Sapir-Whorf hypothesis and/or Linguistic relativity

サピア=ウォーフの仮説または言語相対説

Sapir-Whorf hypothesis and/or Linguistic relativity

解説:池田光穂

言語が人間の世界観という認識や思考を形作るという学問上の 見解である。ここでいう認識とは、我々が自分たちがお かれている状況についてみたり、感じたりすることである。これらは経験様式(文化や思考)とよばれ ることもある。このような主張を幅広い言語学上の事実か ら説明した、2名の言語人類学者のエド ワード・サピア(Edward Sapir, 1884-1939)とベンジャミン・リー・ウォーフ(Benjamin Lee Whorf, 1897-1941)[前者=サピアは後者=ウォーフの師匠である]から名付けられているが、本人たちが命名したものではない。今日では、ウォーフの主張を、言語学におけるアイン シュタインの相対性理論に匹敵するものだと考えたエドワード・サピアによって、言語相対説/言語相対論(Linguistic relativity)と言われている。

| Linguistic relativity

asserts that language influences worldview or cognition. One form of

linguistic relativity, linguistic determinism, regards peoples'

languages as determining and influencing the scope of cultural

perceptions of their surrounding world.[1] Various colloquialisms refer to linguistic relativism: the Whorf hypothesis; the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis (/səˌpɪər ˈhwɔːrf/ sə-PEER WHORF); the Whorf–Sapir hypothesis; and Whorfianism. The hypothesis is in dispute, with many different variations throughout its history.[2][3] The strong hypothesis of linguistic relativity, now referred to as linguistic determinism, is that language determines thought and that linguistic categories limit and restrict cognitive categories. This was a claim by some earlier linguists pre-World War II;[4] since then it has fallen out of acceptance by contemporary linguists.[5][need quotation to verify] Nevertheless, research has produced positive empirical evidence supporting a weaker version of linguistic relativity:[5][4] that a language's structures influence a speaker's perceptions, without strictly limiting or obstructing them. Although common, the term Sapir–Whorf hypothesis is sometimes considered a misnomer for several reasons. Edward Sapir (1884–1939) and Benjamin Lee Whorf (1897–1941) never co-authored any works and never stated their ideas in terms of a hypothesis. The distinction between a weak and a strong version of this hypothesis is also a later development; Sapir and Whorf never used such a dichotomy, although often their writings and their opinions of this relativity principle expressed it in stronger or weaker terms.[6][7] The principle of linguistic relativity and the relationship between language and thought has also received attention in varying academic fields, including philosophy, psychology and anthropology. It has also influenced works of fiction and the invention of constructed languages. |

言語相対性理論は、言語が世界観や認知に影響を与えると主張する。言語相対性理論の一形態である言語決定論は、人々の言語が周囲の世界に対する文化的認識の範囲を決定し、影響を与えると見なす。[1] 言語相対論を指す様々な俗語がある:ウォーフ仮説、サピア=ウォーフ仮説(/səˌpɪər ˈhwɔːrf/ sə-PEER WHORF)、ウォーフ=サピア仮説、ウォーフ主義などである。 この仮説は議論の的となっており、その歴史を通じて異なる変種が存在する。[2][3] 言語相対性の強固な仮説、現在では言語決定論と呼ばれるものは、言語が思考を決定し、言語的カテゴリーが認知的カテゴリーを制限・制約するというものであ る。これは第二次世界大戦前の初期の言語学者による主張であった[4]。その後、現代の言語学者からは受け入れられなくなった[5][出典を要する]。し かしながら、研究により言語相対性の弱め版を支持する肯定的な実証的証拠が得られている[5][4]。すなわち、言語の構造は話者の認識に影響を与える が、厳密に制限したり妨げたりはしないというものである。 サピア=ウォーフ仮説という呼称は一般的だが、いくつかの理由から誤称と見なされることがある。エドワード・サピア(1884–1939)とベンジャミ ン・リー・ウォーフ(1897–1941)は共同著作を残しておらず、自らの考えを仮説として表明したこともない。この仮説の弱形と強形の区別も後世の展 開である。サピアとウォーフはこのような二分法を用いたことはなく、彼らの著作やこの相対性原理に対する見解は、より強い表現や弱い表現で示されることが 多かったのである。[6][7] 言語相対性の原理と、言語と思考の関係性は、哲学、心理学、人類学など様々な学術分野でも注目されている。また、フィクション作品や人工言語の創作にも影響を与えている。 |

| History The idea was first expressed explicitly by 19th-century thinkers such as Wilhelm von Humboldt and Johann Gottfried Herder, who considered language as the expression of the spirit of a nation. Members of the early 20th-century school of American anthropology including Franz Boas and Edward Sapir also approved versions of the idea to a certain extent, including in a 1928 meeting of the Linguistic Society of America,[8] but Sapir, in particular, wrote more often against than in favor of anything like linguistic determinism. Sapir's student, Benjamin Lee Whorf, came to be considered as the primary proponent as a result of his published observations of how he perceived linguistic differences to have consequences for human cognition and behavior. Harry Hoijer, another of Sapir's students, introduced the term "Sapir–Whorf hypothesis",[9] even though the two scholars never formally advanced any such hypothesis.[10] A strong version of relativist theory was developed from the late 1920s by the German linguist Leo Weisgerber. Whorf's principle of linguistic relativity was reformulated as a testable hypothesis by Roger Brown and Eric Lenneberg who performed experiments designed to determine whether color perception varies between speakers of languages that classified colors differently. As the emphasis of the universal nature of human language and cognition developed during the 1960s, the idea of linguistic relativity became disfavored among linguists. From the late 1980s, a new school of linguistic relativity scholars has examined the effects of differences in linguistic categorization on cognition, finding broad support for non-deterministic versions of the hypothesis in experimental contexts.[11][12] Some effects of linguistic relativity have been shown in several semantic domains, although they are generally weak. Currently, a nuanced opinion of linguistic relativity is espoused by most linguists holding that language influences certain kinds of cognitive processes in non-trivial ways, but that other processes are better considered as developing from connectionist factors. Research emphasizes exploring the manners and extent to which language influences thought.[11] |

歴史 この考えは、19世紀の思想家であるヴィルヘルム・フォン・フンボルトやヨハン・ゴットフリート・ヘルダーらによって初めて明確に表現された。彼らは言語 を国民の精神の表現と見なした。フランツ・ボアズやエドワード・サピアら20世紀初頭のアメリカ人類学派のメンバーも、1928年のアメリカ言語学会会議 [8]を含む場で、この考えの一端をある程度支持した。しかし特にサピアは、言語決定論に類する主張に対して賛成よりも反対の立場を頻繁に表明した。サピ アの弟子ベンジャミン・リー・ウォーフは、言語の違いが人間の認知や行動に及ぼす影響についての観察結果を公表したことで、この理論の主要な提唱者と見な されるようになった。同じくサピアの弟子であるハリー・ホイヤーは「サピア=ウォーフ仮説」という用語を導入したが、両学者は正式にそのような仮説を提唱 したことは一度もなかった。[10] 相対主義理論の強硬版は、1920年代後半からドイツの言語学者レオ・ヴァイスガーバーによって発展した。ウォーフの言語相対性原理は、ロジャー・ブラウ ンとエリック・レネバーグによって検証可能な仮説として再構築された。彼らは、色を異なる方法で分類する言語を話す者間で色知覚が異なるかどうかを確かめ る実験を行った。 1960年代に人間言語と認知の普遍性が強調されるにつれ、言語相対性の考え方は言語学者たちの間で敬遠されるようになった。1980年代後半からは、言 語相対性を研究する新たな学派が登場し、言語の分類が異なることが認知に与える影響を検証。実験的文脈において、この仮説の非決定論的解釈を広く支持する 結果を得ている。[11] [12] 言語相対性の影響はいくつかの意味領域で確認されているが、その効果は概して弱い。現在、言語相対性について多くの言語学者が支持する見解は、言語が特定 の認知プロセスに非自明な形で影響を与える一方、他のプロセスは接続主義的要因から発展すると考える方が適切だという微妙な立場である。研究は、言語が思 考に影響を与える様式と程度を探求することに重点を置いている。[11] |

| Ancient philosophy to the Enlightenment The idea that language and thought are intertwined is ancient. In his dialogue Cratylus, Plato explores the idea that conceptions of reality, such as Heraclitean flux, are embedded in language. But Plato has been read as arguing against sophist thinkers such as Gorgias of Leontini, who claimed that the physical world cannot be experienced except through language; this made the question of truth dependent on aesthetic preferences or functional consequences. Plato may have held instead that the world consisted of eternal ideas and that language should represent these ideas as accurately as possible.[13] Nevertheless, Plato's Seventh Letter claims that ultimate truth is inexpressible in words. Following Plato, St. Augustine, for example, argued that language was merely like labels applied to concepts existing already. This opinion remained prevalent throughout the Middle Ages.[14] Roger Bacon had the opinion that language was but a veil covering eternal truths, hiding them from human experience. For Immanuel Kant, language was but one of several methods used by humans to experience the world. German Romantic philosophers During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the idea of the existence of different national characters, or Volksgeister, of different ethnic groups was a major motivator for the German romantics school and the beginning ideologies of ethnic nationalism.[15] Johann Georg Hamann Johann Georg Hamann is often suggested to be the first among the actual German Romantics to discuss the concept of the "genius" of a language.[16][17] In his "Essay Concerning an Academic Question", Hamann suggests that a people's language affects their worldview: The lineaments of their language will thus correspond to the direction of their mentality.[18] |

古代哲学から啓蒙主義へ 言語と思考が密接に結びついているという考えは古代から存在する。プラトンは対話篇『クラテュロス』において、ヘラクレイトスの流転説のような現実観念が 言語に内在しているという思想を探求している。しかしプラトンは、レオティニのゴルギアスらソフィスト思想家に対する反論として解釈されてきた。ゴルギア スらは「物理的世界は言語を介さなければ経験できない」と主張し、真実の問題を美的嗜好や機能的帰結に依存させるものとした。プラトンはむしろ、世界は永 遠の理念から成り立ち、言語はこれらの理念を可能な限り正確に表現すべきだと考えていたのかもしれない[13]。とはいえプラトンの『第七書簡』は、究極 の真実は言葉で表現できないと述べている。 プラトンに続き、例えば聖アウグスティヌスは、言語は既に存在する概念に貼られたラベルに過ぎないと論じた。この見解は中世を通じて主流であり続けた [14]。ロジャー・ベーコンは、言語は永遠の真理を覆い隠すベールに過ぎず、人間の経験からそれらを隠していると考えた。イマヌエル・カントにとって、 言語は人間が世界を経験するために用いる数ある方法の一つに過ぎなかった。 ドイツ・ロマン主義哲学者 18世紀末から19世紀初頭にかけて、異なる民族集団に固有の国民性(フォルクスガイスター)が存在するとの考えは、ドイツ・ロマン主義学派や民族ナショナリズムの初期イデオロギーにとって主要な動機となった。[15] ヨハン・ゲオルク・ハーマン ヨハン・ゲオルク・ハーマンは、実際のドイツ・ロマン派の中で初めて「言語の精霊」という概念を論じた人物とよく言われる[16][17]。彼の『学問的疑問に関する論考』において、ハーマンは人々の言語が彼らの世界観に影響を与えると示唆している: したがって、彼らの言語の特徴は、彼らの精神性の方向性と対応するであろう[18]。 |

