赤をみる:意識のハード・プロブレム

Seeing Red: Hard problem of

consciousness

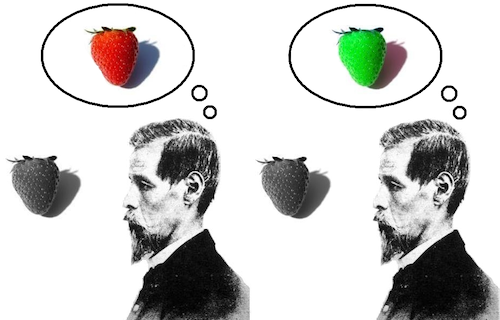

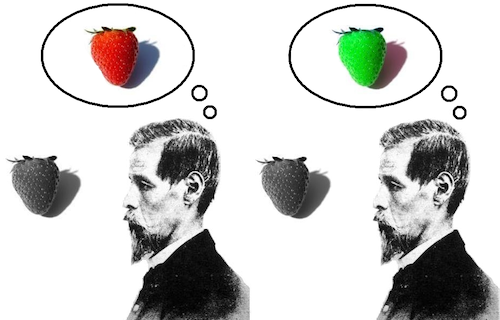

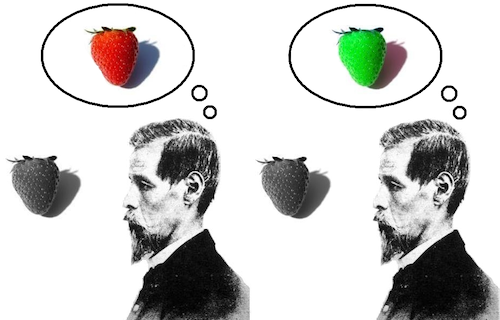

ハード・プロブレムは、可視スペクトルの反転という論理的可能性を例に挙げて説明されることが多い。

もし色覚が反転する可能性に論理的矛盾がないならば、視覚処理の機械論的説明は、色を見る体験の本質を決定づけるものではないということになる

★「クオリアとは意識をともなう個人的な主観的な体験、 感情、感覚のすべて」(=クオリアとは人間の内的経験)である(エーデルマ ン 1995:135)。クオリアの存在をめぐっては、哲学者の間 でおおきな論争があり、存在しない、(議論そのものに)意味がない、存在する、という議論が分かれてい る。また、哲学者以外の人は、クオリアを体験の同義語として使うことがあり、それらの定義の多様性によって、クオリアの存在論に対して、大いなる混乱 が生じている。

比較的素朴な主観と客観の二分法を用い て、「客観的であるはずの脳」が、どうして「主観的なクオリア」経験をするのかという重要な問題があると 考えたのは、ディビッド・チャーマーズ(David John Chalmers, 1966- )である。彼はこれを、意識のハード・プ ロブレム(困難な問題の困難と、脳のハードウェアをかけた駄洒落)だとした。

★意識のハード・プロ ブレムとは、人間がなぜ、そしてどのようにクオリア、すなわち現象体験を持つのかを説明する問題であるが、人間や他の動物に識別能力や情報 統合能力などを与えている物理システムを説明するという 「イージーな問題」とは対照的である。

哲学者のデービッド・チャルマーズは、脳や経験に関するこのような問題をすべて解決しても、なお「難しい問題=ハー ド・プロブレム」が残 ると書いている。【上掲の図】The hard problem is often illustrated by appealing to the logical possibility of inverted visible spectra. Since there is no logical contradiction in supposing that one's colour vision could be inverted, it seems that mechanistic explanations of visual processing do not determine facts about what it is like to see colours. このハード・プロブレムは、可視スペクトルの反転の論理的可能性に訴えることでしばしば説明される。色覚が反転していると仮定することに論理的矛盾はない ので、視覚処理の機械論的説明は、色の見え方に関する事実を決定しないように思われる。

| hard

problem of consciousness The hard problem of consciousness is the problem of explaining why and how humans have qualia[note 1] or phenomenal experiences.[2] This is in contrast to the "easy problems" of explaining the physical systems that give us and other animals the ability to discriminate, integrate information, and so forth. These problems are seen as relatively easy because all that is required for their solution is to specify the mechanisms that perform such functions.[3][4] Philosopher David Chalmers writes that even once we have solved all such problems about the brain and experience, the hard problem will still persist.[3] The existence of a "hard problem" is controversial. It has been accepted by philosophers of mind such as Joseph Levine,[5] Colin McGinn,[6] and Ned Block[7] and cognitive neuroscientists such as Francisco Varela,[8] Giulio Tononi,[9][10] and Christof Koch.[9][10] However, its existence is disputed by philosophers of mind such as Daniel Dennett,[11] Massimo Pigliucci,[12] Thomas Metzinger, Patricia Churchland,[13] and Keith Frankish,[14] and cognitive neuroscientists such as Stanislas Dehaene,[15] Bernard Baars,[16] Anil Seth,[17] and Antonio Damasio.[18] |

意

識のハード・プロブレム(hard

problem of consciousness) 意 識のハード・プロブレムとは、人間がなぜ、そしてどのようにクオリア[注 1]、すなわち現象体験を持つのかを説明する問題である[2]が、人間や他の動物に識別能力や情報統合能力などを与えている物理システムを説明するという 「イージーな問題」とは対照的である。哲学者のデービッド・チャルマーズは、脳や経験に関するこのような問題をすべて解決しても、なお「難しい問題」が残 ると書いている[3]。 困難な問題」の存在については議論がある。ジョセフ・レヴィン[5]、コリン・マギン[6]、ネッド・ブロック[7]などの心の哲学者や、フランシスコ・ バレラ[8]、ジュリオ・トノニ[9][10]、クリストフ・コッチなどの認知神経科学者によって受け入れられている[9][10]が、この問題は「難し い問題」である。 [しかし、ダニエル・デネット[11]、マッシモ・ピグルッチ[12]、トーマス・メッツィンガー、パトリシア・チャーチランド[13]、キース・フラン キッシュなどの心の哲学者、スタニスラス・デハーネ[15]、ベルナルド・バース[16]、アニール・セス[17]、アントニオ・ダマシオなどの認知神経 科学者によってその存在には異論が呈されている[18]。 |

| David

Chalmers first formulated the hard problem in his paper "Facing up to

the problem of consciousness" (1995)[3] and expanded upon it in his

book The Conscious Mind (1996). His works have proven to be

provocative. Some, such as David Lewis and Steven Pinker, have praised

Chalmers for his argumentative rigour and "impeccable clarity".[19]

Others, such as Daniel Dennett and Patricia Churchland, believe that

the hard problem is best seen as a collection of easy problems and will

be solved through further analysis of the brain and behaviour.[20][21] Consciousness is an ambiguous term. It can be used to mean self consciousness, awareness, the state of being awake, and so on. Chalmers uses Thomas Nagel's definition of consciousness: the feeling of what it is like to be something. Consciousness, in this sense, is synonymous with experience.[22][19] Chalmers' formulation . . .even when we have explained the performance of all the cognitive and behavioral functions in the vicinity of experience—perceptual discrimination, categorization, internal access, verbal report—there may still remain a further unanswered question: Why is the performance of these functions accompanied by experience? — David Chalmers, Facing up to the problem of consciousness The problem of consciousness, Chalmers argues, is two problems: the easy problems and the hard problem.  The hard problem is often illustrated by appealing to the logical possibility of inverted visible spectra. If there is no logical contradiction in supposing that one's colour vision could be inverted, it follows that mechanistic explanations of visual processing do not determine facts about what it is like to see colours. |

デ

イヴィッド・チャルマースは、論文「意識の問題に直面して」(1995年)[3]でハードプロブレムを初めて定式化し、著書「意識する心」(1996年)

でそれを発展させた。彼の著作は挑発的であることが証明されている。デイヴィッド・ルイスやスティーブン・ピンカーのように、チャルマースの議論の厳密さ

と「非の打ち所のない明瞭さ」を賞賛する者もいる[19]。ダニエル・デネットやパトリシア・チャーチランドのように、難しい問題は簡単な問題の集合体と

見るのが最善で、脳と行動のさらなる分析を通じて解決されると考える者もいる[20][21]。 意識は曖昧な言葉である。それは自己意識、意識、目覚めている状態などを意味するために使われることがある。チャルマースはトーマス・ナーゲルの意識の定 義を使われている:それが何かであることのようであるという感覚。この意味での意識は、経験と同義である[22][19]。 チャルマーズの定式化 . また、「経験」の周辺にあるすべての認知・行動機能(知覚的弁別、分類、内的アクセス、言語的報告)の遂行を説明しても、さらに未解決の問いが残るかもし れない。これらの機能の遂行には、なぜ経験が伴うのだろうか? - デイヴィッド・チャルマーズ、意識の問題に直面して 意識の問題は、簡単な問題と難しい問題の二つである、とチャルマーズは主張する。  ハード・プロブレムは、可視スペクトルの反転という論理的可能性を例に挙げて説明されることが多い。もし色覚が反転する可能性に論理的矛盾がないならば、視覚処理の機械論的説明は、色を見る体験の本質を決定づけるものではないということになる。 |

| Easy problems The easy problems are problems concerned with behaviour, and mechanistic analysis of the relevant neural processes that accompany that behaviour. Examples of these include how sensory systems work, how such data is processed in the brain, how that data influences behaviour or verbal reports, the neural basis of thought and emotion, and so on. These are problems that can be analyzed through "structures and functions".[19] Chalmers' use of the word easy is "tongue-in-cheek".[23] As Steven Pinker puts it, they are about as easy as going to Mars or curing cancer. "That is, scientists more or less know what to look for, and with enough brainpower and funding, they would probably crack it in this century."[24] The easy problems are amenable to reductive inquiry. They are a logical consequence of lower level facts about the world, similar to how a clock's ability to tell time is a logical consequence of its clockwork and structure, or a hurricane is a logical consequence of the structures and functions of certain weather patterns. A clock, a hurricane, and the easy problems, are all the sum of their parts (as are most things).[19] |

