生物言語学

Biolinguistics

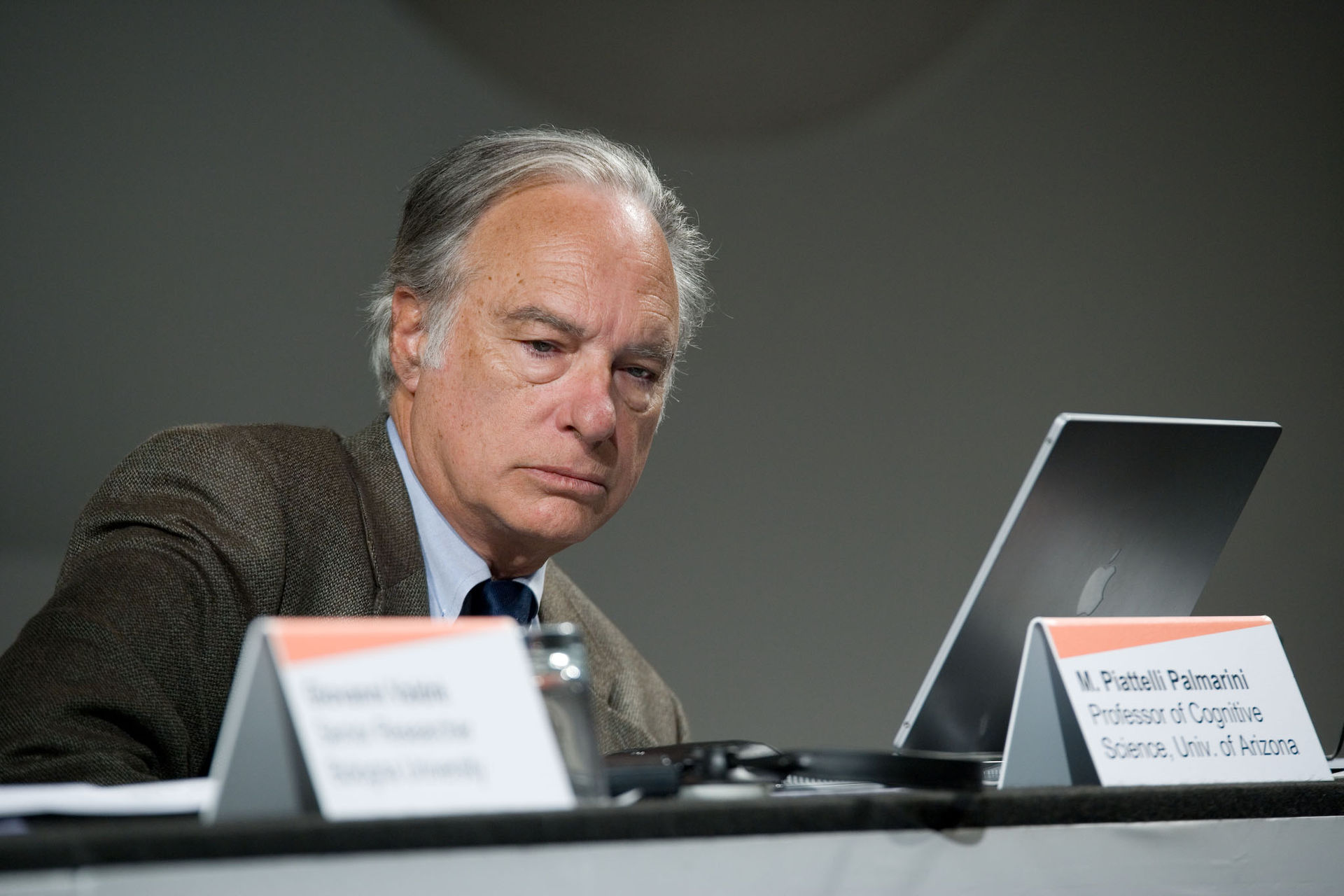

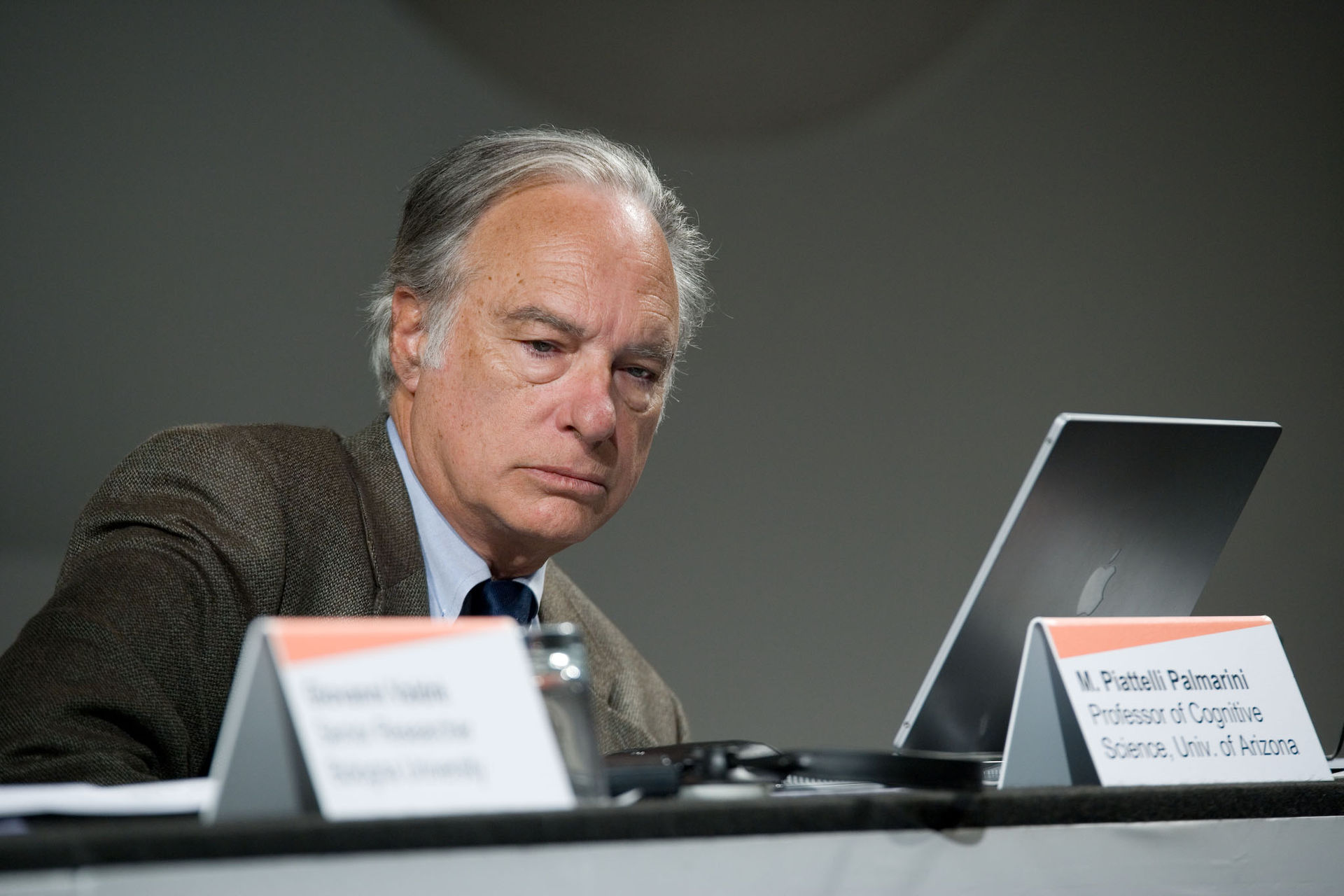

☆ 生物言語学(Biolinguistics) は、言語の生物学的・進化的研究と定義できる。社会生物学、言語学、心理学、人類学、数学、神経言語学など、多様な分野から知見を借りて言語の形成を解明 する点で、極めて学際的な学問だ。言語の能力の根本原理を理解するための枠組みを確立することを目指している。この分野は、アリゾナ大学言語学・認知科学 教授のマッシモ・ピアッテッリ=パルマリーニによって初めて提唱された。1971年にマサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)で開催された国際会議で初めて紹 介された。 生物言語学は、生物言語学的研究や生物言語学的アプローチとも呼ばれ、1950年代にノーム・チョムスキーとエリック・レンネバーグが、当時主流だった行 動主義パラダイムへの反論として始めた言語獲得の研究にその起源があるとされている。本質的に、生物言語学は、人間の言語獲得を刺激と反応の相互作用や関 連性に基づく行動として捉える見方を否定している。[1] チョムスキーとレンネバーグは、言語の先天的な知識を主張することでこれに反対した。チョムスキーは1960年代に、言語獲得のための仮説的なツールとし て「言語獲得装置(LAD)」を提唱した。同様に、レンネバーグ(1967年)[2]は、言語習得は生物学的に制約されているという主要な考えを提唱した 「臨界期仮説」を提唱しました。これらの研究は、言語研究におけるパラダイム転換の始まりにおいて、生物言語学の思想形成の先駆者として評価されている。 [3]

Biolinguistics can

be defined as the biological and evolutionary study of language. It is

highly interdisciplinary as it draws from various fields such as

sociobiology, linguistics, psychology, anthropology, mathematics, and

neurolinguistics to elucidate the formation of language. It seeks to

yield a framework by which one can understand the fundamentals of the

faculty of language. This field was first introduced by Massimo

Piattelli-Palmarini, professor of Linguistics and Cognitive Science at

the University of Arizona. It was first introduced in 1971, at an

international meeting at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

(MIT). Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini Biolinguistics, also called the biolinguistic enterprise or the biolinguistic approach, is believed to have its origins in Noam Chomsky's and Eric Lenneberg's work on language acquisition that began in the 1950s as a reaction to the then-dominant behaviorist paradigm. Fundamentally, biolinguistics challenges the view of human language acquisition as a behavior based on stimulus-response interactions and associations.[1] Chomsky and Lenneberg militated against it by arguing for the innate knowledge of language. Chomsky in 1960s proposed the Language Acquisition Device (LAD) as a hypothetical tool for language acquisition that only humans are born with. Similarly, Lenneberg (1967)[2] formulated the Critical Period Hypothesis, the main idea of which being that language acquisition is biologically constrained. These works were regarded as pioneers in the shaping of biolinguistic thought, in what was the beginning of a change in paradigm in the study of language.[3] |

生物言語学は、言語の生物学的・進化的研究と定義できる。社会生物学、

言語学、心理学、人類学、数学、神経言語学など、多様な分野から知見を借りて言語の形成を解明する点で、極めて学際的な学問だ。言語の能力の根本原理を理

解するための枠組みを確立することを目指している。この分野は、アリゾナ大学言語学・認知科学教授のマッシモ・ピアッテッリ=パルマリーニによって初めて

提唱された。1971年にマサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)で開催された国際会議で初めて紹介された。 マッシモ・ピアッテッリ=パルマリーニ 生物言語学は、生物言語学的研究や生物言語学的アプローチとも呼ばれ、1950年代にノーム・チョムスキーとエリック・レンネバーグが、当時主流だった行 動主義パラダイムへの反論として始めた言語獲得の研究にその起源があるとされている。本質的に、生物言語学は、人間の言語獲得を刺激と反応の相互作用や関 連性に基づく行動として捉える見方を否定している。[1] チョムスキーとレンネバーグは、言語の先天的な知識を主張することでこれに反対した。チョムスキーは1960年代に、言語獲得のための仮説的なツールとし て「言語獲得装置(LAD)」を提唱した。同様に、レンネバーグ(1967年)[2]は、言語習得は生物学的に制約されているという主要な考えを提唱した 「臨界期仮説」を提唱しました。これらの研究は、言語研究におけるパラダイム転換の始まりにおいて、生物言語学の思想形成の先駆者として評価されている。 [3] |

| Origins of biolinguistics The investigation of the biological foundations of language is associated with two historical periods, namely that of the 19th century (primarily via Darwinian evolutionary theory) and the 20th century (primarily via the integration of the mathematical linguistics (in the form of Chomskyan generative grammar) with neuroscience. 19th century: Darwin's theory of evolution Darwinism inspired many researchers to study language, in particular the evolution of language, via the lens of biology. Darwin's theory regarding the origin of language attempts to answer three important questions:[4] Did individuals undergo something like selection as they evolved? Did selection play a role in producing the capacity for language in humans? If selection did play a role, was selection primarily responsible for the emergence of language, was it just one of the several contributing causes? Dating back to 1821, German linguist August Schleicher was the representative pioneer of biolinguistics, discussing the evolution of language based on Darwin's theory of evolution. Since linguistics had been believed to be a form of historical science under the influence of the Société de Linguistique de Paris, speculations of the origin of language were not permitted.[5] As a result, hardly did any prominent linguist write about the origin of language apart from German linguist Hugo Schuchardt. Darwinism addressed the arguments of other researchers and scholars much as Max Müller by arguing that language use, while requiring a certain mental capacity, also stimulates brain development, enabling long trains of thought and strengthening power. Darwin drew an extended analogy between the evolution of languages and species, noting in each domain the presence of rudiments, of crossing and blending, and variation, and remarking on how each development gradually through a process of struggle.[6] |

