アーサー・シック

Arthur Szyk, 1894-1951

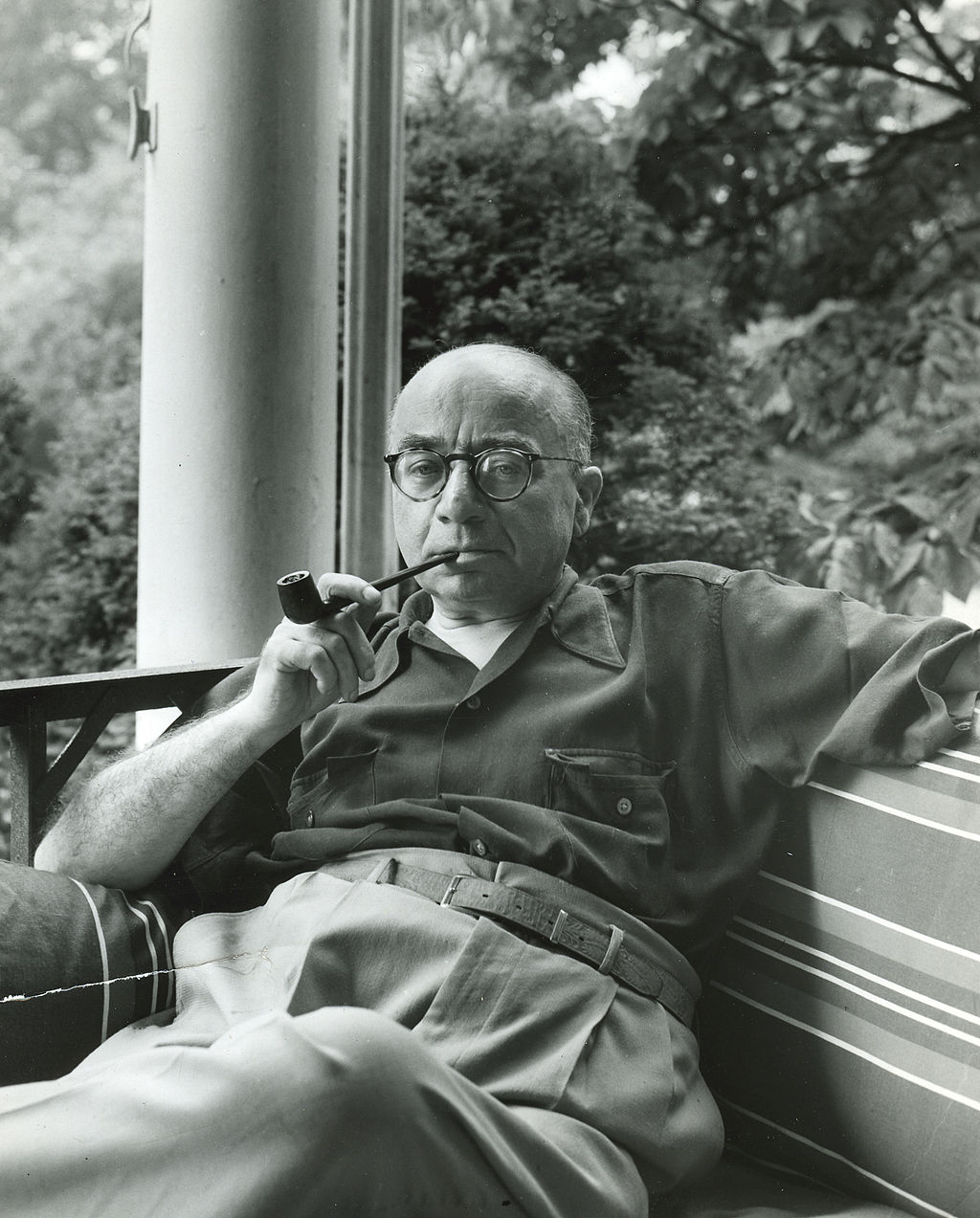

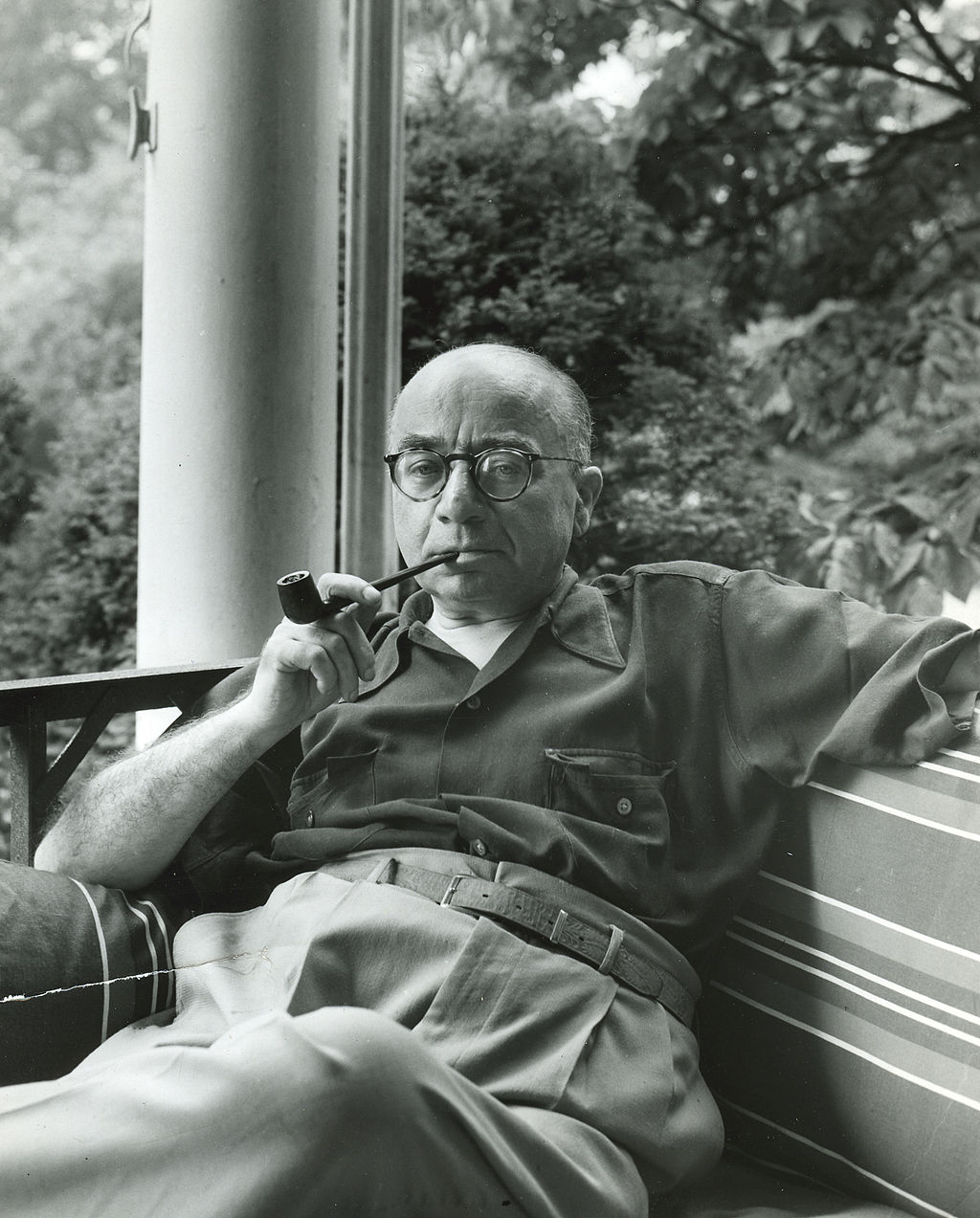

☆ アーサー・シックあるいは、アルトゥール・シーク(ポーランド語: Artur Szyk [ʂ ʂ↪Ll_268]; 1894年6月3日 - 1951年9月13日[1])はポーランド生まれのユダヤ人画家で、そのキャリアを通して主に本の挿絵画家、政治画家として活動した。アルトゥール・シー クは、19世紀にロシアの支配下にあったポーランドのロチュの裕福な中産階級のユダヤ人家庭に生まれた。1921年からは主にフランスとポー ランドで生活し、作品を創作した。1940年にはアメリカに永住し、1948年にはアメリカ市民権を取得した。

| Arthur

Szyk (Polish: Artur Szyk [ˈar.tur ʂɨk]; see Polish phonology); June 3,

1894 – September 13, 1951[1]) was a Polish-born Jewish artist who

worked primarily as a book illustrator and political artist throughout

his career. Arthur Szyk was born into a prosperous middle-class Jewish

family in Łódź,[2][3] in the part of Poland which was under Russian

rule in the 19th century. An acculturated Polish Jew, Szyk always

proudly regarded himself both as a Pole and a Jew.[4] From 1921, he

lived and created his works mainly in France and Poland, and in 1937 he

moved to the United Kingdom. In 1940, he settled permanently in the

United States, where he was granted American citizenship in 1948. Arthur Szyk became a renowned artist and book illustrator as early as the interwar period. His works were exhibited and published not only in Poland but also in France, the United Kingdom, Israel and the United States. However, he gained broad popularity in the United States primarily through his political caricatures, in which, after the outbreak of World War II, he savaged the policies and personalities of the leaders of the Axis powers. After the war, he also devoted himself to Zionist political issues, especially the support of the creation of the state of Israel. Szyk's work is characterized in its material content by social and political commitment, and in its formal aspect by its rejection of modernism and embrace of the traditions of medieval and renaissance painting, especially illuminated manuscripts from those periods. Today, Szyk is known and exhibited only in his last country of residence, the United States. |

ア

ルトゥール・シーク(ポーランド語: Artur Szyk [ʂ ʂ↪Ll_268]; 1894年6月3日 -

1951年9月13日[1])はポーランド生まれのユダヤ人画家で、そのキャリアを通して主に本の挿絵画家、政治画家として活動した。アルトゥール・シー

クは、19世紀にロシアの支配下にあったポーランドのロチュの裕福な中産階級のユダヤ人家庭に生まれた[2][3]。1921年からは主にフランスとポー

ランドで生活し、作品を創作した。1940年にはアメリカに永住し、1948年にはアメリカ市民権を取得した。 アーサー・シックは、戦間期には早くも有名な画家、挿絵画家となった。彼の作品はポーランドだけでなく、フランス、イギリス、イスラエル、アメリカでも展 示され、出版された。第二次世界大戦勃発後、枢軸国の指導者たちの政策や人格を痛烈に批判した政治風刺画で、主にアメリカで幅広い人気を得た。戦後はシオ ニストの政治問題、特にイスラエル建国支援にも力を注いだ。 シークの作品は、その物質的な内容において社会的・政治的なコミットメントを特徴とし、形式的な側面においては、モダニズムを拒否し、中世・ルネサンス絵画の伝統、特にこれらの時代の彩飾写本を受け入れている。 今日、シックは最後の居住国であるアメリカでのみ知られ、展示されている。 |

| Background and youth Arthur Szyk,[5] the son of Solomon Szyk and his wife Eugenia, was born in Łódź, in Russian partition of Poland, on June 3, 1894. Solomon Szyk was a textile factory director, a quiet occupation until June 1905, when, during the so-called Łódź insurrection, one of his workers threw acid in his face, permanently blinding him.  Portrait of Julia Szyk. Paris, 1926. Szyk showed artistic talent as a child; when he was six years old, he reportedly drew sketches of the Boxer Rebellion in China.[6] Even though his family was culturally assimilated and did not practice Orthodox Judaism, Arthur also liked drawing biblical scenes from the Hebrew Bible. These interests and talents prompted his father, upon the advice of Szyk's teachers, to send Szyk to Paris to study at Académie Julian,[7] a studio school popular among French and foreign students. In Paris, Szyk was exposed to all modern trends in art; however, he decided to follow his own way, which hewed closely to tradition. He was especially attracted by the medieval art of illuminating manuscripts, which greatly influenced his later works. When studying in Paris, Szyk remained closely involved with the social and civic life of Łódź. During the years 1912–1914 the teenage artist produced numerous drawings and caricatures on contemporary political themes that were published in the Łódź satirical magazine Śmiech ("Laughter"). After four years in France, Szyk returned to Poland in 1913 and continued his studies in Teodor Axentowicz's class at Jan Matejko Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków, which was under Austrian rule at that time. He not only attended lectures and classes, but he also actively participated in Kraków's cultural life. He did not forget his home city Łódź – he designed the stage sets and costumes for the Łódź-based Bi Ba Bo cabaret. The political and national engagement of the artist also deepened during that time – Szyk regarded himself as a Polish patriot but he was also proud of being Jewish and he often opposed antisemitism in his works. At the beginning of 1914, Szyk in a group with other Polish-Jewish artists and writers set off on a journey to Palestine, organized by the Jewish Cultural Society Hazamir (Hebrew: nightingale). There he observed the efforts of Jewish settlers working for the benefit of the future Jewish state.[8] The visit was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I. Szyk, who was a Russian subject, had to leave Palestine, which was part of the Ottoman Empire at that time, and go back to his home country in August 1914. He was conscripted into the Russian army and fought at the battle of Łódź in November/December 1914, but at the beginning of 1915, he managed to escape from the army and spent the rest of the war in his home city. He also used the time spent in the Russian army to draw Russian soldiers and published these drawings as postcards in the same year (1915).[9] On September 14, 1916, Arthur Szyk married Julia Likerman. Their son George was born in the following year, and their daughter Alexandra in 1922. |

生い立ちと少年時代 ソロモン・シクとその妻エウゲニアの息子であるアルトゥール・シクは[5]、1894年6月3日にポーランドのロシア分割領であるウッチで生まれた。1905年6月、いわゆるロッチの反乱の際、労働者の一人が彼の顔に酸を投げつけ、彼の目は永久に見えなくなった。  ユリア・シークの肖像。1926年、パリ。 6歳のとき、中国の義和団の乱のスケッチを描いたと伝えられている[6]。彼の家族は文化的に同化しており、正統派のユダヤ教を信仰していなかったが、 アーサーはヘブライ語の聖書の一場面も好んで描いていた。このような興味と才能から、父親はシークの教師の勧めで、シークをパリに送り、フランス人学生や 外国人学生に人気のあるアトリエ学校、アカデミー・ジュリアン[7]で学ばせた。パリでシークはあらゆる近代的な芸術の潮流に触れたが、伝統に忠実な自分 の道を歩むことを決めた。特に中世の写本に光を当てる技法に惹かれ、後の作品に大きな影響を与えた。パリ留学中も、シークはウッチの社会生活や市民生活に 深く関わっていた。1912年から1914年にかけて、10代の画家は現代の政治的テーマを題材にしたデッサンや風刺画を数多く制作し、ウッチの風刺雑誌 『シュミエヒ』(『笑い』)に掲載された。 フランスで4年間過ごした後、1913年にポーランドに戻ったシークは、当時オーストリアの支配下にあったクラクフのヤン・マテヒコ美術アカデミーのテオ ドール・アクセントヴィッチのクラスで勉強を続けた。講義や授業に出席するだけでなく、クラクフの文化生活にも積極的に参加した。故郷のロチュのことも忘 れず、ロチュを拠点とするキャバレー「ビ・バ・ボ」の舞台装置や衣装をデザインした。シックは自らをポーランドの愛国者だと考えていたが、ユダヤ人である ことにも誇りを持ち、作品の中でしばしば反ユダヤ主義に反対した。1914年の初め、シークは他のポーランド系ユダヤ人の芸術家や作家とともに、ユダヤ文 化協会ハザミール(ヘブライ語でナイチンゲール)の主催するパレスチナへの旅に出た。そこで彼は、将来のユダヤ人国家のために働くユダヤ人入植者たちの努 力を見学した[8]。 この訪問は第一次世界大戦の勃発によって中断された。ロシアの臣民であったシークは、1914年8月に当時オスマン帝国の一部であったパレスチナを離れ、 母国に戻らなければならなかった。ロシア軍に徴兵され、1914年11月から12月にかけてのロチュの戦いで戦ったが、1915年の初めには脱走に成功 し、残りの戦争期間を故郷で過ごした。1916年9月14日、アルトゥール・シークはユリア・リカーマンと結婚。翌年には息子のジョージが、1922年に は娘のアレクサンドラが生まれた。 |

