認知的不協和

Cognitive dissonance

☆ 心理学の分野では、認知的不協和とは、矛盾する情報の知覚とその精神的負担のことである。関連する情報には、人の行動、感情、考え、信念、環境における価 値観などが含まれる。この理論によると、ある行動や考えが他と心理的に矛盾しているとき、人はどちらかを変えるためにあらゆる力を尽くし、矛盾がなくなる ようにする(→「フェスティンガーの「認知的不協和」論」)。

| In

the field of psychology, cognitive dissonance is the perception of

contradictory information and its mental toll. Relevant items of

information include a person's actions, feelings, ideas, beliefs, and

values in the environment. Cognitive dissonance is typically

experienced as psychological stress when persons participate in an

action that contradicts one or more of those factors.[1] According to

this theory, when an action or idea is psychologically inconsistent

with the other, people do all in their power to change either so that

they become consistent.[1][2] The discomfort is triggered by the

person's belief clashing with new information perceived, wherein the

individual tries to find a way to resolve the contradiction to reduce

their discomfort.[1][2][3] In When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group That Predicted the Destruction of the World (1956) and A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (1957), Leon Festinger proposed that human beings strive for internal psychological consistency to function mentally in the real world.[1] A person who experiences internal inconsistency tends to become psychologically uncomfortable and is motivated to reduce the cognitive dissonance.[1][2] They tend to make changes to justify the stressful behavior, either by adding new parts to the cognition causing the psychological dissonance (rationalization) or by avoiding circumstances and contradictory information likely to increase the magnitude of the cognitive dissonance (confirmation bias).[1][2][3] Coping with the nuances of contradictory ideas or experiences is mentally stressful, as it requires energy and effort to sit with those seemingly opposite things that all seem true. Festinger argued that some people would inevitably resolve the dissonance by blindly believing whatever they wanted to believe. |

心

理学の分野では、認知的不協和とは、矛盾する情報の知覚とその精神的負担のことである。関連する情報には、人の行動、感情、考え、信念、環境における価値

観などが含まれる。この理論によると、ある行動や考えが他と心理的に矛盾しているとき、人はどちらかを変えるためにあらゆる力を尽くし、矛盾がなくなるよ

うにする[1][2]。 予言が失敗するとき: レオン・フェスティンガーはWhen Propcy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group That Predicted the Destruction of the World (1956)とA Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (1957)の中で、人間は現実世界で精神的に機能するために心理学的な内的整合性を求めると提唱している。 [1][2]心理的不協和を引き起こしている認知に新たな部分を追加したり(合理化)、認知的不協和の大きさを増大させる可能性が高い状況や矛盾する情報 を避けたり(確証バイアス)して、ストレスの多い行動を正当化するために変更を加える傾向がある[1][2][3]。 矛盾する考えや経験のニュアンスに対処することは精神的なストレスであり、すべてが真実であるように見えるそれらの一見正反対な事柄に寄り添うエネルギー と努力を必要とするからである。フェスティンガーは、自分が信じたいものは何でも盲目的に信じることで、必然的に不協和を解消する人もいると主張した。 |

| Relations among cognitions To function in the reality of society, human beings continually adjust the correspondence of their mental attitudes and personal actions; such continual adjustments, between cognition and action, result in one of three relationships with reality:[3] Consonant relationship: A cognition or action consistent with the other, e.g., not wanting to become drunk when out for dinner and ordering water rather than wine Irrelevant relationship: A cognition or action unrelated to the other, e.g. not wanting to become drunk when out and wearing a shirt Dissonant relationship: A cognition or action inconsistent with the other, e.g. not wanting to become drunk when out, but then drinking more wine anyway Magnitude of dissonance The term "magnitude of dissonance" refers to the level of discomfort caused to the person. This can be caused by the relationship between two different internal beliefs, or an action that is incompatible with the beliefs of the person.[2] Two factors determine the degree of psychological dissonance caused by two conflicting cognitions or by two conflicting actions: The importance of cognitions: the greater the personal value of the elements, the greater the magnitude of the dissonance in the relation. When the value of the importance of the two dissonant items is high, it is difficult to determine which action or thought is correct. Both have had a place of truth, at least subjectively, in the mind of the person. Therefore, when the ideals or actions now clash, it is difficult for the individual to decide which takes priority. Ratio of cognitions: the proportion of dissonant-to-consonant elements. There is a level of discomfort within each person that is acceptable for living. When a person is within that comfort level, the dissonant factors do not interfere with functioning. However, when dissonant factors are abundant and not enough in line with each other, one goes through a process to regulate and bring the ratio back to an acceptable level. Once a subject chooses to keep one of the dissonant factors, they quickly forget the other to restore peace of mind.[5] There is always some degree of dissonance within a person as they go about making decisions, due to the changing quantity and quality of knowledge and wisdom that they gain. The magnitude itself is a subjective measurement since the reports are self relayed, and there is no objective way as yet to get a clear measurement of the level of discomfort.[6] |

認知間の関係 社会という現実の中で機能するために、人間は自分の心的態度と個人的行動の対応関係を絶えず調整している。このような認識と行動の間の絶え間ない調整は、現実との次の3つの関係のうちの1つをもたらす[3]。 一致した関係: 例えば、外食時に酔いたくない、ワインではなく水を注文する。 無関係な関係: 無関係な関係:認知や行動が他と無関係であること。 不協和な関係: 不協和関係:認知や行動が他と矛盾している。 不協和の大きさ 不協和の大きさ」とは、その人に生じる不快感の程度を指す。これは2つの異なる内的信念の関係、またはその人の信念と相容れない行動によって引き起こされる: 認知の重要性:要素の個人的価値が大きいほど、関係における不協和の大きさは大きくなる。2つの不協和項目の重要性の値が高い場合、どちらの行動や思考が 正しいかを判断することは難しい。少なくとも主観的には、どちらもその人の心の中で真実の位置を占めている。そのため、理想や行動が衝突したとき、どちら が優先されるかを決めるのは困難である。 認知の比率:不協和音と子音の要素の比率。各人の中には、生きていく上で許容できる不快感のレベルがある。人がその快適さの範囲内にいるとき、不協和要素 は機能を妨げない。しかし、不協和な要素が多く、互いの比率が十分でない場合、人はその比率を調整し、受け入れ可能なレベルに戻すプロセスを経る。対象者 が不協和因子の一方を維持することを選択すると、心の平穏を取り戻すためにもう一方はすぐに忘れてしまう[5]。 知識や知恵の量や質が変化するため、意思決定をしていく中で、人の中には常にある程度の不協和が存在する。不協和の大きさそのものは、自己申告であるため主観的な測定であり、不協和のレベルを明確に測定する客観的な方法はまだない[6]。 |

| Reduction Cognitive dissonance theory proposes that people seek psychological consistency between their expectations of life and the existential reality of the world. To function by that expectation of existential consistency, people continually reduce their cognitive dissonance in order to align their cognitions (perceptions of the world) with their actions. The creation and establishment of psychological consistency allows the person affected with cognitive dissonance to lessen mental stress by actions that reduce the magnitude of the dissonance, realized either by changing with or by justifying against or by being indifferent to the existential contradiction that is inducing the mental stress.[3] In practice, people reduce the magnitude of their cognitive dissonance in four ways: Change the behavior or the cognition ("I'll eat no more of this doughnut.") Justify the behavior or the cognition, by changing the conflicting cognition ("I'm allowed to cheat my diet every once in a while.") Justify the behavior or the cognition by adding new behaviors or cognitions ("I'll spend thirty extra minutes at the gymnasium to work off the doughnut.") Ignore or deny information that conflicts with existing beliefs ("This doughnut is not a high-sugar food.") Three cognitive biases are components of dissonance theory. There is a bias where one feels they do not have any biases. The bias where one is "better, kinder, smarter, more moral and nicer than average" is confirmation bias.[7] That consistent psychology is required for functioning in the real world also was indicated in the results of The Psychology of Prejudice (2006), wherein people facilitate their functioning in the real world by employing human categories (i.e. sex and gender, age and race, etc.) with which they manage their social interactions with other people. Based on a brief overview of models and theories related to cognitive consistency from many different scientific fields, such as social psychology, perception, neurocognition, learning, motor control, system control, ethology, and stress, it has even been proposed that "all behaviour involving cognitive processing is caused by the activation of inconsistent cognitions and functions to increase perceived consistency"; that is, all behaviour functions to reduce cognitive inconsistency at some level of information processing.[8] Indeed, the involvement of cognitive inconsistency has long been suggested for behaviors related to for instance curiosity,[9][10] and aggression and fear,[11][12] while it has also been suggested that the inability to satisfactorily reduce cognitive inconsistency may – dependent on the type and size of the inconsistency – result in stress.[8][13] Selective exposure Another means to reduce cognitive dissonance is selective exposure. This theory has been discussed since the early days of Festinger's proposal of cognitive dissonance. He noticed that people would selectively expose themselves to some media over others; specifically, they would avoid dissonant messages and prefer consonant messages.[14] Through selective exposure, people actively (and selectively) choose what to watch, view, or read that fit to their current state of mind, mood or beliefs.[15] In other words, consumers select attitude-consistent information and avoid attitude-challenging information.[16] This can be applied to media, news, music, and any other messaging channel. The idea is, choosing something that is in opposition to how you feel or believe in will increase cognitive dissonance. For example, a study was done in an elderly home in 1992 on the loneliest residents—those that did not have family or frequent visitors. The residents were shown a series of documentaries: three that featured a "very happy, successful elderly person", and three that featured an "unhappy, lonely elderly person."[17] After watching the documentaries, the residents indicated they preferred the media featuring the unhappy, lonely person over the happy person. This can be attested to them feeling lonely, and experiencing cognitive dissonance watching somebody their age feeling happy and being successful. This study explains how people select media that aligns with their mood, as in selectively exposing themselves to people and experiences they are already experiencing. It is more comfortable to see a movie about a character that is similar to you than to watch one about someone who is your age who is more successful than you. Another example to note is how people mostly consume media that aligns with their political views. In a study done in 2015, participants were shown "attitudinally consistent, challenging, or politically balanced online news."[16]: 3 Results showed that the participants trusted attitude-consistent news the most out of all the others, regardless of the source. It is evident that the participants actively selected media that aligns with their beliefs rather than opposing media.[16] In fact, recent research has suggested that while a discrepancy between cognitions drives individuals to crave for attitude-consistent information, the experience of negative emotions drives individuals to avoid counter attitudinal information. In other words, it is the psychological discomfort which activates selective exposure as a dissonance-reduction strategy.[18] |

