チカーナ・フェミニズム

Chicana feminism

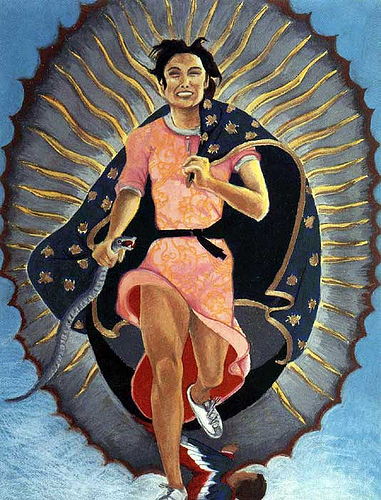

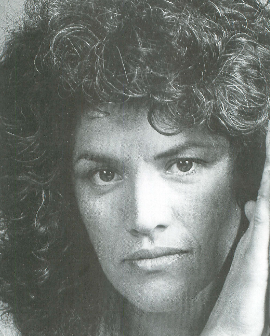

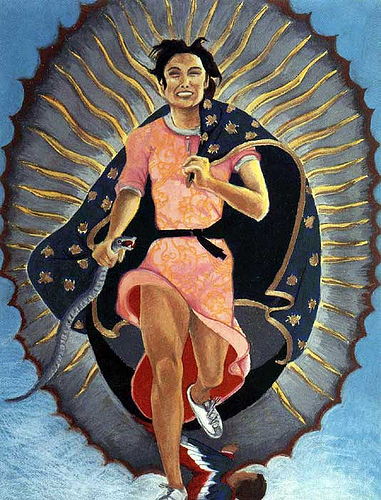

Yolanda

Lopez's 1978 rendition of La Virgen de Guadalupe, titled 'Portrait of

the Artist as the Virgen of Guadalupe.'

☆ チカーナ・フェミニズムは、米国のチカーナおよびチカーナ/oコミュニティに影響を与える歴史的、文化的、精神的、教育的、経済的な交差点を精査する社会 政治運動、理論、実践である。[1] チカーナ・フェミニズムは、制度化された社会規範に立ち向かう力を女性に与え、コミュニティにおける女性の抑圧の終結のために戦う者をフェミニストとみな す。[1][2] チカーノ・フェミニズムは、1960年代から1970年代にかけてのチカーノ運動と第二波フェミニズム運動の狭間で、女性たちが自分たちの存在意義を取り 戻すことを奨励した。[1] チカーノ・フェミニストたちは、女性たちに力を与えることがチカーノ/oコミュニティに力を与えることを認識していたが、日常的に反対に直面していた。 [1][3] チカーノ・レズビアン・フェミニストたちを含むこの分野における重要な発展は、従来の理解を超えてチカーノの限定的な考え方を拡大した。[3] 1994年にアナ・キャスティージョが提唱した「Xicanisma」は、チカーノ・フェミニズムを再活性化し、チカーノ運動以降に生じた意識の変化を認 識するための重要な介入策として形成された。これは、チカニズモの延長および拡大として位置づけられている。[6] これは、 。 チカーノのアイデンティティの形成に影響を与えた。[7] チカーノの芸術、文学、詩、音楽、映画などのチカーノ文化の作品は、新たな方向性でチカーノフェミニズムを形成し続けている。[8] チカーノフェミニズムは、脱植民地フェミニズムとの関連で語られることが多い。[9][10]

| Chicana feminism is

a sociopolitical movement, theory, and praxis that scrutinizes the

historical, cultural, spiritual, educational, and economic

intersections impacting Chicanas and the Chicana/o community in the

United States.[1] Chicana feminism empowers women to challenge

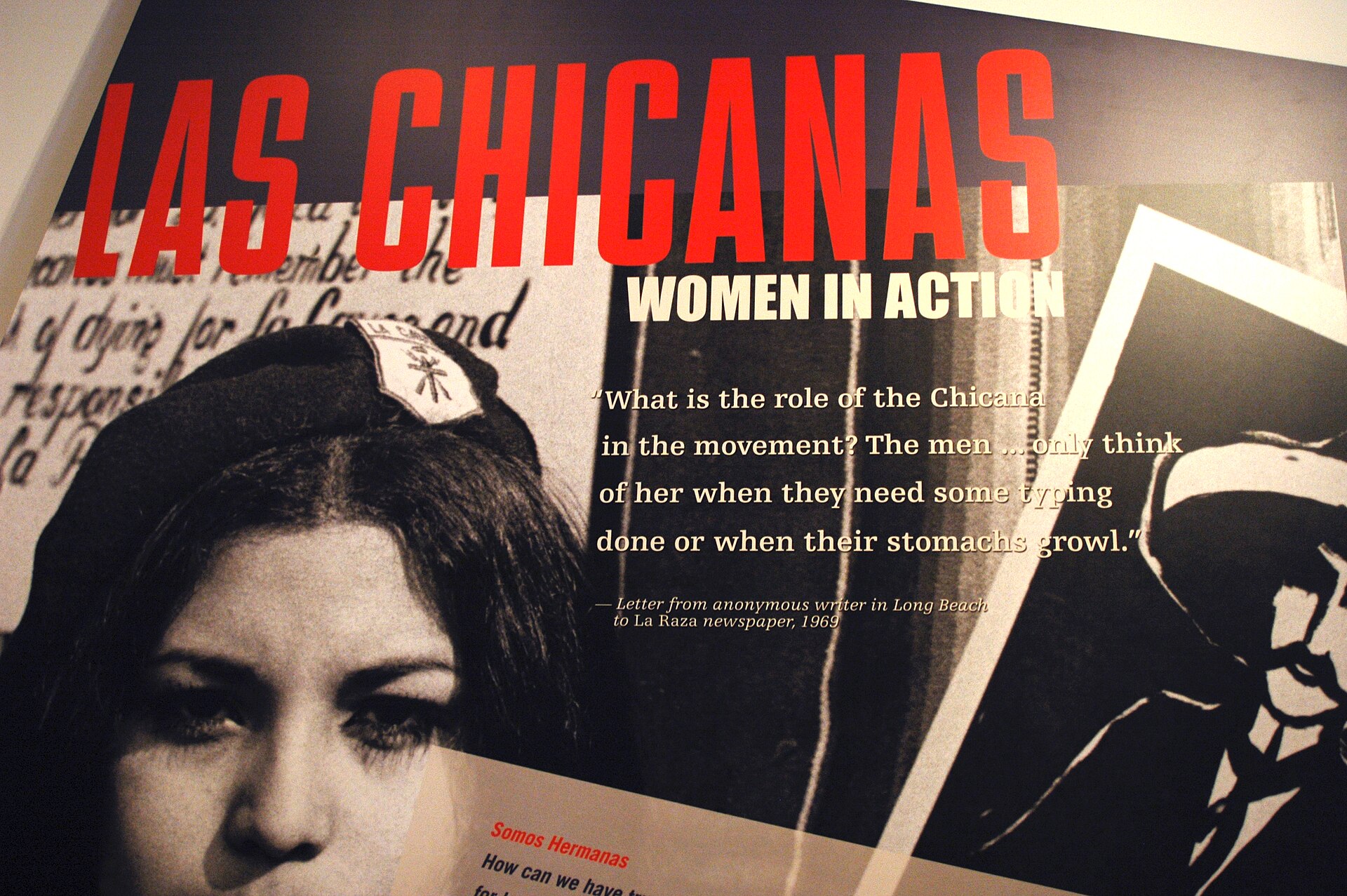

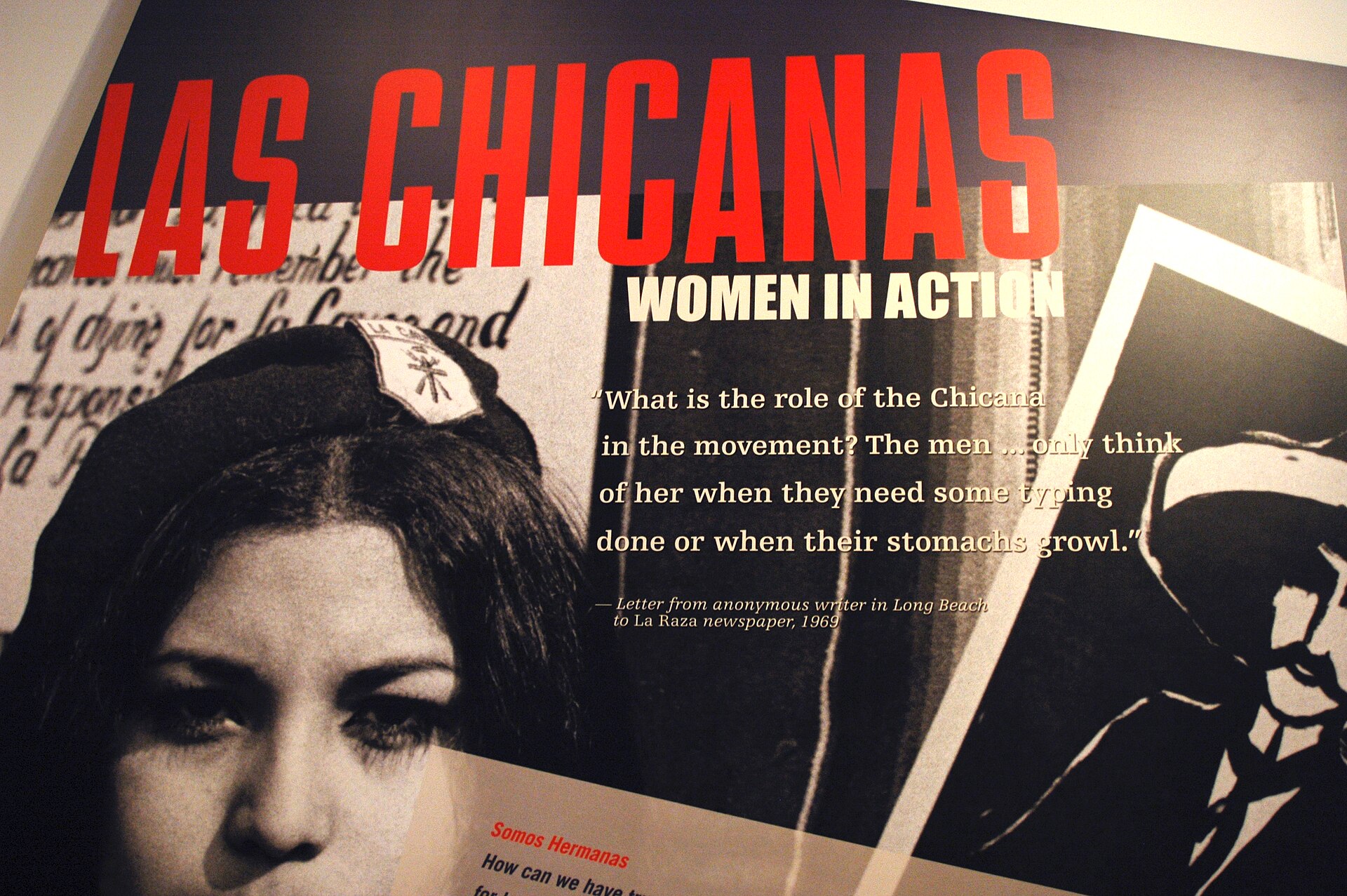

institutionalized social norms and regards anyone a feminist who fights

for the end of women's oppression in the community.[1][2] Chicana feminism encouraged women to reclaim their existence between and among the Chicano Movement and second-wave feminist movements from the 1960s to the 1970s.[1] Chicana feminists recognized that empowering women would empower the Chicana/o community, yet routinely faced opposition.[1][3] Critical developments in the field, including from Chicana lesbian feminists, expanded limited ideas of the Chicana beyond conventional understandings.[3] Xicanisma formed as a significant intervention developed by Ana Castillo in 1994 to reinvigorate Chicana feminism and recognize a shift in consciousness that had occurred since the Chicano Movement,[4][5] as an extension and expansion of Chicanismo.[6] It partly inspired the formation of Xicanx identity.[7] Chicana cultural productions, including Chicana art, literature, poetry, music, and film continue to shape Chicana feminism in new directions.[8] Chicana feminism is often placed in conversation with decolonial feminism.[9][10]  Las Chicanas Poster at LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes |

チカーナ・フェミニズムは、米国のチカーナおよびチカーナ/oコミュニ

ティに影響を与える歴史的、文化的、精神的、教育的、経済的な交差点を精査する社会政治運動、理論、実践である。[1]

チカーナ・フェミニズムは、制度化された社会規範に立ち向かう力を女性に与え、コミュニティにおける女性の抑圧の終結のために戦う者をフェミニストとみな

す。[1][2] チカーノ・フェミニズムは、1960年代から1970年代にかけてのチカーノ運動と第二波フェミニズム運動の狭間で、女性たちが自分たちの存在意義を取り 戻すことを奨励した。[1] チカーノ・フェミニストたちは、女性たちに力を与えることがチカーノ/oコミュニティに力を与えることを認識していたが、日常的に反対に直面していた。 [1][3] チカーノ・レズビアン・フェミニストたちを含むこの分野における重要な発展は、従来の理解を超えてチカーノの限定的な考え方を拡大した。[3] 1994年にアナ・カスティージョが提唱した「Xicanisma」は、チカーノ・フェミニズムを再活性化し、チカーノ運動以降に生じた意識の変化を認 識するための重要な介入策として形成された。これは、チカニズモの延長および拡大として位置づけられている。[6] これは、 。 チカーノのアイデンティティの形成に影響を与えた。[7] チカーノの芸術、文学、詩、音楽、映画などのチカーノ文化の作品は、新たな方向性でチカーノフェミニズムを形成し続けている。[8] チカーノフェミニズムは、脱植民地フェミニズムとの関連で語られることが多い。[9][10]  Las Chicanas Poster at LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes |

