哲学的ゾンビ1.0

p-zombie or philosophical

zombie, 1.0

哲学的ゾンビ1.0

p-zombie or philosophical

zombie, 1.0

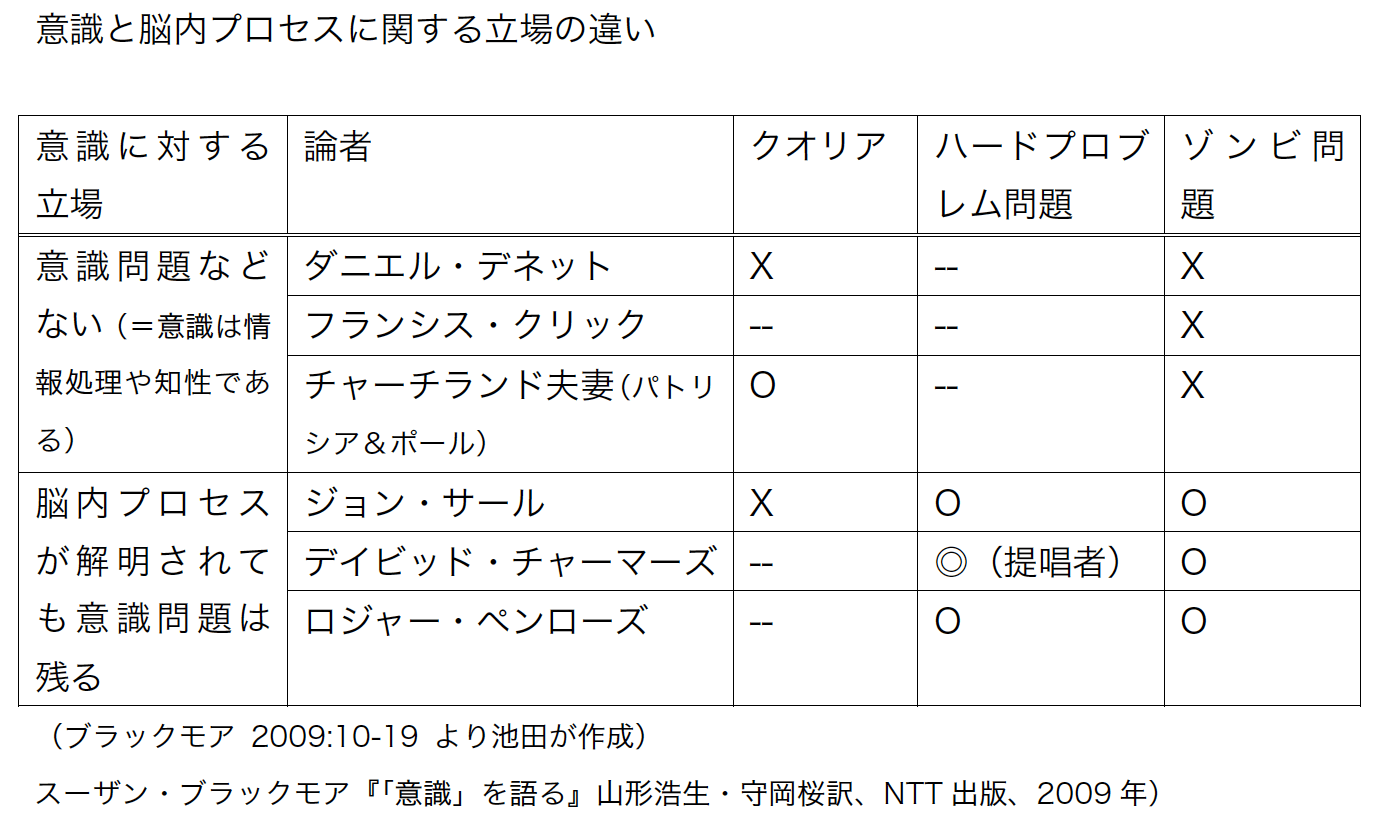

★哲学的ゾンビ(philosophical zombie)あるいはP-ゾンビ(p-zombie argument)とは、通常の人間と物理的に同一で区別がつかないが、意識経験、クオリア、感覚を持たない仮想の存在を想像する心の哲学における思考実 験である。 例えば、哲学的ゾンビが鋭いもので突かれた場合、内面では痛みを感じないが、外面では痛みを感じるように振る舞い、痛みを表現する言葉も発せられるとする ものである(→行動的ゾンビ Behavioral Zombie)。また、ゾンビの世界とは、私たちの世界と区別がつかないが、すべての生物が意識を持たない仮想的な世界のことである(→出典「ゾンビ学入門」→「哲学的ゾンビ 2.0」「君はゾンビを見たか?」)。

☆哲学的ゾンビ(Neurological Zombie)とは「脳の神経細胞の状態まで含む、すべての観測可能な物理的状態に関して、普通の人間と区別する事が出来ないゾンビ」で「心の哲学の分野 における純粋な理論的なアイデアであって、単なる議論の道具であり、「外面的には普通の人間と全く同じように振る舞うが、その際に内面的な経験(意識やク オリア)を持たない人間」という形で定義された仮想の存在である。哲学的ゾンビが実際にいる、と信じている人は哲学者の中にもほとんどおらず「哲学的ゾン ビは存在可能なのか」「なぜ我々は哲学的ゾンビではないのか」などが心の哲学の他の諸問題と絡めて議論される」そうである(→出典「哲学的ゾンビ」)。

| ゾンビ問題("philosophical zombie" または「意識のゾンビ」問題)について言及したことで最も有名な哲学者は デイヴィッド・チャーマーズ(David Chalmers) である。 デイヴィッド・チャーマーズとゾンビ問題

チャーマーズは1990年代に、「意識のハード・プロブレム(hard problem of consciousness)」を提起したことで知られている。その文脈で彼は「哲学的ゾンビ(philosophical zombie)」という思考実験を使った。

ゾンビとは何か? 哲学的ゾンビとは: 1)外見や行動は完全に普通の人間と同じ。

2)内的な意識(クオリア)がまったくない存在。 この思考実験の目的は、意識は物理的な事実だけでは説明できない可能性を示すことである。つまり、ゾンビが物理的には私たちと同一でありながら、意識を持たないとしたら、意識は何か別のものによって成立しているのではないか、という問題提起である。 ちなみに、チャーマーズ以前にも類似のアイデアを語った哲学者はいたが、「哲学的ゾンビ」という明確な用語とその有名な形での使用は、チャーマーズが決定的な役割を果たした。 |

★哲学的ゾンビは難問の議論でよく使われる思考実験である[38][39]。デイヴィッド・チャー

マーズ、

ジョセフ・レヴィン(Joseph Levine)、フランシス・クリプキなどの哲学者はゾンビ

を自然の範囲では不可能だが論理の範囲では可能だと考えている[41]。これは経験に関する事実は「物理的」事実によって論理的に内包されていないことを

意味しているのであろう。それゆえ、意識は還元可能である。チャルマーズの言葉を借りれば、「神が(仮に)世界を創造した後、彼にはもっとやるべきことが

あった」[42][page needed]

心の哲学者であるダニエル・デネットはこの分野の「ゾンビの予感」の使用を批判し、彼は「ジャガイモのように捨てられる」べき「恥」だと考えている

[43][20](出典「赤をみる:意識のハード・プロブレム」)。

+++++++++++++++++++

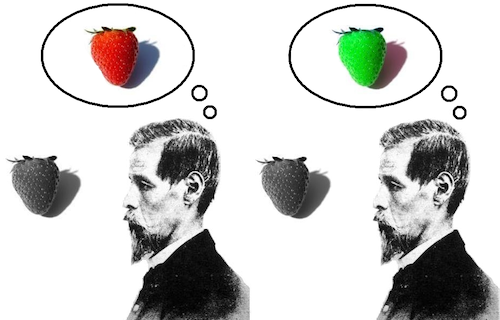

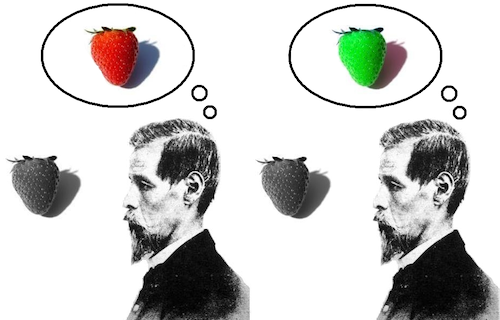

【クオリアとは何か?】意識経験には質的な側面がある。意識にともなう質的な状態をクオリア

(gualia)と名づけられている。クオリアの語形は複数形で、その単数

形表現はクアリ(guale)であり、個々の質的な状態を表現する用語となる。「クオリアとは意識をともなう個人的な主観的な体験、感情、感覚のすべてで

ある」(エーデルマン 1995:135)