削減 認知的不協和理論では、人は人生に対する期待と世界の実存的現実との間に心理的整合性を求めると提唱している。その実存的な一貫性への期待によって機能するために、人は自分の認知(世界に対する認識)と自分の行動を一致させるために、認知的不協和を継続的に減少させる。 心理的一貫性の創造と確立によって、認知的不協和の影響を受けている人は、精神的ストレスを引き起こしている実存的矛盾と一緒に変化するか、それに対して 正当化するか、無関心であることによって実現される、不協和の大きさを減少させる行動によって精神的ストレスを軽減することができる[3]。 実際には、人は4つの方法で認知的不協和の大きさを減少させる: 行動や認知を変える(「このドーナツはもう食べない」)。 矛盾する認知を変えることで、行動や認知を正当化する(「たまにはダイエットをごまかしてもいいんだ」)。 新しい行動や認知を追加することで、その行動や認知を正当化する(「ドーナツを食べるために、体育館で30分余計に過ごす」)。 既存の信念と矛盾する情報を無視したり否定したりする(「このドーナツは糖分の高い食べ物ではない」)。 つの認知バイアスは不協和理論の構成要素である。自分にはバイアスがないと感じるバイアスがある。平均よりも優れていて、親切で、賢く、道徳的で、親切である」というバイアスは確証バイアスである[7]。 一貫した心理学が現実世界で機能するために必要であることは、『偏見の心理学』(2006年)の結果にも示されており、人々は他の人々との社会的相互作用を管理する人間のカテゴリー(すなわち、性別や年齢や人種など)を用いることによって、現実世界での機能を促進する。 社会心理学、知覚、神経認知、学習、運動制御、システム制御、倫理学、ストレスなど、多くの異なる科学分野から認知的一貫性に関連するモデルや理論を簡単 に概観すると、「認知処理を伴うすべての行動は、一貫性のない認知の活性化によって引き起こされ、知覚される一貫性を高めるように機能する」、つまり、す べての行動は、情報処理のあるレベルにおいて認知的一貫性の欠如を減らすように機能する、とさえ提唱されている。 [8]実際、認知的矛盾の関与は、例えば好奇心[9][10]や攻撃性や恐怖に関連する行動[11][12]について長い間示唆されており、認知的矛盾を 満足に低減できないことが-矛盾の種類や大きさにもよるが-ストレスにつながる可能性も示唆されている[8][13]。 選択的暴露 認知的不協和を減少させるもう一つの手段は、選択的暴露である。この理論は、フェスティンガーが認知的不協和を提唱した初期から議論されている。フェス ティンガーは、人々が他のメディアよりもあるメディ アに選択的に身をさらすことに気づいた。特に、人々は不協和的なメッセー ジを避け、共和的なメッセージを好むのである[14]。選択的曝露を通 じて、人々は積極的に(そして選択的に)、自分の現在の心 の状態、気分、信念に合ったものを見たり、見たり、読んだり することを選ぶ[15]。つまり、自分がどう感じているか、どう信じているかに反するものを選ぶと、認知的不協和が増大するという考え方である。 例えば、1992年にある老人ホームで、最も孤独な入所者、つまり家族や頻繁な訪問者がいない入所者を対象にした研究が行われた。それは、「とても幸せで 成功した高齢者」が登場する3つのドキュメンタリーと、「不幸で孤独な高齢者」が登場する3つのドキュメンタリーであった[17]。ドキュメンタリーを見 た後、入居者は幸せな人よりも不幸で孤独な人が登場するメディアの方を好むと答えた。これは、彼らが孤独を感じており、同年代の誰かが幸せで成功している のを見て、認知的不協和を経験していることを証明することができる。この研究は、人がいかに自分の気分に合ったメディアを選ぶか、つまり、すでに経験して いる人々や経験に選択的に自分をさらすかを説明している。同年代で自分より成功している人物の映画を見るより、自分と似た人物の映画を見る方が心地よいの だ。 もうひとつ注目すべき例は、人々が自分の政治的見解に沿ったメディアを消費することが多いということだ。2015年に行われた研究では、参加者に「態度に 一貫性があり、挑戦的で、政治的にバランスの取れたオンラインニュース」を見せた[16]: 3 その結果、参加者は出典にかかわらず、態度に一貫性のあるニュースを他のすべてのニュースの中で最も信頼していることがわかった。これは、参加者が反対の メディアではなく、自分の信念に沿ったメディアを積極的に選択していることを示している[16]。 実際、最近の研究では、認知の不一致が個人の態度一致情報を切望させる一方で、否定的な感情の経験が個人の態度不一致情報を回避させることが示唆されている。言い換えれば、不協和低減戦略としての選択的暴露を活性化させるのは心理的不快感である[18]。 |

| Paradigms There are four theoretic paradigms of cognitive dissonance, the mental stress people experienced when exposed to information that is inconsistent with their beliefs, ideals or values: Belief Disconfirmation, Induced Compliance, Free Choice, and Effort Justification, which respectively explain what happens after a person acts inconsistently, relative to their intellectual perspectives; what happens after a person makes decisions and what are the effects upon a person who has expended much effort to achieve a goal. Common to each paradigm of cognitive-dissonance theory is the tenet: People invested in a given perspective shall—when confronted with contrary evidence—expend great effort to justify retaining the challenged perspective.[19] Belief disconfirmation Main article: Disconfirmed expectancy The contradiction of a belief, ideal, or system of values causes cognitive dissonance that can be resolved by changing the challenged belief, yet, instead of effecting change, the resultant mental stress restores psychological consonance to the person by misperception, rejection, or refutation of the contradiction, seeking moral support from people who share the contradicted beliefs or acting to persuade other people that the contradiction is unreal.[20][21]: 123 The early hypothesis of belief contradiction presented in When Prophecy Fails (1956) reported that faith deepened among the members of an apocalyptic religious cult, despite the failed prophecy of an alien spacecraft soon to land on Earth to rescue them from earthly corruption. At the determined place and time, the cult assembled; they believed that only they would survive planetary destruction; yet the spaceship did not arrive to Earth. The confounded prophecy caused them acute cognitive-dissonance: Had they been victims of a hoax? Had they vainly donated away their material possessions? To resolve the dissonance between apocalyptic, end-of-the-world religious beliefs and earthly, material reality, most of the cult restored their psychological consonance by choosing to believe a less mentally-stressful idea to explain the missed landing: that the aliens had given planet Earth a second chance at existence, which, in turn, empowered them to re-direct their religious cult to environmentalism and social advocacy to end human damage to planet Earth. On overcoming the confounded belief by changing to global environmentalism, the cult increased in numbers by proselytism.[22] The study of The Rebbe, the Messiah, and the Scandal of Orthodox Indifference (2008) reported the belief contradiction that occurred in the Chabad Orthodox Jewish congregation, who believed that their Rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, was the Messiah. When he died of a stroke in 1994, instead of accepting that their Rebbe was not the Messiah, some of the congregation proved indifferent to that contradictory fact, and continued claiming that Schneerson was the Messiah and that he would soon return from the dead.[23] Induced compliance See also: Forced compliance theory  After performing dissonant behavior (lying) a person might find external, consonant elements. Therefore, a snake oil salesman might find a psychological self-justification (great profit) for promoting medical falsehoods, but, otherwise, might need to change his beliefs about the falsehoods. In the Cognitive Consequences of Forced Compliance (1959), the investigators Leon Festinger and Merrill Carlsmith asked students to spend an hour doing tedious tasks; e.g. turning pegs a quarter-turn, at fixed intervals. This procedure included seventy-one male students attending Stanford University. Students were asked to complete a series of repetitive, mundane tasks, then asked to convince a separate group of participants that the task was fun and exciting. Once the subjects had done the tasks, the experimenters asked one group of subjects to speak with another subject (an actor) and persuade that impostor-subject that the tedious tasks were interesting and engaging. Subjects of one group were paid twenty dollars ($20); those in a second group were paid one dollar ($1) and those in the control group were not asked to speak with the imposter-subject.[24] At the conclusion of the study, when asked to rate the tedious tasks, the subjects of the second group (paid $1) rated the tasks more positively than did the subjects in the first group (paid $20), and the first group (paid $20) rated the tasks just slightly more positively than did the subjects of the control group; the responses of the paid subjects were evidence of cognitive dissonance. The researchers, Festinger and Carlsmith, proposed that the subjects experienced dissonance between the conflicting cognitions. "I told someone that the task was interesting" and "I actually found it boring." The subjects paid one dollar were induced to comply, compelled to internalize the "interesting task" mental attitude because they had no other justification. The subjects paid twenty dollars were induced to comply by way of an obvious, external justification for internalizing the "interesting task" mental attitude and experienced a lower degree of cognitive dissonance than did those only paid one dollar.[24] They did not receive sufficient compensation for the lie they were asked to tell. Because of this insufficiency, the participants convinced themselves to believe that what they were doing was exciting. This way, they felt better about telling the next group of participants that it was exciting because, technically, they weren't lying.[25] Forbidden behavior paradigm In the Effect of the Severity of Threat on the Devaluation of Forbidden Behavior (1963), a variant of the induced-compliance paradigm, by Elliot Aronson and Carlsmith, examined self-justification in children.[26] Children were left in a room with toys, including a greatly desirable steam shovel, the forbidden toy. Upon leaving the room, the experimenter told one-half of the group of children that there would be severe punishment if they played with the steam-shovel toy and told the second half of the group that there would be a mild punishment for playing with the forbidden toy. All of the children refrained from playing with the forbidden toy (the steam shovel).[26] Later, when the children were told that they could freely play with any toy they wanted, the children in the mild-punishment group were less likely to play with the steam shovel (the forbidden toy), despite the removal of the threat of mild punishment. The children threatened with mild punishment had to justify, to themselves, why they did not play with the forbidden toy. The degree of punishment was insufficiently strong to resolve their cognitive dissonance; the children had to convince themselves that playing with the forbidden toy was not worth the effort.[26] In The Efficacy of Musical Emotions Provoked by Mozart's Music for the Reconciliation of Cognitive Dissonance (2012), a variant of the forbidden-toy paradigm, indicated that listening to music reduces the development of cognitive dissonance.[27] Without music in the background, the control group of four-year-old children were told to avoid playing with a forbidden toy. After playing alone, the control-group children later devalued the importance of the forbidden toy. In the variable group, classical music played in the background while the children played alone. In the second group, the children did not later devalue the forbidden toy. The researchers, Nobuo Masataka and Leonid Perlovsky, concluded that music might inhibit cognitions that induce cognitive dissonance.[27] Music is a stimulus that can diminish post-decisional dissonance; in an earlier experiment, Washing Away Postdecisional Dissonance (2010), the researchers indicated that the actions of hand-washing might inhibit the cognitions that induce cognitive dissonance.[28] That study later failed to replicate.[29] Free choice In the study Post-decision Changes in Desirability of Alternatives (1956) 225 female students rated domestic appliances and then were asked to choose one of two appliances as a gift. The results of the second round of ratings indicated that the women students increased their ratings of the domestic appliance they had selected as a gift and decreased their ratings of the appliances they rejected.[30] This type of cognitive dissonance occurs in a person who is faced with a difficult decision and when the rejected choice may still have desirable characteristics to the chooser. The action of deciding provokes the psychological dissonance consequent to choosing X instead of Y, despite little difference between X and Y; the decision "I chose X" is dissonant with the cognition that "There are some aspects of Y that I like". The study Choice-induced Preferences in the Absence of Choice: Evidence from a Blind Two-choice Paradigm with Young Children and Capuchin Monkeys (2010) reports similar results in the occurrence of cognitive dissonance in human beings and in animals.[31] Peer Effects in Pro-Social Behavior: Social Norms or Social Preferences? (2013) indicated that with internal deliberation, the structuring of decisions among people can influence how a person acts. The study suggested that social preferences and social norms can explain peer effects in decision making. The study observed that choices made by the second participant would influence the first participant's effort to make choices and that inequity aversion, the preference for fairness, is the paramount concern of the participants.[32] Effort justification Further information: Effort justification Cognitive dissonance occurs in a person who voluntarily engages in (physically or ethically) unpleasant activities to achieve a goal. The mental stress caused by the dissonance can be reduced by the person exaggerating the desirability of the goal. In The Effect of Severity of Initiation on Liking for a Group (1956), to qualify for admission to a discussion group, two groups of people underwent an embarrassing initiation of varied psychological severity. The first group of subjects were to read aloud twelve sexual words considered obscene; the second group of subjects were to read aloud twelve sexual words not considered obscene.[33] Both groups were given headphones to unknowingly listen to a recorded discussion about animal sexual behaviour, which the researchers designed to be dull and banal. As the subjects of the experiment, the groups of people were told that the animal-sexuality discussion actually was occurring in the next room. The subjects whose strong initiation required reading aloud obscene words evaluated the people of their group as more-interesting persons than the people of the group who underwent the mild initiation to the discussion group.[33] In Washing Away Your Sins: Threatened Morality and Physical Cleansing (2006), the results indicated that a person washing their hands is an action that helps resolve post-decisional cognitive dissonance because the mental stress usually was caused by the person's ethical–moral self-disgust, which is an emotion related to the physical disgust caused by a dirty environment.[28][34] The study The Neural Basis of Rationalization: Cognitive Dissonance Reduction During Decision-making (2011) indicated that participants rated 80 names and 80 paintings based on how much they liked the names and paintings. To give meaning to the decisions, the participants were asked to select names that they might give to their children. For rating the paintings, the participants were asked to base their ratings on whether or not they would display such art at home.[35] The results indicated that when the decision is meaningful to the person deciding value, the likely rating is based on their attitudes (positive, neutral or negative) towards the name and towards the painting in question. The participants also were asked to rate some of the objects twice and believed that, at session's end, they would receive two of the paintings they had positively rated. The results indicated a great increase in the positive attitude of the participant towards the liked pair of things, whilst also increasing the negative attitude towards the disliked pair of things. The double-ratings of pairs of things, towards which the rating participant had a neutral attitude, showed no changes during the rating period. The existing attitudes of the participant were reinforced during the rating period and the participants experienced cognitive dissonance when confronted by a liked-name paired with a disliked-painting.[35] |

