Hauntology,

ひょうざいろん

Hauntology,

ひょうざいろん

憑在論(ひょうざいろん:ハウントロ ジー:hauntology, L'hantologie)あるいは憑在学(ひょうざいがく)とは、ジャッ ク・デリダの『マルクスの亡霊たち』(原著, 1993/2007a:37)に登場する用語で、「存在でもないが、かといって不在でもない、死んでいるのでもないが、かといって生きているでも ない」ような亡霊の姿をとってあらわれる、延期されたオリジナル(res extensa)ではないものよっ て表現される、置き換えられた、時間的・歴史的・存在論的脱節(temporal, historical, and ontological disjunction)の状態のことをさす。我々が常態的であると信じ込んでいる、オリジナル(本物性)とアイデンティティ(同一性)、オリジナルものの存在的な ゆるぎのなさ(→存在論)、を解体するデリダ流の脱構築の方法のレパートリーとしてみることができる。

これは、ただ単に人を驚かすのみならず、 存在するもののゆるぎのなさが、解体する/別のものによりハックされる、されることで、存在するものと そのアイデンティティを、後者を別のもので置き換えることを通して、存在してきたものの意味をずらし、解体し、そして見直す、認識論的な方法であるとも言 える。

ハウントロジーが存在論の正反対であるという考え方も成り立つが、複数の存在や消え去ってしまった過去[観念があたかも]存在[するかもごとき]回帰したり持続するものとしてハウントロジーを考えると。ハウントロジーは存在論を包摂するものであるとも考えることができる。

つまり、幽霊や亡霊、あるいはそれに憑依

されることを、単なる文化的信念や文学的(あるいは修辞的)虚構として簡単に片付けないことであ

る(→「マルクスの亡霊たち」)。

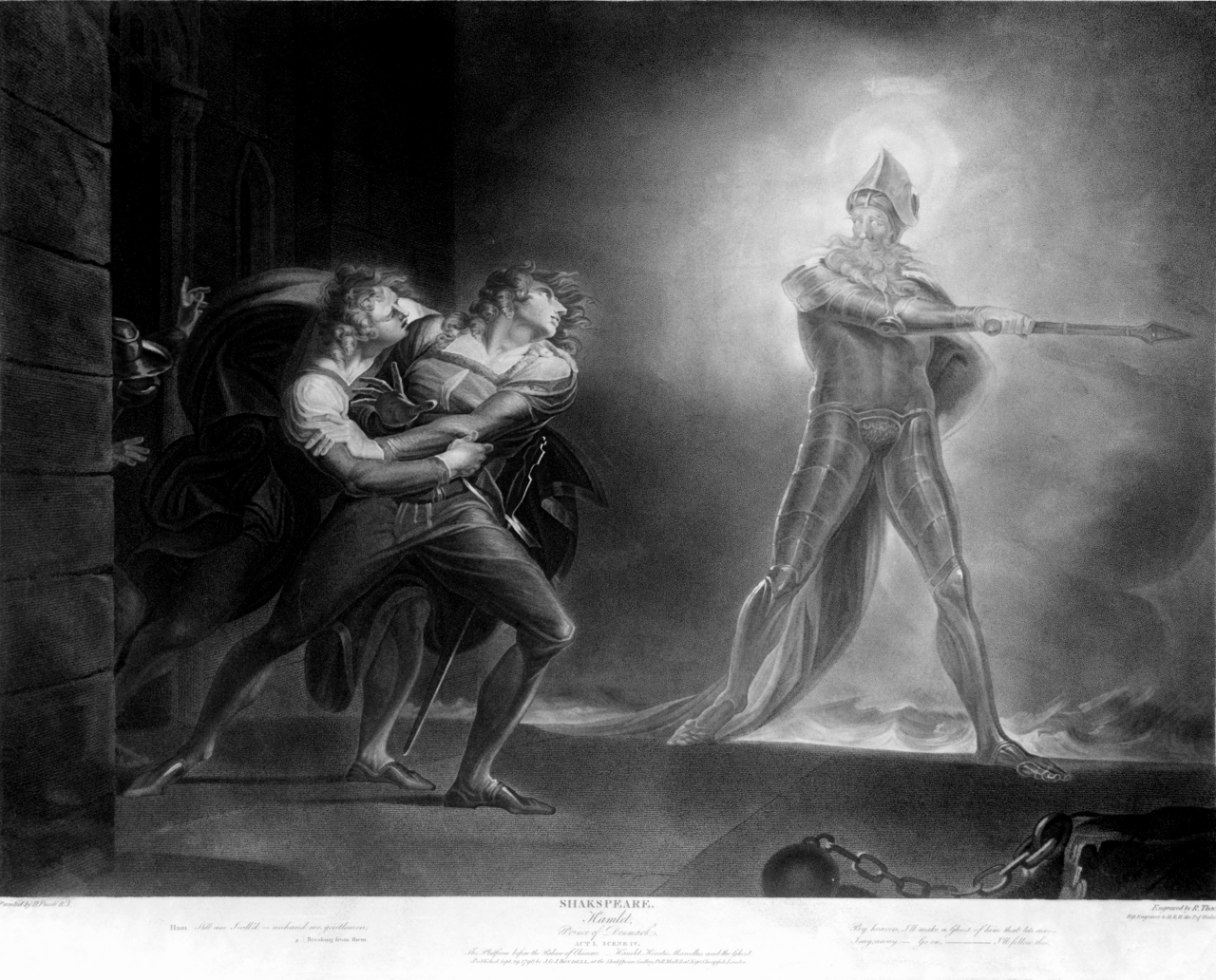

| Hauntology Hauntology (a portmanteau of haunting and ontology, also spectral studies, spectralities, or the spectral turn) is a range of ideas referring to the return or persistence of elements from the social or cultural past, as in the manner of a ghost. The term is a neologism first introduced by French philosopher Jacques Derrida in his 1993 book Spectres of Marx. It has since been invoked in fields such as visual arts, philosophy, electronic music, anthropology, criminology,[1] politics, fiction, and literary criticism.[2] While Christine Brooke-Rose had previously punned "dehauntological" (on "deontological") in Amalgamemnon (1984),[3] Derrida initially used "hauntology" for his idea of the atemporal nature of Marxism and its tendency to "haunt Western society from beyond the grave".[4] It describes a situation of temporal and ontological disjunction in which presence, especially socially and culturally, is replaced by a deferred non-origin.[2] The concept is derived from deconstruction, in which any attempt to locate the origin of identity or history must inevitably find itself dependent on an always-already existing set of linguistic conditions.[5] Despite being the central focus of Spectres of Marx, the word hauntology appears only three times in the book, and there is little consistency in how other writers define the term.[6] In the 2000s, the term was applied to musicians by theorists Simon Reynolds and Mark Fisher, who were said to explore ideas related to temporal disjunction, retrofuturism, cultural memory, and the persistence of the past. Hauntology has been used as a critical lens in various forms of media and theory, including music, aesthetics, political theory, architecture, Africanfuturism, Afrofuturism, Neo-futurism, Metamodernism, anthropology, and psychoanalysis.[2][failed verification][7][page needed] Due to the difficulty in understanding the concept, there is little consistency in how other writers define the term.[6]  Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, Act I, Scene IV by Henry Fuseli (1789) |

