アフリカ人埋葬地国立モニュメント

ニューヨーク

African Burial Ground National Monument

☆ ア フリカ人埋葬地国立モニュメントは、ニューヨーク市ロウアー・マンハッタンのシビック・センター地区、ドゥエイン・ストリートとアフリカ埋葬地通り(エル ク・ストリート)にある史跡であ る。17世紀後半から18世紀にかけて、アフリカ系住民のための植民地時代最大の墓地の一部に埋葬された419人以上のアフリカ人の遺骨がある。この 5~6エーカーの敷地の発掘と調査は、「米国で最も重要な歴史的都市考古学プロジェクト」と呼ばれ、埋葬地はニューヨークで最も古いアフリカ系アメ リカ人の墓地として知られている。

| African Burial

Ground National Monument is a monument at Duane Street and African

Burial Ground Way (Elk Street) in the Civic Center section of Lower

Manhattan, New York City. Its main building is the Ted Weiss Federal

Building at 290 Broadway.[4] The site contains the remains of more than

419 Africans buried during the late 17th and 18th centuries in a

portion of what was the largest colonial-era cemetery for people of

African descent, some free, most enslaved.[5] Historians estimate there

may have been as many as 10,000[6]–20,000 burials in what was called

the Negroes Burial Ground in the 18th century. The five to six acre

site's excavation and study was called "the most important historic

urban archaeological project in the United States."[7] The Burial

Ground site is New York's earliest known African-American cemetery;

studies show an estimated 15,000 African American people were buried

here.[8] The discovery highlighted the forgotten history of enslaved Africans in colonial and federal New York City, who were integral to its development. By the American Revolutionary War, they constituted nearly a quarter of the population in the city. New York had the second-largest number of enslaved Africans in the nation after Charleston, South Carolina. Scholars and African-American civic activists joined to publicize the importance of the site and lobby for its preservation. The site was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1993 and a national monument in 2006 by President George W. Bush. In 2003 Congress appropriated funds for a memorial at the site and directed redesign of the federal courthouse to allow for this. A design competition attracted more than 60 proposals. The memorial was dedicated in 2007 to commemorate the role of Africans and African Americans in colonial and federal New York City, and in United States history. Several pieces of public art were also commissioned for the site. A visitor center opened in 2010 to provide interpretation of the site and African-American history in New York. |

アフリカ埋葬地国定史跡、あるいアフリカ人埋葬地国立モニュメントは、

ニューヨーク市ロウアー・マンハッタンのシビック・センター地区、ドゥエイン・ストリートとアフリカ埋葬地通り(エルク・ストリート)にある史跡である。

17世紀後半から18世紀にかけて、アフリカ系住民のための植民地時代最大の墓地の一部に埋葬された419人以上のアフリカ人の遺骨がある。この5~6

エーカーの敷地の発掘と調査は、「米国で最も重要な歴史的都市考古学プロジェクト」[7]と呼ばれ、埋葬地はニューヨークで最も古いアフリカ系アメリカ人

の墓地として知られている。 この発見は、植民地時代と連邦時代のニューヨークにおいて、忘れ去られていたアフリカ人奴隷の歴史を浮き彫りにした。アメリカ独立戦争までに、彼らは ニューヨークの人口の4分の1近くを占めていた。ニューヨークには、サウスカロライナ州チャールストンに次いで、全米で2番目に多くのアフリカ人奴隷がい た。学者やアフリカ系アメリカ人の市民活動家たちは、この遺跡の重要性を広報し、保存のためのロビー活動に参加した。この遺跡は1993年に国定歴史建造 物に指定され、2006年にはジョージ・W・ブッシュ大統領によって国定記念物に指定された。 2003年、連邦議会はこの場所に記念碑を建てるための資金を計上し、そのために連邦裁判所の再設計を指示した。設計コンペには60以上の提案が集まっ た。記念碑は2007年に献堂され、植民地時代と連邦時代のニューヨーク、そして米国の歴史におけるアフリカ人とアフリカ系アメリカ人の役割を記念してい る。この記念碑のために、いくつかのパブリックアートも制作された。2010年にオープンしたビジター・センターでは、この記念碑とニューヨークにおける アフリカ系アメリカ人の歴史について解説している。 |

| Africans and African Americans

in New York City Main article: History of New York City Pre-Revolutionary War Slavery in the New York City area was introduced by the Dutch West India Company in New Netherland in about 1626 with the arrival of Paul D'Angola, Simon Congo, Lewis Guinea, Jan Guinea, Ascento Angola, and six other men. Their names denote their place of origin- Angola, the Congo, and Guinea. Two years after their arrival three female Angolan slaves arrived. These two groups heralded the beginning of slavery in what would become New York City, and which would continue for two hundred years.[9] The first slave auction in the city took place in 1655 at Pearl Street and Wall Street – then on the East River. Although the Dutch imported Africans as slaves, it was possible for some to gain freedom or "half-freedom" during the time of Dutch rule. In 1643, Paul D'Angola and his companions petitioned the Dutch West India Company for their freedom. Their request was granted, resulting in their acquisition of land on which to build their own houses and farm. By the mid-17th century, farms of free blacks covered 130 acres where Washington Square Park later appeared.[10] Enslaved Africans in chattel bondage were granted certain rights and afforded protections such as the prohibition against arbitrary physical punishment – for example, whipping.[citation needed]  Slave being burned at the stake in N.Y.C. after the 1741 slave revolt. Thirteen slaves were burned.[11] The English seized New Amsterdam in 1664, and renamed the fledgling settlement to New York (after the Duke of York). The new city administration changed the rules governing slavery in the colony. At the time of the seizure, some forty percent of the small population of New Amsterdam were enslaved Africans.[12] The new rules[13] regarding slavery were more restrictive than those of the Dutch, and rescinded many of the former rights and protections of enslaved residents, such as the prohibition against arbitrary physical punishment. In 1697 Trinity Church gained control of the burial grounds in the city and passed an ordinance excluding blacks from the right to be buried in churchyards. When Trinity took control of the municipal burial ground, now its northern graveyard, it barred Africans from interment within the city limits.[12] Through much of the 18th century, the African burying ground was beyond the northern boundary of the city, which was just beyond what is today Chambers Street. As the city population increased, so did the number of residents who held slaves. "In 1703, 42 percent of New York's households had slaves, much more than Philadelphia and Boston combined."[14] Most slaveholding households had only a few slaves, used primarily for domestic work. By the 1740s, 20 percent of the population of New York were slaves,[15] totaling about 2,500 people.[10] Enslaved residents also worked as skilled artisans and craftsmen associated with shipping, construction, and other trades, as well as laborers. By 1775, New York City had the largest number of enslaved residents of any settlement in the Thirteen Colonies excepted Charles Town, South Carolina, and had the highest proportion of Africans to Europeans of any settlement in the Northern colonies.[12] Post-Revolutionary War During the Revolutionary War, the British occupied New York City in the summer of 1776 and they maintained control of the city until the Peace of Paris was signed and they departed on November 25, 1783, a date which came to be known as Evacuation Day. As in the rest of the Thirteen Colonies, the Crown had offered freedom to enslaved peoples who escaped from their Patriot masters and fled to British lines. 3,000 of these individuals were eventually listed in the Book of Negroes. This promise of freedom attracted thousands of slaves to the city who had escaped to British lines. In 1781 the New York legislature offered a financial incentive to Loyalist slaveowners who assigned their slaves to military service, and promised freedom at the war's end for the slaves.[citation needed]  Pierre Toussaint was born into slavery in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) and was emancipated in New York City. By 1780 the African-American community swelled to about 10,000 in New York City, which became the center of free blacks in North America.[15] Among those who escaped to New York were Deborah Squash and her husband Harvey, who fled from George Washington's plantation in Virginia.[15] After the end of the war, according to provisions concerning property in the Treaty of Paris, the Americans demanded the return of all former slaves who had escaped to British lines. The British steadfastly refused the American request and evacuated 3,000 freedmen with their troops in 1783 for resettlement in Nova Scotia, other British colonies, and England. Instead of returning the slaves which had been promised their freedom, the British came to an agreement with the Americans to financially recompensate them for each slave lost.[15] Other freedmen scattered from the city to evade slave catchers.[citation needed] Aided by individual manumissions after war's end, by 1790 about one-third of the blacks in the city were free.[10] The total city population was 33,131, according to the first national census.[16] In 1799 the state legislature passed An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery with little opposition. Similar to Pennsylvania's law, it provided for gradual manumission of slaves. Children born to slave mothers after July 4, 1799, were considered legally free, but had to serve as indentured servants to their mother's master, until age 28 for men and 25 for women, before gaining social freedom. Until reaching age 21, they were considered the property of the mother's master. All slaves already in bondage before July 4, 1799, remained slaves for life, although they were reclassified as "indentured servants."[14][15][17] In 1817, the New York legislature granted freedom to all children born to slaves after July 4, 1799, under the Gradual Emancipation Act,[18] with total abolition of slavery to take effect on July 4, 1827. July 4 is now known as New York's Emancipation Day, more than 10,000 slaves were freed in New York State with no financial compensation to their former owners. Blacks paraded in New York City to celebrate. Under the 1777 New York constitution, all free men had to satisfy a property requirement to vote, which eliminated poorer men from voting, both blacks and whites.[17] A new constitution in 1821 eliminated the property requirement for white men, but kept it for blacks, effectively continuing to disfranchise them. This lasted until passage of the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1870.[17] The early history of free blacks and slaves in New York City became overshadowed by the waves of mid- to late nineteenth century immigration from Europe, which dramatically expanded the population and added to the ethnic diversity. In addition, most of the ancestors of today's African-American population in the city arrived from the South in the Great Migration of the first half of the twentieth century. In a rapidly changing city, the early colonial and federal history of African Americans was lost. |

ニューヨークのアフリカ人とアフリカ系アメリカ人 主な記事 ニューヨークの歴史 独立戦争前 ニューヨーク市域の奴隷制度は、1626年頃にニューネーデルラントのオランダ西インド会社によって導入され、ポール・ダンゴラ、シモン・コンゴ、ルイ ス・ギニア、ヤン・ギニア、アセント・アンゴラ、その他6人が到着した。彼らの名前は、アンゴラ、コンゴ、ギニアという出身地を表しています。彼らの到着 から2年後、3人の女性アンゴラ人奴隷が到着しました。この2つのグループは、後のニューヨークにおける奴隷制度の始まりを告げるものであり、その後 200年にわたり奴隷制度は続いた[9]。オランダはアフリカ人を奴隷として輸入したが、オランダ統治時代には自由または「半自由」を得ることも可能で あった。1643年、ポール・ダンゴラとその仲間たちは、オランダ西インド会社に自由を求めた。彼らの要求は認められ、その結果、彼らは自分たちの家を建 て、農場を作るための土地を手に入れた。17世紀半ばまでに、自由黒人たちの農場は、後にワシントン・スクエア・パークが出現した130エーカーを覆って いた[10]。 動物奴隷として奴隷にされたアフリカ人には一定の権利が認められ、例えば鞭打ちなどの恣意的な体罰の禁止などの保護が与えられていた[要出典]。  1741年の奴隷反乱の後、N.Y.C.で火あぶりにされた奴隷。13人の奴隷が火あぶりにされた[11]。 1664年、イギリスはニューアムステルダムを占領し、まだ始まったばかりの入植地をニューヨーク(ヨーク公の名前にちなんで)と改名した。新しい市政は 植民地内の奴隷制を管理する規則を変更した。奴隷制度に関する新しい規則[13]はオランダの規則よりも厳しく、恣意的な体罰の禁止など、奴隷にされた住 民のかつての権利や保護の多くが取り消された。1697年、トリニティ教会は市内の埋葬地を掌握し、教会墓地に埋葬される権利から黒人を除外する条例を可 決した。トリニティ教会が市営の埋葬地(現在はその北側の墓地)を管理するようになると、市域内でのアフリカ人の埋葬を禁止した[12]。18世紀の大半 を通じて、アフリカ人の埋葬地は市の北側の境界を越えており、それは現在のチェンバーズ・ストリートのすぐ先であった。 市の人口が増加するにつれて、奴隷を所有する住民の数も増加した。「1703年には、ニューヨークの世帯の42パーセントが奴隷を所有しており、フィラデ ルフィアとボストンを合わせたよりもはるかに多かった。1740年代までに、ニューヨークの人口の20パーセントが奴隷であり[15]、その総数は約 2,500人にのぼった[10]。奴隷にされた住民はまた、海運、建設、その他の職業に関連する熟練した職人や職人、労働者として働いた。1775年まで には、ニューヨークはサウスカロライナのチャールズタウンを除く13植民地の入植地の中で最も多くの奴隷住民を抱えており、ヨーロッパ人に対するアフリカ 人の割合は北部植民地の入植地の中で最も高かった[12]。 独立戦争後 独立戦争中、イギリスは1776年夏にニューヨークを占領し、パリの和約が調印されるまでニューヨークの支配を維持した。13植民地の他の地域と同様、王 室は愛国者の主人から逃れてイギリスの戦線に逃れた奴隷の人々に自由を与えていた。このうち3,000人が最終的に「黒人書」に記載された。この自由の約 束は、英国戦線に逃れた何千人もの奴隷たちをこの街に引きつけた。1781年、ニューヨーク議会は、奴隷を軍務に就かせたロイヤリストの奴隷所有者に金銭 的な奨励金を与え、戦争終結時の奴隷の自由を約束した[要出典]。  ピエール・トゥーサンはフランスの植民地サン=ドマング(現在のハイチ)で奴隷として生まれ、ニューヨークで奴隷解放された。(→Black Catholicism) 1780年までにニューヨークのアフリカ系アメリカ人のコミュニティは約10,000人に膨れ上がり、北米における自由黒人の中心地となった[15]。 ニューヨークに逃れた人々の中には、バージニア州にあるジョージ・ワシントンの農園から逃れたデボラ・スカッシュとその夫ハーヴェイがいた[15]。 終戦後、パリ条約の財産に関する条項に従って、アメリカ人はイギリス軍に逃れたすべての元奴隷の返還を要求した。イギリスはアメリカの要求を断固として拒 否し、1783年に3,000人の自由民を軍隊とともにノヴァ・スコシア、他のイギリス植民地、イギリスに移住させるために避難させた。イギリスは自由を 約束した奴隷を返す代わりに、失った奴隷一人一人に金銭的な補償をすることでアメリカ人と合意した[15]。 終戦後の個人的な奴隷解放にも助けられ、1790年までには市内の黒人の約3分の1が自由の身となった[10]。 最初の国勢調査によれば、市の総人口は33,131人であった[16]。 1799年、州議会はほとんど反対することなく、奴隷制の漸進的廃止のための法律を可決した。ペンシルベニア州の法律と同様に、奴隷の漸進的な解放が規定 されていた。1799年7月4日以降に奴隷の母親から生まれた子供は、法的には自由とみなされたが、社会的自由を得る前に、男性は28歳まで、女性は25 歳まで、母親の主人の年季奉公人として仕えなければならなかった。21歳になるまでは、母親の主人の所有物とみなされた。1799年7月4日以前にすでに 拘束されていた奴隷は、「年季奉公人」に再分類されたものの、終生奴隷のままであった[14][15][17]。 1817年、ニューヨーク議会は漸進的奴隷解放法[18]のもと、1799年7月4日以降に奴隷から生まれたすべての子供たちに自由を認め、1827年7 月4日に奴隷制の完全廃止が施行された。7月4日は現在、ニューヨークの奴隷解放記念日として知られ、ニューヨーク州では1万人以上の奴隷が解放された が、元の所有者には金銭的補償はなかった。黒人たちは、これを祝うためにニューヨークでパレードを行った。 1777年に制定されたニューヨーク憲法では、すべての自由人は選挙権を得るために財産要件を満たさなければならず、そのため黒人も白人も、より貧しい人 々は選挙権を得ることができなかった[17]。これは1870年に合衆国憲法修正第15条が成立するまで続いた[17]。 ニューヨークにおける自由黒人と奴隷の初期の歴史は、19世紀半ばから後半にかけてのヨーロッパからの移民の波によって影が薄くなり、人口が劇的に拡大 し、民族の多様性が増した。さらに、今日のアフリカ系アメリカ人の祖先のほとんどは、20世紀前半の大移動で南部からやってきた。急速に変化する都市の中 で、アフリカ系アメリカ人の初期の植民地時代や連邦時代の歴史は失われた。 |