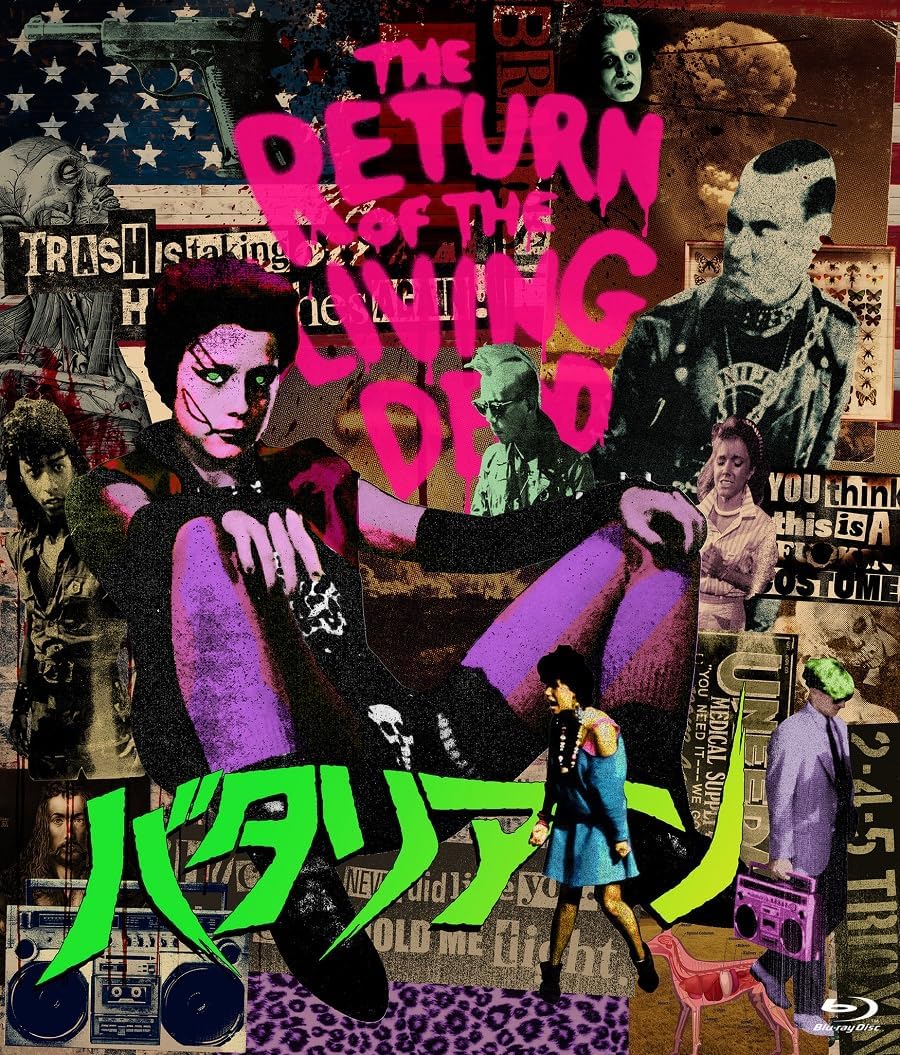

☆(さまざまな民衆文化における)ゾンビの定義は、何者かによって蘇った死人であり、肉体と

精神(精神が後退して無知あるいは人工知能なしのロボットとして描かれる)が外部のエージェント(=先の何者か)によって支配されており、また他の生きて

いる人間を襲うために特化した人造人間兵器でもある。ま

た、吸血鬼伝説のように、ゾンビが襲った人間もまた、今度は一旦死んだあとにゾンビとして蘇り、再生産をするという側面もある。

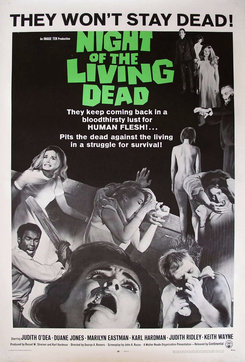

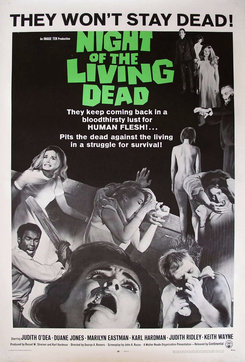

☆1968年のジョージ・A・ロメロのアメリカ映画『ナイト・オブ・ザ・リビングデッド(Night of the Living Dead)』(上掲)で、ゾンビに「噛んだ相手もゾンビになる」という吸血鬼 の特徴が混ぜ込まれ、これが以後のゾンビ映画の基本構造となった。また、ゾンビ作品に触発され、噛まれると感染する蘇った死体としてのキョンシーが香港映 画で1980年代に確立したといわれている。

+++++++++++++++++++

以下、哲 学的ゾンビの目次

+++

| A philosophical

zombie or p-zombie argument is a thought experiment in

philosophy of mind that imagines a hypothetical being that is

physically identical to and indistinguishable from a normal person but

does not have conscious experience, qualia, or sentience.[1] For

example, if a philosophical zombie were poked with a sharp object it

would not inwardly feel any pain, yet it would outwardly behave exactly

as if it did feel pain, including verbally expressing pain. Relatedly,

a zombie world is a hypothetical world indistinguishable from our world

but in which all beings lack conscious experience. Philosophical zombie arguments are used in support of mind-body dualism against forms of physicalism such as materialism, behaviorism and functionalism. These arguments aim to resist the possibility of any physicalist solution to the "hard problem of consciousness" (the problem of accounting for subjective, intrinsic, first-person, what-it's-like-ness). Proponents of philosophical zombie arguments, such as the philosopher David Chalmers, argue that since a philosophical zombie is by definition physically identical to a conscious person, even its logical possibility would refute physicalism, because it would establish the existence of conscious experience as a further fact.[2] Such arguments have been criticized by many philosophers. Some physicalists like Daniel Dennett argue that philosophical zombies are logically incoherent and thus impossible;[3][4] other physicalists like Christopher Hill argue that philosophical zombies are coherent but not metaphysically possible.[5] |

哲

学的ゾンビ(philosophical zombie、p-zombie

argument)とは、通常の人間と物理的に同一で区別がつかないが、意識経験、クオリア、感覚を持たない仮想の存在を想像する心の哲学における思考実

験である[1]。

例えば、哲学的ゾンビが鋭いもので突かれた場合、内面では痛みを感じないが、外面では痛みを感じるように振る舞い、痛みを表現する言葉も発せられるとする

ものである。また、ゾンビの世界とは、私たちの世界と区別がつかないが、すべての生物が意識を持たない仮想的な世界のことである。 哲学的ゾンビ論は、唯物論、行動主義、機能主義などの物理主義に対して、心身二元論を支持するために使われるものである。これらの主張は、「意識の難問」 (主観的、内在的、一人称的、何それっぽい、という問題を説明する問題)に対する物理主義的解決の可能性に抵抗することが目的である。哲学者であるデイ ヴィッド・チャルマーズのような哲学的ゾンビ論の支持者は、哲学的ゾンビは定義上、意識のある人間と同一であるため、その論理的可能性すら物理主義に反論 することになると主張しており、それは意識経験の存在をさらなる事実として立証することになるからだ[2]。このような主張は多くの哲学者から批判されて きた。ダニエル・デネットのような一部の物理学者は哲学的ゾンビは論理的に支離滅裂であり、したがって不可能であると主張している[3][4]。クリスト ファー・ヒルのような他の物理学者は哲学的ゾンビは一貫しているが形而上的に可能ではないと言っている[5]。 (→「ゾンビ・イン・フィロソフィー」「哲学的ゾンビ 2.0」も参考のこと) |

| History Philosophical zombies are associated with David Chalmers, but it was philosopher Robert Kirk who first used the term "zombie" in this context in 1974. Prior to that, Keith Campbell made a similar argument in his 1970 book Body and Mind, using the term "Imitation Man."[6] Chalmers further developed and popularized the idea in his work. In his 1911 Oxford "Life and consciousness" Lectures, Henri Bergson already argues to his audience that it is impossible to prove with mathematical certainty that he is in fact an I, a creature enstowed with consciousness: "I might be a well constructed automaton - going, coming, speaking - without internal consciousness, and the very words by which I declare at this moment that I am conscious being might be words pronounced without conciousness."(Bergson, 1911). Bergson proceeds to argue that we infer from analogy between this other being and ourselves. Following this thought experiment further, Bergson proceeds to argue against the idea that conciousness is restricted to the brain - which he conceives as an organ of choice -, but instead resides in the whole body. (Bergson, 1911) There has been a lively debate about what the zombie argument shows.[6] Critics who primarily argue that zombies are not conceivable include Daniel Dennett, Nigel J. T. Thomas,[7] David Braddon-Mitchell,[8] and Robert Kirk;[9] critics who assert mostly that conceivability does not entail possibility include Katalin Balog,[10] Keith Frankish,[11] Christopher Hill,[5] and Stephen Yablo;[12] and critics who question the logical validity of the argument include George Bealer.[13] In his 2019 update to the article on philosophical zombies in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Kirk summed up the current state of the debate: In spite of the fact that the arguments on both sides have become increasingly sophisticated — or perhaps because of it — they have not become more persuasive. The pull in each direction remains strong.[14] A 2013 survey of professional philosophers conducted by Bourget and Chalmers produced the following results: 35.6% said P Zombies were conceivable but not metaphysically possible; 23.3% said they were metaphysically possible; 16.0% said they were inconceivable; and 25.1% responded "other."[15] In 2020, the same survey yielded "inconceivable" 16%, "conceivable but not possible" 37%, "metaphysically possible" 24%, and "other" 23%.[16] +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Robert Kirk (born 1933)[1] is a British philosopher. He is emeritus professor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Nottingham. Kirk is best known for his work on philosophical zombies—putatively unconscious beings physically and behaviourally identical to human beings. Although Kirk did not invent this idea, he introduced the term zombie in his 1974 papers "Sentience and Behaviour"[2] and "Zombies v. Materialists".[3] In the latter he offered a formulation of physicalism that aimed to make clear that if zombies are possible, physicalism is false: an argument that was not much noticed until David Chalmers's development of it in The Conscious Mind.[4] Kirk himself had reversed his position earlier,[5] and has argued against the zombie idea in a number of books and articles on physicalism and consciousness.[6][7][8][9][10] As well as working on other topics in the philosophy of mind, Kirk has published on the question of how far translation and interpretation are determined by objective facts (see W. V. Quine's Word and Object (1960)). His own book on this topic, Translation Determined,[11] appeared in 1986. Another main interest is relativism.[12] |