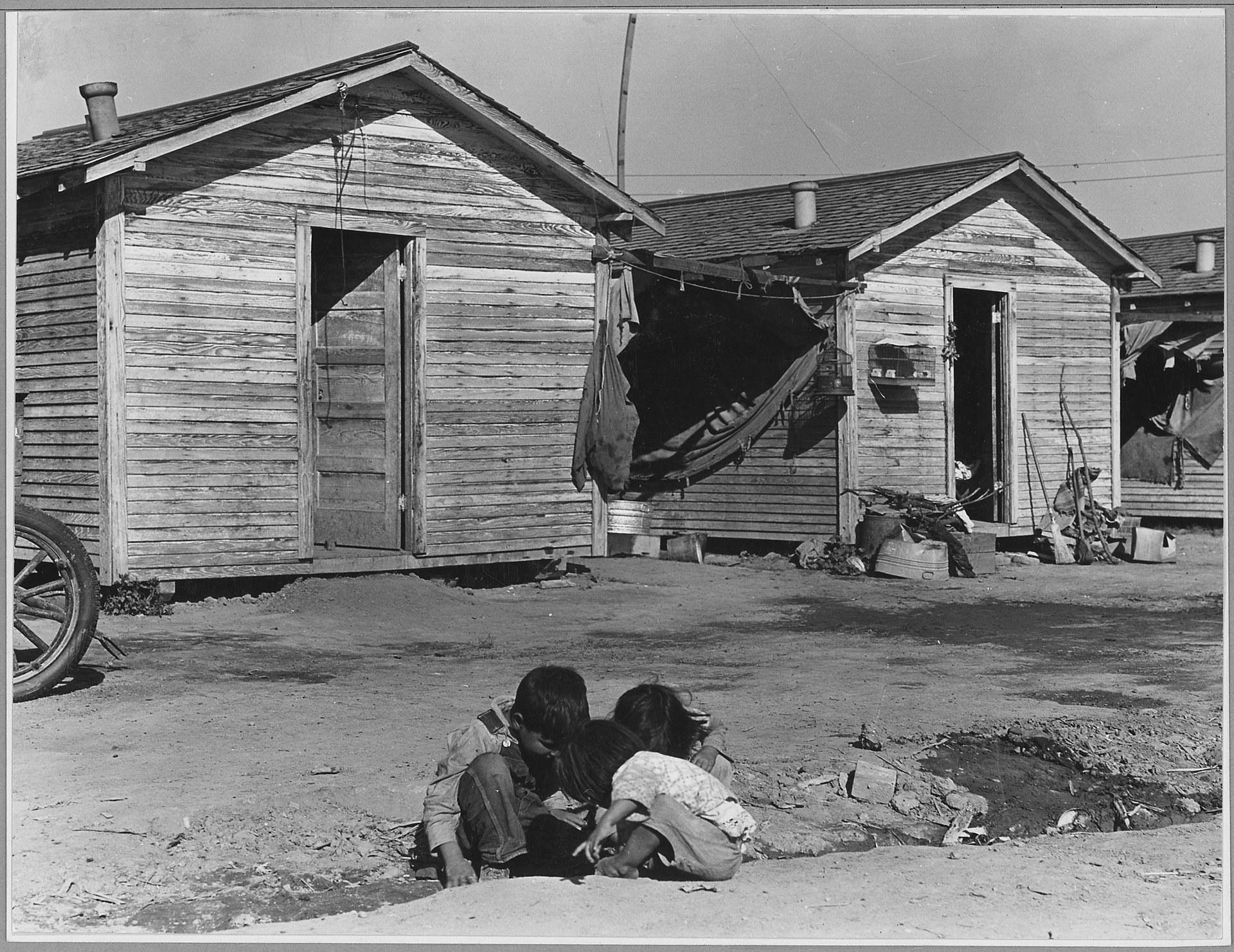

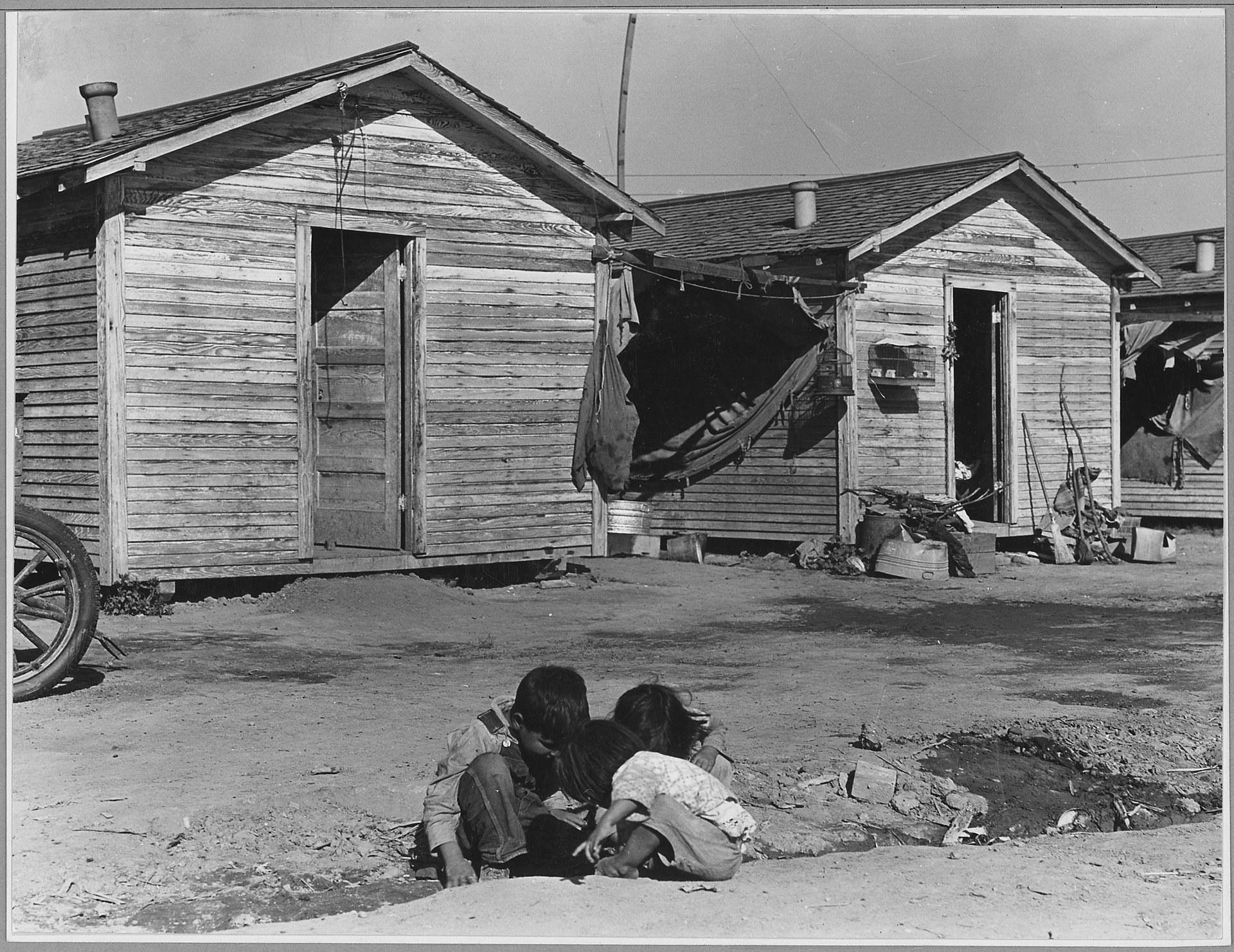

Background Mexican children in a segregated company housing facility in Corcoran, California (1940)[11] Some Mexican American women were involved in the early women's suffrage movement. In the early twentieth century, this included women such as Adelina Otero-Warren and Maria de G.E. Lopez.[12][13] Otero-Warren was born in an elite Hispano family.[12] Most Mexican Americans, especially of low-income and non-white complexion, who did not grow up in elite families were subject to much different conditions.[11][14]  Mendez v. Westminster (1947) overturned de jure racial segregation in schools. The case was initiated when Sylvia Mendez (pictured) was turned away from enrolling at a "white school." Mexican American children, especially of darker skin, were only permitted to learn manual skills education, while white schools taught academic preparation. At the "Mexican schools," girls were only taught sewing and homemaking.[14] Prior to the late 1940s, Mexican American children often grew up in segregated colonias in company towns for the agricultural industry. Mexican children, especially of darker skin, were only allowed by the U.S. government to attend segregated "Mexican schools." While white schools taught academic preparation, girls at "Mexican schools" were only permitted to be taught homemaking and sewing, while boys were taught gardening and bootmaking. This maintained class and income divisions.[11][14] De jure racial segregation was overturned in 1947 with Mendez vs. Westminster, yet segregation still continued in practice in many areas because of continuing racist attitudes and anti-Mexican sentiment.[14]  Pachucas are often ignored in narratives of Mexican American history because of their challenge to gender norms and were treated as "dangerously masculine [and] monstrously feminine."[15] Pachucas, who were the counterpart to Pachucos in the 1940s, have sometimes been reframed through a feminist lens because of their challenge to gender norms, especially during World War II.[15] The Pachuca is often not a celebrated figure in Mexican American history, in Chicano cultural production, or even in Chicana feminist discourse, which has been ascribed to the way Pachucas challenged the role of the woman in the traditional family. Pachucas would often arm themselves with self-defense weapons, prepared to ward off potential attackers.[16] The Pachuca was treated as "dangerously masculine [and] monstrously feminine."[15] Women who reject Chicana identity and prefer to identify themselves as Hispanic may "not see or want to recognize herself" in the Pachuca figure.[17] Unlike women of color, white women rarely had to deal with racism. European-American or white women combated sexism in the white community through waves of feminism; the first wave addressing women's suffrage, and the second wave addressing issues of sexuality, public vs. private spheres, reproductive rights, and marital rape. However, women of color were largely excluded from these movements. This urged Chicanas who were feminists and sought to empower women to offer critiques and responses to their exclusion from both the mainstream Chicano nationalist movement and the second wave feminist movement, which formed the basis of Chicana feminism by the 1960s.[18][19] |

背景 カリフォルニア州コルコランの隔離された企業住宅施設に暮らすメキシコ系アメリカ人の子供たち(1940年)[11] 初期の女性参政権運動には、メキシコ系アメリカ人の女性も参加していた。20世紀初頭には、アデリーナ・オテロ・ウォーレンやマリア・デ・G・E・ロペス などの女性が関与していた。[12][13] オテロ・ウォーレンはエリートヒスパニック系家庭に生まれた。[12] ほとんどのメキシコ系アメリカ人、特にエリート家庭で育たなかった低所得者層や白人でない人々は、かなり異なる状況に置かれていた。[11][14]  メンデス対ウェストミンスター(1947年)は、学校における法的な人種隔離を覆した。この訴訟は、シルヴィア・メンデス(写真)が「白人学校」への入学 を拒否されたことから始まった。メキシコ系アメリカ人の子供たちは、特に肌の色が濃い子供たちは、実用的な技術を教える教育しか許されず、白人学校では学 問の準備を教える教育が行われていた。「メキシコ人学校」では、女の子は裁縫と家事しか教えられなかった。 1940年代後半以前、メキシコ系アメリカ人の子供たちは、農業産業の企業城下町にある分離されたコロニアで育つことが多かった。メキシコ人の子供たち は、特に肌の色が濃い子供たちは、米国政府によって分離された「メキシコ人学校」への通学しか認められていなかった。白人学校では学業準備教育が行われて いたが、「メキシコ人学校」では女子生徒には家庭科と裁縫しか認められておらず、男子生徒には園芸と靴作りが教えられていた。これにより、階級と収入の格 差が維持された。[11][14] 1947年のメンデス対ウェストミンスター訴訟により、法的な人種隔離は覆されたが、人種差別的な態度や反メキシコ感情が根強く残っていたため、多くの地 域では依然として隔離が実質的に続いた。[14]  パチューカは、ジェンダー規範に挑戦したため、メキシコ系アメリカ人の歴史の語りではしばしば無視され、「危険なほど男らしく、怪物のように女らしい」と扱われた。[15] 1940年代のパチューカは、パチューコの対極に位置する存在であり、第二次世界大戦中には特に、ジェンダー規範に異議を唱えたため、フェミニストの視点 から再評価されることもあった。[15] パチューカは、メキシコ系アメリカ人の歴史やチカーノ文化の生産、あるいはチカーノのフェミニストの議論においても、あまり脚光を浴びる存在ではない。こ れは、パチューカが伝統的な家族における女性の役割に異議を唱えたことによるものである。パチューカは、潜在的な攻撃者を撃退する準備として、護身用の武 器を携帯することが多かった。[16] パチューカは「危険なほど男性的で、怪物のように女性的」とみなされていた。[15] チカーナとしてのアイデンティティを拒否し、ヒスパニックとして自らを認識することを好む女性は、パチューカの姿に「自分自身を見出せない、あるいは見出 したくない」かもしれない。[17] 有色人種の女性とは異なり、白人女性は人種差別と向き合うことはほとんどなかった。ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人または白人女性は、フェミニズムの波を通じて白 人社会の性差別と闘った。第一波は女性の参政権、第二波はセクシュアリティ、公的領域と私的領域、生殖に関する権利、婚姻内レイプなどの問題に取り組ん だ。しかし、有色人種の女性たちはこれらの運動からほとんど排除されていた。このため、フェミニストであり、女性の地位向上を求めるチカーナたちは、主流 のチカーノ民族主義運動と、1960年代までにチカーナフェミニズムの基礎を形成した第二波フェミニズム運動の両方から排除されたことへの批判と対応を提 示する必要に迫られた。[18][19] |