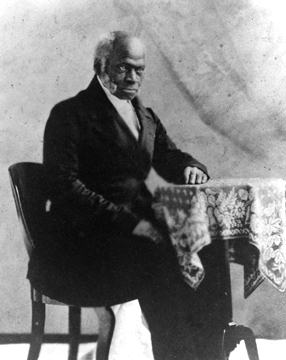

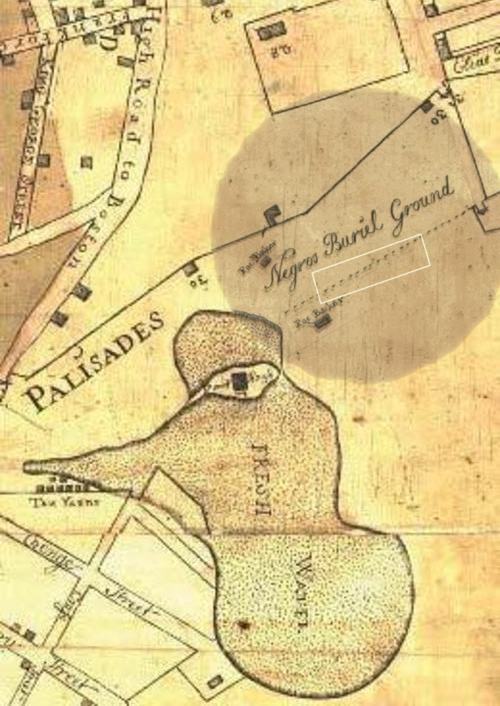

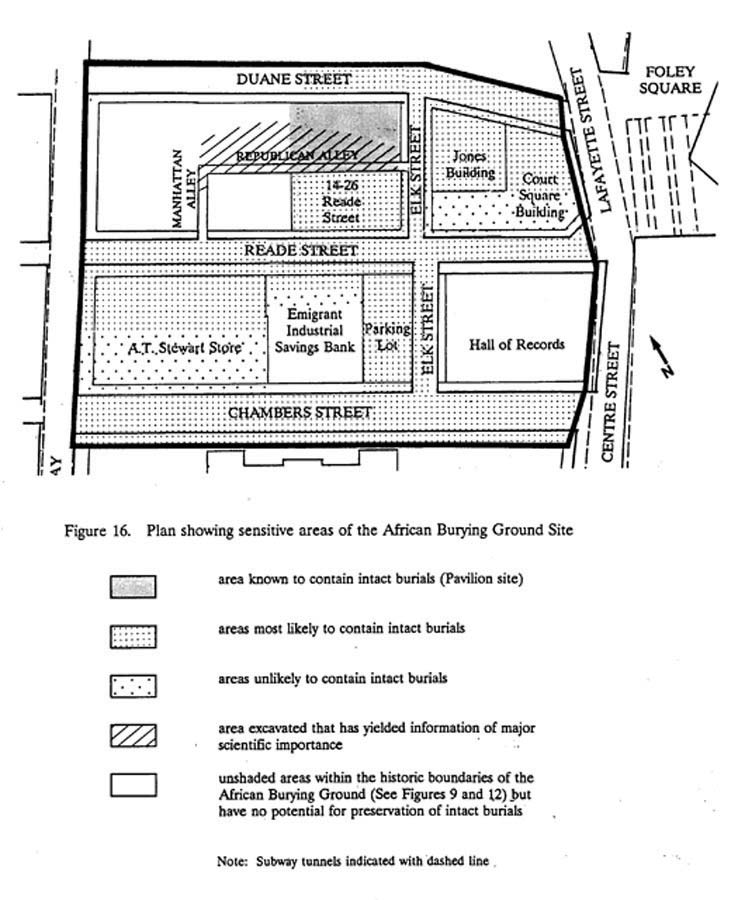

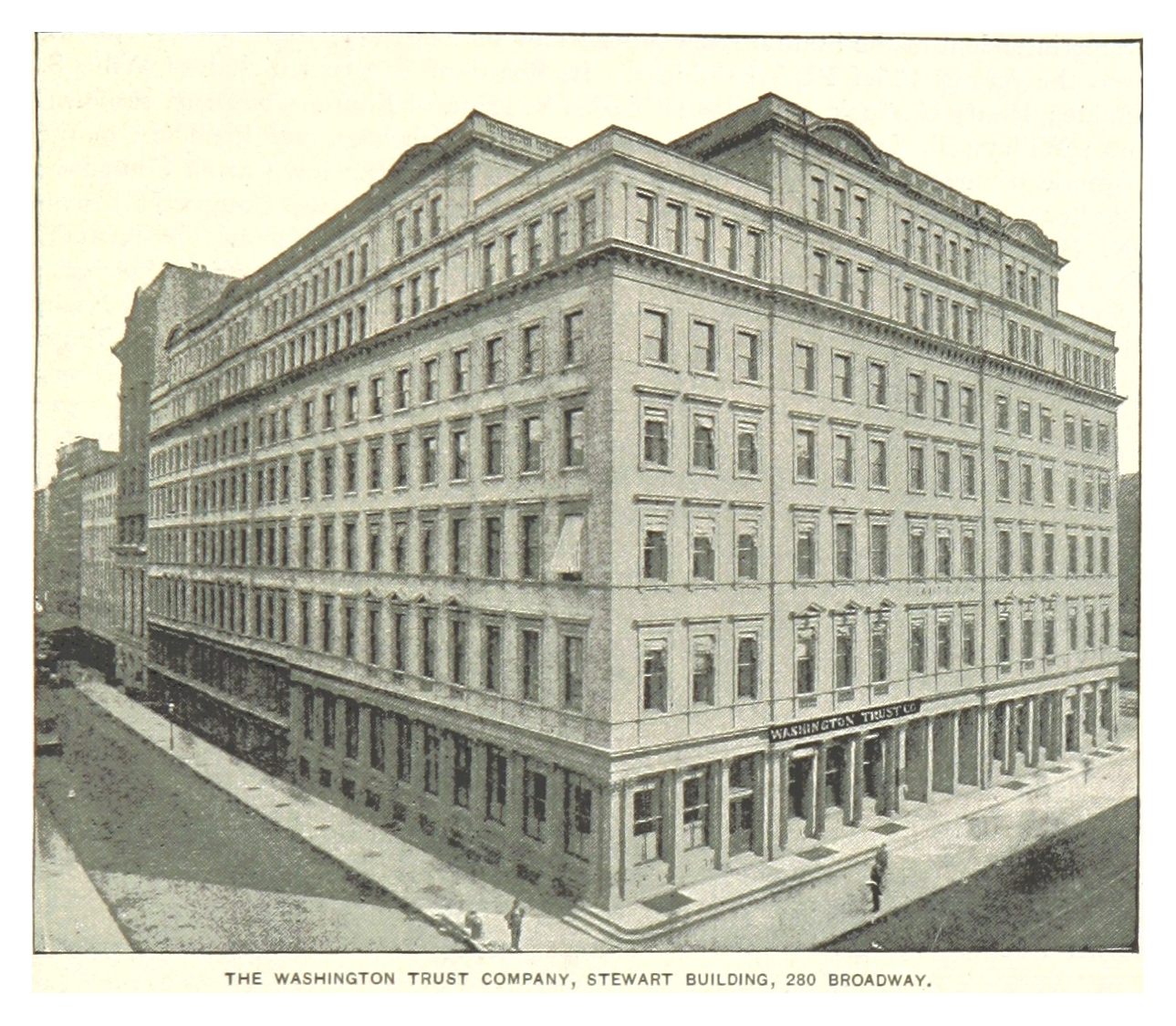

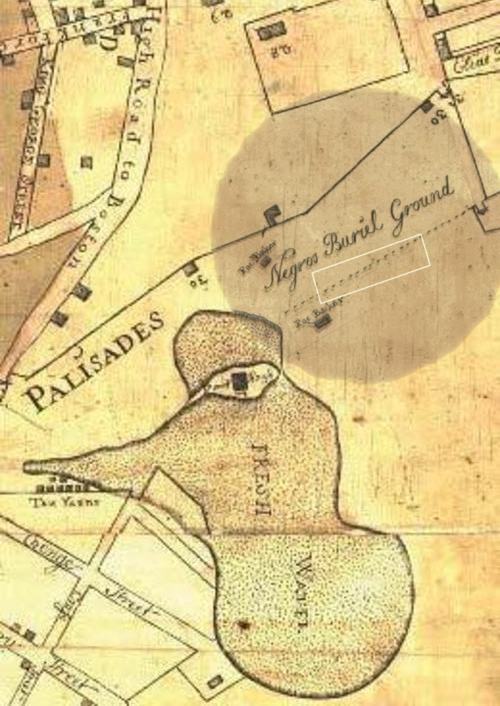

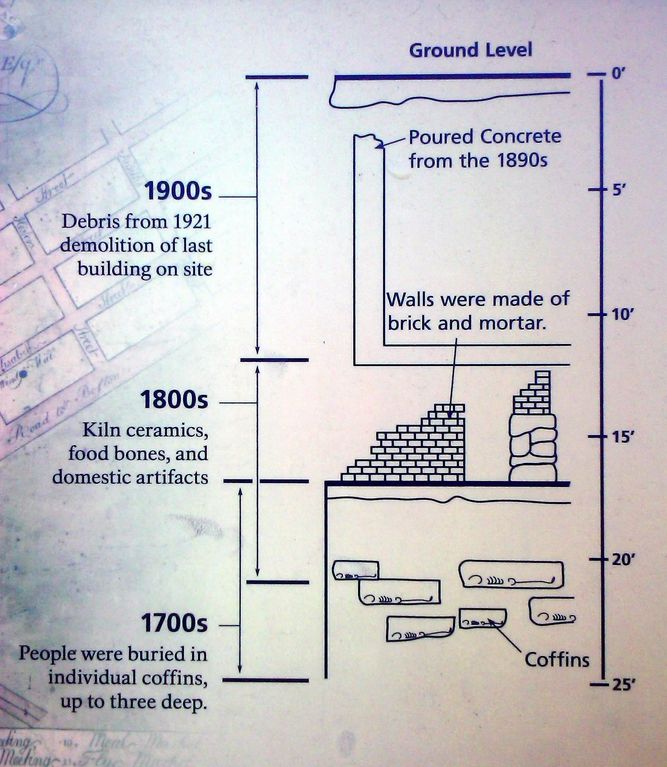

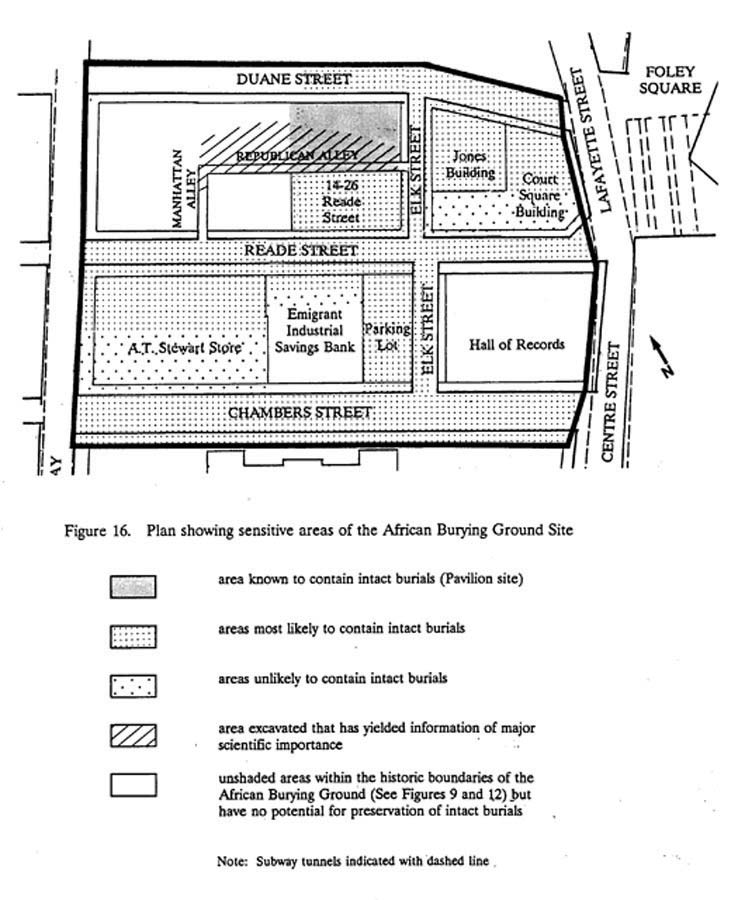

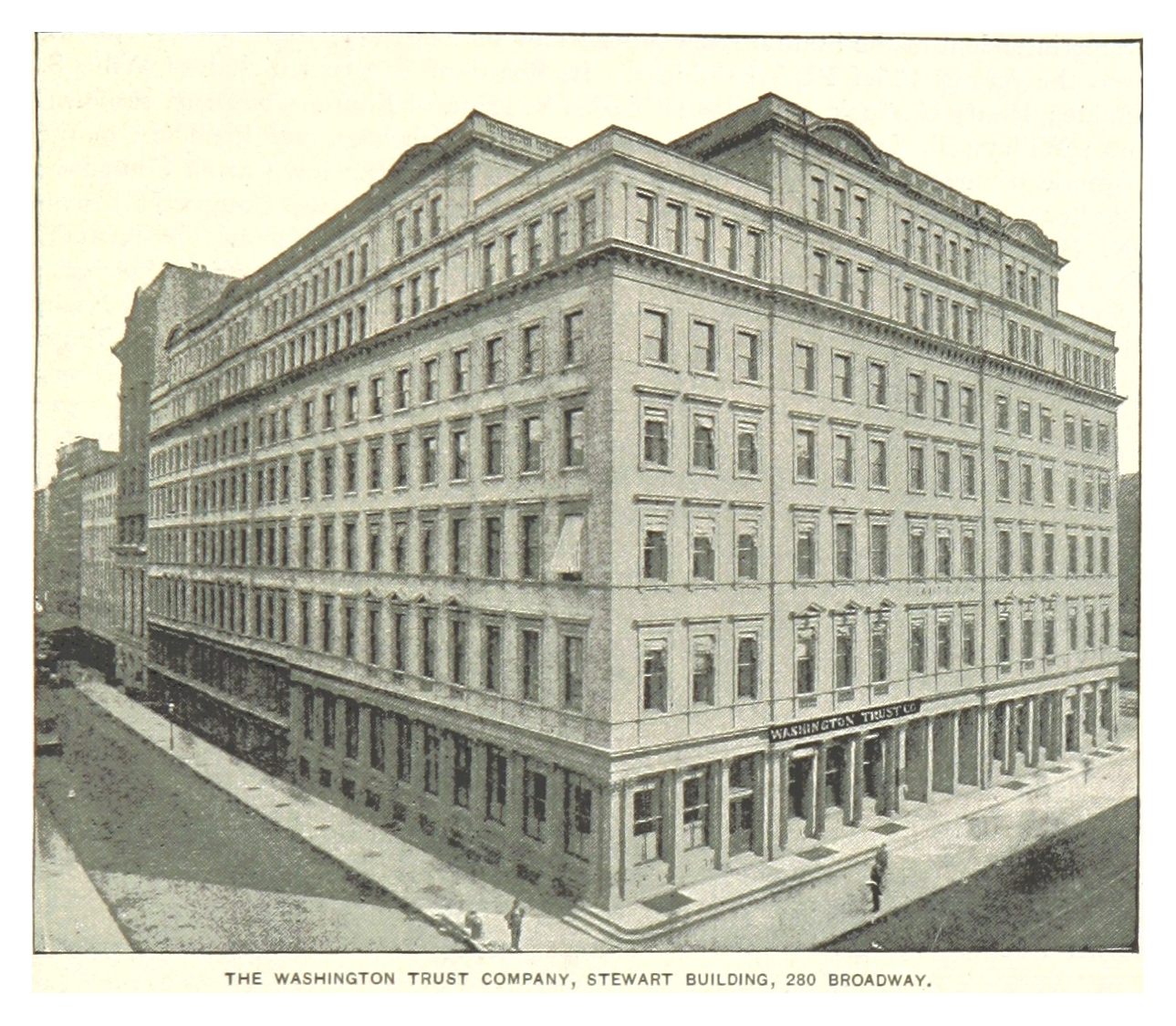

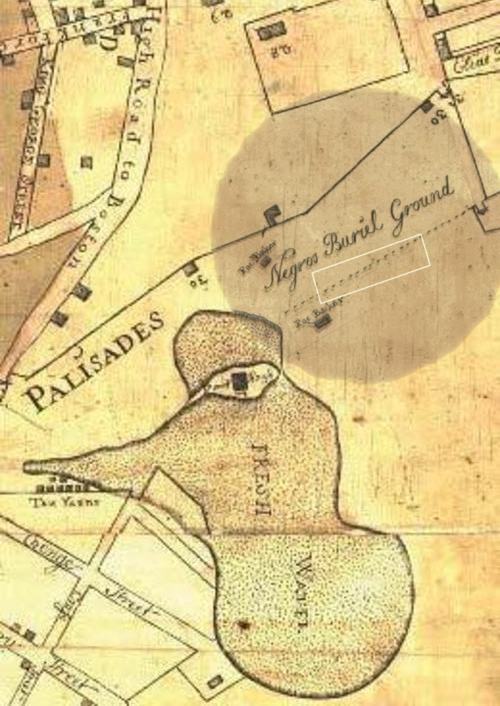

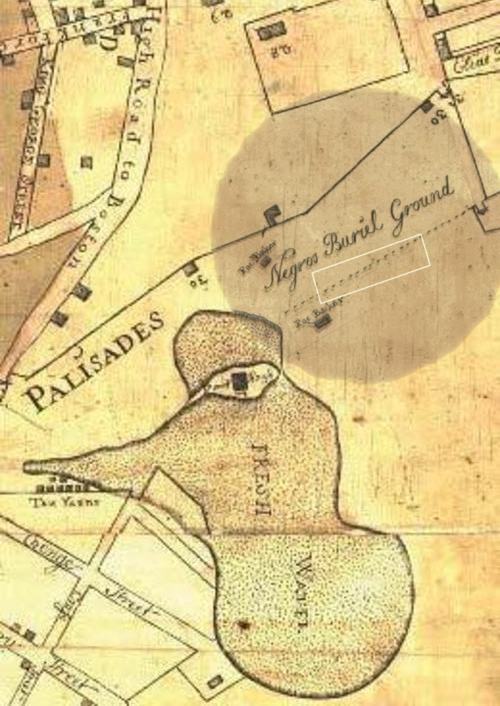

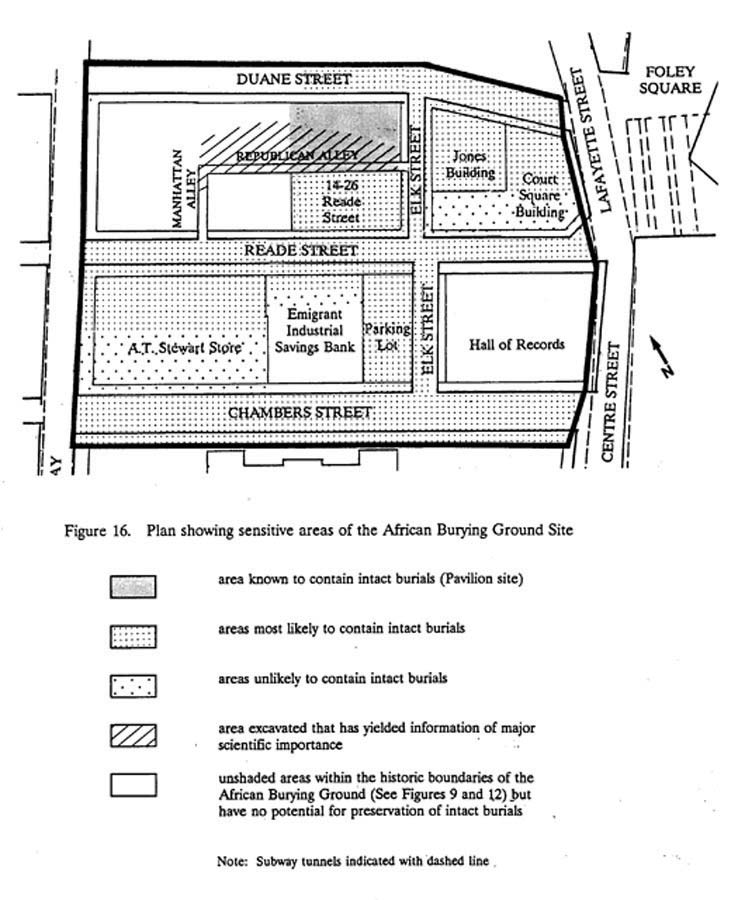

Site history Section of the 1754 Maerschalck plan showing Collect Pond ('Fresh Water') and the Negros Burial Ground; rectangle delineates area of archaeological excavation by Howard University. At least two slaves were hanged on the small island in Collect Pond.[19]  The "Negros Burial Ground" near Collect Pond, looking south (map about 1760) A 1776 map of New York and environs (labeled New York Island instead of Manhattan) the Negro Cemetery was located about 2 blocks southwest of the "Fresh Water" [i.e. Collect Pond] located in the upper left section of the map outside the city limits  Negros Burial Ground The burial ground in use for New York Town residents in the late 1600s was located at what is now the north graveyard of Trinity Church (of the Anglican / Church of England – today the Episcopal Church U.S.A.). The public burial ground was open to all for a fee, including to enslaved Africans. Some burials of deceased slaves were made just south of the public burial ground to avoid the fee. The stockade in this area ran northeast from the present-day corner of Broadway and Chambers Street to Foley Square; the wide street on the top right (southwest) is Broadway. After Trinity was established as a parish church in 1697, the vestryman of the church began taking control of land in Lower Manhattan, including existing public burial grounds. When Trinity purchased the land at Wall Street and Broadway for the construction of their church, they passed a resolution on October 25, 1697: That after the Expiration of four weeks from the dates hereof no Negro's be buried within the bounds & Limitts of the Church Yard of Trinity Church, that is to say, in the rear of the present burying place & that no person or Negro whatsoever, do presume after the terme above Limitted to break up any ground for the burying of his Negro, as they will answer it at their perill & that this order be forthwith publish'd. The "rear of the present burying place" did not include the town cemetery (now the north churchyard). The church petitioned for control of this burial ground, which was granted by the colonial Province of New York on April 22, 1703. This prohibition against the burial of those of African descent necessitated finding another area acceptable to the colonial authorities. What would become the "Negro's Burial Ground" was located on what was then the outskirts of the developed town, just north of present-day Chambers Street and west of the former Collect Pond (later Five Points). The area was part of a land grant issued to Cornelius van Borsum on behalf of his wife Sara Roelofs (1624–1693) for her services as an interpreter between the town of New York and the various Native American tribes in the area, such as the Lenape and Wappinger. The land would remain part of her estate until the late 1790s when the grade was raised with landfill in anticipation of development, and the land subdivided into building lots. Labelled on old maps as the "Negros Burial Ground," the 6.6-acre area was first recorded as being used around 1712 for the burials of enslaved and freed people of African descent. The first burials may date from the late 1690s after Trinity barred African burials in the former city cemetery. The area of the burial ground was in a shallow valley surrounded by low hills on the east, south and west, which enveloped the southern shore of Collect Pond and the Little Collect. The burial ground was outside the stockade marking the northern boundary of the city. The stockade in this area ran northeast from the present-day corner of Broadway and Chambers Street to Foley Square after it had expanded northward, similar in form and function to the former stockade on Wall Street. The revelation that physicians and medical students were illegally digging up bodies for dissection from this burial ground precipitated the 1788 Doctors' Riot. Development After the city closed the cemetery in 1794, the area was platted for development. The grade of the land was raised with up to 25 feet (7.6 metres) of landfill at the lowest points covering the cemetery, thus preserving the burials and the original grade level. As urban development took place over the fill, the burial ground was largely forgotten. The first large-scale development on the land was the construction of the A.T. Stewart Company Store, the country's first department store; it opened in 1846 at the corner of 280 Broadway and Chambers Street. Several skeletons were unearthed during the commencement of building the store.[20] The site's earliest discovery in the early 19th century seems to have aroused little interest. According to an article in The New York Tribune, homeowner James Gemmel, who owned a house at 290 Broadway in the early 19th century, told an unnamed daughter that when the cellar for their house was being dug many human bones were found. He assumed that he had discovered a potter's field.[21] In 1897, when the building at 290 Broadway was demolished to make way for the R. G. Dun and Company Building (later financial firm of Dun & Bradstreet), workers in excavating found a large number of human bones.[22] Some concluded at that time that these were connected to a 1741 incident in which thirteen African Americans were burned at the stake and eighteen were hanged,[21] however others wondered whether the bones were of Dutch or Indian origin.[20][23] Many bones were taken as souvenirs by so-called relic hunters.[20][23] Discovery of site and controversy  A cross section of the African Burial Ground showing landfill, building foundations and underlying graves.  skeleton uncovered at the African Burial Ground in Manhattan.  African Burial Excavation NYC 1991 On October 8, 1991, the federal General Services Administration (GSA) announced the discovery of 8 intact burials during an archaeological survey and excavation (which had started in May 1991[24]) for the construction of a new $275 million federal office building planned at 290 Broadway between Reade and Duane streets.[25][26] The building was to be later known as the Ted Weiss Federal Building, named for deceased U.S. Representative Ted Weiss from New York. Under section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act,[27] the federal government is required to identify and assess the historic presence of a site prior to building on the land. The agency had done an environmental impact statement (EIS) prior to purchase of the site, but the archaeological survey had predicted that human remains would not be found because of the long history of urban development in that area.