レイシズムと遺骨返還と墓地保全

Racism,

Repatriation, and

Reservation of Sacred Place

★人類学者のマイケル・ブレイキーさん(Dr.

Michael Blakey)の活動を通して、人種主義(レイシズム)と遺骨返還と墓地保全について考えるのが、このページの目的である。

| Michael

Blakey (born February 23, 1953) is an American anthropologist who

specializes in physical anthropology and its connection to the history

of African Americans. Since 2001, he has been a National Endowment for

the Humanities professor at the College of William & Mary,[2] where

he directs the Institute for Historical Biology.[1] Previously, he was

a professor at Howard University and the curator of Howard University's

Montague Cobb Biological Anthropology Laboratory.[3] |

マ

イケル・ブレイキー(Michael

Blakey、1953年2月23日生まれ)は、アメリカの人類学者で、自然人類学(ご本人の弁では「生物考古学」)とそのアフリカ系アメリカ人の歴史との関連性を専門としている[1]。

2001年より、ウィリアム・アンド・メアリー大学の全米人文科学基金教授[2]となり、歴史生物学研究所を指導している[1]。

それ以前は、ハワード大学の教授、ハワード大学のモンターグ・コブ生物人類学研究所の館長であった[3]。 |

| Early life and education Blakey obtained his B.A. in Anthropology from Howard University in 1978, and an M.A. (1980) and a Ph.D. (1985) from the University of Massachusetts Amherst.[4] He served as president of the Association of Black Anthropologists from 1987 to 1989.[1][4] |

幼少期と教育 1978年にハワード大学で人類学の学士号を取得し、1980年にマサチューセッツ大学アマースト校で修士号、1985年に博士号を取得した[4]。 1987年から1989年まで黒人人類学者協会の会長を務めた[1][4]。 |

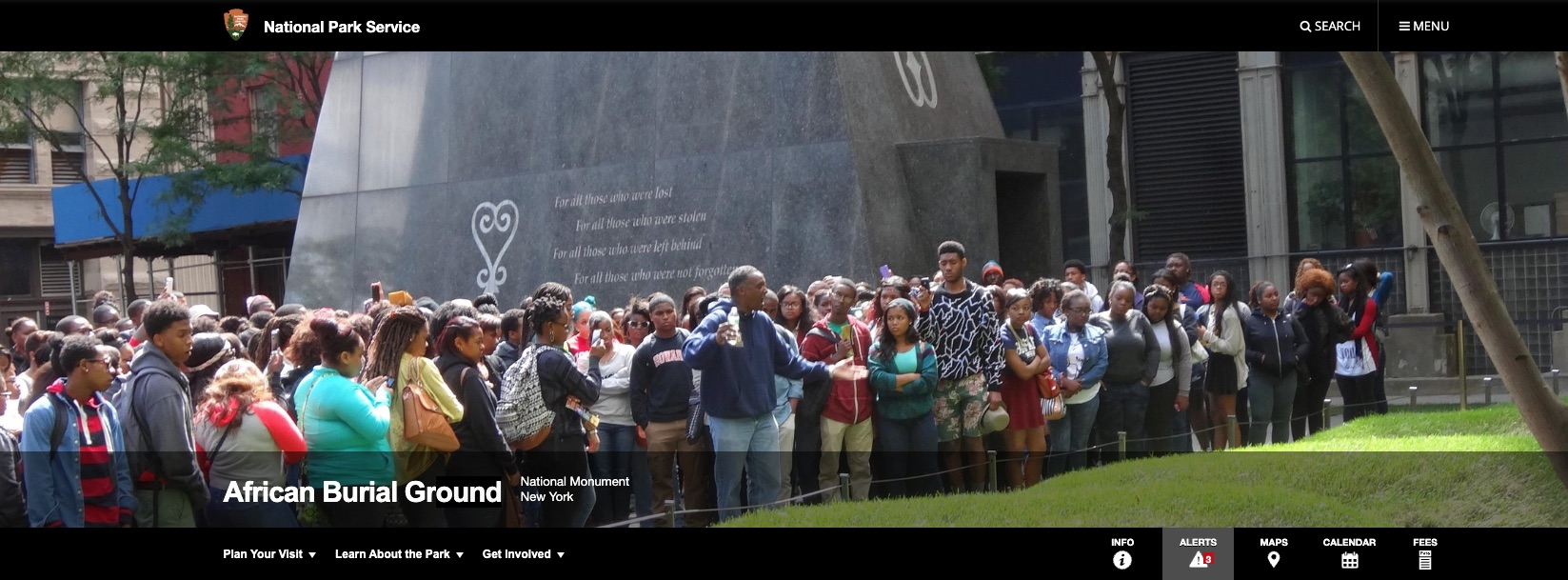

African burial ground in

Manhattan Blakey

was a director of the New York African Burial Ground Project,[5]

