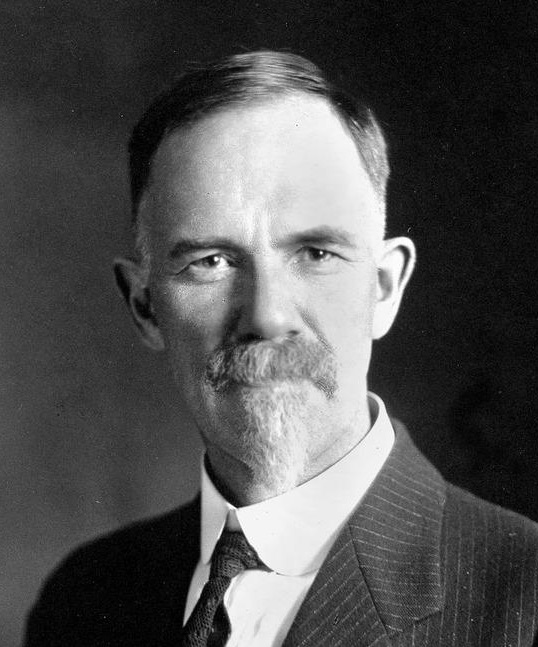

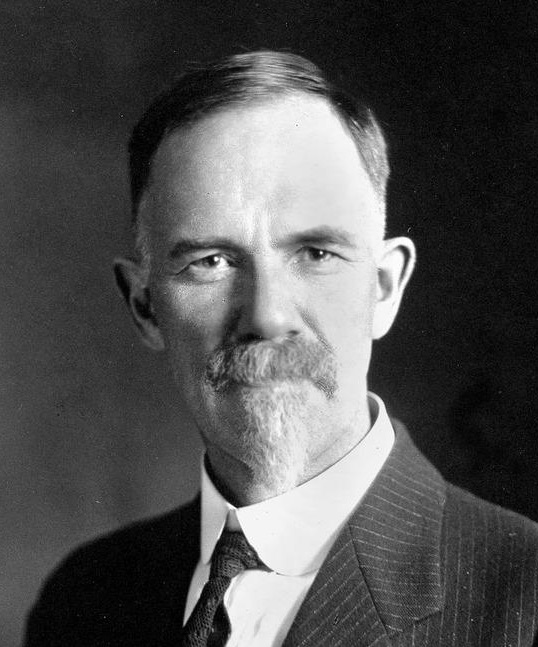

チャールズ・ベネディクト・ダベンポート

Charles Benedict Davenport, 1866-1944

チャールズ・ベネディクト・ダベンポート

Charles Benedict Davenport, 1866-1944

チャールズ・ベネディクト・ダベンポート(1866年6月1日 - 1944年2月18日)は、アメリカの優生学運動に影響を与えた生物学者であり優生学者である。

| Charles

Benedict Davenport (June 1, 1866 – February 18, 1944) was a biologist

and eugenicist influential in the American eugenics movement. |

チャールズ・ベネディクト・ダベンポート(1866年6月1日 - 1944年2月18日)は、アメリカの優生学運動に影響を与えた生物学者であり優生学者である。 |

| Early life and education Davenport was born in Stamford, Connecticut, to Amzi Benedict Davenport, an abolitionist of Puritan ancestry, and his wife Jane Joralemon Dimon (of English, Dutch and Italian ancestry). His father had eleven children by two wives, and Charles grew up with his family on Garden Place in Brooklyn Heights.[1] His mother's strong beliefs tended to rub off onto Charles and he followed the example of his mother. During the summer months, Charles and his family spent their time on a family farm near Stamford.[1] Due to Davenport's father's strong belief in Protestantism, as a young boy Charles was tutored at home. This came about in order for Charles to learn the values of hard work and education. When he was not studying, Charles worked as a janitor and errand boy for his father's business.[2] His father had a significant influence on his early career, as he encouraged Charles to become an engineer.[3] However, this was not his primary interest, and after working for a few years to save up money, Charles enrolled in Harvard College to pursue his genuine interest of becoming a scientist. He graduated with a Bachelor's after two years, and earned a Ph.D in biology in 1892.[3] He married Gertrude Crotty, a zoology graduate of Harvard, in 1894. He had two daughters with Gertrude, Millia Crotty and Jane Davenport Harris di Tomasi.[4] |

