文明の衝突

Clash of Civilizations

☆ 「文明の衝突」とは、冷戦後の世界では人々の文化的・宗教的アイデンティティが紛争の主な原因となるという説である。アメリ カの政治学者サミュエル・P・ハンティントンは、将来の戦争は国家間ではなく文化間で行われると主張した。この考えは、1992年にアメリカ ン・エンタープライズ研究所で行った講演で提唱され、その後、1993年に『フォーリン・アフェアーズ』誌に掲載された「文明の衝突?ハンチントンはその 後、1996年に出版した著書『文明の衝突と世界秩序の変革』で、自身の説をさらに発展させた(→「文明の衝突をめぐって」)。

| The "Clash of

Civilizations" is a thesis that people's cultural and religious

identities will be the primary source of conflict in the post–Cold War

world.[1][2][3][4][5] The American political scientist Samuel P.

Huntington argued that future wars would be fought not between

countries, but between cultures.[1][6] It was proposed in a 1992

lecture at the American Enterprise Institute, which was then developed

in a 1993 Foreign Affairs article titled "The Clash of

Civilizations?",[7] in response to his former student Francis

Fukuyama's 1992 book The End of History and the Last Man. Huntington

later expanded his thesis in a 1996 book The Clash of Civilizations and

the Remaking of World Order.[8] The phrase itself was earlier used by Albert Camus in 1946,[9] by Girilal Jain in his analysis of the Ayodhya dispute in 1988,[10][11] by Bernard Lewis in an article in the September 1990 issue of The Atlantic Monthly titled "The Roots of Muslim Rage"[12] and by Mahdi El Mandjra in his book "La première guerre civilisationnelle" published in 1992.[13][14] Even earlier, the phrase appears in a 1926 book regarding the Middle East by Basil Mathews: Young Islam on Trek: A Study in the Clash of Civilizations (p. 196). This expression derives from "clash of cultures", already used during the colonial period and the Belle Époque.[15] Huntington began his thinking by surveying the diverse theories about the nature of global politics in the post–Cold War period. Some theorists and writers argued that human rights, liberal democracy, and the capitalist free market economy had become the only remaining ideological alternative for nations in the post–Cold War world. Specifically, Francis Fukuyama argued that the world had reached the 'end of history' in a Hegelian sense. Huntington believed that while the age of ideology had ended, the world had only reverted to a normal state of affairs characterized by cultural conflict. In his thesis, he argued that the primary axis of conflict in the future will be along cultural lines.[16] As an extension, he posits that the concept of different civilizations, as the highest category of cultural identity, will become increasingly useful in analyzing the potential for conflict. At the end of his 1993 Foreign Affairs article, "The Clash of Civilizations?", Huntington writes, "This is not to advocate the desirability of conflicts between civilizations. It is to set forth descriptive hypothesis as to what the future may be like."[7] In addition, the clash of civilizations, for Huntington, represents a development of history. In the past, world history was mainly about the struggles between monarchs, nations and ideologies, such as that seen within Western civilization. However, after the end of the Cold War, world politics moved into a new phase, in which non-Western civilizations are no longer the exploited recipients of Western civilization but have become additional important actors joining the West to shape and move world history.[17] |

「文明の衝突」とは、冷戦後の世界では人々の文化的・宗教的アイデン

ティティが紛争の主な原因となるという説である[1][2][3][4][5]。アメリカの政治学者サミュエル・P・ハンティントンは、将来の戦争は国家

間ではなく文化間で行われると主張した[1][6]。この考えは、1992年にアメリカン・エンタープライズ研究所で行った講演で提唱され、その後、

1993年に『フォーリン・アフェアーズ』誌に掲載された「文明の衝突?ハンチントンはその後、1996年に出版した著書『文明の衝突と世界秩序の変革』

で、自身の説をさらに発展させた[8]。 このフレーズ自体は、1946年にアルベール・カミュが[9]、1988年にギリラル・ジャイーンがアーヨーディヤー紛争の分析の中で[10][11]、 1990年9月号の『アトランティック・マンスリー』誌にバーナード・ルイスが「イスラム教徒の怒りの根源」という題で寄稿した[12]、1992年に出 版されたマハディ・エル・マンジュラの著書『最初の文明戦争』の中で[13][14]、それぞれ使用されていた。さらに遡ると、1926年にバジル・マ シューズが中東に関する著書『Young Islam on Trek: A Study in the Clash of Civilizations』(p. 196) 「The Roots of Muslim Rage(イスラム教徒の怒りの根源)」と題された『アトランティック・マンスリー』誌1990年9月号の記事[12]、および1992年に出版されたマ ハディ・エル・マンジュラの著書『La première guerre civilisationnelle(最初の文明戦争)』[13][14]。さらに遡ると、バジル・マシューズによる中東に関する1926年の著書 『Young Islam on Trek: A Study in the Clash of Civilizations(旅する若いイスラム教:文明の衝突の研究)』(196ページ)にもこの表現が登場する。この表現は、植民地時代やベル・エ ポックの時代にも使われていた「文化の衝突」に由来する[15]。 ハンチントンは、冷戦後の世界政治の本質に関するさまざまな理論を調査することから思考を始めた。一部の理論家や作家は、人権、自由民主主義、資本主義的 自由市場経済が、冷戦後の世界において国家にとって唯一のイデオロギー的選択肢となったと主張した。具体的には、フランシス・フクヤマは、ヘーゲル的な意 味において世界は「歴史の終わり」を迎えたと論じた。 ハンチントンは、イデオロギーの時代は終わったが、世界は文化的な対立を特徴とする通常の状態に戻っただけだと考えた。論文の中で、彼は、将来における主 要な対立軸は文化的なものになると主張した[16]。さらに、彼は、異なる文明という概念は、文化的なアイデンティティの最高カテゴリーとして、対立の可 能性を分析する際にますます有用になると仮定している。1993年の『フォーリン・アフェアーズ』誌に掲載された論文「文明の衝突?それは、未来がどのよ うなものになるかについての説明的な仮説を提示することである。」[7] さらに、ハンチントンにとって文明の衝突は歴史の展開を表している。 過去の世界史は、主に西洋文明に見られるような君主、国家、イデオロギー間の闘争についてであった。しかし、冷戦の終結後、世界政治は新たな局面を迎え、 非西洋文明は西洋文明の搾取される対象ではなくなり、西洋文明と並び、世界史を形作り動かす重要なアクターとなった[17]。 |

