History

At first, biographical writings were regarded merely as a subsection of

history with a focus on a particular individual of historical

importance. The independent genre of biography as distinct from general

history writing, began to emerge in the 18th century and reached its

contemporary form at the turn of the 20th century.[1]

Historical biography

Einhard as scribe

Biography is the earliest literary genre in history. According to

Egyptologist Miriam Lichtheim, writing took its first steps toward

literature in the context of the private tomb funerary inscriptions.

These were commemorative biographical texts recounting the careers of

deceased high royal officials.[2] The earliest biographical texts are

from the 26th century BC.

In the 21st century BC, another famous biography was composed in

Mesopotamia about Gilgamesh. One of the five versions could be

historical.

From the same region a couple of centuries later, according to another

famous biography, departed Abraham. He and his 3 descendants became

subjects of ancient Hebrew biographies whether fictional or historical.

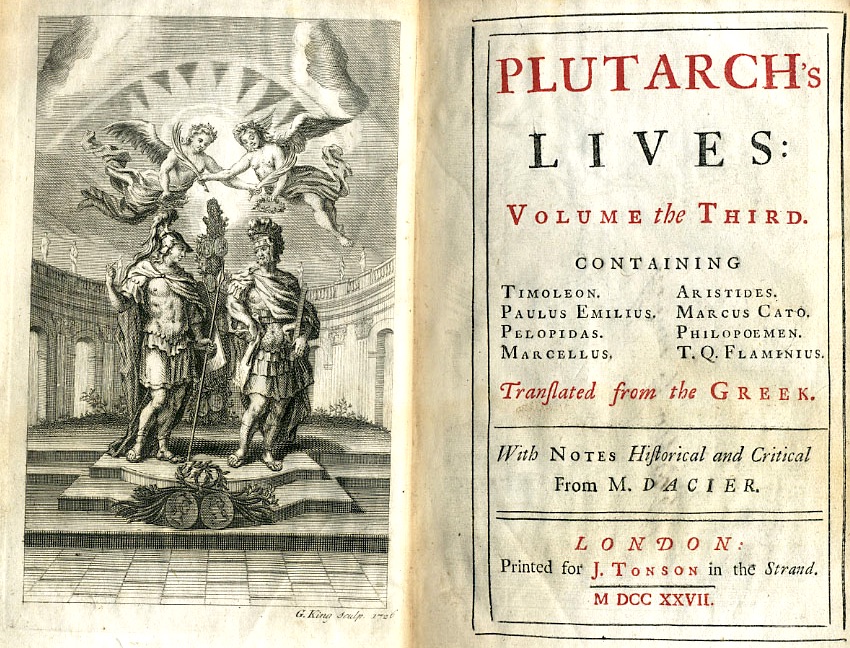

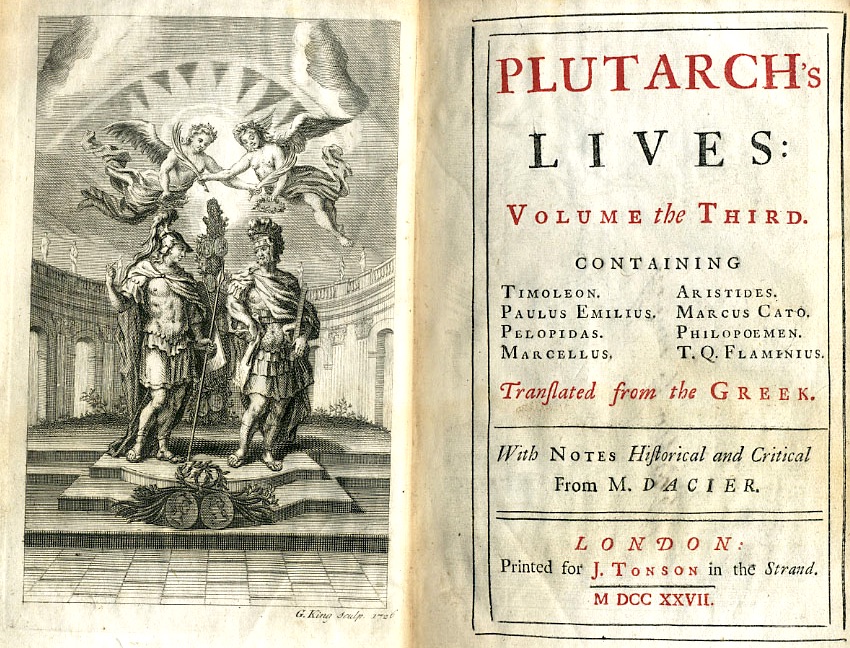

One of the earliest Roman biographers was Cornelius Nepos, who

published his work Excellentium Imperatorum Vitae ("Lives of

outstanding generals") in 44 BC. Longer and more extensive biographies

were written in Greek by Plutarch, in his Parallel Lives, published

about 80 A.D. In this work famous Greeks are paired with famous Romans,

for example, the orators Demosthenes and Cicero, or the generals

Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar; some fifty biographies from the

work survive. Another well-known collection of ancient biographies is

De vita Caesarum ("On the Lives of the Caesars") by Suetonius, written

about AD 121 in the time of the emperor Hadrian. Meanwhile, in the

eastern imperial periphery, Gospel described the life of Jesus.

In the early Middle Ages (AD 400 to 1450), there was a decline in

awareness of the classical culture in Europe. During this time, the

only repositories of knowledge and records of the early history in

Europe were those of the Roman Catholic Church. Hermits, monks, and

priests used this historic period to write biographies. Their subjects

were usually restricted to the church fathers, martyrs, popes, and

saints. Their works were meant to be inspirational to the people and

vehicles for conversion to Christianity (see Hagiography). One

significant secular example of a biography from this period is the life

of Charlemagne by his courtier Einhard.

In Medieval Western India, there was a Sanskrit Jain literary genre of

writing semi-historical biographical narratives about the lives of