幼少期と教育 ダベンポートはコネチカット州スタンフォードで、ピューリタンの血を引く奴隷廃止論者アムジ・ベネディクト・ダベンポートとその妻ジェーン・ジョラレモ ン・ディモン(イギリス、オランダ、イタリアの血を引く)の間に生まれた。父親は2人の妻との間に11人の子供をもうけ、チャールズはブルックリンハイツ のガーデンプレイスで家族とともに育った[1]。母親の強い信念はチャールズにも伝わりやすく、彼は母親を手本にした。夏の間、チャールズと彼の家族はス タンフォードの近くにある家族の農場で過ごした[1]。 ダベンポートの父親がプロテスタントを強く信奉していたため、少年時代のチャールズは家庭教師をつけられた。これは、チャールズに勤勉と教育の価値を学ば せるためであった。父親がエンジニアになるよう勧めたこともあり、彼のキャリアに大きな影響を与えた[3]。 しかし、これは彼の主たる関心事ではなく、数年間働いてお金を貯めた後、科学者になるという純粋な関心を追求するためにハーバード大学に入学することに なった。1894年、ハーバード大学の動物学卒業生であるガートルード・クロッティと結婚した[3]。ガートルードとの間にミリア・クロッティとジェー ン・ダベンポート・ハリス・ディ・トマシの2人の娘をもうけた[4]。 |

| Career Later on, Davenport became a professor of zoology at Harvard. He became one of the most prominent American biologists of his time, pioneering new quantitative standards of taxonomy. Davenport had a tremendous respect for the biometric approach to evolution pioneered by Francis Galton and Karl Pearson, and was involved in Pearson's journal, Biometrika. However, after the re-discovery of Gregor Mendel's laws of heredity, he moved on to become a prominent supporter of Mendelian inheritance. From 1899 to 1904 Davenport worked in Chicago. He was curator of the Zoological Museum of the University of Chicago from 1901 to 1904.[5] In 1904,[2] Davenport became director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory,[6] where he founded the Eugenics Record Office in 1910. During his time at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Davenport began a series of investigations into aspects of the inheritance of human personality and mental traits, and over the years he generated hundreds of papers and several books on the genetics of alcoholism, pellagra (later shown to be due to a vitamin deficiency), criminality, feeblemindedness, seafaringness, bad temper, intelligence, manic depression, and the biological effects of race crossing.[2] Additionally, Davenport mentored many people while working at the Laboratory, such as Massachusetts suffragist, Claiborne Catlin Elliman.[7] Before Charles Davenport came across eugenics, he studied math. He came to know these subjects through Professors Karl Pearson and gentleman amateur Francis Galton. He met them in London. Upon meeting them, he fell in love with the subject matter. In 1901, Biometrika, a journal of which Charles Davenport was a co editor, gave him the opportunity to use the skills that he had learned. Davenport became an advocate of the biometrical approach for the rest of his life.[2] He began to study human heredity, and much of his effort was later turned to promoting eugenics.[8] His 1911 book, Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, was used as a college textbook for many years. The year after it was published Davenport was elected to the National Academy of Sciences. Davenport's work with eugenics caused much controversy among many other eugenicists and scientists. Although his writings were about eugenics, their findings were very simplistic and out of touch with the findings from genetics. This caused much racial and class bias. Only his most ardent admirers regarded it as truly scientific work.[2] During Davenport's tenure at Cold Spring Harbor, several reorganizations took place there. In 1918 the Carnegie Institution of Washington took over funding of the ERO with an additional handsome endowment from Mary Harriman.[2] Davenport was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1907.[9] In 1921 he was elected as a Fellow of the American Statistical Association.[10] Davenport founded the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations (IFEO) in 1925, with Eugen Fischer as chairman of the Commission on Bastardization and Miscegenation (1927). Davenport aspired to found a World Institute for Miscegenations, and "was working on a 'world map' of the 'mixed-race areas,[11] which he introduced for the first time at a meeting of the IFEO in Munich in 1928."[12] |