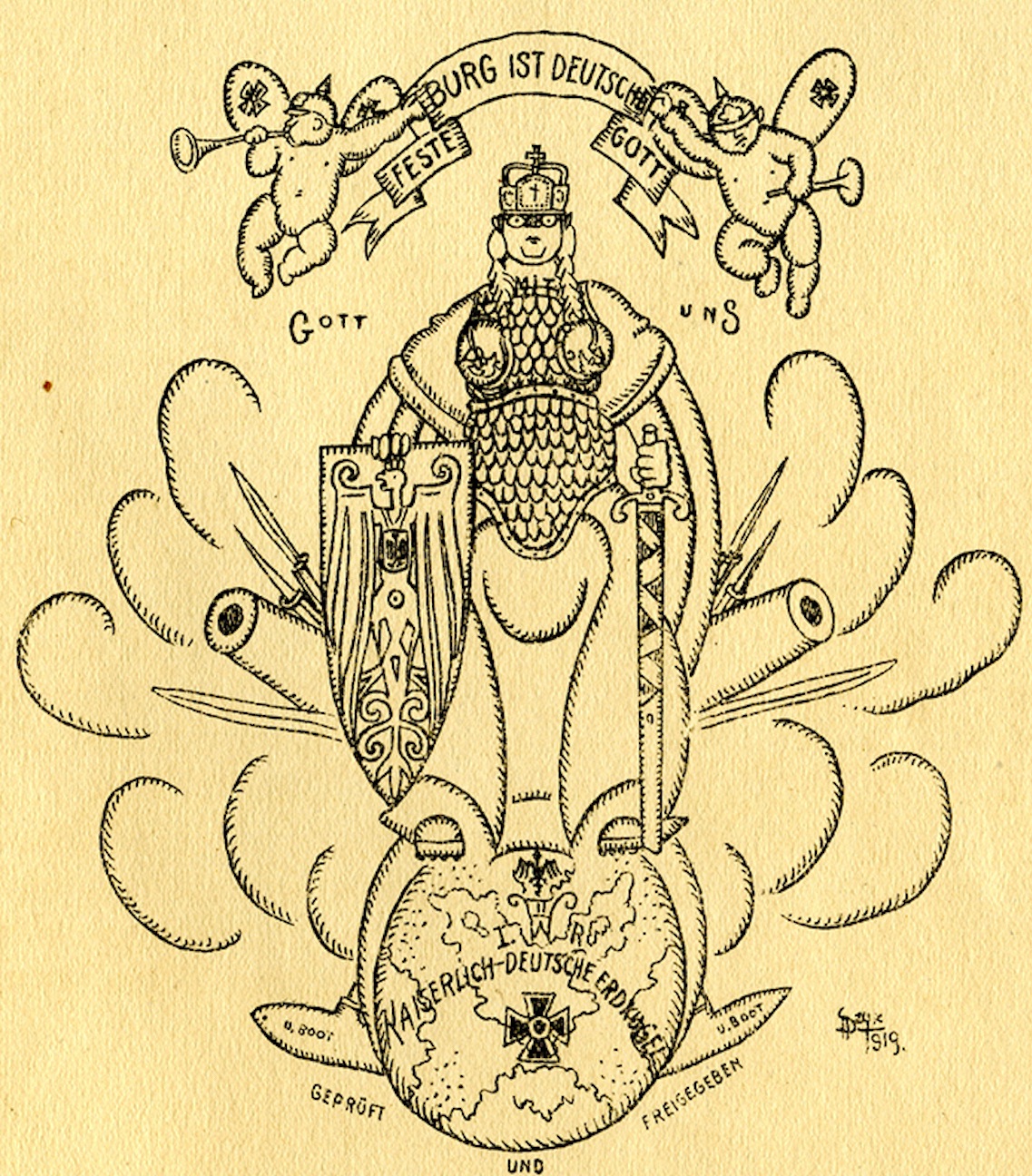

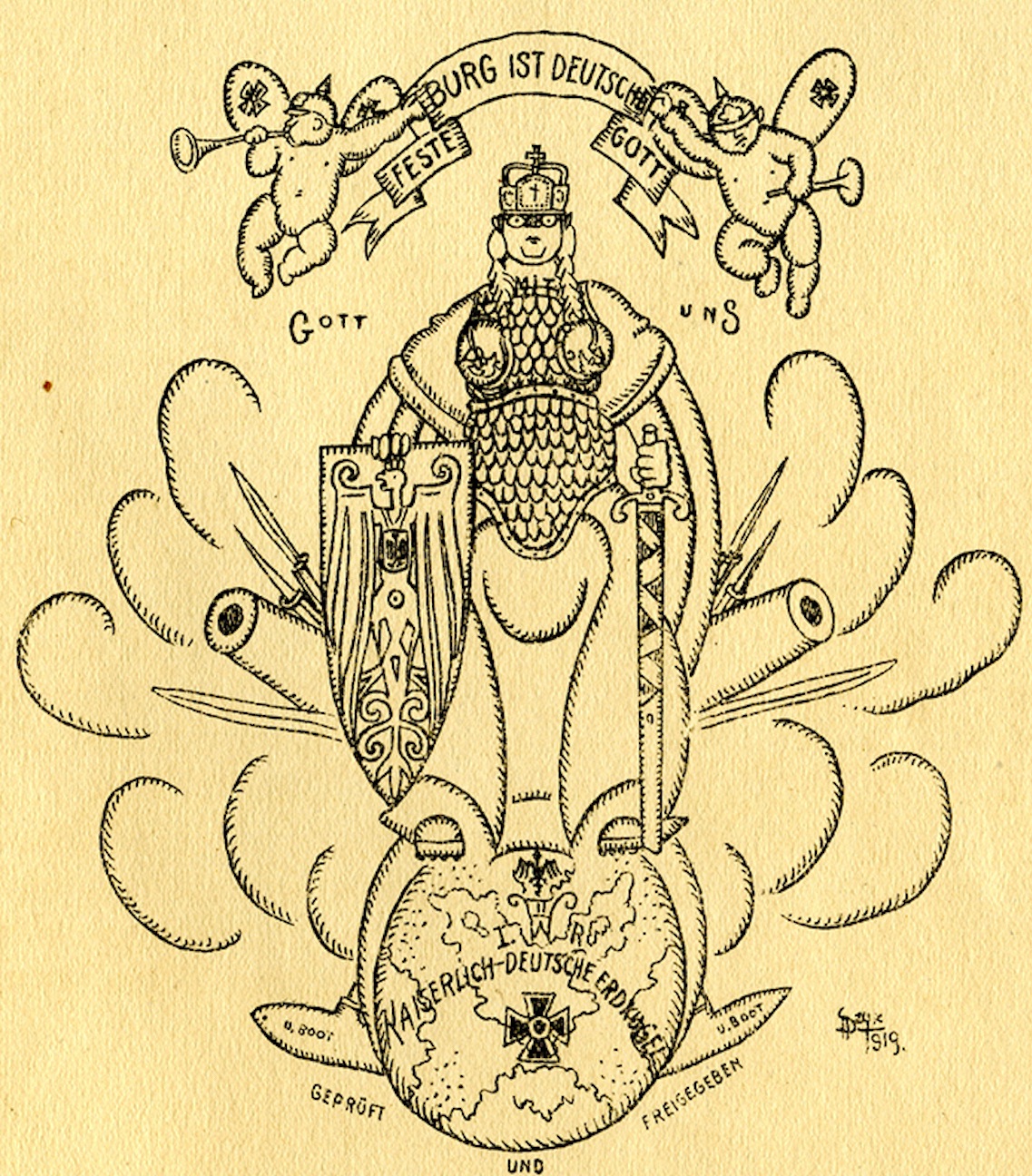

| Between the wars In the Second Polish Republic  In this image from the 1919 book Rewolucja w Niemczech (Revolution in Germany), a Valkyrie-like figure stands on a globe stamped with the Iron Cross (Eisernes Kreuz). After Poland had regained independence in 1918, Szyk fully developed his artistic activity, combining it with political engagement. In 1919, influenced by the events of the German Revolution of 1918–19, he published, together with poet Julian Tuwim, his first book of political illustrations: Rewolucja w Niemczech (Revolution in Germany), which was a satire on the Germans, who need the Kaiser's and the military's consent even to start a revolution.[10] In the same year, Szyk had to take part in warfare again – during the Polish–Soviet War (1919–1920), in which he served as a Polish cavalry officer and as the artistic director of the propaganda department of the Polish army in Łódź.[11][12] In France In 1921 Arthur Szyk and his family moved to Paris where they stayed until 1933. The relocation to Paris is marked by a breakthrough in the formal aspect of Szyk's works. While Szyk's prior book illustrations were drawings in pen and ink (Szyk had illustrated six books before 1925, including three published in the Yiddish language), the illustrations for the books published in Paris were full colour and full of detail. The first book illustrated in this way was the Book of Esther (Le livre d'Esther, 1925), followed by Gustave Flaubert's dialogue The Temptation of Saint Anthony (La tentation de Saint Antoine, 1926), Pierre Benoît's novel Jacob's Well (Le puits de Jacob, 1927) and other books. Those illustrations, which are characterized by a rich diversity of colours and detailed presentation, deliberately referred to the medieval and renaissance traditions of illumination of manuscripts, often with interspersed contemporary elements. Szyk drew himself as one of the characters in the Book of Esther.. The only stylistic exception is illustrations to the two volume collection of humorous anecdotes about Jews Le juif qui rit (1926/27), in which the artist returned to simple black and white graphics. (Paradoxically, the book, one of the best known of his works, met with criticism as repeating antisemitic stereotypes.) The artist's reputation was also enhanced by exhibitions which were organized by Galeries Auguste Decour (the art gallery first exhibited Szyk's works in 1922). Szyk's drawings were purchased by the Minister of Education and Fine Arts Anatole de Monzie and the New York businessman Harry Glemby.[13] Szyk had many opportunities to travel for his art. In 1922, he spent seven weeks in Morocco, then a protectorate of France, where he drew the portrait of the pasha of Marrakech – as a goodwill ambassador he received the Ordre des Palmes Académiques from the French government for this work. In 1931 he was invited to the seat of the League of Nations in Geneva, where he began illustrating the statute of the League. The artist made some of the pages of the statute but did not complete that work as a result of his disappointment with the policies of the organization in the 1930s.[14] |

戦間期 第二次ポーランド共和国時代  1919年に出版された『Rewolucja w Niemczech(ドイツにおける革命)』からの一枚で、鉄十字が刻印された地球儀の上にワルキューレのような人物が立っている。 1918年にポーランドが独立を回復すると、シークは芸術活動を政治活動と結びつけながら本格的に展開する。1919年、1918年から19年にかけての ドイツ革命の出来事に影響を受けた彼は、詩人ユリアン・トゥヴィムとともに、初の政治イラストレーション集を出版した: 同年、ポーランド・ソビエト戦争(1919-1920年)において、ポーランド騎兵将校として、またロッチのポーランド軍宣伝部の芸術監督として、再び戦 場に参加することになる[11][12]。 フランスにて 1921年、アルトゥール・シークは家族とともにパリに移り住み、1933年まで過ごした。パリへの移住は、シークの作品の形式的な側面における飛躍に よって特徴づけられる。それまでの本の挿絵はペンとインクで描かれたものだったが(シックは1925年までにイディッシュ語で出版された3冊を含む6冊の 本の挿絵を描いていた)、パリで出版された本の挿絵はフルカラーで細部まで描き込まれていた。このように挿絵が描かれた最初の本は『エステル記』(Le livre d'Esther、1925年)で、その後、ギュスターヴ・フローベールの対話劇『聖アントニウスの誘惑』(La tentation de Saint Antoine、1926年)、ピエール・ブノワの小説『ヤコブの井戸』(Le puits de Jacob、1927年)などが続いた。これらの挿絵は、豊かな色彩の多様性と細部にわたる表現が特徴で、中世やルネサンス期の写本の照明の伝統を意図的 に参照し、しばしば現代的な要素を散りばめている。シークは、自分自身をエステル記の登場人物の一人として描いている。唯一の様式的例外は、ユダヤ人につ いてのユーモラスな逸話を集めた2巻の挿絵集『Le juif qui rit』(1926/27)で、作者はシンプルな白黒のグラフィックに戻っている。(逆説的だが、この本は彼の作品の中で最もよく知られたもののひとつで あり、反ユダヤ的なステレオタイプを繰り返すという批判を浴びた)。画家の評判は、オーギュスト・デクール画廊が企画した展覧会によっても高まった(同画 廊がシークの作品を初めて展示したのは1922年)。シークのドローイングは、アナトール・ド・モンシー教育・美術大臣やニューヨークの実業家ハリー・グ レンビーに購入された[13]。 シックは芸術のために旅をする機会が多かった。1922年には、当時フランスの保護領であったモロッコに7週間滞在し、マラケシュのパシャの肖像画を描い た。1931年、ジュネーブの国際連盟に招かれ、連盟規約の挿絵を描き始める。画家は規約のページの一部を制作したが、1930年代の国際連盟の政策に失 望した結果、その作品は完成しなかった[14]。 |

Statute of Kalisz and Washington and his Times During his stay in France, Szyk maintained his ties with Poland. He often visited his home country, illustrated books, and exhibited his works there. During the second half of the 1920s, he mainly illustrated the Statute of Kalisz, a charter of liberties which were granted to the Jews by Bolesław the Pious, the Duke of Kalisz, in 1264.[15] In the years 1926–1928, he created a rich graphic setting of the 45-page-long Statute, showing the contribution of the Jews to Polish society; for example their participation in Poland's pro-independence struggle, during the January Uprising of 1863, and in the Polish Legions in World War I commanded by Józef Piłsudski, to whom Szyk also dedicated his work. The Statute of Kalisz was published in book form in Munich in 1932, but it gained popularity even earlier. Postcards with reproductions of Szyk's illustrations were published in Kraków around 1927. The original art was shown at exhibitions in Warsaw, Łódź and Kalisz in 1929, and a "Traveling Exhibition of Artur Szyk's Works" was held in 1932–1933, displaying the Statute at exhibitions in 14 Polish towns and cities. In recognition of his work, Arthur Szyk was decorated with the Gold Cross of Merit by the Polish government.[16][17] Another great historical series Szyk created was Washington and his Times, which he began in Paris in 1930. The series, which included 38 watercolours, depicted the events of the American Revolutionary War and was a tribute to the first president of the United States and the American nation in general. The series was presented at an exhibition at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. in 1934. It brought another decoration to Szyk – this time the George Washington Bicentennial Medal from the American government.[18][19] |