パラダイム 認知的不協和(自分の信念や理想、価値観と矛盾する情報にさらされたときに経験する精神的ストレス)には、4つの理論的パラダイムがある: 信念の不確認」、「誘発された遵守」、「自由選択」、「努力の正当化」であり、それぞれ、人が自分の知的観点に照らして矛盾した行動をとった後に何が起こ るか、人が意思決定をした後に何が起こるか、目標を達成するために多くの努力を費やした人にどのような影響が及ぶかを説明している。認知的不協和理論の各 パラダイムに共通する信条は、「ある観点に投資している人は、反対の証拠に直面したとき、挑戦された観点を保持することを正当化するために多大な努力を払 わなければならない」というものである[19]。 信念の否認 主な記事 期待の不確認 信念、理想、または価値体系の矛盾は認知的不協和を引き起こし、それは挑戦された信念を変えることによって解決することができるにもかかわらず、変化をも たらすのではなく、結果として生じる精神的ストレスは、矛盾の誤認、拒絶、または反論、矛盾した信念を共有する人々からの道徳的支援を求める、または矛盾 が非現実的であることを他の人々に説得するために行動することによって、その人の心理的協和を回復する[20][21]: 123 予言が失敗するとき』(1956年)で示された信念の矛盾に関する初期の仮説は、ある終末的な宗教カルトのメンバーの間で、異星人の宇宙船が間もなく地球 に着陸し、地上の腐敗から救うという予言が失敗したにもかかわらず、信仰が深まったと報告している。決められた場所と時間に教団は集まり、自分たちだけが 惑星破壊を生き延びられると信じていた。しかし、宇宙船は地球に到着しなかった。この混乱した予言は、彼らに深刻な認知的錯誤を引き起こした: 自分たちはデマの犠牲者だったのか?自分たちはデマの犠牲者なのか?終末論的な宗教的信念と地球上の物質的現実との間の不協和音を解消するために、教団の 大半は、着陸失敗を説明するために、より精神的ストレスの少ない考えを信じることを選択することによって、心理的協和を回復した。地球環境主義に変更する ことで混乱した信念を克服すると、教団は布教によって数を増やした[22]。 The Rebbe, the Messiah, and the Scandal of Orthodox Indifference』(2008年)という研究は、チャバド正統派ユダヤ教の信徒に起こった信仰の矛盾を報告している。彼が1994年に脳卒中で亡 くなったとき、彼らのリベがメシアではなかったことを受け入れる代わりに、信徒の一部はその矛盾した事実に無関心であることを証明し、シュネアソンがメシ アであり、彼はすぐに死から戻ってくると主張し続けた[23]。 誘導されたコンプライアンス こちらも参照: 強制コンプライアンス理論  不協和な行動(嘘をつくこと)をした後、人は外的な同意的要素を見つけるかもしれない。したがって、蛇油のセールスマンは、医学的な虚偽を宣伝することに 心理的な自己正当化(大きな利益)を見出すかもしれないが、そうでなければ虚偽についての信念を変える必要があるかもしれない。 『強制遵守の認知的結果』(1959年)の中で、研究者であるレオン・フェスティンガーとメリル・カールスミスは、学生に退屈な作業を1時間してもらっ た。この実験には、スタンフォード大学に通う71人の男子学生が参加した。学生たちは、一連の反復的で平凡な仕事をこなすよう求められた後、別のグループ の参加者に、その仕事が楽しくてエキサイティングなものであることを納得させるよう求められた。被験者が課題をこなした後、実験者は被験者の1グループ に、別の被験者(俳優)と話し、その偽者の被験者に退屈な課題が面白く魅力的であると説得するよう依頼した。一方のグループの被験者には20ドルが支払わ れ、もう一方のグループの被験者には1ドルが支払われ、対照グループの被験者には偽者被験者と話すように求められなかった[24]。 研究の終わりに、退屈なタスクを評価するよう求められたとき、第2グループ(1ドル支払われた)の被験者は第1グループ(20ドル支払われた)の被験者よ りもタスクを肯定的に評価し、第1グループ(20ドル支払われた)は対照グループの被験者よりもタスクをわずかに肯定的に評価した。研究者であるフェス ティンガーとカールスミスは、被験者は相反する認知の間で不協和を経験したと提唱した。"その課題が面白いと誰かに言った "ことと、"実際にはつまらないと思った "ことである。1ドル支払われた被験者は、他に正当な理由がないため、"面白い課題 "という心的態度を内面化せざるを得ず、それに従うように誘導された。20ドル支払われた被験者は、「興味深い課題」という心的態 度を内面化するための明白で外的な正当化によって従 うように誘導され、1ドル支払われた被験者よりも認知的 不協和の程度が低かった[24]。この不十分さのために、参加者たちは自分たちがしていることはエキサイティングなことだと信じ込むように自分自身を納得 させた。こうすることで、厳密には嘘をついていないのだから、次のグループの参加者たちにエキサイティングなことだと話すことがより良く感じられたのであ る[25]。 禁じられた行動のパラダイム エリオット・アロンソンとカールスミスによる「禁じられた行 動の評価低下に対する脅威の厳しさの効果」(1963年) では、誘引-遵守パラダイムの変種が子どもの自己正当化を調 べた。部屋を出るとき、実験者は半分の子どもたちに、蒸気シャベルのおもちゃで遊んだら厳しい罰があると告げ、もう半分の子どもたちには、禁じられたおも ちゃで遊んだら軽い罰があると告げた。子どもたちは全員、禁止されたおもちゃ(蒸気シャベル)で遊ぶことを控えた[26]。 その後、子どもたちが好きなおもちゃで自由に遊んでよいと告げられると、軽い罰を与えるという脅しがなくなったにもかかわらず、軽い罰を与えたグループの 子どもたちは、蒸気シャベル(禁じられたおもちゃ)で遊ぶ可能性が低くなった。軽い罰で脅かされた子どもたちは、なぜ禁止されたおもちゃで遊ばないのかを 自分自身で正当化しなければならなかった。罰の程度は認知的不協和を解消するには不十分であり、子どもたちは禁じられたおもちゃで遊ぶことは努力に値しな いと自分自身を納得させなければならなかった[26]。 The Efficacy of Musical Emotions Provoked by Mozart's Music for the Reconciliation of Cognitive Dissonance (2012)では、禁じられたおもちゃのパラダイムの変種として、音楽を聴くことで認知的不協和の発達が抑えられることが示された[27]。背景に音楽が ない状態で、対照群の4歳児は禁じられたおもちゃで遊ばないように言われた。一人で遊んだ後、対照群の子どもは後に禁じられたおもちゃの重要性を軽視し た。変動群では、子どもたちが一人で遊んでいる間、バックグラウンドにクラシック音楽を流した。第2群では、子どもたちは後に禁じられたおもちゃの重要性 を下げることはなかった。研究者である正高信男とレオニード・ペルロフスキーは、音楽は認知的不協和を誘発する認知を抑制するかもしれないと結論づけた [27]。 音楽は決定後の不協和を減少させることができる刺激である。以前の実験であるWashing Away Postdecisional Dissonance(2010年)において、研究者たちは、手洗いの動作が認知的不協和を誘発する認知を抑制するかもしれないことを示した[28]。 自由選択 代替案の望ましさにおける決定後の変化 (1956年)という研究では、225人の女子学生が家庭用電化製品を評価し、その後2つの電化製品のうち1つを贈り物として選択するよう求められた。2 回目の評価の結果、女子学生は贈り物として選んだ家庭用電化製品の評価を上げ、拒否した電化製品の評価を下げたことが示された[30]。 この種の認知的不協和は、困難な決断に直面し、拒否された 選択肢がまだ選択者にとって望ましい特性を持っている可能 性がある場合に生じる。XとYの間にほとんど違いがないにもかかわらず、Yの代わりにXを選んだ結果、決定という行動が心理的不協和を引き起こす。「私は Xを選んだ」という決定は、「Yには好きな面もある」という認知と不協和になる。この研究は、「選択不在における選択誘発選好」(Choice- induced Preferences in the Absence of Choice: Evidence from a Blind Two-choice Paradigm with Young Children and Capuchin Monkeys (2010)は、認知的不協和の発生について、ヒトと動物で同様の結果を報告している[31]。 親社会的行動における仲間効果: 社会規範か社会的選好か?(2013)は、内的熟慮によって、人々の間の意思決定の構造化が人の行動様式に影響を与える可能性があることを示した。この研 究は、社会的選好と社会規範が意思決定における仲間効果を説明できることを示唆した。この研究では、2人目の参加者が行った選択が1人目の参加者の選択へ の努力に影響を与えること、そして不公平嫌悪、つまり公正さへの選好が参加者の最も重要な関心事であることが観察された[32]。 努力の正当化 さらなる情報 努力の正当化 認知的不協和は、ある目標を達成するために(身体的または倫理的に)不快な活動を自発的に行う人に生じる。不協和によって引き起こされる精神的ストレス は、その人が目標の望ましさを誇張することによって軽減することができる。The Effect of Severity of Initiation on Liking for a Group (1956)では、ディスカッション・グループへの入会資格を得るために、2つのグループの人々が、心理的な厳しさの異なる恥ずかしいイニシエーションを 受けた。最初の被験者グループは、わいせつとみなされる12の性的な単語を音読し、2番目の被験者グループは、わいせつとみなされない12の性的な単語を 音読した[33]。 どちらのグループにもヘッドホンが渡され、研究者が退屈で平凡なように設計した、動物の性行動に関する録音された議論を知らないうちに聞くことになった。 実験の被験者として、両グループは、動物性愛に関する議論が実際に隣の部屋で行われていることを告げられた。わいせつな言葉を音読する必要がある強いイニ シエーションを受けた被験者は、ディスカッション・グループへの軽いイニシエーションを受けたグループの人々よりも、自分たちのグループの人々をより興味 深い人物として評価した[33]。 罪を洗い流す: Threatened Morality and Physical Cleansing (2006)では、人が手を洗うことは決定後の認知的不協和を解消するのに役立つ行動であることが示された。なぜなら、その精神的ストレスは通常、その人 の倫理的道徳的自己嫌悪によって引き起こされたものであり、それは汚れた環境によって引き起こされる身体的嫌悪に関連する感情だからである[28] [34]。 合理化の神経基盤(The Neural Basis of Rationalization)という研究: The Neural Basis of Rationalization: Cognitive Dissonance Reduction During Decision-making (2011)によると、参加者は80の名前と80の絵画を、その名前と絵画がどれだけ好きかに基づいて評価した。意思決定に意味を持たせるために、参加者 は自分の子供につけるかもしれない名前を選ぶよう求められた。絵画の評価については、参加者に、そのような芸術作品を家に飾るかどうかを基準にするよう求 めた[35]。 その結果、価値を決定する人にとって意味のある決定である場合、その名前と問題の絵画に対する態度(肯定的、中立的、否定的)に基づいて評価が決まる可能 性が高いことが示された。参加者はまた、いくつかの対象物を2回評価するよう求められ、セッションの終了時には、肯定的な評価をした絵画のうち2点を受け 取ることができると信じていた。その結果、好きなもののペアに対する肯定的な態度が大きく増加する一方で、嫌いなもののペアに対する否定的な態度も増加す ることが示された。一方、中立的な態度の二重評価では、評価期間中に変化は見られなかった。評定期間中、参加者の既存の態度は強化され、参加者は、好きな 名前と嫌いな絵のペアに直面したとき、認知的不協和を経験した[35]。 |