簡単な問題(イージー・プロブレム) イージー・プロブレムとは、行動に関する問題、およびその行動を伴う関連する神経プロセスの機械論的分析に関する問題である。例えば、感覚系の働き、その データが脳内でどのように処理されるか、そのデータがどのように行動や言語報告に影響を与えるか、思考や感情の神経基盤などである。これらは「構造と機 能」によって分析できる問題である[19]。 チャルマースが簡単という言葉を使ったのは「皮肉」である[23]。 スティーブン・ピンカーが言うように、それらは火星に行くことや癌を治すことと同じくらい簡単なことなのだ。「つまり、科学者は多かれ少なかれ何を探すべ きかを知っており、十分な頭脳と資金があれば、おそらく今世紀中にそれを解き明かすだろう」[24]。時計が時を告げる能力がその時計仕掛けと構造の論理 的帰結であるように、あるいはハリケーンが特定の気象パターンの構造と機能の論理的帰結であるように、それらは世界に関するより低レベルの事実の論理的帰 結である。時計、ハリケーン、そして簡単な問題は、すべてその部分の総和である(ほとんどのものがそうであるように)[19]。 |

| Hard problem The hard problem, in contrast, is the problem of why and how those processes are accompanied by experience.[3] It may further include the question of why these processes are accompanied by this or that particular experience, rather than some other kind of experience. In other words, the hard problem is the problem of explaining why certain mechanisms are accompanied by conscious experience.[19] For example, why should neural processing in the brain lead to the felt sensations of, say, feelings of hunger? And why should those neural firings lead to feelings of hunger rather than some other feeling (such as, for example, feelings of thirst)? Chalmers argues that it is conceivable that the relevant behaviours associated with hunger, or any other feeling, could occur even in the absence of that feeling. This suggests that experience is irreducible to physical systems such as the brain. This is the topic of the next section. |

困難な問題(ハード・プロブレム) これに対して、ハード・プロブレムとは、なぜ、どのようにそれらのプロセスが経験を伴うのかという問題である[3]。さらに、なぜこれらのプロセスが他の 種類の経験ではなく、これまたはこれの特定の経験を伴うのかという問題を含むこともある。言い換えれば、ハードプロブレムとは、なぜ特定のメカニズムが意 識的な経験を伴うのかを説明する問題である[19]。例えば、なぜ脳内の神経処理は、例えば空腹感というフェルト感覚をもたらすべきなのか。そして、なぜ それらの神経発火が他の感覚(例えば、喉の渇きなど)ではなく、空腹の感覚をもたらすべきなのだろうか。 チャルマースは、空腹感や他の感覚に関連する行動は、その感覚がない場合でも起こりうると主張する。このことは、経験は、脳のような物理的システムには還 元できないことを示唆している。これが次のセクションの主題である。 |

| Chalmers

believes that the hard problem is irreducible to the easy problems:

solving the easy problems will not lead to a solution to the hard

problems. This is because the easy problems are problems pertaining to

the causal structure of the world, and the hard problem relates to

consciousness, and facts about consciousness include facts that go

beyond mere causal or structural description. For example, take the experience of pain. Suppose one were to stub their foot and yelp. In this scenario, the easy problems are the various mechanistic explanations that involve the activity of one's nervous system and brain and its relation to the environment (such as the propagation of nerve signals from the toe to the brain, the processing of that information and how it leads to yelping, and so on). The hard problem is the question of why these mechanisms are accompanied by the feeling of pain, or why these feelings of pain feel the particular way that they do. Chalmers argues that facts about the neural mechanisms of pain, and pain behaviours, do not lead to facts about conscious experience. Facts about conscious experience are, instead, further facts, not derivable from facts about the brain. In other words, Chalmers believes that solving the easy problems will not solve the hard problems. This is because the easy problems concern "structures and functions" whereas the hard problem contains "further facts" that are not reducible to structural or functional analysis.[19] To return to the above example, this would mean that understanding the neural processing underpinning pain would not explain why those neural processes are accompanied by the feeling of pain. So even once one has explained all the relevant facts about neural processing, facts about what it is like to feel pain would remain unexplained. Here's an example. If one were to program an AI system, the easy problems concern the problems related to discovering which algorithms are required in order to make this system produce intelligent outputs, or process information in the right sort of ways. The hard problem, in contrast, would concern questions as whether this AI system is conscious, what sort of conscious experiences it is privy to, and how and why this is the case. This suggests that solutions to the easy problem (such as how it the AI is programmed) do not automatically lead to solutions for the hard problem (concerning the potential consciousness of the AI). Chalmers' diagnosis of the situation is that the easy facts concern structural and functional explanations, but facts about consciousness are not derivable from structural and functional facts. So structural and functional descriptions of the world do not fix facts about consciousness. This is because functions and structures of any sort could conceivably exist in the absence of experience. Alternatively, they could exist alongside a different set of experiences. For example, it is logically possible for a perfect replica of Chalmers to have no experience at all, or for it to have a different set of experiences (such as an inverted visible spectrum, so that the blue-yellow red-green axes of its visual field are run backwards). The same cannot be said about clocks, hurricanes, or other physical things. In these cases, a structural or functional description is a complete description. A perfect replica of a clock is a clock, a perfect replica of a hurricane is a hurricane, and so on. The difference is that physical things are nothing more than their physical constituents. For example, water is nothing more than H2O molecules, and understanding everything about H2O molecules is to understand everything there is to know about water. But consciousness is not like this. Knowing everything there is to know about the brain, or any physical system, is not to know everything there is to know about consciousness. So consciousness, then, must not be purely physical.[19] |

チャ

ルマースは、難しい問題は簡単な問題には還元できない、つまり、簡単な問題を解決しても難しい問題の解決にはつながらないと考えている。なぜなら、簡単な

問題は世界の因果構造に関わる問題であり、難しい問題は意識に関わる問題であり、意識に関する事実には単なる因果的、構造的記述を超えた事実が含まれるか

らである。 例えば、痛みの経験を考えてみよう。例えば、足を踏みつけてギャーと叫んだとする。このとき、簡単な問題は、自分の神経系や脳の活動、環境との関係(足の 指から脳への神経信号の伝搬、その情報の処理、それがどのように雄叫びにつながるか、など)に関わる様々なメカニズム的説明である。難しいのは、こうした メカニズムになぜ痛みを感じるのか、あるいは、こうした痛みの感情がなぜ特定の形で感じられるのか、という問題である。チャルマースは、痛みの神経メカニ ズムや痛み行動に関する事実は、意識的経験に関する事実につながらないと主張する。意識的経験に関する事実は、脳に関する事実からは導き出されない、さら なる事実なのである。 つまり、チャルマースは、簡単な問題を解決しても、難しい問題は解決しないと考えているのである。これは、簡単な問題が「構造と機能」に関するものである のに対し、難しい問題は構造や機能の分析には還元できない「さらなる事実」を含んでいるからである[19]。 上の例に戻ると、これは、痛みを支える神経処理を理解しても、なぜその神経処理に痛みを感じることが伴うのかを説明できないことを意味する。つまり、神経 処理に関連する事実をすべて説明しても、痛みを感じるとはどういうことなのかという事実は説明されないままなのである。 例えば、こんな感じである。もしAIシステムをプログラムするとしたら、簡単な問題は、このシステムが知的な出力をするために、あるいは正しい方法で情報 を処理するために、どのアルゴリズムが必要かを発見することに関連した問題である。一方、難しい問題とは、AIシステムが意識を持つかどうか、どのような 意識体験をするのか、どのように、そしてなぜそうなるのか、というような問題である。このことは、簡単な問題(AIがどのようにプログラムされているかな ど)の解決は、難しい問題(AIの潜在的な意識に関する問題)の解決に自動的につながらないことを示唆している。 チャルマーズの診断では、簡単な問題は構造的・機能的な説明に関するものであるが、意識に関する事実は構造的・機能的な事実からは導き出せないということ である。つまり、世界の構造的・機能的な説明は、意識に関する事実を固定化しないのである。なぜなら、どのような種類の機能や構造も、経験のないところに 存在することが考えられるからである。あるいは、別の経験の集合と一緒に存在することもあり得る。例えば、チャルマースの完全なレプリカは、全く経験を持 たないことも、別の経験(例えば、可視スペクトルが反転し、視野の青-黄-赤-緑の軸が逆に走る)を持つことも論理的に可能である。 時計、ハリケーン、その他の物理的なものについては、同じことは言えません。このような場合、構造的または機能的な記述が完全な記述となる。時計の完全な レプリカは時計であり、ハリケーンの完全なレプリカはハリケーンである、というように。違いは、物理的なものはその物理的構成要素にほかならないというこ とである。例えば、水はH2O分子以外の何ものでもなく、H2O分子についてすべてを理解することは、水について知るべきことをすべて理解することにな る。しかし、意識はこれとは違う。脳や物理的なシステムについて知っていることをすべて知っても、意識について知っていることをすべて知ることにはならな い。だから、意識は純粋に物理的であってはならないのだ[19]。 |

| Implications for physicalism Chalmers' idea is significant because it contradicts physicalism (sometimes labelled materialism). This is the view that everything that exists is a physical or material thing, so everything can be reduced to microphysical things (such as subatomic particles and the interactions between them). For example, a desk is a physical thing, because it is nothing more than a complex arrangement of a large number of subatomic particles interacting in a certain way. According to physicalism, everything can be explained by appeal to its microphysical constituents, including consciousness. Chalmers' hard problem presents a counterexample to this view, since it suggests that consciousness cannot be reductively explained by appealing to its microphysical constituents. So if the hard problem is a real problem then physicalism must be false, and if physicalism is true then the hard problem must not be a real problem.[citation needed] Though Chalmers rejects physicalism, he is still a naturalist.[19] |