歴史 哲学的ゾンビはデイヴィッド・チャルマーズと関連しているが、1974年にこの文脈で初めて「ゾンビ」という言葉を使ったのは哲学者のロバート・カークで あった。それ以前にはキース・キャンベルが1970年の著書『身体と心』の中で「模倣人間」という言葉を使って同様の議論をしていた[6]。チャルマーズ はその考えをさらに発展させて彼の作品の中で一般化させたのであった。アンリ・ベル クソンは1911年のオックスフォードでの「生命と意識」講義の中で、すでに聴衆に対して、自分が実際に私であり、意識を付与された生物であることを数学 的に確実に証明することは不可能であると論じている。 「私は、内的な意識を持たない、よくできた自動人形かもしれないし、私がこの瞬間、意識的存在であると宣言した言葉も、意識なしに発音された言葉かもしれ ない」(Bergson, 1911).と。ベルクソンは、この他の存在と自分との間のアナロジーから推論することを進めている。この思考実験をさらに進めると、ベルクソンは、意識 が脳に限定される——彼はそれを選択する器官と考える——のではなく、全身に存在するという考え方に反論を進める。(ベルクソン、1911) ゾンビの議論が示すものについては活発な議論がなされてきた[6]。Thomas、[7] David Braddon-Mitchell、[8] Robert Kirk、[9] 考えられることは可能性を伴わないと主に主張する批評家にはKatalin Balog、[10] Keith Frankish、[11] Christopher Hill、[5] Stephen Yablo、[12] 議論の論理的妥当性を疑う批評家にはGeorge Bealer、[13]が含まれる。 スタンフォード哲学百科事典の哲学的ゾンビに関する記事の2019年の更新で、カークは議論の現状を総括している(→「哲学的ゾンビ 2.0」にある)。 両者の議論がますます洗練されてきているにもかかわらず、あるいはそのために、説得力が増しているわけではありません。それぞれの方向への引きは依然とし て強いのです[14]。 BourgetとChalmersによって行われたプロの哲学者を対象とした2013年の調査では、次のような結果が得られている。 35.6%がゾンビは考えられるが形而上学的に可能ではないと答え、23.3%が形而上学的に可能と答え、16.0%が考えられないと答え、25.1%が 「その他」と答えている[15]。 2020年の同調査では、「考えられない」16%、「考えられるが可能ではない」37%、「形而上学的に可能」24%、「その他」23%という結果だった [16]。 +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ ロバート・カーク(1933年生まれ)[1]はイギリスの哲学者である。ノッティンガム大学哲学科の名誉教授である。 カークは、哲学的ゾンビ-物理的にも行動的にも人間と同じ、仮に無意識の存在-に関する研究で最もよく知られている。カークはこの考えを発明したわけでは ないが、1974年の論文「感覚と行動」[2]と「ゾンビ対唯物論者」[3]でゾンビという言葉を紹介した。後者では、ゾンビが可能であるならば、唯物論 は誤りであることを明らかにすることを目的とした物理主義の定式化を提示した。 [4]。カーク自身はそれ以前に立場を逆転させており[5]、物理主義と意識に関する多くの本や論文でゾンビの考えに対して反論している[6][7] [8][9][10]。 心の哲学における他のトピックに取り組むだけでなく、カークは翻訳と解釈が客観的事実によってどこまで決定されるかという問題について発表している(W. V. クワインの『言葉と対象』(1960年)を参照)。このテーマに関する自著『Translation Determined』[11]は1986年に出版された。もう一つの主な関心は相対主義である[12]。 |

| Types of zombies Though philosophical zombies are widely used in thought experiments, the detailed articulation of the concept is not always the same. P-zombies were introduced primarily to argue against specific types of physicalism such as behaviorism, according to which mental states exist solely as behavior. Belief, desire, thought, consciousness, and so on, are only behavior (whether external behavior or internal behavior) or tendencies towards behaviors. A p-zombie that is behaviorally indistinguishable from a normal human being but lacks conscious experiences is therefore not logically possible according to the behaviorist,[17] so an appeal to the logical possibility of a p-zombie furnishes an argument that behaviorism is false. Proponents of zombie arguments generally accept that p-zombies are not physically possible, while opponents necessarily deny that they are metaphysically or, in some cases, even logically possible. The unifying idea of the zombie is that of a human completely lacking conscious experience. It is possible to distinguish various zombie sub-types used in different thought experiments as follows: - A behavioral zombie that is behaviorally indistinguishable from a human. - A neurological zombie that has a human brain and is generally physiologically indistinguishable from a human.[18] - A soulless zombie that lacks a soul. - An imperfect zombie or imp-zombie that is like a p-zombie but has slightly different behavior than a regular human. They are important in the context of the mind-evolution problem.[19] - A zombie universe that is identical to our world in all physical ways, except no being in that world has qualia. |

ゾンビの種類 哲学的ゾンビは思考実験に広く使われているが、その概念の詳細な表現方法は必ずしも同じではない。P-ゾンビは、主に行動主義のような特定のタイプの物理 主義に反対するために導入された。行動主義によると、精神状態は行動としてのみ存在する。信念、願望、思考、意識などは、行動(外的行動か内的行動かにか かわらず)あるいは行動への傾向でしかない。したがって、行動主義者によれば、行動的には普通の人間と区別がつかないが、意識的な経験を持たないp- zombieは論理的に不可能であり[17]、p-zombieの論理的可能性への訴えは行動主義が誤りであるという論拠を提供するものである。ゾンビ論 の支持者は一般的にp-ゾンビが物理的に不可能であることを受け入れるが、反対者は形而上学的に、あるいは場合によっては論理的にさえ可能であることを否 定する。 ゾンビの統一的なアイデアは、意識的な経験を完全に欠いた人間というものである。さまざまな思考実験に使われるゾンビは、次のように区別することができ る。 - 行動的には人間と見分けがつかない行動的ゾンビ。 - 人間の脳を持ち、一般的に人間と区別がつかない生理学的なゾンビ[18]。 - 魂がないゾンビ - P-ゾンビに似ているが、普通の人間とは少し違う行動をする不完全なゾンビまたはインプ・ゾンビー。これらは、心進化問題の文脈で重要である[19]。 - ゾンビ宇宙は、クオリアを持たないことを除けば、すべての物理的な面で私たちの世界と同じである。 |

| Zombie arguments Zombie arguments often support lines of reasoning that aim to show that zombies are metaphysically possible in order to support some form of dualism – in this case the view that the world includes two kinds of substance (or perhaps two kinds of property): the mental and the physical.[20] In contrast to dualism, in physicalism, material facts determine all other facts. Since any fact other than that of consciousness may be held to be the same for a p-zombie and for a normal conscious human, it follows that physicalism must hold that p-zombies are either not possible or are the same as normal humans. The zombie argument is a version of general modal arguments against physicalism such as that of Saul Kripke.[21][page needed] Further such arguments were notably advanced in the 1970s by Thomas Nagel (1970; 1974) and Robert Kirk (1974) but the general argument was most famously developed in detail by David Chalmers in The Conscious Mind (1996). According to Chalmers one can coherently conceive of an entire zombie world, a world physically indistinguishable from this world but entirely lacking conscious experience. The counterpart of every conscious being in our world would be a p-zombie. Since such a world is conceivable, Chalmers claims, it is metaphysically possible, which is all the argument requires. Chalmers states: "Zombies are probably not naturally possible: they probably cannot exist in our world, with its laws of nature."[22] The outline structure of Chalmers' version of the zombie argument is as follows; 1. According to physicalism, all that exists in our world (including consciousness) is physical. 2. Thus, if physicalism is true, a metaphysically possible world in which all physical facts are the same as those of the actual world must contain everything that exists in our actual world. In particular, conscious experience must exist in such a possible world. 3. Chalmers argues that we can conceive being outside of a world physically indistinguishable from our world but in which there is no consciousness (a zombie world). From this (so Chalmers argues) it follows that such a world is metaphysically possible. Therefore, physicalism is false. (The conclusion follows from 2. and 3. by modus tollens.) 4. The above is a strong formulation of the zombie argument. There are other formulations of the zombies-type argument which follow the same general form. The premises of the general zombies argument are implied by the premises of all the specific zombie arguments. A general zombies argument is in part motivated by potential disagreements between various anti-physicalist views. For example, an anti-physicalist view can consistently assert that p-zombies are metaphysically impossible but that inverted qualia (such as inverted spectra) or absent qualia (partial zombiehood) are metaphysically possible. Premises regarding inverted qualia or partial zombiehood can substitute premises regarding p-zombies to produce variations of the zombie argument. The metaphysical possibility of a physically indistinguishable world with either inverted qualia or partial zombiehood would imply that physical truths do not metaphysically necessitate phenomenal truths. To formulate the general form of the zombies argument, take the sentence 'P' to be true if and only if the conjunct of all microphysical truths of our world obtain, take the sentence 'Q' to be true if some phenomenal truth, that obtains in the actual world, obtains. The general argument goes as follows. 1. It is conceivable that P is true and Q is not true. 2. If it is conceivable that P is true and Q is not true then it is metaphysically possible that P is true and Q not true. 3. If it is metaphysically possible that P is true and Q is not true then physicalism is false. 4. Therefore, physicalism is false.[23] Q can be false in a possible world if any of the following obtains: (1) there exists at least one invert relative to the actual world (2) there is at least one absent quale relative to the actual world (3) all actually conscious beings are p-zombies (all actual qualia are absent qualia). Another way to construe the zombie hypothesis is epistemically – as a problem of causal explanation, rather than as a problem of logical or metaphysical possibility. The "explanatory gap" – also called the "hard problem of consciousness" – is the claim that (to date) no one has provided a convincing causal explanation of how and why we are conscious. It is a manifestation of the very same gap that (to date) no one has provided a convincing causal explanation of how and why we are not zombies.[24] The philosophical zombie argument can also be seen through the counterfeit bill example brought forth by Amy Kind. Amy Kind’s example centers around the idea that you have to imagine a counterfeit 20 dollar bill was made to be exactly like an authentic 20 dollar bill. This is logically possible. And yet the counterfeit bill would not really have the same value. Like the critique against Descartes conceivability argument, are people really logically conceiving of zombies when they say they are? When philosophers claim that zombies are conceivable, they invariably underestimate the task of conception, and end up imagining something that violates their own definition. According to Amy Kind, in her book “Philosophy of Mind: the basics”>, The Zombie Argument can be put in this standard form from a dualist point of view: Zombies, creatures that are microphysically identical to conscious beings but that lack consciousness entirely, are conceivable. If zombies are conceivable then they are possible. Therefore, zombies are possible. If zombies are possible, then consciousness is non-physical. Therefore, consciousness is non-physical.[25] |

