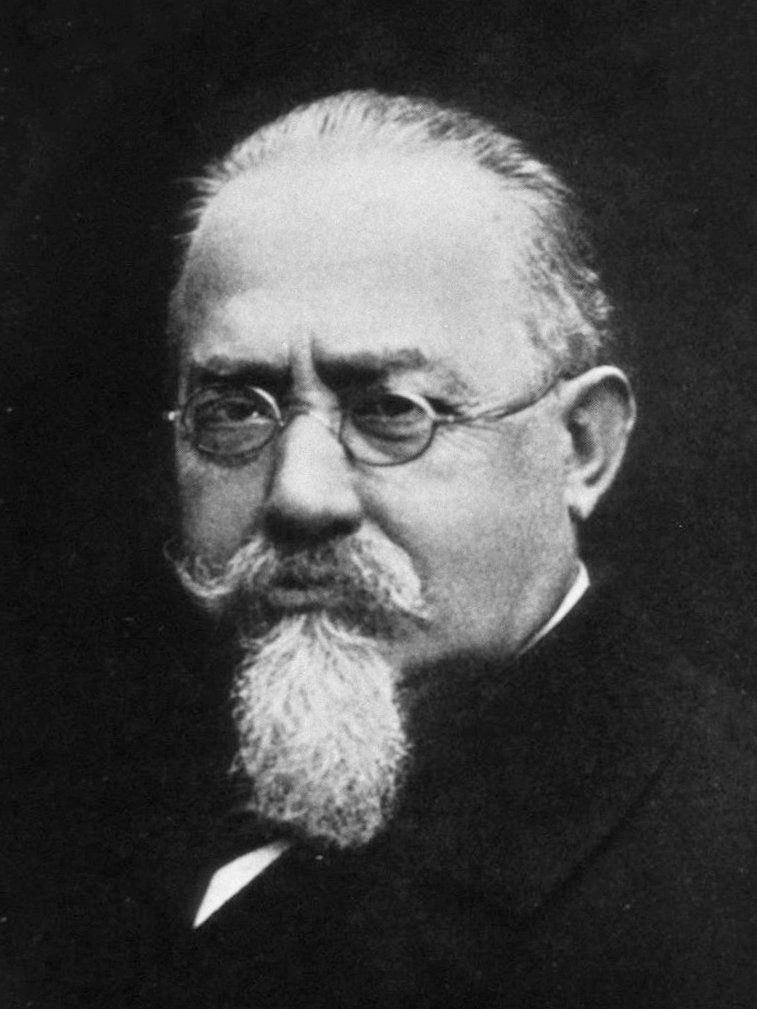

チェザーレ・ロンブローゾ

Cesare Lombroso, 1835-1909

☆ チェーザレ・ロンブローゾ(Cesare Lombroso [1835年11月6日 - 1909年10月19日)は、イタリアの優生学者、犯罪学者、骨相学者、医師であり、イタリア犯罪学派の創始者である。彼は西洋の個人責任の概念を変える ことによって、近代犯罪人類学の創始者と考えられている。ロンブローゾは、犯罪は人間の本性の特徴であるとする古典学派を否定した。その代わりに、人相学、退化論、精神医学、社会ダーウィニズムから引き出された 概念を用いて、ロンブローゾの人類学的犯罪学の理論は、本質的に犯罪性は遺伝するものであり、「生まれながらの犯罪者」は身体的(先天的)欠陥によって識 別することができ、それは犯罪者が未開人または原始人であることを確認するものであると述べた。

| Cesare

Lombroso (/lɒmˈbroʊsoʊ/ lom-BROH-soh,[1][2] US also /lɔːmˈ-/ lawm-,[3]

Italian: [ˈtʃeːzare lomˈbroːzo, ˈtʃɛː-, -oːso]; born Ezechia Marco

Lombroso; 6 November 1835 – 19 October 1909) was an Italian eugenicist,

criminologist, phrenologist, physician, and founder of the Italian

school of criminology. He is considered the founder of modern criminal

anthropology by changing the Western notions of individual

responsibility.[4] Lombroso rejected the established classical school, which held that crime was a characteristic trait of human nature. Instead, using concepts drawn from physiognomy, degeneration theory, psychiatry, and Social Darwinism, Lombroso's theory of anthropological criminology essentially stated that criminality was inherited, and that someone "born criminal" could be identified by physical (congenital) defects, which confirmed a criminal as savage or atavistic. |

チェー

ザレ・ロンブローゾ(/lɒmˈ lom-BROH-soh,[1][2] アメリカ /lɔ⃐mˈ-/ lawm-,[3] イタリア語:

[1835年11月6日 -

1909年10月19日)は、イタリアの優生学者、犯罪学者、骨相学者、医師であり、イタリア犯罪学派の創始者である。彼は西洋の個人責任の概念を変える

ことによって、近代犯罪人類学の創始者と考えられている[4]。 ロンブローゾは、犯罪は人間の本性の特徴であるとする古典学派を否定した。その代わりに、人相学、退化論、精神医学、社会ダーウィニズムから引き出された 概念を用いて、ロンブローゾの人類学的犯罪学の理論は、本質的に犯罪性は遺伝するものであり、「生まれながらの犯罪者」は身体的(先天的)欠陥によって識 別することができ、それは犯罪者が未開人または原始人であることを確認するものであると述べた。 |

| Early life and education Lombroso was born in Verona, Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia, on 6 November 1835 to a wealthy Jewish family.[5] His father was Aronne Lombroso, a tradesman from Verona, and his mother was Zeffora (or Zefira) Levi from Chieri near Turin.[6] Cesare Lombroso descended from a line of rabbis, which led him to study a wide range of topics in university.[7] He studied literature, linguistics, and archæology at the universities of Padua, Vienna, and Paris. Despite pursuing these studies in university, Lombroso eventually settled on pursuing a degree in medicine, which he graduated with from the University of Pavia.[6] |