物理主義への影響 チャルマーズの考えは、物理主義(唯物論と表記されることもある)と矛盾する点で重要である。これは、存在するものはすべて物理的あるいは物質的なもので あり、したがってすべては微物理的なもの(素粒子やその間の相互作用など)に還元できるとする考え方である。例えば、机は物理的なものであり、それは多数 の素粒子がある方法で相互作用し、複雑に配置されたものにほかならないからである。物理主義によれば、意識も含めて、すべては微物理的な構成要素に訴える ことで説明できる。チャルマーズの難問は、意識が微物理的な構成要素に訴えることでは還元的に説明できないことを示唆しているので、この見解に対する反例 となる。つまり、もしハードプロブレムが現実の問題であるならば、物理主義は偽でなければならず、もし物理主義が真であるならば、ハードプロブレムは現実 の問題であってはならない[citation needed]ということになる。 チャルマースは物理主義を否定しているが、それでも彼は自然主義者である[19]。 |

| Historical predecessors The hard problem of consciousness has scholarly antecedents considerably earlier than Chalmers, as Chalmers himself has said.[25][note 2] Among others, thinkers who have made arguments similar to Chalmers' formulation of the hard problem include Isaac Newton,[26] John Locke,[27] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz,[28][26] John Stuart Mill,[29] and Thomas Henry Huxley.[30][26] Likewise, Asian philosophers like Dharmakirti and Guifeng Zongmi discussed the problem of how consciousness arises from unconscious matter.[26][31][32][33] |

意

識のハード・プロブレムには、チャルマース自身が述べているように、チャルマースよりもかなり以前の学問的先例がある[25][注2]。

中でもチャルマースのハード・プロブレムの定式化に似た議論をした思想家には、アイザック・ニュートン[26] ジョン・ロック [27]

ゴットフリート・ウィルヘルム・ライプニッツ [28][26] ジョン・スチュアート・ミル [29]

トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーらが含まれる。 [30][26]

同様に、ダルマキールティや貴峰宗実のようなアジアの哲学者は、意識が無意識の物質からどのように生じるかという問題を論じていた[26][31]

[32][33]。 |

| Commentary on the problem's

explanatory targets The philosopher Raamy Majeed argued in 2016 that the hard problem is, in fact, associated with two "explanatory targets":[34] [PQ] Physical processing gives rise to experiences with a phenomenal character. [Q] Our phenomenal qualities are thus-and-so. The first fact concerns the relationship between the physical and the phenomenal (i.e., how and why are some physical states felt states), whereas the second concerns the very nature of the phenomenal itself (i.e., what does the felt state feel like?). Wolfgang Fasching argues that the hard problem is not about qualia, but about pure what-it-is-like-ness of experience in Nagel's sense, about the very givenness of any phenomenal contents itself: Today there is a strong tendency to simply equate consciousness with the qualia. Yet there is clearly something not quite right about this. The "itchiness of itches" and the "hurtfulness of pain" are qualities we are conscious of. So philosophy of mind tends to treat consciousness as if it consisted simply of the contents of consciousness (the phenomenal qualities), while it really is precisely consciousness of contents, the very givenness of whatever is subjectively given. And therefore the problem of consciousness does not pertain so much to some alleged "mysterious, nonpublic objects", i.e. objects that seem to be only "visible" to the respective subject, but rather to the nature of "seeing" itself (and in today’s philosophy of mind astonishingly little is said about the latter).[35] |

問題の説明対象に関する解説 哲学者のラアミーマジードは、2016年に、ハード問題は、実際には、次の二つの「説明対象」と関連していると主張した[34]。 [PQ] 物理的な処理は、現象的な性質を持つ経験を生じさせる。 [Q] 私たちの現象的な性質はこうであり、こうである。 最初の事実は、物理的なものと現象的なものの間の関係(すなわち、ある物理的な状態がどのように、そしてなぜフェルト状態になるのか)に関係し、第2の事 実は、現象的なもの自体の性質(すなわち、フェルト状態はどのように感じるのか)に関係するものである。 ヴォルフガング・ファッシングは、難しい問題はクオリアではなく、ナーゲルの意味での経験の純粋な「何それっぽい」こと、つまり、あらゆる現象的内容その ものの所与性についてだと論じている。 今日、意識とクオリアとを単純に同一視する傾向が強い。しかし、これには明らかに何か不自然な点がある。痒みの痒み」「痛みの痛み」は、私たちが意識して いる性質です。だから心の哲学では、意識は単に意識の内容(現象的特質)からなるかのように扱われがちだが、本当は内容の意識、つまり主観的に与えられた ものの与え方そのものなのである。したがって、意識の問題は、「神秘的で非公開の対象」、すなわちそれぞれの主体にのみ「見える」ように見える対象がある とされることよりも、むしろ「見る」ことの性質そのものに関わるものである(そして今日の心の哲学では、驚くほど後者についてほとんど語られていない) [35]。 |

| Related concepts "What Is It Like to Be a Bat?" The philosopher Thomas Nagel posited in his 1974 paper "What Is It Like to Be a Bat?" that experiences are essentially subjective (accessible only to the individual undergoing them—i.e., felt only by the one feeling them), while physical states are essentially objective (accessible to multiple individuals). So at this stage, he argued, we have no idea what it could even mean to claim that an essentially subjective state just is an essentially non-subjective state (i.e., how and why a felt state is just a functional state). In other words, we have no idea of what reductivism really amounts to.[22] To explain conscious experience within the physicalist framework requires an adequate account. He believes this is impossible, because "every subjective phenomenon is essentially connected with a single point of view, and it seems inevitable that an objective, physical theory will abandon that point of view."[22] |

関連コンセプト 「コウモリであるとはどういうことか? 哲学者トーマス・ナーゲルは、1974年の論文「コウモリであるとはどんな感じか?」で、経験は本質的に主観的(それを受けている個人にのみアクセス可 能、つまり、それを感じている人にのみ感じられる)であるのに対し、物理状態は本質的に客観的(複数の個人にアクセス可能)であるとした。つまり、現段階 では、本質的に主観的な状態が本質的に非主観的な状態であると主張することの意味(つまり、感じた状態がどのように、なぜ機能的な状態に過ぎないのか)さ えもわからないというのである。言い換えれば、還元主義が本当は何を意味するのかが全く分からないのである[22] 物理主義の枠組みの中で意識的経験を説明するには、適切な説明が必要である。彼はこれが不可能だと考えているが、それは「あらゆる主観的な現象は本質的に 一つの視点と結びついており、客観的で物理的な理論がその視点を放棄することは避けられないと思われる」からだ[22]。 |

| Explanatory gap In 1983, the philosopher Joseph Levine proposed that there is an explanatory gap between our understanding of the physical world and our understanding of consciousness.[36] Levine's argument is directed at the notion that conscious states are reducible neuronal or brain states. Levine famously uses the example of pain (as an example of a conscious state) is reducible to the firing of c-fibers (a kind of nerve cell). The difficulty is as follows: even if consciousness is physical, it is not clear which physical states correspond to which conscious states. The bridges between the two levels of description will be contingent[disambiguation needed], rather than necessary[disambiguation needed]. This is significant because in most contexts, relating two scientific levels of descriptions (such as physics and chemistry) is done with the assurance of necessary connections between the two theories (for example, chemistry follows with necessity from physics).[37] Levine illustrates this point with the following thought experiment. Suppose that humanity were to encounter an alien species, and suppose it is known that the aliens do not have any c-fibers. Even if one knows this, it is not obvious that the aliens do not feel pain: that would remain an open question. This is because the fact that aliens do not have c-fibers does not entail that they do not feel pain (in other words, feelings of pain do not follow with logical necessity from the firing of c-fibers. Levine thinks this and similar thought experiments show that there is an explanatory gap between consciousness and the physical world: even if consciousness is reducible to physical things, consciousness cannot be explained in terms of physical things, because the link between physical things and consciousness is contingent link.[37] Levine does not think that the explanatory gap means that consciousness is not physical: he is open to the idea that the explanatory gap is only an epistemological problem for physicalism.[37] In contrast, Chalmers thinks that the hard problem of consciousness does show that consciousness is not physical.[19] |

説明的ギャップ 1983年に哲学者のJoseph Levineは、物理的世界の理解と意識の理解との間に説明的なギャップがあることを提唱した[36]。 レヴィンの議論は意識的な状態が還元可能なニューロンや脳の状態であるという概念に向けられたものである。レヴィンは有名な例として(意識的な状態の例と して)痛みがc-fibers(神経細胞の一種)の発火に還元可能であることを使っている。難点は、意識が物理的であるとしても、どの物理状態がどの意識 状態に対応するのかが明確でないことである。2つのレベルの記述の間の橋渡しは、必要[disambiguation needed]というよりも、むしろ偶発的[disambiguation needed]になる。ほとんどの文脈において、2つの科学的な記述のレベル(物理と化学など)を関連づけることは、2つの理論間の必要な接続を保証して 行われるため、これは重要である(例えば、化学は物理から必要性を持って従う)[37]。 Levineはこの点を次のような思考実験で説明している。人類が異星人と遭遇し、その異星人がc-ファイバーを持たないことが分かっているとする。この ことが分かっても、宇宙人が痛みを感じないことは明らかではない。それは未解決の問題である。なぜなら、宇宙人がc-fibersを持っていないという事 実は、彼らが痛みを感じないことを意味しないからである(言い換えれば、痛みを感じることは、c-fibersの発火から論理的必然性をもって導かれるわ けではない)。レヴィンはこの実験と同様の思考実験は意識と物理的世界の間に説明のギャップがあることを示していると考えている:意識が物理的なものに還 元可能であるとしても、物理的なものと意識の間のリンクは偶発的なリンクであるので、意識は物理的なものの観点から説明することはできないのである [37]。 レヴィンは説明のギャップが意識が物理的でないことを意味するとは考えておらず、説明のギャップは物理主義にとっての認識論的問題に過ぎないという考えに 前向きである[37]。 これに対してチャルマースは意識のハードプロブレムは意識が物理的ではないと示していると考えている[19]。 |

| Philosophical zombies Philosophical zombies are a thought experiment commonly used in discussions of the hard problem.[38][39] They are hypothetical beings physically identical to humans but that lack conscious experience.[40] Philosophers such as Chalmers, Joseph Levine, and Francis Kripke take zombies as impossible within the bounds of nature but possible within the bounds of logic.[41] This would imply that facts about experience are not logically entailed by the "physical" facts. Therefore, consciousness is irreducible. In Chalmers' words, "after God (hypothetically) created the world, he had more work to do."[42][page needed] Daniel Dennett, a philosopher of mind, has criticised the field's use of "the zombie hunch" which he deems an "embarrassment"[43] that ought to "be dropped like a hot potato".[20] |