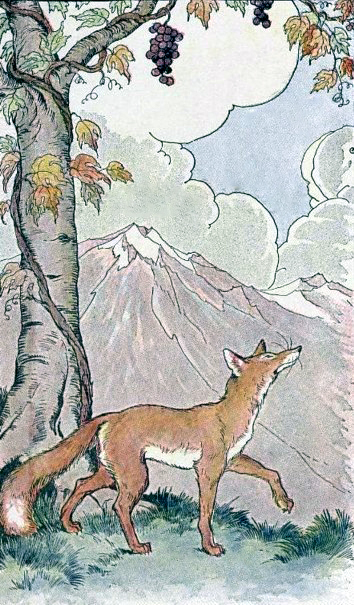

Examples In the fable of "The Fox and the Grapes", by Aesop, on failing to reach the desired bunch of grapes, the fox then decides he does not truly want the fruit because it is sour. The fox's act of rationalization (justification) reduced his anxiety over the cognitive dissonance from the desire he cannot realise. Meat-eating Meat-eating can involve discrepancies between the behavior of eating meat and various ideals that the person holds.[36] Some researchers call this form of moral conflict the meat paradox.[37][38] Hank Rothgerber posited that meat eaters may encounter a conflict between their eating behavior and their affections toward animals.[36] This occurs when the dissonant state involves recognition of one's behavior as a meat eater and a belief, attitude, or value that this behavior contradicts.[36] The person with this state may attempt to employ various methods, including avoidance, willful ignorance, dissociation, perceived behavioral change, and do-gooder derogation to prevent this form of dissonance from occurring.[36] Once occurred, they may reduce it in the form of motivated cognitions, such as denigrating animals, offering pro-meat justifications, or denying responsibility for eating meat.[36] The extent of cognitive dissonance with regards to meat eating can vary depending on the attitudes and values of the individual involved because these can affect whether or not they see any moral conflict with their values and what they eat. For example, individuals who are more dominance minded and who value having a masculine identity are less likely to experience cognitive dissonance because they are less likely to believe eating meat is morally wrong.[37] Others cope with this cognitive dissonance often through ignorance (ignoring the known realities of their food source) or explanations loosely tied to taste. The psychological phenomenon intensifies if mind or human-like qualities of animals are explicitly mentioned.[37] Smoking The study Patterns of Cognitive Dissonance-reducing Beliefs Among Smokers: A Longitudinal Analysis from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey (2012) indicated that smokers use justification beliefs to reduce their cognitive dissonance about smoking tobacco and the negative consequences of smoking it.[39] Continuing smokers (Smoking and no attempt to quit since the previous round of study) Successful quitters (Quit during the study and did not use tobacco from the time of the previous round of study) Failed quitters (Quit during the study, but relapsed to smoking at the time of the study) To reduce cognitive dissonance, the participant smokers adjusted their beliefs to correspond with their actions: Functional beliefs ("Smoking calms me down when I am stressed or upset."; "Smoking helps me concentrate better."; "Smoking is an important part of my life."; and "Smoking makes it easier for me to socialize.") Risk-minimizing beliefs ("The medical evidence that smoking is harmful is exaggerated."; "One has to die of something, so why not enjoy yourself and smoke?"; and "Smoking is no more risky than many other things people do.")[40] Littering Disposing of trash outside, even when knowing this is against the law, wrong, and is harmful for the environment, is a prominent example of cognitive dissonance, especially if the person feels bad after littering but continues to do so. Between November 2015 and March 2016, a study by Xitou Nature Education Area in Taiwan examined littering of tourists. Researchers analyzed the relationships between tourists' environmental attitudes, cognitive dissonance, and vandalism.[41] In this study, 500 questionnaires were distributed and 499 questionnaires were returned.[41] The results of this study indicate that older tourists had better attitudes towards the environment and cared more. The tourists who were older and cared more for outdoor activities were less likely to litter. On the other hand, the younger tourists littered more and experienced more cognitive dissonance.[41] This study showed that younger tourists littered more as a whole and regretted or thought about it after.[41] Unpleasant medical screenings In a study titled Cognitive Dissonance and Attitudes Toward Unpleasant Medical Screenings (2016), researchers Michael R. Ent and Mary A. Gerend informed the study participants about a discomforting test for a specific (fictitious) virus called the "human respiratory virus-27". The study used a fake virus to prevent participants from having thoughts, opinions, and feeling about the virus that would interfere with the experiment. The study participants were in two groups; one group was told that they were actual candidates for the virus-27 test, and the second group were told they were not candidates for the test. The researchers reported, "We predicted that [study] participants who thought that they were candidates for the unpleasant test would experience dissonance associated with knowing that the test was both unpleasant and in their best interest—this dissonance was predicted to result in unfavorable attitudes toward the test."[42] Related phenomena Cognitive dissonance may also occur when people seek to explain or justify their beliefs, often without questioning the validity of their claims. After the earthquake of 1934, Bihar, India, irrational rumors based upon fear quickly reached the adjoining communities unaffected by the disaster because those people, although not in physical danger, psychologically justified their anxieties about the earthquake.[43] The same pattern can be observed when one's convictions are met with a contradictory order. In a study conducted among 6th grade students, after being induced to cheat in an academic examination, students judged cheating less harshly.[44] Nonetheless, the confirmation bias identifies how people readily read information that confirms their established opinions and readily avoid reading information that contradicts their opinions.[45] The confirmation bias is apparent when a person confronts deeply held political beliefs, i.e. when a person is greatly committed to their beliefs, values, and ideas.[45] If a contradiction occurs between how a person feels and how a person acts, one's perceptions and emotions align to alleviate stress. The Ben Franklin effect refers to that statesman's observation that the act of performing a favor for a rival leads to increased positive feelings toward that individual. It is also possible that one's emotions be altered to minimize the regret of irrevocable choices. At a hippodrome, bettors had more confidence in their horses after the betting than before.[46] |

