言語人類学

Linguistic Anthropology

解説:池田光穂

【定 義】言語人類学(Linguistic anthropology)とは、文化人類学と言語学の横断・融 合領域のことである。また四分類人類学の4つの分野のひとつをなす重要な学問分野である。

異文 化・他言語の調査のみならず自文化・自言語(=母語)によって文化人類学のフィールドワークをおこな う際に、基本的な言語学上の知識は欠かせない。また言語学領域においても、記述言語学や社会言語学の研究では、文化人類学的なフィールドワークの技法が欠 かせない。

さらに 文化人類学の理論面においても、ローマン・ヤコブソンの音 韻論がレヴィ=ストロースの構造人類学に 与えた影響は大変大きく、当のヤコブソンは、フランツ・ボアズ(Franz Boas, 1858-1942)によるアメリカ先住民の民族誌研究や(言語学者)サピアの研究から、研究上のさまざまなヒン トを得ている。

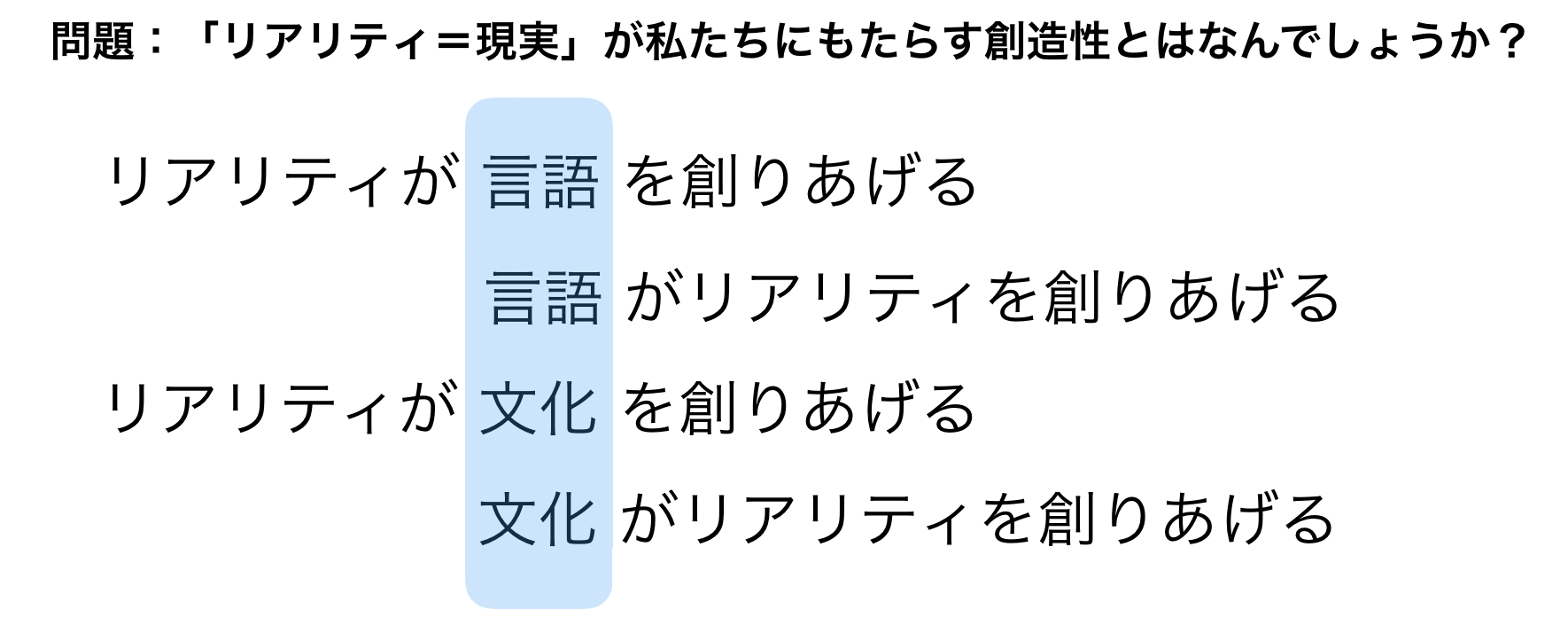

リ アリティ=現実は、私たちに何をもたらすのでしょうか?(「文化」と「言語」/文化人類学と 言語人類学)

| Linguistic anthropology

is the interdisciplinary study of how language influences social life.

It is a branch of anthropology that originated from the endeavor to

document endangered languages and has grown over the past century to

encompass most aspects of language structure and use.[1] Linguistic anthropology explores how language shapes communication, forms social identity and group membership, organizes large-scale cultural beliefs and ideologies, and develops a common cultural representation of natural and social worlds.[2] |

言語人類学とは、言語が社会生活にどのような影響を与えるかを学際的に 研究する学問である。人類学の一分野であり、絶滅の危機に瀕している言語を記録しようとする努力に端を発し、過去100年の間に言語構造と使用のほとんど の側面を包含するまでに成長した[1]。 言語人類学は、言語がどのようにコミュニケーションを形成し、社会的アイデンティティや集団のメンバーシップを形成し、大規模な文化的信念やイデオロギー を組織化し、自然界や社会界の共通の文化的表現を発展させているかを探求する[2]。 |

| Historical development Linguistic anthropology emerged from the development of three distinct paradigms that have set the standard for approaching linguistic anthropology. The first, now known as "anthropological linguistics," focuses on the documentation of languages. The second, known as "linguistic anthropology," engages in theoretical studies of language use. The third, developed over the past two or three decades, studies issues from other subfields of anthropology with linguistic considerations. Though they developed sequentially, all three paradigms are still practiced today.[3] |

