中国語の部屋

Chinese room

☆ 中国語の部屋の議論は、プログラムがどれほどインテリジェントに、あるいは人間のようにコンピュータを動作させるかに関わらず、プログラムを実行するコン ピュータに心や理解、意識があるはずがないというものである。この議論は、哲学者ジョン・サールが1980年に発表した論文「Minds, Brains, and Programs(心、脳、プログラム)」で提示され、学術誌『Behavioral and Brain Sciences』に掲載された。[1] サール以前にも、ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツ(1714年)、アナトリー・ドネプロフ(1961年)、ローレンス・デイヴィス(1974 年)、ネッド・ブロック(1978年)など、同様の議論を展開した人物がいた。サールによるこの議論は、その後長年にわたって広く議論されてきた。[2] サールの議論の中心となるのは、中国語の部屋として知られる思考実験である。[3] この思考実験において、サールは中国語を理解しない人物が、中国語の記号を操作するための詳細な指示が記載された本がある部屋に隔離されている状況を想像 する。中国語の文章がその部屋に持ち込まれると、その人物は本の指示に従って中国語の記号を生成する。その記号は、部屋の外にいる中国語の流暢な話者に とっては、適切な応答のように見える。サールによれば、その人物は意味を理解することなく、文法規則に従っているだけであり、その人物も部屋全体も中国語 を理解しているわけではない。彼は、コンピュータがプログラムを実行するときも同様に、実際の理解や思考を伴うことなく、文法規則を適用しているだけだと 主張している。 この主張は、機能主義と計算論の哲学的な立場に反対するものである。機能主義と計算論は、心は形式的な記号で動作する情報処理システムとして見ることがで きるという立場であり、また、ある精神状態のシミュレーションは、その精神状態の存在を十分に説明できるという立場である。特に、サールが「強いAI仮 説」と呼ぶ立場を論駁することがこの議論の目的である。「適切にプログラムされたコンピュータに適切な入出力があれば、人間が心を持つのと同じ意味で心を 持つことになる」[c] この主張は、当初は人工知能(AI)研究者の主張に対する反論として提示されたが、機械が示すことのできる知的な行動の限界を示していないため、主流の AI研究の目標に対する反論ではない。[6] この主張は、プログラムを実行するデジタルコンピュータのみに適用され、機械一般には適用されない。[4] この主張は広く議論されているが、大きな批判の対象となっており、心の哲学者やAI研究者たちの間で論争が続いている。 [7][8]

| The Chinese room

argument holds that a computer executing a program cannot have a mind,

understanding, or consciousness,[a] regardless of how intelligently or

human-like the program may make the computer behave. The argument was

presented in a 1980 paper by the philosopher John Searle entitled

"Minds, Brains, and Programs" and published in the journal Behavioral

and Brain Sciences.[1] Before Searle, similar arguments had been

presented by figures including Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1714),

Anatoly Dneprov (1961), Lawrence Davis (1974) and Ned Block (1978).

Searle's version has been widely discussed in the years since.[2] The

centerpiece of Searle's argument is a thought experiment known as the

Chinese room.[3] In the thought experiment, Searle imagines a person who does not understand Chinese isolated in a room with a book containing detailed instructions for manipulating Chinese symbols. When Chinese text is passed into the room, the person follows the book's instructions to produce Chinese symbols that, to fluent Chinese speakers outside the room, appear to be appropriate responses. According to Searle, the person is just following syntactic rules without semantic comprehension, and neither the human nor the room as a whole understands Chinese. He contends that when computers execute programs, they are similarly just applying syntactic rules without any real understanding or thinking.[4] The argument is directed against the philosophical positions of functionalism and computationalism,[5] which hold that the mind may be viewed as an information-processing system operating on formal symbols, and that simulation of a given mental state is sufficient for its presence. Specifically, the argument is intended to refute a position Searle calls the strong AI hypothesis:[b] "The appropriately programmed computer with the right inputs and outputs would thereby have a mind in exactly the same sense human beings have minds."[c] Although its proponents originally presented the argument in reaction to statements of artificial intelligence (AI) researchers, it is not an argument against the goals of mainstream AI research because it does not show a limit in the amount of intelligent behavior a machine can display.[6] The argument applies only to digital computers running programs and does not apply to machines in general.[4] While widely discussed, the argument has been subject to significant criticism and remains controversial among philosophers of mind and AI researchers.[7][8] |

中国語の部屋の議論は、プログラムがどれほどインテリジェントに、ある

いは人間のようにコンピュータを動作させるかに関わらず、プログラムを実行するコンピュータに心や理解、意識があるはずがないというものである。この議論

は、哲学者ジョン・サールが1980年に発表した論文「Minds, Brains, and

Programs(心、脳、プログラム)」で提示され、学術誌『Behavioral and Brain Sciences』に掲載された。[1]

サール以前にも、ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツ(1714年)、アナトリー・ドネプロフ(1961年)、ローレンス・デイヴィス(1974

年)、ネッド・ブロック(1978年)など、同様の議論を展開した人物がいた。サールによるこの議論は、その後長年にわたって広く議論されてきた。[2]

サールの議論の中心となるのは、中国語の部屋として知られる思考実験である。[3] この思考実験において、サールは中国語を理解しない人物が、中国語の記号を操作するための詳細な指示が記載された本がある部屋に隔離されている状況を想像 する。中国語の文章がその部屋に持ち込まれると、その人物は本の指示に従って中国語の記号を生成する。その記号は、部屋の外にいる中国語の流暢な話者に とっては、適切な応答のように見える。サールによれば、その人物は意味を理解することなく、文法規則に従っているだけであり、その人物も部屋全体も中国語 を理解しているわけではない。彼は、コンピュータがプログラムを実行するときも同様に、実際の理解や思考を伴うことなく、文法規則を適用しているだけだと 主張している。 この主張は、機能主義と計算論の哲学的な立場に反対するものである。機能主義と計算論は、心は形式的な記号で動作する情報処理システムとして見ることがで きるという立場であり、また、ある精神状態のシミュレーションは、その精神状態の存在を十分に説明できるという立場である。特に、サールが「強いAI仮 説」と呼ぶ立場を論駁することがこの議論の目的である。「適切にプログラムされたコンピュータに適切な入出力があれば、人間が心を持つのと同じ意味で心を 持つことになる」[c] この主張は、当初は人工知能(AI)研究者の主張に対する反論として提示されたが、機械が示すことのできる知的な行動の限界を示していないため、主流の AI研究の目標に対する反論ではない。[6] この主張は、プログラムを実行するデジタルコンピュータのみに適用され、機械一般には適用されない。[4] この主張は広く議論されているが、大きな批判の対象となっており、心の哲学者やAI研究者たちの間で論争が続いている。 [7][8] |

| Searle's thought experiment Suppose that artificial intelligence research has succeeded in programming a computer to behave as if it understands Chinese. The machine accepts Chinese characters as input, carries out each instruction of the program step by step, and then produces Chinese characters as output. The machine does this so perfectly that no one can tell that they are communicating with a machine and not a hidden Chinese speaker.[4] The questions at issue are these: does the machine actually understand the conversation, or is it just simulating the ability to understand the conversation? Does the machine have a mind in exactly the same sense that people do, or is it just acting as if it has a mind?[4] Now suppose that Searle is in a room with an English version of the program, along with sufficient pencils, paper, erasers and filing cabinets. Chinese characters are slipped in under the door, he follows the program step-by-step, which eventually instructs him to slide other Chinese characters back out under the door. If the computer had passed the Turing test this way, it follows that Searle would do so as well, simply by running the program by hand.[4] Searle asserts that there is no essential difference between the roles of the computer and himself in the experiment. Each simply follows a program, step-by-step, producing behavior that makes them appear to understand. However, Searle would not be able to understand the conversation. Therefore, he argues, it follows that the computer would not be able to understand the conversation either.[4] Searle argues that, without "understanding" (or "intentionality"), we cannot describe what the machine is doing as "thinking" and, since it does not think, it does not have a "mind" in the normal sense of the word. Therefore, he concludes that the strong AI hypothesis is false: a computer running a program that simulates a mind would not have a mind in the same sense that human beings have a mind.[4] |

サールによる思考実験 人工知能研究が成功し、コンピュータに中国語を理解しているかのように振る舞うようプログラミングすることに成功したと仮定しよう。この機械は、中国語の 文字を入力として受け入れ、プログラムの各命令を段階的に実行し、中国語の文字を出力として生成する。この機械は、その動作が完璧であるため、誰も機械と コミュニケーションしているのではなく、隠れた中国人スピーカーとコミュニケーションしているとは気づかない。 問題となるのは、次の点である。すなわち、その機械は実際に会話を理解しているのか、それとも、会話を理解しているように見せかけているだけなのか? その機械は、人間とまったく同じ意味で心を持っているのか、それとも、心を持っているように見せかけているだけなのか?[4] ここで、サールが英語版のプログラムと、十分な数の鉛筆、紙、消しゴム、そしてファイリングキャビネットを揃えた部屋にいると仮定しよう。ドアの下から中 国語の文字が差し込まれ、彼はプログラムの手順を一歩一歩追っていく。最終的に、他の中国語の文字をドアの下から差し戻すよう指示される。もしコンピュー タがチューリングテストに合格したのであれば、サールも同様に合格するはずである。つまり、プログラムを手動で実行するだけで合格するはずである。[4] サールは、この実験におけるコンピュータと自身の役割には本質的な違いはないと主張している。どちらも単にプログラムに従って段階的に行動を起こし、理解 しているように見える行動を生み出しているだけである。しかし、サールは会話の内容を理解することはできない。したがって、サールは、コンピュータも会話 の内容を理解することはできないと主張している。[4] サールは、「理解」(または「意図主義」)なしには、機械が「思考」していると表現することはできないと主張している。また、機械は思考しないため、通常 の意味での「心」は持っていない。したがって、彼は強いAI仮説は誤りであると結論づけている。すなわち、人間の心と同じ意味での心は持っていない。 [4] |

