存在論

Ontology

存 在論(オントロジー, ontology)とは、存在自体のことを考えること、あるいは、在るとはどういうことかについて研究する学問。通常、哲学の一分野とみなされている。(→それ以外の「オントロジーについてはこちら」)

ス タンフォード哲学エンサイクロペディアの「存在論 的コミットメント」の冒頭部分には、オントロジーにこんな解説がある。

Ontology, as etymology suggests, is the study of being, of what there is. The ontologist asks: What entities or kinds of entity exist? Are there abstract entities, such as sets or numbers, in addition to concrete entities, such as people and puddles and protons? Are there properties or universals in addition to (or instead of) the particular entities that, as we say, instantiate them? Questions such as these have divided philosophers down the ages, and divide them no less to this day. - Ontological Commitment, by Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

存

在論とは、語源が示すように、「存在すること」、「存在するもの」について研究する学問である。存在論者は問う:

どのような実体や種類の実体が存在するのか?人や水たまりや陽子といった具体的な実体のほかに、集合や数といった抽象的な実体は存在するのか。また、それ

らをインスタンス[=審級つまり審問のレベルを階層]化する特定の実体のほかに(あるいは代わりに)、性質や普遍は存在するのか。このような疑問は、時代を超えて哲学者たちを分断してきた。

「存 在論的問題」は、つぎのような問いの形をとる。 「わたしたちの住んでいるこの世界は、この場所に存在しないことも想像しうるだろうに、いったいどうしてここに存在するようになったのだろうか」 (p.285)——ウィリアム・ジェイムズ「哲学の根本問題」

ショー ペンハウエルによると、人々が形而上学を希求 する原動力は、自分の存在に対する「不安」にもとづくものであるという。その不安は、世界は括弧として存在するか否かという疑問よりも、この世界は存在す るよりも——そのような確信をもっていること事態が不思議ではあるがそれは不問にして——「存在しないほうがましなのではないか」という考えを生みだす (『意志と表象としての世界』補説17章「人間の形而上学的要求」)。

「存 在一般もしくはある形の存在はつねに存在してい たわけであるから、存在の総体を原初の非存在とうまく関係づけることはできない。存在一般は、神としてであれ、物質的原子としてであれ、それ自体、最初の ものであってしかも永遠なものである」(ジェイムズ p.286)——ただし、このような問題に取り組むと、始点より前にある無(=非存在)を想定せざるを、そのような無がなぜ存在に転化したのかという、無 限後退に陥ってしまう。

パ ルメニデスとゼノン:「非存在者は存在せず、存在 者のみが存在するから、存宿するものは必然的に存在者であり、存在者は必然的に存症する」(ジェイムズ 1968:287)

「存在はそれ自体時間的 zeitlich である。それは『テサロニケ前書』における受肉とキリストの再来の時間における特殊性と同じである」(スタイナー 1980:111)

よ り積極的には、存在論的な問いは、一切病的な問い かけだという主張もある(→「 20世紀の〈形而上学〉栄枯盛衰」)。

| Ontology Ontology is the philosophical study of being. It is traditionally understood as the subdiscipline of metaphysics focused on the most general features of reality. As one of the most fundamental concepts, being encompasses all of reality and every entity within it. To articulate the basic structure of being, ontology examines what all things have in common. It also investigates how they can be grouped into basic types, such as the categories of particulars and universals. Particulars are unique, non-repeatable entities, like the person Socrates. Universals are general, repeatable entities, like the color green. Another contrast is between concrete objects existing in space and time, like a tree, and abstract objects existing outside space and time, like the number 7. Systems of categories aim to provide a comprehensive inventory of reality, employing categories such as substance, property, relation, state of affairs, and event. Ontologists disagree about which entities exist on the most basic level. Platonic realism asserts that universals have objective existence. Conceptualism says that universals only exist in the mind while nominalism denies their existence. There are similar disputes about mathematical objects, unobservable objects assumed by scientific theories, and moral facts. Materialism says that, fundamentally, there is only matter while dualism asserts that mind and matter are independent principles. According to some ontologists, there are no objective answers to ontological questions but only perspectives shaped by different linguistic practices. Ontology uses diverse methods of inquiry. They include the analysis of concepts and experience, the use of intuitions and thought experiments, and the integration of findings from natural science. Formal ontology is the branch of ontology investigating the most abstract features of objects. Applied ontology employs ontological theories and principles to study entities belonging to a specific area. For example, social ontology examines basic concepts used in the social sciences. Applied ontology is of particular relevance to information and computer science, which develop conceptual frameworks of limited domains. These frameworks are used to store information in a structured way, such as a college database tracking academic activities. Ontology is relevant to the fields of logic, theology, and anthropology. The origins of ontology lie in the ancient period with speculations about the nature of being and the source of the universe, including ancient Indian, Chinese, and Greek philosophy. In the modern period, philosophers conceived ontology as a distinct academic discipline and coined its name. |

存

在論=オントロジー 存 在論とは、存在についての哲学的研究である。伝統的には、現実の最も一般的な特徴に焦点を当てた形而上学の下位分野として理解されている。最も基本的な概 念のひとつとして、存在とは現実のすべてとその中のあらゆる実体を包含する。存在の基本構造を明確にするために、存在論はすべてのものに共通するものを調 べる。また、特殊と普遍のカテゴリーなど、基本的なタイプにどのようにグループ分けできるかを検討する。特殊とは、ソクラテスという人物のように、ユニー クで反復不可能な存在である。普遍とは、一般的で反復可能な実体のことで、緑という色のようなものである。もう一つの対比は、木のように空間と時間に存在 する具体的なオブジェクトと、数字の7のように空間と時間の外に存在する抽象的なオブジェクトの間である。カテゴリーの体系は、実体、性質、関係、状態、 出来事といったカテゴリーを用い、現実の包括的な目録を提供することを目的としている。 存在論者は、どのような実体が最も基本的なレベルで存在するかについて意見が分かれる。プラトン的実在論は、普遍的なものは客観的な存在を持っていると主 張する。概念主義は、普遍的なものは心の中にしか存在しないとし、名辞主義はその存在を否定する。数学的対象、科学理論が想定する観察不可能な対象、道徳 的事実についても同様の論争がある。唯物論は、基本的には物質しか存在しないとし、二元論は心と物質は独立した原理であると主張する。一部の存在論者によ れば、存在論的な問いに対する客観的な答えは存在せず、さまざまな言語的実践によって形成された視点があるだけだという。 存在論は多様な探求方法を用いる。概念や経験の分析、直感や思考実験の利用、自然科学の知見の統合などである。形式的存在論は、対象の最も抽象的な特徴を 研究する存在論の一分野である。応用存在論は、特定の分野に属する実体を研究するために、存在論的な理論や原理を用いる。例えば、社会存在論は社会科学で 使われる基本的な概念を研究する。応用オントロジーは、限られた領域の概念的枠組みを開発する情報科学やコンピュータ科学に特に関連する。これらのフレー ムワークは、学術活動を追跡する大学のデータベースなど、構造化された方法で情報を保存するために使用される。オントロジーは、論理学、神学、人類学の分 野にも関連している。 存在論の起源は古代にあり、古代インディアン哲学、中国哲学、ギリシャ哲学など、存在の本質や宇宙の根源についての思索が行われた。近代になると、哲学者 たちは存在論を独自の学問分野として捉え、その名称を作り出した。 |

| Definition Ontology is the study of being. It is the branch of philosophy that investigates the nature of existence, the features all entities have in common, and how they are divided into basic categories of being.[1] It aims to discover the foundational building blocks of the world and characterize reality as a whole in its most general aspects.[a] In this regard, ontology contrasts with individual sciences like biology and astronomy, which restrict themselves to a limited domain of entities, such as living entities and celestial phenomena.[3] In some contexts, the term ontology refers not to the general study of being but to a specific ontological theory within this discipline. It can also mean an inventory or a conceptual scheme of a particular domain, such as the ontology of genes.[4] In this context, an inventory is a comprehensive list of elements.[5] A conceptual scheme is a framework of the key concepts and their relationships.[6] Ontology is closely related to metaphysics but the exact relation of these two disciplines is disputed. A traditionally influential characterization asserts that ontology is a subdiscipline of metaphysics. According to this view, metaphysics is the study of various aspects of fundamental reality, whereas ontology restricts itself to the most general features of reality.[7] This view sees ontology as general metaphysics, which is to be distinguished from special metaphysics focused on more specific subject matters, like God, mind, and value.[8] A different conception understands ontology as a preliminary discipline that provides a complete inventory of reality while metaphysics examines the features and structure of the entities in this inventory.[9] Another conception says that metaphysics is about real being while ontology examines possible being or the concept of being.[10] It is not universally accepted that there is a clear boundary between metaphysics and ontology. Some philosophers use both terms as synonyms.[11] The etymology of the word ontology traces back to the ancient Greek terms ὄντως (ontos, meaning 'being') and λογία (logia, meaning 'study of'), literally, 'the study of being'. The ancient Greeks did not use the term ontology, which was coined by philosophers in the 17th century.[12] |

定義 存在論とは、存在についての学問である。哲学の一分野であり、存在の本質、すべての実体が共通して持つ特徴、そしてそれらが存在の基本的なカテゴリーにど のように分けられるかを研究する[1]。 [この点で、存在論は生物学や天文学のような個別科学とは対照的であり、生物学や天文学は生命体や天体現象のような限られた実体の領域に限定している。こ の文脈では、インベントリとは要素の包括的なリストであり、概念スキームとは主要概念とそれらの関係の枠組みである[5]。 存在論は形而上学と密接に関連しているが、これら2つの学問の正確な関係については議論がある。伝統的に有力な特徴は、存在論は形而上学の下位分野である と主張している。この見解によれば、形而上学は基本的な現実の様々な側面を研究する学問であるのに対し、存在論は現実の最も一般的な特徴に限定している [7]。 [形而上学はこの目録に含まれる実体の特徴や構造を検討するのに対して、存在論は現実の完全な目録を提供する予備的な学問であると理解する差延もある [9]。形而上学は現実の存在について研究するのに対して、存在論は可能な存在や存在の概念について研究するとする差延もある。哲学者の中には両方の用語 を同義語として使う者もいる[11]。 存在論の語源は古代ギリシア語のὄντως(ontos、「存在」を意味する)とλογία(logia、「存在の研究」を意味する)に遡る。古代ギリシ ア人は存在論という言葉を使わなかったが、これは17世紀に哲学者によって作られた造語である[12]。 |

| Basic concepts Being Being, or existence, is the main topic of ontology. It is one of the most general and fundamental concepts, encompassing all of reality and every entity within it.[b] In its broadest sense, being only contrasts with non-being or nothingness.[14] It is controversial whether a more substantial analysis of the concept or meaning of being is possible.[15] One proposal understands being as a property possessed by every entity.[16] Critics argue that a thing without being cannot have properties. This means that properties presuppose being and cannot explain it.[17] Another suggestion is that all beings share a set of essential features. According to the Eleatic principle, "power is the mark of being", meaning that only entities with causal influence truly exist.[18] A controversial proposal by philosopher George Berkeley suggests that all existence is mental. He expressed this immaterialism in his slogan "to be is to be perceived".[19] Depending on the context, the term being is sometimes used with a more limited meaning to refer only to certain aspects of reality. In one sense, being is unchanging and permanent, in contrast to becoming, which implies change.[20] Another contrast is between being, as what truly exists, and phenomena, as what appears to exist.[21] In some contexts, being expresses the fact that something is while essence expresses its qualities or what it is like.[22] Ontologists often divide being into fundamental classes or highest kinds, called categories of being.[23] Proposed categories include substance, property, relation, state of affairs, and event.[24] They can be used to provide systems of categories, which offer a comprehensive inventory of reality in which every entity belongs to exactly one category.[23] Some philosophers, like Aristotle, say that entities belonging to different categories exist in distinct ways. Others, like John Duns Scotus, insist that there are no differences in the mode of being, meaning that everything exists in the same way.[25] A related dispute is whether some entities have a higher degree of being than others, an idea already found in Plato's work. The more common view in contemporary philosophy is that a thing either exists or not with no intermediary states or degrees.[26] The relation between being and non-being is a frequent topic in ontology. Influential issues include the status of nonexistent objects[27] and why there is something rather than nothing.[28] |