経歴 その後、ハーバード大学の動物学教授となる。彼は当時最も著名なアメリカ人生物学者の一人となり、新しい定量的な分類法の基準を開拓した。ダベンポート は、ゴルトンとカール・ピアソンが開拓した生物進化論的アプローチに多大な敬意を払い、ピアソンの雑誌『バイオメトリカ』にも関わっていた。しかし、グレ ゴール・メンデルの遺伝の法則が再発見されると、彼はメンデル遺伝の著名な支持者に転じた。 1899年から1904年まで、ダベンポートはシカゴに勤務した。1901年から1904年までシカゴ大学動物学博物館の学芸員であった[5]。 1904年[2]、コールドスプリングハーバー研究所の所長となり、1910年には優生学記録局を設立した[6]。コールドスプリングハーバー研究所にい た頃、ダベンポートは人間の性格や精神的特徴の遺伝の側面について一連の調査を開始し、何年にもわたってアルコール中毒、ペラグラ(後にビタミン不足によ ることが判明)、犯罪性、気弱さ、船乗り気質、悪性、知能、躁鬱、人種交配の生物学的効果などの遺伝について数百の論文と数冊の本を作成した[2]。 [さらに、ダベンポートは研究所で働きながら、マサチューセッツ州の参政権論者、クレイボーン・カトリン・エリマンなど多くの人々を指導した[7]。 チャールズ・ダベンポートは優生学に出会う以前、数学を研究していた。彼は、カール・ピアソン教授と紳士的なアマチュアのフランシス・ゴルトンによって、 これらのテーマを知ることになる。彼はロンドンで彼らに出会った。彼らに会うと、彼はそのテーマに惚れ込んでしまった。1901年、ダベンポートが共同編 集者を務めていた雑誌「バイオメトリカ」が、彼が学んだ技術を生かす機会を与えてくれた。1911 年に出版された著書『優生学に関連する遺伝』は、長年にわたり大学の教科書として使用された[8]。出版された翌年、ダベンポートは全米科学アカデミーに 選出された。ダベンポートの優生学に関する研究は、他の多くの優生学者や科学者の間で多くの論争を引き起こした。彼の著作は優生学に関するものであった が、その発見は非常に単純で、遺伝学からの知見とはかけ離れたものであった。そのため、多くの人種的、階級的偏見が生じた。彼の熱烈な崇拝者だけが、これ を真に科学的な仕事とみなしていた[2]。 ダベンポートがコールド・スプリング・ハーバーに在任中、そこでいくつかの組織再編成が行われた。1918年にはカーネギーワシントン研究所がメアリー・ ハリマンから多額の寄付を受け、EROの資金調達を引き継いだ[2]。 1907年にアメリカ哲学協会に選出され、1921年にはアメリカ統計協会のフェローに選出された[9]。 1925年に優生学機関国際連合(IFEO)を設立し、オイゲン・フィッシャーが「バスタード化と混血に関する委員会」(1927年)の委員長を務めていた。ダベンポートは世界混血研究所の設立を志し、「『混血地域』の『世界地図』に取り組んでおり[11]、1928年にミュンヘンで開かれたIFEOの会議で初めてそれを紹介した」[12]。 |

| Together

with his assistant Morris Steggerda, Davenport attempted to develop a

comprehensive quantitative approach to human miscegenation. The results

of their research was presented in the book Race Crossing in Jamaica

(1929), which attempted to provide statistical evidence for biological

and cultural degradation following interbreeding between white and

black populations. Today it is considered a work of scientific racism,

and was criticized in its time for drawing conclusions which stretched

far beyond (and sometimes counter to) the data it presented.[13]