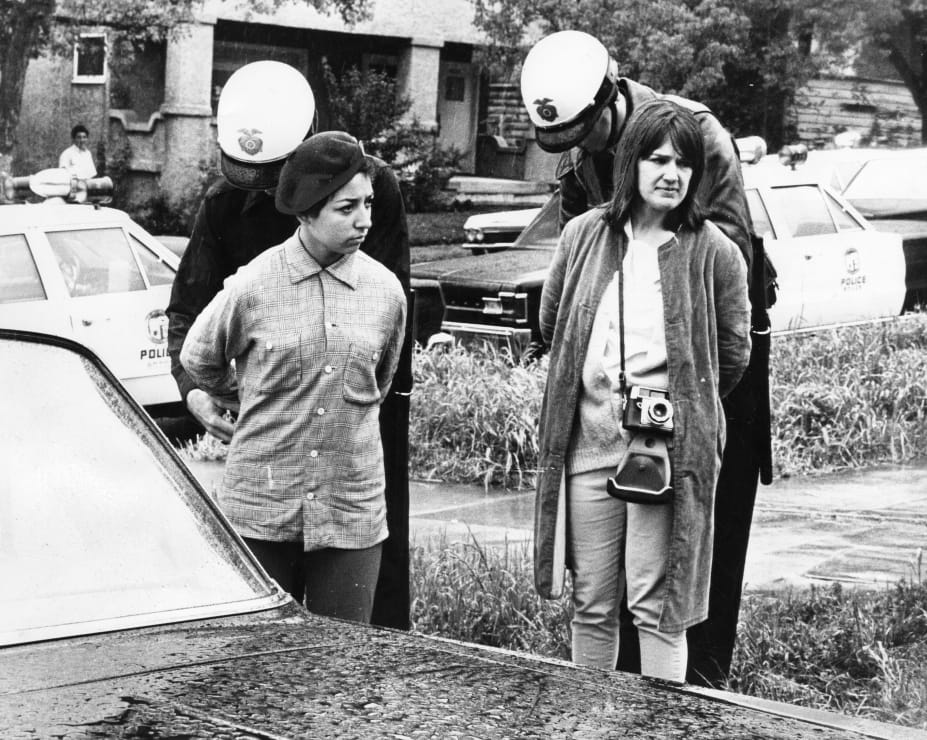

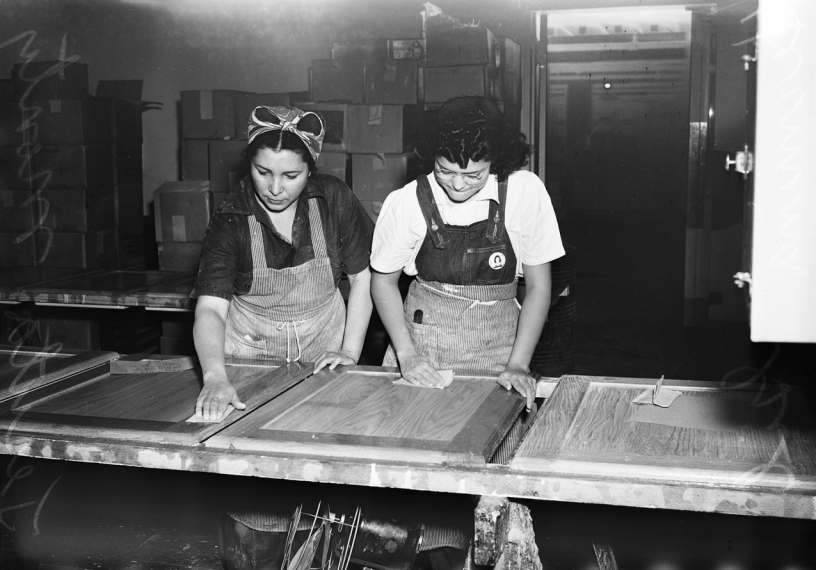

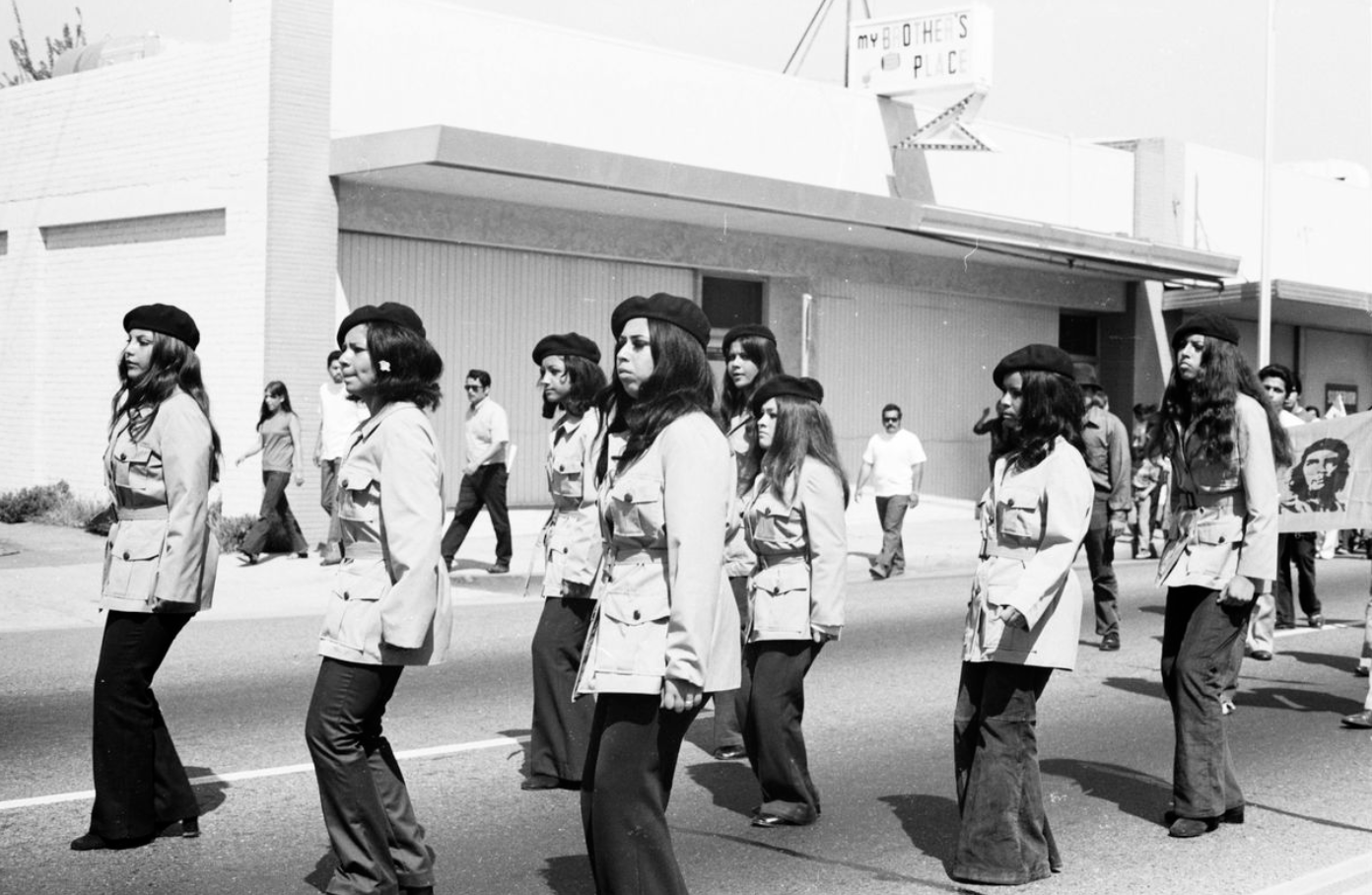

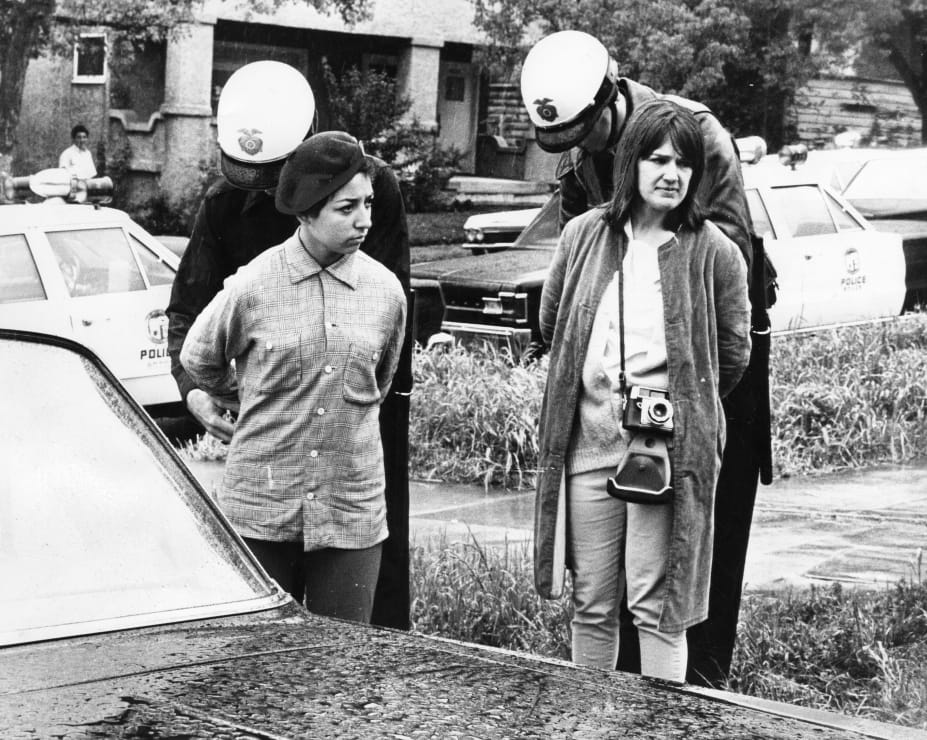

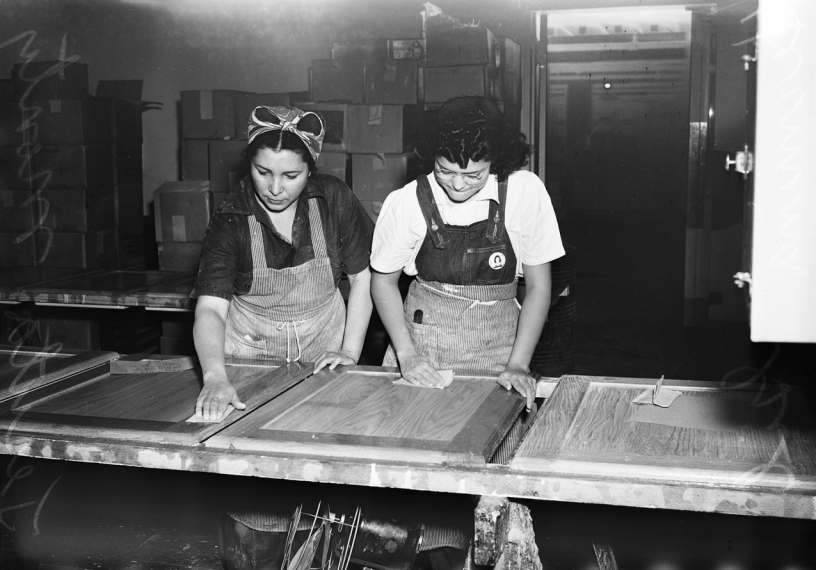

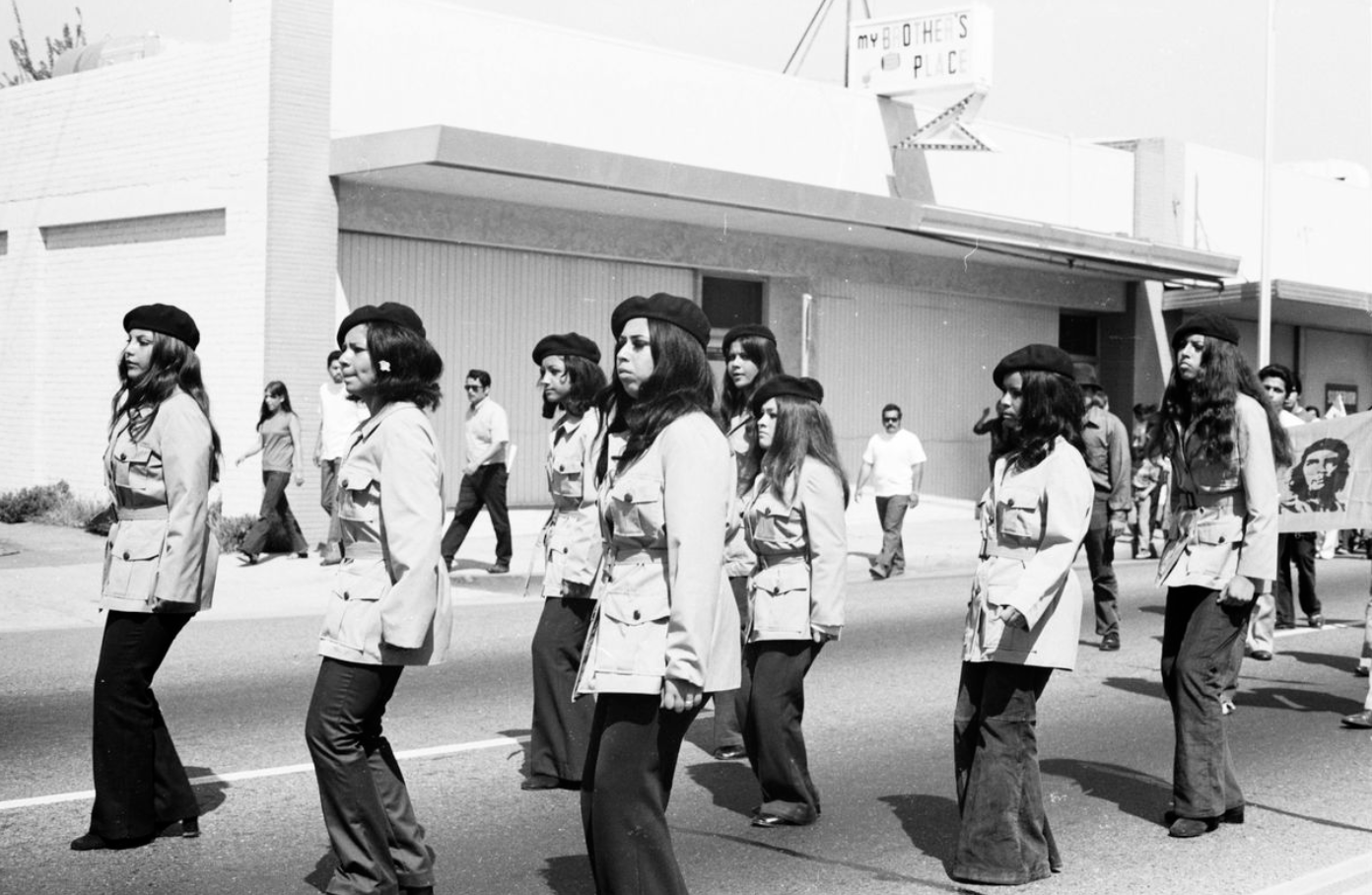

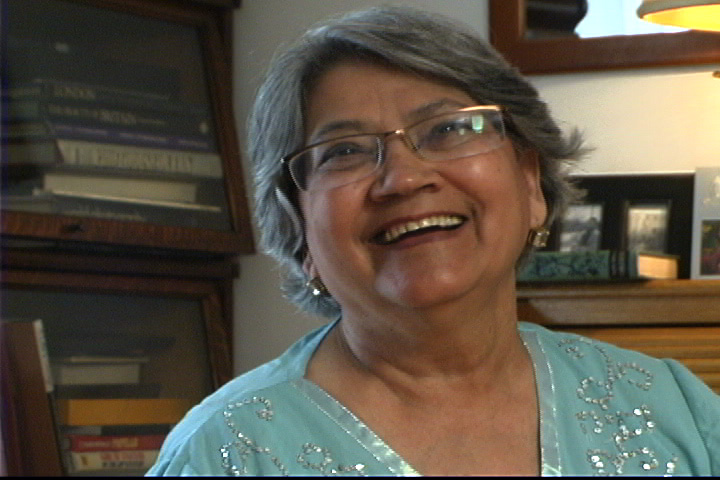

| Timeline Chicanas in the Chicano Movement (1960s–1970s)  A young woman talking with a group of young men in El Segundo Barrio, El Paso (1971) Although the Chicano Movement was organized toward empowering the greater Mexican American community, the narratives and focus of the Movement largely ignored the women that were involved with organizing during this period of civil disobedience.[20][3] Throughout these events, Chicana feminists collectively realized the importance of connecting issues of gender with the other liberatory aims of the Chicano Movement.[21] Chicanas also renounced the mainstream second-wave feminist movement for its inability to include racism and classism in their politics. Chicanas during this time felt excluded from mainstream feminist movements because they had different needs, concerns, and demands. Through persistent objections to their exclusions, women have gone from being called Chicano women to Chicanas to introducing the adoption of a/o or o/a as a way of acknowledging both genders when discussing the community.[1][18] Alma Garcia wrote that the Chicana feminist movement was created to adhere to the specific issues which have affected Chicana women, and originated from their treatment in the Chicano Movement and second-wave feminist movements.[22] They sought to be treated equally and be respected.[22] The Chicana feminist movement influenced many Chicanas to be more active and to defend their rights not just as single women, but as women in solidarity who come together forming a society with equal contribution.[23][24] Chicana walkout organizing (1968)  Founding co-editor of La Raza newspaper Ruth Robinson (right) with Margarita Sanchez at the Belmont High School walkout, part of a series of 1968 student protests for education reform in LA. On March 1, 1968, approximately 15,000 students participated in what became known as the East Los Angeles School Blowouts. Chicano students across seven high schools in the East Los Angeles marched out of their schools in a coordinated protest.[25] Students organized over shared complaints about racism, inadequate funding, and the neglect of Mexican history and culture within current education systems.[26] Male participants of the walkouts received most of the media attention, primarily the thirteen male student organizers who were detained and imprisoned on conspiracy accusations.[25] Dolores Delgado Bernal, a Chicana researcher, claims that by concentrating only on male students, the participation and leadership of girls and women were severely reduced and the efforts required to organize the walkouts were minimized.[26] Later in the mid-1990s, Dolores Delgado Bernal interviewed eight significant female walkout participants or leaders, bringing attention to the women the media had ignored: Celeste Baca, Vickie Castro, Paula Crisostomo, Mita Cuaron, Tanya Luna Mount, Rosalinda M. González, Rachael Ochoa Cervera, and Cassandra Zacarías.[26] The oral histories of these women revealed that they organized community meetings, established connections, between students across various schools and organizations, and published underground newspapers to spread the word of the movement and recruit more student participation and support.[26] National Chicana Conference (1971) A year after the walkouts, the Chicano Youth Liberation Conference was held in 1969. About 1,500 Mexican American teenagers from throughout the country attended the conference, which led to the branding of the words "Chicanismo," "El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán," and MEChA, the nationwide student organization.[27] At the conference, a workshop was arranged to discuss the role of women in the movement and to address feminist concerns. However, the workshop concluded that, "It was the consensus of the group that the Chicana woman does not want to be liberated." Many scholars such as Anna Nieto-Gómez, find this statement to be one of the decisive actions that sparked the Chicana Feminist Movement.[24] Following this statement, the first National Chicana Conference was held in Houston, Texas in May 1971. The conference attracted over 600 women from all over the United States to discuss issues regarding equal access to education, reproductive justice, formation of childcare centers, and more.[28] The conference was organized into nine different workshops: "Sex and the Chicana: Noun and Verb," "Choices for Chicanas: Education and Occupation," "Marriage: Chicana-Style," "Religion," "Feminist Movement - Do We Have a Place in It?," "Exploitation of Women - The Chicana Perspective," "Women in Politics - Is Anyone There," "Militancy/Conservatism: Which Way Is Forward," and "De Colores y Clases: Class and Ethnic Differences."[28] While the event was the first major gathering of its kind, the conference itself was fraught with discord as Chicanas from geographically and ideologically divergent positions sparred over the role of feminism within the Chicano movement. These conflicts led to a walkout on the final day of the conference.[29] According to Anna Nieto-Gómez, "the walkout distinguished the conflict between Chicana feminists and loyalists."[28] Viewed as traitors to the Movement Described as "vendida logic" by scholar Maylei Blackwell, Chicana feminists were often accused of being "vendidas" or traitors to the Chicano movement, described as anti-family, anti-man, and anti-Chicano movement. Alongside vendida, Chicana feminists were called "women's libber," "agringadas," or lesbians. Chicanas who prioritized the Chicano movement and cause were known as Loyalists.[29] Women also sought to battle the internalized struggles of self-hatred rooted in the colonization of their people. This included breaking the mujer buena/mujer mala myth, in which the domestic Spanish Woman is viewed as good and the Indigenous Woman that is a part of the community is viewed as bad. Chicana feminist thought emerged as a response to patriarchy, racism, classism, and colonialism as well as a response to all the ways that these legacies of oppression have become internalized.[30][23] Chicanas in la familia  Mexican American woman washing clothes in San Antonio, Texas (1944) Chicana feminists challenged their prescribed role in la familia, and demanded to have the intersectional experiences that they faced recognized. Chicanas identify as being consciously aware, self-determined, and proud of their roots, heritage, and experience while prioritizing La Raza. With the emergence of the Chicano Movement, the structure of Chicano families saw dramatic changes. Specifically, women began to question the positives and negatives of the established family dynamic and where their place was within the Chicano national struggle.[22][31] Chicanas were not only experienced the effects of racism and imperialism in white America, but also sexism within their own families. In the seminal text “La Chicana”, Elizabeth Martinez, asserts that: "[La Chicana] is oppressed by the forces of racism, imperialism, and sexism. This can be said of all non-white women in the United States. Her oppression by the forces of racism and imperialism is similar to that endured by our men. Oppression by sexism, however, is hers alone."[32] Chicana labor organizing  Mexican American women working at Friedrich Air Conditioning (1942) Emma Tenayuca was an early Mexican American labor organizer and Dolores Huerta was a major force in the labor organization of farmworkers.[33] The testimony of the migrant farm worker activist Maria Elena Lucas reveals the enormous difficulties of organizing farmworkers.[34] The Farah Strike, 1972–1974, labeled the "strike of the century," was organized and led by Mexican American women predominantly in El Paso, Texas.[35] Employees of the Farah Manufacturing Company went on strike to stand for job security and their right to establish and join a union.[36] Chicana Feminist Organizations (1960s–1970s) One of the first Chicana organizations was the East Los Angeles Chicana Welfare Rights Organization, founded by Alicia Escalante in 1967.[37] She became a vocal representative of East Los Angeles at campaign meetings where no one else from the neighborhood was present.[38] She spoke out against the dehumanization of welfare recipients, particularly of Chicana and Black women.[39] In a 1968 article for La Raza newspaper, she wrote that the state believed that welfare recipients "should be ashamed of yourselves for living."[38] She organized to protest the slashing of welfare funds for essential needs that were labeled as "special needs" by the state.[38]  Chicana Brown Berets (1970) The Brown Berets were a youth group that took on a more militant approach to organizing for the Mexican-American community formed in California in the late 1960s.[40] They heavily valued strong bonds between women, stating that women Berets must acknowledge other women in the organization as hermanas en la lucha and encouraging them to stand together. Membership in the Brown Berets helped to give Chicanas autonomy, and the ability to express their own political views without fear.[41] An important Chicana in the Brown Berets was Gloria Arellanes, the only female minister of the Brown Berets.[42] The Hijas de Cuauhtémoc began as an activist rap group and would later become a feminist newspaper by 1971. There was a focus on Mexican feminism that would stand for people on either side of the border. The newspaper included topics such as: “gender equality and liberatory ethics to relationships, sexuality, power, women’s status, labor and leadership, familial bonds, and organizational structures.”[29] The Comisión Femenil Mexicana Nacional (CFMN) was founded in 1973.[43] The concept for the CFMN originated during the National Chicano Issues Conference when a group of attending Chicanas noticed that their concerns were not adequately addressed at the Chicano conference. The women met outside of the conference and drafted a framework for the CFMN that established them as active and knowledgeable community leaders of a people's movement.[44]  Vilma Martinez (pictured) established the Chicana Rights Project in 1974. The Chicana Rights Project was created in 1974 as a Chicana feminist legal organization to defend the legal rights of Mexican American women.[45] It was initiated by Vilma Martinez and addressed issues of employment, health, education, and housing rights for Chicanas.[45] It monitored the implementation of the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA), which successfully led to an increase in Chicana women in San Antonio's programs.[45] The organization also filed lawsuits for the sterilization abuses of Latina women in Texas. It made a difference in the lives of thousands of women.[45] The organization came to an end in 1983.[45] Critical developments (Late 1970s–1980s)  Martha P. Cotera who authored Diosa y Hembra (1976) and The Chicana Feminist (1977) From the late 1970s to the early 1990s, Chicana feminism made significant developments in the forging of Chicana critical consciousness via numerous foundational texts covering Chicana lives and experiences.[3] Many of these works covered themes that had not been examined in depth, including sexuality, gender roles, reproductive rights, sexual violence, environmental racism, and queer of color critique.[46][3] However, despite the critical importance of these texts, many continued to be left out of critical discourse in Chicana/o studies for decades, and are still often ignored.[46] This indicated a lagging refusal of masculine-focused Chicanismo to shift its views and grant serious attention to Chicana discourses.[46] Major texts associated with this period that are foundational to Chicana/o studies, despite not always acknowledged, include:[3][46] Diosa y Hembra: The History and Heritage of Chicanas in the U.S. (1976) by Martha P. Cotera The Chicana Feminist (1977) by Martha P. Cotera Essays on La Mujer (1977) ed. by Rosaura Sánchez and Rosa Martinez Cruz Mexican Women in the United States (1980) by Magdalena Mora and Adelaida R. Del Castillo This Bridge Called My Back (1981) ed. by Gloria Anzaldúa and Cherríe Moraga Loving in the War Years: Lo Que Nunca Pasó Por Sus Labios (1983) by Cherríe Moraga Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987) by Gloria Anzaldúa Companeras: Latina Lesbians (1987) ed. by Juanita Ramos The Sexuality of Latinas (1989) ed. by Norma Alarcon, Ana Castillo, and Cherrie Moraga Chicana Lesbians: The Girls Our Mothers Warned Us About (1991) ed. by Carla Trujillo Xicanisma (1990s–Present)  Ana Castillo developed Xicanisma to reinvigorate Chicana feminism and reflect a shift in consciousness since the Chicano Movement. Xicanisma is an intervention in Chicana feminism proposed by Ana Castillo in Massacre of the Dreamers (1994). The use of the X is a reference to the Spanish colonizers being unable to pronounce the Sh sound in Mesoamerican languages (such as Texcoco, which is pronounced Tesh-KOH-koh) and so they represented this sound with a letter X in the 16th-century Spanish language.[47][48][49] The X in Xicanisma refers to this colonial encounter between the Spanish and Indigenous peoples by reclaiming the X as a literal symbol of being at a crossroads or otherwise embodying hybridity.[48]  The X in Xicanisma is not only a letter, but a symbol of being or existing at a crossroads. This crossroads or X is a reference to Indigenous survival after hundreds of years of colonization.[48] It acknowledges the moment "where the creative power of woman became deliberately appropriated by the male society" through the coloniality of gender being imposed onto women.[5] Xicanisma speaks to the need to not only reclaim one's Indigenous roots and spirituality, but to "reinsert the forsaken feminine into our consciousness" that was subordinated through colonization.[5] It therefore challenges the masculine-focused aspects of the movement and the patriarchal bias of the Spanish language: being Xicanisma rather than Chicanismo.[50][48] Castillo argued that using this X as a symbol of a crossroads was important because "language is the vehicle by which we perceive ourselves in relation to the world."[48] The implication is that if we change the language we use to understand ourselves, we can change how we view and act in the world.[48] The goal of Xicanisma for Castillo is not to replace patriarchy with matriarchy, but to create "a nonmaterialistic and nonexploitative society in which feminine principles of nurturing and community prevail" and where the feminine is recovered from its current place of subordination enforced through the coloniality of gender.[5][48] Themes |