基本コンセプト 存在 存在とは、存在論の主要なテーマである。その最も広義な意味において、存在は非存在または無と対比されるだけである[14]。存在の概念や意味についてよ り本質的な分析が可能かどうかについては議論がある[15]。ある提案では、存在はあらゆる存在に備わる性質であると理解している[16]。これは、性質 が存在することを前提とし、それを説明できないことを意味する[17]。もう一つの提案は、すべての存在は一連の本質的な特徴を共有しているというもので ある。エレアスの原理によれば、「力は存在の印」であり、因果的な影響力を持つ存在のみが真に存在するということである[18]。哲学者ジョージ・バーク レーによる論争の的となる提案は、すべての存在は精神的なものであるというものである。彼はこの非物質主義を「存在するとは知覚されることである」という スローガンで表現した[19]。 文脈によっては、存在という用語は現実の特定の側面のみを指す、より限定的な意味で使われることもある。ある意味では、存在とは不変で永続的なものであ り、変化を意味する存在(becoming)とは対照的である。 存在論者はしばしば、存在のカテゴリーと呼ばれる基本的なクラスや最高の種類に存在を分割する[23]。提案されているカテゴリーには、実体、性質、関 係、状態、出来事などが含まれる[24]。また、ジョン・ドゥンス・スコトゥスのように、存在の様式に差延はなく、すべてが同じように存在すると主張する 者もいる[25]。関連する論争は、ある実体が他の実体よりも高い存在度を持つかどうかであり、プラトンの著作にすでに見られる考え方である。現代の哲学 においてより一般的な見解は、事物は中間的な状態や程度を持たずに存在するかしないかのどちらかであるというものである[26]。 存在と非存在の関係は存在論において頻繁に取り上げられるテーマである。影響力のある問題としては、存在しない物体の地位[27]や、なぜ無ではなく有が 存在するのか[28]などがある。 |

| Particulars and universals Main articles: Particulars and Universals   The Taj Mahal is a particular entity while the color red is a universal entity. A central distinction in ontology is between particular and universal entities. Particulars, also called individuals, are unique, non-repeatable entities, like Socrates, the Taj Mahal, and Mars.[29] Universals are general, repeatable entities, like the color green, the form circularity, and the virtue courage. Universals express aspects or features shared by particulars. For example, Mount Everest and Mount Fuji are particulars characterized by the universal mountain.[30] Universals can take the form of properties or relations.[31][c] Properties describe the characteristics of things. They are features or qualities possessed by an entity.[33] Properties are often divided into essential and accidental properties. A property is essential if an entity must have it; it is accidental if the entity can exist without it.[34] For instance, having three sides is an essential property of a triangle, whereas being red is an accidental property.[35][d] Relations are ways how two or more entities stand to one another. Unlike properties, they apply to several entities and characterize them as a group.[37] For example, being a city is a property while being east of is a relation, as in "Kathmandu is a city" and "Kathmandu is east of New Delhi".[38] Relations are often divided into internal and external relations. Internal relations depend only on the properties of the objects they connect, like the relation of resemblance. External relations express characteristics that go beyond what the connected objects are like, such as spatial relations.[39] Substances[e] play an important role in the history of ontology as the particular entities that underlie and support properties and relations. They are often considered the fundamental building blocks of reality that can exist on their own, while entities like properties and relations cannot exist without substances. Substances persist through changes as they acquire or lose properties. For example, when a tomato ripens, it loses the property green and acquires the property red.[41] States of affairs are complex particular entities that have several other entities as their components. The state of affairs "Socrates is wise" has two components: the individual Socrates and the property wise. States of affairs that correspond to reality are called facts.[42][f] Facts are truthmakers of statements, meaning that whether a statement is true or false depends on the underlying facts.[44] Events are particular entities[g] that occur in time, like the fall of the Berlin Wall and the first moon landing. They usually involve some kind of change, like the lawn becoming dry. In some cases, no change occurs, like the lawn staying wet.[46] Complex events, also called processes, are composed of a sequence of events.[47] |

特殊と普遍 主な記事 特殊と普遍   タージ・マハルは特殊な存在であり、赤色は普遍的な存在である。 存在論の中心的な区別は、特殊な実体と普遍的な実体の間にある。ソクラテス、タージ・マハル、火星のように、個体とも呼ばれる特殊な存在は、ユニークで再 現不可能な存在である[29]。普遍的な存在は、緑という色、円形という形、勇気という美徳のように、一般的で再現可能な存在である。普遍的なものは、特 殊なものが共有する側面や特徴を表す。例えば、エベレストと富士山は、普遍的な山によって特徴づけられる特殊である[30]。 普遍は性質や関係の形をとることができる[31][c] 。性質はしばしば本質的性質と偶然的性質に分けられる。例えば、3つの辺を持つことは三角形の本質的な性質であり、赤色であることは偶発的な性質である。 例えば、「カトマンズは都市である」と「カトマンズはニューデリーの東にある」のように、都市であることは性質であるが、東であることは関係である [37]。内部関係は、類似関係のように、接続する対象の性質にのみ依存する。外的関係は、空間的関係のように、接続された対象がどのようなものであるか を超えた特性を表現する[39]。 実体[e]は、性質と関係の根底にあり、それを支える特定の実体として、存在論の歴史において重要な役割を果たしている。物質[e]はしばしば、それ自体 で存在することができる現実の基本的な構成要素であると考えられているが、一方で性質や関係のような実体は物質なしには存在することができない。物質は、 性質を獲得したり失ったりする変化を通して存続する。例えば、トマトが熟すと、緑色の性質を失い、赤色の性質を獲得する[41]。 事柄の状態とは、いくつかの他の実体を構成要素として持つ複雑な特定の実体である。ソクラテスは賢明である」という状態は、ソクラテスという個人と賢明と いう性質という2つの構成要素を持っている。現実に対応する事物の状態は事実と呼ばれる[42][f]。事実は陳述の真理決定者であり、陳述の真偽が基礎 にある事実に依存することを意味する[44]。 出来事とは、ベルリンの壁の崩壊や最初の月面着陸のように、時間の中で起こる特定の実体[g]である。事象は通常、芝生が乾くなど何らかの変化を伴う。複 雑な事象は過程とも呼ばれ、一連の事象から構成される[47]。 |

| Concrete and abstract objects Main article: Concrete and abstract Concrete objects are entities that exist in space and time, such as a tree, a car, and a planet. They have causal powers and can affect each other, like when a car hits a tree and both are deformed in the process. Abstract objects, by contrast, are outside space and time, such as the number 7 and the set of integers. They lack causal powers and do not undergo changes.[48][h] The existence and nature of abstract objects remain subjects of philosophical debate.[50] Concrete objects encountered in everyday life are complex entities composed of various parts. For example, a book is made up of two covers and the pages between them. Each of these components is itself constituted of smaller parts, like molecules, atoms, and elementary particles.[51] Mereology studies the relation between parts and wholes. One position in mereology says that every collection of entities forms a whole. According to another view, this is only the case for collections that fulfill certain requirements, for instance, that the entities in the collection touch one another.[52] The problem of material constitution asks whether or in what sense a whole should be considered a new object in addition to the collection of parts composing it.[53] Abstract objects are closely related to fictional and intentional objects. Fictional objects are entities invented in works of fiction. They can be things, like the One Ring in J. R. R. Tolkien's book series The Lord of the Rings, and people, like the Monkey King in the novel Journey to the West.[54] Some philosophers say that fictional objects are abstract objects and exist outside space and time. Others understand them as artifacts that are created as the works of fiction are written.[55] Intentional objects are entities that exist within mental states, like perceptions, beliefs, and desires. For example, if a person thinks about the Loch Ness Monster then the Loch Ness Monster is the intentional object of this thought. People can think about existing and non-existing objects. This makes it difficult to assess the ontological status of intentional objects.[56] |

具体物と抽象物 主な記事 具体物と抽象物 具体的な物体とは、空間と時間の中に存在する実体であり、例えば、木、車、惑星などである。それらは因果的な力を持ち、車が木にぶつかり、その過程で両者 が変形するように、互いに影響し合うことができる。対照的に、抽象的な物体は空間と時間の外にあり、例えば数字の7や整数の集合である。抽象的物体の存在 と性質は、依然として哲学的議論の対象である[50]。 日常生活で遭遇する具体的な物体は、様々な部分から構成される複雑な実体である。例えば、1冊の本は2枚の表紙とその間のページから構成されている。これ らの構成要素はそれぞれ、分子、原子、素粒子のように、より小さな部分から構成されている。唯物論のある立場は、実体のあらゆる集合が全体を形成している と言う。別の見解によれば、これは、例えば集合体中の実体が互いに接触しているというような一定の要件を満たす集合体の場合のみである[52]。物質的構 成の問題は、全体を構成する部分の集合体に加えて、どのような意味において全体を新たな対象とみなすべきか否かを問うものである[53]。 抽象的対象は虚構的対象や意図主義的対象と密接に関連している。フィクションの対象とは、フィクション作品の中で創作された実体のことである。それらは J・R・R・トールキンの『指輪物語』シリーズに登場する「一つの指輪」のようなモノであったり、小説『西遊記』に登場する孫悟空のようなヒトであったり する。また、フィクション作品が書かれる際に創作される人工物であると理解する者もいる[55]。意図主義的対象とは、知覚、信念、欲望のような精神状態 の中に存在する実体である。例えば、人がネス湖の怪物について考えるなら、ネス湖の怪物はこの思考の意図的対象である。人は存在する対象についても存在し ない対象についても考えることができる。このことが意図的対象の存在論的地位を評価することを難しくしている。 |

| Other concepts Ontological dependence is a relation between entities. An entity depends ontologically on another entity if the first entity cannot exist without the second entity.[57] For instance, the surface of an apple cannot exist without the apple.[58] An entity is ontologically independent if it does not depend on anything else, meaning that it is fundamental and can exist on its own. Ontological dependence plays a central role in ontology and its attempt to describe reality on its most fundamental level.[59] It is closely related to metaphysical grounding, which is the relation between a ground and the facts it explains.[60]  Photo of Willard Van Orman Quine Willard Van Orman Quine used the concept of Ontological Commitment to analyze theories. An ontological commitment of a person or a theory is an entity that exists according to them.[61] For instance, a person who believes in God has an ontological commitment to God.[62] Ontological commitments can be used to analyze which ontologies people explicitly defend or implicitly assume. They play a central role in contemporary metaphysics when trying to decide between competing theories. For example, the Quine–Putnam indispensability argument defends mathematical Platonism, asserting that numbers exist because the best scientific theories are ontologically committed to numbers.[63] Possibility and necessity are further topics in ontology. Possibility describes what can be the case, as in "it is possible that extraterrestrial life exists". Necessity describes what must be the case, as in "it is necessary that three plus two equals five". Possibility and necessity contrast with actuality, which describes what is the case, as in "Doha is the capital of Qatar". Ontologists often use the concept of possible worlds to analyze possibility and necessity.[64] A possible world is a complete and consistent way how things could have been.[65] For example, Haruki Murakami was born in 1949 in the actual world but there are possible worlds in which he was born at a different date. Using this idea, possible world semantics says that a sentence is possibly true if it is true in at least one possible world. A sentence is necessarily true if it is true in all possible worlds.[66] In ontology, identity means that two things are the same. Philosophers distinguish between qualitative and numerical identity. Two entities are qualitatively identical if they have exactly the same features, such as perfect identical twins. This is also called exact similarity and indiscernibility. Numerical identity, by contrast, means that there is only a single entity. For example, if Fatima is the mother of Leila and Hugo then Leila's mother is numerically identical to Hugo's mother.[67] Another distinction is between synchronic and diachronic identity. Synchronic identity relates an entity to itself at the same time. Diachronic identity relates an entity to itself at different times, as in "the woman who bore Leila three years ago is the same woman who bore Hugo this year".[68] |