哲学的ゾンビ(→「哲学的ゾンビあるいはP-ゾンビ」) 哲学的ゾンビは難問の議論でよく使われる思考実験である[38][39]。チャルマース、ジョセフ・レヴィン、フランシス・クリプキなどの哲学者はゾンビ を自然の範囲では不可能だが論理の範囲では可能だと考えている[41]。これは経験に関する事実は「物理的」事実によって論理的に内包されていないことを 意味しているのであろう。それゆえ、意識は還元可能である。チャルマーズの言葉を借りれば、「神が(仮に)世界を創造した後、彼にはもっとやるべきことが あった」[42][page needed] 心の哲学者であるダニエル・デネットはこの分野の「ゾンビの予感」の使用を批判し、彼は「ジャガイモのように捨てられる」べき「恥」だと考えている [43][20]。 |

| Knowledge argument The knowledge argument, also known as Mary's Room, is another common thought experiment. It centres around a hypothetical neuroscientist named Mary. She has lived her whole life in a black and white room and has never seen colour before. She also happens to know everything there is to know about the brain and colour perception.[44] Chalmers believes that if Mary were to see the colour red for the first time that she would gain new knowledge of the world. That means knowledge of what red looks like is distinct from knowledge of the brain or visual system. In other words knowledge of what red looks like is irreducible to knowledge of the brain or nervous system; therefore, experience is irreducible to the functioning of the brain or nervous system.[42][page needed] Others disagree, saying the same could be said about Mary knowing everything there is to know about bikes and riding one for the first time, or swimming, etc.[45] Elsewhere, Thomas Nagel has put forward a "speculative proposal" of devising a language that could "explain to a person blind from birth what it is like to see."[22] If such a language is possible then the force of the knowledge argument may be undercut. |

知識の議論 メアリーの部屋」とも呼ばれる知識論証も、よくある思考実験である。これは、メアリーという仮想の神経科学者を中心にしたものである。彼女はずっと白黒の 部屋に住んでいて、色を見たことがない。チャルマーズは、もしメアリーが初めて赤という色を見たら、世界についての新しい知識を得るだろうと考えている [44]。つまり、赤がどのように見えるかという知識は、脳や視覚システムに関する知識とは異なるものである。言い換えれば、赤がどのように見えるかとい う知識は脳や神経系の知識に還元できないのであり、したがって経験は脳や神経系の機能には還元できない。 [また、トーマス・ナーゲルは「生まれつき目が見えない人に、見ることがどのようなものかを説明する」ことができる言語を考案するという「推測的提案」を 行っている[22]。 |

| Philosophical responses Chalmers' formulation of the hard problem of consciousness has provoked considerable debate within philosophy of mind as well as scientific research.[37] Some responses accept the problem as real and seek to develop a theory of consciousness' place in the world that can solve it, while others seek to show that the apparent hard problem as distinct from the easy problems dissolves upon analysis. A third response has been to accept the hard problem as real but deny human cognitive faculties can solve it. According to a 2020 Philpapers survey, 29.72% of philosophers surveyed believe that the hard problem does not exist, while 62.42% of philosophers surveyed believe that the hard problem is a genuine problem.[46] |

哲学的応答 チャルマースが定式化した意識の難しい問題は、科学的研究だけでなく、心の哲学においてもかなりの議論を引き起こしている[37] いくつかの反応は、問題を現実のものとして受け入れ、それを解決できる世界における意識の位置についての理論を開発しようとする一方で、簡単な問題とは異 なる明らかな難しい問題が分析によって解消されることを示そうとするものもある。第三の反応は、難問を現実のものとして受け入れつつも、人間の認知能力が それを解決することを否定するものである。 2020年のPhilpapersの調査によれば、調査対象となった哲学者の29.72%が難問は存在しないと考えており、62.42%が難問は本物の問 題であると信じている[46]。 |

| Proposed solutions Different solutions have been proposed to the hard problem of consciousness. One of these, weak reductionism, is the view that while there is an epistemic hard problem of consciousness that will not be solved directly by scientific progress, this is due to our conceptualization, not an ontological gap.[37] A traditional solution gaining renewed popularity is idealism, according to which consciousness is fundamental and not simply an emergent property of matter. It is claimed that this avoids the hard problem entirely.[47] Dualism views consciousness as either a non-physical substance separate from the brain or a non-physical property of the physical brain.[48] Meanwhile, panpsychism and neutral monism, broadly speaking, view consciousness as intrinsic to matter.[49] |

提案されている解決策 意識のハード・プロブレムに対しては、さまざまな解決策が提案されている。これらのうちの1つである弱い還元主義は、科学的進歩によって直接解決されない 意識の認識上の難問が存在するものの、これは存在論的ギャップではなく我々の概念化によるものであるという見解である[37]。新たな人気を得ている伝統 的な解決策は観念論であり、それによれば意識は基本的なものであり、単に物質の出現的な性質ではないというものである[40]。二元論は意識を脳から分離 した非物理的な物質か、物理的な脳の非物理的な性質のどちらかとして見る[48]。一方、汎心論と中立一元論は、広義には意識を物質に内在するものとして 見ている[49]。 |

| Weak reductionism There is a split among those subscribing to reductive materialism between those who hold there is no hard problem of consciousness—"strong reductionists" (see below)—and "weak reductionists" who, while remaining ontologically committed to physicalism, accept an epistemic hard problem of consciousness.[37][49] Put differently, weak reductionists believe there is a gap between two ways of knowing (introspection and neuroscience) that will not be resolved by understanding all the underlying neurobiology, but still believe that consciousness and neurobiology are one and the same in reality.[37] For example, Joseph Levine, who formulated the notion of the explanatory gap (see above), states: "The explanatory gap argument doesn't demonstrate a gap in nature, but a gap in our understanding of nature."[50] He nevertheless contends that a full scientific understanding will not close the gap,[37] and that analogous gaps do not exist for other identities in nature, such as that between water and H2O.[51] The philosophers Ned Block and Robert Stalnaker agree that facts about what a conscious experience is like to the one experiencing it cannot be deduced from knowing all the facts about the underlying physiology, but by contrast argue that such gaps of knowledge are also present in many other cases in nature, such as the distinction between water and H2O.[52][7] To explain why these two ways of knowing (i.e. third-person scientific observation and first-person introspection) yield such different understandings of consciousness, weak reductionists often invoke the phenomenal concepts strategy, which argues the difference stems from our inaccurate phenomenal concepts (i.e., how we think about consciousness), not the nature of consciousness itself.[53][54] Thus, the hard problem of consciousness stems only from a dualism of concepts, not a dualism of properties or substances (see next section).[37] |

弱い還元主義 還元的唯物論に賛同する人々の間では、意識の難しい問題はないとする人々-「強い還元論者」(下記参照)と、存在論的に物理主義にコミットしたまま、意識 の認識上の難しい問題を受け入れる「弱い還元論者」の間で分裂しています。 [37][49] 別の言い方をすれば、弱い還元論者は、2つの知る方法(内省と神経科学)の間にギャップがあり、それは基礎となる神経生物学をすべて理解しても解決しない が、それでも意識と神経生物学は現実には同じであると信じている[37] 例えば、説明的ギャップの概念(上記)を打ち出したヨセフ・レヴィンは、次のように言っている。「説明的ギャップの議論は自然におけるギャップを示してい るのではなく、自然に対する我々の理解におけるギャップを示している」[50]。にもかかわらず彼は、完全な科学的理解はギャップを解消しないし [37]、水とH2Oの間のような自然における他の同一性には類似のギャップは存在しないことを論じている[51]。 [51] 哲学者のネッド・ブロックとロバート・スタルネイカーは、意識的な経験がそれを経験している者にとってどのようなものであるかについての事実は、基礎とな る生理学についての全ての事実を知ることから推論することができないことに同意するが、対照的にそのような知識のギャップは水とH2Oの区別のように自然 界の他の多くのケースにおいても存在していることを主張している[52][7]。 なぜこれらの2つの知る方法(すなわち三人称的な科学的観察と一人称的なイントロスペクション)が意識についてこのように異なる理解をもたらすのかを説明 するために、弱い還元論者はしばしば現象的概念戦略を発動し、その違いは意識そのものの性質ではなく、我々の不正確な現象的概念(すなわち我々が意識につ いてどう考えているか)に起因すると主張している[53][54]。 従って意識の難問は概念についてのみ二元論から生じ、性質や物質についてではなく(次の項参照)、二元論に由来している[37]。 |

| Dualism Dualism is the view that the mind is irreducible to the physical body.[48] There are multiple dualist accounts of the causal relationship between the mental and the physical, of which interactionism and epiphenomenalism are the most common today. Interactionism posits that the mental and physical causally impact one another, and is associated with the thought of René Descartes (1596–1650).[49] Epiphenomalism, by contrast, holds the mental is causally dependent on the physical, but does not in turn causally impact it.[49] In contemporary philosophy, interactionism has been defended by philosophers including Martine Nida-Rümelin,[55] while epiphenomenalism has been defended by philosophers including Frank Jackson[56][57] (although Jackson later changed his stance to physicalism).[58] Chalmers has also defended versions of both positions as plausible.[49] Traditional dualists such as Descartes believed the mental and the physical to be two separate substances, or fundamental types of entities (hence "substance dualism"); some more recent dualists, however, accept only one substance, the physical, but state it has both mental and physical properties (hence "property dualism").[48] |

