フィレンツェ写本

The Florentine Codex

☆ フィレンツェ写本(The Florentine Codex)は、スペインのフランシスコ会修道士ベルナルディーノ・デ・サハグーンによる16世紀のメソアメリカにおける民族誌的研究書である。サハ グンは当初、La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España(英語: The General History of the Things of New Spain)と題したが、翻訳ミスによりHistoria general de las Cosas de Nueva Españaと改題された。最も保存状態の良い写本はフィレンツェ写本と呼ばれ、イタリア・フィレンツェのローレンシャン図書館に所蔵されている。

The Florentine Codex

is a 16th-century ethnographic research study in Mesoamerica by the

Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún. Sahagún originally

titled it La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España (in English:

The General History of the Things of New Spain).[1] After a translation

mistake, it was given the name Historia general de las Cosas de Nueva

España. The best-preserved manuscript is commonly referred to as the

Florentine Codex, as the codex is held in the Laurentian Library of

Florence, Italy. The Florentine Codex

is a 16th-century ethnographic research study in Mesoamerica by the

Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún. Sahagún originally

titled it La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España (in English:

The General History of the Things of New Spain).[1] After a translation

mistake, it was given the name Historia general de las Cosas de Nueva

España. The best-preserved manuscript is commonly referred to as the

Florentine Codex, as the codex is held in the Laurentian Library of

Florence, Italy.In partnership with Nahua elders and authors who were formerly his students at the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, Sahagún conducted research, organized evidence, wrote and edited his findings. He worked on this project from 1545 up until his death in 1590. The work consists of 2,500 pages organized into twelve books; more than 2,000 illustrations drawn by native artists provide vivid images of this era.[2] It documents the culture, religious cosmology (worldview) and ritual practices, society, economics, and natural history of the Aztec people.[2] It has been described as "one of the most remarkable accounts of a non-Western culture ever composed."[3] Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J. O. Anderson were the first to translate the Codex from Nahuatl to English, in a project that took 30 years to complete.[4] In 2012, high-resolution scans of all volumes of the Florentine Codex, in Nahuatl and Spanish, with illustrations, were added to the World Digital Library.[5] In 2015, Sahagún's work was inscribed into the Memory of the World register by UNESCO.[6] In 2023, the Getty Research Institute released the Digital Florentine Codex which gives access to the complete manuscript. |

フィ

レンツェ写本は、スペインのフランシスコ会修道士ベルナルディーノ・デ・サハグーンによる16世紀のメソアメリカにおける民族誌的研究書である。サハグン

は当初、La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España(英語: The General

History of the Things of New Spain)と題したが[1]、翻訳ミスによりHistoria general de

las Cosas de Nueva

Españaと改題された。最も保存状態の良い写本はフィレンツェ写本と呼ばれ、イタリア・フィレンツェのローレンシャン図書館に所蔵されている。 フィ

レンツェ写本は、スペインのフランシスコ会修道士ベルナルディーノ・デ・サハグーンによる16世紀のメソアメリカにおける民族誌的研究書である。サハグン

は当初、La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España(英語: The General

History of the Things of New Spain)と題したが[1]、翻訳ミスによりHistoria general de

las Cosas de Nueva

Españaと改題された。最も保存状態の良い写本はフィレンツェ写本と呼ばれ、イタリア・フィレンツェのローレンシャン図書館に所蔵されている。サハグンは、かつてトラテロルコのサンタ・クルス・カレッジで教え子だったナフア族の長老や作家と協力し、調査、証拠の整理、執筆、編集を行った。彼は 1545年から1590年に亡くなるまでこのプロジェクトに取り組んだ。この著作は2,500ページを12冊の本にまとめたもので、先住民の画家によって 描かれた2,000点以上の挿絵がこの時代の鮮明なイメージを提供している[2]。アステカの人々の文化、宗教的宇宙観(世界観)、儀式習慣、社会、経 済、自然史が記録されており、「これまでに書かれた非西洋文化の記述の中で最も注目に値するもののひとつ」と評されている[3]。 チャールズ・E・ディブルとアーサー・J・O・アンダーソンは、この写本をナワトル語から英語に翻訳した最初の人物で、完成までに30年を要したプロジェ クトであった[4]。2012年、フィレンツェ写本の全巻の高解像度スキャン(ナワトル語とスペイン語、図版付き)が世界デジタル図書館に追加された。 [5]2015年、サハグンの作品はユネスコの世界記憶遺産に登録された[6]。 2023年、ゲッティ研究所は写本全巻にアクセスできるデジタル・フィレンツェ写本を公開した。 |

History of the manuscript Historia general de las Cosas de Nueva España (original from the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana) In 1575 the Council of the Indies suggested to the Spanish Crown to educate the native Americans in Spanish instead of using the indigenous languages; for this reason, the Spanish authorities required Fray Sahagún to hand over all of his documents about the Aztec culture and the results of his research in order to get further details about this matter.[7] In the meantime, the Bishop of Sigüenza, Diego de Espinosa, who was also the Inquisitor General and President of the Royal Council of Castile instructed the cleric Luis Sánchez to report about the situation of the native Americans.[7] The concerning findings of this report triggered a visit of Juan de Ovando to the Council of the Indies because it demonstrated a total ignorance of the Spanish authorities about the native cultures and, in Ovando's opinion, was not possible to make correct decisions without reliable information.[7] As a consequence, the Council of the Indies ordered to the Viceroyalty of Peru in 1568 that they needed to include ethnographic and geographic information regarding any new discovery within their limits. A similar disposition was given to the Vice-Royalty of New Spain in 1569, specifying that 37 chapters were to be reported; in 1570, the extent of the report was modified to required information for 200 chapters.[7] That same year, Phillip II of Spain created a new position as "Cosmógrafo y Cronista Mayor de Indias" to collect and organize this information, being appointed Don Juan López de Velasco, so that he could write "La Historia General de las Indias", namely, a compilation about the history of the Indies.[7] King Phillip II of Spain concluded that was not beneficial for the Spanish colonies in America and, hence, it never took place.[citation needed] That is the reason why the missionaries, including Fray Bernardino de Sahagún continued their missionary work and Fray Bernardino de Sahagun was able to make two more copies of his Historia general. The three bound volumes of the Florentine Codex are found in the Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, Palat. 218-220 in Florence, Italy, with the title Florentine Codex chosen by its English translators, Americans Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles Dibble, following in the tradition of nineteenth-century Mexican scholars Francisco del Paso y Troncoso and Joaquín García Icazbalceta.[8] The manuscript became part of the collection of the library in Florence at some point after its creation in the late sixteenth century. It was not until the late eighteenth century that scholars become aware of it, when the bibliographer Angelo Maria Bandini published a description of it in Latin in 1793.[9] The work became more generally known in the nineteenth century, with a description published by P. Fr. Marcellino da Civezza in 1879.[9] The Spanish Royal Academy of History learned of this work and, at the fifth meeting of the International Congress of Americanists, the find was announced to the larger scholarly community.[9] In 1888 German scholar Eduard Seler presented a description of the illustrations at the 7th meeting of the International Congress of Americanists.[9] Mexican scholar Francisco del Paso y Troncoso received permission in 1893 from the Italian government to copy the alphabetic text and the illustrations.[10] The three-volume manuscript of the Florentine Codex has been intensely analyzed and compared to earlier drafts found in Madrid. The Tolosa Manuscript (Códice Castellano de Madrid) was known in the 1860s and studied by José Fernando Ramírez.[11] The Tolosa Manuscript has been the source for all published editions in Spanish of the Historia General.[12] The English translation of the complete Nahuatl text of all twelve volumes of the Florentine Codex was a decades-long work of Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles Dibble,[13] an important contribution to the scholarship on Mesoamerican ethno-history. In 1979, the Mexican government published a full-color, three-volume facsimile of the Florentine Codex in a limited edition of 2,000, allowing scholars to have easier access to the manuscript. The Archivo General de la Nación (Dra. Alejandra Moreno Toscano, director) supervised the project that was published by the Secretariat of the Interior (Enrique Olivares Santana, Secretary). The 2012 World Digital Library high-resolution digital version of the manuscript makes it fully accessible online to all those interested in this source for Mexican and Aztec history.[14] In 2023, the Getty Research Institute released the Digital Florentine Codex which gives access to the complete manuscript and multiple translations. |