その他の概念 存在論的依存とは、実体間の関係である。例えば、リンゴの表面はリンゴなしでは存在することができない[57]。存在論的依存性は、存在論とその最も基本 的なレベルで現実を記述しようとする試みにおいて中心的な役割を果たしている[59]。それは形而上学的根拠と密接に関連しており、根拠とそれが説明する 事実との関係である[60]。  ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワインの写真 ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワインは理論を分析するために存在論的コミットメント(Ontological Commitment)という概念を用いた。 例えば、神を信じている人は神に対する存在論的コミットメントを持っている。存在論的コミットメントは、現代の形而上学において、競合する理論の間を決定 しようとする際に中心的な役割を果たす。例えば、クワイン=パトナム必須性論は数学的プラトン主義を擁護し、最も優れた科学理論は存在論的に数にコミット しているので数は存在すると主張している[63]。 可能性と必然性は存在論のさらなるトピックである。可能性とは、「地球外生命体が存在する可能性がある」というように、何があり得るかを説明するものであ る。必然性は、「3+2=5であることが必要である」のように、そうでなければならないことを記述する。可能性と必然性は、「ドーハはカタールの首都であ る」のように、何が事実であるかを説明する現実性とは対照的である。存在論者は可能性と必然性を分析するために、しばしば可能世界の概念を用いる [64]。可能世界とは、物事がどのようにあり得たかを示す完全で一貫した方法である[65]。例えば、村上春樹は現実世界では1949年に生まれたが、 別の日に生まれた可能世界が存在する。この考え方を用いて、可能世界意味論では、ある文が少なくとも1つの可能世界において真であれば、その文は真である 可能性があると言う。文は、すべての可能世界で真であれば必然的に真である[66]。 存在論では、同一性とは二つのものが同じであることを意味する。哲学者は質的同一性と数的同一性を区別する。完全な一卵性双生児のように、2つの実体が まったく同じ特徴を持つ場合、質的に同一である。これは正確な類似性、識別不可能性とも呼ばれる。これとは対照的に、数的同一性とは、唯一の実体が存在す ることを意味する。たとえば、ファティマがレイラとヒューゴの母親である場合、レイラの母親はヒューゴの母親と数的に同一である。共時的同一性は実体を同 時にそれ自体に関連付ける。通時的同一性は、「3年前にレイラを産んだ女性は、今年ヒューゴを産んだ女性と同じである」というように、実体を異なる時期の それ自体に関連付ける[68]。 |

| Branches There are different and sometimes overlapping ways to divide ontology into branches. Pure ontology focuses on the most abstract topics associated with the concept and nature of being. It is not restricted to a specific domain of entities and studies existence and the structure of reality as a whole.[69] Pure ontology contrasts with applied ontology, also called domain ontology. Applied ontology examines the application of ontological theories and principles to specific disciplines and domains, often in the field of science.[70] It considers ontological problems in regard to specific entities such as matter, mind, numbers, God, and cultural artifacts.[71] Social ontology, a major subfield of applied ontology, studies social kinds, like money, gender, society, and language. It aims to determine the nature and essential features of these concepts while also examining their mode of existence.[72] According to a common view, social kinds are useful constructions to describe the complexities of social life. This means that they are not pure fictions but, at the same time, lack the objective or mind-independent reality of natural phenomena like elementary particles, lions, and stars.[73] In the fields of computer science, information science, and knowledge representation, applied ontology is interested in the development of formal frameworks to encode and store information about a limited domain of entities in a structured way.[74] A related application in genetics is Gene Ontology, which is a comprehensive framework for the standardized representation of gene-related information across species and databases.[75] Formal ontology is the study of objects in general while focusing on their abstract structures and features. It divides objects into different categories based on the forms they exemplify. Formal ontologists often rely on the tools of formal logic to express their findings in an abstract and general manner.[76][i] Formal ontology contrasts with material ontology, which distinguishes between different areas of objects and examines the features characteristic of a specific area.[78] Examples are ideal spatial beings in the area of geometry and living beings in the area of biology.[79] Descriptive ontology aims to articulate the conceptual scheme underlying how people ordinarily think about the world. Prescriptive ontology departs from common conceptions of the structure of reality and seeks to formulate a new and better conceptualization.[80] Another contrast is between analytic and speculative ontology. Analytic ontology examines the types and categories of being to determine what kinds of things could exist and what features they would have. Speculative ontology aims to determine which entities actually exist, for example, whether there are numbers or whether time is an illusion.[81]  Martin Heidegger proposed fundamental ontology to study the meaning of being. Metaontology studies the underlying concepts, assumptions, and methods of ontology. Unlike other forms of ontology, it does not ask "what exists" but "what does it mean for something to exist" and "how can people determine what exists".[82] It is closely related to fundamental ontology, an approach developed by philosopher Martin Heidegger that seeks to uncover the meaning of being.[83] |

分岐 オントロジーを枝分かれさせる方法には差延があり、時には重複することもある。純粋存在論は、存在の概念と性質に関連する最も抽象的なトピックに焦点を当 てる。純粋存在論は、実体の特定の領域に限定されず、存在と現実の構造を全体として研究する[69]。純粋存在論は、応用存在論(ドメイン存在論とも呼ば れる)と対照的である。応用存在論は、存在論的な理論や原理の特定の学問分野や領域への適用を検討するものであり、多くの場合科学の分野におけるものであ る[70]。応用存在論は、物質、心、数、神、文化的人工物などの特定の実体に関する存在論的な問題を検討する[71]。 応用存在論の主要なサブフィールドである社会存在論は、貨幣、ジェンダー、社会、言語といった社会科学を研究している。一般的な見解によれば、社会的種類 は社会生活の複雑さを記述するのに有用な構造である。コンピュータサイエンス、情報科学、知識表現の分野では、応用オントロジーは、構造化された方法でエ ンティティの限定されたドメインに関する情報をコード化し、格納するための形式的なフレームワークの開発に関心がある[74]。 形式的オントロジーは、抽象的な構造や特徴に焦点を当てながら、対象物全般を研究するものである。オブジェクトを、それらが例示する形態に基づいて異なる カテゴリーに分ける。形式的存在論者は、抽象的かつ一般的な方法で研究結果を表現するために、形式論理学のツールに頼ることが多い[76][i]。形式的 存在論は、物体の異なる領域を区別し、特定の領域に特徴的な特徴を検討する物質的存在論と差延する[78]。 記述的存在論は、人々が世界について通常どのように考えるかの根底にある概念スキームを明確にすることを目的としている。記述的存在論は、現実の構造に関 する一般的な概念から逸脱し、新しくより良い概念化を定式化しようとするものである[80]。 もう一つの対比は、分析的存在論と思弁的存在論である。分析的存在論は、どのような種類のものが存在しうるか、またそれらがどのような特徴を持つかを決定 するために、存在の種類とカテゴリーを検討する。思弁的存在論は、どのような実体が実際に存在するのか、例えば数字が存在するのか、あるいは時間は幻想な のかを決定することを目的としている[81]。  マルティン・ハイデガーは存在の意味を研究するために基礎存在論(Fundamental ontology)を提唱した。 メタ存在論は、存在論の基礎となる概念、仮定、方法を研究する。他の形態の存在論とは異なり、「何が存在するか」ではなく、「何かが存在するとはどういう ことか」、「人はどのようにして何が存在するかを決定することができるのか」を問うものである[82]。哲学者マルティン・ハイデガーによって開発され た、存在の意味を明らかにしようとするアプローチである根源的存在論と密接な関係がある[83]。 |

| Schools of thought Realism and anti-realism Main articles: Philosophical realism and Anti-realism The term realism is used for various theories[j] that affirm that some kind of phenomenon is real or has mind-independent existence. Ontological realism is the view that there are objective facts about what exists and what the nature and categories of being are. Ontological realists do not make claims about what those facts are, for example, whether elementary particles exist. They merely state that there are mind-independent facts that determine which ontological theories are true.[85] This idea is denied by ontological anti-realists, also called ontological deflationists, who say that there are no substantive facts one way or the other.[86] According to philosopher Rudolf Carnap, for example, ontological statements are relative to language and depend on the ontological framework of the speaker. This means that there are no framework-independent ontological facts since different frameworks provide different views while there is no objectively right or wrong framework.[87]  Fresco showing Plato and Aristotle Plato (left) and Aristotle (right) disagreed on whether universals can exist without matter. In a more narrow sense, realism refers to the existence of certain types of entities.[88] Realists about universals say that universals have mind-independent existence. According to Platonic realists, universals exist not only independent of the mind but also independent of particular objects that exemplify them. This means that the universal red could exist by itself even if there were no red objects in the world. Aristotelian realism, also called moderate realism, rejects this idea and says that universals only exist as long as there are objects that exemplify them. Conceptualism, by contrast, is a form of anti-realism, stating that universals only exist in the mind as concepts that people use to understand and categorize the world. Nominalists defend a strong form of anti-realism by saying that universals have no existence. This means that the world is entirely composed of particular objects.[89] Mathematical realism, a closely related view in the philosophy of mathematics, says that mathematical facts exist independently of human language, thought, and practices and are discovered rather than invented. According to mathematical Platonism, this is the case because of the existence of mathematical objects, like numbers and sets. Mathematical Platonists say that mathematical objects are as real as physical objects, like atoms and stars, even though they are not accessible to empirical observation.[90] Influential forms of mathematical anti-realism include conventionalism, which says that mathematical theories are trivially true simply by how mathematical terms are defined, and game formalism, which understands mathematics not as a theory of reality but as a game governed by rules of string manipulation.[91] Modal realism is the theory that in addition to the actual world, there are countless possible worlds as real and concrete as the actual world. The primary difference is that the actual world is inhabited by us while other possible worlds are inhabited by our counterparts. Modal anti-realists reject this view and argue that possible worlds do not have concrete reality but exist in a different sense, for example, as abstract or fictional objects.[92] Scientific realists say that the scientific description of the world is an accurate representation of reality.[k] It is of particular relevance in regard to things that cannot be directly observed by humans but are assumed to exist by scientific theories, like electrons, forces, and laws of nature. Scientific anti-realism says that scientific theories are not descriptions of reality but instruments to predict observations and the outcomes of experiments.[94] Moral realists claim that there exist mind-independent moral facts. According to them, there are objective principles that determine which behavior is morally right. Moral anti-realists either claim that moral principles are subjective and differ between persons and cultures, a position known as moral relativism, or outright deny the existence of moral facts, a view referred to as moral nihilism.[95] |