famous persons called Prabandhas. Prabandhas were written primarily by

Jain scholars from the 13th century onwards and were written in

colloquial Sanskrit (as opposed to Classical Sanskrit).[3] The earliest

collection explicitly titled Prabandha- is Jinabhadra's Prabandhavali

(1234 CE).

In Medieval Islamic Civilization (c. AD 750 to 1258), similar

traditional Muslim biographies of Muhammad and other important figures

in the early history of Islam began to be written, beginning the

Prophetic biography tradition. Early biographical dictionaries were

published as compendia of famous Islamic personalities from the 9th

century onwards. They contained more social data for a large segment of

the population than other works of that period. The earliest

biographical dictionaries initially focused on the lives of the

prophets of Islam and their companions, with one of these early

examples being The Book of The Major Classes by Ibn Sa'd al-Baghdadi.

And then began the documentation of the lives of many other historical

figures (from rulers to scholars) who lived in the medieval Islamic

world.[4]

John Foxe's The Book of Martyrs, was one of the earliest English-language biographies.

By the late Middle Ages, biographies became less church-oriented in

Europe as biographies of kings, knights, and tyrants began to appear.

The most famous of such biographies was Le Morte d'Arthur by Sir Thomas

Malory. The book was an account of the life of the fabled King Arthur

and his Knights of the Round Table. Following Malory, the new emphasis

on humanism during the Renaissance promoted a focus on secular

subjects, such as artists and poets, and encouraged writing in the

vernacular.

Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists (1550) was the landmark biography

focusing on secular lives. Vasari made celebrities of his subjects, as

the Lives became an early "bestseller". Two other developments are

noteworthy: the development of the printing press in the 15th century

and the gradual increase in literacy.

Biographies in the English language began appearing during the reign of

Henry VIII. John Foxe's Actes and Monuments (1563), better known as

Foxe's Book of Martyrs, was essentially the first dictionary of the

biography in Europe, followed by Thomas Fuller's The History of the

Worthies of England (1662), with a distinct focus on public life.

Influential in shaping popular conceptions of pirates, A General

History of the Pyrates (1724), by Charles Johnson, is the prime source

for the biographies of many well-known pirates.[5]

A notable early collection of biographies of eminent men and women in

the United Kingdom was Biographia Britannica (1747–1766) edited by

William Oldys.