生い立ちと教育 ロンブローゾは1835年11月6日、ロンバルディア=ヴェネチア王国のヴェローナで裕福なユダヤ人家庭に生まれた。父はヴェローナの商人アロンネ・ロン ブローゾ、母はトリノ近郊のキエリ出身のゼフォラ(またはゼフィラ)・レヴィだった。チェーザレ・ロンブローゾはラビの家系であったため、大学では幅広い 分野を学んだ。パドヴァ、ウィーン、パリの大学で文学、言語学、考古学を学んだ。ロンブローゾは大学ではこれらの学問を追求したが、最終的には医学の学位 を取得することに落ち着き、パヴィア大学を卒業した。 |

| Lombroso

initially worked as an army surgeon, beginning in 1859 when he enlisted

as a volunteer. He claimed that he developed the theory of atavistic

criminality during this period.[8] In 1866, he was appointed visiting

lecturer at Pavia, and later took charge of the insane asylum at Pesaro

in 1871. His research into the bodily characteristics of soldiers and

asylum inmates became the foundation of his work on criminal

anthropology.[9] He became professor of forensic medicine and hygiene

at Turin in 1878.[10] That year he wrote his most important and

influential work, L'uomo delinquente (Criminal Man in English), which

went through five editions in Italian and was published in various

European languages. Three of his works had been translated into English by 1900, including a partial translation of The Female Offender published in 1895 and read in August of that year by the late nineteenth-century English novelist George Gissing (1857-1903).[11] Lombroso became professor of psychiatry (1896) and of criminal anthropology (1906) at Turin University.[5] |

ロ

ンブローゾは1859年に志願兵として入隊して以来、当初は陸軍外科医として働いていた。ロンブローゾは、この時期に無気力性犯罪の理論を発展させたと主

張している。1866年にはパヴィアで客員講師に任命され、1871年にはペーザロの精神病院を担当した。兵士や精神病院収容者の身体的特徴に関する研究

が、犯罪人類学の基礎となった。1878年、トリノの法医学・衛生学教授に就任。この年、最も重要で影響力のある著作L'uomo

delinquente(英語ではCriminal Man)を著し、イタリア語で5版を重ね、ヨーロッパの様々な言語で出版された。 1895年に出版され、その年の8月に19世紀末のイギリスの小説家ジョージ・ギッシング(1857-1903)が読んだ『The Female Offender』の部分訳を含め、1900年までに3つの作品が英語に翻訳された。 ロンブローゾはトリノ大学で精神医学(1896年)と犯罪人類学(1906年)の教授となった。 |

| Personal life and final years Lombroso married Nina de Benedetti on 10 April 1870. They had five children together, one of whom—Gina—would go on to publish a summary of Lombroso's work after his death. Later in life Lombroso came to be influenced by Gina's husband, Guglielmo Ferrero, who led him to believe that not all criminality comes from one's inborn factors and that social factors also played a significant role in the process of shaping a criminal.[citation needed] |

私生活と晩年 ロンブローゾは1870年4月10日にニーナ・デ・ベネデッティと結婚した。二人の間には5人の子供がいたが、そのうちの一人であるジーナは、ロンブロー ゾの死後、彼の著作の要約を出版することになる。後年、ロンブローゾはジーナの夫であるグリエルモ・フェレーロの影響を受けるようになり、彼はすべての犯 罪性は先天的な要因から来るものではなく、犯罪者が形成される過程には社会的要因も重要な役割を果たすと考えるようになった[要出典]。 |

