ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン

Bernardino

de Sahagún, ca.1499-1590

☆ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン OFM(Bernardino de

Sahagún, 1499

年頃~1590年2月5日)は、フランシスコ会の修道士、布教司祭、先駆的な民族誌学者であり、植民地時代のスペイン領ニュー・スペイン(現在のメキシ

コ)におけるカトリックの布教活動に参加した。1499年にスペインのサアグンで生まれ、1529年にニュー・スペインに渡った。彼はナワトル語を学び、

アステカの信仰、文化、歴史の研究に50年以上を費やした。彼は主に布教活動に専念していたが、先住民の世界観や文化を記録した彼の並外れた業績により、

「最初の人類学者」という称号を得た。また、アステカ帝国の公用語であるナワトル語の記述にも貢献した。彼は詩篇、福音書、教理問答をナワトル語に翻訳し

た。

サアグンは、『新スペインの事物全般史』(以下『事物全般史』)の編纂者として最もよく知られている。『事物全般史』の現存する写本の中で最も有名なのは

「フィレンツェ写本」である。この写本は2,400ページからなり、12の巻に分かれており、先住民アーティストが先住民とヨーロッパの技法を用いて描い

た約2,500点のイラストが収められている。アルファベットテキストはスペイン語とナワトル語の2

か国語で、見開きページに印刷されている。また、図版は3つ目のテキストとして扱われるべきである。この書物はアステカ族の文化、宗教的宇宙観(世界

観)、儀式、社会、経済、歴史を記録しており、第12巻ではテノチティトラン・トラテロルコから見たアステカ帝国の征服について述べている。サアグンは

『一般史』をまとめる過程で、民族誌的情報を収集し、その正確性を検証するための新しい方法を考案した。『一般史』は「西洋以外の文化に関する最も優れた

記録のひとつ」と呼ばれ、サアグンは「アメリカ民族誌学の父」と呼ばれている。2015年には、彼の作品がユネスコの世界遺産に登録された(→「フローレンス古文書」)。

| Bernardino de

Sahagún OFM (c. 1499 – 5 February 1590) was a Franciscan friar,

missionary priest and pioneering ethnographer who participated in the

Catholic evangelization of colonial New Spain (now Mexico). Born in

Sahagún, Spain, in 1499, he journeyed to New Spain in 1529. He learned

Nahuatl and spent more than 50 years in the study of Aztec beliefs,

culture and history. Though he was primarily devoted to his missionary

task, his extraordinary work documenting indigenous worldview and

culture has earned him the title as “the first anthropologist."[1][2]

He also contributed to the description of Nahuatl, the imperial

language of the Aztec Empire. He translated the Psalms, the Gospels,

and a catechism into Nahuatl. Sahagún is perhaps best known as the compiler of the Historia general de las cosas de la Nueva España—in English, General History of the Things of New Spain—(hereinafter referred to as Historia general).[3] The most famous extant manuscript of the Historia general is the Florentine Codex. It is a codex consisting of 2,400 pages organized into twelve books, with approximately 2,500 illustrations drawn by native artists using both native and European techniques. The alphabetic text is bilingual in Spanish and Nahuatl on opposing folios, and the pictorials should be considered a third kind of text. It documents the culture, religious cosmology (worldview), ritual practices, society, economics, and history of the Aztec people, and in Book 12 gives an account of the conquest of the Aztec Empire from the Tenochtitlan-Tlatelolco point of view. In the process of putting together the Historia general, Sahagún pioneered new methods for gathering ethnographic information and validating its accuracy. The Historia general has been called "one of the most remarkable accounts of a non-Western culture ever composed,"[4] and Sahagún has been called the father of American ethnography. In 2015, his work was declared a World Heritage by the UNESCO.[5] |

ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン

OFM(1499年頃~1590年2月5日)は、フランシスコ会の修道士、布教司祭、先駆的な民族誌学者であり、植民地時代のスペイン領ニュー・スペイン

(現在のメキシコ)におけるカトリックの布教活動に参加した。1499年にスペインのサアグンで生まれ、1529年にニュー・スペインに渡った。彼はナワ

トル語を学び、アステカの信仰、文化、歴史の研究に50年以上を費やした。彼は主に布教活動に専念していたが、先住民の世界観や文化を記録した彼の並外れ

た業績により、「最初の人類学者」という称号を得た[1][2]。また、アステカ帝国の公用語であるナワトル語の記述にも貢献した。彼は詩篇、福音書、教

理問答をナワトル語に翻訳した。 サアグンは、『新スペインの事物全般史』(以下『事物全般史』)の編纂者として最もよく知られている。[3] 『事物全般史』の現存する写本の中で最も有名なのは「フィレンツェ写本」である。この写本は2,400ページからなり、12の巻に分かれており、先住民 アーティストが先住民とヨーロッパの技法を用いて描いた約2,500点のイラストが収められている。アルファベットテキストはスペイン語とナワトル語の2 か国語で、見開きページに印刷されている。また、図版は3つ目のテキストとして扱われるべきである。この書物はアステカ族の文化、宗教的宇宙観(世界 観)、儀式、社会、経済、歴史を記録しており、第12巻ではテノチティトラン・トラテロルコから見たアステカ帝国の征服について述べている。サアグンは 『一般史』をまとめる過程で、民族誌的情報を収集し、その正確性を検証するための新しい方法を考案した。『一般史』は「西洋以外の文化に関する最も優れた 記録のひとつ」[4]と呼ばれ、サアグンは「アメリカ民族誌学の父」と呼ばれている。2015年には、彼の作品がユネスコの世界遺産に登録された[5]。 |

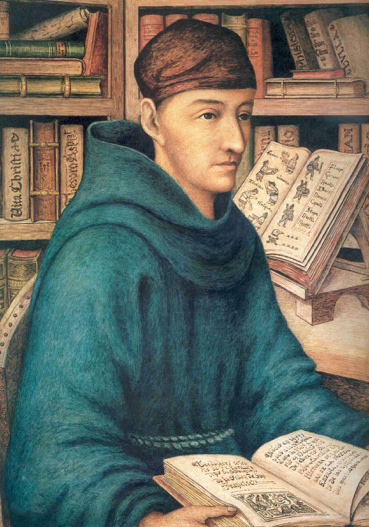

17th-century portrait of Sahagún |

|

| Education in Spain Fray Bernardino was born Bernardino de Rivera (Ribera, Ribeira) 1499 in Sahagún, Spain. He attended the University of Salamanca, where he was exposed to the currents of Renaissance humanism. During this period, the university at Salamanca was strongly influenced by Erasmus, and was a center for Spanish Franciscan intellectual life. It was there that he joined the Order of Friars Minor or Franciscans.[2] He was probably ordained around 1527. Entering the order he followed the Franciscan custom of changing his family name for the name of his birth town, becoming Bernardino de Sahagún. Spanish conquistadores led by Hernán Cortés conquered the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan (on the site of present-day Mexico City) in 1521, and Franciscan missionaries followed shortly thereafter in 1524. Sahagún was not in this first group of twelve friars, which arrived in New Spain in 1524. An account, in both Spanish and Nahuatl, of the disputation that these Franciscan friars held in Tenochtitlan soon after their arrival was made by Sahagún in 1564, in order to provide a model for future missionaries.[6] Thanks to his own academic and religious reputation, Sahagún was recruited in 1529 to join the missionary effort in New Spain.[2] He would spend the next 61 years there. |

スペインでの教育 Fray Bernardinoは、1499年にスペインのサアグンで、Bernardino de Rivera(リベラ、リベイラ)として生まれた。彼はサラマンカ大学に通い、そこでルネサンスの人文主義の潮流に触れた。この時代、サラマンカ大学はエ ラスムスの強い影響を受けており、スペインのフランシスコ会の知的活動の拠点となっていた。そこで彼はフランシスコ会に入会した[2]。おそらく1527 年頃に叙階されたと思われる。入会後、彼はフランシスコ会の慣習に従い、自分の名字を出生地の町名に変更し、ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグンとなった。 1521年、エルナン・コルテスが率いるスペインの征服者たちがアステカの首都テノチティトラン(現在のメキシコシティ)を征服し、その直後に1524年 にはフランシスコ会の宣教師たちが到着した。サアグンは、1524年に新スペインに到着した最初の12人の修道士たちには含まれていなかった。サハグン は、1564年に、これらのフランシスコ会の修道士たちが到着後間もなくテノチティトランで行った論争について、スペイン語とナワトル語で記述した。これ は、将来の宣教師たちの手本となることを目的としたものだった[6]。サハグンは、自身の学問的および宗教的評価のおかげで、1529年にニュー・スペイ ンでの宣教活動に参加するよう勧誘された[2]。彼はその後61年間をそこで過ごすことになる。 |

