ベンジャミン・リー・ウォーフ

Benjamin Lee Whorf,

1897-1941

☆

ベンジャミン・アトウッド・リー・ウォーフ[Benjamin

Atwood Lee

Whorf](/hwɔːrf/; 1897年4月24日 -

1941年7月26日)は、アメリカの言語学者であり防火技術者であった[1]。彼はサピア=ウォーフ仮説(Linguistic relativity)を提唱したことで最もよく知られて

いる。彼は、異なる言語の構造がその話者が世界を認識し概念化する方法を形作るという考えを持っていた。ウォーフは、自身と師であるエドワード・サピアに

因んで名付けられたこの考えを、アインシュタインの物理的相対性原理と同等の含意を持つものと見なした[2]。しかし、この概念は19世紀の哲学やヴィル

ヘルム・フォン・フンボルト[3]、ヴィルヘルム・ヴントといった思想家に起源を持つ。[4]

ウォーフは当初化学工学を志したが、言語学、特に聖書ヘブライ語やメソアメリカの先住民言語に興味を持つようになった。ナワトル語に関する画期的な研究で

評価を得て、メキシコでさらに研究するための助成金を得た。帰国後、ナワトル語に関する影響力のある論文を発表した。その後、防火技術者として働きなが

ら、イェール大学でエドワード・サピアに師事して言語学を学んだ。

イェール大学在学中、ウォーフはホピ語の記述に取り組み、その時間認識に関する注目すべき主張を行った。またウト・アステカ語族の研究も実施し、影響力の

ある論文を発表した。1938年にはサピアの代理としてアメリカインディアン言語学のセミナーを担当した。ウォーフの貢献は言語相対論に留まらず、ホピ語

の文法概要を執筆し、ナワトル語方言を研究し、マヤ象形文字の解読を提案し、ウト・アステカ語族の再構築に貢献した。

1941年に癌で早世した後、同僚たちは彼の原稿を整理し、言語・文化・認知に関する彼の思想を広めた。しかし1960年代、彼の見解は「検証不可能で不

十分な理論構築」との批判により廃れた。近年ではウォーフの研究への関心が再燃し、学者たちは彼の思想を再評価し、理論の深い理解に取り組んでいる。言語

相対性理論の分野は、現在も心理言語学や言語人類学における活発な研究領域であり、相対主義と普遍主義の間の議論や、言語と人種の関係を研究する人種言語

学においても継続的な議論を生んでいる。ウォーフの言語学への貢献、例えば「異音」や「暗号型」といった概念は広く受け入れられている。

| Benjamin

Atwood Lee

Whorf (/hwɔːrf/; April 24, 1897 – July 26, 1941) was an American

linguist and fire prevention engineer[1] best known for proposing the

Sapir–Whorf hypothesis. He believed that the structures of different

languages shape how their speakers perceive and conceptualize the

world. Whorf saw this idea, named after him and his mentor Edward

Sapir, as having implications similar to those of Einstein's principle

of physical relativity.[2] However, the concept originated from

19th-century philosophy and thinkers like Wilhelm von Humboldt[3] and

Wilhelm Wundt.[4] Whorf initially pursued chemical engineering but developed an interest in linguistics, particularly Biblical Hebrew and indigenous Mesoamerican languages. His groundbreaking work on the Nahuatl language earned him recognition, and he received a grant to study it further in Mexico. He presented influential papers on Nahuatl upon his return. Whorf later studied linguistics with Edward Sapir at Yale University while working as a fire prevention engineer. During his time at Yale, Whorf worked on describing the Hopi language and made notable claims about its perception of time. He also conducted research on the Uto-Aztecan languages, publishing influential papers. In 1938, he substituted for Sapir, teaching a seminar on American Indian linguistics. Whorf's contributions extended beyond linguistic relativity; he wrote a grammar sketch of Hopi, studied Nahuatl dialects, proposed a deciphering of Maya hieroglyphic writing, and contributed to Uto-Aztecan reconstruction. After Whorf's premature death from cancer in 1941, his colleagues curated his manuscripts and promoted his ideas regarding language, culture, and cognition. However, in the 1960s, his views fell out of favor due to criticisms claiming his ideas were untestable and poorly formulated. In recent decades, interest in Whorf's work has resurged, with scholars reevaluating his ideas and engaging in a more in-depth understanding of his theories. The field of linguistic relativity remains an active area of research in psycholinguistics and linguistic anthropology, generating ongoing debates between relativism and universalism, as well as in the study of raciolinguistics. Whorf's contributions to linguistics, such as the allophone and the cryptotype, have been widely accepted. |

ベンジャミン・アトウッド・リー・ウォーフ(/hwɔːrf/;

1897年4月24日 -

1941年7月26日)は、アメリカの言語学者であり防火技術者であった[1]。彼はサピア=ウォーフ仮説を提唱したことで最もよく知られている。彼は、

異なる言語の構造がその話者が世界を認識し概念化する方法を形作るという考えを持っていた。ウォーフは、自身と師であるエドワード・サピアに因んで名付け

られたこの考えを、アインシュタインの物理的相対性原理と同等の含意を持つものと見なした[2]。しかし、この概念は19世紀の哲学やヴィルヘルム・フォ

ン・フンボルト[3]、ヴィルヘルム・ヴントといった思想家に起源を持つ。[4] ウォーフは当初化学工学を志したが、言語学、特に聖書ヘブライ語やメソアメリカの先住民言語に興味を持つようになった。ナワトル語に関する画期的な研究で 評価を得て、メキシコでさらに研究するための助成金を得た。帰国後、ナワトル語に関する影響力のある論文を発表した。その後、防火技術者として働きなが ら、イェール大学でエドワード・サピアに師事して言語学を学んだ。 イェール大学在学中、ウォーフはホピ語の記述に取り組み、その時間認識に関する注目すべき主張を行った。またウト・アステカ語族の研究も実施し、影響力の ある論文を発表した。1938年にはサピアの代理としてアメリカインディアン言語学のセミナーを担当した。ウォーフの貢献は言語相対論に留まらず、ホピ語 の文法概要を執筆し、ナワトル語方言を研究し、マヤ象形文字の解読を提案し、ウト・アステカ語族の再構築に貢献した。 1941年に癌で早世した後、同僚たちは彼の原稿を整理し、言語・文化・認知に関する彼の思想を広めた。しかし1960年代、彼の見解は「検証不可能で不 十分な理論構築」との批判により廃れた。近年ではウォーフの研究への関心が再燃し、学者たちは彼の思想を再評価し、理論の深い理解に取り組んでいる。言語 相対性理論の分野は、現在も心理言語学や言語人類学における活発な研究領域であり、相対主義と普遍主義の間の議論や、言語と人種の関係を研究する人種言語 学においても継続的な議論を生んでいる。ウォーフの言語学への貢献、例えば「異音」や「暗号型」といった概念は広く受け入れられている。 |

| Biography Early life The son of Harry Church Whorf and Sarah Edna Lee Whorf, Benjamin Atwood Lee Whorf was born on April 24, 1897, in Winthrop, Massachusetts. His father was an artist, intellectual, and designer – first working as a commercial artist and later as a dramatist. Whorf had two younger brothers, John and Richard, who both went on to become notable artists. John became an internationally renowned painter and illustrator; Richard was an actor in films such as Yankee Doodle Dandy and later an Emmy-nominated television director of such shows as The Beverly Hillbillies. Whorf was the intellectual of the three and started conducting chemical experiments with his father's photographic equipment at a young age.[5] He was also an avid reader, interested in botany, astrology, and Middle American prehistory. He read William H. Prescott's Conquest of Mexico several times. At the age of 17, he began keeping a copious diary in which he recorded his thoughts and dreams.[6] Career in fire prevention In 1918, Whorf graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where his academic performance was of average quality[citation needed], with a degree in chemical engineering. In 1920, he married Celia Inez Peckham; they had three children, Raymond Ben, Robert Peckham and Celia Lee.[6] Around the same time he began work as a fire prevention engineer (an inspector) for the Hartford Fire Insurance Company. He was particularly good at the job and was highly commended by his employers. His job required him to travel to production facilities throughout New England to be inspected. One anecdote describes him arriving at a chemical plant and being denied access by the director, who would not allow anyone to see the production procedure, which was a trade secret. Having been told what the plant produced, Whorf wrote a chemical formula on a piece of paper, saying to the director: "I think this is what you're doing". The surprised director asked Whorf how he knew about the secret procedure, and he simply answered: "You couldn't do it in any other way."[7] Whorf helped to attract new customers to the Fire Insurance Company; they favored his thorough inspections and recommendations. Another famous anecdote from his job was used by Whorf to argue that language use affects habitual behavior.[8] Whorf described a workplace in which full gasoline drums were stored in one room and empty ones in another; he said that because of flammable vapor the "empty" drums were more dangerous than those that were full, although workers handled them less carefully to the point that they smoked in the room with "empty" drums, but not in the room with full ones. Whorf argued that by habitually speaking of the vapor-filled drums as empty and by extension as inert, the workers were oblivious to the risk posed by smoking near the "empty drums".[w 1] Early interest in religion and language Whorf was a spiritual man throughout his lifetime, although what religion he followed has been the subject of debate. As a young man, he produced a manuscript titled "Why I have discarded evolution", causing some scholars to describe him as a devout Methodist, who was impressed with fundamentalism, and perhaps supportive of creationism.[9] However, throughout his life Whorf's main religious interest was Theosophy, a nonsectarian organization based on Buddhist and Hindu teachings that promotes the view of the world as an interconnected whole and the unity and brotherhood of humankind "without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste or color".[10] Some scholars have argued that the conflict between spiritual and scientific inclinations has been a driving force in Whorf's intellectual development, particularly in the attraction by ideas of linguistic relativity.[11] Whorf said that "of all groups of people with whom I have come in contact, Theosophical people seem the most capable of becoming excited about ideas—new ideas."[12] Around 1924, Whorf first became interested in linguistics. Originally, he analyzed Biblical texts, seeking to uncover hidden layers of meaning.[13] Inspired by the esoteric work La langue hebraïque restituée by Antoine Fabre d'Olivet, he began a semantic and grammatical analysis of Biblical Hebrew. Whorf's early manuscripts on Hebrew and Maya have been described as exhibiting a considerable degree of mysticism, as he sought to uncover esoteric meanings of glyphs and letters.[14] |