The American biography followed the English model, incorporating Thomas

Carlyle's view that biography was a part of history. Carlyle asserted

that the lives of great human beings were essential to understanding

society and its institutions. While the historical impulse would remain

a strong element in early American biography, American writers carved

out a distinct approach. What emerged was a rather didactic form of

biography, which sought to shape the individual character of a reader

in the process of defining national character.[6][7]

Emergence of the genre

James Boswell wrote what many consider to be the first modern biography, The Life of Samuel Johnson, in 1791.

The first modern biography, and a work that exerted considerable

influence on the evolution of the genre, was James Boswell's The Life

of Samuel Johnson, a biography of lexicographer and man-of-letters

Samuel Johnson published in 1791.[8][unreliable source?][9][10]

While Boswell's personal acquaintance with his subject only began in

1763, when Johnson was 54 years old, Boswell covered the entirety of

Johnson's life by means of additional research. Itself an important

stage in the development of the modern genre of biography, it has been

claimed to be the greatest biography written in the English language.

Boswell's work was unique in its level of research, which involved

archival study, eye-witness accounts and interviews, its robust and

attractive narrative, and its honest depiction of all aspects of

Johnson's life and character – a formula which serves as the basis of

biographical literature to this day.[11]

Biographical writing generally stagnated during the 19th century – in

many cases there was a reversal to the more familiar hagiographical

method of eulogizing the dead, similar to the biographies of saints

produced in Medieval times. A distinction between mass biography and

literary biography began to form by the middle of the century,

reflecting a breach between high culture and middle-class culture.

However, the number of biographies in print experienced a rapid growth,

thanks to an expanding reading public. This revolution in publishing

made books available to a larger audience of readers. In addition,

affordable paperback editions of popular biographies were published for

the first time. Periodicals began publishing a sequence of biographical

sketches.[12]

Autobiographies became more popular, as with the rise of education and

cheap printing, modern concepts of fame and celebrity began to develop.

Autobiographies were written by authors, such as Charles Dickens (who

incorporated autobiographical elements in his novels) and Anthony

Trollope (his Autobiography appeared posthumously, quickly becoming a

bestseller in London[13]), philosophers, such as John Stuart Mill,

churchmen – John Henry Newman – and entertainers – P. T. Barnum.

Modern biography

The sciences of psychology and sociology were ascendant at the turn of

the 20th century and would heavily influence the new century's

biographies.[14] The demise of the "great man" theory of history was

indicative of the emerging mindset. Human behavior would be explained

through Darwinian theories. "Sociological" biographies conceived of

their subjects' actions as the result of the environment, and tended to

downplay individuality. The development of psychoanalysis led to a more

penetrating and comprehensive understanding of the biographical

subject, and induced biographers to give more emphasis to childhood and

adolescence. Clearly these psychological ideas were changing the way

biographies were written, as a culture of autobiography developed, in

which the telling of one's own story became a form of therapy.[12] The

conventional concept of heroes and narratives of success disappeared in

the obsession with psychological explorations of personality.

Eminent Victorians set the standard for 20th century biographical writing, when it was published in 1918.

British critic Lytton Strachey revolutionized the art of biographical

writing with his 1918 work Eminent Victorians, consisting of

biographies of four leading figures from the Victorian era: Cardinal

Manning, Florence Nightingale, Thomas Arnold, and General Gordon.[15]

Strachey set out to breathe life into the Victorian era for future

generations to read. Up until this point, as Strachey remarked in the

preface, Victorian biographies had been "as familiar as the cortège of

the undertaker", and wore the same air of "slow, funereal barbarism."

Strachey defied the tradition of "two fat volumes ... of undigested

masses of material" and took aim at the four iconic figures. His

narrative demolished the myths that had built up around these cherished

national heroes, whom he regarded as no better than a "set of mouth

bungled hypocrites". The book achieved worldwide fame due to its

irreverent and witty style, its concise and factually accurate nature,

and its artistic prose.[16]

In the 1920s and 1930s, biographical writers sought to capitalize on

Strachey's popularity by imitating his style. This new school featured

iconoclasts, scientific analysts, and fictional biographers and

included Gamaliel Bradford, André Maurois, and Emil Ludwig, among

others. Robert Graves (I, Claudius, 1934) stood out among those

following Strachey's model of "debunking biographies." The trend in

literary biography was accompanied in popular biography by a sort of

"celebrity voyeurism", in the early decades of the century. This latter

form's appeal to readers was based on curiosity more than morality or

patriotism. By World War I, cheap hard-cover reprints had become

popular. The decades of the 1920s witnessed a biographical "boom."

