アレッシュ・ヘルドリチカ

Alois Ferdinand Hrdlička, Aleš Hrdlička,

after 1918, 1869-1943; アレッシュ・フルドリチュカ

☆ アレッシュ・ヘルドリチカ(アレッシュ・フルドリチュカ、あるいはハードリチカ)Alois Ferdinand Hrdlička, [1] 1918年以降はAleš Hrdlička(チェコ語発音: [1869年3月30日[2] - 1943年9月5日)は、チェコ出身の人類学者。ボヘミア(現在のチェコ共和国)のフンポレツに生まれる。以下では、その姓はフルドリチュカ(Hrdlička)で統一する。

| Alois

Ferdinand Hrdlička,[1] after 1918 changed to Aleš Hrdlička (Czech

pronunciation: [ˈa.lɛʃ ˈɦr̩d.lɪtʃ.ka]; March 30,[2] 1869 – September 5,

1943), was a Czech anthropologist who lived in the United States after

his family had moved there in 1881. He was born in Humpolec, Bohemia

(today in the Czech Republic). |

Alois Ferdinand Hrdlička, [1] 1918年以降はAleš Hrdlička(チェコ語発音: [1869年3月30日[2] - 1943年9月5日)、チェコの人類学者。ボヘミア(現在のチェコ共和国)のフンポレツに生まれる。 |

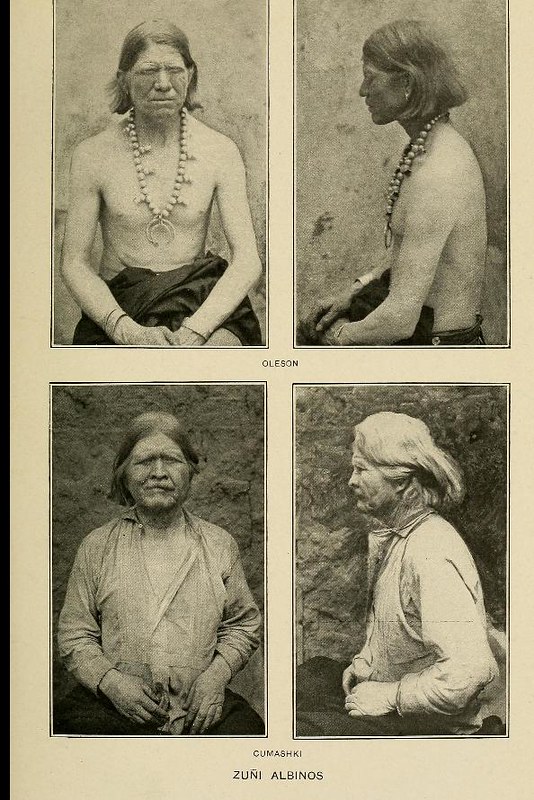

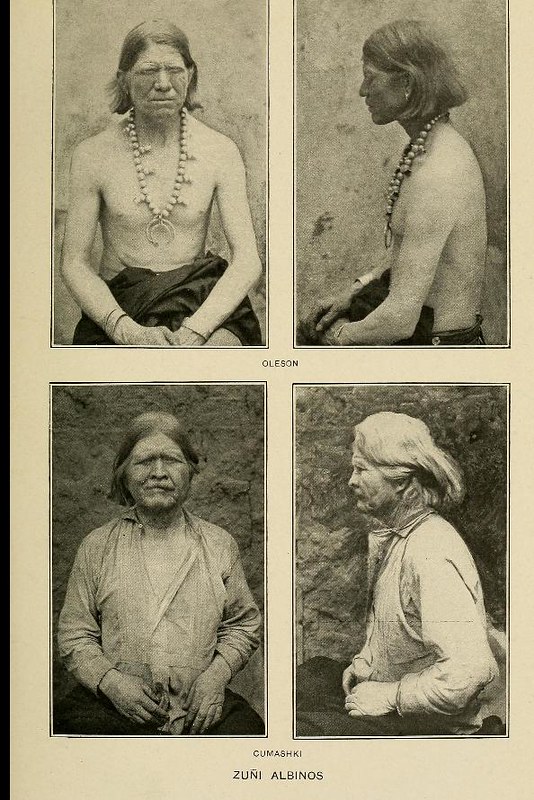

| Life and career Hrdlička was born at Humpolec house 393 on 30 March 1869 and baptized Catholic the next day at the Kostel svatého Mikuláše [cz].[3] His mother, Karolína Hrdličková, educated her child herself; his skills and knowledge made it possible to skip the primary level of school. When he was 13, Hrdlička arrived in New York with his father Maxmilian Hrdlička on 10 September 1881 via the SS Elbe from Bremen.[4] His mother and three younger siblings emigrated to the U.S. separately. After arrival, the promised job brought only a disappointment to his father who started working in a cigar factory along with teenaged Alois to earn a living for the family with six other children. Young Hrdlička attended evening courses to improve his English, and at the age of 18, he decided to study medicine since he had suffered from tuberculosis and experienced the treatment difficulties of those times. In 1889, Hrdlička began studies at Eclectic Medical College and then continued at Homeopathic College in New York. To finish his medical studies, Hrdlička sat for exams in Baltimore in 1894. At first, he worked in the Middletown asylum for mentally affected where he learnt of anthropometry. In 1896, Hrdlička left for Paris, where he started to work as an anthropologist with other experts of the then establishing field of science. Between 1898 and 1903, during his scientific travel across America, Hrdlička became the first scientist to spot and document the theory of human colonization of the American continent from east Asia, which he claimed was only some 3,000 years ago. He argued that the Indians migrated across the Bering Strait from Asia, supporting this theory with detailed field research of skeletal remains as well as studies of the people in Mongolia, Tibet, Siberia, Alaska, and Aleutian Islands. The findings backed up the argument which later contributed to the theory of global origin of human species that was awarded by the Thomas Henry Huxley Award in 1927.  A page from Hrdlička's book Physiological and medical observations among the Indians of southwestern United States and northern Mexico, with four photographs of Zuni Native Americans Aleš Hrdlička founded and became the first curator of physical anthropology of the U.S. National Museum, now the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History in 1903. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1915 and the American Philosophical Society in 1918.[5][6] That same year, he founded the American Journal of Physical Anthropology.[7] After he stepped down, the journal volume number, which had reached Volume 29 in 1942, was restarted at Volume 1 in 1943. In January 1913, Hrdlička embarked on an expedition to Lima, Peru, during which he removed 80 trephined and "otherwise highly interesting" skulls from a grave site in the Andes mountain range. Despite the remains taken from the area, Hrdlička overall disliked the expedition and was disappointed in what he accomplished. The expedition was plagued with constant rain, inconsistent food supply, and treacherous terrain, and Hrdlička directly mentioned his disdain for the local population, claiming that archaeological sites were regularly vandalized, merchants would overcharge him for supplies, and 'ignorant, superstitious, and often drunk people' would provide him with unreliable information. Moreso than any of those factors, Hrdlička was frustrated with his inability to find any 'full-blooded' native people to serve as subjects for his research.[8] Hrdlička was involved in examining a skull to determine that it belonged to Adolph Ruth, who was sensationalized in the press when Ruth went missing in Arizona in 1931 searching for the legendary Lost Dutchman's Gold Mine. He always sponsored his fellow expatriates and also donated the institution of anthropology in Prague, which was founded in 1930 by his co-explorer Jindřich Matiegka, in his native country (the institution later took his name). Between 1936 and 1938, Hrdlička led the excavation of over 50 mummies from caves on Kagamil Island. A small number of the mummies were actually studied, and Hrdlička never recorded any information on the soft tissue of the subjects. This has led to the belief that he may have disposed of the soft tissue without any research due to his focus on skeletal anthropometry.[9] Hrdlička's views on race are inspired by those of Georges Cuvier, who in the 19th century argued that there are "only 3 distinct racial stems: The White, The Black, and The Yellow-Brown." Hrdlička used the "Yellow-Brown" classification as a grouping for non-European and African regions.[10] |