Wilhelm von Humboldt Wilhelm von Humboldt In 1820, Wilhelm von Humboldt associated the study of language with the national romanticist program by proposing that language is the fabric of thought. Thoughts are produced as a kind of internal dialog using the same grammar as the thinker's native language.[19] This opinion was part of a greater idea in which the assumptions of an ethnic nation, their "Weltanschauung", was considered as being represented by the grammar of their language. Von Humboldt argued that languages with an inflectional morphological type, such as German, English and the other Indo-European languages, were the most perfect languages and that accordingly this explained the dominance of their speakers with respect to the speakers of less perfect languages. Wilhelm von Humboldt declared in 1820: The diversity of languages is not a diversity of signs and sounds but a diversity of views of the world.[19] In Humboldt's humanistic understanding of linguistics, each language creates the individual's worldview in its particular way through its lexical and grammatical categories, conceptual organization, and syntactic models.[20] Herder worked alongside Hamann to establish the idea of whether or not language had a human/rational or a divine origin.[21] Herder added the emotional component of the hypothesis and Humboldt then took this information and applied to various languages to expand on the hypothesis. |

ヴィルヘルム・フォン・フンボルト ヴィルヘルム・フォン・フンボルト 1820年、ヴィルヘルム・フォン・フンボルトは言語研究を国民ロマン主義のプログラムと結びつけた。言語は思考の基盤であると提唱したのである。思考 は、思考者の母語と同じ文法を用いた一種の内的対話として生成される。[19] この見解は、国民の前提となる「世界観」がその言語の文法によって表されるとする、より大きな思想の一部であった。フォン・フンボルトは、ドイツ語、英 語、その他のインド・ヨーロッパ語族のように屈折形態論的類型を持つ言語が最も完璧な言語であり、それゆえに、より不完全な言語を話す者たちに対して、そ れらの言語を話す者たちが優位にあることを説明すると主張した。ヴィルヘルム・フォン・フンボルトは1820年にこう宣言した: 言語の多様性は、記号や音の多様性ではなく、世界観の多様性である。[19] フンボルトの人文主義的言語学理解によれば、各言語はその語彙・文法範疇、概念組織、構文モデルを通じて、固有の方法で個人の世界観を形成する。[20] ヘルダーはハーマンと共に、言語が人間的・合理的起源を持つか、それとも神聖な起源を持つかという問題の概念確立に取り組んだ。[21] ヘルダーはこの仮説に感情的要素を加え、フンボルトはその後この情報を様々な言語に適用して仮説を拡張した。 |

Boas and Sapir Franz Boas  Edward Sapir The idea that some languages are superior to others and that lesser languages maintained their speakers in intellectual poverty was widespread during the early 20th century.[22] American linguist William Dwight Whitney, for example, actively strove to eradicate Native American languages, arguing that their speakers were savages and would be better off learning English and adopting a "civilized" way of life.[23] The first anthropologist and linguist to challenge this opinion was Franz Boas.[24] While performing geographical research in northern Canada he became fascinated with the Inuit and decided to become an ethnographer. Boas stressed the equal worth of all cultures and languages, that there was no such thing as a primitive language and that all languages were capable of expressing the same content, albeit by widely differing means.[25] Boas saw language as an inseparable part of culture and he was among the first to require of ethnographers to learn the native language of the culture to be studied and to document verbal culture such as myths and legends in the original language.[26][27] Boas: It does not seem likely [...] that there is any direct relation between the culture of a tribe and the language they speak, except in so far as the form of the language will be moulded by the state of the culture, but not in so far as a certain state of the culture is conditioned by the morphological traits of the language."[28] Boas' student Edward Sapir referred to the Humboldtian idea that languages were a major factor for understanding the cultural assumptions of peoples.[29] He espoused the opinion that because of the differences in the grammatical systems of languages no two languages were similar enough to allow for perfect cross-translation. Sapir also thought because language represented reality differently, it followed that the speakers of different languages would perceive reality differently. Sapir: No two languages are ever sufficiently similar to be considered as representing the same social reality. The worlds in which different societies live are distinct worlds, not merely the same world with different labels attached.[30] However, Sapir explicitly rejected strong linguistic determinism by stating, "It would be naïve to imagine that any analysis of experience is dependent on pattern expressed in language."[31] Sapir was explicit that the associations between language and culture were neither extensive nor particularly profound, if they existed at all: It is easy to show that language and culture are not intrinsically associated. Totally unrelated languages share in one culture; closely related languages—even a single language—belong to distinct culture spheres. There are many excellent examples in Aboriginal America. The Athabaskan languages form as clearly unified, as structurally specialized, a group as any that I know of. The speakers of these languages belong to four distinct culture areas... The cultural adaptability of the Athabaskan-speaking peoples is in the strangest contrast to the inaccessibility to foreign influences of the languages themselves.[32] Sapir offered similar observations about speakers of so-called "world" or "modern" languages, noting, "possession of a common language is still and will continue to be a smoother of the way to a mutual understanding between England and America, but it is very clear that other factors, some of them rapidly cumulative, are working powerfully to counteract this leveling influence. A common language cannot indefinitely set the seal on a common culture when the geographical, physical, and economics determinants of the culture are no longer the same throughout the area."[33] While Sapir never made a practice of studying directly how languages affected thought, some notion of (probably "weak") linguistic relativity affected his basic understanding of language, and would be developed by Whorf.[34] |

ボアズとサピア フランツ・ボアス  エドワード・サピア 20世紀初頭には、ある言語が他の言語より優れており、劣った言語は話者を知的貧困に陥らせるという考えが広く流布していた[22]。例えばアメリカの言 語学者ウィリアム・ドワイト・ホイットニーは、先住民の言語を根絶しようと積極的に活動した。彼は先住民の話者は野蛮人であり、英語を学び「文明化され た」生活様式を採用した方が良いと主張したのである。[23] この見解に初めて異議を唱えた人類学者・言語学者がフランツ・ボアズである。[24] カナダ北部で地理学調査を行っていた彼はイヌイットに魅了され、エスノグラファーになることを決意した. ボアズは全ての文化と言語が等しく価値を持つこと、原始的な言語など存在せず、手段は大きく異なれど全ての言語が同じ内容を表現し得ると強調した。 [25] 彼は言語を文化と不可分の部分と見なし、研究対象の文化の現地語を学ぶこと、神話や伝説といった口承文化を原語で記録することをエスノグラファーに要求し た先駆者の一人であった。[26] [27] ボアズ: 部族の文化と彼らが話す言語の間に直接的な関係があるとは考えにくい。言語の形態が文化の状態によって形作られるという点では関係があるが、特定の文化状態が言語の形態論的特徴によって条件付けられるという点では関係がない。」[28] ボアズの弟子エドワード・サピアは、言語が人民の文化的前提を理解する主要因であるというフンボルトの思想に言及した。[29] 彼は、言語の文法体系の差異ゆえに、完全な相互翻訳を許容するほど類似した二つの言語は存在しないとの見解を支持した。サピアはまた、言語が現実を異なる 形で表すため、異なる言語を話す者たちは現実を異なって認識すると考えた。 サピア: 「二つの言語が同一の社会的現実を表すと見なせるほど十分に類似していることは決してない。異なる社会が生きる世界は、単に異なるラベルが貼られた同一世界ではなく、別個の世界である。」[30] しかしサピアは「経験の分析が言語に表現されたパターンに依存すると考えるのは幼稚である」と述べ、強い言語決定論を明確に否定した。[31] サピアは言語と文化の関連性が、仮に存在したとしても広範でも特に深いものでもないと明言した: 言語と文化が本質的に結びついているわけではないことは容易に示せる。全く無関係な言語が一つの文化を共有し、近縁言語——単一言語でさえ——が異なる文 化圏に属する。アメリカ先住民社会には優れた例が数多く存在する。アサバスカン語群は、私が知る限り最も明確に統一され、構造的に特化したグループを形成 している。これらの言語を話す人々(人々)は四つの異なる文化圏に属している…アサバスカン語を話す人々の文化的適応性は、言語そのものが外部からの影響 を受けにくい性質と奇妙な対照をなしている。[32] サピアは、いわゆる「世界」言語あるいは「現代」言語の話し手についても同様の観察を示し、こう述べている。「共通言語の保有は、今も、そして今後も、イ ギリスとアメリカの相互理解への道を滑らかにするものだ。しかし、他の要因、その中には急速に累積する要素も含まれるが、この平準化作用に強力に対抗して 働いていることは明らかである。」 共通言語は、その文化を形作る地理的・物理的・経済的要因が全域で同一でなくなった場合、共通文化を無限に保証することはできない。」[33] サピアは言語が思考に与える影響を直接研究することは決してなかったが、ある種の(おそらく「弱い」と言語相対性理論が彼の言語に対する基本的な理解に影響を与え、後にウォーフによって発展されることになる。[34] |

| Independent developments in Europe Drawing on influences such as Humboldt and Friedrich Nietzsche, some European thinkers developed ideas similar to those of Sapir and Whorf, generally working in isolation from each other. Prominent in Germany from the late 1920s through the 1960s were the strongly relativist theories of Leo Weisgerber and his concept of a 'linguistic inter-world', mediating between external reality and the forms of a given language, in ways peculiar to that language.[35] Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky read Sapir's work and experimentally studied the ways in which the development of concepts in children was influenced by structures given in language. His 1934 work "Thought and Language"[36] has been compared to Whorf's and taken as mutually supportive evidence of language's influence on cognition.[37] Drawing on Nietzsche's ideas of perspectivism Alfred Korzybski developed the theory of general semantics that has been compared to Whorf's notions of linguistic relativity.[38] Though influential in their own right, this work has not been influential in the debate on linguistic relativity, which has tended to be based on the American paradigm exemplified by Sapir and Whorf. |

ヨーロッパにおける独立した発展 フンボルトやフリードリヒ・ニーチェなどの影響を受け、一部のヨーロッパの思想家はサピアとウォーフの考えに類似した理論を発展させた。彼らは概して互い に孤立して活動していた。1920年代後半から1960年代にかけてドイツで顕著だったのは、レオ・ヴァイスガーバーの強い相対主義的理論と、外部現実と 特定の言語の形式との間を、その言語特有の方法で仲介する「言語間世界」という概念である。[35] ロシアの心理学者レフ・ヴィゴツキーはサピアの著作を読み、言語の構造が子どもの概念形成に与える影響を実験的に研究した。彼の1934年の著作『思考と 言語』[36]はウォーフの理論と比較され、言語が認知に与える影響を相互に裏付ける証拠と見なされてきた。[37] ニーチェの視点主義の思想を基に、アルフレッド・コルジブスキーは一般意味論の理論を発展させた。これはウォーフの言語相対性概念と比較されてきた [38]。それ自体は影響力を持つものの、この研究は言語相対性論争において影響力を及ぼさなかった。同論争はサピアとウォーフに代表されるアメリカ的パ ラダイムに基づいて展開される傾向があった。 |

| Benjamin Lee Whorf Main article: Benjamin Lee Whorf More than any linguist, Benjamin Lee Whorf has become associated with what he termed the "linguistic relativity principle".[39] Studying Native American languages, he attempted to account for the ways in which grammatical systems and language-use differences affected perception. Whorf's opinions regarding the nature of the relation between language and thought remain under contention. However, a version of theory holds some "merit", for example, "different words mean different things in different languages; not every word in every language has a one-to-one exact translation in a different language"[40] Critics such as Lenneberg,[41] Black, and Pinker[42] attribute to Whorf a strong linguistic determinism, while Lucy, Silverstein and Levinson point to Whorf's explicit rejections of determinism, and where he contends that translation and commensuration are possible. Detractors such as Lenneberg,[41] Chomsky and Pinker[43] criticized him for insufficient clarity of his description of how language influences thought, and for not proving his conjectures. Most of his arguments were in the form of anecdotes and speculations that served as attempts to show how "exotic" grammatical traits were associated with what were apparently equally exotic worlds of thought. In Whorf's words: We dissect nature along lines laid down by our native language. The categories and types that we isolate from the world of phenomena we do not find there because they stare every observer in the face; on the contrary, the world is presented in a kaleidoscope flux of impressions which has to be organized by our minds—and this means largely by the linguistic systems of our minds. We cut nature up, organize it into concepts, and ascribe significances as we do, largely because we are parties to an agreement to organize it in this way—an agreement that holds throughout our speech community and is codified in the patterns of our language [...] all observers are not led by the same physical evidence to the same picture of the universe, unless their linguistic backgrounds are similar, or can in some way be calibrated.[44] |

