文明

Civilization

Ancient Egypt is an example of one of the first civilizations, building pyramids starting in the 3rd millennium BCE.

☆文明[civilization](イギリス英語ではcivilisationとも表記される)とは、国家の発展、社会階層化、都市化、そして手話や口頭言語を超えた記号的コミュニケーション体系(すなわち文字体系)を特徴とする複雑な社会を指す。[2][3][4][5][6] 文明は人口密集した集落を中心に組織され、より厳格な階層的分業社会階級に区分される。支配的エリート層と従属的な都市・農村人口が存在し、集約農業、鉱 業、小規模製造業、貿易に従事する。文明は権力を集中させ、自然界全体、さらには他の人間に対する支配を拡大する。[7] 文明は、高度な農業、建築、インフラ、技術的進歩、通貨、課税、規制、労働の分業によって特徴づけられる。[5][6][8] 歴史的に、文明はしばしばより大規模で「より進んだ」文化として理解されてきた。これは暗に、より小規模で進度が劣るとされる文化[9][10][11] [12]、さらには文明内部の社会やその歴史上の段階との対比を意味する。一般的に文明は、遊牧民の文化、新石器時代の社会、狩猟採集民を含む非中央集権 的な部族社会と対比される。文明という言葉はラテン語のcivitas(都市)に由来する。ナショナルジオグラフィック協会が説明するように、「これが文明という言葉を最も基本的に 定義する『都市から成る社会』という理由である」[13]。文明の最も初期の出現は、一般に西アジアにおける新石器革命の最終段階と結びついている。これ は都市革命と国家形成という比較的急速な過程、すなわち統治エリートの出現と関連する政治的発展によって頂点に達した。