ハウントロジー(憑在論) ハウントロジー(憑在論、またはスペクトラル・スタディーズ、スペクト ラリティ、スペクトラル・ターン)とは、社会や文化の過去から、ゴーストのように戻ってくる、あるいは持続する要素を指す一連の概念である。この用語は、 フランスの哲学者ジャック・デリダが1993年の著書『マルクスの亡霊』で初めて使用した新語である。それ以来、視覚芸術、哲学、電子音楽、人類学、犯罪 学、政治、フィクション、文学批評などの分野で使用されるようになった。 クリスティン・ブルック=ローズは1984年の著書『アマルガメイテッド』で「デオントロジー(義務論)」をもじって「デホントロジ(脱義務論)」という 言葉を使っていたが[3]、デリダは当初、「ハウントロジー(憑在論)」という言葉 をマルクス主義の非時間的な性質と、「墓場から西洋社会に憑依する」という傾向を表現するために使っていた[4]。 社会的、文化的に存在するものが、先延ばしにされた起源ではないものに置き換えられるという状況を指す。[2] この概念は脱構築から派生したもので、アイデンティティや歴史の起源を特定しようとする試みは、常にすでに存在する言語的条件に依存していることを避けら れない。[5] 『マルクスの亡霊』の中心的なテーマであるにもかかわらず、ハウントロジーという言葉は同書では3回しか登場せず、他の著者がこの用語を定義する方法には 一貫性がほとんどない。[6] 2000年代には、音楽理論家のサイモン・レイノルズとマーク・フィッシャーが、この用語を音楽家に適用した。彼らは、時間的論理和、レトロフュー チャー、文化的な記憶、過去の持続性に関連するアイデアを探求していると言われている。ハウントロジー=憑在論は、音楽、美学、政治理論、建築、アフリカ 未来主義、アフロ未来主義、ネオ未来主義、メタモダニズム、人類学、精神分析など、さまざまなメディアや理論における批評的なレンズとして用いられてき た。[2][検証失敗][7][要ページ番号] 概念の理解が難しいことから、他の作家がこの用語を定義する方法には一貫性がほとんどない。[6]  ハムレット、デンマークの王子』 第1幕 第4場byヘンリー・フューセリ(1789年) |

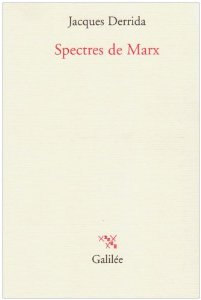

| Development Precursors Main article: Ghost Hauntings and ghost stories have existed for millennia, and reached a heyday in the West during the 19th century.[8] In cultural studies, Terry Castle (in The Apparitional Lesbian) and Anthony Vidler (in The Architectural Uncanny) predate Derrida.[9] Spectres of Marx Main article: Spectres of Marx "Hauntology" originates from Derrida's discussion of Karl Marx in Spectres of Marx, specifically Marx's proclamation that "a spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism" in The Communist Manifesto. Derrida calls on Shakespeare's Hamlet, particularly a phrase spoken by the titular character: "the time is out of joint".[5] The word functions as a deliberate near-homophone to "ontology" in Derrida's native French (cf. "hantologie", [ɑ̃tɔlɔʒi] and "ontologie", [ɔ̃tɔlɔʒi]).[10] Derrida's prior work on deconstruction, on concepts of trace and différance in particular, serves as the foundation of his formulation of hauntology,[2] fundamentally asserting that there is no temporal point of pure origin but only an "always-already absent present".[11] Derrida sees hauntology as not only more powerful than ontology, but that "it would harbor within itself eschatology and teleology themselves".[12] His writing in Spectres is marked by a preoccupation with the "death" of communism after the 1991 fall of the Soviet Union, in particular after theorists such as Francis Fukuyama asserted that capitalism had conclusively triumphed over other political-economic systems and reached the "end of history".[5] 5. Fisher, Mark. "The Metaphysics of Crackle: Afrofuturism and Hauntology". Dance Cult. 6. Whyman, Tom (31 July 2019). "The ghosts of our lives". New Statesman. Despite being the central focus of Spectres of Marx, the word hauntology appears only three times in the book.[6] Peter Buse and Andrew Scott, discussing Derrida's notion of hauntology, explain: Ghosts arrive from the past and appear in the present. However, the ghost cannot be properly said to belong to the past .... Does then the 'historical' person who is identified with the ghost properly belong to the present? Surely not, as the idea of a return from death fractures all traditional conceptions of temporality. The temporality to which the ghost is subject is therefore paradoxical, at once they 'return' and make their apparitional debut [...] any attempt to isolate the origin of language will find its inaugural moment already dependent upon a system of linguistic differences that have been installed prior to the 'originary' moment (11).[5] +++++++++++++++++++++++ Ghosts arrive from the past and appear in the present. However, the ghost cannot be properly said to belong to the past. . . . Does then the ‘historical’ person who is identified with the ghost properly belong to the present? Surely not, as the idea of a return from death fractures all traditional conceptions of temporality. The temporality to which the ghost is subject is therefore paradoxical, at once they ‘return’ and make their apparitional debut. Derrida has been pleased to call this dual movement of return and inauguration a ‘hauntology’, a coinage that suggests a spectrally deferred non-origin within grounding metaphysical terms such as history and identity. This idea will be familiar from other Derridean discussions of event and causality in essays such as “Before The Law”, and “Signature Event Context”. . . . Such an idea also informs the well-known discussion of the origin of language in Of Grammatology, where . . . any attempt to isolate the origin of language will find its inaugural moment already dependent upon a system of linguistic differences that have been installed prior to the ‘originary’ moment (Buse and Scott 1999: 11). +++++++++++++++++++++++ 5. Fisher, Mark. "The Metaphysics of Crackle: Afrofuturism and Hauntology". Dance Cult. 6. 6. Whyman, Tom (31 July 2019). "The ghosts of our lives". New Statesman. In music See also: Hauntology (music) In the 2000s, the term was taken up by critics in reference to paradoxes found in postmodernity, particularly contemporary culture's persistent recycling of retro aesthetics and incapacity to escape old social forms.[5] Writers such as Mark Fisher and Simon Reynolds used the term to describe a musical aesthetic preoccupied with this temporal disjunction and the nostalgia for "lost futures".[4] So-called "hauntological" musicians are described as exploring ideas related to temporal disjunction, retrofuturism, cultural memory, and the persistence of the past.[13][14][5] |