[12] After the discovery of the first intact burials became publicly known, the African-American community became very concerned. With the pressure of construction costs, GSA tried to continue excavation and construction on the site. The community believed it was not being sufficiently consulted and that respect was not being given to the nature of the discoveries. They believed that the burial findings required a better archaeological project design for protection and study of the remains.[12] Protests Initially, GSA had planned full archaeological retrieval of the remains as full mitigation of the effects of its construction project on the burial ground. Within the year, its teams removed the remains of 419[28] persons from the site, but it had become clear that the extent of the burial ground was too large to be fully excavated. In 1992, activists staged a protest at the site about GSA's handling of the burial issue, especially when it was found that some intact burials were broken up during construction excavation at part of the site.[12] GSA halted construction until the site could be thoroughly assessed. It provided additional funding to conduct a further archaeological excavation to reveal any other bodies on the site and to assess the remains.[12] Located between New York City Hall and the federal courts, the site had symbolic value. "The 'invisibility' of Black history in New York City partially accounts for the importance of the Foley Square site"; activists hoped to find a means there to redress "the injustice and the imbalance of the historic record, and to give voice to the silenced ones".[12] Although archaeologists studied the site and the remains for almost a dozen years, critics of the construction project believed GSA's original archaeological research design was inadequate, as it did not require a plan for the treatment of uncovered remains.[12] In addition, the African-descendant community in New York City was not consulted in the development of the research design, nor were any archaeologists who had experience studying the African diaspora, although GSA had distributed the EIS to more than 200 state and local agencies and stakeholders, many recommended by the city.[12] In the early stages of the project, national GSA officials and related Congressional committees directed that excavation and construction proceed.[12] Oversight of the project increased by stakeholders, such as the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation and community activists. After continued protests from a coalition of community members, politicians, and scholars, in 1992 the House Subcommittee on Public Works held budget hearings for GSA in New York, at which it heard testimony from a wide variety of critics of GSA's handling of the project and also heard from the GSA Administrator.[12] Several changes occurred. Control of the burial site was transferred from an archaeological firm in the city to the physical anthropologist Michael Blakey and his team at Howard University, a historically black college in Washington, D.C., for study at the Montague Cobb Biological Anthropology Laboratory. This ensured that African-American students would participate in studies of their ethnic ancestors' remains.[12] Effects of protests  Unearthed (2002) – A bronze sculpture by artist Frank Bender based upon the forensic facial reconstructions of three intact skeletons exhumed at the African Burial Ground.[29] In large part due to activism by the African-American community, the United States Congress passed, and on October 6, 1992, President George H. W. Bush signed, HR 5488 "The Treasury, Postal Service, and General Government Appropriations Act" (which became Public Law 102-393) which ordered the GSA to immediately cease construction, archeological excavation & skeletal exhumation on the pavilion portion of the Ted Weiss Federal Building (where the remains had been found) and to appropriate $3 million to modify the pavilion foundation, prevent further deterioration of the burial ground & memorialize the site. The southern portion of the building, slated to be built on the parcel by Duane and Elk Streets, was eliminated to provide adequate room for a memorial.[12] In addition, activists lobbied for landmark status for the burial ground, and gathered 100,000 signatures to send to the U.S. Department of the Interior. On April 19, 1993, 0.34 acre of the African Burial Ground was listed on the National Register of Historic Places (#93001597) and became a National Historic Landmark. Given its importance, GSA proposed partial mitigation of the adverse effects to the burial ground of the construction of 290 Broadway, by undertaking programs of data analysis, curation, and education.[30] There was also growing support for a museum on the site to interpret African-American experience and history in New York. The discovery and long controversy received national media attention, raising interest and awareness in public archaeology projects. Theresa Singleton, an archaeologist at the Smithsonian Institution said, The media exposure has created a larger, national audience for this type of research. I've been called by dozens of scholars and laypeople, all of them interested in African-American archaeology, all of them curious about why they don't know more about the field. Until recently, even some black scholars considered African-American archaeology a waste of time. That's changed now.[12] Archeologist uncover more of African Burial ground in old Harlem bus depot.[31] Government and private developers learned about the need to "include descendant communities in their salvage excavations, especially when human remains are concerned."[12] The findings at the burial ground already had highlighted some of the losses of slavery, as African Americans had not been recently recognized as a major part of early New York history until then. As the journalist Edward Rothstein wrote, "Among the scars left by the heritage of slavery, one of the greatest is an absence: where are the memorials, cemeteries, architectural structures or sturdy sanctuaries that typically provide the ground for a people’s memory?"[10] Site studies  Map showing excavated area and probable location of more intact burials  280 Broadway, the A.T. Stewart Building In total, the intact remains of 419 men, women and children of African descent were found at the site, where they had been buried individually in wooden boxes. There were no mass burials. Nearly half were children under 12, indicating the high mortality rate of the time. Historians and anthropologists estimate that over the decades, as many as 15,000–20,000 Africans were buried in Lower Manhattan. They have determined that this was the largest colonial-era cemetery for enslaved African people. It is also "possibly the largest and earliest collection of American colonial remains of any ethnic group."[12] Some of the burials included items related to African origins and burial practices. The work of excavation and study of the remains was considered the "most important historic urban archaeological project undertaken in the United States."