Postcolonial feminism argues that by using the term "woman" as a universal group, women are then only defined by their gender and not by social class, race, ethnicity, or sexual preference.[3] Postcolonial feminists also work to incorporate the ideas of indigenous and other Third World feminist movements into mainstream Western feminism. Third World feminism stems from the idea that feminism in Third World countries is not imported from the First World, but originates from internal ideologies and socio-cultural factors.[4]

Postcolonial feminism is sometimes criticized by mainstream feminism, which argues that postcolonial feminism weakens the wider feminist movement by dividing it.[5] It is also often criticized for its Western bias which will be discussed further below.[6]

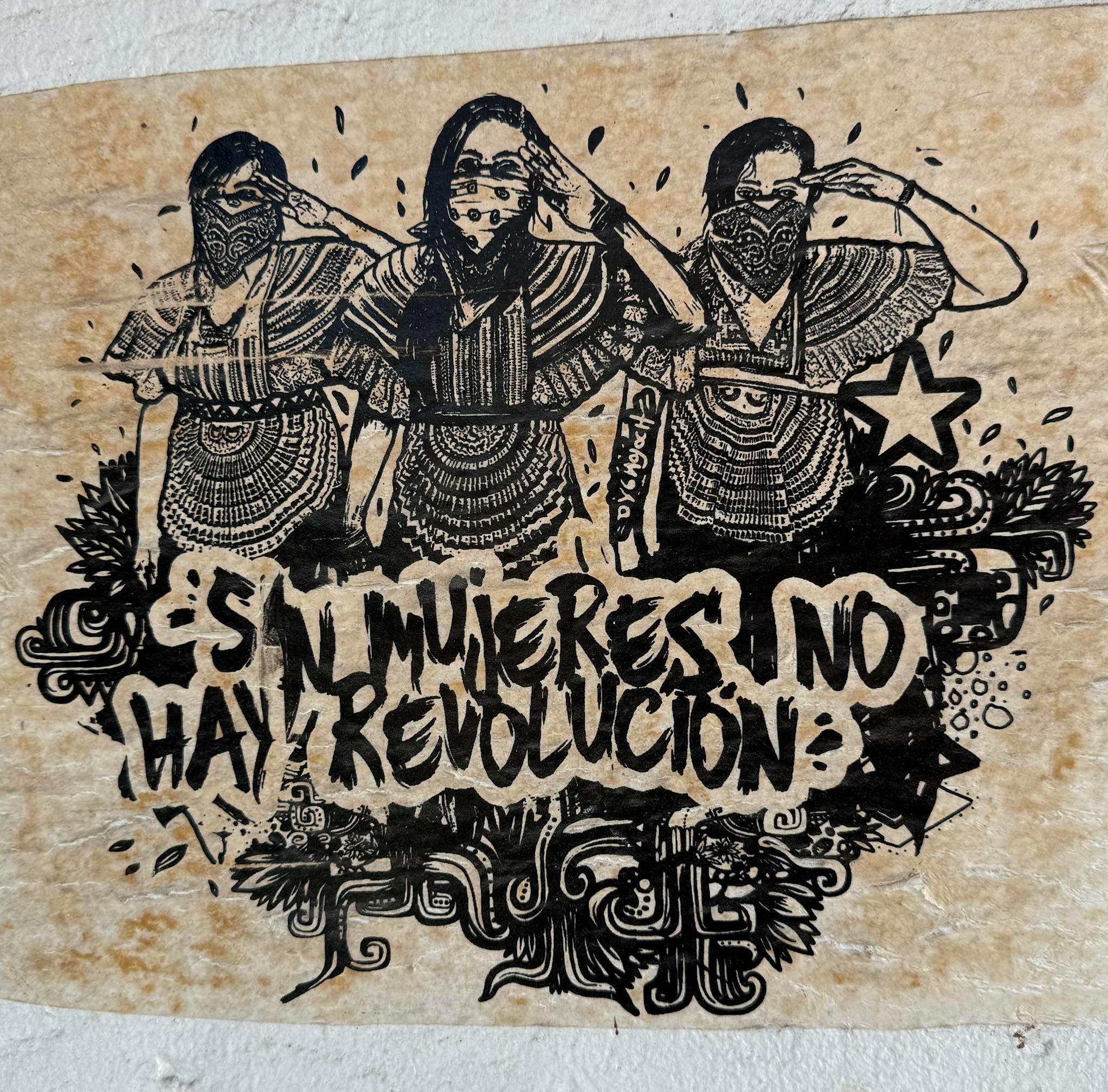

“Without women, there’s no revolution” seen in San Cristobal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico.

ポストコロニアルフェミニズムは、「女性」という用語を普遍的なグループとして使用することで、女性はジェンダーによってのみ定義され、社会階級、人種、 民族、性的嗜好によって定義されないと主張している。[3] ポストコロニアルフェミニストは、先住民族やその他の第三世界のフェミニスト運動の考え方を主流の西洋フェミニズムに組み込むようにも取り組んでいる。第 三世界のフェミニズムは、第三世界のフェミニズムは第一世界から輸入されたものではなく、内部のイデオロギーや社会文化的な要因から生まれたという考え方 に基づいている。[4]

ポストコロニアルフェミニズムは、主流派フェミニズムから批判を受けることもある。主流派フェミニズムは、ポストコロニアルフェミニズムはフェミニズム運 動を分裂させ、より広範なフェミニズム運動を弱体化させると主張している。[5] また、西洋に偏った見方であるという批判もよく受ける。この点については、以下でさらに詳しく説明する。[6]

“Without women, there’s no revolution” seen in San Cristobal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico.

Feminism logo originating in 1970

The history of modern feminist movements can be divided into three waves. When first-wave feminism originated in the late nineteenth century, it arose as a movement among white, middle-class women in the global North who were reasonably able to access both resources and education. Thus, the first wave of feminism almost exclusively addressed the issues of these women who were relatively well off.[7] The first-wavers focused on absolute rights such as suffrage and overturning other barriers to legal gender equality. This population did not include the realities of women of color who felt the force of racial oppression or economically disadvantaged women who were forced out of the home and into blue-collar jobs.[8] However, first-wave feminism did succeed in getting votes for women and also, in certain countries, changing laws relating to divorce and care and maintenance of children.

Second-wave feminism began in the early 1960s and inspired women to look at the sexist power struggles that existed within their personal lives and broadened the conversation to include issues within the workplace, issues of sexuality, family, and reproductive rights. It scored remarkable victories relating to Equal Pay and the removal of gender based discriminatory practices. First and second-wave feminist theory failed to account for differences between women in terms of race and class—it only addressed the needs and issues of white, Western women who started the movement. Postcolonial feminism emerged as part of the third wave of feminism, which began in the 1980s, in tandem with many other racially focused feminist movements in order to reflect the diverse nature of each woman's lived experience.[9] Audre Lorde contributed to the creation of Postcolonial Feminism with her 1984 essay "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House". Chandra Talpade Mohanty's essay "Under Western Eyes" also came out in 1984, analyzing the homogenizing western feminist depiction of the "third world woman." These works, along with many others, were foundational to the formation of postcolonial feminism.

