操り人形と小人

The Puppet and the Dwarf: The Perverse Core of Christianity, by Slavoj Žižek, 2003

★The

Puppet and the Dwarf

では、ラカン派精神分析の視点から、今日の宗教的コンステレーションを精密に読み解いている。彼は、今日のスピリチュアリティの主流であるニューエイジの

グノーシス主義と脱構築主義のレヴィナシウス的ユダヤ教の両方に批判的に立ち向かい、キリスト教の「唯物論的」核心を救済しようとする。彼のキリスト教の

読みは、パウロ的な信者の共同体の中に革命的な集団の最初のバージョンを見いだし、明確に政治的である。今日、ユルゲン・ハーバーマスのような啓蒙主義者

でさえ、「ポスト世俗」時代における倫理的・政治的スタンスの根拠として宗教的ヴィジョンが必要であることを認めている。

☆

JD Davis による『操り人形と小人』の書評レヴュー.

|

Over the past century, Christian theologians have been forced to

contend with Marxist critiques of religion. Traditionally, this

critique often challenged the ways in which religion has been utilized

as a way to cover over and mask material inequality and class

antagonism. As a result, theologians often took one of two routes: they

either rejected these Marxist “opium of the people” critiques as

dangerous secular attacks by the “Godless communists”, or incorporated

them into their theological framework, resulting in movements such as

liberation theology in the 1960s. In recent decades, however, there has

been a marked “theological turn” within contemporary Marxist theory,

inspired by theorists such as Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, and

Louis Althusser and taken up by contemporary writers such as Georgio

Agamben, Alain Badiou, and Terry Eagleton. Many of these thinkers,

following the critiques made by Marx and Engles, work to illuminate the

politically emancipatory potential of religion against the forces of

market capitalism. Following this theological turn, Slovenian philosopher and cultural theorist Slavoj Zizek also incorporates religion into many of his works (even if often tangentially). Following up on his work, The Fragile Absolute: Or, Why Is the Chrisitan Legacy Worth Fighting For? (2000), Zizek dives further into his unique perspective of Christianity in his 2003 book, The Puppet and the Dwarf: The Perverse Core of Christianity. Zizek, in this work, utilizes the work of Freud, Lacan, and Hegel in order to bid the reader to consider the radical nature of Christ’s sacrifice and contemplate its political consequences. https://www.jddavispoet.com/book-reviews/the-puppet-and-the-dwarf-the-perverse-core-of-christianity-slavoj-zizek |

過

去100年にわたり、キリスト教の神学者たちはマルクス主義的な宗教批判と闘うことを余儀なくされてきた。伝統的に、この批判はしばしば、宗教が物質的不

平等や階級対立を覆い隠し、覆い隠す方法として利用されてきたことに異議を唱えてきた。その結果、神学者たちはしばしば二つのルートのどちらかをとった。

すなわち、こうしたマルクス主義的な「民衆の阿片」批判を、「神を信じない共産主義者」による危険な世俗的攻撃として拒絶するか、あるいは神学的枠組みに

組み込んで、1960年代の解放の神学のような運動をもたらしたのである。しかしここ数十年、現代のマルクス主義理論の中で、ヴァルター・ベンヤミン、テ

オドール・アドルノ、ルイ・アルチュセールといった理論家に触発され、ジョルジョ・アガンベン、アラン・バディウ、テリー・イーグルトンといった現代作家

が取り上げた、顕著な「神学的転回」が起こっている。これらの思想家の多くは、マルクスやエングルズによる批判に倣い、市場資本主義の力に対する宗教の政

治的解放の可能性を明らかにしようと努めている。 この神学的転回を受け、スロベニアの哲学者であり文化理論家であるスラヴォイ・ジジェクもまた、多くの著作に宗教を取り入れている(たとえ多くの場合、余 談であったとしても)。彼の著作『The Fragile Absolute: あるいは、なぜクリスチャンの遺産は戦う価値があるのか?(2000年)に続き、ジゼクは2003年の著書『操り人形と小人-キリスト教の倒錯した核心』 において、キリスト教に対する独自の視点にさらに踏み込んでいる。この著作でジゼクは、フロイト、ラカン、ヘーゲルの研究を利用し、キリストの犠牲のラ ディカルな本質を読者に考えさせ、その政治的帰結を熟考させる。 https://x.gd/RAvQE |