[7] These remains stand for the estimated tens of thousands of persons at the burial ground and historically in New York, representing Africans' "critical" role in "the formation and development of this city and, by extension, the Nation."[32][33][34] As a result of public engagement, the Howard University team identified four questions which the community hoped to have answered from studies of the remains: "cultural background and origins of the burial population; the cultural and biological transformations from African to African-American identities; quality of life brought about by enslavement in the Americas; and modes of resistance to enslavement."[35]  A silver pendant recovered during laboratory cleaning of the skeletal remains of burial 254 – a child between 3½ and 5½ years old. Before the erection of the monument, the burial ground had endured an immense amount of abuse. Archeologists found a substantial amount of industrial waste and ceramics while excavating the site.[36] Archaeologists concluded that burial ground was being used as a dumpsite by Europeans during the 18th century. The burial ground was also subject to grave robbing and looting during this time. In April 1788, the Doctor Riot spread throughout New York City. The riots were led by physicians that would steal corpses from graves to study them as the supply of medical corpses was extremely low. Many of these stolen corpses came from the African Burial Ground. There was speculation that the grounds were not only being looted but were overcrowding due to the burial of unclaimed bodies in the place of the stolen remains. Some bodies had items buried with them, as part of personal and cultural rituals. An example is the silver pendant shown at right. Some heads showed filed teeth, an African ritual decoration. Howard University did forensic studies, assessing the remains for nutrition, diseases and indicators of general living conditions for African slaves and free blacks. After the Howard University studies were completed, the 419 skeletons were placed in the Ancestral Reinterment Grove here on October 4, 2003, in a ceremony including the "Rites of Ancestral Return". They were placed in hand-carved wooden coffins made in Ghana & lined with Kente cloth, which were placed in 7 sacrophagi & buried in 7 burial mounds with the heads facing west.[37] The "commemorative ceremony was inclusive and international in scope, and was organized by GSA and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture" of the New York Public Library.[37] This emotional memorial stretched over multiple cities including Washington D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, Newark, and finally Manhattan. Thousands attended the reinterment and commemoration.[37] Memorial Construction and dedication GSA ran a design competition for the site memorial in consultation with stakeholders and community activists, attracting over 60 proposals. The winning memorial design, by Rodney Leon and Nicole Hollant-Denis,[38] was selected in April 2005.[39] The cultural landscape architect for the memorial was Elizabeth Kennedy Landscape Architects.[40] The memorial consists of two components: the 24-foot (7.3 m) tall Ancestral Chamber and the large Circle of the Diaspora. The height of the Ancestral Chamber represents the depth of the discovered graves. The Ancestral Chamber is made from Verde Fontaine green granite from Africa and its engraved heart-shaped Sankifa symbol from West Africa means "Learn from the past to prepare for the future". The Circle of the Diaspora features a map of the Atlantic area in reference to the Middle Passage,[41] by which slaves were transported from Africa to North America. It is built of stone from Africa and North America, to symbolize the two worlds coming together.[42] The Door of Return, refers to "The Door of No Return", a name given to slave ports set up for involvement with the age-old local institution of slavery on the coast of West Africa, from which so many people were transported after sale by their native chiefs, never to see their homeland again. The memorial is designed to reconnect ethnic African Americans to their ancestors' origins.[42] On February 27, 2006, President George W. Bush signed a proclamation designating the burial site as the 123rd National Monument.[43] The federal government also announced plans for a $8 million memorial at the site.[44] The Burial Grounds was transferred to the operating jurisdiction of the National Park Service as its 390th unit. The memorial was dedicated on October 5, 2007, in a ceremony presided over by Mayor Michael Bloomberg and poet Maya Angelou.[42][45] As part of the dedication ceremonies, the city officially renamed Elk Street as African Burial Ground Way.[46] In 2016, Dan Hoeg, CEO of The Hoeg Corporation, tendered a $34.3 million offer and development proposal to purchase 22 Reade Street and the Burial Grounds to the City of New York. The African-American bidding group was led by Dan Hoeg, CEO of the African American owned development firm The Hoeg Corporation; Burial Ground Monument architect, Rodney Leon; and Davide Bizzi, CEO of Italian development company, Bizzi & Partners Development.[47] Visitor Center  Aerial view of the African Burial Ground National Monument. The mounds to the right contain the reinterred remains. On February 27, 2010, a visitor center for the African Burial Ground National Monument opened in the Ted Weiss Federal Building at 290 Broadway, which was built over part of the archaeological site.[10] The visitor center includes a permanent exhibit, "Reclaiming Our History," on the significance of the burial site. Created by Amaze Design, it features a life-sized tableau by StudioEIS depicting a dual funeral for an adult and child. Other parts of the exhibit explore the work-life of Africans in early New York and connection to national history, as well as the late 20th-century community success in preserving the burial ground. The visitor center includes a 40-person theater and a shop. The NPS runs the visitor center and arranges for various cultural exhibitions and events at the site throughout the year.[10] Legacy In addition to earning several historic-landmark designations for the site, the discoveries of the African Burial Ground have changed thinking about early African-American history in New York and the nation. Many new books have been published on this topic. In 2005 the New-York Historical Society mounted its first exhibit ever on slavery in New York;[15] the planned six-month run was extended into 2007 because of its popularity. When the visitor center at the burial ground opened in 2010, Edward Rothstein wrote, A revision in popular understanding has taken place about slavery's history in New York City, evident in several recent books and an impressive series of shows at the New-York Historical Society. In the 18th century slaves may have constituted a quarter of the New York workforce, making this city one of the colonies' largest slave-holding urban centers.[10] |