Many of the first key theorists of postcolonial feminism hail from India and were inspired by their direct experiences with the effects that colonization had left in their society. When colonizers came to India, an importance that was not as prevalent before was placed on gender. Many women lost power and economic autonomy as men gained much more of it, and this had a lasting effect even after India gained independence[10]

In efforts to move away from 'grand narratives' stemmed from 'globalization', postcolonial theory was formed as a scholarly critique of colonial literature.[11] By acknowledging the differences among diverse groups of women, postcolonial feminism addresses what some call the oversimplification of Western feminism as solely a resistance against sexist oppression. Postcolonial feminism, in contrast, also relates gender issues to other spheres of influence within society.[9]

1970年に始まったフェミニズムのロゴ

近代フェミニズム運動の歴史は、3つの波に分けることができる。第一波フェミニズムは19世紀後半に始まり、北半球の先進国における、資源や教育に比較的 アクセスしやすい白人の中流階級の女性たちの運動として発生した。そのため、第一波フェミニズムは、比較的裕福なこれらの女性たちの問題にほぼ限って取り 組んだ。[7] 第一波フェミニストたちは、参政権などの絶対的な権利や、法的な男女平等を阻むその他の障壁の撤廃に焦点を当てた。この集団には、人種的抑圧の力を感じて いた有色人種の女性や、家から追い出されてブルーカラーの仕事に就かざるを得なかった経済的に恵まれない女性の現実が含まれていなかった。[8] しかし、第一波フェミニズムは、女性の投票権を獲得することに成功し、また、特定の国々では、離婚や子供の養育に関する法律の改正にも成功した。

第二波フェミニズムは1960年代初頭に始まり、女性たちに自分たちの私生活内にも存在する性差別的な権力闘争に目を向けるよう促し、職場内での問題、性 的問題、家族、生殖に関する権利などを含む幅広い議論へと発展させた。男女同一賃金や性差別的慣行の撤廃など、目覚ましい勝利を収めた。第一波、第二波 フェミニズム理論は、人種や階級による女性間の相違を考慮していなかった。それは、この運動を始めた白人、西欧の女性のニーズや問題のみを取り上げてい た。ポストコロニアルフェミニズムは、1980年代に始まったフェミニズム第三派の一部として、また、各女性の多様な生活経験を反映させるために、他の多 くの人種に焦点を当てたフェミニズム運動と並行して登場した。[9] オードラ・ローデは、1984年のエッセイ「The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House(支配者の道具では支配者の家は解体できない)」でポストコロニアルフェミニズムの形成に貢献した。チャンドラ・タルパデ・モハンティの論文 「西洋の視点」も1984年に発表され、西洋のフェミニストによる「第三世界の女性」の画一的な描写を分析している。これらの作品は、その他多くの作品と ともに、ポストコロニアル・フェミニズムの形成の基礎となった。

ポストコロニアル・フェミニズムの初期の主要な理論家の多くはインド出身であり、植民地化が自らの社会に残した影響を直接経験したことが彼らを鼓舞した。 植民地化がインドに到来した際、それまでそれほど重要視されていなかったジェンダーが重要視されるようになった。多くの女性が男性に権力と経済的自立を奪 われ、その影響はインドが独立した後も長引いた[10]

ポストコロニアル理論は、植民地文学に対する学術的な批判として、「グローバリゼーション」に起因する「壮大な物語」から離れようとする試みの中で形成さ れた。[11] ポストコロニアル・フェミニズムは、多様な女性グループ間の相違を認識することで、西洋のフェミニズムが性差別的抑圧に対する抵抗のみに焦点を当てている という、一部で指摘されている単純化のし過ぎという問題に対処している。ポストコロニアル・フェミニズムは、対照的に、ジェンダー問題を社会内の他の影響 領域にも関連付けている。[9]

Postcolonial feminism is a relatively new stream of thought, developing primarily out of the work of the postcolonial theorists who concern themselves with evaluating how different colonial and imperial relations throughout the nineteenth century have impacted the way particular cultures view themselves.[12] This particular strain of feminism promotes a wider viewpoint of the complex layers of oppression that exist within any given society.[8]

Postcolonial feminism began simply as a critique of both Western feminism and postcolonial theory, but later became a burgeoning method of analysis to address key issues within both fields.[5] Unlike mainstream postcolonial theory, which focuses on the lingering impacts that colonialism has had on the current economic and political institutions of countries, postcolonial feminist theorists are interested in analyzing why postcolonial theory fails to address issues of gender. Postcolonial feminism also seeks to illuminate the tendency of Western feminist thought to apply its claims to women around the world because the scope of feminist theory is limited.[13] In this way, postcolonial feminism attempts to account for perceived weaknesses within both postcolonial theory and within Western feminism. The concept of colonization occupies many different spaces within postcolonial feminist theory; it can refer to the literal act of acquiring lands or to forms of social, discursive, political, and economic enslavement in a society.

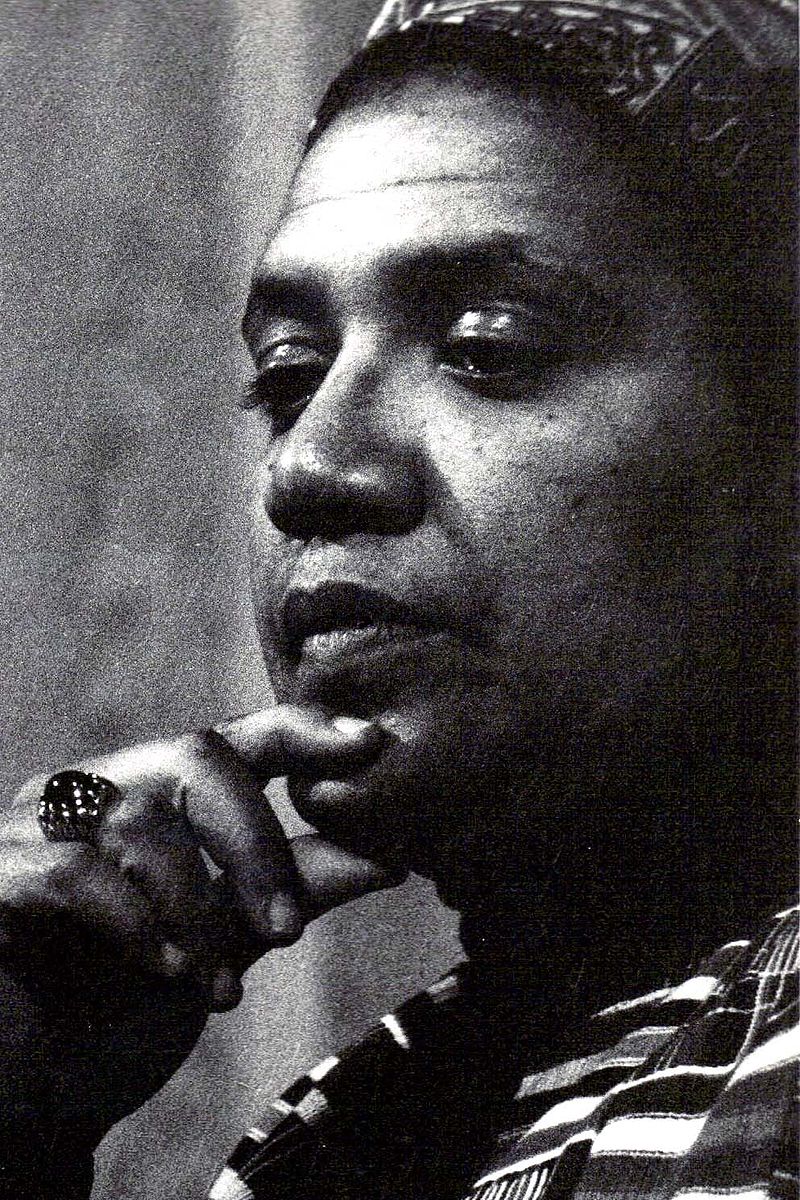

In Audre Lorde's foundational essay, "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House", Lorde uses the metaphor of "the master's tools" and "the master's house" to explain that western feminism is failing to make positive change for third world women by using the same tools used by the patriarchy to oppress women. Lorde found that western feminist literature denied differences between women and discouraged embracing them. The differences between women, Lorde asserts, should be used as strengths to create a community in which women use their different strengths to support each other.[14]

Chandra Talpade Mohanty, a principal theorist within the movement, addresses this issue in her seminal essay "Under Western Eyes".[1] In this essay, Mohanty asserts that Western feminists write about Third World women as a composite, singular construction that is arbitrary and limiting. She states that these women are depicted in writings as victims of masculine control and of traditional culture without incorporating information about historical context and cultural differences with the Third World. This creates a dynamic where Western feminism functions as the norm against which the situation in the developing world is evaluated.[9] Mohanty's primary initiative is to allow Third World women to have agency and voice within the feminist realm.