| Overview: With psychoanalysis and Hegelian dialectics in hand, Zizek seeks to uncover what he sees as the true kernel of Christianity. Zizek starts his analysis by examining religion in general, taking note of the paradox of love, the fidelity of Judas’ betrayal (which Peter Rollins would later take up in his 2008 book The Fidelity of Betrayal: Towards a Church Beyond Belief), and the disavowed violence of Zen Buddhism. Zizek then analyzes the relationship between Christianity, paganism, and prohibition via G.K.Chesterton’s “thrilling romance of orthodoxy.” In the third chapter, Zizek then examines the tension between the Particular and the Universal in politics as he attempts to give an account for Lacan’s category of the Real, arguing that it is “simultaneously the Thing to which direct access is not possible and the obstacle that prevents this direct access” (77). It is here that Zizek begins to delve into the meat of his central argument, as he utilizes these Hegelian categories of negation, subtraction, and the Void of the Real in order to argue that God Himself experiences this separation from Himself as a subject, which leads Zizek to state that “our radical experience of separation from God is the very feature which unites us with Him...only when I experience the infinite pain of separation from God, do I share an experience with God Himself (Christ on the Cross)” (91). In the fourth chapter, Zizek finally hits us with his main thesis: Christ, as the mediator between us and the divine, acts as a Lacanian “subject supposed to know,” who we project our desires and beliefs onto. Yet, on the Cross, when Jesus cries out “Eloi Eloi, lema sabachthani” (“My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?” [Mark 15:34]), Christ suspends his belief momentarily, revealing the fractured nature of the Godhead (God is separated from Himself). Thus, Zizek can make the radical claim that the only way to be a Christian is to, like Christ, become an atheist (and vice-versa), as he writes, “The true communion with Christ, the true imitatio Christi, is to participate in Christ’s doubt and disbelief” (102). In his final chapter, Zizek then goes onto examine the core difference between Judaism and Christianity. He asserts that Christianity essentially exposes the secret that Judaism has tried to keep hidden: that God Himself is impotent. To make this argument, Zizek contrasts the story of Job with the Crucifixion of Christ. In the story of Job, Zizek asserts, God essentially doubles down on his own omnipotence and power in a braggadocious monologue. He doesn’t reveal why he agreed to let Job be tortured, and sides with Job in his insistence that his suffering was indeed meaningless (against the interpretation of Job’s three friends). In Christ, Zizek argues, this secret (that there is nothing behind the veil and God is impotent) is revealed on the Cross. Christ died to show us that the Big Other, the guarantee of meaning, does not exist and that it is up to the community of believers (which Zizek identifies as the Holy Spirit) to carry out the radical vision of Christ on earth. Zizek, in this analysis, believes that he is following in the footsteps of Pauline theology, as he writes, “What matters to him [Paul] is not Jesus as a historical figure, only the fact that he died on the Cross and rose from the dead -- after confirming Jesus’ death and resurrection, Paul goes on to his true Leninist business, that of organizing the new party called the Christian community” (9). The true kernel of Christianity, Zizek argues, is that Christ reveals the gap within God himself as He identified Himself with humanity, thus allowing us to experience the divine within our own shared sense of lack. https://x.gd/RAvQE |