歴史的発展 言語人類学は、3つの異なるパラダイムの発展から生まれ、言語人類学へのアプローチの基準となった。1つ目は、現在「人類学的言語学」として知られている もので、言語の記録化に焦点を当てている。2つ目は「言語人類学」として知られるもので、言語使用の理論的研究に取り組んでいる。3つ目は、過去 20~30年の間に発展したもので、人類学の他のサブフィールドの問題を言語学的な考察を加えて研究するものである。これらは順次発展してきたが、3つの パラダイムはすべて今日でも実践されている[3]。 |

| First paradigm: anthropological linguistics Main article: Anthropological linguistics The first paradigm, anthropological linguistics, is devoted to themes unique to the sub-discipline. This area includes documentation of languages that have been seen as at-risk for extinction, with a particular focus on indigenous languages of native North American tribes. It is also the paradigm most focused on linguistics.[3] Linguistic themes include the following: Grammatical description, Typological classification and Linguistic relativity |

第1のパラダイム:人類学的言語学 主な記事 人類学的言語学 第一のパラダイムである人類学的言語学は、この学問分野特有のテーマに専念している。この分野には、絶滅の危機に瀕しているとされる言語の記録も含まれ、 特に北米先住民族の言語に焦点が当てられている。また、言語学に最も焦点を当てたパラダイムでもある[3]。言語学のテーマには以下のようなものがある: 文法的記述 類型論的分類 言語学的相対性 |

| Second paradigm: linguistic anthropology The second paradigm can be marked by reversing the words. Going from anthropological linguistics to linguistic anthropology, signals a more anthropological focus on the study. This term was preferred by Dell Hymes, who was also responsible, with John Gumperz, for the idea of ethnography of communication. The term linguistic anthropology reflected Hymes' vision of a future where language would be studied in the context of the situation and relative to the community speaking it.[3] This new era would involve many new technological developments, such as mechanical recording. This paradigm developed in critical dialogue with the fields of folklore on the one hand and linguistics on the other. Hymes criticized folklorists' fixation on oral texts rather than the verbal artistry of performance.[4] At the same time, he criticized the cognitivist shift in linguistics heralded by the pioneering work of Noam Chomsky, arguing for an ethnographic focus on language in use. Hymes had many revolutionary contributions to linguistic anthropology, the first of which was a new unit of analysis. Unlike the first paradigm, which focused on linguistic tools like measuring of phonemes and morphemes, the second paradigm's unit of analysis was the "speech event". A speech event is defined as one with speech presented for a significant duration throughout its occurrence (ex., a lecture or debate). This is different from a speech situation, where speech could possibly occur (ex., dinner). Hymes also pioneered a linguistic anthropological approach to ethnopoetics. Hymes had hoped that this paradigm would link linguistic anthropology more to anthropology. However, Hymes' ambition backfired as the second paradigm marked a distancing of the sub-discipline from the rest of anthropology.[5][6] |

第2のパラダイム:言語人類学 第2のパラダイムは、言葉を逆にすることで示すことができる。人類学的言語学から言語人類学へというのは、この研究がより人類学的な焦点に置かれることを 意味する。この用語を好んだのはデル・ハイムズで、彼はジョン・ガンパーズとともにコミュニケーションの民族誌という考え方を提唱した人物でもある。言語 人類学という用語は、言語が状況やそれを話すコミュニティとの関連において研究されるようになるというハイムズの将来のビジョンを反映したものであった [3]。 このパラダイムは、一方では民俗学、他方では言語学の分野との批判的な対話の中で発展していった。同時に彼は、ノーム・チョムスキーの先駆的研究によって 始まった言語学における認識論的転換を批判し、使用されている言語に民族誌学的に焦点を当てるべきだと主張した。 デル・ハイムズは言語人類学に多くの革命的な貢献をしたが、その第一は新しい分析単位であった。音素や形態素の測定といった言語ツールに焦点を当てた第一 のパラダイムとは異なり、第二のパラダイムの分析単位は「発話事象」であった。発話イベントとは、その発生期間中、発話が有意に継続するもの(例:講演や 討論)と定義される。これは、発話が発生する可能性のある状況(例:夕食)とは異なる。Hymesはまた、言語人類学的アプローチによるエスノポエティク スの先駆者でもある。Hymesはこのパラダイムが言語人類学を人類学にもっと結びつけることを期待していた。しかし、ハイムズの野望は裏目に出て、第二 のパラダイムは人類学の他の部分からこのサブディシプリンを遠ざけることになった[5][6]。 |

| Third paradigm: anthropological issues studied via linguistic methods and data The third paradigm, which began in the late 1980s, redirected the primary focus on anthropology by providing a linguistic approach to anthropological issues. Rather than prioritizing the technical components of language, third paradigm anthropologists focus on studying culture through the use of linguistic tools. Themes include: investigations of personal and social identities shared ideologies construction of narrative interactions among individuals Furthermore, similar to how the second paradigm used new technology in its studies, the third paradigm heavily includes use of video documentation to support research.[3] |