遺跡の歴史 1754年のマーシャルプランの一部を示す地図。コレクト・ポンド(「フレッシュ・ウォーター」)とニグロ埋葬地。長方形で囲まれた部分は、ハワード大学による考古学的発掘調査のエリアを示す。少なくとも2人の奴隷がコレクト・ポンドの小さな島で絞首刑にされた。  コレクト・ポンド近くの「ニグロ埋葬地」、南方向(1760年頃の地図)  1776年のニューヨークとその周辺の地図(マンハッタンではなくニューヨーク島と表記)では、ニグロ墓地は、市の境界外の地図左上にある「Fresh Water」(すなわちCollect Pond)の南西約2ブロックの地点に位置していた。 ネグロス墓地 1600年代後半にニューヨーク・タウンの住民が使用していた埋葬地は、現在のトリニティ教会(英国国教会/イングランド教会、現在のエピスコパル教会ア メリカ)の北側の墓地にあった。この共同埋葬地は、奴隷にされたアフリカ人を含め、有料ですべての人に開放されていた。死亡した奴隷の埋葬の中には、埋葬 料を避けるために、公営埋葬地のすぐ南に埋葬されたものもあった。この地域のストックェードは、現在のブロードウェイとチェンバース・ストリートの角から 北東にフォーリー・スクエアまで続いていた。右上(南西)の広い通りがブロードウェイ。 1697年にトリニティが教区教会として設立されると、教会の林務委員は既存の共同埋葬地を含むロウワーマンハッタンの土地を管理し始めた。トリニティが 教会建設のためにウォール・ストリートとブロードウェイの土地を購入したとき、彼らは1697年10月25日に決議を行った: 本決議書の日付から4週間が経過した後は、トリニティ教会のチャーチ・ヤードの境界および制限内、つまり現在の埋葬地の後方に黒人を埋葬しないこと。ま た、上記の制限期間経過後は、いかなる人物または黒人も、その黒人を埋葬するために地面を破壊しようとしないこと。 現在の埋葬地の後方」には、町の墓地(現在の北教会墓地)は含まれていなかった。教会はこの埋葬地の管理を請願し、1703年4月22日にニューヨーク州 から許可された。 アフリカ系住民の埋葬が禁止されたため、植民地当局が受け入れられる別の場所を探す必要があった。後に「黒人埋葬地」となる場所は、現在のチェンバーズ・ ストリートのすぐ北、かつてのコレクト・ポンド(後のファイブ・ポインツ)の西、当時は開発された町の郊外にあった。この地域は、ニューヨークの町と、レ ナペ族やワッピンガー族など、この地域のさまざまなネイティブ・アメリカン部族との間の通訳としての彼女の奉仕に対して、妻サラ・ローロフス(1624年 ~1693年)に代わってコーネリアス・ヴァン・ボルサムに交付された土地の一部であった。この土地は、1790年代後半に開発を見越して埋立地が造成さ れ、土地が宅地に分割されるまで、彼女の所有地の一部であった。 古い地図には「黒人埋葬地」と記されていたこの6.6エーカーの土地は、1712年頃にアフリカ系の奴隷や解放された人々の埋葬に使われたことが記録され ている。最初の埋葬は、トリニティがかつての市営墓地でのアフリカ系住民の埋葬を禁止した後の1690年代後半と思われる。埋葬地は、東、南、西を低い丘 に囲まれた浅い谷にあり、コレクト・ポンドとリトル・コレクトの南岸を囲んでいた。埋葬地は、市の北の境界を示すストックエードの外側にあった。この地域 のストックェードは、現在のブロードウェイとチェンバース・ストリートの角から北東に伸びてフォーリー・スクエアに至り、かつてのウォール・ストリートの ストックェードと形も機能も似ていた。医師や医学生がこの埋葬地から解剖用の遺体を違法に掘り出していたことが発覚し、1788年の医師暴動が起こった。 開発 1794年に市が墓地を閉鎖した後、この地域は開発のために区画整理された。土地の勾配は、墓地を覆う最も低い地点で最大25フィート(7.6メートル) の埋立地によって高くされ、埋葬者と元の勾配が保たれた。盛り土の上に都市開発が行われたため、埋葬地はほとんど忘れ去られた。この土地で最初に大規模な 開発が行われたのは、A.T.スチュワート・カンパニー・ストアの建設であった。A.T.スチュワート・カンパニー・ストアは、国内初のデパートで、 1846年にブロードウェイ280番地とチェンバーズ通りの角にオープンした。1846年にブロードウェイ280番地とチェンバーズストリートの角にオー プンした。 19世紀初頭にこの場所が発見された当初は、ほとんど関心を持たれなかったようだ。ニューヨーク・トリビューン』紙の記事によると、19世紀初頭にブロー ドウェイ290番地に家を所有していた家主のジェームズ・ジェンメルは、無名の娘に、家の地下室を掘っていたときに多くの人骨が見つかったと話したとい う。1897年、R.G.ダン・アンド・カンパニー・ビル(後の金融会社ダン・アンド・ブラッドストリート)を建てるためにブロードウェイ290番地のビ ルが取り壊された際、発掘作業員が大量の人骨を発見した[22]。 [22]当時、これらは13人のアフリカ系アメリカ人が火あぶりにされ、18人が絞首刑になった1741年の事件と関係があると結論づけた者もいたが [21]、オランダ系かインディアン系の骨ではないかと考える者もいた[20][23]。多くの骨はいわゆる遺物ハンターによって土産物として持ち去られ た[20][23]。 遺跡の発見と論争  アフリカ人墓地の断面図。埋め立て、建物の基礎、その下にある墓が示されている。  マンハッタンのアフリカ人墓地で発見された骨格。  1991年のアフリカ埋葬発掘NYC 1991年10月8日、連邦政府一般調達局(GSA)は、リード通りとデュアン通りの間の290ブロードウェイに計画されていた2億7,500万ドルの新 しい連邦オフィスビル建設のための考古学的調査および発掘調査(1991年5月に開始されていた[24])中に8つの無傷の埋葬物を発見したと発表した [25][26]。国家歴史保存法第106条に基づき[27]、連邦政府は土地に建物を建てる前に、その土地の歴史的存在を特定し、評価することが義務付 けられている。連邦政府は、この土地を購入する前に環境影響評価書(EIS)を作成していたが、その地域の都市開発の長い歴史から、考古学的調査では人骨 は発見されないだろうと予測していた[12]。 最初の無傷の埋葬の発見が公になった後、アフリカ系アメリカ人のコミュニティは非常に心配するようになった。建設費の圧力もあり、GSAは発掘と建設を続 けようとした。地域社会は、十分な協議がなされておらず、発見の性質が尊重されていないと考えた。彼らは、埋葬の発見には、遺跡の保護と調査のためのより 良い考古学的プロジェクト設計が必要だと考えていた[12]。 抗議 当初、GSAは建設プロジェクトが埋葬地に及ぼす影響の完全な緩和策として、遺跡の完全な考古学的回収を計画していた。その年のうちに、GSAのチームは 遺跡から419人[28]の遺骨を搬出したが、埋葬地の範囲が広すぎて完全な発掘は不可能であることが明らかになった。1992年、活動家たちはGSAの 埋葬問題への対応、特に現場の一部で建設中の掘削中に無傷の埋葬が破壊されたことが判明したことに抗議し、現場で抗議活動を行った[12]。ニューヨーク 市庁舎と連邦裁判所の間に位置するこの場所には、象徴的な価値があった。ニューヨーク市における黒人の歴史の「不可視化」が、フォーリー・スクエア遺跡の 重要性を部分的に物語っている」。活動家たちは、「歴史的記録の不正義と不均衡を是正し、沈黙している人々に声を与える」手段をそこに見出すことを望んで いた[12]。 考古学者たちはほぼ十数年にわたって遺跡と遺構を調査したが、建設プロジェクトの批評家たちは、GSAの当初の考古学的調査設計は、発掘された遺構の処理 計画を必要としておらず、不十分であると考えていた[12]。 [12]さらに、ニューヨーク市のアフリカ系住民のコミュニティは調査設計の策定において相談を受けておらず、また、GSAはEISを200以上の州や地 方の機関や利害関係者に配布しており、その多くは市から推薦されていたにもかかわらず、アフリカ系住民を研究した経験のある考古学者もいなかった [12]。プロジェクトの初期段階では、GSAの国家公務員と議会の関連委員会は発掘と建設を進めるよう指示した[12]。 歴史保存諮問委員会や地域活動家などの利害関係者によるプロジェクトの監視が強まった。地域住民、政治家、学者の連合からの継続的な抗議の後、1992年 に下院公共事業小委員会はニューヨークでGSAの予算公聴会を開催し、GSAのプロジェクト処理に対する様々な批判者からの証言を聞き、GSA長官からも 話を聞いた。埋葬地の管理は、市内の考古学会社から、ワシントンD.C.にある歴史的に黒人の多いハワード大学の身体人類学者マイケル・ブレイキーと彼の チームに移され、モンタギュー・コブ生物人類学研究所で研究されることになった。これにより、アフリカ系アメリカ人の学生が自分たちの民族の祖先の遺骨の 研究に参加することが保証された[12]。 抗議の効果  Unearthed(2002年)- アフリカ埋葬地で発掘された3体の無傷の頭蓋骨の法医学的顔面復元に基づく、芸術家フランク・ベンダーによるブロンズ彫刻[29]。 アフリカ系アメリカ人コミュニティによる活動により、米国議会はHR5488「アフリカ系アメリカ人埋葬地に関する法律」を可決し、1992年10月6日 にジョージ・H・W・ブッシュ大統領が署名した。ブッシュ大統領は、HR5488「財務省・郵政省・一般政府歳出法」(公法102-393となる)に署名 し、GSAに対し、テッド・ワイス連邦ビルのパビリオン部分(遺骨が発見された場所)の建設、考古学的発掘、骨格発掘を直ちに中止し、パビリオンの基礎を 修正し、埋葬地のさらなる劣化を防ぎ、この場所を記念するために300万ドルを計上するよう命じた。ビルの南側は、ドゥエイン・ストリートとエルク・スト リートの区画に建設される予定だったが、慰霊碑のための十分なスペースを確保するために廃止された[12]。 さらに、活動家たちは埋葬地のランドマーク認定を求め、10万人分の署名を集めてアメリカ内務省に送った。1993年4月19日、アフリカ人埋葬地の 0.34エーカーが国家歴史登録財(#93001597)に登録され、国定歴史建造物となった。その重要性に鑑み、GSAはデータ分析、キュレーション、 教育プログラムを実施することで、290ブロードウェイの建設による埋葬地への悪影響を部分的に緩和することを提案した[30]。また、ニューヨークにお けるアフリカ系アメリカ人の経験と歴史を解説する博物館をこの地に建設することへの支持も高まった。この発見と長期にわたる論争は全国的なメディアの注目 を集め、公共考古学プロジェクトへの関心と認識を高めた。スミソニアン博物館の考古学者、テレサ・シングルトンは言う、 メディアに取り上げられたことで、この種の調査に対する全国的な視聴者が増えました。アフリカ系アメリカ人の考古学に興味を持ち、なぜこの分野について もっと知らないのだろうと不思議に思っている人たちばかりです。つい最近まで、アフリカ系アメリカ人考古学を時間の無駄だと考える黒人学者もいた。それが 今は変わったのだ[12]。 考古学者がハーレムの古いバス車庫でアフリカ人埋葬地の詳細を発見[31]。 政府と民間の開発業者は、「特に人骨が関係する場合は、引き揚げ発掘に子孫のコミュニティを含める」必要性を学んだ[12]。それまでアフリカ系アメリカ 人が初期のニューヨークの歴史の主要部分として認識されていなかったため、埋葬地での発見はすでに奴隷制の損失の一部を浮き彫りにしていた。ジャーナリス トのエドワード・ロススタインが書いたように、「奴隷制の遺産が残した傷跡の中で、最も大きなもののひとつは不在である。 遺跡調査  発掘された地域と、無傷の埋葬があると思われる場所を示す地図  ブロードウェイ280番地、A.T.スチュワート・ビル 合計419人のアフリカ系の男性、女性、子供の無傷の遺骨が発見され、木箱に個別に埋葬されていた。集団埋葬はなかった。半数近くが12歳以下の子供で、 当時の死亡率の高さを物語っている。歴史学者や人類学者は、数十年の間に15,000〜20,000人ものアフリカ人がロウワーマンハッタンに埋葬された と推定している。彼らは、この墓地が植民地時代に奴隷にされたアフリカ人のための最大の墓地であったと断定している。また、「あらゆる民族のアメリカ植民 地時代の遺骨のコレクションとしては、おそらく最大かつ最古のもの」[12]でもある。被葬者の中には、アフリカ人の起源や埋葬習慣に関連するものも含ま れていた。 遺骨の発掘と調査は、「米国で実施された最も重要な歴史的都市考古学プロジェクト」と考えられている[7]。これらの遺骨は、埋葬地と歴史的にニューヨー クで推定される数万人の人々のためにあり、「この都市、ひいては国家の形成と発展」におけるアフリカ人の「重要な」役割を象徴している[32][33] [34]。 市民参加の結果、ハワード大学のチームは、コミュニティが遺骨の調査から答えを得ることを望む4つの質問を特定した: 「埋葬者の文化的背景と起源; アフリカ系からアフリカ系アメリカ人への文化的・生物学的変容; アメリカ大陸での奴隷化がもたらした生活の質、そして 奴隷化に対する抵抗の様式」[35]。  254号埋葬者の骨格の洗浄中に回収された銀のペンダント(3歳半から5歳半の子供)。 記念碑が建てられる前、埋葬地は膨大な量の虐待に耐えていた。考古学者たちは、発掘中にかなりの量の産業廃棄物と陶磁器を発見した[36]。考古学者たち は、埋葬地は18世紀にヨーロッパ人によってゴミ捨て場として使われていたと結論づけた。この時期、埋葬地は墓荒らしや略奪の対象にもなっていた。 1788年4月、医師暴動がニューヨーク中に広がった。この暴動は、医療用死体の供給が極端に少なかったため、墓から死体を盗んで研究しようとする医師た ちが主導したものだった。盗まれた死体の多くは、アフリカ人埋葬地から持ち出されたものだった。墓地は略奪されているだけでなく、盗まれた遺体の代わりに 引き取り手のない遺体が埋葬されたため、過密状態になっているとの憶測もあった。 遺体の中には、個人的な儀式や文化的な儀式の一環として埋葬されたものもあった。右の銀のペンダントはその一例である。頭部には、アフリカの儀式の装飾で あるヤスリで削られた歯が見られるものもあった。ハワード大学は法医学的研究を行い、遺体の栄養状態、病気、アフリカ人奴隷と自由黒人の一般的な生活環境 の指標を評価した。 ハワード大学の調査が終了した後、419体の骸骨は2003年10月4日、「祖先帰還の儀式」を含むセレモニーで、この祖先再葬墓に安置された。彼らは ガーナで作られた手彫りの木製の棺に納められ、ケンテ布で裏打ちされ、7つの聖棺に納められ、頭を西に向けて7つの墳墓に埋葬された[37]。この「記念 式典は、包括的かつ国際的な規模で、GSAとニューヨーク公共図書館のションバーグ黒人文化研究センターによって組織された」[37]。埋葬と追悼には数 千人が参加した[37]。 記念碑 建設と献辞 GSAは、関係者や地域活動家と協議しながら、追悼施設の設計コンペを実施し、60以上の提案を集めた。記念碑の文化的景観設計者はエリザベス・ケネ ディ・ランドスケープ・アーキテクツである[40]。 記念館は、高さ24フィート(7.3メートル)の「祖先の間」と、大きな「ディアスポラの輪」の2つから構成されている。Ancestral Chamberの高さは、発見された墓の深さを表している。Ancestral Chamberはアフリカ産のVerde Fontaine緑花崗岩で作られており、西アフリカのハート型のサンキファのシンボルが刻まれている。ディアスポラの輪」は、奴隷がアフリカから北アメ リカへと運ばれた「中道」[41]にちなんで、大西洋地域の地図が描かれている。この記念碑は、アフリカと北米の石で建てられており、2つの世界がひとつ になることを象徴している[42]。「帰還の扉」は、西アフリカの海岸に古くからある奴隷制度に関与するために設置された奴隷港に付けられた名前である 「帰還不能の扉」を指している。この記念碑は、アフリカ系アメリカ人の民族を彼らの祖先の起源に再び結びつけることを目的としている[42]。 2006年2月27日、ジョージ・W・ブッシュ大統領は、埋葬地を123番目の国定史跡に指定する布告に署名した[43]。 連邦政府はまた、この地に800万ドルの記念碑を建設する計画を発表した[44]。 埋葬地は国立公園局の390番目の部隊として、その運営管轄に移管された。記念碑は2007年10月5日、マイケル・ブルームバーグ市長と詩人のマヤ・ア ンジェロウが司会を務める式典で奉納された[42][45]。奉納式典の一環として、市はエルク通りをアフリカン・バーリアル・グラウンド・ウェイと正式 に改名した[46]。 2016年、ホーグ・コーポレーションのCEOであるダン・ホーグは、ニューヨーク市に対し、リード・ストリート22番地と埋葬地を購入するための 3430万ドルのオファーと開発案を入札した。アフリカ系アメリカ人の入札グループを率いたのは、アフリカ系アメリカ人が経営する開発会社ザ・ホーグ・ コーポレーションのCEOダン・ホーグ、埋葬地記念碑の建築家ロドニー・レオン、イタリアの開発会社ビッツィ&パートナーズ・ディベロップメントCEOの ダヴィデ・ビッツィだった[47]。 ビジターセンター  アフリカ埋葬地国立記念碑の航空写真。右側の墳丘には改葬された遺骨が納められている。 2010年2月27日、アフリカ埋葬地国定史跡のビジターセンターが、遺跡の一部を覆うように建てられたブロードウェイ290番地のテッド・ワイス連邦ビ ルにオープンした[10]。Amaze Designによって制作されたこの展示では、StudioEISによる等身大のタブローが、大人と子供の二人の葬儀を描いている。展示の他のパートで は、初期のニューヨークにおけるアフリカ人の労働生活と国の歴史とのつながり、そして埋葬地の保存に成功した20世紀後半のコミュニティについて探求して いる。ビジター・センターには40人収容のシアターと売店がある。NPSはビジターセンターを運営し、年間を通して様々な文化的展示やイベントを開催して いる[10]。 遺産 アフリカ埋葬地の発見は、この遺跡の歴史的ランドマーク指定に加え、ニューヨークと全米における初期のアフリカ系アメリカ人の歴史についての考え方を変え た。このテーマに関する新しい書籍も数多く出版されている。2005年、ニューヨーク歴史協会は、ニューヨークの奴隷制度に関する史上初の展示会を開催し た[15]。 2010年に埋葬地のビジターセンターがオープンしたとき、エドワード・ロススタインはこう書いた、 ニューヨークにおける奴隷制の歴史について、一般的な理解が見直されつつあることは、最近出版された数冊の本や、ニューヨーク歴史協会で開催された印象的 な一連のショーで明らかである。18世紀には、ニューヨークの労働人口の4分の1を奴隷が占めていたと考えられ、この都市は植民地最大の奴隷保有都市のひ とつであった[10]。 |