In the article "Third World Women and the Inadequacies of Western Feminism", Ethel Crowley, sociology professor at Trinity College of Dublin, writes about how western feminism is lacking when applied to non-western societies. She accuses western feminists of theoretical reductionism when it comes to Third World women. Her major problem with western feminism is that it spends too much time in ideological "nit-picking" instead of formulating strategies to redress the highlighted problems. The most prominent point that Crowley makes in her article is that ethnography can be essential to problem solving, and that freedom does not mean the same thing to all the women of the world.[15][unreliable source?]

ポストコロニアルフェミニズムは比較的新しい思想の流れであり、主に19世紀を通じてのさまざまな植民地支配や帝国主義が特定の文化が自己をどう見るかに どのような影響を与えたかを評価することに関心を持つポストコロニアル理論家の研究から発展したものである。[12] この特定のフェミニズムの潮流は、あらゆる社会に存在する複雑な抑圧の層に対するより広い視点を推進している。[8]

ポストコロニアルフェミニズムは、当初は西洋のフェミニズムとポストコロニアル理論の両方に対する批判として始まったが、その後、両分野における主要な問 題を扱う分析手法として急速に広まった。[5] ポストコロニアル理論の主流派は、植民地主義が現在の各国の経済および政治制度に与えた影響に焦点を当てているが、ポストコロニアルフェミニストの理論家 たちは、ポストコロニアル理論がジェンダーの問題を取り扱わない理由を分析することに関心を持っている。ポストコロニアルフェミニズムはまた、フェミニス ト理論の適用範囲が限られているため、西洋のフェミニスト思想がその主張を世界の女性たちに当てはめようとする傾向を明らかにしようとしている。[13] このように、ポストコロニアルフェミニズムは、ポストコロニアル理論と西洋のフェミニズムの両方に内在する弱点を説明しようとしている。植民地化という概 念は、ポストコロニアルフェミニズム理論のさまざまな領域を占めている。それは文字通りの土地獲得行為を指すこともあれば、社会における社会的、言説的、 政治的、経済的な奴隷化の形態を指すこともある。

オードラ・ローデの基礎となる論文「The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House(支配者の道具では支配者の家は解体できない)」では、「支配者の道具」と「支配者の家」という比喩を用いて、西洋のフェミニズムが女性を抑圧 する家父長制が用いてきたのと同じ道具を用いて、第三世界の女性たちに積極的な変化をもたらすことに失敗していることを説明している。ローデは、西洋の フェミニズムの文献が女性間の相違を否定し、それを受け入れることを妨げていることを発見した。女性間の違いは、女性たちがそれぞれの強みを活かして互い を支え合うコミュニティを築くための強みとして活用されるべきであるとロードは主張している。

この運動の主要な理論家であるチャンドラ・タルパデ・モハンティは、彼女の画期的な論文「西洋の視点」でこの問題を取り上げている。[1] この論文でモハンティは、西洋のフェミニストが第三世界の女性について、恣意的で限定的な単一の集合体として記述していると主張している。彼女は、これら の女性は、歴史的背景や第三世界との文化の違いに関する情報を盛り込まず、男性的な支配や伝統文化の犠牲者として描かれていると述べている。これにより、 西洋のフェミニズムが発展途上国の状況を評価する基準として機能する力学が生み出される。[9] モハンティの主な取り組みは、第三世界の女性がフェミニズムの領域において発言力を持つことを可能にすることである。

エセル・クロウリー(Ethel Crowley)は、トリニティ・カレッジ・ダブリンの社会学教授であり、「第三世界の女性と西洋のフェミニズムの不十分さ」という記事の中で、西洋の フェミニズムが非西洋社会に適用される際にいかに欠けているかを論じている。彼女は、第三世界の女性に関して、西洋のフェミニストが理論的還元主義に陥っ ていると非難している。彼女が西洋のフェミニズムに抱く主な問題は、強調された問題の是正策を打ち出す代わりに、イデオロギー的な「細かいこと」に時間を かけすぎていることである。クロウリーが記事で最も強調しているのは、民族誌学が問題解決に不可欠であるということ、そして、自由という言葉が世界のすべ ての女性にとって同じ意味を持つわけではないということである。[15][信頼できない情報源?]

Postcolonial feminism began as a criticism of the failure of Western feminism to cope with the complexity of postcolonial feminist issues as represented in Third World feminist movements. Postcolonial feminists seek to incorporate the struggle of women in the global South into the wider feminist movement.[16] Western feminists and feminists outside of the West also often differ in terms of race and religion, which is not acknowledged in Western feminism and can cause other differences. Western feminism tends to ignore or deny these differences, which discursively forces Third World women to exist within the world of Western women and their oppression to be ranked on an ethnocentric Western scale.[17]

Postcolonial feminists do not agree that women are a universal group and reject the idea of a global sisterhood. Thus, the examination of what truly binds women together is necessary in order to understand the goals of the feminist movements and the similarities and differences in the struggles of women worldwide.[16] The aim of the postcolonial feminist critique to traditional Western feminism is to strive to understand the simultaneous engagement in more than one distinct but intertwined emancipatory battle.[18]

This is significant because feminist discourses are critical and liberatory in intent and are not thereby exempt from inscription in their internal power relations. The hope of postcolonial feminists is that the wider feminist movement will incorporate these vast arrays of theories which are aimed at reaching a cultural perspective beyond the Western world by acknowledging the individual experiences of women around the world. Ali Suki highlights the lack of representation of women of color in feminist scholarship comparing the weight of whiteness similar to the weight of masculinities.[11] This issue is not due to a shortage of scholarly work in the global South but a lack of recognition and circulation. This reinforces Western hegemony and supports the claim of outweighed representation of white, Western scholars. Most available feminist literature regarding the global South tends to be written by Western theorists resulting in the whitewashing of histories.[19]

Feminist postcolonial theorists are not always unified in their reactions to postcolonial theory and Western feminism, but as a whole, these theorists have significantly weakened the bounds of mainstream feminism.[13] The intent of postcolonial feminism is to reduce homogenizing language coupled with an overall strategy to incorporate all women into the theoretical milieu. While efforts are made to eliminate the idea of the Third World "other", a Western Eurocentric feminist framework often presents the "other" as victim to their culture and traditions. Brina Bose highlights the ongoing process of "alienation and alliance" from other theorists in regards to postcolonial feminism; she emphasizes, "...the obvious danger both in 'speaking for' the silent/silenced as well as in searching for retaliatory power in elusive connections..."[20] There is a tendency throughout many different academic fields and policy strategies to use Western models of societies as a framework for the rest of the world. This critique is supported in other scholarly work including that of Sushmita Chatterjee who describes the complications of adding feminism as a "Western ideological construct to save brown women from their inherently oppressive cultural patriarchy."[6]