伝記 幼少期 ハリー・チャーチ・ウォーフとサラ・エドナ・リー・ウォーフの息子であるベンジャミン・アトウッド・リー・ウォーフは、1897年4月24日にマサチュー セッツ州ウィンスロップで生まれた。父は芸術家、知識人、デザイナーであり、最初は商業美術家として働き、後に劇作家となった。ウォーフにはジョンとリ チャードという二人の弟がおり、二人とも後に著名な芸術家となった。ジョンは国際的に有名な画家・イラストレーターとなり、リチャードは『ヤンキー・ ドゥードル・ダンディ』などの映画俳優を経て、『ビバリーヒルビリーズ』などのエミー賞ノミネート番組を手がけるテレビディレクターとなった。三兄弟の中 で知的なのはウォーフで、幼い頃から父の写真機材を使って化学実験を始めた[5]。また熱心な読書家であり、植物学、占星術、中米先史時代に興味を持って いた。ウィリアム・H・プレスコットの『メキシコ征服』を何度も読んだ。17歳の時、膨大な日記をつけ始め、思考や夢を記録した。[6] 防火技術者としての経歴 1918年、ウォーフはマサチューセッツ工科大学を卒業した。学業成績は平均的だった[出典必要]。化学工学の学位を取得した。1920年、セリア・イネ ス・ペッカムと結婚し、レイモンド・ベン、ロバート・ペッカム、セリア・リーの3人の子をもうけた[6]。同時期にハートフォード火災保険会社の防火検査 技師(検査官)として勤務を開始。特にこの職務に秀でており、雇用主から高く評価された。仕事上、ニューイングランド全域の生産施設を視察するため出張が 必要だった。ある逸話によれば、化学工場を訪れた際、工場長から「製造工程は営業秘密だから誰も見せてやらない」と立ち入りを拒否された。工場の生産品に ついて聞かされたウォーフは、紙に定式を書きながら工場長に言った。「君たちがやっているのはこれだろう」。驚いた所長が「どうやって秘密の工程を知った のか」と尋ねると、彼はただこう答えた。「他の方法では作れないでしょう」[7] ウォーフは火災保険会社に新規顧客を呼び込むのに貢献した。顧客は彼の徹底した検査と提案を高く評価した。彼の仕事に関する別の有名な逸話は、言語の使用 が習慣的な行動に影響を与えるという彼の主張の根拠として用いられた。[8] ウォーフは、満タンのガソリンドラムが1つの部屋に、空のドラムが別の部屋に保管されている職場を説明した。彼は、可燃性蒸気のため「空」のドラムの方が 満タンのドラムよりも危険だと述べた。にもかかわらず、作業員たちは「空」のドラムがある部屋では喫煙するなど、満タンのドラムがある部屋ではしないほ ど、それらを不注意に扱っていた。ウォーフは、労働者が習慣的に蒸気で満たされたドラム缶を「空」と呼び、さらに「無害」と見なすことで、「空のドラム 缶」付近での喫煙がもたらす危険性に気づいていないと論じた。[w 1] 宗教と言語への初期の関心 ウォーフは生涯を通じて精神的な人間であったが、彼がどの宗教を信仰していたかは議論の的となっている。若い頃、彼は「なぜ私は進化論を捨てたのか」とい う題名の原稿を執筆し、一部の学者は彼を敬虔なメソジスト教徒、原理主義に感銘を受けた人物、おそらく創造論を支持する人物と描写した。[9] しかし生涯を通じて、ウォーフの主な宗教的関心は神智学(Theosophy) にあった。これは仏教とヒンドゥー教の教えに基づく非宗派組織で、世界を相互に連関した全体として捉え、「人種、信条、性別、カースト、肌の色による区別 なく」人類の統一と兄弟愛を提唱する。[10] 一部の学者は、精神的傾向と科学的傾向の葛藤がウォーフの知的発展の原動力となり、特に言語相対性理論への傾倒を促したと論じている。[11] ウォーフは「私が接触したあらゆる集団の中で、神智学の人民は新しい思想に対して最も熱狂しやすい」と述べている。[12] 1924年頃、ウォーフは初めて言語学に興味を持った。当初は聖書のテキストを分析し、隠された意味の層を解き明かそうとした[13]。アントワーヌ・ ファブル・ド・オリヴェの難解な著作『復元されたヘブライ語』に触発され、聖書ヘブライ語の意味論的・文法的分析を始めた。ウォーフのヘブライ語とマヤ語 に関する初期の原稿は、象形文字や文字の秘教的な意味を解明しようとしたため、かなりの神秘主義を示していると評されている。[14] |

| Early studies in Mesoamerican linguistics Whorf studied Biblical linguistics mainly at the Watkinson Library (now Hartford Public Library). This library had an extensive collection of materials about Native American linguistics and folklore, originally collected by James Hammond Trumbull.[15] It was at the Watkinson library that Whorf became friends with a young boy, John B. Carroll, who later went on to study psychology under B. F. Skinner, and who in 1956 edited and published a selection of Whorf's essays as Language, Thought and Reality Carroll (1956b). The collection rekindled Whorf's interest in Mesoamerican antiquity. He began studying the Nahuatl language in 1925, and later, beginning in 1928, he studied the collections of Maya hieroglyphic texts. Quickly becoming conversant with the materials, he began a scholarly dialog with Mesoamericanists such as Alfred Tozzer, the Maya archaeologist at Harvard University, and Herbert Spinden of the Brooklyn Museum.[15] In 1928, he first presented a paper at the International Congress of Americanists in which he presented his translation of a Nahuatl document held at the Peabody Museum at Harvard. He also began to study the comparative linguistics of the Uto-Aztecan language family, which Edward Sapir had recently demonstrated to be a linguistic family. In addition to Nahuatl, Whorf studied the Piman and Tepecano languages, while in close correspondence with linguist J. Alden Mason.[15] |

メソアメリカ言語学の初期研究 ウォーフは主にワトキンソン図書館(現ハートフォード公共図書館)で聖書言語学を研究した。この図書館にはジェームズ・ハモンド・トランブルが収集した先 住民言語学と民俗学に関する膨大な資料が所蔵されていた。[15] ワトキンソン図書館で、ウォーフは少年ジョン・B・キャロルと親しくなった。キャロルは後にB・F・スキナーのもとで心理学を学び、1956年にはウォー フの論文集を編集・出版した(キャロル 1956b)。このコレクションはウォーフの中米古代史への関心を再燃させた。彼は1925年にナワトル語の研究を始め、その後1928年からはマヤ象形 文字文書のコレクションを研究した。資料にすぐに精通した彼は、ハーバード大学のマヤ考古学者であるアルフレッド・トザーやブルックリン博物館のハーバー ト・スピンドンといった中米研究者たちと学術的な対話を始めた。[15] 1928年、彼は国際アメリカ研究会議で初めて論文を発表した。その内容はハーバード大学ピーボディ博物館所蔵のナワトル語文書の翻訳だった。またエド ワード・サピアが言語族であることを最近実証したウト・アステカ語族の比較言語学研究も始めた。ナワトル語に加え、ウォーフはピマン語とテペカノ語も研究 した。その間、言語学者J・オールデン・メイソンと緊密な文通を交わしていた。[15] |

| Field studies in Mexico Because of the promise shown by his work on Uto-Aztecan, Tozzer and Spinden advised Whorf to apply for a grant with the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) to support his research. Whorf considered using the money to travel to Mexico to procure Aztec manuscripts for the Watkinson library, but Tozzer suggested he spend the time in Mexico documenting modern Nahuatl dialects.[15] In his application Whorf proposed to establish the oligosynthetic nature of the Nahuatl language. Before leaving Whorf presented the paper "Stem series in Maya" at the Linguistic Society of America conference, in which he argued that in the Mayan languages syllables carry symbolic content. The SSRC awarded Whorf the grant and in 1930 he traveled to Mexico City, where Professor Robert H. Barlow put him in contact with several speakers of Nahuatl to serve as his informants. The outcome of the trip to Mexico was Whorf's sketch of Milpa Alta Nahuatl, published only after his death, and an article on a series of Aztec pictograms found at the Tepozteco monument at Tepoztlán, Morelos in which he noted similarities in form and meaning between Aztec and Maya day signs.[16] |

メキシコにおける現地調査 ウート・アステカ語に関する研究の成果が評価されたため、トザーとスピンドンはウォーフに社会科学研究評議会(SSRC)の助成金を申請するよう助言し た。ウォーフはワトキンソン図書館のためにアステカ語写本を入手する目的でメキシコへ渡航することを考えたが、トザーは現代ナワトル語方言の記録に時間を 費やすよう提案した。[15] 申請書の中でウォーフは、ナワトル語が寡合成語であるという性質を立証することを提案した。出発前にウォーフはアメリカ言語学会で「マヤ語の語幹系列」と 題する論文を発表し、マヤ語族では音節が象徴的内容を運ぶと論じた。SSRCはウォーフに助成金を授与し、1930年に彼はメキシコシティへ渡った。そこ でロバート・H・バーロウ教授が、情報提供者として協力する複数のナワトル語話者を紹介した。メキシコ旅行の成果は、死後になってようやく出版されたミル パ・アルタ・ナワトル語の概説と、モレロス州テポツトランにあるテポツテコ記念碑で発見された一連のアステカ象形文字に関する論文であった。この論文で彼 は、アステカとマヤの日付記号の形態と意味の類似性を指摘している。[16] |

At Yale Edward Sapir, Whorf's mentor in linguistics at Yale Although Whorf had been entirely an autodidact in linguistic theory and field methodology up to this point, he had already made a name for himself in Mesoamerican linguistics. Whorf had met Sapir, the leading US linguist of the day, at professional conferences, and in 1931 Sapir came to Yale from the University of Chicago to take a position as Professor of Anthropology. Alfred Tozzer sent Sapir a copy of Whorf's paper on "Nahuatl tones and saltillo". Sapir replied stating that it "should by all means be published";[17] however, it was not until 1993 that it was prepared for publication by Lyle Campbell and Frances Karttunen.[18] Whorf took Sapir's first course at Yale on "American Indian Linguistics". He enrolled in a program of graduate studies, nominally working towards a PhD in linguistics, but he never actually attempted to obtain a degree, satisfying himself with participating in the intellectual community around Sapir. At Yale, Whorf joined the circle of Sapir's students that included such luminaries as Morris Swadesh, Mary Haas, Harry Hoijer, G. L. Trager and Charles F. Voegelin. Whorf took on a central role among Sapir's students and was well respected.[16][19] Sapir had a profound influence on Whorf's thinking. Sapir's earliest writings had espoused views of the relation between thought and language stemming from the Humboldtian tradition he acquired through Franz Boas, which regarded language as the historical embodiment of volksgeist, or ethnic world view. But Sapir had since become influenced by a current of logical positivism, such as that of Bertrand Russell and the early Ludwig Wittgenstein, particularly through Ogden and Richards' The Meaning of Meaning, from which he adopted the view that natural language potentially obscures, rather than facilitates, the mind to perceive and describe the world as it really is. In this view, proper perception could only be accomplished through formal logics. During his stay at Yale, Whorf acquired this current of thought partly from Sapir and partly through his own readings of Russell and of Ogden and Richards.[14] As Whorf became more influenced by positivist science, he also distanced himself from some approaches to language and meaning that he saw as lacking in rigor and insight. One of these was Polish philosopher Alfred Korzybski's General semantics, which was espoused in the US by Stuart Chase. Chase admired Whorf's work and frequently sought out a reluctant Whorf, who considered Chase to be "utterly incompetent by training and background to handle such a subject."[20] Ironically, Chase would later write the foreword for Carroll's collection of Whorf's writings. |