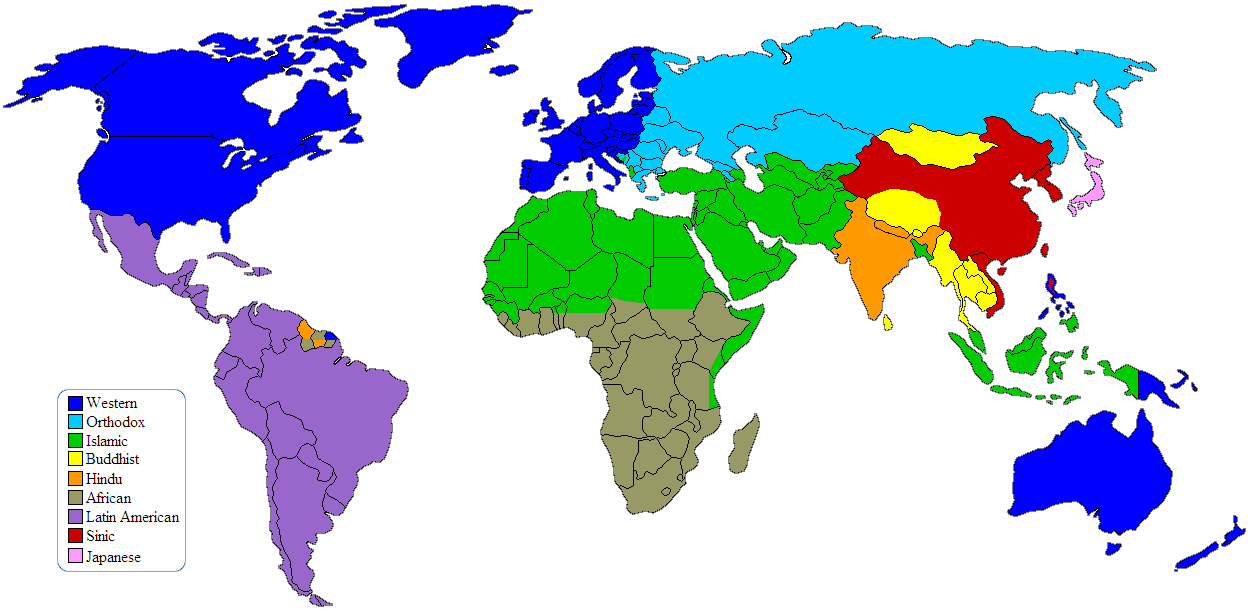

Major civilizations according to Huntington The clash of civilizations according to Huntington (1996) The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order[18] Huntington divided the world into the "major civilizations" in his thesis as such:[19][2] Western civilization, comprising the United States and Canada, Western and Central Europe, most of the Philippines, Australia, and Oceania. Whether Latin America and the former member states of the Soviet Union are included, or are instead their own separate civilizations, will be an important future consideration for those regions, according to Huntington. The traditional Western viewpoint identified Western Civilization with the Western Christian (Catholic-Protestant) countries and culture.[20] Latin American civilization, including South America (excluding Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana), Central America, Mexico, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic may be considered a part of Western civilization. Many people in South America, Central America and Mexico regard themselves as full members of Western civilization. Orthodox civilization, comprising Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece, Romania, great parts of the former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. Countries with a non-Orthodox majority are usually excluded e.g. Muslim Azerbaijan and Muslim Albania and most of Central Asia, as well as majority Muslim regions in the Balkans, Caucasus and central Russian regions such as Tatarstan and Bashkortostan, Roman Catholic Slovenia and Croatia, Protestant and Catholic Baltic states. However, Armenia is included, despite its dominant faith, the Armenian Apostolic Church, being a part of Oriental Orthodoxy rather than the Eastern Orthodox Church, and Kazakhstan is also included, despite its dominant faith being Sunni Islam. The Eastern world is the mix of the Buddhist, Islamic, Chinese, Hindu, and Japonic civilizations. The Sinic civilization of China, the Koreas, Singapore, Taiwan, and Vietnam. This group also includes the Chinese diaspora, especially in relation to Southeast Asia. Japan, considered a hybrid of Chinese civilization and older Altaic patterns. The Buddhist areas of Bhutan, Cambodia, Laos, Mongolia, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand are identified as separate from other civilizations, but Huntington believes that they do not constitute a major civilization in the sense of international affairs. Hindu civilization, located chiefly in India and Nepal, and culturally adhered to by the global Indian diaspora. Part of Islamic, located in Muslim-Majority countries which icludes South Asian countries of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh. South East Asian countries of Indonesia and Malaysia The Muslim world of the Greater Middle East (excluding Armenia, Cyprus, Ethiopia, Georgia, Israel, Malta and South Sudan), northern West Africa, Albania, Pakistan, Bangladesh, parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brunei, Comoros, Indonesia, Malaysia, Maldives and parts of south-western Philippines. The civilization of Sub-Saharan Africa located in southern Africa, Middle Africa (excluding Chad), East Africa (excluding Ethiopia, the Comoros, Mauritius, and the Swahili coast of Kenya and Tanzania), Cape Verde, Ghana, the Ivory Coast, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Considered as a possible eighth civilization by Huntington. Instead of belonging to one of the "major" civilizations, Ethiopia and Haiti are labeled as "Lone" countries. Israel could be considered a unique state with its own civilization, Huntington writes, but one which is extremely similar to the West. Huntington also believes that the Anglophone Caribbean, former British colonies in the Caribbean, constitutes a distinct entity. There are also others which are considered "cleft countries" because they contain very large groups of people identifying with separate civilizations. Examples include Ukraine ("cleft" between its Eastern Rite Catholic-dominated western section and its Orthodox-dominated east), French Guiana (cleft between Latin America, and the West), Benin, Chad, Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Togo (all cleft between Islam and Sub-Saharan Africa), Guyana and Suriname (cleft between Hindu and Sub-Saharan African), Sri Lanka (cleft between Hindu and Buddhist), and the Philippines (cleft between Islam, in the case of south western Mindanao; Sinic, in the case of Cordillera; and the Westernized Christian Majority). Sudan was also included as "cleft" between Islam and Sub-Saharan Africa; this division became a formal split in July 2011 following an overwhelming vote for independence by South Sudan in a January 2011 referendum. |