ポストコロニアル・フェミニズムは、第三世界のフェミニスト運動に代表されるポストコロニアルのフェミニスト問題の複雑性に対処できなかった西洋のフェミ ニズムへの批判として始まった。ポストコロニアル・フェミニストは、南半球の女性たちの闘争をより広範なフェミニスト運動に組み入れることを目指してい る。[16] 西洋のフェミニストと西洋以外のフェミニストの間では、人種や宗教に関する見解も異なることが多く、これは西洋のフェミニズムでは認められておらず、その 他の相違点を生み出す原因ともなっている。西洋のフェミニズムは、これらの相違を無視したり否定したりする傾向があり、その結果、第三世界の女性たちは、 西洋の女性たちの世界の中で存在することを余儀なくされ、彼女たちの抑圧は、西洋中心主義的な尺度で評価されることになる。

ポストコロニアルのフェミニストたちは、女性が普遍的な集団であるという考えには同意せず、世界的な姉妹関係という概念も拒絶している。したがって、フェ ミニスト運動の目標や世界中の女性の闘争における類似点と相違点を理解するためには、女性たちを真に結びつけているものは何かを検証することが必要であ る。[16] ポストコロニアルのフェミニストたちが伝統的な西洋のフェミニズムに対して行う批判の目的は、同時に複数の、しかし絡み合った、明確に異なる解放の闘争に 関与していることを理解することである。[18]

これは重要なことである。なぜなら、フェミニストの言説は批判的かつ解放的な意図を持つものであり、それによってその内部の権力関係に記されることを免れ るものではないからだ。ポストコロニアル・フェミニストの希望は、より広範なフェミニスト運動が、西洋世界を超えた文化的視点に到達することを目的とし た、これらの広大な理論の配列を、世界中の女性の個々の経験を認めることによって取り入れることである。アリ・スキは、フェミニスト学術研究における有色 人種の女性の表現の欠如を、男性性の重みと類似した白人の重みに例えて強調している。[11] この問題は、グローバル・サウスにおける学術研究の不足によるものではなく、認識と流通の不足によるものである。これは西洋のヘゲモニーを強化し、白人で ある西洋の学者の表現が優勢であるという主張を裏付けるものである。南半球に関する入手可能なフェミニストの文献のほとんどは、西洋の理論家によって書か れたものであり、結果として歴史の白人化につながっている。

フェミニストのポストコロニアル理論家たちは、ポストコロニアル理論や西洋のフェミニズムに対する反応において必ずしも一致しているわけではないが、全体 としては、これらの理論家たちは主流のフェミニズムの枠組みを大幅に弱体化させてきた。ポストコロニアルフェミニズムの意図は、すべての女性を理論的環境 に組み込むという全体的な戦略と結びついた、均質化する言語を減らすことである。第三世界の「他者」という概念を排除する努力がなされる一方で、西洋中心 主義のフェミニストの枠組みでは、しばしば「他者」が自らの文化や伝統の犠牲者として描かれる。ブリーナ・ボースは、ポストコロニアルフェミニズムに関し て、他の理論家による「疎外と連帯」の継続的なプロセスを強調している。彼女は、「沈黙させられた人々を代弁することにも、捉えどころのないつながりの中 で報復力を求めることにも、明白な危険性がある」と強調している[20]。この批判は、フェミニズムを「有色人女性を本質的に抑圧的な文化的家父長制から 救うための西洋のイデオロギー的構築物」として追加することの複雑さを論じたスシュミタ・チャタジー(Sushmita Chatterjee)の研究など、他の学術的研究でも支持されている。[6]

The postcolonial feminist movements look at the gendered history of colonialism and how that continues to affect the status of women today. In the 1940s and 1950s, after the formation of the United Nations, former colonies were monitored by the West for what was considered social progress. The definition of social progress was tied to adherence to Western socio-cultural norms. The status of women in the developing world has been monitored by organizations such as the United Nations. As a result, traditional practices and roles taken up by women, sometimes seen as distasteful by Western standards, could be considered a form of rebellion against colonial rule. Some examples of this include women wearing headscarves or female genital mutilation. These practices are generally looked down upon by Western women, but are seen as legitimate cultural practices in many parts of the world fully supported by practicing women.[9] Thus, the imposition of Western cultural norms may desire to improve the status of women but has the potential to lead to conflict.

In order to understand the postcolonial feminist theory, one must first understand the postcolonial theory. In sociology, postcolonial theory is a theory that is preoccupied with understanding and examining the social impacts of European colonialism, its main claim is that the modern world as it is now is impossible to understand without understanding its relation with and history of imperialism and colonial rule.[21] Postcolonialism can provide an outlet for citizens to discuss various experiences from the colonial period. These can include: "migration, slavery, oppression, resistance, representation, difference, race, gender, place and responses to the influential discourses of imperial Europe."[22] Ania Loomba critiques the terminology of 'postcolonial' by arguing the fact that 'post' implicitly implies the aftermath of colonization; she poses the question, "when exactly then, does the 'postcolonial' begin?"[23] Postcolonial feminists see the parallels between recently decolonized nations[24] and the state of women within patriarchy taking "perspective of a socially marginalized subgroup in their relationship to the dominant culture."[22] In this way feminism and postcolonialism can be seen as having a similar goal in giving a voice to those that were voiceless in the traditional dominant social order. While this holds significant value aiding new theory and debate to arise, there is no single story of global histories and Western imperialism is still significant. Loomba suggests that colonialism carries both an inside and outside force in the evolution of a country concluding 'postcolonial' to be loaded with contradictions.[23]

ポストコロニアル・フェミニスト運動は、植民地主義のジェンダー化された歴史と、それが今日でも女性の地位に影響を与え続けている様相を調査している。 1940年代と1950年代、国連が設立された後、旧植民地は欧米諸国によって、社会進歩の観点から監視されていた。社会進歩の定義は、欧米の社会文化規 範の遵守と結びついていた。発展途上国における女性の地位は、国連などの組織によって監視されてきた。その結果、西洋の基準では不快と見なされることもあ る、女性が伝統的に行ってきた慣習や役割が、植民地支配に対する抵抗の一形態と見なされる可能性がある。その例としては、女性がスカーフを着用すること や、女性器切除などが挙げられる。これらの慣習は西洋の女性からは概して軽蔑的に見られるが、世界の多くの地域では正当な文化慣習と見なされており、実際 にそれを行っている女性たちからも全面的に支持されている。[9] したがって、西洋の文化規範を押し付けることは、女性の地位向上を望むものではあるが、紛争につながる可能性もある。

ポストコロニアルフェミニズム理論を理解するためには、まずポストコロニアル理論を理解しなければならない。社会学において、ポストコロニアル理論とは、 ヨーロッパの植民地主義が社会に与えた影響を理解し、検証することに重点を置いた理論である。その主な主張は、現在の近代世界を理解するには、帝国主義と 植民地支配の歴史との関係を理解しなければ不可能であるというものである。ポストコロニアル主義は、植民地時代におけるさまざまな経験について議論する場 を市民に提供することができる。これには、「移民、奴隷、抑圧、抵抗、表現、差異、人種、ジェンダー、場所、そしてヨーロッパ帝国の有力な言説に対する反 応」などが含まれる。[22] アニア・ルンバは、「ポスト」という言葉が植民地化の余波を暗に意味しているという事実を論じて、「ポストコロニアル」という用語を批判している。彼女 は、「では、いったいいつから『ポストコロニアル』が始まるのか?」という疑問を投げかけている。[23] ポストコロニアルフェミニストは、最近まで植民地であった国々[24]と、家父長制社会における女性の状況を比較し、「支配的文化との関係における社会的 に疎外されたサブグループの視点」[22]から考察している。このように、フェミニズムとポストコロニアル主義は、従来の支配的社会秩序の中で声なき人々 に声を届けるという点で、共通の目標を持っていると見なすことができる。これは新たな理論や議論を生み出す上で重要な価値を持つが、世界史には単一のス トーリーはなく、西洋の帝国主義は依然として重要である。 ルンバは、植民地主義は、その国の進化において内側と外側の両方の力をもたらし、ポストコロニアルは矛盾に満ちていると結論づけている。[23]

Audre Lorde wrote about postcolonial feminism and race.