A civilization

(also spelled civilisation in British English) is any complex society

characterized by the development of the state, social stratification,

urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond signed or

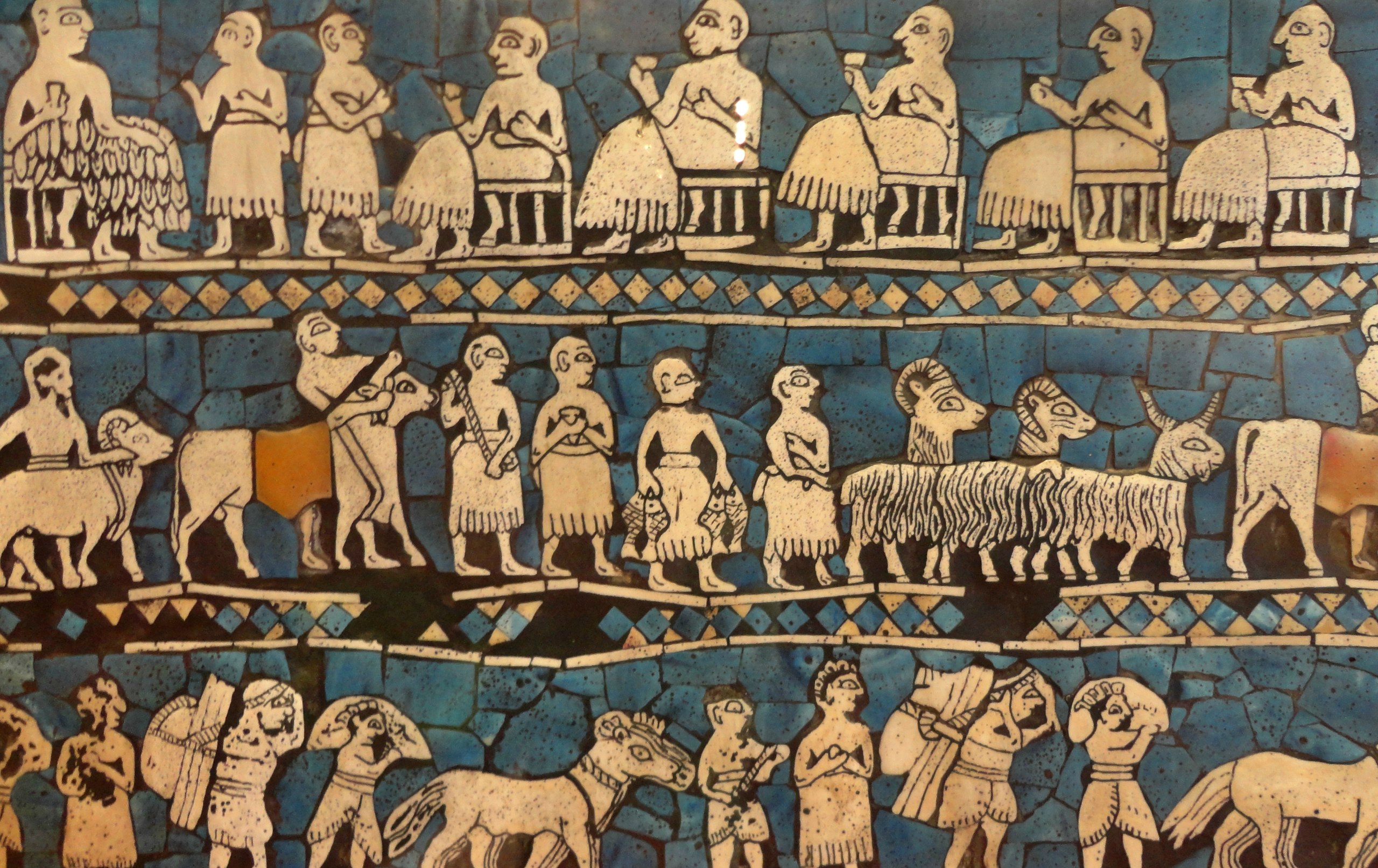

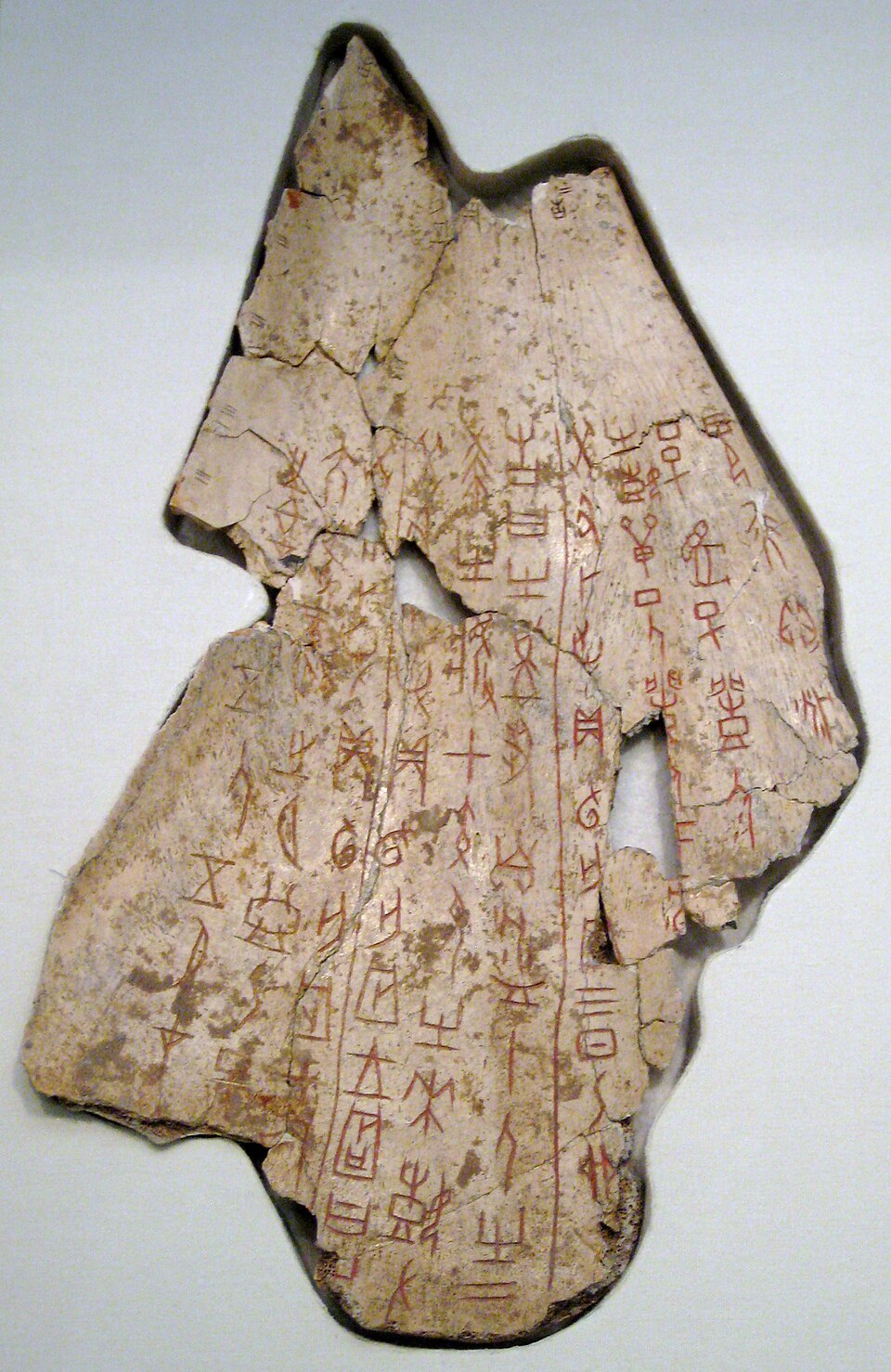

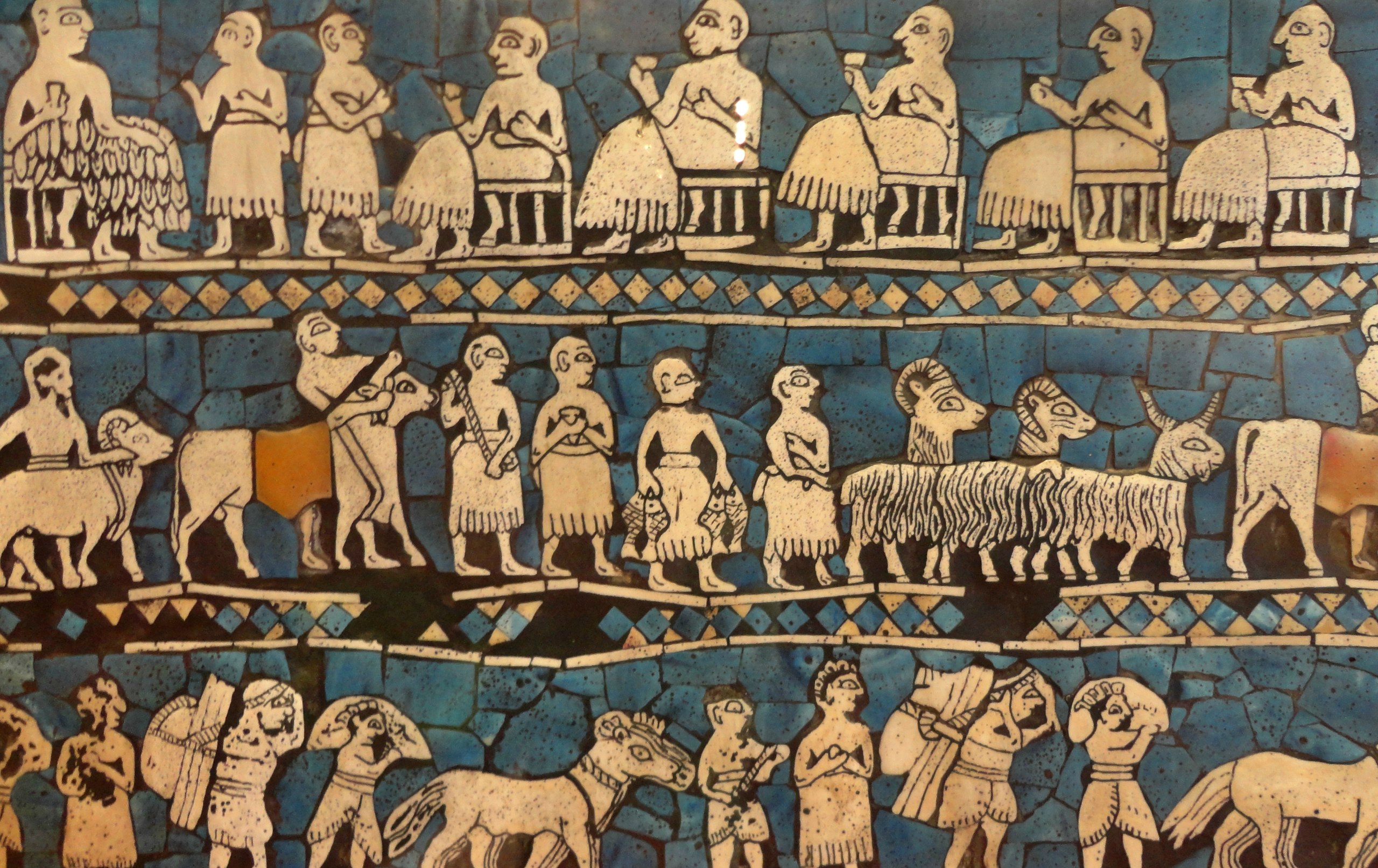

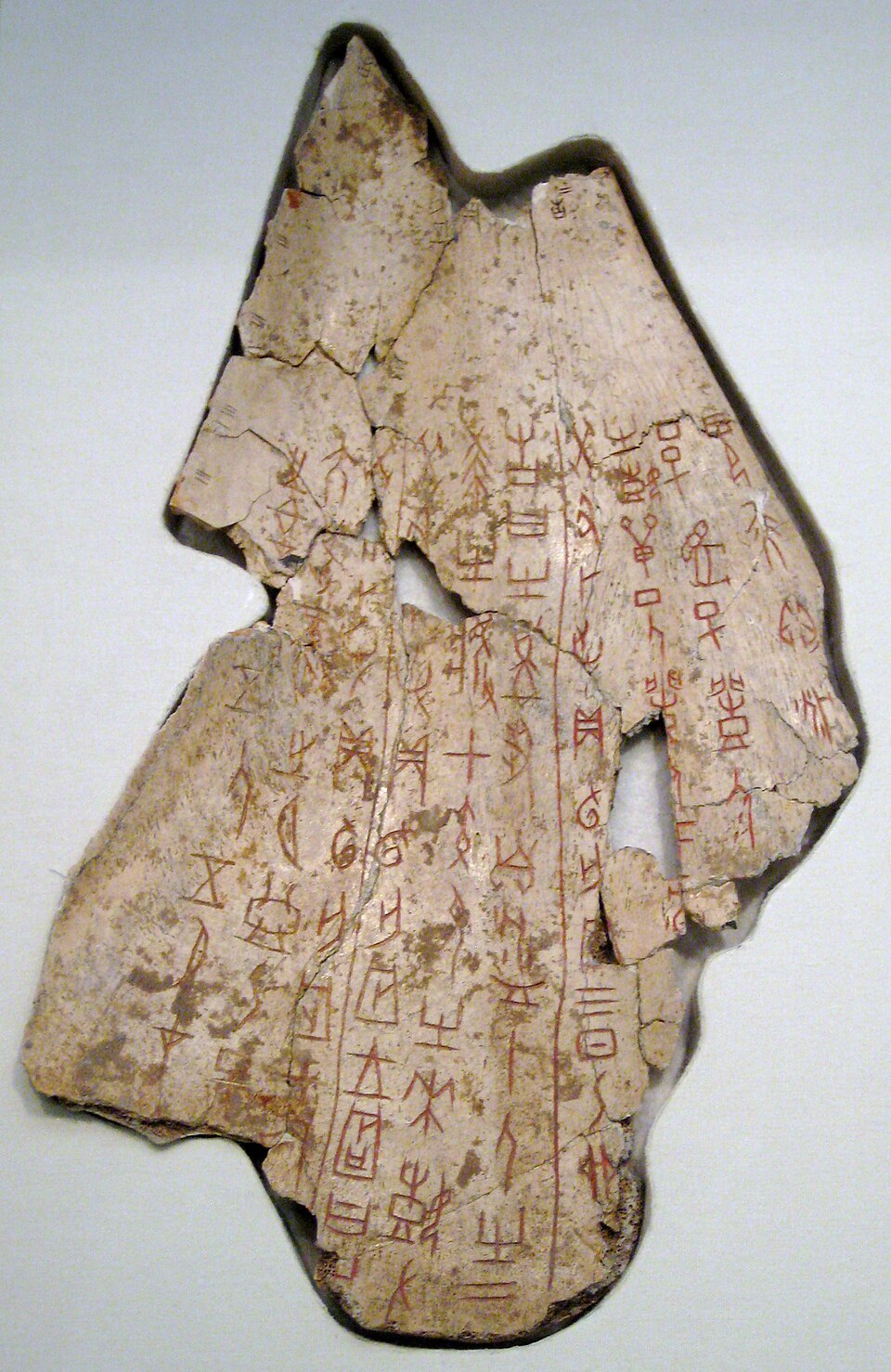

spoken languages (namely, writing systems).[2][3][4][5][6] The ancient Sumerians of Mesopotamia were the oldest civilization in the world, beginning about 4000 BCE, here depicted around 2500 BCE, showing the different social roles in the Sumerian society of Ur. Civilizations are organized around densely populated settlements, divided into more or less rigid hierarchical social classes of division of labour, often with a ruling elite and subordinate urban and rural populations, which engage in intensive agriculture, mining, small-scale manufacture and trade. Civilization concentrates power, extending human control over the rest of nature, including over other human beings.[7] Civilizations are characterized by elaborate agriculture, architecture, infrastructure, technological advancement, currency, taxation, regulation, and specialization of labour.[5][6][8]  China is one of the oldest civilizations in the world, originating in the 21st century BCE and continuing to the present day. Historically, a civilization has often been understood as a larger and "more advanced" culture, in implied contrast to smaller, supposedly less advanced cultures,[9][10][11][12] even societies within civilizations themselves and within their histories. Generally civilization contrasts with non-centralized tribal societies, including the cultures of nomadic pastoralists, Neolithic societies, or hunter-gatherers. The word civilization relates to the Latin civitas or 'city'. As the National Geographic Society has explained it: "This is why the most basic definition of the word civilization is 'a society made up of cities.'"[13] The earliest emergence of civilizations is generally connected with the final stages of the Neolithic Revolution in West Asia, culminating in the relatively rapid process of urban revolution and state formation, a political development associated with the appearance of a governing elite. |

文明[civilization](イギリス英語ではcivilisationとも表記される)とは、国家の発展、社会階層化、都市化、そして手話や口頭言語を超えた記号的コミュニケーション体系(すなわち文字体系)を特徴とする複雑な社会を指す。[2][3][4][5][6] メソポタミアの古代シュメール人は世界最古の文明であり、紀元前4000年頃に始まり、ここでは紀元前2500年頃のウルにおけるシュメール社会の異なる社会的役割が描かれている。 文明は人口密集した集落を中心に組織され、より厳格な階層的分業社会階級に区分される。支配的エリート層と従属的な都市・農村人口が存在し、集約農業、鉱 業、小規模製造業、貿易に従事する。文明は権力を集中させ、自然界全体、さらには他の人間に対する支配を拡大する。[7] 文明は、高度な農業、建築、インフラ、技術的進歩、通貨、課税、規制、労働の分業によって特徴づけられる。[5][6][8]  中国は世界で最も古い文明の一つであり、紀元前21世紀に起源を持ち、現在まで継続している。 歴史的に、文明はしばしばより大規模で「より進んだ」文化として理解されてきた。これは暗に、より小規模で進度が劣るとされる文化[9][10][11] [12]、さらには文明内部の社会やその歴史上の段階との対比を意味する。一般的に文明は、遊牧民の文化、新石器時代の社会、狩猟採集民を含む非中央集権 的な部族社会と対比される。 文明という言葉はラテン語のcivitas(都市)に由来する。ナショナルジオグラフィック協会が説明するように、「これが文明という言葉を最も基本的に 定義する『都市から成る社会』という理由である」[13]。文明の最も初期の出現は、一般に西アジアにおける新石器革命の最終段階と結びついている。これ は都市革命と国家形成という比較的急速な過程、すなわち統治エリートの出現と関連する政治的発展によって頂点に達した。 |

| History of the concept The English word civilization comes from the French civilisé ('civilized'), from Latin: civilis ('civil'), related to civis ('citizen') and civitas ('city').[14] The fundamental treatise is Norbert Elias's The Civilizing Process (1939), which traces social mores from medieval courtly society to the early modern period.[a] In The Philosophy of Civilization (1923), Albert Schweitzer outlines two opinions: one purely material and the other material and ethical. He said that the world crisis was from humanity losing the ethical idea of civilization, "the sum total of all progress made by man in every sphere of action and from every point of view in so far as the progress helps towards the spiritual perfecting of individuals as the progress of all progress".[16]  The End of Dinner by Jules-Alexandre Grün (1913). The emergence of table manners and other forms of etiquette and self-restraint are presented as a characteristic of civilized society by Norbert Elias in his book The Civilizing Process (1939). Related words like "civility" developed in the mid-16th century. The abstract noun "civilization", meaning "civilized condition", came in the 1760s, again from French. The first known use in French is in 1757, by Victor de Riqueti, marquis de Mirabeau, and the first use in English is attributed to Adam Ferguson, who in his 1767 Essay on the History of Civil Society wrote, "Not only the individual advances from infancy to manhood but the species itself from rudeness to civilisation".[17] The word was therefore opposed to barbarism or rudeness, in the active pursuit of progress characteristic of the Age of Enlightenment. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, during the French Revolution, "civilization" was used in the singular, never in the plural, and meant the progress of humanity as a whole. This is still the case in French.[18] The use of "civilizations" as a countable noun was in occasional use in the 19th century,[b] but has become much more common in the later 20th century, sometimes just meaning culture (itself in origin an uncountable noun, made countable in the context of ethnography).[19] Only in this generalized sense does it become possible to speak of a "medieval civilization", which in Elias's sense would have been an oxymoron. Using the terms "civilization" and "culture" as equivalents is controversial and generally rejected, so that, for example, some types of culture are not normally described as civilizations.[20] Already in the 18th century, civilization was not always seen as an improvement. One historically important distinction between culture and civilization is from the writings of Rousseau, particularly his work about education, Emile. Here, civilization, being more rational and socially driven, is not fully in accord with human nature, and "human wholeness is achievable only through the recovery of or approximation to an original discursive or pre-rational natural unity" (see noble savage). From this, a new approach was developed, especially in Germany, first by Johann Gottfried Herder and later by philosophers such as Kierkegaard and Nietzsche. This sees cultures as natural organisms, not defined by "conscious, rational, deliberative acts", but a kind of pre-rational "folk spirit". Civilization, in contrast, though more rational and more successful in material progress, is unnatural and leads to "vices of social life" such as guile, hypocrisy, envy and avarice.[18] In World War II, Leo Strauss, having fled Germany, argued in New York that this opinion of civilization was behind Nazism and German militarism and nihilism.[21] |

概念の歴史 英語の「文明」という言葉は、フランス語の「civilisé」(文明化された)に由来し、ラテン語の「civilis」(市民的な)から派生したもので ある。これは「civis」(市民)や「civitas」(都市)と関連している。[14] 根本的な論考はノルベルト・エリアスの『文明化過程』(1939年)であり、中世の宮廷社会から近世初期にかけての社会的慣習の変遷を辿っている。[a] アルベルト・シュヴァイツァーは『文明の哲学』(1923年)において、二つの見解を提示している。一つは純粋に物質的なものであり、もう一つは物質的か つ倫理的なものである。彼は、世界危機は人類が文明の倫理的理念を失ったことに起因すると述べた。「文明とは、あらゆる行動領域において、あらゆる観点か ら達成された進歩の総体であり、その進歩が個人の精神的完成、すなわちあらゆる進歩の究極目標に寄与する限りにおいて」である。[16]  ジュール=アレクサンドル・グリュン作『夕食の終わり』(1913年)。ノルベルト・エリアスは著書『文明化過程』(1939年)において、テーブルマナーやその他の礼儀作法・自制心の出現を文明社会の特性として提示している。 「礼儀正しさ」のような関連語は 16 世紀半ばに発展した。「文明化」を意味する抽象名詞「civilization」は、1760 年代に、これもフランス語から導入された。フランス語で最初にこの言葉が使われたのは、1757年にヴィクトル・ド・リケティ、ミラボー侯爵によるもので ある。英語で最初にこの言葉が使われたのは、アダム・ファーガソンによるものである。彼は1767年の『市民社会の歴史に関するエッセイ』の中で、「個人 は幼児期から成人期へと成長するだけでなく、人類そのものも無作法から文明へと成長する」と書いている。[17] したがって、この言葉は、啓蒙時代を特徴づける進歩の積極的な追求において、野蛮や粗野とは対極にあるものだった。 1700年代後半から1800年代初頭、フランス革命の時代には、「文明」は単数形で使われ、複数形では決して使われず、人類全体の進歩を意味していた。 これは、フランス語では今でもそうである。[18] 「文明」を可算名詞として用いる用法は19世紀に散見された[b]が、20世紀後半にははるかに一般的になった。時には単に「文化」(元来不可算名詞だ が、民族誌の文脈で可算化された)を意味する場合もある。[19] このような一般化された意味においてのみ、「中世文明」という表現が可能となる。エリアスの意味ではこれは矛盾した表現であった。文明と文化を同義語とし て用いることは議論の余地があり、一般的に拒否される。例えば、ある種の文化は通常、文明とは呼ばれない。[20] 18世紀においてさえ、文明は常に進歩と見なされていたわけではない。文化と文明の歴史的に重要な区別は、ルソーの著作、特に教育論『エミール』に見られ る。ここでは、より合理的で社会的に駆動される文明は人間の本性に完全には合致せず、「人間の全体性は、本来の言説的あるいは前理性的自然的統一性の回復 またはそれに近づくことによってのみ達成可能である」(高貴なる野蛮人参照)。これに基づき、特にドイツで新たなアプローチが発展した。最初にヨハン・ ゴットフリート・ヘルダーが提唱し、後にキルケゴールやニーチェといった哲学者たちが継承した。この見解では、文化は「意識的・合理的・思慮深い行為」に よって定義されるのではなく、一種の非合理的な「民族精神」によって形作られる自然有機体と見なされる。これに対し文明は、より合理的で物質的進歩におい てはより成功しているものの、不自然であり、狡猾さ、偽善、嫉妬、貪欲といった「社会生活の弊害」をもたらす[18]。第二次世界大戦中、ドイツから逃れ たレオ・シュトラウスはニューヨークで、この文明観こそがナチズムやドイツのミリタリズム、ニヒリズムの背景にあると論じた[21]。 |