ベンジャミン・リー・ウォーフ メイン記事: ベンジャミン・リー・ウォーフ ベンジャミン・リー・ウォーフは、他のどの言語学者よりも、彼が「言語相対性原理」と呼んだ概念と結びつけられるようになった。[39] ネイティブアメリカンの言語を研究し、文法体系や言語使用の違いが知覚に与える影響を説明しようとした。言語と思考の関係性に関するウォーフの見解は、今 も議論の的となっている。しかし、ある理論のバージョンには一定の「価値」がある。例えば、「異なる言語では異なる言葉が異なる意味を持つ。あらゆる言語 のあらゆる単語が、別の言語で一対一の正確な訳語を持つわけではない」という主張だ[40]。レネバーグやブラック[41]、ピンカー[42]といった批 判者は、ウォーフに強い言語決定論を認める。一方、ルーシー、シルバースタイン、レヴィンソンは、ウォーフが決定論を明確に否定した点や、翻訳について論 じた点を指摘している。[41] ブラック、ピンカー[42]といった批判者は、ウォーフに強い言語決定論を帰する。一方ルーシー、シルバースタイン、レヴィンソンは、ウォーフが決定論を 明示的に否定し、翻訳や比較可能性が成立し得ると主張した点を指摘する。 レネバーグ[41]、チョムスキー、ピンカー[43]といった批判者は、言語が思考に与える影響についての彼の説明が不明確であること、そして彼の仮説を 証明していないことを非難した。彼の議論の大半は、いわゆる「異質な」文法的特徴が、同様に異質に見える思考の世界とどう結びつくかを示そうとする試みと して、逸話や推測の形でなされていた。ウォーフ自身の言葉を借りれば: 我々は母語が定めた線に沿って自然を解剖する。現象世界から切り離すカテゴリーや類型は、観察者の眼前に明示されているから発見するのではない。むしろ世 界は万華鏡のように移ろいゆく印象の流として提示され、我々の精神によって組織化されねばならない——これは主に我々の精神の言語体系によって行われる。 我々は自然を切り分け、概念に整理し、意味を付与する。その手法の大部分は、言語共同体全体で共有され言語のパターンに規定された「整理方法に関する合 意」に基づくものだ。[...]言語的背景が類似しているか、何らかの方法で調整されない限り、全ての観察者が同じ物理的証拠から同じ宇宙像を導き出すわ けではないのだ[44]。 |

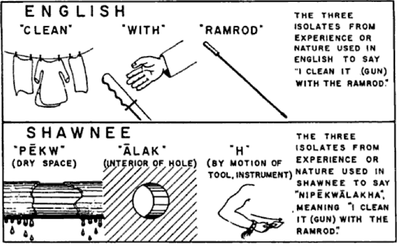

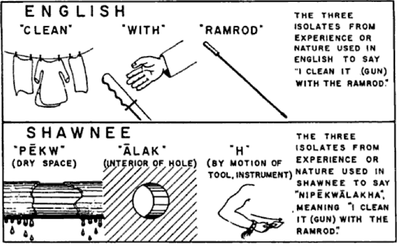

Whorf's illustration of the difference between the English and Shawnee gestalt construction of cleaning a gun with a ramrod. From the article "Science and Linguistics", originally published in the MIT Technology Review, 1940. Several terms for a single concept Among Whorf's best-known examples of linguistic relativity are instances where a non-European language has several terms for a concept that is only described with one word in European languages (Whorf used the acronym SAE "Standard Average European" to allude to the rather similar grammatical structures of the well-studied European languages in contrast to the greater diversity of less-studied languages). One of Whorf's examples was the supposedly large number of words for 'snow' in the Inuit languages, an example that later was contested as a misrepresentation.[45] Another is the Hopi language's words for water, one indicating drinking water in a container and another indicating a natural body of water.[46] These examples of polysemy served the double purpose of showing that non-European languages sometimes made more specific semantic distinctions than European languages and that direct translation between two languages, even of seemingly basic concepts such as snow or water, is not always possible.[47] Another example is from Whorf's experience as a chemical engineer working for an insurance company as a fire inspector.[45] While inspecting a chemical plant he observed that the plant had two storage rooms for gasoline barrels, one for the full barrels and one for the empty ones. He further noticed that while no employees smoked cigarettes in the room for full barrels, no-one minded smoking in the room with empty barrels, although this was potentially much more dangerous because of the flammable vapors still in the barrels. He concluded that the use of the word empty in association to the barrels had resulted in the workers unconsciously regarding them as harmless, although consciously they were probably aware of the risk of explosion. This example was later criticized by Lenneberg[41] as not actually demonstrating causality between the use of the word empty and the action of smoking, but instead was an example of circular reasoning. Pinker in The Language Instinct ridiculed this example, claiming that this was a failing of human insight rather than language.[43] |

ウォーフが示した、銃の掃除棒を使った銃の掃除という行為に対する英語とショーニー語のゲシュタルト構造の異なる点。1940年にMITテクノロジーレビュー誌に掲載された記事「科学と言語学」より。 一つの概念に対する複数の用語 ウォーフが言語相対性理論で最もよく知られる例として挙げたのは、非ヨーロッパ言語が、ヨーロッパ言語では一つの単語でしか表現されない概念に対して複数 の用語を持つ事例である(ウォーフは「標準平均ヨーロッパ語(SAE)」という略語を用いて、よく研究されたヨーロッパ言語の比較的類似した文法構造と、 研究が進んでいない言語の多様性との対比を示唆した)。 ウォーフが挙げた例の一つは、イヌイット語に「雪」を表す単語が多数存在するというものであったが、この例は後に誤った表現として反論された[45]。 別の例はホピ語の水を表す単語で、容器に入った飲料水を示すものと、自然の水域を示すものが別々に存在する。[46] これらの多義性の例は、非ヨーロッパ言語が時にヨーロッパ言語よりも詳細な意味的区別を行うこと、そして雪や水のような一見基本的な概念でさえ、二言語間の直接翻訳が常に可能ではないことを示す二重の目的を果たした。[47] 別の例は、保険会社の火災検査官として化学技術者を務めていたウォーフ自身の経験に基づくものである[45]。化学工場を検査中、彼はガソリン樽用の貯蔵 室が二つあることに気づいた。一つは満タンの樽用、もう一つは空の樽用だった。さらに彼は、満タンドラム用の部屋では従業員がタバコを吸わないのに、空ド ラム用の部屋では誰も気にせず喫煙していることに気づいた。空ドラム用の部屋は、ドラム内に残留する可燃性蒸気のため、潜在的にはるかに危険な場所だっ た。彼は、ドラムに関連して「空」という言葉が使われることで、労働者たちが無意識のうちにそれらを無害なものとして認識している結果だと結論づけた。意 識的には爆発の危険性を認識していたかもしれないが。この例は後にレネバーグ[41]によって批判された。空という語の使用と喫煙行為の因果関係を示して おらず、循環論法に過ぎないというのだ。ピンカーは『言語本能』でこの例を嘲笑し、これは言語の欠陥ではなく人間の洞察力の欠如だと主張した[43]。 |

| Time in Hopi Whorf's most elaborate argument for linguistic relativity regarded what he believed to be a fundamental difference in the understanding of time as a conceptual category among the Hopi.[48] He argued that in contrast to English and other SAE languages, Hopi does not treat the flow of time as a sequence of distinct, countable instances, like "three days" or "five years", but rather as a single process and that consequently it has no nouns referring to units of time as SAE speakers understand them. He proposed that this view of time was fundamental to Hopi culture and explained certain Hopi behavioral patterns. Ekkehart Malotki later claimed that he had found no evidence of Whorf's claims in 1980's era Hopi speakers, nor in historical documents dating back to the arrival of Europeans. Malotki used evidence from archaeological data, calendars, historical documents, and modern speech; he concluded that there was no evidence that Hopi conceptualize time in the way Whorf suggested. Many universalist scholars such as Pinker consider Malotki's study as a final refutation of Whorf's claim about Hopi, whereas relativist scholars such as John A Lucy and Penny Lee criticized Malotki's study for mischaracterizing Whorf's claims and for forcing Hopi grammar into a model of analysis that does not fit the data.[49] |

ホピ族の時間観 ウォーフが言語相対性理論について最も詳細に論じたのは、ホピ族における時間という概念的カテゴリーに対する理解が、根本的に異なる点である。[48] 彼は、英語や他のSAE言語とは対照的に、ホピ語は時間の流れを「3日間」や「5年」のような個別の数え上げ可能な単位の連続として扱わず、むしろ単一の プロセスとして捉えるため、SAE話者が理解するような時間単位を指す名詞が存在しないと主張した。この時間観はホピ文化の根幹をなし、特定のホピの行動 様式を説明すると彼は提案した。 エッケハルト・マロツキは後に、1980年代のホピ語話者にも、ヨーロッパ人到来まで遡る歴史文書にも、ウォーフの主張を裏付ける証拠は見つからなかった と主張した。マロツキは考古学的データ、暦、歴史文書、現代の話し言葉からの証拠を用い、ホピ族がウォーフが示唆した方法で時間を概念化している証拠は存 在しないと結論づけた。ピンカーのような普遍主義学者はマロツキの研究をホピに関するウォーフの主張の最終的な反証と見なす一方、ジョン・A・ルーシーや ペニー・リーのような相対主義学者は、マロツキの研究がウォーフの主張を誤解させ、データを適合させない分析モデルにホピ文法を無理に当てはめたと批判し ている。 |

| Structure-centered approach Whorf's argument about Hopi speakers' conceptualization of time is an example of the structure-centered method of research into linguistic relativity, which Lucy identified as one of three main types of research of the topic.[50] The "structure-centered" method starts with a language's structural peculiarity and examines its possible ramifications for thought and behavior. The defining example is Whorf's observation of discrepancies between the grammar of time expressions in Hopi and English. More recent research in this vein is Lucy's research describing how usage of the categories of grammatical number and of numeral classifiers in the Mayan language Yucatec result in Mayan speakers classifying objects according to material rather than to shape as preferred by English speakers.[51] However, philosophers including Donald Davidson and Jason Josephson Storm have argued that Whorf's Hopi examples are self-refuting, as Whorf had to translate Hopi terms into English in order to explain how they are untranslatable.[52] |

構造中心のアプローチ ホピ語話者の時間概念に関するウォーフの議論は、言語相対性論の研究における構造中心の手法の例である。ルーシーはこの手法を、同テーマの研究における三 つの主要類型の一つと位置付けた[50]。「構造中心」手法は、言語の構造的特徴を出発点とし、それが思考や行動に及ぼす可能性のある影響を検証する。決 定的な例は、ホピ語と英語における時間表現の文法上の相違をウォーフが観察した点だ。この流れにおける近年の研究として、ルーシーはマヤ語の一種であるユ カテコ語における文法的数と量詞のカテゴリー使用が、英語話者が好む形状ではなく材質に基づいて物体を分類するマヤ語話者の傾向を説明している。[51] しかしドナルド・デイヴィッドソンやジェイソン・ジョセフソン・ストームら哲学者たちは、ウォーフのホピ語例証は自己矛盾していると反論している。なぜな らウォーフは、それらの用語が翻訳不可能であることを説明するために、ホピ語の用語を英語に翻訳せざるを得なかったからだ。[52] |

| Whorf dies Whorf died in 1941 at age 44, leaving multiple unpublished papers. His ideas were continued by linguists and anthropologists such as Hoijer and Lee, who both continued investigating the effect of language on habitual thought, and Trager, who prepared a number of Whorf's papers for posthumous publishing. The most important event for the dissemination of Whorf's ideas to a larger public was the publication in 1956 of his major writings on the topic of linguistic relativity in a single volume titled Language, Thought and Reality. |