年表 チカーノ運動におけるチカーナ(1960年代~1970年代  エル・セグンド・バリオ、エル・パソ(1971年)で若い女性が若い男性グループと話している チカーノ運動はメキシコ系アメリカ人コミュニティの強化を目的として組織されたが、この市民的不服従の時期に組織化に関わっていた女性たちは、運動の物語 や焦点からほとんど無視されていた。[20][3] これらの出来事を経て、チカーノのフェミニストたちは、ジェンダーの問題をチカーノ運動の他の解放目的と結びつけることの重要性を認識した。[21] また、主流派の第二波フェミニズム運動が人種差別や階級差別を政治に取り入れることができないとして、チカーナたちはこの運動からも離脱した。この時期の チカーナたちは、自分たちのニーズや関心事、要求が異なるため、主流派のフェミニズム運動から排除されていると感じていた。排除に対する根強い異議申し立 てにより、女性たちは「チカーノ女性」と呼ばれることから「チカーナ」と呼ばれるようになり、コミュニティについて議論する際には、両方の性を認める方法 として a/o または o/a の採用を導入するようになった。 アルマ・ガルシアは、チカーナのフェミニスト運動は、チカーナの女性たちに影響を与えた特定の問題に固執するために作られたものであり、その起源はチカー ノ運動や第二波フェミニズム運動における彼女たちの扱いにあると書いている。[22] 彼女たちは平等な扱いと [22] チカーナのフェミニスト運動は、多くのチカーナに、より積極的な行動を促し、単独の女性としてだけでなく、平等な貢献を行う社会を形成する連帯する女性と して、自らの権利を守ることを求めた。 チカーノのストライキの組織化(1968年)  ラ・ラサ新聞の共同創刊者であるルース・ロビンソン(右)とマルガリータ・サンチェス。1968年にロサンゼルスで教育改革を求めて行われた一連の学生デモの一環として、ベルモント高校でストライキが行われた。 1968年3月1日、およそ15,000人の学生が参加したことで知られるようになった「イーストロサンゼルス学校ストライキ」が発生した。イーストロサ ンゼルスの7つの高校のチカーノ学生たちが、組織的な抗議活動として学校を放棄したのである。[25] 学生たちは、人種差別、不十分な資金、現在の教育システムにおけるメキシコの歴史と文化の軽視に対する共通の不満から、この抗議活動を行った。[26] ストライキに参加した男子学生がメディアの注目を最も集めた 、主に共謀容疑で拘束され投獄された13人の男子学生の組織者たちであった。[25] チカーノ研究者のドロレス・デルガド・ベルナルは、男子学生のみに焦点を当てたことで、女子生徒や女性の参加や指導力が大幅に低下し、また、このストライ キを組織するために必要な努力も最小限に抑えられたと主張している。 その後、1990年代半ばにドロレス・デルガド・ベルナルは、8人の重要な女性スト参加者またはリーダーにインタビューを行い、メディアが無視していた女 性たちに注目を集めた。セレステ・バカ、ヴィッキー・カストロ、ポーラ・クリソストモ、ミタ・クアロン、ターニャ・ルナ・マウント、ロザリンダ・M・ゴン ザレス、レイチェル・オチョア・セルベラ、カサンドラ・ザカリアスである。[26] 彼女たちの口述によると、彼女たちは地域集会を組織し、さまざまな学校や組織に属する学生間のつながりを築き、運動の情報を広め、より多くの学生の参加と 支援を募るために地下新聞を発行した。[26] 全米チカーナ会議(1971年) ストライキから1年後の1969年には、チカーノ青年解放会議が開催された。全米から約1,500人のメキシコ系アメリカ人のティーンエイジャーがこの会 議に参加し、その結果、「チカニズモ」、「エル・プラン・エスピリチュアル・デ・アストラン」、および全米学生組織MEChAという言葉が烙印を押される こととなった。[27] この会議では、運動における女性の役割について話し合い、フェミニストの懸念に対処するためのワークショップが開催された。しかし、ワークショップでは 「グループの総意として、チカーナ女性は解放されたくないという結論に達した」と結論付けられた。アンナ・ニエト=ゴメスをはじめとする多くの学者は、こ の声明がチカーナ・フェミニスト運動の火付け役となった決定的な行動のひとつであると見なしている。 この声明を受けて、1971年5月にテキサス州ヒューストンで初の全米チカーナ会議が開催された。この会議には、全米から600人以上の女性が集まり、教 育機会の平等、リプロダクティブ・ジャスティス、託児所の設立などに関する問題について話し合った。[28] 会議は9つの異なるワークショップに分かれて行われた。「セックスとチカーナ:名詞と動詞」、「チカーナの選択肢: 教育と職業」、「結婚:チカーナ流」、「宗教」、「フェミニスト運動 - 私たちはその中に居場所があるのか?」、「女性の搾取 - チカーナの視点」、「政治における女性 - 誰かそこにいるのか」、「急進主義/保守主義:どちらが前進なのか」、「デ・コロレス・イ・クラス:階級と民族の違い」であった。 このイベントは同種の催しとしては初めての大規模な集会であったが、地理的にも思想的にも異なる立場から来たチカーナたちが、チカーノ運動におけるフェミ ニズムの役割をめぐって激しく対立したため、会議自体は不和に満ちたものとなった。 こうした対立は、会議の最終日に退席者が出るという結果を招いた。[29] アナ・ニエト=ゴメスによると、「この退席は、チカーナ・フェミニストとロイヤリストの間の対立を際立たせるものとなった」という。[28] 運動の裏切り者とみなされた 学者のメイレイ・ブラックウェルは、チカーナ・フェミニストを「ヴェンディダ・ロジック」と表現し、しばしば「ヴェンディダ」すなわちチカーノ運動の裏切 り者と非難された。 ヴェンディダと並んで、チカーナ・フェミニストは「ウーマンリブ派」、「アグリンガダ」、あるいはレズビアンとも呼ばれた。チカーノ運動とその大義を優先 するチカーナはロイヤリストと呼ばれた。[29] 女性たちは、自分たちの民族の植民地化に根ざした自己嫌悪という内面化された葛藤と戦うことも求めた。これには、スペイン人女性は善良で、コミュニティの 一員である先住民女性は悪であるという、良妻賢母神話の打破も含まれていた。チカーノのフェミニスト思想は、家父長制、人種差別、階級差別、植民地主義へ の反応として、また、これらの抑圧の遺産が内面化されてきたあらゆる反応として現れた。[30][23] ラ・ファミリアのチカーノ女性  テキサス州サンアントニオで洗濯をするメキシコ系アメリカ人女性(1944年) チカーノのフェミニストたちは、ラ・ファミリアにおける規定された役割に異議を唱え、直面する複合的な経験を認識されることを要求した。チカーナは、ラ・ ラサを優先しながらも、自らが意識的に自覚し、自己決定し、ルーツや伝統、経験に誇りを持っていると認識している。チカーノ運動の台頭により、チカーノ家 族の構造は劇的に変化した。具体的には、女性たちは、確立された家族の力学のプラス面とマイナス面、そしてチカーノの全国的な闘争における自分たちの居場 所について疑問を抱くようになった。 チカーナは、白人社会における人種差別と帝国主義の影響だけでなく、自身の家族内での性差別も経験していた。エリザベス・マルティネスによる画期的な著作 『ラ・チカーナ』では、「ラ・チカーナは、人種差別、帝国主義、性差別の力によって抑圧されている。これは、米国の非白人女性すべてに言えることである。 人種差別と帝国主義の力による彼女の抑圧は、我々の男性が耐えてきたものに似ている。しかし、性差別による抑圧は彼女だけのものである。」[32] チカーナの労働組合組織  フリードリヒ空調で働くメキシコ系アメリカ人女性(1942年) エマ・テネイユカは初期のメキシコ系アメリカ人労働組合組織者であり、ドロレス・ウエルタは農場労働者の労働組合組織化の主要な推進力であった。[33] 移民農場労働者の活動家マリア・エレナ・ルーカスの証言は、農場労働者の組織化の困難さを明らかにしている。[34] 1972年から1974年にかけて起こった「世紀のストライキ」と称されたファラ・ストライキは、主にテキサス州エル・パソのメキシコ系アメリカ人女性た ちによって組織され、主導された。ファラ・マニュファクチャリング社の従業員たちは、雇用の安定と労働組合の結成および加入の権利を求めてストライキを 行った。 チカーナ系フェミニスト組織(1960年代~1970年代) 最初のチカーナ系組織のひとつは、1967年にアリシア・エスカランテによって創設されたイースト・ロサンゼルス・チカーナ福祉権組織である。[37] 彼女は選挙運動集会でイースト・ロサンゼルスを代表する声高な発言者となり、集会には近隣住民は誰も出席しなかった。[38] 彼女は、生活保護受給者の人間性を否定するような発言に反対し、特にチカーナ系や黒人女性に対しては強く反対した。 特にチカーナや黒人女性に対してはそうであった。[39] 1968年のラ・ラサ紙の記事で、彼女は「州は生活保護受給者を『生きていること自体恥じるべきだ』と考えている」と書いた。[38] 彼女は、州が「特別なニーズ」と称した生活必需品に対する生活保護費の大幅削減に抗議する組織を結成した。[38]  チカーナ・ブラウン・ベレー(1970年) ブラウン・ベレーは、1960年代後半にカリフォルニアで結成された、メキシコ系アメリカ人コミュニティのための組織化に、より好戦的なアプローチを取る 若者グループであった。[40] 彼らは女性間の強い絆を非常に重視し、ベレーの女性たちは組織内の他の女性たちを「hermanas en la lucha(闘いの姉妹)」として認め、団結するよう促した。ブラウン・ベレーのメンバーであることは、チカーナの自立を助け、恐れずに自分自身の政治的 見解を表明する能力を与えた。[41] ブラウン・ベレーで重要な役割を果たしたチカーナの一人に、唯一の女性聖職者であったグロリア・アレリャネスがいる。[42] ヒハス・デ・クアウテモックは、活動的なラップグループとして始まり、1971年にはフェミニスト新聞となった。メキシコのフェミニズムに焦点を当て、国 境のどちら側にいる人々をも代表するものとなった。この新聞には、「男女平等と人間関係、セクシュアリティ、権力、女性の地位、労働とリーダーシップ、家 族の絆、組織構造に関する解放の倫理」といったトピックが含まれていた。 メキシコ女性委員会(Comisión Femenil Mexicana Nacional、CFMN)は1973年に設立された。[43] CFMNの構想は、全国チカーノ問題会議(National Chicano Issues Conference)の際に、参加していたチカーナのグループが、チカーノ会議では自分たちの懸念が十分に扱われていないことに気づいたことから始まっ た。女性たちは会議の場外で会合を開き、CFMNの枠組みを策定し、自分たちを人民運動の活発で知識豊富なコミュニティリーダーとして位置づけた。 [44]  ヴィルマ・マルティネス(写真)は1974年にチカーナ人権プロジェクトを設立した。 チカーナ人権プロジェクトは、メキシコ系アメリカ人女性の法的権利を守ることを目的としたチカーナ人フェミニストの法律団体として1974年に設立され た。[45] ヴィルマ・マルティネスが発起人となり、チカーナ人の雇用、健康、教育、住宅に関する権利の問題に取り組んだ 。[45] 包括的雇用訓練法(CETA)の実施状況を監視し、その結果、サンアントニオ市のプログラムに参加するチカーナ女性の数が増加した。[45] この組織はまた、テキサス州におけるラテン系女性の不適切な避妊手術に対する訴訟も起こした。これにより、何千人もの女性の生活に変化がもたらされた。 [45] この組織は1983年に解散した。[45] 重要な展開(1970年代後半~1980年代  『Diosa y Hembra』(1976年)と『The Chicana Feminist』(1977年)の著者であるマーサ・P・コテラ 1970年代後半から1990年代初頭にかけて、チカーナのフェミニズムは、チカーナの生活や経験を扱った数多くの基礎的な文献を通じて、チカーナの批判 的意識の形成において重要な発展を遂げた。[3] これらの作品の多くは、セクシュアリティ、ジェンダーの役割、生殖に関する権利、性的暴力、環境差別、有色人クィア批評など、これまで深く掘り下げられて こなかったテーマを取り扱っている。[46][3] しかし、これらの文献の持つ重要な意義にもかかわらず、何十年もの間、多くの文献がチカーノ/チカーナ研究における批判的な言説から排除され続け、現在で もなお無視されることが多い。[46] これは、男性的な視点に重点を置くチカーノ主義が、その見解を転換し、チカーナの言説に真剣な注目を与えることを拒み続けてきたことを示している。 [46] この時代に関連する主要な文献は、チカーノ/チカーナ研究の基礎をなすものであるが、必ずしも認められているわけではない。以下が含まれる。[3] [46] Diosa y Hembra: The History and Heritage of Chicanas in the U.S. (1976)(『女神と雌:米国におけるチカーナの歴史と遺産』)マーサ・P・コテラ著 The Chicana Feminist (1977)(『チカーナ・フェミニスト』)マーサ・P・コテラ著 Essays on La Mujer (1977)(『ラ・ムヘールに関するエッセイ』)ロサウラ・サンチェスとロサ・マルティネス・クルーズ編 Mexican Women in the United States (1980)(『米国におけるメキシコ人女性』)マグダレナ・モーラとアデライダ・R・デル・カスティーヨ著 この架け橋は私の背中と呼ばれていた(1981年)編者:グロリア・アンサルドゥア、チェリー・モラガ 戦時中の愛:口にすることのなかったこと(1983年)著者:チェリー・モラガ 国境地方/ラ・フロンテーラ:新しいメスティサ(1987年)著者:グロリア・アンサルドゥア 『コンパネラス:ラテン系レズビアン』(1987年) 編集:フアニータ・ラモス 『ラテン系レズビアンのセクシュアリティ』(1989年) 編集:ノーマ・アルコン、アナ・キャスティージョ、チェリー・モラガ 『チカーナ・レズビアン:私たちの母親が警告した少女たち』(1991年) 編集:カーラ・トルヒージョ 『Xicanisma』(1990年代~現在)  アナ・キャスティージョは、チカーノ・フェミニズムを再活性化し、チカーノ運動以降の意識の変化を反映するために、Xicanismaを開発した。 Xicanismaは、アナ・キャスティージョが著書『The Massacre of the Dreamers』(1994年)で提唱したチカーナ・フェミニズムへの介入である。Xの使用は、スペイン人植民者がメソアメリカ諸語(テスココ語など、 テシュ-コー-コーと発音される)のSh音を発音できず、16世紀のスペイン語ではこの音をXで表記したことに由来する 16世紀のスペイン語では、この音はXで表記されていた。[47][48][49] XicanismaにおけるXは、スペイン人と先住民の間のこの植民地時代の遭遇を、岐路に立つことの文字通りの象徴として、あるいはハイブリッド性を体 現するものとして、Xを再主張することで指し示している。  シカニスムにおけるXは、単なる文字ではなく、岐路に立つこと、あるいは存在することの象徴である。 この岐路あるいはXは、何百年にもわたる植民地化の後に先住民が生き延びたことを指している。[48] それは、ジェンダーの植民地化が女性に押し付けられたことにより、「女性の創造力が男性社会によって意図的に利用されるようになった」瞬間を認めている。 [5] シカニスムは、 先住民としてのルーツや精神性を再発見するだけでなく、植民地化によって従属させられてきた「見捨てられた女性性を我々の意識に再び取り戻す」必要性を訴 えている。[5] したがって、運動における男性的な側面やスペイン語の父系制的な偏りに異議を唱えている。すなわち、ChicanismoではなくXicanismaであ る。[50][48] カスティージョは、このXを岐路の象徴として用いることが重要であると論じた。なぜなら、「言語は、世界との関係において自己を認識する手段である」から だ[48]。この主張の含意は、自己を理解するために用いる言語を変えれば、世界に対する見方や行動を変えることができるということである[48]。 CastilloにとってのXicanismaの目標は、家父長制を母系制に置き換えることではなく、「女性的な育む原理と共同体が優勢な非物質的かつ搾 取のない社会」を創り出すこと、そしてジェンダーの植民地性によって強制される従属的な立場から女性的なものを回復することである。[5][48] テーマ |