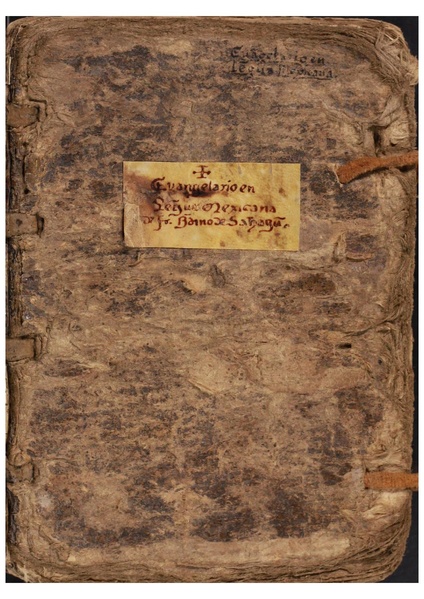

Evangelization of New Spain Evangeliario en lengua mexicana: "Catecism in Mexican language" (Nahuatl) During the Age of Discovery, 1450–1700, Iberian rulers took a great interest in the missionary evangelization of indigenous peoples encountered in newly discovered lands. In Catholic Spain and Portugal, the missionary project was funded by Catholic monarchs under the patronato real issued by the pope to ensure Catholic missionary work was part of a broader project of conquest and colonization. The decades after the Spanish conquest witnessed a dramatic transformation of indigenous culture, a transformation with a religious dimension that contributed to the creation of Mexican culture. People from both the Spanish and indigenous cultures held a wide range of opinions and views about what was happening in this transformation. The evangelization of New Spain was led by Franciscan, Dominican and Augustinian friars.[7] These religious orders established the Catholic Church in colonial New Spain, and directed it during most of the 16th century. The Franciscans in particular were enthusiastic about the new land and its people. Franciscan friars who went to the New World were motivated by a desire to preach the Gospel to new peoples.[8] Many Franciscans were convinced that there was great religious meaning in the discovery and evangelization of these new peoples. They were astonished that such new peoples existed and believed that preaching to them would bring about the return of Christ and the end of time, a set of beliefs called millenarianism.[9] Concurrently, many of the friars were discontent with the corruption of European society, including, at times, the leadership of the Catholic Church. They believed that New Spain was the opportunity to revive the pure spirit of primitive Christianity. During the first decades of the Spanish conquest of Mesoamerica, many indigenous people converted to Christianity, at least superficially. The friars employed a large number of natives for the construction of churches and monasteries, not only for the construction itself, but also as artists, painters and sculptors, and their works were used for decoration and evangelization. In this process, the native artists added many references to their customs and beliefs: flowers, birds or geometric symbols. Friars thought the images were decorative, but the Natives recognized their strong religious connotation.[10][11] The mixture of Christian and Indian symbols has been described as Indocristiano or Indochristian art. Inspired by their Franciscan spirituality and Catholic humanism, the friars organized the indigenous peoples into utopian communities. There were massive waves of indigenous peoples converting to Catholicism, as measured by hundreds of thousands of baptisms in massive evangelization centers set up by the friars.[12] In its initial stages, the colonial evangelization project appeared quite successful, despite the sometimes antagonizing behavior of the conquistadores. However, the indigenous people did not express their Christian faith the ways expected by the missionary friars. Many still practiced their pre-European contact religious rituals and maintained their ancestral beliefs, much as they had for hundreds or thousands of years, while also participating in Catholic worship. The friars had disagreements over how best to approach this problem, as well as disagreements about their mission, and how to determine success. |

新スペインの布教 メキシコ語による福音書:「メキシコ語によるカテキズム」(ナワトル語) 大航海時代(1450年~1700年)に、イベリア半島の支配者たちは、新大陸で出会った先住民への布教活動に非常に興味を抱いていた。カトリックのスペ インとポルトガルでは、カトリックの布教活動が征服と植民地化という広範なプロジェクトの一部となるよう、ローマ教皇が発行したパトロナート・レアル (patronato real)に基づき、布教プロジェクトはカトリックの君主たちによって資金援助されていた。 スペインによる征服から数十年後、先住民の文化は劇的な変貌を遂げ、宗教的な側面も加わったその変貌は、メキシコ文化の形成にも貢献した。スペイン文化と先住民文化の両方の背景を持つ人々は、この変貌についてさまざまな意見や見解を持っていた。 新スペインの布教は、フランシスコ会、ドミニコ会、アウグスティノ会の修道士たちによって主導された[7]。これらの修道会は植民地時代の新スペインにカ トリック教会を設立し、16世紀の大半の間、その教会を統率した。特にフランシスコ会は、新天地とその人々に対して熱意を燃やしていた。 新大陸に渡ったフランシスコ会の修道士たちは、新しい人々に福音を伝えるという強い思いに駆り立てられていた[8]。多くのフランシスコ会修道士たちは、 これらの新しい人々を発見し、彼らに福音を伝えることには大きな宗教的意味があると信じていた。彼らはそのような新しい民族が存在することに驚き、彼らに 布教することはキリストの再臨と終末をもたらすと考え、これを千年王国説と呼んだ[9]。同時に、修道士たちの多くはヨーロッパ社会の腐敗、時にはカト リック教会の指導層にも不満を抱いていた。彼らは、新スペインは原始キリスト教の純粋な精神を復活させる機会であると考えていた。スペインによるメソアメ リカ征服の最初の数十年間に、多くの先住民が少なくとも表面上はキリスト教に改宗した。 修道士たちは、教会や修道院の建設に多くの先住民を雇用し、建設作業だけでなく、芸術家、画家、彫刻家としても彼らを活用し、彼らの作品は装飾や布教にも 使用された。この過程で、先住民の芸術家たちは、彼らの習慣や信念を象徴する花や鳥、幾何学的なシンボルを作品に多く取り入れた。修道士たちはこれらの絵 を装飾的なものと考えていたが、先住民たちはそこに強い宗教的意味合いを見出していた[10][11]。キリスト教とインディオのシンボルが混ざり合った この芸術は、インディクリスティアーノ(Indocristiano)またはインディオクリスチャン(Indochristian)アートと呼ばれてい る。フランシスコ会の精神性とカトリックの人間主義に感化された修道士たちは、先住民たちをユートピア的な共同体へと導いた。修道士たちが設立した大規模 な布教センターで行われた何十万もの洗礼の数から、先住民がカトリックに改宗する大規模な波が起こったことがわかる[12]。 植民地時代の布教事業は、征服者たちの時に敵対的な行動にもかかわらず、初期段階では非常に成功したかのように見えた。しかし、先住民たちは宣教師である 修道士たちが期待するような方法でキリスト教の信仰を表現することはなかった。多くの人々は、ヨーロッパ人との接触前の宗教的儀式を実践し、何百年、何千 年もの間行ってきたように、先祖代々の信仰を維持しながら、カトリックの礼拝にも参加していた。修道士たちは、この問題に対してどのようにアプローチする のが最善かという点でも、また自分たちの使命や成功の定義についても意見が分かれていた。 |

| At the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco Main article: Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco Sahagún helped found the first European school of higher education in the Americas, the Colegio Imperial de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco in 1536, in what is now Mexico City. This later served as a base for his own research activities, as he recruited former students to work with him.[13] The college contributed to the blending of Spanish and indigenous cultures in what is now Mexico. It became a vehicle for evangelization of students, as well as the recruiting and training of native men to the Catholic clergy; it was a center for the study of native languages, especially Nahuatl. The college contributed to the establishment of Catholic Christianity in New Spain and became an important institution for cultural exchange. Sahagún taught Latin and other subjects during its initial years.[14] Other friars taught grammar, history, religion, scripture, and philosophy. Native leaders were recruited to teach about native history and traditions, leading to controversy among colonial officials who were concerned with controlling the indigenous populations.[14] During this period, Franciscans who affirmed the full humanity and capacity of indigenous people were perceived as suspect by colonial officials and the Dominican Order. Some of the latter competitors hinted that the Friars were endorsing idolatry. The friars had to be careful in pursuing and defining their interactions with indigenous people. Sahagún was one of several friars at the school who wrote notable accounts of indigenous life and culture.[15] Two notable products of the scholarship at the college are the first New World "herbal," and a map of what is now the Mexico City region.[16] An "herbal" is a catalog of plants and their uses, including descriptions and their medicinal applications. Such an herbal, the Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis, was written in Latin by Juan Badianus de la Cruz, an Aztec teacher at the college, perhaps with help from students or other teachers.[17] In this document, the plants are drawn, named and presented according to the Aztec system of organization. The text describes where the plants grow and how herbal medicines can be made from them. This "herbal" may have been used to teach indigenous medicine at the college.[18] The Mapa de Santa Cruz shows the urban areas, networks of roads and canals, pictures of activities such as fishing and farming, and the broader landscape context. The herbal and the map show the influence of both the Spanish and the Aztec cultures, and by their structure and style convey the blending of these cultures. |

コレヒオ・デ・サンタ・クルス・デ・トラテロルコにて 主な記事:コレヒオ・デ・サンタ・クルス・デ・トラテロルコ サハグンは、1536年に現在のメキシコシティに、アメリカ大陸初のヨーロッパ式高等教育機関であるコレヒオ・インペリアル・デ・サンタ・クルス・デ・ト ラテロルコを創設した。この学校は後に、サハグンの研究活動の拠点となり、彼はかつての学生たちを仲間に引き入れた。[13] この大学は、現在のメキシコにおけるスペイン文化と先住民文化の融合に貢献した。 この大学は、学生への布教活動や、カトリック聖職者となる先住民男性の募集と訓練の場となり、特にナワトル語をはじめとする先住民の言語研究の中心地と なった。この大学は、新スペインにおけるカトリックキリスト教の確立に貢献し、文化交流の重要な機関となった。サアグンは、設立当初、ラテン語やその他の 科目を教えた[14]。他の修道士たちは、文法、歴史、宗教、聖典、哲学を教えた。先住民の指導者たちが、先住民の伝統や歴史について教えるために採用さ れ、先住民人口の管理に懸念を抱いていた植民地当局の間で論争を引き起こした[14]。この期間、先住民の完全な人間性と能力を確認したフランシスコ会 は、植民地当局とドミニコ会から疑わしい存在と見なされていた。後者の競合相手の一部は、修道士たちが偶像崇拝を是認しているのではないかとほのめかし た。修道士たちは、先住民との関わりを追求し定義する上で慎重を期さなければならなかった。 サハグンは、先住民の生活や文化について優れた記録を残した、この学校の修道士の一人であった[15]。この大学の学問の成果として特筆すべきものは、新 世界初の「薬草書」と、現在のメキシコシティ地域の地図である[16]。薬草書とは、植物の種類と用途を記載したカタログであり、その説明や薬効も含まれ ている。このような薬草書『Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis』は、この大学のアステカの教師フアン・バディアヌス・デ・ラ・クルスが、おそらく学生や他の教師の助けを借りてラテン語で執筆した。この 「薬草」は、カレッジで先住民の医学を教えるために使われた可能性がある[18]。サンタクルス地図には、都市部、道路や運河のネットワーク、漁業や農業 などの活動の様子、より広範囲の景観が示されている。薬草と地図は、スペインとアステカの文化の影響を示しており、その構造とスタイルから、これらの文化 の融合が伝わってくる。 |