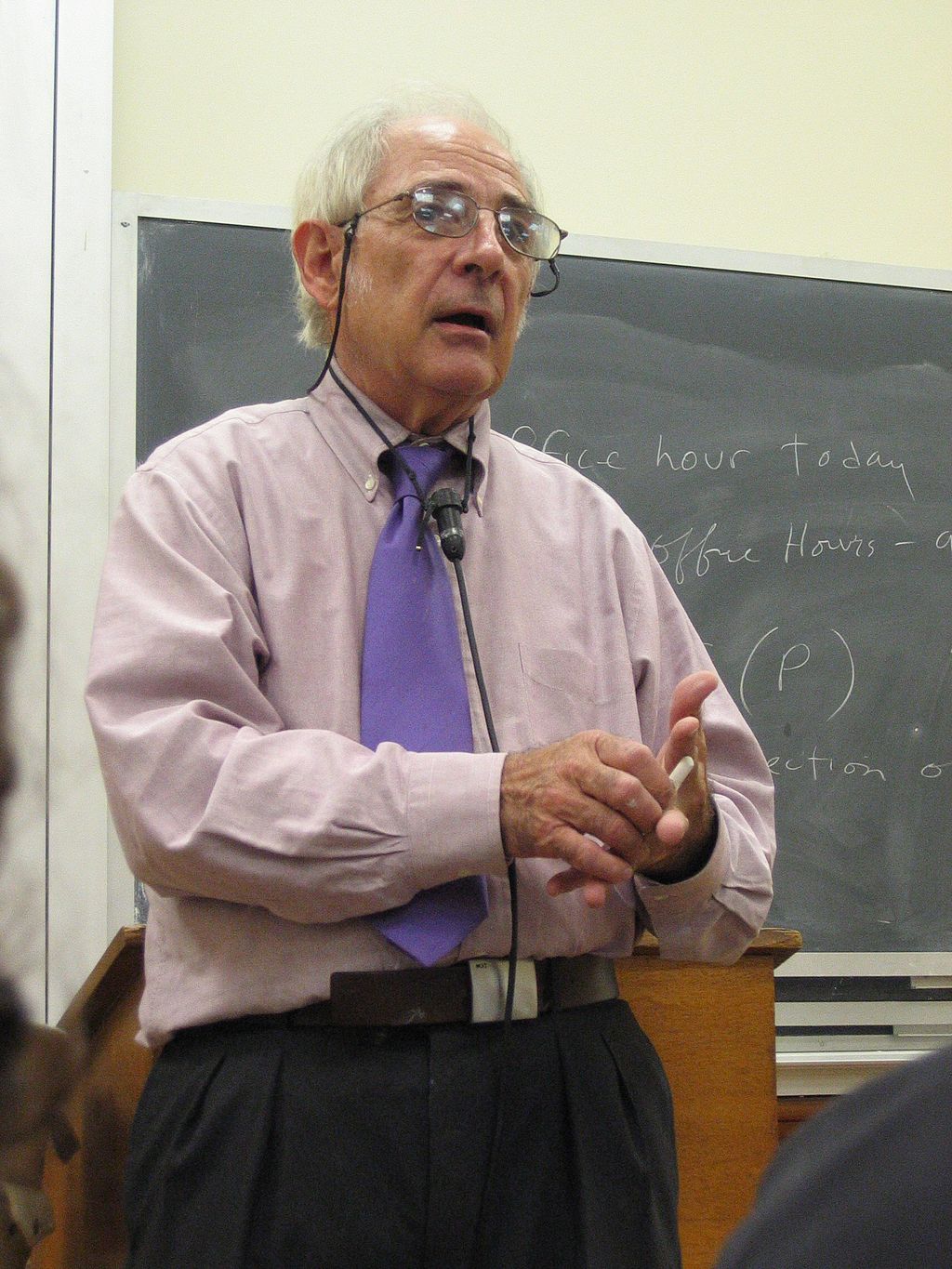

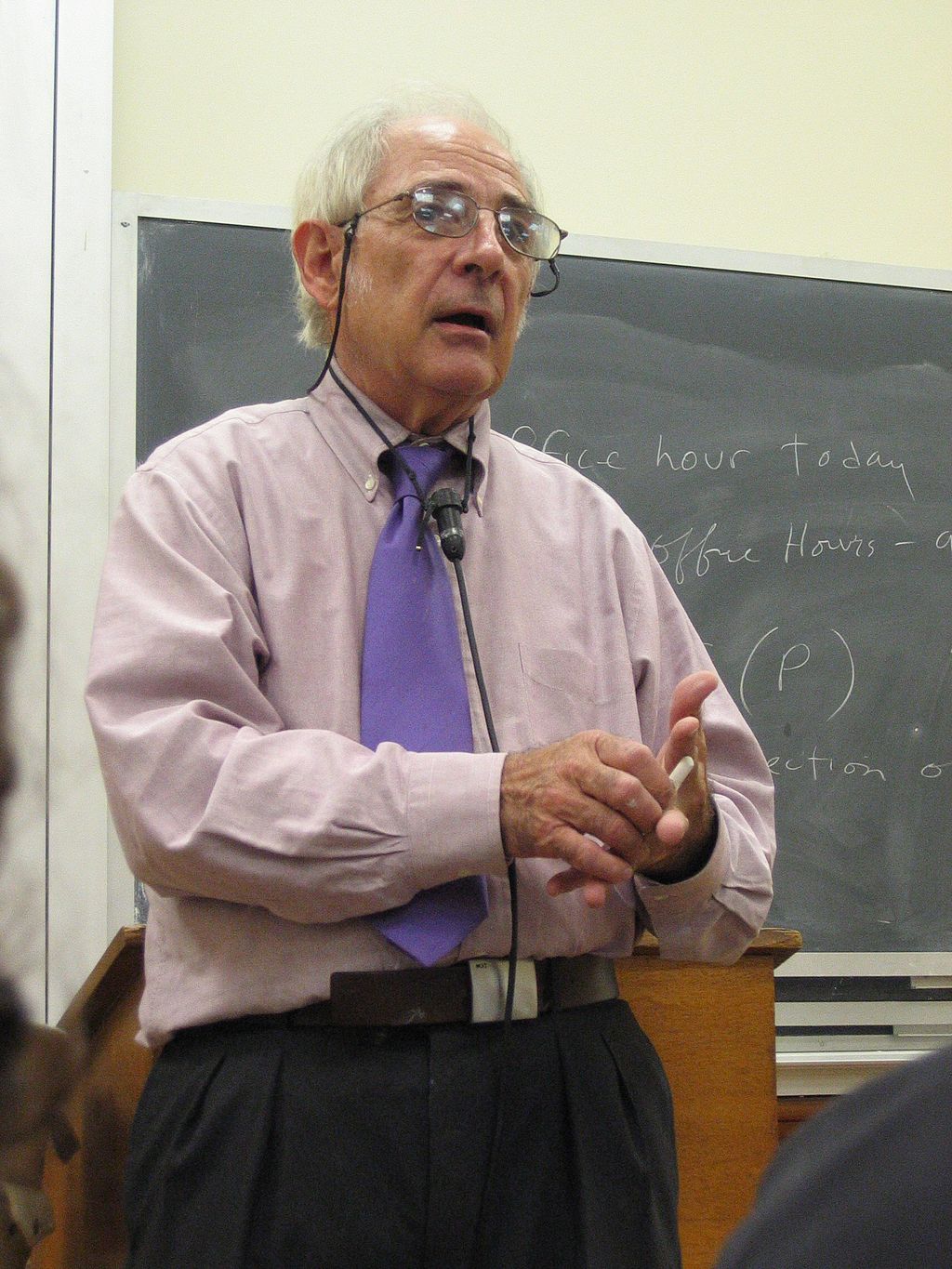

| History Gottfried Leibniz made a similar argument in 1714 against mechanism (the idea that everything that makes up a human being could, in principle, be explained in mechanical terms. In other words, that a person, including their mind, is merely a very complex machine). Leibniz used the thought experiment of expanding the brain until it was the size of a mill.[9] Leibniz found it difficult to imagine that a "mind" capable of "perception" could be constructed using only mechanical processes.[d] Peter Winch made the same point in his book The Idea of a Social Science and its Relation to Philosophy (1958), where he provides an argument to show that "a man who understands Chinese is not a man who has a firm grasp of the statistical probabilities for the occurrence of the various words in the Chinese language" (p. 108). Soviet cyberneticist Anatoly Dneprov made an essentially identical argument in 1961, in the form of the short story "The Game". In it, a stadium of people act as switches and memory cells implementing a program to translate a sentence of Portuguese, a language that none of them know.[10] The game was organized by a "Professor Zarubin" to answer the question "Can mathematical machines think?" Speaking through Zarubin, Dneprov writes "the only way to prove that machines can think is to turn yourself into a machine and examine your thinking process" and he concludes, as Searle does, "We've proven that even the most perfect simulation of machine thinking is not the thinking process itself." In 1974, Lawrence H. Davis imagined duplicating the brain using telephone lines and offices staffed by people, and in 1978 Ned Block envisioned the entire population of China involved in such a brain simulation. This thought experiment is called the China brain, also the "Chinese Nation" or the "Chinese Gym".[11]  John Searle in December 2005 Searle's version appeared in his 1980 paper "Minds, Brains, and Programs", published in Behavioral and Brain Sciences.[1] It eventually became the journal's "most influential target article",[2] generating an enormous number of commentaries and responses in the ensuing decades, and Searle has continued to defend and refine the argument in many papers, popular articles and books. David Cole writes that "the Chinese Room argument has probably been the most widely discussed philosophical argument in cognitive science to appear in the past 25 years".[12] Most of the discussion consists of attempts to refute it. "The overwhelming majority", notes Behavioral and Brain Sciences editor Stevan Harnad,[e] "still think that the Chinese Room Argument is dead wrong".[13] The sheer volume of the literature that has grown up around it inspired Pat Hayes to comment that the field of cognitive science ought to be redefined as "the ongoing research program of showing Searle's Chinese Room Argument to be false".[14] Searle's argument has become "something of a classic in cognitive science", according to Harnad.[13] Varol Akman agrees, and has described the original paper as "an exemplar of philosophical clarity and purity".[15] |

歴史 ゴットフリート・ライプニッツは1714年に、人間を構成するあらゆるものは原理的には機械的な用語で説明できるという考え方(すなわち、心を含めた人格 は、単に非常に複雑な機械にすぎないという考え方)に反対する同様の主張を行っている。ライプニッツは、脳を製粉所の粉引きの臼ほどの大きさまで拡大する という思考実験を用いた。[9] ライプニッツは、「知覚」を可能にする「心」が機械的なプロセスだけで構築できるとは想像しがたいと考えていた。[d] ピーター・ウィンチは著書『社会科学の理念とその哲学との関係』(1958年)で同様の指摘を行い、「中国語を理解する人間は、中国語のさまざまな単語の出現に関する統計的確率をしっかりと把握している人間ではない」という主張を展開している(108ページ)。 ソビエト連邦のサイバネティクス学者アナトリー・ドニエプロフは、1961年に発表した短編小説「ゲーム」の中で、本質的に同じ主張を行っている。この小 説では、ポルトガル語という誰も知らない言語の文章を翻訳するプログラムを実行するスイッチとメモリセルとして、大勢の人々が機能する。ザルービンを通じ て、ドニエプロフは「機械が思考できることを証明する唯一の方法は、自らを機械にして思考プロセスを検証することだ」と述べ、サールと同様に「機械による 思考の最も完璧なシミュレーションでさえ、思考プロセスそのものではないことが証明された」と結論づけている。 1974年にはローレンス・H・デイヴィスが電話回線と人間のスタッフがいるオフィスを使って脳を再現することを想像し、1978年にはネッド・ブロック が中国全人口がそのような脳のシミュレーションに関与することを想像した。この思考実験は「チャイナ・ブレイン」、あるいは「チャイニーズ・ネーショ ン」、「チャイニーズ・ジム」とも呼ばれる。[11]  ジョン・サールは2005年12月に サールは1980年に発表した論文「Minds, Brains, and Programs」の中で、この考えを示している。この論文は『Behavioral and Brain Sciences』誌に掲載された。[1] 最終的にこの論文は同誌の「最も影響力のある標的論文」となり、[2] その後の数十年にわたって膨大な数の論評や反応を引き起こした。サールはその後も多くの論文や一般向けの記事、書籍でこの主張を擁護し、さらに洗練させて きた。デイビッド・コールは、「『中国室』の議論は、おそらく過去25年間で認知科学において最も広く議論された哲学的議論である」と書いている。 [12] その議論のほとんどは、それを反駁しようとする試みで占められている。「圧倒的多数の人々は」、行動科学・脳科学編集者のステヴァン・ハーナッドは指摘し ている。「今でも『チャイニーズルーム論争』は完全に誤りであると考えている」[13]。この論争をめぐって膨大な量の文献が生まれていることに触れ、 パット・ヘイズは、認知科学の分野は「サールの『チャイニーズルーム論争』が誤りであることを示す継続中の研究プログラム」として再定義されるべきである とコメントしている。[14] サールの主張は「認知科学における古典的なもの」となっている、とハルナッドは述べている。[13] ヴァロール・アクマンも同意見であり、元論文を「哲学的な明晰さと純粋さの模範」と評している。[15] |

| Philosophy Although the Chinese Room argument was originally presented in reaction to the statements of artificial intelligence researchers, philosophers have come to consider it as an important part of the philosophy of mind. It is a challenge to functionalism and the computational theory of mind,[f] and is related to such questions as the mind–body problem, the problem of other minds, the symbol grounding problem, and the hard problem of consciousness.[a] Strong AI Searle identified a philosophical position he calls "strong AI": The appropriately programmed computer with the right inputs and outputs would thereby have a mind in exactly the same sense human beings have minds.[c] The definition depends on the distinction between simulating a mind and actually having one. Searle writes that "according to Strong AI, the correct simulation really is a mind. According to Weak AI, the correct simulation is a model of the mind."[22] The claim is implicit in some of the statements of early AI researchers and analysts. For example, in 1955, AI founder Herbert A. Simon declared that "there are now in the world machines that think, that learn and create".[23] Simon, together with Allen Newell and Cliff Shaw, after having completed the first program that could do formal reasoning (the Logic Theorist), claimed that they had "solved the venerable mind–body problem, explaining how a system composed of matter can have the properties of mind."[24] John Haugeland wrote that "AI wants only the genuine article: machines with minds, in the full and literal sense. This is not science fiction, but real science, based on a theoretical conception as deep as it is daring: namely, we are, at root, computers ourselves."[25] Searle also ascribes the following claims to advocates of strong AI: AI systems can be used to explain the mind;[20] The study of the brain is irrelevant to the study of the mind;[g] and The Turing test is adequate for establishing the existence of mental states.[h] |