発展 先駆者 詳細は「ゴースト」を参照 心霊現象や心霊物語は何千年も前から存在しており、西洋では19世紀に最盛期を迎えた。[8] カルチュラル・スタディーズの分野では、テリー・キャッスル(『The Apparitional Lesbian』)やアンソニー・ヴィドラー(『The Architectural Uncanny』)がデリダより先行している。[9] マルクスの亡霊(下で説明) 詳細は「マルクスの亡霊たち」を参照 「ハウントロジー=憑在論」は、デリダが『マルクスの亡霊』でカール・マルクスを論じたことから始まった。特にマルクスの『共産党宣言』における「共産主 義という亡霊がヨーロッパを徘徊している」という宣言である。デリダはシェイクスピアの『ハムレット』、特にタイトルロールのキャラクターが発する 「the time is out of joint」というフレーズを引用している。[5] この言葉は、デリダの母国語であるフランス語では「存在論」とほぼ同音異義語として機能する(「hantologie」[ɑ̃tɔlɔʒi]と 「ontologie」[ɔ̃tɔlɔʒi]を参照)。[10] とりわけ痕跡と差延の概念に関する脱構築に関するデリダの先行研究は、ハウントロジー=憑在論の定式化の基礎となっている。[2] 基本的には、純粋な起源となる時点は存在せず、「常にすでに不在である現在」のみが存在するという主張である。[11] デリダは、ハウントロジー=憑在論は存在論よりも強力であるだけでなく、「 終末論と目的論そのものを内包する」と述べている。[12] 『スペクター』における彼の著作は、1991年のソビエト連邦崩壊後の共産主義の「死」に対する強い関心によって特徴づけられ、特にフランシス・フクヤマ などの理論家が資本主義が他の政治経済システムに決定的に勝利し、「歴史の終わり」に達したと主張した後のことである。[5] 5. Fisher, Mark. "The Metaphysics of Crackle: Afrofuturism and Hauntology". Dance Cult. 6. Whyman, Tom (31 July 2019). "The ghosts of our lives". New Statesman. 『マルクスの亡霊』の中心的なテーマであるにもかかわらず、ハウントロ ジーという言葉は本書ではわずか3回しか登場しない[6] 。ピーター・ビューズとアンドリュー・スコットは、デリダのハウントロジーの概念について論じ、次のように説明している。 幽霊は過去からやって来て現在に現れる。しかし、幽霊は過去に属しているとは正しく言えない。では、幽霊と同一視される「歴史的な」人物は、現在に属して いると言えるだろうか?死からの回帰という考え方は、時間性に関するあらゆる伝統的な概念を打ち砕くものであるため、それはありえない。したがって、亡霊 が従属する時間性は逆説的であり、亡霊が「戻ってきて」幽霊としてデビューする瞬間は、言語の起源を切り離そうとするあらゆる試みは、その始まりの瞬間が すでに「起源的」な瞬間以前に設置された言語の差異の体系に依存していることを明らかにする(11)。[5],p.44. +++++++++++++++++++++++ 幽霊は過去からやって来て、現在に姿を現す。しかし、その幽霊は過去に 属しているとは正しく言えない。では、幽霊と同一視される「歴史上の」人物は、現在に属しているのだろうか? 死からの回帰という考え方は、あらゆる伝統的な時間概念を破壊するものであるため、それはありえない。したがって、幽霊が従属する時間性は逆説的であり、 幽霊は「戻って」きて幽霊としてデビューする。デリダは、この「帰還」と「始動」という二重の動きを「ハウントロジー=憑在論」と呼び、喜んで受け入れて いる。この造語は、歴史やアイデンティティといった形而上学的な用語を基盤とする中で、幽霊のように先送りされた起源を示唆するものである。この考え方は、デリダの「法以前」や「署名・出来事・文脈」といった著作における出来事や因果関係に関する議論から、おなじみのものとなっている。。 このような考え方は、よく知られた『グラマトロジーについて』における言語の起源に関する議論にも見られる。言語の起源を特定しようとする試みは、その起 源の瞬間が訪れる以前にすでに存在していた言語上の差異の体系に依存していることがわかるだろう(Buse and Scott 1999: 11)。 +++++++++++++++++++++++ 5. Fisher, Mark. "The Metaphysics of Crackle: Afrofuturism and Hauntology". Dance Cult. 6. 6. Whyman, Tom (31 July 2019). "The ghosts of our lives". New Statesman. 音楽における 参照:ハウントロジー(音楽) 2000年代には、ポストモダニティに見られるパラドックス、特に現代文化におけるレトロな美学の根強いリサイクルと古い社会形態からの脱却の不可能性を 指して、この用語が批評家によって用いられるようになった。マーク・フィッシャーやサイモン・レイノルズといった作家は、この用語を用いて この時間的並行と「失われた未来」への郷愁に心を奪われた音楽的美学を表現するために用いた。[4] いわゆる「ハウントロジー=憑在論」の音楽家たちは、時間的並行、レトロフューチャー、文化的な記憶、過去の持続に関連するアイデアを探求していると表現 されている。[13][14][5] |

