ボアズ派人類学

Boasian anthropology

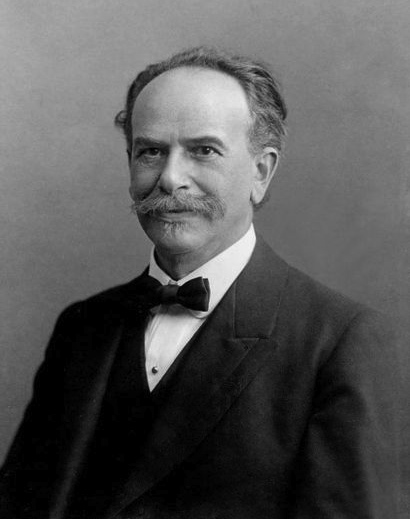

☆ボアズ派人類学(Boasian anthropology)は、19世紀末にフランツ・ボアズが創設したアメリカ人類学の一学派である。文化人類学、言語人類学、自然人類学、考古学の四分野を統合した人類学の四分野モデルを基盤としていた。文化的相対主義を強調し、行動の生物学的決定要因と文化的決定要因の分離を主張した。ボアズは20世紀の人類学において広範な影響力を持ち、多くの学生を育成した。その教え子たちは後に人類学界の主要な地位に就いた。

| Boasian anthropology

was a school within American anthropology founded by Franz Boas in the

late 19th century. It was based on the four-field model of anthropology

uniting the fields of cultural anthropology, linguistic anthropology,

physical anthropology, and archaeology. It stressed cultural

relativism, and separation of biological and cultural determinants of

behavior. Boas was widely influential in 20th century anthropology

training many students who went on to major positions in the field. |

ボ アズ派人類学は、19世紀末にフランツ・ボアズが創設したアメリカ人類学の一学派である。文化人類学、言語人類学、自然人類学、考古学の四分野を統合した 人類学の四分野モデルを基盤としていた。文化的相対主義を強調し、行動の生物学的決定要因と文化的決定要因の分離を主張した。ボアズは20世紀の人類学に おいて広範な影響力を持ち、多くの学生を育成した。その教え子たちは後に人類学界の主要な地位に就いた。 |

| Overview It was based on an understanding of human cultures as malleable and perpetuated through social learning, and understood behavioral differences between peoples as largely separate from and unaffected by innate predispositions stemming from human biology—in this way it rejected the view that cultural differences were essentially biologically based. It also rejected ideas of cultural evolution which ranked societies and cultures according to their degree of "evolution", assuming a single evolutionary path along which cultures can be ranked hierarchically, rather Boas considered societies varying complexities to be the outcome of particular historical processes and circumstances—a perspective described as historical particularism. |

概要 これは、人間の文化は可塑的で社会的学習を通じて継承されるという理解に基づいていた。そして人民間の行動の異なる点は、人間の生物学に由来する生来の傾 向とはほぼ無関係であり、その影響を受けないと理解した。このようにして、文化の違いは本質的に生物学的に基盤を持つという見解を拒否した。また、文化進 化論の考え方も否定した。文化進化論は、文化を「進化」の度合いに基づいてランク付けし、文化を階層的に評価できる単一の進化経路を想定していた。それに 対してボアズは、社会の複雑さの差異は、特定の歴史的過程と状況の結果であると考えていた。この視点は、歴史的個別主義として説明される。 |