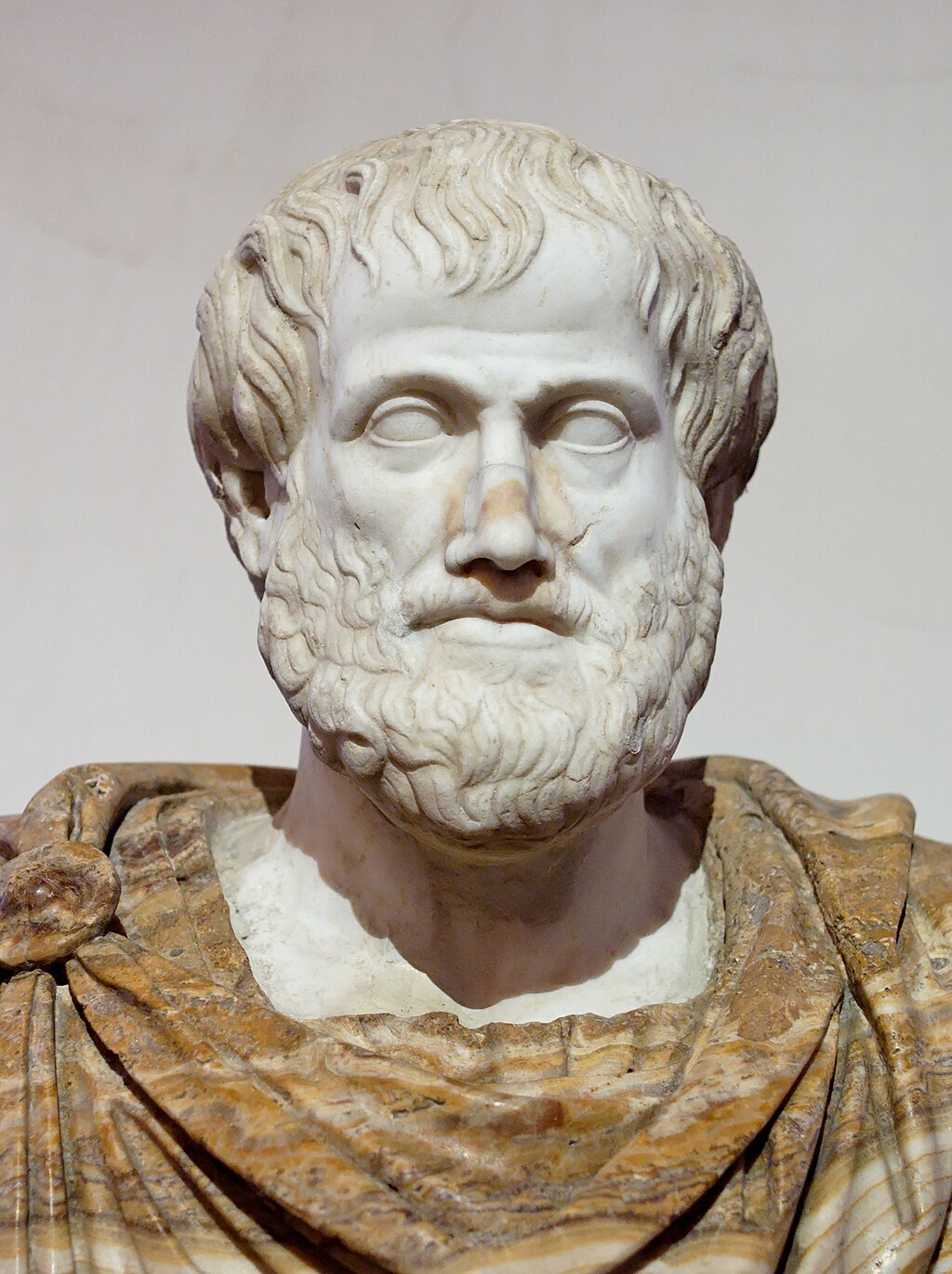

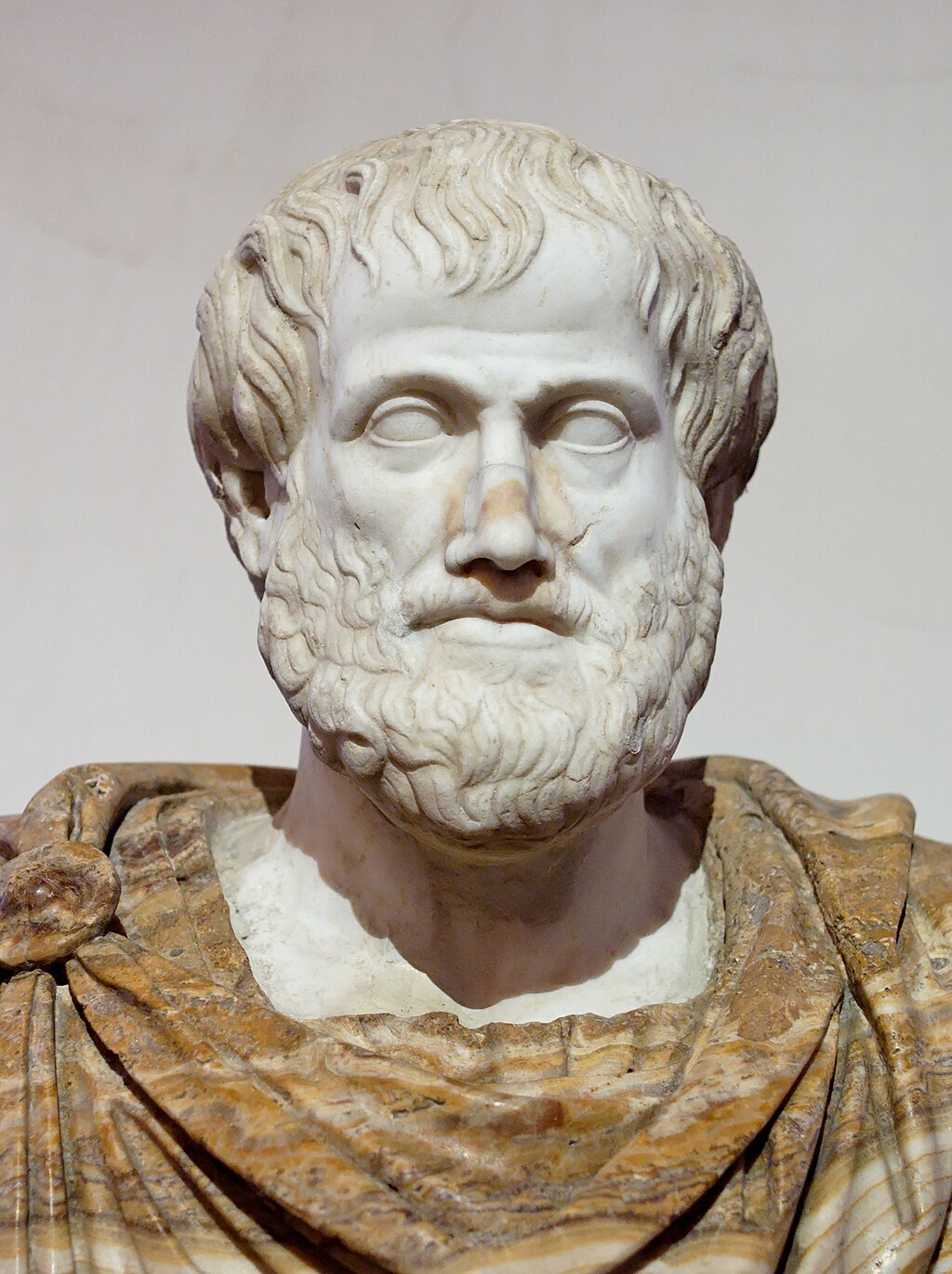

Characteristics The Acropolis of Athens: Greece is traditionally seen as the cradle of a distinct European or "Western" civilization.[22][23] Social scientists such as V. Gordon Childe have named a number of traits that distinguish a civilization from other kinds of society.[24][25] Civilizations have been distinguished by their means of subsistence, types of livelihood, settlement patterns, forms of government, social stratification, economic systems, literacy and other cultural traits. Andrew Nikiforuk argues that "civilizations relied on shackled human muscle. It took the energy of slaves to plant crops, clothe emperors, and build cities" and considers slavery to be a common feature of pre-modern civilizations.[26] All civilizations have depended on agriculture for subsistence, with the possible exception of some early civilizations in Peru which may have depended upon maritime resources.[27][28] Most developed and permanent civilizations depended on cereal agriculture. The traditional "surplus model" postulates that cereal farming results in accumulated storage and a surplus of food, particularly when people use intensive agricultural techniques such as artificial fertilization, irrigation and crop rotation. It is possible but more difficult to accumulate horticultural production, and so civilizations based on horticultural gardening have been very rare.[29] Grain surpluses have been especially important because grain can be stored for a long time. Research from the Journal of Political Economy contradicts the surplus model. It postulates that horticultural gardening was more productive than cereal farming. However, only cereal farming produced civilization because of the appropriability of the yearly harvest. Rural populations that could only grow cereals could be taxed allowing for a taxing elite and urban development. This also had a negative effect on the rural population, increasing relative agricultural output per farmer. Farming efficiency created food surplus and sustained the food surplus through decreasing rural population growth in favour of urban growth. Suitability of highly productive roots and tubers was in fact a curse of plenty, which prevented the emergence of states and impeded economic development.[30][31] A surplus of food permits some people to do things besides producing food for a living: early civilizations included soldiers, artisans, priests and priestesses, and other people with specialized careers. A surplus of food results in a division of labour and a more diverse range of human activity, a defining trait of civilizations. However, in some places hunter-gatherers have had access to food surpluses, such as among some of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest and perhaps during the Mesolithic Natufian culture. It is possible that food surpluses and relatively large scale social organization and division of labour predates plant and animal domestication.[32] Civilizations have distinctly different settlement patterns from other societies. The word civilization is sometimes defined as "living in cities".[33] Non-farmers tend to gather in cities to work and to trade. Compared with other societies, civilizations have a more complex political structure, namely the state.[34] State societies are more stratified[35] than other societies; there is a greater difference among the social classes. The ruling class, normally concentrated in the cities, has control over much of the surplus and exercises its will through the actions of a government or bureaucracy. Morton Fried, a conflict theorist and Elman Service, an integration theorist, have classified human cultures based on political systems and social inequality. This system of classification contains four categories.[36] Hunter-gatherer bands, which are generally egalitarian.[37] Horticultural–pastoralist societies in which there are generally two inherited social classes: chief and commoner. Highly stratified structures, or chiefdoms, with several inherited social classes: king, noble, freemen, serf and slave. Civilizations, with complex social hierarchies and organized, institutional forms of government.[38] Economically, civilizations display more complex patterns of ownership and exchange than less organized societies. Living in one place allows people to accumulate more personal possessions than nomadic people. Some people also acquire landed property, or private ownership of the land. Because a percentage of people in civilizations do not grow their own food, they must trade their goods and services for food in a market system, or receive food through the levy of tribute, redistributive taxation, tariffs or tithes from the food producing segment of the population. Early human cultures functioned through a gift economy supplemented by limited barter systems. By the early Iron Age, contemporary civilizations developed money as a medium of exchange for increasingly complex transactions. In a village, the potter makes a pot for the brewer and the brewer compensates the potter by giving him a certain amount of beer. In a city, the potter may need a new roof, the roofer may need new shoes, the cobbler may need new horseshoes, the blacksmith may need a new coat and the tanner may need a new pot. These people may not be personally acquainted with one another and their needs may not occur all at the same time. A monetary system is a way of organizing these obligations to ensure that they are fulfilled. From the days of the earliest monetarized civilizations, monopolistic controls of monetary systems have benefited the social and political elites. The transition from simpler to more complex economies does not necessarily mean an improvement in the living standards of the populace. For example, although the Middle Ages is often portrayed as an era of decline from the Roman Empire, studies have shown that the average stature of males in the Middle Ages (c. 500 to 1500 CE) was greater than it was for males during the preceding Roman Empire and the succeeding Early Modern Period (c. 1500 to 1800 CE).[39][40] Also, the Plains Indians of North America in the 19th century were taller than their "civilized" American and European counterparts. The average stature of a population is a good measurement of the adequacy of its access to necessities, especially food, and its freedom from disease.[41] Writing, developed first by people in Sumer, is considered a hallmark of civilization and "appears to accompany the rise of complex administrative bureaucracies or the conquest state".[42] Traders and bureaucrats relied on writing to keep accurate records. Like money, the writing was necessitated by the size of the population of a city and the complexity of its commerce among people who are not all personally acquainted with each other. However, writing is not always necessary for civilization, as shown by the Inca civilization of the Andes, which did not use writing at all but except for a complex recording system consisting of knotted strings of different lengths and colours: the "Quipus", and still functioned as a civilized society.  Aristotle, the Ancient Greek philosopher and scientist Aided by their division of labour and central government planning, civilizations have developed many other diverse cultural traits. These include organized religion, development in the arts, and countless new advances in science and technology. Assessments of what level of civilization a polity has reached are based on comparisons of the relative importance of agricultural as opposed to trading or manufacturing capacities, the territorial extensions of its power, the complexity of its division of labour, and the carrying capacity of its urban centres. Secondary elements include a developed transportation system, writing, standardized measurement, currency, contractual and tort-based legal systems, art, architecture, mathematics, scientific understanding, metallurgy, political structures, and organized religion. |