第3のパラダイム:言語学的方法とデータによって研究される人類学的問題 1980年代後半に始まった第3のパラダイムは、人類学的問題への言語学的アプローチを提供することで、人類学の主要な焦点を方向転換させた。第3のパラ ダイムの人類学者は、言語の技術的な要素を優先するのではなく、言語的な道具の使用を通じて文化を研究することに重点を置いている。テーマは以下の通りで ある: 個人的・社会的アイデンティティの調査 共有イデオロギー 個人間の物語的相互作用の構築 さらに、第二のパラダイムがその研究において新しい技術をどのように利用したかと同様に、第三のパラダイムは研究をサポートするためにビデオ・ドキュメン テーションを多用する[3]。 |

| Linguistic anthropology |

***

| Areas of interest Contemporary linguistic anthropology continues research in all three paradigms described above: Documentation of languages Study of language through context The study of identity through linguistic means The third paradigm, the study of anthropological issues through linguistic means, is an affluent area of study for current linguistic anthropologists. |

関心領域:1 現代の言語人類学は、上記の3つのパラダイムすべてにおいて研究を続けている: 言語の記録 文脈を通した言語の研究 言語によるアイデンティティの研究 第3のパラダイムである言語学的手段による人類学的問題の研究は、現在の言語人類学者にとって豊かな研究分野である。 |

| Identity and intersubjectivity A great deal of work in linguistic anthropology investigates questions of sociocultural identity linguistically and discursively. Linguistic anthropologist Don Kulick has done so in relation to identity, for example, in a series of settings, first in a village called Gapun in northern Papua New Guinea.[7] He explored how the use of two languages with and around children in Gapun village: the traditional language (Taiap), not spoken anywhere but in their own village and thus primordially "indexical" of Gapuner identity, and Tok Pisin, the widely circulating official language of New Guinea. ("indexical" points to meanings beyond the immediate context.)[8] To speak the Taiap language is associated with one identity: not only local but "Backward" and also an identity based on the display of hed (personal autonomy). To speak Tok Pisin is to index a modern, Catholic identity, based not on hed but on save, an identity linked with the will and the skill to cooperate. In later work, Kulick demonstrates that certain loud speech performances in Brazil called um escândalo, Brazilian travesti (roughly, 'transvestite') sex workers shame clients. The travesti community, the argument goes, ends up at least making a powerful attempt to transcend the shame the larger Brazilian public might try to foist off on them, again by loud public discourse and other modes of performance.[9] In addition, scholars such as Émile Benveniste,[10] Mary Bucholtz and Kira Hall[11] Benjamin Lee,[12] Paul Kockelman,[13] and Stanton Wortham[14] (among many others) have contributed to understandings of identity as "intersubjectivity" by examining the ways it is discursively constructed. |

アイデンティティと相互主観性 言語人類学の多くの研究は、社会文化的アイデンティティの問題を言語的・言説的に調査している。例えば、言語人類学者のドン・キューリックは、パプア ニューギニア北部のガプンと呼ばれる村での一連の設定において、アイデンティティとの関連においてそのような調査を行っている。(タイアプ語を話すこと は、ひとつのアイデンティティと結びついている。それは、地元語であるだけでなく「後方語」であり、ヘド(個人の自律性)の表示に基づくアイデンティティ でもある。トクピシンを話すことは、近代的でカトリック的なアイデンティティを示すことであり、それはヘドではなくセーブに基づくものであり、協力する意 志と技術に結びついたアイデンティティである。後の研究で、クーリックは、ブラジルのトラヴェスティ(おおざっぱに言えば「女装子」)のセックスワーカー たちが、ブラジルのum escândalo(ウム・エスカンダロ)と呼ばれる大声で話すパフォーマンスで、客を辱めることを実証している。トラヴェスティのコミュニティは、ブラ ジルの一般大衆が彼らに押し付けようとするかもしれない羞恥心を超越しようとする強力な試みを行っている。 加えて、エミール・ベンヴェニステ[10]、メアリー・ブコルツ、キラ・ホール[11]、ベンジャミン・リー[12]、ポール・コッケルマン[13]、ス タントン・ウォルサム[14]といった学者たち(その他多数)は、アイデンティティが言説的に構築される方法を検討することによって、「間主観性」として のアイデンティティの理解に貢献してきた。 |

| Socialization In a series of studies, linguistic anthropologists Elinor Ochs and Bambi Schieffelin addressed the anthropological topic of socialization (the process by which infants, children, and foreigners become members of a community, learning to participate in its culture), using linguistic and other ethnographic methods.[15] They discovered that the processes of enculturation and socialization do not occur apart from the process of language acquisition, but that children acquire language and culture together in what amounts to an integrated process. Ochs and Schieffelin demonstrated that baby talk is not universal, that the direction of adaptation (whether the child is made to adapt to the ongoing situation of speech around it or vice versa) was a variable that correlated, for example, with the direction it was held vis-à-vis a caregiver's body. In many societies caregivers hold a child facing outward so as to orient it to a network of kin whom it must learn to recognize early in life. Ochs and Schieffelin demonstrated that members of all societies socialize children both to and through the use of language. Ochs and Schieffelin uncovered how, through naturally occurring stories told during dinners in white middle class households in Southern California, both mothers and fathers participated in replicating male dominance (the "father knows best" syndrome) by the distribution of participant roles such as protagonist (often a child but sometimes mother and almost never the father) and "problematizer" (often the father, who raised uncomfortable questions or challenged the competence of the protagonist). When mothers collaborated with children to get their stories told, they unwittingly set themselves up to be subject to this process. Schieffelin's more recent research has uncovered the socializing role of pastors and other fairly new Bosavi converts in the Southern Highlands, Papua New Guinea community she studies.[16][17][18][19] Pastors have introduced new ways of conveying knowledge, new linguistic epistemic markers[16]—and new ways of speaking about time.[18] And they have struggled with and largely resisted those parts of the Bible that speak of being able to know the inner states of others (e.g. the gospel of Mark, chapter 2, verses 6–8).[19] |