Themes Issues of self-image have been explored in Latin American feminism more broadly. There are many central themes of Chicana feminism that have been developed by Chicanas. Chicana feminism serves to highlight a much greater movement than generally perceived; a variety of minority groups are given a platform to confront their oppressors whether that be racism, homophobia, and multiple other forms of social injustice.[51][23] Chicana liberation unshackles individuals, as well as the broader group as a whole, allowing them to live lives as they desire – commanding cultural respect and equality.[52] Resilience is an overarching theme of Chicana feminism: the strength it takes to not only divide but bring forth a new mindset of equality.[23] Female archetypes Central to much of Chicana feminism is a reclaiming of the female archetypes La Virgen de Guadalupe, La Llorona, and La Malinche.[53] These archetypes have prevented Chicanas from achieving sexual and bodily agency due to the ways they have been historically constructed as negative categories through the lenses of patriarchy and colonialism.[54] Shifting the discourse from a traditional (patriarchal) representation of these archetypes to a decolonial feminist understanding of them is a crucial element of contemporary Chicana feminism, and represents the starting point for a reclamation of Chicana female power, sexuality, and spirituality. Gloria Anzaldúa's canonical text Borderlands/La Frontera addresses the subversive power of reclaiming Indigenous spirituality to unlearn colonial and patriarchal constructions and restrictions on women, their sexuality, and their understandings of motherhood: "I will no longer be made to feel ashamed of existing. I will have my voice: Indian, Spanish, white."[55][56] Figure of La Virgen de Guadalupe  La Virgen de Guadalupe has been upheld in Chicano and Mexican communities as a symbol of chastity and virtuous motherhood, which are construed as defining characteristics of a woman's worth or status.[56]  La Virgen de Guadalupe, in the Catholic faith, has long been looked to as an exemplary figure of female sexual purity and motherhood, especially in Mexican and Chicano culture. Members of the Chicana feminist movement, such as artist Yolanda Lopez, sought to reclaim the image of La Virgen and deconstruct the ideal that virginity is the only measurement for determining a woman's worth and virtue. For women like Lopez, the image of Guadalupe possessed a significance that was not pertinent to religion at all.[57] The figure of La Virgen de Guadalupe is often contrasted with La Malinche, which suppresses Chicana women's sexuality through the patriarchal dichotomy of puta/virgin: the positive role model and the negative one. These figures are historically and continuously held up before Mexican women and Chicanas as icons and mirrors in which to examine their own self-image and define their self-esteem.[56] Figure of La Malinche  The figure of Malintzin has been used in Chicano and Mexican communities as a symbol to suppress women's liberation, by framing feminism or sexual expression as inherently traitorous.[56] Malintzin (also known as Doña Marina by the Spaniards or "La Malinche" post-Mexican independence from Spain) was born around 1505 to noble indigenous parents in rural Mexico. Since Indigenous women were often used as pawns for political alliances at this time, she was betrayed by her mother and her mother's second husband and sold into slavery to the Mayans to save the inheritance for her newborn brother.[54] Between the ages of 12–14, traded to Hernan Cortés as a concubine, and because of her intelligence and fluency in multiple languages, was promoted to his "wife" and diplomat. She served as Cortés's translator, playing a key role in the Spaniard's conquest of Tenochtitlan and, by extension, the conquest of the Aztec Empire.[58] She bore Cortés a son, Martín, who is considered to be the first mestizo and the beginning of the "Mexican" race.[54] After Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, a scapegoat was needed to justify centuries of colonial rule. Because of Malintzin's relationship with Cortés and her role as translator and informant in Spain's conquest of Mexico, she was seen as a traitor to her race. By contrast, Chicana feminism calls for a different understanding.[54] Since nationalism was a concept unknown to Indigenous people in the 16th century, Malintzin had no sense of herself as "Indian," making it impossible for her to show ethnic loyalty or conscientiously act as a traitor. Malintzin was one of millions of women who were traded and sold in Mexico pre-colonization. With no way to escape a group of men, and inevitably rape, Malintzin showed loyalty to Cortés to ensure her survival.[54][56] La Malinche has become the representative of a female sexuality that is passive, "rape-able," and always guilty of betrayal.[56] Rather than a traitor or a "whore," Chicana feminism calls for an understanding of her as an agent within her limited means, resisting rape and torture (as was common among her peers) by becoming a partner and translator to Cortés.[54] Placing the blame for Mexico's conquest on Malintzin creates a foundation for placing upon women the responsibility to be the moral compasses of society and blames them for their sexuality, which is counterintuitive. It is important to understand Malintzin as a victim not of Cortés, but of myth. Chicana feminism calls for an understanding in which she should be praised for the adaptive resistance she exhibited that ultimately led to her survival.[54] By challenging patriarchal and colonial representations, Chicana writers re-construct their relationship to the figure of La Malinche and these other powerful archetypes, and reclaim them in order to re-frame a spirituality and identity that is both decolonizing and empowering.[59] La Malinche is a victim of centuries of patriarchal myths that permeate the Mexican woman's consciousness, often without her awareness.[56] Duality and "The New Mestiza"  Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa's (September 26, 1942 – May 15, 2004) works and theories were foundational to a resurgence in Chicana feminism. The concept of "The New Mestiza" comes from feminist author Gloria Anzaldúa. In her book, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, she writes: "In a constant state of mental nepantilism, an Aztec word meaning torn between ways, la mestiza is a product of the transfer of the cultural and spiritual values of one group to another. Being tricultural, monolingual, bilingual or multilingual, speaking a patois, and in a state of perpetual transition, the mestiza faces the dilemma of the mixed breed: which collectivity does the daughter of a dark-skinned mother listen to? [...] Within us and within la Cultura Chicana, commonly held beliefs of the white culture attack commonly held beliefs of the Mexican culture, and both attack commonly held beliefs of the indigenous culture. Subconsciously, we see an attack on ourselves and our beliefs as a threat and we attempt to block with a counterstance."[55][23] Anzaldúa presents a mode of being for Chicanas that honors their unique standpoint and lived experience. This theory of embodiment offers a mode of being for Chicanas who are constantly negotiating hybridity and cultural collision, and the ways that inform the way they are continuously making new knowledge and understandings of self, often time concerning intersecting and various forms of oppression. This theory discloses how a counter-stance cannot be a way of life because it depends on hegemonic constructions of domination, in terms of race, nationality, and culture. A counter-stance locks one into a duel of oppressor and oppressed; locked in mortal combat, like the cop and the criminal, both are reduced to a common denominator of violence.[60] Being solely reactionary means nothing is being created, revived, or renewed in place of the dominant culture and that the dominant culture must remain dominant for counterstance to exist. For Anzaldua and this theory of embodiment, there must be space to create something new.[60] The “new mestiza” was a canonical text that redefined what it meant to be Chicana. In this theory, being Chicana entails hybridity, contradictions, tolerance for ambiguity, and plurality, nothing is rejected or excluded from histories and legacies of oppression. Further, this theory of embodiment calls for synthesizing all aspects of identity and creating new meanings, not simply balancing or coming together of different aspects of identity.[60] Mujerista  International Workers' Day (2014) in Oakland, California The term mujerista was defined by Ada María Isasi-Díaz in 1996 and was largely influenced by the African American women's "Womanist" approach proposed by Alice Walker. This Latina feminist identity draws from the main ideas of womanism by combating inequality and oppression through participation in social justice movements within the Latina/o community.[61] Mujerismo is rooted in the relationships built with the community and emphasizes individual experiences in relation to "communal struggles" to redefine the Latina/o identity.[62] Mujerismo represents the body of knowledge while Mujerista refers to the individual who identifies with these beliefs. The origins of these terms began with Gloria Anzaldúa's This Bridge We Call Home (1987), Ana Castillo's Massacre of the Dreamer: Essays in Xicanisma (1994), and Gloria Anzaldúa and Cherríe Moraga's This Bridge Called My Back (1984). Mujerista is a Latina-oriented "womanist" approach to everyday life and relationships. It emphasizes the need to connect the formal, public life of work and education with the private life of culture and the home by privileging cultural experiences.[61] As such, it differs from Feminista which focuses on the historic context of the feminist movement. To be Mujerista is to integrate body, emotion, spirit and community into a single identity.[62] Mujerismo recognizes how personal experiences are valuable sources of knowledge. The development of all these components form a foundation for collective action in the form of activism.[62] Nepantla spirituality See also: Chicano § spirituality Nepantla is a Nahua word which translates to "in the middle of it" or "middle". Nepantla can be described as a concept or spirituality in which multiple realities are experienced at the same time (Duality). As a Chicana, understanding and having indigenous ancestral knowledge of spirituality plays an instrumental role in the path to healing, decolonization, cultural appreciation, self-understanding, and self-love.[63] Nepantla is often associated with author Chicana feminist Gloria Anzaldúa, who coined the term, "Nepantlera." "Nepantleras are threshold people; they move within and among multiple, often conflicting, worlds and refuse to align themselves exclusively with any single individual, group, or belief system."[64] Nepantla is a mode of being for the Chicana and informs the way she experiences the world and various systems of oppression.[64] Body politics Encarnación: Illness and Body Politics in Chicana Feminist Literature by Suzanne Bost discusses how Chicana feminism has changed the way Chicana women look at body politics. Feminism has moved beyond just looking at identity politics, it now looks at how “[...]the intersections between particular bodies, cultural contexts, and political needs”.[65] It now looks beyond just race, and incorporates intersectionality, and how mobility, accessibility, ability, caregivers and their roles in lives, work with the body of Chicanas.[66] Examples of Frida Kahlo and her abilities are discussed, as well as Gloria Anzaldúa's diabetes, to illustrated how ability must be discussed when talking about identity. Bost writes that “Since there is no single or constant locus of identification, our analyses must adapt to different cultural frameworks, shifting feelings, and matter that is fluid.[...] our thinking about bodies, identities, and politics must keep moving.”[65] Bost uses examples of contemporary Chicana artists and literature to illustrate this: Chicana feminism has not ended; it is just manifesting in different ways now.[65] Queer interventions Chicana feminist theory evolved as a theory of embodiment and a theory of flesh due to the canonical works of Gloria Anzaldúa and Cherrie Moraga, both of whom identify as queer. Queer interventions in Chicana feminist thought called for the inclusion and the honoring of the cultures’ jotería.[67] In La Conciencia de la Mestiza, Anzaldúa writes that "the mestizo and the queer exist at this time and point on the evolutionary continuum for a purpose. We are blending that proves that all blood is intricately woven together and that we are spawned out of similar souls."[67] This intervention centers queerness as a focal part of liberation, a lived experience that cannot be ignored or excluded.[67][23] In Queer Aztlán: the Reformation of Chicano Tribe, Cherríe Moraga questions the construction of Chicano identity in relation with queerness. Offering a critique of the exclusion of people of color from mainstream gay movements as well as the homophobia rampant in Chicano nationalist movements.[68] Moraga also discusses Aztlán, the metaphysical land and nation that belongs to Chicano ideologies, as well as how the ideas within the communidad need to move forward into making new forms of culture and community in order to survive.[68] "Feminist critics are committed to the preservation of Chicano culture, but we know that our culture will not survive marital rape, battering, incest, drug and alcohol abuse, AIDS, and the marginalization of lesbian daughters and gay sons."[68] Moraga brings up criticisms of the Chicano Movement and how it has been ignoring the issues within the movement itself, and that needs to be addressed in order for the culture to be preserved.[68] Chicana lesbian feminism See also: Lesbian feminism § Chicana lesbian feminism In Chicana Lesbians: Fear and Loathing in the Chicano Community [69] Carla Trujillo discusses how being a Chicana lesbian is incredibly difficult due to their culture's expectations on family and heteronormativity. Chicana lesbians who become mothers break this expectation and become liberated from the social norms of their culture.[70] Trujillo argues that the lesbian existence itself disrupts an established norm of patriarchal oppression.[31] She argues that Chicana lesbians are perceived as a threat because they challenge a male dominated Chicano movement; they raise the consciousness of many Chicana women regarding independence.[31] She goes on to say that Chicanas, whether they are lesbian or not, are taught to conform to certain modes of behavior regarding their sexuality: women are "taught to suppress our sexual desires and needs by conceding all pleasures to the male."[31] In 1991, Carla Trujillo edited and compiled, the anthology Chicana Lesbians: The Girls Our Mothers Warned Us About (1991), published by Third Woman Press.[69] This anthology featured cover art by Ester Hernandez titled "La Ofrenda."[69] Vincent Carillo argued that the piece challenged conventional depictions of Chicanas and gendered dynamics.[71] This anthology included poetry and essays by Chicana women creating new understandings of self through their sexuality and race.[69] |