生物言語学の起源 言語の生物学的基礎の研究は、19 世紀(主にダーウィンの進化論による)と 20 世紀(主に数学言語学(チョムスキーの生成文法)と神経科学の統合による)という 2 つの歴史的時期に関連している。 19 世紀:ダーウィンの進化論 ダーウィニズムは、多くの研究者に、生物学の観点から言語、特に言語の進化について研究するきっかけを与えた。言語の起源に関するダーウィンの理論は、3つの重要な疑問に答えようとしている[4]。 生物は進化する過程で、選択のようなものを受けたのか? 選択は、人間の言語能力の形成に関与したか? 選択が関与した場合、選択は言語の出現の主な要因だったか、それともいくつかの要因のうちの1つにすぎなかったのか? 1821年に遡るドイツの言語学者アウグスト・シュライヒャーは、ダーウィンの進化論に基づいて言語の進化を議論した生物言語学の代表的な先駆者だった。 言語学は、パリ言語学会の影響を受けて歴史科学の一分野とみなされていたため、言語の起源に関する推測は許されていなかった[5]。その結果、ドイツの言 語学者ヒューゴ・シュッチャートを除いて、言語の起源について書いた著名な言語学者はほとんどいなかった。ダーウィニズムは、マックス・ミュラーのよう に、言語の使用には一定の精神的能力が必要であるが、それは脳の発達を刺激し、長い思考を可能にし、思考力を強化すると主張して、他の研究者や学者の議論 に対抗した。ダーウィンは、言語の進化と種の進化との間に広範な類推を引き、それぞれの領域における原始的要素、交雑と融合、および変異の存在を指摘し、 それぞれの進化が闘争の過程を経て徐々に進行することについて述べた。 |

| 20th century: Biological foundation of language The first phase in the development of biolinguistics runs through the late 1960s with the publication of Lennberg's Biological Foundation of Language (1967). During the first phase, work focused on: specifying the boundary conditions for human language as a system of cognition; language development as it presents itself in the acquisition sequence that children go through when they learn a language genetics of language disorders that create specific language disabilities, including dyslexia and deafness) language evolution. During this period, the greatest progress was made in coming to a better understanding of the defining properties of human language as a system of cognition. Three landmark events shaped the modern field of biolinguistics: two important conferences were convened in the 1970s, and a retrospective article was published in 1997 by Lyle Jenkins. 1974: The first official biolinguistic conference was organized by him in 1974, bringing together evolutionary biologists, neuroscientists, linguists, and others interested in the development of language in the individual, its origins and evolution.[7] 1976: another conference was held by the New York Academy of Science, after which numerous works on the origin of language were published.[8] 1997: For the 40th anniversary of transformational-generative grammar, Lyle Jenkins wrote an article titled "Biolinguistics: Structure development and evolution of language".[9] The second phase began in the late 1970s . In 1976 Chomsky formulated the fundamental questions of biolinguistics as follows: i) function, ii) structure, iii) physical basis, iv) development in the individual, v) evolutionary development. In the late 1980s a great deal of progress was made in answering questions about the development of language. This then prompted further questions about language design, function, and, the evolution of language. The following year, Juan Uriagereka, a graduate student of Howard Lasnik, wrote the introductory text to Minimalist Syntax, Rhyme and Reason. Their work renewed interest in biolinguistics, catalysing many linguists to look into biolinguistics with their colleagues in adjacent scientific disciplines.[10] Both Jenkins and Uriagereka stressed the importance of addressing the emergence of the language faculty in humans. At around the same time, geneticists discovered a link between the language deficit manifest by the KE family members and the gene FOXP2. Although FOXP2 is not the gene responsible for language,[11] this discovery brought many linguists and scientists together to interpret this data, renewing the interest of biolinguistics. Although many linguists have differing opinions when it comes to the history of biolinguistics, Chomsky believes that its history was simply that of transformational grammar. While Professor Anna Maria Di Sciullo claims that the interdisciplinary research of biology and linguistics in the 1950s-1960s led to the rise of biolinguistics. Furthermore, Jenkins believes that biolinguistics was the outcome of transformational grammarians studying human linguistic and biological mechanisms. On the other hand, linguists Martin Nowak and Charles Yang argue that biolinguistics, originating in the 1970s, is distinct transformational grammar; rather a new branch of the linguistics-biology research paradigm initiated by transformational grammar.[12] |

20世紀:言語の生物学的基盤 生物言語学の発展の第一段階は、レンバーグの『言語の生物学的基盤』(1967年)の出版により、1960年代後半にかけて進んだ。この第一段階では、以下の点に重点が置かれた。 認知システムとしての言語の境界条件を明確にする。 子どもが言語を習得する過程における言語の発達。 失読症や難聴などの特定の言語障害を引き起こす言語障害の遺伝学 言語の進化。 この期間、認知システムとしての人間の言語の決定的な特性をより深く理解する上で、最大の進歩が見られた。3つの画期的な出来事が、現代の生物言語学の分 野を形作った。1970年代に2つの重要な会議が開催され、1997年にライル・ジェンキンズによって回顧記事が発表された。 1974年:1974年に、彼によって最初の公式な生物言語学会議が開催され、進化生物学者、神経科学者、言語学者、および個人の言語の発達、その起源と進化に関心のある人々が一堂に会した。[7] 1976年:ニューヨーク科学アカデミーによって別の会議が開催され、その後、言語の起源に関する数多くの著作が発表された。[8] 1997年:変形生成文法の40周年を記念して、ライル・ジェンキンズは「生物言語学:言語の構造の発達と進化」という記事を書いた。[9] 第2段階は1970年代後半に始まった。1976年、チョムスキーは生物言語学の基本的な問題を次のように定式化した。i)機能、ii)構造、iii)物 理的基盤、iv)個人における発達、v)進化の発達。1980年代後半、言語の発達に関する疑問の答えが大幅に前進した。これにより、言語の設計、機能、 そして言語の進化に関するさらなる疑問が提起された。翌年、ハワード・ラスニックの大学院生であるフアン・ウリアゲレカが、ミニマリスト構文の入門書 『Rhyme and Reason』を執筆した。彼らの研究は、生物言語学への関心を再び高め、多くの言語学者が、関連科学分野の同僚たちとともに生物言語学の研究に取り組む きっかけとなった[10]。ジェンキンズとウリアゲレカは、人間における言語能力の出現に取り組むことの重要性を強調した。ほぼ同時期に、遺伝学者は、 KE 家族に見られる言語障害と FOXP2 遺伝子との関連を発見した。FOXP2 は言語を担当する遺伝子ではないが[11]、この発見により、多くの言語学者や科学者がこのデータを解釈するために集まり、生物言語学への関心が再び高 まった。 生物言語学の歴史については、多くの言語学者たちが異なる見解を持っているが、チョムスキーは、その歴史は単に変換文法史に他ならないと主張している。一 方、アンナ・マリア・ディ・スキウロ教授は、1950年代から1960年代にかけての生物学と言語学の学際的研究が、生物言語学の台頭につながったと主張 している。さらに、ジェンキンは、生物言語学は、人間の言語および生物学的メカニズムを研究した変換文法学者たちの成果であると主張している。一方、言語 学者のマーティン・ノワクとチャールズ・ヤンは、1970年代に始まった生物言語学は、変換文法とはまったく別の、変換文法によって開始された言語学と生 物学の研究パラダイムの新しい分野であると主張している。[12] |

| Developments Chomsky's Theories Universal Grammar and Generative Grammar Main article: Universal grammar Noam Chomsky In Aspects of the theory of Syntax, Chomsky proposed that languages are the product of a biologically determined capacity present in all humans, located in the brain. He addresses three core questions of biolinguistics: what constitutes the knowledge of language, how is knowledge acquired, how is the knowledge put to use? A great deal of ours must be innate, supporting his claim with the fact that speakers are capable of producing and understanding novel sentences without explicit instructions. Chomsky proposed that the form of the grammar may emerge from the mental structure afforded by the human brain and argued that formal grammatical categories such as nouns, verbs, and adjectives do not exist. The linguistic theory of generative grammar thereby proposes that sentences are generated by a subconscious set of procedures which are part of an individual's cognitive ability. These procedures are modeled through a set of formal grammatical rules which are thought to generate sentences in a language.[13] Chomsky focuses on the mind of the language learner or user and proposed that internal properties of the language faculty are closely linked to the physical biology of humans. He further introduced the idea of a Universal Grammar (UG) theorized to be inherent to all human beings. From the view of Biolinguistic approach, the process of language acquisition would be fast and smooth because humans naturally obtain the fundamental perceptions toward Universal Grammar, which is opposite to the usage-based approach.[14] UG refers to the initial state of the faculty of language; a biologically innate organ that helps the learner make sense of the data and build up an internal grammar.[15] The theory suggests that all human languages are subject to universal principles or parameters that allow for different choices (values). It also contends that humans possess generative grammar, which is hard-wired into the human brain in some ways and makes it possible for young children to do the rapid and universal acquisition of speech.[16] Elements of linguistic variation then determine the growth of language in the individual, and variation is the result of experience, given the genetic endowment and independent principles reducing complexity. Chomsky's work is often recognized as the weak perspective of biolinguistics as it does not pull from other fields of study outside of linguistics.[17] |

発展 チョムスキーの理論 普遍文法と生成文法 主な記事:普遍文法 ノーム・チョムスキー 『文法理論の諸側面』において、チョムスキーは、言語は、すべての人間に生物学的に決定された能力の産物であり、脳に存在すると提唱した。彼は、生物言語 学の3つの核心的な問題、すなわち「言語の知識とは何であるか」、「知識はどのように獲得されるか」、「知識はどのように活用されるか」を取り上げてい る。その多くは生得的なものでなければならないと主張し、話者は明示的な指示なしに新しい文を生成し理解することができるという事実をその根拠としてい る。チョムスキーは、文法の形式は人間の脳が提供する精神構造から生じると提案し、名詞、動詞、形容詞などの形式的な文法カテゴリーは存在しないと主張し た。生成文法理論は、文は個人の認知能力の一部である無意識のプロセスによって生成されると提案している。これらのプロセスは、言語の文を生成すると考え られる形式的な文法規則のセットを通じてモデル化されている。[13] チョムスキーは言語学習者や使用者の心に焦点を当て、言語能力の内部的特性は人間の物理的生物学と密接に関連していると提唱した。さらに、すべての人間に 内在するとされる「普遍文法(UG)」の概念を導入した。生物言語学的なアプローチの立場から、言語習得のプロセスは迅速かつスムーズであると考えられ る。これは、人間が普遍文法に対する基本的な認識を自然に獲得するためであり、使用に基づくアプローチとは対照的だ。[14] UG は、言語能力の初期状態を指し、学習者がデータを理解し、内部文法構築を支援する、生物学的に生来の器官である。[15] この理論は、すべての人間の言語は、異なる選択(値)を可能にする普遍的な原則またはパラメータに従っていることを示唆している。また、人間は生成文法を 有しており、これが人間の脳に何らかの形で先天的に組み込まれているため、幼い子供が言語を急速かつ普遍的に習得することが可能になると主張している。 [16] 言語の変異の要素が個人の言語の発達を決定し、変異は遺伝的素因と複雑さを減らす独立した原則に基づいて経験から生じる。チョムスキーの著作は、言語学以 外の分野の研究成果を引用していないため、生物言語学の弱点としてよく指摘されている。[17] |

| Modularity Hypothesis According to Chomsky, the human's brains consist of various sections which possess their individual functions, such as the language faculty, visual recognition.[14] |

モジュール性仮説 チョムスキーによると、人間の脳は、言語能力や視覚認識など、それぞれの機能を持つさまざまな部分で構成されている[14]。 |

| Language Acquisition Device Main article: Language Acquisition The acquisition of language is a universal feat and it is believed we are all born with an innate structure initially proposed by Chomsky in the 1960s. The Language Acquisition Device (LAD) was presented as an innate structure in humans which enabled language learning. Individuals are thought to be "wired" with universal grammar rules enabling them to understand and evaluate complex syntactic structures. Proponents of the LAD often quote the argument of the poverty of negative stimulus, suggesting that children rely on the LAD to develop their knowledge of a language despite not being exposed to a rich linguistic environment. Later, Chomsky exchanged this notion instead for that of Universal Grammar, providing evidence for a biological basis of language. |