社会化 言語人類学者のエリナー・オックスとバンビ・シーフェリンは、一連の研究の中で、言語学やその他の民族誌学的手法を用いて、社会化(幼児、子ども、外国人 がコミュニティの一員となり、その文化に参加することを学ぶ過程)という人類学的トピックに取り組んだ[15]。OchsとSchieffelinは、赤 ちゃん言葉が普遍的なものではなく、適応の方向(子どもが周囲の進行中の発話状況に適応させられるか、その逆か)は、例えば、保育者の体に対して抱かれる 方向と相関する変数であることを示した。多くの社会では、養育者は子どもを外側に向けて抱くが、これは子どもが人生の初期に認識することを学ばなければな らない親族のネットワークに方向づけるためである。 OchsとSchieffelinは、すべての社会の構成員が、言語に対して、また言語の使用を通して、子どもを社会化することを示した。オックスとシー フェリンは、南カリフォルニアの白人中流階級の家庭で、夕食時に自然に語られる物語を通して、母親と父親の両方が、主人公(多くの場合子どもだが、母親で あることもあり、父親であることはほとんどない)と「問題提起者」(多くの場合父親で、主人公に不快な疑問を投げかけたり、主人公の能力に異議を唱えたり する)といった参加者の役割分担によって、男性優位(「父親が一番よく知っている」症候群)の再現に参加していることを明らかにした。母親が自分の物語を 語らせるために子どもと協力するとき、母親は知らず知らずのうちに、自分自身がこのプロセスの対象となるように仕向けていたのである。 Schieffelinの最近の研究では、彼女が研究しているパプアニューギニアのサザン・ハイランズのコミュニティにおいて、牧師や他のかなり新しいボ サビ族の改宗者が社会化の役割を担っていることが明らかになった[16][17][18][19]。 [18]そして彼らは、他者の内面的な状態を知ることができると語る聖書の部分(マルコによる福音書2章6節から8節など)と闘争し、その大部分に抵抗し てきた[19]。 |

| Ideologies In a third example of the current (third) paradigm, since Roman Jakobson's student Michael Silverstein opened the way, there has been an increase in the work done by linguistic anthropologists on the major anthropological theme of ideologies,[20]—in this case "language ideologies", sometimes defined as "shared bodies of commonsense notions about the nature of language in the world."[21] Silverstein has demonstrated that these ideologies are not mere false consciousness but actually influence the evolution of linguistic structures, including the dropping of "thee" and "thou" from everyday English usage.[22] Woolard, in her overview of "code switching", or the systematic practice of alternating linguistic varieties within a conversation or even a single utterance, finds the underlying question anthropologists ask of the practice—Why do they do that?—reflects a dominant linguistic ideology. It is the ideology that people should "really" be monoglot and efficiently targeted toward referential clarity rather than diverting themselves with the messiness of multiple varieties in play at a single time.[23] Much research on linguistic ideologies probes subtler influences on language, such as the pull exerted on Tewa, a Kiowa-Tanoan language spoken in certain New Mexican pueblos and on the Hopi Reservation in Arizona, by "kiva speech", discussed in the next section.[24] Other linguists have carried out research in the areas of language contact, language endangerment, and 'English as a global language'. For instance, Indian linguist Braj Kachru investigated local varieties of English in South Asia, the ways in which English functions as a lingua franca among multicultural groups in India.[25] British linguist David Crystal has contributed to investigations of language death attention to the effects of cultural assimilation resulting in the spread of one dominant language in situations of colonialism.[26] |

イデオロギー 現在の(第三の)パラダイムの第三の例として、ローマン・ヤコブソンの弟子であるマイケル・シルヴァースタインが道を開いて以来、人類学の主要テーマであ るイデオロギー[20]に関する言語人類学者による研究が増加している。 「シルバーシュタインは、こうしたイデオロギーが単なる誤った意識ではなく、日常的な英語の用法から「thee」や「thou」が削除されるなど、言語構 造の進化に実際に影響を与えていることを実証している[22]。 ウーラードは、「コード・スイッチング」、つまり会話の中で、あるいは一つの発話の中で、言語品種を交互に使い分ける体系的な実践を概観し、人類学者がそ の実践に対して抱く根本的な疑問-なぜ彼らはそうするのか-が支配的な言語イデオロギーを反映していることを発見した。そのイデオロギーとは、人は一度に 複数の変種が混在して混乱するよりも、「本当は」単一言語であるべきであり、言及の明確さを効率的に目指すべきだというものである[23]。 言語イデオロギーに関する研究の多くは、次のセクションで述べる「キバ・スピーチ」によって、ニューメキシコ州の特定のプエブロやアリゾナ州のホピ居留地 で話されているキオワ・タノア族の言語であるテワ語に及ぼされている影響など、言語に対する微妙な影響を調査している[24]。 他の言語学者も言語接触、言語の絶滅危惧、「グローバル言語としての英語」の分野で研究を行っている。例えば、インドの言語学者であるブラジ・カチュル は、南アジアにおける英語の地域的変種や、インドにおける多文化集団の間で英語が共通語として機能する方法について調査している[25]。イギリスの言語 学者であるデイヴィッド・クリスタルは、植民地主義の状況において1つの支配的な言語が広まることによる文化的同化の影響に注目し、言語死の研究に貢献し ている[26]。 |

| Heritage language ideologies More recently, a new line of ideology work is beginning to enter the field of linguistics in relation to heritage languages. Specifically, applied linguist Martin Guardado has posited that heritage language ideologies are "somewhat fluid sets of understandings, justifications, beliefs, and judgments that linguistic minorities hold about their languages."[27] Guardado goes on to argue that ideologies of heritage languages also contain the expectations and desires of linguistic minority families "regarding the relevance of these languages in their children’s lives as well as when, where, how, and to what ends these languages should be used." Although this is arguably a fledgling line of language ideology research, this work is poised to contribute to the understanding of how ideologies of language operate in a variety of settings. |