カリシュ憲章とワシントンとその時代 フランス滞在中、シークはポーランドとの絆を保っていた。彼はしばしば母国を訪れ、本の挿絵を描き、作品を展示した。1920年代後半、彼は主に、 1264年にカリシュ公ボレスワフがユダヤ人に与えた自由憲章である「カリシュ憲章」の挿絵を担当した[15]。 [15]1926年から1928年にかけて、彼は45ページに及ぶこの憲章を豊かなグラフィックで構成し、ポーランド社会におけるユダヤ人の貢献、例え ば、1863年の1月蜂起におけるポーランド独立派の闘争への参加、第一次世界大戦におけるヨゼフ・ピウスツキの指揮するポーランド軍への参加などを示し た。カリシュの憲章』は1932年にミュンヘンで書籍として出版されたが、それ以前に人気を博していた。1927年頃、クラクフでシークのイラストを複製 した絵葉書が出版された。原画は1929年にワルシャワ、ウッチ、カリシュで開催された展覧会で展示され、1932年から1933年にかけては「アル トゥール・シークの作品巡回展」が開催され、ポーランドの14の町や都市で展覧会が開催された。その功績が認められ、アルトゥール・シークはポーランド政 府から功労金十字勲章を授与された[16][17]。 シィクが制作したもうひとつの偉大な歴史シリーズは、1930年にパリで始めた『ワシントンとその時代』である。このシリーズには38点の水彩画が含ま れ、アメリカ独立戦争の出来事が描かれ、アメリカ合衆国の初代大統領とアメリカ国家一般への賛辞であった。このシリーズは1934年にワシントンD.C. の議会図書館で開催された展覧会で発表された。この展覧会は、アメリカ政府からジョージ・ワシントン生誕200年記念メダルを授与されるなど、シズクに新 たな勲章をもたらした[18][19]。 |

The Haggadah and moving to London. Arthur Szyk (1894–1951). Hitler as Pharaoh, c. 1933. This sketch depicts the newly appointed Chancellor of Germany Adolf Hitler dressed as an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, a clear reference to the antagonist in the biblical story of the Exodus of the Hebrew slaves from Egypt. Szyk's art became even more politically engaged when Adolf Hitler took power in Germany in 1933. Szyk started drawing caricatures of Germany's Führer as early as 1933; probably the first was a pencil drawing of Hitler dressed as an ancient Egyptian pharaoh.[20] These drawings anticipated another great series of Szyk's drawings – the Haggadah, which is considered his magnum opus. The Haggadah is a very important and popular story in Jewish culture and religion about the Exodus or departure of the Israelites from ancient Egypt, which is read every year during the Passover Seder.[21] Szyk illustrated the Haggadah in 48 miniature paintings in the years 1934–1936. The antisemitic politics in Germany led Szyk to introduce some contemporary elements to it. For example, he painted the Jewish parable of the Four Sons, in which the "wicked son" was portrayed as a man wearing German clothes, with a Hitler-like moustache and a green Alpine hat. The political intent of the series was even stronger in its original version: he painted upon the red snakes the swastika, the symbol of the Third Reich. In 1937, Arthur Szyk went to London to supervise the publication of the Haggadah. However, in the three years leading to its publication, the artist had to agree to many compromises, including painting over the swastikas. It is not clear whether he did it under the pressure from his publisher or from British politicians who pursued the policy of appeasement with to Germany. The Haggadah was at last published in 1940, dedicated it to King George VI and with a translation (of the Hebrew) and commentary by British Jewish historian Cecil Roth. The work was widely acclaimed by critics; according to The Times of London Literary Supplement, it was "worthy to be placed among the most beautiful of books that the hand of man has ever produced".[22][23] It was the most expensive new book in the world at the time, with each of the 250 limited edition copies of vellum selling for 100 guineas or US$520.[24] |

ハガダーとロンドンへの移住 アーサー・シック(1894-1951)。ファラオとしてのヒトラー、1933年頃。このスケッチは、新しくドイツ首相に任命されたアドルフ・ヒトラーが 古代エジプトのファラオに扮している様子を描いたもので、聖書に登場するヘブライ人奴隷のエジプト出エジプトの物語における敵役を明確に引用している。 1933年にアドルフ・ヒトラーがドイツで権力を握ると、シークの芸術はさらに政治的な関与を強めた。おそらく最初のものは、古代エジプトのファラオに扮 したヒトラーを鉛筆で描いたものであろう[20]。これらの絵は、シークのもうひとつの偉大な絵のシリーズ、大作とされる『ハガダー』を先取りしていた。 ハガダーとは、古代エジプトからのイスラエルの民の出エジプトを描いた、ユダヤの文化や宗教において非常に重要で人気のある物語であり、毎年過越のセーデ ルの際に朗読される[21]。ドイツにおける反ユダヤ主義的な政治は、シークにいくつかの現代的な要素を導入させた。例えば、彼はユダヤ人の「4人の息 子」のたとえ話を描いたが、その中で「悪い息子」はドイツ服を着て、ヒトラーのような口ひげを生やし、緑色のアルペンハットをかぶった男として描かれた。 このシリーズの政治的意図は、オリジナル版ではさらに強く、彼は赤い蛇の上に第三帝国のシンボルである鉤十字を描いた。 1937年、Arthur SzykはHaggadahの出版を監督するためにロンドンに赴いた。しかし、出版までの3年間で、画家は鉤十字を塗りつぶすなど、多くの妥協に同意しな ければならなかった。彼が出版社からの圧力でそうしたのか、対独宥和政策を追求するイギリスの政治家たちからの圧力でそうしたのかは定かではない。ハガ ダーは1940年にようやく出版され、国王ジョージ6世に捧げられ、イギリスのユダヤ人歴史家セシル・ロスによる翻訳(ヘブライ語)と解説が加えられた。 The Times of London Literary Supplementによれば、「人間の手がこれまでに生み出した最も美しい書物のひとつに数えられるに値する」[22][23]とされ、当時世界で最も 高価な新書であり、限定250部のヴェラムはそれぞれ100ギニーまたは520米ドルで販売された[24]。 |

| New York World's Fair, 1939 The last major exhibition of Szyk's works before the outbreak of World War II was the presentation of his paintings at the 1939 New York World's Fair, which opened in April 1939 in New York.[25] The Polish Pavilion prominently featured Szyk's twenty-three paintings depicting the contribution of the Poles to the history of the United States; many works specifically highlighted the historic political connections between the two countries, as if to remind the viewer that Poland remained a suitable ally in a turbulent time.. (Twenty of the images were reproduced as postcards in Kraków in 1938 and were available for sale.). In this series, Szyk depicted the contribution of the Poles to the history of the United States, and highlighted historic connections between the two countries.[26] |

ニューヨーク万国博覧会、1939年 第二次世界大戦勃発前最後の大規模な展覧会は、1939年4月にニューヨークで開催された1939年ニューヨーク万国博覧会での彼の絵画の展示であった [25]。 [25]ポーランド館では、アメリカの歴史におけるポーランド人の貢献を描いたシックの23点の絵画が目立つように展示された。多くの作品は、激動の時代 にもポーランドが適切な同盟国であり続けたことを見る者に思い出させるかのように、両国の歴史的な政治的つながりを特に強調していた(そのうちの20点 は、1938年にクラクフで絵葉書として複製され、販売された)。このシリーズでシークは、アメリカの歴史におけるポーランド人の貢献を描き、両国の歴史 的なつながりを強調した[26]。 |