思想の学派 リアリズムと反リアリズム 主な記事 哲学的実在論と反実在論 実在論という用語は、ある種の現象が実在する、あるいは心とは独立した存在であると断言する様々な理論[j]に対して使われる。存在論的実在論とは、何が 存在し、存在の本質とカテゴリーが何であるかについて客観的事実が存在するという見解である。存在論的実在論者は、例えば素粒子が存在するかどうかなど、 それらの事実が何であるかについては主張しない。この考えは存在論的反実在論者(存在論的デフレ論者とも呼ばれる)によって否定され、彼らは一方的な実体 的事実は存在しないと言う[86]。例えば哲学者のルドルフ・カルナップによれば、存在論的言明は言語に相対的であり、話者の存在論的枠組みに依存する。 つまり、異なる枠組みは異なる見解を提供する一方で、客観的に正しい、あるいは間違っているという枠組みは存在しないため、枠組みに依存しない存在論的事 実は存在しないということである[87]。  プラトンとアリストテレスを示すフレスコ画 プラトン(左)とアリストテレス(右)は、普遍が物質なしに存在しうるかどうかについて意見が対立していた。 より狭い意味では、実在論とはある種の実体の存在を指す[88]。普遍に関する実在論者は、普遍は心に依存しない存在であると言う。プラトン的実在論者に よれば、普遍は心から独立して存在するだけでなく、それを例証する特定の対象からも独立して存在する。つまり、普遍的な赤は、たとえ世界に赤の対象がな かったとしても、それだけで存在しうるということだ。穏健実在論とも呼ばれるアリストテレス的実在論は、この考えを否定し、普遍はそれを例証する対象があ る限り存在するだけだと言う。対照的に、概念主義は反実在論の一形態であり、普遍的なものは、人々が世界を理解し分類するために用いる概念として、心の中 にのみ存在すると述べる。名辞論者は、普遍的なものは存在しないとすることで、反現実主義の強い形態を擁護する。これは、世界は完全に特定の対象から構成 されているということを意味する[89]。 数学的実在論は、数学哲学において密接に関連する見解であり、数学的事実は人間の言語、思考、実践とは無関係に存在し、発明されるのではなく発見されると 言う。数学的プラトン主義によれば、これは数や集合のような数学的対象が存在するからである。数学的プラトン主義者によれば、数学的対象は経験的観察には アクセスできないが、原子や星のような物理的対象と同様に実在する[90]。数学的反実在論の影響力のある形態としては、数学用語がどのように定義されて いるかによって数学理論が些細なことでも真になるとする慣習主義や、数学を現実の理論としてではなく、文字列操作のルールに支配されたゲームとして理解す るゲーム形式主義がある[91]。 様相実在論とは、現実世界に加えて、現実世界と同様に現実的で具体的な無数の可能世界が存在するという理論である。主な差延は、現実世界がわれわれの住む 世界であるのに対して、他の可能世界はわれわれの同等者の住む世界であるということである。様相的反実在論者はこの見方を否定し、可能世界は具体的な実在 を持たず、別の意味で、例えば抽象的なものや架空のものとして存在すると主張している[92]。 科学的実在論者は、世界の科学的記述は現実の正確な表現であると言う[k]。これは、電子、力、自然法則のように、人間が直接観察することはできないが、 科学理論によって存在すると仮定されているものに関して特に関連している。科学的反実在論は、科学理論は現実の記述ではなく、観察や実験の結果を予測する ための道具であると言う[94]。 道徳的実在論者は、心に依存しない道徳的事実が存在すると主張する。彼らによれば、どの行動が道徳的に正しいかを決定する客観的原則が存在する。道徳的反 実在論者は、道徳的原理は主観的なものであり、人や文化によって異なると主張し、道徳的相対主義として知られる立場をとるか、道徳的事実の存在を真っ向か ら否定し、道徳的ニヒリズムと呼ばれる考え方をとる[95]。 |

| By number of categories Monocategorical theories say that there is only one fundamental category, meaning that every single entity belongs to the same universal class.[96] For example, some forms of nominalism state that only concrete particulars exist while some forms of bundle theory state that only properties exist.[97] Polycategorical theories, by contrast, hold that there is more than one basic category, meaning that entities are divided into two or more fundamental classes. They take the form of systems of categories, which list the highest genera of being to provide a comprehensive inventory of everything.[98] The closely related discussion between monism and dualism is about the most fundamental types that make up reality. According to monism, there is only one kind of thing or substance on the most basic level.[99] Materialism is an influential monist view; it says that everything is material. This means that mental phenomena, such as beliefs, emotions, and consciousness, either do not exist or exist as aspects of matter, like brain states. Idealists take the converse perspective, arguing that everything is mental. They may understand physical phenomena, like rocks, trees, and planets, as ideas or perceptions of conscious minds.[100] Neutral monism occupies a middle ground by saying that both mind and matter are derivative phenomena.[101] Dualists state that mind and matter exist as independent principles, either as distinct substances or different types of properties.[102] In a slightly different sense, monism contrasts with pluralism as a view not about the number of basic types but the number of entities. In this sense, monism is the controversial position that only a single all-encompassing entity exists in all of reality.[l] Pluralism is more commonly accepted and says that several distinct entities exist.[104] |

カテゴリーの数 単範疇論は、基本的な範疇は1つしかないとするものであり、あらゆる実体が同じ普遍的な類に属することを意味する[96]。それらはカテゴリーの体系とい う形をとり、あらゆるものの包括的な目録を提供するために存在の最高属を列挙する[98]。 一元論と二元論の間の密接に関連した議論は、現実を構成する最も基本的な種類に関するものである。一元論によれば、最も基本的なレベルでは物事や物質は一 種類しか存在しない[99]。唯物論は影響力のある一元論の見解であり、すべては物質的であるとする。これは、信念、感情、意識などの心的現象は存在しな いか、脳の状 態のように物質の側面として存在するかのどちらかであることを意味する。観念論者は逆の立場をとり、すべては精神的なものだと主張する。中立的な一元論 は、心と物質の両方が派生的な現象であるとすることで、中間的な立場を占める[100]。 二元論は、心と物質は独立した原理として存在し、別個の物質として、あるいは異なるタイプの性質として存在するとする[102]。少し異なる意味では、一 元論は、基本的なタイプの数ではなく、実体の数についての見解として多元主義と対照をなす。この意味において、一元論とは、現実のすべてにおいて単一のす べてを包含する実体のみが存在するという論争的な立場である[l]。 多元論はより一般的に受け入れられており、いくつかの異なる実体が存在すると言っている[104]。 |

| By fundamental categories The historically influential substance-attribute ontology is a polycategorical theory. It says that reality is at its most fundamental level made up of unanalyzable substances that are characterized by universals, such as the properties an individual substance has or relations that exist between substances.[105] The closely related to substratum theory says that each concrete object is made up of properties and a substratum. The difference is that the substratum is not characterized by properties: it is a featureless or bare particular that merely supports the properties.[106] Various alternative ontological theories have been proposed that deny the role of substances as the foundational building blocks of reality.[107] Stuff ontologies say that the world is not populated by distinct entities but by continuous stuff that fills space. This stuff may take various forms and is often conceived as infinitely divisible.[108][m] According to process ontology, processes or events are the fundamental entities. This view usually emphasizes that nothing in reality is static, meaning that being is dynamic and characterized by constant change.[110] Bundle theories state that there are no regular objects but only bundles of co-present properties. For example, a lemon may be understood as a bundle that includes the properties yellow, sour, and round. According to traditional bundle theory, the bundled properties are universals, meaning that the same property may belong to several different bundles. According to trope bundle theory, properties are particular entities that belong to a single bundle.[111] Some ontologies focus not on distinct objects but on interrelatedness. According to relationalism, all of reality is relational at its most fundamental level.[112][n] Ontic structural realism agrees with this basic idea and focuses on how these relations form complex structures. Some structural realists state that there is nothing but relations, meaning that individual objects do not exist. Others say that individual objects exist but depend on the structures in which they participate.[114] Fact ontologies present a different approach by focusing on how entities belonging to different categories come together to constitute the world. Facts, also known as states of affairs, are complex entities; for example, the fact that the Earth is a planet consists of the particular object the Earth and the property being a planet. Fact ontologies state that facts are the fundamental constituents of reality, meaning that objects, properties, and relations cannot exist on their own and only form part of reality to the extent that they participate in facts.[115][o] In the history of philosophy, various ontological theories based on several fundamental categories have been proposed. One of the first theories of categories was suggested by Aristotle, whose system includes ten categories: substance, quantity, quality, relation, place, date, posture, state, action, and passion.[117] An early influential system of categories in Indian philosophy, first proposed in the Vaisheshika school, distinguishes between six categories: substance, quality, motion, universal, individuator, and inherence.[118] Immanuel Kant's transcendental idealism includes a system of twelve categories, which Kant saw as pure concepts of understanding. They are subdivided into four classes: quantity, quality, relation, and modality.[119] In more recent philosophy, theories of categories were developed by C. S. Peirce, Edmund Husserl, Samuel Alexander, Roderick Chisholm, and E. J. Lowe.[120] |

基本カテゴリーによって 歴史的に影響力のある物質属性存在論は多範疇論である。この理論では、現実は最も基本的なレベルでは分析不可能な物質で構成されており、個々の物質が持つ 性質や物質間に存在する関係といった普遍的なものによって特徴づけられているとする[105]。基層論と密接に関連する理論では、それぞれの具体的な対象 は性質と基層から構成されているとする。差延は、基層は特性によって特徴付けられるのではなく、単に特性を支えるだけの特徴のない、あるいは裸の特定物で あるという点である[106]。 現実の基礎的な構成要素としての物質の役割を否定する様々な代替的存在論的理論が提唱されている[107]。物質存在論は、世界は明確な実体によって占め られているのではなく、空間を満たす連続的な物質によって占められているとする。この物質は様々な形をとることがあり、しばしば無限に分割可能であると考 えられている[108][m]。プロセス存在論によれば、プロセスまたは事象が基本的な実体である。この見解は通常、現実には静的なものは何もなく、存在 とは動的なものであり、絶え間ない変化によって特徴づけられるということを強調している[110]。束理論では、規則的な物体は存在せず、共存する特性の 束だけが存在するとする。例えば、レモンは黄色、酸っぱい、丸いという性質を含む束として理解することができる。伝統的なバンドル理論によれば、バンドル された性質は普遍的であり、同じ性質が複数の異なるバンドルに属する可能性があることを意味する。トロープ・バンドル理論によれば、特性は単一のバンドル に属する特定の実体である[111]。 オントロジーの中には、別個の対象ではなく、相互関係に焦点を当てるものがある。関係主義によれば、現実のすべてはその最も基本的なレベルにおいて関係的 である[112][n]。存在論的構造実在論はこの基本的な考えに同意し、これらの関係がいかに複雑な構造を形成しているかに焦点を当てている。構造的実 在論者の中には、関係以外には何も存在しない、つまり個々の物体は存在しないと述べる者もいる。事実存在論は、異なるカテゴリーに属する実体がどのように 集まって世界を構成しているかに焦点を当てることで、異なるアプローチを提示している。例えば、地球が惑星であるという事実は、地球という特定のオブジェ クトと惑星であるという特性から構成される。事実オントロジーは、事実が現実の基本的な構成要素であると述べている。つまり、オブジェクト、特性、関係は それ自体では存在することができず、それらが事実に関与する程度においてのみ現実の一部を形成することを意味している[115][o]。 哲学の歴史において、いくつかの基本的なカテゴリーに基づく様々な存在論的理論が提案されてきた。最初のカテゴリー理論のひとつはアリストテレスによって 提案されたものであり、その体系には物質、量、質、関係、場所、日付、姿勢、状態、行為、情熱という10のカテゴリーが含まれている[117]。インド哲 学における初期の影響力のあるカテゴリー体系は、ヴァイシェシカ学派において最初に提案されたものであり、物質、質、運動、普遍、個体、内在という6つの カテゴリーを区別している[118]。それらは量、質、関係、モダリティの4つのクラスに細分化されている[119]。より近年の哲学においては、 C.S.パース、エドムント・フッサール、サミュエル・アレクサンダー、ロデリック・チショルム、E.J.ロウによってカテゴリーの理論が展開されている [120]。 |

| Others The dispute between constituent and relational ontologies[p] concerns the internal structure of concrete particular objects. Constituent ontologies say that objects have an internal structure with properties as their component parts. Bundle theories are an example of this position: they state that objects are bundles of properties. This view is rejected by relational ontologies, which say that objects have no internal structure, meaning that properties do not inhere in them but are externally related to them. According to one analogy, objects are like pin-cushions and properties are pins that can be stuck to objects and removed again without becoming a real part of objects. Relational ontologies are common in certain forms of nominalism that reject the existence of universal properties.[122] Hierarchical ontologies state that the world is organized into levels. Entities on all levels are real but low-level entities are more fundamental than high-level entities. This means that they can exist without high-level entities while high-level entities cannot exist without low-level entities.[123] One hierarchical ontology says that elementary particles are more fundamental than the macroscopic objects they compose, like chairs and tables. Other hierarchical theories assert that substances are more fundamental than their properties and that nature is more fundamental than culture.[124] Flat ontologies, by contrast, deny that any entity has a privileged status, meaning that all entities exist on the same level. For them, the main question is only whether something exists rather than identifying the level at which it exists.[125][q] The ontological theories of endurantism and perdurantism aim to explain how material objects persist through time. Endurantism is the view that material objects are three-dimensional entities that travel through time while being fully present in each moment. They remain the same even when they gain or lose properties as they change. Perdurantism is the view that material objects are four-dimensional entities that extend not just through space but also through time. This means that they are composed of temporal parts and, at any moment, only one part of them is present but not the others. According to perdurantists, change means that an earlier part exhibits different qualities than a later part. When a tree loses its leaves, for instance, there is an earlier temporal part with leaves and a later temporal part without leaves.[127] Differential ontology is a poststructuralist approach interested in the relation between the concepts of identity and difference. It says that traditional ontology sees identity as the more basic term by first characterizing things in terms of their essential features and then elaborating differences based on this conception. Differential ontologists, by contrast, privilege difference and say that the identity of a thing is a secondary determination that depends on how this thing differs from other things.[128] Object-oriented ontology belongs to the school of speculative realism and examines the nature and role of objects. It sees objects as the fundamental building blocks of reality. As a flat ontology, it denies that some entities have a more fundamental form of existence than others. It uses this idea to argue that objects exist independently of human thought and perception.[129] |