ハンティントンによる主要な文明 ハンティントンによる文明の衝突(1996年)『文明の衝突と世界秩序の再構築』[18] ハンティントンは、論文の中で世界を次のように「主要な文明」に分類した:[19][2] アメリカ合衆国とカナダ、西ヨーロッパと中欧、フィリピン、オーストラリア、オセアニアの大半からなる西洋文明。ラテンアメリカや旧ソ連加盟国が含まれる のか、それとも別の文明として扱われるのかは、それらの地域にとって今後の重要な検討課題であるとハンティントンは述べている。 伝統的な西洋の視点では、西洋文明は西洋のキリスト教(カトリックとプロテスタント)の国々や文化と同一視されていた[20]。 南アメリカ(ガイアナ、スリナム、フランス領ギアナを除く)、中央アメリカ、メキシコ、キューバ、ドミニカ共和国を含むラテンアメリカ文明は、西洋文明の一部と考えられる。南米、中央アメリカ、メキシコでは、多くの人々が自らを西洋文明の完全な一員であるとみなしている。 正教文明は、ブルガリア、キプロス、グルジア、ギリシャ、ルーマニア、旧ソビエト連邦の大部分、ユーゴスラビアで構成される。 正教徒が多数派でない国は通常、イスラム教徒が多数派を占めるアゼルバイジャンやアルバニア、中央アジアの大部分、バルカン半島、コーカサス地方、ロシア 中央部のタタルスタンやバシコルトスタンといったイスラム教徒が多数派を占める地域、ローマ・カトリックのスロベニアやクロアチア、プロテスタントとカト リックのバルト諸国など、正教徒が多数派を占める国々から除外される。しかし、アルメニアは、その支配的な信仰であるアルメニア使徒教会が東方正教会では なく、東洋正教会の一部であるにもかかわらず、また、カザフスタンは、その支配的な信仰がスンニ派イスラム教であるにもかかわらず、含まれている。 東洋世界は、仏教、イスラム教、中国、ヒンドゥー教、そして日本文明の混合である。 中国のシナ文明、朝鮮半島、シンガポール、台湾、ベトナム。このグループには、特に東南アジアに関連した華人ディアスポラも含まれる。 中国文明と古いアルタイ系パターンのハイブリッドと見なされる日本。 ブータン、カンボジア、ラオス、モンゴル、ミャンマー、スリランカ、タイの仏教地域は、他の文明とは区別されるが、ハンティントンは、国際情勢という意味では、これらは主要な文明を構成していないと考えている。 主にインドとネパールに位置し、世界中に散らばるインド系ディアスポラによって文化的に継承されているヒンドゥー文明。 イスラム教文明の一部。イスラム教徒が多数派を占める国々で、南アジアのパキスタン、アフガニスタン、バングラデシュを含む。東南アジアのインドネシアとマレーシア 大中東のイスラム世界(アルメニア、キプロス、エチオピア、グルジア、イスラエル、マルタ、南スーダンを除く)、西アフリカ北部、アルバニア、パキスタ ン、バングラデシュ、ボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナの一部、ブルネイ、コモロ、インドネシア、マレーシア、モルディブ、フィリピン南西部の一部 サハラ以南のアフリカ文明は、南部アフリカ、中部アフリカ(チャドを除く)、東アフリカ(エチオピア、コモロ、モーリシャス、ケニアとタンザニアのスワヒ リ海岸を除く)、カーボベルデ、ガーナ、コートジボワール、リベリア、シエラレオネに位置する。ハンティントンは、サハラ以南のアフリカ文明を8番目の文 明として分類している。 「主要」文明のどれにも属さないため、エチオピアとハイチは「孤高」国家と分類されている。イスラエルは独自の文明を持つユニークな国家である、とハン ティントンは書いているが、それは西洋と非常に類似している。ハンティントンはまた、カリブ海地域の英語圏諸国(旧イギリス植民地)は、それぞれ独立した 存在であると信じている。 また、別の文明に属する非常に大きな集団を含むため、「分裂国家」と見なされる国々もある。その例としては、ウクライナ(東方正教会が支配的な西部と、正 教会が支配的な東部の「分裂」)、フランス領ギアナ(ラテンアメリカと西部の「分裂」)、ベナン、チャド、ケニア、ナイジェリア、タンザニア、トーゴ(い ずれもイスラム教とサハラ以南アフリカの「分裂」)、ガイアナとスリナム(ヒンドゥー教とサハラ以南アフリカの「分裂」)、スリランカ(ヒンドゥー教と仏 教の「分裂」)、フィリピン(南西ミンダナオの場合はイスラム教、コルディリェラの場合はシナチズン、西側 ガイアナとスリナム(ヒンドゥー教とサハラ以南のアフリカの間の分裂)、スリランカ(ヒンドゥー教と仏教の間の分裂)、フィリピン(南西ミンダナオの場合 はイスラム教、コルディリェラの場合はシナチズン、西洋化されたキリスト教徒多数派の場合はキリスト教徒多数派)などである。スーダンも、イスラム教とサ ハラ以南のアフリカの「分断」に含まれていた。この区分は、2011年1月の住民投票で南スーダンが独立を圧倒的多数で支持したことを受け、2011年7 月に正式に分割された。 |