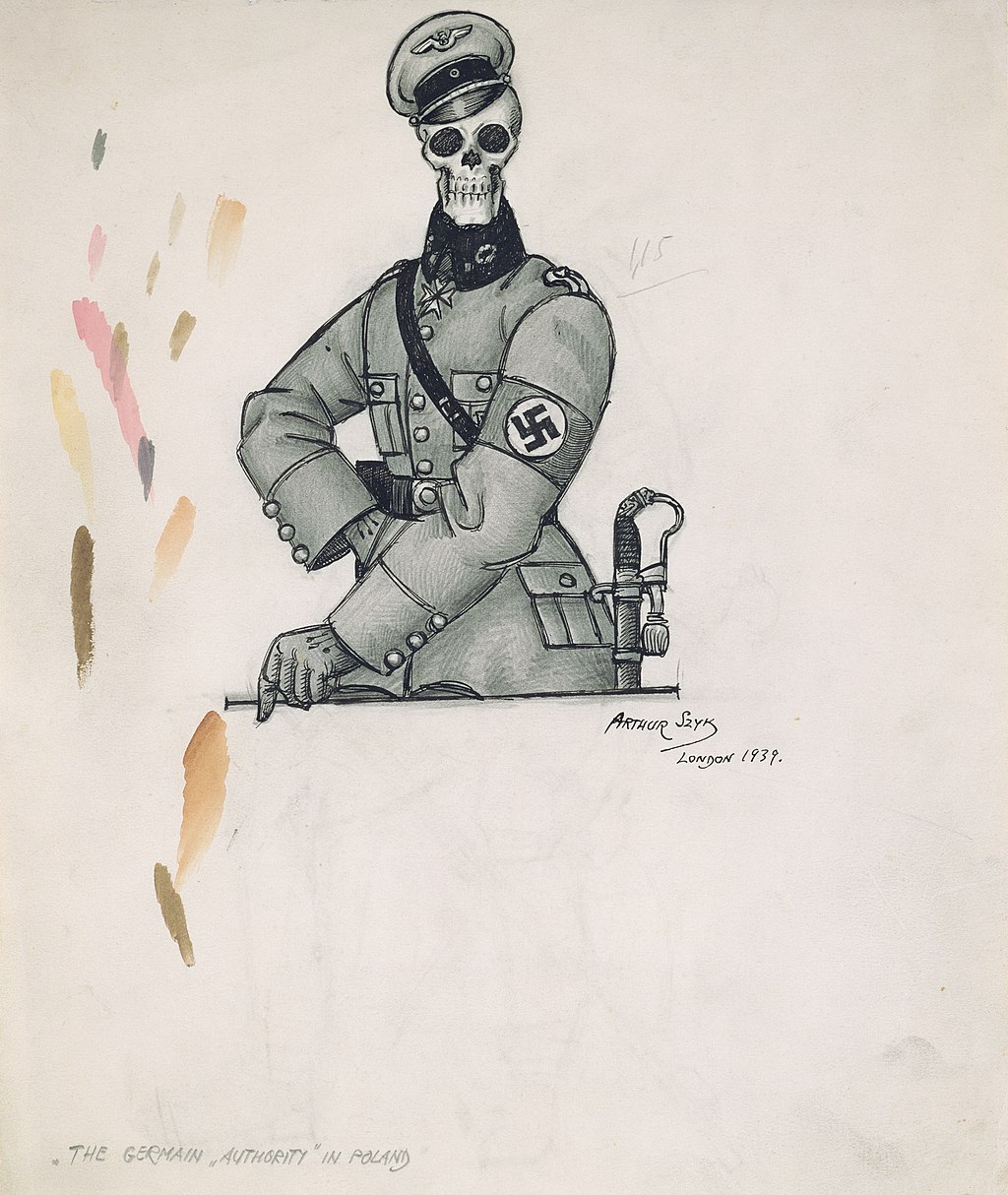

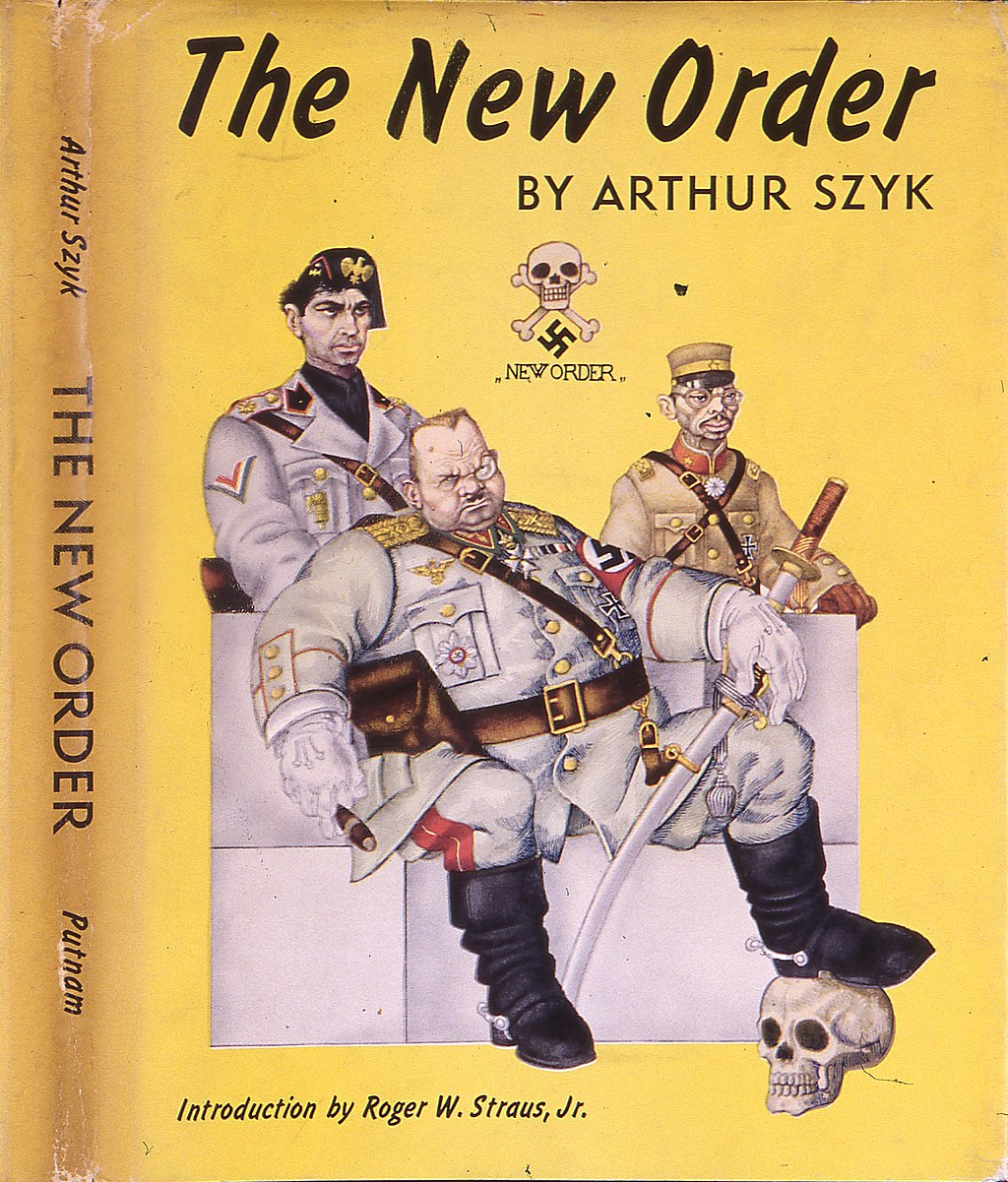

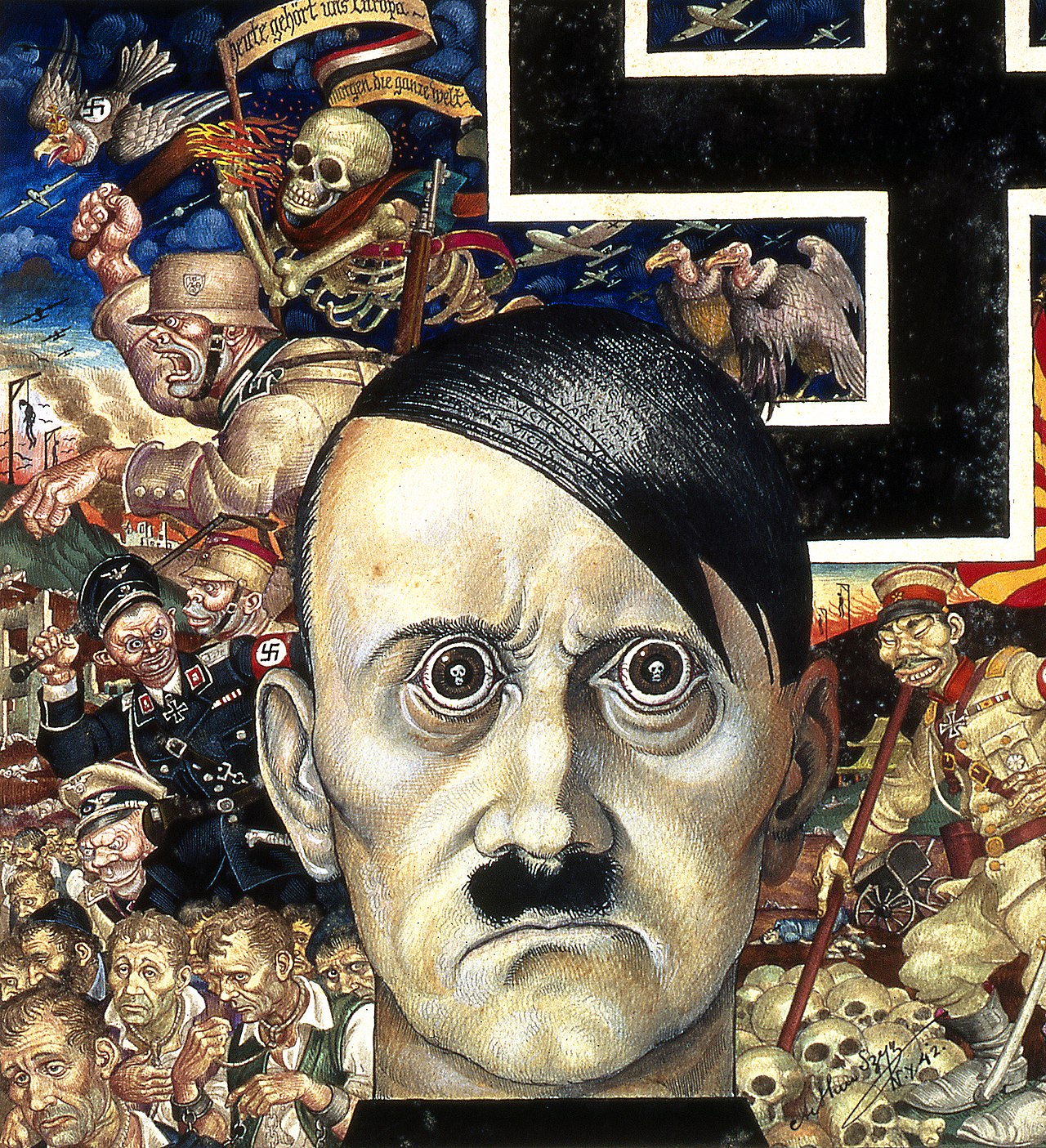

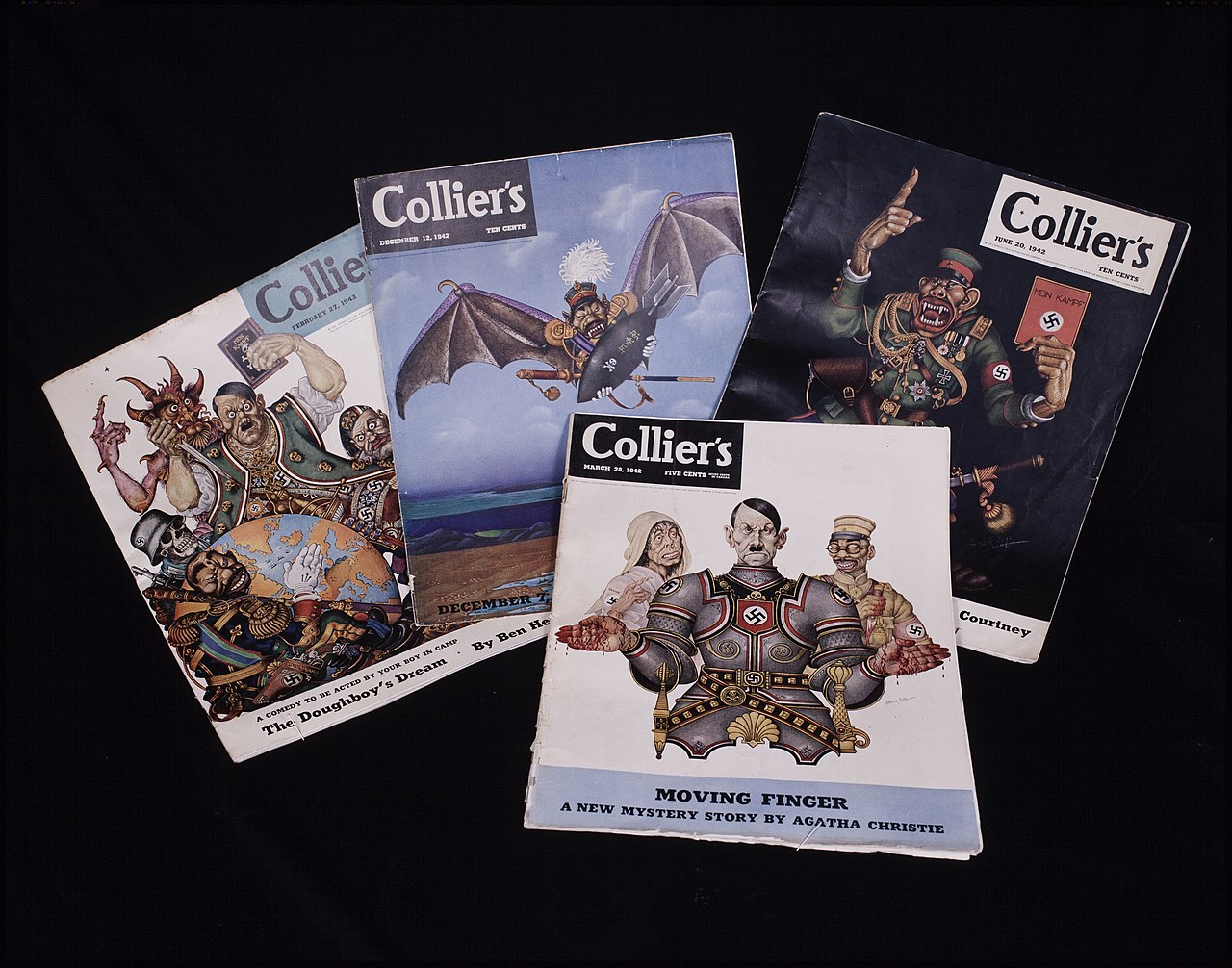

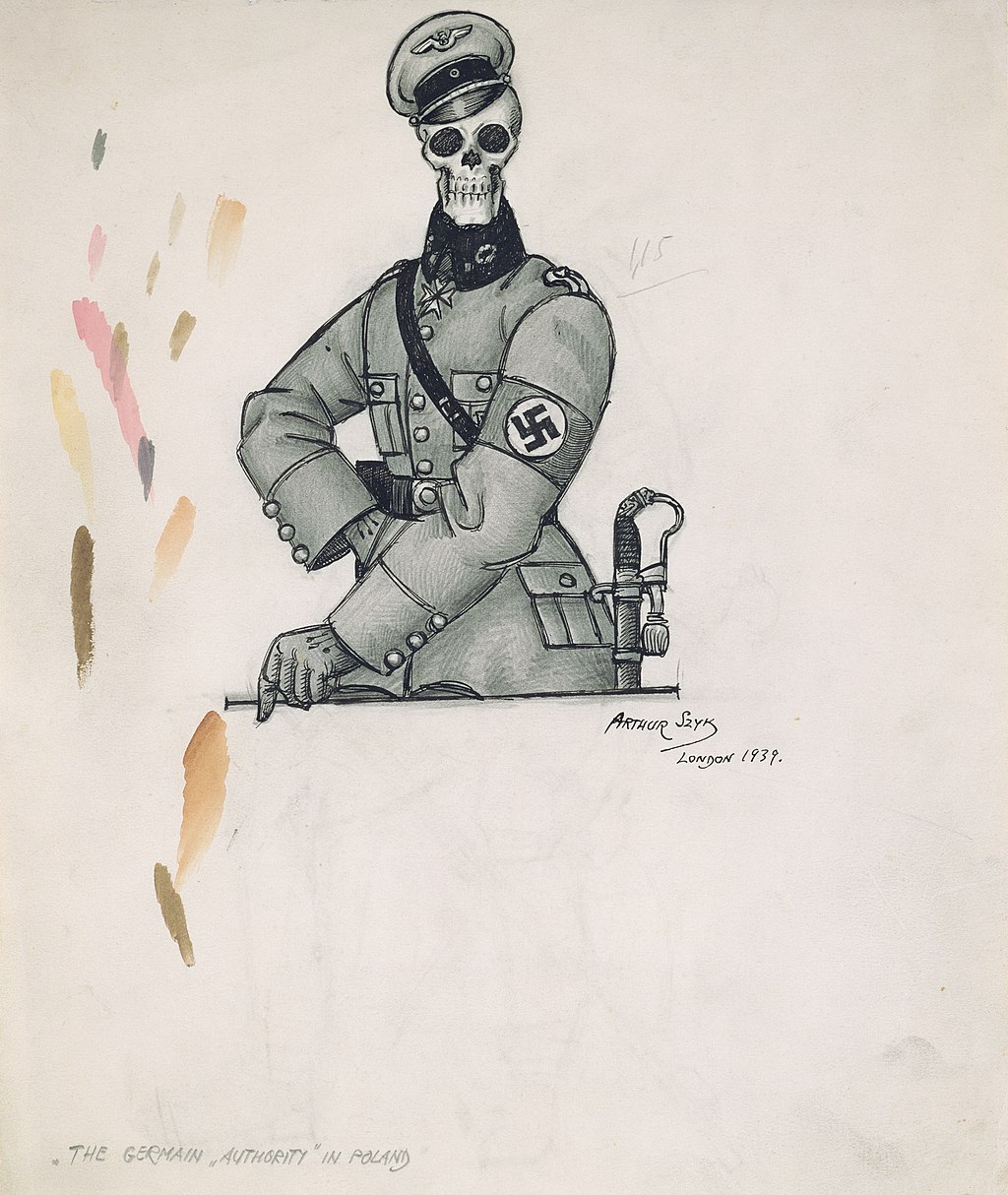

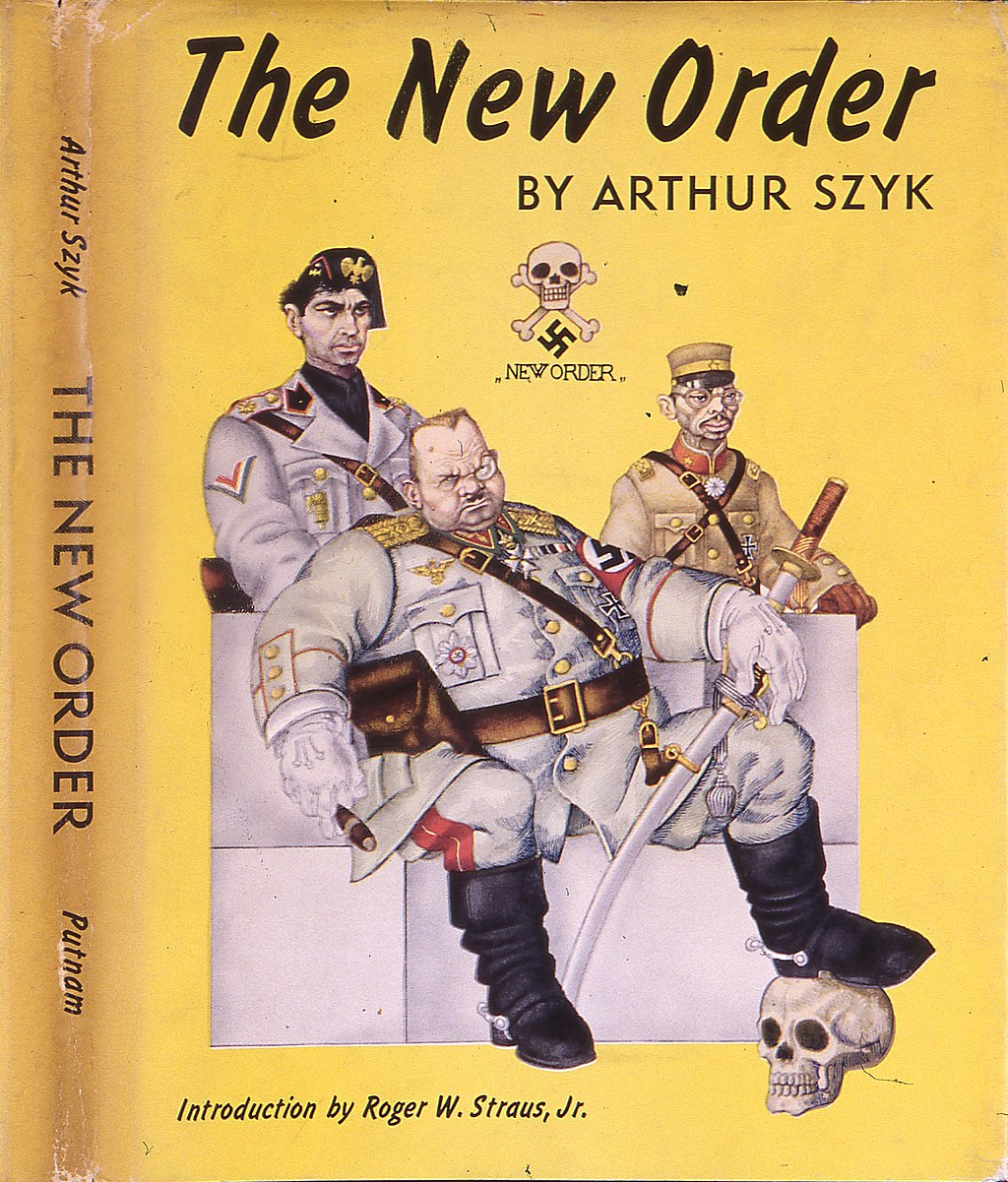

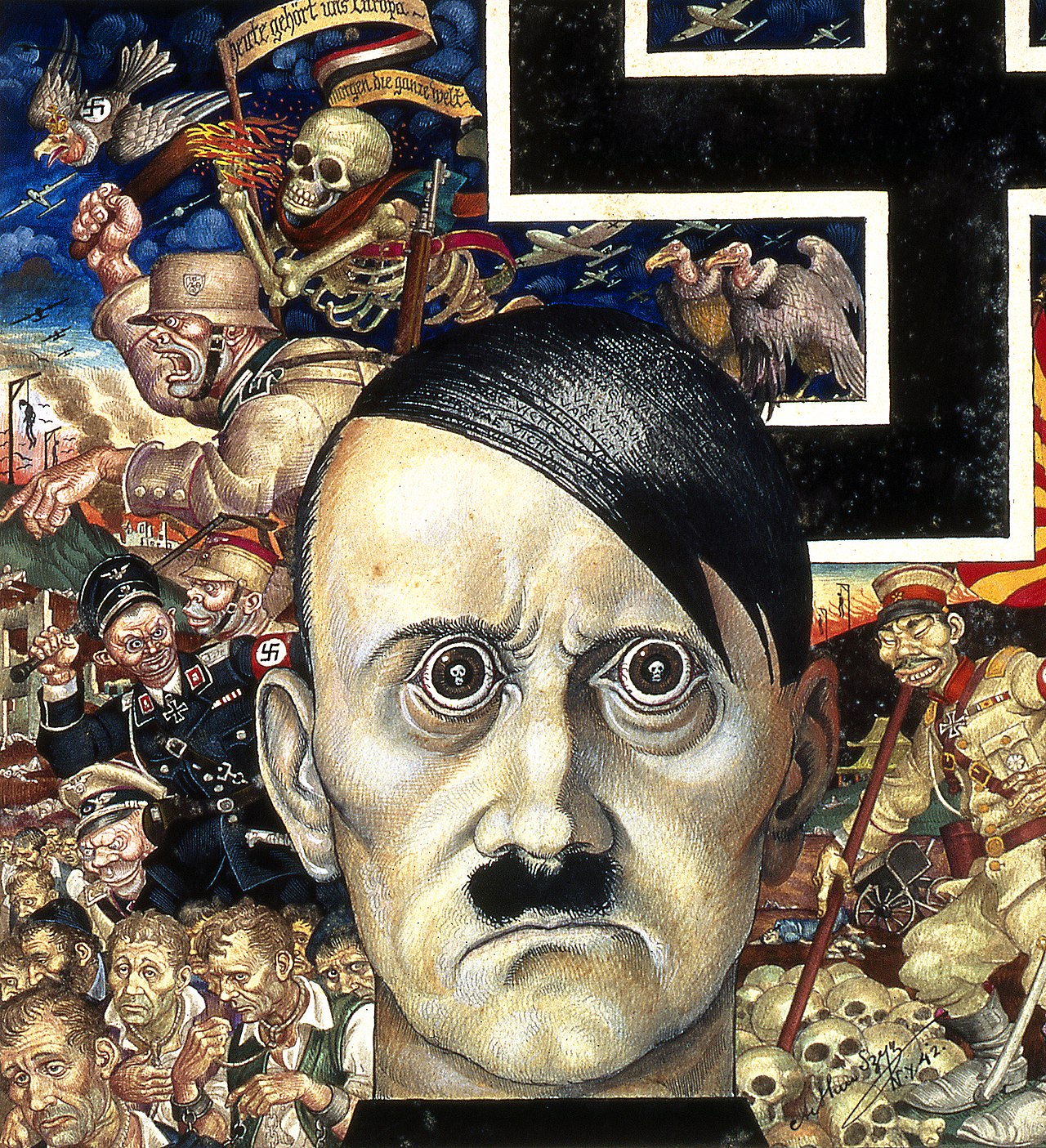

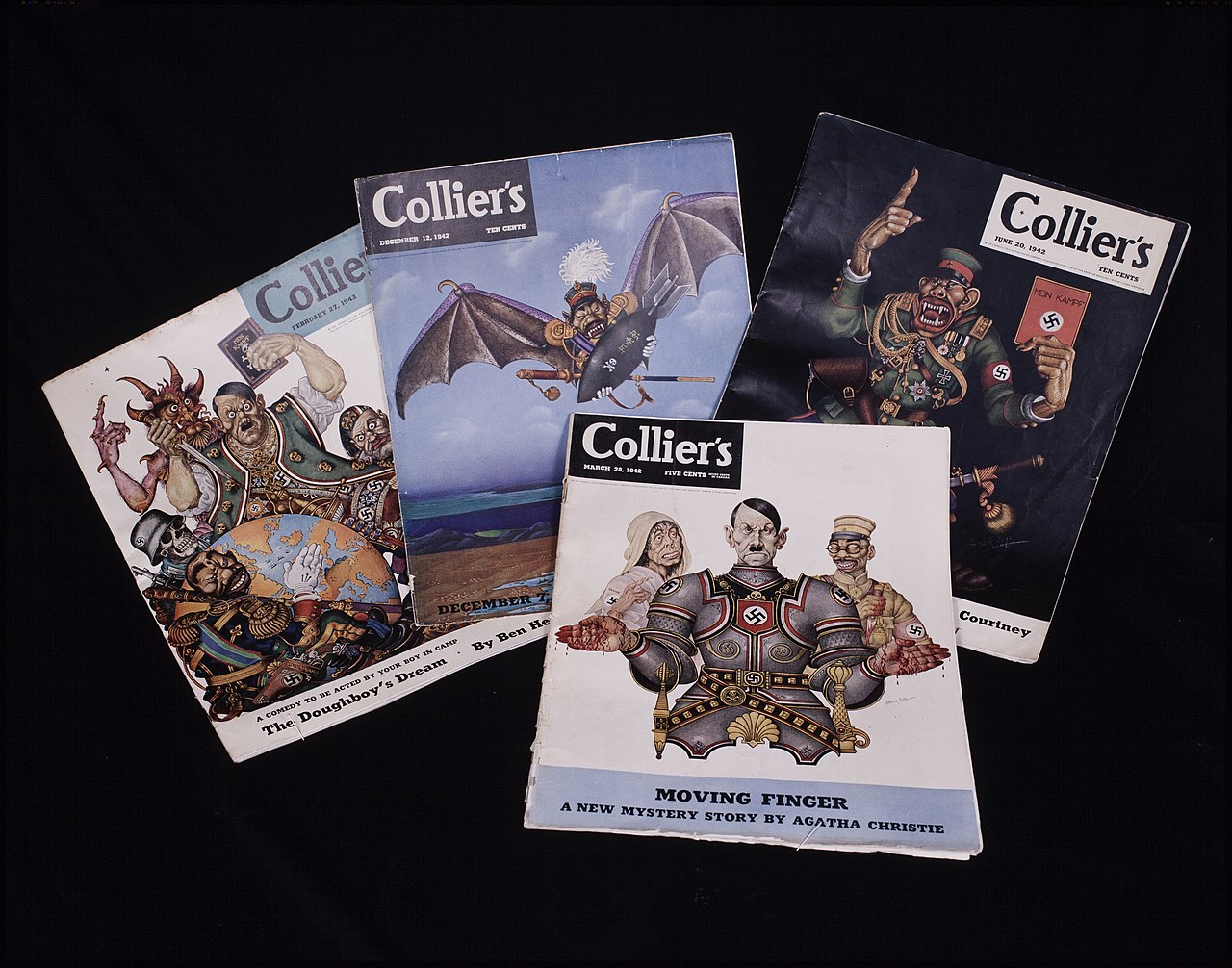

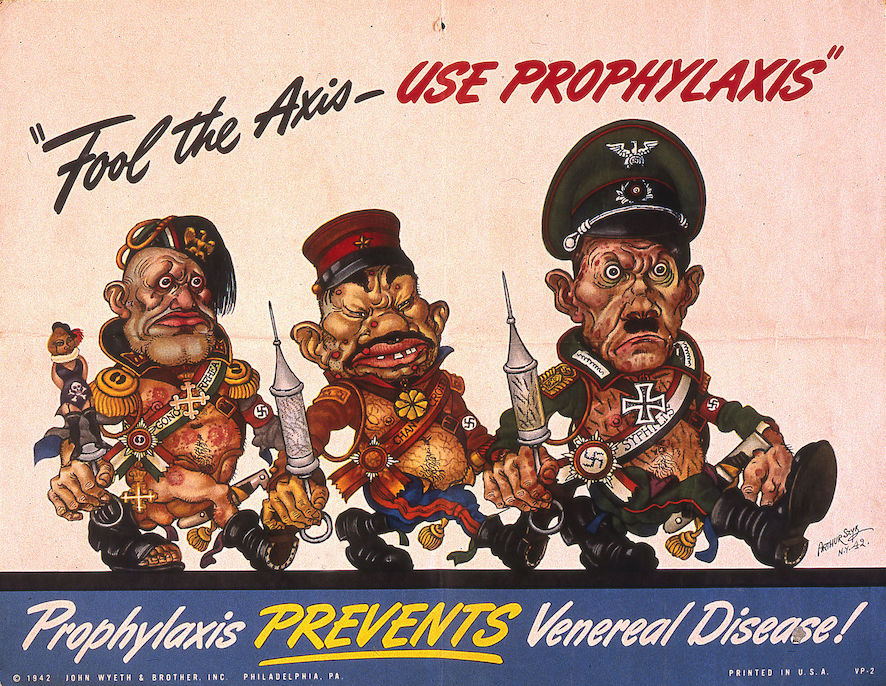

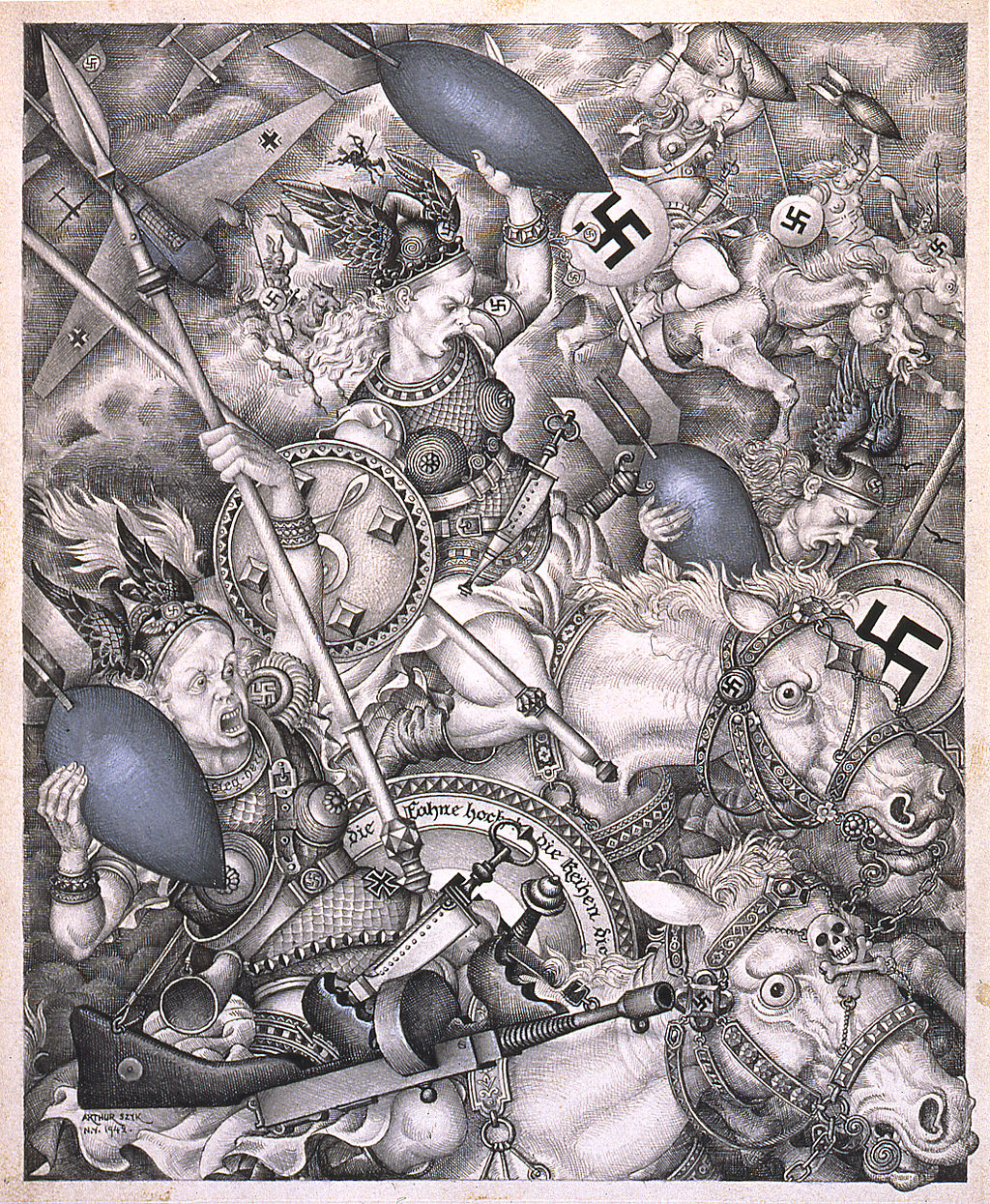

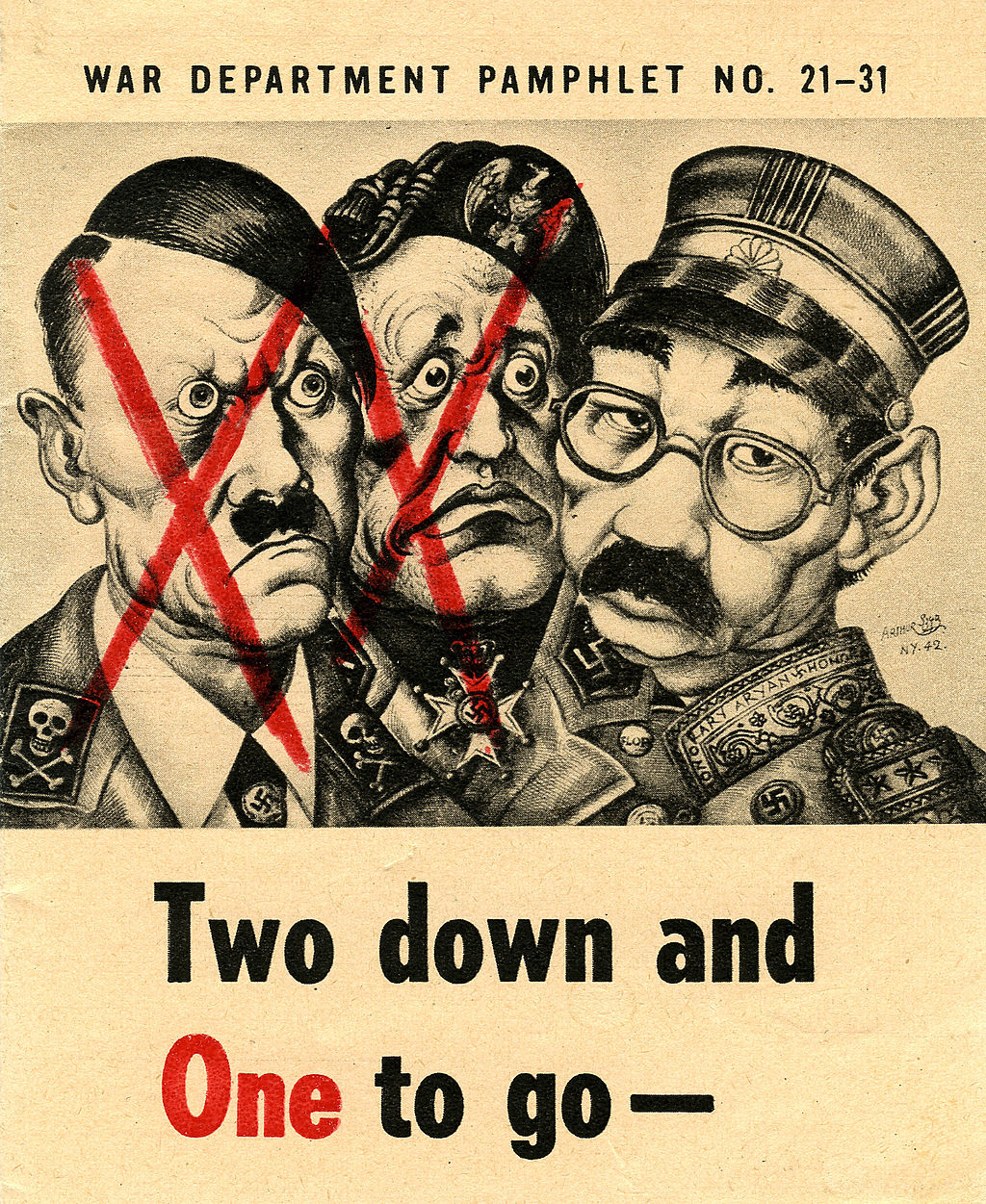

| World War II Reaction to the outbreak of the war  The Germain 'Authority' in Poland (1939), London  The New Order (dust jacket). New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1941 The German invasion of Poland found Szyk in Britain where he supervised the publication of the Haggadah and continued to exhibit his works. The artist immediately reacted to the outbreak of World War II by producing war-themed works. One feature which distinguished Szyk from other caricaturists who were active during World War II was that he concentrated on the presentation of the enemy in his works and seldom depicted the leaders or soldiers of the Allies. This was a characteristic feature of Szyk's work till the end of the war.[27] In January 1940, the exhibition of his 72 caricatures entitled War and "Kultur" in Poland opened at the Fine Art Society in London, and was well received by the critics. As the reviewer of The Times wrote: There are three leading motives in the exhibition: the brutality of the Germans – and the more primitive savagery of the Russians, the heroism of the Poles, and the suffering of the Jews. The cumulative effect of the exhibition is immensely powerful because nothing in it appears to be a hasty judgment, but part of the unrelenting pursuit of an evil so firmly grasped that it can be dwelt upon with artistic satisfaction.[28] Szyk drew more and more caricatures directed at the Axis powers and their leaders, and his popularity steadily grew. In 1940, the American publisher G.P. Putnam's Sons offered to publish a collection of his drawings. Szyk agreed, and the result was the 1941 book The New Order, available months before the United States joined the war. Thomas Craven declared on the dust jacket of The New Order that Szyk: ...makes not only cartoons but beautifully composed pictures which suggest, in their curiously decorative quality, the inspired illuminations of the early religious manuscripts. His designs are as compact as a bomb, extraordinarily lucid in statement, firm and incisive in line, and deadly in their characterizations. (...) These are remarkable documents.[29] Some years later, in 1946, art critic Carl Van Doren said of Szyk: There is no one more certain to be alive two hundred years from now. Just as we turn back to Hogarth and Goya for the living images of their age, so our descendants will turn back to Arthur Szyk for the most graphic history of Hitler and Hirohito and Mussolini. Here is the damning essence of what has happened; here is the piercing summary of what men have thought and felt. Moving to the United States and war caricatures  Arthur Szyk, 1942, Anti-Christ, watercolor and gouache on paper. Szyk's portrayal of Adolf Hitler as the embodiment of evil: his eyes reflect human skulls, his black hair the Latin words "Vae Victis" [woe to the vanquished (ones)].  Arthur Szyk illustrated numerous covers for Collier's magazine during World War II. At the beginning of July 1940, with the support of the British government and the Polish government-in-exile, Arthur Szyk left Britain for North America, on assignment to popularize in the New World the struggle of the British and Polish nations against Nazism. His first destination on the continent was Canada, where he was welcomed enthusiastically by the media: they wrote about his engagement in the fight with Nazi Germany, and the Halifax-based Morning Herald even reported about the alleged bounty Hitler had put on Szyk.