特徴 アテネのアクロポリス:ギリシャは伝統的に、独自のヨーロッパあるいは「西洋」文明の発祥地と見なされてきた。[22][23] V. ゴードン・チャイルドなどの社会科学者は、文明を他の種類の社会と区別するいくつかの特徴を挙げている。[24][25] 文明は、その生計手段、生活様式、居住パターン、政府の形態、社会階層、経済システム、識字率、その他の文化的特徴によって区別されてきた。アンドルー・ ニキフォロックは、「文明は束縛された人間の筋肉に依存していた。作物を植え、皇帝に衣服を供給し、都市を建設するには奴隷のエネルギーが必要だった」と 述べ、奴隷制度は前近代文明の共通の特徴であると考えている。[26] すべての文明は、ペルーの初期文明の一部が海洋資源に依存していた可能性を除いて、生計を農業に依存してきた。[27][28] ほとんどの先進的かつ永続的な文明は、穀物農業に依存していた。伝統的な「余剰モデル」は、穀物栽培が蓄積された貯蔵と食料の余剰をもたらすと仮定する。 特に人工施肥、灌漑、輪作といった集約的農業技術を用いる場合だ。園芸生産の蓄積は可能だがより困難であり、園芸栽培に基づく文明は極めて稀であった [29]。穀物の余剰は特に重要だった。穀物は長期保存が可能だからだ。 『政治経済学ジャーナル』の研究は余剰モデルに反論している。園芸栽培は穀物栽培より生産性が高かったと主張する。しかし、年間の収穫を独占できる特性ゆ えに、文明を生み出したのは穀物栽培だけだった。穀物しか栽培できない農村人口は課税可能であり、課税する支配層と都市発展を可能にした。これは農村人口 に悪影響も及ぼし、農民一人当たりの相対的農業生産性を高めた。農業効率は食糧余剰を生み出し、都市成長を優先して農村人口増加を抑制することで食糧余剰 を持続させた。高生産性の根菜・塊茎の適性は、実は豊穣の呪いであり、国家の出現を阻み経済発展を妨げたのである。[30][31] 食糧余剰は、一部の人々が食糧生産以外の活動に従事することを可能にした。初期文明には兵士、職人、神官・巫女、その他専門職が存在する。食料の余剰は分 業と多様な人間活動をもたらし、これが文明の特徴だ。ただし、太平洋岸北西部の先住民や中石器時代のナトゥフィアン文化など、狩猟採集民が食料余剰を享受 した例もある。植物・動物の家畜化以前に、食料余剰と比較的大きな社会組織・分業が存在した可能性もある。[32] 文明は、他の社会とは明らかに異なる居住パターンを持っている。文明という言葉は、「都市に住むこと」と定義されることもある。[33] 非農民は、仕事や取引のために都市に集まる傾向がある。 他の社会と比較して、文明はより複雑な政治構造、すなわち国家を持っている。[34] 国家社会は他の社会よりも階層化[35] しており、社会階級間の格差が大きい。通常、都市に集中する支配階級は、余剰生産物の大部分を支配し、政府や官僚機構の行動を通じてその意志を行使する。 紛争理論家のモートン・フリードと統合理論家のエルマン・サービスは、政治体制と社会的不平等に基づいて人間文化を分類した。この分類体系には 4 つのカテゴリーがある。[36] 一般的に平等主義的な狩猟採集民の集団。[37] 園芸・牧畜社会。一般的に、首長と平民という 2 つの世襲社会階級がある。 高度に階層化された構造、すなわち首長制。王、貴族、自由民、農奴、奴隷といういくつかの世襲社会階級がある。 文明。複雑な社会階層と、組織化された制度的な政府形態を持つ。[38] 経済的には、文明は、組織化されていない社会よりも複雑な所有権と交換のパターンを示す。定住生活は遊牧民より多くの個人的財産の蓄積を可能にする。土地 所有権、すなわち土地の私有権を獲得する者も現れる。文明社会では人口の一部が自給自足を行わないため、市場システムで物資やサービスを食糧と交換する か、食糧生産層からの貢納・再分配的課税・関税・十分の一税を通じて食糧を調達する必要がある。初期の人類文化は、限定的な物々交換制度を補完する贈与経 済によって機能していた。鉄器時代初期までに、当時の文明はますます複雑化する取引の交換手段として貨幣を発達させた。村では、陶工が醸造業者に壺を作 り、醸造業者は陶工に一定量のビールを与えることで報酬を支払う。都市では、陶工が新しい屋根を必要とし、屋根職人が新しい靴を必要とし、靴職人が新しい 蹄鉄を必要とし、鍛冶職人が新しい上着を必要とし、皮革職人が新しい壺を必要とするかもしれない。これらの人々は互いに個人的な知り合いではなく、彼らの 必要が同時に生じるわけでもない。貨幣制度とは、こうした義務を組織化し確実に履行させる手段である。貨幣が流通し始めた初期の文明時代から、貨幣制度の 独占的支配は社会的・政治的エリート層に利益をもたらしてきた。 より単純な経済から複雑な経済への移行は、必ずしも民衆の生活水準向上を意味しない。例えば、中世はローマ帝国からの衰退期と描かれることが多いが、研究 によれば中世(西暦500年~1500年頃)の男性の平均身長は、前時代のローマ帝国や後世の近世(西暦1500年~1800年頃)の男性よりも高かっ た。[39][40] また、19世紀の北米平原インディアンは、「文明化された」アメリカ人やヨーロッパ人よりも背が高かった。人口の平均身長は、必需品(特に食料)へのアク セスが十分かどうか、また疾病から自由であるかどうかを測る良い指標となる。[41] シュメール人によって最初に開発された文字は、文明の象徴と見なされ、「複雑な行政官僚機構や征服国家の台頭に伴って出現した」とされる。[42] 商人や官僚は正確な記録を保持するために文字に依存した。貨幣と同様に、文字は都市の人口規模と、互いに個人的に面識のない人々間の商業の複雑さによって 必要とされた。しかし、アンデス山脈のインカ文明が示すように、文字は必ずしも文明に必要ではない。インカ文明は文字を全く使用せず、長さと色が異なる結 び紐からなる複雑な記録システム「キプ」を用いることで、文明社会として機能していたのである。  古代ギリシャの哲学者であり科学者であるアリストテレス 分業と中央政府による計画の助けを借りて、文明は他の多くの多様な文化的特徴を発展させてきた。これには組織化された宗教、芸術の発展、そして科学技術における無数の新たな進歩が含まれる。 ある政治共同体がどの程度の文明レベルに達しているかの評価は、農業能力と貿易・製造業能力の相対的重要性の比較、権力の領土的拡張、分業の複雑さ、都市 中心部の収容力に基づいて行われる。二次的な要素には、発達した交通システム、文字、標準化された測定単位、通貨、契約法と不法行為法に基づく法制度、芸 術、建築、数学、科学的理解、冶金学、政治構造、組織化された宗教が含まれる。 |

| As a contrast with other societies The idea of civilization implies a progression or development from a previous "uncivilized" state. Traditionally, cultures that defined themselves as "civilized" often did so in contrast to other societies or human groupings viewed as less civilized, calling the latter barbarians, savages, and primitives. Indeed, the modern Western idea of civilization developed as a contrast to the indigenous cultures European settlers encountered during the European colonization of the Americas and Australia.[43] The term "primitive," though once used in anthropology, has now been largely condemned by anthropologists because of its derogatory connotations and because it implies that the cultures it refers to are relics of a past time that do not change or progress.[44] Because of this, societies regarding themselves as "civilized" have sometimes sought to dominate and assimilate "uncivilized" cultures into a "civilized" way of living.[45] In the 19th century, the idea of European culture as "civilized" and superior to "uncivilized" non-European cultures was fully developed, and civilization became a core part of European identity.[46] The idea of civilization can also be used as a justification for dominating another culture and dispossessing a people of their land. For example, in Australia, British settlers justified the displacement of Indigenous Australians by observing that the land appeared uncultivated and wild, which to them reflected that the inhabitants were not civilized enough to "improve" it.[43] The behaviours and modes of subsistence that characterize civilization have been spread by colonization, invasion, religious conversion, the extension of bureaucratic control and trade, and by the introduction of new technologies to cultures that did not previously have them. Though aspects of culture associated with civilization can be freely adopted through contact between cultures, since early modern times Eurocentric ideals of "civilization" have been widely imposed upon cultures through coercion and dominance. These ideals complemented a philosophy that assumed there were innate differences between "civilized" and "uncivilized" peoples.[46] |

他の社会との対比として 文明という概念は、以前の「未開」の状態からの進歩や発展を意味する。伝統的に、自らを「文明的」と定義した文化は、しばしばより未開と見なされた他の社 会や集団との対比においてそうし、後者を野蛮人、未開人、原始人と呼んだ。実際、近代西洋の文明観念は、ヨーロッパ人入植者がアメリカ大陸やオーストラリ アの先住民文化と接触した際に形成された対比概念として発展した[43]。「原始的」という用語はかつて人類学で使われたが、蔑称的意味合いを持つこと、 また対象文化を変化や進歩のない過去の遺物と暗示することから、現在では人類学者によってほぼ非難されている。[44] このため、「文明化された」と自認する社会は、「未開」な文化を支配し、「文明化された」生活様式へ同化させようとする場合があった。[45] 19世紀には、ヨーロッパ文化が「文明化」され、非ヨーロッパの「未開」文化より優れているという考えが完全に確立され、文明はヨーロッパのアイデンティ ティの中核となった。[46] 文明という概念は、他文化を支配し、人々から土地を奪うことの正当化にも用いられる。例えばオーストラリアでは、英国入植者たちが先住民の土地追放を正当 化するため、その土地が未開で荒れ果てていると指摘した。彼らにとってそれは、住民が土地を「改良」するに足る文明化を成し遂げていない証左だったのだ。 [43] 文明を特徴づける行動様式や生業形態は、植民地化、侵略、宗教改宗、官僚的支配と貿易の拡大、そして新たな技術の導入を通じて、それまでそれらを持たな かった文化圏に広められてきた。文明に関連する文化の側面は、文化間の接触を通じて自由に採用される可能性があるものの、近世以降、「文明」というヨー ロッパ中心的な理想は、強制と支配によって広く文化に押し付けられてきた。これらの理想は、「文明化された」人々と「未開」な人々との間に生来の差異があ ると仮定する哲学を補完するものだった。 |

| Cultural identity Further information: Cultural area and culture "Civilization" can also refer to the culture of a complex society, not just the society itself. Every society, civilization or not, has a specific set of ideas and customs, and a certain set of manufactures and arts that make it unique. Civilizations tend to develop intricate cultures, including a state-based decision-making apparatus, a literature, professional art, architecture, organized religion and complex customs of education, coercion and control associated with maintaining the elite. The intricate culture associated with civilization has a tendency to spread to and influence other cultures, sometimes assimilating them into the civilization, a classic example being Chinese civilization and its influence on nearby civilizations such as Korea, Japan and Vietnam[47] Many civilizations are actually large cultural spheres containing many nations and regions. The civilization in which someone lives is that person's broadest cultural identity.[48][49]  A Blue Shield International mission in Libya during the war in 2011 to protect the cultural assets there. It is precisely the protection of this cultural identity that is becoming increasingly important nationally and internationally. According to international law, the United Nations and UNESCO try to set up and enforce relevant rules. The aim is to preserve the cultural heritage of humanity and also the cultural identity, especially in the case of war and armed conflict. According to Karl von Habsburg, President of Blue Shield International, the destruction of cultural assets is also part of psychological warfare. The target of the attack is often the opponent's cultural identity, which is why symbolic cultural assets become a main target. It is also intended to destroy the particularly sensitive cultural memory (museums, archives, monuments, etc.), the grown cultural diversity, and the economic basis (such as tourism) of a state, region or community.[50][51][52][53][54][55] Many historians have focused on these broad cultural spheres and have treated civilizations as discrete units. Early twentieth-century philosopher Oswald Spengler,[56] uses the German word Kultur, "culture", for what many call a "civilization". Spengler believed a civilization's coherence is based on a single primary cultural symbol. Cultures experience cycles of birth, life, decline, and death, often supplanted by a potent new culture, formed around a compelling new cultural symbol. Spengler states civilization is the beginning of the decline of a culture as "the most external and artificial states of which a species of developed humanity is capable".[56] This "unified culture" concept of civilization also influenced the theories of historian Arnold J. Toynbee in the mid-twentieth century. Toynbee explored civilization processes in his multi-volume A Study of History, which traced the rise and, in most cases, the decline of 21 civilizations and five "arrested civilizations". Civilizations generally declined and fell, according to Toynbee, because of the failure of a "creative minority", through moral or religious decline, to meet some important challenge, rather than mere economic or environmental causes. Samuel P. Huntington defines civilization as "the highest cultural grouping of people and the broadest level of cultural identity people have short of that which distinguishes humans from other species".[48] |