ゾンビの議論 ゾンビ論はしばしば、ある種の二元論(この場合、世界は精神と肉体という2種類の物質(あるいは2種類の性質)を含むという見解)を支持するために、ゾン ビが形而上学的に可能であることを示すことを目的とした推論のラインを支持している[20]。 二元論とは対照的に、物理主義では物質的な事実が他のすべての事実を決定している。意識以外のあらゆる事実は、p-ゾンビと普通の意識ある人間にとって同 じであるとすることができるので、物理主義はp-ゾンビはありえないか、普通の人間と同じであるとしなければならないことになる。 21][page needed]このような議論は1970年代にThomas Nagel (1970; 1974) とRobert Kirk (1974) によって進められましたが、一般的な議論はDavid ChalmersがThe Conscious Mind (1996) で詳細に展開したことが最も有名な例です。 チャルマーズによれば、この世界と物理的に区別できないが、意識的な経験がまったくないゾンビの世界というものを首尾よく考えることができる。この世界の すべての意識的存在と対をなすのは、P-ゾンビであろう。このような世界は考えられるので、形而上学的に可能である、とチャルマースは主張する。チャル マースはこう言っている。「ゾンビはおそらく自然にはありえない。自然の法則があるこの世界にはおそらく存在できない」[22] チャルマーズ版のゾンビ論の概略構造は以下の通りである。 1. 物理主義によれば、我々の世界に存在するもの(意識を含む)はすべて物理的である。 2. 物理主義が正しいとすれば、物理的事実がすべて現実の世界と同じである形而上学的に可能な世界には、現実の世界に存在するものがすべて含まれるはずであ る。特に、意識的な経験は、そのような可能な世界に存在するはずである。 3. チャルマースは、私たちの世界と物理的に区別できないが、意識のない世界(ゾンビ世界)の外に存在することを考えることができると主張する。このことから (チャルマースは)、そのような世界は形而上学的に可能であることが導かれる。(結論は、2.と3.からモーダス・トレンスで導かれる)。 4. 上記はゾンビ論証の強い定式化である。ゾンビ型論証の定式化は他にもあり、同じ一般的な形式を踏襲している。一般的なゾンビ論証の前提は、すべての特定の ゾンビ論証の前提によって暗示される。 一般的なゾンビ論は、様々な反物理主義者の見解の間の潜在的な不一致に動機づけられている部分がある。例えば、ある反物理主義者は、p-ゾンビは形而上学 的に不可能だが、反転クオリア(反転スペクトルなど)や欠落クオリア(部分的ゾンビ化)は形而上学的に可能だと一貫して主張することができます。反転クオ リアや部分的ゾンビ性についての前提は、p-ゾンビについての前提の代わりになり、ゾンビ論のバリエーションを生み出すことができる。 物理的に区別できない世界に逆クオリアや部分的なゾンビが存在する形而上学的可能性は、物理的真理が現象的真理を形而上学的に必要としないことを意味する ことになる。 ゾンビ論の一般的な形式を定式化すると、我々の世界のすべての微物理的真理の結合が得られる場合にのみ、文「P」が真であるとし、実際の世界で得られる何 らかの現象的真理が得られる場合に、文「Q」が真であるとする。一般的な論法は次のようになる。 1. Pが真でQが真でないことは考えうる。 2. Pが真でQが真でないことが考えられるなら、Pが真でQが真でないことは形而上学的に可能である。 3. もしPが真でQが真でないことが形而上学的に可能なら、物理主義は偽である。 4. したがって、物理主義は偽である[23]。 Qは次のいずれかが得られる場合、可能世界において偽となりうる:(1)現実世界に対して少なくとも一つの反転が存在する(2)現実世界に対して少なくと も一つの不在クオールが存在する(3)実際に意識を持つ存在はすべてp-ゾンビ(すべての実際のクオリアが不在クオリア)である。 ゾンビ仮説のもう一つの解釈は、認識論的なもので、論理的・形而上学的な可能性の問題ではなく、因果的な説明の問題である。説明のギャップ」(「意識の ハードプロブレム」とも呼ばれる)とは、人間がどのように、そしてなぜ意識を持つのかについて、納得のいく因果的な説明を誰もしていないという主張です。 これは、(現在に至るまで)私たちがどのように、そしてなぜゾンビではないのかということについて、誰も説得力のある因果的な説明をしていないというのと 全く同じギャップの現れである[24]。 哲学的なゾンビの議論はエイミー・カインドによってもたらされた偽札の例を通しても見ることができる。エイミー・カインドの例は、20ドル札の偽札が本物 の20ドル札と全く同じように作られたと想像しなければならないという考えを中心に据えたものである。これは論理的に可能である。しかし、その偽札が本当 に同じ価値を持つとは限らない。デカルトの想起可能性論に対する批判と同じように、人々がゾンビを論理的に想起していると言うとき、本当にそうなのだろう か?哲学者が「ゾンビは想起可能である」と主張するとき、彼らは必ずといっていいほど想起という作業を軽視し、自らの定義に反するものを想起してしまうの です。 エイミー・カインドが著書『心の哲学:基礎編』>で述べているように、『ゾンビ論』は二元論者の立場からすると、このような標準的な形になるのである。 ゾンビは、微物理的には意識ある存在と同じだが、意識を完全に欠いている生物であり、考えうるものである。もしゾンビが考えうるものであるなら、それは可 能である。したがって、ゾンビは可能である。もしゾンビが可能であるなら、意識は非物理的である。したがって、意識は非物理的である[25]。 |

| Responses Galen Strawson argues that it is not possible to establish the conceivability of zombies, so that the argument, lacking its first premise, can never get going.[26] Chalmers has argued that zombies are conceivable, saying "it certainly seems that a coherent situation is described; I can discern no contradiction in the description."[27] Many physicalist philosophers[who?] have argued that this scenario eliminates itself by its description; the basis of a physicalist argument is that the world is defined entirely by physicality; thus, a world that was physically identical would necessarily contain consciousness, as consciousness would necessarily be generated from any set of physical circumstances identical to our own. The zombie argument claims that one can tell by the power of reason that such a "zombie scenario" is metaphysically possible. Chalmers states; "From the conceivability of zombies, proponents of the argument infer their metaphysical possibility"[22] and argues that this inference, while not generally legitimate, is legitimate for phenomenal concepts such as consciousness since we must adhere to "Kripke's insight that for phenomenal concepts, there is no gap between reference-fixers and reference (or between primary and secondary intentions)." That is, for phenomenal concepts, conceivability implies possibility. According to Chalmers, whatever is logically possible is also, in the sense relevant here, metaphysically possible.[28] Another response is the denial of the idea that qualia and related phenomenal notions of the mind are in the first place coherent concepts. Daniel Dennett and others argue that while consciousness and subjective experience exist in some sense, they are not as the zombie argument proponent claims. The experience of pain, for example, is not something that can be stripped off a person's mental life without bringing about any behavioral or physiological differences. Dennett believes that consciousness is a complex series of functions and ideas. If we all can have these experiences the idea of the p-zombie is meaningless. Dennett argues that "when philosophers claim that zombies are conceivable, they invariably underestimate the task of conception (or imagination), and end up imagining something that violates their own definition".[3][4] He coined the term "zimboes" – p-zombies that have second-order beliefs – to argue that the idea of a p-zombie is incoherent;[29] "Zimboes thinkZ they are conscious, thinkZ they have qualia, thinkZ they suffer pains – they are just 'wrong' (according to this lamentable tradition), in ways that neither they nor we could ever discover!".[4] Michael Lynch agrees with Dennett, arguing that the zombie conceivability argument forces us to either question whether or not we actually have consciousness or accept that zombies are not possible. If zombies falsely believe they are conscious, how can we be sure we are not zombies? We may believe we are experiencing conscious mental states when, in fact, we merely hold a false belief. Lynch thinks denying the possibility of zombies is more reasonable than questioning our own consciousness.[30] Furthermore, when concept of self is deemed to correspond to physical reality alone (reductive physicalism), philosophical zombies are denied by definition. When a distinction is made in one's mind between a hypothetical zombie and oneself (assumed not to be a zombie), the hypothetical zombie, being a subset of the concept of oneself, must entail a deficit in observables (cognitive systems), a "seductive error"[4] contradicting the original definition of a zombie. Thomas Metzinger dismisses the argument as no longer relevant to the consciousness community, calling it a weak argument that covertly relies on the difficulty in defining "consciousness", calling it an "ill-defined folk psychological umbrella term". [31] Verificationism[1] states that, for words to have meaning, their use must be open to public verification. Since it is assumed that we can talk about our qualia, the existence of zombies is impossible. Artificial intelligence researcher Marvin Minsky saw the argument as circular. The proposition of the possibility of something physically identical to a human but without subjective experience assumes that the physical characteristics of humans are not what produces those experiences, which is exactly what the argument was claiming to prove.[32] Richard Brown agrees that the zombie argument is circular. To show this, he proposes "zoombies", which are creatures nonphysically identical to people in every way and lacking phenomenal consciousness. If zoombies existed, they would refute dualism because they would show that consciousness is not nonphysical, i.e., is physical. Paralleling the argument from Chalmers: It is conceivable that zoombies exist, so it is possible they exist, so dualism is false. Given the symmetry between the zombie and zoombie arguments, we cannot arbitrate the physicalism/dualism question a priori.[33] Similarly, Gualtiero Piccinini argues that the zombie conceivability argument is circular. Piccinini’s argument questions whether the possible worlds where zombies exist are accessible from our world. If physicalism is true in our world, then physicalism is one of the relevant facts about our world for determining whether a possible zombie world is accessible from our world. Therefore, asking whether zombies are metaphysically possible in our world is equivalent to asking whether physicalism is true in our world. [34] Stephen Yablo's (1998) response is to provide an error theory to account for the intuition that zombies are possible. Notions of what counts as physical and as physically possible change over time so conceptual analysis is not reliable here. Yablo says he is "braced for the information that is going to make zombies inconceivable, even though I have no real idea what form the information is going to take."[35] The zombie argument is difficult to assess because it brings to light fundamental disagreements about the method and scope of philosophy itself and the nature and abilities of conceptual analysis. Proponents of the zombie argument may think that conceptual analysis is a central part of (if not the only part of) philosophy and that it certainly can do a great deal of philosophical work. However, others, such as Dennett, Paul Churchland and W.V.O. Quine, have fundamentally different views. For this reason, discussion of the zombie argument remains vigorous in philosophy. Some accept modal reasoning in general but deny it in the zombie case. Christopher S. Hill and Brian P. Mclaughlin suggest that the zombie thought experiment combines imagination of a "sympathetic" nature (putting oneself in a phenomenal state) and a "perceptual" nature (imagining becoming aware of something in the outside world). Each type of imagination may work on its own, but they're not guaranteed to work when both used at the same time. Hence Chalmers's argument need not go through.[36]: 448 Moreover, while Chalmers defuses criticisms of the view that conceivability can tell us about possibility, he provides no positive defense of the principle. As an analogy, the generalized continuum hypothesis has no known counterexamples, but this does not mean we must accept it. And indeed, the fact that Chalmers concludes we have epiphenomenal mental states that do not cause our physical behavior seems one reason to reject his principle.[36]: 449–51 |