[30] In December 1940, Szyk and his wife and daughter went to New York City, where he lived till 1945. His son, George, had enlisted in the Free French Forces commanded by General Charles de Gaulle.[31] Soon after his arrival in the U.S., Szyk was inspired by Roosevelt's 1941 "Four Freedoms" State of the Union speech to illustrate the Four Freedoms, preceding Norman Rockwell's Four Freedoms by two years;[32] these were used as poster stamps during the war, and appeared on the Four Freedoms Award which was presented to Harry Truman, George Marshall and Herbert H. Lehman. Szyk became an immensely popular artist in his new home country the war, especially after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the entry of the United States into the war. His caricatures of the leaders of the Axis powers (Hitler, Mussolini, Hirohito) and other drawings appeared practically everywhere: in newspapers, magazines (including Time (cover caricature of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto in December 1941), Esquire, and Collier's), on posters, postcards and stamps, in secular, religious and military publications, on public and military buildings. He also produced advertisements for Coca-Cola and U.S. Steel, and exhibited in the galleries of M. Knodler & Co., Andre Seligmann, Inc., Messrs. Wildenstein & Co., the Philadelphia Art Alliance, the Brooklyn Museum, the Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco, and the White House. More than 25 exhibitions were staged altogether in the United States during the war years. At the end of the war, in 1945, his drawing Two Down and One to Go was used in a propaganda film calling American soldiers to the final assault on Japan. According to the Esquire magazine, the posters with Szyk's drawings enjoyed even bigger popularity with American soldiers than pin-up girls put on the walls of American military bases.[33] In total, more than one million American soldiers saw Szyk's in reproduction at some 500 locations administered by the United Services Organization.[34] |

第二次世界大戦 開戦への反応  ポーランドのドイツ人「権威」(1939年)、ロンドン  新秩序(ジャケット)。ニューヨーク G.P.パトナム社、1941年 ドイツ軍のポーランド侵攻により、シークはイギリスに滞在し、ハガダの出版を監修し、作品の展示を続けた。作家は第二次世界大戦の勃発に即座に反応し、戦 争をテーマにした作品を制作した。第二次世界大戦中に活躍した他の風刺画家とシィクを区別する特徴のひとつは、作品の中で敵の表現に集中し、連合国の指導 者や兵士を描くことがほとんどなかったことである。1940年1月、ポーランドの戦争と「文化」と題された72点の風刺画展がロンドンのファイン・アー ト・ソサエティで開かれ、批評家から好評を博した。タイムズ』紙の批評家はこう書いている: この展覧会には3つの主要な動機がある:ドイツ人の残忍さ、そしてロシア人のより原始的な野蛮さ、ポーランド人のヒロイズム、そしてユダヤ人の苦しみであ る。この展覧会の累積的な効果は絶大なものである。なぜなら、この展覧会には性急な判断によるものは何一つ見られず、芸術的な満足感をもってじっくりと考 えることができるほど、しっかりと把握された悪に対する絶え間ない追求の一部に見えるからである[28]。 シークは枢軸国やその指導者に向けた風刺画をどんどん描き、その人気は着実に高まっていった。1940年、アメリカの出版社G.P.Putnam's Sonsは彼の画集を出版することを申し出た。シークはこれを承諾し、1941年に『The New Order』として出版された。トーマス・クレイヴンは『The New Order』のダストジャケットにこう書いている: 漫画だけでなく、美しく構成された絵は、その不思議な装飾性において、初期の宗教的写本に描かれた霊感に満ちたイルミネーションを彷彿とさせる。彼のデザ インは爆弾のようにコンパクトで、非常に明晰で、線がしっかりしていて鋭く、その特徴を致命的に表現している。(これらは驚くべき文書である。 数年後の1946年、美術評論家のカール・ヴァン・ドーレンはシジェクについてこう述べている: 今から200年後に生きていることがこれほど確実な人物はいない。われわれがホガースやゴヤにその時代の生きたイメージを求めるように、われわれの子孫は ヒトラーやヒロヒトやムッソリーニの最も生々しい歴史を求めて、アーサー・シィクに立ち返るだろう」。ここにあるのは、起こったことの忌まわしい本質であ り、ここにあるのは、人間が何を考え、何を感じたかを突き刺すように要約したものである。 アメリカへの移動と戦争風刺画  アーサー・シック、1942年、反キリスト、紙に水彩とグワッシュ。彼の目は人間の頭蓋骨を映し出し、彼の黒髪はラテン語の "Vae Victis"[敗者(者)に災いあれ]を表している。  アーサー・シークは第二次世界大戦中、『コリアーズ』誌の表紙を数多く飾った。 1940年7月初め、イギリス政府とポーランド亡命政府の支援を受けて、アーサー・シックはイギリスから北米に向かった。ハリファックスを拠点とするモー ニング・ヘラルド紙は、ヒトラーがシックにかけたとされる懸賞金について報じたほどであった。息子のジョージはシャルル・ド・ゴール将軍が指揮する自由フ ランス軍に入隊していた[31]。 アメリカに到着して間もなく、シークは1941年のルーズベルトの「4つの自由」一般教書演説に触発され、ノーマン・ロックウェルの「4つの自由」に2年 先駆けて「4つの自由」のイラストを描いた[32]。これらは戦時中にポスター切手として使用され、ハリー・トルーマン、ジョージ・マーシャル、ハーバー ト・H・リーマンに贈られた「4つの自由賞」に登場した。シークは戦争中、特に日本の真珠湾攻撃と米国の参戦後、新天地で絶大な人気を誇る画家となった。 彼の描いた枢軸国の指導者たち(ヒトラー、ムッソリーニ、ヒロヒト)の風刺画やその他の絵は、新聞、雑誌(『タイム』(1941年12月の山本五十六提督 の風刺画が表紙)、『エスクァイア』、『コリアーズ』など)、ポスター、絵葉書、切手、世俗的、宗教的、軍事的出版物、公共施設や軍事施設など、事実上あ らゆるところに掲載された。また、コカ・コーラやU.S.スチールの広告も手がけ、M.クノドラー社、アンドレ・セリグマン社、ワイルデンスタイン社、 フィラデルフィア美術同盟、ブルックリン美術館、サンフランシスコのレジオン・ドヌール宮殿、ホワイトハウスなどのギャラリーで展覧会を開催した。戦争 中、アメリカでは全部で25以上の展覧会が開催された。戦争末期の1945年、彼のドローイング「Two Down and One to Go」は、アメリカ兵を日本への最終攻撃に呼びかけるプロパガンダ・フィルムに使用された。エスクァイア』誌によれば、シックの絵が描かれたポスターは、 米軍基地の壁に貼られたピンナップ・ガールよりもアメリカ兵に人気があった[33]。 合わせて100万人以上のアメリカ兵が、連合軍組織によって管理された約500の場所でシックの複製画を目にした[34]。 |