文化的アイデンティティ 詳細情報:文化圏と文化 「文明」とは、複雑な社会そのものだけでなく、その社会の文化を指すこともある。あらゆる社会は、文明であるか否かにかかわらず、固有の思想や慣習、そし て特定の工芸品や芸術を有し、それらがその社会を独特なものにしている。文明は複雑な文化を発展させる傾向があり、国家に基づく意思決定機構、文学、専門 的な芸術、建築、組織化された宗教、そしてエリート層を維持するための教育、強制、統制に関する複雑な慣習を含む。 文明に伴う複雑な文化は、他の文化へ拡散し影響を与える傾向があり、時にはそれらを文明へ同化させることもある。典型的な例が中国文明と、その周辺文明 (韓国、日本、ベトナムなど)への影響である[47]。多くの文明は実際には、多数の国民や地域を含む広大な文化的圏である。個人が生きる文明こそが、そ の人にとって最も広範な文化的アイデンティティとなる[48]。[49]  2011年のリビア内戦時、現地の文化資産保護を目的としたブルーシールド・インターナショナルの活動。 まさにこの文化的アイデンティティの保護が、国内外の国民間でますます重要になっている。国際法に基づき、国連とユネスコは関連規則の制定と施行を試みて いる。目的は人類の文化遺産と文化的アイデンティティを、特に戦争や武力紛争時に保存することだ。ブルーシールド・インターナショナルのカール・フォン・ ハプスブルク会長によれば、文化財の破壊は心理戦の一環でもある。攻撃の標的は往々にして敵対者の文化的アイデンティティであり、そのため象徴的な文化財 が主たる標的となる。また国家・地域・共同体の特に敏感な文化的記憶(博物館・公文書館・記念碑など)、培われた文化的多様性、経済基盤(観光業など)を 破壊することも意図されている。[50][51][52][53][54][55] 多くの歴史家はこうした広範な文化的領域に注目し、文明を独立した単位として扱ってきた。20世紀初頭の哲学者オズワルド・シュペングラー[56]は、多 くの人が「文明」と呼ぶものを指すドイツ語「Kultur(文化)」を用いている。シュペングラーは、文明の一体性は単一の主要な文化的象徴に基づくと考 えた。文化は誕生、繁栄、衰退、死のサイクルを経験し、しばしば強力な新たな文化的象徴を中心に形成された新たな文化に取って代わられる。シュペングラー は文明を「発達した人類種が到達しうる最も外面的で人工的な状態」として、文化の衰退の始まりと位置づけた。[56] この「統一文化」概念は、20世紀中頃の歴史家アーノルド・J・トインビーの理論にも影響を与えた。トインビーは多巻にわたる『歴史の研究』で文明の過程 を探求し、21の文明と5つの「停滞文明」の興隆と、大半の場合における衰退を追跡した。トインビーによれば、文明が衰退し滅びるのは、単なる経済的・環 境的要因ではなく、道徳的・宗教的衰退を通じて「創造的少数派」が重要な課題に対処できなかったためである。 サミュエル・P・ハンティントンは文明を「人類を他の種と区別する要素に次ぐ、人々の文化的帰属意識における最高次元の集団」と定義している。[48] |

| Complex systems Depiction of united Medes and Persians at the Apadana, Persepolis. Another group of theorists, making use of systems theory, looks at a civilization as a complex system, i.e., a framework by which a group of objects can be analysed that work in concert to produce some result. Civilizations can be seen as networks of cities that emerge from pre-urban cultures and are defined by the economic, political, military, diplomatic, social and cultural interactions among them. Any organization is a complex social system and a civilization is a large organization. Systems theory helps guard against superficial and misleading analogies in the study and description of civilizations. Systems theorists look at many types of relations between cities, including economic relations, cultural exchanges and political/diplomatic/military relations. These spheres often occur on different scales. For example, trade networks were, until the nineteenth century, much larger than either cultural spheres or political spheres. Extensive trade routes, including the Silk Road through Central Asia and Indian Ocean sea routes linking the Roman Empire, Persian Empire, India and China, were well established 2000 years ago when these civilizations scarcely shared any political, diplomatic, military, or cultural relations. The first evidence of such long-distance trade is in the ancient world. During the Uruk period, Guillermo Algaze has argued that trade relations connected Egypt, Mesopotamia, Iran and Afghanistan.[57] Resin found later in the Royal Cemetery at Ur is suggested was traded northwards from Mozambique. Many theorists argue that the entire world has already become integrated into a single "world system", a process known as globalization. Different civilizations and societies all over the globe are economically, politically, and even culturally interdependent in many ways. There is debate over when this integration began, and what sort of integration – cultural, technological, economic, political, or military-diplomatic – is the key indicator in determining the extent of a civilization. David Wilkinson has proposed that economic and military-diplomatic integration of the Mesopotamian and Egyptian civilizations resulted in the creation of what he calls the "Central Civilization" around 1500 BCE.[58] Central Civilization later expanded to include the entire Middle East and Europe, and then expanded to a global scale with European colonization, integrating the Americas, Australia, China and Japan by the nineteenth century. According to Wilkinson, civilizations can be culturally heterogeneous, like the Central Civilization, or homogeneous, like the Japanese civilization. What Huntington calls the "clash of civilizations" might be characterized by Wilkinson as a clash of cultural spheres within a single global civilization. Others point to the Crusading movement as the first step in globalization. The more conventional viewpoint is that networks of societies have expanded and shrunk since ancient times, and that the current globalized economy and culture is a product of recent European colonialism.[citation needed] |

複雑なシステム ペルセポリス、アパダーナ宮殿に描かれた統一されたメディア人とペルシア人。 別の理論家グループはシステム理論を活用し、文明を複雑系として捉える。つまり、何らかの結果を生み出すために協調して機能する対象群を分析する枠組みと してである。文明は都市ネットワークと見なせる。それは前都市文化から出現し、都市間の経済的・政治的・軍事的・外交的・社会的・文化的相互作用によって 定義される。あらゆる組織は複雑な社会システムであり、文明は巨大な組織である。システム理論は、文明の研究や記述における表面的で誤解を招く類推を防ぐ のに役立つ。 システム理論家は、経済関係、文化交流、政治・外交・軍事関係など、都市間の多様な関係性を考察する。これらの領域はしばしば異なる規模で存在する。例え ば、19世紀まで貿易ネットワークは文化圏や政治圏よりもはるかに広範であった。中央アジアを通るシルクロードや、ローマ帝国・ペルシャ帝国・インド・中 国を結ぶインド洋海路を含む広範な交易路は、2000年前には既に確立されていた。当時、これらの文明は政治的・外交的・軍事的・文化的関係をほとんど共 有していなかった。こうした長距離交易の最初の証拠は古代世界に存在する。ウルク時代には、ギジェルモ・アルガゼが主張するように、エジプト・メソポタミ ア・イラン・アフガニスタンを結ぶ交易関係があった。[57] 後にウル王墓で発見された樹脂は、モザンビークから北へ交易されたものと推測される。 多くの理論家は、世界全体がすでに単一の「世界システム」に統合され、グローバル化と呼ばれる過程を辿っていると主張する。地球上の異なる文明や社会は、 経済的、政治的、さらには文化的にも、多くの面で相互依存関係にある。この統合がいつ始まったか、また文明の規模を測る上で文化的・技術的・経済的・政治 的・軍事外交的統合のどれが主要な指標となるかについては議論がある。デイヴィッド・ウィルキンソンは、紀元前1500年頃にメソポタミアとエジプトの文 明が経済的・軍事外交的に統合され、彼が「中央文明」と呼ぶものが形成されたと提唱している。[58] 中央文明は後に中東全域とヨーロッパを包含する規模に拡大し、さらにヨーロッパの植民地化によって世界規模へと広がった。19世紀までにアメリカ大陸、 オーストラリア、中国、日本が統合されたのである。ウィルキンソンによれば、文明は中央文明のように文化的に異質な場合もあれば、日本文明のように同質な 場合もある。ハンティントンが「文明の衝突」と呼ぶ現象は、ウィルキンソンによれば単一のグローバル文明内における文化圏の衝突と特徴づけられるかもしれ ない。他の人々は、十字軍運動をグローバル化の第一歩として指摘する。より従来の見解では、社会のネットワークは古代から拡大と縮小を繰り返しており、現 在のグローバル化した経済と文化は近年のヨーロッパ植民地主義の産物であるという。[出典が必要] |

| History See also: Human history The notion of human history as a succession of "civilizations" is an entirely modern one. In the European Age of Discovery, emerging Modernity was put into stark contrast with the Neolithic and Mesolithic stage of the cultures of many of the peoples they encountered.[59][obsolete source] Nonetheless, developments in the Neolithic stage, such as agriculture and sedentary settlement, were critical to the development of modern conceptions of civilization.[60][61] Urban Revolution Main articles: Neolithic, Bronze Age, Cradle of civilization, and River valley civilization The Natufian culture in the Levantine corridor provides the earliest case of a Neolithic Revolution, with the planting of cereal crops attested from c. 11,000 BCE.[62][63] The earliest neolithic technology and lifestyle were established first in Western Asia (for example at Göbekli Tepe, from about 9,130 BCE), later in the Yellow River and Yangtze basins in China (for example the Peiligang and Pengtoushan cultures), and from these cores spread across Eurasia. Mesopotamia is the site of the earliest civilizations developing from 7,400 years ago. This area has been evaluated by Beverley Milton-Edwards as having "inspired some of the most important developments in human history including the invention of the wheel, the building of the earliest cities and the development of written cursive script".[64] Similar pre-civilized "neolithic revolutions" also began independently from 7,000 BCE in northwestern South America (the Caral-Supe civilization)[65] and in Mesoamerica.[66] The Black Sea area served as a cradle of European civilization. The site of Solnitsata – a prehistoric fortified (walled) stone settlement (prehistoric proto-city) (5500–4200 BCE) – is believed by some archaeologists to be the oldest known town in present-day Europe.[67][68][69][70] The 8.2 Kiloyear Arid Event and the 5.9 Kiloyear Inter-pluvial saw the drying out of semiarid regions and a major spread of deserts.[71] This climate change shifted the cost-benefit ratio of endemic violence between communities, which saw the abandonment of unwalled village communities and the appearance of walled cities, seen by some as a characteristic of early civilizations.[72]  The ruins of Mesoamerican city Teotihuacan This "urban revolution"—a term introduced by Childe in the 1930s—from the 4th millennium BCE,[73] marked the beginning of the accumulation of transferable economic surpluses, which helped economies and cities develop. Urban revolutions were associated with the state monopoly of violence, the appearance of a warrior (or soldier) class and endemic warfare (a state of continual or frequent warfare), the rapid development of hierarchies, and the use of human sacrifice.[74][75] The civilized urban revolution in turn was dependent upon the development of sedentism, the domestication of grains, plants and animals, the permanence of settlements and development of lifestyles that facilitated economies of scale and accumulation of surplus production by particular social sectors. The transition from complex cultures to civilizations, while still disputed, seems to be associated with the development of state structures, in which power was further monopolized by an elite ruling class[76] who practiced human sacrifice.[77] Towards the end of the Neolithic period, various elitist Chalcolithic civilizations began to rise in various "cradles" from around 3600 BCE beginning with Mesopotamia, expanding into large-scale kingdoms and empires in the course of the Bronze Age (Akkadian Empire, Indus Valley Civilization, Old Kingdom of Egypt, Neo-Sumerian Empire, Middle Assyrian Empire, Babylonian Empire, Hittite Empire, and to some degree the territorial expansions of the Elamites, Hurrians, Amorites and Ebla). Outside the Old World, development took place independently in the Pre-Columbian Americas. Urbanization in the Caral-Supe civilization in what is now coastal Peru began about 3500 BCE.[78] In North America, the Olmec civilization emerged about 1200 BCE; the oldest known Mayan city, located in what is now Guatemala, dates to about 750 BCE.[79] and Teotihuacan (near the modern Mexico City) was one of the largest cities in the world in 350 CE, with a population of about 125,000.[80] |

歴史 関連項目: 人類史 人類史を「文明」の連続として捉える考え方は、完全に近代的な概念である。ヨーロッパの大航海時代において、台頭しつつあった近代性は、彼らが遭遇した多 くの民族の文化が新石器時代や中石器時代の段階にあることと、鮮明に対比された[59][廃止された出典]。しかしながら、農業や定住といった新石器時代 の段階における発展は、文明の近代的概念の形成にとって極めて重要であった[60]。[61] 都市革命 主な記事:新石器時代、青銅器時代、文明発祥の地、河川流域文明 レバント回廊におけるナトゥフィアン文化は、紀元前11,000年頃に穀物作物の栽培が確認されるなど、新石器革命の最も初期の事例を提供する。[62] [63] 最古の新石器時代の技術と生活様式は、まず西アジア(例えば紀元前9130年頃のゲベクリ・テペ)で確立され、後に中国の黄河・長江流域(例えばペイリガ ン文化や彭頭山文化)で発展し、これらの中心地からユーラシア全域に広がった。メソポタミアは7400年前から発展した最古の文明の舞台である。この地域 はベバリー・ミルトン=エドワーズによって「車輪の発明、最古の都市建設、筆記用筆記体の発達など、人類史上最も重要な発展のいくつかを促した」と評価さ れている。[64] 同様の文明以前の「新石器革命」は紀元前7000年から南米北西部(カラル・スペ文明)[65]やメソアメリカ[66]でも独立して始まった。黒海地域は ヨーロッパ文明の発祥地となった。ソルニツァタ遺跡(紀元前5500~4200年)は、先史時代の要塞化された(城壁に囲まれた)石造集落(先史時代の原 始都市)であり、一部の考古学者によって現代ヨーロッパ最古の町と見なされている[67][68][69]。[70] 8.2キロイヤー乾燥期と5.9キロイヤー間降雨期には、半乾燥地域の乾燥化と砂漠の大規模な拡大が起きた[71]。この気候変動は、共同体間の固有の暴 力の費用対効果比率を変え、無壁の村落共同体の放棄と城壁都市の出現をもたらした。これは初期文明の特徴と見なされることもある。[72]  メソアメリカ都市テオティワカンの遺跡 この「都市革命」―チャイルドが1930年代に提唱した用語―は紀元前4千年紀[73]に始まり、移転可能な経済的余剰の蓄積の始まりを告げた。これは経 済と都市の発展に寄与した。都市革命は、国家による暴力の独占、戦士(または兵士)階級の出現と常態化した戦争(継続的または頻繁な戦争状態)、階層構造 の急速な発展、そして人身供犠の使用と関連していた[74][75]。 文明化された都市革命は、定住性の発達、穀物・植物・動物の家畜化、定住地の永続化、そして特定の社会階層による規模の経済と余剰生産の蓄積を可能にする 生活様式の発展に依存していた。複雑な文化から文明への移行は、依然として議論の余地があるものの、国家構造の発達と関連しているようだ。そこでは権力 が、人祭を実践する支配階級のエリートによってさらに独占された[76]。[77] 新石器時代末期、紀元前3600年頃からメソポタミアを起点に、様々な「発祥地」で様々なエリート主義的な銅石器時代の文明が台頭し始めた。これらは青銅 器時代を通じて大規模な王国や帝国へと拡大した(アッカド帝国、インダス文明、古代エジプト王国、 新シュメール帝国、アッシリア帝国中期、バビロニア帝国、ヒッタイト帝国、そしてある程度エラム人、フルリ人、アモリ人、エブラの領土拡大も含まれる)。 旧世界以外では、コロンブス以前のアメリカ大陸で独自の発展が見られた。現在のペルー沿岸部におけるカラル・スペ文明の都市化は紀元前3500年頃に始 まった。[78] 北アメリカでは、オルメカ文明が紀元前1200年頃に現れた。最古のマヤ都市は現在のグアテマラに位置し、紀元前750年頃に遡る[79]。またテオティ ワカン(現代のメキシコシティ近郊)は、西暦350年時点で人口約12万5千人を擁する世界最大級の都市の一つであった[80]。 |