| In anthropology Anthropology has seen a widespread usage of hauntology as a methodology across ethnography, archaeology, and psychological anthropology. In 2019 Ethos, the journal of the Society for Psychological Anthropology dedicated a full issue to hauntology, titled Hauntology in Psychological Anthropology, and numerous books and journal articles have since appeared on the topic. In a book titled The Hauntology of Everyday Life, psychological anthropologist Sadeq Rahimi asserts, "the very experience of everyday life is built around a process that we can call hauntogenic, and whose major by-product is a steady stream of ghosts."[15] As method Justin Armstrong, building on Derrida, proposes a "spectral ethnography" that "sees beyond the boundaries of actually spoken language and direct human contact to the interplay between space, place, objects, and temporality".[16] Jeff Ferrell and Theo Kidynis, building on Armstrong, have developed further ideas of "ghost ethnography".[17] Primary and secondary hauntings See also: Primary source – First-hand account of information and Secondary source – Document that discusses information originally presented elsewhere Anthropologists Martha and Bruce Lincoln make a distinction between primary hauntings, in which the haunted recognize the reality and autonomy of metaphysical entities in relatively uncritical, literal manner; and secondary hauntings, which identify "textual residues" history, or as tropes for "collective intrapsychic states" such as trauma and grief. As a case study, they use the example of Ba Chúc's secondary haunting, in which the state-controlled museums display the skulls of the dead and memorabilia, as opposed to traditional Vietnamese burial customs. This is contrasted with the "primary haunting" of Ba Chúc, the paranormal activity said to occur at an execution site marked by a tree.[18] Kit Bauserman notes that for literary and critical theorists, the ghost is "pure metaphor" and "a fictional vessel that co-opts their social agenda", whereas ethnographers and anthropologists "come the closest to engaging ghosts as beings".[19] Some scholars have argued that the "neat distinction quickly breaks down in ethnographic analysis" and that "it is far from clear that the presence of ghosts as metaphysical entities is primary."[20] 15. Rahimi, Sadeq (2021). The Hauntology of Everyday Life. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 3. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-78992-3. ISBN 978-3-030-78992-3. 16. Armstrong, Justin (2010-01-26). "On the Possibility of Spectral Ethnography". Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies. 10 (3). SAGE Publications: 243–250. doi:10.1177/1532708609359510. ISSN 1532-7086. S2CID 144608146. 17. Kindynis, Theo (2017-09-17). "Excavating ghosts: Urban exploration as graffiti archaeology". Crime, Media, Culture. 15 (1). SAGE Publications: 25–45. doi:10.1177/1741659017730435. ISSN 1741-6590. S2CID 149232587. 18. Lincoln, Martha; Lincoln, Bruce (2015). "Toward a Critical Hauntology: Bare Afterlife and the Ghosts of Ba Chúc". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 57 (1). Cambridge University Press (CUP): 191–220. doi:10.1017/s0010417514000644. ISSN 0010-4175. S2CID 147023375. 19. Bauserman, Kit (12 September 2022). "Seeing and Speaking to Ghosts: Hauntology's Limits for Understanding Ghosts as Beings". JHI Blog. University of Pennsylvania Press. Retrieved 30 November 2024. 20. Good, Byron J.; Chiovenda, Andrea; Rahimi, Sadeq (2022-10-24). "The Anthropology of Being Haunted: On the Emergence of an Anthropological Hauntology". Annual Review of Anthropology. 51 (1). Annual Reviews: 437–453. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-101819-110224. ISSN 0084-6570. S2CID 251145093. |

人類学では 人類学では、民族誌学、考古学、心理人類学の分野で、ハウントロジーが方法論として広く用いられている。2019年には、心理人類学協会の機関誌『エト ス』がハウントロジーを特集し、その号は『心理人類学におけるハウントロジー』と題された。それ以来、このテーマに関する多数の書籍や学術誌の記事が発表 されている。『The Hauntology of Everyday Life』という著書の中で、心理人類学者のサデク・ラヒミは、「日常生活の経験そのものが、憑在起源的と呼ぶべきプロセスを中心に構築されており、その 主な副産物は絶え間なく生み出されるゴーストである」と主張している。[15] 方法論として ジャスティン・アームストロングは、デリダを基に、「実際に話される言語や直接的な人間的接触の境界を越えて、空間、場所、物体、時間性との相互作用を視 る」という「幽霊民族誌学」を提案している。[16] ジェフ・フェレルとテオ・キディニスは、アームストロングを基に、「幽霊民族誌学」の考え方をさらに発展させている。[17] 一次的および二次的な取り憑き 参照:一次資料 - 情報に関する一次的な証言、二次資料 - 他の場所で提示された情報を論じた文書 人類学者のマーサ・リンカーンとブルース・リンカーンは、取り憑かれた人々が形而上学的な実体の現実性と自律性を比較的批判的ではなく、文字通りの方法で 認識する一次的な取り憑きと、歴史の「テキストの残滓」、あるいはトラウマや悲しみなどの「集団的心的状態」の表現として特定する二次的な取り憑きを区別 している。事例研究として、彼らは、ベトナムの伝統的な埋葬の風習とは対照的に、国家管理の博物館が死者の頭蓋骨や遺品を展示しているバ・チュックの二次 的な祟りの例を挙げている。これは、処刑の場所を示す木がある場所で起こるとされる超常現象であるバ・チュックの「一次的な祟り」と対比されている。 文学および批評理論家にとって、ゴーストは「純粋な隠喩」であり、「彼らの社会的アジェンダを援用するフィクションの器」であるが、民族誌学者や人類学者 は「ゴーストを実体として捉えることに最も近い」と、キット・バウアーマンは指摘している。[19] 一部の学者は、「この明確な区別は民族誌的分析ではすぐに崩壊する」と主張し、「形而上学的な実体としてのゴーストの存在が第一義的であるとは必ずしも言 えない」と述べている。[20] 15. ラヒミ、サデク(2021年)。『日常生活のハウントロジー=憑在論』。ロンドン:パルグレーブ・マクミラン。p. 3. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-78992-3. ISBN 978-3-030-78992-3. 16. Armstrong, Justin (2010-01-26). 「On the Possibility of Spectral Ethnography」. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies. 10 (3). SAGE Publications: 243–250. doi:10.1177/1532708609359510. ISSN 1532-7086. S2CID 144608146. 17. Kindynis, Theo (2017-09-17). 「Excavating ghosts: Urban exploration as graffiti archaeology」. Crime, Media, Culture. 15 (1). SAGE Publications: 25–45. doi:10.1177/1741659017730435. ISSN 1741-6590. S2CID 149232587. 18. リンカーン、マーサ; リンカーン、ブルース (2015年). 「批判的ハウントロジー=憑在論へ:ベトナムの裸の死後とバ・チュックの亡霊」. 『社会と歴史の比較研究』. 57 (1). ケンブリッジ大学出版局 (CUP): 191–220. doi:10.1017/s0010417514000644. ISSN 0010-4175. S2CID 147023375. 19. Bauserman, Kit (2022年9月12日). 「Seeing and Speaking to Ghosts: Hauntology's Limits for Understanding Ghosts as Beings」. JHI Blog. University of Pennsylvania Press. 2024年11月30日閲覧。 20. Good, Byron J.; Chiovenda, Andrea; Rahimi, Sadeq (2022-10-24). 「取り憑かれることの文化人類学:文化人類学的ハウントロジーの出現について」『Annual Review of Anthropology』第51巻第1号。Annual Reviews: 437–453. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-101819-110224. ISSN 0084-6570. S2CID 251145093.[pdf 仮訳 with password] |

| Good, Byron J.; Chiovenda,

Andrea; Rahimi, Sadeq (2022-10-24). "The

Anthropology of Being Haunted: On the Emergence of an Anthropological

Hauntology".