哲学 チャイニーズルームの議論は、もともと人工知能研究者の主張に対する反論として提示されたものだが、哲学者たちはそれを心の哲学の重要な一部として考える ようになった。これは機能主義と心の計算理論への挑戦であり、心身問題、他者の心の問題、記号の根拠付け問題、意識のハード問題といった問題に関連してい る。 強いAI サールは、自身が「強いAI」と呼ぶ哲学上の立場を次のように定義している。 適切にプログラムされたコンピュータに適切な入力と出力を与えれば、人間が心を持つのと同じ意味で、コンピュータにも心があることになる。 この定義は、心をシミュレートすることと実際に心を持つことの区別によって決まる。サールは「ストロングAIによれば、正しいシミュレーションは実際に心である。ウィークAIによれば、正しいシミュレーションは心のモデルである」と書いている。[22] この主張は初期のAI研究者やアナリストのいくつかの発言に暗に示されている。例えば、1955年にはAIの創始者であるハーバート・A・サイモンが「世 界には今、思考し、学習し、創造する機械がある」と宣言している。[23] サイモンはアラン・ニューウェルとクリフ・ショーとともに、形式的な推論を行う最初のプログラム(Logic Theorist)を完成させた後、「物質で構成されたシステムが心の特性を持つことができることを説明し、由緒ある心身問題を解決した」と主張した。 [24] ジョン・ホーゲランドは、「AIが求めるのは本物だけだ。文字通りの意味で心を持つ機械、つまり、人間そのものなのだ。これはSFではなく、大胆かつ深い 理論的構想に基づく現実の科学である。すなわち、人間は本質的にはコンピュータそのものなのだ」と書いている。[25] また、サールは強力なAIの支持者たちに次のような主張を帰している。 AIシステムは心の説明に利用できる。[20] 脳の研究は心の研究とは無関係である。[g] チューリングテストは心的状態の存在を立証するのに十分である。[h] |

| Strong AI as computationalism or functionalism In more recent presentations of the Chinese room argument, Searle has identified "strong AI" as "computer functionalism" (a term he attributes to Daniel Dennett).[5][30] Functionalism is a position in modern philosophy of mind that holds that we can define mental phenomena (such as beliefs, desires, and perceptions) by describing their functions in relation to each other and to the outside world. Because a computer program can accurately represent functional relationships as relationships between symbols, a computer can have mental phenomena if it runs the right program, according to functionalism. Stevan Harnad argues that Searle's depictions of strong AI can be reformulated as "recognizable tenets of computationalism, a position (unlike "strong AI") that is actually held by many thinkers, and hence one worth refuting."[31] Computationalism[i] is the position in the philosophy of mind which argues that the mind can be accurately described as an information-processing system. Each of the following, according to Harnad, is a "tenet" of computationalism:[34] Mental states are computational states (which is why computers can have mental states and help to explain the mind); Computational states are implementation-independent—in other words, it is the software that determines the computational state, not the hardware (which is why the brain, being hardware, is irrelevant); and that Since implementation is unimportant, the only empirical data that matters is how the system functions; hence the Turing test is definitive. Recent philosophical discussions have revisited the implications of computationalism for artificial intelligence. Goldstein and Levinstein explore whether large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT can possess minds, focusing on their ability to exhibit folk psychology, including beliefs, desires, and intentions. The authors argue that LLMs satisfy several philosophical theories of mental representation, such as informational, causal, and structural theories, by demonstrating robust internal representations of the world. However, they highlight that the evidence for LLMs having action dispositions necessary for belief-desire psychology remains inconclusive. Additionally, they refute common skeptical challenges, such as the "stochastic parrots" argument and concerns over memorization, asserting that LLMs exhibit structured internal representations that align with these philosophical criteria.[35] David Chalmers suggests that while current LLMs lack features like recurrent processing and unified agency, advancements in AI could address these limitations within the next decade, potentially enabling systems to achieve consciousness. This perspective challenges Searle's original claim that purely "syntactic" processing cannot yield understanding or consciousness, arguing instead that such systems could have authentic mental states.[36] |

計算論または機能主義としての強いAI 中国室の議論に関するより最近の発表において、サールは「強いAI」を「コンピュータ機能主義」(この用語はダニエル・デネットによるもの)と定義してい る。[5][30] 機能主義は、精神に関する現代哲学における立場であり、信念、欲求、知覚などの精神現象を、それら相互および外界との関係における機能として記述すること で定義できるとするものである。コンピュータプログラムは、記号間の関係として機能的な関係性を正確に表現できるため、機能主義によれば、適切なプログラ ムを実行すれば、コンピュータにも精神現象が存在しうる。 ステヴァン・ハーナッドは、サールによる強いAIの描写は「計算論の認識できる原則として再定式化できる」と主張している。計算論は、「強いAIとは異な り」実際には多くの思想家によって支持されている立場であり、したがって反論する価値がある。計算論は、心の哲学における立場であり、心は情報処理システ ムとして正確に記述できると主張する。 ハーナッドによると、以下はそれぞれ計算論の「主張」である。 精神状態は計算状態である(これが、コンピュータが精神状態を持つことができ、心の説明に役立つ理由である)。 計算状態は実装に依存しない。つまり、計算状態を決定するのはハードウェアではなくソフトウェアである(これが、ハードウェアである脳は無関係である理由である)。 実装は重要ではないため、唯一重要な経験的データはシステムの機能である。したがって、チューリングテストが決定打となる。 最近の哲学的な議論では、計算論主義が人工知能に与える影響が再検討されている。ゴールドスタインとレビンスタインは、信念、欲求、意図などの民俗心理学 を示す能力に焦点を当て、チャットGPTのような大規模言語モデル(LLM)が心を持つことができるかどうかを調査している。著者は、LLMが世界に対す る堅牢な内部表現を示すことで、情報理論、因果理論、構造理論などの精神表現に関するいくつかの哲学理論を満たしていると主張している。しかし、LLMが 信念・欲求心理学に必要な行動傾向を持つという証拠は、依然として決定的ではないと強調している。さらに、彼らは「確率オウム」論や暗記に関する懸念な ど、一般的な懐疑的な課題を否定し、LLMはこれらの哲学的な基準に沿った構造化された内部表現を示すと主張している。 デビッド・チャーマーズは、現在のLLMは再帰処理や統一された行動のような機能を備えていないが、AIの進歩により今後10年以内にこれらの限界が克服 され、システムが意識を持つ可能性があると指摘している。この見解は、純粋に「構文」処理では理解や意識は生まれないというサールの当初の主張に異議を唱 え、そのようなシステムにも本物の精神状態が備わる可能性があると主張している。[36] |

| Strong AI vs. biological naturalism Searle holds a philosophical position he calls "biological naturalism": that consciousness[a] and understanding require specific biological machinery that are found in brains. He writes "brains cause minds"[37] and that "actual human mental phenomena [are] dependent on actual physical–chemical properties of actual human brains".[37] Searle argues that this machinery (known in neuroscience as the "neural correlates of consciousness") must have some causal powers that permit the human experience of consciousness.[38] Searle's belief in the existence of these powers has been criticized. Searle does not disagree with the notion that machines can have consciousness and understanding, because, as he writes, "we are precisely such machines".[4] Searle holds that the brain is, in fact, a machine, but that the brain gives rise to consciousness and understanding using specific machinery. If neuroscience is able to isolate the mechanical process that gives rise to consciousness, then Searle grants that it may be possible to create machines that have consciousness and understanding. However, without the specific machinery required, Searle does not believe that consciousness can occur. Biological naturalism implies that one cannot determine if the experience of consciousness is occurring merely by examining how a system functions, because the specific machinery of the brain is essential. Thus, biological naturalism is directly opposed to both behaviorism and functionalism (including "computer functionalism" or "strong AI").[39] Biological naturalism is similar to identity theory (the position that mental states are "identical to" or "composed of" neurological events); however, Searle has specific technical objections to identity theory.[40][j] Searle's biological naturalism and strong AI are both opposed to Cartesian dualism,[39] the classical idea that the brain and mind are made of different "substances". Indeed, Searle accuses strong AI of dualism, writing that "strong AI only makes sense given the dualistic assumption that, where the mind is concerned, the brain doesn't matter".[26] |

強力なAI vs. 生物学的自然主義 サールは「生物学的自然主義」と呼ぶ哲学上の立場を保持している。すなわち、意識[a]と理解には脳に存在する特定の生物学的機構が必要だという立場であ る。彼は「脳が心を生み出す」[37]と書き、「実際の人間の精神現象は、実際の人間の脳の実際の物理的・化学的特性に依存している」[37]と主張して いる。サールは、このメカニズム(神経科学では「意識の神経相関」として知られている)には、人間の意識経験を可能にする何らかの因果力があるはずだと主 張している。[38] サールがこうした力を信じていることには批判もある。 サールは、機械が意識や理解を持つことができるという考えに反対しているわけではない。なぜなら、彼自身が「我々はまさにそのような機械である」と書いて いるからだ。[4] サールは、脳は実際には機械であるが、脳は特定の機械装置を使って意識や理解を生み出していると主張している。神経科学が意識を生み出す機械的プロセスを 特定できるのであれば、意識と理解を持つ機械を作り出すことが可能であるかもしれないとサールは認める。しかし、必要な特定の機械がなければ、意識が生じ ることはありえないとサールは考えている。 生物学的自然主義は、意識の経験が起こっているかどうかを、システムの機能の仕方だけを調べただけでは判断できないことを意味する。なぜなら、脳の特定の 機械が不可欠だからである。したがって、生物学的自然主義は、行動主義と機能主義(「コンピュータ機能主義」や「強いAI」を含む)の両方に真っ向から反 対するものである。[39] 生物学的自然主義は同一説(精神状態は神経学的出来事と「同一である」または「神経学的出来事から構成される」という立場)に類似しているが、サールは同 一説に対して具体的な技術的な異論を唱えている。 [40][j] サールの生物学的自然主義と強いAIは、いずれもデカルト主義的二元論に反対している。[39] デカルト主義的二元論とは、脳と心は異なる「物質」で構成されているという古典的な考え方である。実際、サールは強いAIを二元論的であると非難し、「強 いAIは、心に関わる場合、脳は重要ではないという二元論的仮定を前提として初めて意味をなす」と書いている。[26] |

| Consciousness Searle's original presentation emphasized understanding—that is, mental states with intentionality—and did not directly address other closely related ideas such as "consciousness". However, in more recent presentations, Searle has included consciousness as the real target of the argument.[5] Computational models of consciousness are not sufficient by themselves for consciousness. The computational model for consciousness stands to consciousness in the same way the computational model of anything stands to the domain being modelled. Nobody supposes that the computational model of rainstorms in London will leave us all wet. But they make the mistake of supposing that the computational model of consciousness is somehow conscious. It is the same mistake in both cases.[41] — John R. Searle, Consciousness and Language, p. 16 David Chalmers writes, "it is fairly clear that consciousness is at the root of the matter" of the Chinese room.[42] Colin McGinn argues that the Chinese room provides strong evidence that the hard problem of consciousness is fundamentally insoluble. The argument, to be clear, is not about whether a machine can be conscious, but about whether it (or anything else for that matter) can be shown to be conscious. It is plain that any other method of probing the occupant of a Chinese room has the same difficulties in principle as exchanging questions and answers in Chinese. It is simply not possible to divine whether a conscious agency or some clever simulation inhabits the room.[43] Searle argues that this is only true for an observer outside of the room. The whole point of the thought experiment is to put someone inside the room, where they can directly observe the operations of consciousness. Searle claims that from his vantage point within the room there is nothing he can see that could imaginably give rise to consciousness, other than himself, and clearly he does not have a mind that can speak Chinese. In Searle's words, "the computer has nothing more than I have in the case where I understand nothing".[44] |

意識 サールによる当初の発表では、理解、すなわち意図性を持つ精神状態が強調され、「意識」のような密接に関連する他の概念には直接言及していなかった。しかし、より最近の発表では、サールは意識を議論の真の対象として含めている。[5] 意識の計算モデルは、それだけでは意識としては不十分である。意識の計算モデルは、モデル化される領域に対するあらゆる計算モデルと同じように、意識に対 しては不十分である。ロンドンの暴風雨の計算モデルが私たちを濡らすことはないが、意識の計算モデルが何らかの形で意識を持つと考えるのは誤りである。こ の2つのケースでは同じ誤りを犯している。 —ジョン・サール、『意識と言語』、16ページ デビッド・チャーマーズは、「意識が問題の根底にあることは明らかである」と書いている。[42] コリン・マギンは、チャイニーズ・ルームは意識の難問が本質的に解決不可能であるという強い証拠を提供していると主張している。この議論は、はっきりさせ ておくと、機械が意識を持つことができるかどうかではなく、機械(あるいは他の何であれ)が意識を持つと示すことができるかどうかについてのものである。 チャイニーズ・ルームの住人を調べる他の方法も、中国語での質疑応答と同じ原理的な困難を抱えていることは明らかである。意識を持つ存在、あるいは巧妙な シミュレーションがその部屋にいるかどうかを占うことは、単純に不可能である。 サールは、これは部屋の外にいる観察者にのみ当てはまることだと主張している。思考実験の要点は、意識の働きを直接観察できる人物を部屋の中に入れること にある。サールは、部屋の中の自分の視点からは、意識を生み出す可能性のあるものは自分以外には何も見えないと主張している。そして、サールには中国語を 話す能力はない。サールは次のように述べている。「コンピューターが理解できるのは、私が理解できることだけだ。」[44] |

