心臓中心主義

Cardiocentric hypothesis

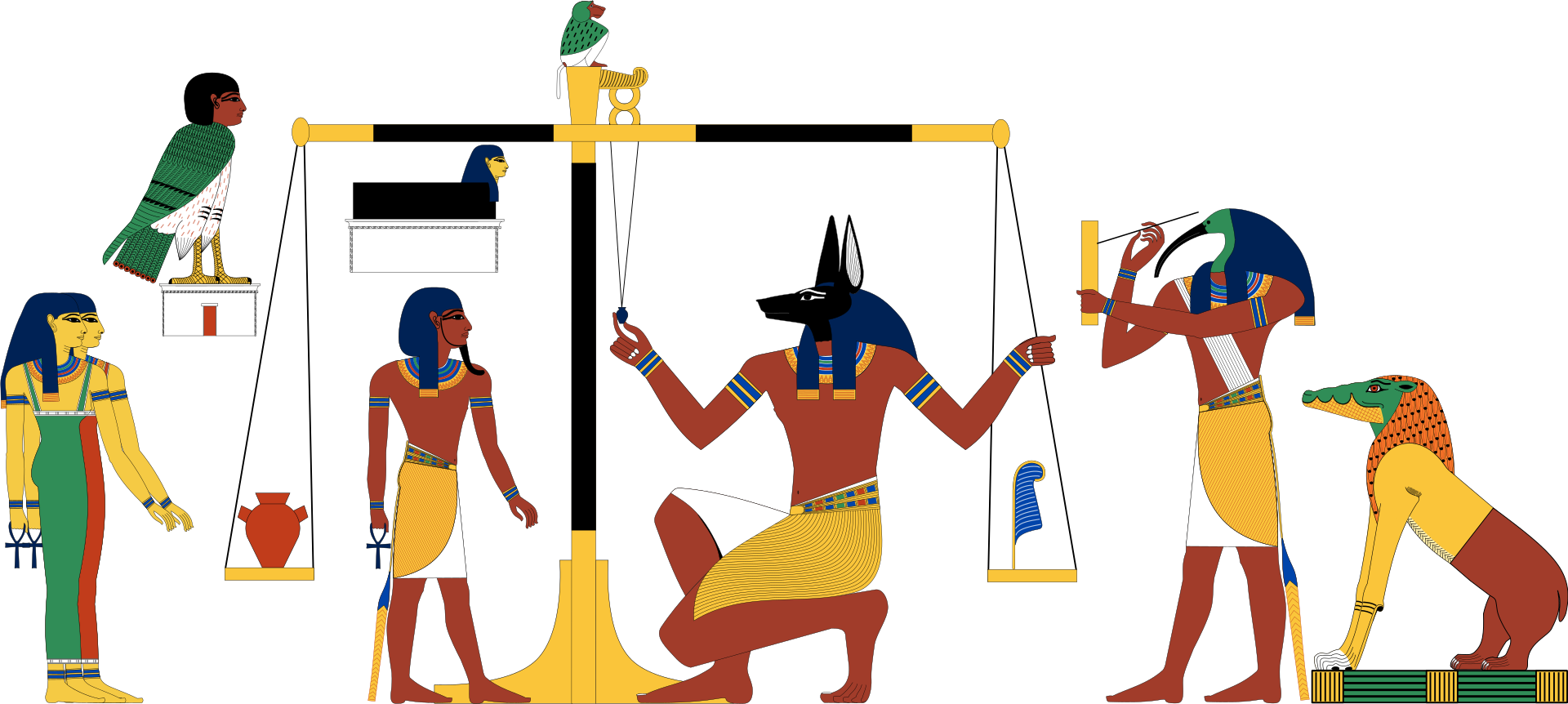

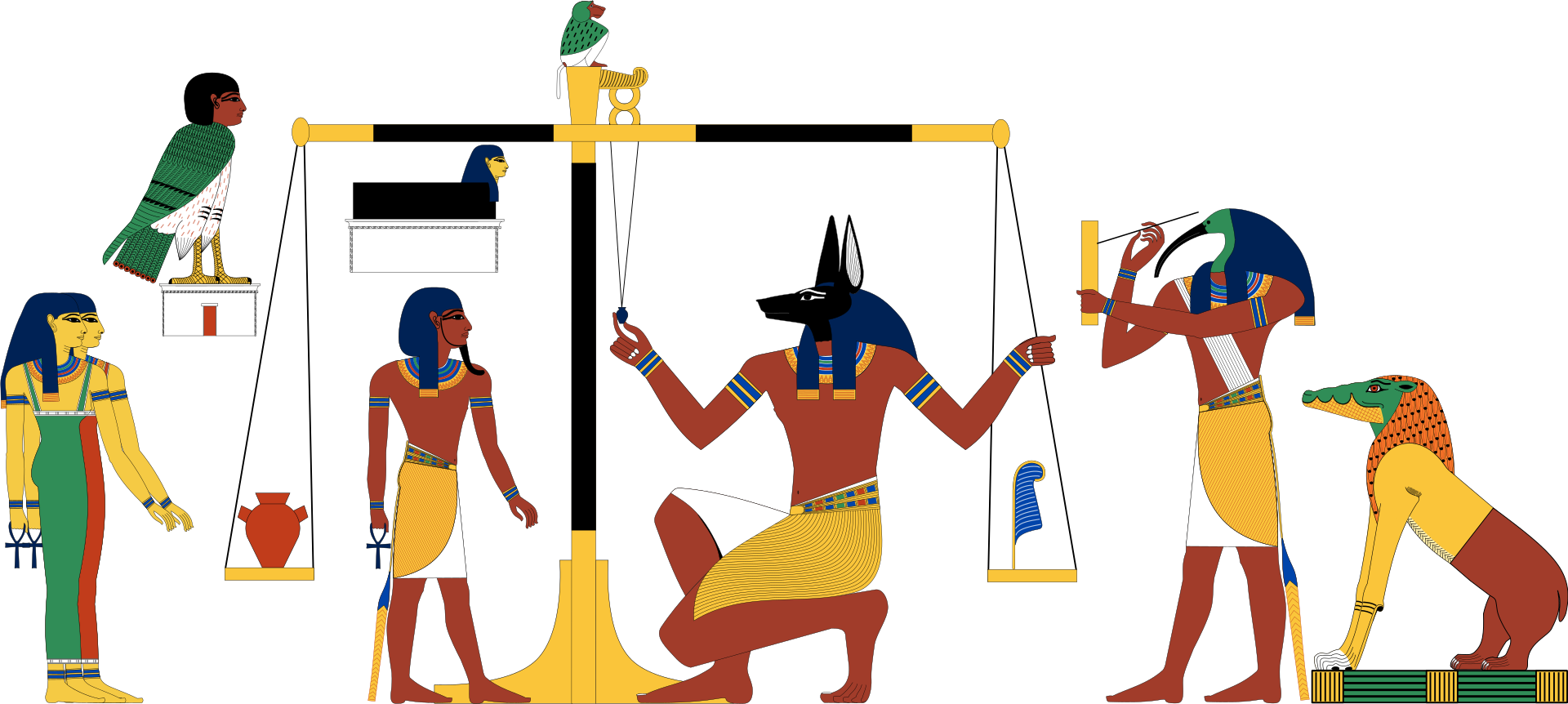