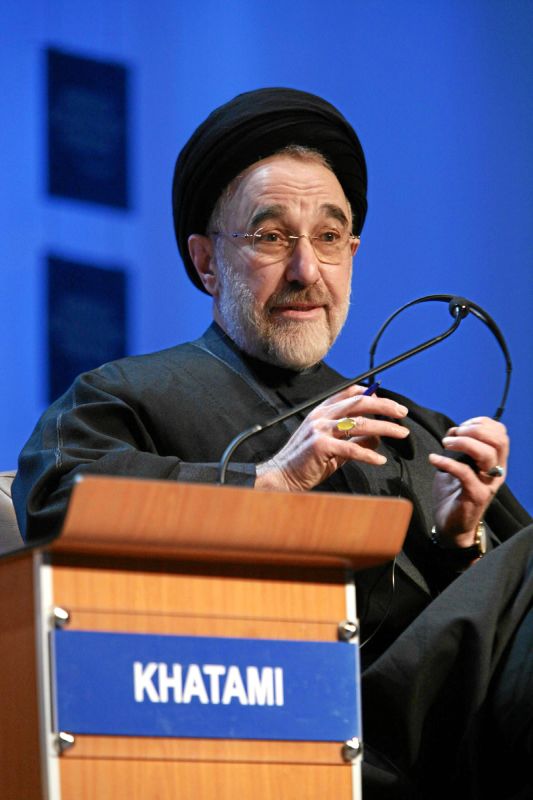

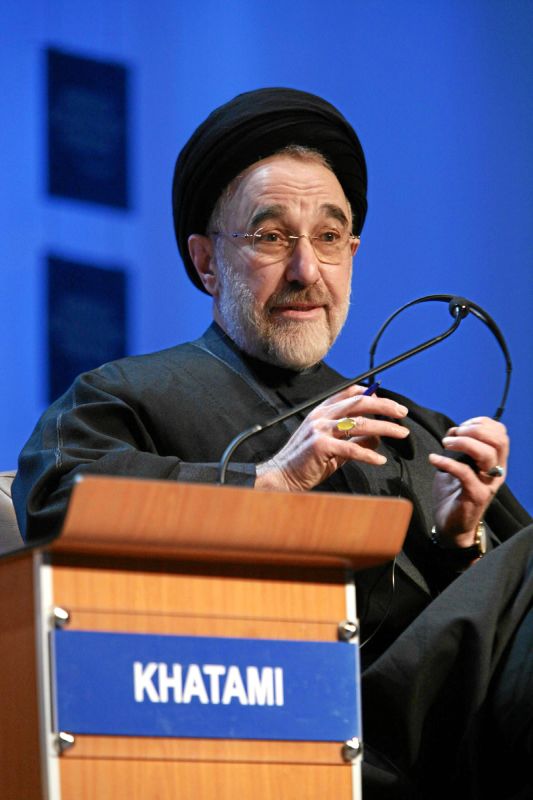

Huntington's thesis of civilizational clash Huntington at the 2004 World Economic Forum Huntington argues that the trends of global conflict after the end of the Cold War are increasingly appearing at these civilizational divisions. Wars such as those following the break up of Yugoslavia, in Chechnya, and between India and Pakistan were cited as evidence of inter-civilizational conflict. He also argues that the widespread Western belief in the universality of the West's values and political systems is naïve and that continued insistence on democratization and such "universal" norms will only further antagonize other civilizations. Huntington sees the West as reluctant to accept this because it built the international system, wrote its laws, and gave it substance in the form of the United Nations. Huntington identifies a major shift of economic, military, and political power from the West to the other civilizations of the world, most significantly to what he identifies as the two "challenger civilizations", Sinic and Islam. In Huntington's view, East Asian Sinic civilization is culturally asserting itself and its values relative to the West due to its rapid economic growth. Specifically, he believes that China's goals are to reassert itself as the regional hegemon, and that other countries in the region will 'bandwagon' with China due to the history of hierarchical command structures implicit in the Confucian Sinic civilization, as opposed to the individualism and pluralism valued in the West. Regional powers such as the two Koreas and Vietnam will acquiesce to Chinese demands and become more supportive of China rather than attempting to oppose it. Huntington therefore believes that the rise of China poses one of the most significant problems and the most powerful long-term threat to the West, as Chinese cultural assertion clashes with the American desire for the lack of a regional hegemony in East Asia.[citation needed] Huntington argues that the Islamic civilization has experienced a massive population explosion which is fueling instability both on the borders of Islam and in its interior, where fundamentalist movements are becoming increasingly popular. Manifestations of what he terms the "Islamic Resurgence" include the 1979 Iranian revolution and the first Gulf War. Perhaps the most controversial statement Huntington made in the Foreign Affairs article was that "Islam has bloody borders". Huntington believes this to be a real consequence of several factors, including the previously mentioned Muslim youth bulge and population growth and Islamic proximity to many civilizations including Sinic, Orthodox, Western, and African. Huntington sees Islamic civilization as a potential ally to China, both having more revisionist goals and sharing common conflicts with other civilizations, especially the West. Specifically, he identifies common Chinese and Islamic interests in the areas of weapons proliferation, human rights, and democracy that conflict with those of the West, and feels that these are areas in which the two civilizations will cooperate. Russia, Japan, and India are what Huntington terms 'swing civilizations' and may favor either side. Russia, for example, clashes with the many Muslim ethnic groups on its southern border (such as Chechnya) but—according to Huntington—cooperates with Iran to avoid further Muslim-Orthodox violence in Southern Russia, and to help continue the flow of oil. Huntington argues that a "Sino-Islamic connection" is emerging in which China will cooperate more closely with Iran, Pakistan, and other states to augment its international position. Huntington also argues that civilizational conflicts are "particularly prevalent between Muslims and non-Muslims", identifying the "bloody borders" between Islamic and non-Islamic civilizations. This conflict dates back as far as the initial thrust of Islam into Europe, its eventual expulsion in the Iberian reconquest, the attacks of the Ottoman Turks on Eastern Europe and Vienna, and the European imperial division of the Islamic nations in the 1800s and 1900s. Huntington also believes that some of the factors contributing to this conflict are that both Christianity (upon which Western civilization is based) and Islam are: Missionary religions, seeking conversion of others Universal, "all-or-nothing" religions, in the sense that it is believed by both sides that only their faith is the correct one Teleological religions, that is, that their values and beliefs represent the goals of existence and purpose in human existence. More recent factors contributing to a Western–Islamic clash, Huntington wrote, are the Islamic Resurgence and demographic explosion in Islam, coupled with the values of Western universalism—that is, the view that all civilizations should adopt Western values—that infuriate Islamic fundamentalists. All these historical and modern factors combined, Huntington wrote briefly in his Foreign Affairs article and in much more detail in his 1996 book, would lead to a bloody clash between the Islamic and Western civilizations. Why civilizations will clash Huntington offers six explanations for why civilizations will clash: Differences among civilizations are too basic in that civilizations are differentiated from each other by history, language, culture, tradition, and, most importantly, religion. These fundamental differences are the product of centuries and the foundations of different civilizations, meaning they will not be gone soon. The world is becoming a smaller place. As a result, interactions across the world are increasing, which intensify "civilization consciousness" and the awareness of differences between civilizations and commonalities within civilizations. Due to economic modernization and social change, people are separated from longstanding local identities. Instead, religion has replaced this gap, which provides a basis for identity and commitment that transcends national boundaries and unites civilizations. The growth of civilization-consciousness is enhanced by the dual role of the West. On the one hand, the West is at a peak of power. At the same time, a return-to-the-roots phenomenon is occurring among non-Western civilizations. A West at the peak of its power confronts non-Western countries that increasingly have the desire, the will and the resources to shape the world in non-Western ways. Cultural characteristics and differences are less mutable and hence less easily compromised and resolved than political and economic ones. Economic regionalism is increasing. Successful economic regionalism will reinforce civilization-consciousness. Economic regionalism may succeed only when it is rooted in a common civilization. The West versus the Rest Huntington suggests that in the future the central axis of world politics tends to be the conflict between Western and non-Western civilizations, in Stuart Hall's phrase, the conflict between "the West and the Rest". He offers three forms of general and fundamental actions that non-Western civilization can take in response to Western countries.[21] Non-Western countries can attempt to achieve isolation in order to preserve their own values and protect themselves from Western invasion. However, Huntington argues that the costs of this action are high and only a few states can pursue it. According to the theory of "band-wagoning", non-Western countries can join and accept Western values. Non-Western countries can make an effort to balance Western power through modernization. They can develop economic/military power and cooperate with other non-Western countries against the West while still preserving their own values and institutions. Huntington believes that the increasing power of non-Western civilizations in international society will make the West begin to develop a better understanding of the cultural fundamentals underlying other civilizations. Therefore, Western civilization will cease to be regarded as "universal" but different civilizations will learn to coexist and join to shape the future world. Core state and fault line conflicts In Huntington's view, intercivilizational conflict manifests itself in two forms: fault line conflicts and core state conflicts. Fault line conflicts are on a local level and occur between adjacent states belonging to different civilizations or within states that are home to populations from different civilizations. Core state conflicts are on a global level between the major states of different civilizations. Core state conflicts can arise out of fault line conflicts when core states become involved.[22] These conflicts may result from a number of causes, such as: relative influence or power (military or economic), discrimination against people from a different civilization, intervention to protect kinsmen in a different civilization, or different values and culture, particularly when one civilization attempts to impose its values on people of a different civilization.[22] Modernization, Westernization, and "torn countries" Japan, China and the Four Asian Tigers have modernized in many respects while maintaining traditional or authoritarian societies which distinguish them from the West. Some of these countries have clashed with the West and some have not. Perhaps the ultimate example of non-Western modernization is Russia, the core state of the Orthodox civilization. Huntington argues that Russia is primarily a non-Western state although he seems to agree that it shares a considerable amount of cultural ancestry with the modern West. According to Huntington, the West is distinguished from Orthodox Christian countries by its experience of the Renaissance, Reformation, the Enlightenment; by overseas colonialism rather than contiguous expansion and colonialism; and by the infusion of Classical culture through ancient Greece rather than through the continuous trajectory of the Byzantine Empire. Huntington refers to countries that are seeking to affiliate with another civilization as "torn countries". Turkey, whose political leadership has systematically tried to Westernize the country since the 1920s, is his chief example. Turkey's history, culture, and traditions are derived from Islamic civilization, but Turkey's elite, beginning with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk who took power as first President in 1923, imposed Western institutions and dress, embraced the Latin alphabet, joined NATO, and has sought to join the European Union. Mexico and Russia are also considered to be torn by Huntington. He also gives the example of Australia as a country torn between its Western civilizational heritage and its growing economic engagement with Asia. According to Huntington, a torn country must meet three requirements to redefine its civilizational identity. Its political and economic elite must support the move. Second, the public must be willing to accept the redefinition. Third, the elites of the civilization that the torn country is trying to join must accept the country. The book claims that to date no torn country has successfully redefined its civilizational identity, this mostly due to the elites of the 'host' civilization refusing to accept the torn country, though if Turkey gained membership in the European Union, it has been noted that many of its people would support Westernization, as in the following quote by EU Minister Egemen Bağış: "This is what Europe needs to do: they need to say that when Turkey fulfills all requirements, Turkey will become a member of the EU on date X. Then, we will regain the Turkish public opinion support in one day."[23] If this were to happen, it would, according to Huntington, be the first to redefine its civilizational identity. |