ウォーフは死去した ウォーフは1941年、44歳で死去し、多数の未発表論文を残した。彼の思想は、言語が習慣的な思考に与える影響を研究を続けたホイヤーやリーといった言 語学者・人類学者、またウォーフの論文を死後出版のために準備したトレーガーらによって継承された。ウォーフの思想が広く一般に知られるようになった最大 の契機は、1956年に言語相対性論に関する主要著作が『言語、思考、現実』という単行本として刊行されたことである。 |

| Brown and Lenneberg In 1953, Eric Lenneberg criticized Whorf's examples from an objectivist philosophy of language, claiming that languages are principally meant to represent events in the real world, and that even though languages express these ideas in various ways, the meanings of such expressions and therefore the thoughts of the speaker are equivalent. He argued that Whorf's English descriptions of a Hopi speaker's idea of time were in fact translations of the Hopi concept into English, therefore disproving linguistic relativity. However Whorf was concerned with how the habitual use of language influences habitual behavior, rather than translatability. Whorf's point was that while English speakers may be able to understand how a Hopi speaker thinks, they do not think in that way.[53] Lenneberg's main criticism of Whorf's works was that he never showed the necessary association between a linguistic phenomenon and a mental phenomenon. With Brown, Lenneberg proposed that proving such an association required directly matching linguistic phenomena with behavior. They assessed linguistic relativity experimentally and published their findings in 1954. Since neither Sapir nor Whorf had ever stated a formal hypothesis, Brown and Lenneberg formulated their own. Their two tenets were (i) "the world is differently experienced and conceived in different linguistic communities" and (ii) "language causes a particular cognitive structure".[54] Brown later developed them into the so-called "weak" and "strong" formulation: Structural differences between language systems will, in general, be paralleled by nonlinguistic cognitive differences, of an unspecified sort, in the native speakers of the language. The structure of anyone's native language strongly influences or fully determines the worldview he will acquire as he learns the language.[55] Brown's formulations became known widely and were retrospectively attributed to Whorf and Sapir although the second formulation, verging on linguistic determinism, was never advanced by either of them. |

ブラウンとレネバーグ 1953年、エリック・レネバーグは客観主義言語哲学の立場からウォーフの例を批判した。言語は主に現実世界の事象を表現するためのものであり、言語がこ れらの概念を様々な方法で表現するとしても、そうした表現の意味、ひいては話者の思考は同等だと主張したのだ。彼は、ホピ族話者の時間観を英語で説明した ウォーフの記述は、実際にはホピの概念を英語に翻訳したものであり、言語相対論を否定する証拠だと主張した。しかしウォーフが関心を持っていたのは、翻訳 可能性ではなく、言語の習慣的用法が習慣的行動に与える影響であった。ウォーフの主張は、英語話者はホピ族話者の思考方法を理解できても、そのように思考 することはないという点にあった。[53] レネバーグがウォーフの研究に対して主にした批判は、言語現象と精神現象の間に必要な関連性を示さなかった点である。ブラウンと共に、レネバーグはそうし た関連性を証明するには言語現象と行動を直接対応させる必要があると提唱した。彼らは言語相対性を実験的に検証し、1954年にその結果を発表した。サピ アもウォーフも正式な仮説を提示したことがなかったため、ブラウンとレネバーグは独自の仮説を構築した。彼らの二つの基本命題は、(i)「世界は異なる言 語共同体において異なって経験され、概念化される」および (ii)「言語は特定の認知構造を引き起こす」であった。[54] ブラウンは後にこれらをいわゆる「弱」命題と「強」命題に発展させた: 言語体系間の構造的差異は、一般に、その言語の母語話者における非言語的認知的差異(その種類は特定されない)と並行する。 誰であれ、その人の母語の構造は、言語を学ぶ過程で獲得する世界観を強く影響するか、あるいは完全に決定する。[55] ブラウンの定式化は広く知られるようになり、後世においてウォーフとサピールの思想に帰せられるようになった。ただし、言語決定論に限りなく近い第二の定式化は、彼ら二人が提唱したものではない。 |

| Joshua Fishman's "Whorfianism of the third kind" Joshua Fishman argued that Whorf's true assertion was largely overlooked. In 1978, he suggested that Whorf was a "neo-Herderian champion"[56] and in 1982, he proposed "Whorfianism of the third kind" in an attempt to reemphasize what he claimed was Whorf's real interest, namely the intrinsic value of "little peoples" and "little languages".[57] Whorf had criticized Ogden's Basic English thus: But to restrict thinking to the patterns merely of English [...] is to lose a power of thought which, once lost, can never be regained. It is the 'plainest' English which contains the greatest number of unconscious assumptions about nature. [...] We handle even our plain English with much greater effect if we direct it from the vantage point of a multilingual awareness.[58] Where Brown's weak version of the linguistic relativity hypothesis proposes that language influences thought and the strong version that language determines thought, Fishman's "Whorfianism of the third kind" proposes that language is a key to culture. Leiden school The Leiden school is a linguistic theory that models languages as parasites. Notable proponent Frederik Kortlandt, in a 1985 paper outlining Leiden school theory, advocates for a form of linguistic relativity: "The observation that in all Yuman languages the word for 'work' is a loan from Spanish should be a major blow to any current economic theory." In the next paragraph, he quotes directly from Sapir: "Even in the most primitive cultures the strategic word is likely to be more powerful than the direct blow."[59] |

ジョシュア・フィッシュマンの「第三種ウォーフ主義」 ジョシュア・フィッシュマンは、ウォーフの真の主張がほとんど見過ごされてきたと論じた。1978年には、ウォーフを「新ヘルダー主義の擁護者」[56] と位置づけ、1982年には「第三のウォーフ主義」を提唱した。これはウォーフの真の関心事、すなわち「小さな民族」と「小さな言語」の本質的価値を再強 調しようとする試みであった[57]。ウォーフはオグデンのベーシック・イングリッシュをこう批判していた: 思考を英語のパターンに限定することは[...]思考力を失うことであり、一度失われたその力は二度と取り戻せない。最も「平易な」英語こそが、自然に関 する無意識の前提を最も多く含んでいる。[...]多言語的認識という視点から平易な英語を扱うことで、我々はより大きな効果を得られるのだ。[58] ブラウンの言語相対性仮説の弱形が「言語は思考に影響を与える」と主張し、強形が「言語は思考を決定する」と主張するのに対し、フィッシュマンの「第三のウォーフ主義」は「言語は文化の鍵である」と提唱する。 ライデン学派 ライデン学派は言語を寄生虫としてモデル化する言語理論である。主要な提唱者であるフレデリック・コルトランドは、1985年の論文でライデン学派の理論 を概説し、言語相対性の形態を主張している:「ユマン語族の全言語において『仕事』を表す語がスペイン語からの借用語であるという観察は、あらゆる現行の 経済理論に対する重大な打撃となるべきだ」 次の段落ではサピアの言葉を直接引用している:「最も原始的な文化でさえ、戦略的な言葉は直接的な打撃よりも強力である可能性が高い」[59] |

| Rethinking Linguistic Relativity The publication of the 1996 anthology Rethinking Linguistic Relativity edited by Gumperz and Levinson began a new period of linguistic relativity studies that emphasized cognitive and social aspects. The book included studies on linguistic relativity and universalist traditions. Levinson documented significant linguistic relativity effects in the different linguistic conceptualization of spatial categories in different languages. For example, men speaking the Guugu Yimithirr language in Queensland gave accurate navigation instructions using a compass-like system of north, south, east and west, along with a hand gesture pointing to the starting direction.[60] Lucy defines this method as "domain-centered" because researchers select a semantic domain and compare it across linguistic and cultural groups.[50] Space is another semantic domain that has proven fruitful for linguistic relativity studies.[61] Spatial categories vary greatly across languages. Speakers rely on the linguistic conceptualization of space in performing many ordinary tasks. Levinson and others reported three basic spatial categorizations. While many languages use combinations of them, some languages exhibit only one type and related behaviors. For example, Yimithirr only uses absolute directions when describing spatial relations—the position of everything is described by using the cardinal directions. Speakers define a location as "north of the house", while an English speaker may use relative positions, saying "in front of the house" or "to the left of the house".[62] Separate studies by Bowerman and Slobin analyzed the role of language in cognitive processes. Bowerman showed that some basic cognitive functions, such as early spatial reasoning and object categorization in infants, develop largely independently of language. This suggests that not all aspects of cognition are shaped by linguistic structures, and therefore some cognitive processes may fall outside the scope of linguistic relativity.[63] Slobin described another kind of cognitive process that he named "thinking for speaking"—- the kind of process in which perceptional data and other kinds of prelinguistic cognition are translated into linguistic terms for communication.[clarification needed] These, Slobin argues, are the kinds of cognitive process that are the basis of linguistic relativity.[64] |

言語相対性の再考 1996年にガンペルツとレヴィンソンが編集した論文集『言語相対性の再考』の出版は、認知的・社会的側面を強調する言語相対性研究の新たな時代を切り開 いた。本書には言語相対論と普遍主義の伝統に関する研究が収録された。レヴィンソンは、言語によって異なる空間概念の言語化において、顕著な言語相対論的 効果を実証した。例えばクイーンズランド州のググ・イミティール語話者は、北・南・東・西という方位磁針のようなシステムと、出発方向を指し示す手のジェ スチャーを用いて正確な航法指示を与えた。[60] ルーシーはこの手法を「領域中心型」と定義している。研究者が意味領域を選択し、言語・文化集団間で比較するためだ。[50] 空間もまた、言語相対性研究において実り多い意味領域である。[61] 空間カテゴリーは言語間で大きく異なる。話者は日常的な作業を行う際、言語による空間概念化に依存している。レヴィンソンらは三つの基本空間分類を報告し た。多くの言語がこれらを組み合わせて使用するが、一部の言語では1種類のみと関連行動が見られる。例えばイミティール語は空間関係の説明に絶対方向のみ を用いる——あらゆる位置は方位を用いて記述される。話者は場所を「家の北側」と定義するが、英語話者は「家の前」や「家の左側」といった相対的位置を用 いるかもしれない。[62] バウアーマンとスロービンの別々の研究は、認知プロセスにおける言語の役割を分析した。バウアーマンは、乳児の初期空間推論や物体分類といった基本的な認 知機能が、言語とはほぼ独立して発達することを示した。これは、認知のあらゆる側面が言語構造によって形作られるわけではなく、したがって一部の認知プロ セスは言語相対性の範囲外にある可能性を示唆している。[63] スロビンは「話すための思考」と名付けた別の認知プロセスを説明した。これは知覚データや言語以前の認知が、コミュニケーションのために言語的表現へ変換 されるプロセスである。スロビンによれば、こうした認知プロセスこそが言語相対性の基盤となる。 |

| Colour terminology Main article: Linguistic relativity and the color naming debate Brown and Lenneberg Since Brown and Lenneberg believed that the objective reality denoted by language was the same for speakers of all languages, they decided to test how different languages codified the same message differently and whether differences in codification could be proven to affect behavior. Brown and Lenneberg designed experiments involving the codification of colors. In their first experiment, they investigated whether it was easier for speakers of English to remember color shades for which they had a specific name than to remember colors that were not as easily definable by words. This allowed them to compare the linguistic categorization directly to a non-linguistic task. In a later experiment, speakers of two languages that categorize colors differently (English and Zuni) were asked to recognize colors. In this manner, it could be determined whether the differing color categories of the two speakers would determine their ability to recognize nuances within color categories. Brown and Lenneberg found that Zuni speakers who classify orange and yellow together as a single color did have trouble recognizing and remembering nuances within the orange/yellow category.[65] This method, which Lucy later classified as domain-centered,[50] is acknowledged to be sub-optimal, because color perception, unlike other semantic domains, is hardwired into the neural system and as such is subject to more universal restrictions than other semantic domains. |