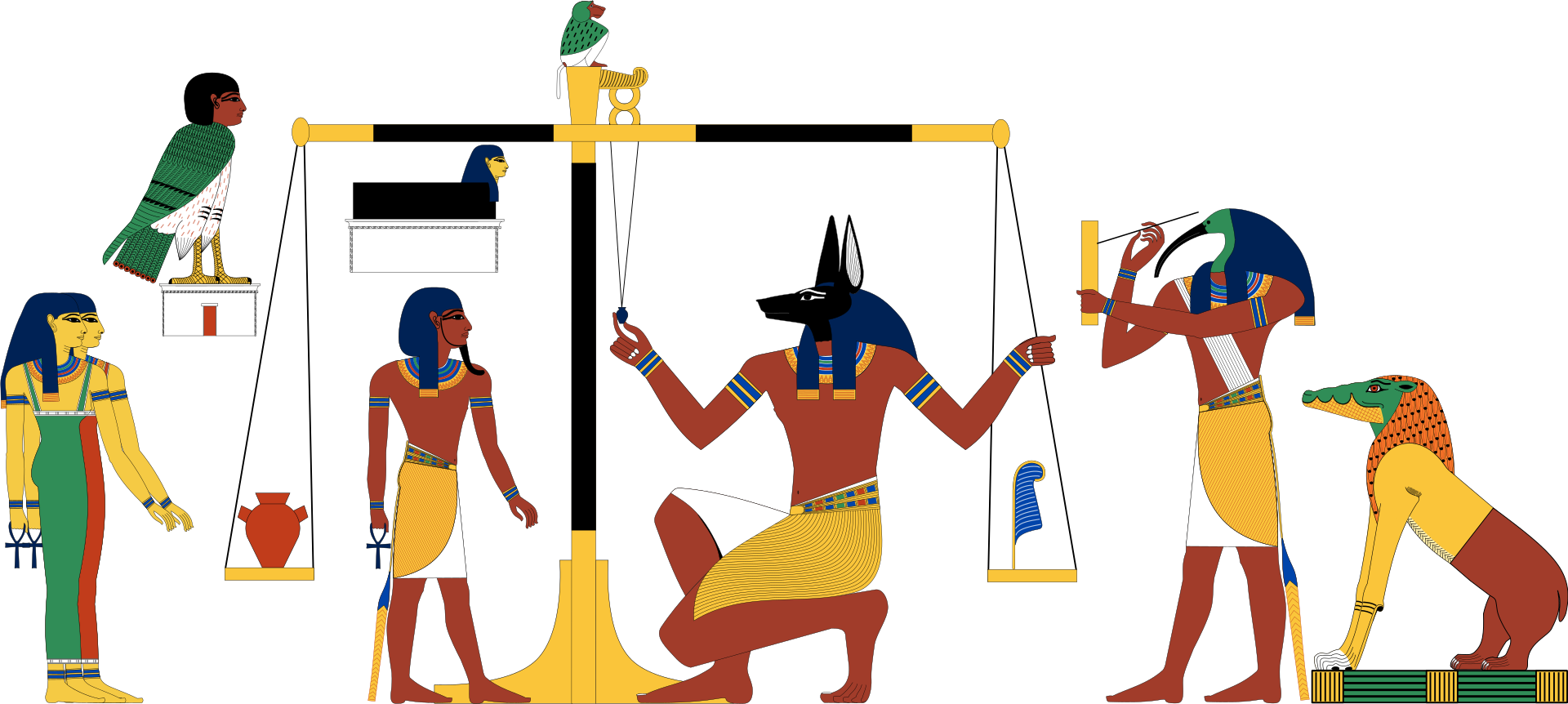

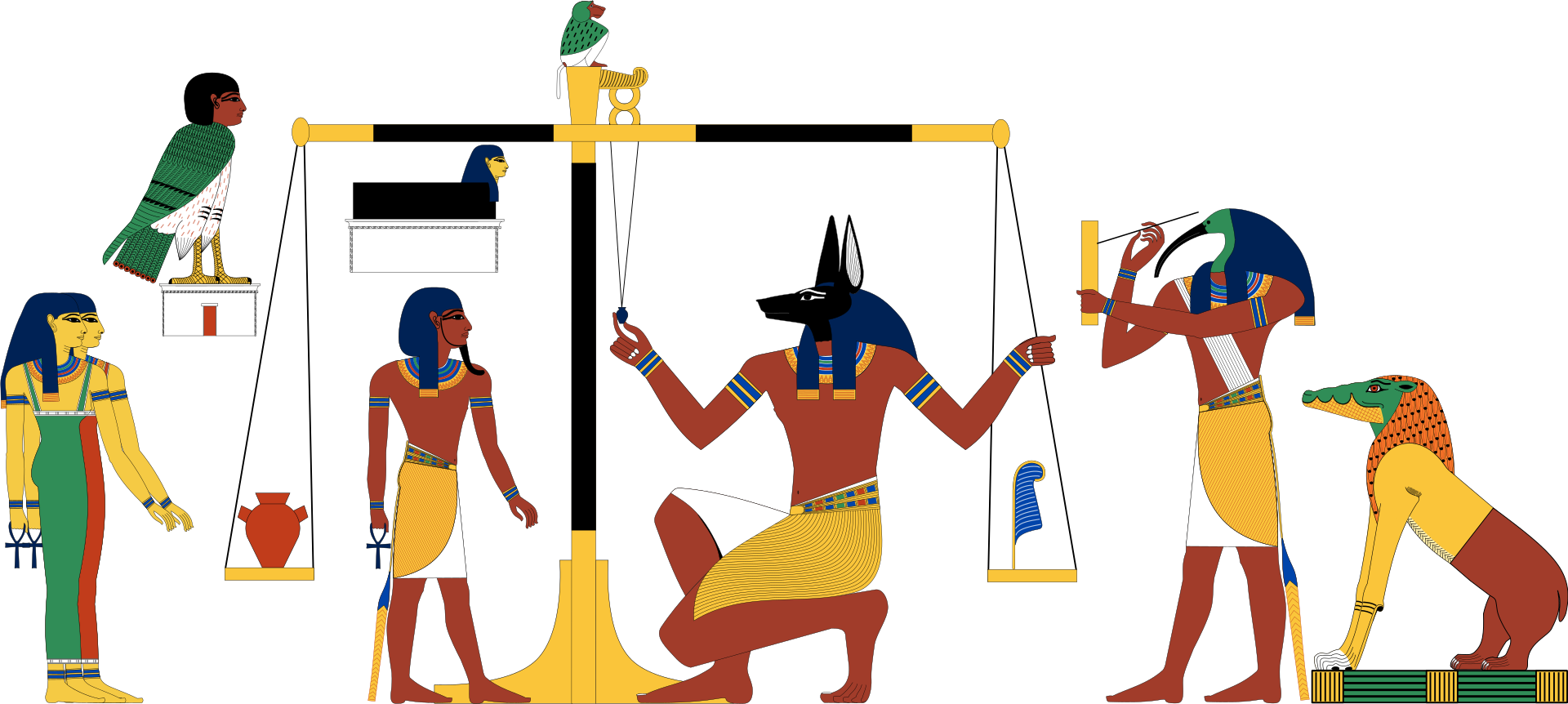

Weighing

of the heart

☆

心臓中心説によると、心臓は人間の感情、認識、意識の主要な発生源である。[1]

この概念は、心臓が単なる物理的な臓器ではなく、感情や知恵の貯蔵庫であるとみなされていた古代エジプトやギリシャ文明にまで遡ることができる。[2]