言語習得装置 主な記事:言語習得 言語の習得は普遍的な能力であり、1960年代にチョムスキーが最初に提唱した、人間には生まれつき備わっている構造があると考えられている。言語習得装 置(LAD)は、言語の学習を可能にする、人間生まれつきの構造として提唱された。人間は、複雑な構文構造を理解し評価することを可能にする、普遍的な文 法規則が「組み込まれている」と考えられている。LADの支持者は、否定的な刺激の貧困という論拠を引用し、子どもたちは豊かな言語環境にさらされていな いにもかかわらず、LADに依存して言語の知識を発達させると主張している。その後、チョムスキーはこの概念を普遍文法に置き換え、言語の生物学的基盤を 示す証拠を提供した。 |

| Minimalist Program Main article: Minimalist Program The Minimalist Program (MP) was introduced by Chomsky in 1993, and it focuses on the parallel between language and the design of natural concepts. Those invested in the Minimalist Program are interested in the physics and mathematics of language and its parallels with our natural world. For example, Piatelli-Palmarini[18] studied the isomorphic relationship between the Minimalist Program and Quantum Field Theory. The Minimalist Program aims to figure out how much of the Principles and Parameters model can be taken as a result of the hypothetical optimal and computationally efficient design of the human language faculty and more developed versions of the Principles and Parameters approach in turn provide technical principles from which the minimalist program can be seen to follow.[19] The program further aims to develop ideas involving the economy of derivation and economy of representation, which had started to become an independent theory in the early 1990s, but were then still considered as peripherals of transformational grammar.[20] |

ミニマリスト・プログラム 主な記事:ミニマリスト・プログラム ミニマリスト・プログラム(MP)は、1993年にチョムスキーによって提唱され、言語と自然概念の設計との類似性に焦点を当てている。ミニマリスト・プ ログラムに関心のある人々は、言語の物理学や数学、そしてそれらが私たちの自然界と類似している点に関心を持っている。例えば、ピアテッリ=パルマーニ [18]は、ミニマリスト・プログラムと量子場理論の同型関係を研究した。ミニマリスト・プログラムは、原則とパラメータモデルのうち、人間の言語能力の 仮説的な最適で計算効率の高い設計の結果として説明できる部分がどの程度あるかを明らかにすることを目的としている。さらに、原則とパラメータアプローチ のより発展したバージョンは、ミニマリスト・プログラムが導かれる技術的原則を提供するものとなる。[19] このプログラムはさらに、1990年代初頭に独立した理論として台頭し始めた「導出の経済性」と「表象の経済性」に関するアイデアを発展させることを目指 している。しかし、これらのアイデアは当時、変換文法の一部の周辺概念として捉えられていた。[20] |

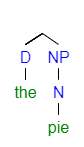

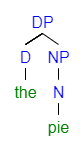

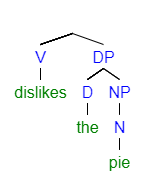

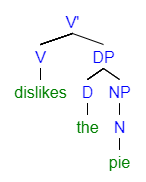

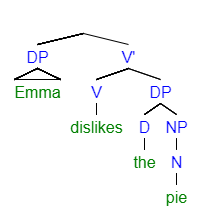

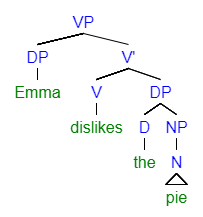

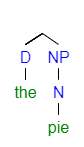

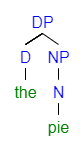

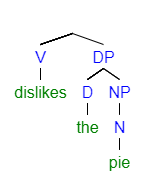

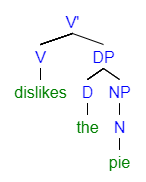

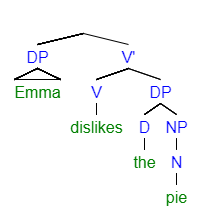

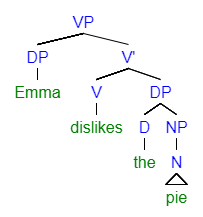

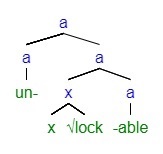

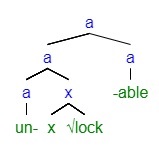

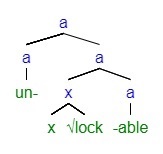

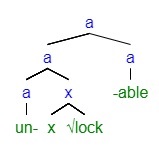

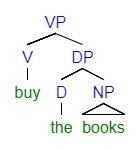

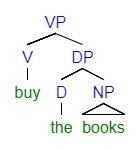

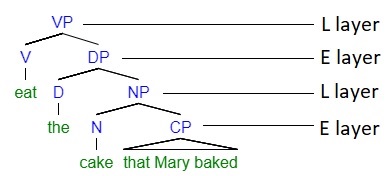

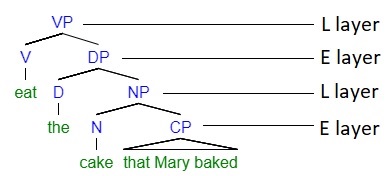

| Merge The Merge operation is used by Chomsky to explain the structure of syntax trees within the Minimalist program. Merge itself is a process which provides the basis of phrasal formation as a result of taking two elements within a phrase and combining them[21] In A.M. Di Sciullo & D. Isac's The Asymmetry of Merge (2008), they highlight the two key bases of Merge by Chomsky; Merge is binary Merge is recursive In order to understand this, take the following sentence: Emma dislikes the pie This phrase can be broken down into its lexical items: [VP [DP Emma] [V' [V dislikes] [DP [D the] [NP pie]]]] The above phrasal representation allows for an understanding of each lexical item. In order to build a tree using Merge, using bottom-up formation the two final elements of the phrase are selected and then combined to form a new element on the tree. In image a) you can see that the determiner the and the Noun Phrase pie are both selected. Through the process of Merge, the new formed element on the tree is the determiner Phrase (DP) which holds, the pie, which is visible in b). |

マージ マージ操作は、チョムスキーがミニマリストプログラム内の構文木の構造を説明するために使用する。マージ自体は、句内の2つの要素を取り出してそれらを結 合することで、句の形成の基礎を提供するプロセスだ[21]。A.M. Di Sciullo & D. Isacの『The Asymmetry of Merge』(2008)では、チョムスキーによるマージの2つの重要な基盤が強調されている。 Merge は二項操作である Merge は再帰的である これを理解するために、次の文を考えてみよう:Emma dislikes the pie このフレーズは、その語彙項目に分解することができる: [VP [DP Emma] [V' [V dislikes] [DP [D the] [NP pie]]]] 上記のフレーズ表現により、各語彙項目の理解が可能になる。Mergeを使用して木構造を構築するには、ボトムアップ形成を用いて、句の最終要素を2つ選 択し、それらを結合して木構造上の新しい要素を形成する。図a)では、限定詞theと名詞句pieが選択されていることがわかる。Mergeのプロセスを 通じて、木構造上に形成された新しい要素は、限定詞句(DP)であり、これにはpieが含まれる。これは図b)で確認できる。 |

a) Selection of the final two element of the phrase  b) The two selected elements are then "merged" and they produce one new constituent, known as the Determiner Phrase (DP)  c) Selection of DP the pie with V dislikes  d) Merge operation has occurred, yielded new element on tree, V' (V-bar)  e) Selection of V' dislikes the pie and DP subject Emma  f) Merge operation has undergone, yielded new element on tree; VP |

a) フレーズから最後の 2 つの要素を選択する  b) 選択された 2 つの要素は「マージ」され、1 つの新しい構成要素、つまり限定句 (DP) を作成する  c) DP「the pie with V」の選択  d) 合併操作が発生し、木に新しい要素 V『(V-bar)が生成された  e) V' がパイを嫌うという選択と、DP の主語 Emma  f) 合併操作が実行され、木に新しい要素 VP が生成された |

| Core components In a minimalist approach, there are three core components of the language faculty proposed: Sensory-Motor system (SM), Conceptual-Intentional system (CI), and Narrow Syntax (NS).[22] SM includes biological requisites for language production and perception, such as articulatory organs, and CI meets the biological requirements related to inference, interpretation, and reasoning, those involved in other cognitive functions. As SM and CI are finite, the main function of NS is to make it possible to produce infinite numbers of sound-meaning pairs. |

コアコンポーネント ミニマリストのアプローチでは、言語能力には 3 つのコアコンポーネントがあることが提案されている。感覚運動システム (SM)、概念意図システム (CI)、および狭義の構文 (NS) だ[22]。SM には、発声器官など、言語の生成と認識に必要な生物学的要件が含まれ、CI は、他の認知機能に関与する推論、解釈、推論に関連する生物学的要件を満たしている。SMとCIは有限であるため、NSの主な機能は、無限の音と意味のペ アを生成可能にすることです。 |

| Relevance of Natural Law It is possible that the core principles of The Faculty of Language be correlated to natural laws (such as for example, the Fibonacci sequence— an array of numbers where each consecutive number is a sum of the two that precede it, see for example the discussion Uriagereka 1997 and Carnie and Medeiros 2005).[23] According to the hypothesis being developed, the essential properties of language arise from nature itself: the efficient growth requirement appears everywhere, from the pattern of petals in flowers, leaf arrangements in trees and the spirals of a seashell to the structure of DNA and proportions of human head and body. Natural Law in this case would provide insight on concepts such as binary branching in syntactic trees and well as the Merge operation. This would translate to thinking it in terms of taking two elements on a syntax tree and such that their sum yields another element that falls below on the given syntax tree (Refer to trees above in Minimalist Program). By adhering to this sum of two elements that precede it, provides support for binary structures. Furthermore, the possibility of ternary branching would deviate from the Fibonacci sequence and consequently would not hold as strong support to the relevance of Natural Law in syntax.[24] |

自然法則の関連性 言語学部の基本原則は、自然法則(例えば、フィボナッチ数列(連続する数字の2つを足した数字が次の数字になる数列、例えば Uriagereka 1997 および Carnie and Medeiros 2005 の議論を参照)など)と相関している可能性がある。[23] 開発中の仮説によると、言語の根本的な性質は自然そのものから生じている:効率的な成長の要件は、花の petals のパターン、木の葉の配置、貝殻の螺旋から、DNA の構造や人間の頭と体の比例まで、至る所に現れる。この場合の自然法則は、構文木における二分木分岐や Merge 操作といった概念への洞察を提供する。これは、文法木上の2つの要素を取り、その和が与えられた文法木の下に属する別の要素を生成するものと考えることに 相当する(ミニマリスト・プログラムの上記の樹形図を参照)。この2つの要素の和が先行する構造に従うことで、二分構造の支持が得られる。さらに、三元分 岐の可能性はフィボナッチ数列から逸脱し、その結果、構文における自然法則の関連性を強く支持する根拠とはならない。[24] |

| Biolinguistics: Challenging the Usage-Based Approach As mentioned above, biolinguistics challenges the idea that the acquisition of language is a result of behavior based learning. This alternative approach the biolinguistics challenges is known as the usage-based (UB) approach. UB supports that idea that knowledge of human language is acquired via exposure and usage.[25] One of the primary issues that is highlighted when arguing against the Usage-Based approach, is that UB fails to address the issue of poverty of stimulus,[26] whereas biolinguistics addresses this by way of the Language Acquisition Device.[27] |

生物言語学:使用に基づくアプローチへの挑戦 前述のように、生物言語学は、言語の習得は行動に基づく学習の結果であるという考えに異議を唱えている。生物言語学が挑戦しているこの代替的なアプローチ は、使用に基づく(UB)アプローチとして知られている。UBは、人間の言語の知識は曝露と使用を通じて獲得されるという考えを支持している。[25] 使用に基づくアプローチに反対する際に指摘される主要な問題の一つは、UBが刺激の貧困の問題に対応していない点である。[26] 一方、生物言語学は言語獲得装置(Language Acquisition Device)を通じてこの問題に対応している。[27] |

| Lenneberg and the Role of Genes Another major contributor to the field is Eric Lenneberg. In is book Biological Foundation of Languages,[2] Lenneberg (1967) suggests that different aspects of human biology that putatively contribute to language more than genes at play. This integration of other fields to explain language is recognized as the strong view in biolinguistics[28] While they are obviously essential, and while genomes are associated with specific organisms, genes do not store traits (or "faculties") in the way that linguists—including Chomskyans—sometimes seem to imply. Contrary to the concept of the existence of a language faculty as suggested by Chomsky, Lenneberg argues that while there are specific regions and networks crucially involved in the production of language, there is no single region to which language capacity is confined and that speech, as well as language, is not confined to the cerebral cortex. Lenneberg considered language as a species-specific mental organ with significant biological properties. He suggested that this organ grows in the mind/brain of a child in the same way that other biological organs grow, showing that the child's path to language displays the hallmark of biological growth. According to Lenneberg, genetic mechanisms plays an important role in the development of an individual's behavior and is characterized by two aspects: The acknowledgement of an indirect relationship between genes and traits, and; The rejection of the existence of 'special' genes for language, that is, the rejection of the need for a specifically linguistic genotype; Based on this, Lenneberg goes on further to claim that no kind of functional principle could be stored in an individual's genes, rejecting the idea that there exist genes for specific traits, including language. In other words, that genes can contain traits. He then proposed that the way in which genes influence the general patterns of structure and function is by means of their action upon ontogenesis of genes as a causal agent which is individually the direct and unique responsible for a specific phenotype, criticizing prior hypothesis by Charles Goodwin.[29] |