Particularly caustic was the review of the book published by Karl

Pearson at Nature, where he considered that "the only thing that is

apparent in the whole of this lengthy treatise is that the samples are

too small and drawn from too heterogeneous a population to provide any

trustworthy conclusions at all".[14] The entire eugenics movement was

criticized for being supposedly based on racist and classist

assumptions set out to prove the unfitness of wide sections of the

American population which Davenport and his followers considered

"degenerate", using methods criticized even by British eugenicists as

unscientific.[15][clarification needed] In 1907 and 1910 Charles

Davenport and his wife wrote four essays that pertained to human

hereditary genes. These essays included hair color, eye color, and skin

pigmentation. These essays helped pave the way for eugenics to be

taught in class. Many of the topics and discussions belonged to Dr. and

Mrs. Charles Davenport but the information for one essay in particular

came from friends of theirs involved in the same topic. Many problems

occurred when they started to use other information. As Davenport and

other eugenicist professors and experts began to and continued to study

more in-depth eugenics, they had to start to come up with original

ideas so as not to conflict with past ideas.[2] |

ダ

ベンポートは、助手のモリス・ステッガーダとともに、人間の異種交配に関する包括的な定量的アプローチを開発しようとした。その研究成果は、『ジャマイカ

における人種交雑』(1929年)として発表され、白人と黒人の交雑に伴う生物学的・文化的劣化を統計的に証明しようとしたものであった。今日、この本は

科学的人種差別の作品とみなされており、当時は提示したデータをはるかに超えた(時にはそれに反する)結論を導き出したとして批判された[13]。 特

に辛辣だったのはカール・ピアソンがネイチャー誌に発表したこの本のレビューで、彼は「この長い論文全体から明らかになる唯一のことは、信頼できる結論を

まったく提供するにはサンプルがあまりにも少なく、あまりにも不均質な集団から抽出されているということ」であると主張した[14]。

[14]

優生学運動全体は、ダベンポートとその信奉者が「退廃的」とみなしたアメリカの人口の広い部分の不適性を証明するために、人種差別的、階級差別的な仮定に

基づいているとされ、イギリスの優生学者にさえ非科学的と批判された方法を使っていると批判された[15][clarification

needed]

1907年と1910年にチャールズダベンポートとその妻は人間の遺伝遺伝子に関する4つのエッセーを書いている。これらのエッセイには、髪の色、目の

色、皮膚の色素沈着が含まれていた。これらのエッセイは、優生学が授業で教えられるようになるための道を開く助けとなった。このエッセイの多くは、ダベン

ポート夫妻のものであったが、特にあるエッセイのための情報は、同じテーマに取り組んでいた夫妻の友人から得たものであった。しかし、それ以外の情報を使

い始めると、いろいろと問題が出てくる。ダベンポートをはじめとする優生学主義者の教授や専門家が優生学をより深く研究し始めると、過去の考えと矛盾しな

いように、独自の考えを持ち始める必要があったのである[2]。 |

| Influence on immigration policy in the United States Another way Charles Davenport's work manifested in the public sphere is regarding the topic of immigration. He believed that race determined behavior, and that many mental and behavioral traits were hereditary.[1] He drew these conclusions by studying family pedigrees, and was criticized by some of his peers for making unfounded conclusions.[1] Regardless, Davenport believed that the biological differences between the races justified a strict immigration policy, and that people of races deemed “undesirable” should not be allowed into the country.[16] His support of Mendelian genetics fueled this belief, as he believed allowing certain groups of people to enter the country would negatively impact the nation's genetic pool. Domestically, he also supported the prevention of "negative eugenics" through sterilization and sexual segregation of people who were considered genetically inferior. Sharing the racist views of many scientists during this time, those that Davenport considered to be genetically inferior included Black people and Southeastern Europeans.[1] In addition to supporting these beliefs through his scientific work, he was actively involved in lobbying members of Congress. Charles Davenport spoke regularly with Congressman Albert Johnson, who was a cosponsor of the Immigration Act of 1924, and encouraged him to restrict immigration in that legislation. Davenport was not alone in this effort to influence policy, as Harry Laughlin, the superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office, appeared before Congress on multiple occasions to promote strict immigration laws and the belief that immigration was a "biological problem".[16] In all, Davenport’s efforts served to provide scientific justification to social policies he supported, and immigration was one way this manifested in the beginning of the 20th century. |