Applied ethics Sitting in the combat information center aboard a warship—proposed as a real-life analog to the Chinese room Patrick Hew used the Chinese Room argument to deduce requirements from military command and control systems if they are to preserve a commander's moral agency. He drew an analogy between a commander in their command center and the person in the Chinese Room, and analyzed it under a reading of Aristotle's notions of "compulsory" and "ignorance". Information could be "down converted" from meaning to symbols, and manipulated symbolically, but moral agency could be undermined if there was inadequate 'up conversion' into meaning. Hew cited examples from the USS Vincennes incident.[45] |

応用倫理学 戦艦の戦闘情報センターに座る—中国室の実生活におけるアナログとして提案された パトリック・ヒューは、指揮官の道徳的権限を維持するために、軍の指揮統制システムから要件を導き出すために、中国室の議論を利用した。彼は、指揮セン ターにいる指揮官と中国室にいる人格を比較し、アリストテレスの「強制」と「無知」の概念を引用して分析した。情報は意味から記号へと「ダウン変換」さ れ、記号的に操作されるが、意味への不十分な「アップ変換」があれば、道徳的行為は損なわれる可能性がある。ヒューは、USSヴィンチェンズ事件の例を挙 げた。[45] |

| Computer science The Chinese room argument is primarily an argument in the philosophy of mind, and both major computer scientists and artificial intelligence researchers consider it irrelevant to their fields.[6] However, several concepts developed by computer scientists are essential to understanding the argument, including symbol processing, Turing machines, Turing completeness, and the Turing test. Strong AI vs. AI research Searle's arguments are not usually considered an issue for AI research. The primary mission of artificial intelligence research is only to create useful systems that act intelligently and it does not matter if the intelligence is "merely" a simulation. AI researchers Stuart J. Russell and Peter Norvig wrote in 2021: "We are interested in programs that behave intelligently. Individual aspects of consciousness—awareness, self-awareness, attention—can be programmed and can be part of an intelligent machine. The additional project making a machine conscious in exactly the way humans are is not one that we are equipped to take on."[6] Searle does not disagree that AI research can create machines that are capable of highly intelligent behavior. The Chinese room argument leaves open the possibility that a digital machine could be built that acts more intelligently than a person, but does not have a mind or intentionality in the same way that brains do. Searle's "strong AI hypothesis" should not be confused with "strong AI" as defined by Ray Kurzweil and other futurists,[46][21] who use the term to describe machine intelligence that rivals or exceeds human intelligence—that is, artificial general intelligence, human level AI or superintelligence. Kurzweil is referring primarily to the amount of intelligence displayed by the machine, whereas Searle's argument sets no limit on this. Searle argues that a superintelligent machine would not necessarily have a mind and consciousness. |

コンピュータサイエンス 「チャイニーズルーム」論争は、主として心の哲学における論争であり、著名なコンピュータ科学者や人工知能研究者の両者は、この論争は自分たちの分野とは 無関係であると考えている。[6] しかし、コンピュータ科学者が開発したいくつかの概念は、この論争を理解する上で不可欠である。その概念には、記号処理、チューリングマシン、チューリン グ完全性、チューリングテストなどがある。 強いAI vs. AI研究 サールの論争は、通常、AI研究の問題とは考えられていない。人工知能研究の主な使命は、知的に行動する有用なシステムを創り出すことだけである。その知 性が「単なる」シミュレーションであるかどうかは問題ではない。AI研究者のスチュアート・J・ラッセルとピーター・ノーヴィグは2021年に次のように 述べている。「我々は知的に行動するプログラムに関心を持っている。意識の個々の側面、すなわち、認識、自己認識、注意はプログラム可能であり、知的な機 械の一部となり得る。人間と同じように機械に意識を持たせるという追加プロジェクトは、我々には手に負えないものである。」[6] サールは、AI研究が高度な知性を持つ機械を作り出す可能性があるという意見には反対していない。「チャイニーズ・ルーム」の議論では、デジタル機械が人間よりも高度な知性を持つ可能性は残されているが、脳と同じような心や意図性を持つことはない。 サールによる「強いAI仮説」は、レイ・カーツワイルやその他の未来学者が定義する「強いAI」と混同すべきではない。[46][21] 彼らは、この用語を人間の知性を凌駕する、あるいは超える機械知性を表現するために使用している。つまり、汎用人工知能、人間レベルのAI、超知能などで ある。カーツワイルは主に機械が示す知性の量について言及しているが、サールの主張にはこの点について制限はない。サールは、超知能の機械が必ずしも心や 意識を持つわけではないと主張している。 |

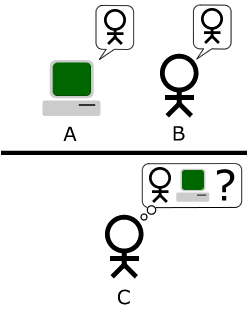

| Turing test Main article: Turing test  The "standard interpretation" of the Turing Test, in which player C, the interrogator, is given the task of trying to determine which player—A or B—is a computer and which is a human. The interrogator is limited to using the responses to written questions to make the determination. Image adapted from Saygin, et al. 2000.[47] The Chinese room implements a version of the Turing test.[48] Alan Turing introduced the test in 1950 to help answer the question "can machines think?" In the standard version, a human judge engages in a natural language conversation with a human and a machine designed to generate performance indistinguishable from that of a human being. All participants are separated from one another. If the judge cannot reliably tell the machine from the human, the machine is said to have passed the test. Turing then considered each possible objection to the proposal "machines can think", and found that there are simple, obvious answers if the question is de-mystified in this way. He did not, however, intend for the test to measure for the presence of "consciousness" or "understanding". He did not believe this was relevant to the issues that he was addressing. He wrote: I do not wish to give the impression that I think there is no mystery about consciousness. There is, for instance, something of a paradox connected with any attempt to localise it. But I do not think these mysteries necessarily need to be solved before we can answer the question with which we are concerned in this paper.[48] To Searle, as a philosopher investigating in the nature of mind and consciousness, these are the relevant mysteries. The Chinese room is designed to show that the Turing test is insufficient to detect the presence of consciousness, even if the room can behave or function as a conscious mind would. |

チューリングテスト 主な記事 チューリングテスト  チューリング・テストの「標準的な解釈」。尋問者であるプレイヤーCは、プレイヤーAとBのどちらがコンピューターでどちらが人間かを判断するという任務 を与えられる。尋問者は、その判定を行うために、書かれた質問に対する回答を使用するよう制限されている。画像はSaygin, et al. 中国の部屋はチューリングテストのバージョンを実装している[48]。アラン・チューリングは1950年に 「機械は考えることができるか?」という質問に答えるのを助けるためにこのテストを導入した。標準的なバージョンでは、人間の審査員が、人間と見分けがつ かないパフォーマンスを生成するように設計された機械と自然言語で会話する。すべての参加者は互いに分離されている。審査員が機械と人間を確実に見分ける ことができなければ、機械はテストに合格したことになる。 チューリングは次に、「機械は考えることができる」という提案に対する反論の可能性を一つ一つ検討し、このように問題を非神秘化すれば、単純明快な答えが あることを発見した。しかしチューリングは、このテストで「意識」や「理解」の有無を測定するつもりはなかった。彼はこのことが、自分が取り上げている問 題と関係があるとは考えていなかったのである。彼はこう書いている: 意識に謎がないかのような印象を与えたくはない。例えば、意識を局在化させようとする試みにはパラドックスのようなものがある。しかし、この論文で私たちが関心を抱いている問いに答える前に、これらの謎が必ずしも解決される必要があるとは思わない」[48]。 心と意識の本質を研究する哲学者であるサールにとって、これらの謎は関連する謎なのである。中国の部屋は、チューリング・テストが意識の存在を検出するには不十分であることを示すために設計されている。 |

| Symbol processing Main article: Physical symbol system Computers manipulate physical objects in order to carry out calculations and do simulations. AI researchers Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon called this kind of machine a physical symbol system. It is also equivalent to the formal systems used in the field of mathematical logic. Searle emphasizes the fact that this kind of symbol manipulation is syntactic (borrowing a term from the study of grammar). The computer manipulates the symbols using a form of syntax, without any knowledge of the symbol's semantics (that is, their meaning). Newell and Simon had conjectured that a physical symbol system (such as a digital computer) had all the necessary machinery for "general intelligent action", or, as it is known today, artificial general intelligence. They framed this as a philosophical position, the physical symbol system hypothesis: "A physical symbol system has the necessary and sufficient means for general intelligent action."[49][50] The Chinese room argument does not refute this, because it is framed in terms of "intelligent action", i.e. the external behavior of the machine, rather than the presence or absence of understanding, consciousness and mind. Twenty-first century AI programs (such as "deep learning") do mathematical operations on huge matrixes of unidentified numbers and bear little resemblance to the symbolic processing used by AI programs at the time Searle wrote his critique in 1980. Nils Nilsson describes systems like these as "dynamic" rather than "symbolic". Nilsson notes that these are essentially digitized representations of dynamic systems—the individual numbers do not have a specific semantics, but are instead samples or data points from a dynamic signal, and it is the signal being approximated which would have semantics. Nilsson argues it is not reasonable to consider these signals as "symbol processing" in the same sense as the physical symbol systems hypothesis.[51] |

シンボル処理 主な記事 物理記号システム コンピュータは物理的な物体を操作して計算やシミュレーションを行う。AI研究者のアレン・ニューウェルとハーバート・A・サイモンは、この種の機械を物理記号システムと呼んだ。また、数理論理学の分野で使われる形式的システムにも相当する。 サールは、この種の記号操作が統語的(文法研究の用語を借用)であることを強調している。コンピュータは、記号の意味論(つまりその意味)についての知識なしに、構文の形式を使って記号を操作するのである。 ニューウェルとサイモンは、(デジタル・コンピュータのような)物理的な記号システムには、「一般的な知的行動」、今日で言うところの「人工的な一般知 能」に必要な機械がすべて備わっていると推測していた。彼らはこれを哲学的な立場である物理的記号システム仮説「物理的記号システムは、一般的な知的行動 のために必要かつ十分な手段を持っている」とした[49][50]。中国の部屋の議論では、理解、意識、心の有無ではなく、「知的行動」、すなわち機械の 外的行動という観点から組み立てられているため、これに反論することはできない。 21世紀のAIプログラム(「ディープラーニング」など)は、正体不明の膨大な数の行列に対して数学的演算を行っており、サールが1980年に批評を書い た当時のAIプログラムが用いていた記号処理とは似ても似つかない。ニルス・ニルソンは、このようなシステムを「記号的」ではなく「動的」と表現してい る。個々の数値は特定の意味を持っているのではなく、動的な信号のサンプルまたはデータ点であり、意味を持っているのは近似された信号である。ニルソン は、これらの信号を物理的シンボルシステム仮説と同じ意味で「シンボル処理」と見なすのは妥当ではないと主張している[51]。 |

| Chinese room and Turing completeness See also: Turing completeness and Church–Turing thesis The Chinese room has a design analogous to that of a modern computer. It has a Von Neumann architecture, which consists of a program (the book of instructions), some memory (the papers and file cabinets), a machine that follows the instructions (the man), and a means to write symbols in memory (the pencil and eraser). A machine with this design is known in theoretical computer science as "Turing complete", because it has the necessary machinery to carry out any computation that a Turing machine can do, and therefore it is capable of doing a step-by-step simulation of any other digital machine, given enough memory and time. Turing writes, "all digital computers are in a sense equivalent."[52] The widely accepted Church–Turing thesis holds that any function computable by an effective procedure is computable by a Turing machine. The Turing completeness of the Chinese room implies that it can do whatever any other digital computer can do (albeit much, much more slowly). Thus, if the Chinese room does not or can not contain a Chinese-speaking mind, then no other digital computer can contain a mind. Some replies to Searle begin by arguing that the room, as described, cannot have a Chinese-speaking mind. Arguments of this form, according to Stevan Harnad, are "no refutation (but rather an affirmation)"[53] of the Chinese room argument, because these arguments actually imply that no digital computers can have a mind.[28] There are some critics, such as Hanoch Ben-Yami, who argue that the Chinese room cannot simulate all the abilities of a digital computer, such as being able to determine the current time.[54] |