Annual Review of Anthropology. 51 (1). Annual Reviews: 437–453.

doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-101819-110224. ISSN 0084-6570. S2CID

251145093. Since the appearance of Derrida's Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International in 1994, there has been an outpouring of writing in cultural studies around the themes of hauntology and spectralities. This article asks broadly whether a form of hauntology has emerged within anthropology; if so, when and how it has appeared; and what constitutes such a field as distinctive. This article asks what comprises being haunted as a specific affective state within anthropological writing, what theory of the subject is assumed by such writings, and what distinguishes ethnographic analyses that do not dismiss the presence of ghosts as simply cultural beliefs or literary fictions, as is common in cultural studies. It reviews the literature on the haunting remains of traumatic violence, examines writing that juxtaposes hauntological and ontological theorizing, describes the appearance of an incipient hauntological voice within ethnographic writing, and concludes with a discussion of the emergence of a hauntological ethics. Keywords haunting, hauntology, anthropological hauntology, spectralities, traumatic historical memory, hauntological ethics |

Good, Byron J.; Chiovenda,

Andrea; Rahimi, Sadeq (2022-10-24).

「取り憑かれることの文化人類学:文化人類学的ハウントロジーの出現について」『Annual Review of

Anthropology』第51巻第1号。Annual Reviews: 437–453.

doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-101819-110224. ISSN 0084-6570. S2CID

251145093. 1994年にデリダの『マルクスの亡霊:負債、労働、新国際』が出版されて以来、カルチュラル・スタディーズの分野では、ハウントロジー(憑在論)とスペ クトラリティ(幽霊性)をテーマにした著作が数多く発表されている。本稿では、人類学の分野においてハウントロジーの一形態が現れたかどうか、現れたとす ればそれはいつ、どのようにして現れたのか、また、そのような分野を特徴づけるものは何か、といった点を広く問う。本稿では、人類学の研究において「取り 憑かれること」がどのような特定の情動状態として構成されているのか、また、そうした研究ではどのような主体論が前提されているのか、そして、文化研究で よく見られるように、単なる文化的信念や文学的虚構として幽霊の存在を簡単に片づけない民族誌的分析とはどのようなものなのかを問う。本稿では、トラウマ 的な暴力の残滓に関する文献をレビューし、ハウントロジー=憑在論と存在論を並置する文章を検証し、民族誌的な文章の中に現れ始めたハウントロジー=憑在 論的な声の兆しを描写し、ハウントロジー=憑在論的な倫理の台頭について考察して結論とする。 キーワード 憑依、ハウントロジー、人類学的なハウントロジー、スペクトラル、トラウマ的な歴史的記憶、ハウントロジー=憑在論的な倫理 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hauntology |

|

★マルクスの亡霊たち:Specters of Marx(→「デリダ『マルクスの亡霊たち』」)

Ontological perversion

| Specters of Marx:

The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International

(French: Spectres de Marx: l'état de la dette, le travail du deuil et

la nouvelle Internationale) is a 1993 book by the French philosopher

Jacques Derrida. It was first presented as a series of lectures during

"Whither Marxism?", a conference on the future of Marxism held at the

University of California, Riverside in 1993. It is the source of the

term hauntology. |

『マルクスの亡霊:負債の状態、喪に服する作業、そして新しいインター ナショナル』(仏語:Spectres de Marx: l'état de la dette, le travail du deuil et la nouvelle Internationale)は、フランスの哲学者ジャック・デリダによる1993年の著書である。1993年にカリフォルニア大学リバーサイド校で開 催されたマルクス主義の将来に関する会議「マルクス主義はどこへ向かうのか?」で、一連の講義として初めて発表された。ハウントロジー=憑在論という用語 の起源である。 |

| Summary The title Spectres of Marx is an allusion to Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels' statement at the beginning of The Communist Manifesto that a "spectre [is] haunting Europe." For Derrida, the spirit of Marx is even more relevant since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the demise of communism. With its death the spectre of communism begins to make visits on the Earth. Derrida seeks to do the work of inheriting from Marx, that is, not communism, but of the philosophy of responsibility, and of Marx's spirit of radical critique. Derrida first notes that, in the wake of the fall of communism, many in the west had become triumphalist, as is evidenced in the formation of a neoconservative grouping and the displacement of the left in third way political formations. At the intellectual level, it is apparent in Francis Fukuyama's proclamation of the end of ideology. Derrida commented on the reasons for that spectre of Marx: |

概要 『マルクスの亡霊』というタイトルは、カール・マルクスとフリードリヒ・エンゲルスが『共産党宣言』の冒頭で述べた、「ヨーロッパには亡霊が取り憑いてい る 」という言葉を暗示している。1989年にベルリンの壁が崩壊し、共産主義が終焉して以来、デリダにとってマルクスの精神はさらに重要な意味を持つ。その 死によって、共産主義の亡霊が地球を訪れ始めたのである。デリダは、マルクスから、つまり共産主義からではなく、責任哲学から、そしてマルクスのラディカ ルな批評精神を継承する作業を行おうとしている。デリダはまず、共産主義の崩壊後、新保守主義的な集団の形成や、第三極的な政治形成における左派の置き換 えに見られるように、西側の多くの人々が勝利至上主義的になっていたことを指摘する。知的レベルでは、フランシス・フクヤマがイデオロギーの終焉を宣言し たことに表れている。デリダは、マルクスのその亡霊の理由についてこう述べている: |

| For it must be cried out, at a

time when some have the audacity to neo-evangelise in the name of the

ideal of a liberal democracy that has finally realised itself as the

ideal of human history: never have violence, inequality, exclusion,

famine, and thus economic oppression affected as many human beings in

the history of the earth and of humanity. Instead of singing the advent

of the ideal of liberal democracy and of the capitalist market in the

euphoria of the end of history, instead of celebrating the ‘end of

ideologies’ and the end of the great emancipatory discourses, let us

never neglect this obvious macroscopic fact, made up of innumerable

singular sites of suffering: no degree of progress allows one to ignore

that never before, in absolute figures, have so many men, women and

children been subjugated, starved or exterminated on the earth.[1] |

人類史の理想としてついに実現したリベラル・デモクラシーの理想の名の 下に、大胆にも新福音主義を唱える者がいる今、それは叫ばれなければならない。暴力、不平等、排除、飢餓、そして経済的抑圧が、地球と人類の歴史の中で、 これほど多くの人間に影響を与えたことはない。自由民主主義と資本主義市場の理想の到来を、歴史の終わりという陶酔の中で歌うのではなく、「イデオロギー の終わり」と偉大な解放の言説の終わりを祝うのではなく、無数の苦しみの特異な現場からなる、この明白な巨視的事実を決して無視してはならない。 |