二元論 二元論とは、精神は肉体に還元できないとする見解である[48]。精神と肉体の因果関係については複数の二元論的説明があり、その中で相互作用論と表象論 が今日最も一般的なものである。相互作用論は精神と肉体が因果的に影響し合うとし、ルネ・デカルト(1596-1650)の思想と関連している[49]。 対照的に、エピフェノマリズムは精神が肉体に対して因果的に依存するが、今度はそれに因果的に影響を与えないとする。 現代の哲学では、相互作用論はマルティーヌ・ニーダ=リューメリンを含む哲学者によって擁護されており[55]、エピフェノメンタル主義はフランク・ジャ クソンを含む哲学者によって擁護されている[56][57](ただしジャクソンは後に物理主義に立場を変えている)[58]。 [デカルトのような伝統的な二元論者は精神と肉体を2つの別々の物質、または存在の基本的なタイプであると信じていた(それゆえ「物質二元論」)。しか し、より最近の二元論者の中には、肉体という一つの物質だけを受け入れ、それが精神と肉体両方の性質を持つと述べる者もいる(それゆえ「性質二元論」) [48]。 |

| Panpsychism and neutral monism In its most basic form, panpsychism holds that all physical entities have minds (though its proponents in fact take more qualified positions),[59] while neutral monism, in at least some variations, holds that entities are composed of a substance with mental and physical aspects—and is thus sometimes described as a type of panpsychism.[60] Forms of panpsychism and neutral monism were defended in the early twentieth century by the psychologist William James,[61][62][note 3] the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead,[62] the physicist Arthur Eddington,[63][64] and the philosopher Bertrand Russell,[59][60] and interest in these views has been revived in recent decades by philosophers including Thomas Nagel,[62] Galen Strawson,[62][65] and David Chalmers.[59] Chalmers describes his overall view as "naturalistic dualism",[3] but he says panpsychism is in a sense a form of physicalism,[49] as does Strawson.[65] Proponents of panpsychism argue it solves the hard problem of consciousness parsimoniously by making consciousness a fundamental feature of reality.[37][66] |

汎心論と中立的一元論 汎心論はその最も基本的な形式において、すべての物理的実体が心を持つとするものであり[59]、一方、中立的一元論は少なくともいくつかのバリエーショ ンにおいて、実体が精神的側面と物理的側面を持つ物質から構成されているとし、したがって汎心論の一種として表現されることもある[60]. [汎心論と中立的一元論の形態は、20世紀初頭に心理学者のウィリアム・ジェームズ[61][62][注3]、哲学者のアルフレッド・ノース・ホワイト ヘッド[62]、物理学者のアーサー・エディントン[63][64]、哲学者のバートランド・ラッセルによって弁護され、これらの見解に対する関心は、ト マス・ネイグルやゲイレン・ストローソン[62][65]、デイヴィッド・チャルマースを含む哲学者により最近十年間に再来されてきている。 [汎心論の支持者は、意識を現実の基本的な特徴とすることによって、意識という難問を簡潔に解決していると主張している[37][66]。 |

| Objective idealism and

cosmopsychism Objective idealism and cosmopsychism consider mind or consciousness to be the fundamental substance of the universe. Proponents claim that this approach is immune to both the hard problem of consciousness and the combination problem that affects panpsychism.[67][68][69] From an idealist perspective, matter is a representation or image of mental processes, and supporters suggest that this avoids the problems associated with the materialist view of mind as an emergent property of a physical brain.[70] Critics of this approach point out that you then have a decombination problem, in terms of explaining individual subjective experience. In response, Bernardo Kastrup claims that nature has already hinted at a mechanism for this in the condition Dissociative identity disorder (previously known as Multiple Personality Disorder).[71] Kastrup proposes dissociation as an example from nature showing that multiple minds with their own individual subjective experience could develop within a single universal mind. Cognitive psychologist Donald D. Hoffman uses a mathematical model based around conscious agents, within a fundamentally conscious universe, to support conscious realism as a description of nature that falls within the objective idealism approaches to the hard problem: "The objective world, i.e., the world whose existence does not depend on the perceptions of a particular conscious agent, consists entirely of conscious agents."[72] David Chalmers has said this form of idealism is one of "the handful of promising approaches to the mind–body problem."[73] |

目的論的観念論と宇宙心理学 客観的観念論と宇宙心理主義は心または意識が宇宙の基本的な物質であるとみなしている。支持者はこのアプローチが意識のハード問題と汎心論に影響を与える 組み合わせ問題の両方から免れていると主張している[67][68][69]。 観念論的な観点からすると、物質は精神的なプロセスの表象やイメージであり、支持者はこれが物理的な脳の出現的な特性として心を捉える唯物論的な見解に関 連する問題を回避することを示唆している[70]。 このアプローチの批評家は、個人の主観的経験を説明するという点で、その後に組換え問題が発生することを指摘している。これに対してベルナルド・カスト ルップは、自然界は解離性同一性障害(以前は多重人格障害として知られていた)という状態においてすでにこのためのメカニズムを示唆していると主張してい る[71]。カストルップは解離を、単一の普遍的精神の中に個々の主観的経験を持つ複数の心が発展しうることを示す自然界の例として提唱している。 認知心理学者のドナルド・D・ホフマンは意識的なエージェントを中心とした数学的モデルを使い、基本的に意識的な宇宙の中で、困難な問題に対する客観的観 念論のアプローチに属する自然の記述として意識的実在論を支持している:「客観的世界、すなわち存在が特定の意識エージェントの知覚に依存しない世界は、 完全に意識エージェントから成る」[72]。 David Chalmersはこの観念論の形式が「心身問題に対する一握りの有望なアプローチ」の一つであると述べている[73]。 |

| Rejection of the problem Many philosophers have disputed that there is a hard problem of consciousness distinct from what Chalmers calls the easy problems of consciousness. Some among them, who are sometimes termed strong reductionists, hold that phenomenal consciousness (i.e., conscious experience) does exist but that it can be fully understood as reducible to the brain.[37] Others maintain that phenomenal consciousness can be eliminated from the scientific picture of the world, and hence are called eliminative materialists or eliminativists.[37] |

問題の否定 多くの哲学者が、チャルマースが意識の容易な問題と呼ぶものとは異なる意識の困難な問題が存在することに異議を唱えている。そのうちの何人かは強力な還元 論者と呼ばれることがあり、現象的意識(すなわち意識的経験)は存在するが、それは脳に還元可能なものとして完全に理解することができると主張している [37]。また、現象的意識は世界の科学的イメージから排除することができると主張しており、それゆえ排除的唯物論者や排除論者と呼ばれることもある [37]。 |

| Strong reductionism Broadly, strong reductionists accept that conscious experience is real but argue it can be fully understood in functional terms as an emergent property of the material brain.[37] In contrast to weak reductionists (see above), strong reductionists reject ideas used to support the existence of a hard problem (that the same functional organization could exist without consciousness, or that a blind person who understood vision through a textbook would not know everything about sight) as simply mistaken intuitions.[37][49] A notable family of strong reductionist accounts are the higher-order theories of consciousness.[74][37] In 2005, the philosopher Peter Carruthers wrote about "recognitional concepts of experience", that is, "a capacity to recognize [a] type of experience when it occurs in one's own mental life," and suggested that such a capacity could explain phenomenal consciousness without positing qualia.[75] On the higher-order view, since consciousness is a representation, and representation is fully functionally analyzable, there is no hard problem of consciousness.[37] The philosophers Glenn Carruthers and Elizabeth Schier said in 2012 that the main arguments for the existence of a hard problem—philosophical zombies, Mary's room, and Nagel's bats—are only persuasive if one already assumes that "consciousness must be independent of the structure and function of mental states, i.e. that there is a hard problem." Hence, the arguments beg the question. The authors suggest that "instead of letting our conclusions on the thought experiments guide our theories of consciousness, we should let our theories of consciousness guide our conclusions from the thought experiments."[76] The philosopher Massimo Pigliucci argued in 2013 that the hard problem is misguided, resulting from a "category mistake".[12] He said: "Of course an explanation isn't the same as an experience, but that's because the two are completely independent categories, like colors and triangles. It is obvious that I cannot experience what it is like to be you, but I can potentially have a complete explanation of how and why it is possible to be you."[12] In 2017, the philosopher Marco Stango, in a paper on John Dewey's approach to the problem of consciousness (which preceded Chalmers' formulation of the hard problem by over half a century), noted that Dewey's approach would see the hard problem as the consequence of an unjustified assumption that feelings and functional behaviors are not the same physical process: "For the Deweyan philosopher, the 'hard problem' of consciousness is a 'conceptual fact' only in the sense that it is a philosophical mistake: the mistake of failing to see that the physical can be had as an episode of immediate sentiency."[77] The philosopher Thomas Metzinger likens the hard problem of consciousness to vitalism, a formerly widespread view in biology which was not so much solved as abandoned.[78] Brian Jonathan Garrett has also argued that the hard problem suffers from flaws analogous to those of vitalism.[79] |

強力な還元主義 大まかに言えば、強い還元主義者は意識的な経験が実在することを受け入れるが、それは物質的な脳の出現的な特性として機能的な用語で完全に理解することが できると主張する[37]。弱い還元主義者(上記参照)とは対照的に、強い還元主義者は難しい問題の存在をサポートするために使われるアイデア(同じ機能 的な組織が意識なしに存在することができるということや教科書を通して視覚を理解した盲人が視覚についてすべてを知っているということはない)を単に間 違った直観として拒絶する[37][49]。 強い還元主義的な説明の注目すべきファミリーは意識の高次理論である[74][37]。 2005年に哲学者のピーター・カラザーズは「経験の認識概念」、つまり「経験の種類が自身の精神生活において発生するときに認識する[ある]能力」につ いて書き、そのような能力がクオリアを仮定せずに現象意識を説明できることを示唆していた[75]。高次の見解においては意識とは表現であり表現は完全に 機能分析できるので、意識には難しい問題が存在しないのである[37]。 哲学者のグレン・カラザースとエリザベス・シアーは2012年に、難問の存在に対する主な議論-哲学的ゾンビ、マリアの部屋、ナーゲルのコウモリ-は「意 識が精神状態の構造と機能から独立していなければならない、つまり難問がある」と既に仮定している場合にのみ説得力があると述べている。それゆえ、この議 論は疑問を投げかけているのである。著者らは「思考実験に関する結論に意識に関する理論を導かせるのではなく、意識に関する理論に思考実験からの結論を導 かせるべき」と提案している[76]。 哲学者のMassimo Pigliucciは2013年にハード問題は見当違いであり、「カテゴリーの間違い」から生じていると論じていた[12]。"もちろん説明は経験と同じ ではないが、それはこの2つが色と三角形のように完全に独立したカテゴリーであるからだ。私があなたであることがどのようなものであるかを経験できないこ とは明らかであるが、どのように、そしてなぜあなたであることが可能であるかの完全な説明を潜在的に持つことができる」[12]。 2017年、哲学者のマルコ・スタンゴは、ジョン・デューイの意識の問題へのアプローチ(チャルマーズのハード・プロブレムの定式化に半世紀以上先行して いる)に関する論文で、デューイのアプローチでは、感情と機能的行動は同じ物理プロセスではないという不当な前提の結果としてハード問題を捉えるだろうと 指摘しています。デューイ派の哲学者にとって、意識に関する「困難な問題」は、それが哲学的な間違いであるという意味においてのみ「概念的事実」である: 物理的なものが即時感覚のエピソードとして持ちうることを見損なうという間違いである」[77]。 哲学者のトーマス・メッツィンガーは意識のハードプロブレムを、解決されたというよりも放棄された生物学におけるかつて広まった見解であるバイタリズムに なぞらえている[78]。 ブライアン・ジョナサン・ギャレットもハードプロブレムがバイタリズムのものに類似する欠陥に苦しんでいると論じている[79]。 |