例 イソップ寓話『キツネとブドウ』では、キツネは望みのブドウの房にたどり着けなかったとき、その果実は酸っぱいので本当に欲しくないと判断する。キツネの合理化(正当化)行為は、実現できない欲求からの認知的不協和に対する不安を軽減した。 肉食 肉食は、肉を食べるという行動とその人が抱く様々な理想との間の不一致を伴うことがある[36]。このような道徳的葛藤の形態を肉のパラドックスと呼ぶ研 究者もいる[37][38]。ハンク・ロスガーバーは、肉食者は食べるという行動と動物に対する愛情との間の葛藤に遭遇する可能性があると仮定した [36]。これは、不協和状態が肉食者としての自分の行動の認識と、この行動が矛盾する信念、態度、または価値観とを含む場合に生じる。 [36]このような状態にある人は、このような形の不協和の発生を防ぐために、回避、意志的無視、解離、知覚的行動変容、やり手蔑視などの様々な方法を用 いようとすることがある[36]。いったん発生すると、動物を否定したり、親肉食的な正当化を提示したり、肉食の責任を否定したりするなど、動機づけられ た認知の形で不協和を軽減することがある[36]。 肉食に関する認知的不協和の程度は、関係する個人の態度や価値観によって異なる可能性がある。例えば、支配意識が強く、男性的なアイデンティティを持つこ とを重視する人は、肉食が道徳的に間違っていると考える可能性が低いため、認知的不協和を経験する可能性が低い[37]。また、この認知的不協和に対処す るために、多くの場合、無知(食物源の既知の現実を無視する)や味覚と緩やかに結びついた説明によって対処する人もいる。この心理的現象は、動物の心や人 間に似た性質が明示的に言及された場合に強まる[37]。 喫煙 喫煙者の認知的不協和を減少させる信念のパターン: A Longitudinal Analysis from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey (2012) は、喫煙者がタバコを吸うこととタバコを吸うことの否定的な結果についての認知的不協和を軽減するために正当化信念を使用していることを示した[39]。 喫煙継続者(喫煙しており、前回の調査以降禁煙を試みていない) 禁煙成功者(調査期間中に禁煙し、前回の調査時点からタバコを使用していない) 禁煙失敗者(調査期間中に禁煙したが、調査期間中に喫煙を再開した者) 認知的不協和を軽減するために、参加喫煙者は自分の信念を自分の行動と対応するように調整した: 機能的信念(「ストレスや動揺があるとき、タバコを吸うと落ち着く」、「タバコを吸うと集中力が増す」、「タバコは生活の重要な一部である」、「タバコを吸うと人付き合いが楽になる」)。 リスクを最小化する信念(「喫煙が有害であるという医学的証拠は誇張されている」、「人は何かで死ななければならないのだから、タバコを吸って楽しめばいいじゃないか」、「喫煙は他の多くの人がすることに比べればリスクは高くない」)[40]。 ゴミのポイ捨て 法律違反であり、間違いであり、環境にとって有害であることを知っていても、ゴミを外に捨てることは、認知的不協和の顕著な例であり、特にポイ捨てをした後に嫌な気分になるにもかかわらず、それを続ける場合はなおさらである。 2015年11月から2016年3月にかけて、台湾の西投自然教育園区が観光客のポイ捨てについて調査した。研究者たちは、観光客の環境に対する態度、認 知的不協和、破壊行為との関係を分析した[41]。この研究では、500枚のアンケート用紙が配布され、499枚のアンケート用紙が返送された[41]。 この研究の結果は、年配の観光客の方が環境に対する態度が良く、より気にしていることを示している。年配で野外活動に関心が高い観光客は、ポイ捨てをする 可能性が低かった。一方、若い観光客はより多くのポイ捨てをし、より多くの認知的不協和を経験した[41]。この研究は、若い観光客は全体としてより多く のポイ捨てをし、その後に後悔したり考えたりすることを示した[41]。 不快な検診 Cognitive Dissonance and Attitudes Toward Unpleasant Medical Screenings(2016年)と題された研究で、研究者のマイケル・R・エントとメアリー・A・ゲレンドは、「ヒト呼吸器ウイルス-27」と呼ばれ る特定の(架空の)ウイルスの不快な検査について研究参加者に知らせた。この研究では、実験の妨げとなるようなウイルスに関する考えや意見、感情を参加者 が持たないようにするため、偽のウイルスを使用した。研究参加者は2つのグループに分けられ、1つのグループは実際のウイルス-27検査の候補者であると 告げられ、もう1つのグループは検査の候補者ではないと告げられた。研究者は、「不快なテストの候補者であると考えた[研究]参加者は、テストが不快であ ると同時に自分の利益になると知ることに関連した不協和を経験すると予測した-この不協和は、テストに対する好ましくない態度をもたらすと予測された」と 報告した[42]。 関連現象 認知的不協和は、人が自分の信念を説明したり正当化しようとするときにも起こる。インドのビハール州で1934年に発生した地震の後、恐怖に基 づく非合理的な噂が、災害の影響を受けていない隣接するコミュ ニティにもすぐに伝わった。小学6年生を対象に実施された研究では、学力試験でカンニング をするように誘導された後、カンニングをすることをあまり厳しく判断 しなかった[44]。それにもかかわらず、確証バイアスは、人が自分の確立し た意見を確認する情報を読みやすく、自分の意見と矛盾する情報を読 むのを避けやすいことを特定する[45]。確証バイアスは、人が深く抱い ている政治的信念に直面したとき、つまり人が自分の信念、価値観、 考え方に大きく傾倒しているときに明らかになる[45]。 人の感じ方と人の行動の間に矛盾が生じると、人の認識と感情が一致してストレスが緩和される。ベン・フランクリン効果とは、ライバルのために好意を持つと いう行為が、その個人に対する肯定的な感情を増大させるという、この政治家の観察を指す。また、取り返しのつかない選択による後悔を最小限に抑えるため に、感情を変化させることも可能である。ヒポドロームでは、賭博者は賭ける前よりも賭けた後の方が馬に対する信頼感が増した[46]。 |

| Applications Education The management of cognitive dissonance readily influences the apparent motivation of a student to pursue education.[47] The study Turning Play into Work: Effects of Adult Surveillance and Extrinsic Rewards on Children's Intrinsic Motivation (1975) indicated that the application of the effort justification paradigm increased student enthusiasm for education with the offer of an external reward for studying; students in pre-school who completed puzzles based upon an adult promise of reward were later less interested in the puzzles than were students who completed the puzzle-tasks without the promise of a reward.[48] The incorporation of cognitive dissonance into models of basic learning-processes to foster the students' self-awareness of psychological conflicts among their personal beliefs, ideals, and values and the reality of contradictory facts and information, requires the students to defend their personal beliefs. Afterwards, the students are trained to objectively perceive new facts and information to resolve the psychological stress of the conflict between reality and the student's value system.[49] Moreover, educational software that applies the derived principles facilitates the students' ability to successfully handle the questions posed in a complex subject.[50] Meta-analysis of studies indicates that psychological interventions that provoke cognitive dissonance in order to achieve a directed conceptual change do increase students' learning in reading skills and about science.[49] Psychotherapy The general effectiveness of psychotherapy and psychological intervention is partly explained by the theory of cognitive dissonance.[51] In that vein, social psychology proposed that the mental health of the patient is positively influenced by his and her action in freely choosing a specific therapy and in exerting the required, therapeutic effort to overcome cognitive dissonance.[52] That effective phenomenon was indicated in the results of the study Effects of Choice on Behavioral Treatment of Overweight Children (1983), wherein the children's belief that they freely chose the type of therapy received, resulted in each overweight child losing a greater amount of excessive body weight.[53] In the study Reducing Fears and Increasing Attentiveness: The Role of Dissonance Reduction (1980), people with ophidiophobia (fear of snakes) who invested much effort in activities of little therapeutic value for them (experimentally represented as legitimate and relevant) showed improved alleviation of the symptoms of their phobia.[54] Likewise, the results of Cognitive Dissonance and Psychotherapy: The Role of Effort Justification in Inducing Weight Loss (1985) indicated that the patient felt better in justifying their efforts and therapeutic choices towards effectively losing weight. That the therapy of effort expenditure can predict long-term change in the patient's perceptions.[55] Social behavior Cognitive dissonance is used to promote social behaviours considered positive, such as increased condom use.[56] Other studies indicate that cognitive dissonance can be used to encourage people to act pro-socially, such as campaigns against public littering,[57] campaigns against racial prejudice,[58] and compliance with anti-speeding campaigns.[59] The theory can also be used to explain reasons for donating to charity.[60][61] Cognitive dissonance can be applied in social areas such as racism and racial hatred. Acharya of Stanford, Blackwell and Sen of Harvard state cognitive dissonance increases when an individual commits an act of violence toward someone from a different ethnic or racial group and decreases when the individual does not commit any such act of violence. Research from Acharya, Blackwell and Sen shows that individuals committing violence against members of another group develop hostile attitudes towards their victims as a way of minimizing cognitive dissonance. Importantly, the hostile attitudes may persist even after the violence itself declines (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen, 2015). The application provides a social psychological basis for the constructivist viewpoint that ethnic and racial divisions can be socially or individually constructed, possibly from acts of violence (Fearon and Laitin, 2000). Their framework speaks to this possibility by showing how violent actions by individuals can affect individual attitudes, either ethnic or racial animosity (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen, 2015). COVID-19 The COVID-19 pandemic, an extreme public health crisis, cases rose to the hundred million and deaths at nearly four million worldwide. Reputable health organizations such as Lyu and Wehby studied the effects of wearing a face mask on the spread of COVID-19. They found evidence that suggests that COVID patients were reduced by 2%, averting nearly 200,000 cases by the end of the following month.[62] Despite this fact having been proven and encouraged by major health organizations, there was still a resistance to wearing the mask and keeping a safe distance away from others. When the COVID-19 vaccine was eventually released to the public, this only made the resistance stronger. The Ad Council launched an extensive campaign advertising for people to follow the health guidelines established by the CDC and WHO and attempted to persuade people to become vaccinated eventually. After taking polls on public opinion about safety measures to prevent the spreading of the virus, it showed that between 80% and 90% of adults in the United States agree with these safety procedures and vaccines being necessary.[62] The cognitive dissonance arose when people took polls on public behavior. Despite the general opinion that wearing a mask, social distancing, and receiving the vaccine are all things the public should be doing, only 50% of responders admitted to doing these things all or even most of the time.[62] People believe that partaking in preventative measures is essential, but fail to follow through with actually doing them. To convince people to behave in line with their beliefs, it is essential to remind people of a fact that they believe is true, and then remind them of times in the past when they went against this. The hypocrisy paradigm is known for inconsistent cognition resolution through a change in behavior. Data were collected by participants that were asked to write statements supporting mask use and social distancing, which is something they agreed with. Then the participants were told to think about recent situations in which they failed to do this. The prediction was that the dissonance would be a motivating factor in getting people to be compliant with COVID-19 safety measures. After contacting participants one week later, they reported behaviors, including social distancing and mask-wearing.[62] Personal responsibility A study conducted by Cooper and Worchel (1970) examined personal responsibility regarding cognitive dissonance.[63] The goal was to investigate responsibility concerning foreseen consequences and how this might cause dissonance. One hundred twenty-four female participants were asked to complete problem-solving tasks while working with a partner.[64] They had the option to either choose a partner with negative traits, or they were assigned one. A portion of the participants was aware of the negative traits their partner possessed; however, the remaining participants were unaware. Cooper hypothesized that if the participants knew about their negative partner beforehand, they would have cognitive dissonance; however, he also believed that the participants would be inclined to attempt to like their partners in an attempt to reduce this dissonance.[64] The study shows that personal choice has the power to predict attitude changes.[63] Consumer behavior Pleasure is one of the main factors in our modern culture of consumerism.[65] Once a consumer has chosen to purchase a specific item, they often fear that another choice may have brought them more pleasure. Post-purchase dissonance occurs when a purchase is final, voluntary, and significant to the person.[66] This dissonance is a mental discomfort arising from the possibility of dissatisfaction with the purchase, or the regret of not purchasing a different, potentially more useful or satisfactory good.[66] Consequently, the buyer will "seek to reduce dissonance by increasing the perceived attractiveness of the chosen alternative and devaluing the non chosen item, seeking out information to confirm the decision, or changing attitudes to conform to the decision."[65] In other words, the buyer justifies their purchase to themselves in whatever way they can, in an attempt to convince themselves that they made the right decision and to diminish regret. Usually these feelings of regret are more prevalent after online purchases as opposed to in-store purchases. This happens because an online consumer does not have the opportunity to experience the product in its entirety, and must rely on what information is available through photos and descriptions.[67] On the other hand, in-store shopping can sometimes be even more of an issue for consumers in regards to impulse buying. While the ease of online shopping proves hard to resist for impulse buyers, in-store shoppers may be influenced by who they are with. Shopping with friends increases the risk of impulse buying, especially compared to shopping with people such as one's parents.[68] Post-purchase dissonance does not only affect the consumer; brands are dependent on customer loyalty, and cognitive dissonance can influence that loyalty. The more positive experiences and emotions that a customer associates with a specific brand, the more likely they are to buy from that brand in the future, recommend it to friends, etc. The opposite is also true, meaning any feelings of discomfort, dissatisfaction, and regret will weaken the consumer's perception of the brand and make them less likely to return as a customer.[69] The study Beyond Reference Pricing: Understanding Consumers' Encounters with Unexpected Prices (2003), indicated that when consumers experience an unexpected price encounter, they adopt three methods to reduce cognitive dissonance: (i) Employ a strategy of continual information; (ii) Employ a change in attitude; and (iii) Engage in minimisation. Consumers employ the strategy of continual information by engaging in bias and searching for information that supports prior beliefs. Consumers might search for information about other retailers and substitute products consistent with their beliefs.[70] Alternatively, consumers might change attitude, such as re-evaluating price in relation to external reference-prices or associating high prices and low prices with quality. Minimisation reduces the importance of the elements of the dissonance; consumers tend to minimise the importance of money, and thus of shopping around, saving, and finding a better deal.[71] Politics Cognitive dissonance theory might suggest that since votes are an expression of preference or beliefs, even the act of voting might cause someone to defend the actions of the candidate for whom they voted,[72][self-published source?] and if the decision was close then the effects of cognitive dissonance should be greater. This effect was studied over the 6 presidential elections of the United States between 1972 and 1996,[73] and it was found that the opinion differential between the candidates changed more before and after the election than the opinion differential of non-voters. In addition, elections where the voter had a favorable attitude toward both candidates, making the choice more difficult, had the opinion differential of the candidates change more dramatically than those who only had a favorable opinion of one candidate. What wasn't studied were the cognitive dissonance effects in cases where the person had unfavorable attitudes toward both candidates. The 2016 U.S. election held historically high unfavorable ratings for both candidates.[74] After the 2020 United States presidential election, which was won by Joe Biden, supporters of former President Donald Trump, who had lost the election to Biden, questioned the outcome of the election, citing voter fraud. This continued after such claims were dismissed as false by numerous judges, election officials, U.S. state governors, and federal government agencies.[75] This was described as an example of Trump supporters experiencing cognitive dissonance.[76] Communication Cognitive dissonance theory of communication was initially advanced by American psychologist Leon Festinger in the 1960s. Festinger theorized that cognitive dissonance usually arises when a person holds two or more incompatible beliefs simultaneously.[70] This is a normal occurrence since people encounter different situations that invoke conflicting thought sequences. This conflict results in a psychological discomfort. According to Festinger, people experiencing a thought conflict try to reduce the psychological discomfort by attempting to achieve an emotional equilibrium. This equilibrium is achieved in three main ways. First, the person may downplay the importance of the dissonant thought. Second, the person may attempt to outweigh the dissonant thought with consonant thoughts. Lastly, the person may incorporate the dissonant thought into their current belief system.[77] Dissonance plays an important role in persuasion. To persuade people, you must cause them to experience dissonance, and then offer your proposal as a way to resolve the discomfort. Although there is no guarantee your audience will change their minds, the theory maintains that without dissonance, there can be no persuasion. Without a feeling of discomfort, people are not motivated to change.[78] Similarly, it is the feeling of discomfort which motivates people to perform selective exposure (i.e., avoiding disconfirming information) as a dissonance-reduction strategy.[18] Artificial intelligence It is hypothesized that introducing cognitive dissonance into machine learning[how?] may be able to assist in the long-term aim of developing 'creative autonomy' on the part of agents, including in multi-agent systems (such as games),[79] and ultimately to the development of 'strong' forms of artificial intelligence, including artificial general intelligence.[80] |