now the African Burial Ground National Monument.[6] According to

Blakey, the existence of this burial ground in what is now Lower

Manhattan[5] (where between 10 and 20 thousand people of African

descent were buried in the eighteenth century) was evidence of "false

historical representation" and exposed as a myth the idea that New York

and the northern states were not slave-owning areas.[7] Blakey says

that, in general, educated Americans had the impression that slavery

played little role in the development of the northern American colonies

in general, and New York City in particular. Blakey's research helps

dispel those myths, and offers a "compelling portrait of the

exploitation and violence suffered by enslaved Africans, and equally to

the active resistance of people of African descent to this exploitation

and violence".[7] Blakey concluded that these slaves faced "brutal

working conditions, premature rates of mortality, and excessive

workloads, while nutritional deficiencies were common among young

children."[8] Blakey

was a director of the New York African Burial Ground Project,[5]

now the African Burial Ground National Monument.[6] According to

Blakey, the existence of this burial ground in what is now Lower

Manhattan[5] (where between 10 and 20 thousand people of African

descent were buried in the eighteenth century) was evidence of "false

historical representation" and exposed as a myth the idea that New York

and the northern states were not slave-owning areas.[7] Blakey says

that, in general, educated Americans had the impression that slavery

played little role in the development of the northern American colonies

in general, and New York City in particular. Blakey's research helps

dispel those myths, and offers a "compelling portrait of the

exploitation and violence suffered by enslaved Africans, and equally to

the active resistance of people of African descent to this exploitation

and violence".[7] Blakey concluded that these slaves faced "brutal

working conditions, premature rates of mortality, and excessive

workloads, while nutritional deficiencies were common among young

children."[8]Blakey's research team examined 27 skeletons that had filed or "culturally modified" teeth, which was considered a strong indication of African birth. Previously, only nine such skeletons had been discovered in the Americas. It is likely that these individuals had come to New York previous to 1808, when the importation of slaves from Africa was banned.[9] Blakey's team examined more than 1.5 million artifacts discovered at the site, which included everything "from pottery and glassware to tools and children's toys".[10] His research determined that approximately half of the African people buried at the site were children. After his research was completed, the skeletal remains were reinterred at the site "in 400 hand-carved mahogany coffins"[10] in a 2003 ceremony described as "joyous and bitter all at once".[10] A silver pendant recovered during laboratory cleaning of the skeletal remains of burial 254 – a child between 3½ and 5½ years old. "The very existence of an African Burial Ground in colonial New York raised the issue of false historical representation. The vast majority of educated Americans had learned that there was little if any African presence in New York during the colonial period, and that the northern American colonies had not engaged in the practice of slavery. The Burial Ground helped show that these not ions comprised a kind uf national myth." (Blakey 1995 : 546) |