| Derrida went on, in his talks on

this topic, to list 10 plagues of the

capital or global system. And

then to an account of the claim the creation of a new grouping of

activism, called the "New International". Derrida's ten plagues are: 1. Employment has undergone a change of kind, i.e. underemployment, and requires "another concept". 2. Deportation of immigrants. Reinforcement of territories in a world of supposed freedom of movement. As in, Fortress Europe and in the number of new walls and barriers being erected around the world, in effect multiplying the "fallen" Berlin Wall manifold. 3. Economic war. Both between countries and between international trade blocs: United States - Japan - Europe. 4. Contradictions of the free market. The undecidable conflicts between protectionism and free trade. The unstoppable flow of illegal drugs, arms, etc. 5. Foreign debt. In effect the basis for mass starvation and demoralisation for developing countries. Often the loans benefiting only a small elite, for luxury items, e.g., cars, air conditioning etc. but being paid back by poorer workers. 6. The arms trade. The inability to control to any meaningful extent trade within the biggest ‘black market’ 7. Spread of nuclear weapons. The restriction of nuclear capacity can no longer be maintained by leading states since it is only knowledge and cannot be contained. 8. Inter-ethnic wars. The phantom of mythic national identities fueling tension in semi-developed countries. 9. Phantom-states within organised crime. In particular the non-democratic power gained by drug cartels. 10. International law and its institutions. The hypocrisy of such statutes in the face of unilateral aggression on the part of the economically dominant states. International law is mainly exercised against the weaker nations. |

デリダはこのテーマに関する講演で、資本やグローバル・システムの10

の災いを挙げた。そして、「ニュー・インターナショナル」と呼ばれる新しい活動家集団の創設を主張する。 デリダの10の災いとは次のようなものである: 1. 雇用は種類の変化、すなわち不完全雇用を経て、「別の概念」を必要とする。 2. 移民の国外追放。移動の自由があるとされる世界における領土の強化。ヨーロッパ要塞のように、また世界中に築かれる新たな壁や障壁の数のように、事実上 「崩壊した」ベルリンの壁を何倍にも増やしている。 3. 経済戦争。国家間でも、アメリカ-日本-ヨーロッパという国際貿易圏の間でも。 4. 自由市場の矛盾。保護主義と自由貿易の間の決定できない対立。違法な麻薬や武器などの流れは止められない。 5. 対外債務。事実上、発展途上国の飢餓と戦意喪失の基盤となっている。多くの場合、自動車やエアコンなどの贅沢品のための借金は一部のエリートにしか利益を もたらさないが、貧しい労働者が返済している。 6. 武器貿易。最大の「闇市場」内の貿易を意味のある範囲で管理することができない。 7. 核兵器の拡散。核兵器は単なる知識であり、封じ込めることはできないため、核兵器保有能力の制限はもはや主要国によって維持することはできない。 8. 民族間戦争。神話的な国民アイデンティティのナショナリズムが、半先進国の緊張を煽っている。 9. 組織犯罪の中にある幻の国家。特に、麻薬カルテルが獲得した非民主的権力である。 10. 国際法とその制度。経済的に支配的な国家による一方的な侵略に直面したときの、そのような法規の偽善。国際法は主に弱い国民に対して行使される。 |

| On the New International,

Derrida has this to say: |

ニュー・インターナショナルについて、デリダは次のように語っている: |

| The 'New International' is an

untimely link, without status ... without coordination, without party,

without country, without national community, without co-citizenship,

without common belonging to a class. The name of New International is

given here to what calls to the friendship of an alliance without

institution among those who ... continue to be inspired by at least one

of the spirits of Marx or of Marxism. It is a call for them to ally

themselves, in a new, concrete and real way, even if this alliance no

longer takes the form of a party or a workers' international, in the

critique of the state of international law, the concepts of State and

nation, and so forth: in order to renew this critique, and especially

to radicalise it.[2] |

新インターナショナル」は、時期尚早の結びつきであり、地位もな

く......協調もなく、党もなく、国もなく、国民共同体もなく、共同市民権もなく、階級への共通の帰属もない。新インターナショナルの名

は、......マルクスまたはマルクス主義の精神の少なくとも一つに鼓舞され続ける人々の間で、制度なき同盟の友好を呼びかけるものに、ここで与えられ

ている。それは、たとえこの同盟がもはや党や労働者インターナショナルの形をとらないとしても、新しい具体的で現実的な方法で、国際法のあり方、国家と国

民といった概念に対する批判において、この批判を刷新するために、とりわけそれを急進化させるために、同盟することを呼びかけるものである[2]。 |

| Reception Further information: Jacques Derrida § Criticism from Marxists Fredric Jameson, Werner Hamacher, Antonio Negri, Warren Montag, Rastko Mocnik, Terry Eagleton, Pierre Macherey, Tom Lewis, Aijaz Ahmad responded to Specters of Marx in Ghostly Demarcations,[3] to which Derrida responded in Marx & Sons.[4] |

レセプション さらなる情報 ジャック・デリダ§マルクス主義者からの批判 フレドリック・ジェイムソン、ヴェルナー・ハマッハー、アントニオ・ネグリ、ウォーレン・モンターグ、ラストコ・モクニク、テリー・イーグルトン、ピエー ル・マチェリー、トム・ルイス、アイジャズ・アフマドは『幽霊のような分界』の中で『マルクスの妖怪』に対して反応し[3]、それに対してデリダは『マル クスと息子たち』の中で反論している[4]。 |

| Deconstruction Hauntology Hauntology (music) Post-Marxism |

脱構築 ハウントロジー=憑在論 ハウントロジー=憑在論(音楽) ポスト・マルクス主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Specters_of_Marx |

★デリダ『マルクスの亡霊』(フランス語 ウィキペディア解説)

| Spectres de Marx

est

un livre du philosophe français Jacques Derrida paru aux éditions

Galilée en 1993. Il fait suite à une conférence prononcée à

l'université de Californie à Riverside la même année, lors d'un

colloque consacré à la pensée de Karl Marx intitulé Whither marxism?