| Eliminative materialism Eliminative materialism or eliminativism is the view that many or all of the mental states used in folk psychology (i.e., common-sense ways of discussing the mind) do not, upon scientific examination, correspond to real brain mechanisms.[80] While Patricia Churchland and Paul Churchland have famously applied eliminative materialism to propositional attitudes, philosophers including Daniel Dennett, Georges Rey, and Keith Frankish have applied it to qualia or phenomenal consciousness (i.e., conscious experience).[80] On their view, it is mistaken not only to believe there is a hard problem of consciousness, but to believe consciousness exists at all (in the sense of phenomenal consciousness).[14][81] Dennett asserts that the so-called "hard problem" will be solved in the process of solving what Chalmers terms the "easy problems".[11] He compares consciousness to stage magic and its capability to create extraordinary illusions out of ordinary things.[82] To show how people might be commonly fooled into overstating the accuracy of their introspective abilities, he describes a phenomenon called change blindness, a visual process that involves failure to detect scenery changes in a series of alternating images.[83][page needed] He accordingly argues that consciousness need not be what it seems to be based on introspection. To address the question of the hard problem, or how and why physical processes give rise to experience, Dennett states that the phenomenon of having experience is nothing more than the performance of functions or the production of behavior, which can also be referred to as the easy problems of consciousness.[11] Thus, Dennett argues that the hard problem of experience is included among—not separate from—the easy problems, and therefore they can only be explained together as a cohesive unit.[82] In 2013, the philosopher Elizabeth Irvine argued that both science and folk psychology do not treat mental states as having phenomenal properties, and therefore "the hard problem of consciousness may not be a genuine problem for non-philosophers (despite its overwhelming obviousness to philosophers), and questions about consciousness may well 'shatter' into more specific questions about particular capacities."[84] In 2016, Frankish proposed the term "illusionism" as superior to "eliminativism" for describing the position that phenomenal consciousness is an illusion. In the introduction to his paper, he states: "Theories of consciousness typically address the hard problem. They accept that phenomenal consciousness is real and aim to explain how it comes to exist. There is, however, another approach, which holds that phenomenal consciousness is an illusion and aims to explain why it seems to exist."[14] After offering arguments in favor and responding to objections, Frankish concludes that illusionism "replaces the hard problem with the illusion problem—the problem of explaining how the illusion of phenomenality arises and why it is so powerful."[14] In 2022, Jacy Reese Anthis published Consciousness Semanticism: A Precise Eliminativist Theory of Consciousness. The consciousness semanticism position, a formulation of eliminative materialism, highlights semantic ambiguity in discussions of consciousness. Anthis argues that while many philosophers have engaged in "intuition jousting," we can instead approach the hard problem with "formal argumentation from precise semantics." On this view, there is no hard problem because consciousness does not exist as a property beyond what can be understood through logical and empirical analysis.[85] A complete illusionist theory of consciousness must include the description of a mechanism by which the apparently subjective aspect of consciousness is perceived and reported by people. Various philosophers and scientists have proposed possible theories.[86] For example, in his book Consciousness and the Social Brain neuroscientist Michael Graziano advocates what he calls attention schema theory, in which our perception of being conscious is merely an error in perception, held by brains which evolved to hold erroneous and incomplete models of their own internal workings, just as they hold erroneous and incomplete models of their own bodies and of the external world.[87][88] |

消去的唯名論 パトリシア・チャーチランドとポール・チャーチランドが命題的態度に消去的唯物論を適用したことは有名であるが、ダニエル・デネット、ジョルジュ・レイ、 キース・フランキーなどの哲学者はクオリアまたは現象的意識(すなわち意識的経験)に適用している[80]。彼らの見解では、意識の難しい問題があると信 じるだけでなく、意識が(現象的な意識という意味で)全く存在しないと信じることも間違いである[14][81]。 デネットはいわゆる「難しい問題」はチャルマースが「簡単な問題」と呼ぶものを解く過程で解決されると主張している[11]。彼は意識を舞台マジックと普 通のものから並外れた幻想を作り出すその能力になぞらえている。 [82] 人がどのように一般的に騙されて自分の内省的な能力の正確さを誇張してしまうかを示すために、彼は変化盲と呼ばれる現象、つまり一連の交互するイメージに おける風景の変化を検出できない視覚プロセスについて説明している[83][page needed] それに従って彼は意識が内省に基づいてあるように見えるものでなくてもいいと論じている。このように、デネットは経験のハード・プロブレム、すなわち物理 的プロセスがどのように、そしてなぜ経験を生み出すのかという問題に対して、経験を持つという現象は機能の遂行や行動の生成に他ならず、それは意識の容易 な問題とも呼ばれる[11]と述べている。 したがって、経験のハード・プロブレムは容易な問題から分離してではなくそこに含まれており、したがってそれらはまとまった単位としてのみ説明できる [82]。 2013年、哲学者のエリザベス・アーバインは、科学と民間心理学の両方が精神状態を現象的な特性を持つものとして扱っておらず、それゆえ「意識のハード 問題は(哲学者にとって圧倒的な明白さにもかかわらず)非哲学者にとって本物の問題ではないかもしれないし、意識に関する質問は特定の能力に関するより具 体的な質問に『粉砕』する可能性が十分にある」[84]と論じていた。 2016年、フランキッシュは、現象意識は幻想であるという立場を表す言葉として、「消去主義」よりも優れた「幻想主義」という言葉を提唱した。論文の序 文で、彼はこう述べている。"意識の理論は通常、難しい問題に取り組んでいる。彼らは、現象的な意識が実在することを認め、それがどのように存在するよう になったかを説明することを目的としている。しかしながら、もう一つのアプローチがあり、それは現象的な意識は幻想であるとし、なぜそれが存在するように 見えるのかを説明することを目指している」[14]。賛成論を述べ、反論に答えた後、フランキッシュは幻想主義を「ハード問題を幻想問題-現象性の幻想が どのように生じ、なぜそれがそれほど強力であるかを説明する問題-に置き換える」と結論付けている[14]。 2022年、ジェーシー・リース・アンシスは『意識意味論』を発表した。A Precise Eliminativist Theory of Consciousness』を出版した。排除的唯名論を定式化した意識意味論の立場は、意識についての議論における意味的な曖昧さを強調している。アン ティスは、多くの哲学者が "直感的な駆け引き "をしている一方で、我々は代わりに "正確な意味論からの形式的な議論 "で難しい問題にアプローチすることができると主張している。この見解では、意識は論理的かつ経験的な分析を通して理解することができるものを超えた性質 として存在しないので、難しい問題は存在しない[85]。 意識に関する完全な幻想論は、意識の明らかに主観的な側面が人々によって知覚され報告されるメカニズムの記述を含まなければならない。例えば、神経科学者 のマイケル・グラツィアーノは彼の著書『Consciousness and the Social Brain』において、意識があるという認識は単に知覚のエラーであり、自分の身体や外界について誤った不完全なモデルを持つように進化した脳が自身の内 部動作について誤った不完全なモデルを持つことによって保持されるという注意スキーマ理論というものを主張している[86][87][88]。 |

| Other views The philosopher Peter Hacker argues that the hard problem is misguided in that it asks how consciousness can emerge from matter, whereas in fact sentience emerges from the evolution of living organisms.[89] He states: "The hard problem isn’t a hard problem at all. The really hard problems are the problems the scientists are dealing with. [...] The philosophical problem, like all philosophical problems, is a confusion in the conceptual scheme."[89] Hacker's critique extends beyond Chalmers and the hard problem and is directed against contemporary philosophy of mind and neuroscience more broadly. Along with the neuroscientist Max Bennett, he has argued that most of contemporary neuroscience remains implicitly dualistic in its conceptualizations and is predicated on the mereological fallacy of ascribing psychological concepts to the brain that can properly be ascribed only to the person as a whole.[90] Hacker further states that "consciousness studies", as it exists today, is "literally a total waste of time":[89] The whole endeavour of the consciousness studies community is absurd—they are in pursuit of a chimera. They misunderstand the nature of consciousness. The conception of consciousness which they have is incoherent. The questions they are asking don't make sense. They have to go back to the drawing board and start all over again. |