| Axial Age Main article: Axial Age Further information: Iron Age, Stoicism, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, Spread of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism The Bronze Age collapse was followed by the Iron Age around 1200 BCE, during which a number of new civilizations emerged, culminating in a period from the 8th to the 3rd century BCE which Karl Jaspers termed the Axial Age, presented as a critical transitional phase leading to classical civilization.[81] Modernity Main article: Modernity Further information: Middle Ages, Early modern period, Great Divergence, and Age of Discovery See also: Culture, Major religious groups, World language, and Clash of Civilizations A major technological and cultural transition to modernity began approximately 1500 CE in Western Europe, and from this beginning new approaches to science and law spread rapidly around the world, incorporating earlier cultures into the technological and industrial society of the present.[77][82] |

軸心時代 詳細記事: 軸心時代 関連項目: 鉄器時代、ストア派、ユダヤ教、ゾロアスター教、ヒンドゥー教、仏教の伝播、儒教、道教 青銅器時代の崩壊に続き、紀元前1200年頃に鉄器時代が始まった。この時代には数多くの新しい文明が出現し、紀元前8世紀から3世紀にかけての期間が頂 点に達した。カール・ヤスパースはこの時代を「軸心時代」と呼び、古典文明へと至る重要な過渡期として提示した。[81] 近代 主な記事:近代 詳細情報:中世、近世、大分岐、大航海時代 関連項目:文化、主要宗教団体、世界言語、文明の衝突 近代への主要な技術的・文化的転換は西暦1500年頃に西ヨーロッパで始まり、この出発点から科学と法への新たなアプローチが急速に世界に広がり、以前の文化を現在の技術的・産業社会に取り込んだ。[77][82] |