この分野で著名なギリシャの哲学者アリストテレスは、心臓が感情と知性の両方の中心であると考え、この概念に貢献した。彼は、心臓が心身の生理システムの

中心であり、感覚、思考、身体の動きを制御する役割を担っていると考えた。また、心臓は体内の静脈の起点であり、心臓に存在するプネウマ(気体)がメッセ

ンジャーとして血管を伝って感覚を生み出す役割を果たしていると観察した。[3]

この見解は、中世からルネサンス時代を経て、医学や知的論争に影響を与えながら、歴史を通じて残った。[2]

脳が身体を制御する上で支配的な役割を果たしているという「頭部中心説」と呼ばれる対立する理論は、紀元前550年にピタゴラスが初めて提唱した。ピタゴ

ラスは、魂は脳に宿り、不滅であると主張した。[4]

彼の主張は、プラトン、ヒポクラテス、ペルガモンのガレノスによって支持された。プラトンは、肉体は心と魂の「監獄」であり、死によって心と魂は肉体から

分離すると考えた。つまり、どちらも死ぬことはないということである。[5]

| According to the

cardiocentric hypothesis, the heart is the primary location of human

emotions, cognition, and awareness.[1] This notion may be traced back

to ancient civilizations such as Egypt and Greece, where the heart was

regarded not only as a physical organ but also as a repository of

emotions and wisdom.[2] Aristotle, a well-known Greek philosopher in

this field, contributed to the notion by thinking the heart to be the

centre of both emotions and intellect. He believed that the heart was

the center of the psycho-physiological system and that it was

responsible for controlling sensation, thought, and body movement. He

also observed that the heart was the origin of the veins in the body

and that the existence of pneuma in the heart was to function as a

messenger, traveling through blood vessels to produce sensation.[3]

This point of view remained throughout history, spanning the Middle

Ages and Renaissance, influencing medical and intellectual debate.[2] An opposing theory called "cephalocentrism", which proposed that the brain played the dominant role in controlling the body, was first introduced by Pythagoras in 550 BC, who argued that the soul resides in the brain and is immortal.[4] His statements were supported by Plato, Hippocrates, and Galen of Pergamon. Plato believed that the body is a "prison" of the mind and soul and that in death the mind and soul become separated from the body, meaning that neither one of them could die.[5] |

心臓中心説によると、心臓は人間の感情、認識、意識の主要な発生源であ

る。[1]

この概念は、心臓が単なる物理的な臓器ではなく、感情や知恵の貯蔵庫であるとみなされていた古代エジプトやギリシャ文明にまで遡ることができる。[2]

この分野で著名なギリシャの哲学者アリストテレスは、心臓が感情と知性の両方の中心であると考え、この概念に貢献した。彼は、心臓が心身の生理システムの

中心であり、感覚、思考、身体の動きを制御する役割を担っていると考えた。また、心臓は体内の静脈の起点であり、心臓に存在するプネウマ(気体)がメッセ

ンジャーとして血管を伝って感覚を生み出す役割を果たしていると観察した。[3]

この見解は、中世からルネサンス時代を経て、医学や知的論争に影響を与えながら、歴史を通じて残った。[2] 脳が身体を制御する上で支配的な役割を果たしているという「頭部中心説」と呼ばれる対立する理論は、紀元前550年にピタゴラスが初めて提唱した。ピタゴ ラスは、魂は脳に宿り、不滅であると主張した。[4] 彼の主張は、プラトン、ヒポクラテス、ペルガモンのガレノスによって支持された。プラトンは、肉体は心と魂の「監獄」であり、死によって心と魂は肉体から 分離すると考えた。つまり、どちらも死ぬことはないということである。[5] |

| History Ancient Egypt  Weighing of the heart In ancient Egypt, people believed that the heart is the seat of the soul and the origin of the channels to all other parts of the body, including arteries, veins, nerves, and tendons. The heart was also depicted as determining the fate of ancient Egyptians after they died. It was believed that Anubis, the god of mummification, would weigh the deceased person's heart against a feather. If the heart was too heavy, it would be considered guilty and consumed by the Ammit, a mythological creature. If it was lighter than the feather, the spirit of the deceased would be allowed to go to heaven. Therefore, the heart was kept in the mummy while other organs were generally removed.[6] |

歴史 古代エジプト  心臓の重さを量る 古代エジプトでは、心臓は魂の座であり、動脈、静脈、神経、腱など、身体の他の部分すべてに通じるチャネルの起点であると考えられていた。また、心臓は、 古代エジプト人が死後にその運命を決定すると考えられていた。ミイラ化の神アヌビスが、死者の心臓を羽根と比較して重さを量ると信じられていた。心臓が重 すぎると有罪と見なされ、アミットという神話上の生き物に食われてしまう。心臓が羽よりも軽ければ、故人の魂は天国に行けるとされた。そのため、心臓はミ イラに残し、他の臓器は通常取り除かれた。[6] |

| Ancient Near East In the ancient Near East, the heart (libbu) was considered the seat of consciousness, moral agency, cognition, wisdom, understanding, and of the emotions subject to the will (desire, love, friendship, etc). Emotional expressions in Mesopotamian texts link a positive relationship between the heart and the occurrence of feelings of pride, desire, love, and notions of sexual arousal and shame. Idioms like "his heart is awake" were used to describe an individual regaining their consciousness, and "as it pleases the heart" could be used to describe the sensation of pleasure that one experiences. The heart is the source of both the good and evil in a person, as well as the center of the human capacity of religiosity.[7][8] |