Section of the 1754 Maerschalck plan showing

Collect Pond ('Fresh Water') and the Negros Burial Ground; rectangle

delineates area of archaeological excavation by Howard University. At

least two slaves were hanged on the small island in Collect Pond.[19] Section of the 1754 Maerschalck plan showing

Collect Pond ('Fresh Water') and the Negros Burial Ground; rectangle

delineates area of archaeological excavation by Howard University. At

least two slaves were hanged on the small island in Collect Pond.[19] |

コレクト・ポンド(「フレッシュ・ウォーター」)とネグロス埋葬地を示す1754年のマースシャルクの平面図

の断面。少なくとも2人の奴隷がコレクト池の小島で絞首刑になった[19 コレクト・ポンド(「フレッシュ・ウォーター」)とネグロス埋葬地を示す1754年のマースシャルクの平面図

の断面。少なくとも2人の奴隷がコレクト池の小島で絞首刑になった[19 |

The "Negros

Burial Ground" near Collect Pond, looking south (map about 1760) The "Negros

Burial Ground" near Collect Pond, looking south (map about 1760) |

コレクト・ポンド近くの「ネグロス

埋葬地」を南から見る(1760年頃の地図) コレクト・ポンド近くの「ネグロス

埋葬地」を南から見る(1760年頃の地図) |

A 1776 map of New York and environs (labeled New York

Island instead of Manhattan) the Negro Cemetery was located about 2

blocks southwest of the "Fresh Water" [i.e. Collect Pond] located in

the upper left section of the map outside the city limits A 1776 map of New York and environs (labeled New York

Island instead of Manhattan) the Negro Cemetery was located about 2

blocks southwest of the "Fresh Water" [i.e. Collect Pond] located in

the upper left section of the map outside the city limits |

1776年のニューヨークとその周辺の地図(マンハッタンではなく

ニューヨーク島と表示されている)には、黒人墓地は、地図の左上部分にある「フレッシュ・ウォーター」[すなわちコレクト・ポンド]の南西約2ブロックの

市外に位置していた。 |

Archeologist

uncover more of African Burial ground in old Harlem bus depot.[31] Archeologist

uncover more of African Burial ground in old Harlem bus depot.[31] |

Map showing

excavated area and probable location of more intact burials Map showing

excavated area and probable location of more intact burials |

| List of buildings and structures

on Broadway in Manhattan List of National Historic Landmarks in New York City List of national monuments of the United States History of slavery in New York History of slavery in New Jersey Flatbush African Burial Ground |

マンハッタンのブロードウェイにある建造物・構造物の一覧 ニューヨーク市の国定歴史建造物一覧 アメリカ合衆国の国定記念物一覧 ニューヨークにおける奴隷制度の歴史 ニュージャージー州における奴隷制度の歴史 フラットブッシュ・アフリカン・バーリング・グラウンド |

| The importation of enslaved

Africans to what became New York began as part of the Dutch slave

trade. The Dutch West India Company imported eleven African slaves to

New Amsterdam in 1626, with the first slave auction held in New

Amsterdam in 1655.[1] With the second-highest proportion of any city in

the colonies (after Charleston, South Carolina), more than 42% of New

York City households held slaves by 1703, often as domestic servants

and laborers.[2] Others worked as artisans or in shipping and various

trades in the city. Slaves were also used in farming on Long Island and

in the Hudson Valley, as well as the Mohawk Valley region. During the American Revolutionary War, the British troops occupied New York City in 1776. The Philipsburg Proclamation promised freedom to slaves who left rebel masters, and thousands moved to the city for refuge with the British. By 1780, 10,000 black people lived in New York. Many were slaves who had escaped from their owners in both northern and southern colonies. After the war, the British evacuated about 3,000 slaves from New York, taking most of them to resettle as free people in Nova Scotia, where they are known as Black Loyalists. Of the Northern states, New York was next to last in abolishing slavery. (In New Jersey, mandatory, unpaid "apprenticeships" did not end until the Thirteenth Amendment ended slavery, in 1865.)[3]: 44 After the American Revolution, the New York Manumission Society was founded in 1785 to work for the abolition of slavery and to aid free blacks. The state passed a 1799 law for gradual abolition, a law which freed no living slave. After that date, children born to slave mothers were required to work for the mother's master as indentured servants until age 28 (men) and 25 (women). The last slaves were freed of this obligation on July 4, 1827 (28 years after 1799).[1] African Americans celebrated with a parade. Upstate New York, in contrast with New York City, was an anti-slavery leader. The first meeting of the New York State Anti-Slavery Society opened in Utica, although local hostility caused the meeting to be moved to the home of Gerrit Smith, in nearby Peterboro. The Oneida Institute, near Utica, briefly the center of American abolitionism, accepted both black and white male enrolees on an equal basis. New-York Central College, near Cortland, was an abolitionist institution of higher learning founded by Cyrus Pitt Grosvenor, that accepted all students without prejudice: male and female, white, Black, and native American, the first college in the United States to do so. It was also the first college to have black professors teaching white students. However, when a black male faculty member, William G. Allen, married a white student, they had to flee the country for England, never to return. |

奴隷となったアフリカ人のニューヨークへの輸入は、オランダの奴隷貿易

の一環として始まった。1626年にオランダ西インド会社が11人のアフリカ人奴隷をニューアムステルダムに輸入し、1655年にニューアムステルダムで

最初の奴隷オークションが開催された[1]。植民地の都市の中ではサウスカロライナ州チャールストンに次いで2番目に高い割合で、1703年までにニュー

ヨーク市の世帯の42%以上が奴隷を雇っており、その多くは家事使用人や労働者として働いていた[2]。また、ロングアイランドやハドソン渓谷、モホーク

渓谷地域の農業にも奴隷が使われた。 アメリカ独立戦争中、イギリス軍は1776年にニューヨークを占領した。フィリップスバーグ宣言は、反乱軍の主人のもとを去った奴隷に自由を約束し、何千 人もの奴隷がイギリス軍に避難するためにこの街に移り住んだ。1780年までに、ニューヨークには1万人の黒人が住むようになった。その多くは、北部と南 部の植民地の所有者から逃れた奴隷だった。戦後、イギリスはニューヨークから約3,000人の奴隷を避難させ、その大半をノヴァ・スコシアに自由民として 再定住させた。 北部諸州の中で、ニューヨークは奴隷制廃止の最後発だった。(ニュージャージー州では、強制的で無給の「徒弟制度」は、1865年に修正第13条で奴隷制 度が廃止されるまで廃止されなかった)[3]: 44 アメリカ独立後、1785年にニューヨーク奴隷解放協会が設立され、奴隷制度の廃止と自由黒人の援助に努めた。同州は1799年に漸進的廃止法を可決した が、この法律は生きている奴隷を解放するものではなかった。この日以降、奴隷の母親から生まれた子供は、28歳(男性)、25歳(女性)まで年季奉公人と して母親の主人のもとで働くことが義務づけられた。最後の奴隷がこの義務から解放されたのは1827年7月4日(1799年から28年後)であった [1]。アフリカ系アメリカ人はパレードで祝った。 ニューヨーク市とは対照的に、ニューヨーク州北部は反奴隷制のリーダーであった。ニューヨーク州反奴隷制協会の最初の会合はユティカで開かれたが、地元の 敵意により、会合は近くのピーターボロにあるゲリット・スミスの自宅に移された。ユティカ近郊のオナイダ・インスティテュートは、一時はアメリカ奴隷廃止 主義の中心地となり、黒人男性と白人男性の両方を平等に受け入れました。コートランド近郊にあるニューヨーク・セントラル・カレッジは、サイラス・ピッ ト・グロブナーによって設立された奴隷廃止主義の高等教育機関で、男女、白人、黒人、ネイティブ・アメリカンなど、すべての学生を偏見なく受け入れてい た。また、黒人の教授陣が白人の学生を教えた最初の大学でもあった。しかし、黒人の男性教員ウィリアム・G・アレンが白人の学生と結婚したため、2人はイ ギリスへ逃亡し、二度と戻ることはなかった。 |

| Dutch rule Initial group of slaves In 1613, Juan (Jan) Rodriguez from Santo Domingo became the first non-indigenous person to settle in what was then known as New Amsterdam. Of Portuguese and West African descent, he was a free man.[4] Systematic slavery began in 1626, when eleven captive Africans arrived on a Dutch West India Company ship in the New Amsterdam harbor.[5][4] Historian Ira Berlin called them Atlantic Creoles who had European and African ancestry and spoke many languages. In some cases, they attained their European heritage in Africa when European traders conceived children with African women. Some were Africans who were crew members on ships and some came from ports of the Americas.[6][a] Their first names—like Paul, Simon, and John—indicated if they had European heritage. Their last names indicated where they came from, like Portuguese, d'Congo, or d'Angola. People from the Congo or Angola were known for their mechanical skills and docile manners. Six slaves had names that indicated a connection with New Amsterdam, such as Manuel Gerritsen, which he likely received after their arrival in New Amsterdam and to differentiate from repeated first names.[6] Men were laborers who worked the fields, built forts and roads, and performed other forms of labor.[5] According to the principle of partus sequitur ventrem adopted from southern colonies, children born to enslaved women were considered born into slavery, regardless of the ethnicity or status of the father.[1] Jacob van Meurs, Novum Amsterodamum [New Amsterdam], 1671. In the center of the picture a man hangs by his middle, suspended by a hook in his ribs, a usual punishment for runaway slaves. In February 1644, the eleven slaves petitioned Willem Kieft, the director general for the colony, for their freedom. This was a time when there were skirmishes with Native American people and the Dutch wanted blacks to help protect their settlements and did not want the slaves to join the Native Americans. These eleven slaves were granted partial freedom, where they could buy land and a home and earn a wage from their master, and later full freedom. Their children remained in slavery. By 1664, the original eleven slaves, as well as other slaves who had attained half-freedom, for a total of at least 30 black landowners, lived on Manhattan near the Fresh Water Pond.[7][4] Slave trade For more than two decades after the first shipment, the Dutch West India Company was dominant in the importation of slaves from the coasts of Africa. A number of slaves were imported directly from the company's stations in Angola to New Netherland.[5] Due to a lack of workers in the colony, it relied upon on African slaves, who were described by the Dutch as "proud and treacherous", a stereotype for African-born slaves.[5] The Dutch West India Company allowed New Netherlanders to trade slaves from Angola for "seasoned" African slaves from the Dutch West Indies, particularly Curaçao, who sold for more than other slaves. They also bought slaves that came from privateers of Spanish slave ships.[5] For instance, La Garce a French privateer, arrived in New Amsterdam in 1642 with Spanish Negroes that were captured from a Spanish ship. Although they claimed to be free, and not African, the Dutch sold them as slaves due to their skin color.[6] Unlike slaves from other colonies, slaves in New Amsterdam could sue another person whether white or black. Early instances included suits filed for lost wages and damages when a slave's pig was injured by a white man's dog. Slaves could also be sued.[b] Partial and full freedom By 1644, some slaves had earned partial freedom, or half-freedom, in New Amsterdam and were able to earn wages. Under Roman-Dutch law they had other rights in the commercial economy, and intermarriage with working-class whites was frequent.[9] Land grant records show that Land of the Blacks was located just north of New Amsterdam. As the English began to seize New Amsterdam in 1664, the Dutch freed about 40 men and women who had been granted half-slave status, to ensure that the English would not keep them enslaved. The new freemen had their original land grants finalized and all grants were officially marked as owned by the new freemen.[10] English rule A 1798 watercolor of Fresh Water Pond. Bayard's Mount, a 110-foot (34 m) hillock, is in the left foreground. Prior to being levelled around 1811 it was located near the current intersection of Mott and Grand Streets. New York City, which then extended to a stockade which ran approximately north–southeast from today's Chambers Street and Broadway, is visible beyond the southern shore. In 1664, the English took over New Amsterdam and the colony. They continued to import slaves to support the work needed. Enslaved Africans performed a wide variety of skilled and unskilled jobs, mostly in the burgeoning port city and surrounding agricultural areas. In 1703, more than 42% of New York City's households held slaves, a percentage higher than in the cities of Boston and Philadelphia, and second only to Charleston in the South.[2] In 1708, the New York Colonial Assembly passed a law entitled "Act for Preventing the Conspiracy of Slaves" which prescribed a death sentence for any slave who murdered or attempted to murder his or her master. This law, one of the first of its kind in Colonial America, was in part a reaction to the murder of William Hallet III and his family in Newtown (Queens).[11] In 1711, a formal slave market was established at the end of Wall Street on the East River, and it operated until 1762.[12] An act of the New York General Assembly, passed in 1730, the last of a series of New York slave codes, provided that: Forasmuch as the number of slaves in the cities of New York and Albany, as also within the several counties, towns and manors within this colony, doth daily increase, and that they have oftentimes been guilty of confederating together in running away, and of other ill and dangerous practices, be it therefore unlawful for above three slaves to meet together at any time, nor at any other place, than when it shall happen they meet in some servile employment for their masters' or mistresses' profit, and by their masters' or mistresses' consent, upon penalty of being whipped upon the naked back, at the discretion of any one justice of the peace, not exceeding forty lashes for each offense.[13] Manors and towns could appoint a common whipper at no more than three shillings per person.[14] Blacks were given the lowest status jobs, the ones the Dutch did not want to perform, like meting out corporal punishment and executions.[15] Slave being burned at the stake in N.Y.C. after the 1741 slave insurrection As in other slaveholding societies, the city was swept by periodic fears of slave revolt. Incidents were misinterpreted under such conditions. In what was called the New York Conspiracy of 1741, city officials believed a revolt had started. Over weeks, they arrested more than 150 slaves and 20 white men, trying and executing several, in the belief they had planned a revolt. Historian Jill Lepore believes whites unjustly accused and executed many blacks in this event.[16] In 1753, the Assembly provided there should be paid "for every negro, mulatto or other slave, of four years old and upwards, imported directly from Africa, five ounces of Sevil[le] Pillar or Mexico plate [silver], or forty shillings in bills of credit made current in this colony."[17] Slaves in the north were often owned by notable people like Benjamin Franklin, William Penn and John Hancock. William Henry Seward grew up in a slave-owning family in Upstate New York. Against slavery, he became Abraham Lincoln's Secretary of State during the Civil War.[18] |