概要 精神分析とヘーゲル弁証法を手に、ジジェクはキリスト教の真の核心と思われるものを明らかにしようとする。ジジェクは宗教一般を検証すること から分析を始め、愛のパラドックス、ユダの裏切りの忠実さ(これは後にピーター・ロリンズが2008年に出版した『裏切りの忠実さ』で取り上げることにな る)に注目する: 信条を超えた教会へ)、そして禅宗の否定された暴力に注目する。そしてジゼックは、G.K.チェスタトンの「正統性のスリリングなロマンス」を通して、キ リスト教、異教、禁教の関係を分析する。 第3章では、ジジェクは政治における特殊と普遍の間の緊張を検証し、ラカンの「実在」のカテゴリーを説明しようと試み、それは「直接アクセス が不可能なものであると同時に、この直接アクセスを妨げる障害」(77)であると主張する。ジゼックはここで、否定、引き算、実在の空虚といったヘーゲル 的なカテゴリーを利用して、神自身が主体として自分自身からの分離を経験していると主張し、「神からの分離という私たちの根本的な経験は、私たちを神と結 びつける特徴そのものである......私が神からの分離という無限の苦痛を経験するときだけ、私は神自身(十字架上のキリスト)と経験を共有するのであ る」(91)と述べている。 第4章で、ジジェクはついに彼の主要なテーゼを私たちにぶつける: キリストは私たちと神との仲介者として、ラカン的な「知っているはずの主体」として振る舞い、私たちはその主体に自分の欲望や信念を投影する。しかし、十 字架上でイエスが「エロイエロイ、レマ・サバクタニ」(「わが神、わが神、なぜ私をお見捨てになったのですか」[マルコ15:34])と叫ぶとき、キリス トは自分の信念を一時的に中断し、神格の分裂した性質(神は自分自身から分離している)を明らかにする。キリストとの真の交わり、真のキリストへの模倣と は、キリストの疑念と不信仰に参加することである」(102)。 ジジェクは最終章で、ユダヤ教とキリスト教の核心的な違いを考察する。彼は、キリスト教は本質的に、ユダヤ教が隠そうとしてきた秘密、すなわち神自身が無 力であることを暴露していると主張する。この主張をするために、ジゼックはヨブ記とキリストの磔刑を対比させる。ジゼックは、ヨブの物語では、神は本質的 に、自慢げな独白の中で自らの全能と力を倍増させていると主張する。ヨブが拷問されることに同意した理由を明かさず、ヨブの苦しみは実に無意味であったと 主張するヨブの味方をする(ヨブの3人の友人の解釈に反して)。ジゼックは、キリストにおいて、この秘密(ベールの向こうには何もなく、神は無力であると いうこと)が十字架上で明らかにされたと主張する。キリストは、意味の保証である大きな他者が存在しないこと、そしてキリストのラディカルなヴィジョンを 地上で実行するのは信者の共同体(ジゼクはこれを聖霊としている)次第であることを示すために死んだのである。ジゼックはこの分析において、自分がパウロ 神学の足跡をたどっていると考えている。「彼(パウロ)にとって重要なのは、歴史上の人物としてのイエスではなく、イエスが十字架上で死に、死からよみが えったという事実だけである--イエスの死と復活を確認した後、パウロは、キリスト教共同体という新しい党を組織するという、彼の真のレーニン主義的な仕 事にとりかかる」(9)。キリスト教の真の核心は、キリストが人間と同一化することによって、神自身の中にある隔たりを明らかにし、その結果、われわれが 共有する欠乏感の中で神を体験できるようにすることだとジジェクは主張する。 |

| Commendations: First of all, Zizek challenges us to reexamine our preconceived notions of Christianity and theology. Throughout his work, Zizek utilizes Hegelian dialectics to give a materialist reading of the Christian Gospel. This affords us a unique perspective into the radical potential of Christianity from an “outsider” perspective. In his examination, Zizek raises many interesting arguments and perspectives on the nature of the Crucifixion and its potential application towards building a community unified in a shared lack (via the Holy Spirit). Zizek’s work is immensely important in drawing back towards a materialist understanding of the Christian narrative, correcting many of the ways in which modern Christianity is deeply Gnostic. For Zizek, the Christian God is the one who risks it all, even himself, to the point of madness and dereliction on the Cross. Against a Hellenistic (Greek) philosophy that tends to elevate the realm of perfect ideas over the imperfect material world, Zizek’s analysis of Christianity elevates the role of imperfection, arguing that imperfection is the very site from which love can thence spring forward. In typical fashion, Zizek utilizes a wide range of philosophy, scientific theories, and cultural artifacts such as film and television to illustrate his points. While Christianity is the main subject of this book, Zizek also uses this work to tackle a wide range of cultural, social, and religious issues, from the failure of liberal politics in recent decades to the Western appropriation of Buddhist teachings and principles. He seamlessly weaves together movie references, crass jokes, and existential philosophy often on the same page. This leads to a dynamic and relevant read, as Zizek deftly navigates from Biblical literature and critical theory to political crises in an increasingly globalized, capitalist society. While he does tend to pull all of these strings together to make a larger point more in this work than some of his other books, this tangential component also leads us to a central critique. https://x.gd/RAvQE |