古代近東 古代近東では、心臓(リブ)は意識、道徳的行為、認知、知恵、理解、そして意志(欲望、愛、友情など)に従う感情の座であると考えられていた。メソポタミ アのテキストにおける感情表現は、心臓と誇り、欲望、愛、性的興奮や羞恥心といった感情の発生との間に肯定的な関係があることを示している。「彼の心は目 覚めている」のような慣用句は、個人が意識を取り戻すことを表現するために用いられ、「心にかなう」は人が経験する喜びの感覚を表現するために用いられ た。心は、人格における善と悪の両方の源であり、宗教的な人間的能力の中心でもある。[7][8] |

| Ancient Greece However, the ancient Greeks, Aristotle promoted the cardiocentric hypothesis based on his experience with animal dissection.[9] He found that certain primitive animals could move and feel without the brain, and so deduced that the brain was not responsible for movement or feeling. Apart from that, he pointed out that the brain was at the top of the body, far from the centre of the body, and felt cold. He also performed anatomical examinations after strangling the specimen, which would cause vasoconstriction of the arterioles in the lungs. This likely had the effect of forcing blood to engorge the veins and make them more visible in the following dissection. Aristotle observed that the heart was the origin of the veins in the body, and concluded that the heart was the centre of the psycho-physiological system. He also stated that the existence of pneuma in the heart was to function as a messenger, traveling through blood vessels to produce sensation. Movement of body parts was thought to be controlled by the heart as well. From Aristotle's perspective, the heart was composed of sinews which allowed the body to move.[10] In the fourth century BC, Diocles of Carystus reasserted that the heart was the physiological centre of sensation and thought. He also recognised that the heart had two cardiac ears. Although Diocles also proposed that the left brain was responsible for intelligence and the right one was for sensation, he believed that the heart was dominant over the brain for listening and understanding.[11] Praxagoras of Cos was a follower of Aristotle's cardiocentric theory and was the first one to distinguish arteries and veins. He conjectured that arteries carry pneuma while transporting blood.[clarification needed] He also proved that a pulse can be detected from the arteries and explained that the arteries' ends narrowed into nerves.[12] Lucretius stated around 55 BCE, "The dominant force in the whole body is that guiding principle which we term mind or intellect. This is firmly lodged in the midregion of the breast. Here is the place where fear and alarm pulsate. Here is felt the caressing touch of joy. Here, then, is the seat of the intellect and the mind."[13][14] |

古代ギリシャ しかし、古代ギリシャのアリストテレスは、動物の解剖の経験に基づいて心臓中心説を唱えた。[9] 彼は、ある種の原始的な動物は脳がなくても動いたり感じたりできることを発見し、脳は運動や感覚には関与していないと推論した。それとは別に、彼は脳は身 体の頂点にあり、身体の中心から離れており、冷たいと感じると指摘した。また、解剖実験では、被験者を絞殺した後に解剖を行い、肺の細動脈の血管収縮を引 き起こした。これにより、血液が静脈に集中し、その後の解剖で静脈がよりはっきりと見えるようになるという効果があったと考えられる。アリストテレスは、 心臓が体内の静脈の起点であることを観察し、心臓が精神生理学システムの中心であると結論付けた。また、心臓に存在するプネウマ(気体)は、感覚を生み出 すために血管を伝って移動するメッセンジャーとして機能すると述べた。身体各部の動きも心臓によって制御されていると考えられていた。アリストテレスの見 解では、心臓は身体を動かすための腱で構成されているとされていた。 紀元前4世紀、カリストスのディオクレスは、心臓は感覚と思考の生理学的中心であると再び主張した。また、心臓には2つの心耳があることも認識していた。 ディオクレスは、左脳が知性を司り、右脳が感覚を司るとも提唱したが、心臓は聴覚と理解力において脳よりも優位にあると考えていた。[11] コスのプラクシゴラスは、アリストテレスの心臓中心説の信奉者であり、動脈と静脈を区別した最初の人物である。彼は、動脈は血液を運搬しながらプニューマ を運んでいると推測した。[要出典] また、動脈から脈拍が検出できることを証明し、動脈の末端は神経に狭まっていると説明した。[12] ルクレティウスは紀元前55年頃に「全身を支配する力は、我々が心あるいは知性と呼ぶその指針である。これは胸の中央部にしっかりと定着している。恐怖や 驚愕が脈打つ場所はここである。喜びの愛撫するような感触が感じられるのもここである。したがって、知性と心の座はここにある」と述べた。[13] [14] |

| Islamic world Cardiocentrism is accepted in the Quran.[15] The Islamic philosopher and physician Avicenna followed Galen of Pergamon, believing that one's spirit was confined in three chambers of the brain and accepted that nerves originate from the brain and spinal cord, which control body movement and sensation. However, he maintained the earlier cardiocentric hypothesis. He stated that activation for voluntary movement began in the heart and was then transported to the brain. Similarly, messages were delivered from a peripheral environment to the brain and then via the vagus nerve to the heart.[citation needed] |