オランダの支配 奴隷の初期グループ 1613年、サント・ドミンゴ出身のフアン(ヤン)・ロドリゲスが、当時ニュー・アムステルダムとして知られていた場所に定住した最初の非原住民となっ た。ポルトガル人と西アフリカ人の血を引く彼は自由人であった[4]。 1626年、11人の捕虜となったアフリカ人がオランダ西インド会社の船でニューアムステルダムの港に到着したときから、組織的な奴隷制度が始まった [5][4]。歴史家のアイラ・バーリンは、彼らをヨーロッパ人とアフリカ人の祖先を持ち、多くの言語を話すアトランティック・クレオールと呼んだ。ヨー ロッパの商人たちがアフリカ人女性との間に子供をもうけたことで、アフリカでヨーロッパの血統を受け継ぐようになったケースもある。ポール、サイモン、 ジョンといったファーストネームは、彼らがヨーロッパ人の血を引いているかどうかを示していた。名字はポルトガル人、コンゴ人、アンゴラ人など、出身地を 示していた。コンゴやアンゴラ出身の人々は、機械技術と従順な態度で知られていた。6人の奴隷はニュー・アムステルダムとのつながりを示す名前を持ってお り、例えばマヌエル・ゲリッツェン(Manuel Gerritsen)は、ニュー・アムステルダムに到着した後に、繰り返されるファースト・ネームと区別するために付けられたと思われる[6]。 男性は畑仕事、砦や道路の建設、その他の労働を行う労働者であった[5]。 南部植民地から採用されたpartus sequitur ventremの原則によれば、奴隷にされた女性から生まれた子供は、父親の民族や地位に関係なく、奴隷として生まれたとみなされた[1]。 ヤコブ・ファン・ムース『ニュー・アムステルダム』1671年。絵の中央では、男が肋骨に鉤を刺されて吊るされている。 1644年2月、11人の奴隷たちは、植民地の総監督であるウィレム・キフトに自由を請願した。当時はネイティブ・アメリカンとの小競り合いがあった時期 で、オランダは入植地を守るために黒人を必要としており、奴隷がネイティブ・アメリカンに加わることを望んでいなかった。この11人の奴隷たちは、土地と 家を購入し、主人から賃金を得ることができる部分的な自由を与えられ、後に完全な自由が与えられた。彼らの子供たちは奴隷のままだった。1664年までに は、当初の11人の奴隷と、半自由を得た他の奴隷、合計少なくとも30人の黒人の地主が、フレッシュ・ウォーター・ポンド近くのマンハッタンに住んでいた [7][4]。 奴隷貿易 最初の出荷から20年以上、オランダ西インド会社はアフリカ沿岸からの奴隷の輸入で支配的であった。アンゴラにあった会社の拠点からニューネーデルランド に直接輸入された奴隷も多数いた[5]。 オランダ西インド会社はニューネーデルラント人にアンゴラからの奴隷とオランダ領西インド諸島、特にキュラソー島の「熟練した」アフリカ人奴隷を交換する ことを許し、彼らは他の奴隷よりも高く売れた。彼らはまた、スペインの奴隷船の私掠船から来た奴隷も購入した[5]。例えば、フランスの私掠船ラ・ガルス は、1642年にスペイン船から拿捕したスペイン系黒人を連れてニューアムステルダムに到着した。彼らはアフリカ人ではなく自由人であると主張したが、オ ランダ人は彼らの肌の色のために奴隷として彼らを売った[6]。 他の植民地の奴隷とは異なり、ニューアムステルダムの奴隷は白人であろうと黒人であろうと他人を訴えることができた。初期の例としては、賃金の損失や、奴 隷の豚が白人の飼い犬に怪我を負わされたときの損害賠償請求訴訟などがあった。奴隷もまた訴えられる可能性があった[b]。 部分的自由と完全な自由 1644年までに、一部の奴隷はニューアムステルダムで部分的自由(半自由)を獲得し、賃金を得ることができるようになった。ローマ・オランダ法の下で は、彼らは商業経済における他の権利も有しており、労働者階級の白人との婚姻も頻繁に行われていた[9]。土地付与の記録によれば、黒人の土地はニューア ムステルダムのすぐ北に位置していた。1664年にイングランドがニューアムステルダムを占領し始めると、オランダはイングランドが彼らを奴隷として維持 しないようにするため、半奴隷の地位を与えられていた約40人の男女を解放した。新たな自由民は当初の土地付与を確定させ、すべての付与は新たな自由民の 所有であると公式に記された[10]。 イングランドの支配 1798年に描かれたフレッシュ・ウォーター・ポンドの水彩画。左手前に見えるのは、110フィート(約34m)の小高い丘、ベイヤーズ・マウント (Bayard's Mount)。1811年頃に平らにされる前は、現在のモット・ストリートとグランド・ストリートの交差点付近にあった。現在のチェンバーズ・ストリート とブロードウェイからほぼ北南東に伸びるストックヤードが南岸の向こうに見える。 1664年、イギリスはニューアムステルダムと植民地を占領した。彼らは必要な仕事を支えるために奴隷を輸入し続けた。奴隷にされたアフリカ人は、主に急 成長する港町とその周辺の農業地帯で、熟練した仕事から未熟練な仕事まで幅広くこなした。1703年には、ニューヨークの世帯の42%以上が奴隷を所有し ており、この割合はボストンやフィラデルフィアの都市よりも高く、南部のチャールストンに次ぐものであった[2]。 1708年、ニューヨーク植民地議会は「奴隷の陰謀を防止するための法律」と題する法律を可決し、主人を殺害した、または殺害しようとした奴隷に対して死 刑を宣告することを規定した。この法律は植民地時代のアメリカでは最初のものの1つであり、ニュータウン(クイーンズ)で起きたウィリアム・ハレット3世 一家殺害事件への反動もあった[11]。 1711年、イースト・リバーのウォール・ストリートの端に正式な奴隷市場が設立され、1762年まで運営された[12]。 1730年に可決されたニューヨーク総会法は、一連のニューヨーク奴隷法の最後のものであり、次のように規定していた: ニューヨーク市とオルバニー市、およびこの植民地内のいくつかの郡、町、荘園では、奴隷の数が日々増加しており、また奴隷が連合して逃亡したり、その他の 悪質で危険な行為に及んだりすることがしばしばあるため、3人以上の奴隷がいつでも集まることは違法とする、 ただし、主人または愛人の利益のために、主人または愛人の同意のもとに、奴隷が何らかの隷属的な仕事に従事するために集まった場合に限る。 [13] 荘園や町は、一人当たり3シリング以下の鞭打ちを任命することができた[14]。黒人は、体罰や処刑のようなオランダ人がやりたがらない最も身分の低い仕 事を与えられた[15]。 1741年の奴隷反乱の後、N.Y.C.で火あぶりにされる奴隷 他の奴隷社会と同様に、ニューヨークは奴隷の反乱の恐怖に定期的に襲われた。このような状況下で、事件は誤って解釈された。1741年のニューヨークの陰 謀と呼ばれる事件では、市当局は反乱が始まったと考えた。数週間にわたり、150人以上の奴隷と20人の白人を逮捕し、彼らが反乱を計画していたと考え、 数人を裁判にかけて処刑した。歴史家のジル・ルポアは、この事件で白人が多くの黒人を不当に告発し、処刑したと考えている[16]。 1753年、議会は「アフリカから直輸入された4歳以上の黒人、混血、その他の奴隷1人につき5オンスのセヴィルピラーまたはメキシコプレート(銀)、ま たはこの植民地で流通する信用手形40シリング」を支払うよう定めた[17]。 北部の奴隷は、ベンジャミン・フランクリン、ウィリアム・ペン、ジョン・ハンコックのような著名人によって所有されることが多かった。ウィリアム・ヘン リー・スワードは、ニューヨーク州北部の奴隷所有家庭に育った。奴隷制度に反対した彼は、南北戦争中にエイブラハム・リンカーンの国務長官となった [18]。 |

| American Revolution Runaway slave advertisement (1774) African Americans fought on both sides in the American Revolution. Many slaves chose to fight for the British, as they were promised freedom by General Guy Carleton in exchange for their service. After the British occupied New York City in 1776, slaves escaped to their lines for freedom. The black population in New York grew to 10,000 by 1780, and the city became a center of free blacks in North America.[9] The fugitives included Deborah Squash and her husband Harvey, slaves of George Washington, who escaped from his plantation in Virginia and reached freedom in New York.[9] In 1781, the state of New York offered slaveholders a financial incentive to assign their slaves to the military, with the promise of freedom at war's end for the slaves. In 1783, black men made up one-quarter of the rebel militia in White Plains, who were to march to Yorktown, Virginia, for the last engagements.[9] By the Treaty of Paris (1783), the United States required that all American property, including slaves, be left in place, but General Guy Carleton followed through on his commitment to the freedmen. When the British evacuated from New York, they transported 3,000 Black Loyalists on ships to Nova Scotia (now Maritime Canada), as recorded in the Book of Negroes at the National Archives of Great Britain and the Black Loyalists Directory at the National Archives at Washington.[9][19] With British support, in 1792 a large group of these Black Britons left Nova Scotia to create an independent colony in Sierra Leone.[20] Further information: Black Nova Scotians and Sierra Leone Creole people Gradual abolition In 1781, the state legislature voted to free those slaves who had fought for three years with the rebels or were regularly discharged during the Revolution.[21] The New York Manumission Society was founded in 1785, and worked to prohibit the international slave trade and to achieve abolition. It established the African Free School in New York City, the first formal educational institution for blacks in North America. It served both free and slave children. The school expanded to seven locations and produced some of its students advanced to higher education and careers. These included James McCune Smith, who gained his medical degree with honors at the University of Glasgow after being denied admittance to two New York colleges. He returned to practice in New York and also published numerous articles in medical and other journals.[9] In 1785, Aaron Burr introduced a bill in the state legislature for immediate emancipation that was defeated 33–13 . A more limited bill was soon introduced, providing for gradual emancipation, but restricting voting, prohibiting intermarriage and black testimony against whites. It was also defeated, 27–17.[22][23] By 1790, one in three blacks in New York state were free. Especially in areas of concentrated population, such as New York City, they organized as an independent community, with their own churches, benevolent and civic organizations, and businesses that catered to their interests.[9] Starting in the 1830s, and particularly between 1850 and 1860, following passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, professional bounty hunters, vigilance committees, and the underground railroad could be found in New York. Abolitionist leaders such as David Ruggles, black and white, helped fugitive slaves escape to Canada or safer locations. One famous abolitionist leader and writer who was helped by Ruggles was Frederick Douglass. The cause was aided by white abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison and Sydney Howard Gay. Harriet Tubman made at least two trips to New York as a "captain" of the underground railroad.[24] Conversion to indentured servitude Although there was movement towards abolition of slavery, the legislature took steps to characterize indentured servitude for blacks in a way that redefined slavery in the state. Slavery was important economically, both in New York City and in agricultural areas, such as Brooklyn. In 1799, the legislature passed the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery. It freed no living slave. It declared children of slaves born after July 4, 1799, to be legally free, but the children had to serve an extended period of indentured servitude: to the age of 28 for males and to 25 for females. Slaves born before that date were redefined as indentured servants and could not be sold, but they had to continue their unpaid labor.[25] From 1800 to 1827, white and black abolitionists worked to end slavery and attain full citizenship in New York. During this time, there was a rise in white supremacy, which was at odds with the increased anti-slavery efforts of the early 19th century.[26] Peter Williams Jr., an influential black abolitionist and minister, encouraged other blacks to "by a strict obedience and respect to the laws of the land, form an invulnerable bulwark against the shafts of malice" to better the chances of freedom and a better life.[27] African Americans' participation as soldiers in defending the state during the War of 1812 added to public support for their full rights to freedom. In 1817, the state freed all slaves born before July 4, 1799 (the date of the gradual abolition law), to be effective in 1827. It continued with the indenture of children born to slave mothers until their 20s, as noted above.[25] Because of the gradual abolition laws, there were children still bound in apprenticeships when their parents were free.[28] This encouraged African-American anti-slavery activists.[28] In Sketches of America (1818), British author Henry Bradshaw Fearon, who visited the young United States on a fact-finding mission to inform Britons considering emigration, described the situation in New York City as he found it in August 1817: Advertisements for slaves in the New York Daily Advertiser in 1817, as reproduced in Henry Bradshaw Fearon's Sketches of America (1818) New York is called a "free state:" that it may be so so theoretically, or when compared with its southern neighbors; but if, in England, we saw in the Times newspaper such advertisements as the following [see image to right], we should conclude that freedom from slavery existed only in words.[29] Full freedom in 1827 On July 5, 1827, the African-American community celebrated final emancipation in the state with a parade through New York City.[27][30] A distinctive Fifth of July celebration was chosen over July 4, because the national holiday was not seen as meant for blacks, as Frederick Douglass stated later in his famous What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July? speech of July 5, 1852.[30] The memoirs of Daniel M. Tredwell, a native New Yorker who kept a diary beginning in 1838, include his recollections of formerly enslaved people associated with the family's Long Island homestead:[31] The old slave quarters at our homestead survived to our day, and were located about four hundred feet in the rear of our dwelling. We remember them many years after they had ceased to be used as quarters for negroes, and when they were used as a shelter and stable for horses and cows. The old building had a thatch roof and the clapboards were of oak. It was burned in 1834. Slaves were manumitted in this state in 1827 by an amended act of 1811 which required that those of a certaia age should be provided for during life with a home on the estate. We distinctly remember two of them who left home every spring, tramped all summer and invariably came home in winter to board. Right to vote New York residents were less willing to give blacks equal voting rights. By the constitution of 1777, voting was restricted to free men who could satisfy certain property requirements for value of real estate. This property requirement disfranchised poor men among both blacks and whites. The reformed Constitution of 1821 eliminated the property requirement for white men, but set a prohibitive requirement of $250 (equivalent to $5,000 in 2022), about the price of a modest house,[32] for black men.[25] In the 1826 election, only 16 blacks voted in New York City.[3]: 47 In 1846, a referendum to repeal this property requirement was roundly defeated.[33] "As late as 1869, a majority of the state's voters cast ballots in favor of retaining property qualifications that kept New York's polls closed to many blacks. African-American men did not obtain equal voting rights in New York until ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, in 1870."[25] Freedom's Journal The first issue of the Freedom's Journal, the first African-American newspaper, on March 16, 1827 Beginning March 16, 1827, John Brown Russwurm published Freedom's Journal, written by and directed to African Americans.[34][35] Samuel Cornish and John Russwurm were editors of the journal; they used it to appeal to African Americans across the nation.[36] The powerful words published spread rapid positive influence to African Americans who could help establish a new community. The emergence of an African-American journal was a very important movement in New York. It showed that blacks could gain education and be part of literate society.[37] White newspapers published a fictional "Bobalition" print series. This was made in mockery of blacks, using the way an uneducated colored person would pronounce abolition.[38] New York City and Brooklyn Further information: Partition and secession in New York § Civil War era New York City Mayor Fernando Wood was strongly pro-slavery. He was a leader of the peace Democrats, and in the opposition to the 13th Amendment ending slavery. Just before the Civil War he had seriously proposed to the City Council that the city secede from the Union to form the Free City of Tri-Insula (insula means "island" in Latin), incorporating Manhattan, Staten Island, and Long Island except for pro-Union Brooklyn. The City Council approved the plan, but rescinded its approval three months later, after the Battle of Fort Sumter.[39] In contrast, Brooklyn was "a sanctuary city before its time", with one of the largest and most politically aware Black communities in the United States.[40] Henry Ward Beecher, brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, pastor at the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn Heights, was one of the country's most active abolitionists. African Burial Ground In 1991, a construction project required an archaeological and cultural study of 290 Broadway in Lower Manhattan to comply with the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 before construction could begin. During the excavation and study, human remains were found in a former six-acre burial ground for African Americans that dated from the mid-1630s to 1795. It is believed that there are more than 15,000 skeletal remains of colonial New York's free and enslaved blacks. It is the country's largest and earliest burial ground for African-Americans.[41] This discovery demonstrated the large-scale importance of slavery and African Americans to New York and national history and economy. The African Burial Ground has been designated as a National Historic Landmark and a National Monument for its significance. A memorial and interpretive center for the African Burial Ground have been created to honor those buried and to explore the many contributions of African Americans and their descendants to New York and the nation.[42] |