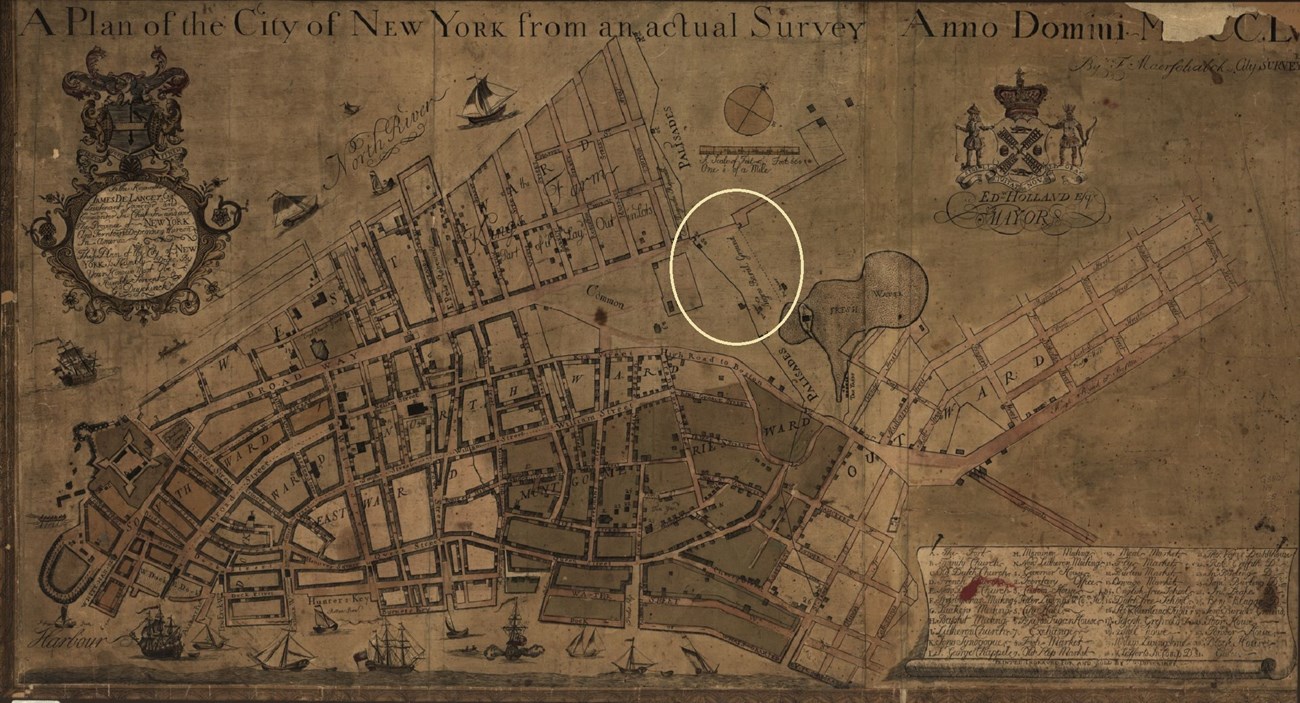

マンハッタンにあるアフリカ人埋葬地 ブ

レイキーは、ニューヨーク・アフリカ埋葬地プロジェクト[5](現在のアフリカ埋葬地国定公園)のディレクターであった[6]。

ブレイキーによれば、現在のロウワーマンハッタンの地にこの埋葬地が存在すること[5]は「誤った歴史表現」の証拠であり、ニューヨークと北部諸州は奴隷

を所有する地域ではなかったという考えを神話として暴露するものであったと述べている[6]。 [7]

ブレイキーによれば、一般に、教育を受けたアメリカ人は、アメリカ北部植民地全般、特にニューヨークの発展において、奴隷制はほとんど役割を果たしていな

いという印象を抱いていたという。ブレイキーの研究はそれらの神話を払拭するのに役立ち、「奴隷にされたアフリカ人が受けた搾取と暴力、そしてこの搾取と

暴力に対するアフリカ系の人々の積極的な抵抗についても同様に説得力のある描写」を提供している[7]。

ブレイキーはこれらの奴隷が「残忍な労働条件、早期死亡率、過労、そして栄養不足が幼児によく見られた」ことを結論づけた[8]。 ブ

レイキーは、ニューヨーク・アフリカ埋葬地プロジェクト[5](現在のアフリカ埋葬地国定公園)のディレクターであった[6]。

ブレイキーによれば、現在のロウワーマンハッタンの地にこの埋葬地が存在すること[5]は「誤った歴史表現」の証拠であり、ニューヨークと北部諸州は奴隷

を所有する地域ではなかったという考えを神話として暴露するものであったと述べている[6]。 [7]

ブレイキーによれば、一般に、教育を受けたアメリカ人は、アメリカ北部植民地全般、特にニューヨークの発展において、奴隷制はほとんど役割を果たしていな

いという印象を抱いていたという。ブレイキーの研究はそれらの神話を払拭するのに役立ち、「奴隷にされたアフリカ人が受けた搾取と暴力、そしてこの搾取と

暴力に対するアフリカ系の人々の積極的な抵抗についても同様に説得力のある描写」を提供している[7]。

ブレイキーはこれらの奴隷が「残忍な労働条件、早期死亡率、過労、そして栄養不足が幼児によく見られた」ことを結論づけた[8]。ブレイキーの研究チームは、アフリカ生まれであることを強く示すと考えられていた、ヤスリで削った歯や「文化的に修正された」歯を持つ27体の骸骨を調査 した。それまで、このような骸骨はアメリカ大陸で9体しか発見されていなかった。ブレイキーのチームは、「陶器、ガラス製品、工具、子供のおもちゃなど」 150万点以上の遺物を調査し、埋葬されたアフリカ人の約半数が子供であることを突き止めた[10]。彼の研究が完了した後、骨格は「手彫りの400個の マホガニーの棺に」[10]埋葬され、2003年の式典は「喜びと苦みが同時にやってきた」と表現された[10]。 ※254号埋葬者(3歳半から5歳半の子供)の骨格のクリーニング中に発見された銀のペンダント。 「植民地時代のニューヨークにアフリカ人埋葬地が存在すること自体が、誤った歴史表現の問題を提起した。教育を受けたアメリカ人の大多数は、植民地時代の ニューヨークにはアフリカ人はほとんど存在せず、アメリカ北部の植民地では奴隷制度は行われていなかったと学んでいた。埋葬地』は、これらが一種の国家神 話を構成していることを示すのに役立った」(Blakey 1995 : 546)。(ブレイキー 1995 : 546) |