イスラム世界 心臓中心説はコーランで受け入れられている。[15] イスラムの哲学者であり医師でもあったアヴィセンナは、ペルガモンのガレノスに従い、人間の精神は脳の3つの部屋に閉じ込められていると信じ、神経は脳と 脊髄から発生し、身体の動きと感覚を制御していると認めていた。しかし、彼は以前の心臓中心説を維持していた。彼は、随意運動の活性化は心臓で始まり、そ の後脳に伝達されると述べた。同様に、末梢環境から脳へ、そして迷走神経を経由して心臓へとメッセージが伝達された。[要出典] |

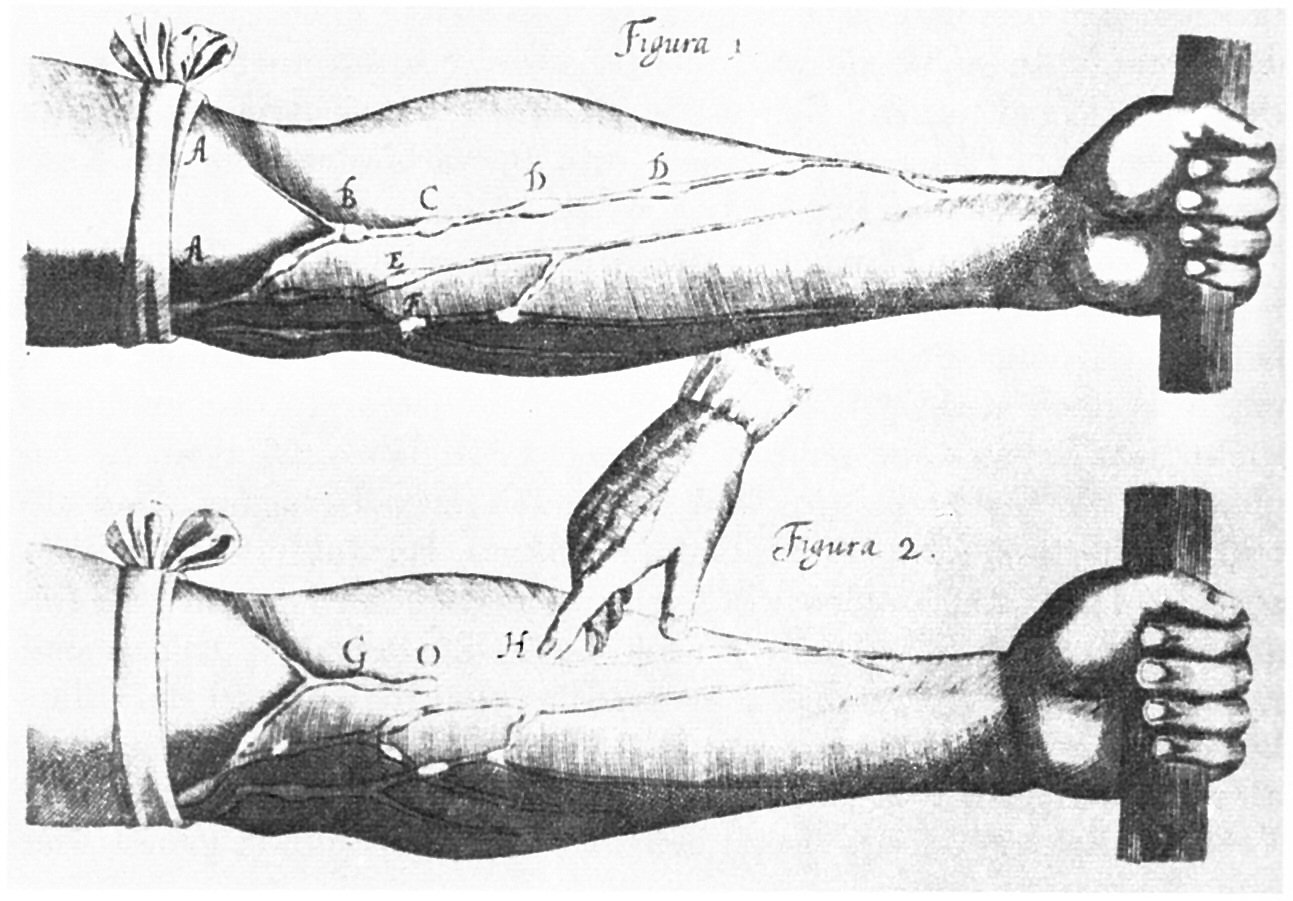

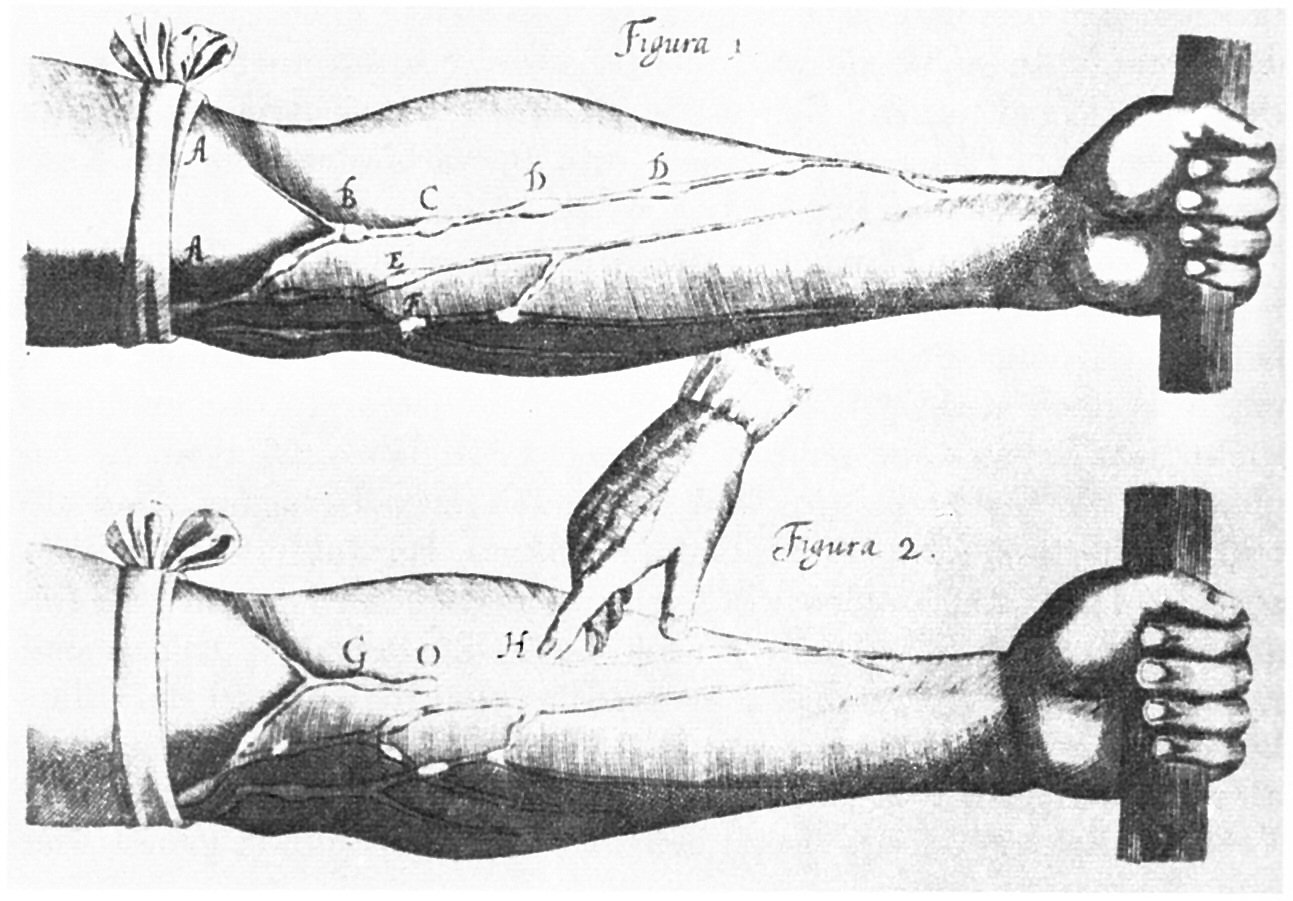

| Europe In the Middle Ages, the German Catholic friar Albertus Magnus made contributions to physiology and biology. His treatise was based on Galen's cephalocentric theory and was profoundly affected by Avicenna's preeminent Canon, which itself had been influenced by Aristotle. He combined these ideas in a new way which suggested that nerves branched off from the brain but that the origin was the heart. He concluded that philosophically, all matters originated from the heart, and in the corporeal explanation, all nerves started from the brain.[citation needed]  Image of veins by William Harvey William Harvey, an early modern English physiologist, also agreed with Aristotle's cardiocentric view. He was the first to describe the basic operation of the circulatory system, by which blood was pumped by the heart to the rest of the body, in detail. He explained that the heart was the centre of the body and the source of life in his treatise De Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus. |