イェール大学にて エドワード・サピアは、イェール大学でウォーフの言語学の師であった ウォーフは、この時点まで言語理論とフィールド調査の方法論において完全に独学であったが、メソアメリカ言語学の分野では既に名を馳せていた。ウォーフ は、当時の米国を代表する言語学者であるサピアと専門会議で出会い、1931年にサピアはシカゴ大学からイェール大学に移り、人類学の教授に就任した。ア ルフレッド・トッザーは、ウォーフの「ナワトル語の音調とサルティージョ」に関する論文の写しをサピアに送った。サピアは「ぜひとも出版すべきだ」と返事 を送った[17]。しかし、ライル・キャンベルとフランシス・カートゥネンによって出版の準備が整ったのは、1993年になってからのことだった [18]。 ウォーフは、イェール大学でサピアが初めて開講した「アメリカインディアン言語学」の講義を受講した。彼は大学院課程に入学し、名目上は言語学の博士号取 得を目指したが、実際には学位の取得を試みることはなく、サピアを中心とした知的コミュニティに参加することで満足していた。イェール大学では、ウォーフ は、モリス・スワデッシュ、メアリー・ハース、ハリー・ホイジャー、G・L・トレーガー、チャールズ・F・フォーゲリンなどの著名な学者たちを含む、サピ アの学生たちのサークルに加わった。ウォーフはサピアの学生たちの中で中心的な役割を担い、高く評価されていた。[16][19] サピアはウォーフの思考に深い影響を与えた。サピアの初期の著作は、フランツ・ボアズを通じて得たフンボルトの伝統に由来する、思考と言語の関係に関する 見解を支持していた。それは言語を民族精神(フォルクスガイスト)あるいは民族的世界観の歴史的体現と見なすものであった。しかしその後、サピアは論理実 証主義の流れ、特にバートランド・ラッセルや初期ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの影響を受けるようになった。特にオグデンとリチャーズの『意味の意 味』を通じて、自然言語は世界をありのままに知覚し記述することを促進するのではなく、むしろ潜在的に妨げるとの見解を採用したのである。この見解では、 適切な認識は形式論理によってのみ達成できるとされた。イェール大学在学中、ウォーフはこの思想の流れを、一部はサピアから、一部はラッセルやオグデン、 リチャーズの著作を自ら読んだことから得た[14]。ウォーフは実証主義的な科学の影響を強く受けるにつれて、厳密さや洞察力に欠けると思われる言語や意 味に対するいくつかのアプローチからも距離を置くようになった。その一つが、ポーランドの哲学者アルフレッド・コルジブスキーの一般意味論であり、これは スチュワート・チェイスによって米国で支持されていた。チェイスはウォーフの仕事を賞賛し、チェイスを「その訓練と経歴から、このような主題を扱うには まったく無能である」と考えていたウォーフを、しぶしぶながら頻繁に訪ねた[20]。皮肉なことに、チェイスは後に、キャロルが編集したウォーフの著作集 の序文を執筆することになった。 |

| Work on Hopi and descriptive linguistics Sapir also encouraged Whorf to continue his work on the historical and descriptive linguistics of Uto-Aztecan. Whorf published several articles on that topic in this period, some of them with G. L. Trager, who had become his close friend. Whorf took a special interest in the Hopi language and started working with Ernest Naquayouma, a speaker of Hopi from Toreva village living in Manhattan, New York. Whorf credited Naquayouma as the source of most of his information on the Hopi language, although in 1938 he took a short field trip to the village of Mishongnovi, on the Second Mesa of the Hopi Reservation in Arizona.[21] In 1936, Whorf was appointed honorary research fellow in anthropology at Yale, and he was invited by Franz Boas to serve on the committee of the Society of American Linguistics (later Linguistic Society of America). In 1937, Yale awarded him the Sterling Fellowship.[22] He was a lecturer in anthropology from 1937 through 1938, replacing Sapir, who was gravely ill.[23] Whorf gave graduate level lectures on "Problems of American Indian Linguistics". In 1938 with Trager's assistance he elaborated a report on the progress of linguistic research at the department of anthropology at Yale. The report includes some of Whorf's influential contributions to linguistic theory, such as the concept of the allophone and of covert grammatical categories. Lee (1996) has argued, that in this report Whorf's linguistic theories exist in a condensed form, and that it was mainly through this report that Whorf exerted influence on the discipline of descriptive linguistics.[n 1] |

ホピ語と記述言語学に関する研究 サピアはまた、ウォーフにウト・アステカ語族の歴史言語学および記述言語学の研究を続けるよう勧めた。ウォーフはこの時期にその主題に関する数本の論文を 発表し、その一部は親しい友人となったG・L・トレーガーとの共著であった。ウォーフは特にホピ語に関心を持ち、ニューヨーク州マンハッタン在住のトレバ 村出身のホピ語話者、アーネスト・ナクアイウマとの共同研究を開始した。ウォーフはホピ語に関する情報のほとんどをナクアイウマから得たと認めているが、 1938年にはアリゾナ州ホピ保留地のセカンドメサにあるミションノビ村へ短期の現地調査を行った。[21] 1936年、ウォーフはイェール大学の人類学名誉研究員に任命され、フランツ・ボアズからアメリカ言語学会(後のアメリカ言語学会)の委員会への参加を要 請された。1937年にはイェール大学からスターリング研究員に選ばれた。[22] 1937年から1938年にかけて、重病のサピアに代わり人類学の講師を務めた。[23] ウォーフは大学院レベルで「アメリカインディアン言語学の問題」に関する講義を行った。1938年にはトレーガーの協力を得て、イェール大学人類学部にお ける言語研究の進捗状況に関する報告書をまとめた。この報告書には、異音概念や潜在的文法範疇といった、ウォーフの言語理論への影響力ある貢献が含まれて いる。リー(1996)は、この報告書にウォーフの言語理論が凝縮された形で存在し、主にこの報告書を通じてウォーフが記述言語学の分野に影響を与えたと 論じている。[n 1] |

| Final years In late 1938, Whorf's own health declined. After an operation for cancer, he fell into an unproductive period. He was also deeply affected by Sapir's death in early 1939. It was in the writings of his last two years that he laid out the research program of linguistic relativity. His 1939 memorial article for Sapir, "The Relation of Habitual Thought And Behavior to Language",[w 1] in particular has been taken to be Whorf's definitive statement of the issue, and is his most frequently quoted piece.[24] In his last year Whorf also published three articles in the MIT Technology Review titled "Science and Linguistics",[w 2] "Linguistics as an Exact Science" and "Language and Logic". He was also invited to contribute an article to a theosophical journal, Theosophist, published in Madras, India, for which he wrote "Language, Mind and Reality".[w 3] In these final pieces, he offered a critique of Western science in which he suggested that non-European languages often referred to physical phenomena in ways that more directly reflected aspects of reality than many European languages, and that science ought to pay attention to the effects of linguistic categorization in its efforts to describe the physical world. He particularly criticized the Indo-European languages for promoting a mistaken essentialist world view, which had been disproved by advances in the science, in contrast suggesting that other languages dedicated more attention to processes and dynamics rather than stable essences.[14] Whorf argued that paying attention to how other physical phenomena are described across languages could make valuable contributions to science by pointing out the ways in which certain assumptions about reality are implicit in the structure of language itself, and how language guides the attention of speakers towards certain phenomena in the world; these phenomena risk becoming overemphasized while leaving other phenomena at risk of being overlooked.[25] |

晩年 1938年後半、ウォーフ自身の健康が悪化した。癌の手術後、彼は生産性の低い時期に陥った。また1939年初頭のサピアの死にも深く心を痛めた。言語相 対性理論の研究計画を提示したのは、彼の最後の2年間の著作においてであった。特に1939年にサピアを追悼して書いた論文「習慣的思考と行動と言語の関 係」[w 1]は、ウォーフのこの問題に関する決定的な主張と見なされ、最も頻繁に引用される作品である。[24] 最期の年には『MITテクノロジーレビュー』誌に「科学と言語学」[w 2]、「精密科学としての言語学」、「言語と論理」の三編を寄稿した。またインド・マドラス発行の神智学雑誌『神智学者』から寄稿を依頼され、「言語、精 神、現実」を執筆している。[w 3] これらの最終論文において、彼は西洋科学に対する批判を展開した。非ヨーロッパ言語は物理現象を、多くのヨーロッパ言語よりも現実の側面をより直接的に反 映する形で表現することが多いと示唆し、科学は物理世界を記述する努力において言語的分類の影響に注意を払うべきだと主張したのである。彼は特にインド・ ヨーロッパ語族が誤った本質主義的世界観を助長していると批判した。この世界観は科学の進歩によってすでに否定されていた。対照的に、他の言語は安定した 本質よりもプロセスや動態により多くの注意を払っていると示唆したのである。[14] ウォーフは、言語間で物理現象がどのように記述されるかに注目することで、現実に関する特定の前提が言語構造自体に暗黙的に含まれている点や、言語が話者 の注意を世界の特定現象へ向けさせる仕組みを指摘し、科学に貴重な貢献ができると主張した。こうした現象は過度に強調されるリスクがある一方で、他の現象 は見過ごされる危険性があるのだ。[25] |

| Posthumous reception and legacy At Whorf's death, his friend G. L. Trager was appointed as curator of his unpublished manuscripts. Some of them were published in the years after his death by another of Whorf's friends, Harry Hoijer. In the decade following, Trager and particularly Hoijer did much to popularize Whorf's ideas about linguistic relativity, and it was Hoijer who coined the term "Sapir–Whorf hypothesis" at a 1954 conference.[26] Trager then published an article titled "The systematization of the Whorf hypothesis",[27] which contributed to the idea that Whorf had proposed a hypothesis that should be the basis for a program of empirical research. Hoijer also published studies of Indigenous languages and cultures of the American South West in which Whorf found correspondences between cultural patterns and linguistic ones. The term, even though technically a misnomer, went on to become the most widely known label for Whorf's ideas.[28] According to John A. Lucy, "Whorf's work in linguistics was and still is recognized as being of superb professional quality by linguists".[29] |