| Analysis of racism Blakey says that physical anthropology has a "pattern of denial" about racism, which has its origins in the dominant view that social differences are due to the inherent characteristics of individuals, and less on political and economic factors.[11] Blakey maintains that the history of physical anthropology has been "sterilized", downplaying the role that eugenics and scientific racism had in its origins.[11] Discussing a museum exhibit about race at the Science Museum of Virginia, Blakey criticized the contemporary reluctance to discuss racism, maintaining that "it has become illegitimate to talk about racism" and that failing to do so is "the new racism".[12] |

人種差別の分析 ブレイキーは身体人類学には人種主義についての「否定のパターン」があり、その起源は社会的差異が個人の固有の特性によるものであり、政治的・経済的要因 によるものではないという支配的な見解にあると言う[11]。 ブレイキーは身体人類学の歴史が「殺菌」され、優生学と科学的人種主義がその起源において持っていた役割を軽視してきたと主張している[11]。 バージニア科学博物館で行われた人種に関する博物館の展示について議論したブレイキーは、人種差別について議論することに消極的な現代を批判し、「人種差 別について話すことは違法となった」、そうしないことが「新しい人種差別」であると主張している[12]。 |

| Blakey

on the New York African Burial Ground Project Blakey interviewed on National Public Radio in 2007 - Unearthing New York's Forgotten Slavery Era. African Burial Ground National Monument |

※被葬者数の推定は、1万〜2万人 ※1795年には放棄 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Blakey_(anthropologist) |

|

| Dr. Michael Blakey From 1991 to 1994, Blakey served as the director of the African Burial Ground Project in New York City, one of the most important archaeological finds in the United States during the 20th century. Blakey’s research team examined 27 skeletons that had filed or culturally modified teeth, which was considered a strong indication of African birth. Previously, only nine such skeletons had been discovered in the Americas. Blakey’s team examined more than 1.5 million artifacts discovered at the site, which included everything from pottery and glassware to tools and children’s toys. His research determined that approximately half of the African people buried at the site were children. “We were also doing something that scholars within the African diaspora have been doing for about 150 years and that is realizing that history has political implications of empowerment and disempowerment. That history is not just to be discovered but to be re-discovered, to be corrected, and that African-American history is distorted. Omissions are made in order to create a convenient view of national and white identity at the expense of our understanding our world and also at the expense of African-American identity,” Dr. Blakey said in 2003 interview with the Archaeological Institute of America. https://eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/drabikgallery/2016/06/01/dr-michael-blakey/ |

マイケル・ブレイキー博士 1991年から1994年まで、ブレイキーはニューヨークの「アフリカ埋葬地プロジェクト」のディレクターを務めた。これは20世紀の米国で最も重要な考 古学的発見の一つである。ブレイキーの研究チームは、アフリカ人の出生の有力な証拠とされる、歯を削ったり、文化的に変化させた27体の骸骨を調査した。 それまでは、このような骸骨はアメリカ大陸ではわずか9体しか発見されていなかった。ブレイキー氏のチームは、陶器やガラス製品、工具、子供のおもちゃな ど、遺跡から発見された150万点以上の遺物を調査した。彼の研究によると、この遺跡に埋葬されたアフリカ人の約半数は子供であった。 「私たちはまた、アフリカン・ディアスポラの学者が150年ほど前から行ってきたことを行っていました。歴史は発見されるだけでなく、再発見され、修正さ れるものであり、アフリカ系アメリカ人の歴史は歪曲されているのです。ブレイキー博士は、2003年の米国考古学協会とのインタビューで、「私たちの世界 に対する理解を犠牲にし、またアフリカ系アメリカ人のアイデンティティを犠牲にして、国民と白人のアイデンティティという都合の良い見方をするために、省 略が行われています」と述べている。 |