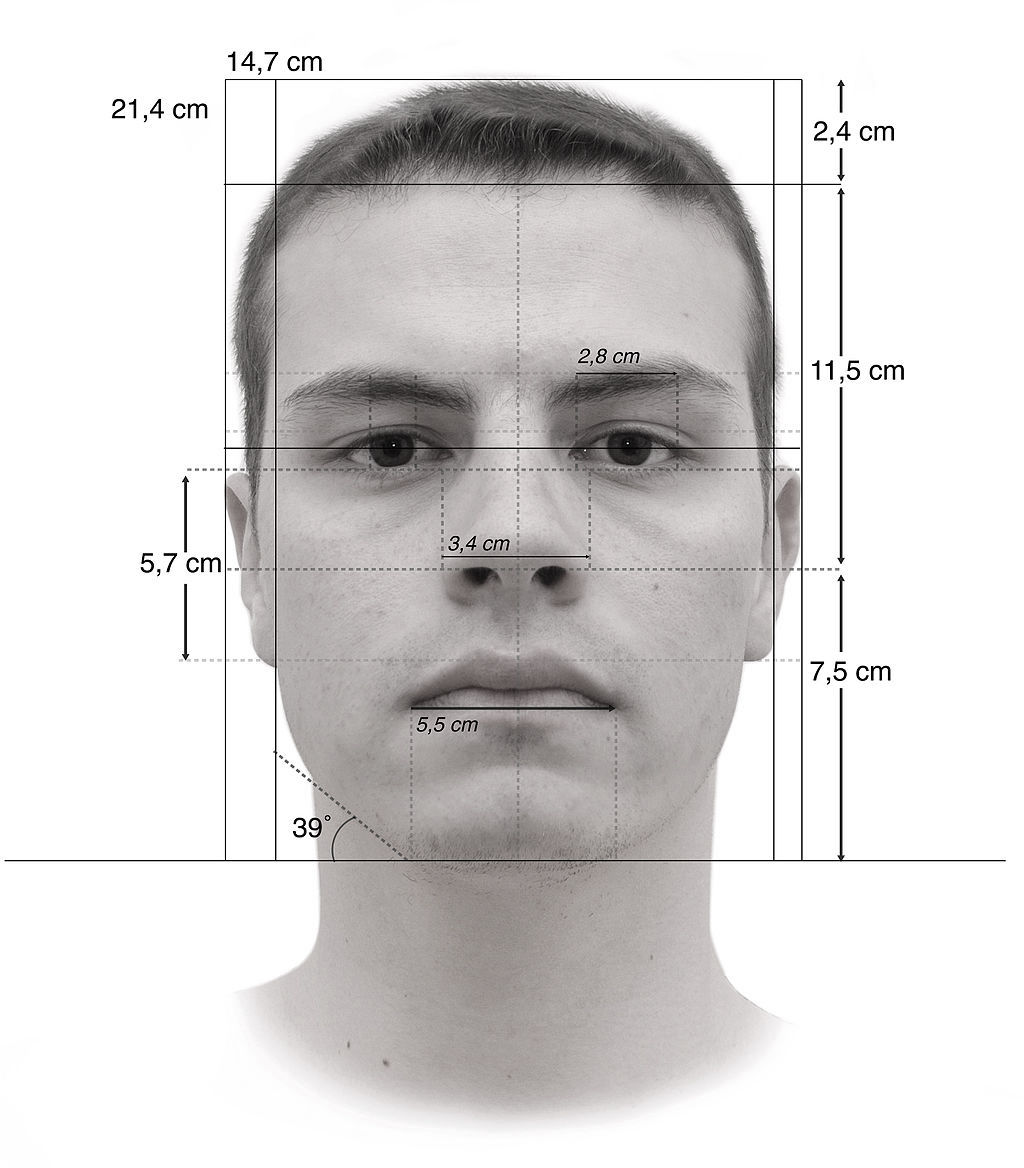

Concept of criminal atavism Face measurements based on Lombroso's criminal anthropology Lombroso's general theory suggested that criminals are distinguished from noncriminals by multiple physical anomalies. He postulated that criminals represented a reversion to a primitive or subhuman type of person characterized by physical features reminiscent of apes, lower primates, and early humans and to some extent preserved, he said, in modern "savages". The behavior of these biological "throwbacks" will inevitably be contrary to the rules and expectations of modern civilized society.[citation needed] Through years of postmortem examinations and anthropometric studies of criminals, the insane, and normal individuals, Lombroso became convinced that the "born criminal" (reo nato, a term given by Ferri) could be anatomically identified by such items as a sloping forehead, ears of unusual size, asymmetry of the face, prognathism, excessive length of arms, asymmetry of the cranium, and other "physical stigmata". Specific criminals, such as thieves, rapists, and murderers, could be distinguished by specific characteristics, he believed. Lombroso also maintained that criminals had less sensitivity to pain and touch; more acute sight; a lack of moral sense, including an absence of remorse; more vanity, impulsiveness, vindictiveness, and cruelty; and other manifestations, such as a special criminal argot and the excessive use of tattooing.[citation needed] Besides the "born criminal", Lombroso also described "criminaloids", or occasional criminals, criminals by passion, moral imbeciles, and criminal epileptics. He recognized the diminished role of organic factors in many habitual offenders and referred to the delicate balance between predisposing factors (organic, genetic) and precipitating factors such as one's environment, opportunity, or poverty.[citation needed] In Criminal Woman, as introduced in an English translation by Nicole Hahn Rafter and Mary Gibson, Lombroso used his theory of atavism to explain women's criminal offending. In the text, Lombroso outlines a comparative analysis of "normal women" as opposed to "criminal women" such as "the prostitute."[13] However, Lombroso's "obdurate beliefs" about women presented an "intractable problem" for this theory: "Because he was convinced that women are inferior to men Lombroso was unable to argue, based on his theory of the born criminal, that women's lesser involvement in crime reflected their comparatively lower levels of atavism."[14] Lombroso's research methods were clinical and descriptive, with precise details of skull dimensions and other measurements. He did not engage in rigorous statistical comparisons of criminals and non-criminals. Although he gave some recognition in his later years to psychological and sociological factors in the etiology of crime, he remained convinced of and identified with, criminal anthropometry. After he died, his skull and brain were measured according to his own theories by a colleague as he requested in his will; his head was preserved in a jar and is still displayed with his collection at the Museum of Psychiatry and Criminology in Turin.[15] Lombroso's theories were disapproved throughout Europe, especially in schools of medicine: notably by Alexandre Lacassagne in France.[16] His notions of physical differentiation between criminals and non-criminals were seriously challenged by Charles Goring (The English Convict, 1913), who made elaborate comparisons and found insignificant statistical differences. |