ハンチントンの文明の衝突説 2004年世界経済フォーラムでのハンチントン ハンチントンは、冷戦終結後の世界的な紛争の傾向は、これらの文明の分断においてますます顕著になっていると主張している。ユーゴスラビアの崩壊、チェ チェン、インドとパキスタンの間の戦争などの戦争は、文明間の紛争の証拠として挙げられた。また、西洋の価値観や政治システムの普遍性を信じる西洋の考え 方は甘いと主張し、民主化や「普遍的」規範の主張を続けることは、他の文明との対立を助長するだけだと述べている。 ハンチントンは、西洋が国際システムの構築、法整備、国連という形での実質化を行ったため、これを認めようとしないと考えている。 ハンチントンは、経済、軍事、政治のパワーが西側から世界の他の文明、特に彼が「挑戦文明」と呼ぶシナ文明とイスラム文明へと大きくシフトすると考えている。 ハンチントンの見解では、東アジアのシナ文明は、急速な経済成長により、西洋に対してその文化と価値観を主張している。具体的には、中国の目標は地域覇権 国としての地位を再確立することであり、儒教の儒教文化に内在する上下関係に基づく命令系統の歴史から、西洋で重視される個人主義や多元主義とは対照的 に、この地域の他の国々は中国に同調するだろう、と彼は考えている。 2つの韓国やベトナムなどの地域大国は中国の要求を受け入れ、中国に反対しようとするよりも、中国を支持するようになるだろう。したがって、ハンティント ンは、中国の台頭は、東アジアにおける地域覇権主義の不在を望むアメリカと、中国の文化的な主張が衝突することから、西洋にとって最も重要な問題であり、 最も強力な長期的な脅威の一つであると考える。 ハンティントンは、イスラム文明は人口爆発を経験しており、それがイスラム教の境界と内部の両方で不安定性を助長していると主張している。彼が「イスラム 復興」と呼ぶ現象には、1979年のイラン革命や第一次湾岸戦争などが含まれる。 ハンティントンが『フォーリン・アフェアーズ』誌上で述べた中で最も物議を醸した発言は、「イスラムには血塗られた国境がある」というものであった。ハン ティントンは、このことは、先に述べたイスラム教徒の若年層人口の増加や人口増加、そしてイスラム教が中国、正教、西洋、アフリカなど多くの文明と地理的 に近いことなど、いくつかの要因が引き起こした結果であると考える。 ハンティントンは、イスラム文明を中国にとって潜在的な同盟国と見ている。両者とも、より修正主義的な目標を持ち、西洋をはじめとする他の文明と共通の対 立を抱えているからだ。具体的には、武器拡散、人権、民主主義といった分野において、西洋と対立する共通の利益があると彼は指摘し、この分野において両文 明が協力するだろうと予測している。 ハンティントンが「揺れる文明」と呼ぶロシア、日本、インドは、どちらの側にも味方する可能性がある。例えば、ロシアは南部の国境沿いにある多くのイスラ ム系民族(チェチェンなど)と対立しているが、ハンチントンによると、ロシア南部でのイスラム教徒と正教徒のさらなる衝突を回避し、石油の流れを維持する ためにイランと協力している。ハンチントンは、「中国とイスラム教のつながり」が浮上しており、中国が国際的地位を高めるためにイラン、パキスタン、その 他の国々とより緊密に協力するようになると主張している。 またハンチントンは、文明間の対立は「特にイスラム教徒と非イスラム教徒の間で顕著」であり、イスラム文明と非イスラム文明の「血塗られた境界」を指摘し ている。この対立は、イスラム教がヨーロッパに最初に伝わったとき、イベリア半島再征服で最終的に追放されたとき、オスマン・トルコが東ヨーロッパと ウィーンを攻撃したとき、そして1800年代と1900年代にイスラム諸国がヨーロッパ帝国に分割されたときまでさかのぼる。 ハンティントンは、この対立の一因として、西洋文明の基盤となっているキリスト教とイスラム教が、 他者の改宗を求める布教型の宗教であること 双方とも自分たちの信仰だけが正しいと信じているという意味で、普遍的かつ「白か黒か」の宗教であること 彼らの価値観や信念が、人間存在の目的や意義を表しているとする目的論的宗教であること、を挙げている。 ハンティントンは、西洋とイスラムの衝突を助長する最近の要因として、イスラム復興とイスラム人口の爆発的増加、そして西洋の普遍主義的価値観(すなわ ち、すべての文明は西洋の価値観を採用すべきであるという考え方)を挙げている。 これらの歴史的および現代的な要因がすべて組み合わさることで、ハンティントンは『フォーリン・アフェアーズ』誌の記事で簡潔に、また1996年の著書で はより詳細に述べているように、イスラム文明と西洋文明の間の流血の衝突につながると述べている。 文明が衝突する理由 ハンチントンは、文明が衝突する理由を6つ挙げている。 文明間の違いはあまりにも基本的である。なぜなら、文明は歴史、言語、文化、伝統、そして最も重要な宗教によって互いに区別されているからだ。これらの根本的な違いは、何世紀にもわたる文明の基盤から生まれたものであり、すぐに消えるものではない。 世界は小さくなりつつある。その結果、世界中で交流が活発化し、「文明意識」や文明間の違い、文明内の共通点に対する認識が高まっている。 経済近代化や社会変化により、人々は長年にわたって培ってきた地域的なアイデンティティから切り離されている。その代わりに、宗教が人々のアイデンティティやコミットメントの基盤となり、国境を越えて文明を結びつけている。 文明意識の高まりは、西洋の2つの役割によってさらに強化されている。一方では西洋が絶頂期の力を誇っている。同時に、非西洋文明では原点回帰の現象が起 こっている。絶頂期の力を誇る西洋は、西洋以外の方法で世界を形作ろうとする意欲と意志、そして資源を持つ国々に対峙している。 文化的な特徴や違いは、政治や経済的なものよりも変化しにくく、妥協や解決が難しい。 経済的な地域主義が高まっている。経済地域主義が成功すれば、文明意識が強化されるだろう。経済地域主義が成功するのは、それが共通の文明に根ざしている場合のみである。 西洋対その他 ハンティントンは、将来、世界政治の中心軸は西洋文明と非西洋文明の対立、すなわちスチュアート・ホールの表現を借りれば「西洋とその他」の対立になる傾 向があると指摘している。彼は、西洋諸国に対する非西洋文明の一般的な基本的行動として、3つの形態を提案している[21]。 非西洋諸国は、自らの価値観を守り、西洋の侵略から身を守るために孤立化を図ることができる。しかし、ハンティントンは、この行動には多大な犠牲が伴うため、実行できる国は限られていると主張している。 バンドワゴン理論によると、非西洋諸国は西洋の価値観を受け入れ、それに加わることができる。 非西洋諸国は、近代化を通じて西洋のパワーバランスに挑むことができる。経済力や軍事力を高め、西洋に対抗する他の非西洋諸国と協力しながら、自国の価値 観や制度を維持することができる。ハンティントンは、国際社会における非西洋文明の台頭により、西洋は他の文明の根底にある文化的な基盤についてより深い 理解を育むようになるだろうと考えている。したがって、西洋文明は「普遍的」と見なされなくなり、異なる文明が共存し、未来の世界を形成するようになるだ ろう。 中心国家と断層線上の紛争 ハンチントンの見解では、文明間の紛争は断層線上の紛争と中心国家間の紛争という2つの形態で現れる。 断層線上の紛争は地域レベルであり、異なる文明に属する隣接国家間、または異なる文明に属する人口が居住する国家内で発生する。 コア国家間の紛争は、異なる文明の主要国家間のグローバルなレベルでの紛争である。中心国家間の紛争は、中心国家が関与することで断層線紛争から生じる可能性がある[22]。 これらの紛争は、次のような多くの原因から生じる可能性がある。相対的な影響力や力(軍事力や経済力)、異なる文明の人々に対する差別、異なる文明の親族 を保護するための介入、異なる価値観や文化、特にある文明が別の文明の人々にその価値観を押し付けようとする場合などである[22]。特に、ある文明が別 の文明の人々にその価値観を押し付けようとする場合などである[22]。 近代化、西洋化、そして「分裂国家」 日本、中国、そしてアジアの4つの虎は、西洋とは異なる伝統的または権威主義的社会を維持しながら、多くの点で近代化してきた。これらの国々の中には西洋と衝突した国もあれば、衝突しなかった国もある。 西洋化していない近代化の究極の例は、正教文明の中核国家であるロシアだろう。ハンティントンは、ロシアは主に西洋化していない国家であると主張している が、ロシアが現代の西洋と多くの文化的共通点を持っていることには同意しているようだ。ハンティントンによると、西洋はルネサンス、宗教改革、啓蒙主義を 経験したこと、連続的な拡大や植民地主義ではなく海外植民地主義を行ったこと、ビザンティン帝国の継続的な発展ではなく古代ギリシャを通じて古典文化が流 入したこと、といった点において正教会諸国と区別される。 ハンティントンは、他の文明との提携を求める国々を「分裂国家」と呼んでいる。1920年代以降、政治指導部が組織的に西洋化を試みてきたトルコがその最 たる例である。トルコの歴史、文化、伝統はイスラム文明に由来しているが、1923年に初代大統領に就任したムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクを皮切り に、トルコのエリート層は西洋の制度や服装を強制し、ラテンアルファベットを採用し、NATOに加盟し、EUへの加盟を目指してきた。 メキシコとロシアも、ハンティントンによれば分裂している。また、オーストラリアを、西洋文明の遺産とアジアとの経済的な結びつきの間で揺れる国として例に挙げている。 ハンティントンによれば、分裂した国が文明的なアイデンティティを再定義するには、3つの条件を満たす必要がある。まず、政治と経済のエリート層が再定義 を支持すること。次に、国民が再定義を受け入れる意思があること。そして最後に、分裂した国が加盟しようとしている文明のエリート層が、その国を受け入れ ることである。 同書によると、これまで文明のアイデンティティを再定義することに成功した分裂国家はない。その主な原因は、分裂国家を受け入れない「ホスト」文明のエ リート層にあるが、トルコが欧州連合(EU)に加盟すれば、EU担当相エゲメン・バギシュ氏の次の言葉にあるように、多くの国民が西洋化に賛成するだろ う。「これがヨーロッパがすべきことだ。トルコがすべての条件を満たしたら、X 日付でトルコは EU の一員になると言わなければならない。そうすれば、私たちは 1 日でトルコの世論の支持を取り戻すことができるだろう。」[23] もしこれが実現すれば、ハンチントンによれば、文明的なアイデンティティを再定義した最初の国となる。 |