| "Today,

the monument on Manhattan Island in New York City is not dedicated to

its unknown African founders, but to people with an international

history to be explored, debated and identified with at the

Visitor Center. Not only is a story told of the past, but the

intensive late twentieth-century struggle for human dignity

of the people who refer to that past as ‘we’ has become an

important part of the story. The government’s initial plan was to mount

a plaque on the wall of their building and provide for a study of race

differences in skeletal observations. African-Americans asserted their

group rights, the right to know what happened during slavery, and the

obligation of memorialization as a human right and a warning not to

repeat the past. Archaeologists, biological anthropologists and

historians are no more objective when they disregard these public goals

than when they attend to them. In our case, we are certain many of the

research questions were both different and better than those created

exclusively among our specialist colleagues behind the walls of the

academy. The claim that we are objective by not attending to the

expressed needs of the people most affected by the

history we construct (descendant communities)

simply constitutes serving the needs of others. What is the harm in a

people’s self-definition and why should they tolerate

other people’s interference in their efforts to tell

their own story? In increasingly diverse cosmopolitan societies, the

issue of group rights and heritage loom large. Recognition of intrinsic

human subjectivity in the production of knowledge requires one to be

ethical in ways that concur with the consistent use of scientific

method yet go beyond it. Democratization

of knowledge

that accommodates the diverse perspectives of plural states is

both an ethical and epistemic process. We offer a

paradigm, not

limited to African-Americans or cemetery sites,

of cooperation that frees voices to be more

fully heard in healthy, if difficult, conversations

about how, why and what ‘we’ have come to be." Michael L. Blakey, African Burial Ground Project: paradigm for cooperation? ISSN 1350-0775, No. 245–246 (Vol. 62, No. 1–2, 2010) ª UNESCO 2010 |

「今

日、ニューヨークのマンハッタン島にあるこの記念碑は、その無名のアフリカ人創設者に捧げられたものではなく、ビジターセンターで探求し、議論し、識別す

るための国際的な歴史を持つ人々に捧げられています。過去の物語が語られるだけでなく、その過去を「私たち」と呼ぶ人々の人間の尊厳を求める20世紀末の

集中的な闘いが、物語の重要な一部となっている。政府の当初の計画は、建物の壁にプレートを取り付け、骨格観察における人種差の研究に供するというもの

だった。アフリカ系アメリカ人は、自分たちの集団の権利、奴隷時代に何が起こったかを知る権利、そして人権と過去を繰り返さないための警告としての記念化

の義務を主張した。考古学者、生物人類学者、歴史家は、これらの公的な目標を無視するとき、それに出席するときと同じように客観的ではない。私たちの場

合、研究課題の多くが、アカデミーの壁の向こうの専門家仲間だけで作られたものとは異なり、より良いものであったことは確かである。私たちが構築した歴史

によって最も影響を受ける人々(子孫コミュニティ)の表明されたニーズに応えないことで、私たちが客観的であるという主張は、単に他者のニーズに応えると

いうことに他なりません。民族の自己定義に何の弊害があるのか、また、なぜ民族が自らの物語を語ろうとする努力に他者が干渉することを容認しなければなら

ないのか?多様化が進むコスモポリタン社会では、集団の権利や遺産の問題が大きくクローズアップされる。知識の生産における人間の本質的な主観性を認識す

ることは、科学的方法の一貫した使用と一致しながらも、それを超える方法で倫理的であることを要求する。複数の国家の多様な視点を受け入れる知識の民主化は、倫理的かつ認識論的なプロセスである。