犯罪の残忍性の概念 ロンブローゾの犯罪人類学に基づく顔面測定 ロンブローゾの一般理論は、犯罪者は複数の身体的異常によって非犯罪者と区別されることを示唆した。ロンブローゾは、犯罪者は類人猿、下等霊長類、初期の 人類を彷彿とさせる身体的特徴によって特徴づけられ、現代の「未開人」にもある程度保存されている、原始的な、あるいは人間以下のタイプの人間への回帰を 表していると仮定した。このような生物学的な「後戻り者」の行動は、必然的に現代の文明社会のルールや期待に反することになる[要出典]。 ロンブローゾは、犯罪者、精神異常者、健常者の死後検査や人体計測の研究を何年も続けるうちに、「生まれながらの犯罪者」(reo nato、フェリによる呼称)は、額の傾斜、異常な大きさの耳、顔の非対称性、前突症、腕の長さ、頭蓋の非対称性、その他の「身体的汚名」によって解剖学 的に識別できると確信するようになった。窃盗犯、強姦犯、殺人犯といった特定の犯罪者は、特定の特徴によって区別できると彼は考えた。ロンブローゾはま た、犯罪者は痛みや触覚に対する感受性が低く、視力が鋭く、自責の念がないなど道徳観念が欠如しており、虚栄心、衝動性、執念深さ、残虐性が強く、特殊な 犯罪用語や刺青の多用など、その他の症状もあると主張した[要出典]。 生まれながらの犯罪者」の他に、ロンブローゾは「クリミナルロイド」、つまり時折犯罪者になる者、情熱による犯罪者、道徳的無能者、犯罪てんかん患者につ いても述べた。ロンブローゾは、多くの常習犯において器質的要因の役割が低下していることを認識し、素因(器質的、遺伝的)と環境、機会、貧困などの誘発 要因との微妙なバランスについて言及した[要出典]。 ニコール・ハーン・ラフターとメアリー・ギブソンによって英訳された『Criminal Woman』において、ロンブローゾは、女性の犯罪を説明するために、彼の原罪論を用いた。本文中でロンブローゾは、「娼婦」のような「犯罪を犯す女性」 とは対照的な「普通の女性」の比較分析を概説している[13]。しかし、女性に対するロンブローゾの「不屈の信念」は、この理論にとって「難解な問題」を 提示した。「ロンブローゾは、女性が男性よりも劣っていると確信していたため、生まれながらの犯罪者という彼の理論に基づいて、女性の犯罪への関与が少な いのは、女性の無原罪性のレベルが比較的低いことを反映していると主張することができなかった」[14]。 ロンブローゾの研究方法は臨床的かつ記述的であり、頭蓋骨の寸法やその他の測定値を詳細に測定していた。犯罪者と非犯罪者の厳密な統計的比較は行わなかっ た。彼は晩年、犯罪の病因における心理学的・社会学的要因に一定の評価を与えたが、犯罪者身体測定学に確信と同調を持ち続けた。ロンブローゾが亡くなった 後、彼の頭蓋骨と脳は、彼の遺言に従って、同僚によって彼自身の理論に従って測定された。彼の頭部は瓶に保存され、現在もトリノの精神医学・犯罪学博物館 に彼のコレクションとともに展示されている[15]。 ロンブローゾの理論は、特にフランスのアレクサンドル・ラカサーニュによって、ヨーロッパ中、特に医学部で否定された[16]。犯罪者と非犯罪者の間の身 体的差異に関する彼の概念は、チャールズ・ゴーリング(『The English Convict』1913年)によって深刻な挑戦を受けた。 |

| Legacy Self-proclaimed the founder of modern scientific psychiatry, Lombroso is purported to have coined the term criminology. He institutionalized the science of psychiatry in universities.[17] His graduating thesis from the University of Pavia dealt with "endemic cretinism".[18] Over the next several years, Lombroso's fascination with criminal behavior and society began, and he gained experience managing a mental institution.[19] After a brief stint in the Italian army, Lombroso returned to the University of Pavia and became the first professor specializing in mental health.[18] By the 1880s, his theories had reached the pinnacle of their fame, and his accolades championed them throughout the fields dedicated to examining mental illness.[18] Lombroso differentiated himself from his predecessor and rival, Cesare Beccaria, through depicting his positivist school in opposition to Beccaria's classist one (which centered around the idea that criminal behavior is born out of free will rather than inherited physical traits).[19] Lombroso's psychiatric theories were conglomerated and collectively called the positivist school by his followers,[19] which included Antonio Marro and Alfredo Niceforo. Ideas similar to Lombroso's assessment of white and northern-European supremacy over other races would be used by fascists to gird, for example, the promulgation of Italian racial laws. His school of thought was only truly abandoned in Italian universities' curriculum after World War II.[19] Through his various publications, Lombroso established a school of psychiatry based on biological determinism and the idea that mental illness was via genetic factors.[18] A person's predisposition to mental illness was determinable through his appearance, as explained in the aforementioned criminal atavism segment. Lombroso's theory has been cited as possibly "the most influential doctrine" in all areas studying human behavior, and indeed, its impact extended far and wide.[17] According to Lombroso, criminal appearance was not just based on inherited physiognomy such as nose or skull shape, but also could be judged through superficial features like tattoos on the body.[20] In particular, Lombroso began searching for a relationship between tattoos and an agglomeration of symptoms eut (which are currently diagnosed as borderline personality disorder).[18] He also believed that tattoos indicated a certain type of criminal. Through his observations of sex workers and criminals, Lombroso hypothesized a correlation between left-handedness, criminality, and degenerate behavior.[20] He also propagated the idea that left-handedness lead to other disabilities, by linking left-handedness with neurodegeneration and alcoholism.[20] Lombroso's theories were likely accepted due to the pre-existing regional stigma against left-handedness, and greatly influenced the reception of left-handedness in the 20th century. His hypothesis even manifested in a new way during the 1980s and 1990s with a series of research studies grouping left-handedness with psychiatric disorders and autoimmune diseases.[20] Despite his stance on inherited immorality and biologically destined criminal behavior, Lombroso believed in socialism and supposedly sympathized with stigmatization of lower socioeconomic statuses, placing him at odds with the biological determinism he espoused.[21] His work stereotyping degenerates can even be seen as an influence behind Benito Mussolini's movement to clean the streets of Italy.[21] Many adherents to Lombroso's positivist school stayed powerful during Mussolini's rule, because of the seamless way criminal atavism and biological determinism justified both the racial theories and eugenic tendencies of fascism.[19] However, certain legal institutions did press back against the idea that criminal behavior is biologically determined. Within the penal system, Lombroso's work led to new forms of punishment, where occasionally punishment varied based on the defendant's biological background. There are a few instances in which case the physiognomy of the defendant actually mattered more than witness testimony and the defendant was subjected to harsher sentences.[17] During the period in Italy between the 1850s and 1880s, the Italian government debated legislation for the insanity plea. Judges and lawyers backed Beccaria's classist school, tending to favor the idea that wrongdoers are breaking a societal contract with the option to exercise free will, tying into Beccaria's classist school of social misbehavior.[19] Lombroso and his followers argued for a criminal code, in which the criminal understood as unable to act with free will due to their biological predisposition to crime.[19] Since his research tied criminal behavior together with the insane, Lombroso is closely credited with the genesis of the criminal insane asylum and forensic psychiatry.[19] His work sponsored the creation of institutions where the criminally insane would be treated for mental illness, rather than placed in jails with their saner counterparts. One example of an asylum for the criminally insane is Bridgewater State Hospital, which is located in the United States. Other examples of these institutions are Matteawan State Hospital and Danvers State Hospital. Most have closed down, but the concept is kept alive with modern correctional facilities like Cook County Jail. This facility houses the largest population of prisoners with mental illness in the United States. However, criminal insane asylums did exist outside of Italy while Lombroso was establishing them within the country. His influence on the asylum was at first regional, but eventually percolated to other countries who adopted some of Lombroso's measures for treating the criminally insane.[19] In addition to influencing criminal atavism, Lombroso wrote a book called Genio e Follia, in which he discussed the link between genius and insanity.[18] He believed that genius was an evolutionarily beneficial form of insanity, stemming from the same root as other mental illnesses.[18] This hypothesis led to his request to examine Leo Tolstoy for degenerate qualities during his attendance at the 12th International Medical Congress in Moscow in 1897. The meeting went poorly, and Tolstoy's novel Resurrection shows great disdain for Lombroso's methodology.[18] Towards the end of his life, Lombroso began to study pellagra, a disease which Joseph Goldberger simultaneously was researching, in rural Italy.[18] He postulated that pellagra came from a nutrition deficit, officially proven by Goldberger.[18] This disease also found its roots in the same poverty that caused cretinism, which Lombroso studied at the start of his medical career. Furthermore, before Lombroso's death the Italian government passed a law in 1904 standardizing treatment in mental asylums and codifying procedural admittance for mentally ill criminals.[19] This law gave psychiatrists free rein within the criminal insane asylum, validating the field of psychiatry through giving the psychiatrists the sole authority to define and treat the causes of criminal behavior (a position which Lombroso argued for from his early teaching days to his death).[19] |