称賛に値する: まず第一に、ジジェクは、キリスト教と神学に対する先入観を再検討するよう私たちに挑戦している。 ジジェクはヘーゲル弁証法を駆使して、キリスト教の福音を唯物論的に読み解く。これは、「アウトサイダー」の視点からキリスト教の急進的な可能性について のユニークな視点を与えてくれる。その考察の中で、ジジェクは十字架刑の本質と、(聖霊を介して)共有された欠如の中で統一された共同体を構築するための 潜在的な適用について、多くの興味深い議論と視点を提起している。 ジジェクの仕事は、キリスト教の物語を唯物論的な理解へと引き戻し、現代のキリスト教が深くグノーシス主義的である多くの点を修正する上で非常に重要であ る。ジジェクにとって、キリスト教の神とは、十字架上で狂気と放縦の限りを尽くし、自分自身さえも危険にさらす存在である。不完全な物質世界よりも完全な 観念の領域を高く評価する傾向のあるヘレニズム(ギリシャ)哲学に対して、ジジェクのキリスト教分析は不完全さの役割を高め、不完全さこそがそこから愛が 湧き出る場所そのものであると主張する。 ジジェクは、哲学、科学理論、映画やテレビのような文化的成果物など、幅広い分野を駆使して自らの主張を説明する。キリスト教が本書の主な主題である一方 で、ジジェクは本書を通じて、ここ数十年のリベラル政治の失敗から、仏教の教えや原則の西洋的流用に至るまで、幅広い文化的、社会的、宗教的問題に取り組 んでいる。彼は、映画の引用、下品なジョーク、実存哲学をしばしば同じページにシームレスに織り込んでいる。聖書文学や批評理論から、ますますグローバル 化する資本主義社会における政治的危機まで、ジゼクが巧みにナビゲートしていく。この作品では、ジジェクは他の著作よりも大きな主張をするために、これら すべての糸を引っ張る傾向があるが、この余談的な要素もまた、私たちを中心的な批判へと導いてくれる。 |

| Critique: As with many of Zizek’s works, the central argument is a bit difficult to follow, and occasionally gets lost in the midst of all the disparate connections he makes. Zizek, as usual, tends to divert into multiple tangents and rabbit trails that are often dense and full of insight but stray from the central argument he’s trying to make. To be fair, this book is much more focused than some of his other books, but it still remains a criticism (and one that he is acutely aware of). Furthermore, for the more casual reader, this book will be largely impenetrable. To follow along, one must have a basic understanding of Lacan, and at least a passing comprehension of Hegel and Kant. Even for me, who does have background knowledge of these thinkers, Zizek’s chapters ebb and flow without any real building conclusion. There are many hidden gems of wisdom and insight to be found in these chapters, to be sure, but it often takes a significant amount of digging to find and excavate them. As always with Zizek, the more you read him, the easier it becomes to understand his particular nuances and ways of framing arguments. While this book might be great for those who have already read a book or two from Zizek, however, it certainly is not the best introduction to his work. Relatedly, as a brief side note, Zizek also casually utilizes the “N-word” in recounting the name of a French candy, and while not malicious in intent by any means, it will probably cause most American audiences to cringe or turn away from his work, which truly is a shame since I think his voice is important in our contemporary cultural/political atmosphere. Furthermore, in terms of his argument, I do have one major critique, namely: How does the Resurrection of Christ factor into Zizek’s analysis? much emphasis is placed on the “che voix?” cry of dereliction on the Cross (Eloi Eloi…), and I understand Zizek’s interpretation of the material emergence of the Spirit as the community of believers; yet, in order for Zizek’s argument of Divine impotence via Job to hold any water, the material nature of the Resurrection must be addressed. Zizek takes Christ’s cry of dereliction on the Cross as the final word on divine abandonment (also misquoting the cry by writing “Father, Father,” instead of “My God, my God…”). This cry is central to Zizek’s critique, without considering Christ’s other words on the Cross that are addressed to the Divine Father in Luke’s Gospel account (“Father, into your hands I commit my Spirit” Luke 23:46). Just as the Song of Songs cannot be viewed as only a metaphor between the Jewish people and Hashem, this return to the Father and the eventual physical Resurrection must also be contended within a materialist manner. To be clear, Zizek has no intention of creating a systematic theology, reconciling every bit of the Christian Scriptures. Rather, he finds the kernel of Christianity within the death of Christ and the emergence of the Holy Spirit and thus takes what is useful towards building an emancipatory community of radical love. Yet, Zizek seems to be caught in a sort of dilemma here. While he argues, along with Girard, that the Crucifixion was the fracturing Event that revealed the impotence of sacrifice towards an ultimate guarantor of meaning (aka. God), Zizek relies on this very framework of divine abandonment and violent sacrifice to serve as the ahistorical kernel that serves as the horizon for building a political movement. The question we have to ask is this: in thinking in terms of dispossession, do we accept a theology of total loss and abandonment, thus rendering us perpetual victims, or can dispossession also include the recovery of the Absolute? In other words, while Zizek’s vision to unite us in a universal lack (a feeling of abandonment by God) which allows us to show solidarity with the Other in their shared lack, how can we thus move forward in a politically emancipatory manner while resisting the impulse to relegate ourselves to perpetual victimhood? This is where a theology of Resurrection is helpful, even necessary, to be truly progressive and emancipatory in our politics. In this way, we can relate to the other not only in our radical lack, but also in a radically new way via resurrection and new life, where we become brothers, sisters, and comrades, accountable to one another in a shared, positive theo-political movement. |