継承語イデオロギー より最近では、遺産言語に関する言語学の分野に、新たなイデオロギーの研究が入り始めている。具体的には、応用言語学者のマーティン・グアルダード (Martin Guardado)が、継承語イデオロギーとは「言語的マイノリティが自分たちの言語について抱いている、やや流動的な理解、正当化、信念、判断の集合」 [27]であると提唱している。さらにグアルダードは、継承語イデオロギーには、言語的マイノリティである家族の「子どもたちの生活におけるこれらの言語 の関連性や、これらの言語をいつ、どこで、どのように、どのような目的で使用すべきかという期待や願望」も含まれていると主張している。これは言語イデオ ロギー研究の中では間違いなく発展途上の分野であるが、この研究は、さまざまな環境において言語のイデオロギーがどのように作用しているのかを理解する上 で貢献する態勢を整えている。 |

| Social space In a final example of this third paradigm, a group of linguistic anthropologists have done very creative work on the idea of social space. Duranti published a groundbreaking article on Samoan greetings and their use and transformation of social space.[28] Before that, Indonesianist Joseph Errington, making use of earlier work by Indonesianists not necessarily concerned with language issues per se, brought linguistic anthropological methods (and semiotic theory) to bear on the notion of the exemplary center, the center of political and ritual power from which emanated exemplary behavior.[29] Errington demonstrated how the Javanese priyayi, whose ancestors served at the Javanese royal courts, became emissaries, so to speak, long after those courts had ceased to exist, representing throughout Java the highest example of "refined speech." The work of Joel Kuipers develops this theme vis-a-vis the island of Sumba, Indonesia. And, even though it pertains to Tewa Indians in Arizona rather than Indonesians, Paul Kroskrity's argument that speech forms originating in the Tewa kiva (or underground ceremonial space) forms the dominant model for all Tewa speech can be seen as a direct parallel. Silverstein tries to find the maximum theoretical significance and applicability in this idea of exemplary centers. He feels, in fact, that the exemplary center idea is one of linguistic anthropology's three most important findings. He generalizes the notion thus, arguing "there are wider-scale institutional 'orders of interactionality,' historically contingent yet structured. Within such large-scale, macrosocial orders, in-effect ritual centers of semiosis come to exert a structuring, value-conferring influence on any particular event of discursive interaction with respect to the meanings and significance of the verbal and other semiotic forms used in it."[30] Current approaches to such classic anthropological topics as ritual by linguistic anthropologists emphasize not static linguistic structures but the unfolding in realtime of a "'hypertrophic' set of parallel orders of iconicity and indexicality that seem to cause the ritual to create its own sacred space through what appears, often, to be the magic of textual and nontextual metricalizations, synchronized."[30][31] |

社会空間 この第3のパラダイムの最後の例として、言語人類学者のグループが、社会空間という概念について非常に創造的な研究を行っている。デュランティは、サモア の挨拶とその社会的空間の使用と変容に関する画期的な論文を発表した[28]。それ以前には、インドネシア人のジョセフ・エリントンが、必ずしも言語問題 そのものに関心があるわけではないインドネシア人研究者による先行研究を利用し、模範的な行動から発せられる政治的・儀礼的権力の中心である模範的中心と いう概念に言語人類学的手法(と記号論的理論)を持ち込んだ[29]。 [29]エリントンは、ジャワの王宮に仕えた祖先を持つジャワのプリヤイが、王宮が消滅した後も、いわば使者となり、ジャワ全土で「洗練された言語」の最 高の模範となったことを示した。ジョエル・カイパースの研究は、インドネシアのスンバ島についてこのテーマを展開している。また、インドネシア人ではなく アリゾナ州のテワ・インディアンに関するものではあるが、テワ族のキバ(地下の儀式場)に由来する発話形態がすべてのテワ族の発話の支配的なモデルを形成 しているというポール・クロスクリティの議論は、直接の並行研究として見ることができる。 シルヴァスタインは、この模範的中心という考え方に最大の理論的意義と適用可能性を見出そうとしている。実際彼は、模範的中心という考え方は言語人類学の 最も重要な3つの発見の一つであると感じている。彼はこの考え方を一般化し、「歴史的に偶発的でありながら構造化された、より大規模な制度的『相互作用性 の秩序』が存在する」と主張する。そのような大規模なマクロ社会的秩序の中で、事実上儀式的なセミオシスの中心は、言説的相互作用のあらゆる特定の出来事 に対して、そこで使われる言語やその他のセミオティクス形式の意味や意義に関して、構造化し、価値を与える影響力を及ぼすようになる。 30] 言語人類学者による儀礼のような古典的な人類学的トピックへの現在のアプローチは、静的な言語構造ではなく、「象徴性と指標性の並列的な秩序の『肥大化』 セット」がリアルタイムで展開することを強調している |