写本の歴史 ヌエバ・エスパーニャの歴史(原書はローレンツィアーナ図書館所蔵) 1575年、インド評議会はスペイン王室に対し、アメリカ先住民を先住民の言語を使わずにスペイン語で教育することを提案した。このためスペイン当局は、 この問題についてさらに詳しく知るために、フレイ・サハグンに対し、アステカ文化に関するすべての文書と調査結果を引き渡すよう要求した[7]。 [7] 一方、シギュエンサ司教のディエゴ・デ・エスピノサは、カスティーリャ王国の奉行総長兼評議会議長でもあり、聖職者のルイス・サンチェスにアメリカ先住民 の状況について報告するよう指示した。 [7]この報告書が先住民の文化についてスペイン当局がまったく無知であることを示すものであり、信頼できる情報なしには正しい決定を下すことはできない というのがオバンドの意見であった。1569年、新スペイン副王領にも同様の命令が下され、37章を報告するよう指定された。1570年には、報告書の範 囲が変更され、200章分の情報が必要とされた。 [7] 同年、スペイン王フィリップ2世は、これらの情報を収集・整理するために「インディアスのコスモグラフォとクロニスタ・マヨール」という新しい役職を設 け、ドン・フアン・ロペス・デ・ベラスコを任命し、『インディアスの歴史』(La Historia General de las Indias)を執筆させた[7]。 スペイン国王フィリップ2世は、それはアメリカにおけるスペインの植民地にとって有益ではないという結論に達し、それゆえそれは行われなかった[要出 典]。それが、フレイ・ベルナルディーノ・デ・サハグンを含む宣教師たちが布教活動を続けた理由であり、フレイ・ベルナルディーノ・デ・サハグンは、彼の 『ヒストリア・ジェネラル』をさらに2部作ることができた。フィレンツェ写本の3巻は、フィレンツェのBiblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, Palat. フィレンツェ写本というタイトルは、19世紀のメキシコの学者フランシスコ・デル・パソ・イ・トロンコソとホアキン・ガルシア・イカスバルセタの伝統に倣 い、英訳者であるアメリカ人のアーサー・J・O・アンダーソンとチャールズ・ディブルがつけたものである[8]。 この写本は、16世紀後半にフィレンツェの図書館で作成された後、ある時点でフィレンツェの図書館のコレクションの一部となった。18世紀後半になって、 書誌学者であるアンジェロ・マリア・バンディーニが1793年にラテン語でその解説を出版し、学者たちに知られるようになった[9]。 1888年、ドイツの学者エドゥアルド・セラーが第7回国際アメリカニスト会議で挿絵の説明を発表した[9]。1893年、メキシコの学者フランシスコ・デル・パソ・イ・トロンコーソがイタリア政府からアルファベットテキストと挿絵の複製許可を得た[10]。 フィレンツェ写本の3巻の写本は、マドリードで発見された初期の写本と比較され、精力的に分析されてきた。トロサ写本(Códice Castellano de Madrid)は1860年代に知られ、ホセ・フェルナンド・ラミレスによって研究された[11]。トロサ写本は、『ヒストリア・ジェネラル』のスペイン 語版のすべての出版物の原典となっている[12]。 フィレンツェ写本全12巻のナワトル語全文の英訳は、アーサー・J.O.アンダーソンとチャールズ・ディブルの数十年にわたる仕事であり[13]、メソア メリカ民族史研究への重要な貢献であった。1979年、メキシコ政府はフィレンツェ写本のフルカラー3巻ファクシミリを2,000部限定で出版し、学者が 写本に容易にアクセスできるようにした。Archivo General de la Nación (Dra. Alejandra Moreno Toscano, director)が監修し、Secretariat of the Interior (Enrique Olivares Santana, Secretary)が出版した。2012年、世界デジタル図書館がこの写本を高解像度デジタル化したことで、メキシコとアステカの歴史に関するこの資料 に興味を持つすべての人が、オンラインで完全にアクセスできるようになった[14]。2023年、ゲッティ研究所は、写本全体と複数の翻訳にアクセスでき るデジタル・フロレンティン・コーデックスをリリースした。 |

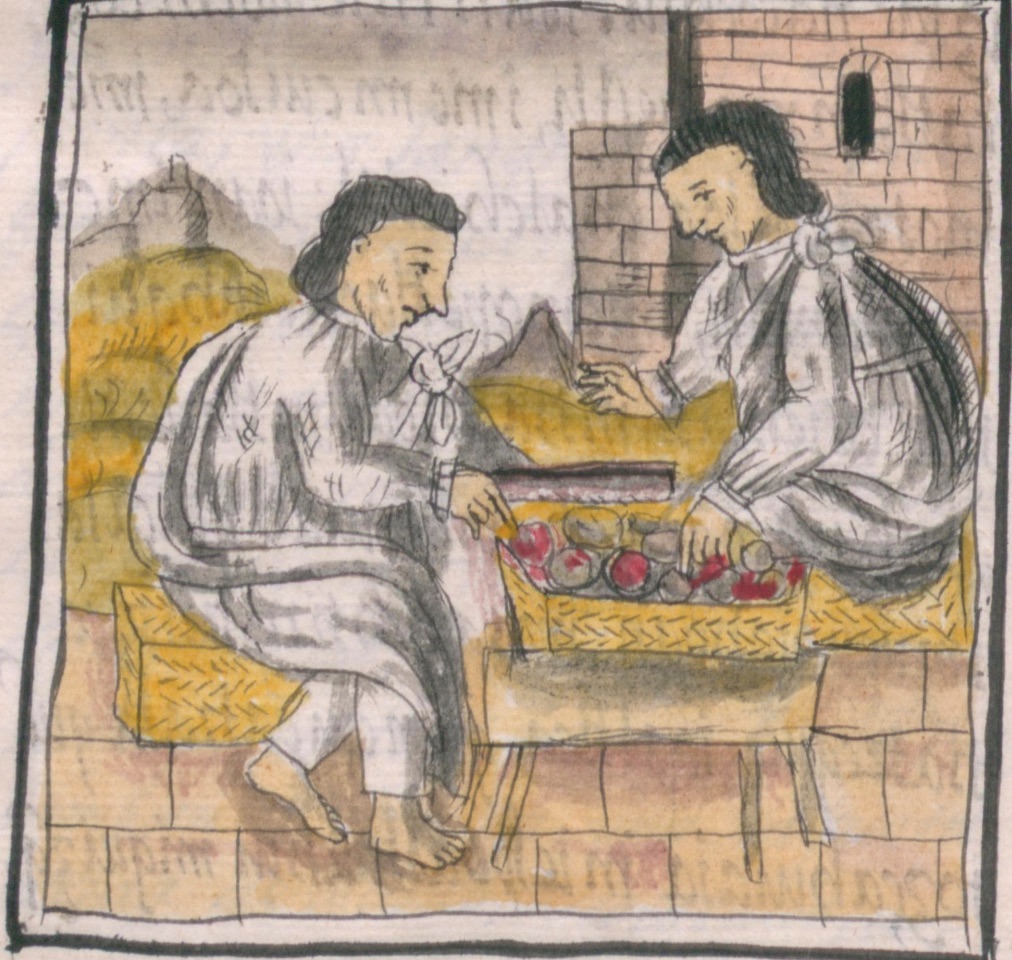

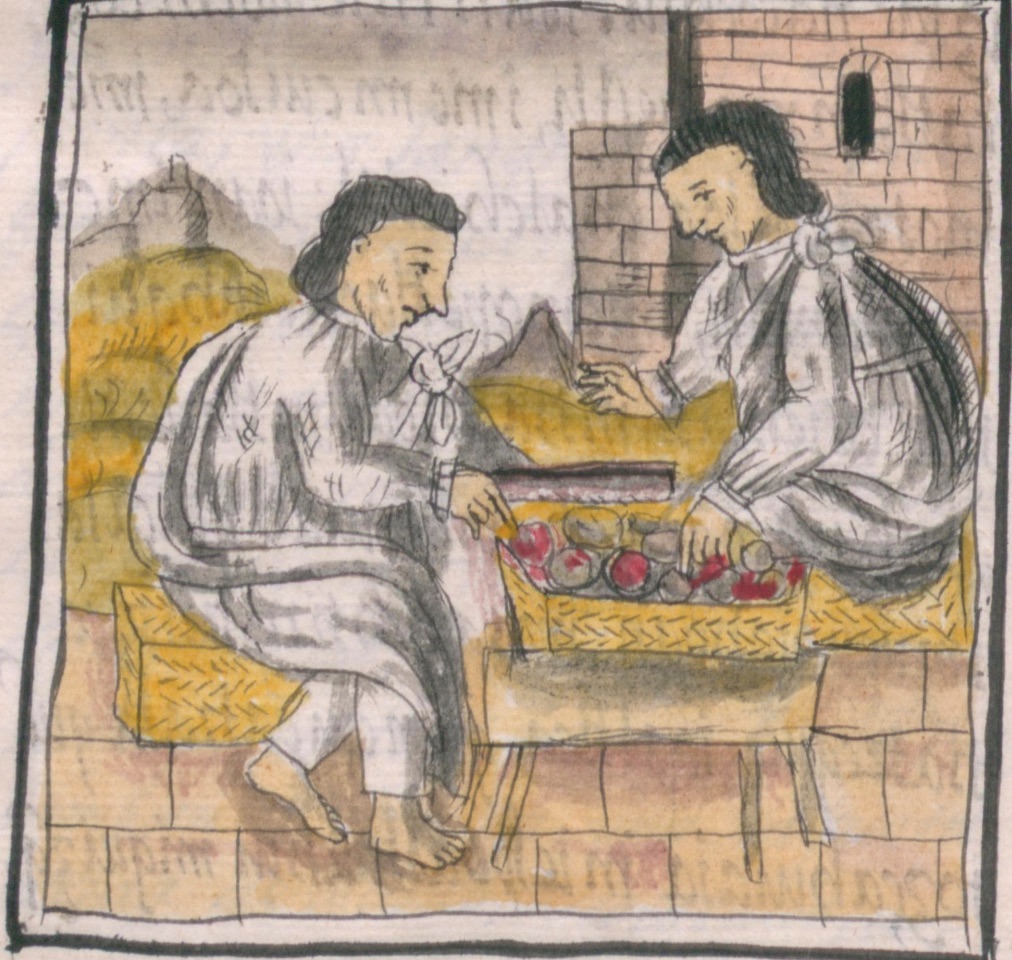

Sahagún's motivations for research Goldsmith measuring a gold article The missionary Sahagún had the goal of evangelizing the indigenous Mesoamerican peoples, and his writings were devoted to this end. He described this work as an explanation of the "divine, or rather idolatrous, human, and natural things of New Spain".[15] He compared its body of knowledge to that needed by a physician to cure the "patient" suffering from idolatry. He had three overarching goals for his research: 1. To describe and explain ancient Indigenous religion, beliefs, practices, deities. This was to help friars and others understand this "idolatrous" religion in order to evangelize the Aztecs. 2. To create a vocabulary of the Aztec language, Nahuatl. This provides more than definitions from a dictionary, as it gives an explanation of their cultural origins, with pictures. This was to help friars and others learn Nahuatl and to understand the cultural context of the language. 3. To record and document the great cultural inheritance of the Indigenous peoples of New Spain.[16] Sahagún conducted research for several decades, edited and revised his work over several decades, created several versions of a 2,400-page manuscript, and addressed a cluster of religious, cultural and nature themes.[17] Copies of the work were sent by ship to the royal court of Spain and to the Vatican in the late-sixteenth century to explain Aztec culture. The copies of the work were essentially lost for about two centuries, until a scholar rediscovered it in the Laurentian Library (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana) an archive library in Florence, Italy. The Spanish also had earlier drafts in their archives. A scholarly community of historians, anthropologists, art historians, and linguists has since been investigating Sahagún's work, its subtleties and mysteries, for more than 200 years.[18] |