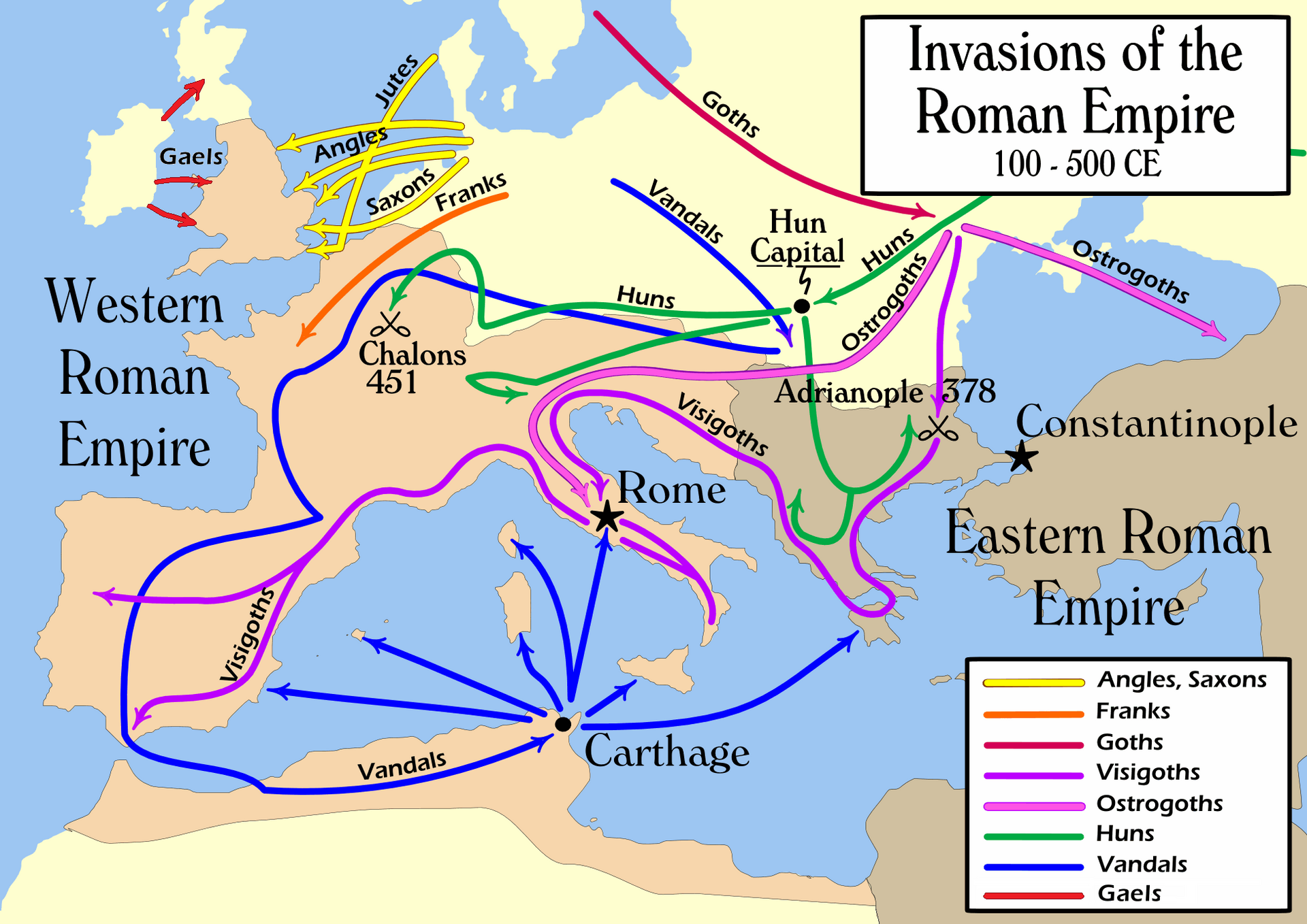

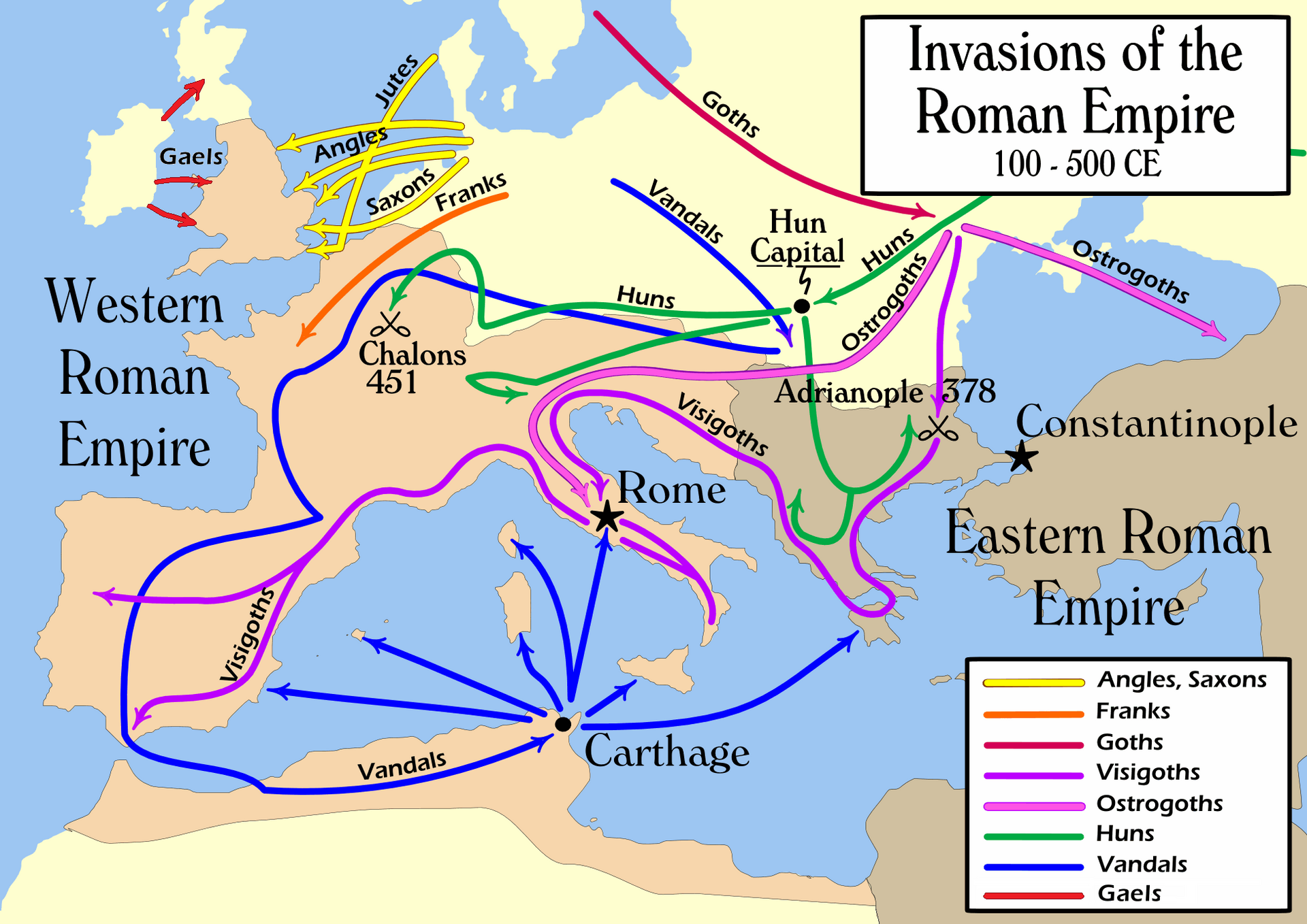

| Fall of civilizations Main article: Societal collapse Civilizations are traditionally understood as ending in one of two ways; either through incorporation into another expanding civilization (e.g. as Ancient Egypt was incorporated into Hellenistic Greek, and subsequently Roman civilizations), or by collapsing and reverting to a simpler form of living, as happens in so-called Dark Ages.[83] There have been many explanations put forward for the collapse of civilization. Some focus on historical examples, and others on general theory. Ibn Khaldun's Muqaddimah influenced theories of the analysis, growth, and decline of the Islamic civilization.[84] He suggested repeated invasions from nomadic peoples limited development and led to social collapse.  Barbarian invasions played an important role in the fall of the Roman Empire. Edward Gibbon's work The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire is a well-known and detailed analysis of the fall of Roman civilization. Gibbon suggested the final act of the collapse of Rome was the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 CE. For Gibbon, "The decline of Rome was the natural and inevitable effect of immoderate greatness. Prosperity ripened the principle of decay; the cause of the destruction multiplied with the extent of conquest; and, as soon as time or accident had removed the artificial supports, the stupendous fabric yielded to the pressure of its own weight. The story of the ruin is simple and obvious; and instead of inquiring why the Roman Empire was destroyed, we should rather be surprised that it has subsisted for so long".[85] Theodor Mommsen in his History of Rome suggested Rome collapsed with the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE and he also tended towards a biological analogy of "genesis", "growth", "senescence", "collapse" and "decay". Oswald Spengler, in his Decline of the West rejected Petrarch's chronological division, and suggested that there had been only eight "mature civilizations". Growing cultures, he argued, tend to develop into imperialistic civilizations, which expand and ultimately collapse, with democratic forms of government ushering in plutocracy and ultimately imperialism. Arnold J. Toynbee in his A Study of History suggested that there had been a much larger number of civilizations, including a small number of arrested civilizations, and that all civilizations tended to go through the cycle identified by Mommsen. The cause of the fall of a civilization occurred when a cultural elite became a parasitic elite, leading to the rise of internal and external proletariats. Joseph Tainter in The Collapse of Complex Societies suggested that there were diminishing returns to complexity, due to which, as states achieved a maximum permissible complexity, they would decline when further increases actually produced a negative return. Tainter suggested that Rome achieved this figure in the 2nd century CE. Jared Diamond in his 2005 book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed suggests five major reasons for the collapse of 41 studied cultures: environmental damage, such as deforestation and soil erosion; climate change; dependence upon long-distance trade for needed resources; increasing levels of internal and external violence, such as war or invasion; and societal responses to internal and environmental problems. Peter Turchin in his Historical Dynamics and Andrey Korotayev et al. in their Introduction to Social Macrodynamics, Secular Cycles, and Millennial Trends suggest a number of mathematical models describing collapse of agrarian civilizations. For example, the basic logic of Turchin's "fiscal-demographic" model can be outlined as follows: during the initial phase of a sociodemographic cycle we observe relatively high levels of per capita production and consumption, which leads not only to relatively high population growth rates, but also to relatively high rates of surplus production. As a result, during this phase the population can afford to pay taxes without great problems, the taxes are quite easily collectible, and the population growth is accompanied by the growth of state revenues. During the intermediate phase, the increasing population growth leads to the decrease of per capita production and consumption levels, it becomes more and more difficult to collect taxes, and state revenues stop growing, whereas the state expenditures grow due to the growth of the population controlled by the state. As a result, during this phase the state starts experiencing considerable fiscal problems. During the final pre-collapse phases the overpopulation leads to further decrease of per capita production, the surplus production further decreases, state revenues shrink, but the state needs more and more resources to control the growing (though with lower and lower rates) population. Eventually this leads to famines, epidemics, state breakdown, and demographic and civilization collapse.[86][87] Peter Heather argues in his book The Fall of the Roman Empire: a New History of Rome and the Barbarians[88] that this civilization did not end for moral or economic reasons, but because centuries of contact with barbarians across the frontier generated its own nemesis by making them a more sophisticated and dangerous adversary. The fact that Rome needed to generate ever greater revenues to equip and re-equip armies that were for the first time repeatedly defeated in the field, led to the dismemberment of the Empire. Although this argument is specific to Rome, it can also be applied to the Asiatic Empire of the Egyptians, to the Han and Tang dynasties of China, to the Muslim Abbasid Caliphate and others. Bryan Ward-Perkins, in his book The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization,[89] argues from mostly archaeological evidence that the collapse of Roman civilization in western Europe had deleterious impacts on the living standards of the population, unlike some historians who downplay this. The collapse of complex society meant that even basic plumbing for the elite disappeared from the continent for 1,000 years. Similar impacts have been postulated for the Dark Age after the Late Bronze Age collapse in the Eastern Mediterranean, the collapse of the Maya, on Easter Island and elsewhere. Arthur Demarest argues in Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization,[90] using a holistic perspective to the most recent evidence from archaeology, paleoecology, and epigraphy, that no one explanation is sufficient but that a series of erratic, complex events, including loss of soil fertility, drought and rising levels of internal and external violence led to the disintegration of the courts of Mayan kingdoms, which began a spiral of decline and decay. He argues that the collapse of the Maya has lessons for civilization today. Jeffrey A. McNeely has recently suggested that "a review of historical evidence shows that past civilizations have tended to over-exploit their forests, and that such abuse of important resources has been a significant factor in the decline of the over-exploiting society".[91] Thomas Homer-Dixon considers the fall in the energy return on investments. The energy expended to energy yield ratio is central to limiting the survival of civilizations. The degree of social complexity is associated strongly, he suggests, with the amount of disposable energy environmental, economic and technological systems allow. When this amount decreases civilizations either have to access new energy sources or collapse.[92] Feliks Koneczny in his work "On the Plurality of Civilizations" calls his study the science on civilizations. He asserts that civilizations fall not because they must or there exist some cyclical or a "biological" life span and that there stil exist two ancient civilizations – Brahmin-Hindu and Chinese – which are not ready to fall any time soon. Koneczny claimed that civilizations cannot be mixed into hybrids, an inferior civilization when given equal rights within a highly developed civilization will overcome it. One of Koneczny's claims in his study on civilizations is that "a person cannot be civilized in two or more ways" without falling into what he calls an "abcivilized state" (as in abnormal). He also stated that when two or more civilizations exist next to one another and as long as they are vital, they will be in an existential combat imposing its own "method of organizing social life" upon the other.[93] Absorbing alien "method of organizing social life" that is civilization and giving it equal rights yields a process of decay and decomposition. |

文明の崩壊 主な記事: 社会の崩壊 文明は伝統的に、二つの方法で終焉を迎えると考えられてきた。一つは拡大する別の文明に吸収されること(例えば古代エジプトがヘレニズム時代のギリシャ文 明、そして後にローマ文明に吸収されたように)、もう一つは崩壊してより単純な生活様式に戻ることであり、いわゆる暗黒時代で起こったように[83]。 文明崩壊の理由については多くの説明がなされてきた。歴史的事例に焦点を当てるものもあれば、一般理論に焦点を当てるものもある。 イブン・ハルドゥーンの『序説』は、イスラム文明の分析・成長・衰退に関する理論に影響を与えた[84]。彼は遊牧民による繰り返しの侵略が発展を制限し、社会崩壊につながったと示唆した。  蛮族の侵入はローマ帝国崩壊において重要な役割を果たした。 エドワード・ギボンの著作『ローマ帝国衰亡史』は、ローマ文明の崩壊を詳細に分析した著名な研究である。ギボンは、ローマ崩壊の最終局面を西暦1453年 のコンスタンティノープル陥落(オスマン・トルコによる)と位置づけた。彼によれば「ローマの衰退は、度を越した偉大さがもたらす自然かつ必然の結果で あった。繁栄は衰退の原理を熟成させ、征服の広がりと共に破壊の原因は増幅した。そして時間や偶然が人工的な支柱を取り除くと、巨大な建造物は自らの重み に耐えきれず崩れ落ちた。滅亡の経緯は単純明快であり、ローマ帝国がなぜ滅んだのかを問うよりも、むしろこれほど長く存続したこと自体に驚嘆すべきであ る」。[85] テオドール・モムゼンは『ローマ史』において、ローマは西ローマ帝国の崩壊(西暦476年)と共に滅びたと示唆し、「創生」「成長」「老衰」「崩壊」「衰退」という生物学的比喩を用いる傾向があった。 オズワルド・シュペングラーは『西欧の没落』において、ペトラルカの年代区分を否定し、成熟した文明は八つしか存在しなかったと主張した。成長する文化は 帝国主義的文明へと発展し、拡大の末に崩壊する傾向があると論じ、民主的な統治形態は金権政治を招き、最終的には帝国主義へと至ると述べた。 アーノルド・J・トインビーは『歴史の研究』において、文明の数ははるかに多く、少数の停滞文明も含むと示唆した。また全ての文明はモムゼンが特定したサ イクルを経る傾向があると述べた。文明の衰退の原因は、文化的エリートが寄生的なエリートへと変質し、内外のプロレタリアートが台頭することにあると指摘 した。 ジョセフ・テインターは『複雑社会の崩壊』において、複雑性には限界点があり、国家が許容可能な最大複雑性に達すると、それ以上の増加はむしろ負の効果を生むと論じた。テインターによれば、ローマはこの限界点を西暦2世紀に達成したという。 ジャレド・ダイアモンドは2005年の著書『崩壊:社会はなぜ滅びるのか』で、41の文化が崩壊した主な原因として五つを挙げている:森林伐採や土壌侵食 などの環境破壊、気候変動、必要な資源を長距離貿易に依存すること、戦争や侵略などの内外の暴力の増加、そして内部・環境問題に対する社会の対応だ。 ピーター・ターチンは『歴史的ダイナミクス』、アンドレイ・コロタエフらは『社会マクロダイナミクス入門、世俗的循環、千年単位の傾向』において、農業文 明の崩壊を説明する数多くの数学的モデルを提案している。例えば、ターチンの「財政・人口統計モデル」の基本的な論理は次のように概説できる。社会人口統 計サイクルの初期段階では、一人当たりの生産と消費が比較的高い水準にある。これは人口増加率の高さだけでなく、余剰生産の高さももたらす。その結果、こ の段階では国民は大きな問題なく税金を支払う余裕があり、税収も比較的容易に徴収できる。人口増加は国家歳入の増加を伴う。中間段階では、人口増加の加速 により一人当たり生産・消費水準が低下し、税収の徴収が次第に困難になる。国家歳入の伸びは止まる一方、国家が管理する人口の増加に伴い国家支出は増加す る。結果として、この段階では国家は深刻な財政問題に直面し始める。崩壊直前段階では、人口過剰が一人当たり生産量のさらなる低下を招き、余剰生産はさら に減少し、国家収入は縮小する。しかし国家は、増加する(ただし増加率は低下している)人口を統制するため、ますます多くの資源を必要とする。最終的にこ れは飢饉、疫病、国家崩壊、そして人口と文明の崩壊へとつながる。[86] [87] ピーター・ヘザーは著書『ローマ帝国崩壊:ローマと蛮族の新歴史』[88]において、この文明が道徳的・経済的理由ではなく、国境を越えた蛮族との数世紀 にわたる接触が、彼らをより洗練され危険な敵へと変貌させることで自らの破滅を招いたと論じている。ローマは、戦場で初めて繰り返し敗北した軍隊を装備 し、再装備するために、これまで以上に大きな収入を生み出す必要があったという事実が、帝国の解体につながった。この議論はローマに特有のものだが、エジ プトのアジア帝国、中国の漢王朝や唐王朝、イスラムのアッバース朝カリフ制などにも当てはまる。 ブライアン・ウォード・パーキンズは、著書『ローマの没落と文明の終焉』[89] の中で、西ヨーロッパにおけるローマ文明の崩壊は、これを軽視する一部の歴史家たちとは違って、住民の生活水準に悪影響を及ぼしたと、主に考古学的証拠に 基づいて論じている。複雑な社会の崩壊は、エリート層のための基本的な配管設備さえも、1000年にわたって大陸から姿を消したことを意味した。同様の影 響は、東地中海における青銅器時代後期の崩壊、マヤの崩壊、イースター島などにおける暗黒時代にも見られたと推測されている。 アーサー・デマレストは『古代マヤ:熱帯雨林文明の興亡』[90]の中で、考古学、古生態学、碑文学の最新の証拠を総合的な視点で考察し、単一の説では不 十分であり、一連の不安定な要因が相まって崩壊をもたらしたと論じている。『熱帯雨林文明の興亡』[90]において、考古学・古生態学・碑文研究の最新知 見を総合的に考察し、単一の説明では不十分であり、土壌肥沃度の喪失・干ばつ・内外の暴力激化といった不規則で複雑な連鎖的要因がマヤ王国の宮廷体制崩壊 を招き、衰退の悪循環が始まったと論じている。彼はマヤの崩壊が現代文明への教訓となると主張する。 ジェフリー・A・マクニーリーは最近「歴史的証拠の検証から、過去の文明は森林を過剰に搾取する傾向にあり、こうした重要資源の乱用が搾取社会衰退の重大因であった」と示唆している。[91] トーマス・ホーマー=ディクソンは、エネルギー投資収益率の低下を考察している。エネルギー消費量とエネルギー生産量の比率は、文明の存続を制限する核心 的要素である。彼は、社会の複雑さの度合いは、環境・経済・技術システムが許容する利用可能エネルギー量と強く関連していると示唆する。この量が減少する と、文明は新たなエネルギー源にアクセスするか、崩壊するかのいずれかを選択せざるを得なくなる。[92] フェリクス・コネツニーは著書『文明の多元性』において、自らの研究を「文明科学」と呼んだ。彼は文明が崩壊するのは必然でもなければ、周期的な「生物学 的」寿命が存在するわけでもないと主張する。さらにブラフマン・ヒンドゥー文明と中国文明という二つの古代文明が依然として存続しており、これらは近い将 来崩壊する兆候を見せていないと述べた。コネツニーは文明が混血のハイブリッド化することは不可能だと主張した。高度に発達した文明の中で平等な権利を与 えられた劣った文明は、やがてそれを凌駕する。彼の文明研究における主張の一つは、「人格は二通り以上の方法で文明化することはできない」というもので、 そうしようとすると彼が「非文明状態」(異常な状態)と呼ぶものに陥るとした。 |