レネバーグと遺伝子の役割 この分野に多大な貢献をしたもう一人の人物は、エリック・レネバーグだ。レネバーグ(1967)は著書『Biological Foundation of Languages』[2] の中で、言語の発達には遺伝子よりも、人間の生物学的特性のさまざまな側面が影響していると示唆している。言語を説明するために他の分野を統合するこのア プローチは、生物言語学における強固な見解として認識されている[28]。遺伝子は明らかに不可欠であり、特定の生物と関連しているが、言語学者(チョム スキー派を含む)が時折示唆するように、遺伝子は特性(または「能力」)を保存するものではない。 チョムスキーが提唱する言語能力の存在概念に反して、レンネバーグは、言語の生成に不可欠な特定の領域やネットワークは存在するが、言語能力が限定される 単一の領域は存在せず、言語と同様に発話も大脳皮質に限定されないことを主張している。レンネバーグは、言語を種特異的な精神器官として捉え、生物学的な 特性を持つものとして考えた。彼は、この器官が他の生物の器官と同様に、子供の心/脳で成長し、子供の言語獲得の過程が生物学的成長の特性を示すことを示 した。レンネバーグによると、遺伝的メカニズムは個体の行動の発達に重要な役割を果たし、以下の2つの特徴を有する: 遺伝子と形質の間には間接的な関係があること、および; 言語のための「特別な」遺伝子の存在を否定すること、つまり、言語に特化した遺伝型が必要であるという考えを否定すること; これに基づいて、レンネバーグはさらに、個体の遺伝子に機能的な原理が保存されていることはないと主張し、言語を含む特定の形質のための遺伝子が存在する という考えを否定した。つまり、遺伝子は特性を包含する可能性があるということです。彼はさらに、遺伝子が構造と機能の一般的なパターンに影響を与える方 法は、個々の表現型に対して直接的かつ唯一の原因となる因果的要因として、遺伝子の発生過程に作用することによるものだと提案し、チャールズ・グッドウィ ンの以前の仮説を批判しています。[29] |

| Recent Developments Generative Procedure Accepted At Present & Its Developments In biolinguistics, language is recognised to be based on recursive generative procedure that retrieves words from the lexicon and applies them repeatedly to output phrases.[30][31] This generative procedure was hypothesised to be a result of a minor brain mutation due to evidence that word ordering is limited to externalisation and plays no role in core syntax or semantics. Thus, different lines of inquiry to explain this were explored. The most commonly accepted line of inquiry to explain this is Noam Chomsky's minimalist approach to syntactic representations. In 2016, Chomsky and Berwick defined the minimalist program under the Strong Minimalist Thesis in their book Why Only Us by saying that language is mandated by efficient computations and, thus, keeps to the simplest recursive operations.[11] The main basic operation in the minimalist program is merge. Under merge there are two ways in which larger expressions can be constructed: externally and internally. Lexical items that are merged externally build argument representations with disjoint constituents. The internal merge creates constituent structures where one is a part of another. This induces displacement, the capacity to pronounce phrases in one position, but interpret them elsewhere. Recent investigations of displacement concur to a slight rewiring in cortical brain regions that could have occurred historically and perpetuated generative grammar. Upkeeping this line of thought, in 2009, Ramus and Fishers speculated that a single gene could create a signalling molecule to facilitate new brain connections or a new area of the brain altogether via prenatally defined brain regions. This would result in information processing greatly important to language, as we know it. The spread of this advantage trait could be responsible for secondary externalisation and the interaction we engage in.[11] If this holds, then the objective of biolinguistics is to find out as much as we can about the principles underlying mental recursion. |

最近の動向 現在受け入れられている生成手続きとその発展 生物言語学では、言語は、語彙から単語を取り出し、それを繰り返し出力フレーズに適用する再帰的な生成手順に基づいていると認識されている[30] [31]。この生成手順は、単語の順序は外部化に限定されており、コアの構文や意味論には何の影響も与えないという証拠から、軽微な脳の突然変異の結果で あると仮定された。そこで、これを説明するためのさまざまな研究が探求された。 この現象を説明する最も広く受け入れられている研究アプローチは、ノーム・チョムスキーの文法表現に関するミニマリストアプローチだ。2016年、チョム スキーとバーウィックは、著書『Why Only Us』において、言語は効率的な計算によって規定され、したがって最も単純な再帰的操作に限定されるという「強固なミニマリストテーゼ」の下でミニマリス トプログラムを定義した。[11] ミニマリストプログラムにおける主要な基本操作は「マージ」だ。マージの下では、より大きな表現を構築する2つの方法がある:外部と内部。外部マージで は、語彙項目が離散的な構成要素で論理構造を構築する。内部マージでは、一つの構成要素が別の構成要素の一部となる構成要素構造が作成される。これによ り、フレーズをある位置で発音するが、別の位置で解釈する能力である「置換」が生じる。 置換に関する最近の研究は、歴史的に発生し、生成文法を永続させた可能性のある皮質脳領域の軽微な再配線と一致している。この考え方を維持し、2009年 にRamusとFishersは、単一の遺伝子が、胎児期に定義された脳領域を介して新しい脳接続や新しい脳領域全体を促進するシグナル分子を生成する可 能性を推測した。これは、私たちが知る言語にとって極めて重要な情報処理をもたらす。この有利な特性の拡散が、二次的な外部化と私たちが関与する相互作用 の責任者である可能性がある。[11] これが正しい場合、生物言語学の目的は、精神的な再帰の基盤となる原則について可能な限り多くのことを明らかにすることになる。 |

| Human versus Animal Communication Compared to other topics in linguistics where data can be displayed with evidence cross-linguistically, due to the nature of biolinguistics, and that it is applies to the entirety of linguistics rather than just a specific subsection, examining other species can assist in providing data. Although animals do not have the same linguistic competencies as humans, it is assumed that they can provide evidence for some linguistic competence. The relatively new science of evo-devo that suggests everyone is a common descendant from a single tree has opened pathways into gene and biochemical study. One way in which this manifested within biolinguistics is through the suggestion of a common language gene, namely FOXP2. Though this gene is subject to debate, there have been interesting recent discoveries made concerning it and the part it plays in the secondary externalization process. Recent studies of birds and mice resulted in an emerging consensus that FOXP2 is not a blueprint for internal syntax nor the narrow faculty of language, but rather makes up the regulatory machinery pertaining to the process of externalization. It has been found to assist sequencing sound or gesture one after the next, hence implying that FOXP2 helps transfer knowledge from declarative to procedural memory. Therefore, FOXP2 has been discovered to be an aid in formulating a linguistic input-output system that runs smoothly.[11] |

人間と動物のコミュニケーション 言語学の他の分野では、言語横断的な証拠を用いてデータを示すことが可能ですが、生物言語学の性質上、特定のサブ分野ではなく言語学全体に適用されるた め、他の種を調査することはデータ提供に役立ちます。動物は人間と同じ言語能力を持っていませんが、一部の言語能力に関する証拠を提供できると仮定されて います。 進化発生生物学(エボデボ)という比較的新しい科学は、すべての生物が単一の系統樹から共通の祖先を持つと提唱し、遺伝子や生化学的研究への道を開いた。 この概念が生物言語学において具体化した一つが、共通の言語遺伝子として提唱されたFOXP2だ。この遺伝子は議論の的となっているが、最近、その役割に 関する興味深い発見が報告されている。鳥とマウスに関する最近の研究では、FOXP2は内部文法の設計図や言語の狭義の機能ではなく、外部化プロセスに関 連する調節機構を構成するものであるという共通の見解が浮上している。この遺伝子は、音やジェスチャーを順番に並べるのを助けることが判明しており、これ によりFOXP2が宣言的記憶から手続き的記憶への知識の転送を助けることが示唆されている。したがって、FOXP2は、言語の入力-出力システムをス ムーズに機能させるための支援因子であることが発見された。[11] |

| The Integration Hypothesis According to the Integration Hypothesis, human language is the combination of the Expressive (E) component and the Lexical (L) component. At the level of words, the L component contains the concept and meaning that we want to convey. The E component contains grammatical information and inflection. For phrases, we often see an alternation between the two components. In sentences, the E component is responsible for providing the shape and structure to the base-level lexical words, while these lexical items and their corresponding meanings found in the lexicon make up the L component.[32] This has consequences for our understanding of: (i) the origins of the E and L components found in bird and monkey communication systems; (ii) the rapid emergence of human language as related to words; (iii) evidence of hierarchical structure within compound words; (iv) the role of phrases in the detection of the structure building operation Merge; and (v) the application of E and L components to sentences. In this way, we see that the Integration Hypothesis can be applied to all levels of language: the word, phrasal, and sentence level. |

統合仮説 統合仮説によると、人間の言語は表現成分(E)と語彙成分(L)の組み合わせである。単語のレベルでは、L 成分には、私たちが伝えたい概念や意味が含まれている。E 成分には、文法情報や活用形が含まれている。句では、この2つの要素が交互に現れることがよく見られる。文では、E要素は基底レベルの語彙単語の形と構造 を提供し、語彙辞書に存在するこれらの語彙項目とその対応する意味がL要素を構成する。[32]これは、以下の理解に重要な意味を持つ: (i) 鳥と猿のコミュニケーションシステムにおけるEとLの成分の起源;(ii) 単語に関連する人間の言語の急速な出現;(iii) 複合語内の階層構造の証拠;(iv) 構造構築操作Mergeの検出における句の役割;および(v) 文へのEとLの成分の適用。このように、統合仮説は言語のすべてのレベル(単語、句、文)に適用可能であることがわかる。 |

| The Origins of the E and L systems in Bird and Monkey Communication Systems Through the application of the Integration Hypothesis, it can be seen that the interaction between the E and L components enables language structure (E component) and lexical items (L component) to operate simultaneously within one form of complex communication: human language. However, these two components are thought to have emerged from two pre-existing, separate, communication systems in the animal world.[32] The communication systems of birds[33] and monkeys[34] have been found to be antecedents to human language. The bird song communication system is made up entirely of the E component while the alarm call system used by monkeys is made up of the L component. Human language is thought to be the byproduct of these two separate systems found in birds and monkeys, due to parallels between human communication and these two animal communication systems. The communication systems of songbirds is commonly described as a system that is based on syntactic operations. Specifically, bird song enables the systematic combination of sound elements in order to string together a song. Likewise, human languages also operate syntactically through the combination of words, which are calculated systematically. While the mechanics of bird song thrives off of syntax, it appears as though the notes, syllables, and motifs that are combined in order to elicit the different songs may not necessarily contain any meaning.[35] The communication system of songbirds' also lacks a lexicon[36] that contains a set of any sort of meaning-to-referent pairs. Essentially, this means that an individual sound produced by a songbird does not have meaning associated with it, the way a word does in human language. Bird song is capable of being structured, but it is not capable of carrying meaning. In this way, the prominence of syntax and the absence of lexical meaning presents bird song as a strong candidate for being a simplified antecedent of the E component that is found in human language, as this component also lacks lexical information. While birds that use bird song can rely on just this E component to communicate, human utterances require lexical meaning in addition to structural operations a part of the E component, as human language is unable to operate with just syntactic structure or structural function words alone. This is evident as human communication does in fact consist of a lexicon, and humans produce combined sequences of words that are meaningful, best known as sentences. This suggests that part of human language must have been adapted from another animal's communication system in order for the L component to arise . A well known study by Seyfarth et al.[34] investigated the referential nature of the alarm calls of vervet monkeys. These monkeys have three set alarm calls, with each call directly mapping on to one of the following referents: a leopard, an eagle, or a snake. Each call is used to warn other monkeys about the presence of one of these three predators in their immediate environmental surroundings. The main idea is that the alarm call contains lexical information that can be used to represent the referent that is being referred to. Essentially, the entire communication system used by monkeys is made up of the L system such that only these lexical-based calls are needed to effectively communicate. This is similar to the L component found in human language in which content words are used to refer to a referent in the real world, containing the relevant lexical information. The L component in human language is, however, a much more complex variant of the L component found in vervet monkey communication systems: humans use many more than just 3 word-forms to communicate. While vervet monkeys are capable of communicating solely with the L component, humans are not, as communication with just content words does not output well-formed grammatical sentences. It is for this reason that the L component is combined with the E component responsible for syntactic structure in order to output human language. |