| Areas of interest, part 2 |

関心領域2 |

| Race, class, and gender Addressing the broad central concerns of the subfield and drawing from its core theories, many scholars focus on the intersections of language and the particularly salient social constructs of race (and ethnicity), class, and gender (and sexuality). These works generally consider the roles of social structures (e.g., ideologies and institutions) related to race, class, and gender (e.g., marriage, labor, pop culture, education) in terms of their constructions and in terms of individuals' lived experiences. A short list of linguistic anthropological texts that address these topics follows: Race and ethnicity Alim, H. Samy, John R. Rickford, and Arnetha F. Ball. 2016. Raciolinguistics: How Language Shapes Our Ideas about Race. Oxford University Press. Bucholtz, Mary. 2001. "The Whiteness of Nerds: Superstandard English and Racial Markedness." Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 11 (1): 84–100. doi:10.1525/jlin.2001.11.1.84. Bucholtz, Mary. 2010. White Kids: Language, Race, and Styles of Youth Identity. Cambridge University Press. Davis, Jenny L. 2018. Talking Indian: Identity and Language Revitalization in the Chickasaw Renaissance. University of Arizona Press. Dick, H. 2011. "Making Immigrants Illegal in Small-Town USA." Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 21(S1):E35-E55. Hill, Jane H. 1998. "Language, Race, and White Public Space." American Anthropologist 100 (3): 680–89. doi:10.1525/aa.1998.100.3.680. Hill, Jane H. 2008. The Everyday Language of White Racism. Wiley-Blackwell. García-Sánchez, Inmaculada M. 2014. Language and Muslim Immigrant Childhoods: The Politics of Belonging. John Wiley & Sons. Ibrahim, Awad. 2014. The Rhizome of Blackness: A Critical Ethnography of Hip-Hop Culture, Language, Identity, and the Politics of Becoming. 1 edition. New York: Peter Lang Publishing Inc. Rosa, Jonathan. 2019. Looking like a Language, Sounding like a Race: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and the Learning of Latinidad. Oxford University Press. Smalls, Krystal. 2018. "Fighting Words: Antiblackness and Discursive Violence in an American High School." Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 23(3):356-383. Spears, Arthur Kean. 1999. Race and Ideology: Language, Symbolism, and Popular Culture. Wayne State University Press. Urciuoli, Bonnie. 2013. Exposing Prejudice: Puerto Rican Experiences of Language, Race, and Class. Waveland Press. Wirtz, Kristina. 2011. "Cuban Performances of Blackness as the Timeless Past Still Among Us." Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 21(S1):E11-E34. Class Fox, Aaron A. 2004. Real Country: Music and Language in Working-Class Culture. Duke University Press. Shankar, Shalini. 2008. Desi Land: Teen Culture, Class, and Success in Silicon Valley. Duke University Press. Nakassis, Constantine V. 2016. Doing Style: Youth and Mass Mediation in South India. University of Chicago Press. Gender and sexuality Bucholtz, Mary. 1999. "'Why be normal?': Language and Identity Practices in a Community of Nerd Girls". Language in Society. 28 (2): 207–210. Fader, Ayala. 2009. Mitzvah Girls: Bringing Up the Next Generation of Hasidic Jews in Brooklyn. Princeton University Press. Gaudio, Rudolf Pell. 2011. Allah Made Us: Sexual Outlaws in an Islamic African City. John Wiley & Sons. Hall, Kira, and Mary Bucholtz. 1995. Gender Articulated: Language and the Socially Constructed Self. New York: Routledge. Jacobs-Huey, Lanita. 2006. From the Kitchen to the Parlor: Language and Becoming in African American Women's Hair Care. Oxford University Press. Kulick, Don. 2000. "Gay and Lesbian Language." Annual Review of Anthropology 29 (1): 243–85. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.29.1.243. Kulick, Don. 2008. "Gender Politics." Men and Masculinities 11 (2): 186–92. doi:10.1177/1097184X08315098. Kulick, Don. 1997. "The Gender of Brazilian Transgendered Prostitutes." American Anthropologist 99 (3): 574–85. Livia, Anna, and Kira Hall. 1997. Queerly Phrased: Language, Gender, and Sexuality. Oxford University Press. Manalansan, Martin F. IV. "'Performing' the Filipino Gay Experiences in America: Linguistic Strategies in a Transnational Context." Beyond the Lavender Lexicon: Authenticity, Imagination and Appropriation in Lesbian and Gay Language. Ed. William L Leap. New York: Gordon and Breach, 1997. 249–266 Mendoza-Denton, Norma. 2014. Homegirls: Language and Cultural Practice Among Latina Youth Gangs. John Wiley & Sons. Rampton, Ben. 1995. Crossing: Language and Ethnicity Among Adolescents. Longman. Zimman, Lal, Jenny L. Davis, and Joshua Raclaw. 2014. Queer Excursions: Retheorizing Binaries in Language, Gender, and Sexuality. Oxford University Press. |