| Criticism The book has been criticized by various academic writers, who have empirically, historically, logically, or ideologically challenged its claims.[24][25][26][27] Political scientist Paul Musgrave writes that Clash of Civilization "enjoys great cachet among the sort of policymaker who enjoys name-dropping Sun Tzu, but few specialists in international relations rely on it or even cite it approvingly. Bluntly, Clash has not proven to be a useful or accurate guide to understanding the world."[28] In an article explicitly referring to Huntington, scholar Amartya Sen (1999) argues that "diversity is a feature of most cultures in the world. Western civilization is no exception. The practice of democracy that has won out in the modern West is largely a result of a consensus that has emerged since the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, and particularly in the last century or so. To read in this a historical commitment of the West—over the millennia—to democracy, and then to contrast it with non-Western traditions (treating each as monolithic) would be a great mistake."[29]: 16 In his 2003 book Terror and Liberalism, Paul Berman argues that distinct cultural boundaries do not exist in the present day. He argues there is no "Islamic civilization" nor a "Western civilization", and that the evidence for a civilization clash is not convincing, especially when considering relationships such as that between the United States and Saudi Arabia. In addition, he cites the fact that many Islamic extremists spent a significant amount of time living or studying in the Western world. According to Berman, conflict arises because of philosophical beliefs various groups share (or do not share), regardless of cultural or religious identity.[30] Timothy Garton Ash objects to the 'extreme cultural determinism... crude to the point of parody' of Huntington's idea that Catholic and Protestant Europe is headed for democracy, but that Orthodox Christian and Islamic Europe must accept dictatorship.[31] Edward Said issued a response to Huntington's thesis in his 2001 article, "The Clash of Ignorance".[32] Said argues that Huntington's categorization of the world's fixed "civilizations" omits the dynamic interdependency and interaction of culture. A longtime critic of the Huntingtonian paradigm, and an outspoken proponent of Arab issues, Said (2004) also argues that the clash of civilizations thesis is an example of "the purest invidious racism, a sort of parody of Hitlerian science directed today against Arabs and Muslims" (p. 293).[33] Noam Chomsky has criticized the concept of the clash of civilizations as just being a new justification for the United States "for any atrocities that they wanted to carry out", which was required after the Cold War as the Soviet Union was no longer a viable threat.[34] In 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, Yuval Noah Harari called the clash of civilizations a misleading thesis. He wrote that Islamic fundamentalism is more of a threat to a global civilization, rather than a confrontation with the West. He also argued that talking about civilizations using analogies from evolutionary biology is wrong.[35] Intermediate Region Huntington's geopolitical model, especially the structures for North Africa and Eurasia, is largely derived from the "Intermediate Region" geopolitical model first formulated by Dimitri Kitsikis and published in 1978.[36] The Intermediate Region, which spans the Adriatic Sea and the Indus River, is neither Western nor Eastern (at least, with respect to the Far East) but is considered distinct. Concerning this region, Huntington departs from Kitsikis contending that a civilizational fault line exists between the two dominant yet differing religions (Eastern Orthodoxy and Sunni Islam), hence a dynamic of external conflict. However, Kitsikis establishes an integrated civilization comprising these two peoples along with those belonging to the less dominant religions of Shia Islam, Alevism, and Judaism. They have a set of mutual cultural, social, economic and political views and norms which radically differ from those in the West and the Far East. In the Intermediate Region, therefore, one cannot speak of a civilizational clash or external conflict, but rather an internal conflict, not for cultural domination, but for political succession. This has been successfully demonstrated by documenting the rise of Christianity from the Hellenized Roman Empire, the rise of the Islamic caliphates from the Christianized Roman Empire and the rise of Ottoman rule from the Islamic caliphates and the Christianized Roman Empire.  Mohammad Khatami, reformist president of Iran (in office 1997–2005), introduced the theory of Dialogue Among Civilizations as a response to Huntington's theory. Opposing concepts In recent years, the theory of Dialogue Among Civilizations, a response to Huntington's Clash of Civilizations, has become the center of some international attention. The concept was originally coined by Austrian philosopher Hans Köchler in an essay on cultural identity (1972).[37] In a letter to UNESCO, Köchler had earlier proposed that the cultural organization of the United Nations should take up the issue of a "dialogue between different civilizations" (dialogue entre les différentes civilisations).[38] In 2001, Iranian president Mohammad Khatami introduced the concept at the global level. At his initiative, the United Nations proclaimed the year 2001 as the "United Nations Year of Dialogue among Civilizations".[39][40][41] The Alliance of Civilizations (AOC) initiative was proposed at the 59th General Assembly of the United Nations in 2005 by the Spanish Prime Minister, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero and co-sponsored by the Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The initiative is intended to galvanize collective action across diverse societies to combat extremism, to overcome cultural and social barriers between mainly the Western and predominantly Muslim worlds, and to reduce the tensions and polarization between societies which differ in religious and cultural values. |

