばしば、その生産を構成する長い交換と使用の人生の後に、その商品経路から転用される。キャサリン・A・スピールマンによれば、儀式用具 の価値は空間と時間を通して蓄積される。儀礼対象はすぐに完成品として生産されるのではなく、歴史を積み重ね、流通を通じて物理的に修正され、精巧になる ことで生産される[24]と彼女は説明する。例えば、メラネシアでは、最も大きく、最も薄く、最も明らかに精巧な斧が儀式用具として使用されている。同様 に、南西部では、最も高度に磨かれ、精巧に作られた釉薬焼きの土器が重要な儀式用具となっている[25]。 |

| Commodity Pathway Diversion in

Art According to Appadurai, "the best examples of the diversion of commodities from their original nexus is to be found in the domain of fashion, domestic display, and collecting in the modern West."[26] In these domains, tastes, markets, and ideologies play a significant role commodity pathway diversion. The value of tourist Art—objects produced in small-scale societies for ceremonial, sumptuary, or aesthetic use which are diverted through commoditization— is predicated on the tastes and markets of larger economies.[27] Though not produced in a small-scale society, current tastes and market demands (2010) for Chinese jade artwork has caused previously enclaved objects – once belonging to royalty – with aesthetic and sumptuary value, to be commoditized by European collectors and auctioneers(4/28/2010)[1]. There is also the possibility of commoditization by diversion, "where value in the art or fashion market, is accelerated or enhanced by placing objects and things in unlikely contexts" or by framing and aestheticizing an everyday commodity as art. Artistic movements such as Bauhaus and Dada, and artists like Andy Warhol — reacting against consumerism and commoditization — have, by taking critical aim at prevailing tastes, markets, and ideologies, commoditized mundane objects by diverting them from their commodity pathways. Dada artist Marcel Duchamp's now famous work "Fountain" was meant to be understood as a rejection of art and a questioning of value (1968). By diverting a urinal from its commodity pathway and exhibiting it as art in a museum, Duchamp created an enclaved item out of a commodity, thus increasing its social value, and commoditized mundane items by affecting artistic tastes. Artist William Morris argued that "under industrial capitalism artificial needs and superficial ideas about luxury are imposed on the consumer from without and …as a result, art becomes a commodity" (1985:8-9). Bauhaus artists like Morris and Walter Gropius understood commodities in purely Marxian terms as things which are immediately produced, having inherent market value. They reacted against this perceived commoditization of art by producing what they considered decommodified art. However, as Kopytoff argued, "commodities must be not only produced materially as things, but also culturally marked as being a certain kind of thing."[28] Thus, when diverting industrial materials from their commodity pathways to produce art became culturally valuable, the objects themselves gained value (1985). Finally, pop artist Andy Warhol, created artwork couched in what Appadurai refers to as the "aesthetics of decontextualization."[29] In his famous Campbell's Soup painting, Warhol diverts advertising from its commodity pathway by reproducing it as a work of art. By placing this Campbell's soup advertisement in a museum, Warhol enhances the value of the advertisement by making the image iconic.  |

芸術における商品経路の転用 アパデュライによれば、「商品がその本来の結びつきから転用される最も良い例は、近代西洋におけるファッション、家庭内ディスプレイ、収集の領域に見られ る」[26]。これらの領域では、嗜好、市場、イデオロギーが商品経路の転用に大きな役割を演じている。 小規模な社会で生産され、儀式的、装飾的、あるいは美的な用途に使用され、商品化によって転用される観光芸術の価値は、より大きな経済の嗜好と市場を前提 にしている[27] 小規模な社会では生産されていないが、中国のヒスイ芸術品に対する現在の嗜好と市場の需要(2010)は、かつて王族のものであり美的、装飾的価値を持 つ、封じられたものをヨーロッパの収集家やオークショニアによって商品化されている(2010/4/28)[1]. また、転用による商品化の可能性もある。「美術やファッションの市場における価値は、物や事物をありもしない文脈に置くことで加速したり高められたりす る」、あるいは日常品を芸術として枠付けし美化することで、商品化される。 バウハウスやダダのような芸術運動や、アンディ・ウォーホルのような アーティストは、消費主義や商品化に反発し、一般的な嗜好や市場、イデオロギーを批判的にとらえ、ありふれたものを商品化の道筋からそらし、商品化した。 ダダのアーティスト、マルセル・デュシャンの有名な作品「噴水」は、芸術の否定と価値への疑問として理解されることを意図している(1968年)。デュ シャンは、小便器をその商品経路から迂回させ、美術館でアートとして展示することで、商品から囲い込みを行い、その社会的価値を高めるとともに、芸術的嗜 好に影響を与えることで日常品を商品化したのである。 芸術家ウィリアム・モリスは、「産業資本主義のもとでは、人工的な欲求や贅沢に関する表面的な考え方が、外部から消費者に押しつけられ、......その 結果、芸術は商品となる」(1985:8-9)と論じている。モリスやヴァルター・グロピウスのようなバウハウスの芸術家たちは、商品を純粋にマルクス主 義的に理解し、すぐに生産されるもの、固有の市場価値を持つものとしていた。彼らは、脱商品化された芸術を生み出すことで、このような芸術の商品化に対し て反 発した。しかしながら、コピトフが論じたように、「商品はモノとして物質的に生産されるだけでなく、ある種のモノであると文化的にマークされなければなら ない」[28]。したがって、工業材料をその商品経路から芸術を生み出すために転用することが文化的に価値を持つようになると、モノ自体が価値を持つよう になる(1985年)。 最後に、ポップアーティストのアンディ・ウォーホルは、アパデュライが「脱文脈化の美学」[29] と呼ぶもので表現されたアートワークを(結果的に)制作したことになる。このキャンベル・スープの広告を美術館に置くことで、ウォーホルはイメージを象徴 的にすることで、広告の価値を高めている。(→これには池田はおおいに異論がある)  |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commodity_pathway_diversion |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099