American professional historiography gives a limited role to biography,

preferring instead to emphasize deeper social and cultural influences.

Political biographers historically incorporated moralizing judgments

into their work, with scholarly biography being an uncommon genre

before the mid-1920s. Allan Nevins was a major contributor in the 1930s

to the multivolume Dictionary of American Biography. Nevins also

sponsored a series of long political biographies. Later biographers

sought to show how political figures balanced power and responsibility.

However, many biographers found that their subjects were not as morally

pure as they originally thought, and young historians after 1960 tended

to be more critical. The exception is Robert Remini whose books on

Andrew Jackson idolize its hero and fends off criticisms. The study of

decision-making in politics is important for scholarly political

biographers, who can take different approaches such as focusing on

psychology/personality, bureaucracy/interests, fundamental ideas, or

societal forces. However, most documentation favors the first approach,

which emphasizes personalities. Biographers often neglect the voting

blocs and legislative positions of politicians and the organizational

structures of bureaucracies. A more promising approach is to locate a

person's ideas through intellectual history, but this has become more

difficult with the philosophical shallowness of political figures in

recent times. Political biography can be frustrating and challenging to

integrate with other fields of political history.[17]

The feminist scholar Carolyn Heilbrun observed that women's biographies

and autobiographies began to change character during the second wave of

feminist activism. She cited Nancy Milford's 1970 biography Zelda, as

the "beginning of a new period of women's biography, because "[only] in

1970 were we ready to read not that Zelda had destroyed Fitzgerald, but

Fitzgerald her: he had usurped her narrative." Heilbrun named 1973 as

the turning point in women's autobiography, with the publication of May

Sarton's Journal of a Solitude, for that was the first instance where a

woman told her life story, not as finding "beauty even in pain" and

transforming "rage into spiritual acceptance," but acknowledging what

had previously been forbidden to women: their pain, their rage, and

their "open admission of the desire for power and control over one's

life."[18]

Recent years

In recent years, multimedia biography has become more popular than

traditional literary forms. Along with documentary biographical films,

Hollywood produced numerous commercial films based on the lives of

famous people. The popularity of these forms of biography have led to

the proliferation of TV channels dedicated to biography, including

A&E, The Biography Channel, and The History Channel.

CD-ROM and online biographies have also appeared. Unlike books and

films, they often do not tell a chronological narrative: instead they

are archives of many discrete media elements related to an individual

person, including video clips, photographs, and text articles.

Biography-Portraits were created in 2001, by the German artist Ralph

Ueltzhoeffer. Media scholar Lev Manovich says that such archives

exemplify the database form, allowing users to navigate the materials

in many ways.[19] General "life writing" techniques are a subject of

scholarly study.[20]

In recent years, debates have arisen as to whether all biographies are

fiction, especially when authors are writing about figures from the

past. President of Wolfson College at Oxford University, Hermione Lee

argues that all history is seen through a perspective that is the

product of one's contemporary society and as a result, biographical

truths are constantly shifting. So, the history biographers write about

will not be the way that it happened; it will be the way they

remembered it.[21] Debates have also arisen concerning the importance

of space in life-writing.[22]

Daniel R. Meister in 2017 argued that:

Biography Studies is emerging as an independent discipline, especially

in the Netherlands. This Dutch School of biography is moving biography

studies away from the less scholarly life writing tradition and towards

history by encouraging its practitioners to utilize an approach adapted

from microhistory.[23]

Biographical research

Biographical research is defined by Miller as a research method that

collects and analyses a person's whole life, or portion of a life,

through the in-depth and unstructured interview, or sometimes

reinforced by semi-structured interview or personal documents.[24] It

is a way of viewing social life in procedural terms, rather than static

terms. The information can come from "oral history, personal narrative,

biography and autobiography" or "diaries, letters, memoranda and other

materials".[25] The central aim of biographical research is to produce

rich descriptions of persons or "conceptualise structural types of

actions", which means to "understand the action logics or how persons

and structures are interlinked".[26] This method can be used to

understand an individual's life within its social context or understand

the cultural phenomena.