アメリカ独立戦争 逃亡奴隷の広告(1774年) アメリカ独立戦争では、アフリカ系アメリカ人が両陣営で戦った。ガイ・カールトン将軍から戦功と引き換えに自由を約束されたため、多くの奴隷が英国側で戦 うことを選んだ。1776年にイギリス軍がニューヨークを占領した後、奴隷たちは自由のために彼らの陣地へと逃れた。逃亡者の中には、ジョージ・ワシント ンの奴隷であったデボラ・スクワッシュとその夫ハーヴェイも含まれており、彼らはヴァージニアの彼の農園から逃亡し、ニューヨークで自由を得た[9]。 1781年、ニューヨーク州は奴隷所有者に対し、奴隷の戦争終結時の自由を約束し、奴隷を軍に配属する金銭的インセンティブを提供した。1783年には、 ホワイトプレーンズの反乱軍民兵の4分の1を黒人が占め、彼らは最後の交戦のためにヴァージニアのヨークタウンに進軍することになっていた[9]。 パリ条約(1783年)によって、アメリカは奴隷を含むすべてのアメリカ人の財産をそのままにしておくことを要求したが、ガイ・キャールトン将軍は自由民 に対する公約を実行に移した。イギリスはニューヨークから避難する際、3,000人の黒人ロイヤリストを船でノヴァ・スコシア(現マリティム・カナダ)へ 輸送したことが、グレートブリテン国立公文書館の『Book of Negroes』やワシントンの国立公文書館の『Black Loyalists Directory』に記録されている[9][19] 。 さらなる情報 黒人ノバスコシア人とシエラレオネ・クレオール人 段階的な廃止 1781年、州議会は反乱軍と共に3年間戦った奴隷、または革命中に定期的に除隊した奴隷を解放することを決議した[21]。 ニューヨーク奴隷解放協会は1785年に設立され、国際奴隷貿易の禁止と奴隷廃止の実現に取り組んだ。同協会は、北米で最初の黒人のための正式な教育機関 であるアフリカン・フリー・スクールをニューヨークに設立した。この学校は、自由と奴隷の両方の子供たちを対象としていた。この学校は7カ所に拡大し、高 等教育や職業に進んだ生徒も輩出した。その中には、ニューヨークの2つの大学で入学を拒否された後、グラスゴー大学で優秀な成績で医学の学位を取得した ジェームズ・マキューン・スミスも含まれている。彼はニューヨークで開業し、医学雑誌などに多くの論文を発表した[9]。 1785年、アーロン・バーは州議会に即時奴隷解放法案を提出したが、33対13で否決された。すぐに、より限定的な法案が提出され、段階的な奴隷解放が 規定されたが、投票権の制限、異種婚姻の禁止、白人に対する黒人の証言などが規定された。これも27対17で否決された[22][23]。 1790年までに、ニューヨーク州では黒人の3人に1人が自由になった。特にニューヨークのような人口が集中する地域では、彼らは独立したコミュニティと して組織され、独自の教会、慈善団体、市民団体、そして彼らの利益を目的としたビジネスを展開していた[9]。 1830年代から始まり、特に1850年の逃亡奴隷法の成立後の1850年から1860年にかけて、ニューヨークでは、プロの賞金稼ぎ、自警委員会、地下 鉄が見られるようになった。デイヴィッド・ラグルズのような奴隷廃止論指導者たちは、白人と黒人を問わず、逃亡奴隷がカナダやより安全な場所に逃れるのを 助けた。ラグルスに助けられた有名な奴隷廃止運動指導者であり作家の一人に、フレデリック・ダグラスがいる。この運動は、ウィリアム・ロイド・ギャリソン やシドニー・ハワード・ゲイといった白人の奴隷廃止論者たちにも助けられました。ハリエット・タブマンは、地下鉄道の「隊長」として少なくとも2回ニュー ヨークを訪れた[24]。 年季奉公への転換 奴隷制廃止の動きはあったものの、州議会は黒人に対する年季奉公を、州における奴隷制を再定義する形で特徴づける措置をとった。ニューヨーク市やブルック リンなどの農業地域では、奴隷制度は経済的に重要であった。1799年、議会は奴隷制漸進的廃止法を可決した。この法律は生きている奴隷を解放するもので はなかった。この法律は、1799年7月4日以降に生まれた奴隷の子供は法的に自由であると宣言したが、子供は年季奉公の期間を延長しなければならなかっ た。それ以前に生まれた奴隷は年季奉公人と再定義され、売ることはできなかったが、無給の労働を続けなければならなかった[25]。 1800年から1827年まで、白人と黒人の奴隷廃止論者たちは、ニューヨークで奴隷制を廃止し、完全な市民権を得るために活動した。この時期、白人至上 主義が台頭し、19世紀初頭に活発化した反奴隷制の取り組みと対立していた[26]。 有力な黒人奴隷廃止論者であり牧師であったピーター・ウィリアムズ・ジュニアは、自由とより良い生活の可能性を高めるために、他の黒人たちに「土地の法律 を厳格に遵守し尊重することで、悪意の矢に対して不死身の防壁を形成する」ことを奨励した[27]。 1812年の戦争中、アフリカ系アメリカ人が州を守る兵士として参加したことは、彼らの自由への完全な権利に対する国民の支持に拍車をかけた。1817 年、州は1799年7月4日(段階的廃止法の制定日)以前に生まれたすべての奴隷を解放し、1827年に発効させた。漸進的廃止法のため、親が自由になっ ても徒弟制度で縛られている子供たちがいた[28]。このことはアフリカ系アメリカ人の反奴隷運動家を勇気づけた[28]。 Sketches of America』(1818年)の中で、移住を考えているイギリス人に情報を提供するため、実情調査で若きアメリカを訪れたイギリスの作家ヘンリー・ブ ラッドショー・フィーロンは、1817年8月に彼が見たニューヨークの状況を描写している: ヘンリー・ブラッドショー・フィーロンの『スケッチ・オブ・アメリカ』(1818年)に掲載された、1817年の『ニューヨーク・デイリー・アドバタイ ザー』紙の奴隷募集広告。 ニューヨークは「自由な州」と呼ばれている。理論的にはそうかもしれないし、南部の近隣諸国と比較すればそうかもしれない。しかし、もしイギリスで『タイ ムズ』紙に次のような広告[右の画像参照]が掲載されていたら、奴隷制からの自由は言葉の上だけに存在していたと結論づけるだろう[29]。 1827年の完全な自由 1827年7月5日、アフリカ系アメリカ人のコミュニティはニューヨークをパレードして州における最終的な奴隷解放を祝った[27][30]。後にフレデ リック・ダグラスが1852年7月5日の有名な演説で述べているように、国の祝日は黒人のためのものではないと考えられていたため、7月4日よりも特徴的 な7月5日のお祝いが選ばれた[30]。 1838年から日記をつけていた生粋のニューヨーカー、ダニエル・M・トレッドウェルの回想録には、一家のロングアイランドのホームステッドに関連する、 かつて奴隷だった人々の回想が含まれている[31]。 私たちのホームステッドの古い奴隷宿舎は、私たちの時代まで残っており、私たちの住居の後方約400フィートに位置していた。奴隷の宿舎として使われなく なって何年も経ち、馬や牛の隠れ家や馬小屋として使われていた頃のことを覚えている。古い建物は茅葺き屋根で、下見板はオーク材だった。1834年に焼失 した。この州では、1811年に制定された法律が改正され、一定の年齢に達した奴隷は生涯、土地に住居を提供することが義務づけられたため、1827年に 奴隷解放が行われた。私たちは、毎年春になると家を出て、夏の間は放浪し、冬になると必ず家に戻って食事をした2人の奴隷をはっきりと覚えている。 選挙権 ニューヨークの住民は、黒人に平等な選挙権を与えることにあまり積極的ではなかった。1777年の憲法では、投票権は不動産の価値に関する一定の財産要件 を満たす自由人に制限されていた。この財産要件は、黒人も白人も貧しい男性の選挙権を奪っていた。1821年に改正された憲法では、白人の財産要件は撤廃 されたが、黒人の財産要件は250ドル(2022年の5,000ドルに相当)という、ささやかな家の価格程度の禁止的なものとされた[32]: 47 1846年、この財産要件を撤廃する住民投票は大敗した[33]。「1869年の時点で、州の有権者の過半数が、ニューヨークの投票所を多くの黒人に対し て閉鎖したままにしていた財産要件を維持することに賛成の票を投じていた。1870年に合衆国憲法修正第15条が批准されるまで、ニューヨークでアフリカ 系アメリカ人男性が平等な選挙権を獲得することはなかった」[25]。 フリーダムズ・ジャーナル 1827年3月16日、アフリカ系アメリカ人初の新聞『フリーダムズ・ジャーナル』創刊号 1827年3月16日、ジョン・ブラウン・ラズヴルムは、アフリカ系アメリカ人によって書かれ、アフリカ系アメリカ人に向けられた『フリーダムズ・ジャー ナル』を創刊した[34][35]。サミュエル・コーニッシュとジョン・ラズヴルムはこのジャーナルの編集者であり、彼らはこのジャーナルを使って全米の アフリカ系アメリカ人に訴えた[36]。出版された力強い言葉は、新しいコミュニティの確立に貢献できるアフリカ系アメリカ人に急速な好影響を広げた。ア フリカ系アメリカ人の雑誌の出現は、ニューヨークにおいて非常に重要な動きであった。それは黒人が教育を受け、識字社会の一員になれることを示した [37]。 白人の新聞は、架空の「ボバリション」という活字シリーズを発行した。これは、無学な有色人種が廃絶を発音する方法を用いて黒人を嘲笑するものであった [38]。 ニューヨークとブルックリン さらなる情報 ニューヨークの分割と分離独立 § 南北戦争時代 ニューヨーク市長のフェルナンド・ウッドは強く奴隷制支持者であった。彼は平和民主党のリーダーであり、奴隷制を廃止する修正第13条に反対していた。南 北戦争の直前、彼は市議会に、マンハッタン、スタテン島、ロングアイランド(親連邦派のブルックリンを除く)を統合した自由都市トリ・インスラ(インスラ はラテン語で「島」を意味する)を結成するため、市を連邦から分離独立させることを真剣に提案した。市議会はこの計画を承認したが、サムター要塞の戦いの 後、3ヵ月後に承認を取り消した[39]。 対照的に、ブルックリンは「時代以前の聖域都市」であり、米国で最大かつ最も政治意識の高い黒人コミュニティのひとつであった[40]。 ブルックリンハイツのプリマス教会の牧師であったハリエット・ビーチャー・ストウの弟ヘンリー・ウォード・ビーチャーは、米国で最も積極的な奴隷廃止論者 のひとりであった。 アフリカ人墓地 1991年、ローワーマンハッタンのブロードウェイ290番地で、建設プロジェクトが着工する前に1966年の国家歴史保存法に準拠した考古学的・文化的 調査が必要となった。発掘調査の結果、1630年代半ばから1795年までのアフリカ系アメリカ人の埋葬地(6エーカー)から人骨が発見された。植民地時 代のニューヨークの自由奴隷となった黒人の骸骨は15,000体以上あると考えられている。アフリカ系アメリカ人の埋葬地としては、国内最大かつ最古のも のである[41]。 この発見は、ニューヨークと国の歴史と経済における奴隷制とアフリカ系アメリカ人の大規模な重要性を実証した。アフリカ人埋葬地は、その重要性から国定歴 史建造物および国定記念物に指定されている。アフリカ埋葬地の記念碑と解説センターは、埋葬された人々に敬意を表し、アフリカ系アメリカ人とその子孫が ニューヨークと全米にもたらした多くの貢献を探求するために作られた[42]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_slavery_in_New_York_(state) |

|