その他 構成オントロジーと関係オントロジー[p]の論争は、具体的な特定のオブジェクトの内部構造に関するものである。構成的オントロジーは、オブジェクトはプ ロパティを構成要素とする内部構造を持つとする。束理論がこの立場の一例であり、オブジェクトはプロパティの束であるとする。この考え方は、関係存在論に よって否定される。関係存在論は、物体は内部構造を持たず、プロパティは物体の中に存在するのではなく、外部に関係しているとする。あるアナロジーによれ ば、オブジェクトはピンクッションのようなものであり、プロパティはオブジェクトの本当の一部となることなく、オブジェクトにくっついたり外したりできる ピンのようなものである。関係論的オントロジーは、普遍的性質の存在を否定するある種の名辞主義において一般的である[122]。 階層的オントロジーは、世界はレベルに組織化されているとする。すべてのレベルの実体は実在するが、低レベルの実体は高レベルの実体よりも基本的である。 ある階層的存在論は、素粒子はそれらが構成する椅子やテーブルのような巨視的物体よりも基本的であるとする。他の階層的な理論では、物質はその性質よりも 基本的であり、自然は文化よりも基本的であると主張している[124]。対照的に、フラットな存在論は、どのようなエンティティも特権的な地位を持つこと を否定し、すべてのエンティティが同じレベルに存在することを意味する。彼らにとっての主要な問題は、何かが存在するかどうかであり、むしろそれが存在す るレベルを特定することである[125][q]。 エンデュランティズムとパーデュランティズムの存在論的理論は、物質的対象が時間を通じてどのように持続するかを説明することを目的としている。持久主義 とは、物質的対象は、それぞれの瞬間に完全に存在しながら時間を旅する三次元の実体であるという見解である。物質が変化して特性を得たり失ったりしても、 それは変わらない。パーデュランティズムとは、物質的対象は空間だけでなく時間にも広がる4次元の実体であるとする考え方である。つまり、物体は時間的な 部分から構成され、どの瞬間にもその一部分だけが存在し、他の部分は存在しないということである。パーデュランティストによれば、変化とは、以前の部分が 後の部分とは異なる性質を示すことを意味する。例えば、木が葉を失うとき、葉のある先の時間的部分と葉のない後の時間的部分が存在する[127]。 差延存在論は、同一性と差延の概念間の関係に関心を持つポスト構造主義のアプローチである。伝統的な存在論は、まず本質的な特徴という観点から物事を特徴 づけ、次にこの概念に基づいて差延を精緻化することによって、同一性をより基本的な用語とみなすという。対照的に、差異存在論者は差異を特権化し、事物の 同一性は、この事物が他の事物とどのように異なるかに依存する二次的な決定であると言う[128]。 オブジェクト指向の存在論は思弁的実在論の学派に属し、オブジェクトの性質と役割を検討している。オブジェクトを現実の基本的な構成要素として捉えてい る。フラットな存在論として、ある実体が他の実体よりも根本的な存在形態を持つことを否定する。この考えを用いて、物体は人間の思考や知覚とは無関係に存 在すると主張する[129]。 |

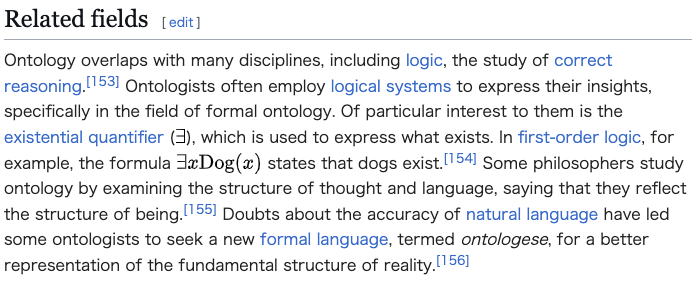

| Methods Methods of ontology are ways of conducting ontological inquiry and deciding between competing theories. There is no single standard method; the diverse approaches are studied by metaontology.[130] Conceptual analysis is a method to understand ontological concepts and clarify their meaning.[131] It proceeds by analyzing their component parts and the necessary and sufficient conditions under which a concept applies to an entity.[132] This information can help ontologists decide whether a certain type of entity, such as numbers, exists.[133] Eidetic variation is a related method in phenomenological ontology that aims to identify the essential features of different types of objects. Phenomenologists start by imagining an example of the investigated type. They proceed by varying the imagined features to determine which ones cannot be changed, meaning they are essential.[134][r] The transcendental method begins with a simple observation that a certain entity exists. In the following step, it studies the ontological repercussions of this observation by examining how it is possible or which conditions are required for this entity to exist.[136] Another approach is based on intuitions in the form of non-inferential impressions about the correctness of general principles.[137] These principles can be used as the foundation on which an ontological system is built and expanded using deductive reasoning.[138] A further intuition-based method relies on thought experiments to evoke new intuitions. This happens by imagining a situation relevant to an ontological issue and then employing counterfactual thinking to assess the consequences of this situation.[139] For example, some ontologists examine the relation between mind and matter by imagining creatures identical to humans but without consciousness.[140] Naturalistic methods rely on the insights of the natural sciences to determine what exists.[141] According to an influential approach by Willard Van Orman Quine, ontology can be conducted by analyzing[s] the ontological commitments of scientific theories. This method is based on the idea that scientific theories provide the most reliable description of reality and that their power can be harnessed by investigating the ontological assumptions underlying them.[143]  Portrait of William of Ockham William of Ockham proposed Ockham's Razor, a principle to decide between competing theories. Principles of theory choice offer guidelines for assessing the advantages and disadvantages of ontological theories rather than guiding their construction.[144] The principle of Ockham's Razor says that simple theories are preferable.[145] A theory can be simple in different respects, for example, by using very few basic types or by describing the world with a small number of fundamental entities.[146] Ontologists are also interested in the explanatory power of theories and give preference to theories that can explain many observations.[147] A further factor is how close a theory is to common sense. Some ontologists use this principle as an argument against theories that are very different from how ordinary people think about the issue.[148] In applied ontology, ontological engineering is the process of creating and refining conceptual models of specific domains.[149] Developing a new ontology from scratch involves various preparatory steps, such as delineating the scope of the domain one intends to model and specifying the purpose and use cases of the ontology. Once the foundational concepts within the area have been identified, ontology engineers proceed by defining them and characterizing the relations between them. This is usually done in a formal language to ensure precision and, in some cases, automatic computability. In the following review phase, the validity of the ontology is assessed using test data.[150] Various more specific instructions for how to carry out the different steps have been suggested. They include the Cyc method, Grüninger and Fox's methodology, and so-called METHONTOLOGY.[151] In some cases, it is feasible to adapt a pre-existing ontology to fit a specific domain and purpose rather than creating a new one from scratch.[152] |

方法論 存在論の方法とは、存在論的探究を行い、競合する理論間の判断を下す方法である。単一の標準的な方法は存在せず、多様なアプローチがメタ存在論によって研 究されている[130]。 概念分析は、存在論的概念を理解し、その意味を明らかにするための方法である[131]。この方法は、概念の構成部分と、概念が実体に適用される必要十分 条件[132]を分析することによって進められる。現象学者は調査されたタイプの例を想像することから始める。超越論的方法は、ある実体が存在するという 単純な観察から始まる。次のステップでは、この実体が存在することがどのようにして可能なのか、あるいはどのような条件が必要なのかを検討することによっ て、この観察の存在論的な反響を研究する[136]。 これらの原理は、演繹的推論を用いて存在論的システムを構築し拡張するための基礎として使用することができる[137]。これは存在論的問題に関連する状 況を想像し、その状況の結果を評価するために反事実的思考を用いることによって行われる[139]。例えば、存在論者の中には、人間と同じであるが意識を 持たない生物を想像することによって、心と物質の関係を検討する者もいる[140]。 ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワインによる影響力のあるアプローチによれば、存在論は科学的理論の存在論的コミットメントを分析することによって行う ことができる。この方法は、科学的理論が現実の最も信頼できる記述を提供し、その根底にある存在論的仮定を調査することによってその力を利用することがで きるという考えに基づいている[143]。  オッカムのウィリアムの肖像 オッカムのウィリアムはオッカムの剃刀を提唱した。 理論選択の原則は存在論的理論の構築を導くというよりも、その長所と短所を評価するためのガイドラインを提供するものである[144]。 [また存在論者は理論の説明力にも関心があり、多くの観察を説明できる理論を優先する[147]。一部の存在論者はこの原則を、一般人がその問題について 考える方法と大きく異なる理論に対する反論として用いている[148]。 応用オントロジーでは、オントロジー工学は特定のドメインの概念モデルを作成し、改良するプロセスである[149]。新しいオントロジーをゼロから開発す るには、モデル化しようとするドメインの範囲を明確にし、オントロジーの目的とユースケースを特定するなど、さまざまな準備段階が必要である。領域内の基 礎となる概念が特定されると、オントロジーエンジニアはそれらを定義し、それらの間の関係を特徴付けることによって作業を進める。これは通常、正確さと、 場合によっては自動計算可能性を確保するために、形式言語で行われる。次のレビュー段階では、テストデータを使ってオントロジーの妥当性が評価される。 Cyc法、GrüningerとFoxの方法論、いわゆるMETHONTOLOGYなどがある[151]。場合によっては、ゼロから新しいオントロジーを 作成するのではなく、既存のオントロジーを特定のドメインや目的に適合させることが可能である[152]。 |