ヨーロッパ 中世において、ドイツのカトリック修道士アルベルトゥス・マグヌスは生理学と生物学に貢献した。彼の論文はガレノスの頭部中心説を基にしており、アヴィセ ンナの優れた『医学集成』に強く影響を受けていた。この『医学集成』自体がアリストテレスの影響を受けていた。彼はこれらの考えを新しい方法で組み合わ せ、神経は脳から分岐しているが、その起源は心臓であると示唆した。彼は哲学的にはすべての事柄は心臓から生じ、肉体的な説明ではすべての神経は脳から始 まるという結論に達した。  ウィリアム・ハーヴェイによる静脈のイメージ 初期近代のイギリスの生理学者ウィリアム・ハーヴェイも、アリストテレスの心臓中心説に同意していた。彼は、血液が心臓から全身に送り出されるという循環 系の基本的な仕組みを初めて詳細に説明した人物である。彼は著書『動物における心臓と血液の運動について』の中で、心臓は身体の中心であり、生命の源であ ると説明している。 |

| Cephalocentric perspective Main article: Central nervous system Hippocrates of Kos was the first to suggest that the brain was the seat of the soul and intelligence. From his treatise De morbo sacro, he pointed out that the brain controls the rest of the body and is responsible for sensation and understanding. Apart from that, he believed that all feelings originated from the brain. Galen of Pergamon was a biologist and physician. His approach to the investigation of the brain was due to his rigorous anatomical methodology. He pointed out that only correct dissection will support the incontrovertible statement. He reached the conclusion that the brain was responsible for sensation and thought, and that nerves originated at the spinal cord and brain.[16] |

頭部中心の視点 詳細は「中枢神経系」を参照 コス島のヒポクラテスは、脳が魂と知性の座であると最初に示唆した人物である。彼の論文『神聖な病』では、脳が身体の他の部分を制御し、感覚と理解を司っていると指摘している。それ以外にも、彼はすべての感情は脳から生じると考えていた。 ペルガモンのガレノスは生物学者であり医師であった。彼の脳の研究へのアプローチは、厳格な解剖学的手法によるものであった。彼は、正しい解剖によっての み、議論の余地のない主張が裏付けられると指摘した。彼は、脳が感覚と思考を司り、神経は脊髄と脳で発生するという結論に達した。[16] |

| Brain in heart This article relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this article by adding secondary or tertiary sources. Find sources: "Cardiocentric hypothesis" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The "little brain in the heart" is an intricate system of nerve cells that control and regulate the heart's activity. It is also called the intrinsic cardiac nervous system (ICNS).[17] It consists of about 40,000 neurons that form clusters or ganglia around the heart, especially near the top where the blood vessels enter and exit. These neurons communicate with each other and with the brain through chemical and electrical signals.[18] The intrinsic cardiac nervous system has several functions, such as: Adjusting the heart rate and rhythm according to the body's needs and emotions.[17] Sensing and responding to changes in blood pressure, oxygen levels, hormones, and inflammation.[19] Protecting the heart from damage during a heart attack or other stress.[17] Learning and remembering from past experiences and influencing the brain’s memory and emotions.[19] |

心臓の中の脳 この記事は一次資料への言及に過度に依存している。 二次資料または三次資料を追加して、この記事の改善にご協力ください。 出典: 「心臓中心説」 – ニュース · 新聞 · 書籍 · 学者 · JSTOR (2024年3月) (どのようにして、いつこのメッセージを削除するかについて学ぶ) 「心臓の小さな脳」は、心臓の活動を制御し調節する神経細胞の複雑なシステムである。これは、内在性心臓神経系(ICNS)とも呼ばれる。[17] 約4万個のニューロンから構成され、心臓の周囲、特に血管が出入りする先端付近にクラスターまたは神経節を形成している。これらのニューロンは、化学的お よび電気的シグナルを介して互いに、また脳と通信している。[18] 心臓の内在性神経系には、以下のようないくつかの機能がある。 身体の必要性や感情に応じて心拍数とリズムを調整する。 血圧、酸素レベル、ホルモン、炎症の変化を感知し、反応する。 心臓発作やその他のストレスによる心臓へのダメージを防ぐ。 過去の経験から学習し、記憶し、脳の記憶と感情に影響を与える。 |

| Loukas,

Marios; Youssef, Pamela; Gielecki, Jerzy; Walocha, Jerzy; Natsis,

Kostantinos; Tubbs, R. Shane (2016-03-11). "History of cardiac anatomy:

A comprehensive review from the egyptians to today". Clinical Anatomy.

29 (3): 270–284. doi:10.1002/ca.22705. ISSN 0897-3806. PMID 26918296.

S2CID 30362746. |

Loukas,

Marios; Youssef, Pamela; Gielecki, Jerzy; Walocha, Jerzy; Natsis,

Kostantinos; Tubbs, R. Shane (2016-03-11).

「心臓解剖学の歴史:エジプト人から今日までの包括的なレビュー」. Clinical Anatomy. 29 (3): 270–284.

doi:10.1002/ca.22705. ISSN 0897-3806. PMID 26918296. S2CID 30362746. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cardiocentric_hypothesis |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Sagrado Corazón de Jesús. Antonio Illanes, 1944. Iglesia de la Concepción, Sevilla, Andalucía, España.

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099