批評: ジジェクの作品の多くがそうであるように、中心的な論旨を追うのは少々困難であり、時折、異質なつながりの中で迷子になってしまう。 ジジェクはいつものように、複数の余談や兎の道へと話をそらす傾向があり、それはしばしば濃密で洞察に満ちているが、彼が主張しようとしている中心的な論 点からはずれている。公平を期すために、本書は彼の他の著書よりもずっと焦点を絞っているが、それでも批判は残る(そしてそれは彼も痛感している)。 さらに、カジュアルな読者にとっては、本書はほとんど理解できないだろう。ついていくには、ラカンについての基本的な理解と、ヘーゲルとカントについての 最低限の理解が必要だ。これらの思想家についての予備知識がある私でさえ、ジゼクの章は、結論に達することなく、浮き沈みしている。これらの章には、知恵 と洞察の隠れた宝石がたくさんあるのは確かだが、それを見つけて掘り起こすには、かなりの量の掘り起こしが必要になることが多い。ジジェクはいつもそうだ が、読めば読むほど、彼特有のニュアンスや議論の組み立て方を理解しやすくなる。本書は、すでにジゼクの本を1、2冊読んだことのある人には最適かもしれ ないが、彼の仕事を知るための最良の入門書ではないことは確かだ。それに関連して、簡単な余談だが、ジジェクはフランスのお菓子の名前を語る際、さりげな く「Nワード」を使っている。決して悪意があるわけではないが、おそらくほとんどのアメリカ人読者は、彼の作品にギョッとするか、目を背けることになるだ ろう。 さらに、彼の主張に関して、私は一つの大きな批判を持っている: キリストの復活は、ジゼクの分析にどのように関わっているのだろうか。十字架上の無念の叫び(エロイエロイ...)に多くの重点が置かれており、信者の共 同体としての精神の物質的な出現についてのジジェクの解釈は理解できる。ジゼックは、十字架上でのキリストの見捨てられた叫びを、神の見捨てに関する最終 的な言葉としている(また、「わが神、わが神...」ではなく「父よ、父よ」と書くことによって、この叫びを誤って引用している)。この叫びはジゼックの 批評の中心であり、ルカによる福音書の記述にある、キリストが十字架上で神である父に語りかけた他の言葉(「父よ、御手にわたしの霊をゆだねます」ルカ 23:46)は考慮されていない。 歌の歌をユダヤの民とハシェムとの間の比喩としてだけ見ることができないように、この父への帰還と最終的な肉体的復活もまた、唯物論的な方法で争われなけ ればならない。はっきりさせておきたいのは、ジジェクは体系的な神学を構築し、キリスト教聖書の隅々まで和解させるつもりはないということだ。むしろ彼 は、キリストの死と聖霊の出現の中にキリスト教の核を見出し、ラディカルな愛の解放的共同体の構築に向けて有用なものを取り上げるのである。 しかし、ジジェクはここで一種のジレンマに陥っているようだ。彼はジラールとともに、磔刑は意味の究極的な保証者(別名、神)に対する犠牲の無力さを明ら かにした分断の出来事であったと主張する一方で、ジジェクは政治運動を構築するための地平として機能する非歴史的な核としての役割を果たすために、神の放 棄と暴力的な犠牲というまさにこの枠組みに依存している。私たちが問わねばならないのは次のようなことである。所有権の剥奪という観点から考えるとき、私 たちは完全な喪失と放棄の神学を受け入れ、それによって私たちを永遠の犠牲者とするのか、それとも所有権の剥奪は絶対的なものの回復をも含みうるのか。 言い換えれば、普遍的な欠乏(神に見捨てられたという感覚)において私 たちをひとつにするジジェクのヴィジョンは、欠乏を共有する他者と連帯することを可能にするが、その一方で、自らを永遠の犠牲者へと追いやる衝動に抗いな がら、政治的に解放的な方法で前進するにはどうすればよいのだろうか。政治において真に進歩的で解放的であるためには、復活の神学が役に立つし、必要でさえある。このようにして、私たちは過激な欠落の中でだけでなく、復活と新しい生命を通して、根本的に新しい方法で他者と関わることができるのである。 |