遺産 近代科学精神医学の創始者を自称するロンブローゾは、犯罪学という言葉を生み出したと言われている。パヴィア大学の卒業論文は「風土病のクレチン症」を 扱ったものであった[18]。その後数年間、ロンブローゾは犯罪行動と社会に魅了され始め、精神病院の経営経験を積む。 [1880年代までに、ロンブローゾの理論はその名声の頂点に達し、彼の称賛は精神疾患を研究する分野全体にわたって支持された。 [ロンブローゾの精神医学理論は、アントニオ・マッロやアルフレード・ニケフォロら彼の信奉者たちによって統合され、全体として実証主義学派と呼ばれるよ うになった。白人と北ヨーロッパ人が他の人種に対して優位に立つというロンブルッソの評価に似た考え方は、ファシストたちによって、例えばイタリアの人種 法の公布のために利用された。ロンブローゾの学派は、第二次世界大戦後、イタリアの大学のカリキュラムにおいてのみ真に放棄された[19]。 ロンブローゾは様々な出版物を通じて、生物学的決定論と精神疾患は遺伝的要因を介しているという考えに基づく精神医学の学派を確立した。ロンブローゾの理 論は、人間行動を研究するあらゆる分野において、おそらく「最も影響力のある教義」として引用されており、実際、その影響は広範囲に及んでいた[17]。 ロンブローゾによれば、犯罪者の外見は、鼻や頭蓋骨の形といった先天的な人相に基づくだけでなく、身体の入れ墨のような表面的な特徴によっても判断するこ とができた。 [20]特にロンブローゾは、刺青と、現在境界性パーソナリティ障害と診断されているユート症状の集積との関係を探し始めた[18]。 風俗嬢や犯罪者の観察を通じて、ロンブローゾは左利きと犯罪性、そして退廃的な行動との間に相関関係があるという仮説を立てた[20]。 彼はまた、左利きを神経変性やアルコール中毒と結びつけることによって、左利きが他の障害につながるという考えを広めた[20]。 ロンブローゾの理論は、左利きに対する地域的なスティグマがあらかじめ存在していたために受け入れられたと考えられ、20世紀における左利きの受容に大き な影響を与えた。彼の仮説は、1980年代から1990年代にかけて、左利きを精神疾患や自己免疫疾患とグループ化する一連の研究によって、新たな形で顕 在化した[20]。 ロンブローゾは、遺伝的な不道徳性や生物学的に運命づけられた犯罪行為に対するスタンスにもかかわらず、社会主義を信じ、社会経済的地位の低い人々に対す る汚名を着せることに共感していたとされ、彼の信奉する生物学的決定論とは対立する立場にあった。 [21] ロンブローゾの実証主義学派の信奉者の多くは、ムッソリーニの支配下でも勢力を保っていた。犯罪者の先天性と生物学的決定論が、ファシズムの人種論と優生 学的傾向の両方を正当化する隙のない方法だったからである。 刑事制度においては、ロンブローゾの研究により、被告人の生物学的背景によって刑罰を変えるという新しい刑罰形態が生まれた。被告人の人相が証人の証言よりも実際に重要であり、被告人がより厳しい刑に処された例もいくつかある[17]。 イタリアでは、1850年代から1880年代にかけて、イタリア政府は心神喪失の主張に関する法制化を議論していた。裁判官や弁護士はベッカリーアの階級 主義学派を支持し、悪事を働く者は自由意志を行使する選択肢を持つ社会的契約を破っているという考えを支持する傾向にあり、社会的不品行に関するベッカ リーアの階級主義学派と結びついていた[19]。ロンブローゾとその支持者たちは、犯罪者は犯罪に対する生物学的素因のために自由意志を持って行動するこ とができないと理解される刑法[19]を主張した。 ロンブローゾの研究は、犯罪行為と心神喪失者を結びつけるものであったため、ロンブローゾは犯罪者の精神病院と法医学的精神医学の発端となった。心神喪失 者のための精神病院の一例は、米国にあるブリッジウォーター州立病院である。その他の例としては、マテワン州立病院やダンバース州立病院がある。大半は閉 鎖されたが、クック郡刑務所のような近代的な矯正施設では、このコンセプトが生かされている。この施設には、米国最大の精神病囚が収容されている。しか し、ロンブローゾがイタリア国内に精神病院を設立していた頃、犯罪者用の精神病院はイタリア国外にも存在していた。ロンブローゾの精神病院への影響は、当 初は地域的なものであったが、やがて他の国々にも浸透し、ロンブローゾの犯罪性精神障害者の治療法の一部が採用された[19]。 この仮説は、1897年にモスクワで開催された第12回国際医学会議に出席した際に、レオ・トルストイに退廃的な資質がないか検査するよう要請することに つながった[18]。会議は不調に終わり、トルストイの小説『復活』はロンブローゾの方法論を非常に軽蔑していることを示している[18]。 ロンブローゾはその生涯の終わり頃、ジョセフ・ゴールドベルガーが同時に研究していたペラグラという病気をイタリアの農村で研究し始めた[18]。彼はペ ラグラが栄養不足に起因すると仮定し、ゴールドベルガーによって公式に証明された[18]。さらにロンブローゾが亡くなる前、イタリア政府は1904年に 精神病院での治療を標準化し、精神障害者の入所手続きを成文化する法律を可決した[19]。この法律は、精神科医に犯罪行動の原因を定義し、治療する唯一 の権限を与えることで、精神医学という分野を正当化し、精神科医に犯罪者精神病院内での自由裁量権を与えた(ロンブローゾは初期の指導時代から亡くなるま で、この立場を主張していた)[19]。 |