中国の部屋とチューリングの完全性 も参照のこと: チューリング完全性とチャーチ・チューリング論文 チャイニーズ・ルームは、現代のコンピュータの設計に類似している。これはフォン・ノイマン・アーキテクチャで、プログラム(命令書)、いくつかのメモリ (書類とファイルキャビネット)、命令に従う機械(人間)、メモリに記号を書き込む手段(鉛筆と消しゴム)から構成されている。このような設計の機械は、 理論計算機科学では「チューリング完全体」として知られている。チューリング機械ができるあらゆる計算を実行するのに必要な機械を持っているため、十分な メモリと時間があれば、他のあらゆるデジタル機械のシミュレーションを段階的に行うことができるからである。チューリングは「すべてのデジタル・コン ピュータはある意味で等価である」と書いている[52]。広く受け入れられているチャーチ・チューリング論文は、有効な手続きによって計算可能なあらゆる 関数はチューリング機械によって計算可能であるとしている。 チャイニーズ・ルームのチューリング完全性は、チャイニーズ・ルームが他のどんなデジタル・コンピュータでも(ずっとずっと遅いとはいえ)できることは何 でもできるということを意味している。したがって、もし中国の部屋に中国語を話す心が存在しない、あるいは存在し得ないのであれば、他のどんなデジタル・ コンピューターにも心は存在し得ないことになる。サールに対するいくつかの反論は、説明されたような部屋には中国語を話す心は存在し得ないという議論から 始まる。Stevan Harnadによれば、この形式の議論は、中国の部屋の議論に対する「反論ではなく(むしろ肯定)」[53]である。 ハノク・ベン・ヤミのように、中国語の部屋はデジタル・コンピュータのすべての能力、例えば現在時刻を決定することができるような能力をシミュレートすることはできないと主張する批評家もいる[54]。 |

| Complete argument Searle has produced a more formal version of the argument of which the Chinese Room forms a part. He presented the first version in 1984. The version given below is from 1990.[55][k] The Chinese room thought experiment is intended to prove point A3.[l] He begins with three axioms: (A1) "Programs are formal (syntactic)." A program uses syntax to manipulate symbols and pays no attention to the semantics of the symbols. It knows where to put the symbols and how to move them around, but it does not know what they stand for or what they mean. For the program, the symbols are just physical objects like any others. (A2) "Minds have mental contents (semantics)." Unlike the symbols used by a program, our thoughts have meaning: they represent things and we know what it is they represent. (A3) "Syntax by itself is neither constitutive of nor sufficient for semantics." This is what the Chinese room thought experiment is intended to prove: the Chinese room has syntax (because there is a man in there moving symbols around). The Chinese room has no semantics (because, according to Searle, there is no one or nothing in the room that understands what the symbols mean). Therefore, having syntax is not enough to generate semantics. Searle posits that these lead directly to this conclusion: (C1) Programs are neither constitutive of nor sufficient for minds. This should follow without controversy from the first three: Programs don't have semantics. Programs have only syntax, and syntax is insufficient for semantics. Every mind has semantics. Therefore no programs are minds. This much of the argument is intended to show that artificial intelligence can never produce a machine with a mind by writing programs that manipulate symbols. The remainder of the argument addresses a different issue. Is the human brain running a program? In other words, is the computational theory of mind correct?[f] He begins with an axiom that is intended to express the basic modern scientific consensus about brains and minds: (A4) Brains cause minds. Searle claims that we can derive "immediately" and "trivially"[56] that: (C2) Any other system capable of causing minds would have to have causal powers (at least) equivalent to those of brains. Brains must have something that causes a mind to exist. Science has yet to determine exactly what it is, but it must exist, because minds exist. Searle calls it "causal powers". "Causal powers" is whatever the brain uses to create a mind. If anything else can cause a mind to exist, it must have "equivalent causal powers". "Equivalent causal powers" is whatever else that could be used to make a mind. And from this he derives the further conclusions: (C3) Any artifact that produced mental phenomena, any artificial brain, would have to be able to duplicate the specific causal powers of brains, and it could not do that just by running a formal program. This follows from C1 and C2: Since no program can produce a mind, and "equivalent causal powers" produce minds, it follows that programs do not have "equivalent causal powers." (C4) The way that human brains actually produce mental phenomena cannot be solely by virtue of running a computer program. Since programs do not have "equivalent causal powers", "equivalent causal powers" produce minds, and brains produce minds, it follows that brains do not use programs to produce minds. Refutations of Searle's argument take many different forms (see below). Computationalists and functionalists reject A3, arguing that "syntax" (as Searle describes it) can have "semantics" if the syntax has the right functional structure. Eliminative materialists reject A2, arguing that minds don't actually have "semantics"—that thoughts and other mental phenomena are inherently meaningless but nevertheless function as if they had meaning. |

完全な議論 サールは、「中国の部屋」がその一部を構成している議論を、より正式なものにした。最初のバージョンは1984年に発表された。以下に示すバージョンは1990年のものである[55][k]。チャイニーズ・ルームの思考実験は論点A3を証明するためのものである[l]。 彼は3つの公理から始める: (A1)「プログラムは形式的(構文的)である」。 プログラムは構文を使って記号を操作し、記号の意味論には注意を払わない。記号をどこに置き、どのように移動させるかは知っているが、記号が何を表し、何を意味するかは知らない。プログラムにとって、記号は他のものと同じ物理的な物体にすぎない。 (A2)「心には心の内容(意味)がある」。 プログラムによって使用される記号とは異なり、私たちの思考には意味がある:それらは物事を表し、私たちはそれが何を表しているのかを知っている。 (A3)「構文それ自体は意味論を構成するものでもなければ、意味論にとって十分なものでもない」。 中国の部屋の思考実験が証明しようとしているのは、このことである。中国の部屋には構文がある(なぜなら、そこには記号を動かしている人間がいるから だ)。中国の部屋には意味論がない(サールによれば、記号の意味を理解するものは部屋の中には誰もいないし、何もいないからだ)。したがって、構文がある だけでは意味論は生まれない。 サールは、これらがこの結論に直結すると仮定する: (C1) プログラムは心を構成するものでもなければ、心を構成するのに十分なものでもない。 C1)プログラムは心を構成するものでもなければ、心を構成するのに十分なものでもない: プログラムは意味論を持たない。プログラムには意味論がない。プログラムには構文しかなく、構文は意味論には不十分である。すべての心は意味論を持ってい る。したがって、プログラムが心であることはない。 ここまでの議論は、人工知能が記号を操作するプログラムを書くことによって、心を持つ機械を作り出すことは決してできないことを示すためのものである。議 論の残りの部分は、異なる問題を扱っている。人間の脳はプログラムを実行しているのだろうか?言い換えれば、心の計算理論は正しいのだろうか?[f] 彼は、脳と心に関する基本的な現代科学のコンセンサスを表現することを意図した公理から始める: (A4)脳が心を引き起こす。 サールは、我々は「直ちに」かつ「些細なことから」[56]次のことを導くことができると主張している: (C2)心を引き起こすことができる他のシステムは、(少なくとも)脳と同等の因果力を持たなければならない。 脳には、心を存在させる何かがなければならない。科学はそれが何であるかをまだ正確に決定していないが、心が存在する以上、それは存在しなければならな い。サールはそれを「因果力」と呼んでいる。「因果力」とは、脳が心を生み出すために使うものである。もし他の何かが心を存在させることができるのであれ ば、それは「同等の因果力」を持っているはずである。「等価な因果的力」とは、心を作るために使われる可能性のある他のものである。 そしてここから、彼はさらなる結論を導き出す: (C3)精神現象を生み出す人工物、つまり人工頭脳は、頭脳の持つ特定の因果力を複製できなければならないが、形式的なプログラムを実行するだけではそれはできない。 これはC1とC2から導かれる。いかなるプログラムも心を生み出すことはできず、「同等の因果力」が心を生み出すのだから、プログラムは「同等の因果力」を持っていないということになる。 (C4) 人間の脳が実際に心的現象を生成する方法は、コンピュータ・プログラムを実行する ことだけではありえない。 プログラムは「等価な因果力」を持たず、「等価な因果力」は心を生成し、脳は心を生成するので、脳はプログラムを使って心を生成することはない。 サールの議論に対する反論は、さまざまな形をとっている(下記参照)。計算論者と機能論者はA3を否定し、(サールの言う)「構文」は、構文が適切な機能 構造を持っていれば「意味」を持つことができると主張する。排除的唯物論者はA2を否定し、心には実際には「意味」はないと主張する。思考やその他の心的 現象は本質的に無意味であるが、それにもかかわらず意味があるかのように機能すると主張する。 |

| Replies Replies to Searle's argument may be classified according to what they claim to show:[m] Those which identify who speaks Chinese Those which demonstrate how meaningless symbols can become meaningful Those which suggest that the Chinese room should be redesigned in some way Those which contend that Searle's argument is misleading Those which argue that the argument makes false assumptions about subjective conscious experience and therefore proves nothing Some of the arguments (robot and brain simulation, for example) fall into multiple categories. |

返信 サールの議論に対する反論は、何を示していると主張するかによって分類することができる[m]。 誰が中国語を話すかを特定するもの 意味のない記号がどのようにして意味を持つようになるかを示すもの 中国語の部屋を何らかの方法で設計し直すべきであることを示唆するもの サールの議論は誤解を招くと主張するもの この議論は主観的な意識経験について誤った仮定をしており、したがって何も証明していないと主張するもの いくつかの議論(ロボットや脳のシミュレーションなど)は、複数のカテゴリーに分類される。 |

| Systems and virtual mind replies: finding the mind These replies attempt to answer the question: since the man in the room does not speak Chinese, where is the mind that does? These replies address the key ontological issues of mind versus body and simulation vs. reality. All of the replies that identify the mind in the room are versions of "the system reply". |

システムとバーチャル・マインドへの回答:マインドを見つける 部屋にいる男は中国語を話さないのだから、中国語を話す心はどこにあるのか?これらの回答は、心対身体、シミュレーション対現実という存在論上の重要な問題を扱っている。部屋の中の心を特定する返答はすべて「システム返答」のバージョンである。 |

| System reply The basic version of the system reply argues that it is the "whole system" that understands Chinese.[61][n] While the man understands only English, when he is combined with the program, scratch paper, pencils and file cabinets, they form a system that can understand Chinese. "Here, understanding is not being ascribed to the mere individual; rather it is being ascribed to this whole system of which he is a part" Searle explains.[29] Searle notes that (in this simple version of the reply) the "system" is nothing more than a collection of ordinary physical objects; it grants the power of understanding and consciousness to "the conjunction of that person and bits of paper"[29] without making any effort to explain how this pile of objects has become a conscious, thinking being. Searle argues that no reasonable person should be satisfied with the reply, unless they are "under the grip of an ideology;"[29] In order for this reply to be remotely plausible, one must take it for granted that consciousness can be the product of an information processing "system", and does not require anything resembling the actual biology of the brain. Searle then responds by simplifying this list of physical objects: he asks what happens if the man memorizes the rules and keeps track of everything in his head? Then the whole system consists of just one object: the man himself. Searle argues that if the man does not understand Chinese then the system does not understand Chinese either because now "the system" and "the man" both describe exactly the same object.[29] Critics of Searle's response argue that the program has allowed the man to have two minds in one head.[who?] If we assume a "mind" is a form of information processing, then the theory of computation can account for two computations occurring at once, namely (1) the computation for universal programmability (which is the function instantiated by the person and note-taking materials independently from any particular program contents) and (2) the computation of the Turing machine that is described by the program (which is instantiated by everything including the specific program).[63] The theory of computation thus formally explains the open possibility that the second computation in the Chinese Room could entail a human-equivalent semantic understanding of the Chinese inputs. The focus belongs on the program's Turing machine rather than on the person's.[64] However, from Searle's perspective, this argument is circular. The question at issue is whether consciousness is a form of information processing, and this reply requires that we make that assumption. More sophisticated versions of the systems reply try to identify more precisely what "the system" is and they differ in exactly how they describe it. According to these replies,[who?] the "mind that speaks Chinese" could be such things as: the "software", a "program", a "running program", a simulation of the "neural correlates of consciousness", the "functional system", a "simulated mind", an "emergent property", or "a virtual mind". |