| Conclusion: In short, Zizek uses this work to challenge our common assumptions regarding the nature of Christ’s death on the Cross, and what implications it might have for building a community of radical solidarity and love. While I do believe that Resurrection is critical for such a project, Zizek’s work is still incredibly useful, providing us a refreshing critical lens through which to view the Christian narrative. To be sure, some of Zizek’s language can be over the top and intentionally controversial, as he likes to flip conventional wisdom on its head. Yet, Zizek’s unorthodox methods also continue to surprise us, as he employs the help of some unlikely friends, such as Chesterton, to critique much of spirituality in the West today, such as New Age spiritualism, Western appropriations of Eastern religions, and post-secular appropriations of Judaism. Zizek’s work is immensely important, as he makes us consider the roles of desire, lack, violence, and language in the constitution of our religious and political beliefs. As such, Zizek’s work is important to consider, especially in our contemporary theological spaces. He reminds us that a faith that guarantees wholeness and peace without delving into the brokenness and messiness of our cultural, social, and political realities ultimately serves to maintain the status quo of global capital. He reminds us that the categories of the sacred and the secular are not so distant after all, as the Incarnation occupies a liminal space on the Möbius strip. While not for the philosophically faint-hearted, echoing the sentiments of one of my favorite poets Richard Wilber, Zizek’s materialist Christianity reminds us that despite all of our philosophizing, “love calls us to the things of this world.” JD Davis. https://x.gd/RAvQE |

結論 要するに、ジジェクはこの作品を使って、キリストの十字架上の死の本質に関する私たちの一般的な仮定に挑戦し、それが急進的な連帯と愛の共同体を築くため にどのような意味を持つのかに挑戦しているのである。このようなプロジェクトにとって『復活』が重要であることは確かだが、ジジェクの著作は、キリスト教 の物語を見るための新鮮で批判的なレンズを提供してくれる。確かにツィツェクの言葉には、従来の常識をひっくり返すような大げさなものもあり、意図的に物 議を醸すこともある。しかし、チェスタートンのような思いがけない友人の助けを借りて、ニューエイジ精神主義、東洋宗教の西洋的流用、ユダヤ教のポスト世 俗的流用など、今日の西洋におけるスピリチュアリティの多くを批判しているのだから。欲望、欠乏、暴力、言語が私たちの宗教的・政治的信条を構成する上で 果たす役割を考えさせるジジェクの仕事は、非常に重要である。 このように、ジジェクの仕事は、特に現代の神学的空間において考慮すべき重要なものである。彼は、私たちの文化的、社会的、政治的現実の破れや混乱を掘り 下げることなく、全体性と平和を保証する信仰が、結局はグローバル資本の現状維持に役立つことを私たちに思い起こさせる。受肉がメビウスの帯のようなリミ ナルな空間を占めているように、聖なるものと世俗的なものの範疇は、結局のところそれほど遠いものではないのだと、彼は私たちに気づかせてくれる。ジジェ クの唯物論的キリスト教は、哲学的な思考が苦手な人には向かないが、私の好きな詩人の一人であるリチャード・ウィルバーの言葉に共鳴し、哲学的な思考にも かかわらず、"愛が私たちをこの世のものに呼び寄せている "ことを思い出させてくれる。 |

| Series Foreword vii Introduction: The Puppet Called Theology 2 1 When East Meets West 12 2 The "Thrilling Romance of Orthodoxy" 34 3 The Swerve of the Real 58 4 From Law to Love ... and Back 92 s Subtraction, Jewish and Christian 122 Appendix: IdeologyToday 144 Notes 173 |

序 神学という名の操り人形 東洋と西洋が出会うとき 「正統の戦慄に満ちたロマンス」 〈現実的なもの〉という逸脱 法から愛へ……そしてまた法へ 差し引くこと——ユダヤ的に、キリスト教的に 附論:今日のイデオロギー 注 |