私たちは、アフリカ系アメリカ人や墓地の敷地内に限らず、「私たち」がどのように、なぜ、そしてどのような存在になったのかについて、困難ではあっても健

全な会話において、声をより十分に聞くことができるようにする協力のパラダイムを提供するのだ」。 |

| African

Burial Ground National

Monument is a monument at Duane Street and African Burial Ground

Way

(Elk Street) in the Civic Center section of Lower Manhattan, New York

City. Its main building is the Ted Weiss Federal Building at 290

Broadway.[4] The site contains the remains of more than 419 Africans

buried during the late 17th and 18th centuries in a portion of what was

the largest colonial-era cemetery for people of African descent, some

free, most enslaved.[5] Historians estimate there may have been as many

as 10,000[6]–20,000 burials in what was called the Negroes Burial

Ground in the 18th century. The five to six acre site's excavation and

study was called "the most important historic urban archaeological

project in the United States."[7] The Burial Ground site is New York's

earliest known African-American cemetery; studies show an estimated

15,000 African American people were buried here.[8] The discovery highlighted the forgotten history of enslaved Africans in colonial and federal New York City, who were integral to its development. By the American Revolutionary War, they constituted nearly a quarter of the population in the city. New York had the second-largest number of enslaved Africans in the nation after Charleston, South Carolina. Scholars and African-American civic activists joined to publicize the importance of the site and lobby for its preservation. The site was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1993 and a national monument in 2006 by President George W. Bush. In 2003 Congress appropriated funds for a memorial at the site and directed redesign of the federal courthouse to allow for this. A design competition attracted more than 60 proposals. The memorial was dedicated in 2007 to commemorate the role of Africans and African Americans in colonial and federal New York City, and in United States history. Several pieces of public art were also commissioned for the site. A visitor center opened in 2010 to provide interpretation of the site and African-American history in New York. |

アフリカ埋葬地国定史跡は、ニューヨーク市ロウアー・マンハッタンのシ

ビック・センター地区、ドゥエイン・ストリートとアフリカ埋葬地通り(エルク・ストリート)にある史跡である。17世紀後半から18世紀にかけて、アフリ

カ系住民のための植民地時代最大の墓地の一部に埋葬された419人以上のアフリカ人の遺骨がある。この5~6エーカーの敷地の発掘と調査は、「米国で最も

重要な歴史的都市考古学プロジェクト」[7]と呼ばれ、埋葬地はニューヨークで最も古いアフリカ系アメリカ人の墓地として知られている。 この発見は、植民地時代と連邦時代のニューヨークで、その発展に欠かせなかったアフリカ人奴隷の忘れられた歴史を浮き彫りにした。アメリカ独立戦争まで に、彼らはニューヨークの人口の4分の1近くを占めていた。ニューヨークには、サウスカロライナ州チャールストンに次いで、全米で2番目に多くのアフリカ 人奴隷がいた。学者やアフリカ系アメリカ人の市民活動家たちは、この遺跡の重要性を広報し、保存のためのロビー活動に参加した。この遺跡は1993年に国 定歴史建造物に指定され、2006年にはジョージ・W・ブッシュ大統領によって国定記念物に指定された。 2003年、連邦議会はこの場所に記念碑を建てるための資金を計上し、そのために連邦裁判所の再設計を指示した。設計コンペには60以上の提案が集まっ た。記念碑は2007年に献堂され、植民地時代と連邦時代のニューヨーク、そして米国の歴史におけるアフリカ人とアフリカ系アメリカ人の役割を記念してい る。この記念碑のために、いくつかのパブリックアートも制作された。2010年には、この場所とニューヨークにおけるアフリカ系アメリカ人の歴史について の解説を提供するビジター・センターがオープンした。 |

| アフリカ

人墓地ナショナル・モニュメント(日本語ウィキペディア解説) |

|

| Charleston

honors Black ancestors, with both science and ceremony BY LIZZIE WADE https://www.science.org/content/article/racist-scientist-built-collection-human-skulls-should-we-still-study-them |