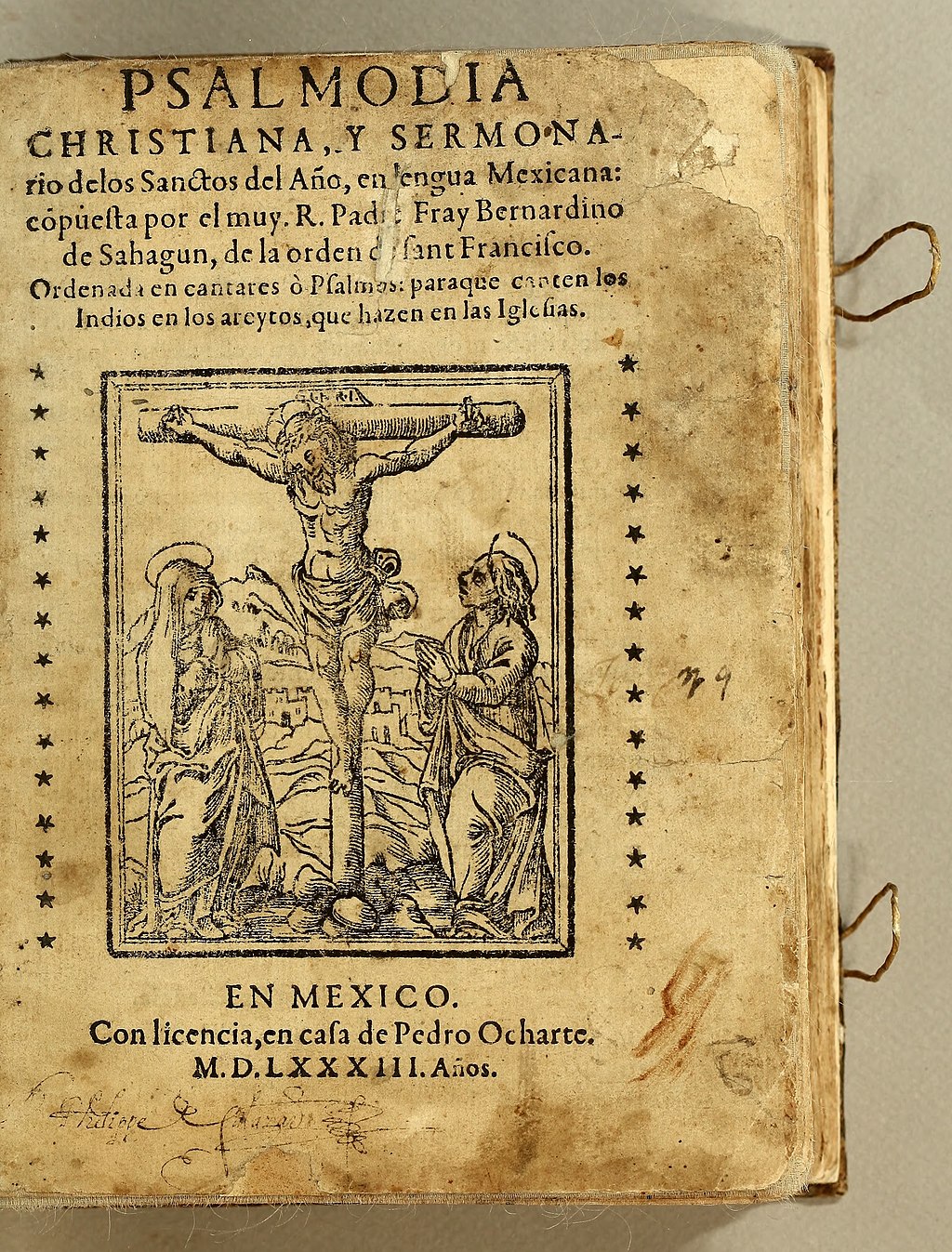

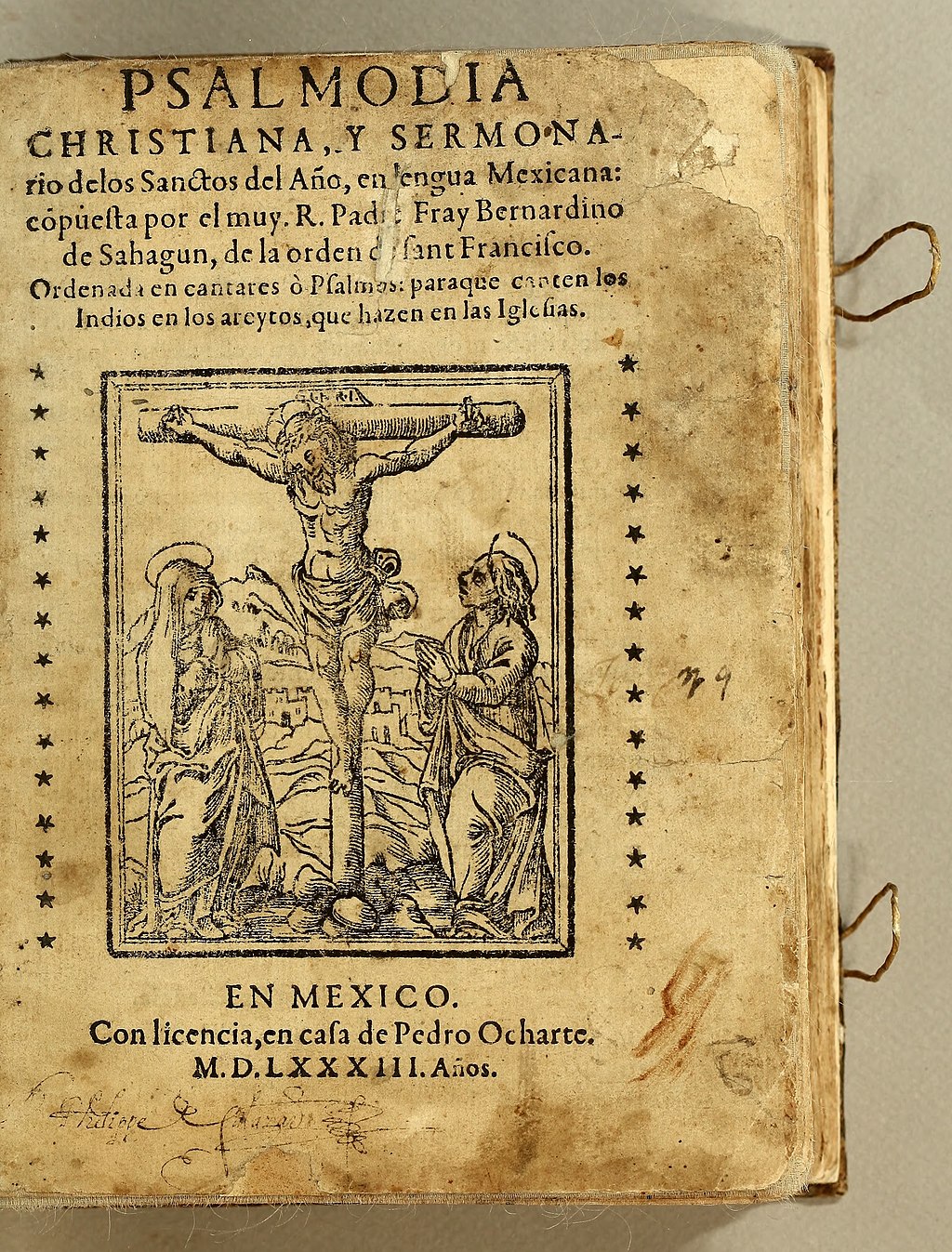

Work as a missionary Title page, Psalmodia Christiana, 1583 In addition to teaching, Sahagún spent several extended periods outside of Mexico City, including in Tlalmanalco (1530–32); Xochimilco (1535), where he is known to have performed a marriage;[19] Tepepulco (1559–61), Huexotzinco, and also evangelized, led religious services, and provided religious instruction.[20] He was first and foremost a missionary, whose goal was to bring the peoples of the New World to the Catholic faith. He spent much time with the indigenous people in remote rural villages, as a Catholic priest, teacher, and missionary. Sahagún was a gifted linguist, one of several Franciscans. As an Order, the Franciscans emphasized evangelization of the indigenous peoples in their own languages. Sahagún began his study of Nahuatl while traveling across the Atlantic, learning from indigenous nobles who were returning to the New World from Spain. Later he was recognized as one of the Spaniards most proficient in this language.[2] Most of his writings reflect his Catholic missionary interests, and were designed to help churchmen preach in Nahuatl, or translate the Bible into Nahuatl, or provide religious instruction to indigenous peoples. Among his works in Nahuatl was a translation of the Psalms and a catechism.[21] He likely composed his Psalmodia Christiana in Tepepolco when he was gathering material for the Primeros Memoriales. It was published in 1583 by Pedro Ocharte, but circulated in New Spain prior to that in order to replace with Christian texts the songs and poetry of the Nahuas.[22] His curiosity drew him to learn more about the worldview of the Aztecs, and his linguistic skills enabled him to do so. Thus, Sahagún had the motivation, skills and disposition to study the people and their culture. He conducted field research in the indigenous language of Nahuatl. In 1547, he collected and recorded huehuetlatolli (Nahuatl: "Words of the old men"), Aztec formal orations given by elders for moral instruction, education of youth, and cultural construction of meaning.[2] Between 1553 and 1555 he interviewed indigenous leaders in order to gain their perspective on the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire.[14] In 1585 he wrote a revision of the conquest narrative, published as Book 12 of the Florentine Codex, one of his last works before his death in 1590. |