| In

recognition for his services in the fight against Nazism, Fascism, and

the Japanese aggression, Eleanor Roosevelt, First Lady and wife of

President F. D. Roosevelt, wrote about Szyk several times in her

newspaper column, My Day.[35] On January 8, 1943, she wrote: ...I had a few minutes to stop in to see an exhibition of war satires and miniatures by Arthur Szyk at the Seligman Galleries on East 57th Street. This exhibition is sponsored by the Writers' War Board. I know of no other miniaturist doing quite this kind of work. In its way it fights the war against Hitlerism as truly as any of us who cannot actually be on the fighting fronts today. |

ナ

チズム、ファシズム、そして日本の侵略との戦いにおける彼の功績を称え、F・D・ルーズベルト大統領の妻でありファーストレディであったエレノア・ルーズ

ベルトは、自身の新聞コラム『My Day』に何度かシズクについて書いている[35]。1943年1月8日、彼女はこう書いている: 東57丁目のセリグマン・ギャラリーで開催されているアーサー・シックの戦争風刺と細密画の展覧会を見に、少し時間があったので立ち寄りました。この展覧 会はWriters' War Boardが主催している。私は、このような作品を描いている細密画家を他に知らない。この作品は、今日実際に戦場に立つことのできない私たちと同じよう に、ヒトラー主義との戦いに真摯に立ち向かっている。 |

| Social justice on the home front Though Szyk was a fierce opponent of Nazi Germany and the rest of the Axis Powers, he did not avoid topics or themes which presented the Allies in a less favourable light. Szyk criticized the United Kingdom for its policies in the Middle East, especially its practice of imposing limits on Jewish emigration to Palestine.[36][37] Szyk also criticized the apparent passivity of American-Jewish organizations towards the tragedy of their European fellows.[38] He supported the work of Hillel Kook, also known as Peter Bergson, a member of the Zionist organization Irgun, who mounted a publicity campaign in American society whose aim was to draw the American public's attention to the fate of the European Jews. Szyk illustrated for example full-page advertisements (sometimes with copy by screenwriter Ben Hecht) which were published in The New York Times. The artist also spoke against racial tensions in the United States and criticized the fact that the black population did not have the same rights as the whites. In one of his drawings, there are two American soldiers – one black and one white – escorting German prisoners of war. When the white one asks the black: "And what would you do with Hitler?", the black one answers: "I would have made him a Negro and dropped him somewhere in the U.S.A."[39] Szyk's attitude to his mother country, Poland, was very interesting and full of contradictions. Even though he regarded himself both as Jewish and Polish and showed the suffering of the Poles (not only those of Jewish descent) in the Russian-occupied Polish territories in his drawings, even though he benefited from financial support of the Polish government-in-exile (at least at the beginning of the war), Szyk sometimes presented that government in a negative light, especially at the end of World War II. In a controversial drawing dated 1944, a group of debating Polish politicians are shown as opponents of Roosevelt, Joseph Stalin, the "Bolshevik agent" Winston Churchill, and at the same time adherents of Father Charles Coughlin, known for his antisemitic views, as well as "(national) democracy"[40] and "(national) socialism." Around 1943, Szyk, a former participant in the Polish–Soviet War, also completely changed his opinions on the Soviet Union. His drawing from 1944 already depicts outright a soldier of the Moscow-supported People's Army of Poland next to a Red Army soldier, both liberating Poland.[41] Whatever his political views, in July 1942 Szyk took the time to look after the family of the Polish diplomat and poet General Bolesław Wieniawa-Długoszowski when the General committed suicide. He invited his wife Bronisława Wieniawa-Długoszowska and daughter Zuzanna to stay with his family for six weeks in the country. |