生涯と経歴 1869年3月30日、フルドリチュカはフンポレツ家393で生まれ、翌日Kostel svatého Mikuláše [cz]でカトリックの洗礼を受けた[3]。母親のカロリナ・フルドリチコヴァーは自ら子供の教育を行った。13歳のとき、父マックスミリアン・フルドリ チュカとともに1881年9月10日にブレーメンからSSエルベ号でニューヨークに到着した[4]。母と3人の弟妹は別々にアメリカに移住した。到着後、 約束された仕事は父に失望をもたらすだけであった。父は、6人の子供たちとともに一家の生計を立てるため、10代のアロイスとともに葉巻工場で働き始め た。18歳の時、結核を患い、当時の治療の難しさを経験したため、医学を学ぶことを決意した。1889年、HrdličkaはEclectic Medical Collegeで勉強を始め、その後ニューヨークのHomeopathic Collegeで勉強を続けた。1894年、医学を修了するためにボルチモアで試験を受ける。最初はミドルタウンの精神病院で働き、そこで人体測定を学ん だ。1896年、彼はパリに渡り、人類学者として当時確立されつつあった科学分野の専門家たちと仕事を始めた。 1898年から1903年にかけて、アメリカ大陸を科学的に旅する中で、彼は東アジアからアメリカ大陸に人類が植民地化したという説を発見し、文書化した最初の科学者となった。 彼は、インディアンはアジアからベーリング海峡を渡って移住してきたと主張し、モンゴル、チベット、シベリア、アラスカ、アリューシャン列島の人々の研究 だけでなく、骨格の詳細な現地調査によってこの説を支持した。この研究結果は、後にトーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリー賞(1927年)を受賞した人類種の地 球起源説に貢献した。  Hrdličkaの著書『Physiological and medical observations among the Indians of southwestern United States and northern Mexico』の1ページ。 ア レッシュ・フルドリチュカは、1903年に米国国立博物館(現スミソニアン協会国立自然史博物館)を設立し、人類学の初代学芸員となった。1915年にア メリカ芸術科学アカデミー、1918年にアメリカ哲学協会の会員に選出された。[5][6] 同年、彼は『アメリカ自然人類学ジャーナル』を創刊した。[7] 退任後、1942年に第29巻まで刊行されていた同誌は、1943年に第1巻から再スタートした。 1913年1月、フルド リチュカ(Hrdlička)はペルーのリマへの遠征に出発し、その間、アンデス山脈の墓から80個の穿頭された形跡のある「その他にも非常に興味深い」 頭蓋骨を採取した。この地域から遺骨が持ち出されたにもかかわらず、フルドリチュカは全体としてこの遠征を嫌っており、自分が成し遂げたことに対して落胆 していた。この遠征は、絶え間ない雨、不安定な食糧供給、危険な地形に悩まされ、フルドリチュカは現地住民に対する軽蔑を直接的に述べ、考古学遺跡が定期 的に破壊され、商人から食糧を法外な値段で買わされ、「無知で迷信的で、しばしば酔っ払っている」人々から信頼できない情報を提供されると主張した。それ らの要因よりも何よりも、フルドリチュカは、研究対象となる「純粋な」原住民を見つけられないことに苛立ちを感じていた。[8] 1931年にルースがアリゾナで伝説的なロストダッチマンの金鉱を探して行方不明になったとき、彼はマスコミにセンセーショナルに報道された。 彼は常に仲間の海外駐在員のスポンサーとなり、また1930年に彼の共同探検家であったジンドジッチ・マティエグカによって設立されたプラハの人類学機関 を母国に寄付した(この機関は後に彼の名前となる)。1936年から1938年にかけて、フルドリチュカはカガミル島の洞窟から50体以上のミイラの発掘 を指揮した。実際に調査されたミイラはごく少数で、Hrdličkaは対象者の軟部組織に関する情報を記録していない。このことから、彼は骨格人体測定に 重点を置いていたため、軟部組織を調査することなく処分したのではないかと考えられている[9]。 フルドリチュカの人種に関する見解は、19世紀に「3つの異なる人種の幹のみが存在する」と主張したジョルジュ・キュヴィエの見解に影響を受けている: 白人、黒人、黄褐色人種」である。フルドリチュカは「黄褐色」の分類を非ヨーロッパとアフリカ地域のグループ分けとして使用した[10]。 |