Postcolonial feminism has strong ties with indigenous movements and wider postcolonial theory. It is also closely affiliated with black feminism because both black feminists and postcolonial feminists argue that mainstream Western feminism fails to adequately account for racial differences. Racism has a major role to play in the discussion of postcolonial feminism. Postcolonial feminists seek to tackle the ethnic conflict and racism that still exist and aims to bring these issues into feminist discourse. In the past, mainstream Western feminism has largely avoided the issue of race, relegating it to a secondary issue behind patriarchy and somewhat separate from feminism. Until more recent discourse, race was not seen as an issue that white women needed to address.[25]

In her article "Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference", Lorde succinctly explained that, "as white women ignore their built-in privilege and define woman in terms of their own experiences alone, then women of Color become 'other'..." which prevents the literary work produced by women of color from being represented in mainstream feminism.[26]

Postcolonial feminism attempts to avoid speaking as if women were a homogeneous population with no differences in race, sexual preference, class, or even age. The notion of whiteness, or lack thereof, is a key issue within the postcolonial feminist movement.[27] This is primarily due to the perceived relationship between postcolonial feminism and other racially based feminist movements, especially Black feminism and indigenous feminisms. In Western culture, racism is sometimes viewed as an institutionalized, ingrained facet of society. Postcolonial feminists want to force feminist theory to address how individual people can acknowledge racist presumptions, practices, and prejudices within their own lives attempting to halt its perpetuation through awareness.[27]

Vera C. Mackie describes the history of feminist rights and women's activism in Japan from the late nineteenth century to present day. Women in Japan began questioning their place in the social class system and began questioning their roles as subjects under the Emperor. The book goes into detail about iconic Japanese women who stood out against gender oppression, including documents from Japanese feminists themselves. Japan's oppression of women is written about displaying that women from yet another culture do not live under the same circumstances as women from western/white cultures. There are different social conducts that occur in Asian countries that may seem oppressive to white feminists; according to Third World feminist ideologies, it is ideal to respect the culture that these women are living in while also implementing the same belief that they should not be oppressed or seen in any sort of sexist light.[28] Chilla Bulbeck discusses how feminism strives to fight for equality of the sexes through equal pay, equal opportunity, reproductive rights, and education. She also goes on to write about how these rights apply to women in the global South as well but that depending on their country and culture, each individual's experience and needs are unique.

"False consciousness" is perpetuated throughout mainstream feminism assuming that people in the global South don't know what is best for them. Postcolonial framework attempts to shed light on these women as "full moral agents" who willingly uphold their cultural practices as a resistance to Western imperialism.[29] For example, representation of the Middle East and Islam focuses on the traditional practice of veiling as a way of oppressing women. While Westerners may view the practice in this way, many women of the Middle East disagree and cannot understand how Western standards of oversexualized dress offer women liberation.[30] Such Eurocentric claims have been referred to by some as imperial feminism.

オードラ・ローダ(Audre Lorde)はポストコロニアルフェミニズムと人種について書いた。

ポストコロニアルフェミニズムは、先住民運動やより広義のポストコロニアル理論と強い結びつきがある。また、黒人フェミニズムとも密接な関係がある。なぜ なら、黒人フェミニストとポストコロニアルフェミニストは、主流派の西洋フェミニズムが人種的差異を十分に考慮していないと主張しているからだ。ポストコ ロニアルフェミニズムの議論においては、人種差別が重要な役割を果たしている。ポストコロニアルフェミニストは、現在も存在する民族紛争や人種差別に取り 組むことを目指し、これらの問題をフェミニストの議論に取り入れることを目指している。 かつては、西洋の主流派フェミニズムは人種問題をほとんど避けており、それは家父長制の二次的な問題として、フェミニズムとはやや別個のものとして扱われ ていた。 ごく最近まで、人種は白人女性が取り組むべき問題とは見なされていなかった。

彼女の論文「年齢、人種、階級、性別:違いを再定義する女性たち」の中で、ロードは簡潔に次のように説明している。「白人女性が生まれながらに持つ特権を 無視し、自身の経験のみに基づいて女性を定義するならば、有色人種の女性は『その他』となる。」これが、有色人種の女性が創作した文学作品が主流派フェミ ニズムで正当に評価されない理由である。

ポストコロニアルフェミニズムは、女性が人種、性的指向、階級、さらには年齢においても違いのない均質な集団であるかのように語ることを避けようとしてい る。白人であること、あるいは白人でないことという概念は、ポストコロニアルフェミニズム運動における重要な問題である。[27] これは主に、ポストコロニアルフェミニズムと他の人種に基づくフェミニズム運動、特に黒人フェミニズムや先住民フェミニズムとの関係が認識されていること による。西洋文化では、人種差別は時に制度化され、社会に根付いた側面として捉えられる。ポストコロニアルフェミニストは、人種差別的な思い込み、慣習、 偏見を個々人が自らの生活の中で認識し、意識することでその永続化を阻止しようとしている。

ヴェラ・C・マッキーは、19世紀後半から現代までの日本のフェミニストの権利と女性の活動の歴史について述べている。日本の女性たちは、社会階級制度に おける自分の立場を疑問視し、天皇の臣民としての役割を疑問視し始めた。この本では、ジェンダーによる抑圧に立ち向かった象徴的な日本の女性たちについ て、日本のフェミニスト自身による文書を含め、詳細に述べられている。日本の女性に対する抑圧は、西洋/白人文化の女性たちと同じ状況下で暮らしているわ けではないことを示すものとして書かれている。アジア諸国では、白人フェミニストにとっては抑圧的に見えるような社会慣習が存在する。第三世界のフェミニ ストのイデオロギーによると、女性たちが暮らす文化を尊重しながら、同時に女性たちが抑圧されたり性差別的な見方をされるべきではないという信念を実践す ることが理想とされている。[28] チーラ・ブルベックは、フェミニズムが男女平等、平等な賃金、平等な機会、生殖に関する権利、教育などを通じて男女平等をどのように実現しようとしている かを論じている。また、これらの権利は南半球の女性にも適用されるが、国や文化によって、個々人の経験やニーズはそれぞれ異なる、とも述べている。