サハグンの研究動機 金製品を測定する鍛治師 宣教師サハグンは、メソアメリカの先住民を伝道することを目的としており、彼の著作はこの目的のために捧げられた。彼はこの著作を「ニュースペインの神的なもの、むしろ偶像崇拝的なもの、人間的なもの、自然的なもの」の説明と表現した[15]。 彼の研究には3つの包括的な目標があった: 1. 古代先住民の宗教、信仰、慣習、神々について説明し、説明すること。これは、アステカ人を伝道するために、修道士や他の人々がこの「偶像崇拝的」宗教を理解するのを助けるためであった。 2. アステカ語ナワトル語の語彙を作る。これは辞書に載っている定義以上のもので、彼らの文化的起源を写真付きで説明している。これは、修道士やその他の人々がナワト語を学び、この言語の文化的背景を理解するのに役立つものであった。 3. ニュースペインの先住民の偉大な文化的遺産を記録し、文書化するためである[16]。 サハグンは数十年にわたり調査を行い、数十年にわたり編集と改訂を行い、2,400ページに及ぶ原稿のいくつかのバージョンを作成し、宗教、文化、自然の テーマ群を扱った[17]。この著作のコピーは、アステカ文化を説明するために、16世紀後半に船でスペイン王宮とバチカンに送られた。この作品のコピー は、イタリアのフィレンツェにあるアーカイブ図書館のローレンシャン図書館(Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana)で学者が再発見するまで、約2世紀にわたって基本的に失われていた。スペインにも初期の草稿が保管されていた。それ以来、歴史学 者、人類学者、美術史家、言語学者からなる学術コミュニティが、200年以上にわたってサハグンの作品、その繊細さと謎を調査してきた[18]。 |

Evolution, format, and structure An illustration of the "One Flower" ceremony, from the 16th-century Florentine Codex. The two drums are the teponaztli (foreground) and the huehuetl (background). The Florentine Codex is a complex document, assembled, edited, and appended over decades. Essentially it is three integral texts: (1) in Nahuatl; (2) a Spanish text; (3) pictorials. The final version of the Florentine Codex was completed in 1569.[19] Sahagún's goals of orienting fellow missionaries to Aztec culture, providing a rich Nahuatl vocabulary, and recording the indigenous cultural heritage are at times in competition within the work. The manuscript pages are generally arranged in two columns, with Nahuatl, written first, on the right and a Spanish gloss or translation on the left. Diverse voices, views, and opinions are expressed in these 2,400 pages, and the result is a document that is sometimes contradictory.[18] Scholars have proposed several classical and medieval worldbook authors who inspired Sahagún, such as Aristotle, Pliny the Elder, Isidore of Seville, and Bartholomeus Anglicus. These shaped the late medieval approach to the organization of knowledge.[20] The twelve books of the Florentine Codex are organized in the following way: Gods, religious beliefs and rituals, cosmology, and moral philosophy, Humanity (society, politics, economics, including anatomy and disease), Natural history. Book 12, the account of the conquest of the Aztec Empire from the point of view of the conquered of Tenochtitlan-Tlatelolco is the only strictly historical book of the Historia General. This work follows the organizational logic found in medieval encyclopedias, in particular the 19-volume De proprietatibus rerum of Sahagún's fellow Franciscan Friar Bartholomew the Englishman. One scholar has argued that Bartholomew's work served as a conceptual model for Sahagún, although evidence is circumstantial.[21] Both men present descriptions of the cosmos, society and nature of the late medieval paradigm.[20] Additionally, in one of the prologues, Sahagún assumes full responsibility for dividing the Nahuatl text into books and chapters, quite late into the evolution of the Codex (approximately 1566–1568).[22] "Very likely," historian James Lockhart notes, "Sahagún himself devised the chapter titles, in Spanish, and the Nahuatl chapter titles may well be a translation of them, reversing the usual process."[23] |

進化、形式、構造 16世紀のフィレンツェ写本に描かれた「一つの花」の儀式の図。2つの太鼓はテポナズトリ(手前)とフエトル(奥)である。 フィレンツェ写本は複雑な文書で、数十年かけて組み立てられ、編集され、追加された。基本的には3つのテキストから成る: (1)ナワトル語、(2)スペイン語、(3)絵画である。フィレンツェ写本の最終版は1569年に完成した[19]。サハグンの目的は、宣教師仲間にアス テカ文化を紹介すること、豊富なナワトル語の語彙を提供すること、そして先住民の文化遺産を記録することであり、それらは時に作品内で競合する。原稿は一 般的に2段組になっており、最初に書かれたナワトル語が右側に、スペイン語の注釈や翻訳が左側に書かれている。この2,400ページには多様な意見、見 解、見解が表明されており、その結果、時に矛盾した文書となっている[18]。 学者たちは、アリストテレス、長老プリニウス、セヴィリアのイシドール、バルトロメウス・アングリクスなど、サハグンに影響を与えた古典的・中世的世界書の著者を何人か提唱している。これらは知識の組織化に対する中世後期のアプローチを形成した[20]。 フィレンツェ写本の12冊の書物は以下のように構成されている: 神々、宗教的信仰と儀式、宇宙論、道徳哲学、 人間性(社会、政治、経済、解剖学や病気を含む)、 自然史。 第12巻は、テノチティトラン・トラテロルコの被征服者の視点から見たアステカ帝国の征服に関する記述であり、『ヒストリア・ジェネラル』の中で唯一の厳密な歴史書である。 この著作は、中世の百科事典、特にサハグンの同僚であったフランシスコ会修道士バルトロメウの『De proprietatibus rerum』(全19巻)に見られる組織論理に従っている。ある学者は、バーソロミューの著作がサハグンの概念モデルとなったと主張しているが、その証拠 は状況証拠にすぎない[21]。 [20]さらに、プロローグのひとつで、サハグンはナワトル語のテキストを書物と章に分けることに全責任を負っているが、これは写本の進化のかなり後期 (およそ1566年から1568年)のことである[22]。「非常にありそうなことだが、歴史家のジェームズ・ロックハートは、「サハグン自身がスペイン 語で章のタイトルを考案し、ナワトル語の章のタイトルは、通常のプロセスを逆にして、それを翻訳したものである可能性が高い」と指摘している[23]。 |