批判 この本は、さまざまな学術研究者の批判にさらされてきた。彼らは、経験的、歴史的、論理的、あるいはイデオロギー的な観点から、この本の主張に異議を唱え てきた[24][25][26][27]。政治学者のポール・マスグレイブは、『文明の衝突』は「孫子を引き合いに出すことを好む政策立案者の間で高い評 価を得ているが、国際関係論の専門家でこれを信頼したり、肯定的に引用したりする者はほとんどいない。率直に言えば、『文明の衝突』は、世界を理解するた めの有益で正確な指針とは証明されていない」[28]。 ハンチントンを明示的に参照した論文の中で、学者アマルティア・セン(1999)は、「多様性は世界のほとんどの文化の特徴である。西洋文明も例外ではな い。近代西洋で勝利を収めた民主主義の慣行は、啓蒙思想や産業革命以降、特にここ100年ほどで生まれたコンセンサスの結果である。これを、西洋が数千年 にもわたって民主主義に傾倒してきた歴史的経緯ととらえ、非西洋の伝統(それぞれを一元的に捉える)と対比するのは大きな誤りである。 2003年に出版されたポール・バーマンの著書『テロとリベラリズム』では、現代において明確な文化の境界線は存在しないという主張が展開されている。彼 は、「イスラム文明」も「西洋文明」も存在しないとし、文明の衝突を裏付ける証拠は説得力がない、特にアメリカとサウジアラビアの関係などを考慮すると、 なおさらだと主張している。さらに、彼は、多くのイスラム過激派が西洋で生活したり学んだりした経験があることを挙げている。バーマンによると、対立は、 文化や宗教のアイデンティティに関係なく、さまざまなグループが共有する(または共有しない)哲学的信念が原因で生じるという[30]。 ティモシー・ガートン・アッシュは、カトリックとプロテスタントのヨーロッパは民主主義に向かうが、正教キリスト教とイスラム教のヨーロッパは独裁政治を 受け入れざるを得ないというハンチントンの考えの「極端な文化的決定論...パロディの域に達するほど粗野な」ものに異議を唱えている[31]。イスラム 教徒のヨーロッパは独裁政治を受け入れなければならないというハンティントンの考えに、ティモシー・ガートン・アッシュは「極端な文化決定論...パロ ディの域に達するほど粗野」だと反論している[31]。 エドワード・サイードは、2001年の論文「無知の衝突」でハンティントンの説に反論した[32]。サイードは、ハンティントンの世界の「文明」の固定的 な分類は、文化のダイナミックな相互依存と相互作用を無視していると主張している。ハンチントンのパラダイムを長年批判し、アラブ問題について率直に発言 してきたサイード(2004)は、文明の衝突論は「最も純粋な悪意に満ちた人種差別であり、今日アラブ人とイスラム教徒に向けられたヒトラー的科学のパロ ディのようなものだ」(293ページ)とも主張している[33]。 ノーム・チョムスキー 文明の衝突という概念は、冷戦後にソ連が脅威ではなくなったため必要となった、米国が「実行したい残虐行為」の新たな正当化にすぎない、と批判している[34]。 21 Lessons for the 21st Century』の中で、ユヴァル・ノア・ハラリは文明の衝突を誤解を招く説と呼んだ。彼は、イスラム原理主義は西洋との対立というよりも、むしろ世界文 明に対する脅威であると書いている。また、進化生物学からの類推を用いて文明について語ることは間違っているとも主張した[35]。 中間地域 ハンチントンの地政学モデル、特に北アフリカとユーラシアの構造は、主にディミトリ・キツィキスが1978年に発表した地政学モデル「中間地域」から派生 したものである[36]。1978年にディミトリ・キツィキスが提唱し、発表した地政学モデルである[36]。アドリア海とインダス川にまたがる中間地域 は、西洋でも東洋でもない(少なくとも極東に関しては)が、明確に区別される地域であると考えられている。この地域に関して、ハンティントンは、2つの支 配的だが異なる宗教(東方正教会とスンニ派イスラム教)の間に文明の断層線が存在し、それゆえ外部との衝突の力学が生じると主張し、キティキスと意見が分 かれる。しかし、キティキスは、これら2つの民族と、シーア派イスラム教、アレヴィズム、ユダヤ教という、それほど支配的ではない宗教に属する人々で構成 される統合された文明を提唱している。彼らは西洋や極東のそれとは根本的に異なる、相互の文化的、社会的、経済的、政治的見解や規範を持っている。した がって中間地域では、文明の衝突や外部からの紛争ではなく、文化的支配ではなく政治的継承を目的とした内部紛争について語ることができる。これは、ヘレニ ズム化されたローマ帝国からキリスト教が台頭したこと、キリスト教化されたローマ帝国からイスラム教カリフ制が台頭したこと、そしてイスラム教カリフ制と キリスト教化されたローマ帝国からオスマン帝国の支配が台頭したことを示すことで、うまく説明できる。  改革派のイラン大統領(在任期間:1997年~2005年)であったモハンマド・ハタミは、ハンチントンの理論に対する反論として「文明間の対話」理論を打ち出した。 対立する概念 近年、ハンチントンの文明の衝突に対する文明間の対話理論が、国際的な注目を集めるようになった。この概念は、もともとオーストリアの哲学者ハンス・ケヒ ラーが文化アイデンティティに関する論文(1972年)で提唱したものである[37]。ケヒラーは以前、ユネスコ宛ての手紙で、国連文化機関が「異なる文 明間の対話」(dialogue entre les différentes civilisations)の問題に取り組むべきだと提案していた[38]。2001年、イランのモハンマド・ハタミ大統領が世界レベルでこの概念を紹 介した。彼の主導により、国連は2001年を「文明間の対話に関する国際連合年」と宣言した[39][40][41]。 文明間の同盟(AOC)構想は、2005年の第59回国連総会で、スペインのホセ・ルイス・ロドリゲス・サパテロ首相が提案し、トルコのレジェップ・タイ イップ・エルドアン首相が共同提案した。このイニシアティブは、過激主義と闘い、主に西洋とイスラム教世界間の文化的・社会的障壁を克服し、宗教的・文化 的価値観が異なる社会間の緊張や二極化を緩和するために、多様な社会全体で共同行動を起こすことを目的としている。 |