| The Man of Genius Lombroso believed that genius was closely related to madness.[22] In his attempts to develop these notions, while in Moscow in 1897 he traveled to Yasnaya Polyana to meet Lev Tolstoy in hopes of elucidating and providing evidence for his theory of genius reverting or degenerating into insanity.[22] Lombroso published The Man of Genius in 1889, a book which argued that artistic genius was a form of hereditary insanity. In order to support this assertion, he began assembling a large collection of "psychiatric art". He published an article on the subject in 1880 in which he isolated thirteen typical features of the "art of the insane." Although his criteria are generally regarded as outdated today, his work inspired later writers on the subject, particularly Hans Prinzhorn. Lombroso's The Man of Genius provided inspiration for Max Nordau's work, as evidenced by his dedication of Degeneration to Lombroso, whom he considered to be his "dear and honored master".[23] In his exploration of geniuses descending into madness, Lombroso stated that he could only find six men who did not exhibit symptoms of "degeneration" or madness: Galileo, Da Vinci, Voltaire, Machiavelli, Michelangelo and Darwin.[23] By contrast, Lombroso cited that men such as Shakespeare, Plato, Aristotle, Mozart and Dante all displayed "degenerate symptoms".[23] In order to classify geniuses as "degenerate," or insane, Lombroso judged each genius by whether they exhibited "degenerate symptoms," such as precocity, longevity, versatility and inspiration.[23] Lombroso supplemented these psychological observations with skeletal and cranial measurements, including facial angles, "abnormalities" in bone structure, and volumes of brain fluid.[23][24] Measurements of skulls taken included those from Immanuel Kant, Alessandro Volta, Ugo Foscolo, and Ambrogio Fusinieri.[24] Lombroso's reference to skull measurements was inspired by the phrenological work and research of German doctor Franz Joseph Gall.[25] In commenting on skull measurements, Lombroso made observations such as, "I have noted several characters which anthropologists consider to belong to the lower races, such as prominence of the styloid apophysis". This observation was recorded in response to his analysis of Alessandro Volta's skull.[24] Lombroso connected geniuses to various health disorders as well, by listing signs of degeneration in chapter two of his work, some of which include abnormalities and discrepancies in height and pallor.[24] Lombroso listed the following geniuses, among others, as "sickly and weak during childhood": Demosthenes, Francis Bacon, Descartes, Isaac Newton, John Locke, Adam Smith, Robert Boyle, Alexander Pope, John Flaxman, Nelson, Albrecht von Haller, Körner and Blaise Pascal.[24] Other physical afflictions that Lombroso associated with degeneracy included rickets, emaciation, sterility, lefthandedness, unconsciousness, stupidity, somnambulism, smallness or disproportionality of the body, and amnesia.[24] In his explanation of the connection between genius and the "degenerative marker" of height, Lombroso cites the following people: Robert and Elizabeth Browning, Henrik Ibsen, George Eliot, Thiers, Louis Blanc and Algernon Charles Swinburne, among others.[24] He continues by listing the only "great men of tall stature" that he knows of, including Petrarch, Friedrich Schiller, Foscolo, Bismarck, Charlemagne, Dumas, George Washington, Peter the Great, and Voltaire.[24] Lombroso further cited certain personality traits as markers of degeneracy, such as "a fondness for special words" and "the inspiration of genius".[24] Lombroso's methods and explanations in The Man of Genius were rebutted and questioned by the American Journal of Psychiatry. In a review of The Man of Genius they stated, "Here we have an hypothesis claiming to be the result of strict scientific investigation and reluctant conviction, bolstered by half-told truths, misrepresentations and assumptions."[26] Lombroso's work was also criticized by Italian anthropologist Giuseppe Sergi, who, in his review of Lombroso's The Man of Genius—and specifically his classifications and definitions of "the genius"—stated, "By creating a genius according to his own fancy, an ideal and abstract being, and not by examining the personality of a real living genius, he naturally arrives at the conclusion that all theories by which the origin of genius is sought to be explained on a basis of observation, and especially that particular one which finds in degeneration the cause or one of the causes of genius, are erroneous."[27] Sergi went on to state that such theorists are "like the worshippers of the saints or of fetishes, who do not recognize the material from which the fetish is made, or the human origin from which the saint has sprung".[27] |