テーマ 自己イメージの問題は、ラテンアメリカフェミニズムにおいてより広く研究されてきた。 チカーナフェミニズムには、チカーナたちによって発展してきた多くの中心的なテーマがある。チカーナフェミニズムは、一般的に認識されているよりもはるか に大きな運動を強調する役割を果たしている。人種差別、同性愛嫌悪、その他さまざまな社会的不正義など、さまざまなマイノリティグループが、抑圧者と対峙 するための基盤を与えられている。[51][23] チカーナの解放は、個人を束縛から解放し、 個人だけでなく、より広範な集団全体を束縛から解放し、彼らが望むように生きることを可能にする。すなわち、文化的敬意と平等を勝ち取ることを可能にする のである。[52] レジリエンス(回復力)は、チカーナフェミニズムの包括的なテーマである。それは、分断するだけでなく、平等という新たな考え方を生み出す強さである。 [23] 女性像 チカーナ・フェミニズムの多くは、ラ・ビルヘン・デ・グアダルーペ、ラ・ジョローナ、ラ・マリンチェといった女性像の再定義に重点を置いている。[53] これらの女性像は、家父長制と植民地主義の観点から否定的なカテゴリーとして歴史的に構築されてきたため、チカーナが性的および肉体的な主体性を獲得する ことを妨げてきた。。 これらの典型を伝統的な(家父長制的な)表現から脱植民地主義的なフェミニストの理解へと転換することは、現代のチカーナ・フェミニズムの重要な要素であ り、チカーナ女性の力、セクシュアリティ、スピリチュアリティの回復の出発点となる。グロリア・アンザルドゥアの代表作『ボーダーランズ/ラ・フロンテー ラ』では、植民地主義や家父長制が女性やその性的な側面、母性に対する理解に課してきた構築や制限を「脱植民地化」し、先住民の精神性を回復することの破 壊的な力が論じられている。「私はもはや、存在することに恥じ入ることはない。私は自分の声を獲得する。インディアン、スペイン人、白人として。」 [55][56] グアダルーペの聖母の図  グアダルーペの聖母は、貞操と徳の高い母性の象徴として、チカーノやメキシコ系住民のコミュニティで支持されてきた。これらは、女性の価値や地位を定義する特徴であると解釈されている。[56]  グアダルーペの聖母は、カトリックの信仰において、特にメキシコやチカーノ文化において、女性の性的純潔と母性の模範的な象徴として長い間見られてきた。 アーティストのヨランダ・ロペス(Yolanda Lopez)のようなチカーノ女性運動のメンバーは、聖母のイメージを再評価し、処女性が女性の価値や徳を決定する唯一の尺度であるという理想を解体しよ うとした。ロペスのような女性にとって、グアダルーペのイメージは宗教とはまったく関係のない意味を持っていた。 グアダルーペの聖母のイメージは、しばしばラ・マルインチェと対比される。ラ・マルインチェは、プタ(娼婦)とバージン(処女)という家父長制の二元論に よって、チカーナ女性の性を抑圧する存在である。これらのイメージは、メキシコ人女性やチカーナにとって、歴史的に、そして現在もなお、自己イメージを検 証し、自尊心を定義するためのアイコンや鏡として存在し続けている。 ラ・マルインチェのイメージ  マリンツィンのイメージは、フェミニズムや性的表現を本質的に裏切り的であると位置づけることで、女性の解放を抑圧する象徴として、チカーノやメキシコ系コミュニティで利用されてきた。 マリンツィン(スペイン人からはドニャ・マリーナ、スペインからのメキシコ独立後は「ラ・マリンチェ」とも呼ばれる)は、1505年頃にメキシコの田舎で 貴族の原住民の両親の間に生まれた。当時、先住民の女性は政治的同盟の駒として利用されることが多かったため、彼女は母親とその再婚相手に裏切られ、生ま れたばかりの弟のために遺産を確保するためにマヤ人に奴隷として売られた。[54] 12歳から14歳の間に、側室としてエルナン・コルテスに売られ、知性と複数の言語に堪能だったため、コルテスの「妻」および外交官に昇進した。彼女はコ ルテスの通訳を務め、スペイン人のテノチティトラン征服、ひいてはアステカ帝国征服において重要な役割を果たした。[58] 彼女はコルテスとの間にマルティンという名の息子をもうけた。マルティンは最初の混血であり、「メキシコ人」の始まりとされている。[54] 1821年にメキシコがスペインから独立した後、数世紀にわたる植民地支配を正当化するためにスケープゴートが必要となった。マリンツィンは、コルテスと の関係や、スペインによるメキシコ征服における通訳および情報提供者としての役割から、自らの民族に対する裏切り者と見なされた。それに対して、チカー ノ・フェミニズムは異なる理解を求めている。[54] 16世紀の原住民にとって、ナショナリズムは未知の概念であったため、マルティンは「インディオ」としての意識を持たず、民族的な忠誠心を示すことも、裏 切り者として誠実に行動することも不可能であった。マルティンは、メキシコ植民地化以前に売買されていた数百万人の女性のうちの一人であった。男たちから 逃れる術もなく、必然的にレイプされる状況にあったラ・マルティンは、生き延びるためにコルテスに忠誠を示したのである。[54][56] ラ・マルティンは、受動的で「レイプされやすく」、常に裏切りを犯しているような女性の性的な象徴とされてきた。[56] チカーナ・フェミニズムは、彼女を裏切り者や「娼婦」ではなく、限られた手段の中で、レイプや拷問(同時代の女性たちに共通していた)に抵抗し、コルテス のパートナーや通訳者となることで、その役割を担った人物として理解しようと呼びかけている。同時代の女性たちに共通していたように)コルテスのパート ナーや通訳者となることで、強姦や拷問に抵抗したのだ。[54] メキシコ征服の責任をマルティンスに押し付けることは、女性に社会の道徳的指針となる責任を負わせ、女性の性を責めることにつながる。これは直感に反す る。マリンチェをコルテスの犠牲者ではなく、神話の犠牲者として理解することが重要である。チカーナ・フェミニズムは、彼女が適応抵抗を示し、最終的に生 き残ったことを称賛すべきであると主張している。 家父長制や植民地主義の表現に異議を唱えることで、チカーナの作家たちはラ・マルインチェやその他の強力な原型像との関係を再構築し、それらを再主張する ことで、脱植民地化とエンパワーメントを両立する精神性とアイデンティティを再構築しようとしている。[59] ラ・マルインチェは、メキシコ人女性の意識に浸透している家父長制の神話の犠牲者であり、多くの場合、彼女自身は気づいていない。[56] 二面性と「ニュー・メスティサ  グロリア・エヴァンヘリナ・アンサルドゥア(Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa、1942年9月26日 - 2004年5月15日)の作品と理論は、チカーナ・フェミニズムの復活の基礎となった。 「ニュー・メスティサ」という概念は、フェミニスト作家のグロリア・アンサルドゥアによるものである。著書『ボーダーランド/ラ・フロンテラ:ニュー・メ スティサ』の中で、彼女は次のように書いている。「精神的なネパティリスム(被支配者意識)の状態にあるメスティサは、アステカ語で「引き裂かれる」を意 味する言葉であり、ある集団から別の集団への文化的・精神的価値の移転の結果生じるものである。メスチーサは、3文化、単一言語、2言語、多言語、訛りの ある言葉を使い、絶え間なく変化し続ける状態にあるため、混血のジレンマに直面する。色黒の母親を持つ娘は、どの集団の意見に耳を傾けるのか? [...] 私たちの中にも、そしてチカーナ文化の中にも、白人文化の一般的な信念がメキシコ文化の一般的な信念を攻撃し、両者が先住民文化の一般的な信念を攻撃す る。無意識のうちに、私たちは自分自身や自分たちの信念に対する攻撃を脅威と見なし、対抗手段でそれを阻止しようとする。」[55][23] アンサルドゥアは、自分たちのユニークな立場と経験を尊重するチカーナのあり方を提示している。この身体化理論は、絶えずハイブリッド性と文化の衝突を調 整しているチカーナのあり方を提示しており、そのあり方は、交差するさまざまな形態の抑圧に関する自己の新たな知識と理解を絶えず作り出す方法に影響を与 える。この理論は、カウンタースタンスが生き方になり得ない理由を明らかにする。それは、人種、国籍、文化という観点において、支配のヘゲモニックな構築 に依存しているからである。カウンタースタンスは、抑圧者と抑圧された者の決闘に人を巻き込む。警官と犯罪者のように、死闘に身を投じ、両者は暴力という 共通項に還元されてしまうのだ。 反動的であるだけでは、支配的文化に代わるものが創造、復活、刷新されることはなく、反動的文化が存在するためには支配的文化が支配的であり続けなければ ならない。アンサルドゥアとこの身体化理論にとって、何か新しいものを創造する余地がなければならない。「新しいメスティサ」は、チカーナであることの意 味を再定義した正典的なテキストであった。この理論では、チカーナであるということは、混血、矛盾、曖昧さへの寛容、多様性を意味し、抑圧の歴史や遺産か ら拒絶されたり排除されたりするものは何もない。さらに、この身体化理論では、アイデンティティのあらゆる側面を統合し、新しい意味を創造することが求め られる。単にアイデンティティの異なる側面をバランスよく組み合わせたり、融合したりするのではない。 ムヘリスタ  国際労働の日(2014年)カリフォルニア州オークランド ムヘリスタという用語は1996年にAda María Isasi-Díazによって定義されたもので、Alice Walkerが提唱したアフリカ系アメリカ人女性の「ウーマニスト」アプローチに強く影響を受けている。このラテン系フェミニストのアイデンティティは、 ラテン系コミュニティ内の社会正義運動への参加を通じて、不平等や抑圧と闘うというウーマニズムの主な考え方から影響を受けている。[61] ムヘリズモは、コミュニティとの関係構築に根ざしており、ラテン系アイデンティティを再定義するための「共同の闘い」に関連する個人の経験を強調してい る。[62] ムヘリズモは知識体系を代表するものであり、ムヘリストはこれらの信念を信奉する個人を指す。これらの用語の起源は、グロリア・アンザルドゥアの著書 『This Bridge We Call Home』(1987年)、アナ・キャスティージョの著書『Massacre of the Dreamer: Essays in Xicanisma』(1994年)、グロリア・アンザルドゥアとチェリー・モラガの著書『This Bridge Called My Back』(1984年)に始まる。ムヘリスタは、ラテン系女性による日常生活や人間関係に対する「ウーマニスト」的アプローチである。文化的な経験を重 視することで、仕事や教育といった公的な生活と、文化や家庭といった私的な生活とを結びつける必要性を強調している。[61] そのため、フェミニスト運動の歴史的背景に焦点を当てるフェミニスタとは異なる。ムヘリスタであるということは、身体、感情、精神、そしてコミュニティを ひとつのアイデンティティに統合することである。[62] ムヘリズモは、個人的な経験が知識の貴重な源であることを認識している。これらの要素のすべてが発展することで、活動家としての集団行動の基盤が形成され る。[62] ネパントラの精神性 関連項目:チカーノ § 精神性 ネパントラはナワ語で「その中」または「中間」を意味する。ネパントラは、複数の現実が同時に経験されるという概念または精神性(二元性)として説明する ことができる。チカーナとして、精神性に関する先住民の祖先伝来の知識を理解し、それを身につけることは、癒し、脱植民地化、文化の尊重、自己理解、自己 愛への道において重要な役割を果たす。[63] ネパントラは、この用語を考案した作家でチカーナのフェミニストであるグロリア・アンザルドゥアと関連付けられることが多い。「ネパントラーは境界に生き る人々である。彼らは、しばしば相反する複数の世界の間を移動し、単一の個人、グループ、あるいは信念体系にのみ自らを限定することを拒否する」[64] ネパントラはチカーナにとって存在様式であり、彼女が世界やさまざまな抑圧のシステムを経験する方法を決定づけるものである。[64] 身体政治 エンカルナシオン:チカーナ系フェミニズム文学における病気と身体政治』の著者スザンヌ・ボストは、チカーナ系フェミニズムがチカーナ系女性が身体政治を どう見るかにどのような変化をもたらしたかを論じている。フェミニズムはアイデンティティ政治を単に見るだけにとどまらず、現在は「特定の身体、文化的背 景、政治的ニーズの交差点」をどう見るかにまで発展している。[65] 現在は人種だけにとどまらず、交差性を取り入れ、チカーナ系女性の身体における移動性、アクセス性、能力、 介護者、そしてそれらがチカーナの身体にどのような影響を与えるか、という点についても考察している。[66] フリーダ・カーロやグロリア・アンザルドゥアの糖尿病の例が挙げられ、アイデンティティについて語る際に能力についてどのように論じなければならないかが 説明されている。ボストは「同一性の拠点は一つではなく、また一定でもないため、私たちの分析は異なる文化的枠組み、移り変わる感情、流動的な事柄に適応 していかなければならない。[... ] 身体、アイデンティティ、政治に関する私たちの思考は、常に変化し続けなければならない」と書いている。[65] ボストは、現代のチカーナのアーティストや文学の例を挙げてこれを説明している。チカーナのフェミニズムは終わっていない。ただ、現在は異なる形で現れて いるだけだ。[65] クィアの介入 チカーナのフェミニスト理論は、グロリア・アンザルドゥアとシェリー・モラガの正典的作品により、身体化理論および肉体理論として発展した。両者とも自身 をクィアと認識している。チカーノ・フェミニスト思想におけるクィアの介入は、その文化のジョテリア(jotería)の包含と尊重を求めた。[67] アンサルドゥアは著書『ラ・コンシエンシア・デ・ラ・メスティサ(La Conciencia de la Mestiza)』の中で、「混血とクィアは、進化の連続体におけるこの時点とこの地点に、ある目的を持って存在している。私たちは混ざり合っている。そ れは、すべての血が複雑に絡み合っていること、そして私たちが似た魂から生まれたことを証明している」[67] この介入は、解放の中心的な部分としてクィアネスを位置づけ、無視したり排除したりできない生きられた経験であると主張している。[67][23] 『Queer Aztlán: the Reformation of Chicano Tribe』の中で、チェリー・モラガは、クィアネスとの関連において、チカーノのアイデンティティの構築を問うている。主流派のゲイ運動から有色人種が 排除されていることや、チカーノ民族主義運動に蔓延する同性愛嫌悪に対する批判を提示している。[68] モラガはまた、チカーノのイデオロギーに属する形而上学的土地および国家であるアズトランについても論じ、コミュニダ内の考え方が、生き残るために新しい 文化やコミュニティの形を作り出すために前進する必要性についても論じている。[68] 「フェミニスト批評家たちは フェミニスト批評家たちは、チカーノ文化の保存に尽力しているが、私たちは、私たちの文化が、結婚内レイプ、家庭内暴力、近親相姦、薬物やアルコールの乱 用、エイズ、レズビアンの娘やゲイの息子の疎外といった問題を乗り越えることはできないと知っている」[68] モラガは、チカーノ運動の批判を取り上げ、運動自体が運動内の問題を無視してきたことを指摘し、文化を保存するためには、この問題に取り組む必要があると 主張している。 チカーノ・レズビアン・フェミニズム 参照:レズビアン・フェミニズム § チカーノ・レズビアン・フェミニズム 『チカーノ・レズビアン:チカーノ・コミュニティにおける恐怖と嫌悪』[69] において、カルラ・トルヒージョは、チカーノ文化における家族への期待や異性愛規範により、チカーノ・レズビアンであることが非常に困難であることを論じ ている。母親となったチカーナのレズビアンは、この期待を打ち破り、自らの文化の社会的規範から解放される。[70] トルヒジョは、レズビアンという存在自体が、家父長制による抑圧の確立された規範を破壊すると主張している。[31] 彼女は、チカーナのレズビアンが男性優位のチカーノ運動に異議を唱えるため、脅威とみなされると主張している。自立に関して多くのチカーナ女性たちの意識 を高めているからである。[31] さらに彼女は、レズビアンであるか否かに関わらず、チカーナの女性たちは、自身のセクシュアリティに関して特定の行動様式に従うよう教えられていると述べ ている。女性たちは「男性にすべての快楽を譲り渡すことで、私たちの性的欲望やニーズを抑えるよう教えられている」のである。[31] 1991年、カルラ・トルヒージョは編集と編纂を担当したアンソロジー『Chicana Lesbians: The Girls Our Mothers Warned Us About (1991)(私たちの母親が警告した少女たち)を編集・編纂し、Third Woman Pressから出版した。[69] このアンソロジーの表紙には、エステル・ヘルナンデスによる「La Ofrenda」というタイトルのアートが使われた。[69] ヴィンセント・カリロは、この作品がチカーナ女性とジェンダーの力学に関する従来の描写に異議を唱えていると論じた。[71] このアンソロジーには、自身のセクシュアリティと人種を通して新たな自己理解を生み出したチカーナ女性による詩とエッセイが収録された。[69] |