システム回答 システム回答の基本的なバージョンは、中国語を理解するのは「システム全体」であると主張する[61][n]。男性は英語しか理解できないが、彼がプログ ラム、スクラッチペーパー、鉛筆、ファイルキャビネットと組み合わされるとき、それらは中国語を理解できるシステムを形成する。「ここでは、理解は単なる 個人に帰属しているのではなく、むしろ彼がその一部であるこのシステム全体に帰属しているのである」とサールは説明する[29]。 サールは、(この回答の単純なバージョンでは)「システム」は普通の物理的な物体の集まりにすぎず、この物体の山がどのようにして意識的で思考する存在に なったのかを説明する努力をすることなく、「その人格と紙片の結合」[29]に理解と意識の力を付与しているのだと指摘している。サールは、「イデオロ ギーに支配されている」のでない限り、理性的な人格はこの返答に満足すべきではないと主張する[29]。この返答が少しでも妥当であるためには、意識は情 報処理「システム」の産物でありうるのであって、脳の実際の生物学的性質に似たものを必要としないということを当然視しなければならない。 サールは次に、この物理的対象のリストを単純化することで反論する。「もしその人がルールを記憶し、頭の中ですべてを把握していたらどうなるだろうか?そ うすると、システム全体はただ一つの物体、つまり人間自身から構成されることになる。サールは、もし男が中国語を理解しないのであれば、システムも中国語 を理解しないと主張する。 サールの回答を批判する人々は、プログラムによって男は1つの頭の中に2つの心を持つことができるようになったと主張する[who? もし「心」が情報処理の一形態であると仮定すると、計算の理論は一度に発生する2つの計算を説明することができる。すなわち、(1)普遍的なプログラム可 能性のための計算(これは特定のプログラムの内容とは無関係に人格とメモを取る材料によってインスタンス化される機能である)と、(2)プログラムによっ て記述されるチューリング機械の計算(これは特定のプログラムを含むすべてのものによってインスタンス化される)である。) [このように、計算の理論は、「中国語の部屋」における第二の計算が、中国語入力の人間にとって等価な意味理解を伴いうるという開かれた可能性を形式的に 説明する。しかし、サールの観点からすると、この議論は循環している。問題になっているのは意識が情報処理の一形態であるかどうかということであり、この 回答はその仮定を立てることを要求している。 より洗練されたバージョンのシステム論への反論は、「システム」が何であるかをより正確に特定しようとするものであり、それをどのように記述するかという 点で異なっている。これらの返答によれば、「中国語を話す心」は、「ソフトウェア」、「プログラム」、「実行中のプログラム」、「意識の神経相関」のシ ミュレーション、「機能システム」、「シミュレートされた心」、「創発的特性」、「バーチャルな心」などの可能性がある。 |

| Virtual mind reply Marvin Minsky suggested a version of the system reply known as the "virtual mind reply".[o] The term "virtual" is used in computer science to describe an object that appears to exist "in" a computer (or computer network) only because software makes it appear to exist. The objects "inside" computers (including files, folders, and so on) are all "virtual", except for the computer's electronic components. Similarly, Minsky that a computer may contain a "mind" that is virtual in the same sense as virtual machines, virtual communities and virtual reality. To clarify the distinction between the simple systems reply given above and virtual mind reply, David Cole notes that two simulations could be running on one system at the same time: one speaking Chinese and one speaking Korean. While there is only one system, there can be multiple "virtual minds," thus the "system" cannot be the "mind".[68] Searle responds that such a mind is at best a simulation, and writes: "No one supposes that computer simulations of a five-alarm fire will burn the neighborhood down or that a computer simulation of a rainstorm will leave us all drenched."[69] Nicholas Fearn responds that, for some things, simulation is as good as the real thing. "When we call up the pocket calculator function on a desktop computer, the image of a pocket calculator appears on the screen. We don't complain that it isn't really a calculator, because the physical attributes of the device do not matter."[70] The question is, is the human mind like the pocket calculator, essentially composed of information, where a perfect simulation of the thing just is the thing? Or is the mind like the rainstorm, a thing in the world that is more than just its simulation, and not realizable in full by a computer simulation? For decades, this question of simulation has led AI researchers and philosophers to consider whether the term "synthetic intelligence" is more appropriate than the common description of such intelligences as "artificial." These replies provide an explanation of exactly who it is that understands Chinese. If there is something besides the man in the room that can understand Chinese, Searle cannot argue that (1) the man does not understand Chinese, therefore (2) nothing in the room understands Chinese. This, according to those who make this reply, shows that Searle's argument fails to prove that "strong AI" is false.[p] These replies, by themselves, do not provide any evidence that strong AI is true, however. They do not show that the system (or the virtual mind) understands Chinese, other than the hypothetical premise that it passes the Turing test. Searle argues that, if we are to consider Strong AI remotely plausible, the Chinese Room is an example that requires explanation, and it is difficult or impossible to explain how consciousness might "emerge" from the room or how the system would have consciousness. As Searle writes "the systems reply simply begs the question by insisting that the system must understand Chinese"[29] and thus is dodging the question or hopelessly circular. |

仮想的な心の応答 マービン・ミンスキーは、「バーチャル・マインド・リプライ」として知られるシステム・リプライのバージョンを提案した[o]。「バーチャル」という用語 はコンピュータサイエンスで使われ、ソフトウェアが存在するように見せているだけで、コンピュータ(またはコンピュータネットワーク)の「中」に存在して いるように見えるオブジェクトを表す。コンピュータの「内部」のオブジェクト(ファイル、フォルダなどを含む)は、コンピュータの電子部品を除いて、すべ て「仮想」である。同様に、ミンスキーは、コンピューターには、バーチャル・マシン、バーチャル・コミュニティ、バーチャル・リアリティと同じ意味でバー チャルな「心」が含まれているかもしれないと述べている。 デビッド・コールは、上記の単純なシステムに関する回答とバーチャル・マインドに関する回答の区別を明確にするために、1つのシステム上で同時に2つのシ ミュレーションを実行することができると指摘している。システムは一つしか存在しないが、「仮想の心」は複数存在しうるので、「システム」が「心」である ことはありえない[68]。 サールは、そのような心はせいぜいシミュレーションであると答え、「5つの警報が鳴る火事のコンピュータ・シミュレーションが近所を焼き尽くすとか、暴風 雨のコンピュータ・シミュレーションがわれわれ全員をずぶ濡れにするとか、そんなことは誰も仮定していない」と書いている[69]。「デスクトップコン ピュータでポケット電卓機能を呼び出すと、ポケット電卓の画像が画面に表示される。私たちはそれが本当の電卓でないことに文句を言わないが、それは電卓の 物理的属性が重要ではないからである。それとも、心は暴風雨のようなもので、シミュレーション以上のものであり、コンピュータのシミュレーションでは完全 には実現できない世界なのだろうか?何十年もの間、このシミュレーションに関する疑問から、AIの研究者や哲学者は、このような知性を 「人工的 」と表現するよりも、「合成知性 」と表現する方が適切かどうかを検討してきた。 これらの回答は、中国語を理解するのがいったい誰なのかについて説明するものである。部屋にいる男以外に中国語を理解できるものがいるとすれば、サール は、(1)男は中国語を理解していない、したがって(2)部屋には中国語を理解できるものはいない、と主張することはできない。この返事をする人によれ ば、サールの議論は「強いAI」が誤りであることを証明できていないことになる[p]。 しかし、これらの反論は、それ自体、強いAIが真であることの証拠にはならない。チューリング・テストに合格するという仮定の前提以外には、システム(あ るいはバーチャル・マインド)が中国語を理解していることを示すものではない。サールは、強力なAIが少しでももっともらしいと考えるのであれば、「中国 の部屋」は説明を必要とする例であり、この部屋からどのように意識が「出現」するのか、あるいはシステムがどのように意識を持つのかを説明することは困難 か不可能であると主張する。サールが書いているように、「システムの回答は、システムが中国語を理解しなければならないと主張することで、単に問題をごま かしている」[29]。 |

| Robot and semantics replies: finding the meaning As far as the person in the room is concerned, the symbols are just meaningless "squiggles." But if the Chinese room really "understands" what it is saying, then the symbols must get their meaning from somewhere. These arguments attempt to connect the symbols to the things they symbolize. These replies address Searle's concerns about intentionality, symbol grounding and syntax vs. semantics. |

ロボットとセマンティクスの回答:意味を見つける 部屋にいる人格が考える限り、記号は無意味な 「四角形 」にすぎない。しかし、もし中国の部屋が何を言っているのか本当に「理解している」のであれば、記号はどこかから意味を得ているはずだ。これらの議論は、 記号と記号が象徴するものを結びつけようとするものである。これらの反論は、意図主義、記号の根拠、構文対意味論に関するサールの懸念に対処するものであ る。 |

| Robot reply Suppose that instead of a room, the program was placed into a robot that could wander around and interact with its environment. This would allow a "causal connection" between the symbols and things they represent.[72][q] Hans Moravec comments: "If we could graft a robot to a reasoning program, we wouldn't need a person to provide the meaning anymore: it would come from the physical world."[74][r] Searle's reply is to suppose that, unbeknownst to the individual in the Chinese room, some of the inputs came directly from a camera mounted on a robot, and some of the outputs were used to manipulate the arms and legs of the robot. Nevertheless, the person in the room is still just following the rules, and does not know what the symbols mean. Searle writes "he doesn't see what comes into the robot's eyes."[76] |

ロボットからの返答 仮に、部屋の代わりに、歩き回り、環境と相互作用できるロボットにプログラムを入れたとしよう。そうすれば、記号と記号が表すものとの間に「因果的なつな がり」ができるようになる[72][q] ハンス・モラヴェックはこうコメントしている: 「もしロボットを推論プログラムに接ぎ木することができれば、意味を提供する人格はもう必要なくなる。 サールの答えは、中国の部屋にいる個人は知らないが、入力の一部はロボットに取り付けられたカメラから直接来ており、出力の一部はロボットの腕や足を操作 するために使われていると仮定することである。とはいえ、部屋にいる人格はまだルールに従うだけで、記号が何を意味するのかわかっていない。サールは「彼 はロボットの目に入ってくるものを見ていない」と書いている[76]。 |

| Derived meaning Some respond that the room, as Searle describes it, is connected to the world: through the Chinese speakers that it is "talking" to and through the programmers who designed the knowledge base in his file cabinet. The symbols Searle manipulates are already meaningful, they are just not meaningful to him.[77][s] Searle says that the symbols only have a "derived" meaning, like the meaning of words in books. The meaning of the symbols depends on the conscious understanding of the Chinese speakers and the programmers outside the room. The room, like a book, has no understanding of its own.[t] |

派生した意味 サールが説明するように、この部屋は世界とつながっている、と答える人もいる。それは、この部屋が「会話」している中国のスピーカーや、彼のファイルキャ ビネットの知識ベースを設計したプログラマーを通してである。サールが操作する記号はすでに意味があるのだが、彼にとっては意味がないだけなのである [77][s]。 サールは、記号は本の中の単語の意味のように「派生した」意味しか持たないと言う。記号の意味は、部屋の外にいる中国語話者やプログラマーの意識的な理解に依存している。部屋は本のように、それ自身の理解を持っていない。 |

| Contextualist reply Some have argued that the meanings of the symbols would come from a vast "background" of commonsense knowledge encoded in the program and the filing cabinets. This would provide a "context" that would give the symbols their meaning.[75][u] Searle agrees that this background exists, but he does not agree that it can be built into programs. Hubert Dreyfus has also criticized the idea that the "background" can be represented symbolically.[80] To each of these suggestions, Searle's response is the same: no matter how much knowledge is written into the program and no matter how the program is connected to the world, he is still in the room manipulating symbols according to rules. His actions are syntactic and this can never explain to him what the symbols stand for. Searle writes "syntax is insufficient for semantics."[81][v] However, for those who accept that Searle's actions simulate a mind, separate from his own, the important question is not what the symbols mean to Searle, what is important is what they mean to the virtual mind. While Searle is trapped in the room, the virtual mind is not: it is connected to the outside world through the Chinese speakers it speaks to, through the programmers who gave it world knowledge, and through the cameras and other sensors that roboticists can supply. |