天才という人間 ロンブローゾは、天才は狂気と密接な関係があると信じていた[22]。こうした考えを発展させようと、1897年にモスクワに滞在していたとき、ヤスナ ヤ・ポリャーナまで行ってレフ・トルストイに会い、天才が狂気に回帰または堕落するという彼の理論を解明し、その証拠を提供することを望んだ[22]。 ロンブローゾは1889年に『天才の男』を出版し、芸術的天才は遺伝性の狂気の一形態であると主張した。この主張を支持するために、彼は「精神医学的芸 術」の大規模なコレクションを集め始めた。彼は1880年にこのテーマに関する論文を発表し、その中で「精神異常者の芸術」の13の典型的な特徴を分離し た。彼の基準は今日では一般に時代遅れと見なされているが、彼の研究はこのテーマに関する後世の作家、特にハンス・プリンツホルンに影響を与えた。 ロンブローゾの『天才の男』は、マックス・ノルダウの仕事にインスピレーションを与えた。ロンブローゾが『退化』を「親愛なる、尊敬すべき師」と仰ぐロン ブローゾに捧げていることからも明らかである: ガリレオ、ダ・ヴィンチ、ヴォルテール、マキャベリ、ミケランジェロ、ダーウィンである[23]。対照的に、ロンブローゾは、シェイクスピア、プラトン、 アリストテレス、モーツァルト、ダンテといった人物はすべて「退廃的な症状」を示していたと述べている。 [23]ロンブローゾは天才を「退廃的」、つまり精神異常者として分類するために、早熟さ、長寿、多才さ、ひらめきといった「退廃的症状」を示しているか どうかで各天才を判断した[23]。ロンブローゾはこれらの心理学的観察を、顔の角度、骨構造の「異常」、脳液の量といった骨格や頭蓋の測定で補った。 [23][24]頭蓋骨の測定には、イマヌエル・カント、アレッサンドロ・ヴォルタ、ウーゴ・フォスコロ、アンブロージョ・フジニエリらのものが含まれて いた[24]。ロンブローゾが頭蓋骨の測定に言及したのは、ドイツ人医師フランツ・ヨーゼフ・ガールの骨相学の仕事と研究に触発されたものであった。 [25]ロンブローゾは頭蓋骨の計測についてコメントする中で、「私は、人類学者が低人種に属すると考えるいくつかの特徴、例えば、舌骨端突起の隆起に注 目した」というような観察を行った。この観察は、アレッサンドロ・ヴォルタの頭蓋骨の分析に対して記録されたものである[24]。ロンブローゾは、彼の著 作の第2章で、退化の兆候を列挙することによって、天才を様々な健康障害とも結びつけており、その中には、身長や顔色の異常や不一致も含まれている [24]。ロンブローゾは、とりわけ以下の天才を「幼少期に病弱であった」と挙げている: デモステネス、フランシス・ベーコン、デカルト、アイザック・ニュートン、ジョン・ロック、アダム・スミス、ロバート・ボイル、アレクサンダー・ポープ、 ジョン・フラックスマン、ネルソン、アルブレヒト・フォン・ハラー、ケルナー、ブレーズ・パスカル。 [24] ロンブローゾが退化と関連づけたその他の身体的苦悩には、くる病、やせ、不妊、左利き、無意識、愚鈍、夢遊病、身体の小ささや不釣り合い、記憶喪失などが あった[24]。ロンブローゾは、天才と身長という「退化的マーカー」との関連についての説明の中で、以下の人物を挙げている: ロバート・ブラウニングとエリザベス・ブラウニング、ヘンリック・イプセン、ジョージ・エリオット、ティエール、ルイ・ブラン、アルジャーノン・チャール ズ・スウィンバーンなどである[24]。ロンブローゾは続けて、ペトラルカ、フリードリヒ・シラー、フォスコロ、ビスマルク、カール大帝、デュマ、ジョー ジ・ワシントン、ピョートル大帝、ヴォルテールなど、彼が知っている唯一の「長身の偉人」を挙げている。 [24]ロンブローゾはさらに、「特別な言葉への憧れ」や「天才のひらめき」など、ある種の性格的特徴を退廃の目印として挙げている[24]。 ロンブローゾの『天才の男』における方法と説明は、American Journal of Psychiatryによって反論され、疑問視された。ロンブローゾは『天才の男』の書評の中で、「ここにあるのは、厳密な科学的調査と消極的な確信の結 果であると主張する仮説であり、中途半端に語られた真実、誤った表現、仮定によって補強されている」と述べている[26]。 ロンブローゾの著作は、イタリアの人類学者ジュゼッペ・セルジからも批判された。セルジは、ロンブローゾの『天才の男』、特に「天才」の分類と定義につい ての書評の中で、次のように述べている、 天才の起源を観察に基づいて説明しようとするすべての理論、特に退化に天才の原因または原因の一つを見出す特別な理論は誤りであるという結論に、彼は自然 に到達する。 「セルジはさらに、このような理論家は「聖人やフェティッシュの崇拝者のようなもので、フェティッシュが作られた素材や、聖人が生まれた人間の起源を認識 していない」と述べている[27]。 |