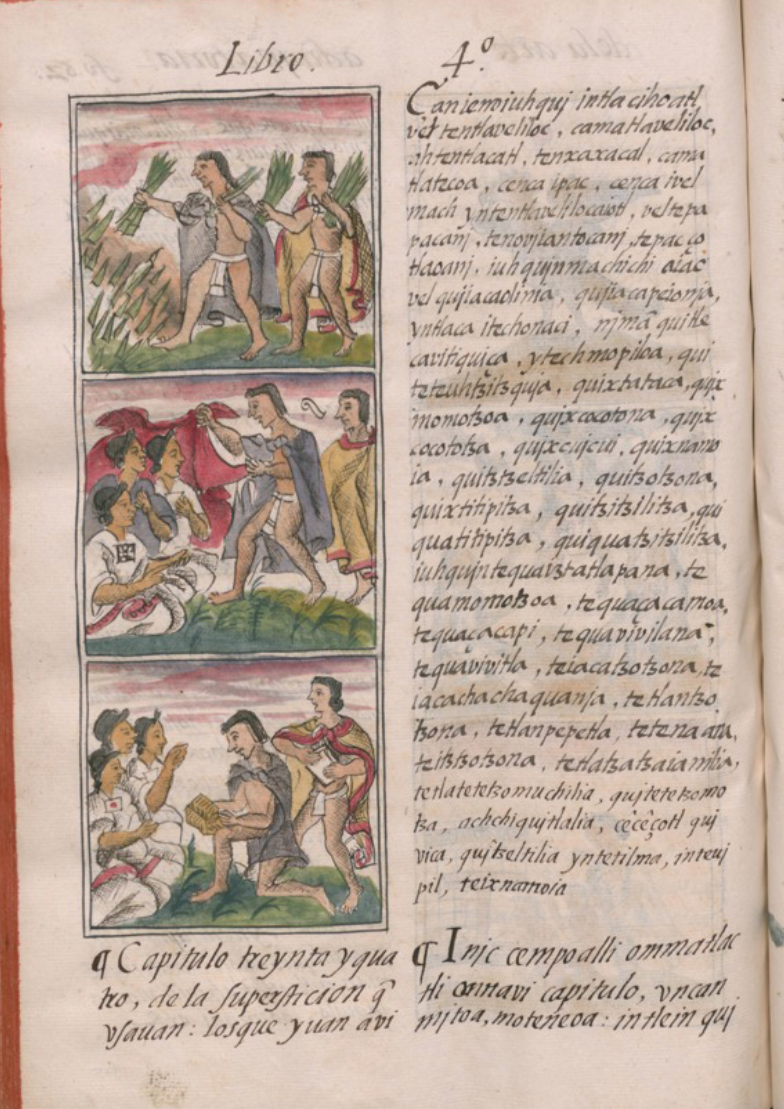

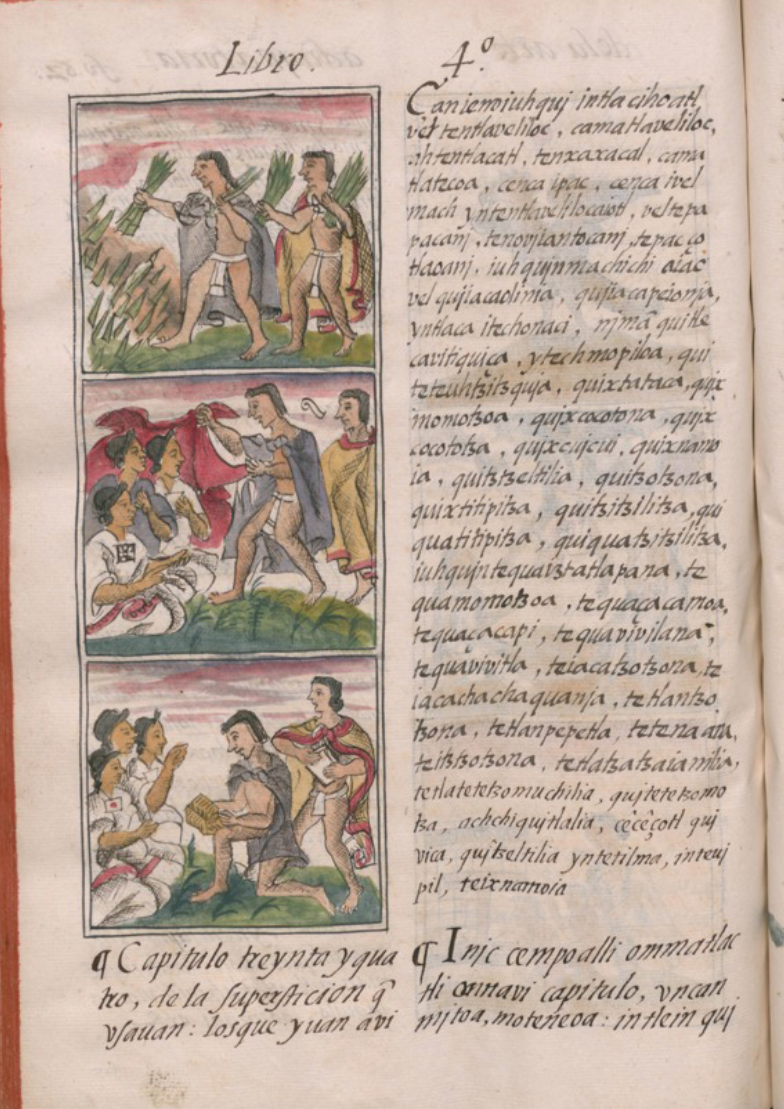

| Images within the Florentine Codex After the facsimile edition became available generally in 1979, the illustrations of the Florentine Codex could be analyzed in detail. Previously, the images were known mainly through the black-and-white drawings found in various earlier publications, which were separated from the alphabetic text.[24] The images in the Florentine Codex were created as an integral element of the larger work. Although many of the images show evidence of European influence, a careful analysis by one scholar posits that they were created by "members of the hereditary profession of tlacuilo or native scribe-painter".[25] The images were inserted in places in the text left open for them, and in some cases the blank space has not been filled. This strongly suggests that when the manuscripts were sent to Spain, they were as yet unfinished.[26] The images are of two types, what can be called "primary figures" that amplify the meaning of the alphabetic texts, and "ornamentals" that were decorative.[27] The majority of the nearly 2,500 images are "primary figures" (approximately 2000), with the remainder ornamental.[28] The figures were drawn in black outline first, with color added later.[28] Scholars have concluded that several artists, of varying skill, created the images.[29] It was deduced that twenty-two artists worked on the images in the Codex. This was done by analyzing the different ways that forms of body were drawn, such as the eyes, profile, and proportions of the body. It is not clear what artistic sources the scribes drew from, but the library of the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco had European books with illustrations and books of engravings.[30] European elements appear in the imagery, as well as pre-Conquest images done in the "native style".[31][32] A number of the images have Christian elements, which Peterson has described as "Christian editorializing".[33] The entirety of the Codex is characterized by the Nahua belief that the use of color activates the image and causes it to embody the true nature, or ixiptla, of the object or person depicted. For the Aztecs, the true self or identity of a person or object was shown via the external layer, or skin. Imparting color onto an image would change it so that it was given the identity of what it was portraying. Color was also used as a vehicle to impart knowledge that worked in tandem with the image itself.[34] |

フィレンツェ写本内の図版 1979年にファクシミリ版が一般に入手できるようになってから、フィレンツェ写本の図版が詳細に分析されるようになった。フィレンツェ写本の図版は、大 きな作品に不可欠な要素として制作された。多くの画像にはヨーロッパの影響が見られるが、ある学者による注意深い分析によれば、それらは「トラクイロまた は土着の書記・画家という世襲的な職業のメンバー」によって作成されたものであると推測されている[25]。 画像は本文の空いている場所に挿入され、場合によっては空白が埋められていないこともある。このことは、写本がスペインに送られた時点では、まだ未完成で あったことを強く示唆している[26]。画像には2種類あり、アルファベットのテキストの意味を増幅させる「主要図形」と呼ばれるものと、装飾的な「装飾 図形」である。 [27]約2500点の図像の大部分(約2000点)は「主要な図像」であり、残りは装飾的なものである[28]。これは、目、横顔、身体のプロポーショ ンなど、身体のフォルムのさまざまな描き方を分析することによって行われた。 写字画家たちがどのような芸術的資料から描いたかは明らかではないが、サンタ・クルス・デ・トラテロルコのコレヒオの図書館には、挿絵が描かれたヨーロッ パの本や版画の本があった[30]。 [31][32]多くの図像はキリスト教的な要素を持っており、ピーターソンはこれを「キリスト教的な編集」と表現している[33]。コーデックスの全体 は、色を使うことで図像が活性化し、描かれた対象や人物の本性(イクシプトラ)を具現化させるというナフアの信仰によって特徴づけられる。アステカ人に とって、人物や物体の真の自己やアイデンティティは、外側の層(皮膚)を通して示される。色彩を与えることでイメージは変化し、描かれたものの正体がわか るようになる。色はまた、イメージそのものと連動して働く知識を伝える手段としても使われた[34]。 |