宣教師として働く 表題ページ、Psalmodia Christiana、1583年 サアグンは、教えることに加えて、メキシコシティ郊外のトラルマナコ(1530~32年)、ソチミルコ(1535年)で、 [19] テペプルコ(1559-61年)、ウエショツィンコでも布教活動を行い、宗教儀式を執り行い、宗教教育も行った[20]。彼は何よりもまず宣教師であり、 その目的は新世界の住民をカトリックの信仰に導くことだった。彼はカトリックの司祭、教師、宣教師として、辺境の農村に住む先住民たちと多くの時間を過ご した。 サハグンは才能ある言語学者であり、フランシスコ会の数人の修道士の1人であった。フランシスコ会は、先住民を彼らの言語で伝道することを重視していた。 サハグンは、大西洋を渡り、スペインから新世界に戻ってきた先住民の貴族から学ぶうちに、ナワトル語の学習を始めた。後に彼は、この言語に最も精通したス ペイン人の一人として認められた[2]。彼の著作のほとんどは、カトリックの布教活動への関心を表しており、教会関係者がナワトル語で説教したり、聖書を ナワトル語に翻訳したり、先住民に宗教的指導を提供したりするのを助けることを目的としていた。ナワトル語で書かれた彼の作品には、詩篇の翻訳やカテキズ ムがある[21]。彼は『テペポルコにおけるキリスト教聖歌』を『プリメロス・メモリアレス』の資料収集中に作曲したと思われる。1583年にペドロ・オ チャルテによって出版されたが、それ以前に新スペインで流通していた。これは、ナワ族の歌や詩をキリスト教のテキストに置き換えるためであった[22]。 サハグンは、アステカ人の世界観についてもっと知りたいという好奇心を抱き、その言語能力によってそれを可能にした。このように、サハグンは人々とその文 化を研究する動機、能力、素質を備えていた。彼は先住民の言語であるナワトル語で現地調査を行った。1547年、彼はアステカの年長者たちが道徳的教訓、 青少年の教育、文化的意味の構築のために行う公式演説「フエウエトルトリ(Nahuatl: 「Words of the old men」)」を収集し、記録した[2]。1553年から1555年にかけて、彼は スペインによるアステカ帝国の征服について、先住民のリーダーたちにインタビューを行い、彼らの見解を聞いた[14]。1585年、彼は征服物語の改訂版 を書き、フィレンツェ写本第12巻として出版した。これは、1590年に彼が亡くなる前の最後の作品の一つである。 |

| Field research After the fervor of the early mass conversions in Mexico had subsided, Franciscan missionaries came to realize that they needed a better understanding of indigenous peoples in order effectively to pursue their work. Sahagún's life changed dramatically in 1558 when the new provincial of New Spain, Fray Francisco de Toral, commissioned him to write in Nahuatl about topics he considered useful for the missionary project. The provincial wanted Sahagún to formalize his study of native language and culture, so that he could share it with others. The priest had a free hand to conduct his investigations.[14] He conducted research for about twenty-five years, and spent the last fifteen or so editing, translating and copying. His field research activities can be grouped into an earlier period (1558–1561) and a later period (1561–1575).[23]  Aztec warriors as shown in the Florentine Codex. From his early research, Sahagún wrote the text known as Primeros Memoriales. This served as the basis for his subsequent, larger Historia general.[24] He conducted his research at Tepeapulco, approximately 50 miles northeast of Mexico City, near present-day Hidalgo. There he spent two years interviewing approximately a dozen village elders in Nahuatl, assisted by native graduates of the college at Tlatelolco. Sahagún questioned the elders about the religious rituals and calendar, family, economic and political customs, and natural history. He interviewed them individually and in groups, and was thus able to evaluate the reliability of the information shared with him. His assistants spoke three languages (Nahuatl, Latin and Spanish). They participated in research and documentation, translation and interpretation, and they also painted illustrations. He published their names, described their work, and gave them credit. The pictures in the Primeros Memoriales convey a blend of indigenous and European artistic elements and influences.[25] Analysis of Sahagún's research activities in this earlier period indicates that he was developing and evaluating his own methods for gathering and verifying this information.[23] During the period 1561–1575, Sahagún returned to Tlatelolco. He interviewed and consulted more elders and cultural authorities. He edited his prior work. He expanded the scope of his earlier research, and further developed his interviewing methods. He recast his project along the lines of the medieval encyclopedias. These were not encyclopedias in the contemporary sense, and can be better described as worldbooks, for they attempt to provide a relatively complete presentation of knowledge about the world.[26] |

現地調査 メキシコで起こった初期の大量改宗の熱狂が収まった後、フランシスコ会の宣教師たちは、自分たちの仕事を効果的に進めるためには、先住民についてより深く 理解する必要があることに気づいた。サアグンは、1558年にニュースペインの新しい地方長官であるフラ・フランシスコ・デ・トラルから、宣教師プロジェ クトに役立つと思われるテーマについてナワトル語で執筆するよう依頼されたことで、人生が一変した。管区長はサアグンに、先住民の言語と文化の研究を正式 なものとし、それを他の人と共有することを望んでいた。司祭は自由に調査を行うことができた[14]。彼は約25年にわたって研究を行い、最後の15年ほ どは編集、翻訳、コピー作業に費やした。彼の現地調査活動は、前期(1558年~1561年)と後期(1561年~1575年)に分けられる[23]。  フィレンツェ写本に描かれたアステカの戦士たち。 初期の調査から、サアグンは『プリメロス・メモリアレス』として知られるテキストを執筆した。これは、後に彼が執筆したより大規模な『一般史』の基礎と なった[24]。彼はメキシコシティの北東約50マイル、現在のイダルゴ州に近いテペアプルコで調査を行った。そこで彼は、トラテロルコの大学を卒業した 現地人の協力を得て、ナワトル語でおよそ12人の村の年長者に2年間インタビューした。サハグンは、年長者たちに宗教儀式や暦、家族、経済、政治の習慣、 自然史について質問した。彼は彼らを個別に、またグループでインタビューし、それによって共有された情報の信頼性を評価することができた。彼の助手たちは 3つの言語(ナワトル語、ラテン語、スペイン語)を話した。彼らは研究と文書化、翻訳と通訳に参加し、またイラストも描いた。彼は彼らの名前を公表し、彼 らの仕事を説明し、彼らに功績を与えた。プリメロス・メモリアレス』の挿絵は、先住民とヨーロッパの芸術的要素と影響が融合したものである[25]。サア グンがこの時期に研究活動を行ったことについての分析から、彼はこの情報を収集し検証するための独自の方法を開発し、評価していたことがわかる[23]。 1561年から1575年の間、サアグンはトラテロルコに戻った。彼はさらに多くの長老や文化の権威者にインタビューし、相談した。彼は以前の著作を編集 した。彼は以前の研究の範囲を広げ、インタビュー方法をさらに発展させた。そして、中世の百科事典のスタイルに沿ってプロジェクトを再構築した。これらは 現代的な意味での百科事典ではなく、世界に関する知識を比較的完全に提供しようとするものであるため、世界書(worldbook)と呼ぶ方がふさわし い。 |

| Methodologies Sahagún was among the first to develop methods and strategies for gathering and validating knowledge of indigenous New World cultures. Much later, the scientific discipline of anthropology would formalize the methods of ethnography as a scientific research strategy for documenting the beliefs, behavior, social roles and relationships, and worldview of another culture, and for explaining these factors with reference to the logic of that culture. His research methods and strategies for validating information provided by his informants are precursors of the methods and strategies of modern ethnography. He systematically gathered knowledge from a range of diverse informants, including women, who were recognized as having knowledge of indigenous culture and tradition. He compared the answers obtained from his various sources. Some passages in his writings appear to be transcriptions of informants' statements about religious beliefs, society or nature. Other passages clearly reflect a consistent set of questions presented to different informants with the aim of eliciting information on specific topics. Some passages reflect Sahagún's own narration of events or commentary. |

方法論 サアグンは、新大陸の先住民文化に関する知識を集め、検証するための方法と戦略を最初に開発した人物の一人である。その後、人類学という学問分野が、他文 化の信念、行動、社会的役割や人間関係、世界観を記録し、その文化の論理を参照しながらこれらの要因を説明する科学的研究戦略として、民族誌の方法論を正 式に確立した。彼の研究方法と情報提供者からの情報を検証する戦略は、現代の民族誌の方法と戦略の先駆けである。 彼は、先住民の文化や伝統に精通していると認められた女性を含む、さまざまな情報提供者から体系的に知識を収集した。そして、さまざまな情報源から得られ た答えを比較した。彼の著作の一部は、宗教的信念、社会、自然に関する情報提供者の発言を文字に起こしたものと思われる。また、特定のトピックに関する情 報を引き出す目的で、異なる情報源に一貫した質問を投げかけたことがはっきりとわかる箇所もある。サアグンの出来事や解説を自ら語った箇所もある。 |

| Significance During the period in which Sahagún conducted his research, the conquering Spaniards were greatly outnumbered by the conquered Aztecs, and were concerned about the threat of a native uprising. Some colonial authorities perceived his writings as potentially dangerous, since they lent credibility to native voices and perspectives. Sahagún was aware of the need to avoid running afoul of the Inquisition, which was established in Mexico in 1570. Sahagún's work was originally conducted only in Nahuatl. To fend off suspicion and criticism, he translated sections of it into Spanish, submitted it to some fellow Franciscans for their review, and sent it to the King of Spain with some Friars returning home. His last years were difficult, because the utopian idealism of the first Franciscans in New Spain was fading while the Spanish colonial project continued as brutal and exploitative. In addition, millions of indigenous people died from repeated epidemics, as they had no immunity to Eurasian diseases. Some of his final writings express feelings of despair. The Crown replaced the religious orders with secular clergy, giving friars a much smaller role in the Catholic life of the colony. Franciscans newly arrived in the colony did not share the earlier Franciscans' faith and zeal about the capacity of the Indians. The pro-indigenous approach of the Franciscans and Sahagún became marginalized with passing years. The use of the Nahuatl Bible was banned, reflecting the broader global retrenchment of Catholicism under the Council of Trent. In 1575 the Council of the Indies banned all scriptures in the indigenous languages and forced Sahagún to hand over all of his documents about the Aztec culture and the results of his research. The respectful study of the local traditions has probably been seen as a possible obstacle to the Christian mission. Despite this ban, Sahagún made two more copies of his Historia general. Sahagún's Historia general was unknown outside Spain for about two centuries. In 1793, a bibliographer catalogued the Florentine Codex in the Laurentian Library in Florence.[27][28] The work is now carefully rebound in three volumes. A scholarly community of historians, anthropologists, art historians, and linguists has been investigating Sahagún's work, its subtleties and mysteries, for more than 200 years.[29] The Historia general is the product of one of the most remarkable social-science research projects ever conducted. It is not unique as a chronicle of encounters with the New World and its people, but it stands out due to Sahagún's effort to gather information about a foreign culture by interviewing people and gathering perspectives from within that culture. As Nicholson has stated, "the scope of the Historia’s coverage of contact-period Central Mexico indigenous culture is remarkable, unmatched by any other sixteenth-century works that attempted to describe the native way of life.”[30] Although in his own mind Sahagún was a Franciscan missionary, he has also been referred to by scholars as the "father of American Ethnography".[1] |