死後の評価と遺産 ウォーフの死後、友人であるG・L・トレーガーが彼の未発表原稿の管理者に任命された。その一部は、ウォーフの別の友人であるハリー・ホイヤーによって死 後数年かけて出版された。その後10年間、トレーガー、特にホイヤーは言語相対性に関するウォーフの考えを広めることに尽力し、1954年の会議で「サピ ア=ウォーフ仮説」という用語を考案したのはホイヤーであった。[26] その後トレーガーは「ウォーフ仮説の体系化」[27]と題する論文を発表し、ウォーフが実証的研究計画の基盤となるべき仮説を提唱したとの見解に貢献し た。ホイヤーもまたアメリカ南西部の先住民言語と文化に関する研究を発表し、ウォーフは文化パターンと言語パターンの対応関係を発見した。この用語は、厳 密には誤称であるにもかかわらず、ウォーフの思想を表す最も広く知られる名称となった[28]。ジョン・A・ルーシーによれば、「ウォーフの言語学におけ る業績は、当時も今も、言語学者によって卓越した専門的品質を持つものと認められている」[29]。 |

| Universalism and anti-Whorfianism Whorf's work began to fall out of favor less than a decade after his death, and he was subjected to severe criticism from scholars of language, culture and psychology. In 1953 and 1954, psychologists Roger Brown and Eric Lenneberg criticized Whorf for his reliance on anecdotal evidence, formulating a hypothesis to scientifically test his ideas, which they limited to an examination of a causal relation between grammatical or lexical structure and cognition or perception. Whorf himself did not advocate a straight causality between language and thought; instead he wrote that "Language and culture had grown up together"; that both were mutually shaped by the other.[w 1] Hence, Lucy (1992a) has argued that because the aim of the formulation of the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis was to test simple causation, it failed to test Whorf's ideas from the outset. Focusing on color terminology, with easily discernible differences between perception and vocabulary, Brown and Lenneberg published in 1954 a study of Zuni color terms that slightly support a weak effect of semantic categorization of color terms on color perception.[30][31] In doing so they began a line of empirical studies that investigated the principle of linguistic relativity.[n 2] Empirical testing of the Whorfian hypothesis declined in the 1960s to 1980s as Noam Chomsky began to redefine linguistics and much of psychology in formal universalist terms. Several studies from that period refuted Whorf's hypothesis, demonstrating that linguistic diversity is a surface veneer that masks underlying universal cognitive principles.[32][33] Many studies were highly critical and disparaging in their language, ridiculing Whorf's analyses and examples or his lack of an academic degree.[n 3] Throughout the 1980s, most mentions of Whorf or of the Sapir–Whorf hypotheses continued to be disparaging, and led to a widespread view that Whorf's ideas had been proven wrong. Because Whorf was treated so severely in the scholarship during those decades, he has been described as "one of the prime whipping boys of introductory texts to linguistics".[34] With the advent of cognitive linguistics and psycholinguistics in the late 1980s, some linguists sought to rehabilitate Whorf's reputation, as scholarship began to question whether earlier critiques of Whorf were justified.[35] By the 1960s, analytical philosophers also became aware of the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, and philosophers such as Max Black and Donald Davidson[36] published scathing critiques of Whorf's strong relativist viewpoints. Black characterized Whorf's ideas about metaphysics as demonstrating "amateurish crudity".[37] According to Black and Davidson, Whorf's viewpoint and the concept of linguistic relativity meant that translation between languages with different conceptual schemes would be impossible.[n 4] Recent assessments such as those by Leavitt and Lee, however, consider Black and Davidson's interpretation to be based on an inaccurate characterization of Whorf's viewpoint, and even rather absurd given the time he spent trying to translate between different conceptual schemes. In their view, the critiques are based on a lack of familiarity with Whorf's writings; according to these recent Whorf scholars a more accurate description of his viewpoint is that he thought translation to be possible, but only through careful attention to the subtle differences between conceptual schemes.[38][39] Eric Lenneberg, Noam Chomsky,[40] and Steven Pinker[41][42] have also criticized Whorf for failing to be sufficiently clear in his formulation of how language influences thought, and for failing to provide real evidence to support his assumptions. Generally Whorf's arguments took the form of examples that were anecdotal or speculative, and functioned as attempts to show how "exotic" grammatical traits were connected to what were considered equally exotic worlds of thought. Even Whorf's defenders admitted that his writing style was often convoluted and couched in neologisms – attributed to his awareness of language use, and his reluctance to use terminology that might have pre-existing connotations.[43] McWhorter (2009:156) argues that Whorf was mesmerized by the foreignness of indigenous languages, and exaggerated and idealized them. According to Lakoff, Whorf's tendency to exoticize data must be judged in the historical context: Whorf and the other Boasians wrote at a time in which racism and jingoism were predominant, and when it was unthinkable to many that "savages" had redeeming qualities, or that their languages were comparable in complexity to those of Europe. For this alone Lakoff argues, Whorf can be considered to be "[n]ot just a pioneer in linguistics, but a pioneer as a human being".[44] Today, many followers of universalist schools of thought continue to oppose the idea of linguistic relativity, seeing it as unsound or even ridiculous.[45] For example, Steven Pinker argues in his book The Language Instinct that thought exists prior to language and independently of it, a view also espoused by philosophers of language such as Jerry Fodor, John Locke and Plato. In this interpretation, language is inconsequential to human thought because humans do not think in "natural" language, i.e. any language used for communication. Rather, we think in a meta-language that precedes natural language, which Pinker following Fodor calls "mentalese." Pinker attacks what he calls "Whorf's radical position", declaring, "the more you examine Whorf's arguments, the less sense they make."[46] Scholars of a more "relativist" bent such as John A. Lucy and Stephen C. Levinson have criticized Pinker for misrepresenting Whorf's views and arguing against strawmen.[47][n 5] |

普遍主義と反ウォーフ主義 ウォーフの業績は彼の死後10年も経たないうちに評価を落とし始め、言語学、文化学、心理学の学者たちから厳しい批判を受けた。1953年と1954年、 心理学者ロジャー・ブラウンとエリック・レンバーグは、ウォーフが事例証拠に依存している点を批判し、彼の考えを科学的に検証する仮説を提唱した。彼らは その検証を、文法的・語彙的構造と認知・知覚の因果関係の検討に限定した。ウォーフ自身は言語と思考の間に単純な因果関係を主張していなかった。むしろ彼 は「言語と文化は共に成長してきた」と記し、両者が互いに形成し合っていると述べた[w 1]。したがってルーシー(1992a)は、サピア=ウォーフ仮説の定式化の目的が単純な因果関係の検証にあったため、当初からウォーフの考えを検証でき ていなかったと論じている。 知覚と語彙の差異が明確に識別可能な色用語に焦点を当て、ブラウンとレネバーグは1954年にズニ族の色用語に関する研究を発表した。この研究は、色用語 の意味的分類が色知覚に及ぼす弱い影響をわずかに支持するものである。[30][31] これにより彼らは言語相対性原理を検証する一連の実証的研究の先駆けとなった。[n 2] ウォーフ仮説の実証的検証は、ノーム・チョムスキーが形式普遍主義の観点から言語学と心理学の大部分を再定義し始めた1960年代から1980年代にかけ て衰退した。この時期の数々の研究は、言語的多様性は普遍的な認知原理を覆い隠す表面的な装飾に過ぎないと示し、ウォーフの仮説を反駁した。[32] [33] 多くの研究は、ウォーフの分析や事例、あるいは彼の学位の欠如を嘲笑し、その表現は極めて批判的で軽蔑的であった。[n 3] 1980年代を通じて、ウォーフやサピア=ウォーフ仮説への言及の大半は依然として軽蔑的であり、ウォーフの考えは誤りだと証明されたという見解が広く浸 透した。この数十年間、学術界でウォーフがこれほど厳しく扱われたため、彼は「言語学入門書における主要なスケープゴートの一人」と評されてきた。 [34] 1980年代後半に認知言語学と心理言語学が登場すると、一部の言語学者はウォーフの評判を回復させようと試みた。学術界が、以前のウォーフ批判が正当 だったかどうかを疑問視し始めたためである。[35] 1960年代までに、分析哲学者の間でもサピア=ウォーフ仮説が認知されるようになり、マックス・ブラックやドナルド・デイヴィッドソン[36]といった 哲学者がウォーフの強い相対主義的見解に対して痛烈な批判を発表した。ブラックはウォーフの形而上学に関する考え方を「素人じみた粗雑さ」の表れだと評し た。[37] ブラックとデイヴィッドソンによれば、ウォーフの見解と言語相対性概念は、異なる概念体系を持つ言語間の翻訳が不可能であることを意味していた[注4]。 しかし、リーヴィットやリーらによる近年の評価では、ブラックとデイヴィッドソンの解釈はウォーフの見解を不正確に特徴づけたものであり、異なる概念体系 間の翻訳を試みた彼の努力を考慮すればむしろ荒唐無稽であるとされている。彼らの見解では、こうした批判はウォーフの著作に対する理解不足に基づいてい る。最近のウォーフ研究者によれば、彼の見解をより正確に表現すると、翻訳は可能だが、概念体系間の微妙な差異に細心の注意を払うことによってのみ可能だ と考えていたという。[38] [39] エリック・レンバーグ、ノーム・チョムスキー[40]、スティーブン・ピンカー[41][42]もまた、言語が思考に与える影響の定式化が不十分であり、 仮説を裏付ける実証的証拠を提供していない点でウォーフを批判している。概してウォーフの議論は、逸話的あるいは推測的な事例を形式とし、「異質な」文法 的特徴が、同様に異質と見なされる思考の世界とどう結びつくかを示そうとする試みとして機能していた。ウォーフの擁護者でさえ、彼の文章スタイルがしばし ば複雑で新語に満ちていることを認めている。これは言語使用への自覚と、既存の含意を持つ用語の使用を嫌ったためとされる[43]。マクワーター (2009:156)は、ウォーフが先住民言語の異質性に魅了され、それらを誇張し理想化したと論じている。レイコフによれば、ウォーフのデータを異国的 に扱う傾向は歴史的文脈で評価すべきだ。ウォーフや他のボアシア派が執筆した時代は人種主義や愛国主義が蔓延し、「野蛮人」に救いようのある性質があるこ とや、彼らの言語がヨーロッパの言語と同等の複雑さを持つことなど、多くの人にとって考えられない時代だった。この点だけで、ウォーフは「言語学の先駆者 であるだけでなく、人間としての先駆者」と見なすことができるとレイコフは主張する。[44] 今日、普遍主義の学派の多くの信奉者は、言語相対性理論を不健全あるいはばかばかしいとみなして、依然として反対している。[45] 例えば、スティーブン・ピンカーは著書『言語本能』の中で、思考は言語に先立って、言語とは独立して存在すると主張している。この見解は、ジェリー・フォ ドル、ジョン・ロック、プラトンなどの言語哲学者も支持している。この解釈では、人間は「自然言語」、つまりコミュニケーションに使用される言語では思考 しないため、言語は人間の思考にとって重要ではない。むしろ、私たちは自然言語に先行するメタ言語、すなわちフォドルに倣ってピンカーが「メンタル語」と 呼ぶ言語で思考している。ピンカーは、彼が「ウォーフの急進的な立場」と呼ぶものを攻撃し、「ウォーフの主張を詳しく検討すればするほど、その主張は意味 をなさなくなる」と宣言している。[46] ジョン・A・ルーシーやスティーブン・C・レビンソンなど、より「相対主義的」な傾向のある学者たちは、ピンカーがウォーフの見解を誤って表現し、詭弁的 な議論をしていると批判している。[47][n 5] |