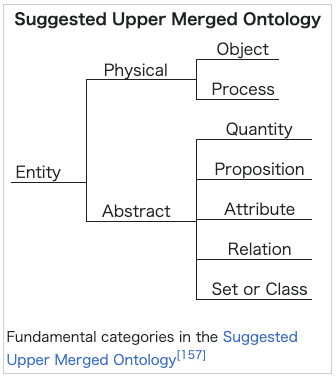

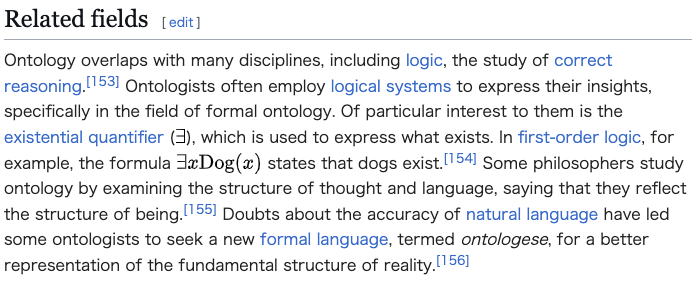

Ontologies are often used in information science to provide a conceptual scheme or inventory of a specific domain, making it possible to classify objects and formally represent information about them. This is of specific interest to computer science, which builds databases to store this information and defines computational processes to automatically transform and use it.[158] For instance, to encode and store information about clients and employees in a database, an organization may use an ontology with categories such as person, company, address, and name.[159] In some cases, it is necessary to exchange information belonging to different domains or to integrate databases using distinct ontologies. This can be achieved with the help of upper ontologies, which are not limited to one specific domain. They use general categories that apply to most or all domains, like Suggested Upper Merged Ontology and Basic Formal Ontology.[160] Similar applications of ontology are found in various fields seeking to manage extensive information within a structured framework. Protein Ontology is a formal framework for the standardized representation of protein-related entities and their relationships.[161] Gene Ontology and Sequence Ontology serve a similar purpose in the field of genetics.[162] Environment Ontology is a knowledge representation focused on ecosystems and environmental processes.[163] Friend of a Friend provides a conceptual framework to represent relations between people and their interests and activities.[164] The topic of ontology has received increased attention in anthropology since the 1990s, sometimes termed the "ontological turn".[165] This type of inquiry is focused on how people from different cultures experience and understand the nature of being. Specific interest has been given to the ontological outlook of Indigenous people and how it differs from a Western perspective.[166] As an example of this contrast, it has been argued that various indigenous communities ascribe intentionality to non-human entities, like plants, forests, or rivers. This outlook is known as animism[167] and is also found in Native American ontologies, which emphasize the interconnectedness of all living entities and the importance of balance and harmony with nature.[168] Ontology is closely related to theology and its interest in the existence of God as an ultimate entity. The ontological argument, first proposed by Anselm of Canterbury, attempts to prove the existence of the divine. It defines God as the greatest conceivable being. From this definition it concludes that God must exist since God would not be the greatest conceivable being if God lacked existence.[169] Another overlap in the two disciplines is found in ontological theories that use God or an ultimate being as the foundational principle of reality. Heidegger criticized this approach, terming it ontotheology.[170] |

オントロジーは情報科学において、特定のドメインの概念スキームやインベントリを提供するためによく使用され、オブジェクトを分類し、それらに関する情報 を正式に表現することを可能にする。これは、情報を格納するためのデータベースを構築し、情報を自動的に変換して使用するための計算プロセスを定義するコ ンピュータ科学にとって、特に興味深いものである[158]。例えば、顧客や従業員に関する情報をエンコードしてデータベースに格納するために、組織は、 人、会社、住所、名前などのカテゴリを持つオントロジーを使用することができる[159]。場合によっては、異なるドメインに属する情報を交換したり、異 なるオントロジーを使用するデータベースを統合したりする必要がある。これは、特定のドメインに限定されない上位オントロジーの助けを借りて実現できる。 上位オントロジーは、Suggested Upper Merged OntologyやBasic Formal Ontologyのように、ほとんどの、あるいはすべてのドメインに適用される一般的なカテゴリーを使用する[160]。 オントロジーの同様の応用は、構造化された枠組みの中で広範な情報を管理しようとする様々な分野で見られる。タンパク質オントロジーは、タンパク質に関連 する実体とその関係を標準化して表現するための正式なフレームワークである[161]。遺伝子オントロジーと配列オントロジーは、遺伝学の分野で同様の目 的を果たしている[162]。環境オントロジーは、生態系と環境プロセスに焦点を当てた知識表現である[163]。Friend of a Friendは、人と人の間の関係とその興味や活動を表現するための概念的なフレームワークを提供している[164]。 オントロジーの差延は1990年代から人類学で注目されるようになり、「オントロジーの転回」と呼ばれることもある[165]。この対照の例として、様々 な先住民のコミュニティが、植物、森林、河川といった人間以外の存在に意図主義を認めていることが論じられている[166]。このような考え方はアニミズ ムとして知られており[167]、アメリカ先住民の存在論にも見られ、すべての生命体の相互関連性や自然とのバランスや調和の重要性を強調している [168]。 存在論は神学と密接に関連しており、究極的な存在としての神の存在に関心がある。カンタベリーのアンセルムが最初に提唱した存在論的議論は、神の存在を証 明しようとするものである。神を考えうる最大の存在と定義する。この定義から、神が存在しないのであれば、神は考えうる最大の存在ではなくなるので、神は 存在しなければならないと結論づける[169]。ハイデガーはこのアプローチを存在神学と呼んで批判した[170]。 |

| History Main article: History of ontology  Depiction of Kapila Kapila was one of the founding fathers of the dualist school of Samkhya.[171] The roots of ontology in ancient philosophy are speculations about the nature of being and the source of the universe. Discussions of the essence of reality are found in the Upanishads, ancient Indian scriptures dating from as early as 700 BCE. They say that the universe has a divine foundation and discuss in what sense ultimate reality is one or many.[172] Samkhya, the first orthodox school of Indian philosophy,[t] formulated an atheist dualist ontology based on the Upanishads, identifying pure consciousness and matter as its two foundational principles.[174] The later Vaisheshika school[u] proposed a comprehensive system of categories.[176] In ancient China, Laozi's (6th century BCE)[v] Taoism examines the underlying order of the universe, known as Tao, and how this order is shaped by the interaction of two basic forces, yin and yang.[178] The philosophical movement of Xuanxue emerged in the 3rd century CE and explored the relation between being and non-being.[179] Starting in the 6th century BCE, Presocratic philosophers in ancient Greece aimed to provide rational explanations of the universe. They suggested that a first principle, such as water or fire, is the primal source of all things.[180] Parmenides (c. 515–450 BCE) is sometimes considered the founder of ontology because of his explicit discussion of the concepts of being and non-being.[181] Inspired by Presocratic philosophy, Plato (427–347 BCE) developed his theory of forms. It distinguishes between unchangeable perfect forms and matter, which has a lower degree of existence and imitates the forms.[182] Aristotle (384–322 BCE) suggested an elaborate system of categories that introduced the concept of substance as the primary kind of being.[183] The school of Neoplatonism arose in the 3rd century CE and proposed an ineffable source of everything, called the One, which is more basic than being itself.[184] The problem of universals was an influential topic in medieval ontology. Boethius (477–524 CE) suggested that universals can exist not only in matter but also in the mind. This view inspired Peter Abelard (1079–1142 CE), who proposed that universals exist only in the mind.[185] Thomas Aquinas (1224–1274 CE) developed and refined fundamental ontological distinctions, such as the contrast between existence and essence, between substance and accidents, and between matter and form.[186] He also discussed the transcendentals, which are the most general properties or modes of being.[187] John Duns Scotus (1266–1308) argued that all entities, including God, exist in the same way and that each entity has a unique essence, called haecceity.[188] William of Ockham (c. 1287–1347 CE) proposed that one can decide between competing ontological theories by assessing which one uses the smallest number of elements, a principle known as Ockham's razor.[189]  Depiction of Zhu Xi The Neo-Confucian philosopher Zhu Xi conceived the concept of li as the organizing principle of the universe.[190] In Arabic-Persian philosophy, Avicenna (980–1037 CE) combined ontology with theology. He identified God as a necessary being that is the source of everything else, which only has contingent existence.[191] In 8th-century Indian philosophy, the school of Advaita Vedanta emerged. It says that only a single all-encompassing entity exists, stating that the impression of a plurality of distinct entities is an illusion.[192] Starting in the 13th century CE, the Navya-Nyāya school built on Vaisheshika ontology with a particular focus on the problem of non-existence and negation.[193] 9th-century China saw the emergence of Neo-Confucianism, which developed the idea that a rational principle, known as li, is the ground of being and order of the cosmos.[194] René Descartes (1596–1650) formulated a dualist ontology at the beginning of the modern period. It distinguishes between mind and matter as distinct substances that causally interact.[195] Rejecting Descartes's dualism, Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) proposed a monist ontology according to which there is only a single entity that is identical to God and nature.[196] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), by contrast, said that the universe is made up of many simple substances, which are synchronized but do not interact with one another.[197] John Locke (1632–1704) proposed his substratum theory, which says that each object has a featureless substratum that supports the object's properties.[198] Christian Wolff (1679–1754) was influential in establishing ontology as a distinct discipline, delimiting its scope from other forms of metaphysical inquiry.[199] George Berkeley (1685–1753) developed an idealist ontology according to which material objects are ideas perceived by minds.[200] Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) rejected the idea that humans can have direct knowledge of independently existing things and their nature, limiting knowledge to the field of appearances. For Kant, ontology does not study external things but provides a system of pure concepts of understanding.[201] Influenced by Kant's philosophy, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) linked ontology and logic. He said that being and thought are identical and examined their foundational structures.[202] Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) rejected Hegel's philosophy and proposed that the world is an expression of a blind and irrational will.[203] Francis Herbert Bradley (1846–1924) saw absolute spirit as the ultimate and all-encompassing reality[204] while denying that there are any external relations.[205] In Indian philosophy, Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902) expanded on Advaita Vedanta, emphasizing the unity of all existence.[206] Sri Aurobindo (1872–1950) sought to understand the world as an evolutionary manifestation of a divine consciousness.[207] At the beginning of the 20th century, Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) developed phenomenology and employed its method, the description of experience, to address ontological problems.[208] This idea inspired his student Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) to clarify the meaning of being by exploring the mode of human existence.[209] Jean-Paul Sartre responded to Heidegger's philosophy by examining the relation between being and nothingness from the perspective of human existence, freedom, and consciousness.[210] Based on the phenomenological method, Nicolai Hartmann (1882–1950) developed a complex hierarchical ontology that divides reality into four levels: inanimate, biological, psychological, and spiritual.[211]  Photo of Alexius Meinong Alexius Meinong proposed that there are nonexistent objects. Alexius Meinong (1853–1920) articulated a controversial ontological theory that includes nonexistent objects as part of being.[212] Arguing against this theory, Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) formulated a fact ontology known as logical atomism. This idea was further refined by the early Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) and inspired D. M. Armstrong's (1926–2014) ontology.[213] Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947), by contrast, developed a process ontology.[214] Rudolf Carnap (1891–1970) questioned the objectivity of ontological theories by claiming that what exists depends on one's linguistic framework.[215] He had a strong influence on Willard Van Orman Quine (1908–2000), who analyzed the ontological commitments of scientific theories to solve ontological problems.[216] Quine's student David Lewis (1941–2001) formulated the position of modal realism, which says that possible worlds are as real and concrete as the actual world.[217] Since the end of the 20th century, interest in applied ontology has risen in computer and information science with the development of conceptual frameworks for specific domains.[218] |