Critical issues

There are many largely unacknowledged pitfalls to writing good

biographies, and these largely concern the relation between firstly the

individual and the context, and, secondly, the private and public. Paul

James writes:

The problems with such conventional biographies are manifold.

Biographies usually treat the public as a reflection of the private,

with the private realm being assumed to be foundational. This is

strange given that biographies are most often written about public

people who project a persona. That is, for such subjects the dominant

passages of the presentation of themselves in everyday life are already

formed by what might be called a 'self-biofication' process.[27]

|

歴史

当初、伝記は歴史的に重要な特定の人物に焦点を当てた歴史の一分野と見なされていた。一般的な歴史書とは異なる伝記という独立したジャンルは、18世紀に出現し始め、20世紀初頭には現代的な形に到達した[1]。

歴史伝記

書記としてのアインハルト

伝記は歴史上最も古い文学ジャンルである。エジプト学者のミリアム・リヒトハイムによれば、文字が文学への第一歩を踏み出したのは、個人の墓に刻まれた碑文の文脈からであった。最も古い伝記は紀元前26世紀のものである[2]。

紀元前21世紀には、メソポタミアでギルガメシュについての有名な伝記が作られた。5つのバージョンのうち1つは歴史的なものである可能性がある。

その数世紀後、同じ地域から、別の有名な伝記によれば、アブラハムが旅立った。彼と彼の3人の子孫は、フィクションであれ史実であれ、古代ヘブライ伝記の題材となった。

ローマ時代初期の伝記作家のひとりはコルネリウス・ネポスで、紀元前44年に『Excellentium Imperatorum

Vitae』(傑出した将軍の生涯)を出版した。この作品では、有名なギリシア人と有名なローマ人が対になっており、たとえば、弁舌家のデモステネスやキ

ケロ、将軍のアレクサンダー大王やユリウス・カエサルなどが登場する。古代の伝記集としては、ハドリアヌス帝時代のAD121年頃に書かれたスエトニウス

の『カエサルの生涯』(De vita Caesarum)も有名である。一方、東方帝国周辺部では、福音書がイエスの生涯を描いた。

中世初期(AD400年から1450年)、ヨーロッパでは古典文化に対する意識が低下した。この時代、ヨーロッパにおける初期史の知識と記録の保管所は、

ローマ・カトリック教会のものだけであった。隠者、修道士、司祭たちは、この歴史的な時期を利用して伝記を書いた。彼らの対象は通常、教父、殉教者、教

皇、聖人に限られていた。彼らの著作は、人々にインスピレーションを与え、キリスト教への改宗を促すものであった(「萩伝」を参照)。この時代の世俗的な

伝記の重要な例としては、彼の廷臣アインハルトによるカール大帝の生涯が挙げられる。

中世の西インドには、プラバンダと呼ばれる著名人の生涯を半歴史的に叙述するサンスクリット・ジャイナ文学のジャンルがあった。プラバンダは主に13世紀

以降のジャイナ教の学者によって書かれ、(古典サンスクリット語とは対照的に)口語サンスクリット語で書かれた[3]。プラバンダと明確に題された最も古

い作品集は、ジナバドラの『プラバンダヴァリ』(1234年)である。

中世イスラム文明(紀元750年頃~1258年)では、ムハンマドやイスラムの初期史における他の重要人物について、同様の伝統的なイスラム伝記が書かれ

始め、預言者伝記の伝統が始まった。初期の伝記辞典は、9世紀以降、イスラムの有名な人物の大要として出版された。この辞典には、当時の他の著作よりも多

くの人々の社会的データが含まれていた。最も初期の伝記辞典は、当初イスラームの預言者とその教友の生涯に焦点を当てたもので、その初期の例のひとつがイ

ブン・サード・アル=バグダーディーによる『主要階級の書』であった。その後、中世イスラーム世界に生きた他の多くの歴史上の人物(支配者から学者まで)