| Corroboration of Whorf's claims The idea that Whorf defended a kind of "linguistic relativity" stems from his article "Language, Mind and Reality" published during the Second World War, where Whorf criticized American scientists, especially some physicists who were searching for a substance where there are only substantive words such as energy and searching for an expenditure of energy where there are only transitive verbs such as transform, thus trying to disprove Einstein's Theory of Relativity, which helps us predict how much mass must be consumed to produce how much energy. Whorf claimed in this article that this "Aryan Western Logic" coming from "Western Languages" was stopping scientists to accept the theory and spend efforts on its applications, such as the creation of the atomic bomb, which could be decisive for the United States to win or lose the war against the Germans. This is a period when some national socialists in Germany were trying to develop an Aryan Physics, free from counterintuitive findings by Jewish physicists such as Albert Einstein.[48] Studies on the construction of experience through meaning [49] have been increasing since the 1990s, and a series of experimental results have corroborated Whorf's claims, when understood as he presented them, especially in cultural psychology and linguistic anthropology.[50] One of the earliest linguistic descriptions directing positive attention towards Whorf's claims that grammatical categories construed meaning was George Lakoff's "Women, Fire and Dangerous Things", in which he argued that Whorf had been on the right track when he claimed that a contrast in grammatical categories is a resource for a contrast in experiencial meaning, thus that the way we usually represent our experience (including through grammatical categories) impacts the way our senses are organised as experience.[51] In 1992 psychologist John A. Lucy published two books on the topic: the first one analyzed the intellectual genealogy of the hypothesis, arguing that previous studies had failed to appreciate the subtleties of Whorf's thinking; they had been unable to formulate a research agenda that would actually test Whorf's claims.[52] Lucy proposed a new research design so that the hypothesis of linguistic relativity could be tested empirically, and to avoid the pitfalls of earlier studies which Lucy claimed had tended to presuppose the universality of the categories they were studying. His second book was an empirical study of the relation between grammatical categories and cognition in the Yucatec Maya language of Mexico.[53] In 1996 Penny Lee's reappraisal of Whorf's writings was published,[54] reinstating Whorf as a serious and capable thinker. Lee argued that previous explorations of the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis had largely ignored Whorf's actual writings, and consequently asked questions very unlike those Whorf had asked.[55] Also in that year a volume, "Rethinking Linguistic Relativity" edited by John J. Gumperz and Stephen C. Levinson gathered a range of researchers working in psycholinguistics, sociolinguistics and linguistic anthropology to bring renewed attention to the issue of how Whorf's theories could be updated, and a subsequent review of the new direction of the linguistic relativity paradigm cemented the development.[56] Since then considerable empirical research into linguistic relativity has been carried out, especially at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics with scholarship motivating two edited volumes of linguistic relativity studies,[57] and in American Institutions by scholars such as Lera Boroditsky and Dedre Gentner.[58] In turn universalist scholars frequently dismiss Whorf's claims as "dull"[59] or "boring",[42] as well as positive findings of influence of grammatical categories on thought or behavior, which are often subtle rather than spectacular.[n 6] Despite the fact that scientists were trying to find substances and loss of energy in the transformation of mass into energy and that Whorf was correct in his critique against such lines of research, these researchers do not mention the context in which Whorf wrote his critique of scientists and claim that Whorf's supposed "linguistic relativity" had promised more spectacular findings than it was able to provide.[60] Whorf's views have been compared to those of philosophers such as Friedrich Nietzsche[61] and the late Ludwig Wittgenstein,[62][63] both of whom considered language to have important bearing on thought and reasoning. His hypotheses have also been compared to the views of psychologists such as Lev Vygotsky,[64] whose social constructivism considers the cognitive development of children to be mediated by the social use of language. Vygotsky shared Whorf's interest in gestalt psychology, and he also read Sapir's works. Others have seen similarities between Whorf's work and the ideas of literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin, who read Whorf and whose approach to textual meaning was similarly holistic and relativistic.[65][66] Whorf's ideas have also been interpreted as a radical critique of positivist science.[25] |

ウォーフの主張の立証 ウォーフが一種の「言語相対性」を擁護したという考えは、第二次世界大戦中に発表された彼の論文『言語と現実』に由来する。そこでウォーフは、エネルギー といった実体的な言葉しか存在しない場所で実体を探し求め、エネルギーの消費しか存在しない場所で消費を探し求めるアメリカ人科学者、特に一部の物理学者 を批判したのである。心と現実」に由来する。この論文でウォーフは、エネルギーといった名詞のみが存在する領域で実体を探し、変換といった他動詞のみが存 在する領域でエネルギー消費を探るアメリカ人科学者、特に一部の物理学者を批判した。彼らはアインシュタインの相対性理論を否定しようとしていた。この理 論は、どの程度のエネルギーを生み出すためにどの程度の質量を消費すべきかを予測するのに役立つ。ウォーフはこの論文で、いわゆる「西洋言語」に由来する 「アーリア的西洋論理」が、科学者たちにこの理論を受け入れさせず、その応用(例えば原子爆弾の開発)に力を注ぐことを妨げていると主張した。原子爆弾 は、アメリカがドイツとの戦争に勝つか負けるかを決定づける可能性があった。これはドイツの国民社会主義者たちが、アルバート・アインシュタインのような ユダヤ人物理学者による直感に反する発見から解放された「アーリア物理学」を開発しようとしていた時期である。[48] 意味を通じた経験の構築に関する研究[49]は1990年代以降増加しており、一連の実験結果がウォーフの主張を裏付けている。特に文化心理学や言語人類 学の分野において、彼が提示した形で理解される場合である。[50] 文法的カテゴリーが意味を構築するというウォーフの主張に肯定的な注目を向けた最も初期の言語学的記述の一つが、ジョージ・レイコフの『女性、火、危険な もの』である。彼はその中で、文法的カテゴリーの対比が経験的意味の対比の資源となり、したがって我々が通常経験を表象する方法(文法的カテゴリーを通じ たものを含む)が、感覚が経験として組織化される方法に影響を与えるというウォーフの主張は正しい方向性であったと論じた。[51] 1992年、心理学者ジョン・A・ルーシーはこの主題に関する二冊の著書を出版した。第一の著書は仮説の知的系譜を分析し、先行研究がウォーフの思考の微 妙な点を理解できていなかったと論じた。それらはウォーフの主張を実際に検証する研究計画を策定できなかったのである。[52] ルーシーは言語相対性仮説を実証的に検証可能な新たな研究設計を提案し、先行研究が研究対象のカテゴリー普遍性を前提とする傾向にあったという落とし穴を 回避した。第二の著作ではメキシコのユカテコ・マヤ語における文法的カテゴリーと認知の関係を実証的に研究した。[53] 1996年、ペニー・リーによるウォーフ著作の再評価が刊行された[54]。これによりウォーフは真摯で有能な思想家として再評価された。リーは、これま でのサピア=ウォーフ仮説の探求がウォーフの実際の著作をほとんど無視してきたため、ウォーフが提起した問題とは全く異なる問いを投げかけてきたと論じ た。[55] 同年にはジョン・J・ガンペルツとスティーブン・C・レビンソン編『言語相対性の再考』が刊行され、心理言語学、社会言語学、言語人類学の研究者たちが集 結。ウォーフ理論の更新可能性に新たな注目が集まり、言語相対性パラダイムの新方向性を検証した論評が発展を確固たるものにした。[56] その後、言語相対性に関する膨大な実証研究が行われた。特にマックス・プランク心理言語学研究所では、言語相対性研究の編集書2冊を出版するほどの学術的 成果が得られた[57]。またアメリカでは、レラ・ボロディツキーやデドレ・ジェントナーら学者による研究が行われた。[58] 一方、普遍主義の学者たちは、ウォーフの主張を「退屈」[59] あるいは「つまらない」[42] と頻繁に退け、文法的カテゴリーが思考や行動に与える影響に関する肯定的な発見も同様に否定する。これらの発見は、派手というよりはむしろ微妙なものであ ることが多い。[n 6] 科学者たちが質量からエネルギーへの変換における物質やエネルギー損失の発見を試みていた事実、そしてウォーフがそうした研究手法に対する批判において正 しかったにもかかわらず、これらの研究者はウォーフが科学者批判を書いた文脈に触れず、ウォーフのいわゆる「言語相対性」が提供できた以上の劇的な発見を 約束していたと主張している。[60] ウォーフの見解は、言語が思考や推論に重要な影響を与えると考えたフリードリヒ・ニーチェ[61]や後期ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン[62] [63]といった哲学者の見解と比較されてきた。彼の仮説はまた、レフ・ヴィゴツキー[64]のような心理学者の見解とも比較されている。ヴィゴツキーの 社会的構成主義は、子どもの認知発達は言語の社会的使用によって媒介されると考える。ヴィゴツキーはウォーフと同様にゲシュタルト心理学に関心を持ち、サ ピアの著作も読んでいた。また、文学理論家ミハイル・バフチンの思想とウォーフの研究には類似点があると指摘する者もいる。バフチンはウォーフの著作を読 み、テキストの意味に対するアプローチも同様に全体論的かつ相対主義的であった[65][66]。ウォーフの思想は実証主義的科学に対する急進的な批判と して解釈されることもある[25]。 |

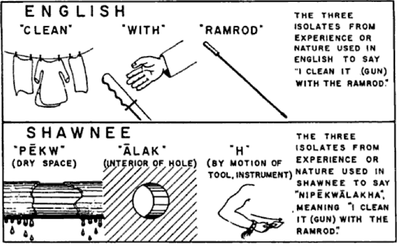

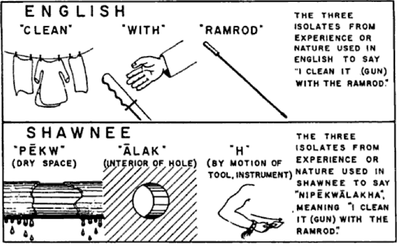

| Work Linguistic relativity Main article: Linguistic relativity Whorf is best known as the main proponent of what he called the principle of linguistic relativity, but which is often known as "the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis", named for him and Edward Sapir. Whorf never stated the principle in the form of a hypothesis, and the idea that linguistic categories influence perception and cognition was shared by many other scholars before him. But because Whorf, in his articles, gave specific examples of how he saw the grammatical categories of specific languages related to conceptual and behavioral patterns, he pointed towards an empirical research program that has been taken up by subsequent scholars, and which is often called "Sapir–Whorf studies".[67] Sources of influence on Whorf's thinking  Whorf's illustration of the difference between the English and Shawnee gestalt construction of cleaning a gun with a ramrod. From the article "Language and Science", originally published in the MIT technology Review, 1940. Image copyright of MIT Press. Whorf and Sapir both drew explicitly on Albert Einstein's principle of general relativity; hence linguistic relativity refers to the concept of grammatical and semantic categories of a specific language providing a frame of reference as a medium through which observations are made.[2][68] Following an original observation by Boas, Sapir demonstrated that speakers of a given language perceive sounds that are acoustically different as the same, if the sound comes from the underlying phoneme and does not contribute to changes in semantic meaning. Furthermore, speakers of languages are attentive to sounds, particularly if the same two sounds come from different phonemes. Such differentiation is an example of how various observational frames of reference leads to different patterns of attention and perception.[69] Whorf was also influenced by gestalt psychology, believing that languages require their speakers to describe the same events as different gestalt constructions, which he called "isolates from experience".[70] An example is how the action of cleaning a gun is different in English and Shawnee: English focuses on the instrumental relation between two objects and the purpose of the action (removing dirt); whereas the Shawnee language focuses on the movement—using an arm to create a dry space in a hole. The event described is the same, but the attention in terms of figure and ground are different.[71] |