沿革 主な記事 存在論の歴史  カピラの描写 カピラは二元論学派であるサムキャ派の創始者の一人である[171]。 古代哲学における存在論のルーツは、存在の本質と宇宙の根源に関する思索である。現実の本質に関する議論は、紀元前700年頃にさかのぼる古代インドの聖 典であるウパニシャッドに見られる。インド哲学の最初の正統派であるサムキヤ学派[t]は、ウパニシャッドに基づいて無神論的な二元論的存在論を定式化 し、純粋意識と物質がその2つの基礎原理であるとした[174]。 [176]古代中国では、老子(前6世紀)[v]の道教は、タオとして知られる宇宙の根本的な秩序と、この秩序が陰と陽という2つの基本的な力の相互作用 によってどのように形成されるかを考察している[178]。前3世紀に出現した玄学の哲学運動は、存在と非存在の関係を探求した[179]。 紀元前6世紀に始まった古代ギリシャのプレソクラテスの哲学者たちは、宇宙の合理的な説明を提供することを目的としていた。パルメニデス(前515年頃- 前450年頃)は存在と非存在の概念について明確に論じたことから、存在論の創始者と見なされることがある[181]。アリストテレス(前384-前 322年)は、存在の第一の種類としての物質という概念を導入した精巧なカテゴリー体系を提案した[183]。 新プラトン主義の学派は前3世紀に発生し、存在そのものよりも基本的なものである「唯一」と呼ばれるすべてのものの不可解な根源を提案した[184]。 普遍の問題は中世の存在論において影響力のあるテーマであった。ボエティウス(477-524CE)は、普遍は物質だけでなく心にも存在しうると示唆し た。この見解はピーター・アベラール(Peter Abelard, 1079-1142 CE)に影響を与え、彼は普遍は心の中にのみ存在すると提唱した[185]。トマス・アクィナス(Thomas Aquinas, 1224-1274 CE)は、存在と本質の対比、物質とアクシデントの対比、物質と形態の対比といった基本的な存在論的区別を発展させ、洗練させた[186]。 [187] ジョン・ドゥンス・スコトゥス(John Duns Scotus, 1266-1308)は、神を含むすべての存在は同じように存在し、各存在はヘセシティと呼ばれる固有の本質を持つと主張した[188]。 オッカムのウィリアム(William of Ockham, 1287頃-1347年)は、オッカムの剃刀として知られる原理である、最小の要素数を使用するものを評価することによって、競合する存在論理論の間で決 定することができると提唱した[189]。  朱熹の描写 新儒教の哲学者である朱熹は「理」の概念を宇宙の組織原理として構想した[190]。 アラビア・ペルシャ哲学では、アヴィセンナ(980年-1037年)が存在論と神学を組み合わせた。8世紀のインディアン哲学では、アドヴァイタ・ヴェー ダーンタの学派が出現した。13世紀に始まったナヴィヤ・ニャーヤ学派は、非存在と否定の問題に特に焦点を当てながらヴァイシェーシカの存在論を基礎とし ていた[193]。9世紀の中国では、理として知られる原理が存在と宇宙の秩序の根拠であるという考えを発展させた新儒教が出現した[194]。 ルネ・デカルト(1596-1650)は、近代の初めに二元論的な存在論を打ち立てた。デカルトの二元論を否定したバルーク・スピノザ(1632- 1677)は、神と自然とが同一である単一の存在のみが存在するという一元論的存在論を提唱した[196]。対照的に、ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ラ イプニッツ(1646-1716)は、宇宙は多くの単純な物質から構成されており、それらは同期しているが互いに相互作用していないと述べた。 [197] ジョン・ロック(1632-1704)は、各物体にはその物体の特性を支える特徴のない基質があるとする基質論を提唱した[198] 。クリスティアン・ヴォルフ(1679-1754)は、存在論を他の形而上学的探究の形態から範囲を区切り、別個の学問分野として確立する上で影響力を 持った[199] 。 イマニュエル・カント(1724-1804)は、人間が独立して存在する事物やその性質について直接的な知識を持つことができるという考えを否定し、知識 を出現の分野に限定した。カントにとって存在論は外部の事物を研究するものではなく、理解するための純粋な概念の体系を提供するものであった[201]。 カントの哲学に影響を受けたゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル(1770-1831)は存在論と論理学を結びつけた。アルトゥール・ショー ペンハウアー(1788-1860)はヘーゲルの哲学を否定し、世界は盲目的で非合理的な意志の表れであると提唱した[203]。フランシス・ハーバー ト・ブラッドリー(1846-1924)は絶対精神を究極的ですべてを包含する現実とみなし[204]、一方で外的関係の存在を否定した。 [205] インディアン哲学では、スワミ・ヴィヴェーカナンダ(1863-1902)がアドヴァイタ・ヴェーダーンタを発展させ、すべての存在の統一性を強調した [206] 。 20世紀初頭、エドムント・フッサール(1859-1938)は現象学を発展させ、その方法である経験の記述を用いて存在論的な問題に取り組んだ [208]。この考えは、彼の弟子であるマルティン・ハイデガー(1889-1976)に、人間存在の様式を探求することによって存在の意味を明らかにす るよう促した。 [ジャン=ポール・サルトルは人間の存在、自由、意識の観点から存在と無の関係を考察することによってハイデガーの哲学に反応した[210]。 ニコライ・ハルトマン(1882-1950)は現象学的方法に基づいて、現実を無生物、生物学的、心理学的、精神的の4つのレベルに分ける複雑な階層的存 在論を展開した[211]。  アレクシウス・マイノングの写真 アレクシウス・マイノングは、存在しない物体があると提唱した。 アレクシウス・マイノン(1853-1920)は、存在しない物体を存在の一部として含む存在論的理論を提唱し、物議を醸した[212]。この理論に反論 して、バートランド・ラッセル(1872-1970)は論理的原子論として知られる事実存在論を定式化した。この考え方は初期のルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲン シュタイン(1889-1951)によってさらに洗練され、D.M.アームストロング(1926-2014)の存在論に影響を与えた[213]。対照的に アルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッド(1861-1947)は過程存在論を展開していた[214]。ルドルフ・カルナップ(1891-1970)は、存 在するものは自分の言語的枠組みに依存すると主張することによって、存在論的理論の客観性に疑問を呈していた。 [215]彼はウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワイン(1908-2000)に強い影響を与え、彼は存在論的問題を解決するために科学理論の存在論的コ ミットメントを分析した[216]。クワインの弟子であるデイヴィッド・ルイス(1941-2001)は、可能世界は現実世界と同様に現実的で具体的であ るとする様相実在論の立場を定式化した[217]。 |

| Hauntology – Return or

persistence of past ideas |

ハウントロジー

=憑在論 - 過去の観念の回帰または持続 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ontology |

☆

「あ る」「存在する」(ウーシア,ト・オン)という 表現のなかに多様な意味があるだろうというポイントから出発する。存在者が存在者の全体であることの全体を指摘するのが存在論。しかし、ハイデガーは「存 在とはなにか?」という問いを隠蔽する——隠したり不問にしたりすること——したのだと指摘して、西洋の存在論には、存在忘却(後述)が綿々と続いてきた と指摘し、古代以来眠っていた存在論の近代的議論の再燃に貢献した。

ブ レンターノ学位論文、Franz Brentano, Von der mannigfachen Bedeutung des Seienden nach Aristoteles. 1862年は、113年後にRolf George により英訳"On the several senses of being in Aristotle"として、カリフォルニア大学出版会から出版されました。「私の仕事の途上において、最初に出会った本が、1907年以来何度も何度 も、Franz Brentano の Von der mannigfachen Bedeutung des Seienden nach Aristoteles だったのです」——このハイデガーの言葉は『言葉への途上』に収載されています。(ブレンターノの本の英訳の解説より)。ブレンターノが整理した、4つの 存在(様式)とは、1. Accidental Being, 2. Being in the Sense of Being True, 3. Potential and Actual Being, 4. Being According to the Figure of the Categories. ですが、最後の4つ目のものについては、15の命題を立てて、存在とカテゴリーの関係(後者は、語の存在様式=秩序という観点から「文法概念」が多用され て)を詳しく検討しています。下記の2つの図は、そこからとられたものです。

Source:

Franz Brentano,

On the several senses of being in Aristotle, University of California

Press, 1975.

「具体化した=身体化したコミュニケーション技術」中の「附論:アリストテレスの存在論」を参照

■

その後の展開

ハー バート・スペンサー(=進化主義的な経験論 者):「「最低の実在性しかもたないものは、もっとも脆く、もっとも微かな、もっとも捕えがたい、もっともうぶなものであり、まっ先にあらわれやすく、非 存在につづいて最初にあらわれるだろう。そして、同様な漸進的なやり方で、より高度な実在性がすこしずつ加えられ、やがてこの全宇宙ができあがったのだ」 と」考えた(ジェイムズ 1968:288)。

ス ピノザ:「他の人びとにとっては、存在の極小値で はなくて極大値が、知性にとって最初のものと考えられた。『ある 物が完全性をもつということは、その物が存在することをさまたげるものではなく、かえって それが存在することを根拠づける』とスピノザは言った」(ジェイムズ 1968:288)。

ア ンセルムスの証明(=存在論的証明):「ある方向 において事物の存立を困難にさせるのは、その事物のぶつかる妨害物であり、この場合、その事物が弱小であればあるほど、妨害物はその事物にたいしていっそ う力をふるうようになる。ある事物は、きわめて偉大で包括的であるがゆえに、存在するということをその本性にふくんでいる」(ジェイムズ 1968:288)。

※

アンセルムス『プロスロギオン』かつデカルト『省

察』

神 の存在証明の大枠:「不完全とみられるものは何ら かの点で欠けるところのあるものだが、存在を欠いていることもあろう。しかし、とくに「もっとも完全な存在」と定義されている神が何かを欠いているとすれ ば、そうした神は神の定義と矛盾するだろう。したがって、神は存在を欠くことはできない。つまり、神は「もっとも完全な存在」であると同時に、「必然的な 存在」であり、「もっとも実在的な存在」である」(ジェイムズ 1968:288)。

ヘー ゲルによる「存在と非存在」を媒介する方法:で も、それは満足できるものではないとジェイムズは言う。

「へー ゲルは『論理学』のはじめのところで、存在 (有)と非存在(無)を媒介する他の方法を追求している。その要点はこうだ。抽象的な意味での「存在」、つまりのっペらぼうのたんなる存在は、特殊な存在 の姿をまったくもたないことを意味するから、「無」と区別できない。したがって、抽象的な意味での「存在」と「無」というこつの概念は同一であるという考 えがなりたち、この同一性は右の二つの概念の一方から他方を導きだすのに何か役にたつかもしれない。こうヘーゲルは漠然と考えたのだろう」(ジェイムズ 1968:288)。

【引 用者による補足説明】

「パ

ルメニデスは存在と思惟との同一性を主張し、ア

リストテレスは己れ自身をその総体において永遠に思惟する存在について語り、スピノザはデカルトから着想を得て思惟は実体の属性であると述べ、シェリング

はそれから着想を得ていたのであった。へーゲルは、自己の哲学に先行するもろもろの哲学のこのような結果に反駁せず、ただ、このような哲学が思い描いてい

た存在と思惟との関係は何ら注目すべきものをもっていない、と述べるに留める」——アレクサンドル・コージェブ「ヘーゲル哲学における死の概念」

p.379『ヘーゲル読解入門』上妻精・今野雅方訳、国文社、1987年

未 解決の問題:「存在の出現するプロセスは、一挙に 全部あらわれるか、すこしずつあらわれるかのいずれかであるが、それはいかにして知的に理解されうるかという論理的な謎は、まったく手つかずのまま残され ている」。ただし、哲学者は、そのような神や存在の質料やエネルギーの増減はないと考えるという矛盾した態度をとりつづける。

「存 在がしだいに発展してきたものとすれば、もちろ ん、存在の量はつねに同一ではなかったはずだし、これから先も同一ではないだろう。だが、たいていの哲学者はこうした考えをおかしいと考えてきた。つま り、かれらは神も質料もエネルギーも増減の余地のないものと考えたのだ。実在の量はいかなることがあろうと保存されるはずであり、わたしたちの現象的経験 の消長は、実在の深部にはふれない上面(うわつら)だけの現象とみるべきだ、というのが正統派の考え方である」(ジェイムズ 1968:289)。

■ ウィリアム・ジェイムズにとって、存在の問題に関 する、きわめて明確な「態度の決定」の立場

起源のことを問いかけたり、なぜそうなるかと、考えるよりも、それが何であ

るのかということを明らかにせよ!