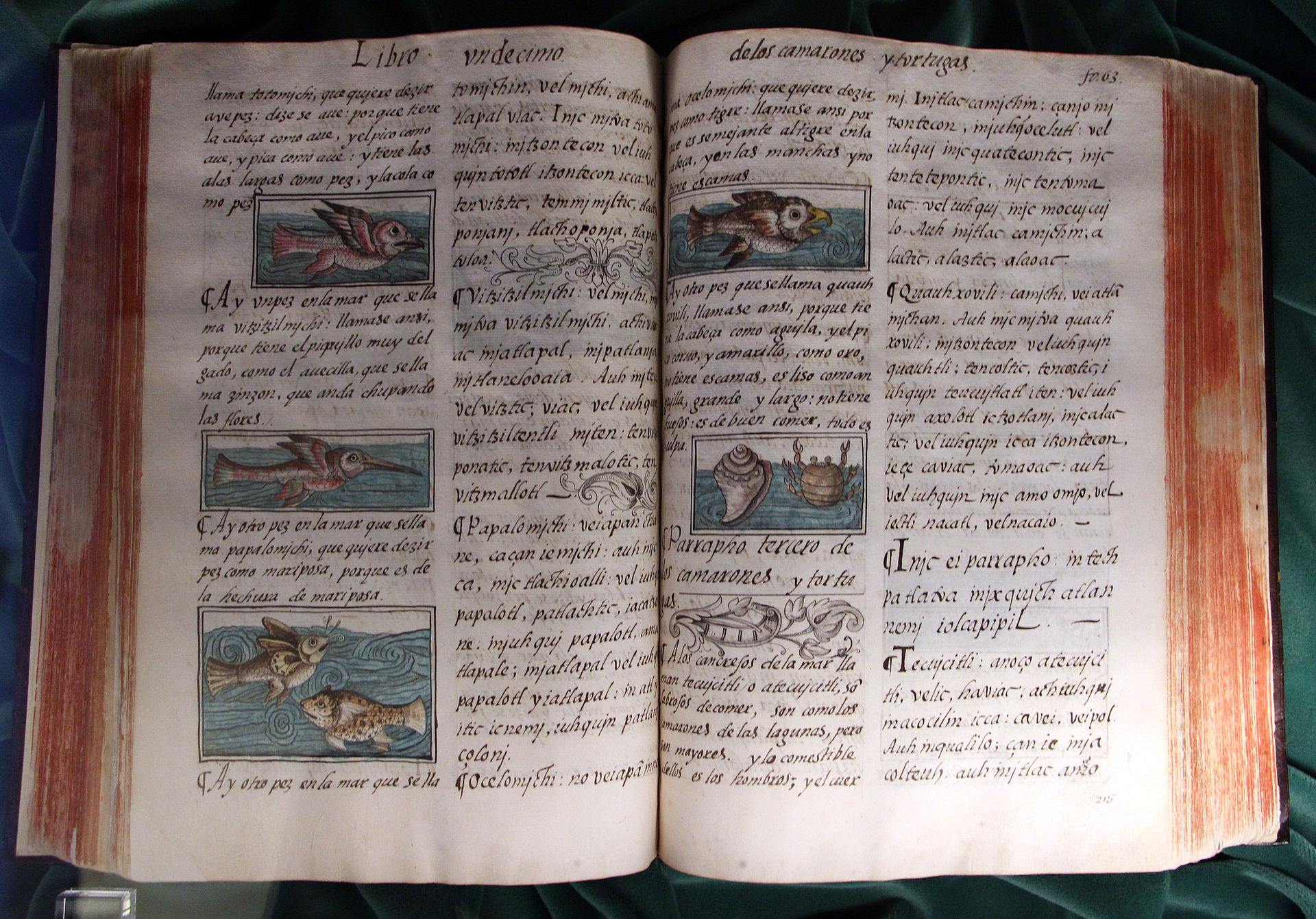

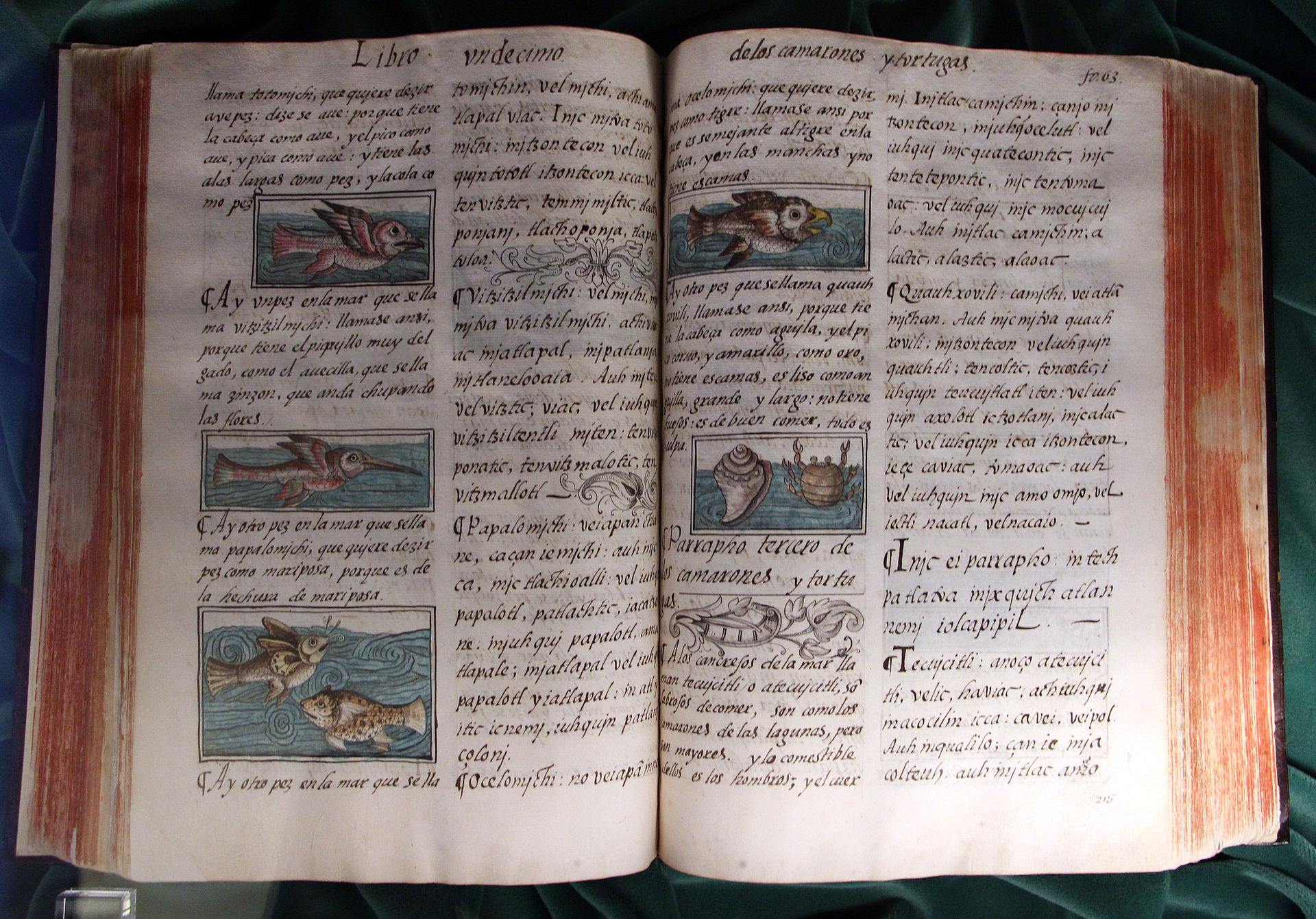

Books Merchants selecting gemstones, from Book 9 of the Codex. The codex is composed of the following twelve books:[35] 1. The Gods. Deals with gods worshipped by the natives of this land, which is New Spain. 2. The Ceremonies. Deals with holidays and sacrifices with which these natives honored their gods in times of infidelity. 3. The Origin of the Gods. About the creation of the gods. 4. The Soothsayers. About Indian judiciary astrology or omens and fortune-telling arts. 5. The Omens. Deals with foretelling these natives made from birds, animals, and insects in order to foretell the future. 6. Rhetoric and Moral Philosophy. About prayers to their gods, rhetoric, moral philosophy, and theology in the same context. 7. The Sun, Moon and Stars, and the Binding of the Years. Deals with the sun, the moon, the stars, and the jubilee year. 8. Kings and Lords. About kings and lords, and the way they held their elections and governed their reigns. 9. The Merchants. About long-distance elite merchants, pochteca, who expanded trade, reconnoitered new areas to conquer, and served as agents-provocateurs. 10. The People. About general history: it explains vices and virtues, spiritual as well as bodily, of all manner of persons. 11. Earthly Things. About properties of animals, birds, fish, trees, herbs, flowers, metals, and stones, and about colors. 12. The Conquest. About the conquest of New Spain from the Tenochtitlan-Tlatelolco point of view. |

書籍 コーデックス第9巻より、宝石を選ぶ商人たち。 写本は以下の12冊で構成されている[35]。 1. 神々。新スペインであるこの土地の原住民が崇拝する神々を扱う。 2. 儀式。原住民が不貞の時代に神々を敬った祭日と生贄を扱う。 3. 神々の起源。神々の創造について。 4. 占い師たち インドの司法占星術や前兆、占い術について。 5. 前兆。鳥、動物、昆虫から未来を予言するために作られた占いを扱う。 6. 修辞学と道徳哲学。彼らの神々への祈り、修辞学、道徳哲学、神学を同じ文脈で扱う。 7. 太陽、月、星、そして年の束縛。太陽、月、星、そして聖年について扱う。 8. 王と領主。王と領主、そして彼らの選挙と統治方法について。 9. 商人たち 長距離のエリート商人、ポチテカについて。彼らは交易を拡大し、征服のために新しい地域を偵察し、代理人-代弁者の役割を果たした。 10. 民衆。一般的な歴史について:あらゆる人物の精神的、肉体的な悪徳と美徳を説明する。 11. 地上のもの。動物、鳥、魚、木、ハーブ、花、金属、石の性質と色について。 12. 征服 テノチティトラン-トラテロルコの視点から見た新スペイン征服について。 |