色彩用語 主な記事: 言語相対性理論と色彩命名論争 ブラウンとレネバーグ ブラウンとレネバーグは、言語が指し示す客観的現実は全ての言語話者にとって同一であると考えた。そこで彼らは、異なる言語が同じメッセージをどのように 異なって符号化するのか、また符号化の差異が行動に影響を与えることを証明できるのかを検証することにした。ブラウンとレネバーグは色彩の符号化に関する 実験を設計した。最初の実験では、英語話者が特定の名称を持つ色調を、言葉で定義しにくい色よりも記憶しやすいかどうかを調べた。これにより言語的分類と 非言語的課題を直接比較できた。後の実験では、色を異なる方法で分類する二言語(英語とズニ語)の話し手に色を認識させた。これにより、異なる色分類体系 を持つ話し手が、色分類内の微妙な差異を認識できるかどうかを判断できた。ブラウンとレンバーグは、オレンジと黄色を同一色として分類するズニ語話者が、 オレンジ/黄色分類内の微妙な差異を認識・記憶するのに困難を抱えていることを発見した。[65] この手法は、ルーシーが後に領域中心型[50]と分類したものだが、最適とは言えないと認められている。なぜなら、色知覚は他の意味領域とは異なり、神経 系に組み込まれており、それゆえ他の意味領域よりも普遍的な制約を受けやすいからである。 |

| Hugo Magnus In a similar study done by German ophthalmologist Hugo Magnus during the 1870s, he circulated a questionnaire to missionaries and traders with ten standardized color samples and instructions for using them. These instructions contained an explicit warning that failure of a language to distinguish lexically between two colors did not necessarily imply that speakers of that language did not distinguish the two colors perceptually. Magnus received completed questionnaires on twenty-five African, fifteen Asian, three Australian, and two European languages. He concluded in part, "As regards the range of the color sense of the primitive peoples tested with our questionnaire, it appears in general to remain within the same bounds as the color sense of the civilized nations. At least, we could not establish a complete lack of the perception of the so-called main colors as a special racial characteristic of any one of the tribes investigated for us. We consider red, yellow, green, and blue as the main representatives of the colors of long and short wavelength; among the tribes we tested not a one lacks the knowledge of any of these four colors" (Magnus 1880, p. 6, as trans. in Berlin and Kay 1969, p. 141). Magnus did find widespread lexical neutralization of green and blue, that is, a single word covering both these colors, as have all subsequent comparative studies of color lexicons.[66] |

ウーゴ・マグヌス 1870年代にドイツの眼科医ウーゴ・マグヌスが実施した類似の研究では、宣教師や商人らに10種類の標準化された色見本と使用説明書付きの質問票を配布 した。この説明書には、言語が二つの色を語彙的に区別できない場合でも、その言語話者が知覚的に二つの色を区別できないとは限らないという明確な警告が含 まれていた。マグヌスは25のアフリカ語、15のアジア語、3つのオーストラリア語、2つのヨーロッパ語について回答済みの質問票を受け取った。彼は結論 の一部として次のように述べている。「我々の質問票で調査した原始人民の色覚の範囲は、概して文明国民の色覚と同じ範囲内に留まっているようだ。」 少なくとも我々が調査した部族のいずれにおいても、いわゆる主要色の知覚が完全に欠如しているという特別な人種的特徴を確認することはできなかった。我々 は赤、黄、緑、青を長波長・短波長色の主要な代表と見なしているが、調査対象部族の中でこれら四色いずれかの知識を欠く部族は一つもなかった」 (マグヌス 1880, p. 6, Berlin and Kay 1969, p. 141 に翻訳)マグヌスは緑と青の広範な語彙中立化、すなわち単一の語で両色を包括する現象を確認した。これはその後の色彩語彙比較研究でも一貫して確認されて いる。[66] |

| Response to Brown and Lenneberg's study Brown and Lenneberg's study began a tradition of investigation of linguistic relativity through color terminology. The studies showed a correlation between color term numbers and ease of recall in both Zuni and English speakers. Researchers attributed this to focal colors having greater codability than less focal colors, and not to linguistic relativity effects. Berlin/Kay found universal typological color principles that are determined by biological rather than linguistic factors.[67] This study sparked studies into typological universals of color terminology. Researchers such as Lucy,[50] Saunders[68] and Levinson[69] argued that Berlin and Kay's study does not refute linguistic relativity in color naming, because of unsupported assumptions in their study (such as whether all cultures in fact have a clearly defined category of "color") and because of related data problems. Researchers such as Maclaury continued investigation into color naming. Like Berlin and Kay, Maclaury concluded that the domain is governed mostly by physical-biological universals.[70][71] |

ブラウンとレネバーグの研究への反論 ブラウンとレネバーグの研究は、色彩用語を通じた言語相対性論の研究の先駆けとなった。この研究はズニ語話者と英語話者の双方において、色彩用語の数と想 起の容易さに相関関係があることを示した。研究者らはこれを、焦点となる色彩が焦点外の色彩よりも符号化されやすい性質によるものであり、言語相対性の効 果によるものではないと説明した。ベルリン/ケイは、言語的要因ではなく生物学的要因によって決定される普遍的な類型論的色彩原理を発見した。[67] この研究は色彩用語の類型論的普遍性に関する研究の火付け役となった。ルーシー[50]、サンダース[68]、レヴィンソン[69]ら研究者は、ベルリン とケイの研究が色彩命名における言語相対性を否定しない理由として、彼らの研究における根拠のない仮定(例えば全ての文化が実際に「色」という明確なカテ ゴリーを持つかどうか)や関連するデータの問題点を挙げた。マクラリーら研究者は色彩命名に関する調査を継続した。ベルリンとケイと同様に、マクラリーも この領域は主に物理的・生物学的普遍性によって支配されていると結論づけた。[70][71] |

| Berlin and Kay Studies by Berlin and Kay continued Lenneberg's color research. They studied color terminology formation and showed clear universal trends in color naming. For example, they found that even though languages have different color terminologies, they generally recognize certain hues as more focal than others. They showed that in languages with few color terms, it is predictable from the number of terms which hues are chosen as focal colors: For example, languages with only three color terms always have the focal colors black, white, and red.[67] The fact that what had been believed to be random differences between color naming in different languages could be shown to follow universal patterns was seen as a powerful argument against linguistic relativity.[72] Berlin and Kay's research has since been criticized by relativists such as Lucy, who argued that Berlin and Kay's conclusions were skewed by their insistence that color terms encode only color information.[51] This, Lucy argues, made them unaware of the instances in which color terms provided other information that might be considered examples of linguistic relativity. |

ベルリンとケイ ベルリンとケイの研究はレネベルグの色研究を継承した。彼らは色彩用語の形成を研究し、色彩命名における明確な普遍的傾向を示した。例えば、言語によって 色彩用語は異なるが、特定の色相が他の色相より焦点として認識される傾向が一般的であることを発見した。彼らは、色彩用語が少ない言語では、用語の数から 焦点色が予測可能であることを示した。例えば、色彩用語が3つしかない言語では、焦点色は常に黒、白、赤である。[67] 異なる言語間の色彩命名における差異が、従来はランダムと考えられていたものが、実は普遍的なパターンに従うことが示された事実は、言語相対論に対する強 力な反論と見なされた。[72] その後、ルーシーら相対論者はベルリンとケイの研究を批判した。彼らは、ベルリンとケイが「色用語は色情報のみを符号化する」と主張したことで結論が歪め られたと論じた。[51] ルーシーによれば、この主張が原因で、色用語が言語相対性の例と見なされる可能性のある他の情報を提供している事例に彼らが気づかなかったという。 |

| Universalism Universalist scholars began a period of dissent from ideas about linguistic relativity. Lenneberg was one of the first cognitive scientists to begin development of the Universalist theory of language that was formulated by Chomsky as universal grammar, effectively arguing that all languages share the same underlying structure. The Chomskyan school also includes the belief that linguistic structures are largely innate and that what are perceived as differences between specific languages are surface phenomena that do not affect the brain's universal cognitive processes. This theory became the dominant paradigm of American linguistics from the 1960s through the 1980s, while linguistic relativity became the object of ridicule.[73] |

普遍主義 普遍主義の学者たちは、言語相対論の考え方に異議を唱える時期を始めた。レンネベルグは、チョムスキーが普遍文法として定式化した言語の普遍主義理論の発 展を始めた最初の認知科学者の一人であり、事実上、全ての言語が同じ基盤構造を共有すると主張した。チョムスキー学派はまた、言語構造は主に生得的なもの であり、特定の言語間の差異と見なされるものは、脳の普遍的な認知プロセスに影響を与えない表面現象に過ぎないという信念も含む。この理論は1960年代 から1980年代にかけてアメリカ言語学の支配的なパラダイムとなり、一方、言語相対論は嘲笑の対象となった。[73] |

| Ekkehart Malotki Other universalist researchers dedicated themselves to dispelling other aspects of linguistic relativity, often attacking Whorf's specific examples. For example, Malotki's monumental study of time expressions in Hopi presented many examples that challenged Whorf's "timeless" interpretation of Hopi language and culture,[74] but seemingly failed to address the linguistic relativist argument actually posed by Whorf (i.e. that the understanding of time by native Hopi speakers differed from that of speakers of European languages due to the differences in the organization and construction of their respective languages; Whorf never claimed that Hopi speakers lacked any concept of time).[75] Malotki himself acknowledges that the conceptualizations are different, but because he ignores Whorf's use of quotes around the word "time" and the qualifier "what we call", takes Whorf to be arguing that the Hopi have no concept of time at all.[76][77][78] |

エッケハルト・マロツキ 他の普遍主義研究者たちは、言語相対性の他の側面を否定することに専念し、しばしばウォーフの具体的な例を攻撃した。例えば、マロツキによるホピ族の時間 表現に関する画期的な研究は、ホピ語と文化に対するウォーフの「時間を超越した」解釈に異議を唱える多くの例を示した[74]。しかし、ウォーフが実際に 提起した言語相対論の主張(すなわち、ホピ語話者の時間の理解がヨーロッパ言語話者とは異なるのは、それぞれの言語の組織と構造の違いによるという主張) には、明らかに言及していないようである(ホピ語話者が時間の概念を欠いているとウォーフが主張したわけではない)。[75] マロツキ自身も、概念化が異なることは認めている。しかし、彼はウォーフが「時間」という言葉に引用符を付けて用いた点を無視している。ウォーフはホピ話 者に時間概念が全く欠如していると主張したことはない)。[75] マロツキ自身も概念化が異なることは認めているが、「時間」という語に付された引用符と「我々が呼ぶところの」という限定語を無視したため、ウォーフがホ ピには時間概念が全く存在しないと主張していると誤解している。[76][77][78] |

| Steven Pinker Currently many believers of the universalist school of thought still oppose linguistic relativity. For example, Pinker argues in The Language Instinct that thought is independent of language, that language is itself meaningless in any fundamental way to human thought, and that human beings do not even think in "natural" language, i.e. any language that we actually communicate in; rather, we think in a meta-language, preceding any natural language, termed "mentalese". Pinker attacks what he terms "Whorf's radical position", declaring, "the more you examine Whorf's arguments, the less sense they make".[43] Pinker and other universalists have been accused by relativists of misrepresenting Whorf's ideas and committing the strawman fallacy.[79][80][53] |