の生涯の記録が始まった[4]。

ジョン・フォクセの『殉教者の書』は、英語で書かれた最も初期の伝記の一つである。

中世後期になると、ヨーロッパでは王や騎士、暴君の伝記が登場するようになり、伝記は教会中心ではなくなっていった。そのような伝記で最も有名なのが、ト

マス・マロリー卿の『アーサー王の死』(Le Morte

d'Arthur)である。この本は、伝説のアーサー王と円卓の騎士たちの生涯を描いたものだった。マロリーに続き、ルネサンス期には人文主義が新たに強

調され、芸術家や詩人といった世俗的な題材に焦点が当てられ、方言での執筆が奨励された。

ジョルジョ・ヴァザーリの『芸術家たちの生涯』(1550年)は、世俗の生活に焦点を当てた画期的な伝記であった。ヴァザーリは、『芸術家列伝』が初期の

「ベストセラー」となったように、対象者を有名人にした。15世紀に印刷機が発達し、識字率が徐々に向上したことである。

英語による伝記はヘンリー8世の治世に登場し始めた。殉教者の書』(Foxe's Book of

Martyrs)として知られるジョン・フォクセ(John Foxe)の『Actes and

Monuments』(1563年)は、実質的にヨーロッパで最初の伝記辞典であり、トマス・フラー(Thomas Fuller)の『The

History of the Worthies of England』(1662年)は、公生涯に焦点を当てたものであった。

海賊に対する一般的な概念の形成に影響を与えたチャールズ・ジョンソンの『A General History of the Pyrates』(1724年)は、多くの有名な海賊の伝記の主要な出典である[5]。