(Où va le marxisme ?). Jacques Derrida introduit dans ce livre la

notion de spectralité et suscite la controverse chez les intellectuels

marxistes par sa méthode de la déconstruction. La conférence était

dédiée à la mémoire du communiste Chris Hani, militant contre

l'apartheid, assassiné le 10 avril 1993. Plan Exorde Chapitre 1 : Injonctions de Marx Chapitre 2 : Conjurer - le marxisme Chapitre 3 : Usures (tableau d'un monde sans âge) Chapitre 4 : Au nom de la révolution, la double barricade (impure "impure impure histoire de fantômes") Chapitre 5 : Apparition de l'inapparent : l'"escamotage" phénoménologique Résumé La notion de spectralité présente dans le titre trouve son origine dans les premières lignes du Manifeste du parti communiste, où Karl Marx écrit : « Un spectre hante l'Europe - le spectre du communisme »1. Derrida commente ce passage en rapport avec la scène d'apparition du spectre dans Hamlet de Shakespeare. Le spectre qui est pensé comme un spectre à venir à l'époque où Marx écrit son texte est pensé par Derrida comme un spectre venu du passé. La notion de spectralité permet de penser cette identité, que Derrida appelle l'hantologie. La question est posée de l'héritage du marxisme et de « l'esprit de Marx » à l'époque de la chute du communisme (chapitre 1). Derrida critique la thèse de Francis Fukuyama inspirée d'Alexandre Kojève concernant la fin de l'histoire 2 et la preuve historique d'une suprématie de la démocratie libérale (chapitre 2). Il fait état, au contraire, de « dix plaies » du « nouvel ordre mondial » en vue d'une « nouvelle Internationale » (chapitre 3). Il entre enfin dans une analyse littérale des textes où apparaît dans la philosophie de Marx lui-même la notion de spectralité : le Manifeste, mais aussi Le dix-huit Brumaire de Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, L'Idéologie allemande et Le Capital (chapitres 4 et 5). Auteurs cités William Shakespeare, Karl Marx, Paul Valéry, Maurice Blanchot, Martin Heidegger, Francis Fukuyama, Sigmund Freud, Hegel, Victor Hugo, Alexandre Kojève, Michel Henry, Emmanuel Lévinas, Max Stirner, Allan Bloom, Étienne Balibar. Critiques Le livre a donné lieu à des questions et objections de lecteurs en majorité marxistes comme Pierre Macherey, Terry Eagleton, Fredric Jameson, Werner Hamacher, Aijaz Ahmad (en) ou Toni Negri rassemblées dans un ouvrage en anglais paru en 1999 (Ghostly Demarcations). Jacques Derrida a répondu dans l'ouvrage Marx & Sons en 2002. |

"Spectres de

Marx"(『マルクスの亡霊』)はフランスの哲学者ジャック・デリダの著書で、1993年にガリレ社から出版された。同年、カリフォルニア大学リバーサ

イド校で開催された「マ

ルクス主義はどこへ向かうのか」と題するカール・マルクスの思想に関する会議での講演に続くものである。この本の中でジャック・デリダは、スペクトルとい

う概念を紹介し、脱構築という手法でマルクス主義知識人たちの論争を引き起こした。この会議は、1993年4月10日に殺害された共産主義者の反アパルト

ヘイト活動家クリス・ハニに捧げられた。 計画 序文 第1章 マルクスの禁止令(Injonctions de Marx) 第2章 呪術-マルクス主義(Conjurer - le marxisme) 第3章:用途(年齢不詳の世界像):Usures (tableau d'un monde sans âge) 第4章 革命の名において、二重のバリケード(不純な「不純な不純な怪談話」):Au nom de la révolution, la double barricade (impure "impure impure histoire de fantômes") 第5章 見えないものの出現--現象学的「エスカモタージュ」:Apparition de l'inapparent : l'"escamotage" phénoménologique まとめ タイトルにある「幽霊」の概念は、『共産党宣言』の冒頭でカール・マルクスが「ヨーロッパには幽霊がとりついている-共産主義の幽霊である」と書いている ことに由来する1。 デリダはこの一節について、シェイクスピアの『ハムレット』で亡霊が登場する場面との関連でコメントしている。マルクスが彼のテクストを書いた時点で、来 るべき亡霊として考えられている亡霊は、デリダによっ ては過去からの亡霊として考えられているのである。妖怪性の概念は、デリダがハントロジーと呼ぶこの同一性について考えることを 可能にする。マルクス主義の遺産と共産主義崩壊時の「マルクスの精神」についての問題が提起される(第1章)。 デリダは、アレクサンドル・コジェーヴに触発されたフランシス・フクヤマの「歴史の終わり2」についてのテーゼと、自由民主主義の優位性の歴史的証明を批 判する(第2章)。 それどころか、「新しい国際」を視野に入れた「新しい世界秩序」の「10の傷」について述べている(第3章)。 最後に、マルクス自身の哲学の中で「スペクトル」の概念が登場するテクスト、すなわち『宣言』、『ルイ・ナポレオン・ボナパルトの18回目の叱責』、『ド イツ・イデオロギー』、『資本論』の文字通りの分析に入る(第4章と第5章)。 引用された作家 ウィリアム・シェイクスピア、カール・マルクス、ポール・ヴァレリー、モーリス・ブランショ、マルティン・ハイデガー、フランシス・フクヤマ、ジークムン ト・フロイト、ヘーゲル、ヴィクトル・ユーゴー、アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ、ミシェル・アンリ、エマニュエル・レヴィナス、マックス・シュティルナー、 アラン・ブルーム、エティエンヌ・バリバール。 書評 本書は、ピエール・マチェリー、テリー・イーグルトン、フレドリック・ジェイムソン、ヴェルナー・ハマッハー、アイジャズ・アフマド、トニ・ネグリといっ た主にマルクス主義の読者から疑問や反論を生み、それらは1999年に英語で出版された本(Ghostly Demarcations)にまとめられた。ジャック・デリダは2002年に『マルクスと息子たち』でこれに反論している。 |

| https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spectres_de_Marx |

マルクスの亡霊たち : 負債状況=国家、喪の作業、新しいインターナショナル / ジャック・デリダ [著] ; 増田一夫訳・解説,藤原書店 , 2007/ Spectres de Marx : l'État de la dette, le travail du deuil et la nouvelle Internationale / Jacques Derrida , Paris : Galilée , c1993. - (Collection La philosophie en effet) |

| 続きは「デリダ『マルクスの亡霊たち』」に |

****

デリダはマルクスの唯物論(=実在的存在論)に対して批判する。唯物論は、過去あ るいは現在の実在(リアリティ)は、観念(=デリダはそれを非 実在の幽霊 [spectres]としてとらえる)抜きになしに理解可能であるという立場をとる。だがそれは、傲慢な考え方ではないか?そのように考える(=脱構築す ると)とマルクスの著作には、霊(spirits)から逃亡しようとして、思索を深めた形跡がある。だが、霊から逃れてはならない(→我々は霊にハック= 取り憑かれる存在だからだ)——抽象的な理念と理念を完全に「肉化」する試みの現実態の中間にあるので、それは存在論ではなく、憑在論と呼ばれるものに相 当する。