意義 サアグンが研究を行っていた時代、征服者であるスペイン人は征服されたアステカ人に比べて圧倒的に数が少なく、先住民による蜂起の脅威に悩まされていた。 彼の著作は先住民の意見や視点を信憑性のあるものとして受け止められる可能性があり、一部の植民地当局はそれを危険視していた。サアグンは、1570年に メキシコに設立された異端審問に反発しないよう努める必要性を認識していた。 サアグンの著作はもともとナワトル語のみで書かれていた。疑惑や批判を避けるため、彼はその一部をスペイン語に翻訳し、仲間のフランシスコ会修道士たちに 確認してもらった上で、スペイン国王に、帰国する修道士たちとともに送った。彼の晩年は困難を極めた。というのも、スペイン植民地計画が残忍かつ搾取的な まま続く一方で、新スペインに最初にやってきたフランシスコ会の修道士たちのユートピア的理想主義は薄れつつあったからだ。さらに、何百万もの先住民が、 ユーラシア大陸由来の病気に免疫を持っていなかったため、繰り返される疫病で命を落とした。彼の最後の著作のいくつかは、絶望的な感情を表している。スペ イン王室は、修道会を世俗の聖職者に置き換え、植民地のカトリック生活における修道士たちの役割を大幅に縮小した。新たに植民地に到着したフランシスコ会 の修道士たちは、先住民の能力に対する先代のフランシスコ会の修道士たちの信念や熱意を共有していなかった。フランシスコ会士とサアグンによる先住民擁護 の姿勢は、時間の経過とともに次第に疎外されていった。ナワトル語聖書の使用が禁止されたことは、トレント公会議によるカトリックの縮小を反映していた。 1575年には、インディーズ会議が先住民の言語によるすべての聖典を禁止し、サアグンにアステカ文化と研究結果に関するすべての文書を引き渡すよう強要 した。現地の伝統を尊重した研究は、キリスト教の布教の妨げになると考えられていたのだろう。この禁止令にもかかわらず、サアグンは『一般史』のコピーを 2部作成した。 サアグンの『一般史』は、約2世紀もの間スペイン国外では知られていなかった。1793年、書誌学者がフィレンツェのローレンツィ図書館でフィレンツェ写 本をカタログ化した[27][28]。この作品は現在、3巻に丁寧に装丁されている。歴史学者、人類学者、美術史家、言語学者からなる学術研究コミュニ ティは、200年以上にわたってサアグンの著作、その繊細さや謎について研究を続けている[29]。 『一般史』は、これまでに実施された社会科学研究プロジェクトの中でも最も注目すべきものの1つである。新世界とその人々との出会いの記録としては独特な ものではないが、サアグンが人々へのインタビューや、その文化内部からの見解の収集を通じて、異文化に関する情報を収集しようとした努力により際立ってい る。ニコルソンは、「『ヒストリア』が接触期の中央メキシコ先住民の文化を扱った範囲は驚くほど広く、先住民の生活様式を描写しようとした16世紀の他の どの作品にも及ばない」と述べている[30]。サアグンは、自身ではフランシスコ会の宣教師と考えていたが、学者からは「アメリカ民族誌学の父」とも呼ば れている[1]。 |

| As a Franciscan Friar Sahagún has been described as a missionary, ethnographer, linguist, folklorist, Renaissance humanist, historian and pro-indigenous.[15] Scholars have explained these roles as emerging from his identity as a missionary priest,[12] a participant in the Spanish evangelical fervor for converting newly encountered peoples,[31] and as a part of the broader Franciscan millenarian project.[9] Founded by Francis of Assisi in the early 13th century, the Franciscan Friars emphasized devotion to the Incarnation, the humanity of Jesus Christ. Saint Francis developed and articulated this devotion based on his experiences of contemplative prayer in front the San Damiano Crucifix and the practice of compassion among lepers and social outcasts. Franciscan prayer includes the conscious remembering of the human life of Jesus[32] and the practice of care for the poor and marginalized. Saint Francis’ intuitive approach was elaborated into a philosophical vision by subsequent Franciscan theologians, such as Bonaventure of Bagnoregio and John Duns Scotus, leading figures in the Franciscan intellectual tradition. The philosophy of Scotus is founded upon the primacy of the Incarnation, and may have been a particularly important influence on Sahagún, since Scotus's philosophy was taught in Spain at this time. Scotus absorbed the intuitive insights of St. Francis of Assisi and his devotion to Jesus Christ as a human being, and expressed them in a broader vision of humanity. A religious philosophical anthropology — a vision of humanity — may shape a missionary's vision of human beings, and in turn the missionary's behavior on a cultural frontier.[31] The pro-indigenous approach of the Franciscan missionaries in New Spain is consistent with the philosophy of Franciscan John Duns Scotus. In particular, he outlined a philosophical anthropology that reflects a Franciscan spirit.[33] Several specific dimensions of Sahagún's work (and that of other Franciscans in New Spain) reflect this philosophical anthropology. The native peoples were believed to have dignity and merited respect as human beings. The friars were, for the most part, deeply disturbed by the conquistadores' abuse of the native peoples. In Sahagún's collaborative approach, in which he consistently gave credit to his collaborators, especially Antonio Valeriano, the Franciscan value of community is expressed.[34] In his five decades of research, he practiced a Franciscan philosophy of knowledge in action. He was not content to speculate about these new peoples, but met with, interviewed and interpreted them and their worldview as an expression of his faith. While others – in Europe and New Spain – were debating whether or not the indigenous peoples were human and had souls, Sahagún was interviewing them, seeking to understand who they were, how they loved each other, what they believed, and how they made sense of the world. Even as he expressed disgust at their continuing practice of human sacrifice and what he perceived as their idolatries, he spent five decades investigating Aztec culture. |

フランシスコ会の修道士として サアグンは、宣教師、民族学者、言語学者、民俗学者、ルネサンス期のヒューマニスト、歴史家、先住民擁護家として知られている[15]。学者たちは、これ らの役割は、宣教師としての彼のアイデンティティから生まれたものであると説明している[12]。スペインにおける福音主義の熱狂的な布教活動に参加し、 新たに出会った人々を改宗させようとしたこと[31]、そしてより広範なフランシスコ会の千年王国プロジェクトの一部としてであった[9]。 13世紀初頭にアッシジのフランチェスコによって設立されたフランシスコ会は、受肉、すなわちイエス・キリストの人間性に献身することを強調した。聖フラ ンシスコは、サン・ダミアーノ十字架の前で瞑想的な祈りを捧げ、ハンセン病患者や社会から疎外された人々に対する思いやりを実践した経験に基づいて、この 信仰を発展させ、明確に表現した。フランシスコ会の祈りには、イエスの人間としての生涯を意識的に思い起こすこと[32]や、貧しい人々や社会から疎外さ れた人々への配慮の実践が含まれる。 聖フランチェスコの直感的なアプローチは、フランシスコ会の知的伝統の第一人者であるボナヴェントゥラ・ディ・バニョレージョやジョン・ダンズ・スコトゥ スといった後世のフランシスコ会神学者たちによって哲学的なビジョンへと発展した。スコトゥスの哲学は受肉説を基盤としており、この時期にスペインでスコ トゥスの哲学が教えられていたことから、サアグンには特に大きな影響を与えた可能性がある。スコトゥスは、アッシジの聖フランチェスコの直感的な洞察力 と、イエス・キリストへの献身を吸収し、それをより広範な人間観として表現した。 宗教哲学的人間学、すなわち人間観は、宣教師の人間観を形成し、ひいては宣教師の文化の境界線における行動に影響を与える可能性がある[31]。新スペイ ンにおけるフランシスコ会の宣教師の先住民擁護的アプローチは、フランシスコ会のジョン・ダンズ・スコトゥスの哲学と一致している。特に、彼はフランシス コ会の精神を反映した哲学的人間学の概要を述べた[33]。 サアグンの著作(および新スペインの他のフランシスコ会士による著作)のいくつかの具体的な側面は、この哲学的人間学を反映している。 先住民は人間としての尊厳を持ち、尊敬に値すると考えられていた。 修道士たちは、ほとんどの場合、征服者による先住民への虐待に深い衝撃を受けていた。サアグンは、共同作業者、特にアントニオ・バレリアーノの功績を常に 評価する姿勢で研究に取り組んだ。 50年にわたる研究の中で、彼は実践的なフランシスコ会の知識哲学を実践した。彼は、これらの新しい人々について憶測するだけでは満足せず、彼らと彼らの 世界観に会い、インタビューし、解釈した。ヨーロッパや新スペインで先住民が人間であり魂を持っているかどうかについて議論が交わされていた頃、サアグン は彼らにインタビューを行い、彼らが何者なのか、どのように愛し合うのか、何を信じているのか、そして世界をどのように理解しているのかを理解しようとし ていた。サアグンは、彼らが人身御供を続けていることや、偶像崇拝を行っていると彼が認識していることに対して嫌悪感を示しながらも、50年にわたってア ステカ文化の調査に没頭した。 |

| Disillusionment with the "spiritual conquest" Learning more about Aztec culture, Sahagún grew increasingly skeptical of the depth of the mass conversions in Mexico. He thought that many if not most of the conversions were superficial. He also became concerned about the tendency of his fellow Franciscan missionaries to misunderstand basic elements of traditional Aztec religious beliefs and cosmology. He became convinced that only by mastering native languages and worldviews could missionaries be effective in dealing with the Aztec people.[14] He began informal studies of indigenous peoples, their beliefs, and religious practices. In the Florentine Codex, Sahagún wrote numerous introductions, addresses "to the reader", and interpolations in which he expresses his own views in Spanish.[35] In Book XI, The Earthly Things, he replaces a Spanish translation of Nahuatl entries on mountains and rocks to describe current idolatrous practices among the people. "Having discussed the springs, waters, and mountains, this seemed to me to be the opportune place to discuss the principal idolatries which were practiced and are still practiced in the waters and mountains."[36] In this section, Sahagún denounces the association of the Virgin of Guadalupe with a pagan Meso-American deity. The Franciscans were then particularly hostile to this cult because of its potential for idolatrous practice, as it conflated the Virgin Mary with an ancient goddess. At this place [Tepeyac], [the Indians] had a temple dedicated to the mother of the gods, whom they called Tonantzin, which means Our Mother. There they performed many sacrifices in honor of this goddess...And now that a church of Our Lady of Guadalupe is built there, they also call her Tonantzin, being motivated by the preachers who called Our Lady, the Mother of God, Tonantzin. It is not known for certain where the beginning of this Tonantzin may have originated, but this we know for certain, that, from its first usage, the word means that ancient Tonantzin. And it is something that should be remedied, for the correct [native] name of the Mother of God, Holy Mary, is not Tonantzin, but Dios inantzin [Nahuatl for: the Mother of God]. It appears to be a Satanic invention to cloak idolatry under the confusion of this name, Tonantzin. And they now come to visit from very far away, as far away as before, which is also suspicious, because everywhere there are many churches of Our Lady and they do not go to them. They come from distant lands to this Tonantzin as in olden times.[37] Sahagún explains that a church of Santa Ana has become a pilgrimage site for Toci (Nahuatl: "our grandmother"). He acknowledges that Saint Ann is the mother of the Virgin Mary, and therefore literally the grandmother of Jesus, but Sahagún writes: All the people who come, as in times past, to the feast of Toci, come on the pretext of Saint Ann, but since the word [grandmother] is ambiguous, and they respect the olden ways, it is believable that they come more for the ancient than the modern. And thus, also in this place, idolatry appears to be cloaked because so many people come from such distant lands without Saint Ann's ever having performed any miracles there. It is more apparent that it is the ancient Toci rather than Saint Ann [whom they worship].[37] But in this same section, Sahagún expressed his profound doubt that the Christian evangelization of the Indians would last in New Spain, particularly since the devastating plague of 1576 decimated the indigenous population and tested the survivors. [A]s regards the Catholic Faith, [Mexico] is a sterile land and very laborious to cultivate, where the Catholic Faith has very shallow roots, and with much labor little fruit is produced, and from little cause that which is planted and cultivated withers. It seems to me the Catholic Faith can endure little time in these parts...And now, in the time of this plague, having tested the faith of those who come to confess, very few respond properly prior to the confession; thus we can be certain that, though preached to more than fifty years, if they were now left alone, if the Spanish nation were not to intercede, I am certain that in less than fifty years there would be no trace of the preaching which has been done for them.[38] |