| Spiritualism Later in his life Lombroso began investigating mediumship. Although originally skeptical, he later became a believer in spiritualism.[28] As an atheist[29] Lombroso discusses his views on the paranormal and spiritualism in his book After Death – What? (1909) which he believed the existence of spirits and claimed the medium Eusapia Palladino was genuine. The article "Exit Eusapia!" was published in the British Medical Journal on November 9, 1895. The article questioned the scientific legitimacy of the Society for Psychical Research for investigating Palladino a medium who had a reputation of being a fraud and imposter and was surprised that Lombroso had been deceived by Palladino.[30] The anthropologist Edward Clodd wrote "[Lombroso] swallowed the lot at a gulp, from table raps to materialisation of the departed, spirit photographs and spirit voices; every story, old or new, alike from savage and civilised sources, confirming his will to believe."[31] Lombroso's daughter Gina Ferrero wrote that during the later years of his life Lombroso suffered from arteriosclerosis and his mental and physical health was wrecked. The skeptic Joseph McCabe wrote that because of this it was not surprising that Palladino managed to fool Lombroso into believing spiritualism by her tricks.[32] |

スピリチュアリズム ロンブローゾは人生の後半になって霊媒について調べ始めた。無神論者[29]であったロンブローゾは、著書『死後とは何か』(1909年)の中で超常現象 やスピリチュアリズムについての見解を述べており、霊魂の存在を信じ、霊媒エウサピア・パラディーノが本物であると主張している。1895年11月9日、 『英国医学雑誌』に「エウサピア退場!」という論文が掲載された。この論文は、詐欺師であり偽者であるという評判のある霊媒パラディーノを調査した心霊研 究協会の科学的正当性に疑問を呈し、ロンブローゾがパラディーノに騙されていたことに驚いていた[30]。 人類学者のエドワード・クロッドは、「ロンブローゾは、テーブル・ラップから亡霊の実体化、霊の写真や霊の声まで、ありとあらゆるものを一息に飲み込ん だ。懐疑論者のジョゼフ・マッケイブは、このため、パラディーノが自分のトリックによってロンブローゾを騙してスピリチュアリズムを信じ込ませることに成 功したのは驚くべきことではなかったと書いている[32]。 |

| Literary impact Historian Daniel Pick argues that Lombroso serves "as a curious footnote to late-nineteenth-century literary studies," due to his referencing in famous books of the time. Jacques in Émile Zola's The Beast Within is described as having a jaw that juts forward on the bottom. It is emphasized especially at the end of the book when he is overwhelmed by the desire to kill. The anarchist Karl Yundt in Joseph Conrad's The Secret Agent, delivers a speech denouncing Lombroso. The assistant prosecutor in Leo Tolstoy's Resurrection uses Lombroso's theories to accuse Maslova of being a congenital criminal. In Bram Stoker's Dracula, Count Dracula is described as having a physical appearance Lombroso would describe as criminal.[33][34] |

文学的影響 歴史学者ダニエル・ピックは、ロンブローゾが「19世紀末の文学研究において、不思議な脚注として機能している」と論じている。エミール・ゾラの『内なる 野獣』に登場するジャックは、下顎が前に突き出ていると描写されている。特に終盤、彼が殺意に圧倒される場面で強調される。ジョセフ・コンラッドの『密 偵』に登場する無政府主義者カール・ユントは、ロンブローゾを糾弾する演説を行う。レオ・トルストイの『復活』に登場する検事補は、ロンブローゾの理論を 使ってマスロヴァを先天性の犯罪者だと非難する。ブラム・ストーカーの『ドラキュラ』では、ドラキュラ伯爵はロンブローゾが犯罪者と表現するような外見を していると描写されている[33][34]。 |

| Works Original Italian 1859 Ricerche sul cretinismo in Lombardia 1864 Genio e follia 1865 Studi clinici sulle mallatie mentali 1871 L'uomo bianco e l'uomo di colore 1873 Sulla microcefala e sul cretinismo con applicazione alla medicina legale 1876 L'uomo delinquente 1879 Considerazioni al processo Passannante 1881 L'amore nel suicidio e nel delitto 1888 L'uomo di genio in rapporto alla psichiatria 1890 Sulla medicina legale del cadavere (second edition) 1891 Palimsesti del carcere 1892 Trattato della pellagra 1893 La Donna Delinquente: La prostituta e la donna normale (Co-authored with Lombroso's son-in-law Guglielmo Ferrero). 1894 Le più recenti scoperte ed applicazioni della psichiatria ed antropologia criminale 1894 Gli anarchici 1894 L'antisemitismo e le scienze moderne 1897 Genio e degenerazione 1898 Les Conquêtes récentes de la psychiatrie 1899 Le crime; causes et remédes 1900 Lezioni de medicina legale 1902 Delitti vecchi e delitti nuovi 1909 Ricerche sui fenomeni ipnotici e spiritici In 1906, a collection of papers on Lombroso was published in Turin as L'opera di Cesare Lombroso nella scienza e nelle sue applicazioni. English translations 1891 The Man of Genius, Walter Scott. 1895 The Female Offender. The 1895 English translation was a partial translation which left out the entire section on the normal woman and which, in true Victorian fashion, sanitised Lombroso's language. 1899 Crime: Its Causes and Remedies 1909 After Death - What? 1911 Criminal Man, According to the Classification of Cesare Lombroso 2004 The Criminal Anthropological Writings of Cesare Lombroso 2004 Criminal Woman, the Prostitute, and the Normal Woman. Translated by Nicole Hahn Rafter and Mary Gibson. 2006 Criminal Man. Translated by Nicole Hahn Rafter and Mary Gibson. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cesare_Lombroso |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