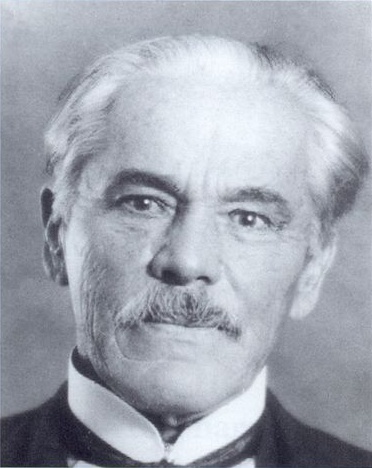

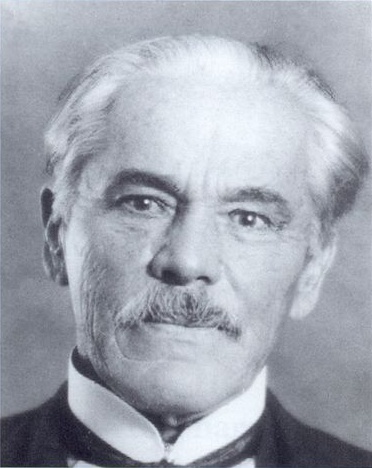

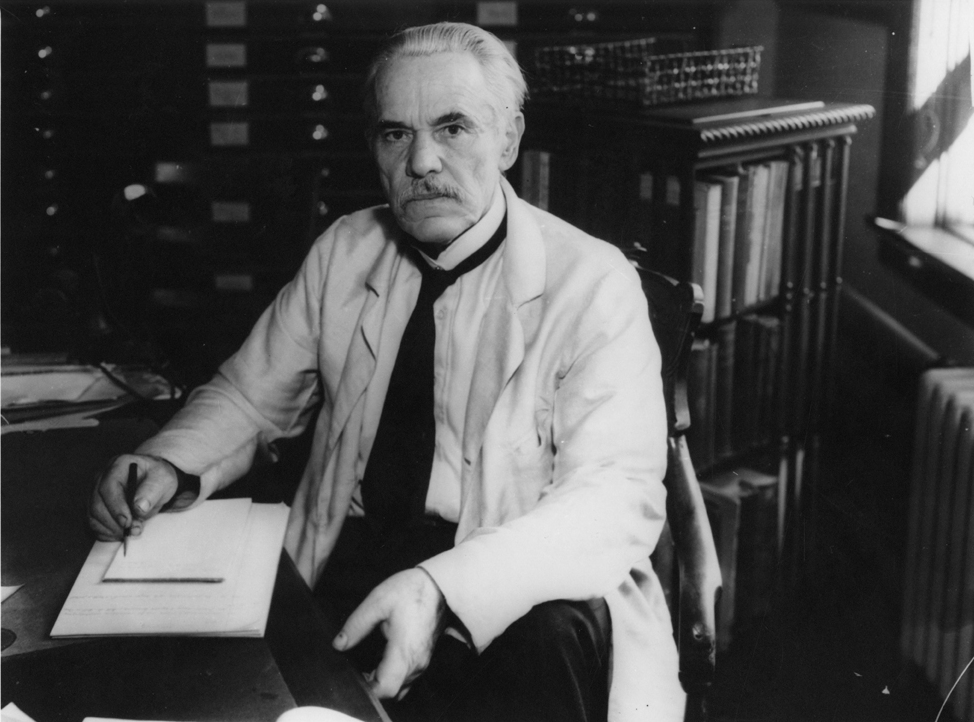

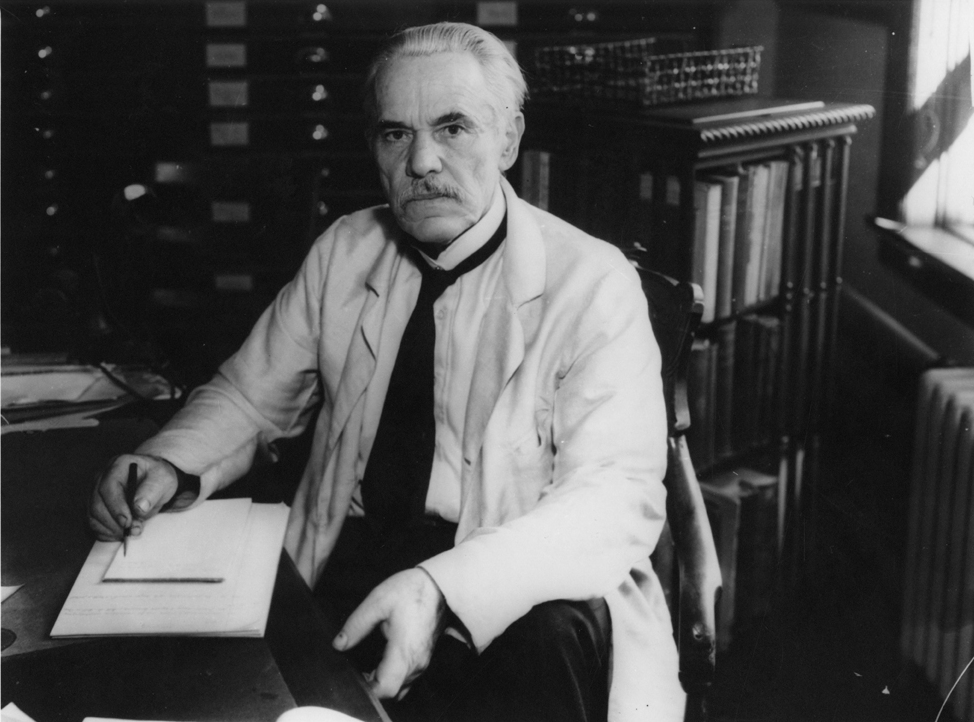

European hypothesis Aleš Hrdlička (1930). Hrdlička was interested in the origin of human beings. He was a critic of hominid evolution as well as the Asia hypothesis, as he claimed there was little evidence to go on for those theories. He dismissed finds such as the Ramapithecus which were labeled as hominids by most scientists, instead believing that they were nothing more than fossil apes, unrelated to human ancestry.[11][12][13] In a lecture on "The Origin of Man", delivered for the American Association for the Advancement of Science, at Cincinnati, Ohio, Hrdlička said that the cradle of man is not in Central Asia but in Central Europe, as Europe is the earliest known location where human skeletal remains have been found. Hrdlička was almost alone in his views. The European hypothesis fell into decline and is now considered an obsolete scientific theory which has been replaced by the Multiregional hypothesis and the Out of Africa hypothesis.[14] |

ヨーロッパ仮説 Aleš Hrdlička(1930年) フルドリチュカ(Hrdlička)は人類の起源に興味を持っていた。彼はヒト科動物の進化やアジア仮説を批判した。彼は、ほとんどの科学者がヒト科の動 物であるとしたラマピテクスなどの発見を否定し、代わりに、それらは化石類人猿に過ぎず、人類の祖先とは無関係であると信じていた[11][12] [13]。 オハイオ州シンシナティで開催されたアメリカ科学振興協会(American Association for the Advancement of Science)で行われた「人間の起源(The Origin of Man)」に関する講演で、フルトリチカは、人間の発祥地は中央アジアではなく中央ヨーロッパであると述べた。 彼の見解はほぼ一人であった。ヨーロッパ仮説は衰退し、現在では時代遅れの科学理論であると考えられており、多地域仮説やアフリカ出アフリカ仮説に取って代わられている[14]。 |

| Controversy and criticism In the early 1900s, Hrdlicka became the chief advocate of the scholarly opinion that man had not lived in the Americas for longer than 3,000 years.[15][16] Hrdlicka and others made it "virtually taboo" for any anthropologist "desirous of a successful career" to advocate a deep antiquity for inhabitants of the Americas. The findings at the Folsom site in New Mexico eventually overturned that archaeological orthodoxy.[17] More recently, Hrdlička's methods have come under scrutiny and criticism with regard to his treatment of Native American remains. An AP newswire article, "Mexico Indian Remains Returned From NY Museum For Burial" from November 17, 2009, recounted his study of Mexico's tribal races, including the beheading of still-decomposing victims of a massacre of Yaqui Indians and removing the flesh from the skulls as part of these studies.[18] He also threw out the corpse of an infant that was found in a cradleboard but forwarded this artifact along with the skulls and other remains to New York's American Museum of Natural History. While these practices are not inconsistent with other ethnographers and human origin researchers of that era, the moral and ethical ramifications of these research practices continues to be debated today. His work has also been linked to the development of American eugenics laws.[19] In 1926, he was an advisory member of the American Eugenics Society.[20] |

論争と批判 1900年代初頭、フルドリチュカは人類はアメリカ大陸に3000年以上住んでいなかったという学説の主唱者となった[15][16]。フルドリチュカを はじめとする人類学者は、アメリカ大陸の住民の古代の深さを主張することを「成功したキャリアを望む」者にとって「事実上タブー」とした。ニューメキシコ のフォルサム遺跡での発見は、やがてその考古学的正統性を覆した[17]。 さらに最近では、ネイティブ・アメリカンの遺骨の扱いに関して、フルドリチュカの方法が精査され、批判を浴びるようになった。2009年11月17日の AP通信の記事「Mexico Indian Remains Returned From NY Museum For Burial(メキシコのインディアンの遺骨がNYの博物館から埋葬のために返還された)」は、メキシコの部族種族に関する彼の研究について記述してお り、その中にはヤキ・インディアンの虐殺でまだ腐敗している犠牲者の首をはね、その研究の一環として頭蓋骨から肉を取り除いたことも含まれている。 [18] 彼はまた、ゆりかごの中から発見された幼児の死体を捨てたが、この遺物は頭蓋骨やその他の遺骨とともにニューヨークのアメリカ自然史博物館に送られた。こ のようなやり方は、当時の他の民族学者や人類起源研究者と矛盾するものではないが、このような研究方法の道徳的・倫理的影響については、今日でも議論が続 いている。1926年、彼はアメリカ優生学会の顧問メンバーであった[20]。 |

| Family On August 6, 1896, Hrdlička married German-American Marie Stickler (whom he had courted since 1892), daughter of Phillip Jakob Strickler from Edenkoben, Bavaria, who immigrated to Manhattan in 1855.[21] Marie died in 1918 of complications of diabetes. In the summer of 1920 Hrdlička married a second time; his fiancée was another German-American woman, Wilhelmina "Mina" Mansfield. Both marriages were childless.[22] |

家族 1855年にマンハッタンに移住したバイエルン州エーデンコーベン出身のフィリップ・ヤコブ・シュトリックラーの娘である[21]。マリーは1918年に 糖尿病の合併症で死去した。1920年の夏、フルドリチュカは2度目の結婚をした。婚約者は同じくドイツ系アメリカ人の女性、ヴィルヘルミナ "ミナ "マンスフィールドだった。どちらの結婚にも子供はいなかった[22]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ale%C5%A1_Hrdli%C4%8Dka |

|

| THE GHOSTS IN THE MUSEUM Anthropologists are reckoning with collections of human remains—and the racism that built them 8 JUL 2021BY LIZZIE WADE |

博物館の亡霊 人類学者が遺骨コレクションとそれを作り上げた人種差別を見直す 8 JUL 2021BY LIZZIE WADE |

| They were buried on a plantation

just outside Havana. Likely few, if any, thought of the place as home.