ホームフロントにおける社会正義 シィクはナチス・ドイツをはじめとする枢軸国に対する激しい反感を抱いていたが、連合国側をあまり好意的に捉えないような話題やテーマも避けてはいなかっ た。彼は、中東におけるイギリスの政策、特にパレスチナへのユダヤ人の移住に制限を課していたイギリスを批判した[36][37]。また、ヨーロッパのユ ダヤ人の悲劇に対するアメリカのユダヤ人団体の明らかな消極性を批判した[38]。彼は、シオニスト組織イルグンのメンバーで、ピーター・ベルクソンとし ても知られるヒレル・クックの活動を支援した。ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙に掲載された全面広告(時には脚本家ベン・ヘヒトのコピー付き)のイラストを描い た。画家はまた、アメリカの人種的緊張に反対し、黒人が白人と同じ権利を持っていないという事実を批判した。彼の絵の中に、ドイツ人捕虜を護衛する黒人と 白人の2人のアメリカ兵がいる。白人が黒人に尋ねる: 「あなたならヒトラーをどうしますか?「私なら彼を黒人にして、アメリカのどこかに落とすだろう」[39]。 母国ポーランドに対するシックの態度は非常に興味深く、矛盾に満ちていた。自らをユダヤ人でありポーランド人であるとみなし、ロシアに占領されたポーラン ド領土におけるポーランド人(ユダヤ系の人々だけではない)の苦しみを絵で表現していたにもかかわらず、(少なくとも戦争が始まった当初は)ポーランド亡 命政府から財政的な支援を受けていたにもかかわらず、特に第二次世界大戦末期には、シークはポーランド政府を否定的に表現することもあった。物議を醸した 1944年の絵では、討論するポーランドの政治家たちが、ルーズベルト、ヨシフ・スターリン、「ボリシェヴィキの代理人」ウィンストン・チャーチルの反対 者として描かれ、同時に、反ユダヤ主義的な見解で知られるチャールズ・コフリン神父や、「(民族)民主主義」[40]、「(民族)社会主義」の信奉者とし て描かれている。1943年頃、ポーランド・ソビエト戦争に参加したことのあるシィクも、ソ連に対する意見を一変させる。1944年の彼のデッサンにはす でに、モスクワが支援するポーランド人民軍の兵士と赤軍の兵士の隣で、ともにポーランドを解放する姿がはっきりと描かれている[41]。 彼の政治的見解がどのようなものであったにせよ、1942年7月、ポーランド外交官で詩人のボレスワフ・ヴィエニャワ=ドウゴショフスキ将軍が自殺した 際、シークはその家族の世話をした。彼は彼の妻ブロニスワワ・ヴィエニアワ=ドウゴショフスカと娘のズザンナを招き、彼の家族と一緒に6週間滞在させた。 |

| Book illustrations Even though caricatures dominated Szyk's artistic output during the war, he was still engaged in other areas of art. In 1940, the American publisher George Macy, who saw his illustrations for the Haggadah at an exhibition in London, asked him to illustrate the Rubaiyat, a collection of poems of the Iranian poet Omar Khayyám.[42] In 1943, the artist started work on illustrations for the Book of Job, published in 1946; he also illustrated collections of fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen (Andersen's Fairy Tales, 1945) and Charles Perrault (Mother Goose, which was not published).[43] |

本の挿絵 戦時中、風刺画がシークの画業の大半を占めていたとはいえ、彼は他の芸術分野にも携わっていた。1940年、ロンドンの展覧会で『ハガダー』の挿絵を見た アメリカの出版社ジョージ・メイシーから、イランの詩人オマル・ハイヤムの詩集『ルバイヤート』の挿絵を依頼された[42]。1943年には、1946年 に出版された『ヨブ記』の挿絵に着手し、ハンス・クリスチャン・アンデルセン(『アンデルセン童話集』、1945年)やシャルル・ペロー(『マザー・グー ス』、出版は見送られた)の童話集の挿絵も手がけた[43]。 |