| Other civilizational models Eurasianism, a Russian geopolitical concept based on the civilization of Eurasia Intermediate Region Islamo-Christian Civilization Pan-Turkism Individuals Richard Bulliet Jacob Burckhardt Niall Ferguson Dimitri Kitsikis Feliks Koneczny Carroll Quigley Oswald Spengler |

その他の文明モデル ユーラシア主義、ロシアの地理政治的概念で、ユーラシア文明に基づく 中間地域 イスラム・キリスト教文明 汎トルコ主義 個人 リチャード・ブリエット ヤコブ・ブルクハルト ニール・ファーガソン ディミトリ・キツィキス フェリクス・コネツニー キャロル・クィグリー オズワルド・シュペングラー |

| Balkanization Civilizing mission Cold War II Criticism of multiculturalism Cultural relativism Eastern Party Fault line war Global policeman Inglehart–Welzel cultural map of the world Opposition to immigration Occidentalism Orientalism Oriental Despotism Potential superpowers Protracted social conflict Religious pluralism East-West Cultural Debate |

バルカン化 文明化ミッション 冷戦II 多文化主義への批判 文化相対主義 東側陣営 断層線戦争 グローバルポリスマン イングルハート=ウェルツェルの文化世界地図 移民への反対 オキュパンティズム オリエンタリズム 東洋的専制政治 潜在的な超大国 長期化する社会紛争 宗教的多様性 東西文化論争 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clash_of_Civilizations |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