| Another

important aspect of Boasian anthropology was its perspective of

cultural relativism which assumes that a culture can only be understood

by first understanding its own standards and values, rather than

assuming that the values and standards of the anthropologist's society,

can be used to judge other cultures. In this way Boasian

anthropologists did not assume as a given that non-Western societies

are necessarily inferior to Western ones, but rather attempt to

understand them on their own terms. From this approach also stemmed an

investment in understanding and protecting cultural minorities, and in

critiquing and relativizing American and Western society through

contrasting its values and norms with those of other societies. Boasian

anthropology in this way tended to consider political activism, through

scientific education about society, a significant part of the

scientific project.[1][2][3][4][5][6] |

ボ

アズ派人類学のもう一つの重要な側面は、文化相対主義の視点であった。これは、ある文化を理解するにはまずその文化自身の基準や価値観を理解すべきであ

り、人類学者の属する社会の価値観や基準で他文化を判断すべきではないと仮定する。このためボアズ派人類学者は、非西洋社会が西洋社会に必ず劣ると当然視

せず、むしろその社会自身の基準で理解しようと試みた。このアプローチから、文化的少数派の理解と保護への取り組み、そしてアメリカや西洋社会の価値観や

規範を他社会と比較することでそれらを批判し相対化する姿勢も生まれた。このようにボアズ派人類学は、社会に関する科学的啓蒙を通じた政治的活動主義を、

科学プロジェクトの重要な一部と見なす傾向があった。[1][2][3][4][5][6] |

| The

program of research and public education activities pursued by Boas,

his former students, and their associates—eventually including most of

the field of anthropology as practiced in the United States—encompassed

a number of discrete areas of inquiry and activity. These include many

anthropological specializations and neighboring inter-disciplines, such

as those known today as museum anthropology, folkloristics, linguistic

anthropology, Native American studies, and

ethnohistory.[7][8][9][10][11][12] |

ボ

アズとその教え子たち、そして協力者たち——最終的にはアメリカで実践される人類学の大半を含む——が推進した研究と公衆教育活動のプログラムは、数多く

の独立した研究領域と活動を包含していた。これには今日、博物館人類学、民俗学、言語人類学、ネイティブ・アメリカン研究、民族史学として知られるよう

な、多くの人類学の専門分野と隣接する学際領域が含まれる。[7][8][9][10][11][12] |

| Boasian anthropologists Boas had a large group of students who dominated the first generation of professional anthropologists in the United States, and went on to found many of the earliest anthropology departments in the country.[13] Among the prominent students of Boas who became exponents of Boasian anthropology were: |

ボアズ派人類学者 ボアズには多くの弟子がおり、彼らはアメリカにおける第一世代の専門人類学者を支配し、国内で最も初期の人類学部門の多くを設立した。[13] ボアズの著名な弟子で、ボアズ派人類学の代表者となったのは以下の通りである: |

| Ruth Benedict Ruth Bunzel Roland Burrage Dixon Alexander Goldenweiser Melville Herskovits Zora Neale Hurston Melville Jacobs Alfred Kroeber Alexander Lesser Robert Lowie Margaret Mead Elsie Clews Parsons Paul Radin Gladys Reichard Edward Sapir Frank Speck Leslie Spier John R. Swanton Ruth Underhill Gene Weltfish |

ルース・ベネディクト ルース・ブンツェル ローランド・ブラッジ・ディクソン アレクサンダー・ゴールデンワイザー メルヴィル・ハースコヴィッツ ゾラ・ニール・ハーストン メルヴィル・ジェイコブス アルフレッド・クローバー アレクサンダー・レッサー ロバート・ローウィ マーガレット・ミード エルシー・クルーズ・パーソンズ ポール・ラディン グラディス・ライチャード エドワード・サピア フランク・スペック レスリー・スピア ジョン・R・スワントン ルース・アンダーヒル ジーン・ウェルトフィッシュ |

| Critiques In the mid 20th century, Boasian anthropology came under critique both from those students who wanted to reintroduce evolutionary processes into the study of culture, and from those who disagreed with its relativist stance and its view that biological differences did not reflect innate differences in human ability or potential. In the late 20th century earlier Boasian anthropology was also critiqued for its acceptance of race as a valid biological category,[14] leading to attempts to redefine a neo-Boasian anthropology which studies the particular historical trajectories leading to the construction of social categories of cultures and races.[15] |

批判 20世紀半ば、ボアズ派人類学は、文化研究に進化論的プロセスを再導入しようとする学生たちから、またその相対主義的立場や生物学的差異が人間の能力や潜 在能力における生得的な差異を反映しないとする見解に反対する者たちから、批判を受けた。20世紀後期には、初期のボアズ派人類学が人種を有効な生物学的 カテゴリーとして受け入れた点も批判された[14]。これにより、文化や人種といった社会的カテゴリーの構築に至る特定の歴史的軌跡を研究する新ボアズ派 人類学の再定義が試みられた[15]。 |