Most apparently grew up in West Africa, surrounded by family and

friends. The exact paths that led to each of them being ripped from

those communities and sold into bondage across the sea cannot be

retraced. We don't know their names and we don't know their stories

because in their new world of enslavement those truths didn't matter to

people with the power to write history. All we can tentatively say:

They were 51 of nearly 5 million enslaved Africans brought to Caribbean

ports and forced to labor in the islands' sugar and coffee fields for

the profit of Europeans. Nor do we know how or when the 51 died. Perhaps they succumbed to disease, or were killed through overwork or by a more explicit act of violence. What we do know about the 51 begins only with a gruesome postscript: In 1840, a Cuban doctor named José Rodriguez Cisneros dug up their bodies, removed their heads, and shipped their skulls to Philadelphia. |

彼らはハバナ郊外の農園に埋葬された。この地を故郷と思う者は、いたと

してもほとんどいなかっただろう。ほとんどは西アフリカで、家族や友人に囲まれて育ったようだ。彼らがそれぞれのコミュニティから引き剥がされ、海を渡っ

て奴隷として売られるに至った正確な道筋をたどることはできない。彼らの名前も、彼らの物語もわからない。なぜなら、奴隷という新しい世界では、歴史を書

く力を持つ人々にとって、それらの真実は重要ではなかったからだ。暫定的に言えることは

彼らはカリブ海の港に連れてこられ、ヨーロッパ人の利益のために島々の砂糖やコーヒー畑で労働を強いられた500万人近い奴隷アフリカ人のうちの51人

だった。 51人がいつ、どのようにして死んだのかもわからない。おそらく病気で死んだのか、過労で死んだのか、あるいはもっと明確な暴力行為で死んだのか。 51人についてわかっているのは、ぞっとするような後書きだけである: 1840年、ホセ・ロドリゲス・シスネロスというキューバ人医師が彼らの遺体を掘り起こし、頭を取り出して頭蓋骨をフィラデルフィアに送った。 |

| He did so at the request of

Samuel Morton, a doctor, anatomist, and the first physical

anthropologist in the United States, who was building a collection of

crania to study racial differences. And thus the skulls of the 51 were

turned into objects to be measured and weighed, filled with lead shot,

and measured again. Morton, who was white, used the skulls of the 51—as he did all of those in his collection—to define the racial categories and hierarchies still etched into our world today. After his death in 1851, his collection continued to be studied, added to, and displayed. In the 1980s, the skulls, now at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, began to be studied again, this time by anthropologists with ideas very different from Morton's. They knew that society, not biology, defines race. They treated the skulls as representatives of one diverse but united human family, beautiful and fascinating in their variation. They also used the history of the Morton collection to expose the evils of racism and slavery, sometimes using skulls in lectures and exhibits on those topics. |

医師であり、解剖学者であり、人種間の違いを研究するために頭蓋のコレクションを作っていたアメリカ初の人類学者であるサミュエル・モートンの依頼で、彼はそうした。こうして51人の頭蓋骨は、測定され、重さを量られ、鉛の弾丸で満たされ、また測定される対象となった。 白人であったモートンは、51人の頭蓋骨を、彼のコレクションに含まれるすべての頭蓋骨と同じように、今日でも私たちの世界に刻まれている人種のカテゴリーと階層を定義するために使用した。1851年の死後も、彼のコレクションは研究され、追加され、展示され続けた。 1980年代、現在ペンシルバニア大学考古学人類学博物館に所蔵されている頭蓋骨は、モートンとはまったく異なる考えを持つ人類学者たちによって再び研究 され始めた。彼らは、人種を定義するのは生物学ではなく社会であることを知っていた。彼らは頭骨を、多様でありながらひとつにまとまった人類一族の代表と して扱い、そのバリエーションが美しく魅力的であるとした。彼らはまた、人種差別や奴隷制の弊害を暴くためにモートンのコレクションの歴史を利用し、それ らのテーマに関する講演や展示に頭蓋骨を使用することもあった。 |

| Then, in summer 2020, the

history of racial injustice in the United States—built partly on the

foundation of science like Morton's—boiled over into protests. The

racial awakening extended to the Morton collection: Academics and

community activists argued that the collection and its use perpetuate

injustice because no one in the collection had wanted to be there, and

because scientists, not descendants, control the skulls' fate. "You don't have consent," says Abdul-Aliy Muhammad, a Black community organizer and writer from Philadelphia. "Black folks deserve to possess and hold the remains of our ancestors. We should be the stewards of those remains." Muhammad and others demanded that the Morton collection, now numbering more than 1300 skulls, be abolished. In July 2020, the Penn Museum put the entire collection in storage and officially halted research. "One of the things we are having to grapple with now is the idea of possession," says Robin Nelson, a Black biological anthropologist at Santa Clara University. When you study biological material from another person, she says, "your research sample is not, in fact, yours." That way of thinking could affect many collections in the United States. For example, the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) holds the remains of more than 30,000 people, many Indigenous and some likely enslaved. Many remains were taken from their graves without permission, by scientists following in Morton's footsteps through the early 20th century. Other remains were from people who died in institutions, who had no say over the fate of their bodies. |

そして2020年夏、モートンのような科学の土台の上に築かれたアメリ

カにおける人種的不公正の歴史が、抗議行動へと沸騰した。人種の目覚めはモートンのコレクションにまで及んだ:

学者や地域活動家たちは、コレクションとその利用は不公正を永続させるものだと主張した。なぜなら、コレクションに含まれる誰もそこにいることを望んでい

なかったからであり、頭蓋骨の運命を握っているのは子孫ではなく科学者だからである。 「フィラデルフィアの黒人コミュニティ・オーガナイザーで作家のアブドゥル=アリイ・ムハンマドは言う。「黒人は先祖の遺骨を所有し、保持する権利があり ます。私たちはその遺骨の管理者になるべきです」。ムハンマドやその他の人々は、現在1300体以上の頭蓋骨があるモートン・コレクションの廃止を要求し た。 2020年7月、ペン博物館は全コレクションを保管庫に入れ、研究を正式に停止した。 「サンタクララ大学の黒人生物人類学者、ロビン・ネルソンは言う。他人の生物試料を研究する場合、"あなたの研究サンプルは、実際にはあなたのものではない "と彼女は言う。 そのような考え方は、アメリカ国内の多くのコレクションに影響を与える可能性がある。例えば、スミソニアン協会の国立自然史博物館(NMNH)は、3万人 以上の人々の遺骨を所蔵している。多くの遺骨は、20世紀初頭までモートンの足跡をたどる科学者たちによって、許可なく墓から持ち出された。また、施設に 収容されて亡くなった人々の遺骨もあり、彼らは自分の遺体の運命について何も言えなかった。 |