レスポンス(反応) Galen Strawsonはゾンビの想起可能性を確立することは不可能であると主張しており、そのためその第一前提を欠いた議論は決して進行することができない [26]。 チャルマースは「確かに首尾一貫した状況が記述されているようであり、私はその記述に矛盾を見出すことができない」と述べ、ゾンビは考え得るものであると 主張している[27]。 多くの物理主義の哲学者[who?]はこのシナリオがその記述によってそれ自体を排除していると主張している。物理主義の議論の基礎は、世界は完全に物理 性によって定義されるということであり、したがって物理的に同一の世界は、意識が我々のものと同一のあらゆる物理的状況の集合から必然的に発生するため、 意識を含むことになるであろう。 ゾンビ論は、このような「ゾンビ・シナリオ」が形而上学的に可能であることを理性の力で言い当てることができると主張する。チャルマースは「ゾンビの想起 可能性から、この議論の支持者はその形而上学的可能性を推論する」[22]と述べ、この推論は一般的には正当ではないが、意識などの現象的概念については 「現象的概念については、参照修正者と参照(あるいは一次意図と二次意図)の間にギャップはないというクリプキの洞察」に従う必要があるから正当だと論じ ている。 つまり、現象的な概念については、conceivabilityはpossibilityを意味するのである。チャルマースによれば、論理的に可能なもの は、ここでいう意味において、形而上学的に可能でもある[28]。 もう一つの反応は、そもそもクオリアやそれに関連する心の現象的概念が首尾一貫した概念であるという考え方の否定である。ダニエル・デネットなどは、意識 や主観的経験はある意味で存在するが、ゾンビ論提唱者が主張するようなものではないとしている。例えば、痛みの経験は、行動や生理的な違いをもたらすこと なく、人の精神生活を剥奪できるようなものではありません。 デネットは、意識は複雑な機能と観念の積み重ねであると考えている。デネットは「哲学者がゾンビが考えられると主張するとき、彼らは必ず構想 (あるいは想像)のタスクを過小評価しており、結局は彼ら自身の定義に違反するものを想像している」と論じている[3][4]。 [3][4] 彼は「ジンボーズ」(二次的信念を持つp-ゾンビ)という言葉を作り、p-ゾンビの考えが支離滅裂であることを論じている[29] 「ジンボーズは意識があると思い、クオリアを持っていると思い、苦痛を受けると思う-彼らはただ(この嘆かわしい伝統に従って)『間違って』いて、彼らも 我々も発見できない方法で!」 [4] と言っているのだ。 マイケル・リンチはデネットに同意し、ゾンビの想起可能性の議論では、私たちが実際に意識を持っているかどうかを問うか、ゾンビが存在しないことを受け入 れるかのどちらかを迫られると主張している。もしゾンビが自分の意識を偽っているとしたら、私たちがゾンビでないとどうして言い切れるのだろうか。私たち は、意識的な精神状態を経験していると信じているかもしれないが、実際には誤った信念を持っているに過ぎないのである。リンチはゾンビの可能性を否定する ことは、自分自身の意識を疑うことよりも合理的であると考えている[30]。 さらに、自己の概念が物理的な現実だけに対応するとみなされるとき(還元的物理主義)、哲学的なゾンビは定義によって否定される。仮定のゾンビと自分(ゾ ンビではないと仮定)を頭の中で区別するとき、仮定のゾンビは自分という概念の部分集合であるため、観察可能なもの(認知システム)の欠損を伴わなければ ならず、ゾンビの本来の定義と矛盾する「誘惑的な誤り」[4]である。 トーマス・メッツィンガーはこの議論を、「意識」の定義の難しさに隠然と依拠した弱い議論であるとし、「定義が不明確な民間心理学の総称」と呼んで、意識 のコミュニティにはもはや関係ないものとして退けている。[31] 検証主義[1]は、言葉が意味を持つためには、その使われ方が公に検証されうるものでなければならないとしている。私たちがクオリアについて語ることがで きると仮定しているため、ゾンビの存在は不可能である。 人工知能研究者のマービン・ミンスキーは、この議論を循環的なものであると考えた。人間と物理的に同じだが主観的な経験を持たないものの可能性という命題 は、人間の物理的特性がそれらの経験を生み出すものではないことを仮定しており、それはまさにこの議論が証明しようと主張していたものであった[32]。 リチャード・ブラウンはゾンビの議論が循環的であることに同意している。これを示すために、彼は「zoombies」を提案し、それはあらゆる点で人間と 非物理的に同一であり、現象的な意識を持たない生物であるとしている。もしズームズービーが存在すれば、意識は非物理的ではなく、すなわち物理的であるこ とを示すので、二元論に反駁できる。チャルマーズの議論と並行する。ズームビーが存在することは考えられるので、存在する可能性があり、二元論が偽であ る。ゾンビの議論とズームの議論の対称性を考えると、物理主義/二元論の問題を先験的に裁定することはできない[33]。 同様に、Gualtiero Piccininiはゾンビの想起可能性の議論が循環的であることを論じている。ピッチニーニの議論は、ゾンビが存在する可能な世界が我々の世界からアク セス可能であるかどうかを問うている。もし物理主義が我々の世界において真であるならば、物理主義は、可能なゾンビの世界が我々の世界からアクセス可能か どうかを決定するための、我々の世界に関する関連する事実の一つである。したがって、我々の世界でゾンビが形而上学的に可能かどうかを問うことは、我々の 世界で物理主義が真であるかどうかを問うことと等価である。[34] Stephen Yablo (1998)の回答は、ゾンビが可能であるという直観を説明するためのエラー理論を提供することである。何が物理的で、何が物理的に可能であるかという概 念は時代とともに変化するので、概念的な分析はここでは信頼できない。Yabloは「ゾンビを考えられないようにする情報に対して身構えているが、その情 報がどのような形を取るのかについては全く考えていない」と述べている[35]。 ゾンビ論は、哲学の方法と範囲、概念分析の性質と能力に関する根本的な不一致を浮き彫りにするため、評価が困難である。ゾンビ論の支持者は概念分析が哲学 の中心的な部分であり(唯一の部分ではないにしても)、確かに多くの哲学的な仕事をすることができると考えているかもしれない。しかし、デネット、ポー ル・チャーチランド、W.V.O.クワインなど、根本的に異なる見解の持ち主もいる。このため、哲学の世界では、ゾンビ論議は依然として活発な議論が行わ れている。 一般に様相推論を認めながらも、ゾンビの場合は否定する者もいる。クリストファー・S・ヒルとブライアン・P・マクラフリンは、ゾンビの思考実験は「共 感」的な想像(自分を現象的な状態に置くこと)と「知覚」的な想像(外界の何かに気づくことを想像すること)が組み合わされていると提案している。それぞ れのタイプの想像力は単独で機能するかもしれないが、両方が同時に使われたときに機能する保証はない。したがってチャルマーズの議論はスルーする必要がな い[36]。 448 さらに、チャルマーズは、発想力が可能性について語ることができるという見解に対する批判をかわす一方で、この原則に対する積極的な擁護は行っていない。 このような場合、一般化された連続体仮説は反例を持たないが、だからといって、それを受け入れなければならないわけではない。そして実際、チャルマースが 我々の物理的行動を引き起こさない表在的な精神状態を持っていると結論付けていることは、彼の原理を否定する一つの理由になっているようだ[36]。 449-51 |

| Related thought experiments Frank Jackson's Mary's room argument is based around a hypothetical scientist, Mary, who is forced to view the world through a black-and-white television screen in a black and white room. Mary is a brilliant scientist who knows everything about the neurobiology of vision. Even though Mary knows everything about color and its perception (e.g. what combination of wavelengths makes the sky seem blue), she has never seen color. If Mary were released from this room and were to experience color for the first time, would she learn anything new? Jackson initially believed this supported epiphenomenalism (mental phenomena are the effects, but not the causes, of physical phenomena) but later changed his views to physicalism, suggesting that Mary is simply discovering a new way for her brain to represent qualities that exist in the world. Swampman is an imaginary character introduced by Donald Davidson. If Davidson goes hiking in a swamp and is struck and killed by a lightning bolt while nearby another lightning bolt spontaneously rearranges a bunch of molecules so that, entirely by coincidence, they take on exactly the same form that Davidson's body had at the moment of his untimely death then this being, 'Swampman', has a brain structurally identical to that which Davidson had and will thus presumably behave exactly like Davidson. He will return to Davidson's office and write the same essays he would have written, recognize all of his friends and family and so forth.[37] John Searle's Chinese room argument deals with the nature of artificial intelligence: it imagines a room in which a conversation is held by means of written Chinese characters that the subject cannot actually read, but is able to manipulate meaningfully using a set of algorithms. Searle holds that a program cannot give a computer a "mind" or "understanding", regardless of how intelligently it may make it behave. Stevan Harnad argues that Searle's critique is really meant to target functionalism and computationalism, and to establish neuroscience as the only correct way to understand the mind.[38] Physicist Adam Brown has suggested constructing a type of philosophical zombie using counterfactual quantum computation, a technique in which a computer is placed into a superposition of running and not running. If the program being executed is a brain simulation, and if one makes the further assumption that brain simulations are conscious, then the simulation can have the same output as a conscious system, yet not be conscious.[39] |