イギリスの著名な人物の伝記を集めた初期の注目すべきものは、ウィリアム・オルディスが編集した『バイオグラフィア・ブリタニカ』(1747-1766)である。

アメリカの伝記はイギリスのモデルに倣い、伝記は歴史の一部であるというトマス・カーライルの見解を取り入れた。カーライルは、社会とその制度を理解する

ためには、偉大な人間の生涯が不可欠であると主張した。歴史的衝動は初期のアメリカの伝記に強く残る要素であったが、アメリカの作家たちは独自のアプロー

チを切り開いた。登場したのは、国民性を定義する過程で読者個人の人格を形成しようとする、むしろ教訓的な形式の伝記であった[6][7]。

ジャンルの出現

ジェームズ・ボズウェルは、1791年に最初の近代的伝記とされる『サミュエル・ジョンソンの生涯』を著した。

最初の近代的な伝記であり、このジャンルの進化に多大な影響を及ぼした作品は、1791年に出版されたジェームズ・ボスウェルの『サミュエル・ジョンソン

の生涯』(The Life of Samuel Johnson)である[8][信頼できない情報源?][9][10]。

ボズウェルの個人的な面識はジョンソン54歳の1763年に始まったばかりであったが、ボズウェルは追加調査によってジョンソンの全生涯を網羅した。それ

自体が伝記という近代的ジャンルの発展における重要な段階であり、英語で書かれた最も偉大な伝記であると主張されている。ボズウェルの作品は、古文書調

査、目撃証言、インタビューを含むその調査レベル、堅固で魅力的な物語、ジョンソンの人生と性格のあらゆる側面の誠実な描写という点で、他に類を見ないも

のであった。

多くの場合、中世に作られた聖人伝のように、死者を讃えるという馴染み深い萩伝的な手法に逆転した。大衆伝記と文学伝記の区別は、世紀半ばまでに形成され

始め、上流文化と中流文化の断絶を反映していた。しかし、出版される伝記の数は、読書人口の拡大により急増した。この出版革命によって、より多くの読者が

本を手にすることができるようになった。さらに、人気のある伝記の手頃なペーパーバック版が初めて出版された。定期刊行物は伝記的なスケッチを連続して掲

載するようになった[12]。

教育や安価な印刷の台頭とともに、名声や有名人に関する近代的な概念が発達し始めたため、自伝はより人気を集めるようになった。自伝は、チャールズ・ディ

ケンズ(彼は自伝的要素を小説に取り入れた)やアンソニー・トロロープ(彼の自伝は死後に出版され、すぐにロンドンでベストセラーになった[13])など

の作家、ジョン・スチュアート・ミルなどの哲学者、ジョン・ヘンリー・ニューマンなどの教会関係者、P・T・バーナムなどの芸能人によって書かれた。

現代の伝記

20世紀に入ると心理学と社会学が台頭し、新世紀の伝記に大きな影響を与えることになる[14]。人間の行動はダーウィンの理論によって説明されるように

なった。「社会学的」伝記は、対象者の行動を環境の結果として考え、個性を軽視する傾向があった。精神分析の発達は、伝記的対象をより深く包括的に理解す

ることにつながり、伝記作家たちは幼年期や青年期をより重視するようになった。こうした心理学的な考え方が伝記の書き方を変えたのは明らかで、自分自身の

物語を語ることがセラピーの一形態となるような自伝文化が発展していったのである[12]。従来の英雄の概念や成功の物語は、個性の心理学的探求に執着す

る中で消えていった。

1918年に出版された20世紀の伝記文学のスタンダードを作ったのは、著名なヴィクトリア朝人たちである。

イギリスの批評家リットン・ストレイシーは、1918年に発表した『エミネント・ヴィクトリアンズ』(Eminent

Victorians)で伝記文学に革命をもたらした:

マニング枢機卿、フローレンス・ナイチンゲール、トーマス・アーノルド、そしてゴードン将軍である[15]。ストレイシーは、後世の人々が読めるように、

ヴィクトリア朝時代に生命を吹き込むことを目指した。序文でストレイチーが述べているように、それまでヴィクトリア朝の伝記は「葬儀屋の葬儀のように馴染

み深い」ものであり、「ゆっくりとした、葬式のような野蛮さ」を帯びていた。ストレイシーは、「未消化の資料の塊のような......太った2冊の本」と

いう伝統に逆らい、4人の象徴的な人物を取り上げた。彼の語り口は、「口先だけの偽善者たち」と見なした、これらの大切な国民的英雄たちの周りに築き上げ

られた神話を打ち壊した。この本は、その不遜で機知に富んだ文体、簡潔で事実に忠実であること、そして芸術的な散文によって、世界的な名声を獲得した

[16]。

1920年代から1930年代にかけて、伝記作家たちはストレイシーのスタイルを模倣することで、その人気にあやかろうとした。この新しい学派は、象徴主

義者、科学的分析者、架空の伝記作家を特色とし、ガマリエル・ブラッドフォード、アンドレ・マウロワ、エミール・ルートヴィヒなどがいた。ロバート・グレ

イヴス(『I, Claudius』、1934年)は、ストレイシーの "論破伝記

"のモデルに倣った人々の中でも際立っていた。文学伝記におけるこの傾向は、今世紀初頭の大衆伝記においては、一種の「有名人覗き見主義」によってもたら

された。後者の読者へのアピールは、道徳や愛国心よりも好奇心に基づいていた。第一次世界大戦までには、安価なハードカバーの復刻版が人気を博した。

1920年代には伝記ブームが起こった。

アメリカの専門的な歴史学は伝記に限られた役割しか与えず、より深い社会的、文化的影響を強調することを好んだ。政治伝記作家は歴史的に道徳的な判断を作

品に取り入れており、学術的な伝記は1920年代半ば以前には珍しいジャンルであった。アラン・ネビンズは1930年代、『アメリカ人名辞典』

(Dictionary of American

Biography)の主要な寄稿者であった。ネヴィンズはまた、一連の長編政治伝記を後援した。後の伝記作家たちは、政治家が権力と責任のバランスをど

のようにとっているかを示そうとした。しかし、多くの伝記作家は、自分たちの対象が当初考えていたほど道徳的に純粋ではなかったことに気づき、1960年

以降の若い歴史家たちは、より批判的になる傾向があった。例外はロバート・レミニで、彼のアンドリュー・ジャクソンに関する著書は英雄を偶像化し、批判を

かわしている。政治における意思決定の研究は、学術的な政治伝記作家にとって重要であり、心理学/人格、官僚制/利害関係、基本的な考え方、社会的な力な

ど、さまざまなアプローチをとることができる。しかし、ほとんどの文献は、人格を重視する最初のアプローチを好んでいる。伝記作家は、政治家の票田や立法

上の地位、官僚組織の組織構造を軽視しがちである。より有望なアプローチは、知的な歴史を通してその人物の思想を突き止めることだが、近年の政治家の哲学

的な浅薄さによって、これはより難しくなっている。政治伝記は、政治史の他の分野と統合するにはもどかしく、困難なものである[17]。

フェミニスト学者のキャロライン・ハイルブランは、女性の伝記や自伝はフェミニズム活動の第二の波の中で性格を変え始めたと観察している。彼女はナン

シー・ミルフォードの1970年の伝記『ゼルダ』を「女性伝記の新しい時代の始まり」として挙げている。「1970年になって初めて、私たちはゼルダが

フィッツジェラルドを破壊したのではなく、フィッツジェラルドが彼女の物語を簒奪したのだと読む準備ができたのです」。ハイルブランは、メイ・サートンの

『ある孤独の日記』が出版された1973年を、女性の自伝の転換点として挙げている。それは、「苦痛の中にも美を見出す」のではなく、「怒りを精神的な受

容に変える」のでもなく、それまで女性に禁じられていたこと、つまり自分の苦痛や怒り、そして「自分の人生に対する権力と支配の欲望を率直に認める」こと

を、女性が自分の人生を語った最初の事例だったからである[18]。

近年

近年、マルチメディア伝記は、伝統的な文学形式よりも人気がある。ドキュメンタリー伝記映画とともに、ハリウッドは著名人の人生を題材にした数多くの商業

映画を製作した。こうした伝記形式の人気は、A&E、バイオグラフィ・チャンネル、ヒストリー・チャンネルなど、伝記専門のテレビチャンネルの普

及につながった。

CD-ROMやオンライン伝記も登場した。書籍や映画とは異なり、時系列的な物語を語らないことが多い。その代わり、ビデオクリップ、写真、テキスト記事

など、一個人に関連する多くの個別メディア要素のアーカイブとなっている。バイオグラフィー・ポートレイトは、ドイツのアーティスト、ラルフ・ウエルツ

ヘッファーによって2001年に制作された。メディア研究者のレフ・マノヴィッチは、このようなアーカイブはデータベース形式の典型であり、ユーザーは様

々な方法で資料をナビゲートすることができると述べている[19]。

近年、伝記はすべてフィクションなのか、特に著者が過去の人物について書いている場合はどうなのかという議論が起きている。オックスフォード大学ウォルフ

ソン・カレッジの学長であるハーマイオニー・リーは、すべての歴史は現代社会の産物である視点を通して見られており、その結果、伝記の真実は常に移り変わ

ると主張している。そのため、伝記作家が書く歴史は、それが起こったとおりのものではなく、彼らが記憶しているとおりのものになる[21]。

ダニエル・R・マイスターは2017年に次のように論じている:

伝記研究は、特にオランダにおいて、独立した学問分野として台頭しつつある。このオランダの伝記学派は、ミクロヒストリーに適応したアプローチを利用する

ことを実践者に奨励することで、伝記研究をあまり学術的でないライフライティングの伝統から歴史学へと移行させている[23]。

伝記研究

伝記的研究は、ミラーによって、構造化されていない綿密なインタビューや、時には半構造化されたインタビューや個人文書によって補強されることによって、

ある人物の全人生や人生の一部を収集・分析する研究方法と定義されている[24]。情報は「オーラルヒストリー、個人的な語り、伝記、自伝」または「日

記、手紙、覚書、その他の資料」から得ることができる[25]。伝記研究の中心的な目的は、人物の豊かな記述を作成すること、または「行動の構造的なタイ

プを概念化する」ことであり、これは「行動の論理、または人物と構造がどのように相互に結びついているかを理解する」ことを意味する[26]。

批判的問題

優れた伝記を書くためには、ほとんど認識されていない落とし穴がたくさんあり、それらは主に、第一に個人と文脈の関係、第二に私的なものと公的なものの関係に関係している。ポール・ジェームズはこう書いている:

このような従来の伝記の問題点は多岐にわたる。伝記は通常、公的なものを私的なものの反映として扱い、私的な領域が基礎であると仮定する。これは、伝記が

ペルソナを投影する公人について書かれることがほとんどであることを考えると、奇妙なことである。つまり、そのような対象にとって、日常生活における自分

自身のプレゼンテーションの支配的な文章は、「自己美化」プロセスとでも呼ぶべきものによってすでに形成されているのである[27]。

|

☆

☆