鳥とサルにおけるEシステムとLシステムの起源 統合仮説を適用すると、E成分とL成分の相互作用により、言語構造(E成分)と語彙項目(L成分)が、複雑なコミュニケーションの一形態である人間言語の 中で同時に機能することがわかる。しかし、これらの2つの成分は、動物界に既に存在していた2つの独立したコミュニケーションシステムから進化したと考え られている。[32] 鳥のコミュニケーションシステム[33]とサル[34]のコミュニケーションシステムは、人間の言語の先駆的な形態であることが判明している。鳥の歌のコ ミュニケーションシステムはE成分のみで構成されており、サルの警戒鳴きシステムはL成分のみで構成されている。人間の言語は、人間のコミュニケーション とこれらの2つの動物のコミュニケーションシステムとの類似点から、鳥類とサルに見られる2つの別々のシステムの副産物であると考えられている。 鳴き鳥のコミュニケーションシステムは、一般的に、構文操作に基づくシステムとして説明されている。具体的には、鳥の鳴き声は、歌をつなげるために音要素 を体系的に組み合わせることを可能にする。同様に、人間の言語も、体系的に計算された単語の組み合わせによって構文的に機能している。鳥の鳴き声のメカニ ズムは構文によって成り立っているが、異なる鳴き声を出すために組み合わせられる音、音節、モチーフには、必ずしも意味が含まれているわけではないようだ [35]。また、鳴き鳥のコミュニケーションシステムには、意味と参照対象を結びつける一連の語彙[36]も存在しない。本質的に、これは歌鳥が生産する 個々の音には、人間の言語における単語のように意味が関連付けられていないことを意味する。鳥の歌は構造化可能だが、意味を伝えることはできない。この点 で、文法の優位性と語彙的意味の欠如は、鳥の歌を人間の言語におけるE成分の単純化された先駆的形態として有力な候補として提示する。このE成分もまた、 語彙情報を欠いているからである。鳥の歌を使用する鳥は、このE成分だけでコミュニケーションが可能ですが、人間の言語は、E成分の一部である構造的操作 に加え、語彙的意味を必要とします。なぜなら、人間の言語は、文法構造や構造的機能語 alone では機能しないからです。これは、人間のコミュニケーションが実際に語彙から成り立ち、人間が意味のある単語の組み合わせである文を生成する事実から明ら かです。これは、L 成分が生まれるためには、人間の言語の一部が他の動物のコミュニケーションシステムから適応された必要があることを示唆している。 Seyfarth ら[34]によるよく知られた研究では、ベールモンキーの警戒鳴き声の参照的性質が調査された。これらのサルは 3 種類の警戒鳴き声を持っており、各鳴き声は次の参照対象のいずれかに直接対応している:ヒョウ、ワシ、ヘビ。各鳴き声は、これらの3つの捕食者のいずれか が直近の環境にいることを他のサルに警告するために使用される。主なアイデアは、警報鳴き声には、参照されている参照対象を表すための語彙情報が含まれて いることだ。本質的に、サルが使用するコミュニケーションシステム全体はLシステムから構成されており、効果的にコミュニケーションを取るためにはこれら の語彙に基づく鳴き声のみが必要だ。これは、人間の言語におけるL成分と類似している。人間の言語では、内容語が現実世界の参照対象を指し、関連する語彙 情報を含む。しかし、人間の言語におけるL成分は、ヴェルヴェットモンキーのコミュニケーションシステムにおけるL成分のより複雑な変種である。人間は、 コミュニケーションに3つの単語形態を超える多くの単語形態を使用する。ヴェルヴェットモンキーはLコンポーネントのみでコミュニケーションが可能です が、人間はそうではありません。なぜなら、内容語のみを使用したコミュニケーションでは、文法的に正しい文を生成できないからです。このため、人間の言語 を生成するためには、Lコンポーネントと文法構造を担当するEコンポーネントが組み合わされています。 |

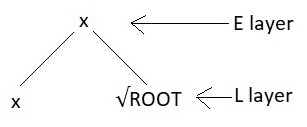

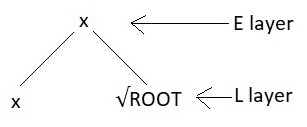

| The Rapid Emergence of Human Language As traces of the E and L components have been found in nature, the integration hypothesis asserts that these two systems existed before human language, and that it was the combination of these two pre-existing systems that rapidly led to the emergence of human language.[32] The Integration Hypothesis posits that it was the grammatical operator, Merge, that triggered the combination of the E and L systems to create human language.[37] In this view, language emerged rapidly and fully formed, already containing syntactical structure. This is in contrast to the Gradualist Approach, where it is thought that early forms of language did not have syntax. Instead, supporters of the Gradualist Approach believe language slowly progressed through a series of stages as a result of a simple combinatory operator that generated flat structures. Beginning with a one-word stage, then a two-word stage, then a three-word stage, etc., language is thought to have developed hierarchy in later stages.[37] In the article, The precedence of syntax in the rapid emergence of human language in evolution as defined by the integration hypothesis,[37] Nóbrega & Miyagawa outline the Integration Hypothesis as it applies to words. To explain the Integration Hypothesis as it relates to words, everyone must first agree on the definition of a 'word'. While this seems fairly straightforward in English, this is not the case for other languages. To allow for cross-linguistic discussion, the idea of a "root" is used instead, where a "root" encapsulates a concept at the most basic level. In order to differentiate between "roots" and "words", it must be noted that "roots" are completely devoid of any information relating to grammatical category or inflection. Therefore, "roots" form the lexical component of the Integration Hypothesis while grammatical category (noun, verb, adjective) and inflectional properties (e.g. case, number, tense, etc.) form the expressive component.  A syntactic tree where the root node x dominates nodes x and ROOT. A "root" (L layer) is integrated with the E layer to show that there is underlying hierarchical structure within words. Adapted from Nórega & Miyagawa (48) Thus, at the most basic level for the formation of a "word" in human language, there must be a combination of the L component with the E component. When we know a "word" in a language, we must know both components: the concept that it relates to as well as its grammatical category and inflection. The former is the L component; the latter is the E component. The Integration Hypothesis suggests that it was the grammatical operator Merge that triggered this combination, occurring when one linguistic object (L layer) satisfies the grammatical feature of another linguistic object (E layer). This means that L components are not expected to directly combine with each other. Based on this analysis, it is believed that human language emerged in a single step. Before this rapid emergence, the L component, "roots", existed individually, lacked grammatical features, and were not combined with each other. However, once this was combined with the E component, it led to the emergence of human language, with all the necessary characteristics. Hierarchical structures of syntax are already present within words because of the integration of these two layers. This pattern is continued when words are combined with each other to make phrases, as well as when phrases are combined into sentences. Therefore, the Integration Hypothesis posits that once these two systems were integrated, human language appeared fully formed, and did not require additional stages. |

人間言語の急速な出現 E と L の要素の痕跡が自然界で発見されていることから、統合仮説は、これら 2 つのシステムが人間言語よりも先に存在し、この 2 つの既存のシステムが組み合わさって、人間言語が急速に出現したと主張している。[32] 統合仮説は、E と L のシステムを組み合わせて人間言語を生み出したのは、文法演算子である Merge であると主張している。[37] この見解では、言語は急速に完全な形で出現し、既に文法構造を含んでいたとされています。これは、初期の言語には文法が存在しなかったと考える漸進的アプ ローチとは対照的です。漸進的アプローチの支持者は、単純な組み合わせ演算子が平坦な構造を生成する過程で、言語が段階的に進化したと信じています。1 語段階、2 語段階、3 語段階と続き、言語は後期の段階で階層化が進んだと考えられている。[37] 記事「統合仮説によって定義される、人間の言語の急速な出現における構文の優先順位」[37] で、Nóbrega と Miyagawa は、単語に適用される統合仮説の概要を説明している。統合仮説を単語に適用して説明するためには、まず「単語」の定義について一致する必要があります。英 語ではこれは比較的単純ですが、他の言語ではそうではありません。言語間の議論を可能にするため、代わりに「根」という概念が用いられます。ここで「根」 とは、概念を最も基本的なレベルで包含する要素を指します。「根」と「単語」を区別するために、根は文法カテゴリーや屈折に関する情報を一切含まない点に 注意が必要だ。したがって、根は統合仮説の語彙的成分を構成し、文法カテゴリー(名詞、動詞、形容詞)や屈折的性質(例:格、数、時制など)は表現的成分 を構成する。  根ノード x がノード x と ROOT を支配する構文木。 「根」(L 層)は E 層と統合され、単語内に階層構造が存在することを示している。Nórega & Miyagawa (48) から改変 したがって、人間の言語における「単語」の形成の最も基本的なレベルでは、L 成分と E 成分の組み合わせが必要だ。言語における「単語」を知っている場合、その単語が関連する概念と、その文法カテゴリーおよび屈折の両方の成分を知らなければ ならない。前者はL成分、後者はE成分である。統合仮説は、この組み合わせを引き起こしたのは文法演算子Mergeであり、1つの言語対象(L層)が別の 言語対象(E層)の文法的特徴を満たす際に発生すると提案している。つまり、L 成分同士が直接結合することは予想されない。 この分析に基づいて、人間の言語は 1 つのステップで出現したと信じられている。この急速な出現以前は、L 成分である「語根」は個別に存在し、文法的な特徴を欠き、互いに結合されていなかった。しかし、これが E 成分と結合すると、必要なすべての特徴を備えた人間の言語が出現した。文法階層構造は、これらの2つの層の統合により、既に単語内に存在している。このパ ターンは、単語が組み合わさって句を形成する際にも、句が組み合わさって文を形成する際にも継続される。したがって、統合仮説は、これらの2つのシステム が統合された時点で、人間言語は完全に形成され、追加の段階を必要としないことを主張している。 |

Evidence of Hierarchical Structure Within Compound Words A phrase structure tree where the phrase "unlock" is adjoined to the suffix -able. One possible internal structure of 'unlockable' is shown. In this image, the meaning is that something is able to be unlocked. Adapted from Nórega & Miyagawa. (39)  A phrase structure tree where the phrase lockable is adjoined to the prefix un-. One possible internal structure of 'unlockable' is shown. In this image, the meaning is that something is not able to locked. Adapted from Nórega & Miyagawa. (39) Compound words are a special point of interest with the Integration Hypothesis, as they are further evidence that words contain internal structure. The Integration Hypothesis, analyzes compound words differently compared to previous gradualist theories of language development. As previously mentioned, in the Gradualist Approach, compound words are thought of as part of a proto-syntax stage to the human language. In this proposal of a lexical protolanguage, compounds are developed in the second stage through a combination of single words by a rudimentary recursive n-ary operation that generates flat structures.[38] However, the Integration Hypothesis challenges this belief, claiming that there is evidence to suggest that words are internally complex. In English for example, the word 'unlockable' is ambiguous because of two possible structures within. It can either mean something that is able to be unlocked (unlock-able), or it can mean something that is not lockable (un-lockable). This ambiguity points to two possible hierarchical structures within the word: it cannot have the flat structure posited by the Gradualist Approach. With this evidence, supporters of the Integration Hypothesis argue that these hierarchical structures in words are formed by Merge, where the L component and E component are combined. Thus, Merge is responsible for the formation of compound words and phrases. This discovery leads to the hypothesis that words, compounds, and all linguistic objects of the human language are derived from this integration system, and provides contradictory evidence to the theory of an existence of a protolanguage.[37] In the view of compounds as "living fossils", Jackendoff[39] alleges that the basic structure of compounds does not provide enough information to offer semantic interpretation. Hence, the semantic interpretation must come from pragmatics. However, Nórega and Miyagawa[37] noticed that this claim of dependency on pragmatics is not a property of compound words that is demonstrated in all languages. The example provided by Nórega and Miyagawa is the comparison between English (a Germanic language) and Brazilian Portuguese (a Romance language). English compound nouns can offer a variety of semantic interpretations. For example, the compound noun "car man" can have several possible understandings such as: a man who sells cars, a man who's passionate about cars, a man who repairs cars, a man who drives cars, etc. In comparison, the Brazilian Portuguese compound noun "peixe-espada" translated as "sword fish", only has one understanding of a fish that resembles a sword.[37] Consequently, when looking at the semantic interpretations available of compound words between Germanic languages and Romance languages, the Romance languages have highly restrictive meanings. This finding presents evidence that in fact, compounds contain more sophisticated internal structures than previously thought. Moreover, Nórega and Miyagawa provide further evidence to counteract the claim of a protolanguage through examining exocentric VN compounds. As defined, one of the key components to Merge is the property of being recursive. Therefore, by observing recursion within exocentric VN compounds of Romance languages, this proves that there must be an existence of an internal hierarchical structure which Merge is responsible for combining. In the data collected by Nórega and Miyagawa,[37] they observe recursion occurring in several occasions within different languages. This happens in Catalan, Italian, and Brazilian Portuguese where a new VN compound is created when a nominal exocentric VN compound is the complement of a verb. For example, referring to the Catalan translation of "windshield wipers", [neteja[para-brises]] lit. clean-stop-breeze, we can identify recursion because [para-brises] is the complement of [neteja]. Additionally, we can also note the occurrence of recursion when the noun of a VN compound contains a list of complements. For example, referring to the Italian translation of "rings, earrings, or small jewels holder", [porta[anelli, orecchini o piccoli monili]] lit. carry-rings-earrings-or-small-jewels, there is recursion because of the string of complements [anelli, orecchini o piccoli monili] containing the noun to the verb [porta]. The common claim that compounds are fossils of language often complements the argument that they contain a flat, linear structure.[40] However, Di Sciullo provided experimental evidence to dispute this.[40] With the knowledge that there is asymmetry in the internal structure of exocentric compounds, she uses the experimental results to show that hierarchical complexity effects are observed from processing of NV compounds in English. In her experiment, sentences containing object-verb compounds and sentences containing adjunct-verb compounds were presented to English speakers, who then assessed the acceptability of these sentences. Di Sciullo has noted that previous works have determined adjunct-verb compounds to have more complex structure than object-verb compounds because adjunct-verb compounds require merge to occur several times.[40] In her experiment, there were 10 English speaking participants who evaluated 60 English sentences. The results revealed that the adjunct-verb compounds had a lower acceptability rate and the object-verb compounds had a higher acceptability rate. In other words, the sentences containing the adjunct-verb compounds were viewed as more "ill-formed" than the sentences containing the object-verb compounds. The findings demonstrated that the human brain is sensitive to the internal structures that these compounds contain. Since adjunct-verb compounds contain complex hierarchical structures from the recursive application of Merge, these words are more difficult to decipher and analyze than the object-verb compounds which encompass simpler hierarchical structures. This is evidence that compounds could not have been fossils of a protolanguage without syntax due to their complex internal hierarchical structures. |