関連する思考実験 フランク・ジャクソンのメアリーの部屋の議論は、白黒の部屋で白黒のテレビ画面を通して世界を見ることを強いられる仮想の科学者、メアリーを中心に展開さ れる。メアリーは、視覚の神経生物学について何でも知っている優秀な科学者である。メアリーは色とその知覚(例えば、どのような波長の組み合わせで空が青 く見えるか)について何でも知っているにもかかわらず、色を見たことがない。もし、メアリーがこの部屋から解放されて、初めて色を体験したら、何か新しい ことを学べるだろうか?ジャクソンは当初、このことはエピフェノメンタル主義(精神現象は物理現象の原因ではなく結果である)を支持すると考えていたが、 後に物理主義に変更し、メアリーは世界に存在する性質を表現する新しい方法を脳が発見しているだけだと示唆する。 スワンプマンとは、ドナルド・デビッドソンが登場させた想像上の人物である。もしデイヴィッドソンが沼地にハイキングに行き、稲妻に打たれて死んだとした ら、その近くで別の稲妻が自然発生的に分子の束を再編成し、まったくの偶然から、デイヴィッドソンの体が早死にした瞬間に持っていた形とまったく同じに なったとしたら、この存在「スワンプマン」は構造的にデイビッドソンと同じ脳を持っていて、おそらくデイビッドソンのように振る舞うと思われます。彼はデ イヴィッドソンのオフィスに戻り、彼が書いたであろうのと同じエッセイを書き、彼の友人や家族のすべてを認めるなどする[37]。 John SearleのChinese room argumentは人工知能の性質を扱っており、被験者が実際には読むことができないが、一連のアルゴリズムを使って意味のある操作をすることができる書 かれた漢字によって会話が行われる部屋を想像している。サールは、プログラムがコンピュータにいかに知的な振る舞いをさせようとも、コンピュータに「心」 や「理解」を与えることはできないとしている。Stevan Harnadはサールの批判は機能主義と計算主義をターゲットにしたものであり、心を理解するための唯一の正しい方法として神経科学を確立することを意図 していると論じている[38]。 物理学者のアダム・ブラウンは、反実仮想的量子計算(コンピュータが実行されたりされなかったりする重ね合わせの状態に置かれる技術)を用いて、一種の哲 学的ゾンビを構築することを提案している。実行されているプログラムが脳のシミュレーションであり、さらに脳のシミュレーションが意識を持つと仮定すれ ば、シミュレーションは意識を持つシステムと同じ出力を持つことができるが、意識を持つことはできない[39]。 |

| Begging the question Blindsight Causality Chinese Room Consciousness Dual-aspect theory Explanatory gap Functionalism (philosophy of mind) Hard problem of consciousness Inverted spectrum Map–territory relation Mind Mind-body problem Neutral monism NPC (meme) No true Scotsman Philosophy of mind Problem of other minds Quantum Night Reverse engineering Sentience Ship of Theseus Solipsism Turing test Zombie Blues |

論点先取 ブラインドサイト 因果関係 中国人の部屋 意識 デュアルアスペクト理論 説明のギャップ 機能主義(心の哲学) 意識の難問 逆スペクトル 地図と領域の関係 心 心身問題 中立的一元論 NPC(ミーム) 真のスコットランド人なし 心の哲学 他の心の問題 量子ナイト リバース・エンジニアリング 感覚 テセウスの船 独我論 チューリングテスト ゾンビ・ブルース |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophical_zombie |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| レトリッ

クとしてのゾンビ論法(→ウィキペディア「哲学的ゾンビ」より) ゾンビ論法(zombie argument)または想像可能性論法(Conceivability Argument)とは物理主義を批判する以下の形式の論証を指す。[1] 1. 我々の世界には意識体験がある。 2. 物理的には我々の世界と同一でありながら、我々の世界の意識に関する肯定的な事実が成り立たない、論理的に可能な世界が存在する。 3. したがって意識に関する事実は、物理的事実とはまた別の、われわれの世界に関する更なる事実である。 4. ゆえに唯物論は偽である。 各段階について説明すると 1.我々の世界には意識体験がある。「意識」「クオリア」「経験」「感覚」など様々な名前で呼ばれるものが、「ある」という主張である。ここは基本的に素 朴な主張である。 2.物理的には我々の世界と同一でありながら、我々の世界の意識に関する肯定的な事実が成り立たない、論理的に可能な世界が存在する。現在の物理学では、 意識・クオリア・経験・感覚を全く欠いた世界が想像可能であることを主張する。この哲学的ゾンビだけがいる世界を、ゾンビワールドと言う。 3.したがって意識に関する事実は、物理的事実とはまた別の、われわれの世界に関する更なる事実である。ゾンビワールドに欠けているが、私達の現実世界に は、意識・クオリア・経験・感覚が備わっているという事実がある。それは、現在の物理法則には含まれていない。 4.ゆえに唯物論は偽である。 以上の点から現在の物理法則・物理量ですべての説明ができるという考えは間違っている。 |

マービン・ミンスキーは、この論法 を循環論法であると主張する。また、文化人類学を学んだ猿でもわかるように、ゾンビ論法の議論は、文化相対主義のジレンマと同じである。ゾンビ論法が唯物 論を否定するように、文化相対主義も、人間のもつ共通の土台である普遍認識をなかなか承認しようにない。現在の物理法則・物理量ですべて説明したい「願 望」とが説明ができるという論証前の「見込み」と説明ができたという「確信」の間にはそれぞれ、齟齬があることは確かだ。これらは論理的誤謬というより も、感情的に虫のいどころが悪いことを拒絶する擬似神学——神学は仮想議論なので擬似であるので擬似神学は冗長語法である——と似ている。 |

| クリプキの様相論法とは?

1970年代、哲学者ソール・クリプキが様相(modality)の概念を用いて行った様相論法(modal argument)と呼ばれる論証がある。 この議論は直感的というよりかなり技巧的なものだが、可能世界論の枠組みの中で、固定指示詞(rigid designator)間の同一性言明は必然的なものでなければならない、という前提にたった上で、神経現象と痛みに代表されるような私たちの持つ心的な 感覚との間の同一性言明(いわゆる同一説)を批判した。 この論証はクリプキの講義録『名指しと必然性』で詳細に論じられている。クリプキは、同書の最終章で論証の結果を以下のような寓話的なストーリで表現して いる[4][5]。 ここからはクリプキの言である→「神様が世界を作ったとする。神様は、この世界にどういう種類の粒子が存在し、かつそれらが互いにどう相互作用するか、そ うした事をすべて定め終わったとする」。 「さて、これで神様の仕事は終わりだろうか?いや、そうではない。神様にはまだやるべき仕事が残されている。神様はある状態にある感覚が伴うよう定める仕 事をしなければならない」。 |

|

| 『名指しと必然性』(Naming and

Necessity)は、1972年の哲学者ソール・クリプキの著作である。 1940年に生まれたクリプキは、1970年からプリンストン大学で指示理論に関する指示の因果説を提唱する講義を行った。この著作は、1970年1月 20日、22日、29日の講義の内容をまとめたものである。固有名はどのように世界の事物を指示するのか、同一性の本質とは何かという分析哲学の問題に関 する研究業績であり、クリプキの代表的な著作でもある。 1960年代までは、バートランド・ラッセルが提唱してゴットロープ・フレーゲにより発展された記述理論の研究により、固有名と確定記述を同義として見な していた。 この著作でのクリプキの研究の目的は、そのような見方に対する批判である。クリプキは、XとYが同一であるならばXがYであることは必然であると考えて、 同一性の必然性を出発点とした。そして、固有名と確定記述が同義ではないことを考察する。アリストテレスという固有名を考えてみると、同一性の必然性から アリストテレスはアレキサンダー大王の教師であるという確定記述は真であるとは限らないが、アリストテレスがアリストテレスであることは必然的に真であ る。 したがって、アリストテレスという固有名とアリストテレスがアレキサンダー大王の教師であるという確定記述は同義ではありえない。なぜならば、アリストテ レスという固有名には固定指示子(rigid designator)がある一方で、確定記述はアレクサンドロス大王の教師であったアリストテレスではない人物を指示することが可能であるためである。 この固有名と確定記述の関係は自然科学の命題にもあてはまり、例えば金という固有名と原子番号79番の元素という確定記述とは、前者の固定性が権利上のも のであるが、後者の固定性が事実上のものであるために同義ではないと指摘される。 |