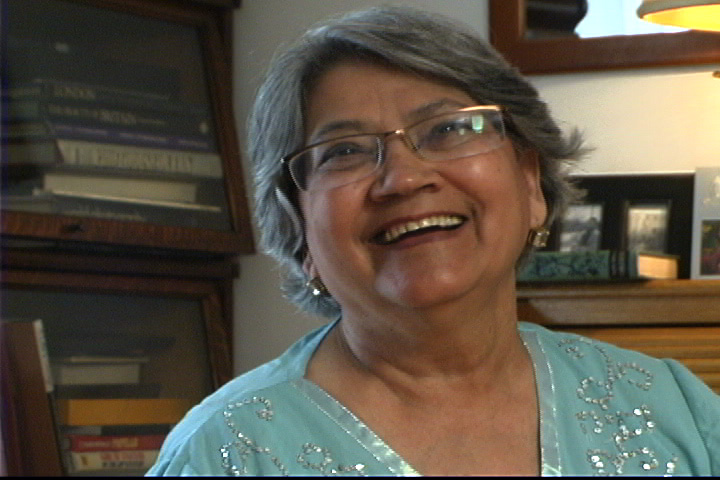

| Chicana art Main article: Chicana art  Chicana interdisciplinary artist Nao Bustamante during an interview (2012) Art gives Chicana women a platform to voice their unique challenges and experiences, such as artists Ester Hernandez and Judite Hernandez.[8] During the Chicano Movement, Chicanas used art to express their political and social resistance. Through different art mediums both past and contemporary, Chicana artists have continued to push the boundaries of traditional Mexican-American values.[8][72] Chicana art utilizes many different mediums to express their views including murals, painting, photography, etc. to embody feminist themes.[8][72] The momentum created from the Chicano Movement spurred a cultural renaissance among Chicanas and Chicanos. Political art was created by poets, writers, playwrights, and artists and used to defend against their oppression as second-class citizens.[73] During the 1970s, Chicana feminist artists differed from their Anglo-feminist counterparts in the way they collaborated. Chicana feminist artists often utilized artistic collaborations and collectives that included men, while Anglo-feminist artists generally utilized women-only participants.[72] Through different art mediums both past and contemporary, Chicana artists have continued to push the boundaries of traditional Mexican-American values.[74] Chicana collectives Mujeres Muralistas  Precita Eyes (2015) formed out of inspiration from Mujeres Muralistas. Mujeres Muralistas was a women's art collective in the Mission District of San Francisco. Members included Patricia Rodriguez, Graciela Carrillo, Consuelo Mendez, Irene Perez, Susan Cervantes, Ester Hernandez, and Miriam Olivo.[75] Las Chicanas Las Chicanas' members were women only and included artists Judy Baca, Judithe Hernández, Olga Muñiz, and Josefina Quesada. In 1976, the group exhibited Venas de la Mujer in the Woman's Building.[72] Los Four Muralist Judithe Hernández joined the all-male art collective in 1974 as its fifth member.[72] The group already included Frank Romero, Beto de la Rocha, Gilbert Luján, and Carlos Almaráz.[76] The collective was active from the 1970s through the early 1980s.[72] Social Public Art Resource Center (SPARC) In 1976, co-founders Judy Baca (the only Chicana), Christina Schlesinger, and Donna Deitch established SPARC. SPARC consisted of studio and workshop spaces for artists. SPARC functioned as an art gallery and also kept records of murals. Today, SPARC is still active and similar to the past, encouraging space for Chicana/o community collaboration in cultural and artistic campaigns.[72] The Woman's Building (1973-1991) The Woman's Building opened in Los Angeles, CA in 1973. In addition to housing women-owned businesses, the center held multiple art galleries and studio spaces. Women of color, including Chicanas, historically experienced racism and discrimination within the building from white feminists. Not many Chicana artists were allowed to participate in the Woman's Building's exhibitions or shows. Chicana artists Olivia Sanchez Brown and Rosalyn Mesquite were among the few included. Additionally, the group Las Chicanas exhibited Venas de la Mujer in 1976.[72] Murals Murals were the preferred medium of street art used by Chicana artists during the Chicano Movement. Judy Baca led the first large-scale-project for SPARC, The Great Wall of Los Angeles. It took five summers to complete the 700-meter-long mural. The mural was completed by Baca, Judithe Hernández, Olga Muñiz, Isabel Castro, Yreina Cervántez, and Patssi Valdez in addition to over 400 more artists and community youth. Located in Tujunga Flood Control Channel in the Valley Glen area of the San Fernando Valley, the mural depicts California's erased history of marginalized people of color and minorities.[72]  The Great Wall of Los Angeles, Judy Baca, Los Angeles, 1978 In 1989, Yreina Cervántez along with assistants Claudia Escobedes, Erick Montenegro, Vladimir Morales, and Sonia Ramos began the mural, La Ofrenda, located in downtown Los Angeles. The mural, a tribute to Latina/o farm workers, features Dolores Huerta at the center with two women on either side to represent women's contributions to the United Farmer Workers Movement. In addition to eight other murals, La Ofrenda was deemed historically significant by the Department of Cultural Affairs. In 2016, the restoration on La Ofrenda began after graffiti and another mural were painted over it.[77] An exhibition curated by LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes and the California Historical Society featuring previously mistreated or censored murals chose Barbara Carrasco's L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective in addition to others. Beginning in 1981 and taking about eight months to finish, the mural consisted of 43 eight-foot panels which tell the history of Los Angeles up to 1981. Carrasco researched the history of Los Angeles and met with historians as she originally planned out the mural. The mural was halted after Carrasco refused alterations demanded from City Hall due to her depictions of formerly enslaved entrepreneur and philanthropist Biddy Mason, the internment of Japanese American citizens during World War II, and the 1943 Zoot Suit Riots.[78] Film  Sylvia Morales has produced documentary films on the Chicana experience through a Chicana feminist lens. The short film Chicana, produced in 1979 by Sylvia Morales, was archived in National Film Registry by the Library of Congress in 2021.[79] The film was noted for its artistic approach to documentary, incorporating a "collage of artworks, stills, documentary footage, narration, and testimonies" through a Chicana feminist lens.[79] Linda García Merchant is an Afro-Chicana filmmaker who was created several films, including Las Mujeres de la Caucus Chicana, Palabras Dulces, Palabras Amargas, and the autobiographical short No Es Facil.[80][81] Performance art  Xandra Ibarra is a prominent Chicana performance artist. Performance art was not as popularly utilized among Chicana artists but it still had its supporters. Patssi Valdez was a member of the performance group Asco from the early 1970s to the mid-1980s. Asco's art spoke about the problems that arise from Chicanas/os unique experience residing at the intersection of racial, gender, and sexual oppression.[72] Photography Laura Aguilar, is known for her "compassionate photography," which often involved using herself as the subject of her work but also individuals who lacked representation in the mainstream: Chicanas, the LBGTQ community, and women of different body types. During the 1990s, Aguilar photographed the patrons of an Eastside Los Angeles lesbian bar. Aguilar utilized her body in the desert as the subject of her photographs wherein she manipulated it to look sculpted from the landscape. In 1990, Aguilar created Three Eagles Flying, a three-panel photograph featuring herself half nude in the center panel with the flag of Mexico and the United States of opposite sides as her body is tied up by the rope and her face covered. The triptych represents the imprisonment she feels by the two cultures she belongs to.[82] Archivists In 2015, Guadalupe Rosales began the Instagram account which would become Veterans and Rucas (@veterans_and_rucas). What started as a way for Rosales family to connect over their shared culture through posting images of Chicana/o history and nostalgia soon grew to an archive dedicated to not only ’90 Chicana/o youth culture but also as far back as the 1940s. Additionally, Rosales has created art installations to display the archive away from its original digital format and exhibited solo shows Echoes of a Collective Memory and Legends Never Die, A Collective Memory.[83] The idea of sharing the erased history of Chicanas/os has been popular among Chicana artists beginning in the 1970s until present day. Judy Baca and Judithe Hernández have both utilized the theme or correcting history in reference to their mural works. In contemporary art, Guadalupe Rosales uses the theme of collective memory to share Chicana/o history and nostalgia. La Virgen  Yolanda Lopez's 1978 rendition of La Virgen de Guadalupe, titled 'Portrait of the Artist as the Virgen of Guadalupe.' Yolanda López and Ester Hernandez are two Chicana feminist artists who used reinterpretations of La Virgen de Guadalupe to empower Chicanas. La Virgen is a symbol of the challenges Chicanas face as a result of the unique oppression they experience religiously, culturally, and through their gender.[84] Ester Hernández references the sacred Virgen de Guadalupe in her painting, La Ofrenda (1988). Painting recognizes lesbian love and challenges the traditional role of la familia. It defied the reverence and holiness of La Virgen by being depicted as a tattoo on a lesbian's back. La Virgen de Guadalupe Defendiendo los Derechos de Los Xicanos (1975) Alma Lopez – Our Lady of Controversy "Irreverent Apparition" (2001). This image is mixed media and is a sacrilegious depiction of La Virgen. See L.A. Times article |

チカーノ・アート 詳細は「チカーノ・アート」を参照  チカーノの学際的アーティスト、ナオ・ブスタマンテのインタビュー(2012年) アートは、アーティストのエステル・ヘルナンデスやジュディテ・ヘルナンデスなど、チカーノ女性が自分たちのユニークな課題や経験を表明するための基盤と なっている。[8] チカーノ運動の間、チカーノの女性たちはアートを用いて政治的・社会的抵抗を表明した。過去から現代までのさまざまな芸術媒体を通じて、チカーノの芸術家 たちは伝統的なメキシコ系アメリカ人の価値観の境界線を押し広げ続けている。[8][72] チカーノの芸術は、壁画、絵画、写真など、さまざまな媒体を用いて彼らの見解を表現し、フェミニストのテーマを体現している。[8][72] チカーノ運動から生まれた勢いは、チカーナとチカーノの文化ルネサンスを促進した。詩人、作家、劇作家、芸術家たちによって生み出された政治的な芸術は、 二級市民としての抑圧に対する抵抗として用いられた。[73] 1970年代には、チカーナのフェミニスト芸術家たちは、その協力の方法において、アングロサクソン系のフェミニスト芸術家たちとは異なっていた。チカー ノのフェミニスト芸術家たちは、男性も含む芸術的なコラボレーションや集団をしばしば活用したが、アングロ・フェミニストの芸術家たちは、女性のみの参加 者を活用することが一般的であった。[72] 過去と現代のさまざまな芸術媒体を通じて、チカーノの芸術家たちは、伝統的なメキシコ系アメリカ人の価値観の境界線を押し広げ続けている。[74] チカーナの集団 Mujeres Muralistas  Precita Eyes (2015) は、Mujeres Muralistas からインスピレーションを受けて結成された。 Mujeres Muralistas は、サンフランシスコのミッション地区にあった女性によるアート集団である。メンバーには、パトリシア・ロドリゲス、グラシエラ・カリロ、コンスエロ・メ ンデス、アイリーン・ペレス、スーザン・セルバンテス、エステル・ヘルナンデス、ミリアム・オリボなどがいた。 ラス・チカーナス ラス・チカーナスのメンバーは女性のみで、アーティストのジュディ・バカ、ジュディス・エルナンデス、オルガ・ムニス、ホセフィーナ・ケサダなどがいた。1976年、このグループはウーマンズ・ビルディングで「Venas de la Mujer」を展示した。 ロス・フォー 壁画画家のジュディス・ヘレラは、1974年に5人目のメンバーとして男性のみで構成されていたこの芸術集団に参加した。[72] グループにはすでにフランク・ロメロ、ベト・デ・ラ・ロチャ、ギルバート・ルハン、カルロス・アルマラスが参加していた。[76] この集団は1970年代から1980年代初頭にかけて活動していた。[72] ソーシャル・パブリック・アート・リソース・センター(SPARC) 1976年、共同設立者のジュディ・バカー(唯一のチカーナ)、クリスティーナ・シュレシンジャー、ドナ・ダイチによりSPARCが設立された。 SPARCはアーティストのためのスタジオやワークショップスペースから構成されていた。SPARCはアートギャラリーとして機能し、壁画の記録も保管し ていた。今日もSPARCは活動を続けており、過去と同様に、文化や芸術キャンペーンにおけるチカーナ/oコミュニティの共同作業のためのスペースを提供 している。 ザ・ウーマンズ・ビルディング(1973年~1991年) ザ・ウーマンズ・ビルディングは1973年にロサンゼルスで開館した。女性が所有する企業が入居するほか、複数のアートギャラリーやスタジオスペースも備 えていた。チカーナを含む有色人種の女性たちは、歴史的に白人フェミニストたちからこのビル内で人種差別や偏見を受けていた。チカーナのアーティストが ウーマンズ・ビルディングの展覧会やショーに参加することを許されることはあまりなかった。チカーナ系アーティストのオリヴィア・サンチェス・ブラウンと ロザリン・メスキートは、その数少ない例外であった。さらに、グループ「ラス・チカーナス」は1976年に「Venas de la Mujer」を展示した。 壁画 壁画は、チカーノ運動の時代にチカーノのアーティストたちが好んで用いたストリート・アートの媒体であった。ジュディ・バチャは、SPARCの最初の大型 プロジェクトである「ロサンゼルスの万里の長城」を主導した。全長700メートルの壁画を完成させるのに5年を要した。壁画は、バカ、ジュディス・エルナ ンデス、オルガ・ムニス、イザベル・カストロ、イレイナ・セルバンテス、パッツイ・バルデスの6名に加え、400名以上のアーティストや地域の若者たちに よって完成した。この壁画は、サンフェルナンド・バレーのバレー・グレン地区にあるトゥハンガ洪水制御水路に描かれており、マイノリティの人種や少数民族 の消されたカリフォルニアの歴史を描いている。  ロサンゼルスの万里の長城、ジュディ・バカ、ロサンゼルス、1978年 1989年、イレイナ・セルバンテスは、アシスタントのクラウディア・エスコベデス、エリック・モンテネグロ、ウラジミール・モラレス、ソニア・ラモスと ともに、ロサンゼルス市街地にある壁画『ラ・オフレンダ』の制作を開始した。この壁画は、ラテン系農場労働者への賛辞であり、中央にドロレス・イウエラを 配し、その両側に2人の女性を描いて、女性たちが全米農場労働者組合運動に貢献したことを表現している。 8つの他の壁画に加えて、ラ・オフレンダは文化局によって歴史的に重要なものとみなされた。 2016年、落書きと別の壁画が上から描かれた後、ラ・オフレンダの修復が始まった。 ロサンゼルス・プラザ・デ・カルチュラ・イ・アルテスとカリフォルニア歴史協会が企画した展覧会では、これまで不当に扱われたり検閲された壁画が展示さ れ、バーバラ・カラスコの『ロサンゼルスの歴史:メキシコ人の視点』も展示された。1981年に制作が開始され、完成までに約8か月を要したこの壁画は、 1981年までのロサンゼルスの歴史を描いた43枚の8フィートのパネルで構成されている。カラスコはロサンゼルスの歴史を研究し、当初の計画通り歴史学 者たちと会った。カラスコが、かつて奴隷として働いていた実業家で慈善家であったビディ・メイソン、第二次世界大戦中の日系アメリカ人の強制収容、 1943年のズート・スーツ暴動を描いたために市役所から修正を要求されたが、これを拒否したため、壁画は中断された。[78] 映画  シルビア・モラレスは、チカーナのフェミニストの視点を通してチカーナの経験を描いたドキュメンタリー映画を制作している。 シルビア・モラレスが1979年に制作した短編映画『チカーナ』は、2021年に米国議会図書館の国立フィルム登録簿に収蔵された。この映画は、チカーナ のフェミニストの視点を通して「芸術作品、静止画、ドキュメンタリー映像、ナレーション、証言」をコラージュした芸術的なアプローチでドキュメンタリーを 制作したことで注目された。 リンダ・ガルシア・マーチャントは、アフリカ系とチカーナ系の血を引く映画制作者であり、『Las Mujeres de la Caucus Chicana』、『Palabras Dulces』、『Palabras Amargas』、自伝的短編映画『No Es Facil』など、数本の映画を制作している。[80][81] パフォーマンスアート  ザンドラ・イバラは著名なチカーナ系パフォーマンスアーティストである。 パフォーマンスアートはチカーナのアーティストの間ではそれほど一般的ではなかったが、それでも支持者はいた。パッツイ・ヴァルデスは1970年代初頭か ら1980年代半ばまでパフォーマンスグループ「アスコ」のメンバーであった。アスコの芸術は、人種、ジェンダー、性的抑圧の交差点に位置するチカーナの ユニークな経験から生じる問題について語っていた。 写真 ローラ・アギラーは、「思いやりのある写真」で知られている。彼女の作品では、しばしば彼女自身が被写体として登場するが、主流派で代表されていない人 々、すなわち、チカーナ、LGBTQコミュニティ、さまざまな体型の女性も被写体となっている。1990年代、アギラーはロサンゼルス東部のレズビアン・ バーの常連客を撮影した。アギラーは、砂漠で自身の身体を被写体として撮影し、風景から彫刻のように見えるように操作した。1990年、アギラーは、自身 が半裸で中央パネルに写り、メキシコと米国の国旗が彼女の身体をロープで縛り、顔を覆っている反対側に配置された3枚組の写真『Three Eagles Flying』を制作した。この3枚組の写真は、彼女が所属する2つの文化によって感じる疎外感を表現している。 アーカイブ担当者 2015年、グアダルーペ・ロザレスは、後に「ベテランズ・アンド・ルカス(Veterans and Rucas)」となるインスタグラムのアカウントを開設した。ロザレスの家族が、チカーナ/oの歴史やノスタルジアの画像を投稿することで、共有する文化 を通じてつながるための手段として始まったこのアカウントは、やがて、1990年代のチカーナ/oの若者文化だけでなく、1940年代にまでさかのぼる アーカイブへと成長した。さらに、ロサレスはアーカイブを元のデジタル形式から離れた場所で展示するためのアートインスタレーションを制作し、 「Echoes of a Collective Memory(集合的記憶のこだま)」と「Legends Never Die, A Collective Memory(伝説は決して死なない、集合的記憶)」という個展を開催した。 チカーナの消された歴史を共有するという考え方は、1970年代から現在に至るまで、チカーナのアーティストの間で人気がある。ジュディ・バカとジュディ ス・エルナンデスは、ともに壁画作品で歴史を修正するというテーマを取り入れている。現代美術では、グアダルーペ・ロサレスが集団の記憶というテーマを用 いて、チカーナの歴史と郷愁を共有している。 ラ・ビルヘン  ヨランダ・ロペスの1978年の作品『ラ・ビルヘン・デ・グアダルーペ』は、『アーティストとしての肖像、ラ・ビルヘン・デ・グアダルーペ』と題されている。 ヨランダ・ロペスとエステル・ヘルナンデスは、ラ・ビルヘン・デ・グアダルーペの再解釈を用いてチカーナの力を強める2人のチカーナ系フェミニストのアー ティストである。ラ・ビルヘンは、宗教的、文化的、そしてジェンダーを通して経験する独特な抑圧の結果として、チカーナが直面する課題の象徴である。 エステル・エルナンデスは、自身の絵画『ラ・オフレンダ』(1988年)で聖なるグアダルーペの聖母を引用している。この絵画はレズビアン・ラブを認め、 伝統的な「ラ・ファミリア」の役割に異議を唱えている。レズビアンの背中にタトゥーとして描かれていることで、聖母の崇敬と神聖さを否定している。ラ・ ヴィルヘン・デ・グアダルーペ・デフェンディエンド・ロス・デレチョス・デ・ロス・チカーノス(1975年) アルマ・ロペス - 論争の聖母「不敬な幻影」(2001年)。この画像はミクストメディアで、聖母を冒涜的に描いている。ロサンゼルス・タイムズの記事を参照。 |