文脈論者の反論 記号の意味は、プログラムとファイリング・キャビネットに符号化された膨大な常識的知識の「背景」に由来すると主張する者もいる。これは記号に意味を与える「文脈」を提供することになる[75][u]。 サールはこの背景が存在することには同意するが、それをプログラムに組み込むことができるということには同意しない。ヒューバート・ドレイファスも「背景」を記号的に表現できるという考えを批判している[80]。 これらの提案のいずれに対しても、サールの回答は同じである。プログラムにどれだけの知識が書き込まれ、プログラムがどのように世界と接続されていても、 彼は部屋の中で規則に従って記号を操作していることに変わりはない。彼の行動は構文的なものであり、記号が何を表しているのかを説明することはできない。 サールは「構文は意味論にとって不十分である」と書いている[81][v]。 しかし、サールの行動が彼自身とは別の心をシミュレートしていることを受け入れる人々にとって、重要な問題は、記号がサールにとって何を意味するかではな く、重要なのは、記号が仮想の心にとって何を意味するかである。サールは部屋に閉じこもっているが、バーチャル・マインドはそうではない。サールは、話し かけた中国語のスピーカーや、世界知識を与えたプログラマーや、ロボット工学者が供給できるカメラやその他のセンサーを通じて、外の世界とつながっている のだ。 |

| Brain simulation and connectionist replies: redesigning the room These arguments are all versions of the systems reply that identify a particular kind of system as being important; they identify some special technology that would create conscious understanding in a machine. (The "robot" and "commonsense knowledge" replies above also specify a certain kind of system as being important.) |

脳シミュレーションとコネクショニストの反論:部屋を再設計する これらの議論はすべて、特定の種類のシステムが重要であることを特定するシステム応答のバージョンであり、機械に意識的理解を生み出すような個別技術を特定するものである。(上記の「ロボット」と「常識的知識」の回答も、ある種のシステムが重要であると特定している)。 |

| Brain simulator reply Suppose that the program simulated in fine detail the action of every neuron in the brain of a Chinese speaker.[83][w] This strengthens the intuition that there would be no significant difference between the operation of the program and the operation of a live human brain. Searle replies that such a simulation does not reproduce the important features of the brain—its causal and intentional states. He is adamant that "human mental phenomena [are] dependent on actual physical–chemical properties of actual human brains."[26] Moreover, he argues: [I]magine that instead of a monolingual man in a room shuffling symbols we have the man operate an elaborate set of water pipes with valves connecting them. When the man receives the Chinese symbols, he looks up in the program, written in English, which valves he has to turn on and off. Each water connection corresponds to a synapse in the Chinese brain, and the whole system is rigged up so that after doing all the right firings, that is after turning on all the right faucets, the Chinese answers pop out at the output end of the series of pipes. Now where is the understanding in this system? It takes Chinese as input, it simulates the formal structure of the synapses of the Chinese brain, and it gives Chinese as output. But the man certainly doesn't understand Chinese, and neither do the water pipes, and if we are tempted to adopt what I think is the absurd view that somehow the conjunction of man and water pipes understands, remember that in principle the man can internalize the formal structure of the water pipes and do all the "neuron firings" in his imagination.[85] |

脳シミュレーターの回答 このプログラムは、中国語を話す人の脳のすべてのニューロンの働きを詳細にシミュレートしているとする[83][w]。このことは、プログラムの動作と生きている人間の脳の動作との間に大きな違いはないだろうという直観を強める。 サールは、このようなシミュレーションでは脳の重要な特徴である因果状態や意図主義状態は再現されないと反論する。彼は「人間の精神現象は実際の人間の脳の実際の物理化学的特性に依存している」と断固として主張する[26]: [部屋の中でモノリンガルの男が記号をシャッフルする代わりに、その男がバルブで結ばれた精巧な水道管のセットを操作しているとしよう。中国語の記号を受 け取った男は、英語で書かれたプログラムで、どのバルブをオン・オフすればいいかを調べる。各水道接続は中国人の脳のシナプスに対応しており、システム全 体は、すべての正しい操作を行った後、つまりすべての正しい蛇口をひねった後、一連のパイプの出力端に中国語の答えが飛び出すように仕掛けられている。さ て、このシステムのどこに理解があるのだろうか?中国語を入力とし、中国人の脳のシナプスの形式的構造をシミュレートし、中国語を出力する。もし私たち が、人間と水道管の結合がどういうわけか理解している、という不合理としか思えない見解を採用したくなったとしても、原理的には、人間は水道管の形式的構 造を内面化し、想像の中ですべての「ニューロンの発火」を行うことができることを思い出してほしい[85]。 |

| China brain What if we ask each citizen of China to simulate one neuron, using the telephone system to simulate the connections between axons and dendrites? In this version, it seems obvious that no individual would have any understanding of what the brain might be saying.[86][x] It is also obvious that this system would be functionally equivalent to a brain, so if consciousness is a function, this system would be conscious. |

中国の脳 軸索と樹状突起の間の接続をシミュレートするために電話システムを使う。86][x]また、このシステムが機能的に脳と等価であることは明らかであるため、意識が機能であるならば、このシステムは意識を持つことになる。 |

| Brain replacement scenario In this, we are asked to imagine that engineers have invented a tiny computer that simulates the action of an individual neuron. What would happen if we replaced one neuron at a time? Replacing one would clearly do nothing to change conscious awareness. Replacing all of them would create a digital computer that simulates a brain. If Searle is right, then conscious awareness must disappear during the procedure (either gradually or all at once). Searle's critics argue that there would be no point during the procedure when he can claim that conscious awareness ends and mindless simulation begins.[88][y][z] (See Ship of Theseus for a similar thought experiment.) |

脳の代替シナリオ このシナリオでは、エンジニアが個々のニューロンの働きをシミュレートする小さなコンピュータを発明したと想像してもらう。ニューロンを1つずつ取り替え たらどうなるだろうか?ひとつを取り替えたところで、意識に変化がないことは明らかだ。すべての神経細胞を交換すれば、脳をシミュレートするデジタル・コ ンピューターが完成する。サールの言う通りであれば、意識はその処置の間に(徐々に、あるいは一度に)消失しなければならない。サールの批評家たちは、意 識的な認識が終わり、無頓着なシミュレーションが始まると主張できる時点は、手続き中には存在しないと主張している[88][y][z](同様の思考実験 として「テセウスの船」を参照)。 |

| Connectionist replies Closely related to the brain simulator reply, this claims that a massively parallel connectionist architecture would be capable of understanding.[aa] Modern deep learning is massively parallel and has successfully displayed intelligent behavior in many domains. Nils Nilsson argues that modern AI is using digitized "dynamic signals" rather than symbols of the kind used by AI in 1980.[51] Here it is the sampled signal which would have the semantics, not the individual numbers manipulated by the program. This is a different kind of machine than the one that Searle visualized. |

コネクショニストからの回答 脳シミュレーターの回答と密接に関連しており、超並列コネクショニスト・アーキテクチャが理解を可能にすると主張している。ニルス・ニルソンは、現代の AIは、1980年にAIによって使用されていた種類の記号ではなく、デジタル化された「動的信号」を使用していると主張している[51]。ここでは、プ ログラムによって操作される個々の数値ではなく、サンプリングされた信号が意味を持っている。これは、サールが視覚化したマシンとは異なる種類のマシンで ある。 |

| Combination reply This response combines the robot reply with the brain simulation reply, arguing that a brain simulation connected to the world through a robot body could have a mind.[93] |

組み合わせ回答 この回答は、ロボットの回答と脳シミュレーションの回答を組み合わせたものであり、ロボットの身体を通して世界とつながっている脳シミュレーションは心を持ちうると主張している[93]。 |

| Many mansions / wait till next year reply Better technology in the future will allow computers to understand.[27][ab] Searle agrees that this is possible, but considers this point irrelevant. Searle agrees that there may be other hardware besides brains that have conscious understanding. These arguments (and the robot or common-sense knowledge replies) identify some special technology that would help create conscious understanding in a machine. They may be interpreted in two ways: either they claim (1) this technology is required for consciousness, the Chinese room does not or cannot implement this technology, and therefore the Chinese room cannot pass the Turing test or (even if it did) it would not have conscious understanding. Or they may be claiming that (2) it is easier to see that the Chinese room has a mind if we visualize this technology as being used to create it. In the first case, where features like a robot body or a connectionist architecture are required, Searle claims that strong AI (as he understands it) has been abandoned.[ac] The Chinese room has all the elements of a Turing complete machine, and thus is capable of simulating any digital computation whatsoever. If Searle's room cannot pass the Turing test then there is no other digital technology that could pass the Turing test. If Searle's room could pass the Turing test, but still does not have a mind, then the Turing test is not sufficient to determine if the room has a "mind". Either way, it denies one or the other of the positions Searle thinks of as "strong AI", proving his argument. The brain arguments in particular deny strong AI if they assume that there is no simpler way to describe the mind than to create a program that is just as mysterious as the brain was. He writes "I thought the whole idea of strong AI was that we don't need to know how the brain works to know how the mind works."[27] If computation does not provide an explanation of the human mind, then strong AI has failed, according to Searle. Other critics hold that the room as Searle described it does, in fact, have a mind, however they argue that it is difficult to see—Searle's description is correct, but misleading. By redesigning the room more realistically they hope to make this more obvious. In this case, these arguments are being used as appeals to intuition (see next section). In fact, the room can just as easily be redesigned to weaken our intuitions. Ned Block's Blockhead argument[94] suggests that the program could, in theory, be rewritten into a simple lookup table of rules of the form "if the user writes S, reply with P and goto X". At least in principle, any program can be rewritten (or "refactored") into this form, even a brain simulation.[ad] In the blockhead scenario, the entire mental state is hidden in the letter X, which represents a memory address—a number associated with the next rule. It is hard to visualize that an instant of one's conscious experience can be captured in a single large number, yet this is exactly what "strong AI" claims. On the other hand, such a lookup table would be ridiculously large (to the point of being physically impossible), and the states could therefore be overly specific. Searle argues that however the program is written or however the machine is connected to the world, the mind is being simulated by a simple step-by-step digital machine (or machines). These machines are always just like the man in the room: they understand nothing and do not speak Chinese. They are merely manipulating symbols without knowing what they mean. Searle writes: "I can have any formal program you like, but I still understand nothing."[95] |

多くの邸宅/来年の返事まで待つ 将来、より優れた技術によって、コンピュータが理解できるようになるだろう[27][ab] サールはこれが可能であることに同意するが、この点は関係ないと考えている。サールは、脳以外にも意識的な理解をするハードウェアが存在するかもしれないことに同意する。 これらの議論(およびロボットや常識的知識の回答)は、機械に意識的理解を生み出すのに役立つ特別な技術を特定している。つまり、(1)この技術は意識に 必要であり、中国の部屋はこの技術を実装していない、あるいは実装できない。したがって、中国の部屋はチューリング・テストに合格できないか、(仮に合格 したとしても)意識的な理解はできない、という主張である。あるいは、(2)中国の部屋を作るためにこの技術が使われていると視覚化すれば、中国の部屋に 心があることがわかりやすいと主張しているのかもしれない。 最初のケースでは、ロボットの体やコネクショニスト・アーキテクチャのような特徴が必要とされるが、サールは(彼の理解する)強力なAIは放棄されたと主 張している[ac]。中国の部屋はチューリング完全機械の要素をすべて備えており、したがって、あらゆるデジタル計算をシミュレートすることができる。も しサールの部屋がチューリング・テストに合格できないのであれば、チューリング・テストに合格できる他のデジタル技術は存在しないことになる。もしサール の部屋がチューリング・テストに合格できても、それでも心を持たないのであれば、チューリング・テストは部屋に「心」があるかどうかを判断するには不十分 である。いずれにせよ、サールが「強いAI」と考える立場のどちらか一方を否定し、彼の議論を証明することになる。 特に脳の議論は、心を記述するのに、脳と同じように神秘的なプログラムを作るより簡単な方法はないと仮定するならば、強いAIを否定することになる。サールによれば、計算が人間の心を説明できないのであれば、強いAIは失敗したことになる。 他の批評家は、サールが説明したような部屋には実際に心があると主張するが、それは見えにくい-サールの説明は正しいが誤解を招く-と主張する。部屋をよ り現実的に設計し直すことで、彼らはこのことをより明白にしたいと考えている。この場合、これらの主張は直感に訴えるものとして使われている(次項参 照)。 実際、部屋は直観を弱めるように設計し直すこともできる。ネッド・ブロックのブロックヘッド論[94]は、理論的には、プログラムを「ユーザがSと書いた らPと答えてXに進む」という形式のルールの単純なルックアップテーブルに書き換えることができることを示唆している。少なくとも原理的には、どのような プログラムも、脳シミュレー ションでさえも、この形に書き換える(あるいは「リファクタリング」する)ことができ る[ad] 。ブロックヘッドのシナリオでは、精神状態全体がXという文字に隠されており、これは メモリアドレス(次のルールに関連する数字)を表している。自分の意識的経験の一瞬が、たった一つの大きな数字にとらえられるというのはイメージしにくい が、これこそが「強いAI」の主張なのである。一方、そのようなルックアップテーブルは(物理的に不可能なほど)ばかばかしいほど大きくなり、したがって 状態は過度に特定される可能性がある。 サールは、プログラムがどのように書かれていようと、マシンがどのように世界に接続されていようと、心は単純なステップ・バイ・ステップのデジタル・マシ ン(またはマシン)によってシミュレートされていると主張する。これらの機械は、常に部屋にいる人間と同じで、何も理解せず、中国語も話さない。記号が何 を意味するのかわからないまま、記号を操作しているにすぎないのだ。サールは次のように書いている:「私はあなたの好きな形式的なプログラムを持つことが できるが、それでも私は何も理解していない」[95]。 |