人種、階級、ジェンダー このサブフィールドの広範で中心的な関心事に取り組み、その中核となる理論から導き出される多くの研究者は、言語と、特に顕著な社会的構成要素である人種 (およびエスニシティ)、階級、ジェンダー(およびセクシュアリティ)との交差に焦点を当てている。これらの研究は一般的に、人種、階級、ジェンダー(結 婚、労働、ポップカルチャー、教育など)に関連する社会構造(イデオロギーや制度など)の役割を、その構築の観点から、また個人の生活経験の観点から考察 している。これらのトピックを扱った言語人類学的テキストの短いリストを以下に示す: ★人種とエスニシティ Alim, H. Samy, John R. Rickford, and Arnetha F. Ball. 2016. Raciolinguistics: How Language Shapes Our Ideas about Race. Oxford University Press. Bucholtz, Mary. 2001. 「The Whiteness of Nerds: The Whiteness of Nerds: Superstandard English and Racial Markedness.". Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 11 (1): 84–100. doi:10.1525/jlin.2001.11.1.84. Bucholtz, Mary. 2010. White Kids: Language, Race, and Styles of Youth Identity. Cambridge University Press. Davis, Jenny L. 2018. Talking Indian: Talking Indian: Identity and Language Revitalization in the Chickasaw Renaissance. University of Arizona Press. Dick, H. 2011. "Making Immigrants Illegal in Small-Town USA.". Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 21(s1):e35-e55. Hill, Jane H. 1998. "Language, Race, and White Public Space.". American Anthropologist 100 (3): 680–89. doi:10.1525/aa.1998.100.3.680. Hill, Jane H. 2008. The Everyday Language of White Racism. Wiley-Blackwell. García-Sánchez, Inmaculada M. 2014. Language and Muslim Immigrant Childhoods: The Politics of Belonging. John Wiley & Sons. Ibrahim, Awad. 2014. The Rhizome of Blackness: The Rhizome of Blackness: A Critical Ethnography of Hip-Hop Culture, Language, Identity, and the Politics of Becoming. 1 edition. New York: Peter Lang Publishing Inc. Rosa, Jonathan. 2019. Looking like a Language, Sounding like a Race: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and the Learning of Latinidad. Oxford University Press. Smalls, Krystal. 2018. "Fighting Words: Antiblackness and Discursive Violence in an American High School.". Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 23(3):356-383. Spears, Arthur Kean. 1999. Race and Ideology: Language, Symbolism, and Popular Culture. Wayne State University Press. Urciuoli, Bonnie. 2013. Exposing Prejudice: Exposing Prejudice: Puerto Rican Experiences of Language, Race, and Class. Waveland Press. Wirtz, Kristina. 2011. "Cuban Performances of Blackness as the Timeless Past Still Among Us.". Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 21(s1):e11-e34. ★階級 Fox, Aaron A. 2004. Real Country: Real Country: Music and Language in Working-Class Culture. Duke University Press. Shankar, Shalini. 2008. Desi Land: Teen Culture, Class, and Success in Silicon Valley. Duke University Press. Nakassis, Constantine V. 2016. Doing Style: Doing Style: Youth and Mass Mediation in South India. University of Chicago Press. ★ジェンダーとセクシュアリティ Bucholtz, Mary. 1999. "'Why be normal? オタク女子のコミュニティにおける言語とアイデンティティの実践". Language in Society. 28 (2): 207-210. Fader, Ayala. 2009. Mitzvah Girls: Mitzvah Girls: Bringing Up the Next Generation of Hasidic Jews in Brooklyn. Princeton University Press. Gaudio, Rudolf Pell. 2011. Allah Made Us: Sexual Outlaws in an Islamic African City. John Wiley & Sons. Hall, Kira, and Mary Bucholtz. 1995. Gender Articulated: Gender Articulated: Language and the Socially Constructed Self. ニューヨーク: Routledge. Jacobs-Huey, Lanita. 2006. From the Kitchen to the Parlor: From Kitchen to Parlor: Language and Becoming in African American Women's Hair Care. Oxford University Press. Kulick, Don. 2000. "Gay and Lesbian Language". Annual Review of Anthropology 29 (1): 243–85. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.29.1.243. Kulick, Don. 2008. "Gender Politics". Men and Masculinities 11 (2): 186–92. doi:10.1177/1097184X08315098. Kulick, Don. 1997. "The Gender of Brazilian Transgendered Prostitutes.". American Anthropologist 99 (3): 574-85. Livia, Anna, and Kira Hall. 1997. Queerly Phrased: Language, Gender, and Sexuality. オックスフォード大学出版局。 Manalansan, Martin F. IV. "'Performing' the Filipino Gay Experiences in America: Performing' Filipino Gay Experiences in America: Linguistic Strategies in a Transnational Context.". Beyond the Lavender Lexicon: Beyond Lavender Lexicon: Authenticity, Imagination and Appropriation in Lesbian and Gay Language. Ed. William L Leap. New York: Gordon and Breach, 1997. 249-266 Mendoza-Denton, Norma. 2014. Homegirls: Language and Cultural Practice Among Latina Youth Gangs. John Wiley & Sons. Rampton, Ben. 1995. Crossing: Crossing: Language and Ethnicity Among Adolescents. Longman. Zimman, Lal, Jenny L. Davis, and Joshua Raclaw. 2014. Queer Excursions: Retheorizing Binaries in Language, Gender, and Sexuality. オックスフォード大学出版局。 |

| Ethnopoetics Main article: Ethnopoetics Ethnopoetics is a method of recording text versions of oral poetry or narrative performances (i.e. verbal lore) that uses poetic lines, verses, and stanzas (instead of prose paragraphs) to capture the formal, poetic performance elements which would otherwise be lost in the written texts. The goal of any ethnopoetic text is to show how the techniques of unique oral performers enhance the aesthetic value of their performances within their specific cultural contexts. Major contributors to ethnopoetic theory include Jerome Rothenberg, Dennis Tedlock, and Dell Hymes. Ethnopoetics is considered a subfield of ethnology, anthropology, folkloristics, stylistics, linguistics, and literature and translation studies. |