「偽りの意識」は、グローバル・サウスに暮らす人々は自分にとって何が最善なのかを知らないという前提のもと、主流派フェミニズム全体に浸透している。ポ ストコロニアルの枠組みでは、これらの女性を、西洋の帝国主義への抵抗として自らの文化的慣習を自発的に維持する「完全な道徳的代理人」として解釈しよう としている。[29] 例えば、中東とイスラム教の描写では、女性を抑圧する手段として伝統的なベール着用に焦点が当てられている。西洋人はそう考えるかもしれないが、中東の多 くの女性はそれに反対であり、西洋の性的な服装を基準とする考え方が、なぜ女性に解放をもたらすのか理解できないのである。[30] このようなヨーロッパ中心主義的な主張は、一部では帝国フェミニズムとも呼ばれている。

The U.S., where Western culture flourishes most, has a majority white population of 77.4% as of the 2014 U.S. census.[31] They have also been the majority of the population since the 16th century. Whites have had their role in the colonialism of the country since their ancestors settlement of Plymouth Colony in 1620. Although they ruled majority of the U.S. since their settlement, it was only the men who did the colonizing. The women were not allowed to have the same freedoms and rights that men had at the time. It was not until the victory of World War I that the Roaring Twenties emerged and gave women a chance to fight for independence.[32] It is also the reason that first-wave feminist were able to protest. Their first major accomplishment was the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. Some of the women that led the first-wave feminist movement were Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Anthony, Stanton, and many other feminist fought for the equality of rights for both women and African Americans; however, their accomplishments only benefited white middle-class women. The majority of equality achieved through first and second wave feminism and other movements still benefits mainly the white population. The lack of acknowledgement and acceptance of white privilege by white people is a main contributor to the inequality of rights in the United States. In the book Privilege Revealed: How Invisible Preference Undermines, Stephanie M. Wildman states, "The notion of privilege... has not been recognized in legal language and doctrine. This failure to acknowledge privilege, to make it visible in legal doctrine, creates a serious gap in legal reasoning, rendering law unable to address issues of systemic unfairness."[33] White privilege, oppression, and exploitation in the U.S. and Western influenced countries are main contributors to the formation of other feminist and philosophical movements such as black feminism, Islamic feminism, Latinx philosophy, and many other movements.

西洋文化が最も栄えている米国では、2014年の国勢調査によると、人口の77.4%を白人が占めている。[31] また、16世紀以来、白人が人口の過半数を占めている。白人は、1620年にプリマス植民地に彼らの祖先が定住して以来、この国の植民地主義において重要 な役割を果たしてきた。入植以来、彼らは米国の大半を支配してきたが、植民地化を行ったのは男性だけだった。女性はその当時、男性が持っていたのと同じ自 由や権利を持つことは許されていなかった。第一次世界大戦の勝利によって、狂乱の20年代が到来し、女性が独立のために戦うチャンスが訪れたのは、その後 のことである。[32] また、これが第一波フェミニストが抗議を行うことができた理由でもある。彼女たちの最初の大きな功績は、憲法修正第19条の批准であった。第一波フェミニ ズム運動を主導した女性には、スーザン・B・ Anthonyやエリザベス・キャディ・スタントンなどがいる。Anthony、Stanton、そして多くの他のフェミニストたちは、女性とアフリカ系 アメリカ人の権利平等を求めて戦ったが、彼らの功績は白人の中流階級の女性にのみ恩恵をもたらした。第一波、第二波フェミニズムやその他の運動によって達 成された平等性の大半は、依然として主に白人層に恩恵をもたらしている。白人自身が白人特権を認識せず、受け入れないことが、米国における権利の不平等を 助長する主な要因となっている。ステファニー・M・ワイルドマン著『Privilege Revealed: How Invisible Preference Undermines』では、「特権という概念は...法的な言語や理論では認識されてこなかった。特権を認めず、法理論において可視化しないというこの 失敗は、法的な推論に深刻なギャップを生み出し、法律が制度的不公平の問題に対処できないものにしてしまう」と述べている。[33] 米国および西欧の影響下にある国々における白人特権、抑圧、搾取は、黒人フェミニズム、イスラム系フェミニズム、ラテン系哲学、その他多くの運動など、他 のフェミニストおよび哲学運動の形成に大きく寄与している。

Depending on feminist literature, Third World and postcolonial feminism can often be used interchangeably. In a review upon other scholars work of the two terms, Nancy A. Naples highlights the differences; "Third World" nations, termed as such by North America and Europe, were characterized as underdeveloped and poor resulting in a dependency of "First World" nations for survival. This term started being widely used in the 1980s but shortly after began to receive criticism from postcolonial scholarship.[34] Naples defines the term 'postcolonial' as, "...typically applied to nations like India where a former colonial power has been removed." Both terms can be argued as problematic due to the reinforced idea of "othering" those from non-Western culture.[35]

Though postcolonial feminism was supposed to represent the evolution of Third World into a more reformed ideology, Ranjoo Seodu Herr argues for Third World Feminism to be reclaimed highlighting the importance of the local/national,"...in order to promote inclusive and democratic feminisms that accommodate diverse and multiple feminist perspectives of Third World women on the ground."[29]

The term is also in relation with other strands of feminism, such as Black feminism and African feminism.

フェミニストの文献によると、第三世界フェミニズムとポストコロニアルフェミニズムは、しばしば互換的に使用される。この2つの用語について他の学者の研 究を論評する中で、ナンシー・A・ナポリスは両者の違いを強調している。「第三世界」諸国は、北米やヨーロッパからそう呼ばれており、発展途上国で貧しい 国々として特徴づけられ、生存のために「第一世界」諸国に依存している。この用語は1980年代に広く使用され始めたが、その後すぐにポストコロニアル学 派から批判を受けるようになった。[34] Naplesは「ポストコロニアル」という用語を「...典型的には、かつての植民地支配国が撤退したインドのような国々に適用される」と定義している。 両用語とも、非西洋文化を「他者」として強調する考え方が問題であると論じられることがある。[35]

ポストコロニアルフェミニズムは、第三世界のより進歩的な思想への進化を象徴するものと考えられていたが、ランジュ・セオドゥ・ハルは、「現地の第三世界 の女性の多様かつ複数のフェミニスト的視点を受け入れる包括的で民主的なフェミニズムを推進するため」に、地域的・国家的視点の重要性を強調し、第三世界 フェミニズムの再評価を主張している。[29]

この用語は、ブラックフェミニズムやアフリカフェミニズムなど、他のフェミニズムの潮流とも関連している。

Double colonization is a term referring to the status of women in the postcolonial world. Postcolonial and feminist theorists state that women are oppressed by both patriarchy and the colonial power, and that this is an ongoing process in many countries even after they achieved independence. Thus, women are colonized in a twofold way by imperialism and male dominance.