「精神的な征服」に対する幻滅 アステカ文化についてさらに知識を深めるにつれ、サアグンはメキシコにおける大規模な改宗の深みにますます懐疑的になった。 彼は、改宗者の大半、あるいは大半ではないにしてもその多くが表面的なものだと考えた。 また、彼は仲間のフランシスコ会の宣教師たちが、アステカの伝統的な宗教的信念や宇宙論の基本的な要素を誤解する傾向があることに懸念を抱くようになっ た。彼は、宣教師がアステカの人々に対して効果的な働きかけを行うには、現地の言語と世界観を習得するしかないという確信を抱くようになった[14]。そ して、先住民、彼らの信仰、宗教的慣習について非公式な研究を始めた。 サアグンは『フローレンシアン・コデックス』に、多数の序文、読者への挨拶、そして自身の見解をスペイン語で述べた挿入文を記した[35]。第11巻「地 上のもの」では、山や岩に関するナワトル語の項目をスペイン語に翻訳し、当時の人々の偶像崇拝の慣習について記述している。「泉、水、山について述べたの で、水や山で今もなお行われている主要な偶像崇拝について述べるのにふさわしい場所だと思った」[36]。 この章でサアグンは、グアダルペの聖母とメソアメリカの異教の神との関連性を非難している。フランシスコ会は、この崇拝が偶像崇拝につながる可能性があったため、特にこの教団に敵意を抱いていた。というのも、この教団は聖母マリアを古代の女神と同一視していたからだ。 この場所(テペヤック)では、インディアンたちは女神の母を祀る神殿を建てていた。彼らはその女神をトナンツィンと呼んでいた。トナンツィンとは「私たち の母」という意味である。そこで彼らは、この女神を称えるために多くの生け贄を捧げた。そして今、グアダルペの聖母教会が建てられたことで、彼らは彼女を トンアンツィンとも呼ぶようになった。これは、聖母マリアをトンアンツィンと呼んだ説教師たちに触発されたものである。このトンアンツィンという言葉がど こから始まったのかは定かではないが、確かなことは、この言葉が最初に使われたとき、それは古代のトンアンツィンを意味していたということだ。そして、こ れは改善されるべきことである。なぜなら、聖母マリアの正しい(先住民の)名前はトナンツィンではなく、ディオス・インアンツィン(ナワトル語で「聖母マ リア」)だからである。トナンツィンという名前の混乱を利用して偶像崇拝を覆い隠すのは、悪魔の策略のように思える。そして、彼らは今、かつてと同じよう に非常に遠くからやって来る。これもまた疑わしい。なぜなら、至る所に聖母マリアの教会がたくさんあるのに、彼らはそれらの教会には行かないからだ。彼ら は遠い国々から、昔と同じようにこのトナンツィンにやって来るのだ。 サアグンは、サンタ・アナ教会がトシ(ナワトル語で「私たちの祖母」)の巡礼地となっていると説明している。彼は、聖アンが聖母マリアの母であり、したがって文字通りイエスの祖母であることを認めているが、サアグンは次のように書いている。 昔と同じように、トシの祭りにやって来る人々は皆、聖アンを口実にしてやって来るが、[祖母]という言葉は曖昧であり、彼らは昔からのやり方を尊重してい るので、彼らがやって来るのは現代よりもむしろ古代のためであると考えられる。そして、このように、この場所でも、偶像崇拝は隠されているように見える。 なぜなら、聖アンが奇跡を起こしたこともないような遠い土地から、非常に多くの人々がやって来るからだ。彼らが崇拝しているのは、聖アンではなく、古代の トシ族である可能性が高い[37]。 しかし、サアグンはこの同じ章で、1576年に発生した壊滅的な疫病により先住民人口が激減し、生き残った人々も試練にさらされたため、特に新スペインにおいてキリスト教によるインディオへの布教が継続するかどうかについて、深い疑念を抱いている。 カトリック信仰に関しては、メキシコは不毛の地であり、耕作には多大な労力を要する。カトリック信仰の定着は浅く、多大な労力を費やしても収穫は少なく、 わずかな原因で植えられ、栽培されたものは枯れてしまう。私には、この地域ではカトリック信仰は長続きしないように思える...そして今、この疫病の時代 に、懺悔に来る人々の信仰を試したところ、懺悔前に適切に答える者はほとんどいなかった。50年以上も説教を続けてきたが、もし今放っておかれ、スペイン 国が介入しなければ、50年も経たないうちに、彼らに対して行われてきた説教の痕跡はまったくなくなってしまうだろう。 |

| Sahagún's histories of the conquest Sahagún wrote two versions of the conquest of the Aztec Empire, the first is Book 12 of the General History (1576) and the second is a revision completed in 1585. The version in the Historia general is the only narration of historical events, as opposed to information on general topics such as religious beliefs and practices and social structure. The 1576 text is exclusively from an indigenous, largely Tlatelolcan viewpoint.[39] He revised the account in 1585 in important ways, adding passages praising the Spanish, especially the conqueror Hernan Cortés, rather than adhering to the indigenous viewpoint.[40] The original of the 1585 manuscript is lost. In the late 20th century, a handwritten copy in Spanish was found by John B. Glass in the Boston Public Library, and has been published in facsimile and English translation, with comparisons to Book 12 of the General History.[41] In his introduction ("To the reader") to Book 12 of the Historia general, Sahagún claimed the history of the conquest was a linguistic tool so that friars would know the language of warfare and weapons.[42] Since compiling a history of the conquest from the point of view of the defeated Tenochtitlan-Tlatelolcan could be controversial for the Spanish crown, Sahagún may have been prudent in trying to shape how the history was perceived.[43] Sahagún's 1585 revision of the conquest narrative, which included praise for Cortés and the Spanish conquest, was completed in a period when work on indigenous texts was under attack. Sahagún likely wrote this version with that political situation well in mind, when a narrative of the conquest entirely from the defeated Mexicans' viewpoint was suspect.[44] |

サアグンの征服史 サアグンはアステカ帝国の征服について 2 つのバージョンを書いている。1 つ目は『一般史』第 12 巻(1576 年)であり、2 つ目は 1585 年に完成した改訂版である。『一般史』のバージョンは、宗教的信念や慣習、社会構造などの一般的なトピックに関する情報とは異なり、歴史的出来事を唯一叙 述している。1576年のテキストは、主にトラテロルカン族の視点に立ったものである[39]。彼は1585年に重要な修正を加え、先住民の視点に固執す るのではなく、スペイン人、特に征服者エルナン・コルテスを称賛する文章を追加した[40]。1585年の原稿の原本は失われている。20世紀後半、ジョ ン・B・グラスがボストン公共図書館でスペイン語の写しを発見し、複製と英語訳が刊行された。一般史』第12巻との比較もなされている[41]。『一般 史』第12巻の序文(「読者の皆様へ」)でサアグンは、征服の歴史は修道士たちが戦争や武器の言語を理解するための言語的ツールであると主張した[ 42] 征服の歴史を、敗者側のテノチティトラン・トラテロルカンの視点からまとめることは、スペイン王室にとって物議を醸す可能性があったため、サアグンは歴史 の受け止め方を形作る上で慎重だったのかもしれない[43]。サアグンが1585年にコルテスとスペインによる征服を称賛する内容に修正を加えた征服物語 は、先住民のテキストに対する批判が高まっていた時期に完成した。サアグンは、征服の物語が完全に敗北したメキシコ人の視点に立っていた場合、疑わしいと いう政治情勢を十分に考慮して、このバージョンを書いた可能性が高い[44]。 |

| Works Coloquios y Doctrina Christiana con que los doce frailes de San Francisco enviados por el papa Adriano VI y por el emperador Carlos V, convirtieron a los indios de la Nueva España. Facsimile edition. Introduction and notes by Miguel León-Portilla. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México 1986. The Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, 12 volumes; translated by Arthur J. O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble; University of Utah Press (January 7, 2002), hardcover, ISBN 087480082X ISBN 978-0874800821 The Conquest of New Spain, 1585 Revision. translated by Howard F. Cline, notes and an introduction by S.L. Cline. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1989 Primeros Memoriales. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1996. Psalmodia Christiana (1583). English translation by Arthur J.O. Anderson. Norman: University of Utah Press 1993. Psalmodia Christiana (1583). Complete digital facsimile of the first edition from the John Carter Brown Library |