|

| Bibliography Alter, T., 2007, ‘On the Conditional Analysis of Phenomenal Concepts’, Philosophical Studies, 134: 235–53. Aranyosi, I., 2010, ‘Powers and the Mind-Body Problem’, International Journal of Philosophy, 18: 57–72. Ball, D., 2009, ‘There Are No Phenomenal Concepts’, Mind, 122: 935–62. Balog, K., 1999, ‘Conceivability, Possibility, and the Mind-Body Problem’, Philosophical Review, 108: 497–528. –––, 2012, ‘In Defense of the Phenomenal Concept Strategy‘, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 84: 1–23. Block, N., 1980a, ‘Troubles with Functionalism’, in Readings in the Philosophy of Psychology, Volume 1, Ned Block (ed.), Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 268–305. –––, 1980b, ‘Are Absent Qualia Impossible?’ Philosophical Review, 89: 257–274. –––, 1981, ‘Psychologism and Behaviorism’, Philosophical Review, 90: 5–43. –––, 1995, ‘On a Confusion about a Function of Consciousness’, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 18: 227–247. –––, 2002, ‘The Harder Problem of Consciousness’, Journal of Philosophy, 99: 391–425. –––, O. Flanagan and G. Güzeldere (eds.), 1997, The Nature of Consciousness: Philosophical Debates, Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press. ––– and R. Stalnaker, 1999, ‘Conceptual Analysis, Dualism, and the Explanatory Gap’, Philosophical Review, 108: 1–46. Braddon-Mitchell, D., 2003, ‘Qualia and Analytical Conditionals’, Journal of Philosophy, 100: 111–135. Brown, R., 2010, ‘Deprioritizing the A Priori Arguments Against Physicalism’, Journal of Consciousness Studies, 17 (3–4): 47–69. Brueckner, A., 2001. ‘Chalmers’s Conceivability Argument for Dualism’, Analysis, 61: 187–193. Campbell, K., 1970, Body and Mind, London: Macmillan. Campbell, D., J. Copeland and Z-R Deng 2017. ‘The Inconceivable Popularity of Conceivability Arguments’, The Philosophical Quarterly, 67: 223—240. Carruth, A., 2016, ‘Powerful qualities, zombies and inconceivability’, The Philosophical Quarterly, 66: 25—46. Carruthers, P., 2005, Consciousness: Essays from a Higher-Order Perspective, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Chalmers, D. J., 1996, The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory, New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. –––, 1999, ‘Materialism and the Metaphysics of Modality’, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 59: 475–496. –––, 2002, ‘Does Conceivability Entail Possibility?’, in Gendler and Hawthorne 2002. –––, 2003, ‘The Content and Epistemology of Phenomenal Belief’, in Q. Smith and A. Jokic (eds.), Consciousness: New Philosophical Perspectives, Oxford: Oxford University Press. –––, 2007, ‘Phenomenal Concepts and the Explanatory Gap’, in T. Alter and S. Walter (eds.), Phenomenal Concepts and Phenomenal Knowledge, New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 167–94. –––, 2010, ‘The Two-Dimensional Argument against Materialism’, in his The Character of Consciousness, New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. ––– and F. Jackson, 2001, ‘Conceptual Analysis and Reductive Explanation’, Philosophical Review, 110: 315–61. Cottrell, A., 1999, ‘Sniffing the Camembert: on the Conceivability of Zombies’, Journal of Consciousness Studies, 6: 4–12. Crane, T., 2005, ‘Papineau on Phenomenal Consciousness’, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 71: 155–62 . Cutter, B, 2020, ‘The Modal Argument Improved’, Analysis, 80: 629–639. Dennett, D. C., 1991, Consciousness Explained, Boston, Toronto, London: Little, Brown. –––, 1995, ‘The Unimagined Preposterousness of Zombies’, Journal of Consciousness Studies, 2: 322–6. –––, 1999, ‘The Zombic Hunch: Extinction of an Intuition?’ Royal Institute of Philosophy Millennial Lecture. Descartes, R., Discourse on the Method; The Objections and Replies, in The Philosophical Writings Of Descartes, 3 vols., translated by J. Cottingham, R. Stoothoff, and D. Murdoch (volume 3, including A. Kenny), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. Flanagan, O., and T. Polger, 1995, ‘Zombies and the Function of Consciousness’, Journal of Consciousness Studies, 2: 313–321. Frankish, K., 2007, ‘The Anti-Zombie Argument’, Philosophical Quarterly, 57: 650–666 . Garrett, B. J., 2009, ‘Causal Essentialism versus the Zombie Worlds’, Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 39: 93–112 . Gendler, T., and J. Hawthorne (eds.), 2002, Conceivability and Possibility, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Goff, P., 2010, ‘Ghosts and Sparse Properties: Why Physicalists Have More to Fear from Ghosts than Zombies’, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 81: 119–37. –––, 2017, Consciousness and Fundamental Reality, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Harnad, S., 1995, ‘Why and How We Are Not Zombies’, Journal of Consciousness Studies, 1: 164–167. Hawthorne, J. P., 2002a, ‘Advice to Physicalists’, Philosophical Studies, 108: 17–52. –––, 2002b. ‘Blocking Definitions of Materialism’, Philosophical Studies, 110: 103–13. Hill, C. S., 1997, ‘Imaginability, Conceivability, Possibility and the Mind-Body Problem’, Philosophical Studies, 87: 61–85. Hill, C. S., and B. P. McLaughlin, 1999, ‘There are Fewer Things in Reality Than Are Dreamt of in Chalmers’s Philosophy’, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 59: 446–454. Howell, R. J., 2013, Consciousness and the Limits of Objectivity: the Case for Subjective Physicalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Jackson, F., 1982, ‘Epiphenomenal Qualia’, Philosophical Quarterly, 32: 127–136. Jackson, F., 1998, From Metaphysics to Ethics, New York: Oxford University Press. James, W., 1890, The Principles of Psychology, New York: Dover (originally published by Holt). Kirk, R., 1974a, ‘Sentience and Behaviour’, Mind, 83: 43–60. –––, 1974b, ‘Zombies v. Materialists’, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 48 (Supplementary): 135–152. –––, 2005, Zombies and Consciousness, Oxford: Clarendon Press. –––, 2008, ‘The Inconceivability of Zombies’, Philosophical Studies, 139: 73–89. –––, 2013, The Conceptual Link from Physical to Mental, Oxford: Oxford University Press. –––, 2017, Robots, Zombies and Us: Understanding Consciousness, London: Bloomsbury. Kriegel, U., 2011, Subjective Consciousness: a self-representational theory, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Kripke, S., 1972/80, Naming and Necessity, Oxford: Blackwell. (Revised and enlarged version of ‘Naming and Necessity’, in Semantics of Natural Language, D. Davidson and G. Harman (eds.), Dordrecht: D. Reidel, 253–355. Latham, Noa, 2000, ‘Chalmers on the Addition of Consciousness to the Physical World’, Philosophical Studies, 98: 71–97. Leuenberger, S., 2008, ‘Ceteris Absentibus Physicalism’, Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, Volume 4, D. Zimmerman (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 145–170. Levine, J., 2001, Purple Haze: The Puzzle of Consciousness, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Loar, B., 1990/1997, ‘Phenomenal States’, in Philosophical Perspectives, Volume 4, J. Tomberlin (ed.), Atascadero: Ridgeview. Revised version repr. in Block, et al. 1997, 597–616. –––, 1999, ‘David Chalmers’s The Conscious Mind’, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 59: 465–472. Lyons, J. C., 2009, Perception and Basic Beliefs: Zombies, Modules and the Problem of the External World, New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. McLaughlin, B. P., 2005, ‘A Priori versus A Posteriori Physicalism’, in Philosophy-Science-Scientific Philosophy, Main Lectures and Colloquia of GAP 5, Fifth International Congress of the Society for Analytical Philosophy (C. Nimtz & A. Beckermann eds.), Mentis. Marcus, E., 2004, ‘Why Zombies are Inconceivable’, Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 82: 477–90. Marton, P., 1998, ‘Zombies vs. materialists: The battle for conceivability’, Southwest Philosophy Review, 14: 131–38. Nagel, T., 1970, ‘Armstrong on the Mind’, Philosophical Review, 79: 394–403. –––, 1974, ‘What is it Like to Be a Bat?’ Philosophical Review, 83: 435–450, reprinted in his Mortal Questions, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979. –––, 1998, ‘Conceiving the Impossible and the Mind-Body Problem’, Philosophy, 73: 337-352. Papineau, D., 2002, Thinking about Consciousness, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Pelczar, M., 2021, ‘Modal arguments against materialism‘, Noûs, 55: 426–444. Pereboom, D., 2011, Consciousness and the Prospects of Physicalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Piccinini, G., 2017, ‘Access Denied to Zombies,’ Topoi, 36: 81–93. Russell, B., 1927, The Analysis of Matter, London: Routledge. Searle, J. R., 1992, The Rediscovery of the Mind, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Sebastián, Miguel Ángel, 2017, ‘On a Confusion About Which Intuitions to Trust: From the Hard Problem to a Not Easy One’, Topoi, 36: 31–40. Shoemaker, S., 1975, ‘Functionalism and Qualia’, Philosophical Studies, 27: 291–315. –––, 1999, ‘On David Chalmers’s The Conscious Mind,’ Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 59: 439–444. Stalnaker, R., 2002, ‘What is it Like to Be a Zombie?’, in Gendler and Hawthorne 2002. Stoljar, D., 2000, ‘Physicalism and the Necessary a Posteriori’, Journal of Philosophy, 97: 33–54. –––, 2001, ‘The Conceivability Argument and Two Conceptions of the Physical’, in Philosophical Perspectives, Volume 15, James E. Tomberlin (ed.), Oxford: Blackwell, 393–413. –––, 2005, ‘Physicalism and Phenomenal Concepts’, Mind and Language, 20: 469–94. –––, 2006, Ignorance and Imagination: The Epistemic Origin of the Problem of Consciousness, Oxford: Oxford University Press. –––, 2020, ‘The Epistemic Approach to the Problem of Consciousness’, in Uriah Kriegel (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Philosophy of Consciousness, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Stout, G. F., 1931, Mind and Matter, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Strawson, G., 2008, Real Materialism: and Other Essays, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Sturgeon, S., 2000, Matters of Mind: Consciousness, reason and nature, London and New York: Routledge. Taylor, Henry, 2017, ‘Powerful qualities, the conceivability argument and the nature of the physical’, Philosophical Studies, 174: 1895–1910. Thomas, N. J. T., 1998, ‘Zombie Killer’, in S. R. Hameroff, A. W. Kaszniak, and A. C. Scott (eds.), Toward a Science of Consciousness II: The Second Tucson Discussions and Debates. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 171–177. Tye, M., 2006. ‘Absent Qualia and the Mind-Body Problem’, Philosophical Review, 115: 139–68. –––, 2008, Consciousness Revisited: Materialism without Phenomenal Concepts, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Webster, W. R., 2006, ‘Human Zombies are Metaphysically Impossible’, Synthese, 151: 297–310. Yablo, S., 1993, ‘Is conceivability a guide to possibility?’, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 53: 1–42. –––, 1999, ‘Concepts and Consciousness’, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 59: 455–463. Zhong, L., 2021, ‘Physicalism without supervenience’, Philosophical Studies, 178: 1529–1544. |