複合語内の階層構造を示す証拠 フレーズ「unlock」が接尾辞「-able」に結合されたフレーズ構造木。 「unlockable」の内部構造の一例を示している。この図では、何かが「開錠できる」という意味を表している。Nórega & Miyagawa から改変。(39)  フレーズ「lockable」が接頭辞「un-」に結合されたフレーズ構造木。 unlockable の内部構造の一つの可能性を示しています。この画像では、何かがロックできないという意味です。Nórega & Miyagawa から引用。(39) 複合語は、単語に内部構造があることのさらなる証拠であるため、統合仮説において特に興味深い点です。統合仮説は、これまでの言語発達の漸進的理論とは異 なって、複合語を分析しています。前述のように、漸進的アプローチでは、複合語は人間の言語の原始構文段階の一部と考えられている。この原始言語の提案で は、複合語は第二段階で、単一の単語を原始的な再帰的 n 項操作によって組み合わせることで、平坦な構造を生成する。[38] しかし、統合仮説は、単語が内部的に複雑であることを示す証拠があると主張し、この信念に異議を唱えている。例えば英語の「unlockable」という 単語は、内部に2つの可能な構造があるため曖昧だ。これは「解錠可能な」という意味(unlock-able)か、「解錠できない」という意味(un- lockable)のどちらかになる。この曖昧さは、単語内に2つの階層構造が存在することを示唆している。つまり、漸進的アプローチが提唱する平坦な構 造では説明できない。この証拠に基づき、統合仮説の支持者は、単語内の階層構造はMergeによって形成されると主張している。Mergeでは、L成分と E成分が結合される。したがって、Mergeは複合語や句の形成に責任を負っている。この発見は、単語、複合語、および人間の言語のすべての言語対象が、 この統合システムから派生したものであるという仮説を導き出し、原言語の存在を主張する理論に矛盾する証拠を提供している。[37] 複合語を「生きた化石」と捉えるジャックエンドフ[39]は、複合語の基本構造は意味解釈を提供する十分な情報を提供しないと主張している。したがって、 意味解釈は語用論から導かれる必要がある。しかし、ノレガとミヤガワ[37]は、この語用論への依存は、すべての言語で示される複合語の特性ではないと指 摘している。ノレガとミヤガワが提示した例は、英語(ゲルマン語族)とブラジルポルトガル語(ロマンス語族)の比較だ。英語の複合名詞は多様な意味解釈を 提供できる。例えば、複合名詞「car man」には、次のような複数の意味解釈が考えられる:車を売る人、車に熱中する人、車を修理する人、車を運転する人、など。一方、ブラジルポルトガル語 の複合名詞「peixe-espada」(「剣魚」)は、剣に似た魚という一つの意味しか持たない。[37] したがって、ゲルマン語とロマンス語の複合語の語義解釈を比較すると、ロマンス語は意味が非常に制限的であることがわかる。この発見は、複合語が従来考え られていたよりも高度な内部構造を有することを示す証拠となる。さらに、ノレガとミヤガワは、外中心的なVN複合語を分析することで、原言語の存在を否定 する主張に反論するさらなる証拠を提供している。Mergeの定義において、再帰性という特性は重要な要素の一つだ。したがって、ロマンス語の外中心的な VN複合語における再帰性を観察することで、Mergeが結合する内部階層構造の存在が証明される。Nórega と Miyagawa が収集したデータ[37]では、異なる言語で再帰が何度か発生していることが確認されている。これは、カタロニア語、イタリア語、ブラジルポルトガル語 で、名詞の外中心 VN 複合語が動詞の補語になると、新しい VN 複合語が作成される場合に発生する。例えば、カタルーニャ語の「ウィンドシールドワイパー」の翻訳 [neteja[para-brises]](直訳:風を止める清掃)では、[para-brises] が [neteja] の補語であるため、再帰を識別できる。さらに、VN複合語の名詞が補語のリストを含む場合にも再帰の発生を指摘できる。例えば、イタリア語の「指輪、イヤ リング、または小さな宝石のホルダー」の翻訳 [porta[anelli, orecchini o piccoli monili]](直訳:指輪・イヤリング・または小さな宝石を運ぶ)では、動詞 [porta] の補語列 [anelli, orecchini o piccoli monili] に名詞が含まれているため、再帰が存在する。 複合語は言語の化石であるという一般的な主張は、複合語が平坦で線形の構造を含むという主張を補強する。[40] しかし、ディ・スィウッロは実験的証拠を提示してこの主張を否定した。[40] 複合語の内部構造に非対称性があることを踏まえ、彼女は実験結果を用いて、英語の NV 複合語の処理において階層的複雑性効果が観察されることを示した。彼女の experiment では、目的語-動詞複合語を含む文と、付帯語-動詞複合語を含む文を英語話者に提示し、これらの文の受け入れ可能性を評価させた。ディ・スィウッロは、以 前の研究で、付帯語-動詞複合語は目的語-動詞複合語よりも複雑な構造を有するとされた理由として、付帯語-動詞複合語では合併が複数回必要となる点を指 摘している。[40] 彼女の experiment では、10人の英語話者が60の英語文を評価した。結果、付加動詞複合語を含む文の受け入れ可能性は低く、目的語動詞複合語を含む文の受け入れ可能性は高 いことが明らかになった。つまり、付加動詞複合語を含む文は、目的語動詞複合語を含む文よりも「不自然な」文と見なされた。この結果は、人間の脳がこれら の複合語が含む内部構造に敏感であることを示している。助動詞複合語は、Mergeの反復適用から複雑な階層構造を含むため、より単純な階層構造を含む目 的語動詞複合語よりも解読や分析が困難だ。これは、複合語が複雑な内部階層構造を持つため、文法のない原言語の化石として存在できなかったことを示す証拠 だ。 |

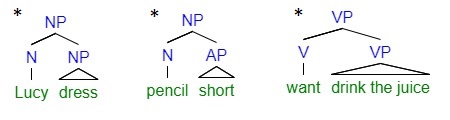

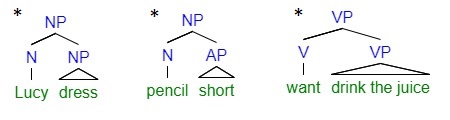

| Interactions Between E and L Components in Phrases of Human Language As previously mentioned, human language is interesting because it necessarily requires elements from both E and L systems - neither can stand alone. Lexical items, or what the Integration Hypothesis refers to as 'roots', are necessary as they refer to things in the world around us. Expression items, that convey information about category or inflection (number, tense, case etc.) are also required to shape the meanings of the roots.  the phrase structure tree for the phrase "buy the books" In the phrase, "buy the books", the category of each phrase is determined by the head. It becomes more clear that neither of these two systems can exist alone with regards to human language when we look at the phenomenon of 'labeling'. This phenomenon refers to how we classify the grammatical category of phrases, where the grammatical category of the phrase is dependent on the grammatical category of one of the words within the phrase, called the head. For example, in the phrase "buy the books", the verb "buy" is the head, and we call the entire phrase a verb-phrase. There is also a smaller phrase within this verb-phrase, a determiner phrase, "the books" because of the determiner "the". What makes this phenomenon interesting is that it allows for hierarchical structure within phrases. This has implications on how we combine words to form phrases and eventually sentences.[41]  Lexical components cannot be directly combined with each other as shown by these ungrammatical phrases. Adapted from Miyagawa et al.(45) This labelling phenomenon has limitations however. Some labels can combine and others cannot. For example, two lexical structure labels cannot directly combine. The two nouns, "Lucy" and "dress" cannot directly be combined. Likewise, neither can the noun "pencil" be merged with the adjective "short", nor can the verbs, "want" and "drink" cannot be merged without anything in between. As represented by the schematic below, all of these examples are impossible lexical structures. This shows that there is a limitation where lexical categories can only be one layer deep. However, these limitations can be overcome with the insertion of an expression layer in between. For example, to combine "John" and "book", adding a determiner such as "-'s" makes this a possible combination.[41] Another limitation regards the recursive nature of the expressive layer. While it is true that CP and TP can come together to form hierarchical structure, this CP TP structure cannot repeat on top of itself: it is only a single layer deep. This restriction is common to both the expressive layer in humans, but also in birdsong. This similarity strengthens the tie between the pre-existing E system posited to have originated in birdsong and the E layers found in human language.[41] |

人間言語のフレーズにおけるE成分とL成分の相互作用 前述のように、人間言語はEシステムとLシステムの両方の要素を必然的に必要とするため、興味深いものです。語彙項目、つまり統合仮説で「根」と呼ばれる ものは、私たちの周りの世界にあるものを指すため、必要不可欠だ。また、カテゴリーや屈折(数、時制、格など)に関する情報を伝える表現項目も、根の意味 を形作るために必要だ。  「本を買う」というフレーズ構造木 「本を買う」というフレーズでは、各フレーズのカテゴリーは頭語によって決定される。 人間の言語において、これらの2つのシステムが単独で存在できないことは、「ラベル付け」という現象を見るとより明確になる。この現象は、句の文法カテゴ リーを分類する方法であり、句の文法カテゴリーは、句内の単語の1つ(頭語)の文法カテゴリーに依存する。例えば、「buy the books」というフレーズでは、動詞「buy」が頭語であり、このフレーズ全体を動詞句と呼ぶ。この動詞句の中には、限定詞「the」を含むより小さな フレーズ、限定詞句「the books」が存在します。この現象が興味深いのは、フレーズ内に階層構造を許す点です。これは、単語を組み合わせてフレーズを形成し、最終的に文を構成 する方法に影響を与えます。[41]  これらの文法的に正しくないフレーズが示すように、語彙成分は直接結合することはできない。Miyagawa et al.(45) から改変 ただし、このラベル付け現象には限界がある。一部のラベルは結合できるが、他のラベルは結合できない。例えば、2 つの語彙構造ラベルは直接結合できない。2 つの名詞「Lucy」と「dress」は直接結合できない。同様に、名詞「pencil」と形容詞「short」を結合することはできず、動詞 「want」と「drink」も間に何も入れずに結合することはできない。以下の模式図に示すように、これらの例はすべて不可能な語彙構造だ。これは、語 彙カテゴリーは1層しか深くなれないという制限があることを示している。しかし、この制限は、表現層を間に挿入することで克服できる。例えば、「ジョン」 と「本」を組み合わせるには、「-'s」のような限定詞を追加することで、この組み合わせが可能になる。[41] もう一つの制限は、表現層の再帰性に関するものだ。CPとTPが階層構造を形成することは可能ですが、このCP-TP構造は自身の上に繰り返し出現するこ とはできません:それは単一の層深さのみです。この制限は、人間の表現層だけでなく、鳥の歌の表現層にも共通しています。この類似性は、鳥の歌から起源し たと仮定される既存のEシステムと、人間の言語で発見されたE層との間の関連性を強化しています。[41] |

There is an alternation between E layers and L layers in order to create well-formed phrases. Adapted from Miyagawa et al. (45) Due to these limitations in each system, where both lexical and expressive categories can only be one layer deep, the recursive and unbounded hierarchical structure of human language is surprising. The Integration hypothesis posits that it is the combination of these two types of layers that results in such a rich hierarchical structure. The alternation between L layers and E layers is what allows human language to reach an arbitrary depth of layers. For example, in the phrase "Eat the cake that Mary baked", the tree structure shows an alternation between L and E layers. This can easily be described by two phrase rules: (i) LP → L EP and (ii) EP → E LP. The recursion that is possible is plainly seen by transforming these phrase rules into bracket notation. The LP in (i) can be written as [L EP]. Then, adding an E layer to this LP to create an EP would result in [E [L EP]]. After, a more complex LP could be obtained by adding an L layer to the EP, resulting in [L [E [L EP]]]. This can continue forever and would result in the recognizable deep structures found in human language.[41] |