その他の見解 哲学者のピーター・ハッカーは、ハードプロブレムは意識が物質からどのように出現しうるかを問うているという点で見当違いであると主張する一方で、実際に は感覚は生物の進化から出現するのだと述べている[89]。「ハードプロブレムはハードプロブレムではありません。本当に難しい問題は、科学者が扱ってい る問題である。[中略)哲学的問題は、すべての哲学的問題と同様に、概念スキームの混乱である」[89] ハッカーの批判はチャルマーズとハード問題に留まらず、現代の心の哲学と神経科学に対してより広く向けられている。神経科学者のマックス・ベネットととも に、彼は現代の神経科学のほとんどがその概念化において暗黙のうちに二元論的であり続け、全体としての人間にのみ適切に帰属させることができる心理的概念 を脳に帰属させるという単なる誤謬を前提としていると主張している[90] ハッカーはさらに、今日存在する「意識研究」は「文字通り時間の無駄である」と述べている[89]。 意識研究のコミュニティの全努力は不合理であり、彼らはキメラを追い求めているのである。彼らは意識の本質を誤解している。彼らが持っている意識に関する 概念は支離滅裂である。彼らが問いかけていることは意味をなさない。彼らは、初心に戻って、もう一度最初からやり直さなければならない。 |

| New mysterianism New mysterianism, most significantly associated with the philosopher Colin McGinn, proposes that the human mind, in its current form, will not be able to explain consciousness.[91][6] McGinn draws on Noam Chomsky's distinction between problems, which are in principle solvable, and mysteries, which human cognitive faculties are unequipped to ever understand, and places the mind-body problem in the latter category.[91] His position is that a naturalistic explanation does exist but that the human mind is cognitively closed to it due to its limited range of intellectual abilities.[91] He cites Jerry Fodor's concept of the modularity of mind in support of cognitive closure.[91] While in McGinn's strong form, new mysterianism states that the relationship between consciousness and the material world can never be understood by the human mind, there are also weaker forms that argue it cannot be understood within existing paradigms but that advances in science or philosophy may open the way to other solutions (see above).[37] The ideas of Thomas Nagel and Joseph Levine fall into the second category.[37] The cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker has also endorsed this weaker version of the view, summarizing it as follows:[24] And then there is the theory put forward by philosopher Colin McGinn that our vertigo when pondering the Hard Problem is itself a quirk of our brains. The brain is a product of evolution, and just as animal brains have their limitations, we have ours. Our brains can't hold a hundred numbers in memory, can't visualize seven-dimensional space and perhaps can't intuitively grasp why neural information processing observed from the outside should give rise to subjective experience on the inside. This is where I place my bet, though I admit that the theory could be demolished when an unborn genius—a Darwin or Einstein of consciousness—comes up with a flabbergasting new idea that suddenly makes it all clear to us. |

新ミステリジアニズム 新・神秘主義とは哲学者であるコリン・マッギンに最も顕著に関連するもので、人間の心は現在の形では意識を説明することができないだろうと提案している [91][6] マッギンはノーム・チョムスキーの問題、それは原理的に解決可能であるが、人間の認知能力は決して理解することができない神秘の間の区別から、心身の問題 を後者に分類している[91] 彼の立場は、自然主義的な説明は存在するが、人間の心は限られた知的能力のために認知的に閉じているということである。 [彼の立場は、自然主義的な説明は存在するが、人間の心はその限られた知的能力の範囲によってそれに対して認知的に閉じているというものである[91]。 彼は認知的閉鎖性を支持するためにジェリー・フォドーの心のモジュール性の概念を引用している[91]。 マッギンの強い形態では、意識と物質世界の関係は人間の心では決して理解できないとする新ミステリアニズムがあるが、既存のパラダイムの中では理解できな いが、科学や哲学の進歩によって他の解決策への道が開けるかもしれないと主張する弱い形態もある(上記参照)[37]。 トーマス・ネーグルやジョセフ・レヴィンの考えは2番目のカテゴリーに入る[37]。 認知心理学者のスティーブン・ピンカーもこの弱いバージョンの見解を支持していて以下の様に要約している[24]。 そして哲学者のコリン・マッギンによって提唱された理論がある。ハードプロブレ ムを熟考しているときのめまいは、それ自体が脳の癖であるというものである。脳は進化の産物であり、動物の脳に限界があるように、私たちにも限界がある。 私たちの脳は、100個の数字を記憶することはできないし、7次元空間を視覚化することもできない。また、外から観察される神経情報処理が、なぜ内側に主 観的な経験をもたらすのかを直観的に理解することもできないかもしれない。しかし、意識のダーウィンやアインシュタインのような、まだ生まれてもいない天 才が、突然すべてを明らかにするような驚くべき新発見をすれば、この理論は崩壊する可能性があることは認めている。 |

| Relationship to scientific

frameworks Most neuroscientists and cognitive scientists believe that Chalmers' alleged hard problem will be solved in the course of solving what he terms the easy problems, although a significant minority disagrees.[24][92][better source needed] Neural correlates of consciousness Further information: Neural correlates of consciousness Since 1990, researchers including the molecular biologist Francis Crick and the neuroscientist Christof Koch have made significant progress toward identifying which neurobiological events occur concurrently to the experience of subjective consciousness.[93] These postulated events are referred to as neural correlates of consciousness or NCCs. However, this research arguably addresses the question of which neurobiological mechanisms are linked to consciousness but not the question of why they should give rise to consciousness at all, the latter being the hard problem of consciousness as Chalmers formulated it. In "On the Search for the Neural Correlate of Consciousness", Chalmers said he is confident that, granting the principle that something such as what he terms global availability can be used as an indicator of consciousness, the neural correlates will be discovered "in a century or two".[94] Nevertheless, he stated regarding their relationship to the hard problem of consciousness: One can always ask why these processes of availability should give rise to consciousness in the first place. As yet we cannot explain why they do so, and it may well be that full details about the processes of availability will still fail to answer this question. Certainly, nothing in the standard methodology I have outlined answers the question; that methodology assumes a relation between availability and consciousness, and therefore does nothing to explain it. [...] So the hard problem remains. But who knows: Somewhere along the line we may be led to the relevant insights that show why the link is there, and the hard problem may then be solved.[94] The neuroscientist and Nobel laureate Eric Kandel wrote that locating the NCCs would not solve the hard problem, but rather one of the so-called easy problems to which the hard problem is contrasted.[95] Kandel went on to note Crick and Koch's suggestion that once the binding problem—understanding what accounts for the unity of experience—is solved, it will be possible to solve the hard problem empirically.[95] However, neuroscientist Anil Seth argued that emphasis on the so-called hard problem is a distraction from what he calls the "real problem": understanding the neurobiology underlying consciousness, namely the neural correlates of various conscious processes.[17] This more modest goal is the focus of most scientists working on consciousness.[95] Psychologist Susan Blackmore believes, by contrast, that the search for the neural correlates of consciousness is futile and itself predicated on an erroneous belief in the hard problem of consciousness.[96] |

科学的枠組みとの関係 ほとんどの神経科学者と認知科学者は、チャルマーズが主張する難しい問題は、彼が簡単な問題と呼ぶものを解く過程で解決されると考えているが、かなりの少 数派は同意していない[24][92][より良い出典が必要]。 意識の神経相関 さらに詳しい情報はこちら。意識の神経的相関 1990年以降、分子生物学者のフランシス・クリックや神経科学者のクリストフ・コッホなどの研究者は、主観的な意識の経験と同時に発生する神経生物学的 事象の特定に向けて大きく前進した[93]。しかし、この研究は、どの神経生物学的メカニズムが意識と結びついているかという問題には間違いなく取り組ん でいるが、なぜそれらが意識を生じさせるのかという問題には全く取り組んでいない、後者はチャルマースが定式化した意識のハードプロブレムである。意識の 神経相関の探索について」でチャルマースは、彼がグローバル・アベイラビリティと呼ぶものが意識の指標として使われうるという原理を認めれば、神経相関は 「1世紀か2世紀のうちに」発見されると確信していると述べた[94]。 それにもかかわらず、彼は意識のハード・プロブレムと彼らの関係について次のように述べている。 そもそもなぜこれらの利用可能性のプロセスが意識を生じさせなければならないのかと常に問うことができる。今のところ、我々はなぜそうなるのかを説明する ことができないし、利用可能性のプロセスに関する完全な詳細がまだこの問いに答えることができないことも十分にあり得る。確かに、私が概説した標準的な方 法論では、この問いに答えるものは何もありません。その方法論は、可用性と意識の間の関係を前提としており、それゆえ、それを説明することは何もできない のです。[だから、難しい問題が残っているのです。しかし、この先、なぜそのような関係があるのかを示す関連する洞察に導かれるかもしれませんし、そうな ればこの難問は解決されるかもしれません[94]。 神経科学者でありノーベル賞受賞者であるエリック・カンデルは、NCCの位置を特定することは難問を解決するのではなく、難問と対比されるいわゆる易問の 一つを解決することになると書いた[95]。カンデルはさらに、結合問題-経験の単一性を説明するものを理解する-が解決すれば、難問を経験的に解決でき るだろうというクリックとコッチの提案に留意している[95]。 [95] しかし神経科学者のアニル・セスは、いわゆる難問を強調することは、彼が「本当の問題」と呼ぶ、意識の根底にある神経生物学、すなわち様々な意識プロセス の神経相関を理解することから注意をそらすものだと論じている[17] このもっと控えめな目標が、意識について研究するほとんどの科学者が焦点を当てている。 95] 対照的に心理学者のスーザン・ブラックモアは、意識の神経相関の探索は無駄で、それ自体が意識の難問に対する誤った信念に基づくと信じている[96] 。 |

| Integrated information theory Integrated information theory (IIT), developed by the neuroscientist and psychiatrist Giulio Tononi in 2004 and more recently also advocated by Koch, is one of the most discussed models of consciousness in neuroscience and elsewhere.[97][98] The theory proposes an identity between consciousness and integrated information, with the latter item (denoted as Φ) defined mathematically and thus in principle measurable.[98][99] The hard problem of consciousness, write Tononi and Koch, may indeed be intractable when working from matter to consciousness.[10] However, because IIT inverts this relationship and works from phenomenological axioms to matter, they say it could be able to solve the hard problem.[10] In this vein, proponents have said the theory goes beyond identifying human neural correlates and can be extrapolated to all physical systems. Tononi wrote (along with two colleagues): While identifying the "neural correlates of consciousness" is undoubtedly important, it is hard to see how it could ever lead to a satisfactory explanation of what consciousness is and how it comes about. As will be illustrated below, IIT offers a way to analyze systems of mechanisms to determine if they are properly structured to give rise to consciousness, how much of it, and of which kind.[100] As part of a broader critique of IIT, Michael Cerullo suggested that the theory's proposed explanation is in fact for what he dubs (following Scott Aaronson) the "Pretty Hard Problem" of methodically inferring which physical systems are conscious—but would not solve Chalmers' hard problem.[98] "Even if IIT is correct," he argues, "it does not explain why integrated information generates (or is) consciousness."[98] Chalmers agrees that IIT, if correct, would solve the "Pretty Hard Problem" rather than the hard problem.[101] |