参考文献 アルター、T.、2007年、「現象的概念の条件分析について」、『哲学研究』、134: 235–53。 アラニョシ、I.、2010年、「力と心身問題」、『国際哲学ジャーナル』、18: 57–72。 ボール、D.、2009年、「現象的概念は存在しない」、Mind、122: 935–62。 バログ、K.、1999年、「想像可能性、可能性、そして心身問題」、Philosophical Review、108: 497–528。 ―――、2012、『現象的概念戦略の擁護』哲学と現象学研究、84: 1–23。 ブロック、N.、1980a、『機能主義の諸問題』心理学哲学の研究論文集第1巻、ネッド・ブロック編、ケンブリッジ、MA: ハーバード大学出版、268–305。 ―――、1980b、「不在のクオリアはありえないか?」Philosophical Review、89: 257–274。 ―――、1981、「心理主義と行動主義」Philosophical Review、90: 5–43。 ―――、1995年、「意識の機能に関する混乱について」、Behavioral and Brain Sciences、18: 227–247。 ―――、2002年、「意識のより困難な問題」、Journal of Philosophy、99: 391–425。 ―――、O. Flanagan、G. Güzeldere(編)、1997、『意識の本質:哲学的論争』、マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジおよびロンドン:MIT Press。 ―――、R. Stalnaker、1999、『「概念分析、二元論、そして説明のギャップ」』、『Philosophical Review』、108: 1–46。 Braddon-Mitchell, D., 2003, ‘Qualia and Analytical Conditionals’, Journal of Philosophy, 100: 111–135. Brown, R., 2010, ‘Deprioritizing the A Priori Arguments Against Physicalism’, Journal of Consciousness Studies, 17 (3–4): 47–69. Brueckner, A., 2001. ‘Chalmers’s Conceivability Argument for Dualism’, Analysis, 61: 187–193. Campbell, K., 1970, Body and Mind, London: Macmillan. キャンベル、D.、J. コープランド、Z-R デン 2017. 「想像可能性の議論の想像を絶する人気」『哲学評論』67: 223—240. キャルス、A. 2016. 「強力な性質、ゾンビ、そして想像不可能性」『哲学評論』66: 25—46. Carruthers, P., 2005, Consciousness: Essays from a Higher-Order Perspective, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Chalmers, D. J., 1996, The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory, New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. ―――、1999年、「唯物論と様相の形而上学」、『哲学・現象学研究』、59: 475–496。 –––, 2002, 「想定可能性は可能性を必然とするか?」Gendler and Hawthorne 2002 所収。 –––, 2003, 「現象的信念の内容と認識論」Q. Smith and A. Jokic (eds.), Consciousness: New Philosophical Perspectives, Oxford: Oxford University Press 所収。 2007年、「現象的概念と説明のギャップ」T. アルターとS. ウォルター(編)『現象的概念と現象的知識』ニューヨークおよびオックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版、167-194ページ。 2010年、「唯物論に対する二次元論」『意識の本質』ニューヨークおよびオックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版。 ―――と F. Jackson、2001、『概念分析と還元論的説明』、Philosophical Review、110: 315–61。 Cottrell, A.、1999、『カマンベールチーズの匂いを嗅ぐ:ゾンビの想像可能性について』、Journal of Consciousness Studies、6: 4–12。 クレーン、T、2005、『パピノーの現象的意識について』哲学と現象学研究、71: 155–62. カッター、B、2020、『様相論証の改善』分析、80: 629–639. デネット、D. C.、1991、『意識の説明』、ボストン、トロント、ロンドン:リトル・ブラウン。 ―――、1995、『「ゾンビ」の想像を絶する馬鹿らしさ』、『意識研究ジャーナル』、2: 322–6。 ―――、1999年、「ゾンビ的直感:直感の消滅?」ロイヤル・インスティテュート・オブ・フィロソフィー・ミレニアム・レクチャー。 デカルト、R.、『方法序説;異議と反論』、J. コットン、R. ストトフ、D. マードック(第3巻、A. ケニーを含む)訳、『デカルトの哲学著作』全3巻、ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1988年。ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1988年。 Flanagan, O., and T. Polger, 1995, ‘Zombies and the Function of Consciousness’, Journal of Consciousness Studies, 2: 313–321. Frankish, K., 2007, ‘The Anti-Zombie Argument’, Philosophical Quarterly, 57: 650–666 . Garrett, B. J., 2009, ‘Causal Essentialism versus the Zombie Worlds’, Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 39: 93–112 . Gendler, T., and J. Hawthorne (eds.), 2002, Conceivability and Possibility, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Goff, P., 2010, ‘Ghosts and Sparse Properties: Why Physicalists Have More to Fear from Ghosts than Zombies’, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 81: 119–37. –––, 2017, Consciousness and Fundamental Reality, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Harnad, S., 1995, ‘Why and How We Are Not Zombies’, Journal of Consciousness Studies, 1: 164–167. Hawthorne, J. P., 2002a, ‘Advice to Physicalists’, Philosophical Studies, 108: 17–52. ―――、2002b. 「唯物論の定義の阻止」、Philosophical Studies、110: 103–13. Hill, C. S., 1997, 「想像可能性、想定可能性、可能性と心身問題」、Philosophical Studies、87: 61–85. Hill, C. S., and B. P. McLaughlin, 1999, ‘There are Fewer Things in Reality Than Are Dreamt of in Chalmers’s Philosophy’, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 59: 446–454. Howell, R. J., 2013, Consciousness and the Limits of Objectivity: the Case for Subjective Physicalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ジャクソン、F.、1982年、「付随現象としてのクオリア」、『哲学評論』、32: 127–136。 ジャクソン、F.、1998年、『形而上学から倫理学へ』、ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。 ジェームズ、W.、1890年、『心理学原理』、ニューヨーク:ドーヴァー(初版はホルト社より刊行)。 カーク、R.、1974a、「感覚と行動」、Mind、83: 43–60。 ――――、1974b、「ゾンビ対唯物論者」、Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society、48(補遺):135–152。 ――――、2005、『ゾンビと意識』、オックスフォード:Clarendon Press。 ―――、2008、『ゾンビの非可思議性』、Philosophical Studies、139: 73–89。 ―――、2013、『物理から精神への概念的つながり』、オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版。 ―――、2017、『ロボット、ゾンビ、そして私たち:意識を理解する』、ロンドン:ブルームズベリー。 Kriegel, U., 2011, Subjective Consciousness: a self-representational theory, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Kripke, S., 1972/80, Naming and Necessity, Oxford: Blackwell. (Revised and enlarged version of ‘Naming and Necessity’, in Semantics of Natural Language, D. Davidson and G. Harman (eds.), Dordrecht: D. Reidel, 253–355. Latham, Noa, 2000, ‘Chalmers on the Addition of Consciousness to the Physical World’, Philosophical Studies, 98: 71–97. Leuenberger, S., 2008, ‘Ceteris Absentibus Physicalism’, Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, Volume 4, D. Zimmerman (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 145–170. Levine, J., 2001, Purple Haze: The Puzzle of Consciousness, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Loar, B., 1990/1997, 「現象状態」、『哲学的視点』第4巻、J. Tomberlin(編)、アタスカデロ:Ridgeview。改訂版はBlock, et al. 1997, 597–616に再録。 ―――、1999年、「デイヴィッド・チャーマーズ著『意識の心』」、『哲学と現象学研究』59: 465–472。 ライオンズ、J. C.、2009年、『知覚と基本信念:ゾンビ、モジュール、外界の問題』、ニューヨークおよびオックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。 マクローリン、B. P.、2005年、「ア・プリオリな物理主義とア・ポステリオリな物理主義」、『哲学・科学・科学的哲学:GAP 5の主要講義およびコロキアム、分析哲学学会第5回国際会議』(C. ニムツ&A. ベッケルマン編)、メンティス。 マーカス、E.、2004年、「なぜゾンビは考えられないのか」、『オーストラレーシア哲学ジャーナル』、82: 477–90。 マートン、P.、1998年、「ゾンビ対唯物論者:考えられるかどうかをめぐる戦い」、『南西部哲学レビュー』、14: 131–38。 ネーゲル、T.、1970年、『アームストロングの心について』Philosophical Review、79: 394–403。 ―――、1974年、「コウモリになるとはどういうことか?」Philosophical Review、83: 435–450、Mortal Questions(ケンブリッジ大学出版、1979年)に再録。 ―――、1998年、「不可能の想像と心身問題」Philosophy、73: 337-352。 パピノー、D.、2002、『意識について考える』、オックスフォード:Clarendon Press。 ペルツァー、M.、2021、『唯物論に対する様相論的論拠』、Noûs、55: 426–444。 ペレブーム、D.、2011、『意識と物理主義の展望』、オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。 Piccinini, G., 2017, ‘Access Denied to Zombies,’ Topoi, 36: 81–93. Russell, B., 1927, The Analysis of Matter, London: Routledge. Searle, J. R., 1992, The Rediscovery of the Mind, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Sebastián, Miguel Ángel, 2017, ‘On a Confusion About Which Intuitions to Trust: From the Hard Problem to a Not Easy One’, Topoi, 36: 31–40. Shoemaker, S., 1975, ‘Functionalism and Qualia’, Philosophical Studies, 27: 291–315. ―――、1999年、「デビッド・チャーマーズ著『意識の心』について」、『哲学と現象学研究』、59: 439–444。 スタルネイカー、R、2002年、「ゾンビであるとはどういうことか?」、ジェンドラーとホーソン編、2002年。 Stoljar, D., 2000, ‘Physicalism and the Necessary a Posteriori’, Journal of Philosophy, 97: 33–54. –––, 2001, ‘The Conceivability Argument and Two Conceptions of the Physical’, in Philosophical Perspectives, Volume 15, James E. Tomberlin (ed.), Oxford: Blackwell, 393–413. 2005年、「物理主義と現象的概念」『Mind and Language』20: 469–94。 2006年、『無知と想像力:意識の問題の認識論的起源』オックスフォード大学出版局。 ――――、2020年、『意識の問題に対する認識論的アプローチ』、ユリア・クリーゲル編、『オックスフォード・ハンドブック・オブ・ザ・フィロソフィー・オブ・コンシャスネス』、オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。 スタウト、G. F.、1931年、『マインド・アンド・マター』、ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 ストローソン、G.、2008年、『リアル・マテリアリズム:アンド・アザー・エッセイ』、オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。 スタージョン、S.、2000、『Matters of Mind: Consciousness, reason and nature』(『心の諸問題:意識、理性、自然』)、ロンドンおよびニューヨーク:Routledge。 テイラー、ヘンリー、2017、『「強力な性質、想像可能性の議論、および物理の本質」』、『Philosophical Studies』、174: 1895–1910。 Thomas, N. J. T., 1998, ‘Zombie Killer’, in S. R. Hameroff, A. W. Kaszniak, and A. C. Scott (eds.), Toward a Science of Consciousness II: The Second Tucson Discussions and Debates. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 171–177. Tye, M., 2006. 『不在のクオリアと心身問題』Philosophical Review, 115: 139–68. –––, 2008, 『意識の再考:現象的概念なき唯物論』マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:MIT Press. ウェブスター、W. R.、2006年、「人間ゾンビは形而上学的に不可能である」、『シンセーゼ』、151: 297–310。 ヤブロ、S.、1993年、「想像可能性は可能性の指針となるか?」、『哲学と現象学研究』、53: 1–42。 ―――、1999年、「概念と意識」、哲学と現象学研究、59: 455–463。 Zhong, L., 2021, ‘Physicalism without supervenience’, Philosophical Studies, 178: 1529–1544. |

| https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/zombies/ |

スタンフォード哲学事典「ゾンビ」の解説は 哲学的ゾンビ 2.0 で解説. |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