仕事 言語相対性 主な記事: 言語相対性 ウォーフは、彼が言語相対性の原理と呼んだものの主な提唱者として最もよく知られている。しかし、それはしばしば彼とエドワード・サピアにちなんで「サピ ア=ウォーフ仮説」として知られる。ウォーフは決してこの原理を仮説の形で述べたことはなく、言語的カテゴリーが知覚や認知に影響を与えるという考えは、 彼以前に多くの他の学者たちも共有していた。しかしウォーフは論文の中で、特定の言語の文法的カテゴリーが概念的・行動的パターンとどう関連するかを具体 的な例で示した。これにより彼は、後続の研究者たちによって取り上げられ、しばしば「サピア=ウォーフ研究」と呼ばれる経験的研究プログラムの方向性を示 したのである。[67] ウォーフの思考に影響を与えた源流  ウォーフによる、銃の掃除をラムロッドで行う際の英語とショーニー語のゲシュタルト構成の違いの図解。1940年『MITテクノロジーレビュー』掲載論文「言語と科学」より。画像著作権はMITプレスに帰属。 ウォーフとサピアは共に、アルバート・アインシュタインの一般相対性理論を明示的に引用した。したがって言語相対性とは、特定の言語の文法的・意味的カテ ゴリーが、観察を行う媒体としての参照枠組みを提供する概念を指す。[2][68] ボアズの先駆的観察に基づき、サピアは次のことを実証した。ある言語の話し手は、音響的に異なる音であっても、それが基盤となる音素に由来し、意味の変化 に寄与しない場合、同じ音として認識する。さらに、言語の話し手は音に注意を払う。特に、同じ二つの音が異なる音素に由来する場合である。このような区別 は、様々な観察の参照枠が、異なる注意と知覚のパターンをもたらす一例である。[69] ウォーフはゲシュタルト心理学の影響も受けており、言語は話者に同じ事象を異なるゲシュタルト構造として記述することを要求すると考えていた。彼はこれを 「経験からの分離」と呼んだ。[70] 例として、銃を掃除する行為が英語とショーニー語で異なる点を挙げよう。英語は二つの物体間の道具的関係と行為の目的(汚れを除去すること)に焦点を当て る。一方ショーニー語は動作そのもの―腕を使って穴の中に乾いた空間を作る行為―に焦点を当てる。描写される事象は同じだが、図と地の観点における注意の 向け方が異なるのだ。[71] |

| Degree of influence of language on thought If read superficially, some of Whorf's statements lend themselves to the interpretation that he supported linguistic determinism. For example, in an often-quoted passage Whorf writes: We dissect nature along lines laid down by our native language. The categories and types that we isolate from the world of phenomena we do not find there because they stare every observer in the face; on the contrary, the world is presented in a kaleidoscope flux of impressions which has to be organized by our minds—and this means largely by the linguistic systems of our minds. We cut nature up, organize it into concepts, and ascribe significances as we do, largely because we are parties to an agreement to organize it in this way—an agreement that holds throughout our speech community and is codified in the patterns of our language. The agreement is of course, an implicit and unstated one, but its terms are absolutely obligatory; we cannot talk at all except by subscribing to the organization and classification of data that the agreement decrees. We are thus introduced to a new principle of relativity, which holds that all observers are not led by the same physical evidence to the same picture of the universe, unless their linguistic backgrounds are similar, or can in some way be calibrated.[w 2] The statements about the obligatory nature of the terms of language have been taken to suggest that Whorf meant that language completely determined the scope of possible conceptualizations.[41] However, neo-Whorfians argue that here Whorf is writing about the terms in which we speak of the world, not the terms in which we think of it.[72] Whorf noted that to communicate thoughts and experiences with members of a speech community speakers must use the linguistic categories of their shared language, which requires moulding experiences into the shape of language to speak them—a process called "thinking for speaking". This interpretation is supported by Whorf's subsequent statement that "No individual is free to describe nature with absolute impartiality, but is constrained by certain modes of interpretation even when he thinks himself most free". Similarly, the statement that observers are led to different pictures of the universe has been understood as an argument that different conceptualizations are not comparable, making translation between different conceptual and linguistic systems impossible. Neo-Whorfians argue this to be a misreading since throughout his work one of his main points was that such systems could be "calibrated" and thereby be made commensurable, but only when we become aware of the differences in conceptual schemes through linguistic analysis.[38] |

言語が思考に及ぼす影響の度合い ウォーフの主張を表面的に読むと、彼が言語決定論を支持していたと解釈されかねない。例えば、よく引用される一節でウォーフはこう書いている: 我々は母語によって定められた線に沿って自然を切り分ける。現象世界から切り離すカテゴリーや類型は、観察者の眼前には存在しない。むしろ世界は万華鏡の ように刻々と変化する印象の集合体として提示され、我々の精神によって組織化されねばならない。そしてこれは主に、我々の精神が持つ言語体系によって行わ れるのである。我々は自然を切り分け、概念に整理し、意味を付与する。その方法の大部分は、我々が「このように整理する」という合意の当事者であるから だ。この合意は言語共同体全体に通用し、言語のパターンに規定されている。合意は当然ながら暗黙的で明文化されていないが、その条件は絶対的な義務であ る。合意が定めるデータの整理・分類に従わなければ、我々は全く話すことができないのだ。こうして我々は新たな相対性の原理に導かれる。それは、言語的背 景が類似しているか、何らかの方法で調整可能でない限り、全ての観察者が同じ物理的証拠から同じ宇宙像に導かれるわけではないと主張する。[w 2] 言語の条件の義務的性質に関する記述は、ウォーフが言語が可能な概念化の範囲を完全に決定すると主張したものと解釈されてきた[41]。しかし新ウォーフ 派は、ここでウォーフが論じているのは世界について語る際の条件であって、世界について考える際の条件ではないと主張する。[72] ウォーフは、言語共同体の成員と思考や経験を伝達するには、共有言語の言語的カテゴリーを用いねばならないと指摘した。これは経験を言語の形に整えて発話 する「話すための思考」と呼ばれる過程を必要とする。この解釈は、ウォーフが後に「いかなる個人も自然を絶対的な公平性をもって記述する自由はなく、自ら 最も自由であると思う時でさえ、特定の解釈様式に制約されている」と述べたことで裏付けられる。同様に、「観察者は異なる宇宙像へと導かれる」という主張 は、異なる概念化は比較不可能であり、異なる概念体系と言語体系間の翻訳は不可能だという論拠と理解されてきた。しかし新ウォーフ派は、これは誤読だと反 論する。なぜならウォーフの著作全体を通じて、彼の主要な主張の一つは、言語分析を通じて概念スキームの差異を認識するならば、そうした体系は「較正」さ れ、それによって比較可能にできるというものだったからだ。[38] |

| Hopi time Main article: Hopi time controversy Whorf's study of Hopi time has been the most widely discussed and criticized example of linguistic relativity. In his analysis he argues that there is a relation between how the Hopi people conceptualize time, how they speak of temporal relations, and the grammar of the Hopi language. Whorf's most elaborate argument for the existence of linguistic relativity was based on what he saw as a fundamental difference in the understanding of time as a conceptual category among the Hopi.[w 1] He argued that the Hopi language, in contrast to English and other SAE languages, does not treat the flow of time as a sequence of distinct countable instances, like "three days" or "five years", but rather as a single process. Because of this difference, the language lacks nouns that refer to units of time. He proposed that the Hopi view of time was fundamental in all aspects of their culture and furthermore explained certain patterns of behavior. In his 1939 memorial essay to Sapir he wrote that "... the Hopi language is seen to contain no words, grammatical forms, construction or expressions that refer directly to what we call 'time', or to past, present, or future..."[w 1] Linguist Ekkehart Malotki challenged Whorf's analyses of Hopi temporal expressions and concepts with numerous examples how the Hopi language refers to time.[33] Malotki argues that in the Hopi language the system of tenses consists of future and non-future and that the single difference between the three-tense system of European languages and the Hopi system, is that the latter combines past and present to form a single category.[n 7] Critics of Whorf frequently refer to Malotki's data, which would appear to contradict Whorf's statements on Hopi, in order to refute his concept of linguistic relativity; while other scholars have defended the analysis of Hopi, arguing that Whorf's claim was not that Hopi lacked words or categories to describe temporality, but that the Hopi concept of time is altogether different from that of English speakers.[21][73] Whorf described the Hopi categories of tense, noting that time is not divided into past, present and future, as is common in European languages, but rather a single tense refers to both present and past while another refers to events that have not yet happened and may or may not happen in the future. He also described a large array of stems that he called "tensors" which describes aspects of temporality, but without referring to countable units of time as in English and most European languages.[74] |

ホピ族の時間観 詳細な記事: ホピ族の時間論争 ウォーフによるホピ族の時間研究は、言語相対性理論において最も広く議論され批判されてきた事例である。彼の分析では、ホピ族が時間を概念化する方法、時 間的関係を表現する方法、そしてホピ語の文法構造の間に相関関係があると主張している。ウォーフが言語相対性の存在を主張する最も精緻な論拠は、ホピ族に おける時間という概念的カテゴリーの理解に根本的な差異があると彼が認識した点に基づいていた。彼は、英語やその他のSAE言語とは対照的に、ホピ語は時 間の流れを「3日間」や「5年間」のような個別の数え上げ可能な事例の連続として扱うのではなく、単一のプロセスとして扱うと論じた。この差異ゆえに、同 言語には時間単位を指す名詞が存在しない。彼はホピ族の時間観が文化のあらゆる側面において根源的であり、さらに特定の行動様式を説明し得ると提案した。 1939年のサピア追悼論文で彼はこう記している。「...ホピ語には、我々が『時間』と呼ぶもの、あるいは過去・現在・未来を直接指す単語、文法形式、 構文、表現は存在しないことが確認される...」[w 1] 言語学者エッケハルト・マロツキは、ホピ語が時間を参照する多数の例を挙げて、ウォーフのホピ時間表現・概念分析に異議を唱えた[33]。マロツキは、ホ ピ語の時制体系は未来形と非未来形で構成され、ヨーロッパ言語の三時制体系とホピ体系の唯一の違いは、後者が過去と現在を単一の範疇に統合している点だと 主張する。[n 7] ウォーフ批判派は、言語相対性理論を反駁するため、ウォーフのホピ語に関する主張と矛盾するように見えるマロツキのデータを頻繁に引用する。一方、他の研 究者はホピ語分析を擁護し、ウォーフの主張は「ホピ語に時間を記述する語彙やカテゴリーが欠如している」のではなく、「ホピ語の時間概念が英語話者のそれ とは根本的に異なる」点にあったと論じている。[21][73] ウォーフはホピ族の時制カテゴリーについて、ヨーロッパ言語で一般的な過去・現在・未来への時間分割ではなく、一つの時制が現在と過去を同時に指し、別の 時制が未発生で将来起こるかどうかわからない事象を指すと説明した。彼はまた「テンソル」と呼ぶ多様な語幹を説明した。これらは時間性の側面を表すが、英 語や大半のヨーロッパ言語のように、数え上げられる時間単位を参照するものではない。[74] |