アメリカの移民政策への影響 ダベンポートは、人種が行動を決定し、精神的、行動的特徴は遺伝すると考えていた[1]。彼は、人種が行動を決定し、多くの精神的、行動的特徴が遺伝する と信じていた[1]。彼は家族の血統を研究することによってこれらの結論を導き出し、根拠のない結論を出したとして一部の仲間から批判された。 [それにもかかわらず、ダベンポートは、人種間の生物学的差異が厳格な移民政策を正当化し、「好ましくない」とみなされる人種の人々を入国させるべきでは ないと考えていた[16]。彼はメンデル遺伝学を支持しており、特定のグループの人々の入国を認めることは国家の遺伝子プールにマイナスの影響を与えると 考え、この信念に拍車をかけていた。国内では、遺伝的に劣っていると考えられる人々の不妊手術や性的隔離による「負の優生学」の防止も支持した。ダベン ポートが遺伝的に劣っていると考えたのは、黒人や南東ヨーロッパ人など、この時代の多くの科学者の人種差別的な考え方に共通するものであった[1]。 科学的な研究を通してこれらの信念を支持するだけでなく、彼は議会議員へのロビー活動にも積極的に参加した。チャールズ・ダベンポートは、1924年の移 民法の共同提案者であった下院議員アルバート・ジョンソンと定期的に話をし、その法律で移民を制限するように勧めた。優生学記録局の管理者であったハ リー・ラフリンは、何度も議会に出席し、厳格な移民法と移民は「生物学的問題」であるという信念を推進した[16]。 全体として、ダベンポートの取り組みは、彼が支持する社会政策に科学的正当性を与える役割を果たし、移民は20世紀初頭にこれが現れた一つの方法だったの である。 |

| End of career and impact After Adolf Hitler's rise to power in Germany, Davenport maintained connections with various Nazi institutions and publications, both before and during World War II. He held editorial positions at two influential German journals, both of which were founded in 1935, and in 1939 he wrote a contribution to the Festschrift for Otto Reche, who became an important figure in the plan to "remove" those populations considered "inferior" in eastern Germany.[17] In a 1938 Letter to the Editor of Life magazine, he included both Franklin Roosevelt and Joseph Goebbels as examples of crippled statesmen who, motivated by their physical defects, have "led revolutions and aspired to dictatorships while burdening their country with heavy taxes and reducing its finances to chaos."[18] Although many other scientists had stopped supporting eugenics due to the rise of Nazism in Germany, Charles Davenport remained a fervent supporter until the end of his life. Six years after he retired in 1934, Davenport held firm to these beliefs even after the Carnegie Institute pulled funding from the eugenics program at Cold Spring Harbor in 1940.[3] While Charles Davenport is remembered primarily for his role in the eugenics movement, he also had a significant influence in increasing funding for genetics research. His success in organizing the financial support for scientific endeavors fueled his success throughout his career, while also allowing for the study of other scientists.[16] Indeed, Cold Spring Harbor saw many prominent geneticists go through its doors while he was its director. He died of pneumonia in 1944 at the age of 77. He is buried in Laurel Hollow, New York.[19] |

キャリアの終焉と影響 アドルフ・ヒトラーがドイツで権力を握った後、ダベンポートは第二次世界大戦の前も後も、ナチスのさまざまな機関や出版物とつながりを持ち続けた。 1939年には、東ドイツで「劣等」とされる人々を「排除」する計画の重要人物となったオットー・レチェの記念誌に寄稿している[17]。 [1938年の『ライフ』誌の編集者への手紙の中で、彼はフランクリン・ルーズベルトとヨーゼフ・ゲッベルスの両者を、身体的欠陥に動機づけられて「革命 を起こし、独裁を志す一方で、国に重税を課し、財政を混沌に陥れた」不具の政治家の例として取り上げている[17]。 ドイツにおけるナチズムの台頭により、他の多くの科学者が優生学の支持をやめた中、チャールズ・ダベンポートは最後まで熱烈な支持者であり続けた。 1934年に引退して6年後、1940年にカーネギー研究所がコールドスプリングハーバーの優生学プログラムから資金を引き上げた後も、ダベンポートはこ の信念を堅持した[3]。 チャールズ・ダベンポートは主に優生学運動における役割で記憶されているが、遺伝学研究に対する資金援助の増加にも大きな影響を及ぼした。科学的な試みに 対する財政的な支援を組織することに成功したことが、彼のキャリアを通じての成功を後押しし、また他の科学者の研究を可能にした[16]。 実際、彼が所長を務めていた間、コールドスプリングハーバーでは多くの著名な遺伝学者がその門をくぐっている。1944年、肺炎のため77歳で死去。 ニューヨーク州ローレル・ホロウに埋葬されている[19]。 |

| Eugenics creed As quoted in the National Academy of Sciences' "Biographical Memoir of Charles Benedict Davenport" by Oscar Riddle, Davenport's Eugenics creed was as follows:[20] "I believe in striving to raise the human race to the highest plane of social organization, of cooperative work and of effective endeavor." "I believe that I am the trustee of the germ plasm that I carry; that this has been passed on to me through thousands of generations before me; and that I betray the trust if (that germ plasm being good) I so act as to jeopardize it, with its excellent possibilities, or, from motives of personal convenience, to unduly limit offspring." "I believe that, having made our choice in marriage carefully, we, the married pair, should seek to have 4 to 6 children in order that our carefully selected germ plasm shall be reproduced in adequate degree and that this preferred stock shall not be swamped by that less carefully selected." "I believe in such a selection of immigrants as shall not tend to adulterate our national germ plasm with socially unfit traits." "I believe in repressing my instincts when to follow them would injure the next generation." |