チャールストン、科学と儀式の両方で黒人の祖先を称える リジー・ウェイド |

| Like the 51 enslaved people of

African descent whose bodies were dug up in Cuba in 1840 for

anthropologist Samuel Morton’s collection, the 36 people buried in

downtown Charleston, South Carolina, were nameless. No record of the

graveyard or those buried in it existed, making it likely they were

also enslaved Africans or their descendants. But the fate of their remains, found during construction in 2013, was different from those in the Morton collection (see Ales_Hrdlicka.html). Instead of being acquired by scientific collectors, the 36—as African American retired teacher La’Sheia Oubré of Charleston calls them—became the responsibility of the city and its Black community, who turned to scientists to help discover their identities and life stories. Called to investigate, archaeologists noted that the 36, also known as the Anson Street Ancestors after the location of their graves, had been buried with care, in regular rows. Nails and brass pins showed many had been wrapped in shrouds. Buttons, including one made of mother-of-pearl, showed they had been dressed by people who mourned them. Pieces of clay tobacco pipes were buried with two men, and a copper coin—a West African tradition—with another person. One man’s incisors had been filed into points, a rite of passage in West Africa. A child had two copper half-pennies placed over their eyes. The half-pennies, minted in 1773, and other offerings helped date the graveyard to between 1760 to 1790, when enslaved Africans made up nearly half of Charleston’s population. The nonprofit Gullah Society, which protects African and African American burial grounds around Charleston, held consultations about the 36 with the city’s Black and African American communities. The community wanted to rebury them with love, honor, and respect. But first they wanted to learn everything they could about the 36, including their genetic ancestry. So Ade Ofunniyin, an African American anthropologist and founder of the Gullah Society, invited anthropological geneticists from the University of Pennsylvania to collaborate. “Right from the get-go it was set up that we were going to try to levy our resources and expertise to answer the questions and [serve the] needs of the community,” says one of the geneticists, Raquel Fleskes, who is white and now at the University of Connecticut, Storrs. When, working alone in a sterile lab, she ground up small pieces of bone from each of the 36 and extracted their DNA, she wore a GoPro camera on her head to share the process with the community. Every bit of sampled bone was saved to be reburied. Other researchers measured strontium isotopes in teeth and bones, which preserve chemical signatures of where a person grew up and lived. Although 35 of the 36 had types of mitochondrial DNA—genetic material inherited through the mother—common in Central and West Africa, one woman’s mtDNA linked her with Native American groups. The finding pointed to the intertwined histories of Black and Indigenous people in Charleston, as people from both communities were enslaved. Most of the 36 had lived in Charleston all their lives. The results were published in October 2020 in biological anthropology’s flagship journal, the American Journal of Physical Anthropology. From what was learned about the heritage and sex of the 36, the Gullah Society organized a ceremony, presided over by Yoruba priests, to give each a name. The child with the half-pennies placed on the eyes is Welela. Welela was buried next to Isi, an adult with an identical mitochondrial genome, so at least two of the 36 were buried with family. On 4 May 2019, a horse-drawn hearse carried some of the remains through Charleston’s streets for reburial near their original resting place. A crowd followed, filling the air with drumming and chants. “Every group of people that were identified within the 36 were part of the ceremony,” remembers Oubré, who works with the Anson Street African Burial Ground project. “Native American, African, Caribbean, children, adults. We had dancing, we had music. … Never before had Charleston seen such grandeur.” The remains were laid in a burial vault with notes written by the community. “To my beloved ancestors, thank you for life and making your journey to Charleston, SC. You are honored and may God bless your souls,” one read. Ofunniyin read out each of the 36 names, and the community echoed them back. “It is our responsibility to take care of our elders,” Oubré says. “Without them, there would be no us.” https://www.science.org/content/article/racist-scientist-built-collection-human-skulls-should-we-still-study-them |