スティーブン・ピンカー 現在でも普遍主義学派の信奉者の多くは言語相対論に反対している。例えばピンカーは『言語本能』において、思考は言語に依存せず、言語そのものは人間の思 考にとって根本的に無意味であり、人間は「自然言語」、つまり実際に意思疎通に用いる言語でさえ思考していないと主張する。むしろ我々は「メンタル語」と 呼ばれる、あらゆる自然言語に先行するメタ言語で思考しているのだ。ピンカーは「ウォーフの急進的立場」と呼ぶものを攻撃し、「ウォーフの議論を精査すれ ばするほど、その論理性は失われる」と宣言している。[43] ピンカーら普遍主義者は、相対主義者からウォーフの思想を歪曲し、藁人形論法に陥っていると非難されている。[79][80][53] |

| Cognitive linguistics Main article: Cognitive linguistics During the late 1980s and early 1990s, advances in cognitive psychology and cognitive linguistics renewed interest in the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis.[81] One of those who adopted a more Whorfian philosophy was George Lakoff. He argued that language is often used metaphorically and that languages use different cultural metaphors that reveal something about how speakers of that language think. For example, English employs conceptual metaphors likening time to money, so that time can be saved and spent and invested, whereas other languages do not talk about time in that manner. Other such metaphors are common to many languages because they are based on general human experience, for example, metaphors associating up with good and bad with down. Lakoff also argued that metaphor plays an important part in political debates such as the "right to life" or the "right to choose"; or "illegal aliens" or "undocumented workers".[82] An unpublished study by Boroditsky et al. in 2003 reported finding empirical evidence favoring the hypothesis and demonstrating that differences in languages' systems of grammatical gender can affect the way speakers of those languages think about objects. Speakers of Spanish and German (which have different gender systems) were asked to use adjectives to describe various objects designated by words that were either masculine or feminine in their respective languages. Speakers tended to describe objects in ways that were consistent with the gender of the noun in their language, indicating that the gender system of a language can influence speakers' perceptions of objects. Despite numerous citations, the experiment was criticised after the reported effects could not be replicated by independent trials.[83][84] Additionally, a large-scale data analysis using word embeddings of language models found no correlation between adjectives and inanimate noun genders,[85] while another study using large text corpora found a slight correlation between the gender of animate and inanimate nouns and their adjectives as well as verbs by measuring their mutual information.[86] Colin Murray Turbayne also argued that the pervasive use of ancient "dead metaphors" by researchers within different linguistic traditions has contributed to needless confusion in the development of modern empirical theories over time.[87] He points to several examples within the Romance and Germanic languages of the subtle manner in which mankind has become unknowingly victimized by such "unmasked metaphors". Cases include the incorporation of mechanistic metaphors first introduced by Rene Descartes and Isaac Newton during the 17th century into scientific theories which were subsequently developed by George Berkeley, David Hume and Immanuel Kant during the 18th century;[88][89][90] and the influence exerted by Platonic metaphors in the dialogue Timaeus upon the development of contemporary theories of language in modern times.[91][92] |

認知言語学 主な記事: 認知言語学 1980年代後半から1990年代初頭にかけて、認知心理学と認知言語学の進歩により、サピア=ウォーフ仮説への関心が再燃した[81]。よりウォーフ的 な哲学を採用した人物の一人がジョージ・レイコフである。彼は、言語はしばしば比喩的に使用され、言語は異なる文化的隠喩を用いることで、その言語を話す 人々の思考様式を明らかにすると主張した。例えば英語では時間を金銭に喩える概念的隠喩を用いるため、時間を節約したり、使ったり、投資したりできるが、 他の言語では時間をそのような形で語らない。他の隠喩は、人間の普遍的な経験に基づいているため多くの言語に共通している。例えば「上」を「良い」と結び つけ、「下」を「悪い」と結びつける隠喩だ。レイコフはまた、隠喩が「生命の権利」や「選択の権利」といった政治的議論、あるいは「不法移民」や「無書類 労働者」といった表現において重要な役割を果たすと主張した[82]。 2003年にボロディツキーらが未発表の研究で報告したところでは、この仮説を支持する実証的証拠が見つかり、言語の文法的性別の体系が異なる点により、 その言語話者の物事の考え方に影響を与えうることを示した。スペイン語とドイツ語(異なる性体系を持つ言語)の話し手に対し、それぞれの言語で男性名詞ま たは女性名詞に指定された様々な物体を形容詞で描写するよう求めた。話し手は、自言語における名詞の性に対応した方法で物体を描写する傾向を示し、言語の 性体系が話し手の物体認識に影響を与え得ることを示唆した。多数の引用があるにもかかわらず、報告された効果は独立した試験で再現できなかったため、この 実験は批判された[83][84]。さらに、言語モデルの単語埋め込みを用いた大規模データ分析では、形容詞と無生物名詞の性との間に相関は見られなかっ た[85]。一方、大規模テキストコーパスを用いた別の研究では、相互情報を測定することで、有生物名詞と無生物名詞の性、およびそれらの形容詞や動詞と の間にわずかな相関が認められた。 コリン・マレー・ターベインもまた、異なる言語学の伝統を持つ研究者による古代の「死んだ隠喩」の広範な使用が、現代の実証的理論の発展において不必要な 混乱を招いてきたと主張している。[87] 彼はロマンス語やゲルマン語におけるいくつかの例を挙げ、人類が知らず知らずのうちにこうした「覆いの取れた隠喩」の犠牲となっている微妙な様相を指摘し ている。事例としては、17世紀にルネ・デカルトとアイザック・ニュートンが導入した機械論的隠喩が、18世紀にジョージ・バークリー、デイヴィッド・ ヒューム、イマヌエル・カントによって発展させた科学理論に取り込まれたこと[88][89][90]、またプラトンの対話篇『ティマイオス』におけるプ ラトン的隠喩が、現代における言語理論の発展に及ぼした影響が挙げられる[91]。[92] |

| Parameters In his 1987 book Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal About the Mind,[53] Lakoff reappraised linguistic relativity and especially Whorf's ideas about how linguistic categorization represents and/or influences mental categories. He concluded that the debate had been confused. He identified four parameters on which researchers differed in their opinions about what constitutes linguistic relativity: The degree and intensity of linguistic relativity. Perhaps a few examples of superficial differences in language and associated behavior are enough to demonstrate the existence of linguistic relativity. Alternatively, perhaps only great differences that permeate the linguistic and cultural system suffice. Whether conceptual systems are absolute or whether they can evolve. Whether the similarity criterion is translatability or the use of linguistic expressions. Whether the emphasis of linguistic relativity is language or the brain. Lakoff concluded that many of Whorf's critics had criticized him using novel definitions of linguistic relativity, rendering their criticisms moot. |

パラメータ 1987年の著書『女性、火、危険なもの:カテゴリーが明かす心の仕組み』[53]において、レイコフは言語相対論、特に言語的カテゴリー化が精神的カテ ゴリーをどのように表象し/影響するかというウォーフの考えを再評価した。彼はこの議論が混乱していたと結論づけた。言語相対論の構成要素について研究者 の見解が異なる四つのパラメータを特定した: 言語相対性の程度と強度。言語と関連行動の表面的な差異の例がいくつかあれば、言語相対性の存在を示すのに十分かもしれない。あるいは、言語と文化システム全体に浸透する大きな差異のみが十分であるかもしれない。 概念体系が絶対的か、それとも進化し得るか。 類似性の基準が翻訳可能性か、言語表現の使用か。 言語相対性の焦点が言語か、脳か。 レイコフは、ウォーフの批判者の多くが言語相対性の新たな定義を用いて彼を批判したため、それらの批判は無意味であると結論づけた。 |

| Refinements Researchers such as Boroditsky, Choi, Majid, Lucy and Levinson believe that language influences thought in more limited ways than the broadest early claims. Researchers examine the interface between thought (or cognition), language and culture and describe the relevant influences. They use experimental data to back up their conclusions.[93][94] Kay ultimately concluded that "[the] Whorf hypothesis is supported in the right visual field but not the left".[95] His findings show that accounting for brain lateralization offers another perspective. Behavior-centered research Recent studies have also used a "behavior-based" method, which starts by comparing behavior across linguistic groups and then searches for causes for that behavior in the linguistic system.[50] In an early example of this method, Whorf attributed the occurrence of fires at a chemical plant to the workers' use of the word 'empty' to describe barrels containing only explosive vapors. More recently, Bloom noticed that speakers of Chinese had unexpected difficulties answering counterfactual questions posed to them in a questionnaire. He concluded that this was related to the way in which counter-factuality is marked grammatically in Chinese. Other researchers attributed this result to Bloom's flawed translations.[96] Strømnes examined why Finnish factories had a greater occurrence of work related accidents than similar Swedish ones. He concluded that cognitive differences between the grammatical usage of Swedish prepositions and Finnish cases could have caused Swedish factories to pay more attention to the work process while Finnish factory organizers paid more attention to the individual worker.[97] Numbers and classifiers Everett's work on the Pirahã language of the Brazilian Amazon[98] found several peculiarities that he interpreted as corresponding to linguistically rare features, such as a lack of numbers and color terms in the way those are otherwise defined and the absence of certain types of clauses. Everett's conclusions were met with skepticism from universalists[99] who claimed that the linguistic deficit is explained by the lack of need for such concepts.[100] Recent research with non-linguistic experiments in languages with different grammatical properties (e.g., languages with and without numeral classifiers or with different gender grammar systems) showed that language differences in human categorization are due to such differences.[101] Experimental research suggests that this linguistic influence on thought diminishes over time, as when speakers of one language are exposed to another.[102] Time perception Research on time-space congruency suggests that temporal perception is shaped by spatial metaphors embedded in language. Casasanto & Boroditsky (2008) found that people often use spatial metaphors to conceptualize time, linking longer distances with longer durations.[103] Research has shown that linguistic differences can influence the perception of time. Swedish, like English, tends to describe time in terms of spatial distance (e.g., "a long meeting"), whereas Spanish often uses quantity-based metaphors (e.g., "a big meeting"). These linguistic patterns correlate with differences in how speakers estimate temporal durations: Swedish speakers are more influenced by spatial length, while Spanish speakers are more sensitive to volume.[104] Expanding on this, research on time-space congruency suggests that temporal perception is shaped by spatial metaphors embedded in language. In many languages, time is conceptualized along a horizontal axis (e.g., "looking forward to the future" in English). However, Mandarin speakers also employ vertical metaphors for time, referring to earlier events as "up" and later events as "down".[105] Experiments have shown that Mandarin speakers are quicker to recognize temporal sequences when they are presented vertically, whereas English speakers exhibit no such bias. Pronoun-dropping and intentionality Kashima & Kashima observed a correlation between the perceived individualism or collectivism in the social norms of a given country, with the tendency to neglect the use of pronouns in the country's language. They argued that explicit reference to "you" and "I" reinforces a distinction between the self and the other in the speaker.[106] Research also suggests that this structural difference influences how speakers attribute intentionality in events. Fausey & Boroditsky (2010) conducted experiments comparing how English and Spanish speakers describe accidental versus intentional actions. Their results showed that English speakers, who are accustomed to using explicit pronouns, were more likely to specify the agent responsible for an accidental event (e.g., "John broke the vase"). In contrast, Spanish speakers, who frequently omit pronouns, were more likely to use agent-neutral descriptions for accidental events (e.g., "The vase broke").[107] Future tense A 2013 study found that those who speak "futureless" languages with no grammatical marking of the future tense save more, retire with more wealth, smoke less, practice safer sex, and are less obese than those who do not.[108] This effect has come to be termed the linguistic-savings hypothesis and has been replicated in several cross-cultural and cross-country studies. However, a study of Chinese, which can be spoken both with and without the grammatical future marking "will", found that subjects do not behave more impatiently when "will" is used repetitively. This laboratory-based finding of elective variation within a single language does not refute the linguistic savings hypothesis but some have suggested that it shows the effect may be due to culture or other non-linguistic factors.[109] Psycholinguistic research Psycholinguistic studies explored motion perception, emotion perception, object representation and memory.[110][111][112][113] The gold standard of psycholinguistic studies on linguistic relativity is now finding non-linguistic cognitive differences[example needed] in speakers of different languages (thus rendering inapplicable Pinker's criticism that linguistic relativity is "circular"). Recent work with bilingual speakers attempts to distinguish the effects of language from those of culture on bilingual cognition including perceptions of time, space, motion, colors and emotion.[114] Researchers described differences between bilinguals and monolinguals in perception of color,[115] representations of time[116][117][118] and other elements of cognition.[119] |