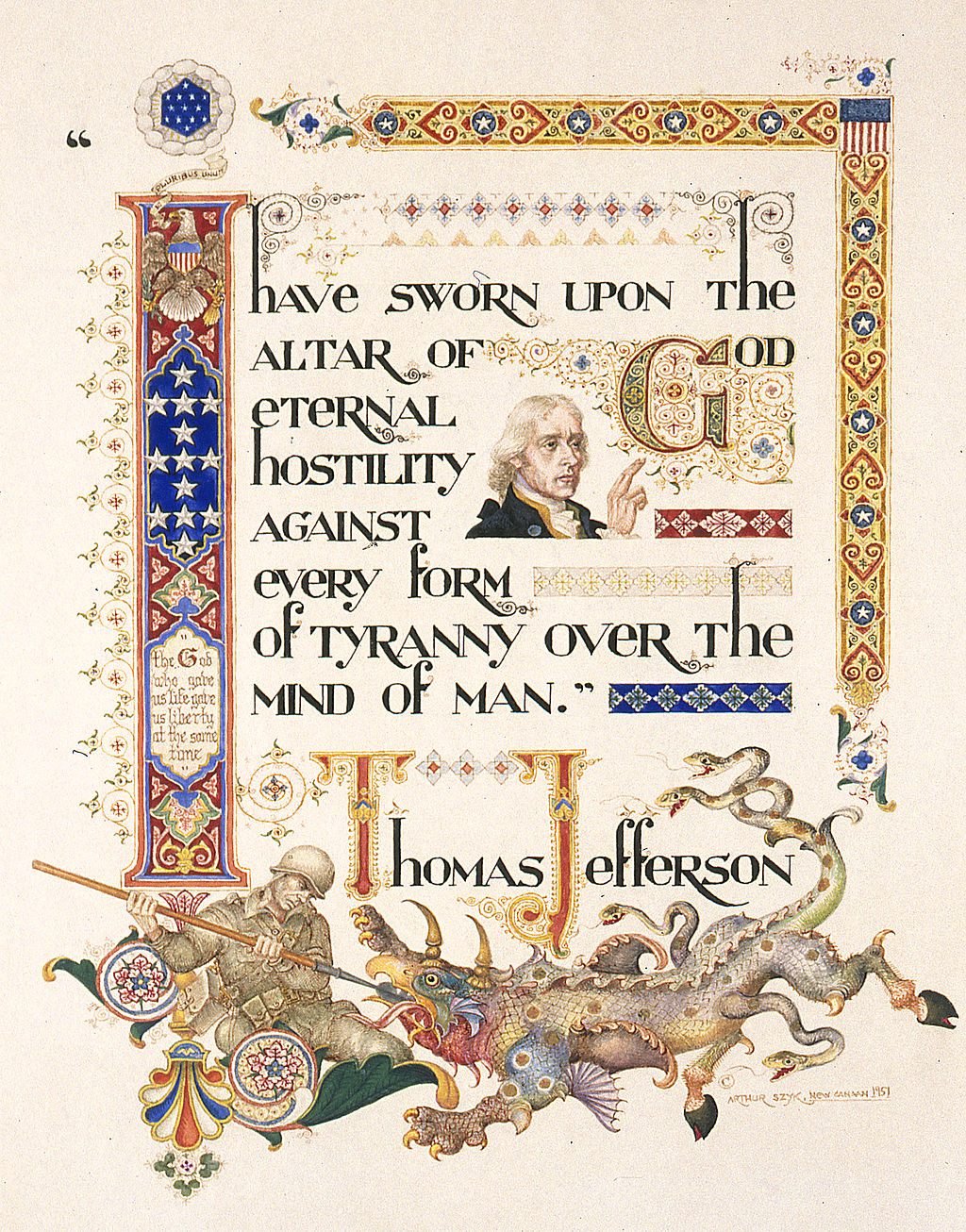

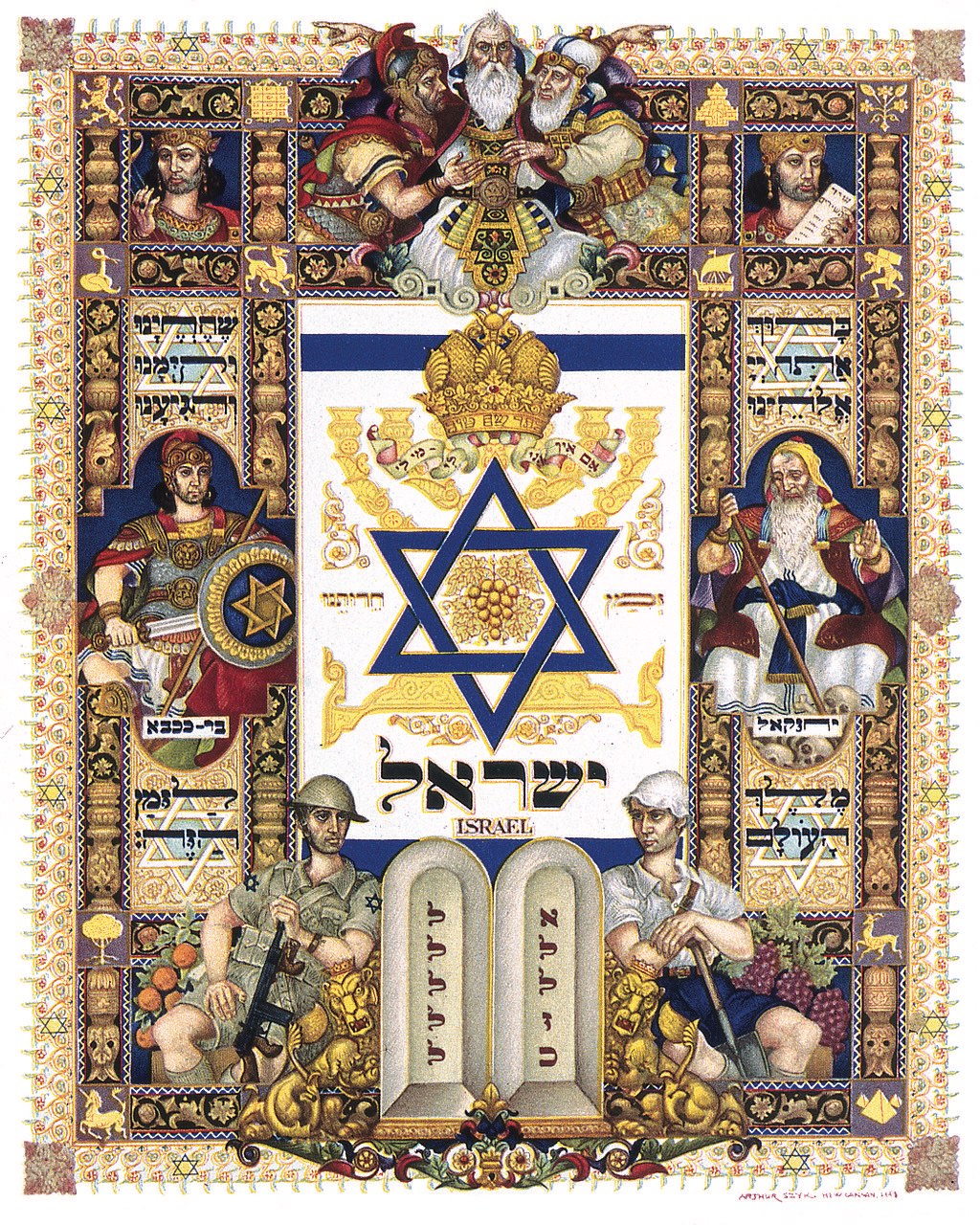

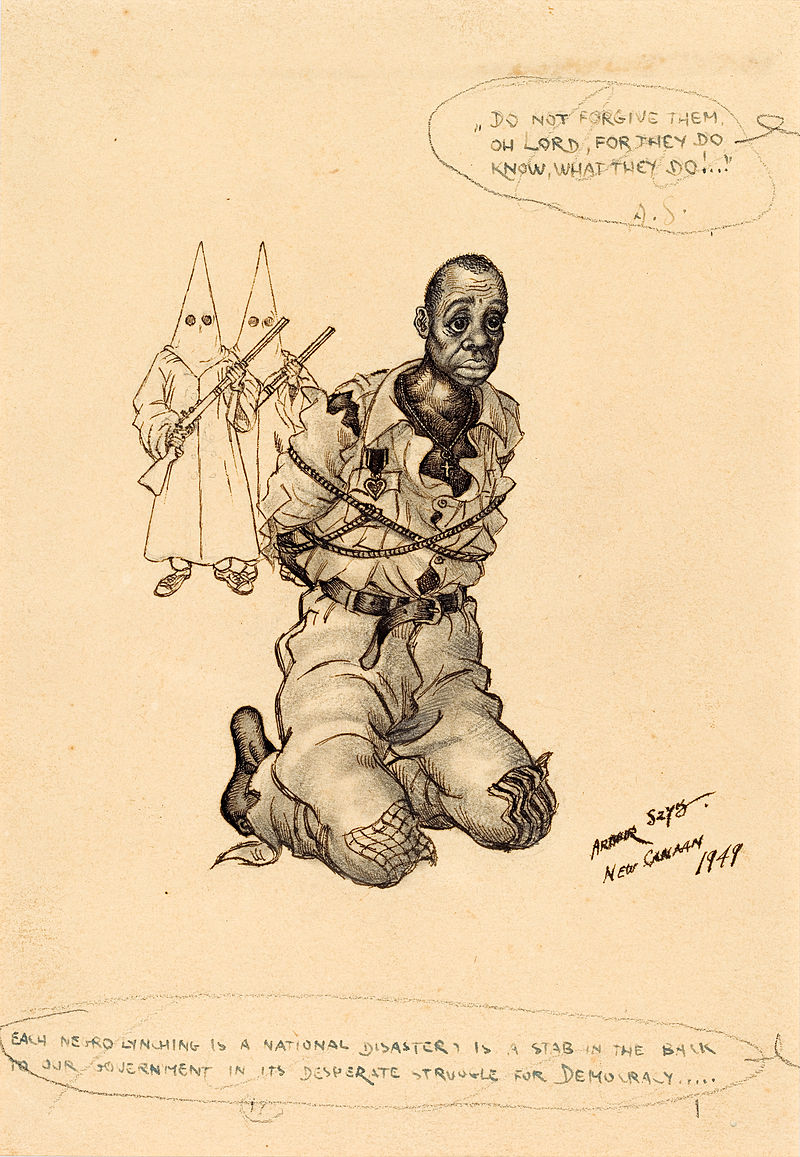

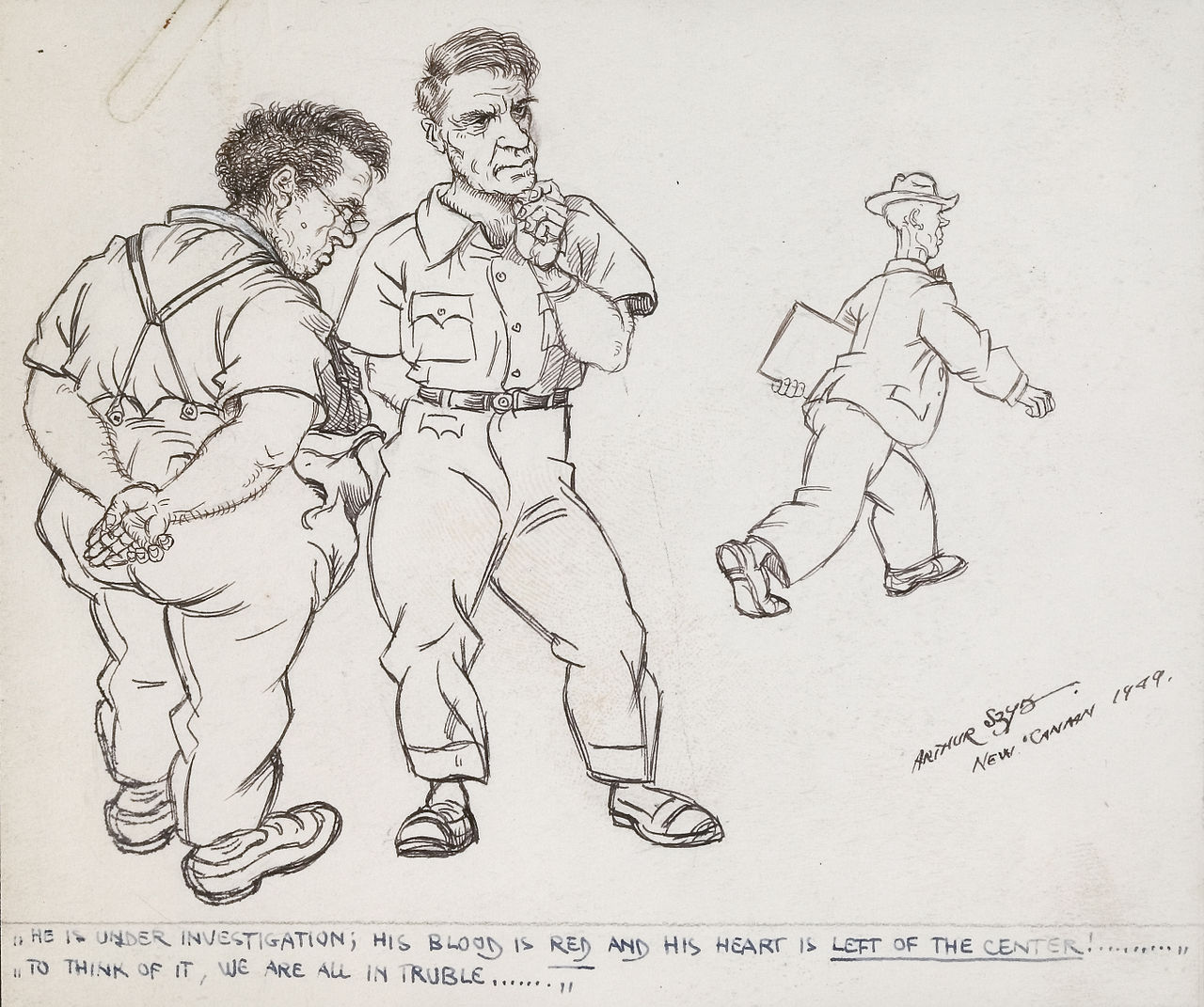

| Postwar: final years In 1945, Arthur Szyk and his family moved from New York City to New Canaan, Connecticut where he lived till the end of his life. The end of the war released him from the duty to fight Nazism through his caricatures; a large collection of drawings from the war period was published by the Heritage Press in 1946 in book form as Ink and Blood: A Book of Drawings. The artist returned to book illustrations, working for example on The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer and, most notably, books telling Bible stories, such as Pathways through the Bible by Mortimer J. Cohen (1946), The Book of Job (1946), The Book of Ruth (1947), The Ten Commandments (1947), The Story of Joseph and his Brothers (1949). Some of the books illustrated by Szyk were also published posthumously, including The Arabian Nights Entertainments (1954) and The Book of Esther (1974). He was also commissioned by Canadian entrepreneur and stamp connoisseur, Kasimir Bileski, to create illustrations for the Visual History of Nations (or United Nations) series of stamps; though the project never came to fruition, Szyk did design stamp album frontispieces for more than a dozen countries,[dubious – discuss][citation needed] including the United States, Poland, the United Kingdom, and Israel. Arthur Szyk was granted American citizenship on May 22, 1948, but he reportedly experienced the happiest day in his life eight days earlier: on May 14, the day of the announcement of the Israeli Declaration of Independence.[44] Arthur Szyk commemorated that event by creating the richly decorated illumination of the Hebrew text of the declaration. Two years later, on July 4, 1950, he also exhibited the richly illuminated text of the United States Declaration of Independence. The artist continued to be politically engaged in his country, criticizing the McCarthyism policy (the ubiquitous atmosphere of suspicion and searching for sympathizers of communism in American artistic and academic circles) and signs of racism. One of his well-known drawings from 1949 shows two armed members of Ku Klux Klan approaching a tied-up African American; the caption for the drawing reads, "Do not forgive them, oh Lord, for they do know what they do." Like many outspoken artists of his era, Szyk was suspected by the House Un-American Activities Committee, which accused him of being a member of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee and six other suspicious organizations. Szyk himself, however, repudiated these accusations of alleged sympathy for communism; his son George sent Judge Simon Rifkind a memorandum outlining his father's innocence.[45] Arthur Szyk died of a heart attack in New Canaan on September 13, 1951.[46] He was eulogized by Rabbi Ben Zion Bokser, who said: :"Arthur Szyk was a great artist. Endowed by God with a rare sensitivity to beauty and with a rare skill in giving it graphic representation, he used his talents to create a series of works of splendor and magnificence that will live forever in the history of art. But Arthur Szyk was more than a great artist. He was a great man, a champion of justice, a fearless warrior in the cause of every humanitarian endeavor. His art was his tool and he used it brilliantly. It was in his hands a weapon of struggle with which he fought for the causes close to his heart"; and by Judge Simon H. Rifkind, who said: "The Arthur Szyk whom the world knows, the Arthur Szyk of the wondrous color, and of the beautiful design, that Arthur Szyk whom the world mourns today—he is indeed not dead at all. How can he be when the Arthur Szyk who is known to mankind lives and is immortal and will remain immortal as long as the love of truth and beauty prevails among mankind?"[47] |

戦後:晩年 1945年、アーサー・シークは家族とともにニューヨークからコネチカット州ニューカナンに移り住み、晩年までそこで暮らした。戦争が終結したことで、風 刺画を通してナチズムと戦う義務から解放された。戦時中のドローイングの大規模なコレクションは、1946年にヘリテージ・プレスから『Ink and Blood』として書籍化された: A Book of Drawings』として出版された。この画家は書籍の挿絵に戻り、例えばジェフリー・チョーサーの『カンタベリー物語』や、特に聖書の物語を描いた本、 例えばモーティマー・J・コーエンの『聖書の道』(1946年)、『ヨブ記』(1946年)、『ルツ記』(1947年)、『十戒』(1947年)、『ヨセ フとその兄弟たちの物語』(1949年)などを手がけた。また、『アラビアン・ナイト・エンターテイメンツ』(1954年)や『エステル記』(1974 年)など、シークが挿絵を描いた本のいくつかは死後に出版された。また、カナダの企業家であり切手愛好家でもあったカシミール・バイルスキーの依頼で、 Visual History of Nations(またはUnited Nations)シリーズの切手の挿絵を手がけた。このプロジェクトは実現しなかったが、シークはアメリカ、ポーランド、イギリス、イスラエルを含む十数 カ国[dubious - discuss][citation needed]の切手アルバムの表紙をデザインした。 アーサー・シックは1948年5月22日にアメリカ市民権を取得したが、その8日前の5月14日、イスラエルの独立宣言が発表された日に、人生で最も幸福 な日を経験したと伝えられている[44]。アーサー・シックはその出来事を記念して、宣言のヘブライ語テキストの豪華な装飾が施されたイルミネーションを 制作した。その2年後の1950年7月4日には、アメリカ合衆国の独立宣言文の豪華なイルミネーションを展示した。画家は、マッカーシズム政策(アメリカ の芸術界や学界で共産主義のシンパを探し、疑惑を抱かせる雰囲気)や人種差別の兆候を批判し、自国の政治に関わり続けた。年の彼の有名なドローイングのひ とつは、武装したクー・クラックス・クランのメンバー2人が、縛られたアフリカ系アメリカ人に近づいていく様子を描いたもので、そのドローイングのキャプ ションには、"主よ、彼らをお赦しください。同時代の多くの率直な芸術家同様、シックは下院非米活動委員会から、反ファシスト難民合同委員会ほか6つの疑 わしい組織のメンバーであると疑われた。しかしシック自身は、共産主義への共感が疑われるこれらの告発を否定し、息子のジョージはサイモン・リフキンド判 事に父の潔白を概説する覚書を送った[45]。 1951年9月13日、アーサー・シックはニューカナンで心臓発作のため死去した[46]: アーサー・シックは偉大な芸術家だった。神によって、美に対する類まれな感受性と、それをグラフィックに表現する類まれな技術を授けられた彼は、その才能 を活かして、芸術の歴史に永遠に残るような、華麗で壮大な作品を次々と生み出した。しかし、アーサー・シックは偉大な芸術家であっただけではない。彼は偉 大な人間であり、正義の擁護者であり、あらゆる人道的努力の大義における恐れを知らぬ戦士であった。芸術は彼の道具であり、彼はそれを見事に使いこなし た。そして、サイモン・H・リフキンド判事の言葉である: 「世界が知っているアーサー・シック、不思議な色彩と美しいデザインのアーサー・シック、今日世界が追悼しているアーサー・シックは、まったく死んでいな い。人類が知っているアーサー・シックは生きていて、不滅であり、真理と美への愛が人類に蔓延する限り不滅であり続けるのに、どうして彼がそうあり得るだ ろうか」[47]。 |

|

Thomas Jefferson's Oath (1951), New Canaan, Connecticut. |

| The

immense popularity Szyk enjoyed in the United States and Europe in his

lifetime gradually flagged after his death. From the 1960s to the end

of the 1980s, the artist's works were seldom exhibited in American

museums. This changed in 1991 when the non-profit organization The

Arthur Szyk Society was established in Orange County, California. The

founder of the Society, George Gooche, rediscovered Szyk's works and

staged the exhibition "Arthur Szyk – Illuminator" in Los Angeles. In

1997, the seat of the Society was transferred to Burlingame,

California, and a new Board of Trustees was elected, headed by rabbi,

curator and antiquarian Irvin Ungar. The Society's work resulted in

staging many exhibitions of Szyk's works in American cities in the

1990s and 2000s. The Society also maintains a large educational

website,[48] holds lectures, and produces publications on the artist.

In April 2017, the Ungar collection of his work, consisting of 450

paintings, drawings and sketches, was purchased for $10.1 million by

the University of California, Berkeley's Magnes Collection of Jewish

Art and Life, through a donation by Taube Philanthropies, the largest

single monetary gift to acquire art in UC Berkeley history.[49][50] Szyk's recent solo exhibitions include: "Arthur Szyk: Soldier in Art", New-York Historical Society, New York City (September 15, 2017 - January 21, 2018)[51] "Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah", Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco (February 13 to June 29, 2014) "Arthur Szyk: Miniature Paintings and Modern Illuminations", California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco (December 10, 2010 to March 27, 2011) "A One-Man Army: The Art of Arthur Szyk", Holocaust Museum Houston (October 20, 2008 – February 8, 2009) "Arthur Szyk – Drawing Against National Socialism and Terror",[52] Deutsches Historisches Museum (DHM), Berlin, Germany (August 29, 2008 – January 4, 2009) "The Art and Politics of Arthur Szyk", United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. (April 10 – October 14, 2002) "Arthur Szyk: Artist for Freedom", Library of Congress (December 9, 1999 – May 6, 2000) "Justice Illuminated: The Art of Arthur Szyk", Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership, Chicago (August 16, 1998 – February 28, 1999)[53] —later traveled throughout Poland: Warsaw, Jewish Historical Institute; Łódź, Museum of the City of Łódź; and Kraków, Center for Jewish Culture. "In Real Times. Arthur Szyk: Art & Human Rights (1926-1951)" The Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, University of California, Berkeley (January 28, 2020 – present)[54] |

生

前、アメリカやヨーロッパで絶大な人気を誇っていたシークの人気は、彼の死後、次第に低迷していった。1960年代から1980年代末まで、アメリカの美

術館で彼の作品が展示されることはほとんどなかった。それが変わったのは1991年、カリフォルニア州オレンジ郡に非営利団体アーサー・シック・ソサエ

ティが設立されたときだった。協会の創設者であるジョージ・グーチェはシックの作品を再発見し、ロサンゼルスで「Arthur Szyk -

Illuminator」展を開催した。1997年、協会の所在地はカリフォルニア州バーリンゲームに移され、ラビ、キュレーター、古美術研究家のアー

ヴィン・ウンガーを会長とする新しい評議員会が選出された。協会の活動により、1990年代から2000年代にかけて、アメリカの各都市でシックの作品展

が数多く開催された。同協会はまた、大規模な教育用ウェブサイトを維持し[48]、レクチャーを開催し、アーティストに関する出版物を制作している。

2017年4月、450点の絵画、ドローイング、スケッチからなる彼の作品のウンガー・コレクションは、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校のマグネス・コレ

クション・オブ・ジューイッシュ・アート・アンド・ライフによって、タウベ・フィランソロピーによる寄付によって、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校史上最

大の美術品取得のための単一金額寄付となる1,010万ドルで購入された[49][50]。 シックの最近の個展は以下の通り: "Arthur Szyk: Soldier in Art", New-York Historical Society, New York City(2017年9月15日~2018年1月21日)[51]。 "Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah", 現代ユダヤ博物館、サンフランシスコ(2014年2月13日~6月29日) "Arthur Szyk: Miniature Paintings and Modern Illuminations"、カリフォルニア・レジオン・オブ・オナー宮殿、サンフランシスコ(2010年12月10日~2011年3月27日) 「アーサー・シックの芸術 アーサー・シックの芸術」、ヒューストン・ホロコースト博物館(2008年10月20日~2009年2月8日) 「Arthur Szyk - Drawing Against National Socialism and Terror",[52] ドイツ歴史博物館(DHM)、ベルリン、ドイツ(2008年8月29日~2009年1月4日) "The Art and Politics of Arthur Szyk"、アメリカ合衆国ホロコースト記念博物館、ワシントンD.C.(2002年4月10日~10月14日) 「アーサー・シック:自由のための芸術家」、米国議会図書館(1999年12月9日~2000年5月6日) "照らされる正義: The Art of Arthur Szyk", Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership, Chicago(1998年8月16日~1999年2月28日)[53] -その後ポーランド各地を巡回: ワルシャワ、ユダヤ歴史研究所、ロチュ、ロチュ市博物館、クラクフ、ユダヤ文化センター。 「In Real Times. アーサー・シック:芸術と人権(1926-1951)" マグネス・コレクション・オブ・ジューイッシュ・アート・アンド・ライフ、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校(2020年1月28日~現在)[54]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Szyk |

|

|

Fool the Axis Use Prophylaxis poster (1942), Philadelphia. |

|

The Nibelungen series, Valhalla (1942), New York. |

|

The Nibelungen series, Ride of the Valkyries (1942), New York. ナチによるワルキューレの騎行だが、ある意味で、ナチの凶暴さを描くのが作者の目的なのに、と同時に「戦争の神」——ヒムラーの愛読書ヴァガヴァッドギー タを想像させる——としてのナチスのイメージを審美的レベルにまでひきあげている、とても不思議で魅力的な、アーサー・シック画:The Nibelungen series, Ride of the Valkyries (1942), New York. |

|

Satan Leads the Ball (1942), New York. |

|

Two Down and One to Go pamphlet (1945), Washington DC. |

|

The Haggadah, The Family at the Seder (1935), Łódź, Poland. |

|

Visual History of Nations, Israel (1948), New Canaan, Connecticut. |

|

"Do Not Forgive Them, O Lord, For They Do Know What They Do!..." (1949), New Canaan, Connecticut. |

|

McCarthyism – "He is Under Investigation, His Blood is Red and His Heart is Left of Center!..." (1949), New Canaan, Connecticut. |

|

The Holiday Series, Rosh Hashanah (1948), New Canaan, Connecticut. |

|

The Book of Esther, Szyk and Haman (1950). New Canaan, Connecticut. |

|

To Be Shot as Dangerous Enemies of the Third Reich (1943), New York. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Szyk |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