アプリケーション 教育 認知的不協和の管理は、教育を追求する生徒の見かけ上の動機づけに容易に影響を与える[47]: 大人の監視と外在的報酬が子どもの内発的動機づけに及ぼす影響(1975年)は、努力正当化パラダイムの適用が、勉強に対する外在的報酬の提供によって生 徒の教育への熱意を増加させることを示した;大人の報酬の約束に基づいてパズルを完成させた就学前の生徒は、報酬の約束なしにパズル・タスクを完成させた 生徒よりも、後にパズルへの関心が低くなった[48]。 認知的不協和を基本的な学習過程のモデルに組み込むことで、生徒の個人的な信念、理想、価値観と、矛盾する事実や情報の現実との間の心理的葛藤に対する生 徒の自己認識を育み、生徒が個人的な信念を守ることを要求する。その後、現実と生徒の価値体系との間の葛藤による心理的ストレスを解決するために、生徒は 新しい事実や情報を客観的に認識するよう訓練される[49]。さらに、導き出された原理を応用した教育用ソフトウェアは、複雑な科目で出された問題をうま く処理する生徒の能力を促進する[50]。 研究のメタ分析によると、指示された概念的変化を達成するために認知的不協和を引き起こす心理的介入は、読解スキルや科学に関する生徒の学習を増加させる ことが示されている[49]。 心理療法 心理療法や心理的介入の一般的な有効性は、認知的不協和の理論によって部分的に説明される[51]。その関連で、社会心理学は、患者の精神的健康は、患者 が特定の療法を自由に選択し、認知的不協和を克服するために必要な治療的努力を行う行動によってプラスの影響を受けると提唱した[52]。 [52] その効果的な現象は、体重過多の子どもの行動療法における選択の効果(Effects of Choice on Behavioral Treatment of Overweight Children)(1983年)という研究の結果で示されており、子どもたちは自分が受ける療法の種類を自由に選んだという信念を持つことで、体重過多 の子どもはそれぞれ、より多くの過度の体重を減らす結果となった [53] 。 恐怖を減らし、注意力を高める: The Role of Dissonance Reduction (1980), ophidiophobia (fear of snakes) people who invested much efforts in activities with little therapeutic value for them (experimentally represented as legitimate and relevant) was improved mitleviation of their phobia. [54] 同様に、Cognitive Dissonance and Psychotherapy (認知的不協和と心理療法) の研究結果: The Role of Effort Justification in Inducing Weight Loss (1985)は、患者が効果的に体重を減らすための努力や治療上の選択を正当化することで、気分がよくなることを示した。努力支出の療法は、患者の認識の 長期的な変化を予測することができること[55]。 社会的行動 認知的不協和は、コンドーム使用の増加のような肯定的と考えられる社会的行動を促進するために使用される[56]。他の研究では、認知的不協和は、公共の ゴミのポイ捨てに反対するキャンペーン、[57]人種的偏見に反対するキャンペーン、[58]速度違反防止キャンペーンの遵守のような、人々が社会的に積 極的に行動することを奨励するために使用できることが示されている[59]。スタンフォード大学のAcharya、ハーバード大学のBlackwellと Senは、認知的不協和は、個人が異なる民族や人種グループの誰かに対して暴力行為を行ったときに増加し、個人がそのような暴力行為を行わなかったときに 減少すると述べている。Acharya、Blackwell、Senの研究によると、別のグループのメンバーに対して暴力をふるう人は、認知的不協和を最 小化する方法として、被害者に対して敵対的態度をとるようになる。重要なのは、暴力そのものが減少した後も、敵対的態度が持続する可能性があることである (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen, 2015)。このアプリケーションは、民族や人種の分断は社会的または個人的に構築されうるという構成主義の視点に社会心理学的根拠を提供し、おそらくは 暴力行為から構築される(Fearon and Laitin, 2000)。彼らのフレームワークは、個人による暴力行為が、民族的あるいは人種的反感といった個人の態度にどのように影響するかを示すことで、この可能 性を語っている(Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen, 2015)。 COVID-19 COVID-19のパンデミックは、公衆衛生上の極度の危機であり、患者数は世界で1億人、死者数は400万人近くに上った。LyuやWehbyといった 評判の高い保健機関は、COVID-19の蔓延に対するフェイスマスク着用の効果を研究した。彼らは、COVID患者が2%減少し、翌月末までに20万人 近くの患者が回避されたことを示唆する証拠を発見した[62]。この事実が証明され、主要な保健機関によって奨励されているにもかかわらず、マスクを着用 し、他人から安全な距離を保つことへの抵抗は依然としてあった。やがてCOVID-19ワクチンが一般に発売されると、抵抗はさらに強まった。 広告協議会は、CDCとWHOが定めた健康指針に従うよう大々的な広告キャンペーンを展開し、人々に最終的にワクチン接種を受けるよう説得しようとした。 ウイルスの蔓延を防ぐための安全対策に関する世論調査を行った結果、アメリカでは成人の80%から90%がこうした安全対策やワクチンの必要性に賛成して いることがわかった[62]。マスクの着用、社会的距離の取り方、ワクチンの接種は、すべて一般市民が行うべきことであるという一般的な意見にもかかわら ず、これらのことをすべて、あるいはほとんど行っていると認めた回答者はわずか50%に過ぎなかった[62]。人々に信念に沿った行動をとるよう説得する には、人々が真実だと信じている事実を思い出させ、次に過去にこれに反した時を思い出させることが不可欠である。偽善パラダイムは、行動の変化を通じて矛 盾した認知を解決することで知られている。データは、マスクの使用や社会的距離を置くことを支持する文を書いてもらい、それに同意した参加者によって収集 された。次に参加者は、最近自分がこれを実行できなかった状況について考えるように言われた。不協和音が、COVID-19の安全対策を遵守させる動機付 けになるだろうという予測である。1週間後に参加者に連絡したところ、参加者は社会的距離を置いたり、マスクを着用したりといった行動を報告した [62]。 個人の責任 CooperとWorchel(1970)によって実施された研究では、認知的不協和に関する個人的責任について検討された[63]。124人の女性参加 者は、パートナーと協力しながら問題解決課題をこなすよう求められた[64]。彼女たちには、否定的な特徴を持つパートナーを選ぶか、1人を割り当てられ るかの選択肢があった。参加者の一部はパートナーが持つ否定的な特質に気づいていたが、残りの参加者は気づいていなかった。クーパーは、参加者が事前に否 定的なパートナーについて知っていた場合、認知的不協和を持つだろうと仮説を立てたが、彼はまた、参加者がこの不協和を軽減しようとしてパートナーを好き になろうとする傾向があるとも考えた[64]。この研究は、個人的選択が態度の変化を予測する力を持つことを示している[63]。 消費者行動 快楽は現代の消費主義文化における主要な要因の1つである[65]。一旦消費者が特定の商品を購入することを選択すると、別の選択の方がより快楽を得られ たかもしれないと恐れることが多い。購入後の不協和は、購入が最終的なものであり、自発的なものであり、その人にとって重要なものである場合に生じる [66]。この不協和は、購入に対する不満の可能性から生じる精神的不快感であり、あるいは別の、潜在的により有用で満足のいく商品を購入しなかったこと に対する後悔である。 [66]その結果、買い手は「選択した代替品の知覚される 魅力を高め、選択しなかった品物の価値を下げたり、決定を確 認するための情報を求めたり、決定に適合するように態度を 変えたりすることで、不協和を軽減しようとする」[65]。言い換えれば、買い 手は、自分が正しい決定をしたと自分自身を納得させ、後悔 の念を薄めようと、どのような方法であれ、自分自身に対して購 入を正当化する。通常、このような後悔の感情は、店舗での購入とは対照的に、オンラインでの購入後に多く見られる。これは、オンラインの消費者は商品をま るごと体験する機会がなく、写真や説明文から得られる情報に頼らざるを得ないためである[67]。一方、店頭での買い物は、衝動買いに関して、消費者に とって時としてさらに大きな問題となることがある。オンライン・ショッピングの手軽さは衝動買いをする人にとって抗いがたいものだが、店頭での買い物客は 一緒にいる人の影響を受けるかもしれない。友人と一緒に買い物をすると、特に両親などと一緒に買い物をする場合と比べて、衝動買いのリスクが高まる [68]。 購入後の不協和は消費者だけに影響を与えるわけではなく、ブランドは顧客の忠誠心に依存しており、認知的不協和はその忠誠心に影響を与える可能性がある。 顧客が特定のブランドから連想する経験や感情がポジティブであればあるほど、将来そのブランドから購入したり、友人に勧めたりする可能性が高くなる。逆も また真なりで、不快感、不満、後悔の感情があれば、消費者のブランドに対する認識は弱まり、顧客として戻ってくる可能性は低くなる[69]。 Beyond Reference Pricing: Beyond Reference Pricing: Understanding Consumers' Encounters with Unexpected Prices (2003)は、消費者が予期せぬ価格との出会いを経験した場合、認知的不協和を軽減するために3つの方法を採用することを示している。消費者は、バイア スに関与し、事前の信念を支持する情報を検索することによって、継続的な情報の戦略を採用する。消費者は、他の小売業者に関する情報を検索し、自分の信念 に一致する製品を代用するかもしれない[70]。あるいは、消費者は、外部の参照価格との関係で価格を再評価したり、高価格や低価格を品質と関連付けたり するなど、態度を変えるかもしれない。不協和の要素の重要性を最小化することで、消費者はお金の重要性を最小化する傾向があり、その結果、買い物をするこ と、節約すること、より良い取引を見つけることを最小化する傾向がある[71]。 政治 認知的不協和理論は、投票は嗜好や信念の表現であるため、投票する行為でさえも、投票した候補者の行動を擁護することを引き起こすかもしれないことを示唆するかもしれない[72]。 この効果は、1972年から1996年の間に行われた米国の6回の大統領選挙で研究され[73]、候補者間の意見差は、非投票者の意見差よりも選挙の前後 でより変化することが判明した。加えて、有権者が両方の候補者に好意的な態度を持っており、選択をより困難にしている選挙では、一方の候補者に好意的な意 見しか持っていない人よりも、候補者の意見差がより劇的に変化していた。研究されていないのは、両方の候補者に対して好ましくない態度をとった場合の認知 的不協和効果である。2016年の米国大統領選挙では、両候補に対して歴史的に高い不支持率が示された[74]。 ジョー・バイデンが勝利した2020年アメリカ合衆国大統領選挙の後、バイデンに敗れたドナルド・トランプ前大統領の支持者は、有権者の不正を理由に選挙結果に疑問を呈した。これは、トランプ支持者が認知的不協和を経験した例として説明された[76]。 コミュニケーション コミュニケーションにおける認知的不協和理論は、1960年代にアメリカの心理学者レオン・フェスティンガーによって提唱された。フェスティンガーは、認 知的不協和は通常、人が2つ以上の相容れない信念を同時に抱くときに生じると理論化した[70]。この葛藤は心理的な不快感をもたらす。フェスティンガー によると、思考の葛藤を経験している人は、感情的 な均衡を達成しようとすることで心理的不快感を軽減しようとする。この均衡は主に3つの方法で達成される。第一に、不協和な思考の重要性を軽視する。次 に、不協和な思考を子音的思考で上回ろうとする。最後に、その人は不協和な考えを自分の現在の信念体系に組み 込むことがある[77]。 不協和は説得において重要な役割を果たす。人を説得するには、相手に不協和を経験させ、その不快感を解消す る方法としてあなたの提案を提示しなければならない。聴衆が考えを変えるという保証はないが、不協和音がなければ説得は成立しないというのがこの理論の主 張である。同様に、不協和低減戦略として選択的暴露(すなわち、不 確認情報を避けること)を行う動機付けとなるのは不快感である[78]。 人工知能 認知的不協和を機械学習[どのように?]に導入することで、マルチエージェントシステム(ゲームなど)[79]を含むエージェント側の「創造的自律性」を 発展させ、最終的には人工一般知能を含む「強い」形態の人工知能を発展させるという長期的な目標を支援できるかもしれないという仮説がある[80]。 |