精緻化 ボロディツキー、チェイ、マジド、ルーシー、レヴィンソンといった研究者らは、言語が思考に影響を与える方法は、初期の広範な主張よりも限定的だと考えて いる。研究者らは思考(あるいは認知)、言語、文化の接点を検証し、関連する影響を記述する。彼らは実験データを用いて結論を裏付けている。[93] [94] ケイは最終的に「ウォーフ仮説は右視野では支持されるが、左視野では支持されない」と結論づけた。[95] 彼の発見は、脳の左右差を考慮することが別の視点を提供することを示している。 行動中心の研究 最近の研究では「行動ベース」の手法も用いられている。これはまず言語集団間の行動を比較し、その行動の原因を言語体系の中で探す方法だ。[50] この手法の初期事例として、ウォーフは化学工場での火災発生を、爆発性蒸気のみを含むドラム缶を労働者が「空」と表現したことに起因すると指摘した。 より近年では、ブルームが中国語話者がアンケートで提示された反事実的質問に予想外の困難を抱えることに気づいた。彼はこれが中国語における反事実性の文 法的標示方法に関連すると結論づけた。他の研究者はこの結果をブルームの翻訳の誤りに帰した[96]。ストロンネスは、フィンランドの工場でスウェーデン の類似工場より労働災害が多発する理由を検証した。彼は、スウェーデン語の前置詞とフィンランド語の格の文法的使用における認知的差異が、スウェーデン工 場では作業工程に、フィンランド工場では個々の労働者に注意が向けられる原因となった可能性を結論付けた[97]。 数詞と量詞 ブラジルのアマゾン地域で話されるピラハ語に関するエバレットの研究[98]は、いくつかの特異性を発見した。彼はこれを、数字や色用語の定義上の欠如、 特定の種類の節の不在など、言語学的に稀な特徴に対応すると解釈した。エバレットの結論は普遍主義者たち[99]から懐疑的に受け止められ、彼らは「その ような概念が必要とされないことが言語的欠如を説明している」と主張した。[100] 異なる文法的特性を持つ言語(例えば、数詞分類語の有無や異なる性文法体系を持つ言語)を対象とした非言語的実験による最近の研究は、人間の分類における 言語差がこうした差異に起因することを示した[101]。実験的研究は、ある言語話者が別の言語に曝露される場合のように、思考に対するこの言語的影響は 時間とともに減衰することを示唆している[102]。 時間知覚 時空間整合性に関する研究は、時間知覚が言語に埋め込まれた空間的隠喩によって形成されることを示唆している。カササント&ボロディツキー(2008) は、人民が時間を概念化する際に空間的隠喩を頻繁に用いること、すなわち長い距離と長い持続時間を結びつけることを発見した。[103] 研究は言語的差異が時間知覚に影響を与え得ることを示している。スウェーデン語は英語と同様、時間を空間的距離で表現する傾向がある(例:「長い会 議」)。一方スペイン語は量に基づく隠喩を用いることが多い(例:「大きな会議」)。これらの言語パターンは、話者が時間的持続時間を推定する方法の違い と相関している。スウェーデン語話者は空間的な長さに影響されやすく、スペイン語話者は体積に敏感である。[104] この点をさらに掘り下げると、時間と空間の一致性に関する研究は、時間的知覚が言語に埋め込まれた空間的隠喩によって形作られることを示唆している。多く の言語では、時間は水平軸に沿って概念化される(例:英語の「未来を楽しみに待つ」)。しかし、中国語話者は時間に対して垂直的隠喩も用いる。過去の出来 事を「上」、未来の出来事を「下」と表現するのだ。[105] 実験では、中国語話者は時間的順序が垂直方向に提示されるとより速く認識するが、英語話者にはそのような偏りが見られないことが示されている。 代名詞省略と意図性 鹿島&鹿島は、特定の国の社会的規範における個人主義または集団主義の認識と、その国の言語における代名詞使用の省略傾向との間に相関関係があることを観 察した。彼らは「あなた」や「私」を明示的に参照することが、話者における自己と他者の区別を強化すると主張した。[106] 研究はまた、この構造的差異が話者が事象に意図主義を帰属させる方法に影響を与えることを示唆している。Fausey & Boroditsky (2010) は、英語話者とスペイン語話者が偶然の行動と意図的な行動をどのように記述するかを比較する実験を行った。その結果、明示的な代名詞の使用に慣れた英語話 者は、偶発的出来事の責任主体を特定する傾向が強かった(例:「ジョンが花瓶を割った」)。一方、代名詞を頻繁に省略するスペイン語話者は、偶発的事象に 対して主体を特定しない表現を用いる傾向が強かった(例:「花瓶が割れた」)。[107] 未来時制 2013年の研究によれば、文法的に未来時制の標示を持たない「未来時制のない言語」を話す人々は、そうでない人々と比べて貯蓄額が多く、退職時の資産が 豊富で、喫煙率が低く、安全な性行為を実践し、肥満率が低いことが判明した。[108] この効果は「言語的貯蓄仮説」と呼ばれ、複数の異文化間・国際比較研究で再現されている。しかし、文法上の未来形「will」の有無で話せる中国語の研究 では、被験者が「will」を繰り返し使用しても行動がより焦燥的になることはなかった。単一言語内での選択的変動を示すこの実験室ベースの知見は言語的 節約仮説を否定しないが、この効果は文化やその他の非言語的要因による可能性を示唆するとの指摘もある。[109] 心理言語学研究 心理言語学研究は、運動知覚、感情知覚、物体表象、記憶を探求した。[110][111][112][113] 言語相対性に関する心理言語学研究のゴールドスタンダードは、現在では異なる言語話者における非言語的認知差異[例が必要]を発見することである(これに より、言語相対性が「循環論法」であるというピンカーの批判は適用不能となる)。 最近のバイリンガル研究では、時間・空間・運動・色彩・感情の知覚を含むバイリンガル認知において、言語効果と文化効果を区別しようとしている。 [114] 研究者らは、色彩知覚[115]、時間表象[116][117][118]、その他の認知要素[119]におけるバイリンガルとモノリンガルの差異を報告 している。 |

| Other domains Linguistic relativity inspired others to consider whether thought and emotion could be influenced by manipulating language. Science and philosophy A major question is whether human psychological faculties are mostly innate or whether they are mostly a result of learning, and hence subject to cultural and social processes such as language. The innate opinion is that humans share the same set of basic faculties, variability due to cultural differences is less important, and the human mind is a mostly biological construction, so all humans who share the same neurological configuration can be expected to have similar cognitive patterns.[citation needed] Multiple alternatives have advocates. The contrary constructivist position holds that human faculties and concepts are largely influenced by socially constructed and learned categories, without many biological restrictions. Another variant is idealist, which holds that human mental capacities are generally unrestricted by biological-material structures. Another is the essentialist position, which holds that inherent biological or psychological differences between individuals or groups, such as genetic, neurological, or cognitive traits, may influence how they experience and conceptualize the world. Yet another is relativist (cultural relativism), which sees different cultural groups as employing different conceptual schemes that are not necessarily compatible or commensurable, nor more or less in accord with external reality.[120] Another debate considers whether thought is a type of internal speech or is independent of and prior to language.[121] In the philosophy of language, the question addresses the relations between language, knowledge and the external world, and the concept of truth. Philosophers such as Putnam, Fodor, Davidson, and Dennett see language as directly representing entities from the objective world, and categorization as reflecting that world. Other philosophers (e.g. Quine, Searle, and Foucault) argue that categorization and conceptualization is subjective and arbitrary. Another view, represented by Jason Storm, seeks a third way by emphasizing how language changes and imperfectly represents reality without being completely divorced from ontology.[122] Another question is whether language is a tool for representing and referring to objects in the world, or whether it is a system used to construct mental representations that can be communicated.[clarification needed] Therapy and self-development Main articles: General semantics and neuro-linguistic programming Sapir/Whorf contemporary Alfred Korzybski was independently developing his theory of general semantics, which was intended to use language's influence of thinking to maximize human cognitive abilities. Korzybski's thinking was influenced by logical philosophy such as Russell and Whitehead's Principia Mathematica and Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.[123] Although Korzybski was not aware of Sapir and Whorf's writings, the philosophy was adopted by Whorf-admirer Stuart Chase, who fused Whorf's interest in cultural-linguistic variation with Korzybski's programme in his popular work "The Tyranny of Words". S. I. Hayakawa was a follower and popularizer of Korzybski's work, writing Language in Thought and Action. The general semantics philosophy influenced the development of neuro-linguistic programming (NLP), another therapeutic technique that seeks to use awareness of language use to influence cognitive patterns.[124] Korzybski independently described a "strong" version of the hypothesis of linguistic relativity.[125] We do not realize what tremendous power the structure of an habitual language has. It is not an exaggeration to say that it enslaves us through the mechanism of s[emantic] r[eactions] and that the structure which a language exhibits, and impresses upon us unconsciously, is automatically projected upon the world around us. — Korzybski (1930)[126] Artificial languages Main articles: Constructed languages and Experimental languages In their fiction, authors such as Ayn Rand and George Orwell explored how linguistic relativity might be exploited for political purposes. In Rand's Anthem, a fictive communist society removed the possibility of individualism by removing the word "I" from the language.[127] In Orwell's 1984 the authoritarian state created the language Newspeak to make it impossible for people to think critically about the government, or even to contemplate that they might be impoverished or oppressed, by reducing the number of words to reduce the thought of the locutor.[128] Others have been fascinated by the possibilities of creating new languages that could enable new, and perhaps better, ways of thinking. Examples of such languages designed to explore the human mind include Loglan, explicitly designed by James Cooke Brown to test the linguistic relativity hypothesis, by exploring whether it would make its speakers think more logically. Suzette Haden Elgin, who was involved with the early development of neuro-linguistic programming, invented the language Láadan to explore linguistic relativity by making it easier to express what Elgin considered the female worldview, as opposed to Standard Average European languages, which she considered to convey a "male centered" worldview.[129] John Quijada's language Ithkuil was designed to explore the limits of the number of cognitive categories a language can keep its speakers aware of at once.[130] Similarly, Sonja Lang's Toki Pona was developed according to a Taoist philosophy for exploring how (or if) such a language would direct human thought.[131] Programming languages APL programming language originator Kenneth E. Iverson believed that the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis applied to computer languages (without actually mentioning it by name). His Turing Award lecture, "Notation as a Tool of Thought", was devoted to this theme, arguing that more powerful notations aided thinking about computer algorithms.[132][133] The essays of Paul Graham explore similar themes, such as a conceptual hierarchy of computer languages, with more expressive and succinct languages at the top. Thus, the so-called blub paradox (after a hypothetical programming language of average complexity called Blub) says that anyone preferentially using some particular programming language will know that it is more powerful than some, but not that it is less powerful than others. The reason is that writing in some language means thinking in that language. Hence the paradox, because typically programmers are "satisfied with whatever language they happen to use, because it dictates the way they think about programs".[134] In a 2003 presentation at an open source convention, Yukihiro Matsumoto, creator of the programming language Ruby, said that one of his inspirations for developing the language was the science fiction novel Babel-17, based on the Whorf Hypothesis.[135] Science fiction Numerous examples of linguistic relativity have appeared in science fiction. The totalitarian regime depicted in George Orwell's 1949 novel Nineteen Eighty Four in effect acts on the basis of the Whorf hypothesis, seeking to replace English with Newspeak, a language constructed specifically with the intention that thoughts subversive of the regime cannot be expressed in it, and therefore people educated to speak and think in it would not have such thoughts. In his 1958 science fiction novel The Languages of Pao the author Jack Vance describes how specialized languages are a major part of a strategy to create specific classes in a society, to enable the population to withstand occupation and develop itself. In Samuel R. Delany's 1966 science fiction novel Babel-17, the author describes an advanced, information-dense language that can be used as a weapon. Learning it turns one into an unwilling traitor as it alters perception and thought.[136] Ted Chiang's 1998 short story "Story of Your Life" developed the concept of the Whorf hypothesis as applied to an alien species that visits Earth. The aliens' biology contributes to their spoken and written languages, which are distinct. In the 2016 American movie Arrival, based on Chiang's short story, the Whorf hypothesis is the premise. The protagonist explains that "the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis is the theory that the language you speak determines how you think".[137] Gene Wolfe's four volume science fiction novel The Book of the New Sun describes the North American "Ascian" people as speaking a language composed entirely of quotations that have been approved by a small ruling class. Sociolinguistics and linguistic relativity Sociolinguistics affects some variables within language, including the manner in which words are pronounced, word selection in certain dialogue, context, and tone. It's suggested that these effects[138] may have implications for linguistic relativity. |