エスノポエティクス(民族詩学) 主な記事 エスノポエティクス エスノポエティクスとは、口承詩や語りのパフォーマンス(すなわち言語伝承)をテキスト化する手法であり、詩的な行や節、スタンザ(散文的な段落の代わ り)を用いて、書かれたテキストでは失われてしまう形式的で詩的なパフォーマンス要素を捉える。エスノポエティック・テキストの目的は、固有の文化的コン テクストの中で、ユニークな口承パフォーマーの技法がいかに彼らのパフォーマンスの美的価値を高めているかを示すことである。エスノポエティック理論の主 な貢献者には、ジェローム・ローゼンバーグ、デニス・テドロック、デル・ハイムズなどがいる。エスノポエティクスは、民族学、人類学、民俗学、文体論、言 語学、文学・翻訳学の一分野と考えられている。 |

| Endangered languages: language documentation and revitalization Endangered languages are languages that are not being passed down to children as their mother tongue or that have declining numbers of speakers for a variety of reasons. Therefore, after a couple generations these languages may no longer be spoken.[32] Anthropologists have been involved with endangered language communities through their involvement in language documentation and revitalization projects. In a language documentation project, researchers work to develop records of the language - these records could be field notes and audio or video recordings. To follow best practices of documentation, these records should be clearly annotated and kept safe within an archive of some kind. Franz Boas was one of the first anthropologists involved in language documentation within North America and he supported the development of three key materials: 1) grammars, 2) texts, and 3) dictionaries. This is now known as the Boasian Trilogy.[33] Language revitalization is the practice of bringing a language back into common use. The revitalization efforts can take the form of teaching the language to new speakers or encouraging the continued use within the community.[34] One example of a language revitalization project is the Lenape language course taught at Swathmore College, Pennsylvania. The course aims to educate indigenous and non-indigenous students about the Lenape language and culture.[35] Language reclamation, as a subset of revitalization, implies that a language has been taken away from a community and addresses their concern in taking back the agency to revitalize their language on their own terms. Language reclamation addresses the power dynamics associated with language loss. Encouraging those who already know the language to use it, increasing the domains of usage, and increasing the overall prestige of the language are all components of reclamation. One example of this is the Miami language being brought back from 'extinct' status through extensive archives.[36] While the field of linguistics has also been focused on the study of the linguistic structures of endangered languages, anthropologists also contribute to this field through their emphasize on ethnographic understandings of the socio-historical context of language endangerment, but also of language revitalization and reclamation projects.[37] |

絶滅危惧言語:言語の文書化と再生 絶滅の危機に瀕している言語とは、さまざまな理由により、母語として子供たちに受け継がれていない言語や、話者の数が減少している言語のことである。その ため、数世代後には、これらの言語はもはや話されていない可能性がある[32]。人類学者は、言語の文書化プロジェクトや活性化プロジェクトに参加するこ とで、絶滅の危機に瀕している言語コミュニティに関わってきた。 言語ドキュメンテーション・プロジェクトでは、研究者は言語の記録を作成する。ドキュメンテーションのベストプラクティスに従うため、これらの記録には明 確な注釈をつけ、何らかのアーカイブの中に安全に保管する必要があります。フランツ・ボースは、北米で言語の文書化に携わった最初の人類学者の一人で、3 つの重要な資料の開発を支援した: 1)文法、2)テキスト、3)辞書である。これは現在ではボアス三部作として知られている[33]。 言語の活性化とは、ある言語を再び一般的に使われるようにすることである。言語活性化の取り組みには、新しい話者にその言語を教えるという形や、コミュニ ティ内での継続的な使用を奨励するという形がある[34]。言語活性化プロジェクトの一例として、ペンシルベニア州のスワスモア大学で教えられているレナ ペ語のコースがある。このコースは、先住民および非先住民の学生にレナペ語と文化について教育することを目的としている[35]。 言語再生は、再活性化のサブセットとして、言語がコミュニティから奪われたことを意味し、自分たちの言葉で自分たちの言語を再活性化させる主体性を取り戻 すことへのコミュニティの関心に取り組むものである。言語の再生は、言語喪失に伴うパワー・ダイナミクスに対処するものである。すでにその言語を知ってい る人々に使用を促し、使用領域を増やし、その言語の全体的な威信を高めることは、すべて再生の要素である。その一例として、マイアミ語が大規模なアーカイ ブによって「絶滅」状態から復活したことが挙げられる[36]。 言語学の分野では、絶滅の危機に瀕した言語の言語構造の研究にも焦点が当てられているが、人類学者もまた、言語が絶滅の危機に瀕している社会歴史的背景の 民族誌的理解、さらには言語の再生や再生プロジェクトに重点を置くことで、この分野に貢献している[37]。 |

| Ethnolinguistics Evolutionary psychology of language Linguistic insecurity List of important publications in anthropology Miyako Inoue Semiotic anthropology Sociocultural linguistics Sociolinguistics Sociology of language World Oral Literature Project |

民族言語学 言語の進化心理学 言語学的不安 人類学における重要論文のリスト 井上都 記号人類学 社会文化言語学 社会言語学 言語社会学 世界口承文芸プロジェクト |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linguistic_anthropology |

|

| 文化の範疇としての言語 |

人間にとっての(有意味な言語とは)分

節言語のことである。一般に人間の文化活動は言語活動のひとつとして考えられている。 |

| 言語の限界が人間の思考の範疇の限界であ

る |

言語の限界が人間の思考の範疇の限界で ある、というのは、古くはウィトゲンシュタインの前期思想(「論理哲学論考)になぞらえてよく理解されている。 |

| 文化の定義 |

文化の定義は研究者の数だけあると言わ

れている。 |

+++

関連リンク

文献

その他の情報

音声学資料

さ

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