| 序:神学という名の操り人形 | ・宗教が単体として独立したものとして「ある」時代、それが現代だ。 ・宗教の役割は、治療的役割と批判的役割である(9) ・判断の論理は、最終的に、無限判断に帰着する ・精神現象学の骨相学の、「精神は骨である」という無限判断。 ・歴史としての精神への移行。 ・『信仰と知』 における、民衆の宗教、実定的宗教、理性の宗教 ・なぜ宗教は現代において必要か?——理性的哲学や科学は一部の人たちのため、宗教こそが大衆(の欲望)に答えることができる。しかし、他方で、理性の時代に宗教は社会を有機的にまとめあげる力をもたない。 ・我々は芸術を賛美するが、芸術の前にひれ伏すことはない。同じことが宗教にもいえる。 ・現代の愚行は、宗教そのものを変えずに、腐敗した倫理体系(と、その制度と法)を変えることだ。--Enzyklopädie der philosophischen Wissenschaften, Felix Meiner Verlag, 1959:436. ・私は知り、行動する、なぜなら、私は自分が信じているものを知らないからだ(12) ・真の弁証法的唯物論者になるためには、キリスト教的経験を経るべきだ(13)。 ・ポストモダニストには(他者の)「信仰心がじつは本当でない」という心的しかけをもっている。そのしかけがなくなると、ポストモダニストは、他者の信仰者の素朴な信仰を容認せざるをえなくなる。 ・ポストモダニストの言い分:「私はそれを信じていない、だがそれは私の文化の一部である」(15) ・バーミアンの古代仏教遺跡の破壊:だれも仏教徒でもないのに、文化遺産を破壊したことで、怒り狂う。 ・シニカルな距離感をもち、実利的御都合主義を標榜する人こそが、自らの認めるのにやぶさかな信仰心よりも、はるかに強い信仰心をもつ。(16) ・アグネス・ヘラー「ユダヤ人イエスの復活」(16) ・ユダヤ的政治神学の創始者としてのパウロ ・パウロはイエスの生前のエピソードには何の関心ももたない。パウロにとって重要なのは、イエスが十字架にかかり死に、そして蘇生したことである(18) ・パウロは、最後の晩餐にはいなかった(イエスとは敵対する位置にいた)。唯一の弟子の中ではユダがパウロの位置にある。なぜなら、イエスの超自然を信じ ることなく、キリストの特異性に膠着しない。その点で、キリストの原理原則に純粋に還元するという意味で、パウロはイエスを「裏切った」(19) ・パウロをユダヤ的伝統から読みとること。これが生成過程にあるキリスト教を理解することだ。パウロがキリストをみている/見ることができたのは、彼がユダヤ教的世界を離脱したからではなく、ユダヤ的伝統から、キリストを理解しようとしたのだ(19-20)。 |

| 東洋と西洋が出会うとき | ・時間は究極の牢獄だ。だが、永遠こそが究極の牢獄、息の詰まるような閉域。時間への転落のみが、人間の経験に「ひらけ(オープニング)」を導入するものだとすれば、どうだろうか?(23) ・時間こそが、存在論的なオープニングにふさわしい名前なのだ。 ・チェスタトンのテーゼ:「愛は人格を求める。それゆえに、愛は分裂を求める」 ・神は、自分自身により放棄される(24) ・「イエスを裏切る者ユダがいった『ラビよ、まさか、この私なのでは?』。イエスは答えた。『それはあなたのいったことだ』」(マタイ 26:25)/ イエスを賣るユダ答へて言ふ『ラビ、我なるか』イエス言ひ給まふ『なんぢの言へる如し』(マタイ福音 26:25) ・イエスは、ユダに自分を裏切るように教唆した?(29) ・企業禅(43) ・軍国主義禅(44) ・禅と剣はおなじものであう(45) ・「真の革命家は強力な愛の感情につき動かされているのだ」——チェ・ゲバラ(48) ・鈴木大拙(27)——Victoria, Zen at War, p.132. ・『バガヴァッド・ギーター』(50) ・愛=暴力、愛による選択は、対象から切り離し、〈モノ〉の位置まで高める(52) |

| 「正統の戦慄に満ちたロマンス」 | ・チェスタトンの議論はつづく(56) ・人間の尊厳を愛するがゆえに、人間の尊厳を守るための拷問を容認(正当化)する(58) ・グローバル化された主観性がいきつくさきは、客観的現実の消失ではない。社会的現実はそのままに、我々の主体性そのものが消えてしまう(60) ・禅の瞑想の目的は、自己の主体を消し去ってしまうことで、これは、西洋型の仏教には存在しない(60-61)。 ・幸福は真理のカテゴリーではなく、たんなる存在のカテゴリーだ(66) ・例外に固執して、理性を救済する(72) ・犠牲(=欲望)を払う(=抑制する)ことなく、存在を肯定する? ・ラカンによれば、欲望は倫理の領域に属する(76) ・欲望において妥協しないこと=おのれの義務を果たせが、重要(76) ・ラカン『精神分析の倫理』セミネールの異様さ(83) ・ラカン「欲望において妥協するな」 ・バタイユ、民主主義に対抗する、全体主義と共産主義(84) ・禁止が取り除かれた時に、主体が直面しなければならないのは、対象と対象=原因とのあいだのギャップである(88) |