Alternative paradigms Dissonant self-perception: A lawyer can experience cognitive dissonance if he must defend as innocent a client he thinks is guilty. From the perspective of The Theory of Cognitive Dissonance: A Current Perspective (1969), the lawyer might experience cognitive dissonance if his false statement about his guilty client contradicts his identity as a lawyer and an honest man. Self-perception theory In Self-perception: An alternative interpretation of cognitive dissonance phenomena (1967), the social psychologist Daryl Bem proposed the self-perception theory whereby people do not think much about their attitudes, even when engaged in a conflict with another person. The Theory of Self-perception proposes that people develop attitudes by observing their own behaviour, and concludes that their attitudes caused the behaviour observed by self-perception; especially true when internal cues either are ambiguous or weak. Therefore, the person is in the same position as an observer who must rely upon external cues to infer their inner state of mind. Self-perception theory proposes that people adopt attitudes without access to their states of mood and cognition.[81] As such, the experimental subjects of the Festinger and Carlsmith study (Cognitive Consequences of Forced Compliance, 1959) inferred their mental attitudes from their own behaviour. When the subject-participants were asked: "Did you find the task interesting?", the participants decided that they must have found the task interesting, because that is what they told the questioner. Their replies suggested that the participants who were paid twenty dollars had an external incentive to adopt that positive attitude, and likely perceived the twenty dollars as the reason for saying the task was interesting, rather than saying the task actually was interesting.[82][81] The theory of self-perception (Bem) and the theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger) make identical predictions, but only the theory of cognitive dissonance predicts the presence of unpleasant arousal, of psychological distress, which were verified in laboratory experiments.[83][84] In The Theory of Cognitive Dissonance: A Current Perspective[85] (Aronson, Berkowitz, 1969), Elliot Aronson linked cognitive dissonance to the self-concept: That mental stress arises when the conflicts among cognitions threatens the person's positive self-image. This reinterpretation of the original Festinger and Carlsmith study, using the induced-compliance paradigm, proposed that the dissonance was between the cognitions "I am an honest person." and "I lied about finding the task interesting."[85] The study Cognitive Dissonance: Private Ratiocination or Public Spectacle?[86] (Tedeschi, Schlenker, etc. 1971) reported that maintaining cognitive consistency, rather than protecting a private self-concept, is how a person protects their public self-image.[86] Moreover, the results reported in the study I'm No Longer Torn After Choice: How Explicit Choices Implicitly Shape Preferences of Odors (2010) contradict such an explanation, by showing the occurrence of revaluation of material items, after the person chose and decided, even after having forgotten the choice.[87] Balance theory Main article: Balance theory Fritz Heider proposed a motivational theory of attitudinal change that derives from the idea that humans are driven to establish and maintain psychological balance. The driving force for this balance is known as the consistency motive, which is an urge to maintain one's values and beliefs consistent over time. Heider's conception of psychological balance has been used in theoretical models measuring cognitive dissonance.[88] According to balance theory, there are three interacting elements: (1) the self (P), (2) another person (O), and (3) an element (X). These are each positioned at one vertex of a triangle and share two relations:[89] Unit relations – things and people that belong together based on similarity, proximity, fate, etc. Sentiment relations – evaluations of people and things (liking, disliking) Under balance theory, human beings seek a balanced state of relations among the three positions. This can take the form of three positives or two negatives and one positive: P = you O = your child X = picture your child drew "I love my child" "She drew me this picture" "I love this picture" People also avoid unbalanced states of relations, such as three negatives or two positives and one negative: P = you O = John X = John's dog "I don't like John" "John has a dog" "I don't like the dog either" Cost–benefit analysis In the study On the Measurement of the Utility of Public Works (1969),[90] Jules Dupuit reported that behaviors and cognitions can be understood from an economic perspective, wherein people engage in the systematic process of comparing the costs and benefits of a decision. The psychological process of cost-benefit comparisons helps the person to assess and justify the feasibility (spending money) of an economic decision, and is the basis for determining if the benefit outweighs the cost, and to what extent. Moreover, although the method of cost-benefit analysis functions in economic circumstances, men and women remain psychologically inefficient at comparing the costs against the benefits of their economic decision.[90] Self-discrepancy theory E. Tory Higgins proposed that people have three selves, to which they compare themselves: Actual self – representation of the attributes the person believes themself to possess (basic self-concept) Ideal self – ideal attributes the person would like to possess (hopes, aspiration, motivations to change) Ought self – ideal attributes the person believes they should possess (duties, obligations, responsibilities) When these self-guides are contradictory psychological distress (cognitive dissonance) results. People are motivated to reduce self-discrepancy (the gap between two self-guides).[91] Averse consequences vs. inconsistency In the 1980s, Cooper and Fazio argued that dissonance was caused by aversive consequences, rather than inconsistency. According to this interpretation, the belief that lying is wrong and hurtful, not the inconsistency between cognitions, is what makes people feel bad.[92] Subsequent research, however, found that people experience dissonance even when they believe they have not done anything wrong. For example, Harmon-Jones and colleagues showed that people experience dissonance even when the consequences of their statements are beneficial—as when they convince sexually active students to use condoms, when they, themselves are not using condoms.[93] Criticism of the free-choice paradigm In the study How Choice Affects and Reflects Preferences: Revisiting the Free-choice Paradigm[94] (Chen, Risen, 2010) the researchers criticized the free-choice paradigm as invalid, because the rank-choice-rank method is inaccurate for the study of cognitive dissonance.[94] That the designing of research-models relies upon the assumption that, if the experimental subject rates options differently in the second survey, then the attitudes of the subject towards the options have changed. That there are other reasons why an experimental subject might achieve different rankings in the second survey; perhaps the subjects were indifferent between choices. Although the results of some follow-up studies (e.g. Do Choices Affect Preferences? Some Doubts and New Evidence, 2013) presented evidence of the unreliability of the rank-choice-rank method,[95] the results of studies such as Neural Correlates of Cognitive Dissonance and Choice-induced Preference Change (2010) have not found the Choice-Rank-Choice method to be invalid, and indicate that making a choice can change the preferences of a person.[31][96][97][98] Action–motivation model Festinger's original theory did not seek to explain how dissonance works. Why is inconsistency so aversive?[99] The action–motivation model seeks to answer this question. It proposes that inconsistencies in a person's cognition cause mental stress because psychological inconsistency interferes with the person's functioning in the real world. Among techniques for coping, the person may choose to exercise a behavior that is inconsistent with their current attitude (a belief, an ideal, a value system), but later try to alter that belief to make it consistent with a current behavior; the cognitive dissonance occurs when the person's cognition does not match the action taken. If the person changes the current attitude, after the dissonance occurs, they are then obligated to commit to that course of behavior. Cognitive dissonance produces a state of negative affect, which motivates the person to reconsider the causative behavior in order to resolve the psychological inconsistency that caused the mental stress.[100][101][102][103][104][105] As the affected person works towards a behavioral commitment, the motivational process then is activated in the left frontal cortex of the brain.[100][101][102][106][104] Predictive dissonance model The predictive dissonance model proposes that cognitive dissonance is fundamentally related to the predictive coding (or predictive processing) model of cognition.[107] A predictive processing account of the mind proposes that perception actively involves the use of a Bayesian hierarchy of acquired prior knowledge, which primarily serves the role of predicting incoming proprioceptive, interoceptive and exteroceptive sensory inputs. Therefore, the brain is an inference machine that attempts to actively predict and explain its sensations. Crucial to this inference is the minimization of prediction error. The predictive dissonance account proposes that the motivation for cognitive dissonance reduction is related to an organism's active drive for reducing prediction error. Moreover, it proposes that human (and perhaps other animal) brains have evolved to selectively ignore contradictory information (as proposed by dissonance theory) to prevent the overfitting of their predictive cognitive models to local and thus non-generalizing conditions. The predictive dissonance account is highly compatible with the action-motivation model since, in practice, prediction error can arise from unsuccessful behavior. |