| The reckoning over Morton's

skulls is also a reckoning for biological anthropology. "The Morton

collection has been a barometer for the discipline from the moment of

its conception," says Pamela Geller, a white bioarchaeologist at the

University of Miami who is working on a book about the collection. Open

racism drove its founding, and a new awakening to that legacy is now

reshaping its future. "It's always been a gauge for where we are as

anthropologists." WHEN THE SKULLS of the 51 were sent to Morton, he was already the world's leading skull collector. Active in the esteemed Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Morton had an extensive network of scientifically minded contacts who responded enthusiastically to his requests to send skulls from every corner of the world. Rodriguez Cisneros wrote that he "procure[d] 50 pure rare African skulls" for Morton's collection. The doctor claimed the Africans had recently been brought to Cuba, but some skulls may have belonged to enslaved Africans born on the island, or to Indigenous Taíno people, who were also enslaved in Cuba at the time. (Whether Rodriguez Cisneros sent 53 skulls or 51 is also somewhat unclear.) As documented in The Skull Collectors: Race, Science, and America's Unburied Dead, by Rutgers University historian Ann Fabian, other scientists who sent skulls to Morton included ornithologist John James Audubon, who nabbed five skulls lying unburied on a battlefield during Texas's war with Mexico; John Lloyd Stephens, whose bestselling accounts of expeditions in southern Mexico and Central America jump-started Maya archaeology; and José María Vargas, an anatomist who was briefly president of Venezuela. Military doctors plucked other skulls from the corpses of Native Americans killed in battles against U.S. forces sent to remove them from their own land. Still other skulls came from the potter's fields of almshouses and public hospitals, where U.S. and European doctors had long sourced bodies for dissection. An 1845 petition to the Philadelphia almshouse board noted that patients, fearing their bodies would be dug up for science, often begged to be buried anywhere but the potter's field "as the last and greatest favor." The Morton collection contains more than 30 skulls from that potter's field—14 from Black people, according to a recent Penn report. "If you were a marginalized or disenfranchised human being, then there's a chance you would end up in Morton's collection," Geller says. Morton sought a diverse collection of skulls because his life's work was to measure and compare the cranial features of what he considered the human races. Like many scientists of his time, Morton delineated five races: Caucasian, Mongolian, American, Malay, and Ethiopian. Their geographic origins are jumbled to modern eyes, showing how social categories determine race. For example, "Caucasians" lived from Europe to India; the Indigenous people of northern Canada and Greenland were considered "Mongolian," like the people in East Asia; and the "Ethiopian" race included people from sub-Saharan Africa and Australia. Morton thought skulls could reveal telltale differences among those races. When a skull arrived, he carefully inked a catalog number on its forehead and affixed a label identifying its race; many of the 51 still bear the words "Negro, born in Africa." Morton meticulously measured each skull's every dimension. He filled them with white peppercorns and, later, lead shot to measure their volumes, a proxy for brain size. The race with the largest brains, he and many scientists thought, would also have the highest intelligence. Morton found a wide range of cranial volumes within each of his racial categories. But he wrested a hierarchy out of averages: By his accounting, skulls of Caucasians had the largest average volume and skulls of Ethiopians, the smallest. Morton used his findings to argue that each race was a separate species of human. Even in the 19th century, not everybody agreed. Charles Darwin, whose theory of evolution wasn't published until 8 years after Morton's death, found Morton's understanding of species facile and his arguments unreliable. Frederick Douglass, in a speech 3 years after Morton's death, called research that ranked the humanity of races "scientific moonshine." "It is strange that there should arise a phalanx of learned men— speaking in the name of science—to forbid the magnificent reunion of mankind in one brotherhood. A mortifying proof is here given, that the moral growth of a nation, or an age, does not always keep pace with the increase of knowledge," he said. It is strange that there should arise a phalanx of learned men—speaking in the name of science—to forbid the magnificent reunion of mankind in one brotherhood. |

モートンの頭蓋骨をめぐる清算は、生物人類学にとっての清算でもある。

「マイアミ大学の白人生物考古学者で、モートンのコレクションに関する本を執筆中のパメラ・ゲラーは言う。公然たる人種差別が創設の原動力となり、その遺

産に対する新たな目覚めが今、その未来を再構築しているのです」。"人類学者として私たちがどこにいるのか、それは常に物差しでした" 51人の頭蓋骨がモートンに送られたとき、彼はすでに世界有数の頭蓋骨コレクターだった。尊敬されるフィラデルフィアの自然科学アカデミーで活躍していた モートンは、科学的見識のある幅広い人脈を持ち、世界中から頭蓋骨を送ってほしいという彼の依頼に熱心に応えていた。ロドリゲス・シスネロスは、モートン のコレクションのために「純粋な珍しいアフリカ人の頭蓋骨を50個調達した」と書いている。博士はアフリカ人が最近キューバに連れてこられたと主張した が、頭蓋骨の中には、キューバで奴隷として生まれたアフリカ人や、当時同じくキューバで奴隷となっていた先住民タイノ族のものもあったかもしれない。(ロ ドリゲス・シスネロスが送った頭蓋骨が53個なのか51個なのかも不明である)。 The Skull Collectors: ラトガース大学の歴史家アン・ファビアン著『The Skull Collectors: Race, Science, and America's Unburied Dead』(邦題『人種、科学、アメリカの埋葬されない死者』)にあるように、モートンに頭蓋骨を送った科学者には、テキサスとメキシコの戦争中に戦場に 埋葬されずに横たわっていた5つの頭蓋骨を発見した鳥類学者ジョン・ジェームズ・オーデュボン、メキシコ南部と中央アメリカでの探検の記録をベストセラー にし、マヤ考古学を飛躍的に発展させたジョン・ロイド・スティーブンス、ベネズエラの大統領を短期間務めた解剖学者ホセ・マリア・バルガスなどがいる。軍 医たちは、ネイティブ・アメリカンを自分たちの土地から追い出すために派遣されたアメリカ軍との戦いで殺された死体から、別の頭蓋骨を抜き取った。 さらに他の頭蓋骨は、米欧の医師たちが長い間解剖のために遺体を集めていた保養所や公立病院の陶器置き場からも出てきた。1845年にフィラデルフィアの 施療院理事会に提出された嘆願書には、科学のために自分の遺体が掘り起こされることを恐れた患者たちが、しばしば「最後にして最大の好意として」陶芸家の 畑以外の場所に埋葬してくれるよう懇願したと記されている。最近のペンシルバニア大学の報告書によれば、モートンのコレクションには、陶芸家の畑から出土 した30以上の頭蓋骨が含まれている。「もしあなたが社会から疎外された、あるいは権利を奪われた人間であったなら、モートンのコレクションに収まる可能 性があります」とゲラーは言う。 モートンが多様な頭蓋骨のコレクションを求めたのは、彼のライフワークが、彼が人類と考えた人種の頭蓋骨の特徴を測定し、比較することだったからである。 当時の多くの科学者と同様、モートンは5つの人種を定義した: 白人、モンゴル人、アメリカ人、マレー人、エチオピア人である。その地理的起源は現代の目にはごちゃごちゃに見え、社会的カテゴリーがいかに人種を決定す るかを示している。例えば、"コーカソイド "はヨーロッパからインドまで、カナダ北部とグリーンランドの先住民は東アジアの人々と同じ "モンゴル人 "とみなされ、"エチオピア人 "にはサハラ以南のアフリカとオーストラリアの人々が含まれていた。 モートンは、頭蓋骨からこれらの人種の違いを明らかにできると考えた。頭蓋骨が届くと、彼は慎重に額にカタログ番号を墨で書き、人種を示すラベルを貼った。 モートンはそれぞれの頭蓋骨の寸法を丹念に測った。彼は頭蓋骨に白胡椒の実を詰め、後には鉛の弾丸を入れて体積を測定した。彼や多くの科学者は、脳が最も大きい人種は知能も高いと考えた。 モートンは、それぞれの人種カテゴリーにおいて、頭蓋の容積に幅があることを発見した。しかし、彼は平均値から階層を導き出した: 彼の計算では、白人の頭蓋骨の平均体積が最も大きく、エチオピア人の頭蓋骨の平均体積が最も小さかった。モートンはこの発見をもとに、それぞれの人種は人 間の別種であると主張した。 19世紀になっても、誰もが同意したわけではない。進化論が発表されたのはモートンの死後8年経ってからであったが、チャールズ・ダーウィンは、モートン の種に関する理解は安易であり、彼の主張は信頼できないと考えた。フレデリック・ダグラスは、モートンの死から3年後の演説で、人種の人間性をランク付け する研究を "科学的密造酒 "と呼んだ。「科学の名のもとに、人類がひとつの兄弟として壮大な再会を果たすことを禁じようとする、学識ある男たちのファランクスが出現するのは奇妙な ことだ。国家や時代の道徳的な成長は、必ずしも知識の増加と歩調を合わせるとは限らないということを、ここに証明するものである。科学の名の下に、人類がひとつの兄弟愛で結ばれる壮大な再会を禁じる学識者たちのファランクスが生まれるのは奇妙なことだ。 |

| Despite those critiques,

Morton's approach helped lay the foundation for the burgeoning field of

physical anthropology. U.S. and European museums vied to build "massive

bone collections," exploiting colonial violence to gather bodies from

all over the world, says Samuel Redman, a white historian at the

University of Massachusetts (UMass), Amherst, and author of Bone Rooms:

From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums. In the early

1900s, Aleš Hrdlička of NMNH, who helped found the American Association

of Physical Anthropologists in 1928, continued to use human remains,

often stolen from Indigenous communities, to study race and promote

eugenics. Hrdlička, who was white and whom Redman describes as "deeply

racist," was the driving force behind NMNH's skeletal collection. Last

month, the association he founded changed its name to the American

Association of Biological Anthropologists to separate itself from the

discipline's overtly racist past. "All of us who stand in this field have inherited this history," says Rick Smith, a white biocultural anthropologist at George Mason University. "It's on us to figure out what to do about it." IN 1982, WHEN JANET MONGE, a white biological anthropologist at the Penn Museum, took charge of the Morton collection, she recognized its potential as a tool to explore anthropology's racist past. She also saw it as a valuable repository of the myriad physical differences among humans, in traits unrelated to the social constructs of race. For example, in the late 1990s, a paper claimed that certain skull traits in the nasal cavity were unique to Neanderthals. But the researchers had only used modern human skulls from Europeans for comparison. A University of Pennsylvania student, Melissa Murphy, studied hundreds of skulls in the Morton collection and found some of the "Neanderthal" traits in non-Europeans. "Working with the Morton collection gave me a background in understanding human variation I never would have had otherwise," says Murphy, who is white and now a biological anthropologist at the University of Wyoming. Between 2004 and 2011, Monge and colleagues expanded scientific access to the Morton collection by using computerized tomography (CT) to scan the skulls and thousands of others held in the Penn Museum. The scans, available online, "really democratized the research process," says Sheela Athreya, a biological anthropologist at Texas A&M University, College Station, who is Indian American and studied with Monge. Monge says more than 70 scientific papers have been published using the Morton scans, on such topics as how tooth alignment has changed over time and how skull growth during childhood affects adult cranial shape. The Penn Museum's website lists more than 100 researchers who used the Morton collection from 2008 to 2018. Meanwhile, the remains of Native Americans in collections became an ethical and legal flashpoint. In 1990, Congress passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), requiring federally funded institutions to inventory Native American remains in their collections and to work with tribes to return them to their descendants. Monge, her students, and colleagues began to dig through historical documents, boosting their efforts to understand where the skulls in the Morton collection came from and contacting tribes about bringing some back home. More than 120 of the 450 or so Native American skulls from the collection have been repatriated. All of us in this field have inherited this history. It's on us to figure out what to do about it. RICK SMITH, GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY |

このような批判にもかかわらず、モートンのアプローチは、急成長する身

体人類学の基礎作りに貢献した。マサチューセッツ大学(UMass)アマースト校の白人歴史学者で、『Bone

Rooms(骨の部屋)』の著者であるサミュエル・レッドマンは言う: From Scientific Racism to Human

Prehistory in Museums.

1900年代初頭、NMNHのアレシュ・ハードリチカは、1928年のアメリカ人類物理学者協会の設立に貢献し、先住民のコミュニティからしばしば盗まれ

た人骨を、人種研究と優生学の推進に利用し続けた。白人であり、レッドマンが「深い人種差別主義者」と形容するハードリチカは、NMNHの骨格コレクショ

ンの原動力であった。先月、彼が創設した協会は、アメリカ生物人類学者協会に名称を変更し、この学問分野のあからさまな人種差別主義の過去から切り離され

た。 「ジョージ・メイソン大学の白人生物文化人類学者リック・スミスは言う。「それをどうするかは、私たちの責任です」。 1982年、ペン博物館の白人生物人類学者であるジャネット・モンジュがモートン・コレクションを管理するようになったとき、彼女は人類学の人種差別的な 過去を探求するツールとしての可能性を認識した。彼女はまた、人種という社会的構築物とは無関係な形質における、人間間の無数の身体的差異を示す貴重な収 蔵庫であるとも考えた。 例えば、1990年代後半、鼻腔にある頭蓋骨の形質がネアンデルタール人特有のものだとする論文が発表された。しかし、研究者たちはヨーロッパ人の現代人 の頭蓋骨しか比較に使っていなかった。ペンシルバニア大学の学生、メリッサ・マーフィーは、モートン・コレクションにある数百の頭蓋骨を研究し、ヨーロッ パ人以外から「ネアンデルタール人」の形質のいくつかを発見した。「マーフィーは白人で、現在はワイオミング大学の生物人類学者である。 2004年から2011年にかけて、モンジュと同僚たちはコンピューター断層撮影法(CT)を使って、ペンシルバニア博物館に所蔵されているモートン・コ レクションの頭蓋骨とその他数千点の頭蓋骨をスキャンし、科学的利用を拡大した。オンラインで利用できるこのスキャンは、「研究プロセスを本当に民主化し ました」と、モンゲとともに学んだテキサスA&M大学カレッジステーションの生物人類学者、シーラ・アスレヤは言う。モンジュによれば、モートン のスキャンデータを使って、歯並びが時代とともにどのように変化してきたか、幼少期の頭蓋骨の成長が成人の頭蓋形状にどのような影響を及ぼすか、といった テーマで70以上の科学論文が発表されている。ペン博物館のウェブサイトには、2008年から2018年までにモートンのコレクションを利用した100人 以上の研究者のリストがある。 一方、コレクションに収蔵されたネイティブ・アメリカンの遺骨は、倫理的・法的な火種となった。1990年、連邦議会は「アメリカ先住民の墓の保護と返還 に関する法律(NAGPRA)」を可決し、連邦政府が資金を提供する機関は、所蔵するアメリカ先住民の遺骨の目録を作成し、部族と協力して子孫に返還する ことを義務づけた。 モンジュと彼女の学生、そして同僚たちは、モートンのコレクションにある頭蓋骨がどこから来たのかを理解し、その一部を故郷に持ち帰ることについて部族に 連絡するための努力を後押しするため、歴史的文書を掘り起こし始めた。コレクションにある約450のネイティブ・アメリカンの頭蓋骨のうち、120以上が 本国に送還された。 この分野に携わる私たちは皆、この歴史を受け継いでいる。それをどうするかは、私たちにかかっている。 ジョージ・メイソン大学、リック・スミス |

| In researching the skulls'