よく形成されたフレーズを作成するために、E 層と L 層が交互に繰り返されます。Miyagawa et al. (45) から引用 各システムにおいて、語彙的カテゴリーと表現的カテゴリーがそれぞれ1層しか持てないという制限があるため、人間の言語の反復的で無制限な階層構造は驚く べきものだ。統合仮説は、これらの2種類の層の組み合わせが、このような豊かな階層構造を生み出していると主張している。L層とE層の交替が、人間の言語 が任意の層の深さに達することを可能にしている。例えば、「メアリーが焼いたケーキを食べる」という文では、木構造にL層とE層の交替が見られる。これ は、次の2つの句規則で簡単に説明できる:(i) LP → L EP と (ii) EP → E LP。これらの句規則を括弧表記に変換することで、再帰の可能性が明確にわかる。(i) のLPは[L EP]と書ける。このLPにE層を追加してEPを作成すると、[E [L EP]]となる。さらに、EPにL層を追加することで、より複雑なLPを得ることができ、[L [E [L EP]]となる。このプロセスは無限に続き、人間言語に見られる認識可能な深い構造が生成される。[41] |

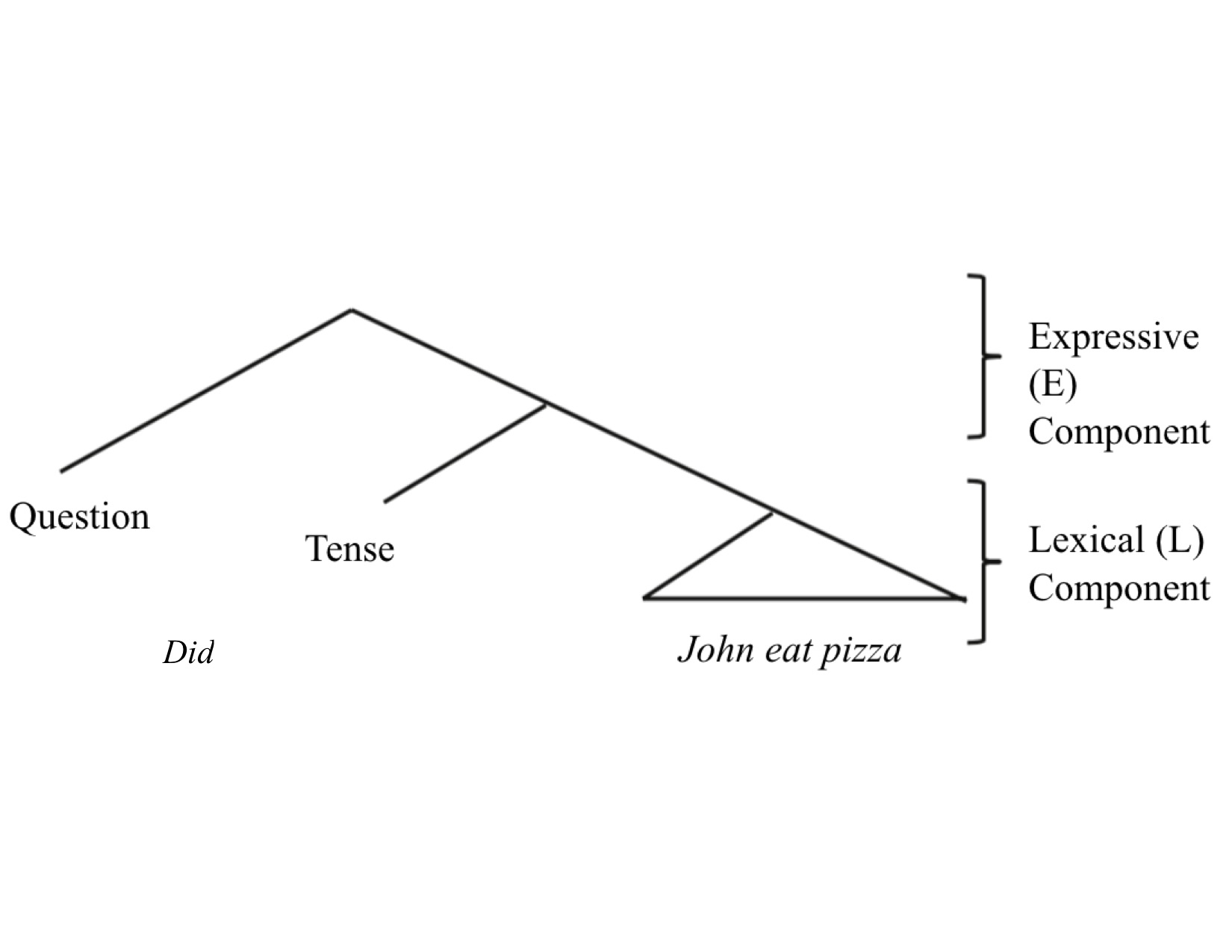

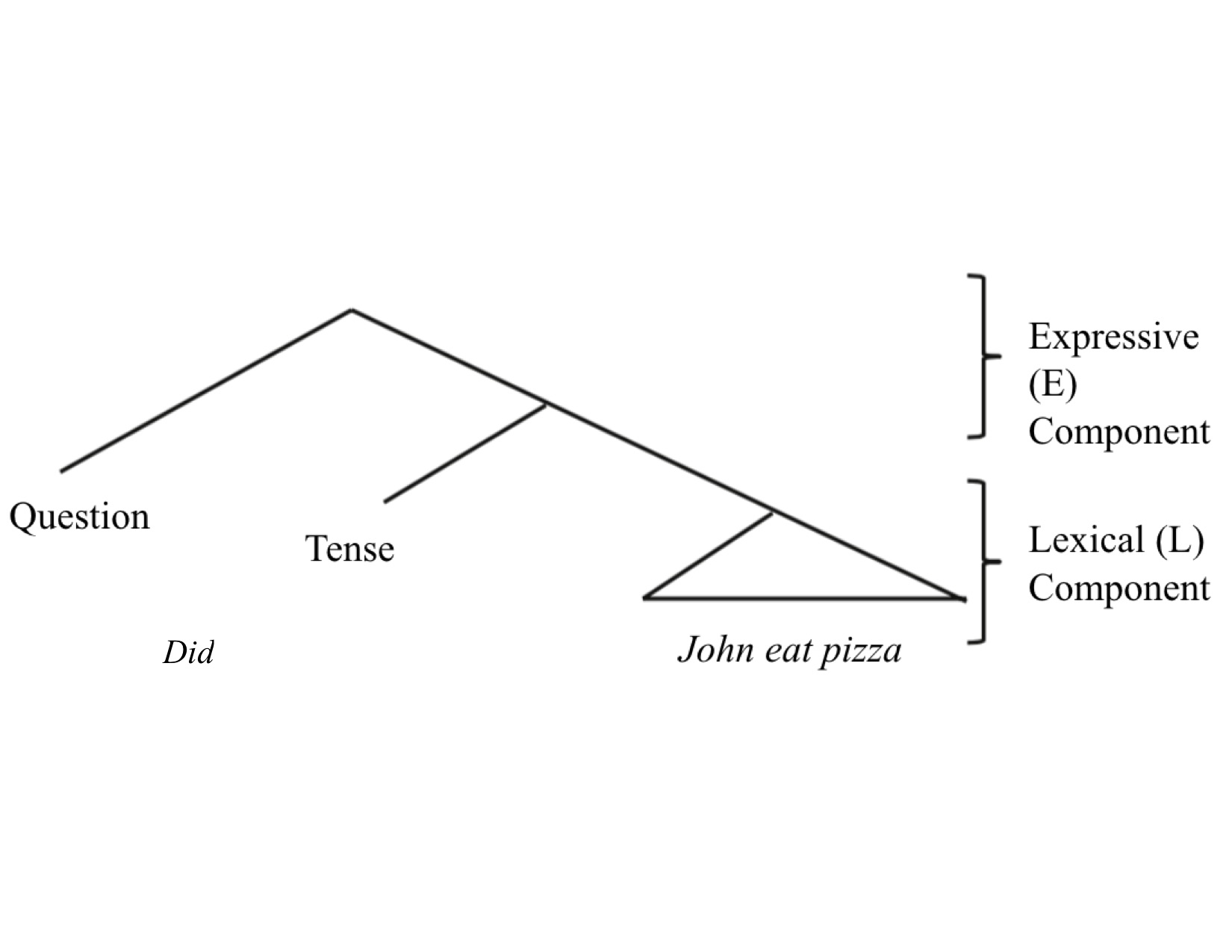

| The Operation of E and L Components in the Syntax of Sentences The E and L components can be used to explain the syntactic structures that make up sentences in human languages. The first component, the L component, contains content words.[41] This component is responsible for carrying the lexical information that relays the underlying meaning behind a sentence. However, combinations consisting solely of L component content words do not result in grammatical sentences. This issue is resolved through the interaction of the L component with the E component. The E component is made up of function words: words that are responsible for inserting syntactic information about the syntactic categories of L component words, as well as morphosyntactic information about clause-typing, question, number, case and focus.[37] Since these added elements complement the content words in the L component, the E component can be thought of as being applied to the L component. Considering that the L component is solely composed of lexical information and the E component is solely composed of syntactic information, they do exist as two independent systems. However, for the rise of such a complex system as human language, the two systems are necessarily reliant on each other. This aligns with Chomsky's proposal of duality of semantics which suggests that human language is composed of these two distinct components.[42] In this way, it is logical as to why the convergence of these two components was necessary in order to enable the functionality of human language as we know it today. Looking at the following example taken from the article The integration hypothesis of human language evolution and the nature of contemporary languages by Miyagawa et al.,[32] each word can be identified as either being either an L component or an E component in the sentence: Did John eat pizza? |

文の構文における E と L の構成要素の働き E 成分と L 成分は、人間の言語における文の構文構造を説明するために使用することができる。最初の成分である L 成分は、内容語を含む。[41] この成分は、文の背後にある基本的な意味を伝える語彙情報を伝達する役割を担っている。しかし、L 成分の内容語のみで構成される組み合わせは、文法的に正しい文にはならない。この問題は、L 成分と E 成分の相互作用によって解決される。E成分は機能語から構成されています。機能語は、L成分の単語の文法カテゴリーに関する文法情報を挿入する役割を担う ほか、句のタイプ、疑問、数、格、焦点に関する形態文法情報も伝達します。[37] これらの追加要素はL成分の内容語を補完するため、E成分はL成分に適用されるものと考えることができます。L成分は純粋に語彙情報から構成され、E成分 は純粋に文法情報から構成されるため、これらは2つの独立したシステムとして存在している。しかし、人間言語のような複雑なシステムの出現には、この2つ のシステムが相互に依存していることが不可欠だ。これは、チョムスキーが提唱した意味の二重性という概念と一致しており、人間言語はこれらの2つの異なる コンポーネントから構成されていると示唆している。[42] このように、人間言語が現在のような機能を果たすために、これらの2つのコンポーネントの統合が不可欠であったことは論理的だ。 宮川らによる論文『人間の言語進化の統合仮説と現代言語の性質』[32] から引用した以下の例を見ると、文中の各単語は、L 成分か E 成分かのいずれかに分類できる:ジョンはピザを食べたか? |

In English, the E component makes up the upper layer of a tree, which adds syntactic shape to the lower layer, which makes up the L component that provides a sentence with its core lexical meaning. Adapted from Miyagawa et al. (30) The L component words of this sentence are the content words John, eat, and pizza. Each word only contains lexical information that directly contributes to the meaning of the sentence. The L component is often referred to as the base or inner component, due to the inwards positioning of this constituent in a phrase structure tree. It is evident that the string of words 'John eat pizza' does not form a grammatically well-formed sentence in English, which suggests that E component words are necessary to syntactically shape and structure this string of words. The E component is typically referred to as the outer component that shapes the inner L component as these elements originate in a position that orbits around the L component in a phrase structure tree. In this example, the E component function word that is implemented is did. By inserting this word, two types of structures are added to the expression: tense and clause typing. The word did is a word that is used to inquire about something that happened in the past, meaning that it adds the structure of the past tense to this expression. In this example, this does not explicitly change the form of the verb, as the verb eat in the past tense still surfaces as eat without any additional tense markers in this particular environment. Instead the tense slot can be thought of as being filled by a null symbol (∅) as this past tense form does not have any phonological content. Although covert, this null tense marker is an important contribution from the E component word did. Tense aside, clause typing is also conveyed through the E component. It is interesting that this function word did surfaces in the sentence initial position because in English, this indicates that the string of words will manifest as a question. The word did determines that the structure of the clause type for this sentence will be in the form of an interrogative question, specifically a yes–no question. Overall, the integration of the E component with the L component forms the well-formed sentence, Did John eat pizza?, and accounts for all other utterances found in human languages. |