他の領域 言語相対性理論は、言語を操作することで思考や感情に影響を与えられるかどうかを考察するきっかけとなった。 科学と哲学 主要な疑問は、人間の心理的機能が大半が先天的なものか、それとも学習の結果であり、したがって言語のような文化的・社会的プロセスに左右されるものかで ある。先天的説は、人間は同じ基本的な機能セットを共有し、文化的差異による変動性は重要ではなく、人間の心は主に生物学的構築物であるため、同じ神経学 的構成を持つすべての人間は類似した認知パターンを持つと予測できるとする。[出典が必要] 複数の代替案が支持されている。反対の構成主義的立場は、人間の能力や概念は生物学的制約が少なく、社会的に構築され学習されたカテゴリーに大きく影響さ れると主張する。別の変種は理想主義的立場で、人間の精神的能力は一般的に生物学的・物質的構造に制限されないとする。また本質主義的立場は、個人や集団 間の遺伝的・神経学的・認知的特性といった生来の生物学的・心理的差異が、世界の経験や概念化に影響を与えうると主張する。さらに別の立場として、相対主 義(文化相対主義)がある。これは、異なる文化集団が、必ずしも互換性や比較可能性を持たない、また外部の現実と多かれ少なかれ一致するとは限らない、異 なる概念体系を採用していると見なすものである。 別の議論では、思考は内部言語の一種なのか、それとも言語とは独立して、言語に先行するものなのかが検討されている。 言語哲学では、この問題は、言語、知識、外部世界、そして真実の概念との関係について論じている。パトナム、フォドル、デイヴィッドソン、デネットなどの 哲学者は、言語は客観的な世界の実体を直接的に表現し、分類はその世界を反映していると見なしている。他の哲学者(クワイン、サール、フーコーなど)は、 分類と概念化は主観的で恣意的であると主張している。ジェイソン・ストームに代表される別の見解は、言語がどのように変化し、存在論から完全に切り離され ることなく現実を不完全な形で表現しているかを強調することで、第三の道を探ろうとしている。 もう一つの疑問は、言語は世界にある物体を表現し、参照するための道具なのか、それとも、伝達可能な精神的表現を構築するために使用されるシステムなのか、ということだ。 セラピーと自己啓発 主な記事:一般意味論と神経言語プログラミング サピア/ウォーフの同時代人であるアルフレッド・コルジブスキーは、人間の認知能力を最大化するために言語が思考に与える影響を利用することを目的とし た、一般意味論の理論を独自に開発していた。コルジブスキーの考えは、ラッセルとホワイトヘッドの『プリンキピア・マテマティカ』やウィトゲンシュタイン の『論理哲学論考』などの論理哲学の影響を受けていた。[123] コジブスキーはサピアとウォーフの著作を知らなかったが、その哲学はウォーフを崇拝するスチュワート・チェイスによって採用され、チェイスはウォーフの文 化言語学的変異への関心を、自身の人気作『言葉の専制』の中でコジブスキーのプログラムと融合させた。S. I. 早川は、コルジブスキーの著作の信奉者であり普及者であり、『思考と行動における言語』を著した。一般意味論の哲学は、言語使用の認識を利用して認知パ ターンに影響を与えようとする別の治療技術である神経言語プログラミング(NLP)の発展に影響を与えた。[124] コルジブスキーは独自に、言語相対性仮説の「強固な」バージョンを記述した[125]。 我々は習慣的な言語構造が持つ途方もない力を認識していない。それが[意味的]反応のメカニズムを通じて我々を隷属させ、言語が示す構造が無意識に我々に刻み込まれ、自動的に周囲の世界に投影されるという主張は誇張ではない。 — コルジブスキー (1930)[126] 人工言語 主な記事: 人工言語と実験的言語 小説において、アイン・ランドやジョージ・オーウェルといった作家は、言語相対性が政治的目的のために如何に利用され得るかを探求した。ランドの『アンセ ム』では、架空の共産主義社会が言語から「私」という単語を排除することで個人主義の可能性を消し去った[127]。オーウェルの『1984』では、権威 主義国家がニューピークという言語を創り出した。語彙数を減らすことで話者の思考を制限し、人民が政府を批判的に考えたり、自分たちが貧困や抑圧に置かれ ている可能性すら想像できないようにするためである。[128] 他方、新たな思考様式、おそらくはより優れた思考様式を可能にする新言語創造の可能性に魅了された者もいる。人間の精神を探求するために設計された言語の 例には、言語相対性仮説を検証するためにジェームズ・クック・ブラウンが明示的に設計したログランがある。これは話者がより論理的に思考するようになるか を検証する目的で考案された。神経言語プログラミングの初期開発に関わったスゼット・ヘイデン・エルギンは、言語相対性を探求するためラーダン語を発明し た。これは彼女が「男性中心」の世界観を伝えると考える標準的な平均的ヨーロッパ言語とは対照的に、エルギンが女性的世界観とみなすものを表現しやすくす るためである。[129] ジョン・キハダの言語イスクイルは、言語が話者に同時に認識させられる認知カテゴリーの限界を探るために設計された。[130] 同様に、ソーニャ・ラングのトキポナは、道教哲学に基づいて開発され、そのような言語が人間の思考をどのように(あるいは果たして)導くかを探るためのも のである. [131] プログラミング言語 APLプログラミング言語の創始者ケネス・E・アイバーソンは、サピア=ウォーフ仮説がコンピュータ言語にも適用されると考えていた(仮説名を直接言及は していない)。彼のチューリング賞受賞講演「思考の道具としての表記法」はこのテーマに捧げられ、より強力な表記法がコンピュータアルゴリズムの思考を助 けると論じた。[132] [133] ポール・グラハムの論考も同様のテーマを探求している。例えばコンピュータ言語の概念的階層構造では、より表現力豊かで簡潔な言語が頂点に位置する。いわ ゆる「ブルブ・パラドックス」(平均的な複雑さを持つ仮説上のプログラミング言語「ブルブ」に由来)によれば、特定のプログラミング言語を優先的に使用す る者は、それが他の言語より強力であることは認識できるが、他の言語より非強力であることは認識できないという。その理由は、ある言語で書くことはその言 語で考えることを意味するからだ。ここにパラドックスが生じる。なぜなら、典型的なプログラマーは「たまたま使う言語に満足している。その言語がプログラ ムの考え方を規定するからだ」というのである。[134] 2003年のオープンソース会議での発表で、プログラミング言語Rubyの生みの親である松本行弘は、言語開発の着想源の一つがウォーフ仮説に基づくSF小説『バベル17』だったと述べている。[135] SF 言語相対性理論の例はSF作品に数多く登場する。 ジョージ・オーウェルの1949年の小説『1984』に描かれた全体主義体制は、事実上、ウォーフの仮説に基づいて行動しており、英語に代わって、体制を破壊する考えを表現できないように特別に構築された言語であるニュースピークを採用しようとしている。 1958年のSF小説『パオの言語』の中で、作家ジャック・ヴァンスは、特殊な言語が、社会の中で特定の階級を作り出し、占領に耐え、自らを発展させる戦略の重要な部分である様子を描いている。 サミュエル・R・ディレイニーの1966年のSF小説『バベル17』では、武器として使える、高度で情報密度の高い言語が描写されている。この言語を学ぶと、知覚や思考が変化し、本人の意思とは無関係に裏切り者になってしまうのだ。 テッド・チャンが1998年に発表した短編小説「あなたの人生の物語」では、地球を訪れた異星人種にウォーフ仮説を適用するというコンセプトが展開されて いる。異星人の生物学的特性は、彼らの話し言葉と書き言葉の差異に寄与している。2016年のアメリカ映画『メッセージ』はチアンの短編を基にしており、 ウォーフ仮説を前提としている。主人公は「サピア=ウォーフ仮説とは、話す言語が思考方法を決定するという理論だ」と説明する[137]。 ジーン・ウルフの4巻からなるSF小説『新太陽の書』では、北米の「アシア人民」が、少数の支配階級によって承認された引用句のみで構成される言語を話す民族として描かれている。 社会言語学と言語相対性 社会言語学は言語内のいくつかの変数に影響を与える。これには単語の発音方法、特定の対話における語彙選択、文脈、トーンが含まれる。これらの影響[138]は言語相対性理論に示唆を与える可能性がある。 |

| A rose by any other name would smell as sweet – Adage from Romeo and Juliet Basic Color Terms: Their Universality and Evolution – Linguistics book by Brent Berlin and Paul Kay Bicameral mentality – Hypothesis in psychology Color term – Word or phrase that refers to a specific color Eskimo words for snow – Linguistic cliché Ethnolinguistics – Academic discipline Hopi time controversy – Academic debate about conceptualization of time in Hopi language Hypocognition – Inability to communicate due to no words for a concept Inherently funny words – Words which have been described as inherently funny Labeling theory – Sociological theory Language and thought – Study of how language influences thought Language planning – Deliberate effort to influence languages or their varieties within a speech community Linguistic anthropology – Study of how language influences social life Linguistic determinism – Idea of language as the principal framework in dictating human thought Logocracy – Form of government by use of words Psycholinguistics – Study of relations between psychology and language Relativism – Philosophical view rejecting objectivity Terministic screen – Term in the theory and criticism of rhetoric |

バラは別の名前でも同じように香る – 『ロミオとジュリエット』の格言 基本色用語:その普遍性と進化 – ブレント・ベルリンとポール・ケイによる言語学書 二院制的思考 – 心理学における仮説 色用語 – 特定の色を指す単語や語句 エスキモーの雪を表す言葉 – 言語学の決まり文句 民族言語学 – 学問分野 ホピ族の時間論争 – ホピ語における時間の概念化に関する学術的議論 概念認知不足 – 概念を表す言葉がないために意思疎通ができない状態 本質的に滑稽な言葉 – 本質的に滑稽と評される言葉 ラベリング理論 – 社会学的理論 言語と思考 – 言語が思考に与える影響の研究 言語計画 – 言語共同体内で言語やその変種に影響を与える意図的な取り組み 言語人類学 – 言語が社会生活に影響を与える方法の研究 言語決定論 – 人間の思考を規定する主要な枠組みとしての言語という考え方 ロゴクラシー – 言葉の使用による統治形態 心理言語学 – 心理学と言語の関係の研究 相対主義 – 客観性を否定する哲学的見解 用語的スクリーン – 修辞学の理論と批評における用語 |

| Citations |

|