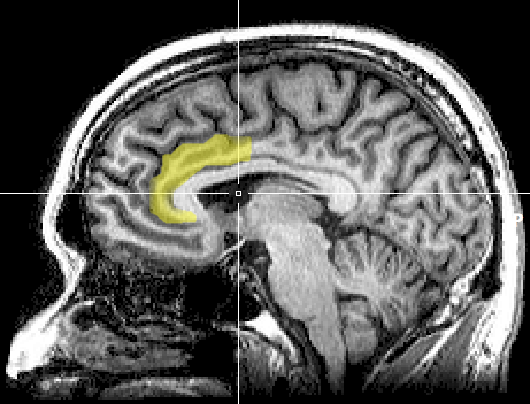

代替パラダイム 自己認識の不一致: 弁護士は、自分が有罪だと思っている依頼人を無罪として弁護しなければならない場合、認知的不協和を経験することがある。認知的不協和の理論: A Current Perspective』(1969年)の観点からすると、有罪の依頼人についての虚偽の供述が、弁護士としてのアイデンティティや誠実な人間としてのア イデンティティと矛盾する場合、弁護士は認知的不協和を経験する可能性がある。 自己認識理論 Self-perception(自己知覚): 社会心理学者のダリル・ベムは、『認知的不協和現象の代替的解釈』(1967年)の中で、人は他人と対立しているときでさえ、自分の態度についてあまり考 えないという自己知覚理論を提唱した。自己知覚理論は、人は自分の行動を観察することによって態度を発達させると提唱し、その態度が自己知覚によって観察 される行動を引き起こしたと結論づける。したがって、人は自分の内的状態を推測するために外的手がかりに頼らなければならない観察者と同じ立場にある。自 己知覚理論は、人は自分の気分や認知の状態にアクセスすることなく態度を採用すると提唱している[81]。 そのため、フェスティンガーとカールスミスの研究(Cognitive Consequences of Forced Compliance, 1959)の実験被験者は、自分自身の行動から心の態度を推測した。被験者-参加者にこう尋ねた: 「と質問されたとき、参加者は、質問者にそう答えたのだから、自分はその課題を面白いと感じたに違いないと判断した。彼らの回答は、20ドルの報酬を得た 参加者がそのような積極的な態度を採用する外的誘因を持っていたことを示唆しており、課題が実際に面白かったと言うよりも、課題が面白かったと言う理由と して20ドルを知覚した可能性が高い[82][81]。 自己知覚の理論(ベム)と認知的不協和の理論(フェスティンガー)は同一の予測をするが、認知的不協和の理論のみが不快な覚醒、心理的苦痛の存在を予測し、それは実験室で検証された[83][84]。 認知的不協和の理論』(Theory of Cognitive Dissonance: A Current Perspective [85] (Aronson, Berkowitz, 1969)において、エリオット・アロンソンは認知的不協和を自己概念に関連づけた: 認知間の葛藤がその人の肯定的な自己イメージを脅かすとき、精神的ストレスが生じる。誘導コンプライアンス・パラダイムを使用したオリジナルのフェスティ ンガーとカールスミスの研究のこの再解釈は、不協和が「私は正直な人間である」という認知と「課題が面白いと思ったというのは嘘である」という認知の間に あることを提案した[85]。 認知的不協和の研究: さらに、I'm No Longer Torn After Choice: How Explicit Choices Implicitly Shape Preferences of Odors (2010)という研究で報告された結果は、人が選択し決定した後に、その選択を忘れた後でも物質的なアイテムの再評価が起こることを示し、そのような説 明と矛盾している[87]。 バランス理論 主な記事 バランス理論 フリッツ・ハイダーは、人間は心理的なバランスを確立し、維持するよう駆り立てられるという考えに由来する、態度変容の動機づけ理論を提唱した。このバラ ンスの原動力は一貫性動機として知られており、自分の価値観や信念を長期にわたって一貫したものに維持しようとする衝動である。ハイダーの心理的バランス の概念は、認知的不協和を測定する理論的モデルに使用されている[88]。 バランス理論によれば、3つの相互作用する要素がある: (1)自己(P)、(2)他人(O)、(3)要素(X)である。これらはそれぞれ三角形の1つの頂点に位置し、以下の2つの関係を共有している[89]。 単位関係 - 類似性、近接性、運命などに基づいて一緒に属する物事や人々。 感情関係 - 人や物事に対する評価(好き、嫌い)。 バランス理論のもとでは、人間は3つの立場の関係が均衡した状態を求める。これは3つのポジティブ、あるいは2つのネガティブと1つのポジティブという形をとる: P = あなた O = あなたの子供 X = 子どもが描いた絵 「私はわが子を愛している 「この絵を描いてくれた "私はこの絵が大好きです" 人はまた、3つの否定や2つの肯定と1つの否定といった、アンバランスな関係の状態も避ける: P = あなた O = ジョン X = ジョンの犬 「私はジョンが嫌いだ "ジョンは犬を飼っている" "私も犬が嫌い" 費用便益分析 ジュール・デュピュイは『公共事業の効用測定について』(1969年)という研究の中で[90]、行動と認知は経済的観点から理解することができると報告 している。費用便益比較の心理的プロセスは、人が経済的意思決定の実現可能性(お金を使うこと)を評価し正当化するのに役立ち、便益が費用を上回るのかど うか、どの程度上回るのかを判断する基礎となる。さらに、費用便益分析の方法は経済状況において機能するが、男性も女性も経済的意思決定の便益に対する費 用を比較することにおいては心理的に非効率なままである[90]。 自己不一致理論 E. トリー・ヒギンズは、人は3つの自己を持ち、それらと自分を比較すると提唱した: 実際の自己-その人が自分自身が持っていると信じている属性の表象(基本的自己概念) 理想的な自己-その人が持ちたいと思う理想的な属性(希望、願望、変化への動機)。 あるべき自分 - その人が持つべきと考えている理想的な属性(義務、義務、責任) これらの自己指針が矛盾する場合、心理的苦痛(認知的不協和)が生じる。人は自己の不一致(2つの自己ガイドの間のギャップ) を減らそうと動機づけられる[91]。 嫌悪結果対矛盾 1980年代、クーパーとファジオは、不協和は矛盾よりもむしろ嫌悪的結果によって引き起こされると主張した。この解釈によれば、嘘をつくことは悪いこと であり、傷つけ ることであるという信念が、認知間の矛盾ではなく、人を嫌な気分に させるのである[92]。しかしその後の研究で、人は自分が何も悪いことをし ていないと信じているときでも不協和を経験することがわかった。例えば、ハーモン・ジョーンズと同僚は、性的に活発な学生にコンドームを使うように説得す るとき、自分自身はコンドームを使っていないときのように、自分の発言の結果が有益なものであっても、人は不協和を経験することを示した[93]。 自由選択パラダイムに対する批判 選択はどのように嗜好に影響を与え、嗜好を反映するか: 研究者らは、自由選択パラダイムは無効であると批判している[94]。実験対象者が2回目の調査で異なる順位になる理由は他にもあり、おそらく被験者は選択肢の間で無関心だったのだろう。 いくつかのフォローアップ研究の結果(例:選択は嗜好に影響するか? Some Doubts and New Evidence, 2013)は、順位-選択肢-順位法の信頼性が低いという証拠を提示しているが[95]、Neural Correlates of Cognitive Dissonance and Choice-induced Preference Change (2010)などの研究結果は、選択肢-順位-選択肢法が無効であることを見出しておらず、選択をすることで人の嗜好を変えることができることを示してい る[31][96][97][98]。 行動動機づけモデル フェスティンガーの当初の理論は、不協和がどのように作用するのかを説明しようとはしていなかった。なぜ矛盾はそれほど嫌悪的なのだろうか?それは、人の 認知における矛盾が精神的ストレスを引き起こすのは、心理的矛盾がその人の現実世界における機能を妨げるからであると提唱している。対処のテクニックの中 で、人は現在の態度(信念、理想、価値体系)と矛盾する行動を選択することがあるが、後でその信念を変更して現在の行動と一致させようとする。認知的不協 和は、その人の認知と取った行動が一致しないときに起こる。不協和が発生した後、その人が現在の態度を変えると、その人はその行動方針にコミットする義務 が生じる。 認知的不協和は否定的な感情の状態を生じさせ、それが精神的ストレスの原因となった心理的矛盾を解決するために、原因となった行動を再考する動機付けとな る[100][101][102][103][104][105]。影響を受けた人が行動のコミットメントに向けて努力するにつれて、脳の左前頭皮質で動 機付けプロセスが活性化される[100][101][102][106][104]。 予測的不協和モデル 予測的不協和モデルは、認知的不協和が認知の予測的符号化(または予測的処理)モデルと基本的に関連していることを提唱している[107]。心の予測的処 理の説明では、知覚は獲得された事前知識のベイズ階層を積極的に使用することを含み、それは主に入ってくる自己受容的、間受容的、外受容的感覚入力を予測 する役割を果たすと提唱している。したがって、脳は積極的に感覚を予測し、説明しようとする推論マシンなのである。この推論にとって重要なのは、予測誤差 を最小化することである。予測的不協和の説明では、認知的不協和を減少させる動機は、予測誤差を減少させようとする生物の能動的意欲に関係していると提唱 している。さらに、人間(そしておそらく他の動物)の脳は、予測認知モデルが局所的な、つまり非一般化的な条件に過剰適合するのを防ぐために、(不協和理 論が提唱するように)矛盾する情報を選択的に無視するように進化してきたと提唱している。予測的不協和の説明は、行動動機づけモデルと非常に相性が良い。 なぜなら、実際には、予測ミスは失敗した行動から生じる可能性があるからである。 |