| Cultural relativism |

文化相対主義 |

| 1. Handler, R. (1990). Boasian anthropology and the critique of American culture. American Quarterly, 42(2), 252–273. 2. Shapiro, W. (1991). Claude Lévi-Strauss Meets Alexander Goldenweiser: Boasian Anthropology and the Study of Totemism. American Anthropologist, 93(3), 599-610. 3. Darnell, R. (1977). Hallowell's "Bear Ceremonialism" and the Emergence of Boasian Anthropology. Ethos, 5(1), 13-30. 4. George W. Stocking. "the basic Assumptions of Boasian Anthropology" in Delimiting Anthropology: Occasional Essays and Reflections, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 2001 5. William Y. Adams. The Boasians: Founding Fathers and Mothers of American Anthropology, Rowman & Littlefield, 2. sep. 2016 6. Regna Darnell. 1998. And Along Came Boas: Continuity and Revolution in Americanist Anthropology. John Benjamins Publishing 7. Greene, Candace (2015). Scott, Robert A; Kosslyn, Stephan M (eds.). "Museum Anthropology" (PDF). Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. doi:10.1002/9781118900772. ISBN 9781118900772. 8. Zumwalt, Rosemary Lévy (1988). American Folklore Scholarship: A Dialogue of Dissent. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 9. Darnell, Regna (1973). "American Anthropology and the Development of Folklore Scholarship: 1890-1920". Journal of the Folklore Institute. 10 (1–2): 23–39. doi:10.2307/3813878. JSTOR 3813878. 10. Epps, Patience L.; Webster, Anthony K.; Woodbury, Anthony C. (2017). "A Holistic Humanities of Speaking: Franz Boas and the Continuing Centrality of Texts". International Journal of American Linguistics. 83 (1): 41–78. doi:10.1086/689547. S2CID 152181161. 11. Andersen, Chris; O'Brien, Jean M., eds. (2016). Sources and Methods in Indigenous Studies. New York: Routledge. 12. Harkin, Michael E. (2010). "Ethnohistory's Ethnohistory: Creating a Discipline from the Ground Up". Social Science History. 34 (2): 113–128. doi:10.1017/S0145553200011184. S2CID 145203874. 13. Frank, G. (1997). Jews, multiculturalism, and Boasian anthropology. American Anthropologist, 99(4), 731–745. 14. Visweswaran, K. (1998). Race and the Culture of Anthropology. American Anthropologist, 100(1), 70-83. 15. Bunzl, M. (2004). Boas, Foucault, and the "Native Anthropologist": Notes toward a Neo-Boasian Anthropology. American Anthropologist, 106(3), 435-442. |

1. ハンドラー, R. (1990). ボアズ派人類学とアメリカ文化批判. American Quarterly, 42(2), 252–273. 2. シャピロ, W. (1991). クロード・レヴィ=ストロースとアレクサンダー・ゴールデンワイザーの出会い:ボアズ派人類学とトーテミズム研究. アメリカ人類学者、93(3)、599-610。 3. ダーネル、R. (1977). ハロウェルの「熊の儀式」とボアズ派人類学の出現。エトス、5(1)、13-30。 4. ジョージ・W・ストッキング. 「ボアズ派人類学の基本的前提」『人類学の境界:随筆と考察』所収, ウィスコンシン大学出版局, 2001年 5. ウィリアム・Y・アダムズ. 『ボアズ派:アメリカ人類学の創始者たち』ローマン・アンド・リトルフィールド社, 2016年9月2日 6. レグナ・ダーネル. 1998. 『そしてボアズが現れた:アメリカ人類学における継続と革命』. ジョン・ベンジャミンズ出版 7. グリーン, キャンディス (2015). スコット, ロバート・A; コスリン, ステファン・M (編). 「博物館人類学」 (PDF). 『社会・行動科学の新潮流』. doi:10.1002/9781118900772. ISBN 9781118900772. 8. ズムウォルト、ローズマリー・レヴィ(1988)。『アメリカ民俗学研究:異議の対話』。ブルーミントン:インディアナ大学出版局。 9. ダーネル、レグナ(1973)。「アメリカ人類学と民俗学研究の発展:1890-1920年」。『民俗学研究所紀要』。10 (1–2): 23–39。doi:10.2307/3813878。JSTOR 3813878。 10. エップス、パティエンス・L.;ウェブスター、アンソニー・K.;ウッドベリー、アンソニー・C.(2017).「話すことに関する総合的人文科学:フラ ンツ・ボアズとテキストの持続的な中心性」.『国際アメリカ言語学ジャーナル』.83 (1): 41–78.doi:10.1086/689547. S2CID 152181161. 11. アンデルセン, クリス; オブライエン, ジャン・M., 編 (2016). 『先住民研究の資料と方法』. ニューヨーク: ラウトレッジ. 12. ハーキン, マイケル・E. (2010). 「エスノヒストリーのエスノヒストリー:一から築き上げた学問領域」. 『社会科学史』. 34 (2): 113–128. doi:10.1017/S0145553200011184. S2CID 145203874. 13. フランク, G. (1997). ユダヤ人、多文化主義、そしてボアズ派人類学. アメリカ人類学者, 99(4), 731–745. 14. ヴィシュヴェスワラン, K. (1998). 人種と人類学の文化. アメリカ人類学者, 100(1), 70-83. 15. ブンツル, M. (2004). ボアズ、フーコー、そして「ネイティブ人類学者」:新ボアズ派人類学への覚書. アメリカ人類学雑誌, 106(3), 435-442. |

| Boasian Anthropology: Historical Particularism and Cultural Relativism. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boasian_anthropology |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099