| Contributions to linguistic theory Whorf's distinction between "overt" (phenotypical) and "covert" (cryptotypical) grammatical categories has become widely influential in linguistics and anthropology. British linguist Michael Halliday wrote about Whorf's notion of the "cryptotype", and the conception of "how grammar models reality", that it would "eventually turn out to be among the major contributions of twentieth century linguistics".[75] Furthermore, Whorf introduced the concept of allophones, which are positional phonetic variants of a single superordinate phoneme; in doing so he placed a cornerstone in consolidating early phoneme theory.[76] The term was popularized by G. L. Trager and Bernard Bloch in a 1941 paper on English phonology[77] and went on to become part of standard usage within the American structuralist tradition.[78] Whorf considered allophones to be another example of linguistic relativity. The principle of allophony describes how acoustically different sounds can be treated as reflections of a single phoneme in a language. This sometimes makes the different sound appear similar to native speakers of the language, even to the point that they are unable to distinguish them auditorily without special training. Whorf wrote that: "[allophones] are also relativistic. Objectively, acoustically, and physiologically the allophones of [a] phoneme may be extremely unlike, hence the impossibility of determining what is what. You always have to keep the observer in the picture. What linguistic pattern makes like is like, and what it makes unlike is unlike".(Whorf, 1940)[n 8] Central to Whorf's inquiries was the approach later described as metalinguistics by G. L. Trager, who in 1950 published four of Whorf's essays as "Four articles on Metalinguistics".[w 4] Whorf was crucially interested in the ways in which speakers come to be aware of the language that they use, and become able to describe and analyze language using language itself to do so.[79] Whorf saw that the ability to arrive at progressively more accurate descriptions of the world hinged partly on the ability to construct a metalanguage to describe how language affects experience, and thus to have the ability to calibrate different conceptual schemes. Whorf's endeavors have since been taken up in the development of the study of metalinguistics and metalinguistic awareness, first by Michael Silverstein who published a radical and influential rereading of Whorf in 1979[80] and subsequently in the field of linguistic anthropology.[81] |

言語理論への貢献 ウォーフが提唱した「顕在的」(表現型)と「潜在的」(隠れた類型)という文法的カテゴリーの区別は、言語学と人類学において広く影響力を持つようになっ た。英国の言語学者マイケル・ハリデイは、ウォーフの「隠れた類型」の概念と「文法が現実をどのようにモデル化するのか」という構想について、「最終的に は20世紀言語学の主要な貢献の一つとなるだろう」と記している。[75] さらにウォーフは、単一の超位音素の位置的音声変異である「異音」の概念を導入した。これにより彼は初期の音素理論を確立する礎を築いた[76]。この用 語は1941年の英語音韻論に関する論文でG. L. トレイガーとバーナード・ブロックによって普及し[77]、アメリカの構造主義的伝統における標準用法の一部となった。[78] ウォーフは異音現象も言語相対性の例と見なした。異音現象の原理は、音響的に異なる音が言語内で単一の音素の反映として扱われる仕組みを説明する。これに より、その言語の母語話者にとって異なる音が類似して聞こえることがあり、特別な訓練なしには聴覚的に区別できないほどになることもある。ウォーフはこう 記している:「[異音]もまた相対的である。客観的・音響的・生理学的に見て、[ある]音素の異音は極めて異なる場合があり、それゆえ何が何であるかを決 定することは不可能だ。観察者を常に視野に入れなければならない。どの言語パターンが類似を類似とし、どのパターンが非類似を非類似とするかである」 (ウォーフ、1940年)[n 8] ウォーフの研究の中心には、後にG. L. トレイガーがメタ言語学として記述したアプローチがあった。トレイガーは1950年にウォーフの論文4編を「メタ言語学に関する四つの論文」として出版し た。[w 4] ウォーフが特に注目したのは、話者が自らが用いる言語を自覚し、言語そのものを使って言語を記述・分析できるようになる過程であった。[79] ウォーフは、世界に対する記述を次第に正確にできる能力は、言語が経験に与える影響を記述するメタ言語を構築する能力、つまり異なる概念体系を調整する能 力にかかっていることに気づいた。ウォーフの試みはその後、メタ言語学およびメタ言語的認識の研究発展において継承された。最初にマイケル・シルバースタ インが1979年にウォーフの画期的で影響力ある再解釈を発表し[80]、続いて言語人類学の分野で展開された[81]。 |

| Studies of Uto-Aztecan languages Whorf conducted important work on the Uto-Aztecan languages, which Sapir had conclusively demonstrated as a valid language family in 1915. Working first on Nahuatl, Tepecano, and Tohono O'odham, he had established familiarity with the language group before he met Sapir in 1928. During Whorf's time at Yale, he published several articles on Uto-Aztecan linguistics, such as "Notes on the Tübatulabal language".[w 5] In 1935 he published "The Comparative Linguistics of Uto-Aztecan",[w 6] and a review of Kroeber's survey of Uto-Aztecan linguistics.[w 7] Whorf's work served to further cement the foundations of comparative Uto-Aztecan studies.[82] The first Native American language Whorf studied was the Uto-Aztecan language Nahuatl, which he first studied from colonial grammars and documents; later, it became the subject of his first field work experience in 1930. Based on his studies of Classical Nahuatl, Whorf argued that Nahuatl was an oligosynthetic language, a typological category that he invented. In Mexico working with native speakers, he studied the dialects of Milpa Alta and Tepoztlán. His grammar sketch of the Milpa Alta dialect of Nahuatl was not published during his lifetime, but it was published posthumously by Harry Hoijer[w 8] and became quite influential and used as the basic description of "Modern Nahuatl" by many scholars. The description of the dialect is quite condensed and in some places difficult to understand because of Whorf's propensity of inventing his own unique terminology for grammatical concepts, but the work has generally been considered to be technically advanced. He also produced an analysis of the prosody of these dialects which he related to the history of the glottal stop and vowel length in Nahuan languages. This work was prepared for publication by Lyle Campbell and Frances Karttunen in 1993, who also considered it a valuable description of the two endangered dialects, and the only one of its kind to include detailed phonetic analysis of supra-segmental phenomena.[18] In Uto-Aztecan linguistics, one of Whorf's achievements was to determine the reason the Nahuatl language has the phoneme /tɬ/, not found in the other languages of the family. The existence of /tɬ/ in Nahuatl had puzzled previous linguists and caused Sapir to reconstruct a /tɬ/ phoneme for proto-Uto-Aztecan based only on evidence from Aztecan. In a 1937 paper[w 9] published in the journal American Anthropologist, Whorf argued that the phoneme resulted from some of the Nahuan or Aztecan languages having undergone a sound change from the original */t/ to [tɬ] in the position before */a/. This sound law is known as "Whorf's law", considered valid although a more detailed understanding of the precise conditions under which it took place has since been developed. Also in 1937, Whorf and his friend G. L. Trager published a paper in which they elaborated on the Azteco-Tanoan[n 9] language family, proposed originally by Sapir as a family comprising the Uto-Aztecan and the Kiowa-Tanoan languages—(the Tewa and Kiowa languages).[w 10] |

ウト・アステカ語族の研究 ウォーフはウト・アステカ語族に関する重要な研究を行った。この語族はサピアが1915年に有効な言語族であることを決定的に証明していた。ウォーフはナ ワトル語、テペカノ語、トホノ・オオダム語を最初に研究対象とし、1928年にサピアと出会う以前からこの言語群に精通していた。ウォーフがイェール大学 に在籍していた時期に、彼はウト・アステカ語族言語学に関する複数の論文を発表した。例えば「トゥバトゥラバル語に関する覚書」などである。[w 5] 1935年には『ウト・アステカ語族の比較言語学』[w 6]と、クロエバーによるウト・アステカ語族言語学概説の書評[w 7]を発表した。ウォーフの研究は比較ウト・アステカ語研究の基盤をさらに固める役割を果たした。[82] ウォーフが最初に研究したアメリカ先住民言語はウト・アステカ語族のナワトル語であった。彼はまず植民地時代の文法書や文書からこの言語を学び、後に 1930年に初めて現地調査の対象とした。古典ナワトル語の研究に基づき、ウォーフはナワトル語が寡合成語(彼が創出した類型論的分類)であると主張し た。メキシコでは現地話者と共に働き、ミルパ・アルタ方言とテポツトラン方言を研究した。ミルパ・アルタ方言の文法概要は生前には出版されなかったが、ハ リー・ホイヤー[w 8]によって死後出版され、非常に影響力を持つようになった。多くの学者によって「現代ナワトル語」の基本記述として用いられたのである。この方言の記述 は、ウォーフが文法概念について独自の用語を発明する傾向があったため、非常に凝縮されており、所々理解が難しい部分もあるが、この著作は技術的に進んだ ものと広く評価されている。また、彼はこれらの方言の韻律分析も行い、それをナワ語族における声門閉鎖音と母音の長さの歴史に関連づけた。この著作は、 1993年にライル・キャンベルとフランシス・カートゥネンによって出版用に編集された。彼らも、この著作を、2つの絶滅の危機にある方言に関する貴重な 記述であり、超分節的現象の詳細な音声学的分析を含む、この種では唯一の著作であると考えていた。 ウト・アステカ語族の言語学において、ウォーフの成果の一つは、ナワトル語に、この語族の他の言語には見られない音素 /tɬ/ が存在する理由を明らかにしたことである。ナワトル語に /tɬ/ が存在することは、それまでの言語学者たちを困惑させ、サピアはアステカ語からの証拠のみに基づいて、原ウト・アステカ語に /tɬ/ 音素を再構築することになった。1937年に『アメリカ人類学雑誌』に掲載された論文[w 9]で、ウォーフはこの音素が、ナワ語族あるいはアステカ語族の一部言語において、*/a/の前で元の */t/ が [tɬ] へと音変化した結果生じたと論じた。この音韻法則は「ウォーフの法則」として知られ、その後、その発生条件に関するより詳細な理解が発展したものの、有効 であると考えられている。 また1937年、ウォーフと友人G. L. トレイガーは論文を発表し、サピールが最初に提唱したアステコ・タノアン語族(ウト・アステカ語族とキオワ・タノアン語族―テワ語とキオワ語―から成る語族)について詳述した[n 9]。[w 10] |

| Maya epigraphy In a series of published and unpublished studies in the 1930s, Whorf argued that Mayan writing was to some extent phonetic.[w 11][w 12] While his work on deciphering the Maya script gained some support from Alfred Tozzer at Harvard, the main authority on Ancient Maya culture at the time, J. E. S. Thompson, strongly rejected Whorf's ideas, saying that Mayan writing lacked a phonetic component and is therefore impossible to decipher based on a linguistic analysis.[83] Whorf argued that it was exactly the reluctance to apply linguistic analysis of Maya languages that had held the decipherment back. Whorf sought for cues to phonetic values within the elements of the specific signs, never realizing that the system was logo-syllabic. Although Whorf's approach to understanding the Maya script is now known to have been misguided, his central claim that the script was phonetic and should be deciphered as such was vindicated by Yuri Knorozov's syllabic decipherment of Mayan writing in the 1950s.[84][85] |