| Speed and complexity: appeals to intuition The following arguments (and the intuitive interpretations of the arguments above) do not directly explain how a Chinese speaking mind could exist in Searle's room, or how the symbols he manipulates could become meaningful. However, by raising doubts about Searle's intuitions they support other positions, such as the system and robot replies. These arguments, if accepted, prevent Searle from claiming that his conclusion is obvious by undermining the intuitions that his certainty requires. Several critics believe that Searle's argument relies entirely on intuitions. Block writes "Searle's argument depends for its force on intuitions that certain entities do not think."[96] Daniel Dennett describes the Chinese room argument as a misleading "intuition pump"[97] and writes "Searle's thought experiment depends, illicitly, on your imagining too simple a case, an irrelevant case, and drawing the obvious conclusion from it."[97] Some of the arguments above also function as appeals to intuition, especially those that are intended to make it seem more plausible that the Chinese room contains a mind, which can include the robot, commonsense knowledge, brain simulation and connectionist replies. Several of the replies above also address the specific issue of complexity. The connectionist reply emphasizes that a working artificial intelligence system would have to be as complex and as interconnected as the human brain. The commonsense knowledge reply emphasizes that any program that passed a Turing test would have to be "an extraordinarily supple, sophisticated, and multilayered system, brimming with 'world knowledge' and meta-knowledge and meta-meta-knowledge", as Daniel Dennett explains.[79] |

スピードと複雑さ:直感に訴える 以下の論証(および上記の論証の直観的解釈)は、中国語を話す心がサールの部屋にどのように存在しうるのか、あるいは彼が操作する記号がどのように意味を 持つようになりうるのかを直接説明するものではない。しかし、サールの直観に疑問を投げかけることで、システムやロボットの回答といった他の立場を支持し ている。これらの議論は、もし受け入れられれば、サールの確信が必要とする直観を損なうことで、サールが自分の結論は自明だと主張することを妨げる。 サールの議論はすべて直観に依存していると考える批評家もいる。ブロックは「サールの議論は、ある実体は考えないという直観にその力を依存している」と書 いている[96]。ダニエル・デネットは中国の部屋の議論を誤解を招く「直観ポンプ」[97]と表現し、「サールの思考実験は、あなたがあまりにも単純な ケース、無関係なケースを想像し、そこから明白な結論を導き出すことに、不正に依存している」と書いている[97]。 上記の議論のいくつかは直感への訴えとしても機能しており、特に、中国の部屋に心があることをよりもっともらしく見せることを意図したもので、ロボット、 常識的知識、脳のシミュレーション、コネクショニストによる返答などが含まれる。上記の回答のいくつかは、複雑さという具体的な問題にも言及している。コ ネクショニストの回答は、実用的な人工知能システムは人間の脳と同じくらい複雑で、相互につながっていなければならないことを強調している。コモンセンス 知識派の回答は、ダニエル・デネットが説明しているように、チューリング・テストに合格するようなプログラムは「『世界知識』とメタ知識とメタメタ知識で 溢れる、非常にしなやかで洗練された多層的なシステム」でなければならないことを強調している[79]。 |

| Speed and complexity replies Many of these critiques emphasize speed and complexity of the human brain,[ae] which processes information at 100 billion operations per second (by some estimates).[99] Several critics point out that the man in the room would probably take millions of years to respond to a simple question, and would require "filing cabinets" of astronomical proportions.[100] This brings the clarity of Searle's intuition into doubt. An especially vivid version of the speed and complexity reply is from Paul and Patricia Churchland. They propose this analogous thought experiment: "Consider a dark room containing a man holding a bar magnet or charged object. If the man pumps the magnet up and down, then, according to Maxwell's theory of artificial luminance (AL), it will initiate a spreading circle of electromagnetic waves and will thus be luminous. But as all of us who have toyed with magnets or charged balls well know, their forces (or any other forces for that matter), even when set in motion produce no luminance at all. It is inconceivable that you might constitute real luminance just by moving forces around!"[87] Churchland's point is that the problem is that he would have to wave the magnet up and down something like 450 trillion times per second in order to see anything.[101] Stevan Harnad is critical of speed and complexity replies when they stray beyond addressing our intuitions. He writes "Some have made a cult of speed and timing, holding that, when accelerated to the right speed, the computational may make a phase transition into the mental. It should be clear that is not a counterargument but merely an ad hoc speculation (as is the view that it is all just a matter of ratcheting up to the right degree of 'complexity.')"[102][af] Searle argues that his critics are also relying on intuitions, however his opponents' intuitions have no empirical basis. He writes that, in order to consider the "system reply" as remotely plausible, a person must be "under the grip of an ideology".[29] The system reply only makes sense (to Searle) if one assumes that any "system" can have consciousness, just by virtue of being a system with the right behavior and functional parts. This assumption, he argues, is not tenable given our experience of consciousness. |

スピードと複雑性への反論 これらの批評の多くは、1秒間に1,000億回の演算で情報を処理する人間の脳[ae]のスピードと複雑さを強調している[99]。 何人かの批評家は、この部屋にいる人間は簡単な質問に答えるのに何百万年もかかるだろうし、天文学的な割合の「ファイリング・キャビネット」が必要だろう と指摘している[100]。このことは、サールの直観の明晰さを疑わせる。 ポールとパトリシアのチャーチランド夫妻は、スピードと複雑さに関する回答の、特に鮮明なバージョンを提示している。彼らはこのような類似の思考実験を提 案している: 「暗い部屋に、棒磁石か帯電した物体を持った人がいるとする。もしその人が磁石を上下に動かすと、マクスウェルの人工輝度(AL)理論によれば、磁石は電 磁波の拡散円を起こし、発光する。しかし、磁石や荷電ボールを弄ったことのある人なら誰でも知っているように、それらの力(あるいはその他の力)は、たと え運動させたとしても、まったく発光しない。力を動かすだけで本当の輝度が得られるとは考えられない!」[87]。チャーチランドの指摘は、何かを見るた めには、磁石を1秒間に450兆回も上下に振らなければならないという問題である[101]。 Stevan Harnadは、スピードと複雑さの回答が、我々の直感に対処することを超えて逸脱している場合に批判的である。スピードとタイミングを崇拝し、適切なス ピードまで加速すると、計算が精神に相転移すると主張する者もいる。それは反論ではなく、単なるアドホックな推測に過ぎないことは明らかであろう(すべて は適切な「複雑さ」の程度までラチェットアップすることの問題に過ぎないという見解と同様である)」[102][af]。 サールは、彼の批判者もまた直観に頼っていると主張するが、しかし彼の反対者の直観には経験的根拠がない。サールは、「システムの回答」を少しでももっと もらしいと考えるためには、人格が「イデオロギーに支配されて」いなければならないと書いている[29]。システムの回答が意味をなすのは(サールにとっ て)、どのような「システム」も、適切な振る舞いと機能的な部分を持つシステムであることをもって、意識を持つことができると仮定した場合だけである。こ の仮定は、われわれの意識の経験からすると、成り立たないとサールは主張する。 |

| Other minds and zombies: meaninglessness Several replies argue that Searle's argument is irrelevant because his assumptions about the mind and consciousness are faulty. Searle believes that human beings directly experience their consciousness, intentionality and the nature of the mind every day, and that this experience of consciousness is not open to question. He writes that we must "presuppose the reality and knowability of the mental."[105] The replies below question whether Searle is justified in using his own experience of consciousness to determine that it is more than mechanical symbol processing. In particular, the other minds reply argues that we cannot use our experience of consciousness to answer questions about other minds (even the mind of a computer), the epiphenoma replies question whether we can make any argument at all about something like consciousness which can not, by definition, be detected by any experiment, and the eliminative materialist reply argues that Searle's own personal consciousness does not "exist" in the sense that Searle thinks it does. |

他の心とゾンビ:無意味 いくつかの回答は、サールの議論は心と意識に関する彼の仮定が誤っているため、無関係であると主張している。サールは、人間は意識、意図性、心の性質を日 々直接的に経験しており、この意識の経験は疑う余地のないものであると考えている。彼は「精神の現実性と認識可能性を前提とする」必要があると書いている [105]。以下の回答では、サールが意識を機械的な記号処理以上のものだと判断するにあたり、自身の意識経験を根拠として用いることが正当であるかどう かを疑問視している。特に、他の心に関する返答では、意識に関する経験を他の心(コンピューターの心でさえ)に関する質問に答えるために用いることはでき ないと主張している。また、付随現象論の返答では、定義上、いかなる実験によっても検出できない意識のようなものについて、いかなる主張も成り立つのかと いう疑問を投げかけている。そして、排除的唯物論の返答では、サール自身の個人的な意識は、サールが考えているような意味では「存在」していないと主張し ている。 |

| Other minds reply The "Other Minds Reply" points out that Searle's argument is a version of the problem of other minds, applied to machines. There is no way we can determine if other people's subjective experience is the same as our own. We can only study their behavior (i.e., by giving them our own Turing test). Critics of Searle argue that he is holding the Chinese room to a higher standard than we would hold an ordinary person.[106][ag] Nils Nilsson writes "If a program behaves as if it were multiplying, most of us would say that it is, in fact, multiplying. For all I know, Searle may only be behaving as if he were thinking deeply about these matters. But, even though I disagree with him, his simulation is pretty good, so I'm willing to credit him with real thought."[108] Turing anticipated Searle's line of argument (which he called "The Argument from Consciousness") in 1950 and makes the other minds reply.[109] He noted that people never consider the problem of other minds when dealing with each other. He writes that "instead of arguing continually over this point it is usual to have the polite convention that everyone thinks."[110] The Turing test simply extends this "polite convention" to machines. He does not intend to solve the problem of other minds (for machines or people) and he does not think we need to.[ah] |

他の心からの返信 「他の心からの返信」では、サールの議論は「他者の心」の問題の1つのバージョンであり、それを機械に適用したものであると指摘している。他者の主観的な 経験が自分と同じであるかどうかを判断する方法はない。我々ができるのは、彼らの行動を研究することだけである(すなわち、彼らにチューリングテストを行 うこと)。サールの批判者たちは、サールが「チャイニーズ・ルーム」に普通の人間よりも高い基準を課していると主張している。[106][ag] ニルス・ニルソンは「プログラムがまるで掛け算をしているかのように振る舞う場合、ほとんどの人は、実際には掛け算をしていると言うだろう。私の知る限 り、サールはこれらの問題について深く考えているかのように振る舞っているだけかもしれない。しかし、たとえ彼に同意できないとしても、彼のシミュレー ションはかなり善いので、私は彼に真の思考を認めるつもりだ。」[108] チューリングは1950年に、サールの主張(彼はこれを「意識からの主張」と呼んだ)を予想し、他の心の返答を想定した。[109] 彼は、人々が互いにやりとりする際に、他者の心の存在について考えたことは一度もないと指摘した。彼は「この点について延々と議論するのではなく、誰もが 考えているという礼儀作法に従うのが一般的である」と書いている。[110] チューリングテストは、この「礼儀作法」を機械に単純に適用したものである。彼は他者の心の問題(機械または人間)を解決しようとしているわけではなく、 また、その必要はないと考えている。[ah] |