Ethnographic methodologies Aztec warriors as shown in the Florentine Codex  Xipe Totec, "Our Lord the Flayed One", an Aztec (Mexica) deity Sahagún was among the first people to develop an array of strategies for gathering and validating knowledge of indigenous New World cultures. Much later, the discipline of anthropology would later formalize these as ethnography. This is the scientific research strategy to document the beliefs, behavior, social roles and relationships, and worldview of another culture, and to explain these within the logic of that culture. Ethnography requires scholars to practice empathy with persons very different from them, and to try to suspend their own cultural beliefs in order to enter into, understand, and explain the worldview of those living in another culture. Sahagún systematically gathered knowledge from a range of diverse persons (now known as informants in anthropology), who were recognized as having expert knowledge of Aztec culture. He did so in the native language of Nahuatl, while comparing the answers from different sources of information. According to James Lockhart, Sahagún collected statements from indigenous people of "relatively advanced age and high status, having what was said written down in Nahuatl by the aids he had trained."[36] Some passages appear to be the transcription of spontaneous narration of religious beliefs, society or nature. Other parts clearly reflect a consistent set of questions presented to different people designed to elicit specific information. Some sections of text report Sahagún's own narration of events or commentary. He developed a methodology with the following elements: 1. He used the indigenous Nahuatl language. 2. He elicited information from elders, cultural authorities publicly recognized as the most knowledgeable. 3. He adapted the project to the ways in which Aztec culture recorded and transmitted knowledge. 4. He used the expertise of his former students at the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, whom he credited by name. 5. He attempted to capture the totality or complete reality of Aztec culture on its own terms. 6. He structured his inquiry by using questionnaires, but also could adapt to using more valuable information shared with him by other means. 7. He attended to the diverse ways that diverse meanings are transmitted through Nahuatl linguistics. 8. He undertook a comparative evaluation of information, drawing from multiple sources, in order to determine the degree of confidence with which he could regard that information. 9. He collected information on the conquest of the Aztec Empire from the point of view of the Tenochtitlan-Tlatelolco, that had been defeated. These methodological innovations substantiate historians' claim that Sahagún was the first anthropologist. Most of the Florentine Codex is alphabetic text in Nahuatl and Spanish, but its 2,000 pictures provide vivid images of sixteenth-century New Spain. Some of these images directly support the alphabetic text; others are thematically related; others are for seemingly decorative purposes. Some are colorful and large, taking up most of a page; others are black and white sketches. The pictorial images offer remarkable detail about life in New Spain, but they do not bear titles, and the relationship of some to the adjoining text is not always self-evident. They can be considered a "third column of language" in the manuscript. Several different artists' hands have been identified, and many questions about their accuracy have been raised. The drawings convey a blend of Indigenous and European artistic elements and cultural influences.[37] Many passages of the texts in the Florentine Codex present descriptions of like items (e.g., gods, classes of people, animals) according to consistent patterns. Because of this, scholars have concluded that Sahagún used a series of questionnaires to structure his interviews and collect data.[20] For instance, the following questions appear to have been used to gather information about the gods for Book One: 1. What are the titles, the attributes, or the characteristics of the god? 2. What were his powers? 3. What ceremonies were performed in his honor? 4. What was his attire? For Book Ten, "The People", a questionnaire may have been used to gather information about the social organization of labor and workers, with questions such as: 1. What is the (trader, artisan) called and why? 2. What particular gods did they venerate? 3. How were their gods attired? 4. How were they worshiped? 5. What do they produce? 6. How did each occupation work? This book also described some other indigenous groups in Mesoamerica. Sahagún was particularly interested in Nahua medicine. The information he collected is a major contribution to the history of medicine generally. His interest was likely related to the high death rate at the time from plagues and diseases. Many thousands of people died, including friars and students at the school. Sections of Books Ten and Eleven describe human anatomy, disease, and medicinal plant remedies.[38] Sahagún named more than a dozen Aztec doctors who dictated and edited these sections. A questionnaire such as the following may have been used in this section: 1. What is the name of the plant (plant part)? 2. What does it look like? 3. What does it cure? 4. How is the medicine prepared? 5. How is it administered? 6.Where is it found? The text in this section provides very detailed information about location, cultivation, and medical uses of plants and plant parts, as well as information about the uses of animal products as medicine. The drawings in this section provide important visual information to amplify the alphabetic text. The information is useful for a wider understanding of the history of botany and the history of zoology. Scholars have speculated that Sahagún was involved in the creation of the Badianus Manuscript, an herbal created in 1552 that has pictorials of medicinal plants and their uses. Although this was originally written in Nahuatl, only the Latin translation has survived.  One of the first images of maize to be sent to Europe Book Eleven, "Earthly Things", has the most text and approximately half of the drawings in the codex. The text describes it as a "forest, garden, orchard of the Mexican language".[39] It describes the Aztec cultural understanding of the animals, birds, insects, fish and trees in Mesoamerica. Sahagún appeared to have asked questions about animals such as the following: 1. What is the name of the animal? 2. What animals does it resemble? 3. Where does it live? 4. Why does it receive this name? 5. What does it look like? 6. What habits does it have? 7. What does it feed on? 8. How does it hunt? 9 What sounds does it make? Plants and animals are described in association with their behavior and natural conditions or habitat. The Nahua presented their information in a way consistent with their worldview. For modern readers, this combination of ways of presenting materials is sometimes contradictory and confusing. Other sections include data on minerals, mining, bridges, roads, types of terrain, and food crops. The Florentine Codex is one of the most remarkable social science research projects ever conducted. It is not unique as a chronicle of encountering the New World and its peoples, for there were others in this era.[citation needed] Sahagún's methods for gathering information from the perspective within a foreign culture were highly unusual for this time. He reported the worldview of people of Central Mexico as they understood it, rather than describing the society exclusively from the European perspective. "The scope of the Historia's coverage of contact-period Central Mexico indigenous culture is remarkable, unmatched by any other sixteenth-century works that attempted to describe the native way of life."[40] Foremost in his own mind, Sahagún was a Franciscan missionary, but he may also rightfully be given the title as Father of American Ethnography.[41] |

民族誌的方法論 フィレンツェ写本に描かれたアステカの戦士たち  アステカ(メヒカ)の神、キシペ・トテック(「皮を剥がされた我らが主」)。 サハグンは、新世界の先住民文化に関する知識を収集し、検証するためのさまざまな戦略を開発した最初の人々の一人である。その後、人類学という学問分野 が、これらをエスノグラフィー(民族誌学)として正式化することになる。エスノグラフィとは、他文化の信仰、行動、社会的役割と関係、世界観を記録し、そ れらをその文化の論理の中で説明する科学的研究戦略である。エスノグラフィーは、学者が自分とはまったく異なる人々との共感を実践し、異文化に生きる人々 の世界観に入り込み、理解し、説明するために、自らの文化的信念を保留しようとすることを要求する。 サハグンは、アステカ文化について専門的な知識を持つと認められたさまざまな人々(現在、人類学ではインフォーマントとして知られている)から、体系的に 知識を集めた。彼は、異なる情報源からの回答を比較しながら、母国語であるナワトル語でそれを行った。ジェームズ・ロックハートによれば、サハグンは「比 較的年齢が高く、身分の高い先住民から発言を集め、彼が訓練した補助者たちにナワトル語で発言内容を書き取らせた」[36]。 いくつかの文章は、宗教的信念、社会、自然についての自然発生的な語りの書き起こしのように見える。他の部分は明らかに、特定の情報を引き出すためにさまざまな人々に提示された一貫した一連の質問を反映している。また、サハグン自身が出来事や解説を語った文章もある。 彼は以下の要素を持つ方法論を開発した: 1. 土着のナワトル語を使用した。 2. 2.長老、つまり最も詳しいと公的に認められている文化的権威から情報を引き出した。 3. アステカ文化が知識を記録し、伝達する方法にプロジェクトを適応させた。 4. トラテロルコのサンタ・クルス・カレッジの元生徒の専門知識を利用した。 5. 5.アステカ文化の全体性、あるいは完全な現実を独自の言葉で捉えようとした。 6. 彼はアンケートを用いて調査を構成したが、他の手段で共有されたより貴重な情報を用いることにも適応できた。 7. 彼はナワトル言語学を通して多様な意味が伝達される多様な方法に注意を払った。 8. 複数の情報源から得た情報を比較評価し、その情報の信頼度を判断した。 9. アステカ帝国の征服について、敗北したテノチティトラン・トラテロルコの視点から情報を収集した。 これらの方法論の革新は、サハグンが最初の人類学者であるという歴史家の主張を立証するものである。 フィレンツェ写本の大部分はナワトル語とスペイン語のアルファベットテキストだが、その2,000枚の写真は16世紀のニュー・スペインの鮮明なイメージ を提供している。これらの絵の中には、アルファベットのテキストを直接支えるものもあれば、テーマに関連したものもあり、また一見装飾的に見えるものもあ る。ページの大半を占めるカラフルで大きなものもあれば、白黒のスケッチもある。絵画的なイメージは、ニュー・スペインの生活に関する驚くべき詳細を提供 するが、タイトルが付されておらず、隣接するテキストとの関係が必ずしも自明でないものもある。それらは写本における「第3の言語列」と考えることができ る。何人かの異なる画家の手が確認されているが、その正確さについては多くの疑問が投げかけられている。描かれた絵は、先住民とヨーロッパの芸術的要素や 文化的影響が混ざり合っていることを伝えている[37]。 フィレンツェ写本のテキストの多くの箇所は、一貫したパターンに従って、同じようなアイテム(例えば、神々、人々のクラス、動物)の説明を示している。こ のことから、学者たちは、サハグンは一連の質問表を用いてインタビューを構成し、データを収集したと結論付けている[20]。 例えば、第一巻の神々に関する情報を収集するために、以下のような質問が用いられたようである: 1. 神の称号、属性、特徴は何か。 2. その神の力は何か? 3. どのような儀式が行われたか? 4. 彼の服装はどのようなものだったか? 第10巻「民衆」については、労働と労働者の社会組織に関する情報を集めるために、次のような質問が使われたかもしれない: 1. 商人、職人)は何と呼ばれているか。 2. 彼らはどのような神々を崇拝していたか? 3. 彼らの神々はどのような服装をしていたか? 4. どのように崇拝していたか? 5. 彼らは何を生産しているか? 6. それぞれの職業はどのように機能していたのか? 本書はメソアメリカの他の先住民族についても記述している。 サハグンは特にナフア族の医学に関心を寄せていた。彼が収集した情報は、一般的な医学史に大きな貢献をしている。彼の関心は、当時の疫病や病気による死亡 率の高さに関係していたと思われる。修道士や学校の生徒を含め、何千人もの人々が亡くなった。第10巻と第11巻には、人体解剖学、病気、薬草療法が記述 されている[38]。サハグンは、これらの部分を口述筆記し編集した10人以上のアステカ人医師の名前を挙げている。このセクションでは、以下のような質 問表が使用された可能性がある: 1. 植物(の一部)の名前は何か。 2. どのような形をしているか? 3. それは何に効くのか? 4. 薬はどのように調合されるか? 5. どのように投与されるか? 6.どこで発見されたか? このセクションの文章は、植物や植物の部分の場所、栽培、医学的利用法、また動物性産物の医学的利用法についての非常に詳細な情報を提供している。このセ クションの図面は、アルファベットの文章を増幅させる重要な視覚的情報を提供している。これらの情報は、植物学の歴史と動物学の歴史をより広く理解するた めに有用である。学者たちは、サハグンが1552年に作成されたバディアヌス手稿の作成に関わったと推測している。バディアヌス手稿には、薬草とその用途 が絵で描かれている。これはもともとナワトル語で書かれたものだが、ラテン語訳だけが残っている。  ヨーロッパに送られたトウモロコシの最初の画像のひとつである。 第11巻「地上のもの」は、写本の中で最も多くの文章と約半分の絵が掲載されている。本文では「メキシコ語の森、庭、果樹園」と表現されており[39]、メソアメリカの動物、鳥、昆虫、魚、樹木に対するアステカの文化的理解が記されている。 サハグンは動物について次のような質問をしているようだ: 1. 1.その動物の名前は? 2. どんな動物に似ているか? 3. どこに住んでいるか? 4. なぜこの名前がついたのか? 5. どんな姿をしているか? 6. どんな習性があるか? 7. 何を餌にしているか? 8. どのように狩りをするのか? 9 どんな鳴き声をするか? 動植物は、その行動や自然条件、生息地と関連付けて説明される。ナフア族は自分たちの世界観に合致した方法で情報を提示した。現代の読者にとって、このよ うな資料の示し方の組み合わせは、時に矛盾し、混乱を招く。他のセクションには、鉱物、採掘、橋、道路、地形の種類、食用作物に関するデータが含まれてい る。 フィレンツェ写本は、これまでに行われた社会科学研究の中で最も注目すべきプロジェクトのひとつである。新大陸とその民族との出会いを記したものとして は、この時代には他にもあったため、特別なものではない。彼は、ヨーロッパ人の視点からのみ社会を記述するのではなく、中央メキシコの人々が理解する世界 観を報告した。「サハグンは、フランシスコ会の宣教師であったが、アメリカ民族誌の父という称号を与えられるのも当然であろう[41]。 |