Postcolonial feminists are still concerned with identifying and revealing the specific effects double colonization has on female writers and how double colonization is represented and referred to in literature. However, there is an ongoing discussion among theorists about whether the patriarchal or the colonial aspect are more pressing and which topic should be addressed more intensively.[36]

The concept of double colonization is particularly significant when referring to colonial and postcolonial women's writing. It was first introduced in 1986 by Kirsten Holst Petersen and Anna Rutherford in their anthology "A Double Colonization: Colonial and Postcolonial Women's Writing", which deals with the question of female visibility and the struggles of female writers in a primarily male's world.[37] As Aritha van Herk, a Canadian writer and editor, puts it in her essay "A Gentle Circumcision": "Try being female and living in the kingdom of the male virgin; try being female and writing in the kingdom of the male virgin."[37]

Chandra Talpade Mohanty

Chandra Talpade Mohanty, author of "Under Western Eyes"

Writers that are usually identified with the topic of double colonization and critique on Western feminism are for example Hazel V. Carby and Chandra Talpade Mohanty. "White Woman Listen!", an essay composed by Carby, harshly critiques Western feminists who she accuses of being prejudiced and oppressors of black women rather than supporters. In this context she also talks about "triple" oppression: "The fact that black women are subject to the simultaneous oppression of patriarchy, class and "race" is the prime reason for not employing parallels that render their position and experience not only marginal but also invisible".[38]

Mohanty's argument in "Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses" goes into the same direction. She blames Western feminists of presenting women of color as one entity and failing to account for diverse experiences.[34]

二重植民地化とは、ポストコロニアル世界における女性の地位を指す用語である。ポストコロニアル理論家やフェミニスト理論家は、女性は家父長制と植民地支 配の両方によって抑圧されており、これは多くの国々で独立を達成した後も継続しているプロセスであると主張している。したがって、女性は帝国主義と男性優 位性の二重の方法で植民地化されている。

ポストコロニアルのフェミニストたちは、二重植民地化が女性作家に与える具体的な影響を特定し、明らかにすること、また、二重植民地化が文学においてどの ように表現され、言及されているかを明らかにすることに、今も関心を寄せている。しかし、理論家たちの間では、家父長制と植民地主義のどちらがより差し 迫った問題であるか、また、どちらのトピックにより重点的に取り組むべきかについて、現在も議論が続いている。

二重植民地化という概念は、植民地時代およびポストコロニアル時代の女性作家の作品を論じる際に特に重要である。この概念は、1986年にキルステン・ホ ルスト・ピーターセンとアンナ・ラザフォードが編集したアンソロジー『二重植民地化: 植民地時代およびポストコロニアル時代の女性作家の作品」というアンソロジーで、主に男性の世界における女性の存在感と女性作家の苦闘の問題を取り上げた ものである。[37] カナダの作家兼編集者であるAritha van Herkは、彼女のエッセイ「A Gentle Circumcision」で次のように述べている。「男性の童貞の王国で女性として生き、男性の童貞の王国で女性として書くことを試してみなさい。」 [37]

チャンドラ・タルパデ・モハンティ

著書『西洋の眼差し』の著者、チャンドラ・タルパデ・モハンティ

二重植民地化と西洋のフェミニズム批判のテーマと関連付けられることが多い作家としては、例えばヘーゼル・V・カービーやチャンドラ・タルパデ・モハン ティなどがいる。カービーの著書『白人の女たちよ、聞け!』は、西洋のフェミニストを厳しく批判する内容であり、彼女は彼らを、黒人女性の支援者ではな く、偏見を持ち、黒人女性を弾圧する者であると非難している。この文脈において、彼女は「三重」の抑圧についても論じている。「黒人女性が家父長制、階 級、そして「人種」の同時的抑圧を受けているという事実は、彼女たちの立場や経験を周辺的であるばかりでなく、見えないものとしてしまう類似性を持ち出す ことをしない主な理由である」[38]。

モハンティの「西洋の視点:フェミニスト学術研究と植民地主義的言説」における主張も同じ方向性を示している。彼女は、有色人種の女性をひとつの存在とし て提示し、多様な経験を説明しようとしない西洋のフェミニストを非難している。[34]

With the continued rise of global debt, labor, and environmental crises, the precarious position of women (especially in the global south) has become a prevalent concern of postcolonial feminist literature.[39] Other themes include the impact of mass migration to metropolitan urban centers, economic terrorism, and how to decolonize the imagination from the multiple binds of writing as a woman of color.[40] Pivotal novels include Nawal El Saadawi's The Fall of the Iman about the lynching of women,[41] Chimamanda Adichie's Half of a Yellow Sun about two sisters in pre and post war Nigeria,[42] and Giannina Braschi's United States of Banana about Puerto Rican independence.[43][44] Other major works of postcolonial feminist literature include novels by Maryse Condé, Fatou Diome, and Marie Ndiaye,[39] poetry by Cherríe Moraga, Giannina Braschi, and Sandra Cisneros, and the autobiography of Audre Lorde (Zami: A New Spelling of My Name).[45]

Maria Lugones’ “Toward a Decolonial Feminism” is another piece of postcolonial feminist literature that explores gender norms in relation to the Indigenous people of the United States and the oppression that came with Christianity and the bourgeoisie.[46]

Further reading

Olive Senior: The Two Grandmothers (belletristic)

Shirley Geok-lin Lim: Between Women (poetry)

Chandra Talpade Mohanty: Feminism Without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity (novel)

世界的な負債、労働、環境危機が継続的に増加する中、女性(特に南半球)の不安定な立場はポストコロニアルフェミニズム文学の一般的な関心事となってい る。[39] その他のテーマには、大都市中心部への大量移住の影響、経済テロ、有色人女性としての執筆の束縛から想像力を解放する方法などがある。[ 40] 重要な小説には、ナワル・エル・サアドウィの『イマームの没落』は女性に対するリンチについて[41]、チママンダ・アディーチの『黄色い半分の太陽』は 戦前・戦後のナイジェリアにおける2人の姉妹について[42]、ジャンニーナ・ブラスキの『バナナ共和国』はプエルトリコの独立について描いている [43][ ] その他の主なポストコロニアルフェミニズム文学には、マリース・コンデ、ファトゥ・ディオメ、マリー・ンディアエの小説[39]、シェリー・モラガ、ジャ ンナ・ブラスキ、サンドラ・シスネロスの詩、オードラ・ローデの自伝(『ザミ:私の名前の新しいつづり』)などがある。[45]

マリア・ルゴネスの「脱植民地主義フェミニズムに向けて」も、米国の先住民とキリスト教およびブルジョワジーによる抑圧との関連におけるジェンダー規範を 探求するポストコロニアル・フェミニズム文学の作品である。

その他の推薦図書

オリーブ・シニア著『二人の祖母』(純文学

シャーリー・ゲック・リン・リム著『Between Women』(詩

チャンドラ・タルパデ・モハンティ著『国境なきフェミニズム:脱植民地化理論、連帯の実践』(小説

As postcolonial feminism is itself a critique of Western feminism, criticism of postcolonial feminism is often understood as a push back from Western feminism in defense of its aims. One way in which the Western feminist movement criticizes postcolonial feminism is on the grounds that breaking down women into smaller groups to address the unique qualities and diversity of each individual causes the entire movement of feminism to lose purpose and power. This criticism claims that postcolonial feminism is divisive, arguing that the overall feminist movement will be stronger if women can present a united front.[5]

Another critique of postcolonial feminism is much the same as the critiques that postcolonial feminism has for Western feminism. Like Western feminism, postcolonial feminism and Third World feminism are also in danger of being ethnocentric, limited by only addressing what is going on in their own culture at the expense of other parts of the world. Colonialism also embodies many different meanings for people and has occurred across the world with different timelines. Chatterjee supports the argument that postcolonial perspective repels "Holistic perspectives of the grand narrative of enlightenment, industrial revolution, and rationality render 'other' histories and people invisible under hegemonic constructions of truth and normalcy."[6] Generalizing colonialism can be extremely problematic as it translates into postcolonial feminism due to the contextual 'when, what, where, which, whose, and how' Suki Ali mentions in determining the postcolonial.[11]