マルクスの人間解放論は、正義のもとでな

されると、その意味で[その社会理論は]、一種の構造的メシアニズム(宗教なきメシアニズム)になる。

****

亡霊の姿は、しばしば現れる度に異なった 様相をもち(同一性を持たない)「延 期されたオリジナルではないもの」としての登場する。反復して登場する、死者の亡霊はつねに「始まり」の姿を露(あらわ)にする。過去の亡 霊の登場は、時間的秩序をゆるがし、解決済みのものではないことを、生者に不安な混乱を通して呼びかけるものである。

そのような、亡霊と生者との間には、理想 的なコミュニケーションな どは不可能であるし、それらの「対話」が、容易なるものがあるだろう。僕たちは、 亡霊を前にして、冷静に相手に対して「対話」などをすることが困難なことは想像に難くない。

デリダは端的に、亡霊の現存在=そこにい る、とはどういうことだと問いをたてる。

現に、亡霊に不安を感じている人はいる。 また、生身を持たず、現前する実在性も、アクチュアリティも現実性ももたぬ亡霊ゆえに、それは過去の遺 物にすぎないとおもっている人も多い(→「アイヌ遺骨の返還問 題について」)。

「鎮まれ、鎮まれ、せっかちな亡霊よ」 (ハムレット)——Horatio says ’tis but our fantasy And will not let belief take hold of him- MARCELLUS

結局のところ「亡霊とは未来なのである、つねに来たるべきものであり、再 -来するかもしれぬもの」(「そのようなものとしてからみずからを現前 させることはない」)(デリダ 2007b:4)

| ■「私が、幽霊と相続と世代=生殖につい

て、幽霊のいくつもの世代=誕生、すなわちわれわれの前

にも、われわれの内にも、われわれの外部にも現前しておらず、現在生きていないある他者たち

について、これから長々と話そうとしているのは、正義の名においてである。まだ存在

しない正義、まだここにはない正義、もはやここにはない正義、すなわちもはや現前せず、法

にも還元できないところにある正義の名においてである。そ

の他者たちがすでに死んでしまったにせよまだ生まれていないにせよ、もはやここに現前して生

きていないあの他者たち、あるいはまだここに現前して生きていないあの他者たち、その他者た

ちの尊重を原理として持たぬいかなる倫理あるいは政治学——その政治学が革命的であろうとな

かろうと——これらのいずれもが可能とも思考可能とも正しいとも思われない限りにおいて幽

霊について話さねばならず、ひいては幽霊に対して話さねばならず、さらには幽霊とともに話さ

ねばならない」(デリダ 2007a:13) ●「一切の生き生き とした現在の彼方における責任=応答可能性、生き生きとした現在の節合をはずすものにおける/ 責任=応答可能性、まだ生まれていない者もしくはすでに死んでしまった者たちの幽霊の前での 責任=応答可能性なしには。その彼らが、戦争ゃ、政治的その他の暴力や、民族主義的、植民地 主義的、性差別的その他の絶滅や、資本主義的帝国主義あるいはあらゆる形態の全体主義による 圧制、それらの犠牲者であろうとなかろうと。生き生きとした現在の、自己に対するこの非-同 時性がなければ、その現在の正確さをひそかに狂わせるものがなければ、ここにはいない者たち ーーすなわち〈もはや〉あるいは〈まだ〉現前してはおらず生きていない者たち——への正義の ための責任と敬意がなければ、「どこに?」、「明日はどこに?(whiter?)」という問いを立て るどんな意味があるというのだろうか」(デリダ 2007a:13-14)。 |

ハムレット(梗概)

(1)王が急死する。王の弟クローディアスは王妃と結婚し、後継者としてデンマーク王の座に就く。

(2)「父王の死」と「母の早い再婚」とで憂いに沈む王子ハムレットは、従臣から「亡き王の亡霊が夜な夜なエルシノアの城壁に現れる」という話を聞き、自 らも確かめる。父の亡霊に会ったハムレットは、実は父の死は「クローディアスによる毒殺」だったと告げられる。

(3)復讐を誓ったハムレットは狂気を装う。王と王妃はその変貌ぶりに憂慮するが、宰相ポローニアスは、その原因を「娘オフィーリアへの実らぬ恋」ゆえだ と察する。父の命令で探りを入れるオフィーリアを、ハムレットは無下に扱う。

(4)やがて、「王が父を暗殺した」という確かな証拠を掴んだハムレットだが、母である王妃と会話しているところを隠れて盗み聞きしていた宰相ポローニア スを、王と誤って刺殺してしまう[10]。

(5)さらに、宰相ポローニアスの娘オフィーリアは度重なる悲しみのあまり狂い、やがて溺死する。宰相ポローニアスの息子レアティーズは、父と妹の仇をと ろうと怒りを募らす。

(6)ハムレットの存在に危険を感じた王クローディアスは、復讐心を持ったレアティーズと結託し、毒剣と毒入りの酒を用意して、ハムレットを剣術試合に招

き、秘かに殺そうとする。しかし試合のさなか、王妃が毒入りとは知らずに酒を飲んで死に、ハムレットとレアティーズ両者とも試合中に毒剣で傷を負ってしま

う。

(7)死にゆくレアティーズから真相を聞かされたハムレットは、王を殺して復讐を果たした後、事の顛末を語り伝えてくれるよう親友ホレイショーに言い残 し、この世を去ってゆく。

https://x.gd/U7T2Q

★憑在論批判

「デリダは、他者を完全に脱存在化するこ

とにより、他者性をきたるべきものに還元し、その結果、約束という幽霊だけが残る」ジジェク『操り人形と小人』(210)」

【設問】

1.

2.

■デリダの『マルクスの亡霊たち』(増田 一夫訳)について

導入

1.マルクスの厳命

2.共謀する=厄祓いする——マルクス主義(を)

3.摩耗(年齢、時代なき世界の描写)

4.革命の名のもとに、二重のバリケード(不純な「不純なる不純な幽霊たちの物語」)ß

5.現れざるものの出現——現象学的「手品」

■共産主義の亡霊

亡霊の比喩は、マルクス・エンゲルスが「共産主義者宣言(共産党宣言)1848年」で、共産主義のこと(das Gespenst des Kumunismus)を比喩して表現した。だが、マルクスの著作のうちフランス三部作「フランスにおける階級闘争」「ルイ・ボナパルトのブリュメール 18日」「フランスの内乱」に登場する。

共産主義者宣言/共産党宣言の憑在論︎▶︎マルクス主義と

いう名のオブセッション▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

リンク(概念用語)

文献

Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1997-2099