英語では、E 成分は木の上層部を構成し、下層部に構文の形を与え、L 成分を構成して文のコアとなる語彙的意味を提供する。Miyagawa et al. (30) から引用 この文のL成分の単語は、内容語である「ジョン」、「食べる」、「ピザ」です。各単語は、文の意味に直接寄与する語彙情報のみを含んでいます。L成分は、 句構造木におけるこの構成要素の内側への配置から、基底成分または内層成分と呼ばれることがあります。単語の列「John eat pizza」は、英語の文法的に正しい文を形成していないことが明らかであり、この単語の列を文法的に形作り構造化するためにE成分の単語が必要であるこ とが示唆される。E成分は、フレーズ構造木においてL成分の周囲を回る位置から発生する要素であるため、内側のL成分を形作る外側成分として一般的に呼ば れる。この例では、実装されているE成分の機能語はdidである。この単語を挿入することで、時制と節のタイプという 2 種類の構造が表現に追加されます。did は、過去に起こったことを尋ねるために使用される単語であり、この表現に過去形の構造を追加します。この例では、この特定の環境では、過去形の動詞 eat は追加の時制マーカーなしで eat のまま表れるため、動詞の形は明示的に変化しません。代わりに、時制スロットは空の記号(∅)で埋められると考えられる。これは、この過去形形式に音韻的 内容がないためだ。隠れた形ではあるが、この空の時制マーカーは E コンポーネントの単語 did の重要な貢献だ。時制とは別に、句のタイプも E コンポーネントを通じて伝達される。この機能単語 did が文の最初に出現することは興味深い。なぜなら、英語ではこれが単語の列が質問として現れることを示すからだ。「did」という単語は、この文の句のタイ プ構造が疑問文、具体的にははい・いいえの質問の形式になることを決定する。全体として、EコンポーネントとLコンポーネントの統合は、よく形成された文 「Did John eat pizza?」を形成し、人間言語で発見される他のすべての発話を説明している。 |

| Critiques Alternative Theoretical Approaches Stemming from the usage-based approach, the Competition Model, developed by Elizabeth Bates and Brian MacWhinney, views language acquisition as consisting of a series of competitive cognitive processes that act upon a linguistic signal. This suggests that language development depends on learning and detecting linguistic cues with the use of competing general cognitive mechanisms rather than innate, language-specific mechanisms. From the side of biosemiotics, there has been a recent claim that meaning-making begins far before the emergence of human language. This meaning-making consists of internal and external cognitive processes. Thus, it holds that such process organisation could not have only given a rise to language alone. According to this perspective all living things possess these processes, regardless of how wide the variation, as a posed to species-specific.[43] |

批判 代替的な理論的アプローチ 使用に基づくアプローチから派生した、エリザベス・ベイツとブライアン・マクウィニーによって開発された競争モデルでは、言語習得は、言語信号に作用する 一連の競争的な認知プロセスから構成されているとみなされています。これは、言語の発達は、先天的な言語固有のメカニズムではなく、競合する一般的な認知 メカニズムを用いて言語的手がかりを学習し、検出することにかかっていることを示唆しています。 バイオセミオティクス(生物記号論)の立場からは、意味の生成は人間の言語の出現はるか以前から始まっているという主張が最近なされている。この意味の生 成は、内部と外部の認知プロセスから成っている。したがって、このようなプロセス組織は言語のみを生み出したわけではなく、その多様性の広さに関わらず、 種特異的なものではなく、すべての生物がこれらのプロセスを保有していると考えられる。[43] |

| Over-Emphasised Weak Stream Focus When talking about biolinguistics there are two senses that are adopted to the term: strong and weak biolinguistics. The weak is founded on theoretical linguistics that is generativist in persuasion. On the other hand, the strong stream goes beyond the commonly explored theoretical linguistics, oriented towards biology, as well as other relevant fields of study. Since the early emergence of biolinguistics to its present day, there has been a focused mainly on the weak stream, seeing little difference between the inquiry into generative linguistics and the biological nature of language as well as heavily relying on the Chomskyan origin of the term.[44] As expressed by research professor and linguist Cedric Boeckx, it is a prevalent opinion that biolinguistics need to focus on biology as to give substance to the linguistic theorizing this field has engaged in. Particular criticisms mentioned include a lack of distinction between generative linguistics and biolinguistics, lack of discoveries pertaining to properties of grammar in the context of biology, and lack of recognition for the importance broader mechanisms, such as biological non-linguistic properties. After all, it is only an advantage to label propensity for language as biological if such insight is used towards a research.[44] David Poeppel, a neuroscientist and linguist, has additionally noted that if neuroscience and linguistics are done wrong, there is a risk of "inter-disciplinary cross-sterilization", arguing that there is a Granularity Mismatch Problem. Due to this different levels of representations used in linguistics and neural science lead to vague metaphors linking brain structures to linguistic components. Poeppel and Embick also introduce the Ontological Incommensurability Problem, where computational processes described in linguistic theory cannot be restored to neural computational processes.[45] A recent critique of biolinguistics and 'biologism' in language sciences in general has been developed by Prakash Mondal who shows that there are inconsistencies and categorical mismatches in any putative bridging constraints that purport to relate neurobiological structures and processes to the logical structures of language that have a cognitive-representational character.[46][47] |

過度に強調された弱い流れの焦点 生物言語学について話す場合、この用語には「強い生物言語学」と「弱い生物言語学」の 2 つの意味がある。弱い生物言語学は、生成言語学的な説得力を持つ理論言語学に基づいている。一方、強い流れは、一般的に研究されている理論言語学を超え て、生物学やその他の関連分野にも向けられています。生物言語学が初期から現在に至るまで、その研究は主に弱い流れに焦点を当て、生成言語学の研究と言語 の生物学的性質との違いをほとんど認識せず、この用語のチョムスキーの起源に大きく依存してきました[44]。 研究教授であり言語学者でもあるセドリック・ボッククスが述べているように、生物言語学は、この分野が取り組んできた言語理論に実体を与えるために、生物 学に焦点を当てるべきであるというのが一般的な見解だ。具体的な批判としては、生成言語学と生物言語学の区別が不明確である、生物学の文脈における文法の 特性に関する発見がない、生物学的非言語的特性などのより広範なメカニズムの重要性が認識されていない、などが挙げられる。結局のところ、言語の傾向を生 物学的であるとラベル付けすることは、その洞察が研究に活用される場合にのみ利点となる。[44] 神経科学者であり言語学者でもあるデビッド・ポッペルは、神経科学と言語学が誤って行われれば、「学際的な相互不毛化」のリスクがあるとし、粒度不一致の 問題があると主張している。このように、言語学と神経科学で使用される表現のレベルが異なるため、脳の構造と言語の構成要素を結びつける曖昧な隠喩が生ま れている。Poeppel と Embick はまた、言語理論で記述される計算プロセスを神経の計算プロセスに復元できないという「存在論的共約不可能性の問題」も紹介している[45]。 言語科学における生物言語学と「生物主義」に対する最近の批判は、プラカシュ・モンドールによって展開されており、神経生物学的構造とプロセスを言語の認 知的・表象的性格を持つ論理的構造に関連付けるとされる仮説的な橋渡し制約に、不一致とカテゴリー的不一致が存在することを示している。[46][47] |

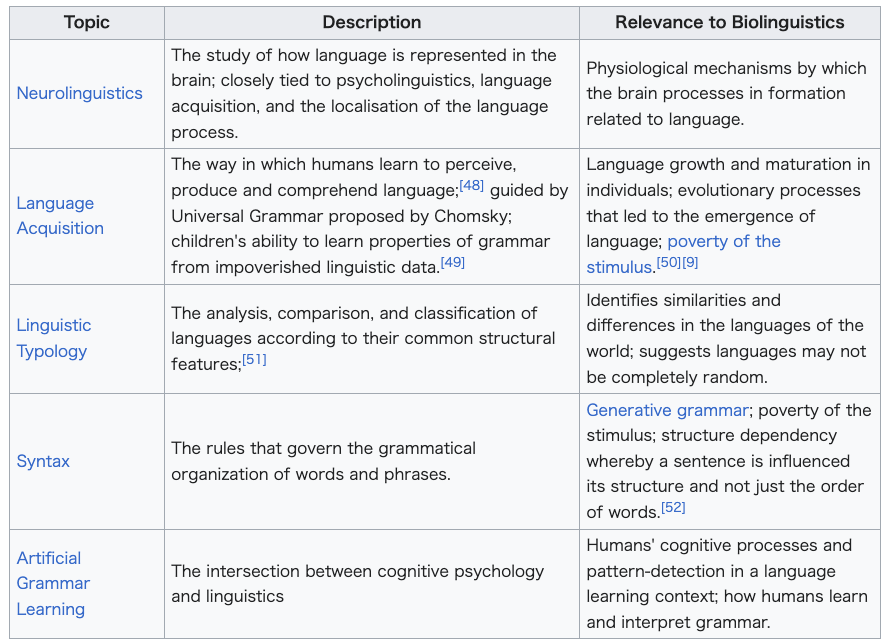

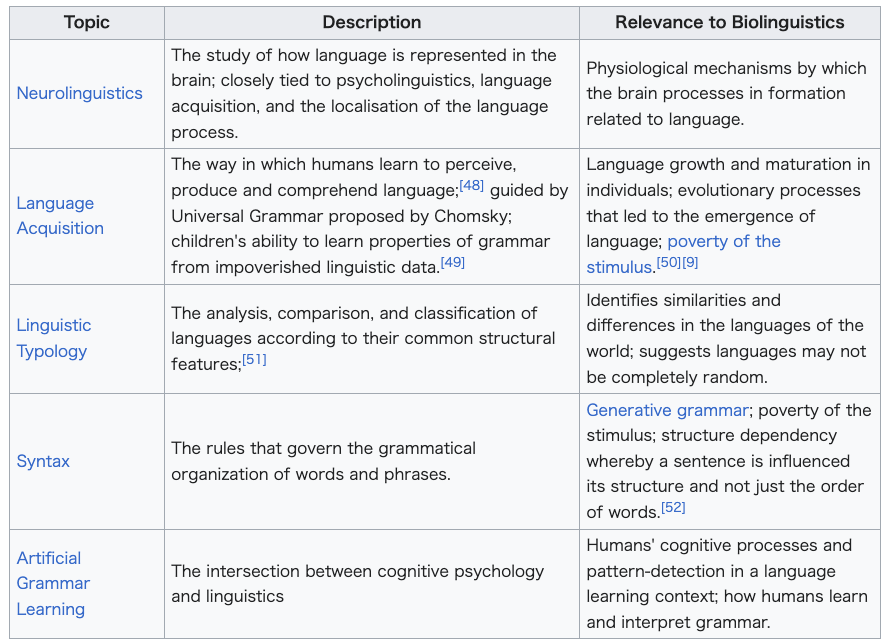

Other Relevant Fields |

それ以外の関連する領域 |

| Some Researchers in Biolinguistics (by alphabetical order of last name) Calixto Agüero-Bautista, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Michael Arbib, University of Southern California Antonio-Benitez Burraco, University of Seville Derek Bickerton, University of Hawaii Cedric Boeckx, Catalan institute for Advanced Studies Andrew Carnie, University of Arizona Anna Maria Di Sciullo, University of Quebec at Montreal Ray C. Dougherty, New York University (NYU) W. Tecumseh Fitch, University of Vienna Dieter Hillert, San Diego State University/UC San Diego Philip Lieberman, Brown University Alec Marantz, NYU/MIT Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini, University of Arizona David Poeppel, NYU Charles Reiss, Concordia University |

生物言語学の研究者(姓のアルファベット順) Calixto Agüero-Bautista、ケベック大学トロワリヴィエール校 Michael Arbib、南カリフォルニア大学 Antonio-Benitez Burraco、セビリア大学 Derek Bickerton、ハワイ大学 Cedric Boeckx、カタルーニャ高等研究所 アンドルー・カーニー、アリゾナ大学 アンナ・マリア・ディ・スキウロ、ケベック大学モントリオール校 レイ・C・ドハティ、ニューヨーク大学(NYU W・テクムセ・フィッチ、ウィーン大学 ディーター・ヒラート、サンディエゴ州立大学/カリフォルニア大学サンディエゴ校 フィリップ・リーバーマン、ブラウン大学 アレック・マランツ、ニューヨーク大学/マサチューセッツ工科大学 マッシモ・ピアテッリ・パルマリーニ、アリゾナ大学 デビッド・ポーペル、ニューヨーク大学 チャールズ・ライス、コンコルディア大学 |

| Origin of language Origin of speech Universal Grammar Generative Grammar Minimalist Program Merge Biosemiotics Evolutionary psychology of language Neurolinguistics [53] [54] [55] [41] [56] [32] [42] [57] |

言語の起源 発話の起源 普遍文法 生成文法 ミニマリストプログラム マージ 生物記号論 言語の進化心理学 神経言語学 [53] [54] [55] [41] [56] [32] [42] [57] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biolinguistics |

|

☆それ以外の関連する領域

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