人類学者サミュエル・モートンのコレクションのために1840年に

キューバで掘り起こされた51人のアフリカ系奴隷と同様に、サウスカロライナ州チャールストンのダウンタウンに埋葬された36人の人々もまた、無名であっ

た。墓地やそこに埋葬された人々の記録は存在しなかったため、彼らもまた奴隷にされたアフリカ人かその子孫である可能性が高い。 しかし、2013年に工事中に発見された彼らの遺骨の運命は、モートン・コレクション(リン ク先)の遺骨とは異なっていた。チャールストンに住むアフリカ系アメリカ人の元教師、ラシェイア・ウーブレが言うように、36体の遺骨は科学的な コレクターによって収集されるのではなく、市とその黒人コミュニティの責任となった。 調査のために呼び出された考古学者たちは、墓の場所にちなんで「アンソン・ストリートの先祖たち」とも呼ばれる36人が、規則正しく並んで丁寧に埋葬され ていることに注目した。釘や真鍮のピンから、多くが覆い被されていたことがわかった。真珠母で作られたものを含むボタンは、彼らを弔う人々によって着飾ら れたことを示していた。粘土製のタバコのパイプの破片が二人の男性と一緒に埋葬され、西アフリカの伝統である銅貨がもう一人と一緒に埋葬されていた。一人 の男性の切歯は、西アフリカの通過儀礼であるヤスリで削られて尖った形になっていた。子どもは2枚の銅貨を目の上に置かれた。 1773年に鋳造されたハーフペニーやその他の供物は、奴隷にされたアフリカ人がチャールストンの人口の半分近くを占めていた1760年から1790年の 間の墓地を年代測定するのに役立った。 チャールストン周辺のアフリカ系およびアフリカ系アメリカ人の埋葬地を保護する非営利団体ガラ・ソサエティは、市内の黒人およびアフリカ系アメリカ人のコ ミュニティと36基について協議を行った。コミュニティは、愛と名誉と敬意をもって埋葬し直すことを望んだ。しかし、その前に彼らは36人について、彼ら の遺伝的な先祖を含め、あらゆることを知りたいと考えた。そこでアフリカ系アメリカ人の人類学者であり、ガラ・ソサエティの創設者であるアデ・オフンニイ ンは、ペンシルベニア大学の人類遺伝学者を招き、共同研究を行った。 「遺伝学者の一人、ラケル・フレスケスは白人で、現在はコネチカット大学ストールズ校に在籍している。無菌の研究室で一人、36人それぞれの骨の小片を粉 砕し、DNAを抽出する際、彼女はGoProカメラを頭に装着し、その過程をコミュニティと共有した。採取された骨はすべて、埋め戻すために保存された。 他の研究者たちは、歯や骨に含まれるストロンチウム同位体を測定した。 36人中35人は、中央アフリカや西アフリカで一般的なミトコンドリアDNA(母親から受け継ぐ遺伝物質)を持っていたが、ある女性のミトコンドリア DNAはネイティブ・アメリカンのグループと結びついていた。この発見は、チャールストンにおける黒人と先住民の歴史が絡み合っていることを指摘するもの である。36人のほとんどは生涯チャールストンに住んでいた。この結果は2020年10月、生物人類学の主要学術誌『American Journal of Physical Anthropology』に掲載された。 36人の血統と性別について判明したことから、ガラ協会はヨルバ族の司祭が主宰する儀式を組織し、それぞれに名前をつけた。目の上に半ペニーを乗せた子供 がウェレラである。Welelaは、同一のミトコンドリアゲノムを持つ大人のIsiの隣に埋葬されたので、36人のうち少なくとも2人は家族とともに埋葬 されたことになる。 2019年5月4日、馬が引く霊柩車がチャールストンの通りを遺体の一部を運び、元の安置場所の近くに改葬した。その後を群衆が追いかけ、太鼓と聖歌で空 気を満たした。アンソン・ストリート・アフリカ埋葬地プロジェクトに携わるウーブレは、「36区内で確認されたあらゆるグループの人々がセレモニーに参加 しました」と振り返る。「ネイティブ・アメリカン、アフリカ系、カリブ系、子供、大人。ダンスも音楽もあった。チャールストンがこのような壮大さを目にし たのは初めてのことでした」。 遺骨は、コミュニティによって書かれたメモとともに埋葬室に安置された。「私の最愛の先祖たちへ、生きてくれて、サウスカロライナ州チャールストンまで旅 をしてくれてありがとう。神のご加護がありますように。オフンニインが36人の名前を読み上げると、コミュニティはそれを反響させた。 「年長者の面倒を見るのは私たちの責任です。「彼らがいなければ、私たちは存在しません」。 |

A Sacred Space in

Manhattan, by

「1991年、ブロードウェイ290番地に位置する 34階建ての連邦政府オフィスタワーが着工され、ゼネラル・サービス・アドミニストレーション(GSA)が監督した。連邦政府が資金を提供する建設プロ ジェクトは、1966年国家歴史保存法の第106条を遵守することが義務付けられている。1989年、建設に先立ち、リパブリカン・アレーの地域で「第 1A段階文化資源調査」が完了した。このコンプライアンス文化調査研究は、ブロードウェイ290番地での建設が考古学的・文化的に及ぼす潜在的な影響を判 断するために考古学者を支援するものであった。

考古学的予備調査の発掘調査では、ブロードウェイの 市道高さ30フィート下に無傷の人骨が発見された。それは、植民地時代のニューヨークに住み、働いていた奴隷や自由アフリカ人の15,000体以上の無傷 の骸骨が埋葬されている6エーカーの埋葬地「Negroes Buriel Ground(黒人埋葬地)」の発掘であった。この埋葬地が再発見されたことで、奴隷制をめぐる理解と学問が変わり、ニューヨークの建設に貢献した。埋葬 地の歴史は1630年代半ばから1795年まで遡る。現在、この埋葬地は米国で再発見された最古かつ最大のアフリカ人埋葬地である。

奴隷にされたアフリカ人の骸骨の記念化と研究は、市 や州の政治指導者を含め、総務庁、アフリカ系アメリカ人の子孫コミュニティ、歴史家、考古学者、人類学者の間で幅広く交渉された。市民参加によって、先祖 代々の遺骨は再発見された元の場所に再び埋葬されることになった。植民地時代のニューヨークで奴隷にされたアフリカ人の経済的・物理的貢献を記念し、彼ら の記憶を称えるために、屋外記念碑、解説センター、研究図書館が建設された。

アフリカ人埋葬地の継続的な物語、またはニューヨー

ク市で最初に奴隷にされた11人のアフリカ人の1人であるグルート・マニュエルの子孫である作家で歴史家のクリストファー・ムーアによって書かれた私たち

のサイトの簡単な歴史については、《こ

こ》をクリック。」https://www.nps.gov/afbg/learn/historyculture/index.htm

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