| Editions Bernardino de Sahagún, translated from Nahuatl to English by Arthur J. O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble; The Florentine Codex : General History of the Things of New Spain, 12 volumes; University of Utah Press (January 7, 2002), hardcover, ISBN 087480082X ISBN 978-0874800821 Sahagún, Bernardino de; Kupriienko, Sergii (2013) [2013]. General history of the affairs of New Spain. Books X-XI: Aztec's Knowledge in medicine and botany. Kyiv: Видавець Купрієнко С.А. ISBN 978-617-7085-07-1. Retrieved 4 September 2013. "We People Here: Nahuatl Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico" contains Book XII translated from Nahuatl to English by James Lockhart (2004) ISBN 9781592446810 |

エディション 編集 Bernardino de Sahagún,Arthur J. O. AndersonandCharles E. Dibble 著;The Florentine Codex : General History of the Things of New Spain, 全12巻; University of Utah Press (January 7, 2002), ハードカバー,ISBN 087480082X ISBN 978-0874800821 Sahagún, Bernardino de; Kupriienko, Sergii (2013) [2013]. 新スペイン事務の通史。第X巻から第XI巻まで: アステカの医学と植物学の知識. Kyiv: Видавець Купрієнко С.А. ISBN 978-617-7085-07-1. 2013年9月4日取得。 "We People Here: Nahuatl Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico" はナワトル語から英語に翻訳された第12巻を含む。 |

| External Links Digital Florentine Codex a multi-disciplinary project from J. Paul Getty Trust. Contains the Spanish and Nahuatl text in parallel and contains scans of a manuscript too. Also includes translations from Spanish to English, Nahuatl to English, and Nahuatl to Spanish. Furthermore, it allows the text to be searchable across numerous translations. General History of the Things of New Spain by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún: The Florentine Codex, at the World Digital Library online. Contains scans of a manuscript. |

外部リンク 編集 Digital Florentine Codex J. Paul Getty Trustによる学際的プロジェクト。スペイン語とナワトル語のテキストが並行して収録されており、写本もスキャンされている。また、スペイン語から英 語、ナワトル語から英語、ナワトル語からスペイン語への翻訳も含まれている。さらに、多数の翻訳を横断してテキストを検索することができる。 Fray Bernardino de Sahagún著『General History of the Things of New Spain: The Florentine Codex |

| Aztec codices Bernardino de Sahagún Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco Diego Durán Pedro Cieza de Leon |

アステカの写本 ベルナルディーノ・デ・サハグン サンタ・クルス・デ・トラテロルコ大学 ディエゴ・デュラン ペドロ・シエサ・デ・レオン |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florentine_Codex |

|

| Bernardino

de Sahagún OFM (c. 1499 – 5 February 1590) was a Franciscan friar,

missionary priest and pioneering ethnographer who participated in the

Catholic evangelization of colonial New Spain (now Mexico). Born in

Sahagún, Spain, in 1499, he journeyed to New Spain in 1529. He learned

Nahuatl and spent more than 50 years in the study of Aztec beliefs,

culture and history. Though he was primarily devoted to his missionary

task, his extraordinary work documenting indigenous worldview and

culture has earned him the title as “the first anthropologist."[1][2]

He also contributed to the description of Nahuatl, the imperial

language of the Aztec Empire. He translated the Psalms, the Gospels,

and a catechism into Nahuatl. Sahagún is perhaps best known as the compiler of the Historia general de las cosas de la Nueva España—in English, General History of the Things of New Spain—(hereinafter referred to as Historia general).[3] The most famous extant manuscript of the Historia general is the Florentine Codex. It is a codex consisting of 2,400 pages organized into twelve books, with approximately 2,500 illustrations drawn by native artists using both native and European techniques. The alphabetic text is bilingual in Spanish and Nahuatl on opposing folios, and the pictorials should be considered a third kind of text. It documents the culture, religious cosmology (worldview), ritual practices, society, economics, and history of the Aztec people, and in Book 12 gives an account of the conquest of the Aztec Empire from the Tenochtitlan-Tlatelolco point of view. In the process of putting together the Historia general, Sahagún pioneered new methods for gathering ethnographic information and validating its accuracy. The Historia general has been called "one of the most remarkable accounts of a non-Western culture ever composed,"[4] and Sahagún has been called the father of American ethnography. In 2015, his work was declared a World Heritage by the UNESCO.[5] |

ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン OFM(Bernardino de Sahagún, 1499 年頃~1590年2月5日)は、フランシスコ会の修道士、布教司祭、先駆的な民族誌学者であり、植民地時代のスペイン領ニュー・スペイン(現在のメキシ コ)におけるカトリックの布教活動に参加した。1499年にスペインのサアグンで生まれ、1529年にニュー・スペインに渡った。彼はナワトル語を学び、 アステカの信仰、文化、歴史の研究に50年以上を費やした。彼は主に布教活動に専念していたが、先住民の世界観や文化を記録した彼の並外れた業績により、 「最初の人類学者」という称号を得た。また、アステカ帝国の公用語であるナワトル語の記述にも貢献した。彼は詩篇、福音書、教理問答をナワトル語に翻訳し た。 サアグンは、『新スペインの事物全般史』(以下『事物全般史』)の編纂者として最もよく知られている。『事物全般史』の現存する写本の中で最も有名なのは 「フィレンツェ写本」である。この写本は2,400ページからなり、12の巻に分かれており、先住民アーティストが先住民とヨーロッパの技法を用いて描い た約2,500点のイラストが収められている。アルファベットテキストはスペイン語とナワトル語の2 か国語で、見開きページに印刷されている。また、図版は3つ目のテキストとして扱われるべきである。この書物はアステカ族の文化、宗教的宇宙観(世界 観)、儀式、社会、経済、歴史を記録しており、第12巻ではテノチティトラン・トラテロルコから見たアステカ帝国の征服について述べている。サアグンは 『一般史』をまとめる過程で、民族誌的情報を収集し、その正確性を検証するための新しい方法を考案した。『一般史』は「西洋以外の文化に関する最も優れた 記録のひとつ」と呼ばれ、サアグンは「アメリカ民族誌学の父」と呼ばれている。2015年には、彼の作品がユネスコの世界遺産に登録された(→「(このページ)フローレンス古文書」)。 |

| Field research After the fervor of the early mass conversions in Mexico had subsided, Franciscan missionaries came to realize that they needed a better understanding of indigenous peoples in order effectively to pursue their work. Sahagún's life changed dramatically in 1558 when the new provincial of New Spain, Fray Francisco de Toral, commissioned him to write in Nahuatl about topics he considered useful for the missionary project. The provincial wanted Sahagún to formalize his study of native language and culture, so that he could share it with others. The priest had a free hand to conduct his investigations.[14] He conducted research for about twenty-five years, and spent the last fifteen or so editing, translating and copying. His field research activities can be grouped into an earlier period (1558–1561) and a later period (1561–1575).[23]  Aztec warriors as shown in the Florentine Codex. From his early research, Sahagún wrote the text known as Primeros Memoriales. This served as the basis for his subsequent, larger Historia general.[24] He conducted his research at Tepeapulco, approximately 50 miles northeast of Mexico City, near present-day Hidalgo. There he spent two years interviewing approximately a dozen village elders in Nahuatl, assisted by native graduates of the college at Tlatelolco. Sahagún questioned the elders about the religious rituals and calendar, family, economic and political customs, and natural history. He interviewed them individually and in groups, and was thus able to evaluate the reliability of the information shared with him. His assistants spoke three languages (Nahuatl, Latin and Spanish). They participated in research and documentation, translation and interpretation, and they also painted illustrations. He published their names, described their work, and gave them credit. The pictures in the Primeros Memoriales convey a blend of indigenous and European artistic elements and influences.[25] Analysis of Sahagún's research activities in this earlier period indicates that he was developing and evaluating his own methods for gathering and verifying this information.[23] During the period 1561–1575, Sahagún returned to Tlatelolco. He interviewed and consulted more elders and cultural authorities. He edited his prior work. He expanded the scope of his earlier research, and further developed his interviewing methods. He recast his project along the lines of the medieval encyclopedias. These were not encyclopedias in the contemporary sense, and can be better described as worldbooks, for they attempt to provide a relatively complete presentation of knowledge about the world.[26] |