作品 Coloquios y Doctrina Christiana con que los doce frailes de San Francisco enviados por el papa Adriano VI y por el emperador Carlos V, convirtieron a los indios de la Nueva España. Facsimile edition. Introduction and notes by Miguel León-Portilla. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México 1986. The Florentine Codex: 『新スペインの事物に関する一般史』全12巻、アーサー・J・O・アンダーソンとチャールズ・E・ディブル訳、ユタ大学出版(2002年1月7日)、ハー ドカバー、ISBN 087480 082X ISBN 978-0874800821 The Conquest of New Spain, 1585 Revision. translated by Howard F. Cline, notes and an introduction by S.L. Cline. ソルトレイクシティ:ユタ大学出版局、1989年 Primeros Memoriales. ノーマン:オクラホマ大学出版局、1996年 Psalmodia Christiana (1583). アーサー・J・O・アンダーソンによる英語訳。ノーマン:ユタ大学出版局、1993年 Psalmodia Christiana (1583). ジョン・カーター・ブラウン図書館所蔵の初版デジタル完全復刻版 |

| Further reading Edmonson, Munro S., ed. Sixteenth-Century Mexico: The Work of Sahagún. School of American Research Advanced Seminar Series 6. Albuquerque 1976. Glass, John B. Sahagún: Reorganization of the Manuscrito de Tlatelolco, 1566-1569, part 1. Conemex Associates, Contributions to the Ethnohistory of Mexico 7. Lincoln Center MA 1978. Nicolau d'Olwer, Luis and Howard F. Cline, "Bernardino de Sahagún, 1499-1590. A Sahagún and his Works," in Handbook of Middle America Indians, vol. 13. Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources, Howard F. Cline, editor. Austin: University of Texas Press 1973, pp. 186–207. Klor de Alva, J. Jorge, et al., eds. The Work of Bernardino de Sahagún: Pioneer Ethnographer of Sixteenth-Century Mexico. Albany: Institute for Mesoamerican Studies SUNY, vol. 2. Austin 1988. León-Portilla, Miguel, Bernardino de Sahagún: First Anthropologist, trans. Mauricio J. Mixco. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 2002. Nicholson, H.B., "Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: A Spanish Missionary in New Spain, 1529-1590," in Representing Aztec Ritual: Performance, Text, and Image in the Work of Sahagún, ed. Eloise Quiñones Keber. Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2002. Schwaller, John Frederick, ed. Sahagún at 500: Essays on the Quincentenary of the Birth of Fr. Bernardino de Sahagún, OFM. Berkeley: Academy of American Franciscan History, 2003. |

さらに詳しく Edmonson, Munro S., ed. Sixteenth-Century Mexico: The Work of Sahagún. School of American Research Advanced Seminar Series 6. Albuquerque 1976. Glass, John B. Sahagún: Reorganization of the Manuscrito de Tlatelolco, 1566-1569, part 1. Conemex Associates, Contributions to the Ethnohistory of Mexico 7. リンカーンセンター、マサチューセッツ、1978年。 Nicolau d'Olwer, Luis and Howard F. Cline, 「Bernardino de Sahagún, 1499-1590. A Sahagún and his Works,」 in Handbook of Middle America Indians, vol. 13. Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources, Howard F. Cline, editor. オースティン:テキサス大学出版局、1973年、186-207ページ。 Klor de Alva, J. Jorge, et al., eds. The Work of Bernardino de Sahagún: Pioneer Ethnographer of Sixteenth-Century Mexico. アルバニー:ニューヨーク州立大学中米研究所、第2巻。オースティン、1988年。 León-Portilla, Miguel, Bernardino de Sahagún: First Anthropologist, trans. Mauricio J. Mixco. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 2002. Nicholson, H.B., 「Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: A Spanish Missionary in New Spain, 1529-1590,」 in Representing Aztec Ritual: Performance, Text, and Image in the Work of Sahagún, ed. Eloise Quiñones Keber. Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2002. ジョン・フレデリック・シュワラー編『サアグン500年:ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン神父生誕500年記念論文集』バークレー:アメリカフランシスコ会歴史アカデミー、2003年。 |

| General History of the Things of New Spain by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún: The Florentine Codex, World Digital Library, Library of Congress, full text online in Spanish and Nahuatl, with illustrations by native artists |

Fray Bernardino de Sahagún著『新スペインの事物に関する一般史』:フィレンツェ写本、世界デジタル図書館、米国議会図書館、スペイン語とナワトル語で書かれた全文をオンラインで閲覧可能。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernardino_de_Sahag%C3%BAn |

|

| References 1. Arthur J.O. Anderson, "Sahagún: Career and Character" in Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: The General History of the Things of New Spain, Introductions and Indices, Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles Dibble, translators. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press 1982, p. 40. 2. M. León-Portilla, Bernardino de Sahagún: The First Anthropologist (University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2002), pp. 3. Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain (Translation of and Introduction to Historia general De Las Cosas De La Nueva España; 12 Volumes in 13 Books ), trans. Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J. O Anderson (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1950-1982). 4. H. B. Nicholson, "Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: A Spanish Missionary in New Spain, 1529-1590," in Representing Aztec Ritual: Performance, Text, and Image in the Work of Sahagún, ed. Eloise Quiñones Keber (Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2002). 5. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. "The work of Fray Bernardino de Sahagún (1499-1590)". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 2020-12-16. 6. David A. Boruchoff, "Sahagún and the Theology of Missionary Work," in Sahagún at 500: Essays on the Quincentenary of the Birth of Fr. Bernardino de Sahagún, OFM, ed. John Frederick Schwaller (Berkeley: Academy of American Franciscan History, 2003), pp. 59–102. 7. Jaime Lara, City, Temple, Stage: Eschatological Architecture and Liturgical Theatrics in New Spain (South Bend: University of Notre Dame, 2005). 8. Edwin Edward Sylvest, Motifs of Franciscan Mission Theory in Sixteenth Century New Spain Province of the Holy Gospel (Washington DC: Academy of American Franciscan History, 1975). 9. John Leddy Phelan, The Millennial Kingdom of the Franciscans in the New World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970). 10. Reyes-Valerio, Constantino, Arte Indocristiano, Escultura y pintura del siglo XVI en México, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 2000 11. Eleanor Wake, Framing the Sacred: The Indian Churches of Early Colonial Mexico, University of Oklahoma Press (17 Mar 2010) 12. Lara, City, Temple, Stage: Eschatological Architecture and Liturgical Theatrics in New Spain. 13. León-Portilla, Bernardino De Sahagún: The First Anthropologist; Michael Mathes, The Americas' First Academic Library: Santa Cruz De Tlatelolco (Sacramento: California State Library, 1985). 14. Nicholson, "Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: A Spanish Missionary in New Spain, 1529-1590. 15. Edmonson, ed., Sixteenth-Century Mexico: The Work of Sahagún. 16. Donald Robertson, Mexican Manuscript Painting of the Early Colonial Period (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959). 155–163. 17. Edmonson, ed., Sixteenth-Century Mexico: The Work of Sahagún., 156-8; William Gates, An Aztec Herbal: The Classic Codex of 1552 (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 1939/2000). 18. Robertson, Mexican Manuscript Painting of the Early Colonial Period., 159. 19. Arthur J.O. Anderson, "Sahagún: Career and Character" in Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: The General History of the Things of New Spain, Introductions and Indices, Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles Dibble, translators. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press 1982, p. 32. 20. "14.Bernardino de Sahagún, 1499-1590. A. Sahagún and His Works" by Luis Nicolau D'Olwer and Howard F. Cline. Handbook of Middle American Indians 13. Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources, Part 2. Howard F. Cline, volume editor. Austin: University of Texas Press 1973, pp. 186-87 21. Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Bernardino de Sahagún" . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 22. Arthur J.O. Anderson, "Introduction" to the Psalmodia Christiana. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press 1993, pp. xv-xvi 23. López Austin, The Research Method of Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: The Questionnaires. 24. Thelma D. Sullivan, Primeros Memoriales: Paleography of Nahuatl Text and English Translation, ed. Arthur J. O. Anderson with H. B. Nicholson, Charles E. Dibble, Eloise Quiñones Keber, and Wayne Ruwet, vol. 200, Civilization of the American Indian (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997). 25. Ellen T. Baird, "Artists of Sahagun's Primeros Memoriales: A Question of Identity," in The Work of Bernardino De Sahagún, Pioneer Ethnographer of Sixteenth-Century Aztec Mexico, ed. J. Jorge Klor de Alva, H. B. Nicholson, and Eloise Quiñones Keber (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1988), Ellen T. Baird, The Drawings of Sahagun's Primeros Memoriales: Structure and Style (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997). 26. Elizabeth Keen, The Journey of a Book: Bartholomew the Englishman and the Properties of Things (Canberra: ANU E-press, 2007). 27. Angelo Maria Bandini, Bibliotheca Leopldina Laurentiana, seu Catalofus Manuscriptorum qui nuper in Laurentiana translati sunt. Florence: typis Regiis, 1791-1793. 28. Dibble, "Sahagun's Historia", p. 16 29. For a history of this scholarly work, see Charles E. Dibble, "Sahagún's Historia in Florentine Codex: Introductions and Indices. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press 1982, pp.9-23; León-Portilla, Bernardino De Sahagún: The First Anthropologist. 30. H.B. Nicholson, "Fray Bernardino de Sahagún: A Spanish Missionary in New Spain, 1529–1590." In Eloise Quiñones Keber, ed. Representing Aztec Ritual: Performance, Text, and Image in the Work of Sahagún, (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2002), page 27. 31. Sylvest, Motifs of Franciscan Mission Theory in Sixteenth Century New Spain Province of the Holy Gospel. 32. Ewert Cousins, "Francis of Assisi and Bonaventure: Mysticism and Theological Interpretation," in The Other Side of God, ed. Peter L. Berger (New York: Anchor Press, 1981), Ewert Cousins, "Francis of Assisi: Christian Mysticism at the Crossroads," in Mysticism and Religious Traditions, ed. S. Katz (New York: Oxford, 1983). 33. Mary Beth Ingham, CSJ, Scotus for Dunces: An Introduction to the Subtle Doctor (St. Bonaventure, NY: Franciscan Institute Publications, 2003). 34. Robert Ricard, The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico, Translated by Lesley Byrd Simpson. Berkeley: University of California Press 1966, p.42. 35. Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: Introductions and Indices, Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles Dibble, translators. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press 1982. 36. Sahagún, Florentine Codex: Introduction and Indices, p.89. 37. Sahagún, Florentine Codex: Introduction and Indices, p. 90. 38. Sahagún, Florentine Codex: Introduction and Indices, pp.93-94,98. 39. Alfredo Lopez-Austin. "The Research Method of Fray Bernardino de Sahagún: The Questionnaires," in Sixteenth-Century Mexico: The Work of Sahagún. Edited by Munro S. Edmonson, 111–49. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1974. 40. S.L. Cline, "Revisionist Conquest History: Sahagún's Book XII," in The Work of Bernardino de Sahagún: Pioneer Ethnographer of Sixteenth-Century Aztec Mexico. Ed. Jorge Klor de Alva et al. Institute for Mesoamerican Studies, Studies on Culture and Society, vol. 2, 93-106. Albany: State University of New York, 1988. 41. Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, Conquest of New Spain, 1585 Revision. Translation by Howard F. Cline. Introduction and notes by S.L. Cline. Salt Lake City, University of Utah Press 1989. 42. Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, Introductions and Indices, Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles Dibble, translators. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press 1982, p. 101. 43. S.L. Cline, "Introduction" Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, Conquest of New Spain, 1585 Revision, Salt Lake City, University of Utah Press 1989, p. 3 44. Cline, "Revisionist Conquest History". |