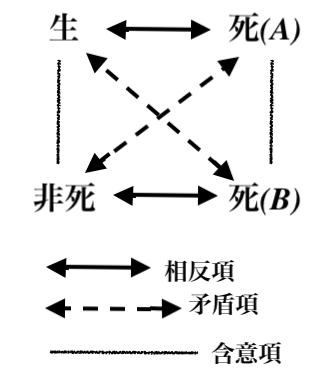

| 〈現実的なもの〉という逸脱 | ・フロイト『快楽原則の彼岸』、いない、いない、ばー(90) ・わたしのなかにある私以上のもの(=大文字の他者?)、それを引き出すには、私を破壊するしかない(91) ・ある対象を欲望するために、その対象を避ける——宮廷恋愛のパラドックス(9) ・他者の享楽(94) ・ジャック・ランシエール(98) ・政治と民主主義は同義語(99)、だから、反民主主義は非政治的 ・ファルスの解釈をめぐって(103) ・現実的なものは、象徴的なものの外部にあるのではない(106)。 ・真のトラウマを隠蔽する(108) ・レヴィ=ストロースのウィネバゴ半族の空間表象解釈(114) ・『コリントの信徒への手紙一』 International Biblical Association, a non-profit organization registered in Macau, China.(135-136) ・愚か者のキリストと自己を同一するパウロ ・神と同一であるということ(138) |

| 法から愛へ……そしてまた法へ | ・涅槃原則(141) ・人生を生きるに値するものは、人生における過剰にほかならない(143) ・生存第一主義=ポスト形而上学(144)  (151) (151)・『存在と時間』でハイデガーは、自分の死は肩代わりできないと主張するが、イエス・キリストは我々が永遠に生きられるように死んだとも言える(152) ・キリストの死の2つの解釈:犠牲論的解釈、参加論的解釈(154) ・慈悲とは過剰な論理(166) ・アガンベンとパウロ解釈(169) ・コリント人への手紙第一、13章の愛をめぐる教説(174) ・バディウのパウロ問題(175) ・贖罪(178) ・官僚機構的知識が象徴的なものと現実的なもののあいだの不条理なずれをもたらす時、我々はそれにより、常識化された現実とは根源的異質な秩序を経験する(182) |

| 差し引くこと——ユダヤ的に、キリスト教的に | ・「雅歌」の読み方は、隠喩なのか、ストレートなのか?(184)[雅歌;サイト内リンク] ・ヨブ記(The Book of Job)の読み方: ・ヨブは耐え忍ぶ受難者ではなく、神に恨みつらみをいい、みずからの(神より与えられた)人生を拒絶する男(187)。 ・ヨブ記27章は、人類最初のイデオロギー批判(188) ・ローゼンツヴァイクの講釈(194)原著 P.129-130. ・ユダヤ人は二重の意味での残余(196) ・特別な(special)の意味(197) ・ベンヤミン、ハバーマス(198) ・残留物(199) ・ユダヤ=パウロ的なメシア的時間と、革命の進行論理とのあいだの構造的類似性(199) ・メシア的時間(ベンヤミン)(200) ・メシア的時間は、客観的な時間のながれに還元できない(201-202) ・キリスト教の時間概念は、すでにメシア的なものが到来したあとの世界(202-203) ・我々は神の助けに頼ることはできない、むしろ、我々は神を助けなければならない(ハンス・ヨナスの発想)(204-205) ・キリスト教の偉業は、〈他者性〉を〈同一性〉に還元したことだ(207) ・脱構築の限界(207) ・脱構築不能ということが、デリダの倫理原則だ(208) ・あらゆる民主主義は失敗の運命にある——失敗してはじめてまともな民主主義が未来に投企される。 ・この民主主義の運命は、宗教の運命でもある(209) ・デリダは、他者を完全に脱存在化することにより、他者性をきたるべきものに還元し、その結果、約束という幽霊だけが残る(→憑在論)(210) ・聖書における倫理的な英雄は、ポンティオ・ピラト、そして、ユダ:「この人を見よ」と言いながら、怪物的余剰であるキリストを指し示すことしかできない(215) |

| 附論:今日のイデオロギー | ・キンダー・チョコレート・エッグ(222-) ・ラカンによる、人間と動物の差異、前者はうんちの処理が必要になること。 ・ジャン・ピエール・デュピュイ(234) ・哲学者ドン・アルフォンソ:「女を信じなさい。でも過度に女を誘惑に晒すな」と、恋人に裏切られた2人の男に助言する(235-236) ・道徳はそれを持てるほど幸福なひとたちにある——ブレヒト(236) ・強制収容所における「ムスルマン(Musulmanen)」(236-237) ・MAD戦略(→核戦略構想;Mutual Assured Destruction,MAD)(242-244) ・キリスト教は、精神分析とは正反対のもの(255) |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