優生学の信条 全米科学アカデミーのオスカー・リドルによる「チャールズ・ベネディクト・ダベンポートの伝記」に引用されているように、ダベンポートの優生学の信条は次のようなものであった[20]。 "私は、人類を社会組織、協同作業、効果的な努力の最高位に引き上げる努力をすることを信じる。" 「私は、自分が持っている生殖質の受託者であり、これは私より前の何千もの世代を通じて私に受け継がれてきたものであり、(その生殖質が良好であるとし て)私がその優れた可能性を危険にさらすような、あるいは個人の便宜という動機から子孫を不当に制限するような行動をとるならば、その信用を裏切ることに なると信じている」[20]。 「慎重に結婚を選択した私たち夫婦は、慎重に選択した遺伝子形質が適切に再生産され、この優先株が慎重に選択されていないものに駆逐されないように、4~6人の子供を持つことを目指すべきであると信じています。 "社会的に不適当な形質を持つ者を""排除するために""移民を選別する""私はそう信じている" "私は、本能に従えば次の世代を傷つけることになる場合、それを抑制することを信じます。" |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Davenport |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| the Eugenics Record Office (ERO) , 1910-1939 in the History of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Between 1910 and 1939, the laboratory was the base of the Eugenics Record Office (ERO) of biologist Charles B. Davenport and his assistant Harry H. Laughlin, two prominent American eugenicists of the period. Davenport was director of the Carnegie Station from its inception until his retirement in 1934. In 1935 the Carnegie Institution sent a team to review the ERO's work, and as a result the ERO was ordered to stop all work. In 1939 the Institution withdrew funding for the ERO entirely, leading to its closure. The ERO's reports, articles, charts, and pedigrees were considered scientific facts in their day, but have since been discredited. Its closure came 15 years after its findings were incorporated into the National Origins Act (Immigration Act of 1924), which severely reduced the number of immigrants to America from southern and eastern Europe who, Harry Laughlin testified, were racially inferior to the Nordic immigrants from England and Germany. Charles Davenport was also the founder and the first director of the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations in 1925. Today, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory maintains the full historical records, communications and artifacts of the ERO for historical,[22] teaching and research purposes. The documents are housed in a campus archive and can be accessed online[23] and in a series of multimedia websites.[24] History of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) |

コールド・スプリング・ハーバー研究所の歴史の中の優生学記録室(ERO), 1910-1939 1910年から1939年にかけて、この研究所は生物学者チャールズ・B・ダベン ポートとその助手ハリー・H・ラフリンの優生学記録室(ERO)の拠点であった。ダベンポートは、カーネギーステーションの設立から1934年の退任まで 所長を務めた。1935年、カーネギー研究所はEROの仕事を見直すためのチームを送り、その結果EROはすべての仕事を停止するよう命じられた。 1939年、カーネギー研究所はEROへの資金援助を打ち切り、EROは閉鎖された。EROの報告書、論文、図表、血統書は、当時は科学的事実とみなされ ていたが、その後、信用を失墜させることになった。この法律は、南ヨーロッパと東ヨーロッパからのアメリカへの移民を厳しく制限するもので、ハリー・ラフ リンは、イギリスとドイツからの北欧系移民より人種的に劣っていると証言している。また、チャールズ・ダベンポートは、1925年に優生学国際連盟機関(IFEO) を設立し、初代理事長に就任した。現在、コールドスプリングハーバー研究所は、歴史的、教育的、研究的目的のために、EROの歴史的記録、通信、遺物をす べて維持している[22]。これらの文書はキャンパス内のアーカイブに保管されており、オンライン[23]や一連のマルチメディアウェブサイトでアクセス することができる[24]。 History of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報