「存 在の問題は哲学の問題のうちでもっともむずかし い。この問題にかんするかぎり、わたしたちは、みんな、与える立場ではなく与えられる立場、つまり物乞いの立場にあり、いかなる学、派も、他の学派をあな どったり、他の学派を見くだしたような態度をとることはできない。なぜなら、事実というものが、みんなにとってひとしく説明の余地のない与件をなしている から。事実は何らかの仕方で成立するのだが、それがどこからあらわれるのかとか、なぜあらわれるのかということよりは、むしろそれが何であるかを明らかに するのが、わたしたちの仕事である」(ジェイムズ 1968:289)。

■ ハイデガーの「不毛な」存在論=形而上学談義であ る「存在忘却(Seinsvergessenheit)」 について

ハ イデガーは、端的に哲学は存在論だと主張してはば からない(ハイデッガー 2009:64)。

「哲

学は「存在論」である。しかも徹底した存在論であり、かつそうしたものとして、現象学的な存在論(実存的、史的--

精神史的に)、もしくは存在論的現象学なのである。(どれを強調するかは、そのつど論争上の立場の設立がどのように敵対

者に向けられているかによる)。哲学の対象、有としての有るものは、それ自身から(原理性格)ふるまいを共に規定する。

ふるまいにおいては、自らの有が原理的なものとして問題である。認識するふるまいは、有としての有るものに対して、ま

ったく原初的かつ根底的な仕方での原理的関係を持つ(その関係は、態度および把捉すること、論ずることではない。その

ふるまいが、把捉することを通してさえ、また把捉することを通してまさに、自らの把捉する当のもので「有り」、またそ

のふるまいは、自らがそうで「有る」ところのものを把捉する、という関係なのである」(ハイデッガー 2009:4)。

基 礎的存在論=現存在の形而上学の第1段階である。

ハ イデガーにとって基礎的形而上学は、人間の存在を 通路とするものである。

そ れと同時に、存在論や形而上学においては、存在者 =das Seiendeとその存在者性=Seiendeheit を問題とする。そこでハイデガーは、(人びとは?)存在者と、存在者をたらしめる存在=Seinを区別すること(しなければならないこと?)を、忘れてい る=忘却していると主張する。これを存在忘却というが、その嚆矢は、なんとアリストテレスそのものである(先述)。(※ハイデガー自身は、自分もまた存在 忘却するような存在ではない、なぜなら、君たちは忘れているよと指摘して、いるわけだから、自分はそれを知る希有な存在、つまり形而上学の本質がわかる存 在、あるいは自分は神だ、ないしは、神のような超越論的な立場を持っていると言っているようなものであるからだ)。また、ハイデガーによると、そのような 存在暴力という(認識論的病気が蔓延している)この世界で、存在の語りかけ(音声言語の比喩を使っていることに注意せよ!)を「待つ」ことが重要である。 語りかけを「待つ」というのも比喩表現である。聞こえることを待つということは、存在を視覚表象をとおして認識することではなく、じっとして耳をすます と、存在からの声が聞こえるという比喩を使う。

そ のようなハイデガーにとって重要な用語を「存在 論的差異= ontologische Differenz」という。つまり、存在論的差異(ontologische Differenz)とは、(A)「君が存在する、僕が存在する、机が存在する、……」という具体的事物の存在と、(B)「存在(という概念)が存在す る」という意味の差異(ちがい)のことである。

い ずれにせよ、存在の語りかけを待つことが人間の責 務であると、ハイデガーは唱える。

参

照:「存在忘却」(コトバンク)https://goo.gl/UgT6oq

■ クワインとオントロジー(Ontologucal Commitment, by Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

"Meta-ontology

concerns

itself with the nature and methodology of ontology, with the

interpretation and significance of ontological questions such as those

exhibited above. The problem of ontological commitment is a problem in

meta-ontology rather than ontology proper. The meta-ontologist asks

(among other things): What entities or kinds of entity exist according

to a given theory or discourse, and thus are among its ontological

commitments? Having a criterion of ontological commitment for theories

is needed, arguably, if one is to systematically and rigorously attack

the problem of ontology: typically, we accept entities into our

ontology via accepting theories that are ontologically committed to

those entities. A criterion of ontological commitment, then, is a

pre-requisite for ontological inquiry."

"Quine's criterion of ontological commitment has dominated ontological discussion in analytic philosophy since the middle of the 20th century; it deserves to be called the orthodox view. For Quine, such a criterion played two distinct roles. First, it allowed one to measure the ontological cost of theories, an important component in deciding which theories to accept; it thus provided a partial foundation for theory choice. Moreover, once one had settled on a total theory, it allowed one to determine which components of the theory were responsible for its ontological costs (see Quine (1960: 270) for the purported benefits of such ontological bookkeeping). Second, it played a polemical role. It could be used to argue that opponents' theories were more costly than the theorists admitted (see Church (1958), who wields the criterion polemically against Ayer, Pap, and Ryle). And it could be used to advance a traditional nominalist agenda because, as Quine saw it, ordinary subject-predicate sentences carry no ontological commitment to properties or universals.

「メ タ存在論は、存在論の本質と方法論、そして上に 示したような存在論的問題の解釈と意義に関わる。存在論的コミットメントの問題は、存在論というよりむしろメタ存在論の問題である。メタ存在論者は(とり わけ)こう問う: ある理論や言説によれば、どのような実体や種類の実体が存在するのか。理論に対する存在論的コミットメントの基準を持つことは、存在論の問題を体系的かつ 厳密に論じるために必要なことである。存在論的コミットメントの基準は、存在論的探究の前提条件である」。

「ク

ワインの存在論的コミットメントの基準は、20

世紀半ば以来、分析哲学における存在論的議論を支配してきた。クワインにとって、このような基準は2つの異なる役割を果たした。第一に、どの理論を受け入

れるべきかを決定する上で重要な要素である、理論の存在論的コストを測定することを可能にし、理論選択のための部分的な基礎を提供した。さらに、一旦全体

的な理論が決まれば、その理論のどの構成要素が存在論的コストの原因となっているかを判断することができる(このような存在論的簿記の利点については

Quine (1960:

270)を参照)。第二に、それは極論的な役割を果たした。反対者の理論が、理論家が認める以上にコストがかかっていることを論証するために使うことがで

きた(Church (1958)

を参照)。また、クワインが考えたように、通常の主語述語文は性質や普遍性に対する存在論的なコミットメントを持たないため、伝統的な名辞論者のアジェン

ダを推進するために使われることもあった」。

The

locus classicus for

Quine's criterion is “On What There Is”. Quine writes:

A theory is committed to those and only those entities to which the bound variables of the theory must be capable of referring in order that the affirmations made in the theory be true. (Quine 1948: 33)

To illustrate: if a theory contains a quantified sentence ‘∃x Electron(x)’, then the bound variable ‘x’ must range over electrons in order for the theory to be true; and so the theory is ontologically committed to electrons. (For an introduction to the logic of quantifiers and bound variables, the basics of which are presupposed in this article, see Shapiro (2013).)

Talk of “commitment” has an unfortunate connotation: it applies more naturally to persons than to theories. But Quine's criterion should be understood as applying to theories primarily, and to persons derivatively by way of the theories they accept (Quine 1953: 103). It would be more perspicuous to speak simply of the existential implications, or ontological presuppositions, of a theory. But ‘ontological commitment’ is well entrenched, and it would be pointless to try to avoid it.

It is important to note at the start that Quine's criterion is descriptive; it should not be confused with the prescriptive account of ontological commitment that is part of his general method of ontology. That method, roughly, is this: first, regiment the competing theories in first-order predicate logic; second, determine which of these theories is epistemically best (where what counts as “epistemically best” depends in part on pragmatic features such as simplicity and fruitfulness); third, choose the epistemically best theory. We can then say: one is ontologically committed to those entities that are needed as values of the bound variables for this chosen epistemically best theory to be true. Put like this, the account may seem circular: ontological commitment depends on what theories are best, which depends in part on the simplicity, and so the ontological commitments, of those theories. But there is no circularity in Quine's ontological method. The above account of ontological commitment is prescriptive, and applies to persons, not to theories. What entities we ought to commit ourselves to depends on a prior descriptive account of what entities theories are committed to. The prescriptive account of ontological commitment serves as a crucial premise in the Quine-Putnam indispensability argument for the existence of abstract entities (the locus classicus is Putnam 1971). This article, however, will focus entirely on descriptive criteria of ontological commitment."

ク

ワインの基準の古典は『あるものについて』である。クワインはこう書いている:

理論は、その理論における肯定が真であるために、その理論の束縛変数が参照しなければならない実体にのみ委ねられる。 (Quine 1948: 33)

例えるなら、ある理論に「∃x

Electron(x)」という量化文が含まれている場合、その理論が真であるためには、束縛変数「x」が電子の範囲を超えなければならない。したがっ

て、理論は存在論的に電子にコミットしていることになる(量化子と束縛変数の論理の入門については、この記事で前提にしている基本的なことは、

Shapiro (2013)を参照されたい)。

コミットメント」という言葉には不幸な含意がある。しかし、クワインの基準は主に理論に適用され、彼らが受け入れる理論によって人に派生的に適用されると

理解すべきである(Quine 1953:

103)。理論の実存的含意、すなわち存在論的前提について単純に語る方が、より明瞭であろう。しかし、「存在論的コミットメント」は確固たるものであ

り、それを避けようとしても無意味である。

クワインの基準は記述的なものであり、彼の存在論の一般的方法の一部である存在論的コミットメントの規定的説明と混同してはならない。その方法とは、第一

に、競合する理論を一階述語論理で整理し、第二に、これらの理論のうちどれが認識論的に最良であるかを決定し(ここで、何を「認識論的に最良」とするか

は、単純さや実り多さといったプラグマティックな特徴に依存する部分もある)、第三に、認識論的に最良の理論を選択する、というものである。第三に、認識

論的に最良の理論を選択する。そして、この選択された認識論的に最良の理論が真であるために、束縛変数の値として必要とされる実体に存在論的にコミットす

る、と言うことができる。つまり、存在論的コミットメントは、どのような理論が最良であるかに依存し、その理論の単純さ、つまり存在論的コミットメントに

部分的に依存するのである。しかし、クワインの存在論的方法には循環性はない。上記の存在論的コミットメントの説明は規定的であり、理論ではなく人物に適

用される。私たちがどのような存在にコミットすべきかは、理論がどのような存在にコミットするかという事前の記述的説明に依存する。存在論的コミットメン

トの記述的説明は、抽象的実体の存在に関するクワイン=パットナムの必須性論証(古典的典拠はパットナム1971年)の重要な前提となっている。しかし、

本稿では、存在論的コミットメントの記述的基準に全面的に焦点を当てる。"

■ オントロジーをみる眼をエピステモロジーとする と、世界はどのように見えるだろうか?(思考実験)→「デサナ・プロジェクト 2010」

単 純なオントロジー(存在論)とエピステモロジー (認識論)の図式で理解可能である。例えばハリウッド映画の『ブレードランナー』は1つ、『マトリクス』は2つ、世界がある。

● 視線とオントロジー(存在論)——見られていると自分の存在を感じるのはなぜ?

● マトリクス・オントロジー

「ウォ

シャウスキー兄弟の監督になるいわゆる「マト

リクス三部作」すなわち"The Matrix"(1998), "The Matrix Reloaded"(2003), "The Matrix

Revolutions"(2003)

は非常に奇妙な映画である。にもかかわらず多くのSF映画ファンを魅了してきており、金字塔と評する熱心なカルトファンも多い。その魅力はそれまでのSF

映画が自己主張していたエージェントやギミックの魅力よりも「現実」と「仮想現実」を対等に並置し、主人公がその往還をおこない自己探求するというダイナ

ミズムにあるように思われる。人類学者にとって民話・神話・インフォーマントの語りなどのいわゆる口頭伝承が、当該文化や社会の分析にとって重要な資料と

なったり、当の社会の人びとが「考えるのに適している」ためにこのような口頭伝承をさまざまな行動を誘発させる原動力としていることをみても、マトリクス

三部作についてそれを題材として取り上げることは僅かばかりでも意味のあることだと思われる」マトリクスオントロジー)。

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