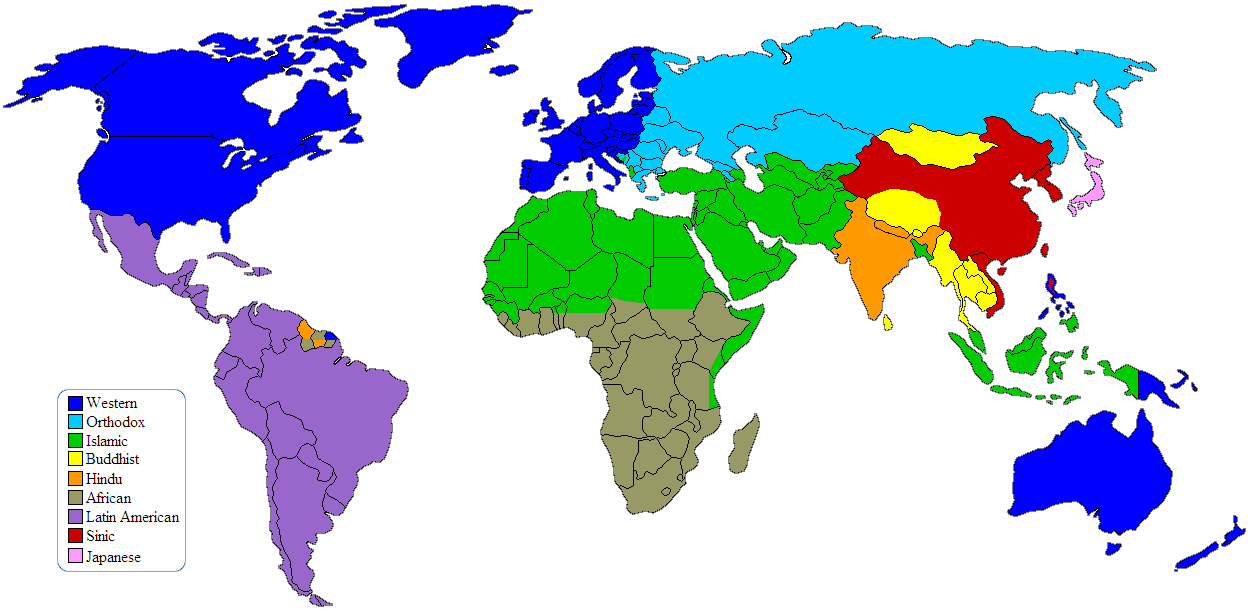

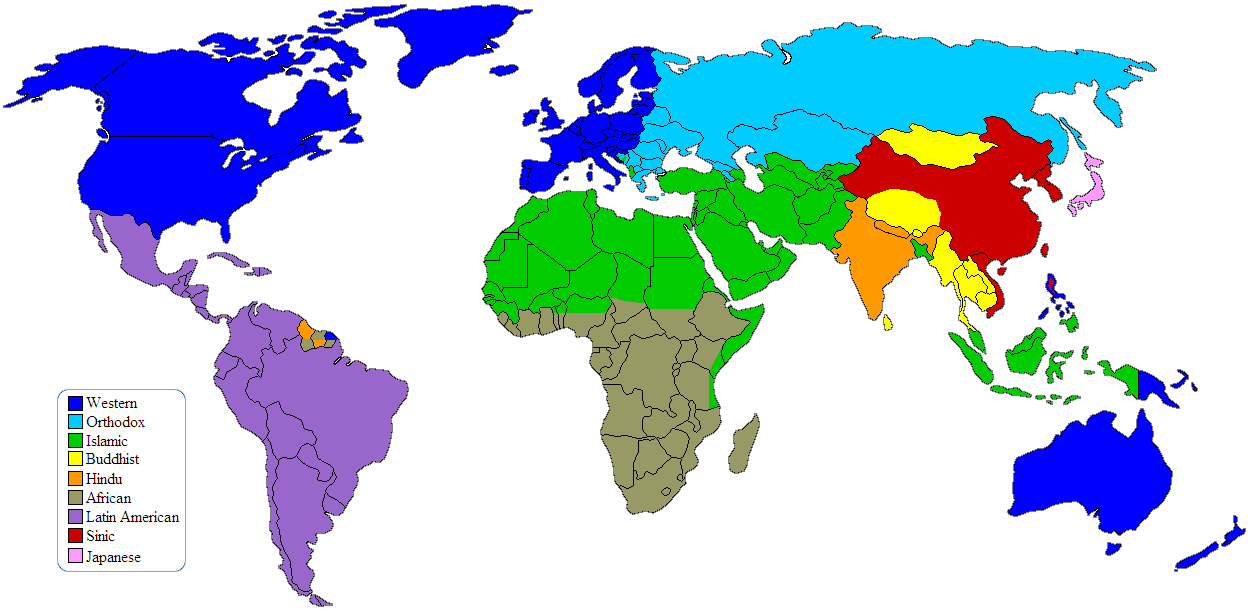

| Future See also: Global catastrophic risk  A world map of major civilizations according to the political hypothesis Clash of Civilizations by Samuel P. Huntington. According to political scientist Samuel P. Huntington, the 21st century will be characterized by a clash of civilizations,[48] which he believes will replace the conflicts between nation-states and ideologies that were prominent in the 19th and 20th centuries. However, this viewpoint has been strongly challenged by others such as Edward Said, Muhammed Asadi and Amartya Sen.[94] Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris have argued that the "true clash of civilizations" between the Muslim world and the West is caused by the Muslim rejection of the West's more liberal sexual values, rather than a difference in political ideology, although they note that this lack of tolerance is likely to lead to an eventual rejection of (true) democracy.[95] In Identity and Violence Sen questions if people should be divided along the lines of a supposed "civilization", defined by religion and culture only. He argues that this ignores the many others identities that make up people and leads to a focus on differences. Cultural historian Morris Berman argues in Dark Ages America: the End of Empire that in the corporate consumerist United States, the very factors that once propelled it to greatness―extreme individualism, territorial and economic expansion, and the pursuit of material wealth―have pushed the United States across a critical threshold where collapse is inevitable. Politically associated with over-reach, and as a result of the environmental exhaustion and polarization of wealth between rich and poor, he concludes the current system is fast arriving at a situation where continuation of the existing system saddled with huge deficits and a hollowed-out economy is physically, socially, economically and politically impossible.[96] Although developed in much more depth, Berman's thesis is similar in some ways to that of Urban Planner, Jane Jacobs who argues that the five pillars of United States culture are in serious decay: community and family; higher education; the effective practice of science; taxation and government; and the self-regulation of the learned professions. The corrosion of these pillars, Jacobs argues, is linked to societal ills such as environmental crisis, racism and the growing gulf between rich and poor.[97] Cultural critic and author Derrick Jensen argues that modern civilization is directed towards the domination of the environment and humanity itself in an intrinsically harmful, unsustainable, and self-destructive fashion.[98] Defending his definition both linguistically and historically, he defines civilization as "a culture... that both leads to and emerges from the growth of cities", with "cities" defined as "people living more or less permanently in one place in densities high enough to require the routine importation of food and other necessities of life".[99] This need for civilizations to import ever more resources, he argues, stems from their over-exploitation and diminution of their own local resources. Therefore, civilizations inherently adopt imperialist and expansionist policies and, to maintain these, highly militarized, hierarchically structured, and coercion-based cultures and lifestyles. The Kardashev scale classifies civilizations based on their level of technological advancement, specifically measured by the amount of energy a civilization is able to harness. The scale is only hypothetical, but it puts energy consumption in a cosmic perspective. The Kardashev scale makes provisions for civilizations far more technologically advanced than any currently known to exist. |

未来 関連項目: 地球規模的破滅リスク  サミュエル・P・ハンティントンによる政治的仮説『文明の衝突』に基づく主要文明の世界地図。 政治学者サミュエル・P・ハンティントンによれば、21世紀は文明の衝突によって特徴づけられる[48]。彼は、19世紀と20世紀に顕著だった国民間・ イデオロギー間の対立に取って代わると考えている。しかし、この見解はエドワード・サイード、ムハンマド・アサディ、アマルティア・センらによって強く反 論されている。[94]ロナルド・イングルハートとピッパ・ノリスは、イスラム世界と西洋の間の「真の文明の衝突」は、政治イデオロギーの違いではなく、 イスラム教徒が西洋のより自由な性的価値観を拒絶することによって引き起こされると主張している。ただし彼らは、この不寛容さが最終的には(真の)民主主 義の拒絶につながる可能性が高いとも指摘している。[95] 『アイデンティティと暴力』においてセンは、宗教と文化のみで定義される「文明」という概念に基づいて人々を分断すべきか疑問を呈している。彼は、この考 え方が人々を構成する他の多くのアイデンティティを無視し、差異に焦点を当てる結果を招くと論じている。 文化史家モリス・バーマンは『暗黒時代のアメリカ:帝国の終焉』において、企業主導の消費主義社会であるアメリカにおいて、かつてその偉大さを支えた要素 ――極端な個人主義、領土的・経済的拡大、物質的富の追求――が、崩壊が避けられない臨界点へとアメリカを押しやったと論じる。政治的には行き過ぎと結び つき、環境の枯渇と貧富の格差拡大の結果として、彼は現在のシステムが巨大な赤字と空洞化した経済を抱えたまま存続することは、物理的・社会的・経済的・ 政治的に不可能となる状況に急速に近づいていると結論づけている。より深く展開されているものの、バーマンの主張は都市計画家ジェーン・ジェイコブズの論 と一部類似している。ジェイコブズは米国文化の五つの支柱――共同体と家族、高等教育、科学の実践、課税と政府、専門職の自律性――が深刻な衰退にあると 論じる。これらの支柱の腐食は、環境危機、人種主義、貧富の格差拡大といった社会病理と結びついていると彼女は主張する。[97] 文化批評家であり著述家でもあるデリック・ジェンセンは、現代文明は本質的に有害で持続不可能、かつ自己破壊的な方法で環境と人類そのものを支配する方向 に向かっていると主張する。[98] 彼は言語学的・歴史的に自らの定義を擁護し、文明を「都市の成長を導き、かつそこから生じる文化」と定義する。ここで「都市」とは「人々がほぼ恒久的に一 箇所に居住し、食糧や生活必需品を日常的に輸入する必要があるほどの高密度」を指す。[99] 文明がますます多くの資源を輸入する必要性は、自らの地域資源を過剰に搾取し枯渇させることに起因すると彼は主張する。したがって文明は本質的に帝国主義 的・拡張主義的政策を採用し、これを維持するために高度にミリタリズム化され、階層構造を持ち、強制に基づく文化と生活様式を採る。 カルダシェフ・スケールは、文明の技術進歩レベル、具体的には文明が利用可能なエネルギー量に基づいて文明を分類する。この尺度自体は仮説に過ぎないが、 エネルギー消費を宇宙的視点で捉えるものである。カルダシェフ・スケールは、現在知られているいかなる文明よりもはるかに技術的に進んだ文明の存在を想定 している。 |

| Non-human civilizations The current scientific consensus is that human beings are the only animal species with the cognitive ability to create civilizations that has emerged on Earth. A recent thought experiment, the silurian hypothesis, however, considers whether it would "be possible to detect an industrial civilization in the geological record" given the paucity of geological information about eras before the quaternary.[100] Astronomers speculate about the existence of communicating intelligent civilizations within and beyond the Milky Way galaxy, usually using variants of the Drake equation.[101] They conduct searches for such intelligences – such as for technological traces, called "technosignatures".[102] The proposed proto-scientific field "xenoarchaeology" is concerned with the study of artifact remains of non-human civilizations to reconstruct and interpret past lives of alien societies if such get discovered and confirmed scientifically.[103][104] |

非人間文明 現在の科学的な共通認識では、地球上で文明を創り出す認知能力を持つ動物種は人類だけだ。しかし最近の思考実験であるシルル紀仮説は、第四紀以前の地質学的情報が乏しいことを踏まえ、「地質記録から工業文明を検出できる可能性」を検討している。[100] 天文学者は、通常ドレイク方程式の変形を用いて、銀河系内外における知的文明の存在について推測している。[101] 彼らは「テクノシグネチャー」と呼ばれる技術的痕跡など、こうした知的生命体の探索を行っている。[102] 提唱されている前科学分野「ゼノアーケオロジー」は、非人類文明の人工物遺存物を研究し、もし発見され科学的に確認されれば、異星社会の過去の生活を再構 築・解釈することを目的としている。[103][104] |

| Anarcho-primitivism Built environment Christendom Civil engineering Civilization state Civilizing mission Colony Cultural development Ecological civilization Evolution of languages Evolutionary anthropology Globalization Human universal Lifestyle Origin of language Outline of culture Outline of society Personal identity Population growth Progress Role of Christianity in civilization Social integration Sociocultural system Sustainability Technological advancement Urban evolution Waterways World community World history Written history |

アナキスト・プリミティヴィズム 建造環境 キリスト教世界 土木工学 文明国家 文明化使命 植民地 文化発展 生態文明 言語の進化 進化人類学 グローバリゼーション 人類普遍 生活様式 言語の起源 文化概論 社会概論 個人的アイデンティティ 人口増加 進歩 文明におけるキリスト教の役割 社会的統合 社会文化システム 持続可能性 技術進歩 都市の進化 水路 世界共同体 世界史 文字による歴史 |

| Notes It remains the most influential sociological study of the topic, spawning its own body of secondary literature. Notably, Hans Peter Duerr attacked it in a major work (3,500 pages in five volumes, published 1988–2002). Elias, at the time a nonagenarian, was still able to respond to the criticism the year before his death. In 2002, Duerr was himself criticized by Michael Hinz's Der Zivilisationsprozeß: Mythos oder Realität (2002), saying that his criticism amounted to hateful defamation of Elias, through excessive standards of political correctness.[15] For example, in the title A narrative of the loss of the Winterton East Indiaman wrecked on the coast of Madagascar in 1792; and of the sufferings connected with that event. To which is subjoined a short account of the natives of Madagascar, with suggestions as to their civilizations by J. Hatchard, L.B. Seeley and T. Hamilton, London, 1820. |

注記 この研究は依然としてこの主題における最も影響力のある社会学的研究であり、独自の二次文献群を生み出している。特に注目すべきは、ハンス・ペーター・ デュールが主要な著作(1988年から2002年にかけて刊行された全5巻、3,500ページ)でこれを批判したことだ。当時90歳を超えていたエリアス は、死の1年前にもなおこの批判に応答することができた。2002年には、デュール自身もミヒャエル・ヒンツの『文明化過程:神話か現実か』(2002 年)によって批判された。ヒンツは、デュールの批判が過剰な政治的正しさの基準を通じて、エリアスに対する憎悪に満ちた誹謗中傷に等しいと述べた。 [15] 例えば、1792年にマダガスカル沿岸で難破したウィンタートン・イースト・インディアマン号の沈没と、その事件に伴う苦悩についての物語。それに付随し て、マダガスカルの先住民に関する簡単な説明と、J. ハッチャード、L.B. シーリー、T. ハミルトンによる彼らの文明に関する考察が、1820年にロンドンで出版された。 |