マヤ碑文学 1930年代に発表された一連の研究と未発表の研究において、ウォーフはマヤ文字がある程度音素的であると主張した。[w 11] [w 12] 彼のマヤ文字解読に関する研究は、ハーバード大学のアルフレッド・トッザーから一定の支持を得たものの、当時の古代マヤ文化の権威であったJ. E. S. トンプソンは、マヤ文字には音素的要素が欠如しており、言語学的分析に基づく解読は不可能だとし、ウォーフの考えを強く否定した。[83] ウォーフは、まさにマヤ語に対する言語学的分析を適用することを躊躇したことが解読を遅らせたと主張した。ウォーフは特定の記号の構成要素の中に音価の手 がかりを求め続けたが、その体系がロゴ・音節文字であることを決して理解しなかった。ウォーフのマヤ文字理解へのアプローチは誤りであったと現在では認識 されているが、文字が音節的でありそのように解読されるべきだという彼の核心的主張は、1950年代にユーリ・クノロゾフがマヤ文字の音節的解読に成功し たことで正当化されたのである。[84][85] |

| Notes 1. The Relation of Habitual Thought And Behavior to Language. Written in 1939 and originally published in "Language, Culture and Personality: Essays in Memory of Edward Sapir" edited by Leslie Spier, 1941, reprinted in Carroll (1956:134–59). The piece is the source of most of the quotes used by Whorf's detractors. 2. "Science and linguistics" first published in 1940 in MIT Technology Review (42:229–31); reprinted in Carroll (1956:212–214) 3. Language Mind and reality. Written in 1941 originally printed by the Theosophical Society in 1942 "The Theosophist" Madras, India. Vol 63:1. 281–91. Reprinted in Carroll (1956:246–270). In 1952 also reprinted in "Etc., a Review of General Semantics, 9:167–188. 4. "Four articles on Metalinguistics" 1950. Foreign Service Institute, Dept. of State 5. Notes on the Tubatulabal Language. 1936. American Anthropologist 38: 341–44. 6. "The Comparative Linguistics of Uto-Aztecan." 1935. American Anthropologist 37:600–608. 7. "review of: Uto-Aztecan Languages of Mexico. A. L. Kroeber" American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 37, No. 2, Part 1 (Apr. – Jun. 1935), pp. 343–345 8. The Milpa Alta dialect of Aztec (with notes on the Classical and the Tepoztlan dialects). Written in 1939, first published in 1946 by Harry Hoijer in Linguistic Structures of Native America, pp. 367–97. Viking Fund Publications in Anthropology, no. 6. New York: Viking Fund. 9. Whorf, B. L. (1937). "The origin of Aztec tl". American Anthropologist. 39 (2): 265–274. doi:10.1525/aa.1937.39.2.02a00070. 10. with George L.Trager. The relationship of Uto-Aztecan and Tanoan. (1937). American Anthropologist, 39:609–624. 11. The Phonetic Value of Certain Characters in Maya Writing. Millwood, N.Y.: Krauss Reprint. 1975 [1933]. 12. Maya Hieroglyphs: An Extract from the Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution for 1941. Seattle: Shorey Book Store. 1970 [1942]. ISBN 978-0-8466-0122-7. |

注記 1. 「習慣的思考と行動と言語の関係」。1939年に執筆され、レスリー・スピア編『言語、文化、人格:エドワード・サピア追悼論文集』(1941年)に初出。キャロル(1956:134–59)に再録。ウォーフ批判派が引用する大半の出典となる。 2. 「科学と言語学」は1940年にMIT Technology Review(42:229–31)で初出。キャロル(1956:212–214)に再録。 3. 「言語・精神・現実」。1941年執筆、1942年に神智学協会がインド・マドラスで発行した『The Theosophist』に掲載。第63巻第1号、281–91頁。キャロル(1956:246–270)に再掲載。1952年には「Etc., a Review of General Semantics」第9巻167–188頁にも再掲載。 4. 「メタ言語学に関する四つの論文」1950年。国務省外交研修所 5. 『トゥバトゥラバル語に関する覚書』1936年。『アメリカ人類学雑誌』38巻: 341–44頁。 6. 「ウト・アステカ語族の比較言語学」1935年。『アメリカ人類学雑誌』37巻:600–608頁。 7. 「書評:『メキシコのウト・アステカ語族』A. L. クロエバー著」『アメリカ人類学雑誌』新シリーズ第37巻第2号第1部(1935年4月–6月)、pp. 343–345 8. 『アステカ語ミルパ・アルタ方言(古典期方言及びテポツトラン方言に関する注記付き)』。1939年執筆、1946年ハリー・ホイヤー著『ネイティブ・ア メリカの言語構造』pp.367–397に初掲載。人類学ヴィキング基金刊行物第6号。ニューヨーク:ヴィキング基金。 9. Whorf, B. L. (1937). 「アステカ語 tl の起源」『アメリカ人類学雑誌』39(2): 265–274. doi:10.1525/aa.1937.39.2.02a00070. 10. ジョージ・L・トレーガーとの共著。ウト・アステカ語族とタノアン語族の関係。(1937). アメリカ人類学者, 39:609–624. 11. マヤ文字における特定文字の音韻的価値。ミルウッド, ニューヨーク: クラウス・リプリント. 1975 [1933]. 12. 『マヤ象形文字:スミソニアン協会1941年度年次報告書からの抜粋』。シアトル:ショリー書店。1970年[1942年]。ISBN 978-0-8466-0122-7。 |

| Commentary notes 1. The report is reprinted in Lee (1996) 2. For more on this topic see: Linguistic relativity and the color naming debate 3. See for example pages 623, 624, 631 in Malotki (1983), which is mild in comparison to later writings by Pinker (1994), Pinker (2007), and McWhorter (2009) 4. Leavitt (2011) notes how Davidson cites an essay by Whorf as claiming that English and Hopi ideas of times cannot 'be calibrated'. But the word "calibrate" does not appear in the essay cited by Davidson, and in the essay where Whorf does use the word he explicitly states that the two conceptualizations can be calibrated. For Leavitt this is characteristic of the way Whorf has been consistently misread, others such as Lee (1996), Alford (1978) and Casasanto (2008) make similar points. 5. See also Nick Yee's evaluation of Pinker's criticism, What Whorf Really Said, and Dan "Moonhawk" Alford's rebuttal of Chomsky's critique at Chomsky's Rebuttal of Whorf: The Annotated Version by Moonhawk, 8/95 Archived January 31, 2020, at the Wayback Machine and The Great Whorf Hypothesis Hoax by Dan Moonhawk Alford Archived September 5, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. 6. McWhorter misquotes Paul Kay and Willett Kempton's 1984 article "What is the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis" (Kay & Kempton (1984)), in which they criticize those of Whorf's interpreters who are only willing to accept spectacular differences in cognition. McWhorter attributes the view to Kay and Kempton that they were in fact criticizing. 7. It is not uncommon for non-Indo-European languages not to have a three way tense distinction, but instead to distinguish between realis (past/present) and irrealis (future) moods, and describe the past distinction using completive aspect. This, for example, is the case in Greenlandic. But this had not been recognized when Whorf wrote. See Bernard Comrie's Comrie (1984) review of Malotki in which he argues that many of Malotki's examples of a tense distinction in fact rather suggest a modality distinction. 8. Unpublished paper quoted in Lee (2000:50) 9. Whorf and Trager suggested the term "Azteco-Tanoan" instead of the label "Aztec-Tanoan" used by Sapir. However, Sapir's original use has stood the test of time. |

解説ノート 1. 本報告書はリー(1996)に再掲載されている (1996)に再掲載されている。 2. この主題に関する詳細は以下を参照のこと:言語相対性理論と色彩命名論争 3. 例えばMalotki (1983)の623、624、631ページを参照のこと。これはPinker (1994)、Pinker (2007)、McWhorter (2009)の著作と比べると穏やかである。 4. Leavitt (2011)は、DavidsonがWhorfの論文を引用し、英語とホピ語の時間概念は「較正できない」と主張していると指摘している。しかし、 Davidsonが引用した論文には「較正」という言葉は登場せず、Whorfがこの言葉を用いた論文では、両概念は較正可能であると明言している。リー ヴィットによれば、これはウォーフが一貫して誤解されてきた典型例である。リー(1996)、アルフォード(1978)、カササント(2008)らも同様 の指摘をしている。 5. ニック・イーによるピンカー批判の評価『ウォーフが実際に述べたこと』、ダン・「ムーンホーク」・アルフォードによるチョムスキー批判への反論『チョムス キーのウォーフ批判:注釈付き版』(ムーンホーク、1995年、1月31日アーカイブ)も参照のこと。アルフォードによるチョムスキー批判への反論『チョ ムスキーによるウォーフ反論:注釈付き版』(ムーンホーク著、1995年8月、ウェイバックマシン2020年1月31日アーカイブ)および『偉大なる ウォーフ仮説のデマ』(ダン・ムーンホーク・アルフォード著、ウェイバックマシン2019年9月5日アーカイブ)も参照のこと。 6. マクワーターは、ポール・ケイとウィレット・ケンプトンによる1984年の論文「サピア=ウォーフ仮説とは何か」(Kay & Kempton (1984))を誤って引用している。同論文では、認知における顕著な差異のみを受け入れるウォーフの解釈者たちを批判している。マクワーターは、実際に は批判対象であった見解を、ケイとケンプトン自身の見解として帰属させている。 7. 非インド・ヨーロッパ語族において、三つの時制区分を持たず、代わりに現実法(過去/現在)と非現実法(未来)を区別し、過去区別を完了相で記述する例は 珍しくない。例えばグリーンランド語がこれに該当する。しかしウォーフが執筆した当時は、この事実は認識されていなかった。バーナード・コムリーによるマ ロツキの書評(コムリー 1984)を参照せよ。同書評では、マロツキの時制区別の例示の多くが、実際には様態区別を示唆していると論じられている。 8. Lee (2000:50) で引用された未発表論文 9. Whorf と Trager は、Sapir が用いた「Aztec-Tanoan」という呼称に代えて「Azteco-Tanoan」という用語を提案した。しかし、Sapir の当初の用法は時の試練に耐えてきた。 |

| References | |