Sara Suleri is a common critic of postcolonial feminism, in her work “Woman Skin Deep: Feminism and the Postcolonial Condition” she questions whether the language used in feminism and ethnicity were not so similar, if racial identity and feminism would be connected or “so radically inseparable” from each other. She also states that postcolonial feminism is “not matched with any logical or theoretical consistency” because it reduces sexuality to “the literal structure of the racial body” which is not consistent with postcolonial feminism's stance on the removal of oppressive labels and categorization.[47]

While postcolonial discourse has brought significant expansion of knowledge regarding feminist work, scholars have begun to rework and critique the field of postcolonial feminism developing a more well-rounded discourse termed transnational feminism. Where postcolonial theory highlighted representation and the "othering" of experience of those in the global South, transnational feminism aids in understanding "new global realities resulting from migrations and the creation of transnational communities."[48]

Postcolonial feminism is also criticized for the implications behind its name. The term "postcolonial", consisting of the prefix "post-" and suffix "colonial", insinuates that the countries it is referring to have left the era of colonialism and are progressing from it. This way of thinking promotes the idea that all developing countries underwent colonizing and began the process of decolonizing at the same time when countries referred to as "postcolonial" have actually endured colonization for different time frames. Some of the countries that are called "postcolonial" can in fact still be considered colonial. Another issue with the term "postcolonial" is that it implies a linear progression of the countries it addresses, which starkly contrasts the goal of postcolonial theory and postcolonial feminism to move away from a presentist narrative.[49]

ポストコロニアルフェミニズムは西洋のフェミニズムに対する批判であるため、ポストコロニアルフェミニズムに対する批判は、西洋のフェミニズムがその目的 を守るために反発していると理解されることが多い。西洋のフェミニズム運動がポストコロニアルフェミニズムを批判する理由の一つは、女性をより小さなグ ループに分けて、個々のユニークな資質や多様性に対応しようとすると、フェミニズム運動全体が目的と力を失ってしまうというものである。この批判は、ポス トコロニアルフェミニズムは分裂的であると主張し、女性が団結すればフェミニズム運動全体がより強固になるだろうと論じている。[5]

ポストコロニアルフェミニズムに対する別の批判は、ポストコロニアルフェミニズムが西洋のフェミニズムに対して抱く批判とほぼ同じである。西洋のフェミニ ズムと同様に、ポストコロニアルフェミニズムや第三世界のフェミニズムも、自文化で起こっていることのみに焦点を当て、世界の他の地域を犠牲にしてしまう という、民族中心主義の危険性がある。植民地主義はまた、人々にとってさまざまな意味合いを持ち、世界中で異なる時間軸で発生してきた。チャタジーは、 「啓蒙主義、産業革命、合理性の壮大な物語の全体論的視点は、真実と正常性のヘゲモニー的な構築の下で、『他者』の歴史や人々を不可視のものとする」とい うポストコロニアルの視点が、この主張を裏付けると主張している。[6] 植民地主義を一般化することは、ポストコロニアルを決定する際にスーキー・アリが言及している文脈上の「いつ、何を、どこで、誰が、どのように」という観 点から、ポストコロニアルフェミニズムに置き換えると、極めて問題となる可能性がある。[11]

サラ・スーレリはポストコロニアルフェミニズムの批判者としてよく知られており、著書『Woman Skin Deep: Feminism and the Postcolonial Condition』の中で、フェミニズムと民族主義で使われる言語はそれほど似通っていないのか、人種的アイデンティティとフェミニズムは結びついてい るのか、あるいは「根本的に切り離せない」のか、といった疑問を投げかけている。また、ポストコロニアルフェミニズムは、抑圧的なレッテル貼りやカテゴ リー化の排除というポストコロニアルフェミニズムの立場と矛盾する「人種的身体の文字通りの構造」に性を還元するものであるため、「いかなる論理的または 理論的な一貫性にも一致しない」とも述べている。

ポストコロニアルの議論はフェミニストの研究に関する知識の大幅な拡大をもたらしたが、学者たちはポストコロニアル・フェミニズムの分野を再構築し、批判 し始め、より包括的なトランスナショナル・フェミニズムと呼ばれる議論を展開している。ポストコロニアル理論がグローバル・サウスにおける経験の表象と 「他者化」を強調したのに対し、トランスナショナル・フェミニズムは「移民とトランスナショナルなコミュニティの創出による新しいグローバルな現実」の理 解を助けるものである。

ポストコロニアル・フェミニズムは、その名称に潜む含意についても批判されている。「ポストコロニアル」という用語は、「ポスト(後)」と「コロニアル (植民地)」という接頭辞と接尾辞から構成されているが、この用語は、その対象となっている国々が植民地主義の時代を脱し、そこから前進していることをほ のめかしている。この考え方は、発展途上国はすべて植民地化を経験し、同時に脱植民地化のプロセスを開始したという考えを助長するが、実際には「ポストコ ロニアル」と呼ばれる国々は、異なる期間にわたって植民地化に耐えてきた。ポストコロニアル」と呼ばれる国の中には、実際には依然として植民地であるとみ なされる国もある。「ポストコロニアル」という用語のもう一つの問題は、対象となる国々が直線的に進歩しているかのように暗示している点である。これは、 ポストコロニアル理論とポストコロニアルフェミニズムの目標である、現在中心の物語からの脱却とは対照的である。[49]

Coloniality of gender

Feminationalism

Global feminism

Gypsy feminism

History of feminism

Imperial feminism

Indigenous feminism

Intersectionality

Islamic feminism

Latinx philosophy

Postfeminism

Purplewashing

Sex segregation and Islam

Transnational feminism

Womanism

ジェンダーの植民地性

フェミニスト・フェミニズム

グローバル・フェミニズム

ジプシー・フェミニズム

フェミニズムの歴史

帝国フェミニズム

先住民フェミニズム

交差性

イスラム・フェミニズム

ラテン系哲学

ポストフェミニズム

パープルウォッシング

性別分離とイスラム

トランスナショナル・フェミニズム

ウーマニズム

Gould, Rebecca Ruth (2014). "Engendering Critique: Postnational Feminism in Postcolonial Syria". Women's Studies Quarterly. 42 (3/4): 213–233. doi:10.1353/wsq.2014.0054. JSTOR 24365004.

Lim, Shirley Geok-lin. Between Women.

Lugo-Lugo, Carmen R (December 2000). "The Right Kind of Feminists?: Third-world Women and the Politics of Feminism". Discontent: A Journal of Theory and Practice. 3 (3). Archived from the original on 9 December 2024.

Mohanty, Chandra Talpade. Feminism Without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity.

Senior, Olive. The Two Grandmothers.

Weedon, Chris (2002). "Key Issues in Postcolonial Feminism: A Western Perspective". Genderealisations. 1. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

Gould, Rebecca Ruth (2014). 「批判のジェンダー化:ポストコロニアル・シリアにおけるポストナショナル・フェミニズム」『Women's Studies Quarterly』42巻3/4号、213–233頁。doi:10.1353/wsq.2014.0054. JSTOR 24365004.

リム、シャーリー・ゲックリン。『女たちの間』

ルゴ=ルゴ、カルメン・R(2000年12月)。「正しいフェミニストとは?:第三世界の女性とフェミニズムの政治学」。『ディスコンテント:理論と実践のジャーナル』。3巻3号。2024年12月9日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。

モハンティ、チャンドラ・タルパデ。『国境なきフェミニズム:脱植民地化理論、連帯の実践』。

シニア、オリーブ。『二人の祖母』。

ウィードン、クリス(2002年)。「ポストコロニアル・フェミニズムの主要課題:西洋的視点」。『ジェンダーリアリゼーションズ』。1号。2016年3月3日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。