現地調査 メキシコで起こった初期の大量改宗の熱狂が収まった後、フランシスコ会の宣教師たちは、自分たちの仕事を効果的に進めるためには、先住民についてより深く 理解する必要があることに気づいた。サアグンは、1558年にニュースペインの新しい地方長官であるフラ・フランシスコ・デ・トラルから、宣教師プロジェ クトに役立つと思われるテーマについてナワトル語で執筆するよう依頼されたことで、人生が一変した。管区長はサアグンに、先住民の言語と文化の研究を正式 なものとし、それを他の人と共有することを望んでいた。司祭は自由に調査を行うことができた[14]。彼は約25年にわたって研究を行い、最後の15年ほ どは編集、翻訳、コピー作業に費やした。彼の現地調査活動は、前期(1558年~1561年)と後期(1561年~1575年)に分けられる[23]。  フィレンツェ写本に描かれたアステカの戦士たち。 初期の調査から、サアグンは『プリメロス・メモリアレス』として知られるテキストを執筆した。これは、後に彼が執筆したより大規模な『一般史』の基礎と なった[24]。彼はメキシコシティの北東約50マイル、現在のイダルゴ州に近いテペアプルコで調査を行った。そこで彼は、トラテロルコの大学を卒業した 現地人の協力を得て、ナワトル語でおよそ12人の村の年長者に2年間インタビューした。サハグンは、年長者たちに宗教儀式や暦、家族、経済、政治の習慣、 自然史について質問した。彼は彼らを個別に、またグループでインタビューし、それによって共有された情報の信頼性を評価することができた。彼の助手たちは 3つの言語(ナワトル語、ラテン語、スペイン語)を話した。彼らは研究と文書化、翻訳と通訳に参加し、またイラストも描いた。彼は彼らの名前を公表し、彼 らの仕事を説明し、彼らに功績を与えた。プリメロス・メモリアレス』の挿絵は、先住民とヨーロッパの芸術的要素と影響が融合したものである[25]。サア グンがこの時期に研究活動を行ったことについての分析から、彼はこの情報を収集し検証するための独自の方法を開発し、評価していたことがわかる[23]。 1561年から1575年の間、サアグンはトラテロルコに戻った。彼はさらに多くの長老や文化の権威者にインタビューし、相談した。彼は以前の著作を編集 した。彼は以前の研究の範囲を広げ、インタビュー方法をさらに発展させた。そして、中世の百科事典のスタイルに沿ってプロジェクトを再構築した。これらは 現代的な意味での百科事典ではなく、世界に関する知識を比較的完全に提供しようとするものであるため、世界書(worldbook)と呼ぶ方がふさわし い。 |

| Methodologies Sahagún was among the first to develop methods and strategies for gathering and validating knowledge of indigenous New World cultures. Much later, the scientific discipline of anthropology would formalize the methods of ethnography as a scientific research strategy for documenting the beliefs, behavior, social roles and relationships, and worldview of another culture, and for explaining these factors with reference to the logic of that culture. His research methods and strategies for validating information provided by his informants are precursors of the methods and strategies of modern ethnography. He systematically gathered knowledge from a range of diverse informants, including women, who were recognized as having knowledge of indigenous culture and tradition. He compared the answers obtained from his various sources. Some passages in his writings appear to be transcriptions of informants' statements about religious beliefs, society or nature. Other passages clearly reflect a consistent set of questions presented to different informants with the aim of eliciting information on specific topics. Some passages reflect Sahagún's own narration of events or commentary. |

方法論 サハグンは、新大陸の先住民文化に関する知識を集め、検証するための方法と戦略を最初に開発した人物の一人である。その後、人類学という学問分野が、他文 化の信念、行動、社会的役割や人間関係、世界観を記録し、その文化の論理を参照しながらこれらの要因を説明する科学的研究戦略として、民族誌の方法論を正 式に確立した。彼の研究方法と情報提供者からの情報を検証する戦略は、現代の民族誌の方法と戦略の先駆けである。 彼は、先住民の文化や伝統に精通していると認められた女性を含む、さまざまな情報提供者から体系的に知識を収集した。そして、さまざまな情報源から得られ た答えを比較した。彼の著作の一部は、宗教的信念、社会、自然に関する情報提供者の発言を文字に起こしたものと思われる。また、特定のトピックに関する情 報を引き出す目的で、異なる情報源に一貫した質問を投げかけたことがはっきりとわかる箇所もある。サハグンの出来事や解説を自ら語った箇所もある。 |

| Significance During the period in which Sahagún conducted his research, the conquering Spaniards were greatly outnumbered by the conquered Aztecs, and were concerned about the threat of a native uprising. Some colonial authorities perceived his writings as potentially dangerous, since they lent credibility to native voices and perspectives. Sahagún was aware of the need to avoid running afoul of the Inquisition, which was established in Mexico in 1570. Sahagún's work was originally conducted only in Nahuatl. To fend off suspicion and criticism, he translated sections of it into Spanish, submitted it to some fellow Franciscans for their review, and sent it to the King of Spain with some Friars returning home. His last years were difficult, because the utopian idealism of the first Franciscans in New Spain was fading while the Spanish colonial project continued as brutal and exploitative. In addition, millions of indigenous people died from repeated epidemics, as they had no immunity to Eurasian diseases. Some of his final writings express feelings of despair. The Crown replaced the religious orders with secular clergy, giving friars a much smaller role in the Catholic life of the colony. Franciscans newly arrived in the colony did not share the earlier Franciscans' faith and zeal about the capacity of the Indians. The pro-indigenous approach of the Franciscans and Sahagún became marginalized with passing years. The use of the Nahuatl Bible was banned, reflecting the broader global retrenchment of Catholicism under the Council of Trent. In 1575 the Council of the Indies banned all scriptures in the indigenous languages and forced Sahagún to hand over all of his documents about the Aztec culture and the results of his research. The respectful study of the local traditions has probably been seen as a possible obstacle to the Christian mission. Despite this ban, Sahagún made two more copies of his Historia general. Sahagún's Historia general was unknown outside Spain for about two centuries. In 1793, a bibliographer catalogued the Florentine Codex in the Laurentian Library in Florence.[27][28] The work is now carefully rebound in three volumes. A scholarly community of historians, anthropologists, art historians, and linguists has been investigating Sahagún's work, its subtleties and mysteries, for more than 200 years.[29] The Historia general is the product of one of the most remarkable social-science research projects ever conducted. It is not unique as a chronicle of encounters with the New World and its people, but it stands out due to Sahagún's effort to gather information about a foreign culture by interviewing people and gathering perspectives from within that culture. As Nicholson has stated, "the scope of the Historia’s coverage of contact-period Central Mexico indigenous culture is remarkable, unmatched by any other sixteenth-century works that attempted to describe the native way of life.”[30] Although in his own mind Sahagún was a Franciscan missionary, he has also been referred to by scholars as the "father of American Ethnography".[1] |

意義 サアグンが研究を行っていた時代、征服者であるスペイン人は征服されたアステカ人に比べて圧倒的に数が少なく、先住民による蜂起の脅威に悩まされていた。 彼の著作は先住民の意見や視点を信憑性のあるものとして受け止められる可能性があり、一部の植民地当局はそれを危険視していた。サアグンは、1570年に メキシコに設立された異端審問に反発しないよう努める必要性を認識していた。 サアグンの著作はもともとナワトル語のみで書かれていた。疑惑や批判を避けるため、彼はその一部をスペイン語に翻訳し、仲間のフランシスコ会修道士たちに 確認してもらった上で、スペイン国王に、帰国する修道士たちとともに送った。彼の晩年は困難を極めた。というのも、スペイン植民地計画が残忍かつ搾取的な まま続く一方で、新スペインに最初にやってきたフランシスコ会の修道士たちのユートピア的理想主義は薄れつつあったからだ。さらに、何百万もの先住民が、 ユーラシア大陸由来の病気に免疫を持っていなかったため、繰り返される疫病で命を落とした。彼の最後の著作のいくつかは、絶望的な感情を表している。スペ イン王室は、修道会を世俗の聖職者に置き換え、植民地のカトリック生活における修道士たちの役割を大幅に縮小した。新たに植民地に到着したフランシスコ会 の修道士たちは、先住民の能力に対する先代のフランシスコ会の修道士たちの信念や熱意を共有していなかった。フランシスコ会士とサアグンによる先住民擁護 の姿勢は、時間の経過とともに次第に疎外されていった。ナワトル語聖書の使用が禁止されたことは、トレント公会議によるカトリックの縮小を反映していた。 1575年には、インディーズ会議が先住民の言語によるすべての聖典を禁止し、サアグンにアステカ文化と研究結果に関するすべての文書を引き渡すよう強要 した。現地の伝統を尊重した研究は、キリスト教の布教の妨げになると考えられていたのだろう。この禁止令にもかかわらず、サアグンは『一般史』のコピーを 2部作成した。 サアグンの『一般史』は、約2世紀もの間スペイン国外では知られていなかった。1793年、書誌学者がフィレンツェのローレンツィ図書館でフィレンツェ写 本をカタログ化した[27][28]。この作品は現在、3巻に丁寧に装丁されている。歴史学者、人類学者、美術史家、言語学者からなる学術研究コミュニ ティは、200年以上にわたってサアグンの著作、その繊細さや謎について研究を続けている[29]。 『一般史』は、これまでに実施された社会科学研究プロジェクトの中でも最も注目すべきものの1つである。新世界とその人々との出会いの記録としては独特な ものではないが、サアグンが人々へのインタビューや、その文化内部からの見解の収集を通じて、異文化に関する情報を収集しようとした努力により際立ってい る。ニコルソンは、「『ヒストリア』が接触期の中央メキシコ先住民の文化を扱った範囲は驚くほど広く、先住民の生活様式を描写しようとした16世紀の他の どの作品にも及ばない」と述べている[30]。サアグンは、自身ではフランシスコ会の宣教師と考えていたが、学者からは「アメリカ民族誌学の父」とも呼ば れている[1]。 |

| Bernardino de Sahagún, ca.1499-1590 |

ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