参考文献 1. アーサー・J・O・アンダーソン、「サアグン:経歴と人物像」『ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン、フィレンツェ写本:新スペインの事物総史、序文と索引』 アーサー・J・O・アンダーソン、チャールズ・ディブル訳、ソルトレイクシティ:ユタ大学出版、1982年、40ページ。 2. M. レオン・ポルティージャ著『ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン:最初の人類学者』(オクラホマ大学出版、ノーマン、2002年)、pp. 3. ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン著『フィレンツェ写本:新スペインの事物に関する一般史』(『Historia general De Las Cosas De La Nueva España』の翻訳および序文、13 冊 12 巻)、チャールズ・E・ディブルおよびアーサー・J・O・アンダーソン訳(ソルトレイクシティ:ユタ大学出版、1950-1982)。 4. H. B. ニコルソン、「フレイ・ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン:新スペインのスペイン人宣教師、1529-1590」、『アステカの儀礼を表現する:サアグンの 作品におけるパフォーマンス、テキスト、イメージ』所収、エロイーズ・キニョネス・ケバー編(ボルダー:コロラド大学出版、2002年)。 5. 国際連合教育科学文化機関。「フラ・ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン(1499-1590)の業績」。www.unesco.org。2020年12月16日取得。 6. デイヴィッド・A・ボルーチョフ「サアグンと宣教活動の神学」、『サアグン生誕500年:フランシスコ会士ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン生誕500年論 集』ジョン・フレデリック・シュワラー編(バークレー:アメリカ・フランシスコ会歴史アカデミー、2003年)、59-102頁。 7. ハイメ・ララ『都市、神殿、舞台:新スペインにおける終末論的建築と典礼的演劇』(サウスベンド:ノートルダム大学出版、2005年)。 8. エドウィン・エドワード・シルベスト『16世紀新スペイン聖福音省におけるフランシスコ会宣教理論のモチーフ』(ワシントンDC:アメリカフランシスコ会歴史アカデミー、1975年)。 9. ジョン・レディ・フェラン『新世界におけるフランシスコ会の千年王国』(バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版局、1970年)。 10. コンスタンティーノ・レイエス=バレリオ『先住民キリスト教美術:16世紀メキシコの彫刻と絵画』(国立人類学歴史研究所、2000年) 11. エレノア・ウェイク『聖なるものの枠組み:植民地初期メキシコのインディオ教会』オクラホマ大学出版局(2010年3月17日) 12. ララ『都市、寺院、舞台:新スペインにおける終末論的建築と典礼的演劇』 13. レオン・ポルティージャ、ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン:最初の人類学者、マイケル・マテス、アメリカ大陸初の学術図書館:サンタ・クルス・デ・トラテロルコ(カリフォルニア州立図書館、1985年)。 14. ニコルソン、「フレイ・ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン:1529年から1590年にかけてのヌエバ・エスパーニャのスペイン人宣教師」。 15. エドモンソン編、『16 世紀のメキシコ:サアグンの仕事』。 16. ドナルド・ロバートソン、『植民地時代初期のメキシコ写本絵画』(ニューヘイブン:イェール大学出版、1959 年)。155–163。 17. エドモンソン編、『16 世紀のメキシコ:サアグンの仕事』、156-8 ページ、ウィリアム・ゲイツ、『アステカの薬草:1552 年の古典的写本』(ニューヨーク州ミネオラ:ドーバー出版、1939/2000)。 18. ロバートソン、『植民地時代初期のメキシコの写本絵画』、159 ページ。 19. アーサー・J・O・アンダーソン、「サアグン:経歴と人物像」『ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン、フィレンツェ写本:新スペインの事物総史、序文と索引』 アーサー・J・O・アンダーソン、チャールズ・ディブル訳。ソルトレイクシティ:ユタ大学出版 1982年、32ページ。 20. 「14. ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン、1499-1590。A. サアグンとその作品」ルイス・ニコラウ・ドルワー、ハワード・F・クライン著。中米インディアンハンドブック 13。民族史的資料ガイド、第 2 部。ハワード・F・クライン、編集者。オースティン:テキサス大学出版局 1973 年、186-87 ページ 21. ハーバーマン、チャールズ編(1913)。「ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン」 『カトリック百科事典』 ニューヨーク:ロバート・アップルトン社。 22. アーサー・J・O・アンダーソン、「Psalmodia Christiana」の「序文」。ソルトレイクシティ:ユタ大学出版 1993年、xv-xvi ページ 23. ロペス・オースティン、『フレイ・ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグーンの研究方法:アンケート調査』。 24. テルマ・D・サリバン、『プリメロス・メモリアレス:ナワトル語テキストの古文書学と英語翻訳』、アーサー・J・O・アンダーソン、H・B・ニコルソン、 チャールズ・E・ディブル、エロイーズ・キニョネス・ケバー、ウェイン・ルウェット編、第 200 巻、アメリカインディアンの文明(ノーマン:オクラホマ大学出版、1997 年)。 25. エレン・T・ベアード、「サアグンの『プリメロス・メモリアレス』の芸術家たち:アイデンティティの問題」、『16世紀アステカ・メキシコの先駆的エスノ グラファー、ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグンの仕事』所収、J・ホルヘ・クロール・デ・アルバ H. B. ニコルソン、エロイーズ・キニョネス・ケバー共編(テキサス州オースティン:テキサス大学出版、1988年)、エレン・T・ベアード『サアグンの「プリメ ロス・メモリアル」の図画:構造と様式』(ノーマン:オクラホマ大学出版、1997年)。 26. エリザベス・キーン著『一冊の本の旅:イギリス人バーソロミューと物事の特性』(キャンベラ:ANU E-press、2007年)。 27. アンジェロ・マリア・バンディーニ著『Bibliotheca Leopldina Laurentiana, seu Catalofus Manuscriptorum qui nuper in Laurentiana translati sunt』(フィレンツェ:typis Regiis、1791-1793年)。 28. ディブル「サアグンの『歴史』」p.16 29. この学術研究の歴史については、チャールズ・E・ディブル「フィレンツェ写本におけるサアグンの『歴史』:序文と索引」ソルトレイクシティ:ユタ大学出版 局1982年、pp.9-23;レオン=ポルティージャ『ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン:最初の人類学者』を参照せよ。 30. H.B. ニコルソン「フラ・ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン:新スペインのスペイン人宣教師、1529–1590年」。エロイーズ・キニョネス・ケベル編『アステ カ儀礼の表現:サアグンの著作におけるパフォーマンス、テキスト、イメージ』(コロラド州ボルダー:コロラド大学出版局、2002年)、27頁。 31. シルベスト『16世紀新スペイン聖福音管区におけるフランシスコ会宣教理論のモチーフ』 32. エワート・カズンズ「アッシジのフランチェスコとボナヴェントゥラ:神秘主義と神学的解釈」『神のもう一つの側面』ピーター・L・バーガー編(ニューヨー ク:アンカー・プレス、1981年)所収。エワート・カズンズ「アッシジのフランチェスコ:岐路に立つキリスト教神秘主義」『神秘主義と宗教的伝統』S・ カッツ編(ニューヨーク:オックスフォード、1983年)所収。。 33. メアリー・ベス・インガム、CSJ、『愚か者のためのスコトゥス:微妙な博士の紹介』(ニューヨーク州セントボナベンチャー、フランシスカン研究所出版、2003年)。 34. ロバート・リカード、『メキシコの精神的征服』、レスリー・バード・シンプソン訳。バークレー、カリフォルニア大学出版、1966年、42ページ。 35. ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン、『フィレンツェ写本:序文と索引』、アーサー・J・O・アンダーソン、チャールズ・ディブル訳。ソルトレイクシティ:ユタ大学出版、1982年。 36. サアグン、『フィレンツェ写本:序文と索引』、89ページ。 37. サアグン、『フィレンツェ写本:序文と索引』、90ページ。 38. サアグン、『フィレンツェ写本:序文と索引』、93-94、98 ページ。 39. アルフレド・ロペス・オースティン。「フレイ・ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグンの研究方法:アンケート」、『16 世紀のメキシコ:サアグンの仕事』所収。マンロ・S・エドモンソン編、111-49 ページ。アルバカーキ:ニューメキシコ大学出版局、1974年。 40. S.L. クライン「修正主義的征服史:サアグーンの書第十二」『ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグーンの業績:16世紀アステカ・メキシコの先駆的エスノグラファー』 所収。ホルヘ・クロール・デ・アルバ他編。メソアメリカ研究所、文化と社会に関する研究、第2巻、93-106頁。オールバニ:ニューヨーク州立大学、 1988年。 41. フレイ・ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン、『新スペイン征服史』、1585年改訂版。ハワード・F・クライン訳。S.L.クラインによる序文と注釈。ソルトレイクシティ、ユタ大学出版局、1989年。 42. ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン、『フィレンツェ写本:新スペインの事物総史』、序文および索引、アーサー・J・O・アンダーソンおよびチャールズ・ディブル訳。ソルトレイクシティ:ユタ大学出版局、1982年、101ページ。 43. S.L. Cline、「序文」Fray Bernardino de Sahagún、Conquest of New Spain、1585 年改訂版、ソルトレイクシティ、ユタ大学出版、1989 年、3 ページ 44. Cline、「修正主義的な征服の歴史」。 |

| World Digital Library,にて "General History of the Things of New Spain by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún"を検索 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099