origins, Monge says, "You come to appreciate the people of the

collection." Other scholars explored the identities of remains not

subject to NAGPRA, often under Monge's guidance. In 2007, one student

completed a dissertation on the 51, combining historical analysis with

a study of the skulls themselves. Some skulls had filed teeth, then a

rite of passage in some West African communities, supporting the idea

that the people had grown up in Africa. The 51 and other skulls were eventually moved to glass-fronted cabinets lining an anthropology classroom at the Penn Museum. There they hovered, year after year, around students learning to study human bones. Monge also used skulls from the collection in classes, public talks, and museum exhibits on how anthropology had helped codify the idea of race and the resulting inhumanity. For example, at the African American Museum in Philadelphia, Monge showed vertebrae fused to the skull of one of the 51, a "major trauma" caused by a painful collar the person was forced to wear. "When you can see what slavery did to the body, it's overwhelmingly powerful," says Monge, who recalls audience members crying. Such honest, public acknowledgment of the collection's violent past was rare among museums, Athreya says. But in 2020, a renewed reckoning with racism prompted yet another re-evaluation of the collection. IN 2017, ON HIS SECOND DAY in an archaeology class held at the Penn Museum, Francisco Diaz looked to his right and found himself staring at a skull with the label "Maya from Yucatan" pasted to its forehead. Diaz, an anthropology doctoral student at Penn, is Yucatec Maya, born on Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula. In class, skulls from Black and Indigenous people were "just made part of classroom décor," he recalls. "You have this institution that has done this type of work on Indigenous people, and then one of you shows up," he says. Seeing that skull in his classroom, "It's kind of like saying, do you really belong here?" This year, he wrote an essay on how study and display of the skulls dehumanized the people they belonged to. The 51 themselves drew renewed attention in 2019, after a presentation by a group of Penn professors and students investigating the university's connections to slavery and scientific racism. "I was shocked by what I heard," says Muhammad, who attended the presentation. Muhammad wrote op-eds and started a petition to return the 51 and skulls from two other enslaved people to a Black community—either their descendants or a Black spiritual community in Philadelphia. "These people did not ask to be prodded, they did not ask to be dissected, they did not ask for numbers and letters to be imprinted upon their remains. They were brutalized and exploited. They had their lives stolen from them. And they deserve rest," Muhammad says. After the murder of George Floyd in May 2020 sparked protests for racial justice around the country, more and more people within and outside Penn began to see the Morton collection as a present-day perpetuation of racism and its harms, rather than just a historic example. Until last summer, most researchers thought "the science is justified because we're doing it thoughtfully. And this moment brought to bear, no, that's not enough," says Rachel Watkins, a Black biological anthropologist at American University. Even with recent research that strove to be respectful, it was almost always scientists who decided how and why to study the skulls, not their descendant communities, Athreya notes. "We were speaking for people without them at the table," she says. To move forward ethically, "Those of us in power are going to have to give up some." Among anthropologists, Nelson says, "There's a mixture of guilt and fear. Guilt for the ways we have engaged with these kinds of materials and benefited from the data collected in ways that we now may find reprehensible. But there's also fear because we don't know what the field is going to look like [without those practices]." Yet examples of inclusive, respectful biological anthropology exist. For example, back in 1991, when construction in New York City uncovered the earliest and largest known African burial ground in the United States, Black New Yorkers who identified themselves as a descendant community guided research, and the more than 400 excavated individuals were reburied in 2003. That project has served as a model for others, including for the remains of 36 enslaved people recently found in Charleston, South Carolina (see sidebar, below). But for remains collected a century or two ago, like the Morton collection, applying the same principles can be challenging. In July 2020, the Penn Museum moved the skulls in the classroom, including the 51, to join the rest of the collection in storage while a committee discussed what to do with it. Protests continued. "Black Ancestors Matter," proclaimed one sign at an 8 April protest. Four days later, the Penn Museum apologized for "the unethical possession of remains" and announced an expanded repatriation plan for the Morton collection. The museum plans to hire an anthropologist of color to direct repatriation, actively identifying and contacting as many descendant communities as possible and welcoming repatriation requests from them, says Penn Museum Director Christopher Woods, who is Black. The museum has also suspended study of the CT scans while it develops a policy, to be enacted this fall, on the research and display of human remains. These people did not ask to be prodded, they did not ask to be dissected. … You don't have consent. ABDUL-ALIY MUHAMMAD, PHILADELPHIA COMMUNITY ORGANIZER |

頭骨の出自を調査するうちに、"コレクションの人たちを理解するように

なる

"とモンジュは言う。NAGPRAの対象外である遺骨の身元を探る学者も、しばしばモンジュの指導を受けた。2007年には、歴史的分析と頭蓋骨そのもの

の研究を組み合わせた51号に関する論文を完成させた学生もいた。いくつかの頭蓋骨には、当時西アフリカの一部のコミュニティで通過儀礼とされていたヤス

リで削られた歯があり、アフリカで成長したという考えを裏付けていた。 51号とその他の頭蓋骨は、やがてペン博物館の人類学教室に並ぶガラス張りのキャビネットに移された。そこでは、毎年毎年、人骨の研究を学ぶ学生たちの周 りに置かれていた。モンジュはまた、人類学がいかに人種とその結果としての非人間性の概念を体系化するのに役立ったかについて、授業や公開講演、博物館の 展示でコレクションの頭蓋骨を使用した。例えば、フィラデルフィアのアフリカ系アメリカ人博物館で、モンジュは51人のうちの1人の頭蓋骨に融合した脊椎 骨を見せた。「奴隷制度が身体にもたらしたものを目の当たりにすると、圧倒的な迫力を感じます」とモンゲは語り、観客が涙を流したことを思い出した。 アスレヤによれば、コレクションの暴力的な過去をこのように正直に公に認めることは、美術館では珍しいことだったという。しかし2020年、人種差別への再認識がコレクションの再評価を促した。 2017年、ペンシルベニア博物館で行われた考古学の授業の2日目、フランシスコ・ディアスは右手を見ると、額に「ユカタン産マヤ」というラベルが貼られ た頭蓋骨を見つめていた。ペンシルベニア大学で人類学の博士課程に在籍するディアスは、メキシコのユカタン半島で生まれたユカテク・マヤ人である。授業 中、黒人や先住民の頭蓋骨は「教室の装飾の一部になっていた」と彼は振り返る。「先住民についてこのような研究をしてきた機関があり、そこにあなた方の一 人が現れたのです」と彼は言う。その頭蓋骨が教室にあるのを見ると、"君は本当にここの人間なのか?"と言っているようなものです」と彼は言う。今年、彼 は頭蓋骨の研究や展示が、いかに帰属する人々の人間性を奪っているかについてエッセイを書いた。 2019年、ペンシルベニア大学の教授と学生たちによる、奴隷制度や科学的人種差別と大学の関係を調査するプレゼンテーションが行われた後、51頭そのも のが再び注目を集めた。発表会に参加したムハンマドは、「私は聞いたことに衝撃を受けました」と言う。ムハンマドは論説を書き、奴隷にされた他の2人の 51人と頭蓋骨を黒人コミュニティ-彼らの子孫かフィラデルフィアの黒人精神コミュニティ-に返すよう嘆願書を始めた。「これらの人々は、突かれること も、解剖されることも、遺骨に数字や文字を刻印されることも望んでいなかった。彼らは残忍に扱われ、搾取された。人生を奪われたのだ。そして彼らは休息に 値する」とムハンマドは言う。 2020年5月にジョージ・フロイドが殺害された事件をきっかけに、全米で人種的正義を求める抗議運動が起こり、ペンシルバニア大学内外の多くの人々が、 モートン・コレクションを単なる歴史的な例ではなく、人種差別とその弊害が現在も続いているものと見なすようになった。昨年の夏までは、ほとんどの研究者 が「科学は思慮深くやっているのだから正当化される」と考えていた。アメリカン大学の黒人生物人類学者レイチェル・ワトキンスは言う。 敬意を払おうとする最近の研究であっても、頭蓋骨を研究する方法や理由を決めるのは、ほとんど常に科学者であり、彼らの子孫コミュニティではなかった、と アスレヤは指摘する。「私たちは、その場にいない人々の代弁者だったのです」。倫理的に前進するためには、"私たちのような権力者は、ある程度あきらめな ければならないでしょう"」と彼女は言う。 人類学者の間では、罪悪感と恐怖が混在しています。私たちがこの種の資料と関わり、収集したデータの恩恵を受けてきたことに対する罪悪感。しかし、(そのような実践がなければ)この分野がどのようになるのかわからないという恐怖もあります」。 しかし、包括的で尊重的な生物人類学の例は存在する。例えば、1991年にニューヨーク市の建設工事で米国最古かつ最大のアフリカ人埋葬地が発見された際 には、子孫コミュニティであることを自認するニューヨーカーの黒人たちが調査を指導し、発掘された400人以上の埋葬者は2003年に再埋葬された。この プロジェクトは、最近サウスカロライナ州チャールストンで発見された36人の奴隷にされた人々の遺骨(下記サイドバー参照)など、他のプロジェクトのモデ ルとなっている。しかし、モートンのコレクションのように、1世紀も2世紀も前に収集された遺骨の場合、同じ原則を適用するのは難しいかもしれない。 2020年7月、ペン・ミュージアムは51体を含む教室内の頭蓋骨を、委員会がこのコレクションをどうするか検討する間、保管されている他のコレクション と一緒に移動させた。抗議は続いた。4月8日の抗議デモでは、「黒人の祖先は重要である(Black Ancestors Matter)」と書かれた看板が掲げられた。 その4日後、ペン博物館は「非倫理的な遺骨の所有」を謝罪し、モートン・コレクションの本国送還計画の拡大を発表した。黒人であるクリストファー・ウッ ズ・ペン博物館館長によれば、同博物館は送還を指揮する有色人種人類学者を雇用し、できるだけ多くの子孫コミュニティを積極的に特定し、連絡を取り、彼ら からの送還要請を歓迎する予定だという。同博物館はまた、今秋制定予定の遺骨の研究・展示に関する方針を策定する間、CTスキャンの研究を一時停止してい る。 この人たちは突かれることも解剖されることも望んでいない。...あなたは同意していないのです アブドゥル・アリー・ムハンマド(フィラデルフィアのコミュニティ・オーガナイザー |