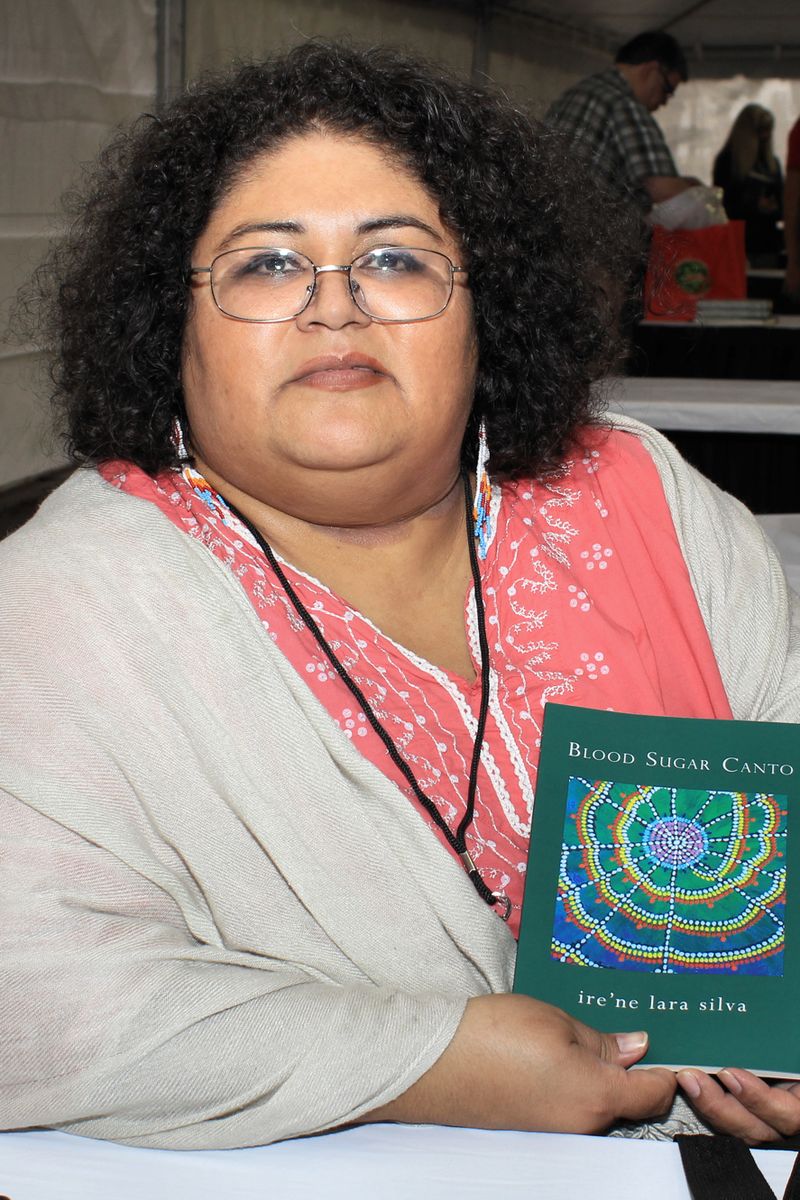

| Chicana literature See also: Xicana literature  Lorna Dee Cervantes (2017) is one of the most influential Chicana feminist poets. Since the 1970s, many Chicana writers (such as Cherríe Moraga, Gloria Anzaldúa and Ana Castillo) have expressed their own definitions of Chicana feminism through their books. Moraga and Anzaldúa edited an anthology of writing by women of color titled This Bridge Called My Back[85] (published by Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press) in the early 1980s. Cherríe Moraga, along with Ana Castillo and Norma Alarcón, adapted this anthology into a Spanish-language text titled Esta Puente, Mi Espalda: Voces de Mujeres Tercermundistas en los Estados Unidos. Anzaldúa also published the bilingual (Spanish/English) anthology, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. Mariana Roma-Carmona, Alma Gómez, and Cherríe Moraga published a collection of stories titled Cuentos: Stories by Latinas, also published by Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press. The Spanish language has been referred to as a vital component to the preservation of Chicana culture.[56][31]  Chicana feminist poet ire'ne lara silva (2016) The first Chicana Feminist Journal was published in 1973, called the Encuentro Femenil: The First Chicana Feminist Journal, which was published by Anna Nieto-Gómez.[86] One of the first Chicana lesbian novels was Sheila Ortiz Taylor's Faultline, published in 1982.[46] Juanita Ramos and the Latina Lesbian History Project compiled an anthology including tatiana de la tierra's first published poem, "De ambiente",[87] and many oral histories of Latina lesbians called Compañeras: Latina Lesbians (1987).[46] Chicana lesbian-feminist poet Gloria Anzaldúa points out that labeling a writer based on their social position allows for readers to understand the writer's' location in society. However, while it is important to recognize that identity characteristics situate the writer, they do not necessarily reflect their writing. Anzaldúa notes that this type of labeling has the potential to marginalize those writers who do not conform to the dominant culture.[88] Since the 1990s, there has been a rise in Chicana literature embracing transnational feminism and transcultural themes, particularly bridging Chicana experiences with the Latin American context.[89] For instance, this is demonstrated in Graciela Limón's works In Search of Bernabe (1997) and Erased Faces (2001).[89] |

チカーナ文学 関連項目: キシカ文学  ローナ・ディー・セルバンテス(2017年)は、最も影響力のあるチカーナのフェミニスト詩人の一人である。 1970年代以降、多くのチカーナの作家(チェリー・モラガ、グロリア・アンザルドゥア、アナ・キャスティージョなど)が、著作を通じてチカーナ・フェミ ニズムの独自の定義を表明してきた。モラガとアンサルドゥアは、有色人女性作家による作品集『This Bridge Called My Back』[85](キッチン・テーブル:ウーマン・オブ・カラー・プレス刊)を1980年代初頭に編集した。チェリー・モラガは、アナ・カスティーヨと ノーマ・アラコンとともに、この作品集をスペイン語に翻訳し、『Esta Puente, Mi Espalda: Voces de Mujeres Tercermundistas en los Estados Unidos』と題して出版した。また、アンサルデュアは、スペイン語と英語のバイリンガルアンソロジー『Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza』も出版した。マリアナ・ローマ=カルモナ、アルマ・ゴメス、チェリー・モラガは、同じくキッチン・テーブル:ウーマン・オブ・カラー・プ レスから出版された『Cuentos: Stories by Latinas』という短編集を出版した。スペイン語は、チカーナ文化の保存に不可欠な要素であるとみなされている。[56][31]  チカーナ系フェミニスト詩人アイリーン・ララ・シルヴァ(2016年) 最初のチカーナ系フェミニスト誌は1973年に『Encuentro Femenil: The First Chicana Feminist Journal』としてアンナ・ニエト=ゴメスによって出版された。[86] 最初のチカーナ系レズビアン小説のひとつは、1982年に出版されたシーラ・オルティス・テイラーの『Faultline』である。[46] フアニータ・ラモスとラティーナ・レズビアン・ヒストリー・プロジェクトは、タティアナ・デ・ラ・ティエラの初めて出版された詩「De ambiente」を含むアンソロジーを編集し[87]、ラティーナ・レズビアンの多くのオーラル・ヒストリーを『Compañeras: Latina Lesbians』(1987年)にまとめた。[46] チカーナ系レズビアン・フェミニストの詩人であるグロリア・アンサルドゥアは、作家をその社会的立場に基づいてラベル付けすることは、読者が作家の社会的 位置を理解する上で役立つと指摘している。しかし、アイデンティティの特徴が作家を位置づけることを認識することは重要であるが、必ずしもその作家の作品 を反映するものではない。アンサルドゥアは、この種のラベル付けは支配的文化に適合しない作家を疎外する可能性があると指摘している。[88] 1990年代以降、特にラテンアメリカとの文脈を結びつけ、越境フェミニズムや異文化をテーマとするチカーナ文学が増加している。[89] 例えば、グラシエラ・リモンの作品『ベルナベを求めて』(1997年)や『消された顔』(2001年)にその傾向がみられる。[89] |

| Chicana music Alice Bag, Chicana punk artist (1980s) Continually left absent from Chicano music history, many Chicana musical artists, such as Rita Vidaurri and María de Luz Flores Aceves, more commonly known as Lucha Reyes, from the 1940s and 50s, can be credited with many of strides that Chicana Feminist movements have made in the past century. For example, Vidaurri and Aceves were among the first mexicana women to wear charro pants while performing rancheras.[90] By challenging their own conflicting backgrounds and ideologies, Chicana musicians have continually broken the gender norms of their culture, and therefore created a space for conversation and change in the Latino communities.[91] There are many important figures in Chicana music history, each one giving a new social identity to Chicanas through their music. An important example of a Chicana musician is Rosita Fernández, an artist from San Antonio, Texas. Popular in the mid 20th century, she was called "San Antonio's First Lady of Song" by Lady Bird Johnson, the Tejano singer is a symbol of Chicana feminism for many Mexican Americans still today.[91] She was described as "larger than life", repeatedly performing in china poblana dresses, throughout her career, which last more than 60 years. However, she never received a great deal of fame outside of the San Antonio, despite her long reign as one of the most active Mexican American woman public performers of the 20th century.[91] Other Chicana musicians and musical groups: Chelo Silva – Tejana Singer[92] Eva Ybarra – Tejana Accordionist (1945–)[93] Ventura Alonzo – Chicana Accordionist (1904–2000)[94] Eva Garza – Tejana Singer[95] Selena Quintanilla-Pérez – Tejana Singer (1971–1995) Gloria Ríos – Hispanic Singer[96] Girl in a Coma – Tejana indie rock band from San Antonio Quetzal – East Los Angeles Chicano alternative rock band[97] Bags – Los Angeles punk rock band, led by Alice Bag. |

チカーナ音楽 アリス・バッグ、チカーナ・パンク・アーティスト(1980年代 チカーナ音楽の歴史から継続的に左派が欠如している中、1940年代から50年代にかけての、リタ・ビダウリやマリア・デ・ルス・フローレス・アセベス (通称ルチャ・レイエス)など、多くのチカーナの音楽アーティストが、この1世紀にチカーナ・フェミニスト運動が成し遂げた多くの進歩に貢献した。例え ば、ビダウリとアセベスは、ランチェラを演奏する際にチャロ・パンツをはいた最初のメキシコ系女性であった。 自分たちの相反する背景やイデオロギーに挑むことで、チカーナのミュージシャンたちは、自らの文化におけるジェンダーの規範を打ち破り、ラテン系コミュニティにおける対話と変化の場を生み出してきた。 チカーナ音楽の歴史には、多くの重要な人物がおり、それぞれが音楽を通じて、チカーナたちに新たな社会的アイデンティティを与えてきた。チカーナのミュー ジシャンとして重要な人物の一人に、テキサス州サンアントニオ出身のアーティスト、ロジータ・フェルナンデスがいる。20世紀半ばに人気を博した彼女は、 レディ・バード・ジョンソン(Lady Bird Johnson)から「サンアントニオの歌姫」と呼ばれた。このテハーノの歌手は、現在でも多くのメキシコ系アメリカ人にとって、チカーナ・フェミニズム の象徴である。[91] 彼女は「実物よりも大きく描かれる」と評され、60年以上にわたるキャリアを通じて、繰り返しチャイナドレスを着てパフォーマンスを行った。しかし、彼女 はサンアントニオ以外の地域ではあまり有名ではなく、20世紀で最も活発なメキシコ系アメリカ人女性パフォーミングアーティストの一人として長年活躍して いたにもかかわらず、その名声はサンアントニオ以外ではあまり知られていない。[91] その他のチカーナ系ミュージシャンおよび音楽グループ: チェロ・シルヴァ - テハーナの歌手[92] エバ・イバラ - テハーナのアコーディオン奏者(1945年~)[93] ベンチュラ・アロンゾ - チカーナのアコーディオン奏者(1904年~2000年)[94] エバ・ガルザ - テハーナの歌手[95] セレナ・キンタニージャ・ペレス - テキサス州サンアントニオ出身の歌手(1971年 - 1995年) グロリア・リオス - ヒスパニック系歌手[96] ガール・イン・ア・コマ - サンアントニオ出身のテキサス州出身のインディーズ・ロックバンド ケツァール - イースト・ロサンゼルス出身のチカーノ系オルタナティブ・ロックバンド[97] バッグス - アリス・バッグが率いるロサンゼルス出身のパンク・ロックバンド。 |

| Notable people See also: Category:Chicana feminists Alma M. Garcia - Professor of Sociology at Santa Clara University. Ana Castillo - Writer, Novelist, Poet, Editor, Essayist and Playwright who is recognized for depicting the true realities of the Chicana feminist experience. Anna Nieto-Gómez – Key organizer of the Chicana Movement and founder of Hijas de Cuauhtémoc. Carla Trujillo - Writer, editor, and lecturer. Chela Sandoval – Associate Professor in the Chicano and Chicana Studies Department at University of California, Santa Barbara. Cherríe Moraga – Essayist, poet, activist educator, and artist in residence at Stanford University. Dolores Huerta - Launched the National Farm Worker's Association with César Chavez in 1962 [98] Ester Hernandez - Through the use of art, using different mediums such as pastels, prints, and illustrations, she is able to depict the Latina/ Native women experience. Gloria Anzaldúa – Scholar of Chicana cultural theory and author of Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, among other influential Chicana literature. Judithe Hernandez - Los Angeles based muralist who worked alongside Cesar Chavez to paint murals that broke the mainstream barrier in order to promote the Chicana movement. Martha Gonzalez (musician) - Chicana artivist and co-leader of Grammy Award-winning Quetzal (band). Martha P. Cotera – Activist and writer during the Chicana Feminist Movement and the Chicano Civil Rights Movement. Norma Alarcón – Influential Chicana feminist author. Sandra Cisneros – Key contributor to Chicana literature. Vicki L. Ruiz - American historian with a focus on Mexican-American women in the twentieth century. Elizabeth Martinez- longtime social justice activist and author. Notable organizations Alianza Hispano-Americana - Founded in 1894, the Alianza members promoted civic virtues and acculturation, provided social activities and various health benefits and insurance for its members.[99] Chicas Rockeras South East Los Angeles – Promotes healing, growth, and confidence for girls through music education California Latinas for Reproductive Justice – Promotes social justice and human rights of Latina women and girls through a reproductive justice framework Las Fotos Project – Empowers Latina youth, helping young girls to build self-esteem and confidence through photography and self-expression Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA) – Located in Long Beach, CA this museum expands knowledge and appreciation of modern and contemporary Latin American art. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) - Civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 by W. E. B. Du Bois, Mary White Ovington, and Moorfield Storey and Ida B. Wells in order to advance justice for African Americans. National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference - Organized by the Crusade for Justice, the event came from El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan, which sought to organize the Chicano people around a nationalist program.[99] National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) - A federal agency founded by Congress in 1935 to administer the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) which protects employees' rights to organize and or serve in unions as bargaining representatives with their employers.[99] Ovarian Psycos - Young feminists of color in East Los Angeles who empower women through their bicycle brigades and rides. Radical Monarchs - a radical social justice group located in California, for young girls of color to earn social justice badges. Influenced by Brown Berets and Black Panthers, these young girls want to create change in their communities.[100] |

著名な人物 関連項目: カテゴリ:チカーノ女性運動家 アルマ・M・ガルシア - サンタクララ大学教授(社会学)。 アナ・キャスティージョ - 作家、小説家、詩人、編集者、エッセイスト、劇作家。チカーノ女性運動の真の現実を描いたことで知られる。 アンナ・ニエト・ゴメス - チカーノ運動の主要な組織者であり、ヒハス・デ・クアウテモックの創設者。 カーラ・トルヒージョ - 作家、編集者、講師。 チェラ・サンドヴァル - カリフォルニア大学サンタバーバラ校のチカーノ・チカーナ研究学科の准教授。 チェリー・モラガ - エッセイスト、詩人、活動家、教育者、スタンフォード大学のアーティスト・イン・レジデンス。 ドロレス・ウエルタ - 1962年にセサル・チャベスとともに全米農場労働者組合を設立した。 エステル・ヘルナンデス - パステル画、版画、イラストなどさまざまな媒体を用いた芸術表現を通じて、ラテン系およびネイティブアメリカンの女性の経験を描く。 グロリア・アンザルドゥア - チカーノ文化論の研究者であり、『ボーダーランド/ラ・フロンテラ:ザ・ニュー・メスティサ』などの影響力のあるチカーノ文学の著者。 ジュディス・ヘルナンデス - ロサンゼルスを拠点に活動する壁画画家。セイザー・チャベスとともに、主流派の障壁を打ち破る壁画を描き、チカーノ運動を推進した。 マーサ・ゴンザレス(ミュージシャン) - チカーノの活動家であり、グラミー賞受賞バンド、ケツァール(Quetzal)の共同リーダー。 マーサ・P・コテラ - チカーノフェミニスト運動およびチカーノ市民権運動の活動家であり、作家。 ノーマ・アラルコン - 影響力のあるチカーノのフェミニスト作家。 サンドラ・シスネロス - チカーナ文学の主要な貢献者。 ヴィッキー・L・ルイズ - 20世紀のメキシコ系アメリカ人女性を専門とするアメリカ人歴史家。 エリザベス・マルティネス - 長年にわたる社会正義活動家および作家。 著名な組織 Alianza Hispano-Americana - 1894年に設立されたAlianzaのメンバーは、市民的美徳と文化の融合を推進し、社会活動やさまざまな健康上の利益や保険をメンバーに提供した。 Chicas Rockeras South East Los Angeles - 音楽教育を通じて少女たちの癒し、成長、自信を促進する California Latinas for Reproductive Justice - リプロダクティブ・ライツの枠組みを通じてラテン系女性と少女の社会的正義と人権を促進する Las Fotos Project - ラテン系若者の力を引き出す。写真と自己表現を通じて少女たちが自尊心と自信を育むのを支援する ラテンアメリカ美術館(MOLAA) - カリフォルニア州ロングビーチにあるこの美術館は、ラテンアメリカ現代美術の知識と理解を深めることを目的としている。 全米有色人地位向上協会(NAACP) - 1909年にW. E. B. デュボイス、メアリー・ホワイト・オーヴィングトン、モアフィールド・ストーリー、アイダ・B・ウェルズによって、アフリカ系アメリカ人の権利向上を目的として設立された米国の市民権団体。 全国チカーノ青年解放会議 - 正義のための運動によって組織されたこのイベントは、民族主義プログラムを中心にチカーノの人々を組織化することを目指した「エル・プラン・エスピリチュアル・デ・アストラン」から派生したものである。 全米労働関係委員会(NLRB) - 1935年に連邦議会によって設立された連邦機関で、従業員が雇用主と交渉する代表者として労働組合を組織したり、組合に加入したりする権利を保護する全米労働関係法(NLRA)を管理する。 Ovarian Psycos - 東ロサンゼルスの有色人種の若いフェミニストたち。自転車部隊やサイクリングを通じて女性を支援している。 Radical Monarchs - カリフォルニア州を拠点とする急進的な社会正義グループ。有色人種の若い女性たちが社会正義バッジを獲得している。ブラウン・ベレーやブラック・パンサーの影響を受け、彼女たちは地域社会に変化をもたらそうとしている。[100] |

| Black feminism Chicano studies Feminism in Mexico Gender inequality in Mexico Gypsy feminism Intersectionality Third-world feminism White feminism Womanism |

ブラック・フェミニズム チカーノ研究 メキシコのフェミニズム メキシコにおけるジェンダーの不平等 ジプシー・フェミニズム 交差性(インターセクショナリティ) 第三世界のフェミニズム ホワイト・フェミニズム ウーマニズム |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chicana_feminism |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