統合情報理論 2004年に神経科学者であり精神科医であるジュリオ・トノーニによって開発され、最近ではコッホによって提唱された統合情報理論(IIT)は、神経科学 やその他の分野で最も議論されている意識のモデルの1つである[97][98] この理論は、意識と統合情報の間の同一性を提案しており、後者(Φとして示される)は数学的に定義されており、したがって原理的には測定が可能となってい る[98][99]。 [98][99]意識の難問は、物質から意識への作業では確かに難解かもしれないとトノニとコッチは書いている[10]。 しかし、IITはこの関係を逆転させ、現象学的公理から物質へと作業するので、難問を解決できるかもしれないと彼らは言う。この静脈で、支持者はこの理論 は人間の神経相関を特定することを超え、すべての物理システムに外挿できると言ってきた[10]。Tononiは(2人の同僚と一緒に)こう書いている。 意識の神経相関」を特定することが重要であることは間違いないが、それが意識とは何か、どのようにして生じるのかについて、満足のいく説明につながるとは 考えにくい。以下で説明されるように、IITはメカニズムのシステムを分析して、それらが意識を生じさせるために適切に構造化されているかどうか、どの程 度、どのような種類のものかを決定する方法を提供する[100]。 IITに対するより広い批評の一部として、マイケル・セルロは、この理論が提案する説明は、彼が(スコット・アーロンソンに倣って)どの物理システムが意 識を持つかを系統的に推測する「かなり難しい問題」に対するものであるが、チャルマーズの難しい問題を解決しないであろうことを示唆した。 [98]「IITが正しいとしても」、彼は「なぜ統合された情報が意識を生み出す(あるいは意識である)のか説明できない」と主張している[98]。チャ ルマーズは、IITが正しいならば、難しい問題ではなく、「かなり難しい問題」を解決するだろうということに同意している[101]。 |

| Global workspace theory Global workspace theory (GWT) is a cognitive architecture and theory of consciousness proposed by the cognitive psychologist Bernard Baars in 1988.[102] Baars explains the theory with the metaphor of a theater, with conscious processes represented by an illuminated stage.[102] This theater integrates inputs from a variety of unconscious and otherwise autonomous networks in the brain and then broadcasts them to unconscious networks (represented in the metaphor by a broad, unlit "audience").[102] The theory has since been expanded upon by other scientists including cognitive neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene.[103] In his original paper outlining the hard problem of consciousness, Chalmers discussed GWT as a theory that only targets one of the "easy problems" of consciousness.[3] In particular, he said GWT provided a promising account of how information in the brain could become globally accessible, but argued that "now the question arises in a different form: why should global accessibility give rise to conscious experience? As always, this bridging question is unanswered."[3] J. W. Dalton similarly criticized GWT on the grounds that it provides, at best, an account of the cognitive function of consciousness, and fails to explain its experiential aspect.[104] By contrast, A. C. Elitzur argued: "While [GWT] does not address the 'hard problem', namely, the very nature of consciousness, it constrains any theory that attempts to do so and provides important insights into the relation between consciousness and cognition."[105] For his part, Baars writes (along with two colleagues) that there is no hard problem of explaining qualia over and above the problem of explaining causal functions, because qualia are entailed by neural activity and themselves causal.[16] Dehaene, in his 2014 book Consciousness and the Brain, rejected the concept of qualia and argued that Chalmers' "easy problems" of consciousness are actually the hard problems.[15] He further stated that the "hard problem" is based only upon ill-defined intuitions that are continually shifting as understanding evolves:[15] Once our intuitions are educated by cognitive neuroscience and computer simulations, Chalmers' hard problem will evaporate. The hypothetical concept of qualia, pure mental experience, detached from any information-processing role, will be viewed as a peculiar idea of the prescientific era, much like vitalism... [Just as science dispatched vitalism] the science of consciousness will keep eating away at the hard problem of consciousness until it vanishes. |

グローバルワークスペース理論 グローバルワークスペース理論(GWT)は、1988年に認知心理学者のバーナード・バースによって提唱された認知アーキテクチャと意識の理論である [102]。バースは、意識プロセスが照明付きのステージによって表される劇場の比喩で理論を説明している。 [102] この劇場は脳内の様々な無意識の、そしてそうでなければ自律的なネットワークからの入力を統合し、そしてそれらを無意識のネットワーク(隠喩では広く、照 明されていない「観客」によって表される)に放送している。 102] この理論はその後認知神経科学者のStanislas Dehaeneなどの他の科学者によって拡張されてきた[103]。 意識のハード・プロブレムを概説した彼のオリジナルの論文において、チャルマースはGWTを意識の「簡単な問題」の一つをターゲットにしているだけの理論 であると論じている[3]。 特に、彼はGWTが脳内の情報がどのようにグローバルにアクセス可能になり得るかについて有望な説明を提供しているとしながら、「今度は別の形で問題が生 じる:なぜグローバルなアクセス性が意識体験を生じさせるべきなのか」と論じている[4]。J. W. Daltonも同様に、GWTはせいぜい意識の認知機能の説明であり、その経験的側面を説明できていないという理由で批判した[104]。 対照的に、A. C. Elitzurは主張した。GWT]は「難しい問題」、すなわち意識の本質に対処しないが、そうしようとするあらゆる理論を制約し、意識と認知の間の関係 に対する重要な洞察を提供している」[105]。 一方、バースは(2人の同僚とともに)クオリアは神経活動によって内包され、それ自体が因果的であるため、因果的機能を説明する問題以上にクオリアを説明 するハードプロブレムは存在しないと書いている。 [16] Dehaeneは2014年の著書『Consciousness and the Brain』でクオリアの概念を否定し、チャルマーズの意識に関する「簡単な問題」が実は難しい問題であると主張した[15]。 さらに彼は「難しい問題」は理解の進化に伴って絶えず変化する定義されていない直感に基づいているだけだと述べている:[15]。 我々の直感が認知神経科学やコンピュータシミュレーションによって教育されれば、チャルマーズのハードプロブレムは蒸発することになる。クオリアという仮 説的概念は、情報処理的役割から切り離された純粋な精神的経験であり、生命論と同様に、前科学時代の特異な考えとみなされるようになるだろう...。[科 学がバイタリズムを退けたように)意識の科学は、意識の難問を消滅させるまで食い潰しつづけるだろう。 |

| The meta-problem In 2018, Chalmers highlighted what he calls the "meta-problem of consciousness", another problem related to the hard problem of consciousness:[86] The meta-problem of consciousness is (to a first approximation) the problem of explaining why we think that there is a [hard] problem of consciousness. In his "second approximation", he says it is the problem of explaining the behavior of "phenomenal reports", and the behavior of expressing a belief that there is a hard problem of consciousness.[86] Explaining its significance, he says:[86] Although the meta-problem is strictly speaking an easy problem, it is deeply connected to the hard problem. We can reasonably hope that a solution to the meta-problem will shed significant light on the hard problem. A particularly strong line holds that a solution to the meta-problem will solve or dissolve the hard problem. A weaker line holds that it will not remove the hard problem, but it will constrain the form of a solution. In other words, the 'strong line' holds that the solution to the meta-problem would provide an explanation of our beliefs about consciousness that is independent of consciousness. That would debunk our beliefs about consciousness, in the same way that explaining beliefs about god in evolutionary terms may provide arguments against theism itself.[106] In popular culture British playwright Sir Tom Stoppard's play The Hard Problem, first produced in 2015, is named after the hard problem of consciousness, which Stoppard defines as having "subjective First Person experiences".[107] |

メタ問題とは 2018年、チャルマーズは意識のハードプロブレムに関連するもう一つの問題である「意識のメタ問題」と呼ぶものを強調した:[86]。 意識のメタ問題とは、(第一近似として)なぜ私たちが意識の[ハード]問題があると思うのかを説明する問題である。 彼の「第二近似」では、それは「現象報告」の振る舞いを説明する問題であり、意識のハードな問題があるという信念を表明する振る舞いであると言っている [86]。 その意義を説明すると、彼は次のように言う[86]。 メタ問題は厳密に言えば容易な問題であるが、困難な問題と深く結びついている。メタ問題の解答が難問に重要な光を当てることを合理的に期待することができ る。特に強いのは、メタ問題を解決すれば難問が解決する、あるいは解決しないという考え方である。一方、メタ問題の解決は、困難な問題を取り除くことはで きないが、解決策の形を制約することになるとする弱者もいる。 言い換えれば、「強い線」は、メタ問題に対する解が、意識から独立した、意識に関する私たちの信念の説明を提供するだろうというものです。それは、神につ いての信念を進化論的な観点から説明することが神論そのものに対する議論を提供することがあるのと同じように、意識についての信念を論破することになるの である[106]。 大衆文化において イギリスの劇作家であるトム・ストッパード卿の戯曲『ハード・プロブレム』は2015年に初演され、ストッパードが「主観的なファーストパーソン体験」を 持つこととして定義している意識のハード・プロブレムにちなんで命名されている[107]。 |

| Animal consciousness Artificial consciousness Binding problem Blindsight Chinese room Cogito, ergo sum Consciousness causes collapse Free will Ideasthesia Information-theoretic death Introspection Knowledge by acquaintance List of unsolved problems in biology Mind–body problem Phenomenalism Philosophy of self Problem of mental causation Problem of other minds Secondary quality Vertiginous question |

動物の意識 人工的な意識 束縛問題 ブラインドサイト チャイニーズルーム 我思う、ゆえに我あり 意識の崩壊を引き起こすもの 自由意志 観念的感覚 情報理論的死 自己反省 知覚による知識 生物学における未解決問題の一覧 心身問題 現象論 自己の哲学 精神的な因果関係の問題 他者の心の問題 二次的性質 めまいがするような問題 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hard_problem_of_consciousness |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