| Repatriation can be the first

step toward building the relationships that make future community-led

research possible, says Dorothy Lippert, an archaeologist and tribal

liaison at NMNH and a citizen of the Choctaw Nation. "People think

about repatriation as something that's going to empty out museum

shelves, but in reality, it fills the museum back up with these

relationships and connections," she says. Monge, too, welcomes the new focus on repatriation. "I see a lot of great—honestly, better!—potential research with the collection," she says. "The science person in me says that science can help us a lot" with identifying descendant communities and answering questions they may have about their ancestors. For the 51, Monge thinks analyzing their DNA could answer long-standing questions about their ancestry and descendant communities, which may include both Black and Indigenous people. Once identified, those communities should have decision-making power over the 51, she says. But some people don't want scientists unilaterally deciding to do more research on the 51. "Healing can't happen at the site of harm," Muhammad says, quoting Black artist Charlyn/Magdaline Griffith/Oro. Muhammad's trust in scientists further eroded beginning 21 April, when news emerged that anthropologists at Princeton University and Penn, including Monge, had kept a sensitive set of remains and used them in teaching: bones presumed to be the remains of Tree and Delisha Africa, who were killed in 1985 when the city of Philadelphia bombed the MOVE community, a Black activist group. (Monge declined to comment because Penn is investigating.) Muhammad thinks repatriating the skulls of enslaved Black people in the Morton collection to a Black spiritual community in Philadelphia would be more meaningful than launching research to trace their genetic ancestry. "Black people have experienced generational displacement, so there are descendants of these people potentially everywhere and nowhere," Muhammad says. "Ultimately I want them to be in the hands of Black people who love Black people." Each repatriation case will be unique, says Sabrina Sholts, a white curator of biological anthropology at NMNH. But she and others will be watching Penn's process. "There are many ways [repatriation of the Morton collection] could go that will be really important for all peer institutions and stakeholders to see," she says. NMNH, like other museums, including the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, is only now beginning to assess how many remains of enslaved African Americans may be in its collection. "What's stunning to me is that we don't even know" how many are held, says Sonya Atalay, a UMass archaeologist who is Anishinaabe-Ojibwe. Ultimately, she and others hope the United States will pass a repatriation law that applies to African American ancestral remains. Many biological anthropologists say institutions should also establish review processes for work with ancestral remains, similar to how institutional review boards evaluate the ethics of research with living people. On 10 June, the Penn Museum announced it had formed a community advisory group, including Muhammad and other members of Philadelphia community organizations and spiritual leaders, to review the case of the 14 Black people from the Philadelphia potter's field and consider how to respectfully rebury them. Woods says he hopes a decision about their future will be made by year's end. That process could inform future work to repatriate the 51. For now, they are still waiting. |

NMNHの考古学者兼部族渉外担当で、チョクトー族の市民でもあるドロシー・リッパート氏は言う。「返還は、博物館の棚を空っぽにするものだと思われていますが、実際には、このような人間関係やつながりで博物館が満たされるのです」と彼女は言う。 モンジュもまた、レパトリエーションに新たに注目が集まることを歓迎している。「コレクションを使った研究には、正直言って、もっといいものがたくさんあ ると思います。「私の中の科学者は、科学は子孫のコミュニティを特定し、彼らが先祖について持つかもしれない疑問に答えることで、私たちを大いに助けてく れると言っています」。モンジュは、51人のDNAを分析することで、彼らの祖先や子孫コミュニティ(黒人や先住民の両方を含むかもしれない)に関する長 年の疑問に答えることができると考えている。一旦特定されれば、それらのコミュニティは51人に対する決定権を持つべきだと彼女は言う。 しかし、科学者が一方的に51号に関する研究を進めることを望まない人々もいる。「癒しは、傷つけられた現場では起こらないのです」と、黒人アーティスト のシャルリン/マグダライン・グリフィス/オロの言葉を引用しながら、ムハンマドは言う。4月21日、モンジュを含むプリンストン大学とペンシルベニア大 学の人類学者が、デリケートな遺骨を保管し、教育に利用していたというニュースが流れた。(モンジュは、ペンが調査中であることを理由にコメントを避け た)。 ムハンマドは、モートンのコレクションにある奴隷にされた黒人の頭蓋骨を、フィラデルフィアの黒人スピリチュアル・コミュニティに送還することは、彼らの 遺伝的祖先をたどる研究を開始するよりも有意義なことだと考えている。「黒人は世代を超えた移住を経験しているので、その子孫はどこにでもいる可能性があ ります。「最終的には、黒人を愛する黒人の手に渡ってほしいのです」。 NMNHの生物人類学の白人学芸員、サブリナ・ショルツは言う。しかし、彼女や他の人たちはペンのプロセスを見守っている。「モートン・コレクションの本国送還には)様々な方法があり、それは同業機関や関係者にとって本当に重要なことです」と彼女は言う。 NMNHは、ニューヨークのアメリカ自然史博物館をはじめとする他の博物館と同様、奴隷にされたアフリカ系アメリカ人の遺骨がどれだけ収蔵されているかを 評価し始めているところである。「アニシナベ・オジブエ族であるUMASSの考古学者、ソーニャ・アタレイは言う。最終的には、アフリカ系アメリカ人の祖 先の遺骨に適用される本国送還法が米国で成立することを、彼女や他の人々は望んでいる。多くの生物人類学者は、機関審査委員会が生きている人間を対象とす る研究の倫理を評価するのと同様に、機関も先祖代々の遺骨を扱う研究の審査プロセスを確立すべきだと言う。 6月10日、ペン博物館は、フィラデルフィアの陶芸家の畑にあった14人の黒人のケースを検討し、敬意をもって彼らを埋葬し直す方法を検討するために、ム ハンマドをはじめとするフィラデルフィアのコミュニティ組織や精神的指導者のメンバーを含むコミュニティ諮問グループを結成したと発表した。ウッズは、彼 らの将来について年内に決定が下されることを望んでいるという。そのプロセスは、51人を送還するための今後の作業に反映されるかもしれない。今のとこ ろ、彼らはまだ待っている。 |

| https://www.science.org/content/article/racist-scientist-built-collection-human-skulls-should-we-still-study-them |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